Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [131] | next >> | Current column |

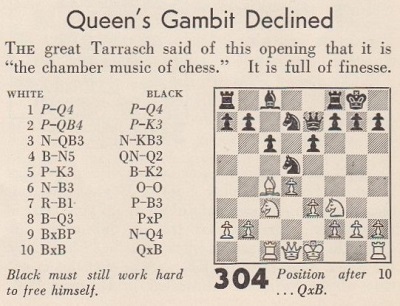

9304. The chamber music of chess

From page 197 of Chess by Fred Reinfeld (London, 1954):

‘The Double Queen Pawn openings have been described as “the chamber music of chess”. This comment is a tribute to their subtlety and to the delicate nuances of positional judgment in which they abound.’

On page 120 of First Book of Chess (New York, 1952) Al Horowitz and Fred Reinfeld were more specific:

‘Queen’s Gambit Declined

The great Tarrasch said of this opening that it is “the chamber music of chess”. It is full of finesse.’

What references to chamber music exist in Tarrasch’s writings?

From page 150 of Grandmasters of Chess by Harold C. Schonberg (Philadelphia and New York, 1973), in a section about Rubinstein:

‘The end game is absolute chess, pure chess, pure technique and imagination, the chamber music of chess.’

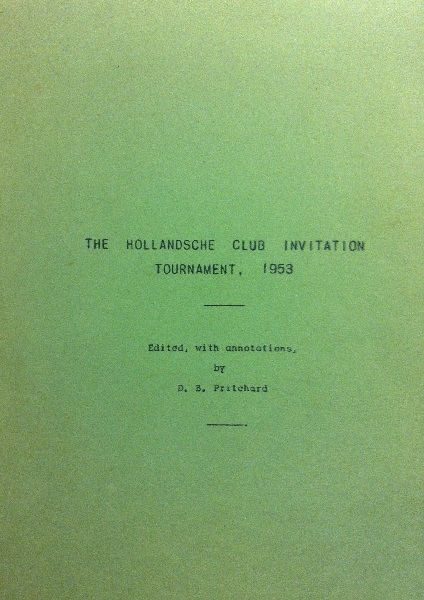

Below is an extract from page 115 of Making History by Stephen Fry (London, 1996):

The passage is in a chapter, ‘Making Moves’, which has a chess theme (pages 112-117).

9305. Negative comments about the Ruy López (C.N. 9298)

E.A. Znosko-Borovsky’s article in Le monde des échecs appeared in an English translation, ‘The Ruy López: A Bad Opening’, on pages 234-237 of Chess World, 1 December 1946. In his introduction Purdy wrote:

‘Even beginners know that the Ruy López has long been considered the strongest opening for White. This is therefore the most provocative article on chess theory ever published.’

See too ‘The Ruy’s Revenge’ by W. Ritson Morry on pages 17-19 of CHESS, October 1947; the second of two annotated games was Znosko-Borovsky’s (readily available) loss to K.P. Charlesworth at Harrogate in August 1947, on the black side of a Ruy López.

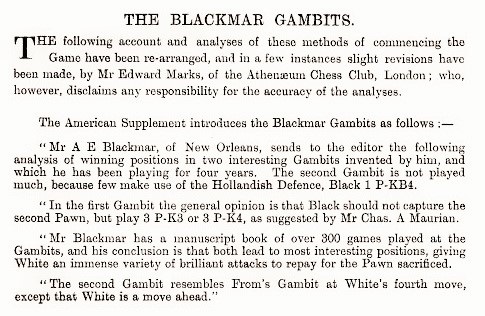

9306. Blackmar Gambits (C.N. 9299)

Rick Kennedy (Columbus, OH, USA) refers to pages 84-89 of The American Supplement to Cook’s “Synopsis” edited by J.W. Miller (London, 1885), which had analysis of two gambits attributed to Blackmar: 1 d4 d5 2 e4 dxe4 3 f3 and 1 d4 f5 2 e4 fxe4 3 f3. From page 84:

9307. Capablanca and simultaneous chess

Our latest feature article is Capablanca’s Simultaneous Displays.

9308. Capablanca in Brazil

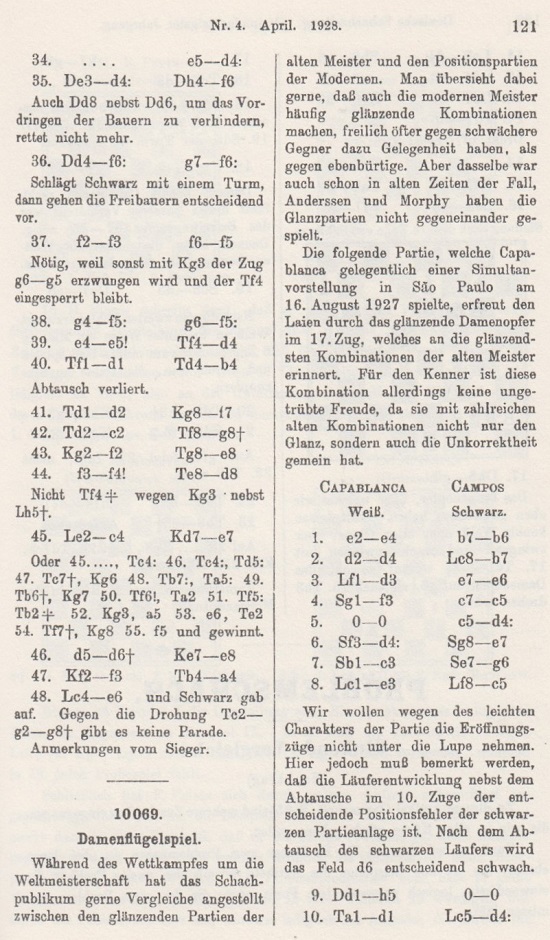

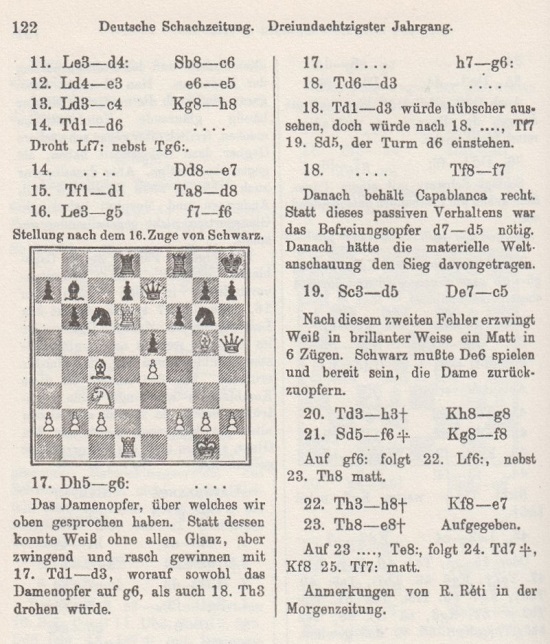

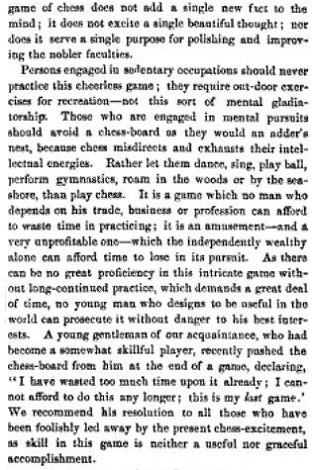

Concerning Capablanca’s well-known game against Campos (São Paulo, 16 August 1927), below are Réti’s annotations in the Morgenzeitung, as reproduced on pages 121-122 of the April 1928 Deutsche Schachzeitung:

9309. A better move (C.N.s 7837, 7841, 8738, 8890 & 9303)

C.N. 7837 referred to the text in Damiano’s 1512 work Questo libro e da imparare giocare a scachi et de le partite, and now Jean Fontaine (Montreal, Canada) points out that the phrase under discussion (‘Si hai bon trato per la mano guarda se nesia altro megliore’) can be viewed on-line.

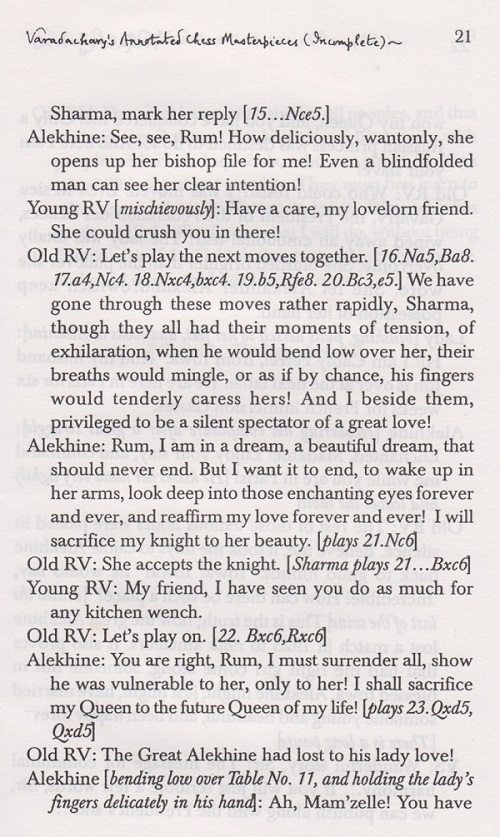

9310. Playlets

Varadachary’s Annotated Chess Masterpieces (Incomplete) by Vithal Rajan (2006) comprises 11 playlets, and a sample page from the first one, ‘Alekhine’s Greatest Defeat’, should suffice:

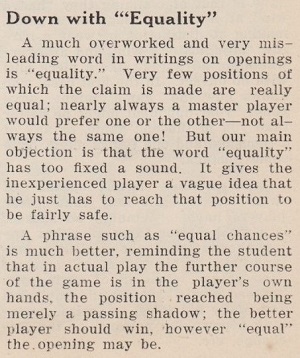

9311. Equality

C.J.S. Purdy’s comments on the word ‘equality’, on page 93 of Chess World, 1 April 1950:

9312. F. Le Lionnais (C.N. 9295)

A photograph of François Le Lionnais from the plate section of Autour de la plage Bonaparte by Rémy (Paris, 1969):

9313. The chamber music of chess (C.N. 9304)

From page 37 of Let’s Play Chess ‘by the Editors of Chess Review’ (New York, 1950):

9314. David Hooper

Our latest feature article is entitled ‘David Hooper (1915-98)’.

