Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [112] | next >> | Current column |

8381. Announced mates (C.N.s 8329, 8334, 8351, 8360 & 8367)

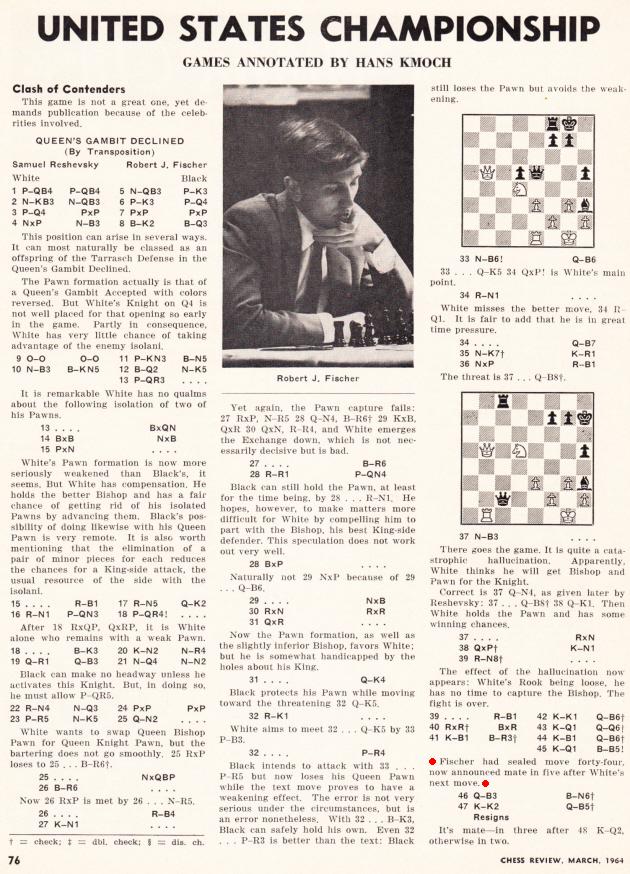

Concerning announced mates, Dan Scoones (Port Coquitlam, BC, Canada) draws attention to comments by Hans Kmoch on page 76 of the March 1964 Chess Review (Reshevsky v Fischer, 1963-64 US championship):

8382. Samuel

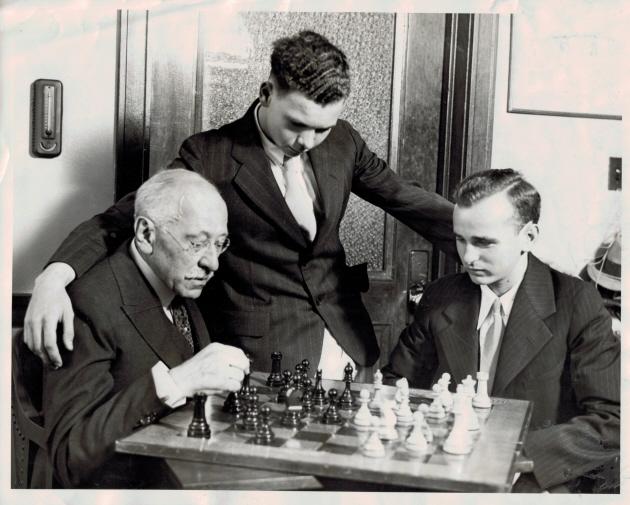

Reshevsky and Julius Rosenwald

Harrie Grondijs (Rijswijk, the Netherlands) forwards a

photograph which he owns:

The board appears to be the wrong way round, but in such cases two other possibilities require consideration: either the photograph has been reversed (unlikely here, since Reshevsky’s hair-parting and breast-pocket are on the left) or, as discussed in C.N. 5124, there is an optical illusion with the shade of the chessboard squares.

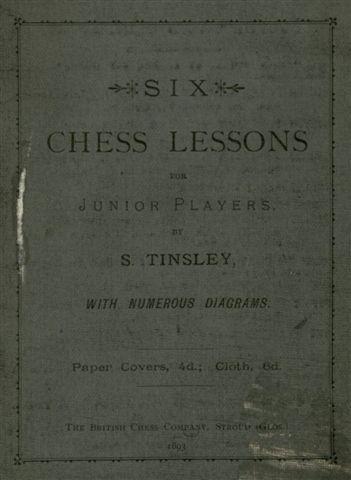

8383. Chess for younger readers (C.N.s 6323 & 6329)

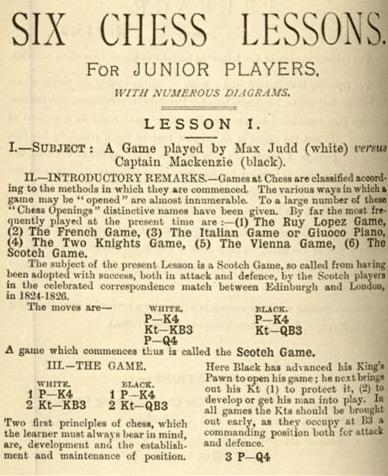

An addition from Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England) can be shown courtesy of the Cleveland Public Library, Six Chess Lessons for Junior Players by S. Tinsley (Stroud, 1893):

8384. Korchnoi’s name deleted from a match book? (C.N. 8279)

No corroboration has been found of Bernard Levin’s

assertion that after Korchnoi’s departure from the Soviet

Union in 1976 ‘a new Soviet book on the 1974

Karpov-Korchnoi championship match had to have all

references to Korchnoi deleted, so that he is simply

referred to throughout as “the opponent”’.

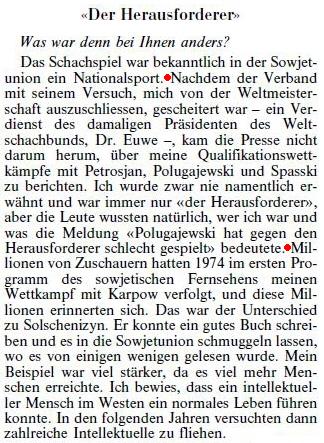

More generally, however, the Soviet press’s practice of

omitting his name has been mentioned by Korchnoi himself.

For instance:

‘Once the Soviet Chess Federation had failed in its attempt to exclude me from the world championship (a service for which I have President of the World Federation Dr Euwe to thank) the press couldn’t cope with having to report my candidates’ matches with Petrosian, Polugayevsky and Spassky. I was never named, and referred to only as “the challenger”, but of course people knew who I was and what the news “Polugayevsky played poorly against the challenger” meant.’

Source: an interview with Korchnoi by Richard Forster in Kingpin, Autumn 2001, pages 15-18 (translation by George Green).

Below is the relevant section of the original interview, published on page 57 of the Neue Zürcher Zeitung, 23 March 2001:

Can readers submit any particularly egregious examples from Soviet publications of the time?

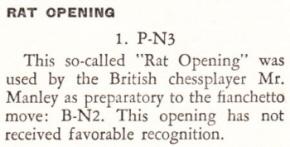

8385. Rat Opening/Defence

C.N. 6861 quoted from page 236 of the May 1891 BCM:

‘One popular character at Purssell’s is Mr Manley, a good old Purssellite, who is best known by his “rat” openings (P to Kt3 and B to Kt2).’

