Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [100] | next >> | Current column |

7829. My 61 Memorable Games (Bobby Fischer)

We are adding material to the feature article as often as possible, with the aim of giving readers a well-rounded overview of the book.

The drawn game Botvinnik v Fischer, Varna Olympiad, 1962 appears on pages 448-481, with much new material, including an assault on ‘the Weinstein “schoolboy analysis” that Botvinnik had the gall to publish way back when’ (page 480).

And from page 476:

‘You have to put things in perspective. “Way back when”, my original plan was to sell a book with my 50 favorite games, with no notes at all! The project evolved over time, especially with the nearly unlimited hard work of Larry Evans. I added two more games, bringing the count to 52, and by this time notes and analysis were planned for as well. Finally, 60 games were included, but I wanted to back out of the deal. My skewed view of the “end of the world” being quite near (why else would I give away my secrets!) was what finally resulted in 1969’s My 60 Memorable Games.’

It should be noted that My 61 Memorable Games freely re-writes Evans’ introductions. The textual changes are vastly more extensive than what Batsford did to Fischer’s prose in the 1995 volume.

7830. Léonard Tauber (C.N. 7821)

Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) has just placed on-line an article about L. Tauber, including two pictures of him. It is stated that Tauber was born in Vienna on 5 June 1857 and died in Paris on 9 March 1944.

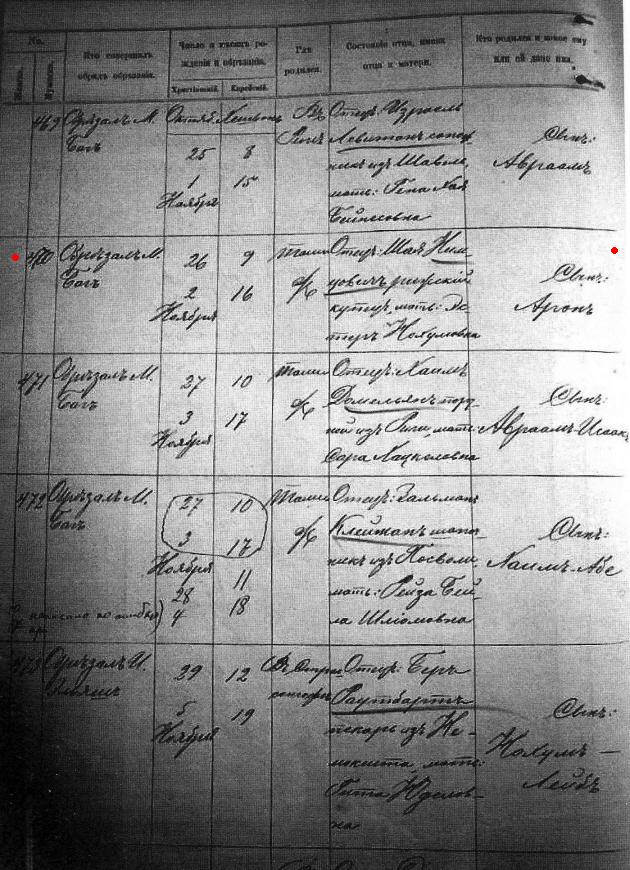

7831. When was Nimzowitsch born? (C.N.s 1894, 1931, 2879 & 3506)

Aron Nimzowitsch On the Road to Chess Mastery, 1886-1924 by Per Skjoldager and Jørn Erik Nielsen (Jefferson, 2012) was briefly mentioned in C.N. 7751. The McFarland chess catalogue has many excellent titles, but even there the Nimzowitsch volume stands out for the excellence of its scholarship.

With regard to Nimzowitsch’s exact date of birth, this paragraph is on page 5 of the Skjoldager/Nielsen book:

‘Aron was born on Heshvan 9 according to the Jewish calendar. This corresponds with 26 October 1886 in the Julian calendar, and both dates are equal to 7 November 1886 in the Gregorian calendar. It should be noted that Aron specified his birthday as 9 November on his application form to the university in Zurich. This was not just a slip of the pen since he repeated the mistake when he registered at the Einwohner und Fremden-kontrolle where he specified his birthday as 27 October/9 November 1886. Both dates are wrong, and it indicates that he was so strongly orientated towards Jewish culture and tradition at that time that he was not even aware of the correct corresponding Julian and Gregorian dates.’

A footnote adds:

‘His birth record is kept in the Latvian Historical Archive (fond 5024, inventory 2, file 735).’

The record is not reproduced in the book, and we are grateful to Per Skjoldager (Fredericia, Denmark) for an opportunity to show it here:

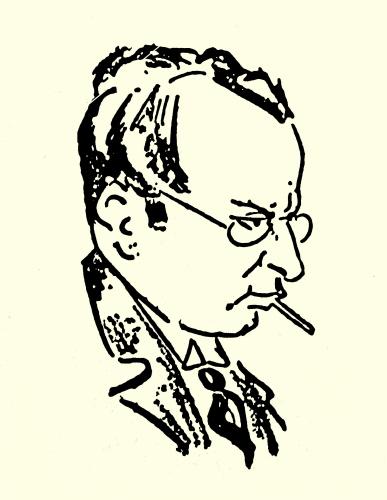

7832. Nimzowitsch and tobacco

Concerning the famous ‘smoking threat’ matter discussed in A Nimzowitsch Story, we note the following on page 369 of Aron Nimzowitsch On the Road to Chess Mastery, 1886-1924:

‘The anecdotes have, of course, left the impression that Nimzowitsch disliked smoking very much. But the drawing of Nimzowitsch from the tournament in Copenhagen 1923, however, discloses Nimzowitsch to be – a smoker. A letter from his younger brother Benno to Professor Becker, written in 1935, confirms, though with a chronological vagueness, that Aron was a diligent smoker “when he was young”. The letter also said that he had to give it up because of health problems. Like many other ex-smokers, Nimzowitsch then developed a strong dislike for tobacco smoke.’

The sketch in question is shown below, courtesy of Mr Skjoldager:

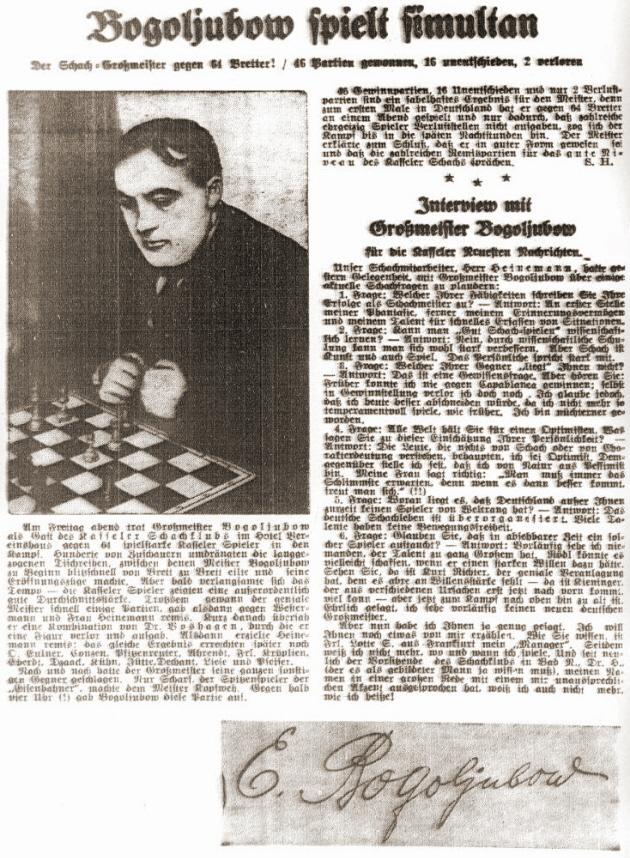

7833. Interview with Bogoljubow (C.N. 5274)

‘People who know nothing about chess or character evaluation claim that I am an optimist. Quite the contrary, though, I am of a pessimistic nature. My wife always says (and quite correctly too), “Always expect the worst; if things then actually turn out better, you’ll be happy”.’

