Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [99] | next >> | Current column |

7794. Graves of Steinitz and Lasker

Further to the article Graves of Chess Masters, Alexander Rietema (Fort Lee, NJ, USA) has forwarded some photographs, which he took in late September/early October 2006, of the graves of Steinitz (Brooklyn, NY) and Lasker (Queens, NY):

It will be noted that the year of birth is incorrect.

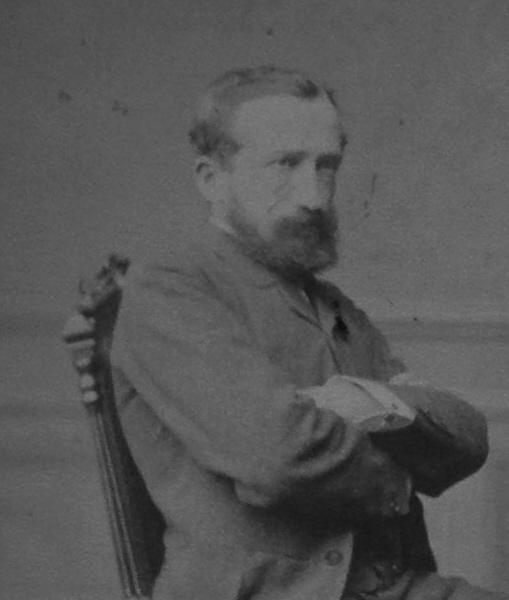

7795. Zukertort v Steinitz

Page 22 of the booklet Schach WM 2008 Deutschland has a photograph of Zukertort and Steinitz which was new to us, and we are grateful to Michael Negele (Wuppertal, Germany) for the opportunity to present it here:

Mr Negele found the photograph in the archives of the Cleveland Public Library in 2007. Although the booklet states that it was taken in 1886, our correspondent suggests that the occasion was Brunswick, 1880, a tournament which, as stated on page 235 of the August 1880 Deutsche Schachzeitung, both Zukertort and Steinitz visited.

J.H. Zukertort

W. Steinitz

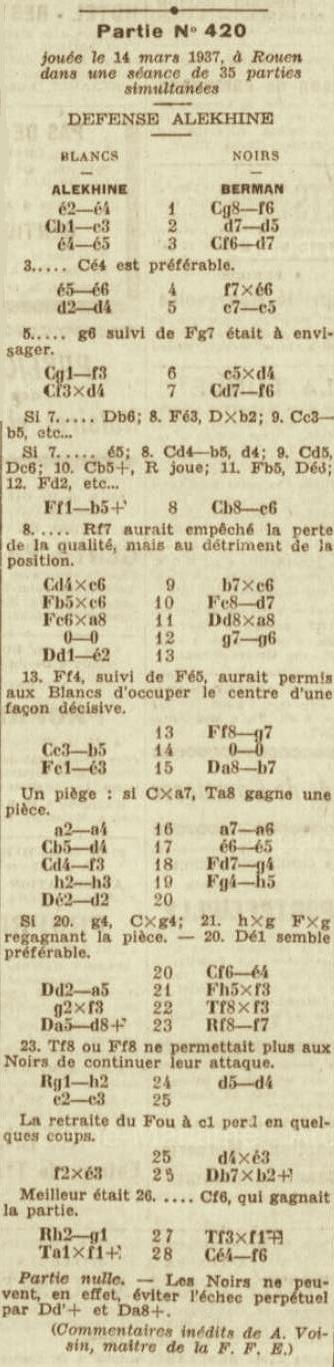

7796. Alekhine simultaneous games in France

Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) has found the following games:

Alexander Alekhine – Cercle Rouennais des Echecs

Paris, 28 February 1932 (simultaneous display against 60

teams/300 players)

Queen’s Gambit Declined

1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 e6 3 c4 d5 4 Nc3 c6 5 Bg5 Nbd7 6 e4 dxe4 7 Nxe4 Bb4+ 8 Nc3 Qa5 9 Bd2 O-O 10 Bd3 Qd8 11 O-O Re8 12 Qc2 Nf8 13 Rad1 b6 14 a3 Be7 15 Rfe1 Bb7 16 b4 c5 17 dxc5 Bxf3 18 gxf3 bxc5 19 Bf4 Qb6 20 b5 Red8 21 Ne4 Ng6 22 Bg3 Rd4 23 Bf1 e5 24 Nc3 Bd6 25 Ne2 Rxd1 26 Rxd1 Bc7 27 Nc3 Qe6 28 Ne4 Qe7 29 Qa4 Nh5 30 Qa6 Bb6 31 Nc3 f5 32 Nd5 Qd8 33 Nxb6 Qxb6 34 Rd6 Qb8 35 Bd3 Qf8 36 Rd7 Nhf4 37 Bf1 Qc8 38 Qxc8+ Rxc8 39 Rxa7 Ne6 40 Bh3 Rd8 41 b6 Nd4 42 b7 Nxf3+ 43 Kf1 f4 44 Ra8 Nd2+ 45 Ke2 Resigns.

Source: Journal de Rouen, 17 March 1932.

Alexander Alekhine – Cercle Rouennais des Echecs

Paris, 28 February 1932 (simultaneous display against 60

teams/300 players)

Vienna Game

1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 Qg4 g6 5 Qg3 Nf6 6 d3 Nh5 7 Qf3 Qf6 8 Nd5 Qxf3 9 Nxf3 Bb6 10 g4 Ng7 11 Bh6 Ne6 12 c3 d6 13 Nf6+ Ke7 14 Nd5+ Ke8 15 b4 Ncd8 16 a4 c6 17 Nxb6 axb6 18 d4 exd4 19 cxd4 b5 20 Bb3 Nc7 21 h3 Be6 22 Bc2 bxa4 23 Rxa4 Rxa4 24 Bxa4 b5 25 Bc2 Kd7 26 Kd2 Bc4 27 Ra1 Nde6 28 Ke3 Ra8 29 Rxa8 Nxa8 30 Nd2 Ba2

31 f4 Nac7 32 f5 Nd8 33 Nf3 f6 34 fxg6 hxg6 35 h4 Nf7 36 Bf4 Be6 37 g5 fxg5 38 hxg5 Na6 Drawn.

Source: Journal de Rouen, 31 March 1932.

Alexander Alekhine – Cercle Rouennais des Echecs

Rouen, 29 May 1932 (clock simultaneous display against

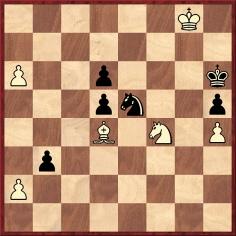

six teams)

Alekhine announced mate in five moves.

Source: Journal de Rouen, 9 June 1932.

The solution was given in the following week’s edition: 51 Kg8 Ne5 52 bxa5 b4 53 a6 b3

54 axb3, followed by 55 Bg7 mate.

Alexander Alekhine – Three members of the Cercle

Rouennais des Echecs

Rouen, 29 May 1932 (clock simultaneous display against

six teams)

Queen’s Gambit Declined

[1 d4 d5 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 Nbd7 5 Nf3 c6 6 e4] dxe4 7 Nxe4 Qa5+ 8 Nc3 Bb4 9 Bd2 O-O 10 a3 Be7 11 Nd5 Qd8 12 Nxe7+ Qxe7 13 Bd3 e5 14 O-O exd4 15 Nxd4 Qd6 16 Bb4 c5 17 Nf3 Qc7 18 Bc3 Re8 19 Re1 Rxe1+ 20 Qxe1 Kf8 21 Rd1 b6

22 Bxh7 Bb7 23 Bf5 Bxf3 24 gxf3 Re8 25 Qd2 Ne5 26 Bxe5 Qxe5 27 Qd6+ Qxd6 28 Rxd6 Re2 29 b4 cxb4 30 axb4 Re5 31 Bh3 Nh5 32 Kf1 Nf4 33 Bc8 Rh5

34 h3 Nxh3 35 Bg4 Rh4 36 Rd8+ Ke7 37 Rd7+ Kf6 38 Rxa7 Nf4 39 Ke1 Nd3+ 40 Ke2 Ne5 41 Rc7 Nxg4 42 fxg4 Rxg4 43 b5 Re4+ 44 Kd3 Re6 45 c5 bxc5 46 Rxc5 Rd6+ 47 Kc3 Ke6 48 Rc7 Rd7 49 Rc4 Ke7 50 Kb4 Kd6 51 b6 Kd5 52 Kb5 g6 53 Rc7 Resigns.

