Edward Winter

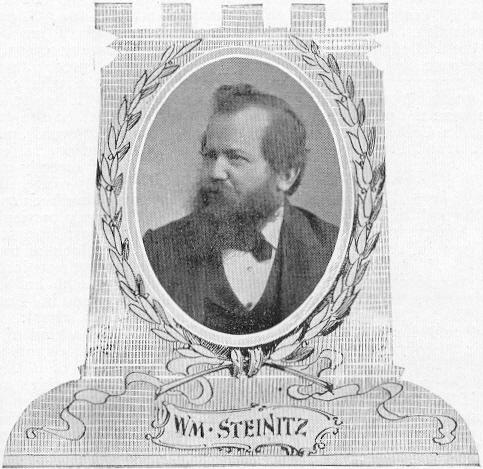

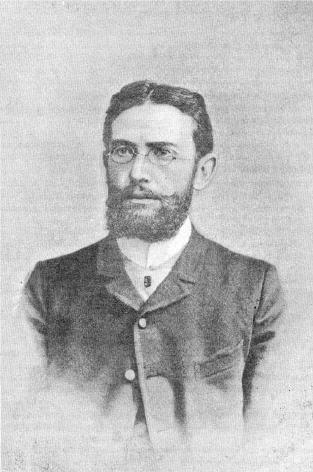

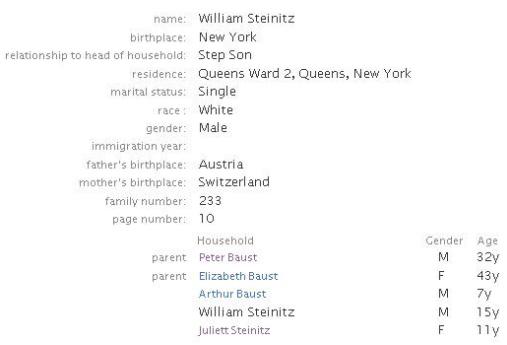

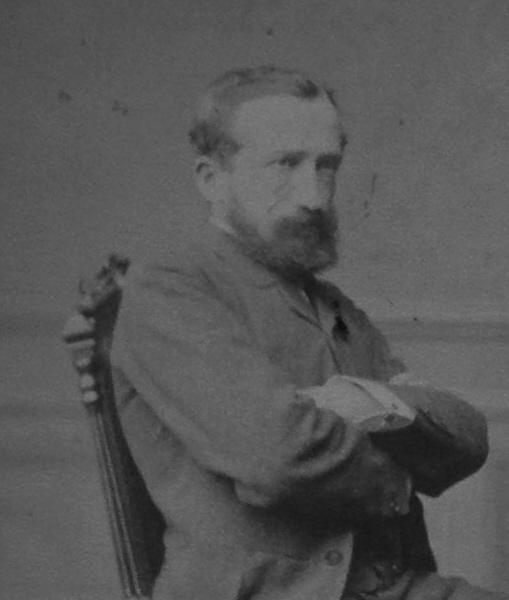

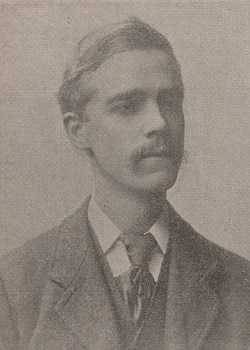

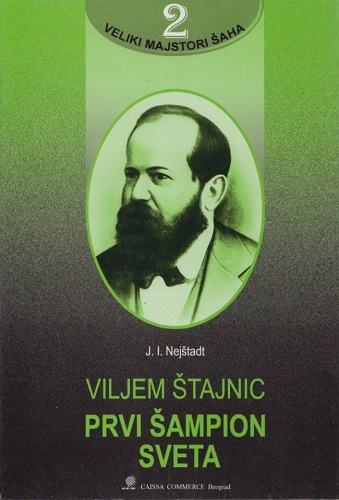

Wilhelm (William) Steinitz. See C.N. 7654 below.

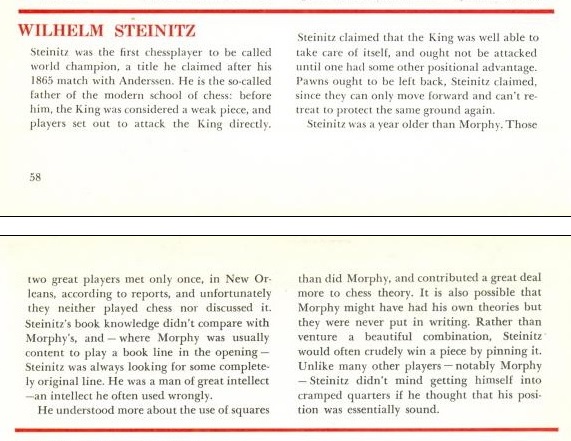

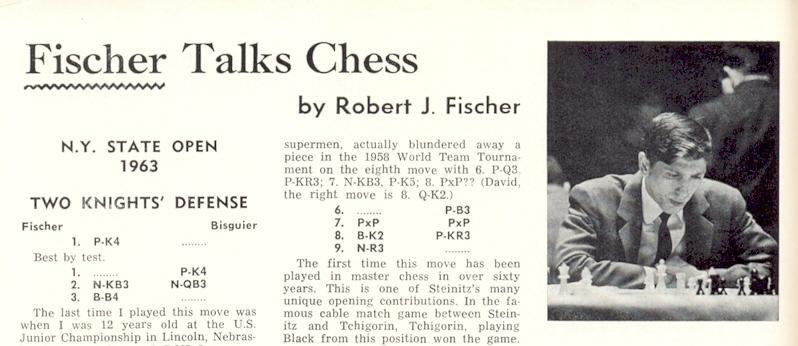

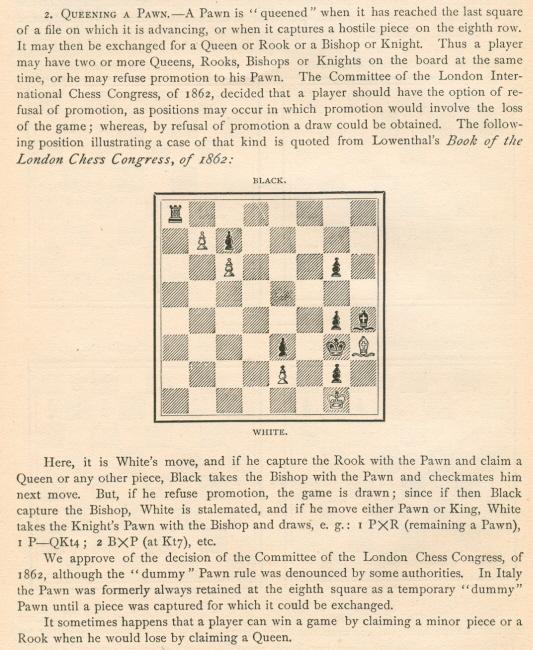

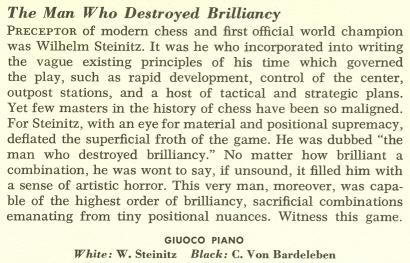

Bobby Fischer’s view of Steinitz appeared in the article ‘The Ten Greatest Masters in History’ (on pages 56-61 of Chessworld, January-February 1964):

Steinitz writing on page 22 of the January 1887 International Chess Magazine (part of the justification provided for his Personal and General column):

‘... to make it disagreeable for dishonest parties who are, I believe, even less numerous proportionately in the chess world than in other walks of life, but more crafty, cunning or “smart” as it is called. Chess must be established as a thoroughly straightforward and honest game first of all before it can be made a real gentlemanly one, and unscrupulous trickery, deception and fraud must be “warned off the track”. But it requires a strong arm to accomplish that, and war on dishonest chessists cannot be made with rose water ...’

See Steinitz Quotes.

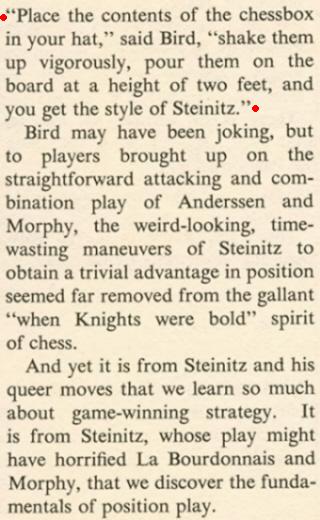

The Chess Beat (Oxford, 1982) is a reproduction of 300 newspaper columns written by Larry Evans.

Poor old Steinitz is fair game for Evans’ knock-about style. Not only is there no discussion of Steinitz’s contribution to chess, there is not a single game by him. (There are 20 by Evans himself. ) The collection does, however, present examples galore of Steinitz’s ‘eccentricity’. (No instances of Evans’ are given.) Perhaps that is what is called historical perspective.

(323)

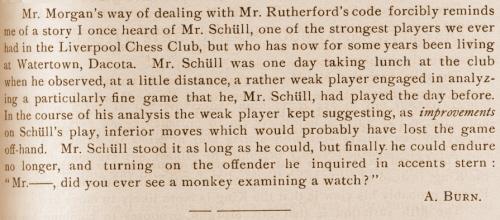

Many anecdotal books (the latest being The Kings of Chess by W. Hartston, page 67) attribute to Steinitz the sharp questioning quip about a monkey examining a watch. This is given on page 37 of the February 1890 International Chess Magazine, but Steinitz is not the speaker. The words were said by Mr Schüll of the Liverpool Chess Club, and are reported by Burn in a published letter to Steinitz.

(1077)

In reality – as briefly mentioned in C.N. 1077 (see page 125 of Chess Explorations) – the words in question were spoken by Ludolph Schüll of the Liverpool Chess Club and were reported by Amos Burn in the final paragraph of a letter (dated 30 December 1889 and concerning a telegraphic chess code) which was published on pages 36-37 of the February 1890 issue of Steinitz’s International Chess Magazine:

(6590)

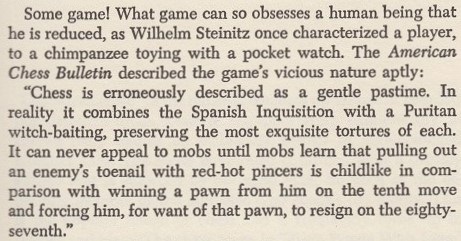

From page 5 of Chess to Enjoy by A. Soltis (New York, 1978):

The Steinitz ‘once’ story was disposed of in C.N.s 1077 and 6590.

As regards the paragraph quoted, Soltis did not bother to state when during its long run (1904-63) the American Chess Bulletin published it.

(9138)

The answer is that the passage appeared on page 25 of the February 1935 American Chess Bulletin but was specifically headed as a feature merely reproduced from elsewhere (‘New York “Sun” Editorial’).

From page 57 of The Kings of Chess by William Hartston (London, 1985):

‘Steinitz defeated Dubois [in 1862], to begin the most impressive match record in the history of chess.’

(9445)

On the subject of Dubois v Steinitz, see Confusion.

Concerning The Moscow Challenge by Raymond Keene (London, 1985):

Page 9: we are told that it is ‘staggering’ that Steinitz’s tournament record during the period he was champion (1886-94) was ‘abysmal’. Should a writer not at least check his facts before so criticizing a great player? The truth is that Steinitz did not play in a single tournament during the period under consideration.

(976)

An addition in Cuttings:

Regarding the remark about Steinitz’s tournament record being ‘abysmal’, we drew attention to the error on page 200 of the May 1985 BCM. On page 256 of the June 1985 issue Mr Keene responded with the astounding claim that ‘in calling Steinitz’s tournament record “abysmal” he was criticising it on the grounds of lack of activity’. By that logic, we pointed out on page 305 of the July 1985 BCM, Fischer’s post-1970 tournament record could be labelled ‘abysmal’.

Mr Keene’s ignorance of Steinitz was also demonstrated on page 35 of his volume Duels of the Mind (London, 1991), where he stated that Steinitz published a book called Modern Chess Theory. No such work exists. (We pointed this out in a footnote on page 266 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves.)

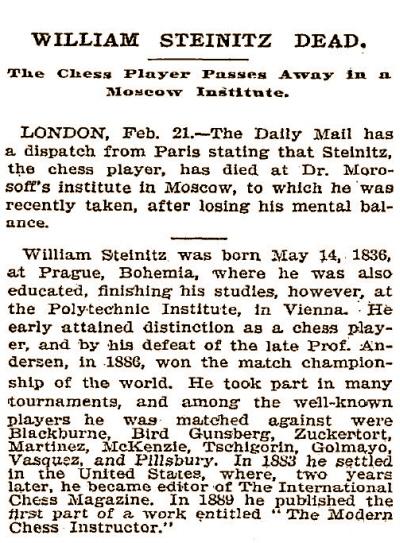

On page 60 of the 2 November 1991 Spectator Raymond Keene stated that Steinitz died in 1901.

