Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [130] | next >> | Current column |

9259. Korchnoi and Karpov

Source: Punch, 14 October 1981, page 652. A chess article on the same page, ‘Above Board?’ by Jonathan Sale, attained a similar level of humour.

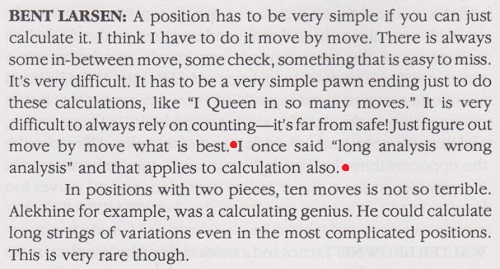

9260. Long and wrong

An article by Julio Kaplan (‘Games from Lone Pine’) on pages 364-366 of the July 1977 Chess Life & Review stated on the final page:

‘... as Lasker used to say: “Long analysis, wrong analysis”.’

Chess literature has references by the barrowful to what this or that master ‘used to say’, but responsible writers do not diffuse such material without secure sources. The ‘long/wrong’ saying is commonly attributed to Larsen, e.g. by A. Soltis on page 190 of The 100 Best Chess Games of the 20th Century, Ranked (Jefferson, 2000) and on page 27 of The Wisest Things Ever Said About Chess (London, 2008). In each case the wording offered was ‘long variation, wrong variation’, and the corroboration offered was zero.

Larsen’s own words are shown below from page 46 of How To Get Better At Chess by L. Evans, J. Silman and B. Roberts (Los Angeles, 1991), in the chapter ‘How Do Top Players See Things So Quickly?’:

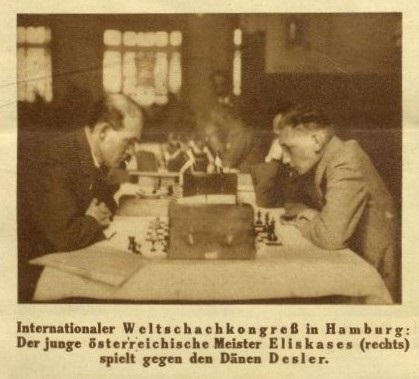

9261. Desler v Eliskases

Jan Kalendovský (Brno, Czech Republic) provides a photograph from page 3 of Das interessante Blatt, 24 July 1930:

A game by Arne Desler was discussed in Chess and The Prisoner.

9262. Threats

‘Threats are the very warp and woof of chess. Every game is an unspoken dialogue of threats and counterthreats.’

Source: page 119 of Complete Book of Chess Stratagems by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1958).

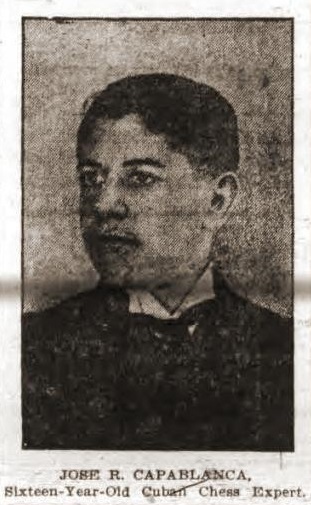

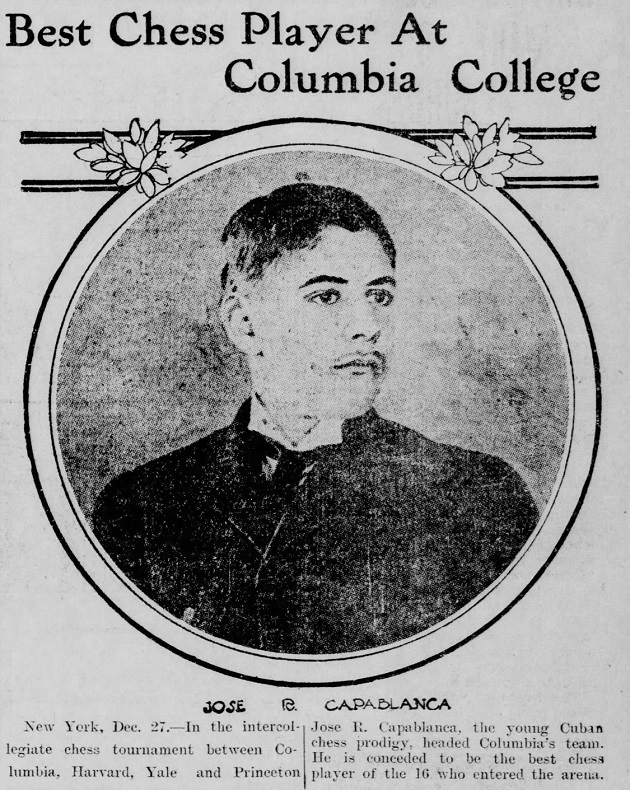

9263. Capablanca in 1905

Brooklyn Standard-Union, 15 January 1905, page 6

American Chess Bulletin, February 1905, page 126

The above illustrations were given in C.N. s 8244 and 3812 respectively. Below is a reverse shot, from page 18 of the Texas newspaper El Paso Herald, 29 December 1906:

9264. The House of Commons v Canberra

From page 7 of the 10 May 1927 edition of the Manchester Guardian:

There was a detailed report on pages 253-254 of the June 1927 BCM. The event will be referred to in our feature articles Chess and the House of Commons and Chess and British Royalty, although so far we have found no apposite pictures of either the Prime Minister (Stanley Baldwin) or the Duke of York (the future King George VI).

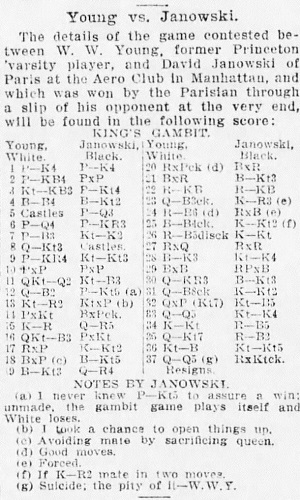

9265. Young v Janowsky

Two cuttings from Steve Wrinn (Homer, NY, USA):

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 30 March 1913, page 6

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 3 April 1913, page 10

William Wallace Young – Dawid Janowsky

New York, 29 March 1913

King’s Gambit Accepted

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 Bc4 Bg7 5 O-O d6 6 d4 h6 7 c3 Ne7 8 Qb3 O-O 9 h4 Ng6 10 hxg5 hxg5 11 Nbd2 Nc6 12 Qc2 g4 13 Nh2 Nxd4 14 cxd4 Bxd4+ 15 Kh1 Qh4

16 Nf3 gxf3 17 Rxf3 Kg7 18 Bxf4 Bg4 19 Bg3 Qh5

20 Rxf7+ Rxf7 21 Bxf7 Bb6 22 Rf1 Rf8 23 Qc3+ Kh6 24 Rf6 Rxf7 25 Bf4+ Kg7 26 Rf5+ Kg8 27 Rxh5 Bxh5 28 Be3 Ne5 29 Bxb6 axb6 30 Qh3 Bg6 31 Qc8+ Kg7 32 Qxb7 Nc4 33 Qd5 Ne5 34 Kg1 Rf4 35 Qb7 Rf7 36 Nf1 Ng4 37 Qd5 Rxf1+ 38 White resigns.

Later that year, W.W. Young (1877-1940) was described by

the American Chess Bulletin (July 1913, page 162)

as an engineer in a full-page feature on ‘The Young

Gambit’, which gave his well-known 13-move win against

Marshall in Bordentown, NJ.