It was not specified whether the moves were played by him as White and/or Black. Below is an entry on page 170 of the Dictionary of Modern Chess by Byrne J. Horton (New York, 1959):

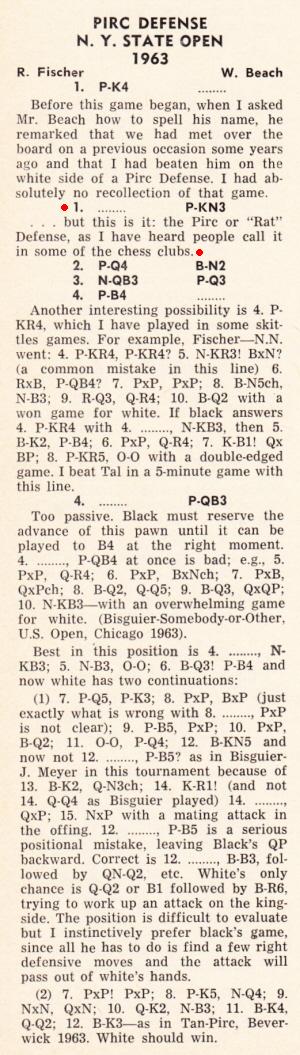

On page 148 of the July 1965 Chess Life John W. Collins wrote:

‘As for 1 P-K4, or 1 P-Q4, P-KN3 2 P-Q4, or 1 P-K4 P-Q3, who knows what to call it? Some say it is the King’s Fianchetto, some the Paulsen, some the Pirc, some the Robatsch, and some the Ufimtsev. Bobby Fischer once dubbed it the Rat Defense.’

Whether Fischer did ‘once’ dub the opening in that way (publicly) seems unclear. The only reference that we can offer is from a game annotated by him on pages 44-45 of the February 1964 Chess Life:

The game-reference in the first paragraph after 4...c6 is also notable.

8386. Sneak openings (C.N. 8368)

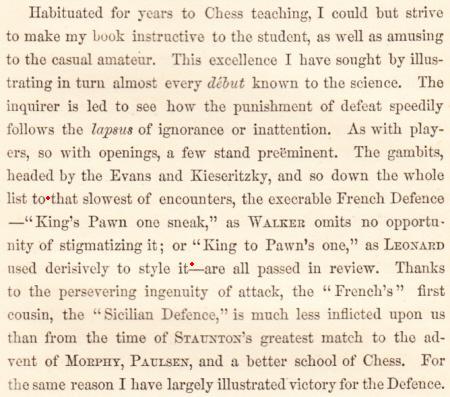

C.N. 8368 quoted a passage from page ix of Brevity and Brilliancy in Chess by Miron J. Hazeltine (New York, 1866):

In an apparent mix-up, the ‘sneak’ reference was attributed to James A. Leonard in item 214 of unit three of Napier’s Amenities and Background of Chess-Play by W.E. Napier (New York, 1935):

‘It was the gifted Leonard, with the “first refusal” of Morphy’s mantle in his pocket, who in this country first spoke of the French Defense as the King’s Pawn Sneaks One. The obloquy of evading open-game amounted, in Civil War days, to a class consciousness. This is not hard to understand when opening play is recalled. What became terrors later on in the Ruy López were then merely growing pains. A player then had to rely on his imagination for his devices; a pre-digested game was as rare then as an original is now.

There was no good reason, many thought, to shirk open, airy, and pelting chess.

The prejudice died hard.’

See too page 211 of Napier’s Paul Morphy and The Golden Age of Chess (New York, 1957), as well as Horowitz’s references to Leonard (based on Napier’s comments) on page 84 of Chess Review, March 1950 and on page 88 of How to Win in the Chess Openings (New York, 1951).

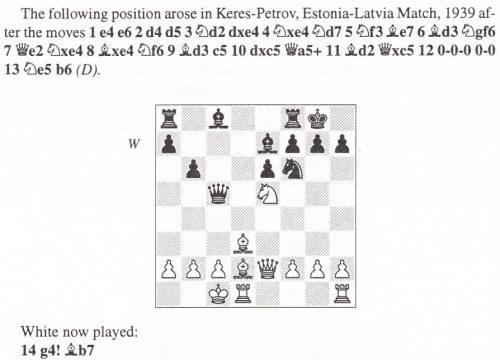

8387. Keres v Petrov

Stuart Rachels (Tuscaloosa, AL, USA) is surprised by the above, from page 210 of The Art of Attack in Chess by V. Vuković (London, 1998), because after 8...Nf6 ...

... the possibility of 9 Bxb7 is not mentioned.

Our initial comment is that in earlier editions of the book (in the descriptive notation – see page 237) the first 13 moves were not given.

Other authors have passed over in silence 9 Bd3 (which, incidentally, was not a novelty in 1939). See, for example, pages 262-263 of Modern Chess Opening Theory by A.S. Suetin (Oxford, 1965).

Keres himself referred to the line in his monograph on the French Defence (Örebro, 1957, page 176, and Moscow, 1958, page 149), giving 9 Bxb7 (‘!’) and making no mention of his game against Petrov.

Below are some annotators’ comments on the relevant phase of the Keres v Petrov game:

- ‘8...Kt-B3? A blunder! It allows 9 BxKtP BxB 10 Q-Kt5ch regaining the B.’

Al Horowitz, Chess Review, May 1939, page 106.

- ‘9 Le4-d3. Vit vinner en bonde: 9 L:b7 L:b7 10 Db5+ jämte 11 D:b7.’

Schackvärlden, June 1939, page 209.

- ‘8...Kt-B3? And this is a direct blunder. ...P-B4 was better. 9 B-Q3. Objectively stronger was the exploitation of Black’s lapse: 9 BxKtP! BxB 10 Q-Kt5ch etc. The omission of such an obvious stratagem may be justly attributed to an oversight in the course of a game between amateurs; but masters like Alekhine, Spielmann and Keres will often avoid the win of a pawn in this manner if it interferes with their contemplated attacking policies.’

Keres’ Best Games of Chess 1931-1940 by F. Reinfeld (London, 1941), page 193.

- ‘9 Bd3. Black automatically played 8...Nf6, and White equally automatically retreated his bishop. After 9 Bxb7 Bxb7 10 Qb5+ Black would have lost a pawn for no compensation.’

Paul Keres Chess Master Class by Y. Neishtadt (Oxford, 1983), page 110.

Even so, there are writers who have suggested that 9 Bd3 may have been preferable to 9 Bxb7:

- ‘9 Le4-d3. Dies dürfte besser sein als 9 Lxb7 Lxb7 10 Db5+ usw., denn Schwarz bekommt für den Verlust des Bauern die Initiative.’

Turniere, Taten und Erfolge by E. Ridala (Berlin, 1959), page 70.

- ‘9 Bd3. Probably more correct than giving up the initiative for a pawn: 9 Bxb7 Bxb7 10 Qb5+ Qd7 11 Qxb7 O-O.’

Paul Keres’ Best Games, volume two, by E. Varnusz (Oxford, 1990), page 139.

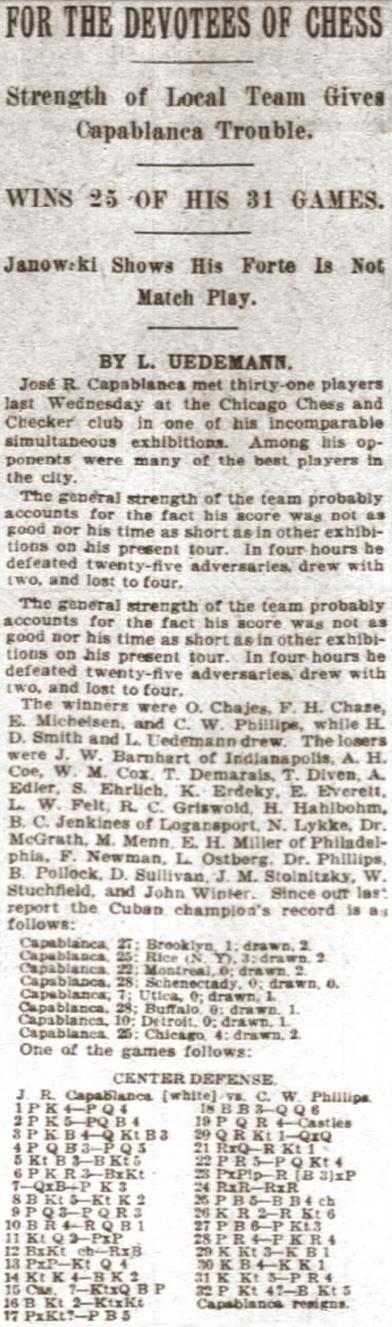

8388. Capablanca v Phillips

A game (from a 31-board display) submitted by Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA):

