Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [95] | next >> | Current column |

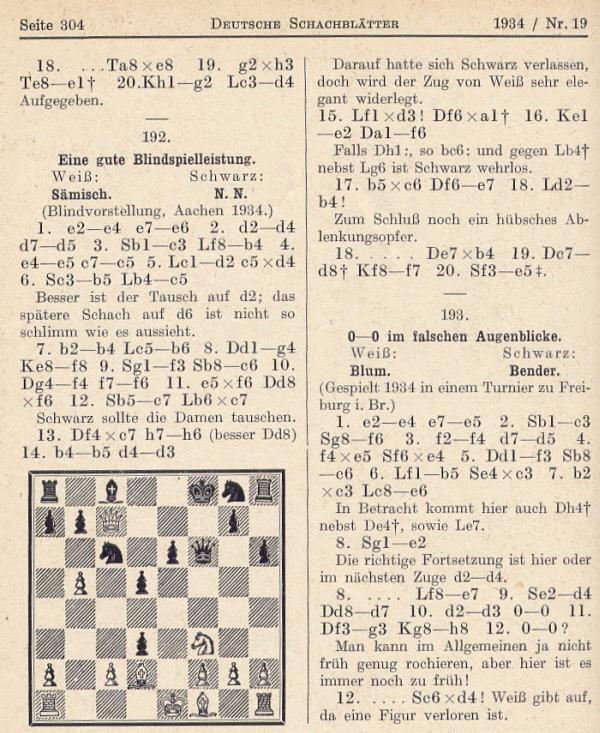

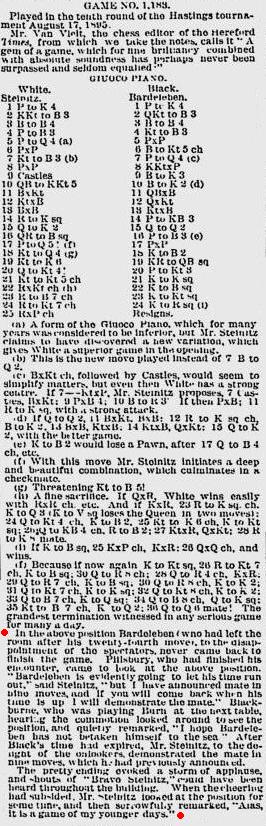

7683. Sämisch blindfold game

A widely-published blindfold game won by F. Sämisch against N.N.:

1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 e5 c5 5 Bd2 cxd4 6 Nb5 Bc5 7 b4 Bb6 8 Qg4 Kf8 9 Nf3 Nc6 10 Qf4 f6 11 exf6 Qxf6 12 Nc7 Bxc7 13 Qxc7 h6 14 b5 d3

15 Bxd3 Qxa1+ 16 Ke2 Qf6 17 bxc6 Qe7 18 Bb4 Qxb4 19 Qd8+ Kf7 20 Ne5 mate.

Wanted regarding this game-score: the oldest possible citations from magazines and columns of the time. But when was ‘the time’? ‘Aachen, 1943’ was the heading when the game was published on pages 174-175 of The Joys of Chess by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1961), but other books tend to give the date as 1934. See, for instance, pages 363-364 of Irving Chernev’s Best Short Games collection, which introduced the game as follows:

‘“Of all the modern masters that I have had occasion to observe playing blindfold chess, it is Sämisch who interests me the most; his great technique, his speed and precision have always made a profound impression on me.” So said Alekhine, himself one of the most magnificent exponents of the art.’

Alekhine made the remark on page 19 of Auf dem Wege zur Weltmeisterschaft (Berlin and Leipzig, 1932):

‘Von allen modernen Meistern, die ich beim Blindspiel zu beobachten Gelegenheit hatte, gefiel mir Sämisch am besten; seine große Technik, seine Schnelligkeit und Sicherheit haben mir imponiert.’

The French version, from page 270 of Deux cents parties d’échecs (Rouen, 1936):

‘De tous les Maîtres modernes que j’ai eu l’occasion d’observer au jeu à l’aveugle, c’est Sämisch qui m’intéresse le plus; sa grande technique, sa rapidité et sa sûreté m’ont toujours fait une profonde impression.’

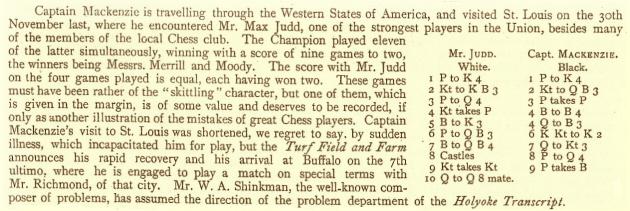

7684. Judd v Mackenzie

From page 193 of the Westminster Papers, 1 January 1879:

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 exd4 4 Nxd4 Bc5 5 Be3 Qf6 6 c3 Nge7 7 Bc4 Qg6 8 O-O d5 9 Nxc6 dxc4 10 Qd8 mate.

A curious, if unspectacular, specimen of what P.H. Clarke termed a ‘mini-miniature’ on page 118 of 100 Soviet Chess Miniatures (London, 1963).

7685. R.P. Michell (C.N. 5061)

Kevin Thurlow (Redhill, England) draws attention to the entry for R.P. Michell in the register of burials in Kingston-upon-Thames, noting that the image available via that page states that Michell died on 19 May 1938, whereas other sources (such as page 314 of the July 1938 BCM) have 20 May. Moreover, Michell’s second forename is specified in the burial register as ‘Pryce’ and not ‘Price’. (The latter spelling is sometimes seen in chess outlets, though not, we believe, in reliable ones.)

