Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [101] | next >> | Current column |

7868. Spanish bibliography

Josep Alió (Tarragona, Spain) informs us of the recent publication of Nuevo Ensayo de Bibliografía Española de Ajedrez 1238-1938 by José A. Garzón, Josep Alió and Miquel Artigas.

The ‘NEBEA’ webpage provides not only ordering details but also a video presentation.

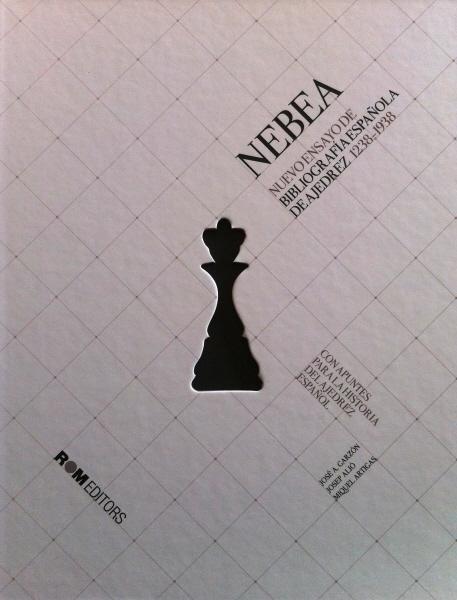

7869. Carlos

Torre Repetto

From Michael Negele (Wuppertal, Germany) comes page 244 of The Good Companion, May 1920:

The page has been added to our feature article Adams v Torre – A Sham?

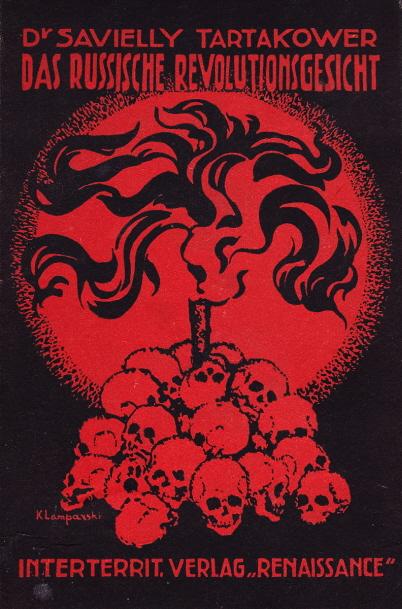

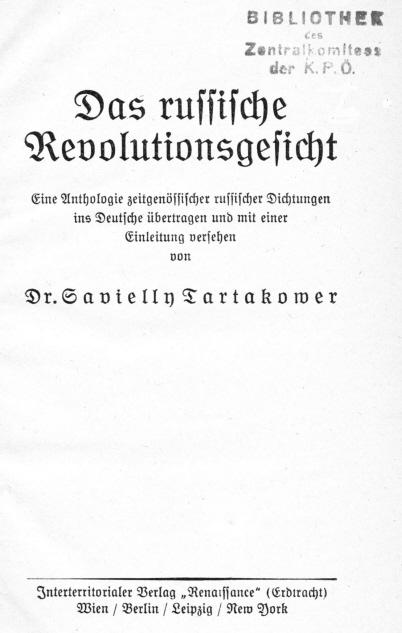

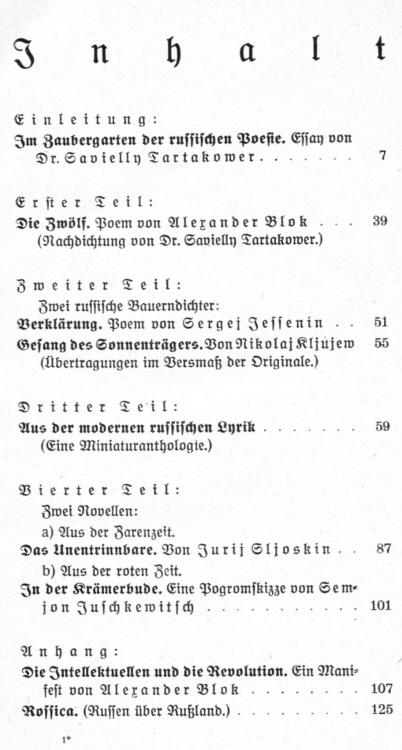

7870. Tartakower’s poetry (C.N.s 3787, 3833, 3863, 4089, 4278 & 4486)

A further contribution from Michael Negele concerns a non-chess book by Tartakower, Das russische Revolutionsgesicht (Vienna, 1923).

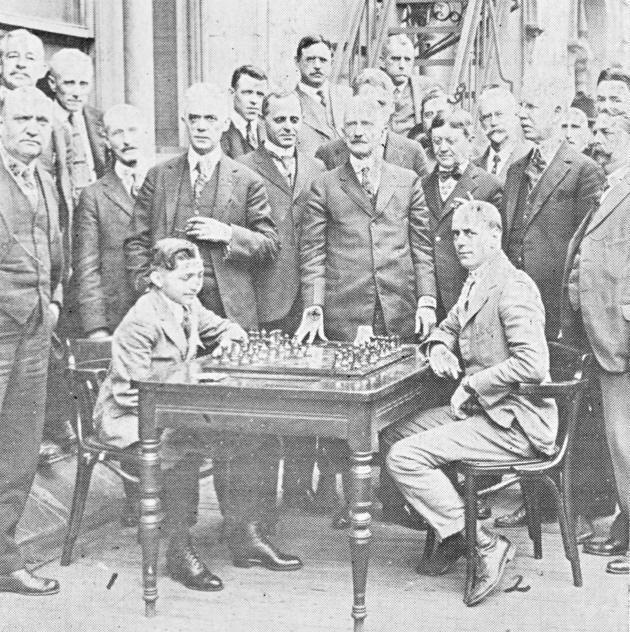

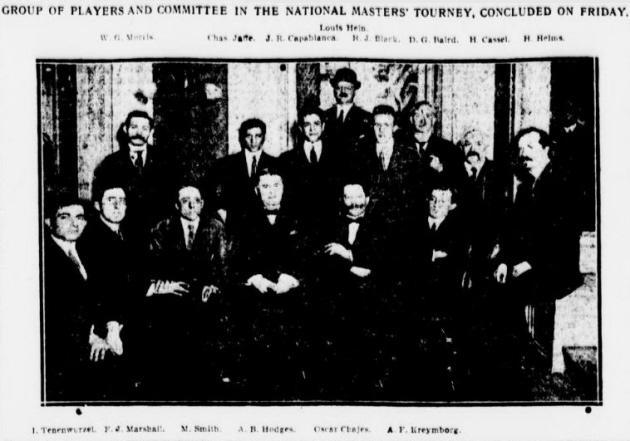

7871. New York, 1911

John Blackstone (Las Vegas, NV, USA) has drawn attention to this photograph on page 9 of section three of the New York Sun, 5 February 1911:

We should very much like to trace a copy of better quality.

7872. Of all the drugs

A familiar quote appears in the heading on page 19 of Combinations The Heart of Chess by Irving Chernev (New York, 1960):

‘For surely, of all the drugs in the world, Chess must be the most permanently pleasurable. Assiac’

Assiac’s remark can also be found countless times on the Internet but, to ask a rhetorical question, how many people have bothered to provide a source?

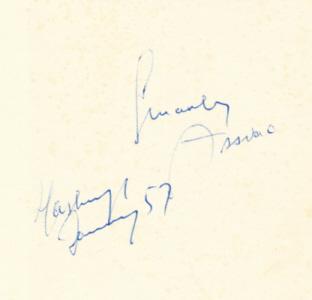

The words come at the end of the Epilogue on page 184 of Adventure in Chess (London, 1951), a book by Assiac published in the United States as The Pleasures of Chess (New York, 1952):

‘We old addicts, of course, are insatiable, but I shall feel doubly rewarded if the book introduces some newcomers to the deeper pleasures of Chess and whets their appetites for more and more of it. For surely, of all the drugs in the world, Chess must be the most permanently pleasurable.’

The German edition, Vergnügliches Schachbuch (Cologne/Berlin, 1953), was presented not as a translation but as by Assiac himself (‘Deutsch von Heinrich Fraenkel’). Page 208 had the following:

‘Denn wo in aller Welt gibt es ein Narkotikum, das so andauernde und niemals schal werdende Genüsse bietet wie das Schach – das einzige Narkotikum, das keinen Katzenjammer hinterläßt, sondern immer nur größeren Appetit und verfeinerte Genußfähigkeit.’

From page 229 of the French edition, Plaisir des échecs (Paris, 1958):

‘Les vieux drogués comme nous sont naturellement insatiables, mais je me sentirai doublement récompensé si ce livre donne à quelques nouveaux venus des notions sur les plaisirs des échecs et aiguise leur appétit pour chercher encore plus loin. Car de toutes les drogues du monde, les échecs doivent être la seule qui donne un plaisir permanent.’

Assiac’s inscription in one of our copies of Adventure in Chess

7873. ‘Excellent’

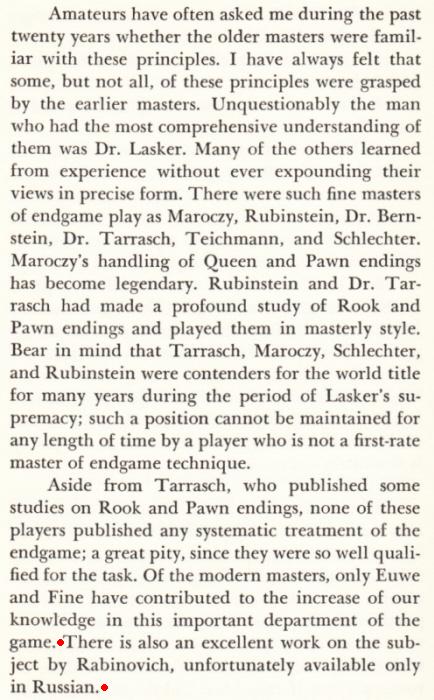

The Russian Endgame Handbook by Ilya Rabinovich (Newton Highlands, 2012) has been ‘translated and revised from the 1938 edition’. It might have mentioned a point made by us on pages 19-20 of the Autumn 1996 Kingpin (see too page 233 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves):

Ilya Rabinovich (1891-1942) has a rare, probably unique, distinction: he wrote a book, Endshpil (two editions, published in 1927 and 1938), which was hailed as ‘excellent’ by both Capablanca and Alekhine. See the ‘Endgame Masters’ chapter of Capablanca’s Last Chess Lectures and Alekhine’s notes to the game against Vidmar at Bled, 1931 in his 1924-1937 Best Games collection.

Below is the relevant passage from Capablanca’s Lectures book (New York, 1966 and London, 1967 – on pages 110 and 114 respectively):

From page 99 of Alekhine’s My Best Games of Chess 1924-1937 (London, 1939)

7874. Charles Dickens

An extensive addition from John Townsend (Wokingham, England) concerning Victoria Tregear has just been made in Charles Dickens and Chess.

7875. Kurt Richter’s Kombinationen

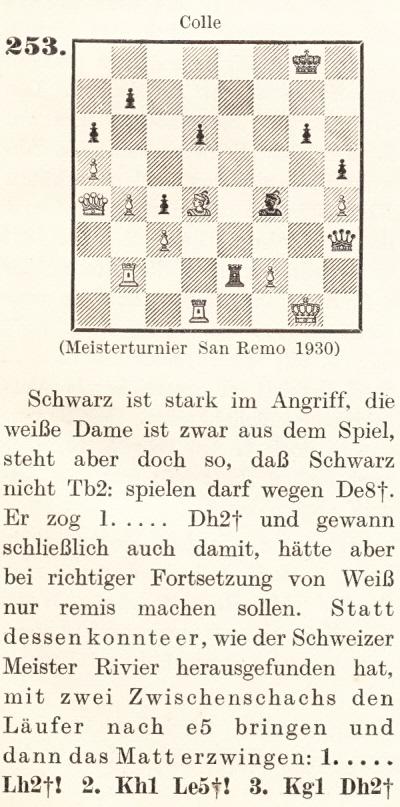

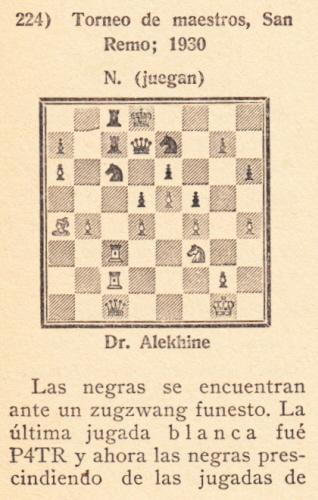

C.N. 2381 (see page 39 of A Chess Omnibus) gave this position from Tartakower v Colle, San Remo, 2 February 1930:

We wrote:

The position was discussed by Kurt Richter on page 113 of his book Kombinationen (Berlin and Leipzig, 1936), with a mention of Rivier:Tartakower has just set a little trap with 35 Rb1-b2. The game ended 35…Qh2+ 36 Kf1 Re7 37 Be3 (In the Lachaga tournament book Becker recommended 37 f3 Qxb2 38 Re1.) 37…Bxe3 38 fxe3 Qh1+ 39 Kf2 Rf7+ 40 Ke2 Qg2+ 41 Ke1 Rf1 mate.

