Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [93] | next >> | Current column |

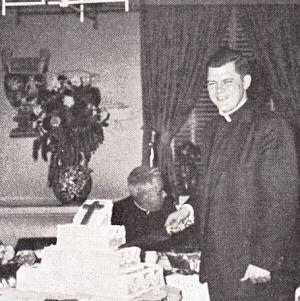

7578. Lombardy

These photographs of ‘Father Lombardy’/ ‘Father Bill’ accompanied the article ‘From Lopez to Lombardy’ by Beth Cassidy on page 229 of the August 1967 Chess Life. It began:

‘When International Grandmaster Bill Lombardy was ordained a Priest on 27 May by Cardinal Spellman in New York, it marked the first time in 400 years that a world renowned chessplayer was also a member of the Roman Catholic Clergy.’

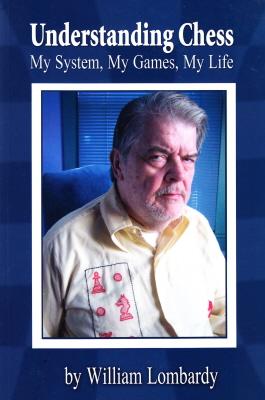

Lombardy himself writes on page 289 of his book Understanding Chess. My System, My Games, My Life (New York, 2011):

‘If someone were to make a list and refuse to place my name ahead of all other ordained chessplaying Clergy, then such a list-maker is unaware of history or the practical appraisal of relative comparisons in strength through games and opponents. I once saw such a list that placed me fifth on the all-time list of strongest clergy chessplayers. Aside from my credentials among those in the chess clergy, I also occupied a prominent place among the best players of my time.’

That is but the plain truth. Lombardy is on weaker ground when, on the next page, he refers to a game supposedly played by Pope Leo XIII. (See the references to Pope Leo in our Factfinder.)

Pages 22-23 have Lombardy’s interestingly unconventional views on castling, and some of his observations are extracted here:

‘The problems posed by the decision to castle are much misunderstood and thereby underrated.

... So, my new advice on castling: it is castling is to be considered a waste of time wrongly expended when there is almost always something more important to achieve. Thus castling is a passive move that nurtures the hope of king safety. I believe that a player who learns how and when to delay castling will certainly improve his/her play. Very often that cherished hope of safety is ill founded. I therefore believe that the maneuver of castling is the most dangerous of all moves and the decision thus requires more attention to delicate judgment.

Not only should one not rush to castle, but should delay that passive maneuver for as long as good judgment relates that there are more urgent, if only slightly better, tasks to accomplish.’

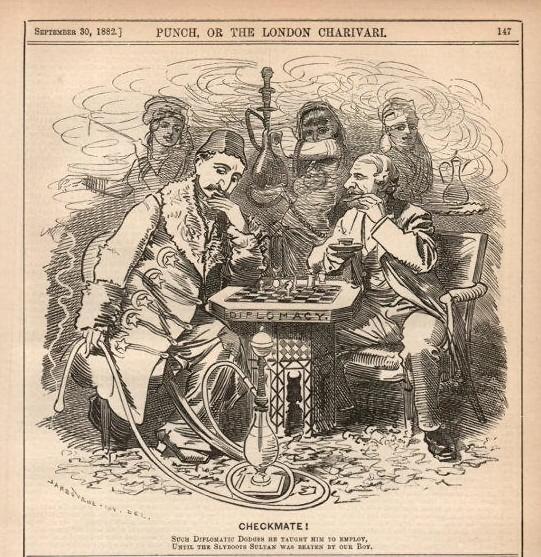

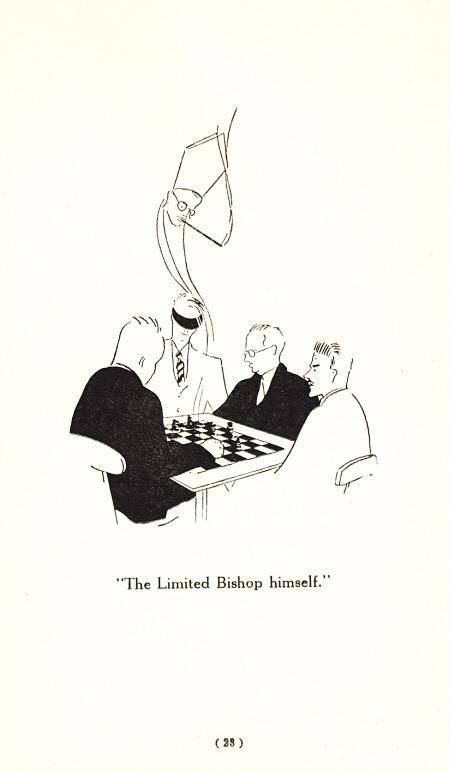

7579. Punch cartoon

Ross Jackson (Raumati South, New Zealand) recently acquired this cartoon, published on page 147 of Punch, 30 September 1882:

7580. Allegro chess

Noting the remark by Capablanca cited in C.N. 7557 (‘were it not for the fact that I have beaten Lasker at rapid chess, he would be considered the foremost rapid chessplayer in the world’), Jonathan Berry (Nanaimo, BC, Canada) writes:

‘I regret the passing of the label “Allegro” in reference to games with a time-control of about 30 minutes. It was in minor usage, persisted in Scotland, but eventually disappeared behind what I regard as inferior (either less descriptive or more ambiguous) labels: “Active”, “Action” and “Rapid”.’

In C.N. 1692 Stewart Reuben (Twickenham, England) gave definitions of about ten names used to describe fast chess, including ‘Allegro (Scotland)’.

7581. Ozols

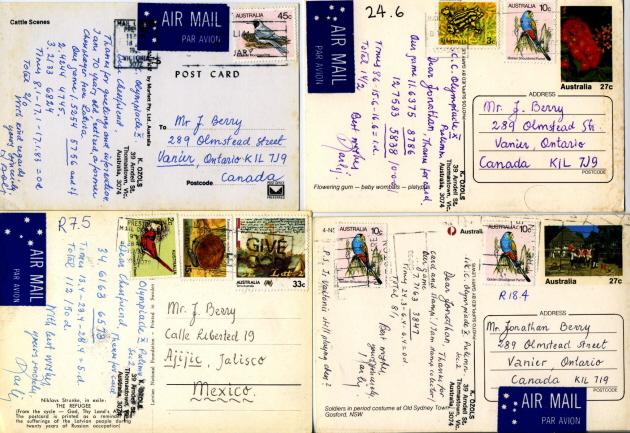

Mr Berry has also forwarded us a number of postcards from a game which he played against Karlis Ozols in the tenth Correspondence Chess Olympiad (1983-84):

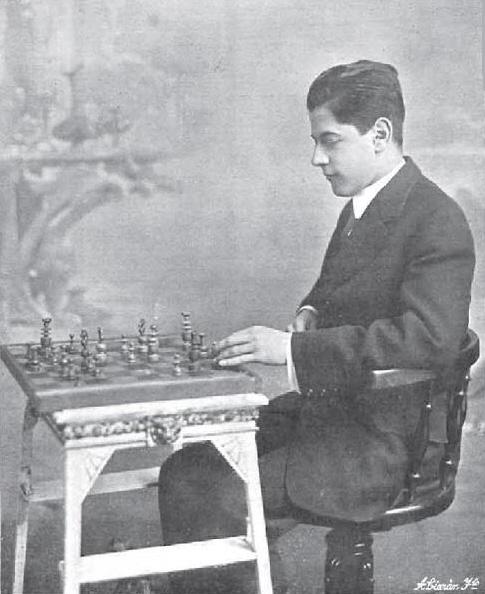

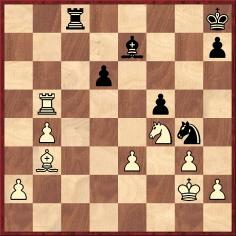

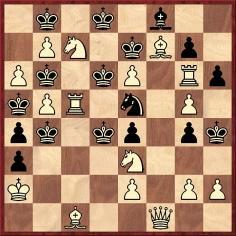

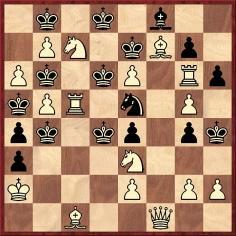

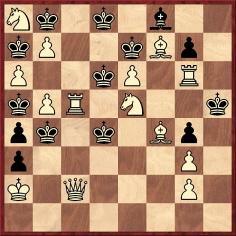

7582. Capablanca at San Sebastián, 1911

From Manuel Fernández Díaz (Estepa, Spain) comes this photograph of Capablanca which appeared on page 192 of the Madrid publication La Ilustración Española y Americana, 30 March 1911:

Readers are invited to examine closely the board set-up.

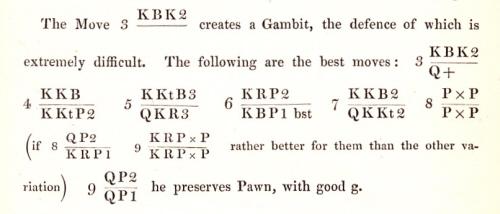

7583. 1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Be2

We offer a selection of references concerning the ‘Lesser Bishop’s Gambit’, an opening to which the names of Jaenisch, Bird, Tartakower and Crowl have been linked. Below is part of page 221 of Jaenisch’s Chess Preceptor (London, 1847):

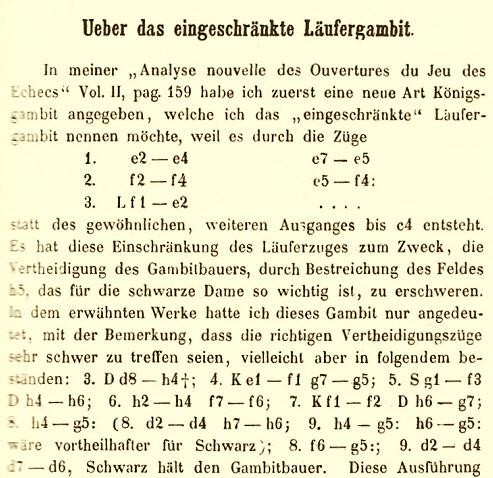

Jaenisch also contributed an article entitled ‘Ueber das eingeschränkte Läufergambit’ on pages 437-440 of the December 1849 Deutsche Schachzeitung:

Max Lange wrote a follow-up article under the same title

on pages 365-370 of the October 1850 issue. See too ‘Das

eingeschränkte Läufergambit’ on pages 148-150 of the

March 1854 Deutsche Schachzeitung. A victory by

Max Lange (White) was given on pages 288-290 of Chess

Praxis by Howard Staunton (London, 1860).

When a game between Bristol and Dublin was published on pages 148-150 of The Bristol Chess Club by J. Burt (Bristol, 1883), 3 Be2 received the following note:

‘This ridiculous mode of continuing the opening is simply third-rate play, styled by its admirers “The Clifton Gambit”. For the credit of the Bristol Club, we trust its sponsors will give their protégé a more deserving title; one in accordance with its merits. The intention of this officer, apparently, was to reconnoitre the enemy’s position at R fifth, instead of attacking it at B fourth.’

Bird’s involvement with 3 Be2 is well known. For instance, he played it against Max Weiss at Bradford, 1888. When the game was published on pages 312-313 of the October 1888 International Chess Magazine Steinitz commented (inaccurately) on 3 Be2:

‘An oddity invented by Mr Bird. We do not think it has any sufficient attacking merit to compensate for the P.’

Pages 41-48 of Bird’s book Chess Novelties (London, 1895) had coverage of 3 Be2, which was called ‘The Lesser, Little, or Limited Bishop’s Gambit’. Bird wrote: ‘There is no opening from which the writer has derived more interesting or enjoyable games than this, which he has played with much zest for ten years.’ In a list of openings on page 10 the name was ‘Bird’s Little Bishop’s Gambit’.

Tartakower’s use of 3 Be2 at New York, 1924 is also familiar. On page 121 of the first volume of his Best Games (London, 1953) he annotated his victory over Yates, commenting regarding 3 Be2:

‘This resurrection of an old ill-famed variation gained for me in the New York tournament, in addition to the present victory, that against Bogoljubow in the very first round of the competition.’

