Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [129] | next >> | Current column |

9200. Steinitz’s date of birth

Thomas Niessen (Aachen, Germany) writes:

‘The website of the National Archives of the Czech Republic has posted online the “Registers of Births, Marriages and Deaths of Jewish Religion Communities from the years 1784-1949”. In one of the registers the second entry on page 277 states that Wilhelm Steinitz was born in Prague, as Wolf Steinitz, on 14 May 1836.’

Our correspondent notes that the register was one of the sources mentioned in the lengthy, though by no means wholly accurate, discussion of Steinitz’s date of birth by Kurt Landsberger on pages 2-3 of William Steinitz, Chess Champion (Jefferson, 1993). (The references to Deutsches Wochenschach and the American Chess Magazine were faulty.) The list of siblings on pages 2-3 of Landsberger’s book indicates that Wolf (Wilhelm) was the ninth of 13, and on page 3 it was concluded that ‘the preponderance of evidence is for the date 14 May 1836’.

See too Steinitz’s passport application (C.N. 7149).

9201. A bad plan (C.N.s 9091 & 9179)

Leonard McLaren (Onehunga, New Zealand) points out a remark by John Nunn on page 53 of Understanding Chess Middlegames (London, 2011), in the section on planning:

‘Perhaps the most important advice is that if you can’t think of a good plan, at least don’t play a bad one.’

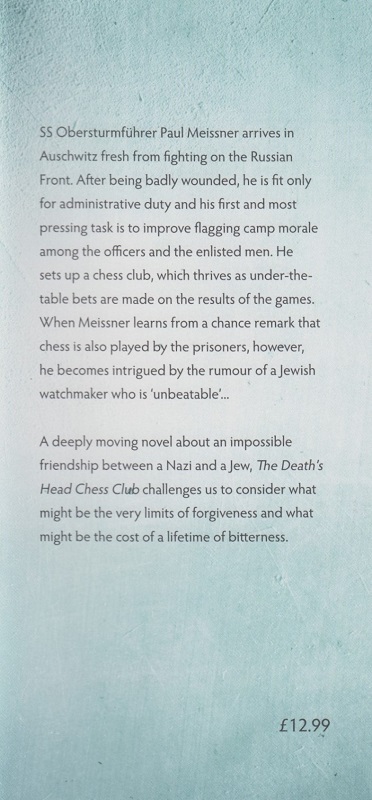

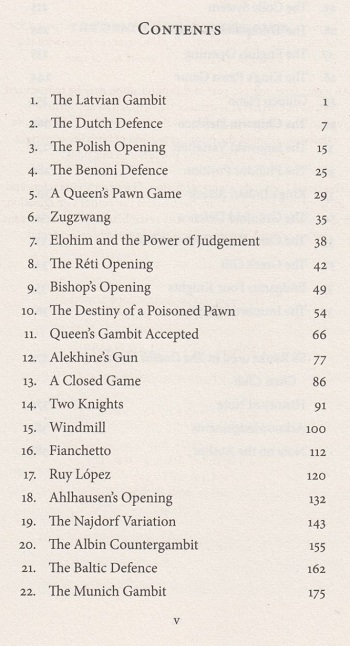

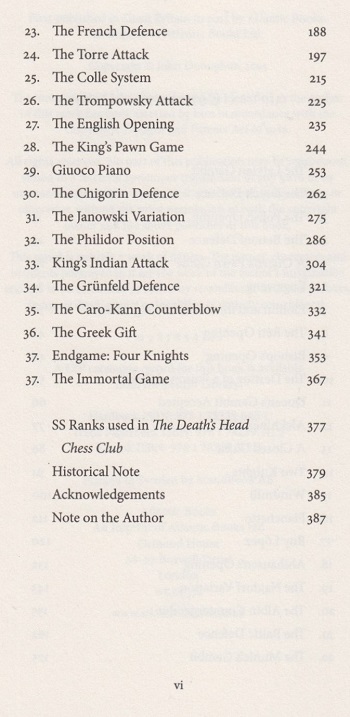

9202. The Death’s Head Chess Club

The inside front flap of the dust-jacket:

Page 383 of John Donoghue’s novel states: ‘Most of the chapter headings relate to chess moves. The moves were chosen to reflect some aspect of the chapter content.’

9203. Grandmasters

An illustration of how casually the term ‘grandmaster’ (in this case ‘Großmeister’) was sometimes used is on page 401 of Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten, December 1929:

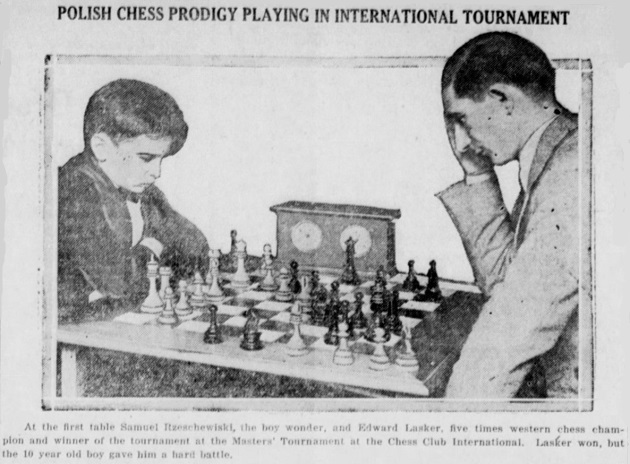

9204. Reshevsky v Edward Lasker

From page 6 of the Brainerd Daily Dispatch, 18 October 1922:

The game was annotated by Lasker on pages 237-242 of Chess Secrets I Learned from the Masters (New York, 1951).

9205.

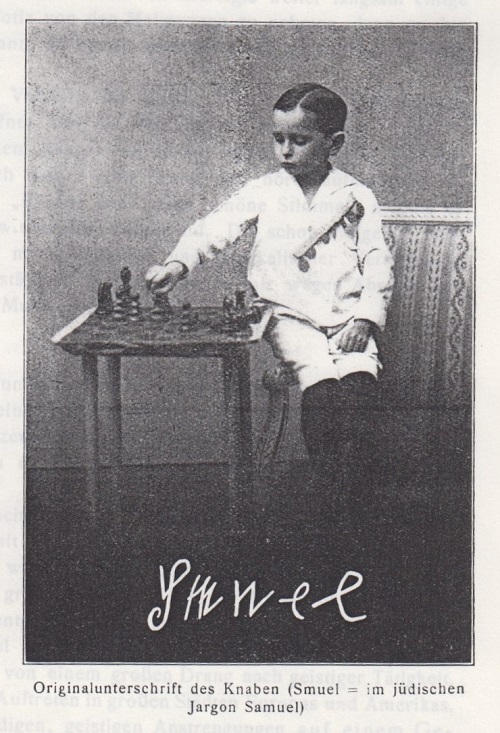

Psychological tests on the prodigy Reshevsky

Praktische Psychologie, 8/1920, page 241

CHESS, 14 May 1939, page 324

Our latest feature article is Testing Reshevsky.

9206. Arthur Lloyd James

Chess and Murder mentions the case of the phonetician Professor Arthur Lloyd James, who killed his wife. Page 81 of the March 1941 CHESS gave the information in a section headed ‘The Funny Side’:

From page 101 of the April 1941 issue:

9207. Claude Bloodgood

A letter published on page 314 of CHESS, July 1971:

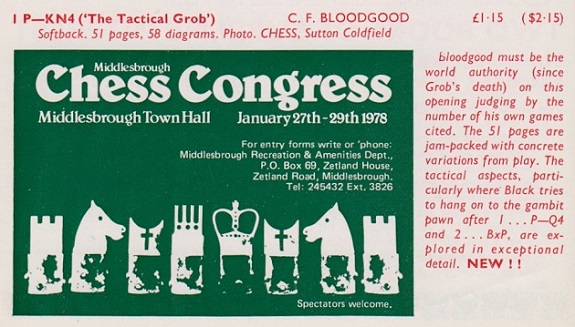

Bloodgood’s best-known book is The Tactical Grob (Sutton Coldfield, 1977), a 51-page monograph on 1 g4. It is undated, and various supposed years of publication have been given. Our ‘1977’ is based on its listing as a new work on the inside front cover of CHESS, November 1977.

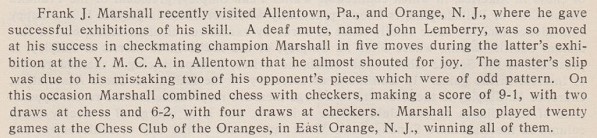

9208. Frank J. Marshall and John Lemberry

From page 72 of the April 1920 American Chess Bulletin:

Hermann Helms also related the story in the New York Evening

Post, 21 February 1920, page 12. On page 11 of the

31 January 1920 edition he had announced that the display

in Allentown was to take place that evening. More details

are sought.

The story about ‘a dumb person’ on page 391 of Garry Kasparov on My Great Predecessors Part I (London, 2003) may be recalled dolefully.

9209. Tony Miles and Othello

A paragraph in CHESS, December 1976, page 65:

‘In November, Tony Miles accepted a £500 challenge to a match at a new game called Othello, losing by 1-2 – an amazing achievement considering that his opponent was unofficial Othello world champion.’

The reference to ‘November’ was incorrect, given that the match, against Fumio Fujita, had been reported in a ‘Diary’ item by P.H.S. on page 14 of the Times, 21 October 1976.

