Edward Winter

We have noted few references to notorious murderers having any interest in chess, but an apparent exception was the lethally charming Neville George Clevely Heath (born 1917). The following passage comes from page 189 of Portrait of a Sadist by Paull Hill (London, 1960) and describes the killer’s last days, at Pentonville Prison, London:

‘He spent a lot of time reading, made copious notes for his legal advisers, played a certain amount of chess with the warders, two of whom were in his cell day and night, and wrote a lot of letters to friends and his family.’

Neville Heath was hanged on 16 October 1946, the same day as, in Nuremberg, Hans Frank suffered the identical fate.

(3670)

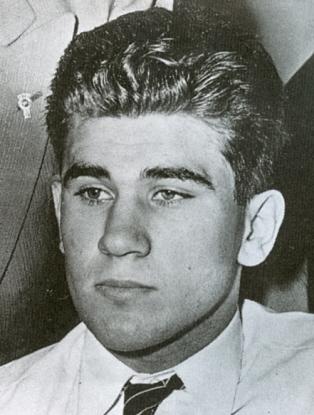

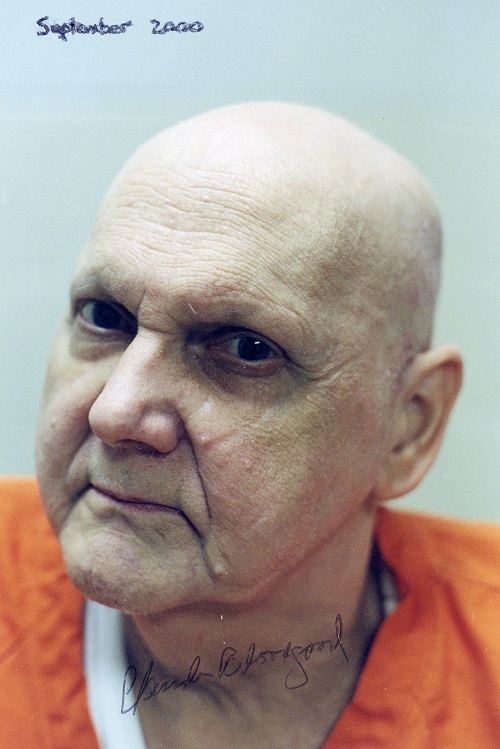

William George Heirens was a 17-year-old student at the University of Chicago when, in 1946, he confessed to three murders. He became known as the ‘Lipstick Killer’ because on a wall in one of the victims’ homes a message was found written in lipstick: ‘For heavens sake catch me before I kill more. I cannot control myself.’ Although the evidence against Heirens has been fiercely disputed, he is, nearly six decades on, still in prison.

William Heirens

Page 102 of “Before I Kill More...” by Lucy Freeman (New York, 1955) relates that at university Heirens had taken up chess, and on page 128 he is quoting as telling her:

‘Later I learned the psychiatrists that examined me were of the type which only consider abnormalities that had a physical relationship, like tumors on the brain, epilepsy and related diseases. They probably couldn’t tell a person was possessed with a dual personality unless they examined a Siamese twin.

There wasn’t a thing I could do about it. My counsel were running the show. I was just a pawn to be pushed around the chess board and sacrificed when it suited their whims.’

(3707)

Heirens died in 2012.

John Hilbert’s latest book, Essays in American Chess History (Yorklyn, 2002), begins (pages 1-18) with a detailed narrative ‘Death of a Chessman: The Sad, Brutal Murder of Major William Cheever Wilson’. It has brought to our mind the case of an even more obscure chess player who was murdered, H.C. James of Coventry, England. From CHESS, 17 September 1938 (page 3):

‘The Reverend H.C. James has been found shot dead in a Paris hotel. This is most grievous news, for he was one of the most delightful and popular personalities we ever knew, a regular attender at BCF congresses. Our sympathy to his more intimate friends in their miserable bereavement comes from the soul.’

Perhaps a reader will be prompted to do some sleuthing, despite the sparseness of the information currently available.

(2743)

The item from CHESS quoted in C.N. 2743 would appear rather misleading, given that suicide was the likely cause of H.C. James’ death according to various newspaper reports now in our possession (i.e. the Midland Daily Telegraph of 1, 2 and 10 September 1938 and the Coventry Standard of 3, 7 and 10 September 1938).

(2752)

From John Hilbert (Amherst, NY, USA):

‘My account of Major William C. Wilson’s death on pages 1-18 of Essays in American Chess History (Yorklyn, 2002) ends in August 1897. But I’ve just learned the circus kept going for some time.

