Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [111] | next >> | Current column |

8325. An unusual queen offer

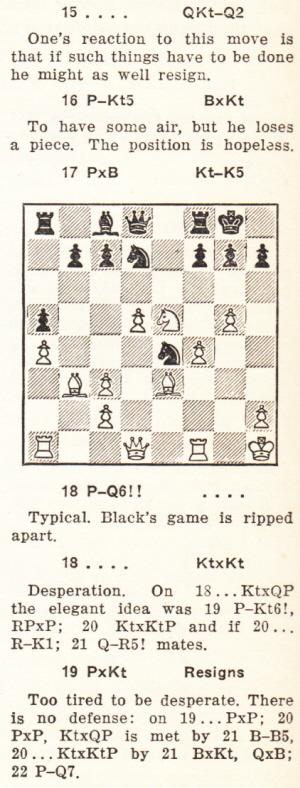

Salo Landau – N.N.

Simultaneous display, Dordrecht, 29 February 1928

Four Knights’ Game

1 Nf3 Nf6 2 b3 Nc6 3 Nc3 e5 4 e4 Bb4 5 Nd5 Nxe4 6 Qe2 f5 7 Nxb4 Nxb4 8 d3 Nf6 9 Qxe5+ Kf7 10 Ng5+ Kg6 11 Qg3 Nh5 12 Qh4 h6 13 Nf3 Nxc2+ 14 Kd1 Nxa1

15 Qxh5+ Kxh5 16 Ne5 g5 17 Be2+ g4 18 h3 Qh4 19 hxg4+ fxg4 20 Bxg4 mate.

Source: page 74 of Combinaties uit de Schaakpartij by Lodewijk Prins (The Hague, 1935):

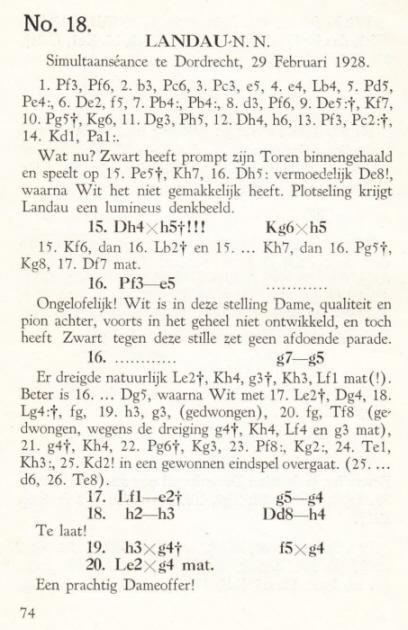

8326. Observations on Euwe

The opening words of the chapter on Euwe on page 199 of The Great Chess Masters and Their Games by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1952):

‘“Dr Euwe is the most underrated player in the world.” Reuben Fine was absolutely correct when he made that flat statement in 1940.’

Fine’s observation, made slightly later than Reinfeld indicated, is given below, from page 200 of the November 1941 Chess Review:

‘To my mind Euwe is the most underrated player in the world. The common opinion (rarely heard in public but held by many people) is that he won the first championship match in 1935 because Alekhine drank too heavily, and that he lost the return match because Alekhine had restored his health.

Nothing could be further from the truth. Alekhine’s chess in the first match was no worse than the quality of chess he had been producing in the four or five years preceding the 1935 debacle, while Euwe’s play in the return encounter was considerably below his best form. For example, Alekhine’s games in his 1934 match against Bogoljubow were certainly no masterpieces, but Bogoljubow simply was not good enough to take advantage of it. And again in the second match Euwe made a number of incredible blunders.’

Source: Aljechin-Euwe by Guus Betlem Jr (Helmond, 1936)

‘He was described as “a man-eating tiger”’, commented page 34 of the February 1982 BCM at the start of ‘Dr Max Euwe (1901-1981) In Memoriam’, without any details being furnished. On page 73 of Max Euwe (Alkmaar, 2001) Alexander Münninghoff provided a ‘once’ version:

‘“An efficient man-eating tiger” was the epithet the American master Napier once coined for Euwe ...’

The phrase had been quoted by Lodewijk Prins on page 166 of Master Chess (London, 1950):

‘Euwe has been described by W.E. Napier as “an efficient, man-eating tiger”. The phrase sounds far-fetched, and many who regard the former world champion as primarily a positional player and theoretician will be surprised at this qualification. The following game from the Dutch championship, 1938 [a draw between van Scheltinga and Euwe] may make them change their minds.’

In item 147 in ‘unit two’ of Napier’s Amenities and Background of Chess-Play (New York, 1934) W.E. Napier wrote:

‘Euwe v Alekhine

As contender for the proud title held by Alekhine, any game between them has special interest.

This one, played in Amsterdam, in 1926, exhibits a challenger of steady nerve, stout heart, and an efficiency like a man-eating tiger’s, – working at his trade.’

Napier then gave the eighth match-game between Euwe and Alekhine (The Hague, 1927, in fact), chopping off the last ten moves by putting ‘32 P-R6 Resigns’.

When the game, still shortened and still misdated, appeared on pages 251-252 of the single-volume edition of Napier’s book, Paul Morphy and The Golden Age of Chess (New York, 1957 and 1971), the introductory text was also curtailed, maladroitly:

‘This game, showing Euwe when he was a contender for Alekhine’s crown [sic – the match took place almost a year before Alekhine became world champion], exhibits a challenger of steady nerve, stout heart, and an efficiency like a man-eating tiger working at his trade.’

8327. Immigration cards

Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) draws attention to a subset of Familysearch.com which comprises Brazilian immigration cards covering the period 1900-65:

‘It shows identity cards of chessplayers who travelled through Brazil from the 1940s to the 1960s, with a photograph, full name, place and date of birth, nationality, marital status, names of father and mother, profession, place of residence and signature. It is therefore possible to see, for instance, the official names of Najdorf: Mojsze Mendel Najdorf as a Polish citizen and Moisés Mendel Najdorf as an Argentine citizen. The cards also indicate that in public Najdorf used Miguel, and signed with that name. This confirms some previous Perlas Ajedrecísticas on my webpage about Najdorf.

I have translated into English one of the other Perlas: Passengers of the Piriápolis. This gives personal details about the participants in the Tournament of Nations in Buenos Aires 1939, compiled from CEMLA, a database of immigrants and passengers. It is possible, for example, to find the full names of Dez, Larsen, Lauberte, Sorensen, and particulars about such lesser-known players as Andersson, Austbo, Gudmundsson, Raclauskiene, Rometti and Winz.’

8328. Sacrifice

An oddity in the online Oxford English Dictionary (registration is required to consult it) is that the entries for ‘sacrifice’, as a noun and a verb in the chess sense, have nine citations without any attempt to quote early examples. The oldest both date from 1915 (pages 25 and 224 of Chess Strategy by Ed. Lasker, translated by J. du Mont), whereas from Google Books it is immediately clear that the term had been in use centuries earlier.

Which was the first chess book to contain the word?

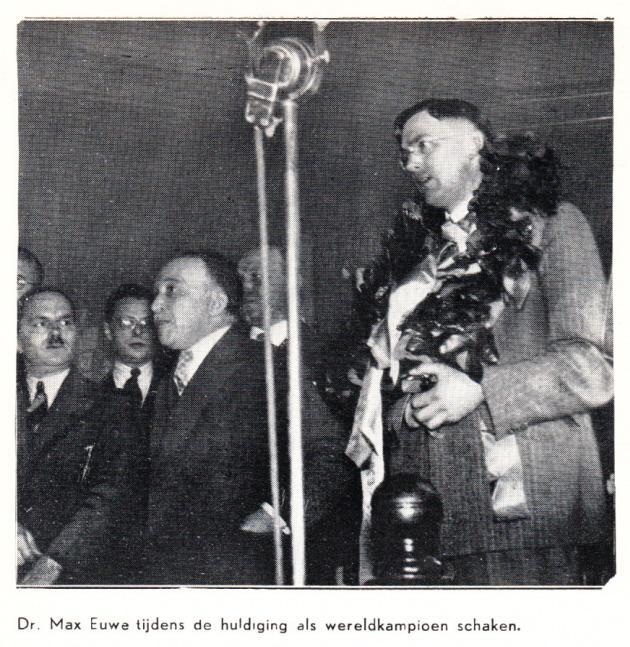

8329. Announced mates

From Stephen Wright (Vancouver, Canada):

‘When and why did the practice of announcing mate in tournament and match games end?’

Is there unanimity today among administrators and officials on the procedure applicable if a player announces mate during a game (and, additionally, in case of an incorrect announcement)? Information will also be welcomed on the most recent games to contain mate announcements. Have there been many significant specimens since Marshall v Bogoljubow, New York, 1924, in which White announced mate in five moves at move 38?

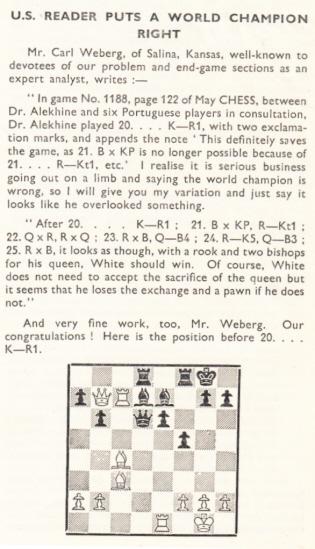

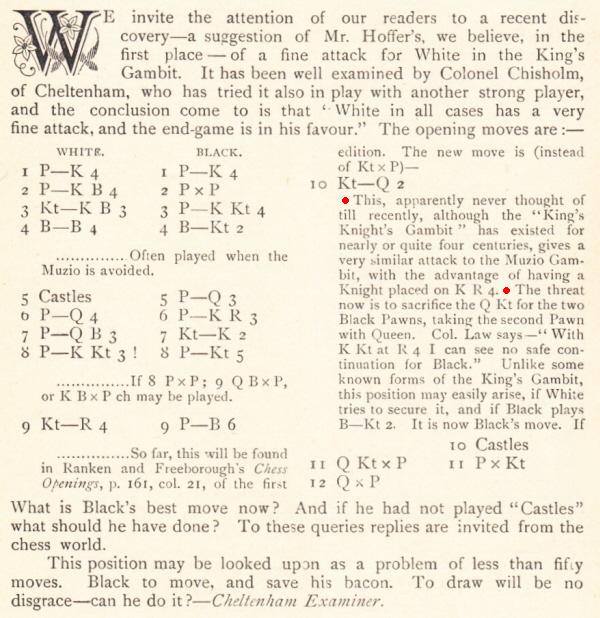

A cutting from page 1 of an untitled scrapbook produced by Dale Brandreth:

The Factfinder refers to a number of older examples of announced mates, and one case of an announced stalemate.

