Edward Winter

(2006, with updates)

From pages 190-191 of The Middle Game in Chess by Reuben Fine (New York, 1952):

‘The story of the Rice Gambit is rather amusing. It begins: 1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 h4 g4 5 Ne5 Nf6 6 Bc4 d5 7 exd5 Bd6. Professor Rice, a New York amateur, had this position once and inadvertently left his knight en prise; then later he won the game. He was so impressed with his success that he immediately interested a number of the prominent masters in the move, which was easy enough to do because he had a lot of money. For several years the gambit was subjected to extensive analysis by the leading American masters.’

Fine naturally did not specify his grounds for asserting that Rice ‘had this position once and inadvertently left his knight en prise’ (i.e. by playing 8 O-O), but references to Professor Rice and his gambit have, for nearly a century now, tended to be accompanied by an almost mandatory sneer. That contrasts vividly with what was written during, and just beyond, his lifetime. He died in late 1915, and the following words by Hartwig Cassel and Hermann Helms concluded the Foreword to Twenty Years of the Rice Gambit (New York, 1916), pages 7-9:

‘“Is the Rice Gambit sound?” was heard on every hand and the question re-echoed across the seven seas. More than once the majority returned a negative response, but Professor Rice and the faithful minority, entrenched in the fullness of his unswervable faith, never faltered, not once wavered and held the line firmly against a foe armed with the nauseating gas of unbelief. And in the end triumph in fullest measure was the reward of him who hewed steadily to the line and would not be turned aside.’

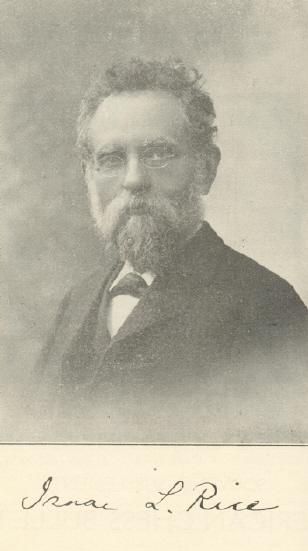

Pages 292-300 had a biographical account which will be reduced

here to the basics. Isaac Leopold Rice was born in Wachenheim,

Bavaria, Germany on 22 February 1850, the son of Maier and Fanny

(Sohn) Rice. The family emigrated to the United States, and Isaac

was educated at the Central High School in Philadelphia. He

graduated in 1880 from the Columbia Law School with the degree of

LL.B. In 1902 he received from Bates College the degree of LL.D.

In 1885 he married Julia Hyneman Barnett in New York City, and the

couple had six children: Muriel, Dorothy, Isaac Leopold Junior,

Marion, Marjorie and Julian. Professor Rice was instructor at the

Columbia Law School and lecturer at the School of Political

Science until 1886, when he resigned and devoted himself

exclusively to railroad law. He reorganized railroad companies in

Brooklyn, St Louis and Texas and also became the virtual founder

of the storage battery industry in the United States. He was the

founder of the electric automobile industry by organizing the

Electric Vehicle Company, of which he became the first president.

Other companies in which he became involved included the Electric

Boat Company, the Consolidated Railway Lighting and Refrigerating

Company and the Forum Publishing Company. He contributed articles

to the North American Review, Forum and Century.

His munificence in the chess world included the gift of an

international trophy worth about $1,300 which was competed for in

matches between British universities (Oxford and Cambridge) and

such US establishments as Columbia, Harvard and Yale. His home,

the Villa Julia on Riverside Drive, New York, had a chess room

which was hewn out of the solid rock in the basement and was

accessible by an automatic elevator which communicated with the

floors above.

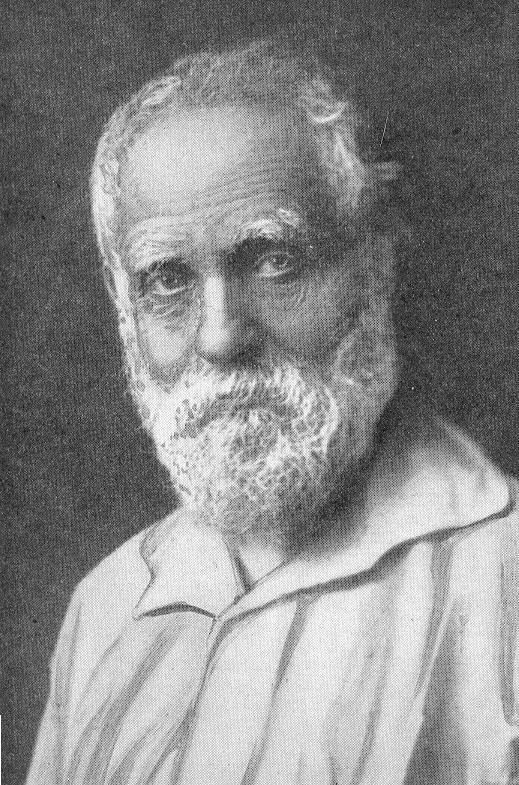

Isaac Leopold Rice

Rice donated huge sums to chess activity far beyond his gambit, and he was regarded, at least in the United States, as the chess world’s leading patron. ‘Maecenas is dead’ was the title of a poem by Maxwell Bukofzer on pages 286-287 of the above-mentioned book on the gambit. After Rice died, on 2 November 1915, the American Chess Bulletin took the unprecedented step of issuing a lengthy ‘memorial supplement’ (pages 257-303). Much of the material later appeared in the book.

As background information on Rice pages 381-386 of the book gave the score of a game won by him in the pre-Rice Gambit days. It had detailed notes by Steinitz from the New York Tribune, but only a few of them are cited below.

