Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [188] | next >> | Current column |

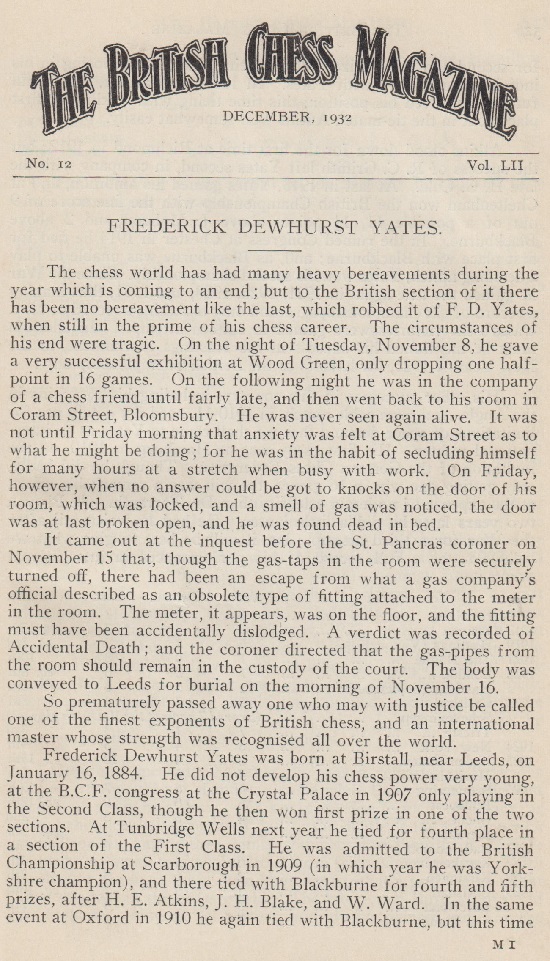

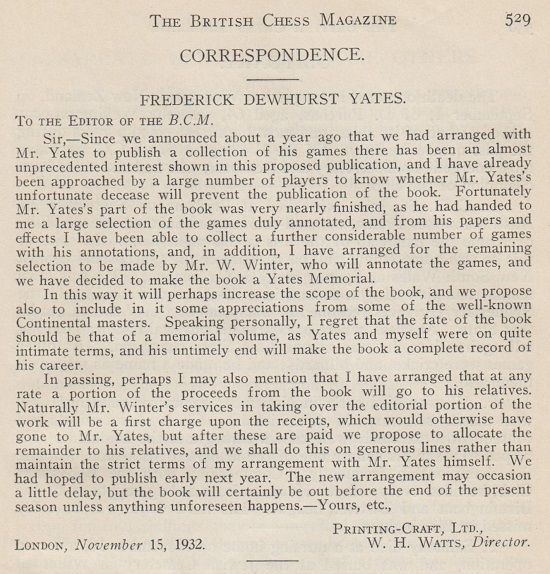

11745. F.D. Yates

Concerning the forenames of F.D. Yates (see, in particular, C.N.s 7910 and 11545), we wonder when the now-discredited form ‘Frederick Dewhurst Yates’ first appeared in print, i.e. what antedates the obituary by P.W. Sergeant on pages 525-528 of the December 1932 BCM, which had two occurrences on the first page:

See too the heading of a letter from W.H. Watts on page 529:

11746. Simultaneous blindfold match (C.N. 11739)

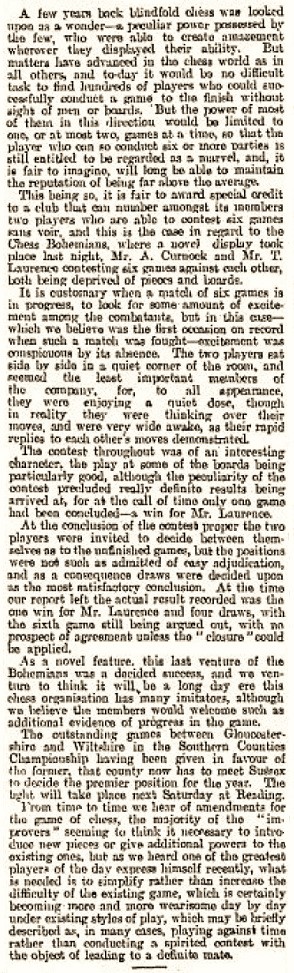

The Curnock v Lawrence match was the subject of negative comment by Louis van Vliet, as reported on page 175 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 26 June 1895:

From page 8 of van Vliet’s Sunday Times chess column, 16 June 1895:

11747. What connection?

What is the connection between the game below and a world chess champion?

11748. Observations by General Congdon

From a letter contributed by James Adams Congdon to the June 1888 International Chess Magazine, pages 173-174:

‘Chess is a great science, beautiful, fine art, and an honorable profession. Hence, its masters are justly entitled to rank intellectually with the greatest Musicians, Painters, Poets, Orators, Mathematicians, Scientists, Statesmen and Warriors. I hope to live to see the time when they will be equally honored and compensated.

It is not a question of the rich paying the poor, but of the enjoyers paying for their enjoyment.’

11749. José Pérez/Perez Mendoza

C.N.s 4591 and 10718 had the above photograph of Emanuel Lasker with a leading Argentinian chess figure, and a number of items have referred to the latter’s 599-page book El Ajedrez en la Argentina (Buenos Aires, 1920).

From page 493:

His entry on page 324 of Chess Personalia by Jeremy Gaige (Jefferson, 1987):

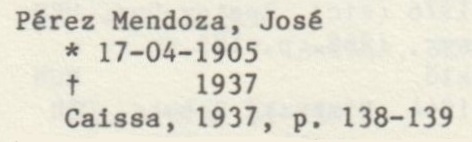

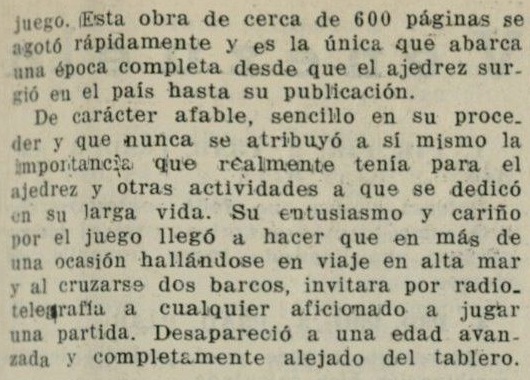

However, as will be seen from Pérez Mendoza’s obituary on pages 138-139 of the June 1937 issue of Caissa (acknowledgement: the Cleveland Public Library), the date 17 April 1905 referred not to his birth but to the founding of the Club Argentino de Ajedrez, and the final paragraph stated that he died at an advanced age:

In El Ajedrez en la Argentina, ‘Perez’, and not ‘Pérez’, was the preferred spelling, and we have consulted Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) on the matter. He points out that under rules dating from 1820 such patronymics as Fernandez, Perez and Sanchez did not take an accent, and that it was not until 1874 that the Real Academia Española revised its position and began to recommend accents on such names, which is the general usage today.

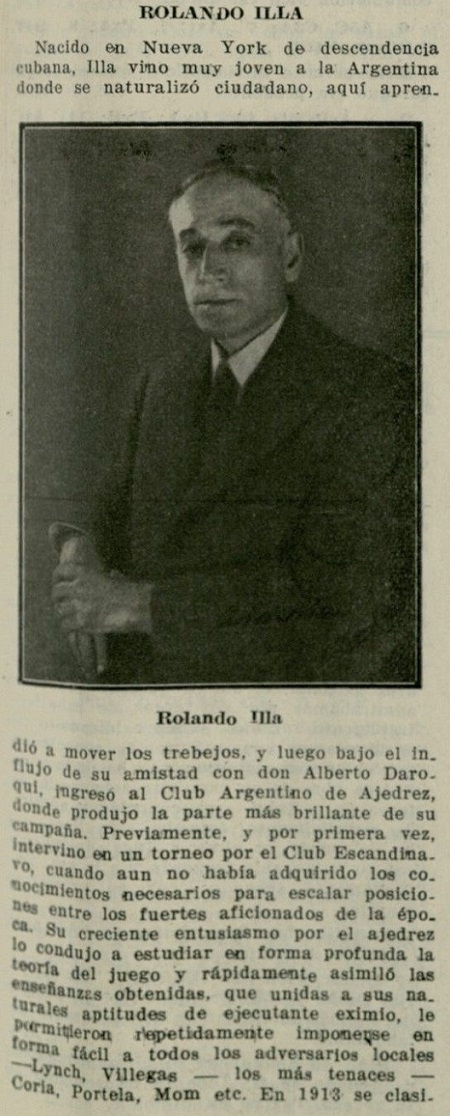

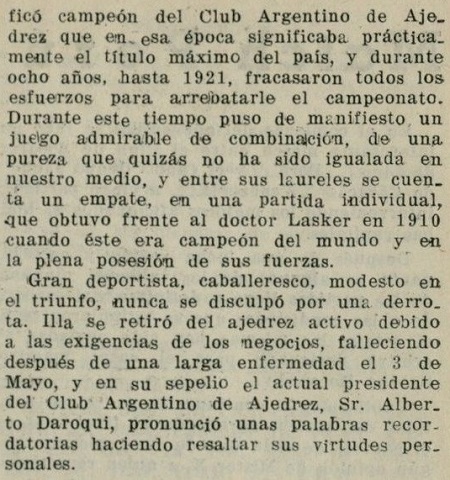

11750. Rolando Illa (C.N. 10714)

Immediately after the obituary discussed in the previous item, the June 1937 issue of Caissa (page 139) recorded the death of Rolando Illa:

Page 180 of the August 1911 American Chess Bulletin:

11751. Capablanca in San Francisco

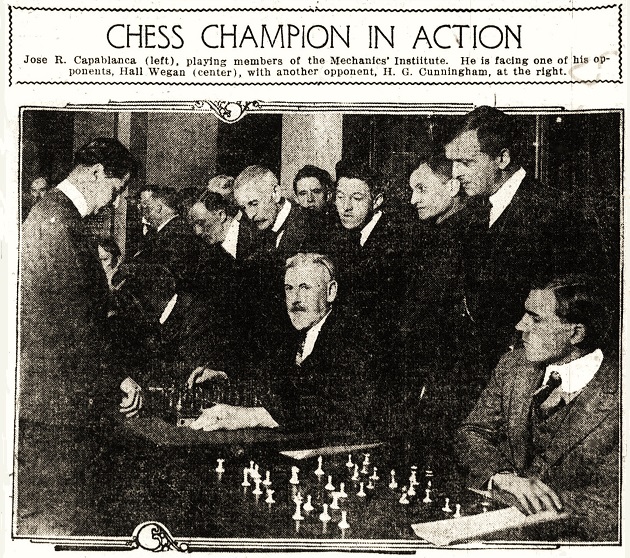

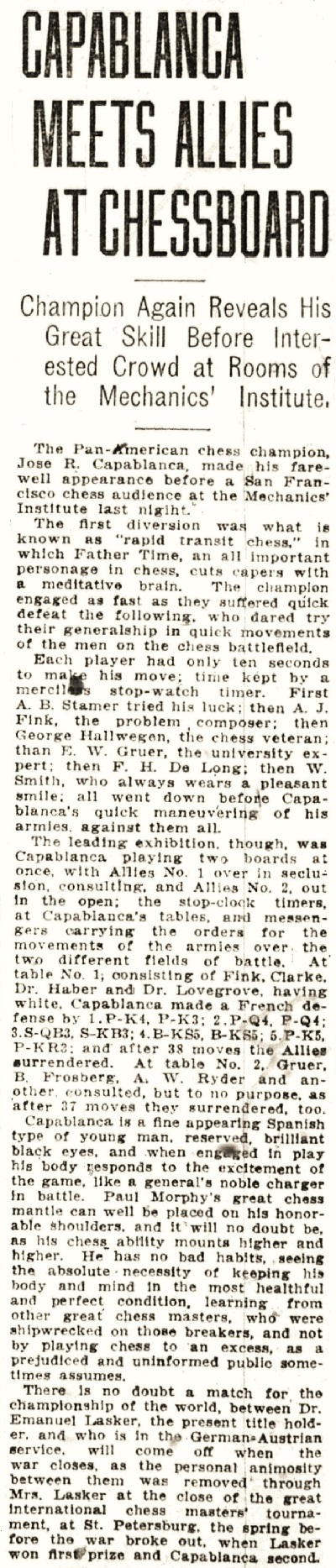

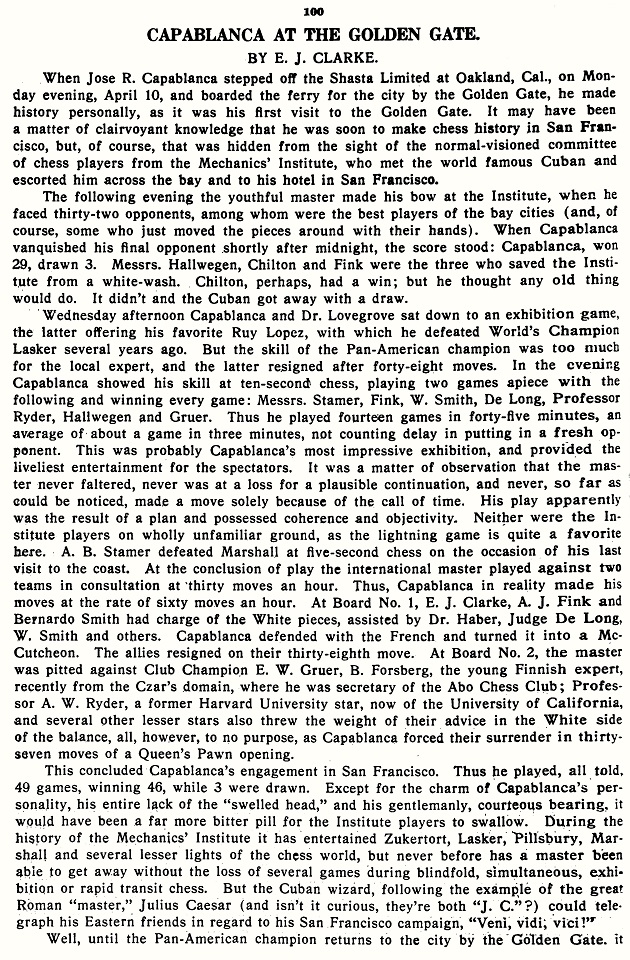

In the 1980s we acquired a poor-quality photostat of a report on Capablanca’s visit to the Mechanics’ Institute, San Francisco in part two of the San Francisco Bulletin, 13 April 1916.

The copy below – better, but a fine version of the photograph is still being sought – has been sent to us by John Donaldson (Berkeley, CA, USA):

A report by E.J. Clarke on pages 100-101 of the May-June 1916 American Chess Bulletin

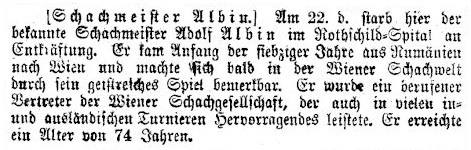

11752. The death of Adolf Albin

From Michael Lorenz (Vienna):

‘Adolf Albin died on 22 March 1920 (and not 1 February 1920, as commonly stated) in the Rothschild-Spital in Vienna (where his wife Caroline, née Samueli, had died on 21 February 1887 of tuberculosis, and where Georg Marco also died, in 1923). The hospital was at Währinger Gürtel 97, and not 95 as stated on this postcard:

This is the entry for Albin in the 1920 Totenbeschauprotokoll:

His death on 22 March was also recorded on page 6 of the Neue Freie Presse, 30 March 1920:

The final address of Albin was Paltaufgasse 26 in Vienna’s 16th district. I took this photograph on 14 May 2019:

Albin’s heir was his only son, David Albin, who, in 1920, was living in Sofia, employed by the Bulgarian paper manufacturer Kniga.’

How did the claim arise that Albin died on 1 February 1920?

11753. Albin’s grave

Michael Lorenz writes:

‘Adolf Albin is buried in Vienna’s Jewish cemetery at gate 4 of the Zentralfriedhof, group 6, row 13, number 45. The grave has no headstone but is between the two headstones in the foreground of this photograph, which I took on 24 May 2019:

The left-hand stone, number 46, is that of Chaim Ber Löwenheck, who died on 24 March 1920; the right-hand one, number 44, is that of Marie Aschenberger, who died on 26 March 1920. This was the burial area for, mainly, poorer members of Vienna’s Jewish population.

Albin’s wife is buried in another grave in the old Jewish cemetery, at gate 1 of the Vienna Zentralfriedhof, together with their daughter, Fanny, who committed suicide in 1896. It seems evident that Adolf Albin was due to be buried there too, but the existence of a family grave was not realized in 1920 because he left no will. His son, David Adolf, was born in Bucharest in 1874, and Fanny was born in 1877, also in Bucharest.’

