Edward Winter

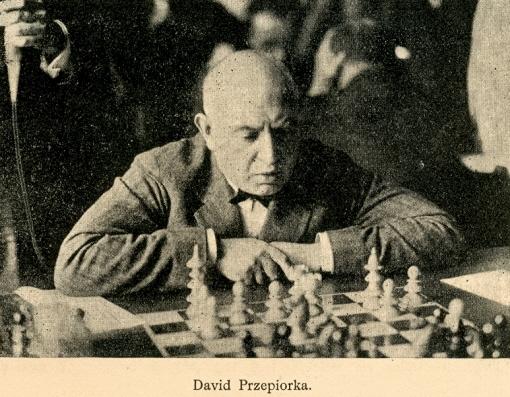

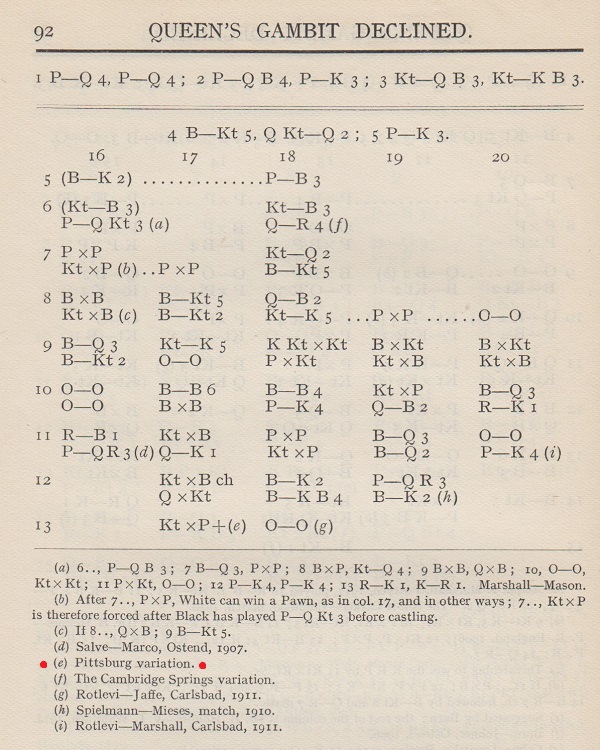

Dawid Przepiórka (L’Echiquier, October 1927)

C.N. 687 provided, courtesy of John Roycroft (London), some extracts from a letter dated 14 October 1983 sent to him by Alexander/Aleksander Goldstein (1911-88), then of Australia and formerly of Poland.

Przepiórka ‘was a round, chubby man with a severe impairment of hearing ... All his life he was a person of ample independent means. ... In problems he used his qualities to promote the chess composition, in chess he rather promoted himself. Przepiórka’s name means partridge [sic – quail] in Polish ... He had a great liking for old and stale jokes and once he caught you, you had to listen. Marian Wróbel was the closest of his collaborators and as his name also means a bird in Polish (sparrow) one can imagine that this was another source of childish enjoyment for the Master, who claimed that a partridge is so much more important than a sparrow. And when someone observed that no-one is hunting sparrows, he laughed and considered it the most witty repartee. On the serious side he was an ardent fighter against the admission of Nazi Germany to FIDE ...’

Mr Goldstein left Poland in September 1939 and, upon his return in May 1946, ‘everything was in ruins. In the domain of chess composition I was probably the only survivor of Jewish origin. Przepiórka, J. Fux, S. Krelenbaum and Kozłowski (the endgame wizard) were all gone’. He mentioned that Wróbel published an article in 1955 (75 years after Przepiórka’s birth) in which he recalled that a makeshift chess club had been organized in a private dwelling and that the Germans made a raid some time in January 1940, arresting about ten players. After a week or so, the non-Jewish persons were released and Przepiórka, according to Wróbel’s statement, was executed in April 1940.

Mr Goldstein’s reminiscences concluded:

‘Now, when I come to think of it, I see how impractical the man was. He was so much exposed to the danger and most likely he had the means to escape. What a folly he committed by staying there, and how to explain it? Was he lured into false security by the image of the Germans he knew from his student days? But he knew and fought the Nazis. Or, probably he considered himself incapable of wandering around in crude conditions in foreign lands. The fact is that he perished, and we can console ourselves that after a period of 60 happy years he suffered only for six months. To conclude: Dawid Przepiórka as I knew him was a problemist only, and I have not enough praise for him as a creator of excellent problems, a man of culture and knowledge and a patron of young problemists of all sorts.’

(6618)

We have found the following text in the Tribune de Genève of 18-19 May 1946, page 9:

‘Voici ce qu’écrit à la Fédération néerlandaise Mlle Emilie Neyman (Mototowska 55 m. 6, Varsovie):

“Lorsqu’en 1939 les Allemands fermèrent les locaux du Cercle d’Echecs de Varsovie, le président Przepiórka et l’un des membres réussirent à transporter tout le matériel dans un appartement privé, où le cercle put continuer ses séances en cachette. Fin janvier 1940, les Allemands eurent vent de ces réunions; tous les membres furent arrêtés et jetés en prison, la fameuse ‘Pawiak’. Après quelques semaines, les Aryens furent relâchés; quant aux Juifs, on n’en a plus jamais entendu parler. ...

Ces nouvelles viennent fort à point réfuter une accusation qui s’était attachée dernièrement au nom du défunt champion Alekhine. Certains ont cru devoir reprocher à Alekhine de n’avoir rien fait pour sauver la vie de Przepiórka, arrêté, disait-on, pour avoir pénétré dans un café prohibé aux Juifs, en 1942. On voit maintenant que le maître polonais est mort deux années auparavant, à une époque où Alekhine se trouvait en France et devait certainement ignorer tout de son sort. Ce n’est qu’en 1942 qu’Alekhine se rendit à Varsovie, sur l’invitation du gauleiter Frank.”’

(441)

As reported in C.N. 1041, a letter from Ossip Bernstein dated 5 October 1945 and published in the November 1945 CHESS (pages 28-29) condemned Alekhine:

‘My profound attachment to chess restrains me from telling all I think of Alekhine, since the fall of France. In May 1940, I played against him in Paris (a so-called “consultation” game) and won. I could not have guessed that he would behave afterwards as he did. I shall never play against him again and I do not even wish to see him. I refused to meet him at Barcelona, when he visited that city to give chess exhibitions.

I think that the above makes my conception of “collaboration” clear.

The chess world is aware of the tragic end of the grand Polish chessmaster and composer Dawid Przepiórka, who was condemned to death for having entered a café where chess was played; he was forbidden to do that, because he was a Jew. But it is not generally known that Alekhine, though on close terms with the Nazi Governor of Poland, Dr Frank, with whom he was photographed for Nazi periodicals published at the time, refused to intervene to secure Przepiórka’s release. This fact of his non-intervention was told me by Sämisch when he came to Barcelona at the end of 1943. I could also mention articles published by Alekhine after 1940 and the chess exhibitions he gave to entertain the Nazi Forces. I refrain from giving further disgusting details about his behaviour. It could be added that he adopted the Nazi salute “Heil Hitler” with outstretched arm.

I am fully aware of what my statements mean, but I consider it my moral duty and I leave it to you to make conclusions.’

Alekhine’s reply was given on page 76 of the January 1946 issue:

‘Dr Alekhine informs us that the attacks quoted in CHESS of Dr Oskam, who was always his friend, were particularly painful to him.

“As for Dr Bernstein’s ‘information’, I can only state that my friend D. Przepiórka was murdered before the end of 1939 (I heard the narrative of his [sic] from an eye-witness) and it is known that I played in Germany and Poland only from the end of 1941. What connection could I have with this tragical event??

I may add that the game Dr Bernstein gives was played at my home and had an absolutely private character – but of course this has no importance at all.”

Dr Alekhine goes on to say that he has been very sick this year but had to go on playing, or starve. He has had a rest at Tenerife and is feeling much better, but ill-health and worry have sapped his playing ability.’

The attack by Oskam was quoted in Was Alekhine a Nazi? Regarding Przepiórka, it is believed that he was killed in April 1940 (see C.N. 6618).

(7181)

The accusation that Alekhine did not intervene on behalf of Dawid Przepiórka was rebutted in a footnote to Alekhine’s obituary on page 87 of the June 1946 Revue suisse d’échecs:

‘Le reproche de ne pas être intervenu en faveur du maître Przepiórka en 1942, lors de son séjour à Varsovie, est infondé. On sait maintenant, par des témoignages récents venant de la capitale polonaise, que le grand maître et compositeur polonais tomba victime de la persécution anti-juive en 1940 déjà, donc deux ans avant la visite d’Alekhine.’

(7182)

The report on FIDE’s 8th Congress (Prague, 22-26 July 1931) indicates that on behalf of the Polish Federation Dawid Przepiórka asked FIDE to draw up a list of International Masters and establish the conditions for the granting of such titles. The President, Dr Rueb, was unenthusiastic, but to study the question a small Committee was formed, with Alekhine, Vidmar, and Przepiórka among the members. It was not until the 12th Congress (Warsaw, 28-31 August 1935) that a text was adopted. This stated that the title of International Master would be awarded by FIDE to any player who won a tournament featuring a minimum of 14 players if at least 70% of the players were International Masters, or who came second twice in such events. Less successful tournament scorers could obtain the title if they also won a recognized match (of at least four games up) against an International Master. Initially, the Committee was to prepare a basic list of recipients. Titles would be awarded for life, and there could be no appeal against the Committee’s decisions.

When a (modified) system was eventually introduced (20th Congress, Paris, 20-22 July 1949), a distinction was made between Grandmaster and International Master. There were under 30 of the former, and fewer than 100 of the latter.

