Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [127] | next >> | Current column |

9076. Reuben Fine and the Second World War

Wanted: documentation about the non-chess activities of Reuben Fine during the Second World War.

For the ‘revised and expanded’ Dover edition of his book The World’s Great Chess Games (New York, 1976) he wrote:

‘During the war I was involved in defense work, remaining in Washington.’

A footnote on the same page:

‘Toward the end of the war I was retained by the Navy to work on a military problem which was in some respects similar to chess. The field of operations research, then entirely novel, has since expanded enormously.’

See too pages 275 and 278 of Reuben Fine by Aidan Woodger (Jefferson, 2004). The former page states:

‘In May 1944 Fine began research work for the Department of the Navy as part of a team employed to determine likely surfacings of U-Boats. This work later extended to attempts to determine the locations of Japanese Kamikaze attacks upon Allied ships.’

Reuben Fine, front cover, Chess Review, June-July 1944

9077. Miss Fatima

Nick Pinkerton (Bracknell, England) sends a report from page 12 of the Hastings and St Leonards Observer, 12 August 1933:

‘History was made at Hastings Chess Club this week when the British Chess Championship and the British Women’s Championship were each won by Indian competitors.

Mir Sultan Khan secured the men’s championship, which he gained last year and previously, and the women’s championship was won by the young Indian lady player, Miss Fatima, who held an unbeaten record throughout the contest.

This remarkable victory of East over West makes memorable the first British championship contest to be held in Hastings since 1904.

Miss Fatima is a young and charming devotee of the game. She speaks little English and is very modest about her success. She is the first of her countrywomen to win the women’s championship.

There was a picturesque gathering in the tournament room yesterday (Friday) morning when Sir Umar Khan, who introduced both Sultan Khan and Miss Fatima, paid a visit to the club. He was accompanied by Indian friends, and the party wore Indian costume.

Sir Umar is adviser on Indian affairs to the British Government and Aide-de-Camp to His Majesty the King. The whole of his extensive staff are keen chessplayers ...

Miss Fatima was a radiant figure in a robe and veil of bright red, bound to her dusky hair with golden bands.’

Our correspondent seeks further information about Miss Fatima, including her background and later life. We have a few newspaper cuttings from the 1930s to give shortly, but nothing about her later life beyond what is indexed in the Factfinder.

9078. Katarina Beskow (C.N. 9073)

From Henrik Malm Lindberg (Stockholm):

‘I wrote an article about Katarina Beskow, “Det tidiga damschacket och Sveriges okända VM-tvåa”, on pages 1-8 of the 49/2014 issue of the Swedish magazine Schackkultur of the Schackets kulturhistoriska sällskap.

She came from a well-known middle-class Swedish family, and her father, Karl-Adolf Beskow, was a captain in the Helsinge regiment. She was brought up in Hälsingland, but later moved to Stockholm. In 1912 she founded, and was chairman of, the first Swedish chess club for women, “Stockholms kvinnliga schackklubb”. She taught other women chess and organized tournaments, and it was only in her later life that her career as a player developed. Second place in the London, 1927 tournament (C.N. 9074) was her most notable achievement, but she did well in Stockholm championships in the 1920s. In simultaneous exhibitions in Stockholm she drew with Alekhine in 1914 and defeated Spielmann in 1920.’

The article gives her year of death as 1937, and since that contradicts the information from Allan Werle referred to in C.N. 9073, we queried the matter with Mr Lindberg. He draws attention to a family webpage which states that she died in Tullstorp, Sweden in 1937.

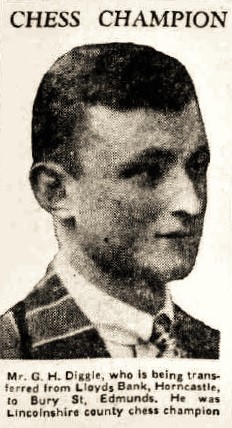

9079. G.H. Diggle

From page 1 of the Lincolnshire Echo, 6 October 1932:

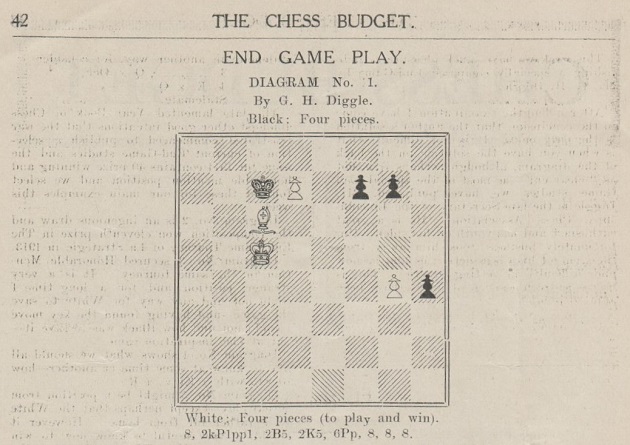

An endgame study by Diggle was published on page 42 of the Chess Budget, 11 November 1925:

The composition was discussed by K. Whyld on page 442 of the August 1993 BCM with this misleading comment:

‘... the Chess Budget, which, unlike “Badmaster” himself, had a brief life. So brief in fact that the solution was never published.’

The very rare Chess Budget continued to be published regularly (weekly) after issue 35 had printed Diggle’s study. We have a run of the next 19 issues (36-54, from 21 November 1925 to 17 April 1926). Although the solution to the Diggle study is not there, the last issue in our collection tantalizingly gave (i.e. on page 197 of issue 54) a full page of solutions to compositions published throughout much of 1925, and the Editor, W.H. Watts, concluded:

‘This brings the solutions up to the end of September [1925]. In our next issue we hope to give a further batch, and subsequently to publish the solutions once a month.’

Was the solution to the Diggle endgame given in any of the three final issues (55, 56 and 57) of the Chess Budget which are mentioned in reference works (e.g. Betts’ Annotated Bibliography)?

Those sources state that the Chess Budget ceased publication with issue 57 on 16 October 1926. The fact that issue 54 was dated 17 April 1926 indicates that the schedule was badly delayed and disrupted towards the end. W.H. Watts’ inability to save his magazine was discussed by Diggle in an article reproduced in C.N. 5316.

9080. Picasso and Duchamp

Picasso and the Chess Player by Larry Witham (Lebanon, 2013) cannot be recommended for its chess content, as on page 159:

‘When Duchamp entered the chess world, all the great moves, problems, and end games had been covered. These could be learned in books, which were a chief source for Duchamp’s self-education.’

The paragraph then refers to ‘José Raúl Casablanca’ (the book’s constant spelling), and the next page has this about Duchamp:

‘In Hamburg he came full circle. He played the US champion Frank Marshall, leading to a draw, which was better than a loss. At the International Paris Tournament he beat the Belgian champion and drew his match with the top winner of the competition.’

Page 327 mentions a book written by Duchamp with Halberstadt ‘to analyze a rare end game when only two kings remain’.

9081. Memory

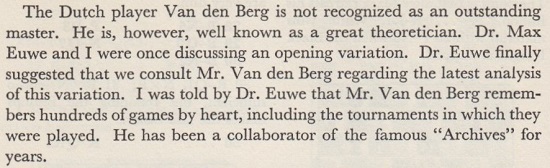

A player and theoretician seldom referred to nowadays is Carel van den Berg (1924-71). A reference to his memory is on page 124 of How Chess Games are Won by Samuel Reshevsky (New York and London, 1962):

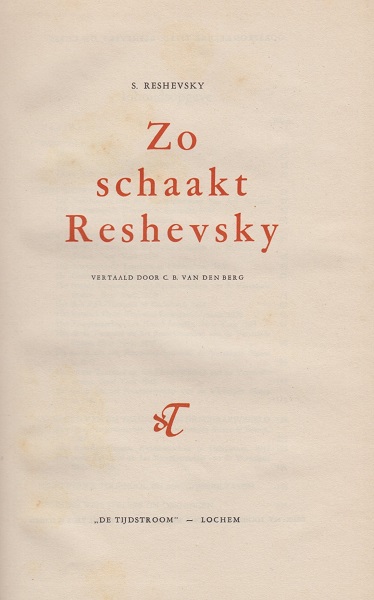

Reshevsky on Chess (New York, 1948) was translated into Dutch by van den Berg under the title Zo schaakt Reshevsky (Lochem, 1950):

9082. Peter Griffiths

In lists of fine chess books and authors the name of Peter Griffiths may well be absent, but the neglect is unjustified. C.N. 330 referred appreciatively to his book Better Chess for Club Players (Wakefield, 1982), and C.N. 1514 praised a work which he co-wrote with John Nunn, Secrets of Grandmaster Play (London, 1987). Another notable volume, which Griffiths wrote for G. Bell & Sons Ltd. in 1976, is The Endings in Modern Theory and Practice.

9083. En passant

C.N. 3139 (see page 99 of Chess Facts and Fables) discussed the game Gunnar Gundersen v A.H. Faul, Melbourne Christmas Tourney, 1928-29, which concluded with mate by an en passant capture.

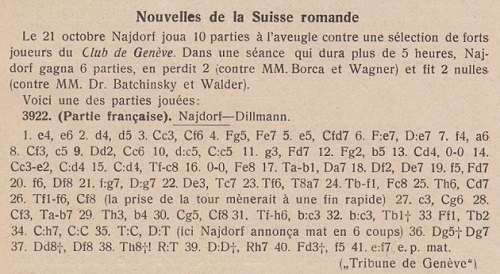

A blindfold game from page 209 of the December 1948 Schweizerische Schachzeitung:

The final move has a typo, of course, and Najdorf’s announced mate was not forced (36...Kh8).

1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 Be7 5 e5 Nfd7 6 Bxe7 Qxe7 7 f4 a6 8 Nf3 c5 9 Qd2 Nc6 10 dxc5 Nxc5 11 g3 Bd7 12 Bg2 b5 13 Nd4 O-O 14 Nce2 Nxd4 15 Nxd4 Rfc8 16 O-O Be8 17 Rab1 Qa7 18 Qf2 Qe7 19 f5 Bd7 20 f6 Qf8 21 fxg7 Qxg7 22 Qe3 Rc7 23 Rf6 Raa7 24 Rbf1 Bc8 25 Rh6 Nd7

26 Rff6 Nf8 27 c3 Ng6 28 Nf3 Rab7 29 Rh3 b4 30 Ng5 Nf8 31 Rfh6 bxc3 32 bxc3 Rb1+ 33 Bf1 Rb2 34 Nxh7 Nxh7 35 Rxh7 Qxh7

The announcement: 36 Qg5+ Qg7 37 Qd8+ Qf8 38 Rh8+ Kxh8 39 Qxf8+ Kh7 40 Bd3+ f5 41 exf6 mate.

Georges Dillmann of Geneva died on 1 August 1983, aged 61 (Schweizerische Schachzeitung, September 1983, page 366).

9084. Steinitz and the king

From page 11 of Maxims of Chess by John W. Collins (New York, 1978):

The remark can be found elsewhere in connection with Steinitz, e.g. on page 26 of the January 1953 Chess Review:

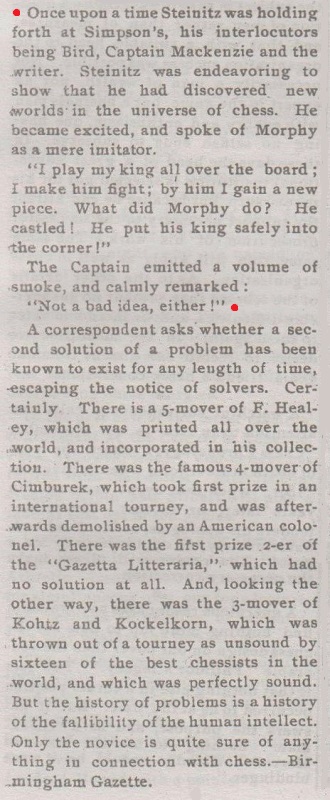

An anecdote on page 13 of The Bright Side of Chess by Irving Chernev (Philadelphia, 1948):

Attempting to trace the story backwards, we find it in these magazines:

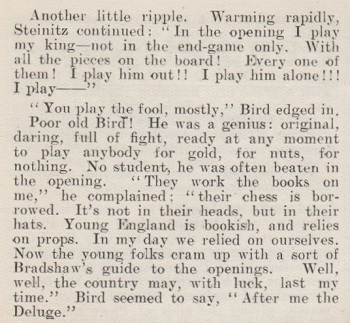

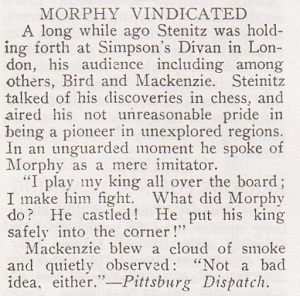

- Chess Amateur, October 1916, page 13: a small item headed ‘Morphy Vindicated’ and ‘From the Pittsburg Dispatch’;

- Chess Amateur, June 1913, pages 270-272: an article ‘Memories of the Masters. H.E. Bird’ by Robert J. Buckley:

- Lasker’s Chess Magazine, November-December 1906, page 38. This was the same text that appeared in the Chess Amateur a decade later:

It is disagreeable to note that Chernev’s The Bright

Side of Chess copied this exact wording. Can the

item in the Pittsburg Dispatch be found?

