11973.

Announced mates

Zachary Saine (Amsterdam) asks how the practice

of Announced

Mates arose.

11974.

Cyril

Pustan (1929-77)

Willibald Müller (Munich, Germany) draws our

attention to a 1967 East German film Die

gefrorenen Blitze, with particular reference

to ‘Cyril Pustan, the second husband of Bobby

Fischer’s mother’:

Preview;

Lengthy

extract

from

the documentary.

We add that the University

of Bradford states:

‘The Cyril Pustan archive collection has

recently been kindly donated to Special

Collections at the University of Bradford’s JB

Priestley Library and will be made available to

researchers in the near future.’

11975.

The

most spectacular queen sacrifice

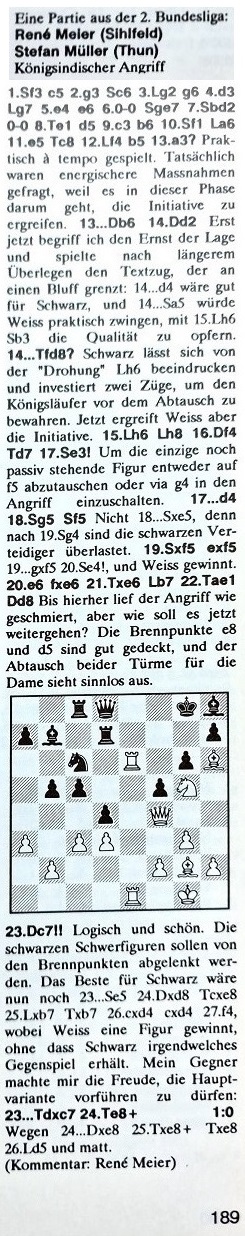

From Richard Forster (Winterthur, Switzerland):

‘When chess.com

presented a list of the ten most spectacular

chess moves of all time in September 2020,

first place went to Shirov’s famous ...Bh3

move against Topalov. However, second place

was taken by a virtually unknown specimen:

White played 1 Qc7, and Black resigned after

1...Rdxc7 2 Re8.

It was pointed out that White had other

winning moves, with Stockfish listing the

spectacular 1 Qc7 only in about fifth

position.

A more interesting question concerns the

circumstances and provenance of the ending.

Chess.com only wrote “Meier was White against

Muller in 1994”, which invited some

speculation in the comments section about the

identities of the players and the authenticity

of the game. Elsewhere on the Internet,

“Germany” can be found added as the country,

but the origins of the game seem to remain a

mystery.

Most likely, the ending was picked up by the

chess.com team (directly or indirectly) from

John Emms’ controversial 2000 book The

Most Amazing Chess Moves of All Time, which

had heavily relied on previous work by Tim

Krabbé and others with scant acknowledgement

(see item

70 on one of Krabbé’s webpages). Emms

gave the caption to puzzle 178 as “R. Meier –

S. Müller, Switzerland 1994”. As already

pointed out in my Late Knight column no. 28 at

Chesscafe.com (“Amazing?”), August 2000, the

source will have been my earlier Late Knight

column no. 2 of June 1998 (“Alpine

Accounting”), where I gave the whole game and

specified that it was played between René

Meier and Stefan Müller in Thun, Switzerland

in 1994.

Here is the full score with all the players’

details and the original source:

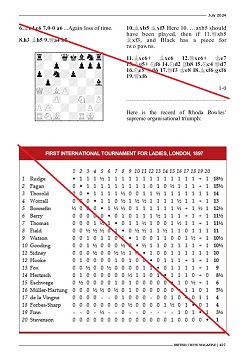

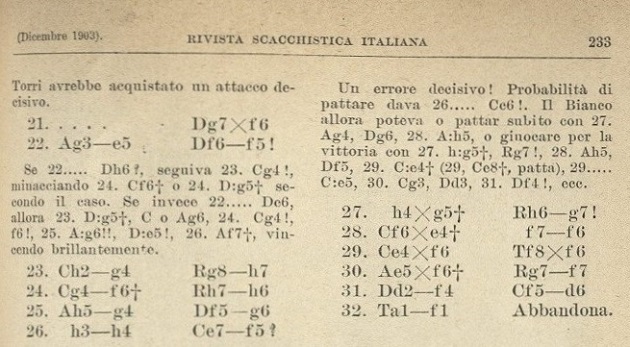

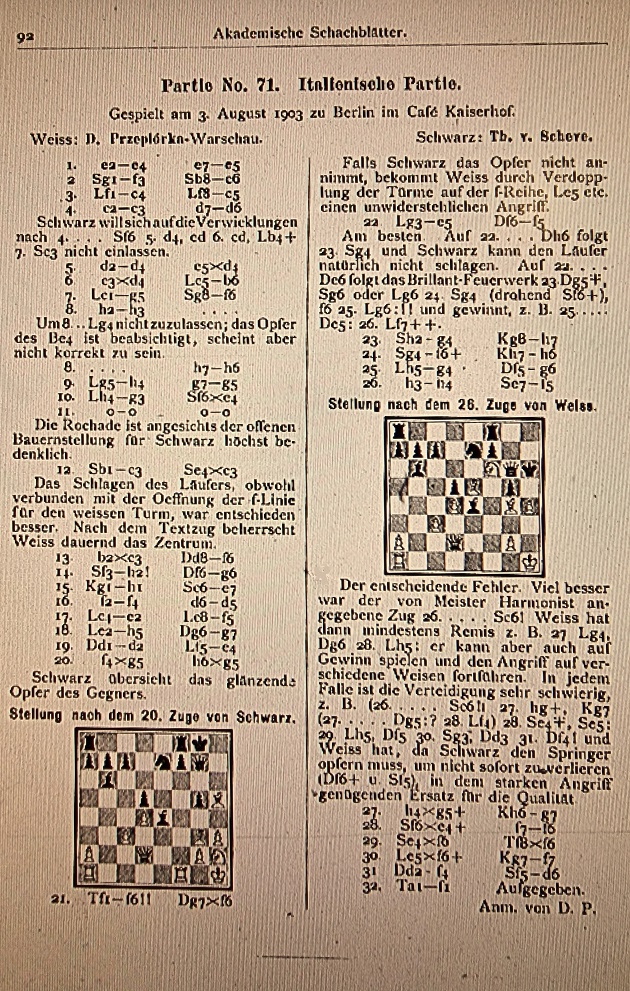

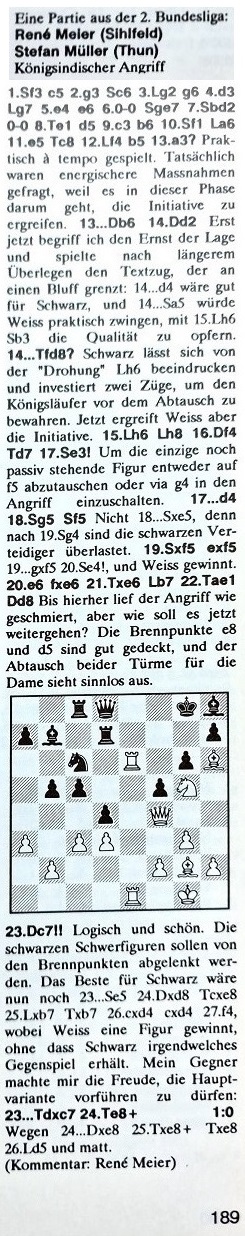

René Meier (Sihlfeld) – Stefan Müller

(Thun), Thun, 7 May 1994. 1 Nf3 c5 2 g3 Nc6 3

Bg2 g6 4 d3 Bg7 5 e4 e6 6 O-O Nge7 7 Nbd2 O-O

8 Re1 d5 9 c3 b6 10 Nf1 Ba6 11 e5 Rc8 12 Bf4

b5 13 a3 Qb6 14 Qd2 Rfd8 15 Bh6 Bh8 16 Qf4 Rd7

17 Ne3 d4 18 Ng5 Nf5 19 Nxf5 exf5 20 e6 fxe6

21 Rxe6 Bb7 22 Rae1 Qd8 23 Qc7 Rdxc7 24 Re8

Resigns.

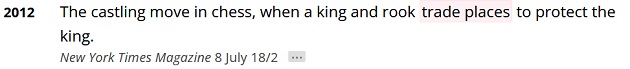

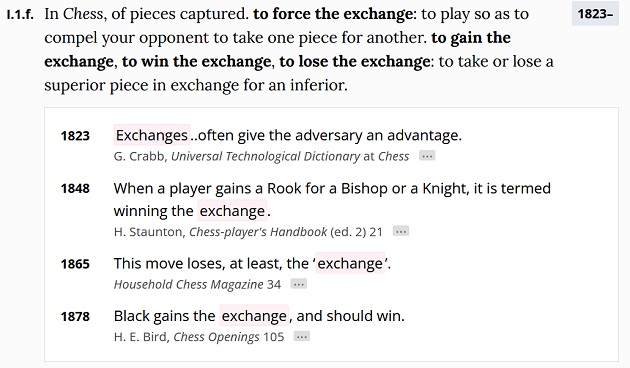

The game was played in round five on the

seventh and last board of a team match in the

second class (“2. Bundesliga”) of the Swiss

workers’ Chess Union league

(“Gruppenmeisterschaft”). It first appeared in

print with a few annotations by the winner in

the Schweizerisches Schach-Magazin,

no. 6, June 1994, page 189.

A curious twist was added in KARL,

no. 3/2023, page 59, when Michael Ehn and

Ernst Strouhal gave the ending as “the most

spectacular queen sacrifice of all time”,

attributing it to “Smith-Walls, USA 1993”

without any further indication of their

source.

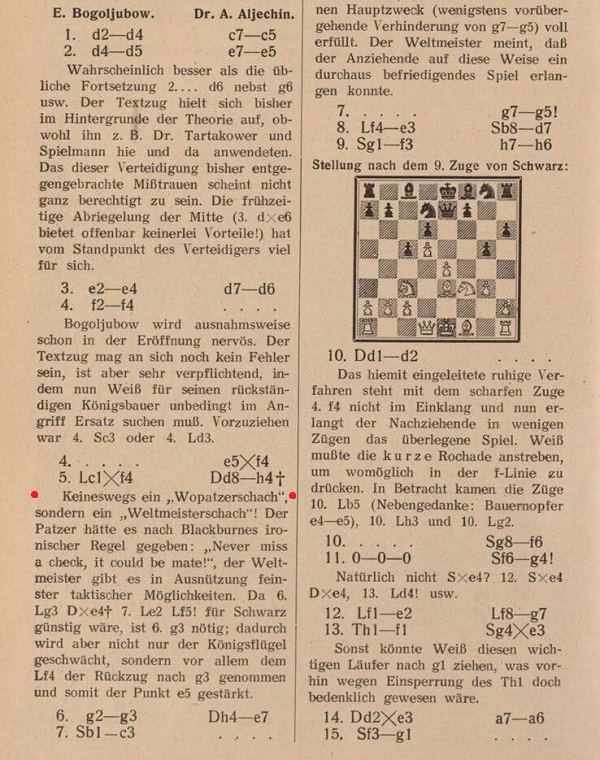

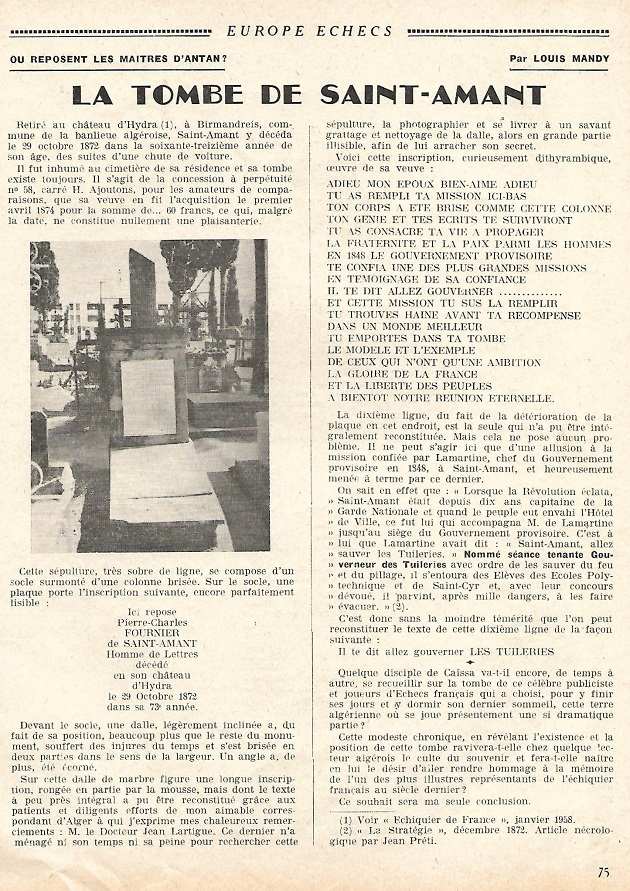

Here for the record is the 1994 publication

of the Meier v Müller game:’

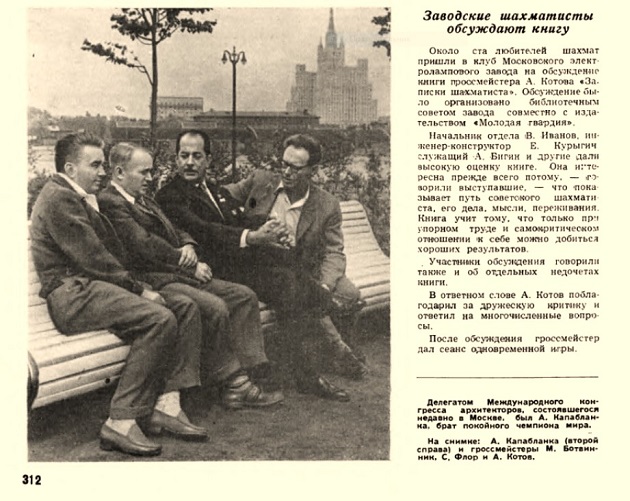

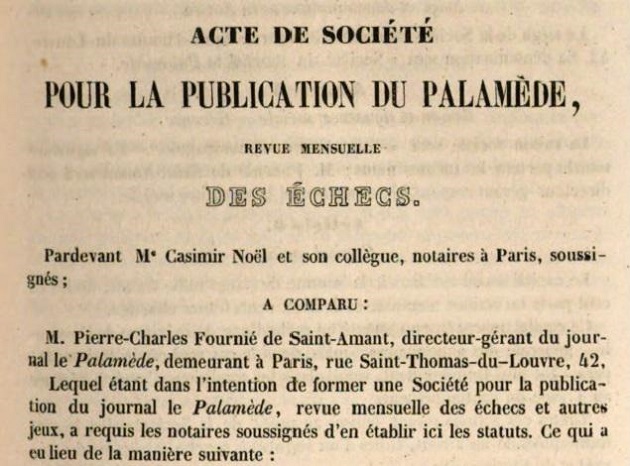

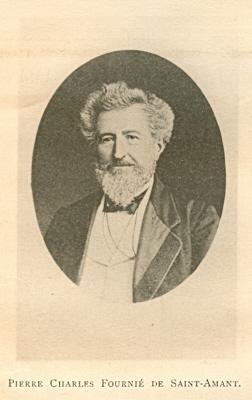

11976.

Alekhine

and Capablanca

Our new feature article on Sir

George Thomas does not yet include a famous

observation attributed to him, because we

currently lack a verifiable source.

From page 161 of The Unknown Capablanca

by David Hooper and Dale Brandreth (London, 1975):

‘One is reminded of a remark made by Sir George

Thomas, “Against Alekhine”, he said, “you never

knew what to expect; against Capablanca you knew

what to expect, but you couldn’t prevent it!”’

From page 77 of Capablanca’s Best Chess

Endings by Irving Chernev (Oxford, 1978):

‘Capablanca’s clear-cut play in this ending

calls to mind a comment by Sir George Thomas,

“Against Alekhine you never knew what to expect;

against Capablanca you knew what to expect, but

you couldn’t prevent it!”’

11977.

Staunton

and religion

John Townsend (Wokingham, England) writes:

‘In his book, The Great Schools of

England, Howard Staunton was a staunch

opponent of flogging. Pages xlii to xliii of

the second edition (1869) contain these

remarks:

“Again and again, in treatises on Education,

and in periodicals, it has been condemned; but

from dread lest England should be ruined, lest

ancient traditions and old-world customs

should perish, the administrators of Public

Schools passionately fight for flogging, as if

it were a kind of sacrament, to be added to

the other seven.”

This last observation about sacraments

earned him the attention of the writer of a

critique in Weekly Review (7 August

1869, page 16), who commented that Staunton’s

own “ecclesiastical standpoint” could be

“gathered” from it. (Presumably, the reviewer

was hinting that, by acknowledging the

existence of as many as seven sacraments,

Staunton was displaying a Catholic point of

view.)

Was anything else ever written which

suggested Staunton’s association with

religion?’

11978.

Cecil

De Vere

Also from Mr Townsend:

‘Cecil De Vere was illegitimate, and the

identity of his father has been a mystery.

Now, some new information has been found in

the death certificate of his mother, Katherine

De Vere (General Register Office, Sept. qtr.

1864, Pancras, volume 1b, page 41). It shows

that she died on 7 July 1864 at 10 Lower

Calthorpe Street (Grays Inn Road, London), the

informant being Eliza Hooker, “present at

death”, of the same address. The cause of

death was “Cancer Uteri 2 years”; her age was

given as 42, and she was described as the

widow of Alexander De Vere, naval surgeon.

The name Alexander De Vere is new. This

occupation of her alleged late husband is

consistent with information entered on Cecil

De Vere’s 1846 birth certificate, where the

father’s name was left blank (indicating

illegitimacy), but his occupation was

nevertheless entered as “surgeon”. The birth

certificate was discussed by Owen Hindle in

the Quotes & Queries column of the BCM,

conducted by Chris Ravilious, in December

2003, February 2004 and November 2005.

Katherine De Vere had already been living at

the address where she died at the time of the

1861 census, when she was described as a

widow, aged 36, born in Wales (National

Archives, RG 9 107, folio 91, page 9). At that

time, she had as lodgers Francis Burden, a

civil engineer, and Albert Lane, a landscape

painter, both chessplayers, who taught the

young De Vere to play.

It has not so far been possible to identify

the individual referred to as Alexander De

Vere, and he will need to be the subject of

ongoing research. Likewise, details of his

supposed marriage to De Vere’s mother have not

been readily found.

De Vere’s mother was buried in Brompton

Cemetery on 11 July 1864 in a private grave

paid for by “Valentine De Vere”, “gentleman”,

of the same address. There was neither probate

nor letters of administration.’

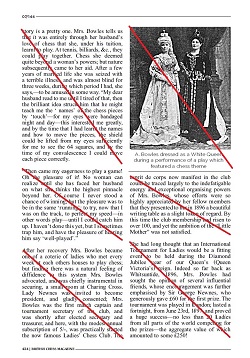

Illustrations of the chessplayer are rare. Below

is a detail of the Redcar, 1866 group photograph

in C.N. 5614:

11979.

Copying

Four recent additions to Copying:

The entirety of our compilation of quotations

from the three volumes of W.E. Napier’s Amenities

and

Background

of Chess-Play has been copy-pasted,

without acknowledgement, on a chessgames.com

page.

There is an Alchetron

page which helps itself to various

illustrations from our Sultan

Khan article. That makes it convenient for

the chessgames.com page on him to be illustrated

as follows:

The Bill

Wall method: ransacking our work on

Capablanca, without credit, and giving worthless,

partial sources.

The ChessBase

contributor

Davide

Nastasio has been lifting a huge number of

C.N. photographs (about 80 in the past week

alone), without credit, acknowledgement or

authorization, for his personal X/Twitter page.

Addition on 22 October 2024:

ChessBase has informed us that Davide Nastasio is

now a former ChessBase author.

11980.

Chess clubs

The first

episode of a new PBS television series, Today

in

Chess, refers to ‘the chess capital of the

US, Saint Louis, Missouri’. Through the

munificence of Rex Sinquefield, the Saint Louis

Chess Club is often described, without

contradiction, as the greatest chess club in the

United States. What comparable chess clubs

(whether in terms of premises, opulence,

membership, activity or any further criteria)

exist in other countries? In short, if the Saint

Louis Chess Club were described as the greatest in

the world, would any clubs have a legitimate

grievance?

This photograph of the Saint Louis Chess Club was

taken for us on 12 February 2024 by Yasser

Seirawan:

11981.

Menchik

v Mieses (C.N. 3687)

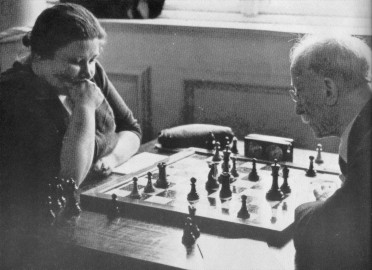

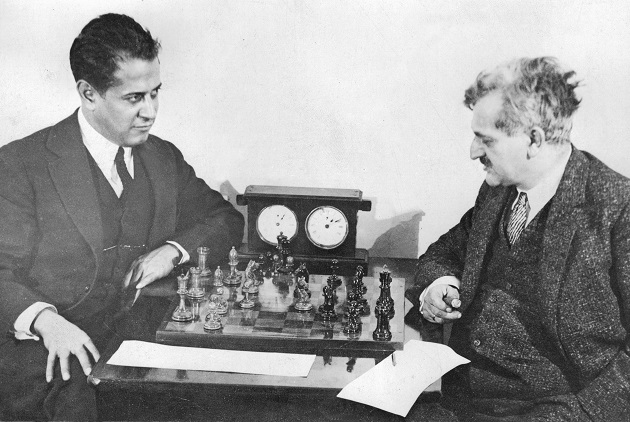

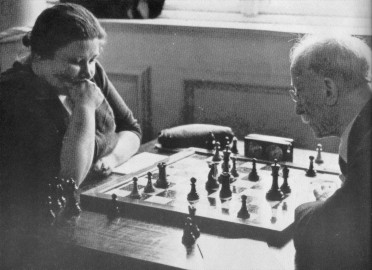

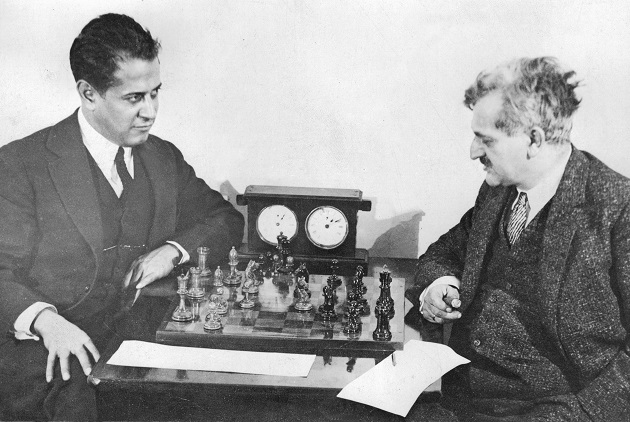

This photograph by Erich Auerbach from The

Quiet Game by J. Montgomerie (London, 1972)

was shown in C.N. 3687, with the question of when

it was taken.