C.N. 5274 quoted this passage from page 986 of L’Echiquier, March-April 1935, which stated that the interview with Bogoljubow had appeared in the Kasseler Neueste Nachrichten, 17 December 1932. We asked whether a copy of that original publication could be found.

Alan McGowan (Waterloo, Ontario, Canada) notes this news item on page 339 of the August 1934 BCM:

‘In his column, the Augsburger Schachblatt, Dr Adolf Seitz recently reprinted an interview with E.D. Bogoljubow, which appeared in the Kasseler Neueste Nachrichten in December 1932, but did not obtain much publicity. In it, among other opinions, Bogoljubow expressed his view that the reason why Germany had ceased to have a master of the world-rank was that German chess was over-organized, to the loss of freedom for talent.’

Is it possible to trace the interview in either of the German-language sources?

7834. Who?

7835. Criticism of draws (New York, 1889 play-off)

John Blackstone (Las Vegas, NV, USA) points out this item on page 14 of the New York Sun, 26 May 1889:

‘The two drawn games which Messrs. Weiss and Chigorin performed, we will not say played, on Thursday and Friday of last week, while in the effort to break their tie for first place, added no glory to the history of chess. Under such deliberate attempts at a draw, chess is put behind the game that ranks next to it, checkers, in which drawn games are the rule and not the exception. The pusillanimous resignation to rivalry with which each of these two leaders of a great intellectual diversion shrank from the attack, hoping that his adversary would make a mistake, is but another phase of the famous meeting in Canada between Mace and Coburn. Those eminent prize-fighters quartered about the ring for hours because neither was willing to lead for the other, and the affair ended in the same sort of fiasco as these concluding encounters of the chess tournament.

Masters Chigorin and Weiss should gird up their loins and be men when they meet tomorrow. Let them abandon their imitation of Mace and Coburn and think of how Chateaubriand used to say, in a language they both can read, “Ce n’est pas la victoire [qui] fait le bonheur des nobles coeurs – c’est le combat.” [This quote is commonly ascribed to Montalembert, with la joie rather than le bonheur.] Not victory, but battle, delights the noble heart. One blow for the honor of chess rather than none for victory. Play for all you are worth.’

Notwithstanding the newspaper’s exhortations, the fourth and final game in the play-off was drawn in 28 moves the next day.

7836. Tartakower’s date of birth

Michael Negele (Wuppertal, Germany) has been looking into Tartakower’s date of birth, on the basis of the citations in Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia (Jefferson, 1987). The consensus (e.g. Deutsche Schachzeitung, January 1918, page 23, and L’Echiquier, 2 December 1933, page 333) is that Tartakower was born on 21 February 1887 (Gregorian calendar), i.e. 9 February 1887 in the Julian calendar.

Our correspondent has raised the matter because the English and French editions of the first volume of Tartakower’s best games, published in 1953, gave 9/22 February 1887. For example, the following appeared in the Introduction to Tartakover vous parle:

‘Ami lecteur, voici ce que tu dois savoir sur moi:

Xavier Tartacover (Tartakower) est né le 9 février (ancien style, correspondant au 22 février du calendrier grégorien) 1887, à Rostoff-sur-le-Don (Russie).’

As mentioned in C.N. 4819, however, in the nineteenth century the gap between the two calendars was 12 days, and not 13.

7837. A better move

Stuart Rachels (Tuscaloosa, AL, USA) asks about the observation ‘When you see a good move, look for a better one’, which he has seen ascribed, without a source, to Emanuel Lasker.

The phrase ‘without a source’ readily takes us, by way of example, to Andrew Soltis. From page 300 of his book The Inner Game of Chess (New York, 1994):

‘White failed to heed Emanuel Lasker’s sage advice: When you see a good move, don’t make it immediately. Look for a better one.’

It is certainly true that the phrase has often been attributed to Lasker; see, for instance, a quote in Alfred Kreymborg and Chess.

It has also been attributed to Tarrasch, and not always favourably. From page 36 of Better Chess by Bill Hartston (London, 1997):

‘But when you’ve fumbled and analysed, and all the signposts point to one particular move, when is the moment to sign contracts and play it? The great German player Dr Siegbert Tarrasch advised: “When you’ve found a good move, look for a better one.” What nonsense! When you’ve found a good move, play it! Good moves are few and far between. Don’t talk yourself out of them. But make sure they are as good as you think.’

A related point regarding Tarrasch was made by Capablanca on page 71 of A Primer of Chess (London, 1935), in the section headed ‘Main rules and ethics of the game’:

‘Do not hover over the pieces too much. It is unethical and it leads to errors. The celebrated German master, Dr Tarrasch, used to sit with his hands under his thighs to avoid hesitation and to keep from moving hastily. It is not bad to move quickly, but it is bad to move hastily.’

Next, a paragraph from page 78 of Chess Catechism by Larry Evans (New York, 1970):

‘It was Steinitz who observed that when you see a good move, wait – and look for a better one.’

Exact citations will be welcome, and in the meantime we offer a comment by Leopold Hoffer in the The Field, 1886, which was quoted on page 121 of Johannes Zukertort Artist of the Chessboard by Jimmy Adams (Yorklyn, 1989):

‘If Zukertort sees a good move, he makes it; if Steinitz sees a good move, he looks out for a better one.’

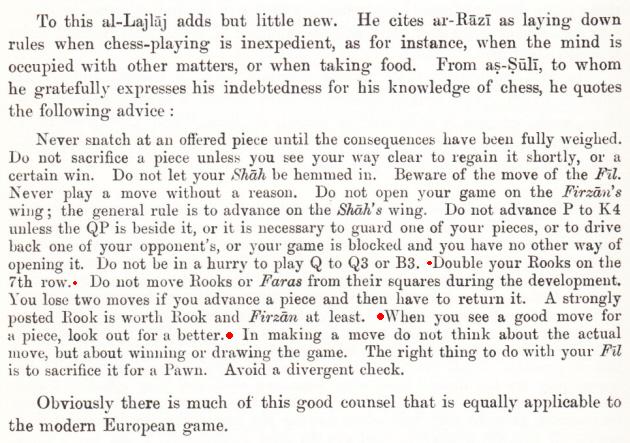

Many other such remarks could be quoted, but in any case the sentiments in question were expressed 500 years ago by Damiano in Questo libro e da imparare giocare a scachi et de le partite, as noted, for instance, by H.J.R. Murray on page 788 of A History of Chess (Oxford, 1913): ‘when you have a good move look for a better’. See too page 95 of Wonders and Curiosities of Chess by Irving Chernev (New York, 1974), in a feature entitled ‘Damiano’s centuries-old advice still good today’.

7838. Oliphant (C.N.s 5408, 5416, 6895 & 6949)

From Thomas Niessen (Aachen, Germany):

‘C.N.s 5408 and 5416 mentioned the Dutch chessplayer Carel Naret Oliphant and provided some biographical information about him. The correct date of his death is 26 September 1867, as given in Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia (Jefferson, 1987), but he died at the age of 86 (and not 88 as stated in the book). This information can be found in various contemporary sources, such as the obituary on page 343 of Sissa, 1867 and in the death notice from the family which was published in the Nieuwe Rotterdamsche Courant and Opregte Haarlemsche Courant on 3 October 1867.

Carel Naret Oliphant was buried in the Groenesteeg cemetery in Leiden. The secretary, Mr Lodewijk Kallenberg, has confirmed the date of death in a message to me, adding that Oliphant was buried on 1 October 1867. However, an incorrect date of death was given in the cemetery’s Nieuwsbrief of January 2012 and on its webpage. (The webpage, which was brought to my attention by a third party, has a photograph of Oliphant dated 1866.)

C.N. 6895 raised the question of whether the chessplayer Carel Naret Oliphant and “a Dutch wigmaker from Leyden” with the same name who was mentioned on the Burke’s Peerage and Gentry webpage were the same person. The chessplayer’s profession was given as “pharmacist” (C.N. 5416) or surgeon (C.N. 6949).

