Edward Winter

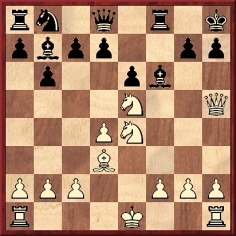

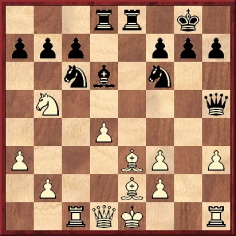

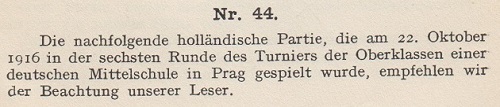

First, a quiz question which should defeat even the most knowledgeable chess enthusiast. Name the player who, in the above position, sacrificed his queen with 11 Qxh7+.

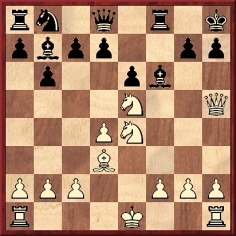

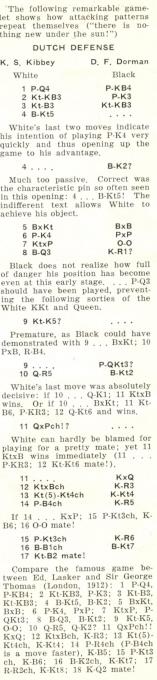

Edward Lasker is the obvious reply, since his brilliancy against George Thomas is one of the most celebrated games in chess literature, but the correct answer is K.S. Kibbey, against D.F. Dorman. Their encounter went 1 d4 f5 2 Nf3 e6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 Be7 5 Bxf6 Bxf6 6 e4 fxe4 7 Nxe4 O-O 8 Bd3 Kh8 9 Ne5 b6 10 Qh5 Bb7 11 Qxh7+ Kxh7 12 Nxf6+ Kh6 13 Neg4+ Kg5 14 f4+ Kh4 15 g3+ Kh3 16 Bf1+ Bg2 17 Nf2 mate, according to page 176 of Chess Review, August-September 1942. Presenting the game, Fred Reinfeld remarked, ‘there is nothing new under the sun’, by which he was, of course, referring to the Lasker v Thomas precedent. That game, though, did not reach the position in the above diagram, since Thomas moved his queen to e7 and did not play his king to h8.

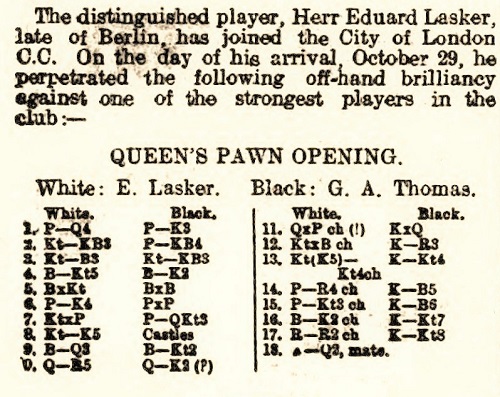

Lasker v Thomas is also one of the most confusing games in chess literature. Firstly, there is the question of when it was played. Although often misdated as 1911 or 1913 (other years have been seen too), it was played in 1912, and page 26 of the January 1913 issue of La Stratégie gave a precise date: 29 October 1912. The French magazine did not present the opening moves; that is the phase where so many discrepancies are to be found, as is shown by the following list:

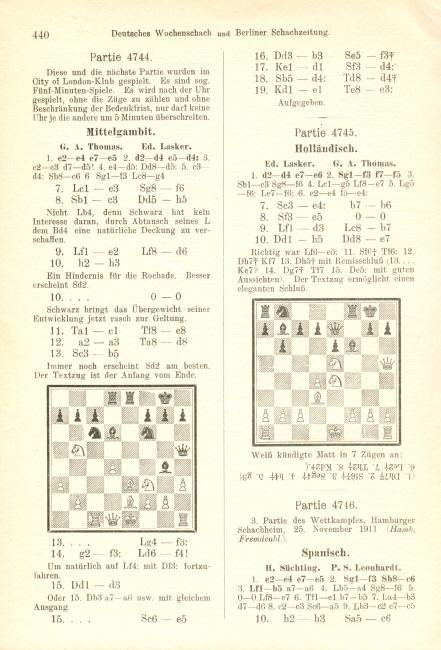

In addition, version 4 appeared not only in Deutsches

Wochenschach, 8 December 1912, page 440, and the Deutsche

Schachzeitung, January 1913, pages 6-7, but also in R.