Most of these title-holders were familiar personalities whose names needed no adornment, but nowadays ‘Grandmaster’, ‘International Master’, etc. are used almost like forenames. Paradoxically, the very top players outgrow their titles; it would be incongruous, and perhaps even insulting, to refer to ‘Grandmaster Fischer’.

(1982)

See Chess Grandmasters.

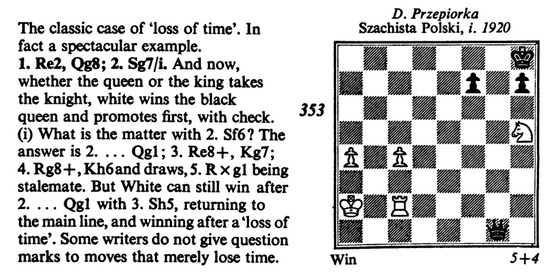

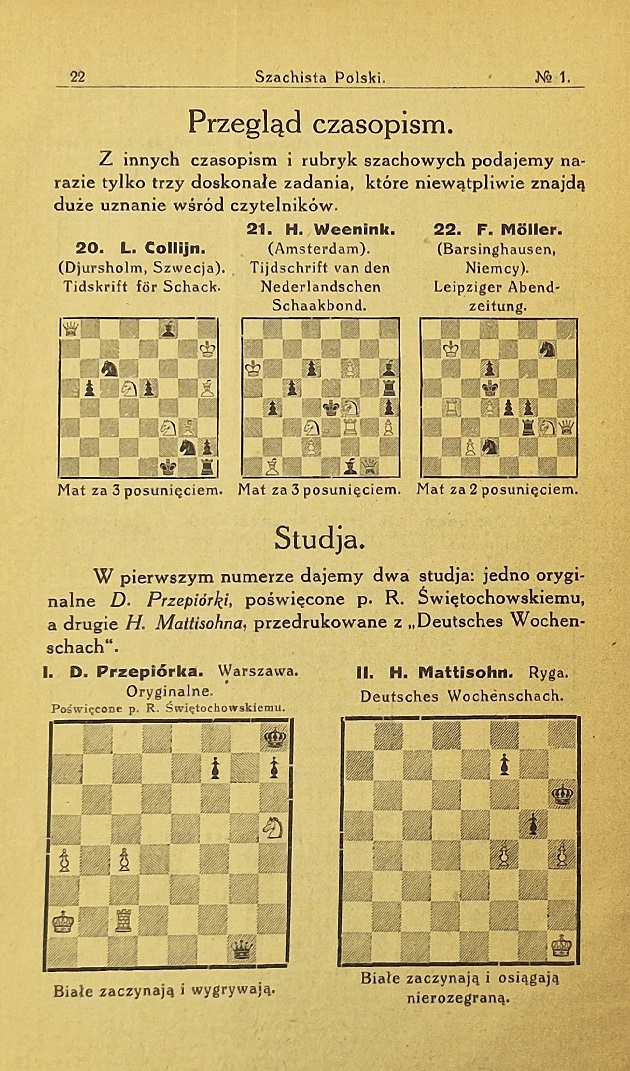

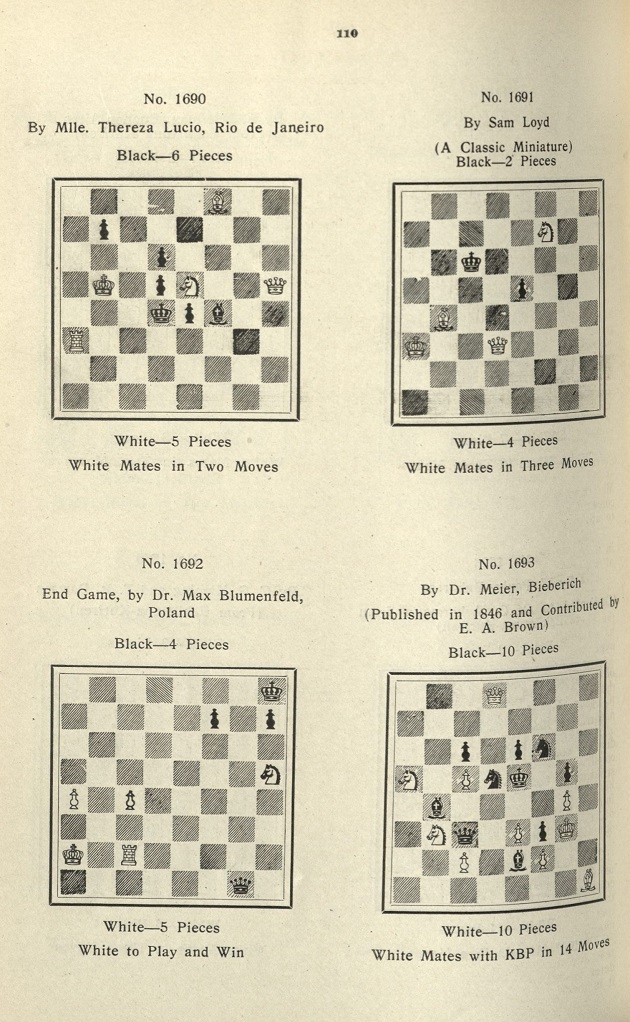

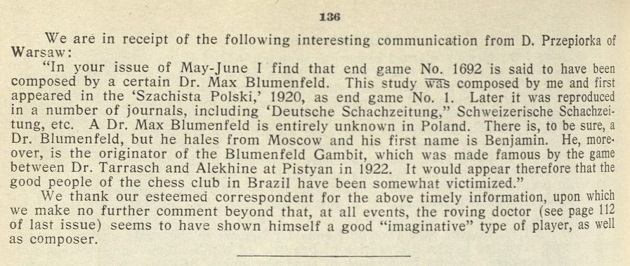

Information about chess impostors will be gratefully received. The May-June 1923 American Chess Bulletin (page 112) quoted from the Brazilian American (Rio de Janeiro) a sceptical account of ‘a visit from a Dr Max Blumenfeld, who had arrived on the Lutetia from Belgium’. Wishing to give a simultaneous display, he said that he was a professional chessplayer who had won tournaments in Warsaw and Vienna and had defeated the Belgian champion, Colle. He claimed to have invented a ‘Blumenfeld Gambit’ in the Queen’s Pawn Opening and ‘he also showed us a couple of end games of his composition, which he has authorized us to publish as original contributions to our column’.

Page 110 of the American Chess Bulletin reproduced one of these, with the heading ‘End Game, by Dr Max Blumenfeld, Poland’. The next issue (July-August, page 136) contained a letter from D. Przepiórka of Warsaw pointing out that the study was by him; it was first published in Szachista Polski in 1920 and repeated in a number of journals. The letter added that no Dr Max Blumenfeld was known in Poland, although Beniamin Blumenfeld of Moscow was the originator of the Blumenfeld Gambit, an opening made famous by the game Tarrasch v Alekhine, Pistyan, 1922.

The study in question may be found, correctly ascribed to Przepiórka, on page 187 of 1234 Modern End-Game Studies by M.A. Sutherland and H.M. Lommer (London, 1938), page 254 of A.J. Roycroft’s Test Tube Chess (London, 1972) and pages 125-126 of David Przepiórka, A Master of Strategy by H. Weenink (Amsterdam, 1932). Where ‘Dr Max Blumenfeld’ came from and went to we do not know.

(2027)

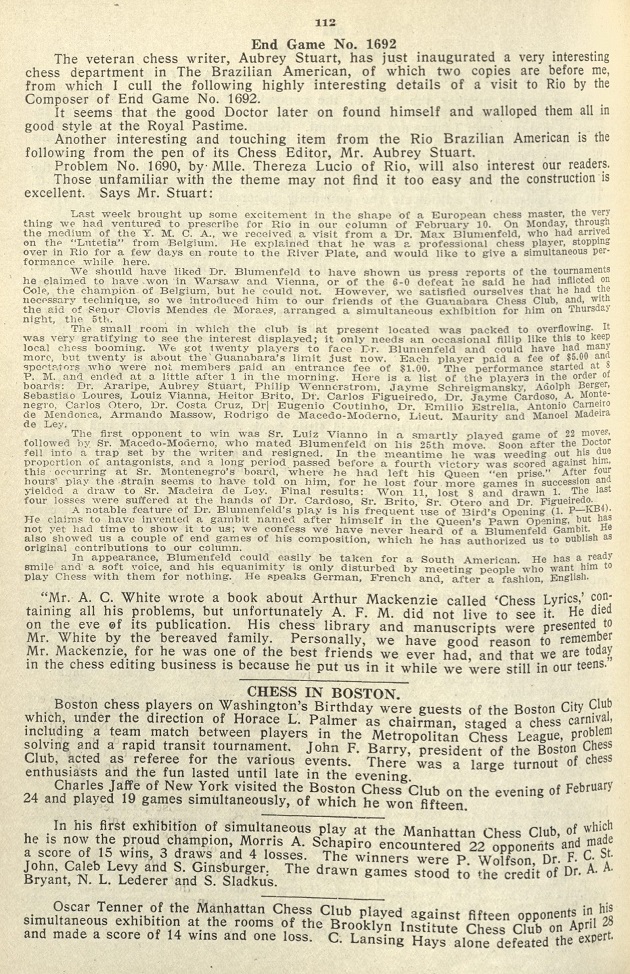

From John Roycroft’s book:

We are grateful to the Royal Dutch Library in The Hague for page 22 of the January 1920 Szachista Polski:

Concerning the misattribution in the American Chess Bulletin, below is page 110 of the May-June 1923 issue:

Page 112:

Lastly, from page 136 of the July-August issue:

The American Chess Bulletin pages have been provided by the Cleveland Public Library.

