Edward Winter

Boris Spassky died on 27 February 2025. An exceptionally fine obituary by Leonard Barden appeared in the Guardian the following day.

A.B. Boxer (Winnipeg, Canada) tells us that at the grandmaster tourney in Winnipeg in 1967 Spassky said to him:

‘I have no further ambitions for the world’s championship.’

This was the year after his defeat by Petrosian in a title match but, as is well known, Spassky squeezed through to victory against the same opponent in 1969.

(280)

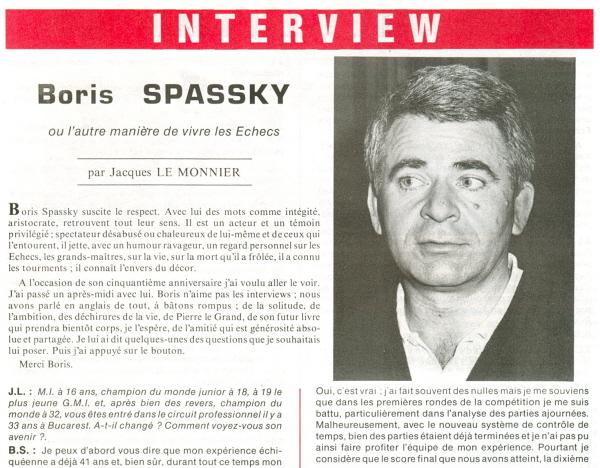

The April 1983 Chess Life (pages 12-13) contains an interview with the former world champion Boris Spassky which concludes with the following, perhaps surprising, quote:

‘Personally, I think the best chessplayer of all time was Capablanca – especially because he was very lazy, and I am lazy too. So I can understand him very easily. But he was a real genius.’

(540)

William Hartston (Cambridge, England) wrote to us in 1983:

‘I had a conversation with Spassky last year which I think throws some light on C.N. 526 (Botvinnik’s match record). I had always supposed that Botvinnik took his first matches rather lightly, in the knowledge that he had the right to a return match if he lost. Spassky’s explanation was more convincing, bearing in mind what we know about Botvinnik’s meticulous approach. He claimed that Botvinnik had already started his preparations for the return match while the first match was in progress. Indeed, one might even accuse him of using the first match as part of those preparations. The exhausting process of winning through the qualifying tournaments, then beating Botvinnik left Smyslov and Tal too exhausted to put up a fight in the “serious” match which followed. With that gloss on chess history, we should perhaps be less impressed with the achievements of Bronstein and Smyslov in 1951 and 1954 in “only” drawing with a man who was just sizing them up for the big fight. Spassky said that he once told Botvinnik of his conclusions; the old man just glared at him and said, “You are very clever”.’

(560)

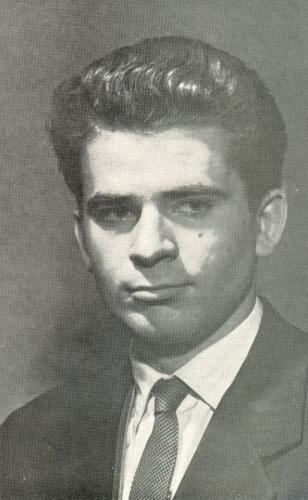

The March 1987 Europe Echecs (pages 159-164) has a terrific interview with Boris Spassky, by Jacques Le Monnier. The former world champion talks candidly about all of his main opponents, singling out Keres as a particularly kind and gentlemanly colleague. The last chess artist was perhaps Larsen, the game having now moved towards a phase of chess ‘killers’. Spassky says that he is still in contact with Fischer: ‘He is poor … it’s tragic. It greatly saddens me to think of his fate; he became world champion and then suddenly everything collapsed’. Fischer ‘will never return’.

Although Spassky will perhaps one day publish a book of his games, he has stopped annotating because it brings in little money. ‘I have written only one book, on my 1977-78 match in Belgrade against Korchnoi’, over which he has been ‘maltreated and defamed’. For six years he could not bring himself to speak to Korchnoi.

We are unclear as to the publication details of this book, and would welcome information. It will be recalled that during the ‘Chess Crisis’ of 1977-78 journalists were almost without exception for Korchnoi; hardly a word was heard in favour of Spassky. As we know from the Termination Affair, the chess press prefers to play its controversies by intuition rather than by serious investigation and analysis.

(1379)

C.N. 1379 asked for information about a book by Spassky on his 1977-78 match against Korchnoi. The former world champion gives an excellent interview to Dirk Jan ten Geuzendam on pages 36-42 of the 7/1988 New in Chess:

‘I wrote two books. One about my loss to Karpov and the second book about my loss to Korchnoi. I called this latter book ‘The Dramatic Match’. I sent it to Schmaus, the publishing house, and they didn’t publish it and I am happy they didn’t publish it. But they still have the manuscript.’

Spassky also states (though how seriously it is difficult to guess) that he is still writing a book on his match against Fischer:

‘I would like to publish this book after my death, because it contains certain memoirs, certain ideas. There is no sense in writing such a book for the money, because it is very poorly paid. Nobody is going to pay you decently for it. If you want to write a good quality book you need time. I have many recollections from my chess career, I met many interesting people, but I wouldn’t like to write a book like, for example, Kasparov did [Child of Change]. This is not a book, I could only read two or three pages of it, this is garbage. As champion of the world I would pay at least one million dollars to get rid of such garbage. A shame: First of all, if you write a book as champion of the world, you should write it personally, without any journalist.’

(1791)

Since Spassky’s side of the story regarding the 1977-78 match against Korchnoi has received little attention, his comments in Europe Echecs are reproduced below:

‘Quant à moi, je n’ai écrit qu’un livre. A propos de mon match contre Kortchnoï en 1977-78 à Belgrade. Il fut considéré comme un match très mystérieux; Kortchnoï m’a accusé d’utiliser des rayons X, les services du KGB etc. Mais à cette époque je me battais pour les droits des joueurs professionnels; personne n’a le droit de gêner un joueur quand c’est à son tour de jouer, quand sa pendule marche. C’était mon principal souci.

... Kortchnoï a presque retourné le problème. Il a spéculé; il m’a accusé d’être le perturbateur pendant la partie.

Personnellement je le respecte beaucoup comme lutteur et comme joueur; il a beaucoup travaillé, il est toujours à la recherche de la nouveauté, il étudie les Echecs très profondément. Je le connais depuis quarante ans. Mais en fin de compte ce qui arriva fut très important. On réalisa que j’avais raison; dans la suite du match on installa des boxes qui protégeaient des influences extérieures. Mais Kortchnoï changea complètement; dans ce cas j’étais l’agresseur. C’est contre cela que je protestais. Après tout peu importe puisque maintenant cela fait partie de l’histoire.

... Le tennis m’a donné un autre bonheur dans la vie. Quand j’écrivais mon livre à propos de mon match contre Kortchnoï, vous savez que j’ai réuni beaucoup de matériel, tant il y eut de bassesse pendant ce match, tant de spéculations.