9210. The Royal Game read by Frazer Kerr

Wanted: details about an audio cassette advertised on the inside back cover of the November 1977 CHESS:

9211. Purdy quote

The ‘thought for the month’ on the inside front cover of the October 1950 Chess Review, in ‘Chernev’s Chess Corner’:‘“Chess is as much a mystery as women” – Purdy.’

See too page 1 of Winning Chess by Irving Chernev and Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1948). How far back can this well-known remark be traced?

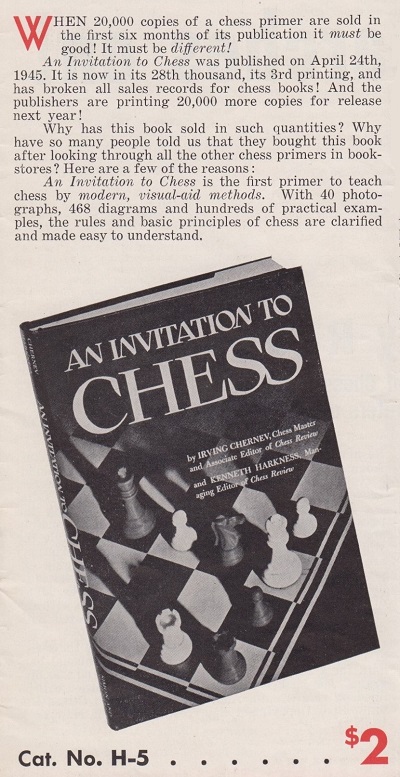

9212. The highest praise

‘One of the chess books of the century’ was discussed by C.J.S. Purdy on page 140 of Chess World, 1 June 1948. ‘We have searched for some fault so that our review should not be all praise, but we have searched in vain. No, we must congratulate the authors on a brilliant idea executed with meticulous attention to every detail.’

Purdy also wrote:

‘... the ordinary beginner’s book plunges into a slough of dull verbiage. But how can you explain chess without words?

Well, the miracle has been accomplished as far as is humanly possible in Invitation to Chess by Kenneth Harkness and Irving Chernev.’

The book, based on material which had appeared in Chess Review, was first published by Simon & Schuster, New York in 1945, and an advertisement on the inside front cover of the June-July 1945 Chess Review called it ‘the most revolutionary chess primer ever published’. The book’s early sales were reported in a full-page advertisement on page 9 of the November 1945 Chess Review. The relevant half of that page:

An Invitation to Chess was also published by Faber and Faber Limited, London in 1947.

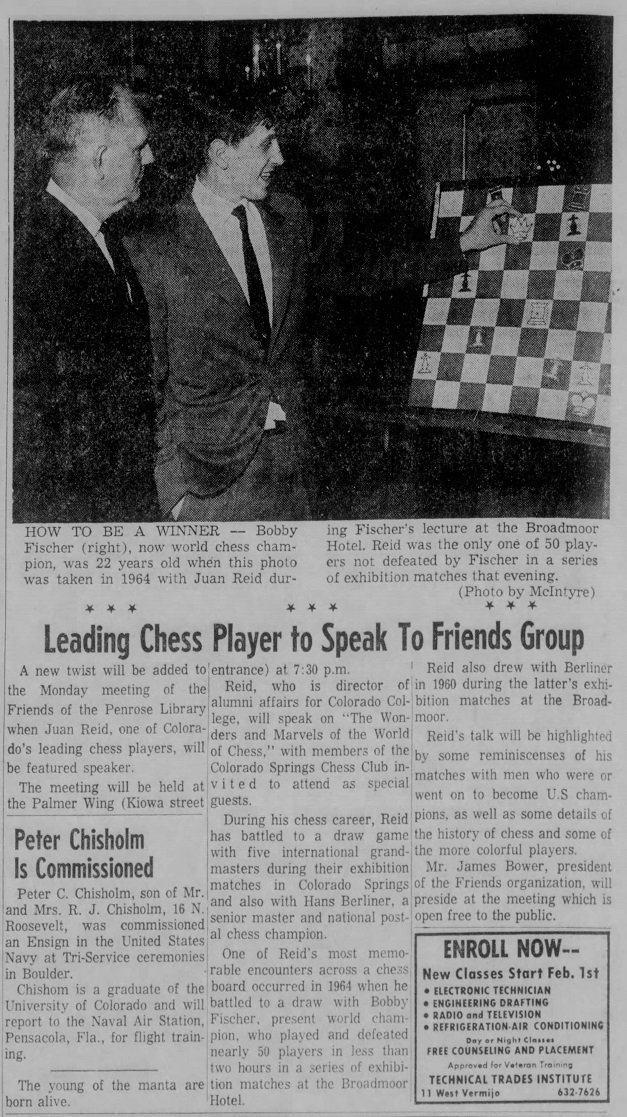

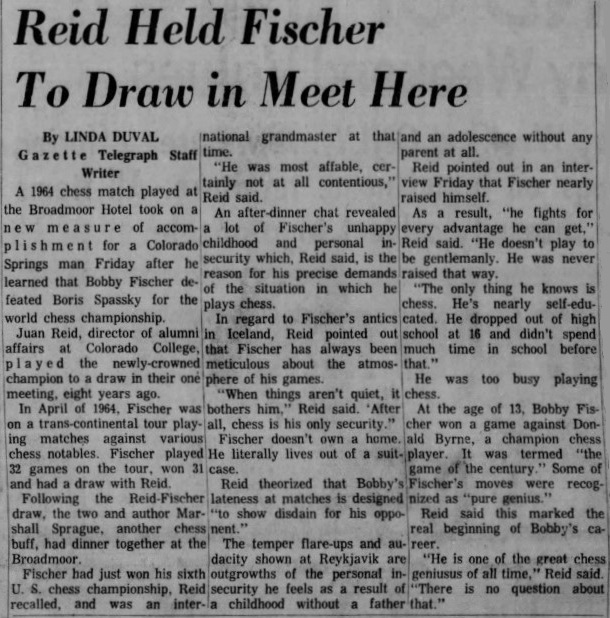

9213. Fischer and Reid

From page 10 of the Colorado Springs Gazette Telegraph, 10 January 1973, page 6:

The position on the demonstration board is the conclusion of Fischer’s win against Celle (Davis, CA, 16 April 1964 – game 50 in My 60 Memorable Games), but what more is known about Fischer’s encounter with Juan Reid?

9214. Alekhine on genius and mathematics

From an article (‘New Chess King Ruled by Fancy’) by Leon Wexelstein in the New York Times, 11 December 1927, page XX10:

‘To find out from Alekhine the ingredients that go into the making of genius in chess was not easy. As well try to learn what makes for a Heifetz, an Einstein, a Walt Whitman, a Tolstoy – or a Tunney. If genius could be readily analyzed, then genius could be made to order – and genius cannot be made to order. It is there – or it isn’t.Does, for instance, mathematical ability play a part? What are the rôles apportioned to fancy, to memory, to prudence? How does it feel to play 26 boards at the same time, and “blindfold”, as Alekhine has done? Does one weary? In what way? These questions were put to Alekhine.

“Mathematical ability?” he said. “Not at all. Dr Emanuel Lasker is the only one who, so far as I know, has any. I haven’t, myself. Or, if anything, very mediocre ability in mathematics. I don’t think it counts – in chess. What does? Well, fancy is one. And a flair for abstract reasoning is another.”

Alekhine laughed a little.

“Anyway”, he said, don’t place too much weight on inheritance. You might be a brilliant player even if no-one in the train of your family had ever seen a chessboard.”’

It would be helpful to know where and when Alekhine made the statements quoted in Wexelstein’s article.

9215. ‘Old Baldhead Alekhine’ (C.N. 9143)

From Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina):

‘The colloquial expression “viejo y peludo” (sometimes with the intensifier “nomás”) is used in Argentina to congratulate, acclaim or praise a sportsman regarding his achievements. For example: “Leguisamo, viejo y peludo nomás”, in a tango sung by Carlos Gardel in 1927; also, “Burruchaga, viejo y peludo nomás”, as shouted by the sports commentator Víctor Hugo Morales during the World Cup final in 1986.

“Viejo y peludo”, of uncertain origin and probably meaning “grown up” or “experienced”, can be translated literally as “old and hairy/bearded”, but not “old baldhead”, which would be “viejo y pelado”.’

