Edward Winter

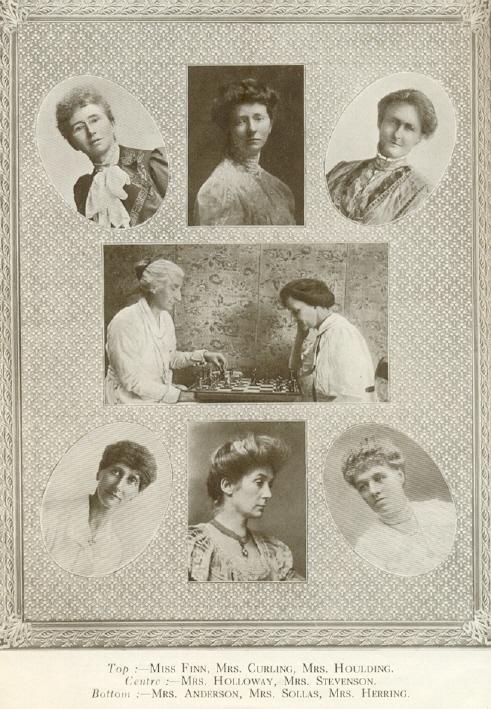

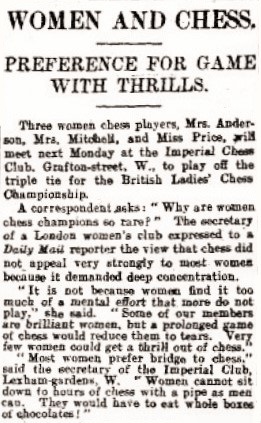

Illustration from Die Schachspieler und ihre Welt by Arpad Bauer (Berlin, 1911)

First, we offer from old literature a digest of quotes and references on the theme of chess and women.

The Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1848 (pages 371-372) had an account of the annual dinner of the Northumberland Chess Club on 2 November of that year, at which J.J. Hunter’s speech was reported as follows:

‘Mr John J. Hunter then said there was one indispensable toast, always sure of a most cordial reception, but which had not yet been given, and, lest it should be omitted, he incurred the responsibility of proposing it. The toast he meant was “The Ladies”. He had found amongst the fair sex many formidable opponents in the chess field, and although some gentlemen professed to make it a point of gallantry to indulge them with a conquest occasionally, he believed they now frequently made a virtue of necessity, and veiled a want of skill under an appearance of respectful deference. On the present occasion, therefore, he proposed “The Ladies, and especially those who are chessplayers”.’

‘Chess and the Fair Sex’, on pages 121-122 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 15 March 1881. The unnamed author’s declarations included the following:

‘… there are none with whom we should imagine the game of chess should find greater favour than with the fair sex. As a rule, they have at their disposal a greater amount of leisure than men have. Their duties are lighter – if, at least, we except from the list those which the inexorable law of fashion requires they should fulfil. It must often happen they grow weary of that terrible ordeal of pleasure in all its ever-varying phases which Society deems imperative. Fashionable novels, after a few experiences, are apt to grow wearisome, and in the evenings especially, when the men folk are at their clubs, ladies must often feel the need of something intellectually attractive – something that is likely to arouse in them a stronger interest than scandal-mongering and the ordinary small talk of the day. There was a time when a knowledge of chess was looked upon by women as well as men as a valuable accomplishment; and there is no reason why it should not be so regarded now.’

‘Moreover, as we read some little time back in a short treatise on the game – “not only should it” – that is, chess – “share the drawing-room, but become an ever-ready resource against listlessness and indolence. Experience vouches its value as a domestic charm; and every young lady will do wisely in acquiring the power of adding its fascination to the attractions of Home”.’

‘We say unreservedly that chess is a game which is worthy of being cultivated by ladies. It is pleasantly quiet, and they possess many of the qualities which should characterize the votary of the game. They have patience, they are nice in calculating, as well as quick in devising a means of attack or defence. It has far too much variety ever to grow tiresome, and especially in the long wintry evenings, if only as affording rest from the unceasing whirl of fashionable pleasure, should it once more find a place among the recognized home pastimes of the day.’

‘Das Schachspiel und die Frauen’ by H. von Gottschall in the May 1893 Deutsche Schachzeitung (pages 129-133). One of the more sympathetic articles on the subject published in the nineteenth century.

‘A Scientific Hint for Women Players’ on page 196 of the September 1897 American Chess Magazine:

‘Verily, this is a world of strange happenings, and still stranger explanations. Many conservative men (a fair correspondent avers they are brutes more or less) have strongly contested the claim that a woman could play a consistently good game at chess. They persistently declare that, though the play of this or that woman may be, at times, of a fair order, it is inevitably erratic, and subject to those illogical aberrations which science, as exemplified in chess, most severely frowns upon. Now, if there is any foundation for this charge, it is evident that the women’s game must be affected by some extraneous cause that does not influence the men, and there has been much puzzled inquiry as to what that cause can be. It has remained for the Troy Times to solve the great mystery. It declares, on the authority of “a great scientist” – what a pity we do not know his name – that the cause of the present intellectual activity of our women-folk is due to the use of wire hair-pins. He explains the matter in a charmingly lucid manner which, as so often happens with scientific explanations, leaves the unscientific reader in rather more of a muddled entanglement than ever, but when “boiled down” it amounts to this: that the wire hair-pins excite “counter-currents of electricity”, whatever they may be, and so bewilder the wearer’s brain with strange vagaries, and lead them to do whimsical things. Now, it would be well for players to take note of this, for the “wire hair-pin” theory explains many things. It is evident that when a woman wears a handful of wire hair-pins there is an amount of electrical disturbance going on around her scalp that puts good chess out of the question. When she wears shell contrivances her head is clear and cool, and she plays the fine, winning game her friends admire. So, in future tournaments, one of the rules governing the play should be: “All ladies-players are requested to wear shell hair-pins.”’

‘Oriental Women Chess Players’ by Margherita Arlina Hamm is a brief article on page 203 of the September 1897 American Chess Magazine.

‘Ladies in Chess’, on pages 61-62 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 19 April 1899. A general article on developments in England.

The above photograph is of Frau Ad. Keller of Elberfeld as Caïssa in the prologue to the operetta Der Seekadett. It appeared opposite page 44 of the Barmen, 1905 tournament book.

Lasker’s Chess Magazine (April 1906, pages 276-277) reproduced an article entitled ‘Women and Chess’ from The Saturday Review. Some extracts follow (see too C.N. 1748 on page 134 of Chess Explorations):

‘… in the whole of its enormous literature there does not appear the name of any woman among the stars of the first, second or third magnitude. One may go through volume after volume containing thousands of games and not find a single one played by women which any editor has thought worthy of a permanent record.’

‘A careful examination of the games of players whom the world recognizes as great reveals the fact that the faculties and qualities of concentration, comprehensiveness, impartiality and, above all, a spark of originality, are to be found in combination and in varying degrees. The absence of these qualities in woman explains why no member of the feminine sex has occupied any high position as a chessplayer.’

‘In the composition of chess problems, the element of competition is absent, and many women are considered good composers. Here the critic can and does exert a little influence. But when we look at the winners of tournaments for composing problems the names of women are again conspicuous by their absence.

It seems quite clear that women have so far been unable to hold their own in open competition. Whether, or to what extent, it is a matter of physical constitution, we are unable to say. But a change in the spirit of women chessplayers might work wonders. The existence of “ladies’ chess clubs” is a means of perpetuating mediocrity among its members. Of course, if exclusiveness is more important to them than improved play, they will continue in this way. If any women have any idea or ambition of holding a high position in the chess world apart and independent of sex, they will endeavor to meet all-comers in practice and so pave the way to take part in general tournaments. No player has ever existed who has been more than a shade superior to his contemporaries, and if women continue to play only with women the best of them cannot hold their own in a general tournament, because of the poor standard of the play they have been engaged in.’

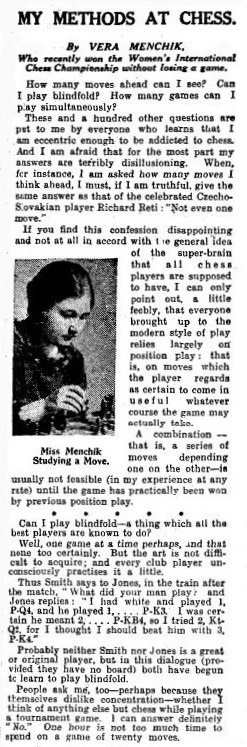

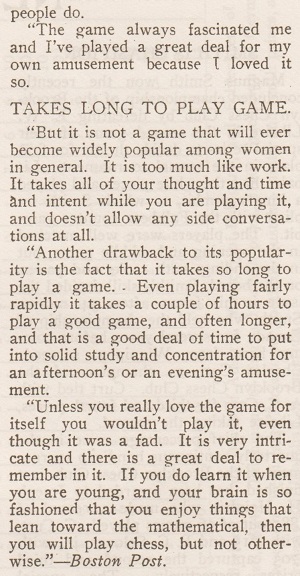

Alekhine was to voice a similar argument regarding Vera Menchik when annotating a 1939 game of hers on pages 220-221 of Gran Ajedrez (Madrid, 1947): ‘… it is totally unfair to persuade a player of an acknowledged superclass like Miss Menchik to defend her title year after year in tournaments composed of very inferior players. It is not surprising that after so many tournaments she has lost much of her interest, and plays some games casually, much below her strength. But such accidental difficulties could not possibly be decisive in a championship, if it were settled, like any title of importance, in a match and not in a tournament.’

Vera Menchik

‘Women’s Sphere in the World of Chess’, an article on pages 4-6 of the January 1908 American Chess Bulletin also quoted a few paragraphs from the above-mentioned Saturday Review article and commented:

‘To all of which we respectfully submit that “the hand that rocks the cradle rules the world” and that women as a class can well afford the loss of any additional prestige the game of chess might hold forth to them.

The home has been and still is woman’s chief stronghold, whence she can achieve conquests that keep mankind under permanent subjection. Surely the average club room, with its smoke-laden atmosphere, is not the magnet to attract her, and it is here where mere man obtains the foundation of his knowledge and experience which his “concentration, comprehensiveness, impartiality and originality” are destined, in isolated cases, to transform into the genius of mastership. That no woman has attained a high position in chess because of the absence of certain qualities, as alleged, clearly is not proven …’

The article in the Bulletin also featured the chess columnist Rosa (Rose) B. Jefferson of Commercial Appeal (Memphis) and Luella Mackenzie of Iowa. The latter ‘furnishes another example of a woman more than holding her own in competition with members of the sterner sex. Correspondence chess is her particular sphere, and this style of play certainly holds forth special attractions to women devotees of the game, most of whom have neither the opportunity nor inclination for cross-board practice at leading clubs.’

‘Das Schach und die Frauen’ by S. Tartakower on pages 122-125 of the January 1921 issue of Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten. In amongst some historical facts about women’s play, Tartakower gave his views on their relative lack of playing strength:

‘Der einzige Grund, warum es die Frau auf dem Schachgebiete noch zu keiner Virtuosität brachte, liegt wohl darin, dass das Schach keine eigentliche Kunst ist, sondern auch einen Kampf darstellt, einen Sieg erstrebt, zu dessen Erreichung stets eine gewisse Rücksichtslosigkeit gehört, welche Eingenschaft eben dem holden Geschlecht viel zu wenig eigen ist.’

‘Sohin sind die Beziehungen des zarten Geschlechts zu unserem edlen Spiele sehr mannigfaltig und, wenn das Schach das Leben verschönt, so verschönert die Frau das Schach.’

Below is an English translation:

‘The only reason why women have not yet achieved virtuosity in the field of chess is probably that chess is not a proper art but also depicts a battle with the aspiration of victory; attainment of victory always calls for a certain ruthlessness, which is precisely a feature far too little present in the fair sex.’

