Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [128] | next >> | Current column |

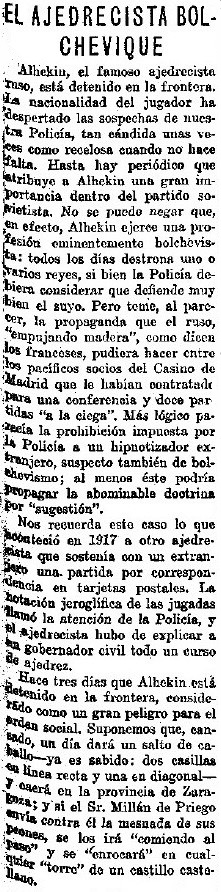

9134. Alekhine detained at the Spanish border

Eladio Mejuto (Madrid) sends an ironic report published on page 5 of El Sol, 23 May 1922 about Alekhine’s detention at the Spanish border on suspicion of being a Bolshevik:

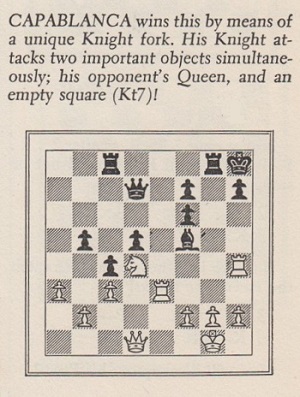

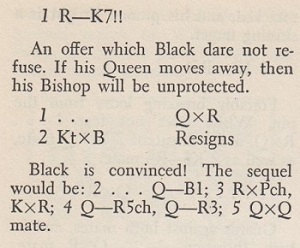

9135. ‘A unique knight fork’

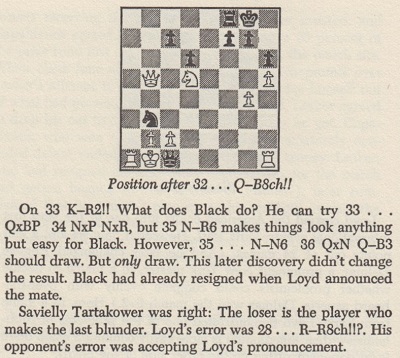

From pages 125-126 of The Fireside Book of Chess by I. Chernev and F. Reinfeld (New York, 1949):

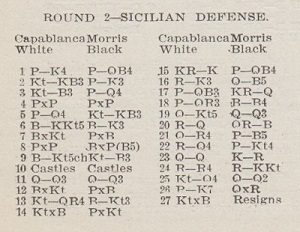

The description ‘a unique knight fork’ may seem an exaggeration. No details about the occasion were given by Chernev and Reinfeld, but the game was won by Capablanca against William G. Morris in the second round of the National Tournament in New York, on 23 January 1911 and was published on page 55 of the March 1911 American Chess Bulletin:

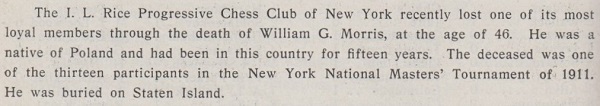

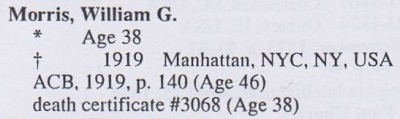

Both players are in the group photograph shown in C.N. 7871. Regarding Morris (misnamed ‘Harry Morris’ on a number of webpages which give his loss to Capablanca), below is the report of his death on page 140 of the May-June 1919 American Chess Bulletin:

That report was referred to unquestioningly in Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia (Jefferson, 1987), but the unpublished 1994 edition had an amendment:

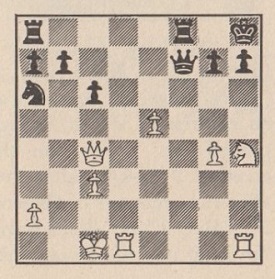

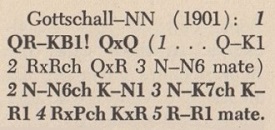

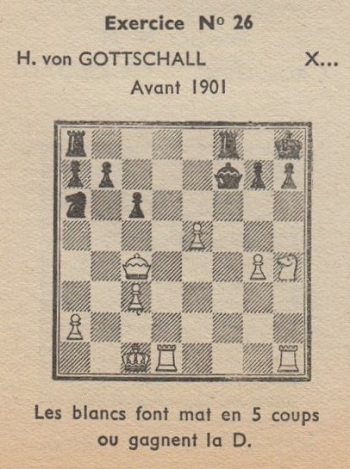

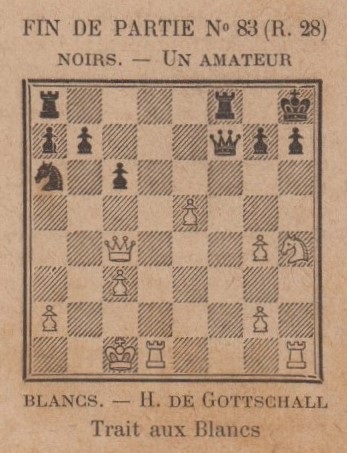

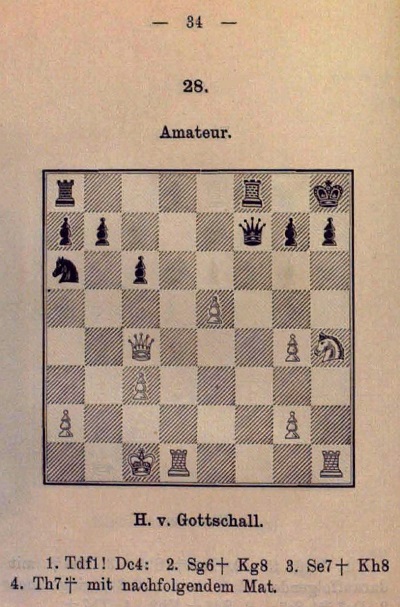

9136. von Gottschall v N.N.

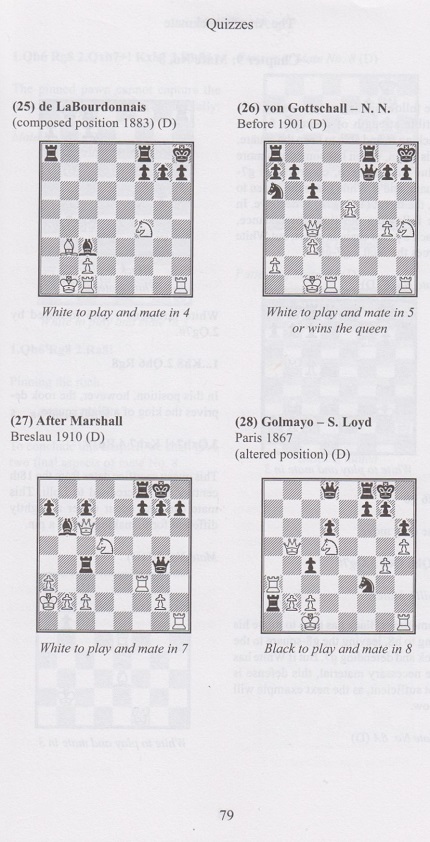

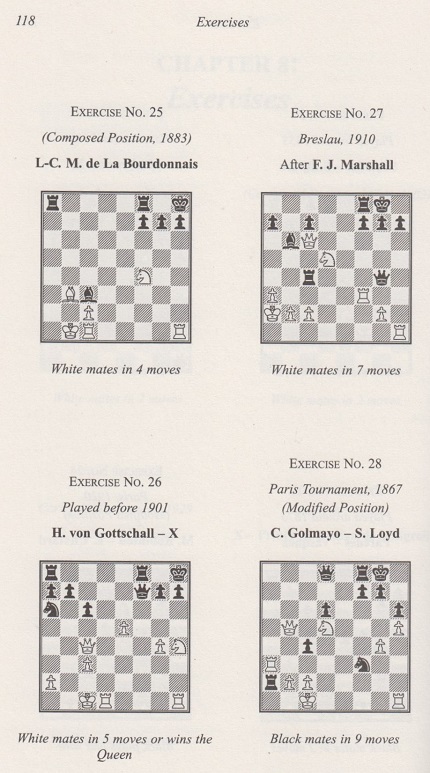

From pages 274-275 of Tal’s Winning Chess Combinations by M. Tal and V. Khenkin (New York, 1979):

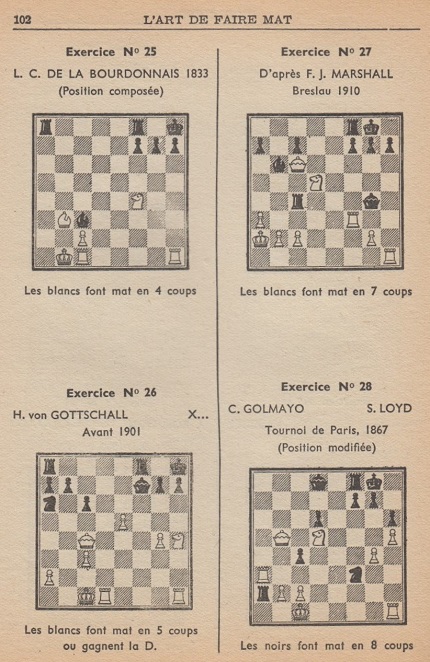

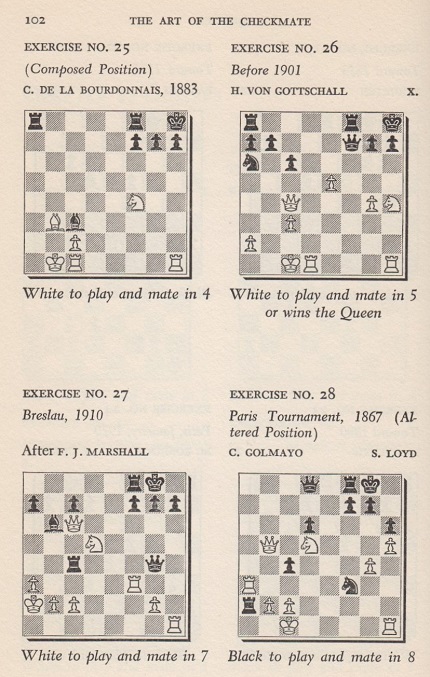

It is unclear why the game is dated 1901. ‘Before 1901’ was the information on page 102 of L’art de faire mat by G. Renaud and V. Kahn (Monaco, 1947), at the end of chapter eight:

We eventually found the position (with a white pawn also on g2) on page 19 of La Stratégie, 15 January 1889:

As explained on the magazine’s previous page, ‘R. 28’ in the heading indicates that it was position 28 in Vademecum der Kombinations-Praxis by A. Roegner (Leipzig, 1889), and we are grateful to Henk Chervet of the Koninklijke Bibliotheek in The Hague for providing the page in question (which gives no further particulars):