8330. The Fischer v Matulović match

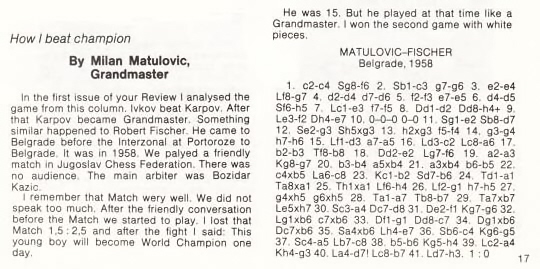

An overview of the Fischer v Matulović match (Belgrade, 1958) is provided in Fischer Mysteries. José Miguel Barrueco Martín (Zamora, Spain) now points out a brief item by Matulović on page 17 of the July 1987 issue of Gens una sumus:

This is the only known game from the match, but it is notable that Matulović does not call it the first of the four.

8331. Tarrasch quote

The haphazard dissemination of quotes is illustrated by a famous Tarrasch remark:

‘Chess is a terrible game. If you have no centre, your opponent has a freer position. If you do have a centre, then you really have something to worry about.’

Some brief observations:

1) The quote appears on countless English-language websites, without any source;

2) No German version is easily traceable on the Internet;

3) The English version was given by F. Reinfeld on pages 61-62 of Tarrasch’s Best Games of Chess (London, 1947) in a note to 19...Nf6 in Schiffers v Tarrasch, Leipzig, 1894;

4) After 16...Rfe8 in the same game, Tarrasch wrote in Dreihundert Schachpartien (the page number varies according to the edition):

‘Ein schreckliches Spiel, das Schachspiel! Hat man kein Zentrum, so hat der Gegner die freiere Stellung; und hat man eins, dann macht es einem schwere Sorge!’

8332. Smyslov and computers

Chess and Computers has a remark concerning Smyslov from page 118 of the April 1963 BCM:

‘He compared chess with music, asserting that just as a mechanical composer could not rival human fantasy, so a machine could not play better chess than a man.’

Stuart Rachels (Tuscaloosa, AL, USA) compares this with a comment of Smyslov’s, dated 30 April 2004, which is quoted on page 122 of The World Champions I Knew by Genna Sosonko (Alkmaar, 2013):

‘I’m working on a book – my 60 best games, I was looking at my game with Savon recently. And I found so many mistakes with the computer, just one mistake after another. And I considered that game one of my best … Yes, the computer can outdo anyone now.’

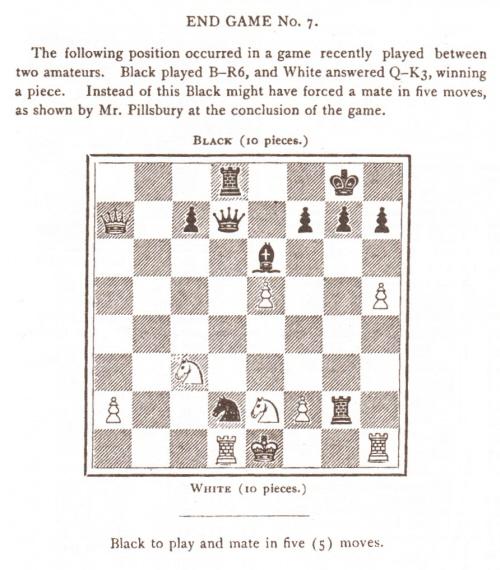

8333. Pointed out by Pillsbury (C.N. 8322)

Page 152 of the August 1892 American Chess Monthly:

The solution was on page 268 of the December 1892 issue:

8334. Announced mates (C.N. 8329)

From Geurt Gijssen (Nijmegen, the Netherlands):

‘For more than 30 years I have worked as a chess arbiter, and it has never happened that a player announced checkmate in x moves.

If it did occur, I would apply Article 12.6 of the current Laws of Chess:

“It is forbidden to distract or annoy the opponent in any manner whatsoever. This includes unreasonable claims, unreasonable offers of a draw or the introduction of a source of noise into the playing area.”

The player can be given a warning, but I would also be inclined to add some extra time to the opponent’s thinking time, and especially if any such remark were made when the opponent was short of time.

In my opinion, announcing checkmate in a certain number of moves is annoying, distracting and also intimidating for the opponent, and it is therefore forbidden.’

8335. Man-eating tiger (C.N. 8326)

‘The American grandmaster Reuben Fine called Euwe an efficient man-eating tiger.’

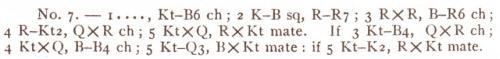

That comes from page 89 of My Chess (Milford, 2013), Hans Ree’s latest collection of superior nattering, but it is unclear why Fine’s name has been introduced. As regards the attribution to Napier (C.N. 8326), the following appeared on page 11 of Euwe’s Meet the Masters (London, 1940):

‘Napier once described Euwe as “an efficient man-eating tiger”.’

Page v of the Preface implies that this section was written by L. Prins and B.H. Wood.

Also from page 11 of Meet the Masters

(immediately after the tiger quote):

‘Alekhine contributed a far more searching analysis of his [Euwe’s] style in an article in the Manchester Guardian soon after the conclusion of the last world’s championship match.’

That article (Manchester Guardian, 28 December 1937, pages 11-12) is given, together with others by Alekhine and Euwe in the same newspaper, in our latest feature article, Euwe and Alekhine on their 1937 Match.

8336. Alekhine’s French citizenship (C.N.s 8054, 8058 & 8284)

Denis Teyssou (Paris) informs us that he has been authorized to post on his website documents relating to Alekhine’s application for French citizenship in the 1920s.

8337. The episode of the fainting lady

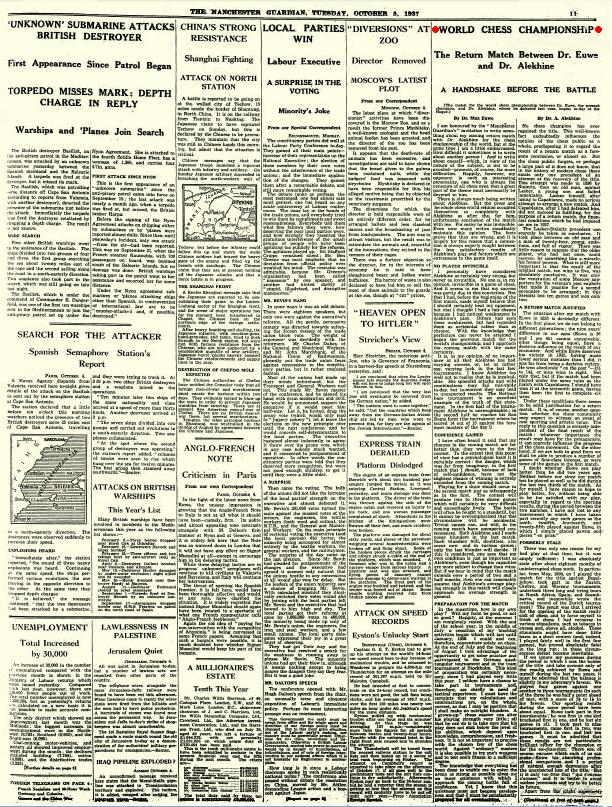

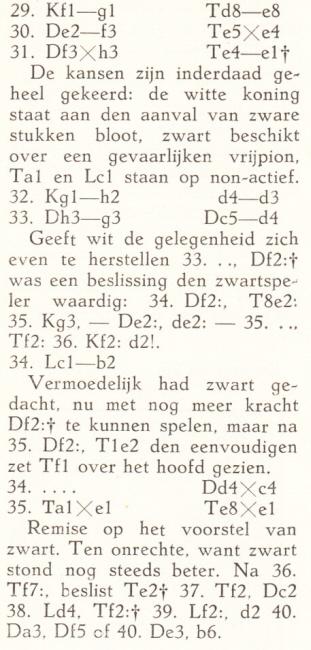

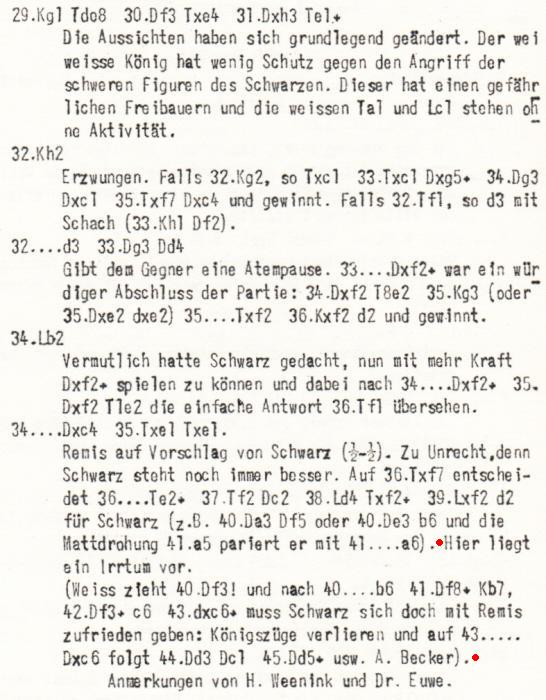

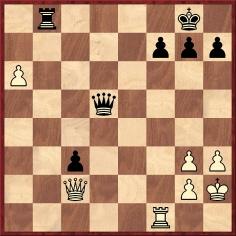

This position arose after 33 Qg3 in Nimzowitsch v Weenink, Liège, 24 August 1930. The Dutchman played 33...Qd4, and the game was agreed drawn two moves later.

It was subsequently indicated that 33...Qxf2+ would

have won. From page 222 of H.G.M. Weenink by M.