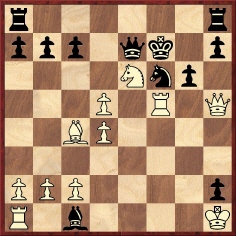

Isaac Leopold Rice – Wordsworth Donisthorpe1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 Be7 4 Bc4 Bh4+ 5 g3 fxg3 6 O-O d5 7 exd5 gxh2+ 8 Kh1 Bh3 9 Qe2+ Kf8 10 Rd1 Bg4 11 d4 Nf6 12 Nc3 Nh5 13 Ne4 f5

14 Rf1 (‘Fine repartee. If Black now take the knight, White recovers with advantage by 15 Nxh4+.’) 14...Nd7 15 Qg2 Bf6 16 Neg5 Qe7 17 Ne6+ Kf7 18 Nfg5+ Bxg5 (‘A beautiful termination is here avoided if 18...Kg6 19 Qxg4 fxg4 20 Bd3+ Kh6 21 Nf7 mate.’) 19 Qxg4 Bxc1 20 Qxh5+ g6 21 Rxf5+ (‘White’s conduct of the attack is of high scientific order. This involves a well devised sacrifice of the exchange which we find sound in various intricate complications.’) 21...Nf6

22 d6 (‘White’s play in the main deserves special marks of distinction.’) 22...cxd6 23 Rxf6+ (‘Quite in keeping with the fine quality of the preceding train of moves on White’s part.’) 23...Qxf6 24 Qd5 (‘White administers the quietus with this very clever stroke.’) 24...b5 25 Qb7+ Qe7 26 Ng5+ Kf6 27 Ne4+ Qxe4+ 28 Qxe4 and wins.

An earlier specimen of Rice’s play is given here from pages 45-46 of the 15 December 1883 issue of the Brooklyn Chess Chronicle. Played at the Manhattan Chess Club, it was one of 12 blindfold games played simultaneously by White.

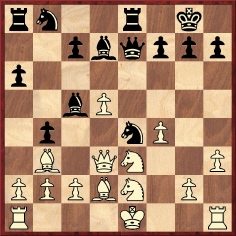

Johannes Hermann Zukertort – Isaac Leopold Rice1 e4 e5 2 f4 d5 3 exd5 e4 4 Bb5+ Bd7 5 Bc4 b5 6 Bb3 Nf6 7 Ne2 Bc5 8 d4 exd3 9 Qxd3 Qe7 10 Nbc3 a6 11 h3 O-O 12 Bd2 b4 13 Nd1 Ne4 14 Ne3 Re8

15 d6 Bxd6 16 g3 Nc5 17 Qd5 Bc6 18 Qxf7+ Qxf7 19 Bxf7+ Kxf7 20 Rg1 Ne4 21 c3 Bc5 22 Nd4 bxc3 23 bxc3 Nxc3 24 Bxc3 Rxe3+ 25 Kd2 Re4 26 Kd3 Bd5 27 Rae1 Rxe1 28 Rxe1 Bxd4 29 Kxd4 Bxa2 30 Kc5 Nd7+ 31 Kc6 Nf6 32 Bxf6 Kxf6 33 Kxc7 a5 34 g4 a4 35 Kb6 Bb3 36 Kb5 Rb8+ 37 Ka5 a3 38 Ka6 a2 39 Ra1 Bc4+ 40 White resigns.

Zukertort gained revenge in a six-board blindfold exhibition at the Harmonie Club the following year:

Johannes Hermann Zukertort – Isaac Leopold Rice1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Nc6 3 f4 Bc5 4 fxe5 Bxg1 5 Rxg1 Qh4+ 6 g3 Qxh2 7 Rg2 Qh3 8 d4 d6 9 exd6 cxd6 10 Bf4 Bg4 11 Qd2 Bf3 12 Rf2 Qh5 13 Bxd6 Rd8 14 e5 Nge7 15 Qf4 Bd5 16 Be2 Qg6 17 O-O-O h6

18 Rdf1 Rd7 19 Bg4 Be6 20 Bxe6 Qxe6 21 Qxf7+ Qxf7 22 Rxf7 Nxd4 23 Nd5 Ndf5 24 R1xf5 Nxf5 25 Rxf5 Kd8 26 c4 b6 27 Bf8 Ke8 28 e6 Rxd5 29 cxd5 Rxf8 30 Rxf8+ Kxf8 31 d6 g5 32 g4 Resigns.

Source: Brooklyn Chess Chronicle, 15 September 1884, page

186.

Isaac Leopold Rice

Now we return to the Rice Gambit. The Professor explained how it came about in the first edition of a monograph on the opening, published in 1898. The account was reproduced on pages 342-344 of Twenty Years of the Rice Gambit.

‘During the winter of 1890-91 I had the privilege of playing a long series of practice games with Mr William Steinitz, in the course of which I frequently essayed the Kieseritzky Gambit. Mr Steinitz was of the opinion that the attack could find no satisfactory continuation against the following: 1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 h4 g4 5 Ne5 Nf6 6 Bc4 d5 7 exd5 Bd6 8 d4 Nh5, followed by 9... c5.

In the course of these games I made many attempts to discover a winning move for White, but without success. Nevertheless, the problem interested me so much that, whenever I had the opportunity, I played the Kieseritzky Gambit. I did not deviate from known lines until the spring of 1893, when I tried the innovation of 9 Bxf4, followed by castling.

This, I found, led to a quite protracted attack, which seemed to offer some winning chances. Among others, Mr Reichhelm noticed it, and published a short account of it in the Philadelphia Times of 7 June 1893, under the heading “The Rice Attack”. I finally became convinced, however, that the attack was not sound.

Notwithstanding these failures, I did not abandon my efforts, and about a year ago it occurred to me that the knight, and not the bishop, should be sacrificed.

