Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [97] | next >> | Current column |

7743. A reminder

A reminder should hardly be necessary, but readers are requested not to help themselves to whatever they please on the Chess Notes pages.

The level of misappropriation can be remarkable. For instance, our feature article Books about Fischer and Kasparov has frequently been lifted en bloc, sometimes even without attribution.

We wonder too when a certain Canadian grandmaster will remove from his website our copyrighted material, including the 2,000-word article A Catastrophic Encyclopedia.

Nor does Chess Notes exist to offer a free scanning service for photographs (some of which we have acquired at considerable expense) to individuals who lack the relevant archive resources of their own.

Finally, it is regrettable that discoveries and other information presented in Chess Notes (including valued contributions from correspondents) are often re-posted by people in a way which suggests that they themselves unearthed the material.

Attention to these elementary points of fair play will be much appreciated.

7744. Stefan Zweig

From Oliver Beck (Seattle, WA, USA):

‘An assessment of Stefan Zweig’s chess ability can be found in Ernst Feder’s contribution to Stefan Zweig: A Tribute to his Life and Work edited by Hanns Arens (London, 1951), page 130. In an essay entitled “Stefan Zweig’ s Last Days” Feder describes visiting Zweig on the eve of his suicide. Finding him increasingly melancholic, and unaware that he and his wife were planning to end their lives shortly after his departure, Feder suggested a game of chess:

“At the time I didn’t know ... why his wife gave him a long astonished look when he agreed to play a game of chess with me. I suggested this because I hoped that the game he enjoyed so much would divert him from his gloomy thoughts. In itself it was no pleasure to be his opponent on the black-and-white board. I am a poor player myself but he knew so little about chess that I had difficulty in wangling an occasional win for him.”’

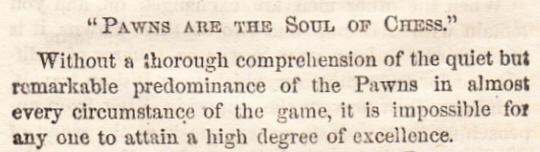

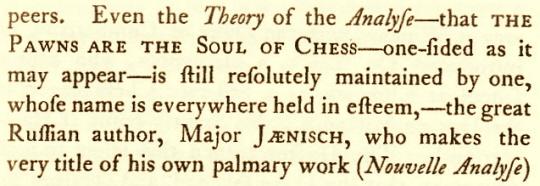

7745. Philidor and pawns (C.N.s 5560, 5762 & 5826)

The question raised in C.N. 5826 (when the exact wording ‘Pawns are the soul of chess’ first appeared in print) remains open.

Below are two citations from the 1860s, the first of which does not name Philidor:

Beadle’s Dime Chess Instructor by Miron Hazeltine (New York, 1860), page 44.

The Life of Philidor by George Allen (New York and Philadelphia, 1865), page 31.

On page 7 of Basic Chess Endings (Philadelphia, 1941) Reuben Fine built on the remark:

‘The pawn, as Philidor put it, is the soul of chess, and we can add that in the ending it is nine-tenths of the body as well.’

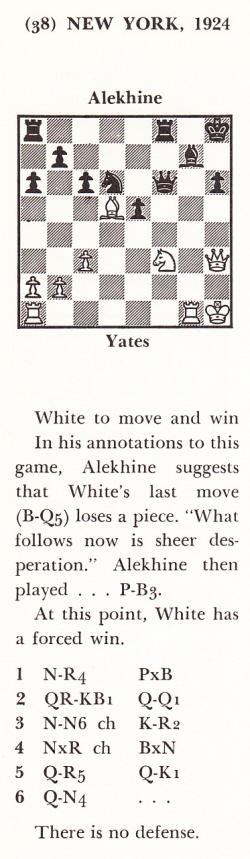

7746. A question of attribution

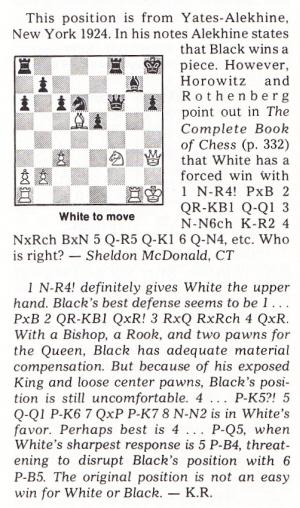

A position from Yates v Alekhine in the first round of the New York, 1924 tournament:

Yates played 29 Bd5, and on pages 17-18 of the tournament book (New York, 1925) Alekhine wrote:

‘Losing a piece. What follows is sheer desperation.’

The continuation was 29...c6 30 Rxg7 Kxg7, and White resigned after Black’s 35th move.

It was later found that White could have played 30 Nh4, but when was the discovery made?

Below is what appeared on page 332 of The Personality of Chess by I.A. Horowitz and P.L. Rothenberg (New York, 1963):

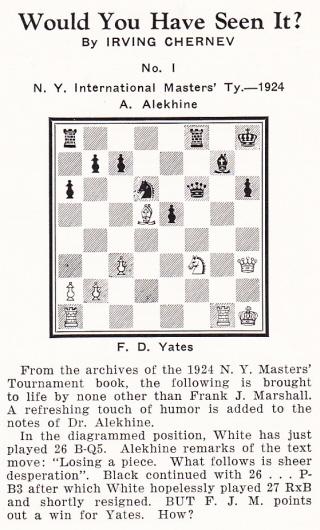

The matter was taken up by Sheldon McDonald of Connecticut on page 16 of the January 1978 Chess Life & Review, in the ‘Ask the Masters’ column, and a reply from Ken Rogoff followed:

The Complete Book of Chess was the new title of the Horowitz/Rothenberg work when it was reissued in 1969. The co-authors’ text leaves the reader to infer that they found 30 Nh4, but such was not the case. Horowitz’s magazine, Chess Review, had the following on page 291 of the December 1938 issue:

The solution on page 301 (also with incorrect move numbers throughout):

Nowadays the possibility of 30 Nh4 is regularly mentioned, though without attribution to Marshall or anyone else. See, for instance, page 43 of the second volume of the Chess Stars work on Alekhine (Sofia, 2002). For his part, Alekhine annotated the game briefly on pages 73-74 of La Stratégie, April 1924 (notes reproduced from Le Canada) and on page 99 of Wiener Schachzeitung, April 1924, but neither set of notes has anything of relevance to the play under discussion here.