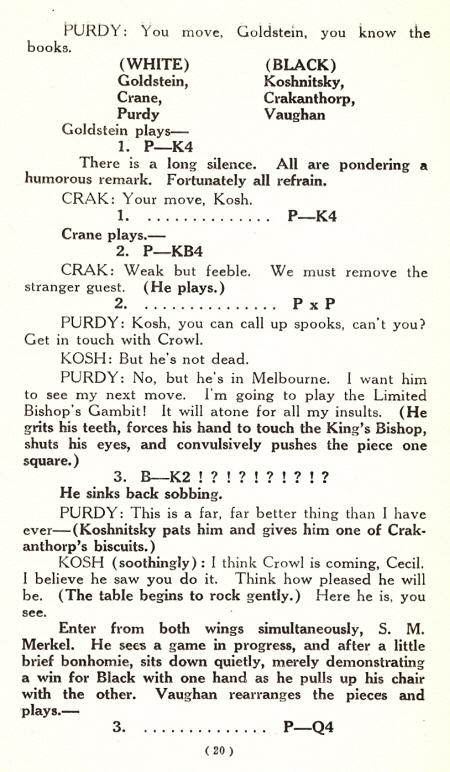

On pages 30-32 of the February 1953 Chess World M.E. Goldstein (Black) annotated his win against F.A. Crowl. The first note, to 3 Be2, began:

‘A favourite début of Tartakower and Crowl. In fact, 20 years ago Crowl played this opening so often that he was nicknamed “the Limited Bishop”.’

A game on pages 135-136 of the November-December 1965 issue of Chess World again mentioned Crowl:

‘The Limited Bishop’s Gambit has probably never been so minutely analysed as in the Australasian Chess Review of 1930. At one time this opening was so actively sponsored by Crowl that F.L. Vaughan christened him the Limited Bishop, and this was where “Chielamangus” [a pseudonym for Purdy] got the title for his one-act play.’

The play had been published on pages 17-26 of “Among These Mates” by “Chielamangus” (Sydney, 1939). Below are pages 20 and 23:

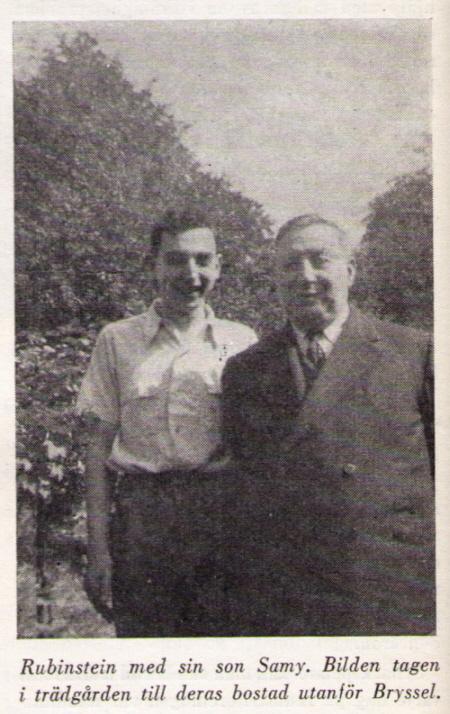

7584. Rubinstein (C.N. 7572)

This sketch of A. Rubinstein by his son Sammy is reproduced courtesy of John Donaldson (Berkeley, CA, USA). It appears on page 380 of the 2011 monograph which he co-wrote with N. Minev (C.N. 7572).

Mr Donaldson comments to us that the latest photograph of Rubinstein known to him was published on page 124 of the June 1949 issue of Tidskrift för Schack. We are grateful to Calle Erlandsson (Lund, Sweden) for the scan below:

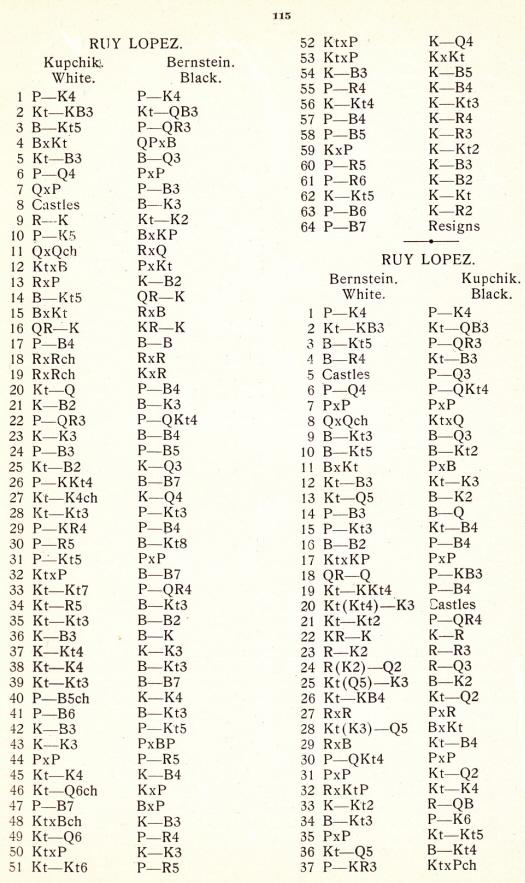

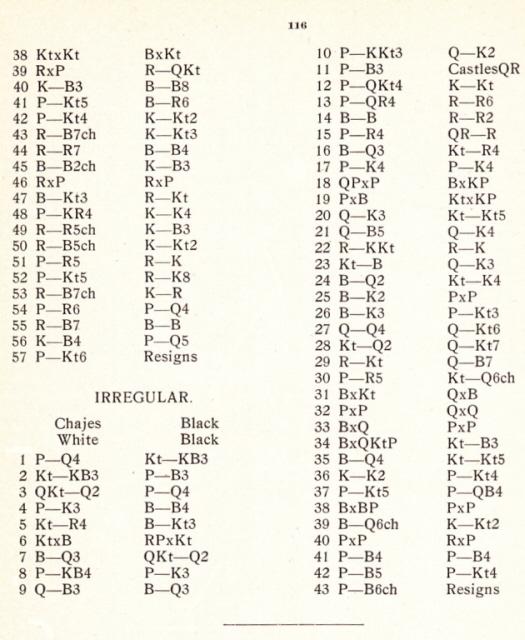

7585. Three games

Marc Hébert (Charny, Canada) remarks that three games were published on pages 115-116 of the May-June 1917 American Chess Bulletin without any introduction or information about the circumstances:

Abraham Kupchik – Jacob Bernstein

Occasion?

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Bxc6 dxc6 5 Nc3 Bd6 6 d4 exd4 7 Qxd4 f6 8 O-O Be6 9 Re1 Ne7 10 e5 Bxe5 11 Qxd8+ Rxd8 12 Nxe5 fxe5 13 Rxe5 Kf7 14 Bg5 Rde8 15 Bxe7 Rxe7 16 Rae1 Rhe8 17 f4 Bc8 18 Rxe7+ Rxe719 Rxe7+ Kxe7

20 Nd1 c5 21 Kf2 Be6 22 a3 b5 23 Ke3 Bf5 24 c3 c4 25 Nf2 Kd6 26 g4 Bc2 27 Ne4+ Kd5 28 Ng3 g6 29 h4 c5 30 h5 Bb1 31 g5 gxh5 32 Nxh5 Bc2 33 Ng7 a5 34 Nh5 Bg6 35 Ng3 Bf7 36 Kf3 Be8 37 Kg4 Ke6 38 Ne4 Bg6 39 Ng3 Bc2 40 f5+ Ke5 41 f6 Bg6 42 Kf3 b4 43 Ke3 bxc3 44 bxc3 a4 45 Ne4 Kf5 46 Nd6+ Kxg5 47 f7 Bxf7 48 Nxf7+ Kf6 49 Nd6 h5 50 Nxc4 Ke6 51 Nb6 h4 52 Nxa4 Kd5 53 Nxc5 Kxc5 54 Kf3 Kc4 55 a4 Kc5 56 Kg4 Kb6 57 c4 Ka5 58 c5 Ka6 59 Kxh4 Kb7 60 a5 Kc6 61 a6 Kc7 62 Kg5 Kb8 63 c6 Ka7 64 c7 Resigns.

Jacob Bernstein – Abraham KupchikOccasion?

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 O-O d6 6 d4 b5 7 dxe5 dxe5 8 Qxd8+ Nxd8 9 Bb3 Bd6 10 Bg5 Bb7 11 Bxf6 gxf6 12 Nc3 Ne6 13 Nd5 Be7 14 c3 Bd8 15 g3 Nc5 16 Bc2 f5 17 Nxe5 fxe4 18 Rad1 f6 19 Ng4 f5 20 Nge3 O-O 21 Ng2 a5 22 Rfe1 Kh8 23 Re2 Ra6 24 Red2 Rd6 25 Nde3 Be7 26 Nf4 Nd7 27 Rxd6 cxd6 28 Ned5 Bxd5 29 Rxd5 Nc5 30 b4 axb4 31 cxb4 Nd7 32 Rxb5 Ne5 33 Kg2 Rc8 34 Bb3 e3 35 fxe3 Ng4

36 Nd5 Bg5 37 h3 Nxe3+ 38 Nxe3 Bxe3 39 Rxf5 Rb8 40 Kf3 Bc1 41 b5 Ba3 42 g4 Kg7 43 Rf7+ Kg6 44 Ra7 Bc5 45 Bc2+ Kf6 46 Rxh7 Rxb5 47 Bb3 Rb8 48 h4 Ke5 49 Rh5+ Kf6 50 Rf5+ Kg7 51 h5 Re8 52 g5 Re1 53 Rf7+ Kh8 54 h6 d5 55 Rc7 Bf8 56 Kf4 d4 57 g6 Resigns.

Oscar Chajes – Roy Turnbull BlackOccasion?

Queen’s Pawn Game

1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 c6 3 Nbd2 d5 4 e3 Bf5 5 Nh4 Bg6 6 Nxg6 hxg6 7 Bd3 Nbd7 8 f4 e6 9 Qf3 Bd6 10 g3 Qe7 11 c3 O-O-O 12 b4 Kb8 13 a4 Rh3 14 Bf1 Rh7 15 h4 Rdh8 16 Bd3 Nh5

17 e4 e5 18 dxe5 Bxe5 19 fxe5 Nxe5 20 Qe3 Ng4 21 Qc5 Qe5 22 Rg1 Re8 23 Nf1 Qe6 24 Bd2 Ne5 25 Be2 dxe4 26 Be3 b6 27 Qd4 Qb3 28 Nd2 Qb2 29 Rb1 Qc2 30 a5 Nd3+ 31 Bxd3 Qxd3 32 axb6 Qxd4 33 Bxd4 axb6 34 Bxb6 Nf6 35 Bd4 Ng4 36 Ke2 g5 37 b5 c5 38 Bxc5 gxh4 39 Bd6+ Kb7 40 gxh4 Rxh4 41 c4 f5 42 c5 g5 43 c6+ Resigns.

Can any further details be found?

7586. Who? (C.N. 7573)

The photograph is of Jack Spence, from page 50 of the American Chess Bulletin, May-June 1949.

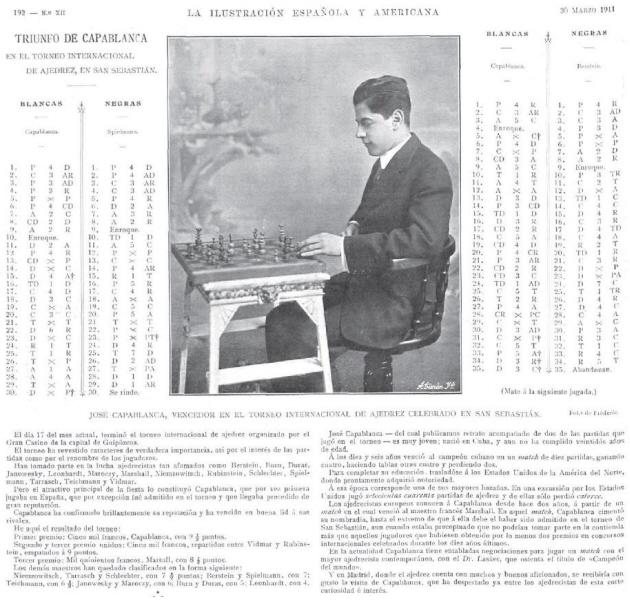

7587. Capablanca at San Sebastián, 1911 (C.N. 7582)

When submitting the photograph of Capablanca given in C.N. 7582, Manuel Fernández Díaz (Estepa, Spain) noted that, despite appearances, the board position does correspond to an actual game, i.e. Capablanca v Ossip Bernstein, with 24 Rc1 being played. Marcelo Sibille (Montevideo, Uruguay) has also mentioned this to us.

Below is the full column (with many factual errors) on page 192 of La Ilustración Española y Americana, 30 March 1911:

7588. Nimzowitsch v Alapin

Our latest feature article concerns the complexities surrounding the celebrated Nimzowitsch v Alapin miniature.

