Edward Winter

‘I’m not good at attention to detail ... I couldn’t have run a corner shop – absolutely impossible!’

Raymond Keene (See the ‘Attention to detail’ section below.)

***

An extensive selection of items demonstrating Raymond Keene’s unreformable slovenliness and worse.

From page 266 of Chess Explorations:

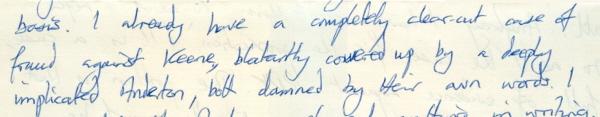

C.N. 331 questioned the exact role in Batsford Chess Openings of Garry Kasparov, who was referred to as a co-author. In a letter dated 16 September 1983 (published in C.N. 583) Raymond Keene therefore offered us a copy of Kasparov’s contribution, in return for a cheque for £50 payable to a chess charity. We immediately accepted, but no material was ever provided, and nearly two years elapsed before Mr Keene offered us a refund.

By then the level of Kasparov’s involvement had been confirmed in two letters received from the book’s ‘Research Editor’, Eric Schiller. Although they were published in full (in C.N.s 844 and 870), Mr Schiller made persistent claims that they had been edited or quoted out of context, a falsehood which he continued to propagate even after C.N. 1737 had reproduced his original letters photographically.

C.N.s 507, 583 and 588 also drew attention to Batsford’s misuse of Kasparov’s name in connection with two other books, Fighting Chess and My Games.

Concerning the £50 matter, on 14 December 1983 Kenneth Whyld (Caistor, England) wrote to us:

‘You’ve called their bluff, but they will wriggle out.’

The following appeared in C.N. 1737:

In 1984 Eric Schiller sent us two letters regarding Batsford Chess Openings. They were published in C.N.s 844 and 870, and in C.N. 1143 (page 53) we reported that C.N. had neither changed nor omitted anything whatsoever (except the correction of one typing error). Many readers of the Chess Linc/Chessline News computer system will therefore have been perplexed to see the following allegation by Mr Schiller dated 23 September 1988:

‘Winter has sent me loaded questions to which I initially replied with honest answers, only to see them manipulated to the point that a letter I sent supporting a position of Ray Keene’s, which was being attacked by Winter, was cited (not quoted in full as requested) as supporting Winter!’

This is pure invention, as the following facts demonstrate:

a) Mr Schiller was the one who opened the correspondence, so he was not replying to ‘loaded questions’ from us.

b) Mr Schiller never made any request that the complete texts be published.

c) Both of his letters were published in full (our own decision).

To prove the above, C.N. 1737 published the two letters again, this time reproduced photographically, exactly as received from Mr Schiller. We then concluded:

Mr Schiller’s allegation that we manipulated his letters is so injurious that readers will understand our reasons for taking up two pages to provide incontestable proof that it was an outright lie. We now await from him an unqualified retraction and apology.

They never came, of course.

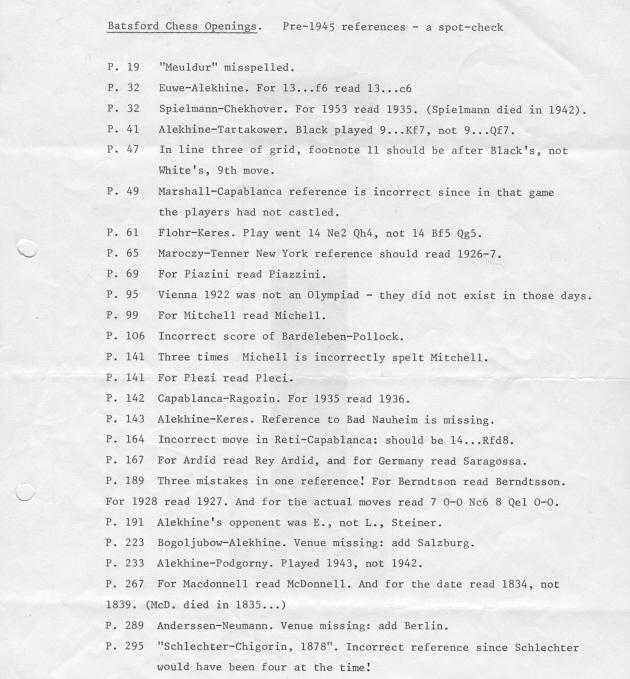

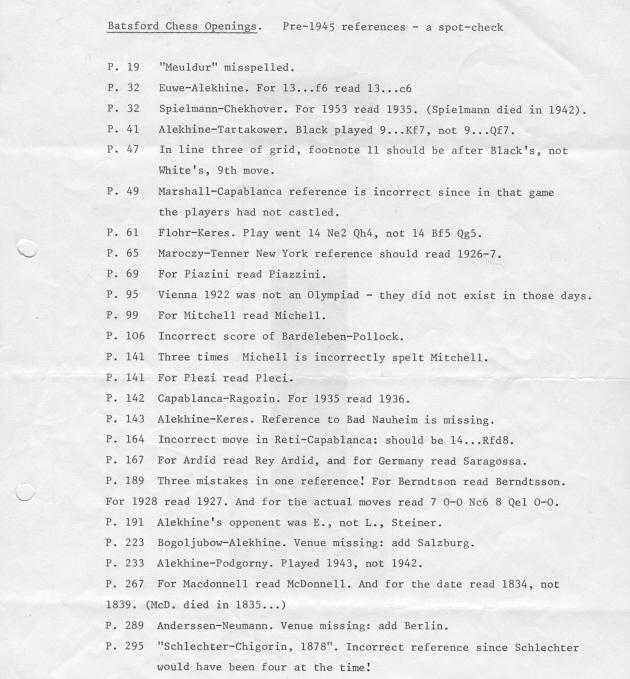

C.N.s 945 and 1159 (given below, and see too pages 150-152 of Chess Explorations) referred to our spot-check of 60 pre-1945 game references in Batsford Chess Openings, which showed that there were errors in no fewer than 36 of them:

As pointed out on page 232 of the Christmas 1984 issue of CHESS, a spot-check that we made of 60 pre-1945 references in Batsford Chess Openings showed factual errors in no fewer than 36.

For instance:

Page 141: Three times Michell is incorrectly spelt Mitchell.

Page 164: Incorrect move in Réti-Capablanca; should be 14...Rfd8.

Page 189: Three mistakes in one reference. For Berndtson read Berndtsson. For 1928 read 1927. And for the actual moves read 7 O-O Nc6 8 Qe1 O-O.

Page 295: ‘Schlechter-Chigorin, 1878’. Incorrect reference since Schlechter would have been four at the time.

Page 297: Maróczy-Marshall. White’s 12th move was Re1, not Rd1.

Page 309: For Fatirni read Fahrni.

Page 333: Reference to Fleissig-Mackenzie, Vienna, 1882 is wrong (completely different position after ...Ng3).

(945)

Regarding our spot-check of Batsford Chess Openings, most of the errors (but not all of them) have been corrected in the ‘4th Revised Impression January 1986’, and we receive an acknowledgement from Raymond Keene in the book. And yet this new BCO is the clearest possible proof that getting facts right is not uppermost in the minds of the Batsford band.

In C.N. 945 we commented: ‘Since doing the above spot-check, we have noted roughly the same percentage of error for other such references in BCO.’ An identical point was made in our letter to Peter Kemmis Betty of Batsford dated 7 February 1985:

‘... you may care to know that subsequent perusal of this unhappy book has shown the same percentage of error. Naturally I should be prepared to pass on details if approached by one of the authors, so that future editions may be corrected.’

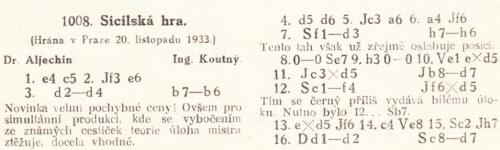

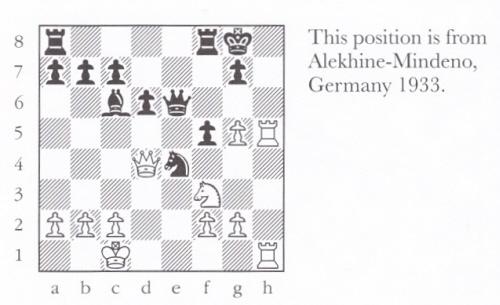

Our offer of a second list was never accepted, and we therefore assumed, with our characteristic naïveté, that the various authors had decided to undertake the necessary correction work themselves. Will we never learn? The ‘4th Revised Impression January 1986’ still has a profusion of deficiencies. To show the extent of the problem as clearly as possible we shall take the references to just one great master, Alekhine. (We select him for no better reason than that he is ‘co-author’ Kasparov’s great hero.) Our spot-check list included the following corrections:

Page 32: Euwe-Alekhine. For 13...f6 read 13...c6.

Page 41: Alekhine-Tartakower. Black played 9...Kf7, not 9...Qf7.

Page 95: Rubinstein-Alekhine. Vienna, 1922 was not an Olympiad.

Page 99: Alekhine’s opponent was Michell, not Mitchell.

Page 167: Alekhine’s opponent was Rey Ardid, not ‘Ardid’, and the game was played at Saragossa, not ‘Germany’.

Page 191: Alekhine’s opponent was E., not L., Steiner.

Page 223: Alekhine-Podgorný. Played in 1943, not 1942.

Page 297: Bernstein-Alekhine. For 1934 read 1933.

But what about all the other examples of carelessness that could just as well have been mentioned, and which still appear incorrectly in BCO (4th attempt)? For instance:

Page 47: Alekhine-Prins. Venue missing.

Page 73: For Alekhine’s opponent read Kussman.

Page 80: Euwe-Alekhine, match 1935. Two mistakes. 14 Ne4 should read 14 Nxe5 and Alekhine, not Euwe, was White.

Page 99: ‘Rubinstein-Alekhine, 1924’. And yet we drew attention to this error in C.N. 917.

Page 143: ‘Euwe-Alekhine, match 1937’. The moves in question did not occur in any of the match games. Would it have been too much trouble to check in Alekhine’s second Best Games volume? That would have given the information that the moves were played in the 1926-27 Euwe-Alekhine match. (It might also have been noted that Alekhine gave 14 Qa4 a ‘?’.)

Page 150: Rabinovich-Alekhine, Moscow, 1920. Omission of an acknowledgement to Alekhine for analysis up to move 17.

Page 157: López Esnaola-Alekhine. For ‘Spain’ read Vitoria. (Checking that in Morán’s book on Alekhine takes a few moments.)

That is one player. It is now the BCO co-authors’ job to undertake a thorough overhaul of references to everyone else before they presume to offer the public a 5th Revised Impression.

(1159)

Below is the original list prepared by us at the time:

Regarding the attempts by those involved in Batsford Chess Openings to dupe the public over its authorship, C.N. 6372 noted that the most recent revelations come in the article Ex Acton ad Astra.

The following is from the biographical note on Raymond Keene on the back cover of his Complete Book of Beginning Chess (Las Vegas, 2018):

‘He was the co-author, with Garry Kasparov and Eric Schiller [our emphasis], of Batsford Chess Openings, the all-time best-selling opening reference book.’

That is not what the public was told at the time (1982):

Batsford Chess Openings deserved to be neither a succès d’estime nor a succès populaire.