From the diagram Colle could have given mate in six: 35…Bh2+ 36 Kh1 Be5+ 37 Kg1 Qh2+ 38 Kf1 Bxd4 39 Qe8+ Rxe8, etc., a line pointed out by W. Rivier in the Schweizerische Schachzeitung, January 1931 (pages 11-12) and March 1931 (page 45).

With a mention of Rivier, but not of Tartakower, because throughout the book the names of various (though not all) Jewish players were deleted. For instance:

- Position 20: Post v unnamed opponent, Mannheim, 1914 (Flamberg);

- Position 167: S. v von Bardeleben, Hastings, 1895 (Steinitz);

- Position 197: von Holzhausen v unnamed opponent, 1912 (Tarrasch);

- Position 239: von Scheve v unnamed opponent, Ostend, 1907 (Rubinstein).

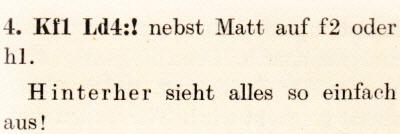

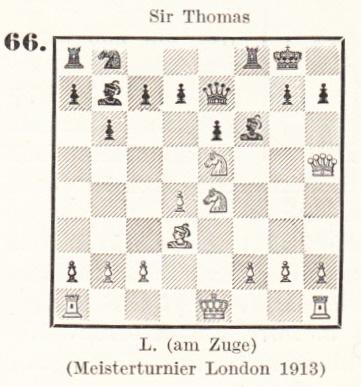

The process was intensified in the second edition of Richter’s book (Berlin, 1940), as shown by position 66 on page 29:

1936 edition

1940 edition

Similarly, in the 1936 edition ‘Dr Lasker’ was named as the opponent of Bogoljubow (Zurich, 1934, in position 107) and of Torre (Moscow, 1925, in position 237). Four years later, the former world champion’s name was reduced in both cases to ‘L.’.

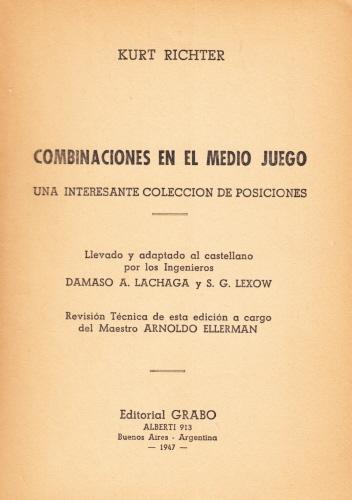

Expurgations were even retained in the post-War translation Combinaciones en el medio juego (Buenos Aires, 1947):

An example from page 158:

In the 1936 German edition Nimzowitsch had been identified in connection with this position, but there was only ‘N.’ in the 1940 volume.

Later editions of Kombinationen restored the masters’ names.

7876. Capablanca dressed for tennis (C.N.s 4114 & 5549)

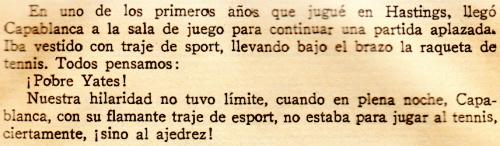

Yet another version of Koltanowski’s anecdote, from page 19 of his book Torneo internacional de Hastings 1935-1936 (Barcelona, 1936):

7877. Nellie Showalter

John Blackstone (Las Vegas, NV, USA) points out an article ‘Chess Playing as a Profession for Women’ by Nellie M. Showalter in the Los Angeles Herald, 6 February 1898, page 24. It includes two sketches of H.N. Pillsbury:

7878. Hamburg, 1910

Mr Blackstone also draws attention to the photographs of Hamburg, 1910 (including Alekhine, Marshall and Nimzowitsch) which were published on page 3 of the New York Sun, 7 August 1910.

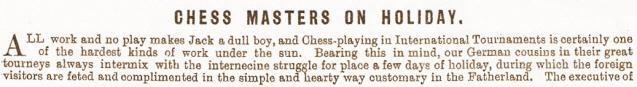

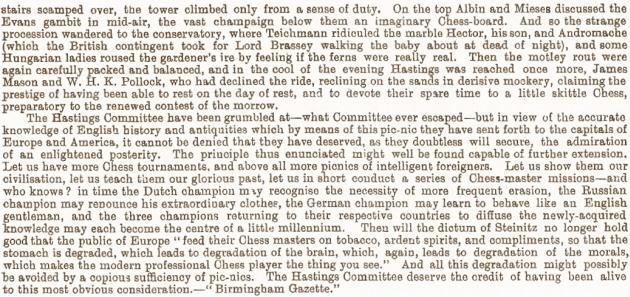

7879. Hastings, 1895 pen portraits

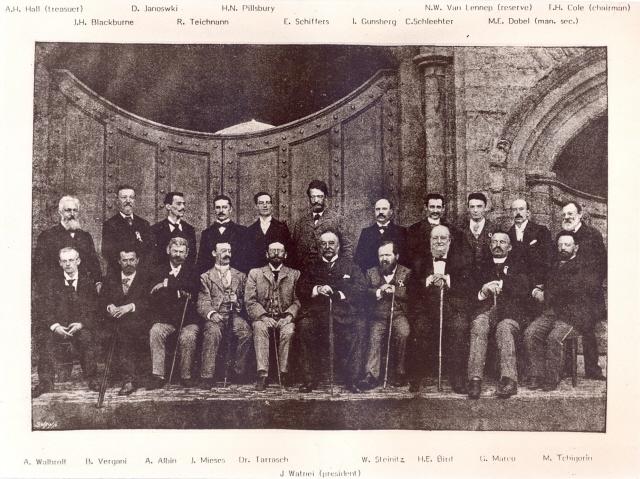

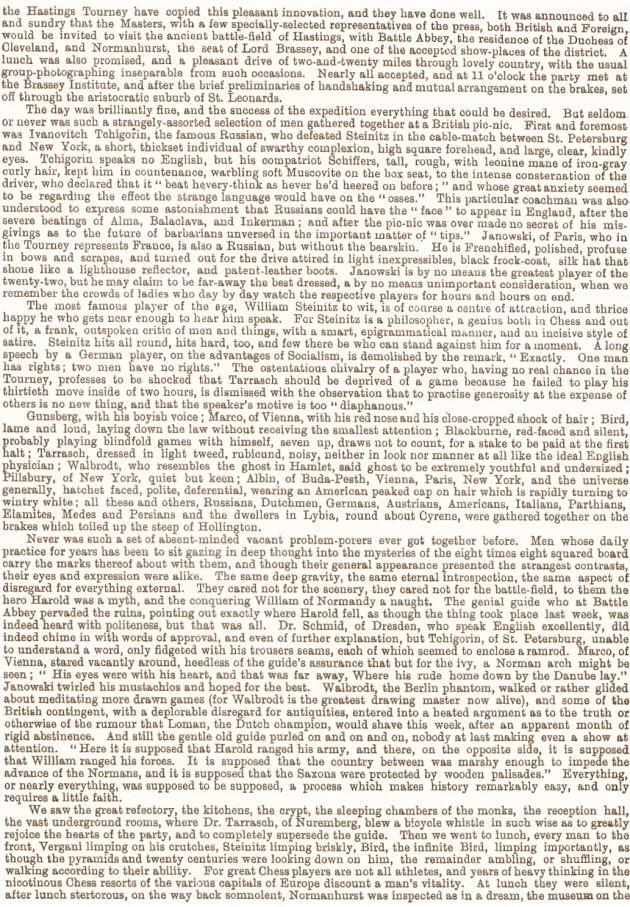

C.N.s 4663, 5832, 5836, 5841 and 7354 discussed this photograph, which was taken at the entrance to Battle Abbey.

Below is an article about the masters’ excursion to Battle, published on pages 258-260 of the 4 September 1895 issue of the Chess Player’s Chronicle. The original source is given as the Birmingham Gazette, and the prose style of R.J. Buckley is recognizable.

7880. ‘Alekhine’s Gun’

C.N. 7875 gave a position from Alekhine v Nimzowitsch, San Remo, 1930, and we should like to know the origins of the term ‘Alekhine’s Gun’, which has been widely applied to a manoeuvre in that game.

For example, after 26 Qc1 Jeremy Silman wrote on pages 280-281 of How to Reassess Your Chess (Los Angeles, 1993):

‘The pressure White exerts on the file is crushing. After this game was played, this form of tripling on a file with both rooks in the lead became known as Alekhine’s Gun.’

In the periodicals of the time that we have checked, 26

Qc1 received no comment at all. When was the ‘Gun’ term

first attached to it?

7881. Seesaw

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) offers a game from the 1958 Spanish championship which has the seesaw manoeuvre:

Arturo Pomar Salamanca – Eduardo Pérez Gonsalves

Valencia, 28 June 1958

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 e6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 a6 5 Nc3 Bb4 6 Qg4 Nf6 7 Qxg7 Rg8 8 Qh6 Rg6 9 Qe3 Ng4 10 Qd3 d5 11 exd5 Qxd5 12 Bd2 Qe5+ 13 Be2 Bc5 14 Be3 Nxe3 15 fxe3 Bd7 16 O-O-O Nc6 17 Bf3 O-O-O 18 Ne4 Be7 19 Qc3 Bf8 20 Rd3 f5 21 Nxc6 Qxc3 22 Na7+ Kb8 23 Nxc3 Kxa7 24 Rhd1 Rg7 25 e4 Kb8 26 exf5 exf5 27 Ne2 Be7 28 Nd4 Rc8 29 Kb1 Bf6 30 Nb3 Bb5 31 Rd5 f4 32 Rf5 Bg5 33 Nc5 Bd8 34 Ne6 Rd7 35 Rxd7 Bxd7

36 Rf7 Bxe6 37 Rxb7+ Ka8 38 Rxh7+ Kb8 39 Rb7+ Ka8 40 Re7+ Kb8 41 Rxe6 a5 42 Rc6 Rxc6 43 Bxc6 Kc7 44 Bf3 Kd6 45 c3 Kc5 46 Kc2 Bf6 47 Kd3 a4 48 Bd1 Kb5 49 Ke4 a3 50 bxa3 Bxc3 51 Kxf4 Kc6 52 h4 Kd6 53 Bb3 Resigns.

Source: El Ajedrez Español, 1958, page 248.

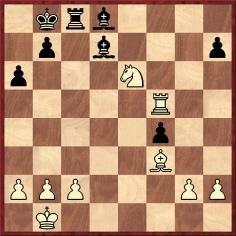

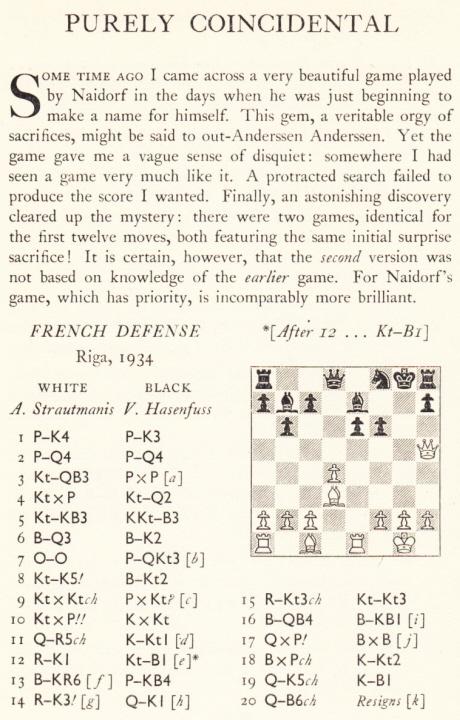

7882. ‘Purely coincidental’

Pages 110 and 111 of Relax with Chess by Fred

Reinfeld (New York, 1948):

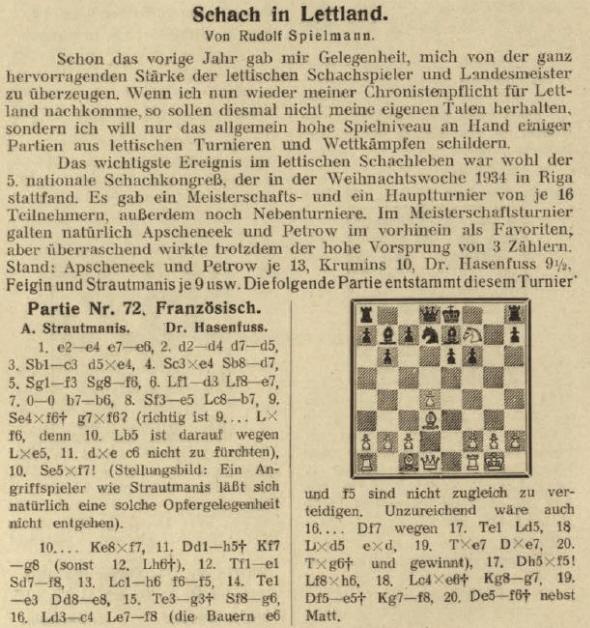

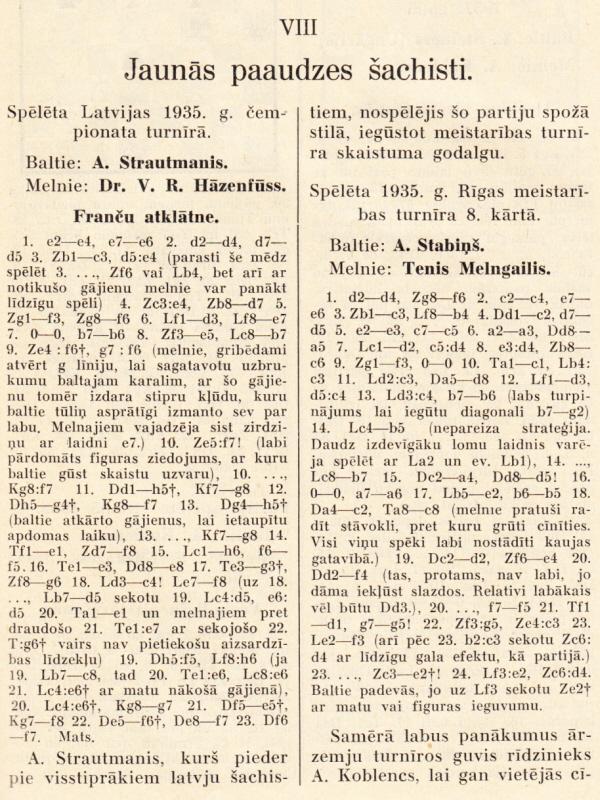

There are complications with this Latvian game but also, particularly, with the Najdorf one mentioned in Reinfeld’s sixth note.

