Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [96] | next >> | Current column |

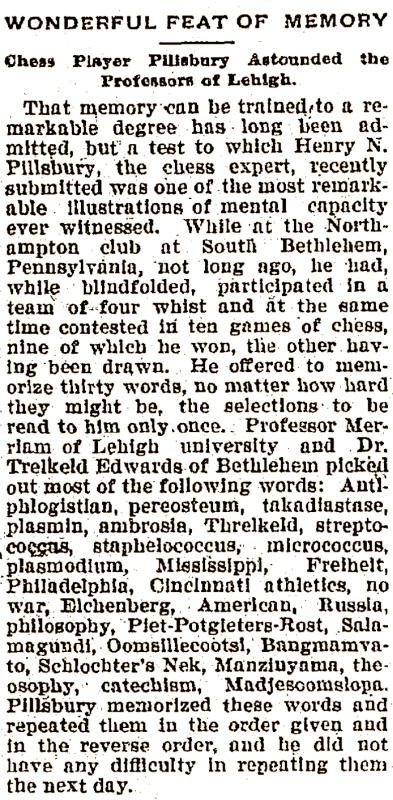

7714. Taubenhaus loss

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 exd4 4 Nxd4 Qh4 5 Nc3 Nf6 6 Nf5 Qh5 7 Be2 Qg6 8 Nh4 Resigns.

This win has been attributed to a player named Fraser or

Frazer (sometimes Persifor Frazer) against Taubenhaus in

Paris, 1888 – or 1988 according to page 94 of 500

Scotch Miniatures by Bill Wall (Moon Township,

1997). It has regularly appeared in collections of short

games, e.g. as ‘Dr Frazer v Taubenhaus’ on page 33 of Schnell

Matt! by Claudius Hüther (Leipzig, 1924). What can

be established about the circumstances of the game and, in

particular, White’s identity?

Whether George B. Fraser was the victor remains to be seen. Certainly he made a study of 4...Qh4 and stated that in 1870 he had invented the ‘Fraser Attack’ (5 Nf3). His two-part article on that line (‘Dundee, 2 February 1876’) was published in the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1 January 1877, pages 1-8, and 1 February 1877, pages 25-30.

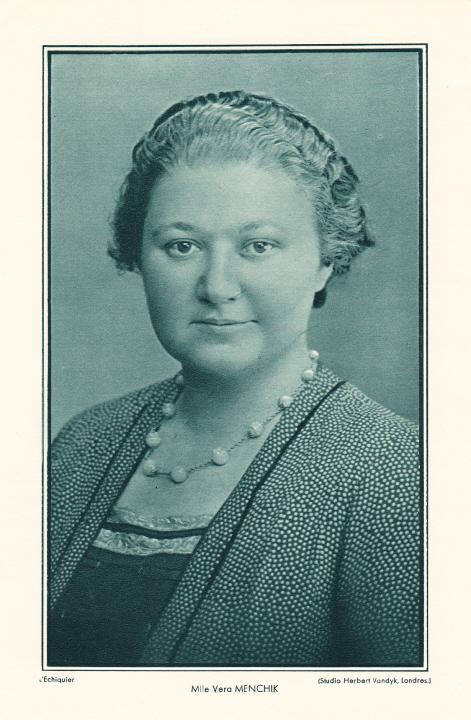

7715. A tall story

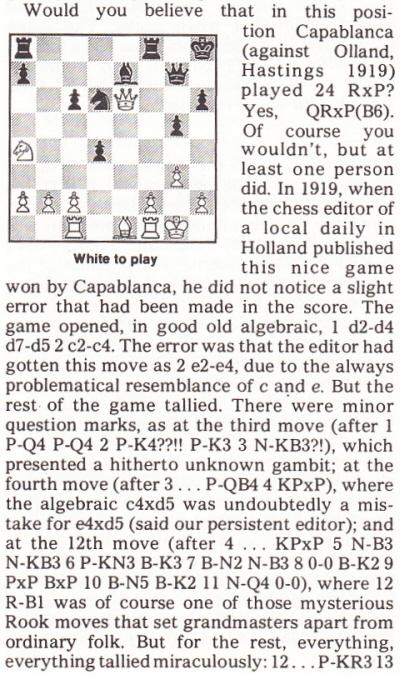

‘Capablanca played 24 Rxc6.’

From page 501 of the September 1976 Chess Life & Review, in an article ‘Breaking the Law’ by Tim Krabbé:

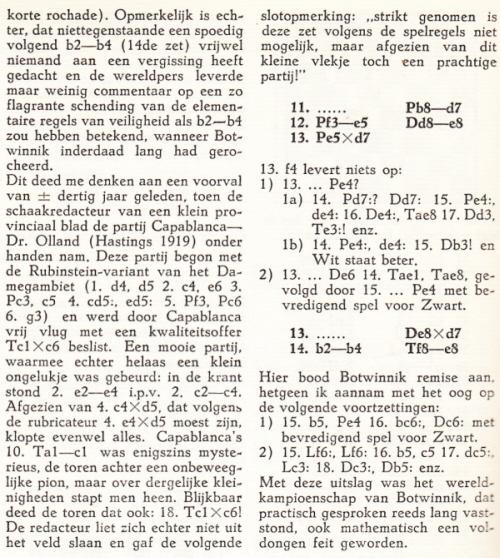

After citing the above text in C.N. 1089 we mentioned that Mr Krabbé had replied to our enquiry as to the source of the story by referring to page 220 of Wereldkampioenschap Schaken 1948 by Max Euwe (Lochem, 1948):

Mr Krabbé also informed us that he recalled Donner’s comment on the story, ‘He made that up’.

7716. Pillsbury and memory (C.N.s 7702, 7710 & 7713)

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) provides a later but clearer version of the news report shown in C.N. 7713:

Source: page 3 of the Dona Ana County Republican (Las Cruces, New Mexico), 12 January 1901.

7717. Warren v Selman (C.N. 7694)

Regarding the correspondence game discussed in C.N. 7694 (1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e5 3 dxe5 Ne4 4 a3 d6 5 exd6 Bxd6 6 g3 Nxf2 7 White resigns) Harrie Grondijs (Rijswijk, the Netherlands) writes:

‘The “I. Selman” of Amsterdam mentioned by Fernschach was John Selman Jr, the Saavedra expert, who called himself “Junior” to avoid being confused with his elder brother Dr Johan Selman. The latter was also a reasonably strong amateur chessplayer, who conducted a chess column in the Limburgs Dagblad. The editor of Fernschach apparently did not notice that the I. Selman in game 127 lived in a different city in the south of the Netherlands and thought that they were the same person.’

7718. Strongest first move (C.N. 1219)

Annotating his victory (as White) over Schlechter at Vienna, 1907 in his first Best Games volume (pages 15-17), Tartakower gave 1 c4 an exclamation mark and wrote:

‘A curious point: 18 years later (in 1925) I published a detailed analysis of this opening, in which I arrived at the conclusion that 1 P-QB4 was “the strongest initial move in the world” – and I was already applying it intuitively with great predilection in the first stages of my chess career.’

In his notes to Alekhine v Sämisch, Baden-Baden, 1925 on pages 106-108 of La Stratégie, May 1925, Tartakower wrote:

‘1 P4FD. “Le début le plus fort du monde!”, comme je l’ai déjà et maintes fois proclamé. Les Blancs se préparent à bouleverser le centre ennemi sans se créer quelque point faible.’

Savielly Tartakower

7719. Alekhine ‘champion of Europe’

At the end of his annotations to the Baden-Baden game mentioned in the previous item Tartakower called Alekhine ‘the champion of Europe’:

‘Une partie des plus animées du tournoi montrant comment le champion d’Europe M. Alekhine brise la résistance de ses adversaires.’

7720. Taubenhaus loss (C.N. 7714)

We have now found the game on page 92 of Chess in Philadelphia by Gustavus C. Reichhelm (Philadelphia, 1898):

Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA) notes that the score was published in the Charleston Sunday News, 4 November 1888. The present evidence thus suggests that White was Dr Persifor Frazer.