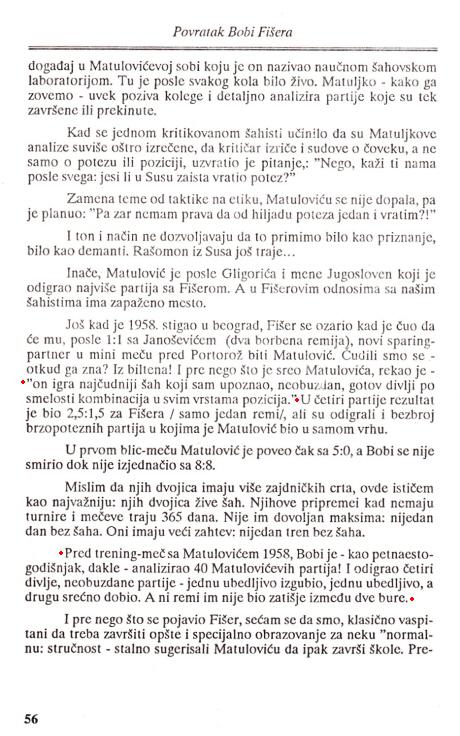

7589. The Fischer v Matulović match

Referring to the 1958 Fischer v Matulović match (won by Fischer 2½-1½), Kiril Penušliski (Skopje, Macedonia) draws attention to page 56 of Povratak Bobi Fišera by B. Ivkov (Novi Sad, 1993):

With regard to the two marked passages our correspondent comments:

‘Ivkov attributes to Fischer (without a source) the following remark concerning Matulović:

“He plays the strangest chess I have ever encountered, fierce, almost wild in the daring of the combinations in all types of positions.”

Towards the bottom of the page Ivkov states:

“Before the 1958 training match with Matulović, Fischer – as a 15 year old – analysed 40 of Matulović’s games. And he played four wild, fierce games – convincingly losing one, winning one convincingly and one luckily. And the drawn game was not a calm between two storms.”

These comments suggest that Ivkov had seen the four games of the Fischer v Matulović match.’

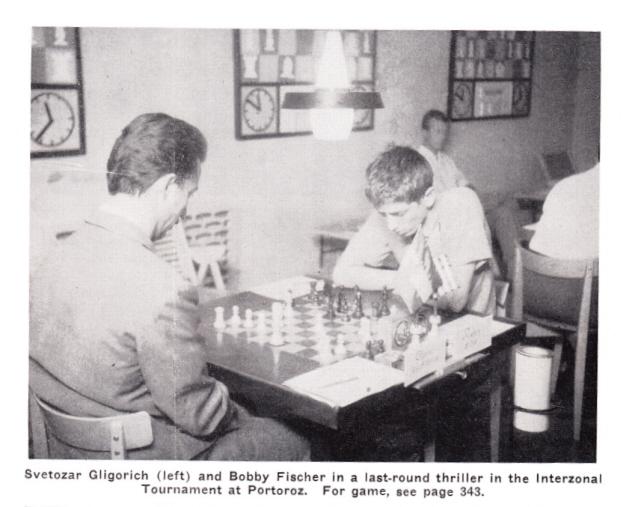

We are aware of no photographs from the match. The shot below, taken six or seven weeks later, comes from page 323 of Chess Review, November 1958:

7590. Maurice Billecard (C.N.s 4798, 7312, 7319 & 7324)

Hans Renette (Bierbeek, Belgium) has found on the Archives nationales d’outre mer website the birth certificate of Maurice Gabriel Anthelme Billecard, who was born on 17 December 1904 in Algiers. His father was identified as Antoine Maurice Anthelme Billecard, a 28-year-old magistrate. That information matches the chessplayer’s year of birth (1876) given by Jeremy Gaige in Chess Personalia (C.N. 4798), as well as the information about his legal profession (C.N. 7319).

Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) comments that the availability of the chessplayer’s full forenames, Antoine Maurice Anthelme, makes it possible to find online further details about him, including his exact date and place of birth: 3 August 1876 in Lure (Haute-Saône). The next task is to discover when and where he died.

7591. Frank Hollings

Adam Douglas (London) writes:

‘Frank Hollings was the trading name of William Edward Redway (1866-1945), the second proprietor of the Frank Hollings bookshop.

There never was a real “Frank Hollings”. The antiquarian bookshop was started in 1892 by James Francis Hollings Shepherd (born 1844), the younger brother of the eccentric writer and bibliographer Richard Herne Shepherd. James Shepherd used his two middle names to create an alternative trading name for his bookshop, as he was already in trade under his real name as a silversmith, having founded the firm Saunders & Shepherd (with Cornelius Desormeaux Saunders) in 1869. From 1873 to 1902 their silver business was conducted at Bartlett’s Passage, Holborn Circus. As the Saunders Shepherd Group, the business continues to this day.

Shepherd opened the Frank Hollings bookshop in 1892, a few hundred yards west of his silversmith premises at 7 Great Turnstile, High Holborn. He also published single author bibliographies under that name, beginning with Buxton Forman’s bibliography of William Morris (1897) and followed by three more, including his brother’s of Coleridge. The last book published by Frank Hollings in its first incarnation was Prideaux’s bibliography of Robert Louis Stevenson, in 1903.

Two of Redway’s brothers, George William Redway (1859-1934) and Frank Albert Redway (1876-1916), were also booksellers and occasional publishers. George Redway ran an occult bookshop at 15 York Street, Covent Garden, where his books were for a time catalogued by the writer Arthur Machen. His youngest brother Frank was a bed-ridden invalid, who nevertheless operated as a bookseller in Wimbledon. George Redway knew Richard Herne Shepherd well – he wrote his obituary notice for The Athenaeum – and also his younger brother James, the proprietor of the Frank Hollings bookshop, two and a half miles away from his own. James died in about 1905, and the Redway family was well placed to make an early offer to buy the business as a going concern.

When William Edward Redway took over the shop after Shepherd’s death, he completely changed the whole tenor of the business. Gone were the expensive author-bibliographies aimed at wealthy Edwardian book collectors, to be replaced by a stream of publications on chess, beginning in 1908 with the first of three parts of The Series of First Class Games edited by the Hungarian-born chessplayer and journalist Leopold Hoffer. Redway was the chess enthusiast solely responsible for the association of the Frank Hollings name with the game.

Redway kept the business going through the Second World War, when the bookshop was blitzed (his own Richmond house was bombed the same day), and he moved the business to 69a Great Queen Street, WC2, off Kingsway. After his death in 1945, his widow continued the business for a couple of years before selling it to its third and last proprietor, Arthur T. (“Dusty”) Miller, who had worked in the bookshop since 1925.

Miller relocated the shop to 45 Cloth Fair, near Smithfield. His interests were literary, and in 1965 he announced that the chess department was to close. Soon afterwards he sold up altogether, and the long-established bookshop of Frank Hollings ceased trading in 1969. Dusty Miller took his remaining stock, expertise and contacts to the modern rare booksellers Bertram Rota, where he sat in the office as a reminder of the old order until his death in 1977.

Both George and Frank Redway became innocently tangled up with the notorious book forger Thomas J. Wise. A good deal of biographical information about them can be gleaned from a short book about the Wise affair, The Firm of Charles Ottley, Landon & Co: Footnote to an Enquiry by John Carter and Graham Pollard (London, 1948).’

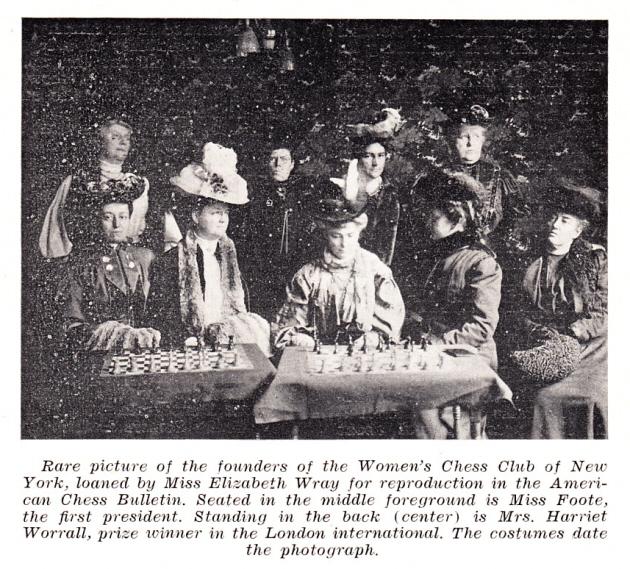

7592. Eliza Campbell Foot (C.N.s 7158 & 7562)

Below is the photograph mentioned in C.N. 7562, from page 66 of the May-June 1949 American Chess Bulletin:

7593. Blackburne miniature (C.N. 7577)

Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA) mentions a further complication: when the Blackburne game was published in the New York Evening Post of 19 March 1895 (page 5) White was identified as ‘N.C.’.

7594. Agnes Stevenson (C.N. 7565)

Roger Mylward (Lower Heswall, England) writes:

‘The following information has been obtained from the Genes Reunited website.

Septimus Lawson married Mary Catherine Bradley during the period July-September 1865 in Stockton, County Durham. In the 1871 census, Septimus and Mary were living with the latter’s parents (John and Agnes Bradley) and other siblings in Stockton; they had a four-year-old son, Thomas. In addition to her mother, Mary had a sister named Agnes.

In the 1881 census, the Lawsons were living at 2 Queen Street, Hartlepool, with Agnes (aged eight) and three other children. In the 1891 census, Mary and eight children (plus a nephew, Charley Bradley) were living at 14 Hanover Street, Hartlepool, with Agnes B. Lawson employed as an elementary school teacher.

The 1901 census has Mary Lawson now living at 32 Mitchell Street, Hartlepool with six of her children. Agnes B. (aged 27) was employed as an assistant schoolmistress. Finally, the 1911 census states that Mary Lawson (now given as a widow) was still at 32 Mitchell Street, with two of her children. Agnes Bradley Lawson (aged 37 and single) was a school teacher, as was her younger sister Ada Lawson (aged 30).

It would therefore seem that Agnes Lawson was born in 1873, as stated in Christian Sánchez’s Family Search evidence and that she was given the family name of Bradley rather than “Braveley”.’

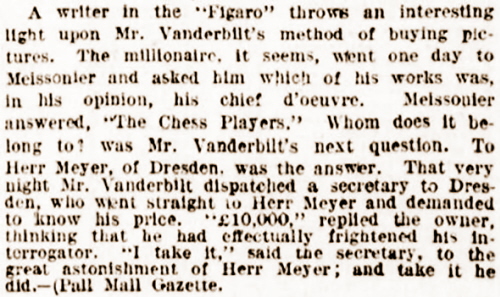

7595. Meissonier

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) notes a report on page 22 of the New York Tribune, 14 August 1892 that the painter Jean-Louis Ernest Meissonier (1815-91) considered his chef d’oeuvre to be ‘The Chess Players’:

Mr Bauzá Mercére writes:

‘A painting of that name was one of the first by Meissonier to be presented publicly, at the Paris Salon in 1836. A different work with the same title was apparently produced in 1856. To complicate matters, there is a third chess-related painting by him, called “Game of Chess” (“Partie d’échecs”), dating from 1841. Which of the three pictures was bought by Vanderbilt?’

We add a sketch of Meissonier from page 491 of Living Leaders of the World (Chicago and St Louis, 1889):

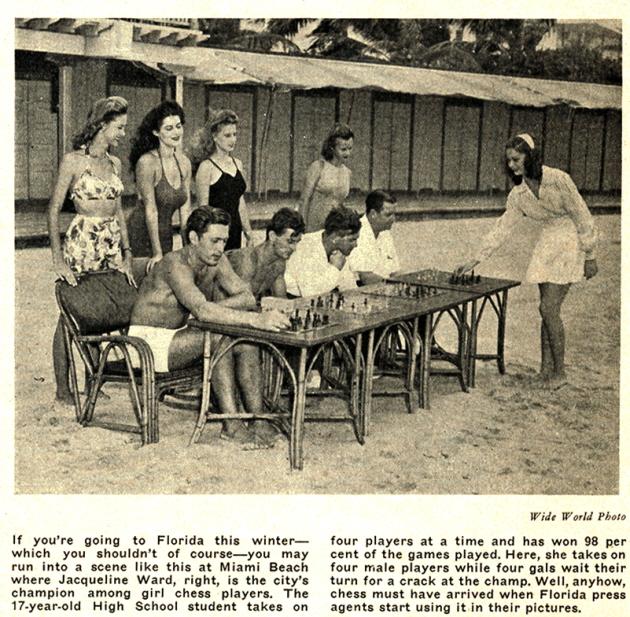

7596. Jacqueline Ward

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) is seeking information about Jacqueline Ward, who was featured in this photograph on page 12 of Chess Review, January 1945:

7597. Who?

From John Donaldson (Berkeley, CA, USA) comes another photograph from the archives of Val Zemitis:

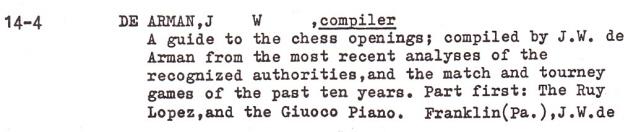

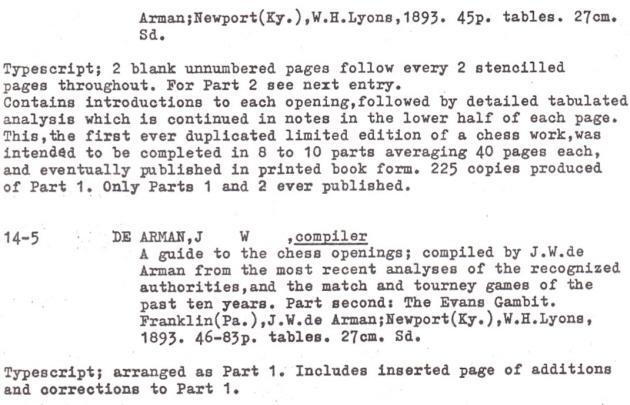

7598. John W. De Arman (C.N. 7572)

The only works by J.W. De Arman mentioned in Douglas A. Betts’ Bibliography (pages 216-217) are two volumes of A Guide to the Chess Openings:

David DeLucia (Darien, CT, USA) reports that he has the two books, and that neither provides biographical information about De Arman. Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA) notes that the name J.W. De Arman appeared with some frequency in old chess columns and that his openings monographs were mentioned in Steinitz’s chess column on page 24 of the New York Daily Tribune of 22 January 1893:

Mr Spinrad also draws attention to the references to De Arman to be found via Google Books, such as this paragraph on page 180 of the August 1912 American Chess Bulletin:

‘Among the speakers at the banquet [of the Los Angeles Young Men’s Christian Association] was J.W. De Arman of Pasadena, and a reference was made to his projected book to be known as Chess Classics. According to the Los Angeles Times, the work was eulogized and requests made for its early publication.’

