Edward Winter

Sergei Prokofiev

The following article by Mikhail Botvinnik was published on pages 281-283 of S. Prokofiev Autobiography Articles Reminiscences (Moscow, 1959). It was dated 1954, the year after Prokofiev’s death.

‘My first introduction to Prokofiev and his music occurred at one of the musical appreciation lessons that were a regular part of the curriculum at school No. 157 in Leningrad which I attended in the early twenties. These lessons were essentially little chamber concerts with explanations by the music teacher. As a rule we were given classical music, but one day our teacher said that she was going to play something rather out of the ordinary.

She told us about a young composer named Sergei Prokofiev and his original style. “It is impossible to be indifferent to his music”, she told us. “Some people believe him to be exceptionally talented, others disapprove of him altogether. When I addressed a gathering of music teachers recently and announced that I was going to play the music of Prokofiev I was given an extremely chill reception. But when I had finished playing, the audience applauded wildly and I had to play an encore. I shall play the same piece to you now.”

If I am not mistaken the name of the piece was Despair. It made a deep impression on all of us. Unfortunately I have never heard it since; if I had I should recognize it at once.

I met Prokofiev in 1936 at the height of the Third International Chess Tournament in Moscow. He was a first-rate chessplayer himself and never missed a match. His position in the tournament was a delicate one and he maintained a strictly neutral attitude throughout, for while his sympathies were naturally with me as the young Soviet champion, he could not wish for the defeat of the ex-world champion Capablanca, who was a personal friend of his.

Several months later Capablanca and I shared first place at the tournament in Nottingham, England. When the tournament was over I received a telegram of congratulations from Sergei Sergeyevich. I was naturally very pleased and, without thinking, I showed the wire to Capablanca, who was with me at the time. At once I saw that I had made a mistake – from the expression on Capablanca’s face I realized he had not received a wire from Prokofiev. Two hours later Capablanca came to me beaming – he had received a telegram too. Of course, Sergei Sergeyevich had sent both wires at the same time, but evidently the Moscow telegraph office clerks had felt that the Soviet champion ought to get his message first.

Sergei Sergeyevich was passionately fond of chess. He took part in the chess activity of the Central Art Workers’ Club. Moscow chessplayers still remember his rather unique match with David Oistrakh – the winner was awarded the Art Workers’ Club prize and the loser had to give a concert for the club members.

I played chess with Prokofiev several times. He played a very vigorous, forthright game. His usual method was to launch an attack which he conducted cleverly and ingeniously. He obviously did not care for defence tactics. His illness did not lessen his interest in chess. In May 1949 the well-known chessplayer J.G. Rokhlin and I paid a visit to Prokofiev at his country place at Nikolina Gora. Sergei Sergeyevich was ill in bed and looked very poorly, but as soon as he saw Rokhlin he livened up. “Where is that volume of the 1894 Steinitz and Lasker chess match you promised me?”, he demanded. Poor Rokhlin, who had clearly forgotten all about it, was much embarrassed.

In the summer of 1951 Sergei Sergeyevich entered as one of the participants in a demonstration of simultaneous play I was to give at Nikolina Gora. His doctors, however, forbade it, but that did not prevent Prokofiev from following the games with his usual avid interest. I believe that was the last chess contest he ever attended.’

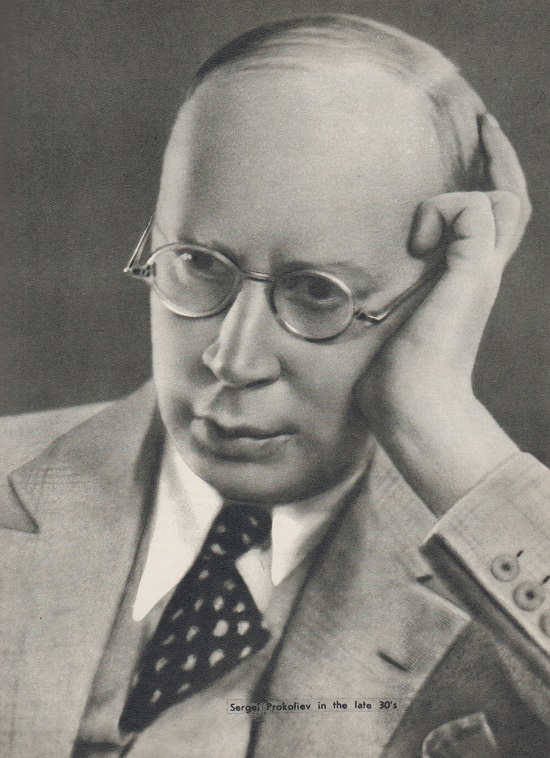

The photograph of Prokofiev at the start of the present item

appeared in the same book. Botvinnik also related the 1936 and

1949 episodes on pages 55 and 126 of his autobiography Achieving

the

Aim (Oxford, 1981).

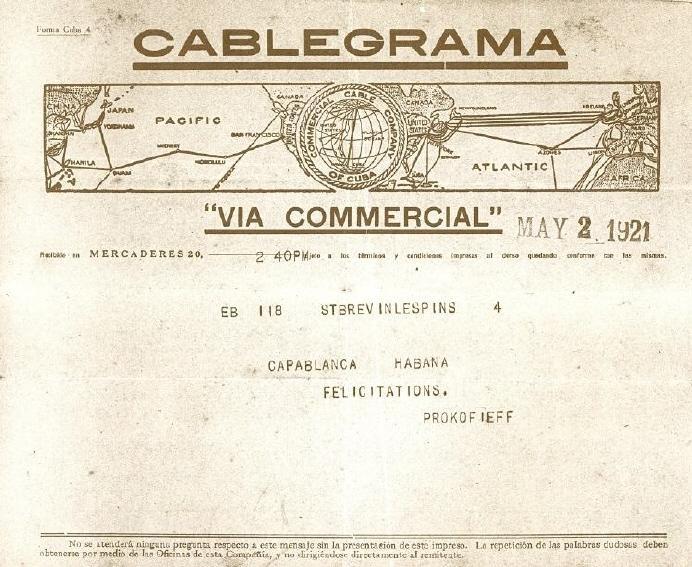

As noted on page 313 of our book on Capablanca, Prokofiev sent a one-word message of congratulations when the Cuban defeated Lasker in 1921:

(4913)

An extract from the entry dated 7 April 1914 (old style calendar) in S. Prokofiev’s diary, regarding the St Petersburg tournament:

‘At eight o’clock I went to the opening of the Chess Championship and found myself translated immediately into an enchanted realm, a realm alive with the most unbelievable activity in all three rooms of the Chess Club itself and three more rooms made available by the Assembly Committee. This tournament is a top-level affair, everyone in tailcoats, and here were the masters themselves each surrounded by a crowd of admirers.