See also World Champion Combinations, which comments regarding page 9 of that book, by Raymond Keene and Eric Schiller:

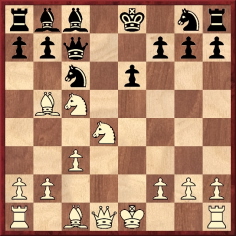

The position from the second game of the 1896-97 world championship match between Lasker and Steinitz has the authors overlooking an elementary mate in two moves (i.e. Nb3+ rather than Re4+, as pointed out on page 366 of the December 1896 Deutsche Schachzeitung).

Raymond Keene’s mistake ‘his book Modern Chess Theory in 1889’ had also appeared earlier, on page 138 of his 1988 Pocket Book of Chess, and despite our above-mentioned correction in Kings, Commoners and Knaves, Mr Keene persisted with it in an online article dated 24 April 2021:

‘His ideas are published in his book Modern Chess Theory in 1889.’

That text remains online today [22 February 2024] even though it was specifically corrected by Tim Harding on the English Chess Forum in May 2021.

The September 1890 International Chess Magazine, pages 273-274, had a letter from Gunsberg to Steinitz explaining the details of ‘the first chess libel suit on record’. The Vienna paper Volksblatt was found guilty and fined for publishing a ‘libelous paragraph’ about the abortive Chigorin-Gunsberg match. According to Gunsberg, Chigorin suppressed the correct facts of the match negotiations and a false insinuation was taken up by the Austrian journal.

The following issue, pages 299-300, featured information on another chess legal case. Again Gunsberg was involved, although this time as the defendant. Francis Joseph Lee – and this is the only time we have ever seen his forenames in full in a contemporary source – sought leave to commence proceedings for libel against the editor and publisher of the Evening News and Post and its chess columnist, Gunsberg. The latter had allegedly ‘imputed or suggested a corrupt motive to Mr Lee in losing to Mr Mason a game in the Manchester Chess Tournament’. Gunsberg denied that he had imputed or suggested anything of the kind. ‘The learned Judge refused to make an order giving leave to prosecute.’

Steinitz commented:

‘In both cases Mr Gunsberg was successful, and we thoroughly sympathized with him in the first case, but cannot do so in the present instance. Mr Lee’s cause of complaint may not have been so strong as to warrant a legal prosecution, but it is to be regretted that even the slightest hint of professional dishonesty should have been given in a chess column, edited by a professional master, without the accusation being capable of absolute proof.’

(1078)

See too Chess in the Courts.

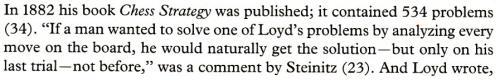

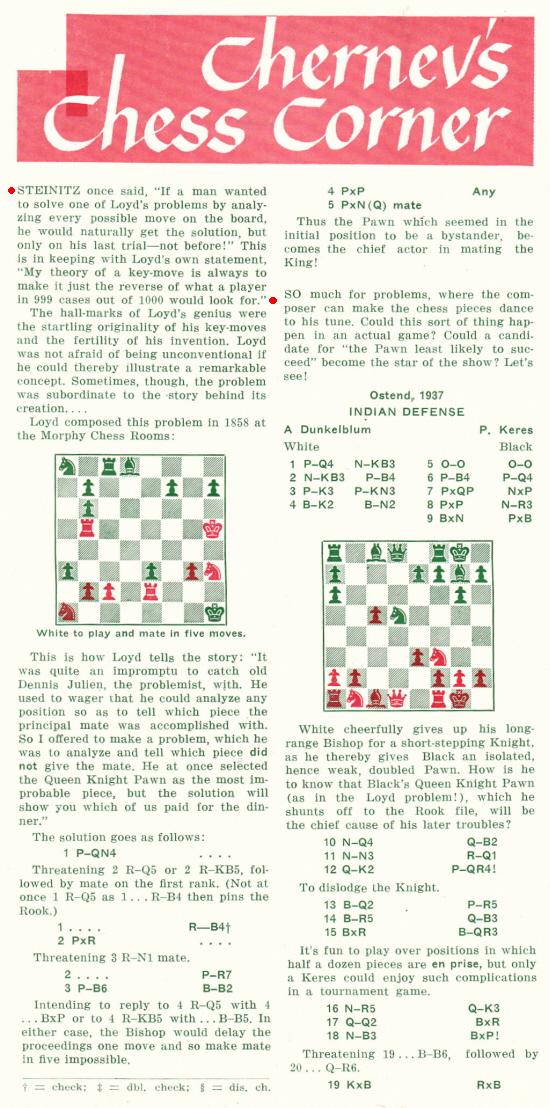

An extract from a letter dated 2 March 1886 written by Sam Loyd to Steinitz and published on pages 71-72 of the March 1886 issue of the International Chess Magazine:

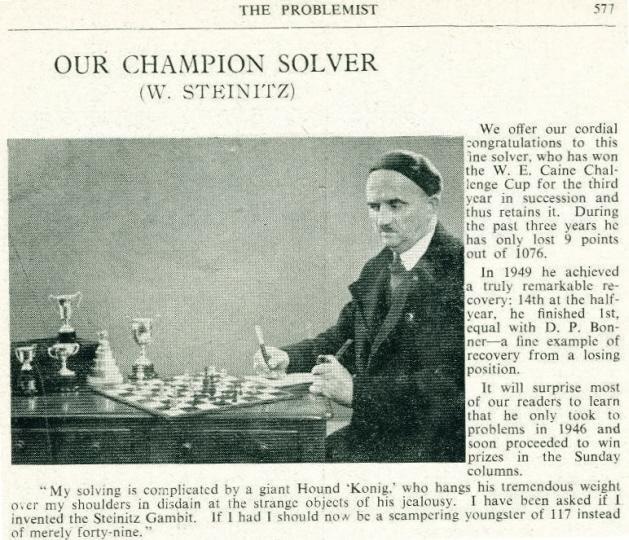

‘In regard to the benefits and advantages of problem solving, I can only reply to the argument that so many good solvers are poor players, with the argument of Horace Greely, before he became a Democratic candidate, that, whereas he was “not prepared to assert that every Democrat was a horse-thief, he was willing to assert that every horse-thief was a Democrat”, just so, while I cannot say that solvers are good players, yet the best solvers I ever met were Morphy, Kolisch, Steinitz, Zukertort, Blackburne, Mackenzie and Mason, all of whom play a fair game.’

(1113)

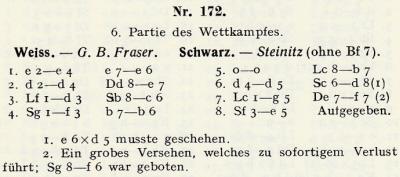

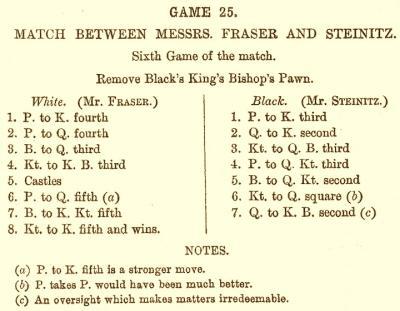

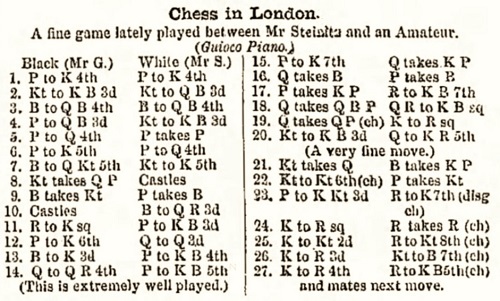

George Brunton Fraser – Wilhelm Steinitz

Sixth match-game, Dundee, 1867

(Remove Black’s f-pawn.)

1 e4 e6 2 d4 Qe7 3 Bd3 Nc6 4 Nf3 b6 5 O-O Bb7 6 d5 Nd8 7 Bg5 Qf7 8 Ne5 Resigns.

Source: volume one of Bachmann’s Schachmeister Steinitz, page 182.

(1216)

Hayoung Wong (Bayside, NY, USA) writes regarding a game at the odds of pawn and move which Steinitz lost to Fraser in 1867. The score was given in C.N. 1216 (see page 56 of Chess Explorations), taken from page 182 of volume one of Schachmeister Steinitz by Ludwig Bachmann (second edition, Ansbach, 1925):

But did Steinitz resign at move eight? Mr Wong notes that when the score was published on page 107 of the Chess Player’s Magazine, April 1867 the conclusion was 8 Ne5 ‘and wins’:

(8779)

From Tim Harding (Dublin):

‘The game was played on 29 January 1867 and was published on 31 January in the Dundee Advertiser, page 3. This was the earliest publication of the game.

After White’s eighth move the newspaper said, “and Mr Steinitz resigns, the queen being lost”.

In general, I have often found with Victorian games that a source may say “and wins” without it necessarily meaning that there were further moves. Sometimes, as here, another source explicitly says “resigns”.’

Our correspondent, it will be recalled, is the author of Eminent Victorian Chess Players (Jefferson, 2012).

(8784)

From page 276 of Ajedrez en Cuba by Carlos Palacio (Havana, 1960):

T. Marrero – F. Melgarejo

Placetas, 1932

Evans Gambit Accepted

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 b4 Bxb4 5 c3 Ba5 6 O-O Nf6 7 d4 O-O 8 dxe5 Nxe4 9 Re1 Nxc3 10 Nxc3 Bxc3 11 Ng5 Nxe5 12 Qh5 h6 13 Rxe5 Bxe5 14 Nxf7 Rxf7 15 Qxf7+ Kh8 16 Bg5 Bf6 17 Re1 Resigns.

This seems to have a familiar look to it. Can a reader quote the same moves from another source?

(1364)

Carl-Eric Erlandsson (Lund, Sweden) has come to the rescue: the game was Steinitz v H. Devidé, Manhattan Chess Club, 1890.

(1459)

See Duplication of Chess Games.

From Chess and Alcohol, concerning James Mason:

On page 237 of the August 1890 International Chess Magazine Steinitz described how in the New York tournament Mason ‘forfeited a game “by time” on the eighth move, and on several occasions, to speak in plain language, simply created disgraceful drunken disturbances’.

A further remark by Steinitz:

‘… Mr Mason when he descends from the heights of his obfuscated philosophy into the sober region of fact, has, so to speak, “no leg to stand upon”, which, of course, does not matter much to Mr Mason, who is notoriously rather unfamiliar with that sensation, outside of chess controversy.’

Source: International Chess Magazine, July 1885, page 208.

On page 138 of the May 1890 issue of his periodical Steinitz wrote: ‘Of course, Mr Mason’s manifesto must be taken cum grano whiskey.’ In the September 1885 number (page 265) a tournament reporter recorded being asked by a friend, ‘How is it that Mason has such a good chance of winning the first prize at Hamburg?’ The answer, with a reference to the tournament tail-ender, was, ‘Because he’s keeping Bier a long way off.’

These matters were originally discussed by us in Kingpin.

On the subject of Emanuel Lasker and money, C.N. 1189 gave two quotes, the first of them from a letter he contributed to page 260 of the June 1907 issue of the BCM:

‘The reviewer of the book [Struggle] comments on the lack of success of chess masters in practical life. He argues that the masters of strategy should be able to achieve success in business if my contention – that all contests follow the same strategic laws – is correct. I think that men like Zukertort and Steinitz would have been great in any enterprise if they would have ardently devoted themselves to it. They did achieve their purpose. Probably they never tried to gain wealth, or, at least, they did not try hard, and chessplayers – this reproach cannot be withheld – were content to buy their success as cheaply as they could. A starving man can, of course, not make a fair bargain. They were the victims of circumstance – like Mozart and Beethoven. Does it denote any great business qualities in Paderewski that he makes a hundred times more money than some of his predecessors no less distinguished in their day?’

The second Lasker quote comes from Der Schachwart No. 3, cited in the July 1913 BCM, page 294:

‘If Idealism means the thrusting of mediocrity into the foreground to the disparagement of perfection, and the failure to display any enthusiasm for the idea of chess-play, then Das Wochenschach bears away the palm for Idealism. If, on the other hand, Materialism implies the striving to raise the social position of the chess master, to extend a true understanding of the deep mentality of chess-play, to get the master treated with some recognition of his rights as a man, instead of being neglected in poverty like Morphy [sic], Harrwitz, Neumann, Steinitz, Pillsbury – then I am a Materialist.’

See Chess and Poverty.

Page 471 of the December 1897 BCM quotes from a speech made by Steinitz at New York on 16 October of that year. How we should love to have been there.