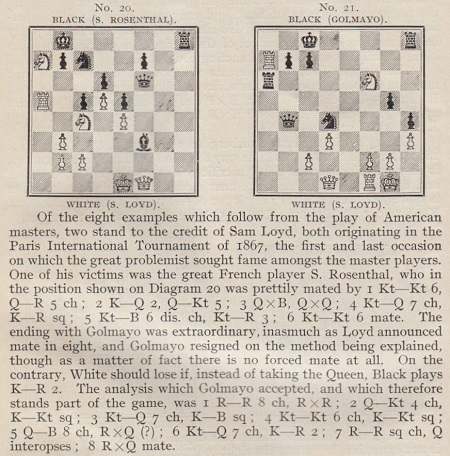

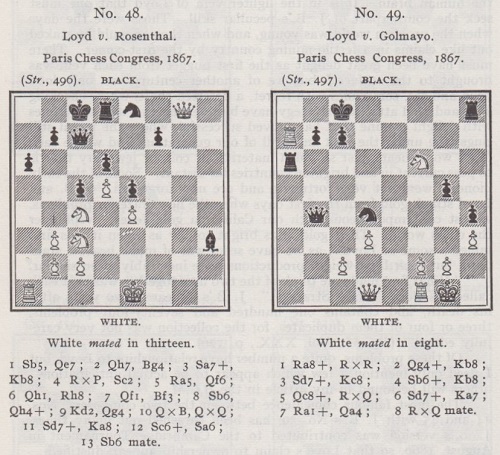

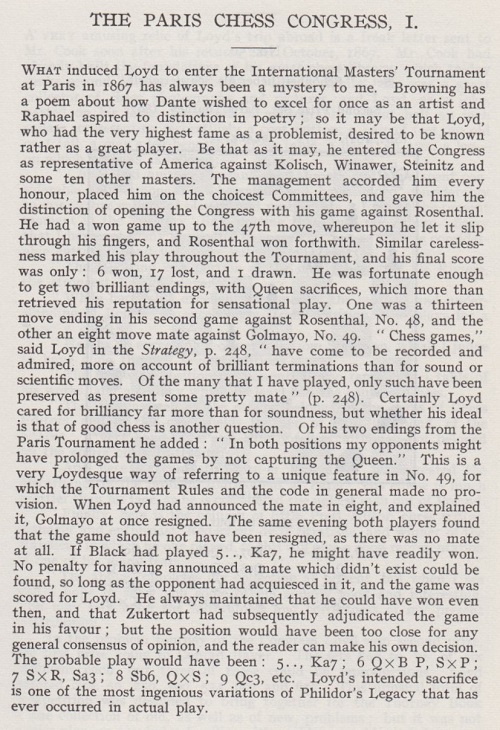

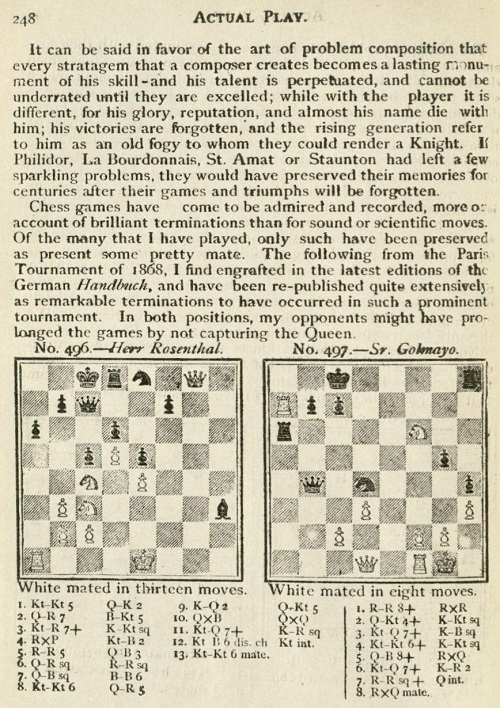

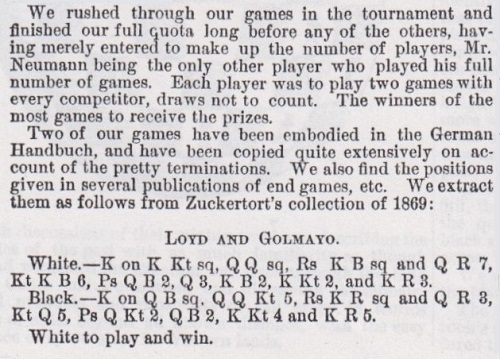

9137. Golmayo v Loyd

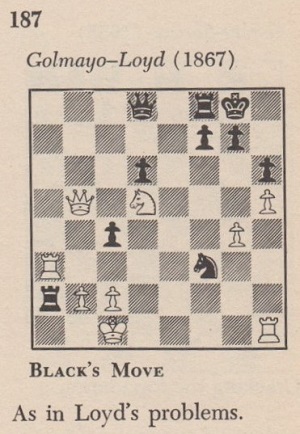

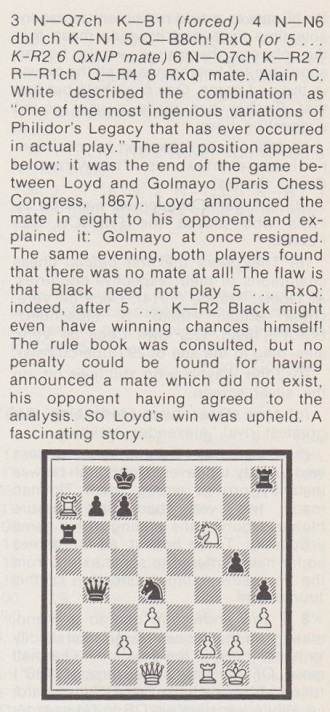

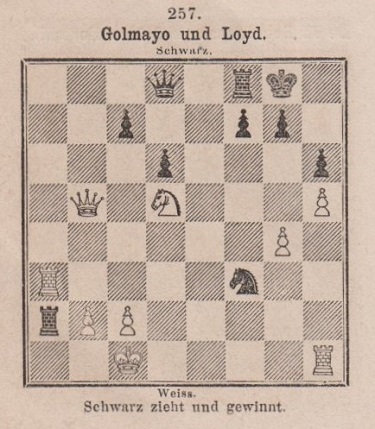

Han Bükülmez (Ecublens, Switzerland) asks for documentation with regard to the contradictory accounts of a famous 1867 game between Celso Golmayo and Sam Loyd.

We begin with a selection of secondary sources, presented with a minimum of comment:

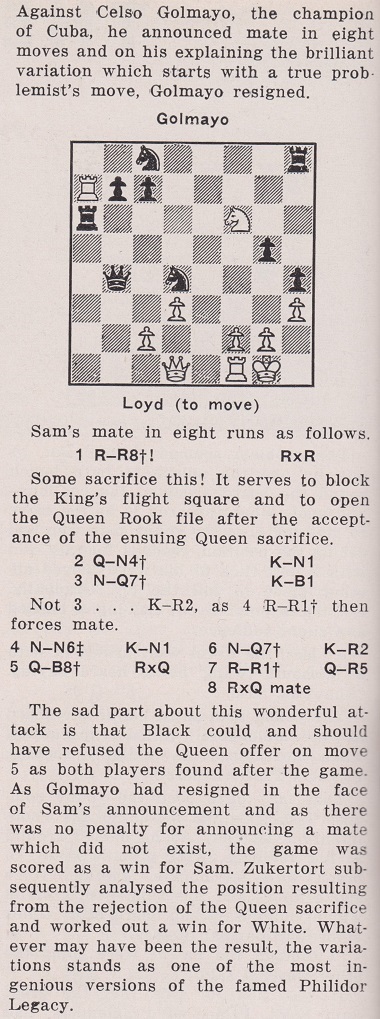

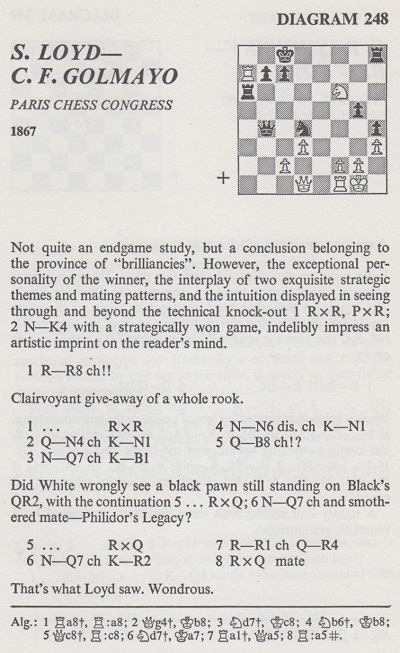

- BCM, November 1917, page 352 (article on queen sacrifices by J.A. Woollard):

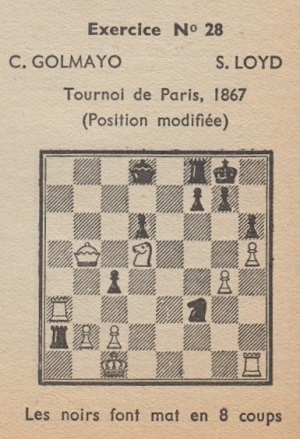

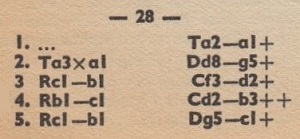

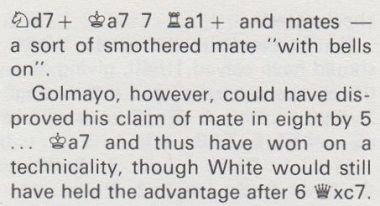

- L’art de faire mat by Georges Renaud and Victor Kahn (Monaco, 1947), pages 102 and 191:

- Chess Review, March 1959, page 78 (from an article entitled ‘The Great Sam’ by Bruce Hayden):

The same position (but with, of course, c8 occupied by the black king) was given by Pal Benko on page 87 of the April 1967 Chess Life.

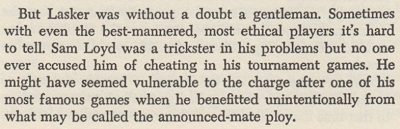

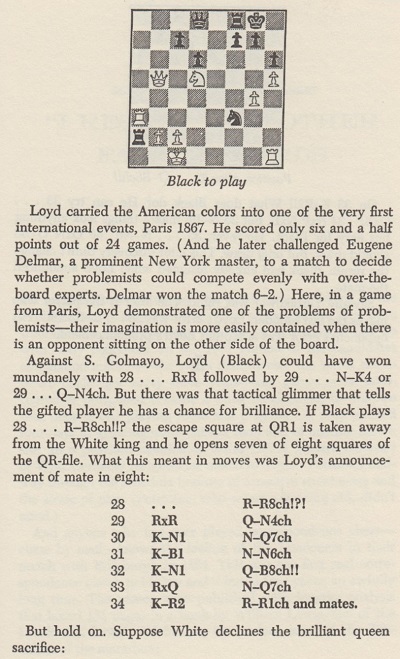

- Chess to Enjoy by Andrew Soltis (New York, 1978), pages 48-50:

The reference to ‘S.’ Golmayo is an evident error.

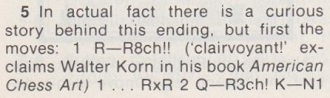

- American Chess Art by Walter Korn (London, 1975), page 367:

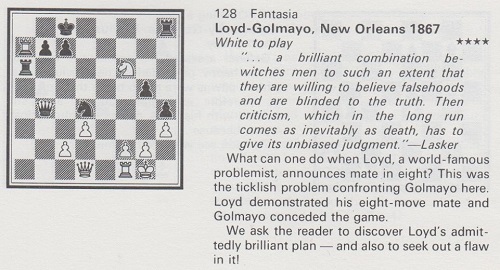

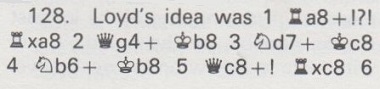

- Blunders and Brilliancies by Ian Mullen and Moe Moss (Oxford, 1990), pages 47 and 113-114:

It is hard to understand why New Orleans, rather than

Paris, was given as the venue. The ‘brilliant combination’

quote comes from the discussion of the Evergreen Game in Lasker’s

Manual of Chess, e.g. on page 303 of the New York,

1927 edition.

- Tal’s Winning Chess Combinations by Mikhail Tal and Victor Khenkin (New York, 1979), pages 289 and 402:

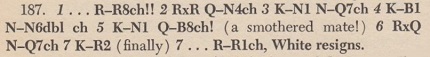

- CHESS, December 1982, pages 212 and 221 (quiz by Hugh Courtney):

For analysis of the conclusion of the game (in which Loyd was Black), see pages 58-59 of Winning Chess Combinations by Yasser Seirawan (London, 2006).

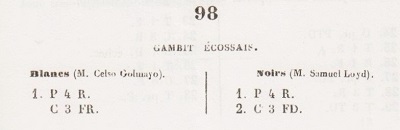

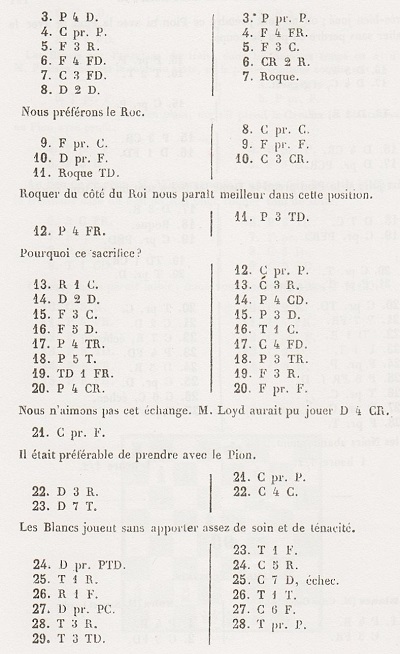

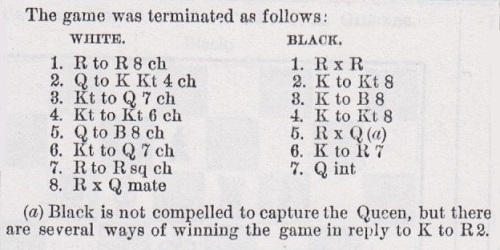

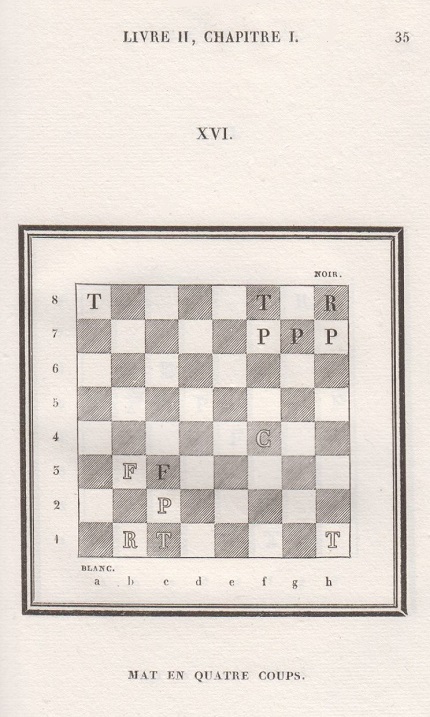

Below is the game as published on pages 191-193 of the Paris, 1867 tournament book, Congrès international des échecs (Paris, 1868):

The statement in the final note that both sides played

the game very quickly is corroborated by the chart on page

lxxii of the tournament book, which added that the game

took place on 27 June 1867. As shown below, Loyd himself

wrote that he played rapidly throughout the tournament.

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 exd4 4 Nxd4 Bc5 5 Be3 Bb6 6 Bc4 Nge7 7 Nc3 O-O 8 Qd2 Nxd4 9 Bxd4 Bxd4 10 Qxd4 Ng6 11 O-O-O a6 12 f4 Nxf4 13 Kb1 Ne6 14 Qd2 b5 15 Bb3 d6 16 Bd5 Rb8 17 h4 Nc5 18 h5 h6 19 Rdf1 Be6 20 g4 Bxd5 21 Nxd5 Nxe4 22 Qe3 Ng5 23 Qa7 Rc8 24 Qxa6 Ne4 25 Re1 Nd2+ 26 Kc1 Ra8 27 Qxb5 Nf3 28 Re3 Rxa2 29 Ra3 Ra1+ 30 Rxa1 Qg5+ 31 Kb1 Nd2+ 32 Kc1 Nb3+ 33 Kb1 Qc1+ 34 Rxc1 Nd2+ 35 Ka2 Ra8+ 36 Q moves R mates.

