Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [113] | next >> | Current column |

8418. Tartakower blindfold game

C.N. 8118 mentioned the rarity of blindfold games played by Tartakower. Below is a specimen (from a five-board display) published on page 138 of Schachjahrbuch für 1909 by Ludwig Bachmann (Ansbach, 1909):

Savielly Tartakower – Häusler

Augsburg, 14 September 1909

Queen’s Gambit Declined

1 d4 d5 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 c5 4 cxd5 exd5 5 e4 dxe4 6 d5 Bf5 7 g4 Bg6 8 Bf4 Bd6 9 Qa4+ Kf8 10 Bxd6+ Qxd6 11 O-O-O Qf4+ 12 Rd2 Nf6 13 h4 h5 14 Nh3 Qxg4 15 Rg1 Qd7 16 Qc4 Na6

17 Rxg6 fxg6 18 Ng5 Re8 19 Bh3 Ng4 20 Ne6+ Kg8 21 Qxe4 Qf7 22 f3 Nf6 23 Qc4 Nc7 24 Ng5 Re1+ 25 Kc2 b5 26 Nxf7 (The Schachjahrbuch does not mention the possibility of 26 Qxc5.) 26...bxc4 27 Nxh8 Kxh8 28 d6 Na6 29 a3 Re8 30 d7 Rd8 31 Ne4 Nxe4 32 fxe4 Kg8 33 e5 Kf8 34 e6 Nc7 35 Rf2+ Ke7 36 Rf7+ Kd6 37 e7 Rxd7 38 e8(Q) Nxe8 39 Rxd7+ Ke5 40 Re7+ Resigns.

8419. The Rice Gambit

Isaac Leopold Rice and Richard Teichmann – Erich

Cohn and Oscar Tenner

Berlin, 16 September 1910

Rice Gambit

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 h4 g4 5 Ne5 Nf6 6 Bc4 d5 7 exd5 Bd6 8 O-O Bxe5 9 Re1 Qe7 10 c3 Nh5 11 d4 Nd7 12 Qxg4 Ndf6

13 Qxc8+ Rxc8 14 Rxe5 Ng4 15 Rxe7+ Kxe7 16 Na3 f5 17 Bd2 Kf6 18 Nc2 Rce8 19 Rf1 Ng3 20 Rf3 Re7 21 d6 Ne2+ 22 Kf1 Nh2+ 23 Kf2 Ng4+ Drawn.

Source: Deutsches Wochenschach, 9 October 1910, page 369. Page 350 of the 25 September 1910 issue reported that the players contested three games beginning with 13 Qxc8+ (two draws and one win for Black).

As shown in Professor Isaac Rice and the Rice Gambit, in the diagrammed position Capablanca played 13 Qe2 in a 1913 consultation game which he lost.

8420. Nimzowitsch’s lamentation (C.N.s 5019 & 6718)

C.N. 5019 quoted from an article by H. Kmoch and F. Reinfeld on page 55 of the February 1950 Chess Review:

‘A man mounting a table, however, and yelling at the top of his voice, “Why must I lose to this idiot!” (“Gegen diesen Idioten muss ich verlieren!”) would be following the example of Nimzowitsch, who thus vented his rage – after losing in the last round of a great rapid transit tournament in Berlin and so missing first prize.’

We mentioned that the tournament in question had not been identified.

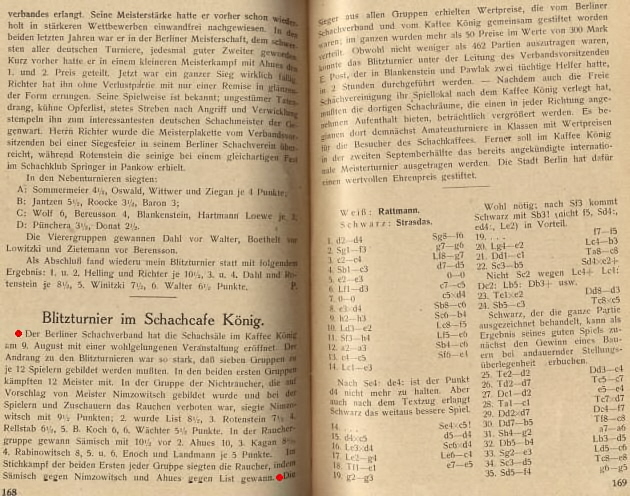

Now, Alan McGowan (Waterloo, Canada) draws attention to pages 168-169 of Schachwart, September 1928:

The magazine states that for the rapid transit tournament in Berlin two preliminary groups were formed: non-smokers (Nimzowitsch being the victor, ahead of List) and smokers (Sämisch finished ahead of Ahues). In the play-off games, the smokers were victorious: Sämisch defeated Nimzowitsch, and Ahues won against List.

8421. Feature articles

Information is sometimes added direct to feature articles. Today, for instance, we have made additions to:

- Kirsan Ilyumzhinov and Aliens

- Pet Moves in Chess

- Professor Isaac Rice and the Rice Gambit

- Stefan Zweig and Chess.

As listed on the Archives page, there are now nearly 340 feature articles.

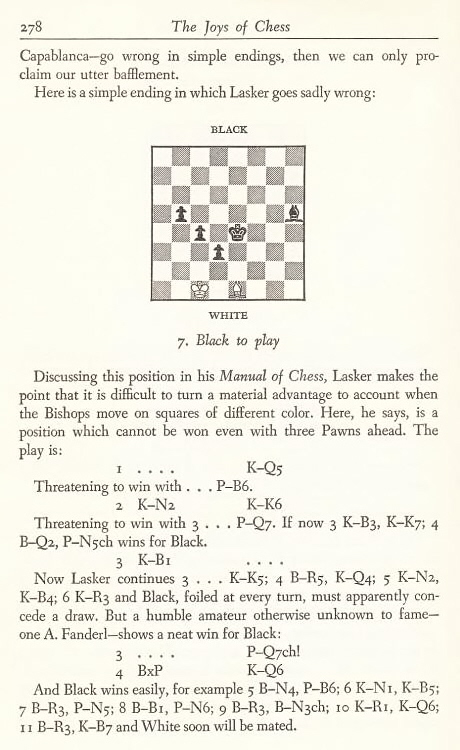

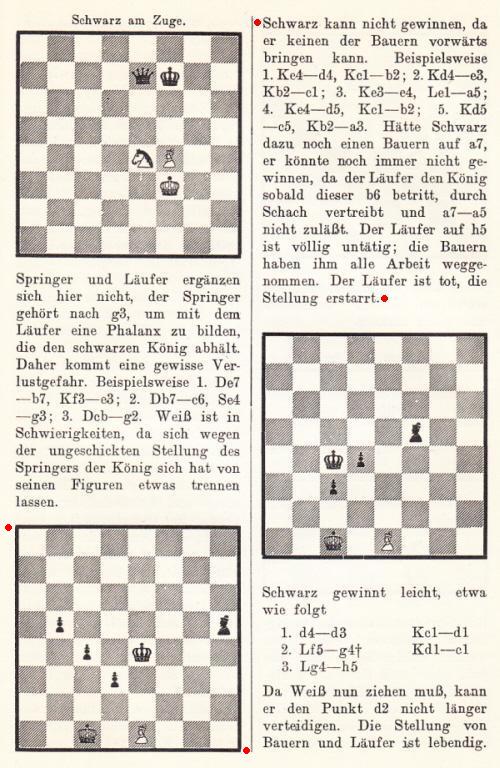

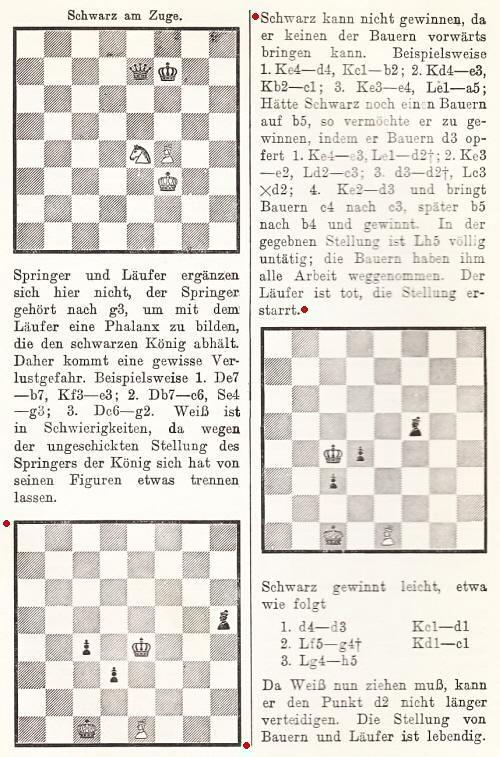

8422. An ending published by Lasker

Our article A Pawn Ending Mystery refers to page 279 of The Joys of Chess by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1961), where a chapter entitled ‘Boners of the Masters’ discussed an alleged mistake by Capablanca in Chess Fundamentals.

