Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [126] | next >> | Current column |

9025. Chess

history as she is written

From page 153 of Check Mate and Word Games by Carlos Tortoza (Denver, 2006):

‘In 1993, Garry Kasparov, then champion created Professional Chess Association (PCA) worldwide for the FIDE, and Nigel Shorts for the organization and marketing of the series of games for the worldwide heading.

Kasparov and Short had accused to the FIDE with the professionalism lack and favoritism. Moreover, the two had refused to yield 25% of the prizes for the FIDE. The FIDE removed the heading of Worldwide Champion of Chess of Kasparov and denied the Shorts the right to defy Kasparov.’

Two years later:

‘The PCA finished for leaving to exist due to sponsorship, when the Intel left to subvention the association ...’

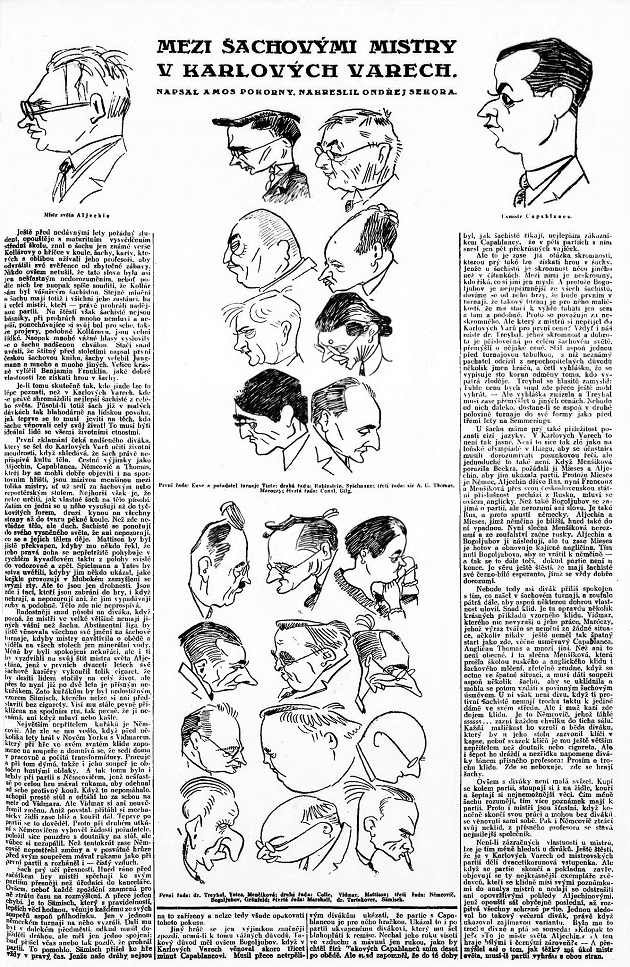

9026. Carlsbad, 1929

From Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France):

Lidové noviny, 11 August 1929, page 17 (Larger version)

Pestrý týden, 17 August 1929, page 8 (Larger version)

9027. Isaacs v Buerger

Black to move.

This was the position after White’s 38th move in the game between L.J. Isaacs and V. Buerger in the Chicago v London cable match, 6 November 1926 (1 e4 d6 2 d4 Nf6 3 Bd3 g6 4 Nf3 Bg7 5 O-O O-O 6 h3 Nc6 7 c3 Nd7 8 Nbd2 e5 9 d5 Ne7 10 g4 Nc5 11 Bc2 f5 12 Nh2 f4 13 f3 Kf7 14 Rf2 Bf6 15 Nb3 Nd7 16 Bd2 h5 17 Rg2 Rh8 18 g5 Bg7 19 h4 Nb6 20 Be1 Nc4 21 Qc1 Bh3 22 Re2 Nc8 23 Bf2 Bf8 24 Bd3 N4b6 25 Na5 Rb8 26 a4 Be7 27 Kh1 Bxg5 28 hxg5 Qxg5 29 Qg1 Qf6 30 Qe1 g5 31 c4 Ne7 32 b4 Ng6 33 c5 Nc8 34 cxd6 cxd6 35 Rc2 g4 36 Rc7+ Nce7 37 Nxb7 g3 38 Bxa7).

One of several magazines which published the game, noting

that it was to be adjudicated by Alekhine, was the American

Chess Bulletin (December 1926, pages 157-158). Page

158 mentioned that a suggestion by Capablanca was

38...Rxb7 39 Rxb7 Rc8. Buerger annotated the game on pages

72-73 of The “British Chess Magazine” Chess Annual

1926 by M.E. Goldstein (Leeds, 1927), without

commenting on the final position.

As reported on, for instance, page 161 of the March 1927 Chess Amateur, Alekhine adjudicated the game as a win for Black, but is it known whether he supplied any analysis or commentary?

9028. The back rank

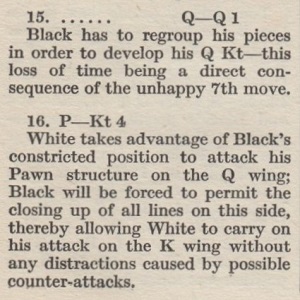

A small oddity in the descriptive notation is the omission by old US publications of the digit 1, e.g. R-Q, and not R-Q1. A surprisingly recent book which adopts that practice is The Pleasures of Learning Chess by Fairfield W. Hoban (New York, 1974).

9029. A statement by Alekhine? (C.N.s 3896 & 3898)

Two more second-hand versions:

‘It was said that you had to beat Alekhine three times in one game to defeat him – once in the opening, once in the midgame, and once in the ending.’

Source: page 237 of Combinations The Heart of Chess by I. Chernev (New York, 1960).

‘... Alekhine’s boast that to lose he had to be beaten three times – once in the opening, once in the middle game, once in the ending.’

Source: page 209 of New Ideas in Chess by L. Evans (Las Vegas, 2011).

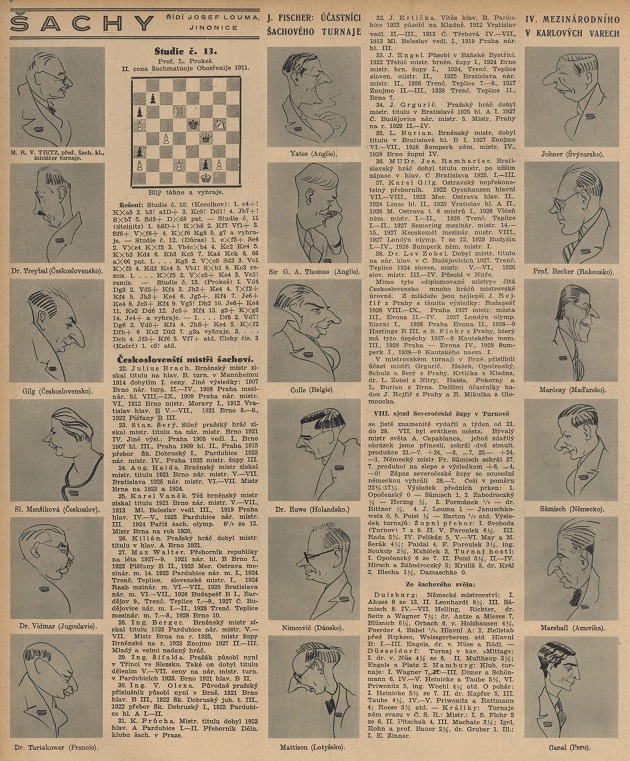

9030. Who? (C.N. 8956)

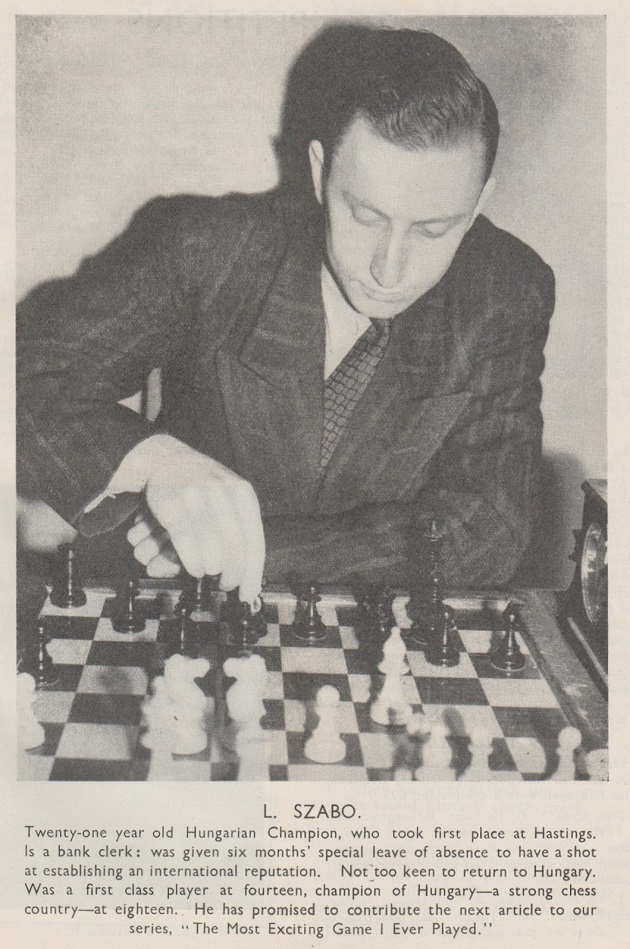

From page 58 of CHESS, January 1941:

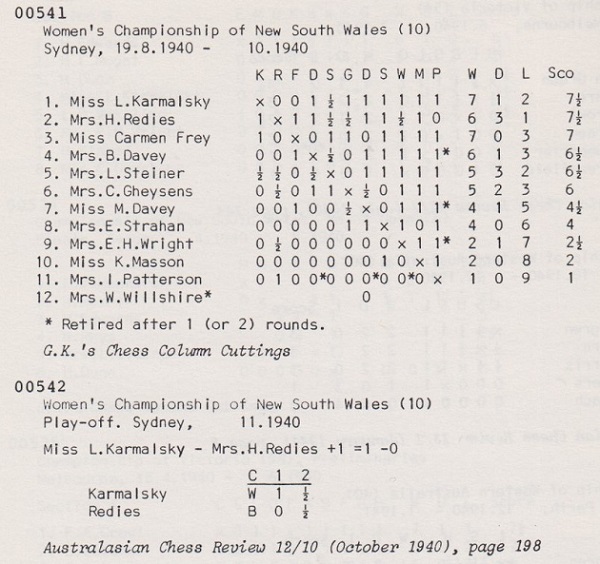

The event in question was the women’s championship of New South Wales, as documented on page 123 of The Records of Australian Chess. Tournament and Match Tables, volume two, by John van Manen (Modbury Heights, 1987):

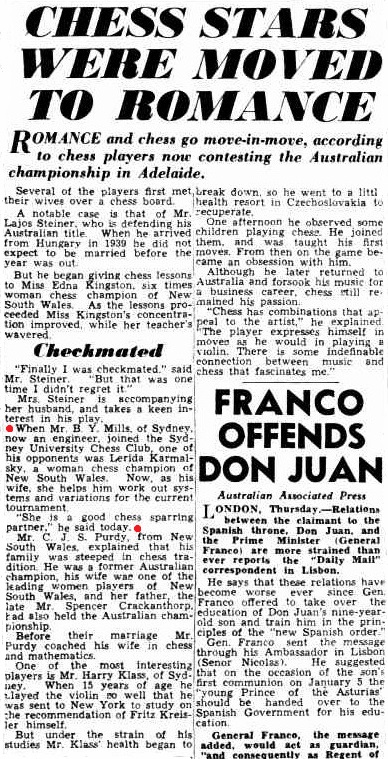

Much information about Lerida Karmalsky (later Lerida Mills) can be found at the National Library of Australia’s Trove website. The cutting below is from page 3 of the 27 December 1946 issue of News (Adelaide):

An obituary of Bernard Mills in the Sydney Morning Herald, 21 May 2011 notes that Lerida Mills died in 1969.