... Le comportement de Kortchnoï ... Je n’ai pas pu lui parler pendant six ans. Maintenant c’est possible. J’écrivais ce livre et c’est le tennis qui m’a permis de supporter et de le terminer; j’avais pris l’engagement vis-à-vis de moi-même de décrire ce qui s’était passé, de dire la vérité. Non seulement j’avais été maltraité mais, comme on dit en anglais, diffamé. Toute ma vie, j’ai été honnête. Aussi ai-je joué au tennis contre un mur pendant une heure. J’étais trempé, je me reposai et je recommençai à écrire. C’est comme cela que j’ai pu finir mon livre. Je le devais, luttant contre ce moulin à vent. Ce genre de procès fut sans doute le plus difficile et le plus dur que j’ai supporté dans ma vie. Pour moi ce fut en quelque sorte la ruine de toutes mes illusions sur les droits de l’homme.’

Commenting in his Times column of 24 June 1978 (page 19) about Raymond Keene’s book on the 1977-78 Korchnoi v Spassky Candidates’ match, Harry Golombek wrote that the account ‘is so partial as to fail to carry any real conviction’.

(5215)

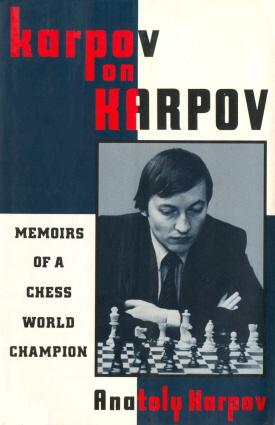

From page 98 of Karpov on Karpov, subtitled ‘Memoirs of a Chess World Champion’ (New York, 1991), a translation from the Russian by Todd Bludeau:

‘I consider myself to be an idler, too, but the dimensions of Spassky’s laziness were astounding.’

(1941)

There follows a list of the books about Spassky in our collection:

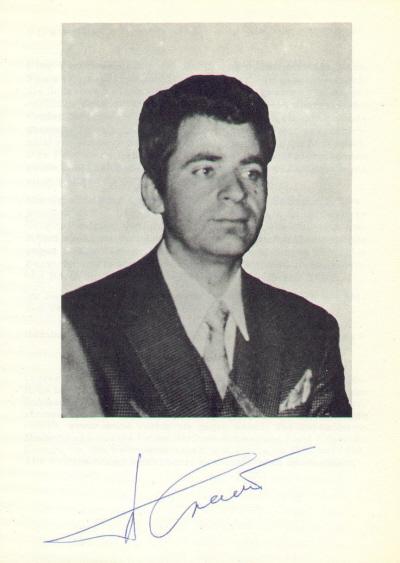

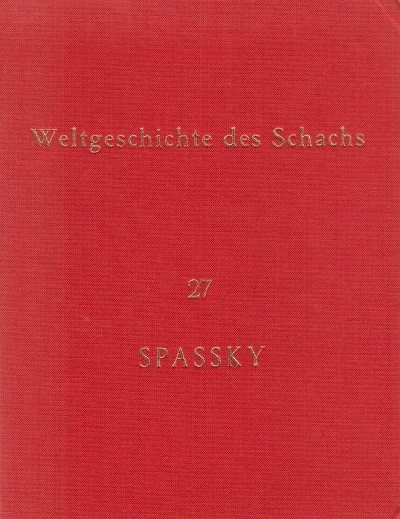

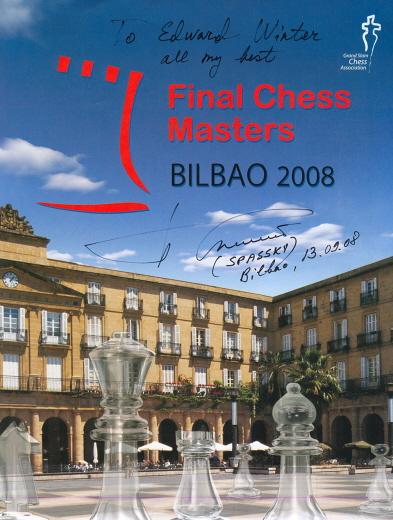

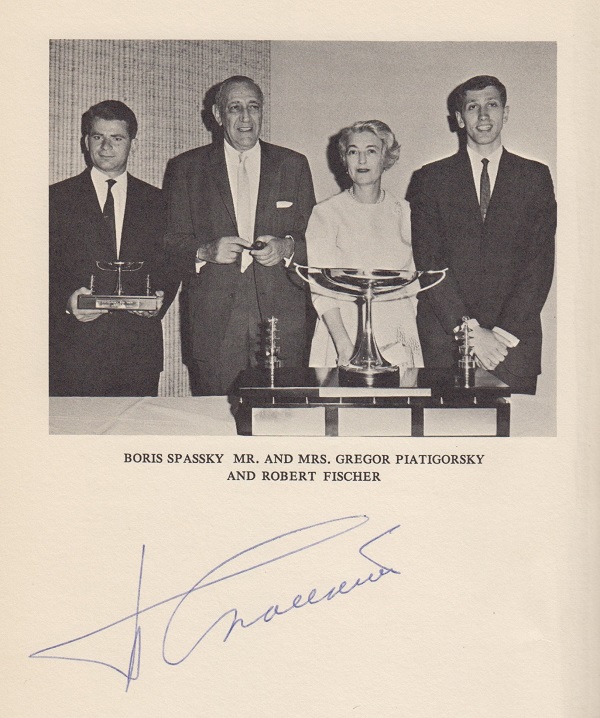

The illustration below shows Spassky’s signature on our copy of the Weltgeschichte des Schachs collection of his games:

This is the famous ‘red book’ so often mentioned at the time of the 1972 world championship match. The opening titles of the film Searching for Bobby Fischer include footage of Fischer studying it, and we note that the game he was analysing is identifiable as Spassky v Langeweg, Sochi, 1967.

(2909)

Regarding the many references in the press to Fischer’s red book on Spassky (including confusion over the Wildhagen volume on Spassky and Robert Wade’s research for Fischer), see C.N.s 8962, 9167, 10677, 10682, 10686 and 10808.

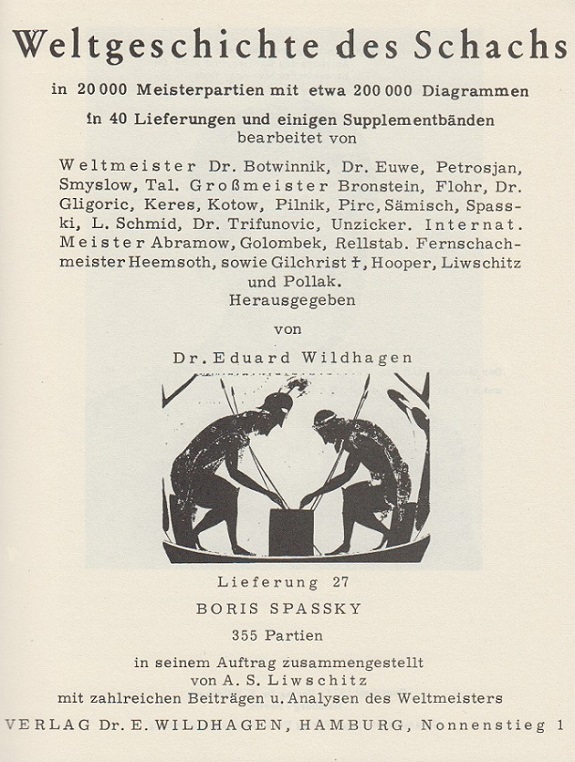

Three images from C.N. 8962:

From page 189 of Bobby Fischers vej til VM by Jens Enevoldsen (Copenhagen, 1972)

Additions to the above list:

The Damsky book was drawn to our attention by Vitaliy Yurchenko (Uhta, Komi, Russian Federation).