From Philip Jurgens (Ottawa, Canada):

‘Vera Menchik and Jacques Mieses played a

ten-game match between 21 May and 13 June

1942. He was aged 77, some 41 years older than

her. Menchik won by four games to one with

five draws. Page 208 of Robert B. Tanner’s

book on Menchik (C.N. 10191) described it as

“the first ever serious match between a woman

and a strong master”.

According to the West

London Chess Club website, Vera Menchik

joined in 1941 after the National Chess Centre

was bombed in the Blitz. Jacques Mieses was

also a club member during the Second World

War. It is therefore quite likely that they

played their match under the auspices of the

West London Chess Club and that the photograph

was taken during that period.

The above website also states:

“During World War II, very few clubs remained

open, but thanks to the determination of the

officers, West London Chess Club persevered

and invited players from other clubs to play.

This brought more strong players to the club,

including the likes of Jacques Mieses, Vera

Menchik, Sir George Thomas, and briefly,

Capablanca [sic].”’

11982.

Georg

Marco

C.N. 4855 reported a remark by Wolfgang

Heidenfeld on page 190 of The Encyclopedia of

Chess by Harry Golombek (London, 1977):

‘... Marco has left an imperishable chess

legacy in his brilliant and witty annotations.’

That is not the only C.N. item in which relevant

quotations from Marco’s writings have been

solicited, without tangible results; see also

C.N.s 5248, 7819 and 11380. Examples of

Heidenfeld’s own brilliance and wit could, and

perhaps should, be compiled, but Marco deserves

priority. Can readers assist?

11983.

J.

Baca-Arús

Jaime Baca-Arús

(C.N. 11881)

Further to The

Capablanca

v

Price/Baca-Arús Mystery, Yandy Rojas Barrios

(Cárdenas, Cuba) has been looking for games played

by Jaime Baca-Arús, and he offers the following:

Jaime Baca-Arús – René Portela

Casual game, Havana, 1912 (?)

Danish Gambit

1 e4 e5 2 d4 exd4 3 c3 dxc3 4 Bc4 cxb2 5 Bxb2 Qe7

6 Nc3 Nf6 7 Nge2 Nxe4 8 O-O Nxc3 9 Nxc3 Qc5 10 Re1

Be7 11 Nd5 Nc6 12 Nxc7 Kd8 13 Nxa8 Qxc4 14 Rc1 Qb4

15 Qc2 Bf6 16 Bxf6 gxf6 17 Qf5 Qd4 18 Rcd1 Qc3 19

Rc1 Ne7 20 Qf4 Nd5 21 Qd6 Qd4 22 Qb8 Ne7 23 Rxc8

Resigns.

Source: El Fígaro, 10 March 1912, page

138.

Jaime Baca-Arús – E.C. de Villaverde

Casual game, Havana, 28 March 1912

Philidor’s Defence

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 d6 3 Nc3 Be7 4 d4 exd4 5 Nxd4 Nf6 6

f4 c5 7 Nf3 O-O 8 Bd3 a6 9 O-O b5 10 b3 Bb7 11 Ng5

h6 12 Kh1 b4 13 Nd5 Nxd5 14 exd5 hxg5 15 Qh5 g6 16

Bxg6 fxg6 17 Qxg6 Kh8 18 Bb2 Bf6 19 Rf3 g4 20 Qh5

Kg8 21 Qxg4 Bg5 22 Qe6 Rf7 23 fxg5 Qe7 24 Qg6 Kf8

25 Raf1 Bxd5 26 Rxf7 Bxf7 27 Qf5 Kg8 28 g6 Be6 29

Qh5 Resigns.

Source: El Fígaro, 21 April 1912, page

238.

Jaime Baca-Arús – René Portela

Round 1, Havana Chess Club Championship, 1912

Queen’s Gambit Declined

1 d4 d5 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 c5 4 cxd5 exd5 5 Nf3 Nc6 6

g3 Nf6 7 Bg2 cxd4 8 Nxd4 Qb6 9 Nxc6 bxc6 10 O-O

Ba6 11 Qa4 Bb5 12 Nxb5 cxb5 13 Qb3 Rd8 14 Bg5 Be7

15 Bxf6 Bxf6 16 a4 O-O 17 axb5 Rfe8 18 Bxd5 Rxe2

19 Bxf7 Kh8 20 Rad1 Rxb2 21 Rxd8 Qxd8 22 Rd1 Qb6

23 Qe3 Qxe3 24 fxe3 Rxb5 25 Rd7 a5 26 Rd5 Rxd5 27

Bxd5 a4 28 Kg2 g6 29 Kf3 Kg7 30 h4 Kf8 31 Kf4 Ke7

32 Ke4 Kd6 33 Ba2 Kc5 34 Kd3 Kb4 35 Kc2 a3 36 Kd3

h5 37 Kc2 Be5 38 Bf7 Drawn.

Source: Capablanca Magazine, 31 July

1912, page 108.

Jaime Baca-Arús – Gustavo Fernández

Casual game, Havana, 8 March 1914

Danish Gambit

1 e4 e5 2 d4 exd4 3 c3 dxc3 4 Bc4 cxb2 5 Bxb2 Qe7

6 Nc3 c6 7 Nge2 b5 8 Bxb5 cxb5 9 Nxb5 Qb4 10 Nec3

Qc5 11 Qd5 Qxd5 12 Nxd5 Na6 13 O-O Rb8 14 a4 Bb7

15 Rfe1 Bc6 16 Bd4 Nf6 17 Bxa7 Rb7 18 Bd4 Bb4 19

Reb1 Bxd5 20 exd5 O-O 21 d6 Ne4 22 f3 Nd2 23 Rxb4

Nxb4 24 Bc3 Nb3 25 Rb1 Nd5 26 Rxb3 Nxc3 27 Rxc3 g6

28 Rc7 Rb6 29 Rxd7 Ra8 30 Rc7 Kf8 31 d7 Ke7 32 Na7

Rab8 33 Nc6 Kd6 34 Rc8 Kxd7 35 Rxb8 Rxc6 36 Rb7

Rc7 37 Rxc7 Kxc7 38 Kf2 Kb6 39 Ke3 Ka5 40 Kf4 Kxa4

41 Ke5 f5 42 g4 Resigns.

Source: El Fígaro (Ajedrez Local, Juan

Corzo),

19 April 1914, unnumbered page.

Jaime Baca-Arús – M.A. Carbonell

Round 1, II Intersocial Tournament, Havana, 1931

Caro-Kann Defence

1 e4 c6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 dxe4 4 Nxe4 Nf6 5 Nxf6 exf6

6 Nf3 Bd6 7 Bd3 Bg4 8 O-O O-O 9 c3 Qc7 10 h3 Bh5

11 c4 Rd8 12 c5 Bh2 13 Kh1 Bf4 14 Be3 g5 15 g4 Bg6

16 Bxg6 hxg6 17 Qd3 Nd7 18 b4 Kg7 19 Rad1 Rh8 20

Kg2 Rad8 21 Rh1 b6 22 Bxf4 Qxf4 23 Qe3 Qb8 24 d5

Rhe8 25 Qc3 cxd5 26 Rxd5 bxc5 27 bxc5 Qc7 28 Rhd1

Nb8 29 Rxd8 Rxd8 30 Rxd8 Qxd8 31 Nxg5 Qd5 32 Nf3

Nc6 33 g5 Ne5 34 gxf6 Kxf6 35 c6 Ke6 36 Qxe5

Resigns.

Source: Diario de la Marina, 13 December

1931, page 18.

Biographical and other information is still being

researched by our correspondent and will be added

in due course.

11984.

Anything

is good enough

As quoted in C.N. 876 (see Book

Notes), Charles W. Warburton wrote the

following on page 42 of My Chess Adventures

(Chicago, 1980) in a discussion of the Caro-Kann

Defence:

‘Typically convincing is the thought of Dr

Emanuel Lasker who was known to say “anything is

good enough to play once”.’

Countless masters are purportedly ‘known’ to have

said countless things, but in this case we can at

least cite a vague attribution from Lasker’s

heyday. On pages 516-517 of the December 1898 BCM

J.H. Blake annotated Tarrasch v Halprin, Vienna,

1898, which began 1 d4 d5 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5

Be7 5 Nf3 h6 6 Bf4 dxc4 7 e3 Nd5 8 Be5 f6 9 Bg3

Bb4 10 Qc2 b5 11 a4 c6 12 axb5 cxb5 13 e4.

After 8 Be5, Blake wrote:

‘Black’s moves six to ten constitute a line of

defence to the attack by B-KB4 in the Q. Gambit,

which is little known, and which, though not

strictly recommendable, may occasionally serve

its turn, in accordance with a maxim attributed

to Lasker, that in the opening “anything is good

enough to play once”. Dr Tarrasch,

however, was on this occasion no stranger to it,

since it was played against him (after 4 B-B4

PxP 5 P-K3 Kt-Q4, etc.) by Maróczy at Buda Pesth

[in 1896]; it is the more surprising therefore

that he should so nearly have fallen a victim to

it here, as his continuation on the previous

occasion by 6 KBxP KtxB 7 PxKt is in the present

position the only good defence, and a perfectly

satisfactory one.’

11985.

Backward

moves and empty squares

Instruction manuals sometimes note the difficulty

of visualizing a) sacrifices on empty squares and

b) backward moves by pieces. Who first made such

observations in print? Also requested: practical

examples (the less well known, the better).

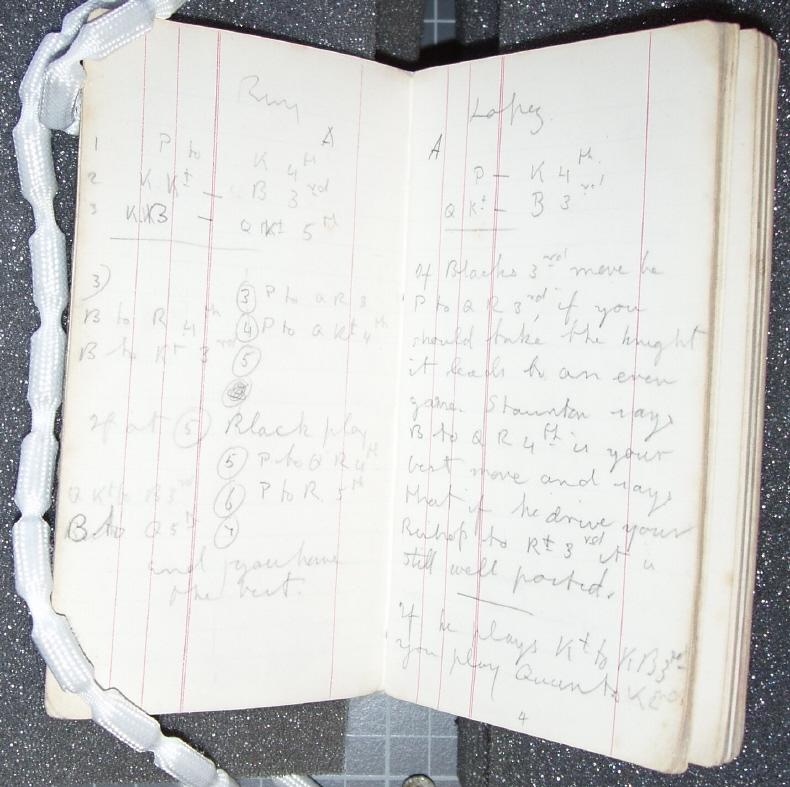

11986.

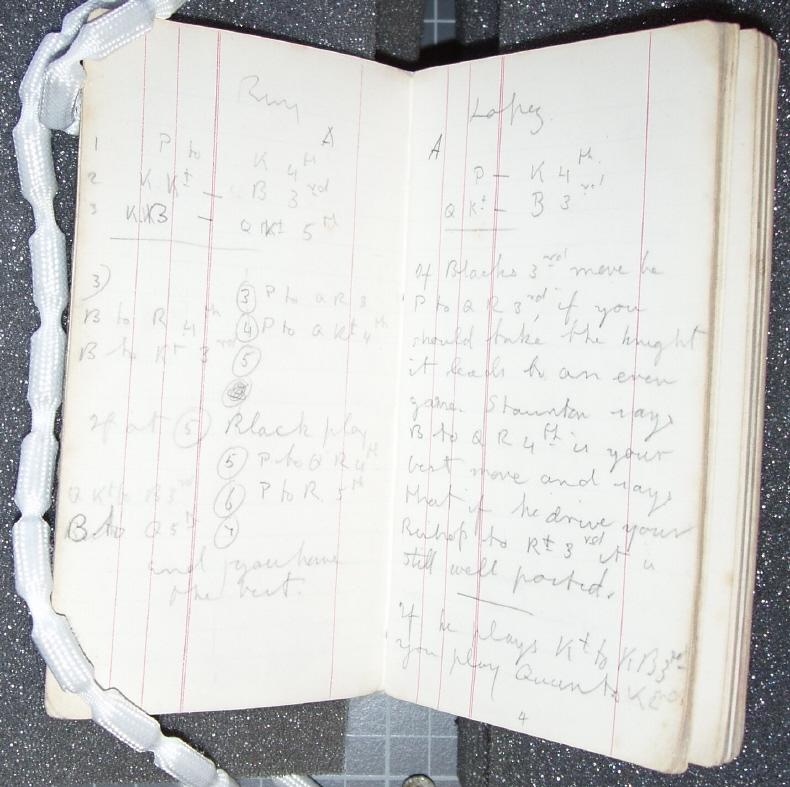

Rupert

Brooke’s notebook

It is still not proving possible to find out more

about the texts included in the notebooks (circa

1902-04) of Rupert Chawner Brooke (1887-1915), as

shown in our feature

article on him. For example:

We observed that Brooke appeared to be copying

openings material from a book or magazine, and

that the reference to Staunton related to remarks

originally published on page 148 of his Handbook

(London, 1847). Can nothing further be found?

From page 69 of Rupert

Brooke by Michael Hastings (London, 1967)

11987.

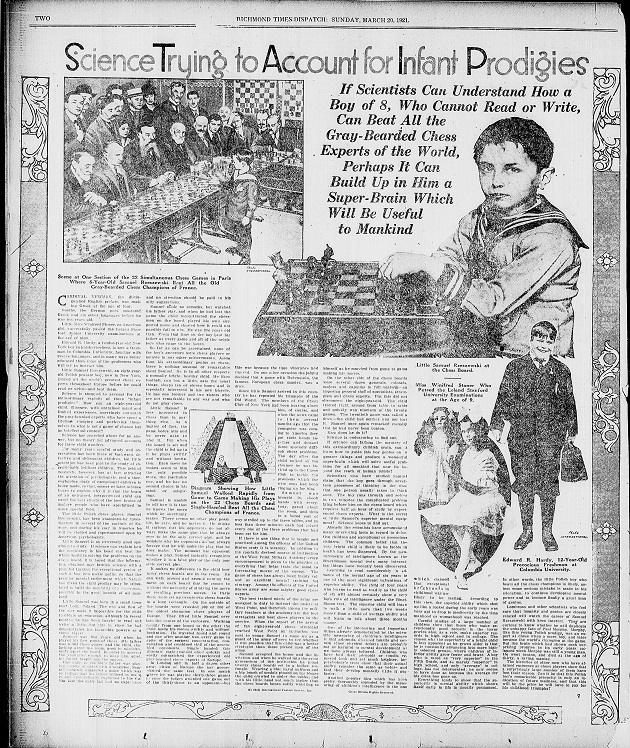

Samuel Reshevsky

Avital Pilpel (Haifa, Israel) sends, courtesy of

Herbert Halsegger, a feature about the prodigy

Reshevsky on page

2

of

part 6 of the Richmond Times-Dispatch,

20 March 1921:

Larger

version

11988.

Preparation

Wanted: little-known accounts by masters of their

chess preparations for important tournaments and

matches.

11989.

Steinitz

and Séguin

Our recent feature article Wilhelm

Steinitz Miscellanea quotes remarks such as

the following by Steinitz about James Séguin, on

page 86 of the International Chess Magazine,

April 1888:

‘And I mean to devote

to the task [i.e. exposing the alleged dishonesty

of James Séguin], if necessary, the space of this

column for the next 12 months, or for as many

years, in case of further literary highway

robberies perpetrated by the same individual, and

provided that I and this journal survive, in order

to statuate for all times, or as long as chess

shall live, an example that the only true champion

of the world for the last 22 years (I may say so

for once), who has always defended his chess

prestige against all-comers, has also a true

regard for true public opinion, and that he can

defy single-handed all the lying manufactories of

press combinations to show any real stain on his

honor; and that he can convict and severely punish

any foul-mouthed editor who, like the shystering

journalistic advocate of New Orleans, attempts to

rob him of his good name outside of the chess

board.’

Has there been a trustworthy investigation of

Steinitz’s objections concerning Séguin?

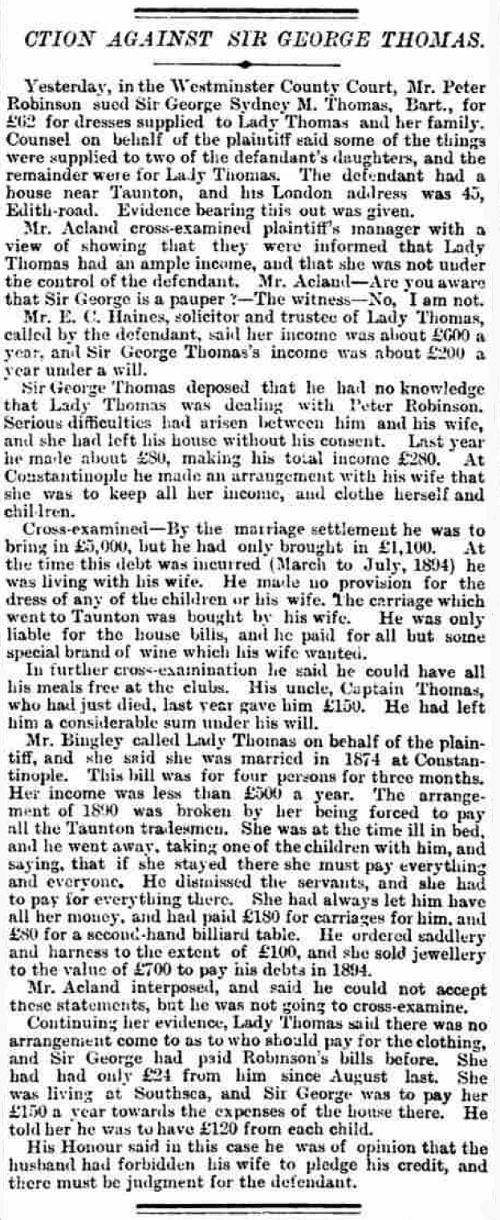

11990.

The

Thomas family

As a supplement to Sir

George Thomas, John Saunders (Kingston upon

Thames, England) submits this report from page 9

of the Morning Post, 22 June 1895:

Our correspondent is the Webmaster of BritBase

– British Chess Game Archive.

11991.

Difficult

to visualize (C.N. 11985)

In addition to backward moves and sacrifices on

empty squares, there can be difficulty in seeing

collinear moves, as discussed, with examples, in

C.N. 4230 and 4233. Those items are in our feature

article on the originator of the term, John

Nunn.

11992. Staunton and Morphy

The text of C.N. 11939:

What was the largest number of games that

either Staunton or Morphy ever played

simultaneously (excluding the latter’s blindfold

displays)?

This surprisingly difficult question has been

mentioned in, for instance, C.N.s 4492 and 11874

(see Howard

Staunton) and C.N. 10423 (see Paul

Morphy). Citations for numbers as low as

three or four will be welcomed, to start the

ball rolling.

The ball still stubbornly stationary, we now

approach the issue from a fresh angle (‘prêcher

le faux pour savoir le vrai’). Let it be

imagined that, excluding Morphy’s blindfold

displays, a chess author were to write:

‘In their entire lives neither Staunton nor

Morphy gave a single normal/regular simultaneous

exhibition.’

What facts could be put forward to refute that

imaginary chess author’s assertion?

11993.

Staunton

correspondence

From John Townsend (Wokingham, England):

‘Sixty-two letters, written 1855-74, by

Howard Staunton to his friend and fellow

Shakespeare scholar, James Orchard

Halliwell-Phillipps, are deposited at

Edinburgh University Library. The chess

content is precisely nil. That is because his

interest by that stage of his life had turned

to Shakespeare and other literary and

historical matters, some of which he pursued

through his contributions to the Illustrated

London News. Nevertheless, the correspondence

has much to offer regarding Staunton the man

and shows him as a person quite different from

the vengeful fiend which he is sometimes

portrayed as being.