Lasker, a little greyer since the 1909 tournament, with his distinctive face, his slight stature and an air of knowing his own worth; Tarrasch – a typically upright German with Kaiser Wilhelm moustaches and an arrogant expression; our own Rubinstein – a coarse, unintelligent-looking face, a touch of the shopkeeper about him, but modest and talented compared to Tarrasch, erratic but dangerous to any opponent; Bernstein, a prosperous-looking man with a handsome, impudent face, shaven head and a colossal nose, dazzling teeth and relentlessly brilliant eyes. Our own gifted Alekhine, with his lawyer’s coat and his slightly pinched, slightly disagreeable lawyer’s features, self-confident as ever but nevertheless a little subdued by the magnificence of the company. Marshall, the American, a typical Yankee, with a touch of Sherlock Holmes about him, ferociously passionate in play but ludicrously taciturn in private. Yanovsky [sic] from Paris, a deserter in his youth from military service and now exceptionally allowed special dispensation to return unmolested for the championship, wearing an exquisitely elegant light grey suit, formerly a famously good-looking breaker of hearts but now in his fifth decade showing his age and wearing gold-rimmed spectacles. The combative vegetarian Nimzowitsch, a typical German student and trouble-maker. Finally two older men, destined to be the victims of all, the portly Gunsberg and, wearing on his face a permanently injured expression, Blackburne, still, despite his 72 years, capable of producing original combinations and elegant developments in his conduct of a match. The crowd’s favourite, Capablanca, young, elegant, gay and with a constant smile on his handsome face, circulated through the hall laughing and chatting with the easy grace of one who already knows himself to be the victor.

Thus it was that I found myself in this irresistibly seductive kingdom, absorbed from the first moment by the forthcoming contest. The speeches began, laying stress on the unprecedented importance of the event with its exceptional galaxy of participants. Journalists from England, Germany, Moscow, Kiev, Vienna, chess masters from Germany, photographers, all added to the splendour of the occasion. The first round begins tomorrow!!!’

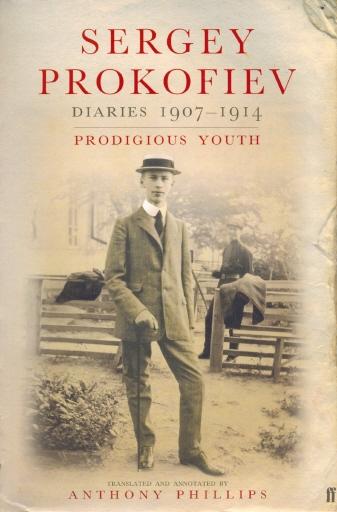

Source: pages 640-641 of Sergey Prokofiev Diaries 1907-1914 translated and annotated by Anthony Phillips (London, 2006).

(4925)

Prokofiev’s reference to photographers is the diary entry quoted in C.N. 4925 prompts a question: have many photographs taken during the St Petersburg, 1914 tournament been published?

Few come to mind. There are, of course, the very famous ‘first five grandmasters’ shot and the group picture; see pages 65 and 76 of A Picture History of Chess by Fred Wilson (New York, 1981). Page 87 of that book has a picture taken during the first game at St Petersburg between Capablanca and Lasker. In Chess Explorations we gave a large, less well-known group photograph, which was an insert (Beilage) to the 31 May 1914 issue of Deutsches Wochenschach:

Has a key to this photograph ever appeared?

Sergey Prokofiev Diaries 1907-1914 contains a rather poor version of the better-known group photograph, which page x incorrectly describes as depicting ‘The 1914 St Petersburg World Chess Championship’.

(4926)

The index to Sergey Prokofiev Diaries 1907-1914 has, on page 819, over 70 references to chess, and the index entry for Capablanca (pages 802-803) is ten lines long, with 16 references. On page 582 (diary, 8 January 1914) Prokofiev writes:

‘Around six o’clock Capablanca came into the Club: he is an utterly irresistible person, lively, handsome, quick-witted, and – this is the point – a genius. You should have seen how quickly he showed up the mistakes of our Petersburg masters: on the spot, the instant their games were finished, and right in front of their very eyes! I was entranced.’

As noted on pages 80-81 of our book on Capablanca, the Cuban gave three simultaneous exhibitions in St Petersburg at which Prokofiev took a board. Capablanca won the first two games and lost the third. We believe that only the third game-score is currently known, but Prokofiev’s diary entry for 15 May 1914 (page 681) gives an extensive account of his second game. He mentions that it began 1 d4 d5 2 Nf3 Bf5 3 c4 Nc6, after which Capablanca (White) ...

‘... stood in front of the board for two or three minutes frowning and pulling at his hair. I was thrilled beyond words at having set the champion a real problem ...’

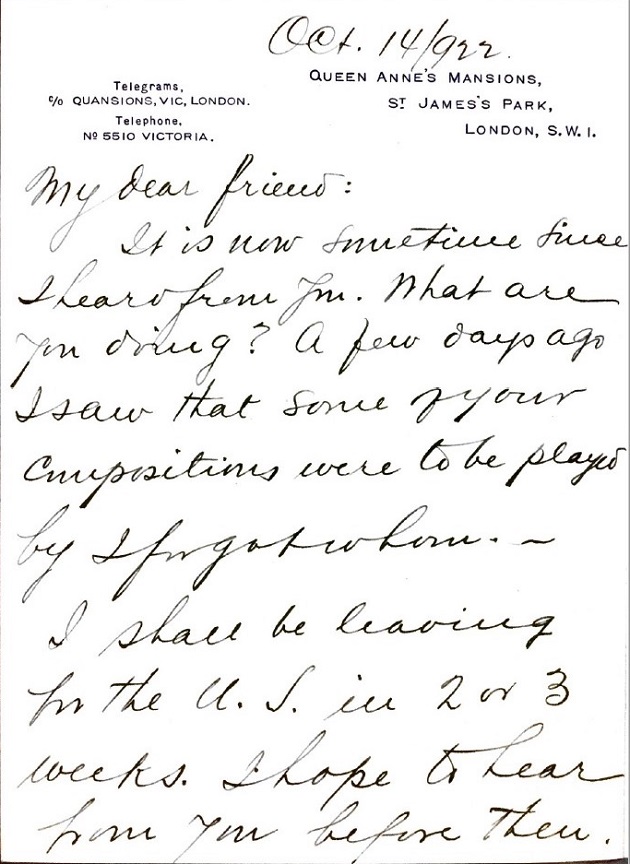

Also on page 80 of our Capablanca book a 20-move simultaneous game ‘Capablanca v Bashtirov’, St Petersburg, 1914 was given, from page 103 of Capablanca-Magazine, 31 July 1914. However, the Diaries contain so many references to Boris Nikolayevich Bashkirov (a ‘wealthy amateur poet’ whose pseudonym was Boris Verin) that it now seems to us almost certain that ‘Bashtirov’ is incorrect. Chess-related references to Bashkirov appear on pages 682-683 and 741 of the Diaries. The latter, which is in an entry dated 21 September 1914, states:

‘While we talked he [Bashkirov] told me many interesting things, among them about a certain Mme Strakhovich, to whom he had introduced Capablanca who had fallen in love with her; it was due to her that he had failed to capture the first prize.’