Despite the different professions, I believe that they were indeed the same person. Apart from the identical names and towns (Leyden is the old spelling of Leiden), both men lived into their 80s and had a son whose initials were “C.A.G.”. The chessplayer’s son signed the above-mentioned death notices and in 1863 he was the Vice-President of the Palamedes Chess Club in Leiden (Sissa, 1863, page 382). The forenames of the wigmaker’s son are given in full on the Burke’s Peerage and Gentry webpage: Charles Agathon Guillaume. The story of the wigmaker is told in more detail in The Oliphants from Gask by Ethel Maxtone Graham (London 1910). One quote, from page 456, may suffice:

“A year after the contract was made, in September 1867, the old man, Carl [sic] Naret Oliphant, died. In less than a year after, his son followed him to the grave.”

A death notice of a C.A.G. Oliphant, who died on 16 September 1868, can be found in the Opregte Haarlemsche Courant of 5 October 1868.’

7839. Alekhine on Keres and Fine as

challengers

Simon Browne (Somerville, Australia) notes the remarks by Alekhine about possible world championship rivals on page 178 of 107 Great Chess Battles (Oxford, 1980):

‘Before 1940 I was quite certain that two masters, Botvinnik and Flohr, wished to fight for this title. Neither of the two matches could be brought about, and the above-mentioned challengers know very well that I had decided to face them.

As regards Keres, his position in 1938-39 was less resolved; he gave the impression of preferring to let a few years pass. But in 1943, perhaps influenced by the disastrous results he obtained against me in recent meetings (+3 =3 –0 in my favour) he resolutely declared that he had not the slightest intention of challenging me to a match. Fine too, in 1940, made an analogous declaration.’

These remarks were originally published on page xix of Alekhine’s book ¡Legado! (Madrid, 1946), and Mr Browne asks whether it is possible to find statements by Keres or Fine along the lines indicated by Alekhine.

Readers’ assistance will be appreciated. Firstly on this topic, we would draw attention to an earlier article by Keres, ‘The World Chess Championship’, published on pages 51-53 of the March 1941 Chess Review.

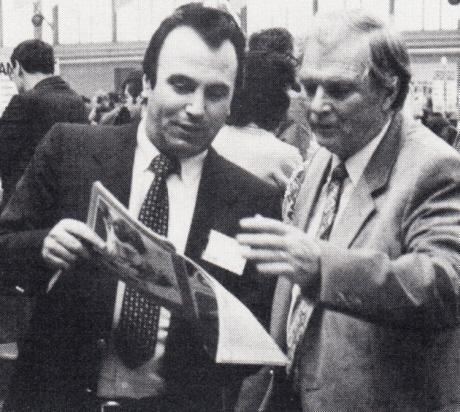

7840. Who? (C.N. 7834)

Alexander Roshal (left) is with Alex A. Aljechin (the world champion’s son) at the 1982 Olympiad in Lucerne. The photograph comes from page 586 of the December 1982 Schweizerische Schachzeitung.

7841. A better move (C.N. 7837)

Mark N. Taylor (Mt Berry, GA, USA) points out the following on page 246 of A History of Chess by H.J.R. Murray (Oxford, 1913):

The advice ‘Double your Rooks on the 7th row’ is also of interest, being relevant to the question asked in C.N. 6844.

7842. Fischer v Najdorf

The draw between Fischer and Najdorf at the 1960 Olympiad in Leipzig has given rise to all manner of stories, and particularly from Najdorf.

As reported on page 25 of the April-August 1996 issue of Ajedrez de estilo, in conversation with Juan Sebastián Morgado in Buenos Aires on 5 July 1996 Fischer ridiculed an interview which Najdorf had given to Jaque in 1992. With regard to stories about the Leipzig game, Fischer stated that Najdorf had lied and that with every year that passed Najdorf exaggerated or changed an anecdote involving Fischer.

An English version, by Jonathan Berry, of Fischer’s remarks appeared on page 7 of the 23 December 1996 Inside Chess. Najdorf’s interview (not a word of which we would take on trust) was published on pages 4-7 of issue 335 of Jaque (September 1992).

7843. Sozin and the Meran Defence (C.N. 7813)

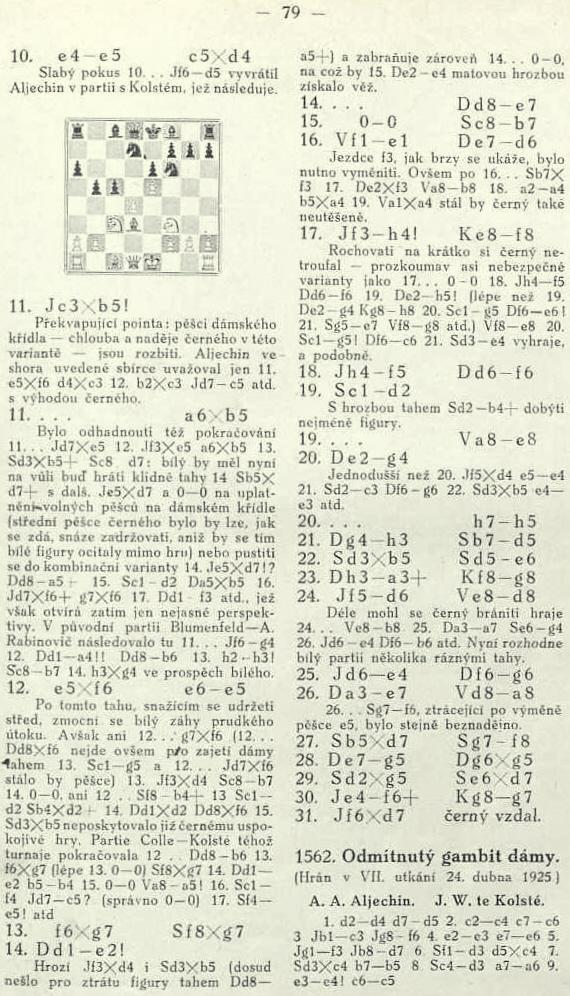

Position after 11 Nxb5

Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) notes that the Italian master Remo Calapso claimed paternity of the 11...Nxe5 variation in the Meran Defence, as recorded in Remo Calapso by E. Giudici and V. Nestler (Santa Maria Capua Vetere, 1976). Page 70 says that Calapso played the move in a correspondence game against Pierre Morra, which is given on pages 71-72 with Calapso’s notes from the October 1926 L’Italia Scacchistica. Moreover, pages 72-74 of the book have his article on the opening from the Italian magazine’s January 1926 issue.

The Morra v Calapso game was played from 28 June 1925 to 30 June 1926, whereas the Rabinovich v Verlinsky game mentioned in C.N. 7813 was played on 29 November 1925.

A footnote on page 70 of the Calapso book adds Tartakower’s statement that Sosin and Calapso discovered the move 11...Nxe5 simultaneously in 1925:

‘Esta réplica fue descubierta simultáneamente por Sosin y por Galapso [sic] en 1925.’

Source: page 97 of Ideas modernas en las aperturas de ajedrez by S. Tartakower (Buenos Aires, various editions).

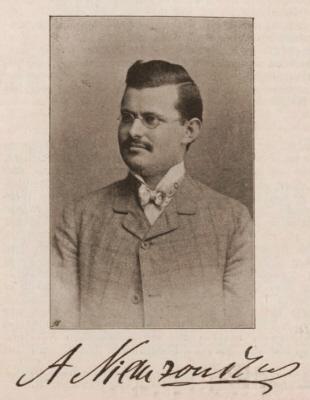

7844. Nimzowitsch signature

From page 344 of the October-November 1910 Wiener Schachzeitung:

Do any specimens exist of Nimzowitsch’s signature in Cyrillic script?

