Edward Winter

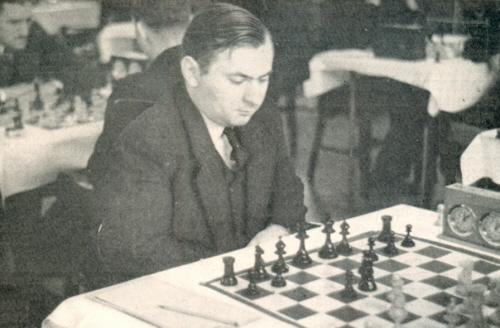

Reuben Fine, Marshall Chess Club,

7 December 1942

Chess Review, January 1943, page 9

Complementary articles on Reuben Fine are:

Borochow v Fine, Pasadena, 1932;

Capablanca v Fine: A Missed Win;

Critical Moments in Chess.

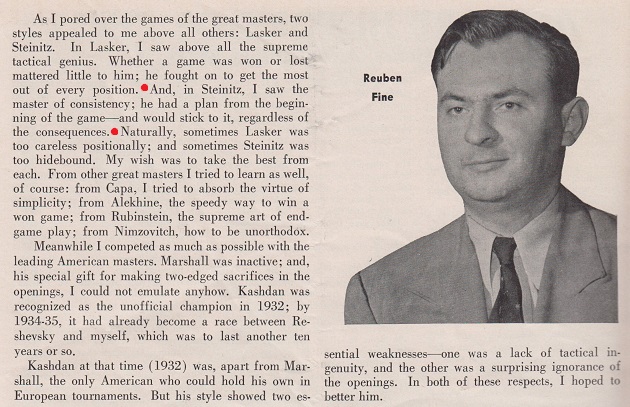

From page xvi of Lessons from My Games by Reuben Fine (New York, 1958):

In 1937 Edward Samuel Tinsley had not ‘just been retired’. He died.

(593)

See The Chess Tinsleys.

We do believe that game annotations, including !s and ?s, should tell a coherent story of mistakes and their exploitation – unless the writer admits that he does not know what is going on. The thought comes to mind after recent perusal of Fine’s (mediocre) book Bobby Fischer’s Conquest of the World Chess Championship. Games 5 and 6 of the 1972 match will suffice as examples. Spassky is alleged to have made a string of bad moves, yet somehow he still has a draw available many moves later.

Sometimes Fine gets facts right: ‘Paul Morphy (1837-1884)’, page 3. Sometimes he gets them wrong: ‘Paul Morphy (1836-1883)’, page 89. His judgements are equally schizophrenic.

An old yarn repeated by Fine (page 79) and also given by Chernev in Curious Chess Facts (page 10) and Wonders and Curiosities of Chess (page 7) is that a German ‘chess book’ once appeared which was completely blank except for the words ‘Halt's Maul’ (Keep your mouth shut/Keep quiet). ‘Three hundred blank pages’, wrote Fine. True?

Many of Fine’s pages would have been better off blank.

(857)

The German publication is discussed in our feature article A Fictitious Chess Book.

On page 152 of the May 1953 CHESS V.W.H. Waller pointed out an interesting disagreement between leading authors over basic chess strategy:

‘Under the heading “Sicilian Defence” at page 85 of his book The Ideas Behind the Chess Openings Fine writes “White almost invariably comes out of the opening with more terrain. Theory tells us that in such cases he must attack ...” Again, on page 86 he writes “3. White must not be passive: he must attack because time is on Black’s side (it usually is in cramped positions).”

In contrast to this, C.H.O’D. Alexander in his book Chess writes at page 63 “An advantage in space is much more enduring than an advantage in time and, generally speaking, you need be in no hurry for a winning attack ...” Also on page 64 he writes “remember that when you have an advantage in space your first object is to restrict the opponent, not to launch a direct attack ...” Further, on page 66, “This game is a masterly example of using space advantage. Notice how White never hurries ...”’

The CHESS Editor then comments, ‘We rather favour Alexander’s view.’

(1540)

From Ed Tassinari (Scarsdale, NY, USA):

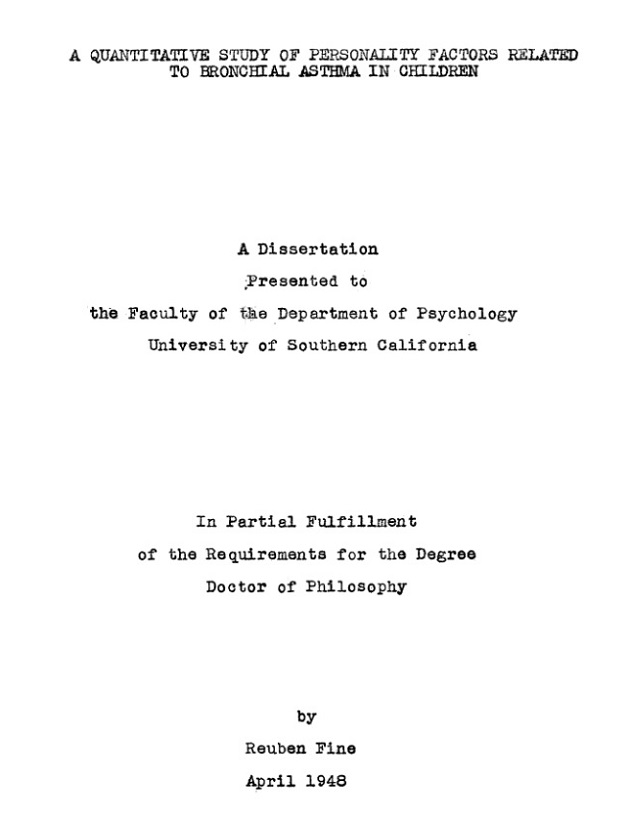

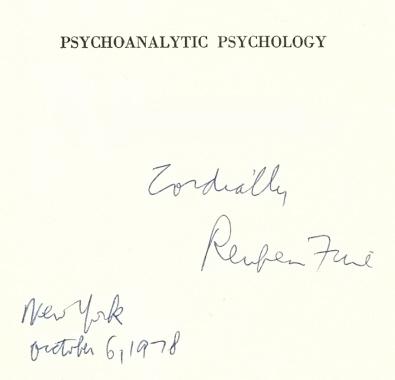

‘Reuben Fine’s doctoral dissertation apparently had nothing to do with chess. The reference work Comprehensive Dissertation Index (Xerox University Microfilms, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA, 1973), which attempts to list US dissertations written between 1861 and 1972, gives Fine’s 1948 dissertation, for the University of Southern California, entitled “The Personality of the Asthmatic Child”.’

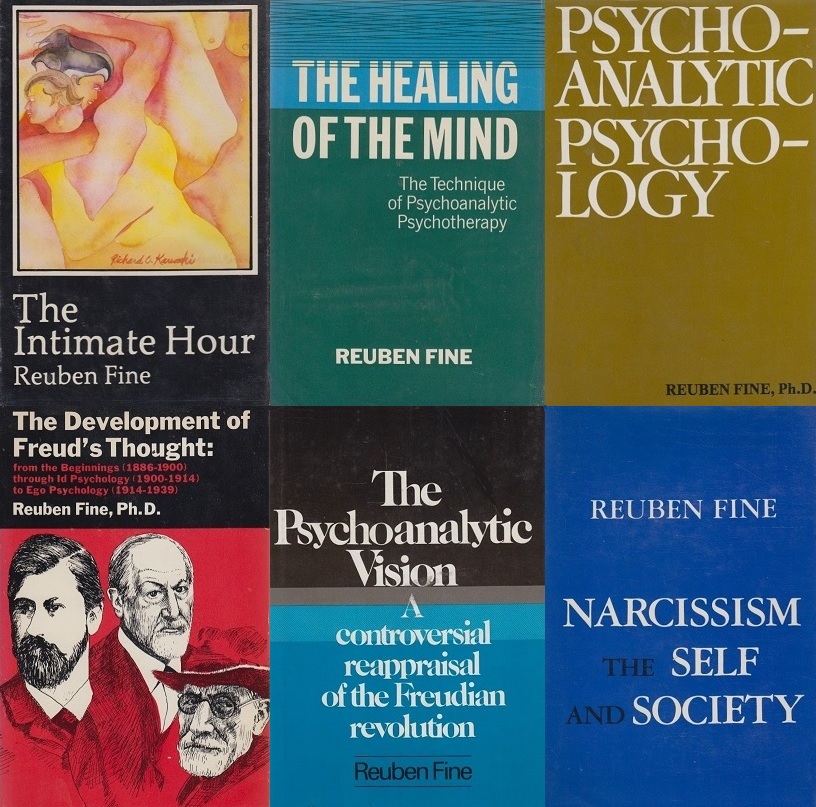

Our collection includes nine books on psychology by Dr Fine. These range from the weighty A History of Psychoanalysis (686 pages) to The Intimate Hour and other raunchy volumes of agony aunt level.

(2243)

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) notes that the website mentioned in C.N. 10470 has the full text of Reuben Fine’s PhD dissertation, ‘A quantitative study of personality factors related to bronchial asthma in children’ (April 1948).

(10471)

Allard Hoogland (Doornspijk, the Netherlands) draws attention to a passage in a book on the alleged American spy Alger Hiss (1904-96). On page 128 of Laughing Last (Boston, 1977) Tony Hiss quoted his father as saying:

‘Dr Rubinfine [sic], my analyst, says I have a phobia against fear and don’t get afraid even when I should get afraid.’

Our correspondent asks whether Reuben Fine is meant.

(2299)

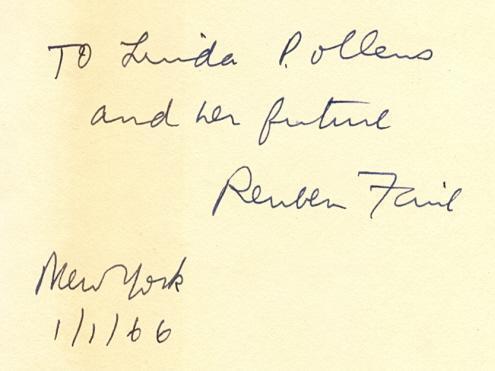

C.N. 2153 quoted from Sidney Bernstein’s letter to us dated 23 January 1987, ‘Dr Ruben (he spells it thus now) Fine’. What more is known about such a change of forename? We find no evidence for it in our collection of books signed by Fine, of which the last is a copy of Love and Work The Value System of Psychoanalysis (New York, 1990).

(3217)

‘Ruben’ Fine is often seen in Spanish-language literature, and even in Fine’s own books. For instance, here is the front cover of the second edition (1962) of the Argentinian version of The Middle Game in Chess:

(3521)

Postings at the Chess Café’s Bulletin Board in 2001 (most notably by Paul Kollar) pointed out many passages published under Larry Evans’ name which were identical or similar to what had appeared in books by Lasker, Réti, Reinfeld and Fine. (Regarding Fine, on page 32 of the February 2002 Chess Life Evans defended himself by affirming that he had collaborated on The World’s Great Chess Games and had himself written the passages in question.)

(2971)

See Copying.

A selection of non-chess works by Reuben Fine:

Noting the expression ‘psychiatric practice’ on page 88 of the 7/2000 New in Chess, Arnold Denker (Fort Lauderdale, FL, USA) asks us about the exact activity of Reuben Fine beyond the chessboard. We have therefore compiled the following notes from information given in Fine’s various books:

He received his Ph.D in 1948 at the University of Southern California, where he was a teaching fellow. Thereafter he entered private practice of psychoanalysis in New York, associated with the Elmhurst General Hospital and the Metropolitan Center for Mental Health. Over the years he taught psychoanalysis at eight universities (including Adelphi University) and was Vice-President of the National Psychological Association for Psychoanalysis, the Visiting Professor of the College of the City of New York and a Fellow of the American Psychological Association. In 1961 he was Visiting Professor of Psychology at the University of Amsterdam. Other titles he received at various times were Director of the New York Center for Psychoanalytic Training and the Center for Creative Living and Dean-designate of the Graduate Department of Psychology at Mercy College.

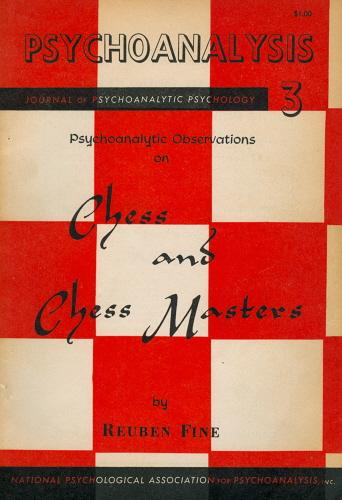

In our view, Fine’s 1956 book Psychoanalytic Observations on Chess and Chess Masters (reprinted by Dover in 1967 as The Psychology of the Chess Player) is inexpressibly awful. Although his book on the 1972 Spassky v Fischer encounter was mauled by the critics, Fine called it ‘the most serious’ of the match books in a self-absorbed bibliography on pages 143-145 of his subsequent work The Teenage Chess Book (New York, 1974 edition).

(2485)

A brief digest from the section on Alekhine (‘the sadist of the chess world’) on pages 52-55 of The Psychology of the Chess Player by Reuben Fine:

‘… we are told that his mother taught him the game at an early age.’

‘His father is reported to have lost two million rubles at Monte Carlo.’

‘Alekhine was reputed to have become a member of the Communist party.’

‘A report was broadcast during the war that Alekhine was confined to a sanatorium in Vichy, France for a while; but I have been unable to obtain any details.’

‘It was said that he became impotent early in life.’

(3082)

For other examples of Fine’s stories about chessplayers, see C.N. 2917 in ‘Fun’.