By way of introduction, on pages 277-278 Reinfeld wrote:

‘When superb masters of the endgame – such outstanding men as Lasker and Capablanca – go wrong in simple endings, then we can only proclaim our utter bafflement.’

He then wrote about ‘a simple ending in which Lasker goes sadly wrong’:

In passing, mention may be made of the notational error 11 B-R3 in the final line.

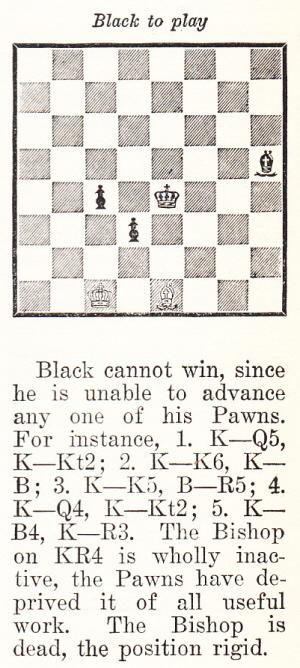

As with the Capablanca position, matters are far more complicated than Reinfeld indicated. Firstly, we have found no edition of the Manual of Chess in which Lasker gave the position shown by Reinfeld. There was, however, a very similar position (no black pawn on b5):

Lasker’s Manual of Chess (New York, 1927), page 258

Lasker’s Manual of Chess (London, 1932), page 232, as well as the edition revised by Reinfeld (Philadelphia, 1947)

It will be noted that the text varies: the original 1927

edition’s ungrammatical wording ‘any one of his Pawns’ was

amended to ‘either of his Pawns’ in the 1932 edition.

Analytically, however, what Lasker wrote was correct.

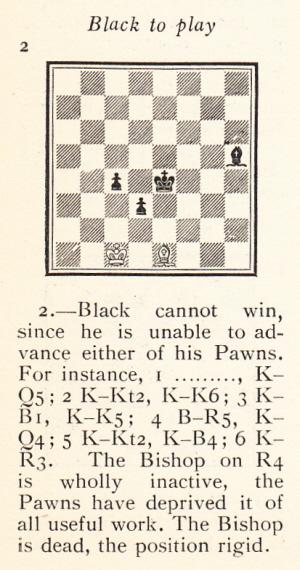

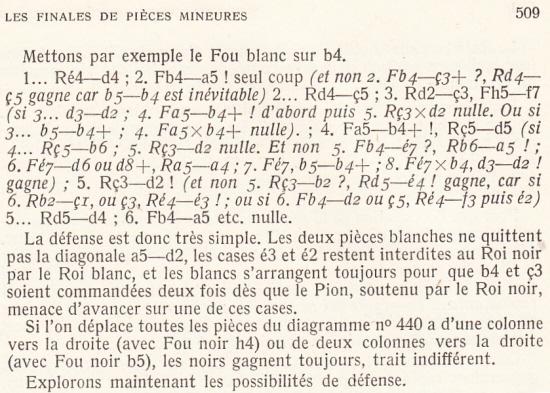

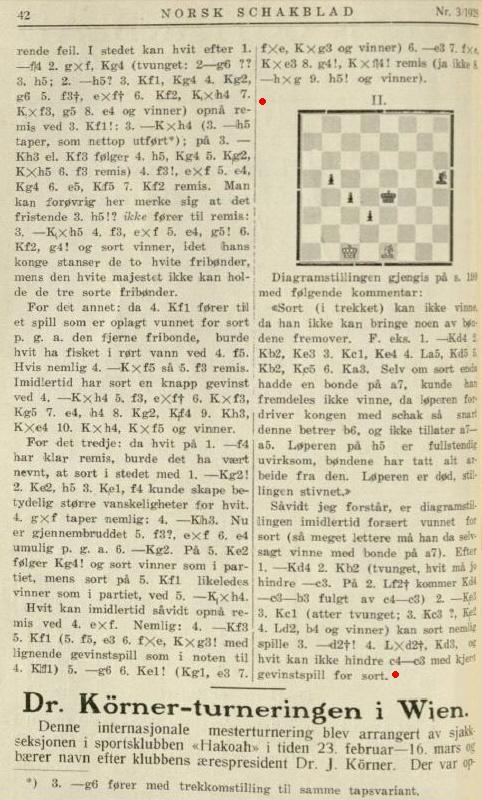

The Manual was a translation/adaptation of Lehrbuch des Schachspiels, first published in Berlin in 1926 and with, it seems, a total of eight editions by 1928. We do not have them all, but the following sample pages show that a position with three black pawns did appear. Subsequently, the b5 pawn was removed, and the text was amended (with a mention of 3...d2+ in case Black had three pawns):

Three pawns: page 199 of Lehrbuch des Schachspiels, third edition (Berlin, 1926)

(‘sechste durchgesehene und vermehrte Auflage’) (Berlin, 1928)

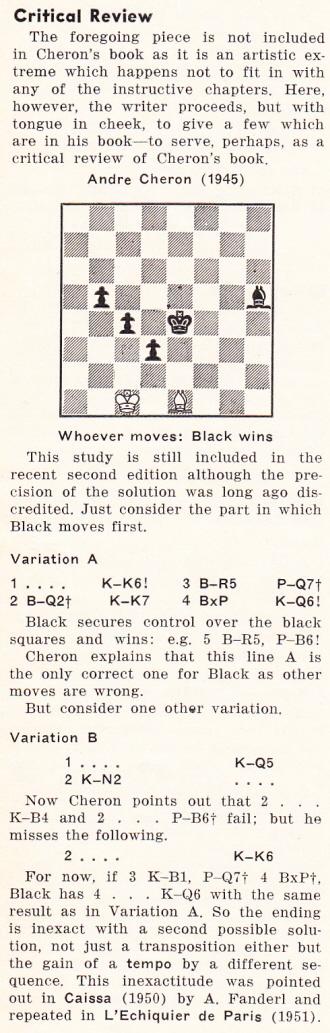

The three-pawn position was discussed by Walter Korn in Chess Review, May 1965, page 143:

It will be appreciated if a reader can provide the items in Caissa (1950) and L’Echiquier de Paris (1951), as well as any other information about A. Fanderl (described by Reinfeld in The Joys of Chess as ‘a humble amateur otherwise unknown to fame’).

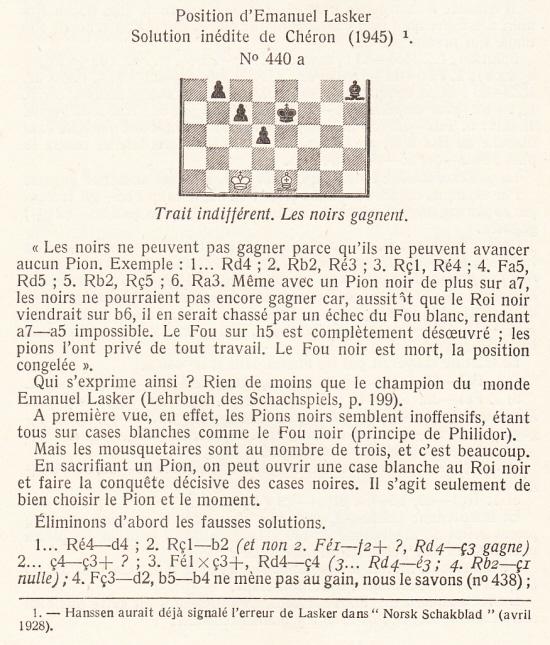

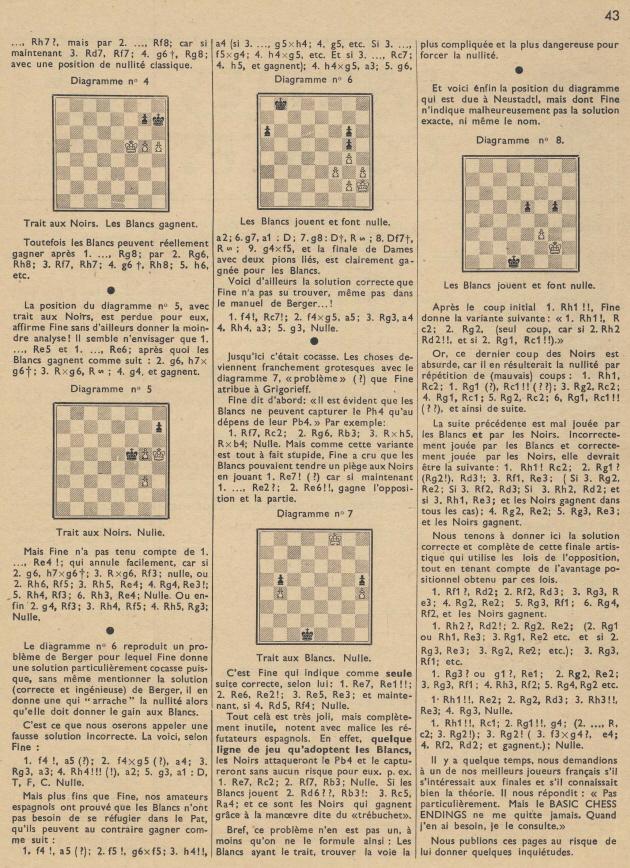

Below is an extract (pages 507-509) from Nouveau traité complet d’échecs. La fin de partie by André Chéron (Lille, 1952):