Euwe, M. Niemeyer, A. Rueb and B.J. van Trotsenburg

(Amsterdam and Haarlem, 1932):

Part of the subsequent analysis was disputed by Albert Becker on page 32 of the Lachaga volume on Liège, 1930 (Martínez, 1976):

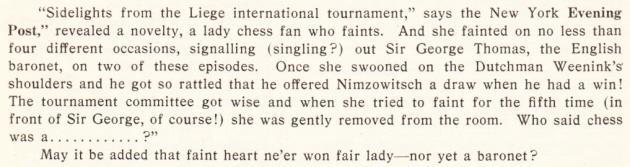

Nimzowitsch’s annotations in Denken und Raten – reproduced on pages 162-164 of Aaron Nimzowitsch 1928-1935 by Rudolf Reinhardt (Berlin, 2010) – shed no analytical light on the finish. Nor did he mention an alleged episode at the end of the game which brings us, not before time, to the title of the present item. A woman at Liège, 1930 kept fainting and distracted Weenink into offering a draw against Nimzowitsch in a won position.

From page 147 of the September-October 1930 American Chess Bulletin:

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) has located the report in Horace Ransom Bigelow’s column (‘The Chessboard’) on page 8 of the New York Evening Post, 27 September 1930. He has also found a follow-up (re-hash) item on page 8 of the newspaper’s 15 November 1930 edition:

‘The episode of the “fainting lady” at the international tournament in Liège, Belgium, recently evoked much amusement among our readers, as some of them evidently did not think that chess was also a lady’s game.

They will appreciate the higher strategy of this unknown member of the gentler sex in the game below. Aron Nimzowitsch, the tourney favorite, was in a tight place, for H. Weenink, the genial Dutch problem composer, well known to our solvers, had succeeded in securing a won position against him. Nothing daunted, Lady “X” evolved a higher stratagem: at the critical moment she fainted on Weenink’s shoulder. So flustered became he that he offered his famous opponent a draw, thereby losing a valuable half point. Who said chess was without a “lighter side”?’

Henri Gerard Marie Weenink (Alt om Skak by B. Nielsen (Odense, 1943), page 471)

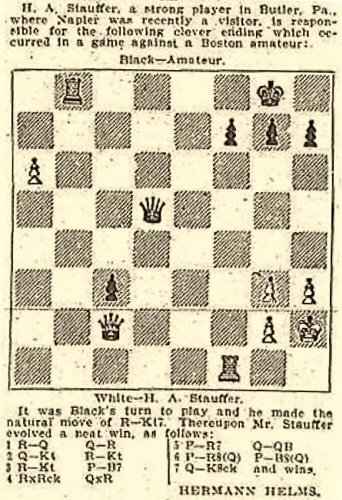

8338. Back-rank tricks (C.N.s 3359 & 3516)

The conclusion was 1...Rb2 2 Rd1 Qa8 3 Qe4 Rb8 4 Rb1 c2 5 Rxb8+ Qxb8 6 a7 Qc8 7 a8(Q) c1(Q) 8 Qe8+ and mate next move.

The full game-score remains elusive, but Olimpiu G. Urcan has found the following on page 7 of the 8 May 1904 edition of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

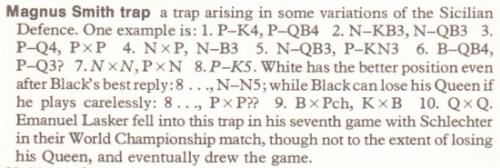

8339. The ‘Magnus Smith trap’ (C.N. 8303)

Further to the final paragraph of C.N. 8303, it is not easy to find the term ‘Magnus Smith trap’ in books, whereas it is frequently seen on webpages. Below is an entry on page 176 of An illustrated Dictionary of Chess by Edward R. Brace (London, 1977):

8340. Walter Pulitzer (C.N.s 8319, 8320 & 8321)

Douglas A. Betts’ Annotated Bibliography lists two chess works by Walter Pulitzer: his collection of problems, Chess Harmonies (New York, 1894), and That Duel at the Château Marsanac (New York and London, 1899).

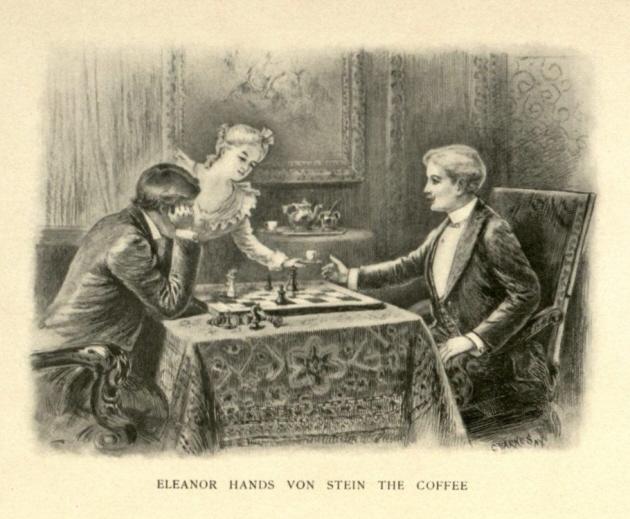

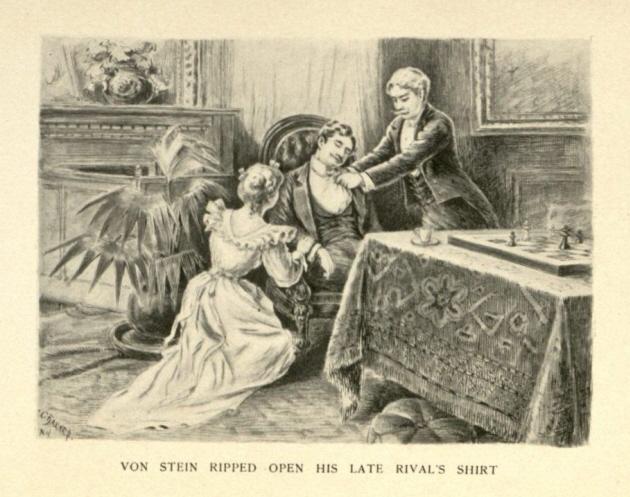

The latter is a novelette about Eleanor Marsanac, who is being courted by Baron Plexus and Count Ferdinand von Stein. The noble inamoratos play a game of chess to determine who will have her hand, and the narrative is given a brief fillip when drugged coffee is served during the playing session.

Few details regarding the game between the Baron and Count are given. From page 90:

‘Plexus moved out his Queen Pawn, and his antagonist followed suit. A few moves later, and the game had developed, rather appropriately, into a Queen’s gambit; but we shall not bore the reader with technicalities.’

Of the three illustrations two feature chess and, courtesy of the Cleveland Public Library, they are shown here:

8341. Draw (C.N. 4666)

From Robert John McCrary (Columbia, SC, USA):

‘In C.N. 4666 I set out my theory that the word “draw” comes from a rule expressed in 1614 in Arthur Saul’s The Famous Game of Chesse-Play. That rule, given verbatim in C.N. 4666, states that a player may “draw stakes” (withdraw from the game) in an “indifferent” game with few men left and no winning prospects. To avoid abuse of this practice, the opponent could increase the stakes and guarantee to win.

I have now found the same theory in another sport. Pages 57-58 of The Dictionary of Cricket by Michael Rundell (Oxford, 1995) have the following in the entry for “Draw”:

“In fact, the word ‘draw’ itself, in its sporting sense, derives from the practice of ‘drawing’ or ‘withdrawing’ the bets made on a contest when its issue was undecided.”

The book gives three examples of this use (“drawn battle”, “they drew stakes” and “London drew with Dartford”) from periodicals’ reports on undecided cricket matches in the 1730s.’

8342. Steinitz sketch

This sketch purportedly of Wilhelm Steinitz comes from page 110 of Schach – mehr als ein Spiel by Herbert R. Grätz (Leipzig, 1964). Is it based on a nineteenth-century picture?

8343. Euwe v Fine, Nottingham, 1936 (C.N. 5394)

C.N. 5394 quoted from two books in which Reuben Fine affirmed that during his game against Euwe at Nottingham, 1936 he received move suggestions from Alekhine and Capablanca, both of whom were anxious to see Euwe do badly.

With all due mistrust we quote now from pages 244-245 of Impact of Genius by R.E. Fauber (Seattle, 1992):

‘The two players who firmly believed that the world championship belonged to them as a birthright – Alekhine and Capablanca – were eaten up that Euwe, a nice guy, almost an amateur, an unassuming competitor now held the crown. Was there no justice in the world? Had insufferable arrogance sunk to such low esteem?

At Nottingham, 1936, where four [sic – five] world champions past, present, or future gathered, the two pretenders – Alekhine and Capablanca – finally found common ground. Although they still hated each other, they volunteered help at all hours to anyone with an adjourned game against Euwe. It would be a disgrace for him to finish ahead of real champions.’

8344. FIDE Congress, Amsterdam, 1954

Stephen Wright (Vancouver, Canada) forwards this photograph which he possesses:

The officials include Marcel Berman, Nathan Divinsky, Harry Golombek, John Prentice, Folke Rogard and Alexander Rueb. We hope to build up, with readers’ assistance, a full key.