On the night of 4 October 1897 a man calling himself William Harris turned himself in to Philadelphia police, claiming he was one of three men who had murdered Major William C. Wilson, “the aged librarian who was killed in his book store”. Harris said he accompanied two men to Wilson’s store with the object of robbing him, then beat him to death. Source: New York Times, 6 October 1897 (attributing the information to Philadelphia, 5 October).

Another account shortly thereafter indicated Harris claimed that they had beaten Wilson to death with a hatchet, and that Wilson’s missing watch “would be found in a potato patch in New Jersey, two miles below Gloucester”. Detectives couldn’t find the watch, “and it is said that other parts of Harris’ so-called confession lack corroboration”. The paragraph appeared under the title “Probably a Fake Confession” in The News (Frederick, MD), 6 October 1897 (attributing the information to Philadelphia the same day).

Philadelphia’s District Attorney Graham and Director of Public Safety Riter were mulling over Harris’ confession, and “the impression is that the prisoner is not of sound mind and is not guilty. It has been learned that his right name is John Tittemary”. (New York Times, 7 October 1897.)

So passes Harris/Tittemary from at least the annals of this crime. The next strand appeared in February 1898, when Philadelphia police let it be known they were looking for “Big Bill” Mason, “a well-known western crook”, in connection with the murder. One source noted that “Mason is said to have Major Wilson’s missing watch in his possession”. (Middletown Daily Argus (Middletown, NY), 6 February 1898.) Just who said Big Bill had the watch, or how it was known, remained unsaid.

William Mason, alias “Big Bill”, now described as “one of the most desperate criminals in the country”, was arrested in July 1898, along with three other criminals: George, alias “Red” Spencer; Thomas Reilly, and Jim Coffey. (The North Adams Transcript (North Adams, MA), 13 July 1898.)

New York granted extradition of Big Bill Mason to Pennsylvania within four days of his arrest. Mason had been captured in New York City the previous Monday night, 11 July 1898. (Middletown Daily Argus (Middletown, NY), 15 July 1898.)

On 7 September 1898 Big Bill’s cohort “Red” Spencer was sentenced to nine months in the penitentiary for carrying burglars’ tools, while Thomas Reilly was given a year. The short paragraph noted Big Bill Mason had been sent to Philadelphia “on a charge of murder”, but nothing more was reported. (New York Times, 8 September 1898.) Nor was there any suggestion Big Bill had been found carrying Wilson’s watch, the serial number of which was in the possession of the police.

And there the trail goes cold once more. I could find nothing else about Big Bill Mason or about Wilson’s Mysterious Murder, as various periodicals called the death of the small chessplayer who had in his younger days escaped Confederate prison, but who could not escape death by bludgeoning in his own shop.’

(3891)

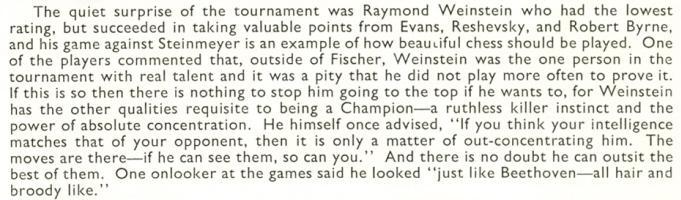

Left to right: Jerry Spann (captain), Raymond Weinstein and William Lombardy (world student team championship in Leningrad)

As recorded on page 127 of Chess Explorations (C.N. 1311), the late Sidney Bernstein informed us in the 1980s:

Bernstein also informed us in C.N. 1311:

‘Incidentally, Raymond once invited me to lunch at his home (before the above troubles, of course). His father, who was also present, struck me as a terrible person who tyrannized and terrorized the family. He was a good chessplayer, but talked incessantly about the golf trophies he had won. In retrospect, it was easy to understand why Raymond and his mother were committed.’

Collins discussed Weinstein’s chess career on pages 195-235 of his book My Seven Chess Prodigies (New York, 1974).

Also in a chess context, it may be recalled that Weinstein was described as having ‘a ruthless killer instinct’ on page 49 of the February 1964 BCM. The phrase was used in Beth Cassidy’s article ‘Fischer the Fantastic’ on the 1963-64 US Championship in New York:

(5069)

For an example of Weinstein’s annotations (a game of his against Lombardy), see page 85 of Chess Life, 20 March 1961.

