Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [117] | next >> | Current column |

8621. Dictionary definitions

Although a very good book overall, the Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary (Oxford, 2010) makes little effort with its definitions of basic chess vocabulary. Page 250 has this entry for the word ‘chess’ itself:

‘A game for two people played on a board marked with black and white squares on which each playing piece (representing a king, queen, castle, etc.) is moved according to special rules. The aim is to put the other player’s king in a position from which it cannot escape.’

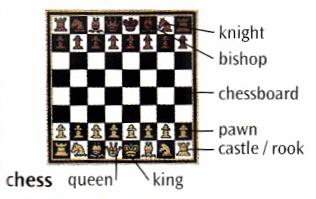

There is a minuscule diagram on page V33:

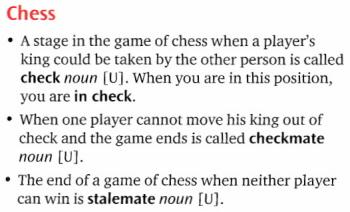

The same page attempts to explain the terms ‘check’, ‘checkmate’ and ‘stalemate’:

The second bullet point does not make sense:

‘When one player cannot move his king out of check and the game ends is called checkmate ...’

That sentence, if such it be, illustrates another difficulty. Although the word ‘his’ is used (which is fine, although the reader was addressed in the second person in the preceding bullet point), page 248 has this definition of ‘checkmate’:

‘A position in which one player cannot prevent his or her king (= the most important piece) being captured and therefore loses the game.’

On page 1502 ‘stalemate’ in the chess sense is defined thus:

‘A situation in which a player cannot successfully move any of their pieces and the game ends without a winner.’

‘A player’ cannot move ‘their pieces’ ...

‘A position in which a player’s king (= the most important piece) can be directly attacked by the other player’s pieces.’

‘Check’ is not ‘a position’, and what to make of ‘can be’ and ‘pieces’?

The best definitions of chess terminology in any general reference work that we have seen are in the Collins English Dictionary.

8622. Spassky in 1972

General reference works customarily avoid hyperbolic editorialization, but the nine-line entry on Spassky on page 1376 of the Chambers Biographical Dictionary edited by Magnus Magnusson (Edinburgh, 1990) has this statement in connection with the 1972 world championship match:

‘His defeat before the full glare of international attention gave him the unfortunate legacy of the most famous loser in sporting history.’

8623. Promotion

power

White to play and win

This position (‘an extraordinary example of the promotion power of the pawn’) comes from pages 49-50 of The Macmillan Handbook of Chess by I.A. Horowitz and Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1956). Did it occur over the board?

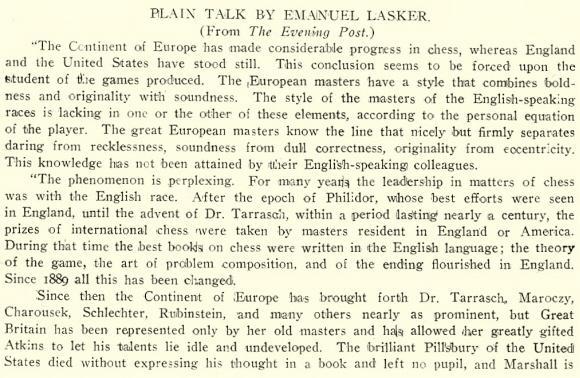

8624. ‘Plain talk’

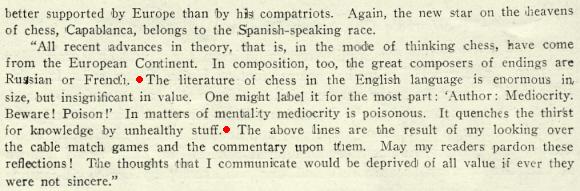

‘The literature of chess in the English language is enormous in size, but insignificant in value. One might label it for the most part: “Author: Mediocrity. Beware! Poison!” In matters of mentality mediocrity is poisonous. It quenches the thirst for knowledge by unhealthy stuff.’

So wrote Emanuel Lasker, and below is the text as it

appeared on pages 171-172 of the August 1911 American

Chess Bulletin. Can the original publication in

the New York Evening Post be found?

8625. Alekhine’s Gun (C.N.s 7880, 7914 & 7972)

Jeremy Silman (Los Angeles, CA, USA) notes that pages 118-119 of Techniques of Positional Play by V. Bronznik and A. Terekhin (Alkmaar, 2013) discuss Blackburne v Rosenthal, Paris, 1878, in which this position arose:

The heading in the book is ‘Brute force: Blackburne’s battering ram’, and the authors comment regarding 23 R1c2 (which was followed by 23...Qd8 24 Qc1):

‘Blackburne brings all three major pieces on to the c-file – and the rooks belong in front of the queen.’

The earliest specimen of the manoeuvre that we can quote is Kennedy v Mayet, London, 1851 (see pages 35-38 of the tournament book):

The game continued 21...Rc5 22 a4 Rfc8 23 Rec1 R8c7 24 h3 Qc8.

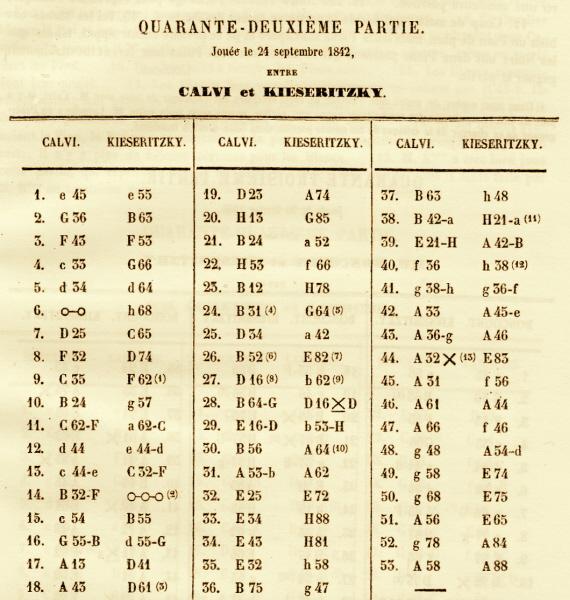

An earlier game in which the major pieces were tripled, though with the queen placed between the rooks, was Calvi v Kieseritzky, third match-game, Paris, 1842:

Play went 19 Qc2 Rd7 20 Rc1.

Below is the full score as given on page 39 of Kieseritzky’s book Cinquante parties jouées au Cercle des Echecs et au Café de la Régence (Paris, 1846):

8626. Promotion power (C.N. 8623)

According to the book by Horowitz and Reinfeld mentioned in C.N. 8623, White won with 1 Rc8 Rxc8 2 Re8+ Nxe8 3 d7 Nd6 4 dxc8(Q) Nxc8 5 axb7.

Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) points out that a similar theme occurred in a position presented by Roberto Grau in volume one of Tratado general de ajedrez:

The winning line is given as 1 Rc8 Rxc8 2 Re8+ Nxe8 3 d7 Nd6 4 dxc8(Q) Nxc8 5 axb7. Grau added that Black would win after 1 Re8+ Nxe8 2 Rc8 Rxa6 3 Kg1 Rxd6.

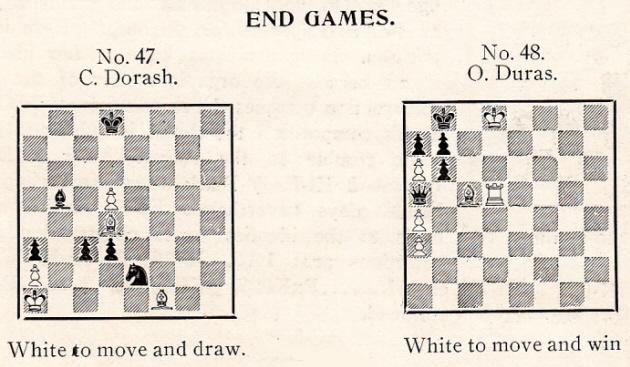

The page references vary according to the edition of Grau’s work. In our copy (Buenos Aires, 1986) the position is discussed on pages 155-156 (in the section entitled ‘Otros errores: trasposiciones’). The diagram caption states only ‘C. Dorash’.

8627. Promotion power (C.N.s 8623 & 8626)

The name ‘C. Dorash’ mentioned at the end of the previous item also appeared in the caption to a study on page 80 of the Chess Weekly, 31 July 1909:

However, that reference, in common with the one in Roberto Grau’s book, is an apparent transcription error. The above ‘White to move and draw’ composition was by C. Dorasil of Troppau (the German name for Opava). See, for instance, page 308 of the October 1907 Deutsche Schachzeitung.

Regarding the position which Grau ascribed to ‘C. Dorash’, Han Bükülmez (Ecublens, Switzerland) notes that it appears in Harold van der Heijden’s endgame database, the composer being named as C. Dorasil and the source given as ‘Bohemia 1906’.

