Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [105] | next >> | Current column |

8019. A diagram after every move

Have any readers seen an edition of Fischer’s My 60 Memorable Games which has a diagram after every move?

From page 134 of Great Chess Books of the Twentieth Century in English by Alex Dunne (Jefferson, 2005):

‘Fischer’s My 60 Memorable Games was published by Cesar Pineda; in it, every move of every game in My 60 Memorable Games was diagrammed.’

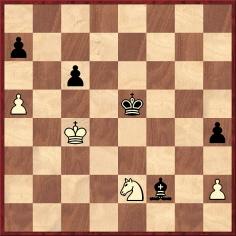

The only volume by Cesar L. Pineda in our collection is 100 Mini Gems of Chess (Fort Washington, 1980):

The back cover of the book, which was published by Datapass Corporation, refers to Pineda as ‘a native of the Philippines’ who ‘migrated to the United States in 1967’ and mentions another work from the same author and publisher: ‘1978 World Chess Championship Games, a move-by-move presentation of all 32 games of the Karpov-Korchnoi match in Baguio City, Philipines [sic]’. Internet sites list a 1998 book by him: The Best 100 Games in 30 Years: Illustrated move-by-move.

8020. Arvid Kubbel (C.N. 8012)

Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England) refers to the article ‘Memories of Famous Composers’ by A. Herbstman on pages 429-433 of the July 1981 EG. From the last two pages:

‘On the outbreak of war [in 1941] the threat to Leningrad became very real. I hurried to Alexey [Troitzky] and tried to persuade him to leave with me. He rejected the idea. He died of starvation during the long blockade.

Having failed to rescue Troitzky I then telephoned [Leonid] Kubbel, asking him to help me with my suitcases to the railway station. He agreed. On the way to the train I already knew that that train was the last to leave Leningrad, and that there was grave doubt whether it would get past Bologoye, a station on the route to Moscow, as it was invested by the Germans. Leonid helped me with the baggage and we found ourselves alone in a compartment. I locked the door and announced that I would not let him out, because he would die if he remained in Leningrad. In a few days the German forces would be there. He began to make objections, saying that he could not leave his brothers behind just like that. He wished me a good trip, and a safe one, and descended to the platform. The train moved off. I never saw him again. All three brothers died in the siege, just as Alexey Troitzky died.’

Since other sources state that Arvid Kubbel died in the late 1930s, we continue to seek clarification.

8021. Steinitz on tournaments

From page 297 of the October 1887 International Chess Magazine:

‘One of the drawbacks of tournament play is that a defeated competitor has not alone to bear the disappointment and chagrin over his losses, but he is also liable to be reproached by his rivals for failures which may have affected their own individual interests in the race.’

8022. Marshall’s birth-date (C.N. 8013)

Russell Miller (Vancouver, WA, USA) notes that 10 August 1877 was the date given for Frank Marshall’s birth in the 1942 World War II Draft Regulation Cards.

Further evidence in favour of 10 August 1877 is Marshall’s passport application, shown in C.N. 7885.

8023. Charosh v L. Jaffe, New York, 1936 (C.N. 3619)

A game on which information is still sought:

1 d4 c5 2 d5 Na6 3 Nf3 d6 4 e4 Bg4

5 Ne5 Qa5+ 6 Bd2 dxe5 7 Bxa5 Bxd1

8 Bb5 mate.

In C.N. 3619 a correspondent quoted the game from page 10 of Irving Chernev’s 1000 Best Short Games of Chess (New York, 1955). The book described White as a problemist, Mannis Charosh – see, for instance, page 74 of The Personality of Chess by I.A. Horowitz and P.L. Rothenberg (New York, 1963). Some databases have rendered White’s name as ‘Karosz’, and on page 55 of Unorthodox Chess Openings (New York, 1998) Eric Schiller put ‘Chrosh’.

To avoid confusion with Charles Jaffe, Chernev’s anthology made a point of specifying that the loser was ‘L. Jaffe’, but who was he?

8024. Last-round losses

From Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina):

‘The conclusion of the Candidates’ tournament in London on 1 April 2013 reminded me of the title of a chapter in Pachman’s book Partidas decisivas, which dealt with Groningen, 1946: “Derrota de los dos en cabeza”.

Have there been other important tournaments in which the two leaders lost their last-round games?’

In the English edition of the book, Pachman’s Decisive Games (London, 1975), the chapter on Groningen, 1946 (pages 118-124) was entitled ‘Defeat of the Two Leaders’.

As Wolfgang Heidenfeld related in the entry on Groningen, 1946 on page 133 of The Encyclopedia of Chess edited by Harry Golombek (London, 1977):

‘The contest immediately developed into a duel between Botvinnik and Euwe, the lead changing several times between these two. At half-way (round ten) Botvinnik had scored 9, from Euwe 7½, Denker and Smyslov 7, but five rounds later the score read Euwe 12½, Botvinnik 11½, Smyslov 10½, Szabó 9½. Both leaders were shaky by now, and after Botvinnik had regained the lead both lost in the last round (one of the most sensational on record) – Botvinnik to Najdorf, and Euwe to Kotov.

Leading scores: Botvinnik 14½, Euwe 14, Smyslov 12½, Najdorf, Szabó 11½.’

The above photograph is taken from Groningen 1946 by M. Euwe and H. Kmoch (Groningen, 1947). With readers’ help we hope to build up a comprehensive key.

8025. Alekhine’s wives (C.N. 8009)

Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) draws attention

to the article ‘Souvenirs d’une époque révolue’ by

Jeanne Léon-Martin published on pages 3, 4 and 22 of the

January 1962 Europe Echecs, having originally

appeared in the Bordeaux newspaper Sud-Ouest. Our

correspondent comments:

‘She and her husband, the problemist Gabriel Léon-Martin, were friends of Alexander Alekhine and his third wife, Madame Vassilieff. There is a detailed explanation of how Jeanne Léon-Martin introduced Grace Freeman to Alekhine, and how this led to his divorce from Madame Vassilieff.

The article must cast serious doubt on the oft-repeated story that Alekhine met Grace Freeman during a simultaneous exhibition in Tokyo, given that Madame Léon-Martin specifies that his separation from Madame Vassilieff occurred earlier and that Grace Freeman “accompanied Alekhine on his world tour”.

The article is also interesting for the details provided regarding Alekhine’s home life (rue de la Croix-Nivert, Paris) and his interest in bridge.

On the other hand, it supplies scant information regarding dates. Madame Léon-Martin was the “pioneer” of women’s chess in France, and she organized the first French championships (starting in 1924). Her article indicates that she introduced Grace Freeman to Alekhine when she, Grace Freeman, had just enrolled for the French championship. The first reference to Grace Freeman that I have found in a list of participants in the French women’s championship is in February 1931. She participated again in 1932 and 1941. (A photograph taken during the 1941 championship may well feature her, but I am not sure.) It would therefore appear that Alekhine and Grace Freeman met in 1931 or 1932, before Alekhine’s world tour (which began at the end of 1932).

I would also mention an article by Genna Sosonko, “Alexander Alekhine, The Paris years” on pages 80-87 of the 1/2010 New in Chess. It relates how Alekhine met Nadezhda Semenovna Vasilieva, née Fabritskaya, at a Russian ball in Paris in 1924, but unfortunately Sosonko provides no sources.’

The Sosonko article can also be found on pages 38-49 of his latest anthology, The World Champions I Knew (Alkmaar, 2013).

We transcribe a few extracts from Jeanne Léon-Martin’s article:

‘Il [Alekhine] fit la connaissance, avant son départ pour l’Amérique d’où il revint champion du monde, de Mme Vassilieff, veuve d’un général ...

Un jour, une Américaine, Mme Freeman, vint me demander de bien vouloir l’inscrire comme participante [in a women’s tournament]. Elle était grande, gaie et paraissait fort enthousiaste du jeu d’échecs. Sur le bateau qui la ramenait des Etats-Unis, un tournoi d’échecs avait été organisé et elle avait gagné un livre d’Alekhine: Deux cents parties d’échecs. Elle habitait un coquet appartement, très moderne, à Montparnasse, et je fus invitée chez elle avec quelques-unes de ses compatriotes. Mme Freeman me confia qu’elle serait très heureuse si Alekhine pouvait lui dédicacer le livre qu’elle avait gagné. [Since Deux cents parties d’échecs was not published until 1936, the book in question may well have been the English edition of Alekhine’s first volume of Best Games, published in 1927.]

... Ayant organisé une rencontre pour “samedi prochain”, j’avais la conscience absolument tranquille et j’étais plutôt satisfaite d’avoir fait plaisir à tous.

Ce samedi-là, lorsque nous sommes arrivés mon mari et moi – Mme Freeman devait venir plus tard – Alekhine chantait une de ses chansons préférées: “J’embrasse votre main, madame”, accompagné au piano par Mme Isnard. Lorsque Mme Freeman fut là et après qu’Alekhine eut dédicacé son livre, je laissai le champion, Mme Freeman et des amis faire une partie de bridge derrière les fameuses tentures ... partie qui durait encore lorsque nous primes congé.