9031. Announcements (C.N. 9011)

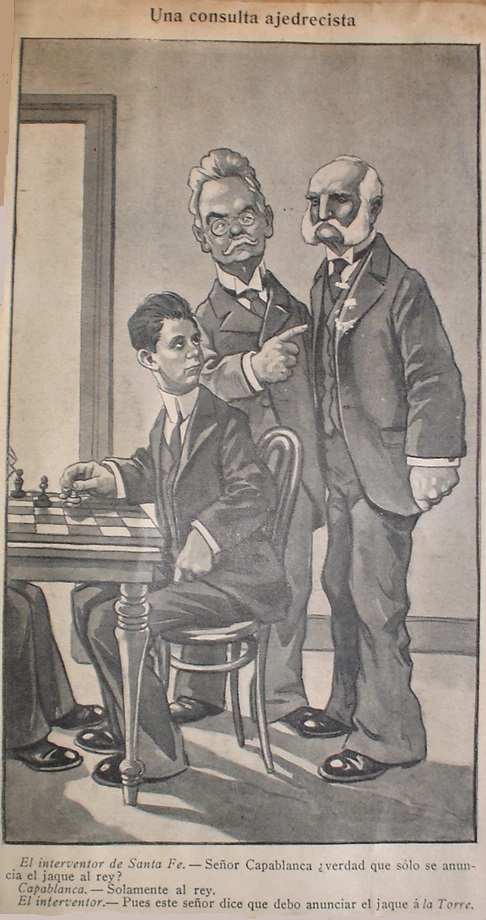

As regards announcing an attack on the rook, we note a caricature of Capablanca in the Argentinian publication La Vida Moderna, 28 June 1911 which was reproduced on page 64 of Los años locos del ajedrez argentino by Juan Sebastián Morgado (Buenos Aires, 2013). The author has kindly provided the ‘chess consultation’ cutting:

From page 63 of the book:

‘El semanario La Vida Moderna, aprovechando la presencia de Capablanca en el país, publica una caricatura muy graciosa, haciendo un chiste sobre este tema. Pueden verse a Capablanca (sentado, jugando), Gil y Lisandro de la Torre, entablándose este diálogo:

Interventor Gil: Señor Capablanca ¿Verdad que sólo se anuncia el jaque al rey?

Capablanca: Solamente al rey.

Interventor Gil: Pues este señor dice que debo anunciar el jaque a la Torre.’

Mr Morgado has sent us this translation:

‘Taking advantage of Capablanca’s presence in the country, the weekly publication La Vida Moderna had a very amusing cartoon, making a joke about this topic. It showed Capablanca (seated and playing), Gil and Lisandro de la Torre having this dialogue:

Interventor Gil: Señor Capablanca, is it true that check is announced only to the king?

Capablanca: Yes, only to the king.

Interventor Gil: But this gentleman says that I have to announce check to the rook.’

Our correspondent also explains the context:

‘There is a pun based on the fact that “this gentleman” was Lisandro de la Torre and that torre is the Spanish word for rook or tower. The political situation in the Santa Fe province was complicated; the elected governor had been removed by the central government, and Anacleto Gil had been appointed to replace him. Lisandro de la Torre was a very popular representative whose political career was in the ascendancy.’

9032. A party trick (C.N. 9022)

White gives mate without making any move.

This is one of two compositions by Arthur John Curnock (‘one of the foremost Metropolitan amateurs’) on page 538 of the December 1902 BCM. The solution was published on page 141 of the March 1903 issue:

‘It is obvious Black has just played an illegal move. White compels him to retrace his move in order to comply with the rules of the game. It will be seen that as White is in check, Black’s rook must have last moved, and also as Black is in double check the king also must have moved, therefore Black must have illegally castled. Replace the pieces and it is found that Black is mated without White having to make a move.’

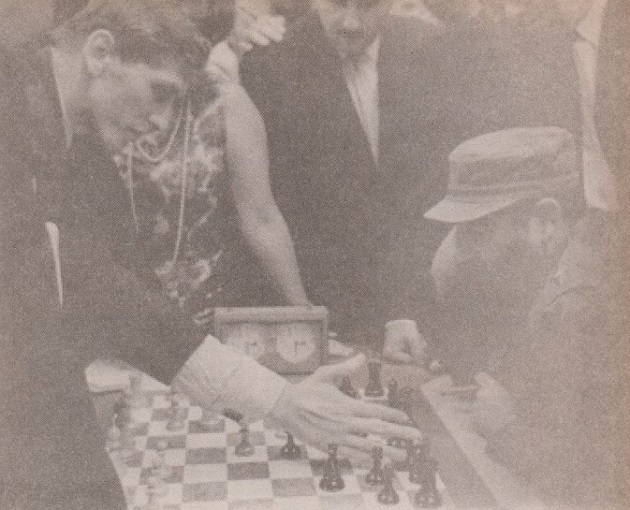

9033. Fischer and Castro

There are a few photographs of Bobby Fischer with Fidel Castro (Havana, 1966), but the shot below (of which a better copy is sought) is slightly different from a well-known one:

Source: El ajedrez en Cuba by José Luis Barreras Meriño (Havana, 2002), in the concluding photographic supplement.

9034. Brian Eley

The entry for Brian Eley in Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia (Jefferson, 1987) had only ‘c1946’ with regard to his birth. The unpublished 1994 edition stated that he was born on 6 July 1946 in Don Valley, England, and the entry amended his name from ‘Brian Ratcliffe Eley’ to ‘Brian Eley’. The source added by Gaige in the 1994 edition was ‘personal interview’.

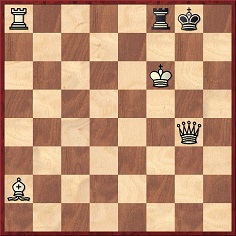

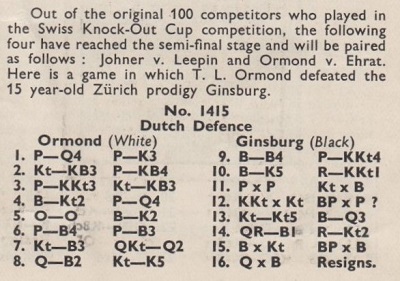

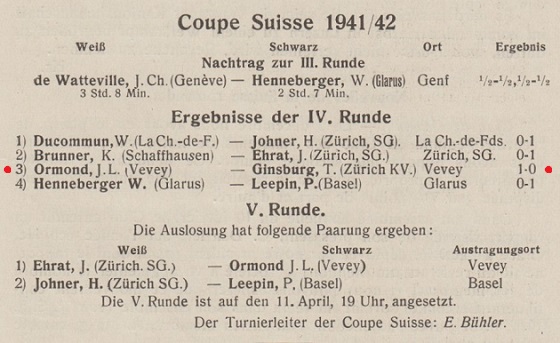

9035. Ormond v Ginsburg

From page 139 of CHESS, June 1942:

1 d4 e6 2 Nf3 f5 3 g3 Nf6 4 Bg2 d5 5 O-O Be7 6 c4 c6 7 Nc3 Nbd7 8 Qc2 Ne4 9 Bf4 g5 10 Be5 Rg8 11 cxd5 Nxe5 12 Nxe5 cxd5 13 Nb5 Bd6 14 Rac1 Rg7 15 Bxe4 fxe4

16 Qxc8 Resigns.

White was Jean-Louis Ormond, and the game was played in Vevey. From page 51 of the April 1942 Schweizerische Schachzeitung:

A photograph from opposite page 104 of the March 1929 issue of L’Echiquier:

Jean-Louis Ormond

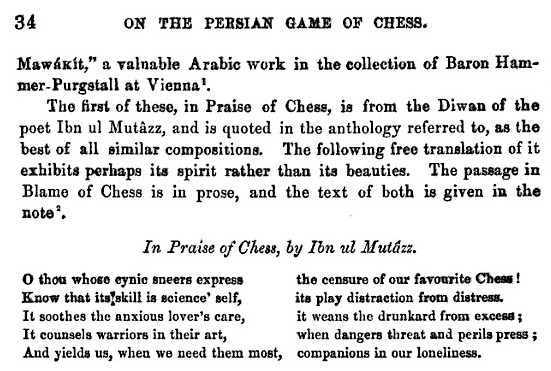

9036. An old poem

The poem given on page 164 of the American Chess Bulletin, November 1933 (see Chess in the Courts) can be traced back to page 34 of The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland (London, 1852), in a paper by Nathaniel Bland ‘On the Persian Game of Chess’, read on 19 June 1847:

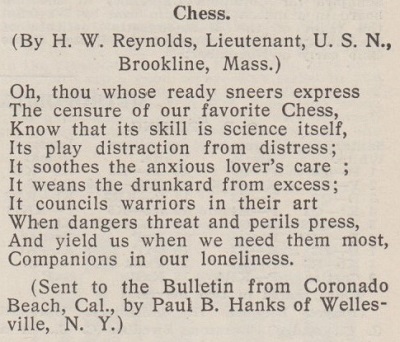

An oddity is the attribution on page 209 of the American Chess Bulletin, December 1921:

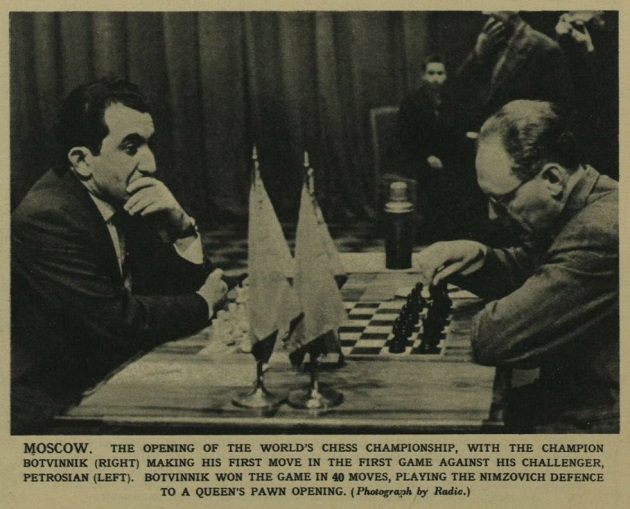

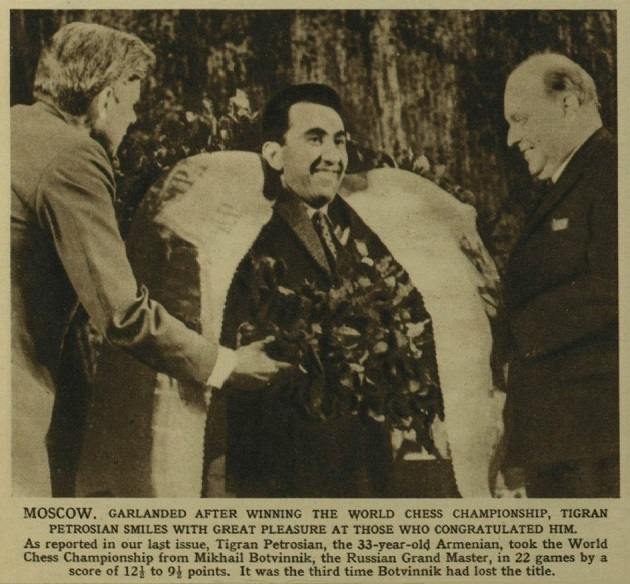

9037. World championship photographs

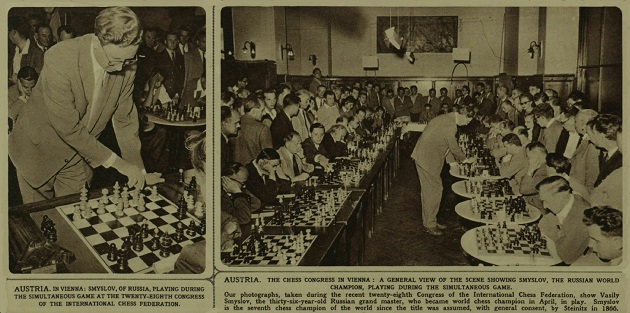

Four photographs received from Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore):

Illustrated London News, 20 May 1961, page 851

Illustrated London News, 30 March 1963, page 456

Illustrated London News, 1 June 1963, page 859

Illustrated London News, 8 June 1963, page 882.

9038. Copyright on chess games

Concerning copyright on chess games Mr Urcan has forwarded B.H. Wood’s column in the Illustrated London News, 14 July 1951, page 74:

9039. Over-potted biography

Page 92 of Chess Made Easy by Muriel Goaman (Toronto, 1973) has one brief paragraph on Morphy:

‘Another child prodigy was Paul Morphy (1837-1884), who was a Master of chess at the age of 13. After three years he gave up international chess.’

9040. A Game of Chance

A Game of Chance by Jon Osborne (London, 2012) has many references to Richard Forster’s book on Amos Burn. See pages 26-27, 46, 66, 159, 224 and 227.

9041. Mannerism

From page 144 of The World Chess Championship 1963 by R.G. Wade (London, 1963):

‘Botvinnik has the mannerism, when he reaches at last a satisfactory position, of straightening his tie.’

A number of Botvinnik’s opponents have remarked upon this mannerism, including Leonard Barden in his Evening Standard column of 7 July 2014, which gave a position from their game in Hastings on 31 December 1961. (He annotated the complete game on pages 85-87 of the March 1962 BCM.)

By playing 33 Qb4 White

missed an opportunity.

From the Evening Standard column:

‘The world champion reacted to my queen move with a thin smile, then adjusted his tie. This was a demoralising gesture for me, for everybody knew that Botvinnik’s tie routine was invariably a signal that the great man was satisfied with his position or had just escaped from danger.’

Further to C.N.s 8979 and 9022, Mr Barden informs us that he has now agreed terms with the Evening Standard for his on-line column to continue.

9042. Luces

y

Sombras del Ajedrez Argentino

A particularly interesting recent book is Luces y Sombras del Ajedrez Argentino by Juan Sebastián Morgado (Buenos Aires, 2014). Highlights include the sections on Che Guevara (pages 13-44), Marcel Duchamp (pages 95-109), Movsa Feigins (pages 212-227) and Adolf Seitz (pages 239-267). The chapter on pages 284-293 offers ‘la versión definitiva’ of a controversy which arose regarding Capablanca v Grau, Buenos Aires, 1939.

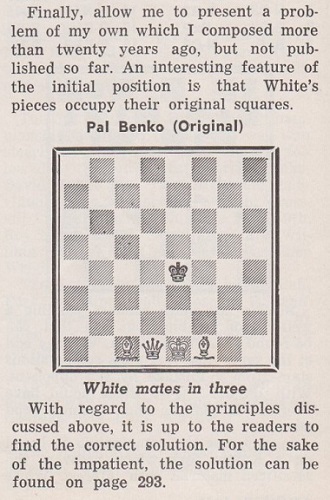

9043. Benko composition

Mate in three

This composition has been widely published, e.g. on page 246 of Miniature Chess Problems From Many Countries by Colin Russ (London, 1981).

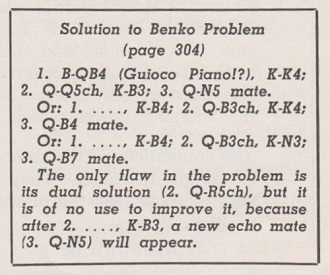

Russ gave it with a correct citation, ‘P. Benko, Chess Life, 1968’. From page 304 of the August 1968 Chess Life, on the second page of an article by Benko entitled ‘Echo and Repetition’:

The solution on page 293:

Benko also published the problem on other occasions, e.g. on page 233 of the April 1977 Chess Life & Review.

In an article dated 22 August 2005 on pages 38-39 of his dire book This Crazy World of Chess (New York, 2007) Larry Evans put the black king on e5 (a change which, curiously, does not affect the key move) and wrote:

‘Bobby Fischer once bet he could solve it in a half hour and lost. ... Bobby then bet Benko he could find a second solution (called a cook) if he could study it overnight. He lost again. There is one and only one key move.’

No source or other information was given, the word

‘once’ being deemed sufficient. The same diagram and text

appeared on pages 41-42 of the ‘new edition’ (Las Vegas,

2009).

On pages 581-582 of Pal Benko My Life, Games and Compositions by P. Benko and J. Silman (Los Angeles, 2003) Benko wrote that it was ...

‘... the last problem I composed as a teenager. It was published many times because its original setup appealed to problem-solvers and tournament players alike.

During the Lugano Olympiad, which Bobby Fischer attended as a spectator, I made a bet with him that he couldn’t solve it in 30 minutes. As time ran out, he became irritated and demanded to see the answer. When I showed it to him, he insisted that other solutions had to exist. Naturally, this led to another bet. After more time passed, he was forced to settle both wagers. The teenage Pal Benko never would have guessed how much mileage he was going to get out of that little problem.’

In a ChessBase article dated 5 September 2011, in which Benko stated that he composed the problem when aged 15, the Fischer story at the Lugano Olympiad was related again.

It should, though, be noted that the Lugano Olympiad took place in October-November 1968 and that, as shown above, Benko had already published the problem in the August 1968 Chess Life.

A sidelight is that page 582 of Benko’s book added:

‘M. Grigoriev imitated this problem by placing Black’s king on b4. He published it in 64 in 1982, claiming a mate in two by 1 Qd5. Unfortunately, he overlooked the cook 1 Qd4+.’

An inscription by Benko on page 47 of our copy of Kandidatenturnier für Schachweltmeisterschaft by S. Gligorić and V. Ragozin (Belgrade, 1960):

Addition: see too our feature article Pal Benko (1928-2019)

9044. A familiar old position (C.N.s 8977 & 8993)

Readers’ games are not usually shown in C.N., but an exception is made for a contribution from Dan Scoones (Coquitlam, BC, Canada). On 1 January 2015, not long after C.N.s 8977 and 8993 appeared, he had the following position as White against Hans Lassnig in a casual game (full score not recorded) at the West Vancouver Chess Club:

White to move

The continuation was 1 Rxa6 Bxa1 2 Ra7+ Rc7

3 Qc6 Resigns. (‘Although resistance was still possible after 3...Rxa7 4 Qxc8 Bc3, the shock proved too much for my opponent, and he immediately resigned.’)

9045. ...b5 in the King’s Gambit Accepted

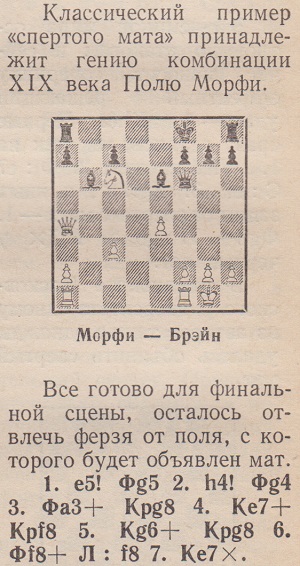

From page 41 of Шахматный калейдоскоп by A. Karpov and Y. Gik (Moscow, 1981):

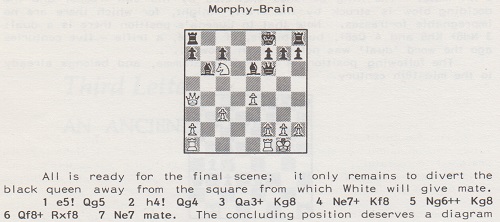

Page 26 of the English edition, Chess Kaleidoscope (Oxford, 1981), named Black as ‘Brain’:

The game between Morphy and Thomas Jefferson Bryan is in most Morphy collections, e.g. on page 280 of Paul Morphy. Skizze aus der Schachwelt by Max Lange (Leipzig, 1881).

Bryan’s name is most commonly seen nowadays in connection with the ‘Bryan Counter-Gambit’: ...b5 after either 1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Bc4 or 1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Bc4 Qh4+ 4 Kf1. For example, various editions of the nineteenth-century work Synopsis of the Chess Openings by William Cook stated that the defence was devised by Bryan and subsequently analysed and recommended by Kieseritzky. The involvement of Kieseritzky in the opening is well documented (quite apart from the Immortal Game), but what about Bryan? And how to explain the fact that, also in the late nineteenth century, editions of Chess by R.F. Green, as well as Green’s ‘Index to the Openings’ appended to reprints of Staunton’s Handbook, called 1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Bc4 b5 ‘Brien’s Counter Gambit’.

Such references to Robert Barnett Brien are surprising, as is a comment by C.E. Ranken on page 119 of the March 1901 BCM, after 1 f4 e5 2 e4 exf4 3 Bc4 b5 in a game between H. Brewer and W. Atkinson:

‘This ingenious counter attack is the invention of Mr S. Calthrop, of Trinity College, Cambridge, and now of New York, who played it frequently in the forties with the late Mr Brien, of Oxford.’

Have these historical discrepancies already been investigated, and perhaps even resolved, by opening theoreticians?

9046. Carlsen v Anand match book

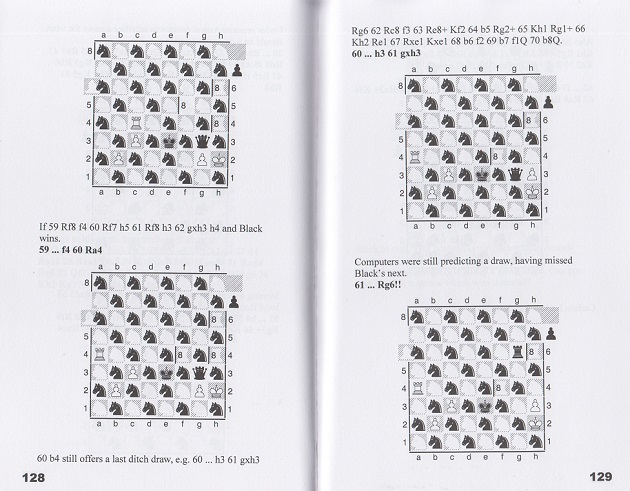

Above are pages 128-129 of Magnus Carlsen – Viswanathan Anand 2014 Re-Match for the World Chess Championship by Raymond Keene (Bronx, 2014).