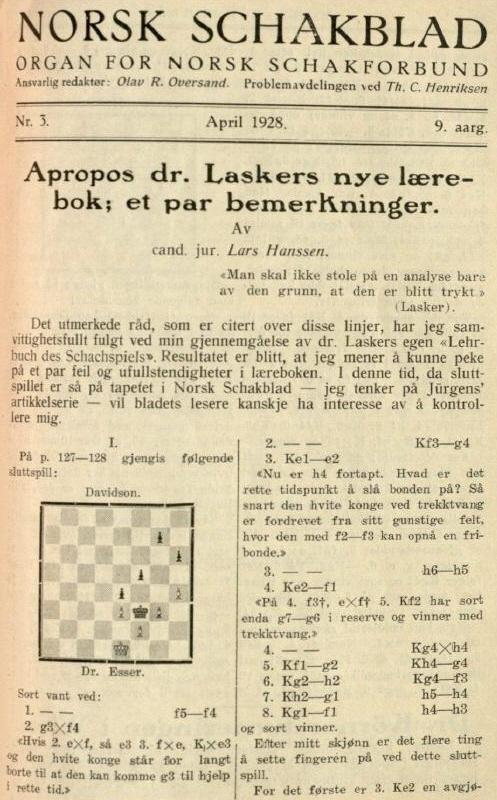

Finally, we add, courtesy of the Cleveland Public Library, the article by Lars Hanssen in Norsk Schakblad which was mentioned by Chéron in the footnote on page 507:

Loose ends currently remain, and it cannot be said when Lasker realized that he was mistaken about the position with three black pawns. As shown above, a correction had already been made (in the New York, 1927 edition of the Manual) before Hanssen wrote about the position in the Norwegian magazine.

8423. Caro-Kann Defence

Regarding the Caro-Kann Defence, Thomas Niessen (Aachen, Germany) draws attention to an article by A. Csánk, ‘Die Vertheidigung 1...c7-c6 als Entgegnung auf 1 e2-e4’, in the Wiener Schachzeitung, 1 September 1887 (pages 49-52) and 1 October 1887 (pages 73-75).

Our correspondent comments:

‘Csánk reports that Marcus Kann, who had died the previous year, was the first to apply the defence, and that Csánk, Ja[c]ques Schwarz and M. Weiss analysed it before Weiss played it at Nuremberg, 1883.’

8424. Repetition

A general provision concerning repetition of position or moves was published on pages 106-107 of Le Palamède, March 1846 (the fifth in a list of possible ways of drawing):

‘1. quand il y a Pat;

2. quand on persiste dans un Echec perpétuel;

3. quand il n’y a plus assez de forces pour donner le Mat;

4. quand, même avec assez de forces, on ne sait pas dans une fin de partie faire Mat en cinquante coups;

5. quand les deux joueurs persistent toujours à jouer le même coup.’

Page 107 contained a brief elucidation of the fifth point:

‘Supposons qu’un joueur persiste à attaquer une pièce avec une des siennes, et que son adversaire persiste à la jouer toujours sur les mêmes cases, ou que de semblables systèmes de répétition soient adoptés de part et d’autre, sans qu’aucun des deux joueurs veuille céder en changeant son coup, alors il est évident que la partie est nulle, car le résultat est en réalité le même que celui d’un Echec perpétuel.’

8425. Drawn positions

‘It is an axiom in chess that he who plays to win a drawn game loses it.’

Source: Chess Player’s Magazine, 1 August 1867, page 229.

8426. An ending published by Lasker (C.N. 8422)

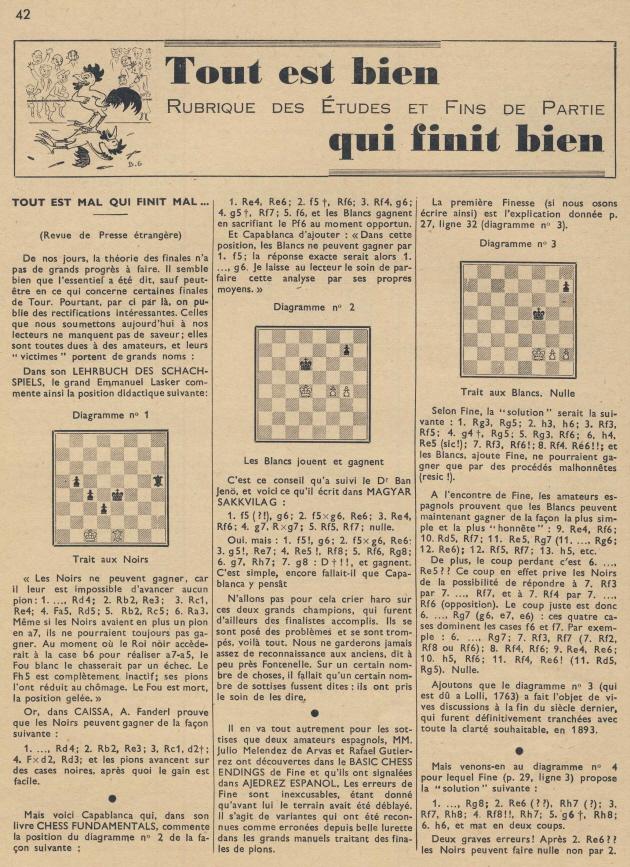

Luc Winants (Boirs, Belgium) has supplied the requested article in L’Echiquier de Paris, published on pages 42-43 of the March-April 1951 issue. It will be noted that the Lasker and Capablanca endings were both given, and that the remainder of the article contained sharp criticism of Reuben Fine’s Basic Chess Endings.

8427. Who? (C.N. 8416)

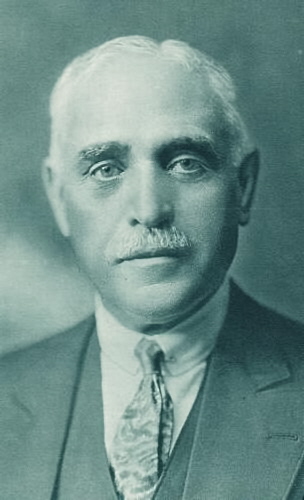

This photograph was published in L’Echiquier, 23 March 1933, with the following information on page 64:

‘Président de la fédération portugaise des échecs, le Docteur João Maria da Costa est certainement la personnalité la plus éminente des milieux échiquéens portugais.’

8428. Capablanca in San Francisco

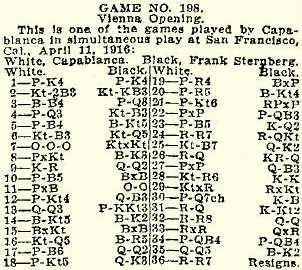

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) has found the game below (from a 32-board simultaneous display) on page 4 of Section Two of the Sunday Oregonian, 13 May 1917:

José Raúl Capablanca – Frank Sternberg

San Francisco, 11 April 1916

Vienna Game

1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Nf6 3 Bc4 d6 4 d3 Nc6 5 f4 Bg4 6 Nf3 Nd4 7 O-O Nxf3+ 8 gxf3 Be6 9 Kh1 Qd7 10 f5 Bxc4 11 dxc4 O-O-O 12 b4 Qc6 13 Qd3 g6 14 Bg5 Be7 15 Bxf6 Bxf6 16 Nd5 Bh4 17 f6 Qd7 18 b5 Qe6 19 a4 Bxf6 20 a5 Bg5 21 b6 axb6 22 axb6 c6

23 c5 Kd7 24 Ra7 Rb8 25 Nc7 Qe7 26 Rd1 Rhd8 27 cxd6 Qf6 28 Na6 Ke8 29 Nxb8 Rxb8 30 d7+ Kf8 31 Rda1 Kg7 32 Ra8 Qd8 33 Rxb8 Qxb8 34 c4 c5 35 Qd5 Be7 36 Ra7 Resigns.

8429. An ending published by Lasker (C.N.s 8422 & 8426)

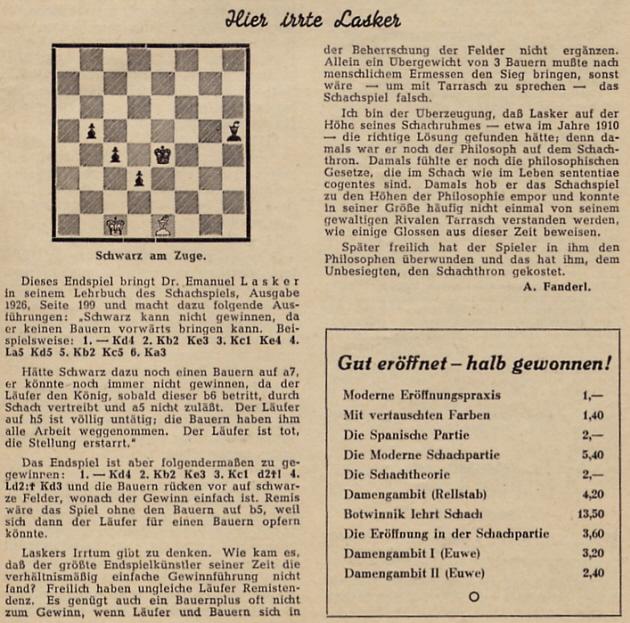

Alan McGowan (Waterloo, Canada) has forwarded the brief article by A. Fanderl which was published on page 133 of the 1 May 1950 issue of Fritz Barkhuis’s periodical Caïssa:

Our correspondent has found no other references to Fanderl, whose ‘discovery’, in any case, was not new.