See also Unintelligible Chess Writing.

As shown in C.N. 2832 (see Chess and War), a writer who made unwise use of The Psychology of the Chess Player was Eric Anton Kreuter, in The Expression of Aggression in the Game of War Using Chess as a Bloodless Model (New York, 1991).

John Roycroft (London) writes:

‘The late and great Reuben Fine is said to have written Basic Chess Endings in six weeks. Is this fact or rumour? If he had a team of helpers, who were they?’

In 1984 Fine gave a three-hour interview to Bruce Pandolfini which was the basis for an article on pages 24-27 of the October 1984 Chess Life. Pandolfini wrote:

‘Undoubtedly, his magnum opus is Basic Chess Endings. Though it took only about an incredible three months to write, it stands out as a great achievement in chess history. Fine says he had no trouble organising the material, but had to work diligently accumulating the examples, many of which he himself created.’

Three months’ work means that Fine wrote, on average, just over six book pages per day.

(1980)

The ‘three months’ reference in Chess Life had also been given in C.N. 1404.

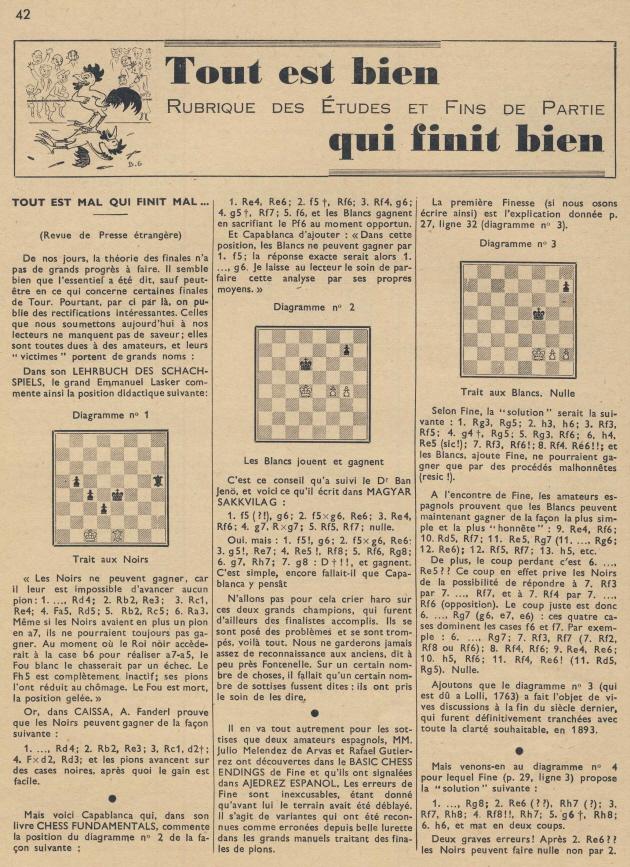

Luc Winants (Boirs, Belgium) has supplied the requested [in C.N. 8422] article in L’Echiquier de Paris, published on pages 42-43 of the March-April 1951 issue. It will be noted that the Lasker and Capablanca endings were both given, and that the remainder of the article contained sharp criticism of Reuben Fine’s Basic Chess Endings.

(8426)

On page 89 of Bobby Fischer’s Conquest of the World’s Chess Championship (New York, 1973) Fine – or, to quote the title page, ‘Reuben Fine, Ph.D., International Chess Champion’ – gave Morphy’s dates as ‘1836-1883’. Both years were similarly wrong on page 72 of the international chess champion’s The Teenage Chess Book (New York, 1965 and 1974).

On page 292 of The Forgotten Man: Understanding the Male Psyche (New York, 1987) Fine forgetfully wrote that Fischer was ‘born in Brooklyn’.

(3336)

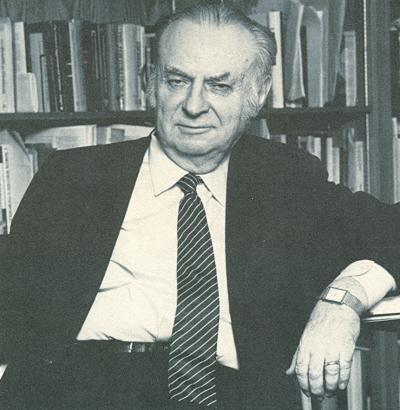

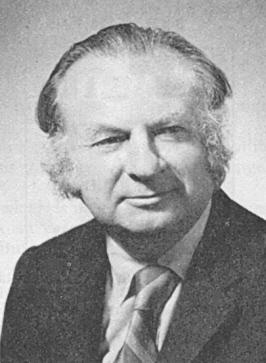

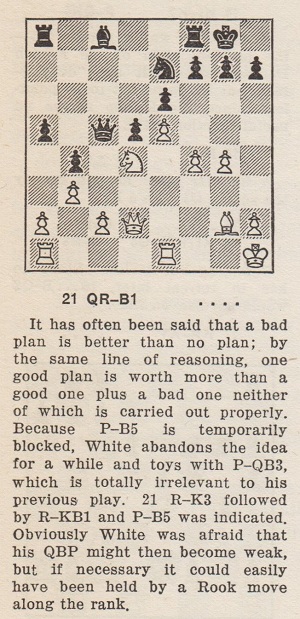

Reuben Fine (Frontispiece of his book The Forgotten Man: Understanding the Male Psyche (New York, 1987))

From page xi of Reuben Fine’s book Lessons from My Games (New York, 1958):

‘Up to that time [Pasadena, 1932] I had not read any chess books. My knowledge of the game came from intensive over-the-board play. One reason was that there was so little worthwhile literature in English. A few books by Marshall and Capablanca were too elementary. I had picked up a tournament book of St Petersburg, 1914, but the notes contained many errors. When I found these errors, I thought that I must be wrong, and that I was not really good enough to play over such games yet; only later did I discover how sloppy many chess authors can be.’

Fine then explained that he had needed to learn German to be able to read, among other volumes, Nimzowitsch’s Mein System; but was he really unaware that an English edition had been published in 1929?

On page 19 Fine set out his views of various prominent writers:

‘Tartakower I found very amusing but shallow. Capablanca had little to teach the serious student; the same was true of Marshall and Lasker.’

Reuben Fine

(3714)

From page 18 of Reuben Fine by Aidan Woodger (Jefferson, 2004):

‘Match with Fred Reinfeld, New York, 25 July-9 August 1931. Fred Reinfeld’s papers indicate that the youngsters contested a six-game match in the late summer. Fine won three games to Reinfeld’s two, the other game being drawn. In addition to the match Fine and Reinfeld were involved in a consultation game on 17 September. Game-scores unavailable. Crosstable unavailable.’

However, we note that on pages 8-9 of the stencilled booklet A Course in the Elements of Modern Chess Strategy (Lesson V, Part II) by Fred Reinfeld and Matthew Green (New York, 1936) the following game was given (annotated by Reinfeld):

Fred Reinfeld – Reuben Fine

‘Impromptu match 1931’

Nimzo-Indian Defence

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 Qb3 c5 5 dxc5 Nc6 6 Nf3 Ne4 7 Bd2 Nxc5 8 Qc2 f5 9 a3 Bxc3 10 Bxc3 O-O 11 g3 b6 12 Bg2 Bb7 13 O-O Qe7 14 Rfd1 d6 15 Nd4 Nxd4 16 Rxd4 Bxg2 17 Kxg2 Rac8 18 Rad1 Rfd8 19 b4 Ne4 20 f3 Ng5 21 Qd3 Nf7 22 e4 Ne5 23 Qe2 Qc7

24 Rxd6 Rxd6 25 Bxe5 Rd2 26 Qxd2 Qxe5 27 Qd7 Rf8 28 Qd4 Qxd4 29 Rxd4 e5 30 Rd5 fxe4 31 fxe4 Rc8 32 c5 bxc5 33 Rxc5 Rxc5 34 bxc5 Kf7 35 Kf3 Ke6 36 Kg4 Resigns.

(3920)

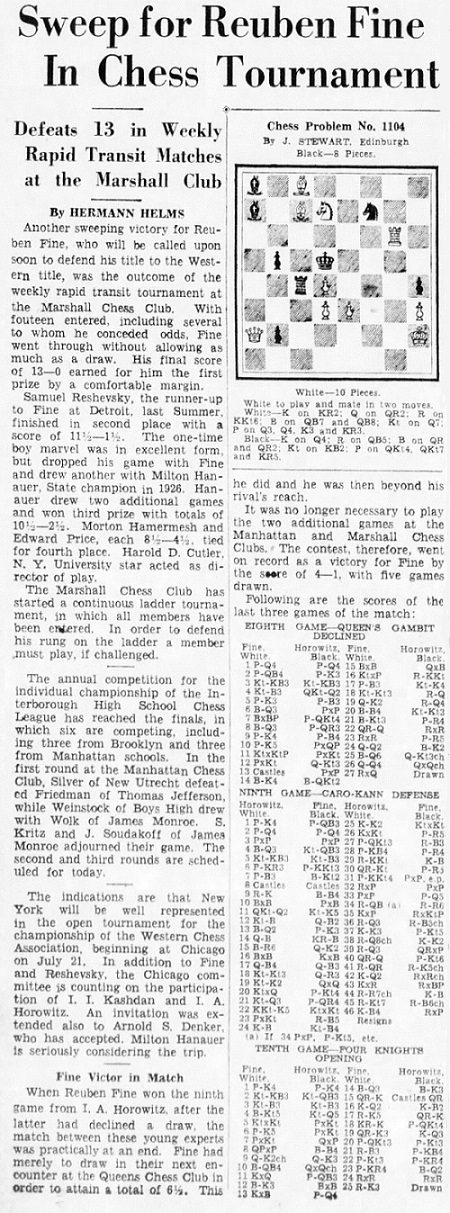

From page 15 of the January 1934 American Chess Bulletin:

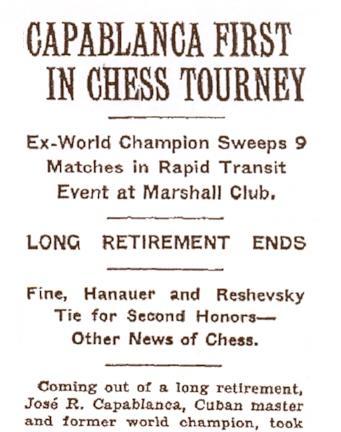

‘Having returned home during the Christmas holidays, José R. Capablanca is still in Havana, where, happily, political conditions are returning to normal. Before leaving New York he visited the Marshall Chess Club and, quite informally, took part in one of its weekly rapid transit tournaments. Winning nine games straight, the famous Cuban carried off the first prize. Reuben Fine, club champion who has to his credit a long series of victories in these weekly bouts, scored 7-2 and divided the second, third and fourth prizes with Milton Hanauer and Samuel Reshevsky.’

Gene Gnandt (Houston, TX, USA) sends us the more detailed report on page 31 of the New York Times, 7 December 1933:

The newspaper gave the complete final standings of the tournament (played on 6 December 1933) as follows: Capablanca 9-0; Fine 7-2, Hanauer 7-2 and Reshevsky 7-2; Chernev 4-5; Hamermesh 4-5; Dunst 2-7, Hammer 2-7 and Simon 2-7; Sack 1-8.

(4817)

Further to a number of masters’ announcements of their intended retirement from chess, and an addition comes now from Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina):

‘Page 282 of Chess Review, December 1938, quotes an interview given by Reuben Fine to Savielly Tartakower that had appeared in De Telegraaf. One passage reads:

“Earlier this year he [Fine] had decided to give up chess as a profession and complete his studies in mathematics. Last May he had asked the AVRO committee to release him, but was forced to live up to his contractual agreement to play.”’

(5021)

Page 197 of The Guinness Book of Chess Grandmasters by William Hartston (Enfield, 1996) quoted a familiar old quip:

‘By the time FIDE organized the world championship tournament in 1948, Fine had begun to shift his attentions from chess to a career in psychoanalysis. He declined an invitation to the 1948 event because it clashed with his final exams. His decision was later described by one wit as “a great loss for chess and at best a draw for psychoanalysis”.’

Who first made that remark, and where?

(5238)

We now note that the familiar comment about Reuben Fine was made by Gilbert Cant in an article ‘Why They Play: The Psychology of Chess’ on pages 44-45 of Time, 4 September 1972:

‘When Fine switched his major interest from chess to psychoanalysis, the result was a loss for chess – and a draw, at best, for psychoanalysis.’

The full article can be read on-line via the link to Time given in C.N. 5819.

(6090)

In a recent book catalogue (List Potpourri-76.4.7Is.1) Dale Brandreth commented on The Psychology of the Chess Player by Reuben Fine (New York, 1967):

‘A very interesting book, though with some very curious errors. For example, on page 50, speaking of Capablanca, he writes: “He never studied, never gave exhibitions, in fact hardly played at all outside of tournaments.” Was Fine daft? Fine himself played in Capa’s magnificent 7th Regiment Armory exhibition against 50 teams in 1931. His simultaneous exhibitions numbered in the hundreds and greatly enhanced his reputation for quick sight of the board considering the extreme rapidity of his play.’

Fine on Capablanca makes a strange contrast with Fine on Staunton. About the latter he remarked on page 11 of The World’s Great Chess Games (New York, 1951):

‘He wrote, he played, he traveled all over, lecturing and giving simultaneous exhibitions.’