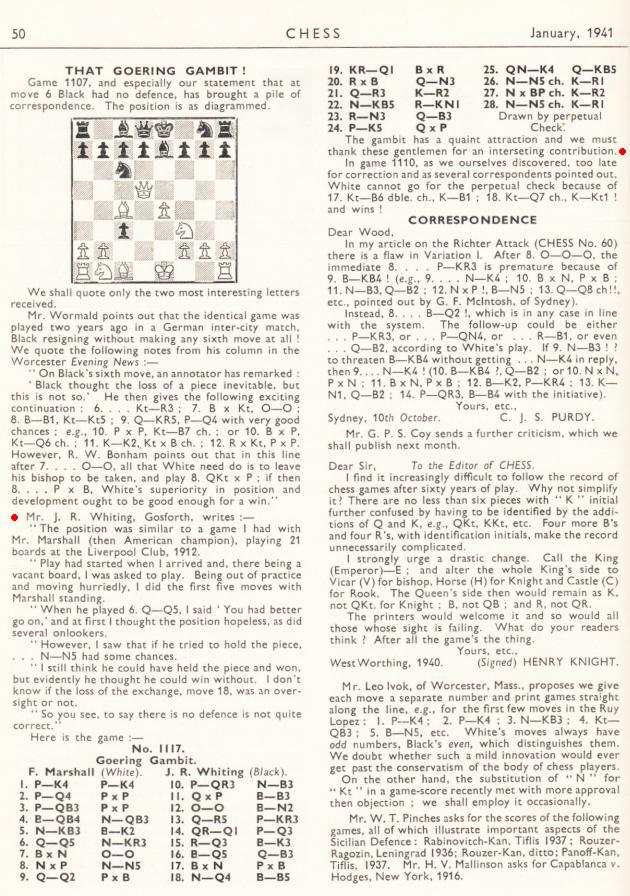

8345. Marshall v Whiting (C.N. 6963)

From page 35 of the December 1940 CHESS:

Publication of that game prompted the following:

8346. H.E. Bird

From page 15 of the Sunday Times, 16 February 1908 (Louis van Vliet’s chess column):

‘We are sorry to learn that the aged chess master Mr H.E. Bird has been ill for some time at 16 Chetwode Road, Upper Tooting. Mr H.A. Richardson, of the St George’s Chess Club, suggests that it would be a real kindness if some of his old friends were occasionally to pay the old gentleman a visit, just to show that he is not quite forgotten.’

Less than two months later Bird died. Funds raised for him at the beginning of the century had eased his last years. The financial appeal had attracted international attention; see, for instance, page 4 of the January 1901 Checkmate and page 158 of the May 1901 Deutsche Schachzeitung. Further details were given on pages 13-14 of the January 1917 BCM.

Page 29 of the hardback edition (1977) of Harry Golombek’s Encyclopedia of Chess illustrated the Bird entry with a picture of Buckle:

The book gave Bird’s year of birth as 1830, the date commonly (unquestioningly) accepted until publication of Eminent Victorian Chess Players by Tim Harding (Jefferson, 2012). Based on detailed research, it reported on page 108 (see too page 364) that Bird was born in Portsea, Hampshire on 14 July 1829 and was baptized on 7 August 1829 (as well as on 28 December 1838).

8347. Naughty

Which master, then aged over 40, was described by B.H. Wood as ‘a naughty boy’?

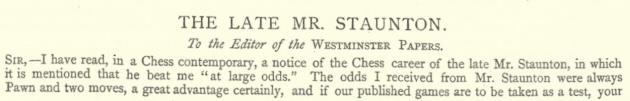

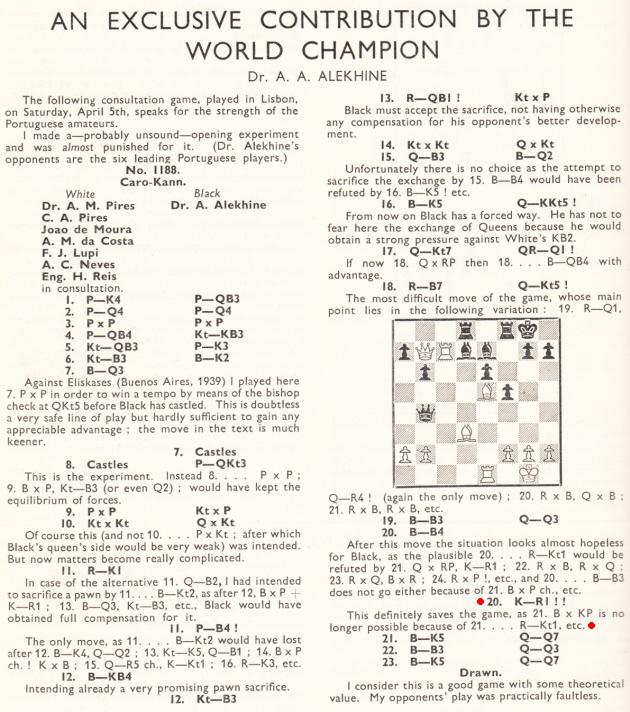

8348. Kennedy on Staunton and Buckle

From pages 88-89 of the Westminster Papers, 1 September 1874:

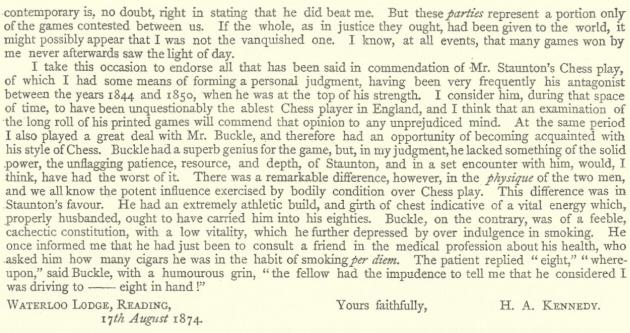

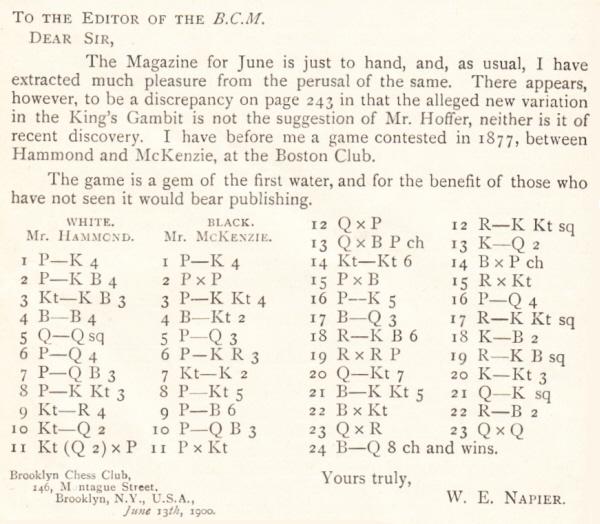

8349. An Alekhine note

In this position Alekhine played 20...Kh8 (‘!!’) and wrote:

‘This definitely saves the game, as 21 Bxe6 is no longer possible because of 21...Rb8, etc.’

He annotated the full game on page 122 of CHESS, May 1941:

On page 161 of the August 1941 issue Carl Weberg disputed Alekhine’s note, giving the line 21 Bxe6 Rb8 22 Qxb8 Rxb8 23 Rxd7 Qc5 24 Re5 Qc6 25 Rxe7:

For a discrepancy over the finish (as from move 21) see pages 656-657 of the Skinner/Verhoeven book on Alekhine. Moreover, we have noted the game-score given incorrectly in a database (... Rfd8 instead of ...Rad8 at move 17).

8350. Simultaneous games

Readers are invited to send in games, preferably unpublished, from simultaneous exhibitions in which they have been involved. For that purpose, and for submitting game-scores in general, a form is now available.

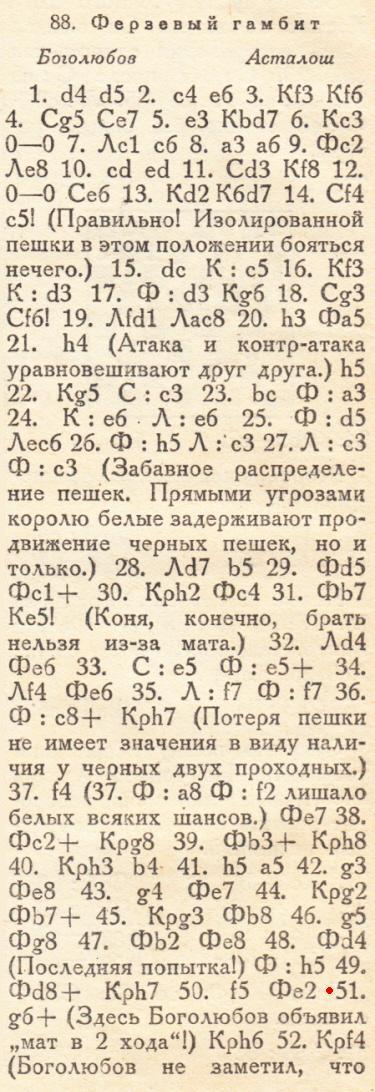

8351. Announced mates (C.N.s 8329 & 8334)

Steve Wrinn (Homer, NY, USA) recalls the report in the Bled, 1931 tournament book by Hans Kmoch that Bogoljubow announced a non-existent mate in two against Asztalos:

Bogoljubow overlooked that after 51 g6+ Kh6 there could occur 52 Qh8+ Kg5 or 52 Qh4+ Qh5.

From pages 110-111 of Kmoch’s tournament book, published in 1934:

The relevant text is on page 121 of Bled 1931 International Chess Tournament translated by Jimmy Adams (Yorklyn, 1987).

Mr Wrinn also mentions that the English edition includes

an article by Salo Flohr, translated from a 1976 issue of

64, which refers to the announced mate (on pages

xi-xii). See too page 29 of the March 2003 CHESS,

in which issue the full Flohr article was reprinted.

8352. 10 Nd2

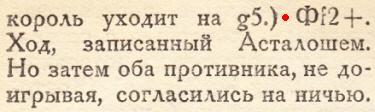

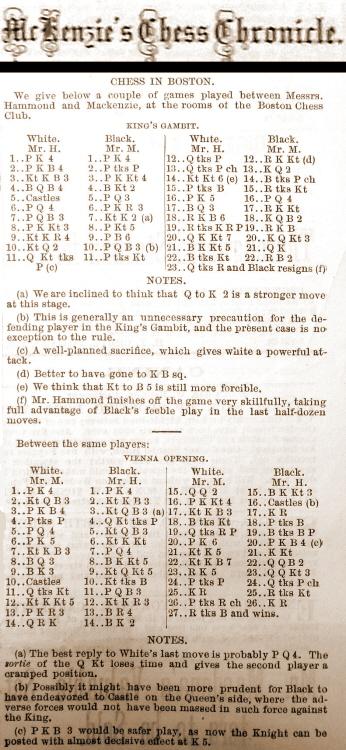

From page 288 of the July 1900 BCM:

Wanted: more information about this game between Hammond and ‘McKenzie’.