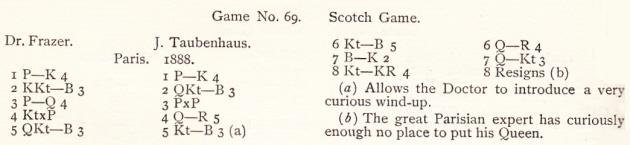

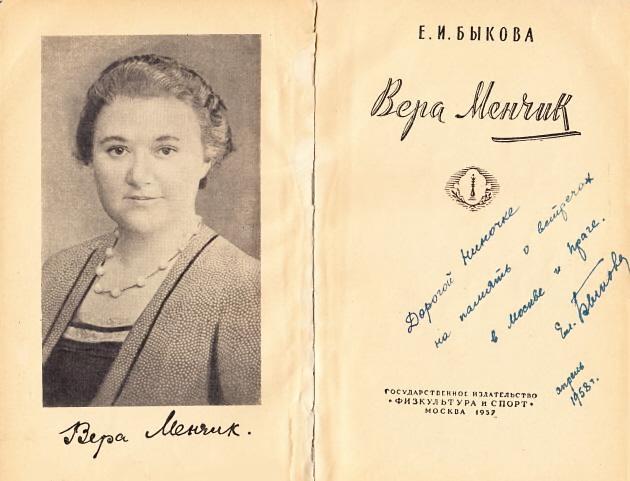

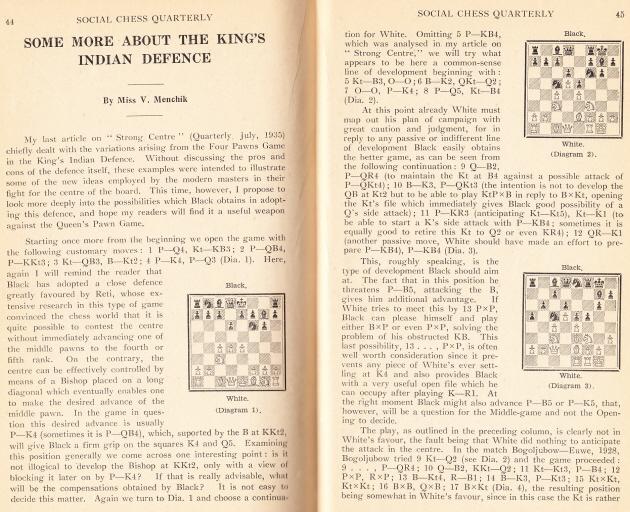

7721. Vera Menchik

The discussion concerning Vera Menchik in C.N. 7711 provides a reminder that justice has yet to be done to her career; C.N. 827 remarked how few games of hers are to be found in the standard anthologies.

Above is the title page of our copy of E.I. Bikova’s 1957 monograph on Menchik, inscribed by the author to Nina Hrušková-Bělská in remembrance of their times together in Moscow and Prague. A high-quality version of the photograph had appeared in L’Echiquier, 2 August 1933:

Vera Menchik’s writings have also been neglected,

although their quality was stressed in an editorial on

page 173 of the August 1944 BCM following her

death:

‘We sympathize with our contemporary CHESS: Vera Menchik was for some years their games editor. Few columns have been conducted with equal skill and efficiency and none, we feel sure, with greater sense of responsibility.’

She had also contributed a number of extensive articles to the Social Chess Quarterly:

- ‘Theory in the End-Game Play’, July 1933, pages 301-304;

- ‘How to Meet an Attack’, January 1935, pages 479-482;

- ‘“A Strong Centre”’, July 1935, pages 542-546;

- “Some More about the King’s Indian Defence’, January 1936, pages 44-47.

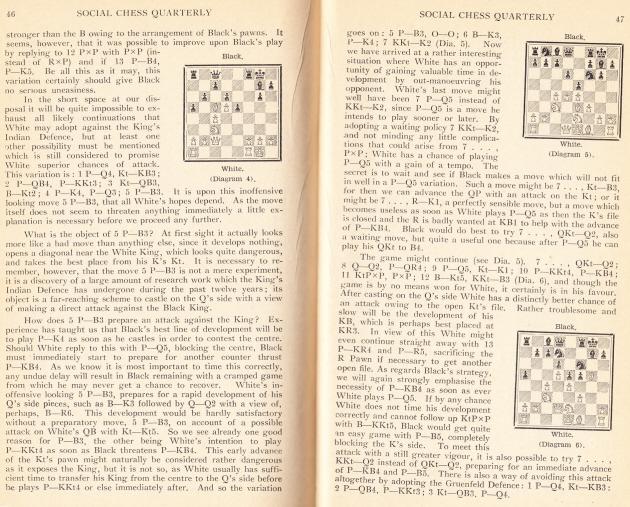

7722. Arthur Ransome

Two extracts from The Autobiography of Arthur Ransome (London, 1976):

Pages 112-113 (concerning the year 1906, when he was aged 22):

‘In Sloane Square there was the Court Theatre and we were regular attendants in the shilling seats at the early performances of Shaw’s plays. There was good music too in a flat on the Chelsea Embankment, close by the power station, and here I used to meet Clifford Bax from Hampstead, and play chess with him. One afternoon a famous chessplayer was there and sat in a room taking tea with our hostess and a friend while Bax and I sat in another room over the chess board. We consulted, agreed over a move and called it out. Laughter and talk went on unceasingly, but the moment we had called out our move, that chessplayer, who had no board to look at, would instantly call out his answering move, and move by move, we consulting, he playing blindfold, our defeat came nearer until at last the voice from the inner room quietly announced “Enough! Mate in three moves”, and it was so.’

Pages 310-311 (regarding a meeting engineered near Moscow in 1923 between Sir Robert MacLeod Hodgson and Maxim Litvinov:

‘The place chosen was an estate with a fine old house that was being used as a rest home for officials. Hodgson and I drove out there and, walking in the woods, we met, by a remarkable accident, Litvinov, also out for a stroll. The convenances were well preserved. Litvinov and Hodgson put up quite a good show of surprise, and I left these two strangers together, and myself went to the old house, found a number of acquaintances from the various Commissariats and was immediately challenged to a game of chess by Krylenko, who was just finishing a game with Ganetzky. We had just ended our game when Litvinov and Hodgson came in for me. Krylenko and I got up from the battlefield, and I introduced both him and Ganetzky.

Hodgson and I said our farewells to Litvinov and, as we drove off on our way back to Moscow, Hodgson asked, “What did you say were the names of your chessplayers?” I told him and shall never forget the horror with which he looked at his own fingers. “What?”, he exclaimed, “And I have shaken hands with that bloody chap.” “Never mind his bloodiness”, said I. “You have shaken much bloodier hands on the other side away in Siberia. And you may have saved a great deal of blood by being here today to shake his.’

There are also references to chess on pages 82, 178, 262, 270, 285, 332, 335, 352 and 353.

7723. No surprise

From page 6 of The Chess Beat by L. Evans (Oxford, 1982), regarding the 1974 Candidates’ quarter-final match in Moscow:

‘To the surprise of nobody, young Karpov romped over his countryman Lev Polugaievsky 5½-2½.’

C.N. 324 quoted that statement, together with another one by Evans on the next page:

‘Bobby [Fischer] told friends he was surprised that Karpov beat Polugaievsky ...’

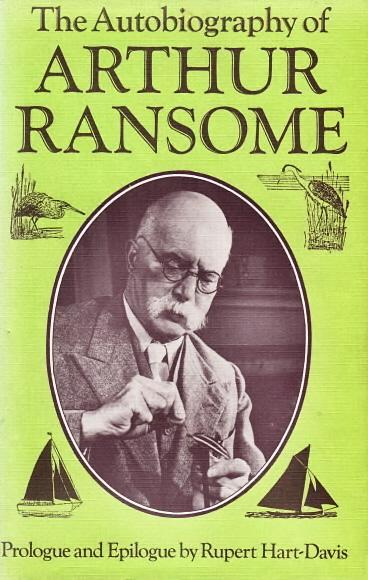

7724. Alekhine v Bogoljubow with Lasker

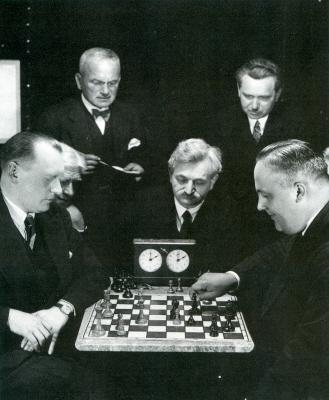

C.N. 6312 showed these three photographs:

Now, Albert Silver (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil) points out some film footage of the occasion, entitled ‘Campionato di scacchi a Berlino’.