9315. Capablanca v Delmar

As shown in our article on David Hooper, C.N. 3227 mentioned a cutting which he sent us for safe keeping on 10 May 1990 regarding a set of games between Capablanca and Delmar. Hooper commented:

‘This is the only written reference I found to a match against Delmar on 27(?) September 1908. It will almost certainly be from Diario de la Marina (Havana) ... As I understand this match, Capablanca, offering pawn and move, undertook to win every game. I believe he won the match, probably picking up a good stake – he desperately needed money at the time.’

Now, Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) has forwarded us the remainder of the newspaper item (a report by Juan Corzo in Diario de la Marina, 27 September 1908), together with a full transcription:

‘El Morphy cubano

Capablanca da ventaja a los maestros

El bien querido amigo de los amateurs ajedrecistas cubanos, por serlo él mismo, D. Arístides Martínez, insustituible Presidente del Manhattan Chess Club de Nueva York y pródigo Mecenas del juego ciencia en Cuba y los Estados Unidos, da cuenta, en reciente e interesante epístola, dirigida al entusiasta Presidente de la Sección de Ajedrez del Ateneo, D. León Paredes, de la última hazaña allí realizada por Raúl Capablanca, quien ha acreditado con ella que merece el calificativo hiperbólico de maestro entre los maestros.

Alguien indicó al notable jugador americano Mr Eugenio Delmar que el adolescente cubano, con quien siempre perdía mano a mano, estaba dispuesto a contender con él dándole peón y salida de ventaja, lo que aceptó en la seguridad de que no perdería un solo juego ni concedería al osado retador el consuelo de unas modestas tablas.

Júzguese cual no sería su asombro al ver que Raúl le ganaba cinco juegos consecutivos y uno de ellos anunciándole mate en 5 jugadas después de haberle entregado la Dama en correcto y brillante sacrificio.

Teniendo en cuenta que Delmar ha sido Champion del Estado de Nueva York y que es todavía uno de los más fuertes y experimentados paladines del Manhattan, su derrota recibiendo partido a manos de “Capa”, como llaman a nuestro campeón en el club neoyorkino, coloca a éste por encima de casi todos los maestros contemporáneos.

El Morphy cubano merece, pues, su glorioso apodo, habiendo sido Delmar para él lo que Owen (“Alter”) fue para el Aguila luisianesa, la piedra de toque de su genio prodigioso y de su enorme fuerza.

Después de la noticia referida cabe asegurar que no sabremos lo que puede dar de sí Capablanca hasta que se bata de igual a igual con el Dr. Lasker.

El Sr. Paredes, haciéndose intérprete de los sentimientos de todos los aficionados al ajedrez en Cuba, ha enviado una muy expresiva felicitación a Raúl por su valioso triunfo, agregando que deseamos verlo pronto figurar en un torneo internacional de maestros en la seguridad de que el pabellón de la estrella solitaria estará en buenas manos y quedará a notable altura.

Juan Corzo.’

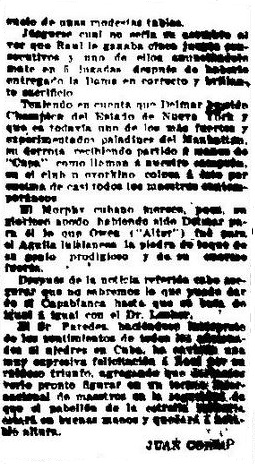

9316. Alekhine and canoeing

C.N. 741 (see page 118 of Chess Explorations) pointed out the reference to canoeing in Alekhine’s Who’s Who entry. Below is the full text, which has some obvious errors, published on page 13 of Who Was Who, 1941-1950 (London, 1952):

Has any researcher looked into the awards and honours attributed to Alekhine?

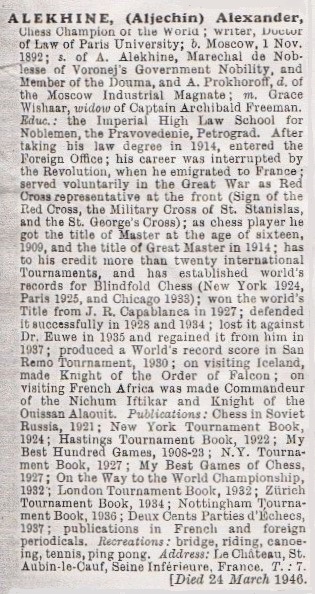

9317. Tsar Nicholas II and the first five grandmasters

Many chess books and articles unquestioningly state that the first five official grandmasters were the finalists at St Petersburg, 1914, and that they received the honour from Tsar Nicholas II. At first sight, there may seem no reason to doubt the story, given what appeared on pages 20-21 of My Fifty Years of Chess by Frank J. Marshall (New York, 1942):

However, complications have been mentioned in C.N. items over the years, as set out in Chess Grandmasters: the claims that Marshall’s autobiography was ghosted, the failure to discover any pre-1940 version of the story, and the Tsar’s absence from St Petersburg during the 1914 tournament.

Even cumulatively, those points naturally do not suffice

to disprove the story about Nicholas II, but they do

suggest a verdict of ‘not proven’ and that, at least, the

tale should not be repeated without reservation. Alas, few

chess writers like expressing reservations or surrendering

the opportunity for name-dropping.

No Russian-language sources dating from 1914 have been traced which shed light on the ‘grandmaster title’ affair. Nor has it been possible, so far, to examine the writings (i.e. diaries) of the Tsar himself for the relevant period. We have the Journal intime de Nicolas II (Paris, 1934), but it begins shortly after the St Petersburg, 1914 tournament.

Nor has positive information been found in secondary sources, such as the biographies of the Tsar by Marc Ferro, Dominic Lieven and Edvard Radzinsky.

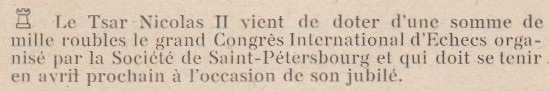

That Nicholas II had involvement of some kind with St Petersburg, 1914 is shown by a brief paragraph on page 79 of La Stratégie, February 1914:

9318. Vasily Filatov (pretender)

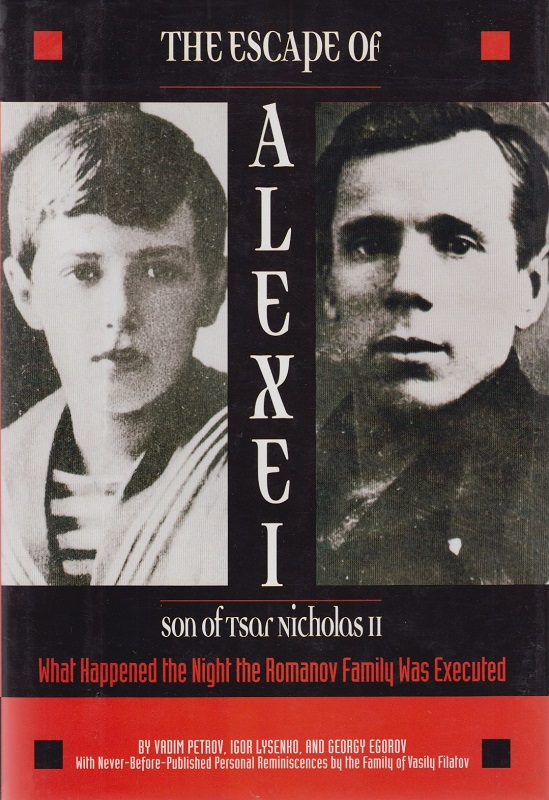

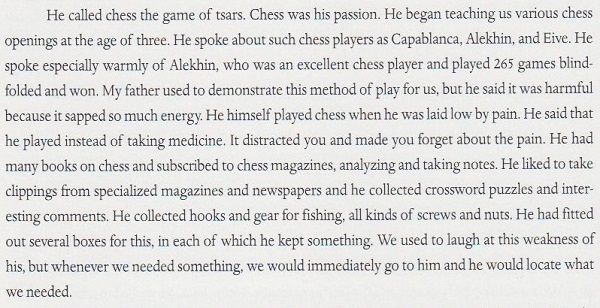

The Escape of Alexei Son of Tsar Nicholas II by Vadim Petrov, Igor Lysenko and Georgy Egorov (New York, 1998) claimed that Alexei Nikolaevich Romanov (born 1904) survived when the imperial family was executed in 1918 and that, to quote from the dust-jacket, ‘Russia’s heir to the throne grew up under the name Vasily Filatov’. From page 142 (in the section entitled ‘Reminiscences of [i.e. by] Oleg Vasilievich Filatov’):

9319. Tarrasch quote

Siegbert Tarrasch’s famous quote about chess, love and music (C.N. 5823) has overshadowed other remarks also on page xi of The Game of Chess (London, 1935):

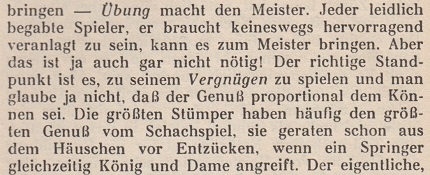

‘... practice makes the master. Any moderately talented player, he need not be exceptionally gifted, can become a master. But really, there is no need for that. The right standpoint is to play for pleasure – and do not think that pleasure is proportional to skill. The greatest bunglers are constantly deriving the greatest pleasure from chess – they go into ecstasies of delight when their knight forks a king and queen.’