‘Now that the drawing for the Candidates’ Matches has been held, it is a natural thing for everyone to make predictions as to who will end up in the challengers’ [sic] seat next year playing against Boris Spassky of the USSR for the world title.’

So wrote George Koltanowski on page 4 of Chess Digest Magazine, January 1971, although an alternative view is that making public predictions is unnatural, pointless and vulgar. In any case, Koltanowski’s chess judgement resulted in the following declaration on Fischer v Taimanov:

‘I believe it will be a very close match, with Fischer winning it 5½-4½.’

Fischer won 6-0.

(3561)

At a press conference in Belgrade on 26 October 1992 Boris Spassky stated that Tigran Petrosian had been ‘the richest man in the Soviet Union’.

Source: page 230 of No Regrets by Y. Seirawan and G. Stefanović (Seattle, 1992).

Can Spassky’s assertion be corroborated?

(4619)

See also the references to Spassky in My 61 Memorable Games (Bobby Fischer).

In the 18 November 2001 edition of the Sunday Telegraph (page 25 of the Review Section), Nigel Short’s chess column discussed Tony Miles at length and concluded with a game ‘of exquisite beauty’, Miles’ victory over Boris Spassky at Montilla, 1978.

Ever since C.N. 4643 raised the question of a dark h1-square on the front cover of chess books we have come across so many cases that only unusual ones seem worth mentioning. One such is referred to by Dale Lichtblau (Reston, VA, USA): as pointed out on page 255 of the May 2006 BCM, the front cover and page 18 of Smart Chip from St Petersburg by Genna Sosonko (Alkmaar, 2006) had a horizontally-reversed photograph of Tal and Spassky:

(4655)

Concerning Chess and the Art of Negotiation A. Karpov and J.-F. Phelizon (Westport, 2006):

Page 57 (page 106 of the French original) states regarding Spassky:

‘Then he became world champion, wrote a book analyzing his various games, and started getting a little older.’

The book in question is named as ‘Boris Spassky, Fifty-One Annotated Games of the New World Champion, FDR Books, 1969’, but how could Karpov be unaware that Spassky wrote no such work and that it was merely a booklet by A. Soltis, published by the United States Chess Federation?

(4743)

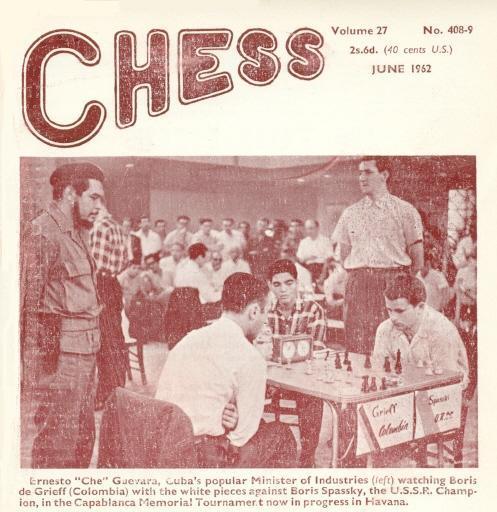

Anthony Stebbings (London) mentions that Che Guevara appeared on the front cover of the June 1962 CHESS:

The caption reads:

‘Ernesto “Che” Guevara, Cuba’s popular Minister of Industries (left) watching Boris de Grieff [sic – de Greiff] (Colombia) with the white pieces against Boris Spassky, the USSR Champion, in the Capablanca Memorial Tournament now in progress in Havana.’

(4809)

An interview of fine quality appeared in ‘Portrait of a World Champion’ by Leonard Barden on pages 7-13 of the January 1970 issue of Chess Life & Review. Much of the interview (conducted in 1966) is quotable, but here we focus on some of Spassky’s comments on other masters:

‘Botvinnik told me that he disagreed with people who like to compare Petrosian with Capablanca. Capablanca, says Botvinnik, was a genius who could always find a new plan in a position. Petrosian doesn’t do that; he begins to maneuver, and this is a great difference, because a chessmaster of the highest class must always be able to find fresh ideas. I feel myself that Botvinnik’s comment is only part of the truth; Petrosian is better than he says. Tal told me that Petrosian is a very careful player; not passive, but a little bit cowardly. He’s a very practical man; a real Armenian. Capablanca was quite the opposite; he was an optimist, and he played very simple and pure chess.’

‘In our time, only when Mikhail Tal appeared did chessplayers see that there could be a different style. Tal has had a great influence on our chess; he stands out in the same way as the old champions. Probably there have been two pure geniuses in chess; Morphy and Capablanca. Tal is also a genius as a tactician, but because he makes a lot of unsound sacrifices this is not pure genius; Morphy and Capablanca hardly ever made tactical mistakes. Perhaps Rubinstein was also a genius of positional chess, and his playing style was also very pure; but he was a bad tactician.’

‘... I believe that the real grandmaster of the super class has to follow the logical course from the beginning to the end of a game. It is necessary to work out all the right tactical decisions which justify your ideas. Sometimes I am too lazy to do this properly, and that is a very, very bad attitude for a grandmaster. I do not believe that Capablanca, Alekhine or Lasker had this particular problem.’

Asked by Barden which of his games had given him the most pleasure, Spassky stated:

‘The game with Keres which I lost, the first of the 1965 match. It was probably my best game, and I made a very good sacrifice, but then I went wrong by playing R-R3 instead of P-Q5, and was crushed. I like this game very much; probably next to that I like the one against Polugayevsky, which I also lost [Moscow, 1961].’

Other interviews:

Below is the most recent Spassky inscription in our collection:

Elmer Sangalang (Manila, the Philippines) writes:

‘In a simultaneous exhibition in 1947 the ten-year-old Boris Spassky won against the future world champion Mikhail Botvinnik. Is the game-score extant? In 1990 Spassky wrote to me that he did not have it.’

For a photograph of the occasion, see the front cover of the 7/1988 New in Chess.