7725. Ernst Klein (C.N.s 5202, 5214,

5281, 5326 & 5510)

From Tony Klein (Uppsala, Sweden):

‘My father Ernst Ludwig Klein was never particularly voluble about his past, so what I have to tell is a combination of fragmentary memories of our conversations and biographical information which has become available to me since his death.

He was born in Vienna on 29 January 1910 and died in Southend-on-Sea on 22 August 1990. His father died of cancer when he was eight, and his mother died of tuberculosis when he was 18. He had a sister, three years older, who emigrated to the United States in 1938.

His paternal grandfather was a prominent Viennese eye surgeon, Salomon Klein, originally from the Hungarian town of Miskolc in the then Austro-Hungarian Empire. His textbook on opthalmology from 1879 has recently been reprinted.

My father’s maternal great-grandmother was Lina Morgenstern (1830-1909), well known in Berlin for her work with soup kitchens, her cookery books, and her progressive writings on kindergarten pedagogics and women’s education.

His maternal grandmother, Else Roth, a resourceful, dynamic and “very Prussian and stern” widow with whom he lived from the age of eight to 11, was also an author, of both cookery books and manuals on woodwork and metalwork, and a pioneer in the introduction of some Swedish concepts of physiotherapy to Germany, after a visit to Stockholm in 1885. My father initially learned chess from Else Roth while living with her.

[Correction from Mr Tony Klein received on 26 December 2015: ‘My father's maternal grandmother, the daughter of Lina Morgenstern, was Clara (and not Else) Roth née Morgenstern, and my father’s mother, my paternal grandmother, was Clara’s daughter Else Klein née Roth (1884-1928).’]

Bedridden for a long time from the age of 14, after a knee injury and consequent serious bone infections which in effect broke off his school education, he also learned chess from a paternal uncle, Victor Klein, who, as I remember my father telling me, had been a Viennese master, although I have traced no information about that. Victor Klein later emigrated to the United States and, I believe, practised gynaecology in New York. I possess a letter which he wrote from the United States to my father during the early 1950s, but unfortunately I have no further details about Victor Klein’s chess career.

Of my father’s chess career before his arrival in England I have sparse information, but it is recorded that he played in tournaments in Vienna, as well as at Győr, 1930. I do know that he lived a wandering kind of life from the age of 18 to 25, when he finally settled in England. Travelling and living in Switzerland, France, Italy and the Netherlands, financially supported, as he said, by a wealthy uncle, he occupied himself exclusively with chess. As I remember, Tartakower and Emanuel Lasker were among those with whom he associated. He played simultaneous blindfold exhibitions; at least one, in Italy, was apparently against 11 boards, although I have no documentation.

Around the age of 18 he had spent some time in a Swiss sanatorium for treatment of his osteomyelitis, the infection which he had contracted in his childhood and which became a persistent affliction that dogged him on and off for the rest of his life, rendering him somewhat lame, obliging him to walk with a stick and in constant pain. In the sanatorium in Switzerland he also learned bridge, and I believe that he became a reasonably good bridge player and continued to play socially well into old age.

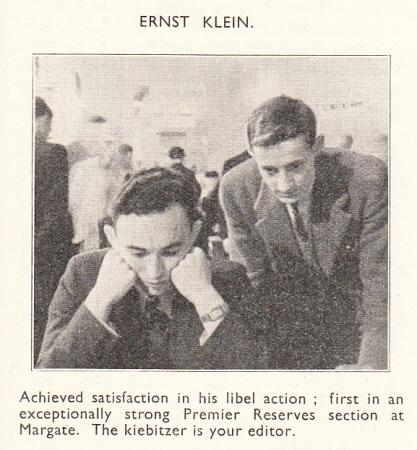

Ernst Klein (BCM, June 1935, page 258)

From CHESS, 14 June 1938, page 361. (See Chess in the Courts.)

He had acquired a second profession – mathematics – by studying for a degree on his own in London during the Second World War, and this was his major occupation from the mid-1950s until his retirement in 1970. Both chess and mathematics were arts rather than sciences, he would always say, although very late in life he admitted to me that he had reluctantly realized that chess is simply about winning against an opponent.

He tried to teach me chess when I was a child. I say “tried”, as I disappointed him by not wanting to study the game in books, and he said, rather unpedagogically, that as long as I did not I was only “playing”. However, I am proud to say that I did manage to win against him when he played with a queen handicap. We often used to play the game of Nine Men’s Morris (called Mühle in German) and had long games at which we were quite evenly matched.

His own account of the 1935 Alekhine-Euwe match incident (discussed in C.N.s 5214, 5281 & 5326) was that he felt betrayed by Alekhine when the latter congratulated, or thanked, him, openly and quite inappropriately. He never even intimated the story of unacceptably violent behaviour on his own part during the incident in question. He maintained a bitter grudge against Alekhine, while never uttering anything but unreserved admiration for his stature as a chess genius.

My father easily took offence and had a short, explosive temper. Despite my personal knowledge of him, I was shocked to read of the complaints made against him in 1935, and I have no specific idea upon what they were based.

Ernst Klein. Source: page 15 of The Anglo-Soviet Radio Chess Match by E. Klein and W. Winter (London, 1947)

My clear impression is that his withdrawal from competitive chess shortly after winning the British championship in 1951 resulted from his personal inability to handle adequately the vicissitudes of a competitive and often internecine world.

I was unaware of his modest return to chess in the early 1970s until I happened to find among his chess literature an account of the London Chess Club Invitation Tournament of 1973, reviewed by Leonard Barden, where my father was apparently the veteran of the tournament and received praise for his stamina, and for playing two of the finest games in the event. I quote from pages 9-10:

“We were very pleased to welcome Ernest Klein for his first tournament since he won the British championship at Swansea 1951. It can’t have been easy for him; at 63, he was the oldest player by more than 20 years and facing a stamina-sapping two rounds a day schedule. Yet his wins over Goodman and Kinlay, achieved with youthful élan, were among the best games of the tournament, while against Markland he found an interesting improvement over the game Fischer-Rubinetti, Buenos Aires, 1970, by 10...Nf6 (Rubinetti chose 10...Bd6) followed by the regrouping manoeuvre with the KR and KN. It was a loss for British chess when Klein gave up active play; quite apart from his tournament achievements, his book on the Anglo-Soviet radio match of 1946 is a model of lucid annotation.”

I feel that I have some particularly valuable legacies from my father, which I see as congruent with both his chess and his mathematical careers. He instilled in me the adage that “a thing worth doing is worth doing well”. He inspired and educated me to approach a problem by always thinking for myself, “from first principles”, rather than relying on pre-existent, often mechanical, methods. He also taught me by example to express myself clearly in writing.’

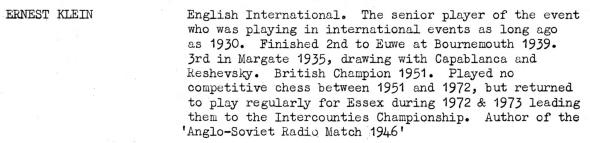

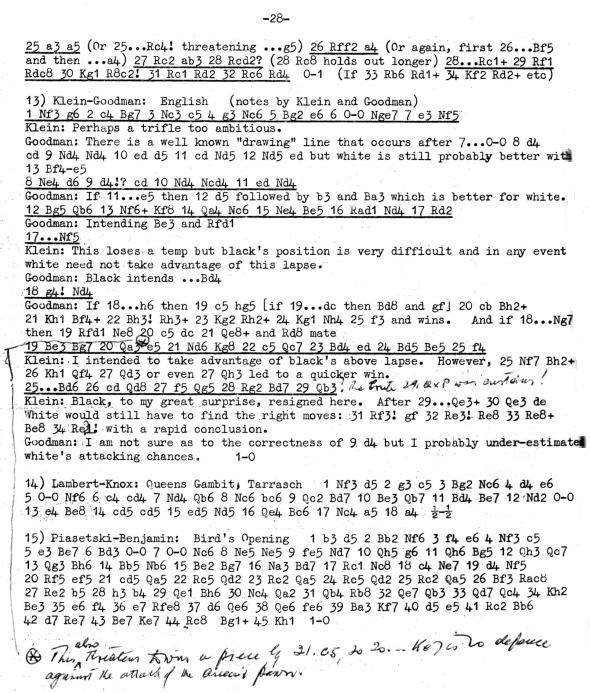

Tony Klein has provided copies of pages from his father’s edition of the monograph on the 1973 tournament, and we reproduce the biographical note on him, as well as the three games mentioned in the above quote (from, respectively, pages 19, 28, 32 and 44):

Ernst Ludwig Klein – David Goodman

London, September 1973

English Opening

1 Nf3 g6 2 c4 Bg7 3 Nc3 c5 4 g3 Nc6 5 Bg2 e6 6 O-O Nge7 7 e3 Nf5 8 Ne4 d6

9 d4 cxd4 10 Nxd4 Ncxd4 11 exd4 Nxd4 12 Bg5 Qb6 13 Nf6+ Kf8 14 Qa4 Nc6 15 Ne4 Be5 16 Rad1 Nd4 17 Rd2 Nf5 18 g4 Nd4 19 Be3 Bg7 20 Qa3 e5 21 Nxd6 Kg8 22 c5 Qc7 23 Bxd4 exd4 24 Bd5 Be5 25 f4 Bxd6 26 cxd6 Qd8 27 f5 Qg5 28 Rg2 Bd7 29 Qb3 Resigns.