The original text by Tarrasch, on page 4 of Das Schachspiel (Berlin, 1931):

9320. Gallica

Jean Fontaine (Montreal, Canada) provides some links to material at the Gallica website:

- A photograph taken in Oran by Félix-Jacques Moulin during his 1856-57 photographic tour of French colonial Algeria. Mr Fontaine suggests that the picture was probably taken in 1856 (since the province of Oran was in the first part of Moulin’s year-and-a-half tour) and he seeks information about the board position.

- Paul Morphy’s 1858 simultaneous blindfold exhibition, Le Monde Illustré, 16 October 1858, page 249. The related article is on page 256.

- A picture dated circa 1860-65 from a photograph album (about the French town of Villers-Cotterêts) which belonged to Alexandre Dumas, fils.

- The Café de la Régence in 1874, Le Monde Illustré, 7 March 1874, page 156. The article by Rosenthal is on pages 155 and 158.

9321. Bosco and his trained dogs

A cartoon by Harrison on page 27 of Let’s Play Chess ‘by the Editors of Chess Review’ (New York, 1950):

9322. Stamma (C.N. 9301)

From John Townsend (Wokingham, England):

‘Further to C.N. 9301, some information about Stamma’s earlier presence in Westminster is to be found in a pamphlet written by Michael Powers and published in London in 1734, entitled A true state of the case between Michael Powers of London, gent. and his Excellency Joseph Coja, Ambassador from Tunis; with a true copy of the note, as well as of the agreement, made between his Excellency and Michael Powers, testified upon oath, by Philip Stamma.

In it Powers is referred to as “Interpreter to the Ambassador from Tunis”, with whom he had a dispute, the pamphlet containing his defence to what he refers to as “the groundless imputations” of Joseph Coja “in the London Evening-Post”. Powers describes “Mr Philip Stamma” as “the Person who brought me acquainted with him” (i.e. the Ambassador).

Included are the texts of two documents signed by “Philippo Stamma”: firstly, an agreement between the Ambassador and Powers, dated 11 February 1733/4, and, secondly, a deposition by Stamma, “sworn at the Publick-Office, 4 April 1734, Before N. Edwards”.

Stamma’s deposition begins:

“Philip Stamma, of the Parish of St Martin in the Fields, in the County of Middlesex, Gentleman, deposeth as follows”,

and refers to events in London which commenced “on or about the tenth of May last” [i.e. 1733]. He relates that some months later Joseph Coja

“employed this Deponent to get a Letter written to a certain Jew in Holland, his Correspondent …”

and

“That before he could have an Answer to the said Letter, this Deponent came to Mr Michael Powers, desiring he would undertake to sollicit [sic] the said Affair.”

The pamphlet, therefore, establishes that Stamma was resident in Westminster during 1733 and 1734 and that he was already acquainted by then with the Tunis Ambassador and had been employed by him.

His association with the Tunis Ambassador was one which continued for many years. A document in the National Archives, T 1/333 (item 31), dated 10 June 1748, describes Stamma as

“Mr Phillip Stamma Interpreter to the Morocco and Tunis Ambassadors &c.”.

It is written by R. Arundell, “Treasurer of the Chambers Office”, who having received a warrant from “the Lord Chamberlain of his Majesty’s Household”, desires payment to Stamma of £224 0s. 6d.,

“being a Present to him from his Majesty”.

The addressee is “the Lord Commissioners of his Majesty’s Treasury”.’

9323. The 50-move rule

Concerning the 50-move rule, Jonathan Hinton (East Horsley, England) writes:

‘Reporting on the Donner Memorial tournament, on pages 516-517 of the October 1995 BCM, John Nunn gave the conclusion of the Khalifman v Salov game from the last round. He covered the interesting point of how to claim a draw under the 50-move rule and contrasted it with the procedure under the threefold-repetition rule. Khalifman incorrectly claimed a draw before making his 75th move, which would have been the 50th under the 50-move rule.’

9324. Physical death

From page 170 of Chess World, 1 July 1949:

‘One of the best things about chess is that physical death means so little to it. Alekhine is just as alive now to millions of players as he ever was in his lifetime. They never saw him. To them, even while he lived, he was simply the games which he played and which they played over. Those games are as alive now as they were when played. The sad part is that there will be no more. Yet there are enough for most players to go on with. It takes immeasurably longer, for instance, to play through the published games of Alekhine intelligently than the published music of Beethoven. And there’s this great advantage, that whereas the ordinary music-lover has to have his Beethoven played by others, the chess-lover can play through his Alekhine himself.

There was a phrase used by Dr Woinarski on page 37 of the ACR [Australasian Chess Review] of March 1943, referring to the late Gunnar Gundersen: “A personal immortal game is chess.” If anyone found it obscure at the time, it will be clear to him now.’

9325.

Photographic archives (1)

From Swiss sources we own a substantial collection of photographs, taken mainly in the 1980s, and batches will be presented from time to time.

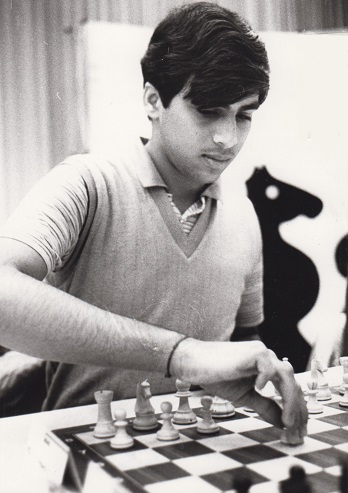

Viswanathan Anand

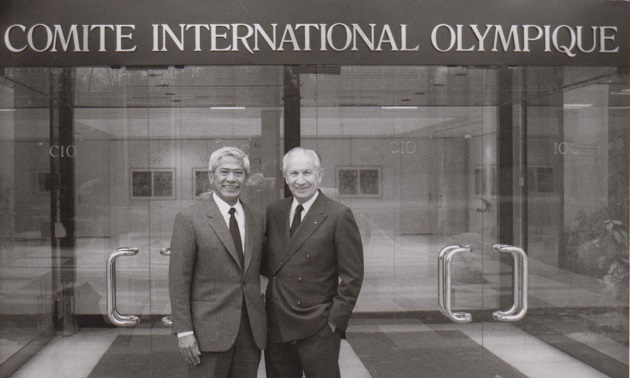

Florencio Campomanes and Juan Antonio Samaranch

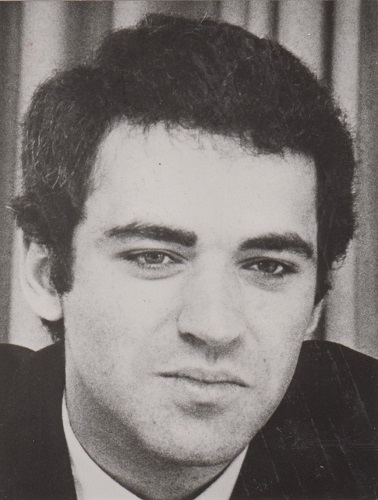

Garry Kasparov

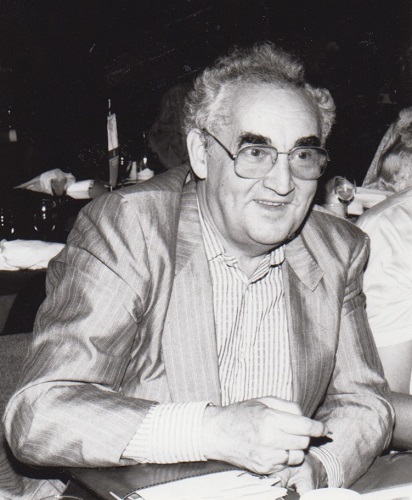

Mark Taimanov

Vladimir Tukmakov

Matthias Wahls

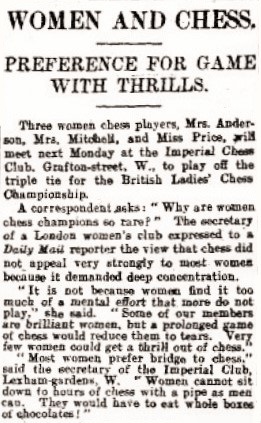

9326. Beyond the ken of women

On the topic of Chess and Women we continue to add quotations, whether lyrical or, more likely, contumelious. From page 5 of the Daily Mail, 5 September 1921:

A further item is on page 678 of the November 1926 BCM:

‘Under the heading of “Chess for Women”, we are told, on the Woman’s Page of a daily paper which once had an excellent chess column, but now ordinarily disregards chess:

“This ‘ancient and most honourable game’ has largely remained beyond the ken of women, but now we read that a woman has taken first place in an open tournament, not through the leniency of man, but by her own brilliance. This has come as something of a shock to many, as the game has always been considered a masculine one.”

It would be interesting to know to what “open tournament” this paragraph refers. The shock does not appear as yet to have produced repercussions in the chess world.’