Beginning with Strautmanis’ victory over Hāzenfūss, we

note that it was published by Spielmann on page 150 of

the May 1935 Wiener Schachzeitung:

A few years later it was given on page 181 of Šachs

Latvijā by K. Bētiņš, A. Kalniņš and V. Petrovs

(Riga, 1940):

In this book the game was dated 1935, rather than 1934, but according to the crosstable on page 23 the tournament was played from 22 to 31 December 1934.

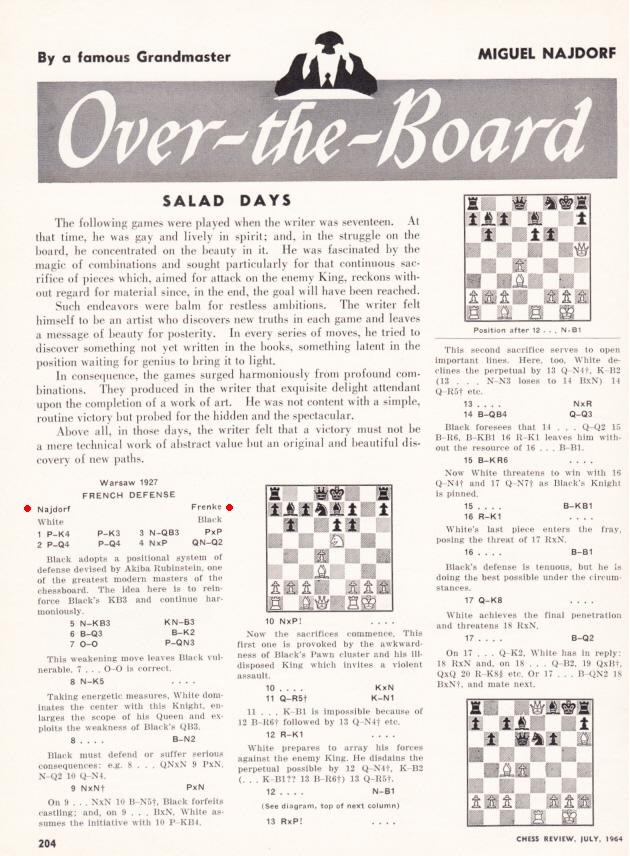

The second discrepancy is the repetition of moves immediately after the white queen’s sortie: 1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 dxe4 4 Nxe4 Nd7 5 Nf3 Ngf6 6 Bd3 Be7 7 O-O b6 8 Ne5 Bb7 9 Nxf6+ gxf6 10 Nxf7 Kxf7 11 Qh5+ Kg8 12 Qg4+ Kf7 13 Qh5+ Kg8 14 Re1 Nf8 15 Bh6 f5 16 Re3 Qe8 17 Rg3+ Ng6 18 Bc4 Bf8 19 Qxf5 Bxh6 20 Bxe6+ Kg7 21 Qe5+ Kf8 22 Qf6+ Qf7 23 Qxf7 mate.The Najdorf game is referred to in our feature article about another brilliancy by him, The Polish Immortal, where it is reported that, according to recent research, his opponent (in the French Defence game) was named Gliksberg and that the occasion was Łódź, 1929. From page 60 of Najdorf: Life and Games by T. Lissowski and A. Mikhalchishin (London, 2005):

‘Numerous sources wrongly give the loser’s name here as Szapiro (or Shapiro, Schapiro). Gliksberg from Łódź should not be confused with the second-category Warsaw player Glücksberg.’

An endnote on page 62 stated:

‘Najdorf’s notes to this game were published in the 1970s. Other sources give White’s eighth move as Nfg5 and omit the repetition at moves 12-13.’

The repetition of moves (identical to the repetition which, according to the Latvian book, occurred in the Strautmanis encounter) would mean that Najdorf’s game ended with 23 Rxf8 mate, and not 21 Rxf8 mate as in the Reinfeld book. See too pages 15-17 of Young Najdorf by T. Lissowski (Nottingham, 2010).

Earlier sources had some other oddities. On pages 243-244

of The Fireside Book of Chess by I. Chernev and F.

Reinfeld (New York, 1949) Najdorf’s opponent was named as

‘Sapiro’, and the occasion was given as Łódź, 1929;

however, pages 410-411 of Chernev’s 1000 Best Short

Games of Chess (New York, 1955) had ‘Sapira’ and

‘Buenos Aires, 1948’. (The latter book also included the

Strautmanis game, on pages 388-389.)

Another venue that has been suggested is Warsaw. See, for instance, pages 63-66 of Miguel Najdorf El hijo de Caissa by Nicolás Capeika Calvo (Buenos Aires, 2002), which named Black as ‘Shapiro’ and gave the occasion as ‘Torneo de Varsovia, 1927?’. Apart from the question mark, the same details were in Najdorf 103 partidas by A.M. Calúa (Buenos Aires, 1985), again on the strength of a quote from Najdorf claiming that the game was played in the same event as the ‘Polish Immortal’, that it won the second brilliancy prize, that he believed that it should have been preferred for the first prize, and that he was aged 17 at the time:

‘Es cuestión de puntos de vista. El jurado optó por la “inmortal polaca”, que ustedes ya conocen, y dieron el segundo premio de belleza a la presente partida con Shapiro, que, a mi juicio, hubiese preferido para ese honor.

Repito que en ese torneo de Varsovia yo tenía 17 años ...’

As mentioned in our Polish Immortal article, Najdorf also claimed to have played the Dutch Defence game at the age of 17. He was born in 1910.

A key question now is when Najdorf’s game against the French Defence was first published.

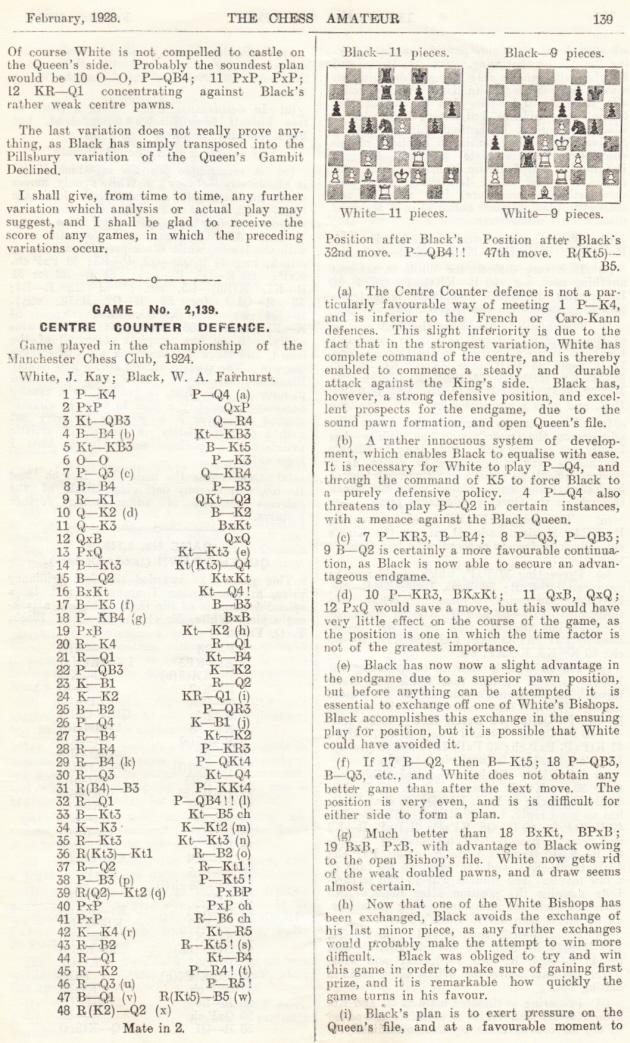

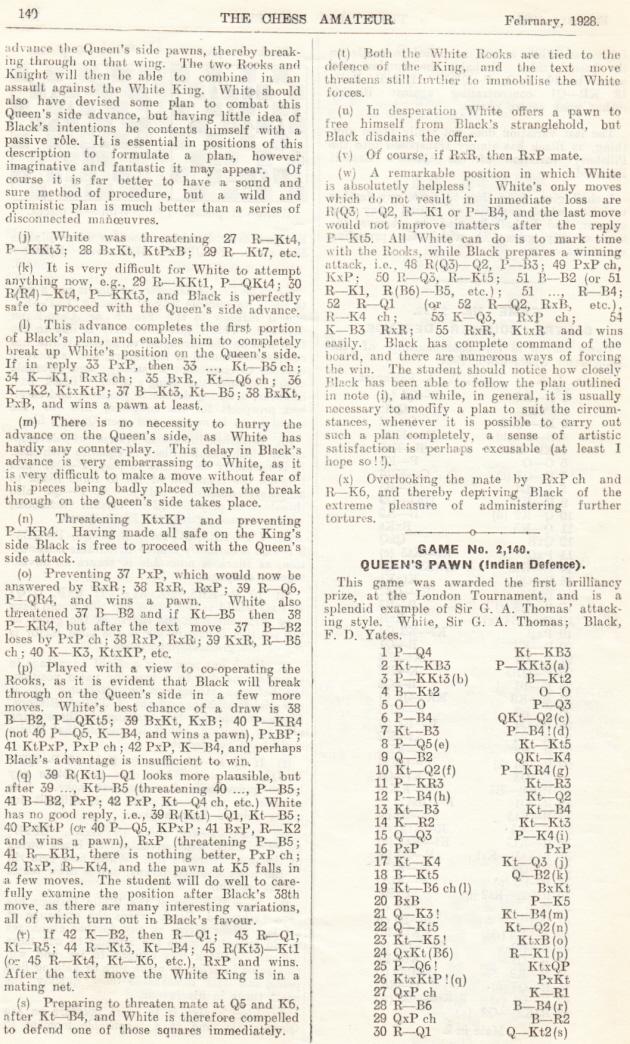

7883. Chess Amateur

In the 1920s the Chess Amateur contained some of the most detailed annotations then available in any periodical, by W.A. Fairhurst. An example:

J. Kay – William Albert Fairhurst

Manchester, 1924

Centre Counter Game

1 e4 d5 2 exd5 Qxd5 3 Nc3 Qa5 4 Bc4 Nf6 5 Nf3 Bg4 6 O-O e6 7 d3 Qh5 8 Bf4 c6 9 Re1 Nbd7 10 Qe2 Be7 11 Qe3 Bxf3 12 Qxf3 Qxf3 13 gxf3 Nb6 14 Bb3 Nbd5 15 Bd2 Nxc3 16 Bxc3 Nd5 17 Be5 Bf6 18 f4 Bxe5 19 fxe5 Ne7 20 Re4 Rd8 21 Rd1 Nf5 22 c3 Ke7 23 Kf1 Rd7 24 Ke2 Rhd8 25 Bc2 a6 26 d4 Kf8 27 Rf4 Ne7 28 Rh4 h6 29 Rf4 b5 30 Rd3 Nd5 31 Rff3 g5 32 Rd1 c5 33 Bb3 Nf4+ 34 Ke3 Kg7 35 Rg3 Ng6 36 Rgg1 Rc7 37 Rd2 Rb8 38 f3 b4 39 Rdg2 bxc3 40 bxc3 cxd4+ 41 cxd4 Rc3+ 42 Ke4 Nh4 43 Rf2 Rb4 44 Rd1 Nf5 45 Re2 a5 46 Rd3

46...a4 47 Bd1 Rbc4 48 Red2, and Black mates in two moves.

7884. Amateur

Page 11 of Killer Chess Tactics by R. Keene, E. Schiller and L. Shamkovich (New York, 2003) states that the ‘second half of the book is a revised and updated version of World Champion Combinations, by Raymond Keene and Eric Schiller’.