Jake Freeman (Salt Lake City, UT, USA) raises the subject of L. Marini v B. Spassky, Mar del Plata, 1960, which appears in databases as follows: 1 c4 Nc6 2 Nc3 Nf6 3 g3 e5 4 Bg2 Bc5 5 a3 a5 6 e3 O-O 7 Nge2 Re8 8 d3 d6 9 h3 Bd7 10 Bd2 Qc8 11 Qc2 Ne7 12 Ne4 Nxe4 13 dxe4 Be6 14 Nc1 a4 15 Nd3 Nc6 16 Nxc5 dxc5 17 f4 f6 18 f5 Bf7 19 g4 Rd8 20 Bf1 g5 21 h4 h6 22 Bc3 Kg7 23 Qh2 Rh8 24 Be2 Qe8 25 Kf2 Rd8 26 Qg3 Qe7 27 Rh3 Na7 28 Rah1 Nc8 29 Qh2 Rhg8 30 hxg5 hxg5 31 Rh7+ Kf8 32 Bd1 Qd7 33 Bc2 Nd6 34 Kf3 Nxc4 35 Rd1 Nd6 36 Qh6+ Ke7 37 Rd5 Qb5 38 Bd3 Qb3

39 Be2 Drawn.

Regarding the diagrammed position Mr Freeman comments:

‘Instead of 39 Be2, there is 39 Bxe5 fxe5 40 Qe6+ Kf8 41 Rxf7+ Nxf7 42 Bc4 Qxc4 43 Rxd8+ Nxd8 44 Qxc4, winning easily. If Black plays 42...Re8, then 43 Qxf7+, followed by 44 Rd7+ and mate next move.’

(6139)

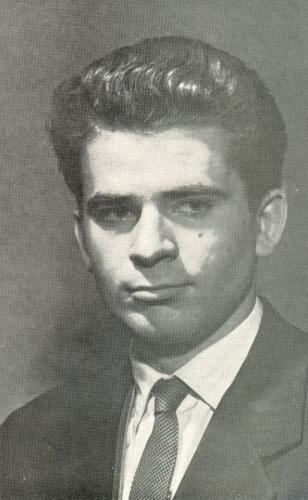

Boris Spassky (Palma de Mallorca, 1969 tournament book)

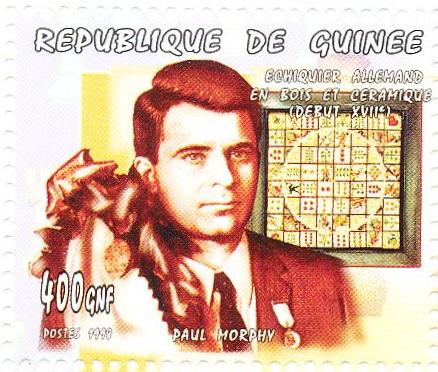

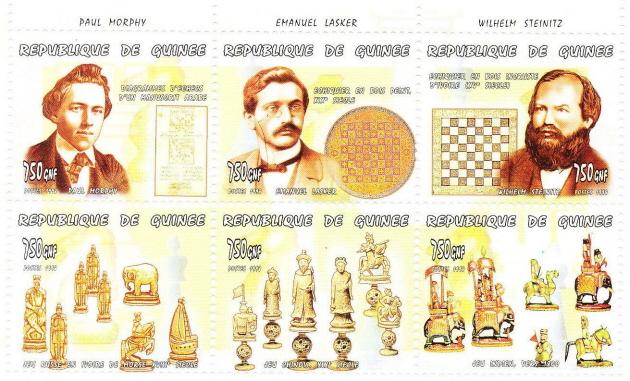

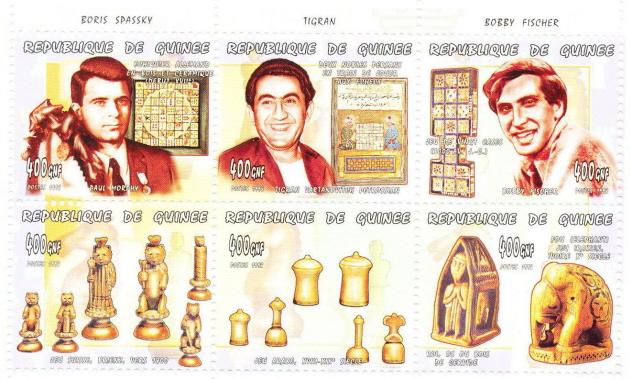

In C.N. 2366 Daniël De Mol (Wetteren, Belgium) reported that in 1998 Guinea issued a postage stamp which misidentified Spassky as Morphy. We are grateful to our correspondent for enabling us to reproduce the faulty stamp here, together with the rest of the set.

(6243)

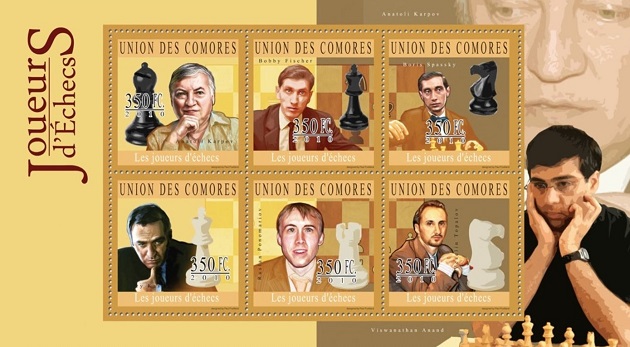

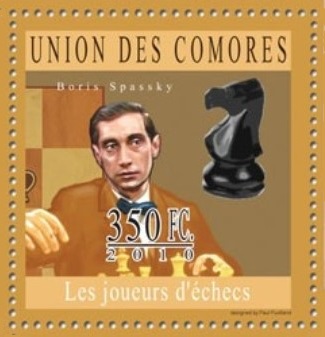

Dan Scoones (Coquitlam, BC, Canada) draws attention to a set of postage stamps:

Our correspondent notes that ‘Boris Spassky’ is Vladek Sheybal, who played the role of Kronsteen in the 1963 film From Russia with Love.

(9658)

See Chess and Postage Stamps and Chess: Mistaken Identity.

‘You can tell a great deal about a chessplayer by the way he looks at the board when it is his turn to move. Spassky always wears the bored expression of a man in a bus queue, in no particular hurry.’

William Hartston, Now!, 11-17 July 1980, page 88.

(6742)

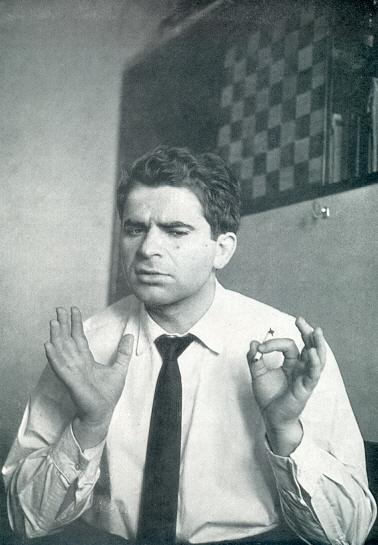

A photograph of Spassky from the Russian book by Boleslavsky and Bondarevsky (Moscow, 1970) on the previous year’s world championship match against Petrosian:

From an article by Boris Spassky ‘The Petrosian-Korchnoi Match: Petrosian Was True to Himself’ on pages 625-627 of the November 1971 Chess Life & Review:

‘The most outstanding feature in the style of ex-world champion Tigran Petrosian is his desire to keep his opponent at his own distance. This can be seen in every game as well as in the overall plan of the match. This is purely his own individual style, his chess character.