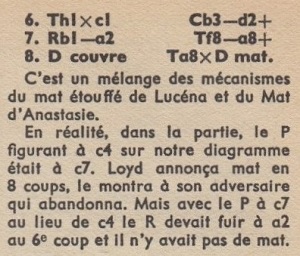

The finish was discussed in detail by Alain C. White on pages 46-47 of Sam Loyd and His Chess Problems (Leeds, 1913):

The passage referred to by A.C. White, from Loyd’s book Chess Strategy (Elizabeth, 1878), is shown below, courtesy of the Cleveland Public Library:

Loyd also wrote about the finish in his column on page 1646 of the Scientific American Supplement, 22 December 1877:

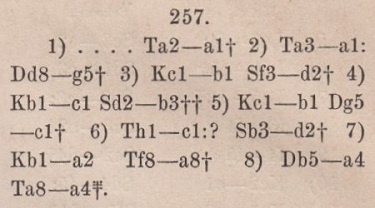

The ‘collection’ referred to in Loyd’s column (and here too he inverted the colours) was Sammlung der auserlesensten Schach-Aufgaben Studien und Partiestellungen by J.H. Zukertort (Berlin, 1869). From pages 46 and 72:

The present item illustrates the degree of confusion that may exist in chess literature even when a game-score, as published in the tournament book, is not in dispute.

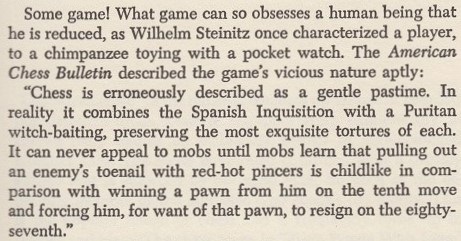

9138. The most exquisite tortures

From page 5 of Chess to Enjoy by A. Soltis (New York, 1978):

The Steinitz ‘once’ story was disposed of in C.N.s 1077 and 6590.

As regards the paragraph quoted, Soltis did not bother to state when during its long run (1904-63) the American Chess Bulletin published it.

9139. Capablanca in Kansas City

Patsy A. D’Eramo (North East, MD, USA) has found a cutting in the Chicago Daily Tribune, 21 February 1909, page 4, which refers to Capablanca and Banks and states:

‘In offhand games the brilliant young Cuban, however, won 11 games and lost only one – this to Newell Banks, the promising young expert at checkers who also plays an excellent game at chess.’

Our correspondent also notes reports about Capablanca in the Kansas City Times of 26 January 1909, page 5, and 6 February 1909, page 8.

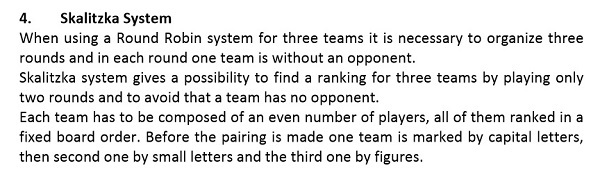

9140. ‘Skalitzka’

Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) asks about the exact justification for ‘Skalitzka’, as found on page 61 of the FIDE Arbiters’ Manual 2014:

A broader question is why FIDE issues documents before they have been converted into proper English.

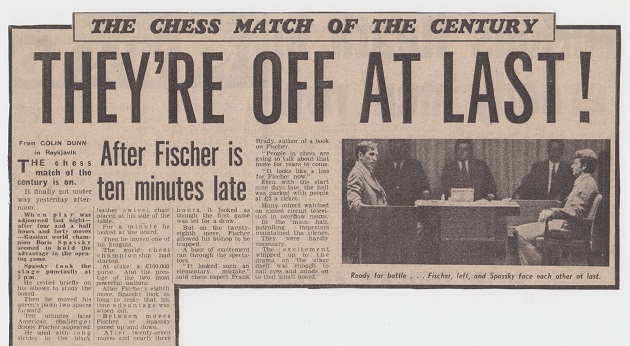

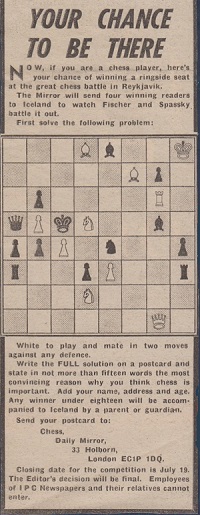

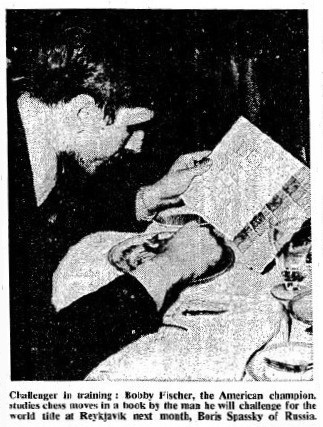

9141. Spassky v Fischer, 1972

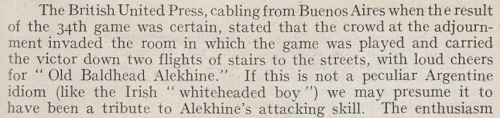

Below, from our archives, is a report in the Daily Mirror (London), 12 July 1972:

The same page had a two-mover by, we believe, Guy W. Chandler:

No record has been found of the Daily Mirror setting a problem-solving competition in 2014 for its readers to win a ringside seat in Sochi.

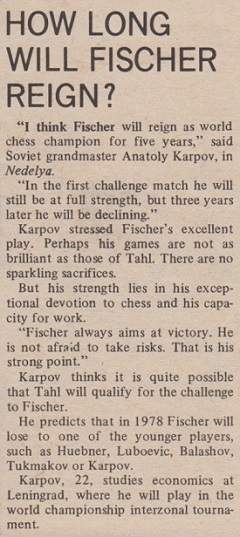

9142. Karpov’s predictions

From page 15 of Soviet Weekly, 2 June 1973:

9143. ‘Old Baldhead Alekhine’

Daily Express, 30 November 1927, page 1

The nickname was referred to on page 1 of the January 1928 BCM:

See too page 109 of The Kings of Chess by William Hartston (London, 1985).

9144. The top five

Daniel King and Yannick Pelletier at Biel, 2013 (photograph by Marie Boyard, reproduced with permission)

After our suggestions as to the top five Internet broadcasters, an item on the top five (current, general) chess magazines in English has been contemplated. Unfortunately, it is difficult to think of suitable candidates for places two to five.

9145. Chandler problem (C.N. 9141)

From Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England):

‘The two-mover from the Daily Mirror was indeed by Guy Chandler. Comins Mansfield quoted it in his Selected Two-Movers column in the September 1972 issue of The Problemist (page 252), although he gave the date of publication as 13 July, and not 12 July as indicated in C.N. 9141.

Mansfield wrote:

“It must be a rare, if not unique, experience for a composer to have one of his problems fetched by a special car from a distance of 12 miles. This happened to our esteemed secretary in July, when he had an urgent telephone call from a national newspaper. It proposed to offer a free holiday in Reykjavik to four readers who would solve a chess problem and answer in not more than 15 words a question such as ‘What makes chess worthwhile?’. The newspaper wanted immediately a ‘tough and entirely original problem’, but all that could be offered on the spot was an original two-mover. They gladly accepted this and sent a car down to Sutton to fetch it. This resulted in the publication of A on 13 July. With its nine variations and clear-cut theme it was just the sort of problem to stimulate popular interest.”’

The date discrepancy referred to by Mr McDowell is explained by the fact that the problem appeared in the Daily Mirror on both 12 and 13 July, the latter time on a page entirely devoted to chess. The problem was on page 9 on both days.

We have found the solution to the competition and the winners’ names on page 2 of the 4 August 1972 edition of the Daily Mirror:

9146. Mary

Kenny on Bobby Fischer

A rummage through boxes of newspaper cuttings on the 1972 world championship match suggests that the sharpest criticism of Fischer was written by Mary Kenny in the London Evening Standard. With no chess knowledge (she mixed up the words game, match and tournament and described Harry Golombek as a grandmaster) she concentrated on human aspects in her reports and wrote good prose. Below is an excerpt from her article ‘Genius maybe – but is he human?’ on page 17 of the 28 July 1972 edition. At that time she had been watching Fischer in Reykjavik for ten days:

‘Fischer, as is widely known, is not merely a megalomaniac but also a monomaniac; all the kilowattage of that 187-IQ brain has been channelled into the game, leaving aside almost everything else in the spectrum of life’s experiences.

He is a chess phenomenon, it is true; but he is also a social illiterate, a political simpleton, a cultural ignoramus and an emotional baby. There are no vibrations of humanity from him; when you look at him, his eyes are blank and unstaring, since he only has eyes for chess. He is a machine.

The article ended on a low note:

‘He will go on to be the undisputed chess king of the world, and destroy all challengers for some time to come. And then what?

Unlike old boxers, for old chess champions there is nothing else. Gligoric, the Yugoslav Grand Master who is writing a book about this very tournament, says that the end for chess geniuses is a towering solitude. They die in their 40s and early 50s. They fall into depression or paranoia, like Nimzowitch and Rubinstein; die alone of drink in foreign hotels like the great Alekhine, or sink into bewildering madness in a hospital straitjacket, like Fischer’s only comparably outstanding compatriot, Paul Morphy.

The way that the game possesses, spends and finally exhausts the minds that become engaged and committed to it is, in one sense, a tribute to its extraordinary magic, its brain-burning bewitchment.’

A curiosity is that the exact phrase about Fischer ‘also a social illiterate, a political simpleton, a cultural ignoramus and an emotional baby’ is in a recent work of fiction, The Sinking of the Basil Hall by James Street.

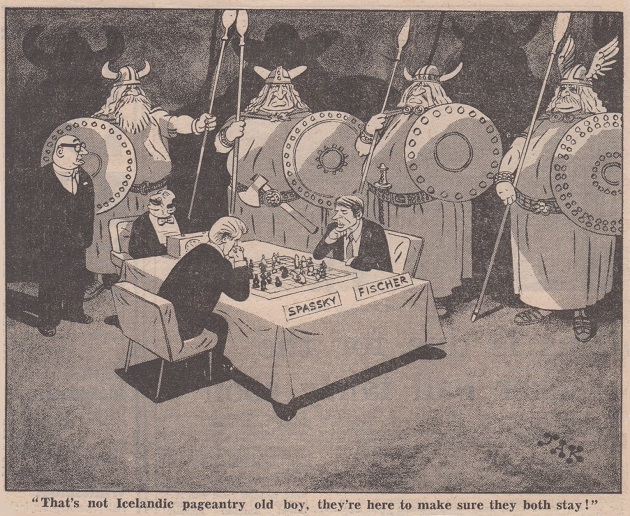

9147. 1972 cartoon by Jak

Evening Standard, 5 July 1972

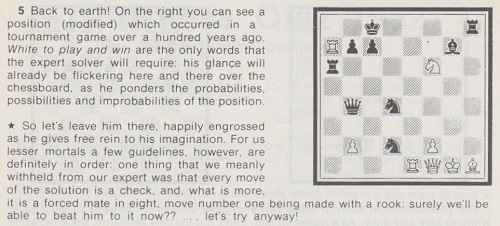

9148. Puzzle book

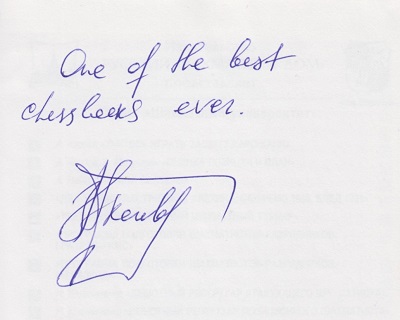

The enlarged edition of John Nunn’s Chess Puzzle Book (London, 2009) has been translated into Russian (Moscow, 2012), and we have a copy with an inscription by Vladislav Tkachiev:

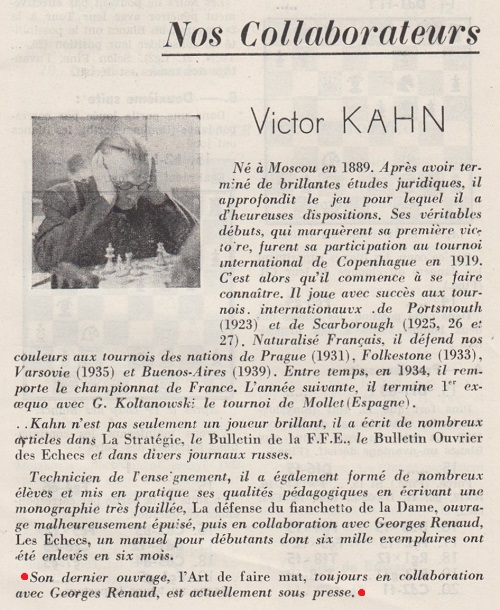

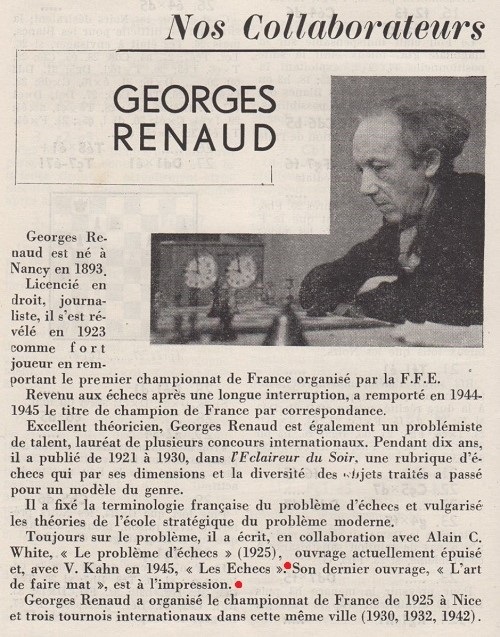

9149. L’art de faire mat

Two algebraic English-language editions of L’art de faire mat by Georges Renaud and Victor Kahn have been published recently, by Russell Enterprises, Inc. (Milford, 2014) and by Batsford (London, 2015). They are entirely different in approach and execution; one is a disaster, the other a missed opportunity.