- Checkmate, December 1902, page 59: a brief paragraph which stated that ‘the writer’ was with Steinitz, Bird and Mackenzie. He was not identified, but the next (ostensibly unrelated) paragraph in the magazine was attributed to the Birmingham Gazette (whose chess columnist was R.J. Buckley):

Steinitz’s views can be found in non-anecdotal form in an

interview on page 3

of the New-York Daily Tribune, 22 March 1883:

‘How would Morphy compare with the players of the present day?’

‘Well, the game has made immense strides since his time. For one first-class player then, there are 20 now, and the science has developed. Morphy would have to alter his style to suit the new conditions. For instance, Morphy considered the king as an object merely of attack and defence, while the modern view is that it is itself a strong piece, to be used throughout the game. You see how frequently I will move my king all over the board to capture a pawn. In the old days that was never done. It sometimes loses me a game on account of the extraordinary foresight required. That is, in a match game it may do so, but in a game by correspondence never.’

9085. Live chess broadcasts on the Internet

From our experience, five hosts stand out for the quality of their live (English-language) commentary on major matches and tournaments. Beyond chess competence, they have a range of attributes which include clarity of expression and an engaging personality that is distinctive but not domineering. For hours on end, alone or in pairs, they explain the obvious and the complex to a heterogeneous audience by no means all of English mother tongue, and when they do not know, they say that too. The gift of omniscience is left to that unseemly brigade (in homes and offices with full computer support) addicted to disrespectful, pointless and illiterate tweeting throughout all waking hours.

The hosts will inevitably be criticized whatever they say or do. Some viewers will want more analysis and gravitas, others more discursiveness and jokes. Some relish passive viewing of the event, while others insist on being in on it. This means that the commentator, already required to scrutinize a number of screens simultaneously, is also expected to handle some of the opinions and questions which, unfortunately, scroll into view from hoi polloi: ‘would carlson of beat fisher?’

The best broadcasters, one feels, would be entertaining too at a local club match or, indeed, if there were no play at all. During any lull, urbane digressions often display a gratifying interest in chess history and lore. When play is over, the commentators switch to showing their interviewing technique and empathy, and not least when the tousled loser arrives for questioning on what caused his demise five minutes earlier. A striking quality of the broadcasts is the absence of national bias. Patriotism and jingoism have no place in them.

Not so long ago, Internet broadcasts could be amiable chaos, with the arrival of a guest causing apparent consternation and a scramble for an extra chair and microphone. Guests often appeared without identification. A background hum indicated a would-be contribution to the proceedings from somebody in the commentators’ area who could be seen and heard only by them. The viewer might see that a move had been played well before the broadcasters realized it. Breakdowns were commonplace.

Technical, logistical and analytical mishaps will always occur, but a nimble, unflappable commentator takes them in his stride and may even exploit them for additional entertainment. A key reason why the broadcasts are enjoyable is that the broadcasters so obviously enjoy them. The whole genre of live commentary is ideally suited to the Internet and, by some miracle, it is provided free of charge. Having mentioned at the start of these observations that five hosts stand out, we name them, in alphabetical order: Jan Gustafsson, Daniel King, Yannick Pelletier, Yasser Seirawan and Nigel Short.

[Feature article including additional material: Chess Broadcasts on the Internet. Subsequently the following were mentioned too: Robin van Kampen, Peter Svidler, Daniel Naroditsky and Jovanka Houska.]

9086. Birth and death dates

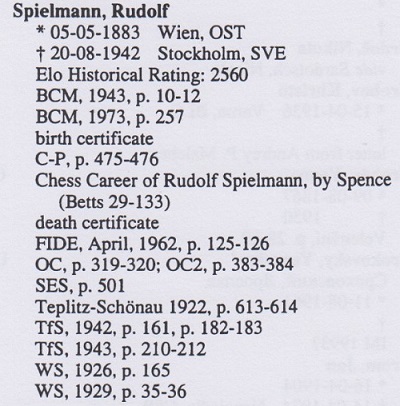

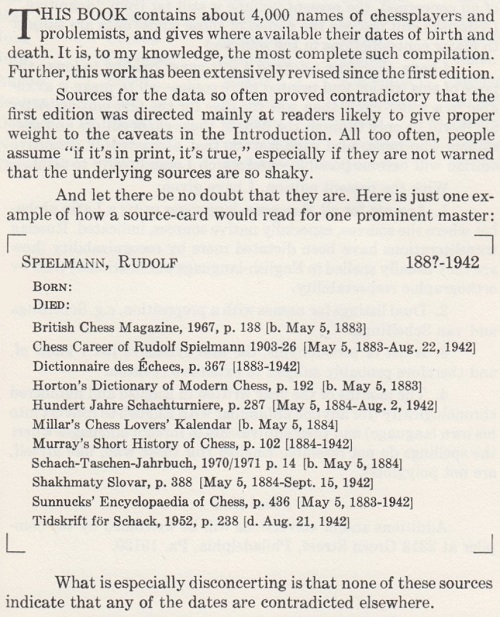

Basic biographical data about some prominent players took much time to establish, one example being Rudolf Spielmann’s date of birth. An extract from page 717 of the unpublished 1994 edition of Chess Personalia by Jeremy Gaige:

Yet a few decades ago it was not known for sure when Spielmann was born. Below is the start of Gaige’s Introduction on page i of A Catalog of Chessplayers & Problemists (Philadelphia, 1971):

Two sentences are worth highlighting:

‘All too often, people assume “if it’s in print, it’s true”, especially if they are not warned that the underlying sources are so shaky.’

‘What is especially disconcerting is that none of these sources indicate that any of the dates are contradicted elsewhere.’

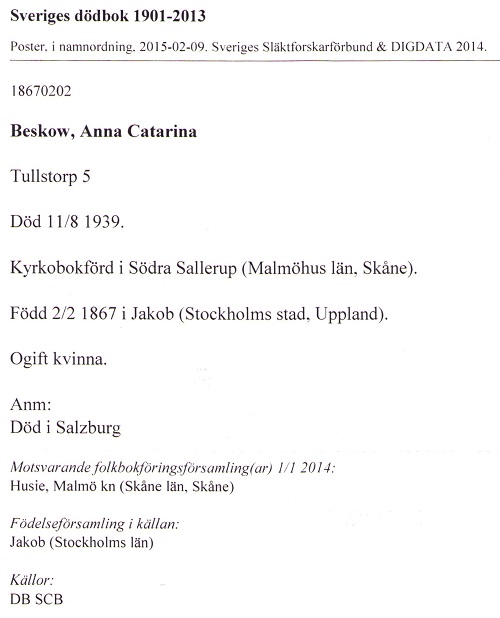

At present, efforts continue to establish the date and place of death of another chess figure connected with Stockholm, Katarina Beskow. C.N. 9073 referred to an article by Allan Werle on pages 99-104 of the 5/1983 issue of Schackkorrespondenten, which gave Salzburg, 12 August 1939. In C.N. 9078 a correspondent mentioned a family website which has Tullstorp, Sweden in 1937.

Now, Calle Erlandsson (Lund, Sweden) forwards an excerpt from the Sveriges Dödbok 1901-2013. It records that Anna Catarina [sic] Beskow was born in Jakob’s parish, Stockholm on 2 February 1867 and was registered at the address Tullstorp 5 in the Södra Sallerup parish (near Malmö) when she died on 11 August 1939 in Salzburg. She was unmarried.

9087. Swedish photograph site

The DigitaltMuseum website has many chess photographs.

9088. Menchik advertisement

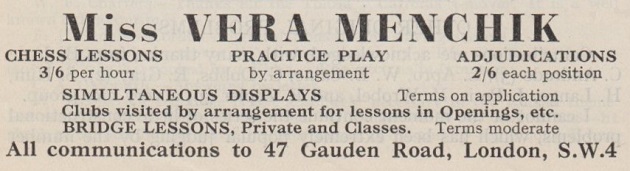

From page 436 of the September 1938 BCM:

9089. Caruana’s games in the 2014 Sinquefield Cup

Lee Walton (Greensboro, NC, USA) draws attention to a webpage showing his ‘system-based drawings’ which record Fabiano Caruana’s victory in the 2014 Sinquefield Cup.

9090. Brilliancy prizes (C.N. 9051)

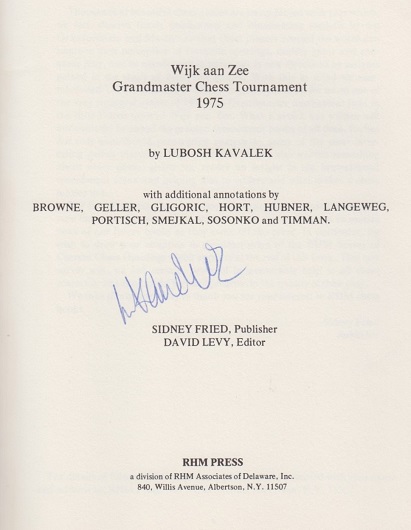

Concerning the brilliancy prizes at Wijk aan Zee, 1975, further information is on pages 11, 169 and 177-178 of Lubosh Kavalek’s book Wijk aan Zee Grandmaster Chess Tournament 1975 (New York, 1976). Hort won the Turover prize for defeating Browne, and Kavalek received the Leo van Kuijk prize for his draw with Portisch. Kavalek’s discussion of the latter game is exceptionally detailed (pages 177-192), and his concluding remark reads:

‘To play games like this one may give us some pleasure, if we suffer our way through it. It may give pleasure to thousands of chess fans when they play it over, and it revives the feeling that the romantic chess art of the last century has not been lost.’

Some other instances of brilliancy prizes awarded to drawn games were referred to in C.N.s 1547 and 1575; see pages 190-191 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves.

9091. Casual remarks and bad plans

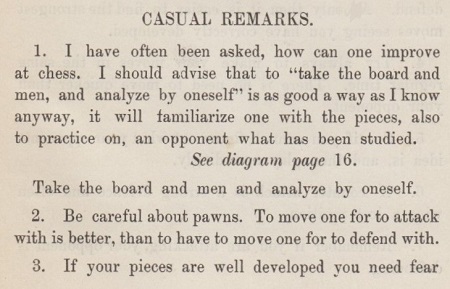

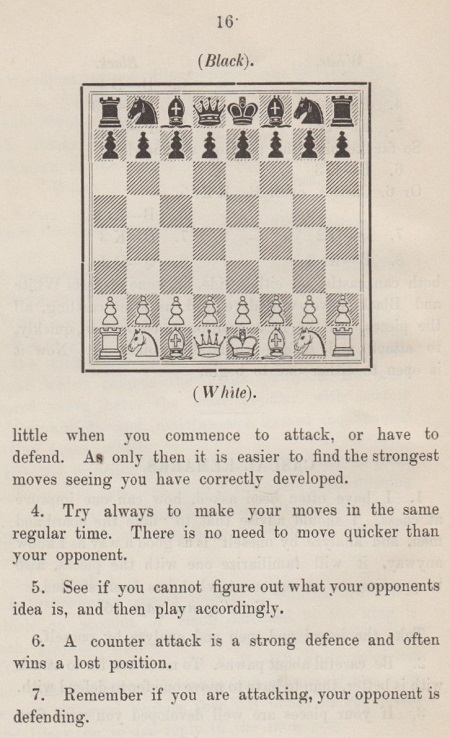

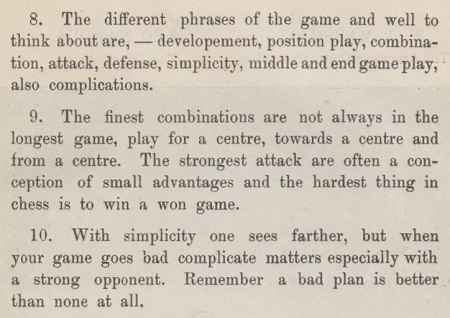

Modern Analysis of the Chess Openings by F.J. Marshall (Amsterdam, 1912/13) has been mentioned a number of times (see, for instance, pages 273-274 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves and page 256 of Chess Facts and Fables). Below, and not for the squeamish, is a complete section of Marshall’s work, from pages 15-17:

C.N. 2019 (see page 383 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves) extracted Marshall’s final remark, ‘a bad plan is better than none at all’. That advice can be traced back to the nineteenth century, e.g. on page 30 of the anonymous work The Chess Player’s Hand-Book (Philadelphia and New York, 1849):

‘Be careful, then, in all commencements of this super-excellent game, to have a prescribed plan – better have a bad plan than no plan at all.’

On page 210 of the April 1978 Chess Life & Review Julio Kaplan wrote:

‘... all good players agree on one thing: even a bad plan is better than no plan at all.’

How much truth lay in that remark in 1978 is impossible to say, but we wonder whether many chess authorities today would write in such terms.