Do readers have more information about the Brazilian American

and its chess columnist Aubrey Stuart? His description of Réti was

quoted in C.N. 2487.

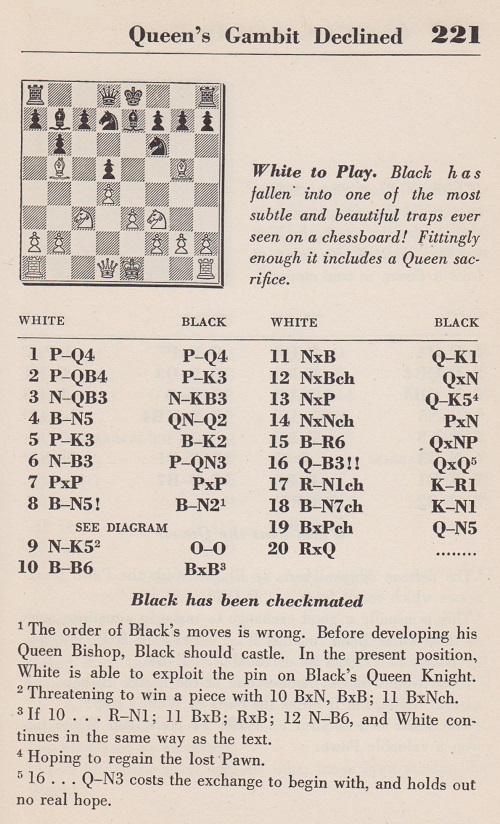

White to move:

K. Reintals-S. Kruger, Australian Championship, Brisbane, 1951

White played 30 Rxc3, which M.E. Goldstein explained as follows in Chess World (October 1951, page 225):

‘Desperately short of time, White here captured his own bishop with his rook! His score sheet clearly reads 30 TxL, which is the Continental rendering of RxB.

The Director of Play rightly ruled that, as White had touched his R at B3 he must move it. As the rook could no longer protect the bishop, a piece is lost and White promptly resigned.’

The magazine’s editor, Purdy, remarked: ‘By the new rules, not yet in force, the FIRST piece touched must be moved; here perhaps it was the bishop. Present rules give the opponent the choice.’

Purdy added, ‘Ahues once took his own pawn in a big tourney’. He was doubtless thinking of the well-known game Przepiórka v Ahues, Kecskemét, 1927, but it was Przepiórka who captured his own bishop. By coincidence, there too the illegal move was ‘RxB’.

(Chess Café, 1998)

The Przepiórka v Ahues position was discussed by Tim Krabbé on page 501 of the September 1976 Chess Life & Review.

C.N. 3692 referred to Flamberg v Levitzky, St Petersburg, 1914, noting that on pages 43-44 of Chess Strategy and Tactics (New York, 1933) Fred Reinfeld and Irving Chernev wrote by way of introduction:

‘The Polish master Alexander Flamberg was a highly gifted player with profound and original ideas. Chronic ill-health prevented him from ever asserting his full powers.

Concerning one of his notable games – one of the most significant in the history of chess – his countryman Przepiórka has commented as follows: “When one examines the opening moves and the subsequent course of the game, it is almost incredible that it was played in 1914 ... The double fianchetto of the bishops, the operations on both wings, and later on the manoeuvers with the black knights and the posting of the queens on the long diagonal – all these ideas are, as we know, considered the very latest achievements of the Hypermoderns.”’

The comments by Przepiórka appeared on page 34 of the February 1926 Wiener Schachzeitung. He used the term ‘A Prophetic Game’ to describe Flamberg’s victory:

Alexander Flamberg – Stepan Mikhailovich Levitzky

All-Russian Masters’ Tournament, St Petersburg, 16 January 1914

Queen’s Indian Defence

1 d4 Nf6 2 Nf3 b6 3 g3 Bb7 4 Bg2 e6 5 O-O Be7 6 b3 O-O 7 Bb2 d6 8 c4 Nbd7 9 Nbd2 c5

10 Ne1 Qc7 11 Rc1 Bxg2 12 Nxg2 Qb7 13 Ne3 cxd4 14 Bxd4 Nc5 15 Qc2 Nce4 16 Nxe4 Nxe4 17 Qb2 e5 18 Bc3 Bg5 19 f4 exf4 20 gxf4 Bf6 21 Bxf6 Nxf6 22 Rcd1 Qe4 23 Rf3 Nh5 24 Nd5 Rae8 25 Kf2 Qf5 26 Rg1 f6 27 Qb1 Qc8 28 Qd3 f5 29 Qc3 Kh8 30 Rh3 Nf6

31 Rxg7 Kxg7 32 Rg3+ Kh6 33 Nxf6 Re6 34 Rg5 Qc5+ 35 Kf1 and wins.

Przepiórka (as well as Reinfeld and Chernev) stated that the game ended 35 Kf1 Re3 36 Ng4+ fxg4 37 Qg7 mate, whereas Black resigned at move 35 according to pages 34-35 of Schachjahrbuch 1914 I Teil by L. Bachmann (Ansbach, 1914).

It may be felt that calling the game ‘one of the most significant in the history of chess’ is an exaggeration, but the play is certainly an early illustration of hypermodern tenets.

(3692)

See also Hypermodern Chess.

From Richard Benjamin (Marietta, GA, USA):

‘I have been collecting chess postcards, stamps and memorabilia for many years and have one of the world’s largest collections of chess postcards. Since I hope to write a book on the subject, I should like to hear from any readers with interesting items, such as the silhouette postcards of Mr Calle Erlandsson which were reproduced in C.N. 4180.’

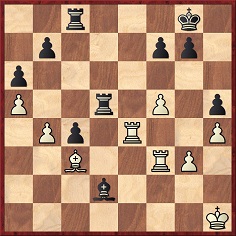

We shall forward to Mr Benjamin any replies received, and in the meantime he has made available for presentation here two postcards from his collection. The first is of Reshevsky [omitted here], and the second was sent by Dawid Przepiórka during Győr, 1924:

(4212)

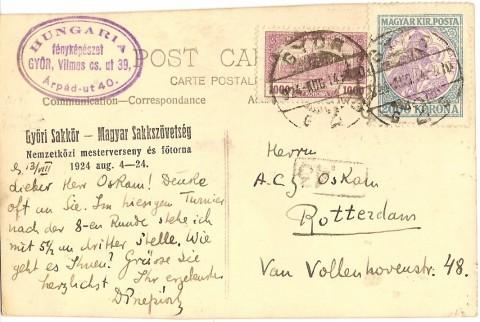

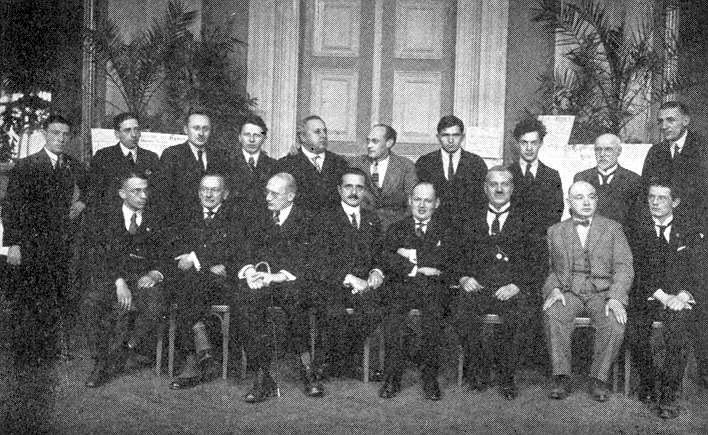

This group photograph of Győr, 1924 (from the tournament book by Maróczy) was shown in C.N. 4808:

Acknowledgement: Cleveland Public Library

Below is a group photograph of Meran, 1924. Readers are invited to try their hand at identifying all present.

(4635)

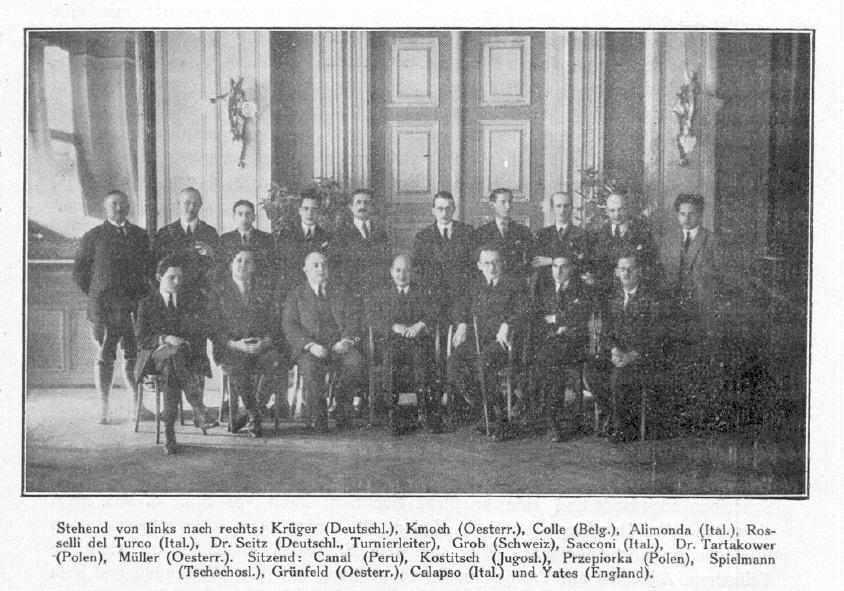

Luca D’Ambrosio (Bolzano, Italy) submits a key based on information in L’Italia Scacchistica, 6 April 1924, page 3, and Het Schaakleven, 15 March 1924, page 125. The names in brackets below were given only by the latter publication.