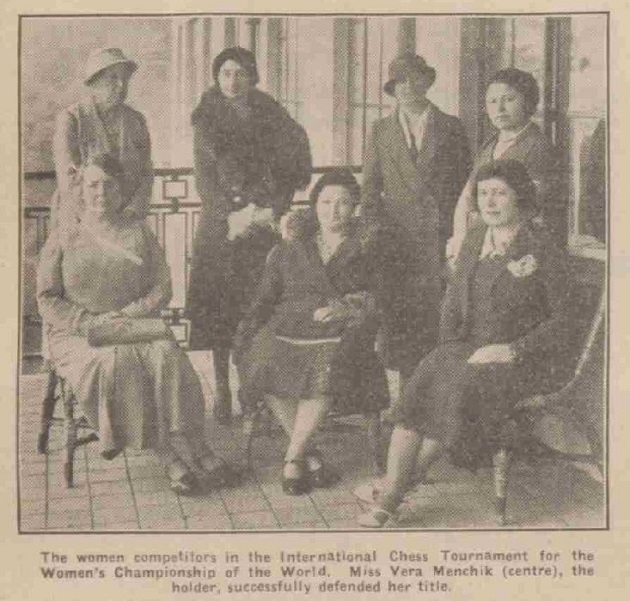

9216. Folkestone, 1933 (C.N.s 5777 & 5974)

C.N.s 5777 and 5974 concerned the ‘balcony shots’ taken during the 1933 Olympiad in Folkestone (the teams of Great Britain, Hungary, Latvia and the United States). Below is a further photograph, from page 16 of the 1 July 1933 edition of the Folkestone, Hythe, Sandgate & Cheriton Herald:

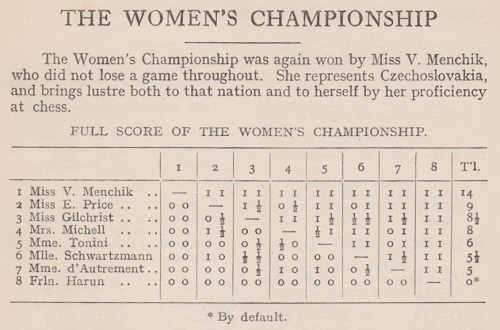

Attempting to provide a complete key would be risky, but below, for now, is the crosstable of the tournament, from page 151 of the Book of the Folkestone 1933 International Chess Team Tournament (Leeds, 1933):

9217. Znosko-Borovsky (C.N.s 5227 & 5451)

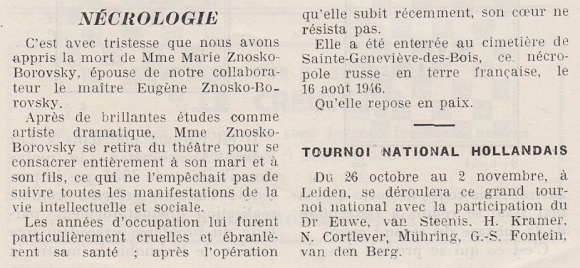

Regarding the non-chess activities of Eugene Znosko-Borovsky it can be added that the obituary of his wife, Marie, on page 274 of Le monde des échecs, September 1946 referred to her theatrical work:

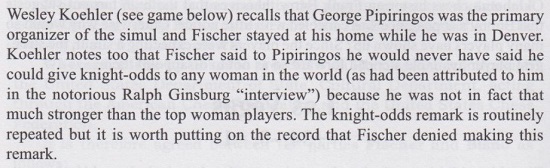

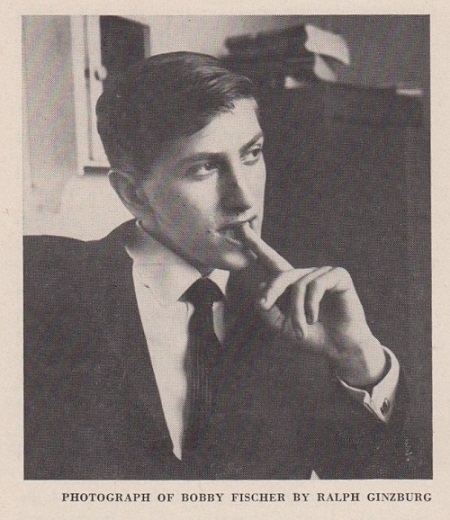

9218. The Ginzburg-Fischer interview (C.N. 9155)

C.N. 9155 asked whether Fischer ever rejected specific points in the article about him by Ralph Ginzburg on pages 49-55 of Harper’s Magazine, January 1962.

From page 158 of A Legend on the Road by John Donaldson (Milford, 2005):

9219. Fischer and Reid (C.N. 9213)

Oliver Beck (Seattle, WA, USA) writes:

‘Juan Reid, who died in 1981, drew against Bobby Fischer in a 32-board simultaneous exhibition at the Broadmoor Hotel in Colorado Springs, CO on 28 April 1964, an event not recorded in John Donaldson’s two books (1994 and 2005) on Fischer’s US tour in 1964.

I received the information from an acquaintance related to Reid. Among the cuttings sent to me was a report on page 1 of the Colorado Springs Gazette Telegraph, 2 September 1972, as well as the game-score itself, published in the column of Bill Woestendiek (which, however, was written in this case by Marshall Sprague) in, I believe, the Colorado Springs Sun.’

The Gazette Telegraph item:

The game in the Woestendiek/Sprague column:

Robert James Fischer – Juan Reid

Colorado Springs, 28 April 1964

Philidor’s Defence

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 d6 3 d4 Nf6 4 Nc3 exd4 5 Nxd4 Be7 6 f3 Nbd7 7 Be3 Ne5 8 Qd2 c5 9 Bb5+ Bd7 10 Nf5 O-O 11 Bxd7 Qxd7 12 O-O-O Nc4 13 Qe2 Nxe3 14 Qxe3 Rfd8

15 g4 Bf8 16 e5 Ne8 17 Ne4 Qc7 18 exd6 Nxd6 19 Nexd6 Bxd6 20 Nxd6 Rxd6 21 Rxd6 Qxd6 22 Rd1 Qxh2 23 Qe7 Qb8 24 Rd7 Qf4+ 25 Kb1 g6 26 Qe2 b6 27 a3 a6 28 Qd3 b5 29 Qd5 Re8 30 Ka2 Re5 Drawn.

9220. Philidor’s Defence

The shortest item in Curious Chess Facts by Irving Chernev (New York, 1937) was on page 14:

‘Philidor never played Philidor’s Defence!’

See too page 13 of Chernev’s Wonders and Curiosities of Chess (New York, 1974).

D.J. Morgan mentioned the matter briefly and cautiously (‘Philidor, it is said, never played the Philidor Defence’) on page 157 of the May 1954 BCM, and a letter from W.S. Mackie of Cape Town was published on page 257 of the August 1954 issue:

Suggestions are invited as to when the name ‘Philidor’s Defence’ was first attached to 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 d6.

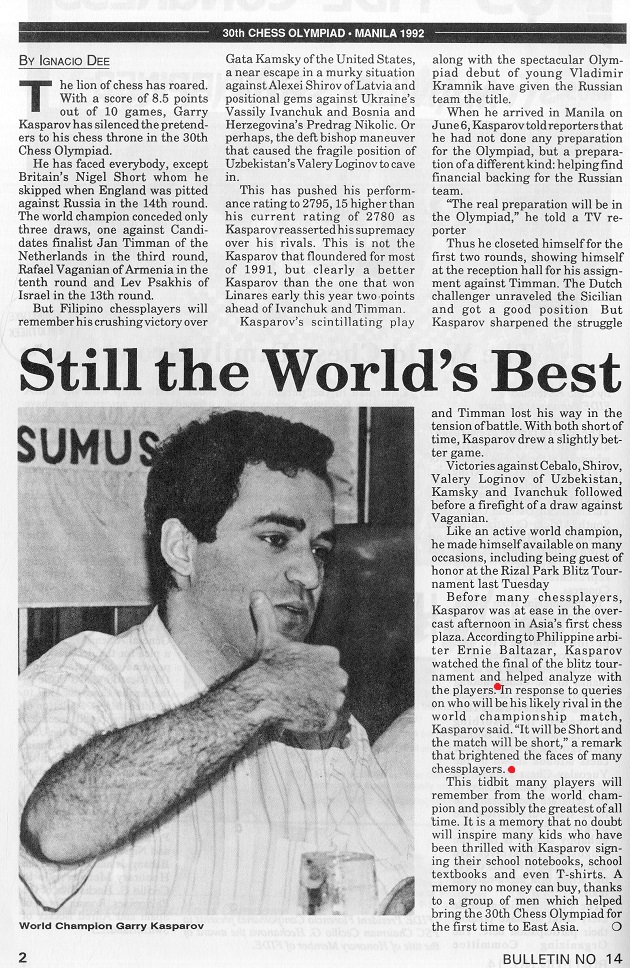

9221. Kasparov on Short (C.N. 8376)

C.N. 8376 pointed out incorrect information about when Kasparov made his ‘it will be short’ quip: it was in June 1992, i.e. some six months before the Short v Timman Candidates’ final.

Kasparov mentioned that the joke was reported in a bulletin of the Manila Olympiad, held in June 1992. Can a reader kindly forward us a copy?

9222. Bloodgood (C.N. 9207)

Above is the listing (CHESS, November 1977) for The Tactical Grob by Claude Bloodgood, which was referred to in C.N. 9207 as evidence that the book was published in 1977.

We have just acquired another book by Bloodgood, Blackburne-Hartlaub Gambit 1 d4 e5 2 dxe5 d6!? (Grand Prairie, 1998), and note that his introductory article, ‘The World of the Chess Hustler’, on pages 10-11 gave 1976 as the year of publication of his book on 1 g4:

However, no mention of the book has been found in CHESS before the November 1977 issue. Moreover, a catalogue page in the April 1977 CHESS listed the magazine’s own publications (15 titles), and The Tactical Grob was not among them.

Below is the first paragraph of Bloodgood’s ‘The World of the Chess Hustler’ item:

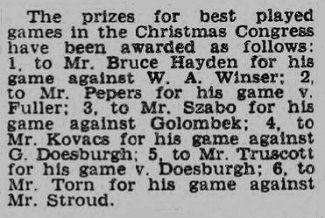

9223. Bruce Hayden (C.N. 4478)

From Alan McGowan (Waterloo, Canada):

‘Bruce Hayden, the author of Cabbage Heads and Chess Kings, was born in Glasgow, Scotland on 7 April 1907. His name was registered as Henry Bruce Cobb Ellenband. His father was Maurice Henry Ellenband, Advertising Contractor, and his mother was Joan Cobb, Table Dresser.

