Chess

Notes

Edward

Winter

When contacting

us

by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include

their name and full

postal address and, when providing

information, to quote exact book and magazine

sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the

subject-line or in the message itself.

5870. Game conclusion (C.N. 5851)

Black to move.

This position was featured in a Sherlock Holmes vignette

‘Chess in Fiction’ by Hotspur on pages 15-16 of the

January 1964 BCM. In a cliff-ledge showdown,

Moriarty played 36...fxg2 (‘Time to resign, I think, Mr

Holmes.’), but ‘Holmes nonchalantly produced his

hypodermic syringe and applied a shot of his favourite

drug Morphy-A’ and played 37 Qe2+ Rxe2 38 Nb4+ cxb4 39

Ra5+. Moriarty then ‘made the only move open to him –

over the cliff – board, men and Moriarty’. As Holmes

later reflected, in the diagrammed position Black could

have played 36...Re1+ 37 Qxe1 Bxb2+, with mate in two

more moves.

Marc Hébert (Charny, Canada) refers to the game given

as ‘Captain Mackenzie-J.M. Hanham, London, 1886’ on

page 57 of Adolf Albin in America by Olimpiu

G. Urcan (Jefferson, 2008). Play began 1 e3 c5, and

Mackenzie is said to have resigned after Black’s 33rd

move.

We note that other publications, such as the June

1886 Chess Monthly, pages 296-297, correctly

gave Mackenzie as Black. Mr Urcan’s source, page 2 of

the New York Times, 15 July 1886, inverted the

players’ names.

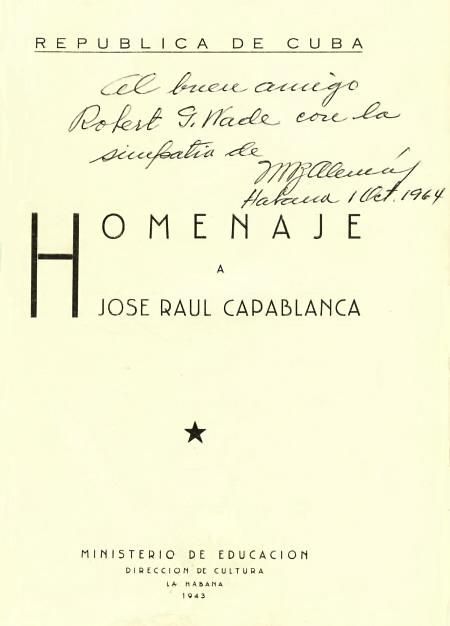

From our collection we reproduce the

title page of Robert G. Wade’s copy of the scarce 1943

book Homenaje a José Raúl Capablanca, inscribed

to him by the Cuban master Miguel Alemán in Havana a few

days after the end of the 1964 Capablanca Memorial

tournament:

From Brian Ridgely (Raleigh, NC, USA):

‘The recent death of Henry Loomis, the former

head of Voice of America, brought to mind his

father, Alfred Loomis. The elder Loomis was one of

America’s wealthiest men in the first half of the

twentieth century and a key, if somewhat unsung,

figure in the winning of World War II. He was also

a chessplayer, and the following appeared on page

19 of Tuxedo Park by Jennet Conant (New

York, 2002):

“By age nine, he was a chess prodigy and [...] by

age 13 he could play ‘mental chess’ without aid of

a board or pieces and could play blindfolded,

carrying on two games simultaneously.”

Other passages tell of Loomis playing blindfold

(sometimes multiple games) well into adulthood. Is

there any record of competitive play by him?’

From Robert John McCrary (Columbia, SC, USA):

‘The Oxford Companion entry on

tournaments was taken from my research paper The

Birth of the Chess Tournament, which is cited in

the Companion entry (second edition) and

has been published in full on pages 19-31 of my

1998 booklet The Hall-of-Fame History of US

Chess. The paper includes much bibliographical

material, including all of Walker’s early uses of

“tournament” that I could find.

The word “tournament” appears to have been

applied by Walker to the early Yorkshire meetings,

which were not “tournaments” in the modern sense.

They were more like “congresses” in the modern

usage, with no apparent structure to the casual

games played there.

The word caught on for general chess gatherings

but does not seem to have been applied to

“tournament” in the modern sense of structured

competition until the 1849 event at the Divan in

London. There is reason to assume, though it is

hard to prove conclusively, that the term

“tournament” in the modern sense then spread from

chess to other games and sports. My review of

other sporting literature has revealed no

occurrences of “tournament” until a few years

after London, 1851.

My paper also includes some references (very

sketchy and lacking players’ names and other

details) to true chess tournaments preceding 1849,

which, ironically, were not called “tournaments”.’

Regarding our question in C.N. 5869 about Amsterdam,

1851 we note the publication Schaakpartijen,

gespeeld in 1851, gedurende den wedstrijd van het

genootschap Philidor, in Amsterdam (Wijk bij

Duurstede, 1852).

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) points

out that the website of the Bibliothèque

nationale

de France has a photograph of Chigorin which is

likely to be new to readers.

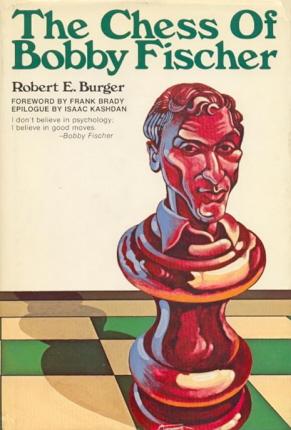

From Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England):

‘The dust jacket of The Golden Dozen by

Irving Chernev (Oxford, 1976) lists other “Oxford

Chess Books”, and the first of these is Chess

technique and Bobby Fischer by R.E. Burger. I

know of no such work being published, but

presumably it would have been the same as Burger’s

The Chess of Bobby Fischer, which the

Chilton Book Company, Radnor had brought out in

1975.’

Further to C.N.s 5471, 5475 and 5491, we add that in

his Foreword to the US book (page viii) Frank Brady

wrote:

‘In previous writings I have cited Fischer’s IQ as

in the range of 180, a very high genius. My source

of information is impeccable: a highly regarded

political scientist who coincidentally happened to

be working in the grade adviser’s office at Erasmus

Hall – Bobby Fischer’s high school in Brooklyn – at

the time Fischer was a student there. He had the

opportunity to study Fischer’s personal records and

there is no reason to believe his figure is

inaccurate. Some critics have claimed that other

teachers at Erasmus Hall at that time remember the

figure to be much lower; but who the teachers are

and what figures they remember have never been made

clear.’

5877. Alapin’s place of birth

Simon Alapin

Georges Bertola (Bussigny-près-Lausanne, Switzerland)

comments that whereas notable sources give S. Alapin’s

place of birth as Vilnius there are also statements that

he was born in St Petersburg. Instances of the latter

version are on page 8 of the Dizionario

enciclopedico degli scacchi by A. Chicco and G.

Porreca (Milan, 1971) and page 206 of Traité-manuel

des échecs by H. Delaire (Paris, 1911).

We note that St Petersburg was specified in the

ten-line obituary of Alapin in the October 1923 BCM,

page 374, on page 333 of Schachjahrbuch 1923 by

L. Bachmann (Ansbach, 1924) and in a number of other

publications of the time.

Going his own way, Byrne J. Horton referred to ‘the

Czechoslovakian chessmaster S. Alapin’ on page 2 of his

Dictionary of Modern Chess (New York, 1959).

Pages 318-349 of the November 2008

issue of the Moscow magazine Караван

(Karavan) have an extensive article

Капабланка: гений игры for which we supplied a number of

photographs of Capablanca and his second wife. The other

illustrations include, courtesy of the Agence

France-Presse, a shot of Alekhine outside the Café de la

Paix, Paris in 1927.

Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA) notes that page 10

of the New York Times of 4 March 1906 and page

8 of the New York Sun of the same date

reported that A. Loomis had played in the annual Yale

v Princeton match in New York. On board ten he

defeated W.L. Richard.

We see that this is confirmed by a reference to A.L.

Loomis as one of the Yale team on page 45 of the March

1906 American Chess Bulletin. The report

states that the match took place at Professor Rice’s

residence and that Capablanca was the adjudicator. The

following page carried a photograph of the occasion.

