Edward Winter

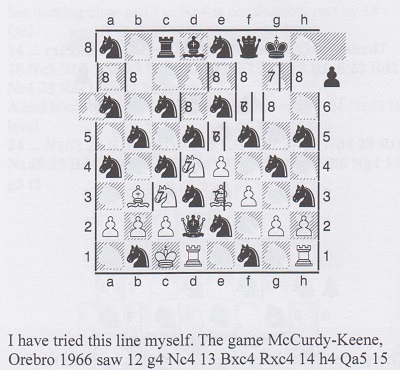

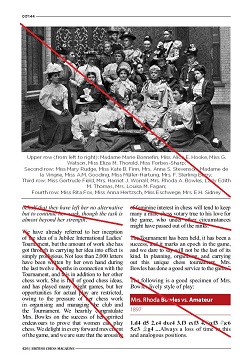

An article under Raymond Keene’s name in the July 2024 BCM. C.N. 12048 stated:

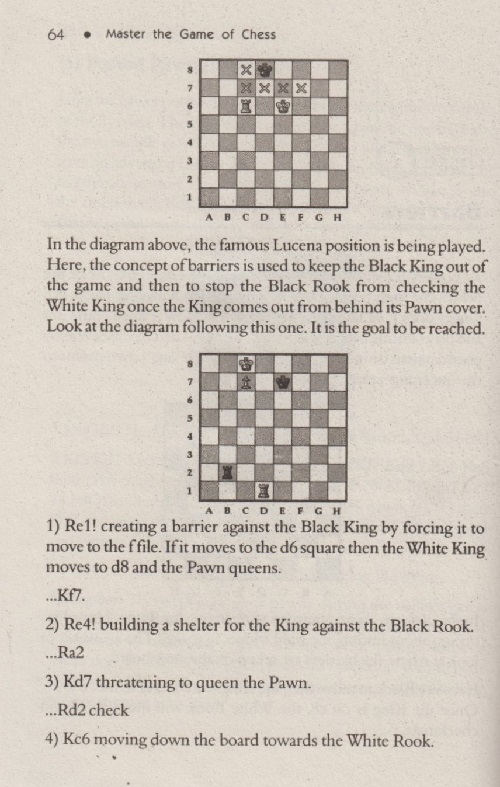

The nine pages are shown below, with red diagonal lines added by us to mark those parts, all uncredited, that anyone could readily copy-paste from other people’s work available online.

We have not marked the last two pages, which quote texts by Jacqueline Eales and Susan Polgar.

The pages are shown here in a small format, in order to protect the copyright of Raymond Keene, OBE, Ctrl+C, Ctrl+V.

***

Some cheat at the chessboard, others at the keyboard. Below are examples of the copying and/or plagiarism perpetrated by a number of individuals in the chess world.

Louis Blair (Knoxville, TN, USA) points out that four passages on page 36 of William Steinitz, Chess Champion by Kurt Landsberger (Jefferson, 1993) repeat, almost word for word, material in the Preface to Championship Chess by P.W. Sergeant (London, 1938). However, whereas Sergeant wrote that Steinitz ‘did not claim any title when he defeated Anderssen in a match in 1866’, Landsberger asserted, ‘When Steinitz defeated Anderssen he announced that he was the world champion’.

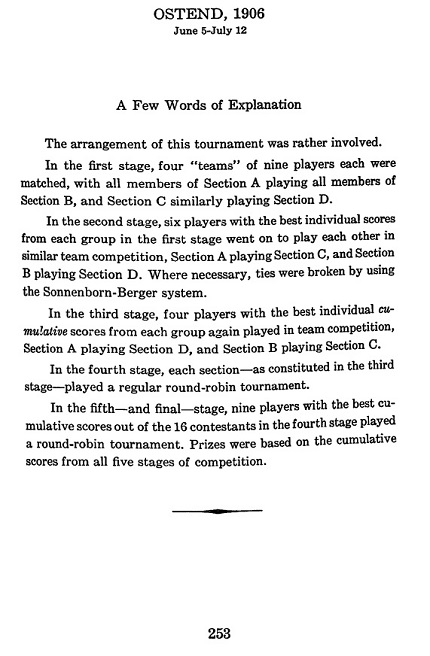

On page 37 of the Autumn 1993 Kingpin we commented that the Landsberger work was ‘often poorly written and edited’. From page 253 of the book:

In a book review published on the Internet (at the Campbell Report/Correspondence Chess site) John Hilbert has justifiably panned Emanuel Lasker Volume 1 by Egon Varnusz (Budapest, 1998) for chronic slovenliness and plagiarism. A dreadful book indeed, notwithstanding what magazines/stockists such as the BCM and CHESS have chosen to tell their readers/customers. We note, with a shiver, that in addition to a second Lasker volume Mr Varnusz has collections of both Capablanca and Alekhine’s games in the pipeline.

(2218)

In a footnote on page 286 of A Chess Omnibus we added:

A second Lasker book duly appeared, followed by two sloppy volumes on Capablanca.

From Over and Out:

Vacuous copying is done by chess writers of many kinds, and the key to breaking out of this vicious circle is research, allowing more and more neglected material to trickle into mainstream works.

Some Editors – pretend to edit –

Use scissors and paste and give no credit.

Source: Columbia Chess Chronicle, 20 August 1887, page 66.

The Chronicle credited this to the Celtic Times, but gave no further particulars.

(2635)

From Worst-ever Chess Book?:

The plagiarist’s customary ineptitude always shines through eventually.

A number of additional cases are listed here pro memoria:

Chess (Basics, Laws and Terms) by B.K. Chaturvedi copied extensively from Chess Made Easy by C.J.S. Purdy and G. Koshnitsky (see A Chess Omnibus, pages 335-337).

Coles Publishing Company pirated editions of books by Capablanca, Marshall, Reinfeld, Rice and Love (see A Publishing Scandal).

Postings at the Chess Café’s Bulletin Board in 2001 (most notably by Paul Kollar) pointed out many passages published under Larry Evans’ name which were identical or similar to what had appeared in books by Lasker, Réti, Reinfeld and Fine. (Regarding Fine, on page 32 of the February 2002 Chess Life Evans defended himself by affirming that he had collaborated on The World’s Great Chess Games and had himself written the passages in question.)

The Batsford Chess Encyclopedia by N. Divinsky copied many entries from The Encyclopedia of Chess by H. Golombek. Despite that, the Divinsky book was billed by the publisher as ‘completely new’.

On pages 8-9 of the 5/1986 New in Chess (see also the account on pages 278-279 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves) Christiaan Bijl related how his volume on Fischer’s games had been abused by Dimitrije Bjelica.

(2971)

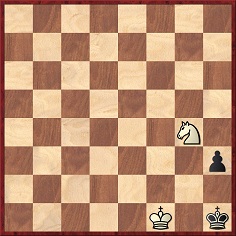

Page 9 of the 5/1999 New in Chess reveals that at least one person is still prepared to defend the gaffe-drenched Batsford Chess Encyclopedia. It may be commented here that among N. Divinsky’s less successful attempts to copy from Golombek’s earlier work was the entry for Zugzwang:

Misunderstanding both the position and Golombek’s commentary thereon, Divinsky wrote: ‘if it were White’s turn to move, the game would in fact be a draw’. Yet White has a forced mate (1 Nf2+ Kh2 2 Ne4 Kh1 3 Kf2 Kh2 4 Nd2 Kh1 5 Nf1 h2 6 Ng3), as was mentioned by John Nunn in a gratifyingly hostile review of Divinsky’s book on pages 26-27 of ChessBase Magazin, July-August 1991.

(2311)

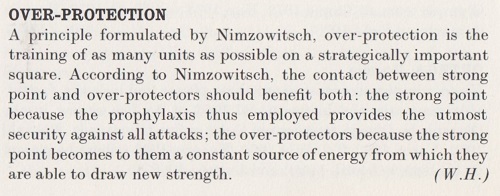

Below is Wolfgang Heidenfeld’s entry on over-protection on page 230 of The Encyclopedia of Chess by Harry Golombek (London, 1977):

We add without comment what Nathan Divinsky gave on page 154 of The Batsford Chess Encyclopedia (London, 1990):

(10453)

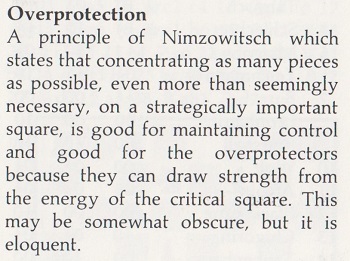

The 18-page Défense Myers! was sent to us by the editor of the Myers Openings Bulletin, Hugh Myers, who wrote on the front cover: ‘This book is outright plagiarism of an MOB article by P. Szeligowski’. The contact address given on the back cover was ‘Henris Luc, 8/C rue du Merlo bte 24, 1180 Bruxelles’.

See also C.N. 4108, regarding Bjelica’s plagiarism of Irving Chernev. Moreover, C.N. 2888 reported on how Sadoscacchi by F. Pezzi and M. Diversi (Rome, 1994) had copied from Chernev’s The Most Instructive Games of Chess Ever Played (New York, 1965); see pages 228-229 of Chess Facts and Fables. Further examples, involving ‘Philip Robar’, are indicated in the references in the Factfinder. As regards the Internet, an individual named Frank Mayer has persistently misappropriated material from Chess Notes.

The full text of C.N. 2888:

Students of copying, though few others, may care to procure Sadoscacchi by Franco Pezzi and Massimo Diversi (Prisma Editori, Rome, 1994) and compare it with The Most Instructive Games of Chess Ever Played. For example, here is the Italian book’s note (page 145) to White’s 22nd move in Tal v Lisitsin, Leningrad, 1956:

‘Un bel sacrificio posizionale! A costo di un pedone il Bianco smembra la struttura dei pedoni avversari sull’ala di Re. In aggiunta, l’accettazione del sacrificio rende quasi cieco l’Alfiere avversario poiché i pedoni (eccetto il derelitto in a7) occupano tutti case bianche.’

Chernev’s book (page 23) had:

‘A fine positional sacrifice. At the cost of a pawn Tal disrupts his opponent’s pawn structure on the king side. In addition to this, the acceptance of the sacrifice leaves Black’s bishop hemmed in by pawns occupying white squares.’

If required, many similar instances from Sadoscacchi can and will be quoted.

Regarding Alpha Teach Yourself Chess in 24 Hours by Zsuzsa Polgar (who, the back cover says, ‘has even defeated, at different events, world champs Anatoly Karpov and Victor Korchnoi’), Hoainhan ‘Paul’ Truong and Leslie Alan Horvitz (Indianapolis, 2002/03), we commented in C.N. 3343:

The lack of effort and thought is also shown by the section on recommended books (pages 321-328). Instead of offering their own observations, the co-authors have often simply lifted text (up to a dozen lines) from the publishers’ blurb and presented it as their own assessments. Examples occur with volumes by John Nunn and Jonathan Rowson and, indeed, with one of our own books.

The full text of C.N. 3343 is given in Chess Jottings.

From pages 98-99 of Black is OK Forever! by A. Adorján (London, 2005):

‘Watch the errors. Yes, there are some really persistent ones which remain undetected for several decades. I’m not talking about the mistakes that fill the trash written on “opening theory” by the dozen. That’s what I call “fortnightly books”. Here is how to produce them: take three existing “works” on your subject, mix them up a little bit, add a lot of fresher games (don’t forget to steal the annotations), and finally – to make it look better – put in something analysed by your latest Fritz (or whatever). That’s all. One gets the impression that those who have already read at least one chess book feel an irresistible urge to write one as well. No wonder Timman said already in the early 1980s: “95% of opening theory books are rubbish.” Unfortunately, the time that has passed since failed to prove the opposite.’

Jan Timman (Amsterdam) informs us:

‘Adorján’s quote is puzzling for me. I don’t recall such a statement from those years. In fact, I valued some opening books that appeared in those days.’

(3914)

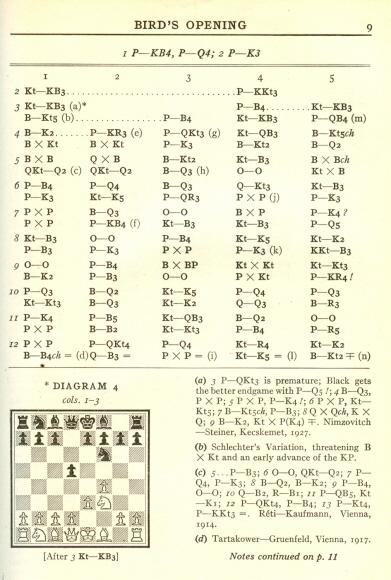

Owen J. Clarkin (Ottawa, Canada) writes:

‘I should like to point out an example concerning:

(i) Modern Chess Openings, seventh edition, revised by W. Korn under the editorship of R.C. Griffith and P.W. Sergeant (London, 1946);

(ii) Practical Chess Openings by R. Fine (Philadelphia, 1948).

Regarding the Center Counter Game, I found that ten columns of variations and the corresponding footnotes are virtually identical. See pages 30-32 of MCO and pages 35-38 of PCO. Other chapters where copying is notable include the following:

Alekhine’s Defense: Columns 1 and 2 of MCO v 1 and 2 of PCO; column 23 of MCO v 20 of PCO; column 21 of MCO v 17 of PCO.

Bird’s Opening is practically identical for most variations and footnotes.

The Bishop’s Opening has many copied sections.

It is not clear to me who copied whom, or whether this copying has been noticed before. The editors of MCO credit Fine as the reviser of the sixth edition of MCO (see page v of the seventh edition), but Fine makes no mention in PCO of his involvement in the sixth edition of MCO.’

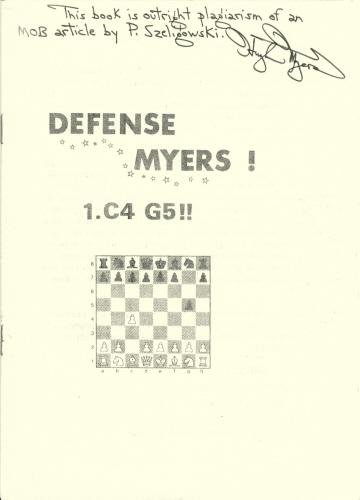

Our correspondent’s final paragraph holds the key to the affair: Reuben Fine had brought out a ‘completely revised’ edition of MCO in 1939. Below is part of the three books’ coverage of one of the above-mentioned openings:

From left to right: MCO-6 by Fine (1939), MCO-7 by Korn (1946), Practical Chess Openings by Fine (1948)

Thus Fine’s material in the sixth edition of MCO was used both by Korn in the seventh edition of MCO and by Fine himself in PCO. The rights and wrongs of such practices seem far from clear-cut.

The following text appeared on the dust-jacket of Practical Chess Openings:

‘Several years ago, when the author was on an exhibition tour, the master of ceremonies in St Louis introduced him to the audience with the remark: “Ladies and Gentlemen, it gives us great pleasure to have with us tonight the author of the Bible.” The “Bible” that he referred to was Modern Chess Openings, sixth edition, to which this book is a sequel.’

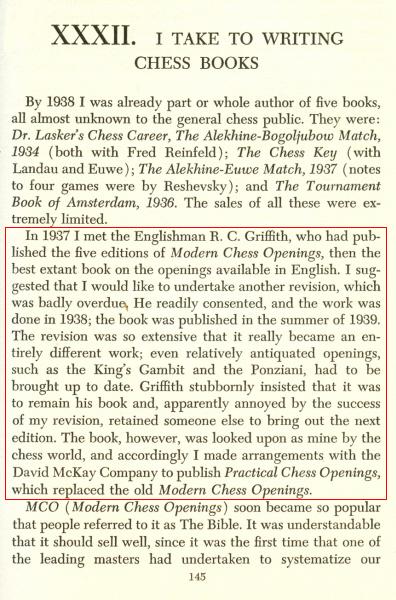

The blurb also asserted: ‘Reuben Fine is the world’s leading authority on chess.’ As regards the MCO/PCO affair, Fine gave his side of the story on page 145 of his book Lessons from My Games (New York, 1958):

(5269)

The start and the conclusion of C.N. 5280:

There has been a recent spate of ‘prose’ chess books woefully lacking in rigour, and the worst may well be Treasure Chess by Bruce Pandolfini (New York, 2007). ‘Trivia, Quotes, Puzzles, and Lore from the World’s Oldest Game [sic]’ is the subtitle, while the acknowledgements page begins with similar insouciance:

‘For a book like Treasure Chess it is not so easy to cite where all my references and impressions came from, so I’m not even going to try.’