Online searches show a Maurice (or Morris) Henry Ellenband, born 1873 in Salford, died 1939 in London. Online searches at the ScotlandsPeople website have failed to confirm background and birth information for Joan Cobb.

Research by Brian Denman in Sussex suggests that Hayden’s mother married William Scott Wilson. Home addresses for Bruce Hayden in the early 1930s (Sussex), 1945 (Surrey) and 1961 show that Joan Wilson was at the same address.

Brian Denman also discovered that the 1911 Census shows a Hendry Bruce Cobb Ellinband residing as a visitor at the home of Thomas Parker, a 58-year-old bricklayer, at Harborne, Moorend Crescent, Moorend Street, Cheltenham.

Hayden’s connection to Cheltenham is strengthened by a note on page 4 of the Cheltenham Chronicle of 4 July 1931, which refers to “Mr Bruce Hayden, formerly of Cheltenham, now the secretary of the Hove CC”. Hayden – using that name – first appeared in Sussex chess records in 1927.

He contributed regular articles to Chess Review, and the following is a footnote on page 308 of the October 1956 issue:

“For the record, Hayden’s full name is Hendry Bruce Cobb Ellenband-Hayden; but he foregoes using the hyphenated surname as being cumbersome. Ed.”

Brian Denman also found that Hayden used the initials H.B.C.E. as late as 1977-78, when he was listed as a patron of the Sussex Chess Association.

How was the name Hayden assumed or acquired?’

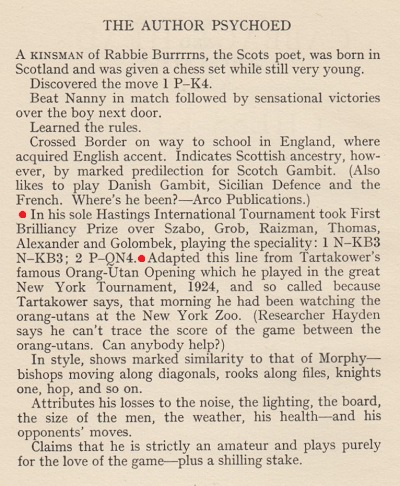

We add that on page 71 of the March 1952 Chess Review

(from which the above photograph is taken) Hayden

presented a light-hearted note about himself which

subsequently appeared opposite the title page of Cabbage

Heads

and Chess Kings (London, 1960). From the book:

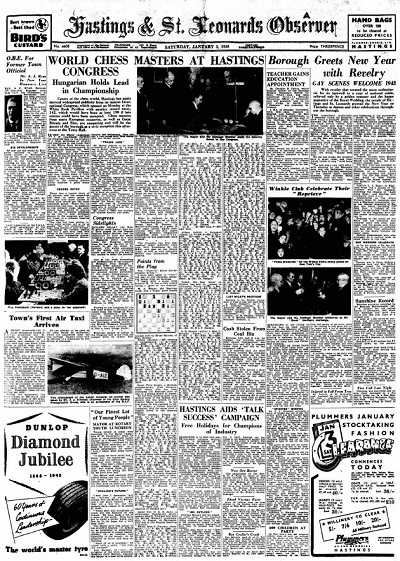

The claim ‘In his sole Hastings International Tournament took First Brilliancy Prize over ...’ is strange. From the masters named it is clear that Hayden was referring to Hastings, 1947-48, but he participated not in the Premier Tournament or even in the Premier (Major) Reserves but merely in one of the minor events (the Premier Reserves B tournament). He finished eighth out of ten players with two wins and a draw (BCM, March, 1948, page 86).

From the previous page:

‘Against Winser, however, Bruce Hayden produced a brilliant game which was awarded the first prize by the Hastings Committee.’

We have yet to find a reference to other brilliancy

prizes being awarded at Hastings, 1947-48. The score of

the Hayden-Winser game was published on page 88 of the

March 1948 BCM with notes from The Field:

1 Nf3 Nf6 2 b4 d5 3 Bb2 Bf5 4 g3 e6 5 a3 Nbd7 6 Bg2 Bd6 7 O-O c6 8 d3 Qe7 9 Nbd2 e5 10 Re1 Nb6 11 c4 Bc7 12 cxd5 cxd5 13 e4 dxe4 14 dxe4 Bd7 15 Rc1 Ba4 16 Qe2 O-O 17 Bh3 Rfd8 18 Nh4 g6 19 Ndf3 Bd6 20 Qe3 Bc6 21 Qh6 Bxe4 22 Ng5 Bc6 23 f4 Qc7

24 Nf5 Bf8 25 Bxe5 Qd7 26 Bxf6 Bxh6 27 Nxh6+ Kf8 28 Nxh7

mate.

The game was also given in the large front-page report in the Hastings & St Leonards Observer of 3 January 1948:

Hayden annotated his victory over William Winser in an article entitled ‘Brilliancy Prize!!’ on pages 82-83 of the March 1962 Chess Review, and again he gave the impression of having played in ‘the’ Hastings tournament (which was won by Szabó):

‘... the first brilliancy prize at Hastings. I was convalescing on my return from overseas and went to that famous seaside chess resort to enjoy some sea air and watch the play at the Christmas Congress of 1947. There was a last-minute vacancy, I was asked to fill it and, on the day of the first round, I threw a temperature – a real one, not a chess one – and this stimulated me to adopt an unusual opening.’

The reference to ‘on the day of the first round’ indicates that the game was played on or around 29 December 1947.

At the end of the article Hayden wrote, ‘This game by an unknown player in the first round caused a minor sensation among the Hastings masters at the time’, after which he related the congratulations and praise that he received from László Szabó, Sir George Thomas (‘who played some beautiful games in this, his last big tournament’), William Winter, Maurice Raizman and Ossip Bernstein.

9224. Ties

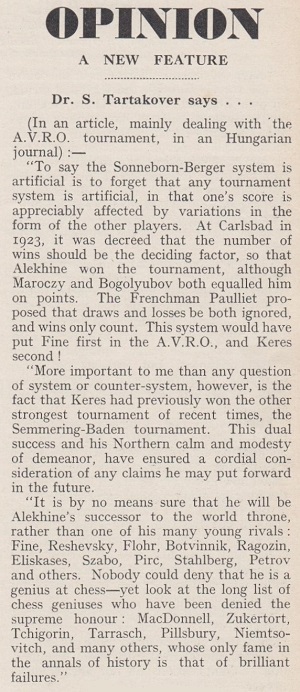

From page 313 of the 14 May 1939 CHESS:

Before any examination of details (e.g. the fact that Alekhine and Bogoljubow both had nine wins at Carlsbad, 1923) we should like to see the original text in the ‘Hungarian journal’.

9225. A

losish game

A remark by Cecil Purdy on page 16 of the Australasian Chess Review, 25 January 1939:

‘It is usually no harder to win a drawish game than a losish game, and the latter has the disadvantage that you may lose.’

9226. Bruce Hayden (C.N.s 4478 & 9223)

Gerard Killoran (Ilkley, England) sends a cutting from a column by ‘A.J.M.’ (Arthur John Mackenzie) on page 7 of the Hastings & St Leonards Observer, 7 February 1948:

Thus a single list of prize-winning games was, strange to say, drawn up from all the tournaments comprising the congress. The games selected came from: 1) Premier Reserves B; 2) Premier Reserves B; 3) Premier; 4) Premier (Major) Reserves; 5) Premier (Major) Reserves; 6) First Class A.

9227. A

saying (C.N. 4326)

Page 59 of Bréviaire des échecs by S. Tartakower (Paris, 1934) attributed this saying to Dawid Janowsky:

‘ll y a des gens qui jouent aux échecs et d’autres qui jouent avec les échecs.’

The English version, on page 46 of A Breviary of Chess (London, 1937):

‘There are people who play chess, and others who play at chess.’

9228. Marshall in Portland

Page 86 of our book on Capablanca related his reaction to having his US record for simultaneous play broken by Marshall in Portland, OR on 23 February 1915 (+77 –4 =11), as discussed on pages 48-49 of the March 1915 American Chess Bulletin.

A report on Marshall’s exhibition was published on page 8

of the Oregon Daily Journal, 24 February 1915, and

the large feature below comes from page 3 of the 28

February 1915 edition of the Oregan Sunday Journal:

Larger version, including a report

The game given in the report, a draw against Marshall W.

Malone, was also published in the above-mentioned issue of

the Bulletin, together with three others also

beginning with the Danish Gambit.

9229. Capablanca in London (C.N. 7633)

Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) points out that the photograph of Capablanca and Princess Tatiana in C.N. 7633 was later published, differently cropped, on page 27 of the 27 May 1930 issue of Estampa, in an article by José Díaz Morales entitled ‘El lento y noble juego del ajedrez’.

9230. Opening speeches

From page 58 of “Among These Mates” by Chielamangus (Sydney, 1939), in an article about the New Zealand championship (Wellington, 1935-36):

‘A chess congress is very like a tin of sardines: it has to be opened. Some notable person comes along and informs the company that he, personally, has never played chess, but has an intense admiration for people who can. The congress is then considered to be open.