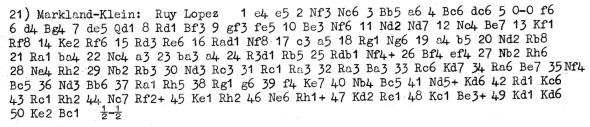

Peter Markland – Ernst Ludwig Klein

London, September 1973

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Bxc6 dxc6 5 O-O f6 6 d4 Bg4 7 dxe5 Qxd1 8 Rxd1 Bxf3 9 gxf3 fxe5 10 Be3

10...Nf6 11 Nd2 Nd7 12 Nc4 Be7 13 Kf1 Rf8 14 Ke2 Rf6 15 Rd3 Re6 16 Rad1 Nf8 17 c3 a5 18 Rg1 Ng6 19 a4 b5 20 Nd2 Rb8 21 Ra1 bxa4 22 Nc4 a3 23 bxa3 a4 24 Rdd1 Rb5 25 Rdb1 Nf4+ 26 Bxf4 exf4 27 Nb2 Rh6 28 Nxa4 Rxh2 29 Nb2 Rb3 30 Nd3 Rxc3 31 Rc1 Rxa3 32 Rxa3 Bxa3 33 Rxc6 Kd7 34 Ra6 Be7 35 Nxf4 Bc5 36 Nd3 Bb6 37 Ra1 Rh5 38 Rg1 g6 39 f4 Ke7 40 Nb4 Bc5 41 Nd5+ Kd6 42 Rd1 Kc6 43 Rc1 Rh2 44 Nxc7 Rxf2+ 45 Ke1 Rh2 46 Ne6 Rh1+ 47 Kd2 Rxc1 48 Kxc1 Be3+ 49 Kd1 Kd6 50 Ke2 Bc1 Drawn.

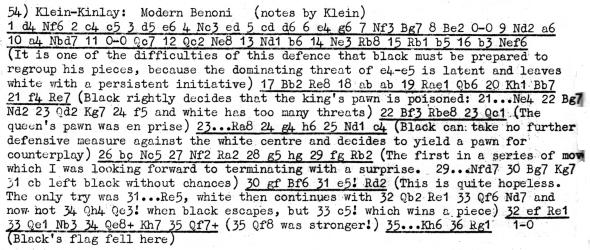

Ernst Ludwig Klein – Jonathan KinlayLondon, September 1973

Benoni Defence

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 c5 3 d5 e6 4 Nc3 exd5 5 cxd5 d6 6 e4 g6 7 Nf3 Bg7 8 Be2 O-O 9 Nd2 a6 10 a4 Nbd7 11 O-O Qc7 12 Qc2 Ne8 13 Nd1 b6 14 Ne3 Rb8 15 Rb1 b5 16 b3 Nef6 17 Bb2 Re8 18 axb5 axb5 19 Rbe1 Qb6 20 Kh1 Bb7 21 f4 Re7 22 Bf3 Rbe8 23 Qc1 Ra8 24 g4 h6 25 Nd1 c4 26 bxc4 Nc5 27 Nf2 Ra2

28 g5 hxg5 29 fxg5 Rxb2 30 gxf6 Bxf6 31 e5 Rxd2 32 exf6 Rxe1 33 Qxe1 Nb3 34 Qe8+ Kh7 35 Qxf7+ Kh6 36 Rg1 and Black lost on time.

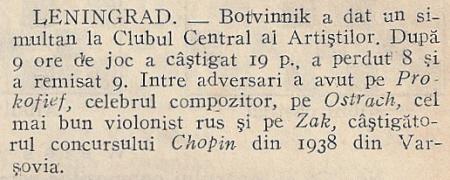

7726. Botvinnik and the musicians

Martin Weissenberg (Savyon, Israel) draws attention to a news item on page 164 of the Revista Română de Şah, 24 August 1939:

It states that Botvinnik gave a simultaneous exhibition at the Central Artists’ Club in Leningrad, scoring, after nine hours’ play, +19 –8 =9, and that his opponents included Prokofiev, Oistrakh and Zak.

Our correspondent writes:

‘What is known about the chess interest of Yakov Zak (1913-76), the winner of the 1937 Warsaw Chopin Competition? (The date 1938 in the Romanian magazine is incorrect.) He was one of the great names in Soviet piano performing and teaching and was famous for his performances of Prokofiev’s music.

Regarding the photograph in your feature article Sergei Prokofiev and Chess, the girl watching Oistrakh and Prokofiev, Elizaveta (Liza) Gilels, was the sister of the pianist Emil Gilels, the wife of the violinist Leonid Kogan, and the mother of the violinist and conductor Pavel Kogan. She herself was an accomplished violinist.’

7727. Capablanca photograph

Ross Jackson (Raumati South, New Zealand) asks for more information about this photograph, which he acquired recently from a vendor who stated that it was taken in Havana in 1935:

7728. Wiener Schachzeitung

From Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) comes the information that the Wiener Schachzeitung (1898-1916 and 1923-38) is now available online at the ANNO website.

7729. Malevolent match captains

This article by the Badmaster, G.H. Diggle, was published in the May 1980 Newsflash and reproduced on page 57 of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984):

‘On Tuesday evenings, just as the “Madding Crowd” are emerging from the City of London bound for suburbia, a small contingent of cadaverous eccentrics is to be seen creeping the other way and furtively entering the massive portals of the Head Offices of all the Joint Stock Banks. These are battle-scarred veterans of the London Banks Chess League, ready to indulge in three and a half hours’ solid gamesmanship.

League Matches are always contested in some obscure venue on the fifth or sixth floors of these giant blocks, and part of the “gamesmanship” consists of the home team’s often changing (without notice) the “obscure venues”, so that members of the visiting team, after getting into the wrong lift and traversing and retraversing whole mazes of corridors and staircases, eventually find themselves in some Ladies’ Rest Room, where they are at length scandalously discovered and ignominiously escorted to the arena (but not till their clocks have already been started) in a very unnerved and flustered state. But all this chivalry between the teams is nothing as compared with the team spirit and healthy rivalry of members of the same team. The last-named admirable quality arises, of course, from “the ladder system”; and it is a common occurrence to see Board No. 5 (with a bad game) eagerly craning his neck over Board No. 6 to reassure himself that his envious colleague, and hopeful supplanter, is worse off still.

The Match Captains are notorious characters. One of them who held sway in the BM’s younger days (hereinafter referred to as “X”) was a perfect brute. Though “X” himself had for some 20 years adorned one of the lowest boards, such was his baleful and despotic personality that if young players of real genius like the BM came and reported defeat he would “hold them with his glittering eye” and subject them to a withering lecture a quarter of an hour long. But his bullying career was finally shattered at an Annual Club Dinner, when he was exposed by one of his victims in a speech which could only be compared with Krushchev’s famous denunciation of Stalin: “Gentlemen, too long have we borne the hideous dictatorship of ‘X’. Only last week, playing against the Westminster, I unhappily lost a piece early on and had to resign. (General sympathetic cheers.) Petrified, I approached and apologetically interrupted the awful ‘X’, whose own game was still going on. ‘I’m afraid I’ve lost’, I whispered. ‘You’ve what?’, thundered ‘X’. ‘Just lost a piece’, I returned, adding with a feeble attempt at facetious bravado, ‘Can’t explain it – it simply came away in my opponent’s hand.’ Then the storm broke. ‘What Club do you imagine you are representing? Lloyds Bank or Wapping Gas Works’ Third Team? Well, you’d better go home – you’re clearly no use here. Why come whining to me – I can’t do anything about it, can I?’ Gentlemen, just as I crept away, I happened to glance at his board and, believe it or not, the old devil was two pieces down himself.” (Prolonged uproar.)’