Victor Korchnoi may be described as a searching chessplayer. To me, he seems more a destroyer of the other player’s plans and positions rather than a creator. His strength is most evident in counter-attacks. He is known for his flexible playing style and colossal energy and working capacity during a game ...

Korchnoi is also a fighter with stubbornness that anyone could envy. He is tenacious in defense and can become quite “angry” – in the sports sense of that word. When he tackles a problem that comes up over the board, I believe the Leningrad grandmaster has a tendency not to trust his intuition; rather, he relies more on hard, cold calculations. His ability to figure out various continuations far in advance helps him in the endgame.

By his style, Korchnoi is more a tournament player than a match player. Sometimes, when he gets carried away by his ideas and original plans he does not reckon with the more prosaic aspects of chess. One of his shortcomings in his “ability” to get into time-trouble.

Comparing the styles of the two players, it must be said that Petrosian is a tough opponent for Korchnoi. After all, during the course of the struggle Korchnoi has to be able to discover his opponent’s plan in order to begin “destroying” it. But Petrosian’s style is often based on waiting, maneuvering, “semi-tones”. That is why the temperamental Korchnoi often had to shoot at blind targets.’

(7005)

Steve Wrinn (Homer, NY, USA) submits this previously unpublished game played in a simultaneous exhibition in Billerica, MA, USA:

Boris Spassky – Steve Wrinn

Billerica, 1 February 1987

Nimzowitsch Defence

1 e4 Nc6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 dxe4 4 d5 Ne5 5 Bf4 Ng6 6 Bg3 a6 7 h4 e5 8 dxe6 Bxe6 9 Qxd8+ Rxd8 10 h5 N6e7 11 Nxe4 Nd5 12 O-O-O Nb4 13 Rxd8+ Kxd8 14 a3 Nc6 15 Nf3 Nh6 16 Be2 Be7 17 Neg5 Bf5 18 Bc4 Rf8 19 Re1 Bd6 20 Bxd6 cxd6 21 Nh4 Ne5 22 Nxf5 Nxf5 23 Bd5 h6 24 Ne4 Kc7 25 Kd2 Ne7 26 Ba2 N5c6 27 Nc3 Kd7 28 Nd5 Nxd5 29 Bxd5 g5 30 b4 f6

31 f4 Re8 32 Rxe8 Kxe8 33 fxg5 fxg5 34 Kd3 Ne5+ 35 Ke4 b6 36 Kf5 Ke7 37 Bb7 Nc4 38 Bxa6 Ne3+ 39 Kg6 d5 40 Bb7 Nxg2 41 Kxh6 g4 42 Bxd5 Ne3 43 Be4 g3 44 Kg7 Nf5+ 45 Kg6 Nh4+ 46 Kg5 g2 47 Bxg2 Nxg2 48 h6 Kf7 49 c4 Ne3 50 c5 b5 51 Kf4 Nc4 52 c6 Kf6 53 Ke4 Ke6 54 h7 Nd6+ 55 Kd4 Resigns.

Mr Wrinn adds that Spassky scored +30 –2 =10, as stated in the report on pages 30-31 and 34-35 of Chess Horizons, April-May 1987. The magazine had four photographs of the occasion (which included a lecture), as well as annotations by Peter Vlahos to his victory over the former world champion.

(7500)

A set of quotes from an article ‘M.M. Botvinnik declares ...’ on pages 3-8 of CHESS, October 1968 (a report on an address by Botvinnik to an audience of 400 in Vladimir in late July):

Geller can play exceptionally well, but he can also play very badly. Spassky’s play is always that of a very good grandmaster.

It is this combination of qualities that has enabled Spassky to achieve outstanding successes.’

Korchnoi can do what the majority of players can’t – stick it out when defending a difficult position and then switch over instantly, if the opportunity comes, to counter-attack. His combination of courage and accurate calculation enables him to overcome the nervous strain caused by difficult situations. Spassky avoids such positions. Hence, it is hard to say which of them will win [in the Candidates’ Final]. Only 12 games makes a pretty short match. The one who manages to win a couple of good deep games will have a great chance of victory.’

(8399)

C.N. 8350 invited readers to submit the scores of simultaneous games in which they were involved.

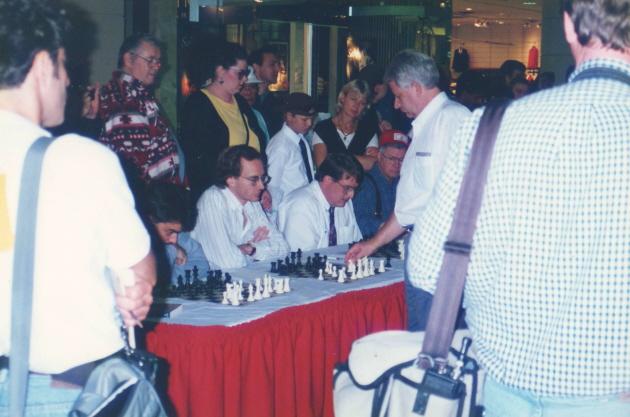

Philip Jurgens (Ottawa, Canada) supplies a photograph taken during his game against Spassky (1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 e5 c5 5 a3 Bxc3 6 bxc3 Ne7 7 Nf3 Nbc6 8 a4 Qa5 9 Bd2 c4 10 h4 Bd7 11 h5 O-O-O 12 h6 gxh6 13 Rxh6 Rdg8 14 g3 Rg6 15 Rh5 Nf5 16 Bh3 Nce7 17 Ng5 Be8 18 Rxh7 Rh6 19 Rxh8 Rxh8 20 Kf1 Bxa4 21 Qc1 b5 22 Kg2 Rf8 23 Bg4 Qc7 24 Qa3 Rg8 25 Qb2 Rg7 26 Rh1 Ng6 27 Bh5 Nfe7 28 Qc1 Qd8 Drawn) in a simultaneous exhibition at the Bayshore Mall in Ottawa on 2 October 1995:

Mr Jurgens mentions that a report on the display on pages 42-44 of En Passant, December 1995 gave two games: Spassky’s draw with Herb Langer and his only loss, to Robert Inkol.

(8685)

Page 198 of the atrocious Batsford Chess Encyclopedia by Nathan Divinsky (London, 1990) speculates implausibly that after the 1972 match ‘Fischer was completely wiped out of chess by Spassky’.

Dan Scoones (Port Coquitlam, BC, Canada) forwards a neglected game for which each player had only five minutes:

Mikhail Tal – Boris Spassky

Rapid championship of Moscow, 1957

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 f5 4 Nc3 Nd4 5 exf5 Nf6 6 Nxe5 Bc5 7 O-O O-O 8 Nf3 c6 9 Nxd4 Bxd4 10 Ne2 Be5 11 Bc4+ d5 12 Bd3 c5 13 Ng3 c4 14 Be2 Bxg3 15 hxg3 Bxf5 16 d3 b5 17 a4 a6 18 axb5 axb5 19 Rxa8 Qxa8 20 dxc4 dxc4 21 Bf3

21...Qa2 22 Re1 Qb1 23 Qd6 Qxc2 24 Bd5+ Nxd5 25 Qxd5+ Kh8

26 Qf7 Rg8 27 Bh6 and White won.

Source: Chess Life, February 1963, page 38.