(4927)

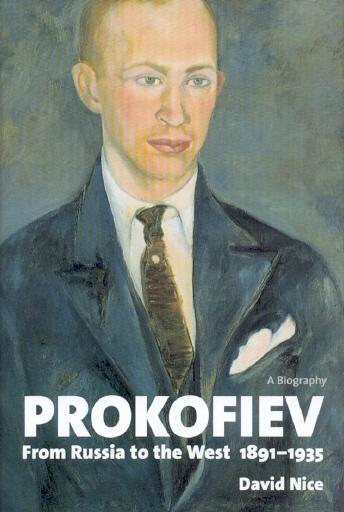

Chess also features extensively in Prokofiev From Russia to the West 1891-1935 by David Nice (New Haven and London, 2003). The plates section has a photograph of Prokofiev ‘playing chess with former neighbour Morolev at Nikopol, 1909’. From page 292 (concerning the early 1930s):

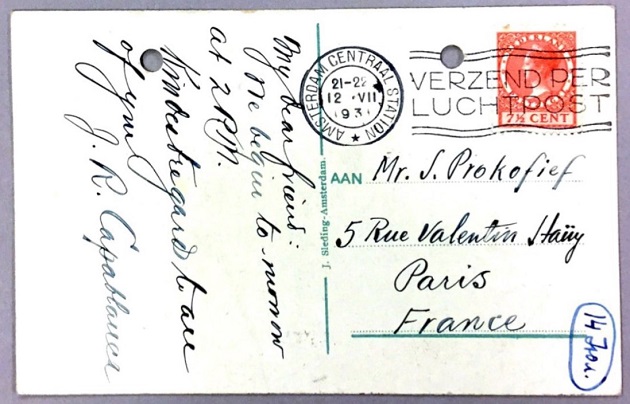

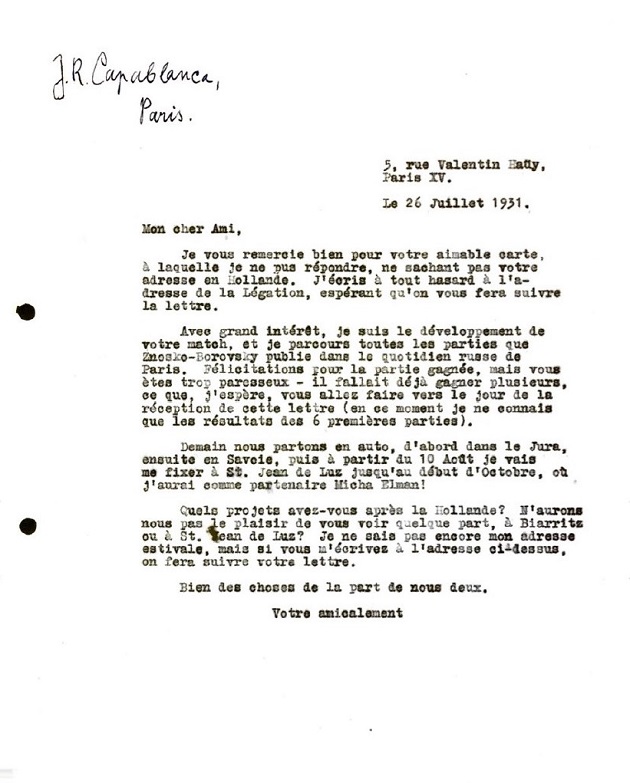

‘There was a good chess companion in Mischa Elman, though it would have been better still to have had the company of Capablanca, whose participation in the Paris congress he had been following with interest – “congratulations for the games you won, but you’re too lazy and you must win more.” [Page 354 states that this comes from a letter from Prokofiev to Capablanca dated 26 July 1931.] Capablanca duly obliged by losing not a single match.’

For ‘Paris congress’ read, presumably, ‘match with Euwe in the

Netherlands’, although that contest had ended on 10 July 1931.

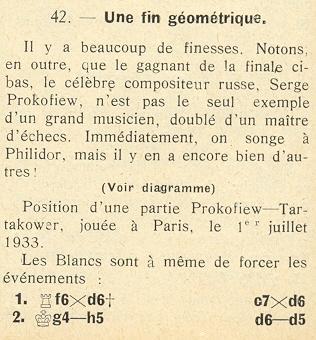

Pages 311-312 of the biography have the following information regarding Prokofiev in 1933:

‘As for chess, which he was still enjoying regularly at Napoleon’s old haunt of the Café de la Régence, he played two games with the famous Saviely Tartakower, winning the first and drawing the second. There seemed no reason why he should not exploit his triumph for publicity purposes in America. “Tartakower is one of the strongest players in the world”, he told Gottlieb in an extended version of the news he had already passed on to Haensel, “and has the title of ‘Grossmeister’ – so you can imagine how proud I was to win. When, after the game was over, I asked Tartakower to show me what mistake he made to lose it, he answered: ‘I made no mistake; simply you played well’.”’

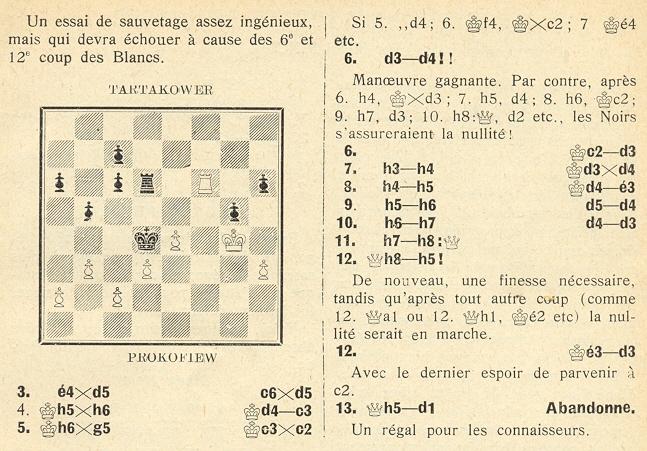

We add that Tartakower annotated the finish on pages 426-427 of L’Echiquier, 17 February 1934:

It may be recalled that Tartakower included a victory over Prokofiev (Paris, February 1934) on pages 46-47 of his second volume of Best Games.

(4928)

Selected Letters of Sergei Prokofiev translated and edited by Harlow Robinson (Boston, 1998) has a few brief references to chess masters. For example, page 15 quotes an item of correspondence which he wrote to Eleonora Damskaya from Newcastle, England on 12 June 1914. The second paragraph reads:

‘A propos, did you get a chance to see Capablanchik in the issue of Novyi Svet of 04/01? Isn’t he sweet?’

Does any reader have access to that issue? An editor’s footnote on the same page stated: ‘Capablanchik is an endearing Russian diminutive for Capablanca. Prokofiev uses it to show his warm feelings for the famous chess player.’ On the previous page a footnote incorrectly described the Cuban as ‘the world champion at the time’ (of the St Petersburg, 1914 tournament).