9266. Hastings, 1929-30

Wanted: a better copy of the photograph below, which has been found by Gerard Killoran (Ilkley, England) on page 17 of the Evening Post, 15 February 1930:

The picture was taken during the first round, the pairings being (from the background to the foreground): Takács v Maróczy, Thomas v Vidmar, Winter v Capablanca, Menchik v Price and Sergeant v Yates.

9267. Mr and Mrs Prim

From page 62 of CHESS, 14 October 1938:

‘Was there a Connection?

L.C.K., Maritzburg, supplies the following (perfectly authentic) item from an American paper:

“Mrs Lottie Prim was granted her divorce from her husband, a chessplayer, on the grounds that he had spoken to her only three times since they were married. She was granted custody of the three children.”’

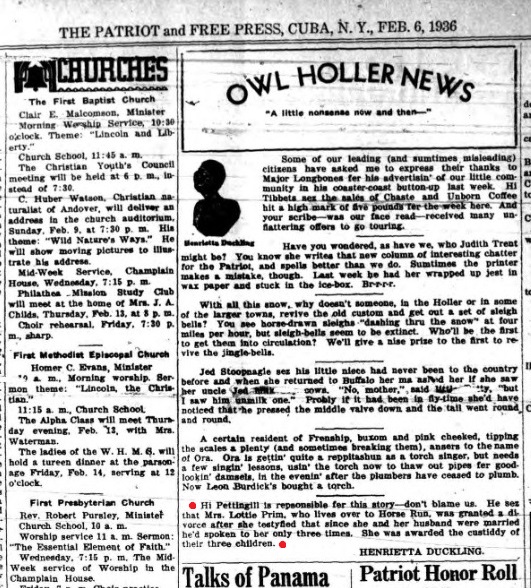

A cursory Internet search (in, for example, Google Books) provides many appearances of the story, and even in a 1934 edition of Petroleum Engineer. An eccentrically written version is shown below from page 2 of the Patriot and Free Press, Cuba, NY, 6 February 1936:

What more is known about the case? It is notable that early reports mentioned no chess connection.

9268.

Fischer interview in 1972

Comments by Bobby Fischer in the article ‘“This little thing between me and Spassky” – Bobby Fischer talks to James Burke’ on pages 51-52 of The Listener, 13 July 1972, further to a BBC-2 television programme broadcast at the beginning of the month:

-

‘I think I’ve been the best since I was about 18 or 19 – somewhere around 1962. I felt I had the talent even before I played the game. I just was always good at games. I like to keep taking on all the top players to really prove that I am the best player in the world today, so that when they go home that night they can’t kid themselves that they’re so hot. And so this is where it’s at, the apex of my whole life, taking on this Spassky. This is really the big match. This is for everything. This is for the title. If I don’t win, it’s not going to be easy to get up to again. This little thing between me and Spassky, it’s a microcosm of the whole world political situation. They always suggest that the two world leaders should fight it out hand to hand, and this is the kind of thing that we’re doing – not with bombs but battling it out over the board.’

-

(Asked whether it was arrogant of Fischer to consider himself the best chessplayer.) ‘If it’s true then it isn’t arrogant.’

-

(On his prospects against Spassky.) ‘It’s not 100 per cent, but it wasn’t 100 per cent that I was going to beat Taimanov or Larsen or Petrosian. I think I am definitely the heavy favourite according to all past results.’

-

(In reply to a question on the most important thing about winning the world title.) ‘I guess knowing that other people regard me as the Champion. I’ve felt all along that I’ve been the best so I’m not proving that much to myself any more. I’d like to prove it to myself as well, but especially to the general public. I’d like to show the Russians too. That’s what I’d enjoy the most about winning the title – reading the Russian magazines, what they’d say about it. Either they’re going to say nothing or they’re going to have some involved nonsensical explanation.’

-

(Did he resent the Russian domination of chess over recent decades?) ‘When I first started playing chess, to me the Russians were heroes, and they still are as chessplayers. I used to study all their literature; most of the first books I read were Russian chess books. But the first time the Russians ever mentioned me – I was 13 – they said: there’s this talented young American player. And they showed this famous game I’d won against Donald Byrne. They showed the game, but on top of the game they said he’s a very fine young player, but all this publicity he’s having will surely do damage to his character. And sure enough, from then on they started attacking my character. They’d never even met me, or knew anything about me. So this kind of attitude really turned me off. They have the title, and the title belongs to them in perpetuity because it’s theirs – that’s their attitude. They don’t have a sporting attitude about it. Their attitude should be: he’s the best, he should have the title. They don’t believe in giving foreigners a chance to play for the title.’

-

(On his early interest in chess.) ‘I just found that I had more of a feel for the game, more of a knack for winning, than others had. I liked games: I was playing a lot of board games at home. We had Pachisi, Monopoly and all these board games, Chinese chequers and what not, but I kept hearing the hardest game was chess, so I finally persuaded my mother to give me that. They thought that it would be too advanced for me, but they finally got me a set, and that is the game that I concentrated on from then on. When I was playing these other games they were too simple. There was something that didn’t turn me on about games like Chinese chequers.

I played a little with my sister, but she wasn’t too interested, so then I started playing games with myself. I would make the white moves and the black moves, and then I would just play through the whole game. My mother started to get worried that it wasn’t too healthy, playing chess by myself all the time, so she got me some opponents, local kids. I started getting lessons from a player in the Brooklyn Chess Club, and that is when I started to advance. I was lucky: he taught me an awful lot of things. I don’t think it would be possible to have a better teacher. We worked together for several years. I was giving him about a dollar a lesson, one a week.

When I was 16 I wanted to play chess all the time. All these invitations kept coming in to travel around and to make money. I’d had enough and I didn’t particularly like high school anyway. I wasn’t really learning that much, and I felt I could learn on my own.’

-

(Asked whether most of his friends are from the chess world.) ‘I think just about all of them. I have a few peripheral friends here and there that don’t play, but I don’t see them too much. I just don’t seem to have too much communication with non-chessplayers. It’s a strange thing.’

-

(In reply to the remark ‘It seems to be a game which demands that you live almost a hermit’s life.’) ‘That’s true. If you start partying around, it just doesn’t go. I like to meet people but I don’t like to meet 80 people at a shot.’

-

(‘You have been said to be among the most particular, the most perfectionist of players in things like light and noise and distraction during the game. Yet, to the outsider, you seem to be someone who concentrates so greatly that that kind of thing might not matter.’) ‘It does matter, if it really gets annoying. I think I have pretty good powers of concentration, but I remember I once played, I think it was in West Berlin, and there was this guy with his head right over the board. That’s the kind of thing I’ve had to put up with. Another time I was playing in Oakland in the States, and this guy whispers a move in my ear. Things like this are not really conducive to high-class play.’

-

(Could a successful fight against Spassky be rather an anti-climax?) ‘After I get the title it’s going to be a lot easier. I know it’s a dangerous way to think, but I will be able to ease up a little bit.’

-

(‘Is there anybody else in sight that you think could topple you afterwards?’) ‘Possibly, eventually. There are a lot of talented players in the West. But I think that if you keep yourself in good shape physically, and you keep in love with the game and keep studying, you should be a top player till you’re in your 60s.’