Sometimes the poor fellow doesn’t know that this is all he has to say, and spends the previous night poring over the chess article in the Encyclopaedia Britannica. I have seen so many congresses prised open that I know that article by heart; sometimes the chairman swots it up, too, and dashes it off while he is supposed to be introducing the notable person, who sits writhing in his chair, thinking up a new speech.’

9231. Submitting problems

From Stuart Rachels (Tuscaloosa, AL, USA):

‘I have recently composed about 20 mate-in-two problems and should like to know: (1) Is there a good list of websites and periodicals to which I might submit them? (2) What is the best way of finding out about problem contests? (3) Is there an accepted etiquette in the chess world as to whether one may submit a problem to multiple places?’

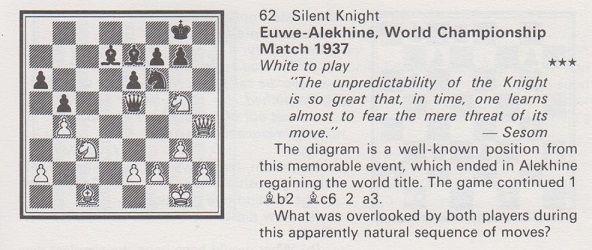

9232. Spot the co-authors’ blunder

From pages 25 and 110 of Blunders and Brilliancies by Ian Mullen and Moe Moss (Oxford, 1990):

9233. World chess champion

Concerning early uses of ‘world chess champion’, Thomas Niessen (Aachen, Germany) adds a reference on page 286 of the Dubuque Chess Journal, June 1875: ‘William Steinitz, the present chess champion of the world.’

9234. Juan

Reid (C.N.s 9213 & 9219)

Richard Buchanan (Manitou Springs, CO, USA) has forwarded some biographical information about Juan Reid (1908-81), together with these two games from the archives of Colorado College:

Samuel Reshevsky – Juan Reid

Simultaneous exhibition, Colorado Springs, 25 February

1963

Queen’s Gambit Declined

1 d4 d5 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 Nbd7 5 cxd5 exd5 6 Qc2 Be7 7 e3 O-O 8 Bd3 c6 9 Nf3 h6 10 Bf4 Re8 11 O-O-O b5 12 g4 b4 13 Na4 Nb6 14 g5 hxg5 15 Bxg5 Nxa4 16 Qxa4 Bg4 17 Be2

17...Ne4 18 Bxe7 Qxe7 19 Rdf1 Bxf3 20 Bxf3 Nxf2 21 Rxf2 Qxe3+ 22 Rd2 Qxf3 23 Rg1 c5 24 dxc5 Qe3 25 Rgd1 Qxc5+ 26 Kb1 Rad8 27 Rxd5 Qe7 Drawn.

Samuel Reshevsky – Juan Reid

Simultaneous exhibition, Colorado Springs, 17 February

1964

Queen’s Gambit Declined

1 d4 d5 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 cxd5 exd5 5 Bg5 Be7 6 e3 O-O 7 Bd3 c6 8 Qc2 h6 9 Bh4 Nh5 10 Bxe7 Qxe7 11 Nge2 Re8 12 O-O Nf6 13 Rab1 Nbd7 14 b4 Nf8 15 b5 Bd7 16 bxc6 Bxc6 17 Qb3 Ne6 18 Bb5 Rab8 19 Qa4 Bxb5 20 Rxb5 a6

21 Nxd5 Nxd5 22 Rxd5 Rec8 23 Rd7 Qe8 24 f4 b5 25 Qb3 Qxd7 26 f5 Ng5 27 Ng3 Re8 28 Rf4 Rbc8 29 h4 Nh7 30 Nh5 Qe7 31 e4 Nf6 32 Ng3 Qc7 33 e5 Nh7 34 Ne4 Qc1+ 35 Rf1 Qc4 36 Qe3 Rcd8 37 Rf4 Qxd4 38 Nf6+ Nxf6 39 Rxd4 Nd7 40 Qd2 Rxe5 41 Rxd7 Rde8 42 Rd8 Kf8 43 Qd6+ Kg8 44 Rxe8+ Rxe8 45 Kf2 Resigns.

9235. Purdy’s interruption

Below, from page 1 of the 1 January 1949 issue of Chess World, is a remark by Purdy at the start of a letter to the editor from J. Hibbert, as quoted in C.N. 1622 (see page 246 of Chess Explorations):

9236. Atkins v Blackburne

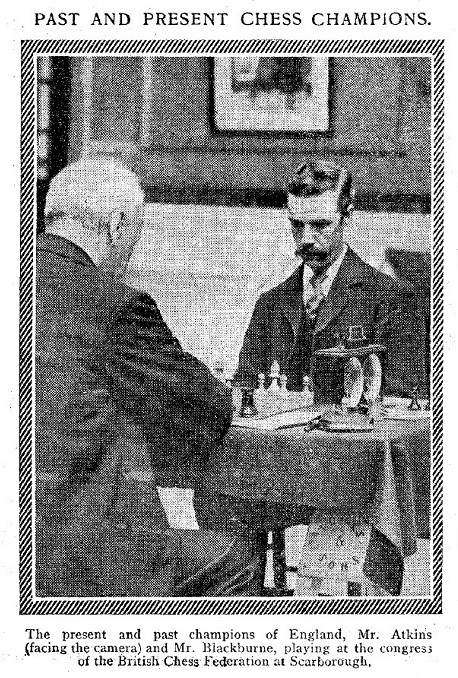

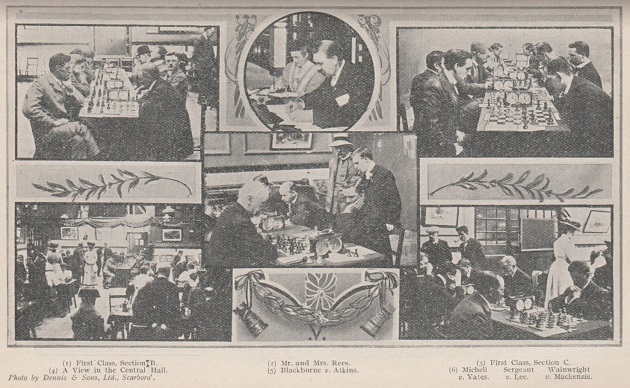

Source: Daily Mirror, 12 August 1909, page 8.

The game, a win for Atkins in 23 moves, was played on 10 August 1909 and published on page 385 of the September 1909 BCM. The photographs on page 371 of the same issue included another shot of the game:

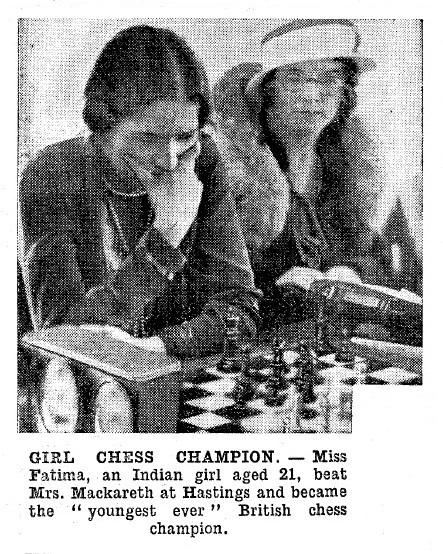

9237. Miss Fatima

Source: Daily Mirror, 11 August 1933, page 28. (For Mackareth read Mackereth.)

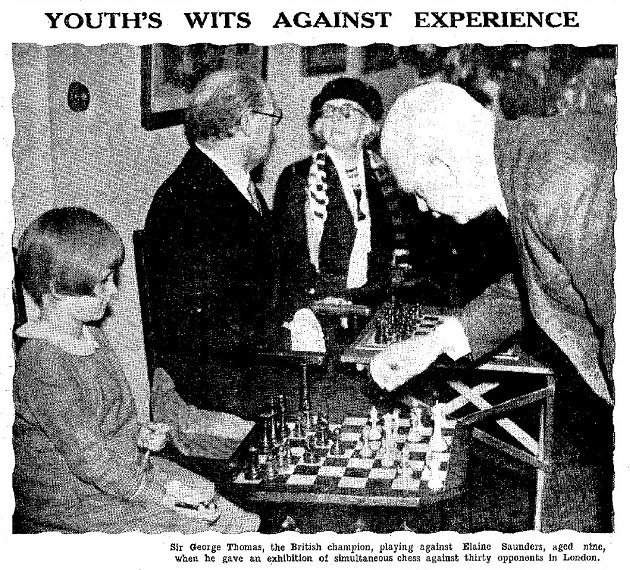

9238. Saunders v Thomas

Source: Daily Mirror, 23 October 1934, page 19.

9239. Eighteenth-century chess clubs

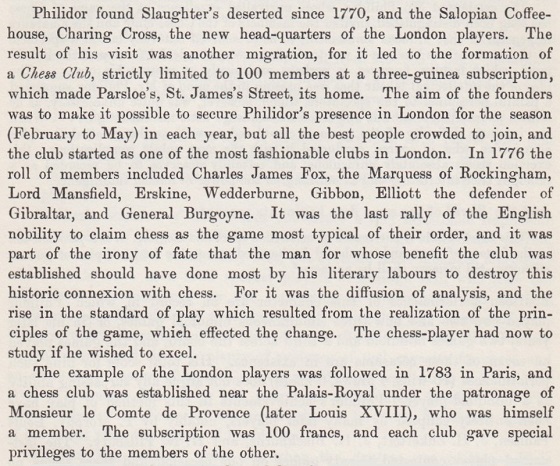

From page 863 of A History of Chess by H.J.R. Murray (Oxford, 1913):

Adrian Harvey (Edgware, England) asks whether information is available on any other eighteenth-century chess clubs in countries apart from Great Britain.