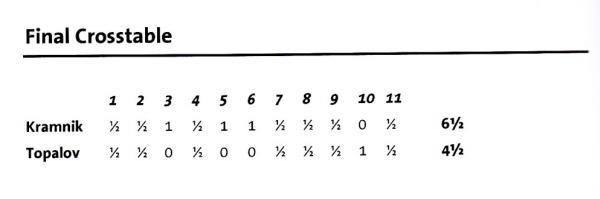

Later, output published under Raymond Keene’s name was no longer a draw, despite regular threefold repetition.

From John Donaldson (Berkeley, CA, USA):

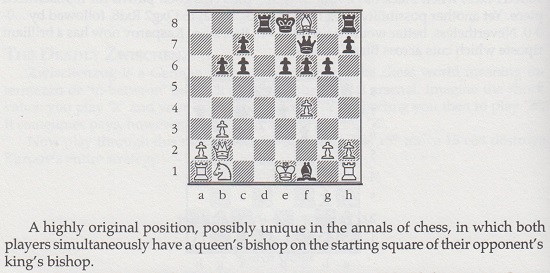

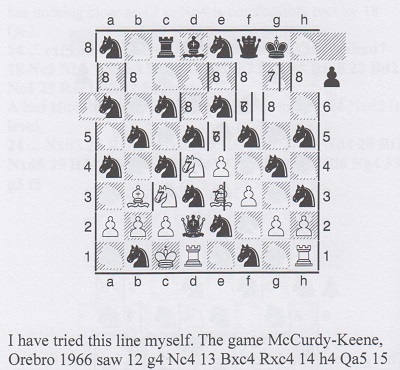

‘Simon Constam of Hamilton, Canada raises a very interesting question. Page 12 of The Grünfeld Defence by William Hartston (London, 1971) gives the sequence 1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 g6 3 Nc3 d5 4 cxd5 Nxd5 5 e4 Nxc3 6 bxc3 c5 7 Nf3 Bg7 8 Be2 O-O 9 O-O b6 10 Be3 Bb7 11 e5 cxd4 12 cxd4 Na6 13 Qa4 Nc7, with the better game for Black, Rubinstein-Alekhine, 1924. I have seen no source on either Rubinstein or Alekhine that gives this game and could find no encounter in MegaDatabase 2005 that reached the position after 13...Nc7. Any help on resolving this mystery would be gratefully appreciated.’

Why and when this faulty game reference started appearing in chess literature is unknown to us, but we mentioned it in C.N. 917 after noting the citation ‘Rubinstein-Alekhine, match 1924’ on page 99 of that gaffes-à-gogo book Batsford Chess Openings (London, 1982).

(3607)

The BCM has produced a neat tournament book (exceptionally well illustrated with photographs of the competitors and of their score-sheets – although in the case of the latter it is not always made clear who was the writer) which has excellent annotations from a wide variety of sources. The editor, Raymond Keene, has not managed to avoid repeating the mistake made in Aron Nimzowitsch: A Reappraisal of stating that New York, 1927 decided who was to challenge Capa for the world championship. As is well-known, Alekhine’s challenge had already been confirmed beforehand.

We were at a loss to understand a quote attributed to William Winter on page 65 of London, 1927:

‘For my win over Nimzowitsch I am partly indebted to Amos Burn. Before the tournament I happened to mention to him that Nimzowitsch was playing a system, beginning with 1 b3 ... The old master told me that in his younger days he had played many games with the Rev. John Owen who regularly adopted this opening ...’

The trouble with all this is that Burn had died nearly two years before the London tourney took place.

(586)

Raymond Keene, a contributor [to Chess Express, a new fortnightly newspaper published by Nathan Goldberg], describes the venture as ‘the biggest publishing event in more than 50 years in this country’. This reference is meaningless since there was no other big event around 1930. (In passing, we were far from pleased with the same writer’s claim that the world championship semi-finals were to be ‘the greatest chess event in Britain since 1851’. But Mr Keene, we now realize, is fond of these anti-historical hypes. We recall another from page 174 of his (and Levy’s) book on the 1974 Nice Olympiad to the effect that actions of FIDE and Euwe ‘represent the biggest scandal the chess world has seen since Staunton refused to play a match with Morphy’. We hope that this wild dumping of inappropriate comparisons and precedents will stop.

(640)

After just one issue of Chess Express had been published some had already made up their minds. Raymond Keene:

‘It is without doubt the best chess publication I have ever seen.’

(677)

Notwithstanding Raymond Keene’s currente calamo praise for Chess Express, the magazine folded after a small number of issues, as noted in C.N. 782. We found it a deeply unimpressive publication.

Welcoming and recycling any praise from Raymond Keene suggests, at best, naivety or lack of principle.

The match was a semi-final.

As ever, Raymond Keene has his finger on the pulse of self-interest.

On 16 September 1983 Raymond Keene submitted to Chess Notes a letter in which he took exception to ‘a totally incorrect comment’ which, he alleged, we had made in C.N. 507 regarding the Batsford book Fighting Chess. He asked us ‘to withdraw your damaging comment in the next issue of your organ’.

His letter was published in full in C.N. 583, together with proof that, as a matter of plain fact, it was he himself who was wrong – yet another example of his lumbering legerdemain.

On pages 111-114 of the August 1984 CHESS we contributed an article ‘Problems with British Chess Literature’, criticizing such trends as the large number of errors and general sloppiness. Although the article did not mention Raymond Keene, he replied on behalf of B.T. Batsford Ltd. on pages 146-147 of the October 1984 CHESS. His first paragraph sought to discredit us by asserting that our argument was:

‘... severely weakened by factual inaccuracies.’

Raymond Keene did not give a single example of a factual inaccuracy by us, and continued to refuse to do so, despite our persistent challenges. Further exchanges appeared in CHESS, and in an article on pages 122-123 of the August 1985 issue he claimed that many points made by us in a letter published on pages 231-233 of the Christmas 1984 issue were:

‘... bogus and misleading.’

In support of this, he presented one alleged example (concerning the Kasparov book My Games) and added:

‘Such a blatant inaccuracy from Mr Winter surely merits an apology or retraction.’

However, as demonstrated by us in the mid-July 1986 issue of CHESS (page 177) and as is clearly shown by the My Games book, it was, once again, Raymond Keene himself who was incorrect. Thus the single example provided by him to support his thesis that we had been ‘bogus and misleading’ was wrong as a matter of public record. Raymond Keene never apologized.

Our response to Raymond Keene’s October 1984 CHESS article was published in edited form. We give here the full original version (letter to B.H. Wood dated 27 October 1984).

An extract from C.N. 587:

And now yet another Batsford book by Kasparov: My Games. Once again it is absolutely unclear how much G.K. was involved in this book apart from writing page XIII and annotating ten games. Some of the game-scores making up the bulk of the book are annotated with symbols but nowhere is it stated whether Kasparov and/or the editors (Marović and Klarić) are responsible for these.

The text of C.N. 608:

In terms of new chess literature this magazine has been accused of being uncommonly hard to please.

We note, however, that the October and November [1983] BCMs review Chess for Tomorrow’s Champions, My Games ‘by Kasparov’ and 100 Classics of the Chessboard with a lack of appreciation that warms the heart.

Particularly in the 1980s, C.N. items criticized the low standard of many chess books and the preponderance of volumes on openings. Those who, at the time, dismissed such grievances may profitably reflect on the situation today [in 2024]. To mention just one example, Quality Chess (Glasgow) produces a vast array of highly impressive titles which are poles apart from what the chess public was expected to tolerate decades ago, such as the ‘Batsford disposables’ referred to in Fischer’s Fury.

(12020)

The main issue arising out of Docklands Encounter by Raymond Keene and others (the identity of the others depends upon which title page one reads) is not the jarring geography (Yasser Seirawan was not ‘born in England’ but in Damascus) or the hapless history (‘Not since the days of Alekhine has the incumbent of the supreme title captured first prize in so many top events’ – in fact Karpov is well ahead in this respect) or the vapid verbiage (‘Vacations, or holidays as we call them rather banally in Britain, are what you make of them’) or the dubious dogma (Korchnoi is ‘greater even than Lasker at defending and saving difficult positions’) or the gruesome grammar (‘With such diverse membership, there will be obviously be conflicts’) or the ... – but no, one should not dwell on such blemishes in this rapidly produced hardback (‘A Batsford/US Chess Federation book’) which has the same breathless spy-thriller style as Kasparov-Korchnoi,The London Contest: ‘Seconds before the event was due to start it was realized that the boards and sets had not arrived. However, swift telephone calls to the Pentagon, the Vatican and That’s Life solved the problem with minutes to spare.’ In short, much of the background material is garbage, or rubbish as we call it rather banally in Britain.

The chief point at stake is not even the book’s curious belief that the reader will view with reverential wonder the glamorous world of wealth and power that is portrayed. Page 17: ‘Richard Desmond did, however, offer everyone a lift in his gold Rolls Royce (number plate RJD 1) ...’ After a line like that one feels that if an Atlantic crossing had to be made, only Concorde would do. And so it proves, on page 135: ‘FIDE President Florencio Campomanes flew by Concorde.’

Far more important than this tinselry is the fact that for the first time a book has gone all the way in publicizing the sponsor of an event. It is true that The London Contest paved the way, notably with a front cover that boldly stated ‘Acorn Computer World Chess Championship’ (thus proving that what counted was the sponsor’s name and not a correct description of the event), but Docklands Encounter goes much further. Chess fans are even offered three gripping photos ‘View across Millwall Dock’, ‘The proposed STOLport site at the Royal Docks’ and ‘Northern and Shell’s spectacular new building on Millwall Dock’. The book starts with eight and a half pages of history of Docklands that show signs of having been stitched on as an afterthought.

Our question to readers is whether we are alone in feeling ill-at-ease about such prominence being given to a sponsor. Is there a case for saying good luck to sponsors in securing all the publicity they can by any means, or do readers share our opinion that books should not be over-run with advertising matter?

Final remarks: the bibliography acknowledges the work’s debt to The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. The annotations are of the Anmerkungen von E. Bogoljubow kind mentioned in C.N. 698. From the dust-jacket (which, surprisingly, features the Docklands) we learn that the author is ‘a regular commentator on BBC-2 chess programmes’.

The last letter received from Mr Keene was dated 5 February 1984. Over a year’s wait and then ...

‘London SW7, 1 April 1985

Dear Mr Winter,

I should like to deal as briefly as possible with the various points of discussion that we have pending:

a) You are correct about my error over the Graz tournament reference in Fighting Chess, and I therefore naturally withdraw my request that you retract your comment.

b) I also accept your correction of my statement in the Batsford catalogue that Fighting Chess is “the very first anthology of Kasparov’s games to appear in the West”.

c) I further acknowledge that at the time the Batsford catalogue twice neglected to mention Nikitin in connection with the Scheveningen Sicilian book, despite my claim to the contrary in my letter to you of 16 September 1983.

d) It is true that you received three contradictory defences of Batsford’s publishing policy in 1983. In view of this confusion I suggested to Mr Peter Kemmis Betty that the subject should be dropped.

e) The letter that Eric Schiller wrote to you (dated 6 October 1984) is, I am afraid to confess to you, not what I expected or hoped. Now that the role of others in Batsford Chess Openings has been revealed, I make a public pledge: no future editions will appear with only Kasparov and myself credited as authors.

f) As regards the question of photocopies, I admit that my conduct has been inexcusable. Not only have I failed to honour my offer but I have not even kept you in touch with the real situation; I note with great shame that even now you have not received your 50 pounds back.

g) I apologise for my statement (16 September 1983) that Batsford were involved in the photocopies question. You can imagine my embarrassment when the Batsford Managing Director wrote to you on 22 October 1984 that the company had no connection with my offer at all.

h) Turning to the subject of my letter in the October 1984 CHESS, I am sorry for having accused you of factual errors. I gave no examples and now accept that there were no mistakes in your August 1984 CHESS article.

i) I accept your counter-arguments in the Christmas CHESS, and in particular your rebuttal of my statistics. But then, as I wrote in Massacre in Merano (page 13), “I studied Modern Languages at Cambridge, not Mathematics”.

j) I regret, too, my “outrageously misleading” reference to the photocopies question in my October article.

k) Your adverse comments in my Docklands Encounter are justified.

l) It is awkward for me to reply to your revelation of the 36-error-spot-check of BCO. I am reluctant to accept much of the blame myself although, since I am referred to as co-author of the book, I suppose I must.