The back cover of the Russell Enterprises, Inc. tome begins by erroneously stating that Renaud and Kahn wrote their book ‘in the early 1950s’, whereas the original appeared in the 1940s. It also proclaims:

‘In this new 21st-Century Edition, the antiquated English descriptive chess notation has been replaced by modern algebraic notation. Otherwise, it has remained true to its roots.’

The title has been changed (from The Art of the Checkmate to The Art of Checkmate, understandably enough), but ‘it has remained true to its roots’ is another way of saying that no attempt has been made to correct the colossal number of factual and other mistakes which appeared in the French original and/or in the English translation. Only very rarely is a glaring error corrected; on page 64 Emanuel Lasker’s year of death has been amended, but on page 21 Réti’s is still wrong. Fresh errors have been added.

The translation, by W.J. Taylor, was first published by Simon and Schuster, New York in 1953. The front of the dust-jacket:

The Batsford edition (just published, and entitled The Art of Checkmate) is described as a ‘new translation by Jimmy Adams’. His Foreword mostly comprises a lengthy quote from C.J.S. Purdy’s review (in Chess World, December 1955, pages 269-270) of the edition published by Bell in 1955. For example, Purdy wrote:

‘... the translation of Renaud’s and Kahn’s work reaches what I sincerely hope is an all-time low. I am no French scholar, but any fourth-former could fault this stuff. It’s murder. [That last sentence does not appear in the Batsford quotation.]

In almost every page one finds sentences that are not translations at all, or even paraphrases ...’

Purdy’s criticisms were justified, yet that is the translation on offer in the ‘new 21st-Century Edition’ from Russell Enterprises, Inc.

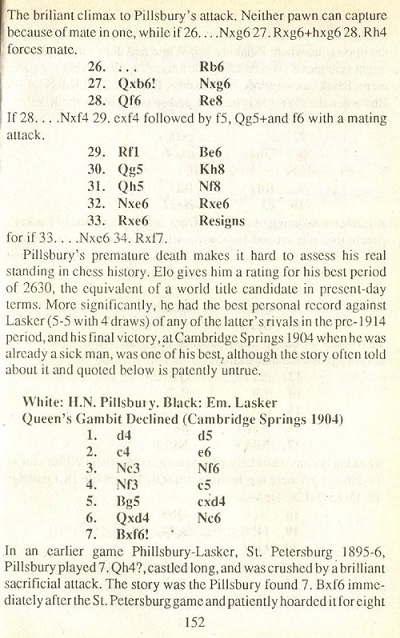

Although a spot-check shows that the Batsford translation is, of course, vastly superior, insufficient effort has been made to improve the game references. As an example, we take page 102 of the original French edition simply because, by chance, it contains two positions (von Gottschall v N.N. and Golmayo v Loyd) which have been discussed in recent C.N. items:

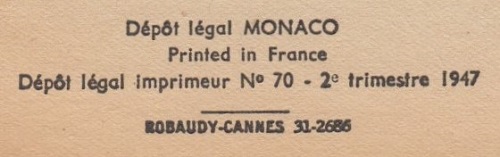

1947

1953

2014

2015

Thus all the English-language editions have ‘1883’ for the Labourdonnais position, even though Renaud and Kahn’s original French text was correct. The position had a page to itself in Labourdonnais’ book Nouveau traité du jeu des échecs (Paris, 1833):

Furthermore, all the editions have an incorrect date (1910 instead of 1912) for the Marshall position, even though it concerns one of the best-known games of all time.

The ‘new 21st-Century Edition’ makes no visible effort of any kind (although/because ‘Editing and proofreading’ are credited to Peter Kurzdorfer), and the Batsford book is disappointingly hit-and-miss with its factual corrections. A murky question is what improvements a translator, editor or publisher should reasonably be expected to make. The Renaud/Kahn book is replete with inaccurate or unduly vague game citations, but it is unrealistic to hope for detailed corrective research into them all. Investigating just one of them, the von Gottschall position (C.N. 9136), was time-consuming and merely showed that Renaud and Kahn’s ‘Avant 1901’ could have been ‘Avant 1889’. Even so, the reader is entitled to find correction of, at least, the most obvious mistakes, such as ‘Alekhine-Freeman’ in Chapter 16. There is no perfect solution, but publishers might consider announcing their plan to bring out a new edition of a given work, asking to be informed of any known errors or additional information. In the case of the Renaud/Kahn book, that could have resulted in a devastatingly long list.

As a final example (and it is a matter already pointed out in C.N. 19 – see pages 264-265 of Chess Explorations) we show two lines from page 73 of the ‘new 21st-Century Edition’ of The Art of Checkmate:

- For James read Joseph;

- For Harry read Henry;

- For 1842 read 1841;

- For 1926 read 1924;

- For Brittain’s read Britain’s.

9150. ChessBase.com

What on earth has happened to the standards of accuracy and integrity usually applied by ChessBase.com in the past?

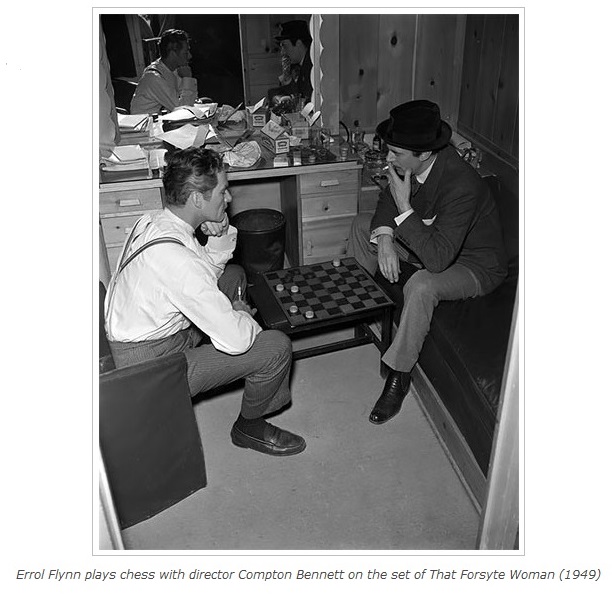

There is, for instance, an individual named Albert Silver who cobbles

together articles by indiscriminately hoovering up images

instantly available via an Internet search.

As regards the indiscriminate nature of his ‘work’, below is what appeared in (but has since been removed from) an article of his about chess and film stars which ChessBase.com posted on 23 February 2015:

9151. chessgames.com

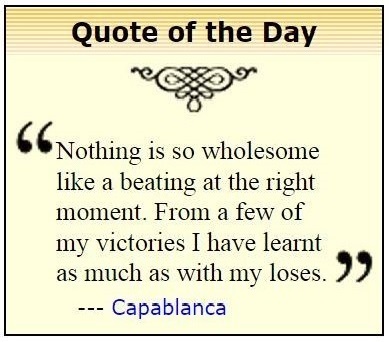

From the main page of chessgames.com, 12 March 2015:

- For ‘Nothing is so wholesome’ read ‘Nothing is so healthy’;

- For ‘like a beating at the right moment’ read ‘as a thrashing at the proper time’;

- For ‘From a few of my victories I have learnt’ read ‘and from few won games have I learned’;

- For ‘as much as with my loses [sic]’ read ‘as much as I have from most of my defeats’;

- For ‘Capablanca’ read ‘Capablanca, My Chess Career (London, 1920), page xv’.

9152. Nardus

Much information about Léonardus Nardus (the index has dozens of references to him) is available in a book published earlier this year in the United States: The William Van Horne Collection by Mary Eggermont-Molenaar.

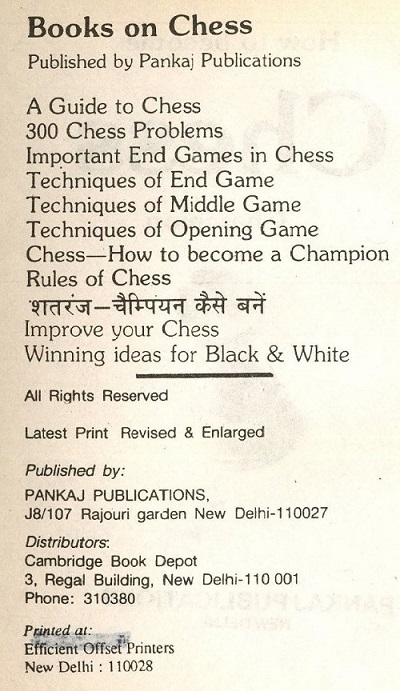

9153. How to become Chess Champion

Gordon Taylor (Kanata, Ontario, Canada) recently acquired

How to become Chess Champion (Pankaj Publications,

New Delhi), a 263-page book with no publication date or

author mentioned. The imprint page:

Our correspondent also noted that an on-line vendor was offering a book with the same title and from the same publisher but with authorship ascribed to Philip Robar, who is mentioned in An Indian Copying Mystery.

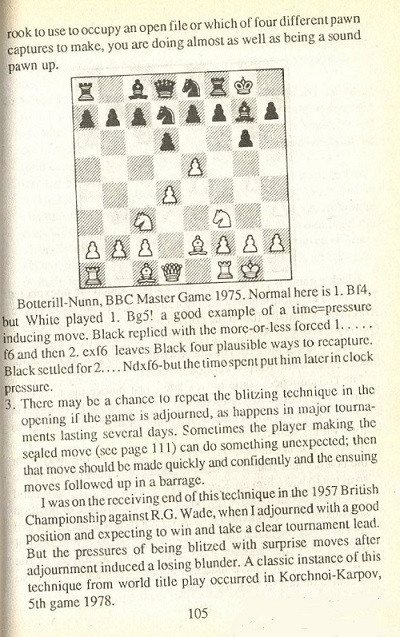

Mr Taylor’s particular attention was drawn to a passage on page 105:

‘Sometimes the player making the sealed move (see page 111) can do something unexpected; then that move should be made quickly and confidently and the ensuing moves followed up in a barrage.

I was on the receiving end of this technique in the 1957 British Championship against R.G. Wade, when I adjourned with a good position and expecting to win and take a clear tournament lead. But the pressures of being blitzed with surprise moves after adjournment induced a losing blunder.’

Mr Taylor concluded that the game in question was Wade v Barden, Plymouth, 1957, and he has asked us to comment on a sample of seven full pages which he has kindly forwarded. They include these two:

We can say that all seven pages are copied, in full, from Play Better Chess by Leonard Barden (London, 1980). The two shown above are from, respectively, pages 143 and 58.

9154. ‘Chess is life’

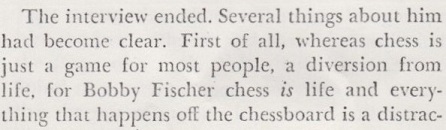

From Stephen Wright (Vancouver, Canada):

‘The phrase “Chess is life” is frequently attributed to Fischer, but with no source given. The January 1962 issue of Harper’s Magazine has an article by Ralph Ginzburg, “Portrait of a Genius As a Young Chess Master”, which contains the following:

“... whereas chess is just a game for most people, a diversion from life, for Bobby Fischer chess is life and everything that happens off the chessboard is a distraction.”

Is this the source of the “Chess is life” phrase, i.e. written by Ginzburg and not a direct quote from Fischer at all, or did Fischer actually say or write these words in a documented source?’

So far we have found no other citations relevant to Mr Wright’s query. Below is the passage as it appeared at the bottom of page 54 of Harper’s Magazine, January 1962:

9155. The Ginzburg-Fischer interview

Ralph Ginzburg’s article was published on pages 49-55 of Harper’s Magazine, January 1962. It was reprinted on pages 189-195 of CHESS, 12 March 1962, and many extracts are on pages 35-39 of Bobby Fischer’s Conquest of the World's Chess Championship by Reuben Fine (New York, 1973).

The circumstances and context of the interview were discussed by Frank Brady on pages 46-47 of Profile of a Prodigy (New York, 1973) and on pages 137-139 of Endgame (New York, 2011). In 1984 (C.N. 718) Frank Skoff (Chicago, IL, USA) gave his view:

‘I doubt very much that Fischer was fairly dealt with. One can tell the truth selectively and still miss the mark. Ginzburg’s disposal of the tapes makes me suspicious since now no-one can check them against the printed interview for accuracy and completeness. Brady does not indicate how Ginzburg “disposed” of the tapes: were they sold or destroyed? Why? After all, Fischer was already a national figure, and surely any interviewer would keep the tapes in order to answer any possible criticisms that might arise after publication of the interview. Fischer did not get a square deal in my opinion.’

Regarding the tapes, in Profile of a Prodigy (page 47) Frank Brady reported Ginzburg’s claim ‘that he had disposed of them years earlier’. Subsequently, in Endgame (page 139), Brady was more specific: ‘Ginzburg said he destroyed all of the research materials that backed up the article.’

It may well be the most ‘colourfully quotable’ article ever written about a leading chess master, but the hallmark of a good writer is self-restraint when in possession of colourful material. How exactly should a biographer of Fischer handle the Ginzburg interview? Is quoting from it unfair to Fischer? If so, which parts? (Is it known whether he accepted some of the article but rejected specific points?) Does a simple forewarning to readers that the article has been disputed by Fischer and others give a chronicler carte blanche to quote salivatingly all the juiciest bits? Or, conversely, is questioning the article’s authenticity unfair to Ginzburg? And can a writer who refrains from using it be accused of pro-Fischer bias? That issue was touched on by W.H. Cozens on page 373 of the October 1974 BCM.

On page 139 of Endgame Brady went beyond the question of accuracy:

‘One can never know the full truth, of course, but even if Ginzburg merely reported verbatim what Bobby had said, it was a cruel piece of journalism, a penned mugging, in that it made a vulnerable teenager appear uneducated, homophobic and misogynistic, none of which was a true portrait.

Previous to this, Bobby had already been wary of journalists. The Ginzburg article, though, sent him into a permanent fury and created a distrust of reporters that lasted the rest of his life.’