11754. The Marshall Gambit

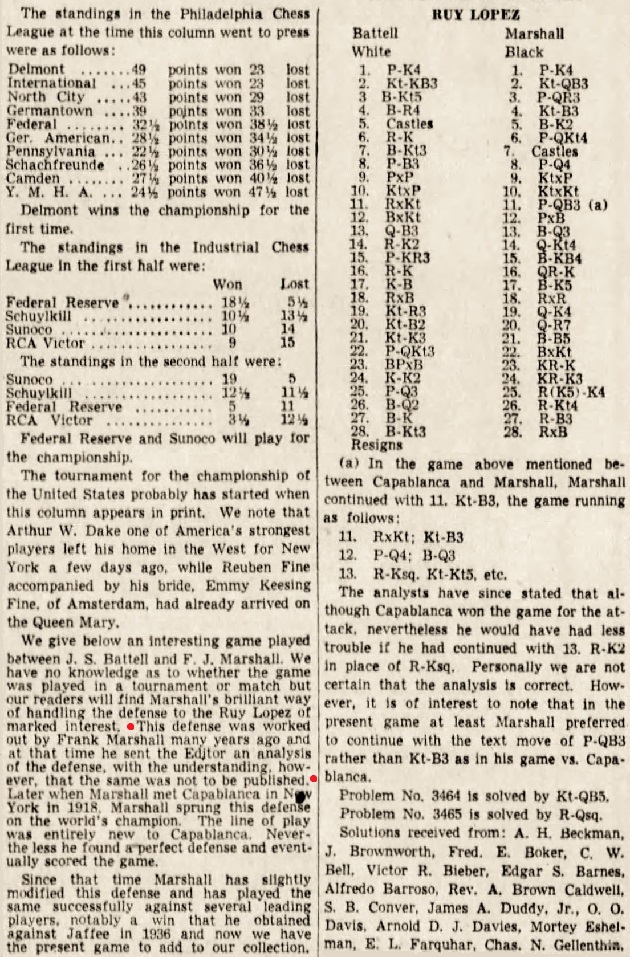

From page 8 A of the Philadelphia Inquirer, 6 March 1938, in Walter Penn Shipley’s ‘Chess and Checkers’ column:

The Battell v Marshall game, played in the Marshall Chess Club Championship, is in databases (the bare score was published on page 7 of the January-February 1938 American Chess Bulletin), but the highlighted comment by Shipley about the Marshall Gambit pre-1918 is noteworthy.

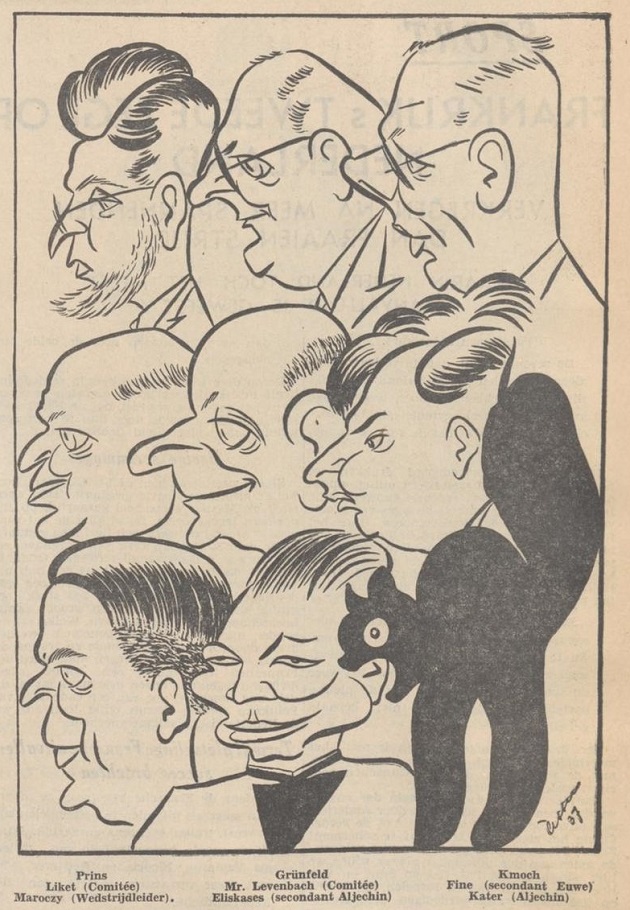

11755. Caricatures

A set of caricatures published on page 18 of Nieuwsblad van het Noorden, 1 November 1937, during the Euwe v Alekhine world championship match:

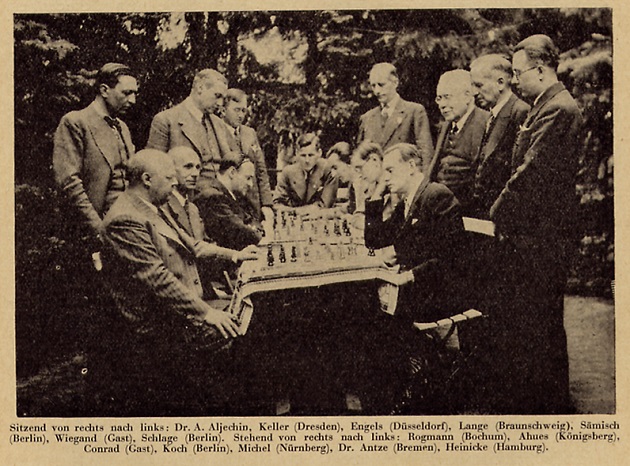

11756. Alekhine v Bogoljubow (C.N.s 5667, 5697, 6312, 7724, 11355 & 11359)

C.N. 5667 showed this photograph, taken in Berlin in 1929, on page 191 of Grandmasters of Chess by Harold C. Schonberg (Philadelphia and New York, 1973):

Suggesting that the unidentified man may have been Otto Conrad, Alan McGowan (Waterloo, Canada) provides these references:

- Schach-Echo, June 1936, page 129:

- Deutsche Schachblätter, 1 November 1937, pages 321-323. ‘Deutsche Turniertafeln’ (Post and Conrad).

- Deutsche Schachzeitung, February 1938, pages 33-35 (‘Die deutschen Turniertafeln’), and March 1938, pages 65-67 (‘Die Deutschen Turniertabellen’ by Conrad).

- Deutsche Schachblätter, 15 July 1938, page 216: a group photograph which appears to include Conrad (standing third from the left):

- Bad Oeynhausen, 1938 tournament book, page 8: a new pairing system attributed to Conrad and Post. (See also page 79.)

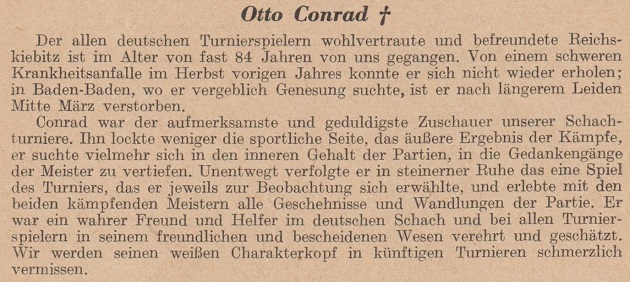

- Deutsche Schachblätter, April 1942, page 51: death notice:

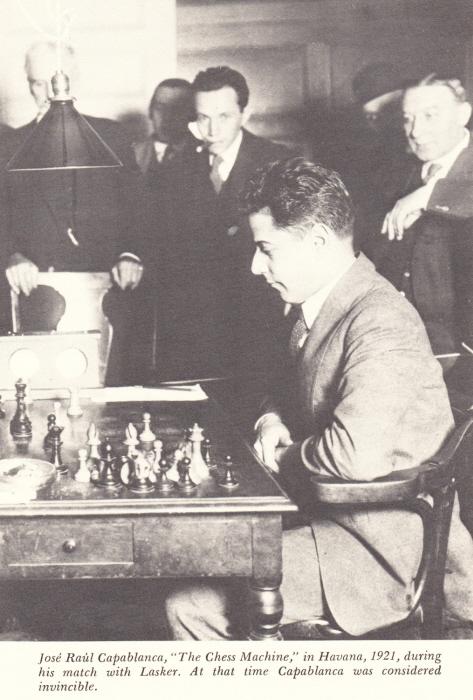

11757. Capablanca photographs

From Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore):

‘C.N. 7815 reproduced the above photograph from page 175 of Grandmasters of Chess by Harold C. Schonberg. It was taken not during the 1921 world title match against Lasker but at New York, 1918. From page 3 (photogravure section) of the 22 December 1918 edition of the Baltimore Sun:

In C.N. 9911 I contributed the picture below from page 394 of Cine-Mundial, June 1921:

It too was taken at New York, 1918, being a cropped version of the picture given by me in C.N. 10910 from the photogravure section (unnumbered page) of the Baltimore Sun, 1 December 1918:’

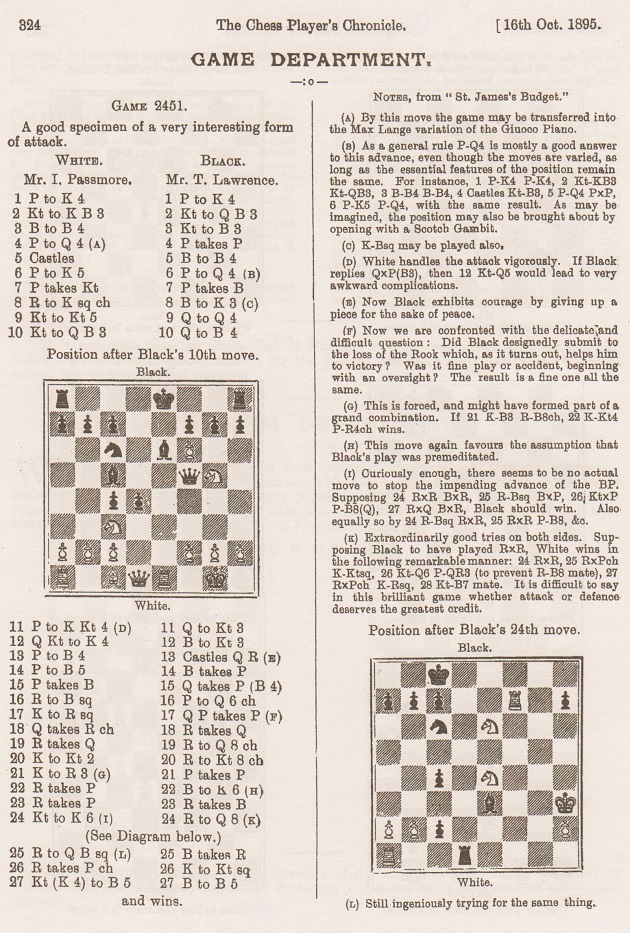

11758. Passmore v Lawrence

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Nf6 4 d4 exd4 5 O-O Bc5 6 e5 d5 7 exf6 dxc4 8 Re1+ Be6 9 Ng5 Qd5 10 Nc3 Qf5 11 g4 Qg6 12 Nce4 Bb6 13 f4 O-O-O 14 f5 Bxf5 15 gxf5 Qxf5 16 Rf1 d3+ 17 Kh1 dxc2 18 Qxd8+ Rxd8 19 Rxf5 Rd1+ 20 Kg2 Rg1+ 21 Kh3 gxf6 22 Rxf6 Be3 23 Rxf7 Rxc1 24 Ne6 Rd1 25 Rc1 Bxc1 26 Rxc7+ Kb8 27 N4c5 Bf4 and wins.

Wanted: details of the occasion, and confirmation of White’s identity. S. (Samuel) Passmore was a familiar figure at the time.

11759. What connection? (C.N. 11747)

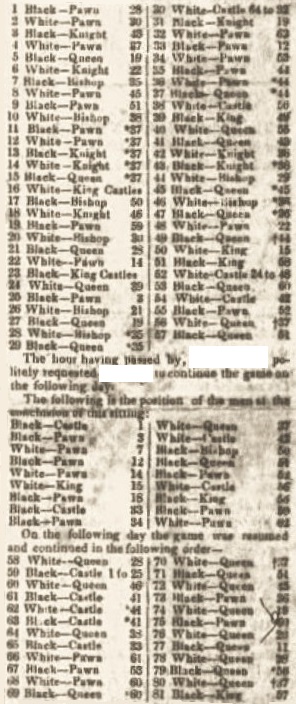

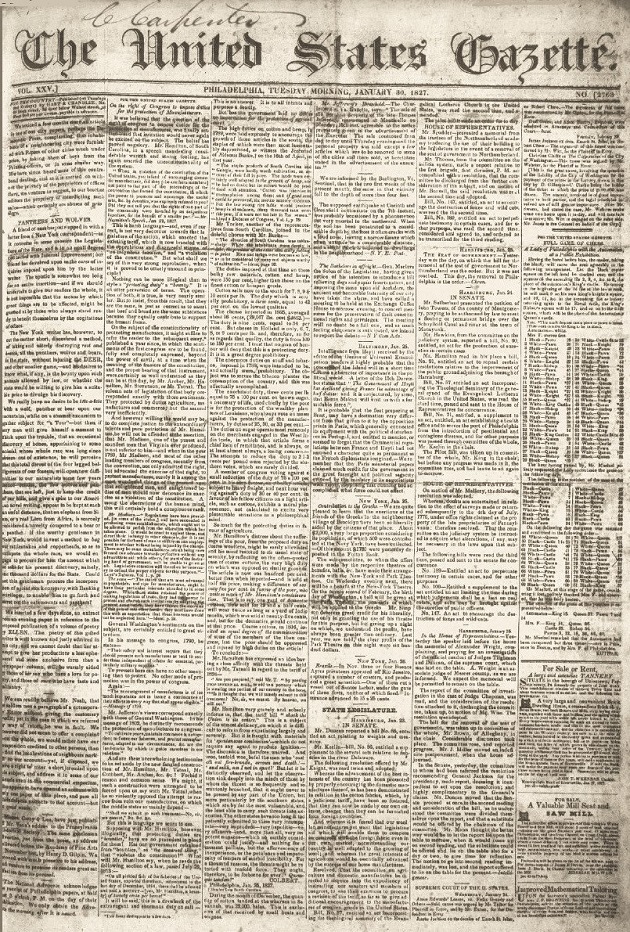

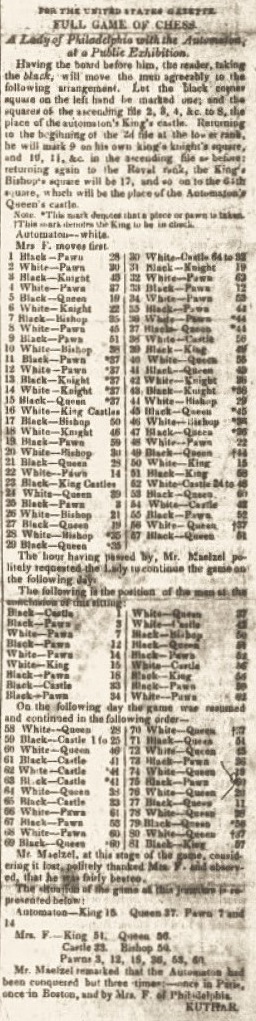

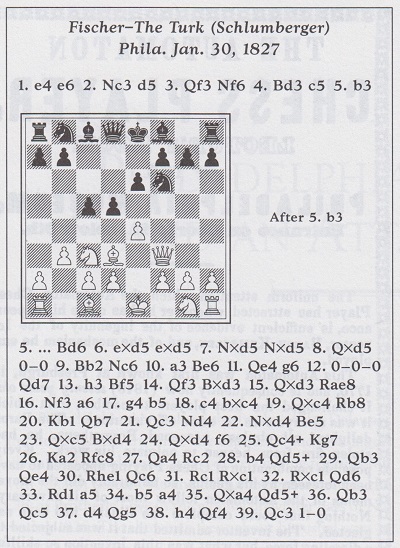

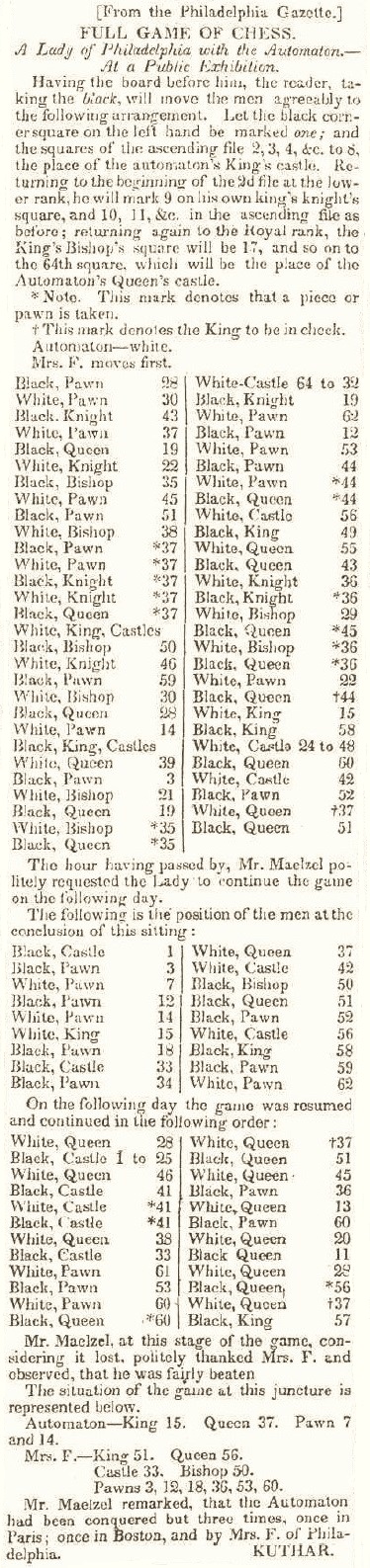

The quiz question about a connection between the above game and a world chess champion was inspired by a contribution from Ian Tregillis (Santa Fe, NM, USA), who forwarded page 1 of the United States Gazette (Philadelphia), 30 January 1827 (a column by ‘Kuthar’):

1 e4 e6 2 Nc3 d5 3 Qf3 Nf6 4 Bd3 c5 5 b3 Bd6 6 exd5 exd5 7 Nxd5 Nxd5 8 Qxd5 O-O 9 Bb2 Nc6 10 a3 Be6 11 Qe4 g6 12 O-O-O Qd7 13 h3 Bf5 14 Qf3 Bxd3 15 Qxd3 Rae8 16 Nf3 a6 17 g4 b5 18 c4 bxc4 19 Qxc4 Rb8 20 Kb1 Qb7 21 Qc3 Nd4 22 Nxd4 Be5 23 Qxc5 Bxd4 24 Qxd4 f6 25 Qc4+ Kg7 26 Ka2 Rfc8 27 Qa4 Rc2 28 b4 Qd5+ 29 Qb3 Qe4 30 Rhe1 Qc6 31 Rc1 Rxc1 32 Rxc1 Qd6 33 Rd1 a5 34 b5 a4 35 Qxa4 Qd5+ 36 Qb3 Qc5 37 d4 Qg5 38 a4 Qf4 39 Qg3 Qe4 40 Qxb8 Qd5+ 41 Ka1 Resigns.