Loman’s column in De Amsterdammer, 17 November 1912.

Two of the sources listed above mention Edward Lasker himself, and we are aware of five occasions when he wrote about the game [for a sixth occasion, see the Afterword below]:

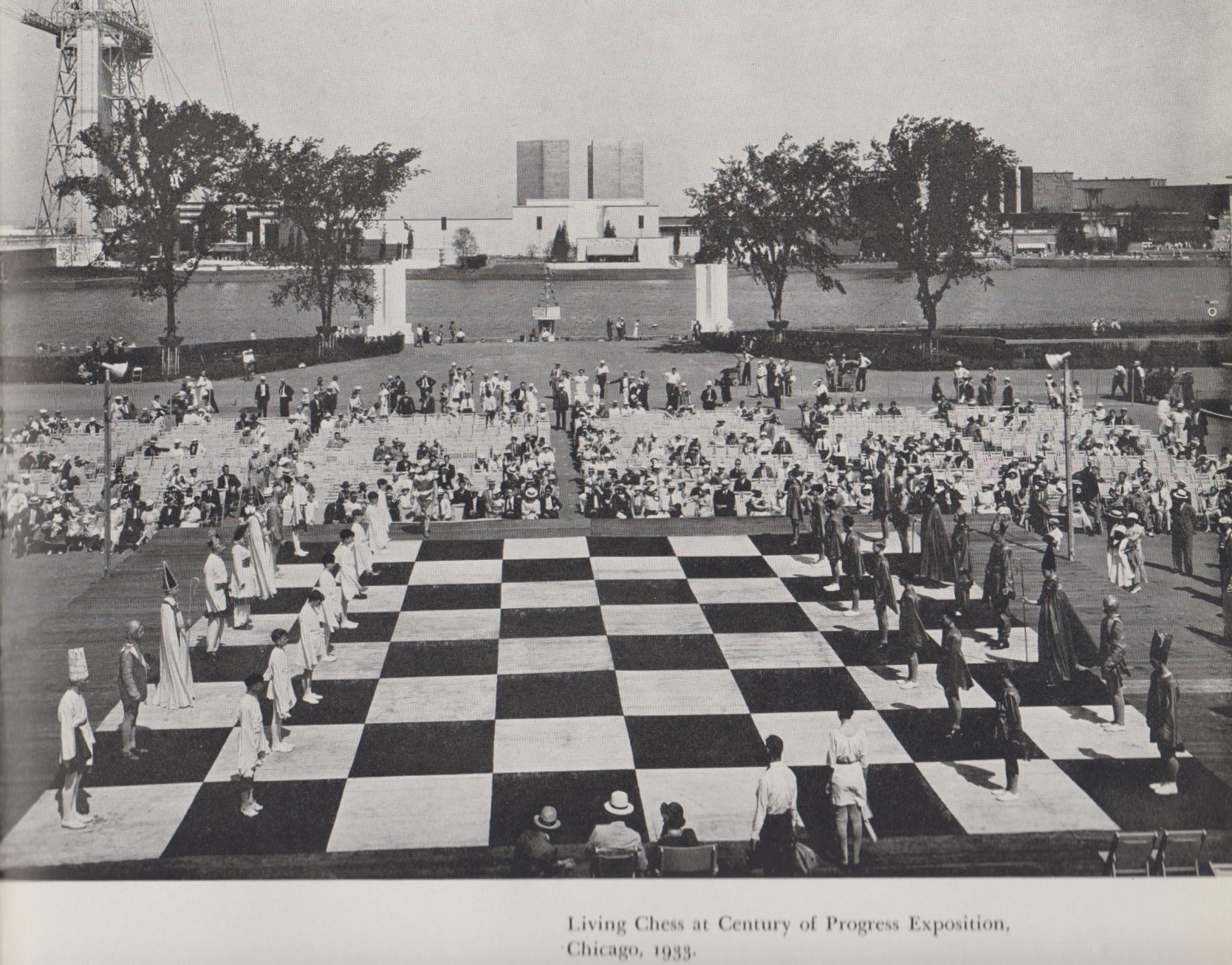

‘In 1912 I went to England in order to learn the English language, and my first visit, of course, was to the City of London Chess Club. I was lucky enough to win the following game against the club champion, G.A. Thomas, which gave me the best possible introduction: 1 d4 f5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 Bg5 e6 4 Nc3 Be7 5 Bxf6 Bxf6 6 e4 fxe4 7 Nxe4 b6 8 Ne5 O-O 9 Bd3 Bb7 10 Qh5 Qe7 11 Qxh7+!! and mate in seven moves.’

Lasker v Thomas. Position before 11 Qxh7+

‘The following game I consider the most beautiful I ever played ... though it was not a tournament game and can, therefore, hardly be classed among the best games’. The score which Lasker then annotated had a different move-order up to move nine, the complete game being presented as follows: 1 d4 f5 2 Nf3 e6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 Be7 5 Bxf6 Bxf6 6 e4 fxe4 7 Nxe4 b6 8 Bd3 Bb7 9 Ne5 O-O 10 Qh5 Qe7 11 Qxh7+ Kxh7 12 Nxf6+ Kh6 13 Neg4+ Kg5 14 h4+ Kf4 15 g3+ Kf3 16 Be2+ Kg2 17 Rh2+ Kg1

18 Kd2 mate.

Lasker’s concluding remark was:

‘This game was played in the City of London Chess Club in 1912. A year later, Alekhine called my attention to the fact, discovered in Moscow, where he went over the game with Bernstein, that I could have mated in seven instead of eight moves by playing 16 Kf1 or O-O, as then Black would have been unable to prevent mate by 17 Nh2.’

After 15...Kf3

Lasker gave the date as 1911 and described the encounter as ‘a so-called “five-minute” game, i.e. a game played with clocks as fast or as slowly as the players like, but with the condition that neither player must exceed the total time of the other by more than five minutes at any stage’.