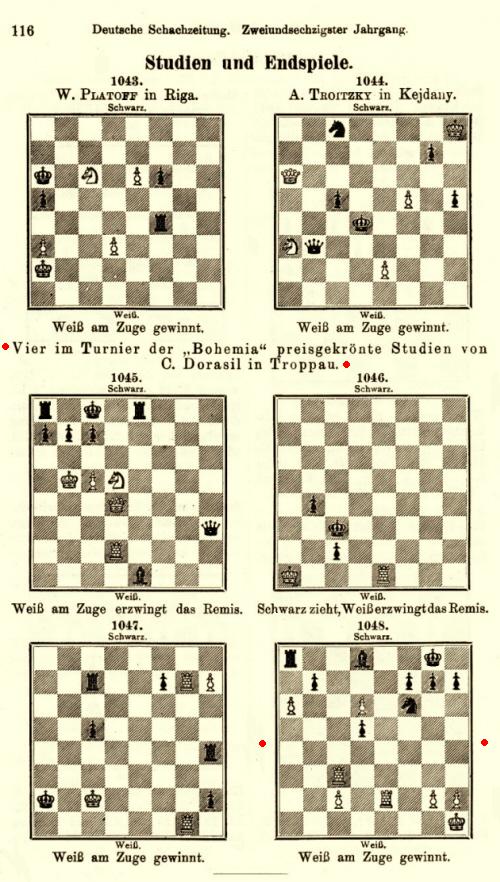

It was one of four compositions by Dorasil published on page 116 of the April 1907 Deutsche Schachzeitung:

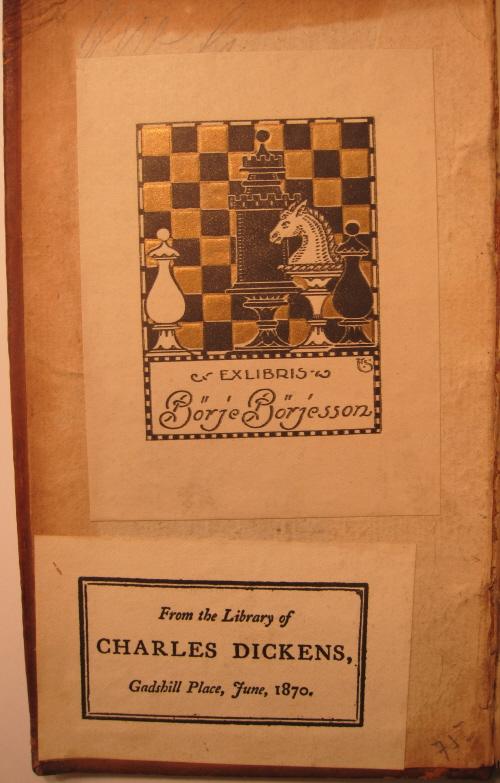

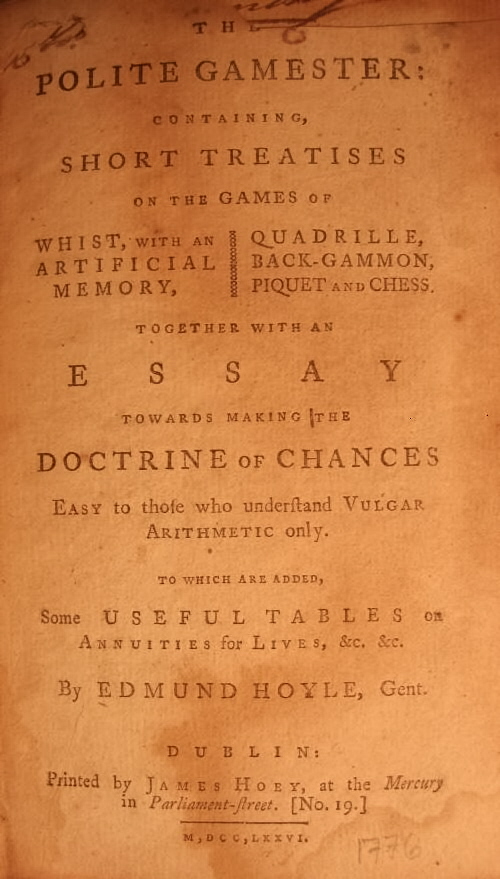

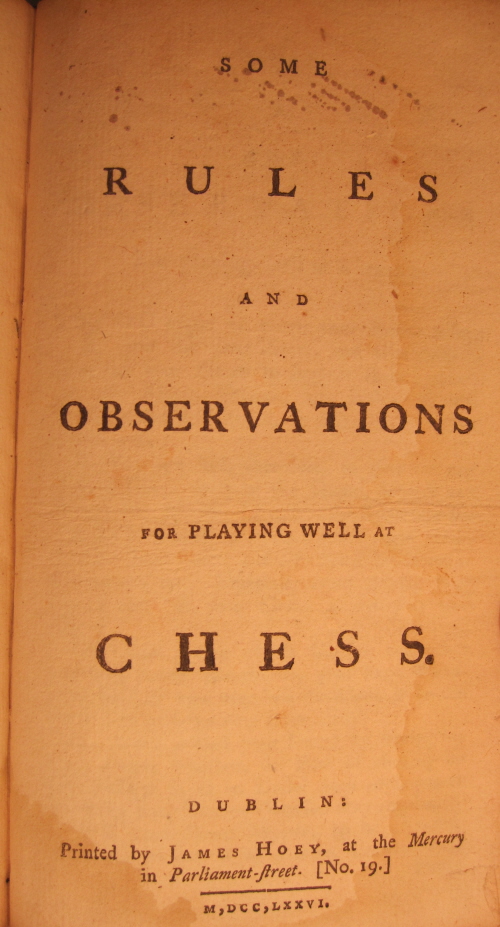

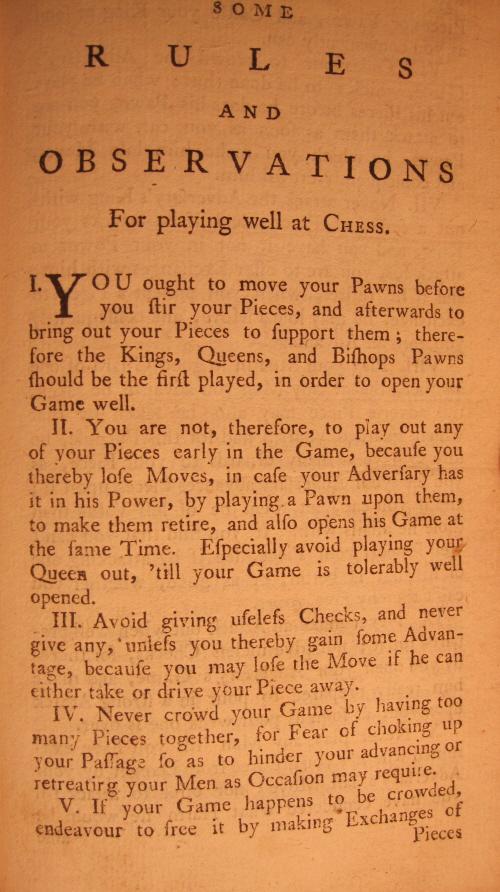

8628. Dickens and Hoyle

Jon Crumiller (Princeton, NJ, USA) reports that he owns a copy of Edmund Hoyle’s The Polite Gamester (Dublin, 1776) which has the bookplate of Charles Dickens:

8629. Richard Réti’s birth record

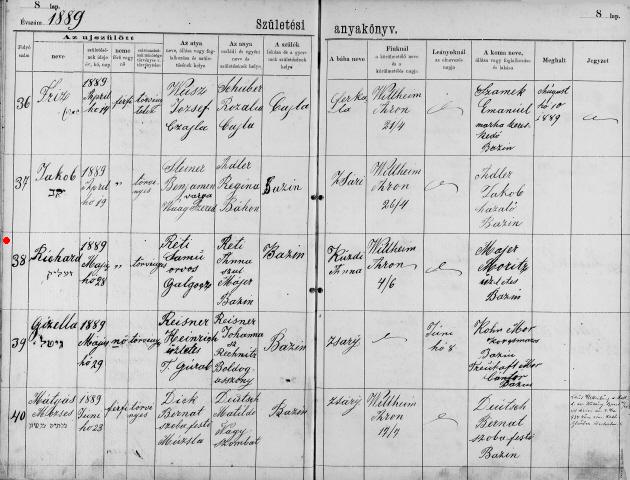

Avital Pilpel (Haifa, Israel) informs us that a colleague of his, Alon Schab, recently noted Richard Réti’s birth record in the database of the Latter-Day Saints church (the Mormon Church):

Mr Pilpel comments:

‘Below the word “Richard” there appears, in Hebrew letters, the name זעליק – “Selig”. If a comparison is made with the other lines, it seems clear that this is Réti’s “Jewish” name, which would make his full name Richard Selig Réti.’