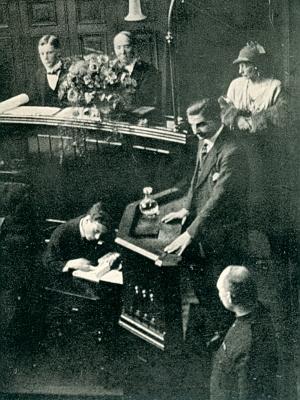

On 5 December 1924 Norman Thorne (1900-25) of Crowborough, England dismembered his fiancée Elsie Cameron. Earlier that day he had bought ‘a game of chess’ in Tunbridge Wells. Source: page 114 of The Trial of Norman Thorne by Helena Normanton (London, circa 1929). Much has been written about that famous murder case, but we recall no other reference to chess in connection with the life of Thorne, who was hanged on 22 April 1925.

John Norman Holmes Thorne giving evidence at his trial, Lewes, 13 March 1925

A fine account of the case appeared on pages 88-126 of Verdict in Dispute by Edgar Lustgarten (London, 1949). From page 108:

‘Spilsbury [the pathologist Sir Bernard Spilsbury, who was the prosecution’s expert witness] had indeed done what few can hope to do; he had become a legend in his own lifetime. To the man in the street he stood for pathology as Hobbs stood for cricket or Dempsey for boxing or Capablanca for chess.’

(5441)

Addition on 9 February 2025:

From page 7 of the Liverpool Post & Mercury, 11 March 1925:

Page 27 of The Even More Complete Chess Addict by M. Fox and R. James (London, 1993) stated that John Reginald Halliday Christie (who lived at 10 Rillington Place) ‘was a goodish chessplayer’ and that ‘Whilst awaiting the ultimate punishment in Brixton, he passed the time thrashing his warders at chess (Chris the chess champion, they nicknamed him).’ The grounds for these assertions remain to be discovered, since much of the book is a source-free zone.

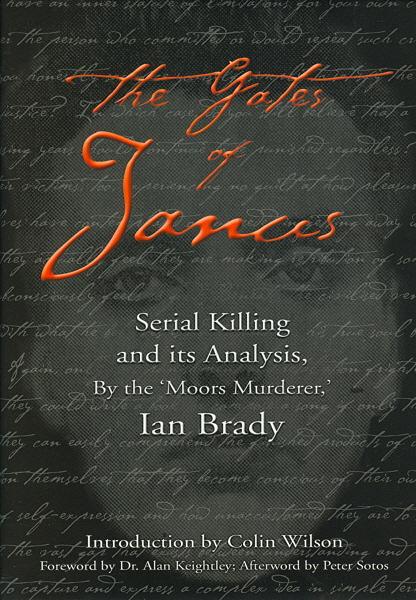

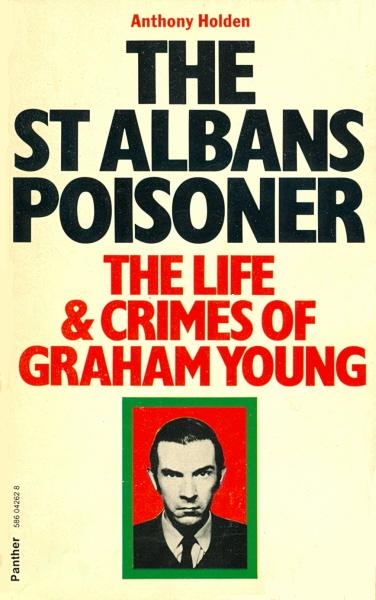

On a documented basis we can add that two other British serial murderers regularly played chess against each other. On page 132 of The Gates of Janus (Los Angeles, 2001) Ian Brady described playing chess against Graham Young in Parkhurst Prison on the Isle of Wight:

‘An inveterate but excitable chessplayer, he rather foolishly favoured the black pieces, likening their potency to the Nazi SS. His daily opponent on the board for years was the author of this book, against whom Young always failed to win a match.’

(5939)

In an article on page 9 of the Radio Times, 26 August-1 September 2017 Steve Crabtree referred to his correspondence with Ian Brady:

‘He wrote about what a fantastic chessplayer he was, the prizes he’d won with his oil paintings, how many books he’d read ...’

From Avital Pilpel (Haifa, Israel):

‘You note that “Ian Brady described playing chess against Graham Young in Parkhurst Prison on the Isle of Wight”. It is worth adding that after Brady’s death, an interview with another British serial killer – Peter Sutcliffe, the “Yorkshire Ripper” – stated that the latter played chess with Brady.

Just as Brady was dismissive of Young’s chess ability, Sutcliffe was dismissive of Brady’s, according to an online Mirror report dated 27 May 2017.’