Quelque temps après, je reçus un coup de téléphone de Madame Alekhine me donnant rendez-vous à la Régence. Cela ne me surprit pas. Nous avions l’habitude de nous rencontrer quelquefois dans Paris pour prendre le thé. “Alors, lui dis-je, comment trouvez-vous Mme Freeman? Sympathique, n’est-ce pas?

– Oui, certainement ... Trop peut-être! Elle a beaucoup plu à Alekhine. Déjà, dès cette première rencontre, à la fin de la partie de bridge, il a tenu à la raccompagner ... C’est fini pour moi. Je sais qu’elle a gagné et que j’ai perdu.”

J’étais bouleversée. Il me semblait que j’étais coupable. Avec l’expérience que la vie lui avait durement inculquée, elle comprit mon désarroi. Très bonne et peut-être un peu fataliste, elle me dit sans animosité:

“Mme Freeman saura garder Alekhine.” J’aurais voulu la consoler. Ce fut elle qui me consola. Sensiblement plus âgée qu’Alekhine, elle devait mourir peu après.

Mme Freeman devint Mme Alekhine. Elle l’accompagna lors de son tour du monde, en Asie, en Indonésie. Ils habitèrent jusqu’à la guerre de 1939 le château d’Arques-la-Bataille, près de Dieppe, propriété de Mme Freeman.’

8026. Automaton

John Blackstone (Las Vegas, NV, USA) submits the following from page 3 of the New York Sun, 27 October 1899:

8027. Chinese

From page 137 of Teach Yourself to Learn a Language by P.J.T. Glendening (London, 1965):

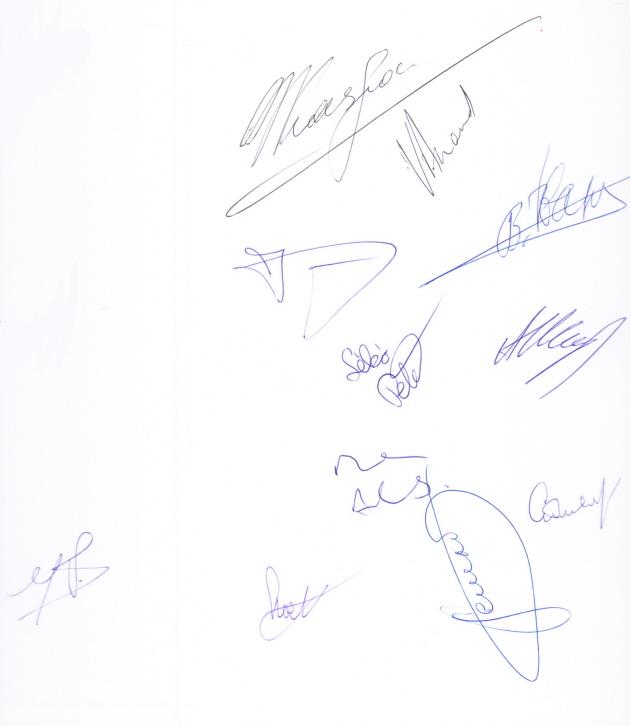

8028. Quiz

question

Readers are invited to identify as many signatures as possible which are shown below, from a book in our collection.

8029. H. du Bourblanc (C.N. 8017)

Rod Edwards (Victoria, BC, Canada) writes:

‘Hypolite du Bourblanc was the younger son of Adélaïde le Cardinal de Kernier (1755-1836) and Saturnin-Marie-Hercule, comte du Bourblanc (1739-1819), who had been the Attorney General at the Parliament of Brittany in Rennes but had emigrated to England with his family in January 1792, as did many other noble families of Brittany following the Revolution. Hypolite’s older brother was Saturnin-François-Alexandre du Bourblanc (1776-1849), who later became the comte du Bourblanc. He also had a sister, Amélie Hélène Alexandrine (born 1780), as well as another sister, probably born later, and two half-sisters. This information is pieced together from the Dictionnaire de la Noblesse, volume 14, 1784, page 117; P. Levot, Biographie Bretonne, volume 1, 1852, pages 168-169, the “pierfit” genealogical website and other sources mentioned below.

After their departure from France, both sons joined their father in two military campaigns, joining a gathering of French nobility on Jersey, as part of the army of the comte de Moira (Levot, 1852, page 169).

These facts make it possible to deduce that Hypolite was born after 1776 but no later than the early 1780s, and probably between 1777 and 1779.

In England in 1796 the comte du Bourblanc established a school of French law for young members of the emigrant community there (Levot, 1852, page 169). His two sons, “M. le chavalier du Bourblanc” (Hypolite) and Saturnin-François-Alexandre, were both students at that school, as was their sister, Amélie (l’Abbé de Lubersac, Journal historique et religieux de l’émigration et déportation du clergé de France en Angleterre …, London, 1802).

From June 1807 to January 1808 “the Chavalier Hippolitte du Bourblanc” was employed by Patrick Craufurd Bruce, a wealthy Scot, as a travel companion for his son, Michael Bruce (1787-1861), for a trip to Germany, Denmark and Sweden. In a letter dated 1 June 1807 the father wrote that Hypolite du Bourblanc was “a steady, correct, well behaved Gentleman, he has resided here these Fifteen Years with his Father who was a Gentleman of Property in Brittany and a Man of the Robe and I believe a Judge in one of the Courts; his Wife is here with him and another Son …” (Ian Bruce, The Nun of Lebanon, 1951, page 47). On this voyage, they visited nobility and royalty along the way, and made a risky visit to Copenhagen immediately after it had been partially destroyed in an attack by the English fleet (Bruce, pages 48-49).

According to an article by P. Cordier, “Les métiers des Emigrés à l’étranger” in L’intermédiaire des Chercheurs et Curieux (volume 24, 10 February 1891, page 89), “Hippolyte du Bourblanc” taught chess at half a guinea per lesson.

Lieutenant Hypolite du Bourblanc appears in records of appointments and promotions in the English army in 1813, although he presumably joined earlier. In early 1813 he was in “Du Dresney’s regiment”, and then in February he briefly joined the 60th foot regiment before being promoted to Meuron’s regiment on 18 February 1813, only to resign that position on 1 July 1813. Meuron’s regiment had once served the Dutch East India Company, but by this time it was British, and was sent to Canada in May 1813. (Royal Military Chronicle, volume 6, May 1813, pages 66 and 166; Royal Military Panorama or Officer’s Companion, April 1813, page 89 and October 1813, page 76; Guy de Meuron, Le régiment Meuron, 1781-1816, 1982, page 306).

The shipwreck in which du Bourblanc died must therefore have taken place in the latter half of 1813.’

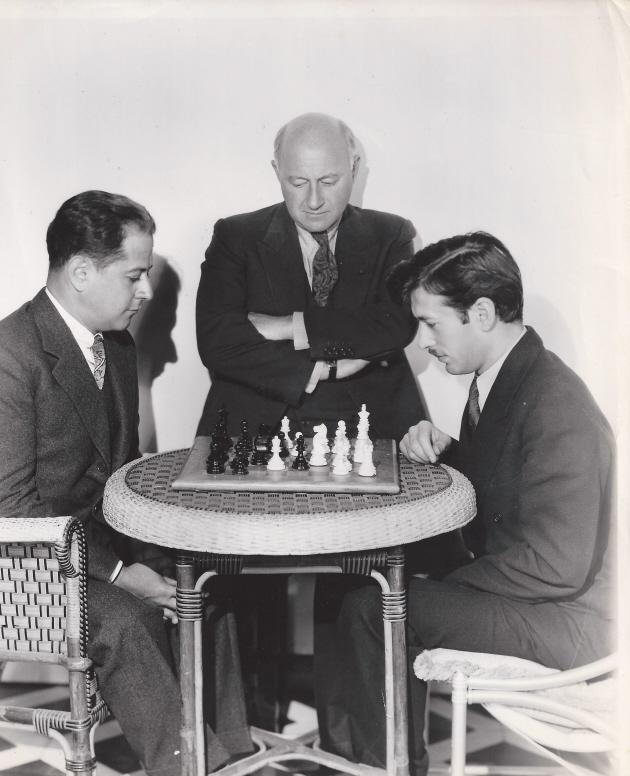

8030. Capablanca v Steiner

From John Donaldson (Berkeley, CA, USA):

‘I have seen pictures of Capablanca and Steiner from Los Angeles 1933, but, until now, not this one with Cecil B. deMille:

It comes from the archives of Jacqueline Piatigorsky, whose chess mentor was Herman Steiner, and has been made available thanks to her family.’

For scrutiny of the position (in the context of the famous game of living chess between Capablanca and Steiner, in which, however, the Cuban had the white pieces) a detail is provided. We have drawn together our material on the game in a new feature article, Capablanca v Steiner (Living Chess).

8031. Practice and study

A remark by Steinitz on page 303 of the October 1888 International Chess Magazine:

‘... a few weeks’ practice with masters is worth years of study.’

8032. Lawson translated into French

We are grateful to Gilles David (Eaubonne, France) for a copy of his translation into French of David Lawson’s monograph on Morphy, under the title Paul Morphy: La Gloire et la Tristesse des Echecs.

One hundred numbered copies have just been produced, and details are available at a website which Mr David is currently developing.

