Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [98] | next >> | Current column |

7768. Front covers

C.N.s 2397 and 2419 (see page 314 of A Chess Omnibus, as well as a Chess Explorations article) gave examples of publishers’ inability to spell an author’s name. Peter Holmgren (Stockholm) now adds this specimen:

7769. The bad bishop

A famous Staunton position, from his eighth match-game against Elijah Williams, London, 1851:

Staunton (White) played 14 Bxf6 Qxf6 15 cxd5 exd5 16 d4.

On page 155 of Better Chess (London, 1997) William Hartston wrote after 16 d4:

‘Envisaging this pawn move, White first exchanged his black-squared bishop to ensure that it would not become bad (though it was another 50 years before anyone came up with the concept of a “bad bishop”).’

When were the concept and the term ‘bad bishop’ first recorded in print?

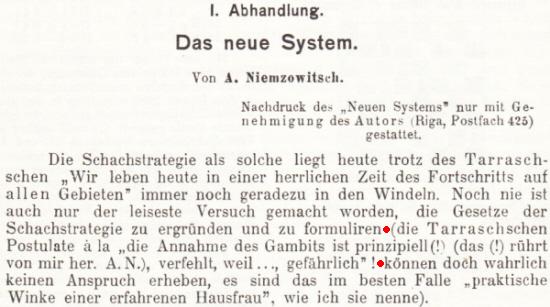

7770. Tarrasch quote (C.N. 7762)

C.N. 7762 asked about a remark attributed by Edward Lasker to Siegbert Tarrasch:

‘To win a pawn in the opening is usually a dangerous thing.’Per Skjoldager (Fredericia, Denmark) notes that on page 294 of the October-November 1913 Wiener Schachzeitung Nimzowitsch attributed to Tarrasch the following observation:

‘Die Annahme des Gambits ist prinzipiell verfehlt, weil gefährlich.’

7771. Warren v Selman (C.N.s 7694 & 7717)

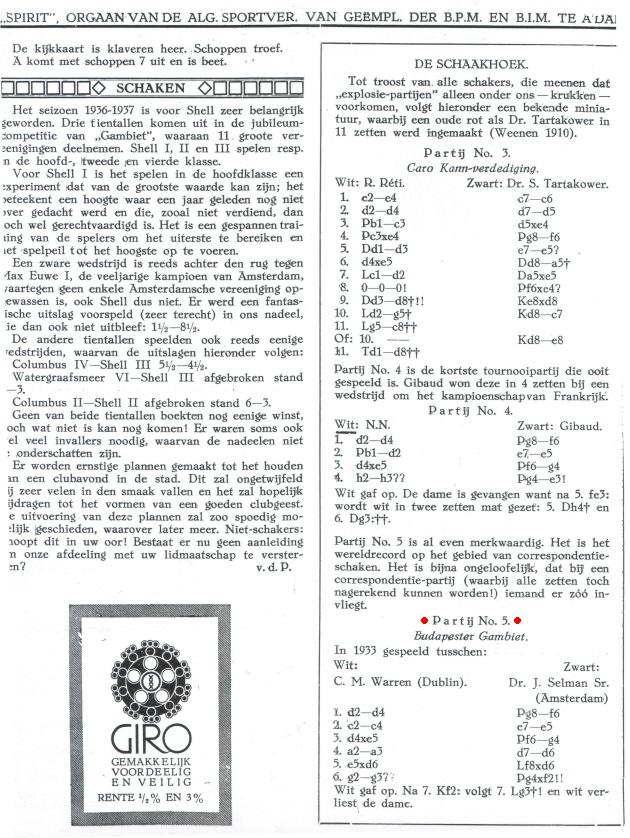

Concerning the Warren v Selman correspondence brevity (1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e5 3 dxe5 Ne4 4 a3 d6 5 exd6 Bxd6 6 g3 Nxf2 7 White resigns), Harrie Grondijs (Rijswijk, the Netherlands) writes:

‘The game appears to have been played by J. (Jan) Selman Senior after all, and not by his younger brother John. In Spirit, a recreational house magazine for the staff of the BPM (Bataafse Petroleum Maatschappij), John Selman Junior, an employee, conducted a column from October 1937 until the War years (taking it up again after the War). Before October 1937 he was on the editorial board of the magazine, and in the chess corner (“Schaakhoek”) in the January 1937 issue the following appeared (with the game misdated 1933):

In the early 1930s both of the Selman brothers studied and/or worked in Amsterdam and even played for the same club team. In a letter dated 25 February 1940 in my possession Selman Junior wrote:

“In the past when my eldest brother and I were members of the same chess club in Amsterdam, next to each other in the same team, this caused considerable confusion ...”