Jean-Pierre Rhéaume (Montreal, Canada) remarks that Google Books also has an entry for End Game Studies by Henri Rinck and J.W. DeArman (‘1912 – 34 pages’). He points out too some books listed on the WorldCat website.

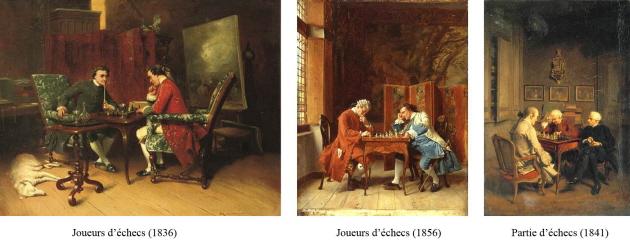

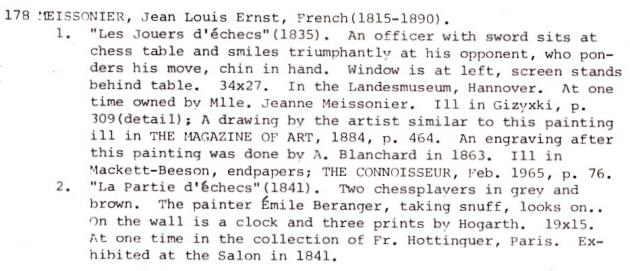

7599. Meissonier (C.N. 7595)

Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England) refers to the entry on Meissonier (four paintings) on pages 18-19 of Chess in Art by Manfred Roesler (Davenport, 1973). It is reproduced here with the permission of the editor, Bob Long (Davenport, IA, USA):

7600. Val Zemitis (1925-2012)

From John Donaldson (Berkeley, CA, USA):

‘Valdemars (Val) Zemitis died on 22 March 2012 in Davis, California, not long before his 87th birthday. An obituary can be found at the California chess history website Chessdryad.

This picture of Val Zemitis with his friend Arthur Dake (left) was taken in front of the latter’s home in Portland, Oregon, in 1996.’

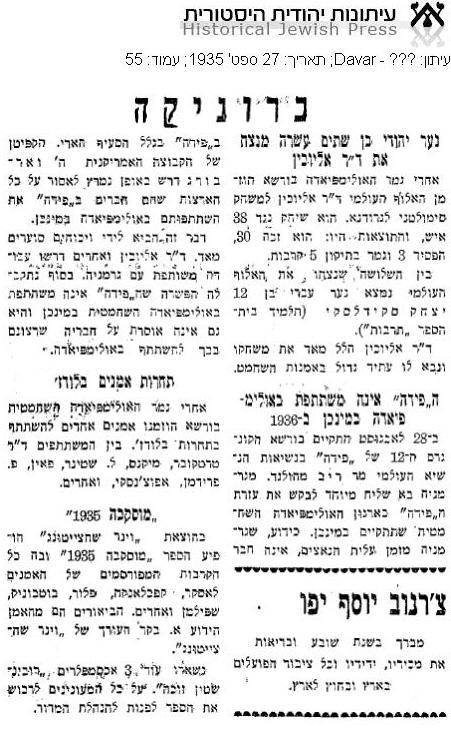

7601. Munich Olympiad, 1936

Avital Pilpel (Haifa, Israel), who conducts the Jewish Chess History website, informs us that Moshe Roytam has found this chess column on page 55 of Davar, 27 September 1935:

The column is available online via the Historical Jewish Press website. Mr Pilpel comments:

‘The editor of the chess column in Davar, Moshe Marmorosh, states that at the 1935 FIDE Congress, the US representative, Wahrburg, demanded that no FIDE member should be allowed to participate in the Munich Olympiad in 1936, owing to Germany’s anti-Semitism. This, reports Marmorosh, “led to a heated discussion”, with “Dr Alekhine and others” advocating “working together with Germany”. Eventually there was a “compromise solution” whereby (as noted in your article The 1936 Munich Chess Olympiad) FIDE would not be officially involved but would allow individual teams freedom of choice.’

Our article on the Munich Olympiad quoted from pages 10-11 of the minutes of FIDE’s Congress, held in Warsaw in August 1935. The matter was also mentioned on page 446 of the October 1935 BCM:

‘The new German C.A. is not affiliated, but a representative was present seeking the support of the FIDE for a team tournament at Munich next year concurrently with the Berlin Olympiad (athletics). Some opposition was offered on account of Germany’s non-affiliation, but eventually on a vote it was left to each country to take its own line on the matter.’

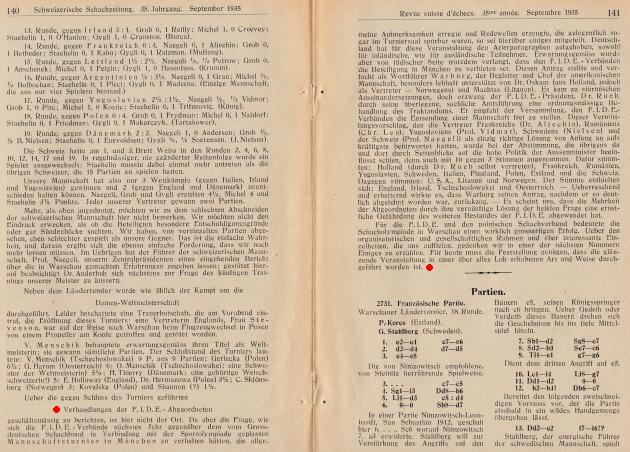

A more detailed account appeared on pages 140-141 of the September 1935 Schweizerische Schachzeitung:

To summarize the Swiss magazine’s report: The FIDE discussions were rather heated and could occasionally even be heard in the playing hall. Germany had removed the Arierparagraph (the ban on non-Aryans) with regard to German and foreign participants. Nevertheless, ‘the Jewish side’ demanded that FIDE member nations be forbidden to participate in the Munich Olympiad. This was proposed by Wahrburg, who received particularly strong support from Oskam and Machtas. Rueb recommended to the Assembly that each nation should be left to decide whether it wished to participate. This compromise, which from the outset was strongly supported by France (whose representative was Alekhine), Romania, Yugoslavia, Sweden and Switzerland as the only correct solution, was eventually accepted by ten votes to three. Great Britain, Ireland, Czechoslovakia and Austria abstained. A surprising and amusing point, the Schweizerische Schachzeitung added, was that Wahrburg withdrew his motion after it had been so clearly rejected. The magazine considered that the FIDE delegates had averted serious danger by finding a sensible solution to a difficult issue.

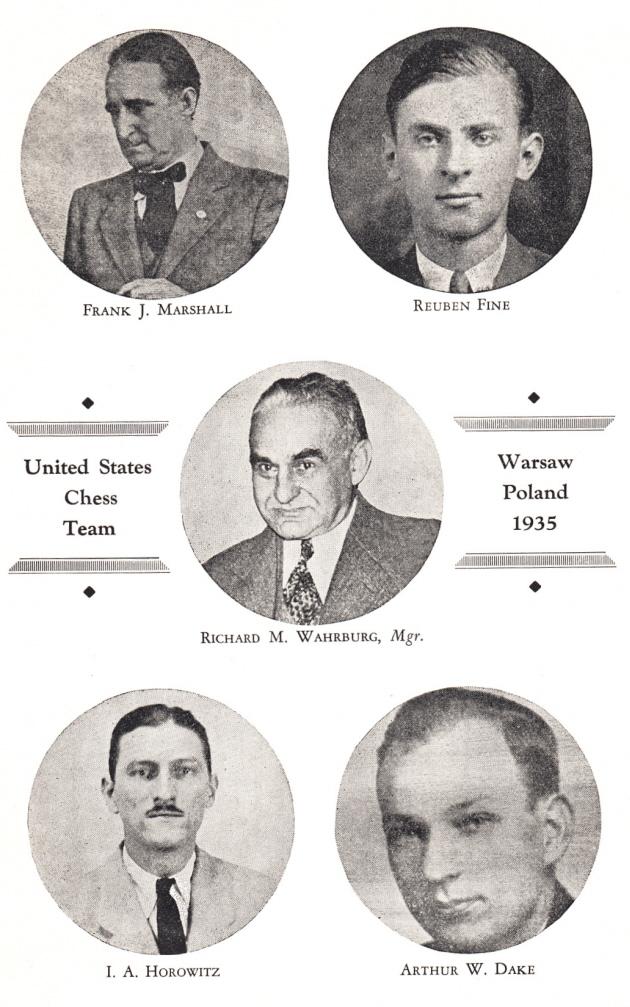

The illustration below, which includes Richard M. Wahrburg, comes from page 175 of the August 1935 Chess Review:

7602. New York, 1927 (C.N. 3716)

From page 60 of the March 1927 American Chess Bulletin:

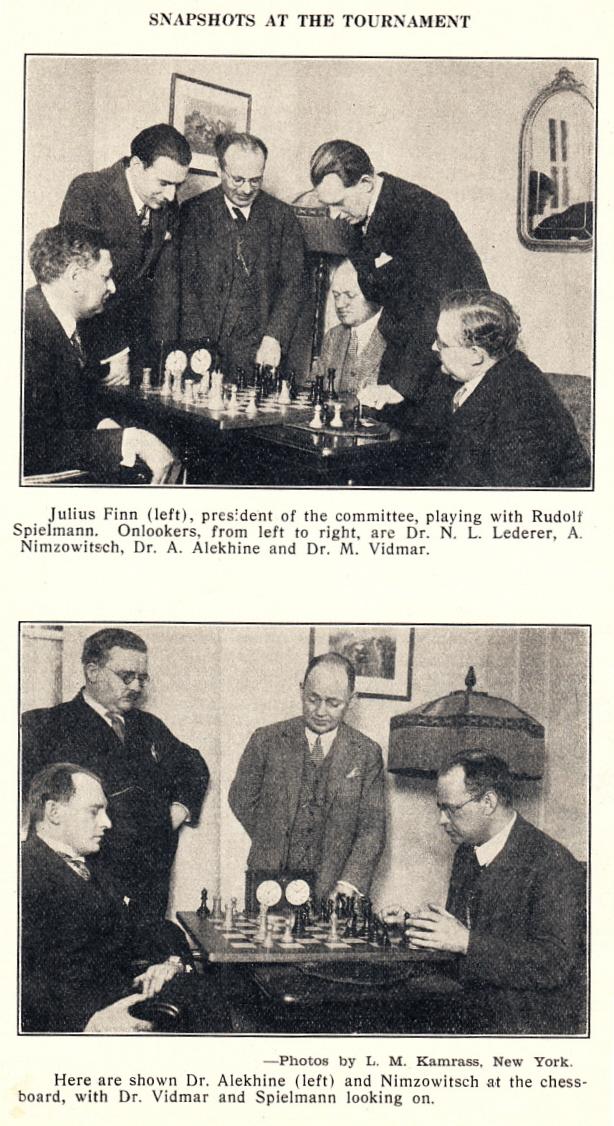

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore), who gave the first photograph on page 226 of his book Julius Finn (Jefferson, 2010), informs us that he has now acquired a much better copy:

Our correspondent identifies the position as arising in analysis of the third-round game at New York, 1927 between Vidmar and Spielmann:

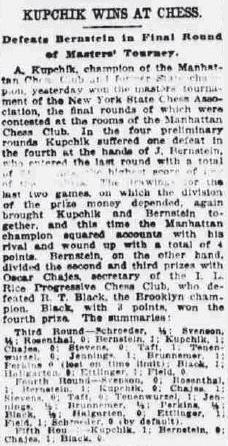

7603. Three games (C.N. 7585)

From John Hilbert (Amherst, NY, USA):

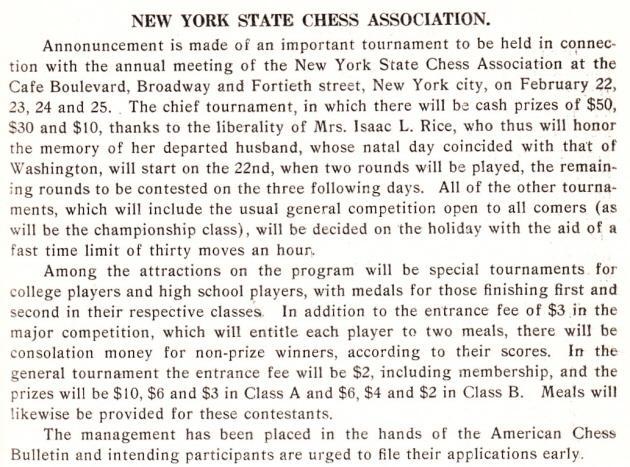

‘It appears that the three games were played in the tournament of the New York State Chess Association, an event mentioned on page 27 of the February 1917 American Chess Bulletin:

Three other games from the tournament (Kupchik v Jennings, Tenenwurzel v Jennings and Black v Svenson) were published on pages 91-92 of the April 1917 issue.’