Source: Journal de Rouen, 23 June 1932. The opening moves were garbled in the newspaper, and the sequence suggested in square brackets above is merely one of a number of possible corrections.

Alexander Alekhine – Charles Dupin

Lille, 3 July 1932 (simultaneous display against 32

players, including two blindfold games)

Queen’s Gambit Declined

1 d4 d5 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 c6 4 Nf3 Nf6 5 Bg5 Nbd7 6 e4 dxe4 7 Nxe4 Be7 8 Nc3 Qc7 9 Qc2 h6 10 Bh4 e5 11 O-O-O exd4 12 Rxd4 O-O13 Bg3 Qa5 14 a3 a6 15 Bd6 Re8 16 Bxe7 Rxe7 17 Bd3 Nf8 18 Rf4 Nh5 19 Rh4 Ne6 20 Re1 Nf6 21 Re5 b5 22 c5 Nd7 23 Re2 Ndxc5 24 Bh7+ Kf8 25 Kb1 Nd7 26 Ne4 Qc7 27 Ng3 Nf6 28 Nf5 Re8 29 Qc3 Nxh7 30 Rxh6 Kg8 31 Ne5 Nf4

32 Nd7 Resigns.

Source: Journal de Rouen, 21 July 1932.

Alexander Alekhine – Pierre Biscay, Marcel Berman and

Marcel Duchamp

Paris, 15 June 1935 (simultaneous display against 36

teams)

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 c5 2 d4 cxd4 3 Nf3 Nc6 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Nc3 d6 6 Bg5 Qb6 7 Bxf6 gxf6 8 Nb3 e6 9 Qf3 Be7 10 O-O-O a6 11 Qg3 Bd7 12 Qg7 O-O-O 13 Qxf7 Qxf2 14 Qh5 Rdg8 15 h4 Ne5 16 Kb1 Be8 17 Qh6 Rg6

18 Qc1 Rhg8 19 Nd4 Bf8 20 b3 Rg3 21 Nce2 Re3 22 g3 Bh5 23 Rh2 Qxh2 24 Qxe3 Bg4 25 Rd2 Qh1 26 Qf2 Nf3 27 Nxf3 Qxf3 28 Qg1 Qxe4 29 Qa7 Bxe2 30 Bxe2 Bh6 31 Rd4 Qh1+ 32 Rd1 Qe4 33 Qa8+ Kc7 34 Qxg8 Qxe2 35 Qxh7+ Kc6 36 Qd3 Qe5 37 g4 Bg7 38 Qd4 f5 39 Qxe5 dxe5 40 g5 e4 41 h5 e3 42 h6 Bf8 43 Rh1 f4 44 Kc1 f3 45 Kd1 Bb4

46 c3 Bxc3 47 Kc2 e2 48 Kxc3 f2 49 White resigns.

Source: Journal de Rouen, 20 June and 4 July 1935.

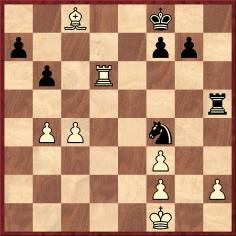

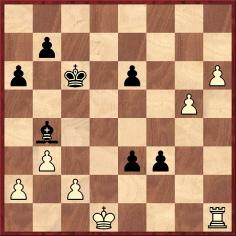

Alexander Alekhine – Marcel Berman

Rouen, 14 March 1937 (simultaneous display against 35

players)

Alekhine’s Defence

1 e4 Nf6 2 Nc3 d5 3 e5 Nfd7 4 e6 fxe6 5 d4 c5 6 Nf3 cxd4 7 Nxd4 Nf6 8 Bb5+ Nc6 9 Nxc6 bxc6 10 Bxc6+ Bd7 11 Bxa8 Qxa8 12 O-O g6 13 Qe2 Bg7 14 Nb5 O-O 15 Be3

15...Qb7 16 a4 a6 17 Nd4 e5 18 Nf3 Bg4 19 h3 Bh5 20 Qd2 Ne4 21 Qa5 Bxf3 22 gxf3 Rxf3 23 Qd8+ Kf7 24 Kh2 d4 25 c3 dxe3 26 fxe3 Qxb2+ 27 Kg1 Rxf1+ 28 Rxf1+ Nf6 Drawn.

Source: Journal de Rouen, 27 March 1937.

Alexander Alekhine – Thierry

Rouen, 14 March 1937 (simultaneous display against 35

players)

Queen’s Gambit Accepted

1 d4 d5 2 c4 dxc4 3 Nf3 Bf5 4 Nc3 e6 5 e4 Bg6 6 Bxc4 Nf6 7 Qe2 Bb4 8 Bd3 O-O 9 O-O Nbd7 10 Rd1 c6 11 Bg5 Be7 12 e5 Bxd3 13 Rxd3 Nd5 14 Bxe7 Qxe7 15 Qd2 Nxc3 16 bxc3 Rad8 17 h3 Nb6 18 a4 f6 19 a5 Nc4 20 Qa2 fxe5 21 Qxc4 e4 22 Re3 exf3 23 Qxe6+ Qxe6 24 Rxe6 fxg2 25 Kxg2 Rd5 26 a6 Kf7 27 Re3 b6 28 Rae1 Rd7 29 Re6 Rc7 30 Rd6 Re8

31 Re3 Rxe3 32 fxe3 Ke7 33 White resigns.

Source: Journal de Rouen, 24 April 1937.

7797. Thomas v Klein (C.N. 7732)

Bruce Hayden also supplied the Thomas v Klein miniature to Assiac for publication. See pages 51-52 of Assiac’s book The Delights of Chess (London, 1960), which stated that ‘the game was played at “lightning speed” (in less than ten minutes)’.

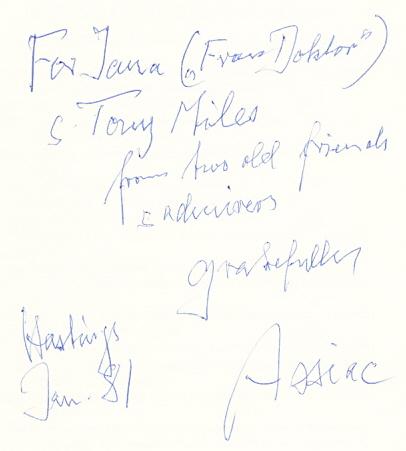

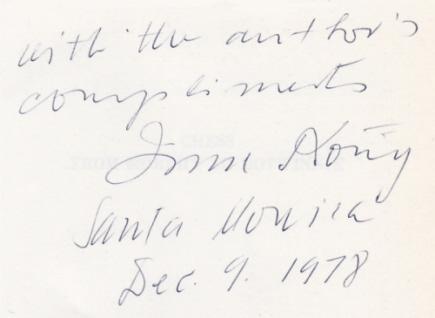

7798. Assiac inscription

Regarding the Dover edition of The Delights of Chess (New York, 1974), we own a copy inscribed by Assiac to Jana and Tony Miles:

7799. Reinfeld quote (C.N.s 3599, 3625 & 4313)

As reported in C.N. 4313, Fred Reinfeld’s remark ‘the pin is mightier than the sword’ was ascribed to him under the chapter heading on page 7 of Winning Chess (New York, 1948), a work which he co-authored with Irving Chernev.

The book was published in or around May 1948 (see page 3 of the 20 May 1948 Chess Life), and a slightly earlier occurrence of the quip can now be offered:

Source: page 147 of Reinfeld’s Nimzovich the Hypermodern (Philadelphia, 1948). The book was reviewed on page 2 of the 5 March 1948 issue of Chess Life.