8430. Leonhardt and blindfold chess

Leonhardt’s name is seldom associated with blindfold chess, but a specimen of his play (in a six-board display) can be given from pages 42-43 of Schachjahrbuch für 1910. II. Teil by L. Bachmann (Ansbach, 1911):

Paul Saladin Leonhardt – Oskar Andresen

Kristiania, 6 May 1909

French Defence

1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 c5 4 exd5 exd5 5 Nf3 Be6 6 Be2 h6 7 O-O Nf6 8 Be3 c4 9 Ne5 Nc6 10 f4 Ne7 11 g4 g6 12 Rf2 a6 13 Qf1 Rg8 14 Kh1 b5 15 f5 gxf5 16 gxf5 Bc8 17 Qh3 Qc7 18 Bh5 Ng6

19 fxg6 fxg6 20 Qf3 Nxh5 21 Nxd5 Qb7 22 Nc7+ Qxc7 23 Qxa8 Qb7+ 24 Qxb7 Bxb7+ 25 Kg1 Bd5 26 Raf1 g5 27 Rf5 Be4 28 Rf7 Nf4 29 Bxf4 gxf4+ 30 Kf2 Rg2+ 31 Ke1 Rxc2 32 Rxf8+ Kxf8 33 Rxf4+ Kg8 34 Rxe4 Resigns.

8431. Learn Chess Fast!

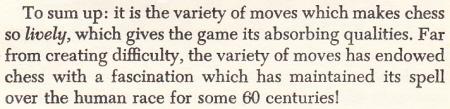

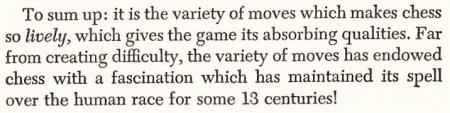

From page 7 of Learn Chess Fast! by S. Reshevsky and F. Reinfeld (London, 1952):

Concerning the reference to ‘some 60 centuries’, we have seen other editions of the book (originally published in the United States in 1947) which have ‘some 13 centuries’:

Readers’ help is requested to determine the chronology of that textual change in the various editions published on both sides of the Atlantic.

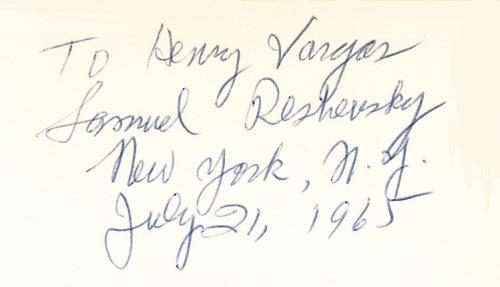

Below is Reshevsky’s inscription in our copy of a New York edition, published by David McKay Company, Inc. (‘Sixth Printing January 1958’):

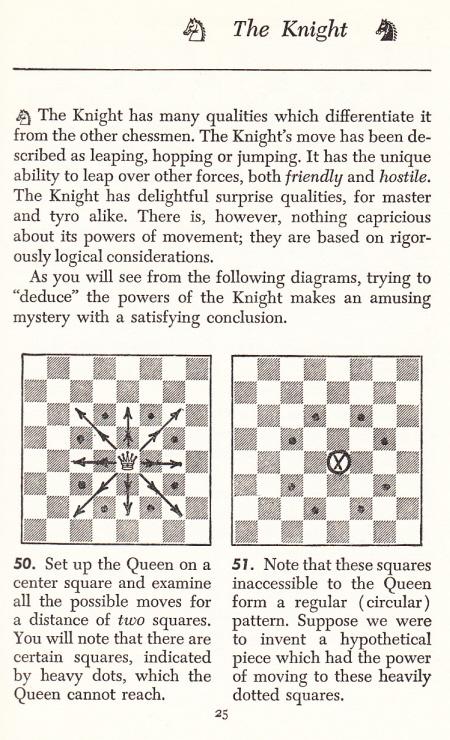

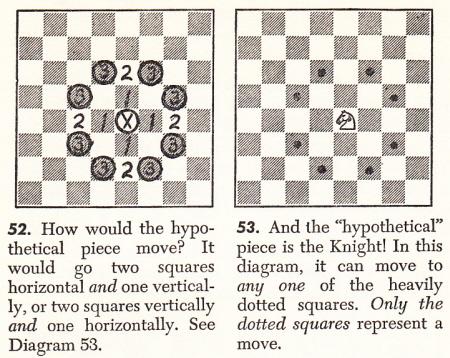

Another curiosity, on pages 25-26, is the presentation of the knight’s move in the captions to diagrams 50-53:

Have many other instructional works explained the knight’s move in this way, i.e. by reference to squares inaccessible to the queen?

8432. Sergiu Samarian

A case that will be added to Gaffes by Chess Publishers and Authors is Opening Tactics for Club Players by ‘Sergio’ Samarian (London, 1980). That was the misspelling of the author’s forename on the title page and imprint page, whereas the dust-jacket was correct:

Wanted: information about the French text which Elaine Pritchard translated.

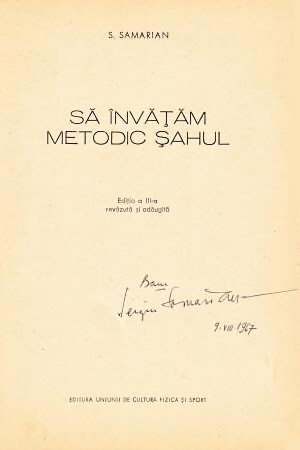

Below, from our collection, is an inscription by Samarian in one of his other works, Să învățăm metodic șahul (Bucharest, 1965):

Sergiu Samarian (1923-91) was a prominent Romanian figure but had no entry in the country’s standard chess encyclopaedia, Şah de la A la Z by Constantin Ştefaniu (Bucharest, 1984). Has the omission ever been explained (e.g. on the grounds of Samarian’s emigration to West Germany)?

8433. The first Cuban grandmaster

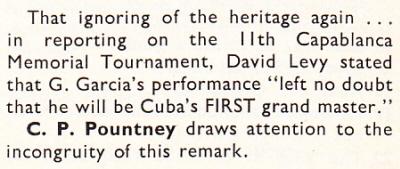

In a report on the 11th Capablanca Memorial Tournament in Camagüey on page 196 of the April 1974 CHESS David Levy stated that Guillermo García ...

‘... had the satisfaction ... of beating three grand masters and he left no doubt that he will be Cuba’s first GM.’

That occasioned a reaction on page 79 of the December 1974 CHESS:

The prediction about Guillermo García proved wrong (he became a grandmaster in 1976, the year after Silvino García), but the matter came back to mind when we saw page 9 of the 8/2013 New in Chess. A reader, John DiLucci of Irving, TX, USA, condemned the statement (‘so ridiculous that it is beyond comprehension’) from page 36 of the 6/2013 issue that ‘in 1975 Cuba’s first grandmaster Silvino García dedicated his title to Che’. Mr DiLucci wondered whether the author of the offending article on Che Guevara (Adam Feinstein) and the New in Chess editorial staff could be ‘so uneducated ’ as to be unaware of Capablanca.

The letter was deemed easy to rebut and, therefore, printworthy, and in the 8/2013 New in Chess about 40 lines were made available for the ‘discussion’, which included the editorial response that Capablanca was never ‘officially’ a grandmaster, given that he died some years before FIDE introduced the title (a perfectly defensible argument).

In fact, though, Mr DiLucci had merely been reacting to a pull-out quote in the 6/2013 issue, and neither he nor the editorial staff apparently realized that on the previous page of Adam Feinstein’s article (i.e. page 35) Capablanca was specifically mentioned:

‘... Silvino García, who in 1975 had fulfilled Guevara’s prophesy [sic] by becoming Cuba’s first grandmaster since the death of Capablanca in 1942.’

8434. Matches against Kasparov

Below are the last two names on a list of challengers on page 279 of Keene On Chess by Raymond Keene (New York, 1999):

The respective dates should obviously be 1993 and 1995.

Mr Keene, though, stuck to his guns. From page 280 of his Complete Book of Beginning Chess (New York, 2003):

8435. Development

From page xvii of Paul Morphy The Pride and Sorrow of Chess by David Lawson (New York, 1976):

‘It is true that Morphy’s time at the chessboard was short; however, before the conclusion of that short time his “secret”, as many have spoken of it, was revealed. But until that secret was revealed, all fell before him. His secret – rapid and consistent development – is now recognized as a basic law of chess, a law that revolutionized the game.’