The move-order was as in Chess Pie. Lasker related that some years after the game was played he received a letter from a chess club in Australia pointing out that, instead of 14 h4+, 14 f4+ mates one move faster (14 f4+ Kh4 15 g3+ Kh3 16 Bf1+ (or 16 O-O) Bg2 17 Nf2 mate), whereas 14...Kxf4 allows 15 g3+ Kf3 16 O-O mate or 15...Kg5 16 h4 mate.

After 13...Kg5

Lasker showed the play from 11 Qxh7+ onwards and praised Thomas’ magnanimity in defeat. A footnote on page 149 referred readers to Chess for Fun & Chess for Blood for the detailed score.

In article entitled ‘Fifty Years Ago...’ Lasker gave the game-score (with the same move-order as in Chess Pie and Chess for Fun & Chess for Blood) and stated that at move 14 he ‘had only about a minute to spare’. He mentioned the above quicker mates and commented as follows on his choice of 18 Kd2 rather than 18 O-O-O:

‘Instead of checkmating with K-Q2 I could have done it by castling, which would perhaps have been more spectacular, as no player has ever been mated that way before, as far as I know. I actually considered castling, but the efficiency-minded engineer in me got the better of it and I played K-Q2 which required moving only one piece.’

Mate by castling had, in fact, already been seen at that time, as noted in our Factfinder under ‘Castling, Mate by’.

Lasker continued in Chess Life:

‘Emanuel Lasker published this game in his chess column in the Berlin daily paper B.Z. am Mittag under the heading “The tragi-comic journey of the black king”. Apparently he did not see the shorter version 14 P-B4 ch either. It was not called to my notice until seven years later, at the end of World War I, when I received a letter from Australia, where master Purdy had discovered the variation.’

This reference to ‘master Purdy’ is also strange, given that in 1919 (seven years after the game was played) C.J.S. Purdy was barely a teenager.