The book has well over 100 similar diagrams.

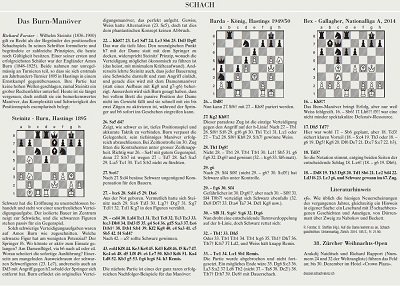

9047. The Burn Manoeuvre

In his column on page 60 of the Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 27 December 2014 Richard Forster offered the term ‘Burn Manoeuvre’ to describe ...Kh8 and ...Qg8, as seen in Steinitz v Burn, Hastings, 1895. He also drew attention to a neglected game in which Black used the manoeuvre in surprising fashion to defend against a dangerous attack on the h-file. At Hastings on 5 January 1950 the position below occurred in the seventh-round game between Olaf Barda and Imre König:

Black to move

26...Qd8 27 Kg2 Kh8 28 Rh1 Qg8

29 g6 fxg6 30 Nf4 Nf8 31 Nxg6+ Nxg6 32 Qxg6 Rb1 33 Qh5 Rxc1 34 Bxc1 Nb1 Drawn. (There are databases which give Black’s final move as the faulty 34...Rb1.)

The game was briefly described, but not given, in the round-by-round reports published in 1950 by the BCM and CHESS. Has it been annotated anywhere?

9048. Record length

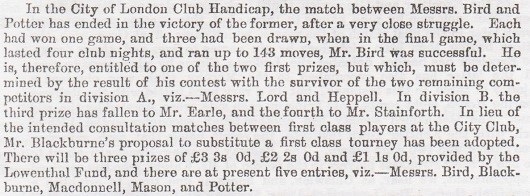

Page 146 of Chess Novelties by H.E. Bird (London, 1895) referred to ‘the 149-move deciding game, Bird and Potter, City of London great handicap, 1879, the longest game on record’.

From page 133 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1 June 1879:

The Potter v Bird game, which did indeed last 143, and not 149, moves, is of considerable interest:

1 f4 f5 2 b3 Nf6 3 Bb2 e6 4 Nf3 Be7 5 e3 O-O 6 Be2 c5 7 O-O Nc6 8 Ne5 Qc7 9 Nxc6 Qxc6 10 Bf3 Qc7 11 c4 a6 12 Nc3 Ra7 13 g3 b6 14 d4 cxd4 15 exd4 Bb7 16 a3 Bxf3 17 Qxf3 Ng4 18 h3 Nh6 19 Rad1 Bf6 20 Rf2 Nf7 21 d5 Raa8 22 Kh1 Nd6 23 Re2 Rae8 24 Rde1 Qb7 25 Kg2 Bxc3 26 Qxc3 Rf7 27 Kh2 Ne4 28 Qd4 exd5 29 cxd5 Qc7 30 b4 Qd6 31 Qd3 h5 32 h4 Rfe7 33 Be5 Qg6 34 d6 Re6 35 Qf3 b5 36 Kg2 Kh7 37 Rd1 Rc8 38 Rd3 Rc4 39 Rb2 Rxe5 40 fxe5 Nxg3 41 Qxg3 Rg4 42 Rf2 Qe6 43 Re3 g6 44 Kh2 Rxg3 45 Kxg3 Kg7 46 Rg2 Qc4 47 Kf3 Qd5+ 48 Kf2 f4 49 Re1 Kf7 50 Rg5 Qd3 51 Rgg1 Ke6 52 Rg5 Kf7 53 Rgg1 Ke8 54 e6 Qd4+ 55 Kf3 Qd5+ 56 Kxf4 dxe6 57 Rd1 Qf5+ 58 Ke3 Qe5+ 59 Kf3 Kd7 60 Rgf1 g5 61 hxg5 Qxg5 62 Rg1 Qf6+ 63 Kg3 e5 64 Rgf1 Qe6 65 Kf3 Qc4 66 Rg1 Qf4+ 67 Ke2 Qe4+ 68 Kf2 Qh7 69 Ke3 h4 70 Rgf1 h3 71 Kf3 Qh4 72 Ke3 h2 73 Rf7+ Ke8 74 Rff1 Kd7 75 Rf7+ Ke6 76 Rff1 Qh6+ 77 Ke2 Qh5+ 78 Ke3 Qg5+ 79 Ke2 Qh5+ 80 Ke3 Kd7 81 Kf2 Qh3 82 Ke2 Qb3 83 Kf2 Qxa3 84 Kg2 Qxb4 85 Kxh2 Qc4 86 Kg3 b4 87 Rh1 Qf4+ 88 Kg2 Qf7 89 Rhf1 Qg6+ 90 Kf3 b3 91 Ke3 a5 92 Rg1 Qh6+ 93 Kd3 Kc6 94 d7 Kxd7 95 Kc3+ Kc6 96 Kxb3 Qf4 97 Rc1+ Kb5 98 Rb1 a4+ 99 Ka3+ Ka5 100 Rgc1 Qf8+ 101 Ka2 Qf7+ 102 Ka3 Qe7+ 103 Ka2 e4 104 Kb2 Qb4+ 105 Ka2 Qd2+ 106 Ka1 Qd4+ 107 Ka2 Qd5+ 108 Ka3 Qd6+ 109 Kb2 e3 110 Kc3 Qd2+ 111 Kc4 e2 112 Rb5+ Ka6 113 Rbb1 Qf4+ 114 Kd3 Qe5 115 Kc4 Qe4+ 116 Kc3 Qe3+ 117 Kc4 a3 118 Kb4 a2 119 Ra1 Qd2+ 120 Kb3 Kb5 121 Rh1 Qb4+ 122 Kc2 Qc4+ 123 Kd2 Ka4 124 Rac1 Qb5 125 Rh4+ Ka5 126 Rhh1 Qb2+ 127 Kd3 Kb4 128 Rh4+ Kb3 129 Rhh1 Qe5 130 Rhe1 Qb5+ 131 Kd2 Ka4 132 Rh1 Qb2+ 133 Kd3 Kb3 134 Rhg1 Qe5 135 Rh1 Qb5+ 136 Kd2 Ka4 137 Rh4+ Ka5 138 Rhh1 Qe5 139 Rhe1 Qe4 140 Kc3 Ka4 141 Rh1 Qe3+ 142 Kc2 Qd4 143 Rhe1 Kb4 144 White resigns.

The game was annotated in depth by Steinitz in his Field column of 31 May 1879, his closing comment being, ‘the final combination is very ingenious’.

For subsequent lengthy games, see a ‘Chess Records’ webpage by Tim Krabbé.

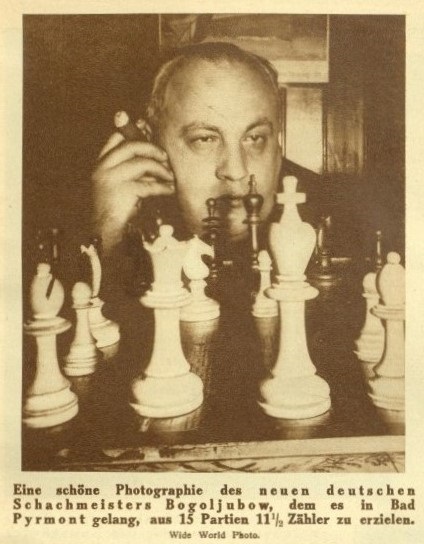

9049. Efim Bogoljubow

Jan Kalendovský (Brno, Czech Republic) submits a photograph from page 3 of Das interessante Blatt, 20 July 1933:

9050. ...b5 in the King’s Gambit Accepted (C.N. 9045)

From John Townsend (Wokingham, England):

‘Samuel Robert Calthrop and Robert Barnett Brien played each other at chess in the 1840s at St Paul’s School, London. Brien’s admission on 8 October 1834, aged seven, is recorded on page 289 of Admission Registers of St Paul’s School, from 1748 to 1876 (published in 1884) In 1844-45 he was Captain. Chapter four of The Boyhood of Rev. Samuel Robert Calthrop, compiled by his daughter, Edith Calthrop Bump, (New York, 1939) notes that he too was at St Paul’s and contains the following paragraph:

“It was at school that I began to play chess with my friend Brian [sic]. We studied openings and by so doing we played ourselves into first class form without knowing it. I became so interested that I used to go to some of the places where some of England’s best players used to congregate. It must have seemed strange to see a boy of 16 playing with some of the best in England.”

On 7 June 1845 Brien matriculated at Balliol College, Oxford. Calthrop went to Trinity College, Cambridge, and C.E. Ranken was at Oxford (Wadham College) at the same time as Brien.’

9051. Brilliance

‘Would’ can be strange, and C.N. 8632 (see Chess and the English Language) mentioned its unnecessary inclusion in historical narratives (‘Alekhine died in 1946, and two years later Botvinnik would become world champion’, instead of simply ‘became world champion’). Another quirk, favoured by presenters of history programmes on television, is recourse to ‘would have’ to disguise speculation or mind-reading: ‘It is in this room that he would have decided to ...’ Then there is all the prolixity in quizzes. ‘Would you be ready?’ is answered not by ‘Yes’ but by ‘I would indeed’, and later we may hear, ‘I wouldn’t have a clue’ or the frightful excuse for ignorance of something uncontemporary: ‘that would be before my time’. Asked in a chess quiz to identify the player who was nicknamed ‘the Black Death’, a contestant could well use four words instead of one: ‘that would be Blackburne’. A more challenging question is: which chess writer used the pseudonym ‘Eze’? That would be Telling.

As shown in C.N. 8677, on page 44 of Brilliance in Chess (London, 1977) Gerald Abrahams stated that a Tartakower v Colle game was ‘played at Eze in 1930’, whereas ‘Eze’ was merely the pseudonym of Oscar Leonidas Telling, who brought out a book on the Nice, 1930 tournament.

The Eze/Nice confusion, which has yet to be explained, recurred on page 84 of Abrahams’ book, where he explicitly wrote:

‘In a tournament at Eze, in the South of France, in 1930, the best player was Tartakower ...’

He then gave two further positions from the event, Colle v O’Hanlon and O’Hanlon v Znosko-Borovsky. The diagrams were respectively labelled ‘Eze 1930’ and ‘Played Eze’. Abrahams wrote that the two games received brilliancy prizes, from a newspaper which, as he had already done on page 44, he called L’Eclairceur de Nice. L’Eclaireur de Nice is/would be correct.

After a few general comments about brilliancy (‘Let us not call every sacrifice brilliant’) Abrahams gave a footnote:

‘There must be something in the air of the South of France because in 1974, at Nice, they awarded the first brilliancy to an English Master (certainly a fine player) who made a sacrifice on K6 for which the board was screaming – and they rejected harder pieces of play.’