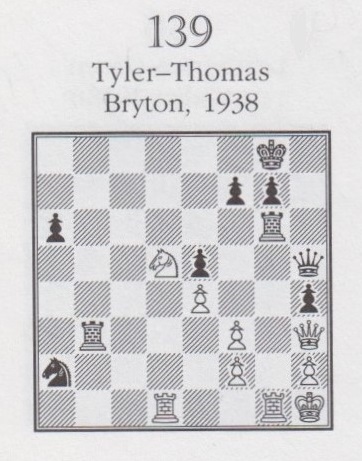

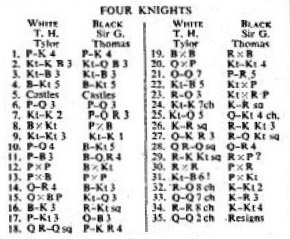

9092. Tylor v Thomas

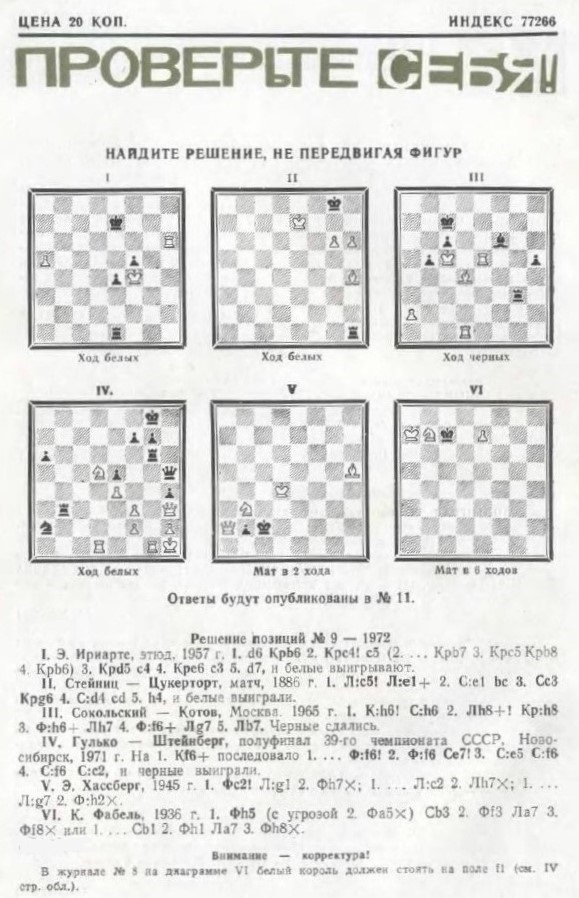

Dan Scoones (Port Coquitlam, BC, Canada) sends the back-cover of the 10/1972 issue of Shakhmaty Riga and draws attention to position IV:

The solution on the back cover of the 11/1972 issue was:

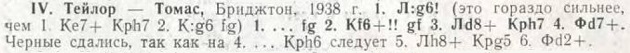

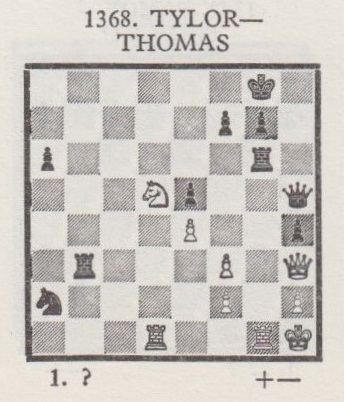

Our correspondent found the same position on page 243 of the Encyclopaedia of Chess Middlegames (Belgrade, 1980), the solution being given (with no mention of the alternative line 1 Ne7+ Kh7 2 Nxg6) on page 249:

In Copying we commented regarding The Big Book of Combinations by Eric Schiller (San Francisco, 1994):

‘Another 1938 game, on page 249 of the Encyclopaedia, was “Tylor – Thomas Bryton 1938”. It may seem obvious that “Bryton” should read Brighton, but it was not obvious enough for Schiller; on page 36 he too uses the spelling “Bryton”, adding for good measure an original mistake of his own by changing Tylor to “Tyler”.’

Mr Scoones found the game-score in a database, which indicated that the above diagrams are wrong. The black king was on h8, and there is thus no alternative solution with Ne7+:

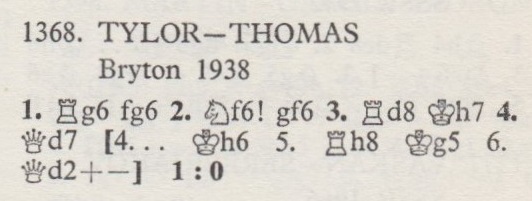

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bb5 Bb4 5 O-O O-O 6 d3 d6 7 Ne2 a6 8 Bxc6 bxc6 9 Ng3 Ne8 10 d4 Bg4 11 c3 Ba5 12 dxe5 Bxf3 13 gxf3 dxe5 14 Qa4 Bb6 15 Qxc6 Nd6 16 Be3 Rb8 17 b3 Qf6 18 Rad1 h5 19 Bxb6 Rxb6 20 Qxc7 Nb5 21 Qd7 h4 22 Nf5 Nxc3 23 Rd3 Nxa2 24 Ne7+ Kh8 25 Nd5 Qg5+ 26 Kh1 Rg6 27 Qh3 Rb8 28 Rdd1 Qh5 29 Rg1 Rxb3

30 Rxg6 fxg6 31 Nf6 gxf6 32 Rd8+ Kg7 33 Qd7+ Kh6 34 Rh8+ Kg5 35 Qd2+ Resigns.

We have checked contemporary sources and can report that the database version is accurate. The BCM (September 1938, page 410) gave only the conclusion of the game, with the black king correctly on h8, but the full score was published on page 12 of The Times, 11 August 1938, having been played in the third round of the British championship the previous day:

The score is confirmed by The Scotsman, 13 August 1938, page 18.

9093. Diggle study (C.N. 9079)

We are grateful to the Koninklijke Bibliotheek in The Hague for checking the three final issues of the Chess Budget (1926). None of them contained the solution to the study by G.H. Diggle.

9094. Both stood up (C.N. 4360)

From John Hilbert (Amherst, NY, USA):

‘C.N. 4360 refers to several versions of the old “once upon a time” story of a toast being offered at a chess banquet “to the world chess champion”, after which both Steinitz and Zukertort stood up. The C.N. item mentions versions of the tale by Chernev, Reinfeld, Soltis, Houška and Opočenský (the last two by way of Landsberger) and MacDonnell. The MacDonnell version offers the most detail and appeared on pages 21-22 of The Knights and Kings of Chess (London, 1894).

The less than fully reliable MacDonnell often, if not invariably, filled his books with material originally in his chess column in the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News. The chess toast story is no exception, and can be found in that publication on 10 April 1884. Of interest here is how MacDonnell prefaced the story in his chess column (material that was left out of his book):

“The Chess Monthly, just issued, is very amusing and interesting. From it I cull the following story, but take the liberty of telling it in my own words.”

MacDonnell’s “own words” included some poor reading. He changed the dinner’s location from New York to Philadelphia, despite having the Manhattan Chess Club host it, and in retelling the story left out particulars that might have made finding its origin much easier, including the reference to the Chess Monthly.

The tale had appeared on page 232 of the April 1884 Chess Monthly. Under the sub-heading “New York”, mention was made of the annual Manhattan Chess Club dinner on 1 March 1884, with over 60 members and guests present. These included Steinitz, Zukertort, Mackenzie, Lipschütz and, importantly for the story’s purpose, Eugene Delmar and David S. Thompson, the latter of Philadelphia. The Manhattan Chess Club’s annual dinner not only offered members and guests an entertaining evening but also provided an opportunity for tournament prizes to be distributed, and for special presentations to be made. In this instance, prizes for the recent handicap tournament, won by George Mackenzie, were given, and the Club’s directors “presented to the Club a life-like portrait of Paul Morphy, by a distinguished American artist – Mr Elliott. The Chairman accepted the valuable gift on behalf of the Club …”

Leopold Hoffer, the joint editor of the Chess Monthly with Zukertort, then printed the toast story, but introduced it with the following words: “Mr D.S. Thompson, in a letter addressed to us, inclosed the following cutting from the Philadelphia Times, with the request of its being published in the Chess Monthly.” Published it was, beginning under the sub-heading “Delmar’s Joke”, continuing through “What Thompson Proposed” and concluding under “They Wouldn’t Sing a Duet”. Hoffer made no comment regarding the cutting from the Philadelphia Times and did not vouch for its truthfulness. The report in the Chess Monthly then shifted to chess news from St Louis.

The chess toast story originally appeared in the Philadelphia Times on 16 March 1884 as follows:

“Delmar’s Joke.

A little incident happened at the recent Manhattan Chess Club dinner which is too good to be lost. It was noticed that Mr Eugene Delmar, who was present at that feast, was constantly endeavoring to get off a toast that he had on his mind, but that his friends – who evidently knew the subject-matter of what he was about to say – were as constantly endeavoring to keep him quiet. About every five minutes, Mr Delmar would rise with, ‘Gentleman, I’m about to off-’ ‘Come, come, Delmar’, his friends would whisper, ‘let up’, and they would pull him down to his seat and smother the thing over. This happened several times and each time the company paused in wonder – Steinitz would cease for a minute in relating his ‘wrongs’ to a neighbor and even Zukertort would forget what a genius he was, in the excitement of the moment.

Finally, however, Delmar could no longer be restrained and he shouted, ‘Here’s to the champion chess player of the world! Let him respond.’ The company immediately ‘caught on’ and the highest kind of hilarity was exhibited by all but two. Zukertort got red and Steinitz began portentously clearing his throat, but no one responded to the toast.

What Thompson Proposed.

The situation began to grow a little embarrassing for at least two of the gentlemen, when Mr D.S. Thompson, of Philadelphia, rose to his feet, saying: ‘Gentlemen, I think I can see a way out of this difficulty. Let Messrs Steinitz and Zukertort sing a duet in response.’

They Wouldn’t Sing a Duet.

But, alas, they wouldn’t sing a duet, and as we were about leaving Mr Steinitz was resuming the thread of his discourse with ‘You see how I’m treated and receive no recogni-’ and Mr Zukertort was again leading off with ‘Yes, sir, even when I was a boy I was a great mathematical geni-’ and then we left.”

Just who is repeating this story is unclear. David S. Thompson is reported in multiple sources as having come from Philadelphia expressly for the Manhattan Chess Club’s dinner. There is no mention of Gustavus Reichhelm, the chess editor of the Philadelphia Times, being present. One would think that Thompson told Reichhelm of the incident on his return from New York, but Thompson is reported in the third person in the narration and the “we” of the final section remains unidentified. Of course, the words attributed to Steinitz and Zukertort are verbal caricatures of the two: Steinitz even then had a reputation for easily taking offense, and Zukertort’s more than healthy ego was well known. That the “we” at the end of the story just happens to hear both chess professionals resuming their stereotypical remarks suggests that the whole story is a jest, the product of an active imagination bent on embarrassing two foreign master players who refused to delight the locals by contesting a match while then in the United States.

The larger context in which the story appeared further suggests that the yarn is simply that – a yarn that Reichhelm, with or without the assistance of Thompson, composed as a dig at both chess professionals. The Manhattan Chess Club’s banquet table was as close as Steinitz and Zukertort came to playing chess while in the United States in 1883-84. Their refusal to play one another probably contributed to the atmosphere in which the chess toast story appeared, as American players in general were disappointed that Steinitz and Zukertort did not take advantage of their proximity to play.

Of interest, too, and decidedly a factor in favor of the chess toast story being nothing more than a yarn, is the absence of mention of it in other contemporary reports covering the dinner. Here is what Henry Clay Allen, then the chess editor of Turf, Field and Farm and a much more reliable source than Reichhelm, wrote in his 7 March 1884 column, page 185, regarding the Manhattan Chess Club dinner:

“The annual dinner of the Manhattan Chess Club came off on Saturday evening last at Martinelli’s Fifth Avenue restaurant, and under the able management of President Green was a successful and enjoyable event. Over 50 gentlemen sat down to a repast prepared and served in Martinelli’s best style. Among those present were George T. Green, President of the Club, who presided, Messrs. Steinitz, Zukertort, Mackenzie, Gilberg, McKay, Delmar, Frere, Baird, Cohn, Lipschurtz [sic], and Thompson, of Philadelphia, the last named having come from that city for the purpose. As is usual at the annual dinners of this Club, the prizes in the handicap tournament were distributed, the recipients making brief acknowledgements. We report the speech of Capt. Mackenzie in full; on receiving the envelope containing his prize, he arose in response to loud cheers and repeated calls, and drawing the paper from its inclosure, said: ‘Mr President and Gentlemen: It is a good plan to follow the maxim of so many chessplayers – Never “miss a check.”’ And sat down. Speeches were made by Mr Steinitz, Mr Zukertort, Mr Frere and others. Mr Frere presented to the Club a fine oil painting of Paul Morphy, which the Directory had purchased; he stated that the portrait was painted by Elliott about 25 years since, and was recently discovered hidden among the long forgotten inutilia of a picture dealer’s establishment.”

Allen does not mention Delmar proposing a toast, or suggest that Steinitz and Zukertort were singled out for any special recognition, let alone embarrassment. He mentions both men giving speeches. He also refers to Mackenzie’s quip at receiving the check for first prize in the Club’s handicap tournament ($50), which is all the more reason to suspect that Allen would have reported such a toast had it been offered by Delmar or anyone else.

Page 81 of the Brooklyn Chess Chronicle, 15 March 1884 expressed general disappointment that Steinitz and Zukertort had not seen fit to contest even a single game in the United States. The two masters undoubtedly had little opportunity to test their strength on this side of the Atlantic, the magazine reported:

“... and for this reason it is the more to be lamented that, having such a tempting field on this neutral ground, for a fair encounter between themselves, which would be regarded as a compliment by the people of this country, the earnest desire on the one side to meet his rival cannot be responded to with an equal disposition on the part of the other. This has been the cause of much disappointment among our chess amateurs, and has certainly dispelled our own expectation of seeing some of the most remarkable games ever played, which a match between these chess giants would undoubtedly produce.”