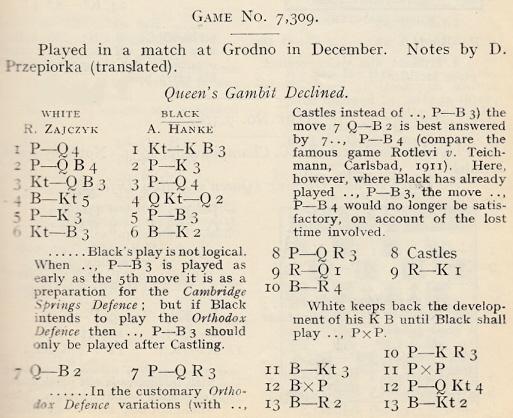

8630. Move order

Wanted: more details about a game published on pages

85-86 of the February 1935 BCM with annotations

by Przepiórka (including an interesting comment at move

23):

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 d5 4 Bg5 Nbd7 5 e3 c6 6 Nf3 Be7 7 Qc2 a6 8 a3 O-O 9 Rd1 Re8 10 Bh4 h6 11 Bg3 dxc4 12 Bxc4 b5 13 Ba2 Bb7 14 Ne5 Nf8 15 O-O Rc8 16 f4 Nd5 17 Qf2 f6 18 f5 fxe5 19 fxe6 Nxe6 20 Nxd5 cxd5 21 Qf7+ Kh8 22 Bxe5 Rc6 23 Bb1 Rg8 24 Qg6 Ng5 and wins.

8631. Julien Gracq

From Oliver Beck (Seattle, WA, USA):

‘In Julien Gracq’s Un beau ténébreux (Paris, 1945) a character’s chess is described as follows:

“Il joue remarquablement, avec une prédilection pour les parties fermées, la Sicilienne, l’Ouest-Indienne, comme tous les joueurs qui sentent ces relations secrètes de case à case qui sommeillent sur l’échiquier, cette puissance explosive latente qui dort dans chaque pièce, et dont l’appréhension intuitive fait toute la supériorité du jeu de fakirs, comme Alekhine, comme Breyer, comme Botwinnik, sur les géomètres [Gracq’s emphasis] de l’échiquier qu’étaient un Morphy ou un Rubinstein” (pages 67-68 in the 1983 José Corti edition).

This description, with the somewhat surprising insertion of Breyer between Alekhine and Botvinnik, may be better understood in light of Gracq’s comment in Lettrines 2 (Paris, 1974):

“... puis, en 1929, le livre de Réti: Modern Ideas in Chess, qui est un peu le Manifeste du Surréalisme échiquéen, me donna à Londres tout un été de découverte et de bonheur” (page 176 in the 1978 José Corti edition).

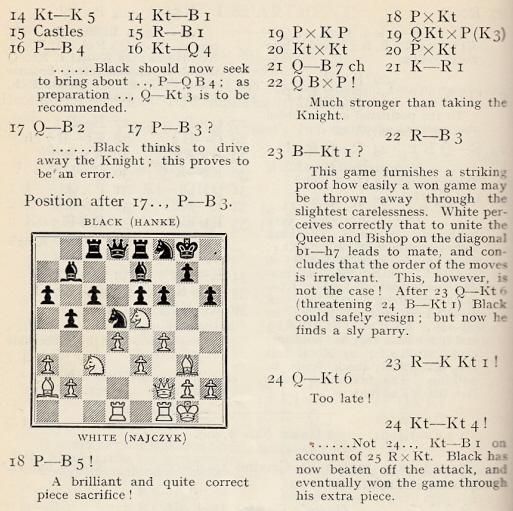

Elsewhere in Lettrines 2, Gracq describes an encounter with E. Znosko-Borovsky:

“Une fois, avec le président du cercle d’échecs de Quimper, nous y conduisîmes Znosko-Borovsky, célèbre joueur d’échecs, que nous avions invité dans notre ville pour une conférence et une séance de simultanées; avec sa moustache taillée en brosse, il avait l’air d’un gentil et courtois bouledogue. Je ne sais pourquoi je le revois encore parfaitement, silhouetté au bord de la falaise, regardant l’horizon du Sud: il y avait dans cette image je ne sais quoi d’incongru et de parfaitement dépaysant. Il ne disait rien. Peut-être rêvait-il, sur ce haut lieu, à la victoire qu’il avait un jour remportée sur Capablanca” (page 38).

Gracq’s reference to Capablanca v Znosko-Borovsky, St Petersburg, 1913 may not seem unusual; it was annotated in the illustrative games section of Capablanca’s Chess Fundamentals and touched upon in Chapter VII of My Chess Career. However, it causes me to wonder whether Znosko-Borovsky ever mentioned it in his writings. Also, considering Capablanca’s incredible success during his second European tour, how much attention was paid to Znosko-Borovsky’s victory at the time?’

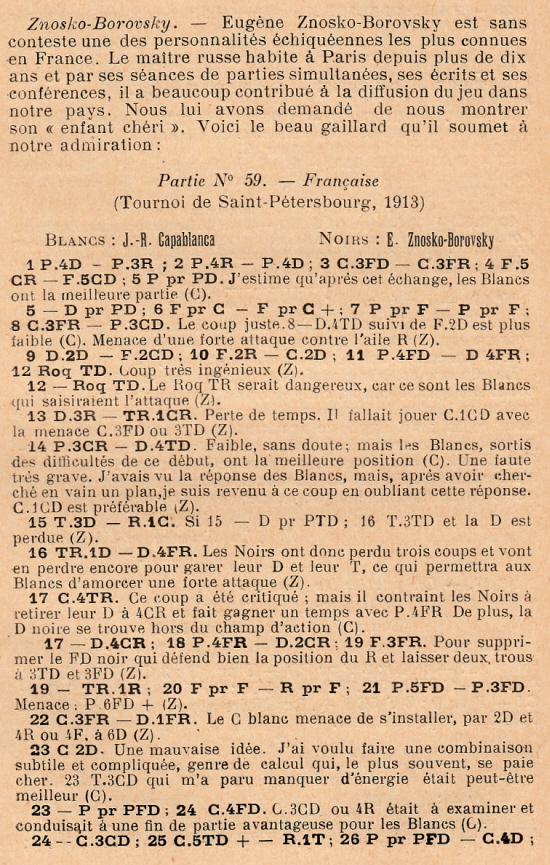

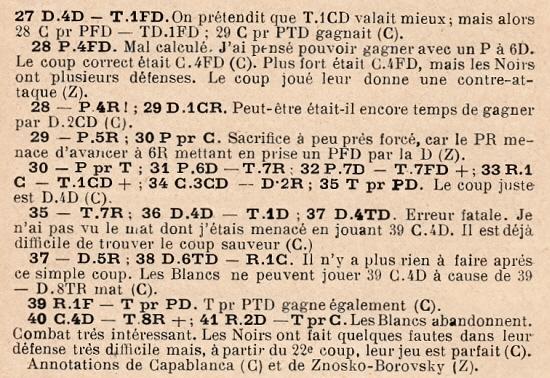

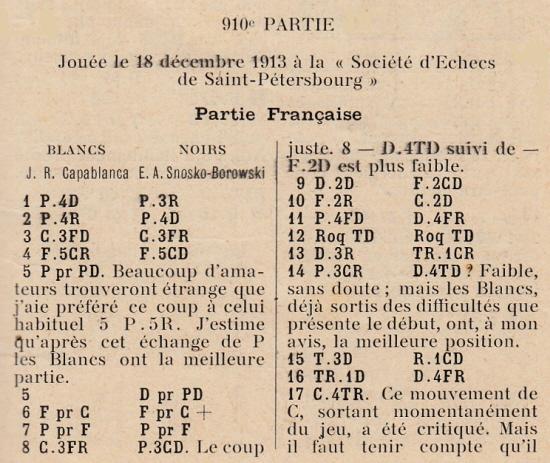

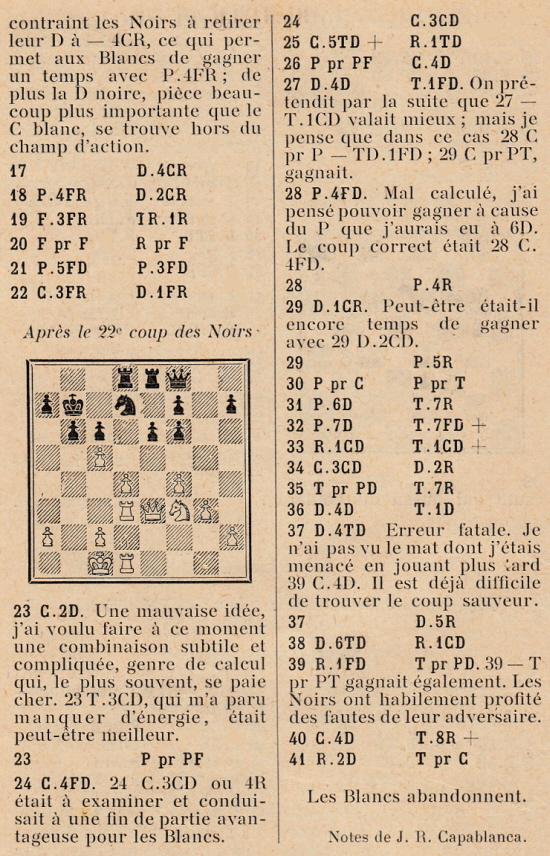

Znosko-Borovsky discussed part of his victory over the Cuban on pages 152-156 of his book The Middle Game in Chess (London, 1922). The full score was published, with notes by both Znosko-Borovsky and Capablanca on pages 189-190 of issue 22 of Les Cahiers de l’Echiquier Français (1930), incorrectly labelled a tournament game:

Capablanca’s earliest set of notes to the game appeared on pages 19-20 of the January 1914 issue of La Stratégie:

Both French publications stated that the game ended 41 Kd2 Rxd4 42 White resigns, whereas in Chess Fundamentals Capablanca wrote that he resigned after 40...Re1+.