The game appeared in an article by Eliot Hearst which reported that the moves had been recorded by B. Weinstein. It was also noted that the same opening had occurred in the game between Tal and Spassky in the USSR championship earlier in 1957.

At move 15 Hearst commented: ‘For the last five moves the two players had consumed two minutes, a considerable time; for the next six moves they used some ten seconds only.’ Spassky spent some time on 21...Qa2, and ‘Tal also thought a while on his reply and prepared a pretty and decisive trap’.

(8513)

‘Turgid’ is hardly a word applicable to Boris Spassky, but it is a charitable description of the prose in Winning Record against World Champions by B. Spassky and I. Gelfer (Rosh Ha’ayin, 2014). Below, for instance, is the start of the former world champion’s Preface:

The entire humdrum book (which misappropriates a number of photographs from C.N. – see, for example, pages 15, 190 and 203) should obviously have been revised by a writer of English mother tongue.

(8921)

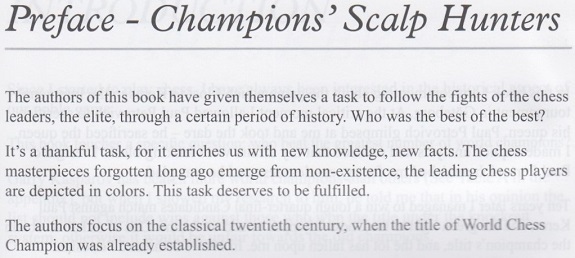

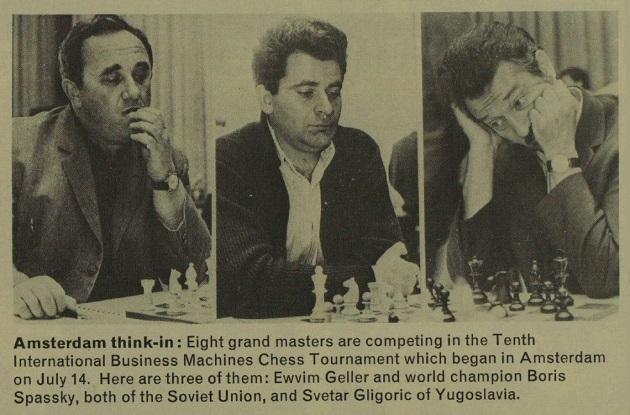

From Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore):

Illustrated London News, 25 July 1970, page 9

Illustrated London News, 12 September 1970, page 7.

(9067)

From an interview with Karpov by Irwin Fisk posted by ChessBase on 2 March 2015:

‘I.F.: Spassky was in preparation to play Fischer for the world championship. Had you played Spassky?

A.K.: Yes, I played a training match with Spassky. He asked me to play training games, but we played only one game. Spassky won this game even though he had a lost position, but I made a stupid mistake, and after this suddenly Spassky said he didn’t want to continue this training match, so maybe he was happy he beat me in that game.

I.F.: Where was this game played?

A.K.: We were near Moscow.’

A similar, though more detailed, account is on pages 98-99 of Karpov on Karpov (New York, 1990):

‘Toward the end of the camp, Spassky, wishing to check his form, decided to play several games with me. In the first game, he selected the Ruy López. I played White and quickly gained a winning position. All I had to do was hold on to it for a little while longer, but, weary from the previous inactivity and irritated by how I was being treated, I decided to show off and embarked upon unnecessary tactical complexities. This gave Spassky a chance to display his customary resourcefulness. I should have regrouped in time, changed the arrangement, and played to at least hold on to what remained. But I already realized my lead was receding, and I overplayed and lost. Spassky liked this game. He decided that his form was superior and there was no reason to continue checking it. My participation in his final prematch training was virtually limited to this one game.’

On page 8 of the September 1989 Chess Life A. Soltis disseminated a different version:

‘In some instances, no details about a match are ever disclosed. Or a smidgen of information surfaces, such as after the 1972 world championship match, when Anatoly Karpov confirmed the rumors that he had played a match to help prepare Boris Spassky for the challenge of Bobby Fischer. All Karpov would say then about the result was “I did not lose”.’

A similar text appeared on page 148 of Soltis’s book Karl Marx Plays Chess (New York, 1991), but in neither case did he offer the reader any source. It is possible that he was relying on a mere rumour published, as an editorial end-note, on page 70 of the February 1973 Chess Life & Review:

(9361)

Thomas Höpfl (Halle, Germany) notes that the Chess in Luxembourg webpage has some fine photographs, including shots of Boris Spassky.

(9433)

In C.N. 8110 (see Chess: The Need for Sources) a correspondent pointed out that in The Immortal Game by David Shenk (New York, 2006) ‘details of Spassky’s chess career are attributed to a Wikipedia entry’. Recent books with no qualms about citing Wikipedia include Miguel A. Sánchez’s volume on Capablanca (C.N. 9456); see pages 509 and 527. From the latter page:

‘According to Wikipedia ... But according to the more reliable version of Andy Soltis in ...’

McFarland books really should do better than that.

(9511)

A paragraph from page 332 of Impact of Genius by R.E. Fauber (Seattle, 1992) which we have doggedly approached from every angle without making sense of it:

‘The paradox of Boris Spassky is that it is hard to remember any of the plentiful immortal games he has created. There is to Spassky’s play a lightness, the deft and delicate touch which makes just the right brush stroke. It can never be repeated nor can it be improved upon. This endows it with inconsequentiality. Spassky plays last year’s beautiful spring – gorgeous but past.’

(9547)

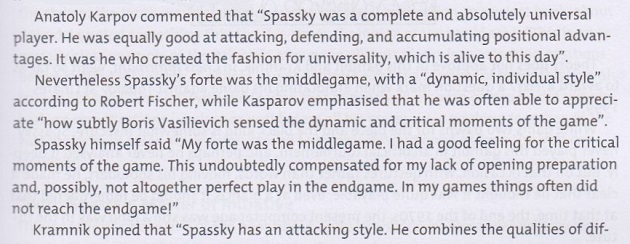

From page 13 of Spassky move by move by Zenón Franco (London, 2015):

And so on. This passage, typical of Franco’s approach to writing, does not state where or when Karpov, Fischer, Kasparov, Spassky and Kramnik made the remarks attributed to them. Why not?

Why can readers of McFarland books expect, or at least hope, to see exact sources for quotations, whereas so many other publishers show no sign of having even considered such a requirement? Why, if McFarland’s overall output is praised for its ‘scholarship’, do reviewers refrain from criticizing other publishers for a lack thereof? In any case, the issue at hand is ‘scholarship’ of a most basic kind. When an author says that someone said something, saying where and when it was said is not a donnish luxury or self-indulgence but an essential service to the reader which should be automatic.