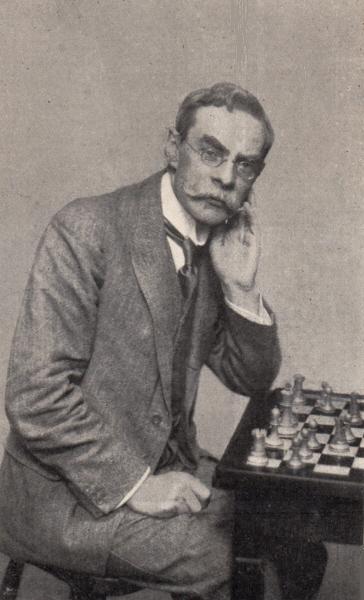

C.N. 5061 gave two photographs of Michell, and below is another one, published on page 314 of the July 1938 BCMand as the frontispiece to the April 1926 issue:

7686. Prince Dadian of Mingrelia

C.N.s 1334, 1490, 1503, 1542 and 1627 gave information about Prince Dadian of Mingrelia, and here we reproduce the last of those items, a contribution in 1988 from the late John van Manen (Modbury Heights, Australia) concerning the Prince’s family background:

‘Andre Dadian’s grandparents were: Levan Gregorievich, Prince of Mingrelia, 1789-1846, and his wife Marthe Zourabovna Tseretelli, whom he married on 20 August 1820, 1792-17 August 1839. (Something is wrong somewhere; perhaps she was his second wife ...)

The next generation: Dawith (David) Dadian Levanovich, Prince of Mingrelia, born on 21 January 1812, died in 1853. Married Ekaterina Alexandrovna Chavchavadze. Children:

(1) Nicholas Davidovich, born on 4 January 1847, died on 6 February 1903. He had a son, Nicholas, born on 12 December 1876, who left a single daughter and was the last male member of that family.

(2) Salome, born on 13 October 1848, died on 23 July 1913, who married on 13 May 1868 Achille Murat (1847-1895), the grandson of Joachim Murat, general and king of Naples.

(3) Andre Dadian (Davidovich), born on 24 October 1850, etc.

Sources of information: Burke’s Royal Families of the World, volume I, Europe and Latin America (1977), page 122. Almanach de Gotha (inter alia 1900, page 394; 1905, page 395; 1927, page 497).’

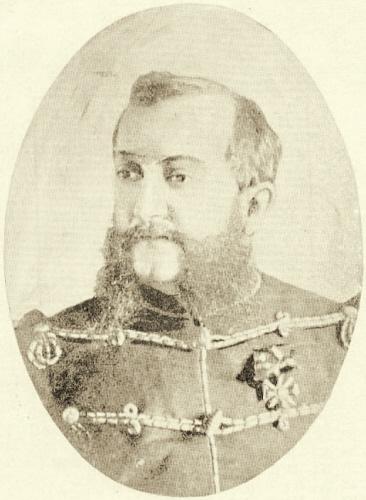

Below is a photograph of the chessplaying Prince from page 109 of the September 1898 American Chess Magazine:

Additional note: photographs of the Prince were shown in C.N. 3031.

7687. Russian photographs

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) points out some Russian photographs (pre-First World War) at a webpage of the Multimedia Art Museum, Moscow.

7688. Thomas Hood and chess (C.N.s 5392 & 6524)

From John Townsend (Wokingham, England) comes this passage by Hood on page 547 of the book Hood’s Own (London, 1839):

‘It is pleasant after a match at Chess, particularly if we have won, to try back, and reconsider those important moves which have had a decisive influence on the result. It is still more interesting, in the game of Life, to recal[l] the critical positions which have occurred during its progress, and review the false or judicious steps that have led to our subsequent good or ill fortune. There is, however, this difference, that chess is a matter of pure skill and calculation, whereas the chequered board of human life is subject to the caprice of Chance – the event being sometimes determined by combinations which never entered into the mind of the player.’

Our correspondent comments:

‘Howard Staunton must have held Hood in high esteem, since he contributed a guinea to the public subscription for a monument to him, which was erected at Kensal Green Cemetery on 18 July 1854, more than nine years after his death. The long list of subscribers can be seen in Eliza Cook’s Journal, 5 August 1854, pages 225-229. They include many literary and theatrical figures, such as Alfred Tennyson, W.M. Thackeray, W.C. Macready, John Timbs, Douglas Jerrold and Charles Mackay.’

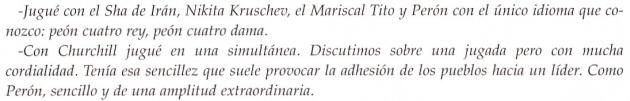

7689. More Najdorf claims

Page 88 of Najdorf x Najdorf by Liliana Najdorf (Buenos Aires, 1999) has a set of claims purportedly made by M. Najdorf about his over-the-board encounters:

Can corroboration of any authoritative kind be found for, in particular, the assertion that Najdorf played against Churchill in a simultaneous display?

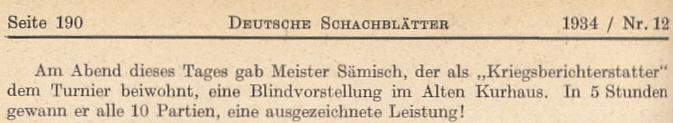

7690. Sämisch blindfold game (C.N. 7683)

Peter Anderberg (Harmstorf, Germany), Hans-Georg Kleinhenz (Munich, Germany) and Alan McGowan (Waterloo, Ontario, Canada) note that the game was published on page 304 of Deutsche Schachblätter, 1 October 1934:

The display, which took place in Aachen on 28 May, was mentioned on page 190 of the 15 June 1934 issue, with the information that Sämisch won all ten blindfold games within five hours:

Mr Kleinhenz adds:

‘The handwritten chronicle of the Aachener Schachverein 1856 (the organizer of the German Championship) does not contain a detailed report of the exhibition but mentions that some were consultation games:

“Saemisch spielt anl. der Dt. Meisterschaft an 10 Brettern blind. Zum Teil Beratungspartien. S. gewinnt alle Partien.”’