Even today, when technology increasingly encourages people, including the uninformed and illiterate, to share their opinions about tout ce qui bouge, it may still seem rather inelegant to dispute brilliancy-prize decisions. The case referred to in Abrahams’ footnote was Michael Stean’s victory over Walter Browne, a game which Harry Golombek published on page 235 of A History of Chess (London, 1976):

‘One of the prettiest games of the [Nice] Olympiad was the following, for which the winner was awarded the Turover Brilliancy prize of $1,000.’

Golombek was one of the three judges, the others being Reuben Fine and Lothar Schmid, as reported on page 667 of the October 1974 Chess Life & Review.

The magazine published the game with Stean’s annotations and also stated:

‘Our own chess philanthropist, I.S. Turover, who has been giving out 100 dollar bills as brilliancy prizes for many years, has decided that a brilliant game’s cash value is high indeed. “I.S.” believes in chess beauty and is willing to pay, in addition to many smaller cash prizes during the year, $1,000 to the “most brilliant game played in the premier tournament of the year”.

This year it was decided to select the winning game from those played in the Final A group at the Nice Olympics. In addition to the money, the winner receives a small trophy which is a replica of a larger trophy to be kept in the United States and on which will be engraved the name of the winner each year.’

The heading of the article was ‘I.S. Turover $1,000 World Brilliancy Prize’, and although many copycat webpages describe the prize as ‘annual’ and Stean as ‘the first winner’, we are not aware that it was ever awarded again.

On pages 281 and 282 of the May 1975 Chess Life & Review L. Kavalek reported that Turover had given a prize for the most brilliant game won at the Wijk aan Zee tournament at the beginning of the year (again Walter Browne was the loser, the victor being Vlastimil Hort), but no ‘World Brilliancy Prize’ seems to have been awarded to any game after Stean v Browne. Would that it had. Turover died in 1978, aged 86.

Isador Samuel Turover, front cover, Chess Life, November 1968

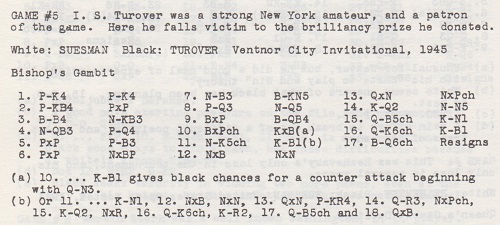

A brilliancy prize oddity was related on page 6 of Chess Games and Chess Problems by W.B. Suesman (Providence, 1980):

The Suesman v Turover game was given in C.N. 2177 (see pages 241-242 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves), but we now note that it was played in 1944, and not 1945. I.A. Horowitz annotated it on pages 4-5 of the August-September 1944 Chess Review, and the brilliancy prize was discussed on page 15 of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 31 August 1944.

C.N. 2177 also mentioned another player who lost a game which received a brilliancy prize donated by himself, and it is an appropriate name with which to end this little stroll: Wood.

9052. A neglected draw

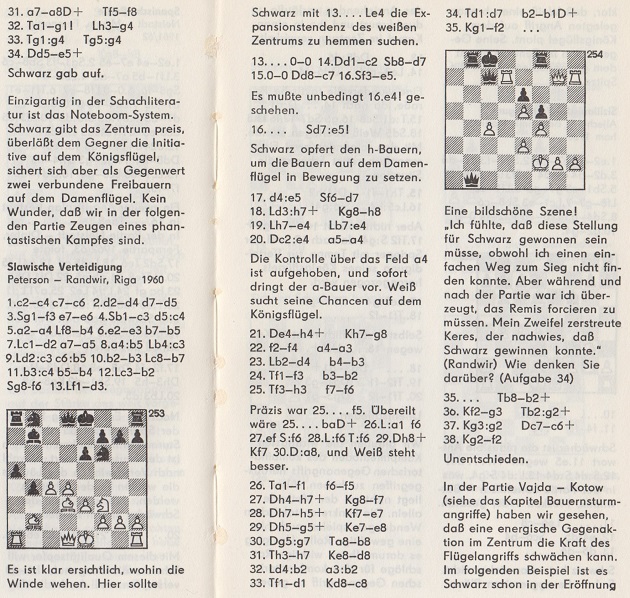

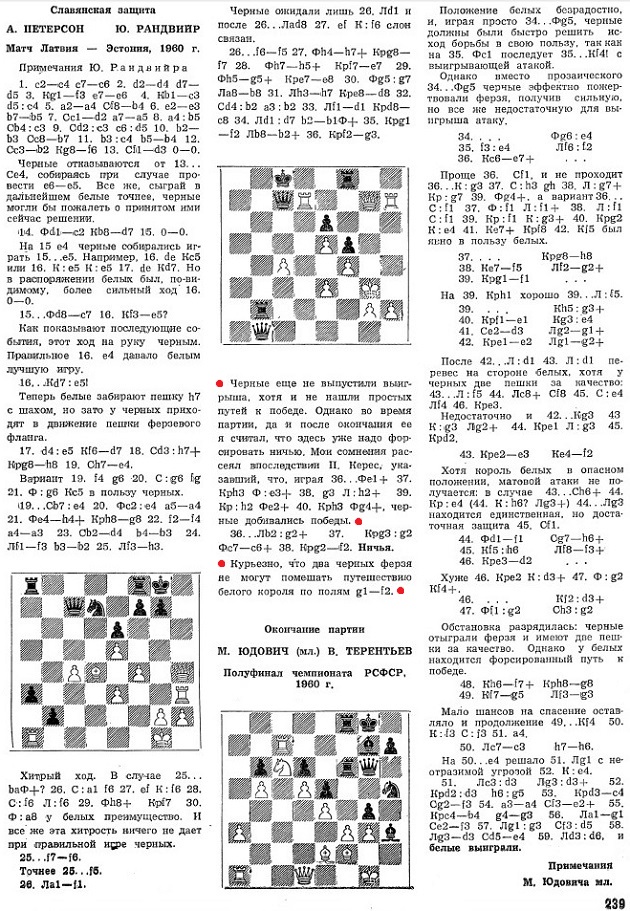

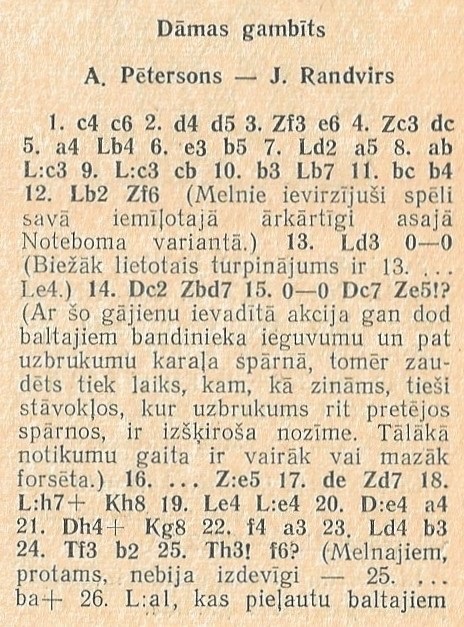

This spectacular game from pages 248-249 of volume two of Lehrbuch der Schachtaktik by Alexander Koblenz (East Berlin, 1972) is not easily found elsewhere:

From page 323:

1 c4 c6 2 d4 d5 3 Nf3 e6 4 Nc3 dxc4 5 a4 Bb4 6 e3 b5 7 Bd2 a5 8 axb5 Bxc3 9 Bxc3 cxb5 10 b3 Bb7 11 bxc4 b4 12 Bb2 Nf6 13 Bd3 O-O 14 Qc2 Nbd7 15 O-O Qc7 16 Ne5 Nxe5 17 dxe5 Nd7 18 Bxh7+ Kh8 19 Be4 Bxe4 20 Qxe4 a4 21 Qh4+ Kg8 22 f4 a3 23 Bd4 b3 24 Rf3 b2

25 Rh3 f6 26 Rf1 f5 27 Qh7+ Kf7 28 Qh5+ Ke7 29 Qg5+ Ke8 30 Qxg7 Rb8 31 Rh7 Kd8 32 Bxb2 axb2 33 Rd1 Kc8 34 Rxd7 b1(Q)+ 35 Kf2 Rb2+ 36 Kg3 Rxg2+ 37 Kxg2 Qc6+ 38 Kf2 Drawn.

Was Black Randviir, and can other details be confirmed?

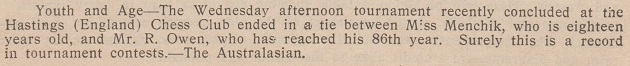

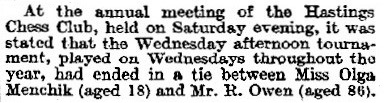

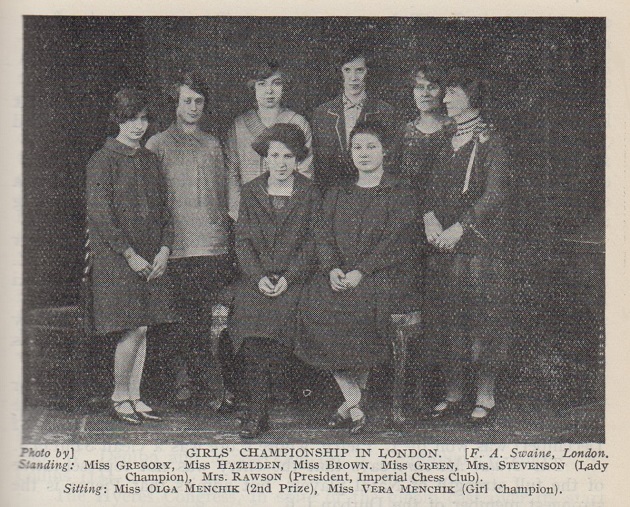

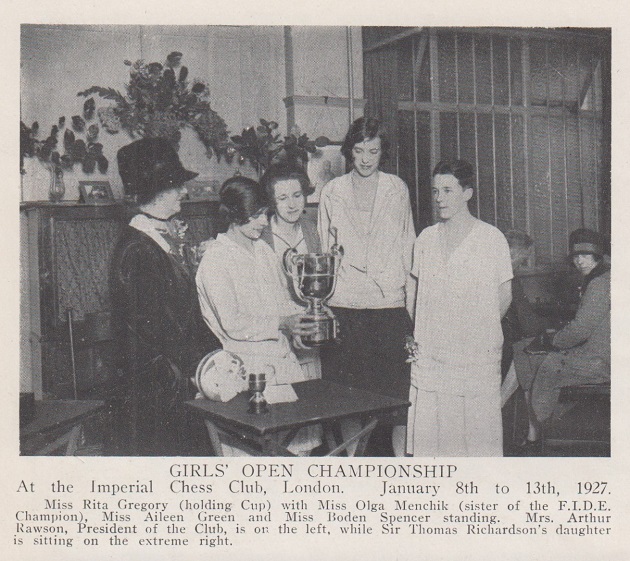

9053. Olga Menchik

From page 5 of the January 1927 American Chess Bulletin:

The reference to the girl’s age indicates that she was not Vera Menchik, and this is shown by a report on page 7 of The Times, 13 September 1926:

Olga Menchik appeared in photographs in C.N.s 5964 and 8774. Two more:

BCM, March 1927, page 113

BCM, February 1928, opposite page 57

After her marriage, briefly reported on page 219 of CHESS, 14 February 1939, she was referred to as ‘Mrs O. Menchik-Rubery’ (BCM, June 1939, page 242), ‘Mrs Rubery’ (BCM, April 1942, page 80) and ‘Mrs Rubery (Olga Menchik)’ (BCM, June 1943, page 128).