‘“Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown”, says the sublime analyst of human nature and character. Mine was not a golden crown, but it was not worthless. Perhaps it might be no more properly compared with a crown of roses, interwoven with all their natural thorns which made my rest uneasy for a greater part of the time. Whatever it was it is now transferred to Mr Lasker, and I can only express a hope that the crown will now be made in reality a golden and yet an easy one, for him or any one else to wear, who may hereafter honourably gain the title of champion. Taking this opportunity, I desire to thank Mr Lasker for having started a similar testimonial in England, and considering that I have ceased to be connected with chess in the old country for 15 years, the generosity of all other English subscribers cannot be too highly commended. To return to my subject, I may state that although I have received such high praise for my labours as an author on the game, I have never been satisfied with myself even in that respect, for this reason: Life has often been compared with a game of chess, and no doubt the comparison fits in many respects, notably in this – that life is now universally recognized among thinking men as a deep scientific study similar to our game, which most unquestionably is a splendid training of our mental powers that govern our thoughts and actions. However, it has been a source of disappointment and dissatisfaction to me for a long time that I myself have never been able yet to give such personal proof of the influence of chess on the reasoning faculties, like the great masters, Buckle and Staunton, who have made indelible marks in the researches of human thought outside of the chess board. The question of the influence of chess on morals has often been discussed, and I may therefore state that our noble game points in the first place to the following moral: Good nature is the first element of a really strong intellect, and there is no really sound human brain without a sound sympathetic heart. Furthermore, that purity of mind is essential to the preservation of intellectual health, not alone among women who recognize truth by instinct, as it may be called, but also among men. In other words, that the virtues as they have been preached by moralists in different ages are based on physical laws which operate at least in our visible existence.’

(Referring to the literary philosophic work Steinitz had in hand.) ‘Many strong reasons prompt me to endeavour to issue such a book as soon as possible, and if I had no other reason it would be this: Since the calamitous breakdown of the mental faculties of Paul Morphy, a prejudice has been created among a great portion of the public against chess as an intellectual exercise. This prejudice was no doubt increased in consequence of my unfortunate confinement at Moscow, and in the interests of chess, as well as in the cause of humanity and toleration, which I intend to advocate, I shall consider it necessary to devote a great part of my attention to literary pursuits of a character which, I feel satisfied, will meet with the approval of thinking men and women all over the world, and will tend to show that the training which I have received in the cultivation of chess has not been lost upon me. To the best of my ability I shall in future endeavour two great causes in a manner which I trust will demonstrate my desire to deserve the patronage of the promoters and supporters of the testimonial fund. Anyhow, your kind action will furnish an additional proof of the maxim that sound and strong minds are governed by kind and sympathetic hearts.’

(1413)

From our scrutiny of Warriors of the Mind by R. Keene and N. Divinsky (Brighton, 1989):

A quote from page 23 about Steinitz (died 1900) is irresistible: ‘One traditionally pictures Steinitz struggling in the trenches. His chess seems almost a symbolic portent of the conflict of the Great War 1914-1918.’ That’s a deep one.

George Stern (Canberra, Australia) writes:

‘When I came across the following passage about F.K. Young by Lawrence J. Fuller on page 503 of Volume I of The Best of Chess Life and Review, my eyebrows went up in disbelief:

“Mr Young was a contemporary of Steinitz, Zukertort and the American champions Mackenzie and Pillsbury, from all of whom he won games which he credited to his system.”

Can it really be that F.K.Y. defeated Steinitz, Zukertort, Mackenzie and Pillsbury? If he did, why is the fact not better known? Why, indeed, did Young himself not boast about it – as a success of his system – in the lattermost of his “Strategetics” series, Chess Strategetics? There are all sorts of other puffery in the “Introductory” to that book, but no mention of victories over world-class contemporaries. Incidentally, I notice that in that book Young made this claim:

“The synthetic method of chessplay ... early received the indorsement [sic] of Emmanuel [sic] Lasker, who, in a personal letter to Mr Edwin C. Howell, collaborator in Minor Tactics, stated that the new method of chess play ‘was replete with logic and common sense’.”

I wonder too whether Young’s claim about Lasker is true. Can you or your correspondents shed any light on either of these matters?’

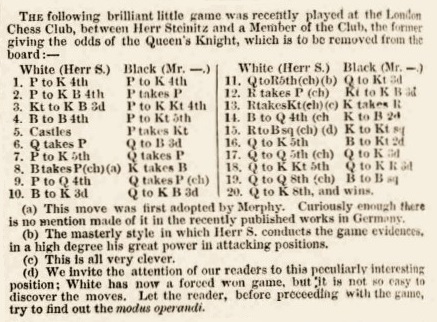

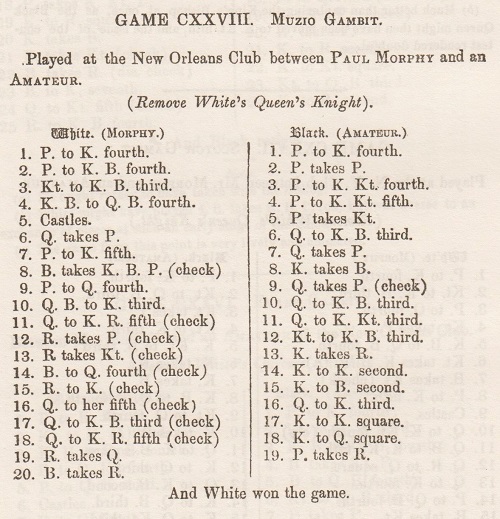

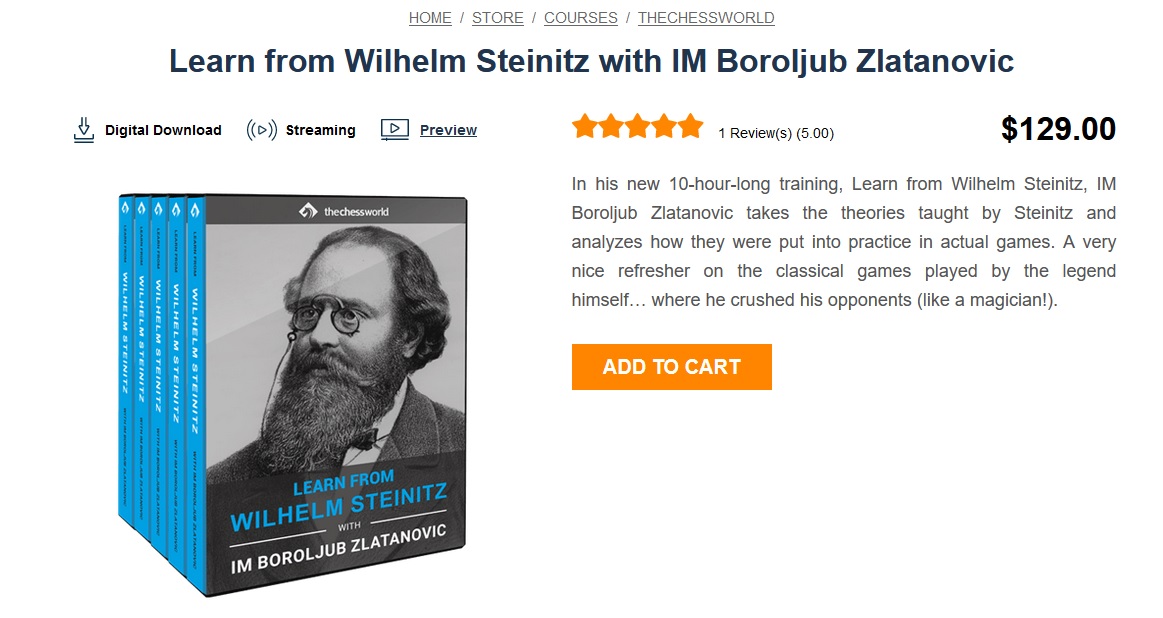

Finding victories by Young is not easy, though his obituary on page 10 of the January 1932 American Chess Bulletin said that ‘in the middle ’80s, contemporary with George Hammond [sic – G.H. died in 1881], Preston Ware, C.F. Burrille [sic] and Charles B. Snow, he was one of the finest players in America’. In an off-hand queen’s knight odds game in Boston in April 1885 Young was defeated by Steinitz. The game appeared on pages 217-218 of the July 1885 issue of the International Chess Magazine. Steinitz described his opponent as ‘one of the strongest local players’ and believed that he ‘would be too strong for such odds in a serious contest’.

(1886)

On pages 443-444 of The Grand Tactics of Chess (Boston, 1905):

Wilhelm Steinitz – Franklin Knowles Young

Boston, 9 July 1886

King’s Gambit Accepted

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 Bc4 g4 5 Ne5 Qh4+ 6 Kf1 Nh6 7 d4 f3 8 Nc3 fxg2+ 9 Kxg2 Qh3+ 10 Kg1 Nc6 11 Bf1 Qh4 12 Bf4 d6 13 Bg3 Qg5 14 Nc4 Bg7 15 Bf2 f5 16 Nd5 O-O 17 Nxc7 Rb8 18 c3

18...g3 19 hxg3 Ng4 20 Qd2 f4 21 gxf4 Qe7 22 Nd5 Qxe4 23 Bg2 Qg6 24 Re1 Be6 25 Nde3 Rxf4 26 Bg3

26...Rxd4 27 cxd4 Bxd4 28 Rh4 h5 29 Rxg4 Qxg4 30 Bf2 Qf4 31 Nd5 Qxf2+ 32 Qxf2 Bxf2+ 33 Kxf2 Rf8+ 34 Kg3 Nd4 35 Nxd6 Rd8 36 Ne4 Kg7 37 Nec3 b6 38 Nf4 Bf7 39 Kh4 Kh6 40 Re5 Rg8 41 Bd5 Rg4+ Drawn.

But on pages 138-139 of Field Book of Chess Generalship it is claimed that there was a much prettier finish and a different result:

26...Nge5 27 dxe5 Qxg3 28 Qe2 Rbf8 29 exd6 Bxc4 30 Nxc4 Nd4 31 cxd4 Bxd4+ 32 Ne3

32...Rf1+ 33 Rxf1 Bxe3+ 34 Qxe3 Qxe3+ 35 Kh2 Qe5+ 36 Kh3 Rxf1 37 Rxf1 Qxd6 and Black won.

(1911)

On page 229 of the October 1911 American Chess Bulletin, Emanuel Lasker responded to a charge that he had written an article in bitterness:

‘... Possibly in writing the article, I thought of Morphy, Mackenzie, Steinitz and Pillsbury. The reflection upon their life is not an agreeable one to me. They were pathfinders, yet their lot was a hard one. They got flattering notice, but received no practical support. And their talents were never sufficiently utilized. A good use might have been made of these men as teachers. Morphy or Steinitz, explaining their theory as to the mode of thinking appropriately, would have been worthy the attention of philosophers. They remained silent, because they were never asked. The curiosity of the men around them was aroused by the question how strong they were and how many games they might be able to play simultaneously or blindfolded, and how they could perform this tour de force or that one. Their real excellence, which was the result their having discovered principles of wide application by no means restricted to chess, was probably not even guessed. At any rate, the chess world did not make the effort to make the two great thinkers speak, and the highly beneficial work which they naturally would have performed if they had been coaxed into action remained undone. The splendid soil of their inner consciousness was allowed to lie uncultivated and to yield far from enough fruit for others.

(1898)

Retirement from Chess includes the following:

As quoted in C.N. 1215, on page 359 of the December 1891 International Chess Magazine Steinitz wrote:

‘... I beg to state that I shall most probably adhere to my intention of retiring from active play altogether, but I do not wish to stand pledged either way.’

C.N. 4160 added a passage from page ix of The Games of the St Petersburg Tournament 1895-96 by J. Mason and W.H.K. Pollock (Leeds, 1896):

‘Steinitz himself, in the Figaro, so far back as 1878 – when he was contemplating retiring from chess – claims that his record was then better than Morphy’s, but left the question of genius an open one.’

Further details about these matters are still being sought.

‘Steinitz played Jack the Ripper’

The lurid headline above could, just possibly, be true. The Ripper & The Royals by Melvyn Fairclough (London, 1991) set out to demonstrate that Jack the Ripper was Winston Churchill’s father, Lord Randolph Churchill (1849-95). From page 89:

‘He further proved his ability to plot ahead when he became a first-class chess player. He once played against the chess champion of the world in a game described by Winston as ‘original, daring, and sometimes brilliant’.