(12013)

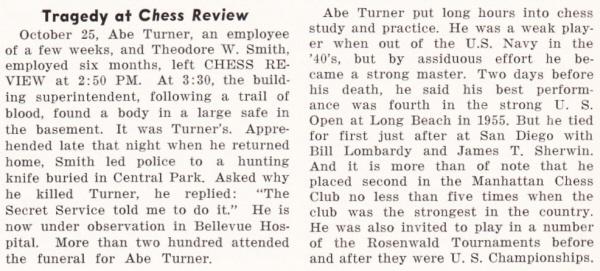

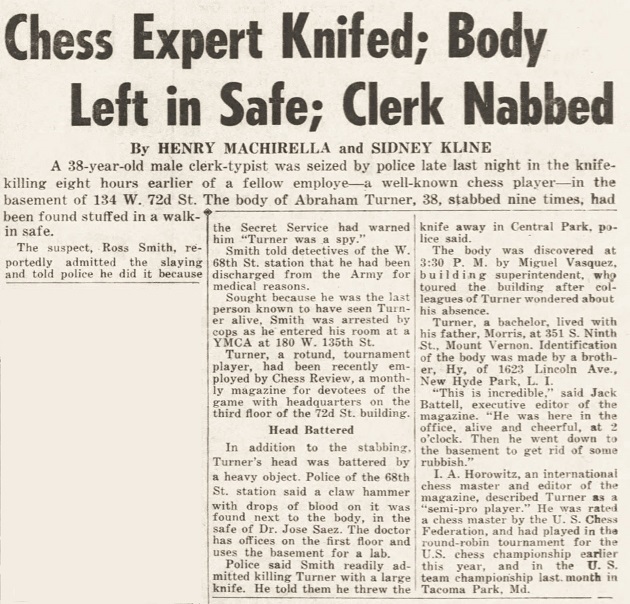

The murder of Abe Turner was referred to on pages 126-127 of Chess Explorations. Below is the report on page 356 of the November 1962 Chess Review:

From page 7 of the Daily News (New York), 26 October 1962:

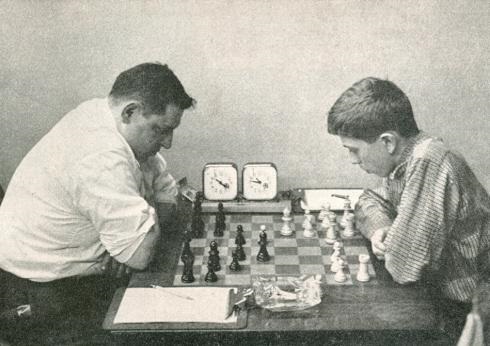

The death of Abe Turner was discussed in C.N.s 1286 and 1311 (see pages 126-127 of Chess Explorations). C.N. 1311 quoted a newspaper report that the killer was Theodore Weldon Smith, a 35-year-old handyman. A photograph of Turner in play against Fischer in the final round of the 1957-58 US Championship in New York was given in C.N. 6423, from page 81 of the March 1958 Chess Review:

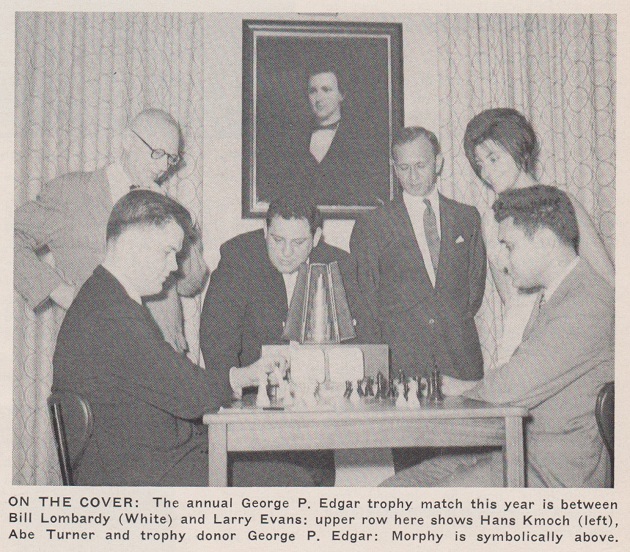

From page 195 of the July 1962 Chess Review:

A paragraph from page 290 of the October 1961 Chess Life:

‘US Master Abe Turner became a movie actor. We spotted him in a party scene of artist-beatniks in a highly humorous film, Bowl of Cherries. He shakes hands with the star.’

We have no further information about the film beyond what is readily available on-line.

(10932)

Steve Wrinn (Homer, NY, USA) notes that the brief scene featuring Abe Turner in the film A Bowl of Cherries begins at about 10’32”.

Abe Turner (left foreground)

(10941)

Regarding Turner see too pages 47-48 of Chess Memoirs by J. Platz (Coraopolis, 1979).