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 Bc4 Bg7 5 O-O d6 6 d4 h6 7 c3 Ne7 8 g3 g4 9 Nh4 f3

10 Nd2 c6 11 Ndxf3 gxf3 12 Qxf3 Rg8 13 Qxf7+ Kd7 14 Ng6 Bxd4+ 15 cxd4 Rxg6 16 e5 d5 17 Bd3 Rg8 18 Rf6 Kc7 19 Rxh6 Rf8 20 Qg7 Kb6 21 Bg5 Qe8

22 Bxe7 Rf7 23 Qxf7 Qxf7 24 Bd8+ and wins.

Below is the relevant Cheltenham Examiner item on page 243 of the June 1900 BCM:

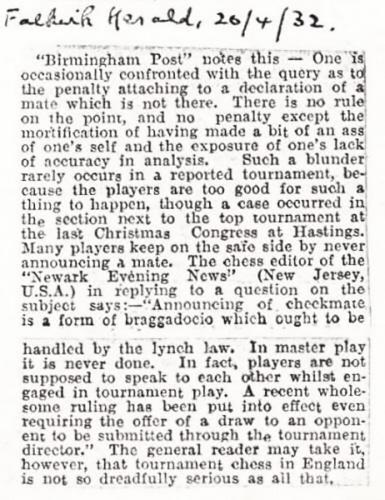

8353. Crime and punishment

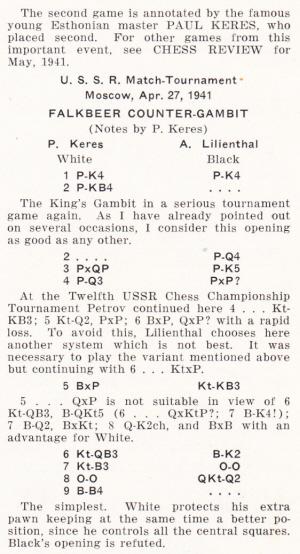

Paul Keres – Andor Lilienthal

USSR Absolute Championship, Moscow, 27 April 1941

Falkbeer Counter-Gambit

1 e4 e5 2 f4 d5 3 exd5 e4 4 d3 exd3 5 Bxd3 Nf6 6 Nc3 Be7 7 Nf3 O-O 8 O-O Nbd7 9 Bc4 Nb6 10 Bb3 a5

11 a4 Bc5+ 12 Kh1 Bf5 13 Ne5 Bb4 14 g4 Bc8 15 Be3 Nbd7 16 g5 Bxc3

17 bxc3 Ne4

18 d6 Nxe5 19 fxe5 Resigns.

The present item will focus on the concluding moves, but a word first about the opening. Some databases give the move order as 4 Nc3 Nf6 5 d3 exd3 6 Bxd3 Be7; seldom can a database be consulted for an old game without an error or discrepancy of some kind being found.

The annotator of a miniature may be tempted to view matters (or, at least, pretend to) as a plain lesson in crime and punishment, the loser being doomed almost from the start and the winner’s play being presented as irreproachable. In Keres v Lilienthal, after 15...Nbd7 Reuben Fine commented:

‘One’s reaction to this move is that if such things have to be done he might as well resign.’

And after 16...Bxc3:

‘To have some air, but he loses a piece. The position is hopeless.’

Following 17 bxc3 Ne4 Fine gave 18 d6 two exclamation marks and wrote:

‘Typical. Black’s game is ripped apart.’

Black’s reply, 18...Nxe5, was labelled ‘desperation’ since 18...Nxd6 allowed an ‘elegant’ mating variation.

Page 82 of Chess Marches On! by Reuben Fine (New York, 1945)

A similar story of inexorable comeuppance was told by Fred Reinfeld. At move 15: ‘Black’s helplessness is touching.’ At move 16 an alternative was rejected because in that case ‘Black has no reasonable continuation’. And, as in the Fine book, two exclamation marks for 18 d6.

Page 225 of Keres’ Best Games of Chess, 1931-1948 by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1949)

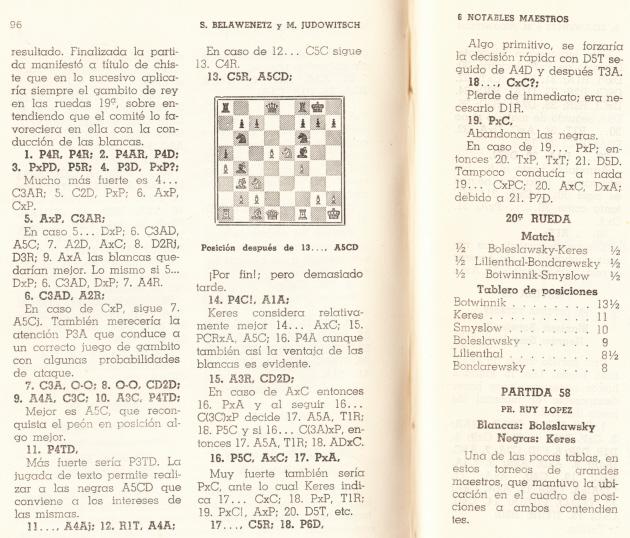

Strange to relate, in 1941 the notes to Keres v Lilienthal were less eulogistic of White’s play at various points. Below is the game’s appearance on pages 96-97 of the tournament book, 6 notables maestros by S. Belawenetz and M. Judowitsch (Buenos Aires, 1941):

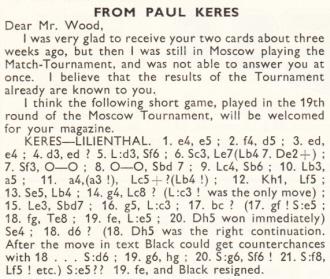

Moreover, Keres himself was critical of his play in two

publications in 1941. The first was in a letter dated 9

May 1941 to B.H. Wood given on page 178 of the September

1941 CHESS. It will be seen that he even appended

a question mark to 18 d6:

Keres annotated the game in detail on pages 207-208 of the November 1941 Chess Review, criticizing his play and stating that at move 18 ‘Lilienthal missed an excellent chance for salvation’:

Finally, below are Botvinnik’s annotations in the English edition of his book on the tournament, on pages 179-180 of Championship Chess (London, 1950):

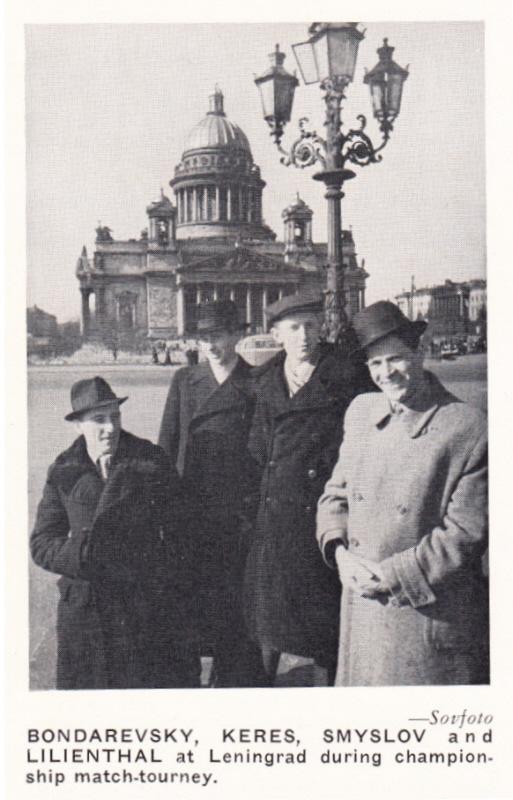

A photograph taken during the Leningrad part of tournament was published on page 206 of the November 1941 Chess Review:

8354. Who?

C.N. 7988 showed Max Blau astride a camel. Below is another master, but who?

8355. Al fresco

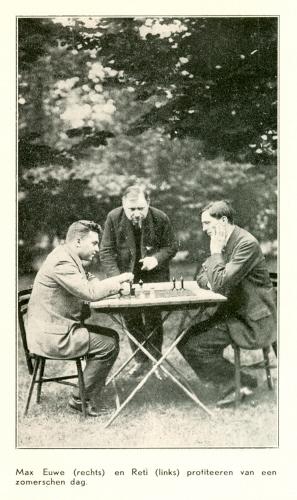

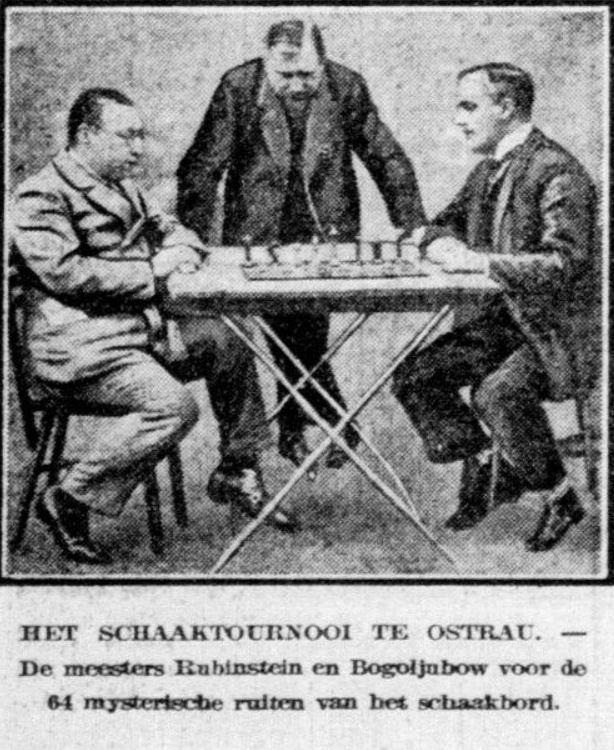

C.N.s 5187 and 5197 gave the above photograph, taken from Aljechin-Euwe by Guus Betlem Jr (Helmond, 1936), and in the latter item Peter de Jong (De Meern, the Netherlands) suggested persuasively that the figure standing between Réti and Euwe was Willem Schelfhout.

Mr de Jong now forwards another picture, from page 4 of De Telegraaf (morning edition), 12 July 1923:

The setting and furniture being similar, our correspondent concludes that the Réti v Euwe picture was also taken during the Mährisch-Ostrau, 1923 tournament.

