Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [94] | next >> | Current column |

7636. Sculpture (C.N. 7614)

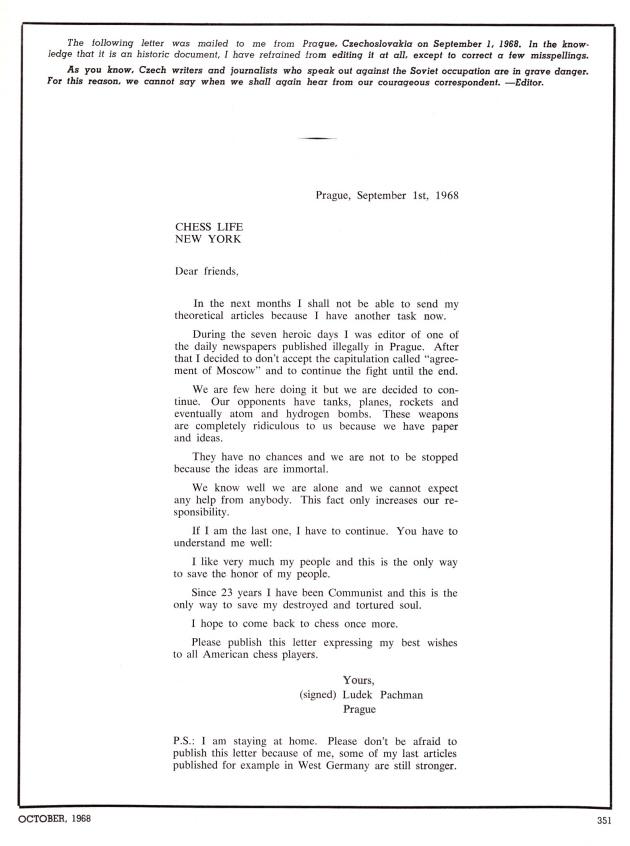

The position provided by Michael McDowell for David Goode’s sculpture was the composition by Stamma on page 269 of Praktische Sammlung bester und höchst interessanter Schachspiel-Probleme by A. Alexandre (Leipzig, 1846):

7637. Seconds

From page 320 of the October 1866 Chess Player’s Magazine:

‘Not having been furnished till recently with the names of the seconds and umpire in the late match between Anderssen and Steinitz, we were unable to state that Messrs Staunton and Hewitt acted as seconds for the former, and Messrs Strode and Boden for the latter. Earl Dartry [sic – Dartrey] was the umpire.’

7638. Steinitz v von Bardeleben

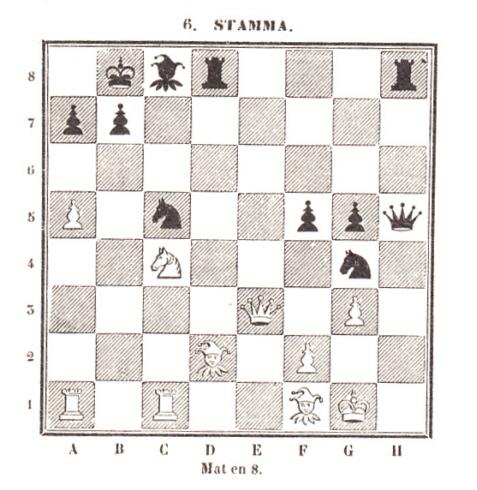

Concerning Steinitz v von Bardeleben (Hastings, 1895) Olimpiu G. Urcan sends this cutting from page 2 of the 8 September 1900 edition of the Newcastle Weekly Courant:

What is the source of the claimed dialogue?

7639. Steinitz and 1 d4

A question from Mr Urcan is thrown open to readers:

‘Is it possible to establish, with reliable historical sources, the first known occasion when Steinitz played 1 d4?’

7640. Veteranitis

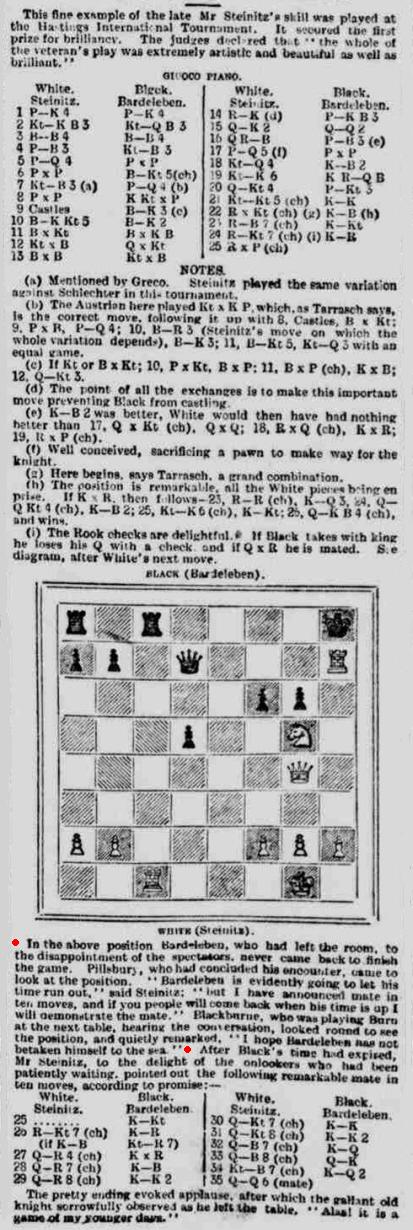

From page 148 of the April 1929 Chess Amateur:

7641. King’s-side attack

From the same issue of the Chess Amateur (pages 153-154) comes this game played at the Liverpool Chess Club:

Frederick Dewhurst Yates – Allies (‘members of the Liverpool Chess Club consulting’)Liverpool, 1929 (?)

Queen’s Gambit Declined

1 d4 d5 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 Nbd7 5 e3 Be7 6 Nf3 O-O 7 Rc1 c6 8 a3 Ne4 9 Bf4 Nxc3 10 Rxc3 Nf6 11 Bd3 dxc4 12 Rxc4 Qa5+ 13 Nd2 b6 14 O-O Bb7 15 Be5 Qd5 16 e4 Qd7 17 Rc3 Ne8 18 Bc4 Bf6 19 Bxf6 Nxf6

20 e5 Nd5 21 Rg3 Ne7 22 Ne4 Ng6 23 Ng5 Rfd8 24 Qh5 Nf8 25 Nxh7 Nxh7 26 Qh6 g6 27 Rh3 Qe8 28 Qxh7+ Kf8 29 Qh4 Resigns.

Are further details available?

7642. Alekhine in Paris, 1941 (C.N.s 7629 & 7634)

Peter Anderberg (Harmstorf, Germany) notes that the first page of the Lower Saxony supplement to the February 1993 issue of Rochade Europa had a second photograph of Alekhine’s simultaneous exhibition:

7643. For solving

White to move

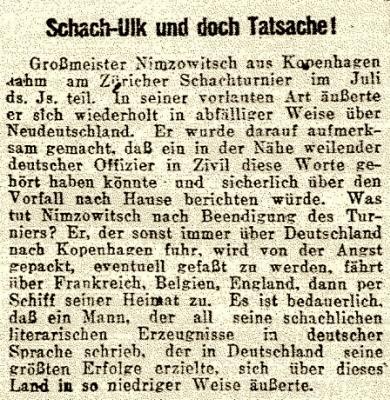

7644. From Zurich to Copenhagen

From Thomas Niessen (Aachen, Germany) comes an item in the chess column of the Aachener Anzeiger/Politisches Tageblatt of 7 September 1934. It states that after that year’s Zurich tournament Nimzowitsch travelled home to Copenhagen via France, Belgium and England, instead of through Germany, because he feared that the German authorities might be aware of negative remarks that he had made about ‘Neudeutschland’ during the tournament:

7645. ‘The Mozart of chess’

Page 317 of People (London, 1954)

Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) enquires about the

origins of a nickname given to Capablanca, ‘The Mozart of

chess’, and wonders when it was first used. We plan to

revert to that matter later on, and readers’ assistance

with citations will be welcomed. Firstly, though, we would

point out that the term has been applied to many masters.

Some examples:

- Paul Morphy:

‘Morphy was the Mozart of chess.’

Page 228 of the Columbia Chess Chronicle, 29 December 1888 (article by G.H.D. Gossip).

Page 305 of the August-September 1884 BCM had stated: ‘What Mozart, as to innate, natural ability, was to music, Morphy likewise was to chess.’

- Emanuel Lasker:

‘The Mozart of chess’

Page 45 of White King and Red Queen by D. Johnson (London, 2007).

- Mikhail Tal:

‘El Mozart del ajedrez’

Page 113 of El campeonato mundial de ajedrez by E. Gufeld and E.M. Lazarev (Barcelona, 2003).

- Boris Spassky:

‘Spassky has been called the Mozart of chess.’

Page 65 of Bobby Fischer Goes to War by D. Edmonds and J. Eidinow (London, 2004).