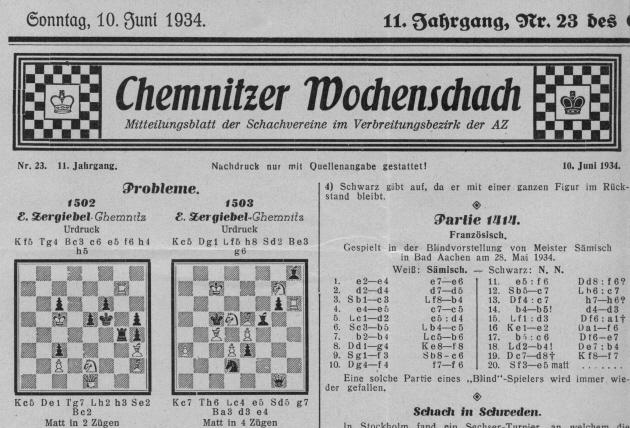

Furthermore, Mr Anderberg notes that the game-score was published in Chemnitzer Wochenschach, 10 June 1934:

7691. Always lucky (C.N. 5448)

C.N. 5448 sought citations for the axiom, often ascribed to Capablanca, that good players are always lucky.

We have found nothing published during the Cuban’s lifetime but can offer the following:

‘As they say in New York, the good player is always lucky.’

That was written by Reuben Fine on page 88 of the April 1942 Chess Review, when introducing a game between Seidman and Reshevsky. See too page 4 of Fine’s book Chess Marches On! (New York, 1945).

On the other hand, Fine wrote on page 131 of The World’s a Chessboard (Philadelphia, 1948):

‘It’s better to be lucky than good, Capa used to say.’

Fine’s book The World’s Great Chess Games (New York, 1951) had this on page 235:

‘... Capablanca’s profound observation that the good player is always lucky’.

7692. Anderssen games

Three games received from Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA):

Sigismund Hamel – Adolf AnderssenBreslau, 1874

Bishop’s Opening

1 e4 e5 2 Bc4 f5 3 exf5 Nf6 4 g4 d5 5 Bb3 h5 6 g5 Ne4 7 d3 Nc5 8 Qe2 Nc6 9 Nf3 Nxb3 10 axb3 Bb4+ 11 c3 Bd6 12 Nh4 b6 13 f4 Kd7 14 d4 Re8 15 fxe5 Nxe5 16 O-O Ng4 17 Qg2 Bxh2+ 18 Kh1

18...Kc6 19 Na3 Kb7 20 Bd2 Bd7 21 Nc2 Re4 22 Rae1 Qg8 23 Rxe4 dxe4 24 c4 Re8 25 Ne3 Nxe3 26 Bxe3 Bd6 27 Bf4 Bb4 28 Be5 Bc6 29 d5 Rxe5 30 dxc6+ Kb8 31 Ng6 Re8 32 f6 Qf7 33 Nf4 e3 34 Ne2 gxf6 35 Rxf6 Qe7 36 Qd5 a5 37 Rf7 Qe6 38 Qxe6 Rxe6 39 Rf6 Rxf6 40 gxf6 Kc8 41 Kg2 Kd8 42 Nf4 Ke8 43 Kf3 h4 44 Kxe3 Kf7 45 Nd5 Bd6 46 Kf2 h3 47 Kg1 Ke6 48 Kh1

48...b5 49 Kg1 a4 50 Nc3 Be5 51 bxa4 Bxc3 52 cxb5 Bb4 53 Kh2 Kxf6 54 Kxh3 Ke6 55 Kg4 Kd6 56 Kf4 Kc5 57 Ke4 Ba5 58 Kd3 Kb4 59 Kd4 Bb6+ 60 White resigns.

Source: Illustrated London News, 10 October 1874, page 355.

Sigismund Hamel – Adolf AnderssenBreslau, 1874

Bishop’s Opening

1 e4 e5 2 Bc4 f5 3 exf5 Nf6 4 g4 d5 5 Bb3 Bc5 6 d3 h5 7 Be3 Bxe3 8 fxe3 Nxg4 9 Qe2 Bxf5 10 Nf3 e4 11 dxe4 Bxe4 12 Nbd2 Nc6 13 O-O-O Qe7 14 Nxe4 dxe4 15 Nd4 Nxd4 16 Rxd4

16...Rf8 17 Qb5+ c6 18 Qxh5+ Resigns.

Source: Illustrated London News, 14 November 1874, page 475.

Adolf Anderssen – Sigismund HamelBreslau, August 1874

Queen’s Fianchetto Defence

1 e4 b6 2 Nf3 Bb7 3 Nc3 e6 4 d4 Bb4 5 Bd3 Nf6 6 Bg5 h6 7 Bxf6 Qxf6 8 O-O Bxc3 9 bxc3 d6 10 Nd2 O-O 11 f4 Qe7 12 f5 exf5 13 Rxf5 Nd7 14 Qe2 Nf6 15 Raf1 Nh7 16 Qh5 Bc8

17 e5 Bxf5 18 Rxf5 Qe6 19 Rf3 Ng5 20 Rg3 f5 21 h4 Qf7 22 Bc4 d5 23 Qxf7+ Nxf7 24 Bxd5 Rad8 25 Bb3 c5 26 e6 cxd4 27 exf7+ Kh7 28 cxd4 Rxd4 29 Nf3 Rg4 30 Rxg4 fxg4 31 Ne5 Rd8 32 Nd7 Resigns.

