Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [102] | next >> | Current column |

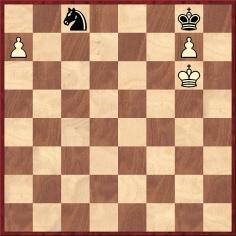

7911. Two pawns (C.N. 7901)

White to move and draw

We took this composition from page 30 of the February 1942 Schweizerische Schachzeitung. The solution was on page 129 of the August 1942 issue: 1 g4+ Kf6 2 g5+ Ke7 3 gxh6 Nf6 4 h7 Re8 5 h8(Q).

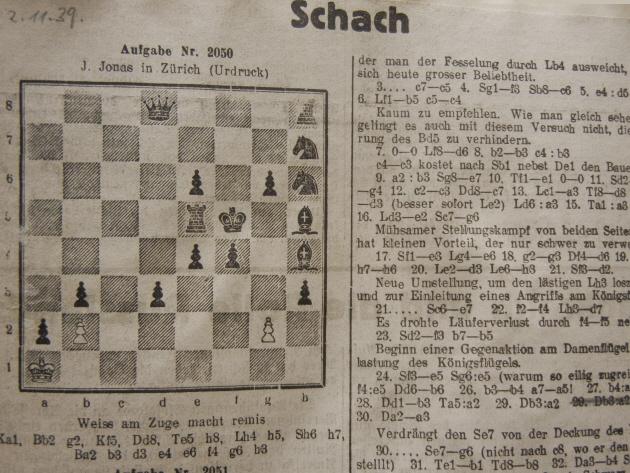

The magazine stated that the composer was J. Jonas of Zurich and that the original source was the National-Zeitung, 1939. Richard Forster (Zurich) has provided cuttings from that newspaper (2 November and 23 November 1939). The second of these reported that the black bishop at h5 needed to be on e2 for the sake of soundness (since otherwise, as our correspondent points out, 1 g4+ Kg5 2 gxh5 offers White no prospect of stalemate).

7912. My 61 Memorable Games

Via Frederic Friedel (Hamburg, Germany) we learn that Garðar Sverrisson, who may be regarded as Fischer’s closest confidant in Iceland, states that Fischer would never have considered bringing out a book such as My 61 Memorable Games without consulting him. Mr Sverrisson writes:

‘When I told Bobby about the forgery in early December 2007 he just became sad and disappointed, exactly as he used to react when he learned about slander or a similar betrayal. At that time his health was deteriorating, and we had other things to worry about than who might be behind this book.

When we discussed the possibility of having My 60 Memorable Games republished he was very much against using any improvements of his own or others (including computers). And changing the notation from the descriptive to the algebraic was out of the question.

We never saw My 61 Memorable Games, and I still have not seen it.’

7913. Rosanes v Anderssen

From Fabrizio Zavatarelli (Milan, Italy):

‘Well-known classics can be surprisingly mysterious. A particular case is the game between J. Rosanes and A. Anderssen (Breslau, 1863), which seems to have appeared in books before it was published in magazines:

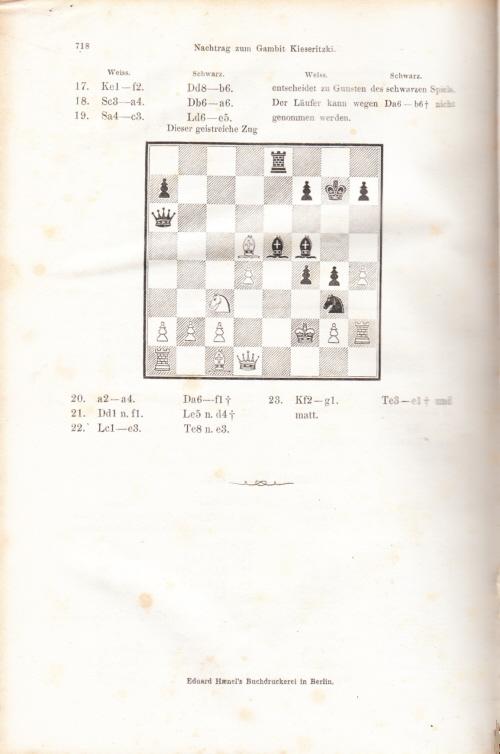

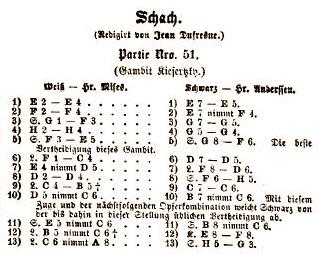

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 h4 g4 5 Ne5 Nf6 6 Bc4 d5 7 exd5 Bd6 8 d4 Nh5 9 Bb5+ c6 10 dxc6 bxc6 11 Nxc6 Nxc6 12 Bxc6+ Kf8 13 Bxa8 Ng3 14 Rh2 Bf5 15 Bd5 Kg7 16 Nc3 Re8+ 17 Kf2 Qb6 18 Na4 Qa6 19 Nc3 Be5 20 a4

20...Qf1+ 21 Qxf1 Bxd4+ 22 Be3 Rxe3 23 Kg1 Re1 mate.

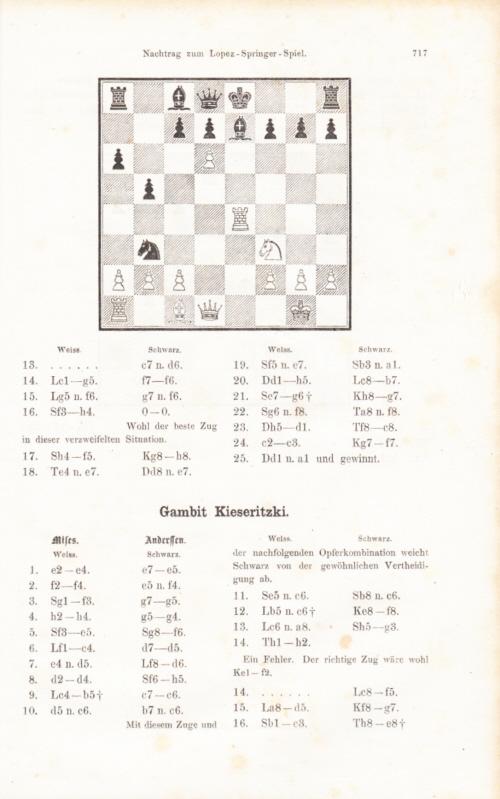

The essential information came out in at least two stages. As far as I know, the game’s first appearance is on pages 717-718 of Dufresne’s Theoretisch-praktisches Handbuch des Schachspiels (Berlin, 1863) with no occasion mentioned and “Mises” named as White:

“Rosanes” and “Breslau, 1863” were later additions, and the first instance that I have found is on page 106 of J.G. Schultz’s Undervisning i schackspelet (Stockholm, 1869).

Both “Rosanes” and the occasion also appear on page 495 of Dufresne and Zukertort’s Grosses Schach-Handbuch, (second edition, Berlin, 1873). I wonder whether the game is also present in the first edition, which was published in 1863 with only Dufresne named as author, as listed by van der Linde in volume two of his Geschichte und Litteratur des Schachspiels (Berlin, 1874), page 23.

Can a more precise date for the game be found? Why was White identified as “Mises” (probably Samuel Mieses) at first? Today, can we be sure that Anderssen’s opponent was Rosanes? Is there a documented explanation as to why the game appeared in books but not in the Deutsche Schachzeitung or the Neue Berliner Schachzeitung?’

7914. Alekhine’s Gun (C.N. 7880)

Jeremy Silman (Los Angeles, CA, USA) informs us that he does not recall the provenance of the term ‘Alekhine’s Gun’, which, as mentioned, in C.N. 7880, he used on pages 280-281 of How to Reassess Your Chess (Los Angeles, 1993).

That remains our first sighting of ‘Alekhine’s Gun’ in print. Can readers find earlier occurrences?

7915. Ebensee, 1933 (C.N. 7908)

James Bell Cooper (Gmunden, Austria) draws attention to an illustrated article by Nina Höllinger about chess in Ebensee on pages 18-25 of Betrifft Widerstand, December 2010.

7916. ‘The Swiss Gambit’

A. Küsel – C.F. Huch

USA (exact occasion?)

1 f4 f5 2 e4 fxe4 3 f5 Nf6 4 Be2 h5 5 Nh3 d5 6 O-O Qd6 7 Nf4 Bxf5 8 Nxh5 Bg6 9 Nxf6+ exf6 10 h3 Qg3 11 Bg4 Bc5+ 12 Kh1 Bd6 13 Kg1 Qh2+ 14 Kf2 f5 15 Be2 and Black gave mate in seven. However, our computer offers 15…e3+ 16 Kxe3 Qe5+ and mate in three more moves.

Source: Deutsche Schachzeitung, June 1872, page 167.

Thomas Niessen (Aachen, Germany) now notes that the game was given in the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin on 22 July 1870. Reichhelm’s column stated that it was played at the Schu[e]tzen Halle in Philadelphia, and he called the opening the ‘Gambit Philadelphienne’ [sic].

Our correspondent adds that on 15 July 1870 the column in the Bulletin had published, without details of the occasion, another game with the same opening, the players being Huch and Bode:

1 f4 f5 2 e4 fxe4 3 f5 Nf6 4 Be2 d5 5 Bh5+ Nxh5 6 Qxh5+ Kd7 7 Nc3 c6 8 b4 b5 9 a4 Ba6 10 Nge2 e6 11 fxe6+ Kxe6 12 Nd4+ Ke7 13 O-O bxa4

‘Mate in three moves.’

7917. Anderssen and Alekhine (C.N. 4353)

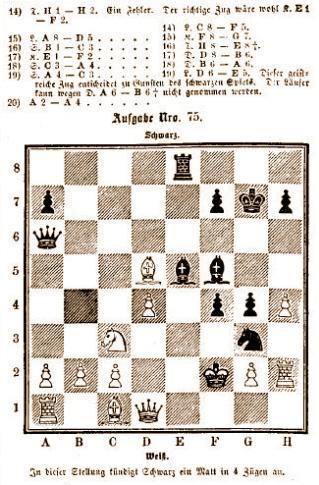

Following the recent expanded version of C.N. 4353, Carl Rundqvist (Stockholm) comments on this position in the game Anderssen v Zukertort, Breslau, 1862:

Black to move

In analysis without sight of the board Alekhine remarked that 1...Rfe8 was the only move permitting Black to prolong resistance. An alternative line given was 1...Rd2 2 Be4+ Kg8 3 Nf5, etc.

The critical move is indeed 1...Rfe8 but, for the record, Mr Rundqvist mentions the result of a computer check: 1...Rfe8 allows mate in nine moves, there is a mate in eight after 1...Rd2, and the move permitting Black to survive the longest is 1...Bc8.