For your information, I have written along similar lines as the above to CHESS, since I now believe that frankness and honesty are essential. You will recall that in the June 1979 issue I wrote that “I would answer anything, on condition that my accuser was courageous enough to put his or her name to any charges they had to make”, although in fact no reply ever appeared from me regarding the allegation made by Mrs Stean that I had dishonoured my contract with Korchnoi. I shall therefore give my belated response to CHESS readers on that question too.

If you would like any other information please do not hesitate to write to me and I undertake to reply to you by return as a service to the cause of truth.

Yours sincerely,

Raymond Keene’

If only, if only ... The above letter has been ‘ghosted’ by us.

(967)

The Karpov-Kasparov world championship match was terminated on Friday, 15 February 1985; just 11 days later we received our ordered copy of The Moscow Challenge by Raymond Keene. Batsford’s speedy publication (and, let it not be forgotten, distribution) is a remarkable tour de force.

Since most reviews will, presumably, concentrate on the game annotations, we prefer to discuss the background and historical features. As regards general ‘atmosphere’ material, the author has adopted the novel approach of writing mainly about himself: ‘Baguio 1978, where I acted as Korchnoi’s chief second’; ‘One day I plan to write the definitive chess bestiary’; ‘He has been taking me out to the Journalists’ Club, Literary Club and other places which house exclusive Moscow restaurants’; ‘I was invited to give a lecture ... I also demonstrated the game Keene-Kovačević, Amsterdam (IBM) 1973, and gave a simultaneous display scoring 65 per cent’; ‘I was being interviewed live on Soviet TV ...’; ‘Before Game 15 I gave another simul and lecture’; ‘I am often stopped in the street for autographs, and in the press centre I can scarcely move from my chair without being deluged with requests for articles, interviews, book translations etc.’; ‘On Sunday, a free day, I went to a Bach organ recital ...’; ‘At the start of the World Championship copies of the book USSR v Rest of the World, which I co-authored with David Goodman, were presented to both Karpov and Kasparov’; ‘Back to London as guest of Bill Hartston for the world première of Tim Rice’s new musical “CHESS”’; ‘This game I annotated in German from the NDR (North German TV) HQ in Hamburg, where I was appearing as guest lecturer on Helmut Pfleger’s weekly programme’; ‘... the main interest switched to Salonika where I was acting as BCF delegate to the FIDE Congress and member of the Olympiad Appeal Committee’; ‘Today I inadvertently joined the Houses of Parliament ...’; ‘When I acted as Korchnoi’s second against Karpov in 1978 at Baguio ...’

Yes, it is as bad as that, often less a match book than a personal diary – or campaign brochure ...

The historical matter is not egocentric, it is simply inaccurate. Page 1 gives the wrong starting-date of the 1927 championship match; on page 2 Raymond Keene repeats yet again his mistaken claim that New York, 1927 decided Capablanca’s challenger (although we drew attention to this error in C.N. 586); is it true (page 4) that ‘in a recent interview the World Champion recalled that the first chess book he studied was written by the great Cuban’? Not according to the April 1982 BCM, page 159, where Karpov is reported as saying that his first book was Panov’s work on Capa; page 6, Mr Keene will see that his views on Hugh Alexander are wrong if he reads C.N. 693; pages 7-10, most of the statistics regarding Lasker are false – he played seven world championship matches, not eight; page 9, we are told that it is ‘staggering’ that Steinitz’s tournament record during the period he was champion (1886-1894) was ‘abysmal’. Should a writer not at least check his facts before so criticizing a great player? The truth is that Steinitz did not play in a single tournament during the period under consideration.

The Moscow Challenge ends with a hurried account of the closing proceedings. Rather than merely giving a non-specialist article (the piece appeared almost word for word in The Spectator of 23 February), the author might have held on for a day or two more in order to present more thorough and reflective coverage.

No doubt the same publishing/writing team will be back in action for the planned K-K ‘re-match’, and we hope to see a vast improvement. Anyone who remains unconvinced by our criticisms of The Moscow Challenge should take a look at page 62, for instance, and decide whether, in all honesty, it can be claimed to say anything of interest or value.

(976)

Regarding the remark about Steinitz’s tournament record being ‘abysmal’, we drew attention to the error on page 200 of the May 1985 BCM. On page 256 of the June 1985 issue Mr Keene responded with the astounding claim that ‘in calling Steinitz’s tournament record “abysmal” he was criticising it on the grounds of lack of activity’. By that logic, we pointed out on page 305 of the July 1985 BCM, Fischer’s post-1970 tournament record could be labelled ‘abysmal’.

Mr Keene’s ignorance of Steinitz was also demonstrated on page 35 of his volume Duels of the Mind (London, 1991), where he stated that Steinitz published a book called Modern Chess Theory. No such work exists. (We pointed this out in a footnote on page 266 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves.)

On page 60 of the 2 November 1991 Spectator Raymond Keene stated that Steinitz died in 1901.

See also World Champion Combinations, which comments regarding page 9 of that book, by Raymond Keene and Eric Schiller:The position from the second game of the 1896-97 world championship match between Lasker and Steinitz has the authors overlooking an elementary mate in two moves (i.e. Nb3+ rather than Re4+, as pointed out on page 366 of the December 1896 Deutsche Schachzeitung).

Raymond Keene’s mistake ‘his book Modern Chess Theory in 1889’ had also appeared earlier, on page 138 of his 1988 Pocket Book of Chess, and despite our above-mentioned correction in Kings, Commoners and Knaves, Mr Keene persisted with it in an online article dated 24 April 2021:

‘His ideas are published in his book Modern Chess Theory in 1889.’

That text remains online today [22 February 2024] even though it was specifically corrected by Tim Harding on the English Chess Forum in May 2021.

Can readers help us collect examples of writings which state the opposite of the intended message? In the Preface to Becoming a Grandmaster (London, 1977) Raymond Keene says he would be pleased if his GM title did not help others involved in a similar quest.

(980)

From Hugh Myers (Davenport, IA, USA):

‘I notice an 1859 Suhle-Anderssen game that started 1 b3 e5 2 Bb2 Nc6 3 e3 Nf6 4 Bb5 Bd6 (0-1, 25). Mr Raymond Keene, who I hear has been writing a book about openings history, said this about that variation in his Nimzowitsch/Larsen Attack (page 14):

“A very interesting idea is William Hartston’s 4...Bd6!?.”’

(999)

See page 191 of Chess Explorations.

The June [1985] BCM correspondence column has a contribution from Raymond Keene which we recommend all C.N. readers to study with close attention. This is not the place for disproof of his letter, but we cannot resist quoting its conclusion:

‘... what annoys me about E.G. Winter’s criticism is that he wields the accusation “error” rather too often against other writers, instead of accepting that they may have weighed up the available evidence and come to their own conclusion!’

An intriguing comment from the person who (forgive us for mentioning it again) accused us in the October 1984 CHESS of ‘factual inaccuracies’ without a scrap of justification.

It seems an appropriate moment to raise some further issues:

a) How many games were played in the 1927 world championship match? The obvious reply is 34, but on page 14 of his 1978 Karpov-Korchnoi book Mr Keene claims 35. As he does again on page 124 ... and yet again on page 138. A triple error? Perhaps, but let us suspend judgement until Mr Keene submits his evidence, ideally a 35th game-score.

b) His article ‘Reflections on Montreal’ (BCM August 1979, page 358) has a ‘Table V’ with an ‘Age of Winner’ column for certain major tournaments. Mr Keene appears to have made seven errors out of ten references – but has he? It could be that he has discovered that the world champions were not born when we all thought they were. Jeremy Gaige should stand by.

c) Batsford’s two classic reprints are superbly produced but cheapened by bad introductions by Mr Keene. For the prestigious Staunton Handbook he has more or less just lifted two chunks out of the BCM Staunton book (pages v and 15 – written by him or by R.N. Coles?). However, it is the introduction to Löwenthal’s Morphy collection that is relevant here, and above all Mr Keene’s treatment of M.’s games with L. himself. R.D.K. states that Morphy was 13 (instead of 12, as given correctly in the book itself, page 350) and says only two games were played. That is what used to be believed but David Lawson’s biography went into the matter in enormous depth to show that there were three games (pages 24-35). Then Raymond Keene claims this Löwenthal collection was ‘endorsed by Morphy himself’. Headlong into another trap. In fact, the preface thought to be by Morphy was not written by him (Lawson, page 30) and ‘Morphy knew nothing about the Bohn edition’ (same page). Instead of getting everything wrong, Mr Keene might have given attention to the fact that the ‘drawn’ Petroff Defence game (Löwenthal, pages 352-355) was actually a win for Morphy, as demonstrated by Lawson. We would hardly dare suggest that Mr Keene was unaware of all this research when penning his introduction, so we look forward to seeing the counter-evidence that convinced him – after tireless weighing-up – that Lawson is not to be believed.