-

(‘Don’t you ever worry that concentration on just one side of your character might prove to have been a mistake?’) ‘I try to broaden myself. I read quite a bit. But it is a problem, because you’re kind of out of touch with real life, being a chessplayer – not having to go to work and deal with people on that level. I’ve thought of giving it up off and on, but I always considered: what else could I do?’

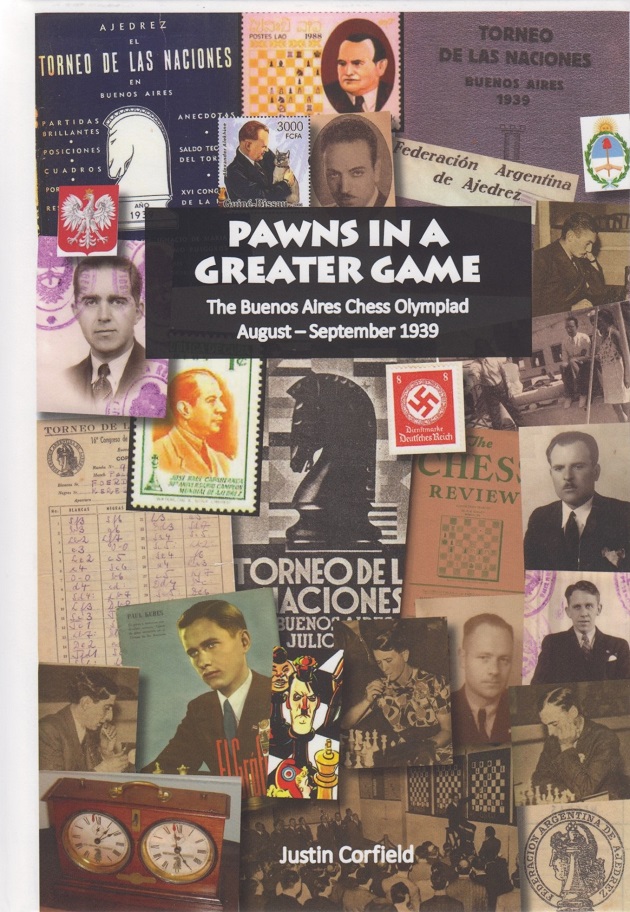

9269. Buenos Aires Olympiad, 1939

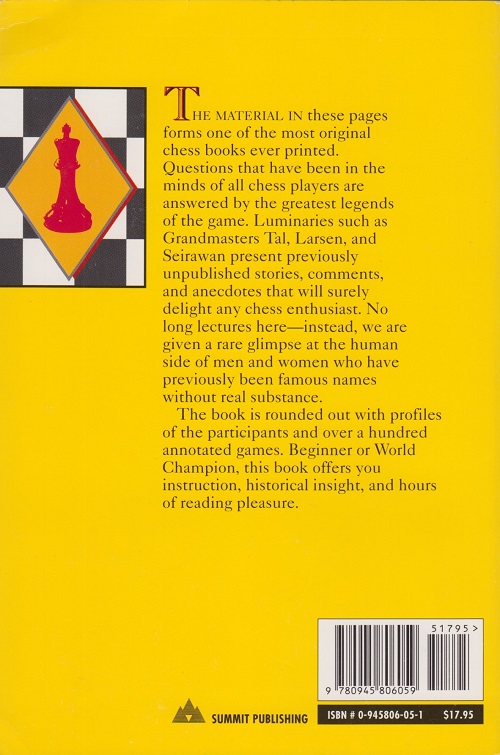

A deeply researched, richly illustrated 384-page hardback has just been received: Pawns in a Greater Game by Justin Corfield (Lara, 2015).

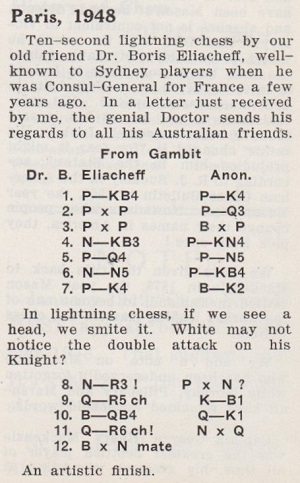

9270. Boris Eliacheff v N.N.

An addition for Fast Chess from page 285 of Chess World, 1 December 1948, in a column written by M.E. Goldstein:

1 f4 e5 2 fxe5 d6 3 exd6 Bxd6 4 Nf3 g5 5 d4 g4 6 Ng5 f5 7 e4 Be7 8 Nh3 gxh3 9 Qh5+ Kf8 10 Bc4 Qe8 11 Qh6+ Nxh6 12 Bxh6 mate.

On page 62 of Irving Chernev’s 1000 Best Short Games of Chess (New York, 1955) White was identified as ‘Eliascheff’.

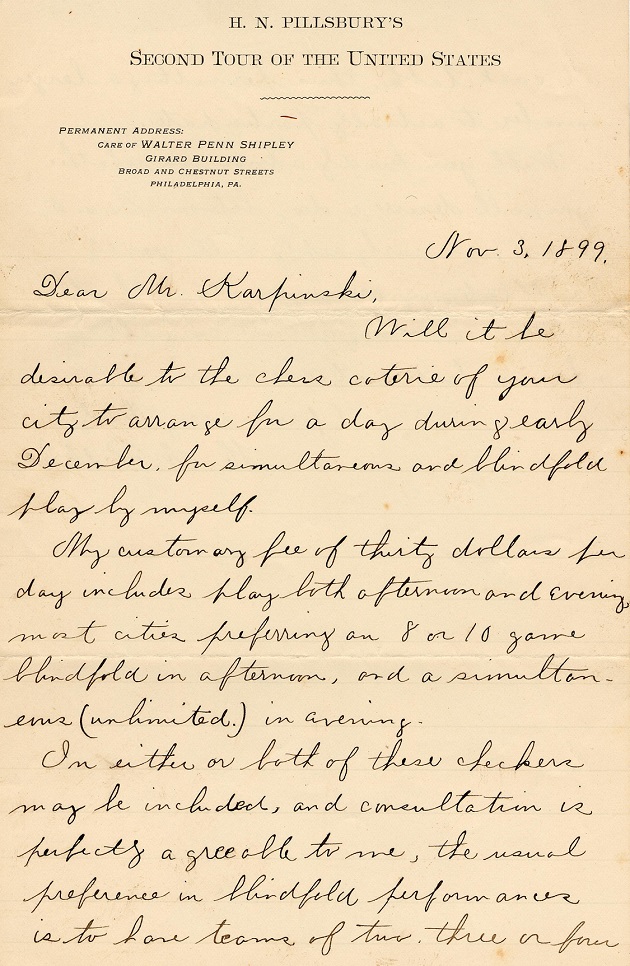

9271. Pillsbury’s correspondence (C.N. 3598)

The letter below was published on page 217 of David DeLucia’s Chess Library A Few Old Friends (Darien, 2007) and is shown here with Mr DeLucia’s permission:

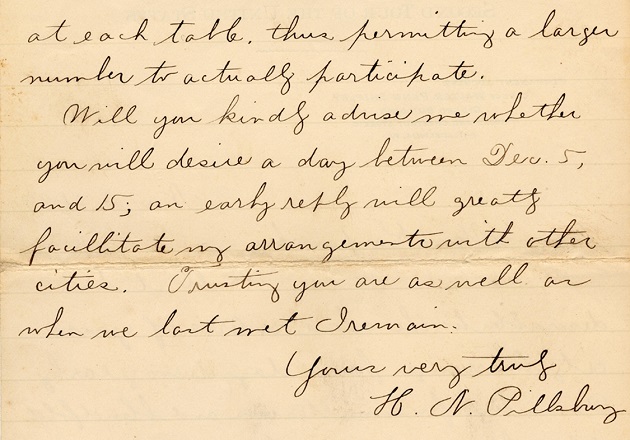

9272. Theta

C.N. 3780 quoted a brief article by ‘Theta’ on page 129

of the Chess Amateur, February 1926. Below is

another one, from page 193 of the April 1927 issue:

Who was ‘Theta’?