8356. ‘A humorous contrast’

At the end of a brief review of Caïssas Weltreich by Max Euwe and Bob Spaak (Berlin-Frohnau, 1956) Harry Golombek wrote on page 63 of the March 1957 BCM that the book ...

‘is embellished by some excellent photographs, especially the one that gives such a humorous contrast between Reshevsky and Euwe’.

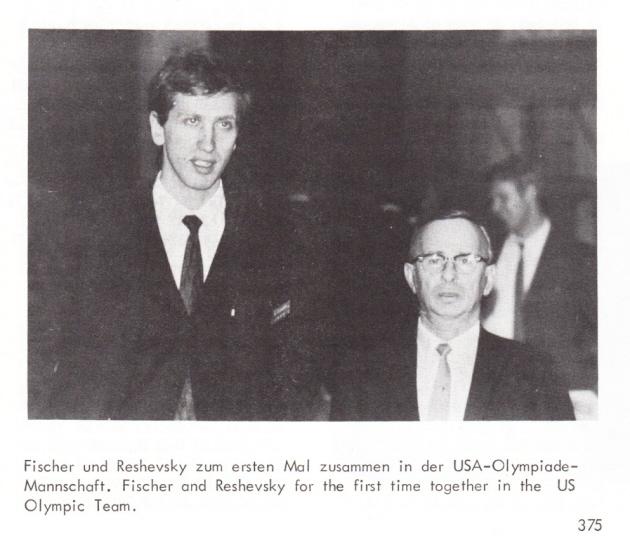

The picture was shown on page 94 of Chess Facts and Fables. On the same theme, the shot below comes from page 375 of Schach Express/Chess Express, October 1970, in a report on the Siegen Olympiad:

8357. 10 Nd2 (C.N. 8352)

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) and John Blackstone (Las Vegas, NV, USA) report that the Hammond v Mackenzie game was published by the latter on page 75 of Turf, Field and Farm, 2 February 1877:

Mr Bauzá Mercére adds that the King’s Gambit miniature was the third game in the series and was played on 18 January 1877, according to the St Louis Globe-Democrat, 4 February 1877.

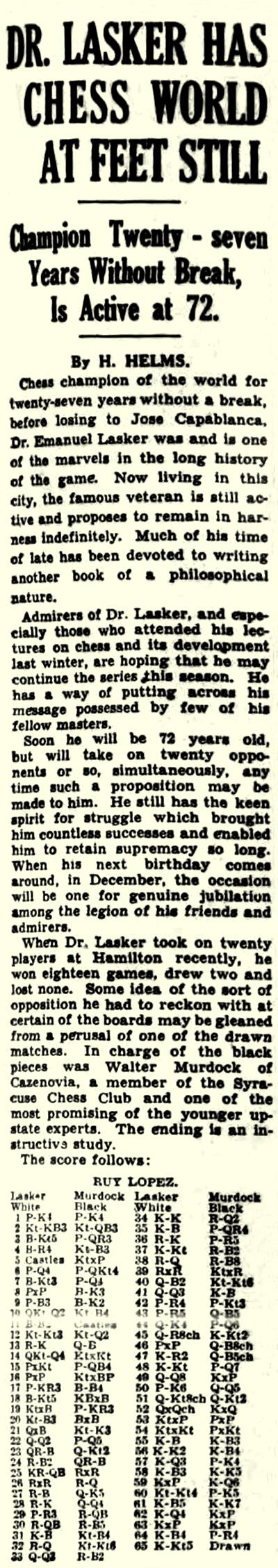

8358. Lasker’s last recorded game

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére has also submitted a report by Hermann Helms on page 35 of the New York Sun, 21 September 1940:

Emanuel Lasker – Walter Murdock

Hamilton, 23 August 1940

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 O-O Nxe4 6 d4 b5 7 Bb3 d5 8 dxe5 Be6 9 c3 Be7 10 Nbd2 Nc5 11 Bc2 O-O 12 Nb3 Nd7 13 Re1 Qc8 14 Nbd4 Nxd4 15 cxd4 c5 16 dxc5 Nxc5 17 h3 Bf5 18 Bg5 Bxg5 19 Nxg5 h6 20 Nf3 Bxc2 21 Qxc2 Ne6 22 Qd2 d4 23 Rac1 Qb7 24 Rc2 Rac8 25 Rec1 Rxc2 26 Rxc2 Rd8 27 Rc1 Qe4 28 Re1 Qd5 29 a3 Rc8 30 Rc1 Rc4 31 Kf1 Nc5 32 Rd1 Nb3 33 Qd3 Rc7 34 Ke1 Rd7 35 Kf1 a5 36 Re1 a4 37 Kg1 Rc7 38 Rd1 Rc1 39 Rxc1 Nxc1 40 Qc2 Nb3 41 Qd3 Kf8

42 h4 g6 43 h5 Qc4 44 Qe4 d3 45 Qa8+ Kg7 46 hxg6 Qc1+ 47 Kh2 Qf4+ 48 Kg1 d2 49 Qd8 Kxg6 50 e6

50...Qd4 51 Qg8+ Qg7 52 Qxg7+ Kxg7 53 Nxd2 fxe6 54 Nxb3 axb3 55 Kf1 Kf6 56 Ke2 Kf5 57 Kd3 e5 58 Kc3 Ke4 59 Kxb3 Kd3 60 Kb4 e4 61 Kc5 Ke2 62 Kd4 Kxf2 63 Kxe4 Kxg2 64 Kf4 h5 65 Kg5 Drawn.

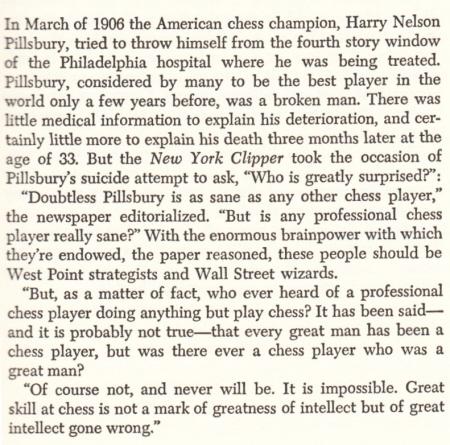

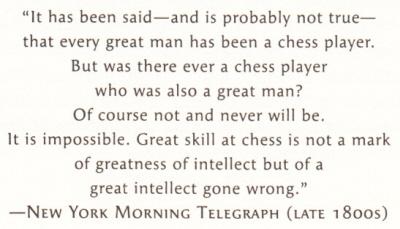

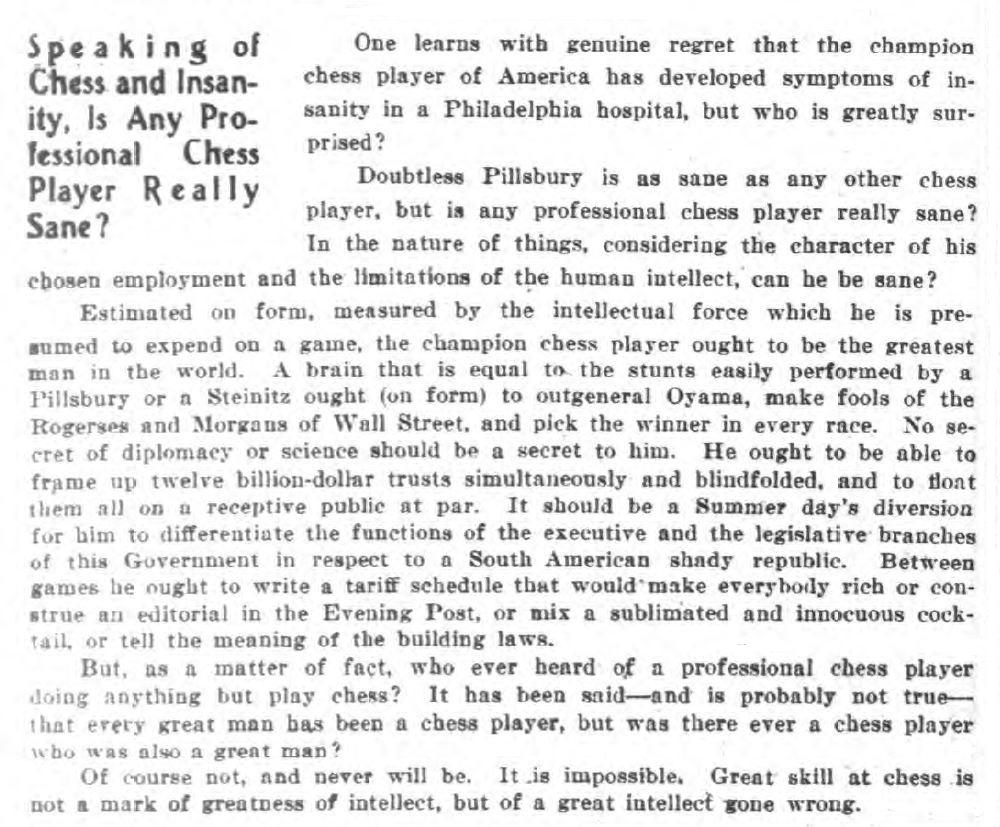

8359. Intellect gone wrong

‘Great skill at chess is not a mark of greatness of intellect, but of a great intellect gone wrong.’

That remark is often quoted with inaccurate and incomplete information. For example, the following comes from page 1 of Chess to Enjoy by A. Soltis (New York, 1978):

Churlish as it may seem to pass strictures upon Soltis when he gives a source of sorts, no date is attached to the New York Clipper, and the reference to Pillsbury in March 1906 is wrong. As shown in Pillsbury’s Torment, the master’s hospitalization in Philadelphia was in 1905.

From page 237 of Treasure Chess by B. Pandolfini (New York, 2007):

‘New York Morning Telegraph (late 1800s)’ may not be much of a source, but by Pandolfini’s standards it is chapter and verse. At first glance, moreover, it seems to improve, however vaguely, on what was on page 7 of Chess Quotations from the Masters by Henry Hunvald (Mount Vernon, 1972):

The text appeared on page 4 of the New York Sunday Telegraph, 2 April 1905:

The article/editorial was quoted on pages 267-268 of Lasker’s Chess Magazine, April 1905, and the final part was reproduced by Eliot Hearst on page 255 of the September 1961 Chess Life. Both provided the exact date of the newspaper, identifying it by its more general title, the New York Morning Telegraph.