8033. Robert Byrne (1928-2013)

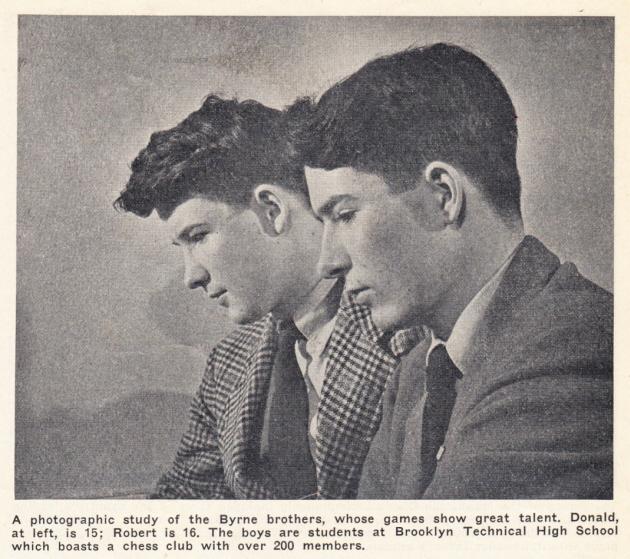

An early photograph of the Byrne brothers was published on page 5 of the February 1945 Chess Review:

The following year (Chess Review, March 1946, page 22) Robert Byrne was described as ‘one of America’s most talented younger players’ when the magazine published his victory over Joseph Platz in the 1945-46 Manhattan Chess Club championship.

Robert Byrne and Lisa Lane

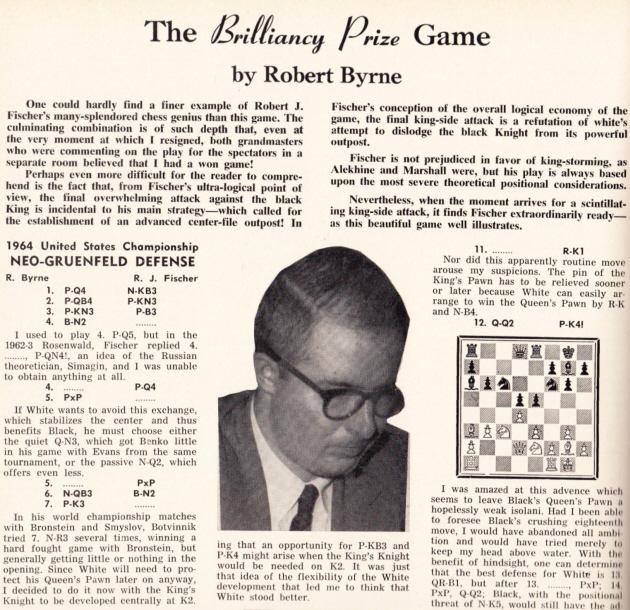

Byrne annotated his most famous game (Fischer’s win in the 1963-64 US championship) in an article entitled ‘The Brilliancy Prize Game’ on pages 142-143 of the June 1964 Chess Life. Some of his magnanimous remarks were quoted in the introduction to Game 48 in My 60 Memorable Games. Byrne’s final comment in Chess Life was ‘A marvelous performance by Fischer’.

He was the subject of a lengthy feature ‘Robert Byrne Amerca’s Newest Grandmaster’ by Beth Cassidy on pages 330-331 of the November 1964 Chess Review. It paid tribute to his ‘unaffected naturalness and unquestionable integrity’ and reported that the chessplayer whom he most admired was Botvinnik.

He seldom gave interviews but did answer a set of questions from Burt Hochberg on page 235 of the October 1966 Chess Life. One reply: ‘I would say Lasker and Botvinnik were the strongest influences, but I have learned from all the great masters.’ In response to the question, ‘the world championship notwithstanding, who is the best player in the world?’, Byrne answered, ‘Bobby Fischer’.

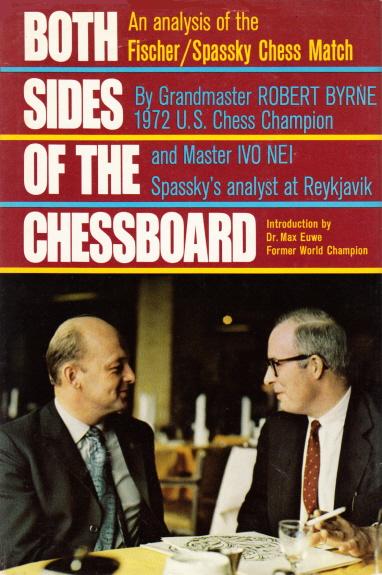

Hochberg, for his part, was one of many admirers of Byrne’s chess writing. The back cover of Both Sides of the Chessboard (New York, 1974), which Byrne co-wrote with Ivo Nei, included the following encomium from Hochberg: ‘The most careful, thorough analysis of a chess match you are ever likely to see.’

8034. Misidentification

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) notes a Dutch website which purports to show a photograph of Capablanca giving a simultaneous exhibition in Havana in 1897.

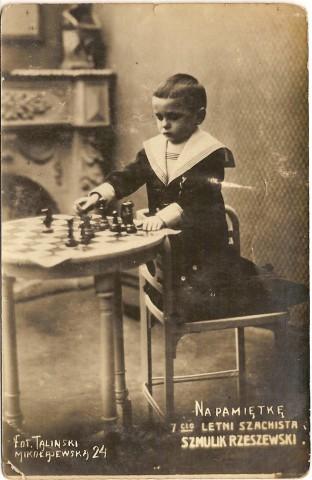

As pointed out by us on page 52 of the Winter 2000 issue of Kingpin, the front page of the Cuban newspaper Juventud Rebelde dated 13 November 1988 also claimed that the picture showed Capablanca ...

... whereas in reality the prodigy was Reshevsky. He was dressed similarly in a photograph given in C.N. 4212:

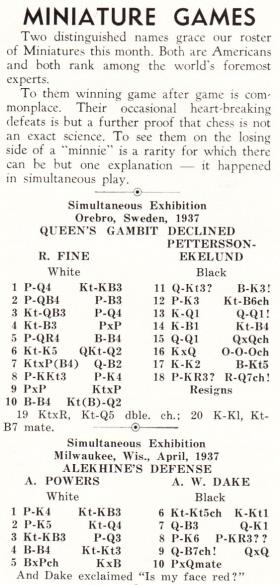

8035. Two Dake losses

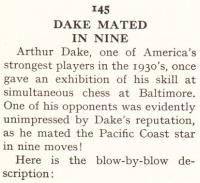

Two items on page 66 of Wonders and Curiosities of Chess by Irving Chernev (New York, 1974):

Chernev had also published the games in his anthology 1000 Best Short Games of Chess (New York, 1955); see pages 15 and 20-21. In the French Defence game (said there to have begun 1 e4, and not 1 d4) White was named as ‘Pauli’ and the date was given as 1936 rather than 1935.

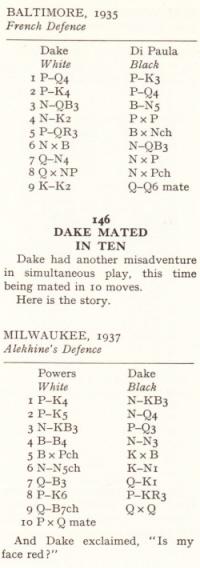

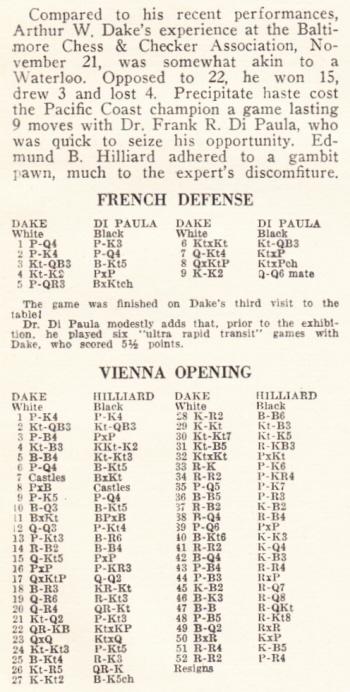

Chess Review of the mid-1930s had references to a player in Baltimore named ‘Dr F. Di Pauli’ (August 1935 issue, page 174) and ‘Dr F.R. DiPauli’ (January 1936, page 19). The latter spelling was used when the brevity was published on page 143 of the June 1936 Chess Review:

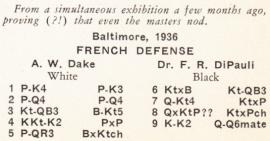

Although the game was dated 1936 above, it had already been published on page 153 of the November 1935 American Chess Bulletin, with a precise date (21 November 1935) and with Black identified as Dr Frank R. Di Paula:

(Dake v Hilliard: 1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Nc6 3 f4 exf4 4 Nf3 Nge7 5 Bc4 Ng6 6 d4 Bb4 7 O-O Bxc3 8 bxc3 O-O 9 e5 d5 10 Bd3 Bg4 11 Bxg6 fxg6 12 Qd3 g5 13 g3 Bh3 14 Rf2 Bf5 15 Qb5 fxg3 16 hxg3 h6 17 Qxb7 Qd7 18 Ba3 Rfb8 19 Qa6 Rb6 20 Qa4 Rab8 21 Nd2 g6 22 Raf1 Nxe5 23 Qxd7 Nxd7 24 Nb3 g4 25 Bb4 Re6 26 Na5 Rbe8 27 Kg2 Be4+ 28 Kh2 Bf3 29 Kg1 Nf6 30 Nb7 Ne4 31 Nc5 Rf6 32 Nxe4 dxe4 33 Re1 e3 34 Rh2 h5 35 d5 e2 36 Bc5 a6 37 Rf2 Kf7 38 Bd4 Rf5 39 d6 cxd6 40 Bb6 Ke6 41 Rh2 Kd5 42 Bd4 Kc6 43 c4 Ra5 44 c3 Rxa2 45 Kf2 Rd2 46 Be3 Rd1 47 Bc1 Rb8 48 c5 Rb1 49 Bd2 Rxe1 50 Bxe1 Kxc5 51 Rh4 Kc4 52 Rh2 a5 53 White resigns.)