In a letter to the same correspondent, written in Ettal, Germany on 5 June 1923, Prokofiev remarked:

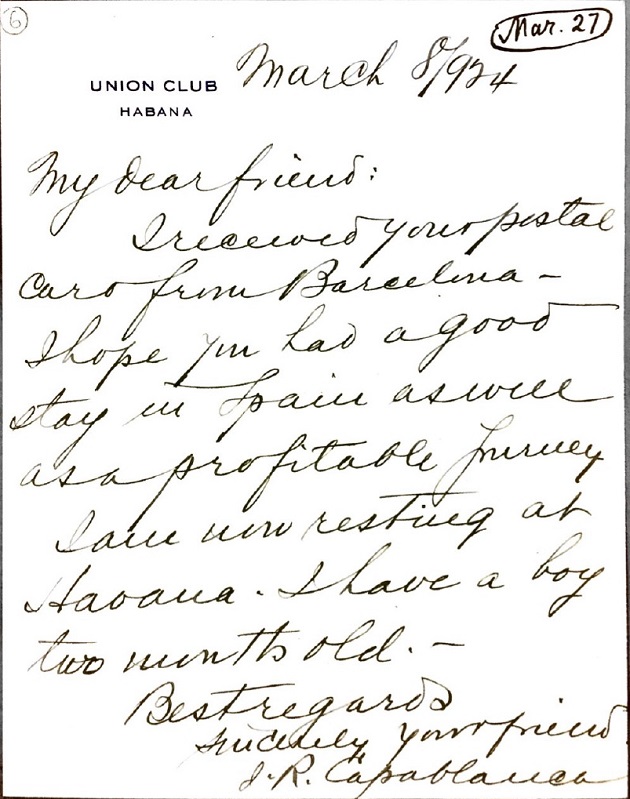

‘Alekhin is reaping international laurels on 64 different fields [sic] of competition, pursues only gray-haired ladies, and is planning to play a chess match with Capablanca for the world championship; Capablanca himself is in Havana, where he is fussing over a newborn child.’

(4946)

From Sergey Prokofiev Diaries 1915-1923 translated and annotated by Anthony Phillips (London, 2008) we quote three passages:

A report, listing Prokofiev as one of the contestants, was published on page 42 of the March 1922 American Chess Bulletin, although the display was misdated 23 January, instead of 23 February. The correct date is confirmed by the report on page 17 of the Sports Section of the New York Times, 24 February 1922.

As in the first volume of Diaries, there are many entries in which the composer referred to chess.

(6063)

We gave the above photograph on page 214 of A Chess Omnibus, from page 154 of the May 1943 Chess Review. The caption in the US magazine stated that Prokofiev (right) was in play against the violinist David Oistrakh in a tournament in Moscow, watched by Liza Hilels, also a violinist. (Her name appears in various sources in different forms, such as Elizaveta Gilels.)

Regarding the above photograph Martin Weissenberg (Savyon, Israel) pointed out in C.N. 7726 that the girl watching Oistrakh and Prokofiev, Elizaveta (Liza) Gilels, was the sister of the pianist Emil Gilels, the wife of the violinist Leonid Kogan, and the mother of the violinist and conductor Pavel Kogan. She herself was an accomplished violinist.

For Olga Capablanca’s observations on Prokofiev, see The Genius and the Princess.