Source: Illustrated London News, 16 December 1874, page 619.

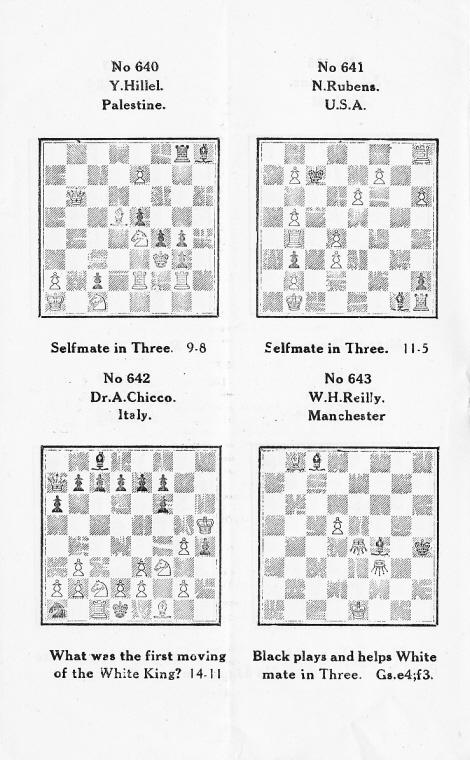

7693. First move by the white king

Which was the first move by the white king – Kf2, Kd1 or O-O-O?

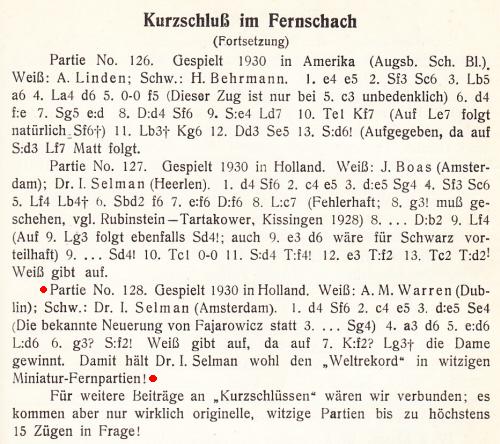

7694. Warren v Selman

The correspondence miniature A.M. Warren v I. Selman (Budapest Defence) was discussed in C.N.s 905 and 933 (see page 50 of Chess Explorations). Below is the game’s appearance on page 71 of Fernschach, September 1931:

7695. Steinitz caricature

From page 213 of the Westminster Papers, 1 March 1876:

The caricature was mentioned by ‘A Looker-on’ in the 15 March 1876 issue of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, page 53:

‘Have you seen the charming portrait of “Herr Wilhelm Steinitz”, and accompanying letterpress, which appear in the Westminster Papers for the current month? The likeness, though somewhat flattering, is, in my humble opinion, admirable, and has given rise to an incredible amount of fun among chessplayers hereabouts, though I hear that the original somewhat objects to it. On dit, though, of course, I do not vouch for the fact, two actions for libel – or, I suppose, two threats of actions – have been brought against the Papers during the past week. But threatened people, they say, live long.’

7696. Judd v Mackenzie (C.N. 7684)

Courtesy of Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) and John Hilbert (Amherst, NY, USA), the other three informal games played by Mackenzie against Judd during his visit to St Louis are added:

Max Judd – George Henry MackenzieSt Louis, 28 November 1878

Greco Counter-Gambit

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 f5 3 d4 fxe4 4 Nxe5 Nf6 5 Nc3 d5 6 Bg5 Be6 7 f3 exf3 8 Qxf3 Be7 9 Bxf6 Bxf6 10 Qh5+ g6 11 Qe2 Qe7 12 O-O-O Nc6 13 g3 Bxe5 14 dxe5 O-O-O 15 Bg2 Qg5+ 16 Rd2 Rhe8 17 Qb5 Nxe5 18 b3 c6 19 Qc5 b6 20 Qa3 Kb7 21 Rhd1 Bg4 22 Rf1 Rd7 23 Rf4 Bf5 24 Ra4 a5 25 Rad4 Ng4 26 Kb2 Ne3 27 Qa4 Nxg2 28 Rxg2 Re1 29 Rgd2 Be6 30 Rf4 Qe5 31 Rfd4

31...c5 32 Qxd7+ Bxd7 33 Rxd5 Qf6 34 Rxd7+ Kc6

35 Rc7+ Kxc7 36 White resigns.

Source: Cincinnati Commercial, 18 December 1878.

George Henry Mackenzie – Max JuddSt Louis, 28 November 1878

Vienna Gambit

1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Bc5 3 f4 d6 4 Nf3 Nf6 5 Bc4 O-O 6 d3 c6 7 Bb3 a5 8 Qe2 b5 9 a4 b4 10 Nd1 Nbd7 11 f5 d5 12 Bg5 dxe4 13 dxe4 Qb6 14 Bxf6 Ba6 15 Bc4 Bxc4 16 Qxc4 Nxf6 17 b3 Rad8 18 Qe2 Bd4 19 Rb1 Rd7 20 Nd2 Rfd8 21 Nc4 Qc5 22 g4 Bg1 23 Qg2 Bd4 24 Qf3 Bg1 25 Qg2 Bd4 26 h4 Ne8 27 Rh3 Nd6 28 Nxd6 Rxd6 29 Rd3 Bc3+ 30 Nxc3 Rxd3 31 cxd3 Qxc3+ 32 Qd2 Rxd3 33 Qxc3 Rxc3

34 Kd2 Kf8 35 g5 Ke7 36 h5 Rh3 37 g6 hxg6 38 hxg6 fxg6 39 fxg6 Rg3 40 Rc1 Kd6 41 Rh1 Rxg6 42 Rh8 Kc5 43 Ra8 Kd4 44 Rxa5 Rg2+ 45 Ke1 c5 46 Rb5 Rb2 47 Rb7 Rxb3 48 Rxg7 Ra3 49 Rd7+ Kxe4. ‘The game was prolonged many moves, and finally won by Black.’