Dake’s loss to A. Powers (Milwaukee, April 1937) was given on page 106 of Chess Review, May 1937:

8036. Dallas, 1957

Courtesy of John Donaldson (Berkeley, CA, USA), below is a photograph from the archives of Jacqueline Piatigorsky:

Mr Donaldson adds that the photograph was published on page 7 of Chess Life, 20 January 1958 with the following information:

Left to right: front row: Emile Gilutin and Fred Tears (the tournament organizers), Landrum (public relations [no forename given]), Jerry Spann (USCF President), Samuel Reshevsky.

Back row: Pal Benko, Larry Evans, Kenneth Smith, Svetožar Gligorić, Bent Larsen, László Szabó, Miguel Najdorf, Friðrik Ólafsson, Daniel Yanofsky and Isaac Kashdan (tournament director).

8037. Life is like a game of chess

John Townsend (Wokingham, England) notes the following poem by ‘Judy’ on page 53 of the Westminster Chess Club Papers, 1 August 1868:

A Game of Chess

Life’s something like a game of Chess,

The board our little sphere;

Alternate bright and darker spots,

Like our existence here.At first, like ‘pawns’, we quickly move,

No checks we meet from Time;

And then the ‘bishops’ cross our path

Ere yet we’ve reached our prime.Onward, like ‘kings’, our duty done

On our appointed square;

Alas! to find our cherish’d hopes

Are ‘castled’ in the air!Like ‘knights’, right boldly we advance,

So firm at first our aim;

Then turn aside away from good,

Afraid to combat shame.Our heart’s ‘queen’ lost! do not despair,

Nor shrink in heartfelt pain;

By breaking thro’ our manhood’s foes,

We’ll win her back again!And having tried our best to win,

We’re ‘mated’ p’r’aps at last!

With hopes fulfill’d and duty done,

May our life’s game be past.The struggle closed; with all we find

A common resting-place,

Where foes can meet without recoil,

And friends without embrace.So life is like a game of Chess,

The board our little sphere;

Alternate bright and darker spots,

Like our existence here.

Regarding comparisons between chess and life see too, for instance, the chapter entitled ‘The Moralities’ in A History of Chess by H.J.R. Murray (Oxford, 1913) and ‘The Morals of Chess’ by Benjamin Franklin. ‘Life is like a game of chess, changing with each move’ is often described as a ‘Chinese proverb’, but on what basis?

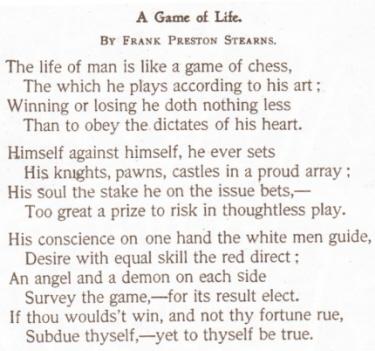

In the present item the focus is on poetry, and we add a

contribution by Frank Preston Stearns to the October 1898

American Chess Magazine, page 156:

Below is an anonymous composition from page 214 of the April 1915 Chess Amateur:

Life is Like a Game of Chess

How often would we fain confess

That life is like a game of chess,

In thought and varied movement;

And looking back it seems so plain

That could we start our game again,

In much we’d make improvement.

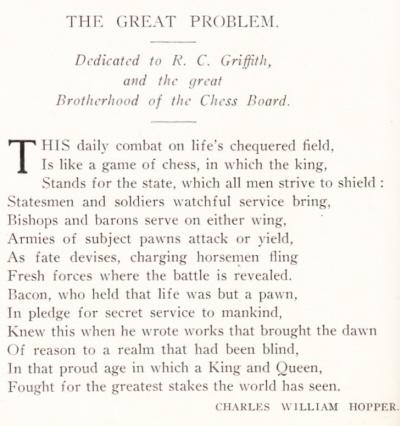

Finally, from the frontispiece to the May 1928 BCM

a composition by Charles William Hopper:

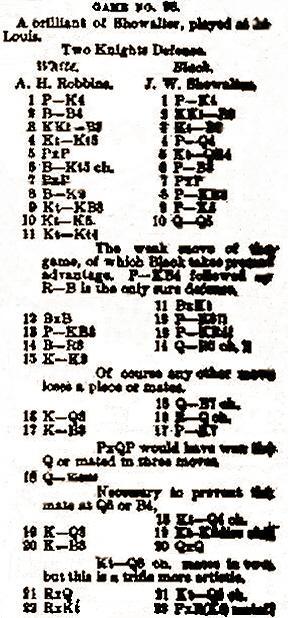

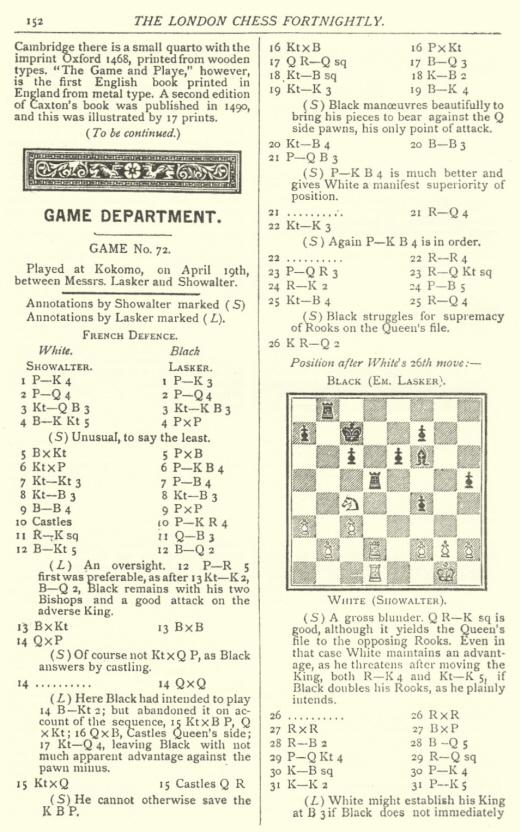

8038. Robbins v Showalter

1 e4 e5 2 Bc4 Nf6 3 Nf3 Nc6 4 Ng5 d5 5 exd5 Na5 6 Bb5+ c6 7 dxc6 bxc6 8 Be2 h6 9 Nf3 e4 10 Ne5 Qd4 11 Ng4 Bxg4 12 Bxg4 e3 13 f3 h5 14 Bh3 Qh4+ 15 Ke2 Qf2+ 16 Kd3 Rd8+ 17 Kc3 e2 18 Qg1 Nd5+ 19 Kd3 Ne3+ 20 Kc3 Qxg1 21 Rxg1 Nd1+ 22 Rxd1

22...exd1(N) mate.

This familiar game is generally said to have been won by J.W. Showalter against A.H. Robbins in Lexington in 1910; see, for example, pages 442-443 of 1000 Best Short Games of Chess by Irving Chernev (New York, 1955).