No identification of the participants was offered, but

the Cuban is recognizable, seated on the left.

‘Participants in the

Intercollegiate Match on ten boards, photographed in

the library of the Villa Julia, New York, 3 March

1906’

5880. A deciphering challenge (C.N.

5860)

The above illustration depicts a game in shorthand:

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 O-O Nf6 5 d4 Bxd4 6 Nxd4

Nxd4 7 f4 Ne6 8 Bxe6 dxe6 9 Qxd8+ Kxd8 10 fxe5 Nxe4 11

Rxf7 Rg8 12 Nc3 Nxc3 13 Bg5+ Ke8 14 Re7+ Kd8 15 Rxg7+

Ke8 16 Rxg8+.

The top line indicates the pieces (king, queen, bishop,

knight, rook and pawn respectively), whereas the second

line represents the numerals 1-8. We assembled the

illustration from an article ‘Chess Shorthand’ by Allen

Watkins on pages 263-267 of the August 1916 BCM.

(He gave Black’s seventh move, in both descriptive

notation and shorthand, as ...B-K3.) A critical

reaction, also entitled ‘Chess Shorthand’, by B.G. Laws

was published on pages 297-298 of the September issue,

and the following month (pages 333-334) Watkins

responded.

The general subject had prompted some interest during,

especially, the late nineteenth century. For example:

- ‘Shorthand Notation’ by Miss M. Barnard on page 24

of the Chess Player’s Annual and Club Directory,

1890 by Mr and Mrs T.B. Rowland (Dublin, 1890).

- ‘Shorthand Notation’ by M. Barnard. Four-page insert

in the Chess Player’s Annual and Club Directory,

1893-94 by Mr and Mrs T.B. Rowland (London and

Stroud, 1893).

- ‘Scoring of Games’. Letter from Charles B.

Boitel-Gill on pages 384-386 of the October 1897 BCM.

From more recent times (1971) there exists a 12-page

mimeographed publication ‘Chess Shorthand’ by Herbert E.

Salzer.

From Dan Scoones (Port Coquitlam, BC, Canada):

‘The caption to the problem from Shakhmatny

Listok is more accurately translated as “cited by

Kolisch”. This implies an acknowledgement that he

was not the composer.’

Ignatz Kolisch

Since when, and on what basis, has Alapin’s place of

birth been given as Vilnius? In old sources we

continue to find St Petersburg, a further example

being page 84 of Schach-Jahrbuch für 1892/93

by Johann Berger (Leipzig, 1893).

Simon Alapin

5883. My 60 Memorable Games

Dennis Monokroussos (South Bend, IN, USA) disputes the

statement on the back cover of the 2008 edition of

Fischer’s My 60 Memorable Games that ‘in

contrast with the previous edition of this book, no

alterations have been made to the text other than the

conversion of moves into algebraic notation, making this

an updated yet accurate reflection of the original

book’, given that the faulty score of a 1959 Fischer v

Tal game has been corrected. Our correspondent asks

whether we are aware of any other changes in the new

edition.

The Fischer v Tal encounter (Game 17) gave rise to the

following position after 50 Kb4:

The game concluded 50...Kc7 51 Rb5 Ba1 52 a4 b2, and

White resigned. Source: Page 275 of Kandidatenturnier

für Schachweltmeisterschaft by S. Gligorić and V.

Ragozin (Belgrade, 1960), as well as other publications

of the time.

However, in the first edition of Fischer’s book (page

122) the final moves were given as ‘50...B-R8 51 P-QR4

P-N7! White resigns’. This would have allowed Fischer to

win with 51 Rc8+. The fact that Tal had played 50...Kc7,

and not 50...Ba1, was pointed out by B.L. Patteson on

page 146 of the March 1970 Chess Life & Review,

in the column ‘Larry Evans On Chess’. Evans commented:

‘Fischer assures us that he caught this error before

the book went to press, but that his correction must

have fallen off the page by the time it reached the

printer. Anyone familiar with the monumental effort

that goes into any book knows that perfection is

impossible.’

The matter was also raised by D.M. Horne on page 19 of

the January 1972 BCM, and the magazine’s editor

confirmed that the score in Fischer’s book was faulty.

The inaccurate sequence ‘50 K-N4 B-R8 51 P-QR4 P-N7!

White resigns’ was amended, in the 1972/73 Faber and

Faber edition, to ‘50 K-N4 K-N4 51 R-N5 B-R8 52 P-QR4

P-N7 White resigns’. This would-be correction remained

in the British publisher’s 1988 edition, but Black’s

50th move should read ...K-B2, and not the impossible

...K-N4.

The Batsford editions of 1995 and 2008 both give the

conclusion of the game accurately.

As regards Mr Monokroussos’ question about other

changes to the 2008 edition, we note that some further

textual corrections have indeed been made. In our

article on pages 45-48 of the January 1997 CHESS

about the 1995 edition

of Fischer’s book, we included a section entitled

‘Mistakes not corrected’:

With the exception of the point regarding Game 32, the

2008 edition has corrected all these matters, silently.

(See also C.N. 4867.)

Batsford was certainly right, in 2008, to wish to

rectify clear-cut factual errors, but we feel that a)

the back-cover claim that the text is unaltered was

ill-advised, and b) any changes should have been

mentioned explicitly and openly, either in footnotes or

in an errata section.

5884. Better Chess

A finely-written book, seldom discussed, forms part of

the ‘Teach Yourself’ series: Better Chess by

William Hartston (London, 1997 and 2003). The page

numbers in our selection of quotes below refer to the

latter edition:

- ‘Always look one move deeper than seems to be

necessary. After any sequence of captures or checks,

look for the sting in the tail.’ (Page 6)

- ‘Weak players assess a position by counting the

captured men; strong players consider only the men

remaining on the board.’ (Page 10)

- ‘Probably more nonsense has been written about

planning in chess than any other aspect of the game.

... In fact, as many games are lost through pursuing

bad plans as are won by pursuing good ones.’ (Page 28)

- ‘There is ... one last, totally unimportant point to

be made about pawns stacked vertically: a player with

sextupled pawns on the a-file or h-file can never

lose. Why? Because it takes 15 captures to get them

there, so the opponent can have only his king left.’

(Page 42)

- ‘Think strategies when it’s your opponent’s turn to

move; sort out the tactics while your own clock is

running.’ (Page 50)

- ‘One of the best excuses I ever heard was from a man

who had just lost to a female opponent. “She

completely disrupted my thought processes”, he

complained. “Every time I tried to calculate

something, I’d begin: ‘I go here, he goes there’, and

then I’d have to correct myself: ‘No, it’s I go here,

she goes there’.”’ (Page 52)

- ‘Ask not what your pieces can do for you, ask what

you can do for your pieces.’ (Page 70)

- ‘There are two easy ways to spoil a good position:

doing nothing when you should be doing something, and

doing something when you should be doing nothing.’

(Page 80)

- ‘More half-points are thrown away by the inability

to recognize a technically won game than through any

other single cause.’ (Page 88)

- ‘The easiest time to blunder is the move after you

have solved all the difficult problems. From proper

hard thinking, you begin to rely on general

principles, forgetting how unprincipled they can be.

It has been said that chess is the only area of human

activity where paranoia is a positive advantage.

Actually there are many such areas, but chess is one

where an element of paranoia is an occupational

necessity. Every move and every position has to be

viewed with mistrust. Once you find yourself thinking

“Nothing can go wrong now” you have set up the

preconditions for something to go wrong. And, as

Grandmaster Murphy pointed out: if anything can go

wrong, it will.’ (Page 94)

- ‘If you hoard your small advantages, the winning

combinations will take care of themselves.’ (Page 114)

- ‘We have mentioned before the Zen koan

concerning the art of archery, which says that the man

who aims for the centre of the target will win the

prize, but the one who aims to win the prize will miss

the target. At the very highest level of chess, a

similar principle applies. Perfectionism is the only

road to ultimate success. At anything below world

championship level, however, practicality tends to

fare better than perfectionism.’ (Page 148)

Regarding the famous game Canal v Amateur (1 e4 d5 2

exd5 Qxd5 3 Nc3 Qa5 4 d4 c6 5 Nf3 Bg4 6 Bf4 e6 7 h3

Bxf3 8 Qxf3 Bb4 9 Be2 Nd7 10 a3 O-O-O 11 axb4 Qxa1+ 12

Kd2 Qxh1 13 Qxc6+ bxc6 14 Ba6 mate) can the basic

facts (the opponent’s name and the occasion) be

established?