In fact, Staunton shunned simultaneous play, as mentioned in C.N. 594 (see pages 237-238 of Chess Explorations), which quoted the following passage from his column on page 371 of the Illustrated London News, 14 April 1866:

‘We have often expressed our opinion of “that silliest of all chess exploits” – the playing a number of games simultaneously against a number of tenth-rate amateurs. To play half-a-dozen games without sight of the chessboards is a real tour de force of which very few are capable. To play half-a-hundred by merely parading up and down before as many chessboards is what any tolerable player can do without difficulty. In such a case, he need only be insensible to the absurdity of the exhibition; and if he is a good walker, or if he can hire a velocipede, his triumph is infallible.’

What detailed records exist of Staunton playing simultaneous chess?

In his Psychology book (page 30) Fine wrote of Staunton, ‘No brilliant games of his have survived ...’, a remark characteristic of much that used to appear about him in US chess literature. Other examples were quoted in our feature article on Frederick Edge; for a particularly ill-natured paragraph about Staunton by Al Horowitz see page 259 of Chess Facts and Fables.

(4492)

C.N. 4492 referred to Reuben Fine’s participation in a 50-board simultaneous display given by Capablanca against consulting groups at the Drill Hall of the Seventh Regiment Armory, New York on 12 February 1931, and now Tony Bronzin (Newark, DE, USA) raises the subject of Fine’s account on pages 3-6 of Lessons from My Games (New York, 1958). Fine headed the game as follows:

Our correspondent comments:

‘However, in the February 1988 Chess Life (pages 12-13) Arnold Denker, when recounting the life of an American chessplayer of the 1930s, Donald MacMurray, wrote:

“The great Cuban seemed to start out well in the game, but Mac and a young Reuben Fine showed some fine endgame technique. Defeating Capablanca was always a notable feat.’

My question is: did Fine exploit his two bishops and better king himself to win the game, or was it a collaborative effort from start to finish?’

We begin by noting that Fine’s coverage of the game had previously appeared in his series of articles ‘My Best Games of Chess’ on pages 296-297 of the October 1955 Chess Review. The game-score was given on page 56 of the March 1931 American Chess Bulletin, where the allies were named as ‘R. Fine, D. MacMurray, E. Schwartz and L.W. Stephens’. Page 50 had the same information. The display lasted nearly eight and a half hours, the final move being made ‘within a minute or two of midnight’ (page 45). Did newspapers of the time give further details of the game under discussion here?

(5390)

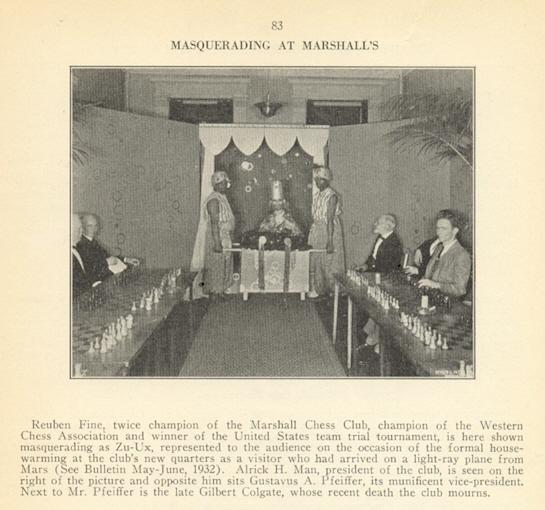

Source: American Chess Bulletin, May-June 1933, page 83.

(4527)

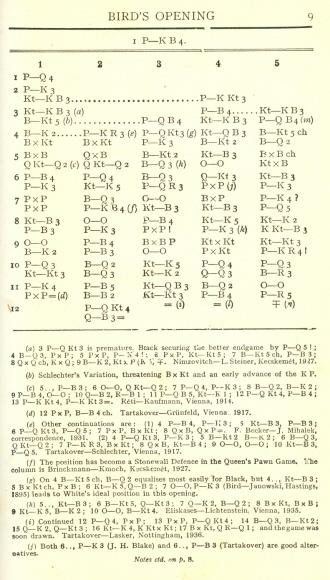

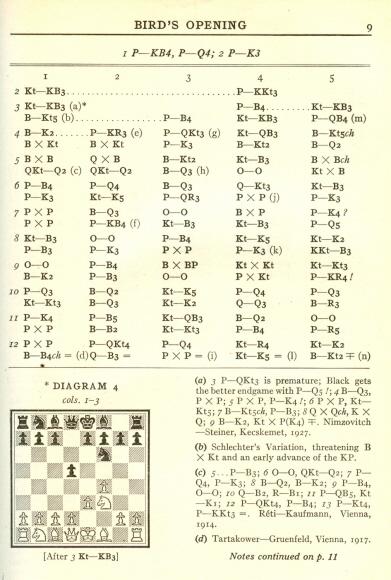

Owen J. Clarkin (Ottawa, Canada) writes on the subject of copying:

‘I should like to point out an example concerning:

(i) Modern Chess Openings, seventh edition, revised by W. Korn under the editorship of R.C. Griffith and P.W. Sergeant (London, 1946);

(ii) Practical Chess Openings by R. Fine (Philadelphia, 1948).

Regarding the Center Counter Game, I found that ten columns of variations and the corresponding footnotes are virtually identical. See pages 30-32 of MCO and pages 35-38 of PCO. Other chapters where copying is notable include the following:

Alekhine’s Defense: Columns 1 and 2 of MCO v 1 and 2 of PCO; column 23 of MCO v 20 of PCO; column 21 of MCO v 17 of PCO.

Bird’s Opening is practically identical for most variations and footnotes.

The Bishop’s Opening has many copied sections.

It is not clear to me who copied whom, or whether this copying has been noticed before. The editors of MCO credit Fine as the reviser of the sixth edition of MCO (see page v of the seventh edition), but Fine makes no mention in PCO of his involvement in the sixth edition of MCO.’

Our correspondent’s final paragraph holds the key to the affair: Reuben Fine had brought out a ‘completely revised’ edition of MCO in 1939. Below is part of the three books’ coverage of one of the above-mentioned openings:

From left to right: MCO-6 by Fine (1939), MCO-7 by Korn (1946), Practical Chess Openings by Fine (1948)

Thus Fine’s material in the sixth edition of MCO was used both by Korn in the seventh edition of MCO and by Fine himself in PCO. The rights and wrongs of such practices seem far from clear-cut.

The following text appeared on the dust-jacket of Practical Chess Openings:

‘Several years ago, when the author was on an exhibition tour, the master of ceremonies in St Louis introduced him to the audience with the remark: “Ladies and Gentlemen, it gives us great pleasure to have with us tonight the author of the Bible.” The “Bible” that he referred to was Modern Chess Openings, sixth edition, to which this book is a sequel.’

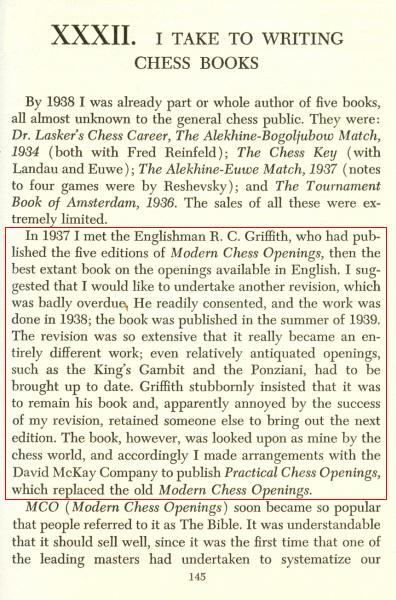

The blurb also asserted: ‘Reuben Fine is the world’s leading authority on chess.’ As regards the MCO/PCO affair, Fine gave his side of the story on page 145 of his book Lessons from My Games (New York, 1958):

(5269)

C.N. 593 quoted from page 80 of Lessons from My Games by Reuben Fine (New York, 1958):

‘Both Alekhine and Capa were anxious to see Euwe do badly. I was rather amused when a most critical situation arose in my game with Euwe and both the ex-world champions whispered suggestions in my ear.’

Reuben Fine

Fine reiterated that claim about the game (a 19-move draw) on page 33 of his book Bobby Fischer’s Conquest of the World’s Chess Championship (New York, 1973):

‘... at the Nottingham tournament in 1936, when I was playing Euwe, then world champion after his defeat of Alekhine in 1935, both Alekhine and Capablanca spontaneously came up to me during the game to suggest moves, even though I had not asked them to do so.’

(5394)

Another remark by Fine in Lessons from My Games (page 92) quoted in C.N. 593:

‘Grünfeld had some obvious psychological weaknesses. Perhaps because of his physical handicap (he had a wooden leg) he had grown increasingly cautious with the passing of the years. His ambition in a tournament was to win one game and draw the rest ... He took a childlike pleasure in his erudition; when he was working for Euwe on the card index of openings, he insisted on entering his contributions on green cards (Grünfeld: green square).’

Two pairs of self-contradictions from Reuben Fine, as given in C.N. 1424:

On page 37 of the November 1953 CHESS Irving Chernev pointed out these statements by Fine:

Reuben Fine

The other example was shown by us on page 10 of CHESS, October 1976:

(5597)

Reuben Fine

C.N. 5597 quoted contradictory statements by Reuben Fine about Alekhine as a psychologist, and we add here some further remarks of Fine’s, in a comparison between Alekhine and Keres on pages 142-143 of his book Chess Marches On! (New York, 1945):

‘Despite the many points of similarity there are a number of important respects in which they differ. Chief among these are Alekhine’s superior grasp of psychological factors and his all-consuming ambition ...

Reliance on psychology has been both an asset and a handicap for Alekhine. The legitimate use of psychology in master play is to maneuver the opponent into positions where he feels ill at ease, which do not “lie right” for him, as the German puts it. Alekhine has been able to apply this principle with consummate skill on a number of occasions – the match with Capablanca is the most notable. At other times, however, chiefly when he was at the height of his fame, around 1932-1934, Alekhine has exaggerated the human factor out of all proportion. In one French tournament he even went so far as to make a serious attempt to win by hypnosis.’

What exactly happened at that ‘one French tournament’?

Another question concerns the extent to which Fine applied (or claimed to apply) ‘psychological factors’ in his own games. That matter is raised tentatively, however, since few topics lend themselves so readily to waffle as does ‘chess psychology’.

(5616)

See also Chess and Hypnosis.

Most readers will be familiar with the Reinfeld/Fine book Dr Lasker’s Chess Career, Part I: 1889-1914 (London and New York, 1935), reprinted in 1965 by Dover under the title Lasker’s Greatest Chess Games 1889-1914. Part II was never published, but a manuscript may still exist. As quoted in C.N. 1500, Reinfeld wrote in the October 1948 CHESS (page 24):

‘Mr Finck’s letter is typical of a number of requests I have had for a Dr Lasker’s Chess Career, Part II. I have had such a manuscript in readiness for a number of years, but I do not know of any publishing firm which has a burning interest in the project. To my deep regret, therefore, the manuscript continues to remain unpublished. If any of your readers know of any way to make publication possible, I shall be deeply grateful.’

Reinfeld did not make it clear whether Fine also collaborated on Part II. As pointed out in C.N. 1572, Fine referred to his participation in Part I on page 80 of his book Lessons from My Games.

‘Petrosian is probably the weakest player who has ever held the world championship.’

Source: The Final Candidates Match Buenos Aires, 1971 by R. Fine (Jackson, 1971), page 4.

(2758)

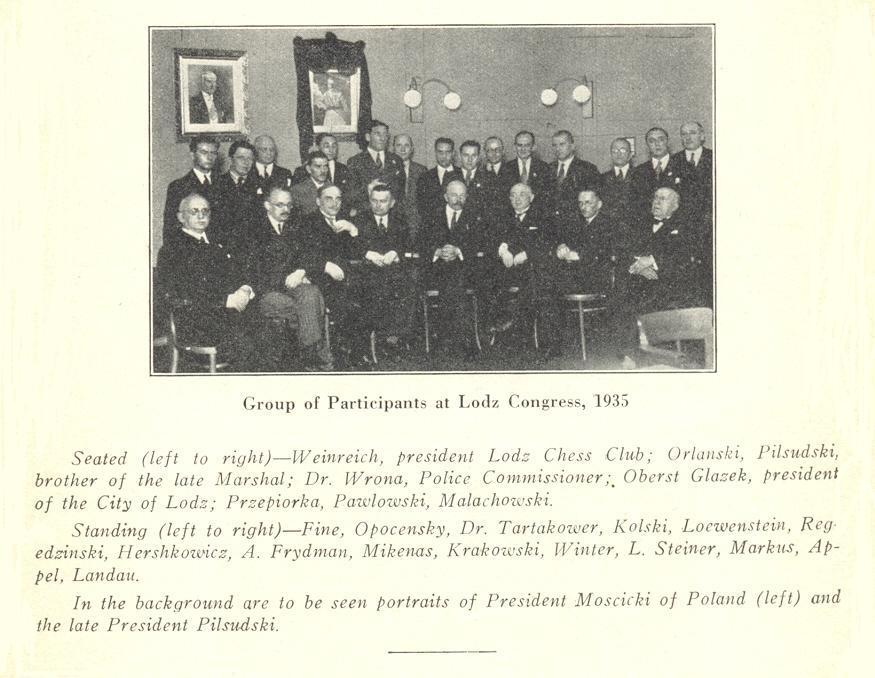

A photograph taken at Łódź, 1935:

Source: American Chess Bulletin, September-October 1935, page 131.

(4734)

Numerous players treat chess problems with indifference or, even, hostility. The matter was discussed by Reuben Fine in his Introduction (pages v-vii) to Irving Chernev’s Chessboard Magic! (New York, 1943):

‘There are some who deprecate the problemist’s art; it does not improve one’s game, they tell you. At times devotees – rather lamely – try to defend the problem by maintaining that it sharpens the imagination or whets the appetite for combinations – and convince nobody, least of all themselves. The problem is a separate province, in some ways as difficult and as complex as the regular game. It needs no justification – qui s’excuse s’accuse. It stands or falls by the pleasure you derive from it – and I need hardly add my small voice to the booming testimony that it can be great.’