7747. Soviet film

Gerhard Thoma (Dornbirn, Austria) draws attention to the 1972 Soviet film Гроссмейстер, which can be watched online. Many masters appear, including Petrosian, Korchnoi, Tal and Kotov.

Our correspondent mentions too the observation by Milan Novković that some of the over-the-board action is based on the spectacular draw between Alatortsev and Kholmov in the 1948 Soviet championship in Moscow.

7748. Nimzowitsch and Müller (C.N.s 5552, 5572 & 5581)

From page 3 of Carlsbad International Chess Tournament 1929 by A. Nimzowitsch (New York, 1981):

‘In this tournament, I played with a greater ease and confidence than usual. The explanation for this is that three months before the tournament began I undertook a strict program of Müller’s exercises. This in turn led to a kind of healthy optimism, which dispelled all my lingering fears and worries, and thereby also dispelled the little psychological crises which formerly used to hobble my successful career.’

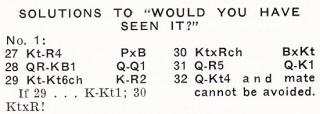

To supplement readers’ imagination, we reproduce a

photograph of J.P. Müller from page 79 of his book Mein

System (Copenhagen and Leipzig, 1904):

7749. Nimzowitsch and Carlsbad, 1929

C.N. 1199 quoted some comments by Nigel Short on pages 40-41 of the 2/1986 New in Chess during an interview with Bert van de Kamp, in reply to the question ‘Do you have a teacher in chess, someone whose ideas have had a big influence on you?’:

‘I always liked Nimzowitsch – until recently. I got this book about Carlsbad, 1929 [IV. internationales Schachmeisterturnier Karlsbad 1929], played through all his games and they were really bad. I thought: If this is what he played like, on average, then he wasn’t a very good player. You can take any player in the world and show their best games and make them look brilliant. Nimzowitsch is not as original as people thought he was. Many of his ideas were extensions of earlier ideas of Steinitz. Actually, I’m more impressed with modern players. I’m still stunned by Fischer and more so recently. Look at his results, my goodness. He has been winning tournaments with a hundred per cent score. How is it possible? And when you play through his games they all look so easy. In 1972 he didn’t behave very well, but I liked him.’

7750. Losing with grace

An article by the Badmaster, G.H. Diggle, which was published in the March 1981 Newsflash and on page 66 of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984):

‘That incorrigible chess satirist, W.R. Hartston, dealing with “etiquette for chessplayers on losing”, recommends (Soft Pawn, page 41) that resignation should be accompanied by “a pertinent congratulatory message” and gives as a textbook example for our guidance: “I hope that makes you happy, you smug bastard.” An alternative worth consideration (which the BM once actually overheard in a League Match) is “Fancy losing to you”, bringing home to the “bastard” that he was not only smug but incredibly lucky.

Chess history records many instances of gracious conduct in adversity. In 1859 the illustrious Henry Thomas Buckle, whose stature earned him a “special licence” as a “disagreeable man”, visited the Boulogne Chess Club, where he was invited to play a total stranger (who was, in fact, Thomas Winter Wood, an able player and the father of Mrs W.J. Baird, the lady problemist of the 1890s). “What odds shall I give you?”, growled the great man brusquely. Observing Winter Wood’s raised eyebrows, Buckle barked out “Never play otherwise” and peremptorily removed his KBP, adding: “I’ll give you pawn and move”. After several exchanges Buckle found himself still a pawn down without compensation, whereupon he abruptly announced: “I don’t feel well – I’ll give it up.” Winter Wood remarks that the great historian was indeed in poor health at the time, and died three years later. [See page 12 of the January 1898 BCM.]

Coming down to resignations at Badmaster level, Monsieur Leduc, a knight player of the Café de la Régence in the 1830s, ended up in a dead drawn position with king against king and pawn, but his opponent (a cantankerous person ignorant of the principles of the opposition) insisted on playing on. After a great deal of ill-natured banging of kings to and fro at a furious rate, the inevitable happened, and poor M. Leduc thumped his unfortunate monarch onto the wrong square. “There”, brayed the triumphant ignoramus, “I told you I would win.” “You have won”, shrieked M. Leduc, “because you do not know how to play.”

The Badmaster, though an experienced resigner, must admit that on one occasion he himself “turned nasty”. His opponent was an exuberant foreign youth from an Eastern clime and the BM, after playing (as he always does) a rook below his real strength, was on the verge of yielding up the ghost with his usual sepulchral grace, when his antagonist presumptuously came to his assistance: “I sink dis is where you give it in. I haf two lovely passed pawns – is it not goodbye?” “Young man”, rejoined the outraged BM, “I have given you no Power of Attorney to resign games on my behalf.” Needless to say, this brilliant shaft was completely wasted on the obtuse visitor, who broke into a beaming smile: “Oh, velly good, sir. Velly good indeed. You lose, and yet (how say you it?) you pull good sporty crack, yes?”’

7751. Books on Fischer and Nimzowitsch

Two books just received present a stark contrast.

A Psychobiography of Bobby Fischer by Joseph G. Ponterotto (Springfield, 2012) shows little discernment between good chess sources and bad ones, although neither type can be blamed for the particular carelessness in the appendices on pages 163-171. For example, it is stated that the second Fischer v Spassky match was in 2002, and that the birth-year of Fischer’s mother and of Paul Morphy was 1949.

Aron Nimzowitsch On the Road to Chess Mastery, 1886-1924 by Per Skjoldager and Jřrn Erik Nielsen (Jefferson, 2012) comes in the best traditions of McFarland hardbacks. It is supremely well researched.