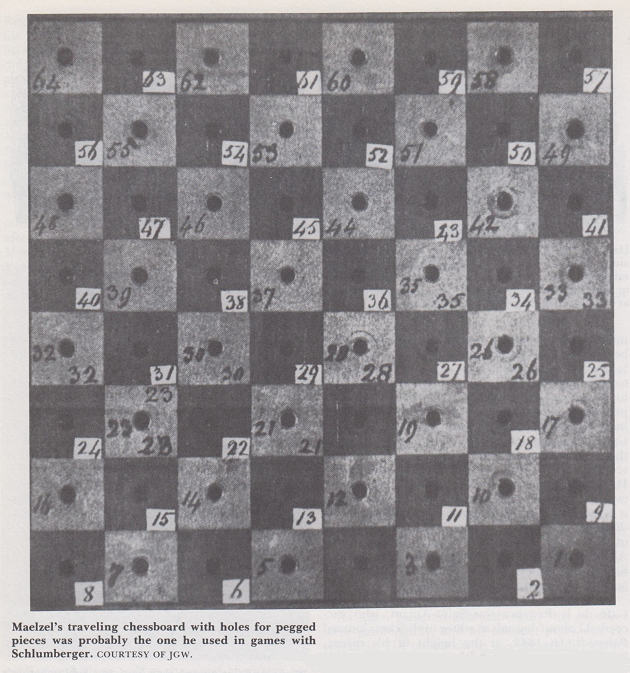

The notation to the game, in which Black played first, is unusual, the squares being counted vertically: h1 = 1; h8 = 8; a1 = 57; a8 = 64.

The same configuration was shown differently on page 96 of Chess: Man vs Machine by Bradley Ewart (London, 1980):

Ewart gave the game, concluding with 38 a4 Qf4 39 Qg3 Resigns, on page 106, dating it 30-31 January 1827.

From page 76 of The Turk, Chess Automaton by Gerald M. Levitt (Jefferson, 2000):

The transcriptions 38 h4 and 39 Qc3 are incorrect. Although Levitt stated that the game was played on 30 January 1827, that is the very date of publication in the Gazette, which, moreover, specified that it was played over two days.

Some information about the winner is on pages 76 and 86 of the Levitt book.

The game was also published, up to 39 Qg3 and with annotations, on pages 57-59 of the American Chess Magazine, 1847 (‘Played many years ago at Philadelphia, and won by a Lady of the celebrated Automaton Chess Player’). See too pages 446 and 464 of the New York, 1857 tournament book (‘Mrs Fisher’). The Fischer/Fisher discrepancy has yet to be clarified.

The best response to C.N. 11747 came from Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA), who added that the column about the defeat of the Turk/Schlumberger was reproduced shortly afterwards (exact date unavailable) in the New York Spectator, duly credited to the Philadelphia Gazette:

11760. Alekhine v Bogoljubow (C.N.s 5667, 5697, 6312, 7724, 11355, 11359 & 11756)

Peter Anderberg (Harmstorf, Germany) identifies the man standing between Alekhine and Bogoljubow as P. Matzdorff, a board member of the Berliner Schachgesellschaft, as shown in this photograph on page 13 of Das internationale Schachmeisterturnier zur Hundertjahrfeier der Berliner Schachgesellschaft by Kurt Richter (Berlin, 1928):

11761. Chess laws in New Zealand

Ross Jackson (Raumati South, New Zealand) points out news items in the chess column of the Otago Witness, 20 July 1899, page 48, and 4 October 1905, page 70:

‘It is surprising to note that provisions such as the touch-move rule and the possibility for a pawn reaching the eighth rank to remain a pawn were officially still in force in New Zealand until the end of September 1905.’

11762. Alexander Kotov

Yuri Kireev (Moscow) has forwarded a photograph which he took in March 2019 of the memorial to Alexander Kotov at the Kuntsevsky Cemetery, Moscow:

11763. Chess Notes

Owing to other commitments, it will be necessary for us to curtail the posting of new C.N. items as from the end of March 2020. Thereafter, additions to the main C.N. page and to feature articles will be possible only occasionally.

This announcement is made already now for the sake of good order, and for the particular benefit of any correspondents who are currently preparing a submission.

All C.N. pages, including the feature articles, will remain openly viewable on-line.

11764. José Pérez/Perez Mendoza (C.N. 11749)

Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) notes that much information about José Pérez/Perez Mendoza is in chapter seven (pages 185-211) of the book mentioned in C.N. 9042, Luces y Sombras del Ajedrez Argentino by Juan Sebastián Morgado (Buenos Aires, 2014). In an article entitled ‘Apuntes sobre mi vida’ page 200 includes his statement that he was born in Buenos Aires on 10 November 1855.

11765. A forthcoming book on Capablanca

From Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore):

‘I am currently finalizing a pictorial biography of Capablanca, comprising some 450 high-quality photographs, illustrations and cartoons of the Cuban, many of them little-known and recently unearthed in archives and other sources. I shall be very grateful for assistance from private collectors, historians and researchers who can provide further such images not readily accessible in the standard digital repositories or on the Internet.’

Anyone able to assist is invited to contact Olimpiu G. Urcan direct by e-mail.

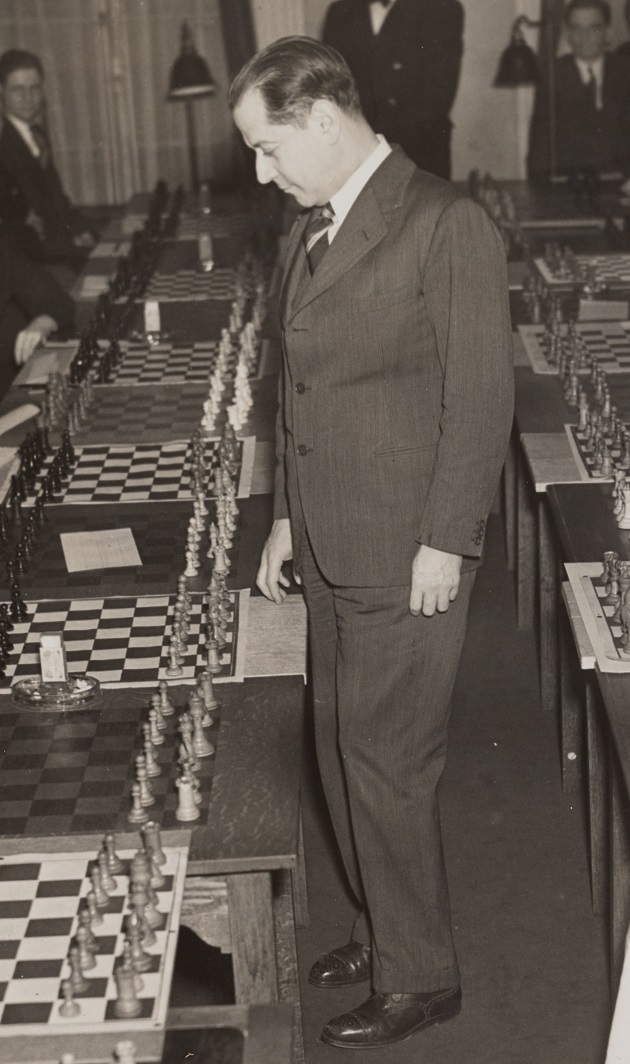

By way of example, our correspondent shares a picture discovered in morgue archives of the New York Sun and digitized upon request. It was taken during a simultaneous display (+28 –1 =3) on 14 December 1936 at the Marshall Chess Club, New York:

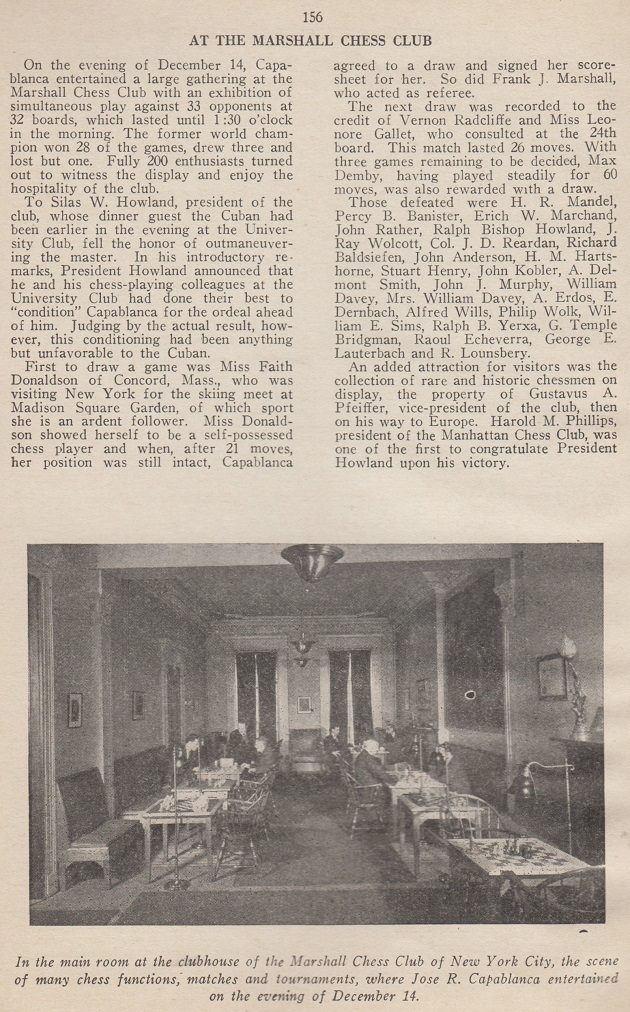

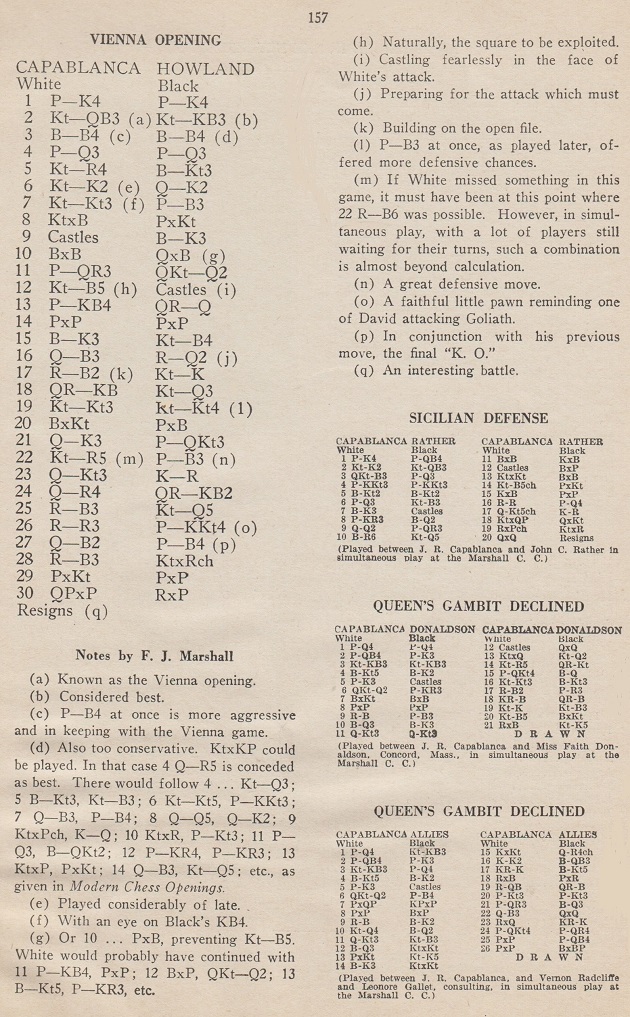

11766. Capablanca at the Marshall Chess Club

In connection with the photograph in the preceding C.N. item, we give the report on pages 156-157 of the November-December 1936 American Chess Bulletin:

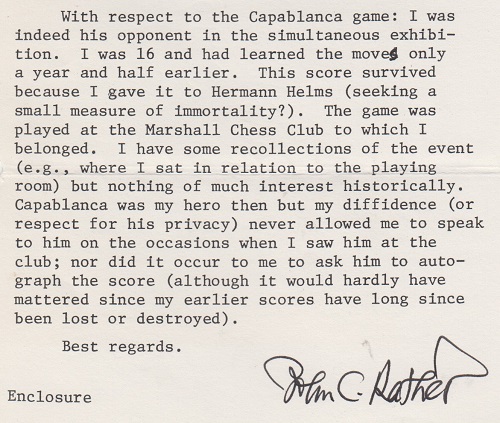

Capablanca’s win over John C. Rather is also on page 166 of The Unknown Capablanca by David Hooper and Dale Brandreth (London, 1975). As mentioned in C.N. 521, Mr Rather told us that he was aged 16 at the time, and below is an extract from his letter to us, dated 16 June 1983:

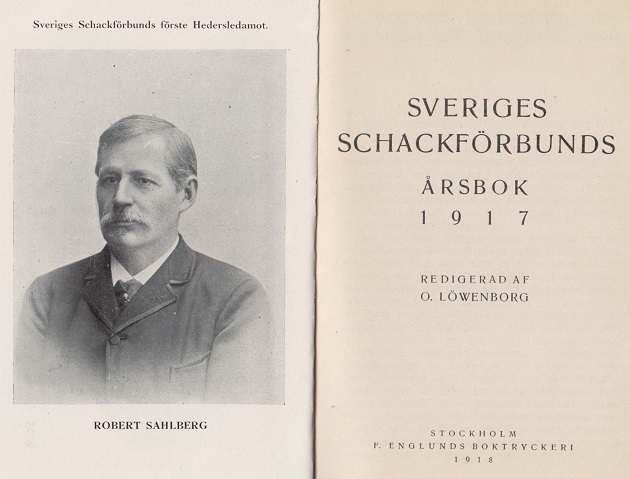

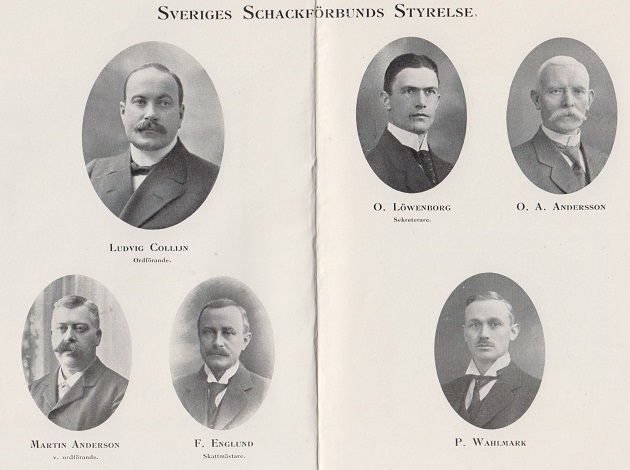

11767. Swedish chess personalities

11768. Bath, 1939

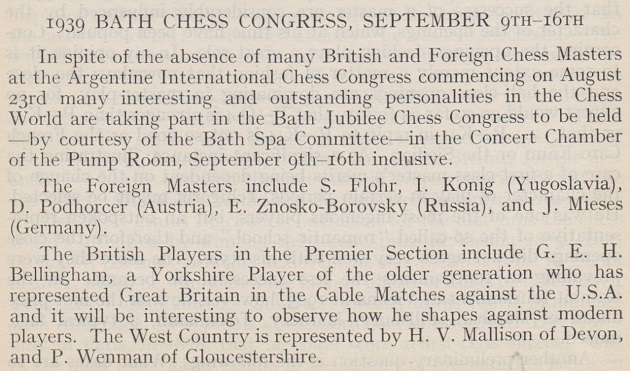

From page 383 of the September 1939 BCM:

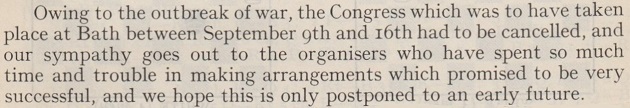

The October 1939 issue (page 443) reported:

11769. A miscellany of photographs

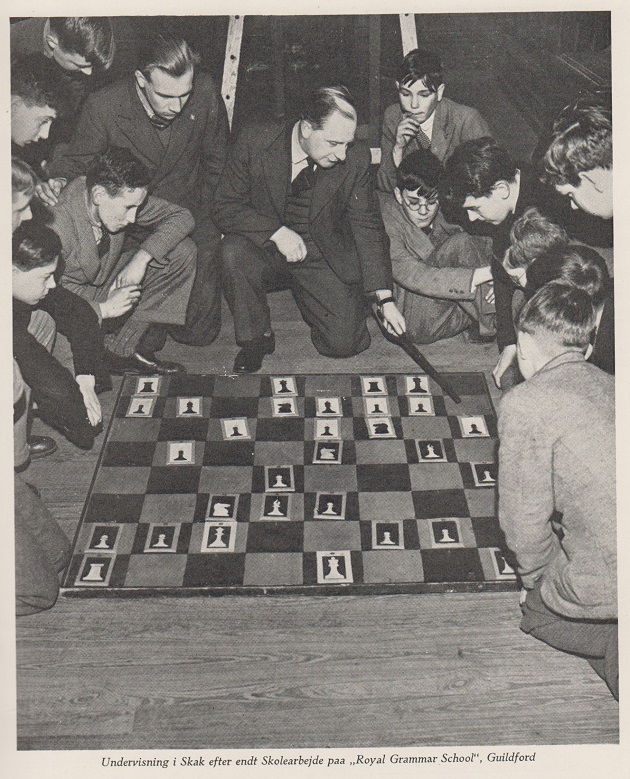

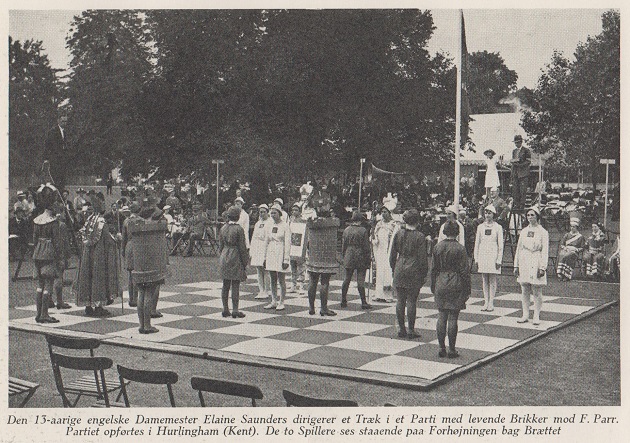

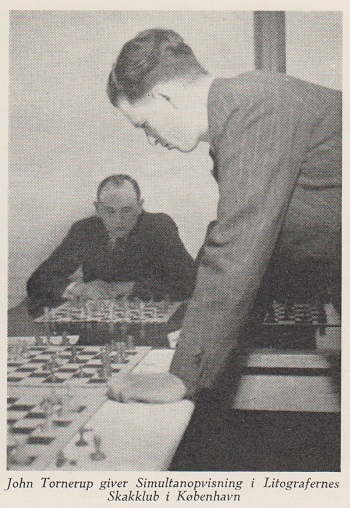

Alt om Skak by Bjørn Nielsen (Odense, 1943) includes several good photographs from unspecified British sources, examples being the portraits of Elaine Saunders (C.N. 7467) and P.J. Quinlivan (C.N. 11548).

Two further shots, from pages 11 and 16 respectively:

The Getty Images website has other photographs of the Royal Grammar School, Guildford and of living chess (Hurlingham).

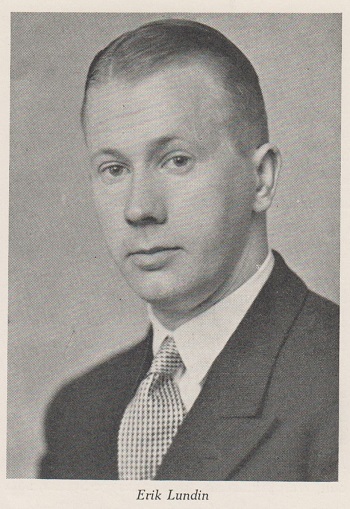

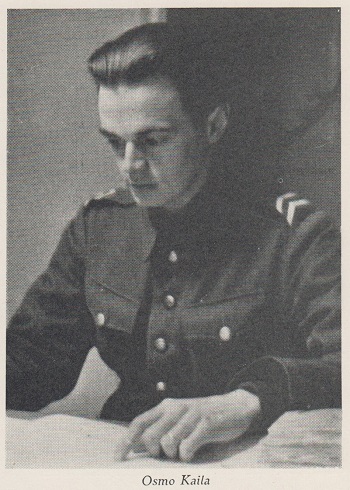

Some further portraits from the Danish book:

Page references: Lundin, page 109; Kaila, page 219; Danielsson, page 234; Tornerup, page 349; Mora; page 476.

11770. Alekhine in 1927

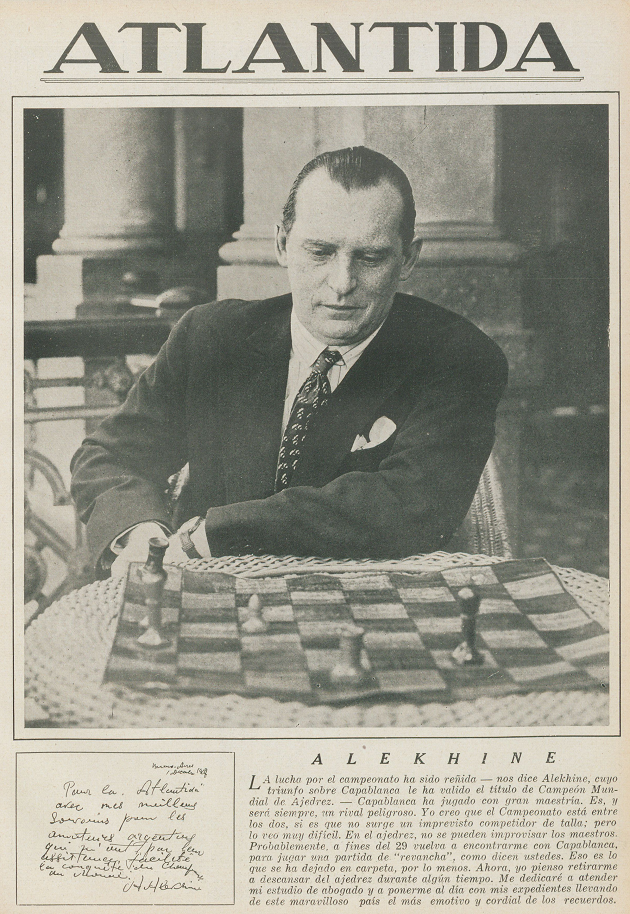

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) has found this feature about Alekhine on an unnumbered page of the 8 December 1927 edition of the Argentinian magazine Atlántida:

Our correspondent adds, further to C.N.s 11564 and 11599, a September 1927 picture of Alekhine’s hand (reference AR_AGN_DDF/Consulta_INV: 61887 from Argentina’s Archivo General de la Nación, courtesy of the Ministerio del Interior, Obras Públicas y Vivienda):

11771. Pawn sacrifices (C.N.s 9859 & 11144)

‘A pawn sacrifice may be more brilliant than a queen sacrifice ...’

Source: Australasian Chess Review, November 1936, page 314, from the introduction to Reshevsky v Vidmar, Nottingham, 1936.

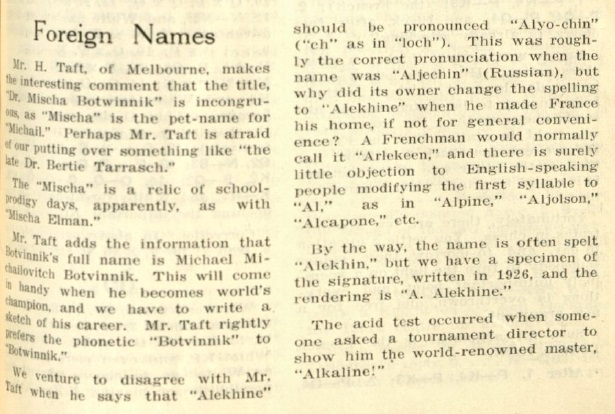

11772. Pronunciation

From page 327 of the Australasian Chess Review, December 1936:

The pronunciation of Alekhine’s name has been discussed in C.N.s 4284, 4289, 4304 and 7974.

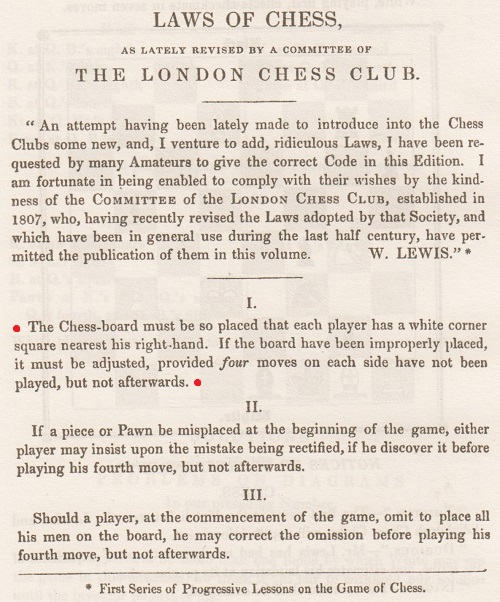

11773. The board (C.N. 4389)

An early occurrence of the rule that the h1 and a8 squares should be light-coloured is shown from page 266 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1842:

11774. The 50-move rule

From the document referred to in the previous item (page 269 of the magazine), a provision regarding the 50-move rule:

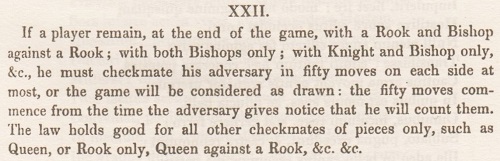

Guy Haworth (Reading, England) notes that a 50-move requirement was mentioned in Libro de la invención liberal y arte del juego del axedrez by Ruy López (Alcalá, 1561), page 68:

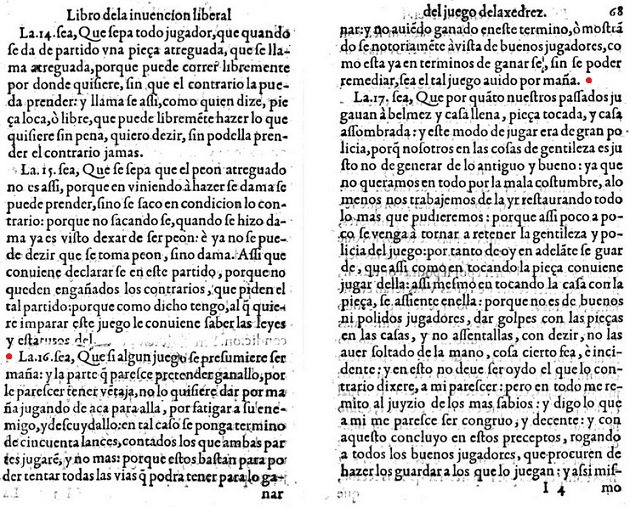

11775. Sitzfleisch (C.N. 4316)

The Oxford English Dictionary has now added two pre-D.H. Lawrence citations:

Nineteenth-century occurrences of the term in a chess context are still welcomed. Steinitz used it in his ‘Personal and General’ column on page 177 of the June 1888 issue of the International Chess Magazine:

‘... a British scholar and a gentleman, who now resides on this side of the ocean, has once before castigated the “Sitzfleisch” of a German chess editor in the pages of the London Chess Monthly.’

From page 235 of the August 1888 edition, also in the ‘Personal and General’ column:

‘Here is our poor patient from New Orleans again with his “Sitzfleisch” on public exhibition, showing that the coagulation of revengeful blood to his head has been somewhat relieved.’

11776. T. Khrennikov

Martin Weissenberg (Savyon, Israel) sends a photograph from page 98 of Russia’s Great Modern Pianists by Mark Zilberquit (Neptune, 1983) which features the composer and pianist Tikhon Khrennikov (1913-2007):

11777. Edward Lowe

From John Townsend (Wokingham, England):

‘The naturalization papers of Edward Lowe (Löwe), who won a match receiving pawn and two against Staunton, are in the National Archives at Kew (reference HO 1/153/6014). A few biographical details can be gleaned, and a naturalization certificate, dated 30 November 1868, is referred to.

A declaration was made on 23 November 1868 by four referees, three of whom were solicitors, who “vouched for his loyalty and respectability”. They stated that, to the best of their belief, he was “by birth an Austrian”, born in Prague “on or about 10 September 1794”; that he had resided at 14 and 15 Surrey Street for more than 20 years, was married, and had one child, then 35 years of age.

On 28 November 1868 Lowe himself made a declaration explaining why his referees were solicitors; presumably, this was in reply to a query by the authorities. He said that he had never had occasion to avail himself of the assistance of a solicitor, and that he had known John Jubilee Spiller, one of the solicitors, personally as a friend for over 20 years.

Page 87 of my book Notes on the life of Howard Staunton commented that John Jubilee Spiller had been, at one time, the employer of Thomas Beeby, the author of the controversial 1848 pamphlet An Account of the Late Chess Match Between Mr Howard Staunton and Mr Lowe, and it was suggested that Spiller and Beeby had remained close friends, Spiller having signed the marriage register as a witness to Beeby’s wedding.

Lowe’s statement that he had never used a solicitor is interesting. As mentioned on page 89 of my book, he had had his estates sequestrated in 1840 and had later incurred a spell in a debtors’ prison, obtaining his release by petitioning the Court for the Relief of Insolvent Debtors. Page 6 of the Berkshire Chronicle of 28 April 1855 reported on a civil action that he brought in the Court of Common Pleas in which he was represented by the chessplaying barrister, Joseph Brown (C.N. 9909), who won the case for him. Did Lowe do all this without using a solicitor?

The National Probate Calendar gives 25 February 1880 as Lowe’s date of death, at Surrey Street, his personal estate being under £4,000.’

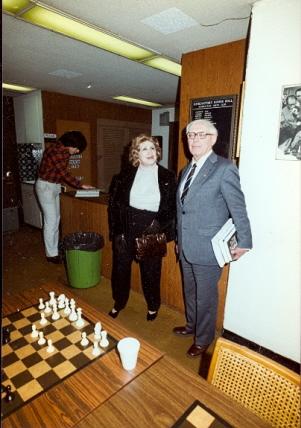

11778. Olga Capablanca and Mikhail Botvinnik (C.N. 4950)

C.N. 4950 reported that Capablanca’s widow gave us the above photograph. No details were available, but we now note the following on page 52 of the ICCA Journal, March 1984:

‘TF’, we believe, is Tom Fürstenberg.

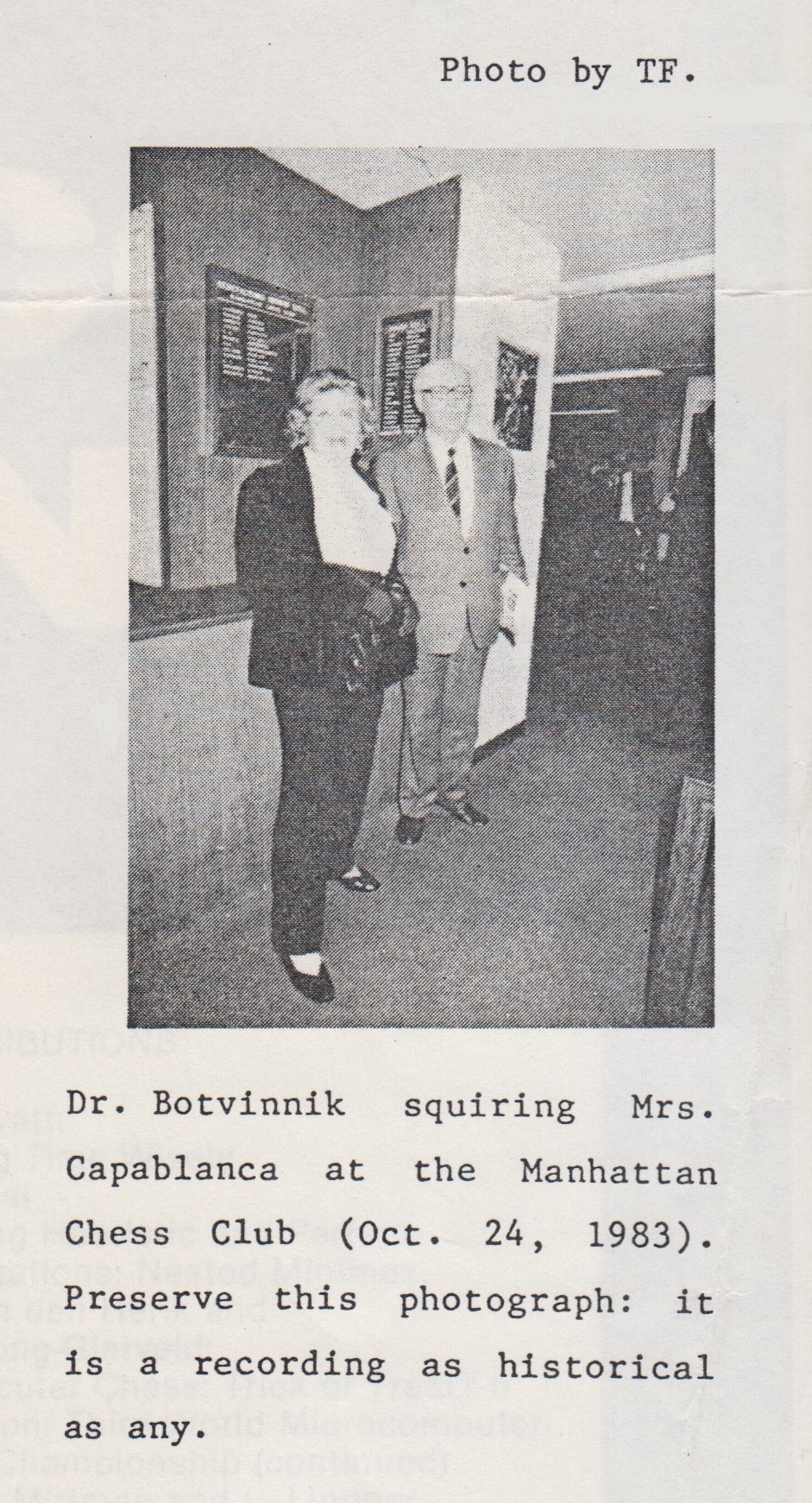

11779. Tartakower in the Great War (C.N. 8198)

Further information about Savielly Tartakower during the Great War is in the 1915 volume of the Wiener Schachzeitung: January-February, page 20; May-June, pages 109-110; July-August, pages 183-184. As mentioned in C.N. 7728, the periodical is available on-line at the ANNO website.