It is commonly stated that the game was played in a

simultaneous exhibition in Budapest in 1934, but can

that be proven? Surprisingly few chess periodicals of

the time published the game-score, an exception being

Chess Review (page 183 of the October 1934

issue). For the occasion it put ‘Played in a

simultaneous exhibition’, which was also the limit of

the information offered on page 521 of the December

1934 BCM.

Maverick suggestions include ‘France 1934’ on page 53

of The Art of Giving Mate by Attila Schneider

(Kecskemét, 2003), but that is a book which began with

a game by Greco dated 1875.

Russ Glover (Alpena, MI, USA) asks whether an errata

list has ever been compiled for the first edition of

Fischer’s My 60 Memorable Games.

Bobby Fischer

5887. Claim attributed to Philidor

Frederick S. Rhine (Park Ridge, IL, USA) is seeking

substantiation of a statement on page 106 of A

History of Chess by Jerzy Giżycki (London, 1972):

‘Philidor thought, for instance, that whoever made

first move and made no mistake would win.’

A complete run (1826-1998) of the Journal de Genève

has recently been made available on-line, and

problem/study enthusiasts will particularly welcome the

opportunity to read André Chéron’s celebrated chess

column, which began on 2 October 1932.

Below is a page from the booklet Mémorial André

Chéron, which was published by the newspaper in

1985:

C.N. 5884 quoted a remark from page 50 of Better

Chess by William Hartston (London, 2003): ‘Think

strategies when it’s your opponent’s turn to move;

sort out the tactics while your own clock is running.’

Paul Dorion (Montreal, Canada) notes a passage on

page 139 of Think Like a Grandmaster by

Alexander Kotov (London, 1971):

‘When later I was busy writing this book I

approached Botvinnik and asked him to tell me what

he did when his opponent was thinking. The former

world title-holder replied in much the following

terms: Basically I do divide my thinking into two

parts. When my opponent’s clock is going I discuss

general considerations in an internal dialogue with

myself. When my own clock is going I analyse

concrete variations.’

Page 141 of Kotov’s Think Like a Grandmaster

professed to quote Steinitz:

‘A chess master has no more right to be ill than a

general on the battle field.’

No source was given, and the closest remark that we

can find is a ‘once’ version on page 195 of the Chess

Monthly, March 1891:

‘It was alleged, and justly so, for that we can

vouch, that Zukertort’s health was failing; but we

agree with Steinitz in the remark he made once: “A

first-class player has no right to be ill.”’

5891. Dorothea (Dodie) Bourdillon

Bob Jones (Exmouth, England) writes:

‘I am currently compiling a history of the

Paignton Congress in readiness for its 60th

anniversary in 2010 (60 years in the same room) and

have come across the name of Mrs Dorothea

Bourdillon, who took part in the second congress in

1952, where she appears to have set male hearts

a-flutter. D. Yanofsky mentioned her in his report

for the BCM, as did B.H. Wood in CHESS.

The magazines carried a brief obituary of her in

1968. Is further information available, including

her maiden name?’

Firstly, we quote below the magazine items referred to

by our correspondent:

- Report on Paignton, 1952 by D.A. Yanofsky on page

318 of the BCM, November 1952:

‘Of [the 96 participants] eight were ladies,

including Mrs Bruce, the British Lady Champion, and

Mrs J. Bourdillon, a charming newcomer from

Gloucester who won her section ahead of seven men.’

- Report on Paignton, 1952 on page 26 of CHESS,

November 1952:

‘The lower sections were marked by the definite

arrival of Mrs Bourdillon, whose unique combination

of beauty, vivacity and sheer skill is going to

affect chess congress atmospheres considerably.’

- An obituary signed ‘E.T.’ (Eileen Tranmer) on page

333 of CHESS, July 1968 (with an almost

identical text by her on page 192 of the July 1968 BCM):

‘Dodie Bourdillon

British Ladies’ chess has sustained a loss in the

recent death of Dodie Bourdillon at a comparatively

early age.

A colourful personality of many talents, she was an

actress before her first marriage, and later became

the leading speed-writing typist to the Courts of

Appeal.

She missed winning the British Ladies’ Championship

in 1958 by the smallest possible margin. Having tied

for first place with Anne Sunnucks, and having led

by 2-0 in the play-off match, with only half a point

necessary for the title, she lost the last three

games.’

Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia (Jefferson,

1987) had only a brief entry for her, but we note that

extensive details were given in the unpublished 1994

edition:

The Family

Search website gives her place of birth as

Ipswich.

Dorothea Rodwell appeared in the 1939 film Little

Ladyship, which starred Lilli Palmer and

Cecil Parker.

5892. Bird brilliancy

From a 20-board simultaneous display against the Chess

Bohemians:

Henry Edward Bird – W.S. Daniels

London, 6 October 1894

Two Knights’ Defence

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Nf6 4 Ng5 d5 5 exd5 Nxd5 6 Nxf7

Kxf7 7 Qf3+ Ke6 8 Nc3 Ne7 9 d4 b5 10 Bb3 c6 11 a4 b4 12

Ne4 Kd7 13 dxe5 Kc7 14 Nd6 Be6 15 Bg5 h6 16 Bh4 g5 17

Bg3 Nc8 18 Ne4 Be7 19 O-O-O g4 20 Qe2 Kb7 21 Nd6+ Nxd6

22 exd6 Bg5+ 23 Kb1 Re8 24 Qd3 Qd7 25 a5 Rab8 26 Rhe1

Bf5 27 a6+ Ka8

28 Qxd5 cxd5 29 Bxd5+ Rb7 30 Rxe8+ Qxe8 31 axb7+ Kb8 32

d7+ Bf4 33 Bxf4+ Qe5 34 Bxe5 mate.

Source: Hampstead & Highgate Express, 10

November 1894.

Our feature article Early Uses of ‘World Chess

Champion’ has remarks by Steinitz on whether he

became the title-holder by defeating Anderssen in 1866.

Now we add a quote from an article ‘Steinitz’s Career

Reviewed’ reproduced on pages 105-106 of the July 1905

issue of Lasker’s Chess Magazine:

‘In 1865 I won the chief prize in Dublin, and it was

then that a match was arranged for the championship of

the world with Anderssen. One of the committee who

arranged that match was the present Lord Chief Justice

of England. I won it by 8 to 6, and became champion

chess player of the world.’

The Lord Chief Justice (from 1894 to 1900) was Lord

Russell of Killowen, whose obituary on page 367 of the

September 1900 BCM mentioned that ‘he was a

supporter of Steinitz in some of his early matches’.

Lasker’s Chess Magazine merely stated that the

article had appeared in ‘a recent issue of the Jewish

Chronicle’, but we can add that it came from a

feature entitled ‘A Chat with Steinitz’ on pages 12-13

of the newspaper’s 4 August 1899 issue.

5894. Stadelman

Lev D. Zilbermints (Newark, NJ, USA) is seeking

information about Samuel Leigh Stadelman of Pennsylvania

(born 1881) and, in particular, any games played by him

which began 1 d4 e5 2 dxe5 Nc6 3 Nf3 Nge7.

From the American

Chess Bulletin, February 1909, page 42.

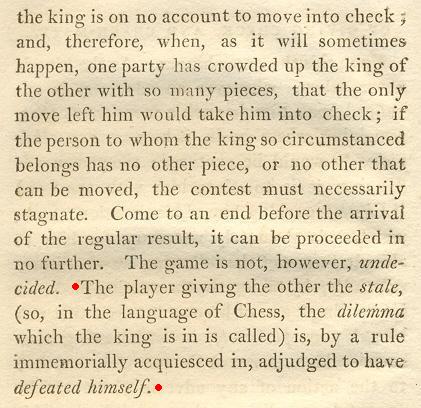

Our feature article on Stalemate referred to

the debate, launched in the 1840s, on whether an en

passant capture is obligatory if no other legal

move exists. We included a straightforward example

presented by Charles Tomlinson:

If White plays 1 g4 it is not stalemate, since the laws

of chess eventually established that in such a case

1...hxg3 is obligatory, and not optional.