Chessboard Magic! was an anthology of endgame studies, and Fine also commented in his Introduction:

‘I have met many who care very little for the ordinary problem; I have never known any who were not overjoyed and bewitched by endings.’

See Chess Problems.

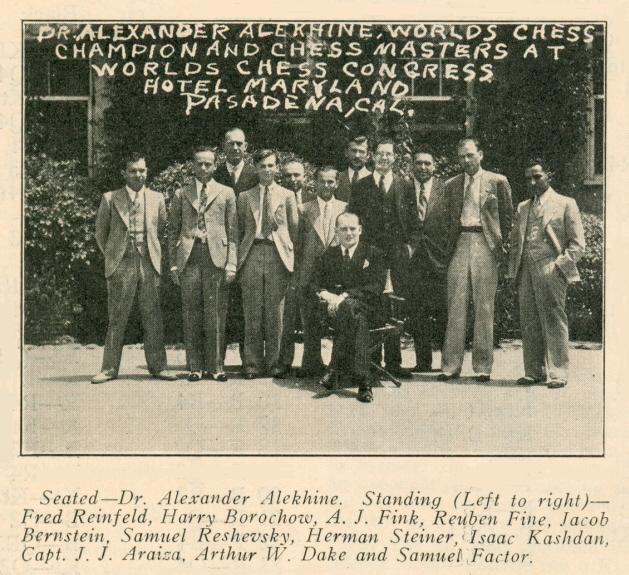

This group photograph was published on page 116 of the July-August 1932 American Chess Bulletin. Does any reader have a better copy?

(5543)

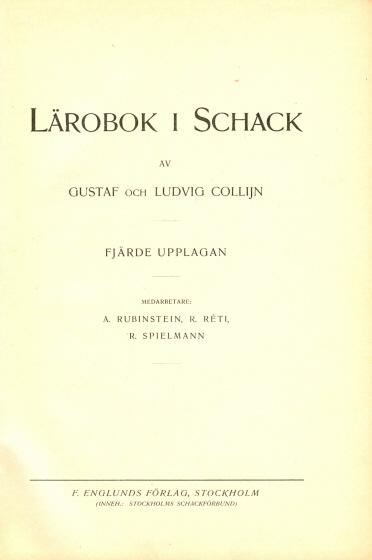

From page 333 of the November 1943 Chess Review (an article on Rubinstein by Reuben Fine):

‘When the famous Swedish Laarobok [sic] was being written right after the last war, the sponsor [sic], Colijn [sic], heard that Rubinstein had a copy of the German Handbuch, with various marginal comments. Colijn [sic] bought the book for a fantastic price, about $1,000, but Rubinstein’s “notes” did not cover two pages when they were put together.’

See also page 81 of Fine’s book The World’s Great Chess Games (New York, 1951). What is the basis for his claim?

The title page of the fourth (1921) edition

(5542)

Our article on Sidney Bernstein related Reuben Fine’s claim on page xviii of Lessons from My Games (New York, 1958) that ‘Bogoljubow had some of his rivals put in concentration camps by the Nazis when they arrived on the scene in Germany’. Pressed to identify these rivals, Fine gave the name of one person, Seitz (who was not in Europe during the Second World War).

We add here that Fine made a slightly different allegation on page 211 of The World’s Great Chess Games (New York, 1951), when Bogoljubow was still alive:

‘In Nazi Germany a famous grandmaster tried to force his journalistic rivals into concentration camps to get their columns away.’

(5660)

C.N. 1257, written in 1986, commented that the concentration camps charge ‘is such a grave one that we believe Fine has an obligation to explain his words’. He never did so.

The text from our feature article on Sidney Bernstein:

As indicated on pages 183-184 of our book (from C.N. 1403), Bernstein also assisted us in trying to sort out the claim by Reuben Fine on page xviii of Lessons from My Games that ‘Bogoljubow had some of his rivals put in concentration camps by the Nazis when they arrived on the scene in Germany’. Below is an expanded account of the affair.

On 23 January 1987 he informed us:

‘Yes, I know Dr Ruben (he spells it thus now) Fine – we went to university together back in the 1930s. He was even then a very brilliant youngster – I recall that after school hours he would give lectures on Symbolic Logic. I haven’t been in touch with him in recent years, but I can give you his current address and phone ...’

On 12 February 1987 we duly wrote the following letter:

‘Dear Dr Fine,

In the November-December 1983 issue of my magazine I quoted your comment about Bogoljubow on page xviii of Lessons from My Games, “Bogoljubow had some of his rivals put in concentration camps by the Nazis when they arrived on the scene in Germany”, and asked what evidence existed for the claim and who were the victims.

Although Chess Notes is read in nearly a hundred countries, nobody has been able to shed any further light on the matter, and I therefore take the liberty of writing to you direct to ask if you could kindly inform me of the source of your information.

It is a delicate matter, of course, but I hope that the enclosed sheet [of testimonials] will show that my magazine can be relied upon to handle issues responsibly.

Your reply will be greatly appreciated.

Yours sincerely,

Edward Winter’

No response was received from Fine, and on 17 April 1987 Bernstein wrote to us:

‘As for Fine – when you originally expressed interest in the matter of Bogoljubow’s activities related to the “concentration camps” I telephoned him. He wasn’t available, so I left my phone number on his tape. But he never returned my call – that’s why I sent you his address. Today, upon receipt of your letter, I phoned him again – and was able to reach him. He stated that he recalled getting your enquiry, but ignored it as he assumed you were “some kind of nut” (his words!). I assured him that he was in error ... Anyway, I brought up the Bogoljubow concentration camp matter. He stated: “Everyone knows he was a Nazi.” I pressed him for details of Bogoljubow’s misdeeds. The only person he could name as having been sent to a camp by Bogoljubow was Dr Seitz (who was, I believe, a chess journalist). Perhaps he (Fine) doesn’t recall the names of those who he alleges were victims ...’

In view of Fine’s inadequate response (as Chess Notes was later to report, Seitz was not even in Europe during the Second World War) we asked Bernstein to press him further. He kindly did so, reporting on 29 April 1987:

‘I’ve phoned Dr Fine’s office per your request and left a message on his answering-service tape. I hope the curmudgeon contacts me ...’

He did not. Bernstein wrote to us on 15 October 1988, ‘my feeling is that he has no remaining interest in chess matters’. On 3 January 1989 he referred to ‘his rather childish nature’, and on 26 January 1989 he commented:

‘Dr Fine is (to me) inscrutable – he and I were college students at the same time, same institution, and I always considered him a strange person …’

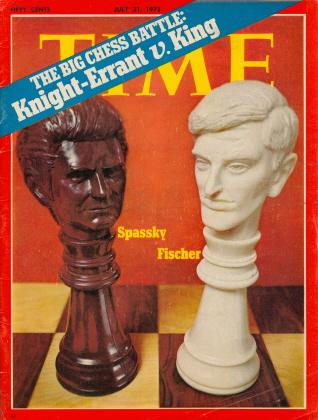

In Time, 31 July 1972, Ray Kennedy was the author of the cover article on pages 32-37 of that issue – a catchpenny thing ‘The Battle of the Brains’ which was mainly about Spassky and Fischer but also leapt gleefully on whatever might serve to ridicule such great players of the past as Morphy, Steinitz and Alekhine. For example (from page 35):

‘Morphy was given to such eccentricities as arranging women’s shoes in a semicircle in his room and prancing around his veranda reciting in French that “the little king will go away unabashed” [sic – an apparent miscopying of ‘all abashed’].’

In short, yet another ‘Fun’ writer for whom Reuben Fine’s The Psychology of the Chess Player was a godsend.

(5559)

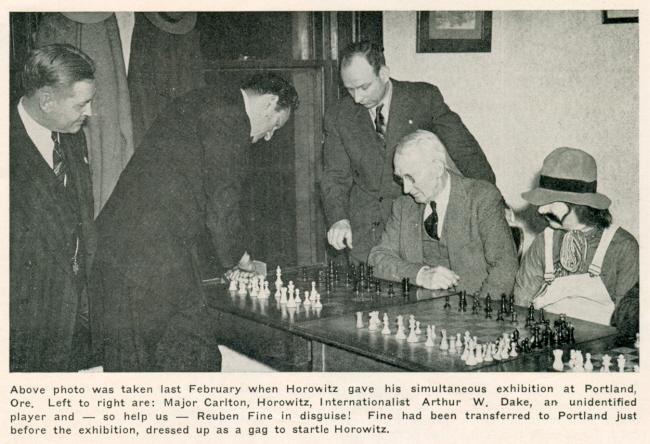

This photograph [given as a spot- the-master quiz question in C.N. 5630] dates from the 1940s, but we introduced a sepia herring. The full picture, from page 219 of the November 1942 Chess Review, appears below:

David Abrams (Syracuse, NY, USA) not only identified Reuben Fine but pointed out this ‘country cousin’ passage on page 25 of Fine’s book Lessons from My Games (New York, 1958):

(5640)

Page 46 of Roberto Grau, el maestro by G.C. Grau, J.R. Delfino and J. Morgado (Buenos Aires, 2007) has a quote from La Nación in 1935 which refers to ‘R.J. Fine’. C.N. 94 mentioned a reference to ‘Edward J. Lasker’, and C.N. 4916 discussed occurrences of ‘Samuel J. Reshevsky’.

(5666)

Two addresses for Reuben Fine have been added to the Where Did They Live? feature article, courtesy of Russell Miller (Camas, WA, USA). Mr Miller points out that in the 1920 USA Federal Census the future chess master’s forename was given as ‘Rubin’. This may be a transcription error, but it brings to mind the claim that in later life he used the spelling ‘Ruben’ (see C.N. 3217, on page 281 of Chess Facts and Fables).

Reuben Fine

(5757)

Aidan Woodger (Halifax, England) has provided the entries for Reuben and Emmy Fine (lines 31 and 32) in the 1940 US Federal Census, which has allowed a small amendment to be made to Where Did They Live?

Our correspondent, the author of the McFarland book on Reuben Fine, adds:

‘I have been looking for documents about the Fine family and have so far found the following: US Federal Census data 1910, 1920, 1930, 1940; New York State census 1915 and 1925; naturalization documents for Bertha (Nedner) Fine and Jacob Fucher (Fine); marriage index for Manhattan 1907-2018.

Jacob is difficult to track as there seem to be no census entries for 1910, 1920 or 1940 which closely match his details.

Contrary to what had been thought, Reuben Fine (born in 1914) was not an only child, but the second. Evelyn (Eva) was born in 1912, and there is still a record of her in 1932. I did not find her in the 1940 census, but that may be because she had married or because there was a mistranscription.

Reuben Fine appears as Ruby (1915), Rubin (1920 and 1925) and Reubin (1921/1924). In addition to the above-mentioned variant Jacob Fucher/Jacob Fine, Bertha signed her name as Feine on her 1932 naturalization documents.

Reuben Fine’s uncle, Reuben Lazarus (who seems to be the person who taught him chess), married Bertha’s sister, Sarah. He also appears as Rubin in documents.’

(11518)

Aidan Woodger expands on the entries for Reuben Fine in Where Did They Live?:

‘1910:

Zlotta (head), Bertha and Sarah Nedner and Rubin Lazarus (boarder);

230 100th Street, Manhattan, New York (USA Federal Census, 1910).

1915:

Jacob, Bertha, Eva and Ruby (the children’s names are diminutives);

71 and 73 East 112th Street, Block I, Election District 16, New York, Assembly District 26, New York County, New York State (New York Census, 1920).

1920-24:

921 Home Street, Bronx Assembly District 5, Bronx County, New York (USA Federal Census, 1920; Jacob Fine’s Petition for Naturalization).

1925:

1155 Simpson Street, Bronx County, Block II, Election District 29, Assembly District 5, New York City, New York State (New York Census, 1925).

1930:

1569 Vyse Avenue, Bronx, Bronx County, New York (USA Federal Census, 1930).

1940:

115-25-84 Ave Cor 116 Street, Borough of Queens, New York (USA Federal Census, 1940).

A link to the census was given in C.N. 11518. A handwritten note at the top of the page indicates that the Fines lived in the Rosesmith Apartments. Further work is required to identify the exact location.

The State census and naturalization documents were found by Jane Daw.’

(11656)

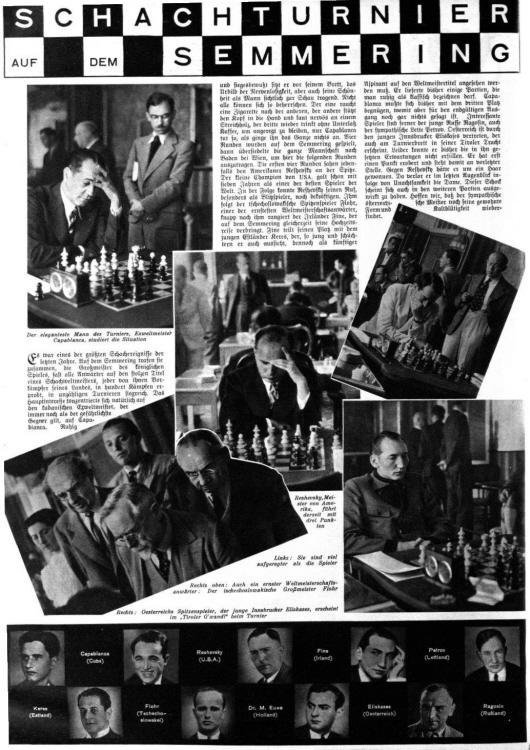

Jan Kalendovský (Brno, Czech Republic) submits this feature from Wiener Bilder, 19 September 1937, page 2:

For a larger version, click here.