Reviewing the book on pages 33-34 of the January 1978 BCM David Hooper wrote:

‘Morphy’s contribution to the game is hardly discussed, except to say that his “secret” was rapid development; however, his match opponents developed no less quickly. His superiority lay in both his technique and his tactical skill.’

The importance of development was often stressed before Morphy came to prominence. For example:

‘– En commençant une partie, quel est votre premier objet?

– De sortir mes pièces et de les placer dans des positions à la fois favorables à l’attaque comme à la défense.’

Source: Le Palamède, April 1846, page 145.

Which was the first occurrence in chess literature of a clear exhortation to develop pieces in the opening?

8436. Views on Fred Reinfeld

From a postcard which David Hooper sent us on 23 August 1975:

‘[X – we omit the individual’s name] should be ignored, given enough rope he will hang himself. History will accord him no place. I have a little sympathy for Reinfeld. He started with some serious books, found they didn’t pay, that the public wanted drivel (How to win in ten moves) and American pace necessitated mass production of drivel, he developed contempt of chessplayers, including many champions. His Lasker book was good, but sales low and no sequel possible. He had a rapid, keen mind, and found chess masters altogether narrow and often stupid. I think he wrote the Marshall book which makes Marshall look like a moron which is not a bad description anyway. He had a fine mind and had to write drivel to live, and lost all the joy of doing a task well.’

C.N.s 644 and 5036 quoted some comments to us about Reinfeld from Irving Chernev, in a letter dated 19 January 1977:

‘I thought I was the only one who saw that The Human Side of Chess was written with venom. But then, Reinfeld hated impartially! He hated Morphy, Alekhine and Capablanca most of all. He hated all chessplayers – except those who bought his books. Those he despised.’

The remarks were also given on page 265 of Chess Explorations, where we added:

On page 127 of America’s Chess Heritage, Walter Korn reported that in 1950 he had questioned Reinfeld about the contrasting quality of his early and late writing. Reinfeld replied: ‘In those days I played and wrote seriously – and got nothing for it. When I pour out mass-produced trash, the royalties come rolling in.’

In C.N. 793 a correspondent in Australia, Bob Meadley, submitted a letter dated 14 January 1965 which Fred Reinfeld’s widow, Beatrice, wrote to C.J.S. Purdy, the Editor of Chess World:

‘I’d like to make a correction – but you need not print it, it does not matter now, but it might give you some picture of the man. The reason Mr Reinfeld wrote so much was that he did not have a steady, or indeed any other, job. He devoted himself entirely to study and writing on subjects that interested him. He had the capacity to do many things at once and he had several desks on which he worked at different projects. No matter what they were, there was always a chessboard there with a magazine, or a book, so that he could turn aside from his work to play over a game or study a position that intrigued him.

You may think his output of chess books was large. But I have files and files of annotated games and positions which were never published. It was not by choice that he gave up writing chess books of the depth of his early ones, which he published himself under the imprint of the Black Knight Press. Fred’s popular books brought many people to a deeper understanding of chess than they otherwise would have had – and we must not look down our noses at the learners and average players. The masters may look down their noses at these books, but we knew that they meant a great deal to many people who did not aspire to tournament play – was it Tarrasch who said something to the effect that “chess, like music” had the power to make men happy”? In his way my husband brought that happiness to many people. He would have preferred to continue to write books like The Human Side of Chess, or his Limited Editions, or his pamphlets on the openings and endings, but they were beyond the average player – and the masters, who complain about his simpler books, certainly gave him no encouragement. So the chess world was indeed a tragic world for him in a sense. However, the breadth and depth of his other interests kept him too busy to worry about that.’

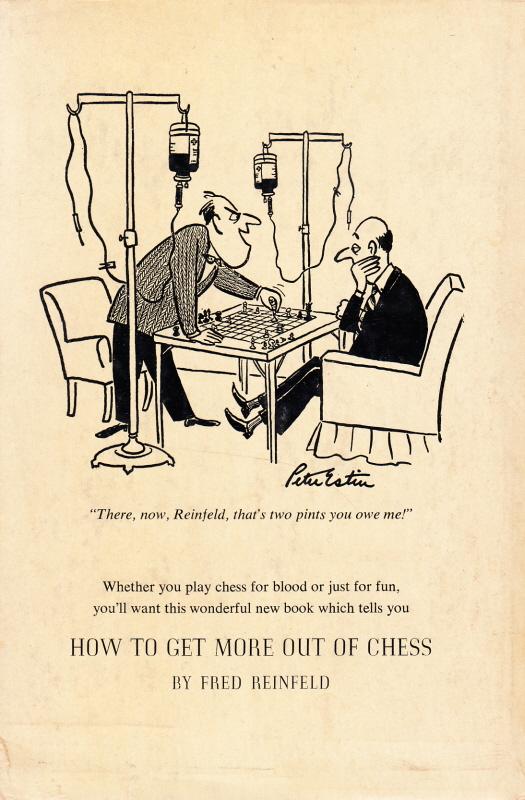

The back of the dust-jacket of How To Get More Out Of Chess by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1957).

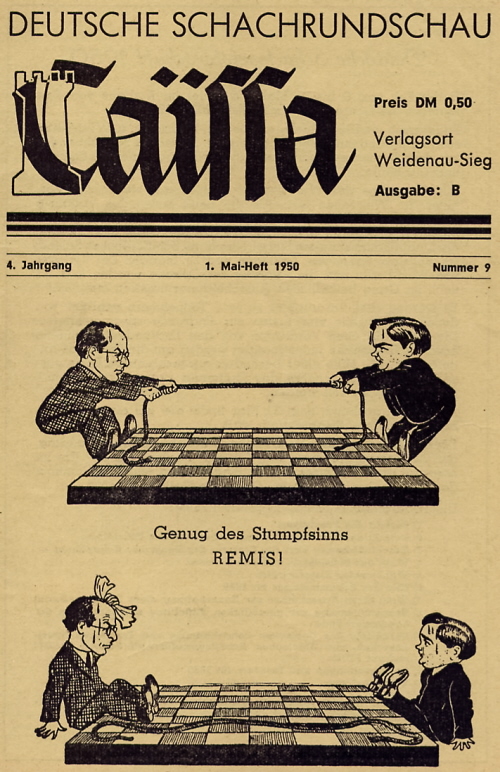

8437. Caïssa front-cover

cartoons

The front cover of Caïssa, 1 May 1950 has been forwarded by Alan McGowan (Waterloo, Canada):

The magazine gave no explanation (concerning the context, for instance, or the rotation of the chessboard), but Mr McGowan notes that, as mentioned on page 129 of the issue, the Candidates’ tournament in Budapest was in progress. One of the games between Bronstein and Kotov was drawn in 15 moves.

8438. Chess for Laughs

A book of cartoons is Chess for Laughs by Joel Rothman (London, 2007). The front and back covers:

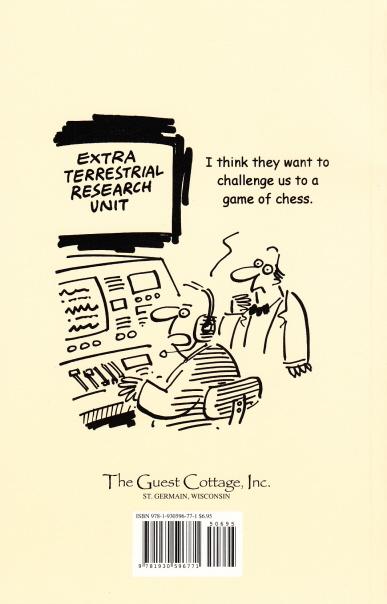

8439. The Incredible Adventures of Chessman

There has also been a comic-strip chess magazine, The Incredible Adventures of Chessman:

We believe that there were only these two issues, published in 1975 and 1982. The text of both was by John Watson, with the artwork credited to Chris Hendrickson (1975) and Svein G. Myreng (1982).

8440. Development (C.N. 8435)

From Robert John McCrary (Columbia, SC, USA):

‘Around 1801, Ercole del Rio prepared a manuscript for publication, but it was not published until 1984, after Christopher Becker found it in the Cleveland Public Library. He presented it with English translations and additional material, in cooperation with Caissa Limited Editions, under the title The War of the Chessmen.

The first of del Rio’s general maxims, as translated on page 11, reads:

“The aim of the first moves should be to develop the pieces in the shortest time possible, and in such a way that none impedes the free movement of another, nor exposes itself to immediate harassment. The economy and the precision of the first moves may well decide the outcome of the game.”’