Two pages later, the Manhattan dinner was discussed in some detail, with no mention of Delmar or anyone else making a toast to the world’s chess champion(s).

Other sources mentioned the Manhattan dinner, and with less reverence than shown by Allen in Turf, Field and Farm or the editors of the Brooklyn Chess Chronicle. The Cincinnati Commercial, 8 March 1884, for instance, repeated Mackenzie’s “never miss a check” joke and then roughly deflated the significance of Frere’s presentation of the Elliott picture of Morphy to the Manhattan Chess Club, describing the painting as one “which the Directors recently rescued from a neglected corner in a picture dealer’s establishment in New York”. Yet this source too, one clearly not enamored with the New York chess scene or Steinitz or Zukertort, did not mention the chess toast story.

I have been unable to find a single additional contemporary source, either from the New York metropolitan area or elsewhere in the United States, that mentions the chess toast story. In an age when chess columnists borrowed heavily from one another, and often did so to joke at the expense of others, whether clubs, players or whole countries, it seems almost inconceivable that the chess toast story, if true, would not have been reported and commented upon. I have found no evidence that any of the principals in the story, including Steinitz, Zukertort, Delmar and Thompson, ever mentioned the toast having taken place.

Finally, Reichhelm often peppered his chess columns with stories whose truth was hardly to be believed. For instance, his Philadelphia Times column for 6 November 1881 ran the following under the title “A New Anecdote About Morphy”:

“One morning at the breakfast table the celebrated Paul Morphy was observed to be deeply cogitating and earnestly gazing at the dishes. Time passed and still he made no sign or movement. Finally a member of his family gently reminded him that his breakfast was becoming cold, when the great master, waking as if from a trance, said ‘Pardon me; but, somehow or other, I was trying to mate the butter dish with the sugar bowl.’”

While the chess toast story regarding Steinitz and Zukertort is a colorful item at the expense of two difficult personalities, I suggest that it holds no more truth than the story about Morphy’s breakfast table.’

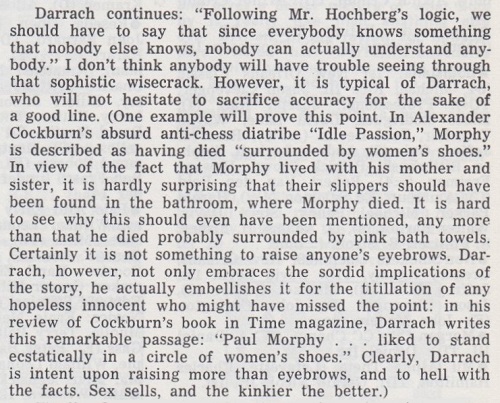

9095. Morphy and shoes

To the citations in ‘Fun’ we shall be adding some observations by Burt Hochberg on page 299 of the May 1975 Chess Life & Review:

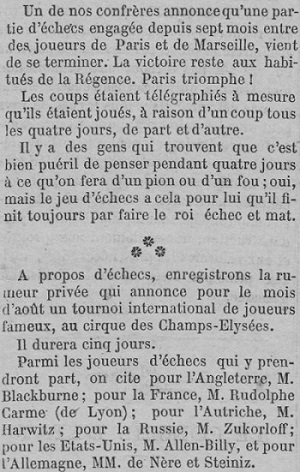

9096. Paris, 1872

Some strange names are in the second part of this cutting supplied by Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA) from page 2 of Le Rappel, 24 July 1872:

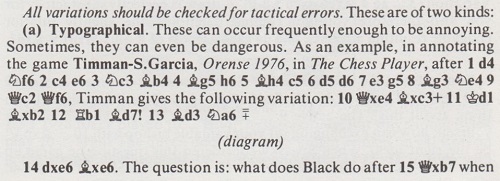

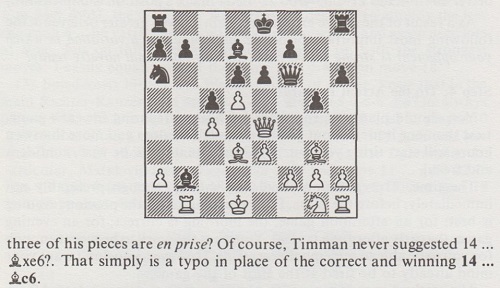

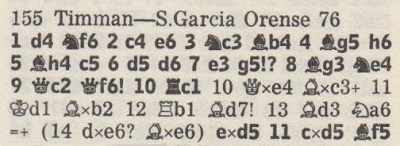

9097. Timman v García

One of the strongest practical – as opposed to moral –

arguments for not copying other writers’ work is that the

work copied may well be wrong.

From pages 53-54 of How to Be a Complete Tournament

Player by Edmar Mednis (London, 1991):

Below is the relevant part of Timman’s annotations, as

well as the game’s conclusion, on pages 56-57 of volume 11

of The Chess Player (Nottingham, 1976):

Any writer today who discusses the game on the basis of

what appeared in The Chess Player faces two

beguiling traps: a) repeating the line 14 dxe6 Bxe6

without realizing that it is faulty, and b) realizing that

it is faulty and blaming Timman. Moreover, those aware

of Mednis’ book may not bother to acknowledge what

he wrote when they themselves call 14...Bxe6 a typo, and

some may even ask how Mednis knew for sure that it was a

typo.

Although The Chess Player and the Mednis book identified Black as S. (i.e. Silvino) García, contemporary sources agree that the participant in Orense, 1976 was Guillermo García González. See, for instance, the crosstable on page 47 of Batsford’s FIDE Chess Yearbook 1976/7 by Kevin J. O’Connell (London, 1977) and on page xiv of the Chess Player volume itself. The crosstable shows that Timman and García drew their game, which underscores another danger: copying from databases. Some have Timman as the winner, and there are duplicates of the game with both G. García and S. García named as Black.

9098. Draw!

The mistakes in players’ names and game venues in Draw!

by Leonid Verkhovsky (Milford, 2014) are so numerous and

obvious that we do not intend to list examples unless

challenged to do so. The imprint page states, ‘Editing and

proofreading by Peter Kurzdorger’. A former Editor of Chess

Life is Peter Kurzdorfer.9099. Diggle study (C.N.s 9079 & 9093)

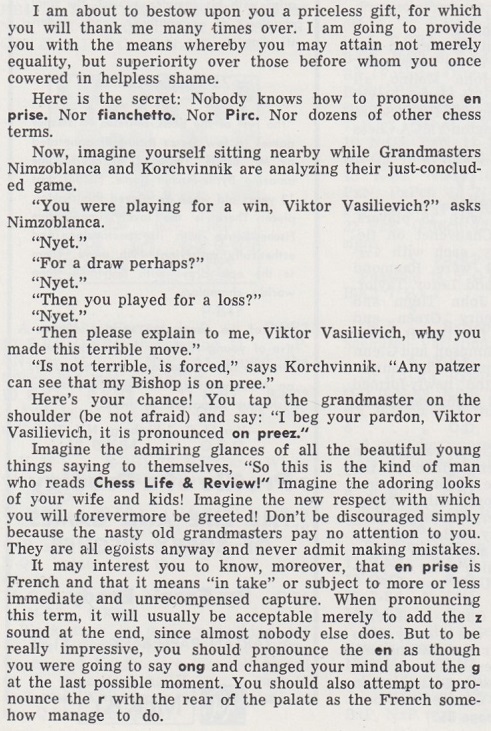

White to move and win

From John Nunn (Chertsey, England):

‘The Diggle study has multiple solutions. Black can never take the white bishop, even when his pawn is on h2, because of the diagonal skewer Qa8+. Therefore there is no rush for the white king to head to the kingside, and in fact any king move wins. There are also other winning possibilities; for example, 1 g5 h3 2 g6 fxg6 3 Kd5 h2 4 Ke6 Kd8 5 Kd6 g5 6 Bh1 g4 7 Bg2 g3 8 Bh1 g5 9 Bg2 g4 10 Bd5 g2 11 Bxg2 g3 12 Ke6, or even 1 d8(Q)+ Kxd8 2 Kd6 h3 3 Bd7 h2 4 Bc6, and Black will soon be forced to play ...Kc8 and allow the white king to penetrate to e7.’

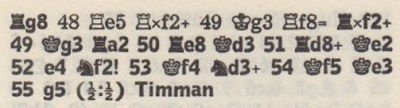

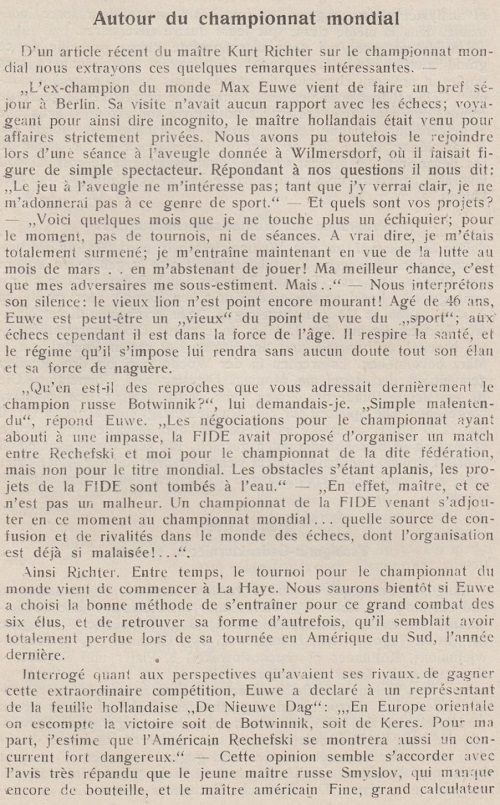

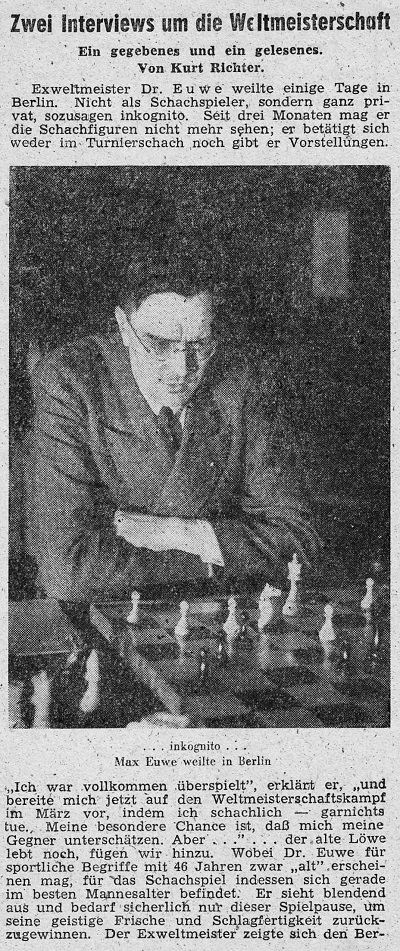

9100. Euwe and Richter

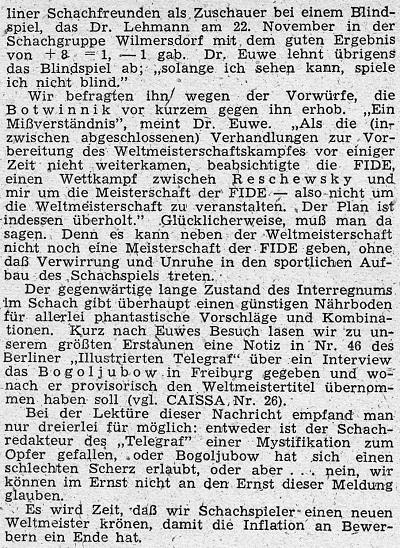

An article by Fritz Gygli and Jean-Charles de Watteville on pages 35-36 of the March 1948 Schweizerische Schachzeitung:

Below, courtesy of Alan McGowan (Waterloo, Canada), is Kurt Richter’s earlier article, on pages 3-4 of Caissa, 2 January 1948:

9101. Faithfully Yours

The front-cover photograph in the January 1952 Chess Review:

Robert Cummings and Ann Sothern

From page 4 of the magazine:

‘Faithfully Yours was the play which featured chess – more than is apparent from our cover picture – for 1951.

It also had quips at psycho-analysis, gorgeous gowns for Ann Southern [sic] and comic antics by Robert Cummings.

It seems that Ann played a daily game with hubby, Bob; but, after ten years, still lost her queen in “that trap in the Tchigorin Variation”. So hubby finally couldn’t stand it any longer.

He blows his top. The psycho-analyst enters. But he doesn’t teach Ann how to play chess either – the cad.’

Faithfully Yours was written by L. Bush-Fekete and Mary Helen Fay.

