Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [114] | next >> | Current column |

8461. Charles Krauthammer

Things That Matter by Charles Krauthammer (New York, 2013) has three brief chess articles, on pages 55-57, 102-104 and 108-111, but the only thing that apparently matters to him about the great masters of the past is using their lives as fodder for ‘fun’.

Page 104 (in an article reproduced from Time, 19 November 1990) has this remark, with the almost mandatory ‘once’:

‘The great Steinitz, who once claimed to have played against God and won (he neglected to leave a record of the game), went quite mad.’

There is nothing else about Steinitz, and the short paragraph moves on seamlessly to three or four lines about Fischer (dental fillings and the KGB).

8462. Alekhine’s passport

Charles Krauthammer (‘current member of Chess Journalists of America’, the dust-jacket of Things That Matter proclaims) has only one thing to say about Alekhine, on page 56 (in an article from the Washington Post, 27 December 2002):

‘... Alexander Alekhine, who in 1935 was stopped while trying to cross the Polish-German frontier without any papers. He offered this declaration instead: “I am Alekhine, chess champion of the world. This is my cat. Her name is Chess. I need no passport.” He was arrested.’

Alekhine’s supposed words replicate what appeared on page 277 of The Golden Dozen by Irving Chernev (Oxford, 1976), but the story has been seen in many forms. Chernev, for instance, made no reference to an arrest or any other consequences.

On page 328 of the November 1956 Chess Review, in an article about the 1935 Olympiad in Warsaw, Reuben Fine wrote:

‘He began by arriving at the border without a passport. When he was asked for one, he replied: “I am Alekhine, chess champion of the world. I have a cat called Chess.” After this episode was straightened out, Alekhine came to the tournament and went through most of his games in a state of mild inebriation. Most remarkably, his play did not seem to be affected, though his eccentricities did cost him the world championship in the match with Euwe a few months later.’

That text was reproduced on page 47 of Fine’s book Lessons from My Games (New York, 1958). ‘After this episode was straightened out ...’ is not much of a dénouement, but the rapid switch to the subject of alcohol helps mask the anti-climax.

When relating the tale on page 59 of his Psychoanalytic Observations on Chess and Chess Masters (New York, 1956) Fine gave Alekhine a little extra dialogue (‘I do not need papers’) and introduced the requisite psychological slant (Alekhine ‘began to show some signs of megalomania’). He also beefed up the finale, adding after the Alekhine quote:

‘The matter had to be straightened out by the highest authorities.’

8463. Celia Neimark

John Blackstone (Las Vegas, NV, USA) has found an early report on Celia Neimark, the ‘chess marvel at six’, on page 8 of the Bismarck Tribune, 10 June 1921. The feature, which uses the spelling ‘Niemark’ throughout, has a photograph of the ‘little bobbed-haired gingham-dressed farmer girl’.

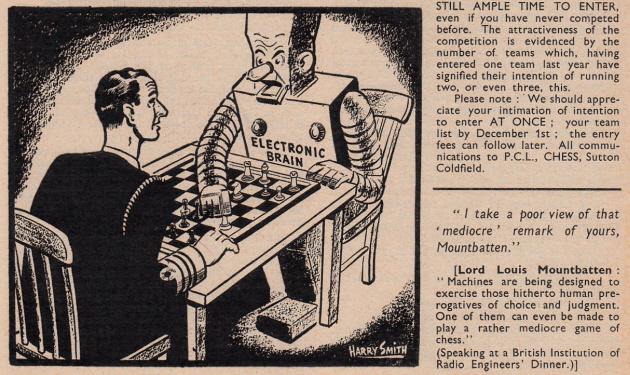

8464. Lord Louis Mountbatten cartoon

Early cartoons depicting computers/machines and chess are always welcome. From page 65 of the December 1946 CHESS:

8465. The knight’s move (C.N. 8431)

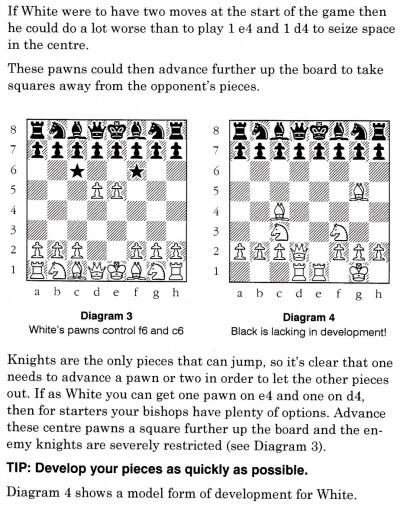

C.N. 8431 asked whether many instructional works had explained the knight’s move by reference to squares inaccessible to the queen, as did Learn Chess Fast! by S. Reshevsky and F. Reinfeld.