7845. Interview with Bogoljubow (C.N.s 5274 & 7833)

Peter Anderberg (Harmstorf, Germany) has found the Bogoljubow feature published in the Kasseler Neueste Nachrichten of 17-18 December 1932:

Our correspondent has also provided this transcript:

‘Interview mit Großmeister Bogoljubow

für die Kasseler Neuesten Nachrichten.Unser Schachmitarbeiter, Herr Heinemann, hatte gestern Gelegenheit, mit Großmeister Bogoljubow über einige aktuelle Schachfragen zu plaudern:

1. Frage: Welcher Ihrer Fähigkeiten schreiben Sie Ihre Erfolge als Schachmeister zu? – Antwort: An erster Stelle meiner Phantasie, ferner meinem Erinnerungsvermögen und meinem Talent für schnelles Erfassen von Situationen.

2. Frage: Kann man “Gut Schach-spielen” wissenschaftlich lernen? – Antwort: Nein, durch wissenschaftliche Schulung kann man sich wohl stark verbessern. Aber Schach ist Kunst und auch Spiel. Das Persönliche spricht stark mit.

3. Frage: Welcher Ihrer Gegner “liegt” Ihnen nicht? – Antwort: Das ist eine Gewissensfrage. Aber hören Sie: Früher konnte ich nie gegen Capablanca gewinnen; selbst in Gewinnstellung verlor ich doch noch. Ich glaube jedoch, daß ich heute besser abschneiden würde, da ich nicht mehr so temperamentvoll spiele, wie früher. Ich bin nüchterner geworden.

4. Frage: Alle Welt hält Sie für einen Optimisten. Was sagen Sie zu dieser Einschätzung Ihrer Persönlichkeit? – Antwort: Die Leute, die nichts von Schach oder von Charakterdeutung verstehen, behaupten, ich sei Optimist. Demgegenüber stelle ich fest, daß ich von Natur aus Pessimist bin. Meine Frau sagt richtig: “Man muß immer das Schlimmste erwarten, denn wenn es dann besser kommt, freut man sich.” (!!)

5. Frage: Woran liegt es, daß Deutschland außer Ihnen zurzeit keinen Spieler von Weltrang hat? – Antwort: Das deutsche Schachleben ist überorganisiert. Viele Talente haben keine Bewegungsfreiheit.

6. Frage: Glauben Sie, daß in absehbarer Zeit ein solcher Spieler auftaucht? – Antwort: Vorläufig sehe ich niemanden, der Talent zu ganz Großem hat. Rödl könnte es vielleicht schaffen, wenn er einen starken Willen dazu hätte. Sehen Sie, da ist Kurt Richter, der geniale Veranlagung hat, dem es aber an Willensstärke fehlt – da ist Kieninger, der aus verschiedenen Ursachen erst jetzt nach vorne kommt, viel kann – aber jetzt zum Kampf nach oben hin viel zu alt ist. Ehrlich gesagt, ich sehe vorläufig keinen neuen deutschen Großmeister.

Aber nun habe ich Ihnen ja genug gesagt. Ich will Ihnen noch etwas von mir erzählen. Wie Sie wissen, ist Frl. Lotte S. aus Frankfurt mein “Manager”. Seitdem weiß ich nicht mehr, wo und wann ich spiele. Und seit neulich der Vorsitzende des Schachklubs in Bad N., Dr. H., (der es als gebildeter Mann ja wissen muß), meinen Namen in einer großen Rede mit einem mir unaussprechlichen Akzent ausgesprochen hat, weiß ich auch nicht mehr, wie ich heiße!’

7846. Modern Chess Preparation

C.N. readers will have seen here most of the photographs of the old-timers used in Modern Chess Preparation by Vladimir Tukmakov (Alkmaar, 2012). They may also note that the picture of Tal on page 70 has been reversed, and below we give the correct version (Tal in play against Sliwa in the 1960 Leipzig Olympiad), from page 29 of the tournament book:

From page 15 of the Tukmakov work, concerning the celebrated Lasker v Capablanca game at St Petersburg, 1914:

‘The young Cuban, who was confidently leading the tournament, needed only not to lose with Black against the current World Champion in order to claim overall tournament victory.’

Some myths endure no matter how often they are disproved, or how easily. Reviewing From Morphy to Fischer by Al Horowitz (London, 1973) W.H. Cozens commented on page 159 of the May 1974 BCM:

‘Horowitz does fall into one historical error – one which has been made by other writers before him – when he speaks [on page 69] of “Lasker’s last-round victory over Capablanca” at St Petersburg, 1914.’

See too, for instance, Larousse du jeu d’échecs. The game was played in the seventh of ten rounds in the final section.

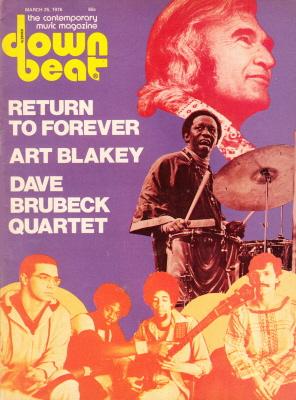

7847. Thelonious Monk

Dan Scoones (Coquitlam, BC, Canada) observes that a number of websites describe the jazz musician Thelonious Monk (1917-82) as ‘excellent at both chess and checkers’, the source specified being an article by John B. Litweiler, ‘Art Blakey: Bu’s Delights and Laments’.

We have found the magazine containing the article (down beat, 25 March 1976, pages 15-17 and page 44), but there is only one brief reference to chess, on page 15:‘Art Blakey on Thelonious Monk: “I have yet to meet the man who can beat him at chess, or even checkers, or ping-pong.’”

7848. Sozin and the Meran Defence (C.N.s 7813 & 7843)

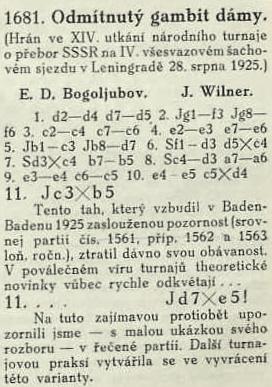

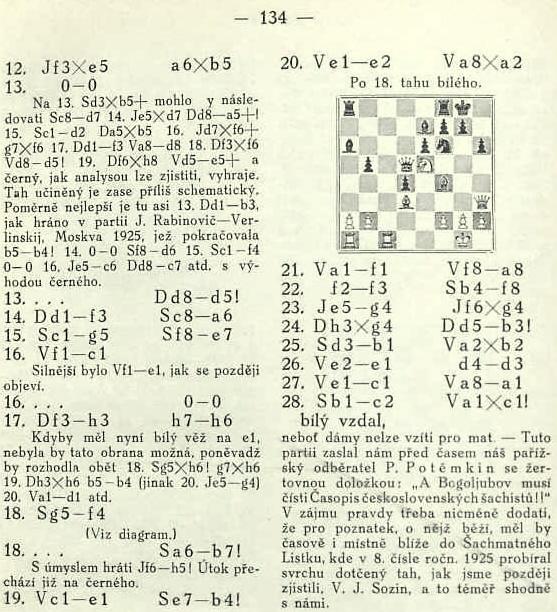

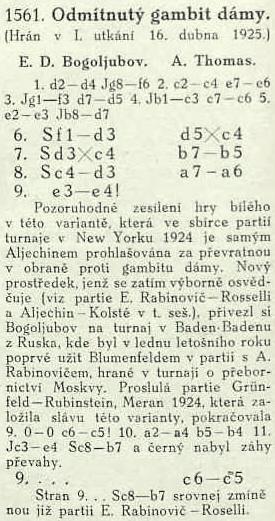

Further to C.N. 7843, Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) notes that Calapso’s article referred to a win by Wilner (or Vilner) against Bogoljubow in the Soviet championship (Leningrad, 1925). Played on 28 August 1925, the game was published on pages 133-134 of the August-September 1926 Časopis Československých Šachistů:

The concluding note is significant for its reference to Sozin and a specific Russian-language source. Below is a translation kindly supplied by Karel Mokrý (Prostejov, Czech Republic):

‘This game was sent to us by our Paris subscriber P. Potemkin some time ago, with a jocular postscript: “And Bogoljubow must now read Časopis československých šachistů!!” However, in the interests of truth it should be added that the information was available to Bogoljubow more immediately – in terms of both time and place – in Shakhmatny Listok; in issue 8 of the 1925 volume, so we found out later, the move mentioned above was analysed by V.I. Sozin, in an almost identical manner.’