Standing, from left to right:

(Balaban), E. Colle, A. Selesniev, K. Opočenský, G. Patay, S.

Takács, L. Steiner [not E. Steiner – see C.N. 4808], G.

Koltanowski, I. Gunsberg, (Michel).

Seated: J.A. Seitz, S. Tarrasch, E. Grünfeld, S.

Rosselli del Turco, R. Spielmann, L. Miliani, D. Przepiórka,

(Grim).

Our correspondent asks whether a group photograph exists of the Meran, 1926 tournament (won by Colle ahead of Canal, Przepiórka and Spielmann).

(4669)

Peter Anderberg (Harmstorf, Germany) reports that such a picture was published in Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten, 1927, ‘Erstes Extrablatt’ (page 153). Since our bound volume of that year’s magazine includes the Extrablatt in photocopy form only, can a reader provide a good copy of the photograph for reproduction here?

(4676)

Michael Negele (Wuppertal, Germany) has provided the group photograph of Meran, 1926 referred to in C.N. 4676:

(4686)

For further details regarding these photographs, see The Meran Variation of the Queen’s Gambit.

Luc Winants (Boirs, Belgium) has taken up the difficult challenge of providing a key to the Liège, 1930 photograph in C.N. 5038:

Left to right,

seated: 1. E. Colle, 2. N.N., 3. A. Alekhine, 4. A. Nimzowitsch,

5. A. Rubinstein, 6. C. Ahues, 7. I. Pleci.

Standing: 8. N.N., 9. F.J. Marshall, 10. D. Przepiórka, 11. G.

Lalevitch, 12. E. Fischer, 13. V. Soultanbéieff, 14. N.N., 15.

A. Jarblum, 16. E. Liubarski, 17. F.D. Yates, 18. E.S. Tinsley.,

19. H. Weenink, 20. N.N., 21. N.N., 22. S. Tartakower, 23. N.N.,

24. H. Kmoch, 25. Sir George Thomas, 26. Sultan Khan, 27. N.N.,

28. I. Kashdan.

Our correspondent, who has been examining the photograph with Alexandre Soultanbéieff, comments:

‘Georges Lalevitch (11), Albert Jarblum (15) and Eugène Liubarski (16) were among the best players of the Liège Chess Club and regular opponents of Victor Soultanbéieff. E. Fischer (12) was once the President of the Club.’

(5070)

Jan Kalendovský (Brno, Czech Republic) has been trying to identify all the figures in the group photograph of Marienbad, 1925:

He offers the following:

‘Seated (left to right): N.N., A. Nimzowitsch, R.P. Michell, A. Rubinstein, I. Gunsberg, N.N., V. Tietz, Sir George Thomas, D. Janowsky, F.J. Marshall, F.D. Yates

Standing: L. Burian, H. Kmoch(?), M. Walter, C. Torre, N.N., D. Przepiórka, R. Spielmann, R. Réti, E. Grünfeld, F. Sämisch, S. Tartakower, A. Haida, K. Opočenský.’

The photograph appeared at the start of the tournament book, with the caption ‘Tournament participants and guests’ (‘Teilnehmer und Gäste des Turniers’). Mr Kalendovský reports that it was originally published on page 8 of the Wiener Bilder, 7 June 1925.

(5119)

Alan McGowan (Waterloo, Canada) mentions that a key to the Marienbad, 1925 group photograph was published on page 89 of the May-June 1925 American Chess Bulletin. The additional information it supplies is:

(5125)

A larger version of the Marienbad, 1925 group photograph.

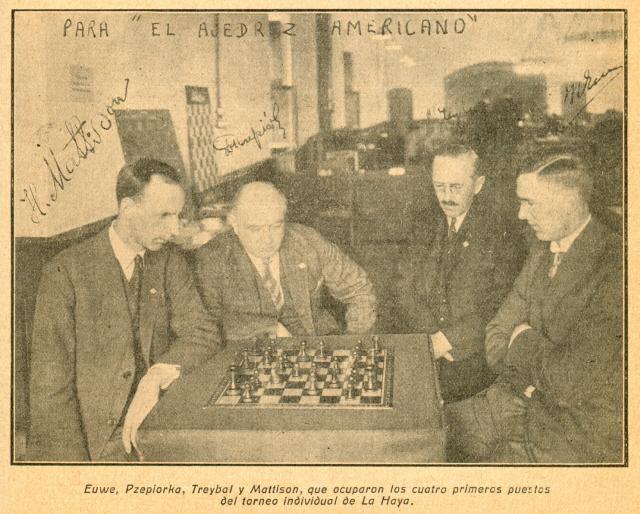

This photograph was published on page 403 of El Ajedrez Americano, October 1928:

(5637)

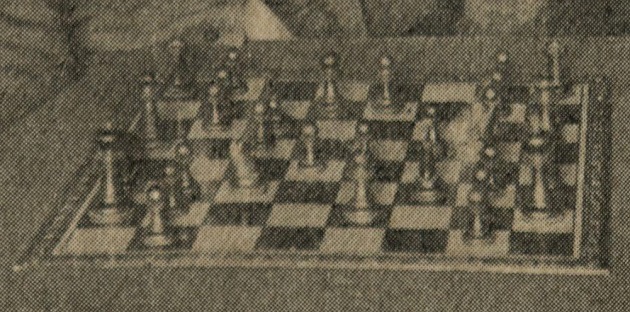

A detail has been provided by the Cleveland Public Library:

It is a Four Knights’ Game position arising after 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bb5 Bb4 5 O-O O-O 6 d3 d6 7 Bg5 Ne7.

(12080)

The detail is taken from the following:

See too A 1928 Chess Photograph.

An untraced game is the brilliancy by Przepiórka, not yet a teenager, against Taubenhaus. From page 13 of David Przepiórka A Master of Strategy by H. Weenink (Amsterdam, 1932):

‘Przepiórka learned chess at the age of seven all by himself, none of his family knowing the game. When only nine years of age he was a true chess prodigy and as a boy of 12 he beat the well-known master Taubenhaus in a brilliant game.’

Page 3 of Dawid Przepiorka His Life and Work by Tomasz Lissowski (Nottingham, 1999) stated:

‘Przepiórka’s debut in a public arena was a competition for solvers where his name was first mentioned in 1891. One year later he had an opportunity to play a game with Jan (Jean) Taubenhaus, a renowned Franco-Polish chess master, who participated in some great international events. The Warsaw press reported, “Przepiórka won his game in a sparkling style”, but the score of this sensational battle has not been preserved.’

Dawid Przepiórka (from H. Weenink’s monograph)

(5768)

Luca D’Ambrosio asks who coined the term ‘cases conjuguées’, which is usually translated into English as ‘conjugate squares’ or ‘sister squares’.

He notes that the issue arose in a dispute on the pages of L’Italia Scacchistica and L’Echiquier in 1932. At the end of June the Belgian magazine brought out the book L’opposition et les cases conjuguées sont réconciliées by Marcel Duchamp and Vitaly Halberstadt. Pages 273-274 of the 15 September 1932 issue of L’Italia Scacchistica published a hostile unsigned article (later identified as written by Stefano Rosselli del Turco) accusing the co-authors of plagiarizing Contributo alla teoria dei finali di soli pedoni by Rinaldo Bianchetti (Florence, 1925). Among the charges was the following:

‘Nel nuovo libro si riscontrano infatti non solo molte delle idee e dei metodi escogitati dall’Ing. Bianchetti, ma perfino gran parte della terminologia da questi adottata. Inoltre l’essenza stessa del libro, contenuta nel titolo, non è altro che la contraffazione della dimostrazione fatta da l’Ing. Bianchetti che l’opposizione è un caso particolare delle case corrispondenti o reciproche, o, se si vuole, delle case coniugate.’

The full article was reproduced, in the original Italian, on pages 1810-1811 of the 3 November 1932 issue of L’Echiquier, together with a half-page denial of plagiarism by Duchamp and Halberstadt. They claimed to have given Bianchetti’s book due credit and stated that, in any case, the phrase ‘cases conjuguées’ predated Bianchetti, having been used by Przepiórka in Munich in 1908:

‘Par esprit d’équité historique nous devons reconnaître D. Przepiórka comme l’auteur de cette phrase si importante dans l’article cité: “L’opposition est un cas particulier des cases conjuguées.” Ceci se passait à Munich en 1908! La question des cases conjuguées n’est pas née en 1925.’

Mr D’Ambrosio asks what contribution Przepiórka made to the subject in 1908.

(6004)

From Harrie Grondijs (Rijswijk, the Netherlands):

‘On pages 24-25 of the second edition of my small book Four Endgame Studies by Emanuel Lasker (Rijswijk, 2008) I wrote that the Akademisches Monatsheft für Schach, May-June 1908 mentioned a talk by Dawid Przepiórka which I believe made it into print only in the Berliner Lokalanzeiger, although I have not seen what that newspaper published. I also noted that the talk was criticized by Johann Berger on pages 115-119 of the April 1909 Deutsche Schachzeitung. Berger referred to the principle of “eindeutige Beziehung”, which may be translated as “one-to-one relationship” and is not far removed from “conjuguées”. It is not clear to me whether Przepiórka used that particular phrase or whether Berger introduced it in his review.

Page 31 of my book gave the first use of the word “corresponding” in this context, from the start of a feature by C.D. Locock on pages 396-399 of the September 1892 BCM:

Finally, on page 34 I reproduced te Kolsté’s table with corresponding squares, from page 59 of the March 1902 Tijdschrift van den Nederlandschen Schaakbond.’