Now, Valery Liskovets (Minsk, Belarus) draws our

attention to two articles he has contributed to Die

Schwalbe: ‘Erzwungener En-Passant-Schlag in

direkten Retro-Problemen’ (December 2007, page 299) and

‘Eine historische Bemerkung zum erzwungenen

En-Passant-Schlag’ (October 2008, page 585). Noting that

the history of the topic can be found in the 1911 book

in A.C. White’s Christmas series, Running the

Gauntlet (subtitled ‘A study of the capture of

pawns en passant in chess problems’ and available

on-line), our correspondent lists nine

compositions in that source which have a forced en

passant capture: 23B, 28, 29, 29B, 40D, 44, 47D,

51A and 59. The last of these, and the oldest specimen

of any kind (i.e. whether forced or unforced), is one by

Adolf Anderssen of which A.C. White wrote on page 181:

‘Probably no other problem has had so distinguished a

role in the history of the game of chess, and as such

we must do it honour.’

Mate in three (Adolf

Anderssen,

Leipzig Illustrirte Zeitung, 31 January 1846)

Solution: 1 Re1 Kxd4 2 e4 fxe3 3 Rd1 mate.

Alain Campbell White

On pages 18-21 White explained the historical

background:

‘The option of capturing is after all a privilege,

and a good deal can be said both for and against its

being compulsory. Indeed, a great deal has been said

about it, and for some ten years beginning in 1846 the

discussion was one of the features of the column in

the Illustrated London News, and elsewhere. It

was begun by Saint-Amant, taken up by Anderssen, and

gradually became general. The correspondence pages of

the magazines bristle with it. We know how the

discussion ended, for today in an otherwise stalemate

position the capture is always compulsory; and we need

not trace all the arguments which were doubtless

cogent enough 65 years ago, but which seem very

trivial now.’

Mr Liskovets adds two compositions with a forced en

passant capture which were published after A.C.

White’s book appeared: a three-mover by N. Hoeg dated

1921 and a composition by V. Korolkov published in Schach

in 1957. He asks for information about further specimens

and adds two questions:

1. Have there been any instances in actual play where

a loss has resulted from an obligation to capture en

passant?

2. Do any theoretically-won endgame positions exist

which feature a forced en passant capture?

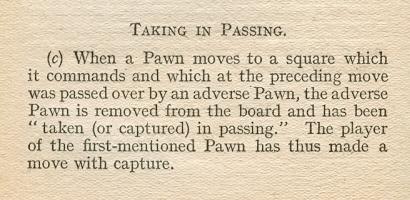

5896. Explanation of en passant

It may be difficult to find a poorer explanation of the

en passant rule than the one published over a

century ago in The British Chess Code and still

retained on page 34 of The International Chess Code

(London and New York, 1918):

C.N. 4421 referred to an essay ‘Capa, hijo de Caissa’

by the Cuban-born writer Guillermo Cabrera Infante

(1929-2005) on pages 211-234 of Vidas para leerlas

(Madrid, 1998).

Previously, the text had appeared on pages 406-422 of

his anthology Mea Cuba (Barcelona, 1992). An

English translation of the book, under the same title,

was published by Faber and Faber in 1994, with a

paperback edition the following year.

Cabrera Infante was unfamiliar with basic facts about

Capablanca’s life, and one passage seems particularly

odd. From pages 421-422 of the translation (by Kenneth

Hall, in conjunction with the author):

‘In the Manhattan Chess Club the Cuban grew close

to one of the greatest American players, Frank

Marshall, whom he would defeat decisively in 1909.

Capablanca was 21 [sic] years old, Marshall

33 [sic]. A very bored Capablanca playing

against Marshall nodded off more than once. With a

sense of humour often absent from across the

chessboard, Marshall tells: “I made the worst move

of the game. I woke up Capablanca.” Capablanca

proceeded to execute a reveille checkmate.’

The original text was on page 409 of the 1992 Spanish

volume:

‘En el club de Ajedrez de Manhattan, Capablanca

intimó con uno de los grandes jugadores

americanos, Frank Marshall, a quien derrotaría

decisivamente en 1909. Capablanca tenía 21 años,

Marshall 33. Marshall relata la ocasión en que un

muy aburrido Capablanca, jugando en su contra,

cabeceó más de una vez. Con un sentido del humor

muchas veces ausente del tablero, contó Marshall:

“Cometí el peor movimiento del juego: desperté a

Capablanca.” Capa ejecutó un jaque mate

fulminante.’

What are the origins of this yarn, which are

reminiscent of the untrue story about Capablanca

falling asleep during a match-game against Alekhine in

1927 (C.N. 5118)? Certainly, though, the Capablanca v

Marshall match dragged on, and we pointed out on page

18 of our monograph on the Cuban that the 1927 world

title match lasted only eight days longer. The cartoon

below appeared on page 33 of the Chess Weekly,

26 June 1909:

5898. Chess masters on film (C.N.

3491)

From Luc Winants (Boirs, Belgium):

‘British Pathé footage (www.britishpathe.com)

is now managed by ITN Source (www.itnsource.com).

There also seem to be clips from other

companies, such as Gaumont.

One brief item is of a simultaneous display given

by Alekhine in Paris (most probably the one on 28

February 1932 – see pages 416-417 of the book by

Skinner and Verhoeven): www.itnsource.com/shotlist//BHC_RTV/1932/01/01/BGT407170046/?s=Paris+chess&st=0&pn=1

Another one, even more spectacular, shows the

tournament in San Remo, 1930. We see them all:

Alekhine, Nimzowitsch, Spielmann, Maróczy, Yates …:

www.itnsource.com/shotlist//BHC_RTV/1930/01/01/BGT407150379/?s=Alekhin&st=0&pn=1’

5899. Wade in Paris

Dominique Thimognier (St Cyr sur Loire, France) draws

our attention to material about Robert Wade in the Bulletin

Ouvrier des Echecs in February and March 1949. Our

correspondent comments:

‘The Bulletin reported that Wade, who was

invited to Paris by the Communist body the FSGT

(Fédération Sportive et Gymnique du Travail), was

due to play a match against Rossolimo in the French

capital but that the Fédération Française des Echecs

banned Rossolimo from playing. Instead, there was a

two-game match between Wade and François Molnar.

Both games were drawn.’

Larger

version

Taylor Kingston (Shelburne, VT, USA) writes:

‘Guillermo Cabrera Infante’s account of

Capablanca supposedly falling asleep while playing

Marshall in 1909 bears a great resemblance to an

incident involving Fischer and Bisguier. One

account is on page 197 of The Even More

Complete Chess Addict by M. Fox and R. James

(London, 1993):

“It’s New York 1963, the last round of the

American championship. Bisguier and Fischer are

equal first. Fischer doesn’t make a move for a

long time. Bisguier looks up and sees his opponent

is fast asleep. In another half-hour, the great

Bobby’s clock will fall, making Bisguier the

champ. That’s where we come to the most gracious

blunder of all. In Bisguier’s words: ‘I made a bad

move. I woke up Bobby Fischer.’ And of course

Bobby, after a couple of yawns, went on to collect

his fifth US title.”

This is almost identical to what Cabrera Infante

reports that Marshall said (“I made the worst move

of the game. I woke up Capablanca”). Could he have

confused Capablanca-Marshall with

Fischer-Bisguier?

Whether he did or not, there is already ample

confusion about if and when Fischer may have

fallen asleep while playing Bisguier. Contemporary

reports on the game which was referred to by Fox

and James, and was played in the last round of the

US Championship in New York on 3 January 1963,

mention no such incident (see, for example, Chess

Life, January 1963, page 3; Chess Review,

February 1963, page 63 and March 1963, pages

76-77).

