Edward Winter

How do such things happen?

(11534)

Before us lie, by chance, two paperbacks, Chess Lists by A. Soltis (McFarland, Jefferson, 2002, $30) and Morecambe & Wise by G. McCann (Fourth Estate, London, £7.99). The latter work (an excellently-researched piece of scholarship on the United Kingdom’s ‘best and funniest double-act’) comprises 398 pages and includes (working backwards) a 22-page index, a four-page general bibliography and a 42-page section of endnotes giving corroborative sources for all the principal information presented. Chess Lists merely has a seven-page general index. Virtually everything in the book is unsubstantiated, leaving readers clueless as to whether the facts/stories proffered are true or false and, in either case, whether they are the fruits of Soltis’ own work/imagination or someone else’s.

(2708)

See too our feature article on Andrew Soltis.

It is doubtful whether many readers of C.N. will have had the misfortune to see an article ‘Just Checking’ in issue 3720 of My Weekly, kindly sent to us by Colin McGuigan (Newtownards, Northern Ireland).

The author is named as Sam Jenkins, and his idea of an entertaining read is to string together uncorroborated anecdotes saturated with exclamation marks. Any chess writer without much sense of shame could knock out such articles by the hundred.

(1058)

From A Catastrophic Encyclopedia:

Divinsky thrives on rumours, and much of what he tells us is like gossip over backyard clothes-lines. Sentences begin with ‘Some say that ...’, ‘It is said that ...’, ‘He is said to have lost ...’, ‘Janowski is reputed to have said that ...’, etc.

Never trust any writer who compiles lists of chess quotations without providing sources.

(2853)

We have occasionally commented on certain chess authors’ indifference to attributing correctly the information they put forth. In our view, any writer who, for instance, lists alleged quotes by chess figures without even attempting to specify sources is not worth a second look.

Yet there are cases of ‘sourcelessness’ concerning entire books. Examples are Robert James Fischer Gesammelte Partien (Nuremberg, 1989 and 1991), the French edition of which is Bobby Fischer Parties choisies, published by ‘Editions Echecs International’. The volume contains not one word about the place or date of publication, although we note that in 1992 a book by K. Pytel, Vie et oeuvre de Boris Spassky, was published by a similarly, but not identically, named company: ‘Edition Echecs International’ of Schifflange in Luxembourg.

In the case of the Fischer book, ‘French edition’ is a tolerant term, since the pseudo-Gallic text goes awry as early as the first words of the Preface (‘Il y 17 ans depuis que …’).

(2870)

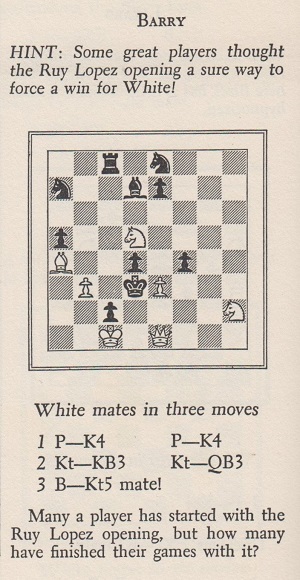

Anyone wishing to make chess history ‘fun’ by spreading unsubstantiated anecdotes and tittle-tattle has only to eschew specifics like dates and places and rely on the shadowy word ‘once’. From 2010 Chess Oddities by A. Dunne (Davenport, 2003) we scoop up the following selection:

‘World Champion Emanuel Lasker was once offered an opium scented cigar …’

‘Aron Nimzovich once broke his leg ...’

‘Aron Nimzovich once stood on his head ...’

‘Pal Benko once thought Mikhail Tal was trying ...’

‘Max Euwe once requested a game for the World Championship be postponed ...’

‘Akiba Rubinstein once won four brilliancy prizes in one tournament.’

‘Anatoly Karpov once listed his hobbies as ...’

‘Mikhail Tal was once signed to play the Devil in a movie ...’

‘Tal was once asked what chess piece he would like to be ...’

(3112)

C.N. 3480

Chess Rules of Thumb by L. Alburt and A. Lawrence (New York, 2003) breaks the first rule of thumb for any chess writer: make an effort. Even some of the best-known quotes in chess history have been garbled. Indeed, the very first one presented (page 9) has the co-authors attributing to John Collins the dictum, ‘Castle when you will, or if you must, but not when you can’. C.N. 2679 quoted the following from Napier’s Amenities and Background of Chess-Play (New York, 1934):

‘Once I asked Pillsbury whether he used any formula for castling. He said his rule was absolute and vital: castle because you will or because you must; but not because you can.’

Why Collins should be brought in is a mystery. Certainly the citation ‘Castle when you will, or if you must, but not when you can’ appears on page 13 of his book Maxims of Chess (New York, 1978), but he clearly (though wrongly) credited it to Napier.

C.N. 2679 also featured another famous Pillsbury quote reported by Napier:

‘So set up your attacks that when the fire is out, it isn’t out.’

Yet on page 129 of Chess Rules of Thumb (which gives no sources at all) the dictum ‘Conduct the attack so that when the fire is out … it isn’t’ is ascribed to Reuben Fine.

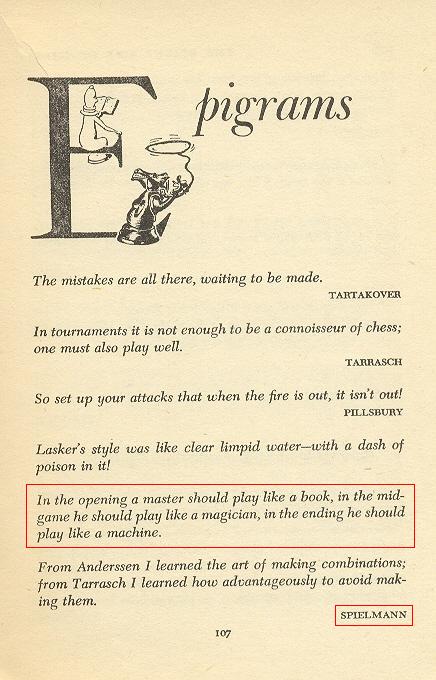

Proper sources are not optional extras or lace frills; they are required as an integral part of chess writing, and without the best possible attribution quotations are worthless. Consequently, little more will be said here about Chess Rules of Thumb, except for a brief mention of two further cases. Page 103 attributes to Spielmann this remark:

‘Play the opening like a book, the middlegame like a magician, and the endgame like a machine.’

Moreover, an alleged statement of Capablanca’s is quoted on page 126:

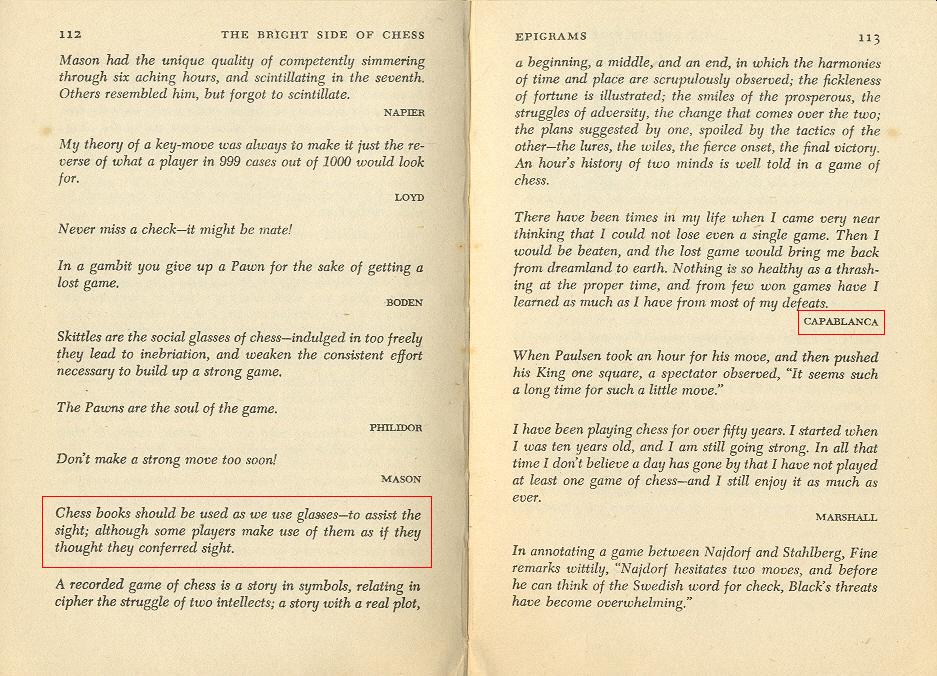

‘Chess books should be used as we use glasses. Use them to assist the sight, although some players make use of them as if they thought they conferred sight.’

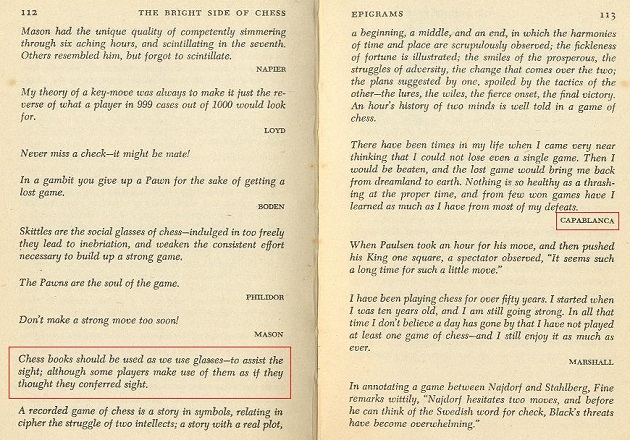

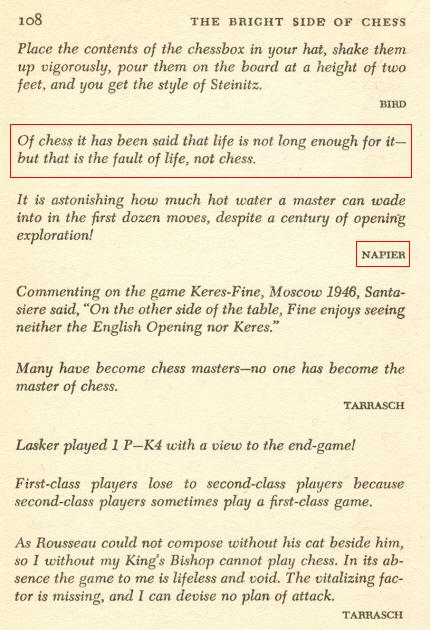

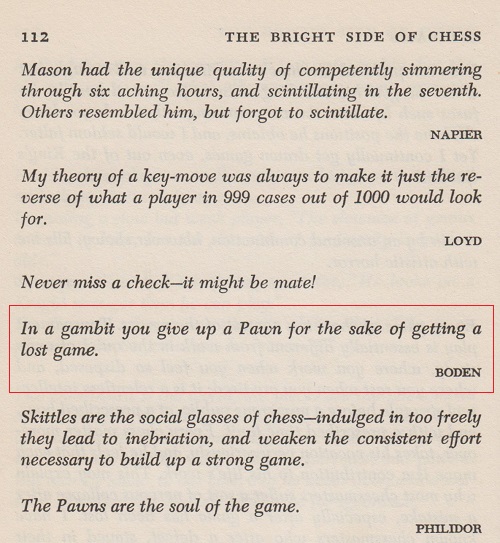

For the reasons explained in C.N.s 325 and 1063 (see page 182 of Chess Explorations) we believe that the lay-out of the epigrams chapter in Chernev’s The Bright Side of Chess (pages 107 and 112-113) caused Spielmann and Capablanca’s names to be unjustifiably attached, long ago, to these quotations. Below is an extract from page 107 of Chernev’s book:

It is evident from other parts of this chapter of Chernev’s that when he gave, for instance, two unattributed quotations followed by an attributed one it was only the last of these that he intended to ascribe to the writer named. Thus in the extract reproduced above the ‘poison’ quote has no more to do with Spielmann than does the ‘book, magician and machine’ comment.