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) informs us that it was played in the United States Chess Association championship in St Louis in February 1890 and that the score was published on page 5 of the Albany Evening Journal, 21 June 1890:

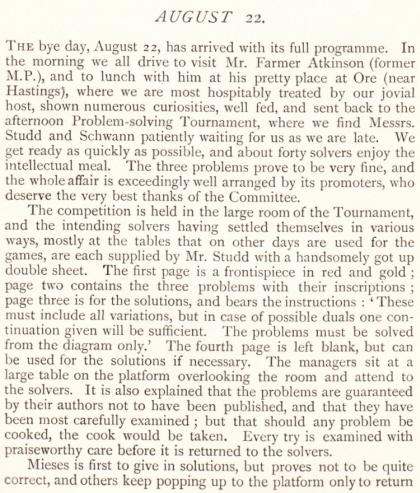

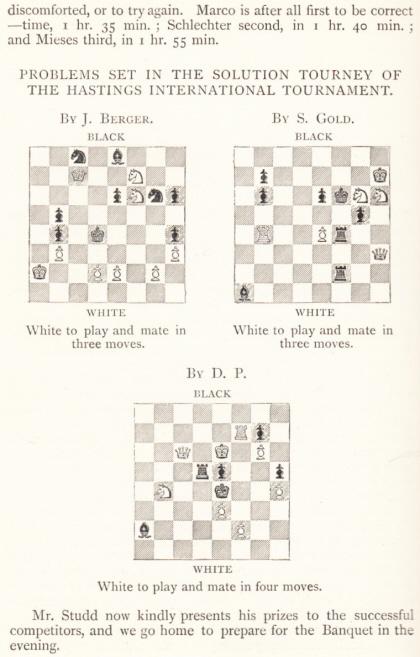

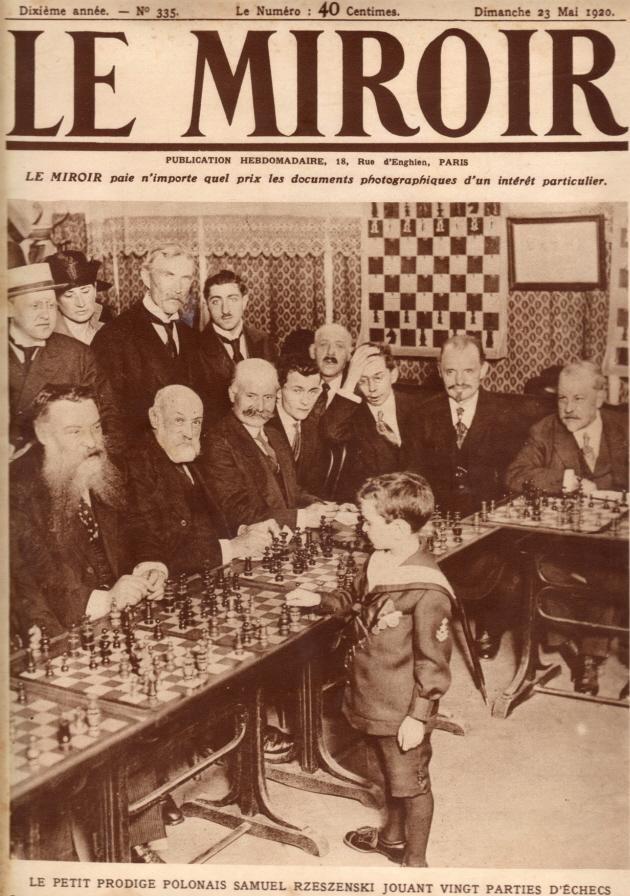

8039. Hastings, 1895 problem-solving competition

On the subject of problem-solving by masters, Michael

McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England) draws attention to

pages 215-216 of The Hastings Chess Tournament 1895 by

Horace F. Cheshire (London, 1896), which recorded the time

taken by Mieses, Marco and Schlechter to solve three

compositions:

From page 368:

Mr McDowell provides information regarding sources:

‘No. 1 (Johann Berger): This appears to have been an original composition contributed to the solving tourney. See problem 165 in Probleme, Studien und Partien von J. Berger 1862-1912 (Leipzig, 1914).

No. 2 (Samuel Gold): In 1895 this problem was published in the Montreal Weekly Gazette.

No. 3 (Dezső Pap): Wiener Salonblatt, 1872. Pap died in 1886.’

Page 88 of Berger’s book mentioned that a black knight on b7 and a black pawn on a7 in the unsound version were replaced by a black knight on c8.

8040. Too short

Our latest feature article concerns ‘Life’s too short for chess’, a remark which has been misattributed to William Ewart Napier, Irving Chernev, Henry James and Lord Byron.

8041. George Mathews

Steven B. Dowd (Birmingham, AL, USA) asks what grounds there may be for a statement at the IMDb website regarding the actor George Mathews (1911-84):

‘In private life, Mathews was the antithesis of the ruffians he often portrayed on screen: amicable and intelligent. Outside of his profession, he was an avid chessplayer and often participated in international tournaments.’

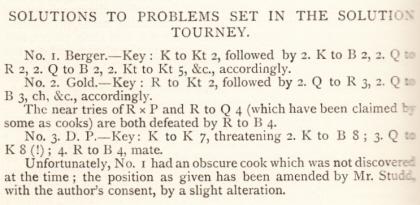

8042. Samuel Reshevsky (C.N. 8034)

From Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) comes the front cover of Le Miroir, 23 May 1920:

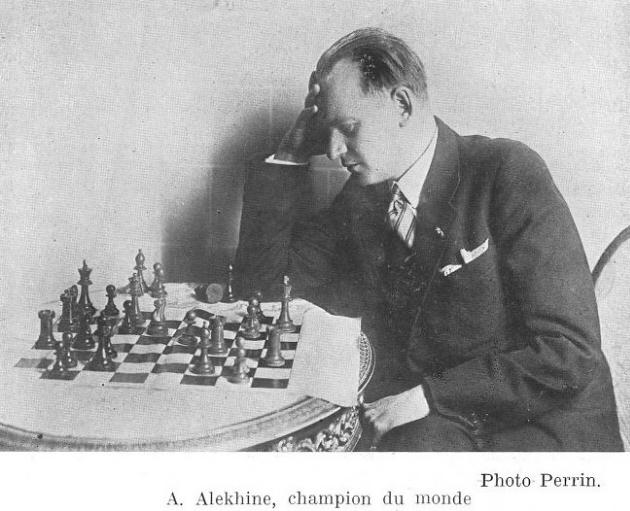

8043. Alekhine photograph

Mr Thimognier has also forwarded a shot of Alekhine which was published on page 29 of La Tunisie Revue Mensuelle Illustrée, February 1938:

Our correspondent adds that according to the article which followed, the photograph was taken during the world champion’s tour of Tunisia in December 1934.

We note that the position is the conclusion of Alekhine’s victory over Lasker in Zurich earlier that year.