(5766)

Ola Winfridsson (Cambridge, England) observes that the Wiener Bilder illustration gave Ireland as Reuben Fine’s country.

We can offer no explanation for the reference.

(5774)

Reuben Fine

A number of C.N. items (see pages 262-263 of Chess Facts and Fables) have discussed why Reuben Fine did not participate in the 1948 world championship match-tournament. For ease of reference, we reproduce here the summary of Fine’s own versions, provided in an article we wrote for ChessBase in 2007:

In C.N.s 1680 and 1915 Edward J. Tassinari quoted various, and varying, explanations by Reuben Fine of his absence from the 1948 world championship match-tournament:

On page 2 of the November 1948 Chess Review Fine wrote:

‘At the time of the tournament, I was not teaching, but working on my doctoral dissertation. I was not bound by any contract to the university. I withdrew from the tournament because I did not care to interrupt my research. Needless to say, nobody had consulted me on whether the dates set were convenient for me.’From pages 151-152 of Lessons from My Games by Reuben Fine (New York, 1958):

‘The next year they [presumably the Russians] changed their minds again, and the tournament was held. By that time I was embarked on my new profession as a psychoanalyst and was unable to play.’Pages 4-5 of Bobby Fischer’s Conquest of the World’s Chess Championship by ‘Reuben Fine, Ph.D., International Chess Champion’ (New York, 1973) claimed that a proposed 1947 tournament for the title was ...

‘… called off by the Russians as part of a kind of blackmail scheme to force the players to compete in Russia. My own refusal to play in 1948 was motivated in part by the uncertainty about whether the Russians would come to the playing hall at all, and if so, under what conditions.’On page 11 of that book Fine related that by the time the 1948 match-tournament was arranged ...

‘... I was absorbed in another profession, psychology, and no longer cared to participate.’In an interview with Bruce Pandolfini on page 25 of Chess Life, October 1984 (‘Reuben Fine: The Man Who Might Have Been King’) Fine stated that he decided not to compete in the 1948 championship because if he had gone to the Netherlands (the site of the first part of the event) the Russians might not have participated and he would have wasted ‘a whole year of his life in preparation. Moreover, it seemed foolish to play in such hostile circumstances.’

Next, an extract from a Fine letter on page 7 of the September 1989 Chess Life:

‘The tournament was finally arranged for 1948, to be played half in the Netherlands and half in the Soviet Union (where the safety of the foreign masters was questionable). I did not play because of the expense involved, most of which I was expected to pay myself; and because I considered the tournament as it was arranged to be illegal. TASS fabricated a story that I had had to desist because of career pressures. (In fact, I was not at that time employed; I was working on my doctorate.) The TASS story was a total fraud.’Page 4 of the February 1948 Chess Review stated that the magazine had received a telegram from Fine: ‘Professional duties make it impossible for me to get away in time to play in the tournament.’

We add that page 158 of The Encyclopaedia of Chess by Anne Sunnucks (London, 1976) stated that Fine ‘refused the invitation because a training match against Steiner had proved that he was out of form’. Did Fine ever make such a claim?

From page 4 of Chess Review, December 1947:

‘California. Drawing the final game in the series, Reuben Fine won his match against Herman Steiner 5-1. Both players played erratic chess.’

See also Interregnum.

Björn Frithiof (Almhult, Sweden) asks about the game R. Fine v C.H.O’D. Alexander, Margate, 1937, which appears as follows in his database (ChessBase) and on pages 154-155 of Reuben Fine by A. Woodger (Jefferson, 2004): 1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 Qc2 Nc6 5 Nf3 d6 6 a3 Bxc3+ 7 Qxc3 O-O 8 b4 e5 9 dxe5 Ne4 10 Qe3 f5 11 Bb2 Nxe5 12 Nxe5 dxe5 13 g3 Be6 14 f3 Nd6 15 Qxe5 Qe7 16 e3 Qf7 17 c5 Nc4 18 Bxc4 Bxc4 19 Kf2 Bb3 20 Bd4 Rae8 21 Qf4 Bd5 22 Be5 Bxf3 23 Bxg7 Bxh1 24 Bxf8 Rxf8 25 Rxh1 Qa2+ 26 Kf1 Qxa3 27 Kg2 Qb2+ 28 Kh3 Qe2 29 Rf1 Qg4+ 30 Kg2 Re8

31 Qxf5 Qxb4

32 Rf4 Qd2+ 33 Kh3 Qxe3 34 Qd7 Qe7 Drawn.

Our correspondent comments:

‘What puzzles me is the conclusion of the game, after 31...Qxb4. White is said to have played 32 Rf4 (instead 32 Qf7+, which wins at once), and after the further moves 32...Qd2+ 33 Kh3 Qxe3, White had an immediate win with 34 Rg4+.’

We believe that White’s 31st move was mistranscribed as Qxf5 instead of Qxc7, i.e. QxKBP rather than QxQBP. The move was given as 31 QxQBP on page 304 of the June 1937 BCM and on pages 51-52 of The best games of C.H.O’D. Alexander by Harry Golombek and Bill Hartston (Oxford, 1976).

(6112)

Frederick S. Rhine (Park Ridge, IL, USA) points out a letter written by Reuben Fine which was reproduced on page 260 of David DeLucia’s Chess Library A Few Old Friends (Darien, 2007). Dated 27 November 1972 and addressed to Norval Wigginton of Bethesda, MD, Fine’s letter reads (last paragraph):

‘I’ve challenged Bobby to a match for the title for a purse of $1 million, which I think could be raised if he would agree to play. But he hasn’t replied to my letter. Maybe you could get a committee together to see whether it could be done.’

Is anything more known about the challenge? The following appeared as a footnote on page 54 of Bobby Fischer’s Conquest of the World’s Chess Championship by ‘Reuben Fine, Ph.D., International Chess Champion’ (New York, 1973):

‘A Las Vegas hotel reportedly offered $1.4 million for a return match with Spassky which Fischer refused, demanding $10 million. I have also challenged Fischer to a match for a purse of $1 million. Some are now openly wondering whether Fischer will ever play again.’

In a review of Fine’s book on page 396 of the June 1974 Chess Life & Review Anthony Saidy referred to ‘Fine’s rather pathetic “$1 million” challenge to Bobby’. On page 467 of the July 1974 issue ‘A Reply from Reuben Fine’ did not comment on that point.

(6165)

Regarding Reuben Fine’s post-Reykjavik challenge to Bobby Fischer for a world title match with a purse of one million dollars, a sourceless paragraph was published on page 125 of the February 1973 CHESS:

‘“I’d play Fischer for the world championship if the stakes were high enough”, said Reuben Fine to Robert Byrne recently. “How high?”, asked Byrne. “Say a million dollars”, replied Fine and was quite upset when Byrne thought he was joking.’

(8273)

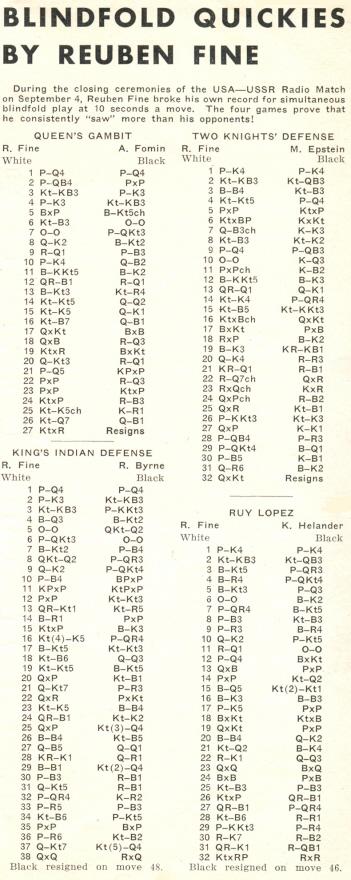

On the subject of Robert Byrne, we add the following from Blindfold Chess:

Source: Chess Review, November 1945, page 29.

In an article ‘Masters and Experts View the Match’ by Bill Goichberg on pages 409-410 of the July 1972 Chess Life & Review several respondents (Herbert Seidman, Harry Borochow, Joseph Platz and John N. Jacobs) predicted that Fischer would defeat Spassky 12½-8½.

Reuben Fine’s prediction, Fischer by 12½-7½, was accompanied by the comment:

‘The odds are now (March) 4 to 2 that the Russians will dodge the match, using it as a political football.’

On page 15 of Bobby Fischer’s Conquest of the World’s Chess Championship (New York, 1973) Fine wrote:

‘The road was now clear for the final match with Spassky. Bobby was the favorite. I predicted that he would win 12½ to 8½. Others came up with other figures.’

(6257)

See Chess Predictions.

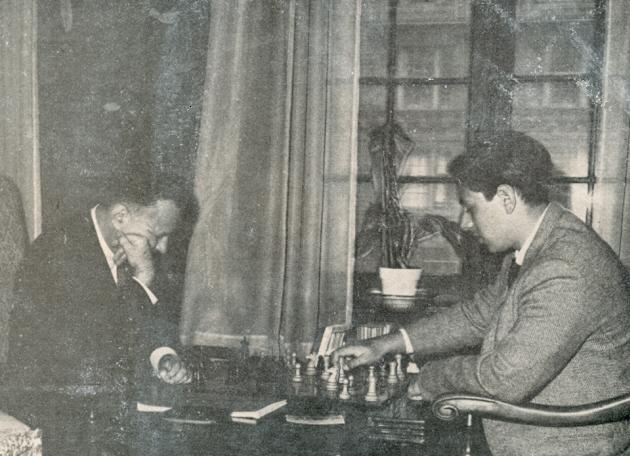

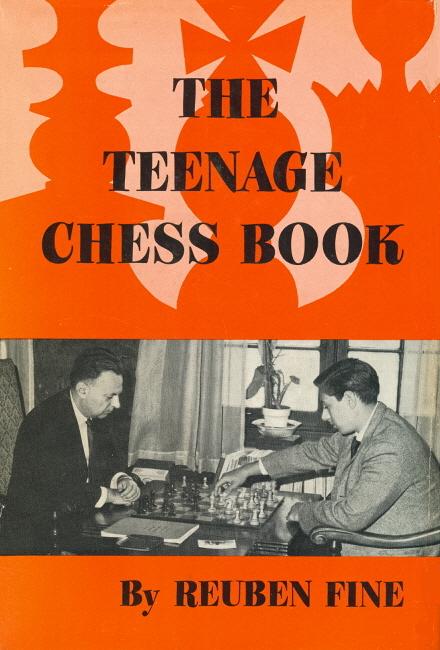

This photograph was published on page 67 of the March 1967 Chess Review with the following caption:

‘Two generations of chess: Dr Reuben Fine and his son Benjamin, authors of The Teenage Chess Book, are caught in this double-Fine photograph by Edward Lasker.’

The dust-jacket of the book (whose title page stated ‘by Reuben Fine with the assistance of Benjamin Fine’) had a further photograph taken by Lasker:

Below is the inscription in one of our copies of that first edition of The Teenage Chess Book (New York, 1965):

(6772)

We note a report of the death of Benjamin Fine on 11 March 2023, aged 74.

The New York Times of 17 August 1932 (sports section, page 20) reported that the first-round encounter between Fine and Reshevsky at Pasadena, 1932 ‘attracted much attention’, but the game-score has yet to be found. See, for instance, pages 26-27 of Reuben Fine by Aidan Woodger (Jefferson, 2004).

The New York Times article added:

‘Before the tournament got under way several of the competitors were taken aloft in the dirigible Volunteer. Kashdan and Dake contested an informal game, with Dr Alekhine acting as referee. The result, which was a draw by repetition of moves, was broadcast from the airship by Dr Alekhine, who expressed the hope that chess might be studied in the schools. He said:

“In several countries, Mexico in particular, and in the United States, at Milwaukee, they already are doing so. It is an intellectual pursuit which affords pleasure and at the same time trains faculties for intelligent activities in everyday life.”’

See also page 429 of the Skinner/Verhoeven book on Alekhine.

(6303)

Regarding Fine v Reshevsky, Pasadena, 1932, C.N. 2429 (see page 170 of A Chess Omnibus) referred to a footnote on page 30 of Fine’s book Bobby Fischer’s Conquest of the World’s Chess Championship (New York, 1973):

Ed Tassinari adds:

‘Page 4 of the August 1949 issue of California Chess News contains a brief comment from Harry Borochow, a competitor at Pasadena, 1932, stating that Fine had been playing bridge with Alekhine and others until three o’clock in the morning after adjourning his game with Reshevsky. When it was time to resume the game no-one woke up Fine, who did not appear for the resumption and accordingly lost the game which, Borochow contends, was “easily won”.’