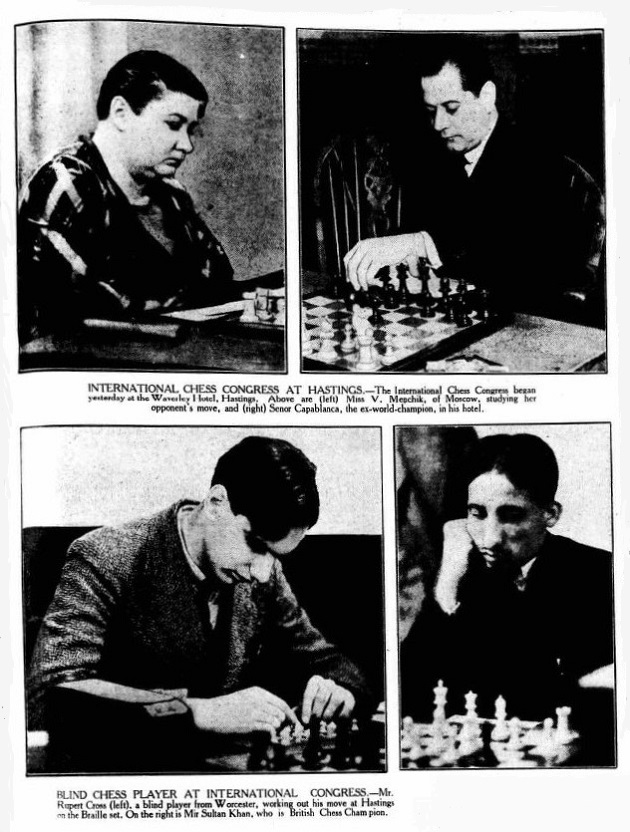

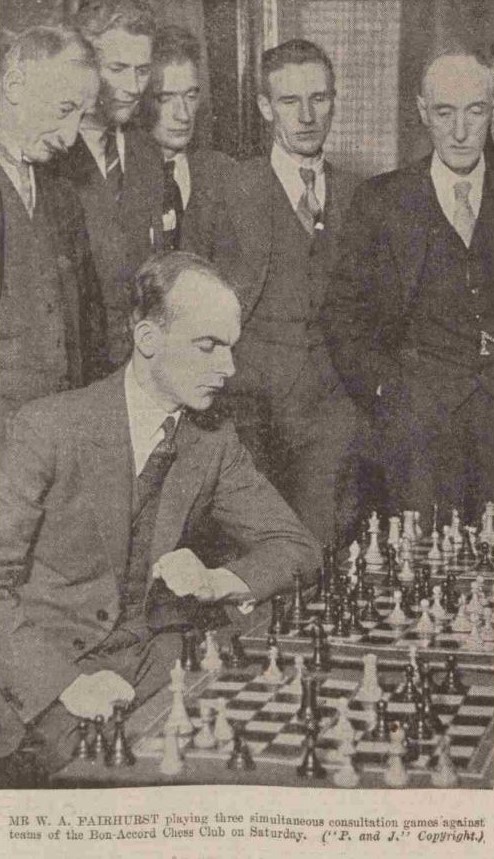

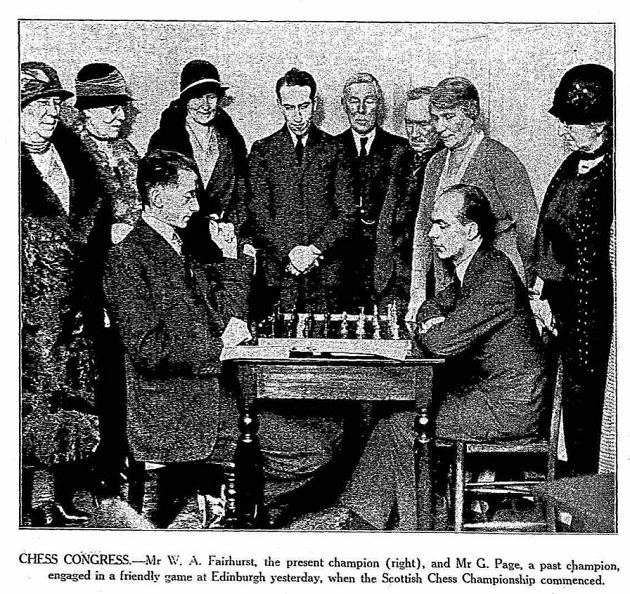

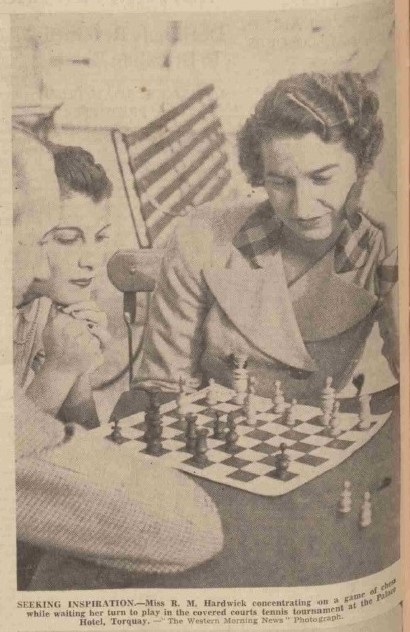

9102. 1930s photographs

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) has found these photographs in publications of the 1930s:

Yorkshire Post, 31 December 1930, page 9

Aberdeen Press and Gazette, 31 October 1932, page 3

The Scotsman, 31 December 1932, page 14

Robert Forbes Combe, Aberdeen Press and Journal, 6 May 1937, page 1

Western Morning News and Daily Gazette, 16 November 1937, page 10.

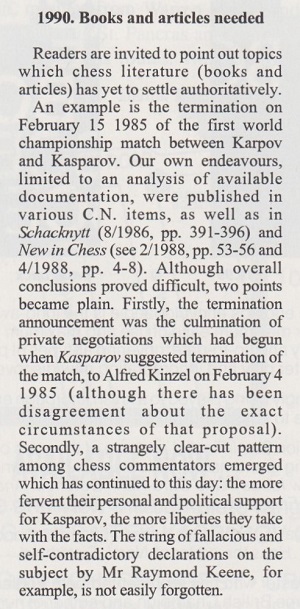

9103. 15 February 1985

Exactly 30 years ago the first world championship match between Karpov and Kasparov was halted by Florencio Campomanes in circumstances which remain unclear to this day. An addition just made to The Termination is the text of C.N. 1990, as published on page 50 of CHESS, November 1993:

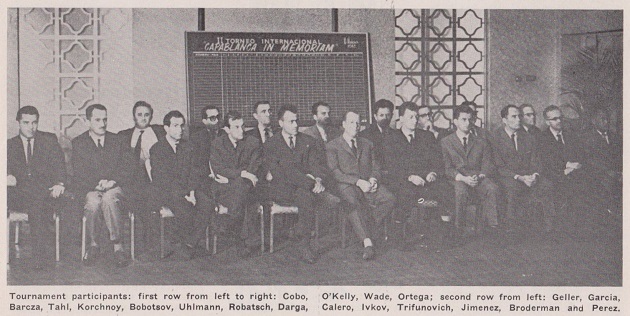

9104. Capablanca Memorial Tournament, Havana, 1963

From page 351 of the November 1963 Chess Review:

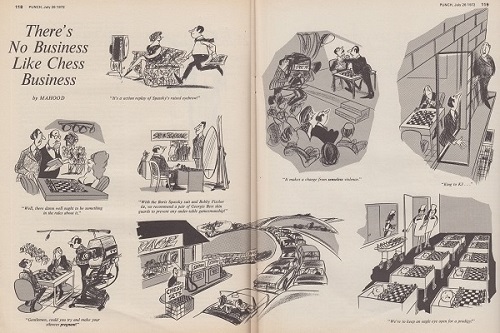

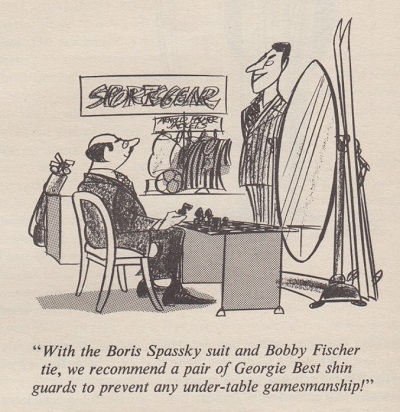

9105. Punch cartoons

The immense popularity of chess in 1972 is demonstrated by a double-page spread of cartoons (‘There’s No Business Like Chess Business’) by Mahood on pages 118-119 of the 26 July-1 August 1972 issue of Punch:

One example:

Page x of the same issue had an advertisement for Isle of Lewis chess sets:

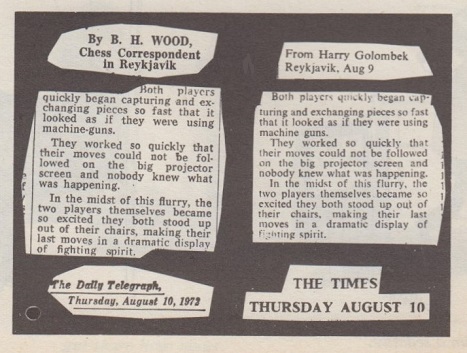

9106. Wood and Golombek

A curious item from page 204 of the 16-22 August 1972 issue of Punch:

Can any reader take the matter further?

Harry Golombek was mentioned in a spoof on page 67 of Punch, 14-20 January 1970:

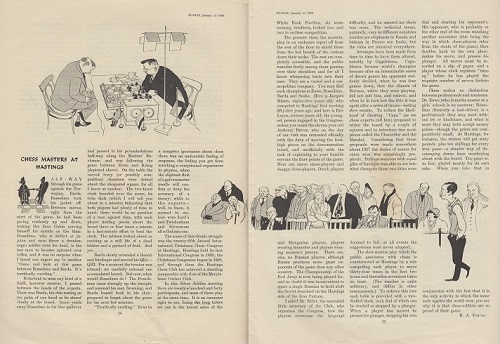

9107. Punch on Hastings, 1949-50

Pages 34-35 of the 11 January 1950 Punch had an article by B.A. Young on Hastings, 1949-50:

Two brief excerpts:

‘Half-way through his game against the Norwegian, Barda, Rossolimo took his jacket off. Between moves, right from the start of the game, he had been pacing restlessly up and down, looking like Jean Gabin nerving himself for suicide on the films. Rossolimo, who is skilled at ju-jutsu and once threw a drunken negro soldier over his head, is the last man to become agitated over trifles ...’

‘Even to a complete ignoramus about chess there was an undeniable feeling of suspense, the feeling you get from watching a complicated experiment in physics, when the slightest flick of a galvanometer needle will confirm or deny the accuracy of a theory; while to the experts – well, to them, it seemed to me, here were Lord’s and Twickenham and Silverstone all rolled into one.’

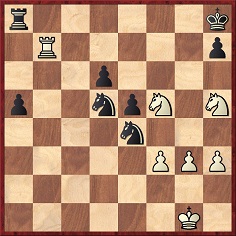

Mention was made of the game between König and Euwe (round three, 31 December 1949), and a cartoon showed a position which arose over the board:

The article also referred to Arthur Rider, the Secretary of the Hastings and St Leonards Chess Club. When he died four years later, he received a 36-line obituary by D.J. Morgan in the March 1954 BCM. The final paragraph, reproduced below, illustrates how well written the BCM used to be:

‘In the international chess arena, as in much else, the limelight is thrown on the performers. They take the stage; they enrich life with their skill. Too often, little is known of the personalities behind the scenes who make all this possible; of their capacity for unremitting and self-sacrificing work, of their gifts for organization, of their powers “to see things whole” combined with great attention to details, of the wisdom and diplomacy which remove friction and set the wheels running smoothly. Amongst such, A.A. Rider was a notable example. We mourn his passing; we are grateful for his achievements. These will long keep his memory green, and will inspire those who take up where he left off.’

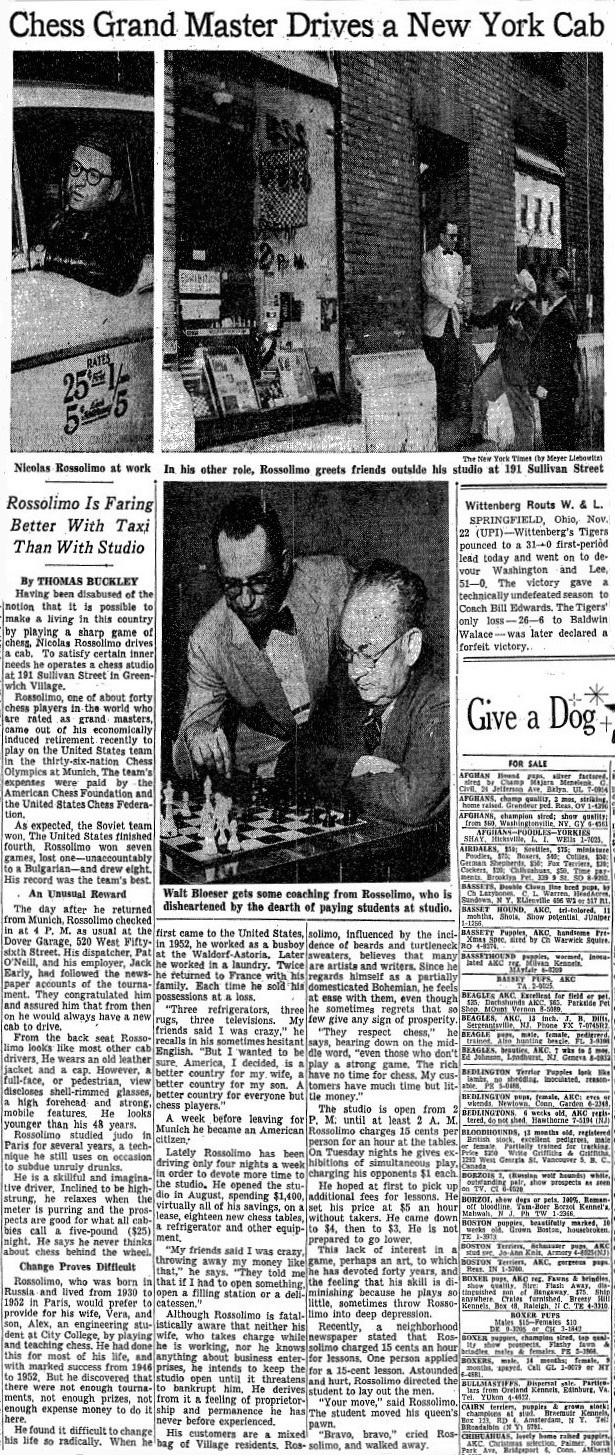

9108. Nicolas Rossolimo

‘America, I decided, is a better country for my wife, a better country for my son. A better country for everyone but chess players.’