9273.

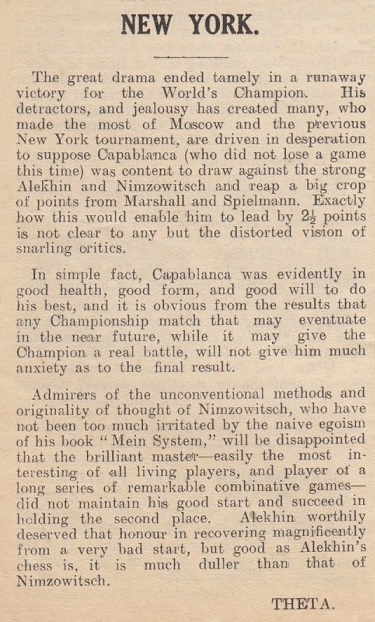

Kasparov, Leko and Kramnik

Steve Wrinn (Homer, NY, USA) draws attention to a passage on page 404 of Garry Kasparov on Garry Kasparov Part III: 1993-2005 (London, 2014) regarding the game Leko v Kasparov, Linares, 2003:

Our correspondent remarks:

‘In the rapid game referred to by Kasparov it was Kramnik who had the rook against Leko’s bishop. Kramnik ultimately won on time at the 133rd move, and his decision to play on in a theoretically drawn position elicited various comments. For example, in the Los Angeles Times, 14 January 2001 Jack Peters wrote:

“The players revealed opposing attitudes to rapid chess in the time scrambles at the end of the seventh and tenth games. In both cases, Kramnik had a nominal advantage that Leko neutralized easily. In the seventh game, Kramnik, with only five seconds remaining, offered a draw to Leko, who had 23 seconds left. Leko graciously accepted. In the tenth game, Kramnik had the edge on the clock and kept playing a drawn position until Leko ran out of time.”’

9274. Two words

There are two words which all readers of chess books, magazines, websites, discussion groups, etc. should be encouraged to write publicly as often as appropriate: ‘Source, please.’

It may be naive to hope that many cheap-jack peddlers of untrue, uncertain and unsubstantiated quotes, anecdotes and other would-be information will care if those two words are, for instance, systematically tagged onto their vacuous Internet postings, but the attempt has to be made. ‘Source, please’ is a measured, much-needed plea for writers to act responsibly and for readers to be treated respectfully.

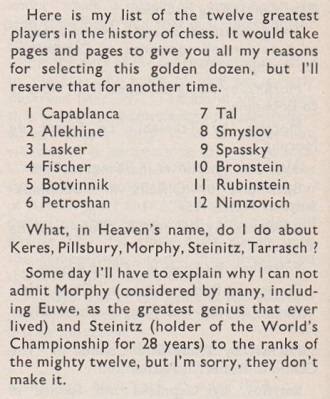

9275. The greatest

players, past and present

On pages 201-202 of the April 1974 CHESS Irving Chernev contributed an article, ‘Who were the greatest?’, which concluded:

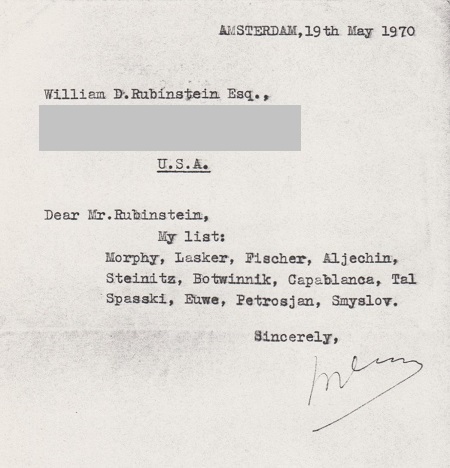

Chernev adhered to the same list in his book The Golden Dozen (Oxford, 1976) but did not explain the omissions. His CHESS article was prompted by a poll conducted a few years earlier by William D. Rubinstein, whose report, ‘Who are, or were, the Greatest?’, was published on pages 75-76 of CHESS, 5 November 1970. Chernev was one of many prominent contributors, and in the 1980s Rubinstein sent us copies of all the correspondence. He has now given us permission to reproduce some of the material here.

In a letter to Rubinstein dated 28 April 1970 Chernev mentioned that his opinions were subject to change but that his current listing was:

‘1 Capablanca; 2 Alekhine; 3 Lasker; 4 Botvinnik; 5 Petrosian; 6 Tal; 7 Fischer; 8 Spassky; 9 Smyslov; 10 Keres; 11 Bronstein; 12 Rubinstein. Pinch hitters: Pillsbury, Tarrasch, Nimzowitsch.’

A late contributor to the poll was Larsen, who replied on 17 November 1970 from Palma de Mallorca. The full letter is reproduced below verbatim:

‘Dear Mr Rubinstein,

If “best” means: “of greatest practical playing strength” my answer is, that the twelve “best” are probably all alive to-day. I know that in an interview, which as far as I remember was also published in Chess Life, I mentioned Alekhine among the ten best, but at second thought I would put Alekhine lower than number 12 on the list. His most brilliant successes were against much weaker opposition than in a good grandmaster tournament to-day.

Of course, when I mention Botvinnik, Keres, Smyslov, Tal and Bronstein, my thoughts go back ten years or more. Then add Petrosyan, Korchnoj and Spassky, these eight russians belong to the list of twelve, in my opinion. So do Fischer and I. The last two I would have to find between Gligoric, Reshevsky, Fine, Najdorf, Portisch and Hort, probably the first two.

To enumerate the ten or twelve is a little difficult, I am not a neutral observer. I would rank Botvinnik higher than Keres, that is about the only thing I can say.

With best regards.

Bent Larsen.’

In an article ‘I Was There’ by Dimitrije Bjelica on pages 49-50 of the February 1968 Chess Life the following exchanges with Larsen were reported:

‘Q: “Who are the best players in chess history?”

A: “The best was Philidor, because he was ahead of the others. Then Morphy, Steinitz, Lasker, Nimzowitsch, Alekhine, Botvinnik ... these are the best.”

Q: “But you have forgotten Capablanca?”

A: “No, I did not forget him. I think he did not give to chess what he could.”

Q: “Who are the most genial [sic] players of all time?”

A: “Philidor, Steinitz, Nimzowitsch.”

Q: “Do you think that Bobby will be world champion?”

A: “He won’t be, because he is too afraid to lose a game.”’

The concluding exchange in ‘Larsen Interviewed’ by Dimitrije Bjelica on pages 283-284 of the May 1970 Chess Life & Review:

‘“And who are the best players in history?”

“Philidor, Steinitz, Lasker, Alekhine, Botvinnik, Tal, Fischer, Petrosian, Spassky and Larsen.”’

See too Larsen’s remarks (e.g. ‘If I were put back in the early 1920s, it would be easy, very easy to be world champion’) in his January 1973 discussion with C.H.O’D. Alexander, as quoted in Bent Larsen (1935-2010).