9054. Punctuation

We are preparing a feature article on punctuation in chess which will include and supplement the material indexed in the Factfinder. Any other curiosities in the way annotators have punctuated games will be appreciated.

A general matter is mentioned here in passing, concerning the use of punctuation in prose.

It may be wondered why so many people nowadays put question marks after indirect questions? And maybe/perhaps stranger still, question marks after maybe/perhaps? And after other ordinary statements which are not questions? We assume that there is some explanation?

9055. A neglected draw (C.N. 9052)

The game given in C.N. 9052 has yet to be traced in a contemporary source, but large modern databases state that it was played between Andrei Peterson and Jurii Randviir in a match between Latvia and Estonia in Riga in 1960, as mentioned to us by Thomas Binder (Berlin), Bent Kølvig (Rødovre, Denmark) and Lonnie Kwartler (Chester, NY, USA).

9056. Szabó v Dake

Page 165 of CHESS, 14 January 1939:

For his article ‘The Most Exciting Game I Ever Played’ on pages 213-215 of CHESS, 14 February 1939, László Szabó chose his win as White against Pirc at Hastings, 1938-39 but commented in his introduction:

‘At Warsaw in 1935 I had a most wonderful game against Dake, of USA, which Dr Alekhine stated to be, for him, the most exciting game of the whole International Team Tournament. It was so exciting, actually, that I think it would be bad for everybody’s nerves to publish it again.’

Full notes to both encounters are in Szabó’s book My Best Games of Chess (Oxford, 1986), and concerning his draw with Dake he wrote on page 12:

‘My greatest chess experience at the Warsaw Olympiad was my meeting with the world champion, Alekhine. Well, I did not meet him across the board, since he was on first board for the French team, and I played fourth position in the Hungarian team. The world champion played against Lajos Steiner, who played on the first board. Alekhine’s behaviour during play aroused my interest. Why did he stand up after most of his moves, go behind his opponent’s back and contemplate the board from there with arms crossed? I have seen this pose of Alekhine’s many times since in pictures, and I used to wonder whether he stood behind his opponent for psychological effect, or to control events on the board from another angle.

... according to many contestants – Alekhine among them – I played the wildest game of the Olympiad against the American Dake.’

In CHESS and in his book Szabó stated that his game against Pirc ended 63 b7 Resigns, whereas page 8 of Hastings 1938/39 International Chess Congress edited by Dale A. Brandreth (Yorklyn, 1978) had 63 b7 Qg5+ 64 Kf3 Qf5+ 65 Ke3 Qg5+ 66 Kd4 1-0.

9057. Simple Chess

Simple Chess by Michael Stean (London, 1978) has received much praise, justifiably. It used the descriptive notation, and an accurate algebraic edition would be welcome. In 2002 Dover Publications, Inc., New York brought out a new version ‘edited and translated into algebraic notation by Fred Wilson’, but it added countless misprints, including ‘Fisher’ (page 42) and ‘Spasky’ (page 63).

9058. Attacking and defending

‘It does not happen too often that one side attacks and defends simultaneously. Usually, one side attacks and the other defends.’

Source: page 51 of How Chess Games are Won by Samuel Reshevsky (New York and London, 1962). The remark was the first paragraph of Reshevsky’s introduction to his game against Wade, Buenos Aires, 1960.

Below from one of our copies of the book is an inscription by Reshevsky which is very similar to the one shown in C.N. 8431:

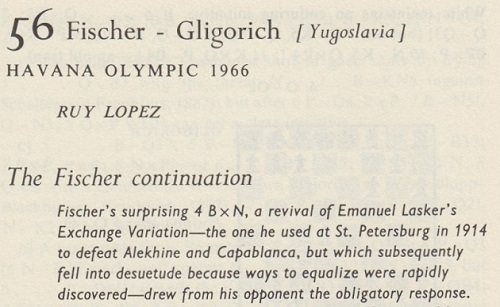

9059. My 60 Memorable Games

In C.N. 6926 (see Fischer’s Fury) a correspondent pointed out a mistake about Pilnik in the introduction to game four in My 60 Memorable Games. Nobody involved in the book ever seemed concerned that the game introductions have many errors, as in game 56:

At St Petersburg, 1914 Lasker’s victory over Alekhine in the Exchange Variation of the Ruy López was with the black pieces.

9060. A neglected draw (C.N.s 9052 & 9055)

Dan Scoones (Coquitlam, BC, Canada) writes:

‘The game was published on page 239 of the 8/1960 issue of Shakhmaty v SSSR, with Randviir’s annotations.

The note after 36 Kg3 reads:

“Black has not allowed the win to slip away just yet, although he has not found the simplest path to victory. However, both during and after the game I considered it necessary to force a draw here. My doubts were later dispelled by Paul Keres, who showed that by playing 36...Qe1+ 37 Kh3 Qxe3+ 38 g3 Rxh2+ 39 Kxh2 Qe2+ 40 Kh3 Qg4+ Black could have won.”

The final note states:

“It is curious that the two black queens cannot stop the white king from moving back and forth between g1 and f2.”

The 1960 team match between Latvia and Estonia was played in Riga on 30 boards and over two rounds, on 24-26 June 1960. Latvia won 36½-23½. According to RusBase, Peterson and Randviir were on board ten, and the crosstable indicates that both of their games were drawn. However, this is contradicted by the moves of their other game (in which Randviir was White), as given in the small database accompanying the crosstable. The moves were 1 e4 d6 2 d4 Nf6 3 Nc3 Nbd7 4 f4 c5 5 e5 cxd4 6 Qxd4 Ng4 7 exd6 exd6 8 Nf3 Ngf6 9 Be2 Be7 10 g4 d5 11 g5 Bc5 12 Qa4 b5 13 Bxb5 Ng4 14 h3 Qe7+ 15 Kf1 Nf2 16 b4 O-O 17 bxc5 Nxh1 18 Kg2 Nxc5 19 Qd4 Ne6 20 Nxd5 Qd8 21 Qe4 Nc5 22 Qe5 Bb7 23 Ne7+ Kh8 24 Be3 Nd7 25 Bxd7 Qxd7 26 Rxh1 f6 27 gxf6 gxf6 28 Qc5 Rae8 29 Nf5 Bxf3+ 30 Kxf3 Qb7+ 31 Kf2 Qxh1 32 Qxa7 Rg8 33 Ke2 Rg2+ 34 Kd3 Qf1+ 35 Kc3 Rc8+ 36 Bc5 Qb5 37 Kd4 Rd2+ 38 Ke4 Qc4+ 39 Bd4 Re8+ 40 Kf3 Qd5+ 41 Kg4 Rg2+ 42 Ng3 Qg8+ 43 White resigns.’

Regarding the game in the Koblenz book, Leonard Skinner (Cowbridge, Wales) notes that it was published (A. Pētersons – J. Randvirs) on pages 19-20 of the 9/1960 issue of the Latvian magazine Šahs:

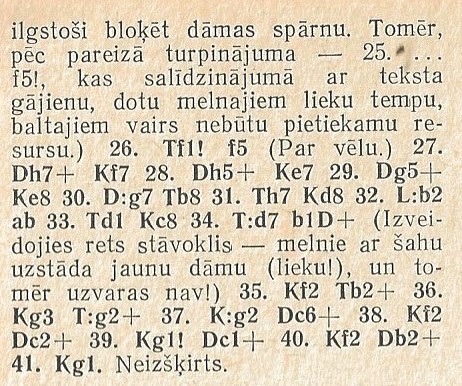

9061. Magazine advertisement

On the subject of Chess in Advertisements Ian Rogers (Carlton, NSW, Australia) sends the following (page 26 of Woman’s Day, 18 May 1959):

On the left is the former (and future) Australian chess champion John Purdy. The page has been provided courtesy of his widow, Felicity.

9062. The match of the century that never was

An addition to Chess as Front-Page News is shown below, from our archives: the Journal de Genève of 2 September 1997.

The report, by Mikhaïl Wadimovich Ramseier, affirmed that a FIDE/PCA reunification contest between Kasparov and Karpov (‘the match of the century’) was likely to take place in the Théâtre impérial de Compiègne, France from 20/21 October to 25 November 1997. The organizer was named as Carol Stroë, the president of a village chess club (Le Plessis-Belleville), and he claimed to be putting forward prizes of ten million French francs for the winner and five million for the loser. There would be no sponsorship for the 22-game match. Funding would come from selling the pictures to 43 television companies for $80,000 each, and from audiences in the 780-seat theatre (200 French francs per ticket).

Following a statement from Kasparov’s representative, Owen Williams, a report on page 10 of the Journal de Genève, 6 September 1997 made it clear that the whole thing was off or, better say, had never been on.

9063. Kolisch

Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA) draws attention to an item on the front page of Gil Blas, 3 November 1886 which contained oblique references to the private life of Baron Kolisch:

9064. A long game

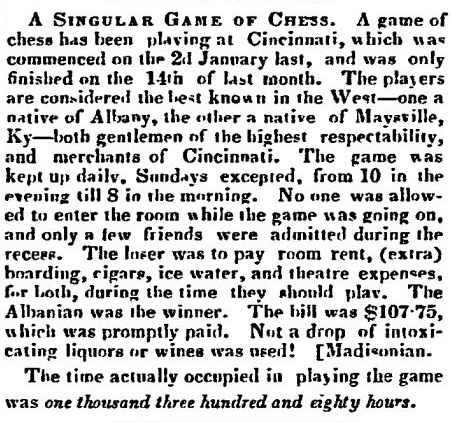

From Ross Jackson (Raumati South, New Zealand) comes a report on page 3 of the Wellington Independent, 3 June 1846 which he found at the Papers Past website:

We note from Google Books this earlier report, on page 390 of Brother Jonathan, 29 July 1843:

9065. Emanuel Lasker at the chessboard

‘His demeanour at the board reminds one of the detached attitude of a judge, weighing up a case and dissecting its strengths and weaknesses. Absolutely unruffled he sits motionless at the board, hardly ever rising from his seat till the game is over, and never exhibiting in the slightest degree either elation in victory or despondency in defeat.’

Source: page 30 of Modern Master-Play by F.D. Yates and W. Winter (London, 1929).

9066. Openings and Morphy

From D.J. Morgan’s column on page 204 of the June 1974 BCM:

This Morganism reminds us of the first sentence of the Preface, on page vii, in Basic Chess Openings by Raymond Edwards (London, 1976):

‘All chess games start with an opening.’

Overleaf (page 1) the book states, more controversially:

‘... it was not until the advent of the famous American master, Paul Morphy (1837-84), that the chess world fully realized the significance of developing pieces as fast as possible.’

C.N.s 8435, 8440 and 8452 gave pre-Morphy citations on this topic, but another question arises: during Morphy’s career where was his practice of rapid development identified, at least to some extent, as an innovation?