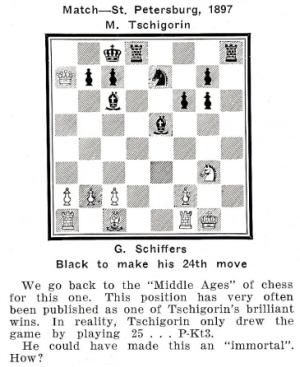

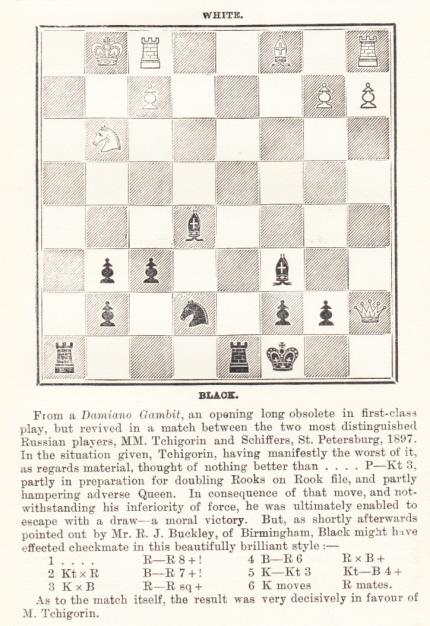

7918. Early Flohr brilliancy

1 d4 d5 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 Nbd7 5 e3 Be7 6 Nf3 O-O 7 Qc2 c6 8 a3 dxc4 9 Bxc4 Nd5 10 Bxe7 Qxe7 11 Ne4 N5f6 12 Bd3 Nxe4 13 Bxe4 h6 14 O-O e5 15 Rfe1 Qf6 16 Rad1 exd4 17 exd4 Nb6 18 Ne5 Be6 19 Re3 Rad8 20 Rf3 Qh4 21 g3 Qh5 22 h4 Bg4 23 Re1 Nd5 24 Rxf7 Rxf7 25 Bh7+ Kh8 26 Bg6 Qxe5 27 dxe5 Rff8 28 e6 Ne7 29 Bf7 Rd4 30 Qc5 Rfd8 31 Qxe7 Bf3 32 Qxd8+ Resigns.

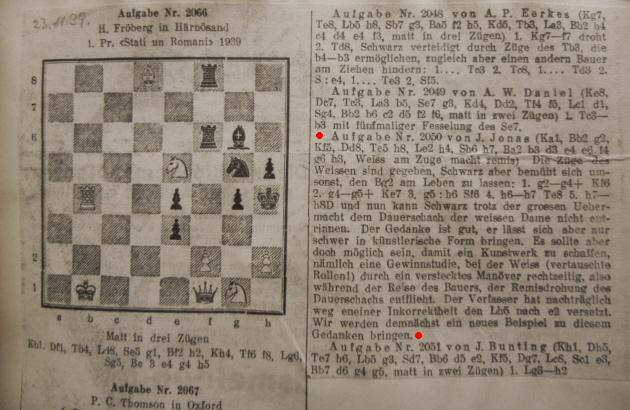

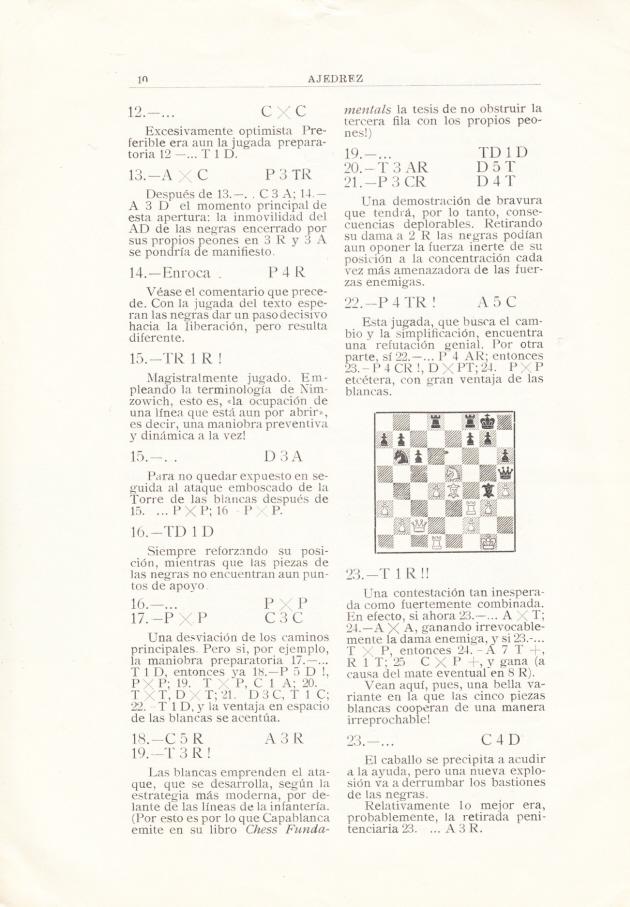

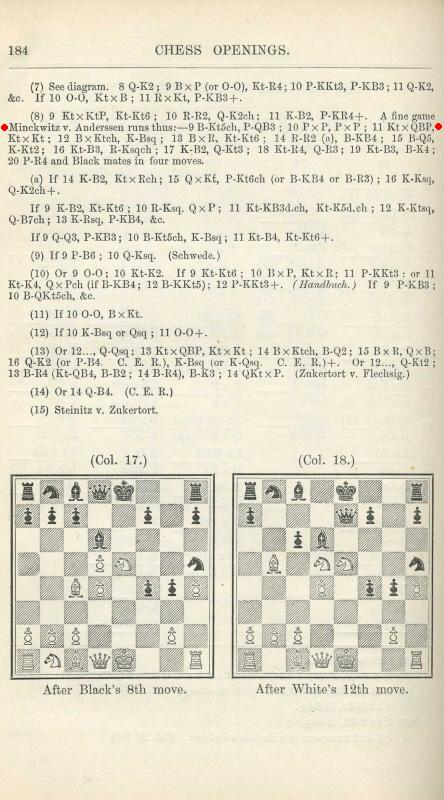

This game was won by Salo Flohr against Karel Vaněk in a team match in Brno between Prague and Brno on 3 November 1929. He annotated it on pages 182-183 of the December 1929 Československý Šach, and a more detailed set of notes was provided by Tartakower on pages 9-11 of the January 1930 issue of Ajedrez (published in Valencia):

Readers are invited to compare Tartakower’s notes with those on pages 28-30 of Salo Flohr Master of Tactics, Master of Technique edited by Jimmy Adams (Nottingham, 1985).

7919. Rosanes v Anderssen (C.N. 7913)

Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA)

mentions an earlier (i.e. pre-1869) appearance of

Rosanes’s name in connection with the Anderssen game:

the New York Albion

of 23 June 1866. The reference in note (a) ‘According to

Anderssen’s Analysis ...’ may be a significant clue.

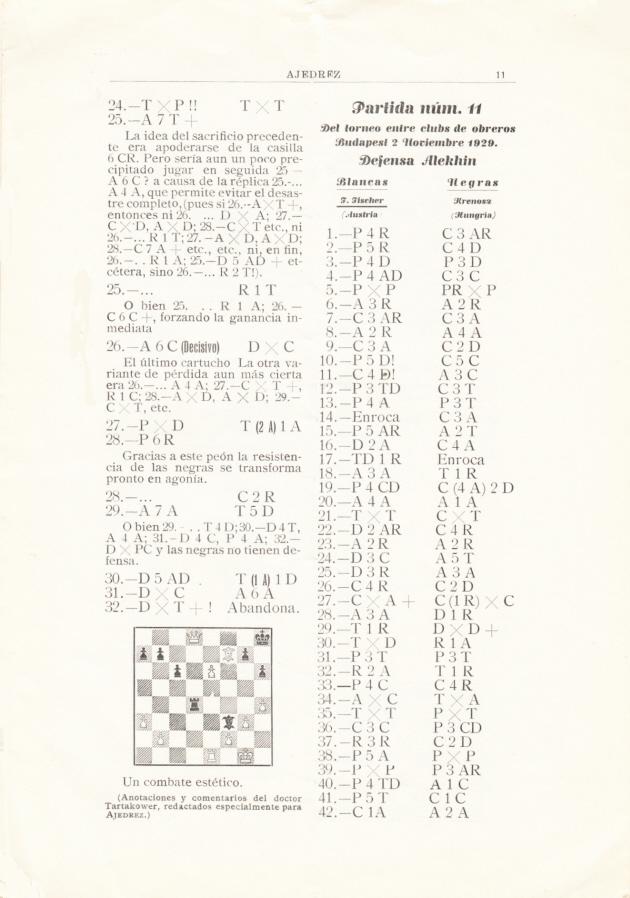

Among the nineteenth-century books which identified White as (Samuel) Mieses we were particularly interested to note Chess Exemplified by William John Greenwell (London, 1890) because of a comment on page 41:

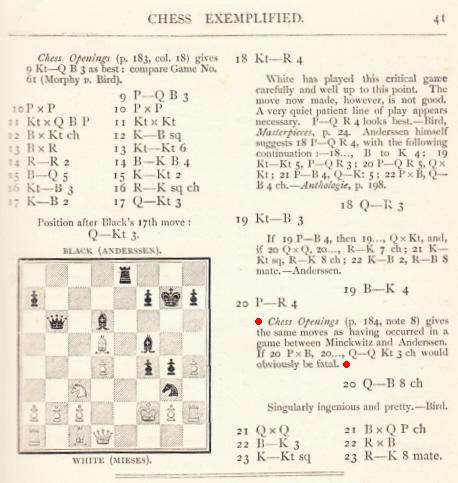

So now, not only Rosanes and Mieses but a third name, Minckwitz. The book referred to is Chess Openings, Ancient and Modern by E. Freeborough and C.E. Ranken (London, 1889), and the relevant page is shown below, courtesy of Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England):

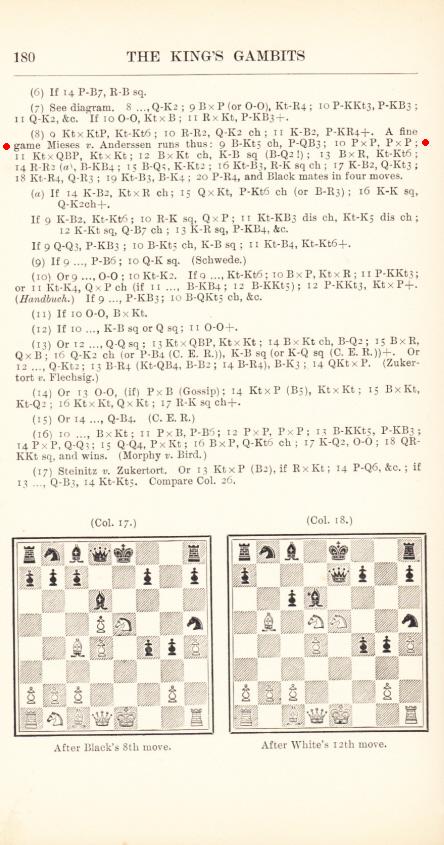

From the second edition onwards, Anderssen’s opponent was named as Mieses. For example, below is page 180 of the fourth edition (London, 1910):

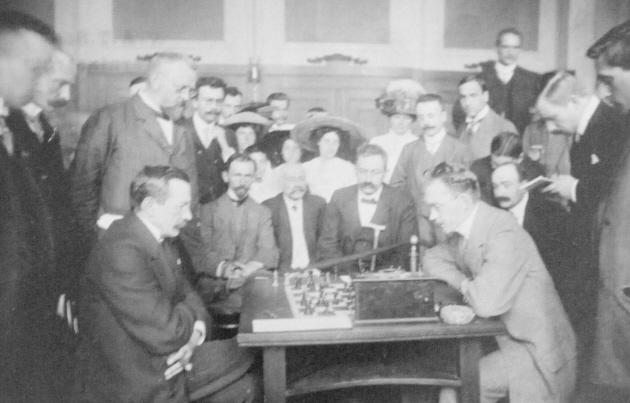

7920. Hamburg, 1910

Michael Negele (Wuppertal, Germany) provides two

photographs which he has found at the Royal Library in The

Hague (Rueb scrapbooks). In each case our correspondent’s

observations are quoted.

‘The Leonhardt-Nimzowitsch game was played in round three, and the position seems to show analysis after move 23, with the better option 23 f3, rather than 23 Rdb1 as played by Leonhardt in the game.’