7730. The Novotny and Plachutta themes in practical play

From Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA):

‘There are a few games with a Novotny interference move, but only one widely-known practical example of the Plachutta sub-category (where a piece is offered on a square where it can be captured by either of two pieces which move similarly): Tarrasch’s win over consultants in 1914, a game discussed in C.N.s 5161, 6279 and 7050.’

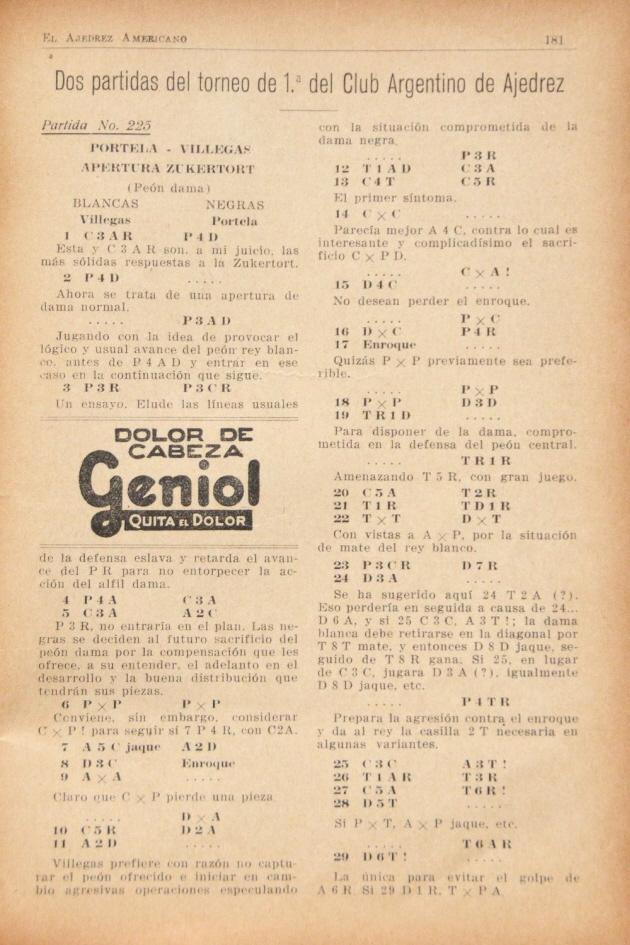

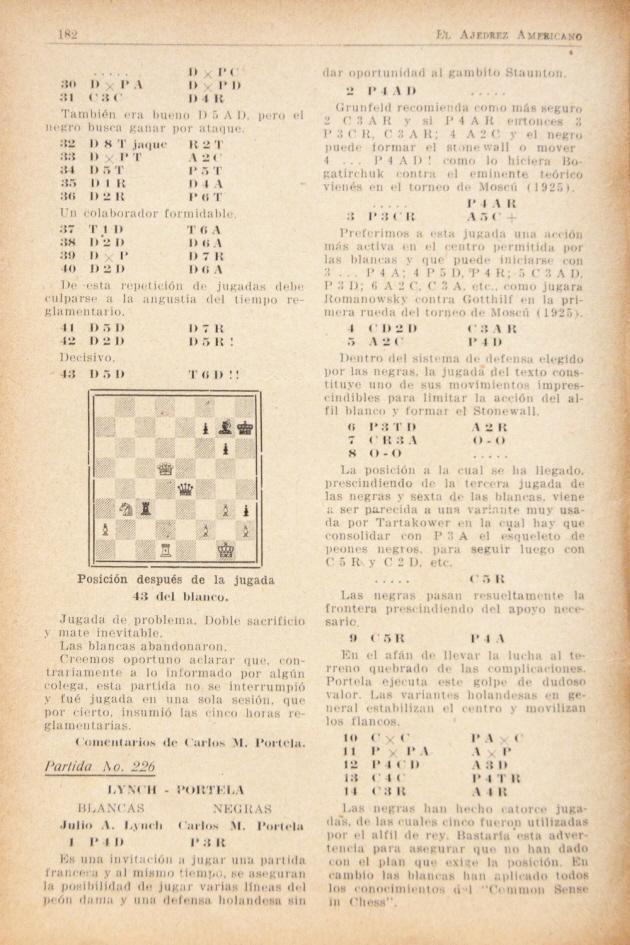

Our correspondent offers another example, from El Ajedrez Americano, June 1929, pages 181-182:

Benito Higinio Villegas – Carlos M. PortelaQueen’s Pawn Game

Buenos Aires, 1929

1 Nf3 d5 2 d4 c6 3 e3 g6 4 c4 Nf6 5 Nc3 Bg7 6 cxd5 cxd5 7 Bb5+ Bd7 8 Qb3 O-O 9 Bxd7 Qxd7 10 Ne5 Qc7 11 Bd2 e6 12 Rc1 Nc6 13 Na4 Ne4 14 Nxc6 Nxd2 15 Qb4 bxc6 16 Qxd2 e5 17 O-O exd4 18 exd4 Qd6 19 Rfd1 Rfe8 20 Nc5 Re7 21 Re1 Rae8 22 Rxe7 Qxe7 23 g3 Qe2 24 Qc3 h5 25 Nb3 Bh6 26 Rf1 Re6 27 Nc5 Re3 28 Qa5 Rf3 29 Qa6 Qxb2 30 Qxc6 Qxd4 31 Nb3 Qe5 32 Qa8+ Kh7 33 Qxa7 Bg7 34 Qa5 h4 35 Qe1 Qf5 36 Qe2 h3 37 Rd1 Rc3 38 Qd2 Qf3 39 Qxd5 Qe2 40 Qd2 Qf3 41 Qd5 Qe2 42 Qd2 Qe4 43 Qd5

43...Rd3 44 White resigns.

Mr Bauzá Mercére also points out that the familiar ‘Novotny move’ 43 Rd5 in this position ...

... did not occur, since Eliskases preferred to play 43 Re5. The game with Eliskases’ annotations was published on pages 314-316 of the October 1929 Wiener Schachzeitung.

Erich Eliskases – HölzlInnsbruck, 23 September 1929

Queen’s Gambit Declined

1 e3 c5 2 c4 Nc6 3 Nf3 Nf6 4 d4 e6 5 Nc3 d5 6 a3 a6 7 Bd3 dxc4 8 Bxc4 b5 9 Ba2 cxd4 10 exd4 Be7 11 O-O O-O 12 Be3 Bb7 13 Qe2 Qc7 14 Rac1 Rad8 15 Rfd1 Rfe8 16 h3 Bf8 17 Bb1 Qb8 18 Bg5 Be7 19 Ne4 Nd5 20 Nc5 Bxg5 21 Nxg5 Nf6 22 Nge4 Ne7 23 Nxf6+ gxf6 24 Qg4+ Ng6 25 h4 Bc8 26 h5 Qf4 27 Qe2 Ne7 28 Ne4 Nd5 29 Rc5 Kh8 30 Rd3 f5 31 Rf3 Qb8 32 Ng5 Re7 33 Rg3 Nf4 34 Qe3 Qd6 35 Rc6 Qb8 36 Bxf5 Bb7 37 Rc5 Qd6 38 Be4 Nd5 39 Bxd5 Bxd5 40 Nf3 Bxf3 41 Qg5 Qxd4 42 Qxe7 Be4 43 Re5 Resigns.

The game is often misdated 1931.

7731. Stefan Zweig and chess (C.N. 6940)

Below are the English editions of Stefan Zweig’s Schachnovelle in our collection. For identification purposes, the first sentence of the story is quoted in each case, i.e. the translation of:

‘Auf dem großen Passagierdampfer, der mitternachts von New York nach Buenos Aires abgehen sollte, herrschte die übliche Geschäftigkeit und Bewegung der letzten Stunde.’

