Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [104] | next >> | Current column |

7987. Fischer and his predecessors

From pages 54-55 of My Seven Chess Prodigies by John W. Collins (New York, 1974):

‘In Bobby Fischer’s Chess Games, by Wade and O’Connell, contributing editor Sir [sic – see C.N. 5674] Harry Golombek remarks on the influence of Capablanca on Bobby’s style and sees a strong resemblance in the respective strategies that run through their games. He recalls that Bobby acknowledged the influence in an interview with Leonard Barden that was broadcast on the BBC, and that Bobby also said he had read and appreciated a book on Capablanca by Golombek. The influence and resemblance are evident, and I have always been aware of it, recent evidence of it being in his third and fifth games with Spassky in Iceland. But I must say that I do not recall Bobby ever dwelling on his admiration of Capablanca or playing over great numbers of Capa’s games, though I assume he played over all of them at some time.

With Anderssen and Steinitz the story is much different. I remember I once lent a brand-new copy of Adolf Anderssen, by Dr Hermann von Gottschall, to him. Some weeks or months later he returned it, and I had good reason to believe he had worked over every game and note in it – all 751 games in the main section, plus 80 problems by Anderssen in another section. And later on Bobby and I played over 36 games that Anderssen played during 1851 to 1859 in Breslau with Louis Eichborn, a banker and good friend of chess. Much to our great glee we found that Anderssen lost them all. Steinitz received even more attention. Bobby was always intrigued by the man and his games, and he has revived many of his discarded variations, one is the Two Knights’ Defense, for instance. And another is the Petroff Defense. As with the Anderssen book, he borrowed my four volumes of Chess Master Steinitz [Schachmeister Steinitz], by Ludwig Bachmann, and thoroughly chewed and digested every one of the 669 games in them. Later, on many an afternoon and evening in my apartment, he and I would go over a score or so of these same Steinitzian struggles again. Bound copies of Steinitz’s The International Chess Magazine also provided us with grand old games and insights into the frightening intellect and acid pen of the “Father of Modern Chess”.’

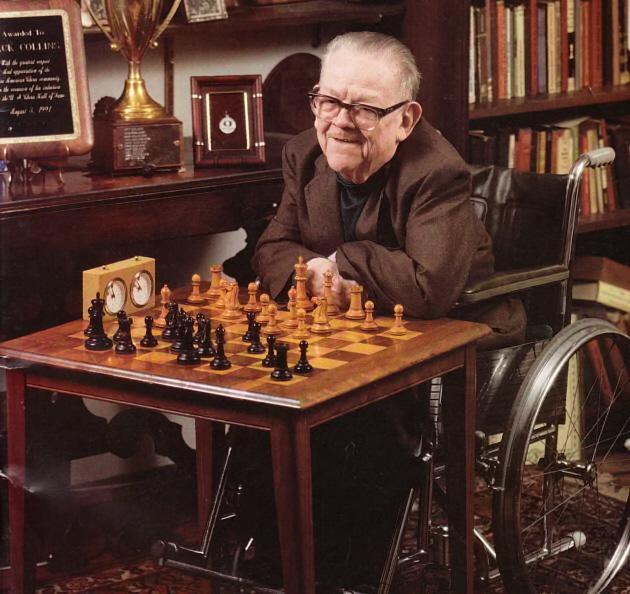

The photograph of Collins below is reproduced from the front cover of a catalogue (numbered 1294) of Maddak Inc., published in 1995:

7988. Quiz question (C.N. 7978)

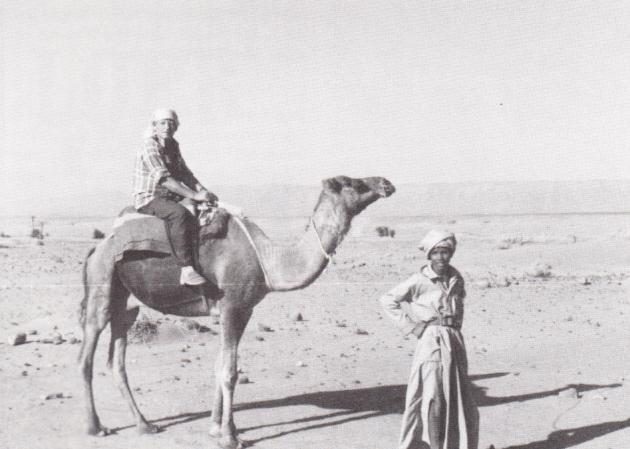

This photograph shows Max Blau and comes from page 27 of the booklet Max-Blau-Memorial Volksbank-Open (Berne, 1987). The next page had another shot:

7989. Royal walkabout

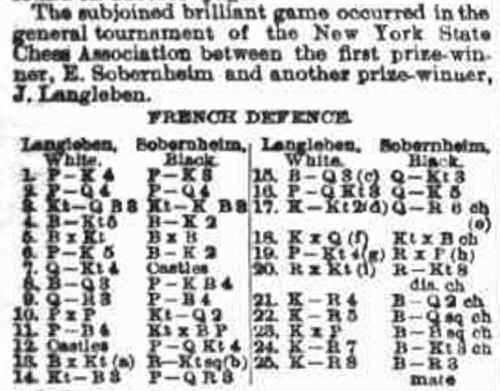

1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 Be7 5 Bxf6 Bxf6 6 e5 Be7 7 Qg4 O-O 8 Bd3 f5 9 Qh3 c5 10 dxc5 Nd7 11 f4 Nxc5 12 O-O-O b5 13 Bxb5 Rb8 14 Nf3 a6 15 Bd3 Qb6 16 b3 Qb4 17 Kb2

17...Qa3+ 18 Kxa3 Nxd3+ 19 b4 Rxb4 20 Rxd3 Rb1+ 21 Ka4 Bd7+ 22 Ka5 Bd8+ 23 Kxa6 Bc8+ 24 Ka7 Bb6+ 25 Ka8

25...Ba6 mate.

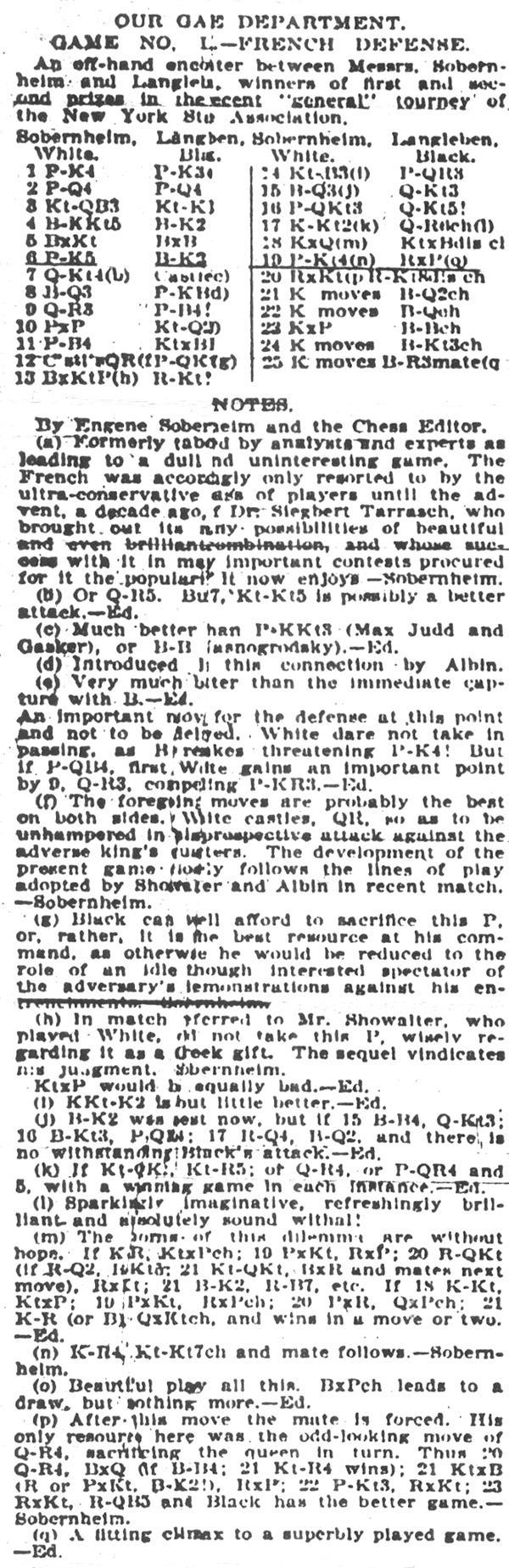

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) points out

two newspaper appearances of this famous miniature, with

a discrepancy over the winner and loser, and over

whether or not it was a formal game.