‘The Leonhardt-Tarrasch game was in round 17. The position comes after the decisive combination 19 Bxc7 Qxc7 20 Re8+ Bxe8 21 Rxe8+ Kh7 22 Bd3+ f5, and White will now capture on h8. For this game Leonhardt won the first brilliancy prize of 300 Marks.’

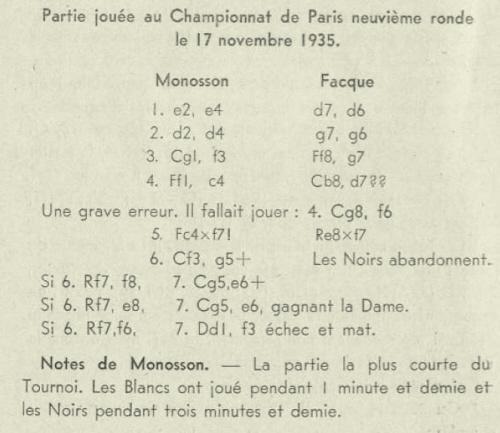

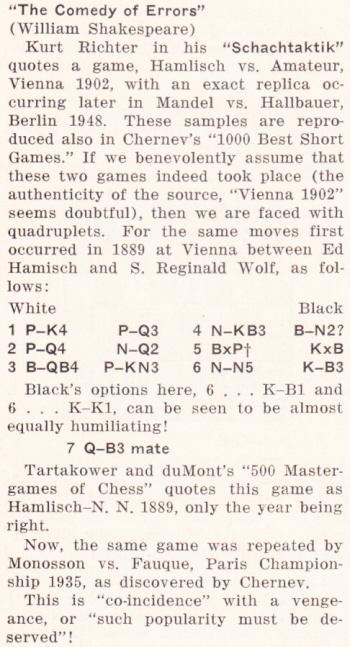

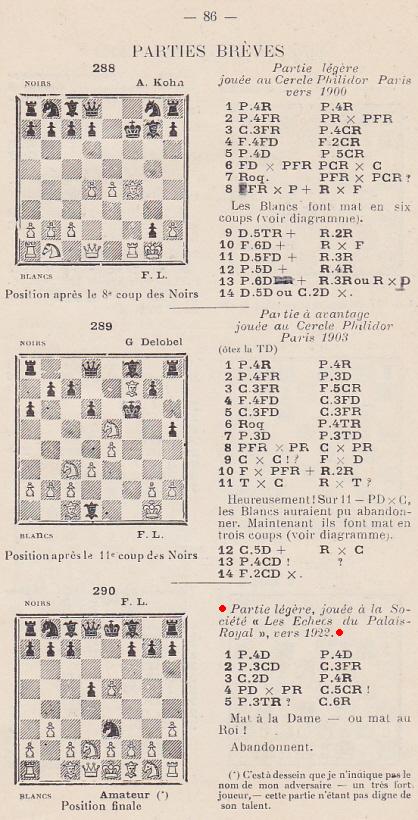

7921. Monosson v Fauque

Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) observes that when the familiar brevity between Léon Monosson and Maurice Fauque in the 1935 Paris championship was published on page 16 of L’Echo des Echecs, November 1935 it was indicated by the winner that the game had lasted five minutes:

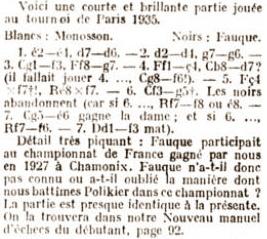

Noting the misspelling of Black’s name, Mr Thimognier comments that although Fauque finished last in the tournament he had participated in the French championship in 1927, 1928 and 1930. A further cutting forwarded to us is the game’s appearance in André Chéron’s column in the Feuille d’Avis de Lausanne, 11 January 1936:

Regarding the famous miniature mentioned in the final paragraph, Chéron v Polikier, Chamonix, 1927, we add that according to a report by Monvoisin in La Liberté, 26 September 1927 (reproduced on pages 722-723 of the September 1927 L’Echiquier) Polikier’s forename was Miroslar. He appeared, with Alekhine, in a group photograph on page 345 of the August 1975 BCM; see too page 544 of the December 1975 issue. When Chéron v Polikier was given on page 21 of 1000 Best Short Games of Chess (New York, 1955) by Irving Chernev it was unimpressively introduced as follows:

‘The story goes that when Monsieur Polikier lost this game, he swore never to play another game of chess again as long as he lived!’

It was by no means the end of his playing career.

Returning to Monosson v Fauque, we conclude by showing the discussion conducted by Walter Korn on page 332 of the November 1963 Chess Review:

See pages 4-5 of Chernev’s Best Short Games book.

7922. Rosanes v Anderssen (C.N.s 7913 & 7919)

From Peter Anderberg (Harmstorf, Germany):

‘The first publication of Anderssen’s win was probably on page 366 of Dufresne’s column in Ueber Land und Meer in March 1863:

Anderssen himself contributed a section to Dufresne’s Anthologie der Schachaufgaben (published in 1864 according to the title page, and with a preface dated September 1863) under the title “Analytische Glossen zu verschiedenen Eröffnungen mit Belegen aus wirklich gespielten Partieen” (pages 186-204). On pages 197-199 Anderssen gave the score of the game in question, but not his opponent’s name. The following comes from the bottom of page 198:

“die hier zunächst eingeschaltete Partie, in welcher der Verfasser im Kampfe mit dem nämlichen Gegner, wie in der zuvor mitgetheilten, wiederum die Vertheidigung leitete ...”

This refers to another game, on page 193, where Anderssen called his opponent “einen Matador des akademischen Schachzirkels zu Breslau”. (The academic chess club was mentioned on page 68 of the January 1861 Deutsche Schachzeitung, where S. Mieses and Rosanes were named as members of the board.)

The first appearance of Rosanes’s name in connection with the game seems to be in G.R. Neumann’s Leitfaden für Anfänger im Schachspiel. The book was published in Berlin in 1865 according to the title page but had already been mentioned on page 304 of the Neue Berliner Schachzeitung, October 1864. The score was given on pages 64-65 under the heading “Rosanes-Anderssen”. Neumann confirmed this in the Neue Berliner Schachzeitung, October 1865, page 319, with an explanation of Dufresne’s mistake.

In short, there is no doubt that Rosanes was Anderssen’s opponent.’

Mr Anderberg has provided all the pages referred to above, and we have incorporated them into a feature article, Rosanes v Anderssen, Breslau, 1863.

7923. Kurt Richter

Further to the discussion in C.N.s 7875 and 7909 on the removal of Jewish masters’ names from Kurt Richter’s book Kombinationen, Alan McGowan (Waterloo, Canada) has prepared a list of the Jewish players whose names were in the games index of the Deutsche Schachblätter during the period 1934-39. (Richter took over the editorship in January 1934.)

1934: Botvinnik, Fine, Flohr, Frydman, Em. Lasker, Levenfish, Nimzowitsch, Reshevsky, Spielmann, Tarrasch, Tartakower;

1935: Botvinnik, Flohr, Kolisch, Em. Lasker, Lilienthal, Najdorf, Nimzowitsch, Reshevsky, Spielmann, Tarrasch;

1936: Botvinnik, Fine, Flohr, Frydman, Kashdan, Levenfish, Reshevsky, Spielmann, E. and L. Steiner, Tartakower;

1937: Fine, Flohr, Reshevsky, Spielmann, E. and L. Steiner;

1938: Fine, Gunsberg, Janowsky, Réti, Tartakower;

1939: none.

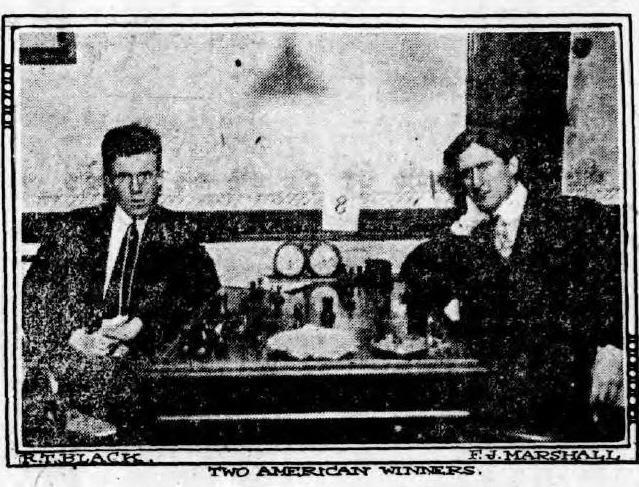

7924. Black and Marshall

John Blackstone (Las Vegas, NV, USA) notes a photograph of Roy T. Black and Frank J. Marshall in the 13 March 1910 issue of the New York Herald:

The occasion was the United States versus Great Britain cable match on 11 and 12 March, a ten-board contest in which Black and Marshall were the only victors on the American side.

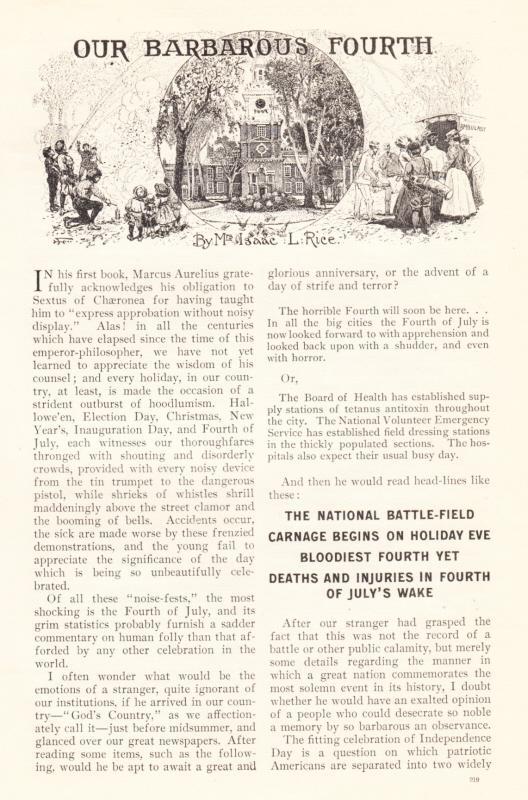

7925. Mrs I.L. Rice

Mr Blackstone also points out an article about I.L. Rice’s wife on page 7 of the New York Sun, 3 February 1907.

Among her writings is an article entitled ‘Our Barbarous Fourth’ on pages 219-226 of The Century Magazine, June 1908. The first page:

For further information about her, see Professor Isaac Rice and the Rice Gambit.