(9583)

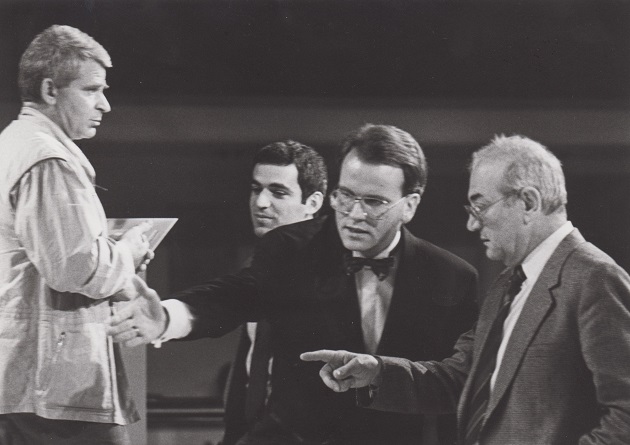

From our collection:

Boris Spassky, Garry Kasparov, Páll Magnússon, Victor Korchnoi (Reykjavik, 1988).

(9787)

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) has forwarded a photograph which he took during the New York Open tournament in 1987:

Michael Rhode, Boris Spassky, Joel Benjamin

(9882)

An inscription by Spassky in one of our copies of the Santa Monica, 1966 tournament book, Second Piatigorsky Cup (Los Angeles, 1968):

Chess Review, October 1966, page 309

See Chess: Jacqueline and Gregor Piatigorsky.

A photograph contributed by Olimpiu G. Urcan to our feature article William Hartston:

European Team Championship, Bath, July 1973 (Hulton Archive)

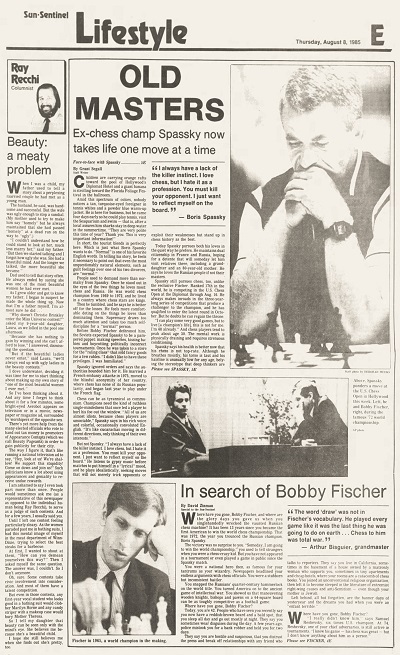

Two remarks by Spassky quoted in an interview/article by Grant Segall on pages 1E and 5E of the Sun-Sentinel (Florida), 8 August 1985:

(10340)

John Donaldson (Berkeley, CA, USA) provides a photograph taken during the Interzonal tournament in Manila, June-July 1976:

Mr Donaldson reports that with the assistance of Lubomir Kavalek, who recalls that the picture was taken after a boat trip on a free day, it has so far been possible to identify (front row, far left) John Grefe; (front row, third, fourth and fifth from the left) Khosro Harandi, Eugenio Torre and Boris Spassky; (second row, second from the left) Lubomir Kavalek; (second row, last four on the right) Florin Gheorghiu, Wolfgang Uhlmann, Vladimir Tukmakov and Orest Averkin; (back row, second from the left) Rodolfo Cardoso.

(10346)