The score is to be found on page 257 of part 1 of Schachmeister Steinitz by Ludwig Bachmann (Ansbach, 1910):

Wilhelm Steinitz (blindfold, simultaneous) – Lord Randolph

Churchill

Oxford, 17 May 1870

King’s Gambit Accepted

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 h4 g4 5 Ne5 Qe7 6 d4 d6 7 Nxg4 Qxe4+ 8 Qe2 d5 9 Ne5 Nh6 l0 Nc3 Bb4 11 Qxe4 dxe4 12 8xf4 Nf5 13 O-O-O Bxc3 14 bxc3 Nd6 15 c4 f6 16 c5 fxe5 17 Bxe5 Nf7 18 Bxh8 Nxh8 19 Re1 b6 20 Rxe4+ Kd8 21 Bc4 Bb7 22 Rg4 Ng6 23 h5 Ne7 24 Re1 Nbc6 25 d5 Nb4 26 c6 Bc8 27 Rg7 Nbxc6 28 dxc6 Nxc6 29 Bb5 Bb7 30 Rd1+ Ke8 31Rxc7 Kf8 32 Rf1+ Kg8 33 Bc4+ and Black is mated in a few moves.

Bachmann also gives (pages 258-259) a drawn consultation game, played in Oxford in August 1870, between Steinitz and Anthony, Churchill and Ranken.

Steinitz himself wrote an admiring sketch of Lord Randolph Churchill (and another parliamentarian, Charles Bradlaugh) in the New York Tribune of 4 February 1891, a text subsequently reprinted on pages 4-6 of the January 1891 issue of the International Chess Magazine. The obituary of Lord Randolph Churchill on page 82 of the February 1895 BCM reported that from his early college days to the beginning of his political career the deceased was, in his own words, ‘an ardent chessplayer’. Further information, including details of Winston Churchill’s enthusiasm for chess, is given on pages 89-90 of King, Queen and Knight by Norman Knight and Will Guy (London, 1975).

This is hardly the place for a discussion of the claim that Lord Randolph Churchill perpetrated the Whitechapel murders of 1888. It need merely be stressed that countless Victorian notables have been accused of involvement by one ‘Ripperologist’ or another.

(Kingpin, 1993)

A footnote on page 314 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves:

Steinitz suggested ironically that the chessplayer and poet Wordsworth Donisthorpe could have been Jack the Ripper. See, in particular, the following issues of the International Chess Magazine: October 1889, page 298; November 1889, pages 333-334; December 1889, page 370; January 1890, page 11.

Another name that has been bandied about in connection with the Whitechapel murders is the heir presumptive to the British throne, the Duke of Clarence (1864-92). Page 64 of the February 1892 BCM contained a notice of his death, though with no chess connection made. Page 24 of the Chess Player’s Annual and Club Directory of 1893-94 reported the Prince’s death and added:

‘The sad event took place on 14 January. The congress of the Hibernian Chess Association, then being held, was immediately adjourned for a week, and the leading chess organs, in common with everyone of Her Majesty’s subjects, expressed profound regret and sympathy. The prince, like most members of the royal family, was a lover of chess, and patronized some of our chess associations.’

(Kingpin, 1999)

The comment below was given on page 387 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves:

‘Of my opponent I am oblivious. For all that I know or note, he might as well be an abstraction or an automaton.’

Steinitz, BCM, September 1894, page 366, from an interview in the St Louis Globe.

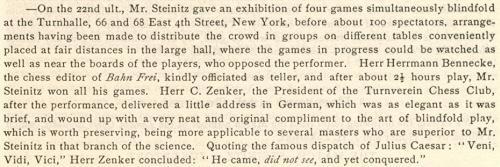

A feature on page 107 of the April 1885 issue of the International Chess Magazine:

(6539)

With respect to the last sentence (and the claim of originality), we now note a report on page 154 of the Westminster Papers, 1 December 1873:

‘Mr Blackburne’s blindfold performance was on this, as on previous occasions, an unqualified success. Against ten opponents he won six games, drew three and lost but one, after a contest of over eight hours. He came, he did not see, but he conquered.’

(7616)

From Brad Thomson (Ottawa, Canada):

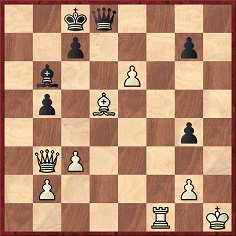

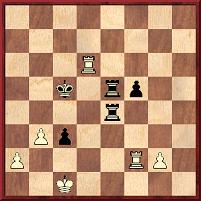

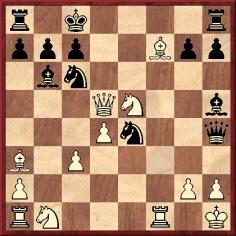

‘While preparing an article (published on pages 34-39 of the June 1994 En Passant) on the 100th anniversary of the Lasker v Steinitz match, which concluded in Montreal, I noticed that the three sources I was using did not agree at one point. In game 17, Steinitz’s last victory, the following position arose:

C. Devidé’s book on Steinitz gives Lasker playing 21 Ne1 c5 22 Qd2 Be6 23 b4 Qc7, and now 24 d5, at which point all sources agree again. But the move order given in The World Chess Championship: Steinitz to Alekhine by P. Morán and in the Weltgeschichte volume on Lasker is 21 b4 Qc7 22 Ne1 c5 23 Qd2 Be6 and now 24 d5, whereupon the transposition is complete.’

We add that the logical latter version is supported by such contemporary sources as the Deutsche Schachzeitung (July 1894, page 202), the BCM (July 1894, page 300) and the Chess Monthly (July 1894, pages 335-336).

(2071)

‘Signor C. Salvioli has reclaimed the birthright of chess literature for Italy. Without exception the first volume of his Teoria e Pratice [del giuoco] degli Scacchi as a collection of games alone is the most valuable chess book extant in any language’.

W. Steinitz, on page 83 of the March 1885 issue of the International Chess Magazine.

(2165)

C. Golmayo-E. Hidalgo, Havana, 1885

White (who had given the odds of his queen’s knight) dealt with the mating threat by playing 1 c4 Qh8+ 2 Qh3 gxh3 3 e7 hxg2+ 4 Kxg2 ‘and wins’, according to the Brooklyn Chess Chronicle, which offered these variations:

a) If 1 Rf3, Black mates in five, beginning with 1…Qh4+.

b) 1 c4 Qh4+ 2 Qh3 gxh3 3 Rf8+ Qd8 4 e7, and White wins.

c) 1 c4 Qh8+ 2 Qh3 gxh3 3 e7 Bc5 4 Bc6 Bxe7 5 Ra1, and White wins.

Steinitz then reprinted the position in his International Chess Magazine, describing it as a ‘beautiful termination’. He added 1 g3 Qh8+ and mate next move, and wrote that Black should have answered 1 c4 with 1…c6, ‘whereupon White could not have saved the game’. However, subsequently (and, characteristically, at the first opportunity) he admitted correction by the Chronicle, which pointed out that 1…c6 allowed White to win by 2 Qg3. By then, though, the Chronicle had made a further discovery of its own, namely that in case of 1 c4 Qh8+ 2 Qh3 gxh3, the move 3 e7 would only draw after 3…Qh5. It nonetheless maintained that White had a win, with 3 Ra1 instead of 3 e7.

Sources: Brooklyn Chess Chronicle: 15 May 1885, page 120; 15 June 1885, page 133; 15 July 1885, page 151. The International Chess Magazine: June 1885, page 185; July 1885, page 222.

(2249)

The follow-up material [in the Brooklyn Chess Chronicle and the International Chess Magazine] was overlooked when the March 1908 Lasker’s Chess Magazine, page 227, published a full-page feature criticizing the 1885 analysis.

(4138)

Lasker’s criticism had appeared in his New York Evening Post column on 22 January 1908, page 12.

The above position is from a consultation game between Steinitz (White, to move) and Lyman and Richardson. Steinitz won with 1 Bc3 Qa3 2 Rh1 f5 3 Qc4+ Rf7 4 Rxh7 Qc5+ 5 Qxc5 bxc5 6 Rh8 mate.

It was later pointed out by three readers of the International Chess Magazine that a more elegant win would have been (1 Bc3 Qa3) 2 Qxh7+ Kxh7 3 Rh1+ Kg6 4 Nf4+ Kf5 5 Rh5+ Ke4 6 Re5 mate.

Sources: the International Chess Magazine, January 1885, page 27 and February 1885, page 57.

(2263)

‘Of course, such literary trickeries are nothing new to me, and I have been used to it for 20 years that according to the constructions in certain journalistic quarters everybody in turn was the champion during that period, excepting myself. The only consolation I had was that most of the defeats I suffered occurred in my own absence.’

Steinitz, writing in the International Chess Magazine, September 1887, page 265.

(2326)

From page vii of Part II of The Modern Chess Instructor by Steinitz:

‘One of the principles laid down in Part I of this work is that the Knight is stronger than the Bishop.’

The final page had an erratum:

‘On page vii of Preface top line read: The Bishop is stronger than the Knight.’

(2348)

An observation by R.C. Griffith on page 155 of the April 1932 BCM:

‘It is most unfortunate that there always seems to be bickering between reigning and past champions. This has been the case for many decades, and it is for this reason that we so strongly advocate that the arrangements for the championship should be in the hands of the FIDE. If the patrons of chess who help to put up the necessary finance would agree that they would only do so through the FIDE, it is possible that our suggestion may be practical politics earlier than we anticipate.’

Steinitz demonstrated his outstanding eloquence and debating skills on umpteen occasions, and was seldom in the wrong. (His writings indicate that he was one of the most intelligent and honest of all the world champions.) He regularly expressed the view that tournaments had much less significance than matches, and during an argument with G.H. Mackenzie about a possible match he wrote (on page 333 of the November 1887 International Chess Magazine):

‘For my part, I would have been satisfied if he had called himself the International tournament champion and had left me the International match championship until such time when he was prepared to contest it, or until I otherwise forfeited my claim.’

‘We have two champions!’, commented La Stratégie of 15 November 1894 (page 357) after quoting a letter dated 10 October 1894 which was signed by ‘W. Steinitz, Chess Champion of the World’. Steinitz was addressing Lasker, reclaiming from him the title he had just lost, on the grounds that Lasker was refusing the agreed rematch:

‘No doubt you could retain the champion title, and prevent your ever being beaten on the checkered board, if the precedent were to be established that the champion could quite alone choose his own time of playing again, and break a positive agreement for a match, first on the plea of “a tour round the world”, and next of “chess and other engagements”, which it was your pleasure to enter into subsequently, instead of making preparations to fulfil your previous promise. But the general public will probably allow that I, as well as my backers, may hold a different opinion on the subject, and I shall therefore take the fullest responsibility of retaining the champion title, which you have forfeited by your letter of 22 June, after the expiration of the time of grace which I gave you for reconsideration.’

(2407)

From Chess and Jews:

‘Dr Hermann Adler and Steinitz’, on page 367 of the Chess Amateur, September 1911:

‘Mr Sharp, chess editor of the Reading Observer, gives a very interesting account of the connection of the late Dr Hermann Adler (Chief Rabbi) with chess. In his younger days, in common with so many learned Jews, he was very fond of chess. Lasker, of course, it is well known, is a Jew, and that great man Steinitz was of the same persuasion. Wilhelm Steinitz once expressed the opinion that the reason why Jews are so clever at chess is because of their patience, pure breeding, and good nature. Having been the most persecuted race in the world, they have had the least power to do harm, and have become the best natured of all peoples. Their religion, also, is a factor which contributes in the same direction, because it is combined with persecution to preserve their morals and good nature. Then the purity of their breed, as Steinitz asserted, largely helps the Jews in every walk of life, and contributes to their remarkable success, even in the science of chess …’

More particulars are sought on the above statements by Steinitz.

It tends to be forgotten that in 1866 there was some criticism of Steinitz’s wish to play a match against Anderssen. For example, the following appeared on page 379 of the February 1866 issue of the Chess World:

‘… the error committed by Mr Steinitz in consenting to this match is as nothing compared to that which he is rumoured to have in contemplation, to wit, the challenging of Mr Anderssen to a contest, upon even terms, for £100 a side! We suspect, however, and hope that this absurd report will prove to be an idle hoax.’

‘This match’ was a reference to Steinitz’s encounter with De Vere, in which he gave the odds of pawn and move. De Vere won with a score of +7 –3 =2.

(2508)

From Luck in Chess:

W. Steinitz on page 236 of the August 1886 International Chess Magazine:

‘Anderssen once said to me: “To win a tournament, a competitor must in the first place play well, but he should also have a good amount of luck.” I quite agree with that, but it naturally follows that there must be also ill luck in tournaments, of which many instances could be cited, notably that of Winawer, who, after having tied for first and second prizes in Vienna, and just a few weeks before he came out chief victor in Nuremberg, did not win in London a single prize out of eight (to include the special one for the best score against the prize-holders). All this would tend to show that, at least, a single tournament, especially one consisting of one round only, cannot be regarded as a test.’

On page 37 of the Autumn 1993 Kingpin we commented that the Landsberger work was ‘often poorly written and edited’. From page 253 of the book:

Louis Blair (Knoxville, TN, USA) points out that four passages on page 36 of William Steinitz, Chess Champion by Kurt Landsberger (Jefferson, 1993) repeat, almost word for word, material in the Preface to Championship Chess by P.W. Sergeant (London, 1938). However, whereas Sergeant wrote that Steinitz ‘did not claim any title when he defeated Anderssen in a match in 1866’, Landsberger asserted, ‘When Steinitz defeated Anderssen he announced that he was the world champion’.

