Edward Winter

The friendship between Prince Leopold and John Ruskin (1819-1900) was discussed extensively in Queen Victoria’s Youngest Son by Charlotte Zeepvat, and this prompts us to cite some references to Ruskin which we have found in chess literature:

‘Chess, on the contrary, I urge pupils to learn, and enjoy it myself, to the point of its becoming a temptation to waste of time often very difficult to resist; and I have really serious thoughts of publishing a selection of favourite old games by chessplayers of real genius and imagination, as opposed to the stupidity called chessplaying in modern days. Pleasant “play”, truly! in which the opponents sit calculating and analysing for 12 hours, tire each other nearly into apoplexy or idiocy and end in a draw or a victory by an odd pawn.’

The full text was also given on pages 172-173 of The Chess Reader by J. Salzmann (New York, 1949). An extract appeared on page 337 of the August 1924 Chess Amateur.

‘In painting and poetry the workers scorn analysis, and the best work defies it, and, so far as chess is capable of analysis, it is neither art nor play.’

John Ruskin (Vanity Fair)

‘Capt. Kennedy’s games and Mr Cochrane’s always amuse me and, I believe, with some of Mr Barnes’s, some of Morphy’s, and a sprinkling of Anderssen, will be very acceptable to players of my own species, and to young people who have other work than chess on hand.’

‘Here we think of Ruskin as a votary of chess – for he was an enthusiastic lover of the game – that is of chess of a sort, for he would have none of the pawn-gaining, wood-shifting, snail-creeping chess. He loved only the “grand style”, the sweeping majesty of a game by Morphy or the glittering beauty of a blindfold gem by Blackburne. He regarded chess from its artistic side – as indeed was to be expected of him. He never played chess in public or in any club, reserving it as a relaxation in his own home; but he took great interest in published games of a brilliant description, and was specially fond of Bird’s bright games of years ago, and on more than one occasion wrote to that master.’

‘Many people may have overlooked the fact that Ruskin loved the game of chess. Some of his letters reveal this interest. He was at one time a constant visitor to Maskelyne & Cooke’s entertainment, where he once played a game with “Psycho”, and he tried his skill against other chess automata. “Indeed, it was a matter of pride to him”, say his latest editors, “that he had obtained more than one victory over the famous Mephisto at the time when it was performing at the Crystal Palace with considerable éclat. He was a Vice-President of the British Chess Association.’

‘That Mr Ruskin’s aversion to dull and colorless chess arose from a genuine love of the game is accentuated by a passage in a letter from him, dated Brantwood, Coniston, 11 July 1885:

“I am usually very thankful”, he wrote, “to escape from them (his books) to chess. Though I have no claims whatever to be ranked among chessplayers any more than among painters properly so called, I enjoy chess as I do drawing, within my limits – and if, indeed, some time you condescended to beat me a game by correspondence it would be a great delight to me.”’

‘That Ruskin’s role as chess critic, though “clouded by enthusiasm” is exempt from even a modest knowledge of the game is made clear at the outset by his notes upon the openings. Both the Centre Counter Gambit and the Falkbeer he regards as “unusual”, which epithet he gives to White’s 3 Bb5 (Ruy López). The “Cunningham” is “most busy and curious”. As to the “Evans’” (although so entitled throughout the book) he says, “This I shall call the Bishop’s Gambit, the knight’s pawn being the bishop’s prey”.

As for the games, it is palpable that Ruskin favoured the “knock-about” school in which whoever first flukes a mate wins. The working-out of an endgame is repellent to him, and an exchange of queens “spoils the game at once”. He is quite unable to comprehend the progressive development of a combination the issue of which shall be simple and conclusive, and in recording the boredom that such processes inflict he has no suspicion that his mental grasp is at fault.’

There followed two pages of examples of Ruskin’s comments on a number of Morphy games and positions.

‘I’ve only begun saying what I have to say about the temper of chess. I think, in general, great players should never give odds but openings, leaving weak points on purpose to show, or find, new forms of the game, and should name the move after which they mean to play their best. Above everything, I want to know, in the great games, where either of the players is first surprised. Andersen (sic) and Morphy seem to me the only ones that never are – they are only beaten by getting tired and making mistakes, or Morphy in trying a new opponent’s style.’

Goulding Brown pointed out that page xviii of Chess History and Reminiscences by H.E. Bird (London, 1893) recorded that Bird had received 28 letters from Ruskin since 1884. An excerpt from one of them, dated 15 December 1886, was cited in the BCM article:

‘I find Blackburne’s games intolerably and unpardonably dull – and am more and more set on my old plan of choosing a set of beautiful games – Cochrane, Kennedy, Barnes, Macdonnel [sic] and the like – with some of your lovely short ones. I find even Morphy a little dull in his security!’

Numerous other chess-related quotes from Ruskin’s pen were presented by Goulding Brown, who concluded:

‘The upshot of it all is that Ruskin loved chess as a game and an art, but hated it as a science.’

(4045)

Page 83 of The Art of Chess Playing by E.V. Mitchell (New York, 1936) provided two quotes by Ruskin about chess, from Letters of John Ruskin to Charles Eliot Norton:

‘Herne Hill, Saturday morning,

St Valentine’s, 1874...I’m going to drive up the hill to the Crystal Palace, and I shall play games of chess with the automaton chess player. I get quite fond of him, and he gives me the most lovely lessons in chess. I say I shall play some games, for I never keep him waiting for moves and he crushes me down steadily, and my mind won’t be all in my play today, any more than Henry 8th at the end of the play – only the automaton won’t say, “Sir, I did never win of you before”.’