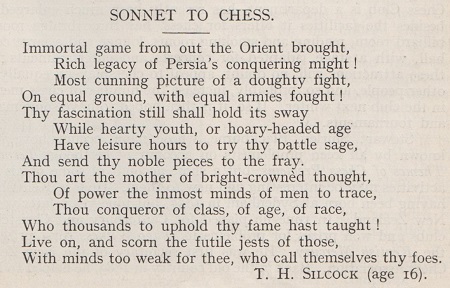

9327. Sonnet to chess

An addition to Chess and Poetry comes from page 281 of the June 1926 BCM:

Page 241 of the June 1927 BCM referred to ‘T.H. Silcock of Taunton Grammar School’. Information about his later life – Thomas Henry Silcock (1910-83) – can be found on the Internet.

9328. Ivanchuk

Vassily Ivanchuk is now included in Books about Leading Modern Chessplayers.

Also from our collection:

9329. Lasker and 1 e4

C.N. 3330 (see page 297 of Chess Facts and Fables) referred to an unattributed quote on page 108 of The Bright Side of Chess by Irving Chernev (Philadelphia, 1948):

‘Lasker played 1 P-K4 with a view to the endgame.’

Our item also cited page 62 of Modern Chess by Barnie F. Winkelman (Philadelphia, 1931):

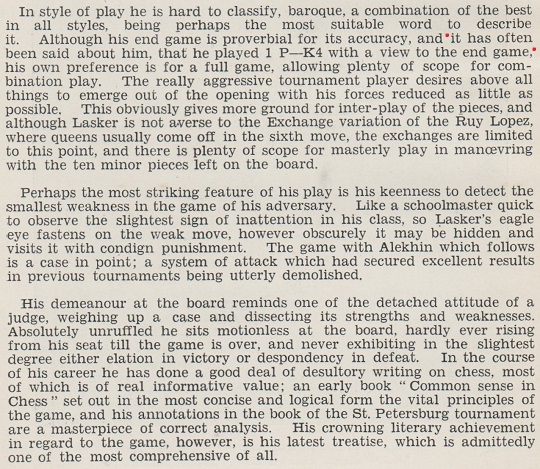

‘But of Lasker it was said that he played P-K4 with a view to the endgame …’

We asked who first made the remark, and in what context. Those questions remain open, but an earlier occurrence can be added here, in the section about Lasker on page 30 of Modern Master-Play by F.D. Yates and W. Winter (London, 1929):

The game against Alekhine referred to in the second paragraph was Lasker’s victory at New York, 1924.

9330. ‘Desperation’

Mike Salter (Sydney, Australia) expresses dislike of annotators’ unhelpful use of the single-word sentence ‘Desperation’ towards the end of games; he has counted 17 occurrences in Lessons from My Games by Reuben Fine (New York, 1958).

Fine also used the word frequently in Chess Marches On! (New York, 1945). One example is in C.N. 8353.

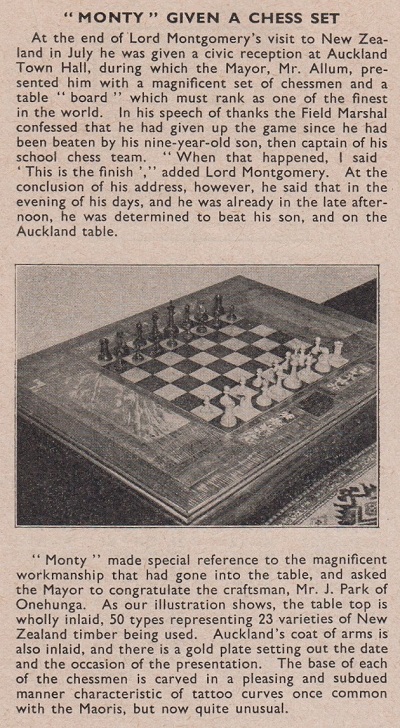

9331.

Montgomery’s chess set

From CHESS, October 1947, page 15:

Larger version of the photograph

9332. The Evans Gambit

C.J.S. Purdy wrote the following at the start of an article about the Evans Gambit, ‘“Evans” in World Title Tourney’, on pages 90-91 of Chess World, 1 April 1950:

‘An Evans Gambit – even if declined and if the game itself is nothing wonderful – is always “news”. This is not only because of its romantic story but because it still stands as one of the few unrefuted genuine gambits.

The Evans Gambit never wore swaddling clothes. Like Minerva it was born in panoply. The very first known game in which it was played was between its inventor and a great master of those days, Alexander McDonnell, and the inventor won.’

The most detailed historical account of William Davies Evans and the gambit is on pages 9-34 of Eminent Victorian Chess Players by Tim Harding (Jefferson, 2012).

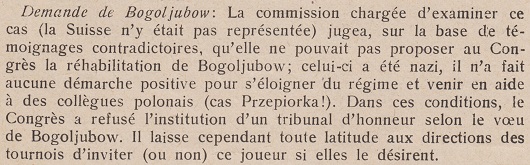

9333. Bogoljubow and the Nazis (C.N. 4821)

Further to C.N. 4821 (see too Interregnum), below is Erwin Voellmy’s summary of the discussion at the FIDE Congress in The Hague (30 July-2 August 1947), from page 155 of the Schweizerische Schachzeitung, October 1947:

9334. Two Knights’ Defence (C.N. 7968)

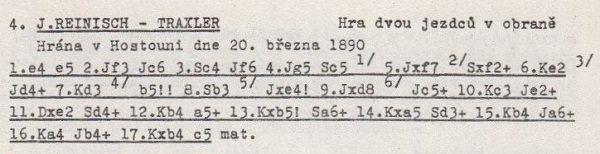

Regarding the 17-move game given in C.N. 7968, Fabrizio Zavatarelli (Milan, Italy) refers to an article which notes that the play occurred in a nineteenth-century game between Reinisch and Traxler. Our correspondent adds that the score was published in Jan Kalendovský’s compilation of Traxler games, i.e. on page 14 of Program XII. ročníku šachového turnaje (Brno, 1987):

The booklet states that the game was played in Hostouň on 20 March 1890, and the following page gives the source as Zlatá Praha, 14 October 1892.

Afterword (16 June 2015): Thomas Niessen (Aachen, Germany) points out that the 1892 publication can be viewed on-line.

9335. The 50-move rule (C.N. 9323)

From Tim Harding (Dublin):

‘The procedure for the two kinds of draw (repetition of position and the 50-move rule) has now been standardized (at least since the rules applicable as from July 2014), i.e. a player can wait for the situation to occur or can write down the move that will bring it about and can call the arbiter.

The FIDE Handbook states:

“9.3 The game is drawn, upon a correct claim by a player having the move, if:

a. he writes his move, which cannot be changed, on his scoresheet and declares to the arbiter his intention to make this move which will result in the last 50 moves by each player having been made without the movement of any pawn and without any capture, or

b. the last 50 moves by each player have been completed without the movement of any pawn and without any capture.”

So what Khalifman did wrongly on the occasion described by John Nunn would now be a valid claim.

At Wijk aan Zee in 1973, when Peter Markland was playing in the B group and I was in the Reserve Master group, he complained to me that his claim of a threefold repetition had been rejected (versus Quinteros). I was very surprised that Markland did not know the rule (although by that time he had played in numerous master tournaments). He had made his 41st move on the board before making the claim, which accordingly, was refused. His opponent played a different move and soon won.’

9336. Lipschütz

Just received: Samuel Lipschütz A Life in Chess by Stephen Davies (Jefferson, 2015).

This book will enhance yet further the reputation of McFarland & Company, Inc. among chess bibliophiles.

9337. Correspondence chess

Page 322 of CHESS, July 1971 reported on the disruption to correspondence chess arising from that year’s strike by postal workers in the United Kingdom. The magazine quoted a player:

‘Between my fifth and sixth moves in this game, I grew a moustache.’

9338. The dark side of Fischer (C.N.s 9245 & 9252)

Despite the rebuttals in C.N.s 9245 and 9252 (see too Brad Darrach and the Dark Side of Bobby Fischer), the 4/2015 issue of New in Chess contains no apology or retraction regarding Dirk Jan ten Geuzendam’s false statement in the previous issue that we have been silent over the dark side of Fischer shown in the documentation which David DeLucia has published from his collection.

Page 16 of the 3/2015 New

in

Chess. The section with the false attack on us is

marked.

The truth is the exact opposite of what New in Chess readers were told, given that we have quoted far more ‘dark’ material from Mr DeLucia’s books than all other chess writers combined.

Before publication of his Fischer article in the 3/2015 New in Chess, Dirk Jan ten Geuzendam sent a preview to Mr DeLucia and was specifically told, in advance of publication, that his intended criticism of us was unfounded. Mr DeLucia has informed us:

‘When he sent me the draft the one comment I made was that he was wrong with his assessment of your view on Fischer. I told him to review past C.N. articles as I knew you had done a number of them regarding Bobby and his craziness. Dirk Jan obviously had a different view.’