Page 123 of the American Chess Magazine, September 1899, quoted a remark by Steinitz in the Glasgow Weekly Herald:

‘No great player blundered oftener than I have done. I was champion of the world for 28 years because I was 20 ahead of my time. I played on certain principles, which neither Zukertort nor anyone else of his time understood. The players of today, such as Lasker, Tarrasch, Pillsbury, Schlechter and others have adopted my principles, and as is only natural they have improved upon what I began, and that is the whole secret of the matter.’

(Kingpin, 1995)

Steinitz wrote at length about Staunton on pages 210-213 of the July 1888 International Chess Magazine. Below is a digest of salient quotes:

‘… this very Mr Staunton had made himself notorious as the literary persecutor of Harrwitz, Löwenthal and Anderssen, whom he assailed with personal hostilities in his various writings including actually the annotations of games.’

After writing that Staunton had ‘tortured poor Morphy’ over the possibility of a match between them, and in particular Staunton’s suppression of a key paragraph in a Morphy letter, Steinitz referred to ‘my having received similar treatment at the hands of this Mr Staunton’.

‘This Mr Staunton was one of my first opponents in the Literary Steinitz Gambit and an editorial patient whom I had to cure … from his journalistic delusions …’

‘At that very time this Mr Staunton was again the almighty ruler of public opinion in the chess world and his performance against Morphy was remembered only by very few. In his usual manner he commenced attacking my play; a mode of warfare which, I can assure you, always left me indifferent. But finding that this did not draw sufficiently, he made during my match with Bird an assault on my private character by means of what I may call at least a combination of suppressio veri and suggestio falsi …’

‘… judging from the effect which the first shots from these journalistic batteries had on myself, I have always suspected, that Morphy’s subsequent apathy and hatred for chess, which was, I believe, not alone the first symptom but also the cause of decay of his powerful genius, must have originated from the treatment which he received from that Mr Staunton …’

Regarding his own grievance (the ‘falsifications in the Illustrated London News’) Steinitz contacted Staunton both publicly and privately:

‘My move turned out a very good one, I can assure you, for its first effect was that this very Mr Staunton, who had the audacity of mutilating one of Morphy’s letters and of refusing to publish the letter’s correction of false statements until a Right Honorable Lord interfered on his (Morphy’s) appeal; this very Staunton felt compelled to publish my letter in full the very next week, though with an alteration of the date in order to make it appear to some innocent people that I had used the “strong language” before writing the letter ...

The result of the publication of the letter was that though Staunton with his satellites and suckers tried with might and main to expel me [from the Westminster Chess Club], as I had of course anticipated, he soon discovered that he would not find the usual two-third quorum for such a purpose.

... This is my analysis of my first Club fight or contempt without silence gambit, which was a victory for me … Proof of my statement is that with the exception of two or three growling articles … I enjoyed complete literary peace for the rest of his life, about seven years long, from this very Mr Staunton, who had always fancied that he could aggrandize himself by assailing his rivals with the grossest falsehoods.’

(Kingpin, 1999)

See Attacks on Howard Staunton.

We have been unable to find game-scores which fit in with the following report, taken from page 315 of the Chess Amateur, July 1908:

‘Referring to “hallucinations that occur in match and tournament play”, Mr Bruno Siegheim mentions in the Johannesburg Sunday Times that in one of the games of the Blackburne-Steinitz match, a check which could have won a rook was left on for several moves. The possibility was seen by everyone present in the room except the two players. Mr Siegheim adds that a still more curious incident occurred at Breslau, in an Alapin-Blackburne game. Mr Blackburne checkmated his opponent, but assuming that Herr Alapin would see the mate, Mr Blackburne did not announce it. Herr Alapin looked at the position intently, trying to find a move, and the spectators smiled and whispered. At the end of five minutes Mr Blackburne relieved his opponent’s anxiety by informing him that he had been checkmated.’

(2557)

On 16 October 1897 Steinitz was the beneficiary of a testimonial concert in New York and had to endure an adulatory address by Edward Hymes. One sentence will be enough here:

‘Steinitz is to chess the man of all men, not of this generation nor of the past, but of all time.’

Source: American Chess Magazine, October 1897, page 265.

(3232)

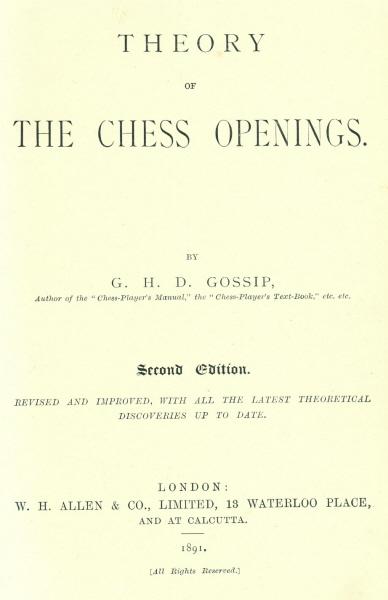

From the entry on G.H.D. Gossip in The Oxford Companion to Chess:

‘He had an unusual talent for making enemies. In his later years Steinitz had the same problem but claimed at the end of his life that he had six chess friends. Gossip had none.’

The grounds for the statement about Gossip are unknown to us, but the other remark seems to be based on R.J. Buckley’s reminiscences about Steinitz referred to in our Chess with Violence article:

‘We never quarrelled. Colonel Showalter [at the London, 1899 tournament] said that he and I were the only exempts. To which Steinitz replied, “No, there are four more, six altogether. From any one of those six I would accept a cigar, and from none other”.’

(3249)

Concerning London, 1899 below is an excerpt from a description of London, 1899 on pages 210-213 of La Stratégie, 15 July 1899 (in our translation from the French). The writer is identified only as ‘André de M.’.

‘The admirers of the veteran Steinitz would have liked to see the old champion obtain a better result than the one he achieved. Even so, his lack of success seems not to have disturbed him too much. On his table Steinitz always had a carafe of pure water, from which he drank large glassfuls while smoking his cigar, which, absent-mindedly, he generally set down, still alight, on the green baize covering the table.’

Where Did They Live? gave these addresses for Steinitz:

2 Princes Street, St Giles without Cripplegate, London, England (1871 British census (C.N. 4756)).

11 Newton Street, Shoreditch, London, England (1881 British census (C.N. 4756)).

328 Classon Avenue, Brooklyn, USA (William Steinitz, Chess Champion by K. Landsberger, pages 173 and 198). Also page 51 of The Steinitz Papers by K. Landsberger, although 318 Classon Avenue was given on page 52.

986 Fulton Street, Brooklyn, USA (William Steinitz, Chess Champion by K. Landsberger, page 198 – see also pages 266-268).

505 26th St., Manhattan, New York, USA (1900 US Federal Census).

A position from page 41 of Les échecs dans le monde by Victor Kahn and Georges Renaud (Monaco, 1952):

White to move

This is stated to be from a game between H.N. Pillsbury and E.F. Wendell in a simultaneous exhibition on 40 boards in Chicago, 1901, the finish being 12 Nxg5 hxg5 13 Qh5 Rxh5 14 Ng8+ Ke8 15 Bxf7 mate.

Did Pillsbury win such a game? The following score was given on pages 319-320 of volume one of the second edition of Schachmeister Steinitz by L. Bachmann (Ansbach, 1925):

Wilhelm Steinitz – N.N.

London, 1873

(Remove White’s rook at a1.)

1 e4 e5 2 f4 Nc6 3 Nf3 Nf6 4 fxe5 Nxe4 5 d3 Nc5 6 d4 Na6 7 Bc4 Qe7 8 Nc3 h6 9 O-O g5 10 Nd5 Qd8 11 Nf6+ Ke7 12 Nxg5 hxg5 13 Qh5 Rxh5 14 Ng8+ Ke8 15 Bxf7 mate.

(3288)

See too page 230 of the City of London Chess Magazine, October 1874, where the Steinitz game was annotated by Zukertort.

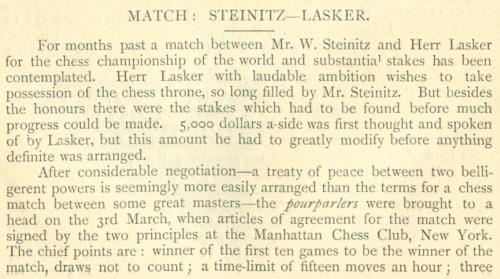

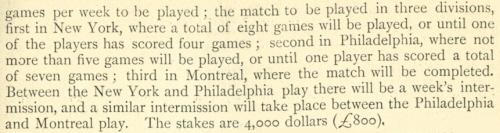

From page 65 of part one of Garry Kasparov on My Great Predecessors (London, 2003), concerning the 1886 world championship match (ten games up) between Steinitz and Zukertort:

‘There was an important nuance: with a score of 9-9 the match would be considered to have ended in a draw, since the players did not want the outcome of such an important duel to rest on the result of one game. Such a rule was to apply later in a number of unlimited matches for the world championship, and it became a stumbling-block in the years when Fischer was champion (as will be described in a later volume).’

It is indeed true that Steinitz and Zukertort’s contract (29 December 1885) stipulated:

‘The Score at Nine Games. Should the score stand at nine (9) games won to each of the players, then the match shall be declared drawn.’

Source: Chess Monthly, January 1886, pages 136-137.

However, on page 118 of the May 1886 International Chess Magazine Steinitz reported that this provision had been amended before the final series of games began in New Orleans on 26 February 1886:

‘Two of the conditions of the match [one of them omitted here, being a minor matter concerning playing hours] were altered by mutual consent of the players, who had agreed, in the first place, to reduce the score, which rendered the match a draw, to eight all, instead of nine all, as previously stipulated. There can be no doubt that both the principals acted bona fide and chiefly in the interest of their backers in agreeing to such a modification of the original terms of the match, for their main reason in adopting the alteration was to exclude all element of chance as much as possible and to avoid rispgg the issues at stake on the result of two games. But, on consideration and in order not to establish a questionable precedent, we feel bound to say that the opinions of some critics, who, without in the least impugning the motives of the two principals, have expressed doubts on the legality of such proceeding, now appear to us reasonable. For it is justly contended that the two players had no right to alter any of the main conditions of the match without consulting their backers, who had deposited their stakes after the chief terms had apparently been finally settled …’

(3324)

Item 264 (unnumbered page) from Napier’s Amenities and Background of Chess-Play (published in three ‘units’, the first two in 1934 and the third the following year)

‘I never see a King’s Bishop Opening without thinking of the first of several lessons I took, when a youngster, from Steinitz. He said, “No doubt you move your knight out on each side before the bishop? And do you know why?” I was stuck for an intelligent answer. He went on to say, “One good reason is that you know where the knight belongs before you know that much of your bishop; certainty is a far better friend than doubt.”’

Emanuel Lasker expressed the following view in an autobiographical article in Lasker’s Chess Magazine, May 1908, page 1:

‘The last tournament held there [in England] was in 1899. The continent has had more than a dozen meanwhile. England has not been the playing ground of a match for the championship of the world since Steinitz beat Anderssen, in 1866.’

The inescapable implication of Lasker’s references to England and to 1866 is that he considered a) that Steinitz’s matches against Zukertort (1872) and Blackburne (1876), both of which took place in London, were not for the world title and b) that, consequently, Steinitz held the world title for 20 years (1866-86) without defending it at all. It is hard to imagine, though, that this was the meaning that Lasker intended to convey.

(3325)

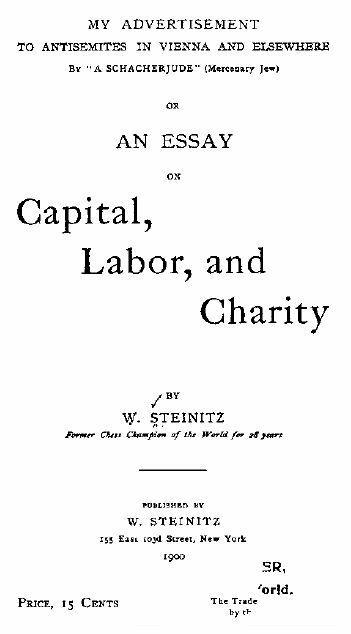

C.N. 3325 gave a series of quotes illustrating various contemporary writers’ views on when Steinitz became world champion. The clearest statement we have seen from Steinitz himself was quoted in his 14 August 1900 obituary in the New York Times, from a pamphlet entitled My advertisement to anti-Semites in Vienna and Elsewhere:

‘And since 1895 I have been obliged at an advanced age and while I was half crippled to export myself in order to import only a portion of my living for myself and family, and this portion did not amount to $250 per annum within the last two years when I deduct traveling expenses and increased cost for staying abroad, although I was chess champion of the world for 28 years!!!’