Wiener Schachzeitung, May-June 1915, page 109

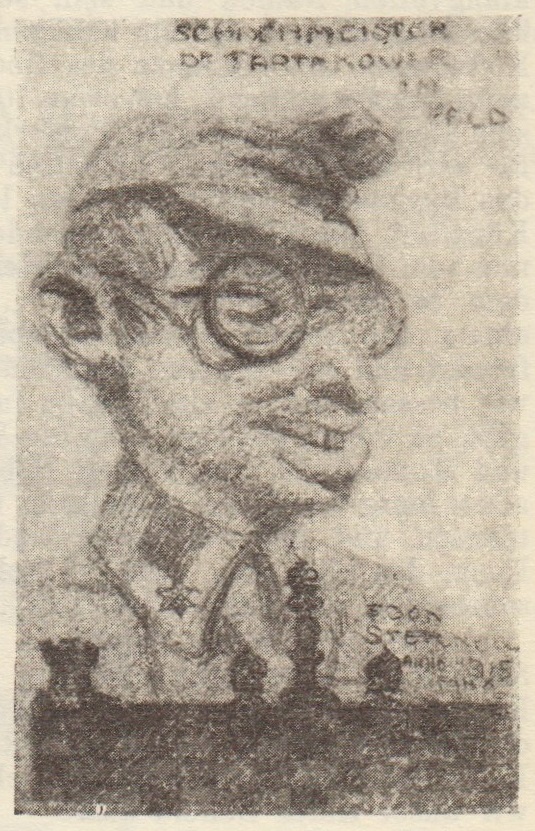

11780. ‘Shortest game on record’ (C.N. 4963)

From page 208 of the April 1928 Chess Amateur:

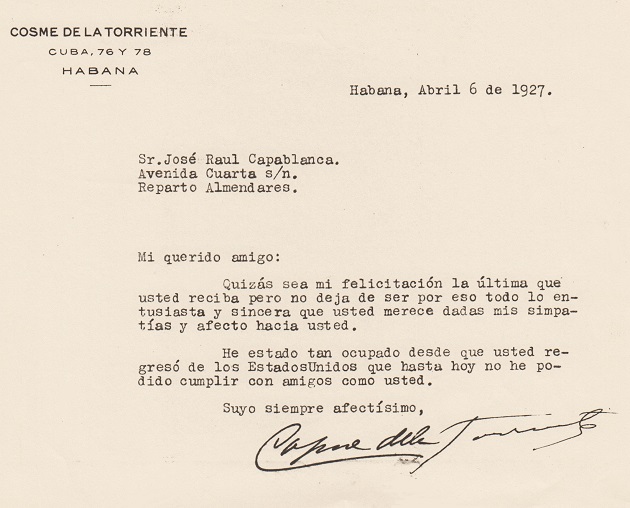

11781. Further letters

C.N. 6133 reproduced a letter dated 28 March 1928 to Capablanca from Carl Laemmle, the President of the Universal Pictures Corporation, which showed the Cuban’s address:

‘Villa Gloria, 4th Ave.,

Buena Vista, Marianao,

Havana, Cuba.’

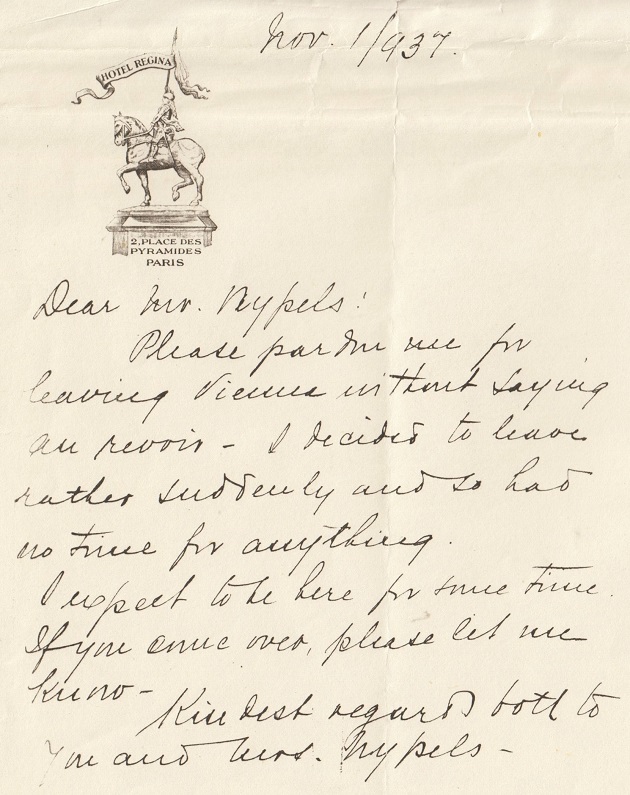

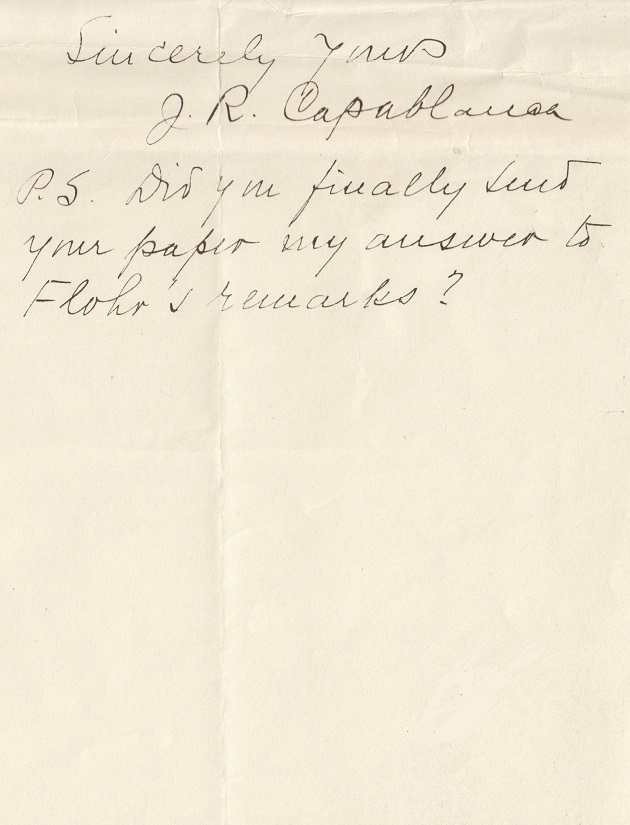

Two further letters of which we have copies:

The recipient appears to be the Dutch journalist George Nypels (1885-1977), the then Vienna correspondent of the Algemeen Handelsblad.

11782. The first move

‘No first move can be bad.’

Source: pages 165-166 of the March 1927 Chess Amateur. In the Games Department, conducted by Charles R. Gurnhill, it was a comment about 1 Nf3 in the game A. Teller v G.M. Norman, Hastings, 4 January 1927.

11783. Béla Bartók

Martin Weissenberg (Savyon, Israel) shares these photographs taken by him at the Budapest home (1932-40) of Béla Bartók, which has been a memorial house since 1981:

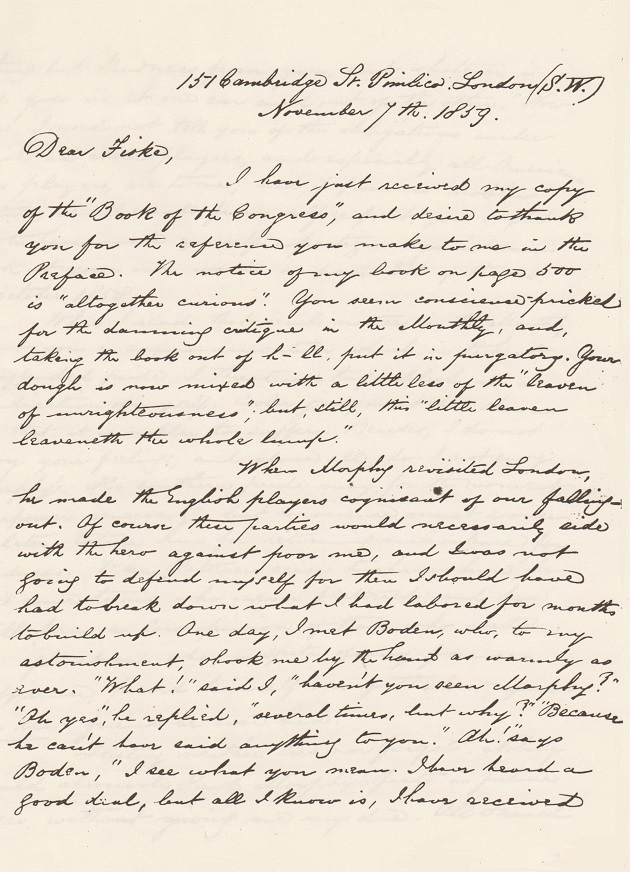

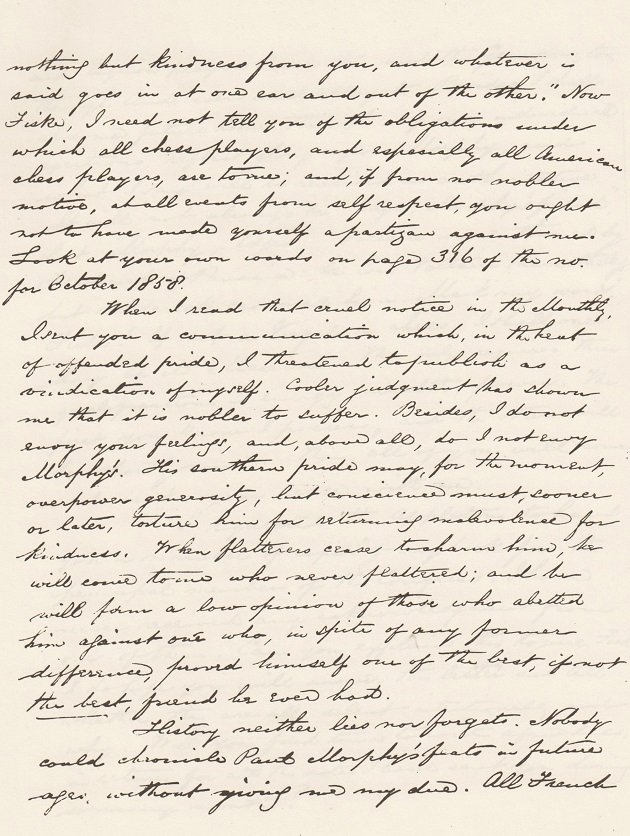

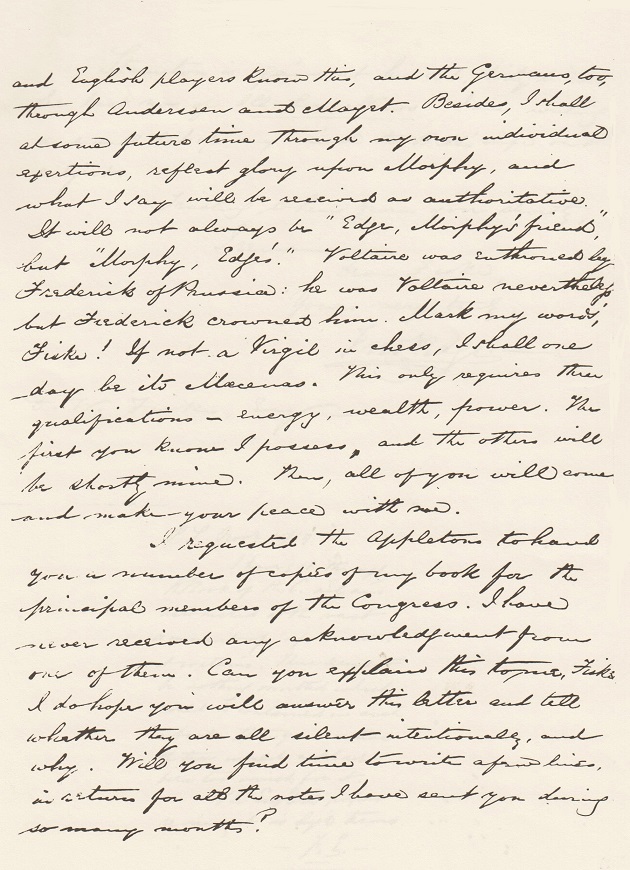

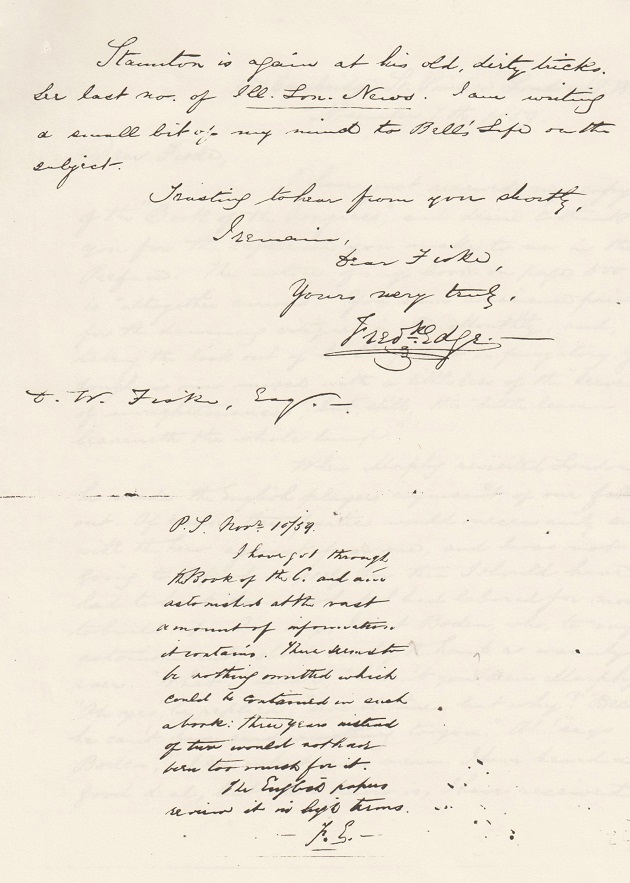

11784. Letters from Edge to Fiske

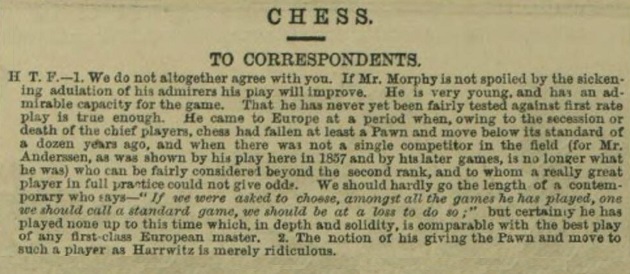

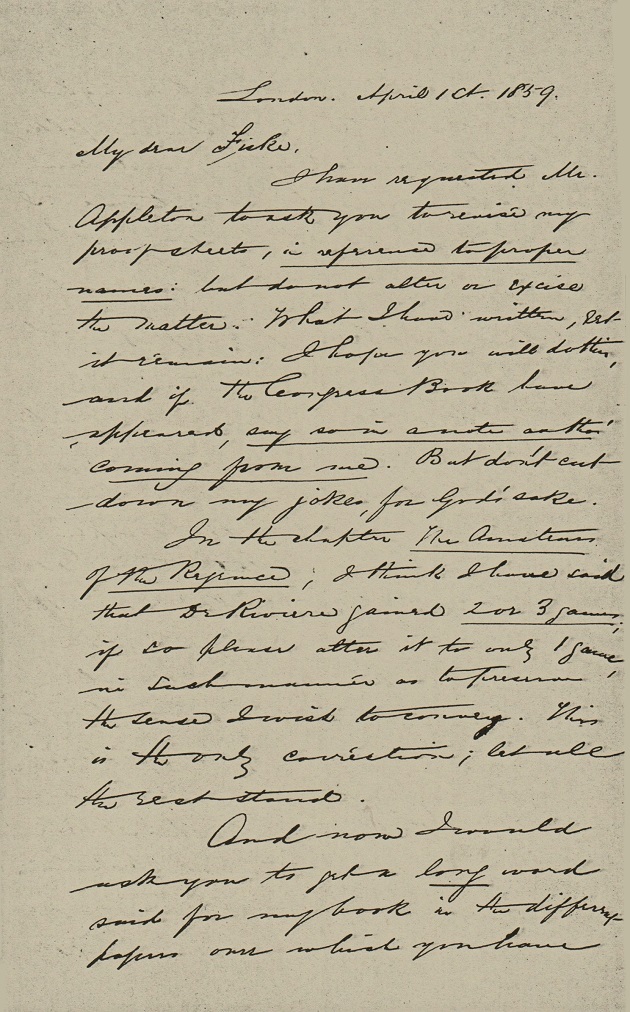

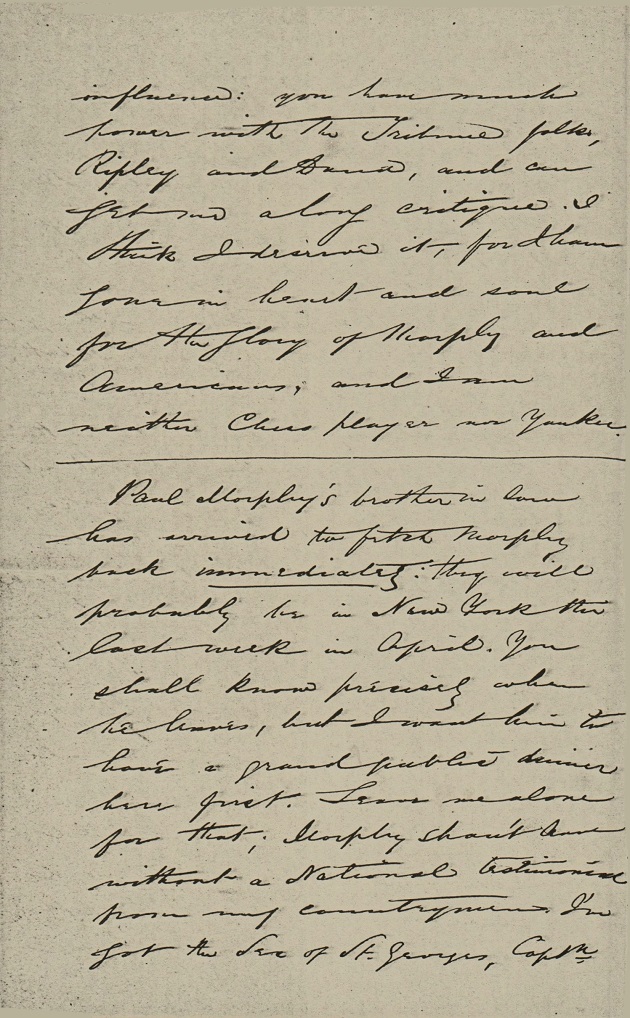

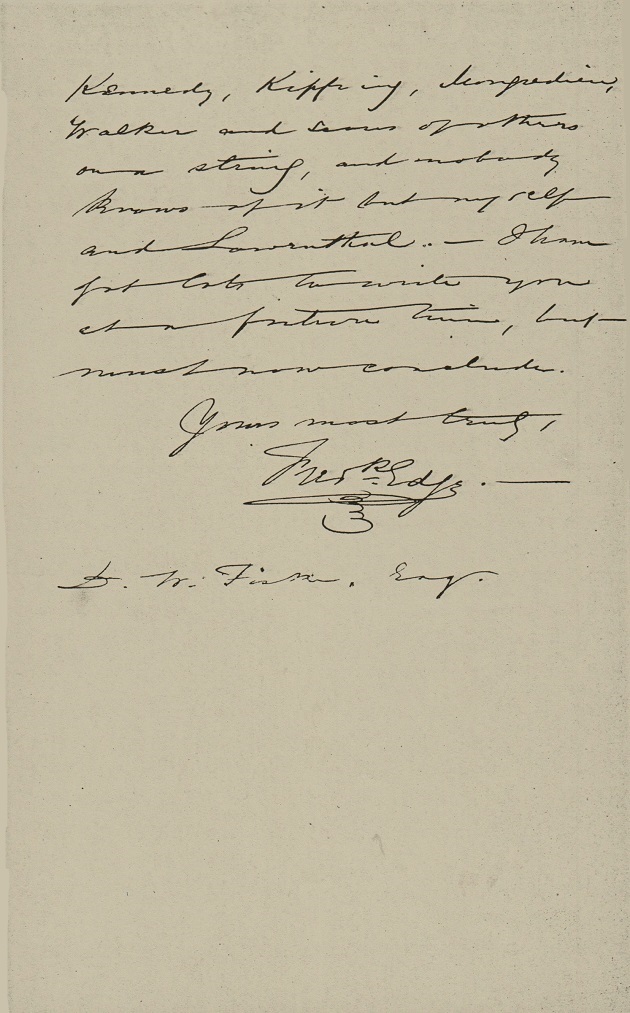

A transcription of this letter, together with information about the context, was given in C.N. 3396 (see pages 337-338 of Chess Facts and Fables) and has now been added to our feature article on correspondence sent by F.M. Edge to D.W. Fiske.

Concerning Edge’s assertion, at the top of the fourth page, that in the most recent edition of the Illustrated London News ‘Staunton is again at his old, dirty tricks’, below is the start of the 5 November 1859 column, page 452:

There follows another letter, of which we acquired a copy from Dale Brandreth, who had obtained much archive material from David Lawson:

It is intended that other letters will be added to the above-mentioned feature article in due course.

For extensive background information and commentary, see Edge, Morphy and Staunton.

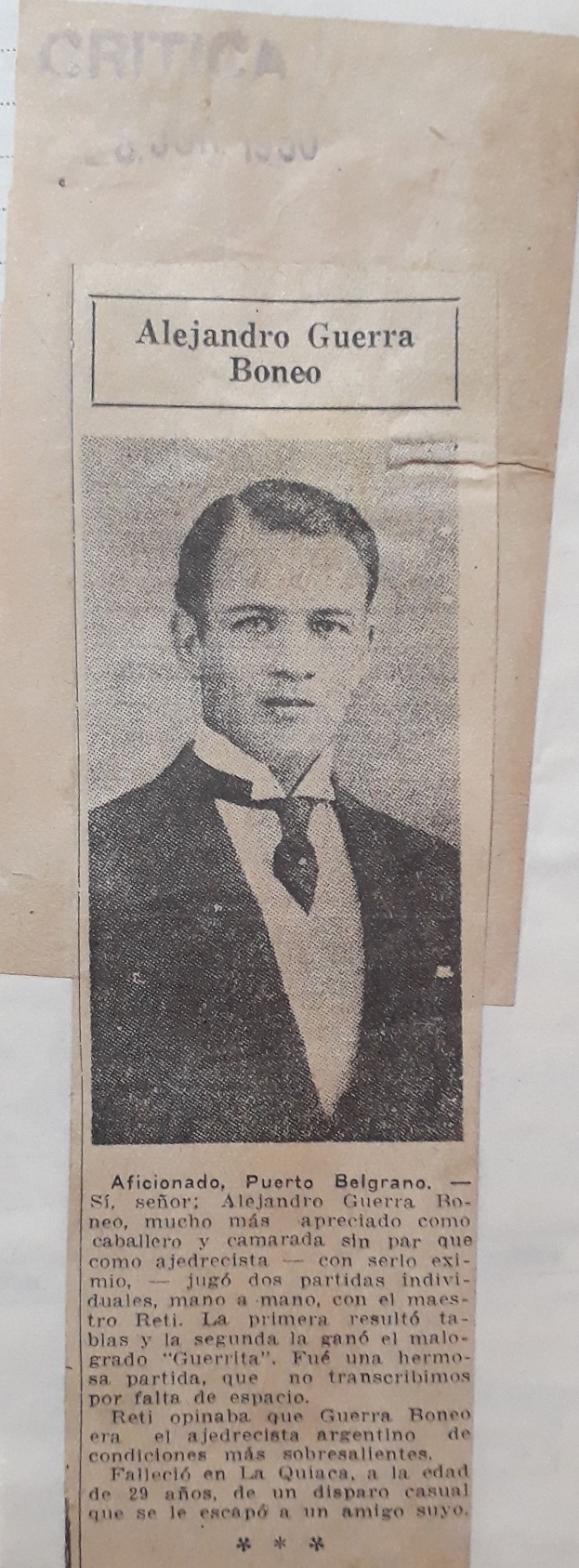

11785. Alejandro Guerra Boneo (C.N. 4777)

Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) provides this cutting (precise source unclear) about Alejandro Guerra Boneo:

The final paragraph reports that a friend accidentally shot him dead.

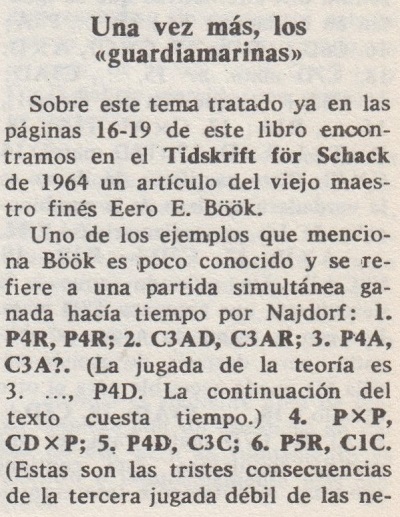

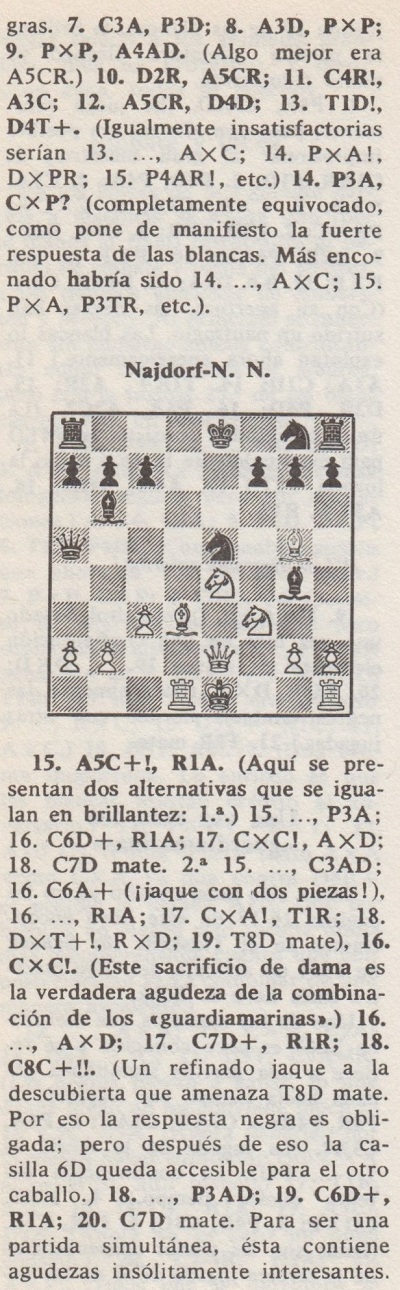

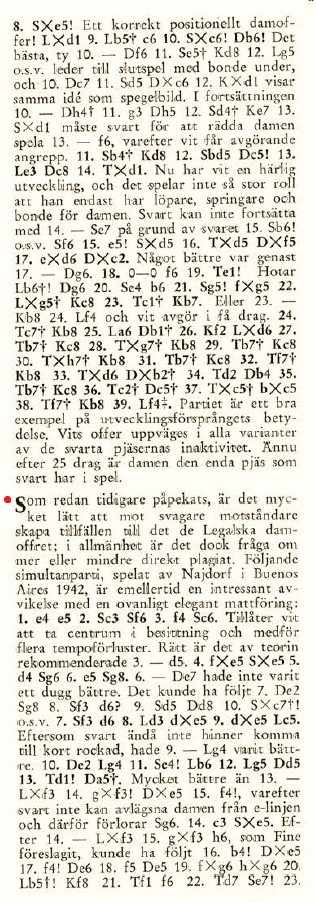

11786. Najdorf and Terrazas

Also from Mr Sánchez:

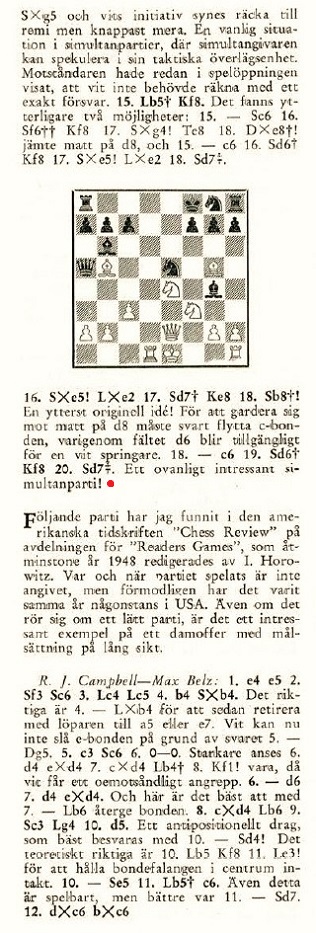

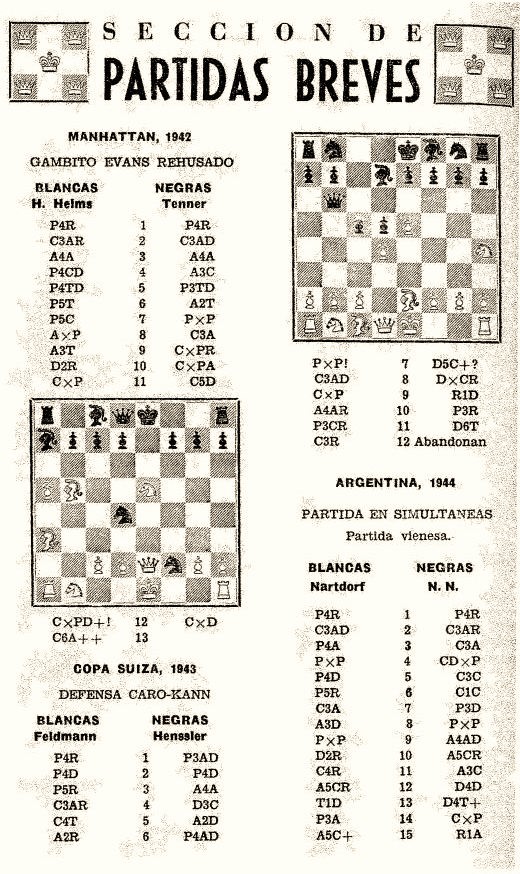

‘On pages 111-112 of Jaque mate (Barcelona, 1972), a book originally published in 1965, Kurt Richter gave a game with a brilliant finish played by M. Najdorf in an undated simultaneous display:

1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Nf6 3 f4 Nc6 4 fxe5 Nxe5 5 d4 Ng6 6 e5 Ng8 7 Nf3 d6 8 Bd3 dxe5 9 dxe5 Bc5 10 Qe2 Bg4 11 Ne4 Bb6 12 Bg5 Qd5 13 Rd1 Qa5+ 14 c3 Nxe5 15 Bb5+ Kf8 16 Nxe5 Bxe2 17 Nd7+ Ke8 18 Nb8+ c6 19 Nd6+ Kf8 20 Nd7 mate.