The game was widely published at the time, without receiving special attention.

8632. English

Chess news reports indicate a growing belief that prose is somehow enlivened if the plainest words are avoided. When a player wins first prize in a tournament, the verb ‘wins’ commonly loses out to ‘bags’, ‘claims’, ‘collects’, ‘grabs’, ‘picks up’, ‘scoops’, ‘takes home’, etc.

Another addition to the musings in Chess and the English Language concerns the use, particularly in the United States, of ‘would’ in historical narratives. For instance, ‘Alekhine died in 1946, and two years later Botvinnik would become world champion’, instead of simply ‘became world champion’.

The following examples come from the first page of the article about Henry Chadwick in Lasker & His Contemporaries which was referred to in Chess and Baseball:

‘A native of England, Chadwick came to the United States with his family in 1837, settled in Brooklyn, became a journalist and would be recognized as the first significant sports writer in the United States. ... As Mac Souders, writing in the Baseball Research Journal for 1986, would describe it, Chadwick would become “a one-man press association for baseball in the New York City area”. Chadwick would report on sports and recreational activities for decades ... And he would author and edit numerous baseball books and pamphlets ... He would receive the title “Father of Baseball” early in his career ...’

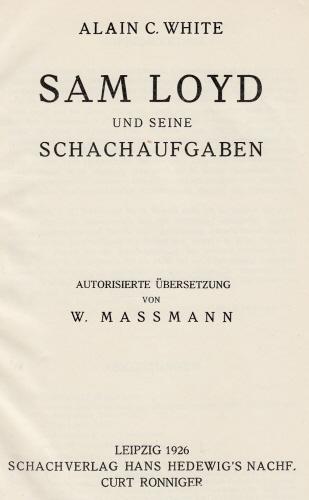

8633. Translations of English-language problem books

Few books on chess problems written in English have appeared in other languages. One case is Sam Loyd and His Chess Problems by Alain C. White (Leeds, 1913), which was translated into German by W. Massmann under the title Sam Loyd und seine Schachaufgaben (Leipzig, 1926).

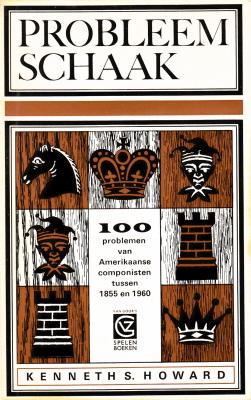

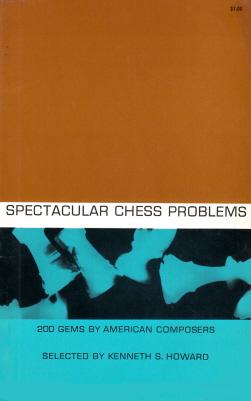

We also have Probleemschaak by Kenneth S. Howard (The Hague and Brussels, 1968). Subtitled ‘100 problemen van Amerikaanse componisten tussen 1854 en 1960’, it gives half of the positions from Spectacular Chess Problems (‘200 gems by American composers’), which was brought out by Dover Publications, Inc., New York, in 1965.

8634. Bobby Fischer Triumph and Despair

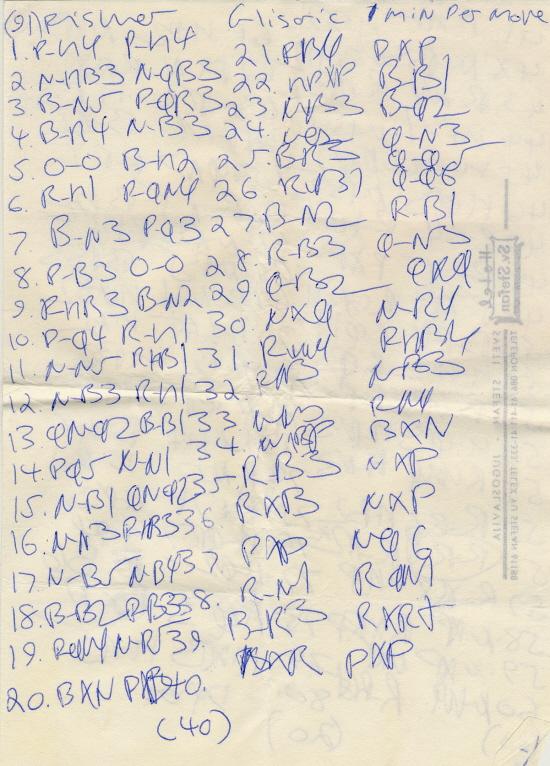

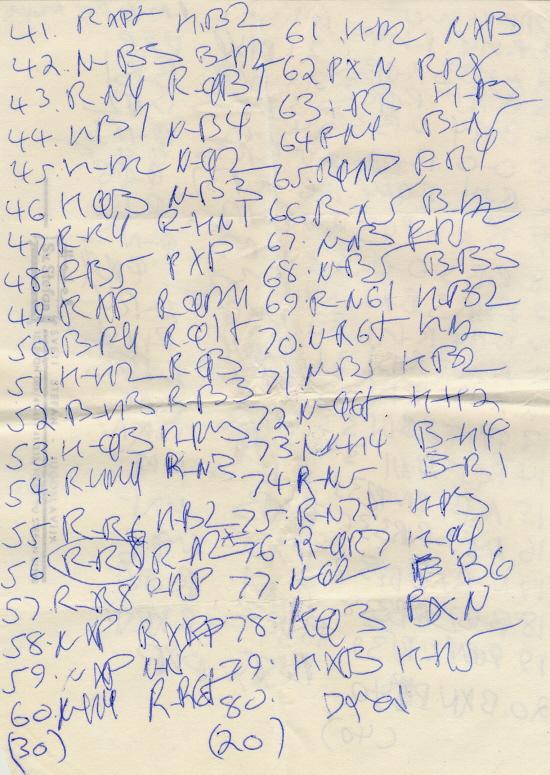

We thank David DeLucia (Darien, CT, USA) for permission to reproduce Fischer’s score-sheet of his first training game against Gligorić, played in 1992:

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 O-O Be7 6 Re1 b5 7 Bb3 d6 8 c3 O-O 9 h3 Bb7 10 d4 Re8 11 Ng5 Rf8 12 Nf3 Re8 13 Nbd2 Bf8 14 d5 Nb8 15 Nf1 Nbd7 16 Ng3 h6 17 Nf5 Nc5 18 Bc2 c6 19 b4 Na4 20 Bxa4 bxa4 21 c4 cxd5 22 exd5 Bc8 23 Ne3 Bd7 24 Nd2 Qb6 25 Ba3 Qd4 26 Rc1 Qd3 27 Bb2 Rac8 28 Rc3 Qg6 29 Qc2 Qxc2 30 Nxc2 Nh5 31 h4 f5 32 g3 Nf6 33 Ne3 g5

34 Nxf5 Bxf5 35 Rf3 Nxd5 36 Rxf5 Nxb4 37 hxg5 Nd3 38 Rb1 Rb8 39 Ba3 Rxb1+ 40 Nxb1 hxg5 41 Rxg5+ Kf7 42 Nc3 Be7 43 Rg4 Rc8 44 Kf1 Nc5 45 Ke2 Nd7 46 Kd3 Nf6 47 Rh4 Rg8 48 c5 dxc5 49 Rxa4 Ra8 50 Bc1 Rd8+ 51 Ke2 Rd6 52 Be3 Rc6 53 Kd3 Ke6 54 Rh4 Rb6 55 Rh6 Kf7 56 Rh8 Rb2 57 Ra8

57...e4+ 58 Nxe4 Rxa2 59 Nxc5 Ng4 60 Ne4 Ra3+ 61 Ke2 Nxe3 62 fxe3 Ra1 63 Ra7 Ke6 64 g4 Bb4 65 Rb7 a5 66 Rb5 Be7 67 Ng3 a4 68 Nf5 Bf6 69 Rb6+ Kf7 70 Nh6+ Kg7 71 Nf5+ Kf7 72 Nd6+ Ke7 73 Ne4 Be5 74 Rb5 Bh8 75 Rb7+ Ke6 76 Ra7 Kd5 77 Nd2 Bc3 78 Kd3 Bxd2 79 Kxd2 Ke4 Drawn.