Whatever effect the article had on Fischer, there is no place for wishful thinking and dramatic assumptions about the immediate general aftermath. Given the many outlandish, and appalling, statements ascribed to Fischer in the Ginzburg interview, it is all too easily imagined that in 1962 the article ‘brought Fischer widespread ridicule and hostility’ and ‘sent shockwaves around the chess world’. Not at all. In the major English-language chess magazines of the time (Chess Review, Chess Life, the American Chess Bulletin, the BCM and CHESS) the reaction to publication of the Harper’s Magazine article was either very muted or non-existent.

9156. chessgames.com (C.N. 9151)

From Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore):

‘Regarding the botched Capablanca quote at chessgames.com (C.N. 9151), the site has not explained where its text came from or why it failed to use Capablanca’s own original English version (of what is, after all, a very famous remark). The faulty text remained as the “Quote of the Day” for a full day before being replaced, unsurprisingly, by another sourceless quote.

Why does chessgames.com treat chess, and the chess public, with so little respect? A couple of weeks ago I commented on my Twitter page: “It is difficult to look at chessgames.com for even 10-15 seconds without seeing something wrong.”

Glancing at the site’s main page today (14 March 2015), I see that it is now attributing a quote to “André Philidor”:

Why would anybody believe that Philidor wrote about “skittles”? My initial search has turned up no pre-twentieth-century occurrences of the quote; it appeared, with no mention of Philidor or anyone else, on page 81 of the December 1904 issue of Lasker’s Chess Magazine. But, of course, the onus is on chessgames.com either to specify an authoritative source or to remove the quote. To avoid further embarrassing mishaps, the site has only to follow the recommendation in C.N. 8651: “Give the source of a quote if it is known. If it is not known, do not give the quote.”’

9157. Simultaneous exhibition in Haarlem

Wanted: more information about this photograph, which is from page 69 of Alt om Skak by B. Nielsen (Odense, 1943), in the chapter on Alekhine:

9158. Punctuation

On the subject of punctuation in chess game-scores, Achim Engelhart (Illerkirchberg, Germany) writes:

‘Robert Hübner’s strict scientific convention is admirable:

“I have attached question marks to the moves which change a winning position into a drawn game, or a drawn position into a losing one, according to my judgement; a move which changes a winning game into a losing one deserves two question marks. I have distributed question marks in brackets to moves which are obviously inaccurate and significantly increase the difficulty of the player’s task, but do not alter the evaluation of the position.” (Source: Twenty-five Annotated Games, page 7, just before the excerpt given in your feature article.)

On page 13 of Chess Life, March 2000 Andrew Soltis referred to a “Laziness Index” for annotators, based on how often they used the symbol “!?”.

It seems that around the beginning of the twentieth century question marks and exclamation marks were still used quite rarely in English-language publications but frequently in German-language ones. However, after the First World War, at the latest, such punctuation appears to have permeated English-language publications too, with a few exceptions.

Was Capablanca the only world champion to eschew question marks? He did not use them in his main works (My Chess Career, Chess Fundamentals, A Primer of Chess and his book on the 1921 world championship match), although he did award exclamation marks. The only Capablanca annotations with question marks that I could find are in your book on him, in chapters 11-13. These are translations from Soviet magazines, and I wonder whether the Russian-language editors added question marks to moves which Capablanca’s text called poor.

Throughout The Basis of Combination in Chess J. du Mont used no punctuation at all. The same applies to Tartakower and du Mont’s 500 Master Games of Chess and 100 Master Games of Modern Chess. This may be relevant to the exact nature of the cooperation between the two authors, bearing in mind that Tartakower was known for a humorous style which lavished all kinds of punctuation on moves.’

9159. Aristide Gromer

A brief item on Aristide Gromer from page 3 of the Democrat-Forum (Maryville, Missouri), 26 April 1923:

9160. L’art de faire mat (C.N. 9149)

In the bibliography on page 354 of The Encyclopedia of Chess (London, 1977) Harry Golombek praised Renaud and Kahn for their ‘outstandingly good’ book on the middlegame, which, he said, was ‘published originally in Monaco 1943’. The date is incorrect. We have double-checked with the Cleveland Public Library and the Koninklijke Bibliotheek in The Hague; both confirm that their copies of the first edition are dated 1947.

Moreover, we note that Le monde des échecs, June 1946, page 149, and July-August 1946, page 218, had articles on Kahn and Renaud which announced that L’art de faire mat would be appearing shortly:

We also have the second edition of L’art de faire mat. Although the title page states ‘Deuxième édition, revue, corrigée et augmentée’, the imprint page has ‘Copyright 1947’, and an otherwise blank page at the end refers to the second quarter of 1947:

Were there really two editions in 1947? Our collection also includes a ‘troisième édition’ (Monaco, 1952), as well as later unnumbered editions. No French-language version has been found which strives for accuracy in the game references.

9161. Renaud, Kahn and Alekhine

From page 140 of the May 1951 Chess Review, in an article entitled ‘Recollections of Alekhine’ by Harry Golombek:

‘Witness, too, his writings on the game, which must rank with the best that the chess world has produced. The number of young players whose imagination has been stirred and for whom fresh vistas have been opened by his My Best Games of Chess 1908-1923 must be legion.

It is true, however, that in writing this book and others, he owed much to other masters and was not always frank in acknowledging the debt. In his collections of games, for example, he owed a great deal to the French masters, Renaud and Kahn.’

Did either Renaud or Kahn ever write about the matter? And did Golombek give more details, e.g. to justify his words ‘this book and others’ and ‘for example’?

9162. Reykjavik, 1972

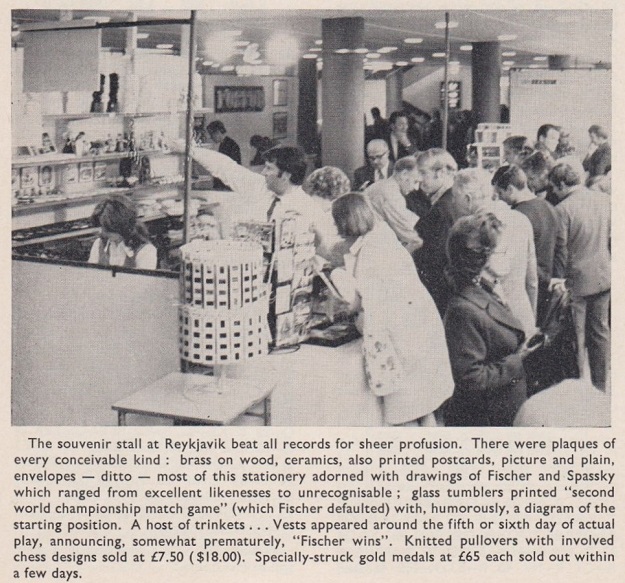

Given the number of journalists present during the Spassky v Fischer world championship match, chess magazines of the time had surprisingly few photographs of the general chess scene in Reykjavik, as opposed to pictures of the champion and challenger. One was on page 5 of CHESS, October 1972:

9163. The French Defence

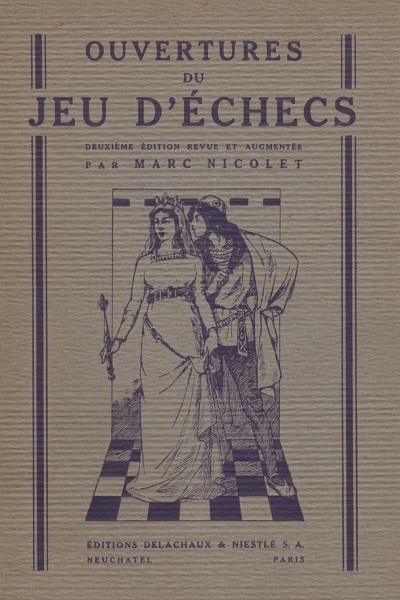

On page 18 of the second edition of Ouvertures du jeu d’échecs (Neuchâtel and Paris, 1929) Marc Nicolet wrote a single sentence on the purpose of 1...e6 after 1 e4:

‘L’idée du coup e7-e6 est de couper l’attaque du F contre le pion f7.’

9164. White moves first (C.N.s 5447 & 5454)

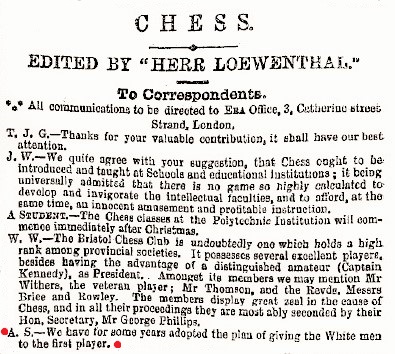

Rod Edwards (Victoria, BC, Canada) sends an extract from the correspondence section in Löwenthal’s column in the Era, 2 December 1860, page 13:

9165. Spielmann

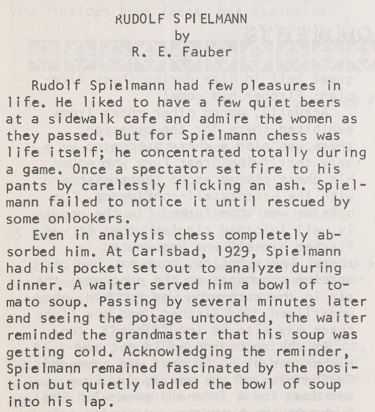

The stories about Rudolf Spielmann referred to in C.N. 8559 can be found at the start of an article by R.E. Fauber on pages 268-269 of the Chess Digest Magazine, December 1974:

This model of how not to write about chess history re-appeared on page 168 of Fauber’s book Impact of Genius (Seattle, 1992).

9166. The English Opening

Wanted: instances during Howard Staunton’s lifetime of 1

c4 being called the English Opening on the basis of his

espousal of the move.

9167. The ‘big red book’ (C.N. 8962)

The photograph shown in C.N. 8962 was also published on page 5 of The Times, 26 June 1972:

As mentioned in the earlier C.N. item, the book was by A.S. Liwschitz (Livshits).

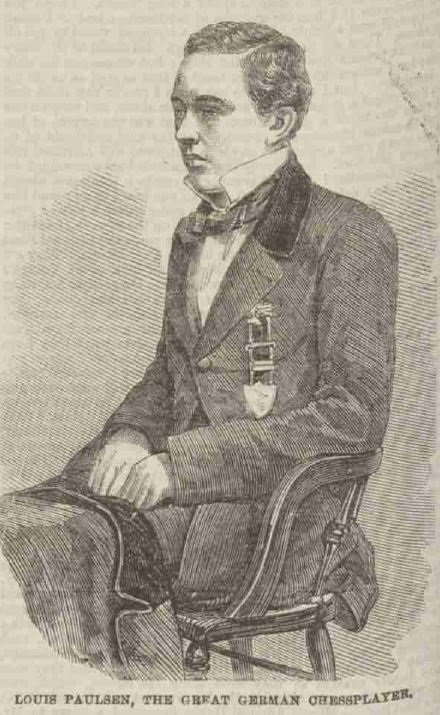

9168. Louis Paulsen

From page 220 of the Penny Illustrated Paper, 3 October 1863:

Two photographs of the medal (New York, 1857) are on page 23 of Louis Paulsen 1833–1891 und das Schachspiel in Lippe 1900–1981 by Horst Paulussen (Detmold, 1982).

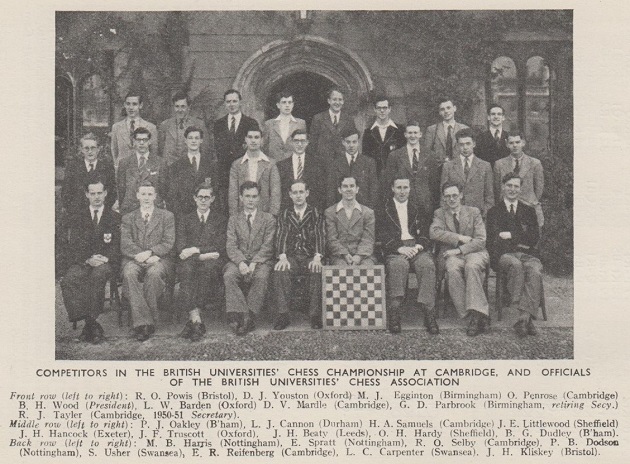

9169. Cambridge, 1950

Oliver Penrose – H.A. Samuels

Cambridge, July 1950

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Nc3 d6 6 Be2 g6 7 O-O Bg7 8 Be3 O-O 9 Nb3 Be6 10 f4 Na5 11 f5 Bc4 12 g4 d5 13 Nxa5 Qxa5 14 Bxc4 dxc4 15 g5 Rad8 16 Qf3 Nd7 17 Nd5 Bxb2 18 Nxe7+ Kh8 19 Qh3 Ne5 20 Rab1 Qa3 21 Rf4 Bd4

22 Qxh7+ Resigns.

This game, won by an eminent member of an eminent family, was played in round nine of the inaugural BUCA (British Universities Chess Association) individual championship, held at Trinity College, Cambridge on 17-28 July 1950. Source: page 11 of the Universities Chess Annual, November 1950. The photograph below was on page 6 (and on page 37 of CHESS, November 1950):

9170. Simultaneous exhibition in Haarlem (C.N. 9157)

Dan Scoones (Port Coquitlam, BC, Canada) points out that the boards and the fact that Alekhine was making a move with his right hand indicate that the photograph has been reversed.

We give an enlarged version in amended form.

Photographic evidence that Alekhine was right-handed can be found in C.N.s 6328 (signing a contract) and 7981 (cutting a cake), but clips in Chess Masters on Film show him making moves with his left hand.

9171. Thomas Jefferson (C.N. 8071)

Stephen L. Carter (New Haven, CT, USA) draws attention to the Monticello.org webpage, which lists many references to chess in Thomas Jefferson’s papers.

9172. The Mozart of chess (C.N.s 7645 & 7662)

‘Si Capablanca dans les échecs était un Mozart ou un Raphaël, au jeu clair et à la technique irréprochable, chez Alekhine, nous trouvons, outre ces qualités, un élément diabolique qui échappe à l'analyse. Son jeu est plein de poison et sa familiarité avec l’échiquier n’a jamais été égalée.’