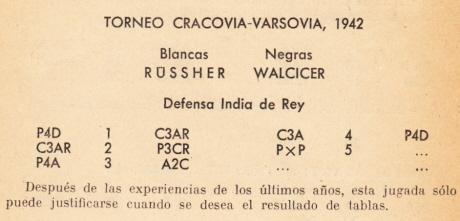

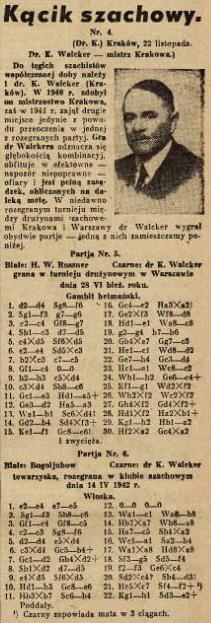

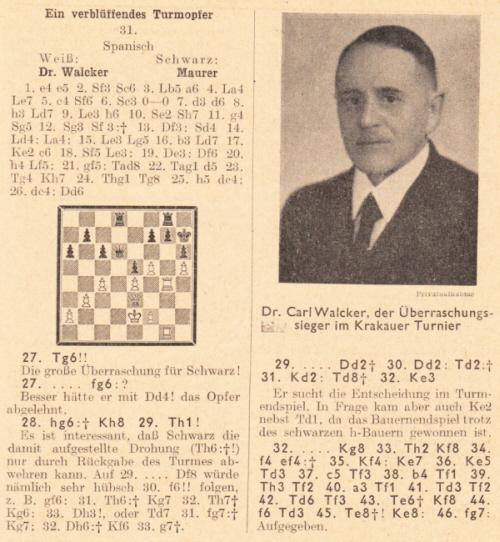

7926. A 1942 brilliancy

From page 278 of Gran Ajedrez by A. Alekhine (Madrid, 1947):

1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 g6 3 c4 Bg7 4 Nc3 d5 5 cxd5 Nxd5 6 e4 Nxc3 7 bxc3 c5 8 Bc4 O-O 9 h3 cxd4 10 cxd4 Nc6 11 Be3 Qa5+ 12 Bd2 Qa3 13 Rb1 Nxd4 14 Bb4 Nxf3+ 15 Kf1

Black played 15...Be6, and the game continued 16 Be2 Qxa2 17 Bxf3 Rfd8 18 Qe1 Rac8 19 g4 b6 20 Bxe7 Bc3 21 Qc1 Rd2 22 Bh4 Bd4 23 Qe1 Rcc2 24 Rh2 Bc4+ 25 Kg1 Rxf2 26 Rxf2 Rxf2 27 Bxf2 Bxf2+ 28 Qxf2 Qxb1+ 29 Kh2 Qa2 30 Qxa2 Bxa2 31 White resigns.

Our translation of Alekhine’s notes was given on pages 174-175 of 107 Great Chess Battles (Oxford, 1980), and below is a comment of ours on the game (see page 202 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves):

Few combinations are unique, and there are often ‘variations on a theme’. A strange example is the so-called ‘Game of the Century’ won by the 13-year-old Fischer against Donald Byrne in the 1956 Rosenwald Trophy Tournament. It was a Grünfeld Defence, the climax to which came when Black ignored the attack on his queen by the white queen’s bishop and played ...Be6, with overwhelming threats to the white king at f1. Yet all that is exactly what also happened in the [above] game, played the year before Fischer was born.

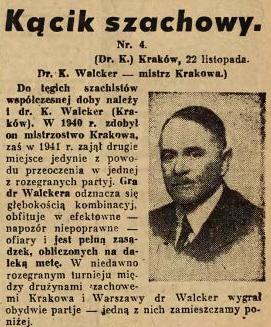

Now, Henryk Konaszczuk (Zabrze, Poland) informs us that he has found the game on page 3 of Goniec Krakowski, 22 November 1942. It was played in Warsaw on 28 June 1942 in a match between Warsaw and Cracow. The players’ names were H.W. Russner and K.Walcker, and not Rüssher and Walcicer. K. Walcker won the championship of Cracow in 1940 and came second in 1941.

The other score in the column was a friendly game played in the Cracow Chess Club:

Efim Bogoljubow – K. Walcker

Cracow, 14 April 1942

Giuoco Piano

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 c3 Nf6 5 d4 exd4 6 cxd4 Bb4+ 7 Bd2 Bxd2+ 8 Nbxd2 d5 9 exd5 Nxd5 10 Qb3 Be6 11 Qxb7 Ncb4 12 O-O O-O 13 Rac1 Rb8 14 Qxa7 Ra8 15 Qc5 Nxa2 16 Ra1 Nab4 17 Rxa8 Qxa8 18 Ng5 Nf4 19 f3 Bxc4 20 Nxc4 Nbd3 21 Qxc7 Ne2+ 22 Kh1

Black announced mate in three moves.

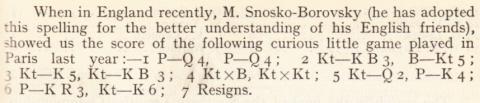

7927. Gibaud v Lazard (C.N. 7904)

Below is the news item quoted in C.N. 7904 from page 221 of the June 1921 BCM:

The text appeared in the ‘Colonial and Foreign News’ section, of which the Editor was apparently P.W. Sergeant (see page 396 of the October 1922 BCM).

Our earlier item included a Chéron cutting which referred to page 86 of Lazard’s book Mes problèmes et études d’échecs (Paris, 1929). That page is shown below, courtesy of Alain Biénabe (Bordeaux, France):

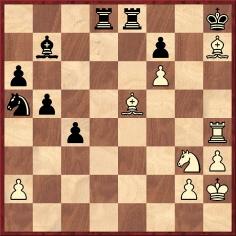

7928. Anderssen and Alekhine (C.N.s 4353 & 7917)

In the Anderssen v Zukertort finale, an interesting possibility deserves mention.

In this position (after 1 Bxg6 Qxe5 2 Bxh7+ Kh8 3 Bxe5 Rfe8) Alekhine described 4 Bc3 (‘!!’) as ‘a profound move’. However, White can leave his queen’s bishop en prise and force mate with 4 Nf5.

7929. 90%

In 1936 which prominent master estimated at 90% Euwe’s chances of retaining the world championship in his return match against Alekhine?

7930. Walcker (C.N. 7926)

Peter Anderberg (Harmstorf, Germany) notes that according to page 61 of the 1 April 1941 issue of Deutsche Schachblätter Walcker’s forename was Carl:

The information in C.N. 7926 about Walcker’s results in

the 1940 Cracow championship (first place) and 1941

event (second place) was taken from page 3 of Goniec

Krakowski, 22 November 1942:

However, Mr Anderberg also mentions that according to page 60 of the 1 April 1941 issue of Deutsche Schachblätter Walcker did win that year’s Cracow championship (with 7½ points out of 9, half a point ahead of Mross). Page 11 of the 1 January 1942 issue of the German magazine reported that the subsequent championship had been won by Mross with a clean score of seven wins and that Walcker had finished equal third with 4½ points.

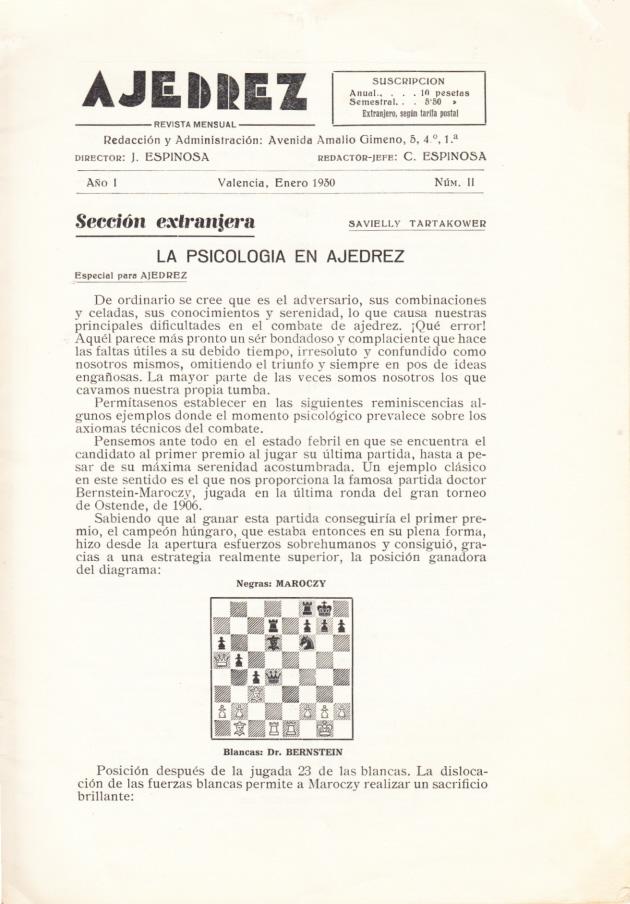

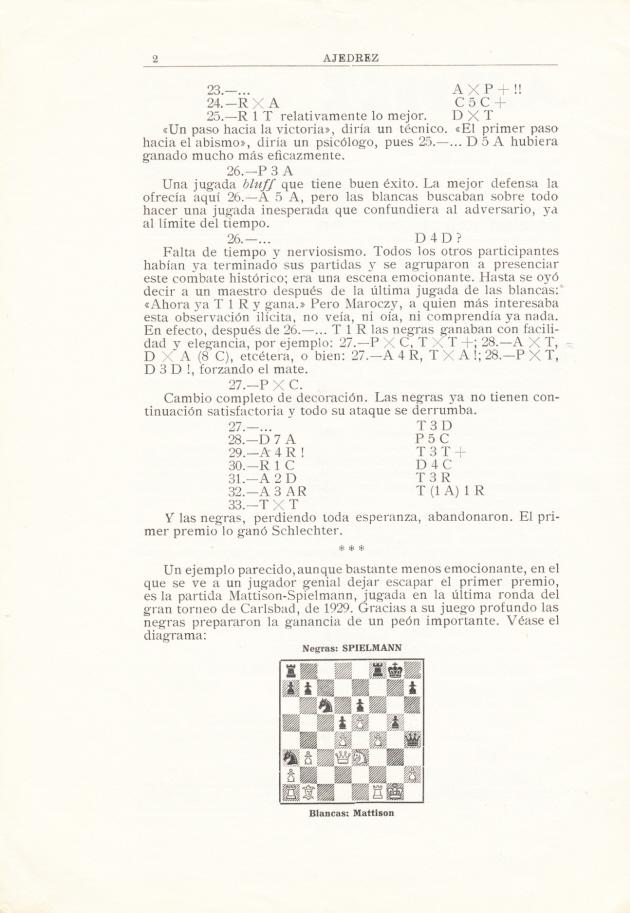

7931. Psychology

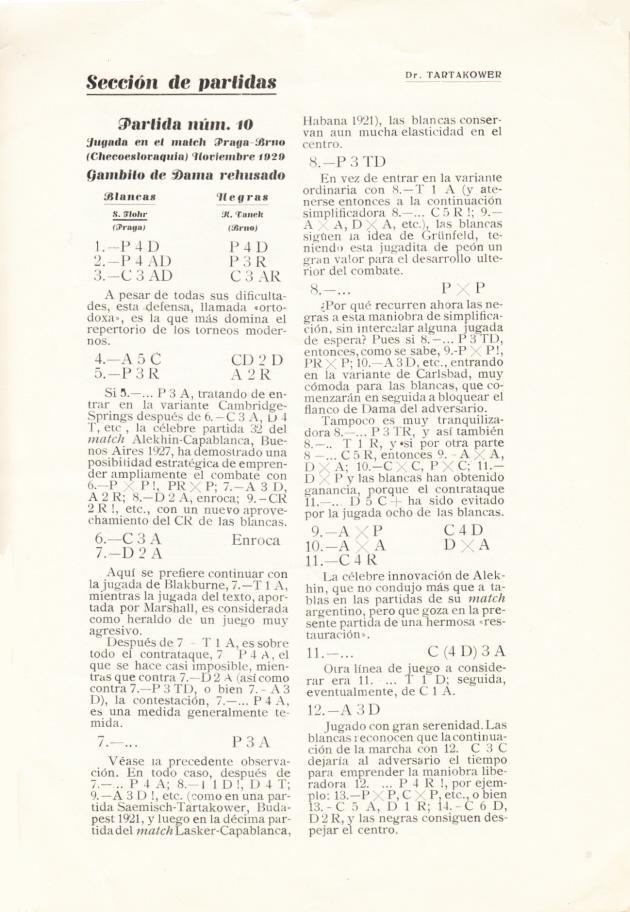

Tartakower was a prolific contributor to the magazine Ajedrez

(1929-30). An annotated game was given in C.N. 7918, and

below is an article on psychology in chess, on pages 1-4

of the January 1930 issue:

Our latest feature article is Chess and Psychology.