The game is given on pages 358-359 of a new compendium of Fischer documentation edited by Mr DeLucia’s daughter, Alessandra: Bobby Fischer Triumph and Despair (Darien, 2014). It is a 786-page volume of the highest imaginable technical quality, and further details are available on a New in Chess page. We shall be pleased to pass on to Mr DeLucia any orders which C.N. readers wish to place direct with him.

A section of particular interest, further to the material in Fischer’s Fury, is on pages 398-457 of Bobby Fischer Triumph and Despair and concerns the 1995 Batsford edition of My 60 Memorable Games. Alessandra DeLucia writes on page 398 that Fischer’s drafts of his grievances against the Batsford book were written and updated over a period of nearly two years and occupy more than a metre of shelf-space.

8635. Historical notes

One hundred copies of Historical notes on some chess

players by John Townsend (Wokingham, 2014) have just

been published. The author has produced a webpage

describing the book and giving ordering details.

8636. British Pathé

Chess Masters on Film has a number of references to British Pathé material. Now, YouTube offers a large quantity of chess-related footage from Pathé.

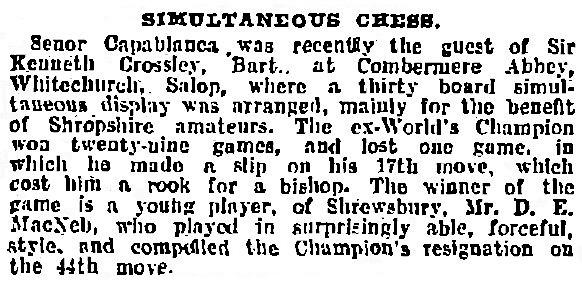

8637. ‘A promising young amateur’

A game submitted by Luc Winants (Boirs, Belgium) shows the difficulties in establishing the key facts about simultaneous displays.

Our correspondent has provided two cuttings, from Louis van Vliet’s chess column in the Sunday Times, 19 May 1929, page 4, and 26 May 1929, page 4:

1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nd2 c5 4 Ngf3 Nc6 5 exd5 exd5 6 Bb5 Qe7+ 7 Qe2 Qxe2+ 8 Kxe2 Bd7 9 dxc5 Bxc5 10 Nb3 Bd6 11 Bg5 f6 12 Bh4 Nge7 13 Bg3 Nf5 14 Bxd6 Nxd6 15 Bd3 Nb4 16 Rad1 Nxd3

17 Rxd3 Bb5 18 Nfd4 Bxd3+ 19 Kxd3 Nc4 20 Rb1 Kf7 21 Ne2 Rhe8 22 Nc3 Ne5+ 23 Ke2 Rad8 24 Kf1 d4 25 Nb5 d3 26 cxd3 Nxd3 27 Na5 Re7 28 Nc4 a6 29 Nbd6+ Kf8 30 a4 Red7 31 Nf5 Nc5 32 Nfe3 Nxa4 33 g4 b5 34 Na5 Rd2 35 b3 Nc3 36 Rc1 Nd1 37 Nf5 Rxf2+ 38 Ke1

38...Re8+ 39 Kxd1 Rf1+ 40 Kd2 Rd8+ 41 Kc2 Rc8+ 42 White resigns.

The first Sunday Times cutting stated that Capablanca resigned at move 44. The game was not dated, and it is a rare case where the list of exhibitions on pages 180-194 of The Unknown Capablanca by D. Hooper and D. Brandreth (London, 1975) does not help. There was, though, a brief report on pages 213-214 of the June 1929 BCM:

‘Señor Capablanca left London for Paris on 17 May. Since the events reported in our last number he has given two displays. The first was at Whitchurch, Salop, at the invitation of Sir Kenneth Crossley, where he won all 35 games.’

However, a correction was printed on page 251 of the July 1929 BCM:

‘We regret to find that an error crept into our report (page 214) of Señor Capablanca’s simultaneous display at Shrewsbury. We stated that the Master won all the games, but this was not so, as in one game he was defeated by D.E. McNab.’

The spelling ‘McNab’ (as opposed to ‘MacNeb’, given three times in the above newspaper reports) is supported by other BCM items about chess in Shropshire (e.g. on page 114 of the March 1938 issue), but there is also a discrepancy over whether Capablanca played 30 or 35 games at Combermere Abbey. Biographical details about the winner of the above game are also sought.

8638. Fischer training games in 1992

Further to the publication of Bobby Fischer Triumph and Despair by Alessandra DeLucia (C.N. 8634), all the known training games played by Fischer in 1992 are now in the public domain. David DeLucia (Darien, CT, USA) has sent us his transcriptions of the full set of scores between Fischer and Gligorić (in all, ten games were played), as well as a training game contested by Fischer and Eugenio Torre.

The exact order of the games in the Gligorić match is not known. Below we follow the sequence in which they appeared in the two DeLucia books (published in 2009 and 2014).

Svetozar Gligorić – Robert James Fischer

Training game, Sveti Stefan, 1992

King’s Indian Defence

1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 g6 3 c4 Bg7 4 Nc3 O-O 5 e4 d6 6 Be2 e5 7 O-O Nc6 8 d5 Ne7 9 Nd2 a5 10 a3 Ne8 11 Rb1 f5 12 b4 Nf6 13 f3 Bh6 14 Nb3 Bxc1 15 Qxc1 axb4 16 axb4 f4 17 c5 g5 18 Nb5 g4 19 cxd6 cxd6 20 Qc7 Qxc7 21 Nxc7 Ra2 22 Nc1 Rc2 23 Nb5 gxf3 24 gxf3 Bh3 25 Rf2 Rfc8 26 Nd3 Ne8 27 Bf1 Bd7 28 Rxc2 Rxc2 29 Rc1 Rc8 30 Rxc8 Nxc8 31 Nxd6 Nexd6 32 Nxe5 Bb5 33 Bxb5 Nxb5 34 Nd3 Nd4 35 Kf2 Nc2 36 e5 Kf7 37 d6 Nxd6 38 exd6 Ke6 Drawn.

Source: Bobby Fischer Uncensored, page 181, with a scan of the score-sheet on page 180.

Svetozar Gligorić – Robert James Fischer

Training game, Sveti Stefan, 1992

King’s Indian Defence

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 g6 3 Nc3 Bg7 4 e4 d6 5 Nf3 O-O 6 Be2 e5 7 O-O Nc6 8 d5 Ne7 9 Nd2 a5 10 a3 Bd7 11 b3 c5 12 Rb1 b6 13 b4 axb4 14 axb4 Bh6 15 bxc5 bxc5 16 Nb3 Bxc1 17 Qxc1 Nc8 18 Ra1 Rb8 19 Ra3 Rb4 20 Qe3 Nb6 21 Nd2 Ng4 22 Bxg4 Bxg4 23 f4 exf4 24 Qxf4 Rb2 25 Ra7 Bd7 26 Nf3 f6 27 Qxd6 Rxg2+ 28 Kh1 Rc2 29 Nd1 Bh3 30 Qxd8 Rxd8 31 Ne3 Bxf1 32 Nxc2 Nxc4 33 Na3 Nd6 34 e5 Be2 35 Ng1 Bd3 36 Nh3 fxe5 37 Ng5 h6 38 Ne6 Rc8 39 Rg7+ Kh8 40 Rd7 Nf5 [See the note at the end of this game.] 41 d6 c4 42 Nd8 Be4+ 43 Kg1 Bd5 44 White resigns.

Source: Bobby Fischer Uncensored, page 181.

[Addition on 20 April 2014: The book gave Black’s 40th move as ...Nb5 instead of ...Nf5. This mistranscription, pointed out to us by Michael Spiekermann (Menden, Germany), has been confirmed by David DeLucia, who reports that Fischer’s score-sheet clearly states ‘N-B4’.] Svetozar Gligorić – Robert James Fischer

Training game, Sveti Stefan, 1992

King’s Indian Defence

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 g6 3 Nc3 Bg7 4 e4 d6 5 Nf3 O-O 6 Be2 e5 7 O-O Nc6 8 d5 Ne7 9 Nd2 a5 10 a3 Bd7 11 b3 c5 12 Bb2 Bh6 13 Qc2 b6 14 Nd1 Bxd2 15 Qxd2 Nxe4 16 Qd3 f5 17 f4 exf4 18 Rxf4 Nf6 19 h4 Rf7 20 Nf2 Qf8 21 Nh3 h6 22 Raf1 Re8 23 Bd1 Nc8 24 Qg3 Rg7 25 Qc3 Re5 26 Qc1 Qe7 27 R4f2 Kh7 28 Nf4 Ne4 29 h5 gxh5 30 Rf3 Qg5 31 Qc2 Ne7 32 Bc1 h4 33 Ne6 Qf6 34 Nxg7 Kxg7 35 Bb2 Ng3 36 Qf2 Qg5 37 Re1 Ng6 38 Bc2 f4 39 Bxg6 Kxg6 40 Bc1 Qe7 41 Rxe5 dxe5 42 Qe1 Qg5 43 Kh2 Bg4 44 Bxf4 exf4 45 Qe8+ Kg7 46 d6 Bxf3 47 Qd7+ Kg8 48 Qc8+ Kf7 49 Qd7+ Kg6 50 Qe8+ Kf5 51 gxf3 Nf1+ 52 Kh1 Ng3+ 53 Kh2 Drawn.