Source: page 16 of Les échecs by G. Renaud and V. Kahn (Monaco, 1944).

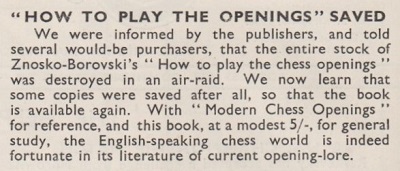

9173. ‘Destroyed in an air-raid’

From page 82 of CHESS, March 1941:

Below is an entry about Znosko-Borovsky’s book on page 204 of Douglas A. Betts’ Annotated Bibliography:

Three of our copies of Znosko-Borovsky’s book have an imprint page stating ‘Reprinted 1941’. In each case the title page specifies ‘Second Edition revised ...’, and no copy with ‘Third Edition’ on the title page has been found.

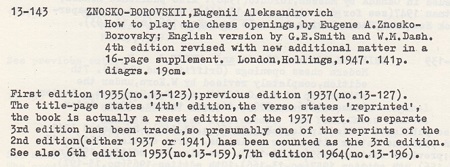

9174. Faithfully Yours (C.N. 9101)

Regarding the play Faithfully Yours we have acquired a playbill dated October 1951. Dominated by cigarette advertisements (Vivian Blaine: ‘A singer must think of her throat. I’ve found the cigarette that suits my throat best is Camel.’ Dennis James: ‘If you want a treat instead of a treatment ... treat yourself to Old Golds.’), the playbill has nothing of interest about Faithfully Yours except some basic information:

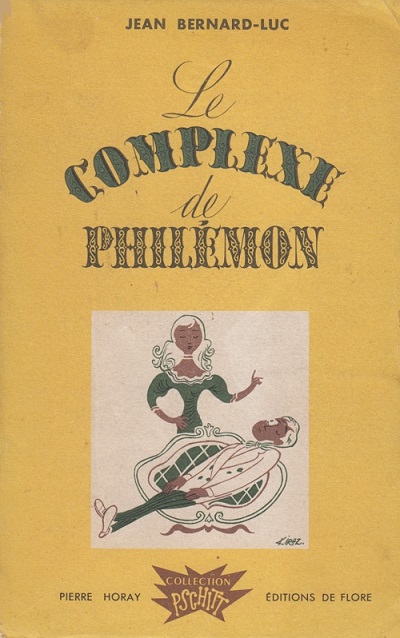

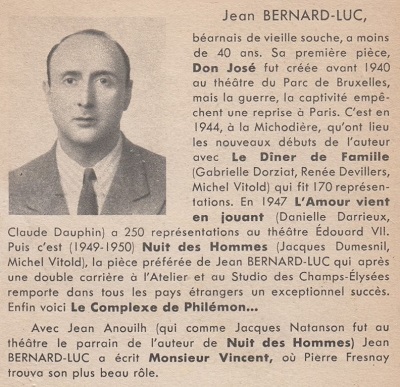

The play by Jean Bernard-Luc is Le complexe de Philémon, a three-act comedy first performed at the Théâtre Montparnasse-Gaston Baty in Paris on 10 December 1950. The text was published the following year:

From the back cover:

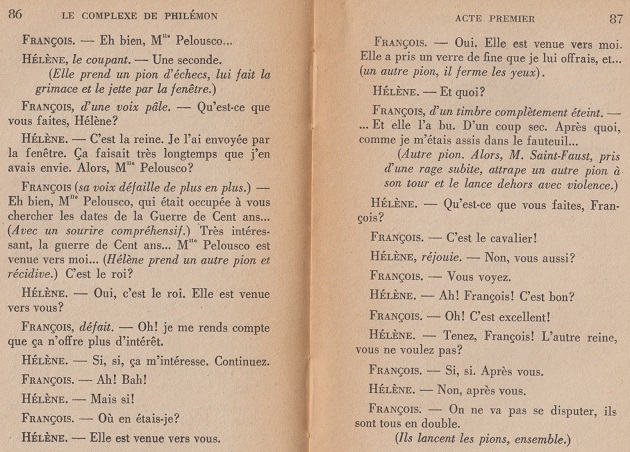

The chess content of Le complexe de Philémon is essentially limited to the throwing of chess pieces. An example:

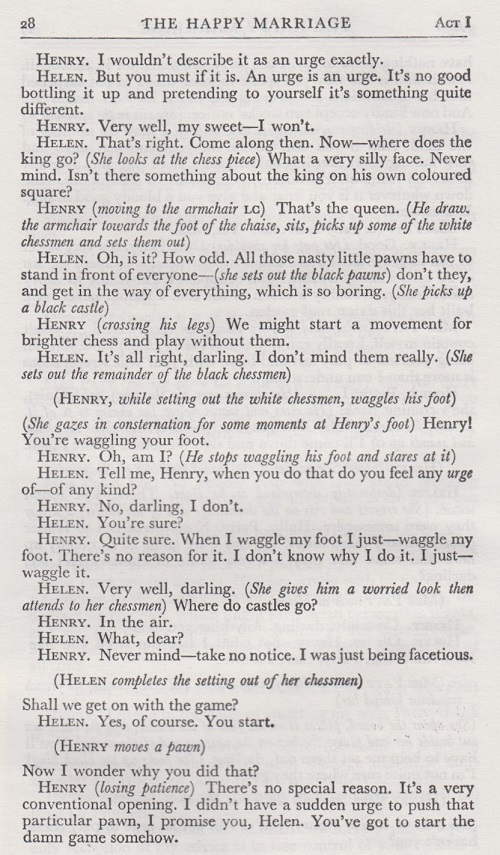

Le complexe de Philémon was also the basis for ‘a farcical comedy’, The Happy Marriage by John Clements, produced at the Duke of York’s Theatre in London on 7 August 1952 and published the following year by Samuel French. Below is a page from that ‘acting edition’:

The text of Faithfully Yours has not yet been found.

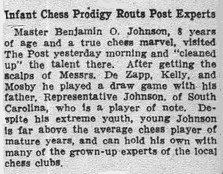

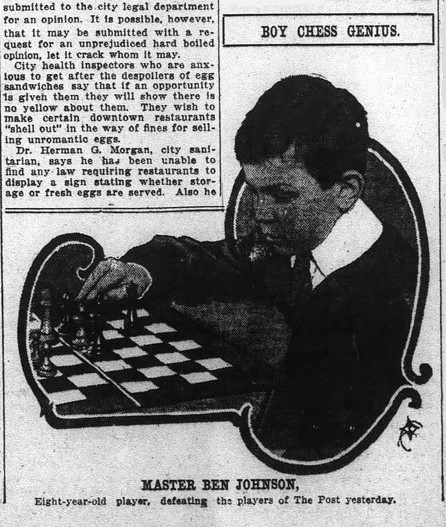

9175. Benjamin O. Johnson

Another ‘boy chess genius’:

Source: Washington Post, 24 January 1915, page 2.

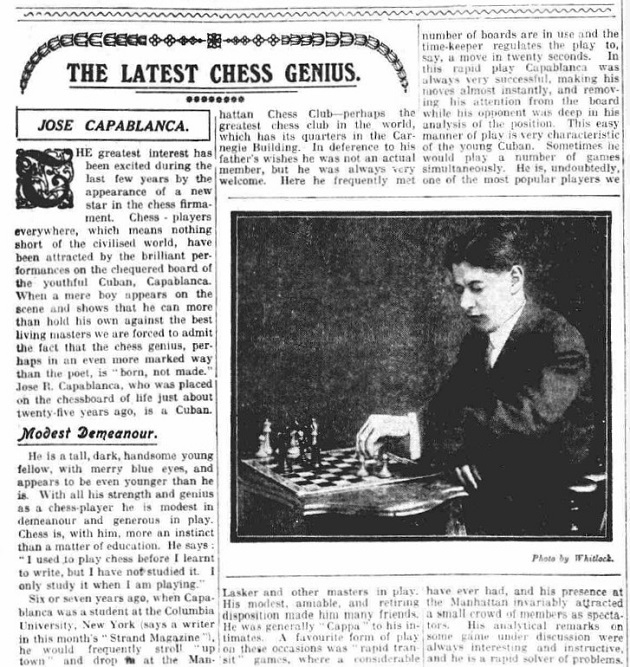

9176. Capablanca photograph

From page 6 of the Evening Despatch (West Midlands, England), 8 January 1914:

Can the board position be identified?

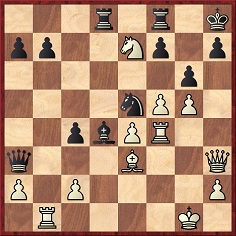

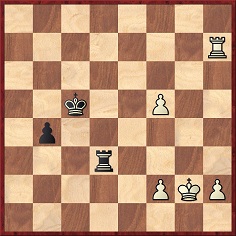

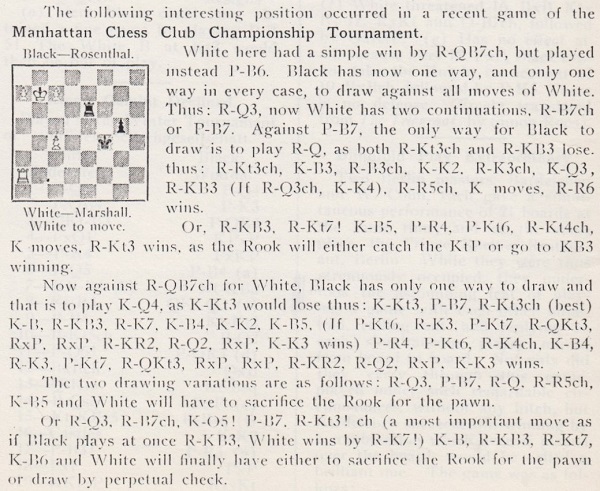

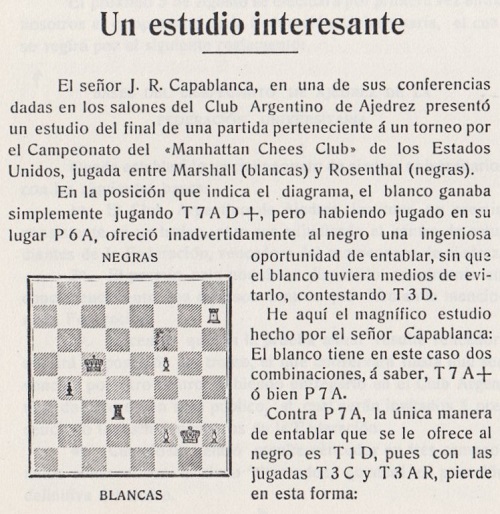

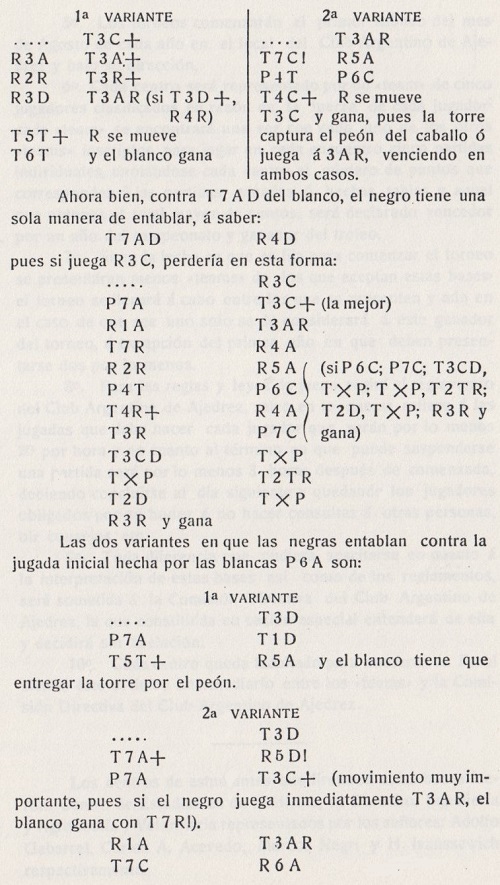

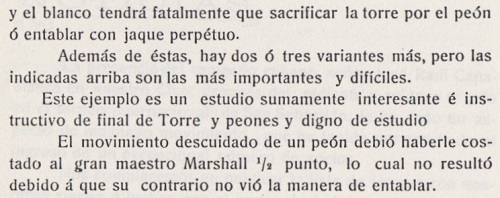

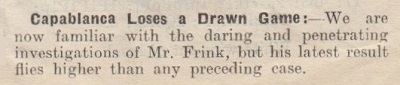

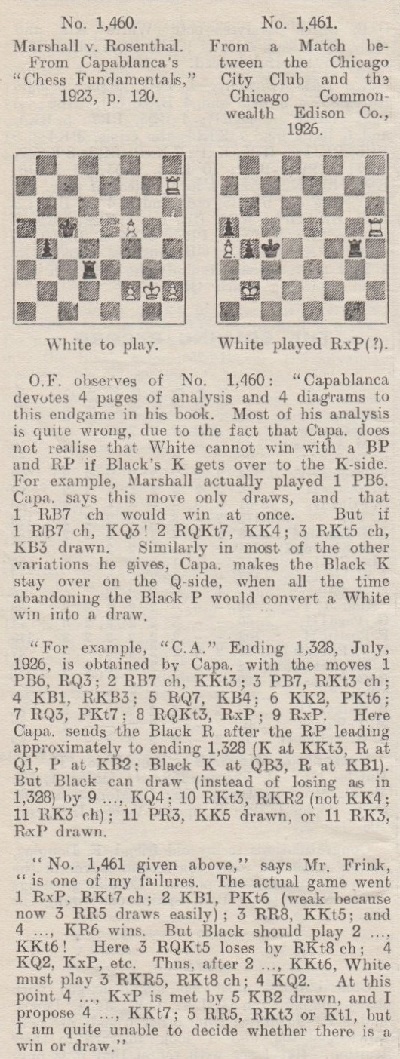

9177. Marshall v Rosenthal

White to move.