Our correspondent has also found two newspaper reports:

Page 11 of the New York Sun,

26 February 1917

Page 19 of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 26 February 1917.

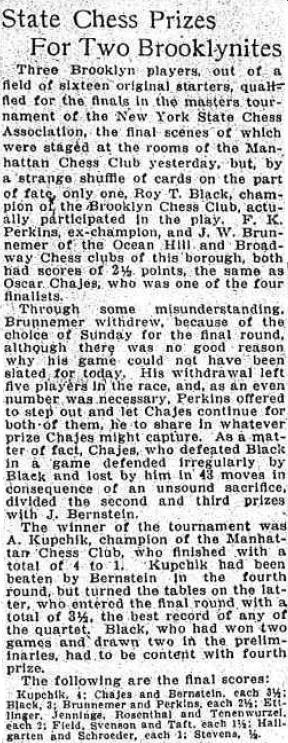

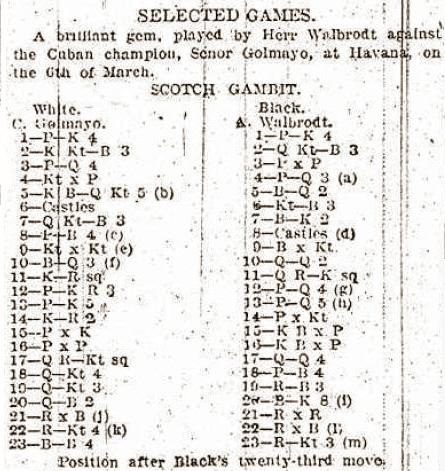

7604. Morphy v

de Rivière (C.N. 4164)

Luc Winants (Boirs, Belgium) has recently acquired this publication of the Morphy v de Rivière picture (‘d’après une photographie de M. Thompson’), on page 208 of L’Illustration, journal universel:

The exact date of the publication appears to be 25 September 1858.

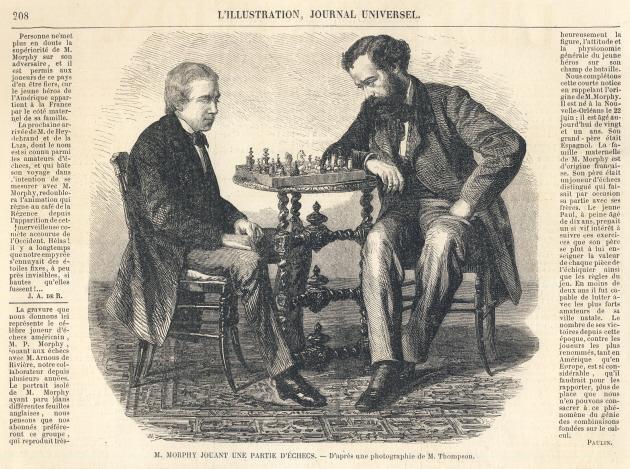

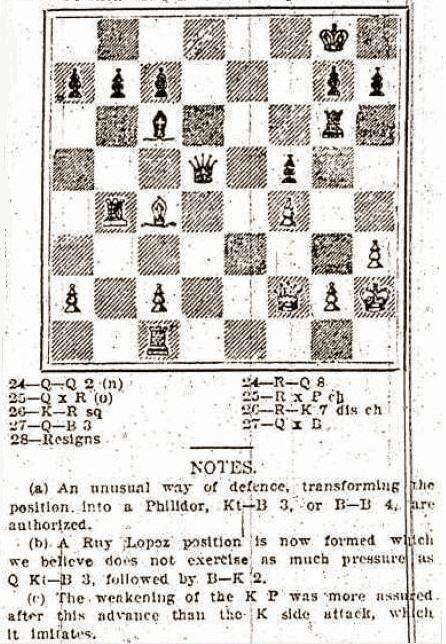

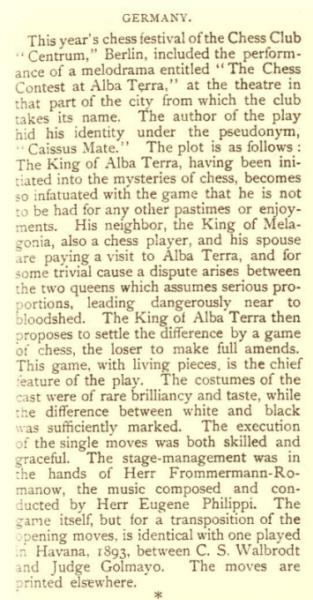

7605. Golmayo v Walbrodt

We offer further information on a game given on pages 108-109 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves.

‘A brilliant gem’ was Steinitz’s comment on page 24 of

the New York Daily Tribune, 26 March 1893:

Havana, 6 March 1893

Scotch Game

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 exd4 4 Nxd4 d6 5 Bb5 Bd7 6 O-O Nf6 7 Nc3 Be7 8 f4 O-O 9 Nxc6 Bxc6 10 Bd3 Qd7 11 Kh1 Rae8 12 h3 d5 13 e5 d4 14 Kh2 dxc3 15 exf6 Bxf6 16 bxc3 Bxc3 17 Rb1 Qd5 18 Qg4 f5 19 Qg3 Rf6 20 Qf2

20...Be1 21 Rxe1 Rxe1 22 Rb4 Rxc1 23 Bc4 Rg6 24 Qd2

24...Rd1 25 Qxd1 Rxg2+ 26 Kh1 Rd2+ 27 Qf3 Qxc4 28 White resigns.

The game was quite widely published at the time (e.g.

on page 124 of the London Chess Fortnightly, 30

March-14 April 1893, pages 136-138 of the May 1893 Deutsche

Schachzeitung and pages 291-292 of the

September-October 1893 American Chess Monthly).

A few years later it was chosen for the performance in

Berlin of a melodrama The Chess Contest at Alba

Terra. From page 105 of the American Chess

Magazine, July 1897:

The game-score was on pages 121-122 of the same issue.

7606. Self-mate and sui-mate

Steven B. Dowd (Birmingham, AL, USA), who is writing a series of articles about Theophilus Thompson at the Chess Drum website, asks us about a claim concerning Thompson on pages 204-205 of America’s Chess Heritage by Walter Korn (New York, 1978):

‘Thompson’s determination, and speedy acquisition of chess mastery, is astounding. He had had no formal education, learned chess from mere observation in April 1872, and had a complete collection of first-class problems published just one year later by the leading chess publisher of the period.

Equally impressive is the literary taste expressed in Thompson’s consistent use of the term “self-mate”. It took the famous originator of fairy chess, T.R. Dawson, of the Chess Amateur, till 1922 to achieve legitimacy for the obviously more natural term “self-mate” in place of the then fashionable expression “sui-mate”. Thompson was also free of the snobism often found in the composers’ community.’

Our correspondent comments:

‘Korn gives Thompson credit for consistent usage of the term self-mate over sui-mate, suggesting that Dawson brought back the term self-mate. In fact, Thompson’s book Chess Problems (Dubuque, 1873) consistently used the term sui-mate, as was common then. The book contains only problems, and no text by Thompson, and I do not know where else he would have “consistently” used the term self-mate. What grounds did Korn have for making the claim about Thompson?’

Readers’ assistance will be welcomed. Since Walter Korn referred to the Chess Amateur, we mention that the October 1919 issue (page 21) began a monthly column entitled ‘Sui-Mates’ by Robert Burnside. Page 207 of the April 1920 Chess Amateur announced that Burnside had given up the column, and it was carried on, still under the title ‘Sui-Mates’, by Duncan Pirnie from June 1920 to August 1922.

7607. Cross-check

Mr Dowd also wishes to establish the first usage of the term cross-check.

We can offer the following from page 133 of Chess: Its Poetry and Its Prose by Arthur F. Mackenzie (Kingston, 1887):

‘Let us now compose an attacking version of the well-known “counter” or “cross check” idea ...’

The word recurred on page 141. See too pages xxiii and xxxii of the collection of Mackenzie’s problems, Chess Lyrics edited by Alain C. White (New York, 1905).

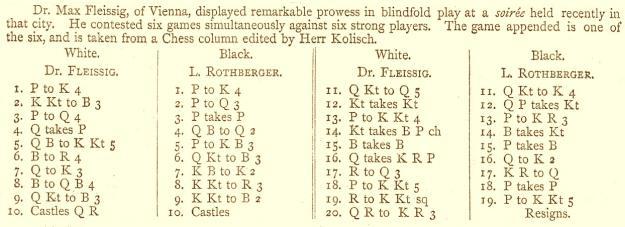

7608. Max Fleissig blindfold game

From the Westminster Papers, 1 June 1872, page 19:

Max Fleissig – L. Rothberger

Vienna, 1872

Philidor’s Defence

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 d6 3 d4 exd4 4 Qxd4 Bd7 5 Bg5 f6 6 Bh4 Nc6 7 Qe3 Be7 8 Bc4 Nh6 9 Nc3 Nf7 10 O-O-O O-O 11 Nd5 Nce5 12 Nxe5 dxe5 13 g4 h6

14 Nxf6+ Bxf6 15 Bxf6 gxf6 16 Qxh6 Qe7 17 Rd3 Rfd8 18 g5 fxg5 19 Rg1 g4 20 Rh3 Resigns.

7609. Saint-Amant’s death (C.N. 300)

On the Archives nationales d’outre mer website Hans Renette (Bierbeek, Belgium) has discovered the death certificate of Pierre Charles Fournier de Saint-Amant. It can be viewed by entering ‘Fournier’ as the surname, with the date 1872.

The document states that Saint-Amant died at three o’clock in the afternoon on 28 October 1872. This contradicts the previously accepted death-date (29 October 1872), which was derived from page 353 of La Stratégie, 15 December 1872.