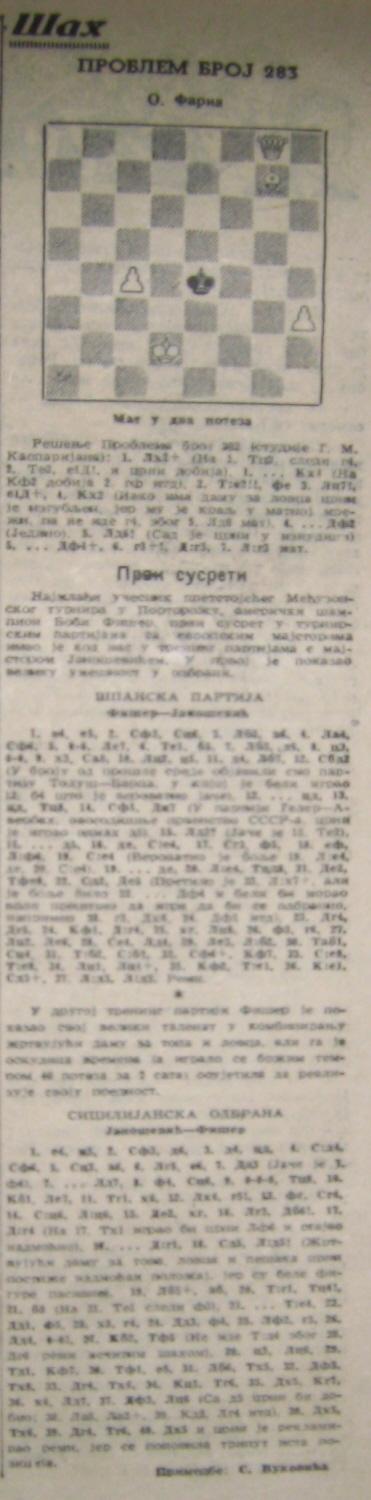

7752. Fischer in Yugoslavia (C.N. 7589)

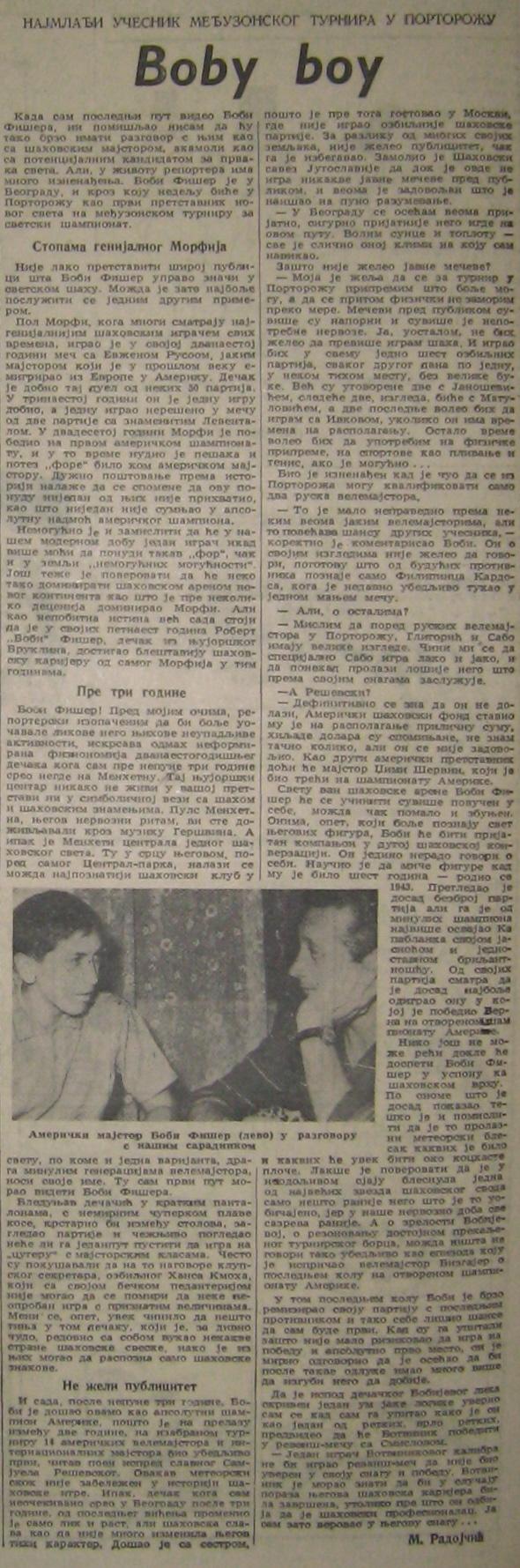

From Kiril Penušliski (Skopje, Macedonia):

‘I have found some further information about the Fischer v Matulović match (Belgrade, 1958) in Politika. Although it was Yugoslavia’s premier daily newspaper at the time, it brought out only one edition per day, which meant that its reports were always a day old. As a starting-point for my research I consulted the collection of Fischer games published by Šahovski Informator (Belgrade, 1992). Page 48 gives the only known game from the Fischer v Matulović match (the first game), but it also provides a score-table of the contest (Fischer lost the first game and won games two and four, whereas the third game was drawn) and supplies dates (20-26 July 1958). The previous page has the two games of the Fischer v Janošević match (both draws), also played in Belgrade, but with only the year indicated (1958).

I went through the complete run of Politika for July and August 1958. The July issues have a great deal of news about the Student Olympiad, and the August editions include a number of reports on the Portorož Interzonal tournament. Here, I focus on the items in Politika which concern Fischer’s matches against Matulović and Janošević. A couple of the copies that I was able to make are rather blurred, but they should serve for identification purposes. Unfortunately, Politika gave none of the missing game-scores from the Matulović match.

10 July 1958:

A short feature concerning the arrival of Fischer (and his sister) in Belgrade, from Moscow. The article presents him as the youngest participant in the Interzonal tournament and gives a brief biography. It recapitulates on his trip to Moscow (where he played some blitz games and gave simultaneous displays) and reports:

“Until the Interzonal tournament begins, Fischer will be playing a few matches in Yugoslavia, but he has stated that he wants to play as few games as possible so that he does not tire before the start of the Interzonal tournament in Portorož.”

13 July 1958:

This issue carried an article by M. Radojčić, who had met Fischer some three years earlier, in New York. There is a particularly interesting passage, in the section entitled “Does not want publicity”, concerning Fischer’s preferences for the forthcoming matches with Yugoslav masters (at the top of the second column):

“He informed the Yugoslav Chess Federation that while he is here he does not wish to play any public matches in front of an audience, and he is very pleased that he found complete understanding.

‘I feel very good in Belgrade, certainly better than anywhere else on this trip. I love the sun and the warmth – everything is like the climate that I am accustomed to.’

Why does he not want to play public matches?