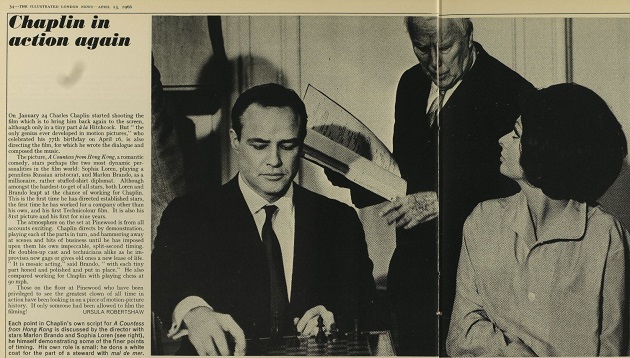

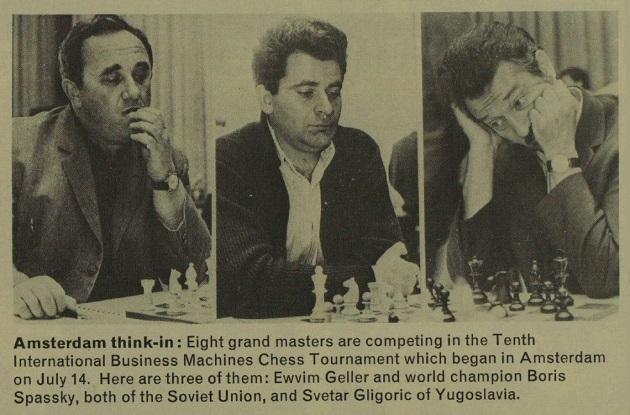

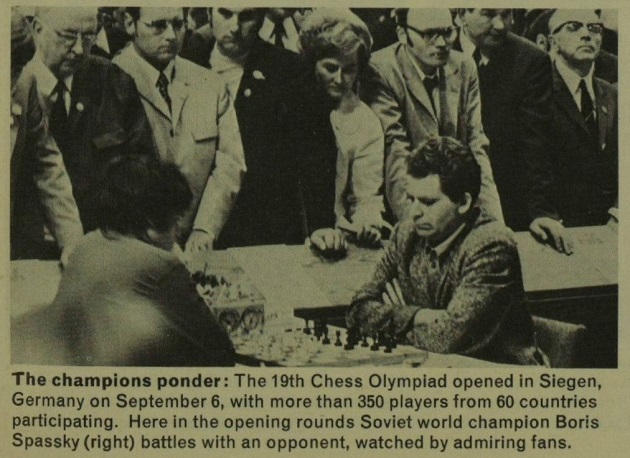

9067. More photographs from the Illustrated London News

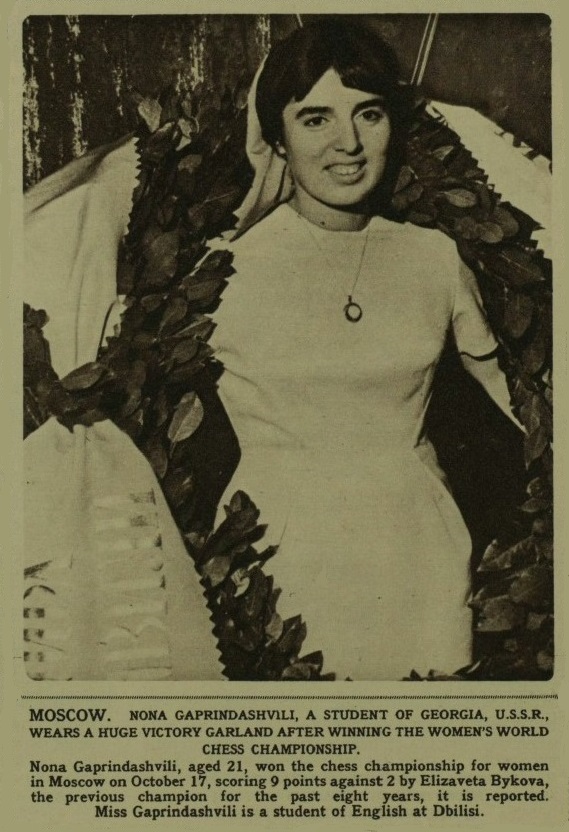

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) has forwarded a further set of pictures:

Illustrated London News, 12 January 1952, page 65

Illustrated London News, 9 October 1954, page 593

Illustrated London News, 31 August 1957, page 332

Illustrated London News, 3 November 1962, page 700

Marlon Brando ‘also compared working for Chaplin with playing chess at 90 mph.’

Illustrated London News, 23 April 1966, pages 34-35.

Illustrated London News, 25 July 1970, page 9

Illustrated London News, 12 September 1970, page 7.

9068. A long game (C.N. 9064)

Mr Urcan adds two early newspaper reports:

Boston Evening

Transcript, 14 July 1843, page 2

Washington Reporter, 29 July 1843, page 1.

9069. Misidentification

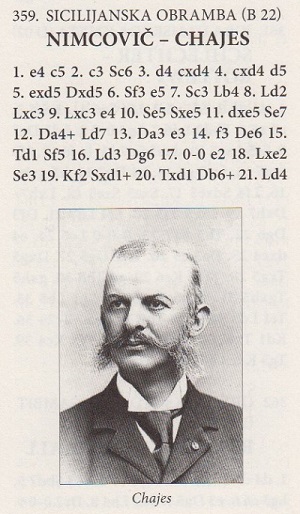

From page 271 of Veliki šahovski turnirji 1851-1911 by Janez Stupica (Ljubljana, 2013):

The photograph is of Julius Adam Kaiser, as shown in C.N.s 6260 and 6290.

9070. Tartakower v Atkins

Ivor Goodman (Stevenage, England) asks about the move order in Tartakower v Atkins, London, 1922. He points out that after 34 Kc2 ...

... databases have the continuation 34...Ra2+ 35 Kc3 Rc8+ 36 Bc6 Rxc6+ 37 Rxc6 Qb4+, whereas 34...Rc8+ 35 Bc6 Rxc6+ 36 Rxc6 Ra2+ 37 Kc3 Qb4+ is given on pages 106-107 of H.E. Atkins Doyen of British Chess Champions by R.N. Coles (London, 1952).

The game was widely published at the time, e.g. in the BCM, Chess Amateur and (with Brian Harley’s notes from page 4 of the Observer, 13 August 1922) American Chess Bulletin. It is in the London, 1922 tournament book by Maróczy with Amos Burn’s annotations from The Field, and it was later anthologized in A Treasury of British Chess Masterpieces by F. Reinfeld (London, 1950) and 500 Master Games of Chess by S. Tartakower and J. du Mont (London, 1952). In all of these publications the move order was 34...Ra2+ 35 Kc3 Rc8+ 36 Bc6 Rxc6+ 37 Rxc6 Qb4+.

Capablanca did not mention the game in his report on the ninth round of the London tournament on page 14 of The Times, 12 August 1922, but the same page had this paragraph ‘by our chess correspondent’:

‘The game between Tartakower and Atkins was the first example of this opening in the tournament, Atkins playing the KtxP variation on his fourth move. The middlegame was even. Tartakower castled on the queen’s side with a view to a king’s-side attack. Mr Atkins countered by an attack on the queen’s side, but again got short of time. However, he seemed to play all the better for it, for with only about 14 minutes to make as many moves he drove Tartakower’s king all over the board by a series of checks, and finally mated him on the 42nd move.’

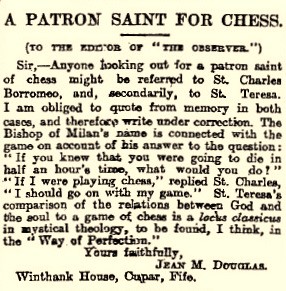

9071. Patron saint of chess

An addition to C.N. 2215 (see page 142 of A Chess Omnibus) comes from page 4 of the Observer, 13 August 1922:

9072. Icelandic book on Karpov

Aðalsteinn Thorarensen (Reykjavik) provides an addition to our list of books about Anatoly Karpov: Karpov by Gunnar Örn Haraldsson (Reykjavik, 1981):

Readers’ vigilance in making the book lists as comprehensive as possible is always appreciated.

9073. Katarina Beskow

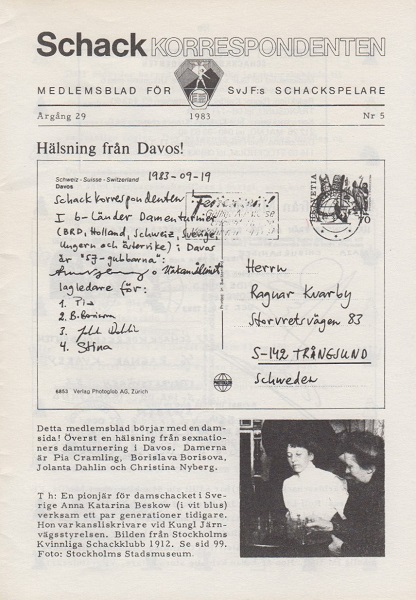

Siegfried Hornecker (Heidenheim, Germany) asks for information about Katarina Beskow of Sweden, who competed in pre-Second World War tournaments for the women’s world championship.

The only article about her that we know is by Allan Werle on pages 99-104 of the 5/1983 issue of the Swedish magazine Schackkorrespondenten. It states that [Anna] Katarina Beskow was born in Stockholm on 2 February 1867 and died in Salzburg on 12 August 1939.

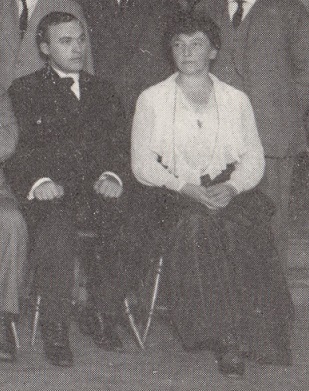

The picture below, showing her with Bogoljubow, is a detail from a group photograph (Göteborg, 1920) which was the frontispiece to the September-October 1920 issue of Tidskrift för Schack:

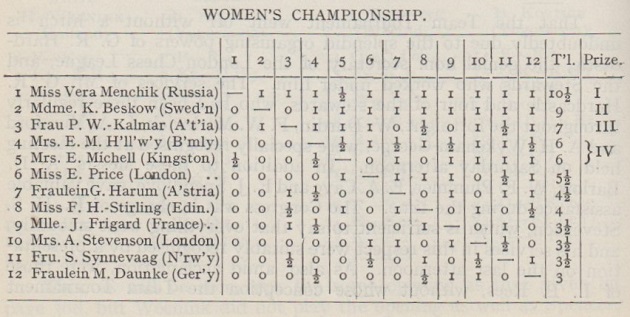

When Vera Menchik became the first women’s world champion by winning a tournament in London in 1927, Katarina Beskow was second, with nine wins, two losses and no draws. She was then nearly three times older than Vera Menchik.