‘Thus the connections between the gentle sex and our noble game are richly diverse, and while chess brightens up life, women brighten up chess.’

Tartakower included the article on pages 9-12 of his booklet Am Baum der Schacherkenntnis (Berlin, 1921).

‘Die Frau im Schachleben’ by Paula Kalmar (‘Austria’s first woman chess master’), on pages 21-23 of the March 1923 Wiener Schachzeitung. The article, originally published in the Neue Freie Presse of 20 February 1923, focused on chess life in Vienna and her own chess career.

‘Die Frau und das Schach’ by K. Ziebert, on pages 33-37 of the February 1926 Deutsche Schachzeitung. A general discussion, with few specific facts.

‘El Ajedrez y la Mujer’: editorial on page 369 of the August 1935 issue of El Ajedrez Español noting the increased interest in chess among women.

‘The Advance in Women’s Chess’ on pages 149-151 of the April 1936 BCM. A discussion of initiatives within FIDE and various national bodies to develop women’s chess.

‘The Present State of Women’s Chess’ on pages 125-130 of the March 1937 BCM was a follow-up article, largely concentrating on England. A ‘postscript’ was published on pages 189-190 of the April 1937 BCM and a ‘second postscript’ on page 260 of the May 1937 issue.

A review, by E.L.W., of women’s chessplaying and organizational activities was given in ‘Women in Chess’ on page 177 of the August 1937 Chess Review.

‘El Ajedrez y la Mujer’ on pages 57-58 of Enroque!!, September 1941. An overview of the development of women’s chess.

A paragraph from Clive James’ television column in The Observer, 11 October 1981, page 48:

‘Why have there been so few important female chessplayers? Arguments about social repression have never satisfactorily answered the question. The Freudian view, summed up in a classic paper by Ernest Jones, is that the game represents a man’s oedipal attempt to kill his father, but a simpler view would suggest that women just aren’t nuts enough. The World Chess Championships (BBC 2) are a case, or perhaps two cases, in point. Korchnoi is fairly obviously some sort of weirdo. We have not forgotten the poisoned yoghurt [sic] and the enemy thought-waves. But Karpov, if you look closely, is even weirder. With Korchnoi some of the obsessiveness remains unfocused and spills out in the form of dingbat behaviour, as it did with Bobby Fischer. But with Karpov it is all beamed straight at the chess-board. Get between him and it and you’ll fry.’

(16)

Concerning From the Opening into the Endgame by Edmar Mednis, here is a line from the Preface:

‘... my deepest gratitude goes to my wonderful blonde wife, Baiba, ... for typing the entire manuscript ...’

She should have refused to type that bit.

(500)

The conclusion of our note on the book Mein Weg zum Erfolg by Barbara Hund:

Presumably Barbara Hund typed the manuscript herself; scrutiny of the text fails to reveal any references to a handy husband – no dashing, dark Dieter to do the dactylo ...

(501)

Following From the Opening into the Endgame (C.N. 500), Edmar Mednis has now written, also for Pergamon but in much better English, From the Middlegame into the Endgame. ... One notes on page viii that Mrs Mednis’s hair has kept its colour.

(1405)

In 20 Partien Capablanca’s B. Kagan gives a game (page 12) against Frau Dr Brock (‘gespielt in einer Simultanvorstellung der Berliner Schachgesellschaft’) – no date. Capa, White, opened 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bb5 a6 5 Bxc6 dxc6 6 O-O Bd6 7 d4 Bg4 8 dxe5 Bxf3 9 Qxf3 Bxe5 10 Bg5 O-O 11 Rad1 Qe8 12 Rfe1 Qe6 13 Bxf6 Bxf6. The Cuban’s next move was of a kind we have never seen elsewhere in his games: 14 Qh3. Is there any explanation for this other than a desire to be gallant? The game was drawn in 35 moves.

(972)

An endnote on page 269 of Chess Explorations:

The game was also given on pages 222-223 of Capablanca-Magazine, 31 December 1913, Black being called ‘Sra. de Broch’ (C.N. 1161).

Page 193 of CHESS, 14 February 1938, quoted from H.W. Hawks in the Newcastle Evening Chronicle: ‘In a long career – over 50 years of chess – Dr Lasker has acquired the unique distinction of never winning a game from a lady. As a chess gallant he is without a peer.’ In fact, Lasker had a 100% record in serious play, derived from his win against Vera Menchik in their only game (Moscow, 1935). We gave a simultaneous display victory by Lasker over Miss A.M. Gooding on page 103 of CHESS, March 1980.

John Graham’s Women in Chess (Jefferson, 1987), though not as bad as his earlier book The Literature of Chess, is still very weak – a cuttings-library job replete with factual misconceptions and wishful thinking. In his Foreword Koltanowski writes meaninglessly: ‘If more attention was given to promoting chess among women, I would not be surprised if before long we have a woman as world champion.’ On the following page Graham claims that ‘the number of women players is still small to be sure, but those at the top are giving male players a good run for their money’. On page x he remarks that ‘nowhere can you find a book in English on Gaprindashvili’s or Chiburdanidze’s career or games’, without adding that the same may be said of dozens of other players with similar ratings.

Yet Graham can also be patronizing; one might even say sexist. He gives photographs and then fully describes what he sees in them. For instance, Rudenko (aged 78) is ‘a large woman, clad in black with a white woven shawl about her shoulders. She has straight white hair neatly cut about her strong and unlined face. She looks calm and serene. She looks like she could be anyone’s grandmother ...’ (page 21). In any case, to be ungallant, the word ‘unlined’ is inappropriate.

Graham’s historical fancifulness is shown by his treatment of Vera Menchik. We are told on page 16 that she ‘was a very good player indeed and equal to most men of her day’. The Companion (page 211) rightly says: ‘In international tournaments which did not exclude men Menchik made little impression’. And why does Graham believe (page 17) that it was in 1944, the year she died, that Menchik was ‘at the height of her chess prowess’? On page 18 he writes: ‘We will never know how good Menchik could have become, but she was better than most men and the equal of some very great players. Among those she beat were ...’ Winning an occasional game from Euwe, Reshevsky, etc. did not make her their equal. In the same paragraph, Tiller should read Golombek. On the next page it is misleading to say that ‘Menchik finished second in London 1932’. She was eighth at the London International Tournament of February 1932 and came second merely in the British Chess Federation Major Open (London, August 1932). On the same page we are told that ‘Capablanca beat her nine times, and although the result was never in doubt, Menchik was never totally outclassed by the world champion as many men might have expected a woman to be outclassed. In the following game she plays for a draw by exchanging pieces ... unfortunately, in hindsight, we know that the Cuban was one of the greatest endgame masters, and a slight advantage was all he needed for a convincing win’. Apart from the fact that Capa was the ex-world champion by the time he first met Menchik, the ‘in hindsight’ is really too much. Finally, one notes Graham’s obsession with Vera Menchik’s death. Page 11: ‘She died in the war in 1944.’ Page 17: ‘... in 1944, the entire Menchik family was wiped out in Kent by one of the last German V-2 buzz bombs to land in Britain.’ Page 21: ‘Menchik was killed by a Nazi bomb in 1944.’ Page 68: ‘Then war intervened, and when it ended Menchik was dead, a victim of a German buzz-bomb.’

(1405)

From Ken Whyld:

‘Women in Chess is less competent than you make it sound. Graham gives several championships as having unavailable details (which he could have found readily in Chess: The Records) but quite cheerfully counts as a world championship a four-game match between Menchik and Graf played in the home of Euwe from 21 to 25 March 1934. True, while they were there they did discuss the possibility of a title match later in the year, but nothing came of it.’

(1437)

The above items were published in the Chess Notes magazine (May-June and July-August 1987 respectively). Over two years later (in a letter dated 2 August 1989) Mr Whyld suddenly reverted to the matter (with many misguided references to and comparisons with the output of Raymond Keene). One assertion was: ‘you were restrained in your criticism of Graham’s book on women’s chess (from “your” publisher), although you did not, indeed could not, overlook its “sloppy history”.’

Our complaints about his reference to ‘from “your” publisher’ (i.e. McFarland, which was to publish our monograph on Capablanca about two and a half years after Women in Chess appeared) resulted in non-apologies (‘I am pleased to note your denial that you were trying to avoid offending the publisher’ and ‘I regret that you detected a smear’, but we persisted and, for our pains, the following Whyld Special was sent to us on 6 October 1989:

‘I have no right to question your opinion if you believe that Women in Chess did not deserve a strong review from you. At the time I found it incredible that you should have been so soft without some external factor colouring your judgment. The fact that you were at an advanced stage of producing a book for that publisher appeared to offer an explanation. If the truth is simply that you are ill-informed about the subject of Graham’s book (without sinking to the author’s level), then I was wrong and I apologize.’

Such conduct by Kenneth Whyld can be no surprise. In Edge, Morphy and Staunton we commented regarding him:

At his best, he was one of the best; at his worst, he was one of the worst.

For other examples of Kenneth Whyld’s behaviour, see Reliability Eroded.

From Ed Tassinari (Scarsdale, NY, USA):

‘In the book The Way It Was: 1876 by Suzanne Hilton (Westminster Press: Westminster, Pennsylvania, 1976), the author cites the following passage from an 1876 work entitled The Young Lady’s Book by Mrs Henry Mackarness, published by George Routledge and Sons:

“Chess is not a game much played by ladies as it requires rather more thought and calculation than women possess”.’

(1681)

The above is a simplification of what was on page 373 of the 1876 book:

The writer was Matilda Anne Mackarness (1825-81).

On pages 210-211 of The Adventure of Chess (New York, 1950) Edward Lasker relates how, in London in 1912, Gunsberg played a trick on him when getting him to play a game against a woman visitor to the Divan. Only after Lasker had lost did Gunsberg tell him that she was Mrs Fagan, who ‘just recently returned from San Remo, where she won the ladies’ world championship’. The story is also related on page 171 of Bradley Ewart’s Chess: Man vs Machine.

A few contemporary sources, such as page 37 of the second volume of Schachjahrbuch für 1911, refer to a ladies’ tournament in San Remo in 1911, but none mentions the title ‘world championship’ or gives Mrs Fagan as a competitor. They all say that the event was won by Miss Kate Finn of London.

Did Lasker mix up the names Finn and Fagan? And what was the basis for the ‘world championship’ claim?

(2120)

The opinion of H.E. Kennedy, as given on page 215 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1844:

‘That ladies do not generally play chess well, is owing, I think, not so much to a deficiency of intellectual capability for the game, but rather that the female physique being more sensitive and easily excitable than that of man, renders it difficult for them to maintain the complete abstraction and concentration of mind and thought, without which it is impossible to become a good player. There is no rule, however, without its exceptions; and I have heard of lady chessplayers contending successfully, upon even ground with the front-rank men of the St George’s Club.’

(2232)

The front cover of Frauen am Schachbrett by Regina Grünberg and Gerd Treppner (Hollfeld, 1991):

An extract from a letter from Emanuel Lasker to Walter Penn Shipley, as quoted on page 249 of the November 1919 American Chess Bulletin:

‘In chess I have become a “duffer”, though with training I might learn the game anew. I am rather sick of war, famine, revolution, immorality and violence. Not that I despair of the world – not at all – but for the moment I should like to be out of the center of the tempest; because my power of endurance is nearly used up, not physically, but morally. I have a longing to be at a quiet spot for a while until I know that fruitful effort is again appreciated. My wife is wonderfully patient and enduring, as, in fact, all good women are.’