Translation by B.W. Huebsch, published by the Viking Press (New York, 1944 and 1945):

‘The big liner, due to sail from New York to Buenos Aires at midnight, was filled with the activity and bustle incident to the last hour.’

Other appearances of this translation are the Armed Services edition (New York, 1944) and the volume published by Pushkin Press (London, 2001 and 2010):

Translation by Jill Sutcliffe, published by Jonathan Cape (London, 1981) and Holmes & Meier Publishers, Inc. (New York, 2000):

‘The usual eleventh-hour bustle and commotion reigned on the big liner that was due to sail from New York to Buenos Aires at midnight.’

Translation by Anthea Bell, published by Penguin Books Ltd. (London, 2006):

‘The usual last-minute bustle of activity reigned on board the large passenger steamer that was to leave New York for Buenos Aires at midnight.’

Translation by Joel Rotenberg, published by New York Review Books (New York, 2006):

‘On the great passenger steamer, due to depart New York for Buenos Aires at midnight, there was the usual last-minute bustle and commotion.’

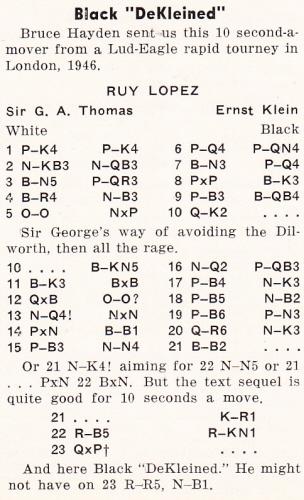

7732. Ernst Klein

Further to the recent material on Ernst Klein, a lightning game on page 219 of the July 1957 Chess Review may be noted:

Sir George Thomas – Ernst Ludwig Klein

London, 1946

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 O-O Nxe4 6 d4 b5 7 Bb3 d5 8 dxe5 Be6 9 c3 Bc5 10 Qe2 Bg4 11 Be3 Bxe3 12 Qxe3 O-O 13 Nd4 Nxd4 14 cxd4 Bc8 15 f3 Ng5 16 Nd2 c6 17 f4 Ne6 18 f5 Nc7 19 f6 g6 20 Qh6 Ne6 21 Bc2 Kh8

22 Rf5 Rg8 23 Qxh7+ Resigns.

Regarding Klein’s dispute at Margate in the late 1930s, we have added to Chess in the Courts a paragraph which appeared on page 269 of the 14 April 1938 CHESS under the heading ‘Klein’s “Honour Vindicated”’:

‘Ernst Klein has withdrawn his libel action against Alekhine, Miss Menchik, Prins and a group of other masters, having obtained an apology, with indemnification for costs. He states that his “honour has now been vindicated”.’

Can other press reports on the affair be traced?

7733. Photographs

The latest feature article is Chess History: Photograph Collections.

7734. The Novotny and Plachutta themes in practical play (C.N. 7730)

Black to move

Further to a correspondent’s contribution in C.N. 7730, Andrew Bull (Cheltenham, England) writes:

‘While 43...Rd3! in Villegas v Portela is an elegant and decisive move, it is not an example of the Plachutta theme as I understand it. To quote from the 1984 edition of The Oxford Companion to Chess by Hooper and Whyld:

- Plachutta theme: “It is similar to the Wurzburg-Plachutta theme, but with sacrifice on the intersection square.” (Page 256.)

- Wurzburg-Plachutta theme: “A black line-piece defends square A and another black line-piece of like movement defends square B. These pieces defend along lines that intersect, and if either piece is moved to the intersection square it will prove unequal to the task of defending both square A and square B.” (Page 380.)

In Villegas v Portela, the queen and rook defend along the same line, rather than lines which intersect; there are no squares which could be identified as A and B to fit the definition above, and if White captures the rook with either queen or rook, the capturing piece is not interfering with the other.’

From Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England):

‘The Villegas v Portela position does not show the Plachutta theme, which in its basic form is a three-move theme defined as mutual interference of like-moving men (R+R, R+Q, B+Q) introduced by a sacrifice on the square of intersection. The point is that each defender has duties to perform, and in capturing the sacrificed piece it takes on the duties of the other piece and becomes overloaded. In the Villegas v Portela position, if the queen or rook captures on d3 that piece does not take over the duty of the other piece in addition to its own, but simply abandons its own duty (the guarding of g2 or e1 respectively). 43...Rd3 is essentially just a fork, although a little more interesting than normal.’

A contribution from Luc Winants (Boirs, Belgium):

‘The Plachutta and Novotny themes are undoubtedly related, but I do not regard the former as a sub-category of the latter.

- A Plachutta is an interference of two pieces which move similarly, with a sacrifice on the cutting-point.

- A Wurzburg-Plachutta is an interference of two pieces which move similarly, but without a sacrifice on the cutting-point.

- A Novotny is an interference of two pieces which move differently, with a sacrifice on the cutting-point.

- A Grimshaw is an interference of two pieces which move differently, but without a sacrifice on the cutting-point.

To quote from page 412 of Le Lionnais and Maget’s Dictionnaire des échecs (Paris, 1967):

“Ce thème [Wurzburg-Plachutta] est au thème Plachutta ce que le Grimshaw est au Novotny.”

See also page 99 of the second edition of The Oxford Companion to Chess, under “Cutting-point themes”.’

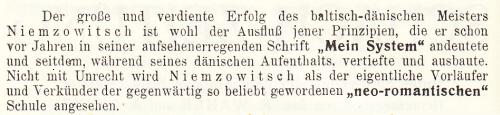

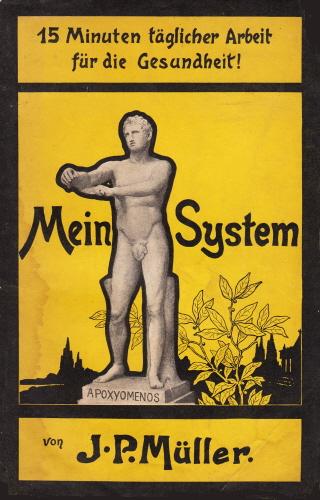

7735. Mein System

The above paragraph (on page 34 of the April 1923 Wiener Schachzeitung) comes from a report by Tartakower on Copenhagen, 1923. It is quoted by Thomas Niessen (Aachen, Germany), who asks which publication entitled Mein System Tartakower had in mind, given that Nimzowitsch’s book of that name had not yet appeared at that time.

C.N. 2839 (see page 73 of Chess Facts and Fables) referred to pages 294-304 of the October-November 1913 Wiener Schachzeitung, where Nimzowitsch wrote about ‘Das neue System’. In C.N. 5552 a correspondent mentioned that page 24 of Nimzowitsch’s booklet Kak ya stal grosmeysterom (Leningrad, 1929) recommended gymnastics with ‘Müller’s system’, i.e. Mein System 15 Minuten täglicher Arbeit für die Gesundheit by J.P. Müller (Copenhagen and Leipzig, 1904). Further information on Müller’s book was given in C.N. 5572.

It is customary to state that Nimzowitsch’s Mein System was published in 1925, the year specified on the title page:

However, the work appeared in five instalments, of which only the first was dated 1925. David DeLucia (Darien, CT, USA) has kindly provided the front covers:

Publication of the first instalment was reported on page 447 of Deutsche Schachblätter, 15 October 1925. We also note that, for instance, the third instalment was scheduled to appear at the end of April 1926, as announced on page 224 of the January-March 1926 Kagans Schachnachrichten. The bound edition of the five instalments was published on 20 February 1927, according to the back page of the ‘Erstes Extrablatt’ (1927) of Kagan’s magazine.

From Per Skjoldager (Fredericia, Denmark):

‘The material published by Nimzowitsch in 1913 (“Das neue System”) is definitely part of “Mein System”, but at the time of the earlier publication Nimzowitsch was not aware of the full scope of the final version of “Mein System”. His article was first and foremost part of his dispute with Tarrasch on the notion of “the centre”. I have no reference to any use of the specific title “Mein System” at that point.

Of course, the final publication Mein System contained far more material, and many more ideas, than “Das neue System”, although much of the material from “Das neue System” found its way into the book. Nimzowitsch wrote on page 28 of Kak ya stal grosmeysterom:

“Although I had felt ‘anxiety’ about them [the elements of Mein System] as early as 1902, I was unable to surmount the enormous difficulties that confronted me for a long time. I conceived isolated parts, e.g. the idea of the outpost, and also the new understanding of the pawn chain, during the period 1911-13.”