I now believe that the miniature games 127 and 128 given by Fernschach in 1931 (where White was named as A.M. Warren in the latter) were played by Jan Selman Senior.’

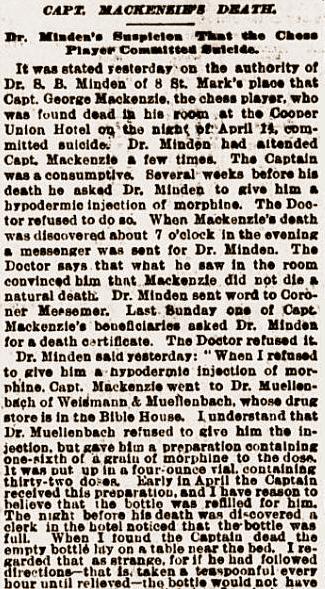

7772. G.H. Mackenzie’s death

Lev Pisarsky (Sunnyvale, CA, USA) notes that secondary sources make a range of claims about the cause of G.H. Mackenzie’s death, on 14 April 1891 at the age of 54, including heart disease, pneumonia, tuberculosis and suicide.

We wish to build up a set of citations from the press of the time. Firstly, here is a brief news item from the previous year (New York Times, 27 April 1890):

‘New Orleans, LA, 26 April. George H. Mackenzie, the champion chessplayer, is a very sick man, probably dying of consumption. He is in the piney woods of St Tammany, hoping for benefit from an atmosphere impregnated with salt and turpentine.’

Mackenzie’s demise was reported in the 15 April 1891 edition of the New York Times (page 2):

‘Capt. George H. Mackenzie, the chessplayer, was found dead last evening in a room on the second floor of the Cooper Union Hotel, at St Mark’s Place and Third Avenue. He was last seen alive when he went to the room Monday night [13 April]. He was then ailing, and the impression was that he was consumptive, but no anxiety was felt about him until five o’clock yesterday afternoon, when it was remembered that he had not been seen during the day. It was found that the key of his room was inside the door, and after much rapping it was thought that he was unconscious or dead, and the room was entered.

Capt. Mackenzie was dead in bed, and the immediate cause of dissolution is supposed to have been pneumonia, the result of a neglected cold. His recent convivial habits are supposed to have contributed to exhaust his vitality. His body was taken to a First Avenue undertaker’s, and a few friends looked at it last night. Arrangements for the funeral will be made today.

About $140 were found on the body, and when a committee of the Manhattan Chess Club, of which he was an honorary member, called at the hotel, they were told that the Coroner would take charge of the funeral.’

Later in the report it was stated:

‘During another visit to Havana he was prostrated by fever, and after returning to New York he caught a violent cold. His constitution being already enfeebled by malaria, the cold developed into consumption, and he steadily grew worse.

He went South for his health, and there gave several brilliant exhibitions in playing blindfold games, and also in playing simultaneous games. He was too weak to take part in the Sixth American Chess Congress and International Tournament, and that fact preyed heavily upon him.’

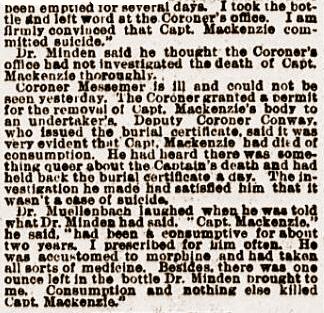

With regard to the possibility of suicide, the following appeared on page 2 of The Sun (New York), 29 April 1891:

7773. Fischer photographs

Wayne Komer (Toronto, Canada) points out a webpage with many high-quality photographs of Fischer by Carl Mydans.