In the early 1990s there were press reports in the United Kingdom (still available on the Internet) about a chess-related case of attempted murder in which the victim was Matthew Hay.

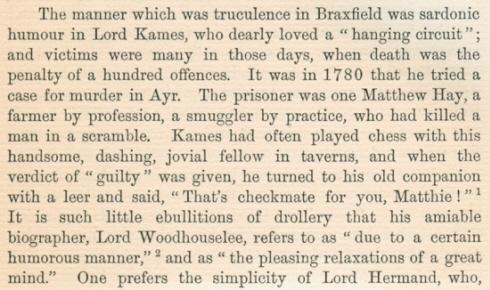

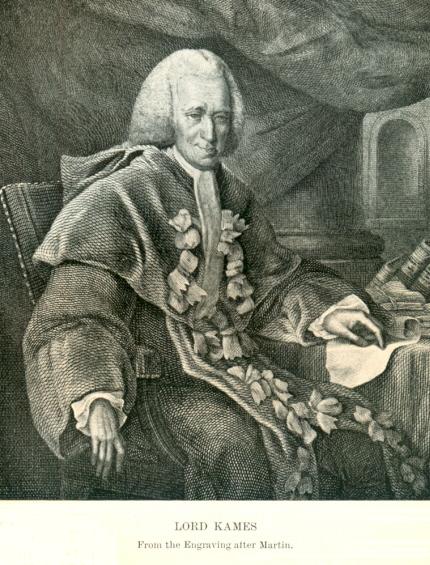

A murderer of the same name was mentioned, with a reference to chess, on page 186 of Scottish Men of Letters in the Eighteenth Century by Henry Grey Graham (London, 1901):

(6968)

Craig Pritchett (Dunbar, Scotland) draws attention to an article (‘Chess and the Common Muir of Ayr Hangman’) which he contributed on page 36 of the June 2008 CHESS.

The sources specified in the article suggest that in the eighteenth-century case Matthew Hay stood accused of two murders and that there is much uncertainty over the alleged ‘That’s checkmate ...’ remark by the judge, Lord Kames.

(6981)

From Mark N. Taylor (Mt Berry, GA, USA):

‘The anecdote about Judge Kames’ “checkmate” comment resembles the better-known Sir Walter Scott story which is attributed to Judge Braxfield – and for good reason. I believe that the earliest published source of the story is pages 569-570 of volume one of Memoirs of the Life of Sir Walter Scott by John Gibson Lockhart. The quote below is taken from the edition published in Philadelphia in 1837:

“Scott told, among others, a story, which he was fond of telling, of his old friend the Lord Justice-Clerk Braxfield; and the commentary of his Royal Highness [the Prince Regent, the future King George IV] on hearing it amused Scott, who often mentioned it afterwards. The anecdote is this: Braxfield, whenever he went on a particular circuit, was in the habit of visiting a gentleman of good fortune in the neighbourhood of one of the assize towns, and staying at least one night, which, being both of them ardent chessplayers, they usually concluded with their favourite game. One Spring circuit the battle was not decided at daybreak, so the Justice-Clerk said, ‘Weel, Donald, I must e’en come back this gate in the harvest, and let the game lie ower for the present’; and back he came in October, but not to his old friend’s hospitable house; for that gentleman had, in the interim, been apprehended on a capital charge (of forgery), and his name stood on the Porteous Roll, or list of those who were about to be tried under his former guest’s auspices. The laird was indicted and tried accordingly, and the jury returned a verdict of guilty. Braxfield forthwith put on his cocked hat (which answers to the black cap in England), and pronounced the sentence of the law in the usual terms, ‘To be hanged by the neck until you be dead; and may the Lord have mercy upon your unhappy soul!’ Having concluded this awful formula in his most sonorous cadence, Braxfield, dismounting his formidable beaver, gave a familiar nod to his unfortunate acquaintance, and said to him, in a sort of chuckling whisper, ‘And now Donald, my man, I think I’ve checkmated you for ance’. The Regent laughed heartily at this specimen of Macqueen’s brutal humour; and ‘I’faith, Walter’, said he, ‘this old big-wig seems to have taken things as coolly as my tyrannical self.’”

Source: Scottish Men of Letters in the Eighteenth Century by Henry Grey Graham (London, 1901)

As Craig Pritchett pointed out in his article in the June 2008 CHESS, the problems with Lockhart’s account were noted by Lord Henry Cockburn on pages 117-118 of Memorials of his Time (Edinburgh, 1856):

“When Lord Kames, an indefatigable and speculative but coarse man, tried Matthew Hay, with whom he used to play at chess, for murder at Ayr in September 1780, he exclaimed, when the verdict of guilty was returned, ‘That’s checkmate to you, Matthew!’ Besides general and uncontradicted notoriety, I had this fact from Lord Hermand, who was one of the counsel at the trial, and never forgot a piece of judicial cruelty which excited his horror and anger.