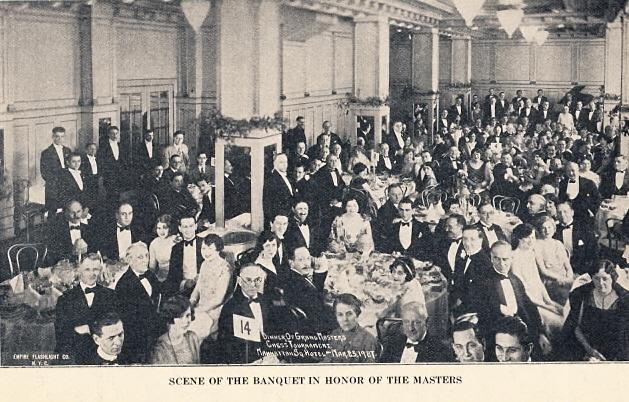

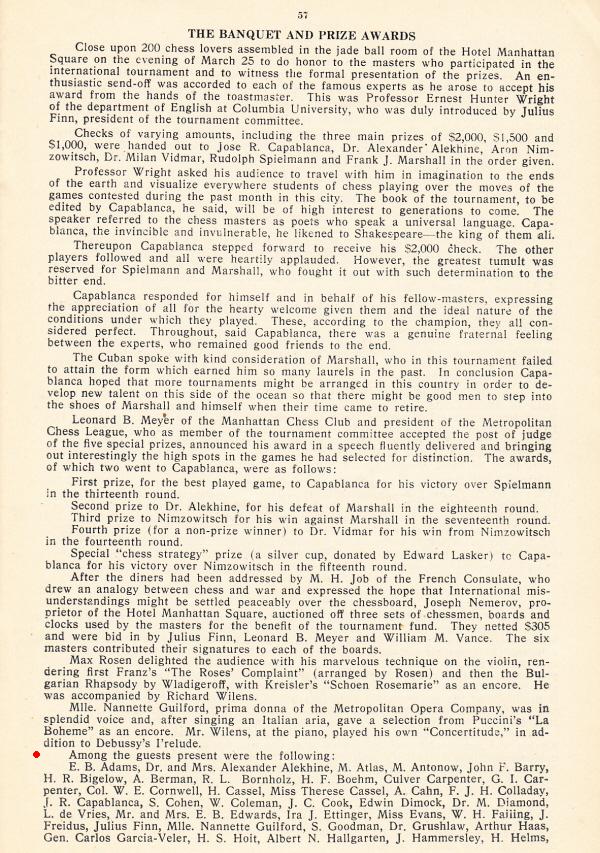

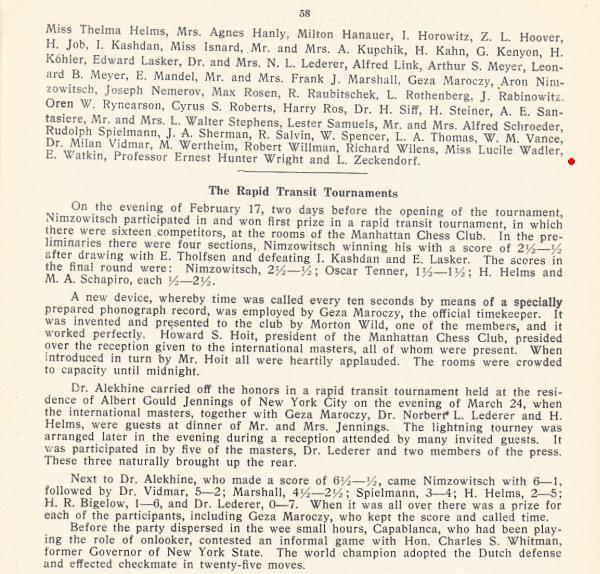

8441. New York, 1927 banquet

The photograph below comes from page 56 of the March 1927 American Chess Bulletin:

There could hardly be a more difficult identification exercise, even with the aid of the report on pages 57-58:

8442. Reshevsky article

John Blackstone (Las Vegas, NV, USA) has submitted a full-page article about Samuel Reshevsky in the New York Tribune, 21 November 1920 (page 5). Can a clearer copy be found?

8443. Keene v Ritson Morry

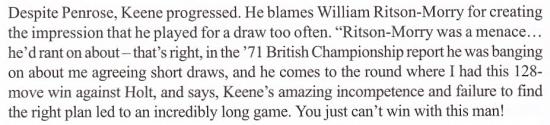

Pages 215-232 of Curse of Kirsan by Sarah Hurst (Milford, 2002) have an interview with Raymond Keene. From page 220:

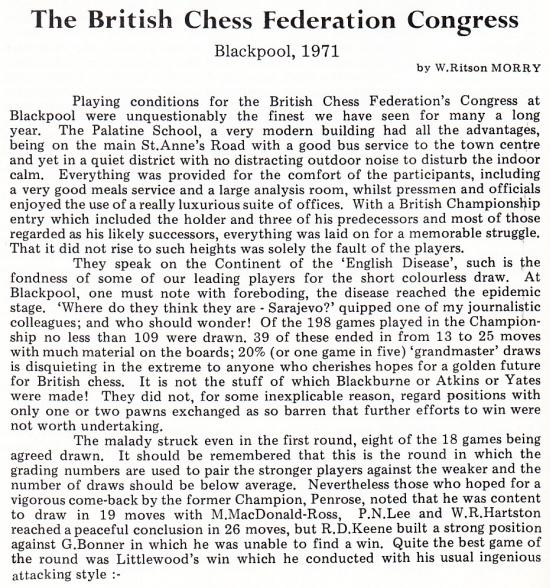

Readers with access to the 1971 BCM will find (September issue, pages 312-320) that W. Ritson Morry wrote very differently. Firstly, most of his criticisms about short draws concerned the players in general. For example, from page 312:

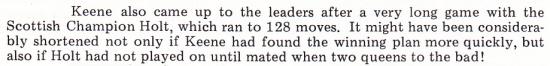

Moreover, what Mr Keene told Sarah Hurst about his game against Holt bears little relation to what Ritson Morry actually wrote in the BCM (page 314):

Pursuing his mendacious vendetta against Ritson Morry, Mr Keene misled readers of chessgames.com (as so often), in a posting dated 23 September 2006:

‘in fact i started out as a very positional player indeed and i made a conscious effort to improve my tactics. a lot of the whingeing about my style was from people like ritson morry who had their own axes to grind-i write about this in my forthcoming book on petrosian-in the context of the criticisms levelled against petrosian in the soviet press after the 1956 candidates tournament.

for example i won the woolacombe international in 1973-the strongest all play all outside hastings in the uk for many years-and in his bcm report ritson morry failed to give any of my wins and only mentioned in passing that i had won the event! the british championship i won included several games of huge length -one over 120 moves- but i was of course criticised by ritson morry for lack of fighting spirit! he was so far off the truth then that there was an outcry and the decline of his influence over the bcm dates from that point.’

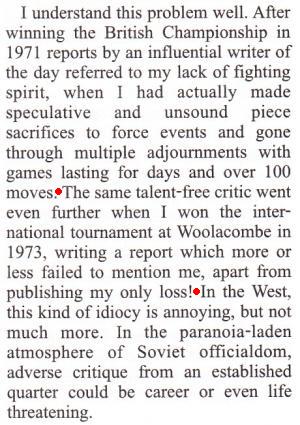

It is true that Ritson Morry’s tournament reports did not praise Mr Keene, but that can hardly justify the way the latter banged on about the matter on page 7 of Petrosian vs the Elite (London, 2006):

Any reader who consults Ritson Morry’s report (BCM,

November 1973, pages 463-467) will find the following:

- ‘international tournament’: only two of the ten players (Cardoso and Bilek) were not from Great Britain. (The BCM report stated that the tournament was ‘on known ratings, at least Category 5’.)

- ‘a report which more or less failed to mention me’:

on page 464 of the BCM there was a complete

crosstable, and in Ritson Morry’s report Mr Keene’s name

appeared a further nine times on the same page.

- ‘apart from publishing my only loss’: the report also gave Mr Keene’s win against Hutchings.

Addition on 16 May 2021:

Despite the above rebuttal, Raymond Keene repeated his same falsehoods in an Article piece dated 8 May 2021:

‘After winning the British Championship in 1971, reports by an influential writer of the day (whose name I shall withhold, according to the formula: de mortuis nihil nisi bonum) referred to my lack of fighting spirit, when I had actually made speculative and unsound sacrifices to force events and gone through multiple adjournments with games lasting for days and over 100 moves. The same, at least in my opinion, talent-free critic went even further when I won the international tournament at Woolacombe in 1973, writing a report which more or less failed to mention me, apart from focusing attention on my only loss! In the West, this kind of idiocy is irritating, annoying even, but not much more. In the paranoia-laden atmosphere of Soviet officialdom, adverse critique from an established quarter could be career or even life-threatening.’

Addition on 18 May 2021:

In a post at the English Chess Forum on 17 May 2021, Olimpiu G. Urcan summarized the matter as follows:

‘With untrue statements, Raymond Keene has repeatedly attacked a deceased chess figure, and has continued recycling those untrue statements even though they have been publicly refuted.’

8444. Internet booksellers (C.N. 8225)

Our reference to Chess for Laughs by Joel Rothman in C.N. 8438 prompts Avital Pilpel (Haifa, Israel) to point out that Amazon.com has two private booksellers offering second-hand copies, at $4,215.00 and $8,787.22 (plus, in each case, $3.99 for shipping).