(3160)

Page 67 of Modern Chess Analysis by Robin Smith (London, 2004) ascribes the following quote to Capablanca:

‘Chess books should be used as we use glasses: to assist the sight, although some players make use of them as if they thought they conferred sight.’

As indicated in C.N.s 325 and 3160, we believe this to be an old misattribution resulting from the lay-out of pages 112-113 of The Bright Side of Chess by Irving Chernev (Philadelphia, 1948):

The intermediate quote beginning ‘A recorded game ...’ is also at variance with Capablanca’s prose style, and it would hardly be logical to regard Philidor as the originator of the skittles quote or Marshall as the writer of the Paulsen anecdote. But can readers help us put this matter beyond all doubt? Certainly we have no recollection of the glasses quote in any of the Cuban’s writings, but had it appeared in print before Chernev’s book was published (in, for instance, an article by Chernev)? And who first conferred the quote upon Capablanca? As regards that last question, the earliest instance known to us is page 85 of Championship Chess and Checkers For All by Larry Evans and Tom Wiswell (New York, 1953).

(3741)

On page 19 of the February 1993 Chess Life Larry Evans gave the misattribution in a different wording:

‘As Capablanca put it, chess books should be used like eyeglasses. They aid sight – they don’t confer it.’

In C.N. 4156 Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) cited the following passage (from the pre-Spielmann era) in the section on Pillsbury on page xiv of The Games of the St Petersburg Tournament 1895-96 by J. Mason and W.H.K. Pollock (Leeds, 1896):

‘A great player was once asked to give his ideas as to how a master ought to play. “In the opening”, was his reply, “a master should play like a book; in the mid-game he should play like a magician; in the ending he should play like a machine.’

C.N. 8510 pointed out an abridged version on the home page of chessgames.com, 30 January 2014:

See too C.N. 8832 for misuse of the quotation in White Death by Daniel Blake (London, 2012).

It is now over 36 years since we queried, in C.N. 325, the above text from page 24 of The Chess Beat by Larry Evans (Oxford, 1982), and it is over 13 years since a correspondent, Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina), pointed out, in C.N. 4156, that the remark had been published well before Rudolf Spielmann’s chess career began, i.e. on page xiv of The Games of the St Petersburg Tournament 1895-96 by J. Mason and W.H.K. Pollock (Leeds, 1896).

Nonetheless, misattribution to Spielmann continues, and Olimpiu G. Urcan notes two occurrences on Twitter on 17 July 2019:

In the second screen-shot we have deleted the photograph (Spielmann v Alatortsev) because, as shown in Copying, the French website (of Mr Philippe Dornbusch) has a habit of taking pictures and other material without permission or acknowledgement. Even the words ‘an Austrian-Jewish chess player of the romantic school, and chess writer’ are a direct copy from Spielmann’s Wikipedia entry.

(11411)

From the Wikipedia page on Rudolf Spielmann:

Spielmann’s forename and surname are misspelled in a dire Wikipedia article entitled ‘Romantic chess’ which includes, for instance, a reference to ‘the 1930s when hypermodernism began to become popular’.

(11422)

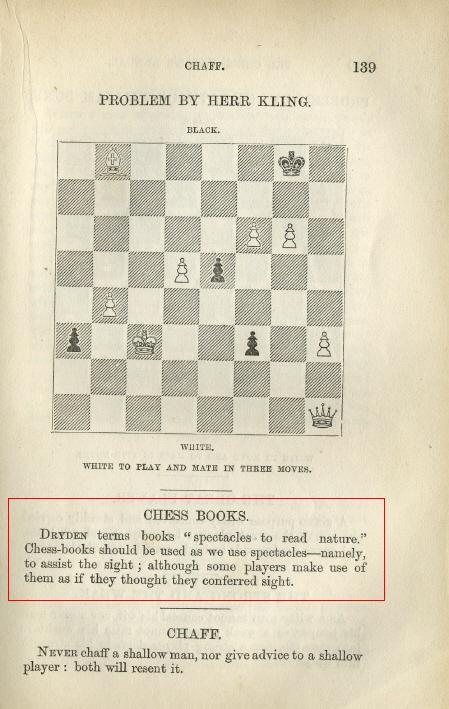

Regarding the ‘conferred sight’ quote misattributed to Capablanca, see the references in the Factfinder. These include C.N. 4209, where Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England) reported having found the remark on page 139 of The Chess-Player’s Annual for the Year 1856 edited by Charles Tomlinson (London, 1856):

The ‘poison’ remark referred to in C.N. 3160 above emanates from Mieses, in an article in the Berliner Tageblatt which was reproduced on page 16 of his San Sebastián, 1911 tournament book:

‘Laskers Stil ist klares Wasser mit einem Tropfen Gift darin, der es opalisieren lässt. Capablancas Stil ist vielleicht noch klarer, aber es fehlt der Tropfen Gift.’

Or, to quote the translation on pages xix-xx of the French edition of the book:

‘Le style de Lasker pourrait être comparé à de l’eau claire recevant une goutte de poison qui la rendrait opaline; le style de Capablanca est peut-être encore plus clair, mais il y manque la goutte de poison.’

An English version was provided by J. du Mont on page 13 of H. Golombek’s book Capablanca’s Hundred Best Games of Chess (London, 1947):

‘Lasker’s style is clear water, but with a drop of poison which is clouding it. Capablanca’s style is perhaps still clearer, but it lacks that drop of poison.’

(3161)

Concerning Spielmann’s remark about Anderssen and Tarrasch quoted in the Chernev book discussed above (see too C.N. 4133), page 168 of the June 1929 Wiener Schachzeitung quoted his reply when asked to name the famous chessplayer from whom he had learned the most:

‘Zuerst von Anderssen das Kombinieren, dann von Dr Tarrasch, wie man vorteilhaft nicht kombiniert.’

Who wrote the following?

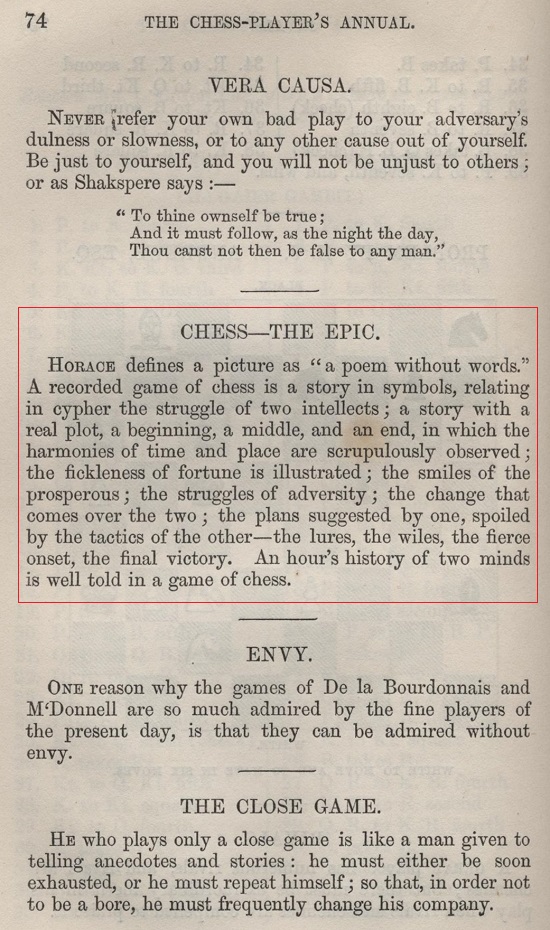

‘A recorded game of chess is a story in symbols, relating in cipher the struggle of two intellects; a story with a real plot, a beginning, a middle, and an end, in which the harmonies of time and place are scrupulously observed; the fickleness of fortune is illustrated; the smiles of the prosperous, the struggles of adversity, the change that comes over the two; the plans suggested by one, spoiled by the tactics of the other – the lures, the wiles, the fierce onset, the final victory. An hour’s history of two minds is well told in a game of chess.’

A casual search on the Internet suggests Capablanca, but that is a misattribution resulting from the same faulty assumption discussed in our feature article Chess: the Need for Sources with regard to the ‘conferred sight’ remark.

C.N. 3741 showed pages 112-113 of The Bright Side of Chess by Irving Chernev (Philadelphia, 1948):

Only the passage beginning ‘There have been times in my life ...’ was written by Capablanca (in My Chess Career). In C.N. 4209 Michael Clapham reported that he had found the ‘Chess books should be used ...’ observation on page 139 of The Chess-Player’s Annual for the Year 1856 edited by Charles Tomlinson (London, 1856).

The second quote of the three, beginning ‘A recorded game of chess ...’, is from page 74 of the same Tomlinson book, and the relevant page is reproduced below, courtesy of Mr Clapham:

Textual differences: the spellings cypher/cipher and the punctuation after ‘prosperous’ and ‘adversity’.

(10959)

It is hard to imagine a more defective area of chess literature than quotations. Writers copy from one another all kinds of unverified or unverifiable phrases without any explanation, context or source.

‘Chess is vanity’, for instance, is widely attributed to Alekhine, but did he use those words and, if so, in which connection? All we can offer so far is the following from page 19 of the January 1929 BCM:

‘Alexander Alekhine, interviewed in Paris by the Eclaireur de Nice on 24 November, said with regard to his victory over Capablanca at Buenos Aires: “Psychology is the most important factor in chess. My success was due solely to my superiority in the sense of psychology. Capablanca played almost entirely by a marvellous gift of intuition, but he lacked the psychological sense.”

From the commencement of the game, the champion continued, a player must know his opponent. “Then the game becomes a question of nerves, personality and vanity. Vanity plays a great part in deciding the result of a game.”

We are indebted to the Central News for the above item of information.’

Perhaps a reader can hunt out the original text of the interview in the French source. Or does the bald statement ‘chess is vanity’ in any case come from somewhere else?

(3225)

It has not yet proved possible to find the original text of the interview in the French source, but here we draw attention to what appeared in the quotes chapter of The Joys of Chess by F. Reinfeld (New York, 1961), page 286:

‘“Chess is a matter of vanity.”

– Alexander Alekhine, Chess Review, 1934.’

However, this proves to be a non-source, for Reinfeld did not make it clear that the item in question was merely an article by Barnie F. Winkelman entitled ‘Vanity and Chess’ on pages 156-157 of the September 1934 Chess Review. The quotation introduced Winkelman’s article, as follows:

‘“Chess is a matter of vanity …”

Dr Alexander Alekhine

(From a reported interview.)’

That is all.

The last two paragraphs of Winkelman’s article discussed the ‘reported’ Alekhine quote (whose authenticity has yet to be established):

‘All this, no doubt, Dr Alekhine had in mind when he emphasized the importance of vanity in match or tournament. But let him not be misunderstood. For in no field is blind conceit more speedily punished, and mere front of so little value.