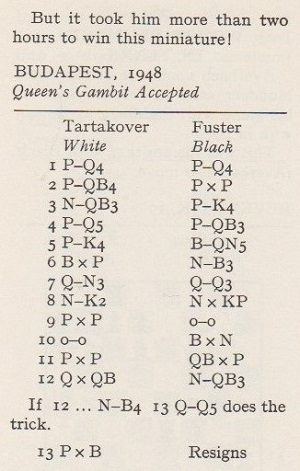

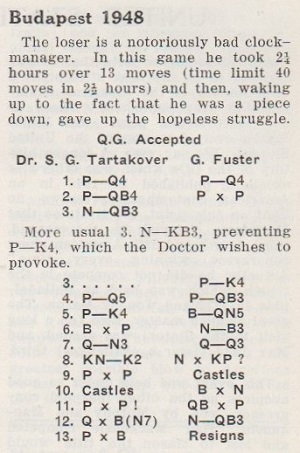

9339. Tartakower v Füster

From page 128 of Wonders and Curiosities of Chess by Irving Chernev (New York, 1974):

There was a different slant on page 285 of Chess World, 1 December 1948:

9340. ‘The Little Capablanca’ (C.N.s 6365, 7054 & 8586)

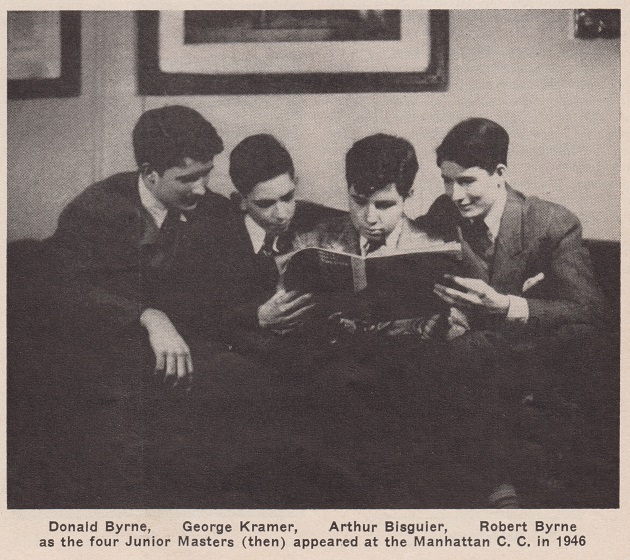

From page 40 of Chess Review, February 1954, in an article by Larry Evans:

‘In style, Robert [Byrne] resembles Nimzowitsch. Donald – not Kashdan – deserves the title of “Der Kleine Capablanca”. His play is lucid, direct and crystal clear. The reason for his amazing success in rapid chess is his quick insight and thorough knowledge of endings – especially rook and pawn. He has an incredible faculty of being able to master complications.’

A photograph on the same page:

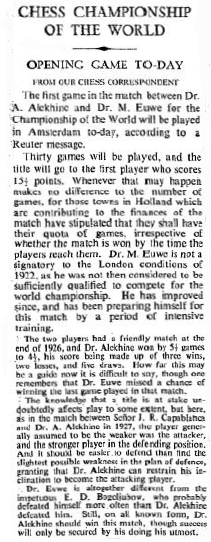

9341. World championship match conditions

From Steve Wrinn (Homer, NY, USA):

‘I have a question concerning the precise regulations governing Alekhine’s world championship matches against Bogoljubow and Euwe. All were scheduled for 30 games, with 15½ points being required for victory and with the added proviso that the victor must score at least six wins. But information on precisely what would have occurred if neither player won the required six games during the first 30 games is often incomplete and contradictory. To take the Alekhine-Euwe 1935 match, for example, here are three widely divergent descriptions of the match conditions:

a) On page 284 of its September 1935 issue the Wiener Schachzeitung stated:

“Die Bedingungen sind gleicher Art wie bei den letzten Weltmeisterschaftskämpfen. Es werden mindestens 30 Partien gewechselt. Wer die Mehrzahl der Punkte erreicht, ist Sieger, vorausgesetzt, daß er sechs Partien gewonnen hat. Andernfalls wird der Wettkampf bis zum sechsten Sieg fortgesetzt.”

This indicates that play would continue after 30 games even if Alekhine were in the lead but had not attained six wins. There is no mention of the possibility of a drawn extended match as referred to in my point b below. Additionally, according to the first sentence, such conditions also held true for Alekhine’s matches against Bogoljubow. (See, however, my point point c below.)

b) Skinner and Verhoeven, on page 534 of Alexander Alekhine’s Chess Games, 1902-1946, cite The Times of 3 and 4 October 1935 and paint a very different picture:

“The match would consist of 30 games and the title would go to the player who first scores 15½ points, with at least six won games. If after 30 games Alekhine has a majority of points, but not necessarily six won games, the match is to be given up as a draw and Alekhine retains the championship. If Euwe is ahead after 30 games have been played but without six wins, then the match will be continued until either Euwe wins six games or Alekhine equals his score. In the latter case Alekhine retains the title and the match is drawn.”

Those last two sentences amount to a de facto requirement that the challenger (in this case Euwe) win an extended match by at least two points; in other words, a 6-5 victory would be impossible to achieve past the 30th game, as the previous 5-5 score would have brought the contest to a close. A related point is that under such conditions only the challenger could win an extended match, as once the trailing champion equalized the score he would retain his title via a drawn result.

Times, 3 October 1935, page 10

Times, 4 October 1935, page 16

c) On page 9 of his Tagebuch vom Wettkampf Aljechin-Euwe (Vienna, 1936) Hans Kmoch stated explicitly that the proviso that the champion would retain his title upon equalizing the score at any time after the 30th game, and the concomitant de facto requirement for the challenger to win an extended match by two points, were not in effect for the 1935 match. He added that they had been in effect for Alekhine’s earlier matches (i.e. the two contests against Bogoljubow). He thus contradicts both points b and a above. Kmoch also wrote that in 1935 a drawn match was possible only if the score was equal after 30 games and each player had won at least six games (the situation that would, in fact, have occurred if Alekhine won the 30th game):

“Wenn nach der 30. Partie ein Stand von 15:15 erreicht wurde und beide Spieler mindestens 6 Partien gewonnen haben, dann wird der Wettkampf als unentschieden abgebrochen und Aljechin behält seinen Titel. Im anderen Falle kann der Wettkampf nicht unentschieden ausgehen und es entscheidet unter allen Umständen die 6. Gewinnpartie. Diese letztere Bestimmung differiert von jenen früherer Wettkämpfe Aljechins: dort hieß es nämlich, daß der Wettkampf zugunsten des Weltmeisters unentschieden abgebrochen werde, falls der Weltmeister nach 30 Partien im Nachteil ist, es ihm aber später gelingt, gleichen Stand zu erreichen.”

That three contemporary sources could give such varying and irreconcilable accounts is remarkable. What were the exact final rules for the 1929, 1934, 1935 and 1937 world championship matches?

Incidentally, Skinner and Verhoeven (pages 364, 490 and 593) briefly mention the 15½ points/six wins requirement for the 1929, 1934, and 1937 world championship matches, but provide no further details, except to note that Euwe as world champion would retain the title if the 1937 match were tied after 30 games. The Wiener Schachzeitung offered the same minimal information (15½ points/six wins) for Alekhine’s 1929 and 1934 matches against Bogoljubow (see page 253 of the August 1929 issue and page 97 of the April 1934 issue), but did not spell out the conditions under which those contests would have continued after the 30th game.’

9342. Photograph collection

A small set of chess photographs from the International Institute of Social History is available on-line. They feature, in particular, Max Euwe.

9343. Looking and seeing ahead

Our latest feature article, chock-full of contradictory quotes and yarns, is How Many Moves Ahead?

9344. Irremediably weak (C.N.s 9244 & 9254)

On pages 36-37 of the 4/2015 New in Chess Nigel Short has written a follow-up article, ‘A Beautiful Minefield’, discussing reaction to ‘Vive la Différence’ (published on pages 50-51 of the 2/2015 issue). A brief extract:

‘On 20 April an article appeared in The Daily Telegraph entitled “Nigel Short: Girls Just Don’t Have the Brains to Play Chess”. Never mind the fact I didn’t say that, it was a catchy headline to set me up as a misogynist pantomime villain. In extraordinary rapid succession came a whole series of similar articles, in The Guardian, The Times, The Independent, many with totally fabricated quotes and grotesque distortions – such as the Daily Mail’s “Women aren’t smart enough to play chess because the game requires logical thinking, says British Grandmaster”, despite me having said nothing at all about logic.’

Indeed so, notwithstanding Raymond Keene’s assertions in an item for the Spectator placed on-line on 22 April 2015 (i.e. over a month after the 2/2015 issue of New in Chess appeared):

‘According to Short’s comments, the female brain fails in the logic department, hence girls will never be able to match boys over the chessboard ...

Even if Nigel has a point about logic, at least one of the greats of chess history is not on his side. As the brilliant tactician and incandescently creative world champion Alexander Alekhine once said, “chess is not only knowledge and logic!”.’

(What Alekhine ‘once said’ can be found in the final note to his victory over Reshevsky, Kemeri, 1937, in his second volume of Best Games.)

Many so-called journalists, from Raymond Keene upwards, have written about Nigel Short’s ‘Vive la Différence’ article without bothering to read it, but it cannot be assumed that they, or the hordes of unpaid opinionizers on-line, would have had anything worth writing even if they had read it. C.N. 9051 observed that ‘technology increasingly encourages people, including the uninformed and illiterate, to share their opinions about tout ce qui bouge’. The complex issues concerning chess and women, and Nigel Short’s views thereon, merit rigorous scrutiny and discussion. That has yet to start.

The tornado of the past two months has contributed virtually nothing, beyond providing a text-book example, notable well beyond the chess world, of how the media often operate nowadays. At their worst, they wake up late, scavenge, copy, misinterpret, invent, pontificate and then move on to wreak havoc elsewhere. The process is aggravated by a recent development: convergence of the viciously shallow press and on-line outlets such as Twitter, so that kneejerk reactions abound and maelstroms are inevitable.

In such circumstances, no mature discussion of the relative weakness, or otherwise, of female chessplayers is possible. What has been on abundant offer, however, is incontrovertible proof of the irremediable weakness of commentators, irrespective of their sex.