Since much of the information provided is false, supplying citations would indeed have been awkward ...

... The imprint page of Treasure Chess warns, ‘No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means’, and anyone who cares about accuracy and truth will unhesitatingly comply.

The back cover of Academic Dictionary of Games edited by Shamshad Ahmed (Delhi, 2005) is full of Eastern promise:

‘The present publication is an up-to-date, authentic and comprehensive dictionary of games ... It aims to provide clear, concise, and correct definitions and descriptions of the terms used in games. ... This work is designed to be a comprehensive reference tool for games professionals, students and laymen interested in games. It is earnestly hoped that it will be an authoritative source to which one can turn with confidence for meaning and knowledge of the common, specialised and latest terms in games and allied fields.’

The Editor’s qualifications for the assignment are then commended:

‘Shamshad Ahmed, a renowned freelance journalist did his postgraduate diploma in journalism and mass communication in 1975. His area of specialisation is sports journalism.’

The 317-page dictionary includes dozens of chess definitions, but there is a difference. Whereas the entries for terms relating to other activities are serious/technical, the chess material is light-hearted. A sample page illustrates this:

Why should that be? Why should such a book have (on page 151) ‘Naidni sgnik’ as the definition/description of ‘King’s Indian reversed’? Was Mr Ahmed aware of anything he was writing? Indeed, was he writing anything?

In reality, all the chess-related entries have been copied, without credit, from a list presented by Eliot Hearst (compiled from readers’ contributions) in an article entitled ‘Chess Kaleidoscope’ on pages 224-225 of the October 1962 Chess Life. Making it even easier for Mr Ahmed to produce his ‘comprehensive reference tool’, the complete list is available on-line (credited to Professor Hearst) at a number of chess webpages, one example being an Addendum in The Campbell Report [broken link].

(6637)

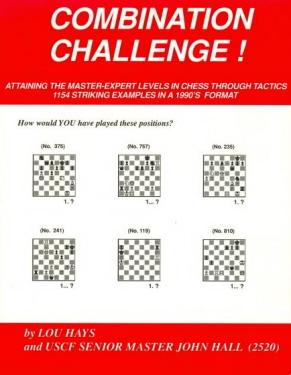

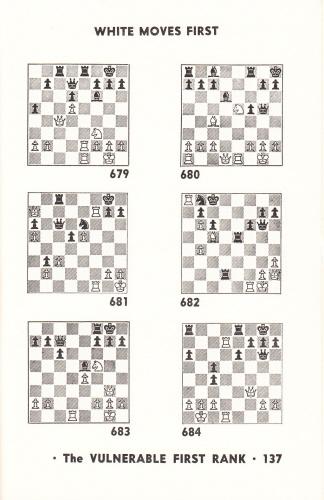

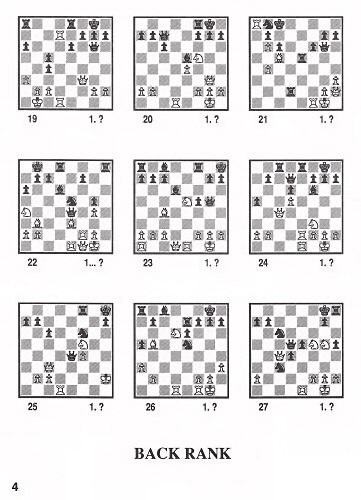

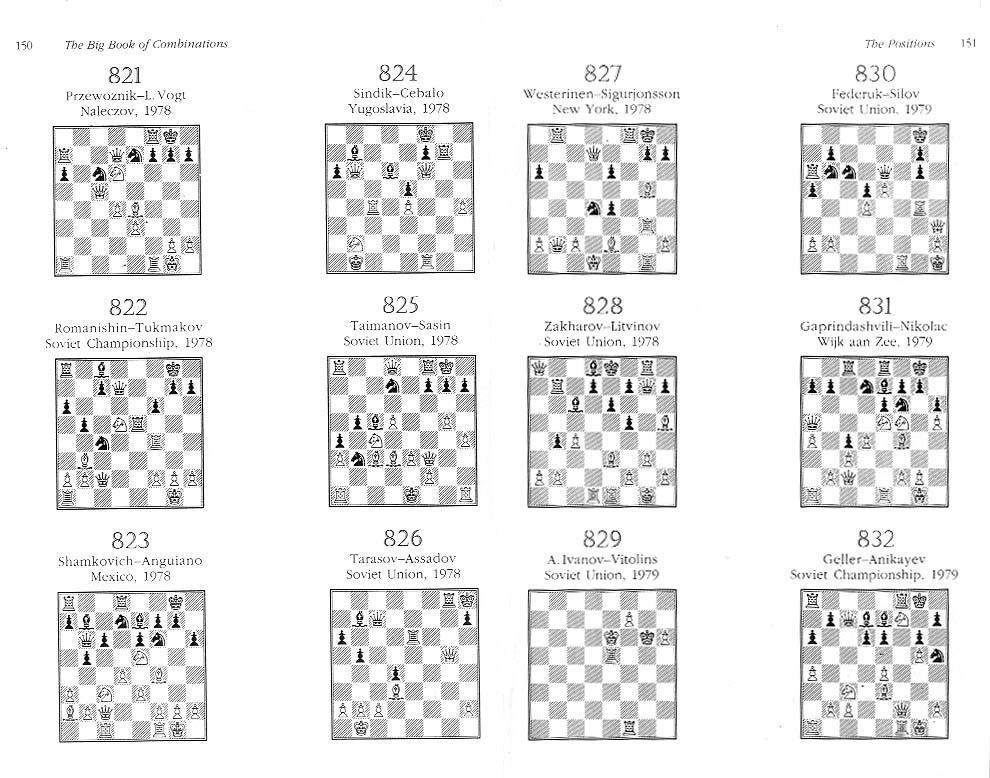

Who first pointed out publicly that Combination Challenge! by L. Hays and J. Hall (Dallas, 1991) was guilty of wholesale plundering from Fred Reinfeld’s 1955 book 1001 Brilliant Chess Sacrifices and Combinations?

We recall, but cannot currently trace, a 1990s magazine item which criticized Hays and Hall for misappropriating so much of Reinfeld’s work. One of the authors subsequently responded that, in fact, a (relatively small) number of the positions came from elsewhere, which prompted the magazine to make a sarcastic remark to the effect, ‘Well, that’s all right then’. Where did those exchanges appear?

The Reinfeld volume has also been published under the titles 1001 Chess Sacrifices and Combinations and 1001 Winning Chess Sacrifices and Combinations. No players’ names or venues were given, but many famous games were included. See, for instance, page 137 (and page 4 of the Hays/Hall monstrosity, which had a total of 1,154 positions).

Left: Reinfeld (1955). Right: Hays/Hall (1991)

Tony Bronzin (Newark, DE, USA) has found that the wholesale copying perpetrated by Combination Challenge! was briefly mentioned in a contribution by Gary Crum to Larry Evans’ column on pages 18-19 of the December 1994 Chess Life:

(7052)

A reminder should hardly be necessary, but readers are requested not to help themselves to whatever they please on the Chess Notes pages.

The level of misappropriation can be remarkable. For instance, our feature article Books about Fischer and Kasparov has frequently been lifted en bloc, sometimes even without attribution.

We wonder too when a certain Canadian grandmaster will remove from his website our copyrighted material, including the 2,000-word article A Catastrophic Encyclopedia.

Nor does Chess Notes exist to offer a free scanning service for photographs (some of which we have acquired at considerable expense) to individuals who lack the relevant archive resources of their own.

Finally, it is regrettable that discoveries and other information presented in Chess Notes (including valued contributions from correspondents) are often re-posted by people in a way which suggests that they themselves unearthed the material.

Attention to these elementary points of fair play will be much appreciated.

(7743)

When we were a contributor to the Chess Café website, at the time it was owned by Hanon Russell, he tried to combat misappropriation of our scans by adding a coloured diagonal band on them. A number of individuals simply reproduced the photographs with the band. An example is Helmut Wieteck in his book Salo Flohr und das Schachleben in der Tschechoslowakei. See the front cover, the title page and about a dozen more pictures in the body of the book.

Many of our scans of photographs appear without permission or acknowledgement at the chessgames.com website and in video productions attributed to Jessica Fischer.

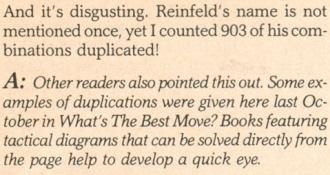

Concerning chessgames.com, an example comes from the page on Rabar v Stoltz, Munich, 1941:

The photograph and information have simply been lifted from C.N. 3917:

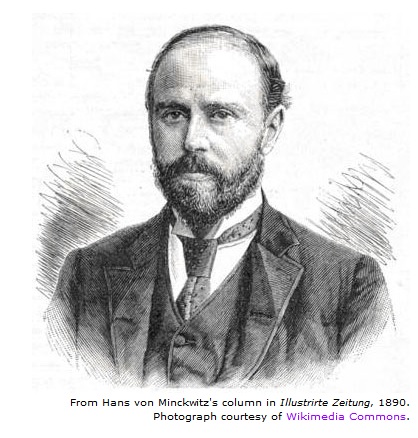

A number of chessgames.com pages devoted to individual players (e.g. Gossip, Gunsberg, Ed. Lasker, Leonard and Lilienthal) have pictures which are scans of ours. Sometimes, as in the case of Gunsberg, they are taken via an indirect route:

In reality, Wikimedia Commons merely took the scan of the Gunsberg picture which we gave in C.N. 5154 after acquiring the original publication at considerable cost. The illustration has also been used by A.J. Gillam on page 59 of his book on Manchester, 1890 (Nottingham, 2011) and, even, on the front cover of his monograph on Bradford, 1888 (Nottingham, 2012). We have many times unavailingly asked Mr Gillam to refrain from lifting material from Chess Notes without permission. For example, C.N. 6137 gave a photograph of Janowsky which we obtained at great expense. Mr Gillam helped himself to it on page 29 of his booklet on Berlin, 1896 and two Vienna, 1896 tournaments (Nottingham, 2011).

The Janowski photograph is also on page 132 of Capablanca Lenda e Realidade by Miguel A. Sánchez (Santana de Parnaíba, 2019). As is customary when photographs are lifted, the factual information accompanying the picture’s first appearance on-line (in this case, in C.N. 5154) was ignored.

Scans of ours appear in articles by Georges Bertola in Europe Echecs (the magazine and on-line). Our repeated requests for such material to be removed from the Internet pages have not been acted upon. We have also asked without success that Dany Sénéchaud refrain from misappropriating scans from Chess Notes (the item about Edouard Pape in C.N. 4119).

Another individual who has frequently taken Chess Notes material without permission is Kevin Spraggett. He even reproduced the entire text of our review of The Batsford Chess Encyclopedia by Nathan Divinsky.

Two photographs included in our feature article on Sultan Khan (courtesy of Knud Lysdal and Olimpiu G. Urcan) were reproduced in ‘The Indian Summers of Mir Sultan Khan’ by John Henderson (CHESS, July 2016, pages 30-32). No source was specified.

A further case regarding Wikimedia Commons and chessgames.com is the misappropriation of our large, high-quality photograph of Horatio Caro.

See also, for instance, our scan of a picture of Norman van Lennep in C.N. 4664, which appears on his chessgames.com page with the credit ‘Photo source findagrave.com’.

Our scan of the image of the Stanley v Turner match (from the scarce 1866 book Brevity and Brilliancy in Chess by M.J. Hazeltine) was given in C.N.s 3503 and 4955. It is has been lifted without credit by (non-exhaustive list): findagrave.com, chessgames.com, Wikipedia, YouTube, ChessBase and the World Chess Hall of Fame.

There is an Alchetron page which helps itself to various illustrations from our Sultan Khan article. That makes it convenient for the chessgames.com page on him to be illustrated as follows:

Sometimes chessgames.com helps itself to scans from our site and adds the deceitful reference ‘Courtesy of chesshistory.com’, as if we had given permission for such conduct.

Examples:

The first of these pictures was taken by chessgames.com for its Alexander McDonnell page, even though our relevant item (C.N. 10131) had specifically stated that the CHESS caption had (obviously) muddled A. McDonnell and G.A. MacDonnell.

A further example, with even the word ‘Courtesy’ misspelt, concerns Enrique Reed:

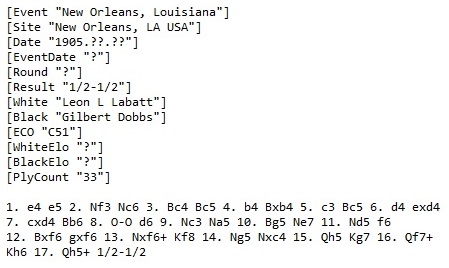

The New Orleans Times-Democrat of 10 September 1905 gives a drawn game, played in the tournament of the New Orleans Chess, Checkers and Whist Club, which was awarded a brilliancy prize:

Leon L. Labatt – Gilbert Dobbs

New Orleans, 1905

Evans Gambit Accepted

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 b4 Bxb4 5 c3 Bc5 6 d4 exd4 7 cxd4 Bb6 8 O-O d6 9 Nc3 Na5 10 Bg5 Ne7 11 Nd5 f6 12 Bxf6 gxf6 13 Nxf6+ Kf8 14 Ng5 Nxc4 15 Qh5 Kg7 16 Qf7+ Kh6 17 Qh5+ Drawn.

We note that these exact moves (extended with ‘17...Kg7 18 Qf7+=’) are given, unattributed, on page 247 of volume C of the Encyclopaedia of Chess Openings.

Since our topic is duplication (and the lack of attribution), we add the following, an example of how the chessgames.com website often copies material without giving any credit:

Concerning criticism of The Most Amazing Chess Moves of All Time by John Emms (London, 2000), see, for instance, the 24 August 2000 diary entry by Tim Krabbé.

In his Huffington Post article Chess: Heavy Lifting dated 24 August 2012 Lubomir Kavalek discusses plagiarism of his writing by Efstratios Grivas.

On 23 May 2013 we were informed of two cases of plagiarism of our work on an Italian chess site, SoloScacchi. Signed by Paolo Bagnoli and devoid of original research, the items were a rehash of material in our feature articles Disappeared and Hypermodern Chess. Following a complaint by us, the two items were taken down, at least temporarily, but a brief look at other pages on the Italian site revealed a number of articles (notably those by Fabio Lotti) which had lifted, also without authorization or acknowledgement, material (in particular, photographs) from Chess Notes.

Misappropriation from websites is all too easy, but no responsible writer or editor would simply help himself to whatever he can find on the Internet in a flash, e.g. courtesy of Google Images. As C.N. 7743 stated: ‘Nor does Chess Notes exist to offer a free scanning service for photographs (some of which we have acquired at considerable expense) to individuals who lack the relevant archive resources of their own.’

It is sometimes argued – by those who lack a) worthwhile material of their own and b) ethics – that on the Internet nothing is protected and that a free-for-all is acceptable, but a moment’s consideration of a concrete case suffices to refute that self-serving contention. We have recently been posting in C.N. a series of fine photographs from the archives of the late Jacqueline Piatigorsky which have kindly been made available to us by her family, via John Donaldson (Berkeley, CA, USA). Each such C.N. item has duly included an acknowledgement to the Piatigorsky archives and to Mr Donaldson. Could anyone seriously argue that it would be legitimate for other sites to reproduce the photographs without permission and without acknowledgement?