Larsen’s view of his own position among the greatest players was referred to by David Hooper in a letter dated 28 March 1971 which was published under the title ‘Are the moderns so wonderful?’ on pages 250-251 of CHESS, 13 April 1971. Below is an abridged version (without the diagrams and moves of the games cited, which are all familiar):

‘Does the standard of play improve all the time? The following positions may interest your readers:

In 1916 Janowsky won a brilliancy prize against Chajes. ... An identical position arose 15 years later when Mikėnas playing against Kashdan took a perpetual check.

In 1906 Chigorin (aged 56, and past his best) played 27 R-B7 [against Rubinstein] and his opponent resigned. Forty years later ... Smyslov (soon to be champion) took a perpetual check [against Lundin].

In 1886 Zukertort defeated Steinitz (world champion) with a crushing attack ... Thirty-eight years later Alekhine (soon to be challenger) drew against Capablanca (champion). [Hooper was referring to the fifth match-game in the 1886 world championship match, which began 1 d4 d5 2 c4 c6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 e3 Bf5 5 cxd5 cxd5 6 Qb3 Bc8 7 Nf3 Nc6 8 Ne5, and Alekhine v Capablanca, New York, 1924, which opened 1 d4 d5 2 c4 c6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 e3 Bf5 5 cxd5 cxd5 6 Qb3 Bc8 7 Nf3 e6 8 Bd3.]

[Taimanov v Larsen]. Black lost after 63...K-K4? instead of 63...R-KR1ch= (Palma de Mallorca, 1970).

It happens I have the scores of about 900 games played by Capablanca. I cannot find one in which he lost a drawn rook and pawn endgame. For a brief moment I thought: was it possible that he played the endgame better than Larsen? But no! Capablanca, of course, only played against Lasker, Rubinstein, Alekhine and other second-raters.’

To pursue the topic of the greatest players past and present, information is sought, in particular, on other occasions when Larsen gave his views.

Further to Larsen’s controversial inclusion of himself on the ‘best’ list, we note Max Euwe’s reply to William D. Rubinstein:

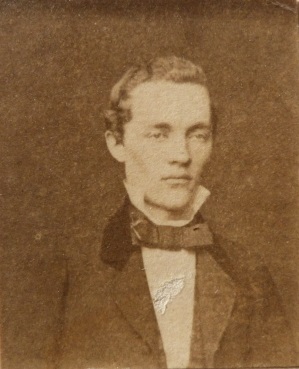

9276. Louis Paulsen

Ross Jackson (Raumati South, New Zealand) forwards a photograph of Louis Paulsen which he owns:

Our correspondent points out that a similar photograph, believed to be taken by Sam Loyd during the New York, 1857 tournament, was reproduced, from the Russell Collection archives, in the International Chess Calendar 1991 (Russell Enterprises, Inc.).

9277. Samuel Reshevsky and Joseph Schwarz

The Gallica website has a photograph of the prodigy Reshevsky with the opera singer Joseph Schwarz (1880-1926).

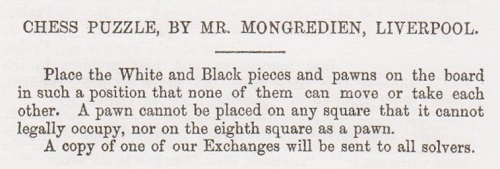

9278. An old task

The 32 units are placed on the board so that none can move.

9279. Exploiting a weak back rank

Michael Schorr (Illingen, Germany) asks for details about this position:

White to move.

Our correspondent notes that according to pages 182 and 185 of Erfolgreich kombinieren by Volkhard Igney (Zurich, 2002) the conclusion was 1 Re1 Rd8 2 Qb5 c6 3 Qb6 Rc8 4 dxc6 Rxg2+ 5 Kh1 and wins, whereas pages 27 and 190 of Improve Your Chess Tactics by Yakov Neishtadt (Alkmaar, 2011) had 1 Re1 Rd8 2 Qb5 Rxg2+ 3 Kh1 Resigns; the headings in the books were, respectively, ‘Wehnert-Liess, Saßnitz 1962’ and ‘Wehnert-Leiss, East Germany 1962’.

9280. The Encyclopaedia of Chess by Anne Sunnucks

On page 399 of the September 1978 BCM W.H. Cozens remarked that The Encyclopaedia of Chess by Anne Sunnucks (London and New York, 1970) was ‘loaded with what we must now call female chauvinism’, and on the following page he pointed out that since the entry for ‘Hastings Christmas Chess Congress’ contained crosstables printed one to a page, that single entry occupied one-thirteenth of the whole book.

When it first appeared, the Encyclopaedia was witheringly criticized by Wolfgang Heidenfeld in letters published on page 233 of the August 1970 BCM and on pages 80-81 of the February 1971 issue. The second letter was in reply to comments by Anne Sunnucks on page 358 of the December 1970 BCM. The specific complaints in Heidenfeld’s first letter included the allocation of only eight lines to Stoltz and four to Richter, ‘but 21 lines are wasted on Miss Sunnucks herself and 25 (!) on a “player” of the strength of Lisa Lane’. (In fact, Lisa Lane’s entry was much longer even than that: 43 lines. On the next page Bent Larsen received 24 lines.)

Heidenfeld’s first letter concluded:

‘This hotch-potch volume reveals not only a lack of judgment to distinguish between what is important and what is not; it has been compiled without even a proper knowledge of chess history, for some of the above omissions cannot be justified on any grounds of selectivity. Unfortunately, good will and great industry are not sufficient for an undertaking of this kind; one needs solid knowledge and mature judgment as well.’

In his second letter Heidenfeld observed:

‘There is, in fact, an enormous over-emphasis on British chess, on the one hand, and on women’s chess on the other – to the detriment of subjects which any moderately informed person knows to be far more important in the chess world.’

CHESS was, at first, more lenient on the Encyclopaedia, and the brief initial notice on page 288 of the 12 May 1970 issue read strangely:

‘The publisher’s claim “More ambitious than both its Russian and French counterparts” does not stand up to scrutiny. The compiler’s inexperience shows up, above all, in an almost comical lack of balance. But the book provides pleasant browsing for many an evening and, its faults rectified, will probably be in print a century hence.’

From page 27 of the 21 August 1970 CHESS:

‘We fear many other defects are coming to light. Three times more space given to the Women’s World Championship than to the World Championship itself; more about Lisa Lane than Spassky; about chess in Romania 13 pages [sic – three pages]; about France or Germany nil; about Sam Loyd, nil; the entire coverage of some themes lifted from out-of-date books. With drastic repairs the Encyclopaedia will yet become a great reference work.’

Some repairs were made in the second edition (London and New York, 1976), but it received little attention.

9281. Harry Benson on Bobby Fischer

Having watched The Story of LIFE Magazine, Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England) points out that the comments about Fischer by the photographer Harry Benson (in the sequence beginning at about 54’15”) are markedly different from what Benson said in the documentary Bobby Fischer Against the World (C.N. 7345).