Well may Alekhine be pardoned the apparent exaggeration of his quotation. For he above and beyond any of our champions builded his own success solidly upon a foundation of native ability, hard work and sheer love of the game – and least of all, upon vanity.’

(3522)

From page 1 of Lessons in Chess, Lessons in Life by Jose A. Fadul (Morrisville and London, 2008):

‘Somebody complained that life is too short to be wasted in trivial games such as chess. But William Napier did retort that such is the fault of life, and not of chess.’

The retort is indeed sometimes attributed to Napier (for example, in a piece which appeared under Frank Elley’s name on page 30 of Chess Life, March 1986), but we do not recall seeing it in Napier’s writings.

As noted in The Most Famous Chess Quotations, ‘Life’s too short for chess’ was a line of dialogue in the play Our Boys by H.J. Byron. Our feature article on Sir John Simon quoted from page 116 of CHESS, 14 December 1937:

‘Deputizing for Sir John at the Sheffield Cutlers’ Feast recently, Dr Burgin, Minister of Transport, referred to the Chancellor’s partiality to chess and added, “Of chess it has been said that life is not long enough for it – but that is the fault of life, not of chess”.’

We commented that the longer quote is often attributed to Irving Chernev, who gave it (without claiming paternity) on page 108 of The Bright Side of Chess (Philadelphia, 1948). Moreover, the book’s layout created the false impression that Chernev was ascribing the remark to Napier.

(6714)

A further illustration of the ‘once’ school of narrative comes from page 24 of Curious Chess Facts by I. Chernev (New York, 1937):

‘Steinitz was once arrested as a spy. Police authorities assumed that the moves made by Steinitz in playing his correspondence games with Chigorin were part of a code by means of which important war secrets could be communicated.’

The identical paragraph appeared on page 31 of Chernev’s Wonders and Curiosities of Chess (New York, 1974), whereas on page 89 of The Fireside Book of Chess by I. Chernev and F. Reinfeld (New York, 1949) the wording was slightly different:

‘Steinitz was once misjudged to be a spy. Police authorities assumed that the moves made by him in playing his correspondence games with Chigorin were part of a code by means of which important war secrets could be transmitted.’

(3345)

For further details see page 243-244 of Chess Facts and Fables.

No reliable anthology of chess quotations exists in any language; to date there has been just the occasional brief throw-together of alleged bons mots, all of them sourceless. Nothing stamps a writer as untrustworthy more swiftly than an expectation that what he writes should be taken on trust.

There is something carefree and almost random about how the chess world attributes many writings and sayings to persons (Tartakower is a safe bet) and nations (‘Old Russian proverb’), and this often makes it impossible for the reader to determine what is genuine, erroneous or bogus. Our recommendation is to dispense with any publication or website which offers ‘chess quotes’ without indicating where and when the statements in question were purportedly made.

On page 279 of The Chess Companion (New York, 1968) I. Chernev attributed the following to Tartakower:

‘The great master places a knight at K5; checkmate follows by itself.’

As was pointed out in C.N. 2194 (see pages 338-339 of A Chess Omnibus), Tartakower merely quoted an onlooker at a game won by O. Bernstein in Paris in 1933. On page 426 of L’Echiquier, 17 February 1934 Tartakower wrote:

‘“Ces grands-maîtres placent leur[s] Cavaliers à é5 et après les mats découlent d’eux-mêmes!” dit en voyant cette catastrophe un spectateur grincheux.’

A similar remark appeared on page 111 of Chernev’s The Bright Side of Chess (various editions, except the New York, 1961 version, which mysteriously omitted the Epigrams chapter):

‘Once get a knight firmly posted at king 6 and you may go to sleep. Your game will then play itself.’

This is attributed to Anderssen, whereas on page 174 of CHESS, 8 January 1955 Steinitz was said to have declared:

‘Let me establish an unassailable knight on K6 and I can go to sleep for the rest of the game.’

(3514)

See also A Knight on K5, K6 or Q6.

Let it be imagined for a moment that C.N. 3589, the ‘Queen trapped’ item, had been altogether different. Supposing that it asserted that the shortest game given there, 1 e4 e6 2 d4 Qf6 3 e5 Qf5 4 Bd3, had occurred in a simultaneous exhibition, with Capablanca as Black, and that, upon resigning at move four, the Cuban had furiously overturned the board, injuring two spectators (one of them seriously) and screaming, ‘Chess is not a game, science or sport, but a loathsome waste of time’. End of item. Incredulous readers would obviously then have asked us to specify our grounds for disseminating such a story and would, no doubt, have expressed shock that, in any case, we had not given chapter and verse unprompted. Where did we believe the display had taken place? From which publication had the game-score been taken? How did we know what Capablanca had shouted? But let it be further assumed that we steadfastly ignored all such enquiries and demands, simply deciding that we had written enough and leaving it to other authors or researchers to pursue the matter if they so wished.

The practical outcome of such an episode would be self-evident: whatever reputation this column may have built up over the years for concern about truth, accuracy and decency would, overnight, be in tatters. Yet although the above Capablanca yarn is, intentionally, an extreme invention, its essence corresponds exactly to what is seen day after day regarding chess history and chess masters: unconfirmed game-scores, uncorroborated facts, unproven anecdotes and unsubstantiated quotations. The only difference is that, unless the circumstances are spectacularly outlandish, few eyebrows are raised.

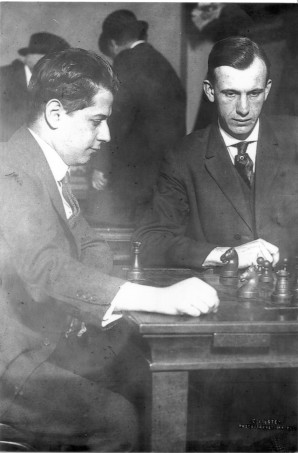

In C.N. 3160 we commented: ‘Proper sources are not optional extras or lace frills; they are required as an integral part of chess writing.’ The remark came back to mind a few days ago when John Donaldson (Berkeley, CA, USA) kindly sent us the following photograph of Capablanca and A.J. Fink:

Mr Donaldson also referred us to a simultaneous game between the two, included in his article at the following webpage: http://chessdryad.com/articles/mi/donaldson.htm

The game, a draw in San Francisco on 11 April 1916, intrigued us,

because after its appearance on page 212 of The Games of José

Raúl Capablanca by R. Caparrós (Yorklyn, 1991) we marked our

copy with a note that at move 35 Capablanca had a forced win (a

forced mate, in fact) by capturing on f7. At the time we wished to

verify the accuracy of the game-score but were unable to ascertain

Caparrós’ source. He specified (see pages 154 and 277) that it was

one of many games gleaned from ‘local papers and chess magazines’.

That was all: ‘local papers and chess magazines’. No titles or

dates, let alone page numbers. Other categories of sources vaguely

lumped together by Caparrós were ‘Cuban papers’, ‘Cleveland

papers’, ‘private research’ and ‘untraceable source’.

John Donaldson has been searching various likely sources for the game, without success so far, which means that it is still not known whether Capablanca really missed such an obvious win at move 35. The score as presented by Caparrós runs: 1 d4 d5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 c4 e6 4 Nc3 Be7 5 Bf4 Nf6 6 e3 a6 7 Rc1 O-O 8 Bd3 dxc4 9 Bxc4 Na5 10 Bd3 c5 11 dxc5 Bxc5 12 O-O Nc6 13 Ne4 Be7 14 Qc2 Nb4 15 Nxf6+ gxf6 16 Bxh7+ Kg7 17 Qb1 f5 18 Rfd1 Qe8 19 Bxf5 exf5 20 Nd4 Nd5 21 Nxf5+ Bxf5 22 Qxf5 Nxf4 23 Qxf4 Rh8 24 Rc7 Rd8 25 Rxd8 Qxd8 26 Qg4+ Bg5 27 Rxb7 Rh4 28 Qf3 Be7 29 b3 Rh6 30 g3 Qd6 31 h4 Rf6 32 Qg4+ Rg6 33 Qf5 Qd1+ 34 Kg2 Bxh4 35 Qf3 Qxf3+ 36 Kxf3 Bf6 37 Rb6 Bc3 38 Rxg6+ Kxg6 39 Kg4 Kf6 40 f4 Ke6 41 e4 f6 42 Kf3 a5 43 Ke3 Be1 44 g4 Kd6 45 g5 fxg5 46 fxg5 Ke5 47 g6 Drawn. It will be noted that Mr Donaldson’s article gave White’s 33rd move as Qf4, not Qf5. In either case this would mean that Capablanca overlooked a forced mate, but a suggestion now from Richard Forster (Zurich), supported by Mr Donaldson, is that it is far more likely that Capablanca played a third move, 33 Qe4, after which the rest of the game makes sense and no mating line was missed. Whether any error in the moves was a mistranscription by Caparrós has yet to be discovered.

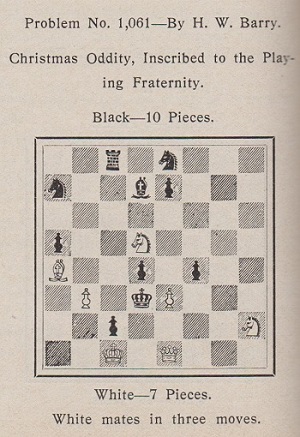

Adolf Jay Fink (1890-1956) was best known as a problemist, and it may be wondered whether, in the photograph above, Capablanca was studying one of his compositions. Page 53 of Chess Pie (1922) stated, ‘Fink is a strong chessplayer and has drawn twice with Capablanca in simultaneous exhibitions’, but it seems that the other game has not been traced.

Caparrós’ book on Capablanca can be relied upon for nothing, and below is another score from the same page as the Fink game: 1 f4 d5 2 e3 e6 3 Nf3 Nf6 4 b3 c5 5 Bb2 Nc6 6 Bb5 Nd7 7 O-O f6 8 d3 Qc7 9 Nbd2 a6 10 Bxc6 bxc6 11 Nh4 g6 12 e4 Rg8 13 f5 e5 14 fxg6 hxg6 15 Nxg6 Rxg6 16 Qh5 Kf7 17 Nf3 Kg7 18 Nh4 Rg5 19 Nf5+ Kg8 20 Qe8 Bb7 21 Qe6+ Kh8 22 Rf3 Rh5 23 Rg3 Rh6 24 Qf7 Resigns. This, Caparrós stated, occurred between Capablanca and A.M. Isaacson, in New York, 1915, and it has been unquestioningly copied by various databases, but if the score is correct Capablanca missed 24 Qg8 mate. Did he really? It seems obvious that Black played 23...Bh6 rather than 23...Rh6 but, again, Caparrós gave no proper source for the game, merely indicating (see pages 154 and 278) ‘Pittsburgh papers’. A ‘revised 2nd edition’, published by Chess Digest, Texas in 1994, was also dire.

Scarcely better is a would-be reference book, Chess Results, 1747-1900 by G. Di Felice (Jefferson, 2004). Much can easily be written about its factual errors, but a more serious general defect is that the reader is offered no clue as to where a given crosstable or match chart came from. Incredibly, the ‘Sources’ amount to a single page (page 209), i.e. a bare list of books and other publications, such as ‘Chess’ and ‘Quebec Morning Chronicle’. No particulars are provided, and no link is made between such publications and any individual table in the book. In short, the ‘Sources’ page is worthless and so, in consequence, is much of the book for anyone wishing to check the information it provides.