Our 1998 article on that earlier book commented that page 18 ...

‘... has a game headed only ‘Morphy-Amateur’, yet a glance at a number of sources (including David Lawson’s biography of Morphy and Chess Explorations) would have sufficed to obtain Black’s name, P.E. Bonford.’

On page 208 of Killer Chess Tactics a correction

to the game heading has been attempted:

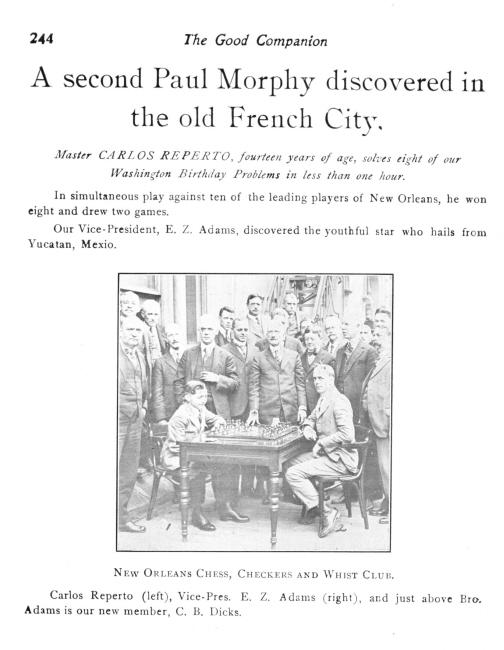

7885. The height of chessplayers and

other details

The pen portrait of Chigorin in C.N. 7879 (‘a short thickset individual of swarthy complexion, high square forehead, and large, clear, kindly eyes’) corroborates a point first discussed in C.N. 1106 (see page 192 of Chess Explorations): contrary to some expectations and assumptions, Chigorin was not a tall man.

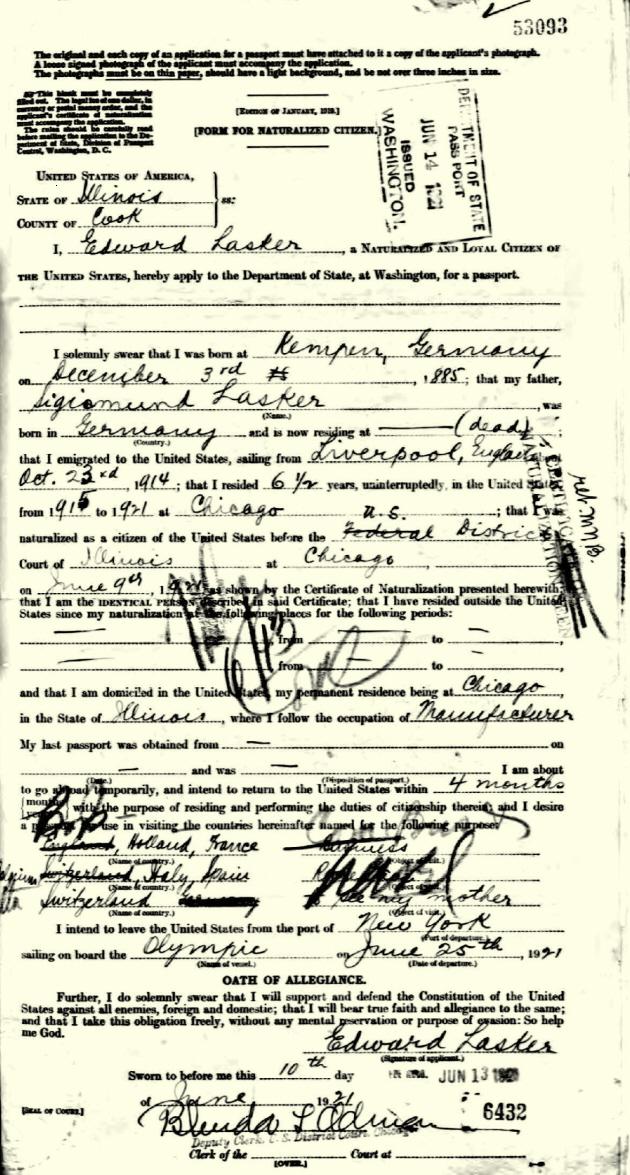

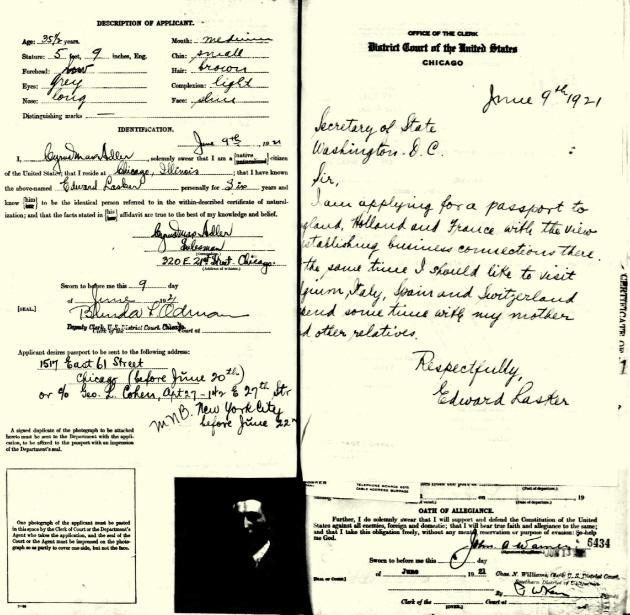

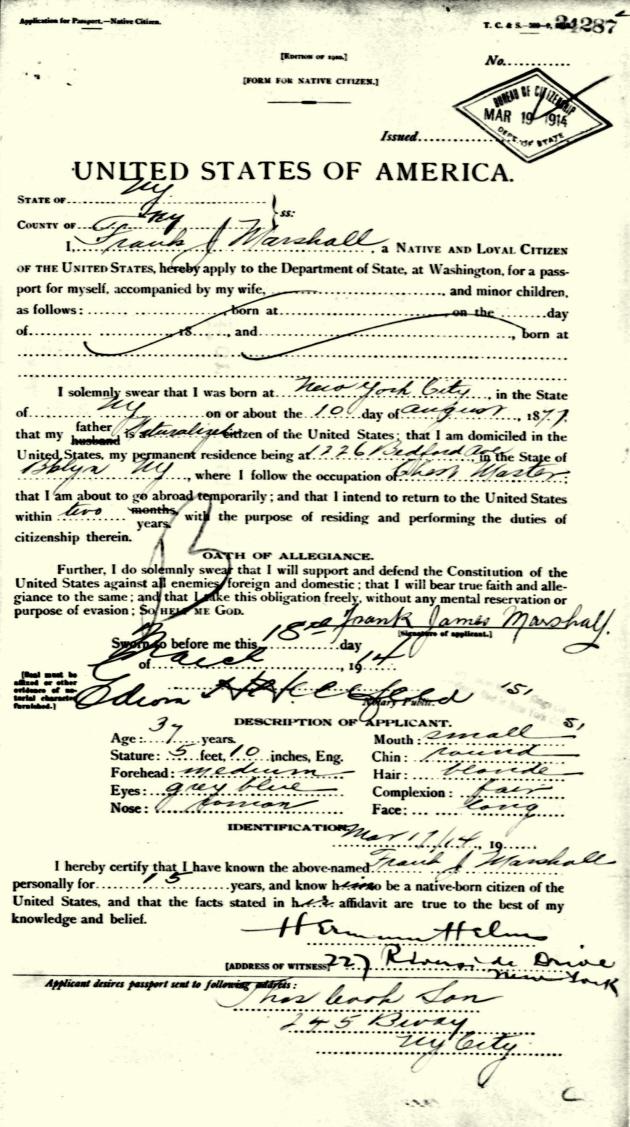

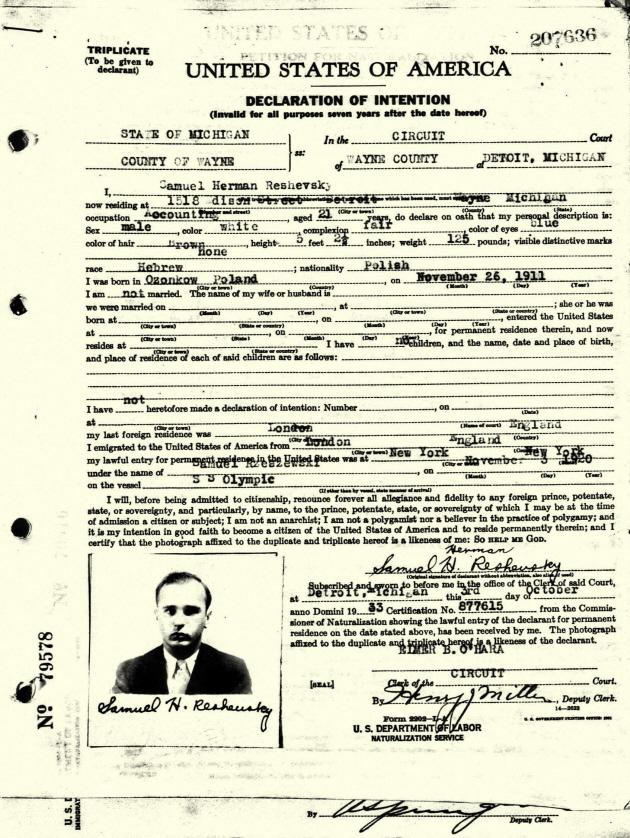

The Factfinder has a

number of references under the entry ‘Size/height of

chessplayers’, and they are now supplemented by Olimpiu G.

Urcan (Singapore). He has sent us documentation on all the

players listed below, and we show four of the records (for

Oscar Chajes, Edward Lasker, Frank James Marshall and

Samuel Reshevsky).

- Hartwig Cassel:

5 feet 4¾ inches – Source: Passport Application (1901), National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington, DC; Passport Applications, 1795-1905; Collection Number: ARC Identifier 566612/MLR Number A1 508; NARA Series: M1372; Roll: 577. Via ancestry.com.

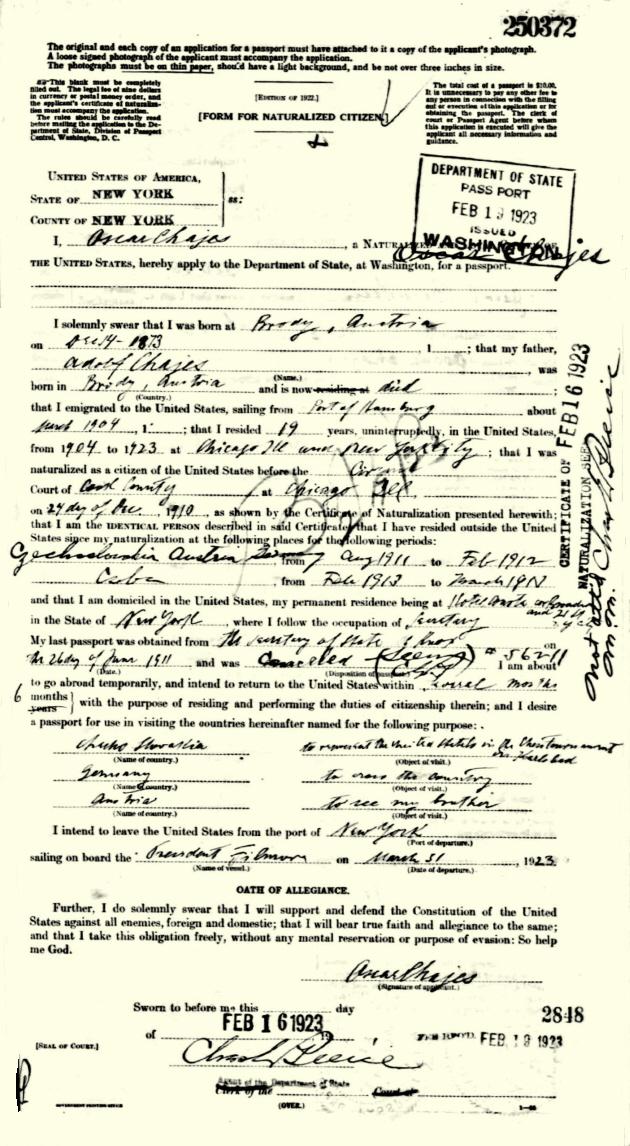

- Oscar Chajes:

5 feet 8 inches – Source: Passport Application (1923), National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington, DC; Passport Applications, 2 January 1906-31 March 1925; Collection Number: ARC Identifier 583830/MLR Number A1 534; NARA Series: M1490; Roll:2184. Via Ancestry.com. (The supporting declaration by Jacob Bernstein is noteworthy.)

- Julius Finn:

5 feet 9 inches – Source: Passport Application (1898), National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington, DC; Passport Applications, 1795-1905; Collection Number: ARC Identifier 566612/MLR Number A1 508; NARA Series: M1372; Roll: 511. Via ancestry.com.

- Charles Jaffe:

5 feet 6 inches – see C.N. 7865.

- Max Judd:

5 feet 6½ inches – Source: Passport Application (1882), National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington, DC; Passport Applications, 1795-1905; Collection Number: ARC Identifier 566612/MLR Number A1 508; NARA Series: M1372; Roll: 247. Via ancestry.com.