Scott is said to have told this story to the Prince Regent. If he did so, he would certainly tell it accurately, because he knew the facts quite well. But in reporting what Sir Walter had said at the royal table, the Lord Chief Commissioner Adam confused the matter, and called the judge Braxfield, the crime forgery, and the circuit town Dumfries; and this inaccurate account was given by Mr Lockhart in his first edition of Scott’s life (chapter 34). Braxfield was one of the judges at Hay’s trial, but he had nothing to do with the checkmate.’

In “Lord Braxfield: The Original Weir of Hermiston” (The New Review, October 1896, pages 437-450), Francis Watt put to rest the Braxfield attribution and is, as far as I can trace, the first to suggest that the comment was made as an aside to Braxfield and not directed at the condemned man. From page 443:

“This story was told in the first edition of Lockhart’s Life of Scott; but Lockhart afterwards expressly apologized to the family for it. Braxfield, it seems, could not play chess at all and the anecdote belongs to another judge, and sets forth, I fancy, an aside to Braxfield, who was present at the trial.”

This brings us to Henry Grey Graham’s heightened retelling in 1901 (cited in C.N. 6968), relishing in the horror of the judge who “dearly loved the ‘hanging circuit’”.

Peter Stein’s 1957 article on the 1780 trial in the Juridical Review (also mentioned by Pritchett) seems to come to the same conclusion as Watt’s and Graham’s “fancy” about the circumstances of the “checkmate” utterance as an aside, but he suggests that it may have been delivered out of the condemned man’s hearing, issued out of “quiet reflection” rather than the vicious cruelty of a “hanging judge”.

The reading of this anecdote has shifted considerably over the years. The anecdote served as the basis of an even more fanciful work, “Checkmate” by Moray McLaren, on pages 66-71 of Scottish Short Stories edited by Fred Urquhart (London, 1957). A judge, named Lord Karnockie, is jealous of Kames’ famous witticism and hopes, in the presence of Kames and Braxfield, to do one better. He is presented with a condemned gentleman accused of manslaughter, named Wattie Stewart, to whom Karnockie always lost at chess. Wattie, however, is able to take revenge in the courtroom, which forces a new and final witticism from the hanging judge.’

We add that an extensive passage from Memoirs of the Life of Sir Walter Scott, including the ‘checkmate’ story, was quoted on pages 238-240 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1842. The anecdote was not mentioned in ‘Sir Walter Scott on Chess’ by H.R.H. on pages 530-531 of the December 1891 BCM (an article included in Reinfeld’s The Treasury of Chess Lore) but was discussed by the magazine in 1907 (January, page 23 and February, pages 67-69).

(7014)

Other murder victims include Gilles Andruet (1958-95) and Simon Webb (1949-2005).