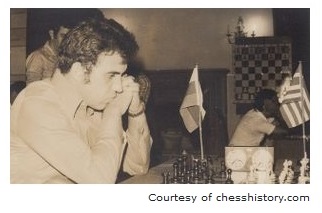

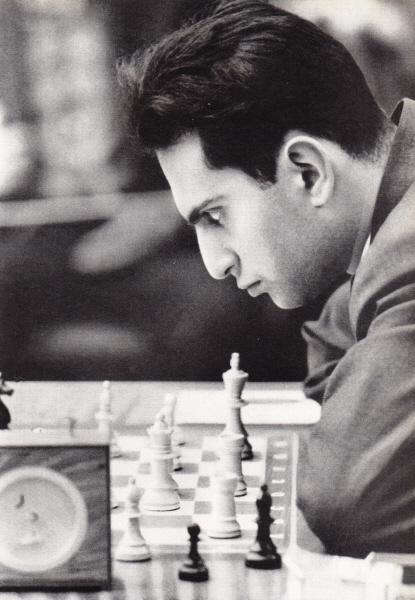

C.N. readers will have seen here most of the photographs of the old-timers used in Modern Chess Preparation by Vladimir Tukmakov (Alkmaar, 2012). They may also note that the picture of Tal on page 70 has been reversed, and below we give the correct version (Tal in play against Sliwa in the 1960 Leipzig Olympiad), from page 29 of the tournament book:

(7846)

From T.R. Dawson’s column on pages 620-621 of the December 1936 BCM:

‘“Warned Off.” Die Schwalbe (November, page 628) reports that an Italian “composer”, E. Battaglia, is definitely guilty of seven new plagiarisms in 1935-36, and should be barred from competing in any tourneys. There have been a few admitted and persistent plagiarists in the past, but I do not recall quite such a blatant public notice as the above. Usually in this country problem-editors exchange private opinions about the occasional misguided swindlers of the kind and quietly drop them.’

(8108)

Peter Treffert (Lorsch, Germany) draws attention to a chess DVD which is piracy on a gigantic scale. [Link no longer working.]

To date, the chess media have given insufficient attention to cases of copying and plagiarism, whereas alleged episodes of cheating in tournaments receive blanket coverage. As we commented in a ChessBase article dated 23 January 2011:

‘Unspecific accusations of dishonesty concerning chess players will result in an international news story. Specific proof of dishonesty concerning chess writers will result in international silence.’

In C.N. 7743 (see above) we commented: ‘Nor does Chess Notes exist to offer a free scanning service for photographs (some of which we have acquired at considerable expense) to individuals who lack the relevant archive resources of their own.’

A new low has been reached by Peter de Jong with his recent book 600 Schaakgezichten, a collection of portraits of chess figures. Hundreds of the pictures (on some pages, virtually all of them) have been lifted from C.N.

(8679)

As recorded in the present Copying article, our work has often been misappropriated. The latest case is ‘chess history’ (‘Sabrina Sörensen’), a website which has stolen a colossal amount of material from Chess Notes.

(8902)

[The above item was posted on 2 November 2014. Two or three weeks later the offending site became inaccessible.]

A comment by us in the concluding paragraph of C.N. 8977:

Loath to provide sources or admit uncertainty, copy-and-bungle writers baldly present their version of the ‘facts’ as ironclad, never informing the reader that something else can be found somewhere else.

One of the strongest practical – as opposed to moral – arguments for not copying other writers’ work is that the work copied may well be wrong.

(9097)

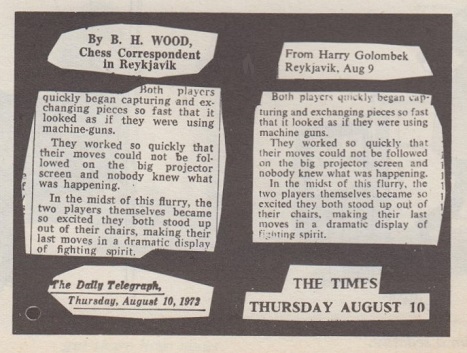

A curious item from page 204 of the 16-22 August 1972 issue of Punch:

Can any reader take the matter further?

(9106)

The entirety of our translation in the feature article Alekhine on Munich, 1941 has been reproduced by chessgames.com without permission, a total of 1,325 words.

[Afterword: on 27 February 2015 our translation was removed from chessgames.com.]

(9131)

Addition on 8 March 2015: scans of ours (Prokofiev and Shostakovich) have been included in a ChessBase article by Albert Silver:

Despite our complaint to the site on 8 March 2015, Mr Silver has been unwilling to remove our scans and to apologize, even though we demonstrated to him that the measurements of the pictures lifted by him correspond exactly to those of our original scans.

Addition on 11 March 2015: in connection with two scans of ours Mr Silver’s article subsequently added false sources, i.e. links to other Internet pages where our scans appear (without permission). In other words, when ChessBase.com is criticized for misappropriating images, its solution is to publicize other websites which have already misappropriated them.

What on earth has happened to the standards of accuracy and integrity usually applied by ChessBase.com in the past?

There is, for instance, an individual named Albert Silver who cobbles together articles by indiscriminately hoovering up images instantly available via an Internet search.

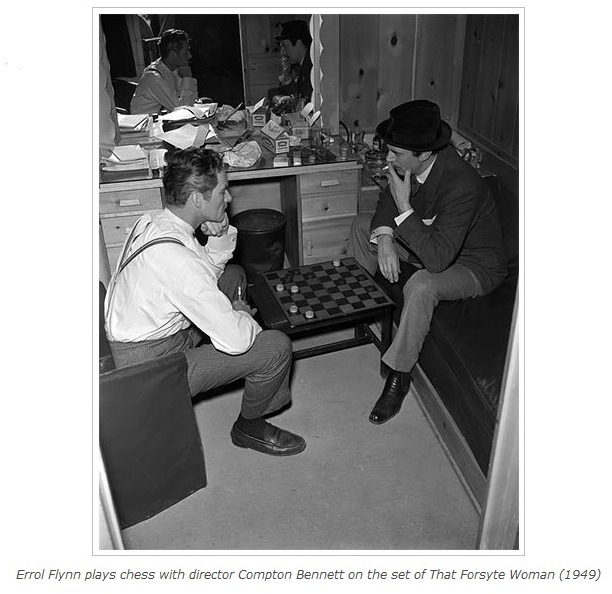

As regards the indiscriminate nature of his ‘work’, below is what appeared in (but has since been removed from) an article of his about chess and film stars which ChessBase.com posted on 23 February 2015:

(9150)

ChessBase articles by André Schulz lift images from Chess Notes. The latest instance (7 April 2021) is in an article about Capablanca, with a group photograph of San Sebastián, 1911 which is the personal property of our correspondent Miquel Artigas (Sabadell, Spain). Mr Artigas, who allowed the picture to be reproduced in C.N. 5663, has confirmed to us that he has not authorized its use by ChessBase or any other party.

Following our complaint, ChessBase removed the photograph from its article.

A website which has often taken scans of ours without permission is ‘Tartajubow On Chess’. The site finds it easy to lift pictures but less so to spell names. An example, concerning Hugh Myers:

On Twitter, photographs are often taken without permission or credit. For example, on 11 July 2015 Gary Lane lifted a photograph that we own (Karpov v Seirawan, from C.N. 9363), in order to mention that he was in the audience.

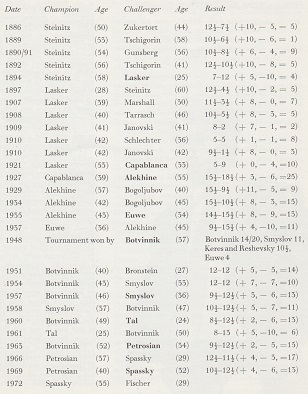

From the 1974 book The World of Chess by Anthony Saidy and Norman Lessing (page 115):

From the 1990 book Chess An Illustrated History by Raymond Keene (page 80):

Sometimes the copier makes no change to the lay-out:

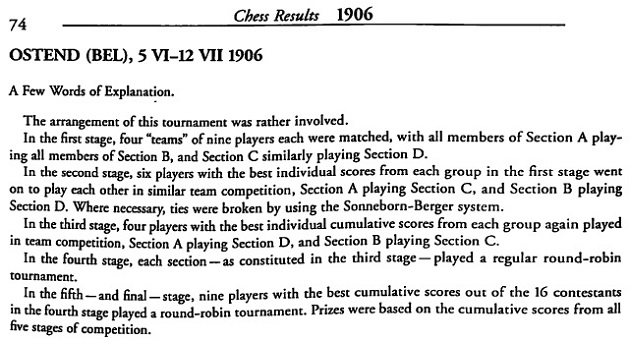

Hayoung Wong (Bayside, NY, USA) sends the following:

Page 253 of Chess Tournament Crosstables, volume two by Jeremy Gaige (Philadelphia, 1971)

Page 74 of Chess Results, 1901-1920 by G. Di Felice, (Jefferson, 2006)

C.N. 6671 mentioned an earlier, briefer instance of duplication. The excellence of Gaige’s research has been acknowledged in the Preface to each book in the Di Felice series. C.N. 3594 criticized the absence of sources in the first volume, Chess Results, 1747-1900 (Jefferson, 2004), a defect corrected as from Chess Results, 1941-1946 (Jefferson, 2008).

(9739)

Another example of the dictum (C.N. 9452) ‘Copying usually goes hand-in-hand with incompetence’ comes from a new Czech edition of Alekhine’s book about his road to the world championship, Na cestě k nejvyšším šachovým cílům, published by Galerie Dolmen (‘Antonín Čížek, 2016’). Images of ours have been used without permission, whereas page 248 has the fake Alekhine-Capablanca photograph.

(10263)

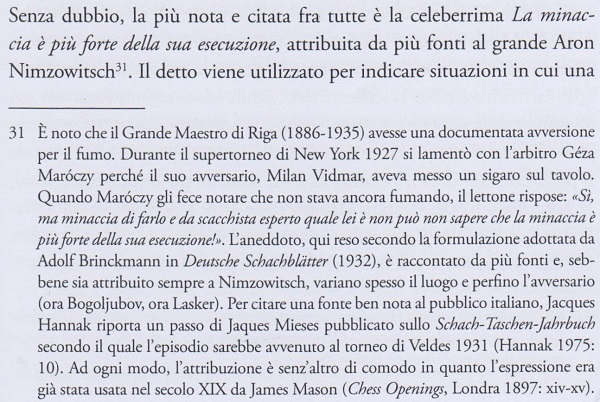

From page 65 of Il lessico degli scacchi by Yuri Garrett (Brescia, 2012):

Any assumption that the footnote is the result of original research by Mr Garrett will be dispelled by scrutiny of our feature article A Nimzowitsch Story. He can, though, take responsibility for ‘Adolf’ (instead of Alfred) Brinckmann, as well as for ‘Jaques’ (instead of Jacques) Mieses.

(10322)

For the remainder of this C.N. item, see the above-mentioned Nimzowitsch feature article.

Material (particularly photographs) from our output has been misappropriated by Miguel Ángel Nepomuceno. See, for instance, his article La verdad de las mentiras: la foto falsa de Capablanca.

C.N. 10433 quoted a number of extracts from Deep Thinking by Garry Kasparov with Mig Greengard (New York, 2017), including the following on page 267:

‘ ... everyone has a super-strong engine at his disposal and feels empowered to scoff at the champion’s mistakes as if they’d found them themselves.’

We commented:

Kasparov’s observation about people pointing out a champion’s mistakes ‘as if they’d found them themselves’ makes us wonder how often he has been the victim of a common piece of annotational malpractice: in a book or article a champion (e.g. Capablanca or Alekhine) presents analysis which is an improvement on his actual play, and a subsequent annotator (e.g. Panov or Kotov) reproduces the same variations anonymously, as if they were his own discovery. There cannot be many areas of human activity where a critic has the opportunity to act that way.

From Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore):

‘Having bought a digital edition of the August 2017 BCM (“Editors: Milan Dinic and Shaun Taulbut”), I saw on pages 498-499 an unsigned article “Did F.D. Yates Kill Himself?”:

You are mentioned briefly near the beginning, but everything (all the facts, quotes, etc.) about Yates’ death in the entire article has been copied from your work, and without mention of your (active) feature article.

That leaves just the BCM’s general introductory paragraph on Yates’ career. It has been lifted from Wikipedia.

So more or less the only “contribution” by the BCM itself is a Wikipedia-sourced photograph of Emanuel Lasker. The magazine identifies him as “Edward Lasker”.’

(10538)

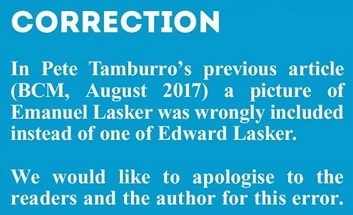

On 5 September 2017 Mr Urcan informed us that page 565 of the September 2017 BCM had this ‘Correction’:

The BCM thus offered not one word of apology for anything other than the Lasker mix-up.

Pete Tamburro (Morristown, NJ, USA) now informs us that, in any case, the correction itself is wrong. His sole contribution to the August 2017 BCM was a separate article on Yates elsewhere in the magazine (‘F.D. Yates and the 5 Bd2 Winawer’, on pages 494-497). The offending article ‘Did F.D. Yates Kill Himself?’ had nothing to do with him.

(10579)

Page 614 of the October 2017 BCM has the following:

We were ‘in touch’ with the BCM in the sense that on 29 September 2017 we responded to a message (nearly 600 words) received the previous day from Mr Milan Dinic of the BCM. His main defence was that the Yates article in the August 2017 BCM had faulty typesetting (misuse of quotation marks), an argument not only absent from the October 2017 ‘Clarification’ but also in direct contradiction with the magazine’s assertion therein beginning ‘We believe that we had made clear ...’

Our e-mail reply of 29 September 2017:

Dear Mr Dinic,

Thank you for your e-mail message of 28 September 2017 regarding the unsigned article ‘Did F.D. Yates Kill Himself?’ on pages 498-499 of the August 2017 BCM. Please ensure that your apology in the magazine presents the following points:

1. Apart from an introductory overview of Yates’ career which the BCM lifted from Wikipedia, the entire BCM article was copied, word for word, from my feature on Yates at ChessBase in 2008. It should be stressed that that complete feature of mine was reproduced. (Please do not mislead your readers by claiming, as your e-mail message does, that you ‘took under a third of the full [ChessBase] article’; that is only because the rest of my ChessBase article consisted of other features which were nothing to do with Yates.)

2. Even without any BCM typesetting mistakes (concerning quotation marks) of the kind that you indicate, the BCM was obviously not entitled to reproduce an entire feature of mine (approximately 700 words). No fewer than 93 lines of the BCM article were written by me, i.e. about 80% of the text in the two-page BCM article.

3. In acknowledgement of its misappropriation of my work, I ask the BCM to make a substantial donation to charity, and I propose Dimbleby Cancer Care. [Updated link.]

Thank you in advance.

Yours sincerely,

Edward Winter

No reply has been received.

(10613)

Below is a letter which we sent on 17 October 2017 by e-mail and registered post to the Editor of the BCM, with a copy to Mr Milan Dinic:

For publication, please

Dear Sirs,

The “clarification” on page 614 of the October 2017 BCM refers misleadingly to my e-mail reply of 29 September to Mr Dinic. As shown by my full text (C.N. 10613 at chesshistory.com), the unsigned F.D. Yates article on pages 498-499 of the August 2017 BCM reproduced, word for word and without permission, an entire ChessBase feature of mine (about 700 words). No fewer than 93 lines of the two-page BCM article were written by me, i.e. about 80% of the whole BCM text.

My e-mail message nominated a charity to which I asked the BCM to make a substantial donation for misappropriating my work.