Sources: St Louis Globe-Democrat, 30 November 1878 and (with annotations by Steinitz) The Field, 18 January 1879.

The third game, the brevity given in C.N. 7684, was played on 29 November and appeared in the St Louis Globe-Democrat,1 December 1878.

The final game:

George Henry Mackenzie – Max JuddSt Louis, 29 November 1878

Evans Gambit Declined

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 b4 Bb6 5 b5 Nce7 6 Nxe5 Nh6 7 d4 d6 8 Bxh6 dxe5 9 Bxg7 Qxd4 10 Qxd4 Bxd4 11 Bxh8 Bxa1

12 c3 Ng6 13 Bf6 a6 14 b6 cxb6 15 Kd2 b5 16 Bd5 b4 17 cxb4 Bd4 18 Rc1 Bb6 19 Na3 Nf4 20 Bxe5 Nxd5 21 exd5 Bxf2 22 Nc4 Bd7 23 Rf1 f6 24 Bxf6 Ba7 25 Nd6+ Kf8 26 Be5+ Kg8 27 Rf7 Ba4 28 Rg7+ Kf8 29 Rxh7 Rd8 30 Rh8+ Ke7 31 Nf5+ Kd7 32 Rh7+ Ke8 33 Ng7+ Resigns.

Sources: St Louis Globe-Democrat, 1 December 1878, reprinted in Turf, Field and Farm, 6 December 1878. It was also annotated in the Cincinnati Commercial, 18 December 1878.

7697. Water and poison

A number of websites continue to ascribe to Spielmann, rather than Mieses, the familiar ‘water and poison’ remark concerning Lasker, so it is worth recalling that C.N. 3161 (see pages 246-247 of Chess Facts and Fables) gave three quotes:

1) From an article by Mieses in the Berliner Tageblatt which was reproduced on page 16 of his San Sebastián, 1911 tournament book:

‘Laskers Stil ist klares Wasser mit einem Tropfen Gift darin, der es opalisieren lässt. Capablancas Stil ist vielleicht noch klarer, aber es fehlt der Tropfen Gift.’

2) The translation on pages xix-xx of the French edition of the book:

‘Le style de Lasker pourrait être comparé à de l’eau claire recevant une goutte de poison qui la rendrait opaline; le style de Capablanca est peut-être encore plus clair, mais il y manque la goutte de poison.’

3) An English version by J. du Mont on page 13 of H. Golombek’s book Capablanca’s Hundred Best Games of Chess (London, 1947):

‘Lasker’s style is clear water, but with a drop of poison which is clouding it. Capablanca’s style is perhaps still clearer, but it lacks that drop of poison.’

Chess Facts and Fables explained the misattribution to Spielmann by reproducing page 107 of Irving Chernev’s The Bright Side of Chess (Philadelphia, 1948):

In C.N. 3160 (see also C.N. 4156) we commented:

‘It is evident from other parts of that chapter of Chernev’s that when he gave, for instance, two unattributed quotations followed by an attributed one it was only the last of these that he intended to ascribe to the writer named. Thus in the extract reproduced above the “poison” quote has no more to do with Spielmann than does the “book, magician and machine” comment.’

C.N.s 3741, 4209 and 6714 provide examples of how the lay-out of that chapter of Chernev’s book caused other quotes to be misascribed (to Capablanca and Napier).

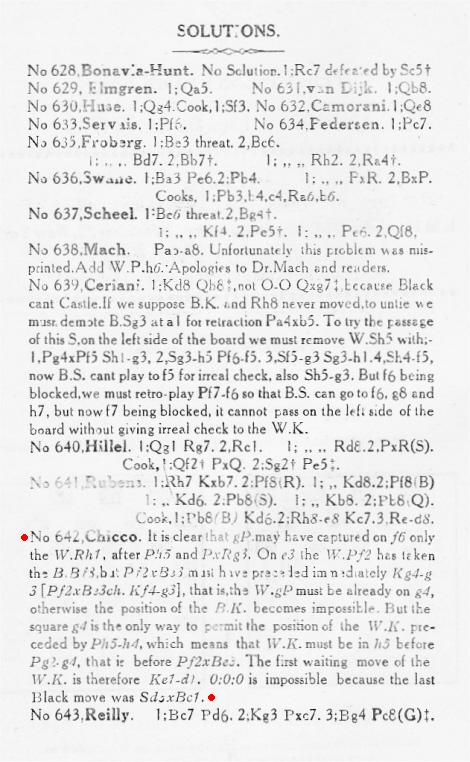

7698. First move by the white king (C.N. 7693)

Steven B. Dowd (Birmingham, AL, USA) has submitted the correct answer (White played Kd1). The problem is by Adriano Chicco, and we took it from page 17 of a work he co-authored with Giorgio Porreca, Dizionario enciclopedico degli scacchi (Milan, 1971). Before giving the full solution from that source, however, we wonder whether any reader has to hand the 1946 issue of The Chess Problem (Editor: R. McClure) in which, according to the Dizionario, the composition first appeared.