8445. Canadian photographs

A number of interesting photographs, including one featuring Magnus Smith, can be viewed at the Libraries and Archives Canada website.

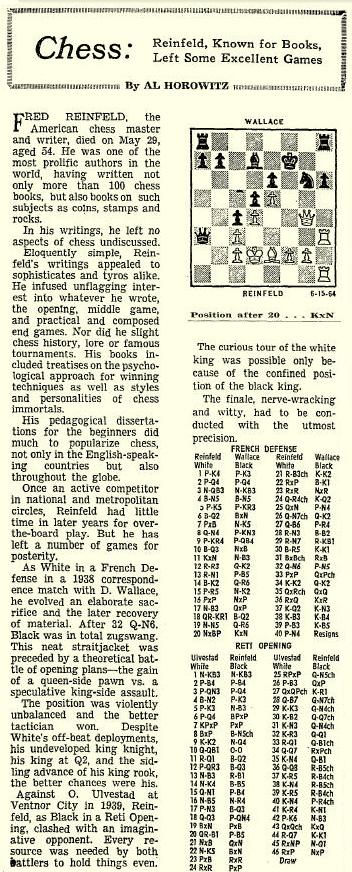

8446. Fred Reinfeld (C.N. 8436)

Dan Scoones (Port Coquitlam BC, Canada) recalls that after Reinfeld died Al Horowitz’s column in the New York Times commented that Reinfeld infused unflagging interest into whatever he wrote.

To complement C.N.s 5906 and 5937, we give below the full article, from page 26 of the 15 June 1964 edition of the New York Times:

8447. Learn Chess Fast! (C.N. 8431)

Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England) mentions that the first US edition of the Reshevsky/Reinfeld book Learn Chess Fast! (published by David McKay Company, Philadelphia in 1947) had the ‘60 centuries’ version with regard to the history of chess.

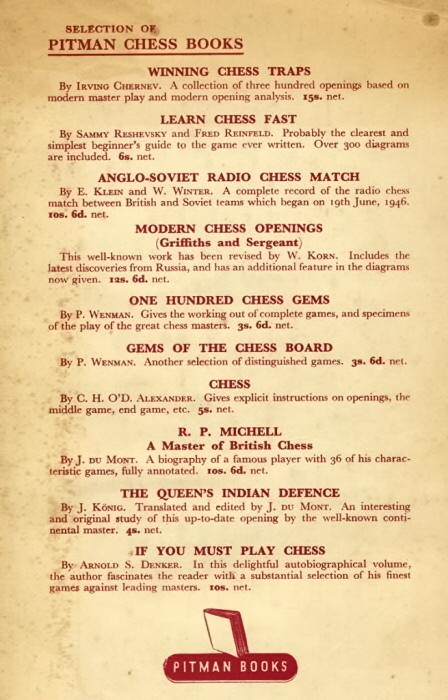

When preparing C.N. 8431 we were unable to trace an edition of the book which, according to Douglas A. Betts’ bibliography (page 116), was issued by Pitman in 1948. Our UK edition was published by Hollis and Carter, London in 1952.

Mr Clapham comments:

‘Betts states that the book was “issued” by Pitman rather than published by that company, and it is possible that Pitman imported the McKay books and distributed them in the United Kingdom. Pitman also “issued” Chess by Yourself by Fred Reinfeld (Betts 11-41). My copy of the latter was published by McKay (copyright date: 1946) but was almost certainly issued in England as it has the CHESS, Sutton Coldfield sticker.

Another US book imported and issued/published by Pitman was Chess Marches On! by Reuben Fine, published by Chess Review, New York in 1945. My copy has Chess Review on the spine, but the original title page has clearly been removed and replaced with another including the imprint of Sir Isaac Pitman.

A brief review of Learn Chess Fast! was published on page 269 of the August 1948 issue of CHESS, mentioning both McKay and Pitman. The book is also included in various advertisements for Pitman books and on dust-jackets of the company’s books, such as Walter Korn’s The Brilliant Touch (London 1950):’

Below is the title page of one of our copies of the first (1942) edition of The Immortal Games of Capablanca by Fred Reinfeld, with a ‘Distributed by Pitman’ sticker:

8448. Morphy beats Anderssen

The article below by G.H. Diggle was published in the December 1983 Newsflash and on pages 106-107 of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984):

‘This Christmas marks the 125th anniversary of a match which caused a tremendous stir in Paris, and indeed throughout Europe, the opponents being Paul Morphy, aged 21, the “unstoppable” prodigy of the New World, who for six hectic months had carried all before him, and the last hope of the Old, Professor Adolf Anderssen, aged 40, winner of the first international tournament of 1851. Yet no great match before or since has been played with such chivalry, such lack of formality or such complete absence of diplomacy. There were no stakes, no time-limit, and no conditions except that the match was to go to the winner of the first seven games. The “seconds” were no more than privileged witnesses especially invited to the Hôtel de Breteuil. The match indeed would have been played in public at the Café de la Régence (a few hundred yards away) but Morphy’s doctor said “No”. The young American had been ill in bed with intestinal influenza for a whole fortnight, and actually had to be helped downstairs when, after the start had been held up for three days, the contest began in a private room in the presence of St. Amant, de Rivière, Journoud, Preti, Carlini, Edge, James Mortimer and Dr Johnston, Paris correspondent of the New York Times. Down the street at the Régence, “the greatest excitement prevailed”, and a large cosmopolitan crowd followed the game on three boards, a messenger carrying the moves from the hotel every half-hour.

The 11 games of the match ( M. 7, A. 2, Drawn 2) were played off in only nine days (20-28 December) two games being played on 23rd, 25th and 27th with one blank day (26th). Anderssen (ignoring the remonstrances of his own countrymen) gave up his Christmas holiday to the match, and travelled in mid-winter 600 miles each way to play – Morphy insisted on paying all his expenses. The great German master opened with a win and a draw, but then Morphy took complete charge and scored the next five games running. The eight-hour sixth game (like the great 13th game between Fischer and Spassky) virtually decided the match – Anderssen with the score 3-1-1 against him had made a great effort, but missed his way just at the end. In the ninth game he was brilliantly slaughtered in “scarcely half an hour”, but rallied bravely in the tenth (played immediately afterwards), which he scored after a “long and trying endgame”. “Mr Morphy wins his games in 17 moves, while I take 77”, said the philosophical Professor. But the end came next day with a seventh American victory, and the two great players parted on excellent terms, never to meet again.

Press coverage of the match, in the hands of such excitable Morphy fans as Fred Edge and the more likeable old French journalist Alphonse Delannoy, makes rollicking reading. According to the fanatical Fred, Anderssen “would sit at the board, examining the frightful positions into which Morphy had forced him, until his whole face was radiant with admiration of his antagonist’s strategy and, positively laughing outright, he would commence resetting the pieces for another game”. Delannoy surpasses even this. At the Régence, after Anderssen had won the first game, “no description of the passionate and frantic boastings of the Germans can be made. ... They opened their purses, put out gold and bank-notes. ... They doubled, tripled their bets in the proportion of two, three and five to one”. Later on, when Morphy turned the tables, “the despair and astonishment which ensued after the battle of Jena are only frous-frous and meows of cats compared to the thundering noise, energetic oaths and the outbursts with which La Régence was then stunned.” This was “vintage Delannoy” at its fizziest, but the best account of the match, of course, is in the late David Lawson’s fine work on Morphy.’

8449. ‘Genug des Stumpfsinns, Remis!’ (C.N. 8437)

Charles Milton Ling (Vienna) asks whether a reliable source is available in support of his recollection that the phrase ‘Genug des Stumpfsinns, Remis!’ (‘Enough tedium, draw!’) has been attributed to Richard Teichmann, who wished to attend a wrestling event rather than play chess.

We can offer a passage about Teichmann from page 58 of Ein Rundflug durch die Schachwelt by Rudolf Spielmann (Berlin and Leipzig, 1929):

‘In einer Wettkampfpartie mit Sämisch begab sich folgendes: Etwa 15 Züge waren geschehen. Sämisch glaubte nach allen Regeln moderner Schachkunst eine aussichtsreiche Stellung erlangt zu haben und war eben eifrig dabei, einen geeigneten Schlachtplan auszuhecken. Während er angestrengt nachdenkt, zieht plötzlich Teichmann die Uhr, steht auf, schiebt die Steine zusammen und bemerkt einfach: “Genug des Stumpfsinns, Remis!” Empfiehlt sich und geht in den Zirkus. Er war höchste Zeit, denn die Ringkämpfe hatten eben begonnen!’

Is it possible to find a match-game between Teichmann and Sämisch which fits this account (i.e. after about 15 moves Sämisch had an apparent advantage, but Teichmann suddenly broken off the game as a draw since he wished to watch wrestling at the circus)?

Page 43 of the February 1922 Deutsche Schachzeitung reported that a brief match between the two masters had taken place in Berlin. Teichmann won with one victory and three draws.