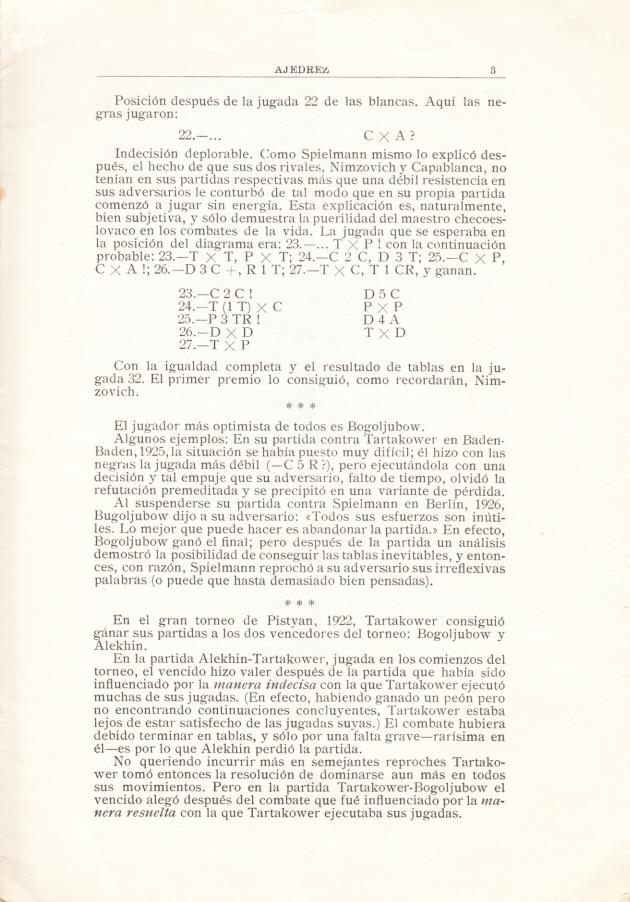

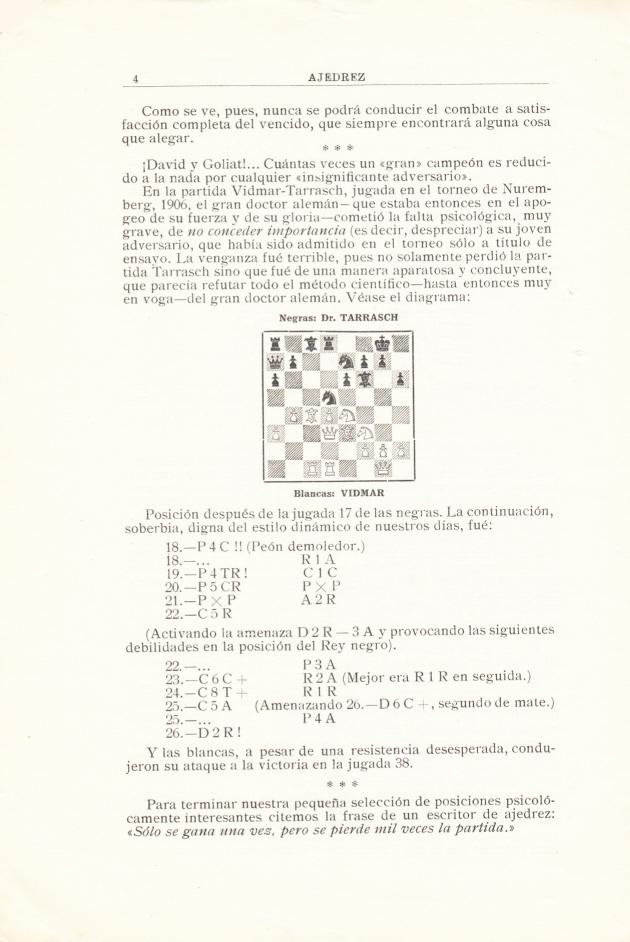

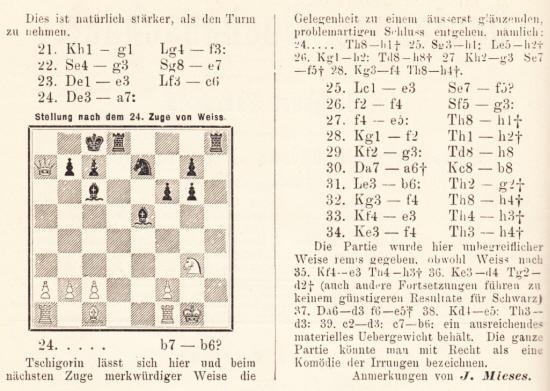

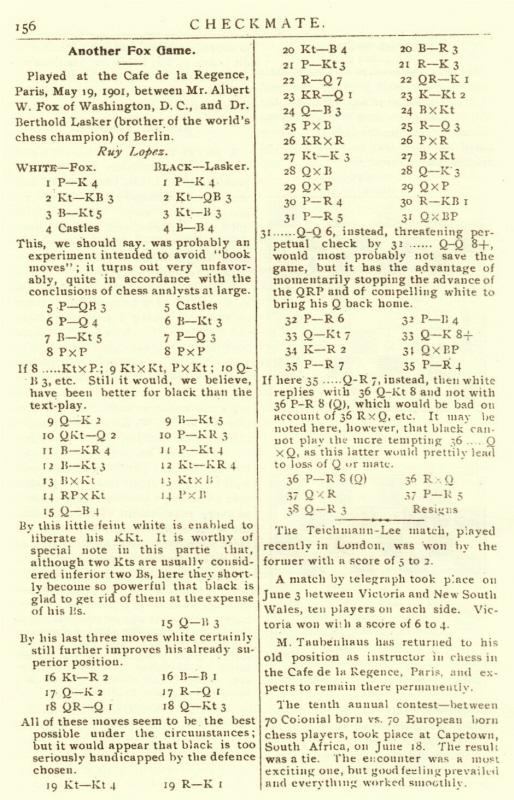

7932. Schiffers v Chigorin

From page 23 of Chess Review, January 1939 (Irving Chernev’s column ‘Would You Have Seen It?’):

Instead of 24...b6, Chigorin could have forced mate with

24...Rh1+ 25 Nxh1 Bh2+, etc., but was Chernev correct to

state that the position had ‘very often’ been published as

a brilliant win by Chigorin? Citations are sought.

‘This is a worthy candidate for the title of Greatest Combination That Was Never Played’, suggested Andy Soltis on page 12 of the December 1990 Chess Life. Apart from writing that the game ended with perpetual check, he had an incorrect venue (Berlin) twice and an incorrect date (1987) once. Berlin was also given in various editions of Renaud and Kahn’s book L’art de faire mat (The Art of the Checkmate).

Who discovered the missed win? Below is one claim, on page 210 of The Art of Chess by James Mason (London, 1905), where the diagram lacks a white pawn on c2:

However, page 264 of the July 1897 BCM stated that ‘in the chess column of the Morning Post Mr Fison points out that Black actually had at this point a beautiful mate in five moves’, whereas the unsigned annotations on page 121 of the July 1897 American Chess Magazine reported that the brilliant finish was ‘pointed out by Mr Schiffers’.

Deutsches Wochenschach and the Deutsche Schachzeitung mentioned that the mating combination could also have been played on the following move (after 25 Be3):

Deutsches Wochenschach, 20 June 1897, page 202

Deutsche Schachzeitung, July 1897, page 204

On pages 75-76 of Schachjahrbuch 1897 by Ludwig Bachmann (Ansbach, 1898) the game-score was slightly shorter (Chigorin was said to have played ...b6 at move 22), and the date of the game was given as 21 May 1897. That information is contradicted by page 10 of the booklet Chigorin v Schiffers 1897 by W.G. Povarov (Nottingham, undated), which reported that the game was drawn after 34 Kf4, was played on 5 (17) May 1897 and was published in the St Petersburger Zeitung of 12 (24) May 1897. Can a reader supply the score as published in the Zeitung?

Finally, the ...Rh1+ brilliancy was indeed played, although only in a subsequent display of living chess. This report comes from pages 262-263 of the July 1897 BCM:

‘An extraordinary exhibition of chess with living pieces took place at St Petersburg on 5 June, which drew an immense crowd to the velodrome of the St Petersburg Cycling Club. The game selected to be played was the 13th of the match between Chigorin and Schiffers, in which, as we have already shown, the former at his 23rd move had a beautiful mate on in five moves. It was intended to illustrate the episode in the Hungarian uprising of 1849 when the dictator Georgey [Görgey], after his unfortunate battle at Világos, was taken prisoner, and surrendered to the Russians, and more or less the costumes adopted called to mind the nationalists of both sides. The large open space in the velodrome was laid out as a gigantic chess board, whose squares were clearly distinguished by sprinkled white sand and dark material. Its size was about 5,000 square metres, and each piece was represented by from three to eight persons. Thus, the king and queen were on horseback, surrounded by servants, pages and warriors. Each knight was represented by three armed riders; the bishops (as we so absurdly call them) consisted of six young ladies clothed in tasteful bright and dark red dresses; the castles were nearly ten feet high, and on their ramparts were cannons and troops; finally, each pawn was embodied in five foot-soldiers. This combination of persons for each piece must have been somewhat confusing, but all seems to have gone off well. The conductors were Chigorin and Schiffers, the former commanding the Russian and the latter the Hungarian army. Each move was heralded by a horn signal, which set the respective divisions of forces in motion.’

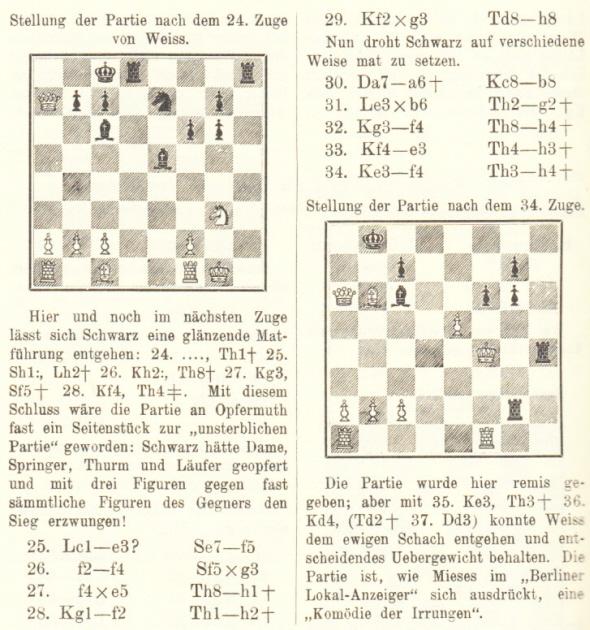

7933. Santasiere on Chigorin

From pages 4-5 of the posthumous book My Love Affair With Tchigorin by A.E. Santasiere (Dallas, 1995):

‘Only a lover of the hero should be privileged to write this book, for Love calls unto Love.

My love affair with Tchigorin began when I carefully studied his monumental 22-game match with Dr Tarrasch ... Tchigorin was the great creative artist, the poet who craved only freedom to dream. He also was a great teacher of and for what he believed in. He was so much a lover, that I truly believe that in the world of chess, he was a saint.’

The 100 cursorily annotated games include two (games 54 and 71) in which Black is named as ‘Beratende’. This misapprehension is familiar from page 135 of Modern Chess Strategy by L. Pachman (London, 1963), translated by Alan S. Russell, where a game was headed ‘Beratende-Nimzowitsch (1921)’. Beratende is a German word for consultants/allies.