Many books deign to give no sources at all – even of the nebulous, dateless ‘Chess’ or ‘private research’ variety – and show disrespect for masters by serving up dubious anecdotes and quotes. An especially awful example, discussed in C.N. 3112, is 2010 Chess Oddities by A. Dunne (Davenport, 2003), and now we see that the same author intends to bring out a volume entitled Great Chess Books of the Twentieth Century in English. What next? A twenty-first century edition of H.J.R. Murray’s A History of Chess, revised and updated by Eric Schiller?

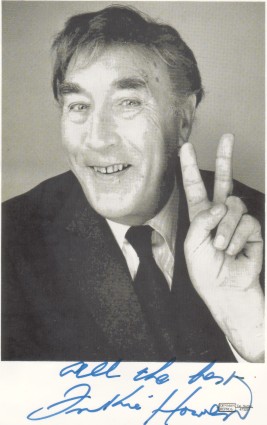

In case anyone considers that a call for sources in chess books is somehow donnish, pedantic or otherwise excessive, we propose another comparison of the kind offered in C.N. 2708 (see page 334 of A Chess Omnibus). In 2004 the British comedian and actor Frankie Howerd (1917-92) was the subject of a popular biography by Graham McCann, published in hardback by Fourth Estate, London at £18.99. It comprises 369 pages, with 41 photographs, but the narrative itself ends at page 289. Then come: a) a detailed 39-page ‘List of Performances’ (stage, radio, television, cinema, recordings) with precise dates and cast-lists, b) a 27-page ‘Notes’ section (giving exact citations for quotations and other references in the body of the book), c) a three-page bibliography and d) a nine-page general index. In short, the reader is treated with respect and informed of the exact provenance of the information presented about Howerd’s life and career. In many fields such ‘academic’ standards are commonplace, but in chess they are rare and have to be fought for, every inch of the way.

(3594)

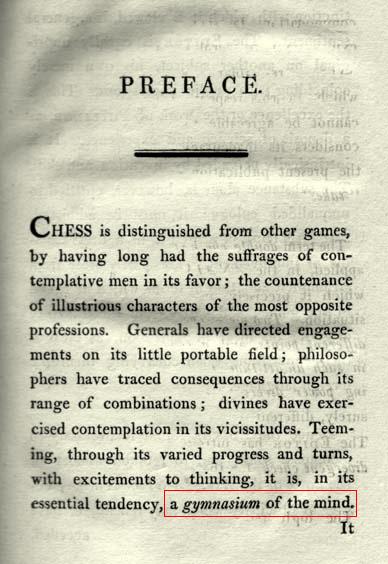

C.N. 2987 mentioned that a BBC television programme had attributed to Lenin the remark about chess being the gymnasium of the mind, which in fact dates back to Studies of Chess by P. Pratt (London, 1803). For the record we reproduce here the exact text in that book (page iii):

‘Chess is distinguished from other games, by having long had the suffrages of contemplative men in its favor; the countenance of illustrious characters of the most opposite professions. Generals have directed engagements on its little portable field; philosophers have traced consequences through its range of combinations; divines have exercised contemplation in its vicissitudes. Teeming, through its varied progress and turns, with excitements to thinking, it is, in its essential tendency, a gymnasium of the mind.’

On a number of webpages which pluck ‘chess quotes’ out of thin air and list them without any attributions or qualms the ‘gymnasium of the mind’ phrase is ascribed to Blaise Pascal, although we have yet to see an (alleged) original French version of the remark. That may be because according to the Robert dictionary the word gymnase is not recorded in the French language (with the meaning in question) until 1704, whereas Pascal died in 1662. Moreover, Georges Renaud wrote on page 28 of issue 17 of Les Cahiers de l’Echiquier Français (1928) that there was ‘aucune allusion directe aux échecs dans l’oeuvre de Pascal ’.

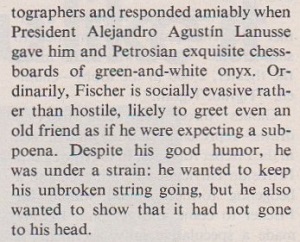

All kinds of chess remarks are put into the mouths or pens of everyone from Confucius to Kasparov, but there is one that is unlikely to be found listed on those awful ‘chess quotes’ webpages: an observation by Fischer during the fourth press conference in Sveti Stefan on 21 September 1992, as transcribed on page 117 of No Regrets by Y. Seirawan and G. Stefanović (Seattle, 1992):

‘– Are you more interested in women now than you were in 1972, when you said that chess was much more interesting?

Fischer: A lot of these quotes about me are not correct. Quotes of things I said.’

That documented remark of Fischer’s will, of course, be ignored, whereas unsubstantiated or invented quotes will continue to be propagated ad infinitum.

(3626)

As regards the gymnasium quote, a similar, though less familiar, phrase is recorded on page 145 of Comparative Chess by F.J. Marshall (Philadelphia, 1932):

‘Chess is the athletics of the mind, as Prof. Rice was often heard to say.’

(3626)

The heading to page 88 of Chess An Illustrated History by Raymond Keene (London, 1990):

Bernard Levin was a British writer of the supposedly highbrow variety who, like Arthur Koestler and George Steiner before him (see C.N.s 3256 and 3266), occasionally wrote about chess, on autopilot, if a world championship match was in the news. We recently came across a piece by Levin on pages 171-174 of his anthology All Things Considered (London, 1988). Endowed with the catchpenny title ‘The mating game’, it had already somehow received space in the (London) Times, of 9 November 1987, and was the usual dollop of flash-fried offal served by writers who think that a readable overview of chess can be rustled up for the populace by cribbing tittle-tattle from books like Cockburn’s Idle Passion, Fine’s The Psychology of the Chess Player and Schonberg’s Grandmasters of Chess.

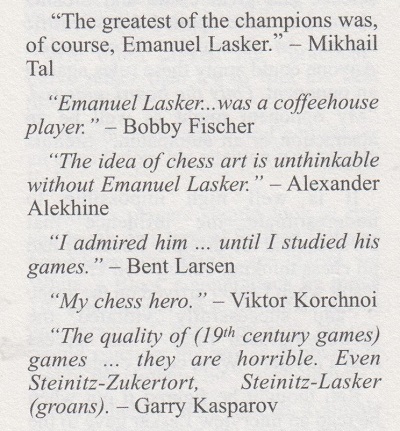

A prime objective of such output is to deride chess masters (particularly dead ones), and we quote just one passage from Levin’s ‘The mating game’, i.e. the sum total, ‘all things considered’, of what he had to impart about Emanuel Lasker:

‘Lasker, for instance, tried a variety of business schemes, all of which came to nothing (or to bankruptcy), his record being a pigeon-breeding establishment which failed, not surprisingly, because he tried to mate two male pigeons to get the thing properly started.’

The pigeon yarn is often seen, and in C.N. 1048, an examination of The Kings of Chess by W. Hartston (London, 1985), we commented:

‘The Lasker chapter captures the German champion vividly but still cannot resist churning out vague claims (page 81) about his “being swindled by all who did business with him”, trying to mate two male pigeons, despising imitation flowers, etc. (We might point out that Dus-Chotimirsky – Lasker & His Contemporaries, issue 4, page 140 – quotes Lasker as saying that he could not stand real flowers, but we have no wish to launch a debate on his floral tastes ...)’

When the unsubstantiated pigeon story about Lasker started circulating is difficult to say, but it was a staple feature of chapter 22 of Emanuel Lasker Biographie eines Schachweltmeisters by J. Hannak (Berlin-Frohnau, 1952) and chapter 21 of the English version, Emanuel Lasker The Life of a Chess Master (London, 1959). Since many parts of Hannak’s book read like a novelette, it may reasonably be felt that something more substantial is required before Lasker is mocked.

If any outsider is to cast an eye over chess and chessplayers, how we wish that it could be a truly outstanding writer with the finest insight, such as Alan Bennett.

(3662)

C.N. 11127 quoted the following from page 3 of the Chess Amateur, October 1925:

‘To the folly of the lay journalist writing about chess there is no end.’

V. Ragozin claimed that it was advantageous to have Black rather than White – or did he? We have frequently stressed the need for quotes and other information to be accompanied by precise sources, since the reader is entitled to know the provenance of all material presented. As an example of the kind of misunderstanding which may otherwise occur, here are some remarks by Almeida Soares of Brazil on page 56 of CHESS, December 1949:

‘It is ingrained in us that the Whites, playing first, have an advantage. It was no small surprise to me therefore when I read an article in the magazine Le Monde des Echecs by V. Ragozin, the master who trained Botvinnik, the world’s champion, asserting that the advantage of the opening move lies with the player of the black pieces.’

Anyone wishing to verify this matter is fortunate that Soares at least provided what might be termed a ‘semi-source’ and that the French magazine named, though not dated, by him ran for less than a year. There is thus no difficulty in tracing the article in question: ‘La défaite des joueurs d’échecs anglais’ on pages 228-229 of the July-August 1946 issue. But this reveals that Ragozin wrote something altogether different:

‘Les joueurs contemporains estiment que la victoire la plus honorable est celle remportée en jouant avec les Noirs.’ [‘Contemporary players consider that the most honorable victories are those achieved with Black.’]

Viacheslav Ragozin

(3771)

Many writers feel that chess is well served by their mentioning, however vaguely, the enthusiasm for the game (allegedly) shown by celebrities. Such name-dropping may not be founded on published evidence, the meretricious preference being to list as ‘a chessplaying celebrity’ almost any recognizable name which has appeared in the same sentence as the word chess. A chapter entitled ‘They all play(ed) chess’ on pages 251-268 of Chess for Success by Maurice Ashley (New York, 2005) has the longest such list we have seen in a book, featuring everyone and anyone from Adolf Hitler to Enid Blyton. Ashley expresses his ‘special thanks to Bill Wall for his comprehensive list’ and, of course, provides not a scrap of substantiation for any name put forward.

(3958)

Our recommendation in C.N. 3514 was ‘to dispense with any publication or website which offers “chess quotes” without indicating where and when the statements in question were purportedly made’. From our recent reading, nothing in this field compares with the quotes section (pages 155-169) of Check Mate and Word Games by Carlos Tortoza (Denver, 2006). A sample follows:

Sourceless quote-dumps are bad enough, but who would bring out a book with such an unmistakable (Germanic) reek of computer translation? A child, perhaps? The back cover provides some biographical information about Carlos Tortoza, who is Brazilian:

‘He is a psychologist and economist, with a postgraduate degree in economic projects, specializing in psychoanalysis. He is an academic professor of psychology, philosophy, sociology and economic business administration.’

(4716)

Anyone can sling together lists of sourceless quotes about chess, and many lackadaisical webpages do so. However, Mark N. Taylor (Mt Barry, GA, USA) points out a rare exception, PoemHunter.com, and observes:

‘The selection is small and almost entirely drawn from non-chess publications. Nonetheless, it is gratifying to see that a webmaster can do it right.’

(5093)

The start and the conclusion of C.N. 5280:

There has been a recent spate of ‘prose’ chess books woefully lacking in rigour, and the worst may well be Treasure Chess by Bruce Pandolfini (New York, 2007). ‘Trivia, Quotes, Puzzles, and Lore from the World’s Oldest Game [sic]’ is the subtitle, while the acknowledgements page begins with similar insouciance:

‘For a book like Treasure Chess it is not so easy to cite where all my references and impressions came from, so I’m not even going to try.’