In the example which follows, Staunton is

elated at the prospect of a visit to Broadway,

Worcestershire, where Halliwell-Phillipps’

wife had inherited the library of her father,

Sir Thomas Phillipps, at Middle Hill. Staunton

also expected that the Cotswolds air would be

beneficial for his chest condition (described

by him elsewhere as bronchitis), and he looked

forward to renewing his friendship with

Halliwell-Phillipps, whose company he very

much enjoyed. He was anxious for his friend to

turn up.

The letter is typical of Staunton’s prose in

his letters to Halliwell-Phillipps: relaxed

and informal, yet studded with literary

allusions.

“117 Lansdowne Road,

Kensington Park (W)

May 17th 1873

Dear Halliwell,

I am off to the famous Cotswolds where Master

Page’s fallow greyhound came off second best.

I hope no mishap will prevent you from joining

me on Monday and, then, ‘What larks!!’

How I long for a tramp over those glorious

hills!

‘Broadway rises to a height of 1,100 feet

above the sea.’

Think of that, Master Brook! Think of the

delicious ozoned oxygen! Think of the road

side pebbles when, as poor Lamb used to say,

‘We have walked a pint’! Think of the fresh

eggs & the streaky bacon! Think of the

neat-handed Phillisses, the Cotsoll Hebes!!

and with these thoughts let no ordinary

impediment deter you from ‘taking the road’.

Give my best regards to the ladies and believe

me

Sincerely Yours

H. Staunton

J.O. Halliwell-Phillipps”

Source: Edinburgh University Library,

Special Collections, Letters to J.O.

Halliwell-Phillipps, 203/20.

The visit was highly successful and he

stayed at the prestigious Lygon Arms in

Broadway. In his James

Orchard

Halliwell and Friends: IV. Howard Staunton

(1997, page 128), Marvin Spevack records

Halliwell-Phillipps’ sentiments expressed in a

letter from Broadway of his trip with Staunton

to Stratford that they were

“as jolly as sandboys [...] how long can

jollity last in the world, and would there be

any without B. and S.”’

11994.

Excuses

‘I had a toothache during the first game. In

the second game I had a headache. In the third

game it was an attack of rheumatism. In the

fourth game, I wasn’t feeling well. And in the

fifth game? Well, must one have to win every

game?’

Anyone using a search-engine for that remark, or

a slightly different wording, will be presented

with countless webpages. Most ascribe the comment

to Tarrasch, some to Tartakower, and none to a

precise source.

In print, it is no surprise to find A. Soltis

writing the following sourcelessly on page 11 of Chess

Life, June 1990:

‘And it was Tartakower who had perhaps the

final word on excuses. Asked how he could lose

so many games in a row at one tournament he

replied: “I had a toothache during the first

game, so I lost. In the second game I had a

headache, so I lost. In the third game an attack

of rheumatism in the left shoulder, so I lost.

In the fourth game I wasn’t feeling at all well,

so I lost. And in the fifth game – well, must I

win every game in a tournament?”’

An earlier version was related by Harry Golombek

on page 91 of the April 1953 BCM in a

report on that year’s tournament in Bucharest, at

which he ‘had a really dreadful phase’:

‘If asked to account for these six successive

losses I think I cannot do better than to quote

Dr Tartakower who on a similar occasion was

explaining why he lost five games in a row in an

international tournament. “The first”, he said,

“I lost because of a very bad headache; during

the second I didn’t feel at all well; I was

afflicted by rheumatic twinges throughout the

third; in the fourth I suffered acute toothache;

and the fifth – well, must one win every game in

a tournament?”’

Readers may care to imagine themselves entrusted

with editing a chess quotations anthology. What to

do with this ‘final word on excuses’? Omit it

owing to the lack of a source? Give in detail the

various versions and attributions? Plump and hope

for the best (the process described in C.N. 9887)?

An attempt may first be made to establish when,

if ever, Tartakower or Tarrasch lost five

consecutive tournament games, and when the story

was first attributed to, if not voiced by, either

of them.

See also Excuses

for

Losing

at

Chess.

11995.

Photographs

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) has provided this

photograph of Bogoljubow and Rubinstein which he

owns. Exact details of the occasion are sought.

Mr Urcan has also sent us this 1976 photograph of

Tony

Miles (Camera Press Archive):

11996.

Staunton

and Morphy (C.N. 11992)

Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA) informs us

that the only simultaneous display by Staunton

which he has seen mentioned in the Chess

Player’s Chronicle is a very small one at

the Rock Ferry Chess Club (July 1853 issue, pages

217-218):

‘A special Meeting of this Society was held on

the evening of the 5th ult. at the Club Rooms,

Rock Ferry Hotel, for the purpose of welcoming

to Cheshire Mr Staunton, who, during his short

visit, was the guest of Mr Morecroft, of the

Manor House ... In the course of the evening

there was some very interesting play. Mr

Staunton conducted simultaneously two games

against the Liverpool gentlemen, in consultation

at one board, giving them the odds of pawn and

two moves, and against the Rock Ferry gentlemen,

at another board, giving them the odds of the

knight.’

After supper and speeches the games were resumed,

but the report did not specify the outcome.

On Morphy, Jerry Spinrad and John Townsend

(Wokingham, England) refer to a simultaneous

display which is well known. Mr Townsend writes:

‘David Lawson, in Paul Morphy, the

Pride and Sorrow of Chess (new edition by

Thomas Aiello, 2010), quoted (on pages

213-214) from an account of a simultaneous

exhibition which took place at the St James’s

Chess Club in London on 26 April 1859, the

source being the Illustrated News of the

World, of “the following Saturday”:

“A highly interesting assembly met in the

splendid saloon of St James’s Hall, on Tuesday

evening last [26 April], when Mr Morphy

encountered five of the best players in the

metropolis.”

The opposition was formidable:

“The first table was occupied by M. de

Rivière; the second, by Mr Boden; the third,

by Mr Barnes; the fourth, by Mr Bird; and the

fifth, by Mr Löwenthal. Mr Morphy played all

these gentlemen simultaneously, walking from

board to board, and making his replies with

extraordinary rapidity and decision. Although

we believe that this is the first performance

of the kind by Mr Morphy, it is a remarkable

fact that he lost but one game. Two other

games were won by him and two were drawn.”’

Those reports, one display apiece by Staunton and

Morphy, are all that can currently be cited here,

although the following may be recalled from C.N.

10423 (concerning Morphy after his match with

Anderssen):

‘He confined himself to simultaneous displays,

playing 20, 30 and even 40 people at once ...’

Source: page 274 of Keene On Chess by R.

Keene (New York, 1999). The identical wording was

on page 275 of Complete Book of Beginning

Chess by R. Keene (New York, 2003).

11997.

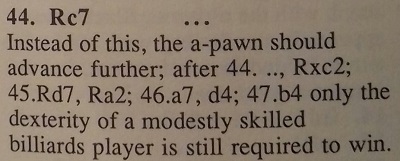

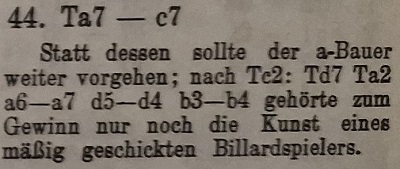

Rook ending note

João Pedro S. Mendonça Correia (Lisbon) draws

attention to this annotation on page 217 of the

Caissa Editions translation (Yorklyn, 1993) of

Tarrasch’s book on St Petersburg, 1914 and wonders

whether any personal acrimony underlies the

reference to billiards:

From the original German edition (page 151):

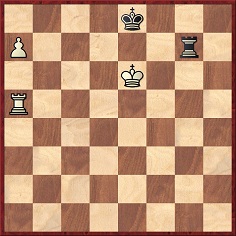

The game was Capablanca v Marshall in round four

of the final section: 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 Nxe5 d6

4 Nf3 Nxe4 5 Qe2 Qe7 6 d3 Nf6 7 Bg5 Be6 8 Nc3 h6 9

Bxf6 Qxf6 10 d4 Be7 11 Qb5+ Nd7 12 Bd3 g5 13 h3

O-O 14 Qxb7 Rab8 15 Qe4 Qg7 16 b3 c5 17 O-O cxd4

18 Nd5 Bd8 19 Bc4 Nc5 20 Qxd4 Qxd4 21 Nxd4 Bxd5 22

Bxd5 Bf6 23 Rad1 Bxd4 24 Rxd4 Kg7 25 Bc4 Rb6 26

Re1 Kf6 27 f4 Ne6 28 fxg5+ hxg5 29 Rf1+ Ke7 30 Rg4

Rg8 31 Rf5 Rc6 32 h4 Rgc8 33 hxg5 Rc5 34 Bxe6 fxe6

35 Rxc5 Rxc5 36 g6 Kf8 37 Rc4 Ra5 38 a4 Kg7 39 Rc6

Rd5 40 Rc7+ Kxg6 41 Rxa7 Rd1+ 42 Kh2 d5 43 a5 Rc1

44 Rc7 Ra1 45 b4 Ra4 46 c3 d4 47 Rc6 dxc3 48 Rxc3

Rxb4 49 Ra3 Rb7 50 a6 Ra7 51 Ra5 Kf6 52 g4 Ke7 53

Kg3 Kd6 54 Kf4 Kc7 55 Ke5 Kd7 56 g5 Ke7 57 g6 Kf8

58 Kxe6 Ke8 59 g7 Rxg7 60 a7 Rg6+ 61 Kf5 Resigns.

Tarrasch also criticized 46 c3, appending a

question mark.

Below is the position after White’s penultimate

move, 60 a7:

Tarrasch called Marshall’s 60...Rg6+ a Racheschach.

It is not a ‘spite

check’ strictu sensu, given that two

of the three possible king moves by White lose.

11998.

A

difficult rook ending

On 25 March 2024 Ben Finegold posted on his

YouTube channel a game with a complicated rook

ending submitted by a viewer. Afterwards, starting

at 13’17”,

Finegold drolly commented that most games from

viewers had seven blunders by one side and eight

by the other.

C.N. 7228 gave two pre-Tartakower (1890 and 1901)

occurrences of the observation that the winner is

the player who makes the last mistake but one, but

information is still sought on when it was first

attached to Tartakower’s name, or to that of other

masters.

In the latter category, Barnie F. Winkelman wrote

on page 205 of Chess Review, September

1935:

‘To Lasker chess was (and remains) a contest, a

personal encounter in which he frequently

avoided the best variations, and sought to give

battle on unfamiliar ground. “The winner of a

game of chess”, he is reported to have said, “is

he who makes the last mistake but one.”’

With terms like ‘is reported to have said’ (and

‘reportedly said’), the floodgates are open for

anyone to write anything.

11999.

Chess

Book Chats

As recorded in the Factfinder,

we have referred to Michael Clapham’s website Chess

Book Chats. In the past month it has been

updated with some more first-class articles.

12000.

My System

As shown in Nimzowitsch’s

My System, C.N. 9792 remarked:

Mein System is a rare case of a chess

book also existing in a simplified version,

edited by Heinz Brunthaler (Zeil am Main, 2007).

Now we note that Russell Enterprises, Inc. has

just produced a ‘FastTrack

Edition’ of My System, edited by

Alex Fishbein.

12001.

The

Pride and Sorrow of Chess

With the increase in digitized publications it

can be hoped that more nineteenth-century

occurrences will be found of ‘The

Pride

and Sorrow of Chess’. At present the

earliest citations that we have given are:

C.N. 4053:

On page 113 of the April 1885 International

Chess Magazine Steinitz wrote:

‘... the fearful misfortune which ultimately

befell “the pride and sorrow of chess”, as

Sheriff Spens justly calls Morphy, can only

evoke the warmest sympathy in every human

breast.’

C.N. 6469:

On page 3 of the January 1885 issue of his

magazine Steinitz had mentioned the phrase with

a second definite article but no reference to

Spens:

‘The pride and the sorrow of chess, as Morphy

has been called, is gone for ever.’

12002.

A

remark by Purdy (C.N.s 10171 & 10182)

Still also being sought: the source of the

following annotation by C.J.S.

Purdy:

‘This is a legal move; it has no other merit.’

12003.

The

Club Argentino de Ajedrez (C.N.s 11330, 11341

& 11349)

Some further photographs provided to us by Carlos

León Cranbourne (Buenos Aires):

12004.

Hanging

There is a difference between ‘hanging

pawns’ and ‘pawns hanging’, and we wonder

how far back one can trace the verb ‘to hang’ in

the sense of to leave en prise or to leave

a resource open to the opponent, as in expressions

such as White ‘hung a rook’, ‘left his queen

hanging’ or, indeed, ‘left a mate in one hanging’.

12005.

Announced

mates (C.N. 11973)

We are grateful to Robert John McCrary (Columbia,

SC, USA) for making an initial search for early

references to announced mates. It may seem logical

to assume that correspondence chess gave an

impetus to the practice, to limit postage outlay,

but hard facts are still lacking.

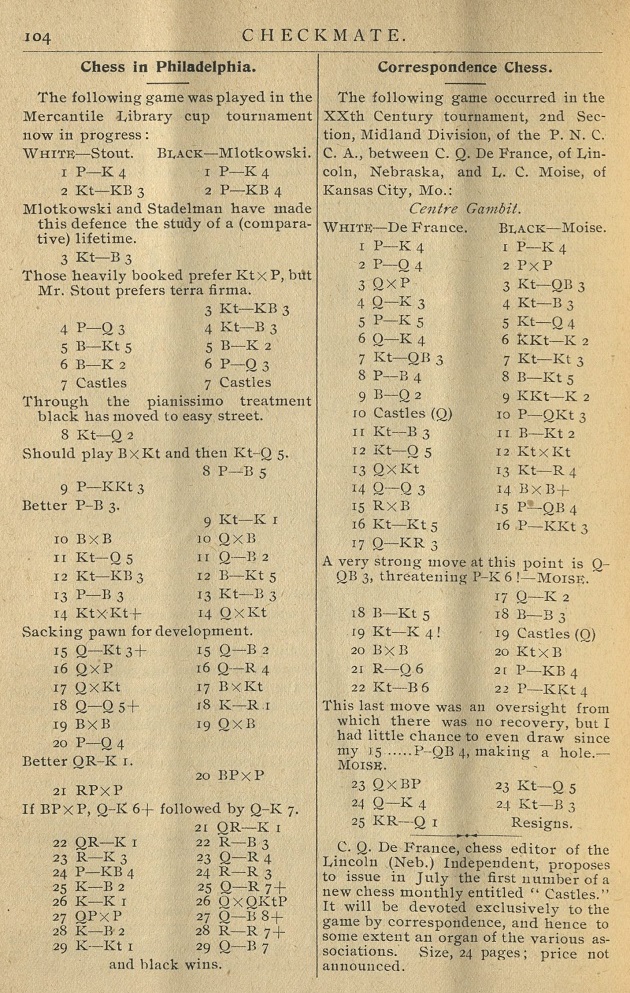

Our correspondent draws attention to page

220 of Volume II of the Chess Player’s

Chronicle, which includes this:

‘M. Chamouillet here announced that he could

force mate in nine moves; and his adversaries,

after examining the position, resigned.’

12006.

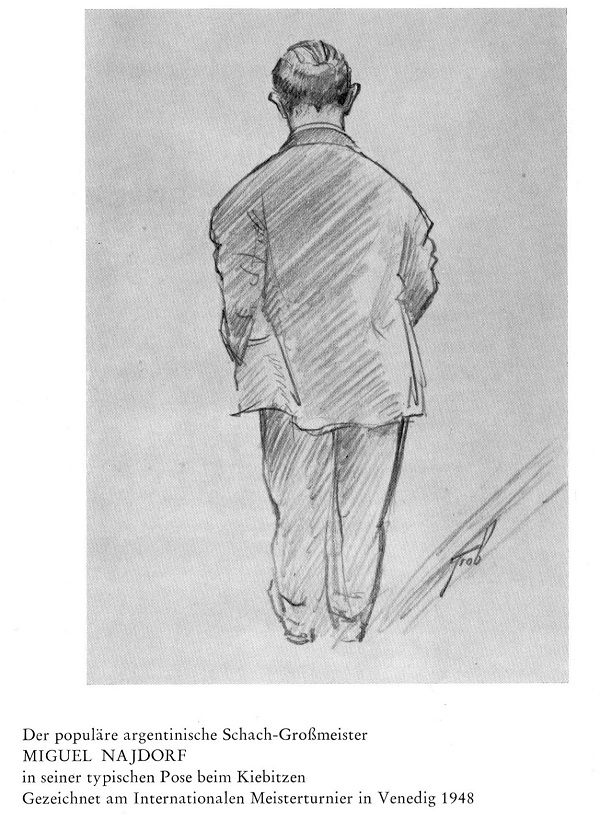

Vienna,

1922

From Avital Pilpel (Haifa, Israel):

‘Herbert Halsegger has drawn my attention to

sketches by L.R. Barteau of some of the

players in the Vienna, 1922 tournament, as

well as the President of the Vienna Chess

Club, Dr Kondor. They appeared on half the

front page of the Illustriertes Wiener

Extrablatt, 18

November 1922. The information about

Kondor is from page 3 of the same issue, in

the chess column.’

12007.

Cheating

Prompted by the swirl of unverified and

unverifiable claims about online cheating,

we suggest the following:

Accusations need corroboration. Insinuations

need expurgation.

12008.

The

spite check

C.N. 11997 referred to the term ‘spite check’ and

the similar, though not identical, German word Racheschach.

As shown in the The

Spite

Check

in Chess, various writers offer various

definitions, but we should like to know of any

(close) equivalents in other languages. Spanish,

for instance, has jaque por despecho.

12009.

The

last mistake but one (C.N. 11998)

Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) points out

the following in an article by Henry Smith

Williams about Samuel

Reshevsky on page

43 of the October 1920 issue of Hearst’s:

‘In the words of Lasker – for many years the

undefeatable champion – the man who wins is the

man who makes the last mistake but one.’

12010.

The

Orthodox Defence

Wanted: early occurrences of the word ‘Orthodox’

(in any language) in connection with the defence 1

d4 d5 2 c4 e6.

12011.

Fischer

on Alekhine

Alexander

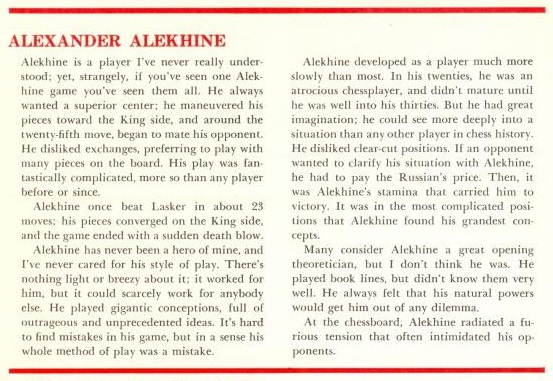

Alekhine Miscellanea begins with Fischer’s

view in the article ‘The

Ten

Greatest

Masters in History’ on pages 56-61 of Chessworld,

January-February 1964):

Would anyone venture to offer serious support to

Fischer’s contention, ‘strangely, if you’ve seen

one Alekhine game you’ve seen them all’?

12012.

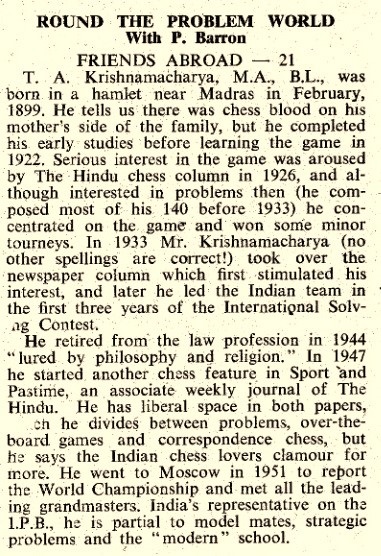

T.A.

Krishnamachariar

Further to Two

Indian

Chess Figures, Michael McDowell

(Westcliff-on-sea, England) notes that although

T.A. Krishnamachariar seems to have had no

obituary in The Problemist, the following

appeared on page 510 of the March 1954 issue:

12013.

Ian

Brady, Graham Young and Peter Sutcliffe

From Avital Pilpel (Haifa, Israel):

‘In Chess

and Murder, you note that “Ian Brady

described playing chess against Graham Young in

Parkhurst Prison on the Isle of Wight”. It is

worth adding that after Brady’s death, an

interview with another British serial killer –

Peter Sutcliffe, the “Yorkshire Ripper” –

stated that the latter played chess with

Brady.

Just as Brady was dismissive of

Young’s chess ability, Sutcliffe was

dismissive of Brady’s, according to an online

Mirror report dated 27 May 2017.’

12014.

Announced

mates (C.N.s 11973 & 12005)

John Townsend (Wokingham, England) writes:

‘Page 23 of William Hartston’s The

Kings of Chess (London, 1985) contains an

example of an announced mate by Philidor. The

occasion was an odds game with Count Brühl at

Parsloe’s in London on 26 January 1789. White

was in check, “and Philidor announced mate in

two moves: 28 Qxf5! and 29 Rh8 mate”.

George Walker’s A Selection of Games at

Chess, actually played by Philidor and his

contemporaries (London, 1835) includes the

game on pages 41-42 with the following

termination:

“27 K. Kt. P. on. Kt. to K. B. fourth, ch. 28

Q takes Kt., and Mates next move with R.”

The Oxford Encyclopedia of Chess Games

by Levy and O’Connell (Oxford, 1981) has the

score (page 15) as concluding with “27 g5 Nf5+

1-0” and gives the source as “MS H.J. Murray

64, Bodleian Oxford, ‘Collection of European

Games’”.’

See also Announced

Mates.

12015.