New York Recorder,

3 March 1895

Evening Post (New

York), 9 March 1895, page 12

The game is commonly given in chess literature as

‘Sobernheim v Langleben, Montreal, 1895’, e.g. on page

525 of 1000 Best Short Games of Chess by Irving

Chernev (New York, 1955). On the other hand, page 126 of

Learn Chess from the Greats by Peter J. Tamburro

(Mineola, 2000) referred to ‘Langleben-Sobenheim [sic]

from a New York tournament from the thirties’. On page 4

of the April 1933 Chess Review Chernev had

presented the game (‘Langleben-Sobenheim’) without a

date, merely stating that it was ‘played in a New York

tournament’. It was also given as Langleben v

Sobenheim/New York/undated when Chernev published it

again on page 256 of the December 1942 Chess Review,

but a few years later, on page 64 of The Bright Side

of Chess (Philadelphia, 1948), he reversed the

names, corrected Sobenheim to Sobernheim and changed New

York to Montreal, 1895.

Those alterations in the 1948 book brought the details into line with what had appeared on pages 169-170 of the June 1895 Deutsches Schachzeitung, which reported that the game had been played recently at the Montreal Chess Club.

Both Sobernheim and Langleben were New York players.

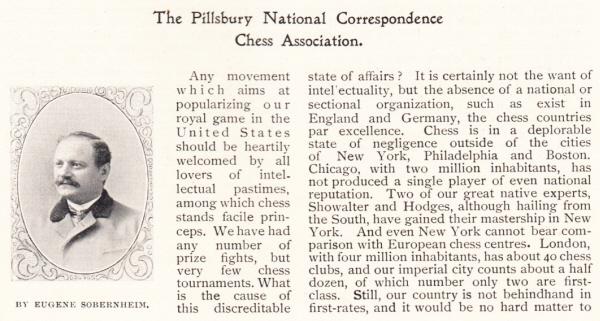

Regarding Eugene Sobernheim, see, for instance, page 285

of the September-October 1893 American Chess Monthly,

as

well as pages 89-90 of the July 1897 American Chess

Magazine, where he contributed an article:

Harry Nelson Pillsbury American Chess Champion

by Jacques N. Pope (Ann Arbor, 1996) published two games

in which Salomon Langleben was an opponent. They were

played at the Buffalo Chess Club, New York and in

Brooklyn.

The following news report, concerning chess in New York, appeared on page 164 of the April 1895 BCM:

‘For the general or free-for-all tourney there were 18 entrants, including Messrs Frère, Helms and other strong players. The outcome was that Mr Soberheim [sic] succeeded in winning the first prize, the others being divided among Messrs Buz, Langleben, T. Lipschütz, Napier and Roething.’

Regarding the nature (i.e. off-hand or

otherwise) of the royal walkabout game, see page 9 of Napier

The Forgotten Chessmaster by John S. Hilbert

(Yorklyn, 1997), as well as the details provided in the

full New York Recorder column of 3 March 1895,

which is available at the Chess

Archaeology website.

How did Montreal, rather than New York, become so widely associated with the game?

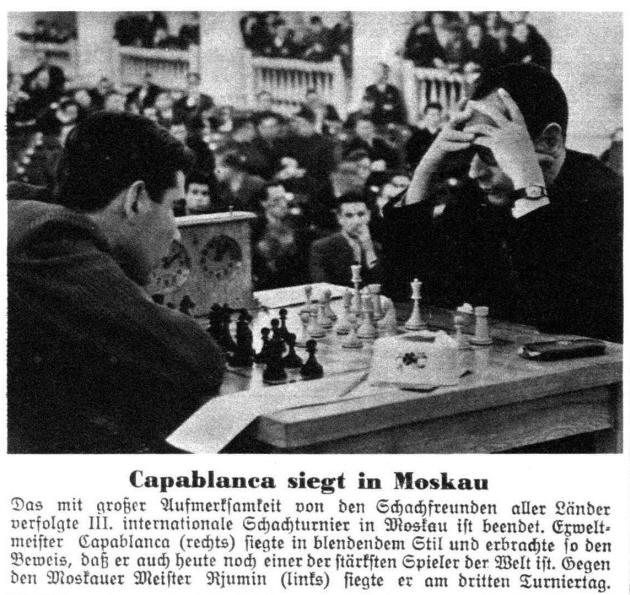

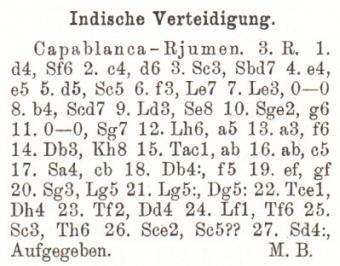

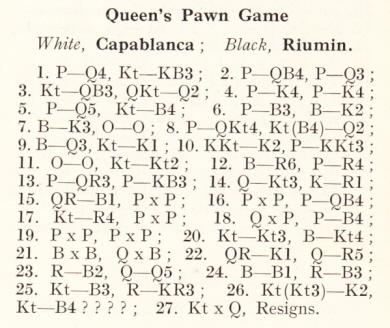

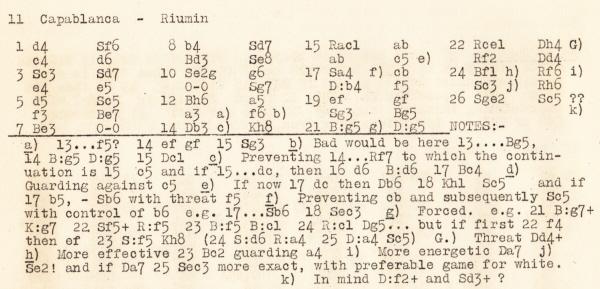

7990. Capablanca v Riumin (C.N. 7981)

Harold Kjallberg (Sussex, WI, USA) observes that the above photograph (Capablanca v Riumin, Moscow, 1936) casts doubt on the move order (1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 d6 3 Nc3 Nbd7 4 e4 e5 5 d5 Nc5 6 f3 Be7 7 Be3 O-O 8 b4 Ncd7 9 Bd3 Ne8 10 Nge2 g6 11 O-O a5 12 a3 Ng7 13 Bh6 f6) given in various sources, including the Russian-language tournament book (of which an English translation was published in 1988 by Caissa Editions) and our 1989 monograph on Capablanca. He comments:

‘In the photograph, the black knight has already moved from e8 to g7. Owing to the camera angle, the black queen on d8 and the black bishop on e7 obscure the view of the black pawn on g6.

It is fairly easy to determine that White has made exactly 11 moves, and since the button on his clock indicates that it is his turn to move, both sides have made 11 moves. However, the black pawn is still on a7.

This photographic evidence suggests to me that the currently recognized move order for the game is incorrect and that the moves played were 11 O-O Ng7 and then 12 a3 a5.’

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) points out that a clearer

version of the photograph is available on-line. From

that copy we give the detail below:

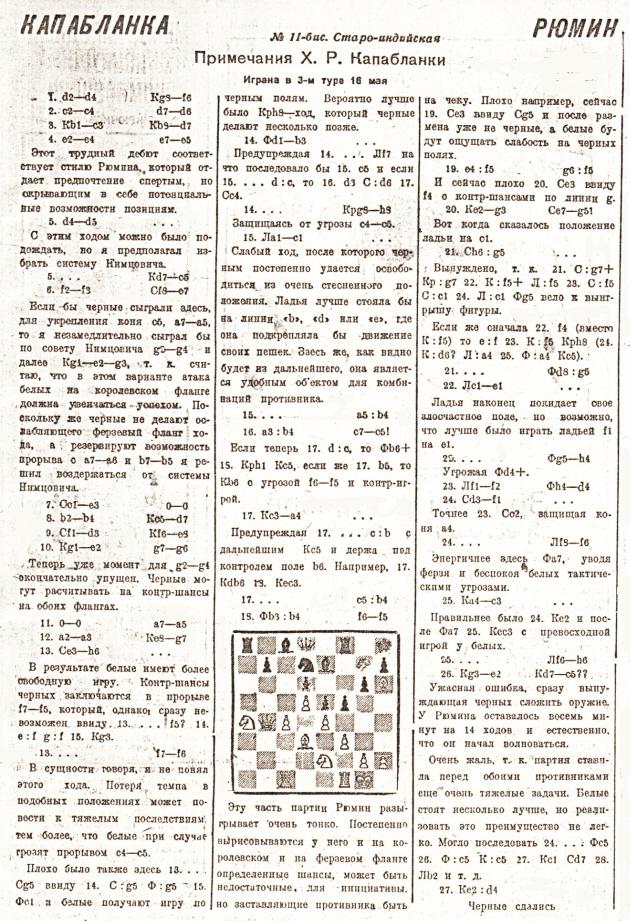

There follow Capablanca’s annotations to the game, as published in the Russian Bulletin of the tournament (special issue of 64), 18 May 1936:

As mentioned by our correspondent, the same move order appeared in the Moscow, 1936 tournament book, where the annotations were by Riumin (who gave 11...a5 a question mark).