(2259)

This passage from the Belfast Northern Whig found its way onto page 190 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1862:

‘Let it be understood that I call marriage an evil only as regards chess; for your new-made wife is a sad drag on your ardent chess-player, and we have even known ladies, married for years, who still cry out loudly, as their lord’s weekly club-night comes round; for that night they make every possible kind of engagement – that night is the only one of the week on which they can entertain their friends, and for that night, of all others, they most gladly accept an invitation. Then the great female failing is antagonistic to the silent game, and players are obliged to dispense with ladies’ society at their meetings. This leads to bachelor parties, another great cause of conjugal offence. I entertain all possible love and reverence for the sex; but still, with this my experience, I cannot refrain from advising the bachelor chessplayer, contemplating matrimony, to pause before he take the fatal leap. He must choose for himself; but let him do it deliberately between his board and his wife – between his chess-box and her band-box. Except through many a matrimonial row, there is no middle way.’

(2572)

An interesting book of which we have a copy inscribed by the author is My Way with Polio by Owen Dixson (London, 1963). On pages 75-76 he describes a visit with a female friend to the Gambit Chess Rooms, Budge Row, London, which were run by ‘a famous British woman player, Miss Price, who had herself won the English Ladies’ championship when in her prime’:

‘As we entered the tea-rooms I was aware of a surprised look on the face of Florrie, the waitress who usually served me, but as she took my order without comment my friend and I sat down at a table and began to set up the men on the board. At that moment there arrived on the scene a very irate Miss Price. As I rose clumsily to my feet she snapped, “The Gambit is for men only – women are not allowed”. I was astonished, never having heard of the ban. “Surely you know”, she went on, “that we don’t permit men to play with girls here. I am afraid she will have to go!”

I looked helplessly at my companion, who was an unusually good woman player whom I had beaten in an inter-borough 100-board match between Woolwich and Greenwich a week or two before and who was anxious to get her revenge. There seemed to be nothing for it but to beat an ignominious retreat. But Miss Price, who was really a very good sportswoman, relented and let us play our game – more than that, she even condescended to watch (and criticize) the closing moves.’

Dixson’s autobiography, which is well worth seeking out, contains many chess reminiscences concerning such figures as Vera Menchik. His off-the-board exploits included participation in the 1959 Daily Mail air race between London and Paris, in which he drove the majestic vehicle shown below:

(2969)

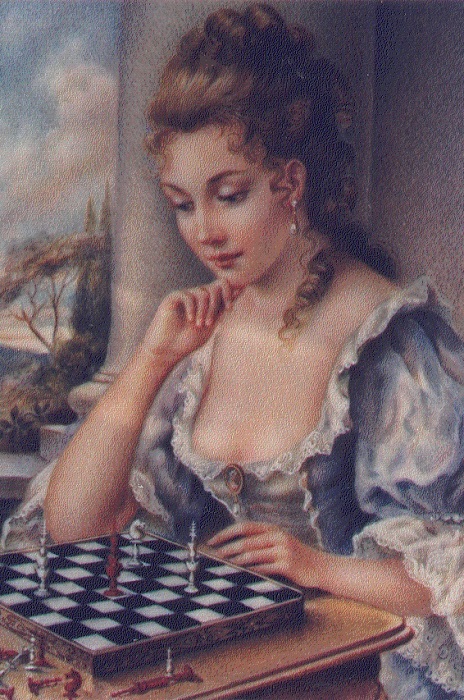

A postcard-size copy of the painting below was sent to us on 31 October 1985 by the late Adriano Chicco, inscribed by him on the reverse:

Can readers provide information about the picture?

(3019)

Mauro Torelli (Milan, Italy) writes:

‘The picture appears (in black and white) on the front page of the book Prontuario del problemista by the well-known Italian problemist Gino Mentasti (published by Scacco!, 1977). It is referred to as a painting by M. Fratta entitled “La soluzione è vicina” (“The solution is near at hand”).’

(3041)

Charles Drury – Mary Rudge

Dublin, 1889

Hungarian Defence

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Be7 4 c3 Nf6 5 d3 O-O 6 O-O d6 7 h3 Na5 8 Bb5 Nc6 9 Nh2 Bd7 10 Ba4 d5 11 Bg5 dxe4 12 Bxf6 Bxf6 13 dxe4 Qe7 14 Na3 Rad8 15 Qe2 a6 16 f4 exf4 17 Rxf4 Bg5 18 Rff1 Ne5 19 Bb3 Ng6 20 Nc2 Nf4 21 Qf3 Qe5 22 Nd4 b5 23 Ne2 Ne6 24 Kh1 c5 25 Ng4 Qc7 26 e5 c4 27 Bc2 Bc6 28 Qf5 g6 29 Nf6+ Kh8 30 Qg4 Qxe5 31 Nxh7 Kxh7 32 Qh5+ Kg8 33 Bxg6 Qg7 34 Bc2 Qh6 35 Qg4 Ng7 36 Nd4 Bb7 37 Rad1 f6 38 Bf5 Qh4 39 Qe2 Rde8 40 Qc2 Re3 41 Nf3 Qh6 42 Rde1 Nxf5 43 Qxf5 Rfe8 44 Rxe3 Rxe3 45 Nd4 and Black gave mate in three moves.

‘Miss Mary Rudge has for long enjoyed the reputation of being the strongest lady chessplayer in the world’, commented the August 1897 BCM (page 289), yet when she died the same magazine (January 1920 issue, page 13) accorded her only three lines:

‘As we go to press we learn with great sorrow of the death, at Streatham last month, of Miss Mary Rudge, winner of the International Ladies’ Tournament in 1897.’

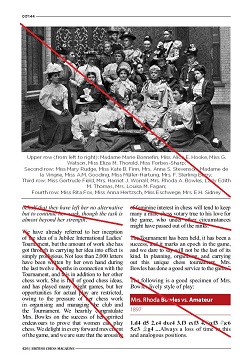

That event, which marked the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Victoria, was certainly the culmination of Mary Rudge’s chess career, and page 287 of the August 1897 BCM observed:

‘Her play was marked throughout by care, exactitude and patience. Someone said of her, “She doesn’t seem to care so much to win a game as to make her opponent lose it”. She risked nothing, she never indulged in fireworks for the purpose of startling the gallery; if she got a pawn, she kept it and won, if she got a piece she kept it and won, if she got a “grip” she kept it and won, if she got a winning position she kept it and won. Not that she always outplayed her opponents in the openings, or even in the mid-games, for the reverse was sometimes the case; but risking nothing she always managed to hold her game together, and then in the end her experience as a tournament player and her skill in end positions came in with powerful effect.’

There follows a sample game from the event:

Mary Rudge – Louisa Matilda Fagan

London, 30 June 1897

Giuoco Piano

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 d3 d6 5 Be3 Bxe3 6 fxe3 Na5 7 Nbd2 Nxc4 8 Nxc4 Be6 9 Ncd2 c6 10 Qe2 Nf6 11 O-O Qb6 12 b3 O-O-O 13 Kh1 h5 14 Ng5 Rde8 15 Nxe6 Rxe6 16 Rae1 Qc7 17 Nf3 d5 18 Ng5 Re7 19 exd5 Nxd5 20 Qf3 f6 21 Qh3+ Qd7 22 Qxd7+ Rxd7 23 Ne4 Nb4 24 Rf2 Rxd3 25 cxd3 Nxd3 26 Rd1 Nxf2+ 27 Nxf2 b5 28 Ne4 Rd8 29 Rxd8+ Kxd8 30 Kg1 Kc7 31 Kf2 Kb6 32 Kg3 f5 33 Nd6 g6 34 Nc8+ Kc5 35 Nxa7 g5 36 a3 Kd5 37 Kf3 Kc5 38 g3 Kd5 39 e4+ fxe4+ 40 Ke3 g4 41 b4 Kc4 42 Nxc6 Resigns.

Sources: Deutsche Schachzeitung, July 1897, pages 207-208 and La Stratégie, 15 August 1897, pages 238-239.

Some background information about her career was given in the above-mentioned BCM item (i.e. on page 289 of the August 1897 number):

‘Miss Mary Rudge has for long enjoyed the reputation of being the strongest lady chessplayer in the world, and the fact that she has carried off the first prize in the present tournament, thereby becoming entitled to style herself lady chess champion of the world, is very satisfactory to her many friends. Miss Rudge comes of a chessplaying family, for she was the daughter of Dr Rudge, who practised as a surgeon in the little town of Leominster, where Miss Rudge was born [on 6 February 1845 according to the Chess Lovers’ Kalendar by Clara Millar]. Dr Rudge was very fond of chess and played a fairly strong game, though he never took part in public chess. He taught the moves to his elder daughters, and they in turn taught Miss Mary. About 15 years ago she won the second prize in Class II at the now defunct Counties’ Chess Association Meeting, at Birmingham, her opponents of course being of the male sex. She also took a prize at the Grantham Meeting of the Counties’ Chess Association.

In 1890, at Cambridge, Miss Rudge won the Ladies’ Challenge Cup, also third prize in Class II against male competitors. In 1896 she won first prize Class II at the Southern Counties’ Tournament, when she played against a strong opposition of nine men. Some years ago Miss Rudge won the Bristol and Clifton Challenge Cup. In the Dublin Mail Correspondence Tourney she tied for second and third prizes, but in the personal encounter she defeated Mr Gunston, who carried off first prize, no mean feat when we remember Mr Gunston’s strength as a player.’

Below is an example of her play taken from pages 171-172 of The Bristol Chess Club by J. Burt (Bristol, 1883):

William Berry – Mary Rudge

Birmingham, August 1874

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 Nf6 4 Nc3 a6 5 Bxc6 dxc6 6 O-O Bd6 7 d4 Qe7 8 Bg5 h6 9 dxe5 Bxe5 10 Nxe5 Qxe5 11 Bxf6 Qxf6 12 f4 Qe7 13 f5 Qe5 14 Qd3 Bd7 15 Rad1 O-O-O 16 Qc4 Rhf8 17 Qd4 Qxd4+ 18 Rxd4 f6 19 Rfd1 Rfe8 20 b4 Re5 21 a3 c5 22 Rd5 Rxd5 23 Rxd5 cxb4 24 axb4 Re8 25 Kf2 Bc6 26 Rd4 Re5 27 Ke3 a5 28 bxa5 Rxa5 29 Kf4 Rc5 30 Rd3 b5 31 h4 Rc4 32 g4 b4 33 Nd5 Bxd5 34 Rxd5 Rxc2 35 g5 hxg5+ 36 hxg5 fxg5+ 37 Kxg5 c5 38 Kg6 b3 39 Kxg7 b2 40 e5 b1(Q) 41 White resigns.

We have noted two occasions when she was the subject of an appeal for funds, the first being on page 231 of the June 1889 BCM:

‘Our readers will be sorry to hear that Miss M. Rudge, of Clifton, is at present in very depressed pecuniary circumstances; so much so that she has felt obliged (though most reluctantly) to give her consent to an appeal being made on her behalf. We are sure English chessplayers will not allow one of their best lady players to remain in actual, though it is to be hoped only temporary, want, and contributions for its relief, however small, will be thankfully received by the Rev. C.E. Ranken, St Ronan’s, Malvern, and acknowledged by him privately to the donors.’

Then in 1912 the Cork Weekly News published the following announcement by Mrs F.F. Rowland:

‘Miss Mary Rudge is the daughter of the late Dr Rudge, and after his death she resided with her brother, who kept a school, but since his decease she is quite unprovided for, her sisters are also dead, and she is without any income of any kind. She lived as companion with various ladies, and was for some years resident with Mrs Rowland, both at Clontarf and Kingstown. Whilst at Clontarf, she played in the Clontarf team in the Armstrong Cup matches, and proved a tough opponent, drawing with J. Howard Parnell and winning many a fine game. She was also engaged at the DBC to teach and play in the afternoons. At the Ladies’ International Congress, London, she took first prize (£60), making the fine score of 19½ in 20, the maximum [18½ from 19, in fact]. Miss Rudge held the Champion Cup of the Bristol Chess Club, prior to Messrs H.J. Cole and F.U. Beamish. Miss Rudge is now quite helpless from rheumatism and is seeking admission into a home or (if possible) the Dublin Hospital for Incurables. A fund is being collected for present expenses, pending her admission, and chessplayers are asked to help – either by influence or money. Donations may be sent to Mrs Rowland, 3 Loretto Terrace, Bray, Co. Wicklow, or to Mrs Talboys, 20 Southfield Park, Cotham, Bristol.’