- Bobby Fischer:

‘Fourteen-Year-Old “Mozart of Chess”’

Page SM38 of the New York Times, 23 February 1958 (article by H.C. Schonberg – see C.N. 5491). Schonberg referred to Capablanca as ‘the Mozart of chess’ on page 181 of Grandmasters of Chess (Philadelphia and New York, 1973).

- Anatoly Karpov:

‘He is the Mozart of the chessboard ...’

Page 21 of Karpov-Korchnoi 1978 by R. Keene (London, 1978).

- Magnus Carlsen:

‘In January 2004, I called Magnus Carlsen the Mozart of chess for the first time. It was a spontaneous, last-minute decision to meet a deadline for my column in the Washington Post. The name was picked up immediately and spread around quickly. It was used, misused, overused.’

Lubomir Kavalek, article dated 23 February 2012.

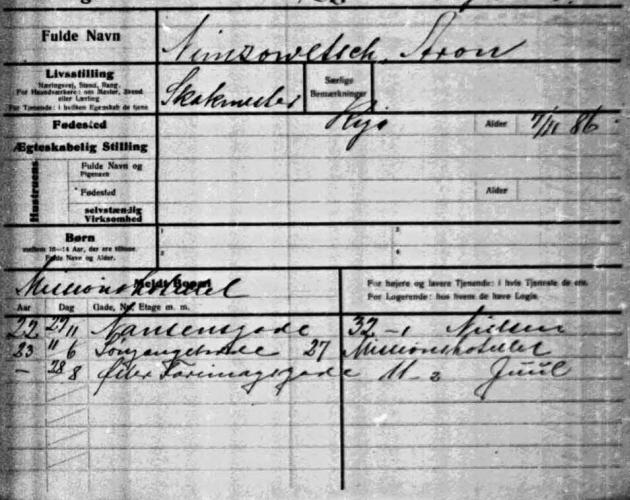

7646. Nimzowitsch in Copenhagen (C.N.

4307)

Philippe Kesmaecker (Maintenon, France) has found the above document at the Danish Politietsregisterblade website.

Per Skjoldager (Fredericia, Denmark), the co-author of a forthcoming book on Nimzowitsch (see C.N.s 7108 and 7310), informs us:

‘This record is of great importance. It shows the dates when Nimzowitsch registered his arrival with the Danish police and specifies:

- Full name: Aron Nimzowitsch. Occupation: chess master. Born in Riga on 7 November 1886.

- On 29 November 1922 he moved to Nansensgade 32, first floor, his landlord being named Nielsen.

- On 11 June 1923 he moved to the Missionshotellet (Missionary Hotel) at Løngangstræde 27.

- On 28 August 1923 he moved to Øster Farimagsgade 11, second floor, where his landlady was Miss Juul.’

Mr Skjoldager has provided two photographs:

Nansensgade 32 is on the left of the Café Stjernen

Øster Farimagsgade 11 is on the right, behind the pedestrian.

7647. The Italics are Mine (C.N. 5415)

John Roycroft (London) sends this passage from pages 35-36 of The Italics are Mine by Nina Berberova (London, 1969), an autobiographical work translated from the Russian by Philippe Radley:

‘... I remember one of my dreams about Dostoevsky. I am playing chess with someone. There are many people in the room. Dostoevsky stands near me and looks attentively at the board. And I say to him, “Well, Fedor Mikhailovich, in chess you can foresee everything and allow for it. If we move here, then all 25 or 35 moves to the very end of the game are foreordained and known beforehand. If we move there, a whole chain of causalities again unfolds, a chain from which there is no escape. But in human life even you cannot foresee what will happen. You can be given a heap of data about two people and you will still not be able to tell us today what they, either together or alone, will do tomorrow. The law of cause and effect is not operative when you talk about men.”

He smiles, squints with one eye, is silent for about a minute, and then says:

“Yes, very likely this is so. Twenty-five or 35 moves you can, of course, foresee, but only on the condition that the ceiling does not collapse during the game and that one of the players does not die of a stroke. If this happens, then chess becomes like life, it moves into a dimension where there are neither social nor biological laws, nor the possibility for the smartest mind to figure out the ‘pattern’ of the future.”

“What! No social or biological laws? Is there really such a place on earth?”

“In the meeting of two people and in man’s creativity”, he answers. “There these laws are not operative.”

I see my opponent take my pawn. Suddenly I notice that Dostoevsky has small, exquisite, well-cared-for hands.’

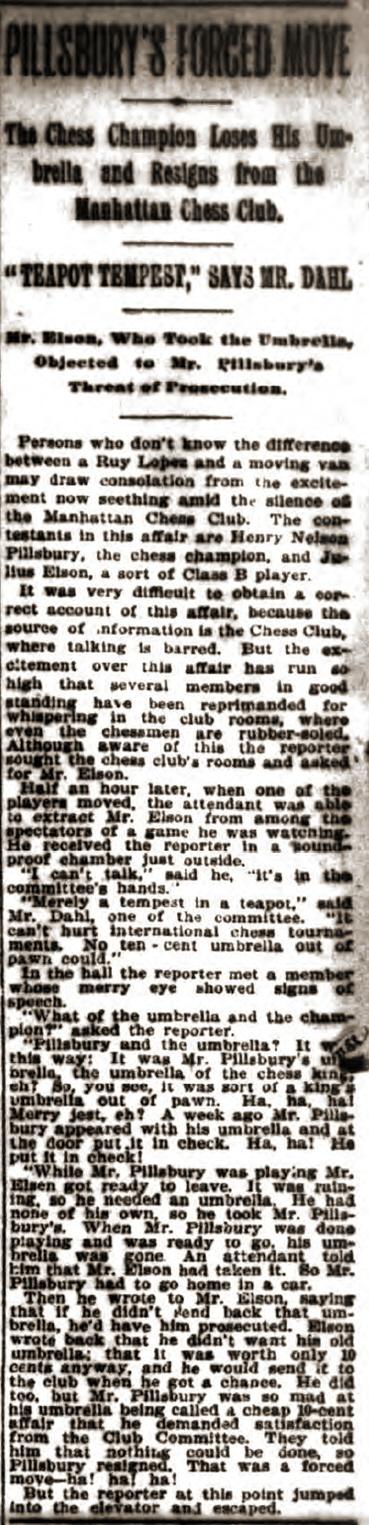

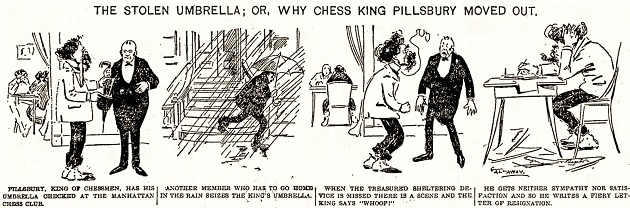

7648. Pillsbury’s umbrella (C.N. 5209)

From Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) come a report and a cartoon published on page 4 of The World (New York), 20 June 1896:

7649. Monte Carlo, 1902 (C.N. 7159)

Mr Urcan has also submitted this photograph taken at Monte Carlo in 1902, from Caras y Caretas, 26 April 1902:

A copy of better quality is sought.

7650. Aphorisms and observations

C.N. 775 gave, from James J. Walsh (Dublin), a selection of aphorisms and observations on the game:

- Rook endings a pawn up are generally drawn – but rook endings a pawn down are usually lost.

- The most attractive combinations are usually just one tempo short of being sound.

- The popular press believes that chess congresses are composed exclusively of child prodigies and octogenarians.

- Players indicate an increasing maturity at the game by not automatically making the en passant capture.

- Players with the greatest theoretical opening knowledge are most likely to get into time-trouble.

- The weakest players in a tournament are generally first to enquire about the prizes.

- Annotations attempt to prove that a game had only one logical sequence.

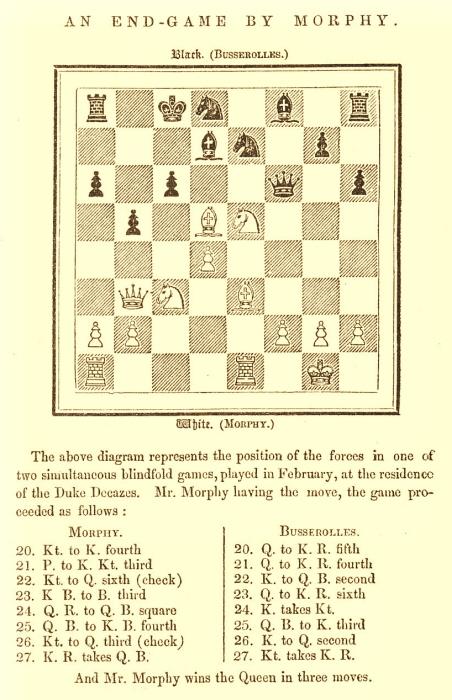

7651. Morphy positions (C.N. 7408)

Further to the reference in C.N. 7408 to an alleged Morphy position against Bousserolle, Bonserolle or Bousserolles, we add that the conclusion of a different game (against Busserolles) was published on page 129 of the April 1859 Chess Monthly:

Page 132 of the same issue had the following regarding Morphy:

‘The Duke Decazes had given him a dinner, at which a number of grave senators and warlike generals assembled to do honor to the young hero. Mr Morphy, at the request of the company, played two simultaneous blindfold games and took part, at the same time, in an animated conversation.’