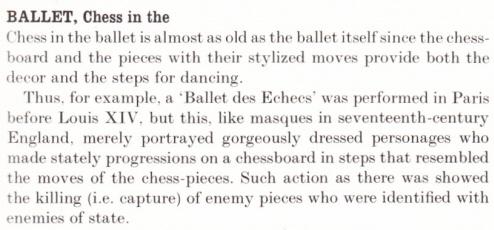

7774. Paul M. List

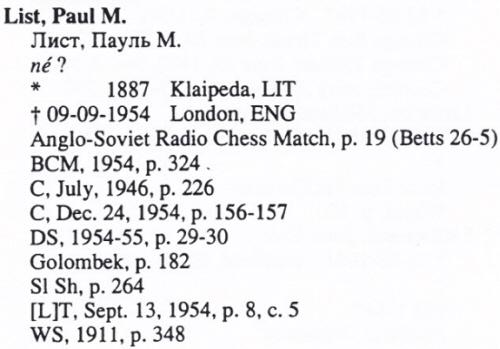

Information about Paul M. List (1887-1954) is sought by Javier Asturiano Molina (Murcia, Spain).

As ever, the best starting-point is Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia, and below is the entry in the privately-circulated 1994 edition:

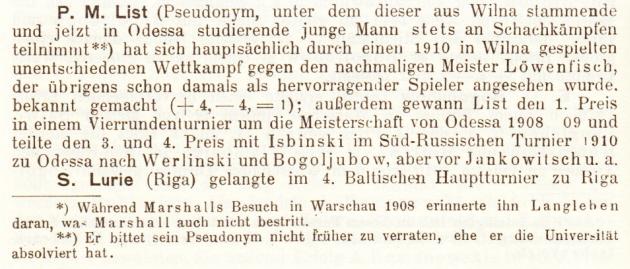

The last of the items listed is on page 348 of the November-December 1911 Wiener Schachzeitung:

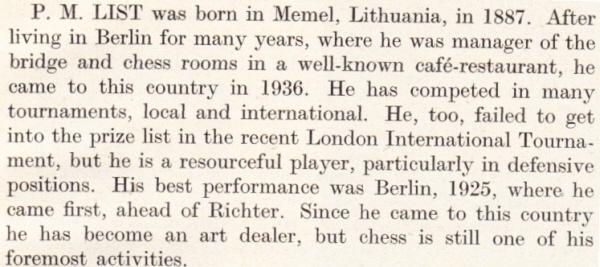

We also give the biographical note on page 19 of The Anglo-Soviet Radio Chess Match by E. Klein and W. Winter (London, 1947):

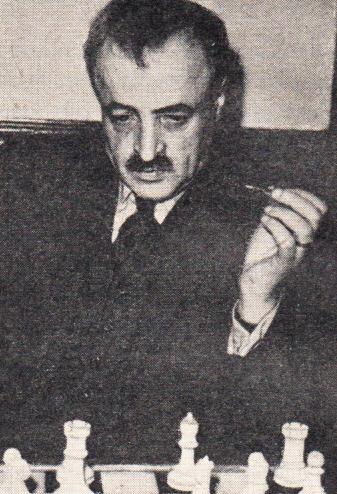

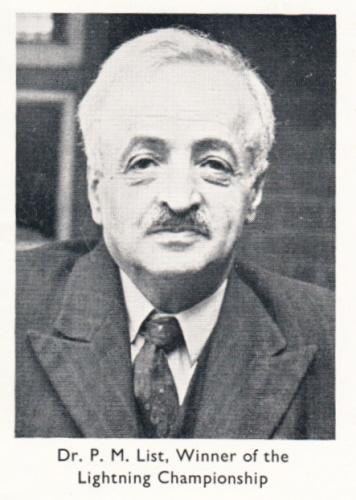

The previous page had this photograph of him:

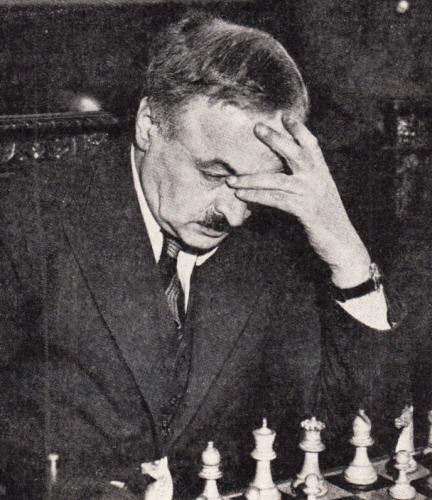

Another shot appeared opposite page 163 of the June 1953 BCM:

The following year (October issue, page 324) his death was recorded briefly:

‘Dr Paul List, the British Lightning Chess Championship winner a year ago (though he could not hold the title because he was not a naturalized Briton), died in London at the age of 66. A player of master strength, Dr List left his native Russia for Germany in the 1920s, and began on his second exile in 1938 when he sought refuge in this country from Germany.’