(1015)

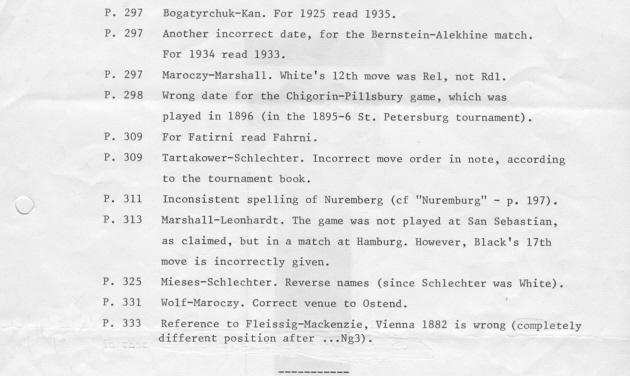

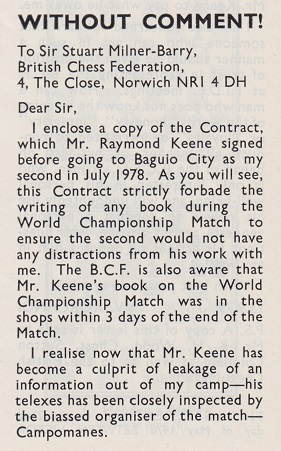

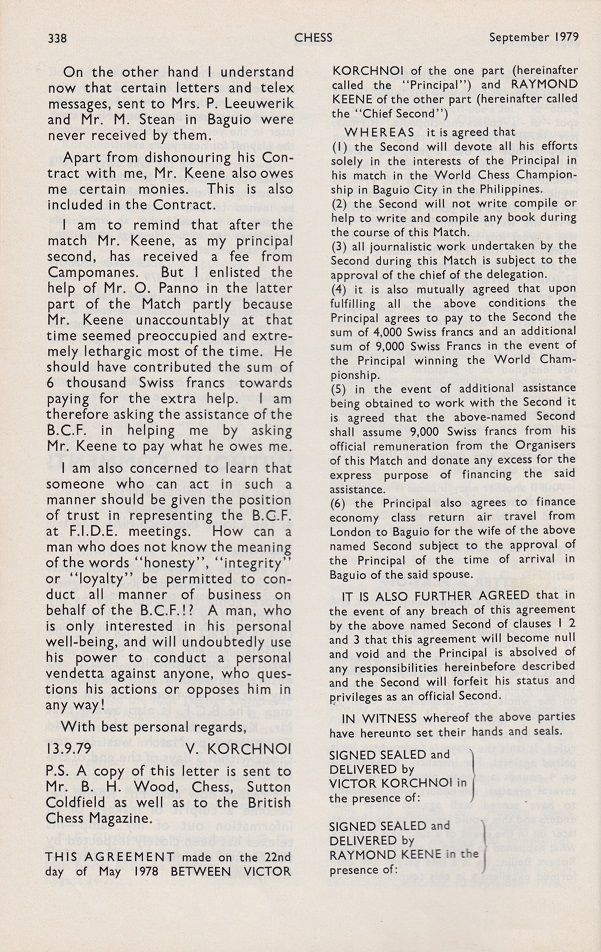

At the Chess Café Bulletin Board on 20 May 2001 Raymond Keene defended himself over the accusation that he had violated his contract with Korchnoi. The complete thread of three postings:

Below is the full letter from Michael Stean’s mother, which was was published on pages 84-85 of the February 1980 CHESS:

Addition on 31 March 2024:

From Mark Erickson (Richland, WA, USA):

‘The authors of Korchnoi Year by Year: Volume II (1969-1980) (Elk and Ruby Publishing House, sine loco, 2024), Hans Renette and Tibor Karolyi, state (page 358) that they had an interview with Raymond Keene. After quoting from Mrs Jean Stean’s letter to CHESS, the book reports, on pages 382-383:

“B.H. Wood, the magazine’s editor, queried Keene about the contract, but he didn’t get a reply. When we spoke to Keene, he stated that Stean’s mother for some reason didn’t want him to write a book. Keene claims that it was necessary to write the book, as otherwise the engagement was not worth it. He knew the contract she drew up was ‘rubbish’ and treated it like that.”

From page 440:

“While Korchnoi was presented as the victim of a boycott, Raymond Keene reacted and blamed his former boss of practising the same recipe on him ...”

This concerned the 1979 Biel tournament (in which Korchnoi played but Mr Keene’s invitation was withdrawn):

“By the end of April, Keene had asked for considerable financial compensation of 10,000 Swiss francs.”’

From page 73 of The English Chess Explosion by M. Chandler and R. Keene (London, 1981):

‘No-one remembers Reshevsky’s losses as an 11-year-old, but everyone knows it was at this age he beat the former World Championship Candidate, Janowski.’

Everyone knows no such thing, for the simple reason that it is untrue. Reshevsky was ten, as the book itself had stated earlier (page 35):

‘Short’s achievement was even more momentous than Capablanca’s match win against Corzo in Havana in 1900 when Capa was 12, and almost on a par with the game won by 10 year old Reshevsky against the veteran GM Janowsky in 1922.’

However, that reference is wrong on other matters. The match took place in 1901, not 1900, and Capa’s age should read 13, not 12. Note too the slapdash inconsistency: two different spellings, Janowski/Janowsky.

Mr Keene’s Times column of 13 July 1985 describes Steinitz as Czech. By that logic he should have called Chigorin Soviet rather than Russian.

Then in The Times of 24 August 1985, page 14 we see Raymond Keene vaunting a scoop:

‘Imagine my delight, then, at discovering the moves of a win by Alekhine against another player of the very highest class, which has so far eluded publication in any of the English language collections of Alekhine’s games. It has been known for some time that Alekhine’s lifetime score against Paul Keres consisted of five wins, one loss and eight draws, yet one of Alekhine’s wins proved impossible to track down.

At last, the score of the game emerged from an obscure Estonian document after a long search through the library of Bob Wade, the British Chess Federation coach. This week, I present this lost game to readers ...’

Before Mr Keene becomes even more carried away with his discovery, perhaps we could point out that the Alekhine-Keres game-score is given, with notes by J.H. Blake, on page 483 of the October 1935 BCM. Finding it there took 30 seconds.

The game was played in the 1935 Olympiad in Warsaw.

There was no correction or apology in The Times. Raymond Keene can shrug off anything.

The value of The Evolution of Chess Opening Theory by Raymond Keene (Oxford, 1985) lies in the provision of a substantial amount of translated material from the old masters which is not readily available elsewhere. A good example is Réti’s article on Tarrasch, which will be quite an eye-opener for anyone tempted to place the classicists and hypermoderns into hermetically-sealed opposing camps.

The linking material between quotations is slight, too slight to give an adequate picture of the evolution referred to in the title. In the Introduction the author writes: ‘I eventually decided to attack the project by quoting, in more or less chronological order, from the writings, analysis and games of those authorities who have done most to influence thinking about opening theory at given moments in chess history ...’ (Which is, of course, the quickest way to fill a book.)

In fact, the trouble with the quotation approach is that it is all or nothing – there is no smooth, balanced, detailed study of opening development. Let us take the example of Alekhine (his predecessor Capablanca and successor Euwe are barely mentioned in the entire book). Alekhine’s influence on opening theory was colossal (one recalls the contemporary quip that opening theory was made up of Alekhine’s games and a few variations), but studious treatment of it would have required detailed examination of his games and writings. Instead of that, we are offered just a chapter on Alekhine’s Defence, which would be an unsatisfactory approach even if that chapter were correctly researched. It is not. It is ‘largely culled’ from one single book – again the easy way out – and everything is left in the air. The reader is not informed that Alekhine himself rather turned against 1 e4 Nf6, to the extent that by the Second World War he was calling it ‘dubious’. This highlights a further defect in the ‘evolution’: for this book it is more or less as if the 1930s and half the 1940s did not exist. The sudden arrival at Bronstein on page 136 gives quite a jolt.

The omission of anything by Euwe, whose contribution to opening theory was also massive, is not to be pardoned simply by being acknowledged in the Introduction. Chapter 15 is Fischer. Chapter 16 is Kasparov. No comment.

Lack of research is also indicated by such statements as the one on page 102: ‘Not that Tarrasch refused to try out hypermodern openings, but when he did it was usually a disaster.’ To see that this is nonsense one has only to take up the tournament books of the 1920s. For the nth time Mr Keene is wrong about New York, 1927 (page 171: a ‘Candidates’ Tournament’). One’s doubts about his concern for historical truth are also reinforced by the reference to Kasparov’s ‘fascinating innovation’ (page 215). We had all that in the January 1983 CHESS. However, in the March-April 1983 issue George Botterill pointed out that the line had already been noted by him (G.B.) in print in 1980. But R.D.K. is not to be disturbed by a trifling fact like that.

There are too many plugs for Raymond Keene’s own books (but barely any for other people’s); we are only one page into the Introduction by the time the habitual ‘when I was Korchnoi’s second’ routine is being run.

(1069)

Raymond Keene on page 205 of the May 1986 BCM:

‘The BCF has never opposed the return match. In fact, we are quite obviously intending to organise it or at least the first half.’

This is in direct contradiction with his reply to Jonathan Mestel in the December 1985 Newsflash:

‘I take your point that the revenge match clause should probably not exist.’

In his public letter of 16 January 1986 to Aly Amin, Mr Keene stated that Karpov had too many privileges, one of which was ‘the right to a revenge match’.

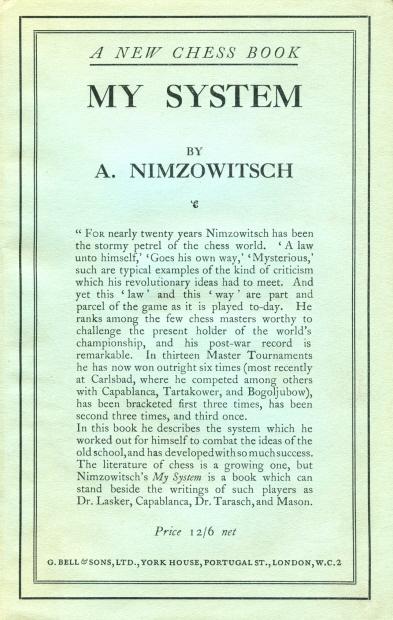

The Chess Tournament – London 1851 by Staunton has just been reprinted – superbly – by Batsford, as has Nimzowitsch’s Chess Praxis. Mr Raymond Keene’s willingness to supply his company with a Foreword to the latter work is not readily comprehensible when one recalls his words on page 4 of Aron Nimzowitsch: A Reappraisal:

‘The English of My System is, by and large, very good and makes a brave effort to capture the spirit of Nimzowitsch’s original German, but, unfortunately, the same cannot be said of the translation of Chess Praxis which I find a poor, maimed torso of Nimzowitsch’s original. If you have no alternative read the translation by all means, but if you possess the merest smattering of German I urge you to read the original. It is well worth the effort.’

(1231)

Yet there are people who find such inconsistencies unblameworthy. After we pointed out Raymond Keene’s Chess Praxis contradiction (C.N. 1231) on page 282 of the September 1986 CHESS, a reply from Mr James Pratt of Basingstoke was printed on page 326 of the November 1986 issue:

‘... Now to Mr Winter. He informs us that Batsford don’t do as good a job as they possibly could. Of course everything can be improved – what is heaven for? Take Chess Praxis by Nimzovich. Keene in A.N. – A Reappraisal – written quite a while ago – points out how poor the translation is in Praxis. Mr Winter points out that he has changed his mind. So what? He’s entitled to. Short and Botterill call Praxis the best chess book they know. If your correspondents wish to attack each other they should either do so over the board or by private letter. “The play’s the thing”.’

Similar crassness from the same Mr Pratt (who is clearly no intellectual power-house) appeared in item b) of C.N. 711. On 21 December 1986 we replied to CHESS, but of course the letter was not published:

The Pratt Guide to Criticism (November CHESS) is fascinating. Since nothing is ever perfect, Winter should not criticize Batsford. Keene, on the other hand, may freely criticize Chess Praxis and contradict himself subsequently. Winter, however, is wrong to criticize such inconsistency. Pratt may write a public letter to criticize Winter for not criticizing Keene in a private letter.

(1424)

Newsflash has a new editor, David Goodman. His first action, it would seem, was to drop the Badmaster column, the only item of permanent value. Mr Goodman has not yet said anything critical about his brother-in-law, Raymond Keene, but no doubt the BCF will insist upon fairness and objectivity. Issue 2 does, however, have an intriguing quote from Mr Jeremy Hanley, the Member of Parliament for Richmond and Barnes: Raymond Keene is the ‘greatest chess Ambassador that Britain has’.