- Emil Kemény:

5 feet 6 inches – Source: Passport Application (1905), National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington, DC; Passport Applications, 1795-1905; Collection Number: ARC Identifier 566612/MLR Number A1 508; NARA Series: M1372; Roll: 511.Via ancestry.com.

- Edward Lasker :

5 feet 9 inches – Source: Passport Application (1921), National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington, DC; Passport Applications, 1795-1905; Collection Number: ARC Identifier 566612/MLR Number A1 508; NARA Series: M1372; Roll #: 247. Via ancestry.com.

- Frank James Marshall:

5 feet 10 inches – Source: Passport Application (1914), National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington, DC; Passport Applications, 2 January 1906-31 March 31 1925; Collection Number: ARC Identifier 583830/MLR Number A1 534; NARA Series: M1490; Roll: 205. Via ancestry.com.

- Harry Nelson Pillsbury:

5 feet 7 inches – see C.N. 6267.

- Samuel Reshevsky:

5 feet 2½ inches – Source: Declaration of Intent (1933), National Archives; Washington, DC; Petitions for Naturalization from the US District Court for the Southern District of New York, 1897-1944; Series: M1972; Roll: 971. Via ancestry.com.

- Walter Penn Shipley:

5 feet 10½ inches – Source 1: Passport Application (1887), National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington, DC; Passport Applications, 1795-1905; Collection Number: ARC Identifier 566612/MLR Number A1 508; NARA Series: M1372; Roll: 297. Source 2: Passport Application (1920), National Archives and Records Administration (NARA); Washington, DC; Passport Applications, 2 January 1906-31 March 1925; Collection Number: ARC Identifier 583830/MLR Number A1 534; NARA Series: M1490; Roll: 1447. Via ancestry.com.

- Wilhelm/William Steinitz:

See C.N. 7149.

7886. Edward Lasker

From page 10 of the January 1976 Chess Life & Review, in an article on Edward Lasker by Mona M. Karff:

‘Lasker is reticent about the tragedies in his life: his charming and talented wife, to whom he had been happily married for only six months, died after a minor operation as a result of a surgeon’s error; and his mother and brother perished in Nazi Germany.’

The death of his wife, Cecile Mathilde Heller, was reported on page 194 of the December 1920 American Chess Bulletin:

From page 156 of Louisiana’s Art Nouveau by S. Ormond and M.E. Irvine (Gretna, 1976):

‘Heller, Cecile Mathilde (1890-1920). Cecile Heller (Mrs Edward Lasker) was awarded a Diploma in Art in 1911. The year before she had received the Holley Medal for highest excellence in watercolor throughout the session. Her father was Rabbi Max Heller, head of Temple Sinai in New Orleans for 40 years.

She married a US chess champion and went to live in Chicago. She had been married only six months when she died at age 30, leaving a portfolio of watercolor paintings of every room of the mansion in which she lived.

She exhibited a bookplate in the crafts show at Newcomb on 2 April 1911, according to the Times Picayune of that day.’

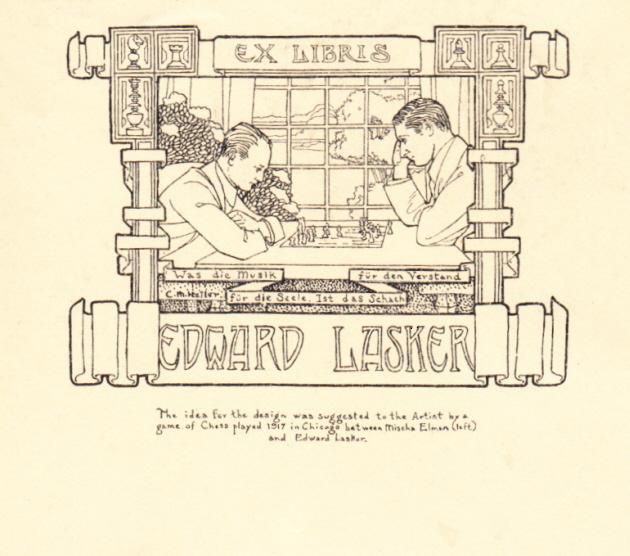

Edward Lasker’s bookplate was discussed in C.N. 2524 (see pages 181-182 of A Chess Omnibus), and below is one of the specimens in our collection, in the 1920 volume of Deutsches Wochenschach. The artist is named as ‘C.M. Heller’.

As mentioned in the earlier C.N. item, the photograph on which the illustration is based (Mischa Elman in play against Lasker) was published on page 27 of the February 1918 American Chess Bulletin:

7887. Los Angeles

The photographs given in Chess and Hollywood included a shot of a game of living chess in August 1945, from page 34 of the October 1945 Chess Review. Luc Winants (Boirs, Belgium) notes that a fine version is available on-line, courtesy of the Los Angeles Times.

From the same website our correspondent also draws attention to a photograph of Bobby Fischer at his 50-board simultaneous display in Los Angeles on 12 April 1964.

7888. Who?

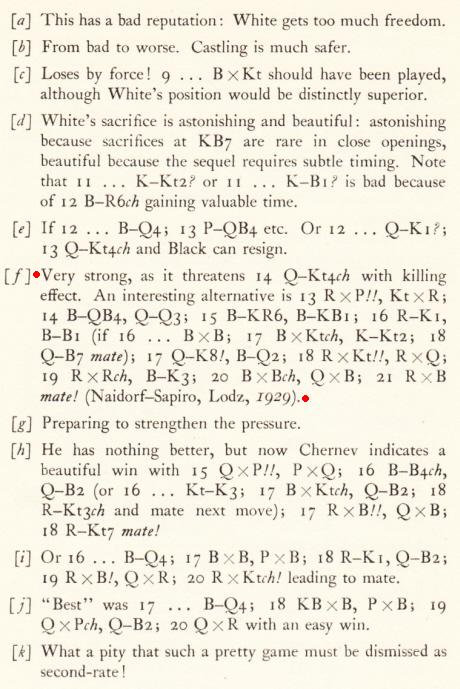

7889. ‘Purely coincidental’ (C.N.

7882)

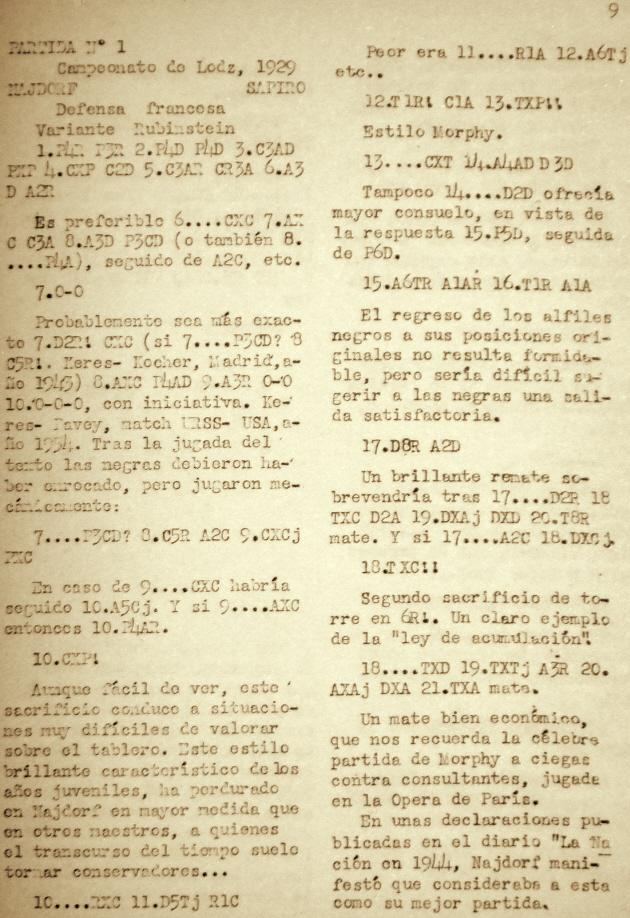

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) submits page 9 of ¡Najdorf! juega y gana by Raúl Castelli (Hurlingham, 1968):

Of particular interest is the last paragraph, which reports a remark by Najdorf in the newspaper La Nación in 1944 that it was his best game.

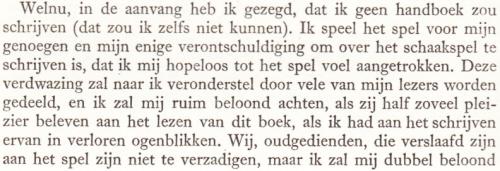

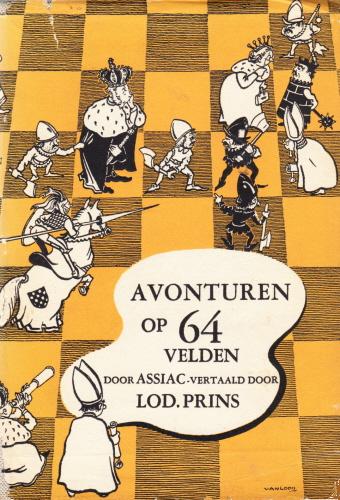

7890. Of all the drugs (C.N. 7872)

Below is the text which appeared on pages 182-183 of the Dutch edition of Assiac’s book, Avonturen op 64 velden (Amsterdam, 1952):

A remark in passing is that on the front of the dust-jacket the author received smaller billing than the translator, Lodewijk Prins:

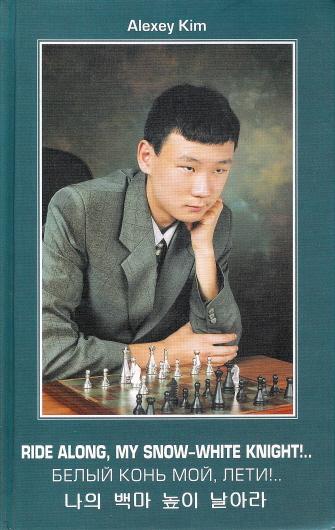

7891. Alexey Kim

Yakov Zusmanovich (Pleasanton, CA, USA) comments that he has only one biographical book devoted to a chessplayer of Korean origin and published with Korean text, Ride Along, My Snow-White Knight!.. by Alexey Kim (Moscow, 2002):

7892. Simpson’s-in-the-Strand

An oft-found statement about Simpson’s-in-the-Strand, London:

‘It also hosted the great tournaments of 1883 and 1899, and the first ever women’s international in 1897.’

By ‘oft-found’ we mean that a Google search currently yields no fewer than 555 results for that exact sentence.

In reality, the venues were:

- London, 1883: Victoria Hall in the Criterion (tournament book, page xviii, and page 260 of the May 1883 Chess Monthly);

- London, 1899: St Stephen’s Hall, Westminster (tournament book, page xvi, and page 141 of the April 1899 BCM);

- London, 1897 (women’s tournament): Masonic Temple/Hall, Hotel Cecil, as well as the Ladies’ Chess Club, Ideal Café, 185 Tottenham Court Road (BCM, August 1897, pages 136, 285 and 287, and the American Chess Magazine, July 1897, page 77).

7893. Andrés Segovia and Capablanca

Paul Herzman (Brooklyn, NY, USA) quotes from page 138 of Don Andrés and Paquita The Life of Segovia in Montevideo (Milwaukee, 2012):

‘[On 19 May 1936] they had tea with composer Sergei Prokofiev, his wife, and the great Cuban chess player José Raúl Capablanca. Our two artists shared one of the other legs of the tour through the Soviet Union with Capablanca, whose second wife, Olga Chagodaev, was Russian ... [Capablanca married her in 1938.]

[After 15 June 1936] they went to Kiev. In the Ukrainian capital they again met Capablanca, with whom they shared several walks; they also attended one of his chess matches.’

Capablanca referred to Segovia on pages 13-14 of Last Lectures (New York, 1966):

‘Several years ago, in the Russian city of Kiev, I ran across Andrés Segovia, the great Spanish guitarist. We had known each other for some time; he as a lover of chess, and I as a lover of music! He was to give a concert and I a simultaneous exhibition. Both of these events were to take place in the great concert hall of Kiev, and naturally each of us invited the other to his performance. The simultaneous exhibition had been arranged for 30 students, boys and girls between ten and 16 years of age. Segovia, his wife and I arrived in the hall in due course, and I noted Segovia’s amazement at the spectacle which met his eyes. The huge hall was completely filled, and its balcony held more than a thousand girls who had come to watch the play. All were students and had learned to play chess in their respective schools. On the stage 30 boys and girls had been seated in a rectangle as is customary in such exhibitions. Most of them were boys, all of them ready to do battle with me. In each corner there had been placed a particularly strong adversary. In back of the players there was a crowd of boys and girls with their teachers and in back of them the guests. It was truly, as Segovia said, a phenomenal spectacle. There were at least three thousand people in the hall, almost all of them children.’