7800. ‘Every chess master was once a beginner’ (C.N. 6725)

From page 89 of the Chernev/Reinfeld book Winning Chess (mentioned in the previous item):

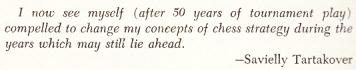

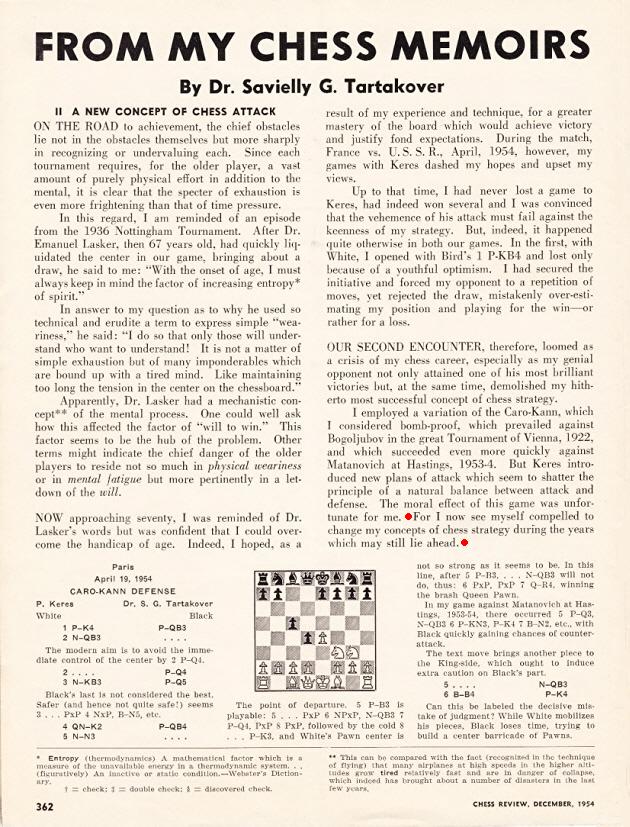

7801. Tartakower, Keres and Fischer

A quote published on page 186 of Combinations The Heart of Chess (New York, 1960) by Irving Chernev:

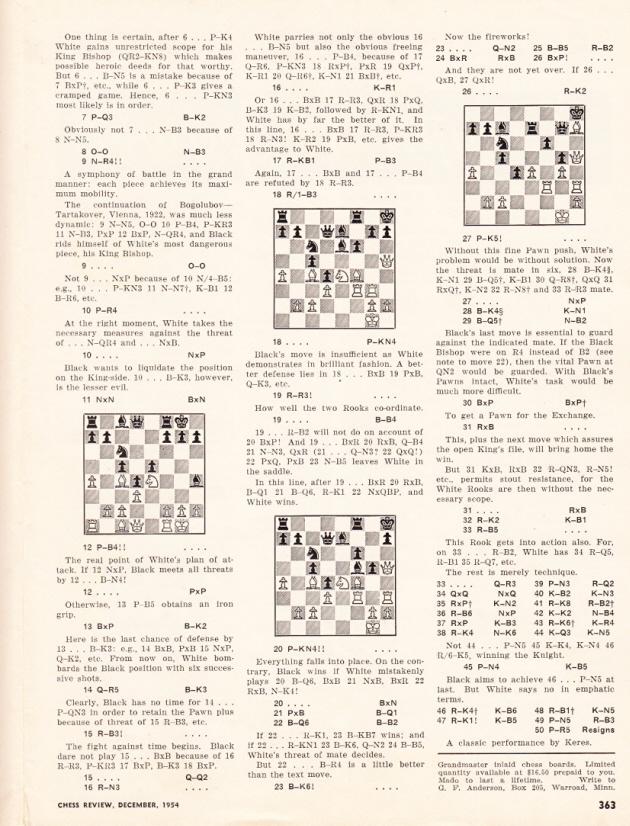

No source was given, but the observation comes from an article by Tartakower on pages 362-363 of the December 1954 Chess Review:

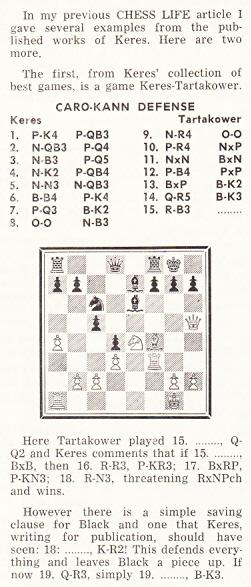

The Keres v Tartakower game was discussed by Fischer on page 172 of the July-August 1963 Chess Life:

In the diagram White’s bishop is missing from c4.

In his previous article (Chess Life, June 1963, page 142) Fischer mentioned that he had been reading Keres’ ‘recent book of his best games (in Estonian)’. Below is the relevant note in the Keres v Tartakower game, from page 381 of that work, Valitud partiid 1931-1958 (Tallinn, 1961):

The position before Fischer’s discovery, 18...Kh7:

7802. Keres photographs

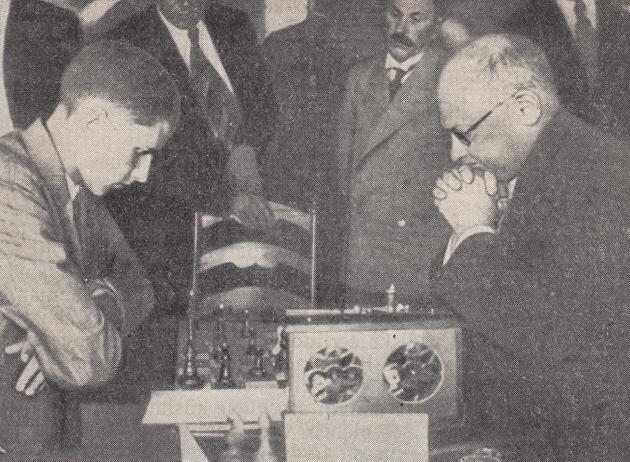

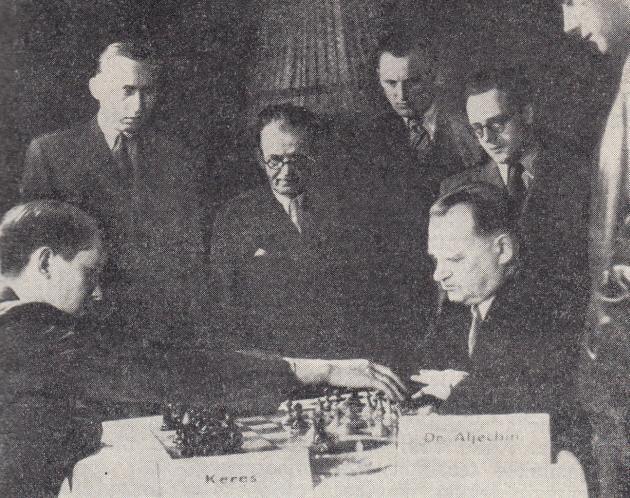

Below are two photographs from Valitud partiid 1931-1958 by Paul Keres (Tallinn, 1961), pages 37 and 201:

Paul Keres v Savielly Tartakower, Kemeri, 1937

Paul Keres v Alexander Alekhine, Prague, 1943

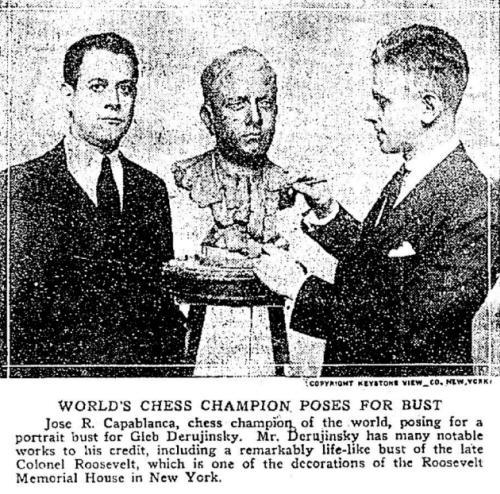

7803. Bust of Capablanca (C.N. 6583)

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) has found on page 40 of the Colorado Springs Gazette, 19 March 1922 an uncropped version of the photograph given in C.N. 6583, and he wonders whether a copy of better quality can be traced.

Information about the whereabouts of chess busts, including those shown in C.N. 6583, will be welcome.

7804. Blackburne Shilling Gambit (C.N.s 3786, 6470, 6479 & 7737)

From a 54-board simultaneous display:

Herman Steiner – R.E. Prouty

Cleveland, 1949

‘Shilling Gambit’

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Nd4 4 Nxe5 Qg5 5 Bxf7+ Ke7 6 Bxg8 Qxg2 7 d3 Qxh1+ 8 Kd2 Qxh2 9 Ng4 Qf4+ 10 Kc3

10...Qxc1 11 Qxc1 Ne2+ 12 Kd2 Nxc1 13 Nc3 Rxg8 14 Nd5+ Kd8 15 Ne5 d6 16 Nf7+ Kd7 17 Ng5 Be7 18 Nxe7 Kxe7 19 White resigns.