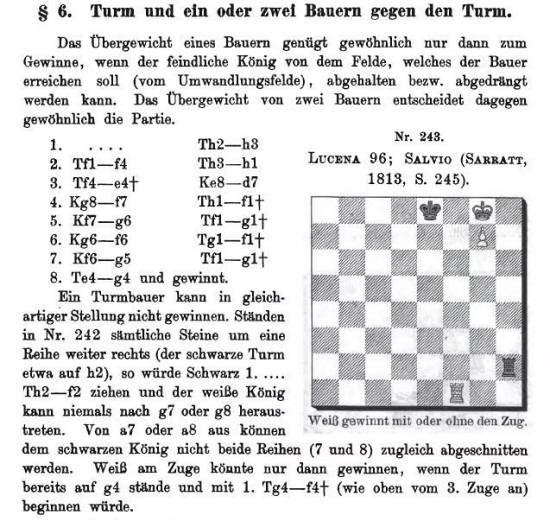

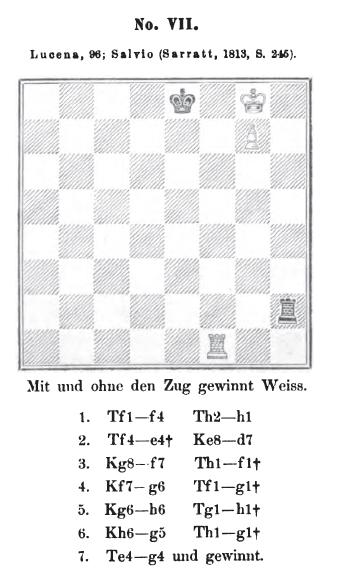

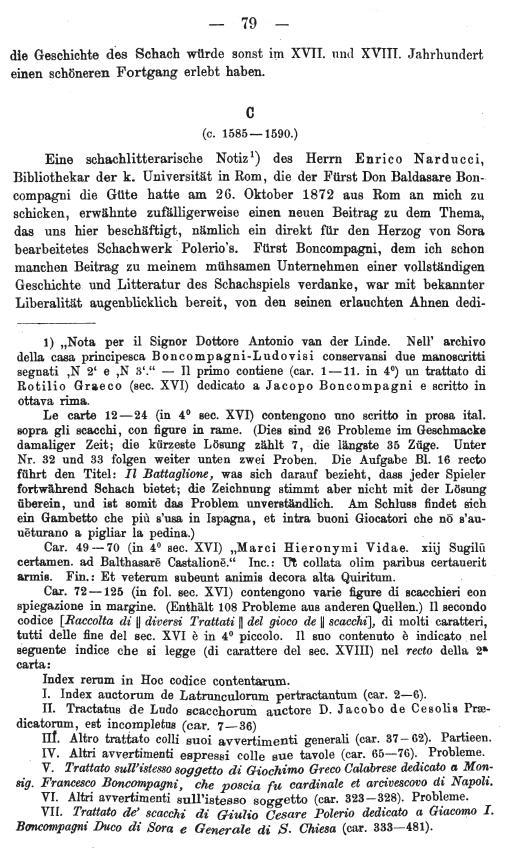

8044. The ‘Lucena Position’ (C.N.s 5536 & 6786)

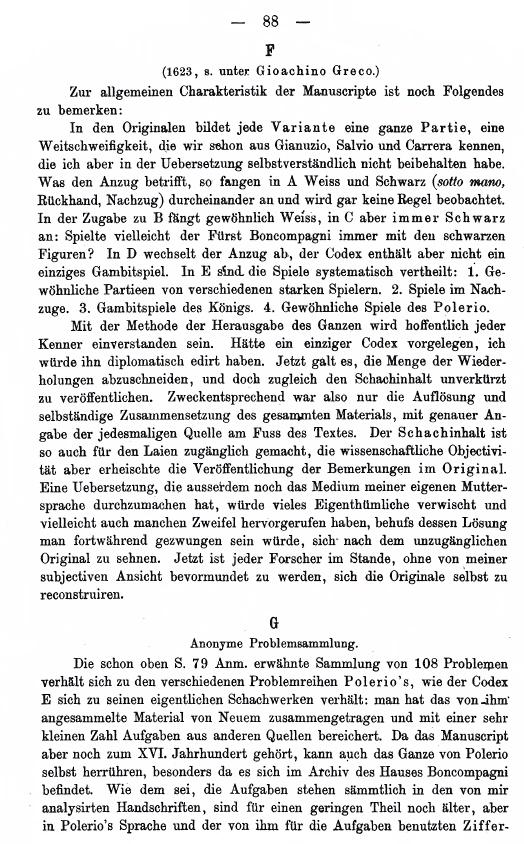

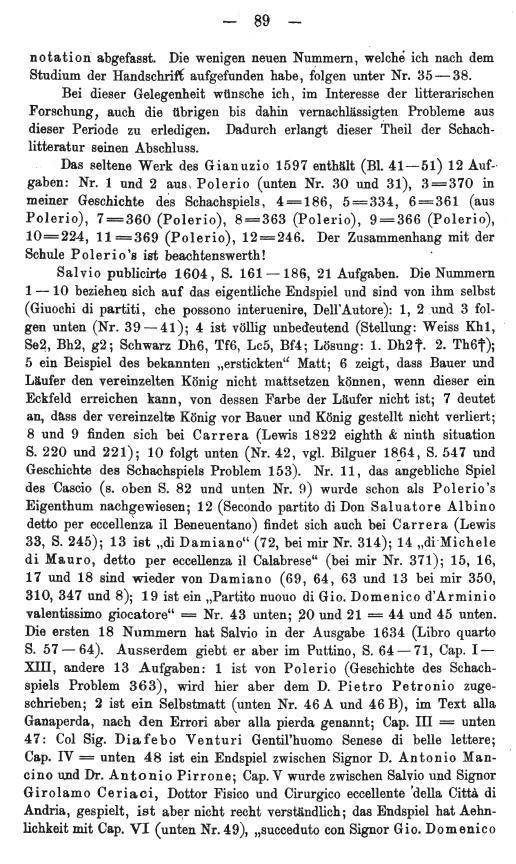

From Thomas Niessen (Aachen, Germany):

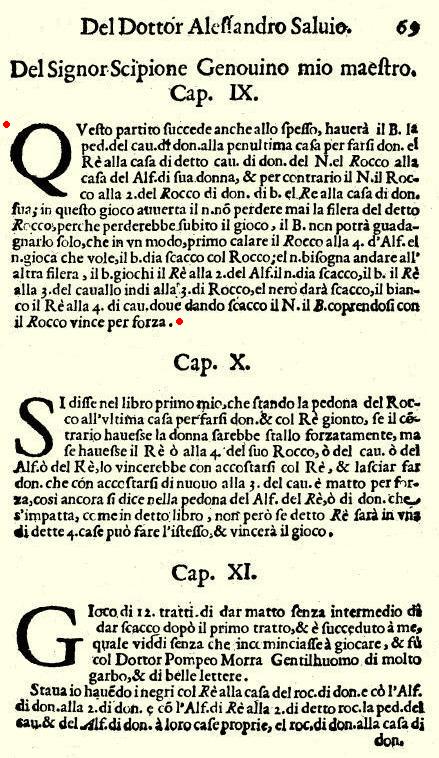

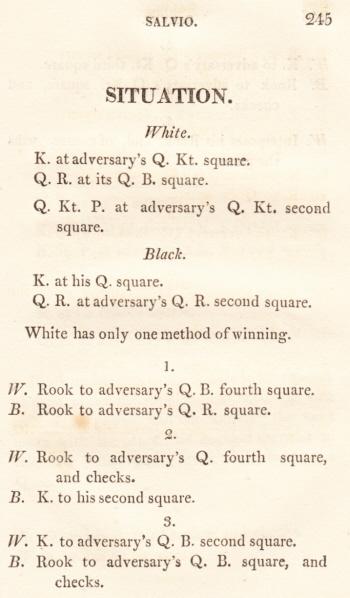

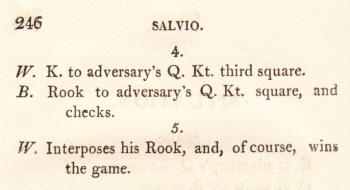

‘I should like to discuss four aspects of the so-called “Lucena Position”. Firstly, the erroneous attribution to Lucena is much older than was previously thought. Secondly, the person who first referred to Lucena was most likely Constantin Schwede. Thirdly, I shall try to explain why the reference is given as “Lucena 96”. Finally, I shall offer a source (a manuscript) containing the “Lucena Position” which is probably older than the following, which appeared in Salvio’s 1634 book Il Puttino:

C.N. 5536 mentioned that the question of whether the “Lucena Position” was in Lucena’s book had been resolved by John Roycroft’s article on pages 160-161 of the April 1982 BCM. According to Roycroft, who was supported by Ricardo Calvo, the position is not in Lucena’s book. That is correct, as anybody can verify nowadays by inspecting a digital copy.

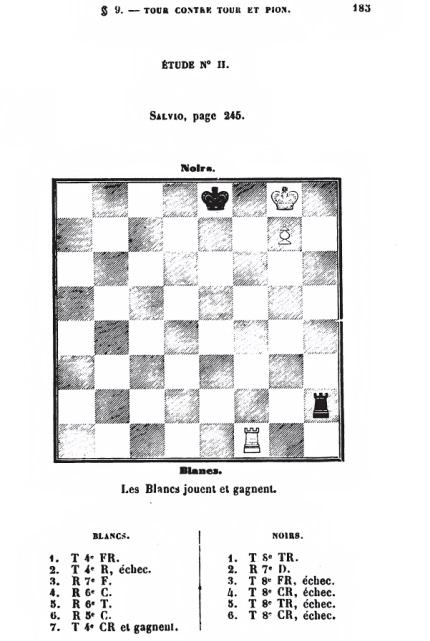

In addition, Roycroft suggested that the error of referring to Lucena’s book stemmed from Johann Berger, on page 273 of his Theorie und Praxis der Endspiele (Berlin and Leipzig, 1922). That volume is a second, expanded edition. The first edition was published in Leipzig in 1890, and I note that the error also appeared there, on page 209:

However, it is probable that Berger merely copied the information about the source from page 629 of the sixth edition of the Handbuch des Schachspiels (Leipzig, 1880), which was edited by Constantin Schwede:

The five previous editions of the Handbuch, all edited by von der Lasa, contained the position and the bridge-building moves, but the reference each time was to Salvio, via pages 245-246 of Sarratt’s translation (London, 1813):

Von der Lasa knew Lucena’s book very well; he found a copy in Rio de Janeiro and made a translation into German, published in the Deutsche Schachzeitung 1858-59 and in the Berliner Schacherinnerungen (Leipzig, 1859).

I therefore believe that Schwede originated the mistaken reference to Lucena. I have checked many of the sources that he lists in the Handbuch, and of those works only two contain the “Lucena Position”, and neither refers to Lucena in connection with it. The position appears, without any reference, on page 729 of Dufresne and Zukertort’s Großes Schach-Handbuch (Berlin, 1872), but there is a reference, to Salvio, on page 185 of J. Preti’s Traité complet, théorétique et pratique sur les fins de parties au jeu des échecs (Paris, 1858):