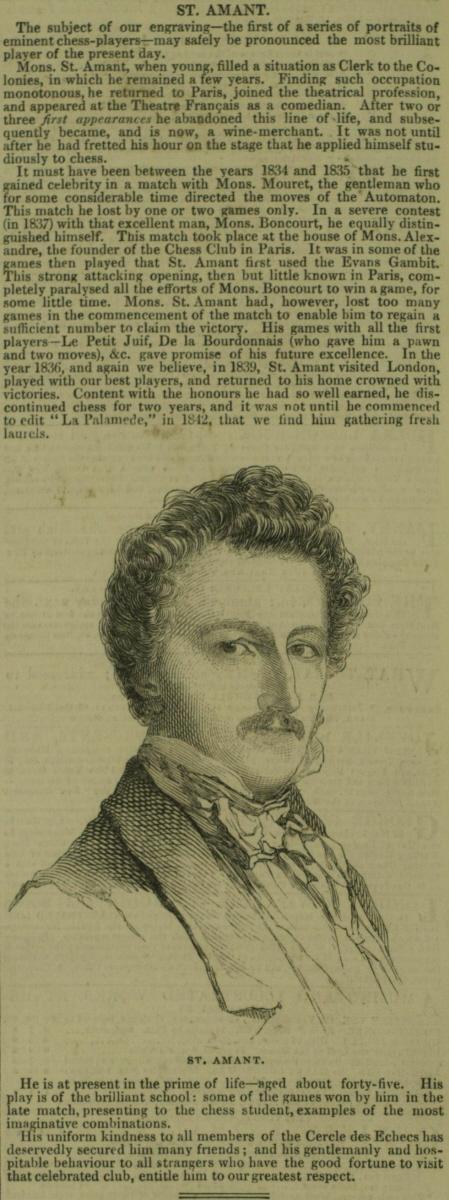

7610. Saint-Amant in the Illustrated

London News

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) forwards this feature from page 416 of the Illustrated London News, 28 December 1844:

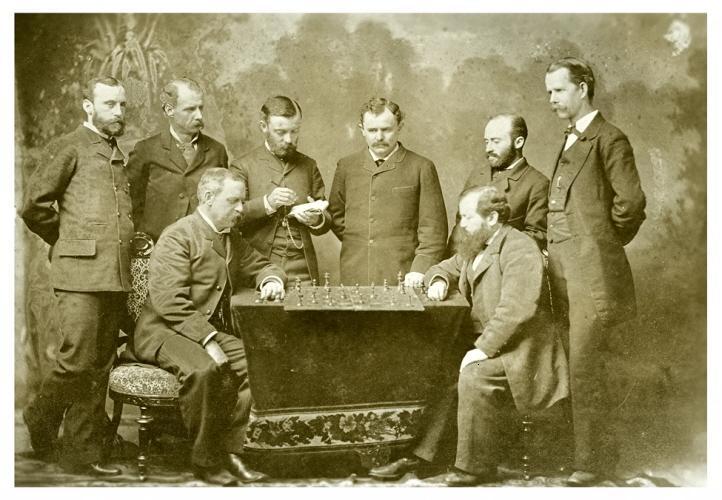

7611. Steinitz and who? (C.N.s 3463 & 5173)

Mr Urcan points out that this photograph appeared on page 2 of the third part of the Daily Times-Picayune (New Orleans) of 9 March 1913 (see the pdf version). The earlier (Cleveland) key did not identify the man standing on the right, but now a name is provided: M.F. Dunn.

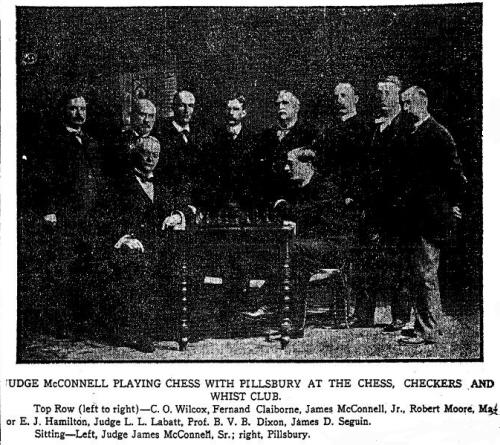

The second group photograph in the newspaper article, which features Pillsbury, is also of much interest:

A copy of good quality is sought.

7612. Further pictures

We are also grateful to Mr Urcan for this series of pictures:

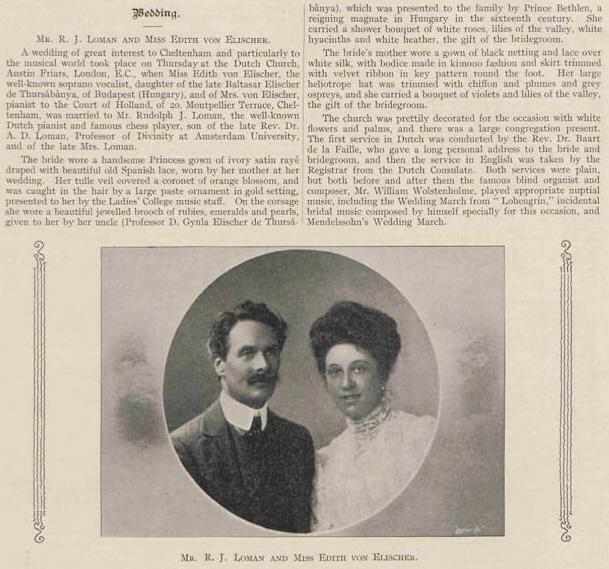

Cheltenham Looker-On, 21 December 1907, page 11

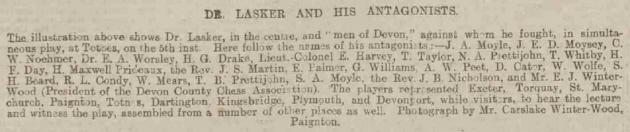

Devon and Exeter Gazette, 13 March 1908, page 14

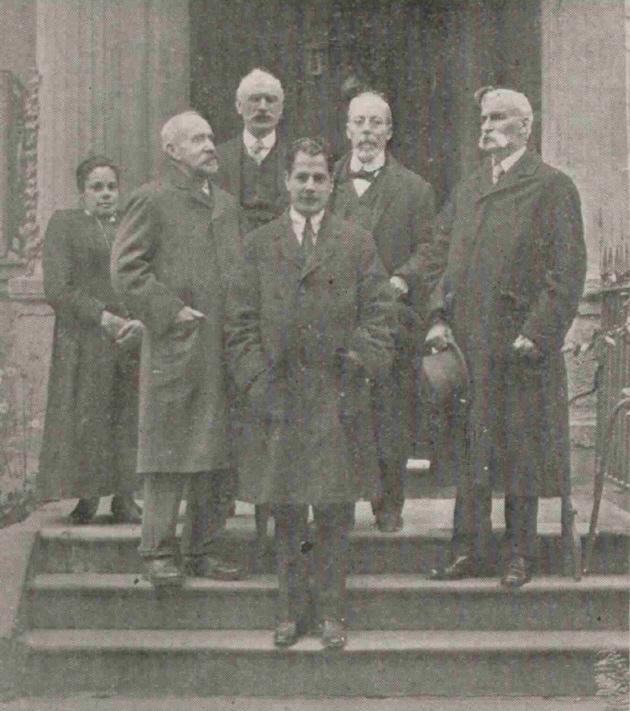

Cheltenham Looker-On,

18 October 1919, page 17

Caption: ‘Señor Capablanca, with Lieut.-Col. Ashburner

and other members on the steps of the Cheltenham Chess

Club’

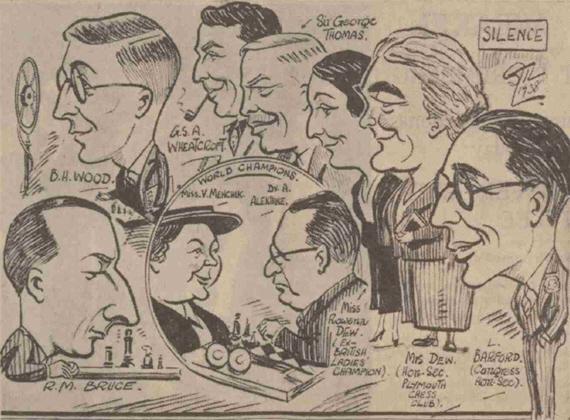

P.S. Milner-Barry v A.

Alekhine (Plymouth tournament, 5 September 1938)

Western Morning News and Daily Gazette, 6

September 1938, page 11

Western Morning News and Daily Gazette, 9 September 1938, page 5

Western Morning News and Daily Gazette, 10 September 1938, page 10.

7613. Steinitz v Zukertort world championship match

This article by G.H. Diggle was originally published in the March 1986 Newsflash and appeared on page 37 of volume two of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1987):

‘One hundred years ago a famous World Championship Match of ten games up excluding draws was played in three sections at New York, St Louis and New Orleans. No American nationalist pride was involved as Steinitz was an Austrian Jew and Zukertort’s antecedents were “shrouded in mystery”. Yet the contest convulsed the American public, partly because it brought back the memory of their own World Champion, whose death only 18 months earlier after years of obscurity had suddenly blazoned forth his name once more in countless nostalgic Obituaries. Thus when the match began at the Manhattan Chess Club, “the same chessboard was employed upon which Morphy fought his famous battles a quarter of a century ago”, with “the veteran Mr Patterson, who called off the moves for Morphy [at New York, 1857] again acting as teller upon the present occasion”. There was a great gathering of “eminent divines, members of the legal profession, and men of letters”, who well remembered Morphy’s brilliant début, and there were many hearty handshakes between players who had not met since then, but were again attracted by the fame of the present masters. [BCM, February 1886, page 54.] In fact, throughout the contest, Morphy’s shade seemed to hover in the background, and in the final section of the match, at New Orleans, Zukertort expressly selected for his second Morphy’s lifelong friend and opponent C.A. Maurian.

The contrast between the two masters is well portrayed by a Reporter in The Republican: “[Steinitz is] a fat phlegmatic little man, with a fine forehead and mussed hair and clothes. His legs are very short, although his circumference around the equator is rather large, and it was a peculiar sight to watch the great chessplayer seated upon an ordinary chair and feeling unsuccessfully for the continent of North America with his feet. Both men are hirsute, but Zukertort is better groomed than Steinitz. Both have fine heads. Steinitz is all curves, Zukertort all angles. ... Steinitz is all solidity and adipose tissue, Zukertort all brilliancy and nerves.” [See pages 161-162 of the February 1886 Chess Monthly.]

The course of the match is well known – Zukertort’s brilliant start at New York (+4 –1 =0), Steinitz’s recovery at St Louis, levelling the score to +4 -4 =1, and then forging ahead at New Orleans to +7 –5 =4. Then came the crucial 17th game, which in its general course bears a striking resemblance to Anderssen’s sixth game against Morphy. Like Anderssen, Zukertort was two games behind. In both cases, they made a supreme effort to reduce the lead, and obtained a clear win, only to fritter it away tragically in the final stages. Zukertort did indeed draw whereas Anderssen lost, but (says P.W. Sergeant in Championship Chess) the game “contributed not a little to his breakdown; or perhaps it should be said that his play in it was symptomatic of the coming breakdown”. For the last three games of the match the exhausted master lost off the reel without a struggle – a strange repetition of his three losses at the end of his great London Tournament of 1883, though there he was so far ahead of the whole field that it did not matter.

It was afterwards suggested that had the whole match been played at New York Zukertort might have won. But Dr Lasker in his Manual had no doubt as to which was the greater player. Zukertort “simply puts his pieces on squares where they enjoy mobility and hopes for complications in which to exercise his talent for combination”. Steinitz “follows a plan”.’

7614. Sculpture

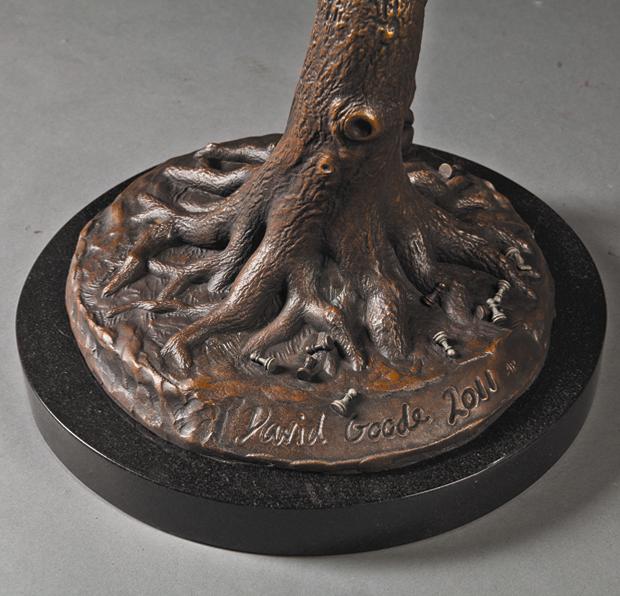

Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England) informs us that two years ago he was asked by the sculptor David Goode of Oxford for a chess position that might be used in a projected work. From the photographs below, kindly sent to us by Mr Goode, the challenge to readers is to identify the position which Michael McDowell provided.

7615. On-line archives

We wish to draw up a brief guide to the best websites at which old chess magazines and newspaper columns can be consulted.

A number of readers have made significant online discoveries, and it will be appreciated if they, and others, can send us links, together with a brief descriptive paragraph or two, regarding the sites which they have found particularly useful.

7616.

Not seeing (C.N. 6539)

C.N. 6539 quoted a paragraph from page 107 of the April 1885 International Chess Magazine:

With respect to the last sentence (and the claim of originality), we now note a report on page 154 of the Westminster Papers, 1 December 1873:

‘Mr Blackburne’s blindfold performance was on this, as on previous occasions, an unqualified success. Against ten opponents he won six games, drew three and lost but one, after a contest of over eight hours. He came, he did not see, but he conquered.’