After some private analysis I ventured upon the innovation in off-hand games at the Manhattan Chess Club, enlisting as opponents some of the best players of that club. As a result of these games, I felt justified in the conclusion that the sacrifice secured at least an even, if not a better, game for White and that, therefore, it was sound. I then was fortunate enough to interest Mr S. Lipschütz, who made a thorough analysis of the gambit with me, testing the same in numerous contests over the board. By reason of this analysis, so many novel positions were brought about that I thought the chess world generally might like to become acquainted with the new continuation and, as Mr Lipschütz kindly consented to act as editor, I decided to publish.

If the analysis in the following pages stands the test of criticism, the effect, in my estimation, will not only be favorable to the Kieseritzky Gambit but will go far to establish the soundness of the King’s Gambit in general.’

In June 1910 the Rice Gambit was even the subject of a monograph by the world champion, Emanuel Lasker. Extracts from his Introduction are given below:

‘Within 15 years a splendid analytic work has been accomplished which I judge now to have come to a state of maturity in which it may claim to be presented to the chess world. This work has been carried through by Professor Isaac L. Rice with a magnificent perseverance and courage. Many minds have put together the raw material for this analysis, and Mr Rice has directed their labors and collected their ideas and assisted them by a position judgment that became especially adapted to the task undertaken and proved itself to be wonderfully effective.’

‘... Let, therefore, the gambit again come into its own. Let us admit, which is most probably true, that the gambit will not yield to the first player as high a percentage of wins as the Ruy López or the queen’s pawn; but let us therefore not sacrifice the beauty hidden in the gambit. I hope that this book will be the forerunner of a number of bigger books devoted to a thorough, accurate and imaginative analysis of all those gambit openings, of which the endeavor of former masters has not been able to unravel the mystery fully.

It was in 1895 that Mr Rice had the idea of sacrificing the knight in that manner which brings about the gambit named after him, and ever since that time he has had a lively struggle against those who scorned that move. Within these 15 years Mr Rice has had to acknowledge defeat as often as Wilhelm von Oranje in his fight against the Spanish, but as often as that great prince has he collected his scattered forces and made an army of them and again given battle, and finally he has achieved the same triumph. The foe was driven, often after a hard and long struggle, from each position that it had hoped to maintain, and the truth finally prevailed.

White is not lost. Black must play exceedingly well not to fall into the numerous traps and to obtain a promising game. The positions which arise in the Rice Gambit give difficult problems to both the first and second player and lend themselves therefore to as fine strategy as a chessplayer might wish to see. The Rice Gambit will ever be a valuable asset for the analyst, the player and the student.’

Five years previously the American Chess Bulletin had produced a huge Rice Gambit ‘Souvenir Supplement’ edited by H. Keidanz, which was published as pages 41-155 of the February 1905 issue. The ‘historical review’ by Cassel and Helms (pages 43-46) commented:

‘What nook or cranny of the civilized world, however remote, but has been reached by the fame of this variation of the Kieseritzky attack? On what other opening has the universal chess mind been so intently focussed during such comparatively brief a period? And, again, what line of play has received the searching investigation of the greatest masters of the day and been subjected to such criticism, both favorable and adverse?’

‘... Clear indeed must be the brain that would thread the labyrinthal mazes of Professor Rice’s innovation, which time and again has been declared hopeless, only to rise phoenix-like from the ashes of condemnation. Each leading variation has in turn faced the determined assaults of analysts, but invariably survived and in the end proved a bulwark of resource.’

That was followed (on pages 47-48) by a statement from Rice himself:

‘When as President of the International Chess Congress, held at Cambridge Springs last year, it devolved upon me to welcome the players, I dubbed them “Athletes of the Intellect” and I think that, upon reflection, all interested in the royal game will agree that this is a proper appellation for its champions.’

‘... I received my education in chess when what was called the modern school was all dominant, and I was taught that all forms of King’s Gambits must be eschewed as unworthy of a serious votary.

I was also taught that if there was an exception to this, it could only be the Kieseritzky Gambit, but that even that gambit had finally to be abandoned as leading to unavoidable disaster.

If the Rice Gambit shows that the sacrifice of a knight can save the Kieseritzky Gambit, it will give the so-called modern school a fatal blow unless it can be shown that other variations of the Kieseritzky Gambit, which, up to the time of the Rice Gambit, was supposed to be inferior for Black, are really superior to it and accomplish the defeat of the King’s Gambit; or, going still further, unless it can be shown that the declining of the King’s Gambit at the very outset leaves the attacking forces in immediate inferiority. I have proposed, therefore, that if it should be admitted that the Rice Gambit is sound, to make exhaustive studies, not only into the other variations of the Kieseritzky Gambit but also the various means of avoiding the Kieseritzky Gambit altogether.’

Isaac Leopold Rice

In the present item we have avoided repeating the most familiar information and games related to Isaac Rice and his gambit. Only a minuscule amount of the material available has been mentioned here, and to offer an idea of how much is on record we give below a non-exhaustive list from chess periodicals during his lifetime:

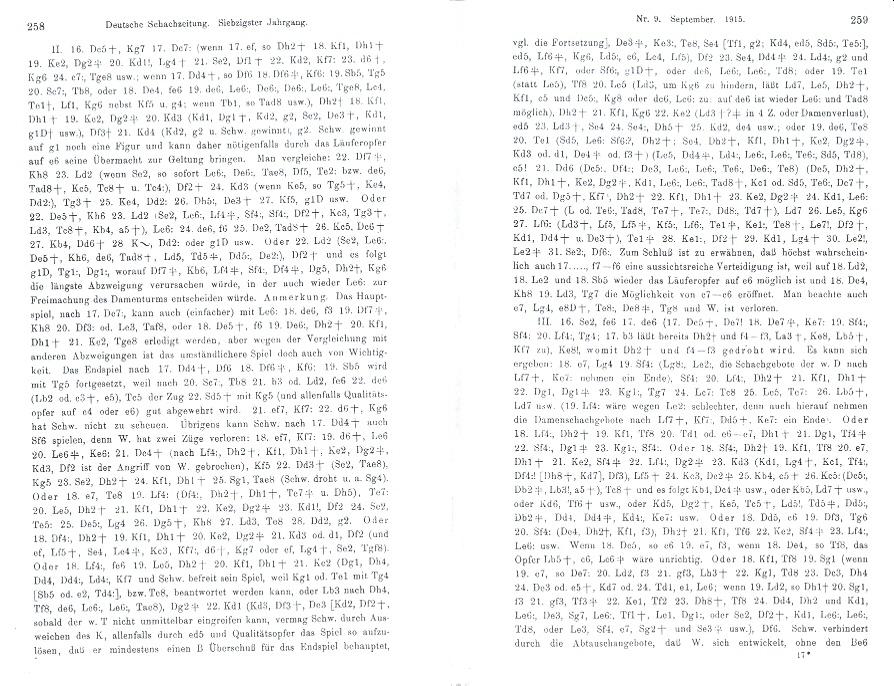

Who would be competent today to pass rational judgment on the soundness of the Rice Gambit, on the overall quality of the analysis undertaken a century ago or on the motives of Rice and the other analysts and players? As an example of the detail sometimes provided, and also as a warning against judgmental glibness, we conclude with an extract from the final item listed:

(4521)

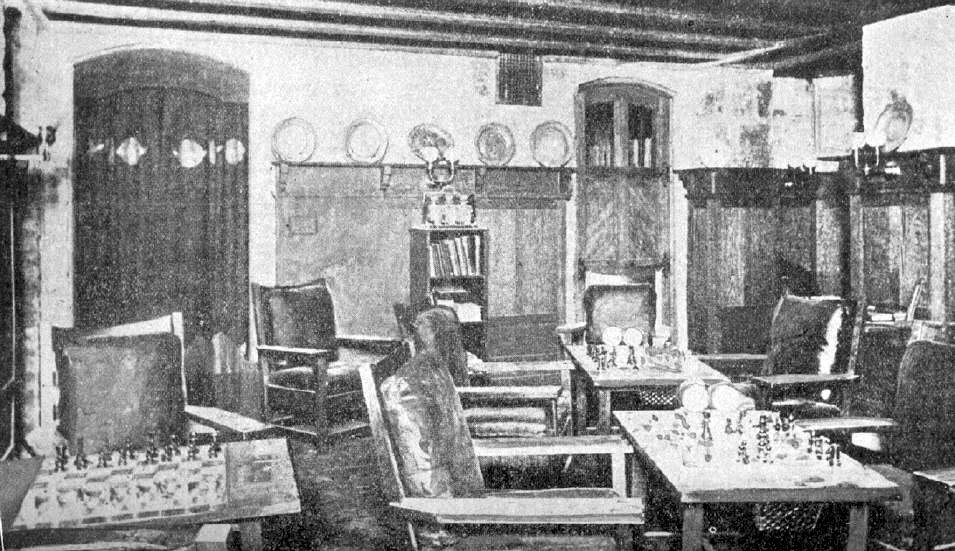

It was reported above regarding Professor Rice that ‘his home, the Villa Julia on Riverside Drive, New York, had a chess room which was hewn out of the solid rock in the basement and was accessible by an automatic elevator which communicated with the floors above’. A little more is now added about the retreat, from an item in the New York Herald which was quoted on pages 21-22 of the November-December 1906 issue of Lasker’s Chess Magazine:

‘Proof against all the din of street and river is the sound-proof shelter deep in the foundations of the villa of Mr and Mrs Isaac L. Rice, at No. 170 Riverside Drive. The Rices are the successful leaders of a campaign against superfluous whistling of the craft which ply in the Hudson and are also the pioneers of a movement which is to bring into being the Society for the Suppression of Unnecessary Noises ...

Despite its walls of rock, unpierced by windows except at the back, this room has a free circulation of air and is one of the most cosy and comfortable apartments imaginable. ... The room is 22 feet square and there is abundant space for six chess tables and numerous leather upholstered chairs.’

The photograph below appeared on page 274 of the 1915 American Chess Bulletin (Memorial Supplement):

(4631)

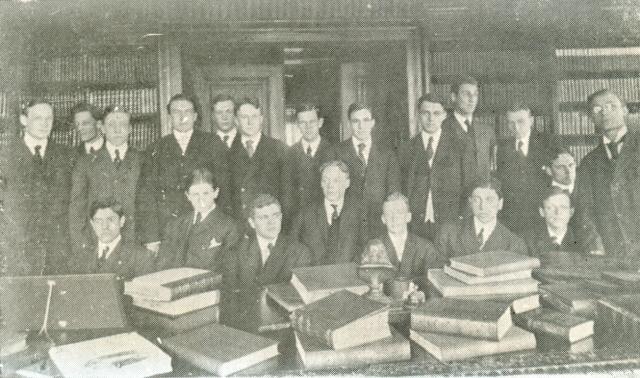

In an item about Alfred Loomis C.N. 5879 noted that he participated in the Yale v Princeton match played at Professor Rice’s residence on 3 March 1906. This photograph (with Capablanca, the adjudicator, seated on the left) was given on page 46 of the March 1906 American Chess Bulletin:

‘Participants in the Intercollegiate Match on ten boards, photographed in the library of the Villa Julia, New York, 3 March 1906’

Page 10 of the January 1906 American Chess Bulletin announced the birth of Frank J. Marshall’s son, who was christened Frank Rice Marshall. Was the unusual second forename chosen in honour of Isaac Rice, the Rice Gambit’s Maecenas?