7652. Lipschütz’s death in Hamburg

From page 208 of the July-August 1906 Wiener Schachzeitung:

‘S. Lipschütz, der bekannte amerikanische Schachmeister, ist Ende November 1905 im Hamburger Krankenhause im Alter von 42 Jahren gestorben. Seine Leiche wurde im Hamburger Krematorium verbrannt.’

Is it really impossible to find anything about Lipschütz (and, in particular, his forename) in archives or other reference sources in Hamburg?

7653. Steinitz and 1 d4 (C.N. 7639)

The question raised in C.N. 7639 was when Steinitz first played 1 d4.

Roland Kensdale (Aberdeen, Scotland) notes the move in Steinitz’s tenth match-game against Zukertort (London, 31 August 1872). The opening 1 d4 f5 2 g3 recurred in the twelfth game. (Westminster Papers, 1 October 1872, page 85.)

Our correspondent also points out Steinitz v Jeney, Vienna, 4 September 1860, which opened 1 c4 e6 2 Nc3 d5 3 e3 Nf6 4 Nf3 Nc6 5 d4. See, for instance, page 383 of volume one of Schachmeister Steinitz by L. Bachmann (Ansbach, 1925).

Finally, Mr Kensdale remarks, a game between Steinitz and Healey (London, 1864), played at king’s knight’s odds, began 1 d4 d5 2 c4 c6. It is on page 88 of the Bachmann book.

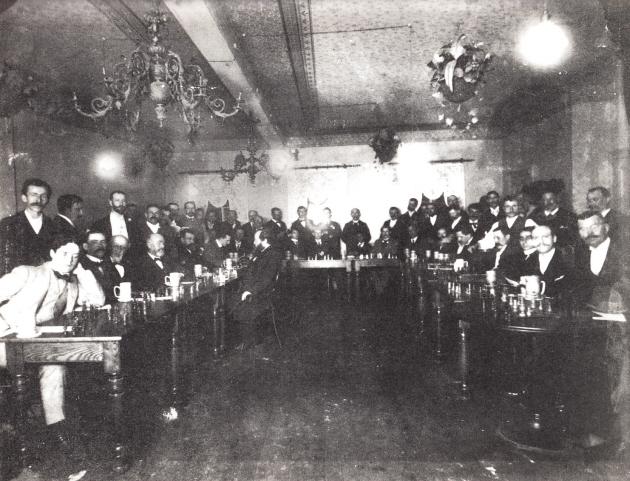

7654. Steinitz photographs

Below are two photographs which appeared, courtesy of David Lawson, on pages 31 and 82 respectively of the Weltgeschichte des Schachs volume on Steinitz by D. Hooper (Hamburg, 1968):

‘Steinitz beim Simultan-Spiel mit 18 Teilnehmern (Hamburg, 1896?)’

7655. Translating Fischer

C.N. 867 (see page 149 of Chess Explorations) noted the flavourless and inaccurate French translation (by Parviz M. Abolgassemi) in Fischer’s Mes 60 meilleures parties (Paris, 1972). The examples given were:

- ‘Once again, time-pressure had Sherwin burying his thumbs in his ears.’ ‘Une fois de plus à court de temps, Sherwin ne veut rien entendre.’ (Game 1)

- ‘Alekhine said, in his prime, ...’ ‘Alékhine disait, au début de sa carrière ...’ (Game 8)

- ‘A good last-ditch try.’ ‘Un excellent coup.’ (Game 16)

- ‘I was informed that Gligorich thought I had blundered a Pawn ...’ ‘Je savais que Gligoric pensait que je m’étais trompé, ...’ (Game 30)

- ‘Relieving the suspense.’ ‘Gardant le suspense.’ (Game 60).

C.N. 867 was published in 1984. Just over a decade later Editions Editéchecs, Paris reissued Fischer’s book, without any attempt to correct the translation.

7656. Najdorf v Che Guevara (C.N.s 4803 & 4809)

Mike Salter (Sydney, Australia) notes that whereas a 16-move draw between Najdorf and Che Guevara at a simultaneous exhibition in Havana in 1962 has been given, an unsourced quote on page 44 of Najdorf: Life and Games by T. Lissowski and A. Mikhalchishin (London, 2005) has Najdorf claiming that he won on that occasion, after refusing a draw because he wanted revenge for a loss to Che Guevara in a display at Mar del Plata in 1947.

How is the discrepancy to be explained?

7657. Lipschütz’s death in Hamburg (C.N. 7652)

From Stephen Davies (Kallista, Australia) comes the registration of Lipschütz’s death, which has been found for him by Mr Ralf Stullich of the website beyond-history.com:

Below is the translation by Mr Stullich:

‘No. 2652

Hamburg, 1 December 1905

Before the undersigned registrar there appeared today, personally known, the deaconess, Sister Anna Johanna Siegrist, residing in Hamburg, at Martinistrasse 46, and reported that Salomon Lipschütz, insurance agent, 42 years and 4 months old, no religion, residing in Hamburg at the address mentioned, born in Ungvaa [sic] in Hungary, on 4 July 1863, unmarried, son of Nathan Lipschütz, residing in New York (profession unknown), and his wife Sallie Nebenzahl, deceased in Hungary, died in the Bethanien Hospital on 30 November in the year 1905 in the afternoon at one p.m, as she, the reporting person, reported from her own knowledge.

Read out, accepted and signed

Johanna Siegrist

The Registrar [signature].’

7658. Capablanca

v Lasker footage

Further to this well-known photograph

of Capablanca and Lasker in Moscow in 1925 (see, for

instance, page 310 of Chess Facts and Fables),

Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) notes a brief

sequence of moving pictures of the two champions (at

about 15:40:40). [Addition on 16 November 2012: the

material is no longer available at the link indicated.]

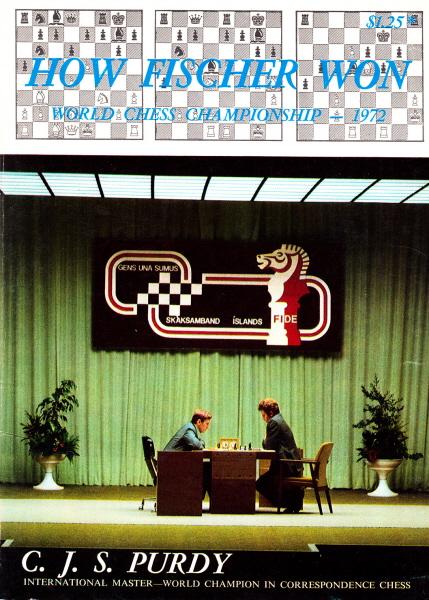

7659. Freud on Spassky v Fischer

C.N. 6081 gave a photograph of Clement Freud presenting a cheque to Robert Bellin, the winner of the London Chess Congress in Islington in December 1972.

Earlier that year, as mentioned on page 222 of Profile of a Prodigy by Frank Brady (New York, 1973), Clement Freud went to Reykjavik for the Spassky v Fischer world championship match. We note that an article by him, ‘A week of waiting for P-Q4’, was published in the Financial Times of 8 July 1972 and reproduced on pages 161-166 of the posthumous anthology A feast of Freud (London, 2009). Some snippets:

- ‘To attempt to be rational about an event as sensationally irrational as the world chess championship of 1972 is no easy matter. The fact is that for five long days officials, players, observers and prospective cash customers have been so bemused by the human tantrums and quirks of fate surrounding the match – or, to be strictly accurate, non-match – that the basic truth escapes them: a brace of players are about to compete for a prestigious title and a lot of money.

If you consider that in the course of seven days God created the universe, it is pretty shameful that in 80% of that time the World Chess Federation, though urged on by a fair section of the world, was unable to bring two men around one chess board. Yet such was the case.’

- ‘There were also contributing factors, like the presence of so large a section of media men that players and officials behaved like prima donnas instead of people. Like the niceness of the Icelandic nationals who, had they acted with the violence of their forebears, would have had the men sitting down and pushing rooks at each other last Tuesday.’

- ‘The reasons, or rather the timing, of the intended walkout [by the Soviets] were obscure and irrational, having about them the insane logic of a man waiting for a delayed train to come into the station before complaining to the railways board that it is too late. “Why did you not complain earlier?”, we asked the Russians over and over again. “How can we complain that he is late when we don’t know when he will come?”, they replied.’

- ‘On the stage behind the chess table there was a drape on which was painted a black knight, a few squares from a chess board, the legend gens una sumus ... the whole decorated by a drawing of what appeared to be a huge devious sardine-can opener.’