Thus I would say that the notion of “Mein System” (as well as the elements) was born no later than 1913.

A further question is when the final version of Mein System was written. It is not possible to give an exact date or period, but it was derived from many articles and game notes published by Nimzowitsch in a variety of newspaper columns and magazines during the years 1911-24. So “Mein System” was something that he had “assembled” and written before any of the instalments were published.

It is worth noting what Nimzowitsch stated about his system on pages 289-290 of the October 1924 Wiener Schachzeitung:

“It is not about the opening but, rather, the middlegame. It is a set of rules about the individual elements of chess strategy such as the open file, the seventh rank, the passed pawn, exchange technique and pawn chains. Everything is there, beautifully arranged and nothing is missing – except a publisher. I have given lectures on “my system” for the last four years in Scandinavia and, for that reason alone, I have hardly felt that my stay here was a self-chosen exile.”

The final point is when his book (concept) was named “Mein System”. As indicated by Nimzowitsch above, he travelled around Scandinavia during the years 1920-24, giving lectures about his “own system”. I have tried to find the first occurrence of the title “Mein System”, but it is not a straightforward matter. Several newspaper articles mention Nimzowitsch “who will lecture on his own system”, but the first specific use of “Mein System” that I have found is in the Swedish newspaper Kalmar Läns Tidning of 21 February 1921:

“Mr N. conducted a lecture under the title ‘My System in Chess’.”

Concerning the interesting question of whether Tartakower’s reference to “Mein System” in 1923 was an anachronism, strictly speaking the answer is probably yes, but I think that he was referring to “Das neue System”, which, as was well known, Nimzowitsch had improved and enhanced during his stay in Scandinavia.’

With respect to individual components of Nimzowitsch’s system, we see the following remark by him on page 300 of the October 1913 Wiener Schachzeitung:

‘Dieser tiefe Ausspruch enthält, wenn auch nur im Keim, mein System der Ch. St. [Charakteristische Stellung im Zentrum]!’

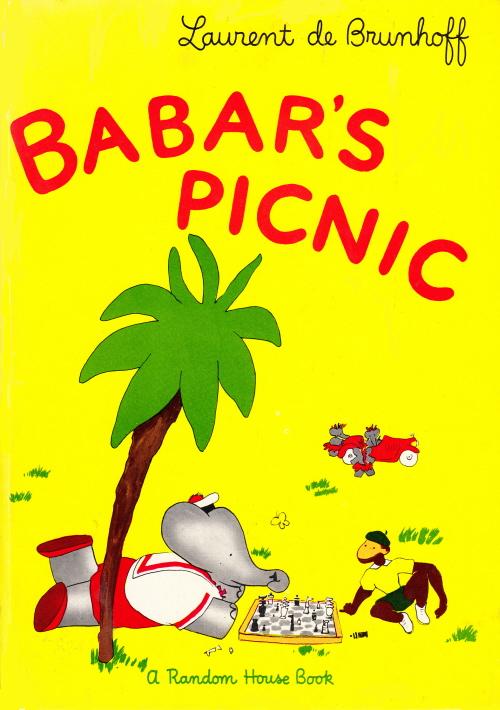

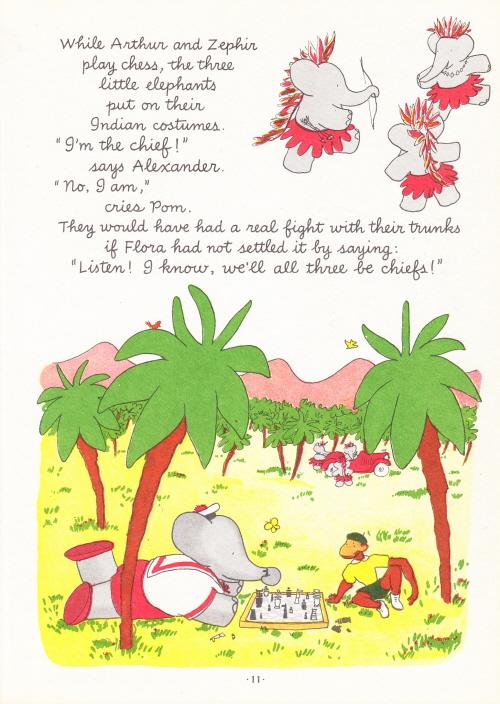

7736. Babar’s Picnic

Chess is seldom depicted on the front cover of children’s books, but below is Babar’s Picnic by Laurent de Brunhoff (New York, undated):

Page 11 of the story:

7737. Blackburne Shilling Gambit (C.N.s 3786, 6470 & 6479)

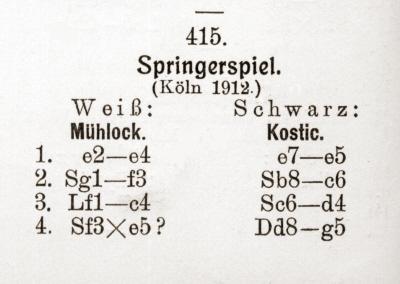

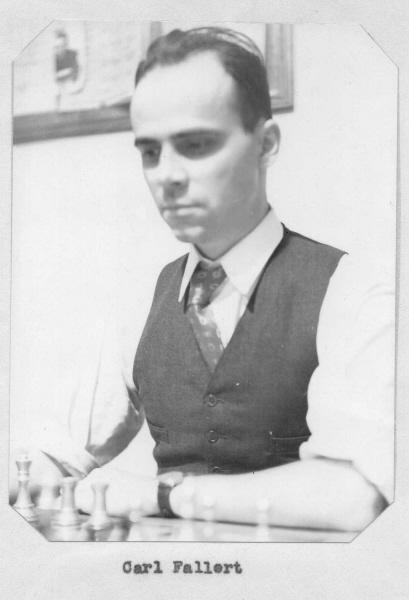

Peter Anderberg (Harmstorf, Germany) has found the Kostić game on pages 144-145 of Deutsche Schachblätter, 15 December 1912, in a set of 15 miniatures:

7738. Emanuel Lasker in Chicago

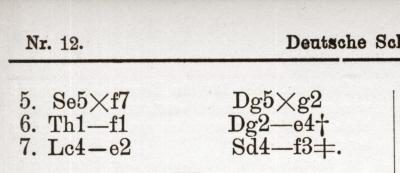

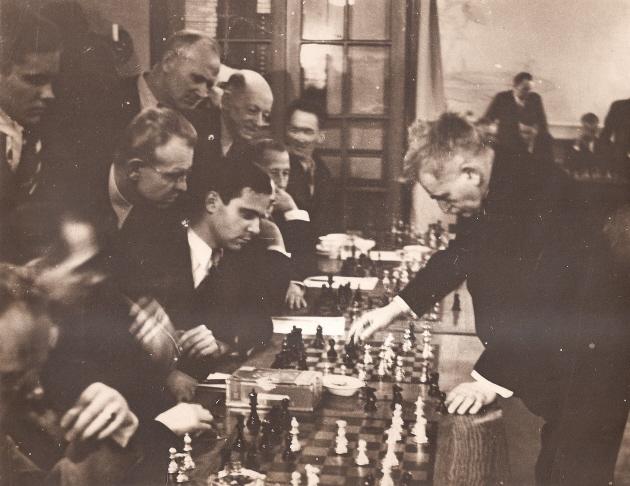

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) has forwarded, courtesy of Alan Fallert (Chicago, IL, USA), two photographs of Emanuel Lasker in Chicago in the 1930s:

Above, Lasker is making a move against Mr Fallert’s father, Carlton Mross Fallert (1911-76).

In the archives owned by Alan Fallert there is also a 26-page notebook of game-scores and photographs pertaining to the Swedish Chess Club, Chicago in 1939-40, including this portrait:

The Lasker photographs are undated, but we note a reference to a simultaneous exhibition by Lasker at the Swedish Chess Club in Chicago on page 61 of the March 1938 Chess Review. Page 13 of The Collected Games of Emanuel Lasker by K. Whyld (Nottingham, 1998) stated that Lasker gave a display against the Swedish Club in Chicago on 10 December 1937, scoring +21 –1 =5.

Addition on 13 August 2022: when Lasker’s result was given on page 13 of the January 1938 Chess Review it was specified that the loss was by adjudication.