We also now add a paragraph from page 50 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 18 July 1883, i.e. shortly after Zukertort won the London, 1883 tournament, three points ahead of Steinitz:

‘The chess championship of the world is a subject which will form a topic of discussion in the chess press for some time to come. The last issue of the Bradford Observer contains some remarks on it. The writer argues that Zukertort may hold the title and yet be “quite right in refusing to enter into so hard an engagement” (the match recently proposed is referred to) “after the trial he had to go through in the International”. We disagree. It is very certain that Steinitz was, at one time, fairly entitled to the position of champion, and under such circumstances would hold it so long as he could defend himself against all comers. He has just taken an inferior place to Zukertort, in a tournament, and for the time being Zukertort, in the opinion of some, becomes champion, but if he desires to hold that title he must defend himself against all comers; so soon as he declines to play a match, unless under very exceptional circumstances, he loses his position, and this is more particularly the case when his would-be opponent happens to be the man who for years past has been recognized as the champion. A tournamental advantage is not considered of much moment as regards the chess championship, and unless it can be maintained by after play we should be inclined to dismiss it as one of the freaks of fortune. Steinitz has challenged the only man who has beaten him since he has been chess champion; if he will not play, then Steinitz will be right in resuming his old title.’

A noteworthy point is that the item made no mention of Morphy, who was still alive.

(3750)

Russell Miller (Chelan, WA, USA) quotes from page 169 of the Brooklyn Chess Chronicle, 15 July 1883:

‘The Glasgow Herald furnishes the following intelligence: “Some important results are likely to spring from the positions occupied in the International Tourney by the ultimate prize winners. We understand that Steinitz is about to challenge Zukertort to play a match for the sum of £300 to £500 and the championship of the world, and it is the opinion of some who are in a position to judge of the matter that the match will come off.”’

Noting that Zukertort was reported by the Brooklyn Chess Chronicle to have turned down the match because he intended ‘to make a year’s tour’, our correspondent asks if Steinitz called himself world champion at that time.

Steinitz’s proposal of a match was reported on page 323 of the July 1883 Chess Monthly (edited by Hoffer and Zukertort):

‘Mr Steinitz has authorized Mr Steel to communicate with Mr Minchin with reference to a match which he seems willing to play with Mr Zukertort. The conditions are £200 a side or more if agreeable; the match to consist of eight or ten games; three or four games to be played a week; £50 to be deposited as forfeit money; and play to commence between October and January. Mr Zukertort has authorized Mr Minchin to reply to Mr Steel that he cannot make arrangements for a match at such a remote future.’

This does not seem an altogether fair reflection of Robert Steel’s letter to Minchin (dated 24 June 1883, the day after the London, 1883 tournament ended), which was published on page 42 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 11 July 1883:

‘... The following are the conditions for the match suggested by Mr Steinitz. If they be approved by Mr Zukertort, any minor conditions may be easily arranged.

1. That the winner of the first eight or ten games be the victor.

2. That the games be played under a time-limit of 15 moves per hour.

3. That play shall be carried on either three days or four days per week, as Mr Zukertort prefers.

4. That Mr Steinitz will accept any suggestion of Mr Zukertort’s as to the hour of the day when play shall commence.

5. That the time for commencement of the match shall be fixed for any date between 1 October and 1 January, which may best suit Mr Zukertort.

6. That the stakes be for any sum not less than £200 a side which Mr Zukertort prefers.

7. That the games shall be the property of both players.Mr Steinitz is of opinion that the contest should, in the interest of both players, take place in a private room, and that admission should be allowed to friends of both parties.

Mr Steinitz is prepared to make an immediate deposit of £50, to bind a match on the basis herein suggested.’

Minchin’s reply to Steel, dated 27 June 1883, was given on the following page of the Chronicle:

‘... [Zukertort] begs me to point out to you that owing to his health and avocations he has always, as Mr Steinitz is aware, refused to bind himself down to play a match of chess at any future period. He cannot, therefore, now accept the conditions offered of binding himself to play at any time between October and January next. As a fact, I fear that Dr Zukertort will not be in England at that period, as I believe he purports starting almost immediately on a protracted tour round the world.

I have no doubt that on his return from this tour Dr Zukertort will be quite ready to make a match with Mr Steinitz on reasonable conditions, such as those offered, to promote which, when the time arrives, I shall be happy to use my good offices.’

It will be noted that no reference to the world championship occurred in these exchanges. However, it was evoked in a follow-up item in the next issue of the Chronicle (18 July 1883, page 50). We quoted it in full in C.N. 3750.

(4163)

From Chess and Music:

Steinitz related an encounter with Richard Wagner on page 213 of the International Chess Magazine, July 1887, page 213.

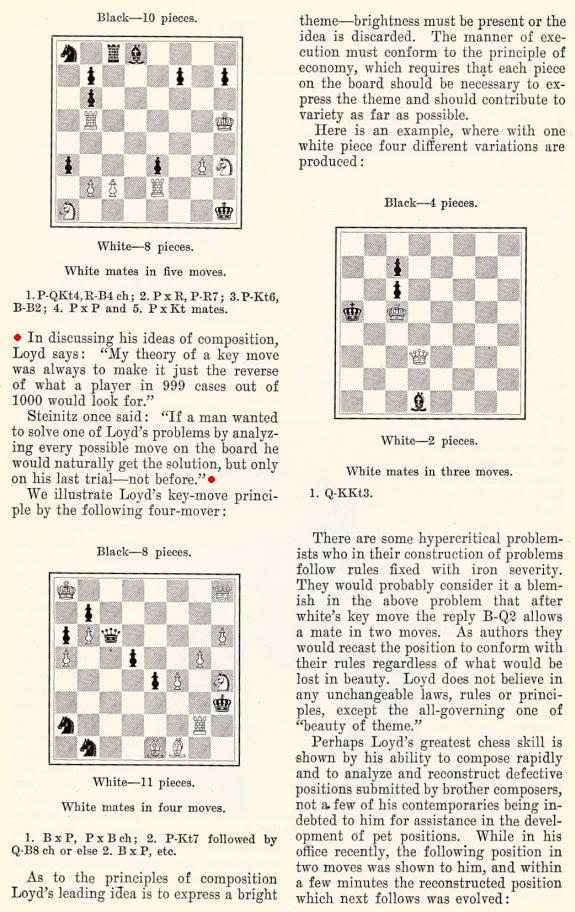

A further illustration of the ‘once’ school of narrative comes from page 24 of Curious Chess Facts by I. Chernev (New York, 1937):

‘Steinitz was once arrested as a spy. Police authorities assumed that the moves made by Steinitz in playing his correspondence games with Chigorin were part of a code by means of which important war secrets could be communicated.’

The identical paragraph appeared on page 31 of Chernev’s Wonders and Curiosities of Chess (New York, 1974), whereas on page 89 of The Fireside Book of Chess by I. Chernev and F. Reinfeld (New York, 1949) the wording was slightly different:

‘Steinitz was once misjudged to be a spy. Police authorities assumed that the moves made by him in playing his correspondence games with Chigorin were part of a code by means of which important war secrets could be transmitted.’

We have yet to find any such incident mentioned in contemporary reports on the two-game cable match in 1890-91 between Steinitz and Chigorin, about which, incidentally, the then world champion wrote on page 107 of the April 1891 International Chess Magazine:

‘Never before in the history of our pastime has a chess contest created such widespread and literally universal interest during its progress as the one just concluded between myself and Mr Chigorin.’

We would, though, draw attention to the following passage by Walter Penn Shipley in the Philadelphia Inquirer, as quoted on page 62 of the American Chess Bulletin, March 1918:

‘We note in the daily papers a curious break in the affairs of Lorenz Hansen, a Dane, but who has been in this country for many years and is a naturalized citizen. Lorenz Hansen has been for many years an enthusiastic chessplayer and an able problem composer. We have published many of his problems in this column, and some of exceptional merit. Lorenz Hansen was recently arrested on a technical charge, the Federal authorities believing that he had a secret code and was communicating with someone at Grand Rapids, Mich. On further examination the secret code appears merely to have been a harmless correspondence game of chess, the moves, as usual, being sent by postal card. It is unnecessary to state that when the true state of affairs became known Mr Hansen was promptly released.

This adventure recalls one of the late William Steinitz. When he played his second match with Lasker at St Petersburg, before leaving this country Steinitz arranged an elaborate code whereby at slight expense he could cable the moves in his match to a syndicate of New York newspapers. Steinitz received a liberal compensation for his work. The old man had spent a great deal of time on perfecting his code, but unfortunately on arriving in St Petersburg the authorities promptly confiscated the code, stating that it was impossible to believe that it was merely for the purpose of cabling chess moves and in reality was to give secret information to parties in America. Being thus deprived of his code, he was unable to cable the moves of his match, and thereby lost the fruit of many months’ hard labor. At the termination of the match the code was returned to Steinitz by the Russian authorities, stating they had found it to be as represented, but then, of course, it was too late to be of any use to the world’s master. Steinitz’ breakdown was unquestionably partially due to his great disappointment in this matter.’

What truth there is in any of the above we have no idea, and for now we merely point out that the second match between Steinitz and Lasker was held in Moscow, not St Petersburg.

(3345)

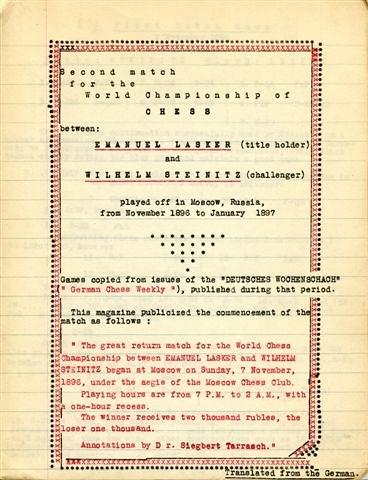

A paragraph from page 468 of the December 1896 BCM:

‘The long-expected return match between Messrs Lasker and Steinitz, for the championship of the world, began at Moscow, on 7 November, having been delayed a few days owing to a political difficulty. Mr Steinitz had arranged to telegraph the games to America in cypher, which cryptogram, however, had to be submitted first to the censorship of the Russian government, and it took some time to convince the authorities that there was nothing nihilistic in the mysterious messages to be sent.’

(6699)

From page 145 of Chessreading Treasure by Wilf Holloway (Nörten-Hardenberg, 1993):

‘In New York in 1893 [sic – 1894] Wilhelm Steinitz lost a game against Adolf Albin and this was not only unusual because Steinitz was generally the better player. That game also went down in history for another reason – it was the first ever recorded grandmaster time claim win. Despite a clear rule it was then still considered unsporting to claim a win, but with an otherwise lost position Albin stuck up for his rights when his opponent overstepped the limit. One must actually ask oneself what is more unsporting, deliberately taking more time than one is allowed or appealing against this sort of thing to avoid being disadvantaged? We see things more clearly perhaps these days but Albin was considered to be a cad that day. Aren’t people strange?’

Regarding the finish to this game, below is the account published on pages 107-108 of the December 1894 Chess Monthly, although caution is invariably required over the Monthly’s writings about Steinitz:

‘Practically, Steinitz only drew one game, against Hymes, whilst he lost one game by exceeding his time in the game with Albin. He ought to have lost this game on its merits, but in the end he had the best of it. An appeal was made to the committee by Steinitz against their decision of scoring the game against him, but the committee maintained their decision, and justly so. It is difficult to see why he should have protested at all; and, if we are not mistaken, Steinitz himself was not slow to avail himself of any infringement of the time-limit rule on former occasions. At the Vienna tournament, 1882, he claimed the game from Winawer when, to ascertain whether the hand of Winawer’s clock had passed the hour, the blade of a penknife had to be used. The eye, unaided by any instrument, could not detect that the hand had passed the figure upon the dial; further, in the same tournament, Bird, who did not take down the game, was under the impression that Mason had exceeded his time, and stopped the game. Upon remonstrance on the part of Mason, the game proceeded, and was won by Mason. Subsequently an agitation by interested competitors was got up (Steinitz amongst them), the matter was brought before the committee, and the game was scored against Mason. In the game with Albin, Steinitz had consumed his allotted two hours for 33 moves instead of 36. It is quite clear that he could not make three more moves in no time; his game was therefore forfeited by the rule governing the time-limit, and he should have resigned the game without protest.’

As noted on page 172 of the Vienna, 1882 tournament book (published by Olms in 1984), another casualty in that event was Noa, who overstepped the time-limit against Zukertort as early as move 15.