7894. Identification poser

Ross Jackson (Raumati South, New Zealand) requests assistance with identifying the individuals in a photograph which he acquired recently:

7895. Humans and machines

The article below by G.H. Diggle was published in the April 1984 Newsflash and on page 1 of volume two of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1987):

‘“The Lloyds Bank Programme” (so reads the envious Badmaster in the March Newsflash) “organized by British Chess Officials and continually identifying and encouraging new talent, aims to help young people in schools and universities to improve their game to top level standards.” Oh, it does, does it? And what does it do to help the old people – worthy pensioners with 50 years’ addled chess fermenting in their brains – to make some stand against these pampered young sixth-formers who invariably wipe them off the board nowadays? When are the “poor old souls” to expect their “meals on wheels” to be accompanied by a visiting Grandmaster to bring them up to date with the Nimzo-Indian, Keene’s Flank Openings, and other horrors of that sort? At present, they are just left to sit at home playing some cheap Computer purchased with their hard-earned savings. The BM himself was once ensnared into taking on one of these brutes. It would occasionally “talk” between the moves – whenever the BM blundered there came clanking out from its bowels some slotted sarcasm such as “IS THIS A TRAP, I WONDER?” After exclaiming, “Enough of this programmed impudence!”, the BM has reverted ever since to playing human beings, finding even the young ones far less objectionable. In fact, recently he played in a ten-minute Tournament against a charming schoolgirl and overlooked a mate in two, whereupon she remarked in a chatty sort of way, quite free of any superciliousness, that she thought his last move was “a bit gaga”. The BM, of course, took refuge in his usual nauseating self-abasement. “Only my last move?”, he intoned with lugubrious deference.

The few young players in the BM’s day had a less spontaneous approach, but they came from Universities rather than from schools. The BM once entered his local club and found a blasé Undergraduate – a complete stranger – lolling on his own in front of a board and looking as if the last thing he wanted was a game of chess. Sensing this, the courteous BM made no advances and started reading the paper, but after some quarter of an hour had elapsed the visitor, as though in the last extremity for something to keep him awake, suddenly drawled: “Care to be murdered?” The obliging BM at once acquiesced, and throughout the opening stages his opponent played and conversed at the same time like a weary chess roué who had encountered all the experts, drained chess dry, weighed it on the balance and found it wanting. “Ah! You’ve played that line? Yes, I’ve seen it before – hopelessly unsound, you know – Milner-Barry used to potter about with it at one time, but Alexander eventually tore it to rags – do you know, I’ve completely forgotten what the right reply is – yes, I’m getting quite senile, in fact I’m playing like a novice, which is probably what I really am ...”’

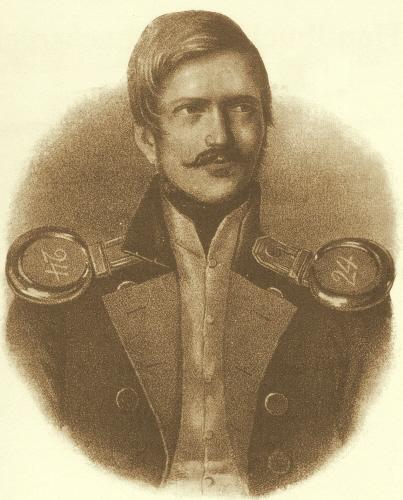

7896. Paul Rudolf von Bilguer

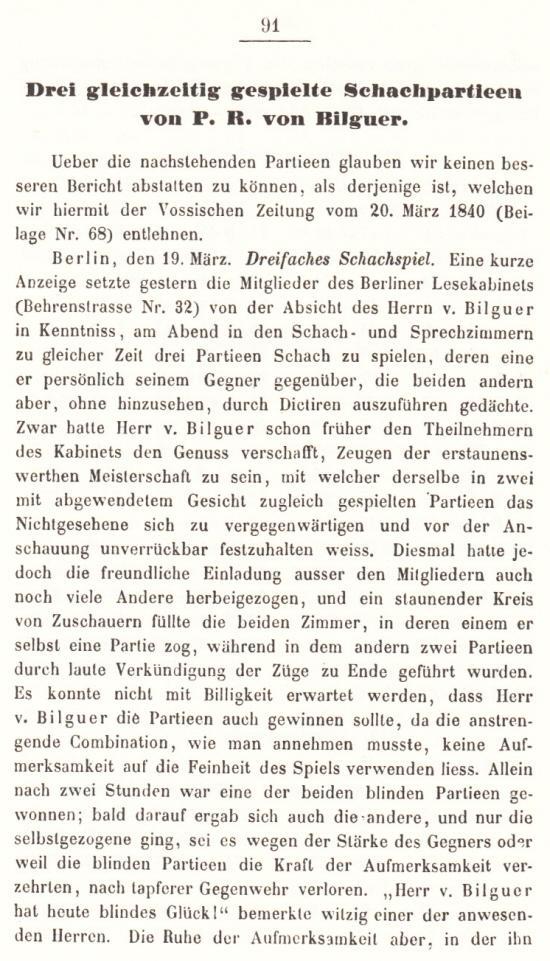

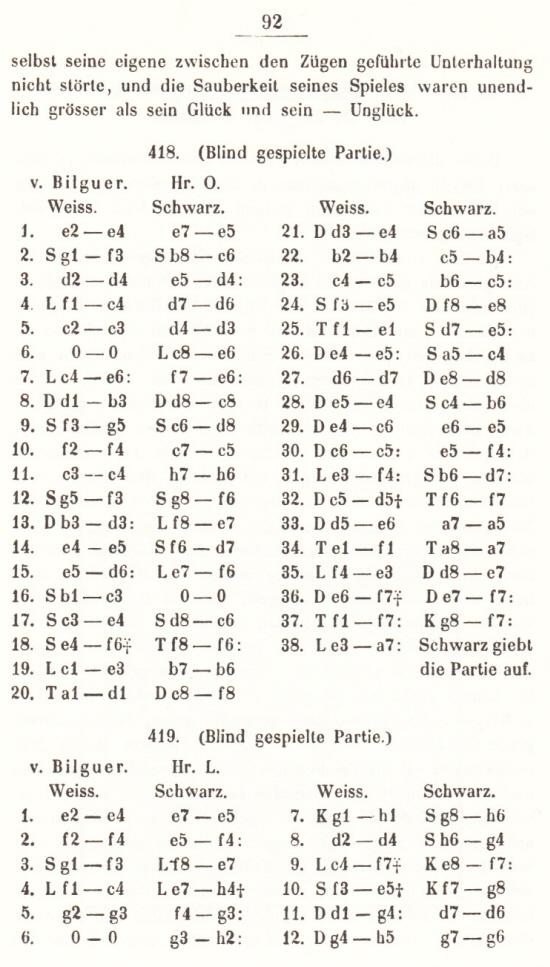

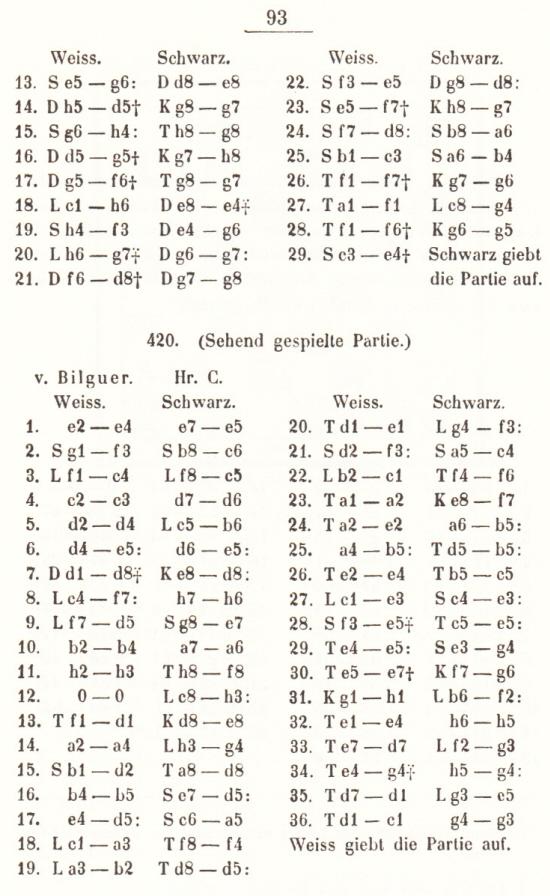

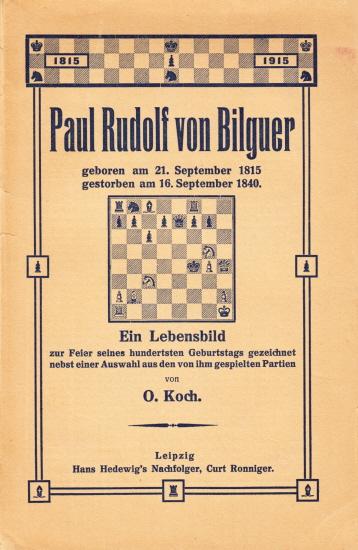

Andreas Lange (Berlin) refers to three games played by Paul Rudolf von Bilguer simultaneously (two of them blindfold) in Berlin on 19 March 1840 and published on pages 91-93 of the March 1852 Deutsche Schachzeitung:

Our correspondent points out that further details about the occasion, as well as the identity of the third opponent (Crelinger), were supplied on pages 628-629 of Der bayrische Volksfreund, 1840:

‘Berlin, 20 März. (Etwas für Schachspieler) Gestern waren wir Zeuge einer in ihrer Art außerordentlichen Begebenheit. Ein Offizier, Hr. v. Bilguer, hatte vor einigen Tagen die merkwürdige Aufgabe gelöst, eine Partie Schach gegen die anwesenden sämmtlichen Schachspieler, und zwar dem Schachbrett den Rücken zuwendend, zu spielen. Er gewann die Parthie in der 7. Viertelstunde. Gestern spielte er mit drei Herren auf drei verschiedenen Brettern zugleich, und zwar so, daß seine beiden Hauptgegner im Nebenzimmer, aber bei offenen Thüren am Schachbrett saßen und zogen, während ein unpartheiischer Herr in der Mitte stand und Zug für Zug angab; sodann zog der Gegner mit dem Hrn. v. B. die dritte. In anderthalb Stunden ergab sich die Partie II, in zwei Stunden war die Partie I matt; aber bald darauf verlor Hr. v. B. die Parthie, die er eigenhändig spielte, an seinen Gegner, Hrn. Crelinger. Aber welch ein außerordentliches Gedächtnis gehört dazu, jeden Zug auf zwei unsichtbaren Schachbrettern mit allen Stellungen zu behalten, und die dritte Parthie, die zu gewinnen er sehr nahe war, auch noch zu dirigiren.’

The three games were lightly annotated (with Crelinger unidentified) on pages 45-48 of Paul Rudolf v. Bilguer by O. Koch (Leipzig, 1915). For two other games from that book see C.N. 1619 and pages 74-76 of Chess Explorations.

7897. The ‘Bellón Gambit’

From Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore):

‘After 1 c4 e5 2 Nc3 Nf6 3 Nf3 e4 4 Ng5 ...

... the move 4...b5 is normally referred to as the “Bellón Gambit” after Juan Manuel Bellón López. Databases indicate that the first two games with this idea were played by Bellón in 1969 and 1971.

From page 9 of Dynamic Chess Strategy by Mihai Şubă (Oxford, 1991):

“The eccentric variation of the English Opening played in the following game is known as the Bellón Gambit. I do not intend to contest the paternity of an interesting idea, but this is the right moment to express my disagreement with some chess nomenclature. We have no Fischer’s Opening or Tal Variation but instead the ‘Poisoned Pawn Variation’, the ‘Classical System’ or the ‘King’s Indian Attack’, while chess literature abounds with obscure names of people who played some bizarre move ‘for the first time’. Bellón is an aficionado of unorthodox openings. This very likeable player also consistently used 1 Nc3 after our game in Bucharest 1976. At that time I showed him some ideas from this opening, which is called the Dunst, although G. Alexandrescu exhaustively analyzed it some 50 years ago and baptized it the ‘Romanian Opening’. The ‘Bellón Gambit’ was known in Romania in the 1960s.”

On page 10, in the note to 4...b5, he wrote:

“The first published game which featured this idea was Reshevsky-Bellón (Palma de Mallorca 1971).”

On page 44 of the extended and updated edition of his book (Alkmaar, 2010) Şubă made some corrections and – quite rare in chess literature at this level – offered an apology:

“The eccentric variation of the English Opening played in this game is known as the Bellón Gambit.

I must rectify the opinion put forward in the old book – that Bellón might not be its initiator – and apologize. That opinion was based on a chat with IM Mititelu. He told me that the gambit has Romanian roots and its premiere occurred in a game he played against IM Ungureanu. There is no record of that game and unfortunately Ghita Mititelu is no longer with us. The fact that Bellón came to Romania several times in the company of Louis Haritver (who was once Romanian) strengthened this idea. Louis was the President of the Malaga Chess Federation in the 1970s. It is now clear that Bellón’s visits to Romania happened after 1970. The only thing I can confirm is that the gambit was known among Romanian players by the beginning of the 1970s. It was feared to such an extent that everybody played 4 Nd4. I did it myself, against Dan Wolf in the Romanian Championship 1972, and Nicolaide also did it several years later against my own second attempt to play the gambit.

Bellón played it first in 1969 in the World Junior Championship.”’