7617. Vidmar v Důras

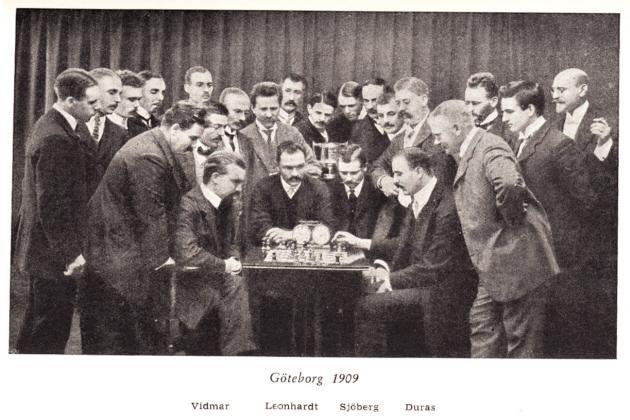

From opposite page 144 of Pol stoletja ob šahovnici by Milan Vidmar (Ljubljana, 1951):

7618. Mate in 11

A solving challenge:

White, to move, mates all nine kings (simultaneously) in 11 moves.

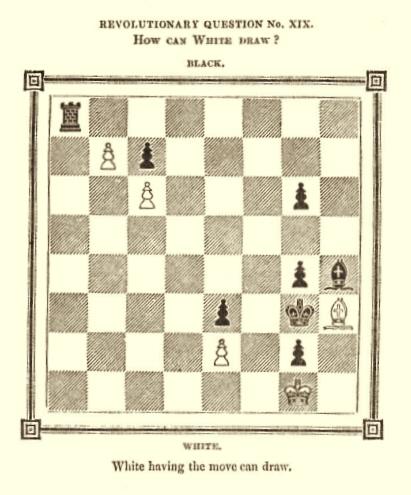

7619. Dummy pawn (C.N. 5791)

From page 76 of the 20 September 1851 issue of the Chess Player (edited by Kling and Horwitz):

The ‘Answers to Correspondents’ section in the same issue (page 80) had the following:

‘We are of opinion that a pawn, when reaching his eighth’s square, is entitled to become any piece the player thinks best; and, naturally enough, if it prove disadvantageous to become a piece, it may still remain a pawn. (See Diagram 19.) This question among others, we thought, should have been discussed at the Tournament.’

Another ‘answer’, on page 96 of the 4 October 1851 Chess Player:

‘We are glad to hear that you think a pawn should also have the privilege of remaining a pawn when reaching the eighth square; but we hardly think it practicable as the law now exists.’

The above composition was referred to on page 175 of the Westminster Papers, 1 December 1873:

‘After mature consideration, we can see no utility in a controversy about the dummy pawn. So far as we know, it was first suggested in this country in 1851, in a two-penny publication called the Chess Player, and was illustrated by an absurd problem, aptly enough baptized by the composer “Revolutionary”. The problem, which in 1851 passed current for a tolerable joke, was in 1862 “adduced” as a serious argument, and appears to have convinced some worthy people that it embodied an excellent principle. To J.M.R., who enquires, “Could not a game be invented to show the usefulness of the regulation?” we answer, yes; and more, the players might be invented also. The wonder is, that the double event has not been “managed” long ago.’

The chess column on page 36 of the 5 September 1874 Illustrated London News referred to the ‘famous “dummy pawn” epidemic’. A more recent curiosity is the entry on page 54 of the Dictionary of Modern Chess by Byrne J. Horton (New York, 1959), which did not make it clear that the dummy pawn rule had long ago become obsolete everywhere:

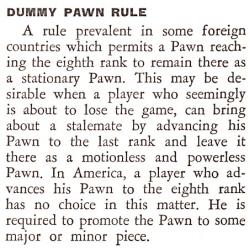

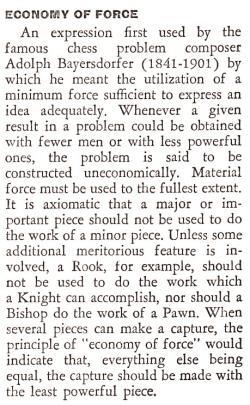

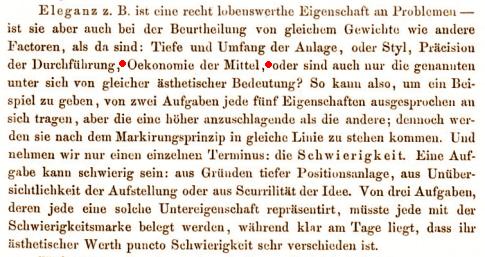

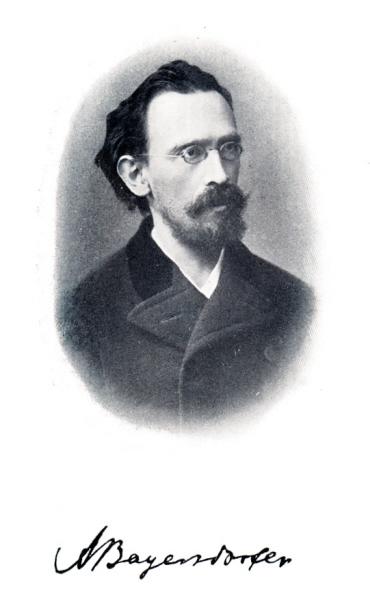

7620. ‘Economy of force’

From page 56 of Horton’s Dictionary of Modern Chess:

Bayersdorfer used the term (‘Oekonomie der Mittel’)

in the final instalment of his article ‘Britische

Vota über Preisprobleme’ on page 353 of the

November 1867 Deutsche Schachzeitung:

For originating the phrase Bayersdorfer was credited on

page 14 of Zur Kenntnis des Schachproblems

edited by J. Kohtz and C. Kockelkorn (Potsdam, 1902):

The book’s frontispiece:

An early occurrence of the English term ‘economy of force’ was in the ‘Answers to Correspondents’ section of the City of London Chess Magazine, February 1874 (page 24):

‘E.G. (London). Your problem is hardly up to publication standard. The idea, like the Claimant behind the sapling, is too plainly seen, and moreover the construction is wanting in that elegance and economy of force which only experience can give.’

That may be contrasted with a remark by J.H. Blackburne on page 201 of the August 1875 issue (in a review of Kohtz and Kockelkorn’s 101 Ausgewählte Schachaufgaben):

‘The five-movers surpass anything that we have as yet seen. We are perfectly aware that many competent judges will not concur in this opinion. Some will discover all sorts of flaws, or what are termed “duals”, while others will talk about “economy of force”, or some such equally ridiculous nonsense. But, however, we have our own foolish ideas on problem construction.’

7621. Motto

A remark by Walter Browne in an interview with Mary Lasher on page 10 of Inside Chess, 10 February 1988:

‘My motto is: when you win you earn, when you lose you learn.’

7622. Graf v Spielmann

The two games below, played in simultaneous displays given by Spielmann, come from pages 121-128 of Sonja Graf’s Así juega una mujer (Buenos Aires, 1941). The book includes Tarrasch’s annotations.

Sonja Graf – Rudolf SpielmannMunich, 1932

Queen’s Gambit Declined

1 d4 d5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 c4 c6 4 Nc3 dxc4 5 a4 Bf5 6 e3 Na6 7 Bxc4 Nb4 8 O-O e6 9 Ne5 Be7 10 Qe2 O-O 11 e4 Bg6 12 Nxg6 hxg6 13 Be3 Qa5 14 f4 Qh5 15 Qxh5 gxh5 16 Rad1 Rad8 17 h3 Rd7 18 Kh1 Rfd8 19 Bb3 h4

20 f5 exf5 21 Rxf5 g6 22 Rf3 Kg7 23 Rdf1 Nh5 24 Rxf7+ Kh8 25 R1f3 Ng3+ 26 Kg1 Bd6 27 Bg5 Rxf7 28 Rxf7 Resigns.

Sonja Graf – Rudolf SpielmannMunich, 1932

Queen’s Pawn Game

1 d4 e6 2 c4 Nf6 3 Bg5 h6 4 Bd2 Ne4 5 Nf3 Nxd2 6 Nbxd2 d5 7 e3 Be7 8 Bd3 O-O 9 O-O Nd7 10 Qe2 Nf6 11 c5 c6 12 Ne5 Bd7 13 f4 Be8 14 g4 Nd7 15 Ndf3 Nxe5 16 Nxe5 Bf6 17 f5 exf5 18 gxf5 Qe7 19 Ng4 Bd7 20 Qg2 Kh8 21 Qh3 Bg5 22 Rf3 Rae8 23 Re1 Bh4 24 Ref1 Bg5 25 Rg3 Bh4 26 Rg2 Bg5 27 Rf3 Qd8 28 b4 a5 29 a3 axb4 30 axb4 Qa8

31 Nxh6 Bxh6 32 Rxg7 Qa1+ 33 Rf1 Qxf1+ 34 Kxf1 Kxg7 35 f6+ Kxf6 36 Qxh6+ Ke7 37 Qd6+ Kd8 38 Bf5 Resigns.

The book has this photograph of Sonja Graf:

7623. Trilingual blindfold exhibition

From page 63 of the London Chess Fortnightly, 14 December 1892:

‘Mr C. Moriau (City champion) gave a wonderful blindfold performance at the Metropolitan Chess Club on 5 December. He was opposed by six opponents, and the games were conducted two in English, two in French, and two in German. Mr Moriau, in the end, scored four wins against two losses. When it is borne in mind that Mr Moriau had to conduct the mental operations of these six games in three distinct notations, the whole performance must be pronounced a wonderful mental feat.’

7624. Rapid transit games

Old specimens of fast chess are fairly scarce. Below are three from a tournament held at Marshall’s Chess Divan, New York on 28 April 1917. The time-limit was 20 seconds per move, and Marshall won the event with 5½ points, ahead of Janowsky (5), Chajes (4½), Jaffe (4), Bernstein (3), Hodges (3), Black (2½) and Beynon (½).

Dawid Janowsky – Jacob BernsteinNew York, 28 April 1917

Four Knights’ Game

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bb5 Bb4 5 O-O O-O 6 d3 d6 7 Bg5 Bxc3 8 bxc3 Qe7 9 Re1 Nd8 10 d4 Ne6 11 Bc1 Rd8 12 Rb1 c5 13 Bc4 b6 14 d5 Nf8 15 h3 Rb8 16 Bd3 a6 17 c4 Bd7 18 Nh2 Ng6 19 Ng4 Nxg4 20 hxg4 b5 21 g3 bxc4 22 Rxb8 Rxb8 23 Bxc4 Bb5 24 Bd3 Bxd3 25 Qxd3 Qb7 26 Bd2 Qb5 27 Qa3 f6 28 Kg2 Nf8

29 g5 Nd7 30 Qf3 fxg5 31 Bxg5 Rf8 32 Qg4 Qb4 33 Re3 Nf6 34 Qe6+ Rf7 35 Bxf6 gxf6 36 Qxd6 a5 37 Qe6 Qc4 38 Qc8+ Rf8 39 Qg4+ Kf7 40 Rb3 Qa6 41 Qd7+ Kg6 42 Rb7 Resigns.

Jacob Bernstein – Frank James MarshallNew York, 28 April 1917

Queen’s Gambit Declined

1 d4 d5 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 c5 4 cxd5 exd5 5 Nf3 Nc6 6 e3 Nf6 7 Be2 Bd6 8 O-O O-O 9 b3 Bg4 10 Bb2 cxd4 11 exd4 Rc8 12 Rc1 Bf4 13 Rb1 Re8 14 h3 Bh5 15 Nh2 Bg6 16 Bd3 Qd6 17 Nf3 Ne4 18 Nb5 Qf6 19 Bxe4 Bxe4 20 Ra1 Bb8 21 Re1 Qf4 22 Ne5 Nxe5 23 dxe5 Qg5 24 f3

24...Rc2 25 Re2 Rxb2 26 fxe4 Rxe2 27 Qxe2 Qxe5 28 Rd1 a6 29 Nd4 Ba7 30 Qd2 dxe4 31 Kh1 Rd8 32 Nc6 Rxd2 33 Rxd2 Qa1+ 34 White resigns.

Charles Jaffe – Roy Turnbull BlackNew York, 28 April 1917

Queen’s Pawn Game

1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 c6 3 e3 d6 4 Nc3 Bg4 5 Be2 Nbd7 6 e4 e5 7 O-O Be7 8 Be3 O-O 9 Nh4 Bxe2 10 Qxe2 Nxe4 11 Nxe4 Bxh4 12 Nxd6 exd4 13 Bxd4 Qc7 14 Nf5 Bf6 15 Rad1 Qf4 16 Ne7+ Kh8 17 Be3 Qc7 18 Nf5 Bxb2 19 Qg4 Rad8 20 Rd4 g6 21 Bh6 Bxd4 22 Qxd4+ Qe5

23 Bg7+ Resigns.

Source: American Chess Bulletin, May-June 1917, pages 110-113.