José Raúl Capablanca – Charles W. Phillips

Chicago, 24 November 1909

Centre Counter Game

1 e4 d5 2 e5 c5 3 f4 Nc6 4 c3 d4 5 Nf3 Bg4 6 h3 Bxf3 7 Qxf3 e6 8 Bb5 Nge7 9 d3 a6 10 Ba4 Rc8 11 Nd2 dxc3 12 Bxc6+ Rxc6 13 bxc3 Nd5 14 Ne4 Be7 15 O-O

15...Nxc3 16 Bb2 Nxe4 17 dxe4 c4 18 Bc3 Qd3 19 a4 O-O 20 Rab1 Qxf3 21 Rxf3 Rb8 22 a5 b5 23 axb6 Rcxb6 24 Rxb6 Rxb6 25 f5 Bc5+ 26 Kh2 Rb3 27 f6 g6 28 h4 h5 29 Kg3 Kf8 30 Kf4 Ke8 31 Kg5 a5 32 g4 Bb4 33 White resigns.

Source: Chicago Tribune, 28 November 1909, page 4:

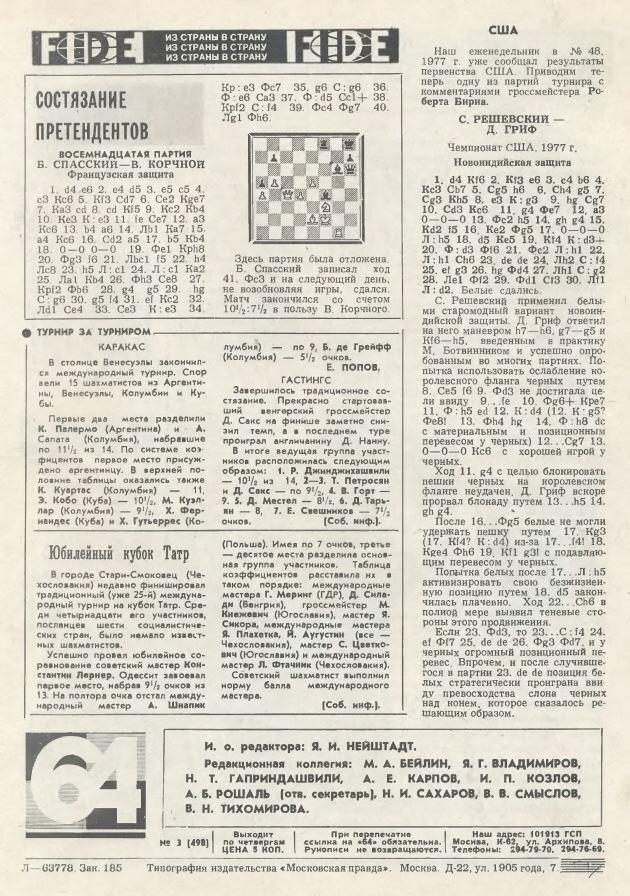

8389. Korchnoi’s name deleted (C.N.s 8279 & 8384)

Dan Scoones (Port Coquitlam, BC, Canada) writes:

‘Victor Korchnoi’s participation in the 1977-78 Candidates’ cycle was covered in rather curious and inconsistent fashion by the leading Soviet chess publications. Unlike mainstream news outlets such as Pravda and Izvestia, the chess publications could hardly suppress his name but they did make a serious effort to suppress his results.

In the weekly newspaper 64 there was detailed coverage of all the Candidates’ matches except the ones involving Korchnoi. The bare results of his matches against Petrosian and Polugayevsky were given, but no games were published. Detailed analysis was provided of all the other games from the quarter-final and semi-final matches. For the final match, Korchnoi v Spassky, only the weekly standings and the final result were given. There was just one exception: the moves of the final game were published.

Shakhmaty Riga followed a policy similar to that of 64. There was detailed analysis of all matches except the ones involving Korchnoi, for which only the bare results were given. For the final match against Spassky, the box score and the moves of three games (4, 12 and 18) were published.

In Shakhmaty v SSSR there was no coverage of the Candidates’ cycle, including the non-Korchnoi matches, except for three or four annotated games from the “non-Korchnoi” quarter-finals. This is remarkable. A leading master qualifies to play a match against the Soviet world champion, and the whole matter is completely ignored by the leading Soviet chess publication.

Shakhmatny Bulletin published all the games of the cycle and did not refrain from identifying Korchnoi by name. In keeping with the magazine’s general editorial policy, there were no annotations and no added comments. However, in the annual index, published in the 12/1977 issue, none of Korchnoi’s games that had appeared in earlier issues was indexed.

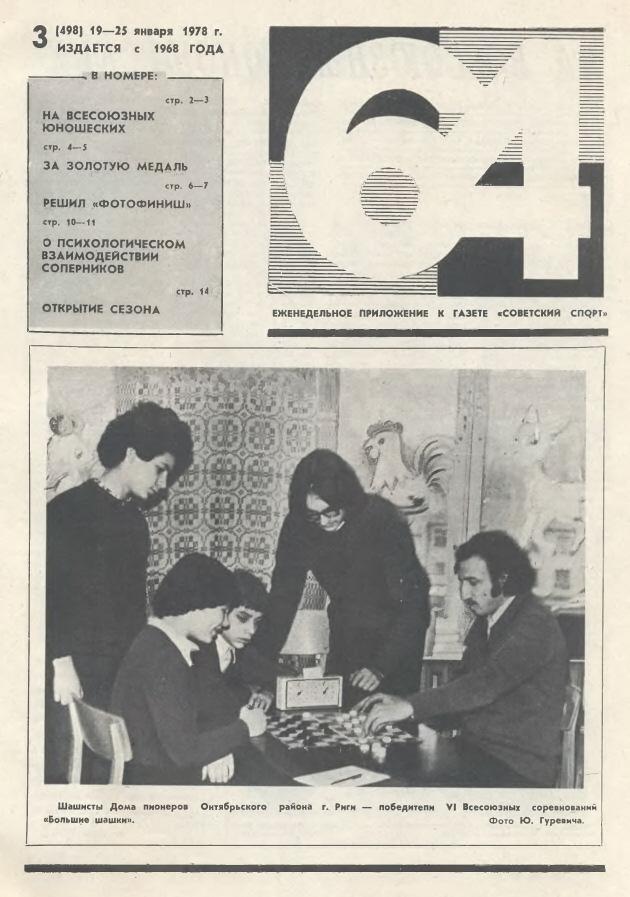

The front and back covers of the 3/1978 issue of 64:

That is the issue which should have announced Korchnoi as Karpov’s official challenger on its front cover. Instead, the news is buried on the back page. This may be contrasted with the front cover of the 48/1974 issue, which announced Karpov as the winner of the 1974 Candidates’ cycle:

The 1978 world championship match received normal coverage in all four publications, but for the Candidates’ matches the general policy seems to have been to ignore Korchnoi as much as possible.’