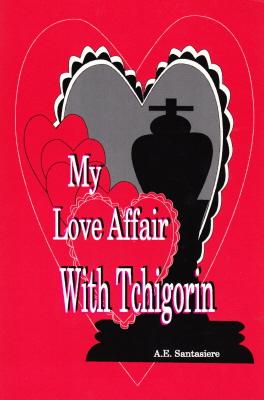

7934. A.W. Fox v B. Lasker

To the games in The Fox Enigma Bruce Monson (Colorado Springs, CO, USA) adds the following from page 156 of Checkmate, September 1901:

Albert Whiting Fox – Berthold Lasker

Paris, 19 May 1901

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 Nf6 4 O-O Bc5 5 c3 O-O 6 d4 Bb6 7 Bg5 d6 8 dxe5 dxe5 9 Qe2 Bg4 10 Nbd2 h6 11 Bh4 g5 12 Bg3 Nh5 13 Bxc6 Nxg3 14 hxg3 bxc6 15 Qc4 Qf6 16 Nh2 Bc8 17 Qe2 Rd8 18 Rad1 Qg6 19 Ng4 Re8 20 Nc4 Ba6 21 b3 Re6

22 Rd7 Rae8 23 Rfd1 Kg7 24 Qf3 Bxc4 25 bxc4 Rd6 26 R1xd6 cxd6 27 Ne3 Bxe3 28 Qxe3 Qe6 29 Qxa7 Qxc4 30 a4 Rf8 31 a5 Qxc3 32 a6 c5 33 Qb7 Qe1+ 34 Kh2 Qxf2 35 a7 h5 36 a8Q Rxa8 37 Qxa8 h4 38 Qa3 Resigns.

7935. Capablanca and Boleslavsky

Further to C.N.s 7893 and 7903, Vitaliy Yurchenko (Uhta, Komi, Russian Federation) refers to pages 107-117 of Kapablanka Vstrechi c Rossiey by A.I. Sizonenko (Moscow, 1988), which comprises a chapter on the Cuban’s visit to Ukraine in 1936. Our correspondent notes, in particular, a brief paragraph on page 114:

Translation: ‘One of these games [played during the simultaneous exhibitions in Dnepropetrovsk] Capablanca lost to a young first-grade player I. Boleslavsky, a future grandmaster.’

As recorded on pages 193-194 of The Unknown Capablanca by David Hooper and Dale Brandreth (London, 1975), Capablanca gave 30-board displays in Dnepropetrovsk on 22 and 23 June 1936.

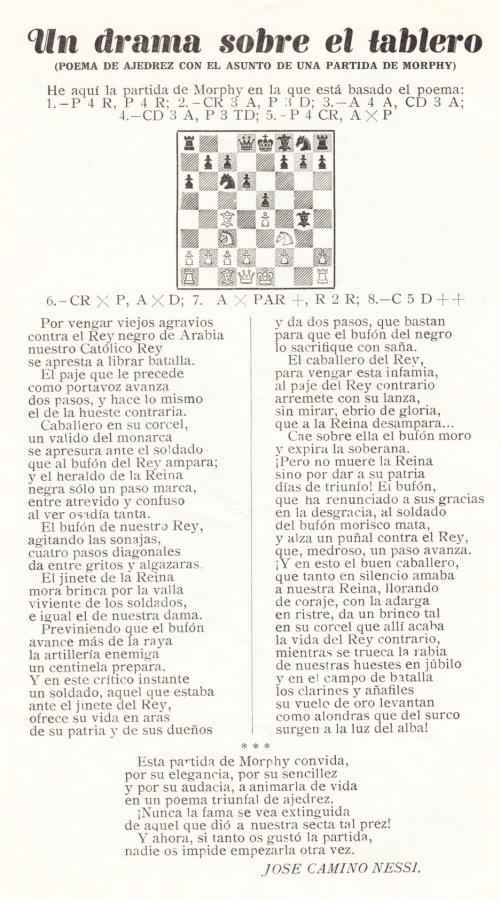

7936. A poem by José Camino Nessi

From page 70 of Ajedrez, March 1930:

How did the game (1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 d6 3 Bc4 Nc6 4 Nc3 a6 5 g4 Bxg4 6 Nxe5 Bxd1 7 Bxf7+ Ke7 8 Nd5 mate) come to be ascribed to Morphy?

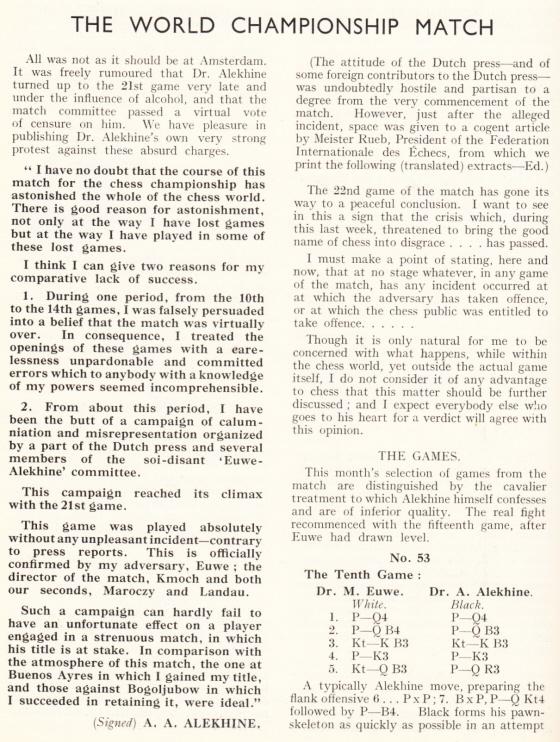

7937. A statement by Alekhine

Below is page 124 of CHESS, 14 December 1935:

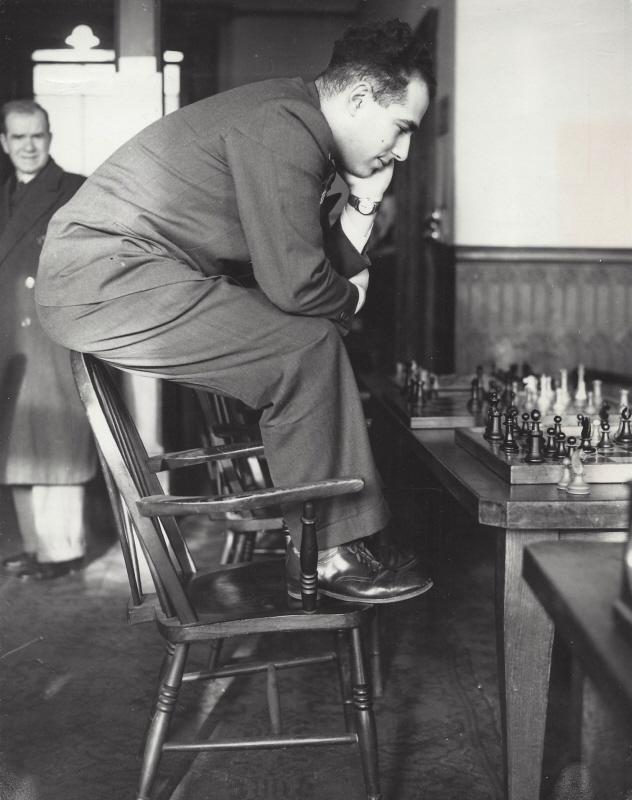

7938. Hans Berliner

Ross Jackson (Raumati South, New Zealand) shows this photograph which he owns:

The label overleaf, dated 30 December 1952, states that the picture was taken at the White Rock Pavilion, Hastings. Berliner participated in the Premier Reserves, Major Section, finishing second to R. Bordell (BCM, February 1953, page 36).

7939. Nimble expurgation (C.N. 6832)

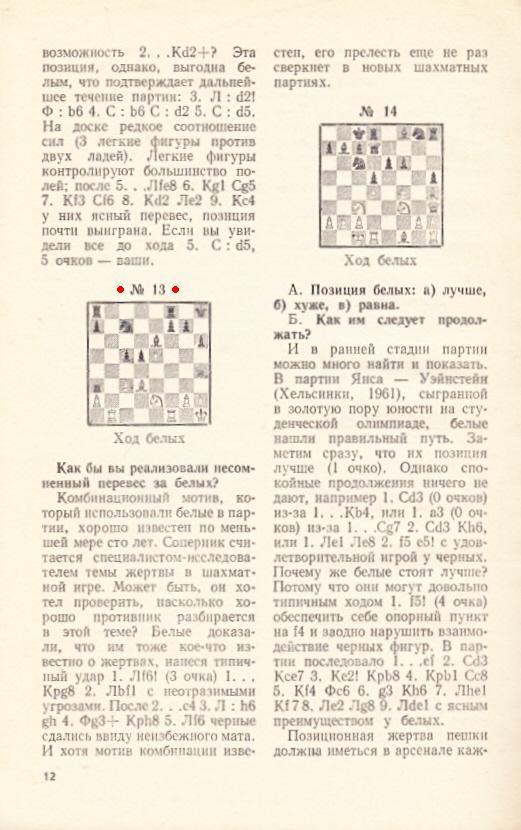

C.N. 6832 discussed the removal of Lubomir Kavalek’s name from the treatment of position 24 in Zahrajte si šachy s velmistry by Vlastimil Hort and Vlastimil Jansa (Prague, 1975), although he was named in the Russian translation (Moscow, 1976).

Vitaly A. Komissaruk (Kasan, Russian Federation) adds that there were deletions in the Russian edition:

‘The text for position 86 has a venue and a year, but White’s name is omitted (Korchnoi). The venue, year and name of a player were removed from positions 104 (Korchnoi), 135 (Korchnoi) and 203 (Sosonko).

Position 13 did not name either player, the venue or the year. What was the game in question?’

The game was Hort v Shamkovich, Moscow, 1962, as stated

on page 21 of the original Czech edition of Hort and

Jansa’s book.

7940. Slonimsky

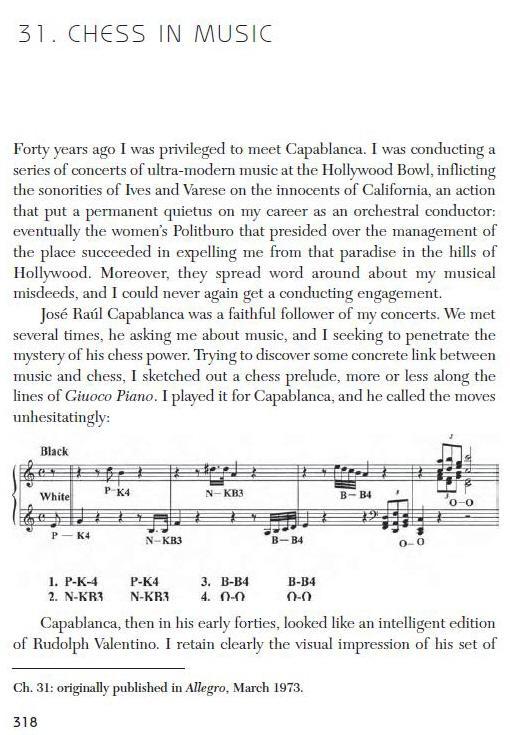

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) draws attention to chapter 31 (pages 318-322) of volume four of Nicolas Slonimsky: Writings on Music (New York and London, 2005).

The chapter also includes a discussion of Prokofiev.