It is not indicated which international chess magazines are read by the Member for Richmond and Barnes. Surely not C.N. Nor the South African Chess Player, which has accused Mr Keene of exploiting the South African issue to gain votes. Nor Europe Echecs (France), which has quoted Korchnoi as stating that he has ‘broken off diplomatic relations with that person’. Nor Schacknytt (Sweden), which called one of Mr Keene’s K-K match books ‘en katastrof’. Nor Schach-Echo (Federal Republic of Germany), which has accused him of ‘dancing at too many weddings’. Nor Die Schachwoche (Switzerland), which scoffs at his role in the termination/telex issue. Nor the Myers Openings Bulletin (USA), which reports that ‘Keene’s hypocrisy is not confined to the termination of the Karpov-Kasparov match’.

Mr Hanley MP ought perhaps to refer to issues 643, 644 and 645 of the British magazine Private Eye, which give detailed accounts of a number of Mr Keene’s ‘wheelings and dealings’. ...

But, above all, the Right Honourable Member should procure copies of the ‘FIDE Facts’ sheets which are being published by the American Friends of FIDE.

(1245)

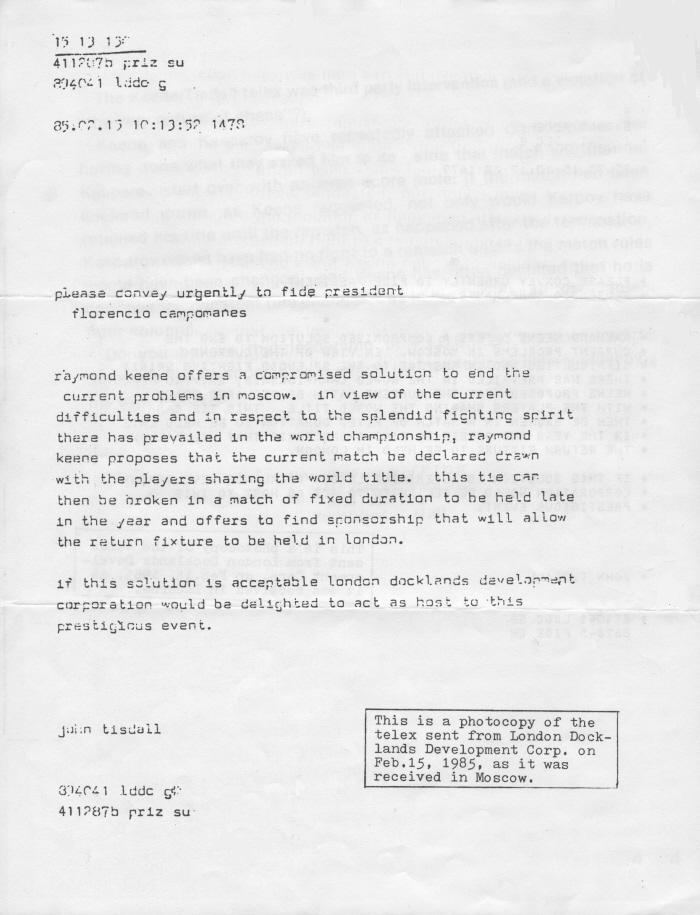

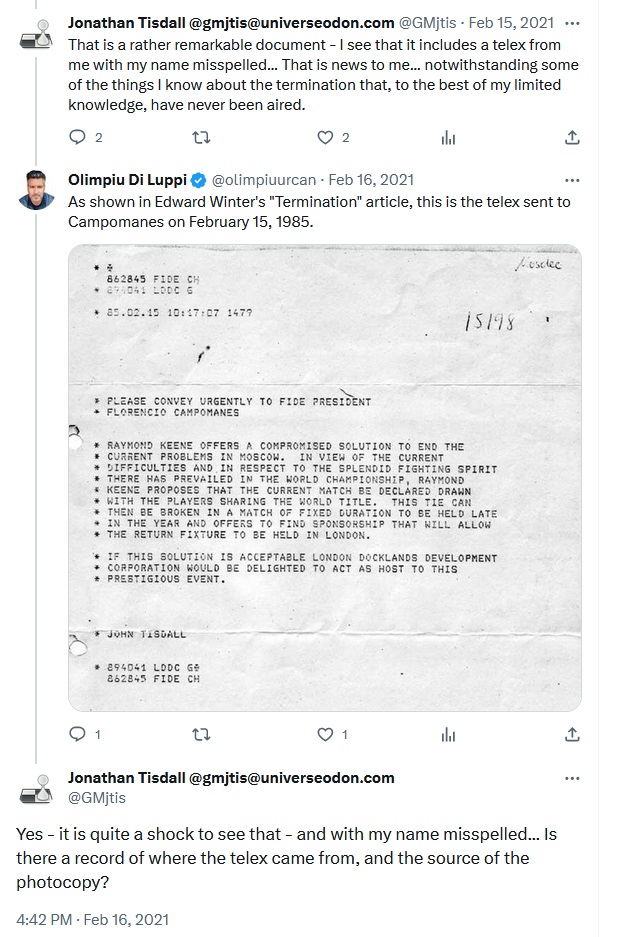

Concerning the Termination, at chessgames.com on 10 January 2008 Raymond Keene wrote the following (quoted here in full):

‘<sitzkrieg> you are in violation of the guidelines and your comments shd be taken down-however i cant resist pointing out a couple of things-

1 i have never knowingly purveyed any kind of falsehood in anything i have written

2 in the extract you quote winter seems to be unable to reconcile the facts that i sent off a telex message in the morning while elsewhere i refer to my message reaching moscow later that day-what he has forgotten -presumably because he does not get out and about much-is that moscow is three hours later in time than the uk, so it was perfectly possible to send a telex in uk morning time, while at the same time it was much later in the afternoon in moscow! that rather obviously explains why it was possible for me to know about events happening in moscow in their afternoon time while it was still morning time in london. this is so blazingly obvious i have never bothered to point it out before.

on top of that-in spite of winters desperate rearguard actions to defend the now defunct corrupt commie state- history has served its verdict on that disgraceful episode-if any umpire or arbiter in any other sport had halted the contest at the point campomanes did he wd have been lynched!’

Mr Keene mentions only one specific matter, and it is untrue. We have never overlooked the obvious existence of a three-hour time-difference between the United Kingdom and Moscow. Indeed, we drew attention to it in C.N. 1222 at the time the Keene/Tisdall telex came to light: ‘the identical text was also sent direct to Moscow, at 10:13:52 GMT (Moscow time minus three).’

On 16 January 2008, on the same chessgames.com page, a reader quoted our above factual rebuttal on the GMT question, and the same day Raymond Keene posted, inter alia, the following:

‘pls dont quote winter here on my section any more-he is very hostile to me and i dont appreciate his comments appearing here especially when he is obfuscating the issue-debating him is a complete waste of time since he is always right and never ever makes mistakes.’

This is classic Keene. We are falsely accused of having made mistakes and never admitting them – in an episode where it is Raymond Keene who has made mistakes and refused to admit them.

It is yet another example of his ineradicable mendacity. Nothing by Raymond Keene should be taken on trust, and especially about his critics, his cronies or himself.

Below are the key parts of a letter to us dated 1 January 1986 from the General Secretary of FIDE, Dr Lim Kok Ann:

We also reproduce here another letter from Lim Kok Ann, dated 13 January 1986:

(11856)

Another observation by Lim Kok Ann:

‘... the abuse heaped on Campo by Western media led by Raymond Keene who averred that Campo had been summoned to Moscow by Karpov to save him, and having to answer the disinformation put out by Keene and his allies.’

Below is the FIDE President’s Circular Letter No. 3 1985/86, dated 25 February 1986. It includes an extensive ‘Review of Press Reports’ by Lim Kok Ann, the Federation’s General Secretary:

FIDE Facts sheet one above mentioned that Lim Kok Ann’s text was published in the May 1986 BCM, followed by a response from Raymond Keene (pages 188-195 and 204-208 respectively).

The text below appeared on pages 1-2 of the FIDE President’s Circular Letter No. 4 1985/86, dated 28 April 1986:

In an interview with Fernando Urías of the Spanish publication Cambio 16, distributed by FIDE to chess federations and journalists on 31 March 1987, Florencio Campomanes answered questions about the 1986 campaign:

We have found no serious, considered statement by the defeated candidates regarding their last-minute abandonment of the campaign in November 1986. See, however, Comic Relief, which includes this statement by Raymond Keene in an interview on page 202 of the April 2017 BCM:

‘One of the reasons I did not stand a fair chance in 1986 is because we just had a war with Argentina.’

The Falklands War had ended on 14 June 1982.

David Anderton died on 1 April 2022. In an article dated 22 July 2023, Raymond Keene wrote of David Anderton:

‘Anderton was a publicly plausible, but privately slippery character. Having pledged his support, and that of the BCF, for my 1986 election bid, strongly supported by Kasparov, to unseat Florencio Campomanes, the then president of FIDE, the world chess federation, Anderton struck a deal with the Filipino to stab our campaign in the back, in exchange for a top post in Campomanes’ administration.’

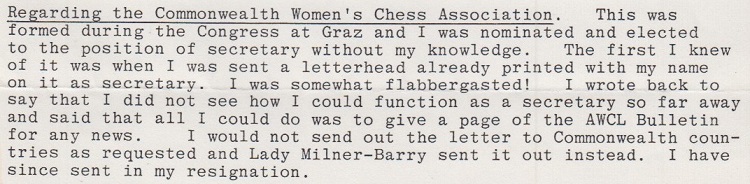

Concerning the Commonwealth Women’s Chess Association (see FIDE Facts sheet six), below is a sample from its documentation:

The letterhead even blunders in the title of the Association, but that was not the fault of the supposed Secretary. On 20 June 1986 Evelyn Koshnitsky informed the FIDE Headquarters in Lucerne:

The Centenary Match Kasparov-Karpov III by Raymond Keene and David Goodman (Batsford) was published very shortly after the match finished, though not as shortly afterwards as Kasparov v Karpov (published by Chequers). The annotations in the Batsford book are probably better than those in the same authors’ Manoeuvres in Moscow, but the introductory and background features are just as abysmal. The aim, at least for the GLC Memorial Half, has been to make everything glitter with the trappings of fame and fortune. ‘First to arrive was Karpov in a blue Mercedes. A few minutes later a cream-coloured Ford drew up and Kasparov emerged with his seconds.’

The result is tawdry. Not a detail is missed of the beloved world champion’s arrival in London (otherwise known as ‘Chess Capital of the World’): ‘... Kasparov was presented with small bouquets of flowers, by Leah, four-year-old daughter of match hospitality officer Adrienne Radford, and Sophie, five-year-old daughter of world championship press chief Jane Krivine ...’ Kasparov was then ‘whisked away’ to his ‘secret address’, just like the hero of some corny espionage film. Two days later Karpov arrived and was ‘driven to another secret London address for a champagne supper’. The preoccupation with ‘exotic’ nourishment is becoming a notable characteristic of Raymond Keene’s writing. Half of page 9 is taken up with the menu of an 1883 banquet, the information being no more interesting now than when Mr Keene printed it in The Spectator of 26 April 1986. On the last page of the match book it is recorded for future generations that in Leningrad Mr Keene was able to tuck into ‘a sumptuous dinner of caviar, stuffed pike and stuffed turkey’.

We are in a world in which everything is sumptuous, stunning or triumphant, and where nobody is nobody. The match opened with ‘a stunning ceremony in the Grand Ballroom of the Park Lane Hotel, co-ordinated by Major Michael Parker, fresh from his triumphant staging of the Royal Tournament at Earls Court’.