8360. Announced mates (C.N.s 8329, 8334 & 8351)

Wanted: early examples of announced mates, as well as information on how the practice began and developed.

8361. Who?

8362. Bird and Northrop

From page 264 of the June 1932 BCM:

‘It is interesting to hear from Newark, New Jersey that George P. Northrop, chess editor of the Newark Evening News, is of the same family on the maternal side as the famous old English master, H.E. Bird, after whom his father, C. Bird Northrop, and also his son were named.’

8363. Man Ray and Alekhine (C.N. 6191)

C.N. 6191 showed two portraits of Alekhine by Man Ray. Now, Jeremy Silman (Los Angeles, CA, USA) draws attention to a third photograph, apparently from the same time. The website dates it circa 1925, which seems to us less likely than the ‘circa 1928’ in the book mentioned in our earlier item, Man Ray’s Paris Portraits: 1921-39 by Timothy Baum (Washington, 1989).

8364. Lightning chess writers

From B.H. Wood’s column in the Illustrated London News, 30 March 1963, page 482:

‘I know of only one book devoted to the saving of lost positions; that is, not unexpectedly, by Fred Reinfeld, who must in the course of his lifetime have racked his brain to think what he could write about next. (His enormous output once prompted David Bronstein to remark that, whilst — — [Wood’s dashes] might possibly be the best writer of chess books in the English language, Fred Reinfeld was obviously the best lightning-chess-writer.) Illuminatingly, this book is one of Reinfeld’s very latest, showing clearly that it is one of the last subjects that even occurred to such a prolific writer.’

And from Wood’s column on page 114 of the 28 May 1977 issue:

‘It was Flohr, I think, who compared him [Golombek] with Reinfeld, who also wrote a great many chess books, describing Reinfeld as the world’s worst lightning chess writer, Golombek as the best (lightning chess is the term for chess played at an average of a few seconds per move). The assessment is hard on Reinfeld; Bob Wade has remarked again and again how poorer players find him helpful. It is kind to Golombek, whose books sometimes exhibit a smooth sameness, who had one rather egocentric period and who can find it difficult (who does not?) to avoid repeating himself.’

Is anything further known about the views attributed to Bronstein and Flohr?

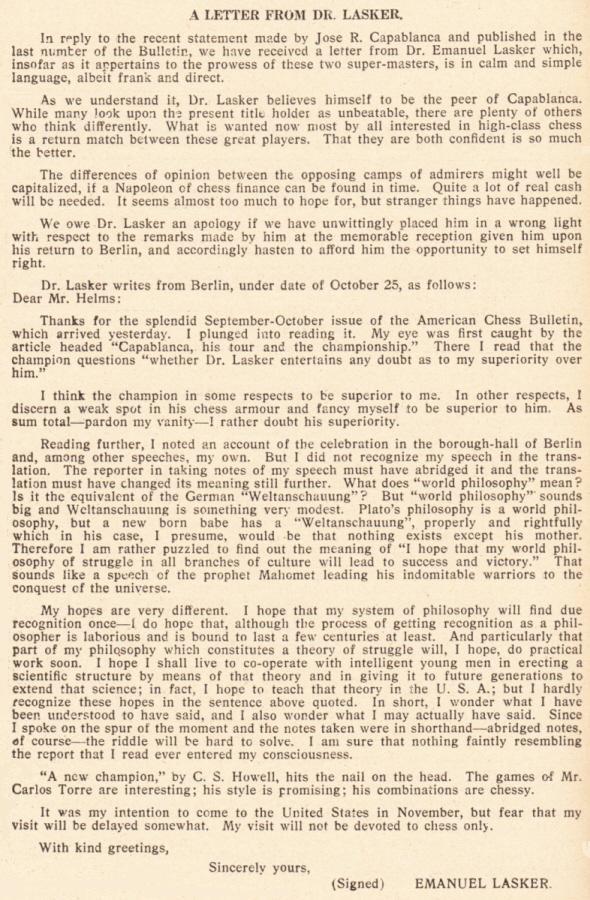

8365. From Lasker

Page 190 of the November 1924 American Chess Bulletin:

The earlier remarks by Capablanca can be found on pages 126-127 of our monograph on him.

8366. Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp

From Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England):

‘Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp played a game of Dadaist Chess in René Clair’s 1924 film Entr’acte. The whole work, about 20 minutes in duration, can be watched online. The chess scene starts at 4’29” and lasts about 40 seconds.’

8367. Announced

mates (C.N.s 8329, 8334, 8351 & 8360)

Rod Edwards (Victoria, BC, Canada) writes:

‘Pages 71-74 of the November 1880 Chess Monthly have an article by Alphonse Delannoy, and page 74 describes an encounter between Labourdonnais and Mouret where the former announced mate in five moves in the final game of a series in which the stakes escalated dramatically. Labourdonnais offered a knight sacrifice, which Mouret accepted. Then Labourdonnais said, in Delannoy’s account: “Well, sir, you have lost the game. You are mated in five moves.”

It is stated that this occurred before Labourdonnais had directly challenged Deschapelles, and therefore presumably before their 1821 contest involving Cochrane as well, but after Mouret had been on a tour as director of the Turk. This places the event around 1820, though possibly a year earlier or later.’

8368. Sneak openings

C.N. 2253 (see page 371 of A Chess Omnibus) quoted from page ix of Brevity and Brilliancy in Chess by Miron J. Hazeltine (New York, 1866):

‘... that slowest of encounters, the execrable French Defence – “King’s Pawn one sneak”, as Walker omits no opportunity of stigmatizing it; or “King to Pawn’s one”, as Leonard used derisively to style it.’

George Walker did indeed dislike the French Defence. The following comes from pages 125-126 of his book The Art of Chess-Play: A New Treatise on the Game of Chess (London, 1846):

In Walker’s column in Bell’s Life in London the word ‘sneak’ was often used, though with reference to a variety of openings (including the Sicilian Defence) in which Black avoided an open game:

- 13 April 1862, page 1 of the supplement (on preparations for that year’s London Congress): ‘The vexed question of king’s pawn two, on both sides, as a rule of play, is to be left in the great tournay to the decision of the players themselves; and if two-thirds vote in its favour the rule to be made absolute. We heartily trust this may be the case, and that the sneak opening is shut out.’

- 1 February 1863, page 2 of the supplement: ‘Steinitz always chooses a brilliant game; no matter at what risk. We wish we had a few more players of his mark. No bush shooting in him, no King’s Pawn one sneak.’

- 5 November 1864, page 12: ‘We regret we do not see more of the great play of Harrwitz, one of the finest players in Europe. No King’s Pawn one sneak about his chess.’

- 6 October 1866, page 9 (a note to Black’s first move in Steinitz v Anderssen, a Sicilian Defence): ‘For the sake of variety Anderssen for once stoops to the “Sneak Opening”.’

- 22 June 1867, page 12 (after 1 e4 g6 in a Steinitz v De Vere game): ‘When Mr De Vere has played more he will eschew these evil ways, cut the sneak dodge, and come out always second player with the King’s Pawn two.’

- 17 January 1871, page 8 (after 1 e4 b6 in a game won by Bird as White): ‘What a horrible case of sneak opening!’

- 8 April 1871, page 8 (after 1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Bc4 in a game between Paulsen and Anderssen): ‘How refreshing it is to find players who in the most important matches boldly come forth and disdain “Sneak Opening” in all its shabby varieties.’

- 29 July 1871, page 12: ‘Game between Messrs Anderssen and De Vere, at the Baden Chess Congress. The “Sneak” Opening, so termed by Pantagruel in the eighteenth volume of his pocket treatise on Chess and Skittles.’ The second annotation reads: ‘Considering we have reached the 22d move, what a dreary waste of thistles is before us. Such is almost always the result of the Sneak Opening.’ The game had begun 1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 e6:

- 18 November 1871, page 5 (a note after 1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 in a Zukertort v Anderssen game): ‘On first meeting with this the student is apt to fear he has encountered merely a new variety of “The Great Sneak Opening”, but is soon restored to animation by discovering this to be the prelude to a new and dashing attack of first-rate excellence, termed the Vienna Gambit.’

- 13 January 1872, page 5 (a note after 1 e4 c5 in a Judd v Smith game): ‘We rarely print specimens of the Sneak Opening, but fine games may be occasionally produced by fine players from any description of opening, even as talented Israelites may have been found in the days of Pharoah to make bricks without straw.’

- 10 February 1872, page 10 (a note to a King’s Gambit game between Anderssen and Zukertort): ‘The position is very interesting, and the practitioners of Sneak Openings would do well to contrast their bush-fighting with this grand style of battle.’

- 31 August 1872, page 10 (annotating a rook’s odds game won by Morphy which began 1 e4 e6): ‘A player who can give you rook can only find reciprocal interest in the prospect of an interesting situation; and if you answer with the sneak opening, will probably plead a prior engagement the next time you ask him to swallow a similar dose.’

8369. Who? (C.N. 8361)

From page 23 of Schach Express/Chess Express, February 1970:

8370. Agatha Christie

Concerning Agatha Christie and Chess, Mike Salter (Sydney, Australia) quotes from page 219 of Sinister Gambits edited by Richard Peyton (London, 1991):

‘[“A Chess Problem”] reveals its author’s knowledge of the game, for she played from her childhood, and to the end of her life continued to enjoy games with her husband, Sir Max Mallowan, as relaxation after a day’s hard plotting.’

Peyton specified no source for this information.

Below is a passage from page 102 of the book shown in C.N. 4105 (in ‘A Chess Problem’, which is Chapter 11 of The Big Four):

8371. A new website

A new website not to be missed: Keenipedia.