8390. Aliens (C.N. 8378)

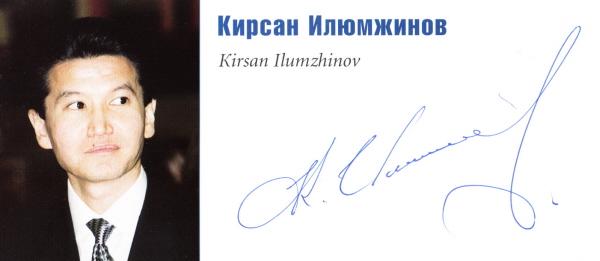

A video interview with Kirsan Ilyumzhinov in English was mentioned by Olimpiu G. Urcan in an article about the FIDE President and ‘Alien Theory’ on pages 48-50 of the Summer 2011 Kingpin. The clip, entitled ‘President Kirsan Ilyumzhinov tells of his invitation to an alien spaceship’, has subtitles, as transcribed below:

‘It happened on 17 September, I remember, in Moscow; it happened in my apartment.

... I was taken from my apartment in Moscow and taken to this spaceship, and we went to some star. After that I asked “Please bring me back” because the next day I should be back in Kalmykia, to Elista, and go to the Ukraine. They said, “No problem Kirsan you have time.”

They are people like us. They have the same mind, the same vision. I talked with them. I understand we are not alone in this whole world. We are not unique.

I am not a crazy man ... but after that when I gave the first interview to Radio Freedom in Russia five years ago thousands, not hundreds, thousands of people wrote me letters and called me on the phone saying “Kirsan, you are a politician and you aren’t afraid to speak about it.” From the United States every year, it is an official statistic, more than four thousand people are contacted in such a way. My theory is that chess comes from space. Why? Because the same rules, 64 squares, black and white, and the same rules in Japan, in China, in Qatar, in Mongolia, in Africa. The rules are the same. Why? I think it seems maybe it is from space.’

A further item will quote other statements on the subject by the FIDE President, and particularly in Russian-language sources.

8391. Ajedrecista

On the subject of Chess and Computers, Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) draws attention to a brief video sequence of the Ajedrecista in action.

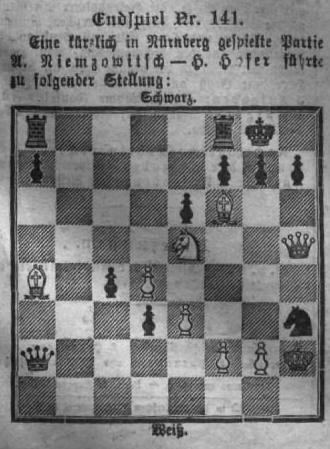

8392. Nimzowitsch v Hofer

Mr Sánchez also writes:

‘Page 15 of the Düna Zeitung, 22 January (4 February) 1905 gave the conclusion of Nimzowitsch v Hofer:’

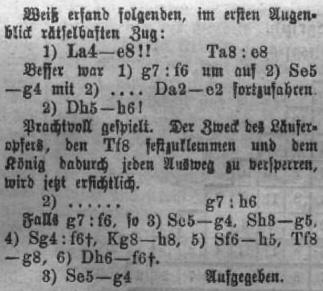

8393. Dus-Chotimirsky v Penin

A further contribution from Mr Sánchez concerns a finish given in The Smothered Mate. Page 152 of the 8 (21) May 1910 issue of the Rigasche Zeitung stated that White gave knight odds and that the game was played at the Café Dominique in St Petersburg:

8394. Aliens

(C.N.s 8378 & 8390)

Thanks to Dan Scoones (Port Coquitlam, BC, Canada) we are able to present a comprehensive new feature article Kirsan Ilyumzhinov and Aliens, with texts in English and Russian.

8395. Repetition

John Nunn (Chertsey, England) writes:

‘I have been looking at some world championship games from the early twentieth century, and I have a query about the repetition rule in force at the time. Two examples:

This is from Schlechter v Lasker, Game 1, Vienna, 1910. Play continued 56 Rxa5 Rc4 57 Ra6+ Ke5 58 Ra5+ Kf6 59 Ra6+ Ke5 60 Ra5+ Kf6.

The position after Black’s 56th move was repeated at Black’s 58th and 60th moves, so under modern rules Black could have claimed a draw before playing 60...Kf6.

The second position occurred in Janowsky v Lasker, Game 8, Berlin, 1910. The game continued 49 Qd6+ Kb7 50 Qe7+ Kc6 51 Qd6+ Kb7 52 Qe7+ Kb6 53 Qd8+ Kb7 54 Qd7+ Kb6 55 Qe6+ Kc7 56 Qf7+ Kb8 57 Qf4+ Kb7 58 Qf7+ Kb8 59 Qf8+ Kc7 60 Qf4+ Kc6 61 Qd6+ Kb7.

The positions after 49...Kb7, 51...Kb7 and 61...Kb7 are identical, so again Black could have claimed a draw (at this point a draw claim would have been perfectly reasonable even though Black actually won the game).

As I understand it, at one time the repetition rule required that the moves had to be repeated, rather than the positions. Thus in the first example the moves leading to the positions were not the same, being ...Rc4 in one case and ...Kf6 in the other two cases. The second specimen is a little different, in that the move preceding the repeated positions was in every case ...Kb7, but the king came from c6 twice and from c7 once.

My main question is whether anyone knows the exact rule which was in force at the time and, in particular, what was the rule for these world championship matches. I would also be interested to know when the modern form of the rule was introduced.

A repetition rule involving moves must be fairly complicated to cater for repetitions which are more than simple to-and-fro sequences (as in the second example). There is also the question as to whether Qg6xPh6+ is the “same” move as Qg6-h6+, for example, not to mention the matter of castling and en passant rights.’

For Lasker’s world championship matches against Schlechter and Janowsky no consolidated versions of the complete regulations have come to light, and we have found nothing specific about repetition of positions or moves, although the possibility of a draw in the Schlechter v Lasker game was mentioned in vague terms on page 24 of the 16 January 1910 issue of Deutsches Wochenschach:

‘Man sieht, Weiß hat das Remis in der Hand, versucht aber begreiflicherweise auf Gewinn zu spielen.’

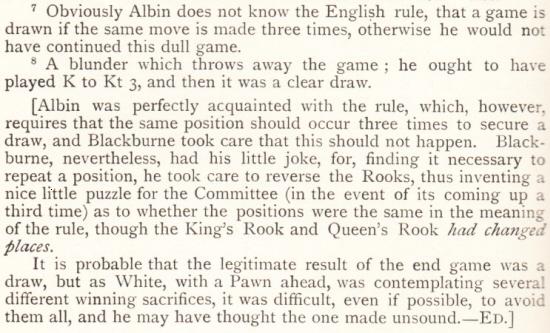

The origins of the repetition rule were discussed in C.N.s 3461 and 5695. The wording quoted in the former item (‘If the same position occurs thrice during a game, it being on each occasion the turn for the same player to move, the game is drawn’) also appeared as Rule VII in the ‘Revised International Code’ on page 9 of the English-language Hastings, 1895 tournament book. In that event a practical case arose during Blackburne’s game against Albin. A note by von Bardeleben to 71...Rc8 was contradicted by the tournament book editors (page 118):

In the British Chess Code (London, 1899 and 1903) the relevant provision was formulated differently:

‘A game is treated as drawn if, before touching a man, the player whose turn it is to play claims that the game be treated as drawn, and proves that the existing position existed, in the game and at the commencement of his turn to play, twice at least before the present turn.’

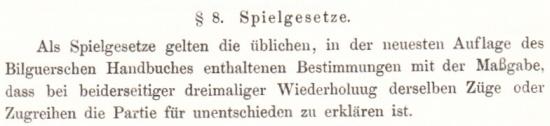

In Germany a different rule had been in force, enshrined in the Statuten und Meisterturnierordnung des Deutschen Schachbundes, which were adopted in Nuremberg on 15 July 1883:

Source: Nuremberg, 1883 tournament book, page 11:

A comparable provision was still applied in the twentieth century. For example, the following was given by Johann Berger on page 95 of the March 1906 Deutsche Schachzeitung:

‘Als unentschieden gilt auch die Partie, wenn dreimal hintereinander beide Gegner dieselben Züge oder Zugreihen machen.’