Frank Brady’s Profile of a Prodigy (New

York, 1973) is unsure, but indicates that

it was more likely in the Western Open at Bay

City, Michigan, in July 1963. Page 70 describes

Fischer playing an all-night set of high-stakes

blitz games and then states:

“The next morning, Fischer faced Bisguier, and

though perhaps apocryphal, it has been said that

he was so tired he actually fell asleep at the

board and had to be awakened. It didn’t affect his

play, however, as he defeated Bisguier soundly.”

Bisguier himself, though, places the incident at

the New York State Open, held in Poughkeepsie, NY

in August-September 1963, on page 69 of The

Art of Bisguier, Selected Games 1961-2003

(Milford, 2008):

“Paired against Bobby in the New York State Open

that year, I noticed that he was taking a long

time to move. Then I saw that he’d fallen sound

asleep. In a few minutes the flag on his clock

would fall, and he’d lose on time. That’s not the

way I like to win games, tourneys or titles. So I

made what some called my biggest blunder of the

tournament. I awakened Fischer. Bobby yawned, made

a move, punched his clock and proceeded to beat

me. It ended up as Game 45 in his My 60

Memorable Games. Later I heard that Fischer

had stayed up late the previous night playing

speed chess for money.”

Brady seems to have confused the Michigan and

New York tournaments. Whether Cabrera Infante has

confused Fischer with Capablanca, I cannot say,

but the two accounts are remarkably similar.’

We note that a) the above-quoted text by Messrs Fox

and James also appeared on page 149 of The

Complete Chess Addict (London, 1987) and b) the

Fox/James book was referred to, in another context, in

Cabrera Infante’s ill-informed essay on Capablanca.

Indeed, he clearly used it for a number of his

‘facts’.

‘Chess is the touchstone of the intellect’ is a

remark commonly ascribed to Goethe, but the matter is

not so simple. The sentiments were ‘merely’ expressed

by a character, Liebetraut, in Goethe’s 1773 play Götz

von Berlichingen, and the precise words ‘chess

is ...’ did not appear. Moreover, Goethe wrote ‘a

(and not the grander the) touchstone’.

Below (from near the beginning of Act II, Scene I, in

which the Bishop and Adelheid are playing chess) is

the translation by Charles E. Passage on page 42 of

the edition of Götz von Berlichingen A Play

which was re-issued by Waveland Press, Inc. in 1991:

The text in German editions in our collection reads

either ‘Es ist wahr, dieß Spiel ist ein

Probirstein des Gehirns’ or ‘Es ist wahr,

das Spiel ist ein Probierstein des Gehirns’.

5902. Speech by Hitler

Our latest feature article, Chess:

Hitler

and Nazi Germany, includes a quote from page 269

of the June 1933 BCM:

‘In his anxiously awaited speech to the Reichstag on

17 May, Herr Adolf Hitler made a curious comparison,

which is thus reported in the telegraphic accounts.

Speaking of the Nazi Storm Troops, he said: “If Storm

Troops are to be called soldiers, then even the chess

and dog-lover clubs are military associations.” Well,

we know that chess has been called effigies belli;

but it has not yet gone to the dogs!’

We see no reference to chess in the official transcript

of Hitler’s speech in Verhandlungen

des Reichstags. The closest passage is the

following (first column of page 51):

Page 1 of the New York Times, 18 May 1933

stated that ‘it was said to have been the first time

that he had ever delivered a written speech’. An English

translation of the full text was given on page 3, and

the relevant sentence read:

‘If today an attempt is being made in Geneva to count

these organizations exclusively serving political

purposes as part of the military force, then one might

as well include fire departments, gymnastic societies,

rowing clubs and sports associations in the military

force.’

Having found no catalogue of books about (not by) the

current world champion, we give a list of the volumes

in our collection:

- Führende Schachmeister der Gegenwart

Wiswanathan Anand by N. Heymann (Maintal,

1992)

- Viswanathan Anand (Elo 2600 series, USA, circa

1992)

- Anand 222 partidas (Madrid, 1993)

- Vishy Anand: Chess Super-Talent by D.

Norwood (London, 1995)

- Vishwanatan Anand (Szolnok, circa

1995)

- Vishy Anand by N. Kalinichenko (Moscow,

2004)

- The Chess Greats of the World: Anand by D.

Lovas (Kecskemét, 2007).

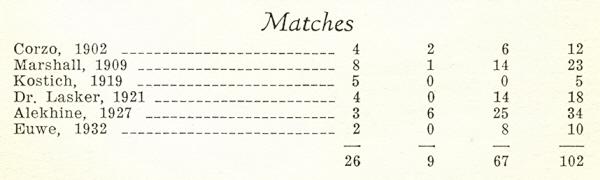

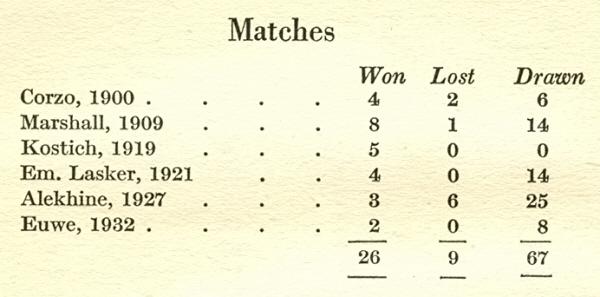

Page 14 of The

Immortal Games of Capablanca by F. Reinfeld

(New York, 1942)

Page 20 of Capablanca’s

Hundred

Best

Games of Chess by H. Golombek (London, 1947)

In the Lasker match there were ten, not 14, draws.

The Euwe match was in 1931, not 1932. The only matter

on which the books disagree is the year of

Capablanca’s match against Corzo, and both are wrong.

It was played in 1901.

The two books have been the subject of modern

reprints which have not bothered to correct these (and

innumerable other) elementary mistakes.

5905.

Réti

story

Maurice Carter (Fairborn, OH, USA) asks whether there

is any truth to a story about Réti told by H. Golombek

on pages iv-v of his Foreword to Réti’s Modern Ideas

in Chess (London, 1943):

‘... There is related an anecdote typical of the man.

In the closing stages of an international tournament

he was playing one of the weaker competitors and had

obtained a won game. It was his turn to move – an

obvious one since all he had to do was to protect a

threatened piece. He seemed to fall into a brown

study, did not move for ten minutes; then suddenly

started up from his chair – still without making his

move – and sought out a friend who was present in the

congress rooms. To him he explained that he had just

conceived an original and entrancing idea for an

endgame study. Not without difficulty his friend

dissuaded Réti from demonstrating and elaborating this

idea on his pocket chess set, and Réti returned,

somewhat disgruntled, to the tournament room, made

some hasty casual moves and soon lost the game.

Without troubling at all about this loss, Réti at

once returned to his hotel and spent almost the whole

of the night in working out his endgame study. As a

consequence he lost his next game through sheer

fatigue and with it went his chances of first prize.

He perfected a beautiful endgame composition at

considerable financial loss.’

Fred Reinfeld, Chess

Review, January 1943, page 29

A question from Frederick S. Rhine (Park Ridge, IL,

USA) is whether anything is known about how Fred

Reinfeld died, on 29 May 1964.

Information seems scarce. J.S. Battell’s obituary of

Reinfeld on pages 193-194 of the July 1964 Chess

Review gave no particulars and, remarkably, in

the 1964 volume of Chess Life we see no

mention at all of Reinfeld’s demise. The obituary on

page 17 of the New York Times, 30 May 1964 did

not specify the cause of death but reported that

Reinfeld had died the previous day ‘at Meadowbrook

Hospital’.

On page 209 of the July 1964 BCM S. Morrison

stated that Reinfeld ‘died of a virus infection at his

home in Long Island’. He was 54.

5907.

Reinfeld quotes

A few quotes from Why You Lose at Chess by Fred

Reinfeld (New York, 1956):

- ‘Some chess masters write as if they were addressing

a convention of grand masters somewhere on Mount

Olympus.’ (Page 1)

- ‘Alexander Alekhine was undoubtedly the greatest

chessplayer in the history of the game, but what he

really prided himself on was his ... bridge playing.