Source: Bobby Fischer Uncensored, page 181.

Robert James Fischer – Svetozar Gligorić

Training game, Sveti Stefan, 1992

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 O-O Be7 6 Re1 b5 7 Bb3 d6 8 c3 O-O 9 h3 Bb7 10 d4 Re8 11 Ng5 Rf8 12 Nf3 Re8 13 Nbd2 Bf8 14 d5 Nb8 15 Nf1 Nbd7 16 Ng3 h6 17 Nf5 Nc5 18 Bc2 c6 19 b4 Na4 20 Bxa4 bxa4 21 c4 cxd5 22 exd5 Bc8 23 Ne3 Bd7 24 Nd2 Qb6 25 Ba3 Qd4 26 Rc1 Qd3 27 Bb2 Rac8 28 Rc3 Qg6 29 Qc2 Qxc2 30 Nxc2 Nh5 31 h4 f5 32 g3 Nf6 33 Ne3 g5 34 Nxf5 Bxf5 35 Rf3 Nxd5 36 Rxf5 Nxb4 37 hxg5 Nd3 38 Rb1 Rb8 39 Ba3 Rxb1+ 40 Nxb1 hxg5 41 Rxg5+ Kf7 42 Nc3 Be7 43 Rg4 Rc8 44 Kf1 Nc5 45 Ke2 Nd7 46 Kd3 Nf6 47 Rh4 Rg8 48 c5 dxc5 49 Rxa4 Ra8 50 Bc1 Rd8+ 51 Ke2 Rd6 52 Be3 Rc6 53 Kd3 Ke6 54 Rh4 Rb6 55 Rh6 Kf7 56 Rh8 Rb2 57 Ra8 e4+ 58 Nxe4 Rxa2 59 Nxc5 Ng4 60 Ne4 Ra3+ 61 Ke2 Nxe3 62 fxe3 Ra1 63 Ra7 Ke6 64 g4 Bb4 65 Rb7 a5 66 Rb5 Be7 67 Ng3 a4 68 Nf5 Bf6 69 Rb6+ Kf7 70 Nh6+ Kg7 71 Nf5+ Kf7 72 Nd6+ Ke7 73 Ne4 Be5 74 Rb5 Bh8 75 Rb7+ Ke6 76 Ra7 Kd5 77 Nd2 Bc3 78 Kd3 Bxd2 79 Kxd2 Ke4 Drawn.

Source: Bobby Fischer Triumph and Despair, pages

358-359, including a scan of the score-sheet. See too C.N.

8634.

Robert James Fischer – Svetozar Gligorić

Training game, Sveti Stefan, 1992

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 O-O Be7 6 Re1 b5 7 Bb3 d6 8 c3 O-O 9 h3 Bb7 10 d4 Re8 11 Ng5 Rf8 12 Nf3 Re8 13 Nbd2 Bf8 14 Bc2 g6 15 d5 Nb8 16 b4 c6 17 dxc6 Nxc6 18 a4 Qc7 19 axb5 axb5 20 Rxa8 Rxa8 21 Bd3 Nd8 22 Bb2 Bc6 23 Qe2 Qb6 24 Nb3 Ne6 25 Bc1 Rc8 26 Na5 Be8 27 Qb2 Qb8 28 Qb3 Bg7 29 Be3 Rd8 30 Ng5 Nxg5 31 Bxg5 Rc8 32 c4 Nh5 33 Rd1 Nf4 34 Bxf4 exf4 35 cxb5 Bxb5 36 Bc4 Be8 37 Bd5 Rc3 38 Qa2 f3 39 gxf3 Rxf3 40 e5 Rf4 41 exd6 Qxd6 42 Qe2 Qf8 43 Bc6 Bxc6 44 Nxc6 Bf6 45 Rd7 Qc8

46 Qe7 Bxe7 47 Nxe7+ Kg7 48 Nxc8 Rxb4 49 Nd6 Rf4 50 Rc7 g5 51 Rc4 Rf3 52 Kg2 Rd3 53 Rd4 Ra3 54 Nf5+ Kg6 55 Ne3 Ra6 56 Nc4 f6 57 Rd6 Ra7 58 Ne5+ Resigns.

Source: Bobby Fischer Triumph and Despair, pages 360-361, including a scan of the score-sheet.

Robert James Fischer – Svetozar Gligorić

Training game, Sveti Stefan, 1992

English Opening

1 c4 c5 2 b3 Nc6 3 g3 Nf6 4 Bg2 d5 5 cxd5 Nxd5 6 f4 e6 7 Bb2 h5 8 Nh3 Nf6 9 Nf2 h4 10 Nc3 hxg3 11 hxg3 Rxh1+ 12 Bxh1 Bd7 13 e3 Qa5 14 g4 O-O-O 15 g5 Ne8 16 Qh5 f5

17 Bxc6 Bxc6 18 Qf7 Nc7 19 Nd3 Rxd3 20 Qxf8+ Ne8 21 Qe7 Rd6 22 O-O-O Qd8 23 Qxd8+ Rxd8 24 Na4 b6 25 Be5 g6 26 Nb2 Rd7 27 Nc4 Bf3 28 Rf1 Bd5 29 Rd1 Rh7 30 a4 Rh3 31 Kc2 Kb7 32 Kc3 a6 33 b4 cxb4+ 34 Kxb4 Rh2 35 a5 Bf3 36 Rc1 b5 37 Nb6 Bc6

38 Nc8 Rxd2 39 Ne7 Bd7 40 Nxg6 Ra2 41 Ne7 Ra4+ 42 Kb3 Re4 43 Rd1 Rxe3+ 44 Kb2 Re2+ 45 Kc1 Resigns.

Source: Bobby Fischer Triumph and Despair, page 362, including a scan of the score-sheet.

Svetozar Gligorić – Robert James Fischer

Training game, Sveti Stefan, 1992

Queen’s Indian Defence

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e6 3 Nf3 b6 4 Nc3 Bb7 5 e3 Ne4 6 Bd3 Nxc3 7 bxc3 Be7 8 e4 d6 9 O-O O-O 10 Be3 Nd7 11 Nd2 e5 12 f4 Bf6 13 Rb1 Re8 14 Qf3 exf4 15 Qxf4 Nf8 16 Qg3 Ng6 17 Rf5 Bc8 18 Rh5 Nf8 19 Rf1 g6 20 Rd5 Bg7

21 e5 Be6 22 Be4 Nd7 23 exd6 c6 24 Rg5 Bxc4 25 Bxg6 hxg6 26 Nxc4 Re6 27 Ne5 Nxe5 28 dxe5 Qd7 29 Bf4 Rae8 30 h4 Rf8 31 h5 Qe8 32 Rg4 c5 33 Qd3 c4 34 Qd5 gxh5

35 Rxg7+ Kxg7 36 Bg5 Qd7 37 Bf6+ Rxf6 38 exf6+ Kg6 39 Qe4+ Kg5 40 Qe5+ Kg6 41 Qe4+ Kg5 42 Qf4+ Kg6 43 Rf3 Resigns.

Source: Bobby Fischer Triumph and Despair, page 363, including a scan of the score-sheet. Gligorić informed David DeLucia that this was the last match-game.

Svetozar Gligorić – Robert James Fischer

Training game, Sveti Stefan, 1992

Queen’s Indian Defence

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e6 3 Nf3 b6 4 Nc3 Bb7 5 e3 Ne4 6 Bd3 Nxc3 7 bxc3 Be7 8 O-O O-O 9 e4 d6 10 Ne1 Nd7 11 Nc2 e5 12 f4 Bf6 13 Rb1 Re8 14 Qf3 Nf8 15 fxe5 dxe5 16 d5 Nd7 17 Ba3 Bc8 18 Qf2 Kh8

19 c5 Nxc5 20 Bxc5 bxc5 21 Bb5 Bd7 22 Qxc5 Be7 23 Qc4 Rb8 24 Bc6 Bxc6 25 Qxc6 Rf8 26 Ne3 Rb6 27 Rxb6 axb6 28 Nf5 Bc5+ 29 Kh1 g6 30 Nh6 Qg5 31 Nxf7+ Kg7 32 Qxc7 Qe7 33 Qxe7 Bxe7 34 g3 Rxf7 35 Kg2 Ba3 36 Rxf7+ Kxf7 37 Kf3 Ke7 38 h4 h5 39 g4 Kd6 40 gxh5 gxh5 41 Ke2 Kc5 42 Kd3 b5 43 White resigns.