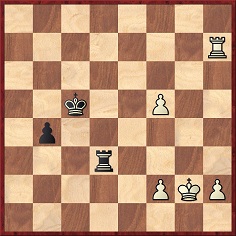

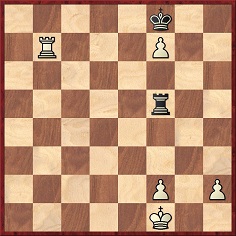

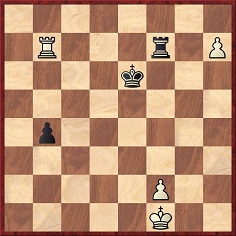

This position was discussed at length by Capablanca in the section ‘The danger of a safe position’ in Chess Fundamentals (London, 1921). As mentioned on page 22 of our book about him, he had analysed the ending on pages 117-118 of the Chess Weekly, 8 January 1910:

Page 310 of our book also noted that the following year Capablanca examined the position in a lecture in Buenos Aires, as reported on pages 54-56 of the Revista del Club Argentino de Ajedrez, April-June 1911:

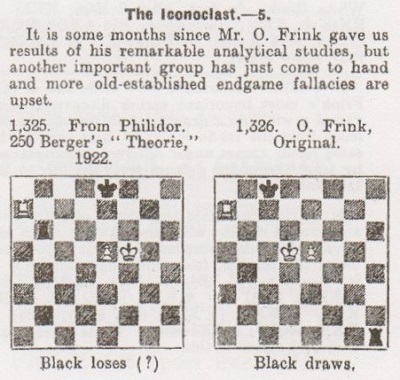

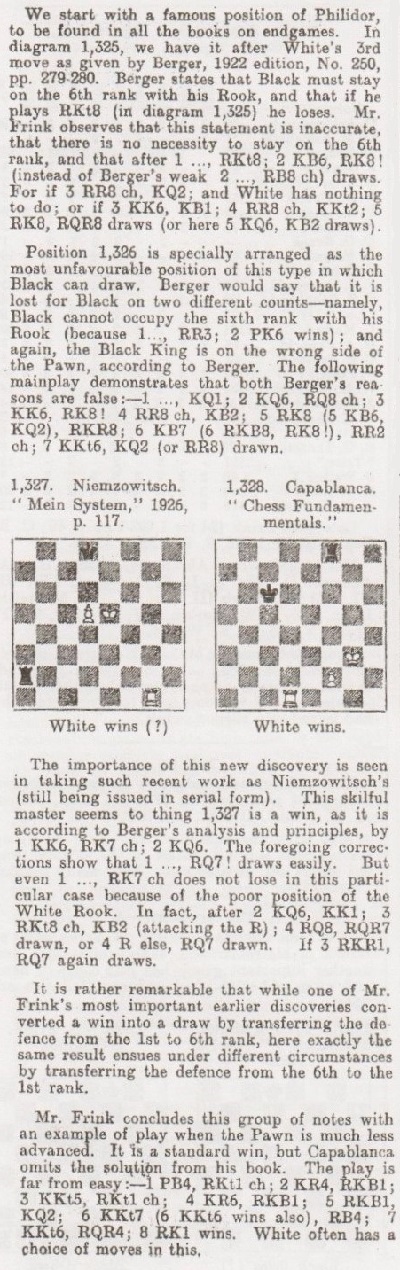

However, an item in T.R. Dawson’s Endings column on pages 297-298 of the July 1927 Chess Amateur should be noted:

Below is the material referred to in the penultimate paragraph, from Dawson’s column on pages 297-298 of the July 1926 Chess Amateur:

Are the analytical and theoretical observations of Orrin Frink correct, and can the full score of the Marshall v Rosenthal game be found?

9178. An incorrigible plagiarist

As related in the feature article The Guinness World Records Slump, over a third of Raymond Keene’s column on page 64 of The Spectator, 7 June 2008 was written by us. His plagiarism of our work was reported by Private Eye later that year and was discussed in detail by Justin Horton on pages 7-9 of the Autumn 2009 issue of Kingpin (an article available on-line).

Of course, such public exposure was not a chastening experience for Mr Keene. We add here that he subsequently plagiarized our Guinness material again, on page 139 of his book The Official Biography of Tony Buzan (Croydon, 2013). The full page can be viewed in our above-mentioned feature article. For example:

- ‘Indeed, the total space devoted to chess in the entire book is less than that accorded on page 113 to an exploit by Kathryn Ratcliffe (UK), who, on 25 October 2003 and with a tally of 138, broke her own record “for the most Smarties eaten in three minutes using chopsticks”.’

Our text in C.N. 3493, posted on 9 December 2004.

- ‘Indeed, the total space devoted to mental records in the entire book is less than that accorded to an exploit by Kathryn Ratcliffe (UK), who, on 25 October 2003 and with a tally of 138, broke her own record “for the most Smarties eaten in three minutes using chopsticks”.’

Raymond Keene in The Spectator, 7 June 2008, page 64.

- ‘Indeed, the total space devoted to Mental World Records in the entire book is less than that accorded to one exploit by Kathryn Ratcliffe (UK), who, on 25 October 2003, and with a tally of 138, broke her own record “for the most Smarties eaten in three minutes using chopsticks”.’

Raymond Keene in The Official Biography of Tony Buzan (Croydon, 2013), page 139.

9179. A bad plan (C.N. 9091)

From page 65 of Bréviaire des échecs by S. Tartakower (Paris, 1934):

‘Formez, au plus tôt, un plan du combat: mieux vaut un plan douteux que pas de plan du tout.’

Page 49 of the English edition, A Breviary of Chess (London, 1937), had:

‘As soon as possible evolve a plan of campaign; better a doubtful plan than no plan at all.’

9180. International grandmaster

Further to the reference to Tartakower in Chess Grandmasters, it is worth noting that on the front cover and the title page of Bréviaire des échecs he was described as ‘Grand maître international’:

9181. Simultaneous exhibition in Haarlem (C.N.s 9157 & 9170)

Bent Kølvig (Rødovre, Denmark) and John Rasmussen (Hicksville, NY, USA) note that the Danish photograph caption states that the world champion won all the games.

The only possibility that we see from the excellently researched list of results on pages 765-786 of Alexander Alekhine’s Chess Games, 1902-1946 by L. Skinner and R. Verhoeven (Jefferson, 1998) is a display in Haarlem on 28 April 1937, although Alekhine, who was not then the world champion, scored 29 wins and one draw from 30 games.

9182. Aristide Gromer (C.N. 9159)

Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) reports that his article on Gromer has been substantially updated since we first drew attention to it, in C.N. 5847. In particular, it is now recorded that Gromer was born in Dunkirk on 11 April 1908 and died on 6 July 1966 in Plouguernével.

Our correspondent also sends the last game of Gromer’s that he has found, a loss as Black to Maurice Raizman in the sixth round of the French championship in Rouen on 10 September 1947: 1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e6 3 g3 d5 4 Bg2 dxc4 5 Qa4+ Nbd7 6 Qxc4 c5 7 Nf3 Nb6 8 Qd3 Be7 9 Nc3 O-O 10 O-O Nfd5 11 dxc5 Nxc3 12 Qxc3 Na4 13 Qc2 Nxc5 14 Rd1 Qe8 15 Be3 Na6 16 Ne5 Nb4 17 Qb3 a5 18 a3 a4 19 Qc4 b5 20 Qc7 Nd5 21 Rxd5 exd5 22 Bxd5 Bd8 23 Qc5 Rb8 24 Qd6 Bf6 25 Nxf7 Bb7 26 Ba2 Rxf7 27 Qc7 Be5 28 Bxf7+ Qxf7 29 Qxe5 Qe8 30 Qxe8+ Rxe8 31 Rc1 Bd5 32 Rc7 h5 33 h4 Bc4 34 Kf1 Rd8 35 f3 Rd1+ 36 Kf2 Rh1 37 Bd4, and Gromer resigned on move 63. The game was published in La Nation Belge, 21 September 1947 and was annotated by Camil Seneca on page 83 of L’Echiquier de Paris, October 1947.

9183. Bierwirth v Jaffe

From page 28 of The Sun (New York), 9 January 1910:

‘The other day A.H. Bierwirth, the well-known local amateur, sat down to a series of offhand games with Charles Jaffe, the expert, at the Cosmopolitan Café in this city, when the following very remarkable game, won by the amateur, was played.’

A.H. Bierwirth – Charles Jaffe

New York, January 1910

Petroff Defence

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 Nxe5 d6 4 Nf3 Nxe4 5 d4 Be7 6 Bd3 d5 7 O-O Bg4 8 Re1 f5 9 c4 c6 10 cxd5 cxd5 11 Qa4+ Nc6 12 Ne5 O-O 13 f3 Nxe5 14 dxe5 Bc5+ 15 Be3 Qg5 16 Bxc5 Nxc5 17 Qd1 Bh3 18 Bf1 Rad8 19 Nc3 d4 20 Nb5 d3 21 e6 Rfe8 22 Nc7 Re7 23 b4 Rxc7 24 bxc5 Rxc5 25 e7 Re8 26 Qb3+ Kh8 27 Qf7 Rcc8 28 Rac1

28...Rb8 (The newspaper had three brief notes but did not mention that Black missed an attractive win with 28...d2 29 Rxc8 Qxg2+.) 29 Qxe8+ Rxe8

30 Rc8 Qg6 31 Rxe8+ Qxe8 32 Bxd3 Resigns.

9184. Ken Neat

Benoit Arsenault (Montreal, Canada) asks how many Russian books Ken Neat has translated into English. A further question will be whether any chess translator, past or present, has matched his tally.

9185. Castling and philosophizing

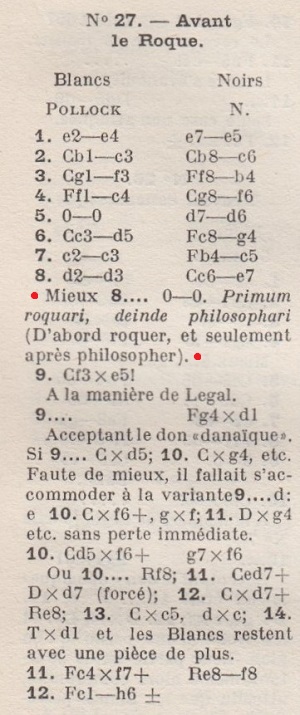

An addition to the many entries on castling in the Factfinder comes from page 108 of Tartakower’s Bréviaire des échecs (Paris, 1934):

The note to Black’s eighth move in the English translation, A Breviary of Chess (London, 1937), page 83:

‘Better would be 8... castles.

Primum roquari, deinde philosophari (First castle, and then philosophize).’

(The Pollock game has been widely published, with inaccurate or incomplete details. Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore), who is co-writing with John Hilbert a monograph on Pollock for McFarland & Co., Inc., informs us that it was a skittles game played in Baltimore on 5 October 1889 against J. Hall and was published by Pollock in his column in the Baltimore Sunday News, 13 October 1889.)

‘First castle, and then philosophize’ may seem enticing as a snappy Tartakower quote, but caution is needed. Below is a note (after 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 O-O Be7 6 Re1 b5 7 Bb3 d6 8 c3 O-O – Bronstein v Panov, Moscow, 1946) on page 22 of 100 Master Games of Modern Chess by S. Tartakower and J. du Mont (London, 1954):

C.N. 6829 noted that Irving Chernev ascribed to Tartakower the remark ‘Capture first and philosophize later’.

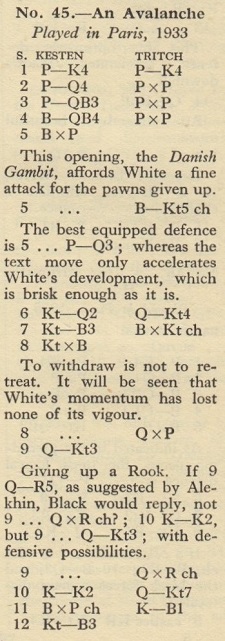

9186. Kesten

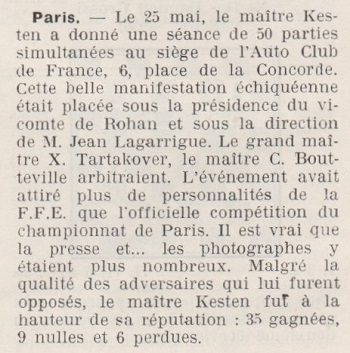

Wanted: information about S. Kesten, who played for France in the 1950 Olympiad in Dubrovnik. A 16-move win against Tritch, Paris, 1933 is on pages 95-96 of Tartakower’s A Breviary of Chess, and the news item below (about a large simultaneous display) comes from Le monde des échecs, June 1946, page 182:

9187. Youthful Reshevsky

From page 61 (page 2 of the Sporting Section) of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 12 December 1920:

Larger version (with the full article)

9188. Marshall v Rosenthal (C.N. 9177)

White to move

From Karsten Müller (Hamburg, Germany):

‘In general, Orrin Frink is right. The position is drawn. The move 1 Rc7+ given by Capablanca in Chess Fundamentals is indeed met by 1...Kd6 2 Rb7 Ke5 3 Rb5+ Kf6=, as Frink states. Another line runs 1 Rb7!? Rd5 2 f6 Rg5+ 3 Kf1 Rf5 4 f7 Kd6 5 Rxb4 Ke7 6 Rb7+ Kf8= despite White’s three extra pawns.

However, Frink makes a mistake in the line 1 f6 Rd6 2 Rc7+. Now, Black must play the active 2...Kd4, when he manages to draw in the resulting pawn race, or 2...Kd5. But 2...Kb6? loses owing to 3 f7 Rg6+ 4 Kf1 Rf6, and now 5 Re7 Kc5 6 Rb7 Kd5 7 h4 Rf4 8 h5 Ke6 9 h6 Rxf7 10 h7 and White wins.’