However, we note that a different version of the score (11 O-O Ng7 12 Bh6 a5 13 a3 f6) was given on page 179 of the June 1936 Deutsche Schachzeitung ...

... and on page 393 of CHESS, 14 June 1936:

Below, furthermore, is an extract from page 6 of the tournament book edited by E.G.R. Cordingley (London, 1936):

Cordingley wrote in his Foreword:

‘The games and the notes as transcribed and translated here were obtained from the special issue of the Russian Chess Paper 64, which is not readily available to the average person ... The names of the annotators (Capablanca, Botvinnik, Flohr, etc.) are not given as my hazy knowledge of the language might attribute to them errors they never committed, but I have endeavoured to extract lines of play that will help the average player when reading over the games.’

Can a reader trace Cordingley’s version of the moves in an issue of 64, and perhaps even an explanation in the Soviet magazine of the discrepancy in the game-score?

7991. Fool’s mate (C.N. 7986)

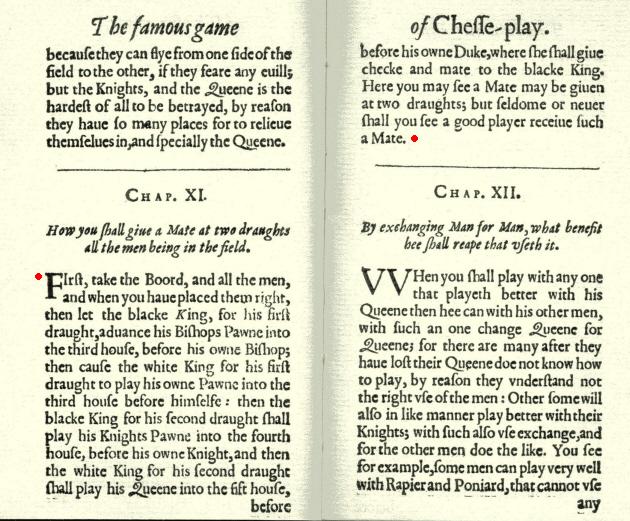

The above illustration has been provided by Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England), who comments:

‘This is the relevant part of the London, 1614 edition of Arthur Saul’s The Famous Game of Chesse-Play. It comes from the facsimile edition published in 1974 by Walter J. Johnson, Inc. and Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, Ltd. Amsterdam.

This first chess manual by an Englishman is one of the rarest of early chess books. Further editions appeared in 1618, 1640, 1652, 1672 and 1680, all edited by J. Barbier.

Page 50 of David DeLucia’s book A Few Old Friends (Darien, 2007) states that only six copies are known of the first (1614) edition; the Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library at Yale University reports that only two complete copies of the 1652 edition are known.

The other editions are probably similarly rare as they virtually never appear on the market, although copies of the 1640 and 1672 editions were included in the sale of the library of Robert Blass at Christie’s in 1992.’

David DeLucia (Darien, CT, USA) informs us that he has the third edition (1640) and that in Chapter XXIIII the following mates are mentioned:

‘The Queenes Mate

The Bishops Mate

The Knights Mate

The Rookes Mate

The Pawnes Mate

Mate of Discovery

Alexanders Mate

An unfortunate Mate

A Cowards Mate

The Blinde Mate

The Stale Mate

The Mate at two draughts, a Fooles Mate.’

Mr DeLucia adds:

‘I also have the fifth edition (1672), and the list of mates there is very similar to, if not the same as, the list in the 1640 edition.’

We should like to see the relevant text in the second edition (1618), i.e. the first in which the term ‘Fool’s mate’ appeared.

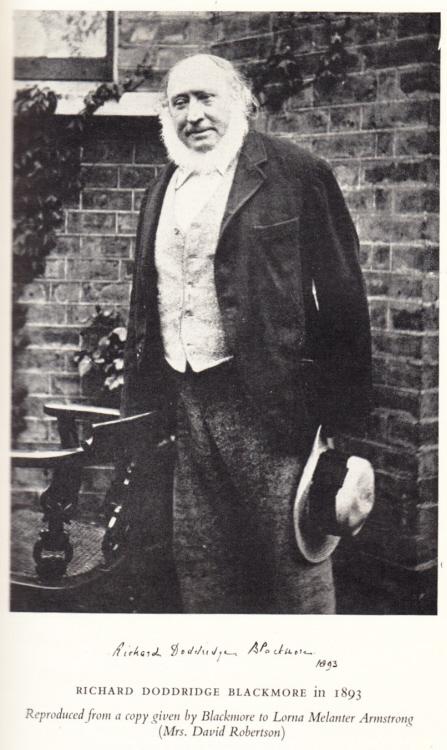

7992. R.D. Blackmore (C.N. 7976)

From pages 174-175 of R.D. Blackmore by Waldo Hilary Dunn (London, 1956):

‘“The game and playe of the chesse” fascinated Blackmore. “The only game worth playing”, he once exclaimed to James Baker. “Think of the genius who invented the knight’s move.” His interest in it brought him into contact with several interesting people besides [Richard] Owen. Among professionals he came to know William Steinitz, author of The Modern Chess Instructor, and H.F.L. Meyer, author of A Complete Guide to the Game of Chess. Nelson Fedden, G.E.N. Ryan and a Dr Günther of Hampton Wick were among his fellow devotees of the game. As early as 1867 he was playing with Meyer, and promising to send his brother-in-law a copy of the games. “I think”, he wrote to Alfredo on 1 September 1867, “I have discovered the wonderful five-move problem, which has been dedicated me.”

Ryan usually went to Gomer House every fortnight to play from four to seven in the evening, and often told his family the pleasure he had in associating with Blackmore. Although devoted to the game, Blackmore had no great opinion of his own ability as a player. “In chess I can have no chance with you”, he wrote to Fedden on 17 February 1873. “You could give me a knight, I am almost sure. The two games you sent have been played over. How did the passage of arms conclude? I would gladly see some more. Do you know ‘the great little man’, to wit Steinitz? He comes sometimes to see me. I love the game, but am not sound. I cannot concentrate my attention enough upon it. And if I could, it would not avail.” On 3 December 1892 Blackmore referred to Fedden, probably for the last time, in a letter to Francis Armstrong. “Mr Fedden is a very strong chessplayer … If you can hold your own with him, you must be very good. I never play, or scarcely ever.”

He was making chessmen as early as the 1850s. “His skill with the lathe”, says Stuart J. Reid, “was quite out of the common, and he carved ivory chessmen delicately and curiously.” He turned them from wood also, as we learn from his letter of 30 March 1854 to Henry Hey Knight. “The pigmy knights advance but slowly, and will never be fit to put with the ivory ones”, he wrote; and then he added a sentence which suggests that even then he was beginning to lose the full power of one of his hands. “The hand so cramped loses all vigour.” It was not, however, until 1887 that his left hand became practically useless. One set of his chessmen carved from wood was given by Adalgisa Pinto-Leite to Eden Phillpotts in 1915, and are now (1953) in his possession.’

Blackmore’s name was mentioned in a long list of acknowledgements on page x of Meyer’s A Complete Guide to the Game of Chess (London, 1882).

Photograph

opposite

page 192 of W.H. Dunn’s book

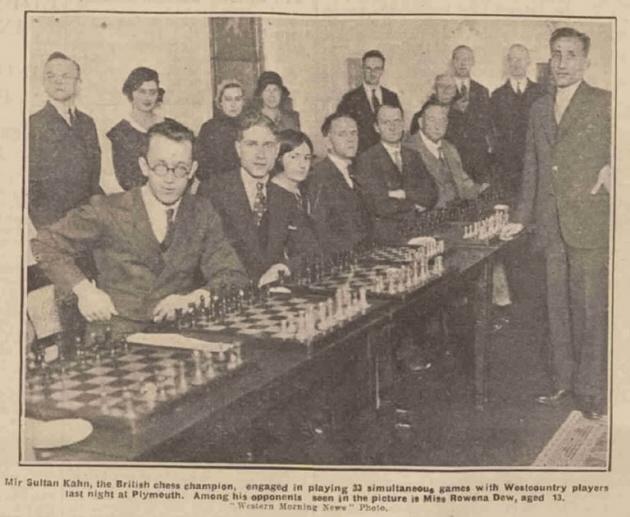

7993. Sultan Khan in Plymouth

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) sends a detailed report about Sultan Khan’s visit to Plymouth, which accompanied the above photograph, on page 5 of the Western Morning News and Daily Gazette, 27 October 1932.