Yours faithfully,

Edward Winter

No reply, whether public or private, having been received, we simply summarize the facts (as shown in detail in C.N.s 10538, 10579 and 10613):

(10644)

An undated volume just acquired is Bobby Fischer World Champion for Political Reasons? by Julio Hidalgo.

Apart from the ISBN number, 9781537399676, on the (blank) back cover, the sole bibliographical information about the book, whose pages are unnumbered, is in the bottom corner of the last page:

An author’s name is mentioned only on the title page, and not on the cover, but even the word ‘author’ is an exaggeration, because the book is essentially an omnium gatherum of other people’s writings. The early part lifts chunks from, among other publications, the Everyman Chess edition of Russians versus Fischer by D. Plisetsky and S. Voronkov (London, 2005), and a small example shows the literary and presentational skills of Julio Hidalgo:

Later, it is Kasparov’s Predecessors work which dominates. Dozens of pages reproduce his text, with minimal linking material. For instance:

Another chapter, over half-a-dozen pages long, consists almost exclusively of text from Kasparov’s Child of Change. Euwe is a casualty too.

Towards the end of the book a chapter entitled ‘A Spassky Interview’ begins:

‘I have selected some paragraphs of [sic] an interview to [sic] Spassky, for Kingpin Magazine ...’

The ‘some paragraphs’ occupy six pages.

Garry Kasparov remains the chief victim of the Fischer book, but in any such case what chance of corrective action exists? How one longs for Kasparov to take a public stand, also supporting fellow victims of rapacity.

(10732)

The first 45 pages of The Indian Chessmaster Malik Mir Sultan Khan by Ulrich Geilmann (Eltmann, 2018) have over a dozen illustrations of the master. Nearly all of them have been lifted, without permission or acknowledgement, from our feature article Sultan Khan.

(10939)

Olimpiu G. Urcan points out a ‘Myths & Legends’ article on pages 40-41 of CHESS, October 2018 in which Charles Higgie discusses Capablanca v Marshall, New York, 1918.

He lists three ‘myths’, and those 32 lines of text contain no facts not given in our feature article on the Marshall Gambit. There is even some verbatim copying, without a word of acknowledgement.

Concerning untrue claims that Marshall saved his Gambit for many years in order to surprise Capablanca, we wrote:

... between 1910 and 1918 the Cuban played 1 e4 against Marshall on six occasions. Five times the American responded with the Petroff Defence and once with the French Defence.

From Charles Higgie’s article:

‘Between 1910 and 1918 the Cuban played 1 e4 against Marshall on six occasions. Five times the American responded with the Petroff Defence and once with the French Defence.’

With regard to the game Frere v Marshall supposedly played in 1917, our article states:

Marshall published the Frere game on pages 110-111 of his rarely-seen book Comparative Chess (Philadelphia, 1932). ... A further curiosity in Comparative Chess is that on page 104 it was 7…O-O, rather than 8…d5, that Marshall emphasized. Of 7…O-O he wrote (incorrectly), ‘This move of mine, I claim to be original’.

Charles Higgie’s version:

‘Marshall published the Frere game on pages 110-111 of his rarely seen book Comparative Chess. A further curiosity in Comparative Chess is that on page 104 it was 7...O-O, rather than 8...d5, which Marshall drew attention to. Of 7...O-O, he wrote (incorrectly), “This move of mine, I claim to be original”.’

From page 3 of that issue of CHESS:

(11056)

On 13 October 2018 we sent CHESS a brief, purely factual, Letter to the Editor. The magazine decided to publish instead, on page 50 of the November 2018 issue, an apology which, though complimentary, was confused and confusing.

Based on a very short browse, below are some extracts from Chess Problems, Play and Personalities by Barry Martin (Beddington, 2018).

The start of an article about Alekhine on pages 41-43:

‘... his father was a landowner, a Marshal of Nobility, and a member of the Russian Duma. His mother was an heiress to an industrial fortune. Alekhine became addicted to the game of chess at the age of 11 ...’

This brings to mind page 5 of The Oxford Companion to Chess by D. Hooper and K. Whyld (Oxford, 1984):

‘His father was a landowner, a Marshal of Nobility, and a member of the Duma, his mother heiress of an industrial fortune. ... Alexander became addicted to the game at the age of about 11 ...’

Similarly, pages 194-195 (the section on Leonard Barden) are little more than pickings from his Wikipedia entry.

Sometimes, though, Mr Martin is self-reliant. From page 70:

‘Howard Staunton, the only English chess player ever to have held the title of World Champion by winning against the generally accepted World Champion, St. Amain in Paris in 1843 ...’

Page 81 discusses St Petersburg, 1914:

‘The combatants in the main tournament were the leading lights at that time of world chess, five of whom had played in a pre-tournament which included 11 players to the main tournament in St Petersburg.’

Page 269 states that Capablanca ...

‘... taught himself the game of chess at the age of 13’.

(11186)

A gross violation of copyright by Mark McCready: at the end of a webpage he gives links to two PDF files comprising his scans of both volumes of Chess Characters by G.H. Diggle which we produced in the 1980s. Over 100 pages have been reproduced without permission.

Afterword:

Several years later, on 13 December 2023, Mark McCready’s webpage posted the following:

‘After some thought and advice from friends, I have decided to remove the links to his works. I thought Diggle would like to be read by a newer generation and although that may well be true, it doesn’t excuse disregarding copyright laws, which I did. I strongly recommend you buy his works, and I regret to inform you it is improper for me to continue to link them here, so I have removed them.’

Pages 40-53 of the 4/2020 issue of Tidskrift för Schack have an article by Jan Løfberg, ‘Schack i Kri(g)stider’, which is illustrated mainly by scans of ours.

A Twitter page which often takes images from our website without acknowledgement is ‘JustChessMiniatures’. And so it is that our images land up on Raymond Keene’s Twitter page, in case of re-tweets by him.

Tolerance of copying is easy for those with nothing worth copying.

See too Copyright on Chess Games.

In a ChessBase article published on 16 October 2007 we commented:

Chess scandals are common enough and tend to concern alleged cheating by players and/or maladministration by officials. The affairs may even briefly interest the mainstream press, but few eyelids are batted, even by insiders, over cases of theft or other malpractice regarding the game’s literature.

On 14 July 2023 the main C.N. page showed the following from the end of an article by Sam Kahn about Janowsky dated 10 July 2023 on Chess.com:

Sam Kahn is the worst offender at Chess.com for appropriating our scans without permission. On 10 September 2024 we wrote to him:

Finally, and most importantly, please note that the C.N. website specifically states that images are not to be lifted for use elsewhere (just as I do not take images from other people’s websites).

No reply.

Why are such people writing so much about chess history with so few resources of their own?

How much longer will chess.com tolerate parasitism?

Below is the full text of our e-mail message to Mr Kahn (sent after receipt from him of an unsolicited ‘galley copy’ of a book, A Century of Chess, which was intended to cover 1900-09 and was not, in our opinion, of publication standard):

Dear Mr Kahn,

Thank you for your message and generous words.

From a quick browse, I note that there are unfortunately numerous errors and typos (as early as the first paragraph of the Foreword).

Concerning sources, the third paragraph of the final message at https://www.ecforum.org.uk/viewtopic.php?f=27&t=5600#p118965 may be noted. In contrast, I saw no mention in your book of the vast amount of excellent work on Emanuel Lasker by Richard Forster and others.

Finally, and most importantly, please note that the C.N. website specifically states that images are not to be lifted for use elsewhere (just as I do not take images from other people’s websites).

Thank you for your attention to these points.

Yours sincerely,

Edward Winter

The entirety of our compilation of quotations from the three volumes of W.E. Napier’s Amenities and Background of Chess-Play has been copy-pasted, without acknowledgement, on a chessgames.com page.

There is an Alchetron page which helps itself to various illustrations from our Sultan Khan article. That makes it convenient for the chessgames.com page on him to be illustrated as follows:

The Bill Wall method: ransacking our work on Capablanca, without credit, and giving worthless, partial sources.

The ChessBase contributor Davide Nastasio has been lifting a huge number of C.N. photographs (about 80 in the past week alone), without credit, acknowledgement or authorization, for his personal X/Twitter page.

(11979)

Despite that item, posted on 28 January 2024, Mr Nastasio has refused to stop his misappropriation. Indeed, on a single recent day, 30 September 2024, he put online over 20 of our images.

(12038)

Posted at the top of the main C.N. page on 8 August 2025:

And in today’s Copying news, on X/Twitter Davide Nastasio lifts without credit an entire C.N. item (over 500 words) on Tartakower, and Raymond Keene reposts it.

Addition on 22 October 2024:

ChessBase has informed us that Davide Nastasio is now a former ChessBase author.

Addition on 8 March 2024:

Cheating is an egregious form of copying, an area which the chess world otherwise finds unnewsworthy.

Our 100th ChessBase article (‘Chess Explorations’) was dated 2 September 2013:

Writer A makes a significant discovery in a 100-year-old newspaper and presents the information with a complete source.

Writer B repeats the information but specifies only the 100-year-old source, as if he had discovered it himself.

Such conduct by Writer B is widespread, and a technical term for it may be sought. Since technical terms are often -isms, one possibility is ‘intermediate source misattribution’.

(12017)

If we received a nominal sum every time a scanned image from chesshistory.com was misappropriated and viewed on YouTube, Wikipedia, X/Twitter, Facebook, Chess.com, or other websites and outlets, we could single-handedly offer to fund future world championship matches.

(12034)

Addition on 11 May 2025:

An article by Samuel Tinsley, ‘Problematic Coincidences’, was published on pages 466-471 of the May 1899 American Chess Magazine.

It includes the following on page 470:

‘The man who can be mean enough to stoop to such traffic as palming off on chess editors and players something as his own, which he has obviously merely taken from a book, is only worthy of contempt.’

Is documentary information available on any codes or conventions applicable to chess columnists of past generations? How was it known when syndication was involved? On what legal and ethical basis could annotations be reproduced verbatim with or without acknowledgement?

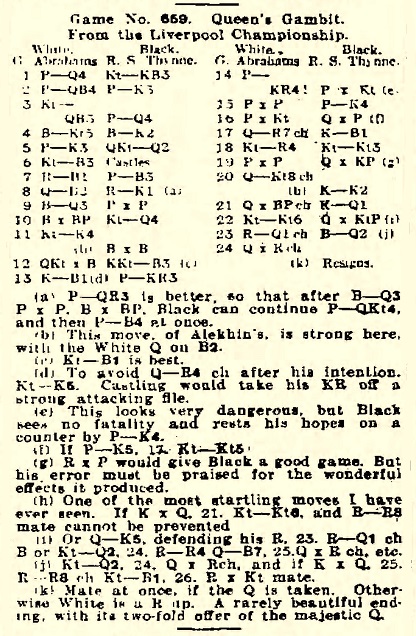

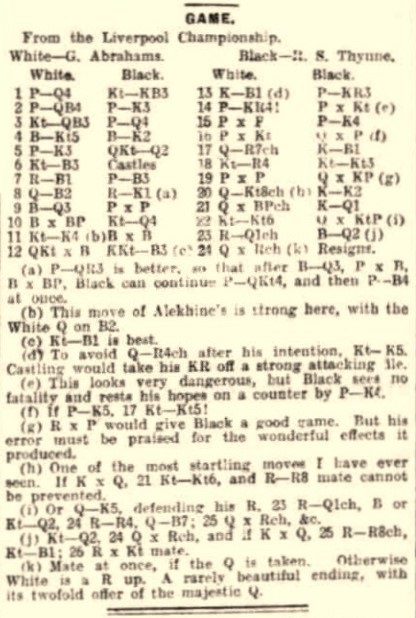

An example from our feature article on Gerald Abrahams:

The Observer, 25 May 1930, page 25 (columnist: Brian Harley)

There are minor textual differences, such as Alekhin/Alekhine in note (b).

The heading in the Northern Whig and Belfast Post column stated that all communications should be addressed to the ‘Chess Editor, Northern Whig, Belfast’. Readers thus had no information as to who the ‘I’ was in note (h), ‘One of the most startling moves I have ever seen’.

(12160)

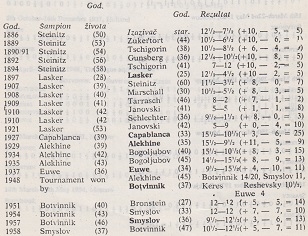

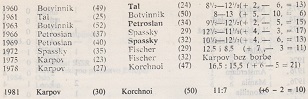

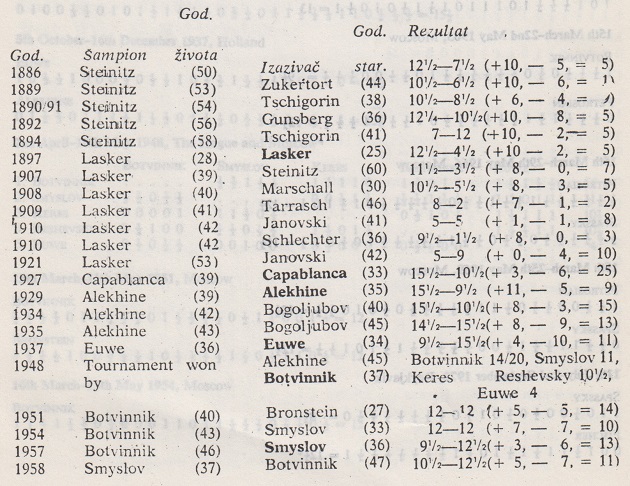

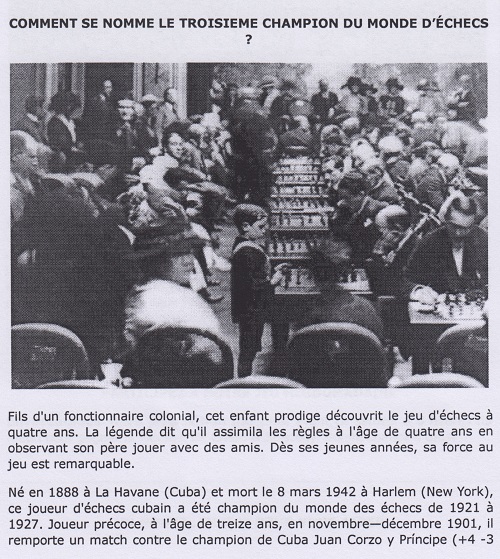

Dimitrije Bjelica’s book Kasparov protiv Karpova (Sarajevo, 1984) has only just come to our attention.