As his source Richter named the Tidskrift för Schack, 1964. The game is on pages 134-135 of the June issue:

Although Böök’s article above stated that the game was played in Buenos Aires in 1942, pages 366-367 of Ajedrez Español, December 1944 had the heading “Argentina, 1944”:

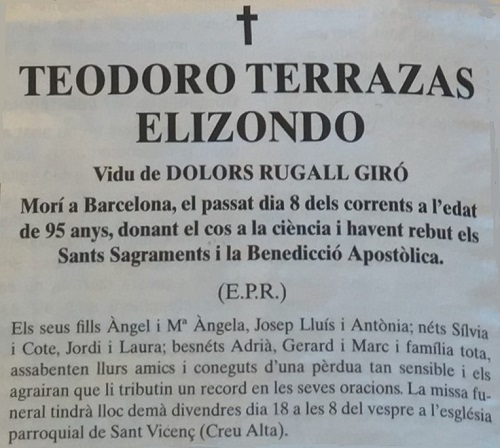

On another matter, the list of subscribers’ names on page 367 is of interest because it includes Teodoro Terrazas Elizondo, who features in the Sabadell mystery. The maternal surname, Elizondo, is further evidence that the non-standard spelling “Elizando” on his club card (C.N. 4015) was wrong:

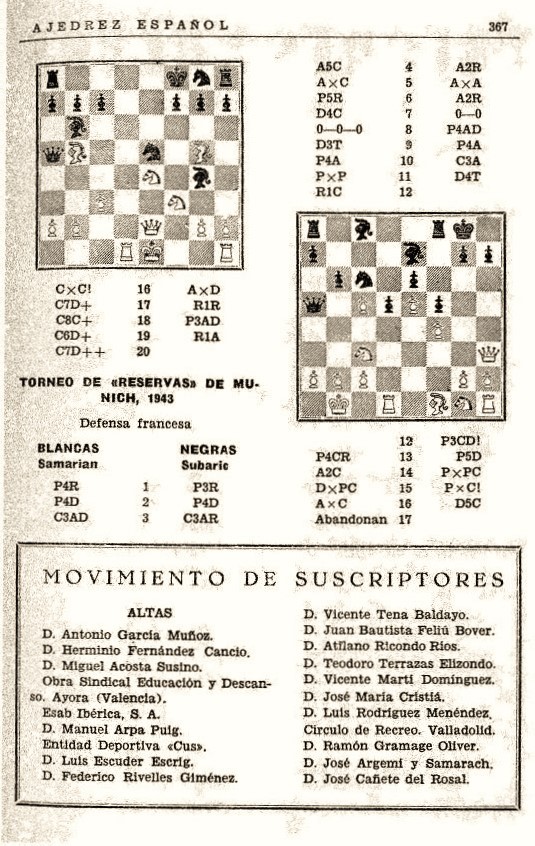

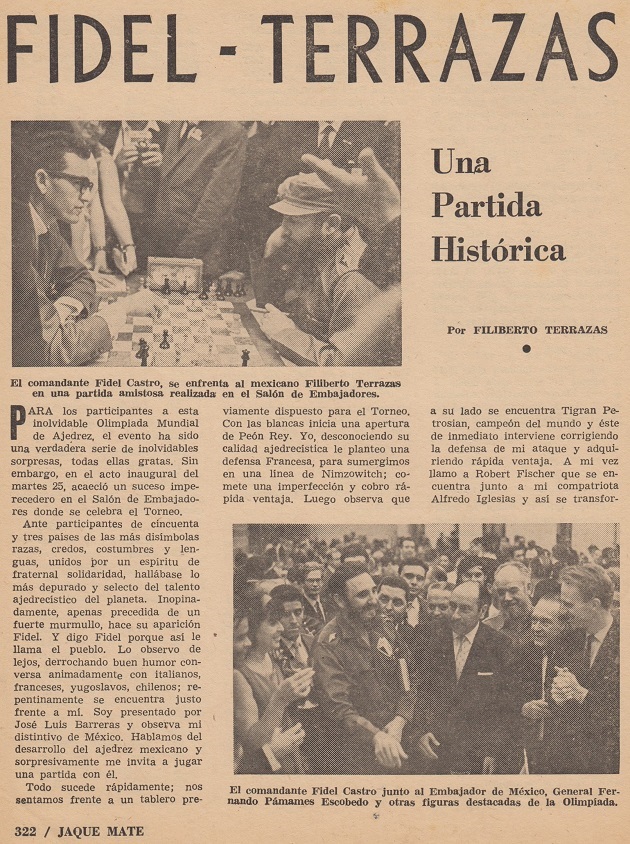

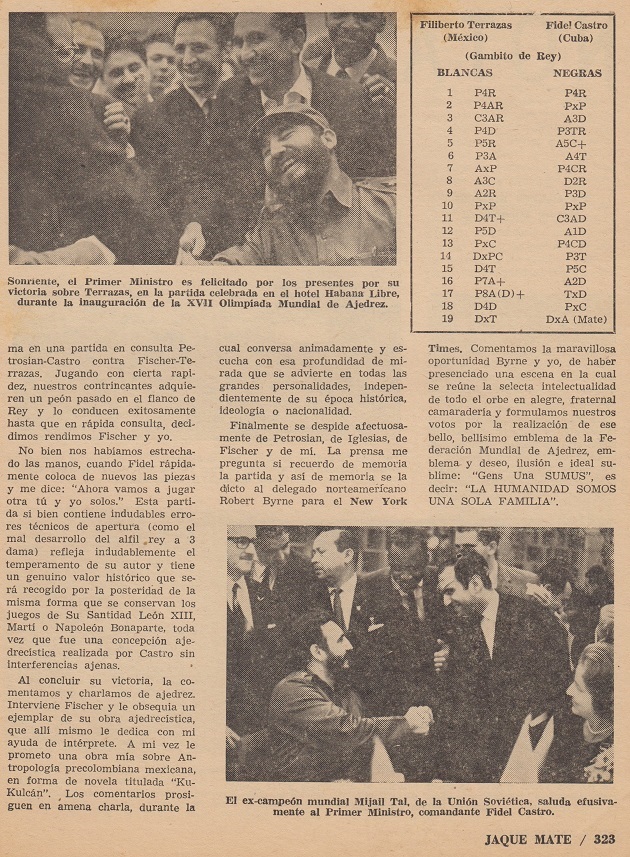

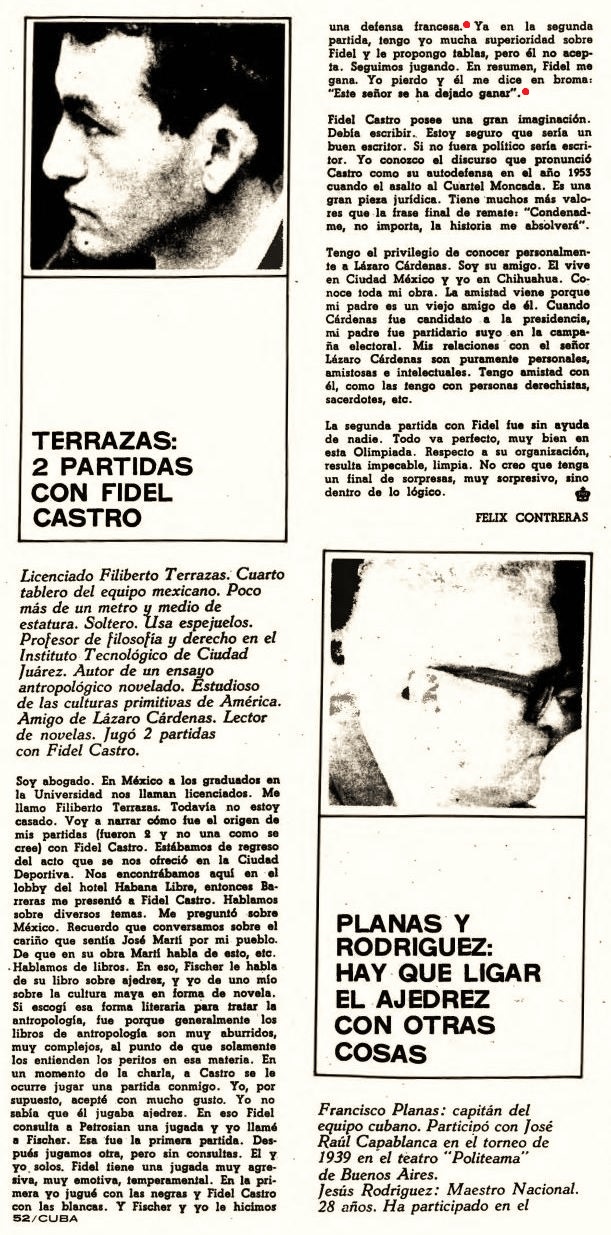

Another Terrazas (Filiberto) has been discussed in several C.N. items, concerning his well-known game with Fidel Castro, and C.N. 11332 showed an article by him on pages 322-323 of the November 1966 edition of the Cuban periodical Jaque Mate:

In that C.N. item you wrote:

“Luke McCullough (Mitchell, SD, USA) asks whether White’s 17th move was really c8(Q), and not cxd8(Q)+. Firstly, we confirm that the improbable-looking 17 c8(Q) was given, although with a check sign, in our source, which was the November 1966 issue of the Cuban magazine Jaque Mate.”

Thus either the “+” sign is to be omitted or “8” should be an “x”.

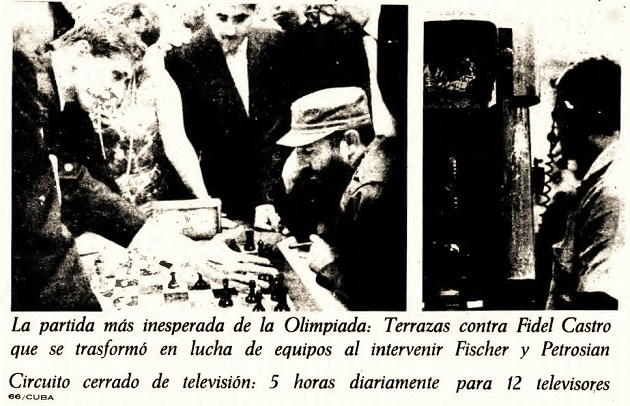

Terrazas presented a more candid account of the event when interviewed by Félix Contreras, and his remarks on page 52 of the magazine Cuba, December 1966 included the following:

“In the second game, I have a large advantage over Fidel and I offer him a draw, but he does not accept. We play on. Eventually, Fidel beats me. I lose, and he says jokingly, ‘This man let me win’.”

The above photograph is on page 66 of Cuba, and the issue has many interesting mini-interviews with participants in the Havana Olympiad.’

11787. The Falkirk Herald

Under the title ‘Attempts to strip Lasker’, C.N. 3272 quoted this paragraph by A.J. Neilson in the Falkirk Herald (14 February 1917, page 4) which was reproduced on page 162 of the March 1917 Chess Amateur:

C.N. 3272 is on page 211 of Chess Facts and Fables and in Patriotism, Nationalism, Jingoism and Racism in Chess.

The frontispiece to the August 1909 BCM:

Below are further extracts from his Falkirk Herald column:

- 7 October 1914, page 4:

- 11 August 1915, page 4 (and reproduced on page 320 of the September 1915 BCM):

- 22 May 1918, page 4:

11788. Teodoro Terrazas Elizondo (C.N. 11786)

Miquel Artigas (Sabadell, Spain) sends the notice published on page 10 of Diari Sabadell, 17 June 2010, which records that Terrazas died in Barcelona on 8 June 2010 at the age of 95 and confirms the spelling Elizondo rather than Elizando:

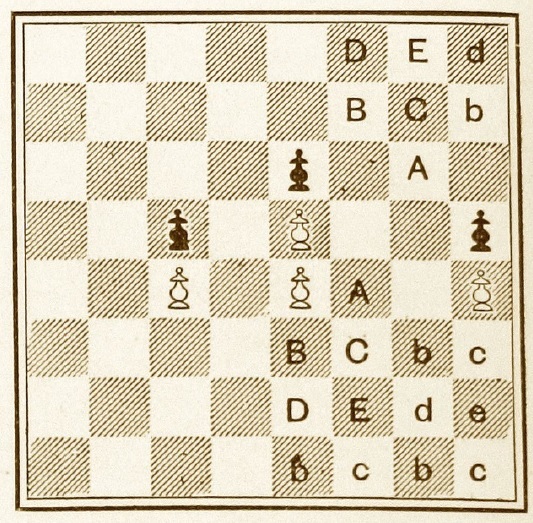

11789. Cases conjuguées (C.N.s 6004 & 6011)

Philippe Frit (Toulouse, France) writes:

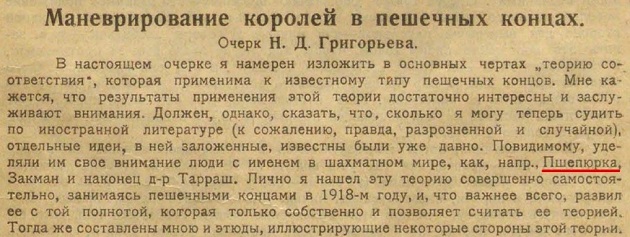

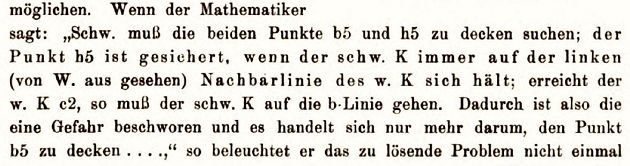

‘The contribution of Dawid Przepiórka to the theory of corresponding squares has been pointed out several times. In the introduction to his series of articles published in 1922-23 in Shakhmaty about “King manoeuvres in pawn endings”, Nikolai Grigoriev mentioned the names of only three predecessors or contemporaries who had become interested in the theory of corresponding squares (“теорию соответствия”): Dawid Przepiórka, Franz Sackmann and Siegbert Tarrasch:

Shakhmaty issue 3, September 1922, page 51 (see lines 6-8)

Transcription: Повидимому, уделяли им свое внимание люди с именем в шахматном мире, как, напр., Пшепюрка, Закман н наконец д-р Тарраш.

Translation: Famous people in the field of chess have apparently paid attention to it, examples being Przepiórka, Sackmann and finally Dr Tarrasch.

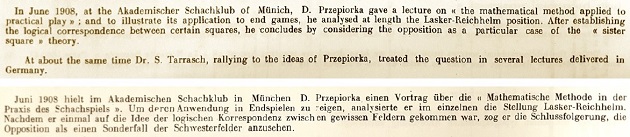

In 1932, the book by Marcel Duchamp and Vitaly Halberstadt Opposition et cases conjuguées sont réconciliées (Opposition and Sister Squares are Reconciled) mentioned a lecture given by Przepiórka at the Munich Chess Club in June 1908. The precise nature of the date and place, as well as the title (“A mathematical method applied to practical play”) and the content of the lecture, suggest that Duchamp and/or Halberstadt actually attended it or obtained their information from a direct witness. Przepiórka is said to have explained in detail a method of solving the Lasker-Reichhelm study using the concept of corresponding squares. According to Duchamp and Halberstadt, Tarrasch was convinced by Przepiórka’s ideas and gave similar lectures in Germany.

Opposition et cases conjuguées sont réconciliées, 1932, page 2 (English and German versions)

As indicated by Harrie Grondijs (C.N. 6011), the lecture by Przepiórka was reported in the Akademisches Monatsheft für Schach.

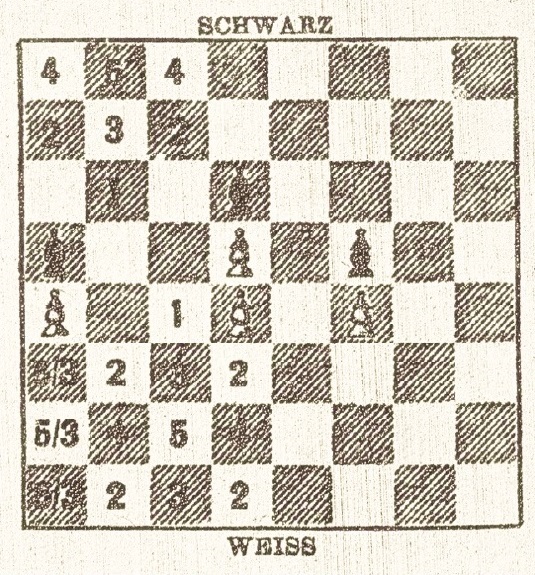

The lectures by Przepiórka and Tarrasch were also confirmed by Walter Bähr in 1936, on page 42 of his book Opposition und kritische Felder (“Opposition and critical squares”). Bähr specifies dates and/or places: 1908 for Przepiórka, and Berlin 1913 for Tarrasch. He even adds the name of Lasker (Berlin) in between, potentially suggesting a lecture by the reigning world champion during that period. According to Bähr, those lectures dealt with the studies by Locock and by Lasker-Reichhelm. More importantly, the method presented is said to use labelled squares.

Opposition und kritische Felder, 1936, page 42

In 1925, in his book Contributo alla teoria dei finali di soli pedoni, Rinaldo Bianchetti refers more precisely to an article published in 1909 by Przepiórka in the Berliner Lokalanzeitung [sic] describing a new kind of opposition (“una nuova specie di opposizione”) which made it possible to tackle certain studies, such as those by Locock and Lasker-Reichhelm, which were intractable within the rules of classical opposition alone.

Contributo alla teoria dei finali di soli pedoni, 1925, page 53

Nonetheless, Bianchetti’s numerous mistakes and approximations regarding dates and names, as well as his occasional tendency to extrapolate and rewrite history, require his output to be treated with caution. A more reliable source about what was supposedly published by Przepiórka is probably the article by Johann Berger which Bianchetti also quotes, as does Harrie Grondijs. In that article, published in the April 1909 issue of the Deutsche Schachzeitung (pages 115-119), Berger indicates that in a lecture given by Przepiórka in Munich, the Lasker-Reichhelm study was presented and subsequently discussed in the Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger. However, Berger gave no exact reference regarding the German newspaper. He did, though, summarize Przepiórka’s idea, which consisted of using a mathematical method of bijective relations between squares, i.e. based on the one-to-one correspondence between squares (“eindeutige Beziehung”); it is simply a matter of corresponding squares, as Mr Grondijs pointed out. According to Berger, this method was presented by Przepiórka as the only valid one, as opposed to empirical methods which come up against an excessively large number of variants to analyze, whereas the rules of opposition are of no practical use here. Berger rejects this idea, which he criticizes quite fiercely.

Later in his article, on page 118, Berger refers to both Przepiórka and Tarrasch, leaving in passing a doubt about the actual author(s) of the Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger article. On the same page, Berger also mentions a diagram with numbered squares used by Przepiórka to solve the study. That diagram, which Berger found unnecessary and unjustified, was not included in his Deutsche Schachzeitung article.

From the foregoing the idea emerges that Dawid Przepiórka was one of the first to understand the correct method of dealing with the Locock and Lasker-Reichhelm studies. The question therefore is what appeared in the Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger between June 1908 (the date of Przepiórka’s lecture in Munich) and April 1909 (the date of Berger’s article in the Deutsche Schachzeitung).