Since much of the information provided is false, supplying citations would indeed have been awkward ...

... The imprint page of Treasure Chess warns, ‘No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means’, and anyone who cares about accuracy and truth will unhesitatingly comply.

Fred Shapiro (New Haven, CT, USA), the editor of The Yale Book of Quotations, notifies us that for the book’s next edition he would welcome suggestions for the ten most famous chess quotations of all time.

Readers’ contributions will be appreciated. The only condition, of course, is that a rock-solid source must be available in each case. As indicated in C.N. 3514, there can be no interest in unreferenced ‘chess quotes’ of the kind cushily listed by so many publications and websites.

(5520)

The result was the feature article The Most Famous Chess Quotations.

The weakest field in all chess literature is surely quotes. Innumerable carefree outlets cite alleged remarks, without any attempt to supply even a vague source, let alone proof of authenticity. Whole books have been written along such lines, and no good volume of chess quotes has yet appeared in any language. Unimpressive websites may have a source-free ‘quote of the day’ or, even, long lists of purported remarks by luminaries, and others, all without substantiation. Writers fall back on know-nothing/tell-nothing introductions such as ‘Botvinnik is quoted as saying ...’, ‘As Tartakower once wrote ...’, ‘I read somewhere that Steinitz claimed ...’, ‘Wasn’t it Alekhine who remarked ...?’, ‘I’ve heard that Tarrasch often observed ...’, ‘Sources I’ve seen say that Lasker stated ...’ and ‘It is widely reported that Fischer said ...’ In short, the whole domain, reflecting an excess of name-dropping and a deficit of rigour, is a shambles.

(5825)

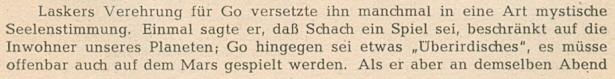

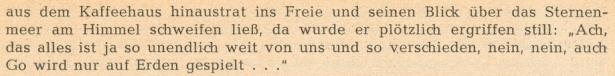

From page 306 of The Book of Games by Jack Botermans (New York, 2008), and yet another instance of what might be termed oncery, oncing or oncitis:

Similar, though not identical, sentiments were attributed to Lasker on pages 253-254 of a book which needs to be treated circumspectly: Emanuel Lasker Biographie eines Schachweltmeisters by J. Hannak (Berlin-Frohnau, 1952):

The passage was quoted from Hannak’s book on page 384 of Emanuel Lasker: Denker Weltenbürger Schachweltmeister edited by R. Forster, S. Hansen and M. Negele (Berlin, 2009). It did not, though, appear in the relevant section (on page 265) of the English-language edition of Hannak’s book (London, 1959).

Can further details about the quote be found?

(6817)

From Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore):

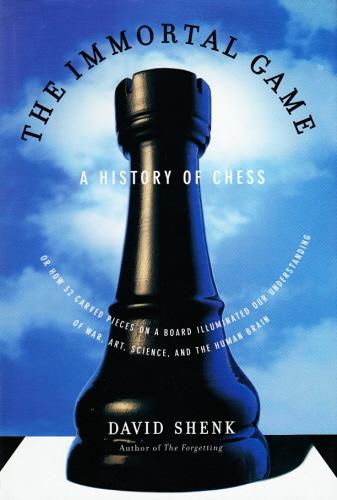

‘It appears that one of the most “popular” books using chess history as an overall theme is David Shenk’s The Immortal Game (New York, 2006), subtitled “A History of Chess or How 32 Carved Pieces on a Board Illuminated Our Understanding of War, Art, Science, and the Human Brain”. I find it exceedingly disappointing in terms of sourcing, as it strikes me as very amateurish, if not downright naïve.

What to make of the dozens of references to notoriously inaccurate websites? The endnotes on pages 287-313 indicate virtually no use of primary sources (the meat of any serious book dealing with history in general) or of reliable secondary sources.

Below are just a few examples of the kind of “authorities” upon whom the text relies (the numbers in brackets refer to the pages where the corresponding endnotes appear):

- Page xvi (287-288): the alleged game between Einstein and Oppenheimer is given as a certainty despite the lack of trustworthy sources (as documented in C.N.s 3533, 3667, 3691 and 4133). An endnote offers no source for the game, merely sending the reader to “an animated version” at a highly undependable website, chessgames.com;

- Page 7 (288): a list of historical religious leaders who attempted to ban chess is sourced to a web article by Bill Wall;

- Page 23 (294): for details about Adolf Anderssen’s life the reader is referred to another online article by Bill Wall;

- Page 35 (294): for a problem by a ninth-century Arab composer we are again sent to a Bill Wall page;

- Page 92 (300): Bill Wall is once more the source for names of members of the eighteenth-century American intellectual elite who played chess;

- Pages 114-115 (303): Samuel Rosenthal’s own words on chess and war are cited, but the endnote credit is incomplete at best: “From obituary in a French newspaper, September 1902”;

- Page 115 (303): we are referred to a logicalchess.com link to prove that Rosenthal “won the first French chess championship in 1880”; the same pages state that Rosenthal “managed to beat legendary players” and that “chessgames.com database has all actual games”;

- Page 143 (305): a number of chessplayers allegedly suffering from mental illness are listed; sourcing includes links to the webpages of Bill Wall and chessgames.com;

- Page 149 (305): Charles Krauthammer is cited as a “writer, psychiatrist, and serious chessplayer”. In his chess-related writings he has often recycled clichés related to the game’s history (see, for instance, his Time essay and the discussion in your Steinitz versus God article);

- Page 164 (306): the statement “When the Germans captured France in 1940, Alekhine agreed to write about and play chess on their behalf in order to protect his family’s assets” is sourced to a Bill Wall webpage;

- Page 168 (306): details of the USA v USSR 1945 radio match are sourced to another Bill Wall webpage;

- Page 173 (307): the statement that “After a tournament in Yugoslavia in 1970, he [Fischer] was able to recall instantly every move from each of his 22 games – totaling more than a thousand” is credited to a Fischer profile on a www.poster-chess.com webpage;

- Page 174 (307): a statement by Henry Kissinger (“I told Fischer to get his butt over to Iceland”) is credited to Rene Chun. In the same paragraph, the author notes that “It is, however, still a matter of dispute whether Fischer actually took Kissinger’s call”;

- Page 175 (307): details of Spassky’s chess career are attributed to a Wikipedia entry;

- Page 226 (312): Kieseritzky’s death details are sourced to a Bill Wall page.

Other deeply unimpressive sources include websites like chessville.com, goddesschess.com and worldchessnetwork.com, as well as individuals like Larry Parr and Andrew Soltis.’

(8110)

For some our own comments about Bill Wall, see A Question of Credibility.

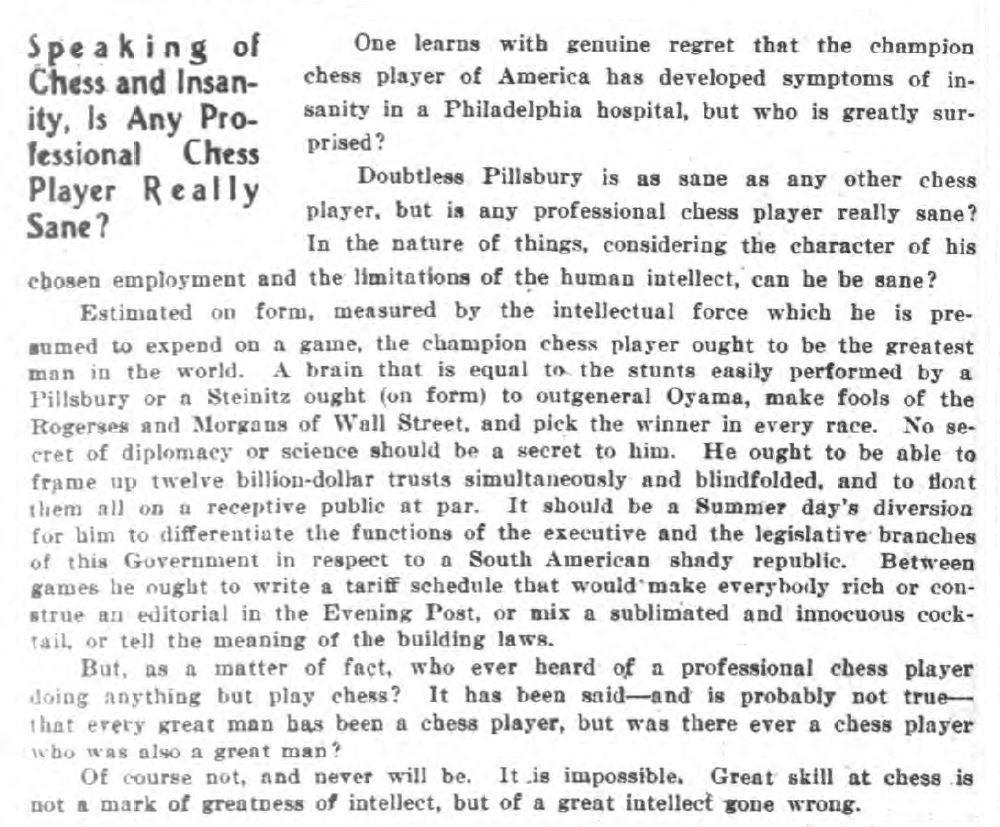

‘Great skill at chess is not a mark of greatness of intellect, but of a great intellect gone wrong.’

That remark is often quoted with inaccurate and incomplete information. For example, the following comes from page 1 of Chess to Enjoy by A. Soltis (New York, 1978):

Churlish as it may seem to pass strictures upon Soltis when he gives a source of sorts, no date is attached to the New York Clipper, and the reference to Pillsbury in March 1906 is wrong. As shown in Pillsbury’s Torment, the master’s hospitalization in Philadelphia was in 1905.

From page 237 of Treasure Chess by B. Pandolfini (New York, 2007):

‘New York Morning Telegraph (late 1800s)’ may not be much of a source, but by Pandolfini’s standards it is chapter and verse. At first glance, moreover, it seems to improve, however vaguely, on what was on page 7 of Chess Quotations from the Masters by Henry Hunvald (Mount Vernon, 1972):

The text appeared on page 4 of the New York Sunday Telegraph, 2 April 1905:

The article/editorial was quoted on pages 267-268 of Lasker’s Chess Magazine, April 1905, and the final part was reproduced by Eliot Hearst on page 255 of the September 1961 Chess Life. Both provided the exact date of the newspaper, identifying it by its more general title, the New York Morning Telegraph.

(8359)

Regarding the trend towards citing inferior websites in bibliographies, the most dismal case that we have seen is the ‘Sources Used’ list on pages 161-162 of Anand-Gelfand Moscow 2012 by Dániel Lovas (Kecskemét, undated).

The ‘Sources of further quotations, commentaries’ section includes ‘Susan Polgar Chess Daily News and Information – susanpolgar.blogspot.com’ and, even, ‘Twitter – twitter.com’.

(8826)

If modern games were to be presented as they often were a century or two ago, the reader would see headings such as ‘A brilliancy by Mr Carlsen a few years back’, ‘Played in Germany’, ‘Another recent skirmish produced by Mr Anand against Mr ****** on the Continent’ and ‘Mr K*****k won this finely contested game against a strong opponent some time since’. In short, the public record of chess games, devoid of exact places, dates and names, would be desolate.