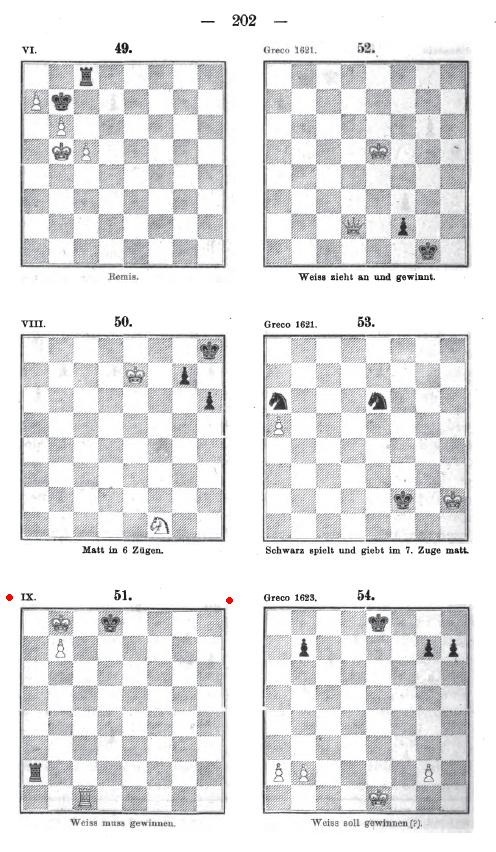

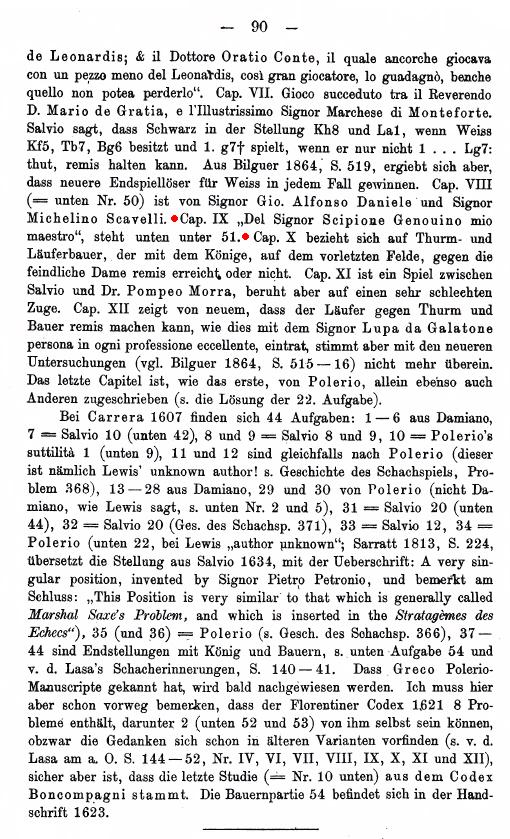

The precise reference given by Schwede and Berger is “Lucena 96”, and I believe that I can explain this. Antonius van der Linde’s work Das Schachspiel des XVI. Jahrhunderts (Berlin, 1874) presented the contents of several manuscripts, mostly by Polerio. Many of the chess compositions in those manuscripts also appeared in a collection of 372 problems which van der Linde published on pages 202-266 of the first volume of his work Die Geschichte und Litteratur des Schachspiels (Berlin, 1874). For simplicity’s sake I shall call these the “old” problems, in contrast to only 54 “new” ones which he collected from the manuscripts and published at the end of the book, on pages 194-202. These new ones are numbered roughly according to their appearance in one of the manuscripts, and among them is what is now known as the “Lucena Position”, numbered 51:

When van der Linde discussed the first manuscript, collected by Polerio, he gave, on pages 71-72, a list of references for the chess problems therein, and among those references is one that reads “51=L. 96=133”. This means that No. 51 in the first manuscript is the same as “Lucena 96”, as well as being No. 133 in the collection of old problems in the other book.

Thus, if Schwede saw Lucena’s position as No. 51 among the new problems, and erroneously thought that the reference on page 72 meant that position, he could easily assign “Lucena 96” to the “Lucena Position”, happily assuming that he had traced back the position further into the past.

Finally, it is of interest to note how the “Lucena Position” came to be on that list of “new” problems as No. 51. On page 88 van der Linde described the contents of an anonymous problem collection which dated from the sixteenth century (so he assumed, based on the letter in footnote 1 on page 79):

In lines 10-11 on page 90, van der Linde wrote: “Cap. IX ‘Del Signor Scipione Genouino mio maestro’ steht unten unter 51.” In other words, the author of this collection was a student of the inventor of the “Lucena Position”.

As noted by Roycroft, the slightly different name Scipione Genovino was given by Salvio (though omitted by Sarratt).

Since Salvio’s book Il Puttino appeared 1634, the problem collection is probably the older source for the “Lucena Position”, although it is only a manuscript.’

8045. Interviews in Izvestia

Does any reader have the original Russian text of an article in Izvestia which was published on pages 142-143 of the April 1968 Chess Life (‘Close to the Grandmasters’) in a translation by Oscar D. Freedman? The masters interviewed, by Yuri Zarubin, were Tal, Gheorghiu, Euwe, Pachman and Najdorf. We should like to examine a number of points, such as Gheorghiu’s supposed reply to the question ‘Will Fischer ever become champion of the world?’:

‘If he plays. However, this is doubtful, though probable.’

Following Freedman’s death later that year, the Editor of Chess Life, Burt Hochberg, wrote on page 316 of the September 1968 issue:

‘Oscar Freedman and I collaborated on the translation of a book (Bronstein’s Zurich 1953), and his name was often seen in Chess Life as a translator.’

For the reasons explained by Hochberg in an introductory

note to the book, eventually published in 1978 under the

title The Chess Struggle In Practice, the original

translation was begun in 1962 and went through many

revisions before appearing in print. ‘Close to the

Grandmasters’ seems not to have been revised by anyone.

8046. Zurich, 1959

John Donaldson (Berkeley, CA, USA) has passed on

another photograph from Jacqueline Piatigorsky’s

archives. It was taken in Zurich in 1959 by Alex

Crisovan and features the then President of the United

States Chess Federation, Jerry Spann, and (right)

Wolfgang Unzicker.

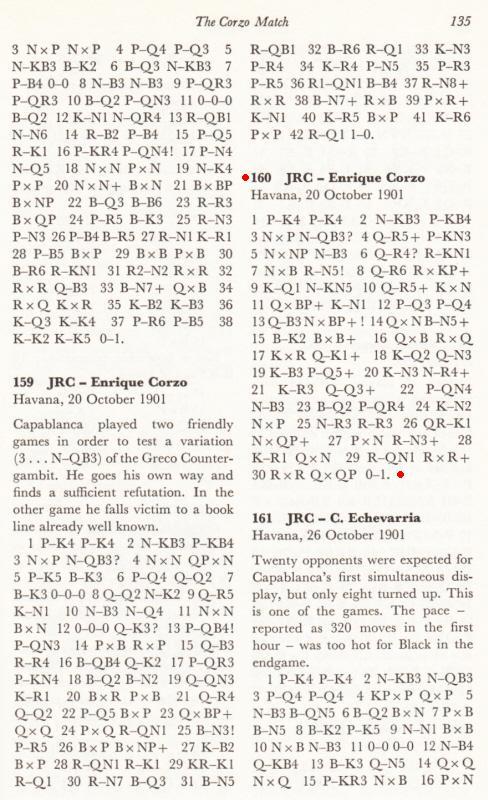

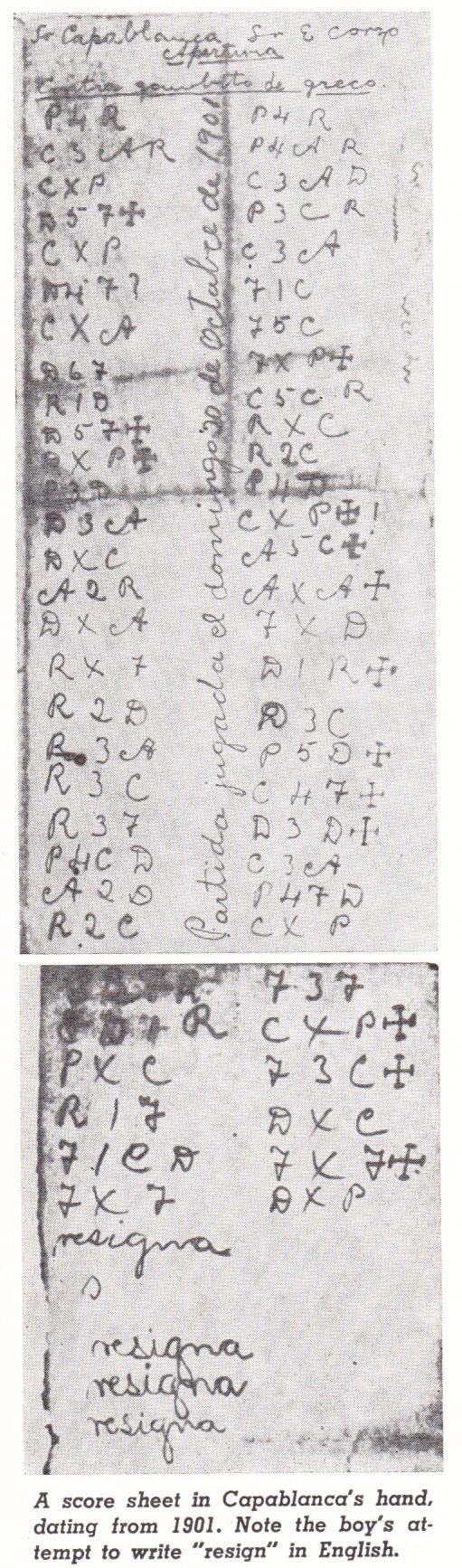

8047. Capablanca v Enrique Corzo

Page 135 of The Unknown Capablanca by David Hooper and Dale Brandreth (London, 1975):

The source for the game highlighted was specified on page 201 as ‘Original score’. Hooper had shown it on page 15 of the January 1968 Chess Life:

And, for the sake of completeness, a minor matter from page 141 of the April 1968 issue:

We note that Capablanca’s score-sheet clearly gave Black’s 11th move as 11...Kg7, and not 11...Kg8 as in The Unknown Capablanca. Moreover, White’s 26th move was Rae1, and not Rad1 as given in the two editions of the Capablanca book by Rogelio Caparrós and, subsequently, in databases.