That remark by Rossolimo comes from an article about him by Thomas Buckley on page 88 of the New York Times, 23 November 1958:

9109. Books by James Plaskett

The Factfinder has an entry for ‘Chess authors’ books on non-chess subjects’, and the present item adds James Plaskett. In 2000 Tamworth Press brought out Coincidences, a book now supplemented by his website. In January 2015 Bojangles Books published Bad Show, co-authored by Plaskett with Bob Woffinden.

Addition on 9 January 2022:

James Plaskett draws to our attention his latest book Bread and the Circus (Kindle).

9110. Helms and Santasiere

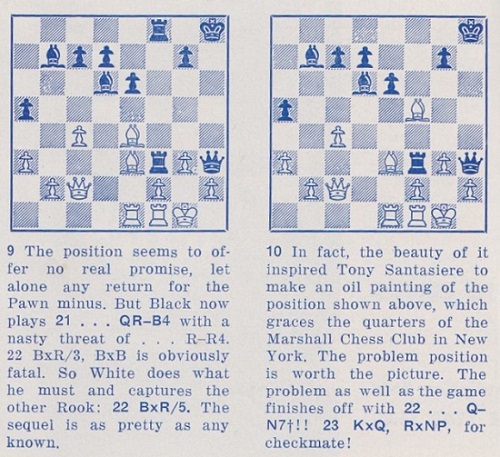

From a ‘Chess Movies’ article on the inside front cover of the January 1959 Chess Review:

Concerning the painting by A.E. Santasiere depicting the game in question, A Brilliancy by Hermann Helms, Ronald Young (Bronx, NY, USA) reports that he saw the picture hanging in the Marshall Chess Club in 2003 and noted that the position reproduced was not precise. He asks whether a photograph can be obtained.

We are grateful to Frank Brady (New York, NY, USA) for taking the following photograph of the painting, which is still in the Marshall Chess Club’s possession:

9111. Kotov, Kots, Kotsch and Koz

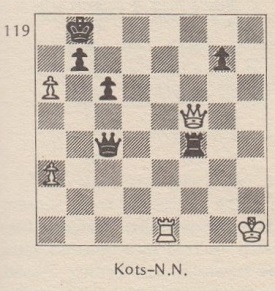

From page 49 of Chess Tactics by Alexander Kotov (London, 1983):

Wanted: information about this ‘Kots-N.N.’ position.

The imprint page describes the book as ‘an adapted and updated version of Lehrluch [sic] der Schachtaktik -1 (Sportverlag Berlin 1972)’. We have three editions of volume one of Kotov’s Lehrbuch der Schacktaktik. None of them indicates any place or date for the position (or a name for Black), and each edition is different with respect to White’s identity:

- 1972 edition, page 98: no name;

- 1974 edition, page 99: ‘Kotsch’;

- 1981 edition, page 104: ‘Koz’.

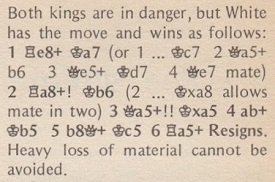

9112. En prise

An addition concerning En Prise comes from an article ‘Tsoogtsvahng and All That’ by Burt Hochberg on pages 350-351 of the June 1972 Chess Life & Review:

9113. A gift of the gods

Some German-language websites ascribe to Tartakower, with no further particulars, this remark about the Evans Gambit: ‘Dieses blendende Angriffsspiel ist dafür erfunden worden, die Menschen zu dem Glauben zu veranlassen, dass die Schachkunst ein Geschenk der Götter ist.’

Readers are invited to add citations to the three shown below:

Die Hypermoderne Schachpartie by S. Tartakower (Vienna, 1924), page 173

La moderna partida de ajedrez by S. Tartakower, volume one (Buenos Aires, 1959), page 161

500 Master Games of Chess by S. Tartakower and J. du Mont (London, 1952), page 29.

9114. Blitz tournament

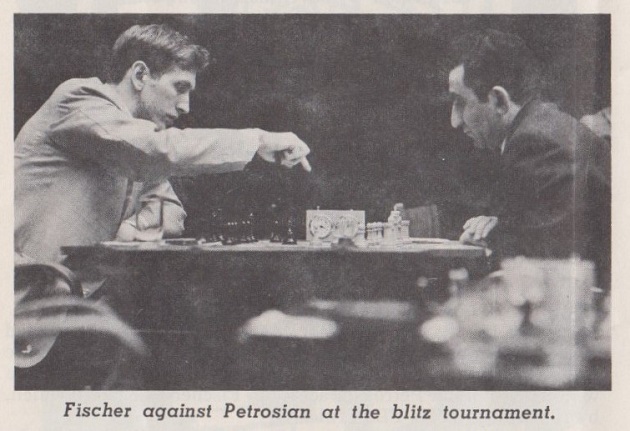

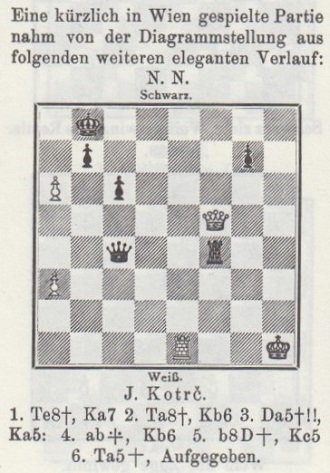

A photograph taken at Herceg Novi, 1970:

Source: Chess Life & Review, June 1970, page 302.

9115. What should White play?

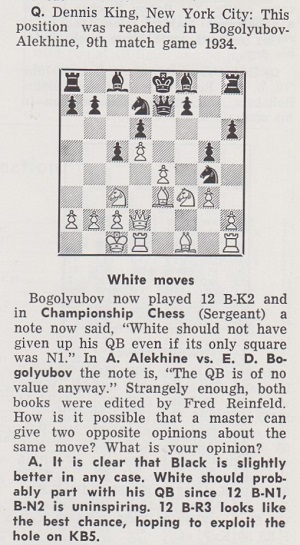

This position, in which Black has just played 11...Ng4, will be discussed in the next C.N. item.

9116. Bogoljubow v Alekhine (C.N. 9115)

From page 81 of the February 1971 Chess Life & Review (‘Larry Evans on Chess’):

It was hardly justified for Dennis King to assert that Reinfeld gave ‘two opposite opinions’ on White’s 12th move. Concerning P.W. Sergeant’s Championship Chess (London, 1938), Reinfeld brought out updated editions (New York, 1960 and 1963), with extra games but without revising Sergeant’s annotations. The other book, A. Alekhine vs. E.D. Bogoljubow (Philadelphia, 1934), was co-written by Reinfeld with Reuben Fine.

Such points passed Evans by, and his cursory remark that 12 Bh3 ‘looks like the best chance’ did not mention that the move was recommended by Bogoljubow, though not by Alekhine.

Below is a non-exhaustive compendium of notes to Bogoljubow’s 12th move (after 1 d4 c5 2 d5 e5 3 e4 d6 4 f4 exf4 5 Bxf4 Qh4+ 6 g3 Qe7 7 Nc3 g5 8 Be3 Nd7 9 Nf3 h6 10 Qd2 Ngf6 11 O-O-O Ng4):

Championship Chess by P.W. Sergeant (London, 1938), page 192

A. Alekhine vs. E.D. Bogoljubow by F. Reinfeld and R. Fine (Philadelphia, 1934), page 28

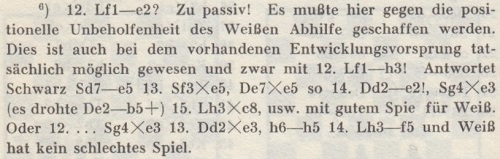

Schachkampf um die Weltmeisterschaft by E. Bogoljubow (Karlsruhe, 1935), page 56

My Best Games of Chess 1924-1937 by A. Alekhine (London, 1939), page 140

Alekhine vs. Bogolubow by I.A. Horowitz and S.S. Cohen (New York, 1934), page 13

Deutsche Schachzeitung, May 1934, page 146 (annotator: M. Blümich)

BCM, June 1934, page 264 (annotator: J.H. Blake)

Alexander Alekhine II Games 1923-1934 by A. Khalifman (Sofia, 2002).

Some annotators made no comment on 12 Be2, examples being Lasker in his match-book (page 38), Kmoch on page 146 of the May-June 1934 Wiener Schachzeitung and Tartakower on page 551 of L’Echiquier, 8 August 1934.

The game was played in Pforzheim on 25 April 1934. Page 55 of Bogoljubow’s above-mentioned match-book gave the players’ times as two hours and 41 minutes for White and 58 minutes for Black. See too pages 96-97 of Wonders and Curiosities of Chess by I. Chernev (New York, 1974).

9117. An epidemic

In his column on page 31 of the Observer, 3 September 1972 Clive James remarked that in sports broadcasts Frank Bough ...

‘puts the emphasis on his prepositions and breaks into a shout when you LEAST expect it ...’

Since then, emphasis on prepositions has been increasingly noticeable, and we have even heard a television news presenter welcoming an interviewee down the line with ‘Good afternoon to you’. On Internet chess broadcasts there is now an epidemic. For example:

‘Let’s have a look at that game.’ ‘A nice move by him.’ ‘Things went really well for him.’ ‘He is now in the lead.’

9118. Kotov, Kots, Kotsch and Koz (C.N. 9111)

From Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina):

‘Page 105 of volume two of Tratado general de ajedrez by Roberto Grau (Buenos Aires, 1943) has a similar position, but with two pawns added, a black one on a4 and a white one on c3. No particulars were given. As Grau’s main source was Kurt Richter’s work, it is no surprise to find the position (without the extra pawns) on page 62 of Kombinationen by Richter (Berlin and Leipzig, 1936), together with many others, in that chapter, in the same order. Richter wrote that the game was J. Kotrc v N.N., Vienna, 1907.’

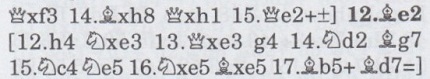

We can add that the position was given as won by J. Kotrč on page 115 of the April 1907 Deutsche Schachzeitung:

9119. Fischer v Petrosian (C.N. 9114)

Dan Scoones (Port Coquitlam, BC, Canada) writes:

‘Despite the caption in Chess Life & Review, I believe that the photograph was taken not during the Herceg Novi blitz tournament but in the second round of the USSR v the Rest of the World match in Belgrade. The Belgrade game began 1 c4 g6 2 Nc3 c5, which corresponds to the position in the photograph, whereas the Herceg Novi game opened 1 c4 Nf6 2 Nc3 g6. Moreover, the design of the players’ chairs is consistent with the ones used in Belgrade, and in all the Herceg Novi photographs that I have seen there were white tablecloths. Finally, the shade of Fischer’s jacket matches other Belgrade photographs, but not pictures taken in Herceg Novi.’

9120. Master the Game of Chess

Anybody who places chess material on the Internet runs the risk of having it stolen, and a grotesque case has just come to our attention: Master the Game of Chess by Neeta Sehgal (Delhi, 2005 and 2006).