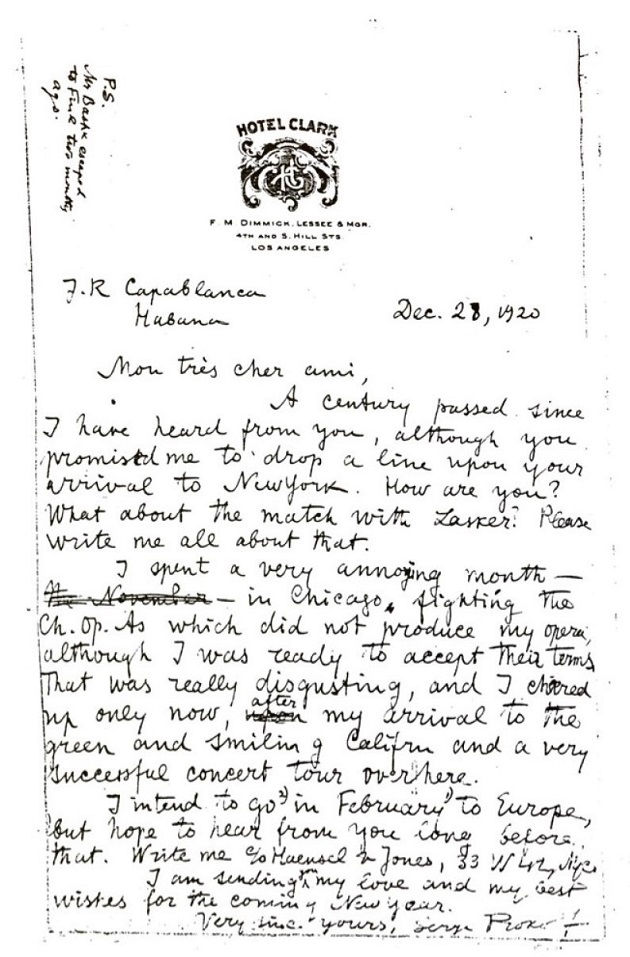

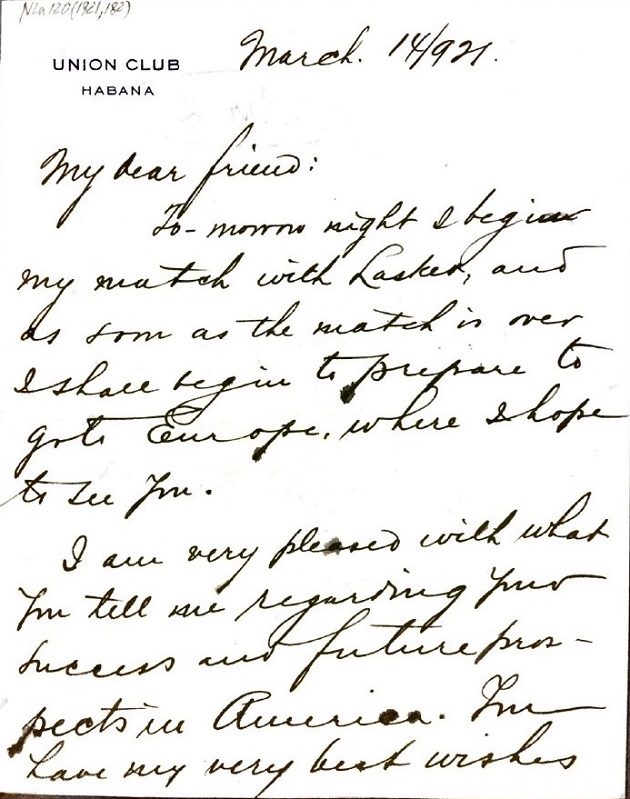

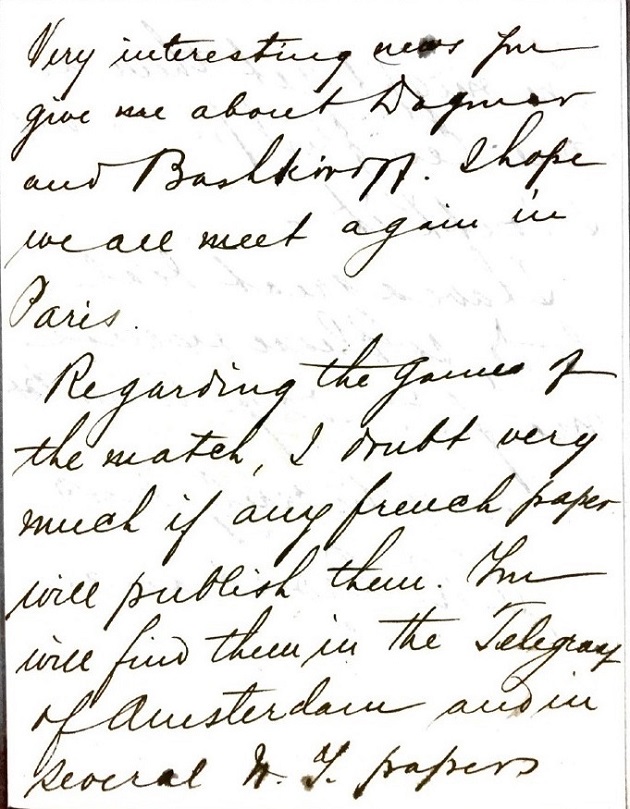

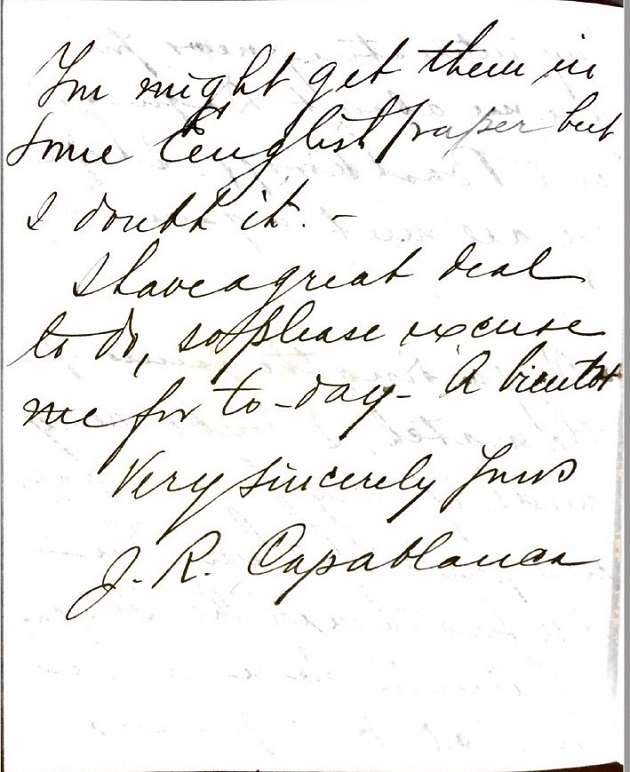

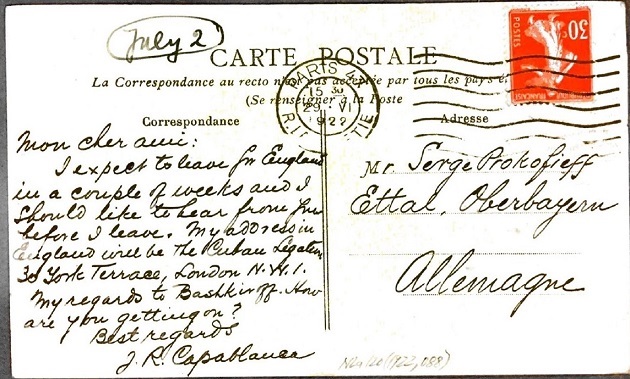

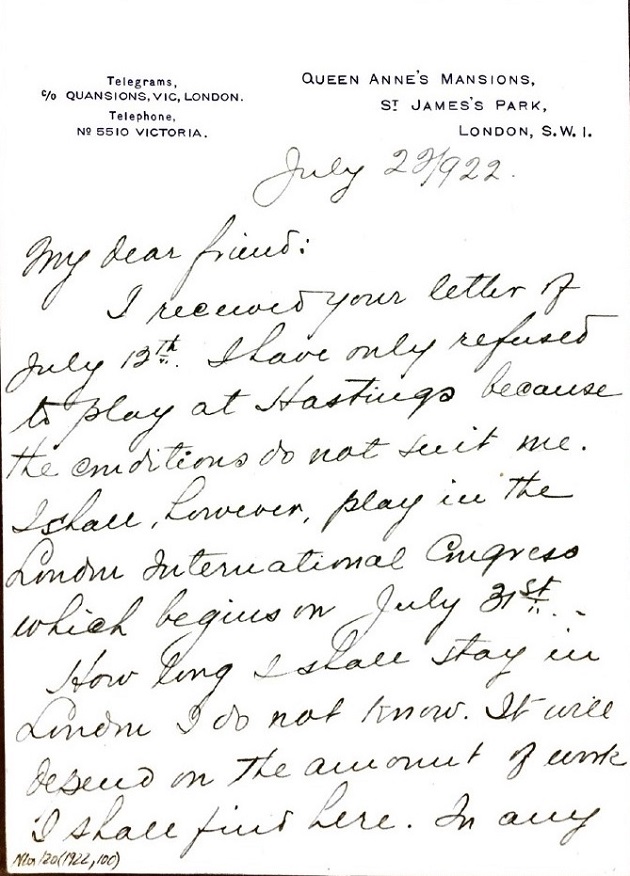

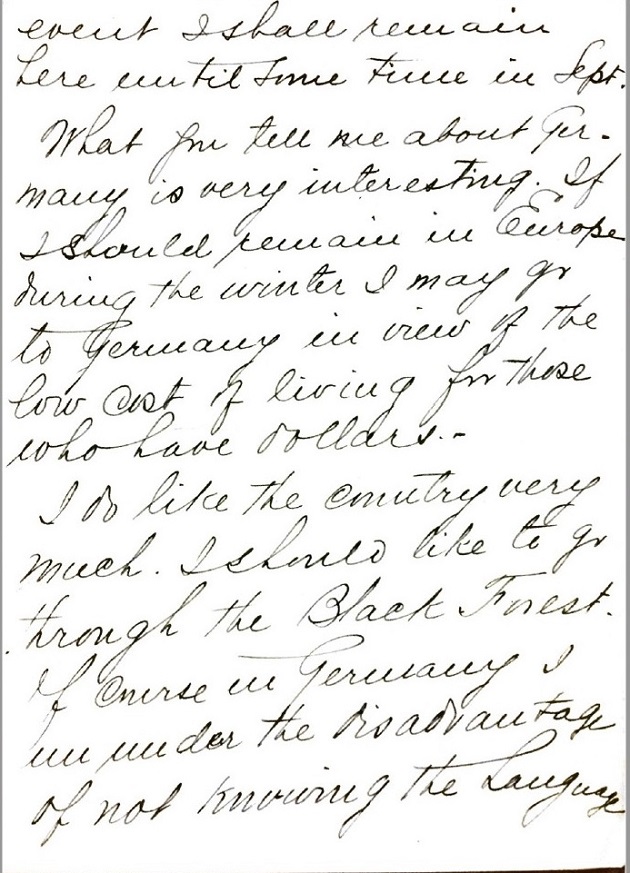

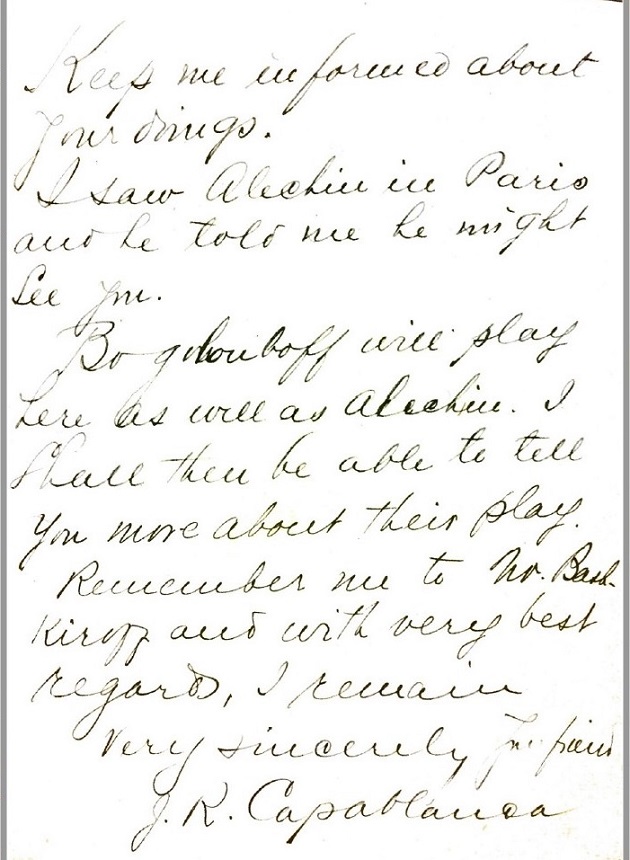

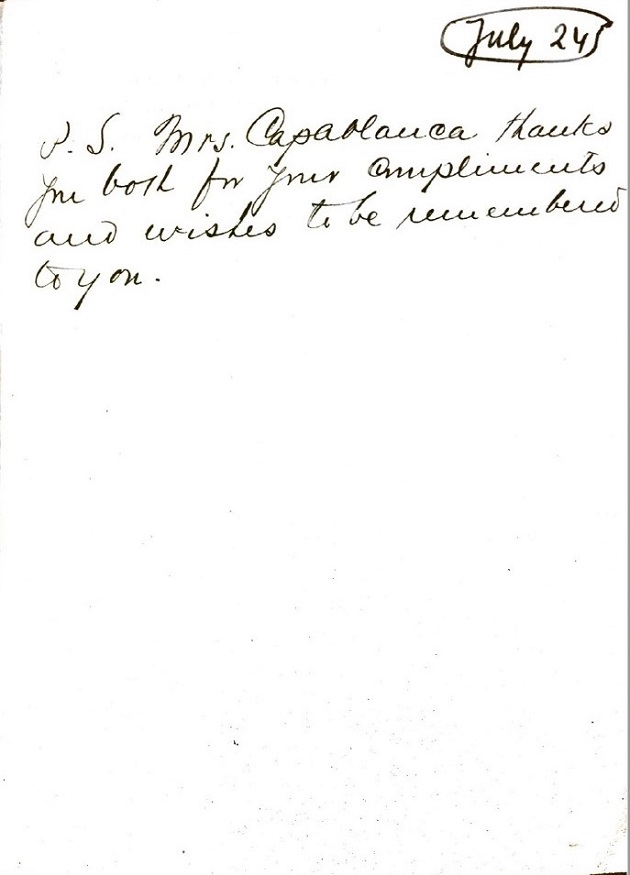

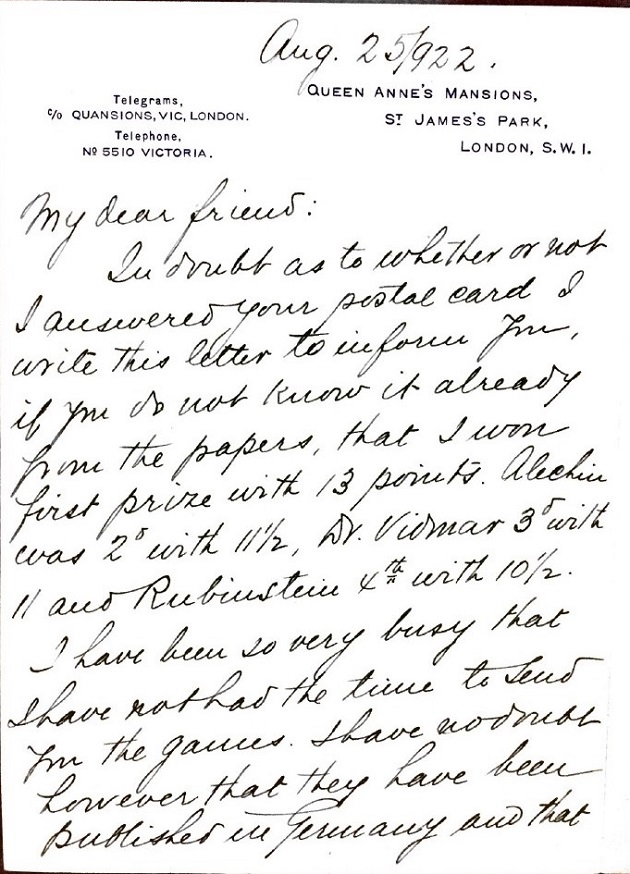

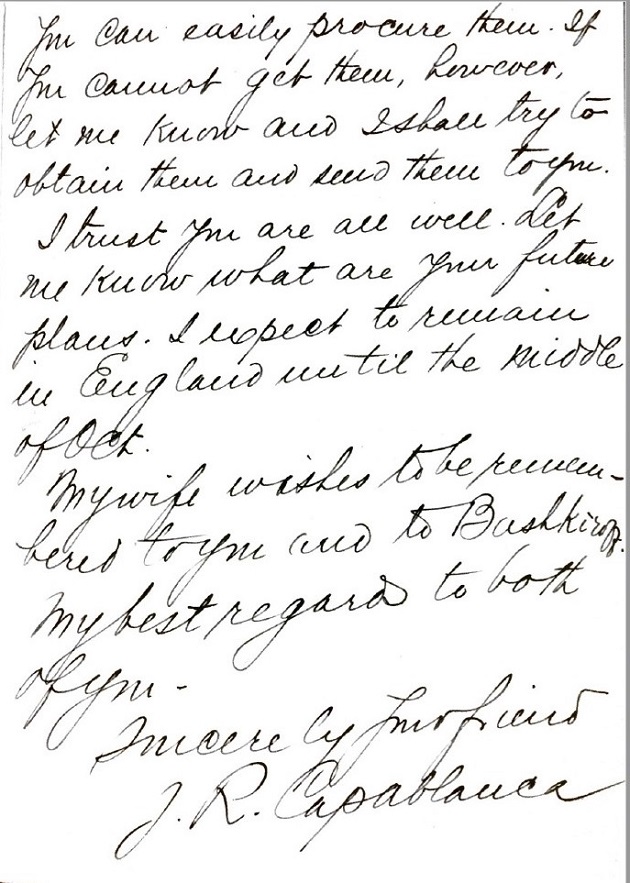

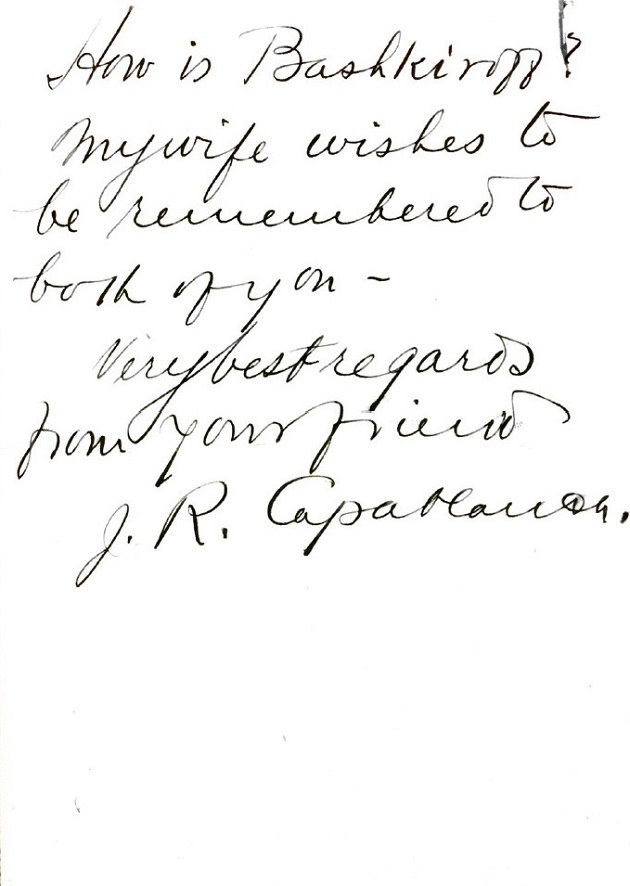

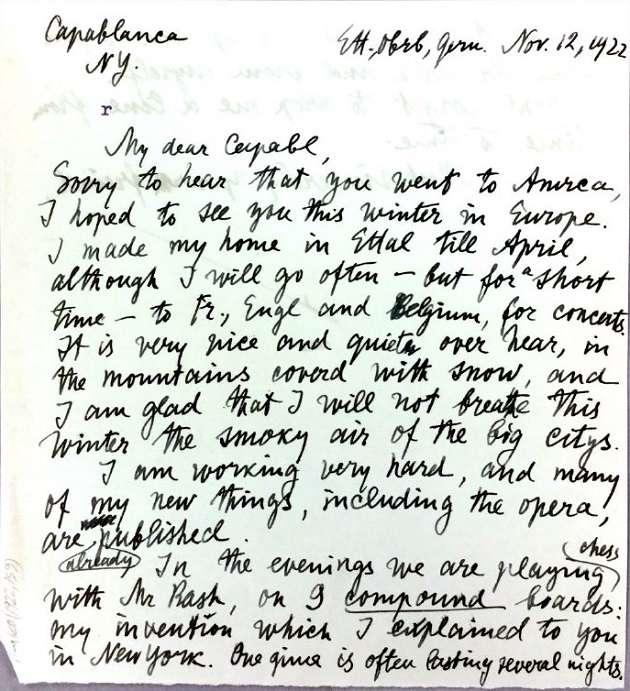

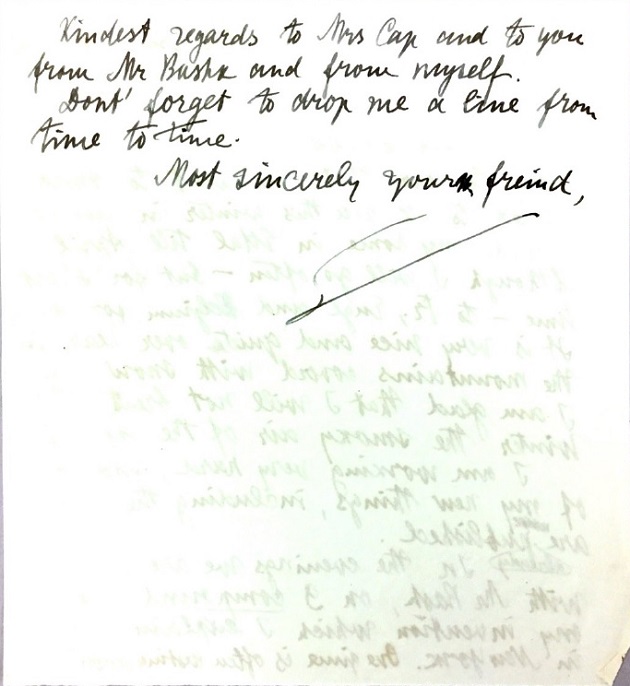

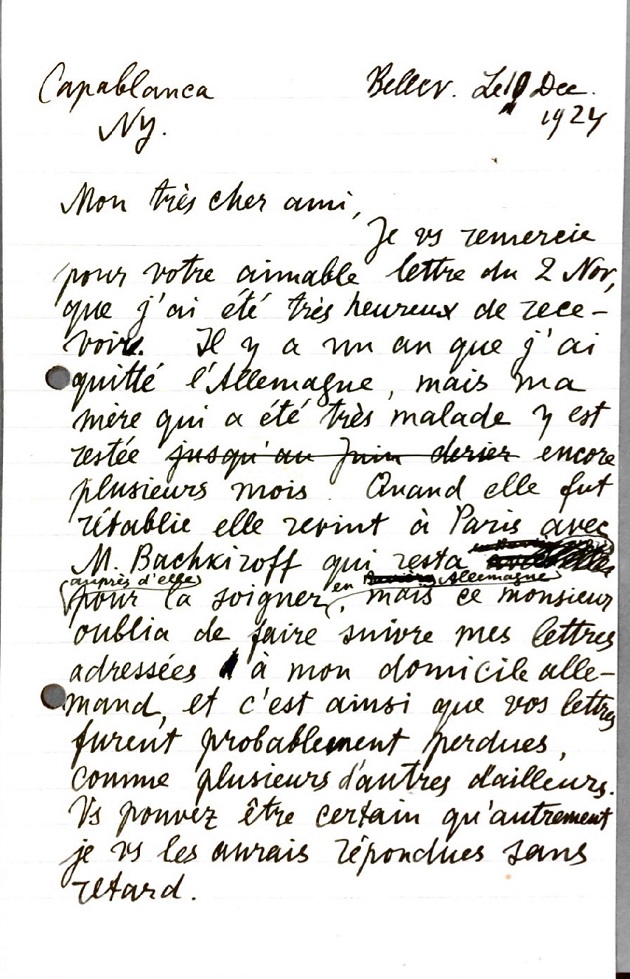

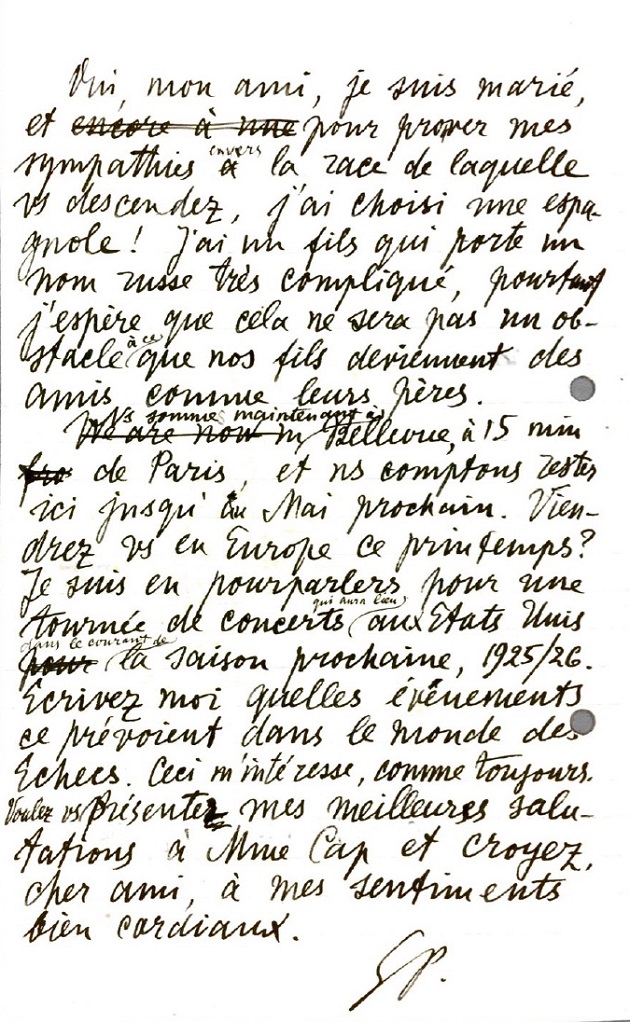

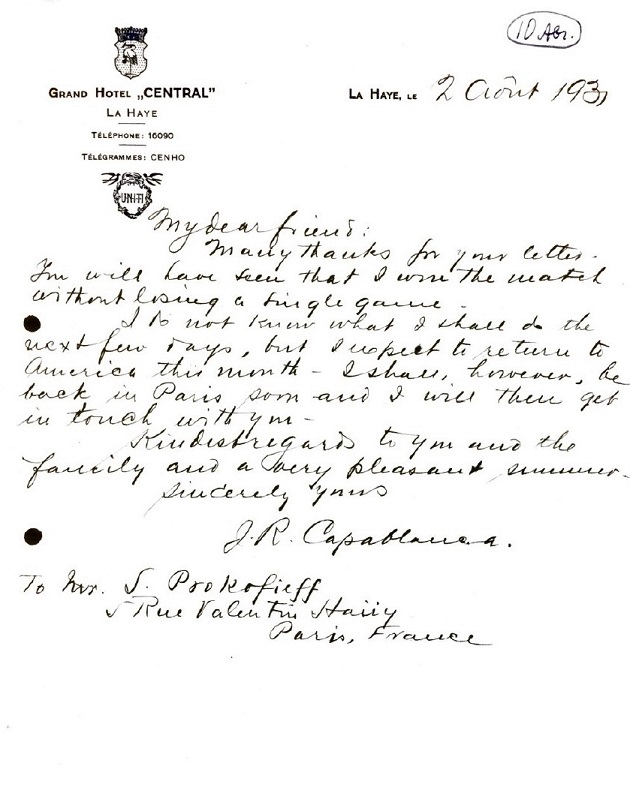

Courtesy of the Butler Library of Columbia University, New York, the present item reproduces some correspondence between Capablanca and Prokofiev, forwarded to us by Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore):