7994. Dogmas and guiding principles

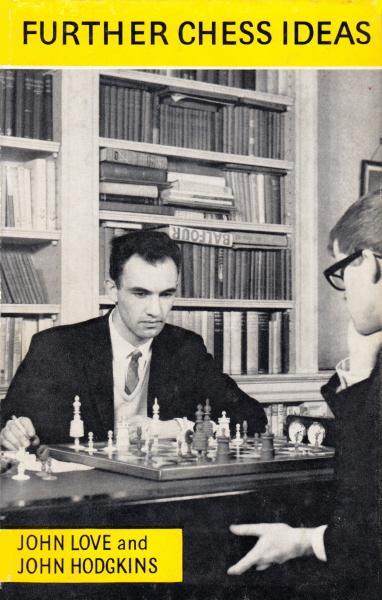

From page v of Further Chess Ideas by John Love and John Hodgkins (London, 1965):

‘Dogmas in chess are a hindrance to the free play of the imagination; guiding principles, on the other hand, are an asset in checking wild flights of fancy which lead to nowhere except defeat.’

Who is on the book’s dust-jacket?

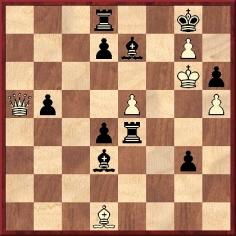

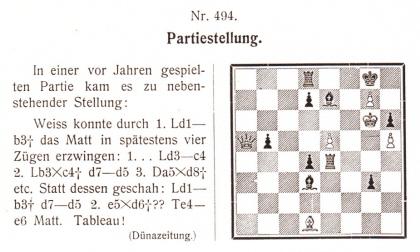

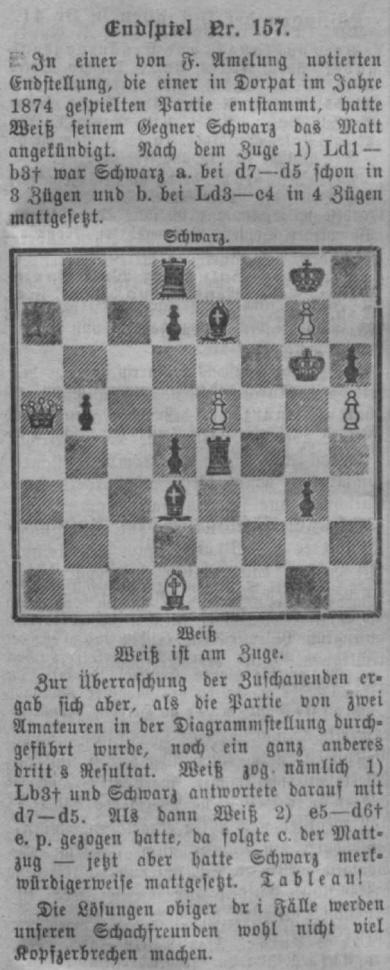

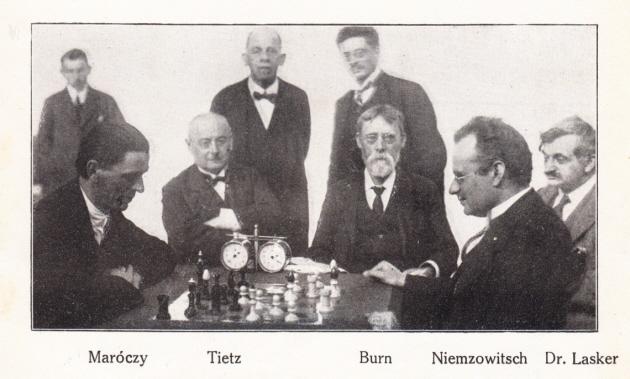

7995. A tableau (C.N. 3127)

Information is still sought regarding the position given in C.N. 3127 (see pages 14-15 of Chess Facts and Fables):

The position arose in a game played in 1874 in Dorpat (present-day name: Tartu) between unnamed opponents. The forced mate is 1 Bb3+ Bc4 2 Bxc4+ d5 3 Qxd8+ Bxd8 4 Bxd5. If 1…d5, White plays 2 Qxd8+ Bxd8 3 Bxd5 mate.

However, it is the third possibility which presents the table-turning tableau: 1 Bb3+ d5 2 exd6+ Re6 mate.

Unfortunately the confusing German text in our source (Baltische Schachblätter, Heft 11, 1908, page 54) does not make it sufficiently clear how the game ended. The magazine credited the position to the Düna-Zeitung, but it remains to be discovered whether that publication had been more explicit.

Below, for reference, is the full text from the Baltische Schachblätter:

‘In einer von F. Amelung notierten Endstellung, die einer in Dorpat im Jahre 1874 gespielten Partie entstammt, hatte Weiss seinem Gegner Schwarz das Mat angekündigt. Nach dem Zuge 1 Ld1-b3+ war Schwarz bei d7-d5 schon in 3 Zügen und bei Ld3-c4 in 4 Zügen matgesetzt.

Zur Überraschung der Zuschauenden ergab sich aber, als die Partie von zwei Amateuren in der Diagrammstellung durchgeführt wurde, noch ein ganz anderes drittes Resultat. Weiss zog nämlich 1 Lb3+ und Schwarz antwortete darauf mit d7-d5. Als dann Weiss 2 exd6+ gezogen hatte, da folgte der Matzug – jetzt aber hatte Schwarz merkwürdigerweise matgesetzt. Tableau!

Die Lösungen obiger drei Fälle werden unseren Schachfreunden wohl nicht viel Kopfzerbrechen machen.’

The only addition currently available is that the position had been published on page 79 of the May 1906 Schweizerische Schachzeitung:

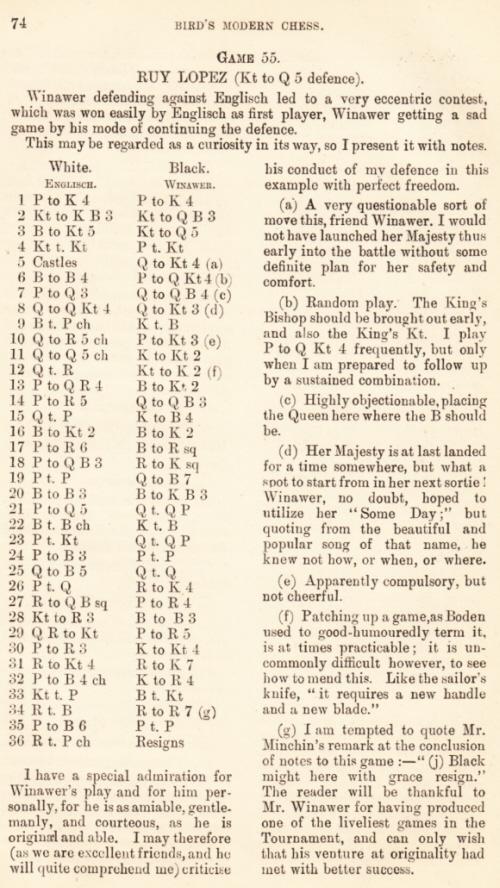

7996. Englisch v Winawer, London, 1883

H.E. Bird’s comment on 12...Ne7:

‘Patching up a game, as Boden used to good-humouredly term it, is at times practicable; it is uncommonly difficult, however, to see how to mend this. Like the sailor’s knife, “it requires a new handle and a new blade”.’

Source: Modern Chess and Chess Masterpieces by H.E. Bird (London, 1887), page 74.

7997. A rare French term (C.N. 3495)

C.N. 3495 referred to the chess term une lunette, in the context of a pawn fork, and quoted a definition on page 140 of Traité d’échecs analytique et progressif by A. Lonchay (Brussels, 1917):

‘Donner une lunette à son adversaire, c’est le mettre en état d’attaquer deux pièces en même temps avec un pion, ce qui arrive quand les deux pièces occupent une case en avant de celle du pion et la touchant diagonalement; on reçoit une lunette, dès que cette éventualité se produit.’

Jean-Pierre Rhéaume (Montreal, Canada) notes that the Dictionnaire Littré provides definitions for lunette concerning both draughts and chess:

‘Au jeu de dame, mettre dans la lunette, placer une dame entre deux dames de son adversaire, en sorte qu’elle ne peut être prise ni par l’une ni par l’autre; locution tirée de la forme des lunettes qu’on met sur le nez.