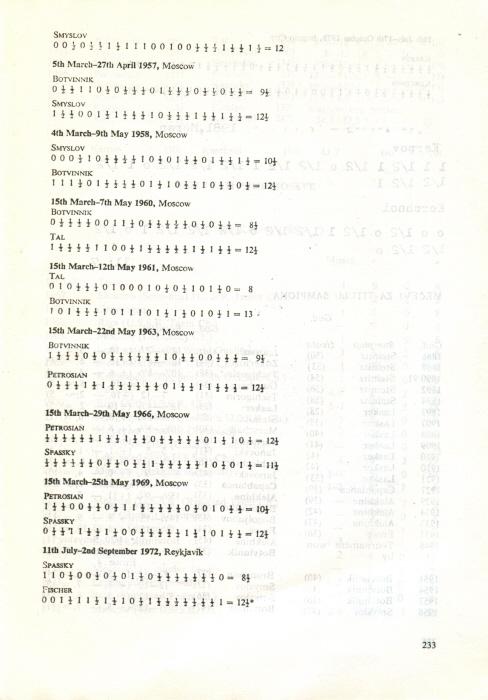

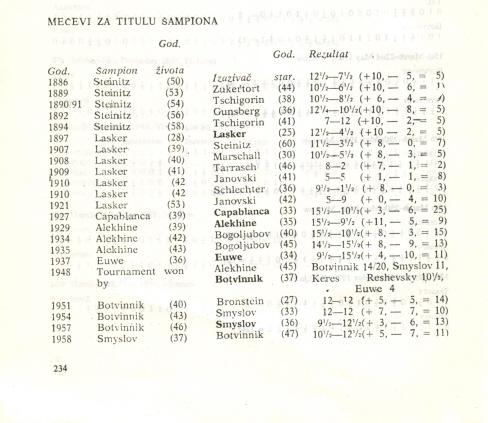

The multiplicity of formats, styles and typefaces pervading the book has an obvious explanation: Mr Bjelica’s clippers and glue-pot have been in action yet again. For example, pages 235-236 have a table of Karpov’s tournament results which is reproduced (without permission or acknowledgement, naturally) from a book edited by us, World Chess Champions (Oxford, 1981). Similarly, on pages 230-234 Mr Bjelica lifts (i.e. steals) from our book the entire list of 28 world championship matches held from 1886 to 1978. By the time Kasparov protiv Karpova was published, of course, Karpov and Korchnoi had played a further match, in Merano, and one can only marvel at the conscientious artistry with which Mr Bjelica updated our work:

(6616)

Sandwiched between material plagiarized from World Chess Champions there appears on page 234 of Mr D. Bjelica’s Kasparov protiv Karpova a chart which, gratifyingly, does not come from our book:

(6617)

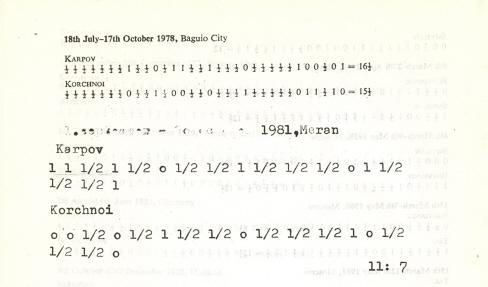

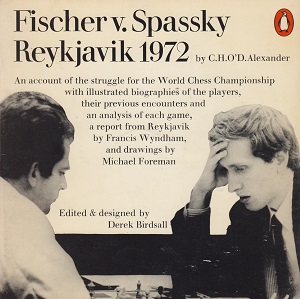

Alan O’Brien (Mitcham, England) points out that the chart of world title match results shown C.N. 6617 was lifted by Dimitrije Bjelica from a book by C.H.O’D. Alexander:

Fischer v. Spassky Reykjavik 1972 by C.H.O’D. Alexander (Harmondsworth, 1972), page 21

Kasparov protiv Karpova by D. Bjelica (Sarajevo, 1984), pages 234-235

C.N. 9452 mentioned that copying usually goes hand-in-hand with incompetence, and it will be noted that misalignment on page 234 of Bjelica’s book resulted in a shambles:

On page 20 of The Times, 22 April 1995 Bjelica was referred to as the Director of the International Chess Writers Association.

(10946)

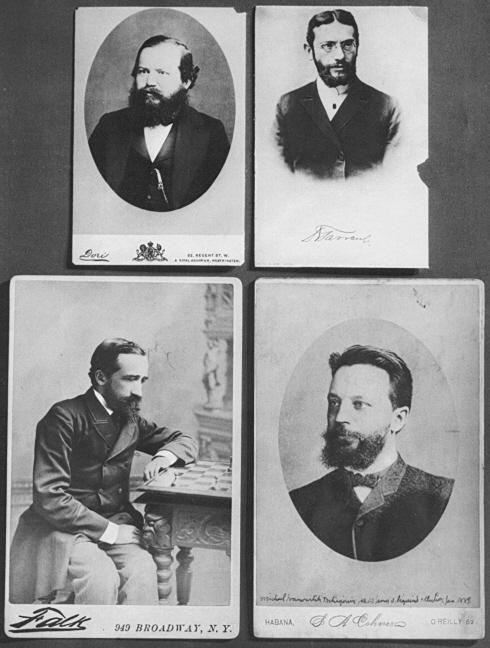

Numerous photographs of Capablanca from our 1989 monograph were misappropriated by Bjelica in his volume José Raúl Capablanca (Madrid, 1993).

See too our feature article on him.

In a letter to us dated 8 March 1990, Dale Brandreth (Yorklyn, DE, USA) expressed anger over the 1988 book Así Jugaba Capablanca by Jorge Daubar, who ‘had the outright gall to copy much of The Unknown Capablanca including the simul records without even a hint as to where he got them from’.

We mentioned the copying in C.N. 1972 after a correspondent, Ed Tassinari (Scarsdale, NY, USA), raised the topic of Cuban books on Capablanca. Another work by Daubar was also mentioned, Capablanca (Havana, 1988 and 1990), which we described as ‘a maundering 240-page “biography” which is rather dense in both senses of the term’.

Copying usually goes hand-in-hand with incompetence.

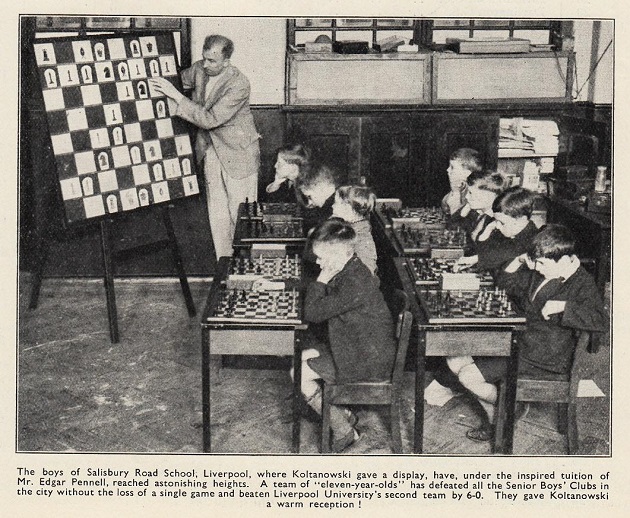

This photograph of Edgar Pennell from page 275 of CHESS, 14 April 1937 was included in C.N. 8894 (see too The Chess Skewer).

In July 2015 our scan (which has ‘Pennell’ in the file name) was lifted for use on the website Chess & Strategy (Philippe Dornbusch) as a quiz question. The CHESS caption was not only deleted but also misunderstood, since the French site imagined that the man at the demonstration board was Koltanowski. It reported that over 700 readers had identified him.

Mr Dornbusch’s page brazenly concludes:

‘© Chess & Strategy - Reproduction et diffusion interdites.’

(9452)

On 20 January 2016 Philippe Dornbusch’s website helped itself, without permission or acknowledgement, to a photograph which we own of Lubomir Kavalek and Bessel Kok (C.N. 9482).

Mr Philippe Dornbusch has announced his candidacy for the post of President of the Fédération Française des Echecs/French Chess Federation (election to be held in December 2016), and his campaign includes a seven-point plan to improve the Federation’s website.

This is the same Philippe Dornbusch whose own website includes a notice ‘© Chess & Strategy - Reproduction et diffusion interdites’ yet, as shown in Copying, makes indiscriminate use of other people’s material, without acknowledgement or permission. Of late, his site has lifted images from Chess Notes which depict, for instance, Fischer, Spassky and Karpov, and the latest case is the fine photograph of Michael Stean which we own (given on 21 June 2016 in C.N. 9997).

The section on Mr Dornbusch in our above-mentioned feature article began with the observation, ‘Copying usually goes hand-in-hand with incompetence’, and demonstrated how he had misappropriated from C.N. 8894 a photograph of Edgar Pennell, chopped off the caption (from CHESS) and misidentified Pennell as Koltanowski.

That is not an isolated case. In another article (May 2016) Mr Dornbusch gave a photograph of Reshevsky but stated that it was Capablanca, even though the facts are set out in our article Chess: Mistaken Identity, where this version was presented:

Reshevsky, not Capablanca

Unaware that he should have been writing about Reshevsky, Philippe Dornbusch added a biography of Capablanca (over 430 words). The entire text was lifted, without any attribution, from the French-language Wikipedia entry on Capablanca.

(10009)

Addendum to C.N. 10009 (posted on the main Chess Notes page on 4 July 2016):

Following the appearance of the above item, Philippe Dornbusch replaced his quiz-question photographs of Pennell and Reshevsky by pictures of Koltanowski and Capablanca which, in accordance with his customary malpractice, he simply lifted from other websites without acknowledgement.

Below is the Reshevsky photograph which was presented in Philippe Dornbusch’s column as a picture of Capablanca:

After C.N. 10009 was posted, Mr Dornbusch also added ‘source Wikipedia’.

In short, even after public criticism has prompted him to make ‘improvements/corrections’ to the column in question, it merely comprises photographs which he lifted from other websites and a biography of Capablanca (over 430 words) of which he wrote nothing.

See too C.N. 11411.

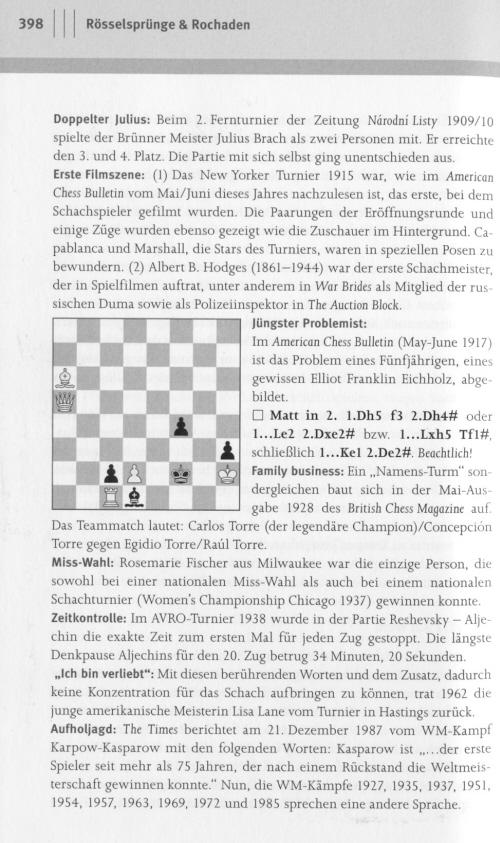

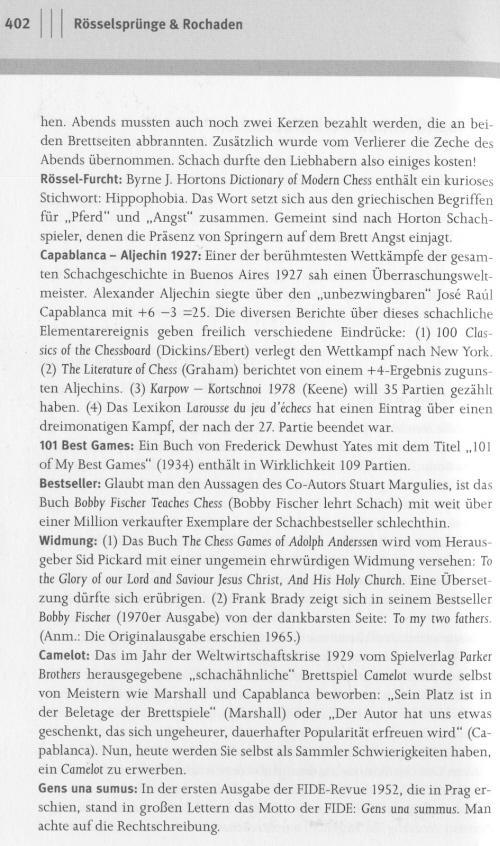

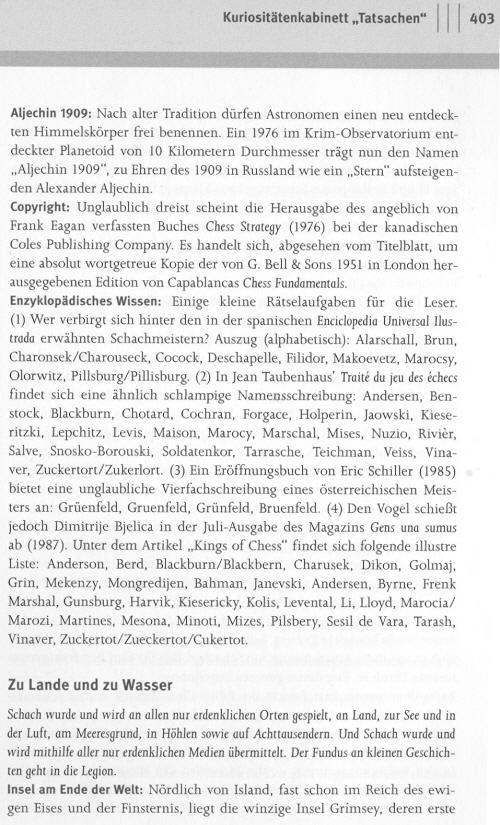

C.N. 7083 drew attention to Christian Hesse’s free and easy way of using other writers’ work in The Joys of Chess (Alkmaar, 2011). Now we are obliged to turn to Alles über Schach by Michael Ehn and Hugo Kastner (Hanover, 2010).

Three complete pages are shown below:

The ‘Doppelter Julius’ and ‘“Ich bin verliebt”’ items have nothing to do with our output. As regards the others:

‘Erste Filmszene’ is taken from pages 340-341 of A Chess Omnibus

‘Jüngster Problemist’ is taken from page 234 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves

‘Family Business’ is taken from page 125 of Chess Explorations

‘Miss-Wahl’ is taken from page 167 of A Chess Omnibus

‘Zeitkontrolle’ is taken from page 241 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves

‘Aufholjagd’ is taken from page 166 of Chess Explorations

The ‘101 Best Games’ item has nothing to do with our output. As regards the others:

‘Rössel-Furcht’ is taken from page 144 of Chess Explorations

‘Capablanca-Aljechin 1927’ is taken from page 263 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves

‘Bestseller’ is taken from page 147 of A Chess Omnibus

‘Widmung’ is taken from page 237 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves

‘Camelot’ is taken from page 172 of A Chess Omnibus

‘Gens una sumus’ is taken from page 189 of Chess Explorations

The ‘Aljechin 1909’ item has nothing to do with our output. As regards the others:

‘Copyright’ is taken from page 332 of A Chess Omnibus

‘Enzyklopädisches Wissen’ is taken from pages 143-144 of Chess Explorations (for the Enciclopedia), page 286 of A Chess Omnibus (for Taubenhaus), page 155 of Chess Explorations (for Schiller) and pages 167-168 of Chess Explorations (for Bjelica).

C.N. 6636 reported that the chapter regarding masters’ mistakes on pages 313-333 of The Personality of Chess by I.A. Horowitz and P.L. Rothenberg (New York, 1963) has 41 positions. About 40% of them are in The 10 Most Common Chess Mistakes by L. Evans (New York, 1998).

The Personality of Chess. All four positions also appeared in The 10 Most Common Chess Mistakes.

On page 34 of the February 1935 Chess Review Irving Chernev wrote in a ‘Curious Chess Facts’ column:

‘Rubinstein, playing a rook ending against Mattison, extracted a win from such a “hopelessly drawn” position that the editors of the tourney book united in the assertion that had this occurred 300 years ago, Rubinstein would have been burned as being in league with evil spirits.’

Chernev used a slightly different wording on page 58 of his book Curious Chess Facts (New York, 1937):

‘Rubinstein, playing a rook and pawn ending against Mattison, extracted a win from such a “hopelessly drawn” position that the editors of the tournament book united in the assertion that had this happened 300 years ago, Rubinstein would have been burned at the stake for being in league with evil spirits.’

Below are three instances of Chernev’s text being copied (without attribution, of course):

‘At Carlsbad, 1929 Rubinstein extracted a win from such a “hopelessly drawn” rook and pawn ending that the editors of the tournament book united in the assertion that had this happened 300 years ago Rubinstein would have been burned at the stake for being in league with evil spirits.’

Source: page 15 of New Ideas in Chess by Larry Evans (New York, 1958).

‘At Carlsbad, 1929 Rubinstein extracted a win from such a “hopelessly drawn” rook-and-pawn ending that the editors of the tournament book united in the assertion that had this happened 300 years earlier Rubinstein would have been burned at the stake for being in league with evil spirits.’