With regard to Przepiórka’s talk, can a reader trace what the Berliner Lokalanzeiger published?

(6011)

Philippe Frit (Toulouse, France) writes:

‘The contribution of Dawid Przepiórka to the theory of corresponding squares has been pointed out several times. In the introduction to his series of articles published in 1922-23 in Shakhmaty about “King manoeuvres in pawn endings”, Nikolai Grigoriev mentioned the names of only three predecessors or contemporaries who had become interested in the theory of corresponding squares (“теорию соответствия”): Dawid Przepiórka, Franz Sackmann and Siegbert Tarrasch:

Shakhmaty issue 3, September 1922, page 51 (see lines 6-8)

Transcription: Повидимому, уделяли им свое внимание люди с именем в шахматном мире, как, напр., Пшепюрка, Закман н наконец д-р Тарраш.

Translation: Famous people in the field of chess have apparently paid attention to it, examples being Przepiórka, Sackmann and finally Dr Tarrasch.

In 1932, the book by Marcel Duchamp and Vitaly Halberstadt Opposition et cases conjuguées sont réconciliées (Opposition and Sister Squares are Reconciled) mentioned a lecture given by Przepiórka at the Munich Chess Club in June 1908. The precise nature of the date and place, as well as the title (“A mathematical method applied to practical play”) and the content of the lecture, suggest that Duchamp and/or Halberstadt actually attended it or obtained their information from a direct witness. Przepiórka is said to have explained in detail a method of solving the Lasker-Reichhelm study using the concept of corresponding squares. According to Duchamp and Halberstadt, Tarrasch was convinced by Przepiórka’s ideas and gave similar lectures in Germany.

Opposition et cases conjuguées sont réconciliées, 1932, page 2 (English and German versions)

As indicated by Harrie Grondijs (C.N. 6011), the lecture by Przepiórka was reported in the Akademisches Monatsheft für Schach.

The lectures by Przepiórka and Tarrasch were also confirmed by Walter Bähr in 1936, on page 42 of his book Opposition und kritische Felder (“Opposition and critical squares”). Bähr specifies dates and/or places: 1908 for Przepiórka, and Berlin 1913 for Tarrasch. He even adds the name of Lasker (Berlin) in between, potentially suggesting a lecture by the reigning world champion during that period. According to Bähr, those lectures dealt with the studies by Locock and by Lasker-Reichhelm. More importantly, the method presented is said to use labelled squares.

Opposition und kritische Felder, 1936, page 42

In 1925, in his book Contributo alla teoria dei finali di soli pedoni, Rinaldo Bianchetti refers more precisely to an article published in 1909 by Przepiórka in the Berliner Lokalanzeitung [sic] describing a new kind of opposition (“una nuova specie di opposizione”) which made it possible to tackle certain studies, such as those by Locock and Lasker-Reichhelm, which were intractable within the rules of classical opposition alone.

Contributo alla teoria dei finali di soli pedoni, 1925, page 53

Nonetheless, Bianchetti’s numerous mistakes and approximations regarding dates and names, as well as his occasional tendency to extrapolate and rewrite history, require his output to be treated with caution. A more reliable source about what was supposedly published by Przepiórka is probably the article by Johann Berger which Bianchetti also quotes, as does Harrie Grondijs. In that article, published in the April 1909 issue of the Deutsche Schachzeitung (pages 115-119), Berger indicates that in a lecture given by Przepiórka in Munich, the Lasker-Reichhelm study was presented and subsequently discussed in the Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger. However, Berger gave no exact reference regarding the German newspaper. He did, though, summarize Przepiórka’s idea, which consisted of using a mathematical method of bijective relations between squares, i.e. based on the one-to-one correspondence between squares (“eindeutige Beziehung”); it is simply a matter of corresponding squares, as Mr Grondijs pointed out. According to Berger, this method was presented by Przepiórka as the only valid one, as opposed to empirical methods which come up against an excessively large number of variants to analyze, whereas the rules of opposition are of no practical use here. Berger rejects this idea, which he criticizes quite fiercely.

Later in his article, on page 118, Berger refers to both Przepiórka and Tarrasch, leaving in passing a doubt about the actual author(s) of the Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger article. On the same page, Berger also mentions a diagram with numbered squares used by Przepiórka to solve the study. That diagram, which Berger found unnecessary and unjustified, was not included in his Deutsche Schachzeitung article.

From the foregoing the idea emerges that Dawid Przepiórka was one of the first to understand the correct method of dealing with the Locock and Lasker-Reichhelm studies. The question therefore is what appeared in the Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger between June 1908 (the date of Przepiórka’s lecture in Munich) and April 1909 (the date of Berger’s article in the Deutsche Schachzeitung).

I have found the article in question in the 21 August 1908 edition of the Entertainment Supplement of the Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger (Unterhaltungs-Beilage des Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger). The diagram in the left-hand column corresponds to Lasker’s study as modified by Reichhelm, although Lasker is the only author cited here. The exact title of the article is “Eine mathematische Methode in ihrer Anwendung auf das praktische Schachspiel” (“A mathematical method applied to chess practice”), which is very close to the title of Przepiórka’s lecture mentioned by Duchamp and Halberstadt (“Mathematische Methode in der Praxis des Schachspiels”).

The sole author of the article seems to be Siegbert Tarrasch, who ran the weekly chess column in the Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger, but in the first paragraph Przepiórka is duly credited for the method presented, which, as stated, was the subject of a lecture he gave in Munich.

Transcription: Wie unlängst der wohlbekannte Schachmeister David [sic] Przepiórka in einem Vortrage zu München auseinandersetzte, muß man vielmehr zur Lösung dieser Aufgabe eine mathematische Methode anwenden: das Prinzip der eindeutigen Beziehung.

Translation: As the famous chess master David [sic] Przepiórka recently explained during a lecture in Munich, it is rather necessary to apply a mathematical method to solve this problem: the principle of bijective relation [i.e. one-to-one relation or correspondence].

This explains why Berger’s criticisms were directed at both Przepiórka and Tarrasch. Furthermore, Berger quotes almost word for word a passage that can be found at the beginning of the second paragraph of the right-hand column. This establishes that the article which I have traced in the Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger is indeed the one referred to by Berger.

Berger, Deutsche Schachzeitung, April 1909, page 115

Tarrasch, Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger, 21 August 1908 (right-hand column, second paragraph)

The interesting part of the article is, of course, the description of the method used to determine the pairs of corresponding squares.

Firstly, Tarrasch identifies the two points of penetration by the white king, i.e. the b5 and h5 squares. He then stresses that to prevent the invasion via h5 it is sufficient for the black king to stay one file to the left of the white king’s file. Next, he identifies the different pairs of corresponding squares starting from the mutual Zugzwang position Kc4/Kb6 and then extending, step by step, to adjacent squares, in a way similar to what can be found in any modern book.

Importantly, each pair of squares is numbered (from 1 to 5), and the result is displayed as a second diagram showing the pawns but not the kings. That makes the Tarrasch article the oldest known publication presenting the solution to the Lasker-Reichhelm study using a diagram with labelled squares.

Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger, 21 August 1908

Until now, this achievement has been attributed to C.E.C. Tattersall, whose book A Thousand End Games (volume one, 1910) published the solutions to the studies of Locock and Lasker-Reichhelm as diagrams with squares marked with letters to indicate the correspondence. Bianchetti and Duchamp-Halberstadt agreed about Tattersall being first:

Contributo alla teoria dei finali di soli pedoni, 1925, page 53

Opposition et cases conjuguées sont réconciliées, 1932, page 3

The position published by Tattersall is reversed from left to right compared to the original one. I do not know why.

Tattersall, volume one of A Thousand End Games, 1910, page 154

One further question: who first noticed the relationship between the studies of Locock and Lasker-Reichhelm?’

(11789)

This position is from a brilliancy prize game between D. Przepiórka and I. Dominik at the Warsaw, 1919 tournament:

Black now played: 26…g3+ 27 Rxg3 Qxg3+ 28 Kxg3 Rg7+ 29 Kh2 Rg2+ 30 Kh1 Bg4 31 Qg1 Bf3 32 Rc2 Kf7 33 Rxg2 hxg2+ 34 Kh2 Rh8+ 35 Kg3 Rh1 36 Kf2 a5 37 Nc8 Ke6 38 f5+ Kf6 39 Nd6 b6 40 Nc8 c5 41 Nxb6 cxd4 42 Nxd5+ Ke5 43 f6 dxe3+ 44 Nxe3 Kxf6 45 b4 axb4 46 Nd5+ Ke6 47 Nxb4 e3+ and White resigned. (There cannot be many games in which a queen remains en prise to a rook for a dozen moves.)

The score was widely published at the time (e.g. BCM, July 1920, pages 218-219, which called it ‘a very fine and interesting game’, and the July 1921 Deutsche Schachzeitung, pages 153-154). However, on page 211 of the December 1921 American Chess Bulletin A.J. Fink of the San Francisco Chronicle observed that the BCM’s notes had given the variation 29 Kf2 Rg2+ 30 Kf1 Bg4 31 Qe1 Bf3 32 Qh4 h2 and 33…Rg1+ and that in this line White could play 33 Rc1 (‘!!!’). He added: ‘In the attacking moves of Black from here on – and there are a good many – I’ve failed to find a win. The fact must not be overlooked that the knight, stationed at b6, does good work.’

Was Fink right in believing that he had ‘cooked’ the brilliancy?