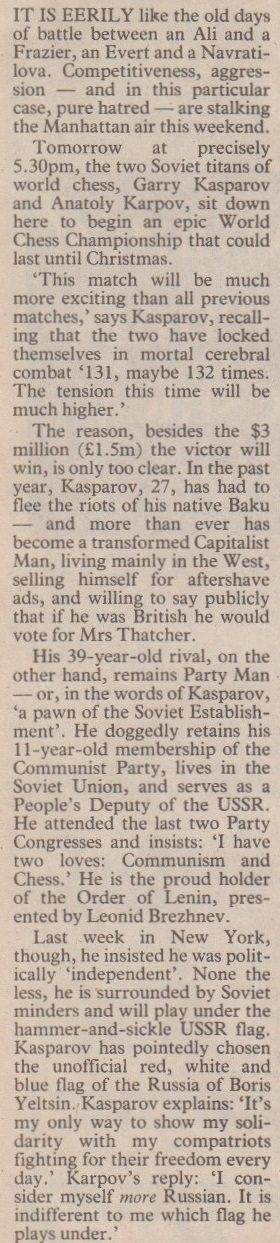

9345. The Kasparov-Karpov rivalry

Below is the first section of an article ‘Pure hatred as Capitalist King meets Party Pawn’ by Andrew Stephen on page 13 of the Observer, 7 October 1990:

There were many similar articles in the 1980s and 1990s. They left no doubt as to the writer’s sympathies, though plenty as to his credentials. Little or nothing is sourced, and the reader cannot know where the information comes from, or judge how trustworthy it is. A single article such as Andrew Stephen’s could provide fodder for a dozen C.N. items soliciting corroboration of the various quotes and assertions.

As regards the rivalry (‘pure hatred’) between Kasparov and Karpov, to what extent have journalists been duped? A remark from page 213 of Karpov on Karpov (New York, 1991), a book referred to in Karpov’s Writings, is worth recalling:

‘Every match is preceded by scandalous situations. Some arise spontaneously, others are planned, but in general a match never comes off without them. Kasparov and I also tried to uphold the ancient tradition and toss the journalists some choice morsels.’

9346. Inadequate obituaries

In a passage quoted in C.N. 7331, G.H. Diggle complained about the ‘lean epitaphs’ with which chess figures are ‘shovelled into the grave’. He was writing over 30 years ago, and there has been, particularly of late, a steep decline in the quality of chess obituaries; many are dumped on-line after hurried copy-pasting. Often nowadays, people are wikipediaed into the grave.

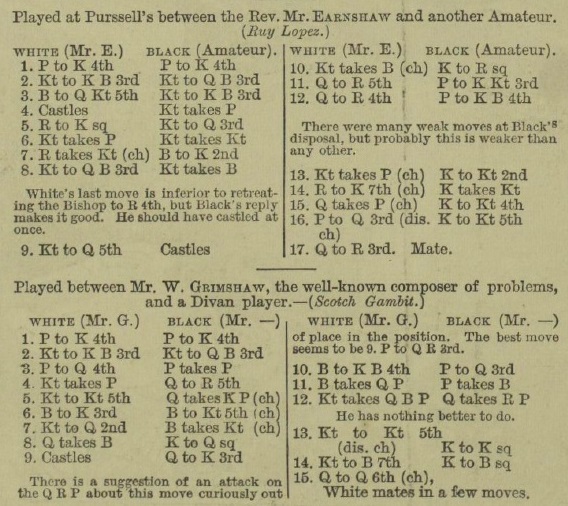

9347. Grimshaw v

Steinitz

Regarding Steinitz’s

alleged loss to Walter Grimshaw, Fabrizio

Zavatarelli (Milan, Italy) notes that the score was

published on page 414 of the Illustrated London News,

23 October 1880, with no mention of Steinitz:

Mr Zavatarelli furthermore observes that the game under

consideration was preceded by one involving Earnshaw,

whose role in the affair is reported in our feature

article.

9348. Openings knowledge

A remark by Imre König about Leonard Barden in a report on the 1949 British championship in Felixstowe:

‘Barden’s knowledge of theory is extraordinary, he is a walking compendium of MCO and Bilguer.’

Source: BCM, September 1949, page 312.

After quoting this on page 282 of the 1 December 1949 Chess World, C.J.S. Purdy wrote:

‘Understatement! He is years ahead of the latest editions of both. Barden is 20 – a modern history student at Oxford.’

9349. Simultaneous displays

On the subject of records over the past decade for the largest number of games played in a simultaneous display, the most detailed series of reports has appeared at ChessBase.com. Below are the relevant links for the records claimed:

- Articles on 31 July 2005 (preparations) and 3 August 2005: display by Susan Polgar in Palm Beach Gardens, FL, USA on 1-2 August 2005 (326 boards);

- Article on 16 September 2005: a letter from Andrew Martin querying the above-mentioned claim, and a reply from Susan Polgar;

- Article on 25 February 2009: display by Kiril Georgiev on 21-22 February 2009 in Sofia, Bulgaria (360 boards);

- Articles on 10 August 2009 (preparations) and 30 August 2009: display by Morteza Mahjoob in Tehran, Iran on 13-14 August 2009 (500 boards);

- Article on 25 October 2010: display by Alik Gershon in Tel Aviv, Israel on 21-22 October 2010 (523 boards);

- Article on 14 February 2011: display by Ehsan Ghaem Maghami in Tehran, Iran on 8-9 February 2011 (604 boards).

9350. Anderssen games (C.N. 7692)

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) submits four

further games played by Anderssen and Hamel:

Adolf Anderssen – Sigismund Hamel

Breslau, summer 1874

Philidor’s Defence

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 d6 3 d4 exd4 4 Qxd4 Bd7 5 Bg5 Qc8 6 Nc3 Nc6 7 Qe3 Nge7 8 Bf4 Ng6 9 Bg3 Be7 10 Nd2 O-O 11 f4 f5 12 O-O-O fxe4 13 Ndxe4 Bf5 14 Bc4+ Kh8 15 h4 Bf6 16 Ng5 Qe8 17 Nf7+ Rxf7 18 Qxe8+ Rxe8 19 Bxf7 Re3 20 Rhe1 Bd4 21 Nd5 resigns.

Source: Illustrated London News, 16 January 1875, page 67.

Sigismund Hamel – Adolf Anderssen

Breslau, 22 September 1876

Giuoco Piano

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 c3 Nf6 5 d3 O-O 6 Bg5 d6 7 O-O Bb6 8 Nbd2 Kh8 9 Bb3 Qe8 10 Nc4 Ng8 11 Nxb6 axb6 12 Nh4 f5 13 exf5 Bxf5 14 f4 Be6 15 Bxe6 Qxe6 16 f5 Qd7 17 Qh5 Nce7 18 Rf3 Nf6 19 Bxf6 Rxf6 20 Raf1 Rh6 21 Qg5 Ng8 22 Rh3 Rf8 23 g4 Nf6

24 Ng6+ hxg6 25 Rxh6+ gxh6 26 Qxh6+ Nh7 27 Qxg6 Rg8 28 Qh5 Rg5 29 Qh4 Qg7 30 h3 Qf6 31 Qg3 Qh6 32 h4 Rg8 33 Rf2

33...e4 34 dxe4 Nf6 35 g5 Nxe4 36 gxh6 Rxg3+ 37 Rg2 Kh7 38 Kh2 Rxg2+ 39 Kxg2 Kxh6 40 Kf3 Nf6 41 Kg3 Kh5 42 c4 c6 43 b3 b5 44 cxb5 cxb5 ‘and, after a few moves, White resigned’.

Source: Illustrated London News, 11 November 1876, page 471.

Adolf Anderssen – Sigismund Hamel

Breslau, September 1876

Two Knights’ Defence

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Nf6 4 Ng5 d5 5 exd5 Nxd5 6 Nxf7 Kxf7 7 Qf3+ Ke6 8 Nc3 Ne7 9 d4 c6 10 dxe5 Kd7 11 Bf4 Kc7 12 O-O-O Be6

13 Rxd5 cxd5 14 Bb3 Qd7 15 Rd1 Rd8 16 a4 Kb8 17 a5 Ka8 18 a6 Bg4 19 Qd3 Bxd1 20 Qxd1 g5 21 Bxg5 Qf5 22 f4 h6 23 g4 Qd7 24 Bf6 Rh7 25 f5

25...h5 26 e6 Qc7 27 Kb1 hxg4 28 axb7+ Kb8 29 Bxe7 Bxe7 30 Bxd5 Rxh2 31 Ne4 Rxd5 32 White resigns.

Source: Illustrated London News, 25 November 1876, page 519.

Sigismund Hamel– Adolf Anderssen

Breslau, September 1876

Bishop’s Opening

1 e4 e5 2 Bc4 f5 3 d3 Nf6 4 Nc3 Bc5 5 Nf3 d6 6 Bg5 c6 7 O-O Qe7 8 exf5 d5 9 Re1 Bd6 10 Bb3 O-O

11 Nxe5 Bxe5 12 d4 Bxh2+ 13 Kxh2 Qd6+ 14 Re5 Na6 15 g4 Nc5 16 Kh3 Nxb3 17 axb3 Bd7 18 Bf4

18...h5 19 f3 hxg4+ 20 fxg4 Kf7 21 Qe2 Rh8+ 22 Kg3 Rh7 23 Re1 Qf8 24 Re7+ Kg8 25 Bd6 Re8 26 Rxe8 Qxe8 27 Qxe8+ Bxe8 28 Re7 Bd7 29 Be5 a5 30 Kf4 g5+ 31 Kxg5 Rxe7 32 Kxf6 Rg7 33 Na4 Rxg4 34 Nb6 Rg7 35 Nxd7 Rxd7

36 Ke6 Rf7 37 f6 Kf8 38 c4 Ke8 39 cxd5 cxd5 40 Kxd5 Kd7 41 Kc5 Rh7 42 d5 Rh3 43 Bc3 Rf3 44 Bxa5 Rxf6 45 b4 Rf2 46 b3 Rf3 47 Kb6 Kc8 48 d6 Rd3 49 Kc5 Rxb3 50 Bc7 Rc3+ 51 Kb6 Rc6+ 52 Ka5 Ra6+ 53 Kb5 Kd7 54 Kc5 Rc6+ 55 Kd5 b5 56 Bb8 Rc4 57 Bc7 Rxb4 58 Kc5 Rb1 59 Kb6 b4 60 Kb5 b3 61 Kb4 Kc6 62 Bb8 Re1 63 Kxb3 Rb1+ 64 White resigns.