7898. ‘Purely coincidental’ (C.N.s 7882 & 7889)

The twists continue with Najdorf’s brilliancy against the French Defence. Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) points out an occasion when Najdorf identified Black as Frenke. Below is an article contributed by Najdorf on pages 204-205 of the July 1964 Chess Review:

7899. Identification poser (C.N. 7894)

Peter de Jong (De Meern, the Netherlands) identifies the player on the right as G.C.A. Oskam. Below is a detail from the Margate, 1923 group photograph given in C.N. 4122:

Left to right: G.C.A. Oskam, E. Colle, P.W. Sergeant

See too C.N. 6343.

7900. Differing opinions

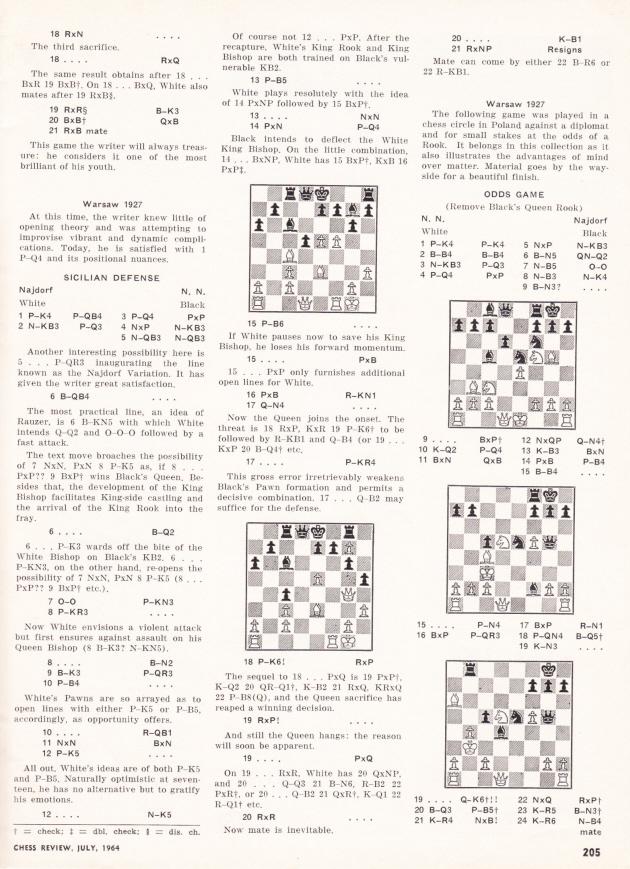

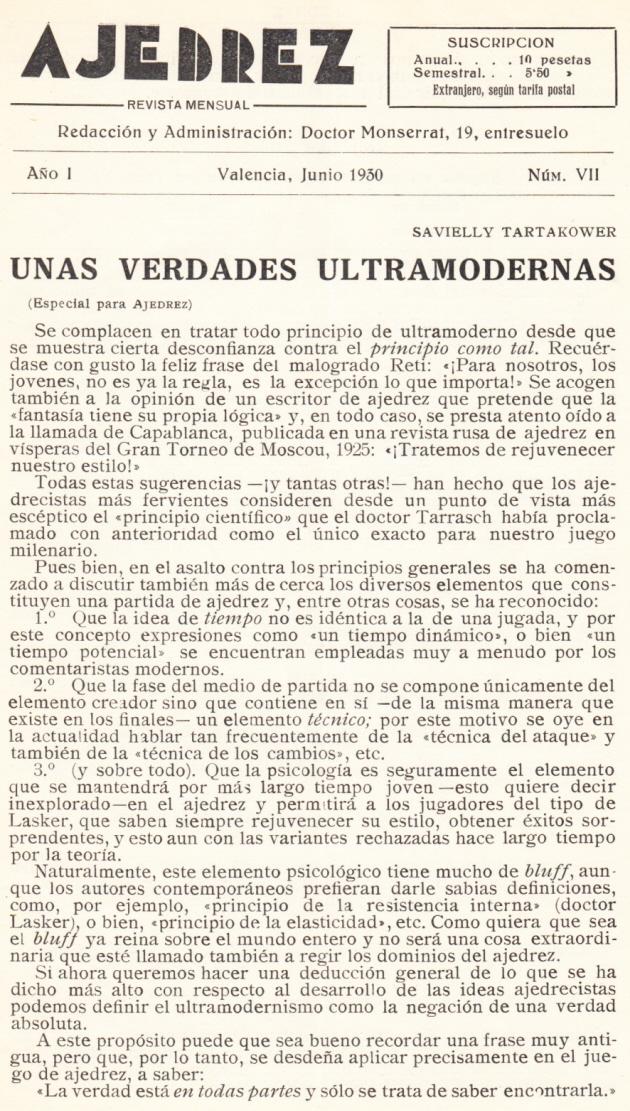

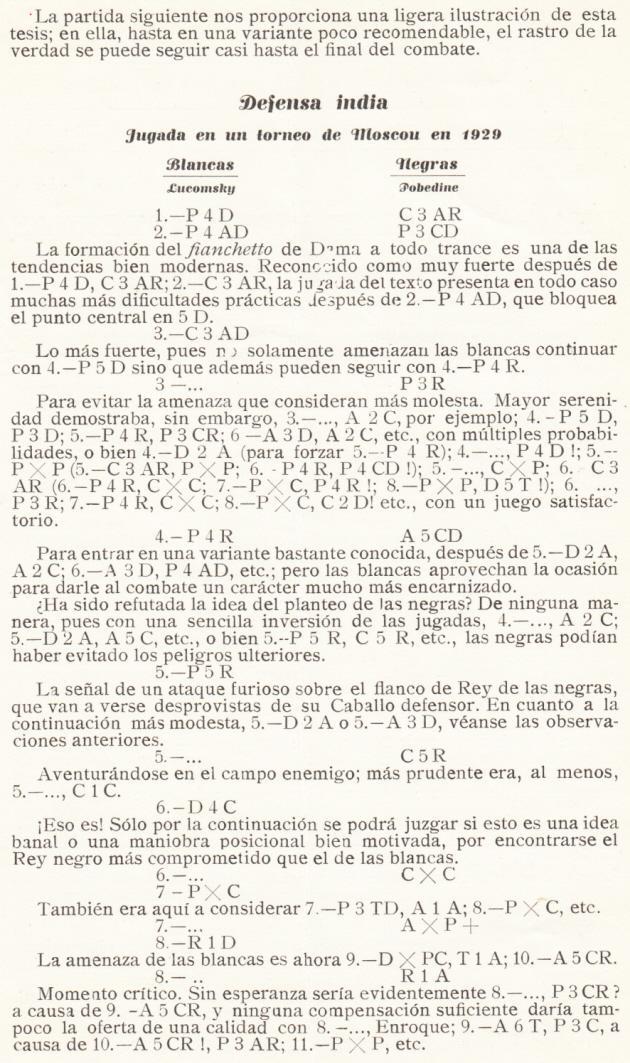

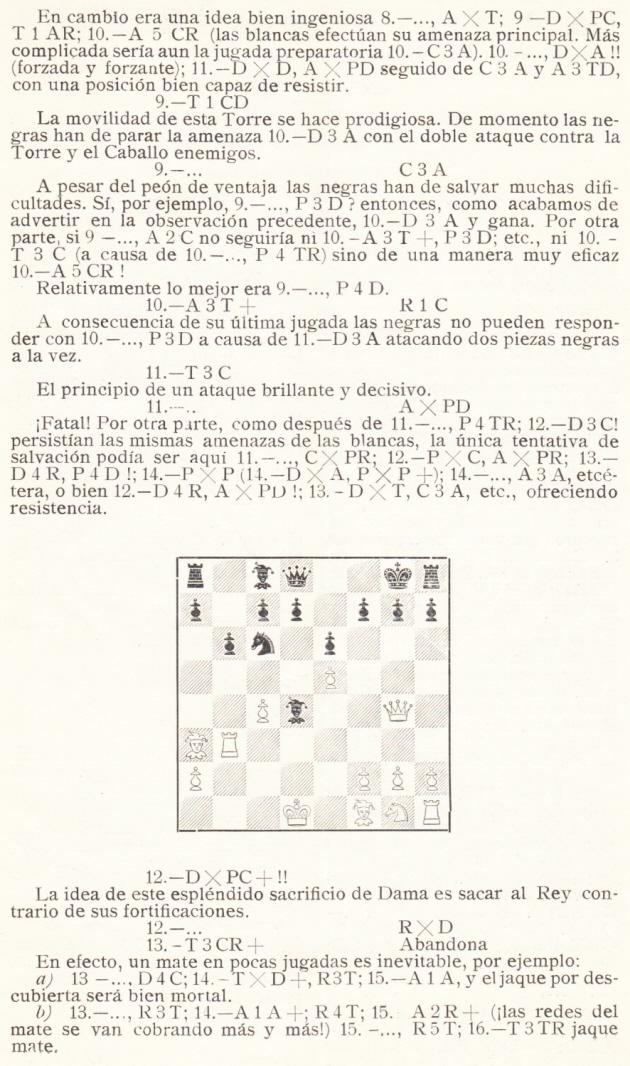

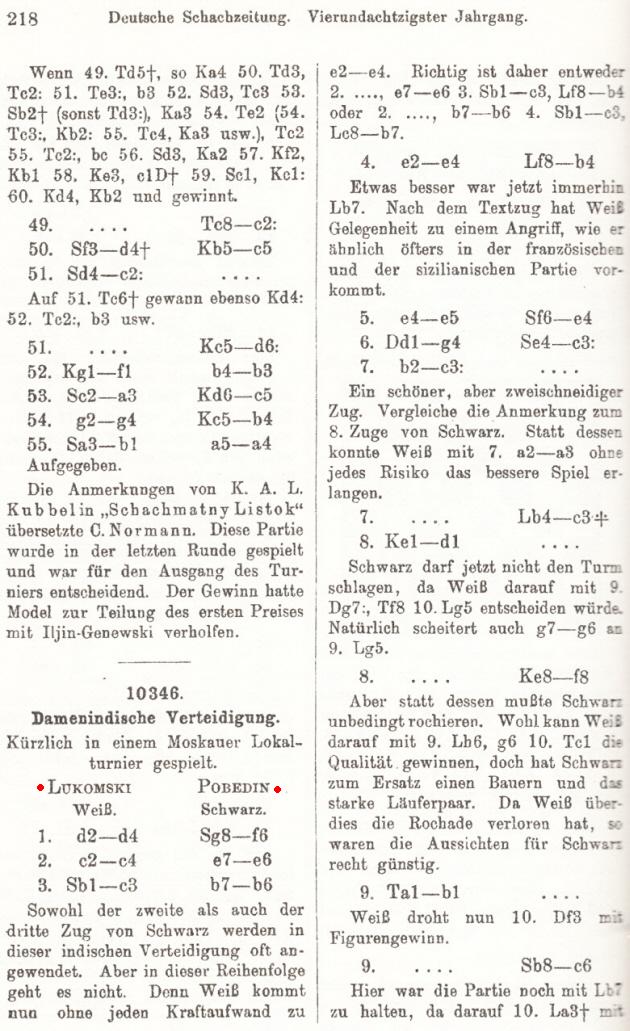

Below is the text of C.N. 3048 (see page 54 of Chess Facts and Fables), concerning a familiar miniature:

Lukomsky – Pobedin

Moscow, 1929

Queen’s Fianchetto Defence1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 b6 3 Nc3 e6 4 e4 Bb4 5 e5 Ne4 6 Qg4 Nxc3 7 bxc3 Bxc3+ 8 Kd1 Kf8 9 Rb1 Nc6 10 Ba3+ Kg8 11 Rb3 Bxd4

12 Qxg7+ Kxg7 13 Rg3+ Resigns.

Some sources (including the Wiener Schachzeitung, June 1929, pages 184-185) gave Pobedin’s name as ‘Podebin’.

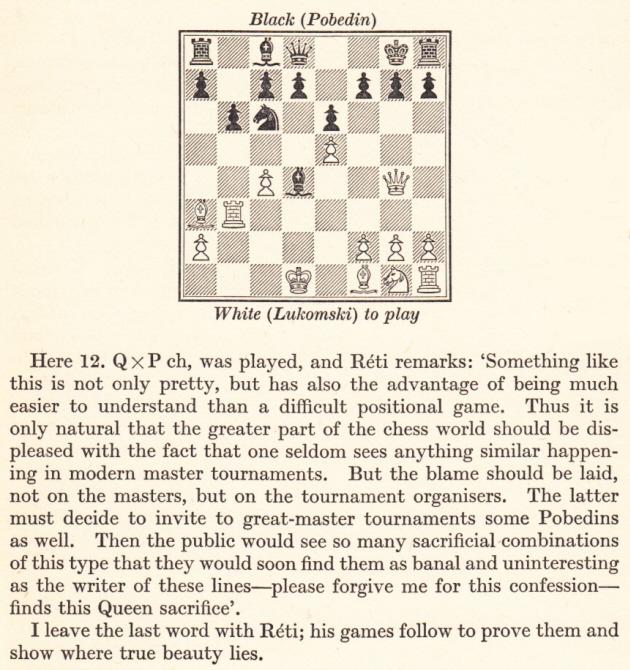

The game illustrates how prominent masters may differ in their appreciation of games and positions. Annotating the miniature on pages 122-124 of the June 1930 Ajedrez, Tartakower gave White’s 12th move two exclamation marks and referred to ‘this splendid queen sacrifice’. On page 178 of 1000 Best Short Games of Chess (New York, 1955) Irving Chernev reported that Marshall ‘was fond of this game’. In contrast, Réti found the combination ‘banal and uninteresting’. He was writing in Morgenzeitung, and his notes were reproduced on pages 218-219 of the July 1929 Deutsche Schachzeitung. See also page 5 of Réti’s Best Games of Chess by H. Golombek (London, 1954).