(2237)

From Das entfesselte Schach by S. Tartakower (Kecskemét, 1926):

(6675)

A new book in Polish, Mistrz Przepiórka by Tomasz Lissowski, Jerzy Konikowski and Jerzy Moraś (Warsaw, 2013), is notable. It is a 271-page softback containing a biography, games, problems and many photographs.

(8266)

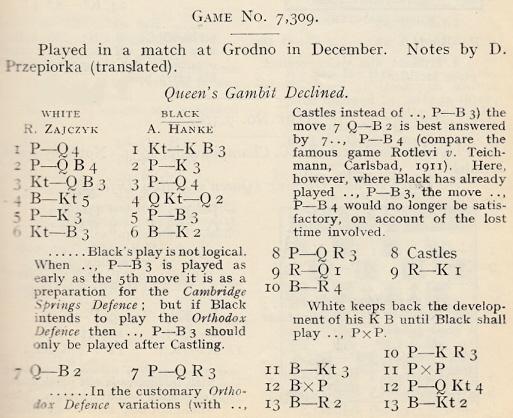

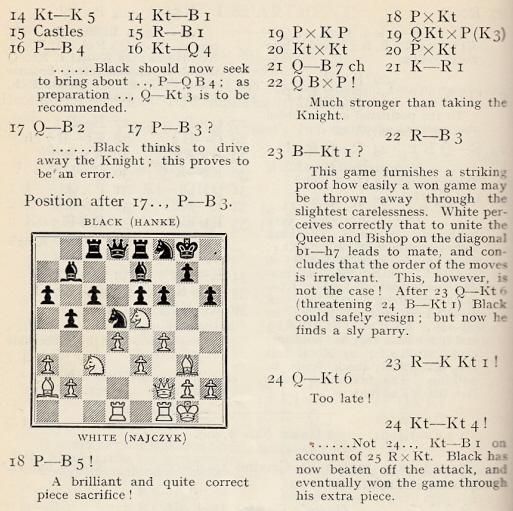

Wanted: more details about a game published on pages 85-86 of the February 1935 BCM with annotations by Przepiórka (including an interesting comment at move 23):

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 d5 4 Bg5 Nbd7 5 e3 c6 6 Nf3 Be7 7 Qc2 a6 8 a3 O-O 9 Rd1 Re8 10 Bh4 h6 11 Bg3 dxc4 12 Bxc4 b5 13 Ba2 Bb7 14 Ne5 Nf8 15 O-O Rc8 16 f4 Nd5 17 Qf2 f6 18 f5 fxe5 19 fxe6 Nxe6 20 Nxd5 cxd5 21 Qf7+ Kh8 22 Bxe5 Rc6 23 Bb1 Rg8 24 Qg6 Ng5 and wins.

(8630)

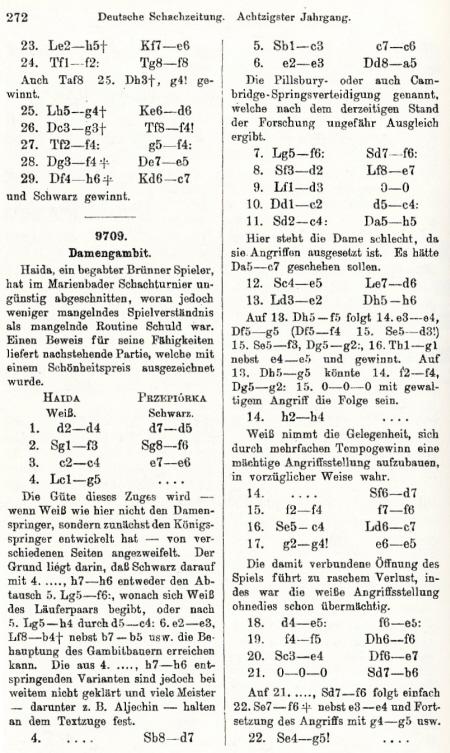

Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia (Jefferson, 1987) records that August Konrad Haida was born in Česká Lípa on 6 July 1887 and died circa 1940. David Clayton (Croydon, England) asks for further biographical details about Haida and, in particular, an explanation of his participation in Marienbad, 1925. Page 13 of the tournament book attributed Haida’s modest performance to rustiness but also referred to his brilliant win over Przepiórka, which, the following page noted, received a prize.

Karel Mokrý (Prostějov, Czech Republic) adds that the Czech magazines of 1925, Časopis Československých Šachistů and Soukup’s Šachový svĕt, do not explain Haida’s participation in Marienbad, 1925. The former merely stated that it was Haida’s first strong event and that he was possibly a better player than his result indicated. Mr Mokrý also points out the entry for Haida on page 119 of Malá encyklopedie šachu by J. Veselý, J. Kalendovský and B. Formánek (Prague, 1989), which stated that he was German, a postal clerk in Brno and a master of the ÚJČŠ (Czechoslovak Chess Union) as from 1921.

For the group photograph of Marienbad, 1925 see C.N.s 5119 and 5125 above. Haida’s victory over Przepiórka was published on pages 272-273 of the September 1925 Deutsche Schachzeitung, with Réti’s notes from the Morgenzeitung:

(8815)

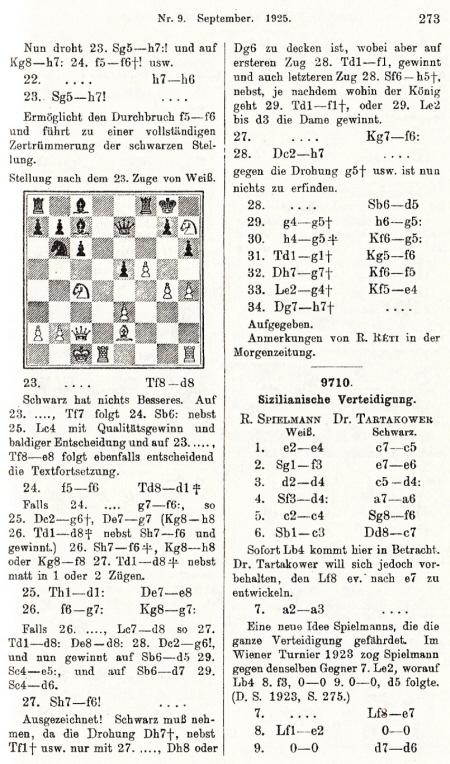

A problem published on page 79 of David Przepiórka A Master of Strategy by H. Weenink (Amsterdam, 1932):

(9521)

White can play 17 Qf3.

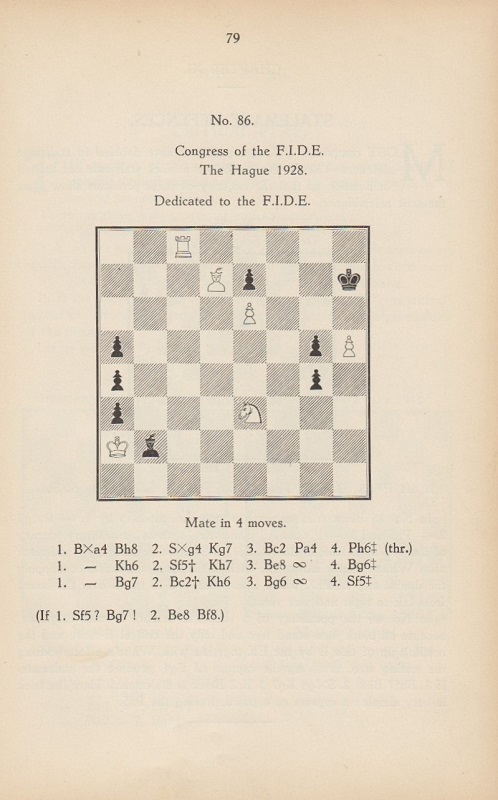

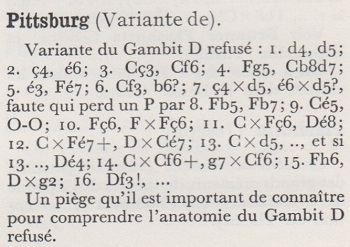

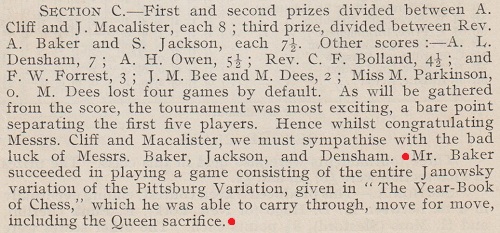

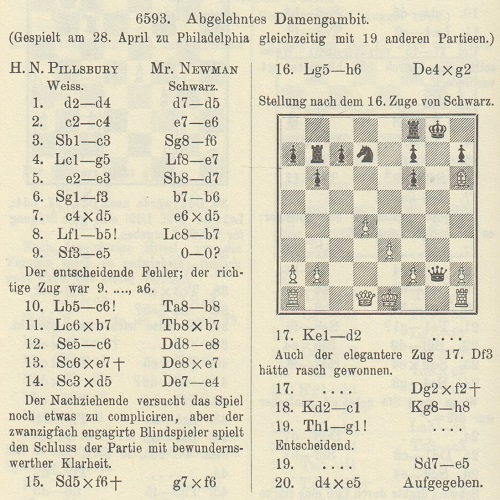

We offer a solution to the long-standing mystery of how the ‘Pittsburg(h) Trap/Variation’ obtained its name(s).

Modern Chess Openings by R.C. Griffith and J.H. White (London, 1913), page 92. (See too many other editions.)