In Chess Life Edward Lasker then gave a different version of the ‘old man’ anecdote which had appeared on page 124 of Chess for Fun & Chess for Blood and supplied details of his arrival in the United States in late 1914 which are at variance with reports in that year’s American Chess Bulletin (e.g. the November 1914 issue, page 233).

In short, Lasker himself was responsible for so many mistakes and

self-contradictions in his accounts of the game that it is hardly

surprising that numerous other writers have misreported it too.

Pages 163-164 of How to Win in the Middle Game of Chess by

I.A. Horowitz (New York, 1955) stated that the game was played in

1915, claimed that the opening moves were 1 d4 e6 2 Nf3 f5 3 Nc3

Nf6, did not mention the faster mates and had as the mating move

not 18 Kd2 but 18 O-O-O. Mate by castling was also given in the

score (which began 1 d4 e6 2 Nf3 f5 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 Be7 5 Bxf6

Bxf6 6 e4 fxe4 7 Nxe4 b6 8 Ne5 O-O 9 Bd3 Bb7) presented on page

234 of the Chess Amateur, May 1913, courtesy of Magyar

Sakkvilág. On page 25 of The Daily Telegraph Chess

Puzzles (London, 1995) David Norwood offered a wrong date

(1910) and the wrong circumstances (it was not a ‘blitz game’),

and on page 33 he did not mention the faster mates that Lasker

missed. It was also described as a ‘blitz game’ on pages 88-89 of

Queen Sacrifice by I. Neishtadt (Oxford, 1991), which dated

it 1911. In contrast, 1913/1914 was the information on page 89 of

Şah Cartea de Aur by Constantin Ştefaniu (Bucharest, 1982).

Page 28 of 666 Kurzpartien by Kurt Richter

(Berlin-Frohnau, 1966) dated the game 1921 and called Black ‘Sir

Thomas’. On page 115 (printed as page 11) of Der Weg zur

Meisterschaft (Berlin and Leipzig, 1919) Franz Gutmayer gave

the conclusion as 11 Qxh7+ Kxh7 12 Nxf6+ Kh8 13 Ng6 mate.

Below is an attempt to summarize what may reliably be said about the game:

Ed. Lasker and George Thomas

Although the game is familiarly referred to as ‘Edward Lasker v Sir George Thomas’, such a heading would be impossible in a contemporary source, since Eduard Lasker had yet to become Edward, and George Thomas was not yet a baronet.

Lasker’s victory with 11 Qxh7+ is not his only recorded game against Thomas in London in 1912. Here is another contest played under the same conditions (i.e. with a maximum gap of five minutes permissible between their clock times):

George Thomas – Edward Lasker

London, 1912

Danish Gambit

1 e4 e5 2 d4 exd4 3 c3 d5 4 exd5 Qxd5 5 cxd4 Nc6 6 Nf3 Bg4 7 Be3 Nf6 8 Nc3 Qh5 9 Be2 Bd6 10 h3 O-O 11 Rc1 Rfe8 12 a3 Rad8 13 Nb5 Bxf3 14 gxf3

14…Bf4 15 Qd3 Ne5 16 Qb3 Nxf3+ 17 Kd1 Nxd4 18 Nxd4 Rxd4+ 19 Ke1 Rxe3 20 White resigns.

Source: Deutsches Wochenschach, 8 December 1912, page 440.

Reverting to the queen-sacrifice game, published on the same page, we add a further discrepancy: after 10...Qe7 Lasker is said by the German magazine to have announced mate in seven (although the line comprised eight moves). Page 100 of Schnell Matt by Claudius Hüther (Munich, 1913), the first book in which we have found the brilliancy, stated that after 10...Qe7 White announced mate in eight moves.

Later, the game was even attributed to Emanuel Lasker (versus an unnamed opponent). See, for instance, page 85 of Emanuel Lasker Volume 3 by K. Whyld (Nottingham, 1976); the game (11 Qxh7+ Resigns) was taken from Els Escacs a Catalunya.