Source: Chess Life, 5 March 1949, page 4.

7805. Where are the bad players?

Below is an article by G.H. Diggle from page 78 of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984). It was originally published in the December 1981 Newsflash.

‘“Where have all the bad players got to nowadays?”, the BM repeatedly moans whenever he attempts some disastrous local reappearance. Sixty years ago there were dotted around the provinces (either in small struggling clubs or once a week in “private house soirées”) players with only each other’s chess intellects to feed on who would loyally stick to the game without improving one iota through whole decades, like stone-deaf persons regularly attending “the proms”. Alas, television has largely exterminated “social chess”, and nearly all these bygone stalwarts have now expired with their eyes glued to the box instead of the board. Yet many of them were characters of as great psychological interest as a Fischer or a Korchnoi; for to imagine that “psychological motifs” and whatnot are the exclusive monopoly of grandmasters is to fall into the snobbish fallacy of the Sergeant Major who (when a poor Private reported sick with a “pain in the abdomen”) roared at him: “You ’ave a stummick! Only orficers has abdomens!”

Brian Harley in Chess for the Fun of It recalls a certain “Miss X” who frankly admitted that she never had a plan. She was well content, she said, “to defend”. Miss X’s defence took the form of placing a piece – pretty well any piece would do – somewhere in the neighbourhood of a piece just played by her opponent. She would never make a capture unless it was a recapture – such gifts were bound to be traps.

One of the BM’s earliest opponents was an eccentric but versatile Spalding lady some 50 years his senior, who for some fantastic reason was absolutely fascinated by the names of the Openings and who would turn over the pages of the BM’s MCO as though it were a picture book. She would even get the BM to go through with her the first three or four moves of any opening with a name that particularly “turned her on”, such as the Giuoco Piano or what she called the Kaiseritzky Gambit. Her main chess ambition was not to win a game (which she was shrewd enough to perceive would never happen) but to play an opening with a good resounding title, which gave her the same feeling of accomplishment as that of a ballroom dancer who had just performed the “Mayfair Quickstep” or the “Royal Empress Tango”. In her quest for additional strings to her bow she once discovered the “Max Lange” (16 columns including innovations from Marshall and Tartakower) and on being informed that Lange was a deceased nineteenth-century Master remarked that “he must have had a brain to have invented all that”. Between this lady and the BM there was a sort of love-hate relationship, for the latter being young and conceited would sometimes over-reach himself trying to pull her leg. Thus she would say on the fourth move: “Now, Badmaster, have I played the Steinitz Defence?” “Have you played it, Mrs B.?”, the falsely ecstatic Badmaster would exclaim, “Why, I’ve never seen it played with such touch and interpretation – just as the great Master himself would have played it.” But though she could see through very little over the board, she could see through the BM. “Badmaster, I can dispense with your fawning embellishments. If you can answer a plain question, do. If you can’t, shut up.”’

7806. Four queens

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Nf6 4 d3 h6 5 Nc3 Bb4 6 O-O Bc5 7 Nd5 O-O 8 a4 a6 9 Be3 Bxe3 10 fxe3 d6 11 Nxf6+ Qxf6 12 Nd4 Qg5 13 Nxc6 bxc6 14 Qf3 Be6 15 Bxe6 fxe6 16 Qh3 Qe7 17 Rf3 Rf6 18 Raf1 Raf8 19 g4 d5 20 Qg3 d4 21 exd4 exd4 22 Rxf6 Rxf6 23 Rxf6 Qxf6 24 Qxc7 e5 25 Qc8+ Kh7 26 Qf5+ Kg8 27 Qxf6 gxf6 28 h4 Kf7

29 c4 dxc3 30 bxc3 Kg6 31 Kf2 h5 32 Kf3 Kh6 33 d4 hxg4+ 34 Kxg4 exd4 35 cxd4 Kg6 36 h5+ Kf7 37 Kf5 Ke7 38 Kg6 Ke6 39 h6 Ke7 40 h7 Ke6 41 h8(Q) Ke7 42 Qxf6+ Kd7 43 Qf5+ Kd6 44 Qc5+ Kc7 45 Qa7+ Kd6 46 Qxa6 Kc7 47 a5 Kd6 48 d5 Kc5 49 Qxc6+ Kd4 50 d6 Ke5 51 d7 Kf4 52 d8(Q) Ke5 53 a6 Kf4 54 a7 Ke5 55 a8(Q) Kf4 56 Qab8+ Kg4 57 e5 Kf4 58 e6+ Ke3 59 e7 Kf2 60 e8(Q) Kf1 61 Qcc8

61...Kf2 62 Qf6+ Kg2 63 Qg4+ Kh1 64 Qh2+ Kxh2 65 Qeh8 mate.

This game has been added to the relevant feature article.

7807. Cheating

Information is still being sought on an alleged incident related in C.N. 1263 (see page 14 of Chess Explorations). In an article ‘Triche, triche et colégram ...’ in Le Courrier (Geneva), 11 April 1986, Fernand Gobet gave the position below, which, he said, was from ‘la partie Biélovski-Tcherniev il y a quelques décades en URSS’:

Here, we are told, White played 1 c7-c8=black bishop, after which 2 Nc7 mate cannot be prevented. Under shock, Black at once resigned, forgetting that the rules require a pawn to be promoted to a piece of the same colour.

7808. Schulten v Morphy (C.N. 6079)

From page 195 of Chess from Morphy to Botwinnik by Imre König (London, 1951):

‘This game has become a classic. It is one of the few early examples in which no improvement, either of opening theory or execution of attack, has been advanced.’

7809. König inscription

From one of our inscribed copies of the König book mentioned in the previous item (in this case, the Dover reprint of 1977):