There was a two-page article ‘Dr Paul List; In Memoriam by Mrs Stephanie List’ on pages 156-157 of CHESS, 24 December 1954. Only the first two paragraphs had any biographical information:

‘Paul List, born in Russia in 1887, was driven out when the Revolution came. In Germany, with the help of chess and the many friends he made, he built up a chess centre in Berlin which became famous. In one very interesting event there, he scored a dual success as organizer and participant. This was a simultaneous display which he gave, together with Emanuel Lasker. Each made alternative moves without consultation. Two against 42. He gave lectures, took part in tournaments, published a weekly chess column until Hitler put a stop to it.

In 1938 he came to England, where he tried once again to build up a new existence. With the help of old and new friends, he succeeded again in creating a place for himself in this haven of refuge and beloved country. It gave him great pleasure to win the British Lightning Chess Championship in 1953, when already a very ill man.’

From page 157 of CHESS, 24 December 1954:

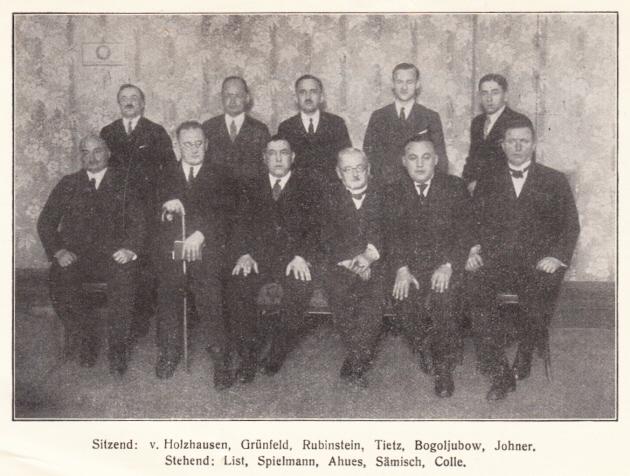

Our final illustration comes from the Berlin, 1926 tournament book:

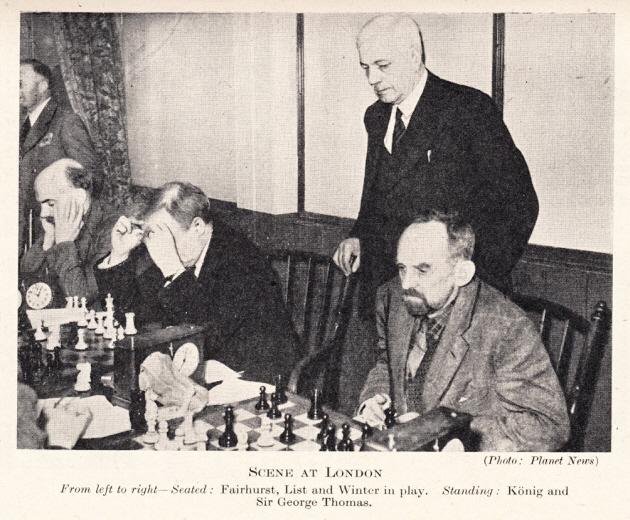

7775. Sir George Thomas

This article by G.H. Diggle comes from page 71 of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984), having originally appeared in the August 1981 Newsflash:

‘Sir George Thomas, the centenary of whose birth was on 14 June, made his first début at the Tunbridge Wells Congress in 1902, where he tied in the “First Class” with R.P. Michell and G.E. Wainwright. He progressed steadily, winning the City of London Championship for the first of many times in 1913 and becoming British Champion in 1923. But (strangely at first sight) his chess strength increased if anything after he had reached middle age. There was a reason for this. Previously he had devoted his leisure to chess, badminton and lawn tennis. When anno domini began to reduce his prowess in the two active games (in both of which he was an “international”) he gave all his attention to chess, and thus culminated at an age when (in his case) he could still stand the physical strain of long tournament sessions. His greatest achievement was at the age of 53 when (having in 1934 again won the British Championship) he was equal first at Hastings, 1934-35 against a tremendous opposition, the scores being Thomas, Euwe and Flohr 6½ each, Capablanca (if you please) 5½ only, Botvinnik and Lilienthal 5 each. In a wonderful spurt Sir George defeated Capablanca in 53 moves, Botvinnik in 60, and Lilienthal in 30, though his win against the Cuban was a little overshadowed by Lilienthal, who also defeated him by a famous queen sacrifice. At the end of the penultimate round everyone eagerly hoped (and expected) to see Sir George end up a clear winner – with a score of 6½ he was half a point ahead of Dr Euwe and a full point or more clear of “the field” and he had only his old friend Michell (who had had an unsuccessful tournament) to meet in the last round. There can be no doubt that Michell would have liked to “go easy”, but such were the rigid principles of both players that he went all out for a win and got it. At the prize-giving Dr Euwe referred to “characteristic British sportsmanship” and Flohr “expressed a wonder whether any other country could have furnished such an example”.