The game was given as ‘an old-time Lasker gem’ (Emanuel Lasker was implied) on page 60 of CHESS, January 1941 (‘Lasker v Thompson’). A correction appeared on page 71 of the February 1941 issue.

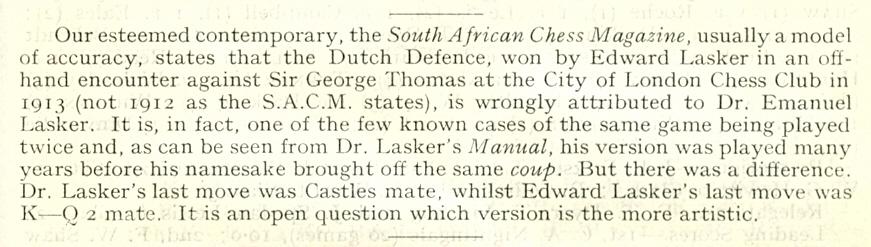

In this connection, one final complication arises from a paragraph on page 239 of the September 1941 BCM:

On page 261 of its October 1941 issue the BCM corrected itself regarding the date of the Ed. Lasker game (1912, not 1913), but on a far more important point the magazine remained oblivious: no such game-score appeared in Lasker’s Manual. A similar remark about Emanuel Lasker having previously played the game was made by the BCM editor, Julius du Mont, on page 240 of his book 200 Miniature Games of Chess (London, 1941), but we are aware of no dependable evidence that Emanuel Lasker ever played a game identical or similar to the Ed. Lasker v G. Thomas one.

There are, though, still writers who believe that Lasker v Thomas, London, 1912 was played by Emanuel Lasker. See, for instance, pages 92-93 of Iniciação ao Xadrez by A.L. Manzano and J.S. Vila (Porto Alegre, 2002).

C.N. 5172 reported that Lasker also published the game on pages 216-217 of the second edition of his book Schachstrategie (Leipzig, 1914). Remarkably, that yields a ninth version of the first nine moves: 1 d4 f5 2 Nf3 e6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 Be7 5 Bxf6 Bxf6 6 e4 fxe4 7 Nxe4 b6 8 Ne5 O-O 9 Bd3 Bb7.

Our feature article mentions that page 26 of the January 1913 issue of La Stratégie gave a precise date for Edward Lasker’s brilliancy: 29 October 1912.

Tony Gillam (Nottingham, England) reports that according to the City of London Chess Club Annual Report for 1913 (page 37) Lasker joined the Club in October 1912. It may be recalled that on pages 147-148 of Chess Secrets I Learned from the Masters (New York, 1951) Lasker stated that he played the game at the City of London Chess Club on the day of his arrival in England.

(5989)

Frederick S. Rhine (Park Ridge, IL, USA) notes that on page 29 of Chess Techniques by A.R.B. Thomas (London, 1975) the conclusion was given as 16 Be2+ Kg2 17 O-O-O Resigns. As previously noted, many writers have stated that Lasker castled on move 18, but is A.R.B. Thomas alone in suggesting that 17 O-O-O was played?

(6057)

Hans-Georg Kleinhenz (Munich, Germany) reports that Lasker’s notebook of the time is being sold at auction in late November 2010 by Antiquariat A. Klittich-Pfankuch GmbH & Co. With the company’s permission we reproduce the game-score in Lasker’s hand:

It will be seen that the move-order on this score-sheet, which dates the game 29 October 1912, does indeed correspond to ‘version 4’ above.

(6791)

Concerning the deletion of Lasker’s name from Kombinationen by Kurt Richter (1936 and 1940 editions), see C.N. 7875.

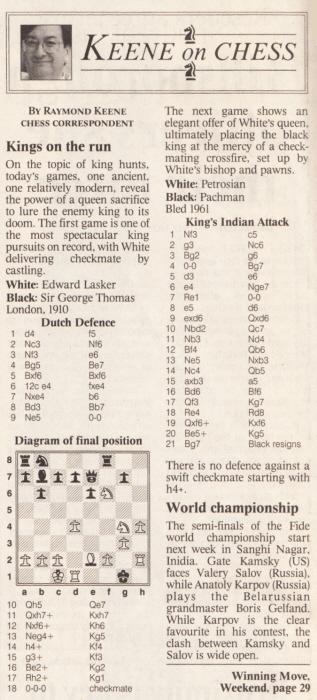

On page 10 of The Times, 4 February 1995 Raymond Keene ‘wrote’:

The Lasker v Thomas game was played in 1912 and not 1910, White’s sixth move was not ‘6 12c e4’, and it is hardly an example of ‘White delivering checkmate by castling’, given that Lasker played 18 Kd2. One notes too the reference to ‘Gate Kamsky’.