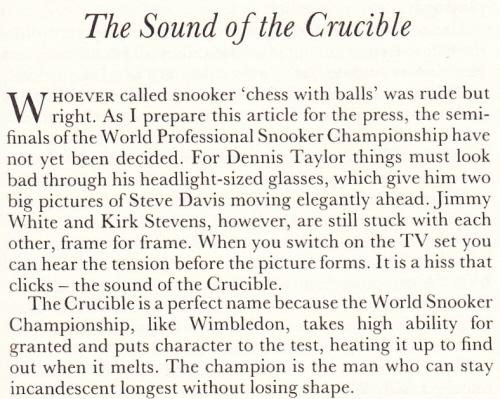

7699. Clive James and chess

In a feature in the Daily Telegraph of 22 June 2012 entitled ‘Clive James: 30 classic quotes’ the penultimate entry is:

‘Whoever called snooker “chess with balls” was rude but right.’

The remark is frequently cited on websites but not, from our reading, with any source specified. We therefore point out that it was the first sentence of an article about snooker, ‘The Sound of the Crucible’ on pages 285-288 of James’ book Snakecharmers in Texas (London, 1988 and 1989). The article was reproduced from page 8 of The Observer of 6 May 1984, although the newspaper did not include the first four sentences.

Clive James’ remarks on chess have been mentioned in C.N.s 16, 4117 and 5315, and here we add a further one, from his television review column on pages 26-27 of The Listener, 6 July 1972:

‘Frank Muir and Groucho Marx unforgivably clashed with Spassky and Bobby Fischer on the two BBC channels. Button-punching only resulted in Frank Muir asking Bobby Fischer questions about his film career. There was nothing for it but to go to bed with a book of end-games and dream through a long night in Capablanca. Groucho threatens White Queen, played by Margaret Dumont.’

Another inscribed item in our collection:

7700. Thirteenth labour

Alex Gorbounov (Cary, NC, USA) draws attention to the short story by Alexander Kazantsev Тринадцатый подвиг Геракла (‘The Thirteenth Labour of Hercules’) and asks whether it has ever been translated into other languages.

7701. First move by the white king (C.N.s 7693 & 7698)

From page 17 of the Dizionario enciclopedico degli

scacchi by A. Chicco and G. Porreca (Milan, 1971):

Alain Biénabe (Bordeaux, France) has kindly provided the following:

And from the 15 January 1947 issue:

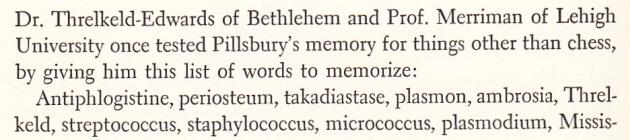

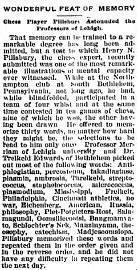

7702. Pillsbury and memory

Memory Feats of Chess Masters refers to the complex list of words which Pillsbury is said to have learned, as related, for instance, in this ‘once’ version on pages 106-107 of The Fireside Book of Chess by I. Chernev and F. Reinfeld (New York, 1949):

It has yet to be established when the list first appeared in print. As regards the individual words, Paul McKeown (Hayes, England) mentions an article dated 2002, ‘Piet Potgelter, Where Are You?’

That website is referred to on page 56 of Blindfold Chess by Eliot Hearst and John Knott (Jefferson, 2009), which indicates that the memory experiment was conducted by Dr Threlkeld-Edwards and Professor Merriman of Lehigh University before Pillsbury began a blindfold exhibition in Philadelphia. The book remarks too:

‘Understandably perhaps, some of these items are spelled differently in different sources. Also, the exact conditions under which Pillsbury was tested are not given consistently from source to source.’

We add that another ‘once’ version of the Pillsbury episode was supplied by Frank Rhoden on page 66 of the February 1971 Chess Life & Review:

‘His superb powers of memory made him one of the finest blindfold players ever. He was once tested by a psychologist, one Dr Maguire, before giving a 20-board simultaneous in Philadelphia. A report of this performance appeared in the Illinois Medical Journal of October 1914. Pillsbury was given a list of words to commit to memory ...’

After listing the words, Rhoden concluded:

‘Pillsbury scrutinized the list, polished off 20 opponents, and then repeated the words perfectly. For good measure, he then repeated the list backwards.’

If a reader has access to the Illinois Medical Journal we should like to see exactly what its October 1914 issue contained.

7703. Capablanca v Burde

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) has found an article by Hermann Helms on page 2 of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle of 9 June 1921 which includes the following:

‘In years to come, when someone other than Capablanca will undertake the labor of publishing a complete collection of the champion’s games, many an interesting score, treasured for years among the chess enthusiasts’ most prized possessions, will no doubt come to light. The Eagle is able to print today the details of a stubbornly fought game which Capablanca won in a western exhibition against H. Burde, one of the leading players in Clinton, Ia.

Mr Burde says that, after conclusion of play, Capablanca referred to it as a “good game”. The loser was particularly impressed by the fact that 11 of the Cuban’s moves were made with his king’s knight. “Capablanca’s knights”, he adds, “seem more erratic than anybody else’s”.’

The game-score given by Helms:

José Raúl Capablanca – H. BurdeOccasion?