Mr Thimognier adds that Calapso’s article also referred to Bogoljubow v Thomas, Baden-Baden, 16 April 1925, and that the Czech magazine’s (anonymous) annotations to that game, in the May-June 1925 issue, pages 78-79, mentioned 11...Nxe5:

Finally, Mr Thimognier points out that Alekhine did not mention 11...Nxe5 in his article ‘La variante de Meran à Baden Baden’ on pages 109-110 of L’Echiquier, June 1925.

7849. Air castles

‘Problems are the air castles of the chessboard.’

This remark was given anonymously on page 81 of Lasker’s Chess Magazine, December 1904 and on page 119 of the June 1907 American Chess Bulletin. Is the author known?

7850. 1 e4 c5 2 Bc4 e6 3 Nc3 Nc6 4 d3 a6

1 e4 c5 2 Bc4 e6 3 Nc3 Nc6 4 d3 a6 5 a3 Qc7 6 f4 b5 7 Ba2 Bb7 8 Nf3 Be7 9 O-O Nf6 10 Be3 O-O 11 Qe2 Rad8 12 e5 Ng4 13 Bd2 d5 14 h3 Nh6 15 g4 Kh8 16 f5 exf5 17 Nxd5

17...Nd4 18 Nxd4 Bxd5 19 Nxf5 Nxf5 20 Rxf5 g6 21 Rff1 Ba8 22 Rxf7 c4 23 Rxf8+ Rxf8 24 Bc3 Qb6+ 25 d4 Qb7 26 Qh2 Qf3 27 White resigns.

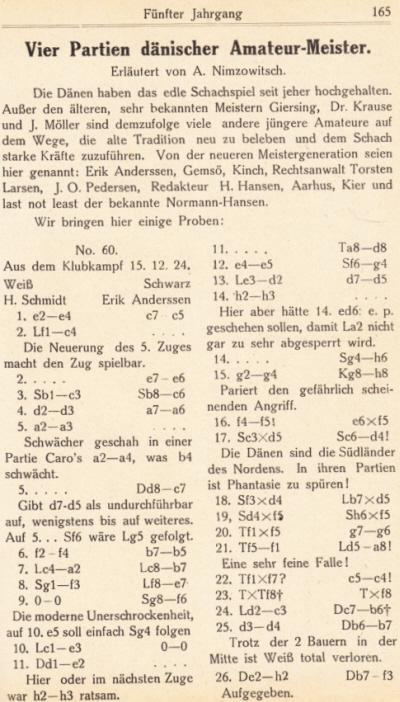

This game between H. Schmidt and Erik Andersen [sic] was published on page 165 of Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten, 1 April 1925 with annotations by Nimzowitsch:

Javier Asturiano Molina (Murcia, Spain) asks whether it is possible to identify the game by Caro to which Nimzowitsch refers in his note to White’s fifth move.

So far we have not found it. It may be mentioned that, in

any case, the move 5 a4 had been seen in the 11th

match-game between Löwenthal and Harrwitz in 1853 (see

pages 368-370 of that year’s Chess Player’s Chronicle).

As recorded on pages 340-341 of the same volume, the

seventh match-game began 1 e4 c5 2 Bc4 e6 3 Nc3 a6 4 a4

Ne7 5 d3 d5. The move 5 a3 had occurred two years

previously (after 1 e4 c5 2 Bc4 Nc6 3 d3 e6 4 Nc3 a6) in

Ranken v Hodges (fourth match-game in the London, 1851

Provincial Tournament). See pages 204-206 of Staunton’s

volume on London, 1851.

7851. Steinitz v Chigorin cable match

John Blackstone (Las Vegas, NV, USA) notes a news report on page 6 of the New York Sun, 20 November 1890 and, in particular, the final paragraph:

‘We imagine that the popular estimate of chess will be revolutionized by these games. As their slow changes are watched by a continually increasing attention on the part of the public, the idea must grow that chess under the ordinary rules is too fast, and that a truly perfect contest must spread over weeks or even months, perhaps years.’

As regards the popularity of the two games, we add that Steinitz wrote on page 4 of the New York Tribune, 1 May 1891:

‘Never before in the history of our pastime has a chess contest created such widespread and literally universal interest during its progress as the one just concluded between myself and Mr Chigorin.’

The full article was reprinted on pages 107-111 of the April 1891 International Chess Magazine.

7852. 1 e4 and 1 d4

From page 8 of Curious Chess Facts by Irving Chernev (New York, 1937):

‘Ern[e]st Grünfeld, probably the greatest living authority on the openings, played 1 P-K4 only once in his whole tournament career (against Capablanca, Carlsbad, 1929). When asked why he avoided 1 P-K4 he replied, “I never make a mistake in the opening”.’

The alleged Grünfeld remark is often quoted, but what is its source?

With regard to Grünfeld’s use of 1 e4, page 260 of Chess Explorations referred to Ernst Franz Grünfeld by Michael Ehn (Vienna, 1993); the book, which goes as far as 1920, has many (minor) games in which Grünfeld played 1 e4. From databases we also note a few specimens from the 1950s.

And from page 17 of Curious Chess Facts:

‘Chigorin, who had so much trouble finding a defence to 1 P-Q4, adopted this move as White only once in his whole tournament career (against Albin, Nuremberg, 1896). He beat Albin easily, and yet he never played 1 P-Q4 again.’

Chigorin had also played 1 d4 against Mackenzie at London, 1883. See pages 153-154 of the tournament book.

A quote from page 72 of The Fireside Book of Chess by Irving Chernev and Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1949):

‘Paul Morphy, considered by many critics the greatest chess genius that ever lived, never played 1 P-Q4.’

Regarding Spielmann’s preferred first move as White, Reinfeld wrote on page 117 of Great Moments in Chess (New York, 1963):

‘There is an interesting story related to the following fine finish, played in the Trentschin-Teplitz tournament of 1928. Réti started the game with 1 P-Q4, and Spielmann was so impressed by the overwhelming drubbing that he received that he thereupon started playing 1 P-Q4 after a lifetime of beginning with 1 P-K4.’

Is there any substance to the story? When the game was published on pages 85-86 of Reinfeld and Chernev’s Chess Strategy and Tactics (New York, 1933) the suggestion was more speculative:

‘One of the many sensations of the great Carlsbad (1929) tournament was Spielmann’s belated renunciation of his beloved P-K4 in favor of Queen’s Pawn openings. The suddenness of the change was no less astonishing than the stubbornness with which Spielmann had previously clung to the King’s Gambit and similar openings. Perhaps the clue to this surprising change will be found in the overwhelming drubbing administered by Réti in the following elegant game.’

The Réti v Spielmann game, played on 23 May 1928, was annotated by Spielmann on pages 146-147 of the May 1928 Wiener Schachzeitung. His closing remark may be quoted in passing:

‘Gerade gegen mich spielt Réti immer das beste Schach. In welchem Gegensatz dazu steht sein auffallend schwaches Spiel in mehreren anderen Partien des gleichen Turniers.’

The Carlsbad tournament began over a year after the Réti

v Spielmann game was played. During the intervening

period, Spielmann played 1 d4 a number of times: v

Bogoljubow at Bad Kissingen, 1928, v Vajda at Budapest,

1928 and v Réti and Capablanca at Berlin, 1928. He had

also played it occasionally earlier in his career.

7853. Value of the pieces (C.N.s C.N. 4897 & 4902)

A question from Stuart Rachels (Tuscaloosa, AL, USA): who introduced the famous elementary system of values (pawn 1, knight 3, bishop 3, rook 5, queen 9)?