Source: American Chess Bulletin, May 1912, page 112.

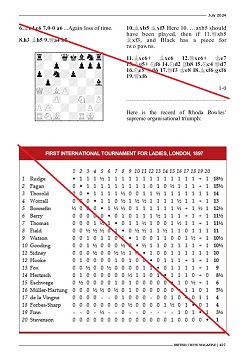

The photograph below, which features the competitors at London, 1897, appeared in the July 1897 American Chess Magazine, without, unfortunately, any identification of them:

(3281)

David McAlister (Hillsborough, England) submits the following game:

W. Cooke (Kingstown) – Mary Rudge (Clontarf)

Armstrong Cup, Dublin, 25 January 1890

Scotch Game

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 exd4 4 Nxd4 Bc5 5 Be3 Qf6 6 c3 Nge7 7 Bb5 O-O 8 Nxc6 dxc6 9 Bxc5 cxb5 10 Na3 Re8 11 f3 Ng6 12 O-O Qg5 13 Bf2 Be6 14 Nc2 Rad8 15 Nd4 Bc4 16 Re1 Nf4 17 Bg3 c5 18 b3

18…Ne2+ 19 Rxe2 Bxe2 20 Qxe2 cxd4 21 f4 Qc5 22 Bf2 Qxc3 23 Rd1 d3 24 Qf3 Qc2 25 Bxa7 Ra8 26 Bd4 Rxe4 27 Qxd3 Re1+ 28 White resigns.

Source: Dublin Evening Mail, 1 May 1890.

(3286)

When was the first mention in chess literature of a title such as ‘women’s chess champion’? The bidding opens here with a paragraph from page 213 of the July 1879 La Stratégie:

‘Madame Gilbert, “la Reine des Echecs”, a accepté un match, par correspondance, avec Melle Ella-M. Blake, de New-Berry, Etats-Unis, dont la réputation comme amateur d’échecs est très grande dans le Nouveau-Monde. Cette lutte intéressante commencera aussitôt que Mme Gilbert aura terminé plusieurs parties qu’elle joue en ce moment. La victorieuse sera le champion des échecs du beau sexe.’

(3293)

The above item was accompanied by this sketch of Mrs Gilbert from the American Chess Journal:

Mark N. Taylor (Mount Berry, GA, USA) points out that when the London, 1897 group photograph (which we culled from that year’s American Chess Magazine) appeared on page 116 of Dame aan Zet/Queen’s Move by R Kruk, Y. Nagel Seirawan, H. Reerink and H. Scholten (The Hague, 2000) a caption identified the players. Despite mentioning the American Chess Magazine, the book published the photograph in reverse form and, cautious to the last pawn, we refrain from listing the players’ names until corroboration has been found.

Further to the recent items on nineteenth-century women players, John McCrary (West Columbia, SC, USA) mentions Amalie Paulsen (1831-1869), the sister of Louis and Wilfried. As noted on page 237 of A Chess Omnibus, volume 1 of our correspondent’s 1998 publication The Hall-of-Fame History of U.S. Chess quoted the statement on pages 85-86 of the New York, 1857 tournament book that she was ‘believed to be the strongest amateur of her sex in the country’.

We add here that two games of hers were given in the feature on pages 115-116 of Horst Paulussen’s valuable book Louis Paulsen 1833-1891 und das Schachspiel in Lippe 1900-1981 (Detmold, 1982):

Amalie Paulsen – Wilfried Paulsen

Nassengrund, 1858

French Defence

1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 exd5 exd5 4 Nf3 Nf6 5 Bd3 c5 6 dxc5 Bxc5 7 Bg5 O-O 8 O-O Qd6 9 Nc3 Be6 10 Nb5 Qb6 11 Ne5 Nbd7 12 Nxd7 Bxd7 13 Bxf6 Qxf6 14 Nc7 Rad8 15 Nxd5 Qg5 16 Nc3 Bc6 17 g3 Qh6 18 Qg4 Rd4 19 Qf5 Bb6 20 Be4 g6 21 Qf3 Rxe4 22 Nxe4 f5 23 Qb3+ Kg7 24 Qc3+ Kf7 25 Qf6+ Ke8 26 Qe6+ Kd8 27 Rfd1+ Kc7 28 Qe5+ Kc8 29 Nd6+ Resigns.

Wilfried Paulsen – Amalie Paulsen

Nassengrund, 1858

Philidor’s Defence

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 d6 3 d4 f5 4 dxe5 fxe4 5 Ng5 d5 6 e6 Nh6 7 f3 Bc5 8 fxe4 O-O 9 exd5 Rf5 10 Nc3 Bb4 11 Bc4 Qf6 12 Ne4 Qh4+ 13 Ng3

13…Re5+ 14 Be2 Nf5 15 Rf1 Nxg3 16 Rf4 Nxe2+ 17 Rxh4 Nxc3+ 18 Kf1 Nxd1 19 Rxb4 Bxe6 20 dxe6 Rxe6 21 Rd4 Ne3+ 22 Bxe3 Rxe3 23 Rd8+ Kf7 24 Rad1 Re8 25 R1d3 Nc6 26 R8d7+ Re7 27 White resigns.

Both games had been published in the January 1870 Deutsche Schachzeitung (pages 6-7), where she was referred to under her married name (i.e. ‘Frau Dr. Lellmann’ and ‘Amalie Lellmann’). Five further games between the same two players (+2 –1 =2 to Wilfried) were given on pages 49-52 of the February 1870 Deutsche Schachzeitung, the liveliest being the following:

Wilfried Paulsen – Amalie Paulsen

Occasion?

Philidor’s Defence

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 d6 3 d4 f5 4 Bc4 Nc6 5 Ng5 Nh6 6 Nxh7 Qh4 7 Bg5 Qxe4+ 8 Kf1 Ng4 9 f3 Ne3+ 10 Bxe3 Qxe3 11 Nxf8 Rxf8 12 dxe5 Nxe5 13 Na3 Bd7 14 Qd5 O-O-O 15 Re1 Qb6 16 Bb3 Rde8 17 c3 Bc6 18 Qd2 Re7 19 f4 Ng6 20 Rxe7 Nxe7 21 Ke1 Re8 22 Kd1 Be4 23 Re1 Rh8 24 g4 g6 25 gxf5 gxf5 26 Qe2 Qc6 27 Kc1 Nd5 28 Qd2 Nb4 29 Bc4 Nd5 30 Rxe4 fxe4 31 Bxd5 Qc5 32 Be6+ Kb8 33 h3 Qg1+ 34 Kc2 e3 35 Qe2 Qg6+ 36 f5 Qg3 37 Nc4 Rxh3 38 Kd3 b5 39 Nxe3 Qe5 40 Qf2 c5 41 f6 c4+ 42 Ke2 Rh2

43 f7 Rxf2+ 44 Kxf2 Qf4+ 45 Ke2 Qh2+ 46 Kf3 Qh5+ 47 Ng4 Qh8 48

Kf4 Kc7 49 Kg5 Qg7+ 50 Kf5 Kd8 51 Nf6 Ke7 52 Nd7 Qh7+ 53 Kg5 Qg7+

Drawn.

(3297)

Information is still being sought on two women players of the 1930s (see page 305 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves).

The first is Maud Flandin. Pages 928-929 of the January-February 1935 L’Echiquier gave two positions from games won by her, with the following text:

‘La championne de France, Mlle Maud Flandin (née a Saïgon) a très vite atteint un haut degré de perfection. Elle va probablement affronter en 1935 la détentrice du titre mondial, Mlle Vera Menchik.’

She never did compete for the women’s world championship, but what can be found out about her?

The other case is even stranger, involving an extravagant claim. In the early 1990s David Pritchard sent us a page from one of his scrapbooks which had an item published in the Daily Sketch in 1936 (exact date not recorded):

‘Miss Angeligi Leoni, of Cyprus, won twenty-seven and drew three of thirty simultaneous games of blindfold chess.’

(4085)

Milan Ninchich (Macquarie, ACT, Australia) writes:

‘I am researching the chess career of Mary Mills Houlding, who was born in May 1850 and lived near Wagga Wagga, NSW (not yet Australia). In 1899 she emigrated to South Wales, where she became a member of the Newport Chess Club. She won the British Ladies’ Championship in Oxford in 1910, was champion again the following year in Glasgow and gained the title a third time in Chester in 1914, when she was 64. In 1928, at the age of 78, she won the Newport Club Championship. She died in Newport on 19 February 1940.’

Our correspondent is, in particular, seeking games played by her, and readers’ assistance will be appreciated.

C.N.s 1133 and 1154 (see pages 53-54 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves) briefly discussed Mrs Houlding, and in the latter item we commented that examples of her play were rare. As the best traceable one we gave her first-brilliancy-prize victory over Alice Taylor in the 1909 British Ladies’ Championship in Scarborough.

C.N. 1154 also stated:

‘We note that Mrs Houlding is to be seen in a group photograph on page 363 of the September 1913 BCM. She appears to be about half the size of everybody else (hence the expression “small Houlding”).’

Below, from page 70 of the 1922 issue of Chess Pie, is a tableau of ‘British Lady Champions – Past and Present’ which includes Mrs Houlding:

(4500)

One of our items (C.N. 4379) on Nick de Firmian’s 2006 edition of Chess Fundamentals drew attention to this remark in his Introduction, concerning the textual changes made to Capablanca’s book:

‘The chess historian should have little trouble deciphering which material is original if he or she is observant.’

We commented:

This ‘he or she’ stuff, incidentally, is de Firmian’s preferred usage, and he foists it on Capablanca throughout. The first sentence in the first chapter of the first part of the original Chess Fundamentals stated: ‘The first thing a student should do, is to familiarise himself with the power of the pieces.’ De Firmian puts instead: ‘The first thing a student should do is to familiarize himself or herself with the power of the pieces.’

A further observation by us, in C.N. 10354:

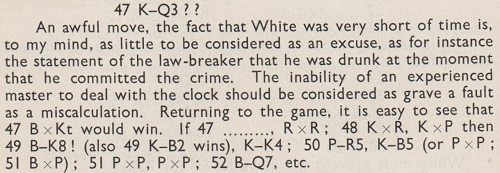

If, heaven forfend, de Firmian were let loose on Alekhine’s book on Nottingham, 1936, he would come to this note, on page 56 of the original, concerning the third-round game between Alekhine and Tylor:

Or, in the ‘style’ imposed by de Firmian:

‘... the statement of the law-breaker that he or she was drunk at the moment that he or she committed the crime.’

Another example can be proposed, in connection with Clive James and Chess, which includes a passage on page 20 of the Introduction to his book From the Land of Shadows (London, 1982), quoted in C.N. 10246:

‘The necessary conceit of the essayist must be that in writing down what is obvious to him he is not wasting his reader’s time. The value of what he does will depend on the quality of his perception, not on the length of his manuscript.’

That could give:

‘The necessary conceit of the essayist must be that in writing down what is obvious to him or her he or she is not wasting his or her reader’s time. The value of what he or she does will depend on the quality of his or her perception, not on the length of his or her manuscript.’

However, the plural is an option:

‘The necessary conceit of essayists must be that in writing down what is obvious to them they are not wasting their reader’s [readers’] time. The value of what they do will depend on the quality of their perception, not on the length of their manuscript.’