7941. The Ponziani Opening

Prompted by Magnus Carlsen’s game with 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 c3 against Pentala Harikrishna in Wijk aan Zee on 15 January 2013, we list some theoretical articles on the Ponziani Opening in old chess magazines:

- Article (with 3...f5 and 3...Nf6) on pages 309-312 of the Deutsche Schachzeitung, August 1854;

- Follow-up feature on pages 337-339 of the Deutsche Schachzeitung, September 1854;

- ‘Queen’s Bishop’s Pawn Opening in the King’s Knight’s Game’ by J. Löwenthal on pages 225-234 of the Chess Monthly, August 1860;

- ‘Englische Springerpartie’ (with 3...f5) by E. von Schmidt on pages 273-275 of the Deutsche Schachzeitung, September 1879;

- ‘The Queen’s Bishop’s Pawn Game’, including two articles by W.N. Potter, on pages 453-455 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 8 April 1885;

- ‘Staunton’s Opening’ (with 3...d5 4 Qa4) on page 74 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 22 July 1885, from Land and Water;

- ‘Englisches Springerspiel’ (with 3...Nf6 4 d4) by C. Schlechter on pages 129-130 of the Deutsche Schachzeitung, May 1912;

- ‘Zur Theorie des englischen Springerspiels’ by J. Krejcik on pages 392-394 of the Wiener Schachzeitung (Supplementheft), 1912;

- ‘A Note upon a “Ponziani” Variation’ by H.M. Prideaux, on page 272 of the BCM, August 1916;

- ‘Zur Ponziani-Eröffnung’ by S. Alapin on page 97 of Deutsches Wochenschach, 28 April 1918;

- ‘Random Suggestions’ by S. Mlotkowski on page 134 of the BCM, May 1918;

- ‘Ponziani Opening’ by S. Mlotkowski on pages 257-259 of the BCM, September 1918;

- ‘Theoretisches zum Englischen Springerspiel’ (with 3...d5 4 Qa4) by C. von Bardeleben on pages 131-132 of the Deutsches Schachzeitung, June 1923.

7942. Chigorin and love

Further to C.N. 7933, which concerned A.E. Santasiere’s book My Love Affair With Tchigorin, a remark by R.E. Fauber about Chigorin is given below, from page 272 of the Chess Digest Magazine, December 1973:

‘He died, mourned by all in 1908. Emanuel Lasker in an uncharacteristic show of emotion declared simply, “I love Mikhail Chigorin”.’

Fauber wrote similarly on page 90 of his book Impact of Genius (Seattle, 1992), but what more is known about such a remark by Lasker?

7943. Dus-Chotimirsky v Lasker

From page 300 of Chess Review, October 1950, in an article ‘The Triumph of Unreason’ by Hans Kmoch and Fred Reinfeld:

‘The following story, no less delightful for probably being apochryphal [sic], conveys Chotimirsky’s qualities admirably: in the St Petersburg tournament of 1909, Chotimirsky defeated both Emanuel Lasker and Rubinstein .. and managed to come 13th in a field of 19. Regarding his win against Lasker, it is said that he infuriated the world champion by pretending to be deeply absorbed in a Japanese translation of Also Sprach Zarathustra during their game.’

The article was reproduced in Reinfeld’s The Treasury of Chess Lore (New York, 1951); see page 161.

The anecdote also appeared (‘There is a story to the effect that ...’, but with no mention of Japanese) on page 131 of another Reinfeld book, The Great Chess Masters and Their Games (New York, 1952). And again on page 82 of a further Reinfeld work, How to Play Winning Chess (New York, 1962):

‘The story is told that during the course of his game with Emanuel Lasker (the world champion) in the St Petersburg tournament of 1909, Chotimirsky read a Japanese translation of Thus Spake Zarathustra. Legend has it that the world champion was so incensed at the young man’s studied insolence that he lost the game. Whatever the cause of his defeat, Lasker was singularly reticent about this encounter.’

Two or three years later Lasker made some remarks about Dus-Chotimirsky in an item in the New York Evening Post, as related on page 67 of the March 1912 American Chess Bulletin, but there was no reference to their game in St Petersburg or to the episode so flimsily recounted by Reinfeld (‘It is said that ...’, ‘There is a story to the effect that ...’, ‘The story is told that ...’ and ‘Legend has it that ...’).

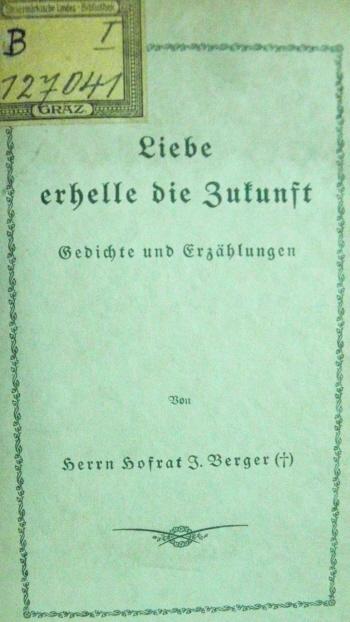

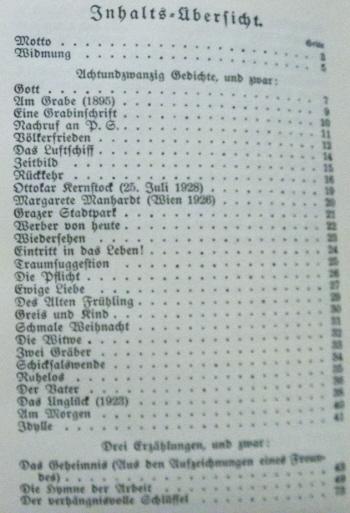

7944. Poetry anthology by Berger

From Michael Negele (Wuppertal, Germany) comes information about a posthumous anthology of verse by Johann Berger, Liebe erhelle die Zukunft (Graz, 1934):

7945. Scotch Game

Concerning the opening discussed in Kasparov, Karpov and the Scotch, below is a game from pages 200-201 of Probleme Studien und Partien by Johann Berger (Leipzig, 1914):

Dr E. v. Engel - Johann Berger

Occasion?

Scotch Game

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 exd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Nxc6 bxc6 6 e5 Qe7 7 Qe2 Nd5 8 c4 Ba6 9 f4 Qb4+ 10 Kd1 Bc5 11 h4 Nb6 12 b3

12...Bxc4 13 bxc4 Bd4 14 Na3 Bxa1 15 Nc2 Qb1 16 Na3 Qg6 17 Nc2 Na4 18 Qf3 Nc3+ 19 Kd2 Nxa2 20 h5 Qf5 21 g4 Bc3+ 22 Qxc3 Qxf4+ 23 Qe3 Qxe3+ 24 Nxe3 Nxc1 25 Kxc1

25...O-O-O 26 c5 d6 27 Ba6+ Kd7 28 cxd6 cxd6 29 exd6 Kxd6 30 Nf5+ Ke5 31 Nxg7 Kf6 32 h6 Rd4 33 Be2 Rhd8 34 Nh5+ Kg6 35 Ng3 R8d5 36 Kb2 Rc5 37 Rh3 Rd2+ 38 Kb3 Re5 39 Bf1 Re3+ 40 Kc4 a5 41 Nf5 Rc2+ 42 Kd4 Rxh3 43 Bxh3 a4 44 Ne3 Rh2 45 White resigns.

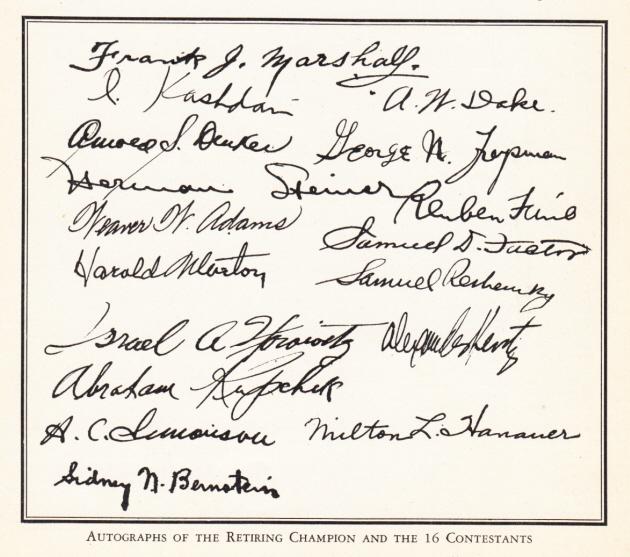

7946. US championship, New York, 1936

From page 131 of the June 1936 Chess Review:

A group photograph of the participants was reproduced in C.N. 7463.

7947. Memorably bad games

An article by G.H. Diggle from the August 1979 Newsflash and reproduced on page 50 of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984):

‘Every player, from a Grandmaster downwards, has at some time in his career produced (by his own standards) a memorably bad game. This is true whether he be Tartakower, who in 1910 crashed to Réti in 11 moves, or the Lincoln bottom board of 1922, who complained that he had “lost his queen about the third move and couldn’t seem to get going after that”. Anderssen in 1859 was once murdered by Max Lange, who on the 11th move announced mate in ten. A decade afterwards Steinitz was crumpled up by Winawer with as little ceremony, and remained for a time in a sort of stupor, muttering in his beard “Can Winawer really do this to me?”. And that fine player R.F. Combe (British Champion, 1946) once created a record by losing in an Olympiad as follows: 1 P-Q4 P-QB4 2 P-QB4 PxP 3 N-KB3 P-K4 4 NxP?? Q-R4ch 5 White resigns. (In fairness, this was played immediately on top of an exhausting 12-hour struggle in the previous round.)

Needless to say, the Badmaster himself has not failed posterity in this field. In a London Banks League Match in 1949, he perpetrated the following as Black: 1 P-K4 P-K4 2 N-QB3 N-KB3 3 B-B4 NxP 4 BxPch KxB 5 NxN N-B3 6 Q-B3ch K-N1?? 7 N-N5 Resigns. His opponent (Mr D. Davids of the Midland) had the decency to look almost as embarrassed as the BM himself. The game had only lasted some two minutes, and as we had started almost before time, the match itself was scarcely under way; and members of both teams were still busy setting out their stalls, heading up their score-sheets, pretending they had forgotten the names and initials of habitual opponents (an indispensable part of Banks League etiquette), testing their clocks and surreptitiously exchanging them for a better pair on the next board, etc. etc. All this gave the discomfited Badmaster a curious sense of going to bed when everyone else was getting up; worse still, when he “crept like snail, unwillingly to his Match Captain” and feebly reported that he was already defunct, he received the impatient reply: “Look, old man, it’s gone six – do stop playing the fool and get started.”

Recovering somewhat on his way home, the BM began to feel curious as to whether he could claim the inverted glory of being the pioneer of such an execrable miniature, or whether down the ages someone had “got in before him”. But all that he could find after long research was some “Advice to a young player” in the BCM of 1901, where virtually the same moves were given and his sixth move was called “a common blunder in this and similar positions”. If this was so, perhaps it gave rise to the famous early twentieth-century ragtime song: “Everybody’s doing it now!”. A “similar position” did occur again quite recently and was “mentioned in dispatches” by Mr Wood in his Daily Telegraph column.

Postscript (1984): However, much later the BM learned that the same moves occurred in Imbusch v Göring, Munich, 1899 and (except for 5...P-Q4 instead of 5...N-B3) in Schottländer v Edward Lasker (of all people). (Game-scores in Chernev’s 1000 Best Short Games of Chess, page 6, and pages 10-12 of Edward Lasker’s Chess Secrets respectively.)’