Nowadays, of course, most games are published with basic factual information as a matter of routine, but is there any valid reason for quotes to be handled quite differently? If a book, magazine or website wishes to notify its readership that A stated B, why omit particulars about the context (e.g. the place and date) of the observation? Were the answer to be that the book, magazine or website does not have the information, why is it disseminating the quote at all?

Chess literature and lore are a bog of ignorance, doubt and error regarding who said/wrote what and when. To give just one example of a book which makes no attempt to guide or inform the reader, below are the last two names in the chapter ‘On Players’ on pages 127-133 of The Chess Scene by David Levy and Stewart Reuben (London, 1974):

Not a source in sight.

We can offer at least some information about the most significant of these quotes, Kmoch on Fischer. Below is the first paragraph of an article, ‘The Selfmate of Bobby Fischer’, by Eliot Hearst on pages 166 and 183 of Chess Life, July 1964:

‘The “selfmate” theme of the chess problemist –a position in which one player compels his opponent to checkmate him – symbolizes suicide on the chess board. The chessplayer who prefers tournament competition to problem solving usually finds this kind of composition more amusing than artistic, and his amusement is probably due to the utter impracticality of the situation; tournament players are known to maintain a firm belief in the dictum that it is better to give checkmate than to receive it. Very few US chessplayers, however, are amused by Bobby Fischer’s equally impractical and unrealistic decision not to compete in the world championship qualification series and thus to surrender all of his rights to a world title match until at least 1969. The same mind that has produced some of the best chess combinations and positional gems of the past decade has also proved responsible for one of the most disappointing moments in American chess. As veteran chess analyst Hans Kmoch, who has observed and written about the games of world champions from Lasker to Petrosian, said in New York recently: “Finally the USA produces its greatest chess genius and he turns out to be just a stubborn boy.”’

Trustworthy writers naturally resist the temptation to repeat unverified material, and especially in a domain such as chess lore which is notoriously infested with imprecision and uncertainty.

From page 220 of Total Chess by David Spanier (London, 1984):

‘I can’t resist repeating that old anecdote about the man going into the café [the Café de la Régence] to watch Voltaire and Rousseau play at chess. Mere scribblers, those two, sniffs an acquaintance. “True, but today they play with Philidor!”’

Information is sought about the tale, which had appeared on page 92 of The World of Chess by A. Saidy and N. Lessing (New York, 1974):

(8866)

A number of feature articles have also discussed the issue of sources. Some extracts:

From Historical Havoc:

Even works with certain scholastic pretensions tend to lack corroborative footnotes and bibliographical references. Sources are considered to be frills; the writings of Andrew Soltis, for instance, optimistically expect the reader to take almost everything on trust. Primary sources (notably old magazines and tournament books) are commonly disregarded, but so too are in-print books of quality. An author’s failure to consult proper, standard sources may be revealed by details which are, of themselves, minor. On pages 124-126 of Modern Chess Miniatures Neil McDonald gave the game Capablanca v Chase, New York, 1922 and wrote: ‘History has not been kind to Mr Chase. We know almost nothing about him, not even his initials.’ Note that coercive ‘we’, as if no reader could possibly have more information than Mr McDonald. Heaven forbid that the latter should have taken the trouble to inspect the American Chess Bulletin of the time, but even The Unknown Capablanca, a top-notch Category B work, would have given him the allegedly elusive initial. For some reason, David Hooper and Dale Brandreth’s book, originally published by Batsford in 1975, has frequently been ignored, even by that publisher’s own chess adviser, Raymond Keene. On page 28 of the July 1988 CHESS he referred to a game ‘Capablanca v Ribeiras 1935’ and indicated that he did not know the occasion on which it was played. All necessary particulars, including the correct spelling Ribera, are on pages 97-98 of The Unknown Capablanca.

From Wanted:

A particularly chaotic field concerns who said/wrote what. Many authors cannot resist slipping in a casual ‘As Tarrasch remarked …’ or ‘Remember Tartakower’s aphorism …’, without any perceptible idea of where the master might actually have made the comment in question. Our library contains a handful of compilations of chess quotes, but in truth none of them has any real value. Seldom are exact sources given, and an epigram may be attributed to Lasker in one book but to Steinitz in another. It will be a brave author who tackles such a project, but sooner or later the work will need to be done by somebody. At the very least, a significant contribution could be made by authors who were to compile quotations on a particular theme (e.g. technical chess advice) or the sayings of an individual master/authority. That, at least, would be a start.

From Steinitz v von Bardeleben:

‘But Bardeleben didn’t resign. He stared at 25 Rxh7+, shot a glance at Steinitz, and without a word got up from his chair and left the room. He didn’t come back. Tournament officials searched and found Bardeleben pacing angrily. No, he wouldn’t return to the board so that outrageous Austrian could mate him.

So Steinitz had to wait for Bardeleben’s time to run out before he could claim the win. Not only claim it – he demonstrated the final ten-move mate and the crowd cheered.’

The author of that apparent exercise in imagination, simultaneously fertile and sterile, is A. Soltis (The Great Chess Tournaments and Their Stories, pages 67-68). He then moved on to discuss ‘John’ Henry Blackburne, but we shall move on to chess history, with a straightforward question: what really happened at the conclusion of Steinitz v von Bardeleben, Hastings, 1895? All kinds of assertions have been made; for instance, page 110 of Kasparov’s first Predecessors book stated (without specifying any source) that von Bardeleben ‘suddenly stood up and silently walked out of the room (later he sent a note by special delivery tendering his resignation)’.

From Reuben Fine, Chess and Psychology:

A brief digest from the section on Alekhine (‘the sadist of the chess world’) on pages 52-55 of The Psychology of the Chess Player by Reuben Fine:

‘… we are told that his mother taught him the game at an early age.’

‘His father is reported to have lost two million rubles at Monte Carlo.’

‘Alekhine was reputed to have become a member of the Communist party.’

‘A report was broadcast during the war that Alekhine was confined to a sanatorium in Vichy, France for a while; but I have been unable to obtain any details.’

‘It was said that he became impotent early in life.’

From ‘Fun’:

From page 79 of the 2002 edition of Chess Lists by A. Soltis:

‘The most tragic case belongs to Paulino Frydman, a little-known Polish master who was invited to the Bad Podĕbrady, Czechoslovakia international of July 1936. Surrounded by several world-class players – including Alexander Alekhine, Salo Flohr, Erich Eliskases and Gideon Stahlberg – he astounded them by allowing only a draw in his first seven games. But two rounds later, with a score of 8-1, he lost to Alekhine and suffered a nervous breakdown. Frydman scored only one and a half points in his last eight games and finished as an also-ran. He was never again a significant figure in chess.’

There were similar words from Sourceless Soltis on page 81 of the 1984 edition of his book. In reality, though, from the field of 18 masters Frydman finished equal sixth with Eliskases, and his significant over-the-board achievements in subsequent years are a matter of public record. As regards the ‘nervous breakdown’ part of the story, it may be wondered if Soltis had any solid information of his own or was merely copying from Wolfgang Heidenfeld’s entry on the Podĕbrady tournament in The Encyclopedia of Chess by Harry Golombek (London, 1977).

From Kasparov and his Predecessors:

The absence of, even, a basic bibliography is shocking in a work which claims to be ‘Garry Kasparov’s long-awaited definitive history of the World Chess Championship’, and a lackadaisical attitude to basic academic standards and historical facts pervades the book. ...

Historical matters are even asserted confidently when the principals have stated something quite different. Kasparov’s claim (on page 43) that an 1883 meeting between Steinitz and Morphy was at the latter’s home, as opposed to merely in the street, is contradicted by Steinitz’s own account in the New York Tribune of 22 March 1883 (see page 309 of David Lawson’s book on Morphy). Kasparov is also under the misapprehension that there was only one meeting between Steinitz and Morphy (if any at all – given that he uses the phrase ‘Legend has it that …’). A similar case concerns Olga Capablanca’s own statement (which we made public some years ago) that she was outside Mount Sinai Hospital when her husband died. On page 339 Kasparov invents the Nice Story that Capa died ‘in the arms of his wife Olga’. The book is also wrong (page 331) to claim that she was already his wife in 1936. The famous ‘I never won against a healthy player’ quip has been attributed to many old-timers (most notably Burn) and is documented from, at least, 1949 onwards (see pages 322-323 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves); it says little for Kasparov’s knowledge of chess lore that page 292 of his book calls it ‘a witty remark by Larsen’. [Subsequently, C.N. 4189 quoted a 1936 attribution of the comment to Bird.]A stew-pot which has evidently involved a number of cooks (we nearly wrote scullions) results in the lack of a clear authorial voice. It is impossible to know who has cooked, or poached, what. Quotes bombard the reader out of the blue (without, in most cases, even the approximate year of origin, as a guide to the reader). We are asked to make do with being told that X said, or wrote, Y at some unspecified time simply because a self-proclaimed ‘definitive’ book tells us so. That may suffice for Matthew Sadler but is unlikely to appeal to those who care about decent standards of historical truth and accuracy.

The lack of sources has itself hampered textual precision and translation. Even famous passages have been unnecessarily translated and re-translated ...

With this carefree approach to the public record, the book frequently creates its own confusion. Page 239, for instance, has Alekhine’s well-known tribute to Capablanca (from pages 105-106 of the April 1956 BCM, although that is naturally not specified) in which he wrote as follows regarding the Cuban’s prowess in 1914: ‘Enough to say that he gave all the St Petersburg masters the odds of 5-1 in quick games – and won!’ In Kasparov’s book the quotation comes in an alternative version: ‘In blitz games he gave all the St Petersburg players odds of five minutes [emphasis added here] to one – and he won’. Why? Since no source of any kind is given, it is impossible for the reader to know. On the subject of information contained in quotations, we also wonder about the identity of the ‘Saburov’ who is described on page 349 as ‘elderly’. (P.P. Saburov was aged 34 at the time, i.e. in 1914.)

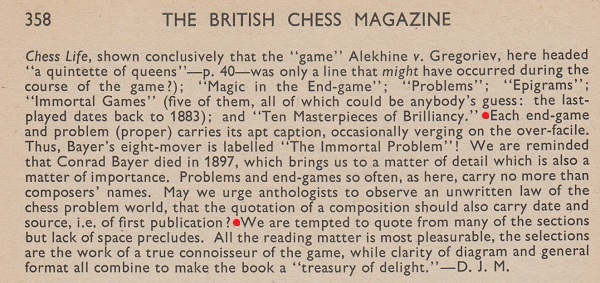

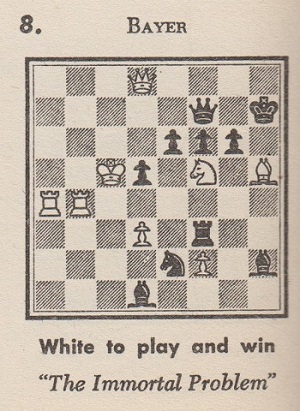

From Chess Morganisms:

‘We regret we find it difficult to work up any interest in scores of games, or bits of scores, which carry no clue of any kind as to source. Please give the who’s who, where’s where, and when’s when.’

D.J. Morgan on page 101 of the April 1958 BCM.

From C.N. 2664:

As ever, the call is for solid information. This is not the place for observations along the lines of ‘If memory serves, my understanding has always been that I read somewhere that maybe there was talk once of a rumour that someone perhaps mentioned an oral tradition that it may possibly have been claimed that it was widely believed that …’.