- ‘Suddenly, at 8.46, they appeared on the stage, and to our amazement they were nice ordinary pleasant-looking soberly-dressed young men.

We had expected Fischer to come loping out of a corner on all fours, frothing at the mouth, bandages hiding the wounds from which surgeons had extracted his horns. He turned out to be a lean, gangling, engaging man wearing an uncontroversial green suit and matching tie.’

We have seen no references to chess in Clement Freud’s autobiography Freud Ego (London, 2001).

Clement Freud’s signature in our copy of Freud Ego.

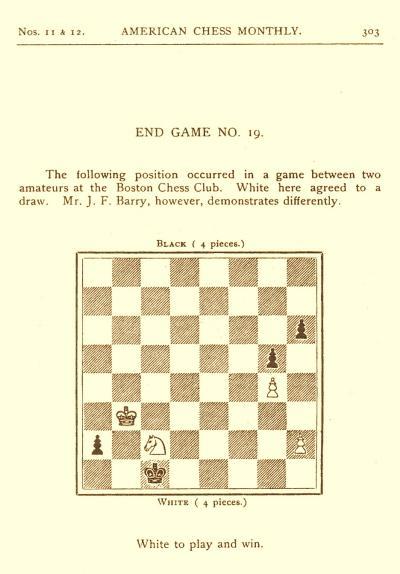

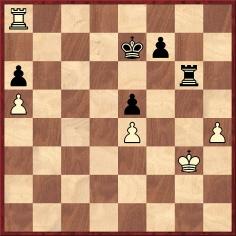

7660. For solving (C.N. 7643)

White to move

Steven B. Dowd (Birmingham, AL, USA) comments that there are two winning moves, 1 h3 and 1 Kc3.

We took the position from page 303 of the American Chess Monthly, September-October 1893:

Since that was the last issue of the Monthly, no solution was published.

Harold van der Heijden’s Endgame study database III gives the position as a composition by ‘unknown’, from the American Chess Monthly of 1926. The solution appears as 1 h3 Kb1 2 Na1 Kxa1 3 Kc2, with the cook 1 Kc3 Kb1 2 Na1 Kxa1 3 Kc2.

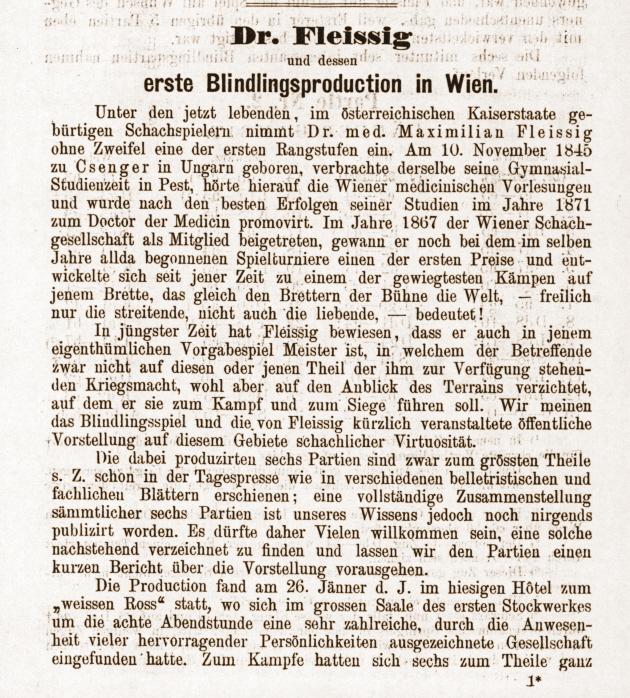

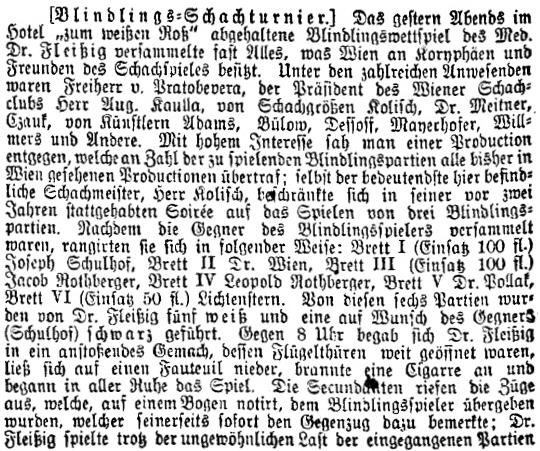

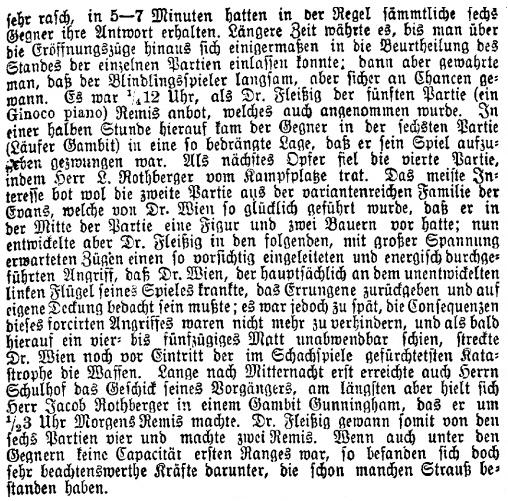

7661. Max Fleissig blindfold display (C.N. 7608)

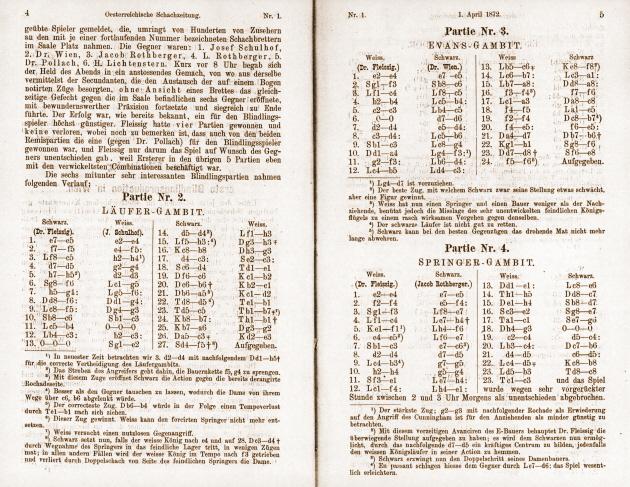

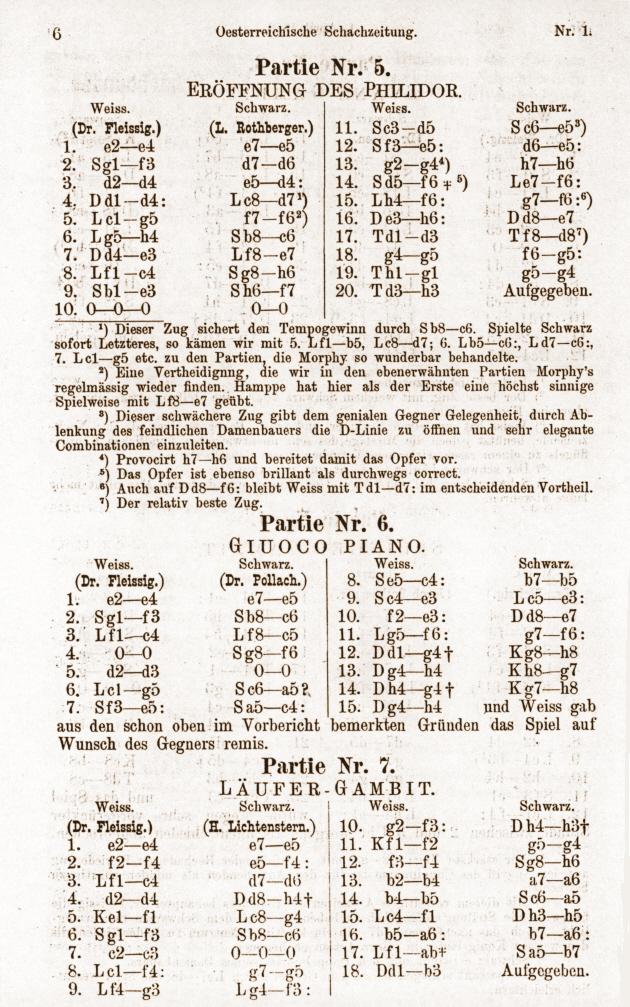

Peter Anderberg (Harmstorf, Germany) adds that all six games in the exhibition were published in the report on pages 3-6 of the Oesterreichische Schachzeitung, 1 April 1872:

Below are the five games not given in C.N. 7608:

Max Fleissig – Josef SchulhofVienna, 26-27 January 1872

King’s Gambit Accepted

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Bc4 h5 4 d4 g5 5 h4 d6 6 Nf3 Bg4 7 hxg5 Bxf3 8 Qxf3 Qxg5 9 Bxf4 Qg6 10 Nc3 Nc6 11 Bb5 O-O-O 12 Bxc6 bxc6 13 O-O-O Ne7 14 d5 Bh6 15 Bxh6 Qxh6+ 16 Kb1 Qg6 17 dxc6 Nxc6 18 Nd5 Rde8 19 Qc3 Kb7 20 Qb3+ Kc8 21 Qa4 Kd7

22 Rd4 Rb8 23 Rc4 Rxb2+ 24 Kxb2 Rb8+ 25 Ka3 Qg7 26 Qxc6+ Ke6 27 Nf4+ Resigns.

Max Fleissig – WienVienna, 26-27 January 1872

Evans Gambit Accepted

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 b4 Bxb4 5 c3 Bc5 6 O-O d6 7 d4 exd4 8 cxd4 Bb6 9 Nc3 Bg4 10 Qa4 Bxf3 11 gxf3 Bxd4

12 Bb5 Bxc3 13 Bxc6+ Kf8 14 Bxb7 Bxa1 15 Bxa8 Qxa8 16 f4 f6 17 Ba3 Qc8 18 f5 Be5 19 f4 Qb7 20 fxe5 fxe5 21 Qd7 Qb6+ 22 Kh1 Nf6 23 Qd8+ Ne8 24 f6 Resigns.