The BM had the opportunity of observing Sir George in 1944-45 both at the West London and Lud-Eagle Clubs. He seemed rather a shy man, with a horror of being treated with anything like undue deference either as a chess master or as a Baronet. Once when the BM merely held a door open for him he almost panicked: “No no no. You first.” Over the board, he was the quietest of men, except on one solitary occasion. The London Championship tournament of October 1945 (the first in this country since the end of the War) had attracted the press. Scarcely had the opening moves in the first round been made when hooded cameramen with crouching stance and the evil mien of medieval executioners appeared from nowhere, encircled the combatants, and blazed away with their flashlights for a full minute. Just as the blitz seemed all over, and the torturers in full retreat, one of them turned on Sir George (presumably as the most distinguished competitor) and honoured him by “discharging a second barrel”. Whereupon the Baronet was distinctly heard to “use a big, big D” but, recovering immediately, he bestowed a sheepish grin on his opponent, and quietly “returned to his muttons”.’

Sir George Thomas

7776. Chessical

An addition just made to Chessy Words is the occurrence of ‘chessical’ in a letter from George Walker which was published on page 27 of the Liverpool Mercury, 24 January 1840:

‘Away with all flimsy excuses; they are not chessical.’

The letter has been found by Rod Edwards (Victoria, BC, Canada).

7777. Chesser

Although the oldest citation of ‘chesser’ currently available dates from 1875, the word’s appearance on page 41 of the Westminster Papers a few years later (1 July 1878, page 41) is also of interest. The passage concerns that year’s Paris tournament:

‘There are several names missing from the roll call, and one, the absence of which excites universal regret – Louis Paulsen, the victor of last year’s tourney at Leipzig, and probably the greatest player of the day. No-one will hesitate to approve Herr Paulsen’s determination to forego the pleasant but somewhat unprofitable honours of chess championship for the discharge of important duties, for to this cause his absence is ascribed and not, we are happy to say, to any infirmity of health or purpose. For those afflicted with the latter development of the sick phase, if there are any such, we have all the sympathy that is usually felt for persons whose sufferings begin the night before the battle, and we entertain a sanguine hope that these will be greatly mollified when the fray is over. We should be sorry to jest about the delicate organizations in which chess genius is usually found, but as a well-known chessplayer observed a few days ago:

“We envy not the Chesser’s skill,

His case is hard, the truth to tell –

He can’t play well, because he’s ill,

Or’s ill because he can’t play well.”’

7778. Michael Frayn

Bradley J. Willis (Edmonton, Canada) quotes from paragraph 275 of Constructions by Michael Frayn (London, 1974):

‘[A small insanity of my own occurred] when I was still at school, and playing a great deal of chess. I began to see people in the street as being in chess relationships to each other. That man standing second in the bus queue and that bus-inspector standing level with the stop on the opposite side of the pavement, I would realize with anxiety, were a knight’s move away from each other; if the man didn’t move he would be taken. Then I would notice, with relief, that he was in fact covered by the woman in the shop doorway, on the diagonal from him. Did the bus-inspector look like a knight? No – I just knew he was, from the fact that he was standing a knight’s move away from his victim. Did I see the pavement laid out in squares? Is this how I knew it was a knight’s move? No – I knew it was a knight’s move because it was a knight threatening the man.’

7779. Grandmaster

Relatively early occurrences of the term ‘grandmaster’ continue to be welcomed. The following, submitted by John Blackstone (Las Vegas, NV, USA), was written by Gunsberg on page 6 of The World, 16 January 1891:

7780. Sir George Thomas (C.N. 7775)

Regarding the above photograph given in C.N. 7775, Kari Tikkanen (Iisalmi, Finland) notes that it shows the game Koltanowski v Thomas in the Hastings, 1935-36 tournament.