Source: Illustrated London News, 30 December 1876, page 639.

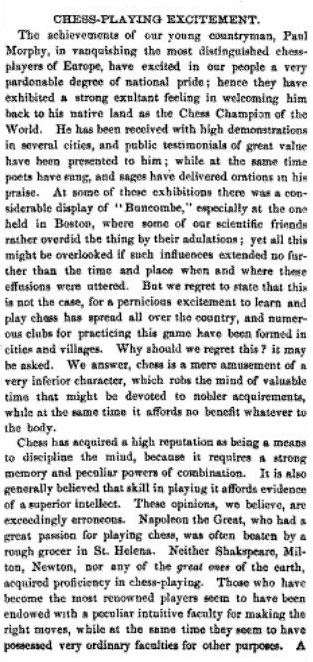

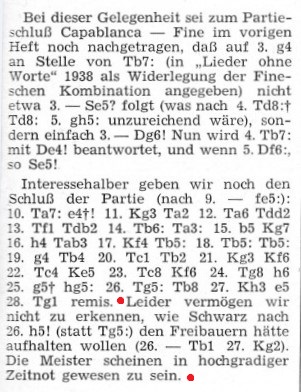

9351. Scientific American

Further to the feature article Early Uses of ‘World Chess Champion’, Hassan Roger Sadeghi (Lausanne, Switzerland) notes the reference to Morphy at the start of an article on page 9 of Scientific American, 2 July 1859:

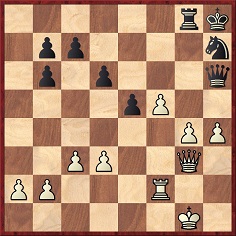

9352. Capablanca v Fine, AVRO, 1938

Capablanca did not play the winning move 40 h5

Alan McGowan (Waterloo, Canada) ties up a loose end about Capablanca v Fine: A Missed Win by providing the conclusion of a column by Paul Schlensker on pages 114-115 of Schach-Echo, 20 April 1958:

Thus Wolfgang Heidenfeld was correct to state on page 8 of Draw! (London, 1982) that Schlensker mentioned in Schach-Echo the possibility of 40 h5 about 20 years after the AVRO tournament, although Heidenfeld did not realize that by that time the move had already been pointed out elsewhere (in the 1951 edition of Teach Yourself Chess by Gerald Abrahams).

A further question now concerns the basis for Schlensker’s reference to time-pressure towards the end of the game.

9353. Leonard Vaux

An entry in Chess Prodigies is from page 50 of the Columbia Chess Chronicle, 15 September 1889:

‘Leonard Vaux, a youth of 16, who has just graduated from the High School at Brockton, Ont., has beaten all the chessplayers in his neighborhood, and is spoken of as a prodigy.’

Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA) notes that information about Francis Leonard Vaux available on the Internet includes a detailed biography on page 262 of The Canadian Journal of Medicine and Surgery (Toronto, 1906). The Journal item (which has been added to our feature article) and other sources indicate that ‘Brockton’ in the Columbia Chess Chronicle should read Brockville.

9354. Sonnet to chess (C.N. 9327)

From Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore):

‘Thomas Henry Silcock (1910-83) was active in chess circles in Malaya and Singapore before and after the Second World War. As from 1938, he was a well-known Professor of Economics at Raffles College, Singapore, and during the Japanese Occupation (1942-45) he was interned at the Changi POW Camp and a number of other camps in Thailand. After 1945, he was associated with the University of Malaya. In addition to some basic biographical information, page 2 of the 27 April 1947 issue of the Straits Times mentioned his interest in chess and alluded to some of his chess-related activities during captivity.

Silcock’s interest in chess can be traced back to the mid-1920s. In April 1926 he was one of 28 competitors in the Sixth Annual Boys’ Congress organized by the Hastings Chess Club, representing Taunton School (Times, 16 April 1926, page 16). He played in the same event in April 1927, this time qualifying for the final (Times, 29 April 1927, page 11 and 2 May 1927, page 11; Sunday Times, 1 May 1927, page 17). Between early 1929 and late 1932, Silcock made numerous appearances on Oxford University teams (often playing for the second team), representing Jesus College. On 18 March 1932 he was in the Combined Universities’ team against the West London Chess Club (11-8), winning his game on one of the lower boards (Times, 19 March 1932, page 10).

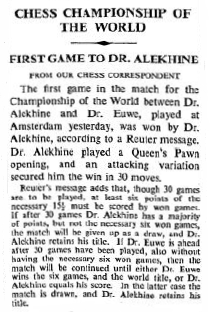

Game-scores by Silcock are scarce, but two (quick losses to H.A.J. Pronk and Elaine Pritchard) were published on pages 5 and 8 of David B. Pritchard’s The Hollandsche Club Invitation Tournament, 1953, a privately published 16-page tournament booklet which is one of the earliest chess publications in Singapore. Silcock finished ninth out of ten players, scoring 2½ points.

Singapore National Archives collections have a fine 1960 photograph of Silcock, taken at the time of his departure from Malaya. During his career he authored a number of volumes on Malayan economic history. He died in Canberra on 25 June 1983, and his obituary appeared in the Canberra Times, 27 June 1983, page 7.’

9355. Problems and studies

With respect to the discussion on chess and women, do the realms of chess problems and studies offer any relevant facts or arguments? In particular, do rigorous articles exist on the relative absence of women from those fields?

9356. An old task (C.N.s 9278 & 9302)

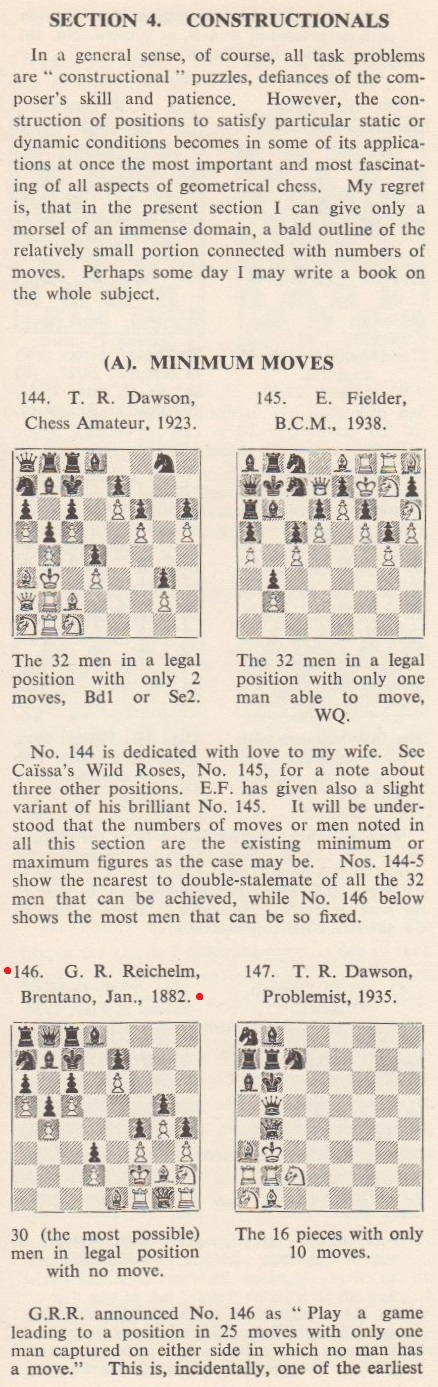

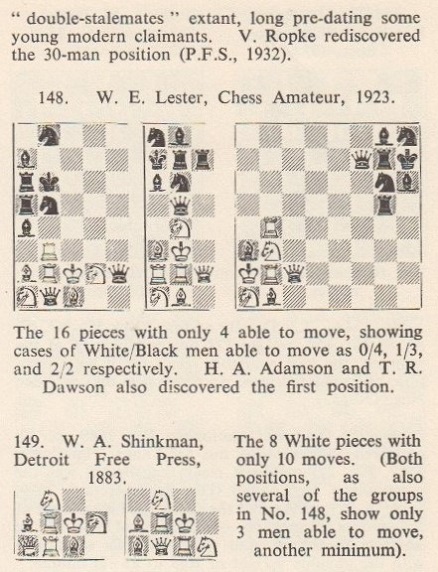

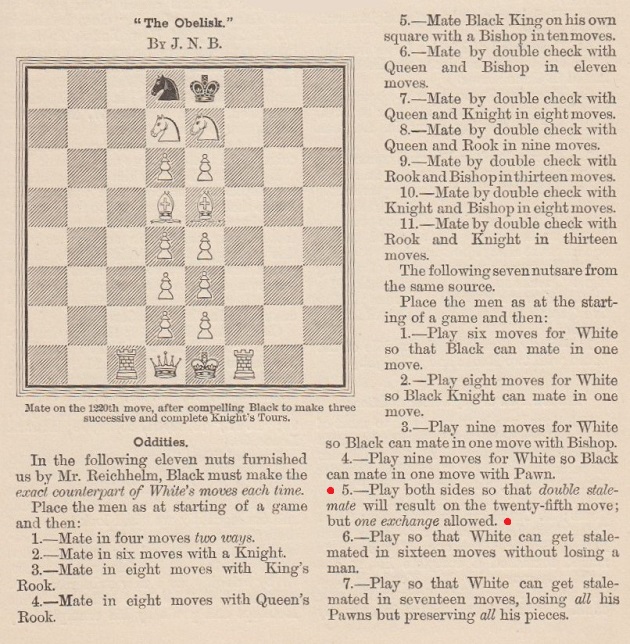

From page 25 of Ultimate Themes by T.R. Dawson (Thornton Heath, 1938):

Concerning the Reichhelm position, in the January 1882 issue of Brentano’s Chess Monthly, the following is on page 455:

We have not found the solution in the magazine, which ceased publication with its August-September 1882 number.