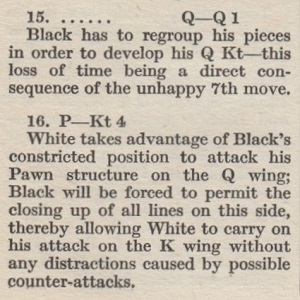

This is from page 231 of Capablanca’s Hundred Best Games of Chess by Harry Golombek (London, 1947). Notwithstanding the terms ‘his pieces’, ‘his QKt’ and ‘his Pawn structure’, Black was Vera Menchik (Moscow, 1935), and the same page also had ‘defended herself’, ‘she gives’, ‘her Pawn position’, ‘her pieces’ and ‘her position’.

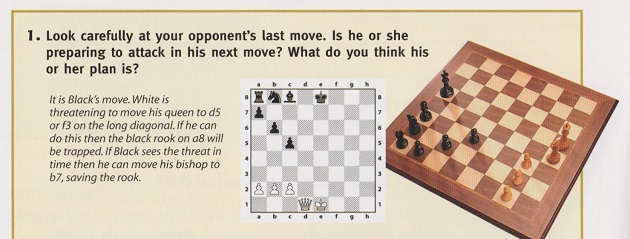

In general cases (e.g. in English-language introductory books and manuals) ‘he’, ‘his’ and ‘himself’ were used automatically until recent times, but today it is a quandary for the writer. He can easily make herself look silly, as shown by page 18 of How to play Chess and Win! by Tanya Jones (London, 2007):

(9075)

On the same theme, below is the start of C.N. 10973:

‘The player who completes his development first is said to have the initiative, because he is thus able to start making blunders while his opponent is still occupied in bringing out his men.’

That remark from page 14 of “Among These Mates” by Chielamangus (Sydney, 1939) was given in C.N. 1858 (see page 246 of Chess Explorations).

A modern alternative:

‘The player who completes his or her development first is said to have the initiative, because he or she is thus able to start making blunders while his or her opponent is still occupied in bringing out his or her men or women.’

Luca D’Ambrosio (Bolzano, Italy) mentions a tournament in Meran in 1924 which occasioned the term ‘unofficial European women’s champion’ on page 4 of the Meraner Zeitung of 26 January 1924:

‘Eine geradezu sensationelle Veranstaltung aber ist das Damenturnier, das Meldungen der besten Spielerinnen des Kontinents und Englands in einer in Europa bisher noch nie gesehenen Besetzung aufweist. Die Siegerin des Turniers darf sich getrost als inoffizielle Europameisterin bezeichnen.’

The final standings were: 1-2 Cotton and Holloway (England) 5½; 3 Stevenson (England) 5; 4 Michell (England) 3½; 5 Kalmar (Austria) 3; 6-7 Gülich (Czechoslovakia) and Pohlner (Austria) 2½; 8 König (Germany) ½.

Of the successful players in Meran, Miss Cotton is probably the least known. Our correspondent notes that she was named in the Kurzeitung und Fremdenliste Meran Nr. 24 of 16 February 1924 (page 3) as ‘Cotton-Meirchin Charlotte Helene, Private, London’.

The crosstable was given on page 104 of Schachjahrbuch 1924. I. Teil by L. Bachmann (Ansbach, 1925). Page 129 of the April 1924 BCM reported that after the tournament three of the participants (Holloway, Cotton and Stevenson) defeated three others (Kalmar, Gülich and Pohlner) in a double-round London v Vienna match which the magazine described as a ‘unique event, we believe, in chess history’. Noting Miss Cotton’s death, page 92 of the March 1929 BCM remarked that ‘on various occasions she competed in the British women’s championship’. We should like to present one or two good games by her.

(4838)

From page 14 of our publication Chess Characters, volume two by G.H. Diggle (Geneva, 1987) we present another article by the ‘Badmaster’ (BM), originally published in the January 1985 Newsflash. It will be recalled that G.H. Diggle (1902-93) wrote of himself in the third person.

‘The December Newsflash quotes some highly interesting remarks from various learned sources on the alleged inferiority of women chessplayers, who it appears are subject to “biologically programmed ‘interrupts’ which prevent them from concentrating on an intellectual task effectively”. The Editor, with superhuman courage, has actually invited readers’ comment.

The BM considers himself admirably qualified to educate the chess public on this subject, having spent a whole afternoon at the BCF Congress last August watching the grandmasters and grandmistresses of tomorrow, i.e. the “Under Elevens”. There were 16 boards in action, manned mainly by the male sex, but with a large sprinkling of “diminutive damsels”. For chessboard deportment the BM was forced to award the ladies the palm. They sat upright – and indeed their wide-awake appearance was such that some of the “slouching seniors” across the gangway did not benefit by the comparison. In matters of tournament ritual and etiquette they clearly “knew their onions”, and though the rate of play was fast and occasionally hectic, there was “no clock vandalism”, and they recorded their moves with the precision of old professionals. One very small maiden, it is true, did discover that she had missed one out and proceeded some distance down her opponent’s lane in the score-sheet motorway, but she then put up her hand to summon the Controller, a kindly man with a beard who sorted things out in no time. Only four boards started with P-K4 for White and Black – there was what Morphy called “that pernicious fondness” for the Sicilian, but both sexes had got hold of the need for development, and one young lady had cleared her back yard and castled long by the ninth move. Middle-game observation was keen-eyed, and there were few blunders. It was in the endgame that the real weakness showed, and here the greater staying power of the males, and the “biologically programmed what’s-its-name” of the fair ones began to come out. Two hours’ tournament chess is hard graft for a girl of nine on a hot day – the attention begins to wander as the pieces thin out, and there is a tendency to give check or to swap rooks just to get the move over, irrespective of “open file” consequences. The longest game of the day was between a lady who could have only just seen nine Summers and a solid youth some months older. During the middle game “the female proved more deadly than the male” and emerged with king, rook and three pawns against “Solidarity’s” mere king and two pawns. But alas, they were passed pawns well up the board, and the unhappy maiden, instead of bringing her king across to face them, went on checking with her rook until it finally went for a Burton, and “Solidarity” emerged with king and queen against king and three poor isolated pawns. Even then, apparently more through caution than sadism, he deliberately mopped up the three harmless stragglers and refrained from embarking on the final attack until “all was safely gathered in”.

While these titanic struggles were in progress, a large muster of parents relaxed in the Tea Lounge. One lady, apparently discussing her daughter’s defeat on the previous day, uttered one of the most profound truths ever heard at a Chess Congress. “It seems”, she observed mysteriously, “that there are some positions you can’t get out of”.’

(5016)

Rod Edwards (Victoria, BC, Canada) writes:

‘Your Chess Records article has given information on the earliest recorded chess clubs but not on the earliest recorded women’s (or ladies’) chess club. I propose the following as a candidate, on the basis of Staunton’s answers to correspondents in the Illustrated London News:

“‘Margaret J.’, Kensington. – The establishment of a Ladies’ Chess Club, is, indeed, an event in the history of the game, and one of the most pleasing evidences of the progress this fine intellectual discipline is making in society. Let us hope the example set by the ladies in Kensington will be followed by our countrywomen in other directions. The game played between Miss E. and Miss M. is excellent in style, and calculated to afford a very high notion of the capabilities of the fair combatants. Can it be possible they have attained such knowledge of the game in three months’ practice only?” (27 November 1847, page 346.)

“‘R.T.C.’–‘V.’–‘Amazon’. – The Ladies’ Chess Club, to which we alluded in our last, is established at Kennington, not Kensington; and is to be called ‘The Penelope Club’. We presume it will be composed exclusively of female members; but, possibly, as an incentive to excellence, an exception to this rule will be admitted in the case of the leading player of the time, who might without impropriety be entitled to the privileges of an ‘Honorary Member’.” (4 December 1847, page 371.)

The game mentioned in the first of these items would seem to be the one published in the January 1848 issue of the Chess Player’s Chronicle (pages 23-24), between “Miss C.” and “Miss M.”, which Staunton claimed to be the first game involving women ever published. You gave the score on pages 63-64 of A Chess Omnibus (C.N. 2447).

There is one other somewhat curious answer to a correspondent (apparently, the same “Margaret J.”):

“‘M.J.’ – We had not overlooked your question, but could hardly imagine you were in earnest. What would be said to such a procedure as giving the names of several private gentlemen, accompanied by comments on their age, looks, personal deportment, and acquirements, in a public newspaper, simply to gratify the curiosity of a few amiable admirers? The proposed name is very appropriate. We shall hope to hear from you again.” (18 December 1847, page 402.)’

(5769)

A contribution from Robert John McCrary (Columbia, SC, USA):

‘Concerning the earliest ladies’ club, the Chess Player’s Chronicle, volume five, 1844, page 64, quotes a toast at the annual dinner of the Liverpool Chess Club as follows:

“Mr W. Lockerby gave ‘The Ladies’, and in so doing stated that the formation of a Ladies’ Chess Club, and the admission of ladies to their annual festivity, would enhance the pleasure of both sexes.”

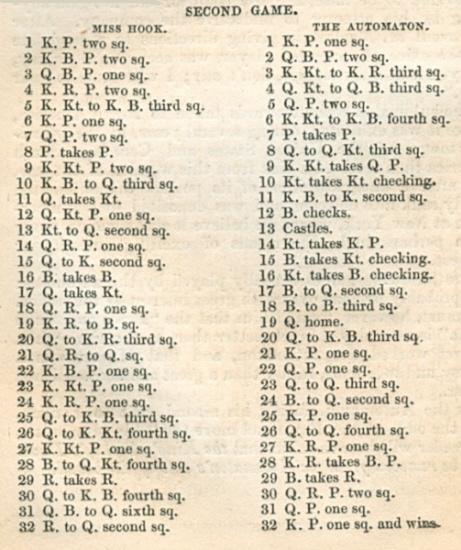

The earliest recorded, actually-played, game involving a woman that I have found is given on page 112 of Amusements in Chess by Charles Tomlinson (London, 1845). He presents the first 32 moves of a pawn-and-move game won by the Automaton against “Miss Hook” in London, evidently in 1819 or 1820:

The same game is on pages 55-56 of The Turk, Chess Automaton by Gerald M. Levitt (Jefferson, 2000), where White is named as “Hook”, without the “Miss”. Levitt gives the date as 1820. Tomlinson concludes with “and wins” after Black’s 32nd move, but Levitt adds four more moves.’

(5775)

From page 52 of Better Chess by William Hartston (London, 2003):

‘One of the best excuses I ever heard was from a man who had just lost to a female opponent. “She completely disrupted my thought processes”, he complained. “Every time I tried to calculate something, I’d begin: ‘I go here, he goes there’, and then I’d have to correct myself: ‘No, it’s I go here, she goes there’.”’

(5884)

Rod Edwards writes:

‘On page 272 of the 25 October 1851 issue of Home Circle, a woman corresponding under the name of “Sybil” issued a challenge to “any chessplayer … not much above the average …” to play a game by correspondence which would be printed as it progressed in the chess column of Home Circle. The 6 December 1851 issue (page 368) reported that she had received several acceptances and had picked one name from an urn: G.B. Fraser of Dundee, who became one of the best players in Scotland in the 1860s and 1870s. Week by week over the next 15 months the moves of the game were reported until at move 51 “The ‘fayre Sybil’ mates with the queen” (Home Circle, 5 March 1853, page 160). The entire game was published with commentary on page 192 of the 19 March 1853 edition and was also reprinted as a game between “A Lady” and “Mr F.” on pages 232-233 of the March 1853 issue of the Chess Player.’