(6314)

From ‘Chernev’s Chess Corner’ on the inside front cover of the October 1951 Chess Review:

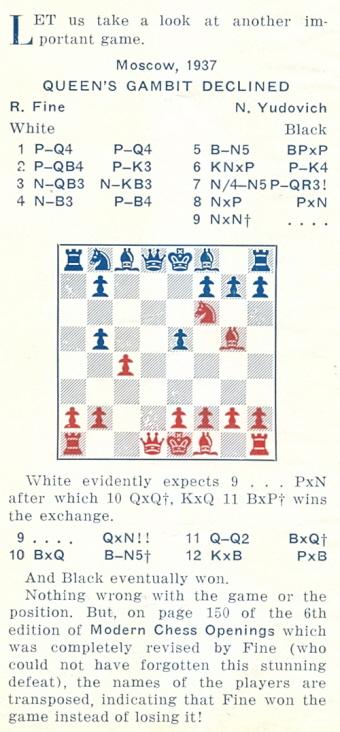

A correspondent (Edward J. Tassinari) referred to Irving Chernev’s feature in C.N. 966 (see page 152 of Chess Explorations). The sixth edition of Modern Chess Openings was published in 1939; as pointed out on page 144 of Reuben Fine by Aidan Woodger (Jefferson, 2004), Fine correctly named himself as White in his later book Practical Chess Openings (Philadelphia, 1948). See page 189. (Page 147 of Woodger’s book published, with notes by Yudovich, the complete score of Fine v Yudovich, which ended 43 Kg5 Ke5 44 White resigns.)

We add that Fine also gave an accurate attribution of the game in an article ‘My Moscow Impressions’ on pages 102-103 of the May 1937 Chess Review (a translation from 64):

(7053)

When Reuben Fine won the 1944 US Lightning Championship (playing, at ten seconds per move, 22 games in a single day), he dropped only one point, in this game:

Julius Partos – Reuben Fine1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 g6 3 Nc3 Bg7 4 Nf3 O-O 5 e4 d6 6 Bd3 Nbd7 7 O-O e5 8 dxe5 dxe5 9 Bc2 c6 10 Bg5 h6 11 Bh4 Qe7 12 Qe2 Nc5 13 Bg3 Nh5 14 Rad1 Ne6 15 Qd2 Nd4 16 Nxd4 exd4 17 Ne2 Rd8 18 Bd3 Be6 19 f4 Nxg3 20 Nxg3 Bg4 21 Rde1 Bd7 22 e5 Re8 23 Ne4 c5 24 Nd6 Reb8

25 f5 Bxe5 26 fxg6 Qxd6 27 Qxh6 Be6 28 gxf7+ Bxf7 29 Qh7+ Kf8 30 Qxf7 mate.

Source: Chess Review, June-July 1944, page 12.

Partos, who finished sixth in the tournament, also inflicted defeats on Kevitz and Denker, as well as drawing with Kashdan. See the coverage on pages 53-69 of The Year Book of the United States Chess Federation 1944 edited by Montgomery Major (Chicago, 1945). Page 58 commented regarding Partos v Fine:

‘Fine’s only loss; and seldom has the Champion been so completely outgeneraled.’

The game was also given in Partos’ obituary on pages 148-150 of the May 1969 Chess Review. He was described as a ‘phenomenon’ who was playing chess at the age of five (‘sometimes with Mrs Mary Bain, who was then living in the same apartment house’) and performed his first simultaneous exhibition when only 11. In blitz chess, the obituary suggested, he was second only to Fine.

...

(7054)

Luc Winants (Boirs, Belgium) notes this passage from page 211 of The World’s Great Chess Games by R. Fine (New York, 1951):

(7081)

Alain Biénabe (Bordeaux, France) enquires about photographs of Reuben Fine’s first wife, Emma Keesing (1916-60).

We recall the following on page 3 of CHESS, 14 September 1937:

She was aged 21 at the time of their marriage.

The same magazine (14 December 1938 issue, page 142) gave this picture in its coverage of AVRO, 1938:

(7136)

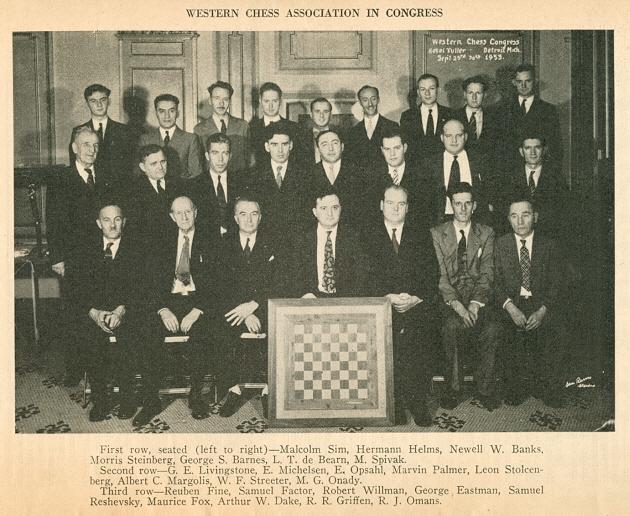

A group photograph from the Western Chess Association tournament, Detroit, 1933:

Source: American Chess Bulletin, September-October 1933, page 128.

(7257)

A note by Reuben Fine on page 818 of the December 1975 Chess Life & Review is quoted without comment:

‘It would please me if you mentioned that I direct a low-cost mental health clinic, known as the Center for Creative Living, located at 9 East 89th Street, New York, NY 10028, (212) 369-3330, which has a special section for the therapy of the creative individual. Any chessplayer in need of help will receive my personal attention.’

Reuben Fine

(6858)

From page 38 of Blunders and Brilliancies by Ian Mullen and Moe Moss (Oxford, 1990):

‘The late Isaac Kashdan who, in the 1920s and 30s, was Alekhine’s heir apparent ...’

(7255)

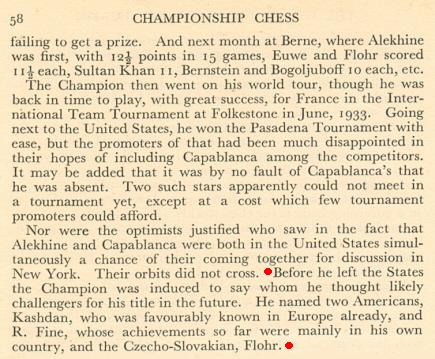

Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England) draws attention to a passage on page 58 of Championship Chess by P.W. Sergeant (London, 1938):

(In the first paragraph the chronology is confusing, the Pasadena tournament having taken place in 1932.) As regards the comment about Kashdan, Fine and Flohr at the end of the second paragraph, we add the following from page 477 of the November 1933 BCM:

‘United States. – Dr Alexander Alekhine, before leaving New York for Europe on 5 [sic] September, told an interviewer that he regarded as specially likely future opponents Kashdan, Fine and Flohr, with the first-named the most probable. “America’s chances of possessing the next champion”, he said, “are excellent”.’

A correction appeared on page 527 of the December 1933 BCM:

‘In our first paragraph under the heading United States last month (page 477) the words “the first-named” should have been “the two first-named”, as Dr Alekhine included Reuben Fine with Isaac Kashdan in his choice of most probable future challengers for the world championship. He is said, indeed, to have described Fine as “a real threat” for the title.’

More information about the interview is sought.

Around the same time, Alekhine was interviewed by Kashdan himself, on pages 9-10 of the September 1933 Chess Review (see C.N. 5631). Alekhine was asked about US masters, but no names were mentioned in his reply:

‘We wanted to know what he thought of the American players, and how they compared with the younger European stars. “Your double success in the International Team Tournaments has put America in the first rank among the chessplaying nations. No other country has so many promising young masters. In New York City alone you have at least a dozen young men who have nothing to fear from the leaders of any country in Europe. I predict many new successes, and you have enough talent developing to keep in the top flight indefinitely.”’

(7259)

Horacio Paletta (Buenos Aires) notes a news item on page 36 of the February 1949 Chess Review:

‘Dr Reuben Fine, a clinical psychologist, announces that he has opened an office at 72 Barrow Street, New York City (REpublic 9-8054). He is available for personality diagnosis and psychotherapy.’

(7346)

On page 7 of Basic Chess Endings (Philadelphia, 1941) Reuben Fine wrote:

‘The pawn, as Philidor put it, is the soul of chess, and we can add that in the ending it is nine-tenths of the body as well.’

(7745)

See Philidor: ‘Pawns are the soul of chess’.

Simon Browne (Somerville, Australia) notes the remarks by Alekhine about possible world championship rivals on page 178 of 107 Great Chess Battles (Oxford, 1980):

‘Before 1940 I was quite certain that two masters, Botvinnik and Flohr, wished to fight for this title. Neither of the two matches could be brought about, and the above-mentioned challengers know very well that I had decided to face them.

As regards Keres, his position in 1938-39 was less resolved; he gave the impression of preferring to let a few years pass. But in 1943, perhaps influenced by the disastrous results he obtained against me in recent meetings (+3 =3 –0 in my favour) he resolutely declared that he had not the slightest intention of challenging me to a match. Fine too, in 1940, made an analogous declaration.’

These remarks were originally published on page xix of Alekhine’s book ¡Legado! (Madrid, 1946), and Mr Browne asks whether it is possible to find statements by Keres or Fine along the lines indicated by Alekhine.

Readers’ assistance will be appreciated. Firstly on this topic, we would draw attention to an earlier article by Keres, ‘The World Chess Championship’, published on pages 51-53 of the March 1941 Chess Review.

(7839)

A question from Stuart Rachels (Tuscaloosa, AL, USA): who introduced the famous elementary system of values (pawn 1, knight 3, bishop 3, rook 5, queen 9)?

We can do no better than quote from page 59 of The Hall-of-Fame History of US Chess by Robert John McCrary (1998):

‘By the 1930s, the idea of a single numerical scale of values seemed to be losing favor. Instead, great players such as Capablanca and Tarrasch were generally avoiding giving a single scale of values in their books, preferring to discuss various kinds of exchanges on a case-by-case basis.

Then in 1942 Reuben Fine published his Chess The Easy Way. On page 23 is the following historically important section:

“Since there are six different kinds of pieces it is necessary to set up a table of equivalents in order to be able to know whether an exchange is favorable or not. Again such a table is based partly on the elementary mates (R can mate, B or Kt cannot) and partly on practise. If we take the pawn as 1 we may set up a table such as this:

pawn = 1

bishop (or knight) = 3

rook =5

queen =9.”Fine goes on to say that his table is satisfactory for rough calculation but not as accurate as a set of equivalents for certain exchanges he gives on the next page. Nevertheless, Fine apparently popularized our modern scale and indeed may have invented it. Does any reader know of an earlier publication of the modern scale? Perhaps Fine then should be considered the true “point-count” man of chess.’

(7853)

See The Value of the Chess Pieces.

From page 37 of Chess Review, January 1947 (an article by I.A. Horowitz):

‘In a match game with Grob, Flohr resigned when he was a piece to the good. He mistakenly believed that he could not stop a mate in one. In a similar situation, Fine resigned to Kevitz when he could force an easy draw by perpetual check.’

No details were given.

As indicated in the Factfinder, Flohr v Grob has been discussed in C.N. several times. The other game, played in the Metropolitan League, is on pages 69-70 of the April 1932 American Chess Bulletin:

Alexander Kevitz (Manhattan Chess Club) – Reuben Fine

(Marshall Chess Club)

New York, 16 April 1932

Dutch Defence

1 c4 f5 2 d4 Nf6 3 g3 e6 4 Bg2 Bb4+ 5 Nc3 O-O 6 Nf3 Nc6 7 O-O Bxc3 8 bxc3 Ne4 9 Qd3 b6 10 Ba3 Re8 11 d5 Na5 12 Bb4 Nc5 13 Qd4 d6 14 dxe6 Nxe6 15 Qd2 Bb7 16 Bxa5 bxa5 17 Rab1 Be4 18 Rb5 c6 19 Rb2 Nc5 20 Nd4 Bxg2 21 Kxg2 Qd7 22 Rfb1 Qf7 23 Nxc6 Qxc4 24 Qxd6 Na4 25 Rb7 Qe4+ 26 Kg1 Nxc3 27 h3 f4 28 Qc7 Qg6 29 Ne5 Rxe5 30 Qxc3 Rae8 31 Qc4+ Kh8 32 Qxf4 Rxe2 33 Rb8 h6 34 Rxe8+ Rxe8 35 Rc1 Qe6 36 Kh2 Qxa2 37 Rc7 Kg8 38 Qd4 Resigns.

C.S. Howell wrote in the Bulletin:

‘A most entertaining game. I am informed that both players were hard pressed for time. As is usual in such cases, the more experienced player wins out. Fine, a truly promising young player, here overlooks 38...R-K4! If White captures the rook, 39...QxPch draws.

Pillsbury once gave me a very useful bit of advice regarding clock difficulties. It was to note the time on the score-sheet after I made each move; after the game to play it over and try to explain to myself why I took so long to make obvious moves or ones that my chess instinct should have indicated. It is good discipline and will help young players who get into trouble with the clock.’

(8585)

Position after 38 Qd4

From Lonnie Kwartler (Chester, NY, USA):

‘The defense suggested for Fine, 38...Re5, prolongs the game, but White still has a win with 39 Qd8+ Kh7 40 Qf6 Rg5 41 h4 Rg6 42 Qf5. (This position can be reached with 39 Rc8+ four moves later.) Of course, 38...Re5 would have been a good try, and if Black does not fall into mate White is “limited” to a clearly won endgame. Black cannot stop White’s attack without exchanging queens.’

(8588)

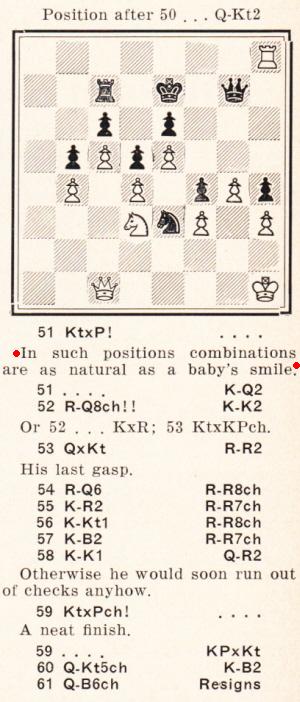

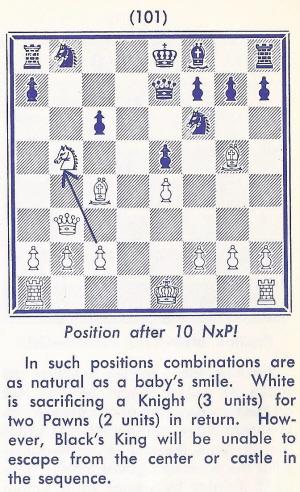

‘It seems that Fine once wrote that in such positions a combination is as natural as a baby’s smile.’