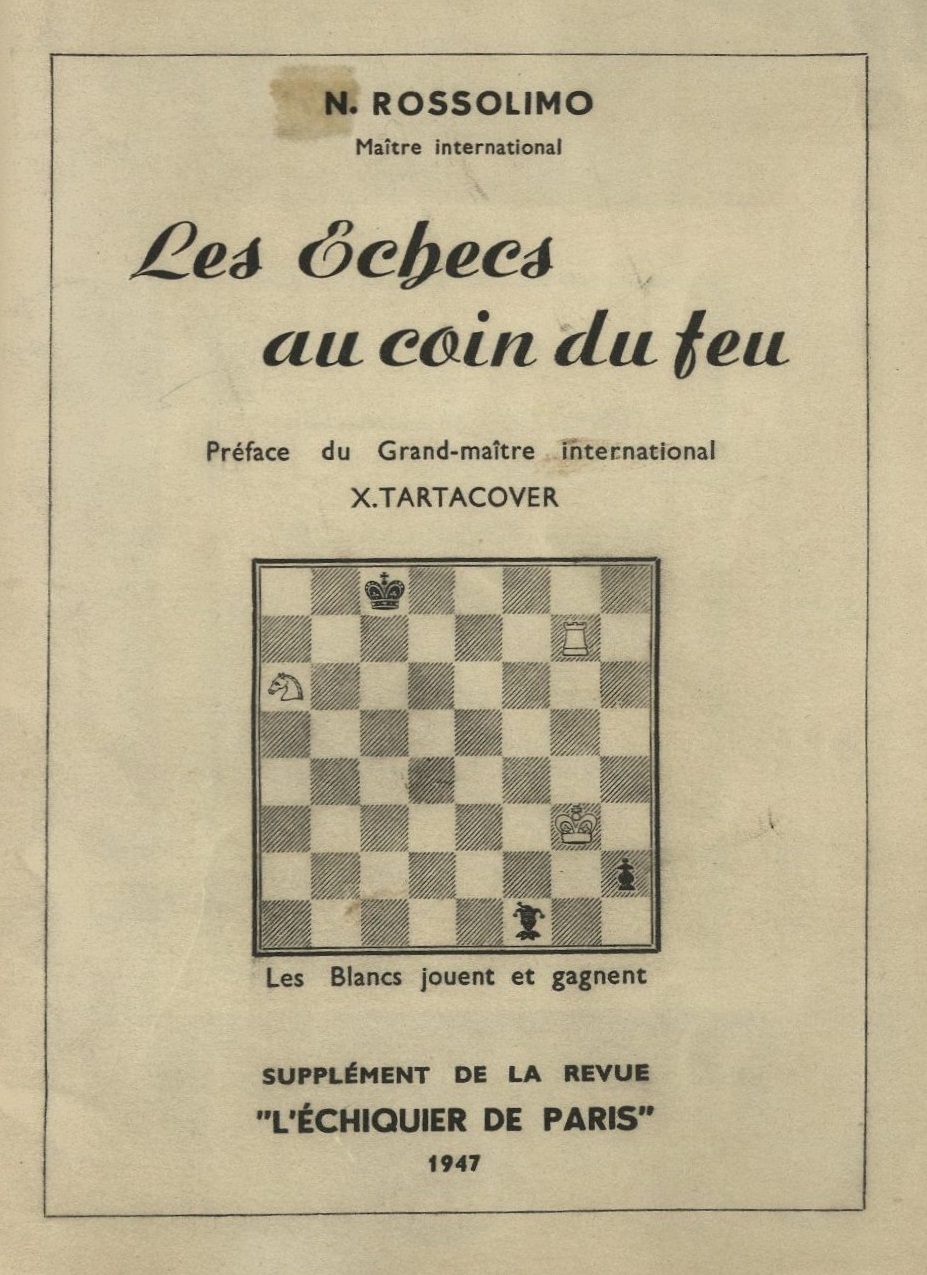

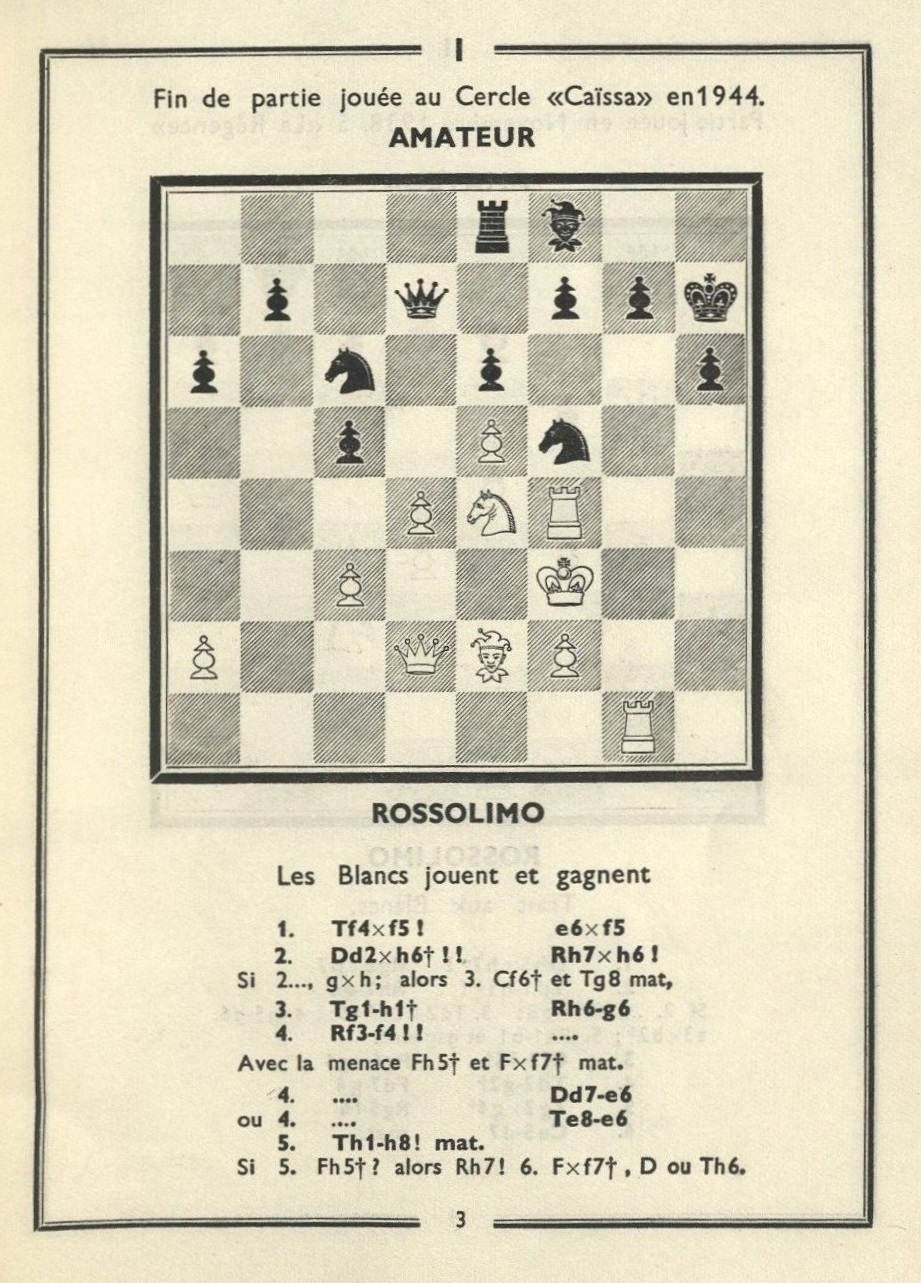

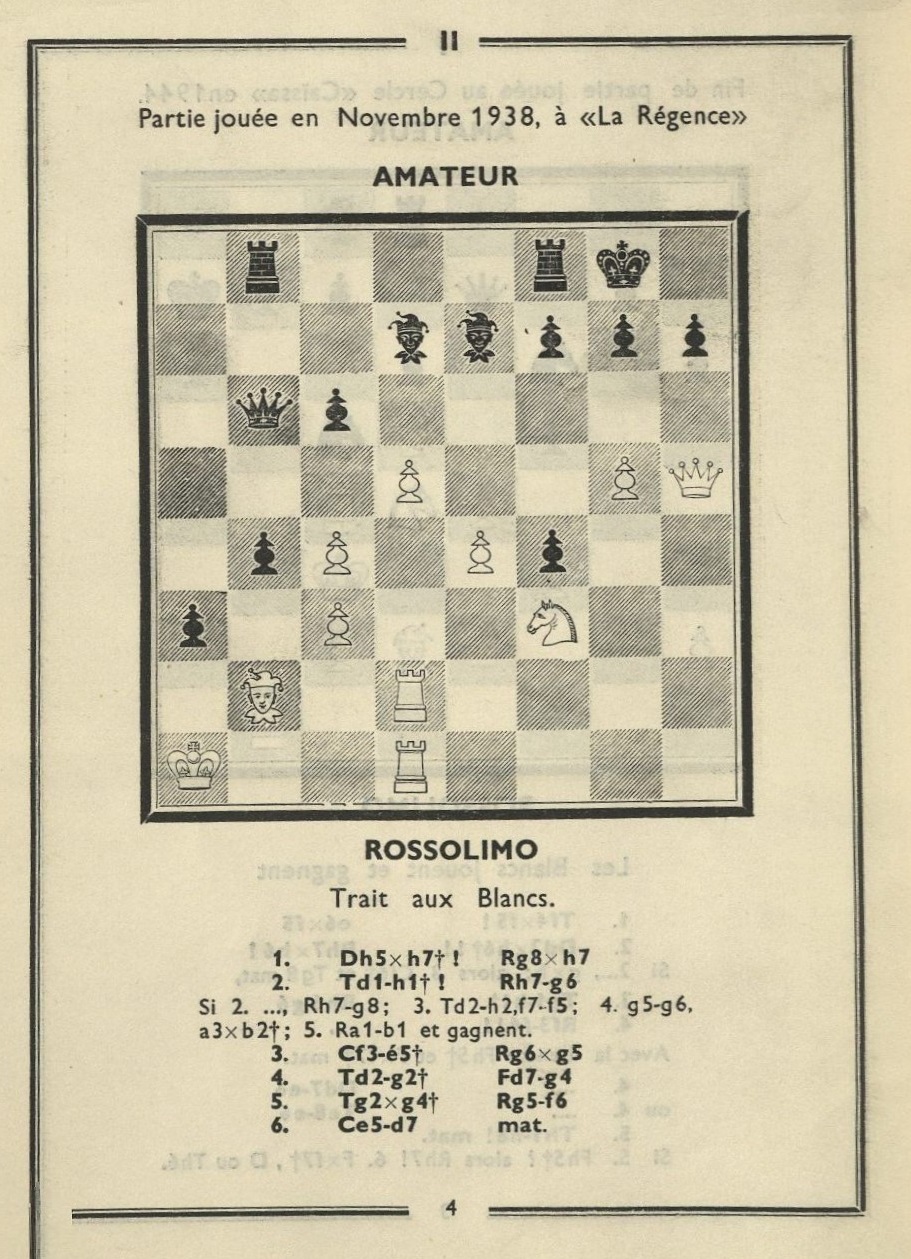

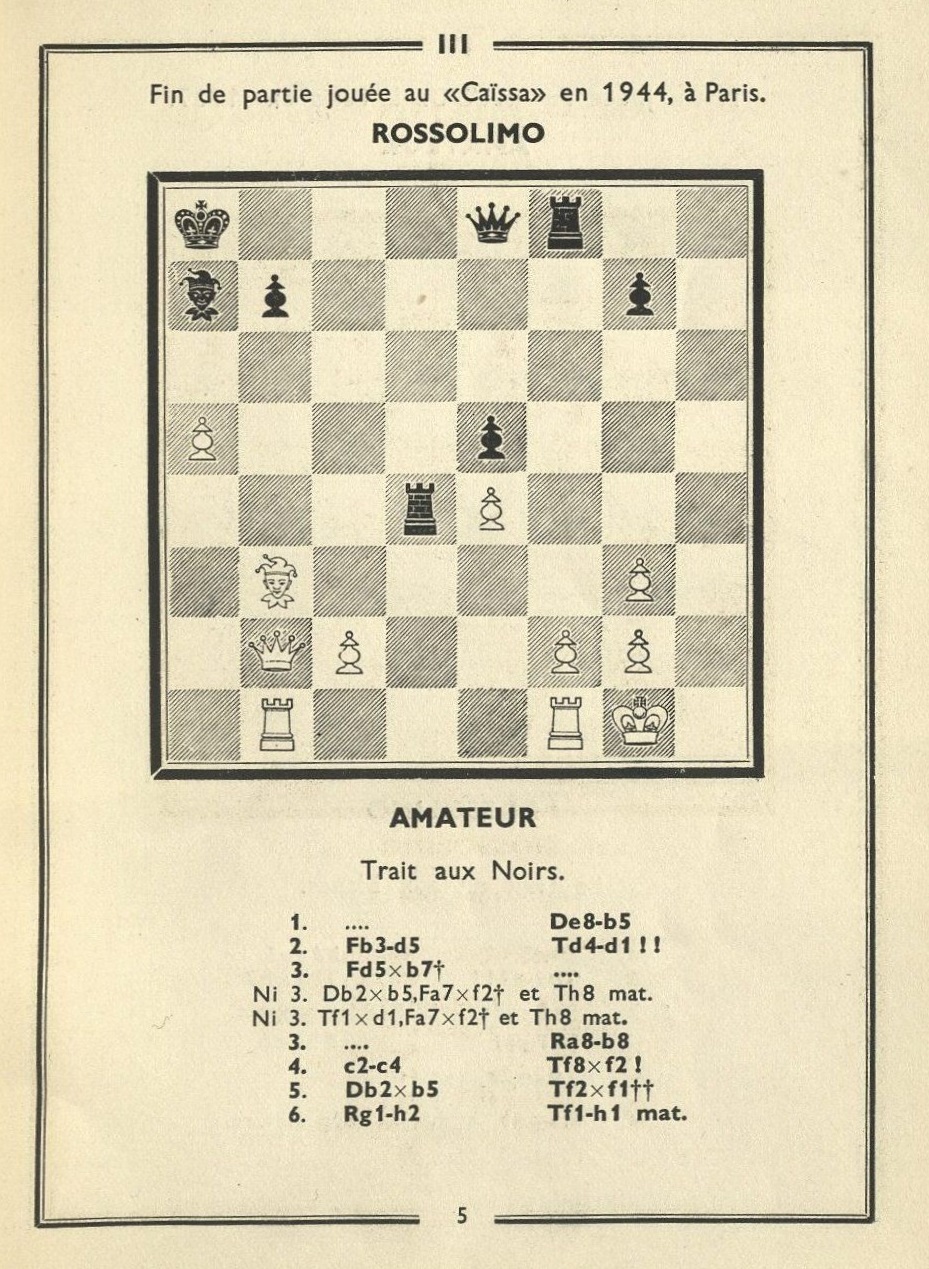

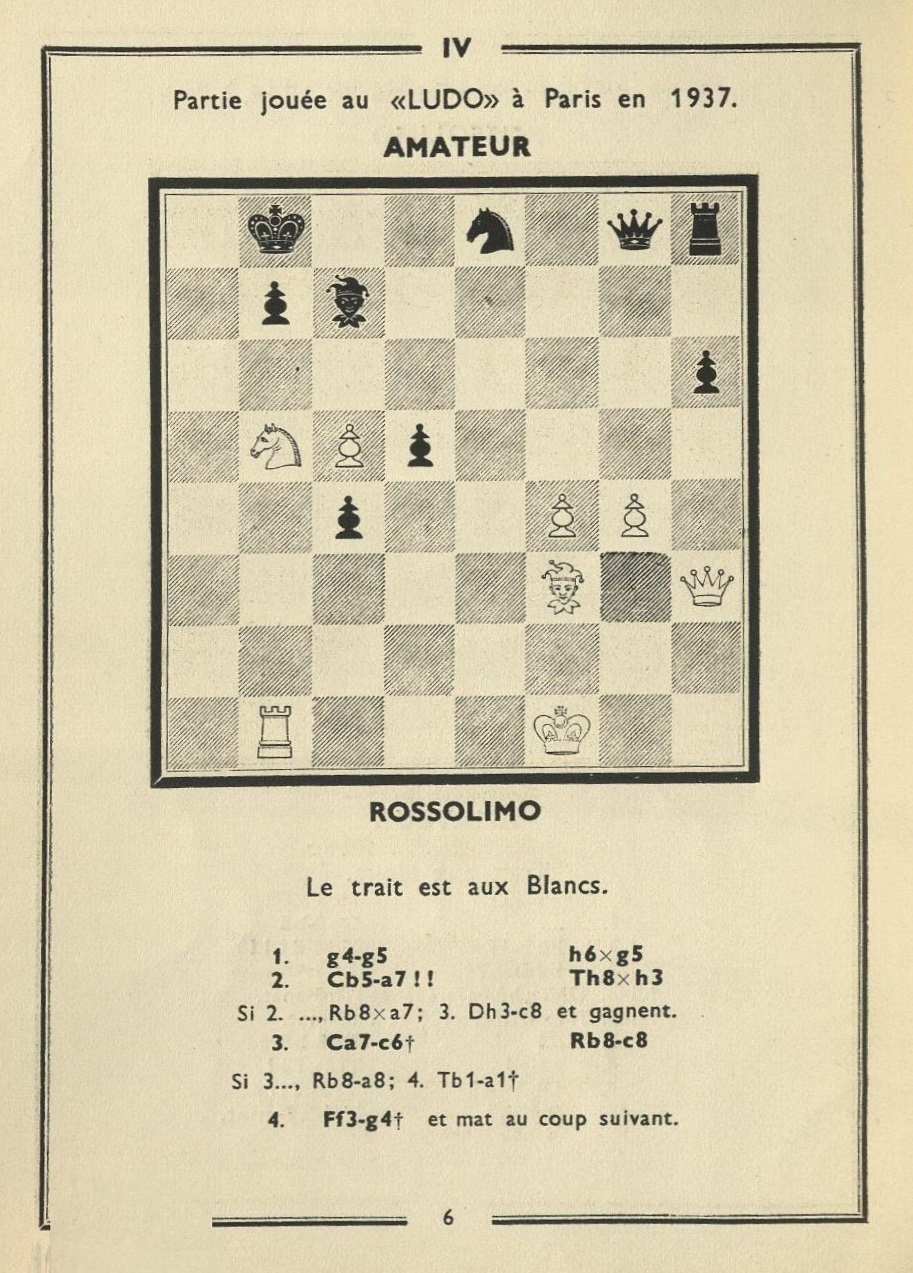

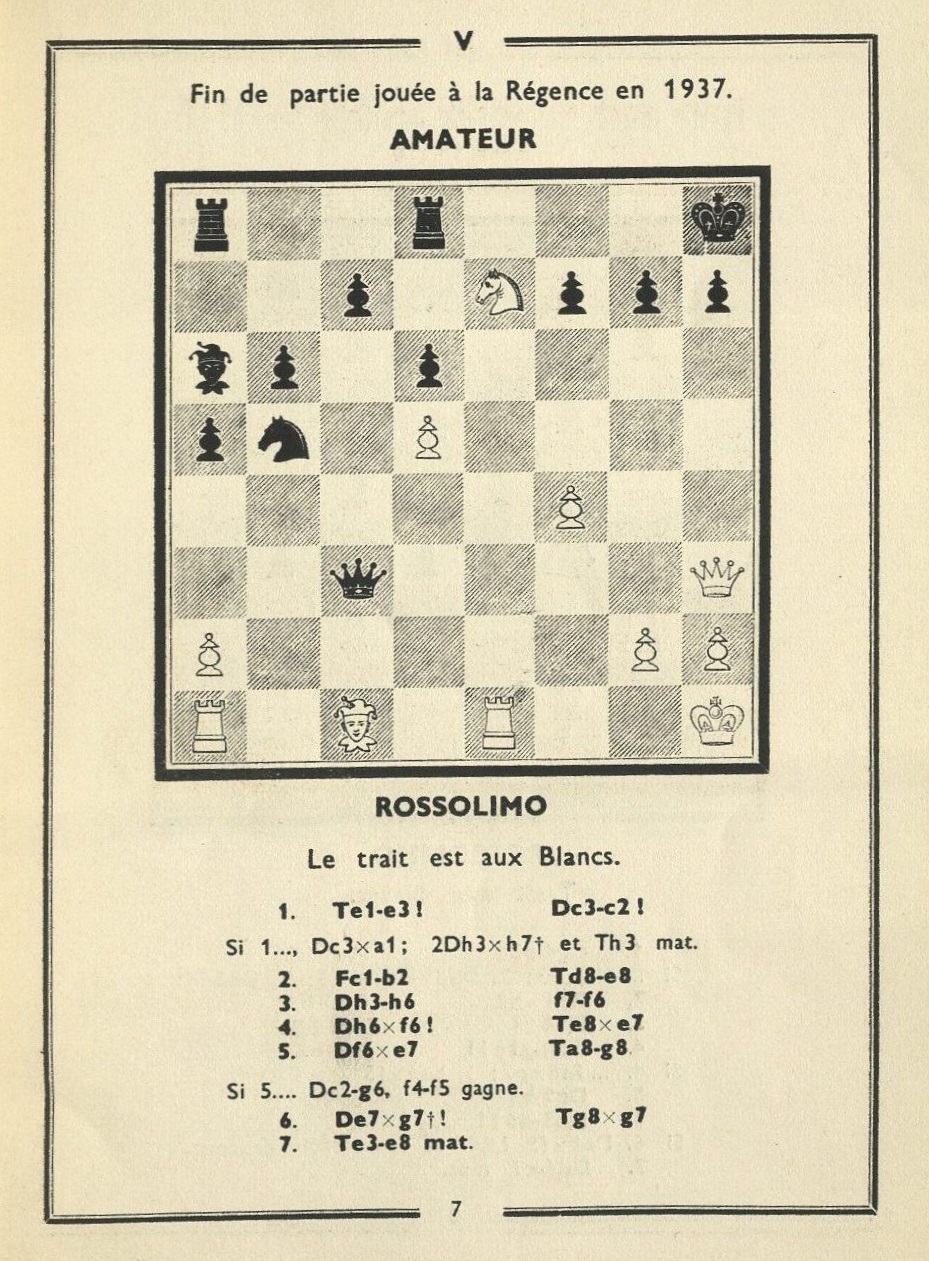

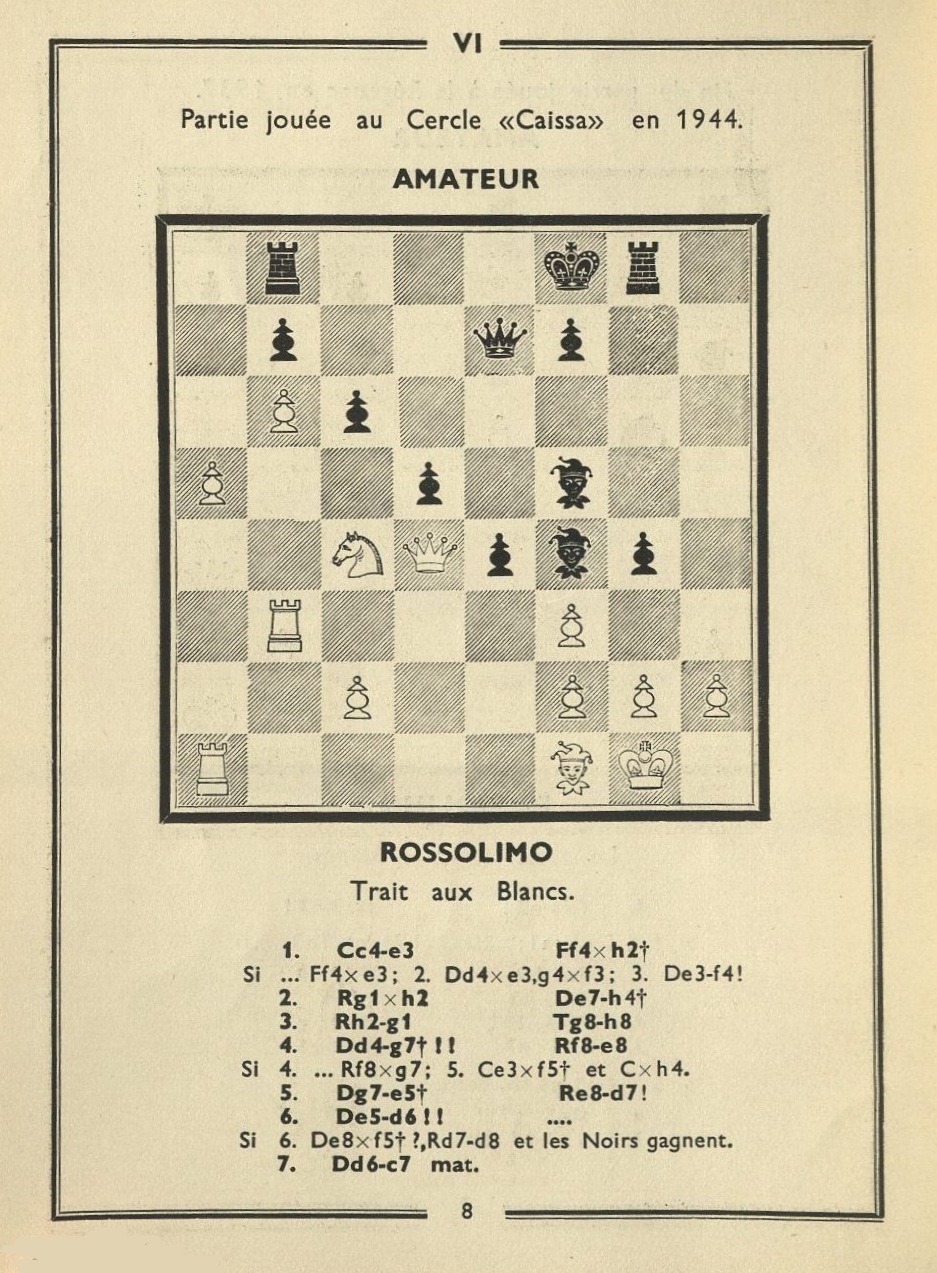

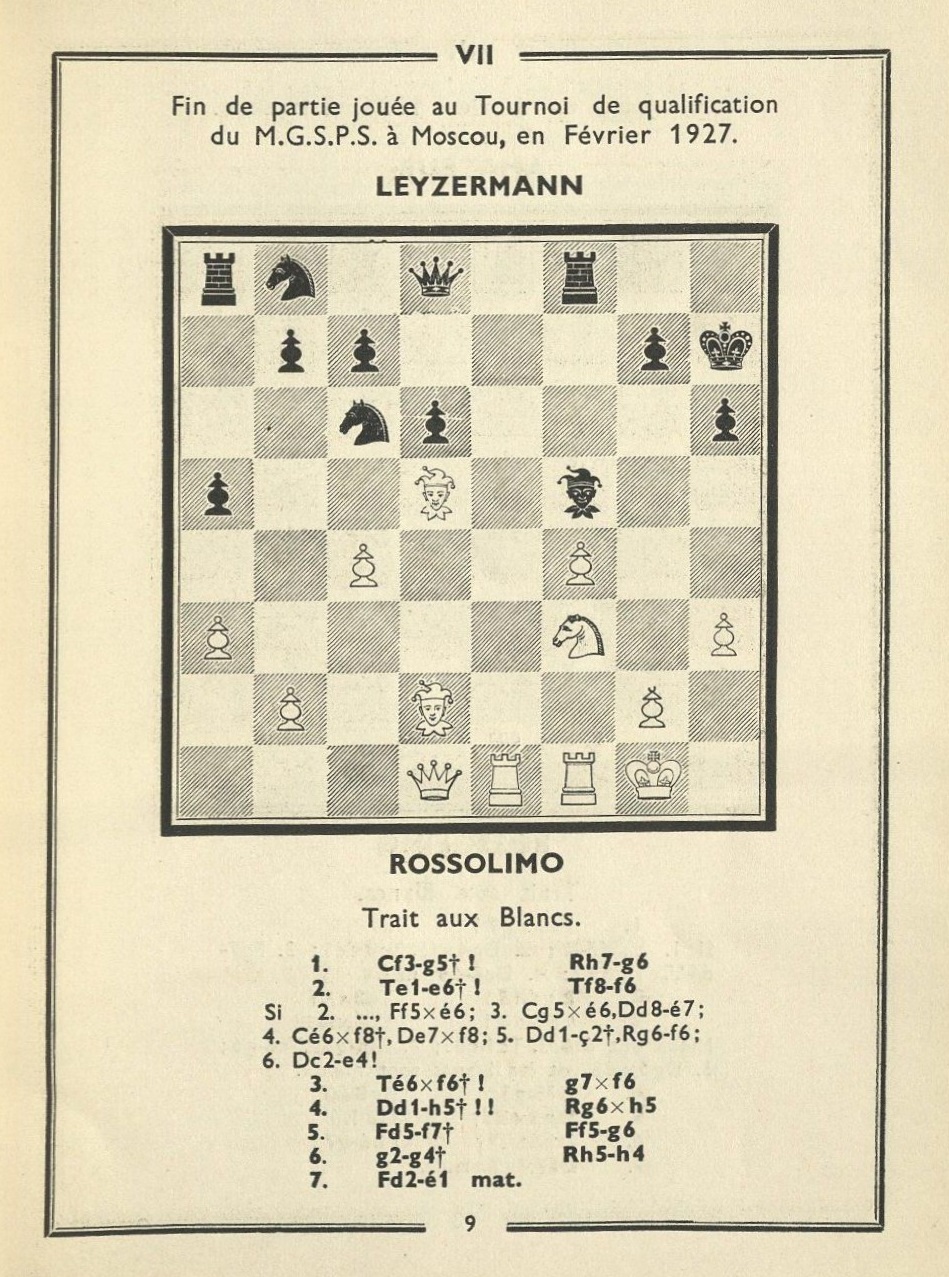

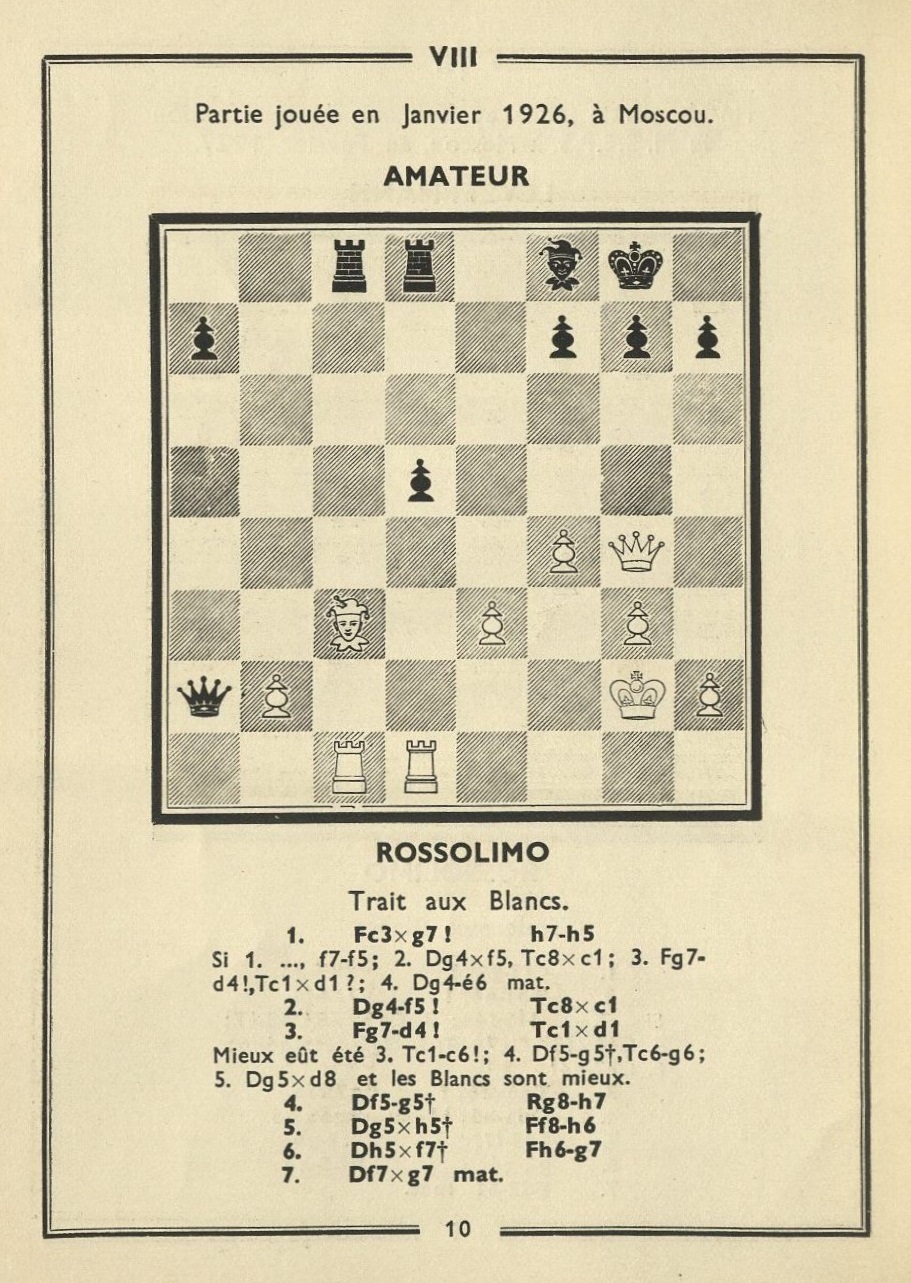

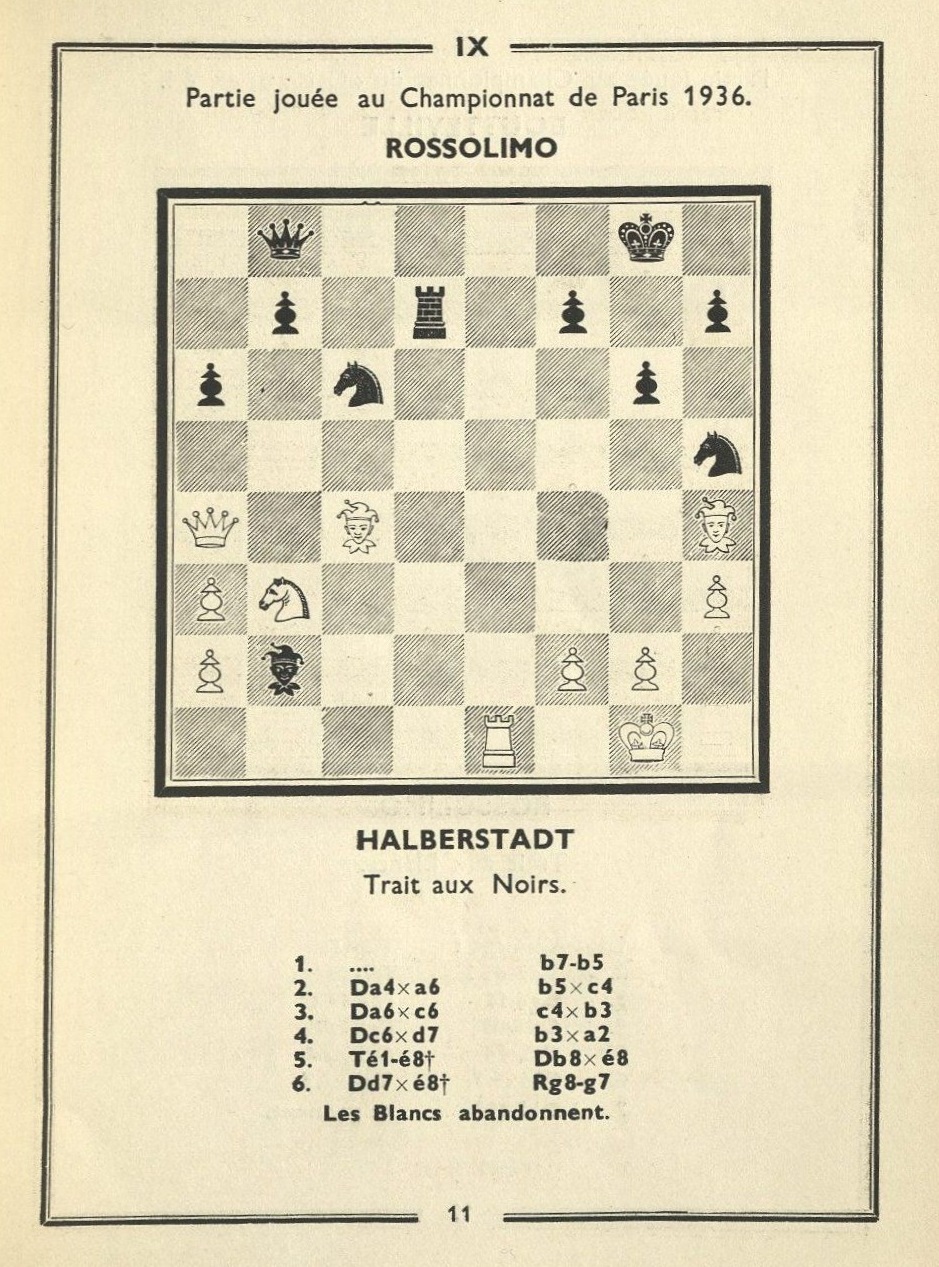

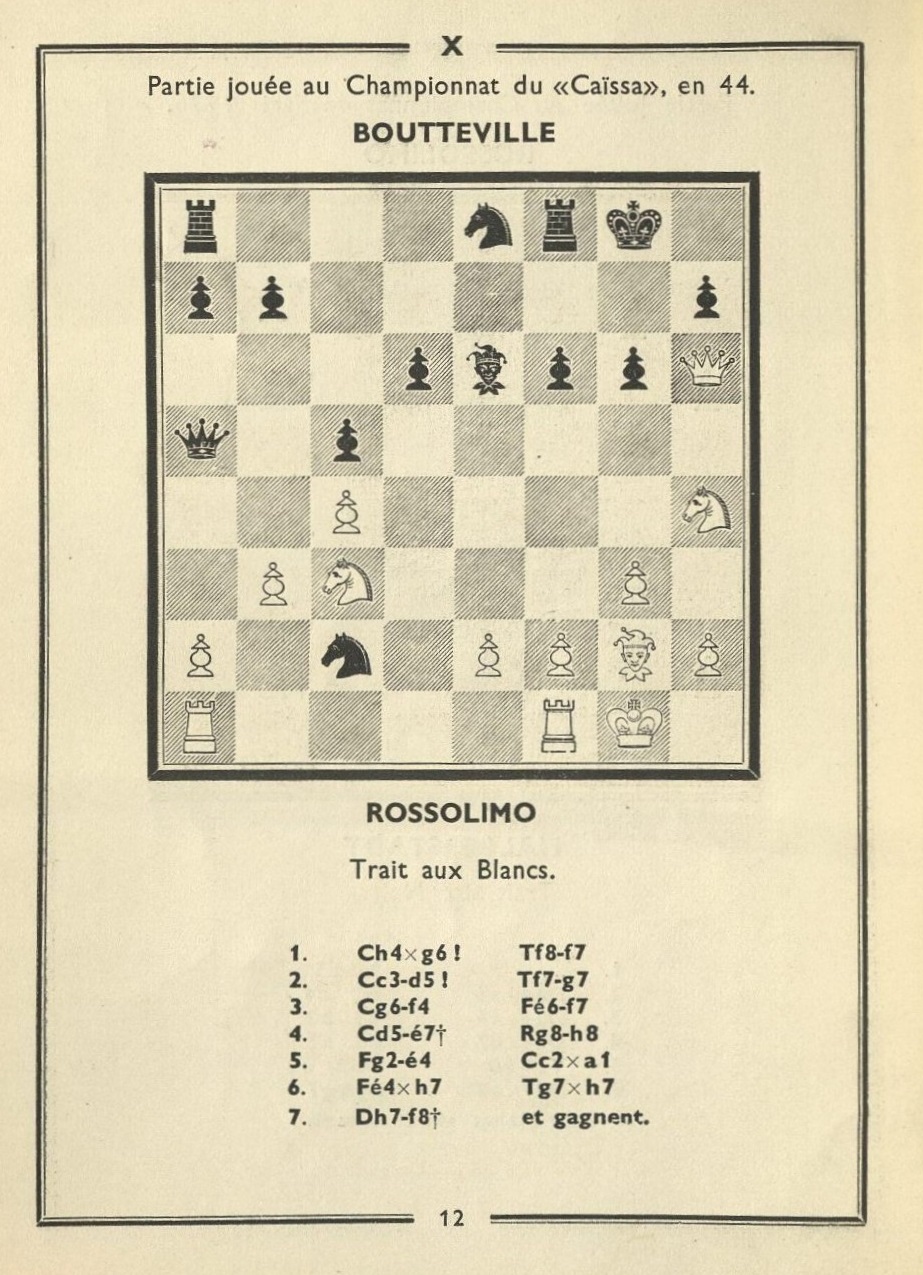

Rossolimo’s

brilliancies

Michael Petrow (Munich, Germany) notes references

to an alleged self-publication by Nicolas

Rossolimo: Rossolimo’s Brilliancy Prizes

(New York, 1970).

It is mentioned in the English-language Wikipedia

entry on Rossolimo, but neither online nor

elsewhere have we found authoritative information

about its existence.

The other chess work referred to in the entry, Les

Échecs

au coin du feu (Paris, 1947) with a Preface

by Tartakower, has 28 pages and, courtesy of the

Cleveland Public Library, a number of them are

shown below:

12016.

Alekhine’s gun (C.N.s 7880, 7914, 7972, 8625

& 8860)

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA)

provides the following game:

George Walker – Alexander McDonnell

Occasion?

(Odds of pawn and two moves. Remove Black’s