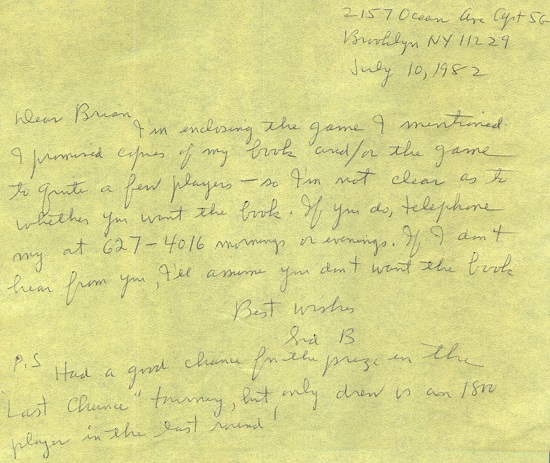

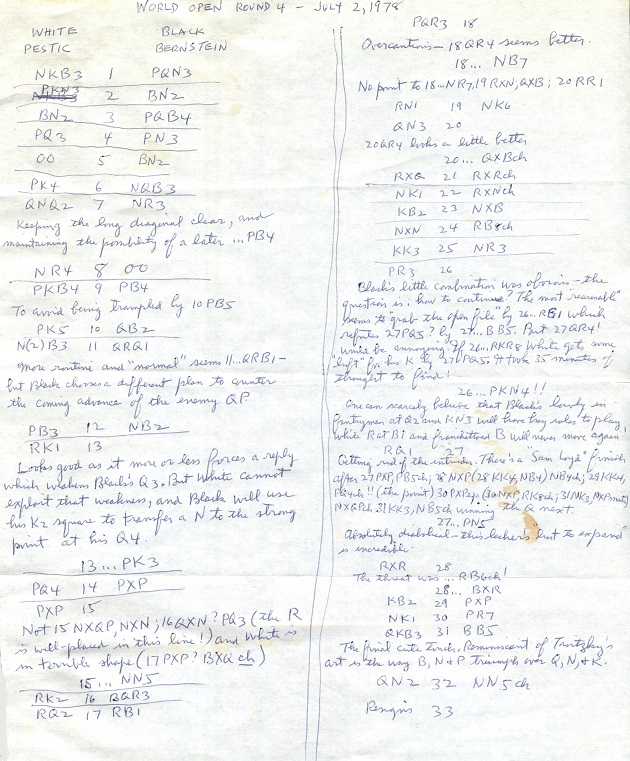

9282. Pestic v Bernstein

As mentioned in our feature article on Sidney Bernstein, in 1986 he told us that the best game he ever played was against R. Pestic, Philadelphia, 1978. Now, Brian Lawson (Douglaston, NY, USA) has forwarded a letter from Bernstein dated 10 July 1982:

9283. A composite picture

From page 15 of A Book of Chess by C.H.O’D. Alexander (London, 1973):

‘... all attempts – I am happy to say – to show that chessplayers have some unique mental faculty (e.g. exceptional memory) have been unsuccessful; the only respects in which they are superior to non-chessplayers of the same general calibre seem to be those in which their experience of chess is directly relevant.

Summing up, can we form any kind of composite picture of a chessplayer? He is likely to be an individualist with a good deal of aggression in his make-up, better with things than with people, mathematically oriented and at home with abstractions, and an opportunist; in his feeling for positions he has something of the artist in him, he has some creative power but on a small scale – he is a miniaturist, better at detail than at large-scale ideas. He is no crazier than anyone else – but when he is crazy, he will probably be paranoiac. But – as is shown by the millions of players in the USSR – there are potentially many of him; given suitable soil, caissa vulgaris is a common enough growth.’

9284. How To Get Better At Chess

C.N.s 2447 (see page 393 of A Chess Omnibus) and 9260 have quoted from How To Get Better At Chess by L. Evans, J. Silman and B. Roberts (Los Angeles, 1991), and Jean-Pierre Rhéaume (Montreal, Canada) asks for details about the genesis of the work.

The introductory section on pages ix-xi states that the book is based on interviews conducted by Betty Roberts, but information is sought as to the circumstances and whether full transcripts are extant.

9285. Open and close games

‘An open game can never be forced upon you, whether you are Black or White; a close game always can.’

Source: C.J.S. Purdy, Chess World, 1 February 1950, page 43.

9286. Exploiting a weak back rank (C.N. 9279)

Alan McGowan (Waterloo, Canada) sends an extract from page 304 of the October 1962 Schach, in an article by Kurt Richter:

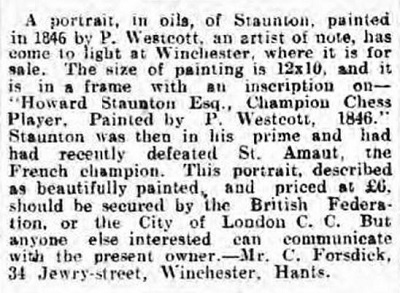

9287. Staunton in oils

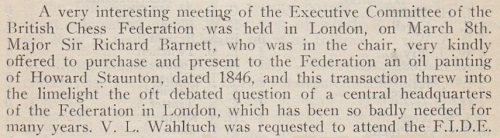

As mentioned in C.N.s 1136 and 3995 (see Pictures of Howard Staunton), page 129 of the April 1930 BCM referred to a Staunton painting on which details are lacking:

John Townsend (Wokingham, England) writes:

‘Page 4 of the Cheltenham Chronicle of 15 February 1930 reported that the owner of the painting was C. Forsdick of 34 Jewry-street, Winchester and gave the following details:

“The size of painting is 12x10, and it is in a frame with an inscription on – ‘Howard Staunton Esq., Champion Chess Player, Painted by P. Westcott, 1846’.”

Later, the Times of 10 March 1930 (page 11) carried a report on the meeting of the Executive Committee of the British Chess Federation that was mentioned in C.N.s 1136 and 3995, and named the artist as Philip Westcott:

“It was announced that an oil painting of the late Howard Staunton, by Philip Westcott, had been offered to the Federation, and that Sir Richard Barnett had arranged to purchase it and present it to the Federation.”

Philip Westcott was a portrait painter, born about 1815 in Liverpool, where he is to be found at the time of the 1841 and 1851 censuses.

Sir Richard Barnett died later in 1930, his obituary appearing in the Times of 18 October, page 14.

Is any information available from BCF records that confirms that the presentation took place and identifies the person to whom custody of the painting was entrusted?’

9288. A problem composed in 1949

White mates in two moves.

9289. Wartime film archives

Alan McGowan (Waterloo, Canada) has found film reports on the tournaments at Prague, 1942 (start: 0’30”) and Prague, 1944 (start: 4’05”). The former newsreel, for instance, includes footage of Alekhine and Junge, and we have made these screen-shots:

9290. Two more newsreel reports

From the same site which provided the footage of Prague, 1942 and Prague, 1944 in the previous item, we point out Dutch film reports on the first part of the world championship match-tournament (The Hague, round nine, 23 March 1948) and the first Women’s World Team Tournament (Emmen, 1957).

Ingrid Larsen

9291. Rules on women’s participation in chess tournaments

Further to Chess and Women (a feature article which has just been greatly expanded), Vladislav Tkachiev (Moscow) asks what rules have ever existed, whether before or after the foundation of FIDE, which specifically permitted women to play in men’s tournaments, or specifically debarred them from doing so.

9292. 1 h4

Our latest feature article is on the ‘fantasy opening’ 1 h4.

9293. Stefan Zweig and Alistair Cooke

As mentioned in the feature articles on Stefan Zweig and Alistair Cooke, the link to a video clip referred to in C.N. 7520 became invalid.

Paolo Bertino (Madrid) has now provided a new link.

9294. Dissertation

Ross Jackson (Raumati South, New Zealand) draws attention to a Ph.D. dissertation ‘Storming Fortresses: A Political History of Chess in the Soviet Union, 1917-1948’ by Michael A. Hudson (September 2013).