So wrote Valery Salov on page 21 of the 5/1989 New in Chess regarding 19 Nxe6 in Kasparov v Salov, Barcelona, 1989. Salov’s remark is quoted on page 258 of Garry Kasparov on Garry Kasparov Part II: 1985-1993 (London, 2013) in a slightly different wording (‘I think it was Reuben Fine who wrote ...’).

It was indeed Fine, on page 195 of the June-July 1943 Chess Review:

The game was Rellstab’s victory over Alekhine at Munich, 1942, although in the heading (page 193) Fine put ‘Monaco’, an error corrected when the article was reproduced on pages 135-141 of his book Chess Marches On! (New York, 1945).

Rellstab’s annotations to the game were published on pages 142-143 of Deutsche Schachblätter, 1 October 1942. The 1 August 1942 issue (page 119) had a photograph of him in play (left) against Schmahl at Bad Oeynhausen, 1942 (‘Schachmeisterschaft von Großdeutschland’):

(8215)

C.N. 8215 quoted a remark by Reuben Fine on page 195 of the June-July 1943 Chess Review: ‘In such positions combinations are as natural as a baby’s smile.’

In a supplement (‘Abracadabra Chess’ by Larry Evans) to the Fall 1962 issue of the American Chess Quarterly the following appeared on page 333, concerning Morphy v the Duke and Count:

Evans had a habit of lifting other writers’ bons mots and prose for presentation as his own.

(8221)

That C.N. 8221 item gave further examples of Evans’ habit.

The entry 10-172 on page 113 of Douglas A. Betts’ Chess An Annotated Bibliography of Works Published in the English Language 1850-1968 (Boston, 1974) concerns an edition of Emanuel Lasker’s Manual edited by Reuben Fine which is unknown to us:

Was it ever published?

(8232)

Rick Kennedy (Columbus, OH, USA) notes an entry at the website of the Cleveland Public Library under the heading ‘Reuben Fine Chess Collection’:

‘Fine’s revision of Emanuel Lasker’s Manual of chess published by Dutton in 1942 (27 cm.).’

We are grateful to the Library for permission to show here some sample pages of the work, which, it seems, was not published.

(8236)

Chapter XI (pages 53-56) of Lessons from My Games by Reuben Fine (New York, 1958) was entitled ‘I Become a Grand Master’, and on page 53 he reiterated a claim already made on page xv: that as a result of winning Hastings, 1935-36 he ‘was officially a grand master’. What is the factual basis of that statement?

Fine also asserted on page 53 that after his first-round victory over Flohr ‘first prize was never in any doubt’. He annotated the game not only in Lessons from My Games but also on pages 3-4 of the January 1936 American Chess Bulletin and on pages 166-167 of CHESS, 14 January 1936.

(8566)

See Chess Grandmasters.

The final note to Foltys v Fine, Margate, 1937 on page 135 of Fine’s book Lessons from My Games (New York, 1958):

‘After this game my opponent made a remark rarely heard among chess masters. He said: “You play better than I do”.’

(8760)

Regarding the familiar quotation ‘Discovered check is the dive-bomber of the chess board’, the exact wording on page 112 of Chess The Easy Way by Reuben Fine (Philadelphia, 1942) was:

‘Discovered check. This is one of the most destructive devices that anybody can think up – it is the dive-bomber of the chess board.’

A variant appeared on page 15 of Fine’s The Middle Game in Chess (Philadelphia, 1952):

‘Discovered check. This is one of the most destructive devices available to the player – it is the hydrogen bomb of the chessboard.’

CHESS, January 1943, page 52.

(8726)

Ivor Goodman (Stevenage, England) asks about the earliest occurrence of the term ‘Mozart symphony’ to describe a chess game. He draws attention to a remark by Reuben Fine on page 162 of Chess Marches On! (New York, 1945):

‘The following game, played in a recent Dutch tournament, is as graceful and pleasing as a Mozart symphony. Euwe has produced a masterpiece of force and elegance.’

We note, firstly, that Fine originally published those words on page 76 of Chess Review, March 1943 when introducing the game in question. In both the magazine and the book, Fine named Black as ‘Van Stenis’, instead of van Steenis. Chess Review merely stated that the game was ‘played in a recent Dutch tournament’. Chess Marches On! referred to the occasion as ‘The Netherlands, 1942’, and databases have followed suit, although Al Horowitz correctly labelled the game ‘Amsterdam, 1941’ on page 505 of Chess Openings Theory and Practice (New York, 1964).

The score was published on page 5 of De Telegraaf, 8 September 1941:

1 d4 d5 2 c4 c6 3 Nf3 Nf6 4 Nc3 e6 5 e3 a6 6 c5 Nbd7 7 b4 Ne4 8 Nxe4 dxe4 9 Nd2 f5 10 f3 exf3 11 Qxf3 Nf6 12 Bc4 Be7 13 O-O Nd5 14 e4 Nxb4 15 Bb2 Nc2 16 exf5 O-O 17 Rad1 Nxd4 18 Qg4 Bxc5 19 Ne4 Ba7 20 f6 g6 21 Ng5 c5 22 f7+ Kg7 23 Qf4 Bb8 24 Rxd4 cxd4 25 Bxd4+ e5 26 Bxe5+ Bxe5 27 Qxe5+ Kh6 28 Ne4 b5 29 g4 Bxg4 30 Nf6 Bf5 31 Ng8+ Rxg8 32 fxg8(Q) Qg5+ 33 Qg3 Resigns.

A few of Fine’s comments on page 77 of the March 1943 Chess Review are notable:

As discussed in C.N. 8726, Fine had called discovered check ‘the dive-bomber of the chess board’ on page 112 of his book Chess The Easy Way (Philadelphia, 1942).

(9548)

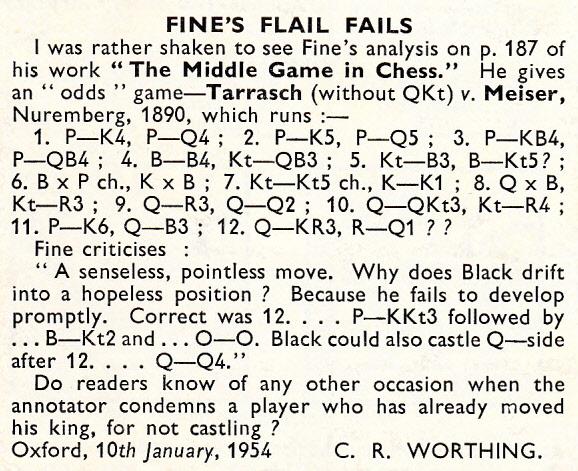

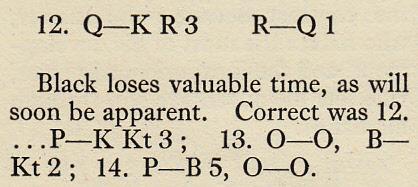

See too ‘The Mozart of Chess’.

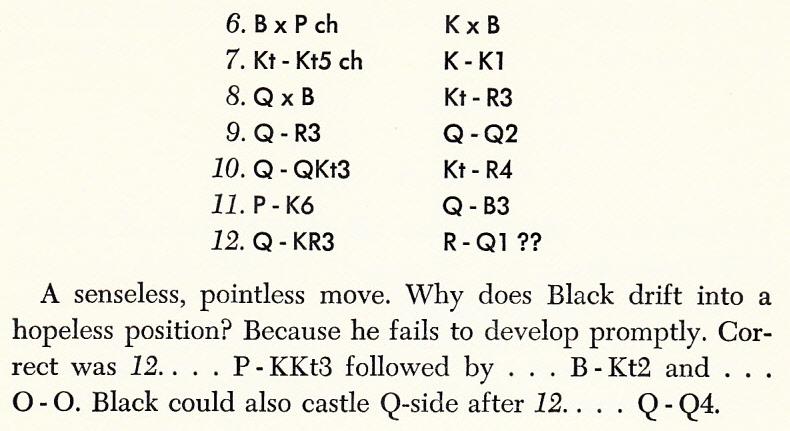

Black to move

Black now played 12...Rd8, but instead should he have attempted to consolidate his position with 12...g6, 13...Bg7 and 14...O-O, or, alternatively, with 12...Qd5, followed by queen’s-side castling?

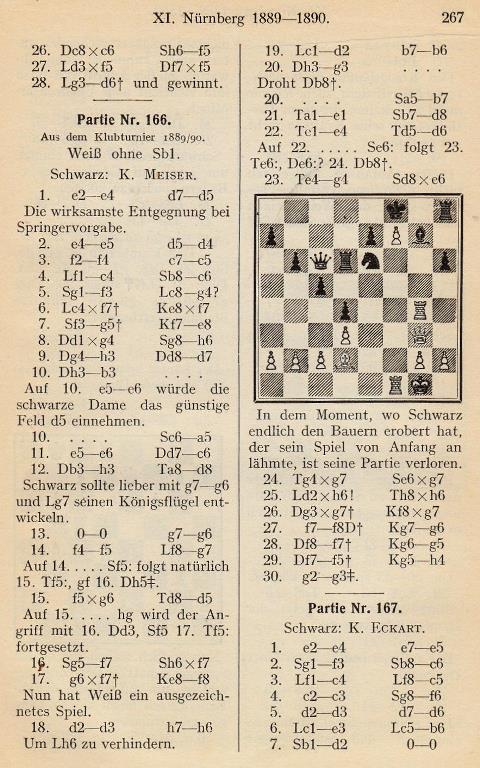

Reuben Fine recommended those ‘correct’ lines on page 188 of The Middle Game in Chess (New York, 1952) when annotating the game Tarrasch v Meiser:

The game was included in Tarrasch’s Dreihundert Schachpartien. Below, for instance, is page 267 of the third edition (Gouda, 1925):

The earliest correction of Fine’s note that we can cite was by C.R. Worthing of Oxford in a letter dated 10 January 1954 on page 98 of the March 1954 CHESS:

The oversight in The Middle Game in Chess was also pointed out by H. Vaughan of Chatswood, Sydney on page 133 of Chess World, July 1960.

(8875)

Pete Klimek (Berkeley, CA, USA) notes that illegal castling was also proposed in the note to the Tarrasch v Meiser game on page 306 of Tarrasch’s Best Games of Chess by Fred Reinfeld (London, 1947):

(8878)

See Castling in Chess.

From Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA):

‘Pages 50-52 of Aidan Woodger’s Reuben Fine A Comprehensive Record of an American Chess Career, 1929-1951 (Jefferson, 2004) have an account, with nine game-scores, of the match played in 1934 between Fine and Al Horowitz. It is stated that the final score was 6-3 in favor of Fine.

In fact, there was a tenth game, a draw, published on page 14 of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 5 July 1934.’

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bb5 Nd4 5 Nxd4 exd4 6 e5 dxc3 7 exf6 Qxf6 8 dxc3 Bc5 9 Qe2+ Qe6 10 Bc4 Qxe2+ 11 Kxe2 c6 12 Be3 Bxe3 13 Kxe3 d5 14 Bd3 Be6 15 Rae1 O-O-O 16 Kd2 Kc7 17 Re5 Rde8 18 Rhe1 b5 19 R5e3 Kd6 20 b3 g6 21 Rf3 f5 22 g3 h5 23 h4 Bd7 24 Rxe8 Rxe8 25 Re3 Drawn.

Page 129 of the August 1934 Chess Review confirmed:

‘Reuben Fine defeated I.A. Horowitz in their match by the score of 4-1 and five draws.’

(8988)

In an e-mail message dated 7 January 2001 Arnold Denker wrote to us regarding Fine:

‘... as a young man he was terribly mixed up and a horrible liar. That is one of the reasons my wife and I both allowed him plenty of space. He had a screwed-up youth and never really overcame his strong feelings of inferiority. Thus the bragging. My fondness for him was more a feeling of sadness.’

Some images from pages 6-7 of the April 1944 Chess Review (in a report on that year’s US championship in New York) were shown in C.N. 8316:

Wanted: documentation about the non-chess activities of Reuben Fine during the Second World War.

For the ‘revised and expanded’ Dover edition of his book The World’s Great Chess Games (New York, 1976) he wrote:

‘During the war I was involved in defense work, remaining in Washington.’

A footnote on the same page:

‘Toward the end of the war I was retained by the Navy to work on a military problem which was in some respects similar to chess. The field of operations research, then entirely novel, has since expanded enormously.’

See too pages 275 and 278 of Reuben Fine by Aidan Woodger (Jefferson, 2004). The former page states:

‘In May 1944 Fine began research work for the Department of the Navy as part of a team employed to determine likely surfacings of U-Boats. This work later extended to attempts to determine the locations of Japanese Kamikaze attacks upon Allied ships.’

Reuben Fine, front cover, Chess Review, June-July 1944

(9076)

C.N. 9582 showed how Dawid Janowsky was derided on page 95 of B.J. Horton’s Dictionary of Modern Chess (New York, 1959). Another example, anchored in tittle-tattle, comes from pages 99-100 of The World’s Great Chess Games by Reuben Fine (New York, 1951) [and includes the words ‘Once, the story goes ...’]:

The famous game published by Fine was against ‘Schallop’ (sic) at Nuremberg, 1896.