(3370)

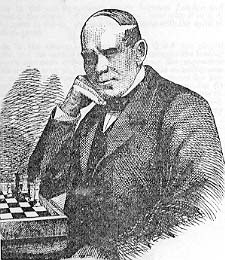

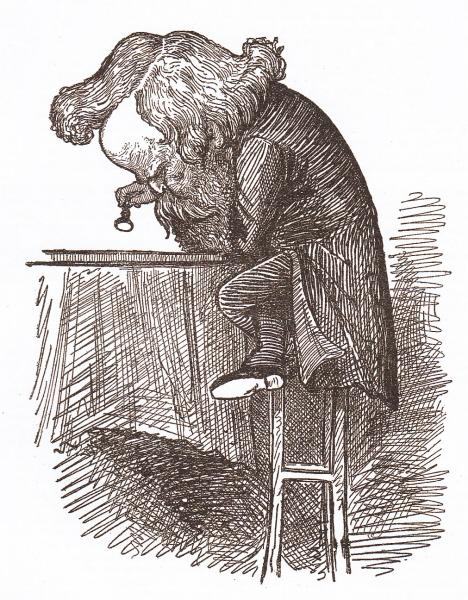

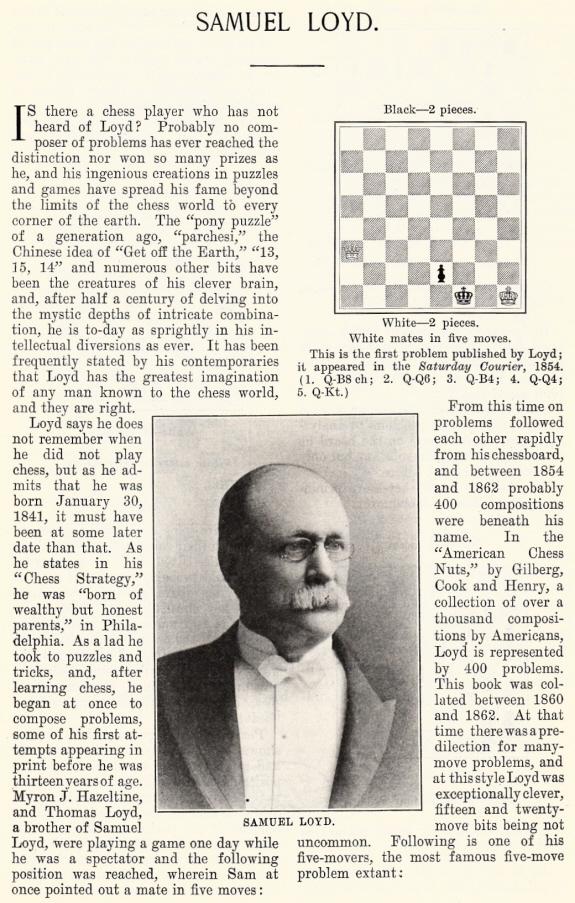

In the Scientific American Supplement, 29 September 1877, page 1454 Sam Loyd had presented:

‘… a portrait of Mr Steinitz as we sketched the little giant half a score of years ago while he was working out a problem to draw with a bishop against knight and pawn.’

‘As we progress … with our proposed record of the important chess events of the past, it will be readily understood why, by common consent, Mr Steinitz has become to be looked upon as the recognized chess champion of Europe.

We have enjoyed the most friendly relations with Mr Steinitz and found him the very pink of honor, and the most jovial little fellow in the world, ready to fight you at chess, or die sooner than give up on some little etiquetical point that he considers correct and proper. His able management of the chess department of the London Field is gaining him a world-wide reputation as the analyst of the day.’

(3397)

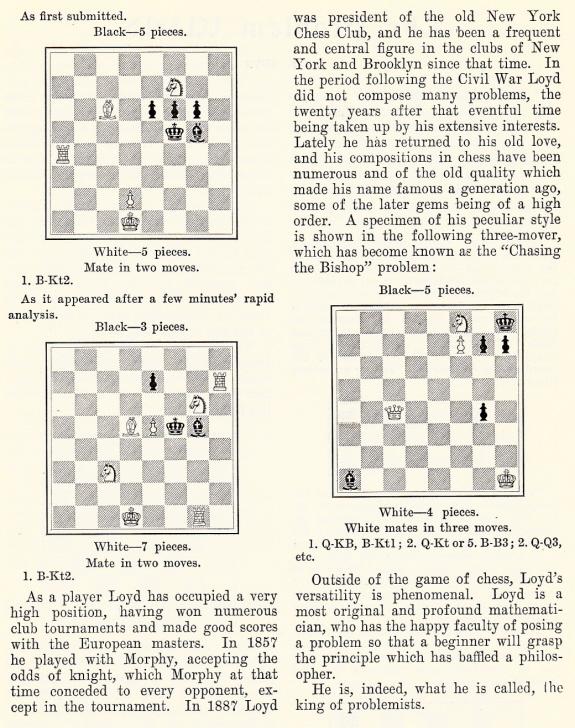

Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England) writes:

‘The woodcut of Steinitz also features a Loyd composition (number 16 in Sam Loyd and His Chess Problems). The incorrectly turned board is presumably Loyd having a little fun at Steinitz’s expense. The woodcut reminds me of a photograph of Steinitz playing Anderssen on page 104 of The World of Chess by A. Saidy and N. Lessing (New York, 1974).’

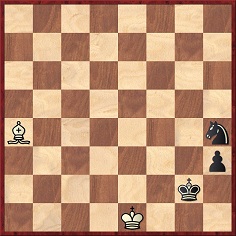

Below is the composition in question, which originally appeared on page 41 of the Chess Monthly, February 1860:

White to play and draw

1 Bd7 h2 2 Bc6+ Kg1 3 Bh1 Kxh1 4 Kf2.

(3400)

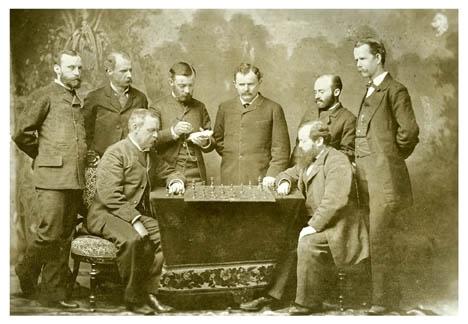

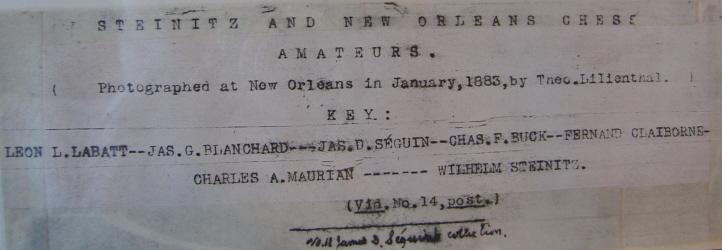

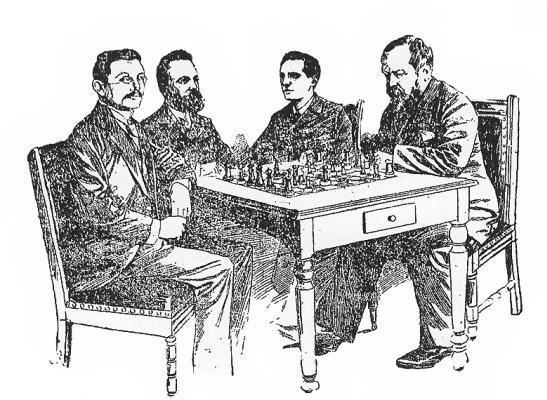

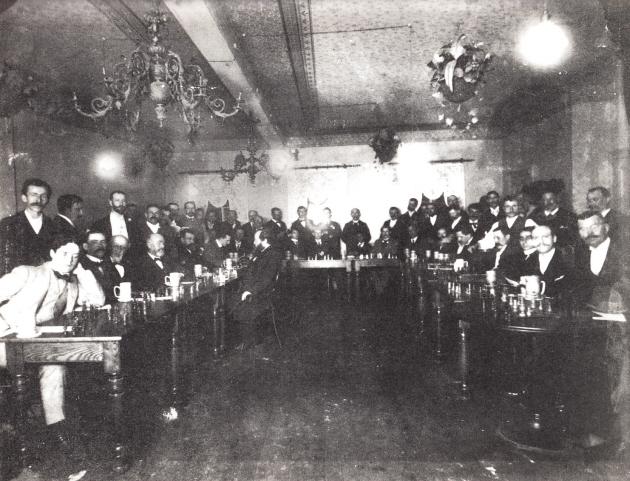

Michael Negele (Wuppertal, Germany) raises the subject of the following photograph in The Steinitz Papers by Kurt Landsberger (Jefferson, 2002):

The caption in the book reads ‘Zukertort (third from left) taking notes as Steinitz (seated at right) plays an unidentified opponent, in a seemingly staged photograph, date unknown’. The picture comes from Mr Landsberger’s private collection and is reproduced here with his permission. We invite readers’ suggestions as to who is who.

For a larger version of the illustration, click here.

(3463)

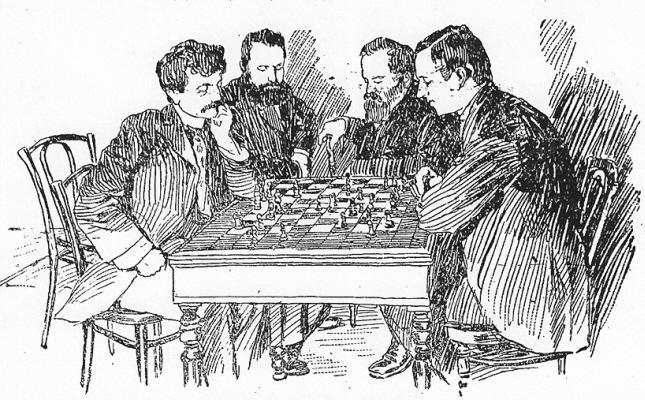

Michael Negele has found an almost complete key in the Cleveland Public Library:

(5173)

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) points out that this photograph appeared on page 2 of the third part of the Daily Times-Picayune (New Orleans) of 9 March 1913 (see the pdf version). The earlier (Cleveland) key did not identify the man standing on the right, but now a name is provided: M.F. Dunn.

(7611)

The photographer was identified in C.N. 5173 as Theodore Lilienthal of New Orleans. From the same period (January 1883) the Cleveland Public Library has a portrait of Steinitz, reproduced below with permission, which also mentions Lilienthal:

(11743)

On page 174 of CHESS, 8 January 1955 Steinitz was said to have declared:

‘Let me establish an unassailable knight on K6 and I can go to sleep for the rest of the game.’

(3514)

From Mark N. Taylor, who is Assistant Professor of English at Berry College, Mt Berry, GA, USA:

‘“Chess and Chessic Motifs in English Prose Narrative Since 1700: An Annotated Bibliography” aims to be a comprehensive listing of narratives which include chess in substantial or significant ways. Each entry will be annotated, summarizing the chess content. The project currently lists over 1,000 titles. The finished list will probably number between 1,500 and 2,000 titles. I welcome any assistance, particularly in identifying the less obvious books and short narratives, especially for the period 1945 to about 1985, including short stories published in chess periodicals. Anyone wishing to contribute relevant information should contact Mark N. Taylor at mtaylor@berry.edu, or at the Department of English, Box 350, Berry College, Mt Berry, GA 30149-0350, USA.’

Our correspondent has provided the following sample entry from his project:

‘Brunner, John. The Squares of the City. New York: Ballantine, 1965. 319 pp. Pbk. Intro. by Edward Lasker. (GENRE: Fantasy thriller novel by a noted science-fiction author. SUMMARY OF CHESS CONTENT: The story is not about chess but about two South American political antagonists and their followers. The main plot, however, is precisely structured according to the moves of the 16th Steinitz-Chigorin world championship match game, Havana, 1892, explained in the author’s end note. Brunner returns to this theme in his 1980 novel, Players at the Game of People, but without explicit chess references. MOTIF: life is like a chess game.)’

(3616)

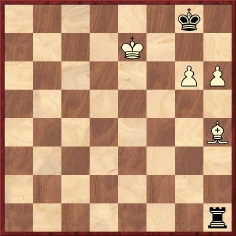

On page 130 of the May 1951 Chess Review a reader, E. Gram-Larsen of Solar, Norway, wrote regarding a Lasker v Steinitz ending:

‘In the 14th game of the second world championship match, the following position occurred after Black’s 52nd move:

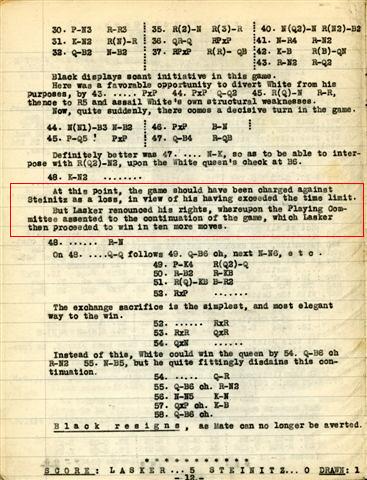

There followed 53 Rc2?? Rxc2+ 54 Kxc2 and Black resigned after White’s 78th move. But if Black had played 53...Ra1+ White might have resigned as his rook on d1 is lost. It could have been Emanuel Lasker’s greatest blunder.