9357. A remark ascribed to Teichmann

Further to C.N. 5006 (see too Hypermodern Chess), below is a remark by Fred Reinfeld on page 106 of Great Moments in Chess (New York, 1963):

‘Teichmann, a stalwart of the old school, made the surly comment that in the first place there was no Hypermodern school, and that in the second place Nimzowitsch was its founder.’

9358. Löwenthal on Morphy

Rod Edwards (Victoria, BC, Canada) forwards a paragraph from J. Löwenthal’s column on page 5 of the Era, 1 December 1861:

‘Mr Paul Morphy. Now that so many distinguished players have had an opportunity of displaying their powers in this country, and under the eye of our most eminent amateurs, an opportunity has been afforded of comparing Mr Morphy’s play with that of others of the highest pretensions, and the conclusion which is come to on all hands, even by these eminent players themselves, is that Mr Paul Morphy stands on a pedestal far above any other living player. We ourselves have long maintained this opinion; but we will not conceal that we have been most anxious to see Europe vindicate its old prestige. However, at present, it must be admitted that America boasts the Chess Champion of the World. Mr Morphy’s games have exhibited in the very highest degree a pre-eminence of skill in every branch. His extraordinary quickness of perception, his power of combination, the accuracy of his strategy, and the genius and originality which characterizes the whole conduct of his play, combine to render him a perfect prodigy of power as a chessplayer. It is hoped that efforts will be made to secure Mr Morphy’s presence in London during the Grand Congress next year. We feel sure that every chess amateur in the country will hail his coming with satisfaction.’

9359. Cartoons by Harrison

Two cartoons from, respectively, page 19 and page 25 of Let’s Play Chess ‘by the Editors of Chess Review’ (New York, 1950):

9360. Openings knowledge (C.N. 9348)

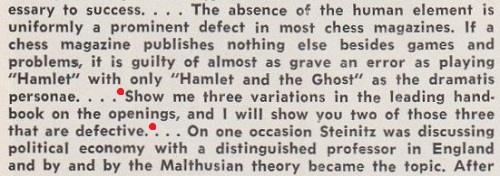

The reference in C.N. 9348 to ‘Bilguer’, i.e. the Handbuch des Schachspiels, is a reminder of the start of a column by A. Soltis on pages 10-11 of the August 1988 Chess Life. The reader does not have to wait long for a ‘once’:

‘“Show me three variations in the German Handbuch”, Emanuel Lasker once said about the foremost opening authority of his day, “and I will show you two that are defective.”

That’s a famous putdown, and one often repeated.’

Soltis repeated it on page 176 of his anthology Karl Marx Plays Chess (New York, 1991), except that ‘the foremost opening authority’ was replaced by ‘the foremost opening publication’. As there was still no source or date, it was impossible to know who was being put down by Lasker. Was it, for instance, his world championship rival Carl Schlechter, who brought out a new edition (the eighth) of the Handbuch des Schachspiels in 1916?

On some low-grade Internet sites the Lasker quote appears, also sourcelessly, in a different wording:

‘Show me three variations in the leading handbook on the openings, and I will show you two of those three that are defective.’

That version is in an article by Eliot Hearst on pages 254-255 of the September 1961 Chess Life, in which some excerpts from 1904-06 issues of Lasker’s Chess Magazine were presented ‘in true Kaleidoscopic fashion’:

Such a remark, phrased differently, appeared on page 51 of the December 1904 issue of Lasker’s Chess Magazine:

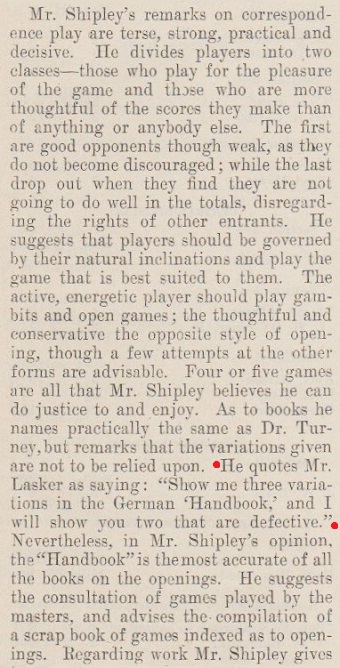

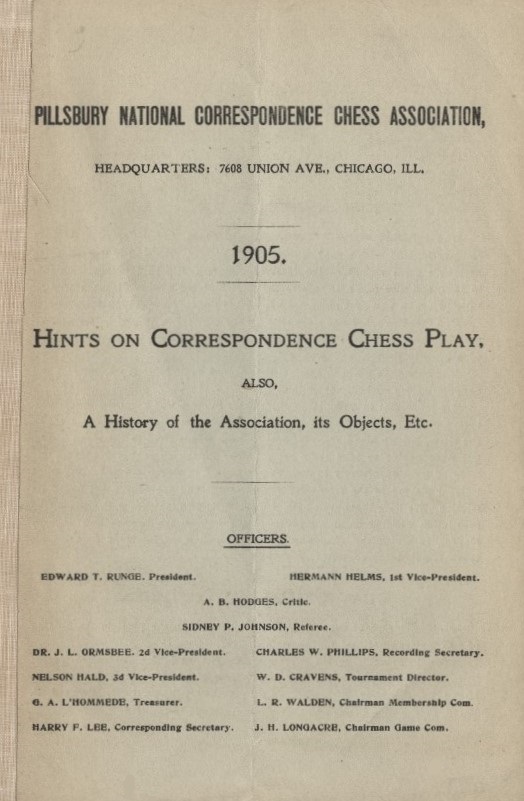

That passage comes from a review, on pages 49-51, headed ‘Pillsbury National Correspondence Chess Association’, which began:

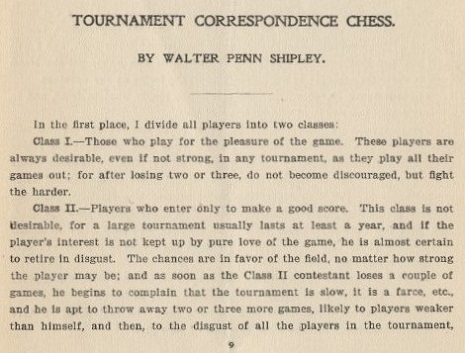

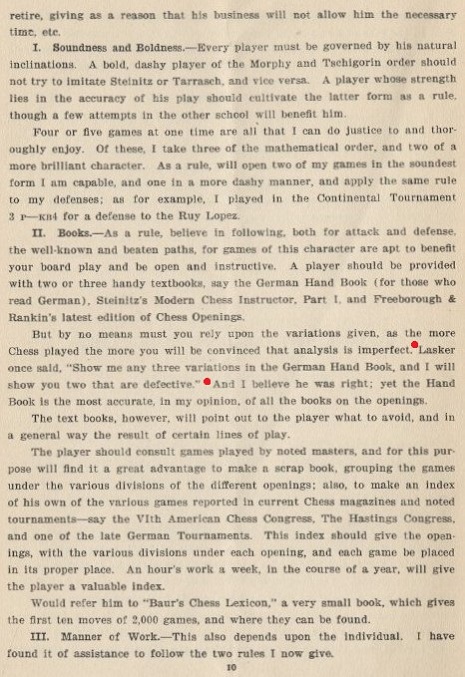

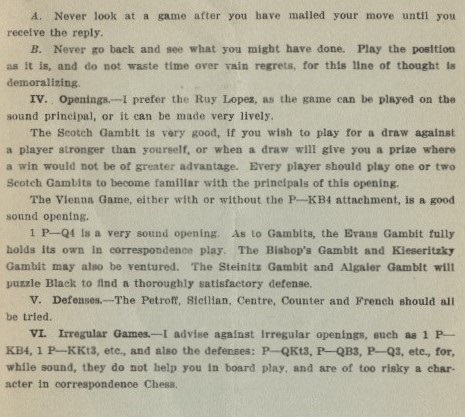

‘A pamphlet has been issued by the Pillsbury Association which contains a history of the Association and articles on correspondence play by Rev. Leander Turney and Walter Penn Shipley. The pamphlet is a sort of yearbook, dated 1905, and evidently is intended as a guide for the members.’

Courtesy of the Cleveland Public Library, below is the relevant part of the pamphlet, an article by Shipley entitled ‘Tournament Correspondence Chess’ on pages 9-11:

There is a minor difference (‘any three’, and not ‘three’ as quoted in Lasker’s Chess Magazine).

After all the foregoing we still have only a ‘once’ version for the Lasker remark, but it was written by an eminent figure, Walter Penn Shipley, who knew Lasker well, and it was repeated in Lasker’s Chess Magazine without contradiction.

| First column | << previous | Archives [131] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.