(9655)

A letter from Fine was on page 6 of the May 1985 Chess Life. Whilst criticizing the historical circumstances, he at least acknowledged that Karpov had become world champion in 1975 and had retained the title since then. Fine opined that ‘for the USSR chess is only a footnote to politics’ and he proposed that ‘the US Chess Federation should undertake bold and constructive action’:

‘I recommend that the United States take the initiative of splitting up FIDE into two separate organizations: one for the free world and one for the communist world. The best player from each world would then meet on as neutral soil as possible to play for the world championship.

If it is feasible, Robert Fischer should be brought back and declared the champion of the free world. If the Soviet champion should then refuse to meet Fischer in a match going to the man who first wins ten games, the Western countries should declare Fischer the world champion and let the two federations go their respective ways.’

(9880)

Fine on Alekhine:

‘When I first met him, at Pasadena in 1932 ...’

Source: The World’s a Chessboard by R. Fine (Philadelphia, 1948), page 165.

‘When I first met Alekhine in New York in 1932 ...’

Source: Bobby Fischer’s Conquest of the World’s Chess Championship by R. Fine (New York, 1973), page 9.

On page 10 of Bobby Fischer’s Conquest of the World’s Chess Championship (New York, 1973) Reuben Fine wrote regarding Alekhine:

‘When World War II ended, in 1945, all the leading masters of that day, incensed by his behavior, objected to his participation in international tournaments. The Soviets broke the boycott by having Botvinnik challenge Alekhine to a match for the title in 1946. Actually this was illegal, since Keres and I had prior claims. But Keres, born in Estonia, was a Soviet citizen, while I was no longer so interested.’

From pages 224 of the ‘revised and expanded edition’ of The World’s Great Chess Games by Fine (New York, 1976):

‘Legally there were various possibilities. Euwe might have reclaimed the title, as the last official champion before Alekhine. Or Keres and Fine could have been declared co-champions on the basis of their joint victory in the AVRO tournament. Or Euwe, Fine and Reshevsky might have played a three-cornered tournament to decide the championship. Or the free world might have chosen a champion, and the communist world been left to choose its own; then the two could have met for the world championship.’

On the next page Fine wrote with respect to AVRO, 1938:

‘As indicated before, on the basis of this victory and in light of the circumstances of international chess in the war period, Keres and I should have been declared co-champions for the period 1946-48, between the death of Alekhine and the 1948 tournament.’

Finally, a comment by Fine on page 151 of Lessons from My Games (New York, 1958):

‘Keres and I tied for first in the AVRO tournament; he was declared winner by the tie-breaking Sonnenborn-Berger [sic] system. Alekhine dodged a match in his usual skillful manner. Then the war intervened and all official chess activity stopped.’

There is a frequent lack of rigour in claims that Alekhine ‘dodged’ opponents, and it is unimpressive to find C.J.S. Purdy writing the following in a review of Lessons from My Games on pages 146-147 of Chess World, September-October 1967:

‘Reuben Fine became one of the world’s greatest players. At the time when his claims to play a match for the world title were unanswerable, he did not get to play a match because Alekhine, once he had regained his title from Euwe, did everything possible to evade a match.’

As regards possible challenges to Alekhine after AVRO, 1938, an observation on page 215 of Reuben Fine by Aidan Woodger (Jefferson, 2004) is noteworthy:

‘Fine seems not to have made any effort at all ...’

(10028)

C.N. 593 quoted Fine from page xviii of Lessons from My Games:

‘I feel certain that I could have beaten Alekhine in a match for the world championship in 1938 or 1939; the same probably holds true for Botvinnik and Reshevsky. But Alekhine would not play and nobody could force him to.’

The same C.N. item also quoted from page 83 of Fine’s book:

‘Botvinnik, like many of his countrymen, often handles the opening very poorly with White, in sharp contrast to the complicated and ingenious defenses he frequently thinks up with Black.’

An extract from C.N. 9500:

The dust-jacket of Players and Pawns (Chicago and London, 2015) states that ‘Gary Alan Fine is the John Evans Professor of Sociology at Northwestern University’ and introduces his book thus:

‘A chess match seems as solitary an endeavor as there is in sports: two minds, on their own, in fierce opposition. In contrast, Gary Alan Fine argues that chess is a social duet: two players in silent dialogue who always take each other into account in their play. Surrounding that one-on-one contest is a community life that can be nearly as dramatic and intense as the across-the-board confrontation.’

Beyond such woolliness, the book is striking for a heavy USA-centric approach, the author’s unfamiliarity with chess history and lore, and a staggering lack of discernment in the sources cited.

As demonstrated by the concluding ‘Notes’ section (pages 227-261), the Professor has no interest in, or access to, primary sources and makes do with material unquestioningly derived from familiar books and webpages which are themselves derivative. Those ‘sources’ in the Notes section include an Internet quotations site (itself devoid of sources) and such embarrassments as ‘Internet Chess Club discussion boards, 2010’.

Professor Gary Alan Fine is unrelated to Reuben Fine, he states on page 1. He makes frequent, naively trusting, mention of his namesake, although his interest has its limits. Page 205 discusses the wonder of databases, which ‘have replaced wood pulp’: ‘Fully 389 of Reuben Fine’s games are archived ...’ There is no awareness of Aidan Woodger’s carefully researched monograph on Reuben Fine, published by McFarland & Company, Inc. in 2004, which has well over twice as many games by Fine as the ‘fully 389’.

McFarland books are of no concern to Professor Fine, who instead goes as far down-market as possible for his raw material and pseudo-sources. No would-be facts have been scrutinized with care.

From page 136 of The World’s a Chessboard by Reuben Fine (Philadelphia, 1948):

(10265)

See The King’s Gambit.

Below is a remark by Reuben Fine on page 34 of Chess Marches On! (New York, 1945), in his annotations to the game between J. Moskowitz (‘Moscowitz’) and A. Yanofsky, Ventnor City, 1942:

Another passage written by Reuben Fine comes from page 11 of the January 1956 issue of Chess Review:

The full article was reproduced on pages 18-23 of Fine’s book Lessons from My Games (New York, 1958).

(10393)

See Chess Planning.

To the range of reports on Reuben Fine’s absence from the 1948 world title match-tournament, Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) adds the following from page 123 of Chess World, 1 June 1948:

‘Arthur Krivis answers in Moscow News the much asked question, why didn’t Fine go?

“The story of the missing contender is a sad one indeed. Grandmaster Reuben Fine, one of the world’s outstanding players, has been compelled to throw away an opportunity that perhaps comes once in a lifetime to vie for world honors because, as the report states, he could not find anyone to take his place at the university for the duration and would not have had the funds to pay a substitute had he found one.

I do not know the particulars of the case but it seems strange that the university authorities where he teaches did not make a real effort to find a pinch-hitter or offer to foot the bill. They left it to Mr Fine as a matter concerning him and him only. But is it really a private matter? Is not Fine a representative of the American people, one of the two Americans honored by the FIDE invitation to contend for the world crown? Or perhaps this is not a sphere of activity that has the blessing of the department headed by Mr Forrestal.

At any rate, we understand Mr Fine’s dilemma. He has a contract with the university which he is honor-bound to fulfill and, besides, a job in the United States is nothing to be sneered at. What was he to do without the patronage of a rich chess daddy – play and lose his job, or hold on to it and give up his fond dream of taking a shot at the world crown? Since the two are often incompatible abroad, the grandmaster made his choice. This could never happen here.”’

(10467)

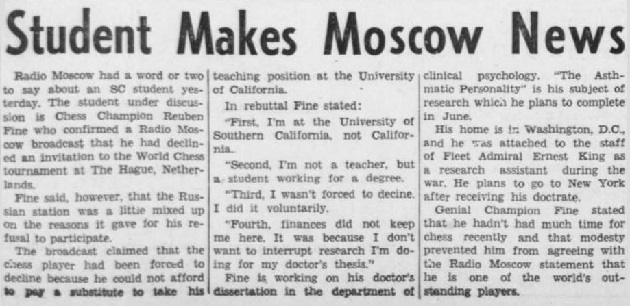

Olimpiu G. Urcan forwards a report from page 1 of the 5 March 1948 issue of the Daily Trojan, a USC student publication digitally available in the University of Southern California Historical Collection:

(10470)

C.N. 10515 gave some ‘once’ quotes from Chess Words of Wisdom by Mike Henebry (Victorville, 2010), and one more will suffice for now, from page 371:

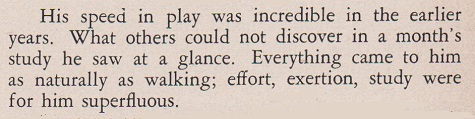

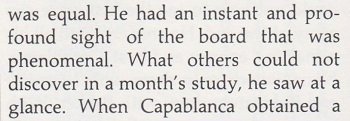

‘Rueben [sic] Fine once said, “What others could not see in a month’s study, he saw at a glance” (Capablanca’s Best Chess Endings, Irving Chernev).’

Why mention Chernev when Fine’s famous remark is easily found on page 111 of his book The World’s Great Chess Games (New York, 1951 and London, 1952)?

Fine had originally published his words on page 288 of Chess Review, October 1943:

It will be noted that Fine consistently wrote ‘What others could not discover’, and not ‘see’, which was Chernev’s small misquotation in Capablanca’s Best Chess Endings, Combinations The Heart of Chess and The Golden Dozen. Chernev put ‘discover’ in Wonders and Curiosities of Chess. The respective page numbers in these four Chernev books are 60, 227, 279 and 55.

When Cyrus Lakdawala gave the Fine sentence, sourcelessly, on page 7 of his book on Capablanca (C.N. 7742), the verb was ‘find’.

Finally, there is the individual who took Fine’s words and presented them as his own:

Source: page 37 of The Batsford Chess Encyclopedia by Nathan Divinsky (London, 1990).

(10540)

Black to move

The above position arose after 11 a4 in Keres v Lilienthal, USSR Absolute Championship, Moscow, 27 April 1941. As shown in C.N. 8353, 11...Bc5+ received this remark from Keres in his annotations on pages 207-208 of the November 1941 Chess Review:

‘What does this check produce? If Black meant to develop his bishop at KB4 he ought to do it immediately; 11...B-QKt5 was, however, preferable, in order to obtain counterplay.’

A briefer criticism of 11...Bc5+, on page 81 of Chess Marches On! by Reuben Fine (New York, 1945), is what passes in the chess world for a dictum/maxim/witticism:

‘Evidently forgetting that nobody ever died of a check.’

(10678)

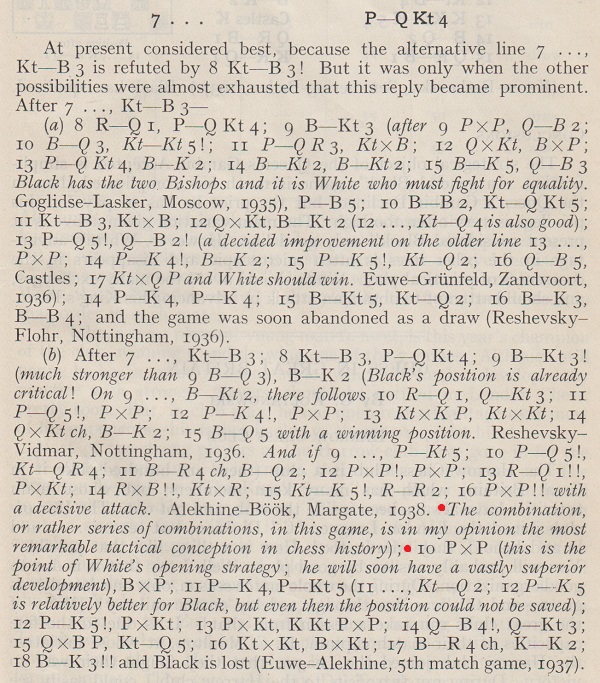

‘The combination, or rather series of combinations, in this game, is in my opinion the most remarkable tactical conception in chess history.’

That observation by Reuben Fine concerns Alekhine v Böök, Margate, 1938 and comes from page 531 of the November 1938 BCM, in a theoretical article on the Queen’s Gambit Accepted. Below is the relevant passage, after discussion of the moves 1 d4 d5 2 c4 dxc4 3 Nf3 Nf6 4 e3 e6 5 Bxc4 c5 6 O-O a6 7 Qe2:

(10676)

From the Los Angeles Times, 8 September 1940, Part L, page 12:

The participants in the tournament were Borochow, Fine, Steiner and Woliston. Page 244 of Reuben Fine by Aidan Woodger (Jefferson, 2004) observed:

‘Fine had a relatively easy time in this tournament (which is erroneously dated 1941 in his autobiography, and hence several other sources).’

(11009)

Ed Tassinari has sent us a photocopy of the New York Times obituary (28 March 1993) of Reuben Fine by Harold Schonberg. To quote just one example of the characteristic Schonbergery, we are informed that Alekhine and Capablanca shared first prize at Nottingham, 1936 and that Fine and Reshevsky were equal second.

(Kingpin, 1993)

Also in 1993, in the 26 June edition of The Times Raymond Keene wrote that one of Reuben Fine’s triumphs in the 1930s was ‘share of first prize with Capablanca at Nottingham, 1936’.

On page 222 of the September 1938 Chess Review, the dictum ‘Passed pawns must be pushed’ was attributed, without any particulars, to Reuben Fine. Can earlier citations (with ‘must’ or ‘should’) be found?

(12070)

See too Chess and Psychology and Chess and Insanity.

To the Chess Notes main page.

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.