Au jeu des échecs, donner une lunette, mettre son adversaire à même d’attaquer deux pièces avec un pion.’

7998. A tableau (C.N.s 3127 & 7995)

Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) has found the ‘tableau’ position on page 63 of the 25 February (old style) 1906 issue of Düna-Zeitung:

7999. A horrible shock

This article by G.H. Diggle (Newsflash, July 1980) was reproduced on page 59 of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984):

‘The BM, “peering and blinking” through the current BCM “as is his custom of an afternoon”, was suddenly roused from lethargy when in the Games Department (Miles v Short ) his eye caught “a horrible move” by White, followed two moves later by “a horrible shock” for the distinguished grandmaster. Out came the BM’s pocket chessboard with all dispatch. For fortunately, in spite of the detested algebraic notation, the score was at least presented in decent columnar form with notes by “W.R.H.”, and not served up (as too often happens) with symbols, brackets, notes and numerals all jumbled into one revolting mass of chess spaghetti.

By the 15th move Nigel (whose positional judgement was more than once praised en route by W.H.R.) was leading by two exclamation marks to nil. But he then thought fit to perpetrate that lowest of all combinational manoeuvres and Badmasters’ talisman – yes, bishop takes king’s rook’s pawn, check!! Needless to say, this gave his eminent antagonist the aforesaid “horrible shock” – probably not so much at “finding himself completely lost” as at such a raspberry having been blown in an exclusive “Phillips & Drew” drawing-room filled with respectable grandmasters. Had nobody told the “wretched boy” that such a move was only permissible in village clubs such as “Toad-in-the-Hole” where (as once recounted in CHESS by a very unreliable authority) a low fellow named Bloggins tried it on with considerable success, “especially against nervous opponents who would not take the bishop, but just moved the king instead, losing a pawn for nothing”?

After this, “the rest” should have been “silence”. But the wily grandmaster proved a most refractory corpse, and we were treated to a further 40 moves’ running battle between two very agile minds. So many pawns had already gone that “strategical motifs”, “strong and weak squares”, “thematic advances” and suchlike mummery were swept into the dustbin, and only pure observation remained. One might have expected the younger and fresher brain to have speedily carried out the burial. But in all such cases the “corpse” has one conspicuous advantage – frequently he has only “Hobson’s choice” to worry about, while his deserving but hesitant foe is so bemused with networks of alternative roads leading to the promised land that he inevitably drives up the only one that doesn’t, and his engine finally stalls. So it was in this case. But no-one will think any the worse of the driver, beset as he must have been by the presence of innumerable well-wishers mentally “honking him on to victory” from the wings.’

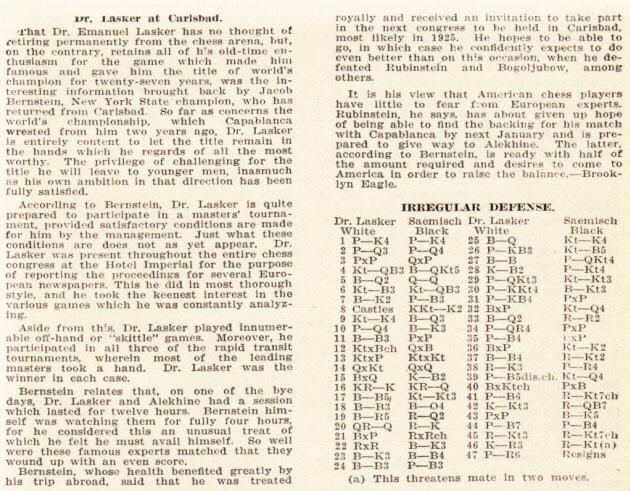

8000. Lasker at Carlsbad, 1923

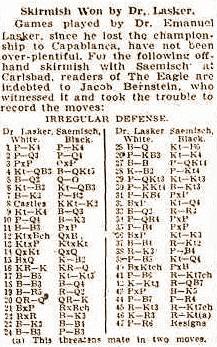

Ronald Spurgeon (Sutton, England) draws attention to a feature on page 169 of the November 1923 American Chess Bulletin:

Our correspondent asks whether anything further is known about the rapid transit tournaments and about the Lasker v Sämisch game given by the Bulletin.

We have found the score on page 6A of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 21 June 1923:

Emanuel Lasker – Friedrich Sämisch

Carlsbad, 1923

King’s Pawn Opening

1 e4 e5 2 d3 d5 3 exd5 Qxd5 4 Nc3 Bb4 5 Bd2 Qd8 6 Nf3 Nc6 7 Be2 f6 8 O-O Nge7 9 Ne4 Bd6 10 d4 Be6 11 Bc3 exd4 12 Nxd6+ Qxd6 13 Nxd4 Nxd4 14 Qxd4 Qxd4 15 Bxd4 Kf7 16 Rfe1 Rhd8 17 Bc5 Ng6 18 Bf3 Bd5 19 Bh5 Rd7 20 Rad1 Re8 21 Bxa7 Rxe1+ 22 Rxe1 Be6 23 Be3 Bf5 24 Bf3 c6 25 Bd1 Ne5 26 f3 Nc4

27 Bc1 b5 28 Kf2 g5 29 b3 Nb6 30 g4 Bg6 31 f4 gxf4 32 Bxf4 Nd5 33 Bd2 Ra7

34 a4 bxa4 35 c4 axb3 36 Bxb3 Ne7 37 Bf4 Rb7 38 Re3 h5 39 c5+ Nd5 40 Bxd5+ cxd5 41 c6 Rb2+ 42 Kg3 Rc2 43 gxh5 Be4 44 c7 f5 45 Rb3 Rg2+ 46 Kh3

46...Rg8 47 h6 Resigns.

Source: Carlsbad, 1923 tournament book

Regarding rapid transit games in Carlsbad, C.N. 1050 (see page 9 of Chess Explorations) gave the conclusion of Tartakower’s win against Alekhine on 8 May 1923.

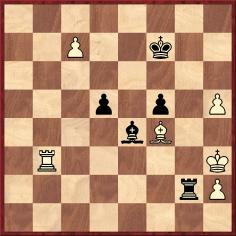

8001. Lasker v Nimzowitsch

A second enquiry from Ronald Spurgeon arises from the caption to a photograph on page 1029 of Emanuel Lasker: Denker Weltenbürger Schachweltmeister edited by R. Forster, S. Hansen and M. Negele (Berlin, 2009). It states that in summer 1925 Lasker and Nimzowitsch played a match of ten off-hand games, Lasker winning 7-3.

We can do no better at present than reproduce the brief report in the source indicated by the book, i.e. from page 309 of Deutsche Schachblätter, 15 July 1925:

8002. Pillsbury National

Correspondence Chess Association pamphlet

From Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England) comes information about a scarce publication in his collection, a pamphlet produced by the Pillsbury National Correspondence Chess Association in 1905:

Mr Clapham writes:

‘The pamphlet has 12 pages, including the covers, and begins with a short history of the Association which states that it was founded in 1896 and was named as “a tribute to our master player Harry N. Pillsbury”. There follows a list of the accomplishments (two) of the Association and details of how its tournaments were arranged.

The second half of the publication has two articles, of about three pages each, giving general advice and recommendations on correspondence chess play. These are by the Reverend Leander Turney and Walter Penn Shipley.

There are no games, but the pamphlet does state that bulletins will be issued containing notable annotated games.’

8003. Hypermodern chess

Further to our feature article Hypermodern Chess, Peter Morris (Kallista, Australia) notes on page 256 of 500 Master Games of Chess by S. Tartakower and J. du Mont (London, 1952) the following annotation in the game Paulsen v Rosenthal, Vienna, 1873, after 1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Nc6 3 g3 Bc5 4 Bg2:

‘In an open game, and at a time when chess went through its “heroic period”, White applies a principle which was later on to be brought to the fore by the masters of “hyper-modern” chess, Breyer, Réti, Nimzowitsch, Bogoljubow, and up to a point by Alekhine and others, namely, control of the centre instead of its occupation.’

The passage is particularly interesting for its reference to Bogoljubow; our article expressed doubts as to whether he should be regarded as a hypermodern player.