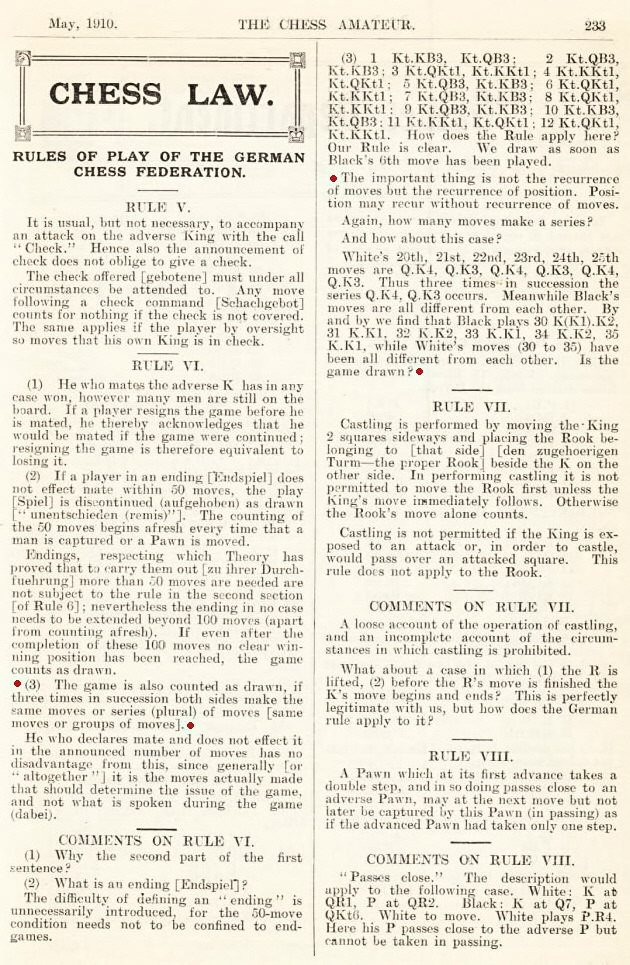

An English translation appeared, with discussion, on page

233 of the May 1910 Chess Amateur:

‘The game is also counted as drawn, if three times in succession both sides make the same moves or series (plural) of moves [same moves or groups of moves].’

Can readers assist with further information?

8396. Alekhine games

The feature articles An Alekhine Blindfold Game and An Alekhine Miniature have been updated to include Raymond Keene’s latest bungling, on successive pages of Little book of Chess Secrets (Glasgow, 2013). Far from rectifying his earlier errors, he goes even further astray (‘Alekhine-Mindeno, Germany, 1933’).

Corrections are one of the few things that Raymond Keene will not copy.

8397. Botvinnik on the world championship

Stuart Rachels (Tuscaloosa, AL, USA) asks whether Hans Ree was right to state on page 128 of the 7/2013 New in Chess:

‘Botvinnik has said that a world championship match, with everything that it involves, would take one year off one’s life.’

The best supporting quote that we can offer is a paragraph by Harry Golombek about the 1963 Botvinnik v Petrosian match, on page 115 of Chess Life, May 1963:

‘Both contestants have shown, on and off, undoubted signs of strain and both have given utterance to their thoughts on the matter. Botvinnik has said that each world championship match has cost him a year of his life. He may have meant by this that the necessary preparation for such a match took a year, but it is still more likely that he meant the anguish and the pain caused by the whole contest shortened his life expectation by one year.’

8398. A German proverb?

‘No fool can play chess, and only fools do.’

Stuart Rachels notes that this was given as ‘a German proverb’ on page 262 of Maxims of Chess by John W. Collins (New York, 1978) and enquires whether that description (also to be found in other publications) is justified.

The observation was referred to as an ‘old adage’ on page 1 of The Pleasures of Chess by Assiac (New York, 1952), in a text reproduced from his New Statesman column, 1949, page 485. There was no suggestion that the sentiments emanated from Germany. Indeed, on page 7 of the German edition of the book, Vergnügliches Schachbuch (Cologne and Berlin, 1953), the phrase was said to be of English origin:

‘... wer immer von der Schachtarantel gestochen ist, wird sehr bald die Wahrheit des alten englischen Sprichworts zugeben müssen: “Ein Narr kann nicht Schach spielen, aber nur Narren tun es”.’

See too Chess Proverbs.

8399. Observations by Botvinnik

We offer a miscellany of observations by Mikhail Botvinnik published in English-language chess magazines. First, some excerpts from an interview in the Latvian magazine Šahs as presented by Eliot Hearst on page 135 of the June 1962 Chess Life:

- ‘Because of your good results in the “sixties”, the Caro-Kann Defense has once again become popular. What can you tell us about this defense?’

‘This defense limits the possibilities of White. When the defenses P-K4, P-K3 or P-QB4 are employed, White has a much bigger choice of variations than in the case of the Caro-Kann Defense, where Black usually has a very solid position. As a result, in match-play the Caro-Kann is a very efficient weapon, since, in a match, one plays as White to win the game, whereas, as Black, one tries to merely obtain a satisfactory defense. And if, in the last Tal match, White got a slight advantage against this defense, the reason was not because of the opening itself, but because of errors committed later in the game.’

- ‘What is your opinion about Tal’s play in the last match and about the style of your opponent in general?’

‘It is said that if one is beaten by someone, it is necessary to criticize the opponent; and if one beats someone, it is necessary to praise him. I think it is better to always be consistent ...

... He is a rather unique player. When the game takes on a more or less open character, and when piece-play is important, nobody can equal Tal. The view that he calculates variations very quickly is widespread, and it is really so.

In other positions he is weaker. Here no calculation can help him. In such positions one can play him entirely peacefully. As for me, it was natural that I would try to obtain such positions against Tal, where he would have difficulties.

Further, I think that one of his shortcomings is that he is lazy. He used to work more, prepare better, particularly in the openings. If you have watched his games over the past two years, you will observe nothing new. He attempted the move 3 P-K5 against the Caro-Kann, but this variation is not very dangerous, and one cannot prepare only one variation for such a catch. This circumstance naturally offered me the possibility of preparing something new for him each time. This facilitated my work during the games.

If Tal had been well-prepared, if he had devoted enough time to the study of typical positions, his talent would render him much more dangerous than he is now. No second can do the player’s work; the player has to work for himself.’

The next set of quotes comes from an article ‘M.M. Botvinnik declares ...’ on pages 3-8 of CHESS, October 1968 (a report on an address by Botvinnik to an audience of 400 in Vladimir in late July):

- ‘Amongst our promising young players only two stand out – Anatoly Karpov from Tula and Mike Steinberg from Kharkov. It is still far from certain that they will make grandmasters of the calibre of Spassky and Tal.’

- ‘I have already mentioned Efim Geller as our leading theoretician. His ideas on the openings and on the transition from opening to middle-game have become common knowledge nowadays. Before his advent, we did not properly understand such modern openings as the Indian set-ups.’

- ‘Spassky is an exceptionally sober player with enviable good health. He is a good psychologist. He is a sound judge of situations and of the balance of strength between himself and his opponent. He rarely gets into time-trouble. You cannot confuse him. He is always in a happy and confident state of mind and does everything equally well.

Geller can play exceptionally well, but he can also play very badly. Spassky’s play is always that of a very good grandmaster.

It is this combination of qualities that has enabled Spassky to achieve outstanding successes.’

- ‘Korchnoi always considers that his fine positional understanding and his deep knowledge of theory (not book theory, but his own theory of the openings) should bring him success.

Korchnoi can do what the majority of players can’t – stick it out when defending a difficult position and then switch over instantly, if the opportunity comes, to counter-attack. His combination of courage and accurate calculation enables him to overcome the nervous strain caused by difficult situations. Spassky avoids such positions. Hence, it is hard to say which of them will win [in the Candidates’ Final]. Only 12 games makes a pretty short match. The one who manages to win a couple of good deep games will have a great chance of victory.’