I have the game from Ludwig Bachmann’s book Schachmeister Steinitz, Vol. 4, Ed. 1921. It was played on 29 December 1896. I thought there might be errors in the score – there are many in other places in the book – but, so far as I can see, the moves leading to the above position are in order.’

We believe, however, that Bachmann erred by putting as White’s 50th move Rd6-d1, rather than Rd6-d8, and that there was thus no blunder by Lasker at move 53.

Position after 49...Kd4-c5

Although 50 Rd1 was also given in the Weltgeschichte des Schachs volume on Steinitz by David Hooper (Hamburg, 1968) and the two editions of Chess World Championships by James H. Gelo (Jefferson, 1988 and 1999), all contemporary magazines verified by us so far have 50 Rd8. Examples are Deutsches Wochenschach, 10 January 1897, pages 6-7 and Deutsche Schachzeitung, February 1897, pages 38-40.

(3847)

From page 166 of Why You Lose at Chess by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1956):

‘Wilhelm Steinitz was one of the three greatest chess masters of all time. (I rank him with Lasker and Alekhine.)’

(5907)

‘The strongest of all the chess-playing reverends in Britain in the nineteenth century’ was Harry Golombek’s description of George Alcock MacDonnell on page 188 of The Encyclopedia of Chess (London, 1977). However, on page 231 he called John Owen ‘probably the strongest of all the chess-playing reverends of the nineteenth century’, a contradiction pointed out by W.H. Cozens on page 400 of the September 1978 BCM which Golombek resolved in the 1981 Penguin edition of his Encyclopedia by demoting Owen to ‘one of the strongest of all the chess-playing reverends of the nineteenth century’. Steinitz, for his part, called MacDonnell ‘the shady irreverend fou’ on page 147 of the May 1891 International Chess Magazine.

Golombek’s Encyclopedia, which gave more space to G.A. MacDonnell than to A. McDonnell and G.H. Mackenzie combined, also observed regarding MacDonnell:

‘He was a lively, entertaining but far from accurate writer on chess, and many of the unauthenticated and even groundless anecdotes about the great players of the nineteenth century stem from his inventive pen. He was “Mars” in the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News and wrote two entertaining books: Chess Life-Pictures, London, 1883, and The Knights and Kings of Chess, London, 1894.’

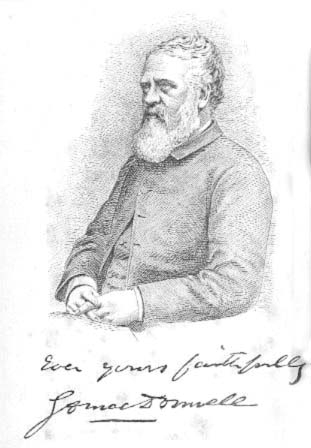

George Alcock MacDonnell

On pages 146-147 of the May 1891 International Chess Magazine Steinitz labelled MacDonnell ‘one of my bitterest and most untruthful persecutors while I was defenseless and powerless to answer’ and stated that MacDonnell ‘has an unconquerable inclination to associate himself with any kind of deception or imposition practiced in the English chess press’.

A notable assertion by MacDonnell was that a negative book review by Steinitz led to the closure of the City of London Chess Magazine. On pages 39-40 of The Knights and Kings of Chess MacDonnell wrote of Steinitz:

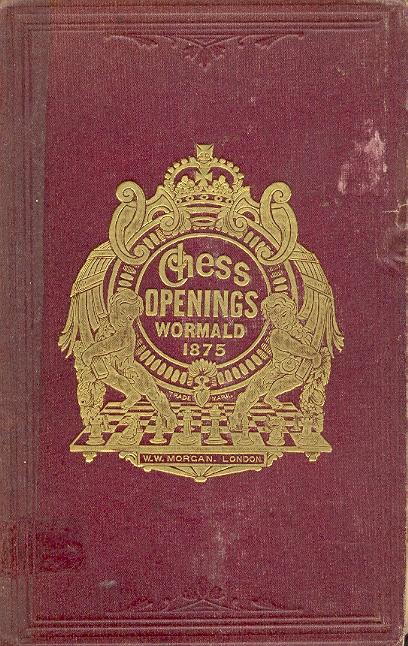

‘Years ago he said to me, “Nothing would induce me to take charge of a chess column”; and when I asked why he replied, “Because I should be so fair in dispensing blame as well as praise that I should be sure to give offence and make enemies.” However, when offered a column in the Field, he accepted it, and conducted it for some time with fairness and decorum. His first false move was his attack on Wormald’s book on the openings. When he showed me the proof of his review, I at once condemned its tone, and advised him to omit personalities. But he declined to do so and, the Field rejecting the article, he was fain to publish it in the City of London [Chess] Magazine, where its appearance caused much confusion, and led ultimately to the extinction of that journal. Of the article, suffice it here to say that it filled eight octavo pages, took Steinitz eight months to write, and took his friends eight years to forget.’

Wilhelm Steinitz

When The Chess Openings by Robert B. Wormald, a 317-page volume, appeared in early 1875 it was warmly welcomed by the reviewers. On pages 44-45 of the March 1875 issue of the City of London Chess Magazine John Wisker wrote that ‘the high praise which has been bestowed upon this work in different quarters seems, on careful examination, to be well deserved’ and he added regarding Wormald:

‘He has executed his task with remarkable accuracy, and has yet limited his pages to the time and memory of every amateur. It is certainly the best book on the openings that exists in English; nor does it appear at all likely that a more convenient or trustworthy guide will be produced just now.’

On page 253 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, April 1875 William Wayte wrote similarly:

‘We shall not follow our contemporaries in discussing Mr Wormald’s treatment of the openings in detail, but we gladly endorse their opinion that we have here the best book on the chess openings in the English language.’

Steinitz’s review of The Chess Openings did not appear in the City of London Chess Magazine until the end of the year, in two parts (November 1875, pages 297-304 and December 1875, pages 331-336). It was thus considerably longer than the eight pages referred to by MacDonnell. Steinitz’s first two and a half pages were an introduction which firstly set out the responsibilities incumbent on chess writers:

‘A chess author is under the obligation of producing in his examinations of each form of play a complete chain of combinations, every link of which is required to be perfect; for if there be the slightest flaw in any of the propositions whereby he supports his conclusions, the whole structure of his analysis tumbles down, like a house made of cards, at the slightest touch. The combined gifts of accuracy, sound originality, correct judgment, and faithful patience – in a word, the chess genius necessary to the fulfilment of such an object – are no common properties, and cannot be accredited to every one who professes to have discovered his own great qualifications for such a purpose by a process similar to the one which enabled the German philosopher to evolve a camel from the depths of his inner consciousness.’

Robert Bownas Wormald

Steinitz then brought in Wormald’s name:

‘Mr Wormald is certainly a problem composer of high merits (of which we shall speak more anon), though we believe he has never succeeded in gaining a prize in any problem competition, and might, therefore, be regarded as scarcely tip-top even in that respect. But, assuming that he ranked highest in the region of chess fiction, it would not give him any title of prominency in the realities of the game, where a multitude of the deepest problems are presented for immediate solution at every stage. No reciprocity has ever been alleged to exist between the qualities requisite for the composition of fine problems and the capacities that command success in the struggles over the board.’

Steinitz commented that ‘we must confess our total ignorance of any achievement on the part of Mr Wormald which would place him on a level even with second-rate players’ and added:

‘Nor have we ever heard of a single good game played by Mr Wormald, against a strong opponent, wherein he might have shown any such marked ability as usually distinguishes the skirmishes of strong masters which appear in the periodical chess publications of the day. So far Mr Wormald has given little indication of his having learned anything before he attempted to teach, and his chess pugnacity seems to have been reserved for the semi-controversial book under our notice, which abounds with attempted exposures of alleged errors that occur in other chess works.’

The next accusation by Steinitz was that Wormald had been too critical of most of the established authorities, with one exception:

‘... we felt, even before investigating the truth of his charges, that some of his long-winded and elaborate demonstrations of the peccadilloes alleged against other writers were doing violence to our toleration. ... Heydebrandt [sic], Jaenisch, Max Lange, Neumann, Suhle – nay, even the combined efforts of Morphy and de Rivière, do not pass the author’s scrutiny unscathed; but we could not find a single instance where he expressly ventured to differ from any recommendations made by the late Mr Staunton in his numerous chess works.’

Nor did Steinitz consider that Wormald had exercised sufficient care ...

‘... on the correction of his proofs, and the expunging of clerical blunders and bewildering misprints, which occur in his book in a larger proportion than in any other existing chess work worthy of the name. This sort of carelessness is in itself quite unpardonable when often recurring; but when we find it also combined with a complete failure of establishing the immense majority of the derogations attempted against contemporaries and previous chess teachers, we are led strongly to suspect that Mr Wormald’s conscience cannot be of a very exact description. ... We have no hesitation in terming Mr Wormald’s Chess Openings a slovenly work, to the contents of which Lessing’s celebrated verdict might be applied, “What is new is not true, and what is true is not new”.’

Steinitz then undertook a detailed spot-check of the book’s analysis. Examples are given below, and we have added in square brackets the relevant opening moves, as well as two diagrams.

‘In the Petroff’s Defence the author gives, in page 14, [1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nf6] 3 d4 exd4 best, which the German Handbook justly considers much inferior to 3...Nxe4, on account of the continuation 4 e5 Ne4 5 Qe2 Bb4+ 6 Kd1, etc. On the same page, fifth line from the bottom, a piece of carelessness occurs which would be most vexatious and perplexing to the beginner, who would rack his brains to find any reason for the suggestion in the book, without thinking it possible that the author only committed a simple blunder by recommending [after 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 d4 exd4 4 e5 Ne4 5 Bd3] as “better still” 5...Qe7, whereby a piece is left en prise without rhyme or reason.’

‘On page 19, fourth line from the top, we are puzzled to find the author’s meaning when he urges [after 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 c3 Nf6 4 d4 exd4 6 e5 d5 7 Bb3] 7...Bb4+ as Black’s best rejoinder. The check is simply impossible, but as a set-off two pieces are left en prise by the move.’

‘Towards the middle of page 25 an addendum is made to a variation which Theorie und Praxis left off without further comment. Had Messrs Neumann and Suhle known how they would be supplemented, perhaps they would have taken a little further trouble; but of course it could not occur to them that any later writer could be so totally devoid of chess instinct as to recommend [after 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 O-O Nf6 5 d4 exd4 6 e5 d5 7 exf6 dxc4 8 Re1+ Kf8 9 fxg7+ Kxg7 10 Ne5 Re8 11 Bh6+ Kg8 12 Nxc6 bxc6 13 Rxe8+ Qxe8 14 Nd2 Qe6 15 Qh5 Qf5 16 Qh4 Be6 17 Ne4] 17...Bb6

and then dismiss the position with the short remark, “and White still has some attack, but Black has a pawn more, [and] a strong position”. It requires little experience to see that Black’s best course consists in securing the draw by 17...Be7, with some chance of winning; for in the position where the author leaves his variation White might still continue 18 Nf6+ Kh8 19 g4 Qg6 best 20 Bf4, threatening 21 Be5 with a strong attack.’

‘... It struck us that in common fairness we ought to take a glance into the author’s treatment of the QBP opening, which has been much commended elsewhere. We have to look no further than to Black’s sixth move, in the first main variation in order to discover a state of hopeless confusion in the author’s remarks, at the top of page 42. He there thinks fit to condemn a move which would strike us as the best at first sight – viz. [after 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 c3 f5 4 d4 d6 5 dxe5 fxe4 6 Ng5] 6...Nxe5. In support of his view he gives a sub-variation wherein the queen checks backwards and forwards [6...Nxe5 7 Nxe4 d5 “best” (Wormald) 8 Qh5+ Ng6 9 Ng5 Nf6 10 Qe2+ Be7 11 Ne6 Bxe6 12 Qxe6 Qd7], which only seems to help the defence to develop and consolidate all his forces in a manner totally opposed to the spirit of an open game.

On the 11th move he overlooks the decisively superior 11...Qd6, whereupon White dare not take the g-pawn ch, on account of the reply 12...Kf7, followed by 13...Bg4; and he innocently concludes his sub-variation with the observation “and Black has the better game”, though he evidently meant to prove at starting that the indicated line of play should turn out to the disadvantage of the defence. Proceeding, however, with the main variation, containing the alleged better line of defence, we would (at the fifth line from the top) much prefer [after 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 c3 f5 4 d4 d6 5 dxe5 fxe4 6 Ng5 d5] 7 Bb5, threatening 8 Qa4, either before or after capturing the knight, according to circumstances, while the author’s 7 e6 is no doubt premature.’