Source: page 133 of Chess Catechism by Larry Evans (New York, 1970).

‘At Carlsbad, 1929 Rubinstein extracted a win from such a “hopelessly drawn” rook and pawn ending that the editors of the tournament book united in the assertion that had it happened 300 years ago he would have been burned at the stake for being in league with evil spirits.’

Source: pages 19-20 of Modern Chess Brilliancies by Larry Evans (New York, 1970).

(7811)

Another one:

‘At Carlsbad, 1929 Rubinstein extracted a win from such a “hopelessly drawn” rook-and-pawn ending that the editors of the tournament book united in the assertion that had it happened 300 years ago he would have been burned at the stake for being in league with evil spirits.’

Source: page 33 of The Chess Beat by Larry Evans (Oxford, 1982).

See The Chesswriting Practices of Christian Hesse.

Two further cases are outlined here. The first concerns the Pakistan Chess Player website, where Lev Khariton presented as his own writing two articles (about Alekhine and Carlsbad, 1929) which, we pointed out in October 2001, had been lifted from pages 77 and 147 of Irving Chernev’s book Wonders and Curiosities of Chess (New York, 1974). It was not until April 2002 that the public protests had any effect and the misappropriated material was grudgingly removed from the website. Since being exposed, Khariton has written various attacks on our book Chess Explorations, systematically misreading, misquoting and misrepresenting its contents.

The second case was referred to by Yasser Seirawan (see page 26 of the Spring 2000 Kingpin) in the following terms:

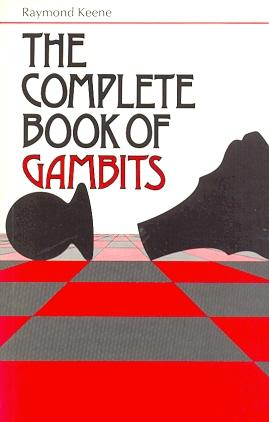

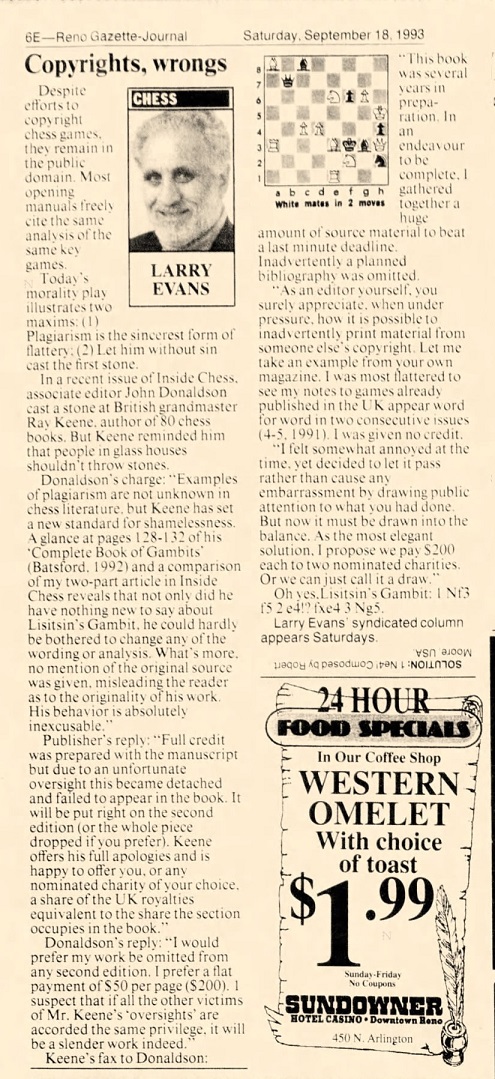

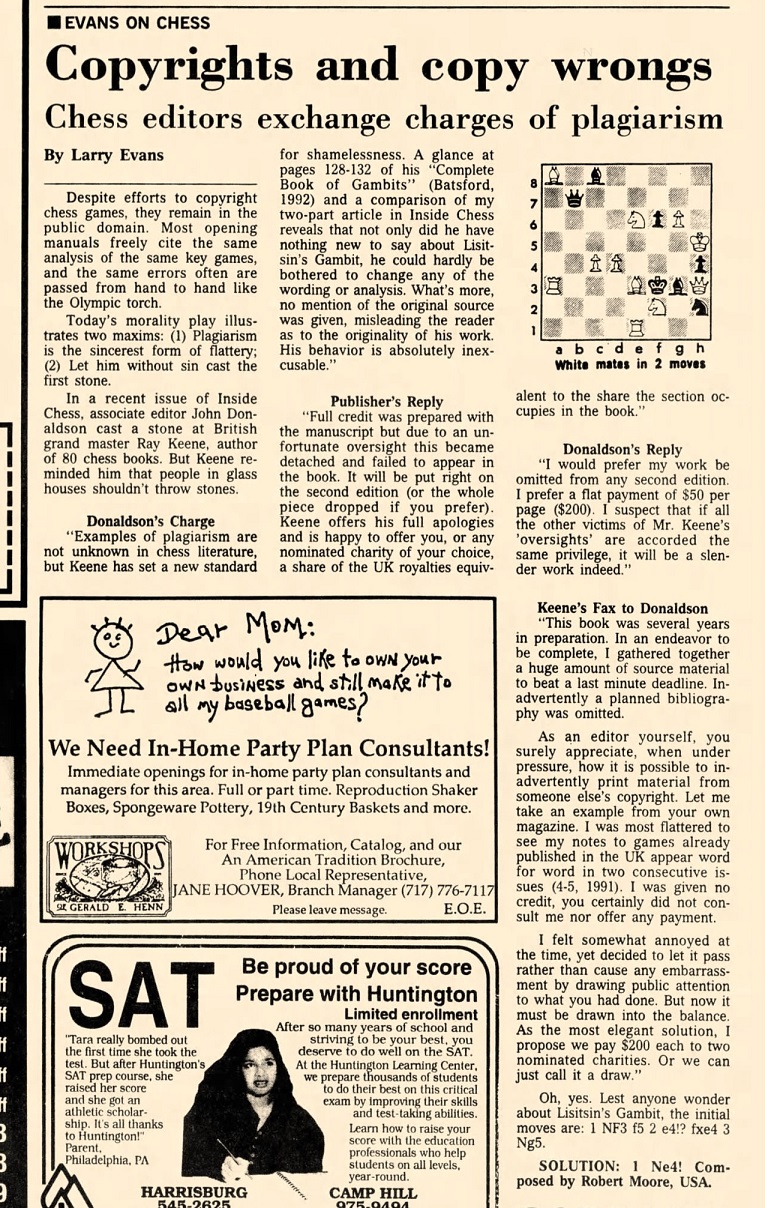

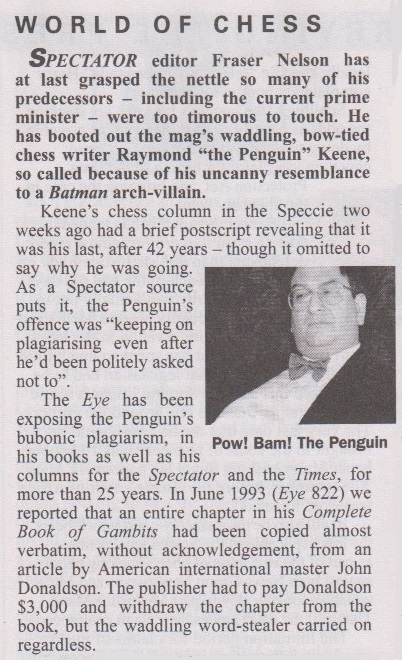

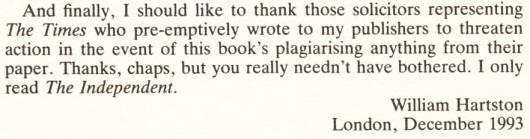

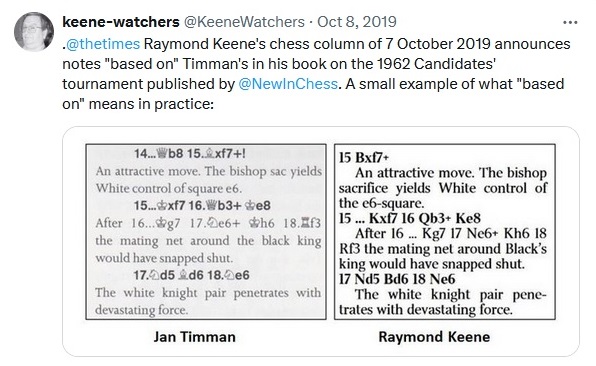

‘Keene was caught red-handed plagiarizing copyrighted material from Inside Chess magazine for one of his potboilers [The Complete Book of Gambits].’

Before the facts are related, one little myth about Chess Notes may be dealt with here, i.e. the occasional claims that C.N. ‘repeatedly’ (or even ‘frequently’) attacks Raymond Keene. Over the past decade the column has hardly ever mentioned his name, but in the present context it is impossible not to.

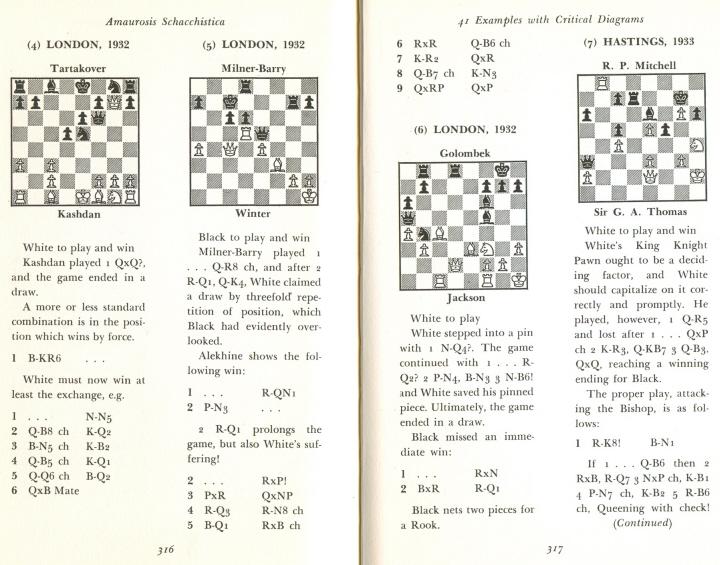

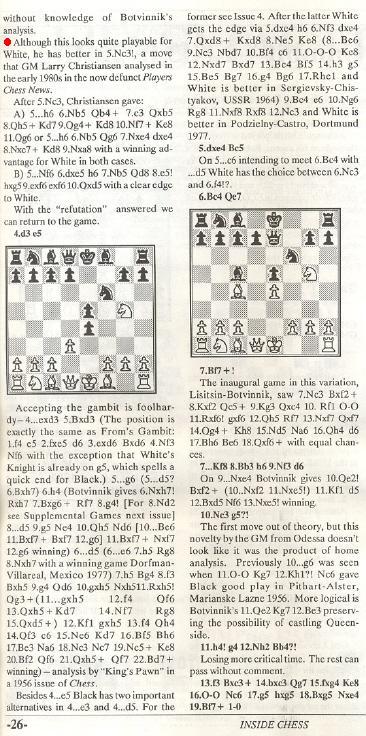

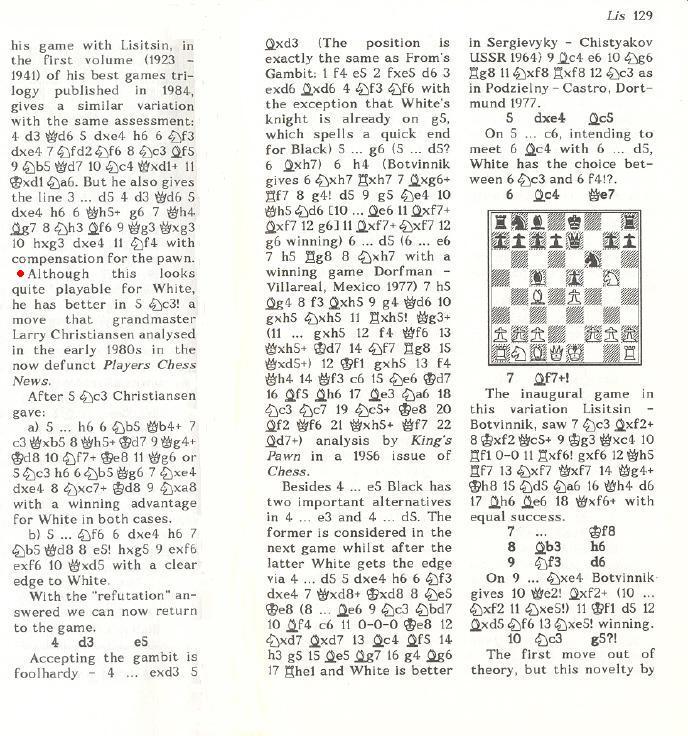

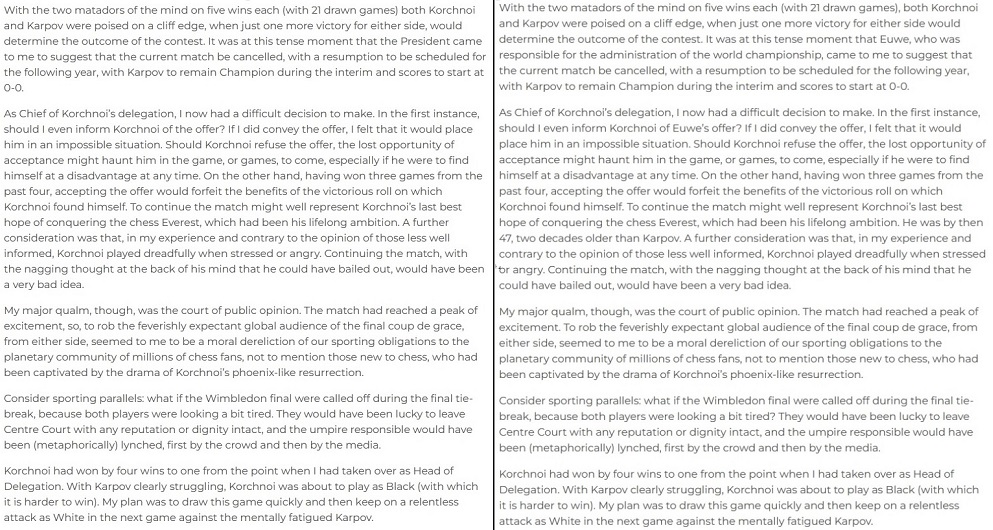

Under the title ‘The Sincerest Form of Flattery?’ John Donaldson wrote an article on pages 24-25 of Inside Chess, 3 May 1993 which began as follows:

‘Examples of plagiarism are not unknown in chess literature, but Raymond Keene has set a new standard for shamelessness in his recent work, The Complete Book of Gambits (Batsford, 1992). ... Unfortunately, Mr Keene has done nothing less than steal another man’s work and pass it off as his own.

A glance at pages 128-132 of his recent book, The Complete Book of Gambits, and a comparison with my two-part article on Lisitsin’s Gambit, which appeared in Inside Chess, Volume 4, Issue 3, pages 25-26, and Issue 4, page 26, early in 1991, reveals that not only did Mr Keene have nothing new to say about Lisitsin’s Gambit, he could hardly be bothered to change any of the wording or analysis from the articles that appeared in Inside Chess other than to truncate them a bit. What’s more, no mention of the original source was given in The Complete Book of Gambits, misleading the reader as to the originality of Mr Keene’s work.

Just how blatant was the plagiarism? Virtually every word and variation in the four and a half pages devoted to Lisitsin’s Gambit in Keene’s book was stolen.’