See Cuttings.

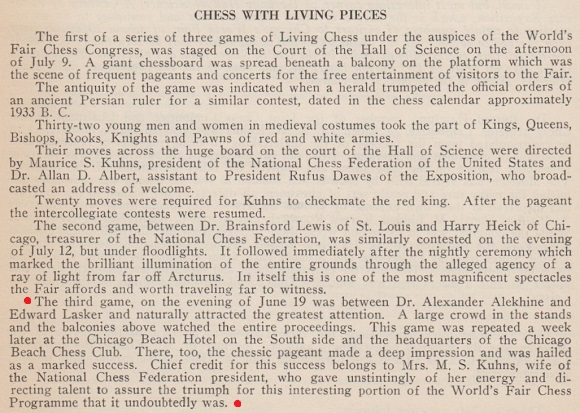

A noteworthy addition is that in 1933 Lasker played the game with the black pieces.

First, an extract from page 109 of the American Chess Bulletin, July-August 1933:

And from page 4 of the September 1933 Chess Review:

‘... on the evening of 19 June came the awaited meeting between Dr Alekhine and Edward Lasker. This naturally drew the largest gathering of any single chess event with the exception of the blindfold display. Alekhine won in good style, but the game itself was less important to the audience than the idea of the spectacle. This game was repeated later at the Chicago Beach Hotel.’

Neither US magazine gave the moves of the Alekhine v Lasker game, which in any case was pre-arranged. From pages 160-161 of Lasker’s The Adventure of Chess (New York, 1950):

‘In a chapter on eccentricities of the game, Liddell’s book [Chessmen by Donald M. Liddell (New York, 1937)] brings a picture of a board with living pieces used in a game played in the open-air amphitheater of the Century of Progress Exposition at Chicago, in 1933. I happened to direct that game, and the picture recalled to my mind a tragicomic incident which occurred toward the end of it. The chess pieces were mostly boys and girls from Chicago high schools, dressed in real old-Indian costumes. On the day of the game a bright, hot sun was shining, and over 5,000 onlookers crowded every available spot in the arena. To the majestic tune of a march especially composed for the occasion by the well-known composer DeLamarter, who was a resident of Chicago, the chess pieces, in impressive array, descended a wide stairway and took their places on the board. The world champion, Alekhine, had been engaged for the occasion to play the game with me which the living pieces were to show, and a tower was provided from which Alekhine and I called our moves through megaphones. To make sure that the performance would not take more than an hour at most, we had decided to select a short game with which we were both familiar, rather than actually engaging in a contest ourselves. The choice of the committee had fallen on a rather well-known game which I had won some 20 years previously against the British champion, Sir George Thomas. Alekhine agreed, but insisted that he should play the winning side. Everything went fine for about a half hour, when suddenly my queen’s rook’s pawn fainted. The poor fellow had been standing motionless in the hot sun all that time, and instead of making it known to someone that he was feeling ill, he held out bravely until he finally collapsed. He was carried out on a stretcher and replaced by an “understudy” whom we had held in readiness in case one of the actors did not show up.

I doubt that a very large percentage of the crowd knew chess, but the colorful spectacle certainly served as a spellbinding introduction to learning the game.’