The dispensability of these details is proved by the book itself, for in the Leningrad half the reader is, in the main, spared such frippery. Also absent is a blow-by-blow account of how the Soviet Chess Federation secured its part of the match, what detailed preparations it made, who offered flowers to whom, etc. The impression is thus unwittingly given that what the USSR is able to organize quietly and efficiently can be achieved in London only with top-pitch frenzy. Quite apart from being counter-productive, chauvinism is illogical and distasteful. Why all the talk about ‘British Chess’ during the third Kasparov v Karpov match from people who never once referred to ‘Italian Chess’ at the time of the 1981 ‘Massacre in Merano’?

The co-authors miss no opportunity to criticize Campomanes; since Mr Keene states in the September CHESS that Batsford is supporting his (RDK’s) political campaign, there is no surprise in that. The cover photo (K and K at the board, surrounded by advertising placards) strongly suggests that FIDE will have to tackle the question of whether the dignity of chess is not impaired when venues start to resemble Brands Hatch. Incidentally, it is interesting to note in that photograph that the Greater London Council (which put up over £600,000) receives no exposure at all. Having been disbanded, it is of no further use to ‘British Chess’.

One historical point. As reported in C.N. 1029, we showed in the 1985 BCM that the 1909 Paris match between Lasker and Janowsky was not for the world championship. This was corroborated by Kenneth Whyld in the August 1986 BCM, page 373. And on page 331 of that same issue the Editor gives a list of world title matches and adds that ‘many recent sources give here a ten-game match Lasker v Janowski, Paris 1909, but the best authorities do not include it’. Exactly so. On page 6 of their book Keene and Goodman do.

The reader looking for background features which do not mock his intelligence will need to turn to the Chequers book. Instead of Messrs Keene and Goodman’s pettishness and kitsch we are given little notebook features, impressively objective, entitled ‘Off the Board’. They certainly give the feel of the event, and it is unfortunate that they peter out about half way through the book.

Pergamon has announced that next year [1987] it will be publishing Kasparov’s book on the match. The news is a godsend for anyone who, like us, would hardly dare venture a comparison of the two works that have been published so far. We did note, however, that in the Chequers book the balance of exclamation marks and question marks in Game 13 makes it very difficult to understand why Kasparov only drew.

(1285)

There follows a further example of Raymond Keene’s toxic imprecision.

In the course of an interview with his then brother-in-law, David Levy, on pages 262-266 of the September 1986 CHESS Raymond Keene declared:

‘Just prior to and during the match [Kasparov v Karpov, 1986], a flood of election literature arrived from an organisation called the American friends of FIDE from Edward Winter in Geneva and Hugh Myers in Iowa. It is quite clear, even if Mr Campomanes had the intention of halting electioneering during the match, the friends and organisations who support him didn’t.’

We responded on page 327 of the November 1986 CHESS:

‘1. I have not written, printed or issued election literature of any kind.

2. I have no connection with the American friends of FIDE.

3. I have not been campaigning for Campomanes.

4. I have never spoken to him, corresponded with him, or even set eyes on him.’

Raymond Keene made no retraction of his falsehood.

‘Why is it that you have been so much more successful than other people?’

That question, actually put to a candidate for a FIDE post and published in a chess magazine, is an extreme example of a longstanding problem mentioned in Chess Thoughts: In proper journalism, the interviewer probes, politely but searchingly. In chess journalism, vacuous servility is the norm.

The word is interview, not intervertisement.

(10856)

The annotations in Speed Chess Challenge Kasparov v Short 1987 by Raymond Keene (Batsford) are directed towards inexperienced players. One interesting comment on page 7: ‘In the endgame, when the king can emerge from its fortress to take an active part in the game, he has about the same value as a bishop or a knight.’ Offhand we cannot recall other attempts to evaluate the king in this way. Apart from that, and some fine photographs, the book is mere garishness, with nearly everybody and everything getting a blown-up description. For example, page 11 refers to ‘experienced presenter Tony Bastable, doyen of the Thames Television World Championship coverage’; page 95 of the March 1987 BCM reported that this Experienced Doyen did not even know the chess difference between ‘game’ and ‘match’.

(1405)

From Raymond Keene’s seven-page Introduction to Mikhail Chigorin Selected Games edited by Colin Leach (London, 1987): ‘occassional’, ‘seperated’, ‘Brelau’, ‘St. Petersburgg’, ‘absolutedly’, ‘Pillusbury’, ‘profansation’, ‘but it is not been refuted’ ‘occassions’ ...

(1491)

The 19/26 December 1987 issue of The Spectator contained a chess history/trivia quiz set by Raymond Keene. Of the 30 questions, under half could be called correct. Some were pure fiction, others had more than one answer, and others still were sheer speculation. John Roycroft has kindly authorized us to say that he has no quarrel with this assessment.

We are most grateful to him; after all, Mr Roycroft was one of the three prize-winners.

(1568)

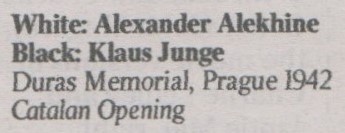

In the quiz this player had to be identified:

‘He switched to milk in 1947. What was the effect?’

The answer given on page 51 of the 23 January 1988 issue of The Spectator was Alekhine, with an explanation that 1947 was a ‘misprint’ for 1937.

In the same quiz, readers were asked, in a section entitled ‘They’re all mad’, which player died in his bath surrounded by women’s shoes. With predictable fallibility, Raymond Keene gave Morphy as the answer.

See ‘Fun’ and Chess and Insanity.

The first two books we have received on the 1987 world championship match are Schach WM 87 by Helmut Pfleger, Otto Borik and Michael Kipp-Thomas (Falken Verlag) and Showdown in Seville by Raymond Keene, David Goodman and David Spanier (Batsford). Both occasionally leave the reader puzzled as to why Kasparov did not do better. For example, the 19th match game was drawn, yet Kasparov’s moves are awarded far more exclamation marks. Neither book offers as much detailed analysis as has already appeared in many chess magazines. (Europe Echecs has been particularly strong in this respect.)

The Batsford annotations have a style all of their own – pure rodomontade. A ‘colossally fascinating’ variation here (game 5), an ‘incredibly minor infringement of normal practice’ there (game 7). That the annotator can do better is admirably shown by games 12 and 14.

The 11-page introduction has little to do with the match, but purports to explain why Campomanes was not defeated in Dubai and how the Grandmasters’ Association resulted. Although commendable restraint is shown (Marcos is not mentioned until page 4) the material is a colossally unfascinating and incredibly major infringement of basic justice. The blame for not beating the FIDE President is placed squarely on Lucena’s shoulders: ‘ ... not even Lucena’s warmest admirers could say that he was a strong candidate. He was kind, amiable, well intentioned, yes – but no public speaker, no vote winner’ (page 5). On the following page we learn that Kasparov ‘was evidently somewhat underwhelmed’ by Lucena. In reality, of course, it was Tartuffe rather than Orgon who was the hustings turn-off. But in fairness it must be pointed out that even Kasparov is verbally savaged by our objective chroniclers: ‘Perhaps Kasparov was a shade naive, understandably so, when it came to politics’ (page 7).

The biased and nugatory introductions to individual games use the familiar hint-and-smear technique, emitting just enough smoke to suggest a raging fire. For example, page 92 attempts to persuade the reader that Karpov engineered Tal’s departure from Seville during the match – just one more ‘scandal’ that is dumped in the reader’s lap without a flicker of evidence.

One of the few historical references in the book is on page 62, where we are told that Grünfeld ‘launched the defence which bears his name with a convincing win against the mighty Alekhine’. This, of course, is nonsense. Presumably the allusion is to Alekhine v Grünfeld, Vienna, 18 November 1922, but by that time 1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 g6 3 Nc3 d5 was no longer a novelty. One earlier game, though probably not the first, in which Grünfeld played these moves as Black was against Sämisch in round seven of the Pistyan tournament in April 1922.

At least there is no repetition of Mr Keene’s claim (opening sentence of his report on page 2 of The Times of 21 December 1987) that Kasparov is ‘the first player in more than 75 years to come from behind to win the world chess championship’. (What about the title matches played in 1927, 1935, 1937, 1951, 1954, 1957, 1963, 1969, 1972 and 1985?)

As ever, we are at a loss to describe adequately Mr Keene’s handling of chess history; there is no entry for ‘Midas touch’ in our dictionary of antonyms.

(1582)

Discussing the FIDE General Assembly in Dubai, 1986, the obituary of Florencio Campomanes in The Times, 6 May 2010, page 68, did not mention Raymond Keene’s participation in the 1986 election campaign or the last-minute withdrawal of the Keene/Lucena ticket. Instead, it asserted that Campomanes ‘went on to retain his presidency by a comfortable margin’, falsely implying that there was a vote at the General Assembly.

The obituary also contained these vague claims: ‘... at a time when the majority of the chess world’s enthusiasts were vilifying him as a KGB sympathiser ...’ and ‘... it was widely assumed the [sic] Campomanes had been acting in concert with the KGB ...’

The outcome of the campaign was reported by Don Schultz, the US Delegate to FIDE, on page 53 of Chess Life, March 1987:

‘FIDE President Florencio Campomanes was easily reelected. Contrary to rumors and other statements, his election was never in doubt. I informed our Policy Board several months prior to the election that Lincoln Lucena’s challenge for the FIDE presidency had no chance and that mostly likely he would withdraw his candidacy prior to the voting. This was exactly what happened, and Campo was elected by voice acclamation.’

An endnote on page 270 of Chess Explorations quoted from page 219 of Kasparov’s Unlimited Challenge (Glasgow, 1990):

‘The anti-Campo forces could muster so little support that there wasn’t even a vote.’

The December 1988 CHESS (page 36) published an advertisement soliciting subscriptions to Raymond Keene’s English Chess Association. It featured a quote (about the Association’s good intentions) which was attributed to the ‘Encyclopedia [sic] Britannica’. CHESS readers will doubtless have been impressed that a reference work of such stature has given recognition to the ECA.

The truth is rather different. The quoted words are not from the Encyclopaedia Britannica at all, but from the 1988 Britannica Book of the Year (page 319). The writer there? Raymond Keene.

(1765)

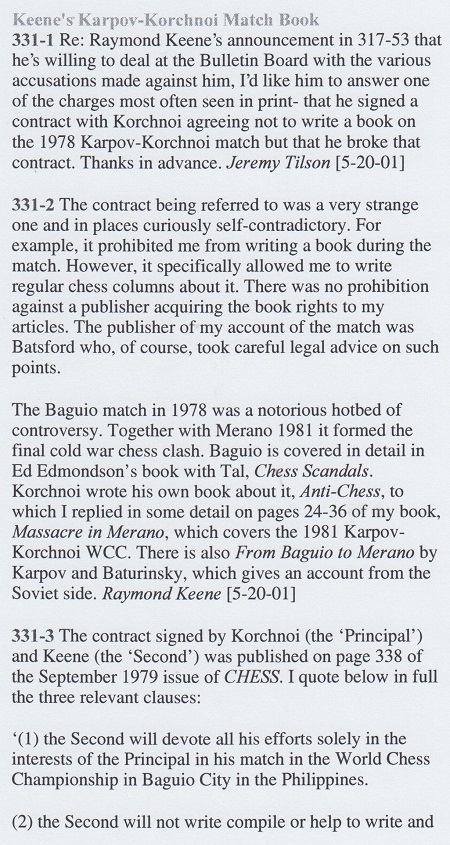

The caption reads: ‘Your move: Raymond Keene has set up a rival group – he awaits defectors’

From an English Chess Association press release dated March/April 1989:

‘It is heartening to write of the recognition accorded us by the Encyclopedia Britannica, which states that the aim of the ECA is “to make chess as popular as snooker and bring grass-roots players into closer contact with Grandmasters and masters”.’