The illiterate back-cover blurb makes startling promises (the book ‘will surely make you a grand master of chess’) and proclaims: ‘There has been lot of research put in to make this book a grand success.’ The imprint page seeks to protect the intellectual property rights of that lot of research:

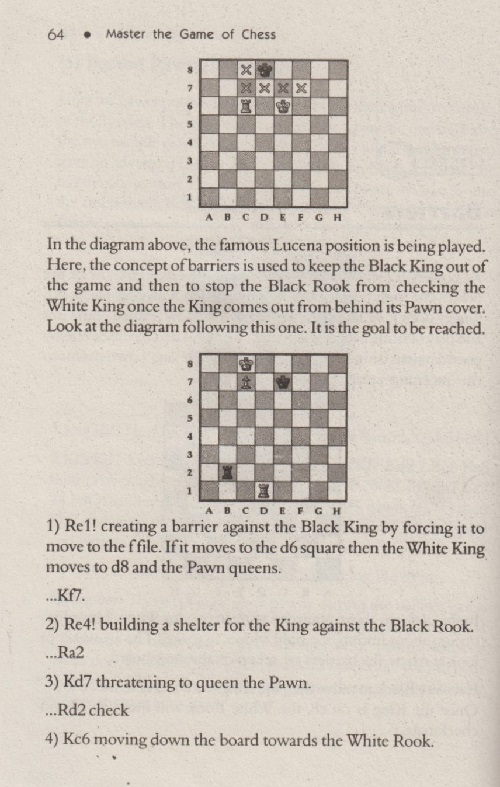

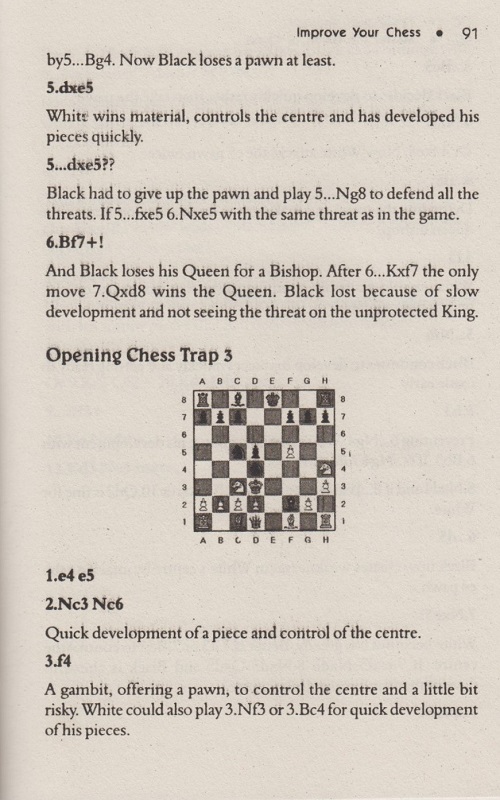

A Google search demonstrates that the entire 160-page book is a crude patchwork of material lifted from Internet sites without attribution. Three pages chosen randomly:

Is there any chance of an explanation from the publisher? No response has ever been received concerning the many cases documented in An Indian Copying Mystery, Copying and A Publishing Scandal.

9121. Capablanca on stalemate

Our Stalemate article has a remark by Capablanca at Nottingham, 1936 that the stalemate rule is illogical. Another comment, made in 1919, was reported by P.W. Sergeant on page 457 of the December 1929 BCM:

‘To take the case of stalemate alone, during the Victory Congress at Hastings I had a discussion with Señor Capablanca, who argued that the old rule that the player who could make no move should lose is far more logical than the present rule, and should be restored.’

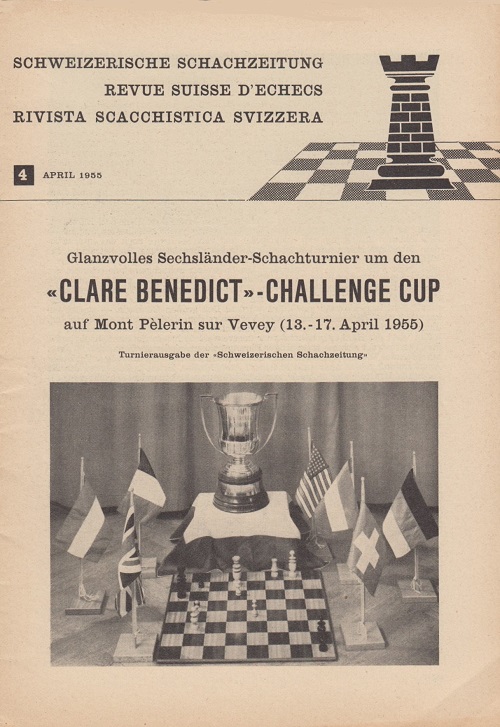

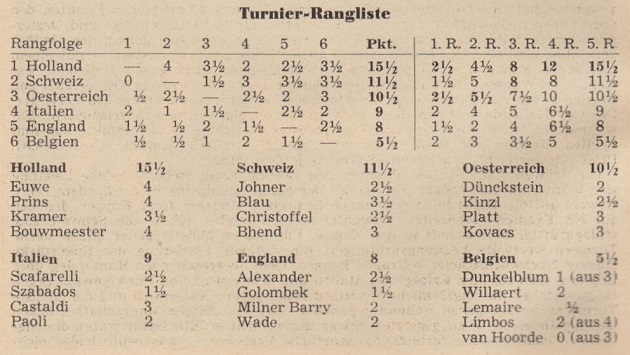

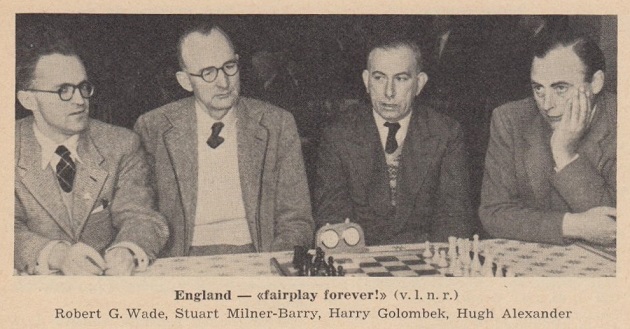

9122. Clare Benedict Challenge Cup, 1955

Gleanings from the coverage in the April 1955 Schweizerische Schachzeitung (pages 66, 67, 69, 71, 73, 75 and 77) of the Clare Benedict tournament in Mont Pèlerin sur Vevey:

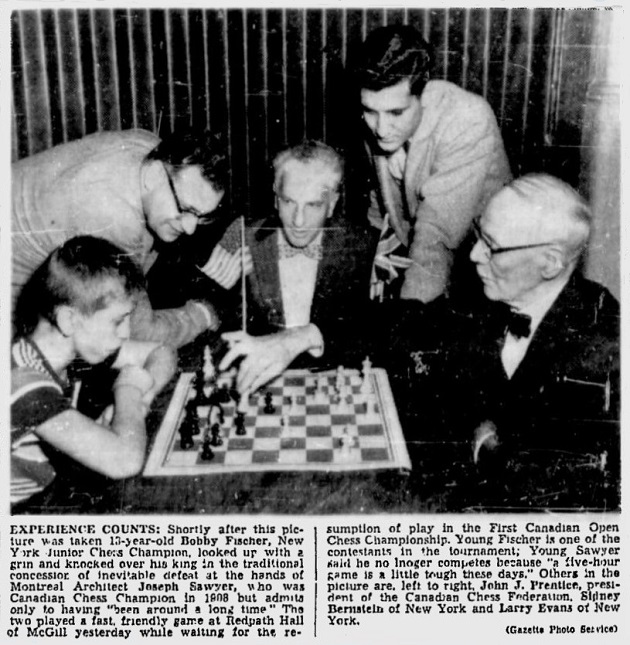

9123. Fischer in Montreal

Alan Smith (Stockport, England) notes a photograph of Bobby Fischer in play against Joseph Sawyer (1874-1965) on page 3 of the Gazette (Montreal), 1 September 1956:

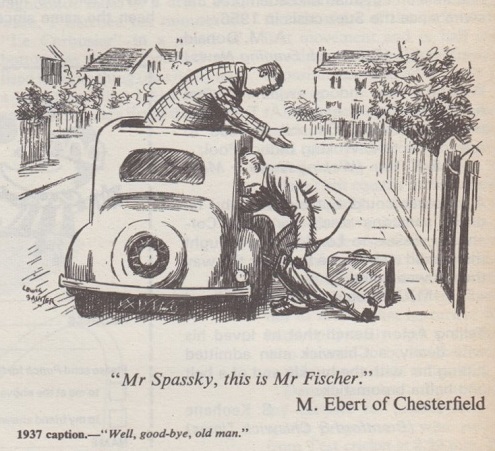

9124. Caption competitions

Punch, 16-22 August 1972, page 220

Punch, 16-22 August 1978, page 66.

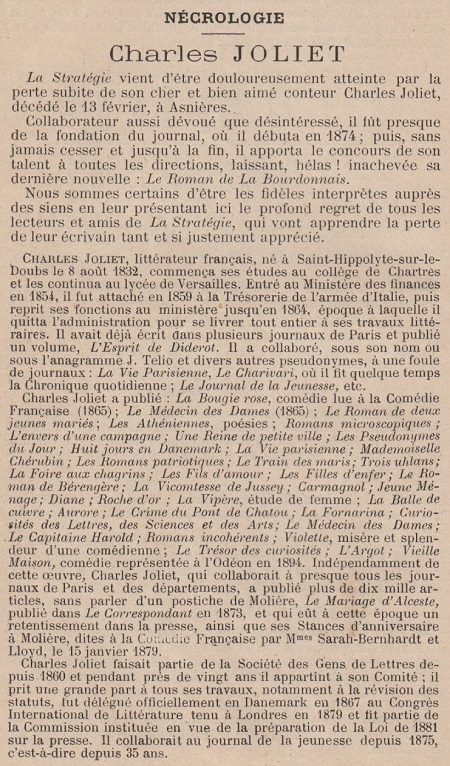

9125. Charles Joliet (C.N. 5378)

Below is the obituary of Charles Joliet in La Stratégie, February 1910, page 64:

One of his novels with references to chess is Trois Hulans (Paris, 1872):

In that chess passage a non-chess matter may be mentioned. The reference on page 11 to ‘un troupeau de lions commandés par des ânes’ is a reminder that the familiar phrase ‘lions led by donkeys’ did not, as sometimes imagined, originate in the First World War.

9126. Twitter (C.N. 9085)

From Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore):

‘On the subject of tweeting, which you mentioned in C.N. 9085, this is the kind of thing all too easily found:’

9127. Na1

In C.N. 410 (see page 41 of Chess Explorations),

W.H. Cozens (Ilminster, England) drew attention to the

rarity of a game finishing with the move Na1. We now add

another interesting specimen, from pages 130-131 of the

August-September 1951 Schweizerische Schachzeitung.

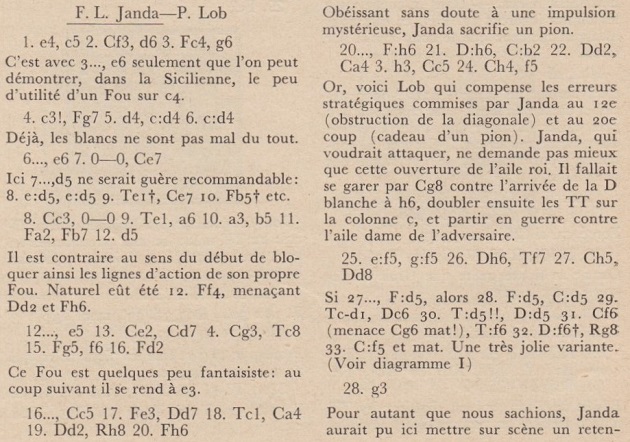

The annotations are by Fritz Gygli.

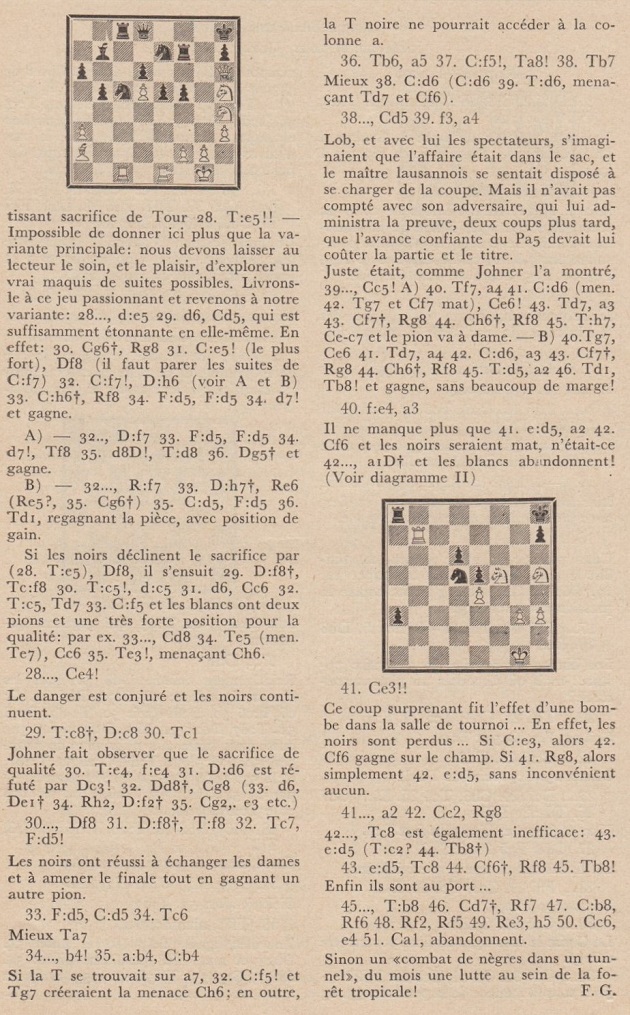

This game between Franz Ludwig Janda and Paulin Lob was played in the final round of the Swiss championship in Geneva on 28 July 1951. The leading scores at the start of the round were 1 Lob (8 points), 2 Grob (7½) and 3 Kupper (7). Grob won the championship by defeating Kupper, given that Lob lost to Janda:

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 d6 3 Bc4 g6 4 c3 Bg7 5 d4 cxd4 6 cxd4 e6 7 O-O Ne7 8 Nc3 O-O 9 Re1 a6 10 a3 b5 11 Ba2 Bb7 12 d5 e5 13 Ne2 Nd7 14 Ng3 Rc8 15 Bg5 f6 16 Bd2 Nc5 17 Be3 Qd7 18 Rc1 Na4 19 Qd2 Kh8 20 Bh6 Bxh6 21 Qxh6 Nxb2 22 Qd2 Na4 23 h3 Nc5 24 Nh4 f5 25 exf5 gxf5 26 Qh6 Rf7 27 Nh5 Qd8 28 g3 Ne4 29 Rxc8 Qxc8 30 Rc1 Qf8 31 Qxf8+ Rxf8 32 Rc7

32...Bxd5 33 Bxd5 Nxd5 34 Rc6 b4 35 axb4 Nxb4 36 Rb6 a5 37 Nxf5 Ra8 38 Rb7 Nd5 39 f3

39...a4 40 fxe4 a3

41 Ne3 a2 42 Nc2 Kg8 43 exd5 Rc8 44 Nf6+ Kf8 45 Rb8 Rxb8 46 Nd7+ Kf7 47 Nxb8 Kf6 48 Kf2 Kf5 49 Ke3 h5 50 Nc6 e4

51 Na1 Resigns.

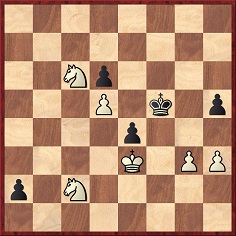

9128. Moskou 1949

An early book exclusively devoted to a women’s chess event:

Notwithstanding the title, the world championship tournament, won by Ludmila Rudenko, took place from 20 December 1949 to 16 January 1950. The frontispiece:

9129. Romark

Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England) refers to Chess and Hypnosis and adds the case of Romark, who was discussed by Harry Golombek on pages 95-96 of Fischer v Spassky (London, 1973). Golombek quoted the following ‘from what I wrote at the time’:

‘Romark, Newcastle’s own Ron Markham, has challenged Bobby Fischer and Boris Spassky to play a consultation game against him at the end of the match and this for a stake of £125,000. Fischer and Spassky are asked to put up £62,500 each as their stake. So confident is Romark of winning that he is putting up £25,000 himself, the remainder being provided by his backers and associates. More, he is prepared to play blindfold against them.

... The reader, if as ill-informed as I was, might now ask who is Romark, what is he? Here are some facts provided by his publicity agents. At present he is based in Durban. At an anti-smoking rally in Newcastle last year he cured 2,000 people of smoking. This year, in Durban, before an audience of doctors, he hung [sic] himself for four minutes, was officially pronounced dead, and then, presumably, recovered. Romark says he is an average chessplayer. He would appear to be a more than average hypnotic medium.’

Golombek’s original article, ‘High drama in Reykjavik’, was written in Iceland during the world championship match and appeared on page 11 of The Times, 19 August 1972. Before coming on to Romark, Golombek indulged in much booksy waffle, contriving to mention Corneille, Agatha Christie and The Mousetrap, Brian Rix’s farces, Racine, Mozart, The Caretaker and Lord of the Flies. He also gave Spassky’s win in the 11th match-game, with brief notes.

A small advertisement on page 23 of The Times, 27 June 1975:

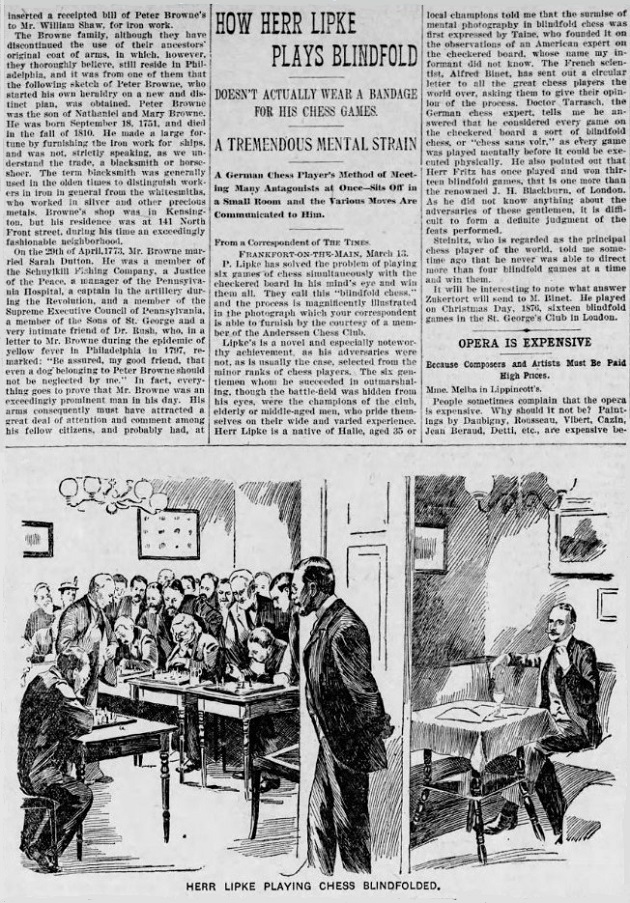

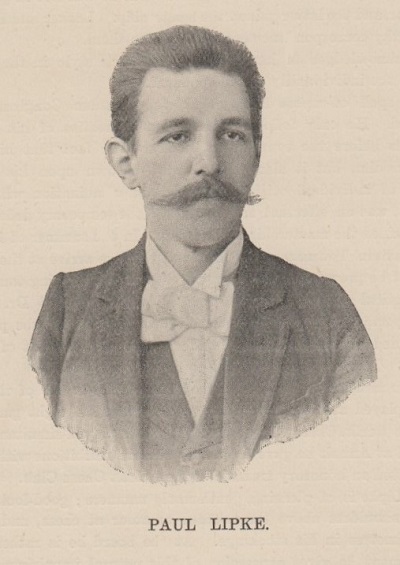

9130. Lipke playing blindfold

Paul Lipke’s name is seldom mentioned nowadays in connection with blindfold chess, but Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) has found this feature on page 21 of the Philadelphia Times, 24 March 1895:

A report on the display was published on page 347 of the November 1894 Deutsche Schachzeitung:

From page 33 of the Chess Monthly, October 1894:

The following page of the magazine stated:

‘Herr Lipke is one of the best living blindfold players. He played at the Berlin Chess Society in 1894 eight games simultaneously, winning all; at the Berlin Chess Club, out of ten games played simultaneously he won nine and drew one; and at Anhalt he gave frequently similar exhibitions with invariable success, so that he was elected an honorary member of the Anhalt Chess Club.’

9131. chessgames.com

The entirety of our translation in the feature article Alekhine on Munich, 1941 has been reproduced by chessgames.com without permission, a total of 1,325 words.

[Afterword: on 27 February 2015 our translation was removed from chessgames.com.]

9132. Vladimir Savon

Jovan Petronić (Belgrade) notes that on the Internet two dates can be found for Vladimir Savon’s birth: 26 February 1940 and 26 September 1940.

Readers’ assistance in clarifying the discrepancy will be appreciated. Although the date usually given is 26 September 1940, there is a significant exception: Savon’s entry on page 347 of Shakhmaty Entsiklopedichesky Slovar edited by Anatoly Karpov (Moscow, 1990) has ‘26.2.1940’.

Robert Byrne, Vladimir Savon and Leonid Stein, front cover, Chess Life, June 1967.

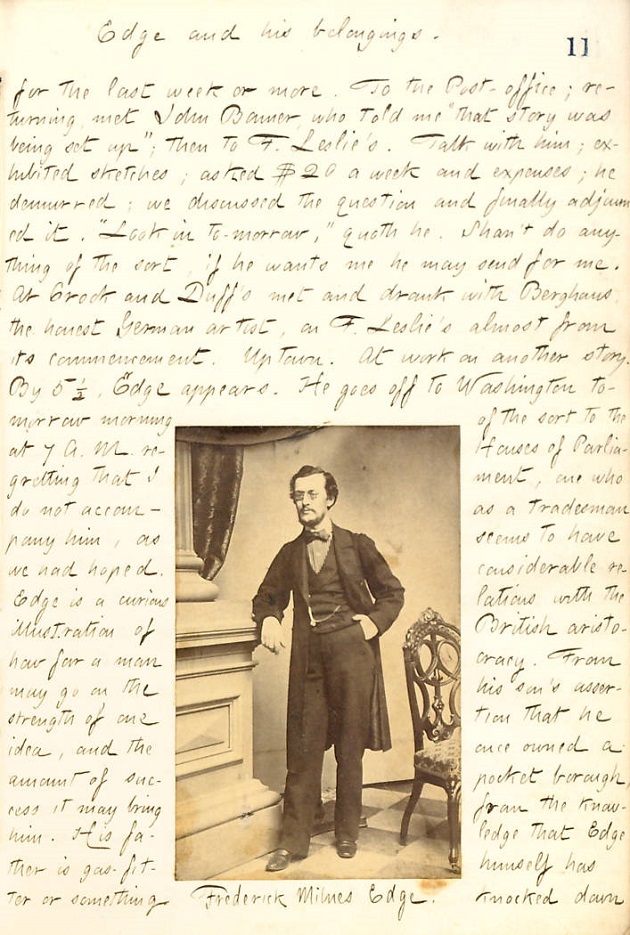

9133. F.M. Edge

Descriptions of the physical appearance of F.M. Edge, together with much other information about him, have been discovered by Harrie Grondijs (Maastricht, the Netherlands) in the diaries of Thomas Butler Gunn. Below are some of the transcripts provided by our correspondent:

- 11 April 1856:

‘I, by the assistance of little Edge, hunted up Carroll, and got particulars of Med. Student matters for book. Also I’ve visited a Chinese Boarding House – in Cherry Street. Book grows apace. Correspondence kept up, as wont.

Little Edge is a character whom a page or two would be well bestowed upon had I the time to write ’em. He and little cockney cub Watson spent some two months or so sleeping in timber yards, desperately hard up, and Watson almost despairing. Little Edge told me lots of stories anent it, how they fished, caught an eel, and bartered it at cook-shop for grub, how he pawned his coat, how they held arguments on all sorts of things, with much more. He is the slimmest, frailest, weakest little spectacled creature you ever saw. He lives with a French modiste à la Paris.’

- 7 March 1857:

‘To Bellew’s in the morning and returned to Bleecker Street with him. Kelly and, afterwards, little Edge called in the afternoon, the latter telling me how he had been in the basement, where the fellows (Eytinge and Cahill) had drunk up a quart of gin that morning and Sol was perfectly insensible. Little Edge has got married to his Alsacian-milliner-mistress and talks of nothing but his position on the Herald and what he is going to be.’

- 22 March 1858:

‘Edge has returned to England, I hear. He owes money to Haney, and actually has borrowed from the boy who waits at Haney’s tavern without repaying him! An odd, little, weak, frail-looking creature, with spectacles and such a general feebleness of aspect that nobody would suspect him of the capacity to contain any vices. He is of good family, I believe, his father being quite wealthy. Edge behaved like a young ass, squandered money, went to races, betted [?] and then ran off to Paris. There he experienced some hard-up-ness, used to frequent theatres, going in free with the claque, When he came to New York it was with a considerable sum of money in his pocket, all of which he gambled away at Pat Hearne’s and other halls, Then he consorted with Watson, the low little cockney. I used to see them for the first time in the Pic Office, Watson being a hanger on of Thad Glover’s and little Edge an admirer and friend of Watson’s. The two did some starving together.’

- 16 November 1858:

‘Little Edge it seems is travelling about with Paul Morphy, the chess phenomenon. I saw a letter from the former, reprinted from a London paper, in today’s Herald. It was dated from a Parisian hotel. Edge knew Morphy here, and reported chess-playing for the Herald. He must be in his glory, just now.’

- 11 May 1859:

‘There is a book advertised, as detailing the exploits of Morphy, the “Chess Champion” in Europe, written by his “late secretary”, little Edge, whose name has appeared in juxtaposition with the celebrity during the last year or so. Edge got acquainted with Morphy when reporting the proceedings of the Chess Club in this city, for the Herald. He lost his position on the paper by attempting to get some man made a policeman and threatening to use the reportorial power he had in being “down upon” the officers in case of refusal. One wrote to Hudson, who expelled Edge. What a contrast must his recent experience of Paris, in connection with Morphy, present to his former visit, when he ran away from home, lived in a garret and obtained admission to the theatres by joining the claque! He’ll be sure to turn up in New York again, some day. Of all cities in the world it would suit him best.’

- 8 February 1862:

‘Little Edge up, prim, spectacled and conversational, talking American about the rebellion, which according to his opinion is to be extinguished in a month or so. He stayed an hour or more, Boweryem [?] being with us during the best part of it, and when he had departed, Edge said he wanted me to be the New York correspondent of the London Star. I had been expressing opinions decidedly opposite to those of that paper throughout the interview! Edge wrote for the Morning Herald in London; he says he has had interviews with Earl Russell, with the Duke of Newcastle, apropos of American affairs, knows Bright and other notabilities. He left his wife among her folks in Switzerland.’

- 19 March 1863:

‘With him down the long pier, and aboard a little steamer, in a violent north-east wind, almost a storm. After some half hour’s delay, put off for the Mississippi. Elwell was there, but left, before our departure. One of the last persons I saw was little Edge on one of the steamers, waving his hand in adieu.’

Shortly after the above extracts were posted, Gerard Killoran (Ilkley, England) pointed out that volume 19 of the diary (7 March 1862) has the following:

| First column | << previous | Archives [127] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.