Below is the photograph mentioned by Lasker, as published opposite page 98 of Liddell’s book (and between pages 132 and 133 of the London, 1976 edition):

(8917)

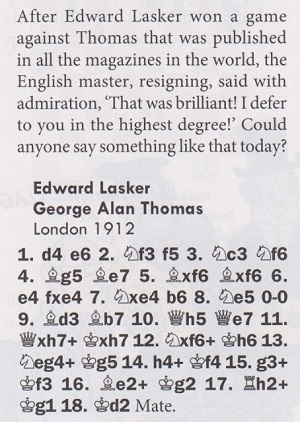

From page 56 of the 3/2015 New in Chess, in an article by Genna Sosonko about resignation:

Sosonko has yet to specify his source for Thomas’ remark, and to explain how the issue of resignation arises in a game which ended in mate.

The game was dated 1921 on pages 169 and 185 L’oeil tactique: l’entraînement à la combinaison by Emmanuel Neiman (Paris, 2003).

C.N. 2647 (see page 330 of A Chess Omnibus and Jaffe and his Primer) included the following observation by us on Jaffe’s 1937 work:

Most of the remainder of the book consisted of a chapter entitled ‘Ten Famous Games’, lightly annotated (‘… we will attempt to illustrate the finer and more complicated mechanism that composes the middle game with an eye towards the opening’.) The first was Edward Lasker’s spectacular miniature against Sir George Thomas (Dutch Defence; 11 Qxh7+), except that Jaffe made Lasker the loser, against Alekhine, affirming that it had been played ‘in the World’s Fair in Chicago with live figures. The combination in this game is so brilliant, so rare that it is difficult to believe that even a master could have worked it out in actual play.’

For information about George Thomas’ birth in 1881 and his inheritance of the baronetcy in 1918, see C.N. 10680.

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) sends this early publication of the Lasker v Thomas miniature in O.C. Müller’s column in The Globe, 9 November 1912, page 8:

(10911)

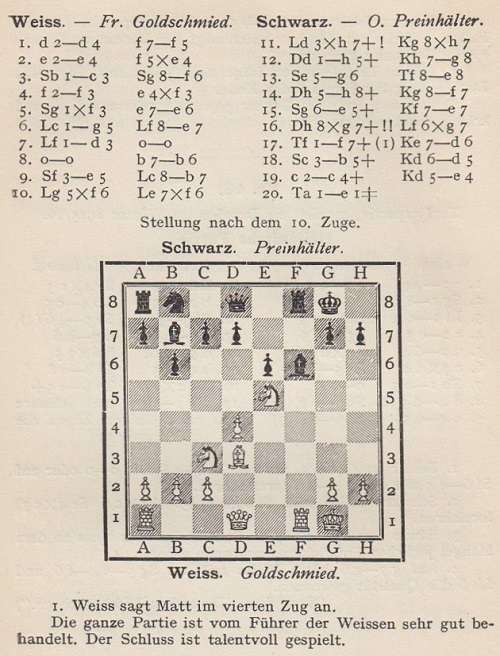

Although familiar from databases, this game is worth adding here for comparison with Lasker v Thomas, London, 1912:

Source: Schachjahrbuch für 1915/16 by Ludwig Bachmann (Ansbach, 1917), pages 61-62.

1 d4 f5 2 e4 fxe4 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 f3 exf3 5 Nxf3 e6 6 Bg5 Be7 7 Bd3 O-O 8 O-O b6 9 Ne5 Bb7 10 Bxf6 Bxf6 11 Bxh7+ Kxh7 12 Qh5+ Kg8 13 Ng6 Re8 14 Qh8+ Kf7 15 Ne5+ Ke7 16 Qxg7+ Bxg7 17 Rf7+ Kd6 18 Nb5+ Kd5 19 c4+ Ke4 20 Re1 mate.

(11281)

On page 58 of The Spectator, 26 October 2019 Luke McShane referred to ‘the aesthetic dilemma on the final move’ in the Lasker v Thomas game. After quoting a remark of Lasker’s shown above (‘I actually considered castling, but the efficiency-minded engineer in me got the better of it and I played K-Q2 which required moving only one piece’), McShane concluded, ‘That light touch has grown on me’.

See too Castling in Chess.