Max Fleissig – Jacob RothbergerVienna, 26-27 January 1872

King’s Gambit Accepted

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 Be7 4 Bc4 Bh4+ 5 Kf1 Bf6 6 e5 Be7 7 Nc3 c6 8 d4 d5 9 Bb3 g5 10 h4 g4 11 Ne1 Bxh4 12 Bxf4 Bxe1 13 Qxe1 Be6 14 Rh5 Qc7 15 Qh4 Nd7 16 Ne2 Ne7

17 Rc1 Ng6 18 Qg3 O-O-O 19 c4 dxc4 20 Bxc4 Qb6 21 d5 cxd5 22 Bxd5+ Kb8 23 Bb3 Rc8 24 Rc3 Drawn.

Max Fleissig – PollachVienna, 26-27 January 1872

Giuoco Piano

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 O-O Nf6 5 d3 O-O 6 Bg5 Na5 7 Nxe5 Nxc4 8 Nxc4 b5 9 Ne3 Bxe3 10 fxe3 Qe7 11 Bxf6 gxf6 12 Qg4+ Kh8 13 Qh4 Kg7 14 Qg4+ Kh8 15 Qh4 Drawn.

Max Fleissig – H. Lichtenstern

Vienna, 26-27 January 1872

King’s Gambit Accepted

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Bc4 d6 4 d4 Qh4+ 5 Kf1 Bg4 6 Nf3 Nc6 7 c3 O-O-O 8 Bxf4 g5 9 Bg3 Bxf3 10 gxf3 Qh3+ 11 Kf2 g4 12 f4 Nh6

13 b4 a6 14 b5 Na5 15 Bf1 Qh5 16 bxa6 bxa6 17 Bxa6+ Nb7 18 Qb3 Resigns.

7662. The Mozart of chess (C.N. 7645)

We have yet to find Capablanca being described during

his lifetime as ‘the Mozart of chess’. As regards other

comparisons, Thomas Niessen (Aachen, Germany) supplies

the following:

‘Loyd’s problems constantly remind us of Mozart’s music: there is the same lack of everything commonplace, forced or manufactured; the same feeling, within us, that these productions, as it were, composed themselves.’

Source: Dubuque Chess Journal, September 1875, page 363.

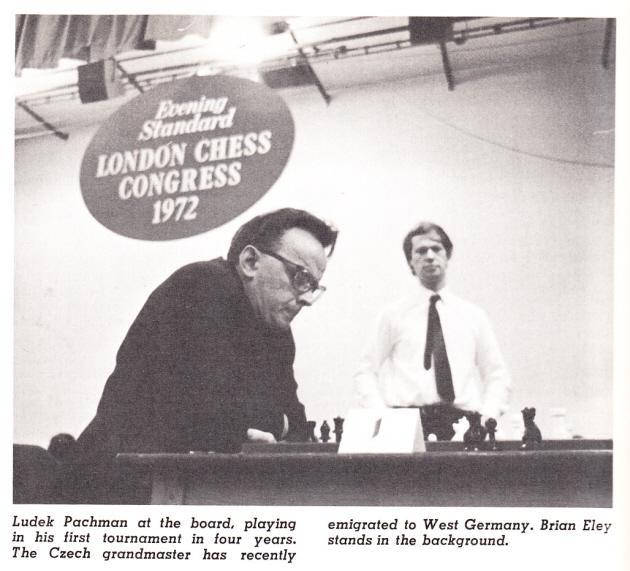

7663. London, 1972 (C.N.s 6081 & 7659)

From page 190 of the April 1973 Chess Life & Review:

The magazine stated that the photograph was taken after Pachman had played 14...b5. Eley won the game in 24 moves and annotated it on pages 266-268 of the June 1973 BCM.

7664. Lasker in Baltimore

Alan Smith (Manchester, England) has found these games, played in a simultaneous exhibition, in the Baltimore American of 9 June 1901 and 16 June 1901:

Emanuel Lasker – A.W. SchofieldBaltimore, 30 May 1901

Evans Gambit Accepted

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 b4 Bxb4 5 c3 Bc5 6 d4 exd4 7 cxd4 Bb6 8 O-O d6 9 Bg5 f6 10 Bf4 Na5 11 Nc3 Nxc4 12 Qa4+ Bd7 13 Qxc4 Ne7 14 a4 a5 15 Rab1 Ng6 16 Bg3 Bg4 17 Nd2 Qd7 18 f4 Qf7 19 Qxf7+ Kxf7

20 Rxb6 cxb6 21 f5 Ne7 22 h3 Rhc8 23 Nb5 Rc2 24 Nxd6+ Kg8 25 Bf4 Be2 26 Re1 Ba6 27 Nf3 Nc6 28 g4 Nb4 29 Rc1 Rxc1+ 30 Bxc1 Rd8 31 Bf4 Nd3 32 Bg3 Nb2 33 e5 Nc4 34 Ne4 fxe5 35 dxe5 b5 36 e6 bxa4 37 f6 gxf6 38 Nxf6+ Kg7 39 e7 Rd1+ 40 Kf2 Bb5 41 e8(Q) Bxe8 42 Nxe8+ Kf7 43 Nc7 a3 44 Ne5+ Nxe5 45 Bxe5 a2 46 Kf3 a1(Q) 47 Bxa1 Rxa1 48 Ke4 Rc1 49 Nb5 Rc6 50 g5 a4 51 h4 Kg6 52 White resigns.

Emanuel Lasker – E.B. AdamsBaltimore, 30 May 1901

Evans Gambit Accepted

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 b4 Bxb4 5 c3 Bc5 6 d4 Bb6 7 dxe5 a6 8 Qd5 Qe7 9 Ba3 Qe6 10 Bb3 Nge7 11 Qd1 Qg6 12 O-O Qh5 13 Nbd2 Nxe5 14 Nxe5 Qxe5 15 Nc4 Qf6 16 e5 Qg6 17 Qf3 Ba7 18 Rfe1 Nf5 19 Re4 h5 20 Rf4 Nh6 21 Re1 Ng4

22 Rxf7 Bxf2+ 23 Kh1 c5 24 e6 dxe6 25 Nd6+ Kd8 26 Rd1 Bd4

27 Bxc5 Nf2+ 28 Qxf2 Bxf2 29 Nxb7+ Ke8 30 Rf8+ Rxf8 31 Rd8+ Kf7 32 Rxf8 mate.

Emanuel Lasker – J. Ross DiggsBaltimore, 30 May 1901

French Defence

1 e4 e6 2 d4 d6 3 Nc3 c6 4 Nf3 Be7 5 Bd3 Bd7 6 O-O Qc7 7 Bf4 Nf6 8 h3 h6 9 Re1 a6 10 Ne2 b5 11 a4 b4 12 a5 c5 13 dxc5 Qxc5 14 Be3 Qc8 15 Qd2 Nc6 16 Ned4 Ne5 17 Qxb4 d5 18 Qd2 Nxf3+ 19 gxf3 e5

20 exd5 Nxd5 21 Nf5 Bxf5 22 Bxf5 Qxf5 23 Qxd5 O-O 24 Kh2 Qxc2 25 Rg1 Bf6 26 Bxh6 Rfd8 27 Qe4 Qxe4 28 fxe4 Rac8 29 Rg2 Rc2 30 Bxg7 Bxg7 31 Rag1 Rdd2 32 Rxg7+ Kf8 33 R1g2 Rxb2 34 Rg8+ Ke7 35 Ra8 Rxf2 36 Rxf2 Rxf2+ 37 Kg3 Rf6 38 h4 Rg6+