We reproduced the picture from page 273 of CHESS, 7 July 1956, but page 236 of the magazine’s 14 February 1936 issue had more:

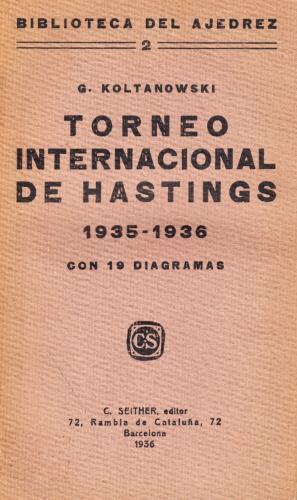

7781. Koltanowski tournament book

The above-mentioned Koltanowski v Thomas game was

played in January 1936, in the seventh round of

Hastings, 1935-36, and it appeared on page 42 of

Koltanowski’s book Torneo internacional de Hastings

1935-1936 (Barcelona, 1936).

The Koltanowski touch is reflected in, for instance, the book’s references to Buenger, Friffith, Gensberg, Golombeck, Gross, Michel, Pire, Rubistein, Tartalkower, Vitmar, Womorsly, Wonorsly and even, on page 32, Koltanowki.

7782. World records

Guinness World Records 2013 has three entries concerning chess. Page 106 offers a reprise of an old item about Karjakin (the youngest grandmaster), and page 197 refers to Kasparov’s loss to Deep Blue in 1997. True to the Guinness tradition, page 109 has a light feature on the Cotswold Olimpicks of 1612, a competition involving this ‘range of rather curious disciplines’: dancing, chess, cockfighting, jumping in sacks, pike drill, shin kicking, spurning the barre and hay bale racing.

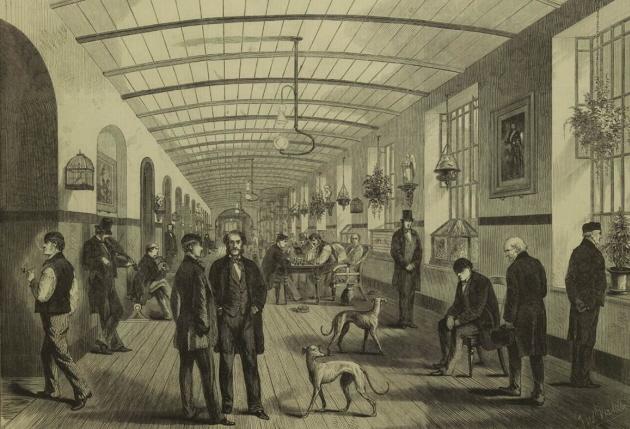

7783. Bethlehem Hospital

Further to The Cambridge v Bedlam Chess Story Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) draws attention to an illustration published on page 308 of the Illustrated London News, 31 March 1860 as part of a report entitled ‘A Visit to the Royal Hospital of Bethlehem’.

7784. Photographs of the masters

Mr Urcan also points out the Süddeutsche Zeitung Photo website. A search for ‘Schach’ yields many photographs of chess masters past and present. We note, for instance, a 1921 shot of Samuel Reshevsky boxing against the Hollywood prodigy Jackie Coogan.

7785. Double blindness

A game in which, on consecutive moves, each player overlooked the possibility of being mated on the spot:

Karl Vill – J.B. MeyenborgNew York, 1 January 1902

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 O-O d6 6 d4 Bd7 7 Nc3 Be7 8 Kh1 O-O 9 d5 Nb8 10 Qd3 Bxa4 11 Nxa4 Nbd7 12 c4 Rb8 13 Nc3 b6 14 b4 Qc8 15 Bg5 Re8 16 Nh4 h6 17 Bd2 Nh7 18 Qg3 Bxh4 19 Qxh4 Qd8 20 Qg3 Kh8 21 f4 Rg8 22 f5 f6 23 Qg4 Qe8 24 Rf3 Qf7 25 Rh3 Ndf8 26 Re1 Rc8 27 Ree3 c6 28 a3 cxd5 29 exd5 Qc7 30 Ne4 Qxc4

31 Nxd6 Qxg4 32 Nf7 mate.

The game was found by Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) on page 5 of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 12 January 1902.