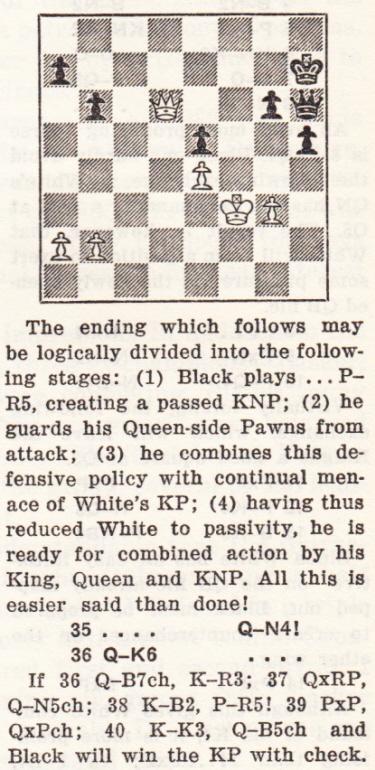

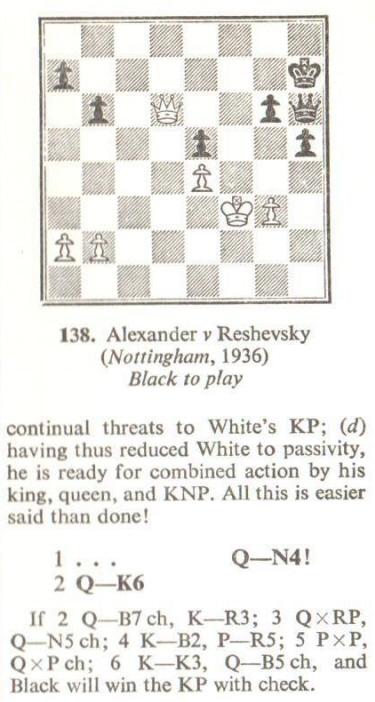

8004. Alexander v Reshevsky

Peter Morris also draws attention to two books which

discuss Alexander v Reshevsky, Nottingham, 1936:

Page 80 of Reshevsky

on Chess by S. Reshevsky (New York, 1948)

Page 84 of How to Play the Endgame in Chess by L. Barden (London and Glasgow, 1975)

We have raised the matter with Leonard Barden (London), who responds:

‘The great majority of my writing was and is solely by me, but I had a collaborator for the Collins book who wrote some chapters and supplied some material, though I personally checked the whole book in proof.

At nearly 40 years’ distance I cannot recall or decide which of us was responsible for Alexander-Reshevsky. In either case I would have expected at least some rephrasing, as occurs in the other notes quoted, so I now think that the neglect to do this was simple human error.

I should add that I find it completely convincing that Reinfeld wrote the Reshevsky book and thus the paragraph in question. When Reshevsky really wrote his own notes, as he did in some late material in Chess Life, the style was terse and arid, in contrast to Reinfeld’s lucid and informative explanations.’

Regarding Reshevsky and ghosting, see pages 321-322 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves, pages 188 and 270 of Chess Facts and Fables and C.N. 3768.

8005. For solving (C.N.s 7955 & 7970)

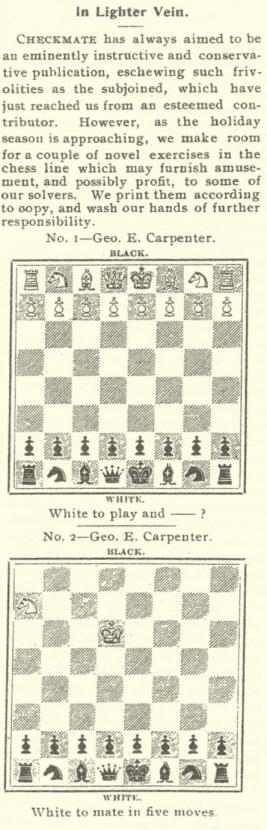

C.N.s 7955 and 7970 showed these two positions by George E. Carpenter as published on page 209 of Checkmate, December 1901, but where did the solutions appear? Indeed, does the first composition have any solution at all? Concerning the second position we can add only that it was included in T.R. Dawson’s ‘Endings’ column on page 362 of the September 1915 Chess Amateur, merely captioned ‘G.E. Carpenter’ and ‘White wins’, and that the solution (White has a mate in seven with 1 Nc6) was published on page 25 of the October 1915 issue.

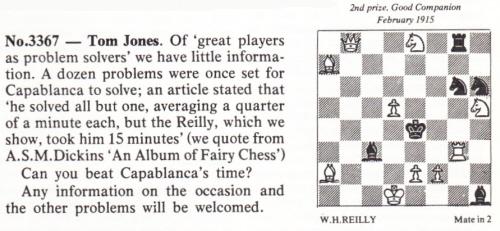

8006. ‘Can you beat Capablanca’s time?’

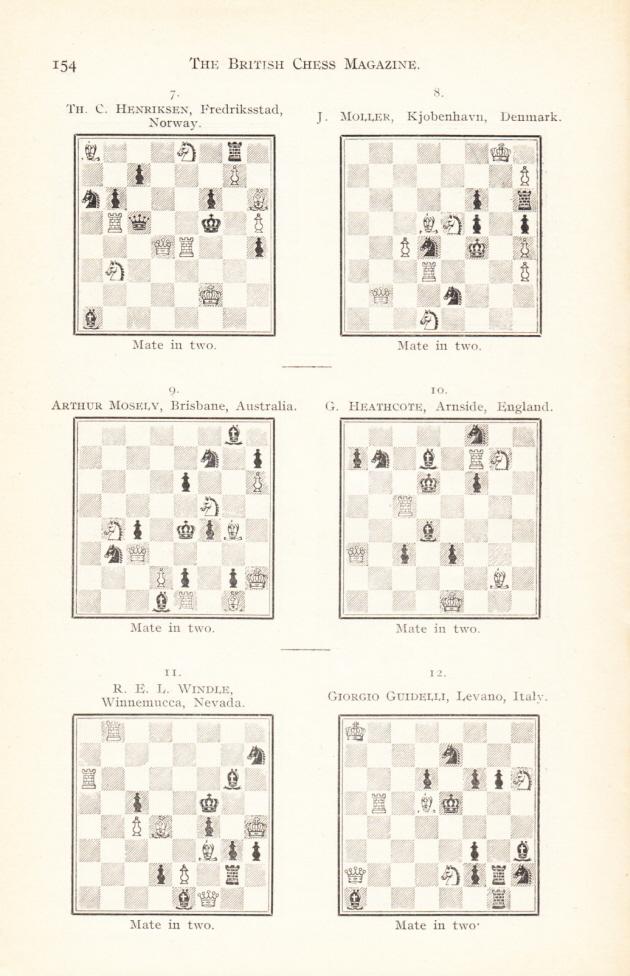

Readers wishing to test their problem-solving skills against Capablanca are invited to time themselves while trying to find the key move in this position:

Mate in two

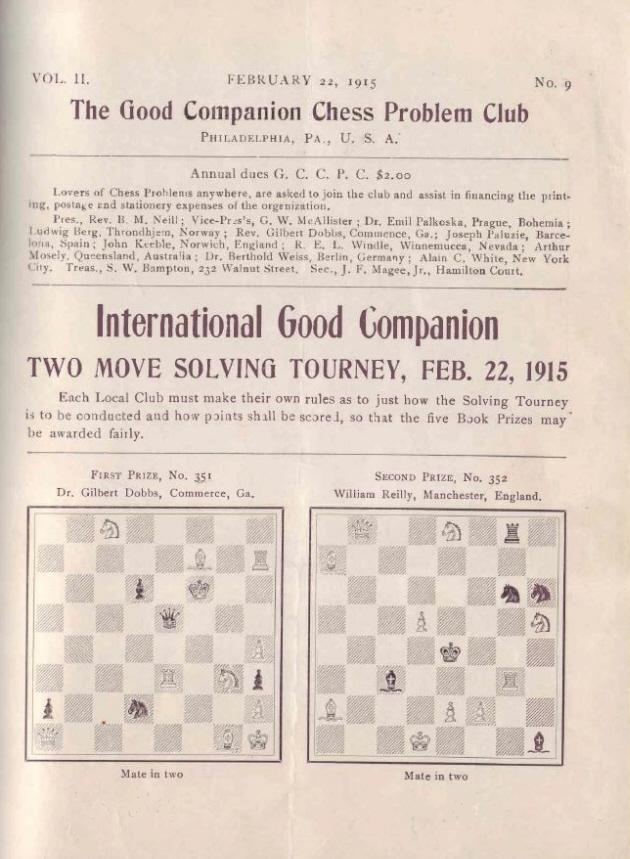

The problem, by William Reilly, was one of 12 in the International Good Companion Two-Move Solving Tourney held on 22 February 1915. Clubs around the world were invited to organize a solving session and to submit their results to the Good Companion Chess Problem Club in Philadelphia.