7739. Sigmund Freud

Rolf-Dietrich Beran (Altlandsberg, Germany) reports that during a visit to the Sigmund Freud Museum in Vienna he took this photograph:

7740. Mate-in-three problem by Alekhine? (C.N.s 7670 & 7682)

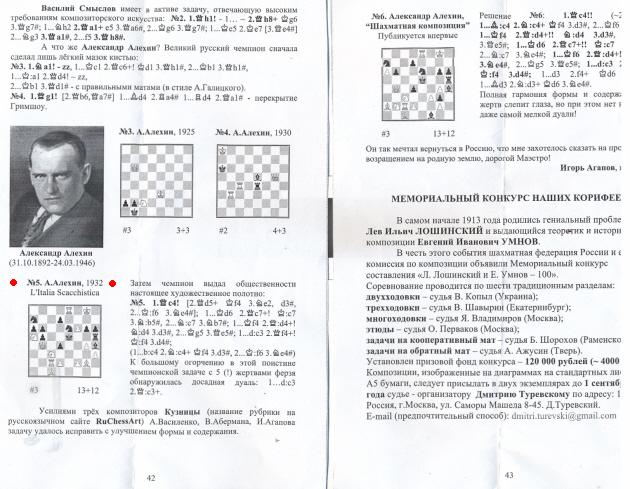

Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England) has forwarded pages 42-43 of the latest issue (105) of the Russian problem magazine Shakhmatnaya Kompozitsiya, in which three composers, A. Vasilenko, V. Aberman and I. Agapov, have improved significantly on the three-mover attributed to Alekhine:

7741. Potter on

De Vere

From page 87 of Cabbage Heads and Chess Kings by B. Hayden (London, 1960):

Where did Potter make the remark ‘Death does not sanctify the lie’? His obituary of De Vere on pages 42-44 of the March 1875 City of London Chess Magazine ended rather differently:

‘We have endeavoured to give an unvarnished account of Mr De Vere’s career, and it is nothing to us that some may disapprove thereof, for we do not share the views of those who hold that the grave sanctifies insincerity.’

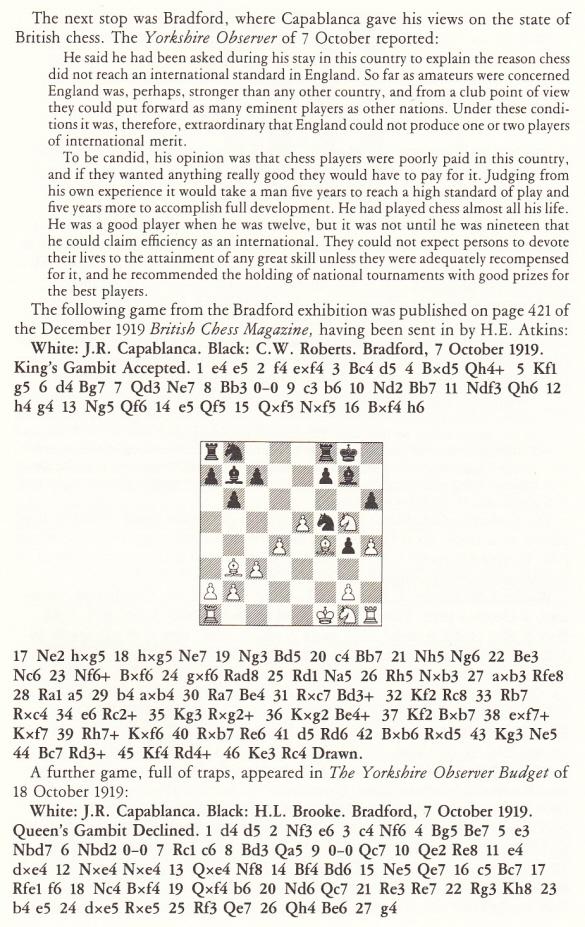

7742. Capablanca in Bradford

From page 9 of Capablanca move by move by Cyrus Lakdawala (London, 2012):

‘Capa easily possessed the most natural talent but was also, unfortunately, the laziest world champion, who couldn’t be bothered to log heavy study hours.’

The extent of the Cuban’s laziness is, of course, a legitimate subject for discussion, but so too is the output of a chess writer who cannot be bothered to log light study minutes.

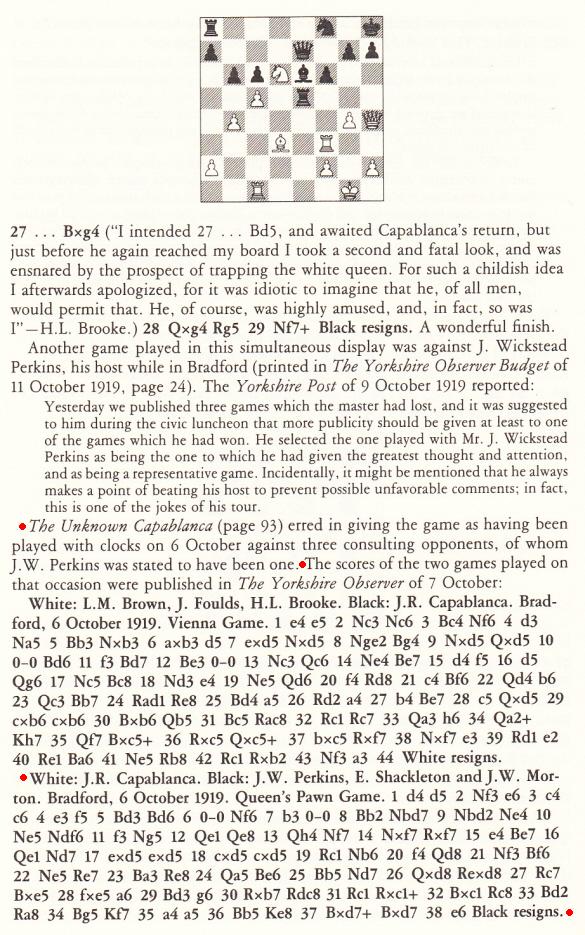

On pages 240-244 Lakdawala annotates ‘J.R. Capablanca – Allies, Consultation game, Bradford 1919’ and writes on page 240:

‘Question: Who were the allies in this game?

Answer: England, the United States and France? I have no idea who they were. Probably a few master-strength players from the region.’

Pages 101-102 of our book on Capablanca discussed his visit to Bradford in 1919, and gave the game in question, with full particulars (including the allies’ names: J.W. Perkins, E. Shackleton and J.W. Morton):

Incidentally, page 268 of Capablanca in the United Kingdom (1911-1920) by V. Fiala (Olomouc, 2006) compounded the error in The Unknown Capablanca by inserting a note from page 93 of the Hooper and Brandreth book into the wrong Bradford game, thereby inviting the reader to note Capablanca’s ‘late castling’ in a game in which he castled at move six.

In the ‘Bibliography’ on page 6 of Capablanca move by move Lakdawala includes our monograph on the Cuban, yet he appears unaware of anything in it. For instance, he goes astray on page 17 by stating that a famous victory by Capablanca with the French Defence (Havana, 1902) was won against ‘J. Corzo y Prinzipe’ (sic – y Príncipe), whereas pages 9-10 of our book demonstrated that White was his brother, Enrique Corzo. On the first page of his Introduction Lakdawala gives the forename of Capa’s father as ‘Jorge’ instead of José María, a mistake which may or may not have been copied from a book referred to in C.N. 6642, José Raúl Capablanca by I. and V. Linder (Milford, 2010). He also believes (page 136) that Capablanca won New York, 1927 3½ points ahead of Alekhine.

Little more will be said about Capablanca move by move, although a comment on page 8 may be quoted:

‘So difficult was Capa to beat that he went ten years without losing a tournament game, from the St Petersburg tournament of 1914 to New York 1924, where he finally lost a game to Réti. (It was believed the only reason for that defeat was loss of composure when Capa’s rumoured mistress walked into the tournament hall while Capa’s wife – and the press! – also attended!)’

In reality, of course, Capablanca lost a tournament game at New York, 1916 (to Chajes). As regards the ‘rumoured mistress’ tittle-tattle (which deviates from the Carlsbad, 1929 versions discussed in C.N. 4712), what kind of writer and publisher would even contemplate printing such a thing?

| First column | << previous | Archives [96] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.