All I know about bridge is that it’s played with a

deck of cards – or maybe two decks (it’s very

confusing) – but people in a position to judge have

told me that Alekhine was a miserable bridge player. I

can well believe it. Just as we misjudge our strong

points, so we misjudge our weaknesses.’ (Page 7)

- ‘... a chessplayer and his alibi are not soon

parted.’ (Page 9)

- ‘... Capablanca, perhaps the greatest single-move

player in chess history.’ (Page 101)

- ‘Never forget this: the most important move in any

game of chess is always ... the very next move.’ (Page

110)

- ‘Wilhelm Steinitz was one of the three greatest

chess masters of all time. (I rank him with Lasker and

Alekhine.)’ (Page 166)

- ‘I shall never forget the description of the final

scene of the 1935 match for the world championship.

Both Alekhine, the defeated champion, and Euwe, the

new champion, were in tears. There was this

difference: Alekhine, the defeated, wept tears of

sorrow. Euwe, the victor, wept tears of joy.’ (Page

237) In which contemporary source did the

‘description’ in question appear?

Mark McCullagh (Belfast, Northern Ireland) writes:

‘In the entry for Capablanca in

your Chess

Prodigies article the captions to two

photographs mention Manuel Márquez Sterling. Is this

the Manuel Márquez Sterling who was very briefly the

President of Cuba?’

One of the photographs is reproduced below, from a

plate section in Glorias del Tablero “Capablanca”

by José A. Gelabert (Havana, 1923):

The person in question was indeed Manuel

Márquez

Sterling

y Loret de Mola (1872-1934). See, firstly, pages

120 and 122 of The Unknown Capablanca by David

Hooper and Dale Brandreth (London, 1975).

We also reproduce the biographical note which appeared

on pages 256-257 of Ajedrez en Cuba by Carlos A.

Palacio (Havana, 1960):

Larger

version

His obituary on page 21 of the New York Times,

10 December 1934 included the following reference:

‘Known as an opponent of the Machado régime, he

served for a few days as Provisional President in Cuba

during the revolutionary crisis following the flight

of the dictator.’

Page 165 of the December 1934 American Chess

Bulletin carried a brief death notice:

‘Dr Manuel Márquez Sterling, who had held the post of

Cuban Ambassador at Washington since January 1934,

died in that city on 9 December, at the age of 62.

Old-timers will recall the name of Dr Sterling as that

of an ardent chess devotee at one time quite active in

Havana, when he was a player of considerable ability.

He was the author also of a text book on the game in

the Spanish language. Dr Sterling was long in the

diplomatic service of his country and, earlier in his

career, was Ambassador to Mexico.’

The text book in question was Un poco de ajedrez (Mexico,

1893):

5909. Hugh Myers

The death of our close colleague and friend Hugh

Myers is a grievous blow. At present, we simply

reproduce for the public record the autobiographical

details which he sent us on 18 November 1983 (C.N. 635):

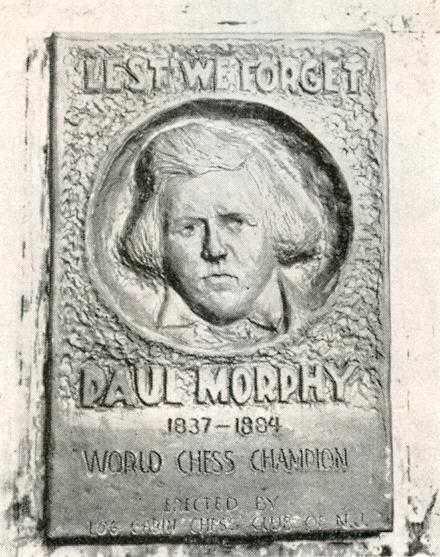

5910. Morphy memorial

From page 320 of Paul Morphy The Pride and Sorrow

of Chess by D. Lawson (New York, 1976):

‘Paul Morphy was memorialized at Spring Hill College

on 27 April 1957, when a plaque and monument presented

by E. Forry Laucks were unveiled by the Mayor of

Mobile, Henry R. Luscher, with an honor guard from the

Spring Hill ROTC.’

A photograph of the ceremony was given on the following

page, and we add below a detail of the plaque, from page

164 of the June 1957 Chess Review:

Richard Forster (Zurich) reports that daily bulletins

were issued during the 1923 Swiss championship in

Berne (six two-page issues, with results and a

selection of games). The championship was combined

with a match between Switzerland and Southern Germany.

David Kuhns (St Paul, MN, USA) asks for references to

illustrations of players using a sand-glass timer

(hour-glass).

The group photograph of Dresden, 1892 was the

frontispiece in Hundert Jahre Schachturniere

by P. Feenstra Kuiper (Amsterdam, 1964). The

apparently tall player was, as in Fred Wilson’s later

book A Picture History of Chess, identified as

Walbrodt:

Larger version

5914. Euwe and Alekhine (C.N. 5907)

Prompted by the Reinfeld quote regarding Euwe and

Alekhine, Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England) has sent us

from his collection a photograph taken at the end of the

1935 world championship match:

From Jan Kalendovský (Brno, Czech Republic) comes a

photograph (source unknown) of Alekhine at the studios

of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer with Renée Adorée (1898-1933)

and Fred Niblo (1874-1948):

Can it be confirmed that the photograph was taken

during Alekhine’s visit to Los Angeles in May 1929?

A game presented by us on page 7 of

issue 23 (Autumn 1994) of Kingpin

(see also pages 62-63 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves):

George Howard Thornton – Boultbee

Occasion?

King’s Gambit Declined

1 e4 e5 2 f4 Bc5 3 Nf3 d6 4 d4 exd4 5 Nxd4 Nf6 6 Nc3

O-O 7 Be3 Qe7 8 Bd3 Re8 9 a3 Ng4 10 Bg1 f5 11 Be2 fxe4

12 Nd5 Qf7 13 Bc4 Be6 14 Nxe6 Rxe6 15 Qxg4 c6 16 Qxe6

Qxe6 17 Ne7+ Kf8 18 Bxe6 Kxe7 19 Bc8 Nd7 20 Bxb7 Rb8 21

Bxc6 Rxb2

22 Bxd7 Kxd7 23 Bxc5 dxc5 24 O-O-O+ Black resigns.

Source: Brooklyn Chess Chronicle, 15 November

1884, page 31, as shown below:

We commented in the earlier item:

‘Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia lists George

Howard Thornton (born in Watertown, NY on 28 April

1851, died in Buffalo, NY on 30 January 1920). Unless

an earlier game can be found, “Thornton castling trap”

might be an appropriate term.’

No earlier games have yet been found, and the term

proposed has sometimes been picked up. A recent example

is on page 219 of The Greatest Ever chess tricks and

traps by Gary Lane (London, 2008).

George Howard Thornton

and other ‘champions’ (page 155 of the October 1898 American

Chess Magazine)

Biographical information about Thornton and a number of

his games are provided on pages 253-261 of Essays in

American Chess History by John Hilbert (Yorklyn,

2002). The material is also available on-line.

5917. A decoding task (C.N. 5867)

This decoding task was mentioned in C.N. 5867 by

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA). The follow-up

item in CHESS was on page 143 of its April 1946

issue:

However, our correspondent proposes a reconstruction

which goes through to move 31: 1 c4 Nf6 2 Nc3 c5 3 Nf3

Nc6 4 d4 cxd4 5 Nxd4 Qb6 6 Nb3 d6 7 Bg5 h6 8 Bxf6 gxf6 9

Nd5 Qd8 10 g3 h5 11 Qd2 Bh6 12 f4 Be6 13 Bg2 Rc8 14 e3

Bg7 15 Rc1 b6 16 Kf2 f5 17 Nd4 Nxd4 18 exd4 Bd7 19 Rhe1

e6 20 Ne3 Qf6 21 Rcd1 O-O 22 Bb7 Rc7 23 Bf3 b5 24 cxb5

Bxb5 25 Qa5 Rc5 26 dxc5 Qxb2+ (The preceding moves are

as unravelled by the readers of CHESS.) 27 Rd2

Qc3 28 Qxc3 Bxc3 29 Rxd6 Bxe1+ 30 Kxe1 Rc8 31 c6 and

White wins.