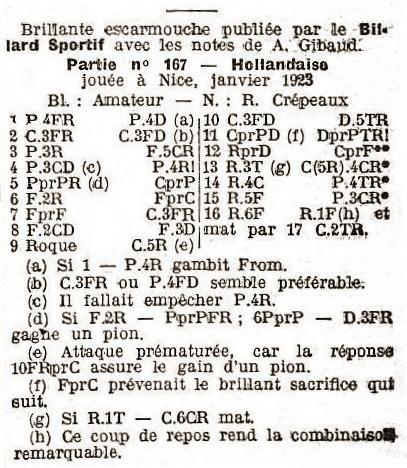

1 f4 d5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 e3 Bg4 4 b3 e5 5 fxe5 Nxe5 6 Be2 Bxf3 7 Bxf3 Nf6 8 Bb2 Bd6 9 O-O Ne4 10 Nc3 Qh4 11 Nxd5

11...Qxh2+ 12 Kxh2 Nxf3+ 13 Kh3 Neg5+ 14 Kg4 h5+ 15 Kf5 g6+ 16 Kf6

16...Kf8 17 White resigns.

Reminiscent of Lasker v Thomas, this well-known gamelet (‘Amateur v Crépeaux, Nice, 1923’) is to be found, with criticism of both sides’ play, on pages 399-400 of Echec et mat de l’initiation à la maîtrise by Frank Lohéac-Ammoun (Les Avirons, 2011). Han Bükülmez (Ecublens, Switzerland) wonders whether it can be demonstrated that the game is genuine.

Although the venue is usually given as Nice, page 272 of 200 Miniature Games of Chess by J. du Mont (London, 1941) had ‘Holland, 1923’. It is by no means easy to build up a list of early appearances of the game in print, and readers’ assistance will be appreciated.

A photograph of Robert Crépeaux, from the September 1925 issue of L’Echiquier, was included in C.N. 3479. He died in 1994 (see Europe Echecs, April 1994, page 13), although Lohéac-Ammoun’s book states (page 399) that Crépeaux ‘mourut prématurément à Paris en 1944’. Indeed, the book’s undoubted qualities are marred by many errors in dates and names. For instance, it is claimed on page 33 that the famous game Capablanca v Fonaroff was played in 1904.

(7376)

Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) supplies references to three appearances of the game in print: Bulletin de La Fédération Française des Echecs, April-June 1923, page 10; the column by Gaston Legrain in L’Action Française, 8 April 1923, page 5; Bulletin de La Fédération Française des Echecs (July 1927, page 22).

All three items have the same annotations by Aimé Gibaud. Two of them state that the game was played in January 1923 and that it had previously been published in the periodical Le Billard Sportif (which has not yet been found).

Below is what appeared in L’Action Française:

(7381)

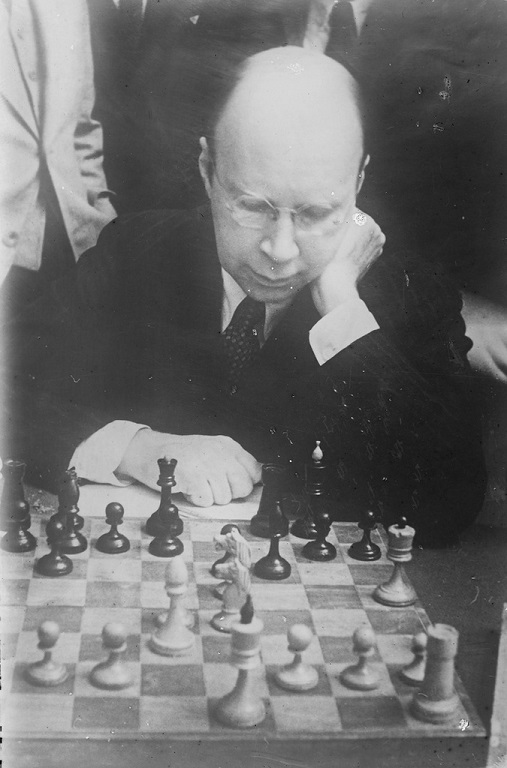

Addition on 21 December 2022:

Douglas Griffin (Insch, Scotland) provides (courtesy of the Russian music museum) this shot of Sergei Prokofiev studying the Lasker v Thomas game:

See too our feature articles Edward Lasker and Sir George Thomas.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.