9074. Championship confusion

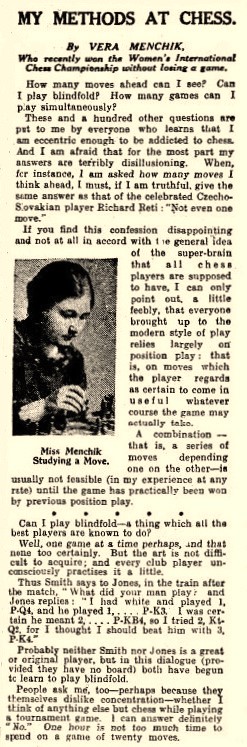

It is difficult to imagine a world championship title being decided in an event whose participants did not know that they were contesting the title, but that happened in 1927.

A 12-player tournament in London was won by Vera Menchik, as shown by the crosstable on page 372 of the September 1927 BCM:

The plans outlined on page 66 of the February 1927 BCM

had merely indicated that one of the events (others were a

premier tournament and a major tournament) that would take

place alongside the International Team Tournament in July

was ‘a women’s tournament (... limited to 12 players)’. It

was held on 18-30 July 1927 and was not billed in advance

as being for the women’s world championship.

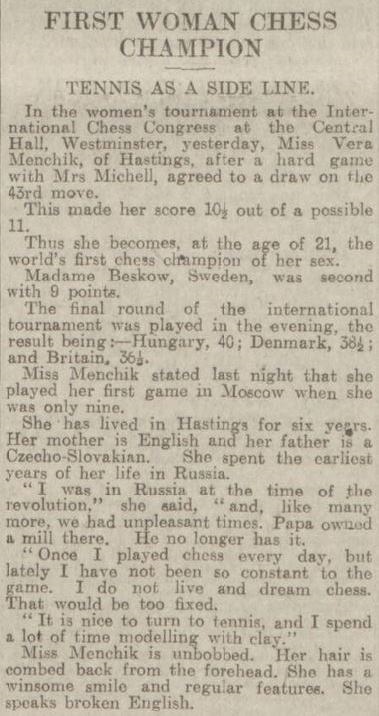

Reports on Vera Menchik’s success mentioned in various terms the title that she had won:

- Page 134 of the July-August 1927 American Chess Bulletin:

‘The title of world’s woman chess champion was established for the first time, the winner being Miss Vera Menchik of Hastings, who has been a resident of England for several years, although she learnt to play chess in Moscow. Her mother is English and her father a Czechoslovakian.’

- Page 218 of the August 1927 Wiener Schachzeitung:

‘Das Damenturnier gestaltete sich zu einer Art Weltmeisterschaft, da die berufensten Anwärterinnen auf diesen Titel mitkämpften. Den Sieg errang Miss Vera Menschik, eine in London lebende junge Russin, deren hohe Begabung schon lange bekannt war.’

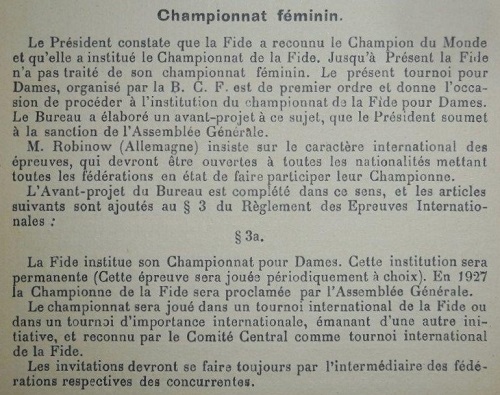

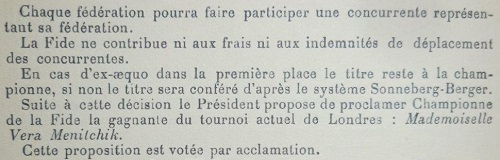

- From the report on the July 1927 FIDE meeting on page 691 of L’Echiquier, August 1927 (which did not even name Vera Menchik):

‘Il a été décidé qu’un championnat FIDE pour Dames serait institué. Les invitations à participer à ce tournoi international devant se faire par l’intermédiare des fédérations respectives des concurrentes.

Un chapitre spécial sera ajouté de ce fait à l’art. 3 du règlement des épreuves de la FIDE.

La gagnante du tournoi organisé par la “British Chess Federation” à l’occasion du IVe Congrès de la FIDE est proclamée Champion de la FIDE.’

- Page 354 of the September 1927 Chess Amateur said that Vera Menchik ‘took the title of FIDE Women’s Champion’.

- Page 260 of the September 1927 Deutsche Schachzeitung:

‘Die Siegerin im Damenturnier erhält den Titel “Schachweltmeisterin” (Woman Champion of the World).’

- A report by Jean-Louis Ormond on the FIDE meeting in

London, on page 139 of the September 1927 Schweizerische

Schachzeitung:

‘Il est décidé d’instituer un championnat FIDE pour dames, celles-ci ne pouvant y participer que par l’intermédiaire de leurs fédérations respectives. La gagnante du tournoi de Londres (Miss Vera Menchik) est proclamée championne de la FIDE.’

In its August 1927 issue (page 326) the BCM referred to ‘the Women’s Tournament, which we understand is to be recognized as for the Women’s Championship of the World by the FIDE’. Page 390 of the September 1927 BCM included the following in its report on the meeting of FIDE delegates (London, 28-30 July 1927):

‘It was agreed that Article 3 of the Rules of the FIDE should be altered to include a Women’s championship of the FIDE, and this was made retrospective so as to award the title to the winner of the Women’s Tournament of the London Congress, 1927.’

The formal position was set out in FIDE’s minutes of the London meeting, i.e. on pages 7-8 of the Procès-verbal du IVe congrès; Londres, 28-30 juillet 1927:

As regards the exact date when the FIDE delegates took their decision, the following comes from page 6 of The Times, 29 July 1927, in a report on the previous day’s FIDE working session:

‘The delegates also decided that the winner of the women’s tournament in the General Congress should be awarded the title of Woman Champion of the World, and this honour will fall to Miss Menchik.’

Throughout its earlier coverage The Times had referred simply to the ‘Women’s Tournament’.

It remains to be ascertained how exactly the decision to award the world title came about. After reporting that for the ‘Women’s Tournament’ there was an entrance fee of £1, that the prizes were £20, £15, £10 and £5, and that non-prize-winners would receive 10/- for each game won, page 200 of the May 1927 BCM stated: ‘It is hoped to persuade the FIDE to nominate the winner of this event their first Women’s Champion.’ That information was provided in an account of the meeting of the British Chess Federation’s Executive Council on 23 April 1927; is it possible to find documentation on the exchanges between the BCF and FIDE in 1927?

Although page 66 of the February 1927 BCM had

recorded that the tournament would be ‘open to the entry

of players of all nationalities’, and although the

magazine’s crosstable, shown above, listed ‘Miss Vera

Menchik (Russia)’, the comments in FIDE’s Procès-verbal

should be borne in mind: for (future) women’s

championships, players could participate only via their

respective federations. Thus María Teresa Mora Iturralde

did not play in a women’s world championship tournament

until 1939, shortly after her country, Cuba, had been

admitted to FIDE. The Soviet Union joined FIDE in 1947.

Parochial considerations naturally played a role in the coverage of Vera Menchik’s victory in London. From page 11 of the Manchester Guardian, 1 August 1927:

‘Miss Menchik appeared in the programme as of Russia, but as she has lived for several years in Hastings and there learnt to become an expert player, Hastings is entitled to claim the credit of providing the first woman chess champion of the world.’

An example of the publicity accorded to her is on page 5 of the Courier and Advertiser (Dundee), 30 July 1927:

Vera Menchik contributed a brief article to the Daily Mail, 5 August 1927, page 8:

As reported on page 3 of the FIDE President’s Compte-Rendu, at the 1928 General Assembly in The Hague Alexander Rueb singled out Vera Menchik’s achievement:

‘Par rapport aux autres tournois de la BCF il faut mentionner spécialement le beau succès de Miss Vera Mentschik [sic] qui a vu couronner sa maîtrise du jeu par le titre de “Championne du Monde”.’

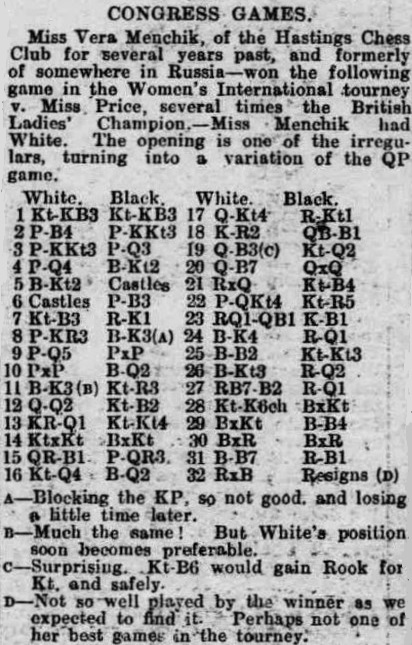

The tournament was indeed a memorable success, but can more be discovered about the circumstances? And, a key additional question, where are the game-scores? Here, at least, is one, Vera Menchik’s win against Edith Price, from page 10 of the Cheltenham Chronicle and Gloucestershire Graphic, 13 August 1927. It was played in round seven on 25 July 1927:

1 Nf3 Nf6 2 c4 g6 3 g3 d6 4 d4 Bg7 5 Bg2 O-O 6 O-O c6 7 Nc3 Re8 8 h3 Be6 9 d5 cxd5 10 cxd5 Bd7 11 Be3 Na6 12 Qd2 Nc7 13 Rfd1 Nb5 14 Nxb5 Bxb5 15 Rac1 a6 16 Nd4 Bd7 17 Qb4 Rb8 18 Kh2 Bc8 19 Qc3 Nd7 20 Qc7 Qxc7 21 Rxc7 Nc5 22 b4 Na4 23 Rdc1 Kf8 24 Be4 Rd8 25 Bc2 Nb6 26 Bb3 Rd7 27 R7c2 Rd8 28 Ne6+ Bxe6 29 Bxb6 Bf5 30 Bxd8 Bxc2 31 Bc7 Rc8 32 Rxc2 Resigns.

9075. His and hers

This is from page 231 of Capablanca’s Hundred Best

Games of Chess by Harry Golombek (London, 1947).

Notwithstanding the terms ‘his pieces’, ‘his QKt’ and ‘his

Pawn structure’, Black was Vera Menchik (Moscow, 1935),

and the same page also had ‘defended herself’, ‘she

gives’, ‘her Pawn position’, ‘her pieces’ and ‘her

position’.

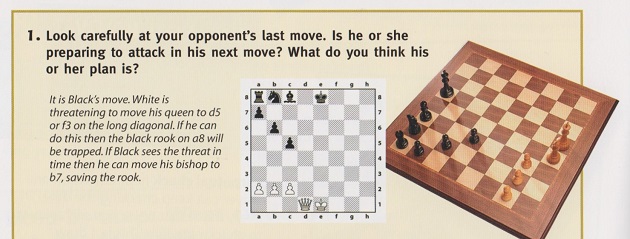

In general cases (e.g. in English-language introductory books and manuals) ‘he’, ‘his’ and ‘himself’ were used automatically until recent times, but today it is a quandary for the writer. He can easily make herself look silly, as shown by page 18 of How to play Chess and Win! by Tanya Jones (London, 2007):

| First column | << previous | Archives [126] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.