f-pawn.)

1 e4 … 2 d4 Nc6 3 e5 d5 4 c3 Bf5 5 g4 Be4 6 f3

Bxb1 7 Rxb1 e6 8 Bf4 h5 9 Bd3 hxg4 10 Bg6+ Kd7 11

fxg4 Qh4+ 12 Bg3 Qg5 13 Bd3 Nh6 14 Be2 Qe3 15 Kf1

Be7 16 Kg2 Raf8 17 Nh3 Nf7 18 Qd3 Qh6 19 Bf4 Qh4

20 Qg3 Qh7 21 Bd3 g6 22 Rbf1 Bh4 23 Qe3 Be7 24 Rf3

Qg7 25 g5 Rh5 26 Rg3 Qh7 27 Rg4 Bd8 28 Bb5 a6 29

Bxc6+ bxc6 30 Rf1 Be7 31 b4 a5 32 a3 axb4 33 cxb4

Rh8

34 Rf3 Nd8 35 Nf2 Nf7 36 h4 Qg8 37 Bg3 R8h7 38

Nd3 Qh8

39 Nc5+ Bxc5 40 bxc5 Qa8 41 Rf6 Rg7 42 Rgf4 Rhh7

43 Qd3 Nh8 44 Rf8 Qb7 45 Rf3 Ke7 46 R8f6 Rg8 47

Kh3 Qb2 48 Qa6 Qb5 49 Qa7 Qb8 50 Qa5 Nf7 51 Kg4

Qb7 52 Qa4 Ra8 53 Qc2 Nh8 54 Rb3 Qa6 55 Qb2 Rg7 56

Rb8 Rg8 57 Rxg8 Rxg8 58 Rf3 Qc8 59 a4 Qa6 60 Qc2

Ra8 61 Ra3 Rf8 62 Rf3 Ra8 63 Ra3 Rf8 64 Qd3 Qa5 65

Qc3 Qa6 66 Qd3 Qa5 67 Qc3 Qa6 68 Qd3 Qa5 69 Ra1

Qb4 70 a5 Qb2 71 Rb1 Qa2 72 Rf1 Rf5 73 a6 Nf7 74

Rxf5 exf5+ 75 Kh3 Qa1 76 Bf2 Nd8 77 Kg2 Ne6 78 Be3

Qa2+ 79 Kg3 Ng7 80 Kf3 Kd7 81 Bf4 Kc8 82 Bg3 Kb8

83 Qe2 Qxe2+ 84 Kxe2 Ka7 85 Bf4 Kxa6 86 Ke3 Kb5 87

Kd3 Ka4 88 Kc3 Ne6 89 Be3 Ka5 90 Bf2 Ka6 91 Kd3

Kb7 92 Ke3 Kc8 93 Bg3 Kd7 94 Bf2 Ng7 95 Kf4 Ke6 96

Bg3 Kd7 97 Ke3 Kc8 98 Bf4 Kd7 99 Ke2 Ke6 100 Bg3

Kd7 101 Kf3 Nh5 102 Bf2 f4 103 Be1 Ke6 104 Kg4 Ke7

105 Bd2 Ng7 106 Be1 Ne6 107 Bf2 Ke8 108 h5 Kf7 109

h6 Kf8 Drawn.