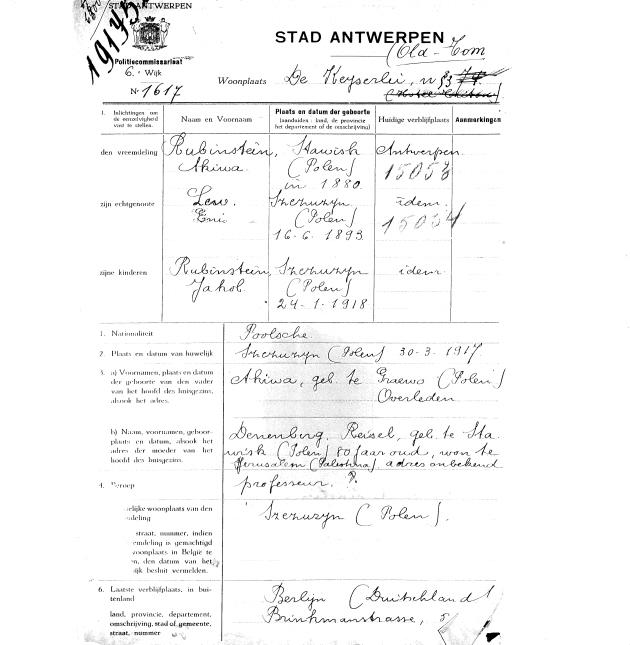

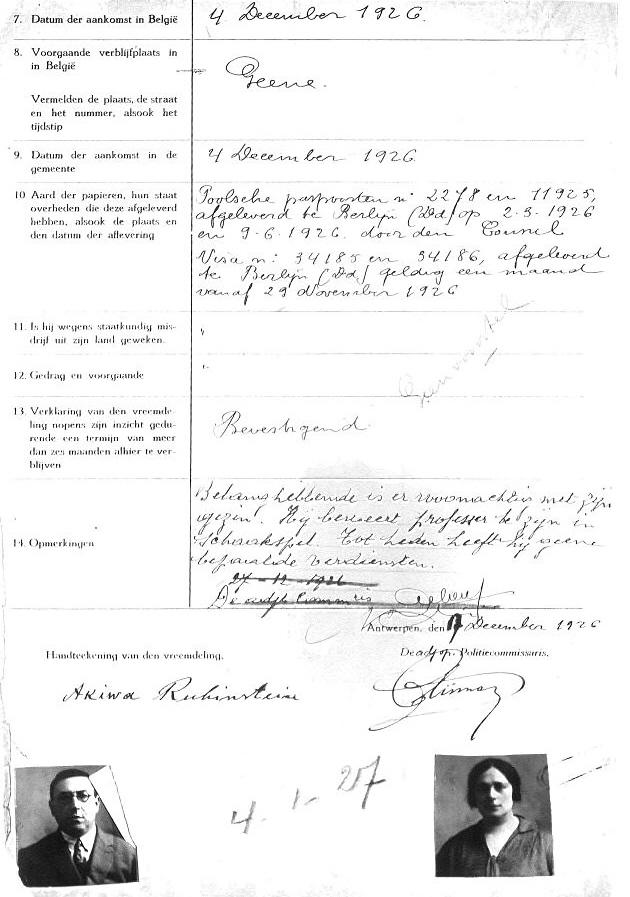

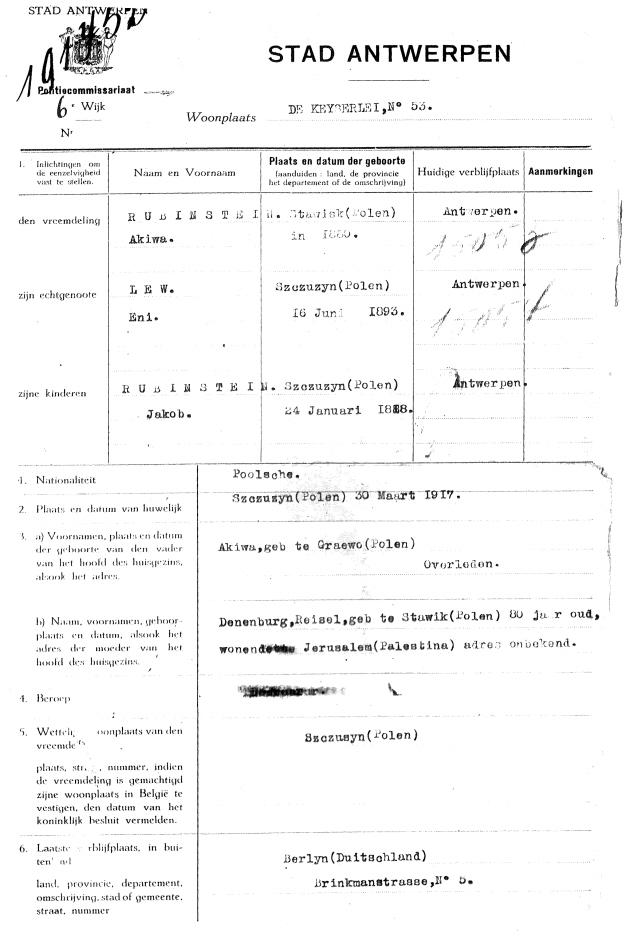

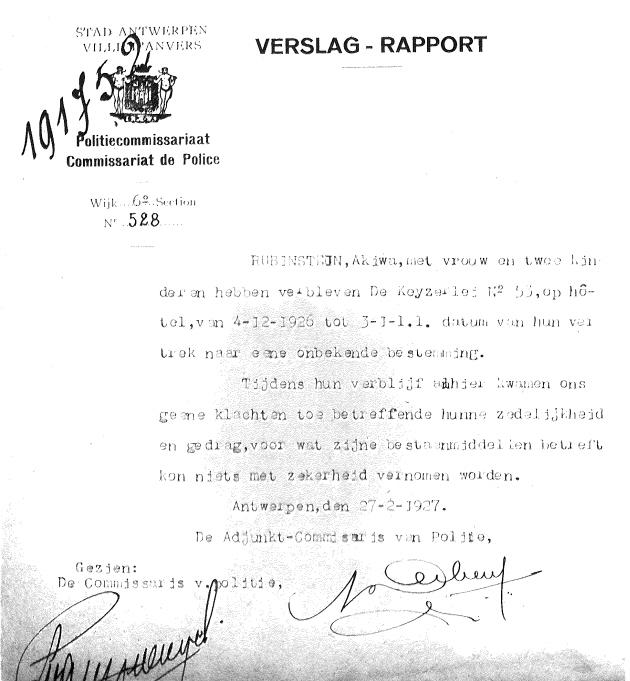

7810. Rubinstein in Antwerp

From Hans Renette (Bierbeek, Belgium):

‘At the end of 1926, just after a tournament in Berlin, A. Rubinstein and his family moved to Belgium, where they took up permanent residence. In early December 1926 they arrived in Antwerp.

In those days, every foreign citizen who spent time in Antwerp received a visit from the local police. A file was opened, in which the police recorded information about the family’s situation and the professional activities of any foreign visitor. These documents have been preserved in the city archives of Antwerp, as part of the police archives. In cooperation with Familysearch.org, the indexes have been digitized and can be consulted online (“Antwerp Police Immigration Index, 1840-1930”).

A report on the interview with Rubinstein by the Antwerp police is dated 17 December 1926. He declared that he had arrived in the city on 4 December 1926 and gave his previous address as Brinkmanstrasse 5, Berlin. In Antwerp the Rubinsteins lived in the Taverne Old Tom hotel, De Keyzerlei 53, the main street leading from the railway station.

The police documentation includes a brief overview of the Rubinstein family. His father, Akiwa, was born in Grajewo, Poland and was deceased. His mother, Reisel Denenburg, was 80 years old and lived in Jerusalem. Rubinstein was in Antwerp with his wife Eni Lew (born in Szczuczyn, 16 June 1893) and their only child, Jakob (born in Szczuczyn on 24 January 1918). The couple had married in that city on 30 March 1917.

Asked about his professional activities, Rubinstein stated that he was a chess teacher. The police report also mentioned that he had no fixed income.

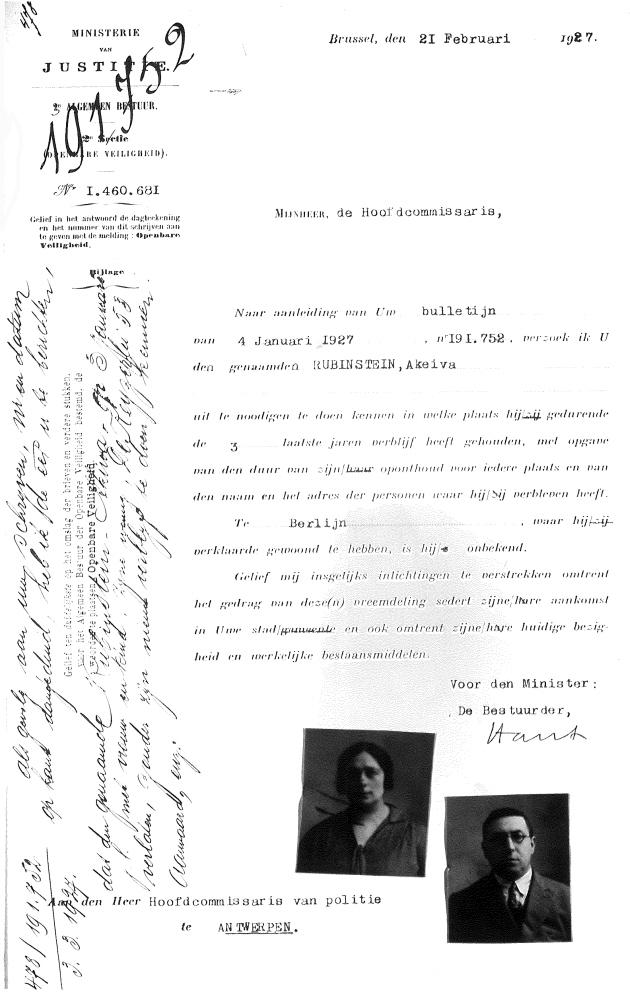

The police report came to the attention of the “Public Security” section of the Ministry of Justice. On 21 February 1927 the Ministry sent the police a request for more information. It seems that Rubinstein’s address in Berlin was checked and that his residence there was unknown to the German authorities. (In this connection, the second entry for Rubinstein in Where Did They Live? may be noted.)

A reply to the Ministry was written by the police on 27 February 1927. It stated that the Rubinsteins had left the hotel, having been there from 4 December 1926 until 3 January 1927. During the Rubinsteins’ stay, the police said, there had been no complaints about their behaviour. No further information had been obtained about their means of subsistence, and the police did not know where the family had gone.’

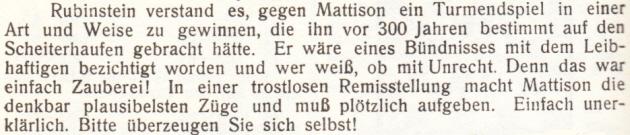

7811. Rubinstein and witchcraft

Pierre Bourget (Quebec, Canada) asks about the exact origins of the remark that Rubinstein’s endgame skill was such that 300 years ago he would have been burned for witchcraft.