‘A Lady’ – George Brunton Fraser

Correspondence, 1851-53

Giuoco Piano

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 c3 Nf6 5 d4 exd4 6 cxd4 Bb6 7 Bg5 d6 8 h3 h6 9 Bxf6 Qxf6 10 Bb5 O-O 11 Bxc6 bxc6 12 Nc3 Qg6 13 Nh4 Qg5 14 g3 f5 15 Nf3 Qg6 16 Nh4 Qf6 17 e5 dxe5 18 dxe5 Qxe5+ 19 Qe2 Qc5 20 O-O f4 21 g4 Bd7 22 Rad1 Rae8 23 Ne4 Qb4 24 Rfe1 Ba5 25 a3 Qb3 26 Rd3 Qf7 27 b4 Bb6 28 Rf3 Be6 29 Qc2 Bd5 30 Nf5

30...Be3 31 Rexe3 fxe3 32 Rxe3 Kh8 33 f3 Qd7 34 Nc5 Qd8 35 Rxe8 Qxe8 36 Kg2 Qe1 37 Nd3 Qe8 38 Nf4 Qf7 39 Ne7 Qxf4 40 Ng6+ Kg8 41 Nxf4 Rxf4 42 Kh2 Rxf3 43 Qa4 Kh7 44 Qxa7 h5 45 gxh5 Kh6 46 a4 Rf7 47 a5 Kg5 48 Qc5 Kxh5 49 a6 Rf1 50 Qe7 g5 51 Qh7 mate.

(5918)

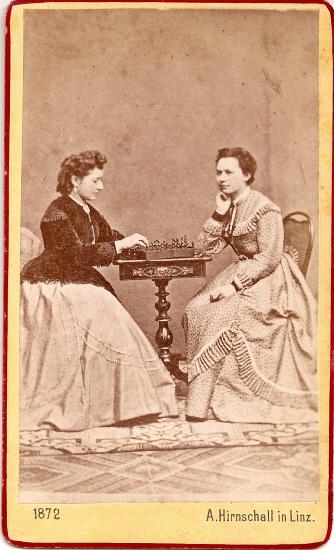

Michael Ehn (Vienna) sends us from his archives a photograph dated 1872:

(6037)

Eliot Hearst (Tucson, AZ, USA) writes:

‘What is the record for the number of simultaneous blindfold games played by a woman? In all the research for our book Blindfold Chess John Knott and I never came across any report of a scheduled, well-regulated blindfold simultaneous display by a woman.’

(6289)

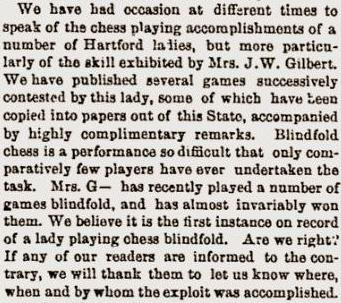

Information on blindfold displays by women is still being sought. In the meantime, Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA) has provided this report concerning Mrs J.W. Gilbert on page 1 of the Hartford Weekly Times, 4 November 1871:

(6468)

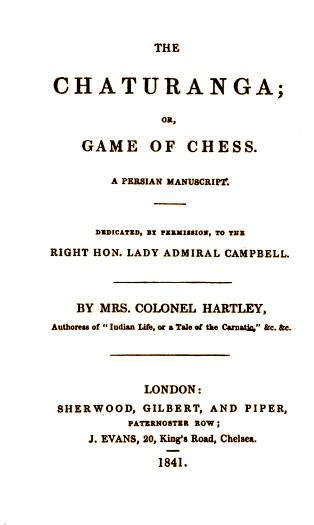

Andreas Lange (Berlin) asks whether there is an older chess book by a woman than The Chaturanga; or, Game of Chess by Mrs Colonel Hartley (London, 1841):

(6386)

‘Lady chessplayers are not so numerous as those of the opposite sex, probably chiefly due to the bump of reason not being as fully developed.’

Source: article in the St Louis Globe-Democrat quoted on page 12 of the January 1917 American Chess Bulletin.

(6651)

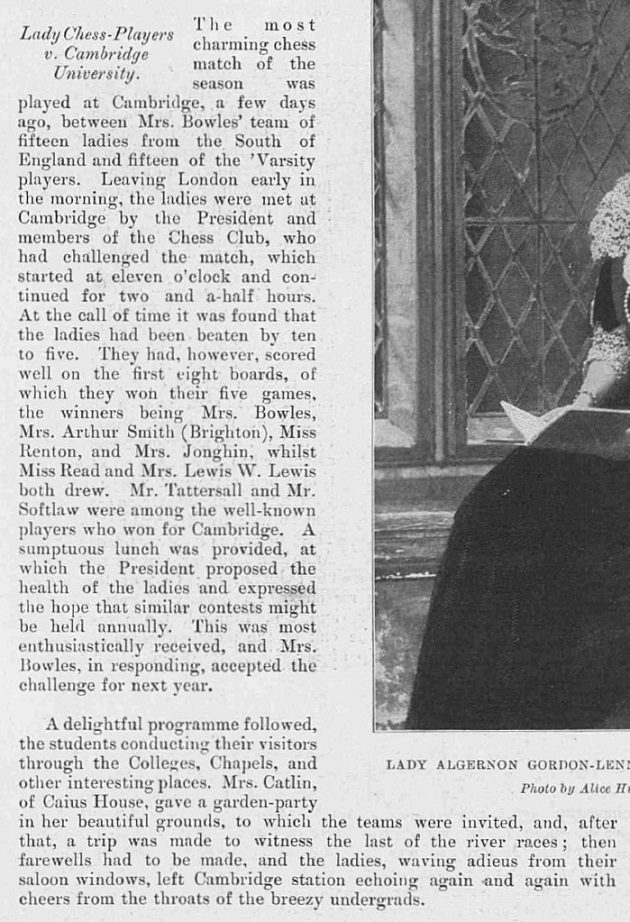

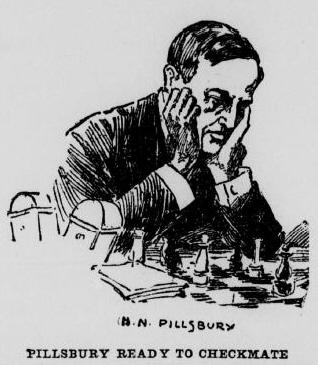

Peter de Jong (De Meern, the Netherlands) sends this article from page 334 of the 14 March 1896 edition of Black and White:

‘Ladies at Chess

By H.N. Pillsbury

Ladies have latterly invaded almost all the fields hitherto occupied by men, but at the beginning of last year they had not yet gone so far as to form a chess club for themselves. That was a state of affairs which only needed to be noticed in order to be remedied, and so the Ladies’ Chess Club came into existence in the month of January 1895. In the beginning it did not include many members, and the members, instead of spending their afternoons in paying calls, used to meet at one another’s houses and study the Royal Game. But the institution was one of the things which, since they meet a long-felt want, are bound to have a rapid success, and before long the list of members had swelled to such dimensions that it was felt to be necessary to have a club-room. This was found, and Monday evenings were devoted to the game, the afternoon visits being still kept up, until the members obtained their present premises, where the weekly meeting is held from three to half-past ten. At the Hastings Tourney, in the section for ladies, no less than seven of the offered prizes were won by LCC members, and they have done very well in their 23 matches against various London clubs. ’Tis true, they have only thrice scored victories, and only twice drawn the match; but, upon the other hand, it must be remembered that they were playing against those who have had vastly more experience than themselves. They might reasonably enough have demanded odds, but they understood that in such a pursuit as this to take a beating intelligently is to go some distance towards gaining the power to inflict a beating at some future encounter, and so they have played on equal terms.

Moreover, although two victories out of 23 matches is not a high rate of success, the record looks better if you say that in the first 20 matches the games lost were 106½, those won 79½. The success of the club as an institution has gone on increasing, and the members already number close upon a hundred. The founders have received the pleasant flattery of imitation, and their happy idea has been copied in Paris, Brooklyn, New York and other cities. There is even talk of a cable match betwixt the club and one or other of the American institutions. The present premises are at 103 Great Russell Street. Lady Newnes is President, while Mrs Bowles, as match captain, has done much to secure the successes which have been chronicled. She is also, for the present, secretary and treasurer. Miss Field is the first lady who has essayed the difficult task of playing blindfold against several opponents simultaneously. Mrs Fagan has played with success in the matches, and is an excellent composer of problems. Lady Thomas, who was the Hastings champion in the Ladies Section, is among the vice presidents. She has played as many as eight games simultaneously. One of the most promising members is Mrs James, who only began to play the game a year ago, and has already won prizes. A tournament has been proceeding with 32 competitors; and the announcement of a 50 players aside match between the Ladies Club and the Metropolitan is a testimony to the energy and enthusiasm displayed.’

An additional paragraph appeared on page 356 of Black and White, 21 March 1896:

‘The Ladies’ Chess Club concerning which Mr Pillsbury lately wrote in Black and White has added another to its list of successes, defeating the Metropolitan Club by 25½ games to 24½. Thirty of the ladies insisted on playing on equal terms with their opponents, but the remaining 20 accepted odds: six of their opponents surrendering a queen, and the others a rook or a knight. Mrs Arthur Smith writes, concerning Mr Pillsbury’s article, that there was a Ladies’ Chess Club in Brighton from 1881 till 1894, when it was merged into the St Ann’s Club.’

Pillsbury’s article was accompanied by photographs of Lady Thomas, Mrs James, Miss Field, Mrs Fagan and Mrs Bowles. The follow-up item had a drawing ‘Ladies at Chess in London’ by J. Barnard Davis.

(6902)

See too Sir George Thomas.

Wayne D. Komer (Toronto, Canada) and Stephen Wright (Vancouver, Canada) submitted in C.N. 7016 an interview with Alekhine by Archibald Lampman which was published in the Toronto Daily Star, 14 November 1932, page 3. The C.N. item gave a full transcript, including the following:

‘“Women good at chess?” “No – they’re not”, he says smiling. And, by the way, if all the Moscow lads smile like that, the home town can’t be so bad after all. “And that’s funny too – because they’re good at bridge and other things – but not chess.” “Just another mystery.” “About women?” “Yes, just one more.”’

This photograph of Gisela Kahn Gresser comes from page 52 of The Year Book of the United States Chess Federation 1944 edited by Montgomery Major (Chicago, 1945).

John Blackstone (Las Vegas, NV, USA) draws attention to an article about her on page 29 of the New York Post, 10 September 1945. We reproduce her views on women’s chess:

‘The usual reason given for men being better players is that chess has been a man’s game for centuries and they’ve had more time ... There may be physical reasons too. There’s great strain involved in tournament chess, and men have more physical endurance than women, as well as more discipline and concentration.

I think maybe the reason they have more concentration ... is that women are too intelligent. They have more important things to do than play chess. To be a really great player you have to give up your whole life to it. Why, I know a musician who started playing chess and it kept him away from home so much that his wife left him. He got fewer and fewer musical engagements and after a while he never knew where his next sandwich was coming from. Now you know women are too realistic for that. But I must say ... he was happy.’

As regards her own chess career (at that time she was the US women’s champion) she stated:

‘I’m afraid ... that chess fascinates me more than anything – and I hate to admit it. I consider it an art, but one of the lower arts. To spend so much time on something that’s not really constructive hurts my conscience. I don’t spend all my time on it ... but I could.’

(7066)

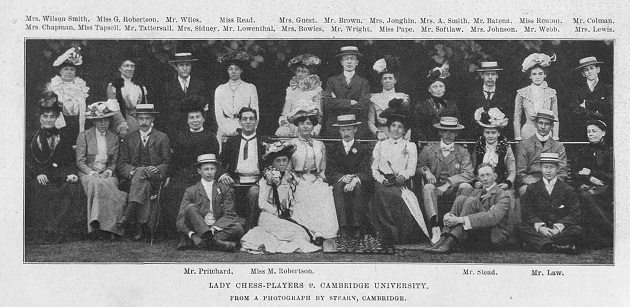

From Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore):

‘Historical photographs involving Oxbridge chessplayers in inter-varsity matches seem scarce. I am particularly interested in group illustrations featuring members of the Cambridge University chess team in the late 1890s and the early twentieth century. Among others, the active members were C.E.C. Tattersall, H.A. Webb, E.E. Colman, H.G. Softlaw, J.E. Wright, C.C. Wiles, B. Goulding Brown, W.S. Ostle, F.K. Loewenthal, F.W. Clarke, and E.W. Burnell.