A further remark, in C.N. 4474:

Concerning the final paragraph, other precursors of nescience include, ‘My best guess would be that ...’, ‘If I had to guess I would say that ...’, ‘I think I read or heard somewhere that ...’ and ‘The last I heard was that ...’

Other phrases not recommended:

‘I have an idea that ...’; ‘It’s a fair bet that ...’; ‘The way I heard it is that ...’

A recommendation prompted by, inter alia, the ‘Fair & Square’ feature in New in Chess:

Give the source of a quote if it is known. If it is not known, do not give the quote.

(8651)

From page 75 of the 5/2014 New in Chess, in the lamentable ‘Fair & Square’ column:

What is known about this alleged remark of Capablanca’s, beyond its availability on a number of websites which document nothing?

(8768)

Two books on the Budapest Defence show contrasting ways of handling a bibliography. The Budapest Fajarowicz by Lev Gutman (London, 2004) has a full page (page 287) of references to books and articles, but with many misprints (including an occurrence of ‘Fajarowitz’). The book section of the bibliography on page 5 of The Budapest Gambit by Timothy Taylor (London, 2009) lists just five works, three of them general (by Alekhine, Horowitz and Kasparov).

The bibliography on pages 5-6 of Play the Ponziani by Dave Taylor and Keith Hayward (London, 2009) includes many books, but virtually all of them are recent. Magazine articles of the kind catalogued in C.N. 7941 are ignored.

The more disorganized a book is, the greater the need for a bibliography, general index and proper sourcing, but none of these can be found in Mannheim 1914 and the Interned Russians by A.J. Gillam (Nottingham, 2014), a 525-page hardback which sorely needed a general editor and an English-language editor.

Another book by Timothy Taylor, True Combat Chess (London, 2009), has this entry in the bibliography on page 5:

To avoid the risk of such mishaps, one possibility is the approach adopted by Efstratios Grivas on page 5 of Beating the Fianchetto Defences (London, 2006):

(8834)

Double sourcelessness.

Ten chapters in the book mentioned in C.N. 8852, Playing Computer Chess by Al Lawrence and Lev Alburt (New York, 1998), start with a chess-related quote. All appear without the slightest source.

Eight of the ten can be found in Chess Quotations from the Masters by H. Hunvald (Mount Vernon, 1972). All appear without the slightest source.

(8857)

‘X’ is an imaginary prolific chess author (‘book-doer’ may be a better term) who decides to bring out an anthology of miniature games won by the world chess champions. A day or two’s casual clicking in his database suffices for the requisite ‘research material’ to be assembled. The book is quickly completed and, no less quickly, warmly welcomed by the review-doers.

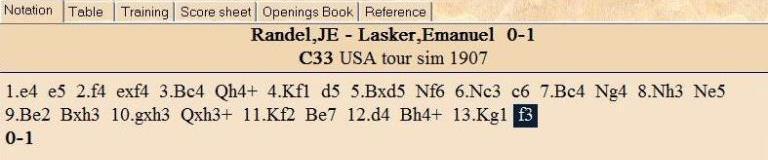

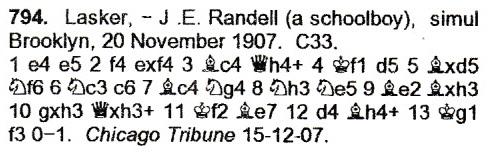

One of the games in the compendium is a 13-move victory by Emanuel Lasker against J.E. Randel, courtesy of (i.e. unquestioningly lifted from) Mega Database 2012:

At best, ‘X’ contributes to chess knowledge by mentioning that Black missed a mate in five at move 11.

A more conscientious writer might wonder whether nothing more precise than ‘USA tour sim 1907’ is available, and whether the unusual spelling ‘Randel’ is correct. If FatBase 2000 is consulted, an exact place, New York, will be found, as well as an unwelcome complication: the loser was identified there as ‘J. Randall’.

‘X’ has long since exhausted his interest in the matter, but others may contemplate the drastic step of ascertaining what has appeared in print, whether in primary or secondary sources.

Page 61 of Emanuel Lasker Volume 3 by K. Whyld (Nottingham, 1976) named White as ‘J.E. Randall’, and two sources for the game were mentioned, without dates: the Chicago Sunday Tribune and the Chess Amateur.

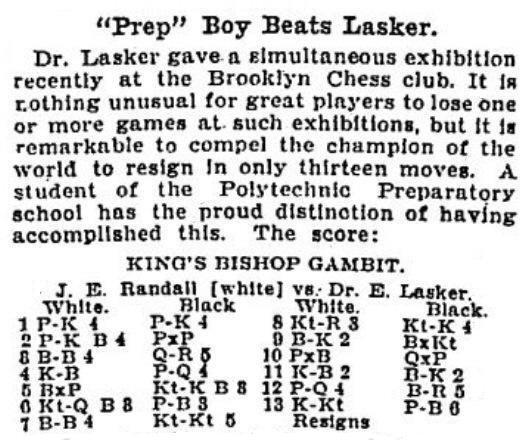

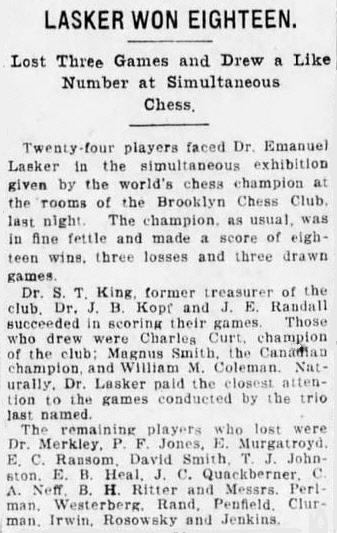

Below is what was published on page 4 III (Sporting section) of the Chicago Sunday Tribune, 15 December 1907:

Something is clearly awry here, because the introductory text says that Lasker lost, whereas the game-score specifies that he won.

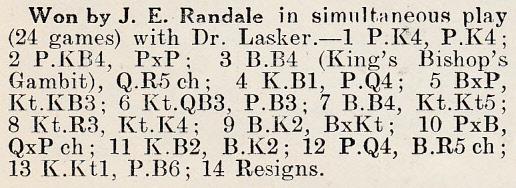

The Chess Amateur also has a surprise to offer. The Lasker game was one of eight bunched together, with scant information, in the ‘Brilliants and Miniatures’ column on page 271 of the June 1908 issue:

So now there is not only another name, ‘J.E. Randale’, but also the statement that he won the game.

The researcher hopeful of discovering the game-score in the American Chess Bulletin will be disappointed, although a vague passage by Thomas J. Johnston may be found hidden away on page 251 of the December 1908 issue:

‘When the world’s champion gave his simultaneous exhibition in Brooklyn, last year, in which the writer’s Caissic scalp hung at his belt with some 20 others, he offered a King’s Gambit to a young student, not a strong player, who defended conventionally with the counter-attack Q-R5ch. At the tenth move or thereabouts, Black advanced a pawn one square, whereupon the champion resigned.’

Next, it is necessary to consider page 127 of K. Whyld’s second anthology on the world champion, The Collected Games of Emanuel Lasker (Nottingham, 1998):

This time it is said that Lasker was White, and Black’s name has become yet another variant, ‘J.E. Randell’.

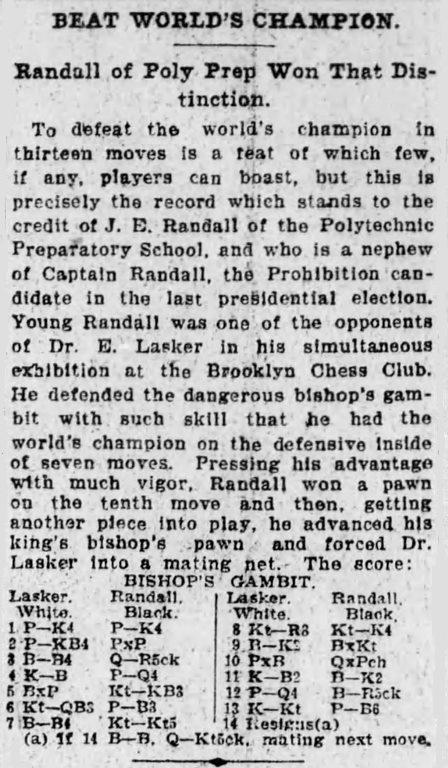

Fortunately, the whole affair is not as intractable as it may seem. The obvious source to consult for a game played in Brooklyn is the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. That newspaper’s chess coverage systematically used the spelling ‘J.E. Randall’, and not least when reporting his victory over Lasker the day after the simultaneous exhibition (on page 18 of the 21 November 1907 edition):

‘J.E. Randall’ was also the spelling when the game-score was published on 8 December 1907 (page 10):

By now, the historian will hardly have grounds for doubting that in Brooklyn on 20 November 1907 Emanuel Lasker lost to J.E. Randall. Although remaining on the look-out for further information, he may find his attention switching to the references in the above Eagle cutting to J.E. Randall and his uncle, Captain Randall, in the hope that some biographical data can be traced.

(8873)

‘Tells of’ is a formulation favoured by writers unconcerned with specifics. From page 133 of The Complete Chess Addict by M. Fox and R. James (London, 1987):

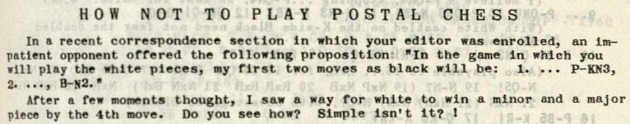

‘B.H. Wood tells of this débâcle in a postal tournament. After 1 e4, Black replied: “...b6 2 Any, Bb7.” Now “any” is a useful postal chess time-saver; it’s shorthand for “any move you care to make”. So White replied with the diabolical “2 Ba6 Bb7 3 Bxb7” (and wins the rook as well).’

Where Wood told of this is not mentioned. We recall, though, that on page 279 of the June 1961 CHESS he reported that another magazine had told of a king’s-side version:

‘Chess Review tells of a postal chess player who rather recklessly wrote his White opponent thus: “Whatever you play, my first two moves are 1...P-KN3 and 2...B-N2.”

No prizes for guessing White’s first three moves.’

However, what Chess Review (April 1961, page 102) had told of contained no ‘Whatever you play ...’ remark and was merely a gleaning from an unspecified issue of another magazine:

‘We appreciatively take this item from the Ohio Chess Bulletin, which describes the “if” moves offered by an impatient player of the black pieces: “In the game in which you will play White, my first two moves as Black will be: 1...P-KN3, 2...B-N2.” Improbable as it may seem at first glance, White can now immediately apply the crusher. Do you see how he wins two pieces?’

Can a reader trace the relevant issue of the Ohio Chess Bulletin or quote other early versions of the story? Some later writers recounted it with details which may or may not have been invented; see, for example, page 66 of Playing Chess by Robert G. Wade (London, 1974).

(8942)

The request at the end of C.N. 8942 has been answered by the Cleveland Public Library, which has provided the following from page 22 of the February 1961 Ohio Chess Bulletin (Editor: David G. Wolford):

We now note an earlier report of the trick. On page 130 of the June 1941 CHESS a reader, J. Jackson of Caldbeck, wrote:

‘... in a recent match between Eire and Ulster, one of the Papists, at a highish board, opened with 1 P-Q4; his opponent replied: “1...P-KKt3; 2 Any, B-Kt2” and resigned on receipt of the laconic answer: “2 B-R6 ... 3 BxB”.’