8450. The Kalashnikov Variation

The death of Mikhail Kalashnikov on 23 December 2013 prompts us to ask when the opening 1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 e5 5 Nb5 d6 first bore his name, and why.

We timidly open the bidding by noting that on page 25 of the April 1991 CHESS, in an article by Ian Rogers, a game between Solomon and Gausel in the 1990 Olympiad in Novi Sad was headed ‘Sicilian Kalashnikov’.

Page 479 of the October 1991 BCM mentioned a monograph by Jeremy Silman, The Neo-Sveshnikov, and commented:

‘The line 4 Nxd4 e5 5 Nb5 d6, known jocosely as “Kalashnikov”, has a band of followers of repute.’

Neil McDonald’s 1995 book on the opening has nothing of direct relevance to the origins of the name ‘Kalashnikov’.

8451. Nimzowitsch v Alapin

Concerning the celebrated Nimzowitsch v Alapin miniature, Randall K. Julian (Zionsville, IN, USA) observes that there are databases which give the opening as a Sicilian Defence, and not a French Defence: 1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 Nc3 d5 4 exd5 Nxd5 5 d4 e6 6 Nxd5 Qxd5 7 Be3 cxd4 8 Nxd4 a6 9 Be2 Qxg2 10 Bf3 Qg6 11 Qd2 e5 12 O-O-O exd4 13 Bxd4 Nc6 14 Bf6 Qxf6 15 Rhe1+ Be7 16 Bxc6+ Kf8 17 Qd8+ Bxd8 18 Re8 mate.

What are the origins of this version of the game-score?

8452. Development (C.N.s 8435 & 8440)

From Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina):

‘Chapter II of Notas ajedrecísticas by Amador Guerra and Jaime Baca Arús (Havana, 1937) deals with the “Concept of Development” by enumerating the definitions given by a number of chess writers, such as Brinckmann, Nimzowitsch, Tarrasch, Grau, Capablanca, Lasker and Réti (including the order in which the pieces should be deployed). From page 22:

“... al antiguo ‘Sortez les pièces’ ya enunciado en el siglo XVIII” [“... the old ‘Sortez les pièces’, formulated as early as the eighteenth century”].’

We should like to trace particularly early occurrences of the French advice, expressed in either the imperative (Sortez) or the infinitive (Sortir).

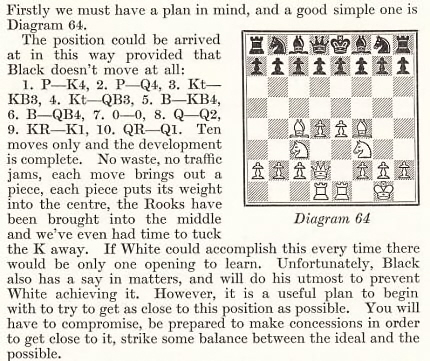

8453. ‘Ideal development’

A comment by John Nunn in his introduction to Vaganian v Sokolov, Bled/Rogaška Slatina, 1991 on page 29 of Sokolov’s Best Games by Ivan Sokolov (London, 1997):

‘When I was young, I had a beginner’s book which included a diagram showing the “ideal development” one should be aiming for in the opening. This consisted of d4, e4, Nc3, Nf3, Bc4, Bf4, O-O, Qd2 and rooks to the centre. The fact that the diagram showed Black’s pieces still on their original squares might explain why I was never able to achieve this “ideal development” in my own games. Whenever I see the opening system which Sokolov employs in this game [1 c4 e5 2 Nc3 Nf6 3 Nf3 Nc6 4 g3 Bc5 5 d3 O-O 6 Bg2 d6 7 O-O h6 8 a3 a5 9 e3 Bf5 10 b3 Qd7], I am reminded of that old beginner’s book. With the exception of ...d5, Black plays virtually all the “ideal developing” moves and it hardly seems likely that this rather naïve system is going to be effective against a sophisticated flank opening, but it is more potent than one might expect.’

There may be a number of books with such a diagram. One that we have found is Chess A New Introduction by John Love (London, 1967). From page 63:

As noted in A Publishing Scandal, in 1980 Love’s book was re-issued by Coles Publishing Company Limited, Toronto under the title Teach yourself Chess without his permission or even knowledge.

8454. The knight’s move

An imminent addition to The Knight Challenge is FIDE’s definition of the knight’s move, which Sven Mühlenhaus (Düsseldorf, Germany) appreciates for its concision:

‘The knight may move to one of the squares nearest to that on which it stands but not on the same rank, file or diagonal.’

8455. Another proverb

From page 313 of the 1843 Chess Player’s Chronicle:

‘There is a French proverb which says, “If you would win a damsel’s heart, always lose to her at chess”. This is probably founded on an anecdote concerning Count Ferrand of Flanders, whose wife conceived so mortal a hatred to him from their misunderstandings over the chessboard that when he was taken prisoner at the battle of Bovines she suffered him to remain in durance for a long time, though she might have easily procured his release.’

See too page 198 of the 1868 Chess World. As previously noted, the entire field of chess proverbs is murky.

8456. The Kalashnikov Variation (C.N. 8450)

Joose Norri (Helsinki) points out the first note by John van der Wiel in his game, as Black, against Nigel Short at the 1988 Olympiad in Thessaloniki:

Source: New in Chess, 1/1989, page 35.

8457. Sketches and photographs

The Center for Jewish History has a number of sketches of leading masters by Emery Gondor. They are dated 1922.

A search for ‘Lasker’ also yields some interesting illustrations, including a fine version of the photograph of Edward Lasker and Emanuel Lasker at the board (given in the Dover reprint of the New York, 1924 tournament book, although not in the original edition).

[Link and text amended on 15 March 2024.]

8458. Mrs Pillsbury (C.N.s 4246 & 5576)

Hassan Roger Sadeghi (Lausanne, Switzerland) has found two webpages which provide information about H.N. Pillsbury’s wife, née Mary Ellen Bush:

WikiTree: Mary Ellen ‘Mamie’ Shearf, born about March 1872 in Sullivan County, NY, the daughter of Albert J. Bush and Charlotte V. (Horton) Pelton, the other children being William H., Henrietta T. Gillespie, Etta and Elvin W. She married Henry D[uBois] Southard in Monticello, NY on 8 October 1890, Harry Nelson Pillsbury in Chicago, IL on 17 January 1901, and Frank Shearf (place and date unknown).

Archives database: Mary B. Shearf was aged 67 at the time of the 1940 US census, and was living at Somers Point, Somers Point City, Atlantic, NJ. The other members of the household were her husband, Frank Shearf, aged 66, and Alberta Shearf, aged 11.

We can add that the 1920 US census does not list Mary Shearf’s husband but states that the couple had a daughter, Ruth, born around 1912 in Pennsylvania. She appeared in the 1930 census under the name Ruth Chaffett (‘widowed’), and a 1/1½-year-old daughter, Alberta Chaffett, was also mentioned.

8459. Milan Vukcevich

Our chess prodigies article focuses on players and problemists predating the Second World War, but Steven B. Dowd (Birmingham, AL, USA) notes the particularly interesting case of Milan Vukcevich, who was born in 1937, learned to play chess at five and entered his first tournament at ten.

Mr Dowd informs us that the first problem by Vukcevich that he has found is a helpmate in two (i.e. Black moves first, and White mates on his second move) in the 2/1949 Šahovski vjesnik:

8460. Discovering Chess

Another explanation to be added to The Knight Challenge:

‘The knights move in a letter L one square orthogonally in one direction and then two squares orthogonally at right angles to the first move, or two squares orthogonally in one direction and then one square at right angles to it.’

Source: Page 11 of the original (Aylesbury, 1976) edition of Discovering Chess by R.C. Bell (‘R.C. Bell MB FRCS’).

From the book’s glossary (pages 4-9):

- ‘Check: When a king is attacked the opponent must call check.’

- ‘Command: A square is commanded when any piece moved on to it may be captured.’

- ‘En passant: The capture of a pawn moving two squares on its initial move, by an opposing pawn that has been passed.’

- ‘Middle game: This begins when theoretical analysis of the opening becomes impossible and ends when the force on each side is reduced to a state when analysis again becomes possible.’

- ‘Protect: Interposing a piece between one in danger and the attack.’

- ‘Smothered mate: A king unable to move for his own men and checkmated by a knight.’

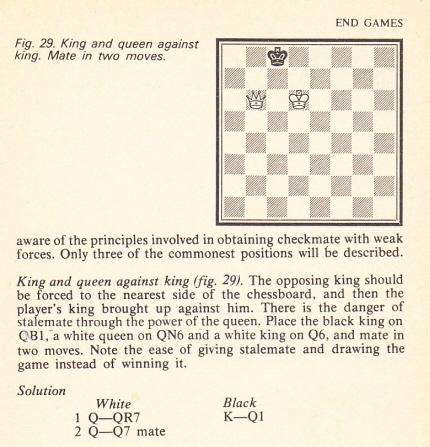

The first of the three diagrams in the ‘End games’ section:

Has there ever been a more elementary ‘analytical error’ in a chess book?

| First column | << previous | Archives [113] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.