One such illustration appeared on page 129 of the July 1901 edition of Womanhood, in Rhoda A. Bowles’ chess column:

Are C.N. readers able to find further such photographs?’

(7470)

Gerard Killoran (Ilkley, England) now sends the following, published on page 335 of The Sketch, 19 June 1901:

The accompanying account:

Mr Killoran also provides a match report on page 3 of the Morning Post, 10 June 1901:

(10624)

Olimpiu G. Urcan forwards this photograph from page 1037 of the Illustrated London News of 1 December 1928:

We add that the person standing next to Capablanca is Mrs Arthur Rawson, the President of the Imperial Chess Club. The following picture comes from opposite page 57 of the February 1928 BCM:

For an exchange of letters between Capablanca and Mrs Rawson see page 247 of our book on the Cuban. The ancestry.com website states that Ella Frances Rawson died in Whissendine on 17 July 1942.

(7496)

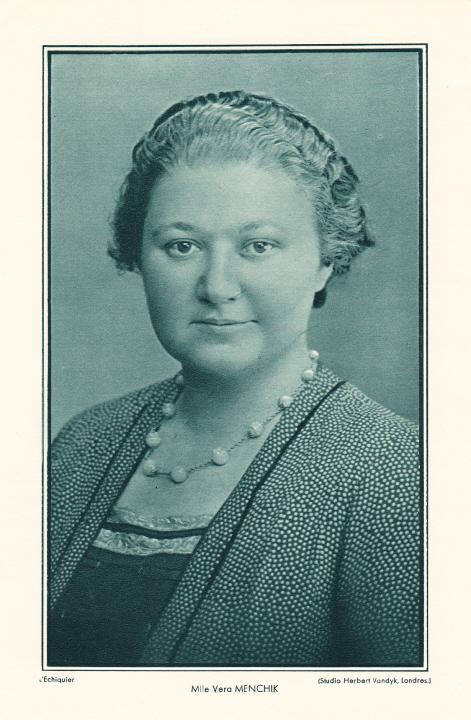

John Blackstone points out an article ‘Chess Playing as a Profession for Women’ by Nellie M. Showalter in the Los Angeles Herald, 6 February 1898, page 24. It includes two sketches of H.N. Pillsbury:

(7877)

An oft-found statement about Simpson’s-in-the-Strand, London:

‘It also hosted the great tournaments of 1883 and 1899, and the first ever women’s international in 1897.’

By ‘oft-found’ we mean that a Google search currently yields no fewer than 555 results for that exact sentence.

In reality, the venues were:

(7892)

‘Women and Chess’ by S. Snell on pages 81-82 of the March 1947 BCM. Personal reminiscences by a writer who was the only woman member of her club. (‘…in a long life-time I have known only two women who played chess – and I taught it to one of them’.)

‘As I owe much in alertness as well as pleasure to this great game, I wish women could share this – with the exception, perhaps, of those whose work requires considerable mental concentration. It is the average woman I have in mind – women whose horizon is bounded by shopping, housework, cooking, mending, and so on, varied by an occasional cinema or play, and a not-so-occasional gossip.

These interests of hers, useful and necessary though they may be, leave a great part of her mind fallow. It is stamped on and trodden down by routine, conventions, hard-and-fast habits. Under such conditions how can anything grow? There are many implements for digging up this fallow soil. The choice lies with individual temperaments. For my own part I have chosen chess …’

‘Women and Chess’ by Elizabeth Westrup on page 203 of Chess Life, July 1961. A brief overview of female chessplayers throughout the centuries. The concluding paragraph read:

‘Why don’t more women in this country play chess? Many, of course, are just too busy with the everyday affairs of life. And yet a number of women do find time for bridge and canasta. Those who do play chess usually hesitate to venture into a chess club where they know there will be few women, if any at all. However, once they learn the game and begin to play seriously, they find a great deal of mental stimulation and pleasure in it. Even getting beat by a good player can be fun, but winning a game from a man who considers himself a top-flight player is one of the most satisfying experiences a woman can have.’

The above quotes appeared in C.N. 3274. A correspondent, Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England), mentioned in C.N. 3282 that pages 12-19 of Chessworld volume 1 number 3 (May-June 1964) had an article by Norman Reider entitled ‘The Natural Inferiority of Women Chessplayers’. Another additional item is ‘Among Women Chess Players’ on page 13 of the January-February 1941 American Chess Bulletin; it provided an overview of women players in the United States.

A priceless addition comes from page 99 of the April 1924 American Chess Bulletin. The passage is by Ernest Reel and was quoted from the Milwaukee Sentinel:

‘A woman’s mind is a market place crowded with so many mental reflections that it is hardly fair to ask her to concentrate on what is purely a man’s game. Chess is the weak spot in her mental armor. When a woman plays at chess she is apt to rest her chin on her hand and incidentally display her rings. While in deep meditation as to how to capture the king she suddenly is attracted by the arrival of a friend clad in exquisite furs. The fair player’s thoughts are diverted to the smart apparel shop. As soon as her strict attention slips its anchor the winning move of the chess game, which would stick like a burr in a man’s mind, rises like a shadow across her memory. Her chess atmosphere then becomes foggy, and the social atmosphere decidedly clear.

Women trying to play chess are like people leading horses they dare not ride. It will never be a woman’s game. Sammy Rzeschewski need only fear the rivalry of Cecil [sic – Celia] Neimark until her avenue of understanding includes the boulevards of dress, society and love. Up to that period a woman may win at chess – after that she has other battles to conquer.’

(8246)

Alasdair Alexander (Dunfermline, Scotland) writes that he has been entertained by the views on women and chess in Donner’s The King (Alkmaar, 2006), e.g. the articles on pages 92-94, 151-152, 162-164, 256-257 and 278-280. Our correspondent quotes a line from page 280, at the end of an annotated game from the 1978 Dutch women’s championship:

‘A game as the one above can only be understood against the gigglingly nervous background – “we’re only girls, you know” – of women’s chess. It ought to be abolished.’

In the article on pages 162-164 Donner discussed the reaction to his view that ‘women cannot play chess’ (which he had expressed on the grounds, inter alia, ‘that women are much more stupid than men. And because they are much more stupid, they lack the ability to amuse themselves’):

‘I was even accused of racial discrimination. “Donner forgot to add blacks to his statement. It should read ‘women and blacks cannot play chess, because they are more stupid than we are’”, was foisted upon me by a lady of Amsterdam. This lady misunderstood. Black men can play chess all right, black women cannot. That is the whole point.’

That article was written in 1972. Mr Alexander observes that Donner adopted a different tone on pages 256-257 when writing about Nona Gaprindashvili after her performance at Lone Pine, 1977:

‘An unprecedented success for the women’s world champion and a severe blow for all those who, in the face of the rising mudslide of feminism, thought they had a final foothold in the conviction that women at least cannot play chess.

... There is no denying it any more: notions as to women’s physical or mental deficiency are as of now no longer based on fact. Even in the field of chess, there is at least one woman who rates as a world-class player. For inveterate masculinists and for those who must write jocular pieces to earn a living, this is a serious setback, which will naturally not prevent us in the least, for that matter, from continuing our courageous struggle unabatedly.’

(8315)

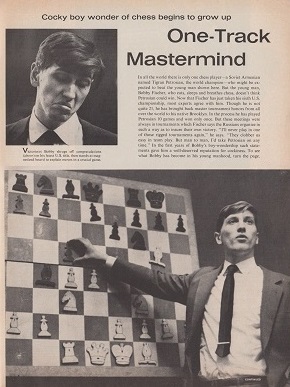

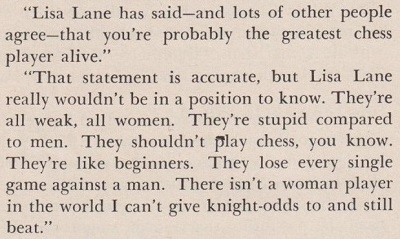

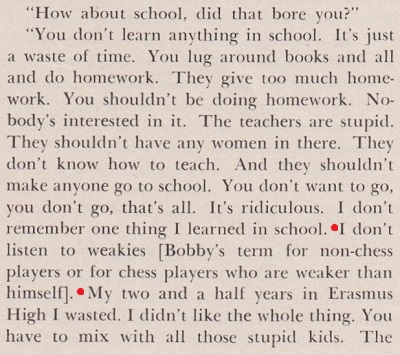

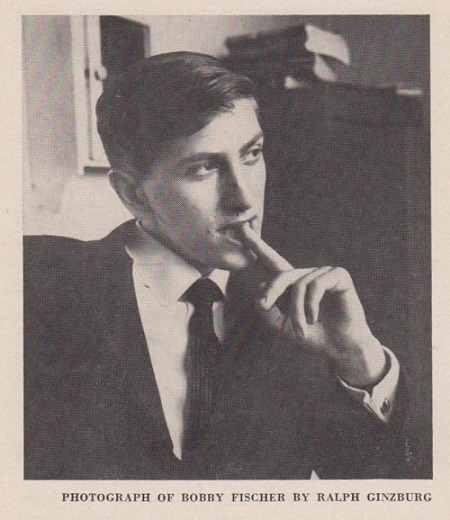

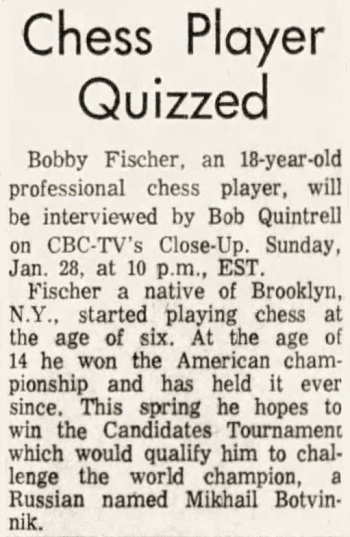

From page 100 of Life, 21 February 1964, in the article ‘One-Track Mastermind’ by Jane Howard which was referred to in C.N. 5200:

‘“Women are lousy at chess”, says Bobby. “They’re meant to stay home. I bet I could take any man of average intelligence, a rank beginner, give him oh, around two months of lessons, and have him at the end of that time beat the women’s world champion.’

Page 97 of Life, 21

February 1964

(9010)

It is difficult to imagine a world championship title being decided in an event whose participants did not know that they were contesting the title, but that happened in 1927.

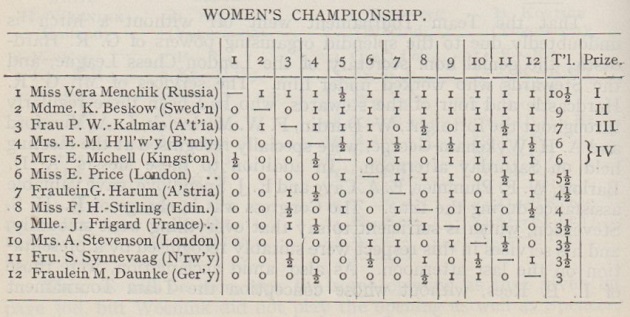

A 12-player tournament in London was won by Vera Menchik, as shown by the crosstable on page 372 of the September 1927 BCM:

The plans outlined on page 66 of the February 1927 BCM had merely indicated that one of the events (others were a premier tournament and a major tournament) that would take place alongside the International Team Tournament in July was ‘a women’s tournament (... limited to 12 players)’. It was held on 18-30 July 1927 and was not billed in advance as being for the women’s world championship.