Further exchanges between Capablanca and Prokofiev will be presented shortly.

(10938)

As mentioned in C.N. 10938, the correspondence has been provided to us by Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore), courtesy of the Butler Library of Columbia University, New York. Further items will follow.

(10945)

The series, presented courtesy of the Butler Library of Columbia University, New York, which provided the material to Olimpiu G. Urcan, is continued below:

(10957)

The final batch of exchanges:

As acknowledged in the three earlier items, the correspondence has been reproduced here courtesy of the Butler Library of Columbia University, New York, which supplied it to Olimpiu G. Urcan.

(10969)

From The Soviet Chess School by A. Kotov and M. Yudovich (Moscow, 1983):

We are grateful for permission to reproduce this photograph of Prokofiev from page 139 of Emanuel Lasker: Denker Weltenbürger Schachweltmeister edited by Richard Forster, Stefan Hansen and Michael Negele (Berlin, 2009):

C.N.s 8809 and 8823 added information about Prokofiev and Edward Lasker, including a game played by them during the composer’s visit to Chicago in 1921-22.

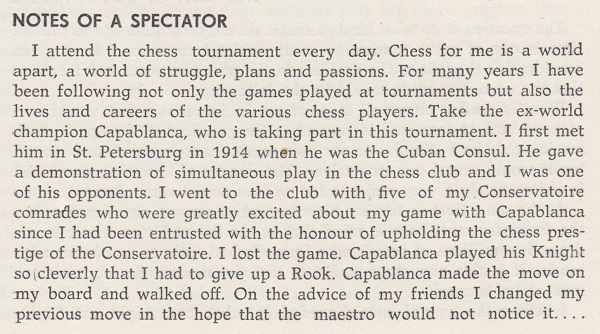

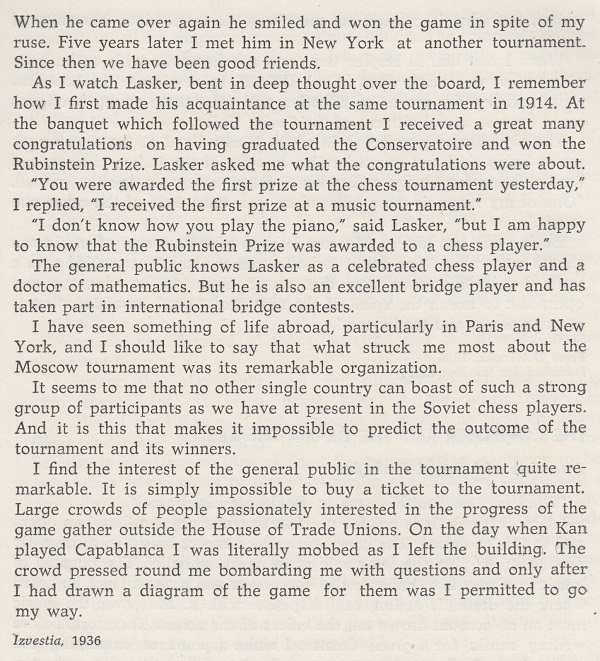

Above is the front of the dust-jacket of S. Prokofiev Autobiography Articles Reminiscences (Moscow, 1959). From pages 101-102, regarding the Moscow, 1936 tournament:

The original, on page 4 of Izvestia, 30 May 1936:

Concerning the first part of the article, an English translation by Kenneth Neat is on pages 80-81 of our book on Capablanca.

From opposite page 104 of the above-mentioned Prokofiev anthology:

(11846)

Addition on 22 December 2022:

Douglas Griffin (Insch, Scotland) provides (courtesy of Russian music museum) a superior version of the portrait of Prokofiev at the top of our article:

From the same source our correspondent provides a shot of Prokofiev studying the famous Edward Lasker v George Thomas miniature:

‘The international tournament [St Petersburg, 1909] revitalized the chess life of Petersburg. No sooner had it concluded than the Chess Assembly arranged mixed tournaments for first- and second-category tournaments, and I decided to test my strength. Strong players took part in the tournament, among them some participants from the All-Russian Amateurs Tournament. I was admitted as a representative of the chess circle of the students from the Technological Institute. It was the first time that I had had to play with clocks, and I was really quite uncertain before my first public entry onto the chess stage.

The draw paired me in the first round with the student of the Conservatory, Seryozha Prokofiev. The city was already talking about the outstanding talent of this youth, who later became our famous composer.’

The text is on page 12 of the original Russian edition.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.