7625. Nottingham, 1936

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) has forwarded this report, which includes an interview with Euwe, on page 10 of the Nottingham Evening Post, 6 August 1936. A larger version of the full page is given in our most recent feature article, Photographs of Nottingham, 1936.

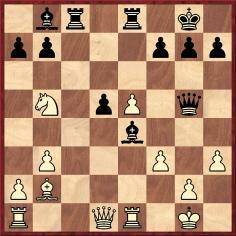

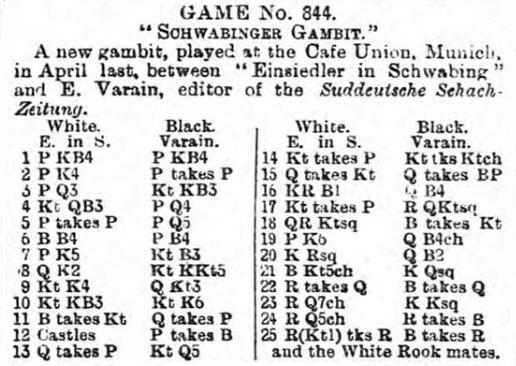

7626. The ‘Schwabinger Gambit’

On page 7 of the 25 March 1893 edition of the Nottinghamshire Guardian Olimpiu G. Urcan has found a game illustrating ‘A new gambit, played at the Café Union, Munich, in April last, between “Einsiedler in Schwabing” and E. Varain, editor of the Süddeutsche Schach-Zeitung’:

1 f4 f5 2 e4 fxe4 3 d3 Nf6 4 Nc3 d5 5 dxe4 d4 6 Bc4 c5 7 e5 Nc6 8 Qe2 Ng4 9 Ne4 Qb6 10 Nf3 Ne3 11 Bxe3 Qxb2 12 O-O dxe3 13 Qxe3 Nd4 14 Nxc5 Nxf3+ 15 Qxf3 Qxc2 16 Rfc1 Qf5 17 Nxb7 Rb8 18 Rab1 Bxb7

19 e6 Qc5+ 20 Kh1 Qc7 21 Bb5+ Kd8 22 Rxc7 Bxf3 23 Rd7+

Ke8 24 Rd5+ Rxb5 25 Rbxb5 Bxd5 and White mates.

See ‘The Swiss Gambit’.

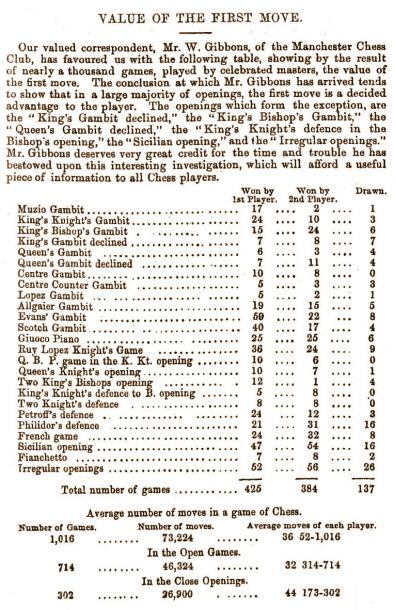

7627. Openings

chart

From page 215 of the July 1865 issue of the Chess Player’s Magazine:

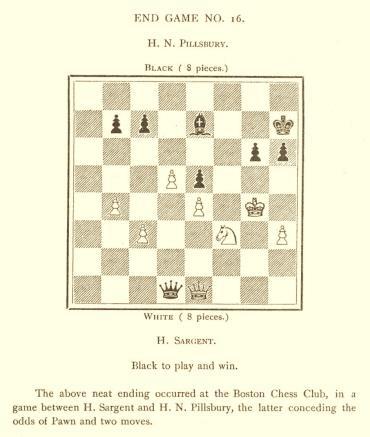

7628. Sargent v Pillsbury

A position on page 240 of the November 1892 American Chess Monthly:

It does not seem that the Monthly reverted to the position, i.e. to give the conclusion (which was presumably 1...h5+ 2 Kg3 Bh4+, etc.).

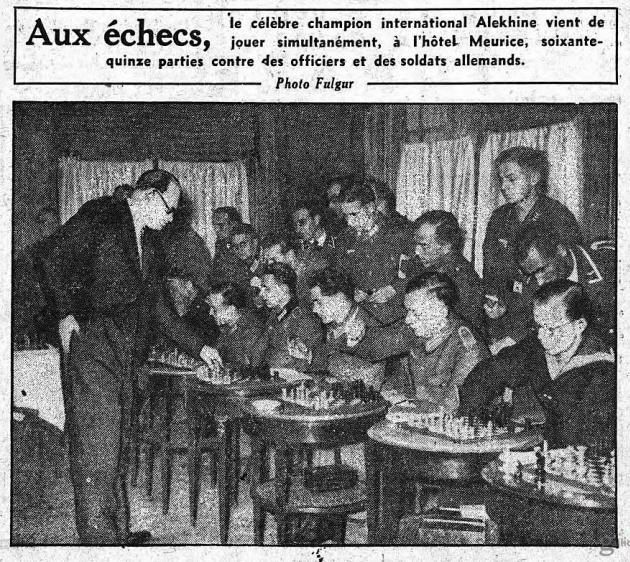

7629. Alekhine in Paris, 1941

Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) supplies this photograph from page 1 of the Paris publication Le Matin of 23 December 1941:

This simultaneous display at the Hôtel Meurice against the German military was mentioned on page 677 of the Skinner/Verhoeven book on Alekhine. There are discrepancies, such as whether Alekhine faced 75 boards or 50.

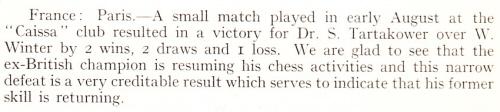

7630. Match in Paris

Mr Thimognier asks whether information, including the full game-scores, is available concerning the match between Savielly Tartakower and William Winter in 1938.

This brief report was on page 457 of the October 1938 BCM:

7631. Mate in 11 (C.N. 7618)

White, to move, mates all nine kings (simultaneously) in 11 moves

This problem, by Charles Henry Waterbury, was published in the Hartford Weekly Times of 25 September 1875 (whose diagram used queens rather than kings). Page 120 of the Westminster Papers, 1 November 1875 wondered whether the composition was solvable, but when it was given on page 140 of the 1 December 1875 issue the Papers commented:

‘Last month we did a great injustice to Mr C.H. Waterbury and his nine king problem, by suggesting that it was impossible of solution. We know better now, and that our readers may suffer something with us, we give the problem in the margin.’

On page 169 of the 1 January 1876 edition ‘H.J.C.A.’ (Henry John Clinton Andrews) observed:

‘Mr Waterbury may fairly be proclaimed the Napoleon of chess strategy. Even the great emperor never excelled, or even rivalled, this feat of checkmating nine hostile monarchs at one stroke and in one pitched battle. Metaphor apart, it must be admitted that this problem, though eccentric, is planned and executed with masterly skill, and I have enjoyed a rare treat in conquering its difficulties.’

In the same issue (page 174) Andrews was named as the Westminster Papers’ only solver of the problem. The solution (which had also been given in the Hartford Weekly Times of 16 October 1875) runs:

1 Qf2+ g3 2 hxg3 Kh5 3 Ng4+ e3 4 Bxe3+ Ke4 5 Na8+ Ka7 6 Nxe5 hxg5 7 Bc1 g4 8 Bf4 Kf5 9 e4+ Kxe4 10 Qc2+ Kd4

11 Nc6 mate.

C.H. Waterbury (Scientific American Supplement, 13 April 1878, page 1900)

For further information about Waterbury, see pages 7-10 of Brentano’s Chess Monthly, June 1882.

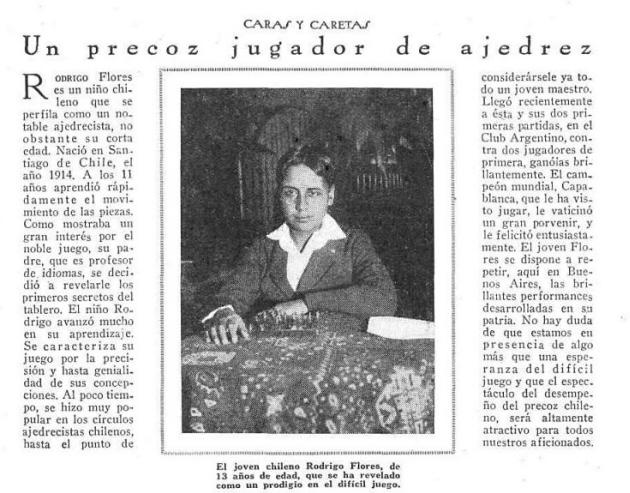

7632. Rodrigo Flores

Further to our feature article The Chess Prodigy Rodrigo Flores Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) notes regarding the Flores v Palau encounter (L’Echiquier, December 1929, pages 541-542) that the Belgian magazine was criticized on page 3 of the January 1930 issue of El Ajedrez Americano for not specifying that it was a skittles game.

Our correspondent adds a feature from Caras y Caretas, 1 October 1927:

Finally, Mr Sánchez draws attention to a posthumous autobiography by Flores (Santiago, 2009), Mis años de ajedrez.

Addition on 8 August 2016: the above link no longer works.

7633. Capablanca in London

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) sends this photograph from the fourth sheet (the photograph page) of De Sumatra Post (Medan) of 14 May 1929:

We add that the exhibition took place at the Selfridges department store in Oxford Street, London on 9 April 1929. From page 170 of the May 1929 Chess Amateur:

‘The ladies on Tuesday included the little Princess Tatiana Wiasemsky, the nine-year-old grand-daughter of Mr Gordon Selfridge. She made a good fight and was one of the last to finish.’

Another photograph taken during the display, and also showing ‘the little Princess’, is in our book on Capablanca, courtesy of Mr David Butler of Selfridges:

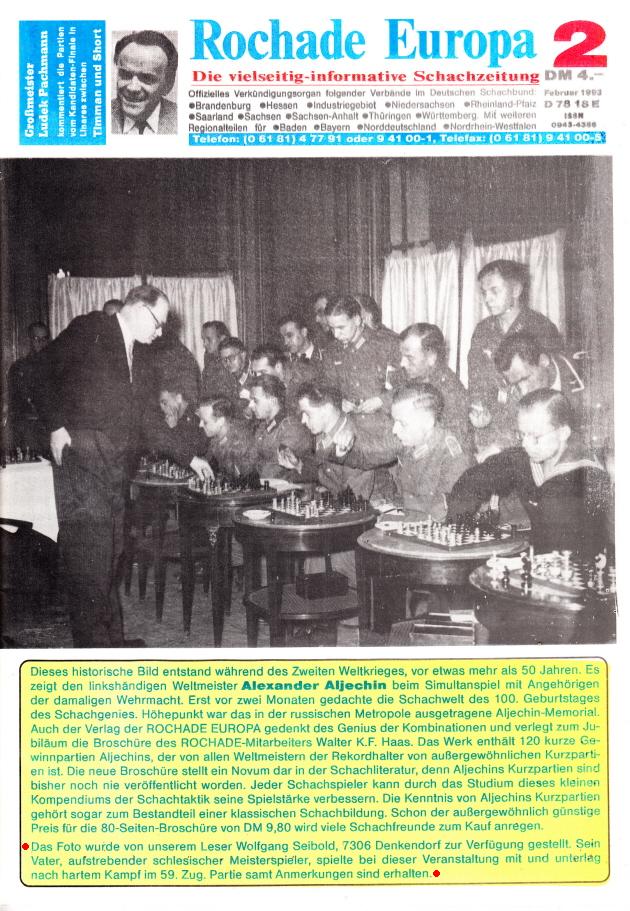

7634. Alekhine in Paris, 1941 (C.N. 7629)

Wolfgang Franz (Oberdiebach, Germany) notes that a better-quality version of the Alekhine photograph was on the front cover of the February 1993 Rochade Europa:

Page 45 of the September 1993 issue gave the game Alekhine v Seibold, dated 21 December 1942 (sic). See page 677 of the Skinner/Verhoeven book on Alekhine.

Mr Franz also points out that the score of the simultaneous display was +40 –4 =6 according to page 5 of the January 1942 Deutsche Schachzeitung but +39 – 4 =7 in this report in La Gerbe of 8 January 1942:

Leonard Skinner (Cowbridge, Wales) provides the report on page 16 of Schach-Echo, 7 January 1942:

Nothing has been found to support the statement in Le Matin (C.N. 7629) that the Alekhine display was on 75 boards.

7635. On-line archives (C.N. 7615)

A new article Chess History Research Online has just been posted. It will be expanded shortly with further contributions from readers.

| First column | << previous | Archives [93] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.