We can do no better than quote from page 59 of The Hall-of-Fame History of US Chess by Robert John McCrary (1998):

‘By the 1930s, the idea of a single numerical scale of values seemed to be losing favor. Instead, great players such as Capablanca and Tarrasch were generally avoiding giving a single scale of values in their books, preferring to discuss various kinds of exchanges on a case-by-case basis.

Then in 1942 Reuben Fine published his Chess The Easy Way. On page 23 is the following historically important section:

“Since there are six different kinds of pieces it is necessary to set up a table of equivalents in order to be able to know whether an exchange is favorable or not. Again such a table is based partly on the elementary mates (R can mate, B or Kt cannot) and partly on practise. If we take the pawn as 1 we may set up a table such as this:

pawn = 1

bishop (or knight) = 3

rook =5

queen =9.”Fine goes on to say that his table is satisfactory for rough calculation but not as accurate as a set of equivalents for certain exchanges he gives on the next page. Nevertheless, Fine apparently popularized our modern scale and indeed may have invented it. Does any reader know of an earlier publication of the modern scale? Perhaps Fine then should be considered the true “point-count” man of chess.’

7854. Demoralization

This article by G.H. Diggle, originally published in Newsflash, April 1981, was given on page 67 of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984):

‘Chess matches have often been abandoned half-way through by demoralized combatants after successive wins have been piled up against them; Harrwitz v Morphy and Kostić v Capablanca are notable examples. Dr Hübner’s recent resignation to Korchnoi is a more unusual case, as he was only potentially 4-6 down with six games to play. In 1851, however, there were two similar match resignations caused (as in Hübner’s case) by stress, though in both cases the stress was not due so much to “world publicity” as to the “intolerable tedium” of pre-time-limit chess. In one of these Staunton, with a level score against Williams, resigned the match (after the 13th game had proceeded for 20 hours) “rather than undergo the torture of another game”. The other case (though recounted in the BCM for February 1940) is less well-known. In one of the “side-shows” of the great 1851 tournament, the youthful Frederic Deacon, burning with eagerness to win his chess spurs, was, though already notorious for slow play, selected very injudiciously by the Committee to play a match of seven games up with Edward Löwe, then a perfunctory old stager nearly 40 years Deacon’s senior. The prizes were £8 to the winner and £3 to the loser, and Deacon won the first two games, with Löwe moaning throughout about Deacon’s slowness. In the third game (Deacon later wrote to the Tournament Committee) “Mr Löwe noted the time I took to consider a move and then delayed double that time before he made his own – this was in the presence of Mr Löwenthal and Mr Williams.” (The BCM comments, “We can imagine Williams scenting tedium and watching this new experiment with the air of a patron.”) Deacon’s attempt to speed things up led to his losing the game in 37 moves after a mere four and a half hours’ play. Finally in the fourth game, as Deacon was considering his 16th move after about two and a half hours’ play “when I had unquestionably the better game” Löwe suddenly resigned the match and walked off. To all arguments to induce him to resume the contest Löwe replied that he found there was no time to fulfil his business engagements if he had to play any more chess with Deacon, to whom he resigned the prize. “I cannot say fairer!” This left Deacon with no other course but to write to Staunton as Secretary of the Tournament troubling the Committee for “the prize which I of course believed to be my due”. Then came the unkindest cut of all. “The Committee were not prepared to award any prize as the conditions of the match had not been fulfilled.” Deacon pointed out with indignant triumph that if this ruling became “case-law” it would always be in the power of one player to prevent his antagonist receiving the prize by resigning the match “even just before he had lost his seventh game”. This so staggered the Committee that they brought pressure to bear on Löwe, who was finally induced to play out the match, Deacon winning 7-2-1. Staunton in annotating the games admits that “the tedium of Mr Deacon’s play is quite insufferable, and although with him this arises from habit only, and not from a design to exhaust and irritate an opponent, the sooner he corrects so grave a fault the better.”’

According to Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia (Jefferson, 1987), Frederic H. Deacon was born in Bruges in about 1829 and died, possibly in Brussels, circa October 1875. However, the privately-circulated 1994 edition gave his full name as Frederick Horace Deacon and stated that he was born in Bruges in about 1830 and died in Brixton, London on 20 November 1875. The additional sources specified by Gaige were the death certificate (reporting that Deacon died at the age of 45) and the probate record.

7855. A disputed draw

Black has just played 32...Ne7-d5, and the game (Marshall v Treybal, played in the penultimate round of the Baden-Baden tournament, on 13 May 1925) was agreed drawn. In his analysis on page 197 of N.I. Grekov’s tournament book N.M. Zubarev wondered about Treybal’s peacefulness in such an advantageous position:

From page xi of Tarrasch’s tournament book:

An account of the incident was provided by Hans Kmoch at the start of an article, ‘Farce Versus Farce’, on page 328 of the November 1962 Chess Review:

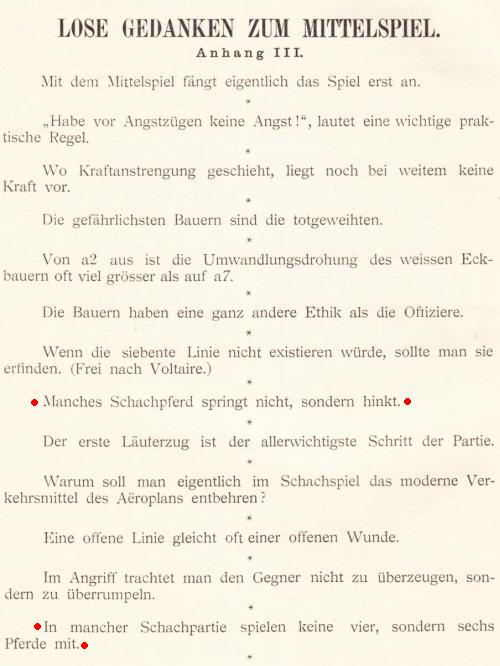

7856. Tartakower witticisms

Two Tartakower witticisms from pages 23 and 109 of The Bright Side of Chess by Irving Chernev (Philadelphia, 1948):

- ‘In some games of chess, there are not four but six horses.’

- ‘Some knights don’t leap – they limp.’

Since quotes without sources are also without value, we reproduce pages 186-187 of Tartakower’s book Das entfesselte Schach (Kecskemét, 1926):

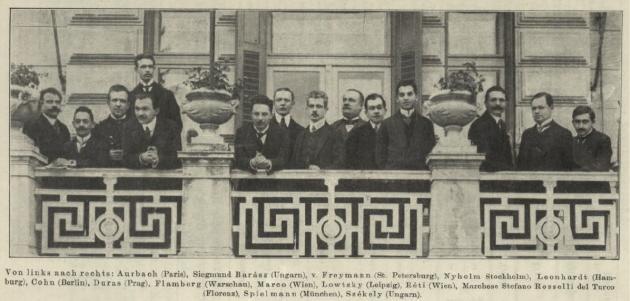

7857. Opatija, 1912

A group photograph on page 12 of Časopis českých šachistů, 1912:

7858. Williams v Staunton (C.N. 7854)

From John Townsend (Wokingham, England):

‘In C.N. 7854 G.H. Diggle reported:

“In one of these Staunton, with a level score against Williams, resigned the match (after the 13th game had proceeded for 20 hours) ‘rather than undergo the torture of another game’.”

Although the match score was level, the same cannot be said of the position on the board, since, at the time of his resignation, Staunton was a piece down in a completely lost endgame. On page 349 of The Chess Tournament (London, 1852) he made a curious remark in a note to his move 41...Kf7 in that game.

“It is clear that Black could have made a drawn battle if he chose, by

41...R to KR’s 8th

42 K to Kt’s 2nd, or 3rd 42 R to QKt’s 8th

43 B to QKt’s 2nd 43 K to B’s 2nd, etc.but it having been long quite evident that his opponent would protract the sitting until he (Black) could no longer support the fatigue (the present game lasted above 20 hours!), he preferred resigning the contest, although two games ahead, to undergoing the torture of another game.”