Dutch Defence

1 d4 e6 2 c4 f5 3 Nc3 c6 4 Nf3 Bb4 5 Bg5 Qa5 6 Qc2 Nf6 7 Bxf6 gxf6 8 e3 d6 9 a3 Bxc3+ 10 bxc3 Nd7 11 Be2 Nf8 12 O-O Ng6

13 Ne1 Bd7 14 Bh5 Ke7 15 f4 Rhg8 16 Nd3 Rg7 17 c5 Qc7 18 c4 d5 19 cxd5 exd5 20 Rab1 Re8 21 Rb3 Kf8 22 Qf2 Bc8

23 Ne1 b6 24 Nf3 Re4 25 Bxg6 hxg6 26 cxb6 axb6 27 Rfb1 b5 28 Rc1 Qd7 29 Rbc3 Bb7 30 Nd2 Re8 31 Nb3 Qc7 32 Nc5 Ba8 33 Na6 Qd6 34 Nb4 Rc7 35 Qf3 Re4 36 Rc5 Ree7 37 R1c3 Kf7 38 Qf2 Ke6 39 Qc2 Kf7 40 Nxd5 Resigns.

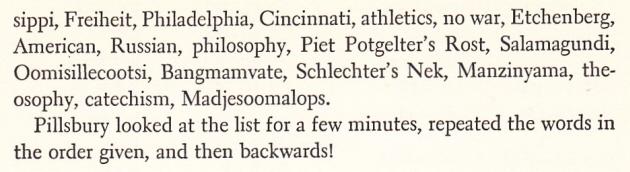

7704. Capablanca photograph

From page 29 of Famous Chess Players by Peter Morris Lerner (Minneapolis, 1973):

Despite also appearing on page 5, the year ‘1921’ is obviously wrong since Capablanca in the photograph is much younger. Moreover, the picture (uncropped) had been published on page 13 of Bohemia, 20 January 1918. The caption in the Cuban publication offered no date but stated that the simultaneous exhibition had been in Berlin.

7705. Politicking

An article by G.H. Diggle published in the March 1980 Newsflash and reprinted on page 55 of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984):

‘In the February Newsflash the Editor refers to the Olympic controversy and invites general comment on “politics and sport” with special reference to chess. The Badmaster, far too timorous and cagey a bird to accept such a gambit as this, will confine himself to recounting what actually took place when a boycott of a famous international chess tournament was attempted 130 years ago. In 1851 England, as the greatest nation in the world, staged the Great Exhibition, and Howard Staunton, as the greatest chessplayer in the world, proposed that England should be host country of the First International Chess Tourney. The conception of this idea was magnificent, and its execution by Staunton a tremendous feat, when travel was still so slow and inter-communication so poor. Yet the success of the tournament was jeopardized not only by these difficulties but by a boycott which, however, emanated not from outside countries’ dislike of Britain but from dislike in certain quarters of Staunton himself. For the great man, splendid chess leader as he was, possessed every quality except tact. His aggressive and overbearing personality had put him at variance with the wealthy and powerful London Chess Club. He himself was confidently expected to win the tournament, if it came off; and (as is now said of the Soviet Union) it was said by his enemies that his real object in organizing the event was to puff himself. Consequently, “the London” would have nothing to do with it; Harrwitz (their professional) did not compete; and out of the much-needed £550 raised in subscriptions by Staunton’s efforts, only two of their members subscribed (John Cochrane then in India and their venerable honorary member William Lewis). In the end seven foreign masters arrived and competed with nine Englishmen not all of their calibre, especially “Mr Mucklow, a player from the country never before even heard of” – his very name, indeed, suggesting a rustic crewyard. Before their boycott, the London Chess Club had toyed with the idea of getting the venue changed from the St George’s Club to their own; and after the tournament (in spite of the boycott) had run to its conclusion on 21 July 1851 they hastily arranged a rival tournament at their own club for foreign masters only, to which they invited Anderssen, Deacon, Harrwitz, Horwitz, Kieseritzky, Ehrmann, Meierhofer, Löwe and Szabo. Each player had to play one game with every other (the very first “American” tournament) but, rather stupidly, the Club offered one prize only (a gold cup valued at 100 guineas). This left no inducement to players who did badly at first to go on playing. Harrwitz, indeed, took flight after losing one game; Kieseritzky had already left London for Paris whither his invitation followed him; but when the luckless French master recrossed the Channel and again reached London, half the players had packed in and he only got three games, losing to Anderssen and Meierhofer and beating Szabo. Only about 20 games were played in all, and Anderssen alone played his full quota, winning the cup with a score of 8-0-1. To sum up, the boycott damaged but did not ruin Staunton’s tournament, and the rival tournament was a shambles. Will history repeat itself in 1980?’

7706. Tandem chess

Wanted: authoritative information on records for tandem (leap-frog) chess.

In 1986 (C.N. 1107) Dragoslav Andrić (Belgrade) informed us that he held, with Borislav Milić, the world record:

‘In the spring of 1950 at the Home of Culture in Novi Sad we played alternately in a simultaneous exhibition against 125 opponents, scoring 99½-25½ in only five hours.’