Source: Bobby Fischer Triumph and Despair, page 364, including a scan of the score-sheet.

Robert James Fischer – Svetozar Gligorić

Training game, Sveti Stefan, 1992

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 O-O Be7 6 Re1 b5 7 Bb3 d6 8 c3 O-O 9 h3 Bb7 10 d4 Re8 11 Ng5 Rf8 12 Nf3 Re8 13 Nbd2 Bf8 14 d5 Nb8 15 Nf1 Nbd7 16 g4 Nc5 17 Bc2 c6 18 b4 Ncd7 19 dxc6 Bxc6 20 Ng3 Nb6 21 Bb3 Rc8 22 g5 Nfd7 23 Nh2 Bb7 24 Qf3 Nc4 25 Ng4 Re6 26 Be3 Be7 27 h4 Nf8 28 Nf5 Qe8 29 a4 Nxe3 30 Rxe3 Ng6 31 axb5 axb5 32 Ra7 Rc7

33 Bd5 Bxd5 34 Rxc7 Bc4 35 h5 Bxg5 36 hxg6 Rxg6 37 Qh3

h6 38 Rg3 Kh7 39 Qh5

39...Qa8 40 Nge3 Qxe4 41 Nxc4 Qxf5 42 Ne3 Qe6 43 Qf3 Bf4 44 Rxg6 Qxg6+ 45 Qg4 Qb1+ 46 Nf1 Resigns.

Source: Bobby Fischer Triumph and Despair, page 365, including a scan of the score-sheet.

Finally, the game below is the reconstruction by Luc Winants (Boirs, Belgium) from an almost illegible score-sheet given in our feature article on the Fischer v Gligorić match:

Robert James Fischer – Svetozar Gligorić

Training game, Sveti Stefan, 1992

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 O-O Be7 6 Re1 b5 7 Bb3 d6 8 c3 O-O 9 h3 Bb7 10 d4 Re8 11 Ng5 Rf8 12 Nf3 Re8 13 Nbd2 Bf8 14 d5 Nb8 15 Nf1 Nbd7 16 Ng3 g6 17 Be3 Bg7 18 Qd2 Qe7 19 Rf1 Nb6 20 a4 bxa4 21 Bxa4 Nxa4 22 Rxa4 c6 23 c4 cxd5 24 cxd5 Bc8 25 Rfa1 Rb8 26 Ne1 h5 27 f3 h4 28 Ne2 Nh5 29 Nd3 f5 30 Nb4 f4 31 Bf2 Qg5 32 Kh2 Ng3 33 Nxa6 Bd7 34 Nxb8 Bxa4 35 Nc3 Rxb8 36 Nxa4 Bf6 37 Nb6 Bd8 38 Nc4 Qe7 39 Qc2 Resigns.

Eugenio Torre – Robert James Fischer

Training game, Sveti Stefan, 1992

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 c5 2 c3 Nf6 3 e5 Nd5 4 d4 cxd4 5 Nf3 Nc6 6 Bc4 e6 7 cxd4 d6 8 O-O Be7 9 Qe2 O-O 10 Qe4 a6 11 a3 b5 12 Bd3 g6 13 Bh6 Re8 14 Nbd2 Bb7 15 Rfe1 Nb6 16 Bf1 Rc8 17 Qf4 Nd5 18 Qg4 dxe5 19 dxe5 Nb8 20 Rac1 Nd7 21 h4 Rxc1 22 Rxc1 Qb8 23 Re1 Qc7 24 Bd3 Nc5 25 Bb1 f5 26 exf6 Nxf6 27 Qd4 Qd6 28 Bg5 Qxd4 29 Nxd4 Bd5 30 Rc1 Na4 31 Nc6 Kf7 32 Ne5+ Kg8

33 Nc6 Kf7 34 Nxe7 Rxe7 35 b3 Nb6 36 f3 Rb7 37 Bd3 Nbd7 38 Kf2 Ne5 39 Be2 Nc6 40 Ke3 Ne7 41 g4 Rd7 42 Bxf6 Kxf6 43 Ne4+ Kg7 44 Nc5 Ra7 45 Bd3 Kf7 46 Be4 a5 47 Bxd5 Nxd5+ 48 Kd4 Nb6 49 Nd3 a4 50 Ne5+ Kf6 51 b4 Nd7 52 g5+ Kf5 53 Nc6 Ra6 54 Ke3 e5 55 Ne7+ Ke6 56 Nc8 Nb8 57 Rc7 Rc6 58 Re7+ Kd5

59 Na7 Rc3+ 60 Kf2 Rxa3 61 Rxh7 e4 62 fxe4+ Kxe4 63 Nxb5 Rb3 64 h5 Rb2+ 65 Kg3 Kf5 66 Nd4+ Kxg5 67 Nf3+ Kf6 68 h6 Rxb4 69 Ra7 Rb5 70 Nh2 Rh5 71 Ng4+ Ke6 72 Rxa4 Nd7 73 Ra6+ Kf7 74 Ra7 Rd5 75 h7 Kg7 76 Nf6 Rd1 Drawn.

Source: Bobby Fischer Triumph and Despair, pages 366-367, including a scan of the score-sheet.

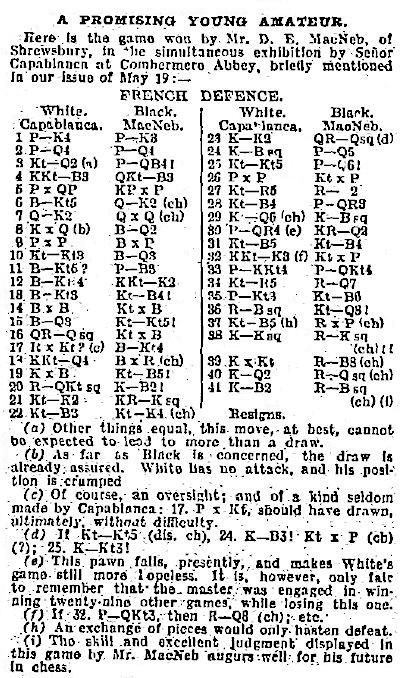

8639. Snowball game

An addition to Unusual Chess Words will be ‘Snowball game’. From page 196 of the July-August 1919 American Chess Bulletin:

The game was mentioned on page 212 of the April 1920 Chess Amateur:

‘A snowball game between East and West Kent resulted in a win for the latter end of the county. The game – a Queen’s Gambit – extended over 38 moves, at which stage it fell to Mr J.W.G. Jamieson’s lot to resign.’

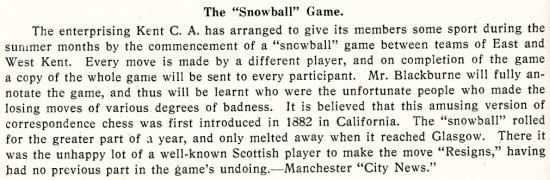

8640. Legall queen offer

A curiosity is the Legall queen offer when the opponent has castled on the queen’s side:

O. Prochazka (Dornachbrugg) – K. v. Wattenwil and

H. Geiler (Geneva)

49th Swiss correspondence tournament

Centre Counter Game

1 e4 d5 2 exd5 Qxd5 3 Nc3 Qa5 4 d4 e5 5 dxe5 Bb4 6 Nf3 Nc6 7 Bd3 Bxc3+ 8 bxc3 Bg4 9 O-O O-O-O 10 Bf4 Nge7 11 h3 Bh5 12 Rb1 Ng6 13 Bh2 Ngxe5

14 Nxe5 Qxe5 15 g4 Qg5 16 f4 Qc5+ 17 Kh1 Bg6 18 f5 Qxc3 19 Qf3 Resigns.

Source: Schweizerische Schachzeitung, November-December 1918, pages 141-142:

8641. Lasker v Marshall world title match

Dwight Weaver (Southaven, MS, USA) draws our attention to his article World Chess Championship in Tennessee – 1907, which includes an account of Marshall’s protest over the use of stop-watches rather than a chess clock.