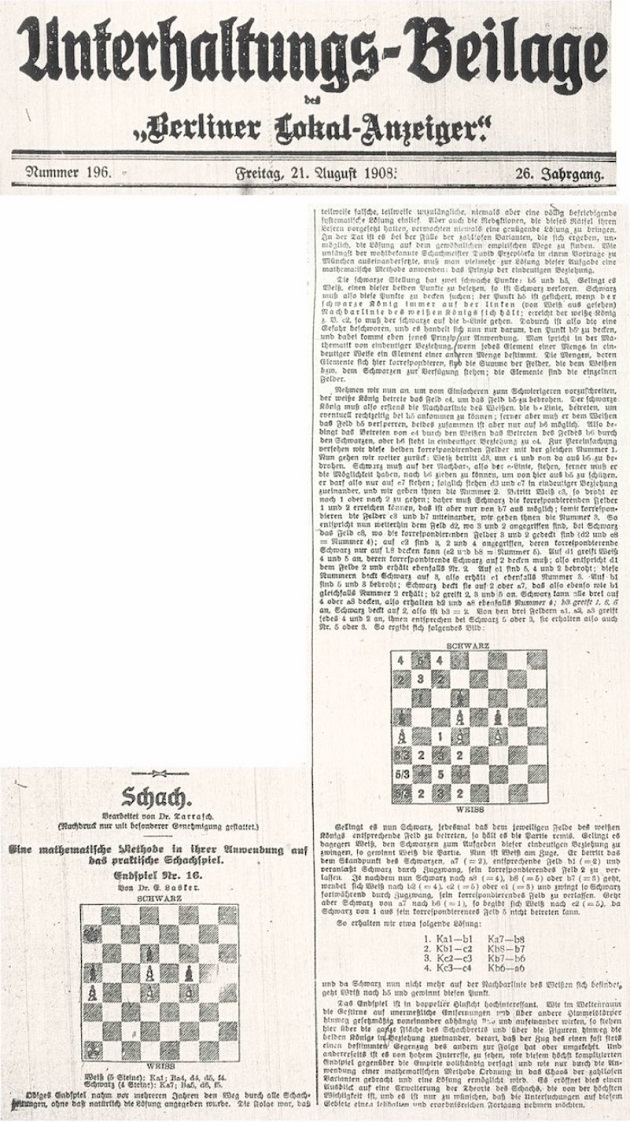

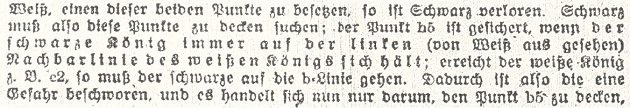

I have found the article in question in the 21 August 1908 edition of the Entertainment Supplement of the Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger (Unterhaltungs-Beilage des Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger). The diagram in the left-hand column corresponds to Lasker’s study as modified by Reichhelm, although Lasker is the only author cited here. The exact title of the article is “Eine mathematische Methode in ihrer Anwendung auf das praktische Schachspiel” (“A mathematical method applied to chess practice”), which is very close to the title of Przepiórka’s lecture mentioned by Duchamp and Halberstadt (“Mathematische Methode in der Praxis des Schachspiels”).

The sole author of the article seems to be Siegbert Tarrasch, who ran the weekly chess column in the Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger, but in the first paragraph Przepiórka is duly credited for the method presented, which, as stated, was the subject of a lecture he gave in Munich.

Transcription: Wie unlängst der wohlbekannte Schachmeister David [sic] Przepiórka in einem Vortrage zu München auseinandersetzte, muß man vielmehr zur Lösung dieser Aufgabe eine mathematische Methode anwenden: das Prinzip der eindeutigen Beziehung.

Translation: As the famous chess master David [sic] Przepiórka recently explained during a lecture in Munich, it is rather necessary to apply a mathematical method to solve this problem: the principle of bijective relation [i.e. one-to-one relation or correspondence].

This explains why Berger’s criticisms were directed at both Przepiórka and Tarrasch. Furthermore, Berger quotes almost word for word a passage that can be found at the beginning of the second paragraph of the right-hand column. This establishes that the article which I have traced in the Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger is indeed the one referred to by Berger.

Berger, Deutsche Schachzeitung, April 1909, page 115

Tarrasch, Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger, 21 August 1908 (right-hand column, second paragraph)

The interesting part of the article is, of course, the description of the method used to determine the pairs of corresponding squares.

Firstly, Tarrasch identifies the two points of penetration by the white king, i.e. the b5 and h5 squares. He then stresses that to prevent the invasion via h5 it is sufficient for the black king to stay one file to the left of the white king’s file. Next, he identifies the different pairs of corresponding squares starting from the mutual Zugzwang position Kc4/Kb6 and then extending, step by step, to adjacent squares, in a way similar to what can be found in any modern book.

Importantly, each pair of squares is numbered (from 1 to 5), and the result is displayed as a second diagram showing the pawns but not the kings. That makes the Tarrasch article the oldest known publication presenting the solution to the Lasker-Reichhelm study using a diagram with labelled squares.

Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger, 21 August 1908

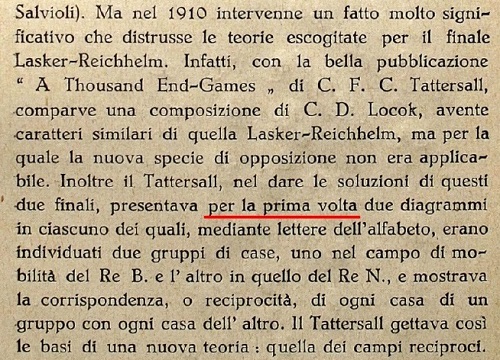

Until now, this achievement has been attributed to C.E.C. Tattersall, whose book A Thousand End Games (volume one, 1910) published the solutions to the studies of Locock and Lasker-Reichhelm as diagrams with squares marked with letters to indicate the correspondence. Bianchetti and Duchamp-Halberstadt agreed about Tattersall being first:

Contributo alla teoria dei finali di soli pedoni, 1925, page 53

Opposition et cases conjuguées sont réconciliées, 1932, page 3

The position published by Tattersall is reversed from left to right compared to the original one. I do not know why.

Tattersall, volume one of A Thousand End Games, 1910, page 154

One further question: who first noticed the relationship between the studies of Locock and Lasker-Reichhelm?’

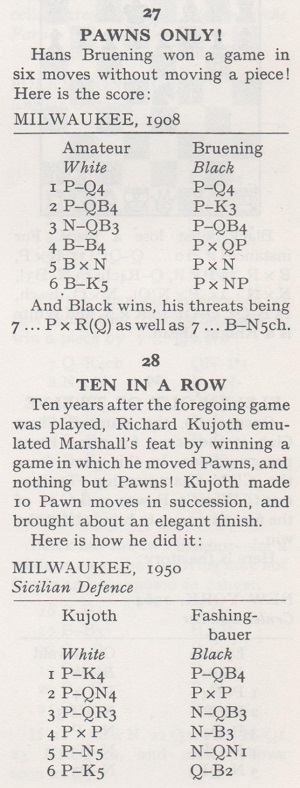

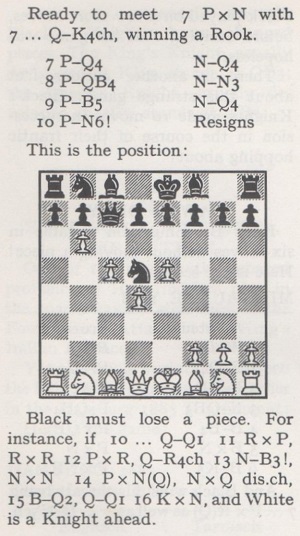

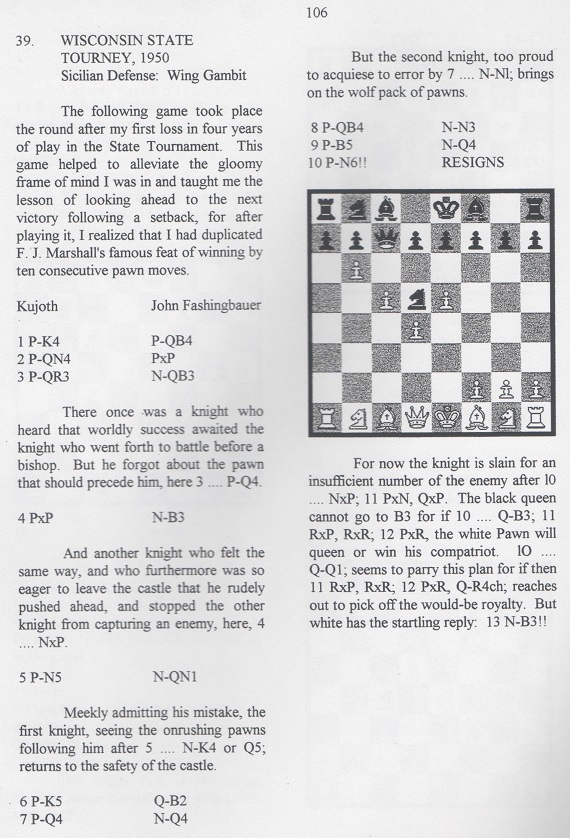

11790. Kujoth v Fashingbauer

From pages 15-16 of Wonders and Curiosities of Chess by Irving Chernev (New York, 1974):

The game N.N. v Bruening was discussed in C.N. 4638.

Regarding Kujoth v Fashingbauer, we have received the following from Mark Erickson (Richland, WA, USA):

‘Andrew Soltis’s “Chess to Enjoy” column on pages 12-13 of the April 2009 Chess Life, entitled “The Hoax is on You”, included the famous miniature Kujoth v Fashingbauer, Milwaukee, 1950 (1 e4 c5 ... 10 b6 “and Black resigned on move 16”) and stated:

“When the game was published, some Europeans laughed at the rather obvious hoax ...” (Soltis cast particular doubt on Black’s name.)

The letters column on page 6 of the August 2009 Chess Life printed a reply from Kujoth. He reported that his book Chess is an Art had two games against John Fashingbauer, and he made some odd statements:

- “The second game, involving ten-consecutive-pawn moves in the Wing Gambit ...” In fact, that was the first of his two games against Fashingbauer given in Chess is an Art (ten-pawn-move game: 1950, game 39; the other game: 1951, game 40);

- Without consulting Kujoth, a columnist named Averill Powers had truncated the well-known game from 28 moves to ten in his column, entitled “The Game of Kings” in the Milwaukee Journal of 21 May 1950. Kujoth also asserted, without further explanation: “I have just completed a discussion with Myron Katz, attorney at law in Milwaukee.”

In his response on the same page of the August 2009 Chess Life, Soltis gave a 28-move version of the Sicilian Defense game supplied by Kujoth (“his original handwritten score of the game”). The issues of Chess Life can be read on-line.

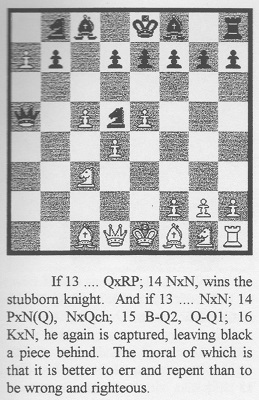

Nonetheless, in his own book, Chess is an Art, published much earlier, Kujoth himself had stated that Black resigned at move ten. From pages 106-107:

Moreover, in his Introduction to the book Kujoth referred approvingly to two works, by Chernev and Sokolsky, which had given the ten-move version.

Why did Kujoth change his position in 2009, denying that the game had lasted only ten moves?’

The title page of the book referred to by Mr Erickson:

We have this edition (where the games against Fashingbauer, numbers 37 and 38, are on pages 47-49):

The 21 May 1950 Milwaukee Journal column has yet to be found.

11791. Chess in China

‘There are now estimated to be about 100,000 international chess players in China.’

Christian Rau (Rüsselsheim, Germany) comments that that sentence in an article on pages 6-7 of the November 1979 CHESS which was quoted in C.N. 9538 (see too How Many People Play Chess?) could be misinterpreted. It is not a reference to players of international standard; ‘international chess’ is the precise translation of the Chinese term (国际象棋) for the ordinary English word ‘chess’.

11792. Najdorf v N.N. (C.N. 11786)

Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England) notes that the Najdorf miniature was published on page 211 of Chess Marches On! by Reuben Fine (New York, 1945). Two exclamation marks were awarded to 16 Nxe5, and three to 18 Nb8+.

Although the heading was ‘Buenos Aires, 1942’, the previous page stated that the game was ‘played by Najdorf in Argentina last year’.

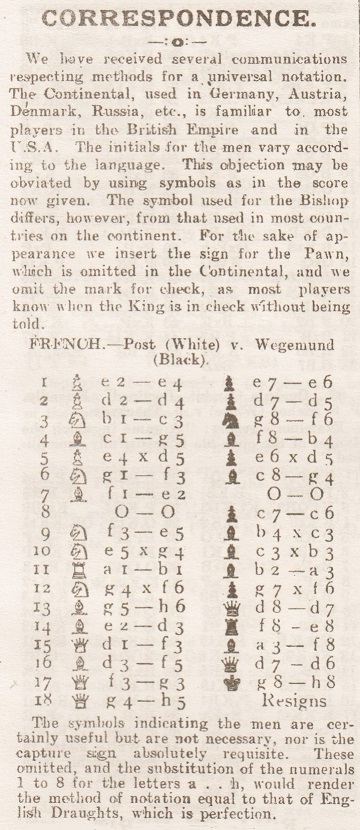

11793. Figurine notation (C.N.s 3724 & 8766)

An early occurrence of the figurine notation in an English-language publication:

Source: page 551 of the March 1912 Chess Amateur.

The Post v Wegemund game, presented with obvious notational errors at moves 10 and 17, was played in the 1908 Berlin championship and had been published on, for instance, page 137 of Deutsches Wochenschach, 18 April 1909.

11794. Rolando Illa (C.N.s 10714 & 11750)

From an unnumbered page in the 22 November 1912 edition of Fray Mocho, a weekly publication in Argentina:

11795. Noah’s Ark Trap

Two citations further to those catalogued in the Factfinder:

- Page 31 of E.A. Michell’s The Year-Book of Chess, 1908 (London, 1908) had an editorial footnote concerning the line (1 d4 d5 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 Nbd7) 5 cxd5 exd5 6 Nxd5 Nxd5 7 Bxd8 Bb4+:

‘Known in England as “Noah’s Ark”.’

- Annotating a synthetic game on pages 463-464 of the December 1911 BCM, C.D. Locock described 8...c5 as:

‘A creditable attempt at “Noah’s Ark”.’

Position after 8 Ba4

The task set by Locock on page 426 of the November 1911 BCM:

‘White gave the odds of Q and QR. The game began 1 P-K4 P-K3 2 P-Q4 P-Q4, and White effected a pure mirror mate on his 23rd move. In the final position all Black’s forces were en prise, and none of White’s. No captures were made on either side.’

1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 Ne7 4 f4 g6 5 Nf3 Bg7 6 Bb5+ Nd7 7 Ne5 a6 8 Ba4 c5 9 O-O O-O 10 Nb5 Bh8 11 Nc7 Kg7 12 Nc4 Kf6 13 e5+ Kf5 14 g4+ Ke4 15 f5 Rg8 16 f6 h5 17 Rf5 h4 18 Rh5 Rg7 19 Rh6 Qe8 20 Nd6+ Kf3 21 g5 c4 22 c3 Nc5

23 Bd1 mate.

11796. Arthur Koestler (C.N.s 3266, 3509, 3580, 6511 & 10803)

Martin Weissenberg (Savyon, Israel) draws attention to the obituary of Koestler by David Pryce-Jones, entitled ‘Chess Man’, on pages 25-28 of Encounter, July-August 1983.

11797. T. Khrennikov (C.N. 11776)

Courtesy of the Russian National Museum of Music, Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) forwards a better copy of the photograph in C.N. 11776:

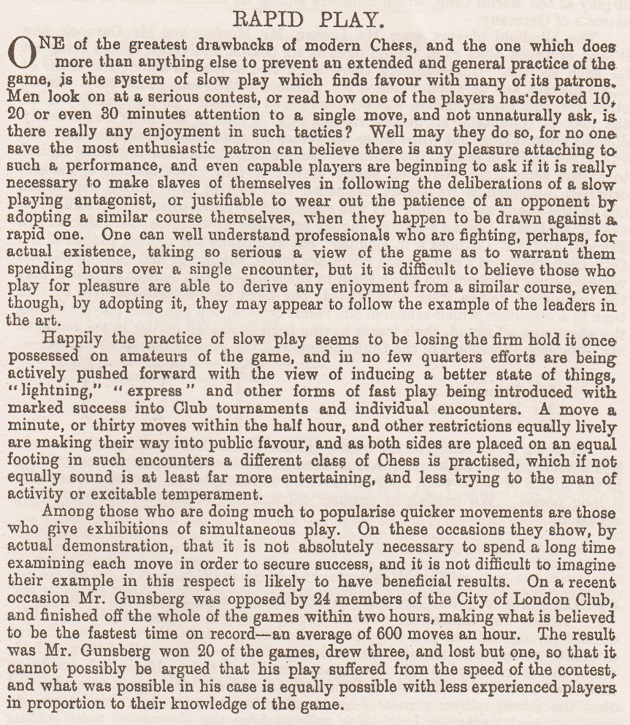

11798. Rapid play

Page 291 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 16 December 1891 provides this addition to Fast Chess:

| First column | << previous | Archives [188] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.