The problem by Reilly was published by D.J. Morgan on page 397 of the September 1973 BCM:

We are grateful to Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England) for providing the relevant text on page 4 of Dickins’ An Album of Fairy Chess (London, 1970):

‘William Henry Reilly

Born 5 October 1892 at Salford, Lancs. Member of FCCC from 1958, and of BCPS from 1968. Fairy problems published in Chess Amateur, The Problemist, Fairy Chess Review and Feenschach. Orthodox problems also in Manchester City News, Manchester Weekly Times, Manchester Guardian, Daily Mail, Western Daily Mercury, Birmingham Daily Post, Daily News, Daily Telegraph and The Chess Problem. Many were reproduced in Australian papers. Mr Reilly has solved orthodox and Fairy problems as a regular solver in all of these journals at various times. Nos. 23 and 24, the only orthodox problems in this Album, are included to mark Mr Reilly’s having also been an orthodox composer, No. 24 being probably his first problem, while No. 23 won the 2nd prize in the Good Companion tourney in February 1915. The latter was included among a dozen problems set for Capablanca to solve; an article stated that “he solved all but one, averaging a quarter of a minute each, but the Reilly took him 15 minutes”. One of his off days?

Mr Reilly has won about 40 prizes (about half of them 1st prizes) and about the same number of mentions, commends, etc. He was a solver in Fairy Chess Review for the complete 27½ years of its existence without a break, and finished up as Champion Solver with 79 ladder ascents and 38 Top of the Month honours. His FCCC contributions have now reached nearly 380, all originals except one, and a third of them subsequently published in Feenschach.’

Dickens then gave 22 annotated fairy compositions by Reilly and two orthodox problems, including the mate-in-two under discussion here.

Mr McDowell adds:

‘I have been unable to find any obituary of Reilly in The Problemist. His last original fairy contribution to the magazine appeared in the January 1983 issue.’

Our correspondent has also sent us, courtesy of Brian Stephenson, the extensive coverage of the problem-solving competition which was published in The Good Companion Chess Problem Club in 1914 and 1915. The 12 two-movers appeared on pages 47-49 of the 22 February 1915 issue, and below is the first of those pages:

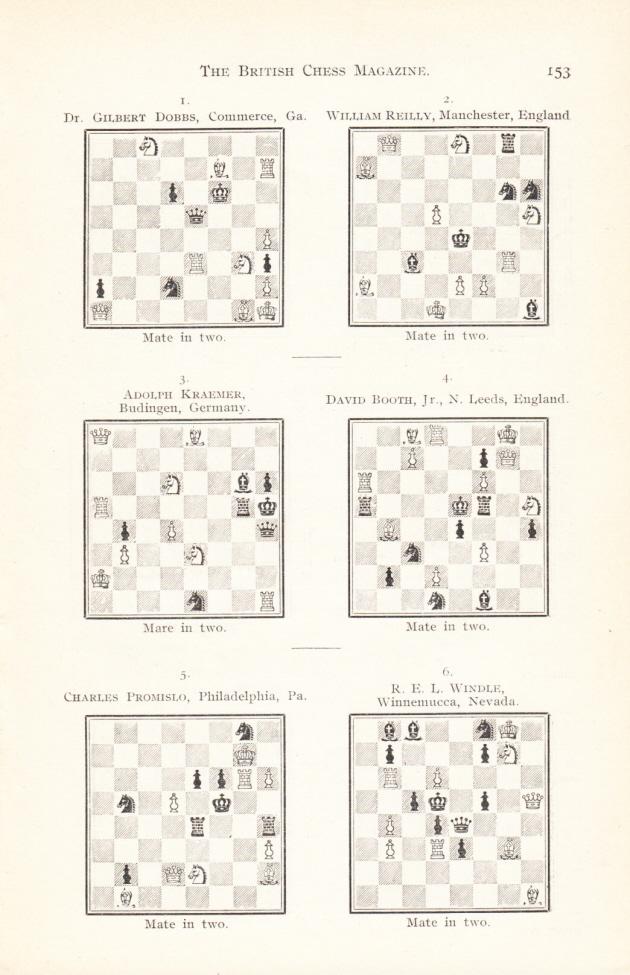

The full set was also given on pages 153-154 of the April 1915 BCM:

The Good Companion publication reproduced extensive reports on the solving competition which were received from club secretaries in various countries, and on pages 93-94 of the 1 May 1915 issue Frank Janet (the pseudonym of Elias Silberstein) presented the minutes of the session held at the Manhattan Chess Club. Edward Lasker solved 11 of the 12 problems in one hour 27 minutes, and Frank J. Marshall solved eight in 37 minutes. Regarding Capablanca, the following was reported by Janet:

‘José R. Capablanca solved all 12 in 15 minutes. Capablanca’s ability to solve problems is nothing short of miraculous. He had 11 of them in 11 minutes. The Reilly, No. 352, held him for four minutes. After the Tourney was over I put a series of swift positions of my own and he had the answers for each almost as soon as it struck the board. He wishes to state that he did not officially enter the Tourney, as he felt it might be unfair to the others, but solved the problems in order to show his interest. He does not wish to be considered for a prize.’

We do not know why Dickins stated that Capablanca took 15, rather than four, minutes on the Reilly composition (key move: 1 Rg2).

For other episodes involving Capablanca and problem-solving, see pages 89-91 of our monograph on him, as well as Steinitz Stuck and Capa Caught.

8007. Tournament draws

Steinitz writing on page 267 of the September 1887 International Chess Magazine:

‘To my mind it is clear from long experience that the greatest evil that has to be contended with in tournaments is the scoring of the draws absolutely, and the system of the London tournament of 1883 is by far the best compromise that can be effected in order to make tournaments a real test of superiority.’

8008. Alekhine’s tournament record

From page 34 of Famous Chess Players by Peter Morris Lerner (Minneapolis, 1973):

‘From 1921 to 1927 Alekhine won practically every tournament in which he played. Only the current world champion, José Capablanca, and ex-world champion Emanuel Lasker could restrain him.’

By no means did Alekhine win practically every tournament during that period, and below is a comment of ours in The Games of Alekhine:

‘As he neared his goal of a match against Capablanca, his playing-record remained patchier than is sometimes imagined, particularly in tournaments which also featured other potential challengers.’

8009. Alekhine’s wives

With readers’ help we hope to draw up an accurate list of Alekhine’s wives with as many biographical dates as possible. As a starting-point, there follows an extract from the obituary of Alekhine by Erwin Voellmy and Jean-Charles de Watteville on pages 85-86 of the June 1946 Schweizerische Schachzeitung:

8010. Lugansky on Alekhine

Chris Turnbow (Memphis, TN, USA) notes a press release concerning the pianist Nikolai Lugansky, who states:

‘Alekhine was always my favourite chessplayer, even in my childhood. I was impressed by his ability to find the thread for a combination of almost any position. The quadruple world champion viewed every chess game as a work of art – as a chess fan, that way of thinking of things is very close to my own.’

The unusual term ‘quadruple world champion’ evidently reflects the fact that Alekhine won four world title matches.

Our correspondent asks whether light can be shed on the following statements about Alekhine (not by Lugansky) in the press release:

‘In 1939, during the chess Olympics in Buenos Aires, he called for the German team to be disqualified because of the German attack on Poland. After the Olympics he performed charity games, with funds going to the Polish Red Cross.’

8011. Nat Halper

A remark by Nat (Nathan) Halper (1907-83) on page 136 of the April 1943 Chess Review:

‘In my early career I knew nothing about chess, but had a certain slyness. In my later career I knew nothing about chess, but had a certain cussedness. I never knew enough to know how to win a game, but because of my orneriness and cunning I have been able to tie games with Kashdan, Horowitz, Hanauer, Reinfeld, Bernstein, Ulvestad, Santasiere, M. Green and L. Levy ... And – were they annoyed!’

8012. Arvid Kubbel

Martin Sims (Upper Hutt, New Zealand) asks whether firm information is available on the circumstances of Arvid Kubbel’s death in the Soviet Union in the late 1930s, e.g. whether reports that he was executed can be substantiated.

8013. An article about Marshall

John Blackstone (Las Vegas, NV, USA) has forwarded an article about Frank Marshall by Harvey T. Woodruff on page B3 of the Chicago Daily Tribune, 31 January 1915. It discusses the US champion’s departure from Mannheim, 1914 but also has some information on his family and early life, such as the following:

‘Marshall was born 37 years ago – on 21 August 1877, to be exact – in New York City, where his father was engaged in the flour business. He is of English-Scotch descent. The head of the family was born in England and the mother, who is still living, is Scotch. When Frank was eight years old his father removed to Montreal, where three brothers were added to the family. Two of them are in the railroad business in Minneapolis, while another is located in Kansas City ...’