Rod Edwards (Victoria, BC, Canada) writes:

‘On page 272 of the 25 October 1851 issue

of Home Circle, a woman corresponding under

the name of “Sybil” issued a challenge to “any

chessplayer … not much above the average …” to play

a game by correspondence which would be printed as

it progressed in the chess column of Home

Circle. The 6 December 1851 issue (page 368)

reported that she had received several acceptances

and had picked one name from an urn: G.B. Fraser of

Dundee, who became one of the best players in

Scotland in the 1860s and 1870s. Week by week over

the next 15 months the moves of the game were

reported until at move 51 “The ‘fayre Sybil’ mates

with the queen” (Home Circle, 5 March 1853,

page 160). The entire game was published with

commentary on page 192 of the 19 March 1853 edition

and was also reprinted as a game between “A Lady”

and “Mr F.” on pages 232-233 of the March 1853 issue

of the Chess Player.’

‘A Lady’ – George Brunton Fraser

Correspondence, 1851-53

Giuoco Piano

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 c3 Nf6 5 d4 exd4 6 cxd4

Bb6 7 Bg5 d6 8 h3 h6 9 Bxf6 Qxf6 10 Bb5 O-O 11 Bxc6

bxc6 12 Nc3 Qg6 13 Nh4 Qg5 14 g3 f5 15 Nf3 Qg6 16 Nh4

Qf6 17 e5 dxe5 18 dxe5 Qxe5+ 19 Qe2 Qc5 20 O-O f4 21

g4 Bd7 22 Rad1 Rae8 23 Ne4 Qb4 24 Rfe1 Ba5 25 a3 Qb3

26 Rd3 Qf7 27 b4 Bb6 28 Rf3 Be6 29 Qc2 Bd5 30 Nf5

30...Be3 31 Rexe3 fxe3 32 Rxe3 Kh8 33 f3 Qd7 34 Nc5

Qd8 35 Rxe8 Qxe8 36 Kg2 Qe1 37 Nd3 Qe8 38 Nf4 Qf7 39

Ne7 Qxf4 40 Ng6+ Kg8 41 Nxf4 Rxf4 42 Kh2 Rxf3 43 Qa4

Kh7 44 Qxa7 h5 45 gxh5 Kh6 46 a4 Rf7 47 a5 Kg5 48 Qc5

Kxh5 49 a6 Rf1 50 Qe7 g5 51 Qh7 mate.

It is impossible not to have

misgivings, both general and particular, about

Wikipedia, but we have recently noticed a great

improvement in some of the chess articles in the

site’s English-language version. There is, for

instance, excellent treatment of G.H.D.

Gossip, and it is also good to see a fine article

on

Hugh Myers.

5920. En passant (C.N. 5895)

Regarding compositions which illustrate the obligatory

nature of the en passant capture, Michael

McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England) quotes a problem by

Fritz Giegold (second prize, Deutsche Schachblätter,

1952):

Mate in three.

The key-move is 1 Bd4. After 1...Kxh4 (if 1...Kh6, then

2 Ra5.) 2 f4 exf3 (forced) 3 Bf6 mate.

The cartoon in C.N. 5897 provides a reminder of the

lack of photographs of the peripatetic match between

Marshall and Capablanca in 1909. The illustration

below, by C.W. Kahles (1878-1931), comes from page 177

of the Chess Weekly, 1 May 1909. On page 345

of A Chess Omnibus we commented that it had

been ‘sketched with some artistic licence’.

In C.N. 5915 we tentatively suggested that this

photograph of Alekhine at MGM was taken during his

visit to Los Angeles in May 1929.

David Picken (Greasby, England) and

Luc Winants (Boirs, Belgium) note that Renée Adorée

played the role of a gypsy in an MGM film directed by

Fred Niblo, Redemption.

Shot in 1929 and starring John Gilbert, it was not

released until 1930. Without the production delays it

would have been his first talking picture.

We add that Redemption was unsuccessful, as

noted, for instance, on page 66 of La fabuleuse

histoire de la Metro Goldwyn Mayer en 1714 films

(Paris, 1977). See also pages 261-262 of volume one of The

Great

Movie Stars by D. Shipman (London, 1989).

According to page 544 of Close-Ups From the

Golden Age of the Silent Cinema by J.R. Finch and

P.A. Elby (New York and London, 1978) Gilbert’s

‘greatest film was The Big Parade with Renée

Adorée’.

A position from page 75 of Better Chess by

William Hartston (London, 2003):

White, to play, gives mate in how many moves?

Solution.

5924. Desperado

An interesting observation by Mark Dvoretsky in his

Foreword to the new algebraic edition of Lasker’s

Manual of Chess (Milford, 2008) – see page 14 – is

that Emanuel Lasker invented the chess term ‘desperado’.

Certainly we can quote nothing which antedates pages

106-107 of the original edition, Lehrbuch des

Schachspiels (Berlin, 1926):

Siegfried Hornecker (Heidenheim, Germany) draws

attention to a photograph of Alain Campbell White on

page 6 of the fifth section of the Pittsburgh

Gazette Times, 30 October 1910:

Wanted: more information about this game: 1 e4 e5 2

Bc4 Nf6 3 d4 c6 4 dxe5 Nxe4 5 Ne2 Nxf2

6 O-O Nxd1 7 Bxf7+ Ke7 8 Bg5 mate.

Page 50 of Schnell Matt! by C. Hüther

(Munich, 1913) merely stated that it was won by

Captain Mackenzie. After giving the moves on pages

151-152 of Teach Yourself Chess (London,

1948), Gerald Abrahams identified the winner as ‘the

late Captain Mackenzie’, but his addition of ‘the

brilliant blind player’ suggests confusion with Arthur

Ford Mackenzie.

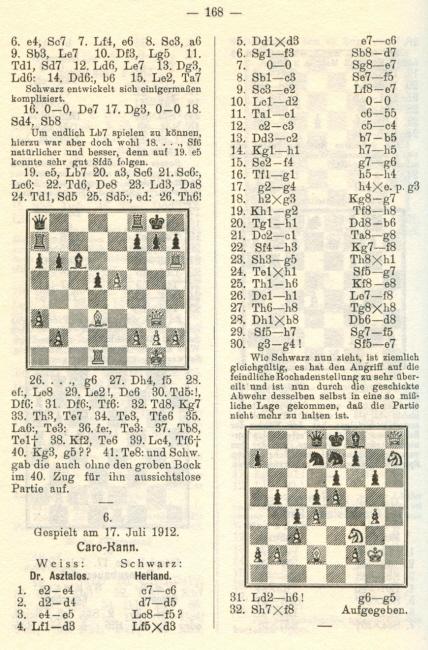

Lajos Asztalos – Sigmund Herland

Breslau (Hauptturnier A), 17 July 1912

Caro-Kann Defence

1 e4 c6 2 d4 d5 3 e5 Bf5 4 Bd3 Bxd3 5 Qxd3 e6 6 Nf3

Nd7 7 O-O Ne7 8 Nc3 Nf5 9 Ne2 Be7 10 Bd2 O-O 11 Rae1

c5 12 c3 c4 13 Qc2 b5 14 Kh1 h5 15 Nf4 g6 16 Rg1 h4 17

g4 hxg3 18 hxg3 Kg7 19 Kg2 Rh8 20 Rh1 Qb6 21 Qc1 Rag8

22 Nh3 Kf8 23 Nhg5 Rxh1 24 Rxh1 Ng7 25 Rh6 Ke8 26 Qh1

Bf8 27 Rh8 Rxh8 28 Qxh8 Qd8 29 Nh7 Nf5 30 g4 Ne7

31 Bh6 g5 32 Nxf8 Resigns.

Source: the Breslau, 1912 tournament book, page 168

(reproduced below).

31 Bh6 was given an exclamation mark, but if the

game-score is correct White overlooked a smothered

mate in two: 31 Qxf8+ Nxf8 32 Nf6. This was pointed

out on page 144 of the November 1919 Schweizerische

Schachzeitung.