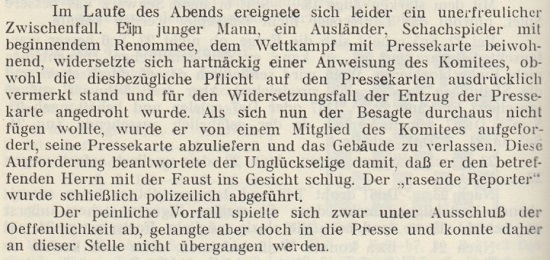

9240. Ernst Klein

Further to the controversy involving Ernst Klein and the 1935 Alekhine v Euwe world title match, Alan McGowan (Waterloo, Canada) notes two more items:

Wiener Schachzeitung, April 1936, page 104

Wiener Schachzeitung, June 1936, page 188.

9241. Spot the co-authors’ blunder (C.N. 9232)

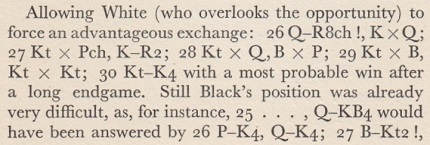

Contrary to what was stated in the book by Mullen and Moss, Alekhine was White and Euwe Black.

Below is the relevant part of the game with Alekhine’s notes from pages 113-114 of his book The World’s Chess Championship 1937 (London, 1938):

9242. Alcohol

In his Field column on 24 January 1880 Steinitz reproduced a paragraph from the Daily Telegraph, 7 January 1880 about an ‘extraordinary’ case involving chess and alcohol. We do not have that original publication but can show what appeared in the Leeds Times three days later, i.e. on page 7 of the 10 January 1880 edition:

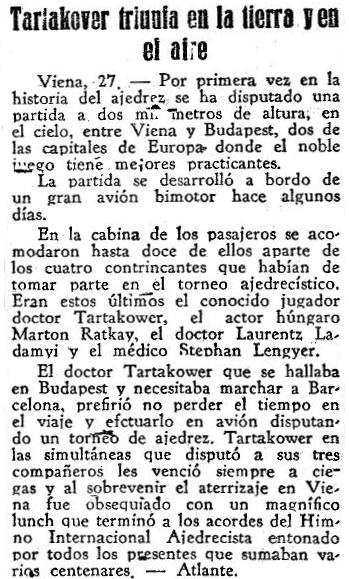

9243. Tartakower in the air (C.N. 9198)

Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) has found a report on page 3 of El Mundo Deportivo, 29 September 1929:

Thus Tartakower’s flight was from Budapest to Vienna. As noted on page 98 of his book on the Budapest, 1929 tournament, the last round was on 16 September. The Barcelona tournament began eight or nine days later, as shown, for instance, in the report by Tartakower on pages 39-49 of Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten, February 1930.

9244. Chess and women

Newspapers are forever reporting alleged anger, fury,

etc. vented ‘last night’. (Profound discontent generally

seems nocturnal.) The original report about Nigel Short,

in the Daily

Telegraph of 20 April 2015, illustrates how

news stories may nowadays be confected from Twitter, and

one tweet grabbed is a claim that Short’s comments were

‘incredibly damaging’. (‘Incredibly’ generally means

‘very’.) Last night’s ire is a curiously delayed reaction

to an article by Short, ‘Vive la Différence’, on pages

50-51 of the 2/2015 New in Chess – an issue which

was published a month ago but evidently remained

unavailable last night, and even today, given that much of

the coverage bears little relation to what Short wrote in

the Dutch magazine.

It is incredibly easy to express simplistic views on the topic of chess and women in ignorance of the key factors, whether biological, cultural, psychological, sociological, etc., which may or may not explain any differences between male and female chessplayers, whether now or in the past. We have made that last sentence as woolly as possible to underscore the futility of such general, synthetic ‘debates’, which concern, in full or in part, questions of opinion and taste.

If Nigel Short’s New in Chess article contained factual mistakes, misquotations, faulty statistics, bad writing or plagiarism, there would be every reason to complain, but we have seen no attempt to rebut, even, this important paragraph of his on page 51:

‘Given Susan Polgar’s undoubted genuine achievements – such as being the first woman to earn the Grandmaster title conventionally by making three norms – it is tragic that her brand is tarnished by extravagant and literally incredible claims like her supposed world record in 2005 of playing 1,131 games consecutively (winning 1,112!) in just 990 minutes. This works out at just 52.5 seconds per game – although it would be somewhat less when one takes into account bathroom breaks. Given that she was walking around the whole time, which causes a second or seconds to be lost on [e]very move, for this record not to be fictitious would require an extraordinary high number of Scholar’s Mates. It is hard to understand why an emotionally stable individual would even imagine anyone else might believe this record to be genuine.’

9245. The dark side of Fischer

Still on the subject of New in Chess and the importance of factual accuracy, we turn to an article entitled ‘Facing Bobby Fischer’ by Dirk Jan ten Geuzendam on pages 12-27 of the 3/2015 issue. It refers to the large amount of ‘unsettling’ material in Bobby Fischer Triumph and Despair edited by Alessandra DeLucia (Darien, 2014) and argues that ‘even to this day, many Fischer fans and people that had known him personally are looking for ways to excuse his outrageous behaviour or gloss over his dark side’ (page 12). The dark side is identified as Fischer’s mental illness and virulent anti-Semitism, and page 16 states that ‘since the book appeared one year ago, it has been surrounded by silence’.

That last remark comes from a lengthy paragraph which, bafflingly, criticizes us for such silence. To quote just the conclusion:

‘It is remarkable that Winter, a historian who loves unearthing historical titbits, often fairly insignificant and from obscure sources, could not find more than a number of unpublished training games in Triumph and Despair to show to his readers. It is hard to come up with another reason than that he had no wish to enter the dark recesses of the mind of a man he admires so much as a chess player.’

Mr ten Geuzendam is referring to C.N. 8634 and, wilfully or not, he omits the obvious explanation for our ‘silence’: by that time we had already discussed Fischer’s dark side on many occasions, on the basis of earlier volumes by Mr David DeLucia.

Below, for instance, is an extract from C.N. 6189, concerning Bobby Fischer Uncensored (Darien, 2009):

Another item in Mr DeLucia’s collection, dated 18 November 1997: ‘a 100-page working typescript by Fischer entitled “What Can You Expect from Baby Mutilators”’.

Numerous illustrations are of books and other publications owned by Fischer, including such titles as The White Man’s Bible, The World Conspiracy and The Myth of the Six Million. His personal notebooks are also reproduced, and it would be impossible to overstate the anti-Semitism with which they are suffused. ‘Hitler was right about the Jews: They want to steal everything I’ve worked for all of my life’ (page 244). On page 285 another note, dated 21 May 1999, is also typical: ‘It’s time for programs against Jews and it’s also time for vigilante killings of Jews – random killings of Jews.’ Page 301 has a draft letter which begins:

‘Dear Mr Osama bin Laden allow me to introduce myself. I am Bobby Fischer, the World Chess Champion. First of all you should know that I share your hatred of ...’, etc., etc.

Mr DeLucia presents such material without editorial comment, rightly leaving readers to supply their own revulsion.

We also wrote about David DeLucia’s collection, again

stressing the dark side of Fischer, in an article

at ChessBase.com in 2012. The same year the feature

article A

Letter from Bobby Fischer to Pal Benko was posted,

again courtesy of Mr DeLucia. We first mentioned the

letter to Benko in C.N. 3165 (‘Fischer on Hitler’ – see

pages 329-330 of Chess Facts and Fables) following

publication of David DeLucia’s Chess

Library: A Few Old Friends (Darien, 2003).

Another article, Instant Fischer, has an Afterword written in 2005, and its conclusion provides further proof that we have not shied away from denouncing Fischer:

From the late 1990s onwards he gave a series of radio interviews in which, egged on by standardless ‘broadcasters’, he came out with the most abject set of utterances ever made by a chess master.

9246. Submitting problems (C.N. 9231)

From Bernd Graefrath (Mülheim an der Ruhr, Germany):

‘In October 2014 I was elected President of the German chess problem society, Schwalbe, which publishes a prestigious magazine, Die Schwalbe. I am also a regular columnist in the British magazine The Problemist, issued by the British Chess Problem Society. Both publications have sections for original two-movers. The standard is very high, and it is often advisable for new composers to submit their work to a more general chess magazine. One list of magazines and tournaments available online is by Andrei Selivanov.

Concerning etiquette, a problem should certainly not be sent to more than one magazine at the same time.

Before a problem is submitted, it may be worthwhile checking a database for possible anticipations. I can recommend the Chess Problem Database Server.’

9247. Terminology

The glossary on pages 154-156 of The Most Valuable Skills in Chess by Maurice Ashley (London, 2009) includes ‘a few expressions that I have felt the need to create in order to crystallize key ideas to my students’. They are:

- ‘Bear Hug Mate: a common checkmate in which a protected queen stands directly in front of an opposing king sitting on the side or edge of the chessboard. It is the most popular mate in all of chess.’