39 Kh3 Rc6 40 h5 Rf6 41 Kh4 Rf4+ 42 Kg5 Rf6 43 h6 Resigns.

7665. Lasker on chess prodigies

Olimpiu G. Urcan has forwarded an article ‘Lasker Explains Chess Prodigies’ by William Weer on page 6 of the Sunday Eagle Magazine (Brooklyn), 16 May 1926:

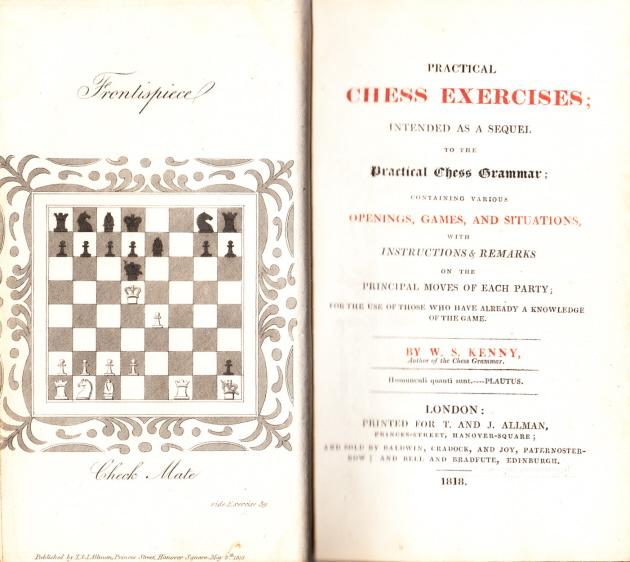

7666. Advice on castling (C.N. 7578)

From page 2 of Practical Chess Exercises by W.S. Kenny (London, 1818) comes this rule:

‘Not to castle, except when necessary, because the move is often lost by it.’

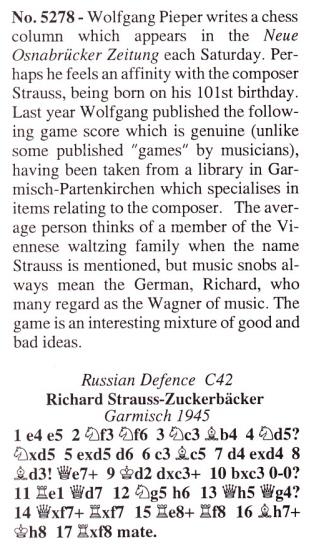

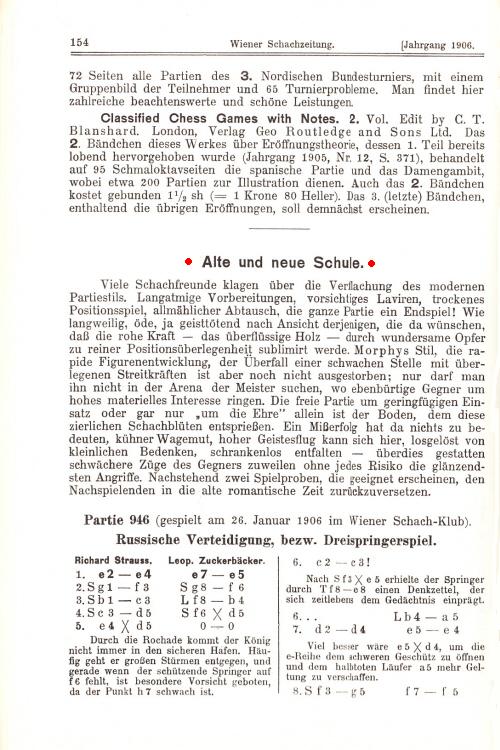

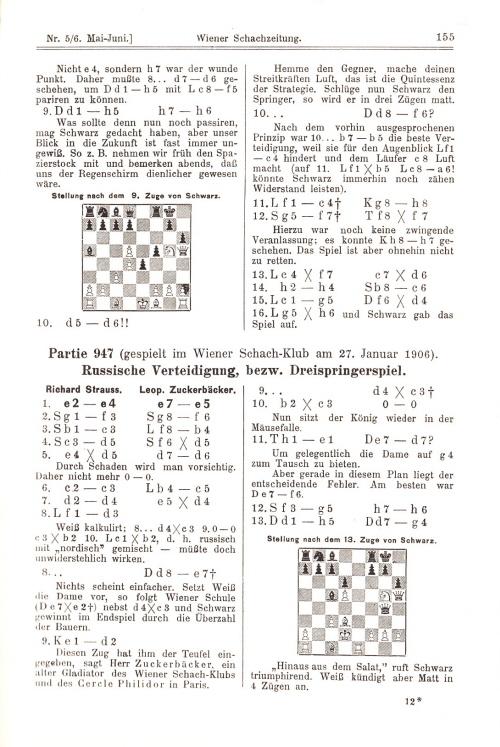

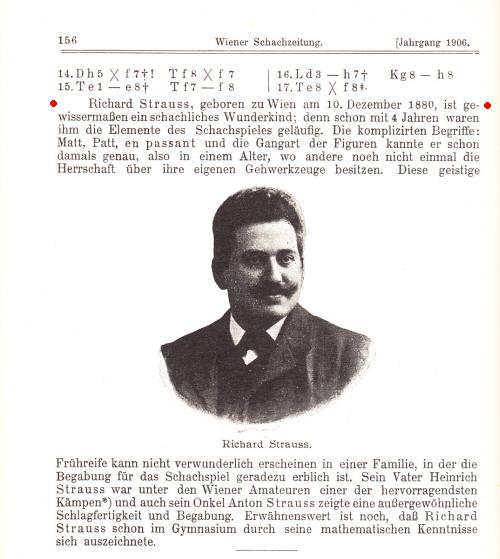

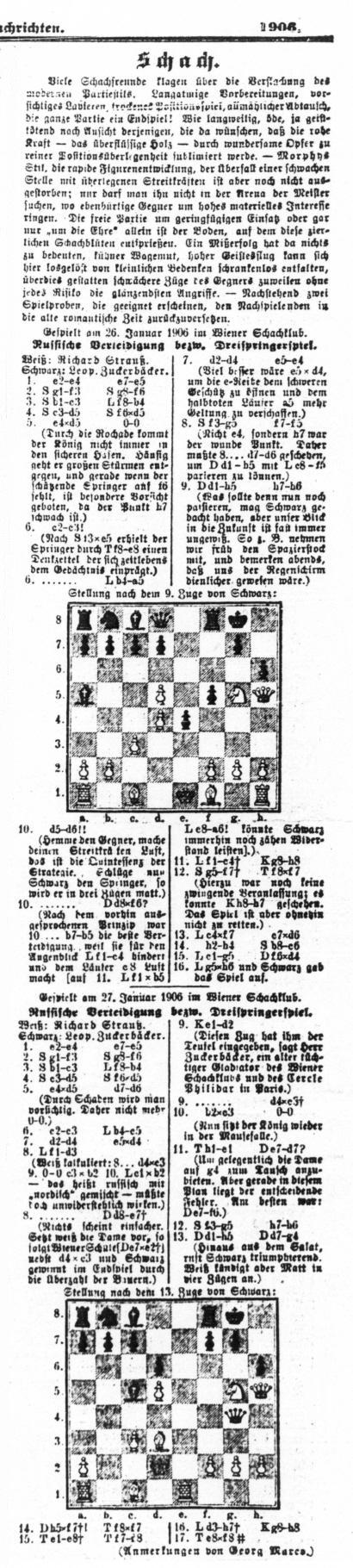

7667. Richard Strauss

On pages 185-186 of Chess to Enjoy (New York, 1978) A. Soltis attributed to the composer Richard Strauss (1864-1949) a 17-move win over ‘Zukkerbrekker’ (Vienna, 1906). Then there was this item by K. Whyld on page 108 of the February 1996 BCM:

In fact, the game was one of two played against Leopold Zuckerbäcker by another Richard Strauss (born in Vienna in 1880) which were published on pages 154-156 of the Wiener Schachzeitung, May-June 1906:

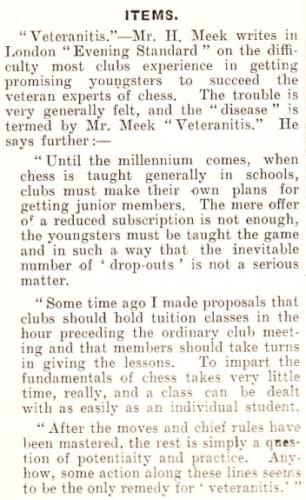

7668. L. Pachman and C. Freud (C.N.s 6081, 7659 & 7663)

From Leonard Barden (London):

‘Pachman played at the Evening Standard tournament in Islington, London in 1972 on my initiative. The Standard naturally wanted a personality to channel publicity for the Open, and news of Pachman’s release from prison and emigration to West Germany came a few weeks before the tournament. I had got on well with him when we met at Olympiads and, even earlier, at Southsea, 1949, and I also knew Wolfgang Unzicker, at whose home in Munich he stayed after his release. The Standard was willing to pay for his trip to London, so he agreed to compete.