What exactly did Staunton mean by the last part of that remark? If he was suggesting that his inferior choice of 41...Kf7 was his way of capitulating, he omitted to explain why he played on for a further 38 moves. His eventual resignation, at move 79, was fully called for. He was, clearly, frustrated by Williams’ slow play, but here he seems to have confused that issue with the subject of his resignation and, hence, to have picked the wrong battlefield on which to attack Williams.

This was the return match after Williams had defeated him in the play-off for third place in the tournament. It was played at Staunton’s “country house” in Cheshunt, the exact location of which is not known. As he led by six wins to three before the 13th game but had given Williams the odds of three games’ start, the Badmaster was correct that the match score stood level. Staunton’s remark quoted above that he was two games ahead must be wrong, unless he meant that, after losing the 13th game, he remained two games ahead. Being two games ahead was useless, since Williams, by scoring his fourth win in the 13th game, reached the target of seven wins needed to secure the match, so for Staunton “undergoing the torture of another game” was no longer an option.’

7859. Deacon (C.N. 7854)

Also from Mr Townsend:

‘G.H. Diggle referred in C.N. 7854 to another slow player, F.H. Deacon. In the 1851 census, Deacon’s description as “Writer of Chess” may well be the earliest reference to that occupation to be found in any census return. He was living in South Lambeth (aged 20), a British subject born in Belgium. (Source: the 1851 census, National Archives, HO 107/1573, f. 347.)

By the time of the 1861 census, “Frederick H. Deacon” had the more orthodox occupation of “clerk in Manchester Ho.”, unmarried, age given as 27, living at 3 Hale’s Place, Langley Lane, Lambeth, described as a son of the head of the household, who was Sarah S. Rogers, a 66-year-old widow, a “fundholder” who had been born in Chelsea. Also in the household were two elder brothers of Frederick, i.e. George L. Deacon and Edward E. Deacon. (Source: 1861 census, National Archives, RG9/357, ff. 126-127.)

As Jeremy Gaige pointed out, the calendar of probate records shows that “Frederick Horace Deacon” died on 20 November 1875, at 37 Vaughan Road, Coldharbour Lane, Brixton. He was “formerly of 3 Hale’s Place, Lambeth”, but “late of 7 Hardiss Road, Cold Harbour Lane, Camberwell”. His will was proved by Edward Erasmus Deacon, a brother, the effects being “under £450”.

The burial register of the South Metropolitan Cemetery (Norwood Road, Lambeth) shows that he was buried there on 26 November 1875, his age being given as 45. The entry specifies the same address as in the calendar of probate records, 37 Vaughan Road, Coldharbour Lane, except that it says Camberwell, and not Brixton.’

7860. Reversed photographs

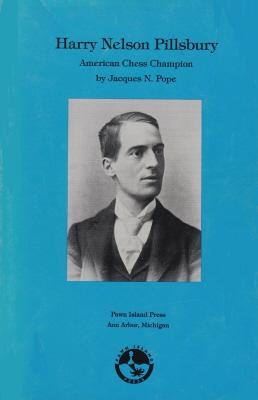

C.N. 7846 referred to a recent book which gave a reversed photograph of Tal. For another instance involving the same master and publisher, see C.N. 4655. The feature article A Chess Whodunit corrects the photograph of D.W. Fiske which was given as the frontispiece to his book Chess in Iceland and in Icelandic Literature (Florence, 1905). Regarding Pillsbury, C.N. 5164 may be mentioned, as well as this book cover:

Dan Scoones (Coquitlam, BC, Canada) adds two cases: the photograph of Kotov on page 124 of A Picture History of Chess by Fred Wilson (New York, 1981) and the full-page colour picture of Fischer at the end of the Buenos Aires section of Bobby Fischer by Harry Benson (Brooklyn, 2011).

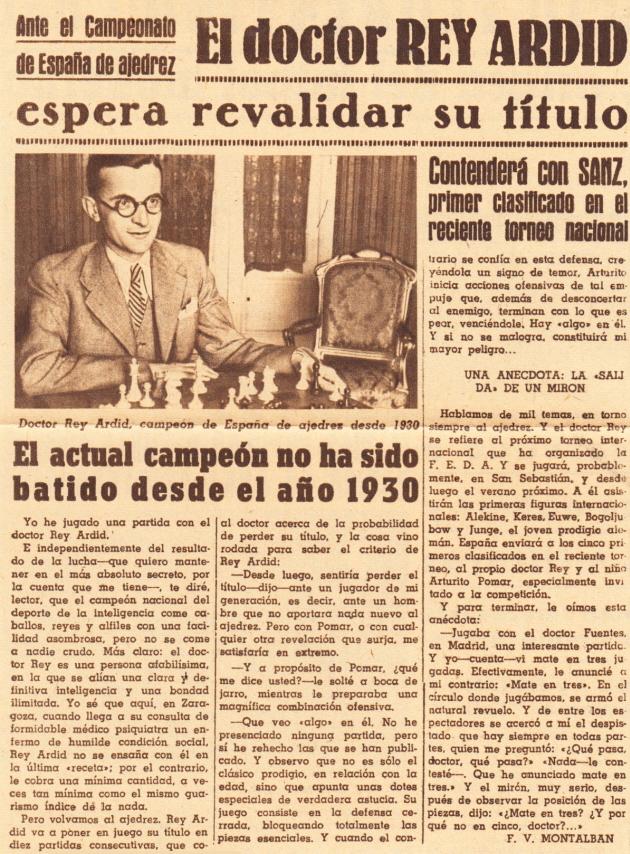

7861. An interview with Rey Ardid

The publication and date are not given on our cutting, but the reference to the games against José Sanz (‘que comenzarán el domingo, día 23 próximo’) indicates that the article dates from May 1943.

Rey Ardid surprisingly, though narrowly, lost his title match against Sanz. An account of the contest, with all ten games annotated, is on pages 179-193 of Campeones y campeonatos de España de ajedrez by Pablo Morán (Madrid, 1974).

7862. Capablanca in Prague

Source: Časopis českých šachistů, 1911, page 189.

7863. Opatija, 1912 (C.N. 7857)

Ola Winfridsson (São Paulo, Brazil) notes discrepancies in the above caption, and we therefore show what appeared on page 35 of the February-March 1912 Wiener Schachzeitung:

7864. Milan Vidmar

Thomas Höpfl (Halle, Germany) points out footage of an anti-Communist rally (Ljubljana, 29 June 1944) in which Milan Vidmar can be seen (beginning at about 2’20”).

The first part of the coverage also shows Vidmar (at about 4’45” into the item).

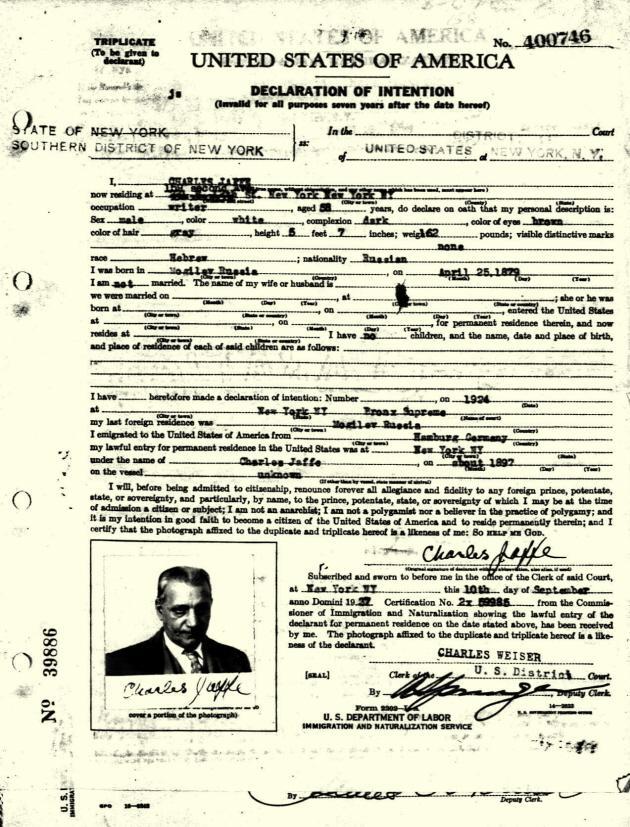

7865. Charles Jaffe

Our article Jaffe and his Primer began by pointing out the difficulties in establishing firm biographical information about Charles Jaffe, and especially his date of birth. Now, Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) has found the document below, dated 10 September 1937, at the Ancestry.com website:

Exact reference source: Declaration of Intent (1937), National Archives; Washington, DC; Petitions for Naturalization from the US District Court for the Southern District of New York, 1897-1944; Series: M1972; Roll: 1288.