(2113)

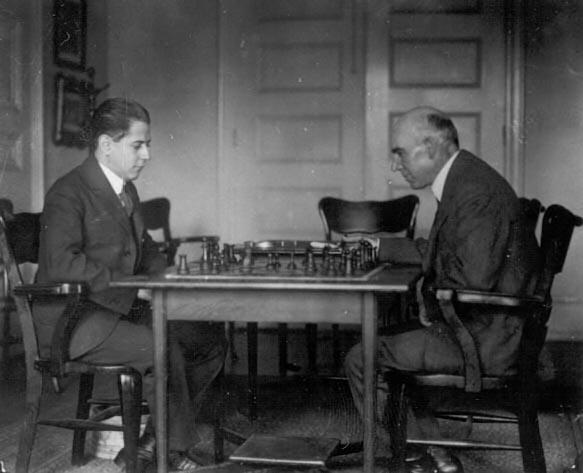

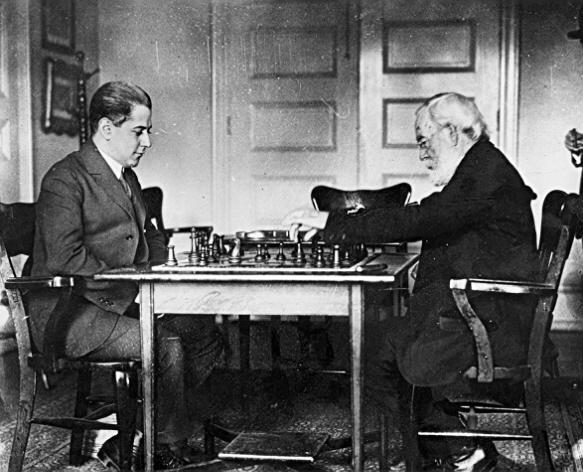

The first photograph below, featuring Mordecai Morgan on the right, was published in Walter Penn Shipley by John S. Hilbert (Jefferson, 2003), and is reproduced here with Dr Hilbert’s permission. In the second photograph, which comes from our collection, Capablanca’s opponent may be Isaac L. Rice. We estimate that the pictures were taken in 1915, but information on the occasion is unavailable. The board positions appear similar, if not identical.

(6271)

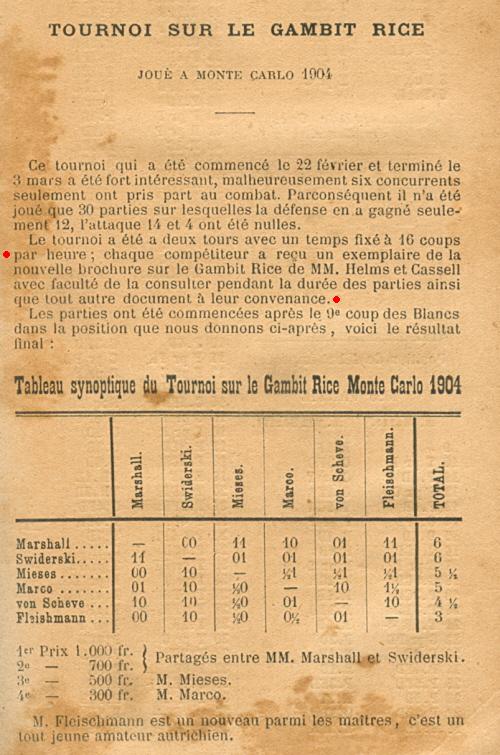

C.N. 1979 (see page 214 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves) mentioned a report on page 65 of La Stratégie, March 1904 that in a Rice Gambit tournament at Monte Carlo that year the competitors received The Rice Gambit by H. Helms and H. Cassel (New York, 1904) and were allowed, during play, to consult it, as well as any other documentation.

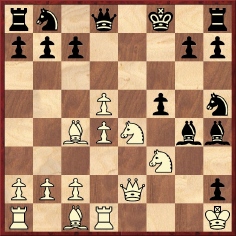

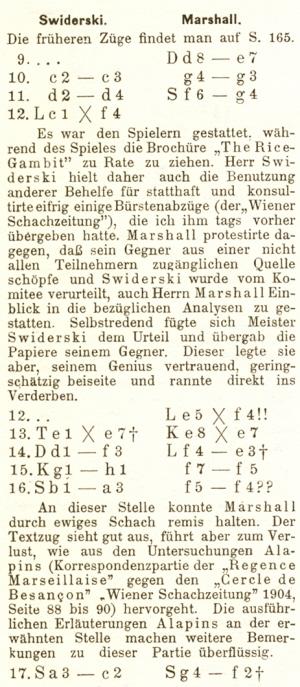

Now, Henk Smout (Leiden, the Netherlands) notes that Georg Marco gave a rather different account of the playing terms on page 168 of the June 1904 Wiener Schachzeitung. The opening moves were 1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 h4 g4 5 Ne5 Nf6 6 Bc4 d5 7 exd5 Bd6 8 O-O Bxe5 9 Re1:

In short, Marshall protested that Swiderski had gone beyond the rules, which merely allowed the booklet The Rice Gambit to be consulted, and not other documentation (such as rough cuts of material due to be published in the Wiener Schachzeitung).

Our correspondent comments:

‘As noted by the Wiener Schachzeitung at move 16, the pages from the magazine which Swiderski was studying and which he was forced to hand over to Marshall (who refused to look at them) included Alapin’s advice on page 90 of the February-March 1904 Wiener Schachzeitung that instead of 16...f4 Black should take the draw by perpetual check.’