7707. Men of the Time

Following J. Löwenthal’s death, page 69 of the Westminster Papers of 1 August 1876 referred to autobiographical information provided by the master to Men of the Time. Below we reproduce his full entry on page 665 of the ninth edition of that book, which was by Thompson Cooper and was published in London in 1875:

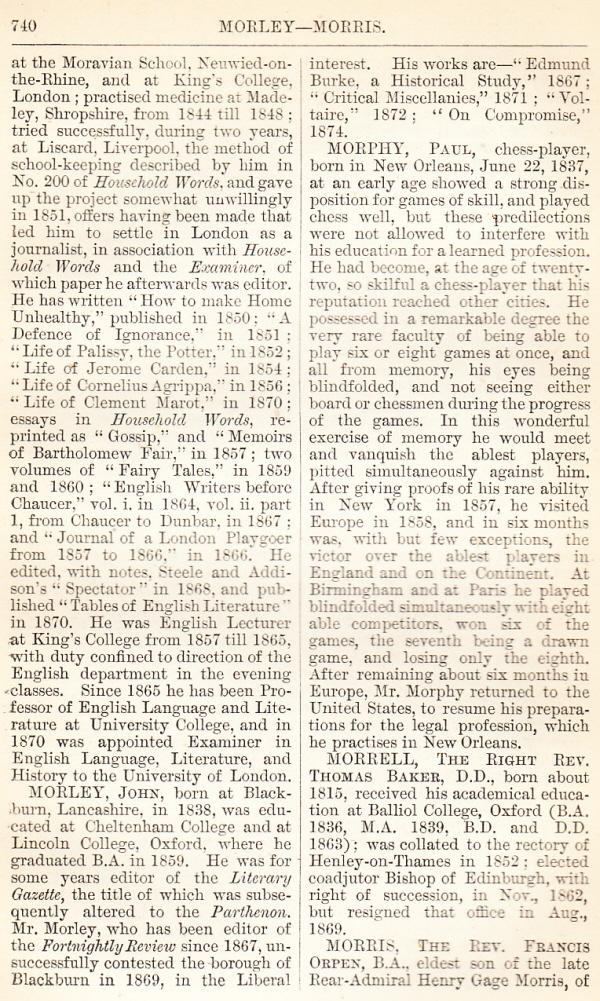

The entry for Morphy on page 740:

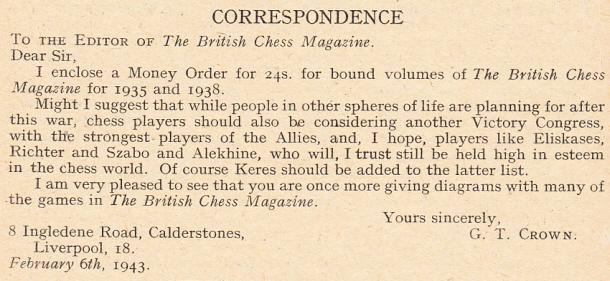

7708. A letter from Gordon Crown

This letter was written when Crown was aged 13:

Source: BCM, March 1943, page 56.

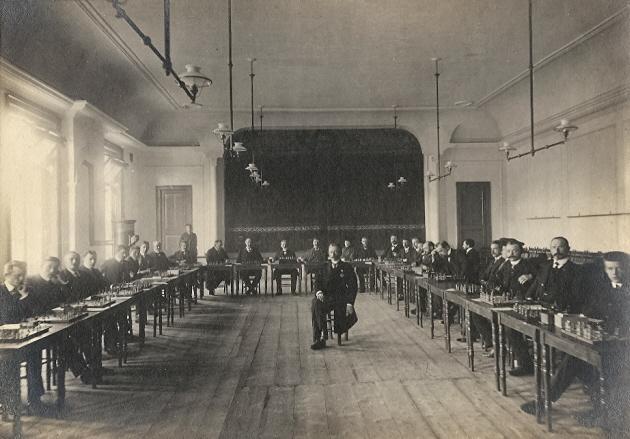

7709. Simultaneous exhibition

Wanted: information about the photograph below, which is owned by Jan Koppenaal (Noordwijkerhout, the Netherlands):

7710. Pillsbury and memory (C.N. 7702)

Richard Reich (Fitchburg, WI, USA) has supplied the requested article, ‘Mental States in Famous Chess Players’ by Louis Miller, published on pages 414-418 of the Illinois Medical Journal, October 1914.

It will be noted that the article, which has a number of obvious factual errors, mentions Pillsbury’s memorization of words on page 415, but without any list.

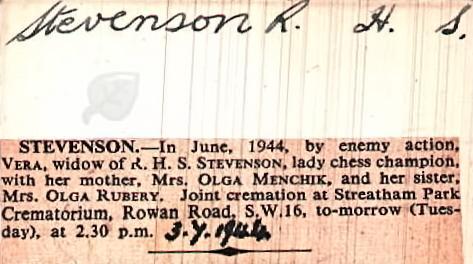

7711. Vera Menchik

Leonard Barden (London) recently raised with us the

subject of Vera Menchik’s death, asking, in particular,

whether references could be found to her burial or

cremation. We are grateful to Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore)

for making a search which revealed this record in the Andrews

Index:

On the basis of the above information Mr Barden then informed us:

‘I contacted the Streatham Park Crematorium, which confirmed that Vera Menchik Stevenson, her mother and her sister were cremated on 4 July 1944 and that their ashes were scattered at a garden of remembrance, whose reference location is known. Whether that is precise enough for a memorial to be considered is arguable. Their house in Gauden Road, London was destroyed, and the policy of English Heritage, even if it could be interested, is to put plaques only where the original building still stands.’

7712. Steinitz v von Bardeleben (C.N. 7638)

From Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA) comes this item on page 13 of the Newark Sunday Call, 22 September 1895:

7713. Pillsbury and memory (C.N.s 7702 & 7710)

Jerry Spinrad has also found the following report on

page 3 of the Littleton Independent of 14

December 1900:

It is not possible to present a larger version here, but, loupe à l’appui, it will be seen that the memory display is said to have taken place ‘recently’ at the Northampton Club in South Bethlehem, Pennsylvania.

Our correspondent adds that the following day the same account appeared on page 3 of another Colorado newspaper, the Eagle County Times.

| First column | << previous | Archives [95] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.