The information provided includes:

Address: 158(?) Second Avenue, New York;

Occupation: writer;

Marital status: unmarried;

Height and weight: 5 feet 7 inches; 162 pounds;

Date and place of birth: 25 April 1879 in Mogilev, Russia;

Emigrated from Hamburg to New York, circa 1897.

The picture of Jaffe in the Declaration of Intention may be compared with this detail from the group photograph (Chicago, 1937) given in C.N. 7351:

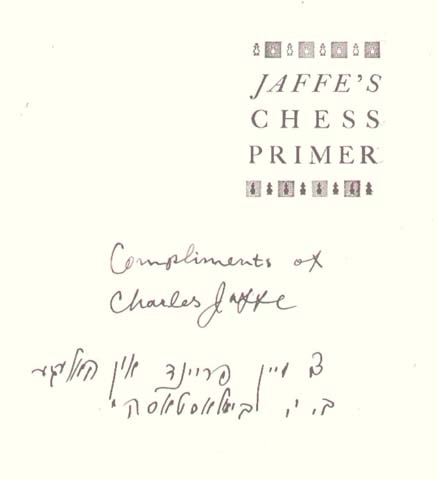

With respect to the signatures on the form, below is the inscription in our copy of Jaffe’s Chess Primer:

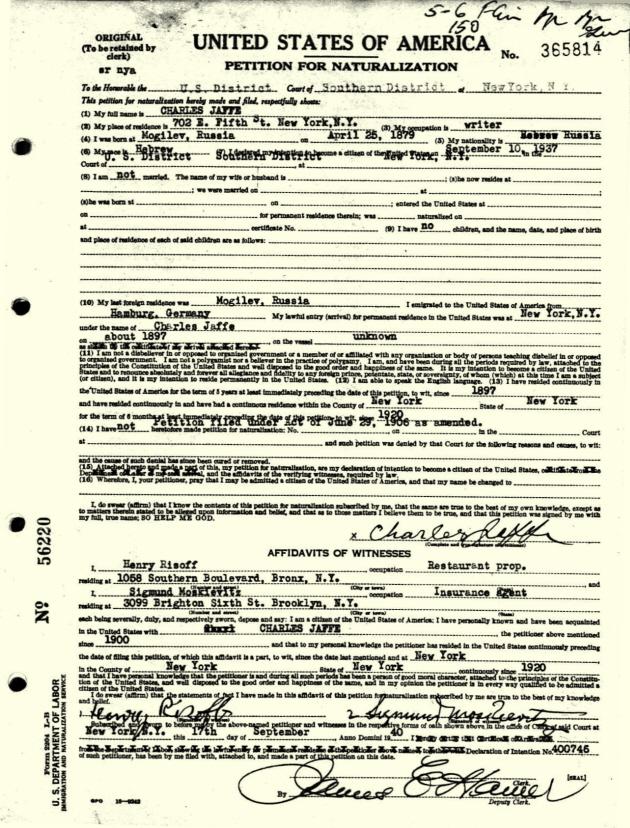

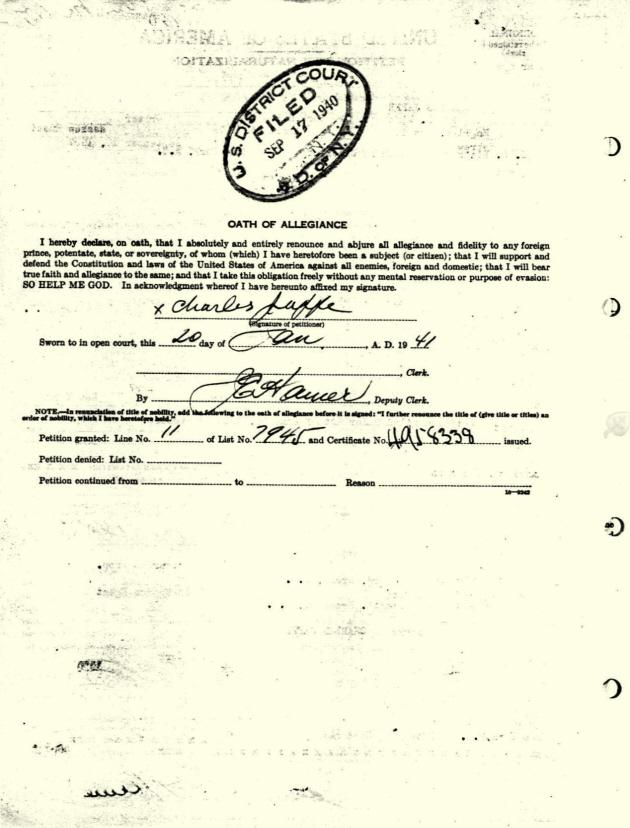

Mr Urcan has also found a subsequent Petition for Naturalization, which gave Jaffe’s address as 702 E. Fifth Street, New York:

Exact reference source: National Archives; Washington, DC; Petitions for Naturalization from the US District Court for the Southern District of New York, 1897-1944; Series: M1972; Roll:1288.

7866. Reversed photographs

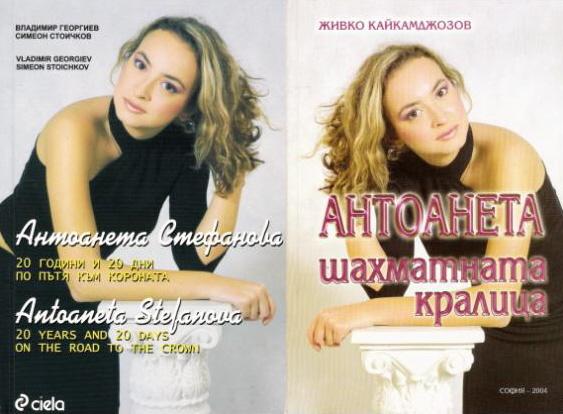

Yakov Zusmanovich (Pleasanton, CA, USA) draws attention to the front covers of Antoaneta Stefanova: 20 Years and 20 Days on the Road to the Crown by Vladimir Georgiev and Simeon Stoichkov (Sofia, 2004) and Antoaneta – shakhmatnaya kralitsa by Jivko/Zhivko Kaikamdzozov (Sofia, 2004):

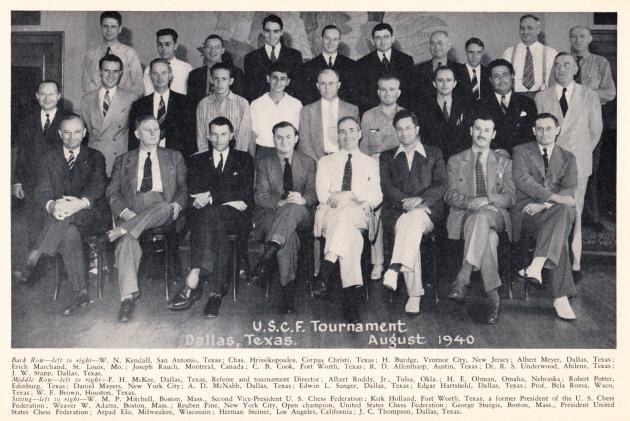

7867. Dallas, 1940

From page vi of The Yearbook of The United States

Chess Federation 1940 edited by Montgomery Major

(New York, 1942):

| First column | << previous | Archives [100] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.