- ‘Co-protective relationship: a state where two pieces or a piece and a pawn mutually defend one another.’

- ‘Crossing point: a square where lines (ranks, files or diagonals) emanating from two pieces intersect.’

- ‘Landmine square: a square on which a piece or pawn would be in immediate danger of being captured.’

- ‘Protector (often used interchangeably with “defender”): a unit that protects another of its forces.’

- ‘Quad mate (Queen along diagonal mate): a common mate where a protected queen mates an opposing king by standing on the closest diagonal square.’

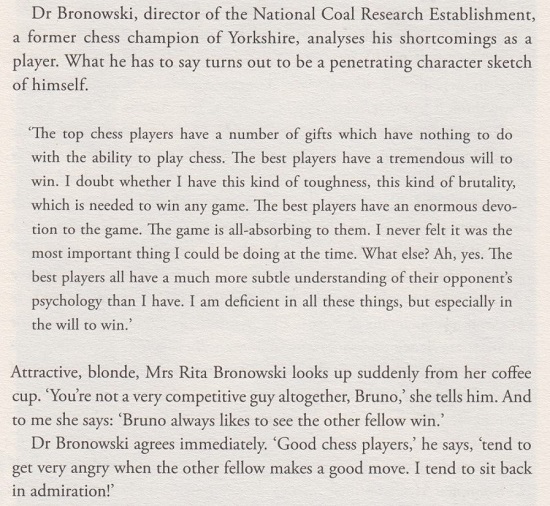

9248. Jacob Bronowski

Gerard Killoran (Ilkley, England) points out a passage about Jacob Bronowski on page 34 of Snapshots. Encounters With Twentieth-Century Legends by Herbert Kretzmer (London, 2014):

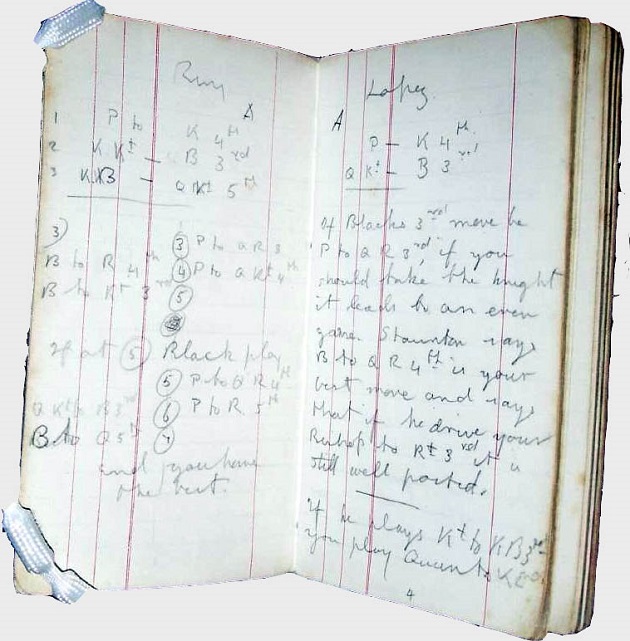

9249. Schoolboy notebook

From page 69 of Rupert Brooke by Michael Hastings (London, 1967)

On the centenary of the death of Rupert Brooke (3 August 1887-23 April 1915) we mention that no progress has been made with identifying the source of the chess material in a notebook of his, such as the following:

There is no reference to chess in the ‘Books from the library of Rupert Brooke’ section on pages 47-50 of Catalogue of Books and Manuscripts by Rupert Brooke, Edward Marsh & Christopher Hassall by John Schroder (Cambridge, 1970), from which we reproduce the poet’s bookplate:

9250. Pion coiffé (C.N. 6093)

From Steinitz’s column in The Field, 7 February 1880:

‘We give the following game in illustration of the curious complications which arise at the odds of the “kept pawn”. This rare advantage was here given by Mr Mortimer, the inventor of the well-known Fraser-Mortimer variation of the Evans Gambit, and the game was played last month at Holloway Prison, where Mr Mortimer is now confined as a first-class misdemeanant, for having allowed a libel to appear in the Figaro, of which paper he is the proprietor. White gives the odds of the KBP coiffé, and undertakes to mate the adversary with that pawn without queening it.’

1 e3 e5 2 d3 d5 3 Nc3 c6 4 g3 Bd6 5 Nf3 Bg4 6 Bg2 e4 7 dxe4 dxe4 8 Nxe4 Bc7 9 Qxd8+ Bxd8 10 Nd6+ Kf8 11 Nxb7 Bb6 12 Nd6 Ne7 13 a4 Bxf3 14 Bxf3 Nd5 15 a5 Bc5 16 Nc4 Bb4+ 17 c3 Be7 18 O-O Nd7 19 Rd1 N7f6 20 Ne5 Rc8 21 c4 Nb4 22 Bd2 c5 23 Bc3 Nc2 24 Rac1 Nb4 25 Nd7+ Nxd7 26 Rxd7 Na2 27 Rc2 Nxc3 28 Rxc3 Bf6 29 Rb3 g6 30 Rbb7 Ke8 31 Rxf7 Bg5 32 Rxh7 Rxh7 33 Rxh7 Rd8 34 Rh8+ Ke7 35 Rxd8 Kxd8 36 Be4 Bf6 37 Bxg6 Bxb2 38 Be4 Kc7 39 Kf1 Bc3 40 a6 Kb6 41 Bb7 Ka5 42 Ke2 Kb4 43 Bd5 Ka5 44 Kd3 Be1 45 f3 Kxa6 46 g4 Bh4 47 f4 Kb6 48 Kc3 Bf6+ 49 Kb3 a5 50 g5 Bg7 51 h4 Ba1 52 h5 Bg7 53 h6 Bh8 54 g6 Bf6 55 g7 Bh4 56 g8(Q) Bf6 57 h7 Kc7 58 h8(R) Kd7 59 Rh7+ Kd6 60 Be4

60...Be5 61 Qd8+ Ke6 62 f5 mate.

Black was identified only as ‘Mr B.’ by Steinitz, who annotated the game in depth. His term ‘kept pawn’ may well be an error for ‘capped pawn’.

9251. Kasparov on Short (C.N.s 8376 & 9221)

The bulletin (June 1992) of the Manila Olympiad has been provided by Henk Chervet of the Koninklijke Bibliotheek in The Hague:

9252. The dark side of Fischer (C.N. 9245)

A retraction and apology are awaited from Mr Dirk Jan ten Geuzendam over his claim on page 16 of the 3/2015 New in Chess that we have been silent about Fischer’s dark side. As demonstrated in C.N. 9245, the truth is the exact opposite: thanks to Mr David DeLucia’s generosity, we have quoted extensively from the series of books which he and his daughter have published over the past dozen years, and much ‘dark’ material has been included.

A further example of non-silence is our conclusion to a ChessBase.com article in 2010:

The extent of Fischer’s depravity, anti-Semitism and, it must be said, apparent insanity was shown when a selection of his personal notes and other memorabilia was reproduced in Bobby Fischer Uncensored by David and Alessandra DeLucia (Darien, 2009).

9253. Fischer and knight-odds for women players

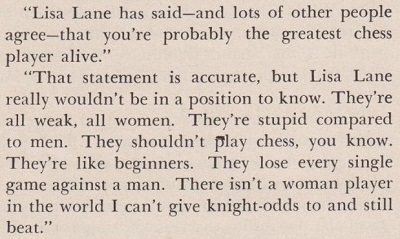

C.N. 9218 reported a denial by Fischer, although not from a primary source, that he had ever claimed an ability to give knight-odds to any woman in the world. The claim was attributed to him in the Ginzburg interview (C.N. 9155), and below is the alleged exchange between Ginzburg and Fischer, on page 50 of Harper’s Magazine, January 1962:

‘“Lisa Lane has said – and lots of other people agree – that you’re probably the greatest chess player alive.”

“That statement is accurate, but Lisa Lane really wouldn’t be in a position to know. They’re all weak, all women. They’re stupid compared to men. They shouldn’t play chess, you know. They’re like beginners. They lose every single game against a man. There isn’t a woman player in the world I can’t give knight-odds to and still beat.”’

Whether or not Fischer spoke those words, or anything similar, they have been widely disseminated, and the name of Nona Gaprindashvili has somehow been drawn in. Below are three passages written by Larry Evans:

‘Why, of [sic] why, are there no lady grandmasters?

This tedious topic was kicked around long before Bobby Fischer proclaimed: “Women are weakies. I can give knight odds to any woman in the world. To Nona even, a knight!” Russia’s Mikhail Tal politely demurred: “Fischer is Fischer, but a knight is a knight!”’

Source: a syndicated column by Evans published in, for instance, the Sunday Oregonian, 2 December 1973, page F3.

‘Bobby Fischer probably regrets ever saying: “They’re all weak, all women. They’re stupid compared to men. They shouldn’t play chess, you know. They’re like beginners. They lose every single game against a man. There isn’t a woman player in the world I can’t give knight-odds to and still beat ... To Nona even, a knight!”’

Source: a syndicated column by Evans published in, for instance, the Oregonian, 15 March 1976, page B6, and reproduced on page 71 of Evans’s book The Chess Beat (Oxford, 1982).