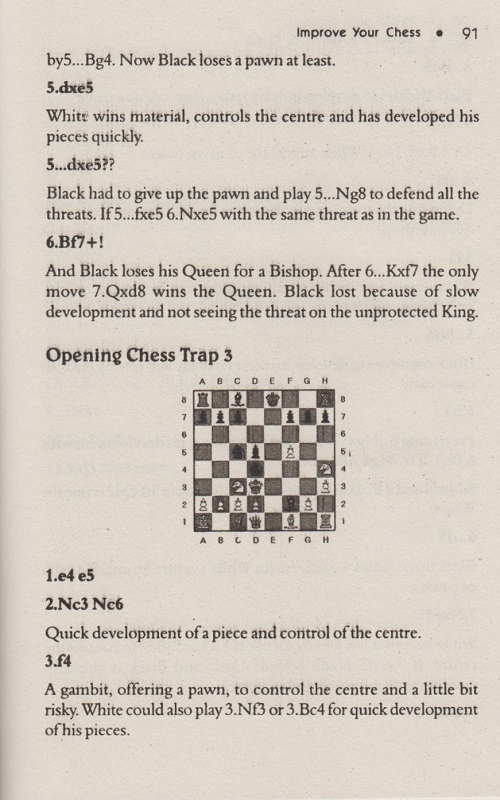

Left: part of John Donaldson’s article in Inside Chess. Right: from pages 128-129 of Raymond Keene’s subsequent The Complete Book of Gambits.

Donaldson then compared the two texts in some detail, pointing out certain discrepancies:

‘The note in The Complete Book of Gambits is exactly the same except that “with equal chances” is changed to “with equal success”. A burst of originality on Mr Keene’s part, or just Fingerfehler? More originality is seen as “Sergievsky” becomes “Sergievyky” at Keene’s hands. Perhaps he would do better to just photocopy other people’s work and print that.

Mr Keene’s behavior is absolutely inexcusable.’

On the next page of Inside Chess there was a brief exchange of correspondence between Andrew Kinsman (the then Chess Editor of Batsford) and Donaldson. Kinsman wrote:

‘I have discussed this matter with Raymond Keene who informs me that a full credit for yourself and Inside Chess was prepared with the manuscript to go into the book. However, due to an oversight on his part this became detached and failed to appear in the book. It was not his intention to publish the piece without due acknowledgement.

Mr Keene offers his full apologies for this unfortunate oversight, which will be put right on the second edition (or the whole piece dropped if you prefer). Furthermore, he is happy to offer you, or any nominated charity of your choice, a share of the UK royalties on the book equivalent to the share that the Lisitsin section occupies in the book. We hope that such a settlement will be amenable to you.’

An extract from Donaldson’s reply (published immediately afterwards) is given below:

‘I would prefer that my work be omitted from any second edition of The Complete Book of Gambits and I suspect that if all the other victims of Mr Keene’s “unfortunate oversights” are accorded the same privilege, it will be a slender work indeed. (The complete lack of any bibliography for this book is typical of Keene.)

As for your generous offer of a share of the UK royalties, I would prefer a flat payment of $50 per page ($200) be sent to me at this address.’

Page 19 of the 14 June 1993 Inside Chess featured a lengthy letter from Keene which intimated that extracting any money from him would be considerably harder than Andrew Kinsman had suggested. Keene’s letter began:

… First of all, I must personally apologize for accidentally printing some of your material in my book on Gambits. This book was several years in preparation and, in an endeavour to be complete, I gathered together a huge amount of source material. In order to beat a last-minute deadline, there was a certain amount of rush. In this process, one of the Chapters I had written, plus the planned notes, including your material, slipped past the net and appeared in print. Of course, I regret this and I am broadly receptive to the proposal you make in your fax of 11 May.’ [Note added by the magazine: ‘That Mr Keene pay for material lifted without credit or permission from Inside Chess.’]

However, Keene went on to claim that Inside Chess itself had printed material of his without permission and, consequently, that:

‘I propose, as the most elegant solution, that both I and Inside Chess pay $200 each to two nominated charities. Alternatively we can just call it a draw.

I leave the choice to you.’

The Keene material in question had appeared two years previously in Cathy Forbes’ report on Hastings, 1990-91. On page 19 of the 14 June 1993 issue of Inside Chess she wrote:

‘In writing my report on Hastings 1990-91, I made extensive use of Ray Keene’s notes from the Hastings Bulletin. I did have permission to use this material, but I neglected to acknowledge the source in the article, which was an error of omission on my part.’

That letter was followed by one from Donaldson to Keene:

‘I’m afraid we will have to refuse your “draw” offer. The two situations are hardly the same. You gave Cathy Forbes permission to use the material in question in her story and she, in turn, gave us permission to use it and we paid her for it. Case closed. We don’t owe you two cents, much less $200.

Since you admit that you owe us for the material you appropriated from our pages, we would appreciate payment as soon as possible, though we understand your reluctance to establish a financially dangerous precedent in this area.’

Contents page, Inside Chess, 14 June 1993. ‘Ray interfectus est’ made fun of Raymond Keene, who had used the Latin text ‘Rex interfectus est’.

Inside Chess did not return to the subject until its 7 February 1994 issue (page 3), when a reader enquired whether Donaldson had ever received the claimed $200. The magazine reported that on 22 July 1993 Donaldson and Henry Holt and Company (‘Keene’s American publisher’) had …

‘… entered into an agreement to settle all claims arising out of Henry Holt and Company’s distribution of The Complete Book of Gambits … Henry Holt and Company agreed to pay Mr Donaldson an undisclosed amount, and agreed to refrain in the future from distributing copies of the book that contained the allegedly infringing material.’

At the Chess Café Bulletin Board on the Internet (a posting dated 30 May 2001) Keene provided another explanation of his conduct over the Gambits book (quoted in full below):

‘I left for a foreign trip while this book was being typeset and accidentally left a complete copy of the Donaldson article with the manuscript. It was a very minor sideline – hardly worth the pages that ended up being devoted to it when the typesetter dutifully put the whole article in! (1 Nf3 f5 2 d3 Nf6 3 e4 I think it was.) I did not agree to pay any damages – Batsford decided unilaterally that this was the simplest solution.’

We add that the book (on the imprint page) thanked ‘Byron Jacobs for his speedy and efficient typesetting’. It is also interesting to note from the above passage that even as late as 2001 Keene appeared unaware that Lisitsin’s Gambit begins 1 Nf3 f5 2 e4.

The remaining question is the extent of the ‘simplest solution’, i.e. the size of the damages which eventually had to be paid out because of Keene’s conduct. The amount of the final settlement was not the $200 which Donaldson had originally sought. It was $3,000.

(2966)

See also our feature article Lisitsin’s Gambit. The plagiarism affair was also discussed in ‘Ex Acton ad Astra’ on pages 18-33 of the Spring 2007 issue of Kingpin.

Addition on 11 February 2025:

In a remarkable attempt to deceive his readers, Larry Evans wrote two newspaper chess columns which chopped off the narrative of the Donaldson-Keene exchanges prematurely, thereby concealing the fact that Donaldson won hands-down:

Sunday Patriot-News (Harrisburg), 19 September 1993, page G10.

Raymond Keene is his own worst enemy in a crowded field.

A) Below is the text of C.N. 4682 (posted on 29 October 2006):

‘“The world’s biggest-selling book” is the boast on the back cover of Guinness World Records 2007 (London, 2006). Two pages include entries on chess: page 99 has a couple of dozen words about Sergei Karjakin being the youngest grandmaster, while page 137 offers brief features on the smallest and largest chess sets, as well as the following: “On 25 June 2005, 12,388 simultaneous games of chess were played at the Ben Gurion Cultural Park in Pachuca, Hidalgo, Mexico.” That is all. The four entries from the 2006 edition have been dropped.

Although poker has five entries on page 136, games such as draughts and bridge receive no treatment at all, and the editorial team’s interests are evidently on a different plane. For example, pages 8-9 document such pivotal attainments as “most heads shaved in 24 hours”, “fastest time to drink a 500-ml milkshake”, “longest tandem bungee jump”, “fastest carrot chopping”, “largest underpants”, “most socks worn on one foot’ and “fastest person with a pricing gun”.’

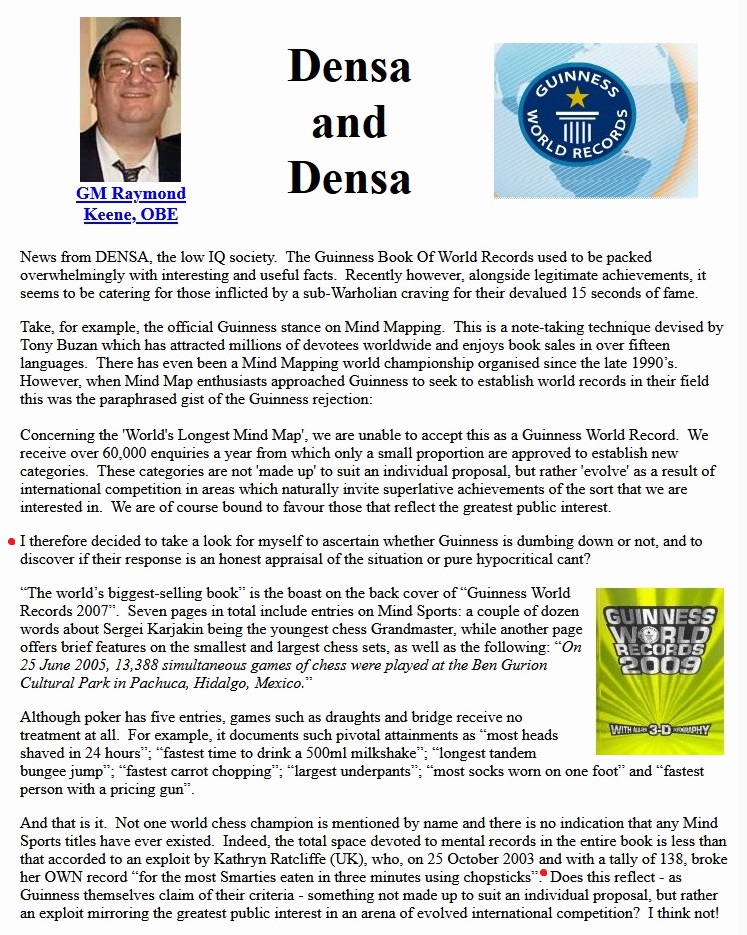

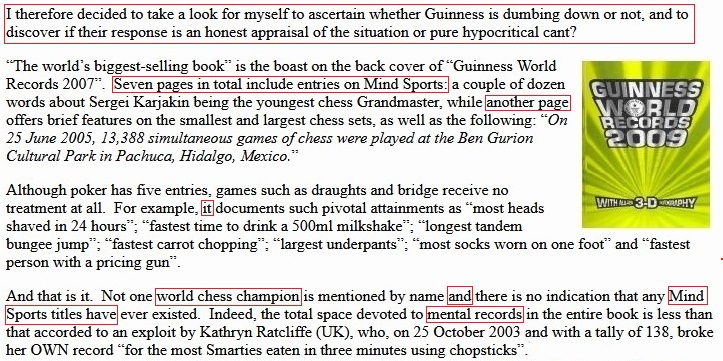

B) From an article ‘Densa and Densa’ (chessville.com) by Raymond Keene (posted on the Internet on 21 September 2008):

‘I therefore decided to take a look for myself to ascertain whether Guinness is dumbing down or not, and to discover if their response is an honest appraisal of the situation or pure hypocritical cant?

“The world’s biggest-selling book” is the boast on the back cover of “Guinness World Records 2007”. Seven pages in total include entries on Mind Sports: a couple of dozen words about Sergei Karjakin being the youngest chess Grandmaster, while another page offers brief features on the smallest and largest chess sets, as well as the following: “On 25 June 2005, 13,388 simultaneous games of chess were played at the Ben Gurion Cultural Park in Pachuca, Hidalgo, Mexico.”

Although poker has five entries, games such as draughts and bridge receive no treatment at all. For example, it documents such pivotal attainments as “most heads shaved in 24 hours”; “fastest time to drink a 500ml milkshake”; “longest tandem bungee jump”; “fastest carrot chopping”; “largest underpants”; “most socks worn on one foot” and “fastest person with a pricing gun”.’

(5771)

C.N. 5771 demonstrated that the text of our item C.N. 4682 (written two years ago) was recently lifted by Mr Raymond Keene for use under his own name in an article on the book Guinness World Records.

The matter has been investigated in detail at the website of the Streatham & Brixton Chess Club (reports dated 30 September, 8 October and 10 October 2008). It may be noted, in particular, that:

a) Mr Keene has made various attempts to explain his copying, and they have been proven untrue;

b) The website to which we referred in C.N. 5771 has now removed from Mr Keene’s article our paragraphs about chess;

c) Mr Keene’s article originally appeared in his weekly column in The Spectator (page 64 of the 7 June 2008 issue);

d) Over a third of ‘his’ article in The Spectator was, in fact, written by us.

(5795)

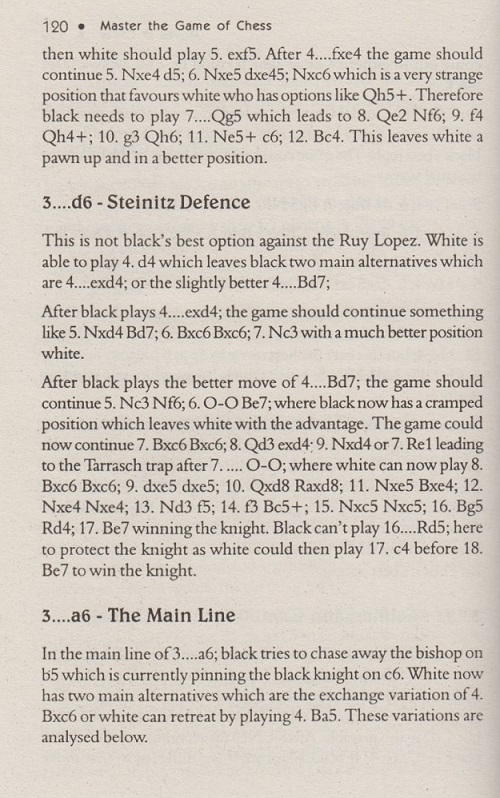

Below is Mr Keene’s column with our text blacked out:

Our writing as it appeared in The Spectator:

On 11 October 2008 we sent the following letter by registered post and e-mail to the then editor of The Spectator (London), Matthew d’Ancona:

‘Dear Mr d’Ancona,

May I advise you that over one third of the chess article by Mr Raymond Keene published on page 64 of The Spectator, 7 June 2008 was simply copied, word for word, from what I wrote some two years ago.

The following links to my Chess Notes webpage provide the facts:

- http://www.chesshistory.com/winter/winter51.html#5795._More_copying_C.N._5771

- http://www.chesshistory.com/winter/winter50.html#5771._More_copying

At no stage have I given permission for my writing to appear under Mr Keene’s name.

Thank you very much in advance for informing me of your proposal for settling this matter.

Yours sincerely,

Edward Winter.’

No reply of any kind was received.

As reported in C.N. 9178 (see below), on page 139 of his book The Official Biography of Tony Buzan (Croydon, 2013) Raymond Keene plagiarized our Guinness material again.

Page 11 of the 7/2015 New in Chess referred to Raymond Keene’s plagiarism of us, but could not bring itself to name him. Instead, the magazine reported that we had ‘kept a “keen” eye on the chess content in the Guinness World Records’ and added:

‘... a certain English chess journalist even managed to set his own personal plagiarism record by shamelessly lifting verbatim several detailed paragraphs by Winter for a column in his own name.’

Raymond Keene’s plagiarism of our work (C.N.s 3493 and 4682) at chessville.com:

The image below highlights in red the only bits written by Mr Keene when he tried to pass off our writing as his own:

A FIDE report [more recent link] dated 13 March 2015 (richly illustrated but poorly written) stated:

‘On March 11, the FIDE President left Reykjavik for London where he visited the editorial office of the Guinness World Records and congratulated the Records with its 60th anniversary. The talks were about the possible cooperation between FIDE and Records that meets the interests of both sides. The Records’ representatives would like to get the various information about chess and proposed to set the necessary criteria for the certification of records and their submission for publishing.’