For ease of reference, we add here the Tartakower and Réti texts:

Finally, the text on page 5 of Golombek’s book on Réti:

In some databases White was named as Lugowski or Lukowski. What is the earliest known publication of the game in a Soviet source?

7901. Two pawns

White to move and draw

7902. Who? (C.N. 7888)

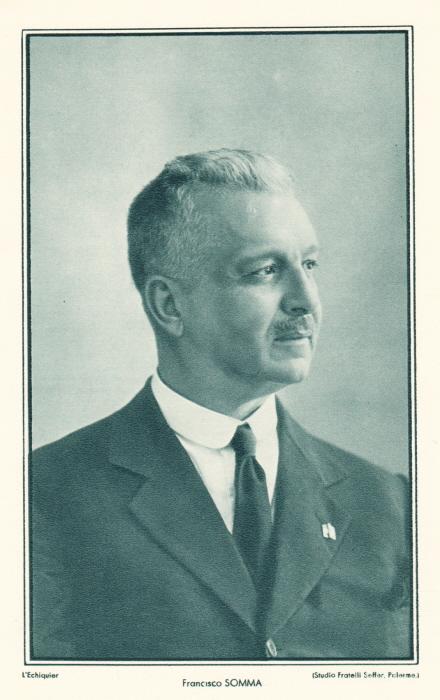

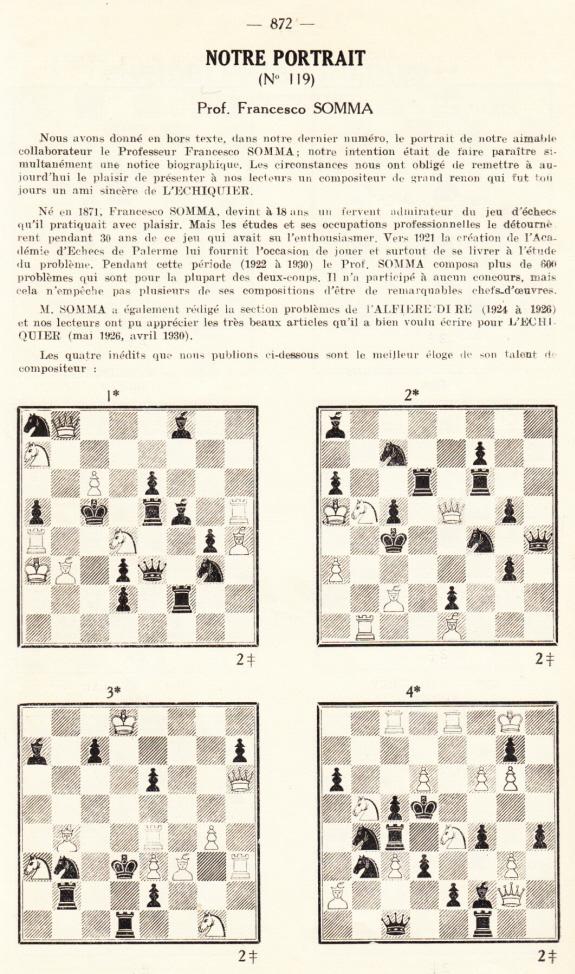

This photograph of Francesco [sic] Somma was published opposite page 776 of L’Echiquier, October-November 1934:

A biographical note and four previously unpublished problems were given on page 872 of the December 1934 issue:

Further biographical information about Somma will be welcome.

7903. Capablanca in Kiev (C.N. 7893)

Page 193 of The Unknown Capablanca by David Hooper and Dale Brandreth (London, 1975) lists two 30-board simultaneous exhibitions in Kiev, on 18 and 19 June 1936.

In one of the displays his opponents included Isaac Lipnitsky (1923-59), as mentioned on page 6 of Vadim Teplitsky’s Russian monograph on Lipnitsky (Bat Yam, 1993):

‘Izya Lipnitsky also participated in that simultaneous exhibition, but we know nothing about how he played against Capablanca.’

The same page, together with an endnote on page 103, indicates that the Cuban faced 29 boys and one girl. Can any further details be found in Russian-language sources of the time?

7904. Gibaud v Lazard

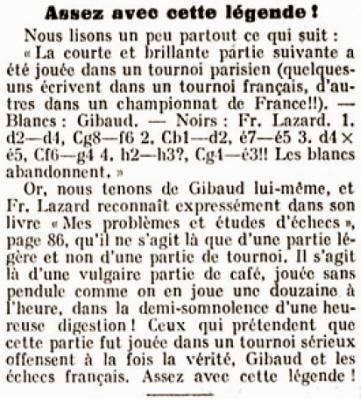

Page 351 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves quoted two passages regarding the alleged Gibaud v Lazard brevity:

‘When in England recently, M. Znosko-Borovsky ... showed us the score of the following curious little game played in Paris last year: 1 d4 d5 2 Nf3 Bg4 3 Ne5 Nf6 4 Nxg4 Nxg4 5 Nd2 e5 6 h3 Ne3 7 White resigns.’

Source: page 221 of the June 1921 BCM.

‘Monsieur Gibaud asks us to correct a mistake made by the author of Curious Chess Facts [Irving Chernev] and quoted by us last month. He never lost any tournament game in four moves. Searching his memory he recalls a “skittles” he once played against Lazard, a game of the most light-hearted variety, in which, his attention momentarily distracted by the arrival of his friend Muffang, he played a move which allowed a combination of this genre – but certainly not four moves after the commencement of the game. Rumour, he said, must have woven strange tales about this game, coupling it perhaps with the theoretical illustration Znosko-Borovsky gives on page 24 of his Comment on devient brillant joueur d’échecs (Paris, 1935).’

Source: page 420 of CHESS, 14 July 1937.

We commented that the shortest version (1 d4 Nf6 2 Nd2 e5 3 dxe5 Ng4 4 h3 Ne3 5 White resigns) regularly appears in books and that in his introduction to Chess Tactics (Ramsbury, 1984) Paul Littlewood even called it ‘the shortest match game known in chess literature – Gibaud-Lazard, Paris, 1927’. Richter’s Kombinationen (various editions) dated it 1935.

Now, Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) forwards a cutting from page 12 of the Feuille d’Avis de Lausanne, 24 June 1933 (chess column by André Chéron):

7905. Frederick M. Edge’s imprisonment (C.N.s 7483 & 7545)

From John Townsend (Wokingham, England):

‘The prison in which Edge was held was the Debtors’ Prison for London and Middlesex, Whitecross Street; it was essentially the same institution which John Henry Huttman had known in 1838 and the early 1840s. The following information is extracted from a return made on 1 July 1865 of the prisoners “within the walls” of that establishment (source: Gaolers’ returns, Whitecross Street Prison, National Archives, B 2/19):

“Name: Edge Frederick Milnes

Date of Imprisonment: 23 May 1865

Creditor: George Best, Rochester Terrace, Westminster

Nature and Amount of Debt: Ca Sa. £30 6s.

Whether such Prisoner is willing or refuses to petition the Court of Bankruptcy, or is unable to do so by reason of poverty: Unwilling

Attorney: B. Peverley, 73 Coleman St.”

Next to Edge’s name have been added in pencil some not very legible annotations, which appear to read: “Adjd/insufficient/In prison.”

The entry “Ca Sa” is a normal abbreviation for Capias ad Satisfaciendum, which is understood to be a type of writ, which a creditor can have issued after obtaining judgment against a debtor, whose body then has to be produced before the court to satisfy the creditor the amount recovered by the judgment. The debtor is kept in prison until he makes the satisfaction awarded.

The period of confinement could, in earlier times, be very prolonged. However, new measures introduced in the 1861 Bankruptcy Act had aimed, generally speaking, to get debtors and bankrupts out of prison, and many were freed after the Act was passed. It is perhaps therefore a little surprising that Edge was kept in prison at a relatively late date for an amount as small as £30 6s.

The creditor, George Best, of 5 Rochester Terrace, Westminster, was listed as an auctioneer and upholsterer in the Post Office London Directory for 1865 (page 852). It is not known how Edge came to owe him money. The same directory (page 1278) lists Edge’s attorney, Benjamin Peverley, as a solicitor at 73 Coleman Street, EC.’

7906. Knight mate

Further to the references in the Factfinder, under ‘Knight (mate by a knight’s first move)’, below is another specimen, published on page 7 of the January 1944 Schweizerische Schachzeitung:

B. Dyner – N.N.

Simultaneous exhibition, Neuchâtel, 30 November

1943

Centre Game

1 e4 e5 2 d4 f6 3 dxe5 fxe5 4 Qh5+ Ke7 5 Qxe5+ Kf7 6 Bc4+ d5 7 Bxd5+ Kg6 8 Qg3+ Kh5 9 Bf7+ g6 10 Qf3+ Bg4 11 Qxg4+ Kxg4 12 h3+ Kh5 13 g4+ Kh4

14 Nf3 mate.

7907. Translating Fischer

C.N. 867 (see page 149 of Chess Explorations and Fischer’s Fury) commented on the flavourless and inaccurate French translation (by Parviz M. Abolgassemi) of Fischer’s Mes 60 meilleures parties (Paris, 1972), even though the book claimed to have been ‘entièrement revu et corrigé par Chantal Chaudé de Silans’. These examples were offered:

A) ‘Once again, time-pressure had Sherwin burying his thumbs in his ears.’ ‘Une fois de plus à court de temps, Sherwin ne veut rien entendre.’ (Game 1)

B) ‘Alekhine said, in his prime, ...’ ‘Alékhine disait, au début de sa carrière ...’ (Game 8)

C) ‘A good last-ditch try.’ ‘Un excellent coup.’ (Game 16)

D) ‘I was informed that Gligorich thought I had blundered a Pawn ...’ ‘Je savais que Gligoric pensait que je m’étais trompé, ...’ (Game 30)

E) ‘Relieving the suspense.’ ‘Gardant le suspense.’ (Game 60).

Now, Louis Morin (Montreal, Canada) notes how these passages had appeared in the first edition of the book (also published by Stock, Paris in 1972):

A) ‘Une fois de plus à court de temps. Comme si Sherwin se refusait à comprendre.’

B) ‘Alékhine a dit, au début de sa carrière ...’

C) ‘Une dernière chance.’

D) ‘J’étais informé que Gligoric pensait que je m’étais trompé, ...’

E) ‘Gardant le suspense.’ (No change to the translation.)

Mr Morin also mentions a case where the translation in the ‘corrected edition’ was made worse. A sentence in the introduction to Game 44 refers to the Evans Gambit and reads:

‘This ploy has all but disappeared from the arena.’

- First edition: ‘Ce gambit, quoique valable, a disparu.’

- ‘Corrected’ edition: ‘Ce gambit est loin d’avoir disparu.’

Below is the front cover of a later reprint of the ‘corrected’ text (Editions Garnier Frères, 1982):

7908. Ebensee, 1933

Michael Negele (Wuppertal, Germany) has found this photograph in the Rueb scrapbooks at the Royal Library in The Hague. He writes:

‘I believe that I have identified most of the players. Standing from left to right are: Hans Müller, Rudolf Spielmann, N.N., Franz Kunert, N.N. and Erich Eliskases. Seated: Theophil Demetriescu, Gisela Harum and Lodewijk Prins.’

7909. Kurt Richter’s Kombinationen (C.N. 7875)

Ola Winfridsson (São Paulo, Brazil) writes:

‘I looked up the Tartakower v Colle game in the third (1955) edition of Kombinationen (position 293 on page 127). Tartakower’s name is still absent, although, as you point out, the names of other Jewish players, such as Flamberg, Nimzowitsch and Steinitz, have been restored. Is Tartakower’s name missing also in other post-War editions of this work?’

Tartakower’s name was added in the fourth (1965) edition.

7910. F.D. Yates

Is ‘Frederick Dewhurst Yates’ correct? That version of his name appeared in his obituary (by P.W. Sergeant) on pages 525-528 of the December 1932 BCM and on page 7 of Yates’ posthumous work One-Hundred-and-One of My Best Games of Chess (London, 1934), which was ‘arranged and completed’ by W. Winter and ‘edited’ by W.H. Watts. Ever since, ‘Frederick Dewhurst Yates’ has been used unquestioningly.

Leonard Barden (London) points out to us a most interesting Yorkshire Chess History webpage which states that ‘the popular rendering of his name as “Frederick Dewhurst Yates” is erroneous’ and that his name was Fred Dewhirst Yates. [Updated link.]

The above photograph, from the 1934 book, was given by us in a ChessBase article about Yates’ death.

| First column | << previous | Archives [101] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.