The score as recorded by Capablanca:

José Raúl Capablanca – Enrique Corzo

Havana, 20 October 1901

Greco Counter-Gambit

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 f5 3 Nxe5 Nc6 4 Qh5+ g6 5 Nxg6 Nf6 6 Qh4 Rg8 7 Nxf8 Rg4 8 Qh6 Rxe4+ 9 Kd1 Ng4 10 Qh5+ Kxf8 11 Qxf5+ Kg7 12 d3 d5 13 Qf3

13...Nxf2+ 14 Qxf2 Bg4+ 15 Be2 Bxe2+ 16 Qxe2 Rxe2 17 Kxe2 Qe8+ 18 Kd2 Qg6 19 Kc3 d4+ 20 Kb3 Na5+ 21 Ka3 Qd6+ 22 b4 Nc6 23 Bd2 a5 24 Kb2 Nxb4 25 Na3 Ra6 26 Rae1

26...Nxd3+ 27 cxd3 Rb6+ 28 Ka1 Qxa3 29 Rb1 Rxb1+ 30 Rxb1 Qxd3 31 White resigns.

8048. Sleeping it off in Brighton

An article by G.H. Diggle published in the September 1980 Newsflash and reproduced on page 61 of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984):

‘On a very warm August Saturday the BM was inveigled by that notorious Chess Editor “T.W.S.” of the Luton News into joining a small party (wives included), lunching sumptuously in Brighton, and then going on to the British Championship in an attempt to sleep it off. But such was the munificence of Messrs Grieveson Grant that the BM found plenty to keep him awake, being quite overawed by the sheer vastness of the magnificent “Centre”. The scene resembled Mercator’s Projection. There was the main Continent (the British Championship itself) and, dotted about at intervals across the oceans, the “Under 21s”, the Ladies’ Championship (a fair and attractive isle past which we were hurried by our “better-’arves” like Odysseus by-passing the sirens) and (so many leagues off that one almost required a telescope) the “Over 60s”, a small forest of hoary heads, shirt-sleeves, and braces.

Surveying the British Championship competitors from the profane side of the “silken ropes”, the ladies of our party – “and the ladies are great observers” – awarded the Sartorial Prize to W.R. Hartston for elegant attire, though “honourable mention” was earned by Messrs Basman, Bellin, Rumens and Cafferty, who actually wore coats; the also-rans were confined to jeans and pullovers, in one case so indifferently donned that a military inspection would have produced the inevitable comment: “Dash it, Sergeant, here’s a fellah half naked!”

The Tournament Officials and Wise Men were as enthralling to watch as the players, being ensconced on a distant sort of Mount Olympus to which “nymphs” ascended from time to time with cups of coffee, and from which one patriarch would occasionally come down, and with a countenance heavy with affairs of state vanish through a secret door. The Press, also, “had their exits and their entrances”. Most impressive of all was that of the renowned doyen and “man of a million Congresses”, “H.G.”. Arriving becomingly late, he proceeded in unhurried swan-like manner right up the hall, bowed gracefully to a passing acquaintance, glided (“such being his prerogative”) into the forbidden area behind the ropes, stood for some moments in a reverie, looking neither to the right nor left, and finally sailed away westwards, the epitome of vast experience and sunset calm.

We settled down to watch Hodgson v Speelman, the younger player, strange to say, appearing more sphinx-like and less fidgety than his formidable adversary. Indeed, he seemed to have an irresistible attack with two rampant knights against two torpid bishops snoring away at KR1 and QR1. But just as things grew really exciting, the ladies of the party, who had long before escaped to the tea room, reappeared with “Shall we shog off?” written all over them. We afterwards heard that the somnolent prelates had, after all, carried the day.’

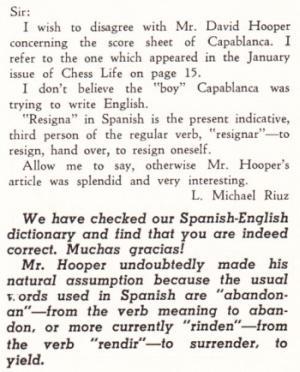

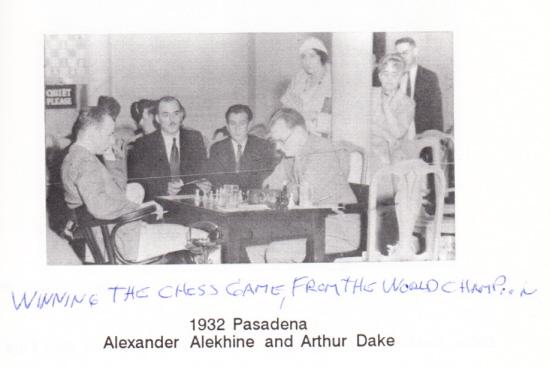

8049. Dake v Alekhine

From John Donaldson (Berkeley, CA, USA) comes a further photograph (Pasadena, 1932) contained in the archives of Jacqueline Piatigorsky:

The shot appeared in small format in the monograph on Dake, Grandmaster from Oregon by Casey Bush (Portland, 1991). As mentioned in C.N. 3306, we have a copy of the book extensively inscribed and annotated by Dake. From the plates section:

From the bottom of the book’s last page:

8050. Two Lasker queries

John Nunn (Chertsey, England) submits two queries about games by Emanuel Lasker:

‘The first relates to Showalter v Lasker, game six of their 1892-93 match:

This position arose after White’s 48th move. The conclusion of the game, as given in both Mega Database and the Weltgeschichte des Schachs book on Lasker (Hamburg, 1958), was 48...Ke6 49 Nc1 h3 50 Nd3 Bg1 51 a6 Kf5 52 Kc3 Bxh2 53 Nf2 Bg1 54 Nxh3 Bb6 0–1.

From the chess point of view, this makes little sense. Although it does not throw away the win, 48...Ke6 has no point whatsoever. Moreover, with these moves 50...Bg1 is a blunder which allows a simple draw by 51 Nf4+, etc. The whole thing makes much more sense if Black had played 48...Ke4 instead, but is there any evidence for this?’

Black’s 48th move was indeed given as ...Ke4, and not ...Ke6, when the game was published, with notes by both players, on pages 152-153 of the 14 July 1893 issue of Lasker’s magazine, the London Chess Fortnightly:

48...Ke4 was also the move specified when the game appeared on pages 298-299 of the September-October 1893 American Chess Monthly. The notes were by Pollock, Lasker and Showalter, the score was from the Pittsburgh Dispatch, and the game was dated 22 April 1893.

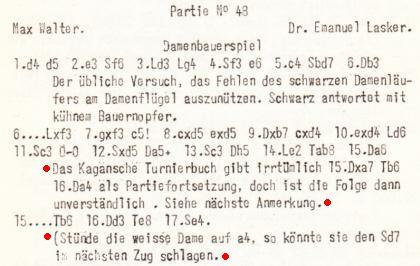

‘My second query relates to the game Walter v Lasker, Mährisch-Ostrau, 1923. After the initial moves 1 d4 d5 2 e3 Nf6 3 Bd3 Bg4 4 Nf3 e6 5 c4 Nbd7 6 Qb3 Bxf3 7 gxf3 c5 8 cxd5 exd5 9 Qxb7 cxd4 10 exd4 Bd6 11 Nc3 O-O 12 Nxd5 Qa5+ 13 Nc3 Qh5 14 Be2 Rab8 there are two versions for the continuation:

Mega Database gives Version A: 15 Qxa7 Rb6 16 Qa4 Re8 17 Ne4 Nd5 18 Nxd6 Rxd6 19 O-O Rde6 20 Re1 Qh3 21 Kh1 Rxe2 0-1, and according to Soltis on pages 234-235 of Why Lasker Matters (London, 2005) this is the version given in the tournament book.

Version B runs 15 Qa6 Rb6 16 Qd3 Re8 17 Ne4 Nd5 18 Nxd6 Rxd6 19 O-O Rde6 20 Re1 Qh3 21 Kh1 Rxe2 0–1, and this is the version which Soltis gives in the afore-mentioned book and which appears in the Weltgeschichte des Schachs book. From the chess point of view, Version B is far more logical (if only because of the missed 18 Qxd7 in version A), but if, as Soltis says, Version A is the one given in the tournament book, what is the source for Version B and how reliable might it be?’

Although 15 Qxa7 was given in the tournament book by Bernhard Kagan (page 50), that version of the score was corrected on page 48 of Albert Becker’s book on the event which was published by M.A. Lachaga in Argentina in 1977:

Contemporary sources confirm that the moves 15 Qa6 Rb6 16 Qd3 were played, an example being pages 180-181 of the August 1923 Deutsche Schachzeitung, where the game was annotated by Ernst Grünfeld.

8051. Jacqueline Piatigorsky

Readers are unlikely to have difficulty in identifying the two masters in this photograph, which has been forwarded by John Donaldson (Berkeley, CA, USA) from the archives of Jacqueline Piatigorsky.

See our new feature article Chess: Jacqueline and Gregor Piatigorsky.

| First column | << previous | Archives [105] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.