The observation appeared on page 82 of the Carlsbad, 1929 tournament book by Nimzowitsch, Spielmann, Becker, Tartakower, Brinckmann and Kmoch, in the introduction to the fourth-round games and in connection with Mattison v Rubinstein:

From page 10 of the January 1951 Chess Review, in an article entitled ‘Only a Draw’ by Hans Kmoch and Fred Reinfeld:

‘It was Kmoch who wrote in the Book of the Carlsbad 1929 Tournament about one of Rubinstein’s most magical endings (against Mattison) that, if Rubinstein had lived in an earlier age, he would have been executed for witchcraft.’

Source: opposite page 26 of Witches and Warlocks by P.W. Sergeant (London, 1936)

On page 34 of the February 1935 Chess Review Irving Chernev wrote in a ‘Curious Chess Facts’ column:

‘Rubinstein, playing a rook ending against Mattison, extracted a win from such a “hopelessly drawn” position that the editors of the tourney book united in the assertion that had this occurred 300 years ago, Rubinstein would have been burned as being in league with evil spirits.’

Chernev used a slightly different wording on page 58 of his book Curious Chess Facts (New York, 1937):

‘Rubinstein, playing a rook and pawn ending against Mattison, extracted a win from such a “hopelessly drawn” position that the editors of the tournament book united in the assertion that had this happened 300 years ago, Rubinstein would have been burned at the stake for being in league with evil spirits.’

Below are three instances of Chernev’s text being

copied (without attribution, of course):

‘At Carlsbad, 1929 Rubinstein extracted a win from such a “hopelessly drawn” rook and pawn ending that the editors of the tournament book united in the assertion that had this happened 300 years ago Rubinstein would have been burned at the stake for being in league with evil spirits.’

Source: page 15 of New Ideas in Chess by Larry Evans (New York, 1958).

‘At Carlsbad, 1929 Rubinstein extracted a win from such a “hopelessly drawn” rook-and-pawn ending that the editors of the tournament book united in the assertion that had this happened 300 years earlier Rubinstein would have been burned at the stake for being in league with evil spirits.’

Source: page 133 of Chess Catechism by Larry Evans (New York, 1970).

‘At Carlsbad, 1929 Rubinstein extracted a win from such a “hopelessly drawn” rook-and-pawn ending that the editors of the tournament book united in the assertion that had it happened 300 years ago he would have been burned at the stake for being in league with evil spirits.’

Source: pages 19-20 of Modern Chess Brilliancies by Larry Evans (New York, 1970).

7812.

Gyula

Breyer (C.N. 7471)

There is a dearth of good photographs of Gyula Breyer, but a particularly fine one appears on page 161 of Schauspiel des Geistes edited by Raj Tischbierek (Berlin, 2012). It is given below with the permission of Michael Negele (Wuppertal, Germany), who found it (on a postcard, dated 1919) in the Rueb scrapbooks at the Royal Library in The Hague:

7813. Sozin and the Meran Defence

The above comes from page 69 of part three of Max Euwe’s Theorie der Schach-Eröffnungen (Berlin-Frohnau, 1966) and has been forwarded by Luca D’Ambrosio (Bolzano, Italy), who asks about Sozin’s exact involvement in the history of the move 11...Nxe5 (after 1 d4 d5 2 c4 c6 3 Nf3 Nf6 4 Nc3 e6 5 e3 Nbd7 6 Bd3 dxc4 7 Bxc4 b5 8 Bd3 a6 9 e4 c5 10 e5 cxd4 11 Nxb5).

We note that on page 165 of Championship Chess (London, 1950) Botvinnik referred to 11...Nxe5 as ‘Sozin’s rejoinder to Blumenfeld’s plan (11 KtxKtP)’. Annotating a game against Reshevsky, Botvinnik wrote on page 274 of the September 1955 Chess Review regarding 11...Nxe5:

‘Black’s witty, clever and safe continuation was found by master B. Sozin 30 years ago.’

See also page 280 of the September 1955 BCM.

On page 139 of the September 1933 Schweizerische Schachzeitung Ernst Grünfeld referred to 11...Nxe5 as ‘le fameux coup indiqué par l’analyste russe Sosin’. An early game in which the move occurred was I. Rabinovich v B. Verlinsky, Moscow, 1925. See pages 157-158 of Bogoljubow’s tournament book.

Readers’ assistance with tracing further information about Sozin and 11...Nxe5 will be appreciated.

7814. Lipschütz

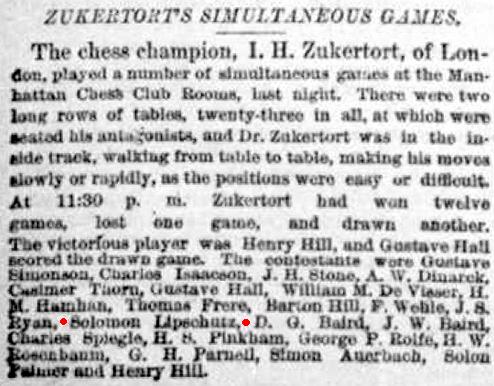

The search for evidence about S. Lipschütz’s forename continues. Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) has found the following on page 2 of the New York Daily Tribune, 3 November 1883:

7815. 1921 world championship match

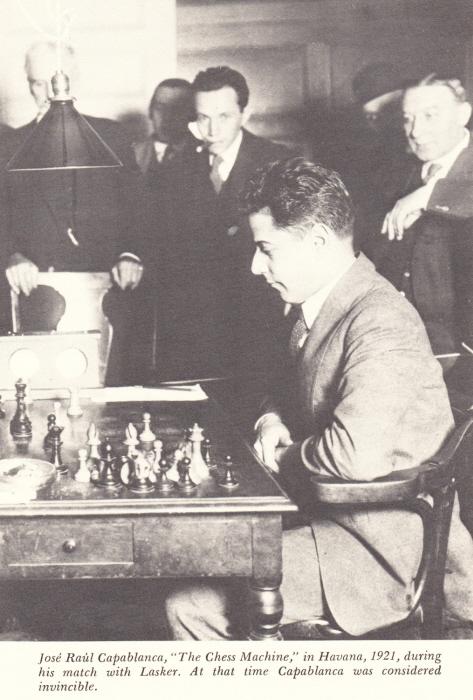

Good-quality photographs of the 1921 Lasker v Capablanca match are scarce, and more details are sought about the shot below, from page 175 of Grandmasters of Chess by Harold C. Schonberg (Philadelphia and New York, 1973):

7816. Open to doubt

Further to Imre König’s remark about Morphy in C.N. 7808, we add a comment by B.H. Wood from the Daily Telegraph chess column of 8 March 1986 which was quoted in C.N. 1130 under the heading ‘Open to doubt’:

‘... you could go through any game by the legendary Paul Morphy and find most of his moves from move six on were not quite the best he could have made.’

7817. Andrei Borisovich Yumashev (1902-88)

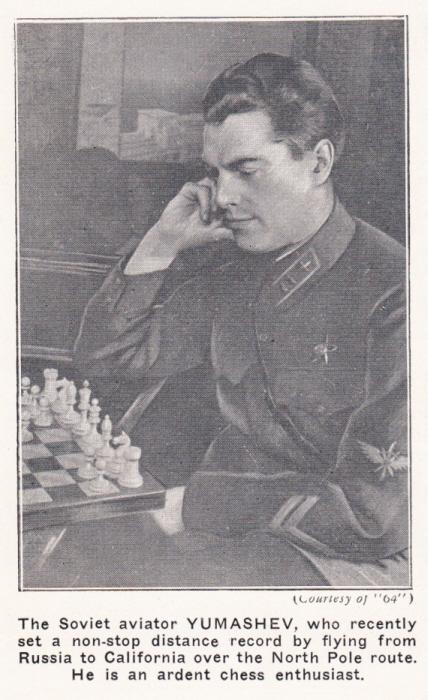

From page 246 of the November 1937 Chess Review:

7818. In the past

An observation by Emanuel Lasker on page 29 of Lasker’s Chess Magazine, November 1904:

‘The chess player is critical and discriminating in his judgment of matters chessic, fastidious in his tastes generally and artistic in his temperament. A chess magazine to please him must therefore be critical and discriminating in the contents of its game, problem and analytical departments, fastidious in its choice of literary contributions and artistic both as to form and substance.’