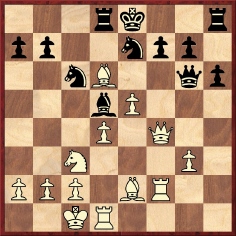

Below is the relevant phase of the Swiderski v Marshall game:

9...Qe7 10 c3 g3 11 d4 Ng4 12 Bxf4

12...Bxf4 13 Rxe7+ Kxe7 14 Qf3 Be3+ 15 Kh1 f5 16 Na3

Here Marshall played 16...f4 and eventually lost.

(6441)

Henk Smout quotes from the Wiener Schachzeitung, April 1905 (pages 119-120) a text which had appeared in the New-Yorker Staatszeitung of 19 March 1905:

‘Die St. Petersburger Schachgesellschaft hatte sich schon vor mehreren Monaten an Herrn Prof. Rice mit der Bitte gewandt, mehrere Preise für ein Ricegambit-Turnier zu stiften, und der Erfinder des Gambits entsprach dem Ansuchen bereitwilligst, jedoch unter der Bedingung, daß das Turnier erst nach Erscheinen der neuen Auflage des Rice-Gambit-Buches beginnen dürfe.

... In derselben Lage, wie die Russen, befanden sich aber auch die beiden Amerikaner Marshall und Napier. Diese Herren sitzen schon seit einigen Tagen kampfbereit in London.’

Our correspondent comments:

‘This sheds light on the “permission” to consult documentation granted to players in Rice Gambit theme tournaments, which seems to be less a favour to them than a precondition by Professor Rice to guarantee in-built progress by ensuring that fully-informed strong players would not re-invent the wheel.

Another telling point is the cablegram which he sent the players during the Monte Carlo theme tournament of 1904 in order to contradict analysis by Johann Berger in the Deutsche Schachzeitung. The cablegram is mentioned in the Wiener Schachzeitung, June 1904, page 171, in the comments to the game Marco v Fleischmann, and the analytical contents were printed at the end of the game, on pages 172-173.

Rice had evidently forgiven Marshall the two earlier losses which could have been avoided through optimal knowledge available at the time. In addition to the case mentioned in C.N. 6441, with colours reversed Marshall (White) lost again to Swiderski in the sixth round of Monte Carlo, 1904 (Wiener Schachzeitung, June 1904, pages 183-184) ...

... with 12 Nd2 Ne3 13 Qh5 Bg7 14 d6 cxd6 15 Nf1 Bg4 16 Qb5+ Qd7 17 Bxe3 fxe3 18 Qg5 O-O 19 Nxe3 h5 20 Nd5 Kh8 21 Rf1 f6 22 Nxf6 Qd8. The same position, there considered lost for White by Alapin, had already been reached, with White’s 18th and 19th moves transposed, on page 89 of the February-March 1904 issue of the Wiener Schachzeitung, where Alapin wrote of Black’s 16th move that any move should win with more or less ease. That is the same article that his opponent had to hand over to him because of Marshall’s protest during the first round. The whole incident would not have happened, of course, had Swiderski kept the article to himself and studied it in his hotel room before the first round began.

On page 12 of the fifth edition of The Rice Gambit (1910) by Emanuel Lasker 20 Rf1 Kh8 21 Rf6 is indicated as giving “a strong game” (for White).

Marshall and Swiderski had prepared together for the eighth round, as mentioned on page 188 of the June 1904 Wiener Schachzeitung in the note to Black’s 14th move in the game Marco v Swiderski (which was mistakenly called Swiderski v Marco). It began 1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 h4 g4 5 Ne5 Nf6 6 Bc4 d5 7 exd5 Bd6 8 O-O Bxe5 9 Re1 Qe7 10 c3 Nh5 11 d4 O-O 12 Rxe5 Qxh4 13 Rxh5 Qxh5 14 Bxf4 Nd7.’

(6519)

As shown above, we have sceptically quoted the following paragraph from pages 190-191 of The Middle Game in Chess by Reuben Fine (New York, 1952):

‘The story of the Rice Gambit is rather amusing. It begins: 1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 h4 g4 5 Ne5 Nf6 6 Bc4 d5 7 exd5 Bd6. Professor Rice, a New York amateur, had this position once and inadvertently left his knight en prise; then later he won the game. He was so impressed with his success that he immediately interested a number of the prominent masters in the move, which was easy enough to do because he had a lot of money. For several years the gambit was subjected to extensive analysis by the leading American masters.’

We now note a passage on page 67 of Riga Match and Correspondence Games (New York, 1916), which had a supplement on the Rice Gambit and various stories about its possible origins:

‘There is another version of this highly interesting episode, which, in years to come, was destined to command the attention of the entire world of chess. It is furnished by Die Moskauer Zeitung. According to that authority, the Rice Gambit, like many another great invention or discovery, was established by a mere chance. Professor Rice, so this yarn goes, was playing at a chess club one day when he inadvertently left his knight en prise. As it was not a game for life or death, he asked to recall the move, but his adversary insisted upon his pound of flesh. He got it, and the game proceeded with the white knight on the discard pile. And so the Rice Gambit was ushered in. This version, however, must be regarded in the light of a little Märchen ...’