9189. W.H. Pratten and E. Bogoljubow

As mentioned on page 63 of the Southsea, 1950 tournament book, Pratten held the post of Honorary Congress Secretary of the Southern Counties Chess Union.

9190. My 61 Memorable Games

Larry Evans wrote a great deal about My 61 Memorable Games,

a 753-page paperback whose provenance is still unknown,

but we are aware of no evidence that he ever saw the book.

9191. L’art de faire mat (C.N.s 9149 & 9160)

A brief addition concerning the title of the English translation of Renaud and Kahn’s book: the second definite article was omitted in the edition published by G. Bell and Sons, Ltd. (London, 1955), on the dust-jacket (below) and on the title page:

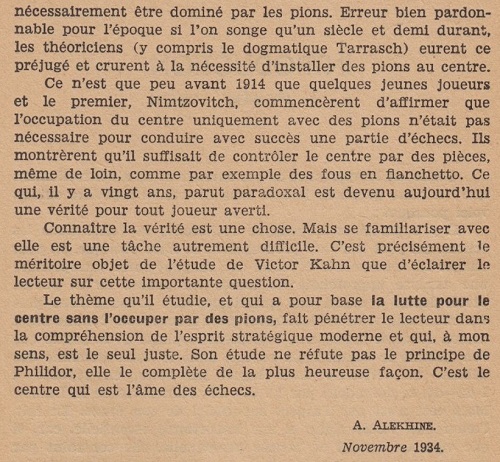

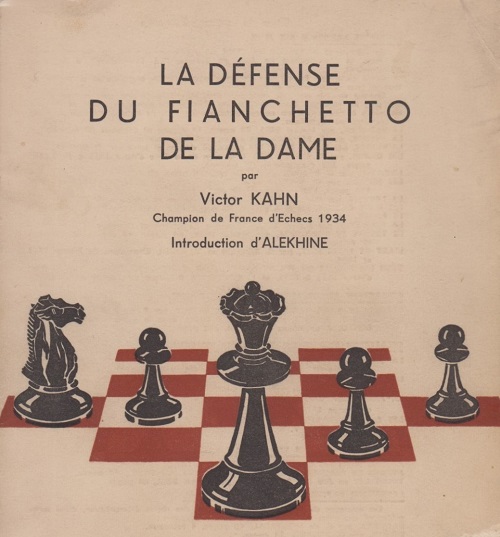

9192. Introduction by Alekhine (C.N. 3977)

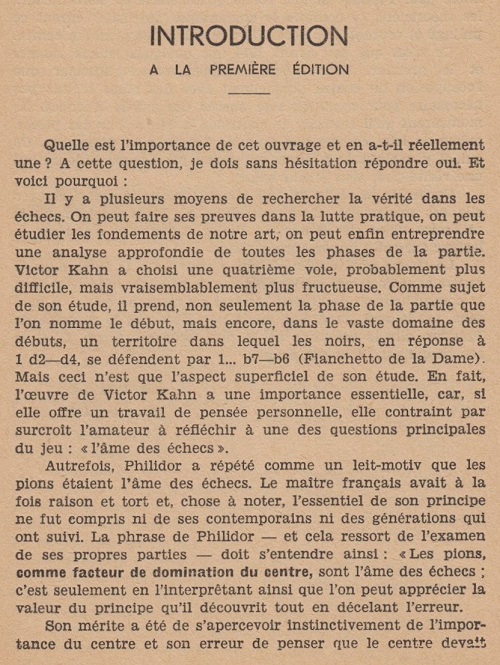

The full Alekhine text mentioned in C.N. 3977, as published on pages 5-6 of La Défense du Fianchetto de la Dame by Victor Kahn (Monaco, 1949):

9193. D.J. Richards

Wanted: a biographical note on D.J. Richards, the author of the scholarly Soviet Chess (Oxford, 1965). The Betts entry for the book gave his forenames as David John. (In Soviet Chess 1917-1991 by Andrew Soltis (Jefferson, 2000) he was referred to as ‘D.B. Richards’.)

From page 311 of the December 1957 BCM:

‘The new County Champion for Oxfordshire is D.J. Richards, of Magdalen College, Oxford.’

He was the translator of Modern Chess Opening Theory by A.S. Suetin (Oxford, 1965), and one of his few other contributions to chess literature was an article ‘Alekhine: The Missing Years’ on pages 191-193 of CHESS, 29 February 1964. It covered the period 1914-21 and was subtitled ‘an authoritative reconstruction of a gap in the chess story by a university lecturer in Russian history’.

On the basis of academic registers, the unpublished 1994 edition of Chess Personalia by Jeremy Gaige states that David John Richards was born on 22 May 1933.

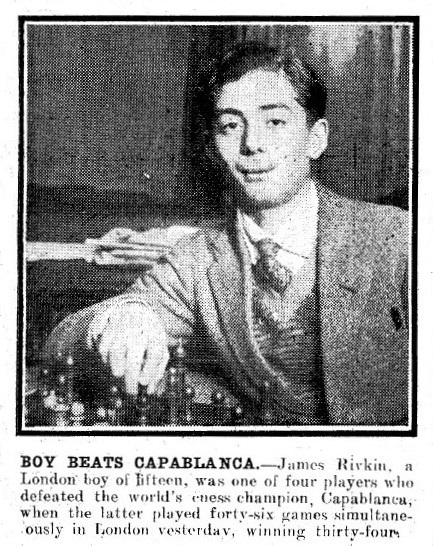

9194. Victory by James Rivkin over Capablanca (C.N. 8841)

A better version of the photograph of Rivkin in C.N. 8841 comes from page 20 of the Daily Mirror, 15 December 1925:

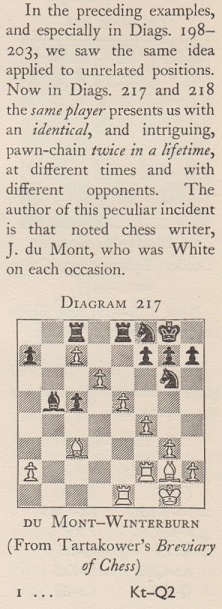

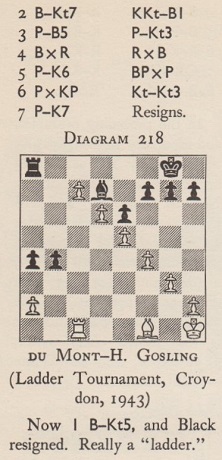

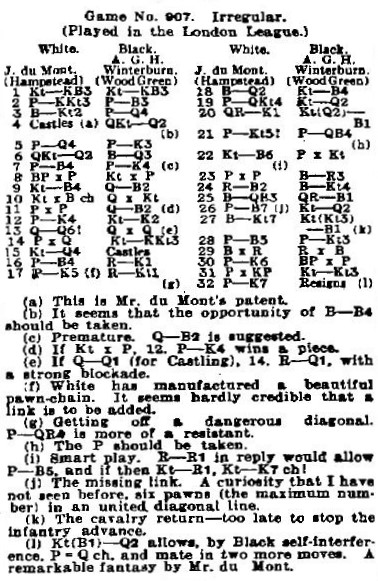

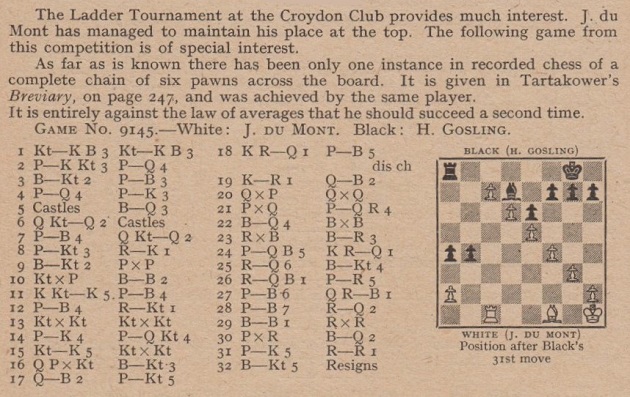

9195. Pawn chains

On page 112 of Wonders and Curiosities of Chess (New York, 1974) Irving Chernev gave the score of a 1943 game between J. du Mont and H. Gosling, introduced as follows:

‘The British chess master J. du Mont built the longest pawn chain ever seen on a chessboard.’

The game is well known and available in databases, but Chernev did not mention that it was du Mont’s second game with the same configuration. From pages 89-90 of The Brilliant Touch by Walter Korn (London, 1950):

Korn also gave both positions on page 212 of Chess Review, July 1960, where he dated the game against Winterburn ‘1937’ (the publication year of Tartakower’s A Breviary of Chess, which gave the ending on page 247). However, the score was published by Brian Harley on page 16 of the Observer 16 April 1933:

1 Nf3 Nf6 2 g3 c6 3 Bg2 d5 4 O-O Nbd7 5 d4 e6 6 Nbd2 Bd6

7 c4 e5 8 cxd5 Nxd5 9 Nc4 Qc7 10 Nxd6+ Qxd6 11 dxe5 Qc7 12

e4 Ne7 13 Qd6 Qxd6 14 exd6 Ng6 15 Nd4 O-O 16 f4 Re8 17 e5

Rb8 18 Bd2 Nc5 19 b4 Nd7 20 Rae1 Ndf8 21 b5 c5 22 Nc6 bxc6

23 bxc6 Ba6 24 Rf2 Bb5 25 Bc3 Rbc8 26 c7 Nd7 27 Bb7 Ngf8

28 f5 g6 29 Bxc8 Rxc8 30 e6 fxe6 31 fxe6 Nb6 32 e7

Resigns.

The game against Gosling was on page 150 of the July 1943 BCM, at which time du Mont was the General Editor:

Later cases reported are Soane v Wharmby, London, 1978 (BCM, May 1979, page 231) and Parry v Hallworth, Rhyl, 1979 (BCM, September 1979, pages 409-410).

9196. Kesten (C.N. 9186)

The game between Kesten and Tritch referred to in C.N. 9186, from pages 95-96 of Tartakower’s A Breviary of Chess (London, 1937):

1 e4 e5 2 d4 exd4 3 c3 dxc3 4 Bc4 cxb2 5 Bxb2 Bb4+ 6 Nd2 Qg5 7 Nf3 Bxd2+ 8 Nxd2 Qxg2 9 Qb3 Qxh1+ 10 Ke2 Qg2 11 Bxf7+ Kf8 12 Nf3 Nh6 13 Bh5 Rg8

14 Qe6 dxe6 15 Ba3+ c5 16 Bxc5 mate.

The game has not been found in any French edition of Tartakower’s book (of which we have half a dozen) or in the Dutch translation by G.H. Goethart, Het schaakspel (Zeist, 1936).

Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) provides biographical information about Kesten on the basis of the obituaries published in L’Echiquier de Paris, July-August 1953, page 122, and the Bulletin de la Fédération Française des Echecs, 1 July 1953, page 16, as well as pages 6-7 of a small work by Roland Lecomte, L’Histoire Authentique d’Inédits Sortis de l’Oubli (Orsay, 2008):

‘Kesten was born Salomon Kestenbaum in Warsaw on 18 July 1888 and took French citizenship in May 1940. Some sources on the Internet give his forename as Stefan, but I have not found instances of his using that name himself. He invariably signed his articles “S. Kesten”.

He taught chess at the Café de la Régence in Paris. All the players left the Café in 1918, but in 1933 play resumed on the premises, until 1943, after which Kesten taught chess in the exclusive Automobile Club de France.

He founded the first chess column in a French daily newspaper after the Second World War, in Combat. His column began in July 1946 and continued until May 1950, and in all he wrote about 200 columns. He gave up the post to create two new chess columns, in L’Observateur and in Franc-Tireur.

Also after the War he represented the Parisian club Caïssa in team matches and participated in matches between France and Belgium in 1948 and 1949. As mentioned in C.N. 9186, he played for France in the 1950 Olympiad in Dubrovnik.

I note that in one of his columns in Combat in August 1946 he gave (with notes by Znosko-Borovsky) the game Kesten v Schenk played in Hastings on 3 January 1946, as well as Parr v Broadbent, Nottingham, 1946. Both games were headed “Début Kesten” (“Kesten Opening”). They began respectively 1 d4 d5 2 e3 Nf6 3 Bd3 g6 4 Nd2 Bg7 5 c3 O-O 6 Qe2 Re8 7 f4 c5 and 1 d4 Nf6 2 e3 d5 3 Bd3 c5 4 c3 Nbd7 5 f4 g6 6 Nd2 Bg7. The game against Schenk was played in the Premier Reserves “A” tournament in Hastings. Kesten finished fourth behind Schenk, Opočenský and A.R.B. Thomas; the crosstable was published on page 152 of the May 1946 BCM.

Kesten died in Paris on 30 June 1953. A photograph of him was given on page 155 of the September-October 1953 issue of L’Echiquier de Paris:’

9197. Redness

An item quoted in a footnote on page 19 of A Chess Omnibus:

Chess Review, May 1948, page 15.

9198. Tartakower in the air

C.N. 1947 (see page 203 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves) cited a report on page 296 of CHESS, 14 April 1936 that Tartakower ‘is the only person to have given a simultaneous exhibition in an aeroplane – between Budapest and Barcelona in 1929’.

From page 29 of the Chess Amateur, November 1929:

‘AERO-CHESS. The first reported display of chess in the air is credited to Dr Tartakower, who recently won three games, blindfold and simultaneous, during a flight from Budapest to Vienna. Dr A. Seitz acted as “teller”.’

9199. Marshall and Gladstone

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 8 January 1923, page 23

Game 127 in My Fifty Years of Chess by Frank J. Marshall (New York, 1942) was played against David Gladstone nearly a decade later, a team match game published on page B7 of the New York Evening Post, 14 May 1932.

| First column | << previous | Archives [128] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.