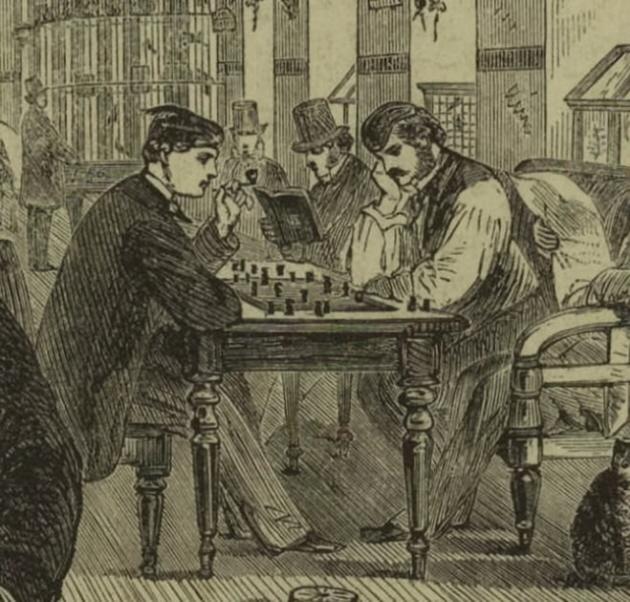

7786. Chess and ballet

Javier Asturiano Molina (Murcia, Spain) asks for information about ‘Le ballet des échecs’, a work mentioned, for instance, on page 23 of The Encyclopedia of Chess by Harry Golombek (London, 1977):

7787. Anglo-Soviet radio match

A photograph on page 67 of The Anglo-Soviet Radio Chess Match by E. Klein and W. Winter (London, 1947):

7788. Two Schlechter games

More information is sought about the circumstances in which these games were played (at the Associazione Scacchistica Milanese):

A. Noto – Carl SchlechterMilan, 6 June 1901

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 e6 3 Nc3 Nc6 4 d4 cxd4 5 Nxd4 Nf6 6 Nxc6 bxc6 7 e5 Nd5 8 Ne4 d6 9 c4

9...dxe5 10 cxd5 exd5 11 Ng3 h5 12 h4 g6 13 Be2 Bg7 14 Qc2 Bd7 15 Bg5 Qb6 16 O-O O-O 17 Rfe1 e4 18 Rad1 Qxb2 19 Qxb2 Bxb2 20 Nxe4 f6 21 Be3 Be5 22 Nc5 Bc8 23 Bf3 Rb8 24 Rb1 Bf5 25 Rxb8 Rxb8 26 Rd1 Rb2 27 g3 Kf8 28 a4 Ke7 29 a5 Kd6 30 a6 Bc8 31 Kg2 Rb5 32 Rc1 d4

33 Ne4+ Kc7 34 Bf4 Bxf4 35 gxf4 f5 36 Nf6 c5 37 Be2 Ra5 38 Bc4 Kd6 39 Re1 Ra4 40 Bb5 Resigns.

Source: Deutsche Schachzeitung, June 1901, pages 173-174.

Vincenzo Noto – Carl SchlechterMilan, 6 June 1901

Nimzowitsch Defence

1 e4 Nc6 2 d4 e5 3 d5 Nce7 4 Nf3 d6 5 c4 f5 6 Nc3 Nf6 7 Bd3 h6 8 Qc2 f4

9 Bxf4 exf4 10 e5 dxe5 11 Nxe5 Qd6 12 Bg6+ Nxg6 13 Qxg6+ Ke7 14 Nf7

14...Bf5 and wins.

Source: Schweizerische Schachzeitung, October 1901, page 8.

7789. Giuseppe Stalda

From page 23 of Keres’ Best Games 1932-1936 by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1937):

‘It has often been observed that certain players are far better at correspondence play than at over-the-board play. A very good example is the Italian player Stalda, who is probably one of the strongest correspondence players in the world, although he has never distinguished himself in a regular tournament.’

7790. Man Machine

In C.N. 1243 (see page 161 of Chess Explorations) W.D. Rubinstein drew attention to a booklet published in Madras in the mid-1980s, Karpov’s Best Games by V. Ravi Kumar (or Ravikumar). From the author’s introduction, entitled ‘Karpov “The Man Machine”’, a few sentences (to use that noun loosely) were quoted:

‘He was awarded the Chess Oscar for his outstanding achievements in Chess. A honour which he won many times in succession Karpov is a Solid Positional Master but if the situation warrants he can glar himself to a tactical Genious. In the chapters that follows of his selected Games from 1980 to 1984 are annotated with my own notes for your entertainment.’