‘... Bobby Fischer’s boast over 30 years ago that he could give a knight to any woman – even world champ Nona Gaprindashvili. “Fischer is Fischer. But a knight is a knight”, pooh-poohed Mikhail Tal.’

Source: Chess Life, February 1995, page 17.

In a discussion of the Harper’s Magazine interview on page 361 of Impact of Genius (Seattle, 1992) R.E. Fauber wrote:

‘He denounced “girls” as “silly” and branded them “weakies”. He offered to give knight odds to any female chess players. The Soviets joined in the general hilarity by offering to pit newly-crowned women’s world champion Nona Gaprindashvili against him, at those odds. Fischer did not respond.’

We offer some factual observations:

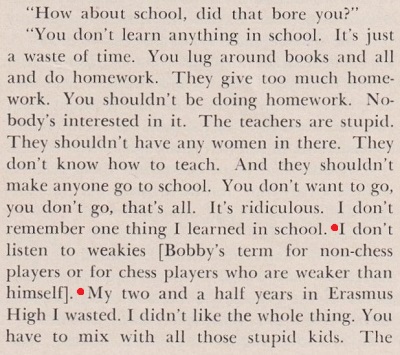

1) The word ‘silly’ is not in the Ginzburg interview. The word ‘weakies’ is on page 51, but in a different context, i.e. not specifically about females who play chess:

2) The words attributed to Fischer by Ginzburg were not an ‘offer’ to give knight odds but a claim that (hypothetically or theoretically) he could give such odds;

3) Nona Gaprindashvili was not mentioned in the Harper’s Magazine interview, and at that time she was not ‘newly crowned’ (Fauber) or ‘world champ’ (Evans). She did not win the women’s world championship title until October 1962, about nine months after publication of the interview.

On page 367 of the December 1963 Chess Review Petar Trifunović wrote:

‘Someone once asserted to the writer that women’s chess is very weak, declaring as proof that Bobby Fischer said he can give knight odds to the women’s champion. The writer doesn’t know that Fischer said anything of the sort, but is sure no-one can give knight odds to Nona Gaprindashvili.’

Chess Review added an editorial footnote:

‘Some years ago a magazine article did quote Fischer to that effect. But he has said he was improperly quoted on many points, out of context or otherwise. Certainly, he did not mention Nona Gaprindashvili as she was not then women’s champion.’

4) We do not know where and when Mikhail Tal may have made the remarks ascribed to him.

5) During the second match between Fischer and Spassky, 30 years after the Ginzburg interview, Fischer was asked about women’s chess by Cathy Forbes at the fifth press conference, on 5 October 1992. Below is the exchange, as transcribed on page 152 of No Regrets by Yasser Seirawan and George Stefanovic (Seattle, 1992):

Forbes: ‘Why, in your opinion, do women generally not play chess as well as men?’

Fischer: ‘Well, it seems to be nature, but perhaps with time they are improving and I assume that they will continue to improve.’

From Harper’s Magazine, January 1962, page 52

9254. Chess and women (C.N. 9244)

Nigel Short’s article was so bad that few, if any, top-level masters have expressed agreement with it. Nigel Short’s article was so good that few, if any, top-level masters have expressed disagreement with it.

There are other possibilities too, of course, and of all the lessons to be learned from the shambolic, sprawling rumpus over ‘Vive la Différence’ (an article still being discussed by individuals who have not read it) a neglected one is mentioned here, in the context of any current issues (as opposed to history and lore): the lack of a proper online chess forum where topical controversies can be discussed in depth; where comprehensive and comprehensible coverage is founded on facts and informed opinions; where contributions bear the writer’s real name; where hearsay is absent; where wit is welcome but glib illiterates are not; where Internet links are supplied only if they lead to something worthwhile; where irrelevancy and repetition are avoided; where strong criticism of people and of ideas is expressed solely if based on substantiated information; where all relevant sources are cited; where points are not deemed true, or even noteworthy, merely because they come from the mainstream media; where press articles by non-chess-specialists are treated not with automatic gratitude but with particular caution; where misquotation is excoriated; where the debate, however lively, is moderated with rigorous even-handedness; where good linguistic standards are ensured; where contributors and readers are treated with the respect that they deserve; where anyone, including top-level masters, would be proud to have a contribution posted.

Wanted: one topical chess forum where 100% of the contributions are worth reading, and not 100 forums where 1% are.

9255. A queen sacrifice by Capablanca

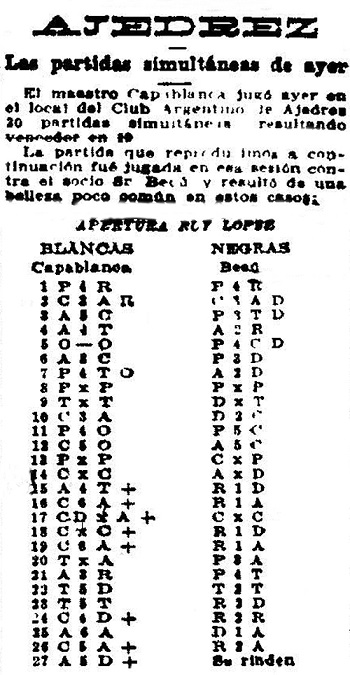

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) has found this

game on page 7 of La Nación, 31 August 1914:

Our correspondent believes that Black was Teodoro Becú, who was mentioned in, for instance, a crosstable on page 115 of the October-December 1909 Revista del Club Argentino de Ajedrez.

José Raúl Capablanca – [Teodoro] Becú

Buenos Aires, 30 August 1914

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Be7 5 O-O b5 6 Bb3 d6 7 a4 Bd7 8 axb5 axb5 9 Rxa8 Qxa8 10 Nc3 Qb7 11 d4 b4 12 Nd5 Bg4 13 dxe5 Nxe5

14 Nxe5 Bxd1 15 Ba4+ Kd8 16 Nc6+ Kc8 17 Ndxe7+ Nxe7 18 Nxe7+ Kd8 19 Nc6+ Kc8 20 Rxd1 f6 21 Be3 h5

22 Rd5 Rh7 23 Ra5 Kd7 24 Nd4+ Ke7 25 Bc6 Qc8 26 Nf5+ Kf7 27 Bd5+ Resigns.

9256. Annotational clichés

‘A knight is a knight’ (C.N. 9253) brings to mind the cliché ‘a pawn is a pawn’ (a phrase used in a brief sketch by ‘W.C.G.’ on page 131 of the April 1885 BCM). C.N.s 642 and 7673 mentioned ‘an interesting game in all its phases’ and ‘the rest is a matter of technique’, and two others are ‘this move is better than its reputation’ and ‘the pawns fall like ripe apples’.

Readers are invited to keep their eyes peeled for any recent annotational clichés which have been spreading like wildfire, left, right and centre.

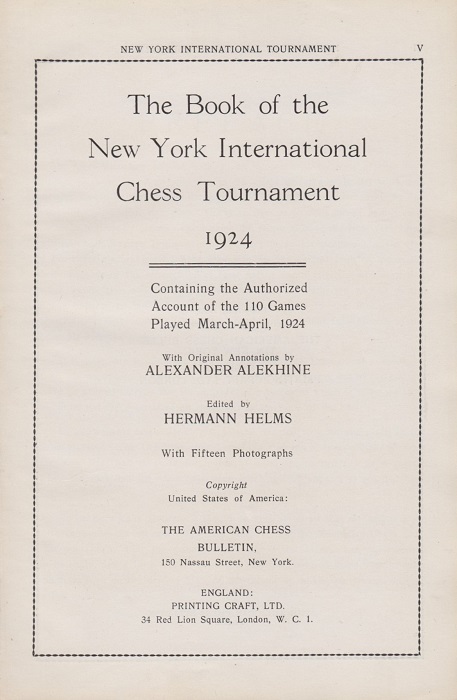

9257. New York, 1924 tournament book

Noting that the ‘21st Century Edition’ of Alekhine’s New York, 1924 tournament book (Milford, 2008) does not identify the translator or the language in which Alekhine wrote, Michel Therrien (Saint-Laurent, Quebec, Canada) remarks that it is not unusual for such information to be omitted when old chess books are reissued.

In the particular case of The Book of the New York International Chess Tournament 1924 (New York and London, 1925), however, we point out that no translator or language was specified in the original edition, although H. Ransom Bigelow was credited with translating Alekhine’s article ‘The Significance of the New York Tournament in the Light of the Theory of the Openings’ (pages 247-267). Readers were thus left to assume that all the annotations were translated by the book’s editor, Hermann Helms, who was mentioned on the title page:

In the ‘21st Century Edition’ Helms was named as editor

on the imprint page, whereas the writer of the two-page

Foreword, A. Soltis, was mentioned on the front cover, the

title page and the imprint page.

C.N. 5414 reported that Das Grossmeister-Turnier New York 1924 was published in or around February 1925 and that a review on pages 42-43 of the March 1925 American Chess Bulletin stated:

‘After many unforeseen and more or less vexatious delays, of which translation from the German was by no means the least, the home edition of the New York Tournament Book has at last reached the bindery ...’

9258. Alekhine and Capablanca

C.N. 741 (see page 118 of Chess Explorations) mentioned that in his Who’s Who entry Alekhine included canoeing as a hobby. We have no further information, or about Capablanca’s possible interest in boating, as suggested by the photograph below, from our collection, in which he is holding a copy of the British magazine The Motor Boat:

| First column | << previous | Archives [129] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.