- ‘At 25, he [Fischer] is nowadays the sort of legendary figure Tal was once. You have to agree at once that he is outstandingly talented. He analyses superbly, plays most energetically, has a fine competitive temperament and great resourcefulness. He can both hold out in defence and attack hard. His nerves respond to any demands on them.

... But there is another Fischer. Apart from his outstanding chess talent there is the question of his general intellectual development. This is probably on about the level of a 14 or 15-year old child. His character is unstable. He is too easily provoked. You could say he is naïve and doesn’t really understand life. He takes hasty decisions which at times harm both himself and the name of chess. It is all very sad. His absence from the Candidates’ contest certainly reduces interest in the event.’

Pages 38-40 of the November 1972 CHESS had an interview with Botvinnik by B.H. Wood, conducted during the Olympiad in Skopje. One question:

- ‘Do you think you would have won against Fischer?’

‘Do you mean against the Fischer of today or when I was at my best? It depends on whether there would be a return match. If this were to be covered by the rules, then perhaps I should have lost the first match against him as I did against Tal, but then have made a serious study of his defects and exploited them in the return match.’

This may be compared with a remark of Spassky’s reported by William Hartston. See C.N. 7137.

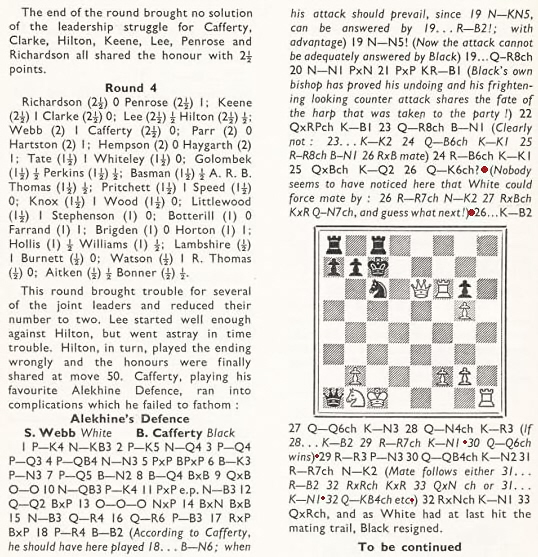

8400. Oversights

From page 13 of the October 1968 CHESS:

‘As many readers have pointed out, Morry in his notes to Webb v Cafferty overlooked for two moves that White’s king was in check.’

The game, played in the British Championship in Bristol, had been published on page 350 of the September 1968 issue:

In this position W. Ritson Morry gave 26 Qe6+ a question mark and affirmed:

‘Nobody seems to have noticed here that White could force mate by: 26 R-R7ch N-K2 27 RxBch [sic] KxR [28] Q-N7ch, and guess what next!’

This line is illegal since 26...Ne7 gives discovered check.

Towards the end of his notes Morry commented that 30 Qd6+ wins, whereas White can give mate on the move with either 30 Qxb7 or 30 Rxb7, and the alleged mating line ending with 32 Qf4+ disregards another discovered check, 32...Ne5+.

8401. James Mavor’s reminiscences

Hans Renette (Bierbeek, Belgium) forwards an excerpt from pages 79-80 of My Windows on the Street of the World by James Mavor (London and New York, 1923):

‘In 1873 or 74 I resumed my interest in chess, and in one or other of these years I joined the Glasgow Chess Club. About the same time Zukertort came to Glasgow to play a series of simultaneous blindfold games, and I was asked to call out the moves for him. I think he played 22 boards. It was a very marvellous performance. One of the players challenged one of Zukertort’s moves. The player had in defiance of all rules been moving about the pieces on his board. Zukertort was not in the least disturbed by the challenge. He repeated the game from the beginning, and then gave the position as it should be. It is needless to say that he was indisputably right and the seeing player wrong.

Within this decade also I became acquainted with Blackburne, with Captain MacKenzie, the celebrated American chessplayer, and more importantly, with Steinitz, with whom I remained on friendly terms until his death. Steinitz was undoubtedly the greatest chess master of his time, and perhaps of any time. He did not distinguish himself beyond the field of chess, but he had other interests. He had either invented or somehow become involved in an invention in marine engineering. This invention consisted in some alleged improvement in the screw-propeller. I got him some information that he wanted from some of my shipbuilding friends, but I do not think his project came to anything. Much more interesting were his philosophical views which he propounded on various occasions. Curiously enough, he regarded his achievements in chess with great modesty; but he really prided himself upon his powers as a philosopher. I cannot say, however, that there was anything original in his philosophy. So far as I could form a judgment, he was a Spinozist. Among his less well-known writings is a little pamphlet called The Economies of Chess [sic], in which he shows for the benefit of the intending chess professional that chess does not pay. This pamphlet promulgates the thesis which he once developed to me viva voce: “Here am I”, he said, “the most successful chess professional of my time, winner of the most important prizes in chess matches and editor of the most important and remunerative chess column” (he edited the chess column of The Field), “and yet, on the average, I have not received more than the wages of an artisan.” Sometimes, in the eighties, I used to play with Bird at Simpson’s Divan in the Strand, and occasionally Steinitz used to look on and make caustic comments on the game.’

Page 45 of Blindfold Chess by Eliot Hearst and John Knott (Jefferson, 2009) notes that the largest number of blindfold games ever played by Zukertort simultaneously was 16. How many exhibitions he gave in Glasgow we do not know, but one such display, on 12 boards, was reported on page 221 of the February 1873 Chess Player’s Chronicle.

8402. The Berlin Defence

Our latest feature article, The Berlin Defence (Ruy López), is a compilation of analysis by, among others, Alapin, Berger, Jaenisch, Tarrasch and von Bardeleben.

8403. A Zugzwang position

This ‘Jung v Szabados’ position from the 1950s (White to move) has been discussed in a number of C.N. items (see pages 77-78 of Chess Facts and Fables and C.N. 4555).

Publications gave the venue as Hungary, Venice and Dessau, and now Riccardo Del Dotto (Picciorana-Lucca, Italy) adds that August Livshitz offered a fourth version: Reggio Emilia. See, for instance, the second volume of Test Your Chess IQ (Oxford, 1981, page 32 and Oxford, 1989, page 26). Our correspondent also notes that the Zugzwang position had been the subject of compositions by Rinck and Troitzky, and he believes that the ‘Jung v Szabados’ ascription is false.

For further details see his article ‘Smascherato un falso storico?’.

8404. An enticing riddle

‘It is one of the most enticing riddles of the centuries-old attractiveness of chess that a phenomenon so deeply rooted in the materialistic and rapacious should offer a satisfaction which is so deeply spiritual and so innocent of harm to one’s fellow man.’

Source: page 119 of How to Improve Your Chess: Second Steps by I.A. Horowitz and Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1952).

8405. Gusev v Auerbach

From Dan Scoones (Port Coquitlam, BC, Canada):

‘On pages 167-170 of 7 Ways to Smash the Sicilian (London, 2009) Yuri Lapshun and Nick Conticello analyse a game cited as “Y. Gusev-Y. Averbakh, Moscow, 1951” and marvel that one of the stalwarts of the Soviet chess establishment could be so comprehensively beaten by a relatively unknown master. The source was stated to be Rolf Schwarz’s 1966 work Die Sizilianische Verteidigung.