Dictionnaire des échecs by F. Le Lionnais and E. Maget (Paris, 1967), page 301

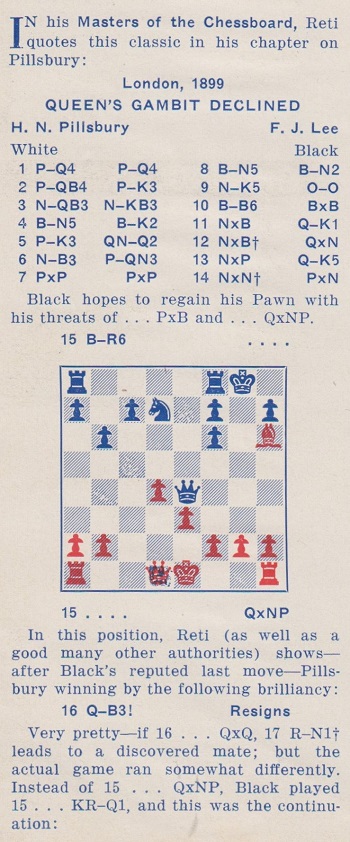

The matter was often referred to by Irving Chernev, e.g. on the inside front cover of the October 1951 issue of Chess Review:

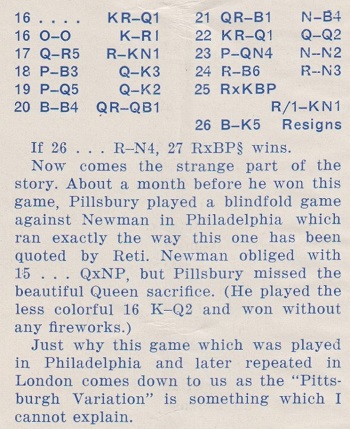

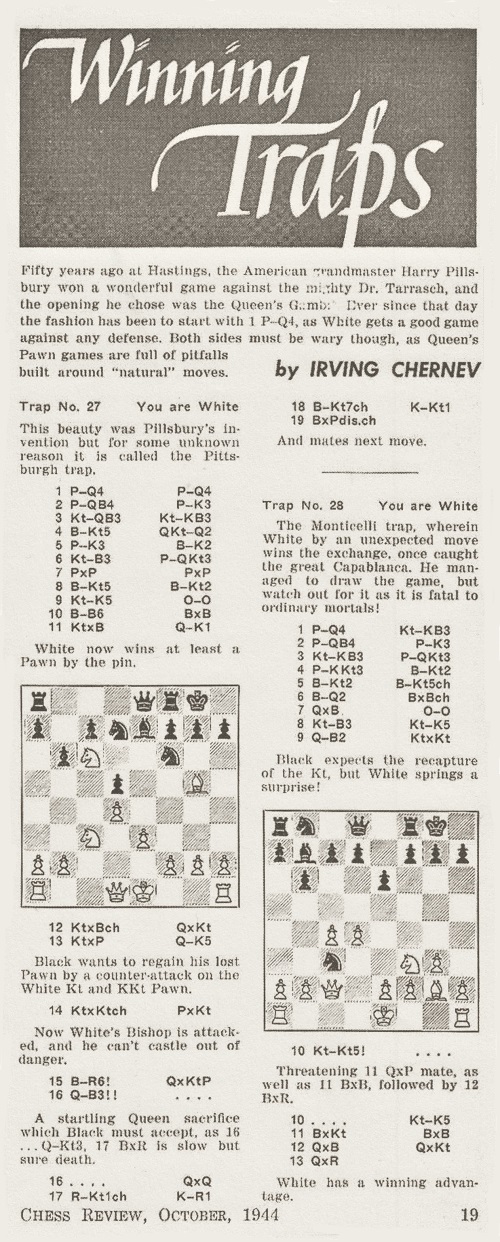

Chernev had written similarly in his ‘Winning Traps’ column on page 19 of the October 1944 Chess Review:

See too pages 52-53 of Chess in an Hour by F.J. Marshall and I. Chernev (New York, 1968), where Chernev wrote in his additions:

‘This beautiful trap was originated by Pillsbury, who used it with great effect against Lee in their tournament game at London in 1899, but for some strange reason it is known as the Pittsburgh trap.’

In a note to Capablanca v Teichmann, Berlin, 1913 on page 57 of Capablanca’s Best Chess Endings (Oxford, 1978) Chernev wrote: ‘the Pittsburgh Trap is subtle, effective and painless – the victim scarcely realizing he is in it until it is too late.’ Without mentioning any names, Chernev gave a similar line on page 221 of Winning Chess Traps (New York, 1946): ‘Black has fallen into one of the most subtle and beautiful traps ever seen on a chessboard’.

Pre-Chernev books which noted the line, without any reference to Pillsbury or Pittsburg(h), included the works on traps by E.A. Greig and E.A. Znosko-Borovsky.

For further background information on Pillsbury’s games against Lee and Newman, as well as references to ‘Pillsbury’s Mate’, see C.N. 5772. It will be noted that in the 1951 Chess Review article shown above Chernev was wrong to state that Pillsbury v Newman was played ‘about a month before’ Pillsbury v Lee. It was played the following year. The London, 1899 tournament book (pages 157-158) missed the possibility of 16 Qf3 in Pillsbury v Lee.

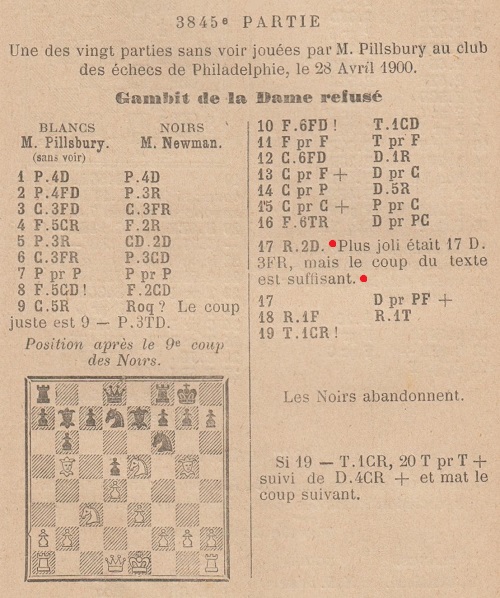

The game against Newman was published on page 299 of La Stratégie, 15 October 1900, with 17 Qf3 mentioned in a note:

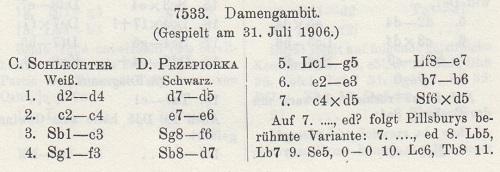

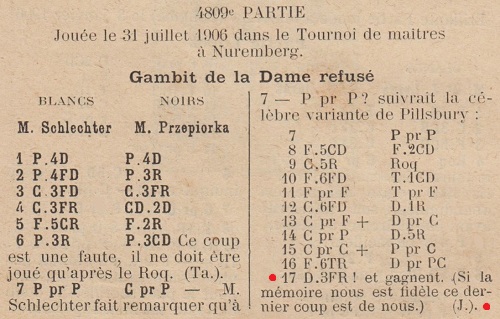

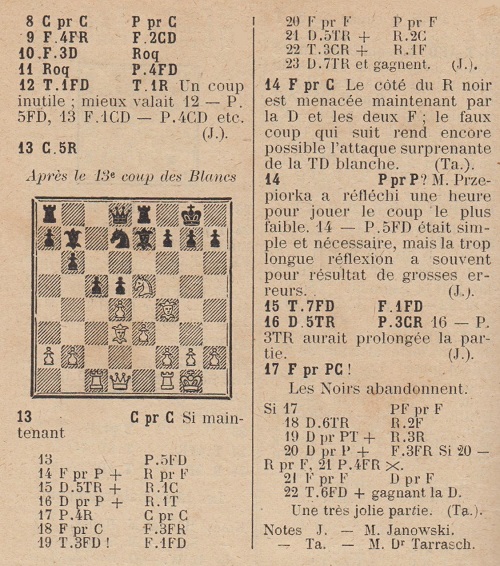

Six years later the move 17 Qf3 was given in annotations to the game Schlechter v Przepiórka, Nuremberg, 1906, on pages 235-236 of the August 1906 Deutsche Schachzeitung (of which Schlechter was the co-editor):

Annotating the game on pages 333-334 of La Stratégie, 19 November 1906, Janowsky referred to Schlechter’s annotations and stated, regarding 17 Qf3:

‘Si la mémoire nous est fidèle ce dernier coup est de nous.’

When the Schlechter v Przepiórka game was published on page 188 of The Year-Book of Chess, 1907 by E.A. Michell (London, 1907) use was made of Janowsky’s annotations:

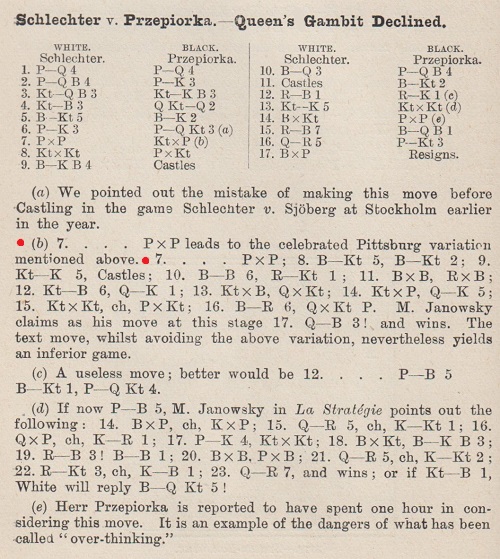

Thus the term written by Schlechter (‘Pillsburys berühmte Variante’) which was quoted by Janowsky (‘la célèbre variante de Pillsbury’) became, in the Year-Book, ‘the celebrated Pittsburg variation’.