7819. Best annotators (C.N. 2545)

In the hope of gathering further material, we reproduce three quotes from C.N. 2545:

1) On page 271 of C.J.S. Purdy’s The Australasian Chess Review, 31 October 1938 the following appeared:

‘We consider Botvinnik the most brilliantly searching annotator in the world – the ordinary junk written by annotators doesn’t go down in Russia, where there are thousands who can pull bad notes to pieces.’

2) A comment on Georg Marco:

‘Even when it took him four years to annotate a game, as it sometimes did, his sense of humor was irrepressible just the same.’

Source: page 171 of Great Moments in Chess by F. Reinfeld (New York, 1963).

Evidence is still being sought regarding the amount of time Marco devoted to annotating. See too C.N.s 4855 and 5248.

3) When asked to name the best annotator, Tartakower replied (Wiener Schachzeitung, June 1929, page 169):

‘Kostić, who always pours out his soul, which is most amusing and instructive.’

C.N. 2543 mentioned that Kostić was hardly illustrious as an annotator, but that the exact point of Tartakower’s apparent quip is unclear.

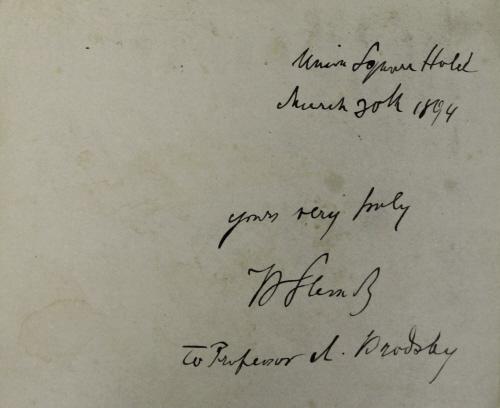

7820. Steinitz inscription

John Townsend (Wokingham, England) notes a catalogue entry for a photograph of Steinitz held by the Royal Northern College of Music in Manchester (reference: AB/235):

‘The date of this photograph was that on which the sixth game of the Lasker match was played at the Union Square Hotel, New York, after which the match moved to Philadelphia. The back of the photo is signed as follows: “Union Square Hotel, March 30th 1894 Yours very truly W Steinitz To Professor A. Brodsky”.’

Having been shown the photograph by the College, we can add that it is the frontispiece to The Steinitz Papers by K. Landsberger (Jefferson, 2002), which reproduced it courtesy of the College. Further details are provided on the book’s imprint page (which gives the date as 20, and not 30, March 1894).

We are grateful to the College for permission to show here Steinitz’s inscription:

7821. L. Tauber

Wanted: details regarding Léonard Tauber, a prominent figure in French chess in the first half of the twentieth century. See, for instance, the references to him in our book on Capablanca. One of his rare game-scores is a draw which he and A. Aurbach secured against the Cuban in Paris on 20 October 1913; on the same occasion Capablanca won against J. Taubenhaus and N. Terestchenko. (Source: La Stratégie, October 1913, page 416 and November 1913, pages 451-453.)

Page 4 of the January-February 1938 American Chess Bulletin noted that the double-round tournament in Paris won by Capablanca ‘was arranged at the Salons Caïssa, 6 rue de Presbourg, Paris from 5 to 16 January, under the auspices of M. Tauber’.

Various webpages have information on Tauber’s involvement with such Parisian establishments as the Hôtel Regina, 2 Place des Pyramides (where the recently-published Capablanca v Tartakower game was played – see The Genius and the Princess) and the Hôtel Raphael, 17 Avenue Kléber. The latter’s website has a photograph of a terrace with a large chess set.

7822. Labourdonnais’ death-mask (C.N.s 3397, 5149 & 5176)

Jean-Michel Péchiné (Arbois, France) points out a high-quality photograph of Labourdonnais’ death-mask.

7823. Word-play

Lame puns on players’ names are depressingly commonplace (they require no skill, knowledge, wit or thought), but we remain intrigued by a remark, whether or not intentional, in an obituary published on pages 166-167 of the April 1931 BCM:‘He has probably conceded more drawn games when having a positional advantage than any other chess player.’

As mentioned on page 387 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves, the obituary was of J.A.J. Drewitt.

7824. István Abonyi

From page 52 of the March-April 1915 Wiener Schachzeitung:

7825. S. Popel

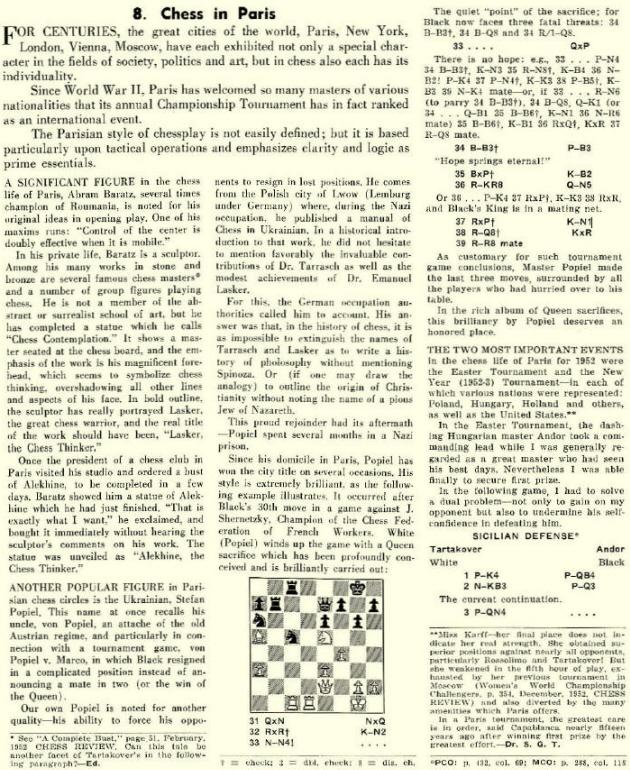

Marc Hébert (Charny, Canada) draws attention to an article by Tartakower, ‘Chess in Paris’ on pages 74-75 and 96 of the March 1953 Chess Review. The first page:

Further details about the various interesting points made by Tartakower will be welcome.

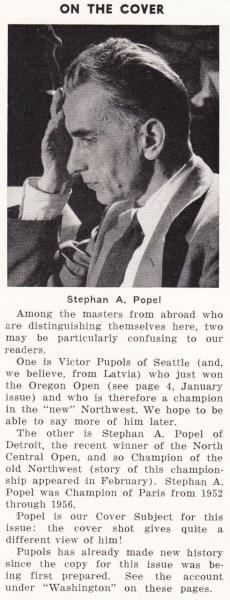

Stephan A. Popel subsequently moved to the United States and was on the front cover of the March 1958 Chess Review:

From page 68 of the same issue:

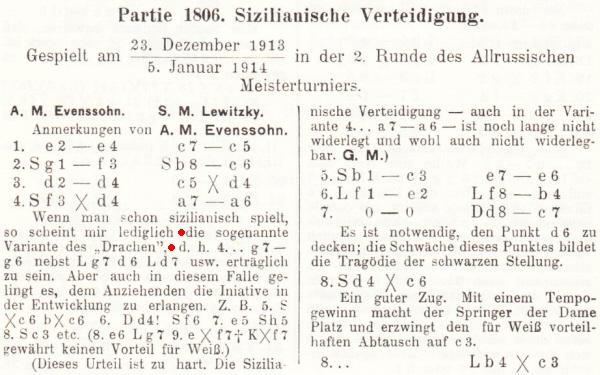

7826. The Dragon Variation (C.N. 5135)

With regard to the earliest appearance of the term

‘Dragon Variation’, Thomas Niessen (Aachen, Germany)

mentions that Tartakower referred to ‘Die

Drachenvariante’ in a note to Alekhine v Sämisch,

Vienna, 1922 (after 1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4

g6) on page 270 of Die hypermoderne Schachpartie

(published in instalments in 1924-25, as mentioned in

C.N. 5279).

Looking further into the matter, we can cite an annotation by Heinrich Wolf on page 164 of the June 1924 Wiener Schachzeitung, after 1 c4 e5 2 a3 Nf6 3 e3 Be7 4 Qc2 in Tartakower v Lasker, New York, 1924:

‘Damit ist eine wohlbekannte Variante aus der sizilianischen Verteidigung (die sogenannte Paulsensche Drachenvariante) entstanden, nur mit dem Unterschied, dass Weiss vorläufig die Rolle des Verteidigers freiwillig auf sich genommen hat.’