Our correspondent’s source is pages 88-91 of A

Selection of Games at Chess ... by

William Greenwood Walker (London, 1836).

The set of C.N. items on this theme has now been

brought together in Alekhine’s

Gun.

12017.

Sourcing

Writer A makes a significant discovery in a

100-year-old newspaper and presents the

information with a complete source.

Writer B repeats the information but specifies

only the 100-year-old source, as if he had

discovered it himself.

Such conduct by Writer B is widespread, and a

technical term for it may be sought. Since

technical terms are often -isms, one possibility

is ‘intermediate source misattribution’.

12018.

Reversed

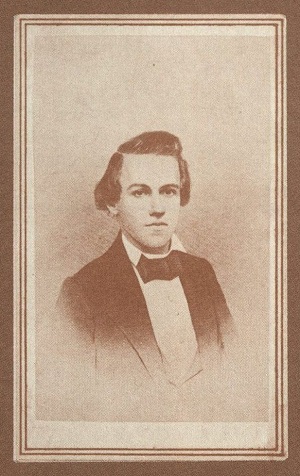

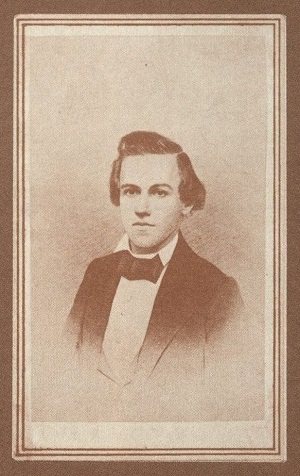

images

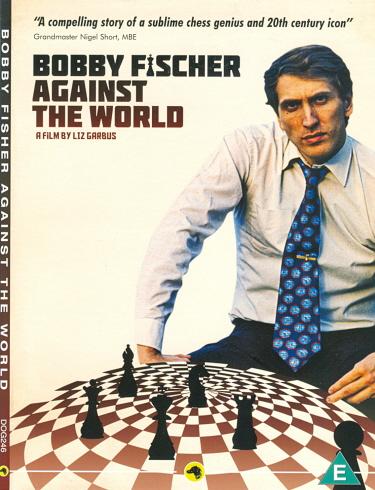

C.N. 7345 (see Chess

and Insanity) quoted slighting remarks about

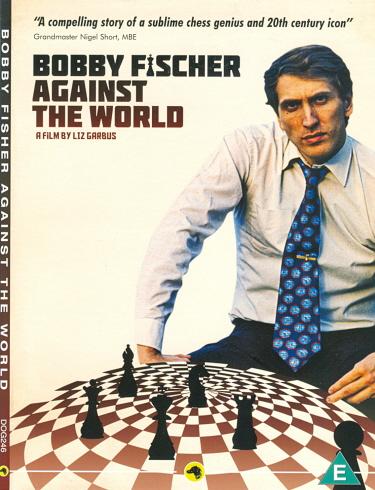

leading masters by interviewees in Liz Garbus’s

documentary film (2011) Bobby Fischer Against

the World. The CD cover above is a famous

shot by Harry Benson but in reverse form;

Fischer parted his hair on the left. See, however,

C.N. 7860 (included in Gaffes

by

Chess

Publishers and Authors), which mentions a

book by Benson himself, as well as a work on

Pillsbury with a flipped image on its front cover.

As shown by numerous pictures, Morphy too parted

his hair on the left; see our comment on a mirror

image in C.N. 5150. Another mistake occurred on

page 53 of Chessworld, January-February

1964, in a lengthy, richly illustrated article on

Morphy by David Lawson:

Left: published

mirror image – Right: corrected

New in Chess has announced the forthcoming

publication of The

Real

Paul

Morphy by Charles Hertan:

Addition on 28 August 2024:

As shown on the above-mentioned New in Chess

webpage, the front cover has been changed:

12019.

The

Star of David

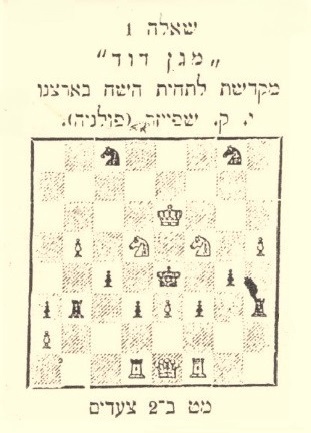

From Avital Pilpel (Haifa, Israel):

‘Further to your feature article Letters

and

Numbers

in

Chess Problems, sometimes the depiction

is not of a letter or number but an object. In

Sivan 5684 (the Hebrew month equivalent to

June 1924), Ha’shachmat – the magazine

of the “Lasker” chess club in Jerusalem –

published its first chess problems (volume

one, number three, page 1). The very first of

these problems was composed specifically for a

Palestinian chess publication. Zionist

sentiment is emphasized, and it is entitled

“Star of David” and “dedicated to the revival

of chess in our country” by the Jewish-Polish

problemist Jakob Kopel Speiser.’

12020.

Chess

literature

Particularly in the 1980s, C.N. items criticized

the low standard of many chess books and the

preponderance of volumes on openings. Those who,

at the time, dismissed such grievances may

profitably reflect on the situation today. To

mention just one example, Quality

Chess (Glasgow) produces a vast array of

highly impressive titles which are poles apart

from what the chess public was expected to

tolerate decades ago, such as the ‘Batsford

disposables’ referred to in Fischer’s

Fury.

12021.

References

to chess in language courses (C.N.s 8684 &

11023)

Another rare example comes from page 49 of A

First German by L. Stringer, illustrated by

Alfred Jackson (London, 1966):

12022.

Stalwarts

In hurriedly penned ‘obituaries’ of minor chess

figures who have just died (they have ‘passed

sadly’ and will be ‘missed sadly’) minor

memorialists often reach for that curious

noun/adjective ‘stalwart’. Never applied to

oneself, it hints at an elderly, unfêted club

member, more notable for his presence than his

prowess, who gladly stays behind to tidy up and

rinse the cups. Our use of ‘his’ is intentional;

chess stalwarts are not female.

12023.

Electronic

resources

Asked by another C.N. correspondent whether he

had researched all of Staunton’s Illustrated

London News columns, G.H.

Diggle replied in 1987 (see C.N.

1439):

‘Of course I have, and broken my shins on

them.’

The days of grappling with bulky annual volumes

in reference libraries have largely gone, home- or

office-based electronic searches having

transformed the task, or joy, of historical

investigation. With Google

Books alone much thirst for knowledge,

whether serious or trivial, can be slaked in

moments by entering key words or phrases.

If, for instance, a chess enthusiast wants to

know about players of past centuries slaking their

thirst in coffee houses, and wonders how the term

became derogatory, innumerable citations can be

found, perhaps beginning with Staunton’s remark on

page 111

of the London, 1851 tournament book that his

second game against Anderssen ‘would be

discreditable to two third-rate players of a

coffee-house’, and culminating in Fischer’s

dismissal of Emanuel Lasker as ‘a

coffee-house player’ in 1964. The words of Georg

Marco will be found too: he considered that the

game Pettersson

v

Nimzowitsch, Barmen, 1905 was ‘played in the

worst coffeehouse style’.

In that game, the spectacle of Nimzowitsch

replying to the Ruy López with 3...f5 may spark

our interest in early analysis of that

opening/defence/gambit/counter-gambit (commonly

named after either of two players who died within

a couple of months of each other, C.F. von

Jaenisch and A.K.W. Schliemann).

To take Jaenisch as an example, Google Books

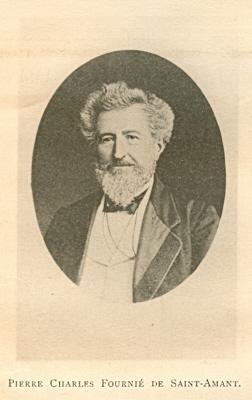

painlessly leads to a run of Le Palamède.

In the December 1847 issue, Jaenisch contributed a

lengthy article (pages 530-560)

on 1 e4 e5, which he termed ‘Le début royal’.

Beginning on page 538

he analysed the ‘very interesting’ move 3...f5,

with four options for White’s fourth move: d4,

exf5, Bxc6 and d3. He explained on page 538 that

he was temporarily holding back from readers of Le

Palamède his suggestion of a winning method

for White, but that December 1847 issue marked the

abrupt end of the periodical’s run.

Again thanks to Google Books it can be seen how

Jaenisch resolved the difficulty. In 1848 an

abridged version of his original article was

published in the Chess Player’s Chronicle

(pages 216-221,

248-253

and 274-279).

The

move

3...f5

was examined on pages 220-221 and 248-249. In the

1849 volume (pages 362-366)

Jaenisch provided a further article, incorporating

the analysis intended for Le Palamède.

(See too pages 313-315

and 344-345

of the Deutsche Schachzeitung, 1848.)

Leaving aside the awkward question of whether

somebody nowadays writing a book on 3...f5 is

likely to take account of Jaenisch’s detailed

articles, we conclude these random musings with a

curiosity highlighted by him on page 363

of the 1849 Chess Player’s Chronicle,

where he gave a line which ...

‘... exhibits in the theory of regular openings

the unique example of a triple pawn’.

Analysis after

11...bxc6

Jaenisch’s analysis continued this line to move

27.

12024.

Cramling v Pérez

Jon Ludvig Hammer is one of the best commentators

on YouTube and Twitch, blending lucidity with dry

whimsy.

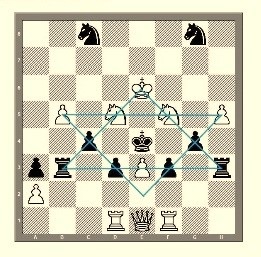

During his live commentary on the seventh-round

women’s match between Sweden and Paraguay at the

Budapest Olympiad on 18 September 2024, he

discussed this position (Pia Cramling v Jennifer

Pérez), starting at about 4:03:30 in the transmission:

White has played

46 Rb7-c7, and Black resigned.

Instead of surrendering, why not produce some

fireworks with 46...Qa6 47 Rxd7+ Kh8 48 Qh6

(threatening mate on the move) 48...Qxf1+ 49 Kxf1

Rc1 mate?

Hammer gave the answer: 49...Rc1 is not mate.

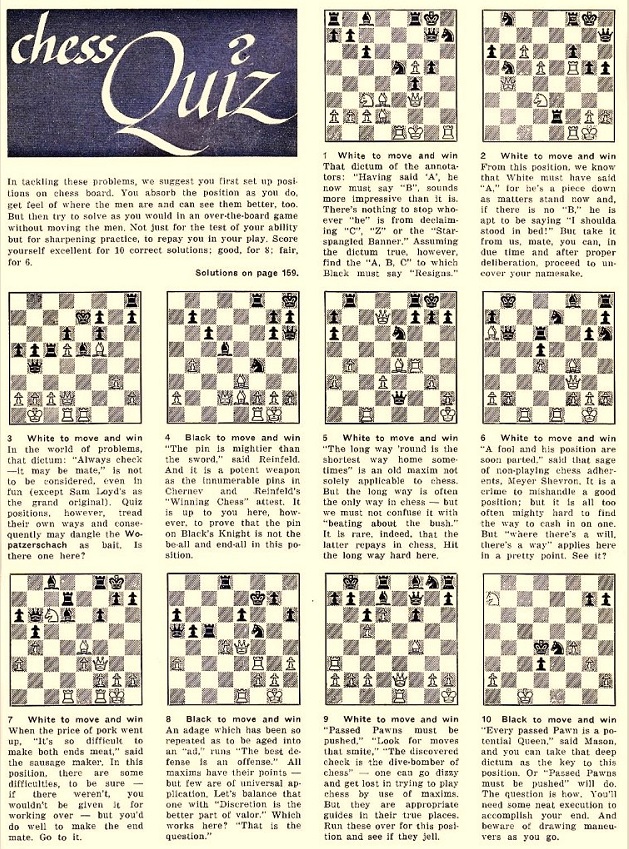

12025.

Mate

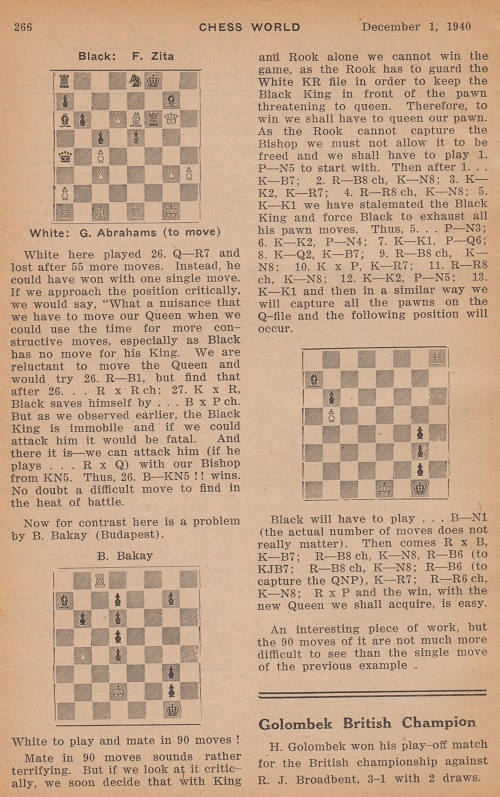

in 90 moves (C.N.s 10035 & 10061)

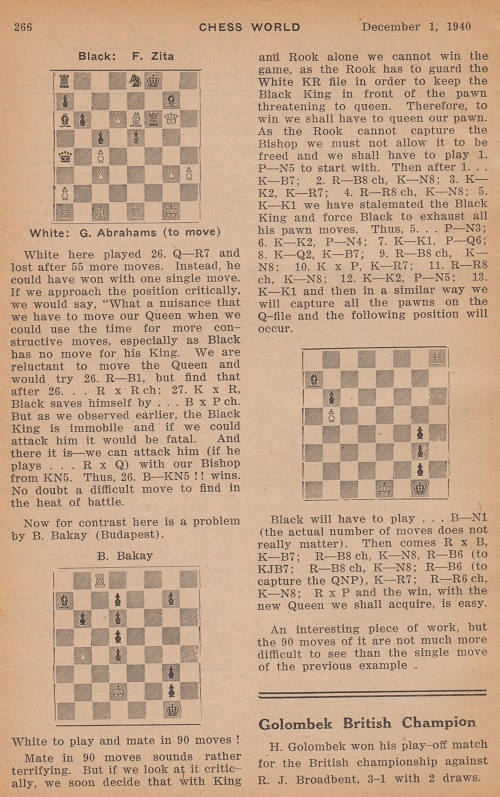

C.N. 10061 (see also How

Many

Moves

Ahead?) showed page 266 of the 1 December

1947 [sic] issue of Chess World,

from an article by Lajos Steiner:

In the Bakay composition, Lindsay Ridland

(Edinburgh) points out a motif which secures Black

a draw: 10…Bb8 11 Rxb8 Kf2 12 Rf8+ Ke1.

12026.

Chess

and poker

From page 406 of the September 1979 BCM (Quotes

and

Queries item 3986 by Kenneth

Whyld):

‘The mention of Franklin Knowles Young

(1857-1931) reminds me of a bon mot

which may be new to readers. Young wrote several

weird chess books which no doubt deceived

military theoreticians into believing that they

understood chess. His fellow American, Clarence

Seaman Howell (1881-1936) wrote of Young’s

“theories of that vague and dreamy and

word-opulent character which abound in art, but

are unwholesome in chess”. This led to a

challenge to a duel over the chess-board. “As to

the matter of stakes”, said Young, “you can put

your money in your pocket. When I play for money

I play poker.” Howell said “I admire your wisdom

in preferring to back your luck rather than your

skill.”’

Two points stand out: the satisfying chess-poker

quip and the troubling absence of any source for

anything.

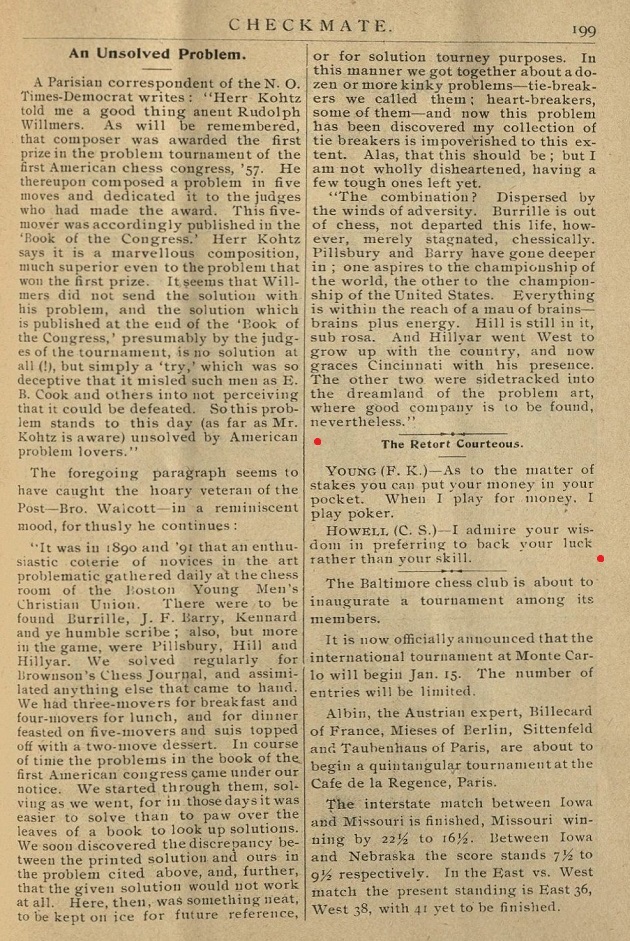

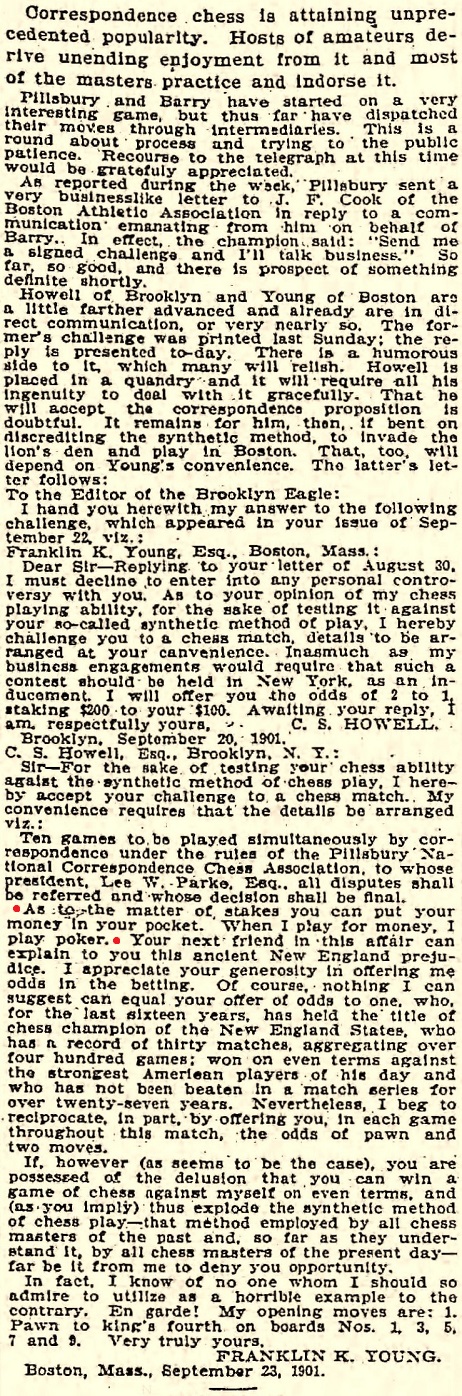

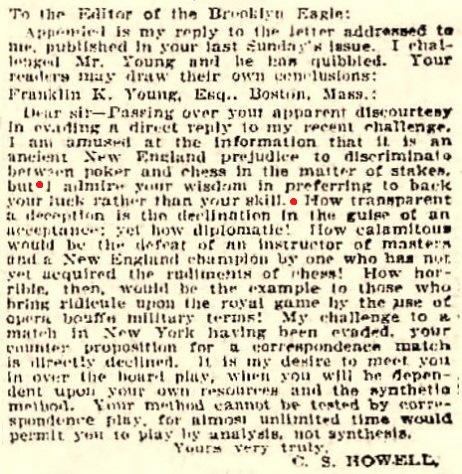

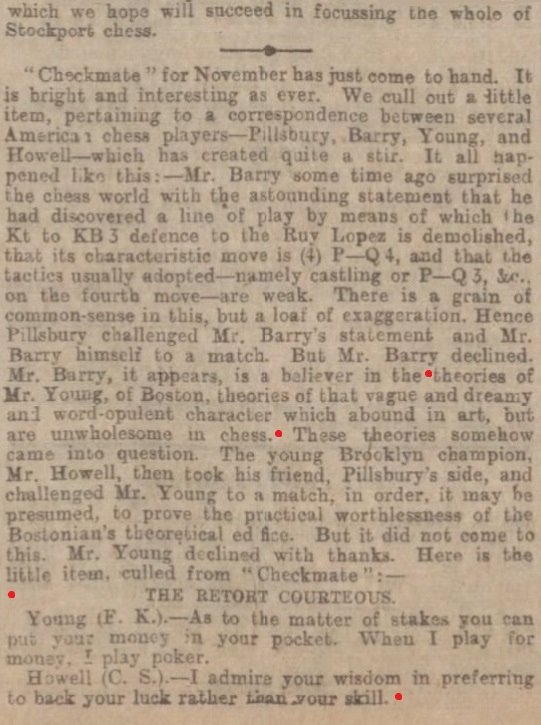

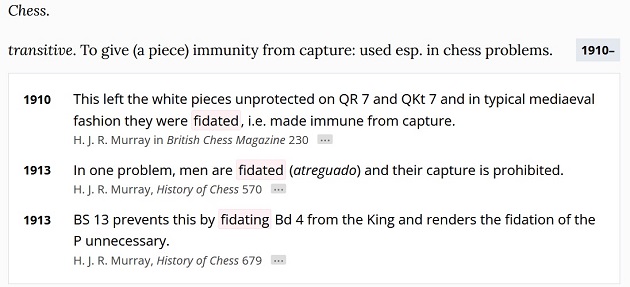

For a documented account, page 199 of the

November 1901 issue of Checkmate is the

first port of call:

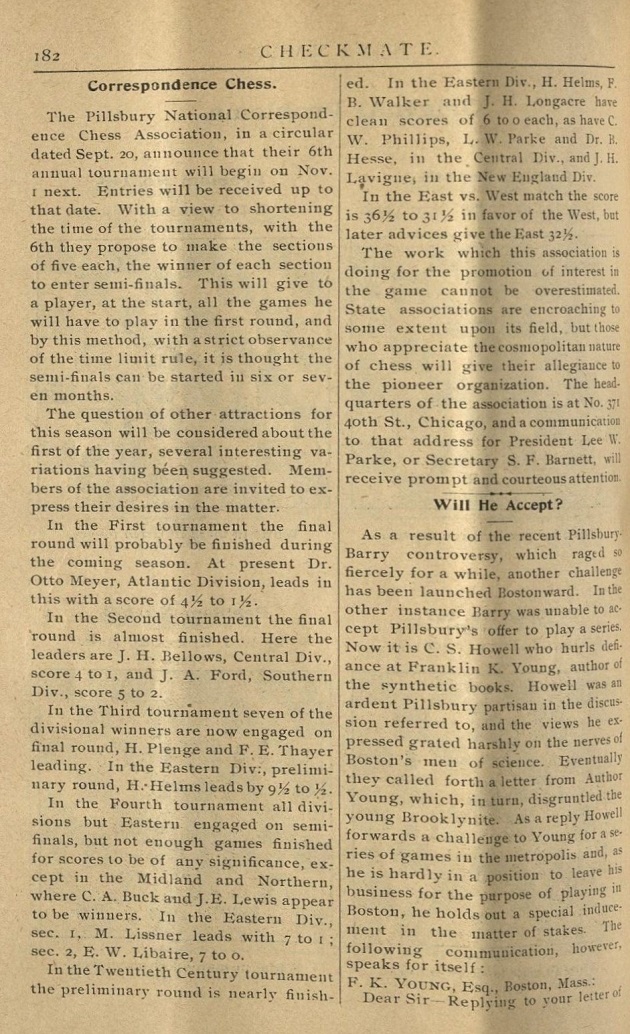

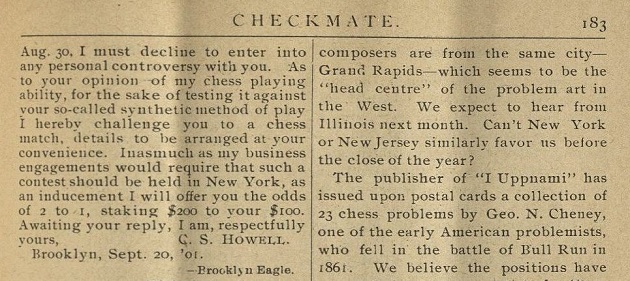

The account of the Pillsbury-Barry controversy

was the sequel to what had appeared on pages

182-183 of the October 1901 issue of the Canadian

magazine:

Acknowledgement

for the Checkmate scans: the Cleveland

Public Library.

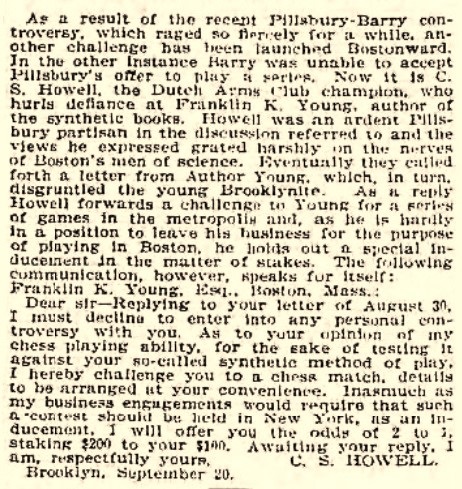

Below is the letter from Howell to Young as

published in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 22

September 1901, page 32:

Subsequent editions of the Brooklyn Daily

Eagle included these items with the chess

and poker comments:

29 September 1901,

page 20

20 October 1901,

page 23

None of this explains why K. Whyld indicated that

the words ‘theories of that vague and dreamy and

word-opulent character which abound in art, but

are unwholesome in chess’ were written by Howell

and led to the challenge.

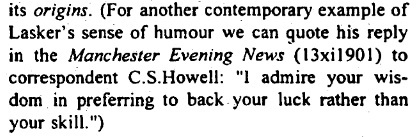

The BCM item contained no reference to

Emanuel Lasker, yet it was the world champion who

wrote the following in his column on page 6 of the

Manchester Evening News, 13 November 1901:

Tailpiece: the Lasker column was mentioned by

John Roycroft on page 909 of the October

1996

issue of EG:

In an uncharacteristic mistake, the final

section, ‘The Retort Courteous’, in the Manchester

Evening News was apparently misinterpreted

by EG as being Lasker’s answers to two

correspondents.

12027.

EG

In any list of the greatest chess periodicals, EG,

founded by John Roycroft in 1965, commands a high

position. The run is freely available online.

12028.

Anderssen

v Schallopp

Alan Smith (Stockport, England) reports that Chess Archaeology

provides a link to the third volume (1887) of Brüderschaft.

The periodical, edited by Schallopp and Heyde,

published, at intervals from page 104 onwards, 14

games between Anderssen and Schallopp, few of

which are commonly seen today.

12029. A

pawn

An item on page 153 of the July 1912 American

Chess Bulletin will be added to Chess

and War:

‘An incident of the Boer War

P.A. Hatchard of Albany, NY favors us with the

following touching incident from the Boer war:

Following one of the many engagements that took

place in this war, when the usual rounds were

made to ascertain the number of the killed and

wounded, there was found placed on the knapsack

of one of the former a single chess pawn, the

wounded man having evidently withdrawn it from

the box he carried and placed it in that

conspicuous position ere he succumbed. Many

papers at that period commented on this simple

act as being a silent interpreter of the poor

soldier’s thoughts, comparing himself to a lowly

pawn in the great and terrible game of war.’

12030.

Thousand

Islands, 1897

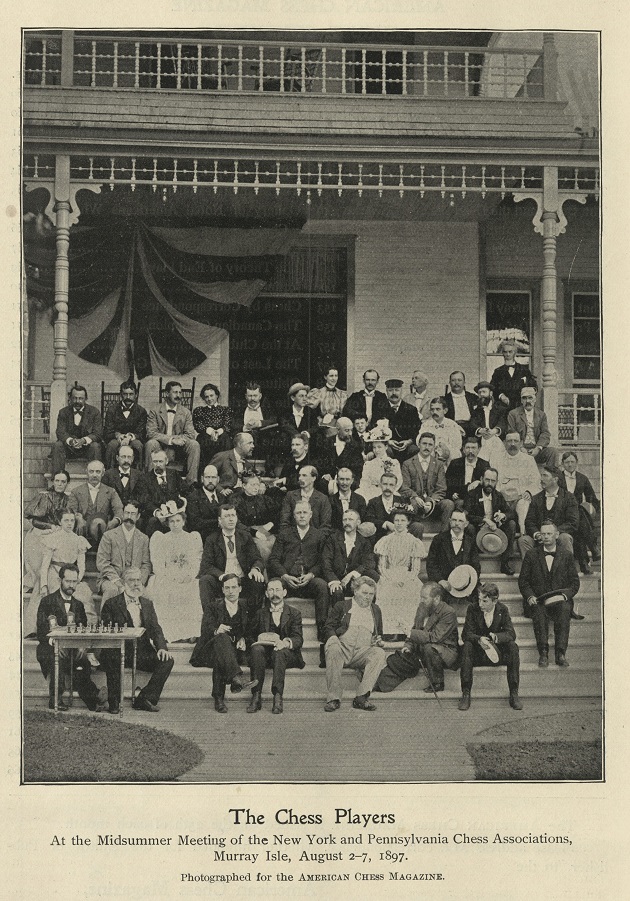

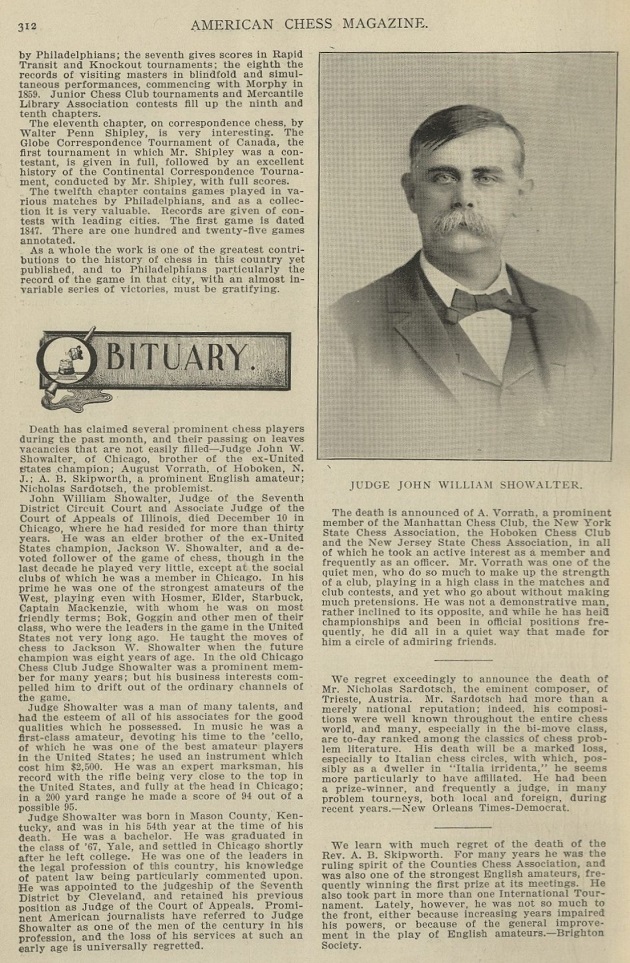

This photograph was published on page 129 of the

August 1897 American Chess Magazine:

Larger

version and detail of the front

row

We see no caption in the American Chess

Magazine, but as mentioned on page 408 of

the first of two volumes on Pillsbury by Nick Pope

(see the end of our article Harry

Nelson Pillsbury), those seated nearest to

the camera are Borsodi, Hanham, Pillsbury,

Lipschütz, Pieczonka, Steinitz and Napier.

An Albert

Pieczonka webpage shows another photograph

from the same location.

Page 148 of the August 1897 American Chess

Magazine has the group portrait given in

C.N. 5550, and the following is on page 149:

Larger

version

The above images have been provided by the

Cleveland Public Library.

12031.

Letters

and numbers

Concerning Letters

and

Numbers

in Chess Problems, Michael McDowell

(Westcliff-on-sea, England) writes:

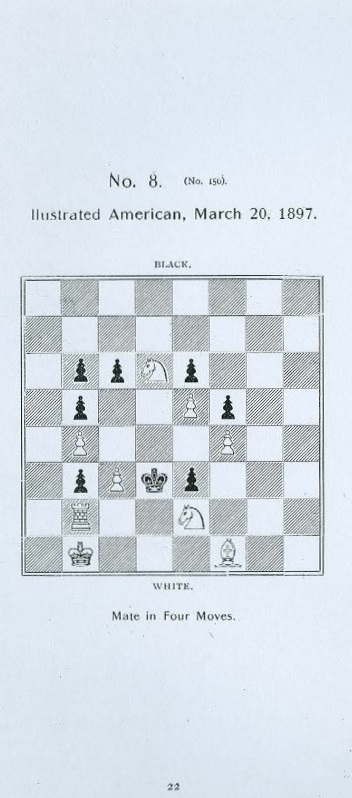

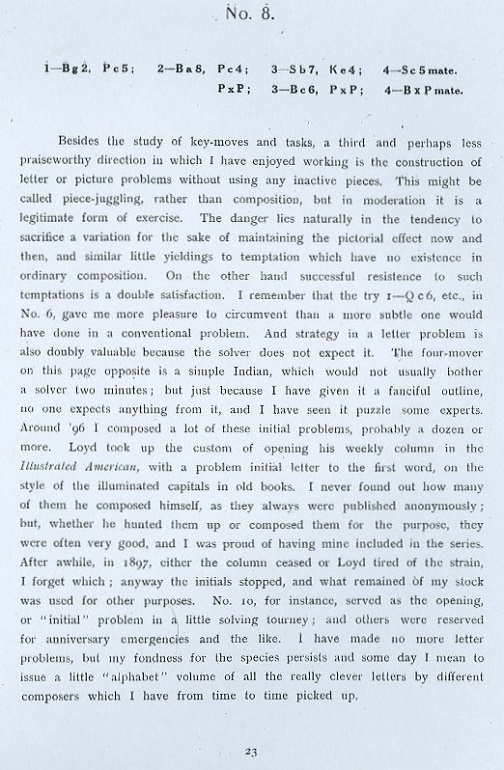

‘The composition on pages 22-23 of A.C.

White’s 1909 book Memories of My

Chessboard (Stroud, 1909) remains one of my

favourite letter problems, not least because

there are no pieces used simply to fill in the

shape. He was probably still 16 when he

composed it.’

12032.

Auguste

d’Orville

Auguste d’Orville (1804-64) was described on page

529

of Le Palamède, December 1847 as ‘le

maître des maîtres en fait de problèmes’,

yet he currently has a Wikipedia entry in only

French, German, Italian and Latvian.

The online availability of Some

problems by Auguste d’Orville by John

Beasley (1940-2024) is drawn to our attention by

Michael McDowell. See under ‘Problems’ in

‘Orthodox Chess’.

12033.

Ordinal

numbers

When and where did the practice arise of

referring to world chess champions with ordinal

numbers, at least until the 1993 bifurcation?

Kasparov is known as the 13th in the lineage, but

did writers in 1972, for instance, see any reason

to describe Spassky and Fischer as the 10th and

11th?

12034.

Images

If we received a nominal sum every time a scanned

image from chesshistory.com was misappropriated

and viewed on YouTube, Wikipedia, X/Twitter,

Facebook, chess.com, or other websites and

outlets, we could single-handedly offer to fund

future world championship matches.

See Copying.

12035.

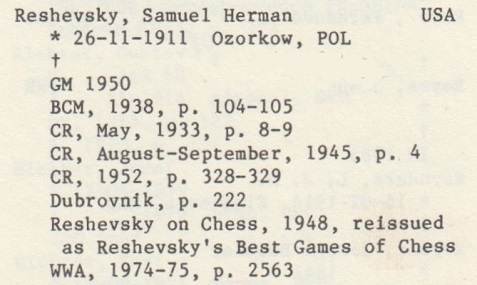

Samuel Reshevsky’s birth-date

C.N. 11994 invited readers to imagine themselves

as the editor of a chess quotations anthology

faced with handling a remark attributed, in

various wordings, to both Tarrasch and Tartakower.

Now, let readers see themselves as the editor of a

single-volume chess encyclopaedia and having to

decide what date of birth to give in the entry on

Samuel Reshevsky.

The natural course may be to follow Jeremy

Gaige’s Chess Personalia (Jefferson, 1987)

and take the precaution of also checking the

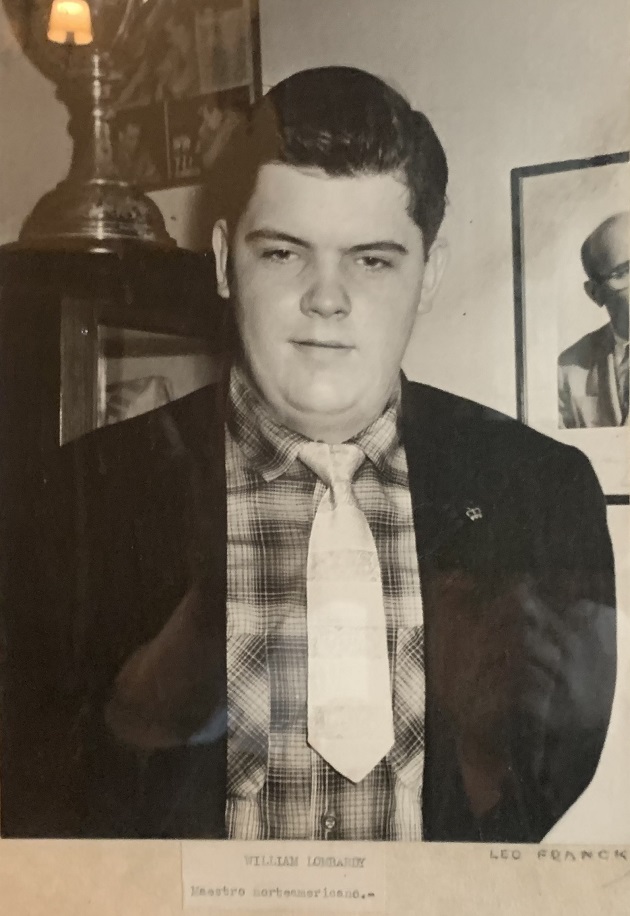

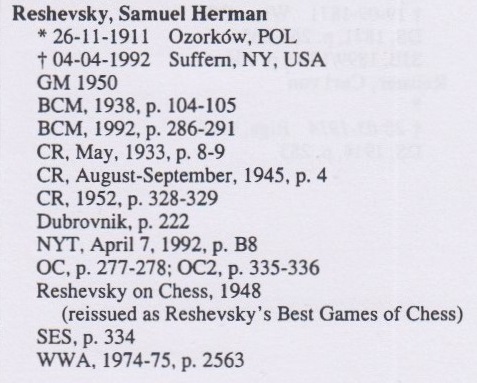

privately circulated 1994 edition:

‘26 November 1911’ is in both editions, but the

encyclopaedist may worryingly recall an article by

Andrew

Soltis on pages 10-11 of the August 1992 Chess

Life:

From C.N. 1943:

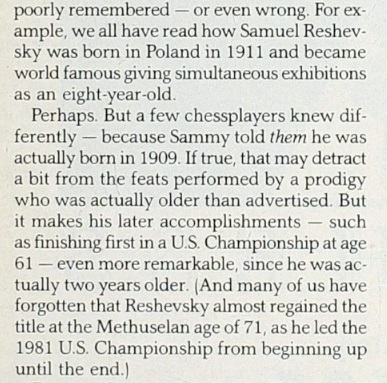

On page 10 of the August 1992 Chess Life

Andy Soltis wrote that Reshevsky had told a

number of chessplayers that he was born in 1909,

and not 1911 as commonly believed.

Page 202 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves

added a footnote:

However, in an interview with Hanon Russell in

August 1991, Reshevsky insisted that he had

indeed been born in 1911.

C.N. 11199 reverted to the subject:

... a claim emerged in the early 1990s that

Samuel Reshevsky was born in 1909 and not, as

commonly accepted, in 1911.

The matter is discussed by Bruce Monson in an

article about Reshevsky on pages 46-55 of the

1/2019 New in Chess.

Here, we quote the start of Monson’s

investigation of the birth-date matter (page 51):

‘But in the 1990s other information started

percolating to the surface, no doubt in the wake

of Sammy’s death on 4 April 1992. In the August

1992 Chess Life Andy Soltis revealed

that Reshevsky had told a number of chessplayers

that he was actually born in 1909 and not in

1911. Unfortunately, Soltis did not identify

these individuals. However, it is plausible.

Reshevsky was known on occasion to inadvertently

spill the beans about other “secrets” from his

past, such as the assertion that he had never

studied chess as a child, which is simply not

true, only to later try to shove the genie back

in the bottle.’

Difficult to summarize, Monson’s article is

important and should be read in full. It contains

both documentation and speculation, marked as

such. One image is a Łódź registration card dated

1919 which indicates that Samuel Reshevsky was

born in 1909 (with no exact date). Using this and

other materials and inferences, Monson wrote on

page 53 of the New in Chess article:

‘Conclusion: Reshevsky’s birthday should – at

the bare minimum – be adjusted to 26 November

1909. And in all probability his actual date of

birth was 26 May 1909, adding an additional six

months to his age.’

What, then, should our hypothetical

encyclopaedist put in the Reshevsky entry?