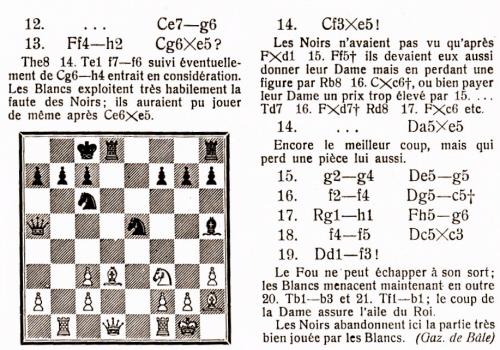

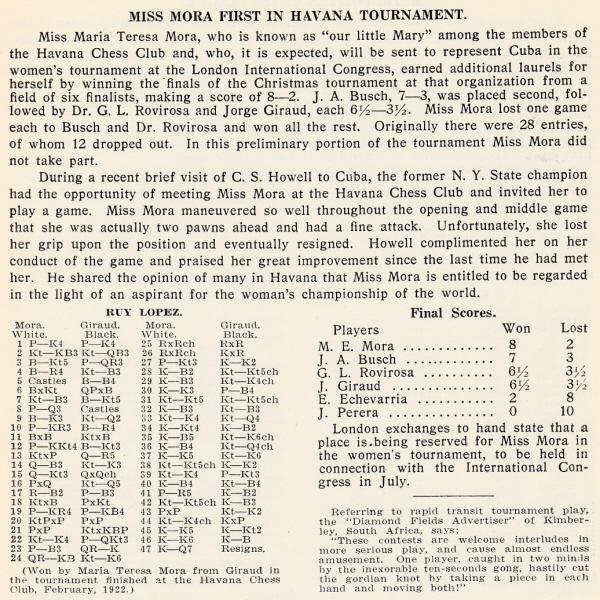

8642. María Teresa Mora

A news item about María Teresa Mora was published on page 47 of the March 1922 American Chess Bulletin:

The score of her victory over Jorge Giraud:

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 O-O Bc5 6 Bxc6 dxc6 7 Nc3 Bg4 8 d3 O-O 9 Be3 Nd7 10 h3 Bh5 11 Bxc5 Nxc5 12 g4 Bg6 13 Nxe5 Qh4 14 Qf3 Ne6 15 Qg3 Qxg3+ 16 fxg3 Nd4 17 Rf2 f6 18 Nxg6 hxg6

19 h4 f5 20 gxf5 gxf5 21 exf5 Nxf5 22 Ne4 b6 23 c3 Rae8 24 Raf1 Ne3 25 Rxf8+ Rxf8 26 Rxf8+ Kxf8 27 b3 Ke7 28 Kf2 Ng4+ 29 Kf3 Ne5+ 30 Ke3 c5 31 Ng5 Ng4+ 32 Kf3 Nf6 33 Ne4 Nd5 34 Kg4 Kf7 35 Kf5 Ne3+ 36 Kf4 Nd5+ 37 Ke5 Ne3 38 Ng5+ Ke7 39 Ne4 g6 40 Kf4 Nf5 41 h5 Kf7 42 Ng5+ Kf6 43 hxg6 Ne7 44 Ne4+ Kxg6 45 Ke5 Kg7 46 Ke6 Kf8 47 Kd7 Resigns.

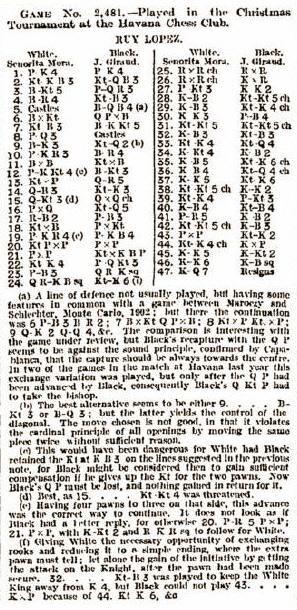

The game was annotated on page 264 of the Times Literary Supplement, 20 April 1922:

For another set of notes, see page 261 of the June 1922 Chess Amateur.

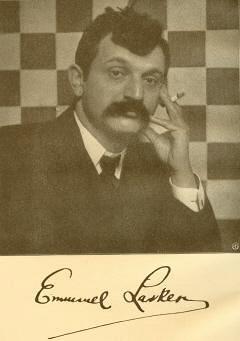

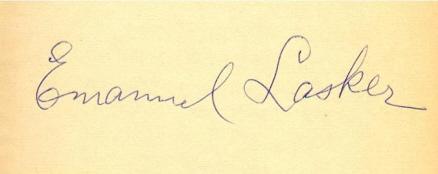

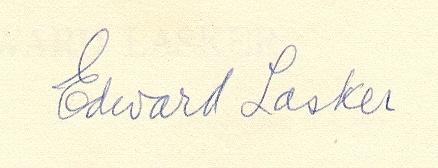

8643. Lasker signatures

Hassan Roger Sadeghi (Lausanne, Switzerland) refers to the spelling of Lasker’s name (‘Emmanuel’) in the signature shown in a picture from the C.N. gallery:

Is it possible to draw up a list of other instances of that non-standard spelling in Lasker’s own hand?

C.N. 2997 (see page 89 of Chess Facts and Fables) remarked upon the similarity of the signatures of Emanuel and Edward Lasker, as illustrated by two specimens in our collection:

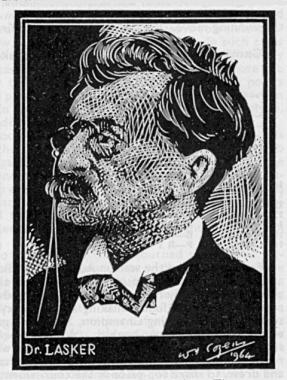

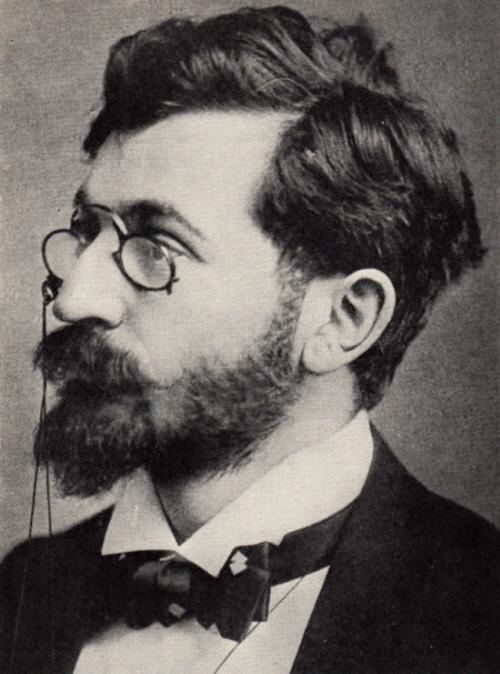

8644. Lasker illustration

C.N. 5059 gave this picture by W.H. Cozens from page 323 of the November 1964 BCM:

We add here that it was based on a photograph of a bearded Lasker on page 81 of the earliest editions of Chess by C.H.O’D. Alexander:

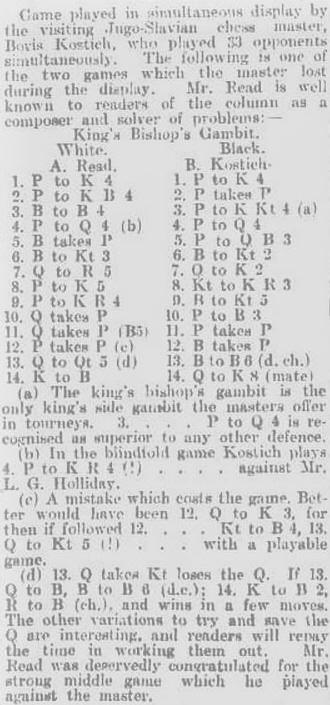

8645. Boris Kostić in Australia

Wanted: further details regarding a short loss by Kostić in 1924 to A. Read in a simultaneous exhibition in Australia:

The source, provided by Graham Clayton (South Windsor, NSW, Australia), is the Adelaide Chronicle, 31 May 1924, page 23. The newspaper inverted the players’ names in the game heading.

B. Kostić v A. Read: 1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Bc4 g5 4 d4 d5 5 Bxd5 c6 6 Bb3 Bg7 7 Qh5 Qe7 8 e5 Nh6

9 h4 Bg4 10 Qxg5 f6 11 Qxf4 fxe5 12 dxe5 Bxe5 13 Qg5 Bc3+ 14 Kf1 Qe1 mate.

8646. Legall queen offer (C.N. 8640)

A database search provides these further specimens of the Legall queen offer after the opponent has castled on the queen’s side:

Ludwig Herrmann v Max Eisinger, Hamburg, 1937: 11 Nxe5

Erwin L’Ami v Mark Smits, Utrecht, 1999: 18 Nxe5

Davorin Komljenović v Isaura Sanjuan Morigosa, Dos Hermanas, 2002: 10 Nxe5

Erik van den Doel v Sergei Tiviakov, Leeuwarden, 2005: 12 Nxe5

Vassily Ivanchuk v Liviu-Dieter Nisipeanu, Foros, 2007: 10...Nxe4.

The penultimate game was a short draw, and the other four were won by White. Herrmann annotated his game against Eisinger on pages 194-195 of Deutsche Schachblätter, 1 July 1937.

| First column | << previous | Archives [117] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.