This perpetuates the misrepresentation described in C.N. 1765. The reference to the ‘Encyclopedia Britannica’ is an untruth and, in any case, the ‘heartening ... recognition’ was from the pen of none other than the founder of the Association.

No writers or journalists in Britain appear to have published criticism of the ECA for advertising under false pretences. One can imagine the column inches they would have found if FIDE had been the guilty party.

Addition on 8 December 2019: This is still on-line despite Raymond Keene’s journalistic meltdown, at a website entitled The Mother & Child Foundation:

Two excerpts from a letter to us from Stewart Reuben (Twickenham, England) dated 21 July 1988:

‘I shall accept my view of you has been coloured by comments made about you by some of my friends.’

‘I really wouldn’t want to be drawn into being an apologist for Ray Keene. I am well aware that some of the criticism of him has been accurate. One must accept friends warts and all.’

From Raymond Keene’s chess column in The Spectator, 13 May 1989, page 51:

‘In 1847 he was elected MP for Richmond, Yorkshire, a seat he held until 1868, barring a break of two years. ... He played in no further tournaments, although it is said that he retained an interest in chess throughout his life.’

From page 381 of the Oxford Companion to Chess by D. Hooper and K. Whyld (Oxford, 1984):

‘In 1847 he was elected Member of Parliament for Richmond, Yorkshire, a seat he held until 1868 except for a break of two years ... Although he played in no more tournaments he retained an interest in the game throughout his life.’

From page 7 of How to Beat Gary Kasparov by Raymond Keene (London, 1990):

‘Beating Gary Kasparov at chess is considerably more difficult than climbing Mount Everest or becoming a dollar billionaire. In fact when I rang up the British Mountaineering Council I learnt that it was six times easier to reach the peak of Everest, while on contacting Fortune Magazine, I found it was five times easier to acquire more than $1,000,000,000.’

Page 114 of Deep Thinking by Garry Kasparov with Mig Greengard (New York, 2017) quoted that passage, adding a wry comment.

From page 17 of CHESS, November 1990 (Raymond Keene interviewed by Cathy Forbes, concerning Florencio Campomanes):

‘He’s being opposed in the forthcoming elections by Román Torán (President of the Spanish Chess Federation) and the coalition of forces against Campomanes this time looks overwhelming, including the whole of Latin America, most of Europe – Karpov himself is supporting Torán. So I think Campo is doomed this time, he’s absolutely had it.’

From page 5 of CHESS, February 1991 (news report):

‘Florencio Campomanes, Philippines, was re-elected President of FIDE in Novi Sad ... as he collected 79 votes to Román Torán’s 26 and Rabell Méndez’s 9.’

All reference books claim that Frank J. Marshall died in 1944, but the consensus has now been broken by Raymond Keene in The Complete Book of Gambits. Page 81 has a game which is headed ‘Lewitzky-Marshall, Breslau 1991’, and page 184 presents ‘Marshall-Duras, San Sebastian 1991’.

(1944)

Page 268 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves added this footnote:

The book naturally has many other clangers, such as the statement on page 31 that it was Tarrasch, rather than Alekhine, who won their game at Pistyan, 1922.

The entry on Hans Fahrni by Raymond Keene in Golombek’s Encyclopedia (hardback and paperback editions) stated that in 1909 the Swiss player won a tournament in Monaco.

The place in question is Munich. The mix-up presumably stems from Monaco in Italian meaning either Munich or Monaco.

(1978)

The Times, 19 March 1991, page 22

A mere 39 days later there was a correction of what had been ‘misprinted’ in that ‘recent’ column:

The Times, 27 April 1991, page 54[S]

There was no correction, however, of the bizarre spelling ‘Maitrer’. In this famous Schlechter game Black was Meitner.

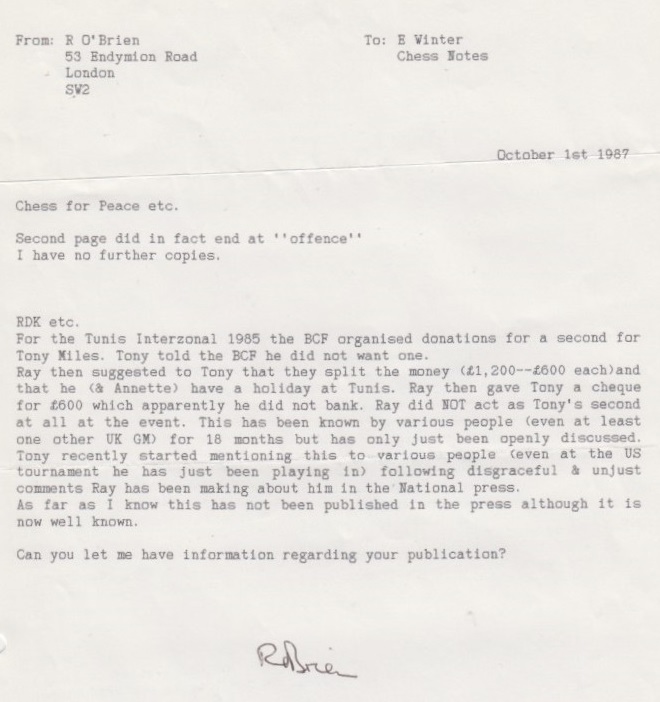

A letter to us from Richard O’Brien (London) dated 1 October 1987:

C.N. 7291 referred to a letter from Tony Miles regarding the 1985 Tunis Interzonal affair, on pages 18-19 of the July 1991 CHESS:

The suggestion which the CHESS Editor considered ‘not publishable’:

As shown in our ChessBase article posted on 12 November 2011, Tony Miles informed us in a letter dated 15 July 1989 that he was working on a project under the inspired title Raymond Keene: A Reappraisal.

From a letter written to us by Tony Miles on 22 August 1989:

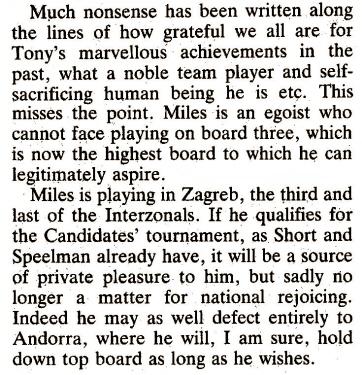

Raymond Keene wrote about Miles as follows in his Spectator column of 8 August 1987 (page 44):

A further attack on Miles came in Raymond Keene’s Spectator column of 3 April 1993, page 44:

‘The [British Chess Federation] press release is co-signed by that well-known patriot and globetrotter Grandmaster Tony Miles, the former top board for Andorra, or was it the US, or Australia, I forget.’

As reported in Tony Miles, on 24 July 1989 he wrote to us:

‘... I spent several months in hospital from the end of September 87 – a result of banging my head against a bureaucratic brick wall ...’

Regarding the 1985 Tunis Interzonal affair, the journalist Nick Pitt who investigated the matter on pages 16-22 of the Sunday Times Magazine, 13 January 1991, wrote on page 19 of CHESS, July 1991:

‘Keene’s own version of events in Tunis, given in an interview conducted by officers of the BCF during a preliminary inquiry, and subsequently in letters and an interview with myself, has changed, and some of his statements on the affair are contradicted by the documentary evidence.’

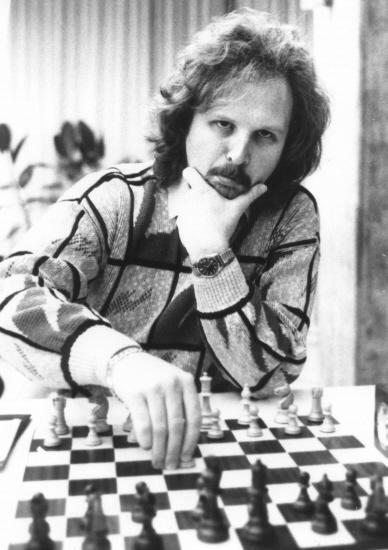

Tony Miles

On 10 October [1987] the Policy Board of the United States Chess Federation decided by a vote of 7-1 to dismiss the editor of Chess Life, Mr Larry Parr.

On 13 October [1987] the British Chess Federation accepted the resignation of Mr Raymond Keene as the BCF’s Publicity Director and FIDE Delegate.

Neither occurrence was premature.

(1506)

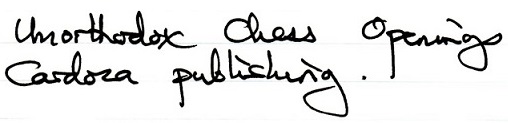

Concerning Tony Miles’ celebrated two-word review in Kingpin of Unorthodox Chess Openings by Eric Schiller, Raymond Keene wrote the following utter piffle on Schiller’s chessgames.com page:

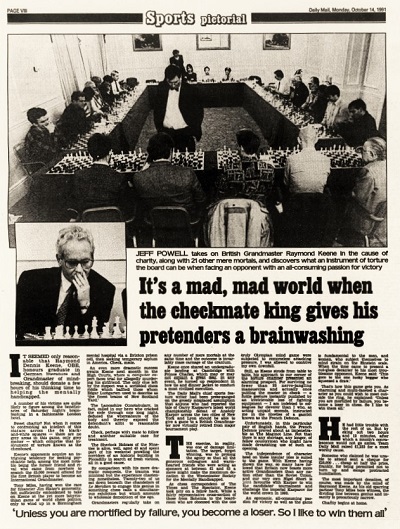

An article (‘It’s a mad, mad world when the checkmate king gives his pretenders a brainwashing’) by Jeff Powell, on page VIII of the Daily Mail, 14 October 1991:

An extract from the early part:

‘Keene’s opponents acquire an intriguing tendency for seeking psychiatric help, among the most notable being the former friend and rival who came from nowhere to snatch the £5,000 reward offered for the first British player to become an International Grandmaster.

Tony Miles, having won the race for financier Jim Slater’s generosity, felt sufficiently emboldened to take on Keene at the yet more labyrinthian game of world chess politics, only to wind up in a Birmingham mental hospital via a Brixton prison cell, then seeking temporary asylum in America. Check, mate.

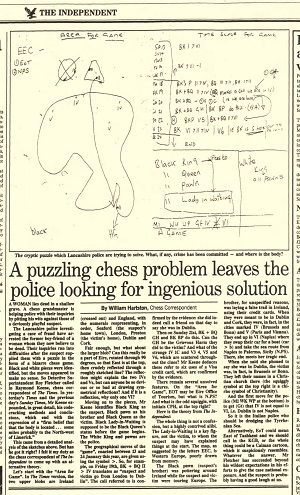

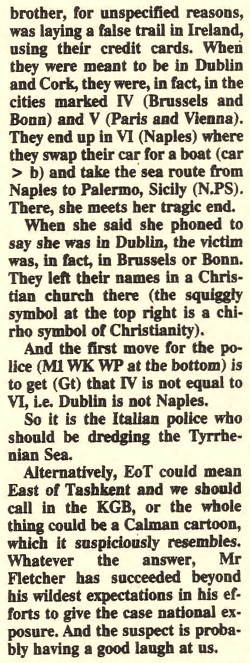

An even more dramatic success awaits Keene next month in the High Courts, where a computer expert faces trial for allegedly murdering his girlfriend. The only clue left by the suspect was a scribbled chess riddle which baffled those whom Edgar Lustgarten used to describe as “the finest brains of New Scotland Yard”.