In two photographs Kirsan Ilyumzhinov beamingly held a copy of Guinness World Records 2015.

Since 2004 we have been posting annual accounts of the chess content of Guinness World Records, and it can now be mentioned that the 2016 book has just been published.

Number of chess-related items in the 2016 edition: zero.

(9481)

Page 11 of the 7/2015 New in Chess had an item on Guinness World Records, mentioning our yearly reports and Raymond Keene’s plagiarism of C.N. 4682 in the Spectator. (As so often, Mr Keene escaped being named; the reference was just to ‘a certain English chess journalist’.) The main thrust of the New in Chess feature was the absence of any chess content in the 2016 Guinness World Records volume despite Kirsan Ilyumzhinov’s contact with the company, and it all gave the impression of supplementing our own observations. In reality, New in Chess was merely repeating the very point made in C.N. 9481.

In a series of articles at the website of the Streatham & Brixton Chess Club, Justin Horton has reported on the conduct of Raymond Keene. The latest exposé of plagiarism concerns the game Alekhine v Rubinstein, Carlsbad, 1923, which Mr Keene published in The Spectator of 4 May 2013 with annotations lifted from volume one of Kasparov’s My Great Predecessors series.

(8099)

See too Mr Horton’s article dated 26 June 2013, concerning Réti v Capablanca, New York, 1924. Further instances have continued to be demonstrated at the Streatham & Brixton site in a series of articles about the duplicitous duplicator.

While the rest of us are reading a new chess book, Raymond Keene is casing the joint.

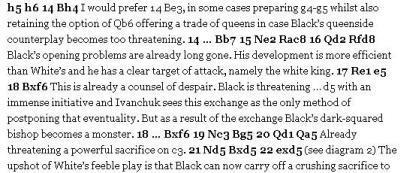

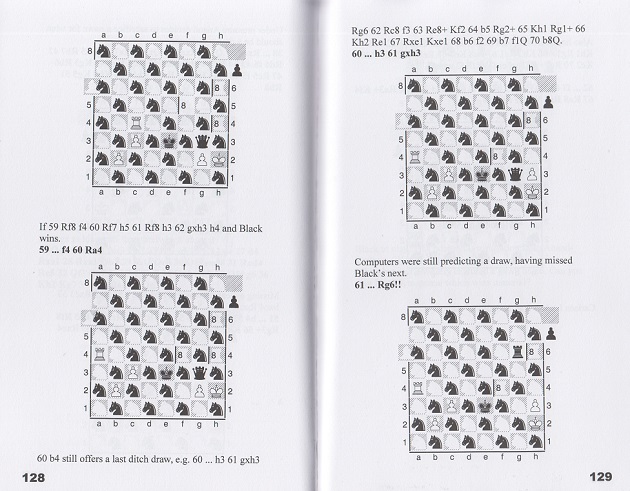

Raymond Keene’s latest chess column in The Spectator (22 June 2013, page 66), available on-line [broken link], reveals another handy method of avoiding exertion. The column features the game Ivanchuk v Anand, Linares, 1998, without mentioning that the annotations merely repeat, word for word, what Mr Keene was paid for writing in his column on page 60 of The Spectator, 21 March 1998.

For example:

The Spectator (2013)

The Spectator (1998)

(8100)

Addition on 28 June 2013: Pablo Byrne (London) points out a third occurrence in The Spectator of the same annotations to the Ivanchuk v Anand game, on page 58 of the 5 May 2012 issue.

C.N. 8099 briefly referred to Raymond Keene’s plagiarism, but since then the scale of it has become evident from the continuing series of articles by Justin Horton at the Streatham & Brixton website. Readers can examine the eye-popping details for themselves via a convenient ‘plagiarism index’ which is being kept updated.

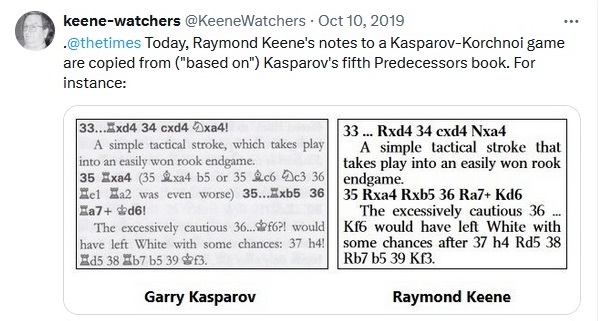

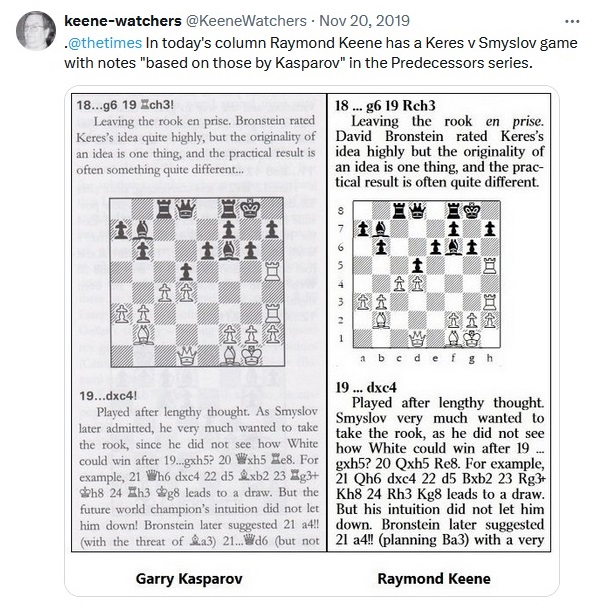

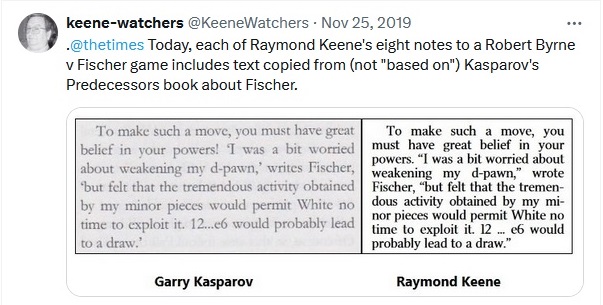

Executive summary: in addition to shuttling his own writing, or what was imagined to be, from one Times or Spectator column to another (his columns being pale shadows of their former pale shadows), Raymond Keene has often used those outlets to pass off material, particularly from the Kasparov Predecessors books, as his own writing. It is not just occasional phrases, sentences or paragraphs that have been misappropriated, but material to fill entire columns. And, we now know, frequently.

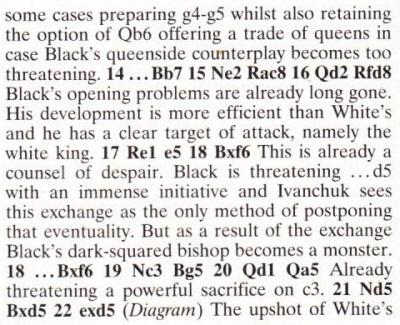

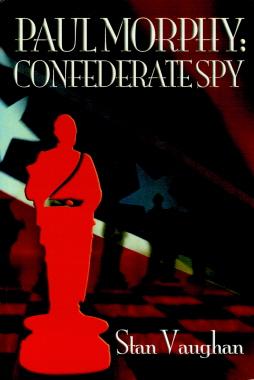

Page 29 of the 28 June-11 July 2013 issue of Private Eye (a feature nearly 90 lines long – shown above in a small format for illustration only) discussed bluntly the behaviour of ‘this absurd comic-book thief’, but what can be said about the chess world’s reaction, or lack thereof, to the affair? To date, it has been a case of ‘lack thereof’. Such pusillanimity is nothing new, there being a longstanding belief among editors (including his employers) that the best place for unsavoury information about Raymond Keene is under the carpet. Now, though, given the sheer extent and seriousness of what he has done, why would any editors or columnists (and not only British ones) wish to continue concealing the facts from their readers? After all, if they were to persist in shielding Raymond Keene, how could they legitimately criticize anybody else for anything?

(8151)

A further article, ‘Chequered Mate’ [broken link], appeared on page 7 of the 6-19 September 2013 issue of Private Eye.

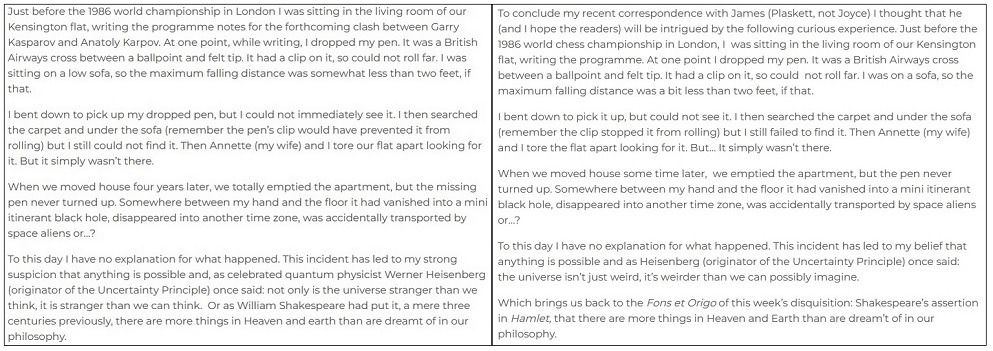

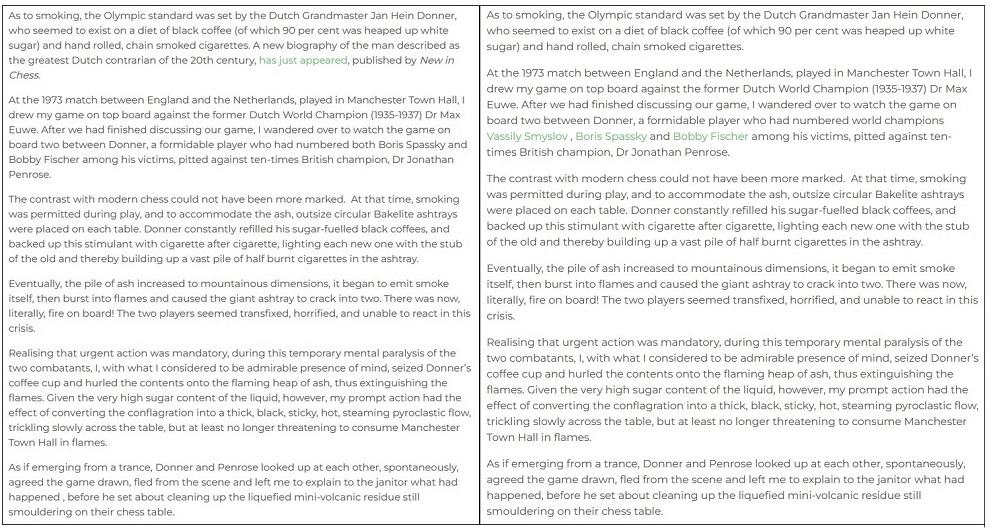

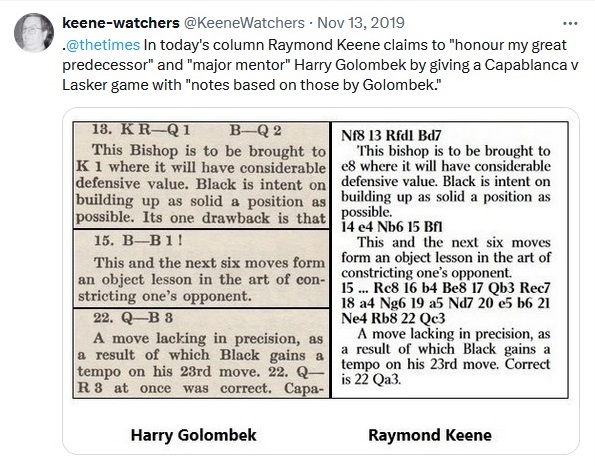

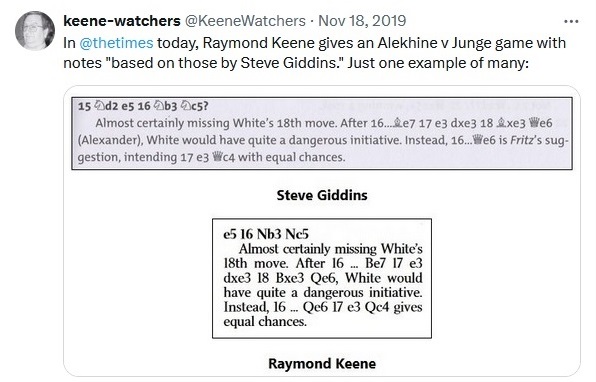

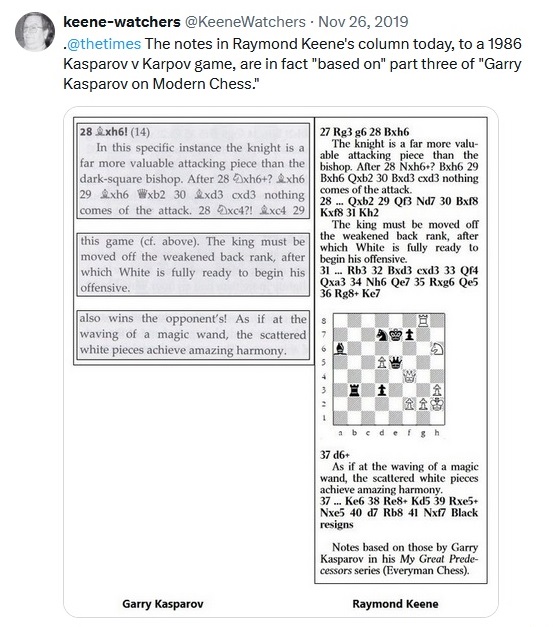

Sometimes Raymond Keene mentions the Predecessors series by name when helping himself to annotations. ‘Notes based on’ is Keenese for ‘Notes copied from’.

The ‘based on’ method is also seen in a brief article on Raymond Keene by Olimpiu G. Urcan.

Another piece by Mr Urcan is ‘Meal Ticket’, referred to in C.N. 11126.

In his Spectator column of 28 September 2019 Raymond Keene wrote:

‘After 42 years without missing a week, this is my last column for The Spectator.’

The assertion about not missing a week is untrue. For instance (as reported by Olimpiu G. Urcan at the English Chess Forum), in 1985 nine Spectator chess columns were by writers other than Raymond Keene. In a run of six columns in October-November 1986 four were written by other people.

In his Times column of 1 November 2019 Raymond Keene wrote:

‘Today I announce my retirement from writing The Times chess column. I shall be standing down at the end of November ...’

On his Twitter page on 31 July 2020 Raymond Keene wrote, misleadingly and ungrammatically:

‘I am 72. Last year, at the age of 71, both The Spectator and The Times fired me after respectively serving for 42 years and 34 years without missing a single column. And frequently topping the poll for most read chess column. So good luck youngsters!!’

Age was indeed the problem – the age of his material.

Summary regarding Raymond Keene’s chess columns:

Sunday Times: terminated in August 2017;

The Spectator: terminated in September 2019;

The Times: terminated in November 2019.

From page 9 of Private Eye, 18-31 October 2019:

(Reduced format, for reference only)

‘As a Spectator source puts it, the Penguin’s offence was “keeping on plagiarising even after he’d been politely asked not to’’.’

The final paragraph of the column asked whether the ‘beleaguered’ Raymond Keene could survive at The Times. That question was answered, in the negative, by Private Eye on page 8 of its 15-28 November 2019 edition.

Quite by chance we have just discovered the following:

‘On Tuesday the chess official who asked Tony to send a cable to London if he became a Grand Master received a laconic telegram which said simply “A cable. Tony Miles.”

The steel behind this casual facade becomes evident in Miles’s dedicated effort at the chessboard. His play is aggressive, precise, and above all fearless of reputations ...’