‘I would like to be as well prepared as possible for the tournament in Portorož, and not to be physically tired. Matches played in front of an audience are too exhausting, and there is too much unnecessary nervousness. Besides, I would not like to play too much chess. I would like to play about six serious games, one every other day, in some quiet place, without much noise. Two games have already been arranged with Janošević, the next two most probably will be with Matulović, and the last two I should like to play with Ivkov, if he has the time and is available. The rest of the time I have I would like to spend on physical training, sports like tennis and swimming if it is possible.’”

These comments seem to tally with Ivkov’s statement (on page 24 of his 1993 book Povratak Bobija Fišera) that he was invited to play a match with Fischer in 1958.

The last paragraph of the Radojčić article has an interesting statement concerning Botvinnik:

“I was convinced that underneath Bobby’s child-like appearance there is a strong, logical mind when I asked him how it was that he had been one of the very few who predicted that Botvinnik would win his return match with Smyslov.

‘A player of Botvinnik’s calibre would not be playing a return match if he was not convinced of his own strength and of victory. Botvinnik must have known that in case of defeat his chess career would have been finished, and even more so as he refuses the notion that he is a chess professional. That is why I believed in his strength ...’”

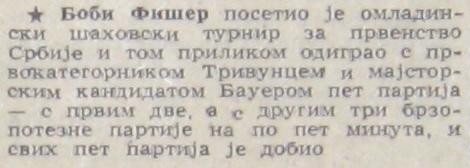

16 July 1958:

Fischer visited the Serbian junior championship tournament and played five blitz games; two with Trivunac, and three with Bauer. He won all five games.

19 July 1958:

This edition carried two items of relevance to the Fischer matches. The first (above) is the publication of both games from the Fischer v Janošević match, in a special children’s section of the newspaper. This is significant as it provides us with a terminus ante quem for that match. Moreover, the following day, 20 July, Janošević was playing in the Serbian championship.

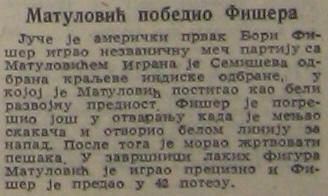

The second item (above) is a brief report that Matulović defeated Fischer in “an unofficial game”. There is a short description with a reference to the opening (a Sämisch King’s Indian Defence) and an indication of a possible error on Fischer’s part (the exchange of a knight which opened up a line for White’s attack). The report says that Fischer resigned at move 42, whereas the game-score in the Šahovski Informator book on Fischer ends “41 Bh3 1:0”.

26 July 1958:

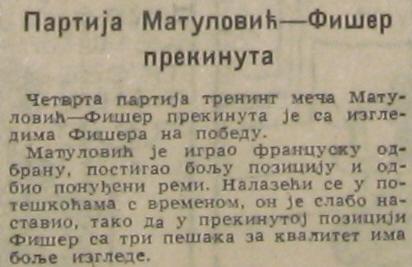

This is just a brief note stating that the fourth game of the Fischer v Matulović match has been adjourned, with Fischer standing better and holding winning chances. It also reports that Matulović played the French Defence, achieved the better position and turned down a draw offer. However, in time-trouble he played poorly, so that in the adjourned position Fischer had three pawns for the exchange and winning chances.

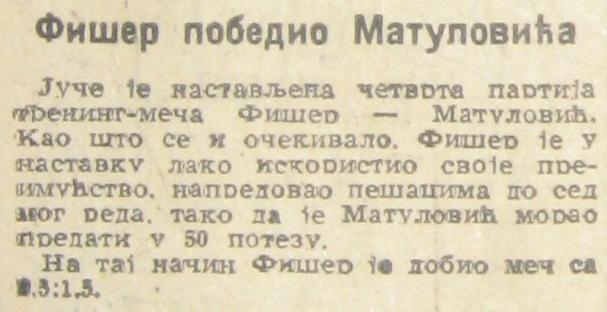

27 July 1958:

A report that Fischer defeated Matulović when the fourth game was resumed the previous day. As expected, Fischer easily exploited his advantage, advancing his pawns to the seventh rank and forcing Matulović to resign at move 50.

The preceding two items confirm Ivkov’s statement on page 56 of his above-mentioned book that Fischer won one game convincingly and one with some luck.

It can also be concluded that the dates for the Matulović match (20-26 July 1958) given in the Šahovski Informator book on Fischer are wrong. The match started on 18 July and ended on 26 July. If we take into account Fischer’s statement as to when the games were to be played (every other day) and the fact that the first game lasted 41 or 42 moves and did not require adjournment, whereas the fourth game started on 25 July and was played over two days, we have the schedule. The first game was played on 18 July, after which there was a free day. The second game was begun on 20 July. Either the second game or the third exceeded 40 moves and was played over two days. The fourth game was played on 25 and 26 July.’

7753. Soviet film (C.N. 7747)

Regarding the 1972 film Гроссмейстер Javier Asturiano Molina (Murcia, Spain) quotes from pages 83-84 of Chess is my Life by Victor Korchnoi (London, 1977):

‘In 1972 I happened to do some acting, in a professional studio, for a film. This was a film about chess, and was called Grossmeister (Grandmaster). It told of a boy who became a grandmaster, and I played the role of his trainer. The very fact that a film about chess was made was a good thing. But the film itself turned out to be rather poor. It was not by accident that I was praised as being the best actor in the film. After all, I was playing in a professional company, among some really talented actors. It can happen that way; if the script is primitive, then even the actors have no means of expressing themselves. Nevertheless, the film was a success among chessplayers in the USSR and in Eastern Europe.’