While in prison Pachman had sent an emotional rallying call to chessplayers which was published on page 351 of the October 1968 Chess Life. At the end of the opening ceremony at London, 1972 I read out this message to the players, after which Pachman entered the hall and walked, applauded, to the stage. As I recollect, many of my audience looked fidgety, obviously not very interested and evidently keen for the first round to start.

We wanted him to have an interesting first-round opponent, so Stewart Reuben adjusted the draw slightly so that Pachman was paired with Jonathan Speelman, then aged 16. Pachman won. Of course, he was not technically or psychologically prepared for a weekend tournament with three rounds on the Saturday, so it was no great surprise that the next day Brian Eley caught him in the “DERLD” [the Delayed Exchange Ruy López Deferred], which was then a much analysed opening in England.

I was at that time the chess adviser to Faber and Faber, whose director, Charles Monteith, had a celebrated record for spotting and publishing winners – which had included Waiting for Godot and Look Back in Anger. Faber and Faber had a mutual arrangement with Simon & Schuster and was offered the British rights (for a low figure) to Fischer’s My 60 Memorable Games, which Monteith took up on my enthusiastic recommendation.

So when I knew Pachman was coming and that he had announced that he was preparing his memoirs, I told Monteith. Another publisher was also in the hunt. When Pachman arrived at Heathrow Airport there were flowers to greet him from the rival publisher, but Monteith was there with a contract ready for signature. “Flowers good, contract better”, said Pachman. The memoirs, Checkmate in Prague, were published by Faber and Faber in 1975 but, alas, were written in a rather turgid style and were a marketing flop.

Clement Freud was invited to award the prizes at the 1972 Evening Standard congress because Stewart Reuben had read Freud’s articles on the Spassky v Fischer match; he was suitable as the high-profile personality we wanted to justify the Standard’s backing.

As well as money, offered without my asking for it by the legendary editor Charles Wintour, the Standard provided daily advance mentions of the forthcoming congress, which, added to the Fischer boom effects, brought about the then world record entry (a total of 1,208 entrants for the five events).’

7669. The rattle of the tumbrils

This article by G.H. Diggle, the Badmaster, first appeared in the September 1978 Newsflash and was given on page 38 of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984):

‘The Lincolnshire Chess Association celebrated its Centenary last April. The Lincoln Chess Club (which the Badmaster remembers with affection as his first one) goes back still further, and was in existence as early as 1853. It was not honoured, however, by the BM’s presence until 1921, when he joined as a youth. The Club then consisted of some 12 “good men and true” – to wit, three retail tradesmen, two schoolmasters, the Vicar of Bassingham a few miles out, a chemist, a Collector of Taxes, the foreman of a brickworks at Bracebridge, a plumber, a retired coal merchant, and a warder from Lincoln Prison (a very mild man like Mr Barraclough in Porridge) – he always had a lost game and would keep on repeating whenever his opponent moved: “Yes, I hear the rattle of the tumbrils!” The Club met on Fridays at the Arcadia Café on the High Bridge over the canal; the subscription was 5/- per annum; the club assets were a dozen weather-beaten sets kept in blue bags, and one asthmatical chess clock, only used on state occasions such as the final game of the County Championship, which had to be played “at Lincoln, and in public”. The club team boasted one eminent problem composer (the late A.M. Sparke), but after our three top boards (Sparke, J.H. Todd and R. Combes) the standard of our lower echelons can be gauged from the fact that in some cases their entire “Opening Theory” did not extend beyond the first three moves of the Giuoco Piano, and there was one member of 40 years’ standing who never found out that to win with K and P against K, the K should lead the P and not follow it. Competing at this technical level, the BM soon rose like a meteor to half-way up the team in club matches; indeed, with his combinative powers budding forth at this “romantic” era of his career, it would be quite unjust to him to aver that “the only tune that he could play” was Bishop takes King’s Rook’s Pawn check. Like Anderssen and Zukertort, he had his great moments – he once sacrificed his Queen in an off-hand game and would doubtless have “electrified the spectators” had they not, to his disgust, persisted in crowding round a neighbouring board where someone was beating up a solitary King with a Queen and a couple of Rooks. Two of the club members were devout Sabbatarians who would never let a chessboard see the light of day on Sundays; yet with strange inconsistency they would come out of chapel, and not only stand about discussing how they ought to have won last Friday, but would even attempt to draw “unclear” diagrams on the gravel with their walking-sticks to enforce their arguments.’

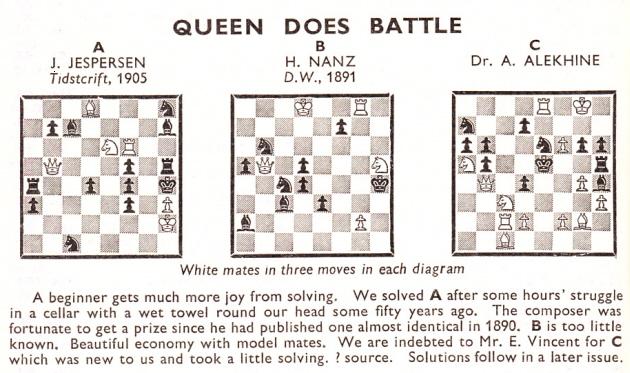

7670. Mate-in-three problem by Alekhine?

Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England) asks whether information is available about the problem ascribed to Alekhine on page 370 of CHESS, 28 May 1955:

The key move was given on page 443 of the 10 August 1955 issue, but without further particulars about the source of the composition.

7671. Najdorf v Che Guevara (C.N.s 4803, 4809 & 7656)

Further complications arise, as Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) draws attention to an account by Najdorf quoted on page 86 of Liliana Najdorf’s book Najdorf x Najdorf (Buenos Aires, 1999):

‘Luego de ganar el torneo en memoria de Capablanca, el Che me invitó a jugar diez simultáneas a ciegas contra el equipo ministerial. Acepté. Él ocupó el tablero número tres. Participaron Raúl Castro, hermano de Fidel, el capitán Osmani Cienfuegos, sobrino de Camilo, el comandante Alberto Bayo y otros. El Che era un jugador bastante fuerte. Prefería el juego agresivo y dado a los sacrificios, pero bien preparados. Con él llegué a estar un poco mejor y le ofrecí tablas. Las rechazó.

– Mire, maestro – me dijo – siendo estudiante de medicina perdí contra usted en una exhibición que dio contra quince tableros en el hotel Provincial de Mar del Plata y ahora prefiero la derrota o buscar el desquite.

Acepté la invitación a la lucha y tuve que ganarle.’

Thus, compared to the version quoted in C.N. 7656 the roles of Najdorf and Che Guevara are reversed. This time, Najdorf says that he made a draw offer and that Che Guevara rejected it. See too Najdorf’s words quoted in a ChessBase article (which, incidentally, mis-dates ‘The Polish Immortal’). Moreover, the ChessBase article also refers to the Najdorf v Che Guevara game in the context of a blindfold display, which prompts Mr Sánchez to wonder whether there was more than one exhibition in Havana involving the two players.

Our correspondent has found five photographs taken during the game given in C.N. 4809 (showing Che Guevara pondering the moves 2...Nc6, 3...a6, 5...Be7 and 15...Nxc6). The five pictures include the ones given in C.N.s 4809 and 6500, as well as the following from pages 82-83 of Najdorf x Najdorf:

7672. Tal’s early childhood

Mark Josephson (Highland Park, IL, USA) is seeking information on ‘how Mikhail Tal and his family avoided the Nazis, as they were Jews from Riga’.

We note this passage on page 21 of Tal’s 100 Best Games 1961-1973 by B. Cafferty (London, 1975):

‘In 1969 Tal gave a long interview for the correspondent of the Latvian young people’s paper Padomju Jaunatne which was later reproduced in the Latvian chess magazine ...

“Q. Tell us about your personal background.”

“A. I was born 9 November 1936 in Riga in a doctor’s family. During the Great Fatherland War (i.e. 1941-45) I was evacuated to Yurla (central Ural region). I first went to school at seven and was soon put into the third class. I returned to Riga as soon as it was freed in November 1944 ...”’

Wanted: accounts giving more details.

7673. Annotational clichés

C.N. 642 suggested ‘an interesting game in all its phases’ as ‘the Crown Prince of chess clichés’. For the title of King, ‘the rest is a matter of technique’ is doubtless a front-runner. Wanted: other nominations.

7674. Walbrodt’s height (C.N.s 5832, 5913 & 7570)

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) quotes a remark about Carl Walbrodt in the Brooklyn Daily Standard Union, 1 April 1893:

‘He is about five feet five inches in height.’