9295. F. Le Lionnais

Oliver Beck (Seattle, WA, USA) writes:

‘In 1944, for his participation in the French Resistance, François Le Lionnais was arrested and deported to the concentration camp Dora-Mittelbau. On pages 294-302 of Autour de la plage Bonaparte (Paris, 1969), in a chapter entitled “Le Joueur d’échecs”, the author, Rémy, recounts a conversation in which Le Lionnais described how his internment was made more tolerable when his guards learned of his expertise in chess.

At Dora, each day in his cell Le Lionnais was given a piece of paper, often taken from a newspaper or book, for intimate use. One day there occurred a remarkable coincidence:

“A ma stupéfaction, j'ai retrouvé un beau jour sur le rectangle de papier un morceau d’un article sur les échecs publié naguère sous ma signature dans la collection l’Empreinte” (page 294).

With this Le Lionnais was able to gain the attention of a high-ranking guard who sought his advice on adjourned positions of games he was playing against other guards, and because of this relationship his situation began to improve. Although he continued to be subjected to brutal interrogations, he was now treated with some measure of respect. He began to receive Red Cross parcels previously unavailable to him, and was given access to books to satisfy his insatiable desire to read.

Eventually he was able to convince another guard, a cousin of Rudolf Hess, that he could produce a valuable treatise on chess. He was thus able to obtain writing materials, enabling him to slip an important message to a fellow prisoner, and his handcuffs were removed. He then began work on his book, “en commençant par l’histoire du jeu d’échecs, suivie d’un exposé théorique et d’exemples concrets choisis parmi les centaines de parties que je connaissais par cœur” (page 299). The completed manuscript was called “Le Labyrinthe des échecs”, and upon his return to France he was told that it had been recovered: “Je suis ainsi rentré en possession de mon travail, qui figure aujourd’hui au musée de la Déportation, où vous pourrez le voir si vous allez aux Invalides” (page 302).

Is more information available regarding this manuscript?

An example of Le Lionnais’ chess column in the collection de l’Empreinte can be found on pages 251-255 of Epitaphe pour un espion (Paris, 1939), a translation of Eric Ambler’s Epitaph for a Spy.’

9296. Lasker and Blackburne

From Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore):

‘I have found photographs of Lasker and Blackburne in several large scrapbooks containing application forms for copyright registration filed with the Copyright Office of the Stationers’ Company (digitized via the Nineteenth Century Collections Online Database). The application forms reveal further information about the photographers, as well as the approximate date when each picture was taken.’

Emanuel Lasker. Photograph taken by Frederick Thomas Downey (July-September 1892)

Joseph Henry Blackburne. Photographs taken by David James Scott (January 1892).

9297. 1 h4

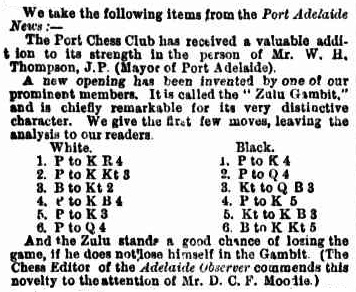

With regard to the opening 1 h4, Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA) points out an item on the ‘Zulu Gambit’ on page 747 of the Adelaide Observer, 23 April 1881:

9298. Negative comments about the Ruy López

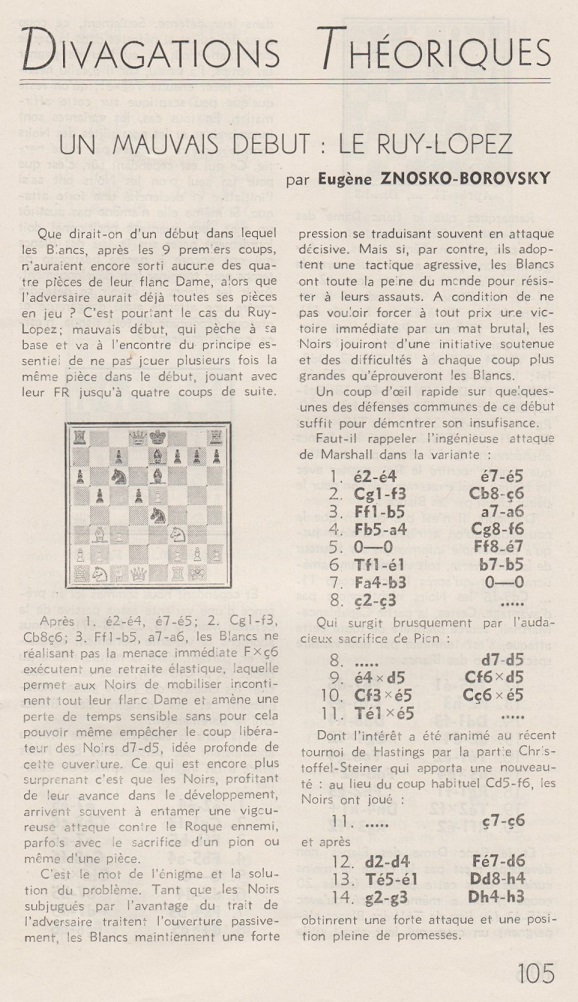

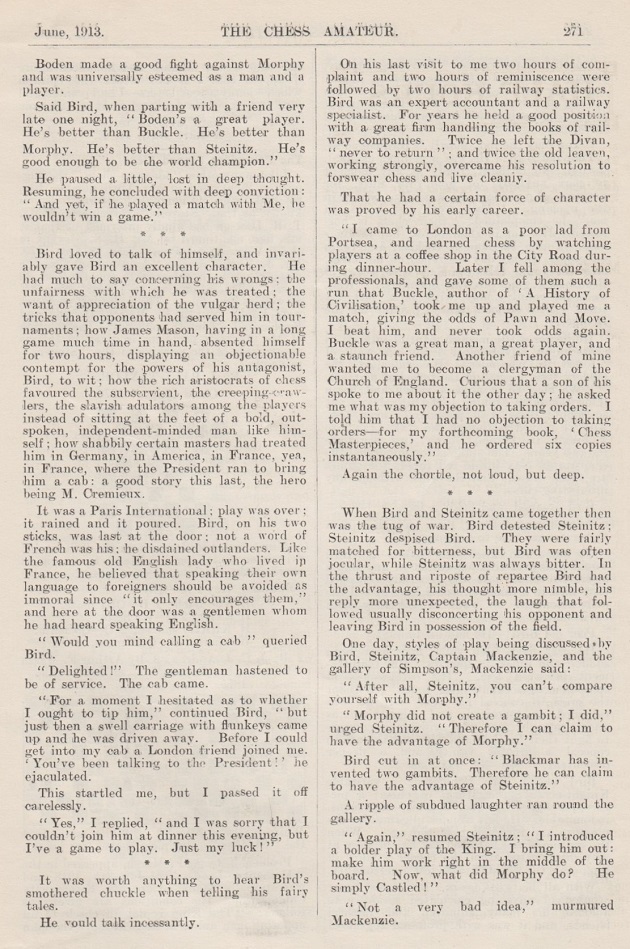

On page 192 of the US edition of his book on Morphy (New York, 1859) F.M. Edge wrote that Anderssen ‘played that disgusting arrangement, the Ruy López’. A twentieth-century master who made surprisingly negative comments about that opening was E.A. Znosko-Borovsky, in an article on pages 105-108 of Le monde des échecs, May 1946. Below are the first page and the last two paragraphs:

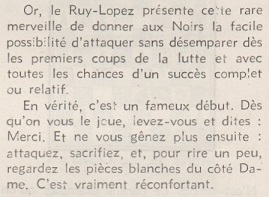

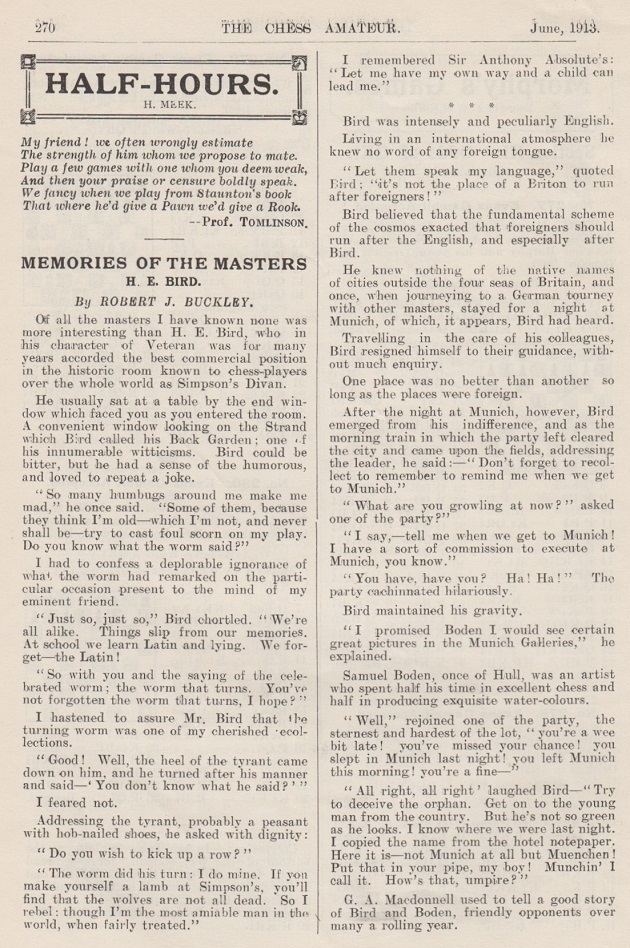

9299. Bird, Blackmar and Buckley

Hans Renette (Bierbeek, Belgium) asks what grounds Bird had for stating that ‘Blackmar has invented two gambits’ (C.N. 9084). Readers’ suggestions are invited as to the second gambit.

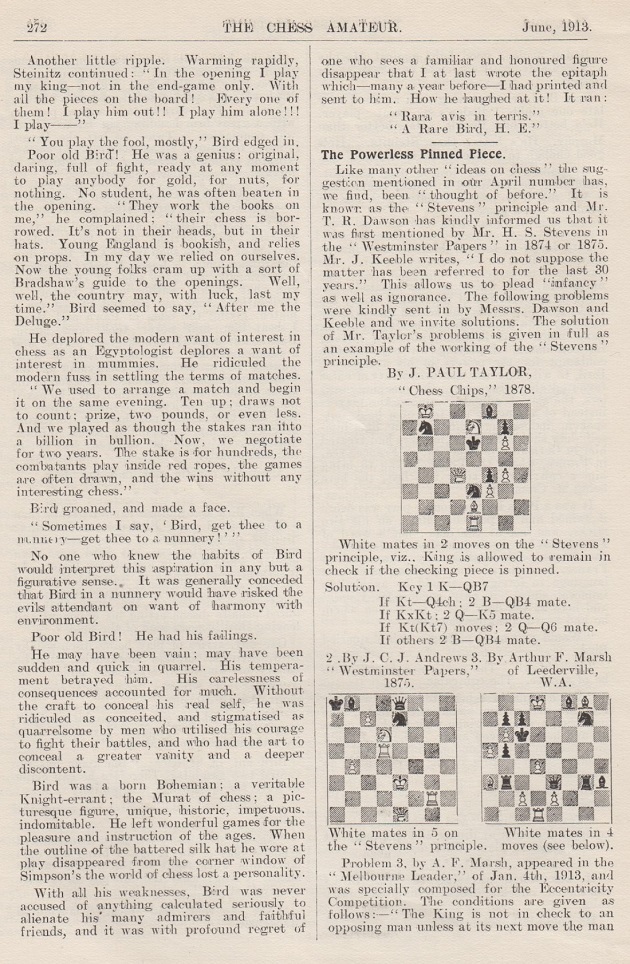

The full article in question is shown below, from the Chess

Amateur, June 1913, pages 270-272 (‘Memories of the

Masters. H.E. Bird’ by Robert

J.

Buckley). The Blackmar comment is near the bottom of

page 271.

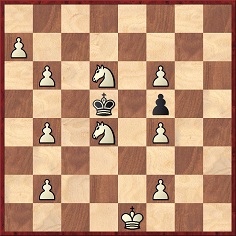

9300. A problem composed in 1949 (C.N. 9288)

White mates in two moves.

The solution is 1 a8(R). If 1...Kxd6, 2 Rd8 mate, and if 1...Kxd4 then 2 O-O-O mate.

The latter line depends on a perceived flaw in the chess laws of the time (Article 8). The problem, by Jose Benardete [sic] and Edgar Holladay, was published on page 2 of Chess Life, 20 October 1949. It was given too on page 46 of Chess World, 1 February 1950:

9301. Stamma

William D. Rubinstein (Melbourne, Australia) reports that the latest supplement to the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography includes a chess figure, P. Stamma. The article, by John-Paul Ghobrial, is available online.

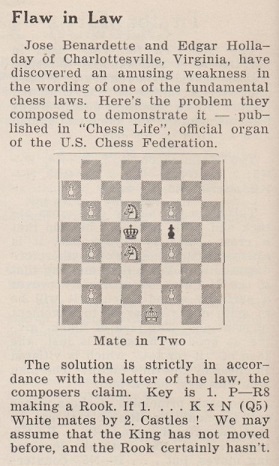

9302. An old task (C.N. 9278)

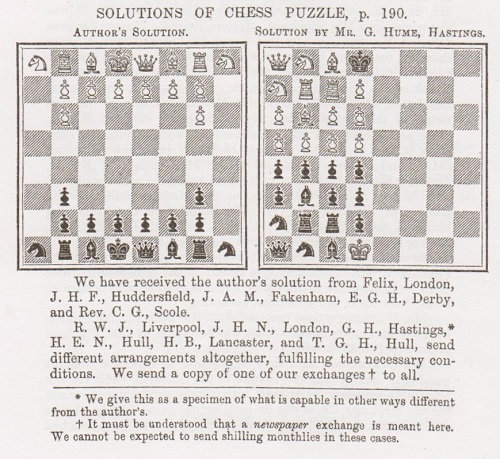

The task was set on page 190 of the Huddersfield College Magazine, April 1880:

The solutions on page 215 of the May 1880 issue:

9303. A better move (C.N.s 7837, 7841, 8738 & 8890)

From page 164 of Das Schachspiel by Siegbert Tarrasch (Berlin, 1931):

‘Wenn man einen starken, selbst einen entscheidenden Zug sieht, muß man sich immer die Frage vorlegen, ob es nicht einen noch stärkeren gibt!’

The English version on page 122 of The Game of Chess (London, 1935):

‘When one sees a strong, even a decisive move, one must always ask oneself if there is not a still stronger one.’

| First column | << previous | Archives [130] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.