Also regarding the introduction, it remains to be discovered on what grounds the author attributed this remark to Botvinnik:

‘Anatoly Karpov is unquestionably the strongest chess player of the century.’

7791. Benko Gambit (C.N.s 3957, 3967, 5457 & 5461)

Further to a correspondent’s remark in C.N. 5461 that Black’s sacrifice of a queen’s-side pawn for pressure on the opened files occurred in Nimzowitsch v Capablanca, St Petersburg, 1914, Gerd Entrup (Herne, Germany) points out the game Viakhirev v Romanovsky, as annotated on pages xxvi-xxvii of Emanuel Lasker’s Der internationale Schachkongress zu St. Petersburg 1909 (Berlin, 1909):

1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Nf6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 d3 d6 5 f4 Nc6 6 f5 (‘Schwarz hat nun ein schwieriges Problem zu lösen. Wie soll er dem drohenden Lc1-g5 begegnen und zugleich das ihn einschnürende Zentrum sprengen? Wäre d6-d5 möglich, so bestände keine Gefahr; aber Weiß hat den Punkt mehr als ausreichend gesichert.’) 6...Na5 7 Qf3 Nxc4 8 dxc4 c6 9 Bg5

9...b5 (‘Schwarz löst die Aufgabe in mutiger Weise. Er opfert zwei Bauern, um an den schwachen Punkt des Gegners, e4, gelangen zu können.’) 10 cxb5 Qa5 11 bxc6 Rb8 12 Bd2 (‘Wenn 12 Ta1-b1 Sf6xe4 13 Df3xe4 Tb8xb2.’) 12...Qb6 (‘Sehr gut. Wenn nun 13 Sc3-a4 Dxc6 14 Sxc5 Dxc5. Schwarz bedroht neben dem c- und b-Bauern auch e4 durch Lb7.’) 13 Nge2 Qxc6 14 b3 Bb7 and Black eventually won (at move 43).

7792. Misidentification

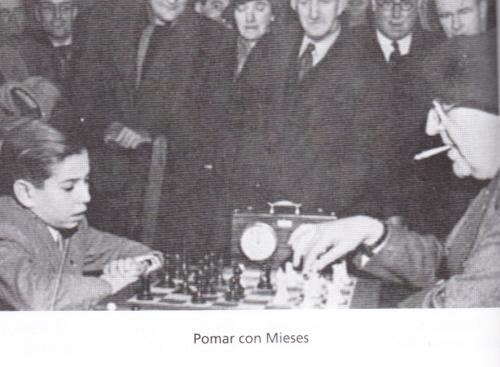

A case of misidentification concerning the Pomar v Bernstein photograph given in C.N. 6573 occurs on page 68 of Arturo Pomar. Una vida dedicada al ajedrez by Antonio López Manzano and Joan Segura Vila (Badalona, 2009):

7793. Two Schlechter games (C.N. 7788)

Gene Gnandt (Houston, TX, USA) notes an account of Schlechter’s visit to Italy on page 189 of the 8/1901 Nuova Rivista degli Scacchi:

‘Alcune città d’Italia, tra cui Milano e Venezia, hanno avuto il piacere nel passato Giugno di ospitare l’illustre maestro Carlo Schlechter di Vienna, reduce da i suoi trionfi e avventure di Montecarlo. A Venezia la mancanza in quella città del presidente del Circolo comm. Vergara, e dell’avv. Salvioli, ha portato la non lieta conseguenza che il valente scacchista non ha potuto ricevere l’accoglienza che si meritava. Ad ogni modo sappiamo che ha giocato con molti dilettanti di quella città e ha giocato con rara facilità, non disdegnando rompere una lancia con avversari a lui ben inferiori. Una qualità questa ben preziosa in un maestro di primo rango. Il gioco dello Schlechter fu trovato addirittura meraviglioso, e sebbene egli per avventura nei giorni in cui fu in Venezia non abbia potuto trovare alcun avversario degno di stargli a fronte, pure ha saputo dimostrare egualmente quelle splendide qualità di giocatore che fanno di lui uno dei primissimi campioni moderni. In Milano invece egli colse un momento più propizio. Giocò alcune belle partite col V. Noto, e potè essere festeggiato in modo più degno del suo nome.’

We add that according to page 8 of the October 1901 Schweizerische Schachzeitung the 1 e4 Nc6 game in C.N. 7788 had previously appeared in the Eco degli scacchi (Palmero).

| First column | << previous | Archives [98] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.