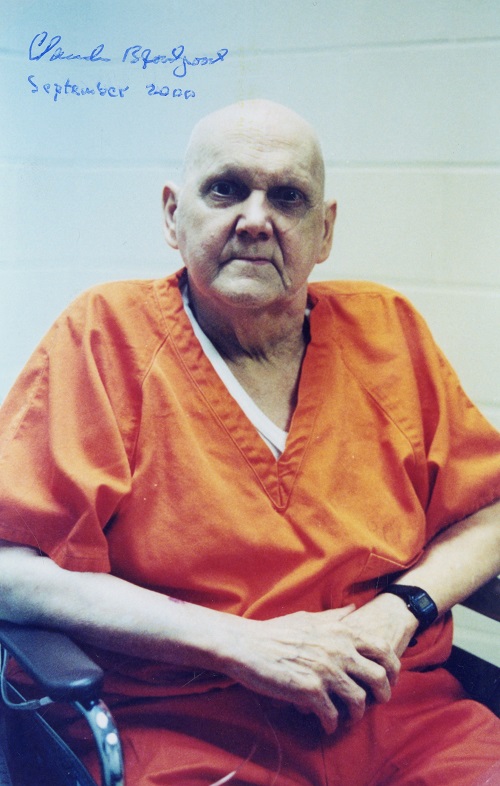

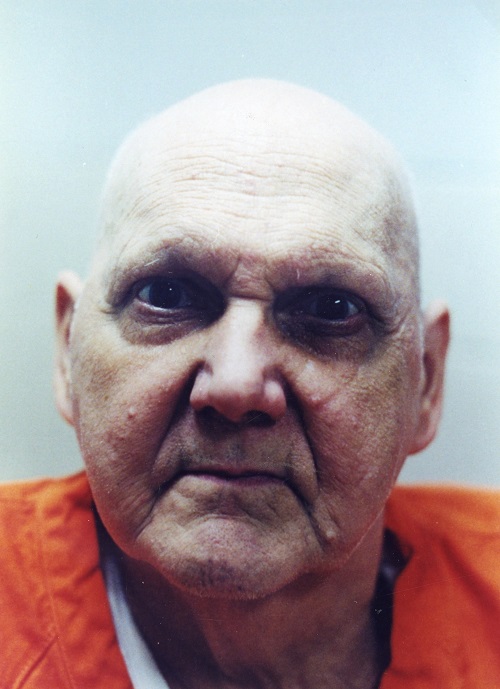

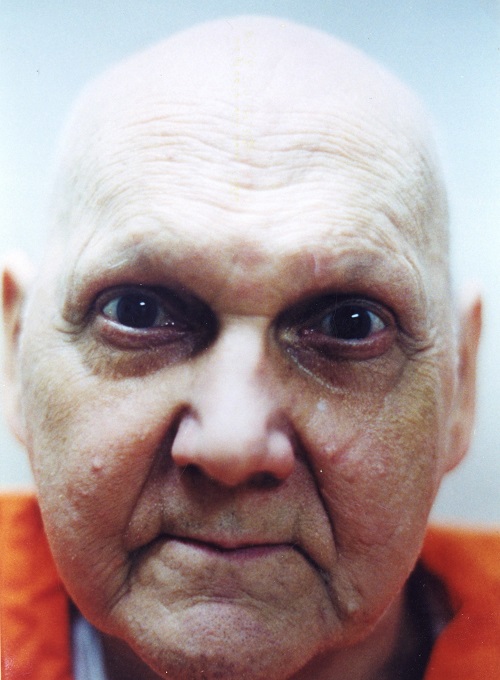

The case of the killer Claude Bloodgood (1937-2001) is well known. See C.N.s 9207 and 9222. With regard to the Claude Bloodgood Chess Collection at the Cleveland Public Library, C.N. 10712 reproduced with the Library’s permission these four photographs:

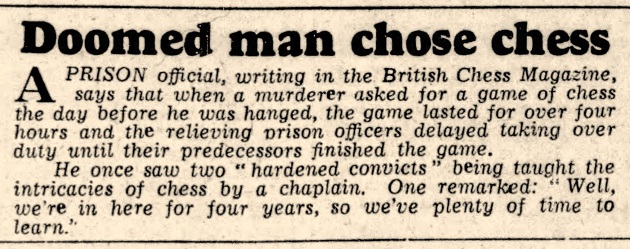

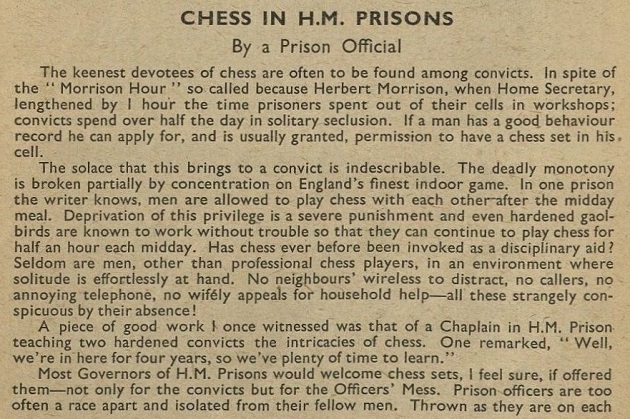

From page 34 of CHESS, December 1940:

‘“Perfect Prisoner” – A Chess Addict

Percival Leonard Taylor was released from Parkhurst recently after serving 12 years’ penal servitude. He had been sentenced to death in 1928, with two others, for the murder of a 67-years-old Brighton druggist. They declared their innocence. They were reprieved within 13 hours of the time fixed for execution. Taylor acted as an ordinary convict for two years. Then he decided to become a “model prisoner”; and thenceforth earned one remission after another. “I am going to live”, he said to himself, “so that every man here will be my friend. When I get outside, I will be able to turn to any of them to speak for me.”

“I think it was chess that saved my reason. A man taught me to play, and I got all the library books. I used to sit hour after hour working out problems. I captained chess and draughts teams.”

He gained a remission of one year for stopping a runaway horse and saving the lives of three children.’