Janowsky’s notes had also been mentioned on page 185 of the Year-Book (in connection with Marshall v Spielmann, Nuremberg, 1906); the Schlechter v Sjöberg game was on pages 47-48.

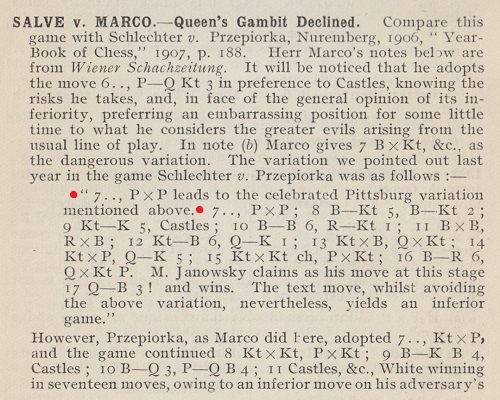

The Pillsbury/Pittsburg mix-up was repeated when Salwe v Marco, Ostend, 1907 was published on pages 174-177 of Michell’s The Year-Book of Chess, 1908 (London, 1908). The introductory note:

A third occurrence of ‘Pittsburg Variation’ (this time, ‘the entire Janowsky variation of the Pittsburg Variation’) came in a report on Scarborough, 1909 on page 142 of The Year-Book of Chess, 1910 (London, 1910), also edited by E.A. Michell:

Following the confusion between Pillsbury and Pittsburg, confusion between Pittsburg and Pittsburgh was inevitable, and both spellings became common. For example, the 1918 BCM volume had ‘Pittsburg variation’ (January, page 21) and ‘Pittsburgh variation’ (August, page 240). Use of a place name was not queried, and ‘The Pittsburg variation’ even appeared (referring to 8 Bb5) when Pillsbury v Newman was published on page 204 of Pillsbury’s Chess Career by P.W. Sergeant and W.H. Watts (London, 1923).

(10272)

The possibility of 17 Qf3 was also pointed out on page 242 of the August 1900 Deutsche Schachzeitung (edited by Berger and Schlechter):

(10286)

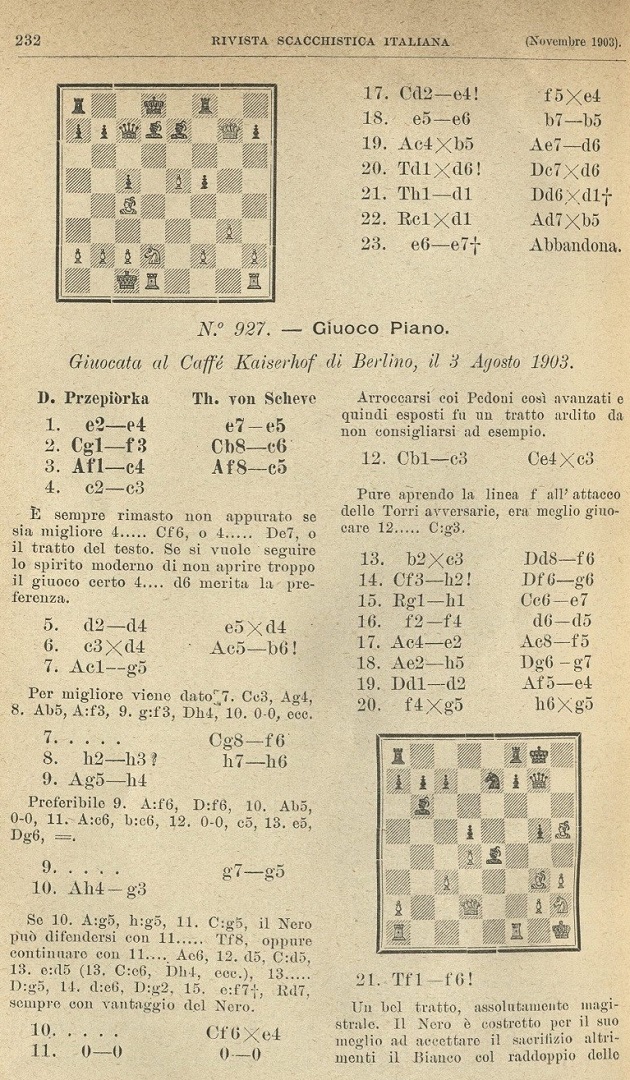

As mentioned in C.N. 2476 (see The Best Chess Games), pages 222-223 of volume two of Les Cahiers de l’Echiquier Français (issue 23, 1930) stated that Dawid Przepiórka’s favourite game was an offhand encounter (against Theodor von Scheve):

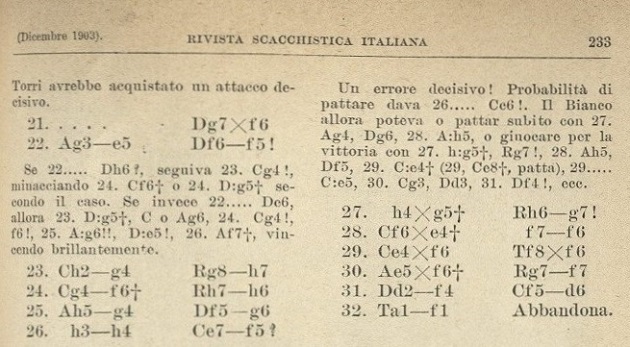

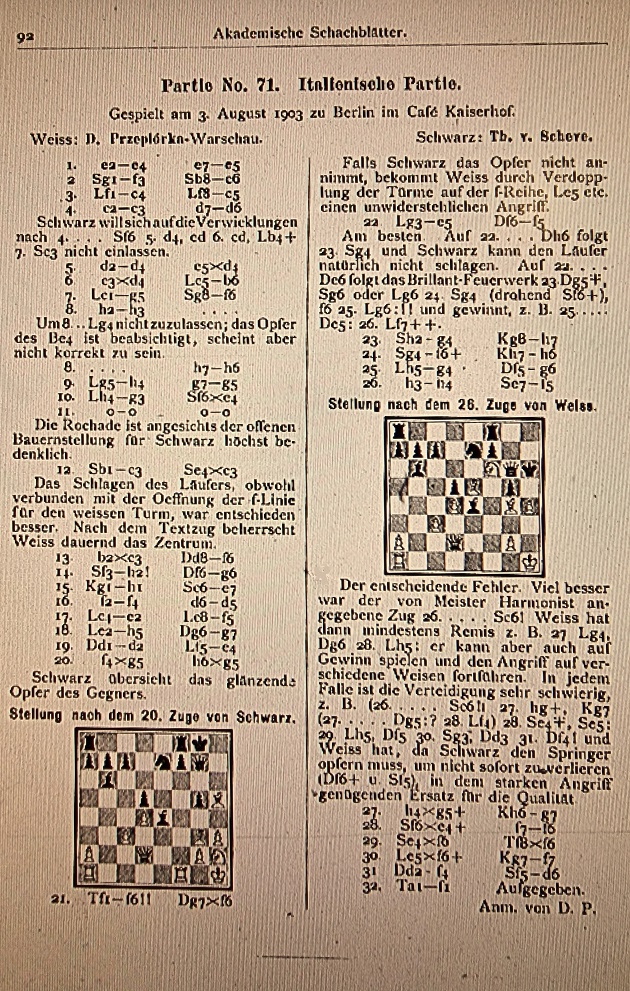

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 c3 d6 5 d4 exd4 6 cxd4 Bb6 7 Bg5 Nf6 8 h3 h6 9 Bh4 g5 10 Bg3 Nxe4 11 O-O O-O 12 Nc3 Nxc3 13 bxc3 Qf6 14 Nh2 Qg6 15 Kh1 Ne7 16 f4 d5 17 Be2 Bf5 18 Bh5 Qg7 19 Qd2 Be4 20 fxg5 hxg5

21 Rf6 Qxf6 22 Be5 Qf5 23 Ng4 Kh7 24 Nf6+ Kh6 25 Bg4 Qg6 26 h4

26...Nf5 27 hxg5+ Kg7 28 Nxe4+ f6 29 Nxf6 Rxf6 30 Bxf6+ Kf7 31 Qf4 Nd6 32 Rf1 Resigns.

Without stating where or when the game was played, the Cahier included some annotations, the source being merely ‘Rivista Scacchistica Italiana’.

Below, courtesy of the Cleveland Public Library, is the game’s appearance on pages 232-233 of the November/December 1903 issue:

The game had been annotated by Przepiórka himself on page 92 of Akademische Schachblätter, September/October 1903:

Pages 8-9 of the booklet referred to in C.N. 5768, Dawid Przepiorka His Life and Work by Tomasz Lissowski (Nottingham, 1999), noted what had appeared in the Rivista Scacchistica Italiana but dated the game 1904 (as we did too in C.N. 2746). The correct date, 1903, was included in a later, more detailed monograph (mentioned in C.N. 8266): Mistrz Przepiórka by Tomasz Lissowski, Jerzy Konikowski and Jerzy Moraś (Warsaw, 2013). The book’s annotations to the game against von Scheve (on pages 147-148) refer to Akademische Schachblätter (not to the Rivista Scacchistica Italiana), but with a fresh assessment. In particular, Przepiórka’s ‘21 Rf6!!’ becomes ‘21 Rf6?’.

(12081)

Przepiórka, D.: Elisabethstrasse 26, Munich, Germany (Ranneforths Schach-Kalender, 1915, page 73).

Przepiórka, D.: Polna 64, Warsaw, Poland (Ranneforths Schach-Kalender, 1929, page 66).

To the Archives for other feature articles.

Copyright Edward Winter. All rights reserved.