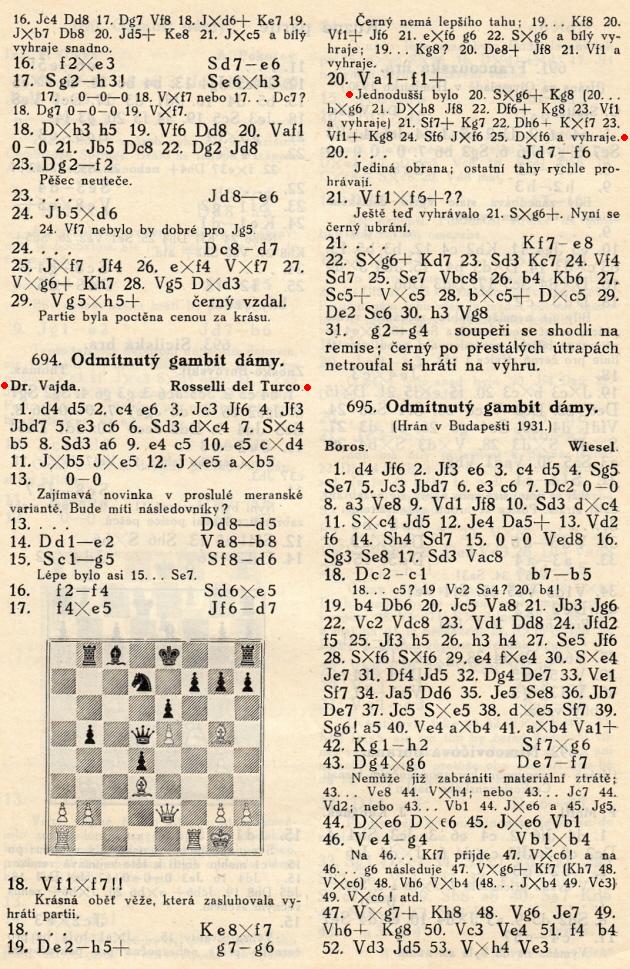

7754. Vajda v Rosselli del Turco

Some jottings are offered on a game which used to be fairly well-known, and especially to opening theoreticians:

Arpád Vajda – Stefano Rosselli del TurcoNice, 12 March 1931

Queen’s Gambit Declined

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 d5 4 Nf3 Nbd7 5 e3 c6 6 Bd3 dxc4 7 Bxc4 b5 8 Bd3 a6 9 e4 c5 10 e5 cxd4 11 Nxb5 Nxe5 12 Nxe5 axb5

13 O-O Qd5 14 Qe2 Rb8 15 Bg5 Bd6 16 f4 Bxe5 17 fxe5 Nd7 18 Rxf7 Kxf7 19 Qh5+ g6 20 Rf1+ Nf6 21 Rxf6+ Ke8 22 Bxg6+ Kd7 23 Bd3 Kc7 24 Rf4 Bd7 25 Be7 Rbc8 26 b4 Kb6 27 Bc5+ Rxc5 28 bxc5+ Qxc5 29 Qe2 Bc6 30 h3 Rg8 31 g4 Drawn.

The game’s appearance on page 98 of the May-June 1931 issue of Československý Šach:

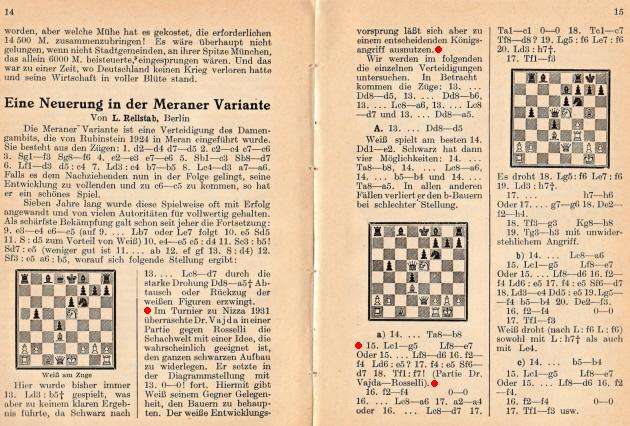

There was scrutiny of Vajda’s opening play in the article ‘Eine Neuerung in der Meraner Variante’ by L. Rellstab on pages 14-18 of Ranneforths Schachkalender 1932. Below are the first two pages:

Our particular interest, though, is the note to White’s 20th move in the Czech magazine, which states that in this position ...

... instead of 20 Rf1+ it was simpler to play 20 Bxg6+, one variation being 20...hxg6 21 Qxh8 Nf8 22 Qf6+ Kg8 23 Rf1 and wins.

However, in that line Black has a straightforward, if uncommon, way of staying a piece ahead:

21...Qxg2+ 22 Kxg2 Bb7+.

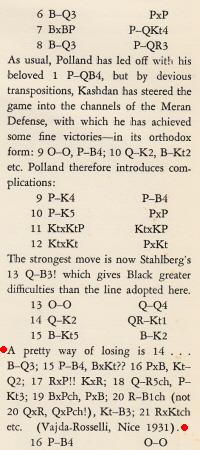

This was pointed out by a reader of Chess Review, J.J. Leary of Philadelphia, on page 229 of the October 1938 issue in connection with a game between Polland and Kashdan which followed Vajda v Rosselli del Turco until move 15. It had been annotated by Fred Reinfeld on pages 186-187 of the August 1938 Chess Review.

David Polland – Isaac KashdanBoston, July 1938

Queen’s Gambit Declined

1 c4 Nf6 2 Nf3 e6 3 Nc3 d5 4 d4 c6 5 e3 Nbd7 6 Bd3 dxc4 7 Bxc4 b5 8 Bd3 a6 9 e4 c5 10 e5 cxd4 11 Nxb5 Nxe5 12 Nxe5 axb5 13 O-O Qd5 14 Qe2 Rb8 15 Bg5 Be7 (‘A pretty way of losing is 15...Bd6 16 f4 Bxe5?? 17 fxe5 Nd7 18 Rxf7!! Kxf7 19 Qh5+ g6 20 Bxg6+ hxg6 21 Qxh8 and 22 Rf1+ butchers Black (analysis by Vajda)’ – Reinfeld.) 16 f4 O-O 17 Rf3 h6 18 Rh3 Bb7 19 Rf1 Rfc8 20 Bxf6 Bxf6 21 Ng4 Kf8 22 Nxf6 gxf6 23 Rxh6 Ke7 24 b3 Rc3 25 Rh5 f5 26 Rxf5 Qxg2+ 27 Qxg2 Bxg2 28 Re1 Bh3 29 Rxb5 Rg8+ 30 White resigns.

The moves in Reinfeld’s note were misnumbered, and

‘Vadja’ was given instead of Vajda. The misspelling and

analysis were corrected when the Polland v Kashdan game

was published on pages 59-60 of Reinfeld’s Year Book

of the American Chess Federation (New York, 1939):

Had Reinfeld been correct to suggest in Chess Review that Vajda himself missed 21...Qxg2+ in analysis?