More significantly, we have found the following on page 30 of the January-February 1914 issue of the Wiener Schachzeitung:

7827. A little skit

A game given here solely because White was the problemist

Murray Marble (see C.N. 5370):

Source: The Literary Digest, 15 July 1899, page 90.

Murray Marble – N.N.

Occasion?

King’s Pawn Opening

1 e4 f5 2 exf5 d5 3 Qh5+ g6 4 fxg6 Kd7 5 gxh7 Nf6 6 Qf5+ e6 7 Qg6 Rxh7 8 Nf3 Rg7 9 Qh6 Rg8 10 Qh3 Be7 11 d4 Ne4 12 Ne5+ Kd6 13 Bb5 Rf8 14 c4 dxc4 15 Nxc4+ Kd5 16 Nc3+ Nxc3 17 bxc3 Nd7 18 Qg3 Bh4 19 Ne3+ Ke4 20 f3+ Rxf3 21 gxf3 mate.

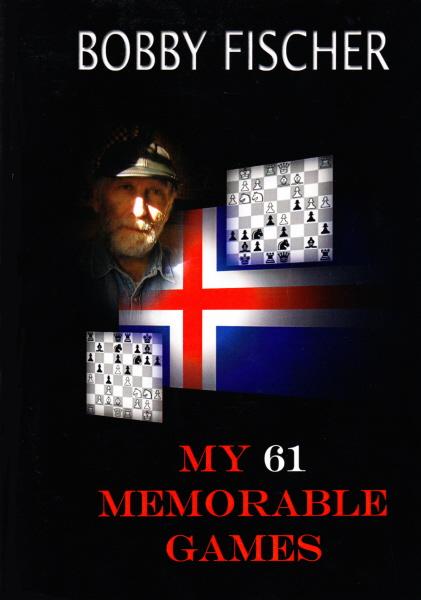

7828. My 61 Memorable Games (Bobby Fischer)

No discussion of My 61 Memorable Games has previously appeared in C.N., but we have now acquired a copy of the book. The issue of authenticity has been widely debated, with much assertion, guess-work and vituperation expressed by various individuals (whether or not they have actually seen the book). For our part, we shall aim for a serene, objective approach, and the present introductory item therefore mainly comprises a factual overview of the book.

It is a 753-page paperback described, opposite the title page, as ‘Second Printing’, with the additional information ‘ISBN 0-9666673-0-1’ and ‘Printed in Iceland’. No publisher or editor is named; nor is there a date of publication. The contents are as follows:

- Page i: a Preface signed ‘Robert J. Fischer,

Reykjavik, Iceland, November 9, 2007’ stating, inter

alia, that the book is ‘an official version of my

book u pdated [sic] in algebraic notation, with a

few minor corrections’. [The words ‘official version’

are underlined.]

- Page ii: a facsimile of a letter dated 10 June 2005 from Gunnar Gudmundsson, an attorney, to the UBS in Zurich about Fischer’s account with the Swiss bank.

- Page iii: Fischer’s original Preface to My 60 Memorable Games.

- Pages iv-viii: ‘Editor’s Notes (2007)’. These comprise a series of often brash points, both general and particular, by an unnamed writer. For example:

‘To those of you who take out the 1969 version of the book, and compare it line for line with this one so that you can triumphantly point out minute differences: Get a life! [The last three words are in bold type and underlined.]

We know that there are differences in the text. We know that there are differences in the annotations. Whereas the 1969 version has curt remarks such as “But by now I felt there was more in the offing” (page 17), in this modern version, you’ll actually read a proper English sentence in its place.’

Various ‘errors’ in the earlier version are mentioned, and on pages vi-vii Larry Evans’ introductions are criticized, e.g. on account of their prose style and punctuation. (On the subject of Evans, we note that his article about the book on pages 5-8 of the March 2008 CHESS was illustrated by a sample page that he had been sent (concerning the first game, Fischer v Sherwin). For reasons yet to be explained, the text varies slightly from what appears in the book in our possession, and the figurine symbols in the notation are in a different style. Evans also referred to ‘a 12-page foreword’, supposedly penned by Fischer, with the errors ‘United Bank of Switzerland’ and ‘Borris Spassky’. In the book we have received, the (one-page) Preface has Union and Boris.)

- The final part of the ‘Editor’s Notes (2007)’, on page viii:

‘We are also aware of the debacle governing the “Batsford remake” of 1995. We did not fall into the trap of “arbitrary editing” as more than one reviewer had pointed out regarding the mess that Batsford created. Our edits were necessary for the overall improvement of the book. [The preceding sentence is underlined.] The revised annotations are Fischer’s and do not belong to anybody else.

We stand by this edition of the book as the best version that we could possibly create under the supervision and authorization of Bobby Fischer. Bobby has seen, commented on, and approved every page of this book. [This paragraph appears in bold type.]

Bobby says that anyone who claims this book is not an improvement over the 1969 edition can just “Go to hell.”.’

- After a photograph (there are many throughout the book, in colour and black and white) and a list of the 61 games (the 61st is the first match-game Fischer v Spassky, Sveti Stefan, 1992), there come the annotated games (pages 1-742). A number of (purported) quotes from masters of the past have also been added as fillers. In the case of the original 60 games, the annotational differences are extensive, with frequent improvements proposed. The final game of the 60 (Fischer v Stein, Sousse, 1967) is followed by a detailed article (pages 715-729) about Fischer’s withdrawal from that tournament. It concludes: ‘Bobby Fischer, August 11, 2007.’

- A cartoon is on page 743, and the book then has a three-page article (‘The Future Outlook for Chess’) which begins:

‘As I see it, there are two main detractors hurting the chess world right now.

1. The game.

2. The politics.’

- Then comes (pages 748-750) ‘Bobby Fischer’s Tournament and Match Record’, which is labelled ‘Appendix A’, although there are no other appendices. The book ends (pages 751-753) with an index of the ‘Games Sorted by Opening’.

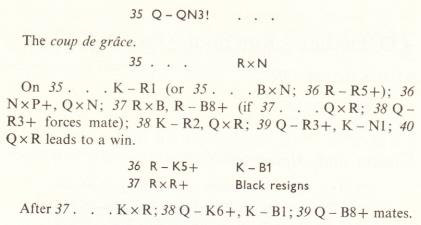

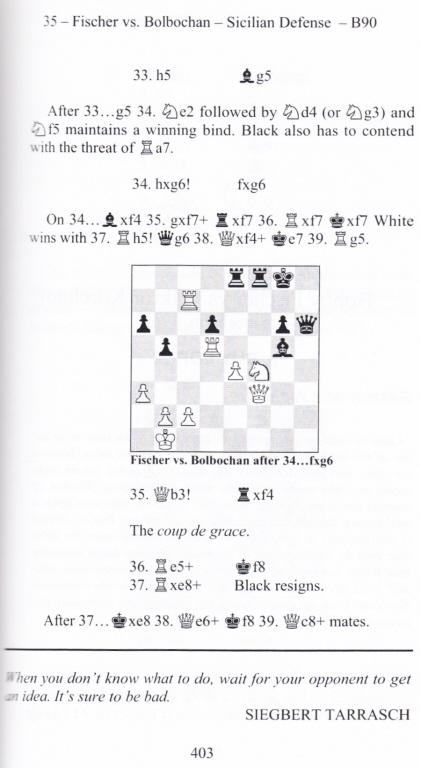

This preliminary C.N. item concludes by showing a

complete page of My 61 Memorable Games, and it is

natural for us to pick the finish to the Fischer v

Bolbochán game discussed in Fischer’s

Fury (i.e. the affair of the forced mate containing

an illegal move). This occasions a major surprise because

the original Fischer note ‘incorrectly corrected’ by the

1995 Batsford edition is simply absent from My 61

Memorable Games. Moreover, Fischer’s annotation ‘The

coup de grâce’ in the 1969 book, concerning his

move 35 Qb3, has been transferred to after Black’s reply,

35...Rxf4.

We are reproducing the present C.N. item in a feature

article, My 61 Memorable

Games (Bobby Fischer), where additions will be

made from time to time. The intention is to build up a

solid factual basis for assessing the book’s authenticity.

| First column | << previous | Archives [99] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.