‘Professor Arthur Lloyd James, the languages adviser to the BBC, who murdered his wife in a fit of insanity, played chess whilst awaiting trial. [His favourite game.]’

Source: CHESS, March 1941, page 81.

As mentioned in C.N. 9206, CHESS gave the information in a section headed ‘The Funny Side’:

From page 101 of the April 1941 issue:

Sean Robinson (Tacoma, WA, USA) informs us of the death of Robert B. Long earlier this month [January 2020]. He was murdered at his home in Davenport, IA, USA.

Bob Long was a chess editor, bookseller and writer whose magazines included the Chess Gazette, Lasker & His Contemporaries and Squares. The most prominent of the many books published by his company, Thinkers’ Press, was a series of compilations of C.J.S. Purdy’s writings.

Bob Long

Squares, Fall 2005, page 34

The hundreds of entries in Chess and the Law An Anthology of Anecdotes and Analogies by Andrew J. Field (‘Amazon Fulfillment’, Wrocław, 2019) range from a brief paragraph on a minor court-case to four pages on Norman Tweed Whitaker and nine on William Henry Russ. An unnumbered introductory page states that the book ‘surveys the many interesting and unusual ways that the game of chess has intersected with the practice of law in the United States’ and warns that ‘this book is not appropriate for children’. Many violent cases are discussed.

(11681)

In the United Kingdom a number of individuals convicted of capital offences played chess against prison warders. The following appeared under W.H. Wallace’s name on pages 8-9 of John Bull, 14 May 1932:

‘I see clearly in the freedom of my bedroom the faces of the warders of the death-watch at the condemned cell – the faces that will never leave me, day or night, until the end comes.

I see myself again playing chess with them. ... I wonder – do they still play chess? I taught them.’

Wallace described on page 19 of John Bull, 30 April 1932 how he was publicly perceived:

‘I was not only “the man Wallace” but “another Rouse”.

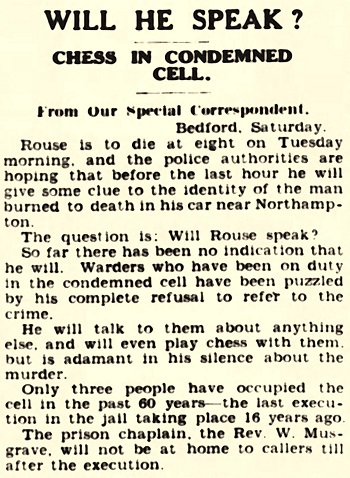

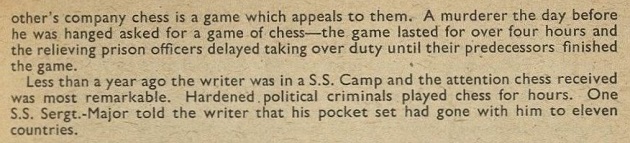

He was referring to Alfred Arthur Rouse (1894-1931), the ‘blazing car murderer’. A report about Rouse on page 1 of the (London) Evening Standard, 7 March 1931 stated:

‘In the condemned cell he is guarded day and night by two warders. During the daytime he has exercised in the small prison yard and in the cell he plays draughts and chess with the “death guard”.’

From the front page of the (Sunday) People, 8 March 1931:

Page 6 of the Evening Express (Liverpool), 7 March 1931 described Rouse as ‘an expert chess and draughts player’. Journalists often misapply ‘expert’ and ‘champion’ to prisoners and prodigies.

Another case was John George Haigh (1909-49), the ‘acid bath murderer’. From page 3 of the Daily Herald, 21 July 1949:

Chess and Murder mentions Neville George Clevely Heath (1917-46), who ‘played a certain amount of chess with the warders, two of whom were in his cell day and night’. Concerning William Joyce (1906-46), C.N. 11446 related that, before being hanged for high treason, ‘in the condemned cell he has played chess with the prisoner officers’.

From page 1 of the Evening Despatch (Birmingham), 31 August 1948:

The article was on pages 314-315 of the September 1948 BCM:

Acknowledgement for the BCM scan: Cleveland Public Library

(12134)

Concerning Rouse, a slightly earlier report was on page 11 of the Daily Express, 6 March 1931:

An addition is Dr Buck Ruxton (1899-1936). From page 1 of the Daily Express, 28 April 1936:

Dr Ruxton was hanged in Manchester on 12 May 1936.

(12184)

See also ‘Steinitz played Jack the Ripper’ in Blindfold Chess.

See too:

Chess and the Wallace

Murder Case

Chessplayer Shot Dead in Hastings

Hans Frank and Chess

War Crimes (Karlis Ozols)

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.