7755. Chess in Singapore

From Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore):

‘A team of researchers is working on a potential chess history of Singapore (1945-2012) and is particularly interested in finding more information about Pat Aherne, Michael Davis and J.C. Hickey, three foreign players active in Singapore and Malaya in the 1950s.

David and Elaine Pritchard spent several years in Singapore during that decade and appear in a photograph with some of the leading players of that time:

David Pritchard sent me the picture without a caption, but I believe that it was taken during the Hollandsche Club Chess Invitational tournament in January 1955 and that he is playing Baris Hutagalung of Indonesia in the last round. Standing on the right are H.A.J. Pronk (a Singapore-based Dutch player) and Elaine Pritchard. The man on the far left is Tay Kheng Hong, a Chinese-born Singaporean player, and next to him is Lim Kok Ann (1920-2003), one of the pioneers of post-1945 Singapore chess and a highly respected person here.’

7756. Chess Fundamentals

In 2006 there was an edition of Chess Fundamentals revised by Nick de Firmian which purported to improve on the text by giving the reader less Capablanca and more de Firmian.

Now, Emereo Publishing has brought out ‘The original classic edition’ of Capablanca’s work:

All the diagrams have been dropped, and the book is therefore unusable. For instance:

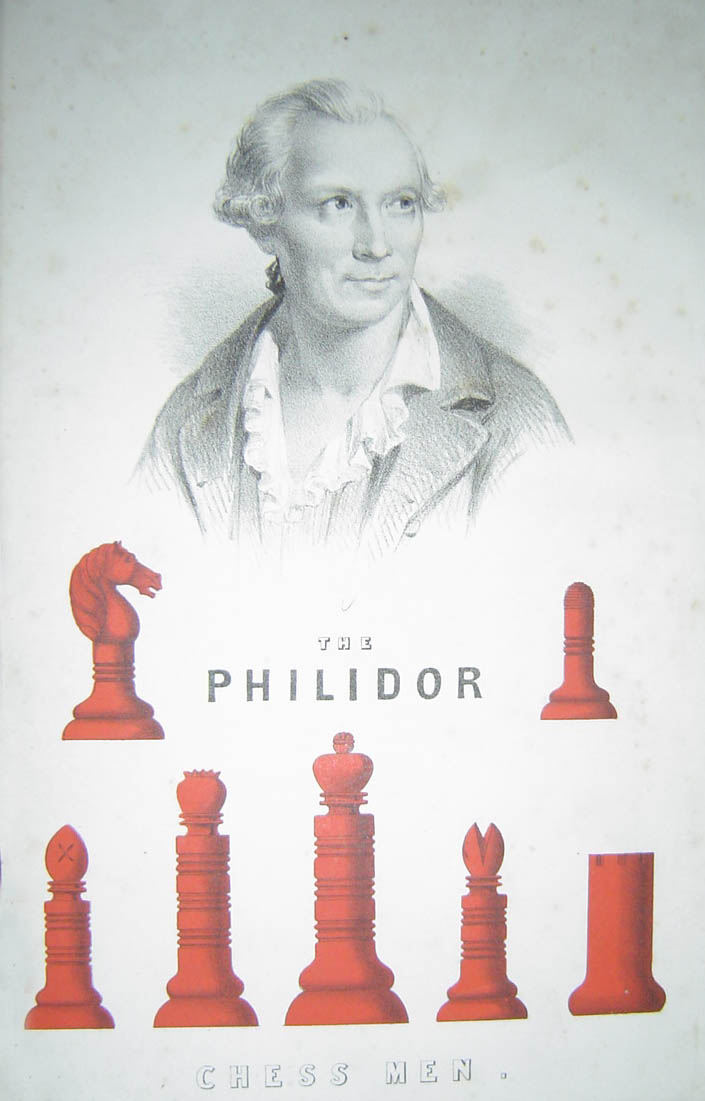

7757. Philidor chess men (C.N.s 3446, 3591 & 3652)

From John Townsend (Wokingham, England):

‘I have looked up the “representation” of the design in the National Archives (BT 43/57, page 135). The design was registered with the Board of Trade under the Ornamental Design Act of 1842. An illustration of the design, approximately five inches by five inches, has been mounted in the record book. It carries the registration number 69599 and the words “THE PHILIDOR CHESS MEN”, with the pieces printed in red. In most respects it is the same as the illustration in C.N. 3446, but it has no portrait of Philidor.

At the bottom is printed “M. & N. HANHART IMPT.”. The Post Office London Directory for 1851 (page 774) shows that Hanhart, Michael & N., were lithographic printers, draughtsmen, and printers in colours, at 64 Charlotte Street, Fitzroy Square.

Unfortunately, the appropriate register for Class 2 (Wood) designs (BT 44/6) does not begin until 13 January 1851 (registration number 75737), the early pages being deficient. The “representation” submission is not dated, but it seems safe to conclude that it was made after 8 February 1850 (the date of registration number 67245) but before 13 January 1851 (the date of registration number 75737).

My search has not identified the owner of the design. During 1851 Sarah Ann Graydon registered three chessmen designs, registration numbers 76039, 76317 and 76779 (see BT 44/6 and BT 44/8). The earliest of her addresses in the register (BT 44/8), 32 Store Street, is only about 300 yards from the premises of the printers of the Philidor design at 64 Charlotte Street. Some brief observations about her appeared on page 109 of my book Notes on the life of Howard Staunton.’

7758. Vajda v Rosselli del Turco (C.N. 7754)

Lonnie Kwartler (Chester, NY, USA) points out that in the note to move 20 page 98 of the May-June 1931 issue of Československý Šach gave in this position ...

... the line 20 Bxg6 Kg8 21 Bf7+ Kg7 and now 22 Qh6+ instead of 22 Bh6 mate.

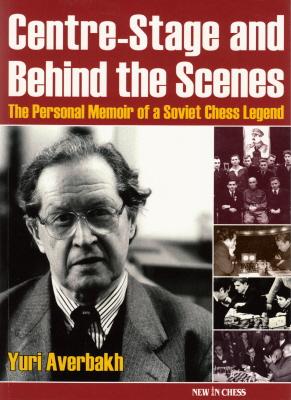

7759. Averbakh’s memoirs

Simon Spivack (London) informs us that he has been studying Centre-Stage and Behind the Scenes by Yuri Averbakh (Alkmaar, 2011), comparing it with the original Russian, and that he is posting regular reports on his findings.