‘Corpus Christi College, Oxford

15 February 1874... I played three games with the automaton – not bad ones, considering. Two others played him, also, – an hour and a half went in five games.’

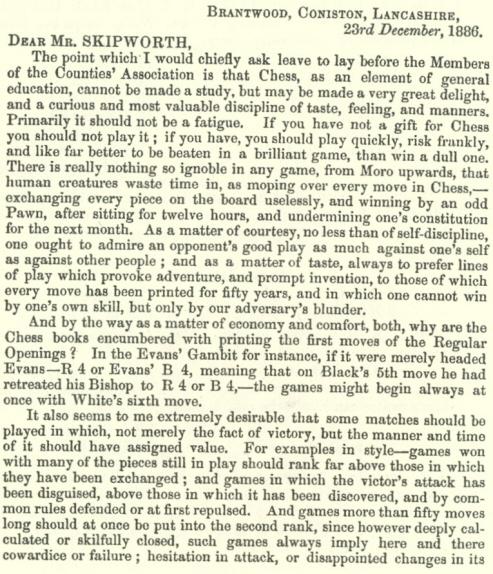

Also on the subject of Ruskin, Morgan Daniels (Bury St Edmunds, England) submits the following item from page 5 of The Times, 25 June 1885:

(4466)

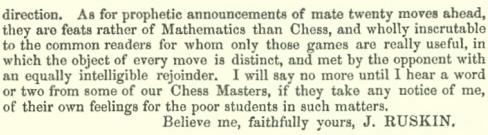

From pages 94-95 of The Book of the Counties’ Chess Association by A.B. Skipworth (London, 1886):

(6806)

See too the references to Ruskin in H.E. Bird by Hans Renette (Jefferson, 2016).

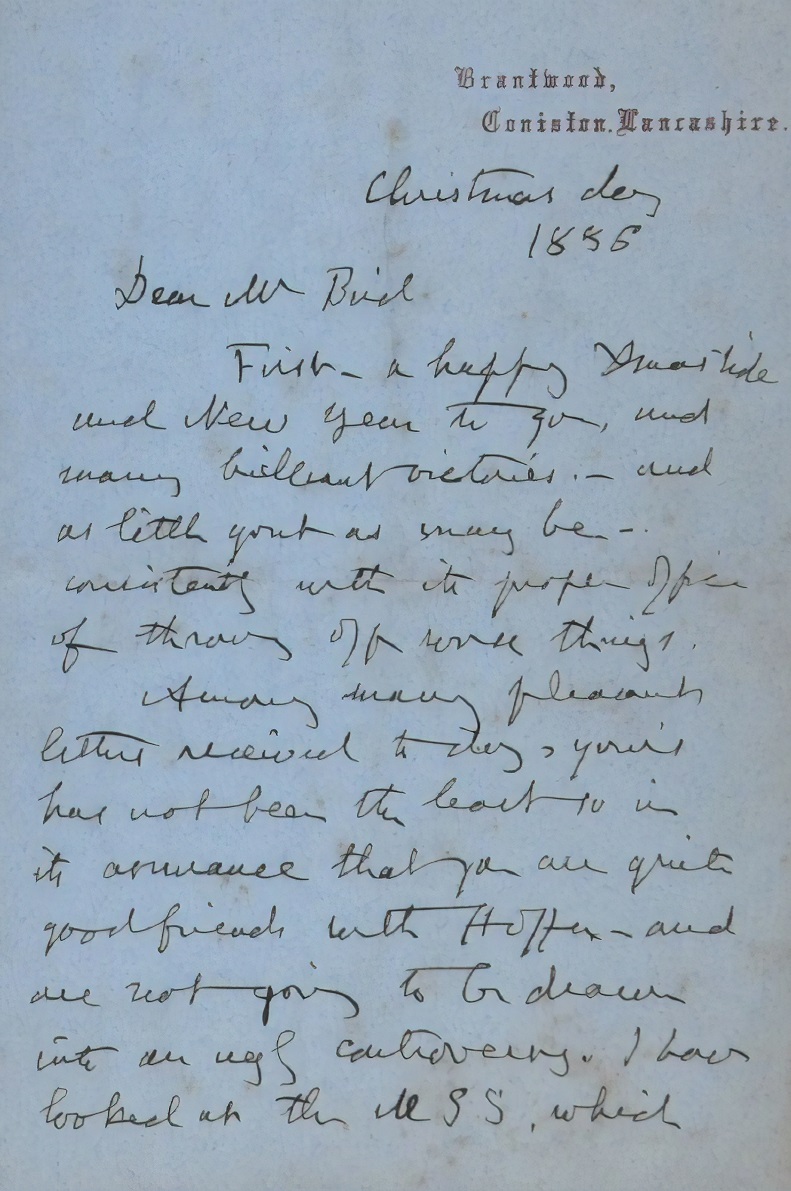

On 27 January 2020 Olimpiu G. Urcan added to his Patreon page a set of letters from Ruskin to Bird. A sample extract, reproduced with permission:

Addition on 30 December 2024:

The beginning of Emanuel Lasker’s column in the New York Evening Post, 10 July 1907, page 5:

‘In modern chess the beautiful is less on the surface than in the games of the past. It requires somewhat of a search before one can enjoy the full charm of the games of today. There has been a good deal of discussion over the comparative merits of the old and the modern school in chess. Even so astute a critic as Ruskin saw more beauty in the superficial chess of the old school, and inveighed against the painstaking methods of the present.

It would be easy to examine modern games and discover beautiful things which are not shown in the scores, because they consist in the avoidance of efforts which, though tempting, are not entirely sound.’

See also The Chess Masters of To-day by Leopold Hoffer.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.