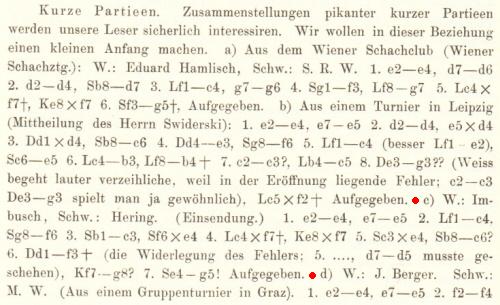

The move-order in the Combe game was discussed in C.N.s 4063 and 4099. Concerning the Imbusch game mentioned in G.H. Diggle’s postscript, we seek contemporary reports. Below is an extract from page 94 of the March 1901 Deutsche Schachzeitung, which named Black as Hering:

7948. Schiffers v Chigorin (C.N. 7932)

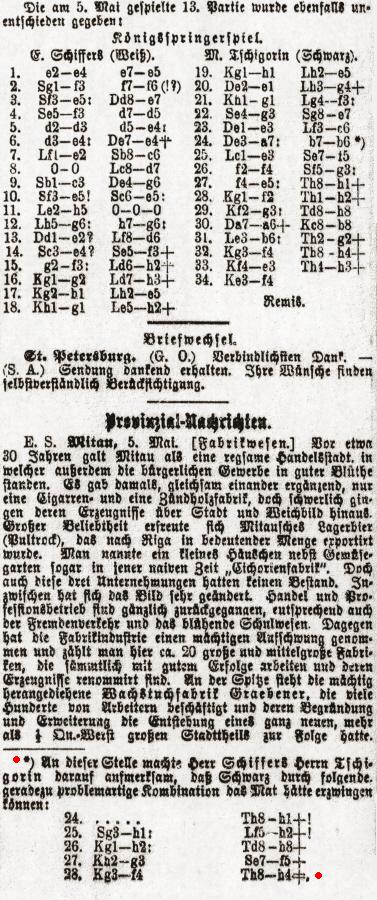

Responding to the request in C.N. 7932, Peter Anderberg (Harmstorf, Germany) supplies the Schiffers v Chigorin game-score as published in the St Petersburger Zeitung of 12 (24) May 1897, page 2:

It will be noted that Chigorin’s missed win was indeed pointed out by Schiffers.

7949. Euwe v computer

Charles Sullivan (Davis, CA, USA) submits a game which he believes has not previously been published:

Max Euwe – Sargon 2.5

Detroit, 29 October 1979

King’s Fianchetto Defence

1 e4 g6 2 d4 Bg7 3 g3 Nf6 4 Bg2 d6 5 Ne2 O-O 6 O-O e5 7 c3 c5 8 d5 b6 9 f4 Bb7 10 fxe5 dxe5 11 Nd2 Nbd7 12 a4 Qc7 13 Nc4 Rae8 14 Qb3 Ng4 15 a5 bxa5 16 Rxa5 a6 17 h3 Ngf6 18 g4 Rb8 19 Qa2 Rfe8 20 Ng3 (Mr Sullivan points out the possibility 20 g5 Nh5 21 Rxf7.) 20...Bf8 21 g5 Nh5 22 Nxh5 gxh5 23 h4 Nb6 24 Nxb6 Qxb6 25 Be3 Rbd8 26 b4 Rc8

27 Qf2 Qg6 28 bxc5 Rcd8 29 c6 Bc8 30 Bb6 Rd6 31 Bc7 Re7 32 Bxd6 Qxd6 33 Qf6 Qxf6 34 Rxf6 Bg7 35 Rf1 Ra7 36 d6 Be6 37 d7 Ra8 38 Rxa6 Rb8 39 c7 Rf8 40 d8(Q) h6 41 Rxe6 fxe6 42 Rxf8+ Bxf8 43 Qxf8+ Kxf8 44 c8(Q)+ Kg7 45 Qxe6 hxg5 46 hxg5 Kf8 47 Qf6+ Ke8 48 g6 Kd7 49 Bh3+ Ke8 50 Qf7+ Kd8 51 Qd7 mate.

Our correspondent comments:

‘I recorded the game while standing next to Euwe. It was played between rounds two and three of the Tenth North American Computer Chess Championship in Detroit. Both sides played a move every five to 15 seconds or so, and Euwe stood for the entire game, which lasted approximately 20 minutes. Although he had no difficulty dispatching the computer, I was struck by how carefully he seemed to play, certainly not making his moves at blitz speed.’

7950. Promotion to a bishop

From Robert John McCrary (Columbia, SC, USA):

‘What is the simplest or most sparse legal position, in terms of number of units and strength of material, in which the only winning move is promotion to a bishop? In 1969 I composed this pair of positions:

White wins with 1 b8(B). If 1 b8(N) Nf7+ 2 Kg6 Ng5.

Again, promoting to a bishop is the only winning move, although the defenses are different (beginning with 1...Ne7+ 2 Kf6 Kh7).

A related question concerns the simplest or most sparse legal position in which promotion to a bishop is the only way to draw (by self-stalemate.)’

7951. Fahrni in Augsburg

Page 155 of the May 1914 Deutsche Schachzeitung reported that on 27 March Hans Fahrni had given a simultaneous exhibition (+28 –4 =11) in Augsburg. No games were published, but two losses, both with unusual openings, were presented on pages 78-79 of Schachjahrbuch für 1914 II. Teil by L. Bachmann (Ansbach, 1914):

P. von Stetten – Hans Fahrni

Augsburg, 27 March 1914

Bishop’s Opening

1 e4 e5 2 Bc4 c6 3 Qh5 Qe7 4 Nf3 d6 5 d3 Nf6 6 Qh4 d5 7 exd5 cxd5 8 Bb3 Nc6 9 O-O h6 10 Re1 Bg4

11 Nxe5 Nxe5 12 Ba4+ Bd7 13 Nc3 Bxa4 14 Qxa4+ Nfd7 15 Bf4 f6 16 d4 g5 17 dxe5 Qb4 18 exf6+ Kd8 19 f7 Bc5

20 Bc7+ Kc8 21 Re8+ Kxc7 22 Nxd5+ Kd6 23 Nxb4 Rhxe8 24 Rd1+ Kc7 25 Qxd7+ Resigns.

M. Abrell – Hans Fahrni

Augsburg, 27 March 1914

Queen’s Fianchetto Defence

1 d4 b6 2 h3 Bb7 3 Nf3 Nf6 4 Nc3 e6 5 a3 d5 6 Bg5 Be7 7 Bxf6 Bxf6 8 e3 c5 9 Na4 Bc6 10 c4 O-O 11 Rc1 dxc4 12 b4 cxb4 13 axb4 b5 14 Nc5 a5 15 Qd2 a4 16 Ra1 Nd7 17 Be2 Nxc5 18 bxc5 Qa5 19 Qxa5 Rxa5 20 O-O Bd5 21 Rfc1 Bxf3 22 gxf3 a3 23 Rc3 b4 24 Rxc4 b3 25 Rb4 b2

26 Ra2 Raa8 27 Bd3 g6 28 f4 Be7 29 Rb3 Rfb8 30 Raxa3 Rxb3 31 Rxb3 Kg7 32 Bb1 g5 33 fxg5 e5 34 Rxb2 Ra4 35 Rb7 Bxg5 36 d5 Ra5 37 c6 Rxd5 38 c7 Rc5 39 Bf5 Resigns.

7952. Steinitz and anti-Semitism

David Nudelman (Hamden, CT, USA) is seeking information on a publication by Steinitz towards the end of his life about anti-Semitism in Vienna and elsewhere. In various Russian sources the title is given as ‘Мой ответ антисемитам в Вене и где бы то ни было’.

Pages 231-232 of The Steinitz Papers by Kurt Landsberger (Jefferson, 2002) gave an English translation of an article published in the ‘Berliner Anzeigung’ (sic – Anzeiger) of 20 March 1897 which quoted Steinitz as follows:

‘After every match I am always very excited and do not feel well, but it has never been as bad as in Moscow. I am, however, my own doctor; as a passionate Kneippianer I cure myself with cold water, which has always helped me. This time it took longer and I could not hold my thoughts together, which saddened me since I wanted to write my book “Judaism in Chess” as quickly as possible to combat anti-Semitism.’

The newspaper article added:

‘Steinitz had engaged a young Russian with language abilities as secretary since he wanted to dictate it simultaneously for German and English publication.’

The paragraph below comes from page 167 of the May 1897 BCM:

‘Mr Steinitz has been playing off-hand games at Vienna with Herr Schlechter, with about an even result. He is said to be now writing a book entitled “Das Judenthum im Schach” (“The Jewish Element in Chess”).’

A work of that title had been mentioned on page 122 of the April 1897 Deutsche Schachzeitung.

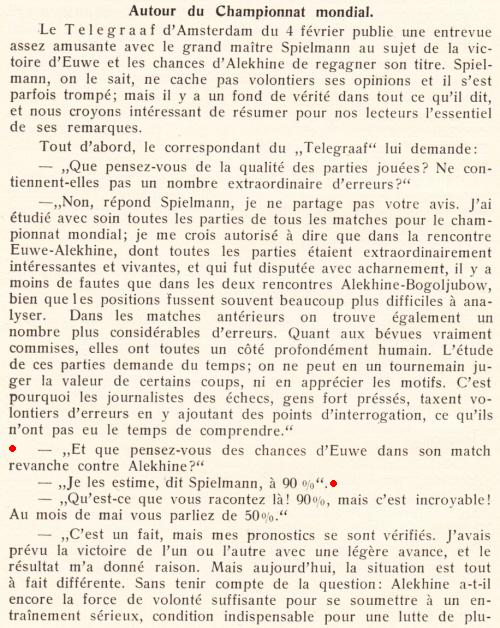

7953. 90% (C.N. 7929)

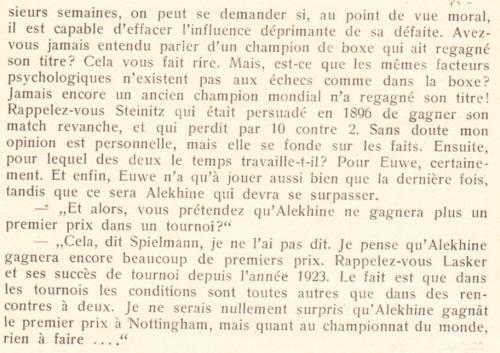

C.N. 7929 asked which prominent master estimated in 1936 that Euwe’s chances of retaining his world title against Alekhine were 90%. The answer is Rudolf Spielmann, as shown by an article on pages 68-69 of the May 1936 Schweizerische Schachzeitung:

7954. Punctuation

Two small points about old usage are mentioned briefly.

Books and magazines sometimes placed an exclamation mark or question mark in brackets to temper its force. For instance, the game Alekhine v Tylor, Margate, 1937 in Alekhine’s My Best Games of Chess 1924-1937 (London, 1939) had ‘7 P-B3?’ and ‘23 BxP(?)’.

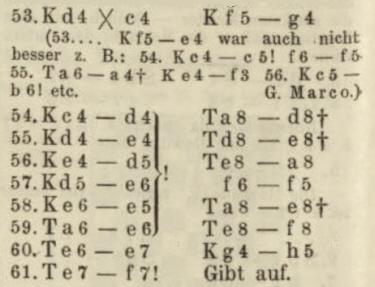

A century or so ago, particularly in German-language chess literature, it was common to spread an exclamation mark or question mark across two or more moves which comprised a manoeuvre or idea. An example is the conclusion of Maróczy v Marco, Monte Carlo, 1902 on page 36 of the January 1904 Wiener Schachzeitung:

7955. For

solving

In both positions below, which are over a century old,

it is White’s move.

| First column | << previous | Archives [102] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.