(6873)

Information is sought about this well-known Rice Gambit game, purportedly won in New York in 1900 by Professor Rice, against an unidentified opponent:

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 h4 g4 5 Ne5 Nf6 6 Bc4 d5 7 exd5 Bd6 8 O-O Bxe5 9 Re1 Qe7 10 c3 g3 11 d4 Ng4 12 Nd2 Qxh4 13 Nf3 Qh6 14 Qa4+ c6 15 Qa3 Nf2 16 Rxe5+ Be6 17 Kf1 Qh1+ 18 Ng1 Nh3 19 gxh3 f3 20 Bg5 Qg2+ 21 Ke1 f2+ 22 Kd2

22...f1(N)+ 23 Kd3 Kd7 24 dxe6+ Kc7 25 Qe7+ Kb6 26 Qd8+ Rxd8 27 Bxd8 mate.

See, for instance, game 30 in One Hundred Chess Gems by P. Wenman (London, 1939), where it was described as ‘one of the best games ever played at [sic] the Rice Gambit’.

Below is the title page of the only Wenman book in our collection inscribed by him:

(6923)

We now note that the game in question is on pages 637-638 of the April-May 1898 issue of the American Chess Magazine, being one of two ‘recent specimens’ of the Rice Gambit won by Isaac L. Rice against J.M. Hanham.

Henk Smout mentions that the score was on pages 42-43 of the fifth edition of The Rice Gambit by Emanuel Lasker (New York, 1910), without any date but introduced thus:

‘In the following game that played a great part in the early evolution of the Rice Gambit, and which is very interesting per se, the white pieces were conducted by Mr Rice against Major Hanham.’

From the above-mentioned item in the American Chess Magazine we add a loss by S. Lipschütz to I.E. Orchard (no exact occasion specified):

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 h4 g4 5 Ne5 Nf6 6 Bc4 d5 7 exd5 Bd6 8 O-O Bxe5 9 Re1 Qe7 10 c3 g3 11 d4 Ng4 12 Nd2 Qxh4 13 Nf3 Qh6 14 Qa4+ c6 15 Bb3 Nf2 16 Kf1 Qh1+ 17 Ke2 Qxg2 18 Rg1

18...Qxf3+ ‘White is now led a merry race to the end. (The charming problem is – Black to win back the queen and victory in seven moves.)’ 19 Kxf3 Bg4+ 20 Kg2 f3+ 21 Kf1 Bh3+ 22 Ke1 Nd3+ 23 Kd2 Bf4+ 24 Kxd3 (The notes in the magazine, which were taken from the New Orleans States, made no mention of 24 Kc2.) 24...Bf5+ 25 Kc4

25...b5+ 26 White resigns. ‘It must have been a new sensation to our analytical Lipschütz to be cuffed about in this unceremonious fashion.’

(6933)

Henk Smout notes that the above game was published in the Minneapolis Journal, 19 March 1898, with the information that it was played at the Manhattan Chess Club, New York on 19 February that year.

A report on page 213 of the December 1929 American Chess Bulletin:

‘The death of Mrs Isaac L. Rice, widow of the late Professor Isaac L. Rice, is reported at Deal, NJ on 4 November. After the death of her husband, whose efforts in behalf of chess American players will always hold in fond remembrance, Mrs Rice helped to organize the Rice Memorial Tournament held in New York in 1916 and kept up her interest in the Isaac L. Rice Progressive Chess Club of that city, which was named after him.’

From page 222 of the October 1937 Chess Review:

‘Isaac L. Rice, Jr has donated to the Rice Progressive Chess Club several hundred copies of a de luxe edition of the outstanding book on the Rice Gambit.’

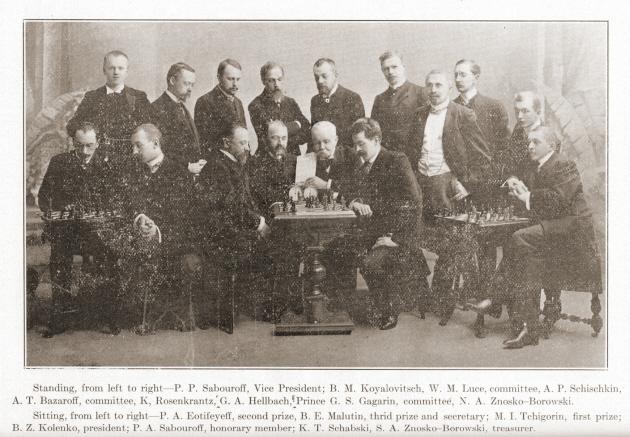

Source: American Chess Bulletin, May 1906, page 88. The occasion was the St Petersburg Chess Club Rice Gambit Tourney.

(7170)

John Blackstone (Las Vegas, NV, USA) points out an article about I.L. Rice’s wife on page 7 of the New York Sun, 3 February 1907.

Among her writings is an article entitled ‘Our Barbarous Fourth’ on pages 219-226 of The Century Magazine, June 1908. The first page:

(7925)

Pages 45-47 of A History of Chess in South Africa by Leonard R. Reitstein (Kenilworth, 2003) discussed a Rice Gambit Tournament held in Johannesburg in 1905. It was won by L.J. Williams, ahead of M. Blieden and B. Siegheim.

From pages 12-13 of our book on Capablanca:

‘Capablanca was even known to lecture on the Rice Gambit (see the Newark Evening News of 12 December 1911, page 23, which gave a brief account of a social event and simultaneous exhibition held the previous evening with Isaac L. Rice in attendance). To observe Capablanca in action with the Gambit one must turn to the August 1913 American Chess Bulletin (page 188), which reported:

“On the afternoon of 13 July José R. Capablanca, at the invitation of Professor Rice, tried his hand at the Rice Gambit in a game against a powerful consultation team, consisting of Oscar Chajes, Professor J. Grommer and Albert Marder, at the rooms of the Rice Chess Club. The combination proved too strong for the ingenious Cuban master, who suffered defeat after 29 moves. Capablanca had been of the opinion that, if the gambit should prove to be sound, it could only be demonstrated by means of Alapin’s variation against the Jasnogrodsky defense, and, accordingly, adopted that line of play ...”