5928. An unusual chess picture (C.N.

3434)

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) writes:

‘The picture which a correspondent enquired about

in C.N. 3434 shows the conjoined twins Eng and Chang

Bunker (1811-74), who used the game of chess in

their exhibitions and stage shows. Page 11 of Western

Civilization in Thailand by Âphâ Phamônbut

(published by the Department of Corrections Press in

1986) mentioned that the twins “played American

games well and were excellent players for the

chess”. Duet for a Lifetime: The Story of the

Original Siamese Twins by Kay Hunter (New York,

1964) gave the above picture of the twins playing

chess.

Among the illustrations in the public domain is

one dated 1839 (also given in the book by Kay

Hunter):

A 16-page pamphlet (1831) entitled An

historical account of the Siamese twin brothers, from

actual observations by James W. Hale had as its

frontispiece an engraving of the twins at one of their

earliest exhibitions, in 1830. Again, a chess motif

was present:

Page 9 of the pamphlet stated:

“They play at chess and draughts remarkably well,

but never in opposition to each other; having been

asked to do it, they replied that no more pleasure

would be derived from it, than by playing with the

right hand against the left.”

Rich primary material is available

on-line at the library of the University of

North Carolina.’

Elmer Sangalang (Manila, the Philippines) asks when

stalemate came to be adjudged a draw.

It is a matter which H.J.R. Murray examined not only

in his book A History of Chess (Oxford, 1913)

but also in an article, ‘Stalemate’, on pages 281-289

of the July 1903 BCM. In the latter source he

noted, regarding ‘parallelism to real warfare’, that

stalemate most closely resembled a situation ‘in which

one monarch retired to an impregnable fortress’ and

that:

‘The issue of such a condition was obviously

doubtful; sometimes the blockaders might succeed in

starving him into surrender, but sometimes with

ample supplies the besieged monarch would succeed in

wearying his opponents until they abandoned what

appeared a hopeless enterprise. With no certain

assistance from actual life, the evaluation of the

position in the game of chess was left to the fancy

of players, and the laws of stalemate have varied

from age to age, and from place to place.’

Further extracts from Murray’s article:

‘The revival of interest in chess as a game, which

dates from the rise of New Chess, towards the end of

the fifteenth century, led to the appearance of

books on chess which were other than mere

collections of problems. From Lucena’s work (1497)

we learn that stalemate was then called in Spain mate

āogado, and the player who was stalemated lost

half his stake. Ruy López calls it mate ahogado,

and gives the same evaluation. To give stalemate was

accordingly reckoned in Spain as an inferior form of

victory, which was yet more profitable than a draw.

With the Italian school, stalemate was reckoned as

identical with a draw.’

‘With the beginning of the seventeenth century, a

new convention with regard to stalemate makes its

appearance, apparently in England. ... Arthur Saul

is the first writer to enunciate the rule that the

player whose king was stalemated had won the game.’

‘Whatever may have been the origin of Saul’s rule,

it rapidly became the accepted rule in English

chess. ... The war against the English rule was

commenced by Philidor, who naturally stood up for

the rules as he had learned them in France. But even

Philidor could not convert a nation at once,

especially a nation which contained so confirmed a

crank as Peter Pratt, the author of that

preposterous attempt to convert chess into a game of

politics, in which kings were to “closet” and not to

castle, with much else of equal absurdity. As a

persistent editor of Philidor’s analysis, Pratt was

able to air his views under the shadow of the

master, and was still in 1806 bravely defending the

English rule of stalemate. To Sarratt, the almost

forgotten master of Lewis, and the re-discoverer of

the open game which most Englishmen still prefer, is

due the credit of finally putting an end to the

schism, which must indeed have in any case soon

ceased with improved methods of inter-communication,

and with the coming of the age of international

matches and tournaments. The convention that

stalemate draws thus became the rule of the European

game ...’

From page 32 of Studies

of Chess by Peter Pratt (London, 1803 edition)

On pages 57-62 of A Short History of Chess

(Oxford, 1963) Murray gave, in a country-by-country

review of rule changes, the following information on

stalemate:

‘Spain (including Portugal). Stalemate and the

baring of the opponent (unless baring and mate

occurred simultaneously) were inferior forms of

victory at least as late as 1634, and possibly as

late as 1750.’

‘Italy. Everywhere stalemate was a draw.’

‘France. Stalemate was a draw.’

‘England. Before 1600 stalemate became a win for

the stalemated player. This ceased to be the rule of

the chess clubs from about 1807 ...’

‘Germany. Hardly any two authors prior to Allgaier

(1795) agree to their rules. [This was a general

remark by Murray on rule changes, and not

specifically related to stalemate.] Gustavus Selenus

(1616): ‘Stalemate is a draw, but in some places the

stalemated king wins.’ G.F.D. v. B. (manuscript of

1728): ‘Stalemate is a win for the stalemated king.’

Klemich (1872): ‘The stalemated king wins.’

We hope to find more specific information about the

role of Sarratt. Murray’s article about him on pages

353-359 of the July 1937 BCM indicated that

matters were unclear:

‘He [Sarratt] was a member, or at least a frequent

visitor, of the London Chess Club, which met at

Tom’s Coffee-house, Cornhill, and is said to have

had a hand in drafting the Laws of Chess for this

club. In these rules the older English rule that the

stalemated player won was abandoned in favour of the

Continental rule that stalemate is a draw.’

Lonnie Kwartler (Chester, NY, USA) notes misprints in

the pages of Lasker’s Lehrbuch des Schachspiels

reproduced in C.N. 5924: ‘Mares’ should read Marco,

and in the next diagram White’s king is missing, from

h1.

The review of the Lehrbuch on page 318 of the

July 1926 BCM commented, ‘There are

unfortunately a large number of misprints, which will

require correction in a second edition.’ Later

versions did indeed make improvements. However, while

including such corrections, the English-language

edition of Lasker’s Manual, first published in

1927, introduced new problems, and we look at one of

them now.

The victim of a famous Alekhine brilliancy (New York,

January 1924) was named as Kußmann (i.e. Kussmann) by

Lasker in his Lehrbuch (see either page 104 or

page 108). In the English edition (page 137) it came

out as ‘Kubmann’, i.e. with apparent confusion between

the Eszett (ß) and the letter b. The spelling

‘Kubmann’ persisted in subsequent editions of Lasker’s

Manual.

In, respectively, Auf dem Wege zur

Weltmeisterschaft and his second volume of Best

Games Alekhine named his opponent as A. Kußman

and A. Kussman. Use of the initial A. may be due to

his having played a draw against Abraham S. Kussman on

another occasion: in a clock simultaneous display in

New York on 23 March 1929 (American Chess Bulletin,

April 1929, pages 62 and 65).

As regards the brilliant miniature which Alekhine

won, it is rather surprising that page 734 of the

Skinner/Verhoeven volume entertained, albeit

tentatively, the possibility that Alekhine played two

almost identical games, against L. Kussman and L.

Kubmann (the sources being, respectively, the

above-mentioned books by Alekhine and Lasker).

So, who had the misfortune in the above position to

face 16 Qb5+ from Alekhine? We wonder whether there is

any reason to doubt the information supplied when the

game was published on page 8 of the January 1924 American

Chess Bulletin:

‘A simultaneous game played between Alexander

Alekhine and Leon Kussman, dramatic editor of the Jewish

Morning Journal, in the former’s exhibition at

the Newspaper Club of New York, January 13, 1924 –

the Russian New Year’s Day.’

George Henry Mackenzie

(BCM, May 1891, page 244)

Fabrizio Zavatarelli (Milan, Italy) has found an

interesting passage on page 172 of the Dubuque

Chess Journal, May 1877 (converted here to the

algebraic notation):

‘Chess in Boston.

The following “chessikin” occurred some years ago

between Capt. MacKenzie and a president of the

Boston Chess Club:

Remove White’s Ng1.

MacKenzie – Mr X.: 1 e4 e5 2 Bc4 Nf6 3 d4 Nxe4 4

dxe5 Nxf2 5 O-O Nxd1

White mates in two moves.’

Chess Notes Archives

Copyright: Edward Winter. All

rights reserved.

|