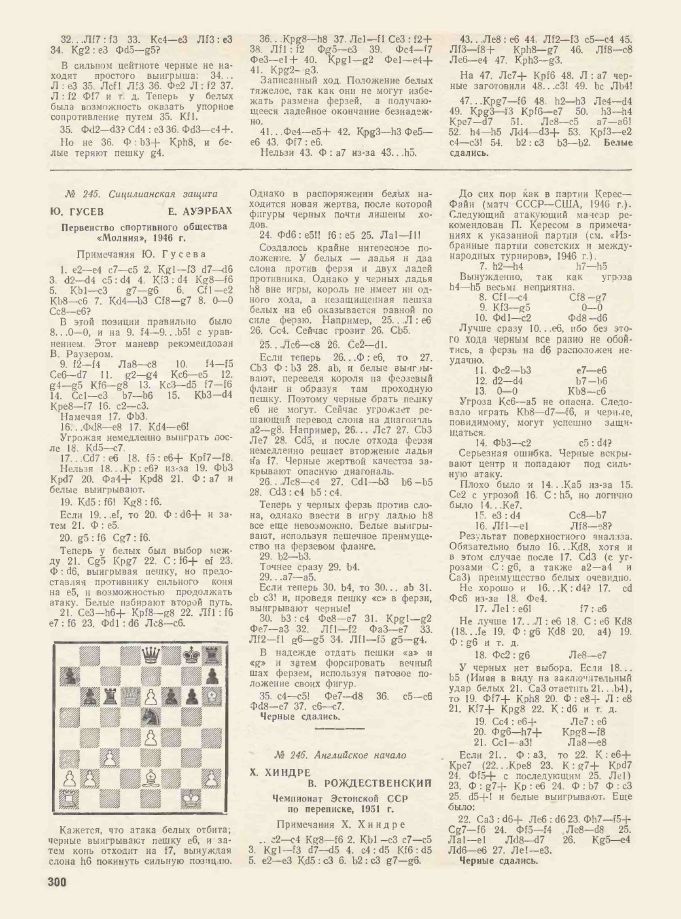

Gusev’s opponent was not Yuri Averbakh but a minor Soviet master named E. Auerbach. The game was played not in Moscow in 1951 but in the championship of the Molniya Sporting Society in 1946. It was published on page 300 of Shakhmaty v SSSR 10/1951:

I have not been able to trace the venue or any other games from the event.’

We note many sources which gave incorrectly Black’s identity and the game’s date. An exception is Queen Sacrifice by I. Neishtadt (Oxford, 1991), which has a footnote on page 210 stating that Black should not be confused with Yuri Averbakh; the occasion was given as ‘Moscow, 1946’. On page 212 Neishtadt commented:

‘Virtually the most impressive of all queen sacrifices.’

8406. The laws of chess in the Handbuch

Repetition of Position or Moves in Chess refers to the code of laws set out in the Handbuch des Schachspiels in the latter part of the nineteenth century. Courtesy of the Cleveland Public Library we give a PDF file comprising the relevant text from the sixth and seventh editions of the Handbuch, published in Leipzig, 1880 and Leipzig, 1891 (pages 15-17 and 26-27 respectively).

8407. A German proverb? (C.N. 8398)

Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA) sends two citations:

‘A man must be a very clever fellow and a fool to make a really good chessplayer.’

Source: Brisbane Courier, 21 April 1884, page 3.

‘It has been said that no fool could be a first-class chessplayer, and none but a fool would be.’

Source: Sydney Mail, 6 March 1897, page 487.

8408. An early Koltanowski game

George Koltanowski (Antwerp) – Jean-Louis Ormond

(Vevey)

Played by correspondence

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 O-O Nxe4 6 d4 exd4 7 Re1 d5 8 Nxd4 Bd6 9 Nxc6 Bxh2+ 10 Kf1 Qh4 11 Be3 O-O 12 Nd4 Bg4 13 Nf3 Qh5 14 Bb3 Rad8 15 c3 Bg3 16 Ke2

16...Nxf2 17 Bxf2 Rfe8+ 18 Kd3 Qf5+ 19 Kd2 Bxf2 20 Rxe8+ Rxe8 21 Qf1 Bxf3 22 gxf3 Qxf3 23 Na3 Qf4+ 24 Kd3 Qf5+ 25 White resigns.

Source: Schweizerische Schachzeitung, October 1921, pages 154-155. As regards the occasion, the heading merely stated that the game had been ‘jouée récemment par correspondance’.

8409. World championship seconds

From Leonard Barden (London):

‘In an interview after his match against Anand, Carlsen said that he had no on-site seconds in Chennai, although he was in contact via Skype with Jon Ludwig Hammer, Norway’s number two player.

When was the last time that a player had no strong assistant at a world championship match? I am referring to assistants of master level capable of providing technical help, and not “seconds” who were effectively managers dealing with match rules and similar matters.’

Precise records of players’ seconds are often difficult to trace, and no list of the kind requested by a correspondent in C.N. 5657 has yet been built up. For example, for the 1929 and 1934 Alekhine-Bogoljubow matches and, even, the 1927 Capablanca v Alekhine encounter it seems unclear which other players were involved in any capacity.

In response to Mr Barden’s enquiry we can offer a quote from page 135 of the June 1962 Chess Life (the item mentioned in C.N. 8399). An interviewer asked Botvinnik:

‘Why did you decide against having a second in the return match with Tal?’

Botvinnik’s response:

‘My friend, the master Goldberg, with whom I have worked these past years, refused to be my second this time. He is older than I, and to second is far more tiring than to play. It is exhausting, and I understand his point of view. For example, when I help as a spectator at a chess tourney, I tire faster than if I play myself. And the second has to be alert for the five-hour duration of the game, as well as afterwards, to analyze the adjourned game throughout the night. So before me rose the question: “Should I engage a new second whom I may not have too much confidence in?” How could we successfully work together without a long friendship and mutual respect? Therefore, I decided not to use a second.

Formerly, when I was young, I always played alone. I decided to take the risk and, as you see, it didn’t turn out badly. It is true that in some games I had difficulties because of poor analysis; I made bad mistakes of analysis in the second and 19th games.’

From page 71 of The World Chess Championship 1963 by R.G. Wade (London, 1963):

‘Each player was entitled to have a “second” to help in openings, preparations and adjournment analysis. Surprisingly Botvinnik had no-one. Petrosian had the benefit of aid from the very capable grandmaster Igor [sic] Boleslavsky. A second, who is temperamentally suited, can make a very appreciable difference. Botvinnik showed the need in the decisive 18th game, where his adjournment homework was not up to his usual standard.’

On page 129 of the May 1963 BCM Harry Golombek, who was the judge in Moscow, wrote of Botvinnik:

‘He has no official second here whereas Petrosian has the redoubtable Boleslavsky as his second.’

Other quotes on this topic will be gratefully received.

8410. Questions to Petrosian

C.N. 13 (see page 232 of Chess Explorations) cited a quip by Petrosian during the 1974 Karpov v Korchnoi match, from page 166 of Anatoly Karpov: Chess is My Life by A. Karpov and A. Roshal (Oxford, 1980):

‘The press centre was linked to the stage by four television screens. Arranged in groups around the chessboards, grandmasters and journalists analysed the position, periodically glancing at the screens. At the start of the match (before his departure to the international tournament in Manila) perhaps the most popular figure in the press centre was Petrosian. The journalists would constantly turn to the ex-world champion: “Tigran Vartanovich, what should be played here?” “When I knew that, I was down on the stage, instead of up here”, was Petrosian’s joking reply.’

8411. Isaac Boleslavsky and Igor Bondarevsky

C.N. 8409 noted R.G. Wade’s reference to ‘Igor Boleslavsky’. As mentioned by a correspondent in C.N. 1148 (see page 158 of Chess Explorations) on page 171 of his book Soviet Chess (London, 1968) Wade made the reverse mistake: ‘Isaac Bondarevsky’.

8412. Matches compared

‘The world championship match Botvinnik-Petrosian was one of the toughest. The Capablanca-Alekhine 1927 encounter was a Sunday afternoon picnic compared with it.’