Yuri Averbakh, Chess Review, November 1952, page 324

7760. Pillsbury on Hastings, 1895

John Blackstone (Las Vegas, NV, USA) draws attention to Pillsbury’s account of Hastings, 1895 in an interview on page 6 of the New York Times, 29 September 1895:

‘The competing masters received me very kindly at Hastings ... especially Chigorin, Tarrasch and Steinitz, and their attitude toward me did not change at all after I had won the championship. When I had beaten Gunsberg in the final round I was applauded, and Tarrasch, Chigorin and Steinitz left their tables and congratulated me on my victory. I appreciated the honor greatly.

I felt strong as a bull when I left New York and, though I did not expect to win the championship, I thought I would be one of the first three at the end. I had not had sufficient practice, but I believed my studies and theories would aid me. I have a good knowledge of the openings, and I know how to take to aggressive movements in the middlegame stage, and I can handle the endgame very fairly. So I thought I had a good chance. I don’t know whether I would win another important tournament, but I don’t see any reason why I should not duplicate my success, for I now have additional and valuable experience and practice.

I was a little nervous when I was scheduled to play with Chigorin in my first game. I considered it hard luck, but during the progress of the game this feeling wore off and changed to mortification when I had to resign the game. I still feel sore on that point. I boiled with rage, but it stimulated me greatly for the subsequent battles. Chigorin plays a fine, dashing game. He is still unable to speak more than a dozen words of English. Owing to his splendid physique I hold him to be the strongest member of the Hastings team.

Lasker has greater analytical knowledge, but his body is too feeble to stand the strain of a long tournament. If advancing years have impaired Steinitz’s powers of crossboard play he is still as keen an analyst as ever. My game with him was the hardest I had to play in the tournament, but Tarrasch gave me a good deal of trouble. So did Tinsley.

I feel Chigorin to be the strongest player alive, so far as match playing is concerned. I should not feel at all troubled if I had to meet either Steinitz, Lasker or Tarrasch in a set match. I fancy my chess is as good as theirs, and if I should not beat either of them I feel pretty certain of not being disgraced. Neither would I fear Chigorin, as I have a good deal of confidence in myself.

There was but one player at the tournament who was younger than myself. He was Schlechter of Vienna. He is called the draw master, and he is certainly ingenious in forcing strong players to break with him on even terms. He was unfortunate at Hastings, for a series of combinations forced him to draw some games he had well in hand.

Vergani was the weakest player of the lot. He is the first Italian who has engaged in an international tournament in 32 years.

English chess men, of course, hoped Blackburne would win, and when they realized that he was defeated I think they preferred that the championship would go to a native-board American. The trouble with them is that they get to a certain point and then stand still. English masters could not afford to give odds to first-class amateurs. British women, on the other hand, are doing much better than American women. They have established chess clubs, and the game is becoming very popular among them.

I think physical training a good thing for a chessplayer before entering a tournament.

Steinitz still wants to play Lasker. He considers himself champion de jure and Lasker champion de facto, but I have left it to the Hastings Chess Club to decide who is champion, and I shall not hesitate to play him whoever he may be. The Hastings Club has already offered a purse for such a match. I shall not challenge the winner of the Lipschütz-Showalter match to be played here. I shall not claim any title, but shall simply stick to business. Then if I can get any I shall go to St Petersburg in November to play in the quintangular tournament ...

I owe my success ... to the application of certain new theories which I had evolved about the game. I studied them a year and a half and found, when the time came, that they were practical. As a matter of fact, I consider myself more advanced in theory than in practice.

If I go to St Petersburg in November I will probably remain in Europe until Spring, when there will be another tournament at Hastings.’

7761. Post-mortem analysis

Rick Lahaye (Rotterdam, the Netherlands) asks about the origins of post-mortem analysis at the chess board, i.e. masters’ oral exchanges immediately after their game. Have there been key moments in the past which helped make the practice commonplace?

As ever, documentary references will be gratefully received.

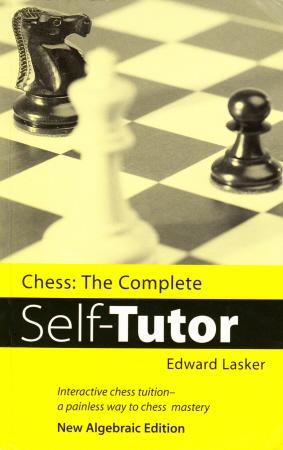

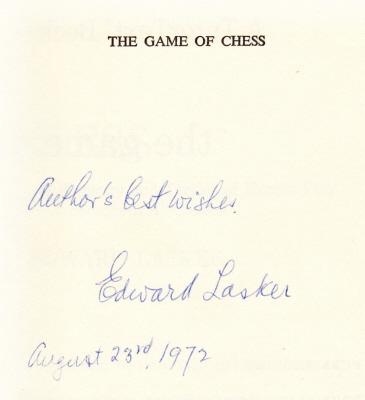

7762. The Game of Chess

Page 446 of The Game of Chess by Edward Lasker (Garden City, 1972) referred to ‘a remark which the great German master Siegbert Tarrasch made some threescore years ago’:

‘To win a pawn in the opening is usually a dangerous thing.’

What more is known about that observation?

In the algebraic edition, typeset and edited by John Nunn (London, 1997), see page 351.

The back cover describes the book as ‘one of the longest established, yet still most innovative, introductory chess manuals’, ‘Lasker’s masterwork’ and ‘the definitive chess teaching manual’. We are, though, struck by the relative lack of publicity accorded to any of the editions published between 1972 and 1997.