In the electronic age a parallel may be drawn with ‘pre-moving’. See, for example, chapters four and five of Bullet Chess One Minute to Mate by H. Nakamura and B. Harper (Milford, 2009).

One of the many disagreeable conclusions to be drawn from Rich As A King by Susan Polgar and Douglas Goldstein (New York, 2015) is that Susan Polgar is interested in the great players of the past solely as name-dropping fodder. Hackneyed stories and quotes are crowbarred in (without any source, naturally) to explain, so the dust-jacket promises, ‘the specific tactics that you can apply right now to turn your bank, brokerage, and retirement accounts into a grandmaster portfolio’.

Even when a quote is sound, the financial counsel tagged on may be shallow and inapposite. From page 103:

On page 229 a quote attributed to Lasker’s impoverished predecessor somehow prompts further platitudinous advice:

The chess content is of the Pandolfini ‘once’ type. From page 209:

More ‘once’ stuff is on page 22:

Humility advocated in a book by Susan Polgar? That is rich.

(8957)

From page 185 of Rich As A King by Susan Polgar and Douglas Goldstein:

The alleged Alekhine quote has been discussed in C.N.s 6587, 6596 and 8138, and below is a chronological compilation of the occurrences already noted, together with a few additional ones:

Page 611 of The Listener, 16 August 1958 (article by C.H.O’D. Alexander).

Page 29 of CHESS, September 1988 (article by Nigel Davies).

Page 8 of Blunders and Brilliancies by Ian Mullen and Moe Moss (Oxford, 1990).

Page 11 of Essential Chess Quotations by John C. Knudsen (Falls Church, 1998).

Page 88 of Treasure Chess by Bruce Pandolfini (New York, 2007).

Page 139 of Counterplay by Robert Desjarlais (Berkeley and Los Angeles, 2011). An endnote on page 233 merely mentioned as the source the 1990 Mullen/Moss book.

Page 26 of Vladimir Nabokov A Literary Life by David Rampton (Basingstoke, 2012).

Page 185 of Rich As A King by Susan Polgar and Douglas Goldstein (New York, 2015).

In short, with regard to Alekhine there has been no primary source, or recognition that, without one, any version of the quote is pointless and unusable.

(8958)

The above item was posted on 5 December 2014. The following appeared on the main page of the chessgames.com website on 5 April 2015:

At the English Chess Forum on 26 July 2013 Tim Harding wrote:

‘I would never dream of using chessgames.com as a source for any kind of historical data.’

A comment by us in the concluding paragraph of C.N. 8977:

Loath to provide sources or admit uncertainty, copy-and-bungle writers baldly present their version of the ‘facts’ as ironclad, never informing the reader that something else can be found somewhere else.

From undiscerning websites based on gossiping, bickering and kibitzing one can count on nothing better, but there are even ‘historians’ who do not bother with sources. For example, Wilhelm Steinitz First World Chess Champion by I. and V. Linder (Milford, 2014) has, on pages 188-190, a section headed ‘World Champions about Steinitz’, comprising a sequence of quotes from Lasker to Kramnik. Many, though not all, mention a year, but not a single one has a source. Capablanca’s comments on Steinitz, for example:

For the information which the book would not give, see Capablanca on his Predecessors.

(9003)

In Chess is Chess by Aleksandar Matanović (Belgrade, 1990) the main source often seems to be thin air. A variant of the ‘Looking one move ahead’ claims listed in the Factfinder is on page 16:

‘When Reshevsky was asked how he managed to triumph over his opponents, he said: “Nothing to it. I just see one move ahead of my opponent.”’

(9013)

From the main page of chessgames.com, 12 March 2015:

(9151)

From Olimpiu G. Urcan:

‘Regarding the botched Capablanca quote at chessgames.com (C.N. 9151), the site has not explained where its text came from or why it failed to use Capablanca’s own original English version (of what is, after all, a very famous remark). The faulty text remained as the “Quote of the Day” for a full day before being replaced, unsurprisingly, by another sourceless quote.

Why does chessgames.com treat chess, and the chess public, with so little respect? A couple of weeks ago I commented on my Twitter page: “It is difficult to look at chessgames.com for even 10-15 seconds without seeing something wrong.”

Glancing at the site’s main page today (14 March 2015), I see that it is now attributing a quote to “André Philidor”:

Why would anybody believe that Philidor wrote about “skittles”? My initial search has turned up no pre-twentieth-century occurrences of the quote; it appeared, with no mention of Philidor or anyone else, on page 81 of the December 1904 issue of Lasker’s Chess Magazine. But, of course, the onus is on chessgames.com either to specify an authoritative source or to remove the quote. To avoid further embarrassing mishaps, the site has only to follow the recommendation in C.N. 8651: “Give the source of a quote if it is known. If it is not known, do not give the quote.”’

(9156)

Once again, it appears that the lay-out of the epigrams chapter in The Bright Side of Chess by Irving Chernev caused the original confusion. See C.N. 3741 above.

An article by Julio Kaplan (‘Games from Lone Pine’) on pages 364-366 of the July 1977 Chess Life & Review stated on the final page:

‘... as Lasker used to say: “Long analysis, wrong analysis”.’

Chess literature has references by the barrowful to what this or that master ‘used to say’, but responsible writers do not diffuse such material without secure sources. The ‘long/wrong’ saying is commonly attributed to Larsen, e.g. by A. Soltis on page 190 of The 100 Best Chess Games of the 20th Century, Ranked (Jefferson, 2000) and on page 27 of The Wisest Things Ever Said About Chess (London, 2008). In each case the wording offered was ‘long variation, wrong variation’, and the corroboration offered was zero.

Larsen’s own words are shown below from page 46 of How To Get Better At Chess by L. Evans, J. Silman and B. Roberts (Los Angeles, 1991), in the chapter ‘How Do Top Players See Things So Quickly?’:

(9260)

There are two words which all readers of chess books, magazines, websites, discussion groups, etc. should be encouraged to write publicly as often as appropriate: ‘Source, please.’

It may be naive to hope that many cheap-jack peddlers of untrue, uncertain and unsubstantiated quotes, anecdotes and other would-be information will care if those two words are, for instance, systematically tagged onto their vacuous Internet postings, but the attempt has to be made. ‘Source, please’ is a measured, much-needed plea for writers to act responsibly and for readers to be treated respectfully.

(9274)

Below is the first section of an article ‘Pure hatred as Capitalist King meets Party Pawn’ by Andrew Stephen on page 13 of the Observer, 7 October 1990:

There were many similar articles in the 1980s and 1990s. They left no doubt as to the writer’s sympathies, though plenty as to his credentials. Little or nothing is sourced, and the reader cannot know where the information comes from, or judge how trustworthy it is. A single article such as Andrew Stephen’s could provide fodder for a dozen C.N. items soliciting corroboration of the various quotes and assertions.

As regards the rivalry (‘pure hatred’) between Kasparov and Karpov, to what extent have journalists been duped? A remark from page 213 of Karpov on Karpov (New York, 1991), a book referred to in Karpov’s Writings, is worth recalling:

‘Every match is preceded by scandalous situations. Some arise spontaneously, others are planned, but in general a match never comes off without them. Kasparov and I also tried to uphold the ancient tradition and toss the journalists some choice morsels.’

(9345)

From the main page of the website chessgames.com, 3 August 2015:

The ‘Spielmann’ remark was by Mieses [see above in the present feature article].

From page 41 of the 5/2015 New in Chess (in the ‘Fair & Square’ feature, which has been mentioned in C.N.s 8651 and 8768):

The ‘Bird’ remark was by Conway. The ‘Simon’ remark was by Bonar Law.

(9409)

The lack of proper source material in the case of obituaries was referred to in C.N. 9346:

In a passage quoted in C.N. 7331, G.H. Diggle complained about the ‘lean epitaphs’ with which chess figures are ‘shovelled into the grave’. He was writing over 30 years ago, and there has been, particularly of late, a steep decline in the quality of chess obituaries; many are dumped on-line after hurried copy-pasting. Often nowadays, people are wikipediaed into the grave.

The dust-jacket of Players and Pawns (Chicago and London, 2015) states that ‘Gary Alan Fine is the John Evans Professor of Sociology at Northwestern University’ and introduces his book thus:

‘A chess match seems as solitary an endeavor as there is in sports: two minds, on their own, in fierce opposition. In contrast, Gary Alan Fine argues that chess is a social duet: two players in silent dialogue who always take each other into account in their play. Surrounding that one-on-one contest is a community life that can be nearly as dramatic and intense as the across-the-board confrontation.’

Beyond such woolliness, the book is striking for a heavy USA-centric approach, the author’s unfamiliarity with chess history and lore, and a staggering lack of discernment in the sources cited.

As demonstrated by the concluding ‘Notes’ section (pages 227-261), the Professor has no interest in, or access to, primary sources and makes do with material unquestioningly derived from familiar books and webpages which are themselves derivative. Those ‘sources’ in the Notes section include an Internet quotations site (itself devoid of sources) and such embarrassments as ‘Internet Chess Club discussion boards, 2010’.

Professor Gary Alan Fine is unrelated to Reuben Fine, he states on page 1. He makes frequent, naively trusting, mention of his namesake, although his interest has its limits. Page 205 discusses the wonder of databases, which ‘have replaced wood pulp’: ‘Fully 389 of Reuben Fine’s games are archived ...’ There is no awareness of Aidan Woodger’s carefully researched monograph on Reuben Fine, published by McFarland & Company, Inc. in 2004, which has well over twice as many games by Fine as the ‘fully 389’.

McFarland books are of no concern to Professor Fine, who instead goes as far down-market as possible for his raw material and pseudo-sources. No would-be facts have been scrutinized with care.

On page 114 he writes:

‘As Rudolf Spielmann advised, “Play the opening like a book, the middle game like a magician, and the end [sic] like a machine”.’

A superscript reference takes the reader to a source note on page 246:

‘Quoted in Kasparov, How Life Imitates Chess, 119.’

That is all. However, as demonstrated in our feature article on How Life Imitates Chess, page 119 of the former world champion’s book (US edition) was wrong, having incorrectly and sourcelessly copied earlier false attributions of the quote to Spielmann, even though the truth had long since been established.

How can anyone, let alone a Professor, be content to use the words ‘Quoted in’, followed by an unverified secondary source? Is that Professor Fine’s customary approach, or only when dealing with chess? Readers are unlikely to care whether he ‘argues that chess is a social duet’, or that it is a social solo, or that it is anything else of his choosing, but basic academic standards can reasonably be expected. The book has been published by the University of Chicago Press.

Our minuscule sample from Players and Pawns concludes with a line from page 169, regarding the title ‘grandmaster’:

‘... in 1914 Czar Nicholas II awarded the title in Russia. It became an official designation in 1950 by edict of the World Chess Federation.’

The source for that information is specified, on page 255, as ‘Olson, The Chess Kings, 95’. Yet what appears on page 95 of The Chess Kings by Calvin Olson (Victoria, 2006) is something very different:

‘The story regarding the Czar has no foundation and must be relegated to the category of fiction.’

(9500)

To state the obvious, or what ought to be, great wariness is required over ‘community’ websites which, instead of trying to get matters correct from the outset, allow individuals, usually unnamed, to post whatever they choose. The onus is placed on others to try to make rectifications if they can be bothered.