The Lancashire Constabulary, in fact, called in our hero who cracked the code through one long night, deduced the whereabouts of the body and thereby exposed the defendant’s alibi to reasonable doubt.

Check, perhaps with mate to follow and another suitable case for treatment.’

In a letter to us dated 20 January 1992 G.H. Diggle commented on the article:

‘I have seldom read such dreadful stuff.’

Quite by chance we have just discovered the following:

‘On Tuesday the chess official who asked Tony to send a cable to London if he became a Grand Master received a laconic telegram which said simply “A cable. Tony Miles.”

The steel behind this casual facade becomes evident in Miles’s dedicated effort at the chessboard. His play is aggressive, precise, and above all fearless of reputations ...’

‘A British chess federation official who had asked Miles to send a cable to London if he ever became a Grandmaster received a laconic telegram which simply read “A cable. Tony Miles”. The steel behind this casual facade becomes evident in Miles’ dedicated effort at the board – aggressive, precise, and above all fearless of reputations.’

‘A British Chess Federation official who had asked Miles to send a cable to London if he ever became a Grandmaster received a laconic telegram which simply read “A cable. Tony Miles”.

The steel behind this casual facade becomes evident in Miles’ dedicated effort at the board – aggressive, precise, and above all fearless of reputations.’

Page 6 of The English Chess Explosion stated, ‘we would like to thank Leonard Barden for permission to quote from his articles in The Guardian and The Financial Times’. The above, of course, is not a case of ‘quotation’.

(8267)

C.N. 8267 reproduced Barden’s full column in the Financial Times of 28 February 1976.

The above-mentioned Sunday Times article occasioned these letters in the newspaper:

Sunday Times, 10 February 1991, page 20

Sunday Times, 17 February 1991, page 23.

Raymond Keene will take many things, but not pains.

How self-sacrificing of Raymond Keene to stress the value of memory, given his history.

‘Chess games were first recorded towards the end of the eighteenth century.’

Raymond Keene, The Times, 16 November 1991 (Saturday Review, page 53).

(Kingpin, 1993)

From Raymond Keene’s column in The Spectator, 1 May 1993, page 52:

‘But what happened in 1928? The answer is amusing. Fidé, recently founded, but with little grip on mainstream world chess events, organised its own “World Chess Championship” in Amsterdam.’

As shown in FIDE Championship (1928), the Federation did not suggest that its tournament was any kind of world chess championship. Moreover, the event took place in The Hague, not Amsterdam.

Source: BCM, May 1993, page 231.

C.N. 10841 showed these excerpts from pages 228 and 232 of the same issue, in an article by Murray Chandler and Bernard Cafferty:

Concerning coverage of Keene-related matters by the BCM in the 1980s, see Rebuttals.

From page 46 of the 3/1993 New in Chess (interview with Anatoly Karpov):

‘You may ask any grandmaster who knows Keene. Everything he is involved in is based on personal interests.’

On page 44 of From Baguio to Merano by A. Karpov and V. Baturinsky (Oxford, 1986) Karpov referred to Raymond Keene’s ‘sharply unpleasant traits’.

The result of Raymond Keene’s attempts at personal advancement is public decline.

Pages 20-24 of Chess Horizons, November/December 1993 had an interview with Raymond Keene by Ganesan conducted about a week before the start of the Kasparov-Short match in London. On page 21 Raymond Keene discussed the projected television coverage of the match in the United Kingdom:

‘If you look now, we’ve actually achieved a guaranteed total of 77 hours on BBC, Channel 4, and Sky TV covering the match which is a world record for chess coverage. If you compare it to the amount of coverage for the Olympic Games, which is 135 hours, it’s more than half that. That is extraordinary. I told them it would be big but it’s unbelievably big, the amount of TV coverage. 77 hours before it even starts, and that’s not counting news coverage. Almost every newspaper has something about chess. It’s going to get bigger and bigger and bigger, and this is just the tip of the iceberg. It’s a total vindication of the magnitude of the match. I think I can already guarantee that this match will have got more publicity than any other in the history of chess. If you take the TV coverage into account, I would say this match already has more coverage than all the previous matches put together.’

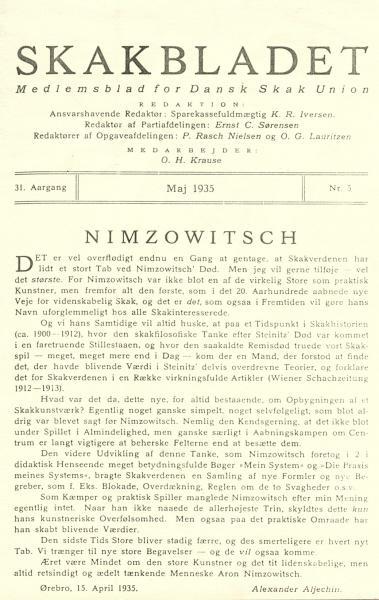

On page 24 Raymond Keene stated that his volume on Nimzowitsch ‘sold around 100,000 copies’ and that, of his books ...

... ‘is the best, easily. That’s a brilliant book. It took five years to research, translations from German and Russian. I’m very pleased with that book, it’s the fruit of many years of deep research. This goes back to your very first question, it’s an undervalued book, the amount of research would have earned me a Ph.D. in many subjects, it’s just that chess is ignored.’

As stated on its final page, the 1986 Russian translation of the Nimzowitsch book had a print-run of 100,000 copies.

In a letter to us dated 23 July 1993, the Editor of The Times, Mr Peter Stothard, professed that it was his newspaper’s practice to correct errors in print. When, however, further factual inaccuracies were brought to his attention, Mr Stothard became uncommunicative.

An example of how The Times’ preference for propaganda rather than facts has already contaminated chess books is offered by the following passage:

‘By 1922 The Times had become so closely linked with world class chess that it was involved with José Capablanca, the Cuban master, in creating what became known as the London Statutes, which set out the rules under which championship matches were played. These lasted until 1946, when the international chess federation FIDE took over organising games as the new world governing body ...’

Source: article by Ian Murray on page 4 of The Times, 18 May 1993.

In reality, the London Rules (not ‘London Statutes’) were used for only one match, Capablanca v Alekhine in 1927, and The Times’ involvement in their preparation was negligible, but that did not stop The Times from including the following in a sequence of advertising puffs in The Even More Complete Chess Addict by M. Fox and R. James (London, 1993):

‘By 1922 The Times was so synonymous with chess that it was involved with the creation of Capablanca’s World Championship Match rules. These rules, which became known as the London Statutes, were in force, with minor modifications, until 1946 when FIDE took over the title for itself.’

The hammering continued on page 11 of Kasparov v Short by Raymond Keene (London, 1993):

‘By 1922 The Times was so central to the world of chess that it was involved with the creation of Capablanca’s World Championship Match rules ... These rules, which became known as the London Statutes, were in force, with minor modifications, until 1946 when FIDE took over the title for itself.’

(Kingpin, 1993-94)

The text by Ian Murray was also reproduced on pages 5-6 of The Times Winning Chess by R. Keene (London, 1995). In the United States that book was published under the title How to Win at Chess (New York, 1995).

An example of the prose in Kasparov v Short (pages 46-47):

‘Nigel is now three and a half points to a half down, his aides are in panic and he must pull himself back quickly from the brink in order to avoid total mental decimation by a champion who is increasingly looking not just like the most powerful champion in the history of chess but a merciless and Protean monster of the mind.’

In Staunton’s City by R. Keene and B. Martin (Aylesbeare, 2004 and 2005) – see pages 79 and 60 respectively – it is stated:

‘[The London Rules] stipulated that the challenger had to raise a minimum prize fund of $10,000 dollars in gold.’

Flatly untrue.

See The London Rules for further details of Raymond Keene’s repeated slovenliness over this ‘gold’ matter.

In C.N. 583 Mr Raymond Keene acknowledged that Fighting Chess, published by Batsford, ‘should have appeared under the joint authorship of Bob Wade and Gary Kasparov ... in future I will try to amend Bob’s position to co-author on the jacket to reflect accurately the colossal amount of work he put into this.’

That did indeed occur, but now the bibliography of a new Batsford book lists ‘Gary Kasparov – Fighting Chess (Batsford). Kasparov’s own collection of his games’, with no mention of Wade. The new book in question is Chess for Absolute Beginners by, of course, Raymond Keene.

In that bibliography, the name of the ‘co-author’ is nonetheless remembered in the case of Batsford Chess Openings. Mention of BCO brings to mind a further example of Batsford’s behaviour. Reviewing the original edition, the BCM (February 1983, page 51) made a number of criticisms but described it as ‘a definite event in chess publishing’. Batsford’s publicity material has systematically misquoted this as ‘a definitive event in chess publishing’.

(Kingpin, 1993-94)

Inscriptions on the front cover of the 1993 Kasparov v Short match bulletins

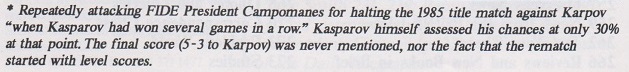

On page 11 of the 7/1993 New in Chess, Hans Ree described The Times’ reporting as ‘an embarrassing collection of hype and half-truths’. But what about the outright untruths too? A few examples follow.

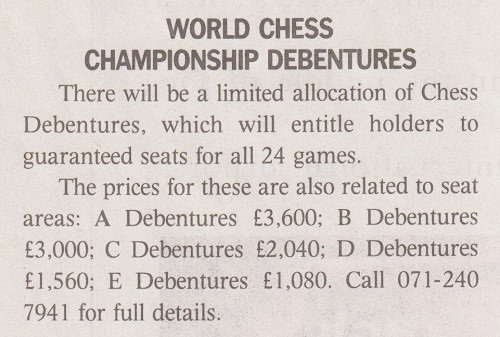

The newspaper’s (premature) announcement, by Daniel Johnson on 31 March 1993, that it had secured the Kasparov v Short match asserted that The Times had offered ‘the largest prize fund in the history of chess’. In fact, it was smaller than the purses for Kasparov v Karpov, 1990 and Fischer v Spassky, 1992.

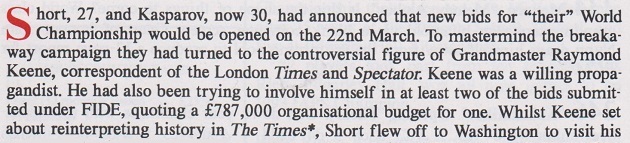

The Times’ frequent references to the closing stages of the 1984-85 Karpov v Kasparov match were flatly false. On 27 February Raymond Keene wrote that ‘Kasparov revived and began to win game after game’. On 1 April Walter Ellis claimed that Campomanes had stopped that match as Kasparov ‘began to move ahead of the “approved” champion, Anatoly Karpov’, while a leading article the same day affirmed that the match was stopped ‘after Kasparov had won several games in a row’.

[Addition on page 271 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves: The misinformation has continued. On page 49 of Man v Machine by Raymond Keene and Byron Jacobs with Tony Buzan, we are told that the match was stopped ‘just as Kasparov had started to win a series of games’.]