8372. Bust of Lasker

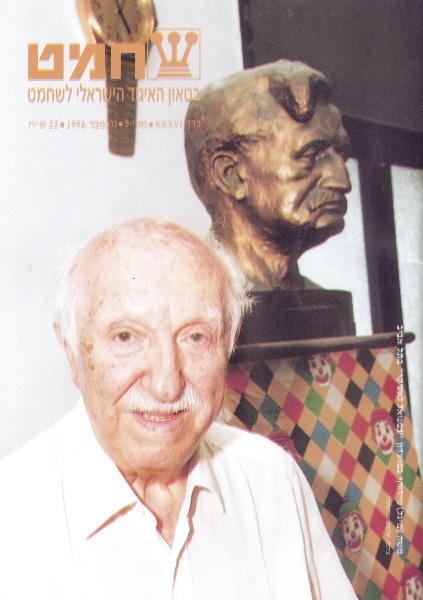

Regarding the Lasker bust, Martin Weissenberg (Savyon, Israel) forwards the front cover of the November 1996 issue of the Israeli magazine Shakhmat and comments:

‘It features Najdorf standing next to the bust of Emanuel Lasker at the Lasker Chess Club in Tel Aviv, and was taken by Shlomo Volkowitz during Najdorf’s last visit to Israel, in Autumn 1996.’

8373. Smothered mate by Rosenthal

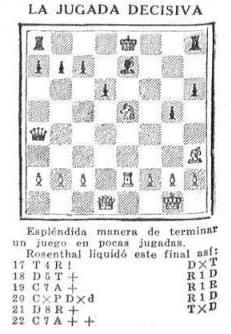

From Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) comes a combinational finish by Samuel Rosenthal which was given in the chess column of Gastón Pedro Dubox on page 52 of the 11 March 1939 issue of Caras y Caretas:

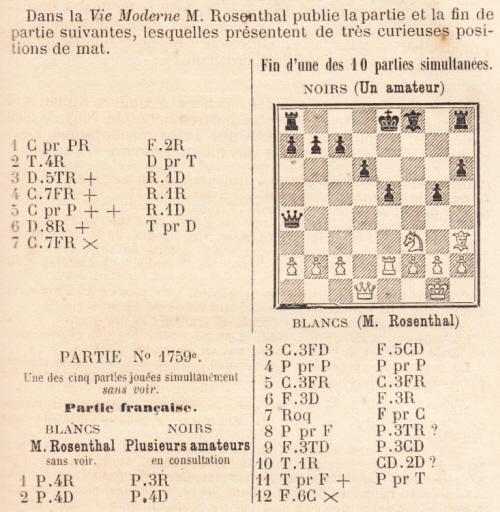

We can add that it was one of two specimens of Rosenthal’s play shown on page 149 of La Stratégie, 15 May 1884:

The blindfold game: 1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 exd5 exd5 5 Nf3 Nf6 6 Bd3 Be6 7 O-O Bxc3 8 bxc3 h6 9 Ba3 b6 10 Re1 Nbd7 11 Rxe6+ fxe6 12 Bg6 mate.

8374. Article about Reshevsky

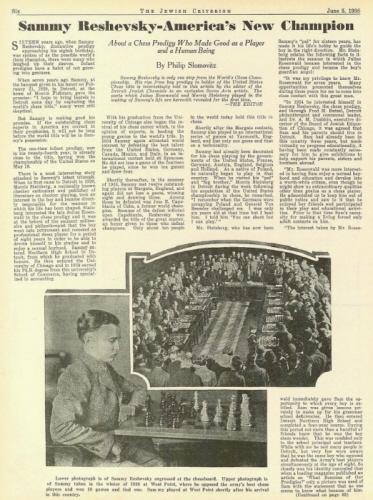

Harrie Grondijs (Rijswijk, the Netherlands) has forwarded an article about Reshevsky by Philip Slomovitz in the Jewish Criterion, 5 June 1936, page 6 and page 32.

8375. Endgame theory

From Karsten Müller (Hamburg, Germany):

‘Are there any books or other sources on the history of chess endgame theory starting with the old Arab compositions with rook against knight and going through to modern times?’

8376. Kasparov on Short

On page 26 of the April 2004 Chess Life Larry Evans wrote:

‘“So it’s to be Short and it will be short”, quipped Kasparov upon learning the name of his challenger (who eliminated Anatoly Karpov and then Jan Timman, to reach the top).’

In reality, the famous quip was made by Kasparov during the Manila Olympiad in June 1992, long before the Short v Timman Candidates’ final (which ended on 30 January 1993). From page 462 of Garry Kasparov on Garry Kasparov Part II: 1985-1993 (London, 2013):

‘... journalists had asked me who would win the forthcoming final Candidates match – Timman or Short? – and how my next world championship match would end. To the first question I replied: “It will be Short.” And, laughing, I made the same reply to the second question: “It will be short.” On learning of this from the tournament bulletin, Short took offence ...’

In an interview with Dirk Jan ten Geuzendam (see page 54 of the 5/1992 New in Chess) Short light-heartedly dismissed Kasparov’s remark (which he gave as ‘It will be Short and it will be short’).

8377. His Spiteful Reverence

An article by G.H. Diggle from the July 1982 Newsflash which was given on page 84 of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984):

‘A fine example of chess longevity was the late O.C. Müller ... He came to England in the early 1880s and for ten years made a meagre living as a professional – but being an excellent linguist he wisely took up translating and interpreting, supplementing his income by Divan Chess. He was an habitué at Purssells (1880-94), Simpsons (1894-1903) and later the famous Gambit Café in Budge Row, where in the ’20s the BM (when in town) spent some pleasant hours losing to the veteran at pawn and move (which was then approaching but not quite on its deathbed) and listening with others to his vast repertoire of anecdotes of days gone by. From a young would-be chess historian’s point of view he was rather irritating in one respect – he would never wear any attempt to turn a monologue into an interview, and “any questions” was simply not on. Once he made a small slip when speaking of the Anderssen-Morphy match, and the BM, bursting to air his knowledge, had the temerity to interrupt. “Surely it was in the sixth game, not the fourth”, piped up the unwary youth. “Indeed?”, replied Müller with great deference, “Personally I vos not there.”

But some of Müller’s opponents in his later days were older even than himself. There was one retired aged clergyman, a fairly strong player but rather deaf and somewhat cantankerous. The BM once saw Müller refute the old cleric’s combination with an unexpected resource, whereupon His Spiteful Reverence barked: “All luck! Sheer luck! You never played for that – it dropped on you like manna from Heaven!” Müller merely winked quietly at the gallery. But on another occasion the old curator of human souls actually scored a win worthy of being “written in letters of gold” in W.R. Hartston’s How to Cheat at Chess. The queens had already been exchanged but “Clericus”, who had an advanced passed pawn, made a series of sacrifices which ensured its promotion. On the eve of “victory”, however, he realized that his new queen would be “all on her own” against two rooks and several minor pieces. Nothing daunted, he “queened” with a tremendous flourish, jumbled up all the remaining pieces on the board as though nobody but a fool could fail to see the game was over, girded up his loins like Elijah the Tishbite, and made for the door at full speed. As his shovel hat disappeared into Budge Row some wit called out “Stop, thief!”, and there was a great roar of laughter.’

8378. Aliens

Further to Garry Kasparov’s candidacy for President of FIDE, it is likely that statements about aliens attributed to Kirsan Ilyumzhinov will often be seen over the coming months. From an article by Dylan Loeb McClain in the New York Times, 28 October 2013:

‘He has said that he believes the game was invented by extraterrestrials, and he claims to have been abducted by aliens in yellow spacesuits on the night of 17 September 1997.’

This is the only time that we intend to quote a second-hand version. Wanted: Ilyumzhinov’s own words on the subject, whether in writings, speeches or interviews, and preferably in the original language. Can readers help us to build up a file of exact quotes and references?

8379. Prins on Capablanca

From page 189 of Master Chess by Lodewijk Prins (London, 1950):

‘For a lover of chess it was a real delight to see Capablanca play. Playing over his brilliant games one would hardly believe that this man would sit at the board as if some comedy were being performed before his eyes and would seize any opportunity to rise and walk around with a smile on his face.’

8380. Lost Battle

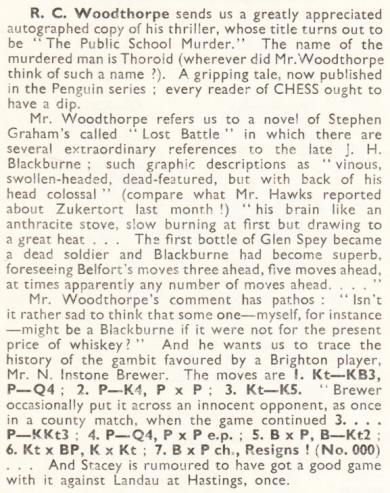

From page 102 of CHESS, April 1941:

The game given (1 Nf3 d5 2 e4 dxe4 3 Ne5 g6 4 d4 exd3 5 Bxd3 Bg7 6 Nxf7 Kxf7 7 Bxg6+ Resigns) recalls the miniature (1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e5 3 dxe5 Ng4 4 a3 d6 5 exd6 Bxd6 6 g3 Nxf2 7 White resigns) discussed in a number of items, including C.N. 7771.

We seek information about N. Instone Brewer and any game-scores involving Stacey and Landau. They met in the Premier Reserves (Section I) at Hastings, 1935-36 (BCM, February 1936, page 52), but the moves have not been found.

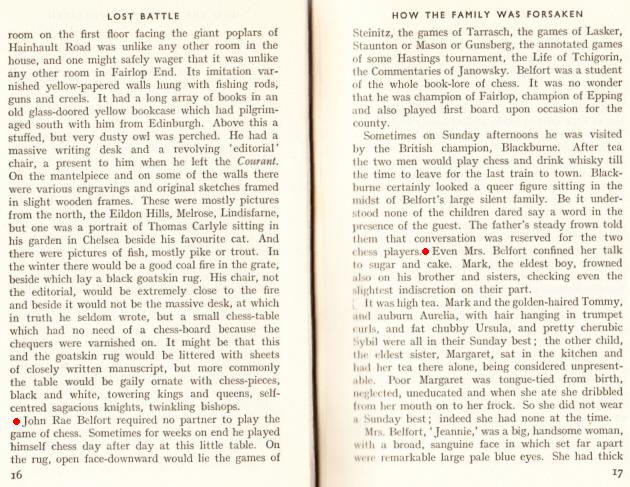

As regards the novel Lost Battle by Stephen Graham (London, 1934), we have an inscribed copy:

Chess is mentioned in the first paragraph and regularly throughout the book. There are many references to old players, and Blackburne in particular. Two sample pages:

| First column | << previous | Archives [111] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.