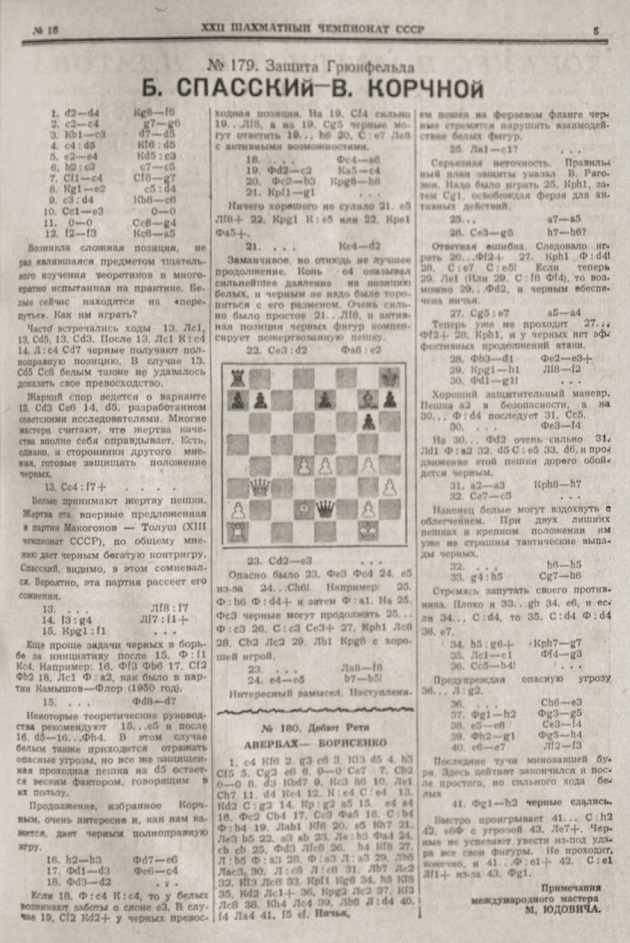

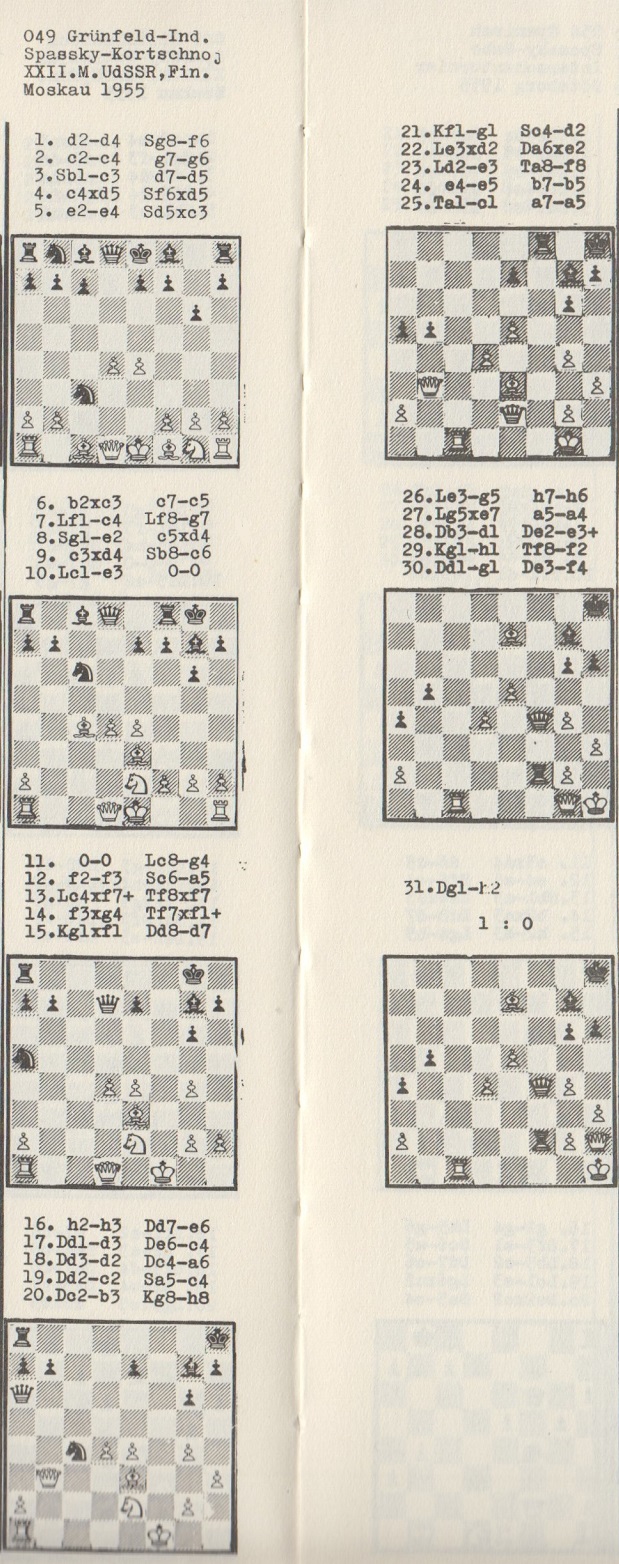

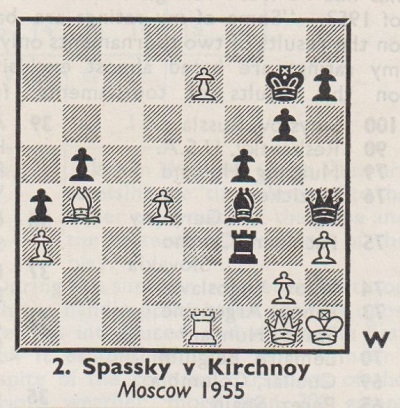

41 Qh2 Resigns

The celebrated move 41 Qh2 was played by Spassky against Korchnoi in the 22nd USSR championship in Moscow, 1955. The full game, with notes by M. Yudovich, was published on page 5 of XXII шахматный чемпионат СССР, 31 March 1955:

The above scan has been provided by the Cleveland Public Library.

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 g6 3 Nc3 d5 4 cxd5 Nxd5 5 e4 Nxc3 6 bxc3 c5 7 Bc4 Bg7 8 Ne2 cxd4 9 cxd4 Nc6 10 Be3 O-O 11 O-O Bg4 12 f3 Na5 13 Bxf7+ Rxf7 14 fxg4 Rxf1+ 15 Kxf1 Qd7 16 h3 Qe6 17 Qd3 Qc4 18 Qd2 Qa6 19 Qc2 Nc4 20 Qb3 Kh8 21 Kg1 Nd2 22 Bxd2 Qxe2 23 Be3 Rf8 24 e5 b5 25 Rc1 a5 26 Bg5 h6 27 Bxe7 a4 28 Qd1 Qe3+ 29 Kh1 Rf2 30 Qg1 Qf4 31 a3 Kh7 32 Bc5 h5 33 gxh5 Bh6 34 hxg6+ Kg7 35 Re1 Qg3 36 Bb4 Be3 37 Qh2 Qg5 38 e6 Bf4 39 Qg1 Qh4 40 e7 Rf3 41 Qh2 Resigns.

Some databases give a different move-order in the opening, and a number of publications have discrepancies over the conclusion. Ten moves were lopped off in the Wildhagen volume of Spassky’s games (the ‘big red book’ – see C.N. 8962):

Page 76 of the Encyclopaedia of Chess Middlegames (Belgrade, 1980) had this position (black king on h7, not g7, and no white pawn on g6) before 41 Qh2:

There were black pawns on h7, g6 and f5 in the ‘Winning Practice from the Masters’ article on page 23 of CHESS, 29 October 1955:

The solution on page 33:

‘1 Q-R2! This seems the only way to nullify complefely [sic] the threat of RxRPch; but now White’s passed pawn wins the game.’

Unaware that the diagram was faulty, CHESS, 12 November 1955, page 41 reported:

‘Some 30 readers point out that in No. 2 of our Winning Practice positions last issue, Korchnoy could have upset Spassky by 1...QxRch 3 [sic] Q-Kt1 RxQch 4 [sic] KxR K-B2 winning the dangerous pawn.

Sir G.A. Thomas, whose card was the first to arrive, points out that by 1 R-K2 White can draw.’

(10387)

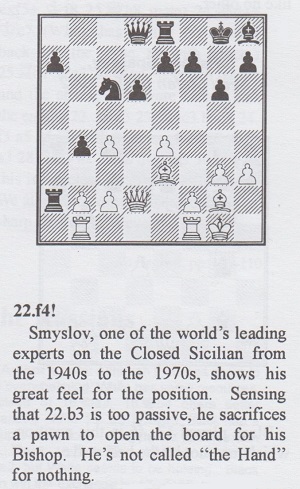

Sean Robinson (Tacoma, WA, USA) notes a remark by Spassky in an interview on page 23 of the Autumn 1998 Kingpin:

‘Smyslov is a chess player with a fantastic intuition. I call him “Hand” because his hand knows exactly on which square to put which piece at a given moment; actually, he does not have to calculate anything.’

Our correspondent asks whether earlier occurrences of the term are known.

He adds this slightly later citation from page 155 of The Unknown Bobby Fischer by John Donaldson and Eric Tangborn (Seattle, 1999):

For observations on the physical appearance of Smyslov’s hands see page 57 of Chess Duels by Yasser Seirawan (London, 2010).

In correspondence with W.H. Cozens in the 1970s we criticized a book(let) by James Schroeder, and (as reported in C.N. 2640) on 29 January 1975 Cozens replied:

‘I was amused (and, uncharitably, rather pleased) at all you had to say about Mr James Schroeder. Soon after the publication of my Spassky’s Road to the Summit in 1966 the BCM sent me a copy of a really vicious review of it, by our Mr Schroeder. We were amused and also puzzled by it, until we discovered the reason: he was himself about to bring out a book of Spassky’s games and he resented us getting in ahead of him. When his book appeared (I forget the exact title) the BCM sportingly asked me to review it and I thought “the Lord hath delivered him into my hand”. But when I saw the book it was so laughable that I refused to review it. To do so would have been a waste of BCM space and readers’ time. If you have found a book worse than that one it must really be something.’

We own Cozens’ copy of Schroeder’s volume, Boris Spassky World’s Greatest Chess Player (Cleveland, 1967):

Does a reader have Schroeder’s review of Spassky’s Road to the Summit?

(10967)

Source: the plates page in the 1969 Petrosian v Spassky match book by I. Boleslavsky and I. Bondarevsky (Moscow, 1970)

Tailpiece: Boris Spassky’s fame was such that he was even mentioned by Alf Garnett in an episode of the BBC-1 television programme Till Death Us Do Part written by Johnny Speight and broadcast on 28 February 1974 (link: starting at about 16:06).

See also Spassky v Fischer, Reykjavik, 1972, as well as our feature article on books about their 1992 match..

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.