7675. Max Fleissig blindfold display (C.N.s 7608 & 7661)

Peter Anderberg (Harmstorf, Germany) has found this detailed report on pages 6-7 of the 28 January 1872 edition of Neue Freie Presse:

7676. Richard Strauss (C.N. 7667)

Mr Anderberg also reports that both of the Strauss v

Zuckerbäcker games had been published by Georg Marco in

his column on page 4 of the supplement to Hamburger

Nachrichten, 11 February 1906:

Our correspondent mentions too that the ‘Garmisch, 1945’ claim was made in an unsigned item ‘Richard Strauss war Schachspieler’ on page 390 of the 14/2000 Schach Magazin 64 and that in the following issue (page 420) he had this correction published:

7677. Bogo/Nimzo-Indian (C.N. 2839)

Below is part of C.N. 2839 (see page 73 of Chess Facts and Fables):

On page 34 of The Encyclopedia of Chess (1977), Golombek called [1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e6 3 Nf3 Bb4+] the ‘Bogoljubow Defence’, observing: ‘Otherwise known under the hideous name of Bogo-Indian Defence, this defence often transposes to other openings (Nimzo-Indian, Queen’s Indian, Catalan, etc.).’ W.H. Cozens observed on page 401 of the September 1978 BCM that Golombek ‘describes the word Bogo-Indian as hideous, while allowing the exactly analogous Nimzo-Indian to pass without stricture’, and the paperback edition of the Encyclopedia (1981) dropped the ‘hideous’ criticism.

We now add that Golombek touched on the matter in his column in The Times of 5 February 1977:

‘Another opening with different and confusing names is the defence introduced by Nimzowitsch to the Queen’s Pawn Opening. Though I have fought for some time against the ugly hybrid form of Nimzoindian Defence, I now have to admit defeat since it does seem the most economical way to describe the opening.’

Elsewhere in that article, about openings nomenclature, Golombek wrote:

‘Where chessplaying is most active and where in consequence opening theory is most rife, there nationalistic feelings rage and madden round the land. The Russians and the Germans, the Dutch and the Yugoslavs, are all most active in this field. In most cases it would take a Solomon, or a Caucasian chalk-circle, to determine the true parent of an opening variation.

I myself have suffered at the hands, or rather the claws, of these predators, having had no less than four lines filched from me in the course of some 40 years of international play. Nor am I the only sufferer. There is the Reynolds variation in the Semi-Slav that the Germans have called the Klaus Junge line and the Abrahams variation of the same opening known to the Dutch as the Noteboom line.

Perhaps one ought to try and form a RSPCOI (a Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Opening Innovators).’

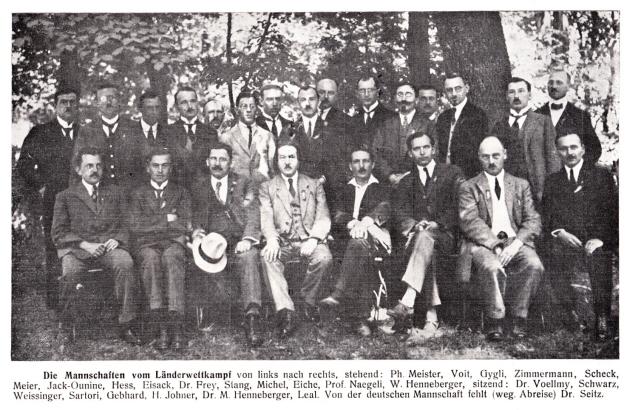

7678. Team match

Participants in the match between Switzerland and Southern Germany (Berne, 27-28 July 1923):

Source: Schweizerische Schachzeitung, August 1923, page 120.

7679. Morphy v Busserolles (C.N.s 7408 & 7651)

Gene Gnandt (Houston, TX, USA) asks whether the full name and birth/death dates of General Busserolles are available.

He also quotes from page 160 of David Lawson’s Paul Morphy The Pride and Sorrow of Chess (New York, 1976):

‘On 14 February (as published in the New Orleans Sunday Delta, 27 March 1859), at a fête given

“by the Duke Decazes ... [Morphy] played two games blindfold against M. Prefect Lacoste and General Busserolles, both fine players, winning both. The moves were transmitted by Mr Lequesne ... and during the whole of the performance Mr Morphy sustained an animated conversation with Mme Decazes and several ladies and gentlemen.”’

7680. Soviet casualites

Page 89 of the September-October 1943 American Chess Bulletin had an interview with Botvinnik published in ‘a recent issue of the “Information Bulletin” of the USSR Embassy at Washington’. The future world champion’s remarks included the following:

‘The War has caused many losses among Soviet chessplayers. The talented young masters Sergei Belavenets, Joseph Rudakovsky and Lev Kaiyev have perished in battle for their country. Mark Stolberg, 18-year-old [sic] Rostov master, is missing in action. A German bomb killed Alexander Ilyin-Zhenevsky, one of the old Russian masters, who at a tournament in Moscow in 1935 [sic – 1925] won a sensational game from Capablanca, then world champion. I was personally indebted to Ilyin-Zhenevsky for organizing my match with Grossmeister Salo Flohr in 1933. Ilyin-Zhenevsky was at that time working in the Soviet diplomatic mission in Prague. Also among the missing are the masters Ilya Rabinovich, participant in many international chess tournaments, and Nikolai Ryumin, whose name swept the entire chess world in 1935 when he won a victory over Capablanca in the first round of the Second Moscow International Tournament.

Other gifted players are taking the places of those who have gone. In the city championship tournament in Tashkent, 16-year-old Mark Makov [sic – Taimanov] shared the first and second prizes with Grossmeister Salo Flohr, who has become a Soviet citizen and is now residing in Tbilisi, capital of Georgia. Considerable improvement is noticeable in the playing of Vasili Smyslov and Isaac Bogoslavsky [sic – Boleslavsky].’

Regarding Rudakovsky, Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia states that he died in 1947, in Chernovtsy.

7681. ‘Won by a Lady’

Georges Bertola (Bussigny, Switzerland) draws attention to a game on pages 18-20 of the Chess Player’s Magazine, January 1867:

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 Bc4 Bg7 5 O-O h6 6 d4 d6 7 Nc3 Ne7 8 b3 Bg4 9 Nd5 O-O 10 Qd3 Nbc6

11 e5 Bxf3 12 Nf6+ Bxf6 13 exf6 Bh5 14 Bxf4 Bg6 15 Qh3 Nf5 16 Bxg5 hxg5 17 Rxf5 Nxd4 18 Qh6 Nxf5 19 Qxg6+ Kh8 20 Qh5+ Kg8 21 Qxg5+ Kh8 22 Qxf5 and wins.

It was merely stated that the game was ‘recently won by a Lady’ and that Black was Löwenthal (the magazine’s Editor). Mr Bertola asks whether White’s identity is known and whether any earlier game-scores exist in which a prominent player was defeated by a woman.

7682. Mate-in-three problem by Alekhine? (C.N. 7670)

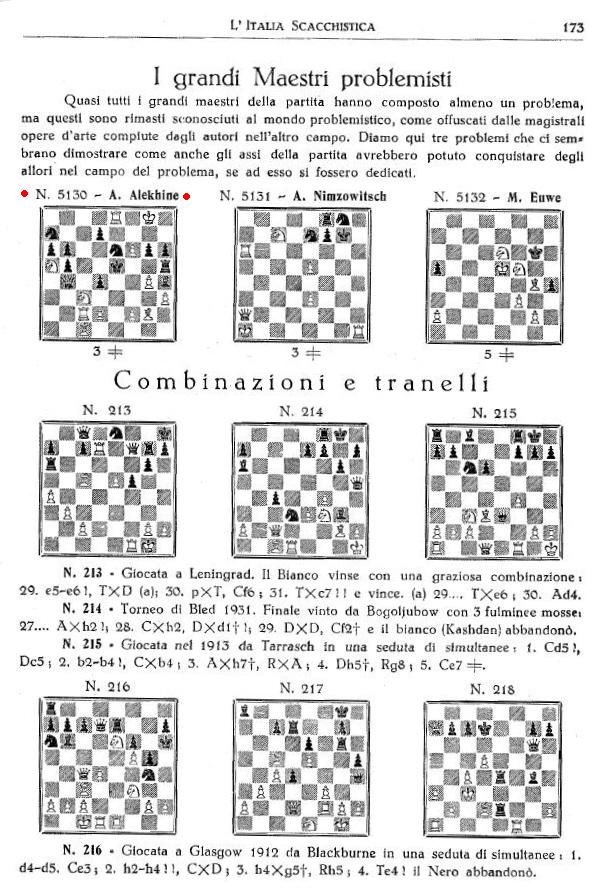

A database showing the alleged Alekhine problem has been pointed out by Han Bükülmez (Ecublens, Switzerland). The source specified there is L’Italia Scacchistica, 1932, and courtesy of Luca D’Ambrosio (Bolzano, Italy) and Alessandro Sanvito (Milan, Italy) we reproduce page 173 of the 1 June 1932 issue:

That, of course, is hardly the end of the story. How much further back can the problem be traced?

| First column | << previous | Archives [94] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.