Below is the inscription in our copy of the original US volume:

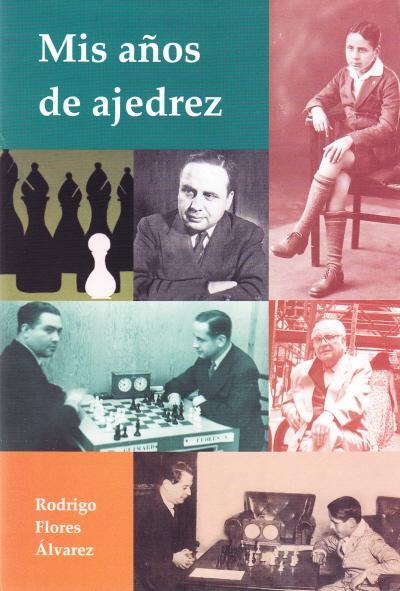

7763. Flores v Palau

Regarding the game Flores v Palau, Buenos Aires, 1927 (C.N. 7632), page 182 of Flores’s posthumous autobiography Mis ańos de ajedrez (Santiago, 2009) refers to our article The Chess Prodigy Rodrigo Flores and states that the game was sent surreptitiously to L’Echiquier by somebody, much to Palau’s annoyance:

‘Una de [mis mejores partidas] es la que jugué contra Luis Palau, en 1927, con ocasión del match Capablanca-Alekhine. La misma que alguien envió subrepticiamente a la revista L’Echiquier, lo que provocó la molestia del maestro argentino que, espero, habrá sabido perdonarme.’

7764. Chess and bridge

Our list of authors of books on both chess and bridge currently stands as follows: G. Abrahams, P. Anderton, J. Enevoldsen, M. Golmayo, K. Harkness, P. Lamford, S. Landau, Emanuel Lasker, J.C.H. Macbeth and S. Novrup.

From our collection:

7765. G.H. Mackenzie in India

From page 245 of the May 1891 BCM, in an obituary of G.H. Mackenzie:

‘He had hardly been 12 months in Germany when his thoughts were diverted from mercantile pursuits by an invitation to join the German legion, a British force then being enrolled for service at the Cape. The idea of a military life seems to have captivated him entirely, for he returned to Scotland shortly afterwards and in May 1856 purchased a commission in the 60th Rifles (the King’s Royal Rifle Corps). He joined the second battalion, then under orders for the Cape, but had hardly arrived out when the regiment received instant orders to India. Here it served during an important part of the Mutiny, but having been strengthened by the addition of two new battalions, Mackenzie received his lieutenancy in the new division, and was ordered home to join it. This was a great disappointment, as may be supposed, and the fact that this new company was stationed in Dublin and in the midst of the best society was but a small consolation.

We cannot find evidence that Lieut. Mackenzie practised chess in India, but on his return to Dublin he joined the Library Club, and quickly became one of the strongest of its small circle of players.’

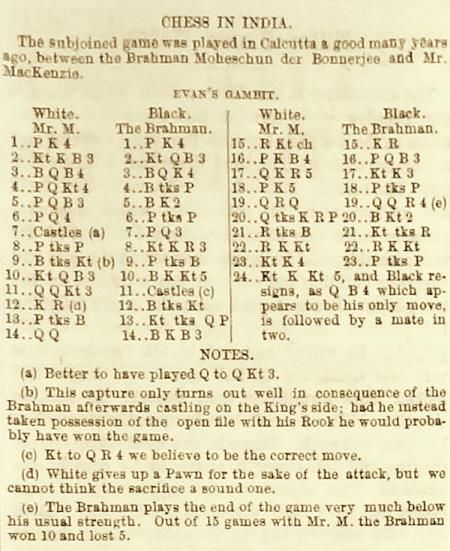

As regards the reference to India in the latter paragraph above, Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) points out the following on page 190 of Turf, Field and Farm, 23 March 1877:

George Henry Mackenzie – Moheschunder Bonnerjee

Calcutta, circa 1857

Evans’ Gambit Accepted

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 b4 Bxb4 5 c3 Be7 6 d4 exd4 7 O-O d6 8 cxd4 Nh6 9 Bxh6 gxh6 10 Nc3 Bg4 11 Qb3 O-O 12 Kh1 Bxf3 13 gxf3 Nxd4 14 Qd1 Bf6 15 Rg1+ Kh8 16 f4 c6 17 Qh5 Ne6 18 e5 dxe5 19 Rad1 Qa5 20 Qxh6 Bg7

21 Rxg7 Nxg7 22 Rg1 Rg8 23 Ne4 exf4 24 Ng5 Resigns.

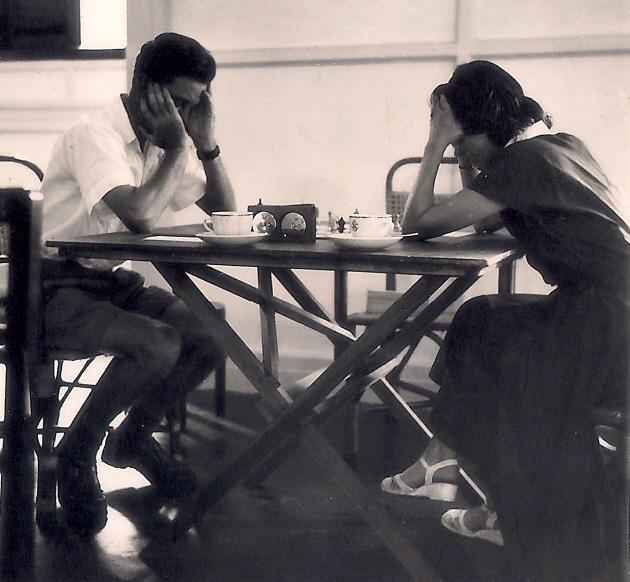

7766. The Pritchards

From Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) comes this photograph of David and Elaine Pritchard, sent to him by their daughter, Wanda Dakin:

The picture was taken in Singapore in the mid-1950s.

7767. Best games

As indicated in the Factfinder under ‘Best games’, several C.N. items have dealt with masters’ nominations for their greatest over-the-board encounters. The players quoted so far are A. Alekhine, J. Barry, J.R. Capablanca, E. Colle, M. Euwe, J. Finn, E. Grünfeld, A.B. Hodges, C. Howell, Ed. Lasker, Em. Lasker, G. Maróczy, F.J. Marshall, J. Mieses, W.E. Napier, A. Nimzowitsch, D. Przepiórka, A. Rubinstein, J. Sawyer, R. Spielmann, S. Tartakower, Sir George Thomas, M. Vidmar, W. Winter, F.D. Yates and E. Znosko-Borovsky. See part one and part two of our Chess Explorations article on this topic, as well as the ‘favourite games’ list in C.N. 5650.

Nikolaos Alimpinisis (Rethymno, Greece) suggests expanding the citations to include nominations by contemporary or recent players regarding their best and/or favourite games. All references will be gratefully received.

| First column | << previous | Archives [97] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.