Reports on Vera Menchik’s success mentioned in various terms the title that she had won:

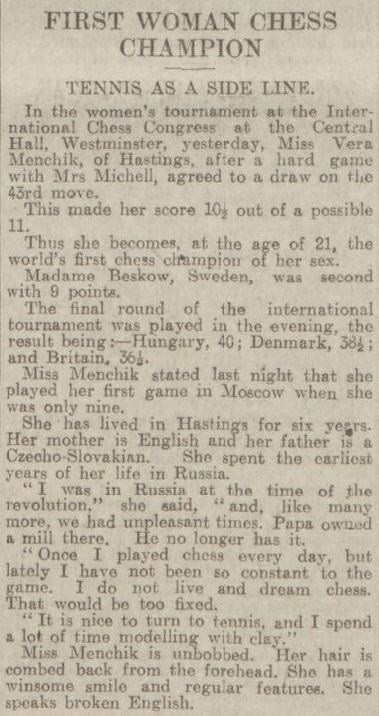

‘The title of world’s woman chess champion was established for the first time, the winner being Miss Vera Menchik of Hastings, who has been a resident of England for several years, although she learnt to play chess in Moscow. Her mother is English and her father a Czechoslovakian.’

‘Das Damenturnier gestaltete sich zu einer Art Weltmeisterschaft, da die berufensten Anwärterinnen auf diesen Titel mitkämpften. Den Sieg errang Miss Vera Menschik, eine in London lebende junge Russin, deren hohe Begabung schon lange bekannt war.’

‘Il a été décidé qu’un championnat FIDE pour Dames serait institué. Les invitations à participer à ce tournoi international devant se faire par l’intermédiare des fédérations respectives des concurrentes.

Un chapitre spécial sera ajouté de ce fait à l’art. 3 du règlement des épreuves de la FIDE.

La gagnante du tournoi organisé par la “British Chess Federation” à l’occasion du IVe Congrès de la FIDE est proclamée Champion de la FIDE.’

‘Die Siegerin im Damenturnier erhält den Titel “Schachweltmeisterin” (Woman Champion of the World).’

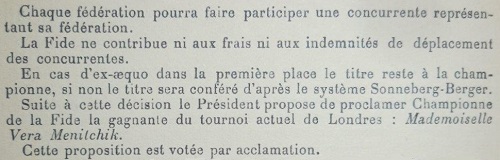

‘Il est décidé d’instituer un championnat FIDE pour dames, celles-ci ne pouvant y participer que par l’intermédiaire de leurs fédérations respectives. La gagnante du tournoi de Londres (Miss Vera Menchik) est proclamée championne de la FIDE.’

In its August 1927 issue (page 326) the BCM referred to ‘the Women’s Tournament, which we understand is to be recognized as for the Women’s Championship of the World by the FIDE’. Page 390 of the September 1927 BCM included the following in its report on the meeting of FIDE delegates (London, 28-30 July 1927):

‘It was agreed that Article 3 of the Rules of the FIDE should be altered to include a Women’s championship of the FIDE, and this was made retrospective so as to award the title to the winner of the Women’s Tournament of the London Congress, 1927.’

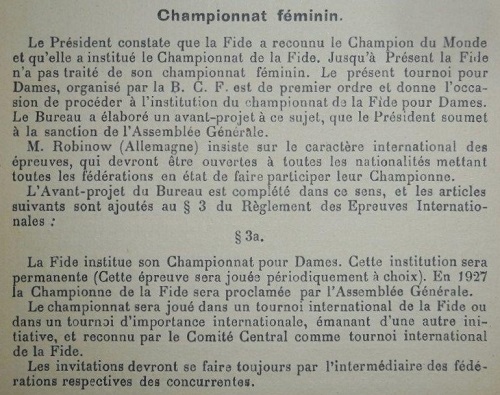

The formal position was set out in FIDE’s minutes of the London meeting, i.e. on pages 7-8 of the Procès-verbal du IVe congrès; Londres, 28-30 juillet 1927:

As regards the exact date when the FIDE delegates took their decision, the following comes from page 6 of The Times, 29 July 1927, in a report on the previous day’s FIDE working session:

‘The delegates also decided that the winner of the women’s tournament in the General Congress should be awarded the title of Woman Champion of the World, and this honour will fall to Miss Menchik.’

Throughout its earlier coverage The Times had referred simply to the ‘Women’s Tournament’.

It remains to be ascertained how exactly the decision to award the world title came about. After reporting that for the ‘Women’s Tournament’ there was an entrance fee of £1, that the prizes were £20, £15, £10 and £5, and that non-prize-winners would receive 10/- for each game won, page 200 of the May 1927 BCM stated: ‘It is hoped to persuade the FIDE to nominate the winner of this event their first Women’s Champion.’ That information was provided in an account of the meeting of the British Chess Federation’s Executive Council on 23 April 1927; is it possible to find documentation on the exchanges between the BCF and FIDE in 1927?

Although page 66 of the February 1927 BCM had recorded that the tournament would be ‘open to the entry of players of all nationalities’, and although the magazine’s crosstable, shown above, listed ‘Miss Vera Menchik (Russia)’, the comments in FIDE’s Procès-verbal should be borne in mind: for (future) women’s championships, players could participate only via their respective federations. Thus María Teresa Mora Iturralde did not play in a women’s world championship tournament until 1939, shortly after her country, Cuba, had been admitted to FIDE. The Soviet Union joined FIDE in 1947.

Parochial considerations naturally played a role in the coverage of Vera Menchik’s victory in London. From page 11 of the Manchester Guardian, 1 August 1927:

‘Miss Menchik appeared in the programme as of Russia, but as she has lived for several years in Hastings and there learnt to become an expert player, Hastings is entitled to claim the credit of providing the first woman chess champion of the world.’

An example of the publicity accorded to her is on page 5 of the Courier and Advertiser (Dundee), 30 July 1927:

Vera Menchik contributed a brief article to the Daily Mail, 5 August 1927, page 8:

As reported on page 3 of the FIDE President’s Compte-Rendu, at the 1928 General Assembly in The Hague Alexander Rueb singled out Vera Menchik’s achievement:

‘Par rapport aux autres tournois de la BCF il faut mentionner spécialement le beau succès de Miss Vera Mentschik [sic] qui a vu couronner sa maîtrise du jeu par le titre de “Championne du Monde”.’

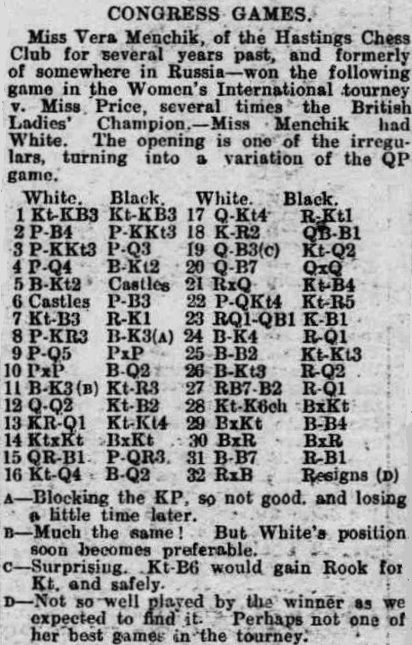

The tournament was indeed a memorable success, but can more be discovered about the circumstances? And, a key additional question, where are the game-scores? Here, at least, is one, Vera Menchik’s win against Edith Price, from page 10 of the Cheltenham Chronicle and Gloucestershire Graphic, 13 August 1927. It was played in round seven on 25 July 1927:

1 Nf3 Nf6 2 c4 g6 3 g3 d6 4 d4 Bg7 5 Bg2 O-O 6 O-O c6 7 Nc3 Re8 8 h3 Be6 9 d5 cxd5 10 cxd5 Bd7 11 Be3 Na6 12 Qd2 Nc7 13 Rfd1 Nb5 14 Nxb5 Bxb5 15 Rac1 a6 16 Nd4 Bd7 17 Qb4 Rb8 18 Kh2 Bc8 19 Qc3 Nd7 20 Qc7 Qxc7 21 Rxc7 Nc5 22 b4 Na4 23 Rdc1 Kf8 24 Be4 Rd8 25 Bc2 Nb6 26 Bb3 Rd7 27 R7c2 Rd8 28 Ne6+ Bxe6 29 Bxb6 Bf5 30 Bxd8 Bxc2 31 Bc7 Rc8 32 Rxc2 Resigns.

(9074)

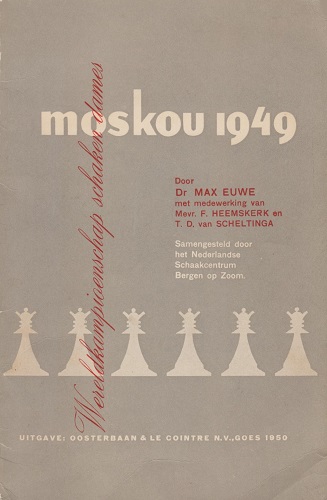

An early book exclusively devoted to a women’s chess event:

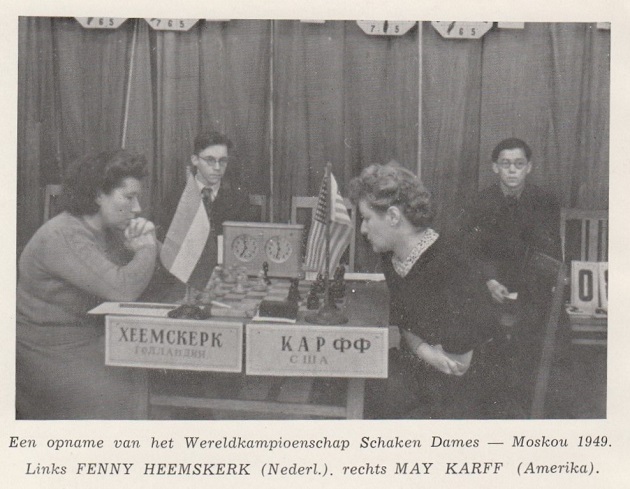

Notwithstanding the title, the world championship tournament, won by Ludmila Rudenko, took place from 20 December 1949 to 16 January 1950. The frontispiece:

(9128)

The ‘thought for the month’ on the inside front cover of the October 1950 Chess Review, in ‘Chernev’s Chess Corner’:

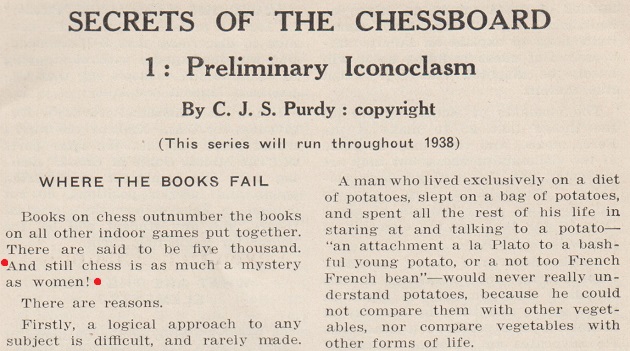

‘“Chess is as much a mystery as women” – Purdy.’

See too page 1 of Winning Chess by Irving Chernev and Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1948). How far back can this well-known remark be traced?

(9211)

We now note the following on page 5 of the Australasian Chess Review, 20 January 1938:

‘And still chess is as much a mystery as women.’

Newspapers are forever reporting alleged anger, fury, etc. vented ‘last night’. (Profound discontent generally seems nocturnal.) The original report about Nigel Short, in the Daily Telegraph of 20 April 2015, illustrates how news stories may nowadays be confected from Twitter, and one tweet grabbed is a claim that Short’s comments were ‘incredibly damaging’. (‘Incredibly’ generally means ‘very’.) Last night’s ire is a curiously delayed reaction to an article by Short, ‘Vive la Différence’, on pages 50-51 of the 2/2015 New in Chess – an issue which was published a month ago but evidently remained unavailable last night, and even today, given that much of the coverage bears little relation to what Short wrote in the Dutch magazine.