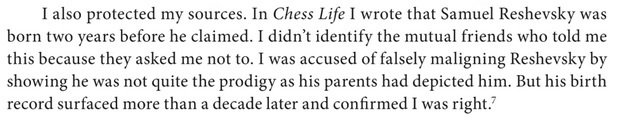

Andrew Soltis has a new book out, a chess memoir

entitled Deadline Grandmaster (Jefferson,

2024). Page 246, which can be viewed online,

includes the following:

Some obvious questions:

1. ‘In Chess Life I wrote that Samuel

Reshevsky was born two years before he claimed.’

Where in Chess Life? Certainly not on

page 10 of the August 1992 issue, where, as

shown above, Soltis mentioned the 1909 date

merely as a possibility derived from hearsay.

2. ‘I was accused of falsely maligning

Reshevsky.’ By whom, where and when?

3. ‘His birth record surfaced more than a

decade later and confirmed I was right.’ Where

and when? And more than a decade later than

what?

4. The Deadline Grandmaster text shown

above ends with a superscript 7. This leads to

the ‘Chapter Notes’, where, on page 356, note 7

reads (in full):

‘New in Chess, Issue 1, 1999.’

Why put that? Issue 1, 1999 of New in Chess

has nothing about Reshevsky’s date of birth.

Addition on 2 October 2024:

From Marek Soszynski (Birmingham, England):

‘I believe I was the first to discover and

publish evidence that Reshevsky was born in

1909, which I presented in my book The

Great Reshevsky: Chess Prodigy and Old Warrior

(Forward Chess, 2018). Bruce Monson briefly

references my findings in his article, and

explained to me at the time that the brevity

was due to editorial cuts by New in Chess.

My later book, Rare and Ruthless

Reshevsky (MarekMedia, 2023), does not

revisit the birthdate issue.’

12036.

Harry

Golombek at university

In the English-language edition of Wikipedia, the

entry on Harry Golombek currently states, for

unclear reasons, that he studied ‘philology at

King’s College, London’.

Our feature

article on him quotes the following:

- ‘Golombek went from Wilson’s Grammar to London

University, though there is no record of his

having completed his degree.’ (William

Hartston);

- ‘Golombek also began, but did not complete, a

general degree at King’s College, London,

leaving in 1932.’ (W.D. Rubinstein);

- ‘Golombek enjoyed a superlative gift for

conveying the drama of battles on the

chessboard, elevating chess commentary to the

literary level of the Icelandic epic sagas which

he had studied for his Doctorate.’ (Raymond

Keene).

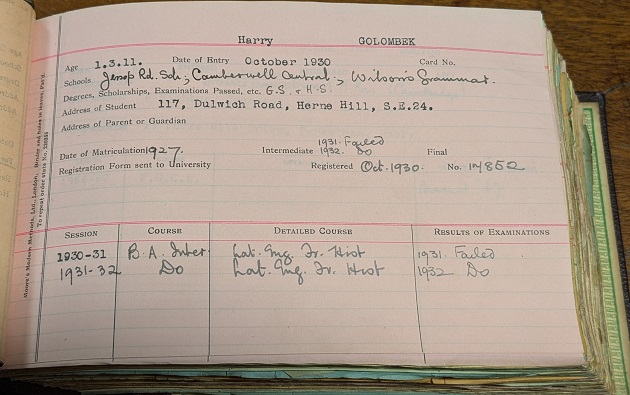

We are grateful to Gemma Hollman (the Senior

Archives Assistant, Libraries & Collections at

King’s College, London), who has searched the

student slip books, the main source for student

records, and has sent us the entry for Harry

Golombek:

Larger

version

It states that Golombek was registered for a

Bachelor of Arts degree (Latin, English, French

and History) from 1930 to 1932. He failed both

years.

12037.

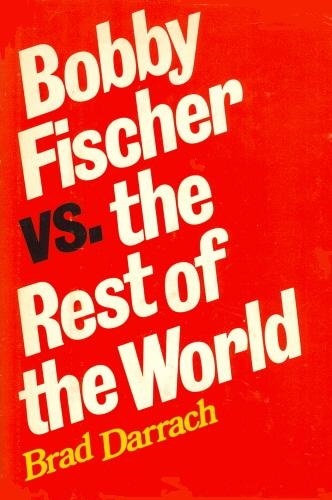

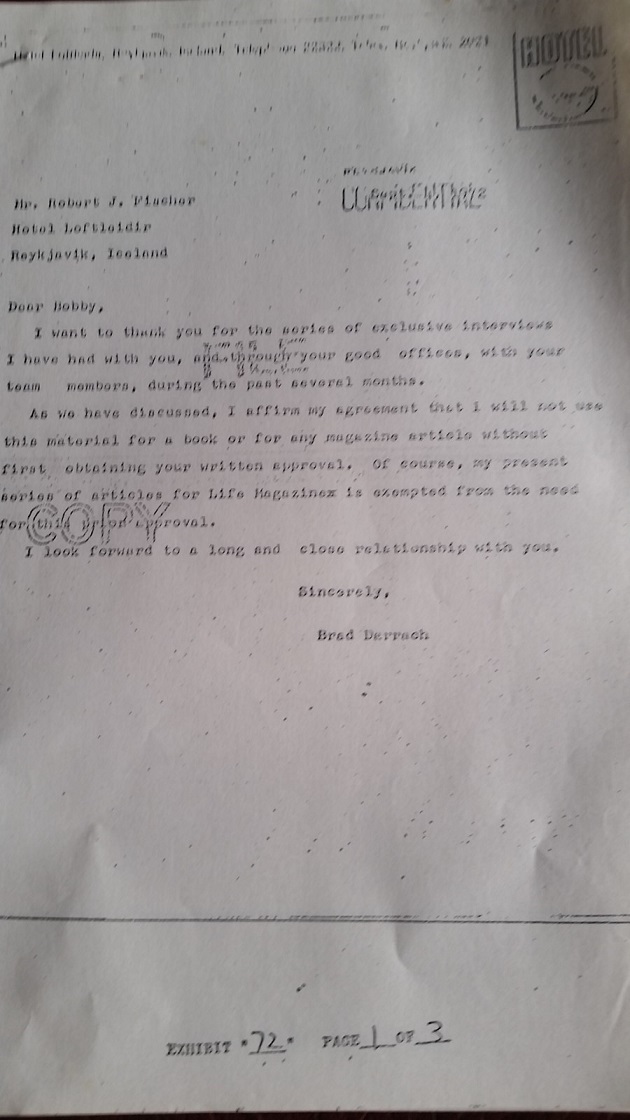

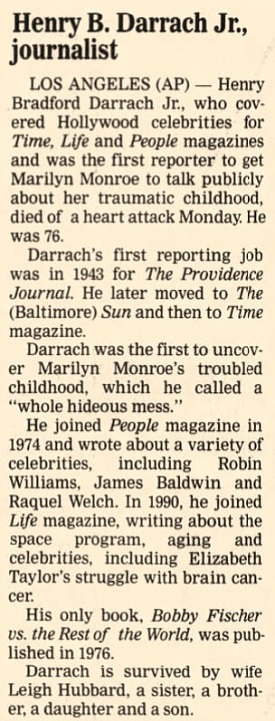

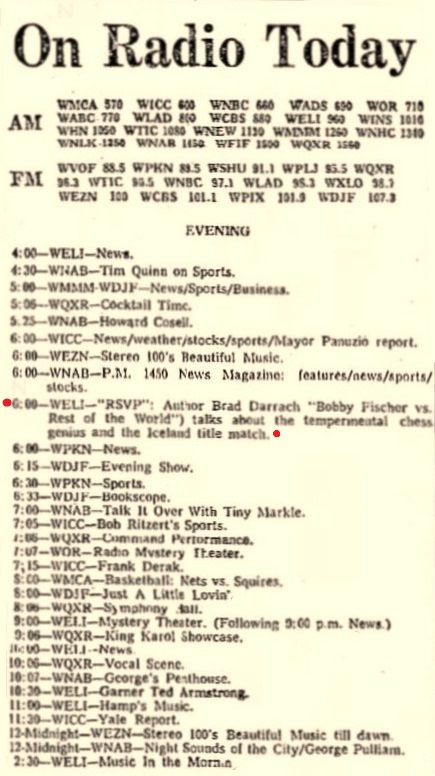

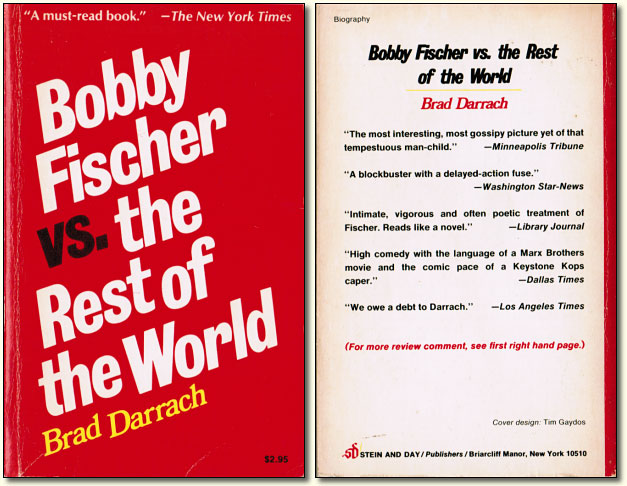

Brad Darrach v Bobby Fischer

Brad

Darrach

and the Dark Side of Bobby Fischer

summarizes the dispute about Darrach’s book Bobby

Fischer

vs. the Rest of the World (New York, 1974)

on pages 299-300 of the May

1975 Chess Life & Review, a

dispute which concerned three pieces in the New

York Times Book Review:

-

13 October 1974, page 6: a review by D. Keith

Mano of the Brad Darrach and George Steiner

books on the 1972 Spassky v Fischer match;

-

17 November 1974, page 59: a letter to the

Editor from Burt Hochberg, which is reproduced

in the May 1975 Chess Life & Review;

-

23 February 1975, pages 41-42: a letter to

the Editor from Brad Darrach in response to

Hochberg. Extracts were reproduced, and

disputed, by Hochberg in the May 1975 Chess

Life & Review.

See also the many references to Darrach indexed

in Bobby Fischer and His World by John

Donaldson (Los Angeles, 2020). These include, on

page 493, a brief comment that Darrach’s

above-mentioned letter was ‘the only public

response by Darrach after the book’s publication’.

Donaldson added:

‘Darrach shows no feelings of remorse in his

lengthy defense to charges by Frank Brady and

Burt Hochberg that he betrayed Bobby’s

confidence and put words in his mouth. Nor does

he comment about breaking his agreement with

Fischer.’

It should, however, be noted that such charges

did not appear in the Hochberg letter to which

Darrach was replying.

We add here some significant passages in

Darrach’s letter (sent from Madison, CT, USA) in

the New York Times Book Review which were

not quoted in Chess Life & Review:

-

‘The world of chess is like the Chinese court

in the story of “The Emperor’s New Clothes”.

The Emperor, Bobby Fischer, wanders about in a

strange condition but nobody dares to say what

everybody can see. In private, chess people

tell grotesque or funny stories about their

encounters with Mr Fischer; in public, they

butter him up. “We don’t dare to offend

Bobby”, one chess official told me. “He might

quit the game, and chess without Bobby would

be about as popular as tiddlywinks.”’

-

‘I take it Mr Hochberg thinks the subhumanity

is overstressed in the book. I can only say it

was overstressed in the man I wrote about.’

-

‘But Mr Hochberg will say I imply

interpretations and judgements of Mr Fischer

in my choice of incidents. I can only say I

tried to let the events speak for themselves.

If I have anywhere redressed reality, it is

only to omit dozens of scenes which, in

aggregate, would have made Mr Fischer seem

weird beyond belief – as in fact he sometimes

was.’

-

‘During the 13 months before the Reykjavik

match, on assignments from Life Magazine,

I visited Bobby, on the average, twice a week,

usually for five or six hours at a stretch;

sometimes I saw him every day for eight or ten

days in a row; when I did not see him we spoke

by telephone sometimes five or six times a

week. I saw him in New York, in Buenos Aires,

at his training camp in the Catskills. I saw

him in a hundred moods and circumstances –

happily scoffing up platefuls of Chinese food,

terrified in the back seat of a small plane,

red-eyed with rage as he kicked a photographer

in the shins, laughing as he romped with a

collie in the open pampas, guffawing at Red

Skelton on TV in a New York hotel room,

casually playing fast chess in an East Side

steak house as he tunneled into a two-inch

thick New York Cut, lying limp with a bad cold

in a stuffy little cell at Grossinger’s.

In Iceland, as the book makes clear, I saw

him every day and often most of the night for

more than two months.’

-

‘If my “viewpoint is severely limited” I’d

like to see the man who could stick with Mr

Fischer long enough to develop a broader one.’

-

‘Mr Hochberg is apparently interested in what

the match revealed about Mr Fischer’s chess; I

am more interested in what the match revealed

about Mr Fischer.

It revealed, among other things, such

murderous force that I find myself smiling at

Mr Hochberg’s attempts to protect Mr Fischer

from my book. The only thing Mr Fischer needs

to be protected from is Mr Fischer. Drifting

in fantasies, chased by terrors, rigidified by

pride, impelled to self-destruction, he will

be very lucky if he can survive his own

character long enough to defend his title

against Anatoly Karpov. If he can beat that

truly formidable young Russian, we may begin

to believe he belongs with the supreme

masters, Steinitz and Lasker and Botvinnik,

who attained the pinnacle and held it. If he

welshes on the match he will be remembered as

a half-mad maverick who could produce great

games and even great years, but lacked the

will and the principle to sustain a great

career.’

12038.

Davide Nastasio (C.N. 11979)

Below is one of the examples of copying

recorded in C.N. 11979:

The ChessBase

contributor

Davide

Nastasio has been lifting a huge number of

C.N. photographs (about 80 in the past week

alone), without credit, acknowledgement or

authorization, for his personal X/Twitter page.

Despite that item, posted on 28 January 2024, Mr

Nastasio has refused to stop his misappropriation.

Indeed, on a single recent day, 30 September 2024,

he put online over 20 of our images.

Addition on 22 October 2024:

ChessBase has informed us that Davide Nastasio is

now a former ChessBase author.

12039.

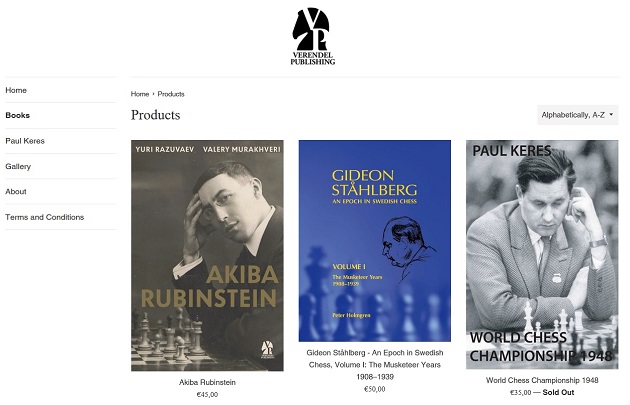

Verendel

It is always a pleasure to acknowledge chess

publishers with high production standards. A

newcomer is Verendel

Publishing:

12040.

Lady

Jane Carew

One of the quotes under the heading ‘Longevity’

in C.N. 4789 was from page 479 of the December

1901 BCM:

‘Death of Centenarian Lady Chessplayer. – The Liverpool

Daily Post of 15 November records the

death of Jane Lady Carew, at the age of 104. The

deceased lady was the grandmother of the present

Lord Carew. She was married the year after

Waterloo, and had been a widow nearly 50 years.

Her active memory included the whole of the

reigns of George IV, William IV and Victoria,

the period during which George III could not

control the affairs of Great Britain and, of

course, the opening of the present era. ...

Until she had passed her 100th birthday she

played a capital game of chess ...’

From John Townsend (Wokingham, England):

‘“It is said that the oldest

Chess-player in the world is Dowager Lady

Carew, who was born in 1798.”

This uncorroborated statement appeared on

page 684 of Digest: Review of Reviews

Incorporating The Literary Digest, in 1901,

the year of her death. Various writers mention

that Lady Jane Carew was a strong chessplayer.

One complimentary description appeared in the

Cheltenham Examiner (20 November 1901,

page 6):

“In middle age she was, for a lady, an

exceptionally strong player.”

A local newspaper, the Waterford

Standard (16 November 1901, page 3), was a

little more restrained, referring to her as

“formerly a chess player of more than average

strength”.

In an article in the Dublin Evening

Herald (16 November 1901, page 9) J.A.

Porterfield Rynd mentioned Lady Carew’s

recollections on the subject of slow play:

“During the last 50 years of her life she had

seen in force the sand-glass and clock

mechanism for regulating the speed of moving;

and for the antecedent period the old lady had

many quaint stories recounting the immoderate

slowness of ancient moving. From the case of a

man who, in desperate condition consumed hours

and days over a single move, and, when asked

why he didn’t move, replied: “Because I should

lose” – to the case of St Amant tiring out

Staunton (the English slow-coach), she seemed

to remember almost every notable instance of

excessive slowness. She had, of course, met

examples of the opposite kind like that of our

still lamented Mr Thos. P. Mason whose average

time for a game was under five minutes.”

The source of Lady Carew’s information is

not known. Staunton’s second, Lieutenant Harry

Wilson, claimed to have measured the length of

the players’ cogitations and found St Amant

the slower. (See, for example, Wilson’s letter

to the Chess Player’s Chronicle,

volume 5, 1845, pages 148-149.) It is unusual

to read of St Amant “tiring out Staunton”,

especially since the latter won the match by

no small margin. One wonders if she or the

author may have confused St Amant with Elijah

Williams, the “Bristol sloth” who,

according to one report, “wore out Staunton”.

Lady Jane Carew made her own special

contribution to longevity by living in three

centuries. According to G.E. Cokayne’s The

Complete

Peerage, 1910-1959, which is widely regarded

as the most accurate of the peerage works, and

certainly the most voluminous (13 volumes in

14), she was born during the month of December

1798 and died on 12 November 1901. Thus, she

attained the advanced age of 102, and not 103

or 104, as are sometimes incorrectly claimed.

Yet a record of her baptism or birth in a

parish register remains to be discovered.

Jane Catherine Cliffe came of military stock

on both sides, being the daughter of Major

Anthony Cliffe, of Ross, and Frances Deane,

the daughter of Colonel Joseph Deane; they had

been married on 16 December 1795. After her

death, the Adelaide Observer of 16

November 1901 (page 26) reported as follows:

“During the insurrection in Ireland in 1798,

the year of Lady Carew’s birth, her father,

Mjr Cliffe, remained to take his part in

quelling it, while his wife and father fled to

England – Haverfordwest – where the baby was

born.”

An Australian writer may perhaps be excused

for placing Haverfordwest (Wales) in England,

and the statement is otherwise correct.

Although Holyhead is given as her birthplace

in some sources, Haverfordwest is confirmed as

her native place by a letter accompanying Biographical

notes on Lady Jane Carew (1798-1901) made by

C. Davies Gilbert, of Trelissick, her

grandson, 1901. Both items are deposited at

the Cornwall Record Office (ref. DG/148/1

& 2).

Her married name became Carew when she tied

the knot with Robert Shapland Carew, son of

Robert Shapland Carew and Anne Pigott, on 16

November 1816 and, after her husband was

elevated to the peerage as first Baron Carew

on 13 June 1834, she was styled Baroness

Carew. They had four children together,

including the second Baron Carew, Robert

Shapland Carew. She became the Dowager Lady

Carew after her husband’s death in 1856.

For many decades, including most of her

widowhood, she resided at Woodstown, in the

county of Waterford. This was particularly

close to Dunmore, in the Bay of Waterford,

which, in an article about chess in Ireland,

Howard Staunton had identified as “ ... the

only spot where real Chess could be met with

...” (Chess Player’s Chronicle, volume

4, 1844, page 147), and, even though she was

not mentioned by name, it seems likely that

this circle of players was familiar to her.

However, Staunton added that, after the

departure of Captain Evans, the circle “fell

to pieces and was dispersed”. An important

product of the school was Sir John Blunden,

who became one of the strongest amateur

players in Ireland. Charles French Smith,

opponent and contemporary of H.E. Bird, was

born at Waterford, circa 1828,

according to the 1851 census.

The Dublin Evening Mail of 13

November 1901 (page 2) indicates that another

focus of her attention was local education,

“to which she was a liberal contributor,

several schools in her neighbourhood being

maintained by her assistance”.

On 15 January 1898 the Wicklow People

(page 5) noted that, although she had been

confined to her room for some years past, she

was in excellent health, read small print

without the aid of spectacles, and played “a

game of chess every evening before going to

bed”.

A writer in Notes and Queries (Series

9, volume X, 2 August 1902, page 92) included

the following note on Carew pronunciation:

“I asked the Hon. Mrs P. B. (daughter of the

late centenarian Lady Jane Carew ... who did

not dance at the Waterloo ball, and whose

parents fled to Haverfordwest, not Holyhead,

as the newspapers stated) how she pronounced

her family name, and she rendered it rather a

trisyllable, in accord with the ancient

spelling in the public records – Cariou, temp.

Hen. II; Karrieu, temp. Ric. I.;

Carrio, temp. John; and Karreu, temp.

Ed. I.”

I would like to acknowledge with thanks the

help received from Brian Denman, of Sussex,

England, who kindly pointed out to me the

existence of several of the newspaper articles

and Biographical notes on Lady Jane Carew

(1798-1901).’

12041.

The initiative

Donald Whitlock (Solihull, England) raises the

subject of the initiative in chess, and we seek

early appearances of the term, with a quest for

the best definition.

‘The player who completes his development first

is said to have the initiative, because he is thus

able to start making blunders while his opponent

is still occupied in bringing out his men’ is a

remark given in C.N. 1858 from page 14 of “Among