Source: The World Chess Championship 1963 by R.G. Wade (London, 1963), page 9.

8413. Bulging bookshelves

An article by G.H. Diggle published in the July 1974 Newsflash and reproduced on page 1 of volume one of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984).

‘Britain is, as never before, teeming with new chess works the purchase and study of which (the more sanguine reviewers imply) will rapidly “people this Isle with grandmasters”.

Speaking as an embittered Local Bad Master of 50 years’ standing, we have our doubts. If no man by taking thought can add one cubit to his stature, can a chessplayer do so by steeping himself in “bookish theoric”? He may keep what chess he has in good running order – he may even pick up a few spare parts – but he will still be saddled with his original brainbox. The great Deschapelles, we are told, never looked at a chess book; Paul Morphy looked at very few; and those of us whose bookshelves bulge with semi-digested works, “without which no chess lover’s library could possibly be complete”, are tempted to think, in our sombre moments, that left on our own we might have achieved fame – as it is, we shall die as we have lived, befuddled by the verbosity of pedantic humbugs.

Our own nasty suspicions of chess literature were first aroused in 1945, when the enterprising officials of the Lud-Eagle chess club arranged for a number of consultation games to be played there in public by the leading players then in London. On hearing what was afoot, we hied us to the Lud-Eagle in a state of delighted anticipation – here was a chance of actually overhearing the experts planning aloud – we expected not only an intellectual but a philological treat, for we naturally supposed that their consultations would be couched in the same mystic language in which they are depicted by twentieth-century annotators as thinking things out when playing on their own. Thus we hoped to hear, as we hovered ecstatically on the fringe of the crowd, such fragments as “From the strategical point of view, Dr X, I am inclined to agree that P-KR3 is positionally indispensable; but a feeling of psychological malaise pervades me as though something more dynamic were called for; and incidentally (though I am loth to distract a man of your calibre with mere tactical trivialities) we must first liquidate the technical obstruction of our king being in check.”

But alas, all we did in fact hear was a series of muffled banalities such as “the snag is, the rook’s pinned”, “if we swap off, the knight pops in”, and once (most deplorable of all) “you swore blind we could hold the bally pawn”.

We came away shaking our hoary head – and we are shaking it still.’

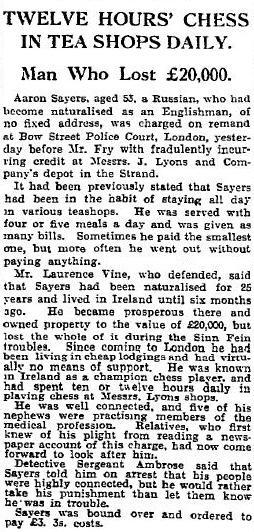

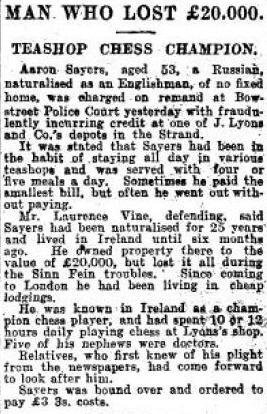

8414. Aaron Sayers

From page 206 of the April 1928 Chess Amateur:

‘Aaron Sayers, aged 53, with no means of support, but with a passion for chess, and alleged to be known in Ireland as a champion chessplayer, was brought before the magistrate at Bow Street Police Court on 15 March, accused of obtaining credit by fraud at a tea-shop. The five nephews who were not aware of his destitute condition heard of the charge and at once rallied round him. The magistrate placed him on probation for 12 months.’

Two contemporary newspaper reports on the ‘teashop chess champion’ from Ireland:

Manchester Guardian, 16 March 1928, page 11

Daily Mail, 16 March 1928, page 7.

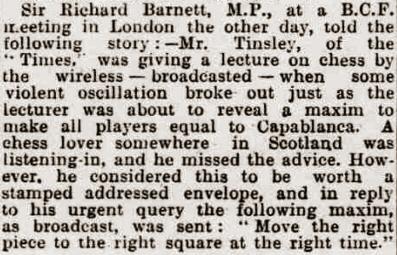

8415. Maxim

From page 19 of the Cheltenham Chronicle and Gloucestershire Graphic, 3 November 1928:

See Chess and Radio for

references to a radio broadcast by S. [sic] Tinsley

(E.S. Tinsley’s brother).

Wanted: other sightings of the maxim ‘Move the right piece to the right square at the right time’.

8416. Who?

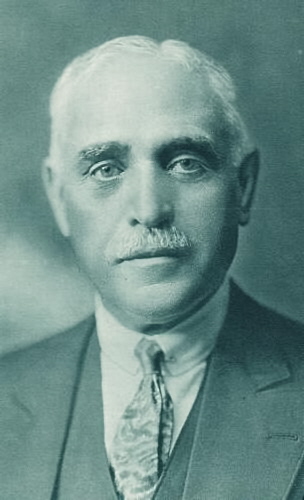

8417. Aaron Sayers (C.N. 8414)

David McAlister (Hillsborough, Northern Ireland) has traced references to ‘A. Sayers’ in the Irish press during the period 1914-27:

‘In the 1914 Leinster Championship he was the runner-up to Charles J. Barry. The latter was the reigning champion, and Sayers seems to have qualified to meet him, the format probably being two all-play-all tournaments with four (probably) qualifiers playing a semi-final before the winner faced the previous year’s champion. Two future Irish champions, Philip Baker and Thomas George Cranston, played in Sayers’ section. Sources: Weekly Irish Times, 21 March 1914, page 16 (there is also a reference to Sayers playing in the Armstrong Cup, the league competition for Dublin clubs) and the Weekly Irish Times, 16 May 1914, page 24.

I have also found a reference to Sayers on board one for the Cairo Chess Club (named after its premises, the Café Cairo) in a friendly match with the Rathmines Chess Club (Weekly Irish Times, 24 January 1914, page 19).

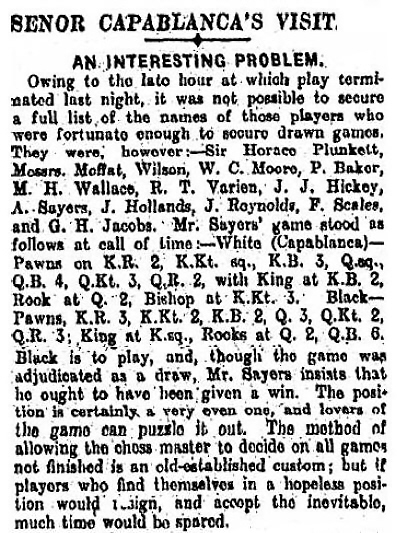

The Irish Times of 6 December 1919, page 7 reported on his game against Capablanca in a simultaneous exhibition in Dublin earlier that month:

The conclusion given in that newspaper report was used on page 339 of Capablanca in the United Kingdom (1911-1920) by V. Fiala (Olomouc, 2006), although with the misspelling “Sayer”, an erroneous position and an unexplained continuation (“1 a3”, even though it was Black’s move). It is, however, difficult to understand what the newspaper meant by white pawns on “K.Kt. sq.” and “Q.sq.”.

In 1924 Sayers competed in the major section of the Tailteann Games, where he came second to Lord Dunsany. There were two qualifying groups and then a final section of six (Irish Times, 19 August 1924, page 6).

In the 1925-26 league season he was a member of the Sackville Chess Club team which won the Armstrong Cup, as reported in the Irish Times, 16 April 1926, page 11, 20 April 1926, page 11, 30 April 1926, page 11 and 5 May 1926, page 10.

In 1927 Sayers played on board 13 in the Belfast v Dublin match; see my article The Time Traveller, which has a photograph of him.’

| First column | << previous | Archives [112] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.