Clarification is sought regarding the discrepancy over Marshall’s birth-date, which was 10 August 1877 according to page 7 of his book Chess Openings (Leeds, 1904) and page 3 of My Fifty Years of Chess (New York, 1942). On the other hand, 21 August 1877 was the date given on, for instance, page 574 of the March 1898 American Chess Magazine, on page 283 of the December 1910 American Chess Bulletin and, even, on page 16 of Marshall’s book Chess Masterpieces (New York, 1928), in a biographical section by J.C.H. Macbeth.

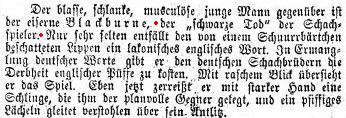

8014. ‘The Black Death’

An enquiry from Rick Kennedy (Columbus, OH, USA) concerning J.H. Blackburne’s nickname ‘The Black Death’ is prompted by the suggestion in a recent ChessBase article that the term relates to the master’s skill as Black.

‘Do you know the origin of the nickname, and whether it had anything to do with Blackburne’s prowess with the black pieces?’

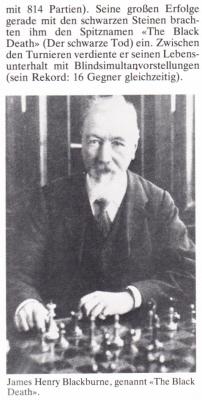

To begin with the second part of Mr Kennedy’s question, we note that such a claim is occasionally seen in chess literature, an example being the entry on Blackburne on page 41 of Lexikon für Schachfreunde by Manfred van Fondern (Lucerne and Frankfurt am Main, 1980):

In that entry Blackburne’s first name was twice given as James, instead of Joseph. We are aware of no primary sources making a connection between ‘The Black Death’ and Blackburne’s handling of the black pieces.

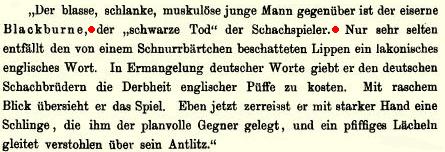

As regards the origin of the sobriquet, below is a passage from pages 8-9 of Mr Blackburne’s Games at Chess by P. Anderson Graham (London, 1899):

‘There was a description published of him in the book of the Vienna tournament of 1873, which, allowing for the changes made by the years, might stand for today. Says the writer: “The pale, lean, muscular young man opposite [i.e. playing against Steinitz] is the iron Blackburne, the Black Death of chessplayers. But very seldom there falls from his moustache-covered lips a laconic English word. He surveys the game with the eye of a hawk; even now he is tearing to bits a snare laid for him by his unsuccessful opponent, and a demure smile steals over his face.”’

The Blackburne entry in the Oxford Companion to Chess

affirmed, ‘The tournament book of Vienna 1873 called him

“der schwarze Tod” (Black Death), a nickname that became

popular’, but it would be more precise to say that Der

erste Wiener internationale Schachcongress im Jahre 1873

edited by H. Lehner and C. Schwede (Leipzig, 1874) merely

quoted, on page 50, from an external source:

Page 48 stated that the writer of the material cited was Dr J. Pollach, in an account first published in a shorter form in the Deutsche Zeitung and later reprinted in full in chess publications.

Peter Anderberg (Harmstorf, Germany) informs us that the abridged text appeared in the Viennese daily Deutsche Zeitung on 2 August 1873, morning edition, page 4. It included the ‘Black Death’ reference:

Mr Anderberg notes furthermore that although the Deutsche Zeitung named the writer only as ‘-ch’, later sources specified ‘Dr J. Pollach’, and that the text in the tournament book was reproduced from the Oesterreichische Schachzeitung, October 1873, pages 293-295.

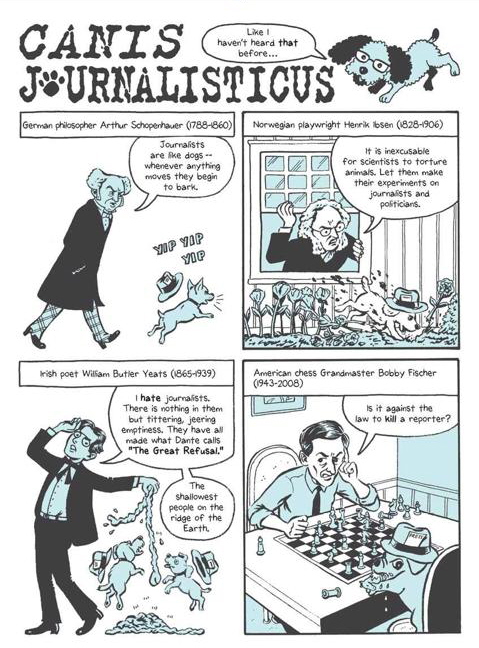

8015. Journalism

Mark N. Taylor (Mt Berry, GA, USA) writes:

‘I found this illustration in a review of Brooke Gladstone’s and Josh Neufeld’s 2011 media studies book The Influencing Machine (Norton). I do not have a copy of the book, so I do not know if the source of the quotation is cited therein.’

We take this opportunity, more generally, to recall that Chess Journalism and Ethics quotes a line, spoken by Jacob Milne, from page 61 of Tom Stoppard’s brilliant play Night and Day (London, 1979):

‘Junk journalism is the evidence of a society that has got at least one thing right, that there should be nobody with the power to dictate where responsible journalism begins.’

A comment by the character Dick Wagner on page 27 is also memorable and of obvious relevance to the chess world:

‘... there’s no way of telling whether he’s lying because he knows the truth or because he doesn’t know anything, so you can’t trust his mendacity either – he could be telling the truth half the time, by accident.’

Later in the same passage there is a comment to which we referred in Instant Fischer:

‘He wants to know which side the Globe thinks it’s on. So I tell him, it’s not on any side, stupid, it’s an objective fact-gathering organization. And he says, yes, but is it objective-for or objective-against?’

Page 45 has a remark which was quoted on page 289 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves:

‘Perhaps I’ll get him a reporter doll for Christmas. Wind it up and it gets it wrong.’

The same character, Ruth Carson, has this line on page 60:

‘I’m with you on the free press. It’s the newspapers I can’t stand.’

8016. Kieseritzky/Kieseritsky (C.N. 7984)

C.N. 7984 asked whether any case at all could be made for the spelling ‘Kieseritsky’.

Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) reports that he has found no instances of that spelling during the player’s years in France. In La Régence and his book Cinquante parties jouées au Cercle des Echecs et au Café de la Régence (Paris, 1846) he invariably used ‘Kieseritzky’.

Our correspondent has also found a copy of Kieseritzky’s death certificate and points out that although it has ‘Kieseritzki’ and ‘19 mai 1853’, pre-1860 registrations in Paris are often unreliable because the records had to be reconstituted following a fire in 1871.

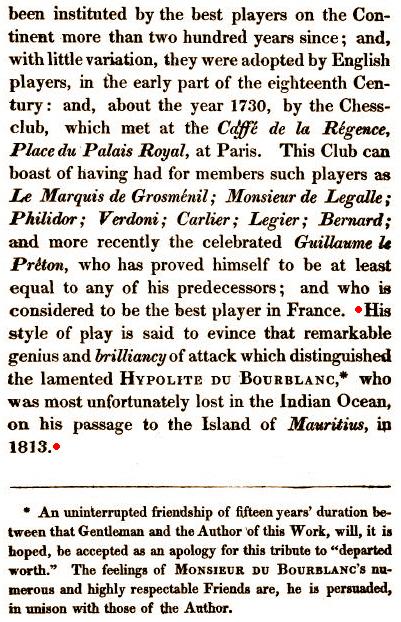

8017. H. du Bourblanc

Mr Thimognier asks for information about Hyp[p]olite du Bourblanc, who was praised on page 29 of volume one of A New Treatise on the Game of Chess by J.H. Sarratt (London, 1821):

A number of references to du Bourblanc in chess literature are readily traced through Google Books, but can additional information about him be found?

8018. A Keres saying

‘The older I grow, the more I value pawns.’

Whether Paul Keres ever wrote down this familiar observation is not known to us, but it was ascribed to him by I.A. Horowitz in an article on page 369 of the December 1955 Chess Review. Horowitz stated that Keres had made the remark ‘to a member of the US team only last summer’ (i.e. when Keres was aged 38).

| First column | << previous | Archives [104] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.