There follows the score:

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 h4 g4 5 Ne5 Nf6 6 Bc4 d5 7 exd5 Bd6 8 O-O Bxe5 9 Re1 Qe7 10 c3 Nh5 11 d4 Nd7 12 Qxg4 Ndf6 13 Qe2 Ng4 14 Qxe5 Nxe5 15 Rxe5 Rg8 16 Rxe7+ Kxe7 17 Kf2 Bf5 18 Be2 Bg4 19 Bd3 Rg7 20 Nd2 Rag8 21 b3 Bd7 22 Ba3+ Kd8 23 Rg1 Nf6 24 Be4 Bh3 25 Bf3 Ng4+ 26 Ke2 Ne3 27 g3 Nf5 28 d6 Rxg3 29 dxc7+ Kxc7 30 White resigns.

On page 35 of The Rice Gambit edited by Emanuel Lasker (fifth edition, New York, 1910) it is claimed that 13...Ng4 initiates a winning attack. It has sometimes been suggested that Lasker’s involvement with the Gambit had little to do with belief in its value, and one may also wonder about Capablanca’s true opinion on the opening; never once did he play a King’s Gambit of any kind in a match or tournament.’

A note on page 309 of our book:

‘An article by Stephen Weissman in the June/December 1975 issue of the Gazette of the Grolier Club mentions a three-page letter dated 3 October 1910 from Capablanca to Walter Penn Shipley discussing the Rice Gambit (and fees for exhibitions).’

Isaac Leopold Rice and Richard Teichmann – Erich Cohn and

Oscar Tenner

Berlin, 16 September 1910

Rice Gambit

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 h4 g4 5 Ne5 Nf6 6 Bc4 d5 7 exd5 Bd6 8 O-O Bxe5 9 Re1 Qe7 10 c3 Nh5 11 d4 Nd7 12 Qxg4 Ndf6

13 Qxc8+ Rxc8 14 Rxe5 Ng4 15 Rxe7+ Kxe7 16 Na3 f5 17 Bd2 Kf6 18 Nc2 Rce8 19 Rf1 Ng3 20 Rf3 Re7 21 d6 Ne2+ 22 Kf1 Nh2+ 23 Kf2 Ng4+ Drawn.

Source: Deutsches Wochenschach, 9 October 1910, page 369. Page 350 of the 25 September 1910 issue reported that the players contested three games beginning with 13 Qxc8+ (two draws and one win for Black).

As shown above, in the diagrammed position Capablanca played 13 Qe2 in a 1913 consultation game which he lost.

(8419)

Henk Smout notes that the game played in Berlin was published on pages 217-220 of the July-August 1912 Wiener Schachzeitung, with detailed notes by W. Therkatz from the Krefelder Zeitung, October 1910.

‘The Rice Gambit Forever’, a song written by Muriel Rice to the tune of ‘Columbia, the Gem of the Ocean’, was published on page 220 of the November 1906 American Chess Bulletin, together with a photograph of her.

An article entitled ‘The Rice Gambit’ is on pages 14-17 of Chess Symposium by J. Halpern (New York, 1904).

Regarding the Rice Gambit match between Carl Schlechter and Emanuel Lasker (Prague, 1908), see C.N.s 6857, 10781, 10789, 10825 and 10857.

A general article is ‘The Professor and his Gambit’ by Frank Rhoden on pages 217-219 of the June 1981 BCM.

See too pages 63-89 of Riga Match and Correspondence Games (New York, 1916).

Our nomination for the consultation game with the finest line-up of players:

Emanuel Lasker, Frank James Marshall, Richard Teichmann,

Mikhail Chigorin – Dawid Janowsky, Thomas Francis Lawrence,

Georg Marco, Carl Schlechter

On board S.S. Pretoria, 13-15 April 1904

King’s Gambit Accepted (Rice Gambit)

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 h4 g4 5 Ne5 Nf6 6 Bc4 d5 7 exd5 Bd6 8 O-O Bxe5 9 Re1 Qe7 10 c3 Bf5 11 d4 Nbd7 12 dxe5 Nh5 13 e6 fxe6 14 dxe6 O-O-O 15 exd7+ Rxd7 16 Qe2 Qxh4 17 Qf2 g3 18 Qxa7 Rd3 19 Nd2 Rxd2 20 Bxd2

20...Qh2+ 21 Kf1 f3 22 Qa8+ Kd7 23 Qa4+ c6

24 Re7+ Kxe7 25 Bg5+ Kd7 26 Rd1+ Kc7 27 Qa5+ Kb8 28 Qe5+ Ka8 29 Qxh8+ Ka7 30 Qd4+ b6 31 Ke1 fxg2 32 Be3 c5 33 Qe5 g1(Q)+ 34 Bxg1 Qxg1+ 35 Kd2 Qf2+ 36 Be2 g2 37 Qe7+ Kb8 38 Qe3 Resigns.

Source: Wiener Schachzeitung, February 1905, pages 33-35.

Since writing C.N. 2160, we have noted that on pages 80-86 of Karl Marx Plays Chess by Andrew Soltis (New York, 1991) there is ‘The Immortal Consultation Game’ played at Voronovo in 1952. The White allies were: Petrosian, Averbakh, Taimanov, Geller, Botvinnik and Smyslov. Black: Keres, Kotov, Tolush and Boleslavsky.

Two UK correspondents, Andrew Butterworth (Mexborough) and Paul Timson (Clitheroe) point out that when the latter game appeared on pages 45-48 of Petrosian’s Legacy (Los Angeles, 1990) it was claimed that Boleslavsky, Botvinnik and Smyslov participated only in the latter part of the game.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.