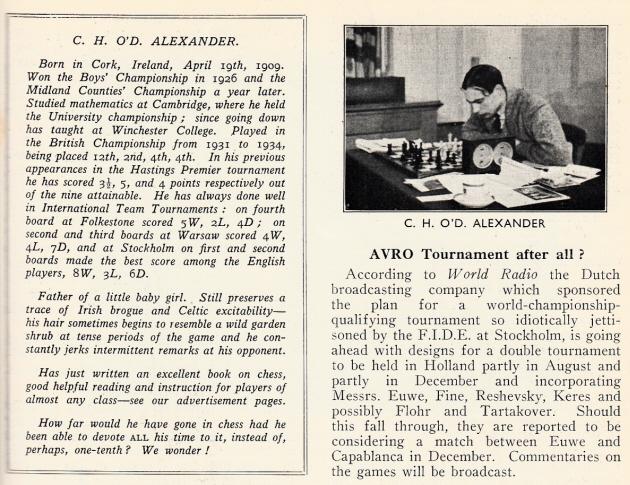

Trevor Moore (Baughurst, England) draws attention to Chess by C.H.O’D. Alexander (London, 1937), as well as the expanded, updated edition, Alexander on Chess (London, 1974). From pages 4-5 of both books:

‘Like the other pieces it [the knight] moves in a straight line, but one less clearly indicated on the board than those of the rook and bishop. The rook moves parallel to the edges of the board, the bishops diagonally and the knight in a direction bisecting the angle between the rook’s and bishop’s move. ... The knight’s move is complementary to that of the queen, as we may easily see in the following way. Place the queen on one of the 16 central squares of the board – it controls 16 of the 24 squares surrounding it. Now place a knight on the square instead – it controls precisely those eight squares not attacked by the queen. ... It is often inaccurately said that the knight “jumps” other pieces – actually, it simply moves between them.’

8466. Alexander’s books

Chess by C.H.O’D. Alexander was warmly praised by both the BCM and CHESS when it first appeared. On page 7 of the January 1938 BCM ‘G.S.A.W.’ (Wheatcroft) commented:

‘It is a pleasure to find an expert player who can expound the essentials of the game as clearly with his pen as with his pieces.’

From page 155 of CHESS, 14 January 1938:

The book went through many editions, all published by Pitman, as was, posthumously, Alexander on Chess. The original edition was also brought out by David McKay Company, Philadelphia in 1938, and in a brief notice on page 218 of Chess Review, September 1938 ‘F.R.’ (Reinfeld) wrote:

‘Alexander is a teacher, and if this book is any indication, he must be a good one. Chess will undoubtedly become the most popular introductory book to the game. It is written with exceptional clearness, and covers so much ground that it will be found useful by those who are by no means mere beginners.’

8467. Grandmasters

Mark Hoffman (Leipsic, OH, USA) asks whether it is possible to name about half-a-dozen players who gained the grandmaster title for over-the-board play at a relatively advanced age. Moreover, from such a list can it be determined who achieved the title the fastest and from the lowest starting-point in terms of playing strength?

8468. Morphy in Paris

From Raymond Kuzanek (Hickory Hills, IL, USA):

‘On page 29 of his book The Genius and the Misery of Chess (Newton Highlands, 2008) Zhivko Kaikamjozov states:

“In 1867, Morphy embarked for Paris for treatment. The most prominent French psychiatric specialists tried hard to help him, but without any success. The only lasting effect was the emptying of his pockets, which soon led to his return to America.”

Unfortunately, Mr Kaikamjozov does not specify his sources of information. Do you recall any prior mention, with substantiation, of Morphy receiving psychiatric care in Paris?’

We do not. C.N. 5855 briefly discussed/dismissed The Genius and the Misery of Chess and singled out the Morphy chapter for particular criticism.

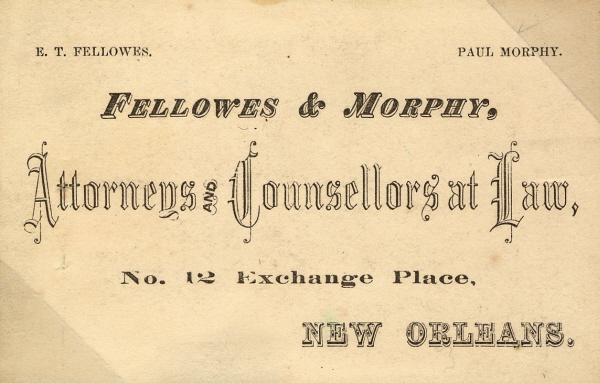

8469. E.T. Fellowes

Wanted: information about E.T. Fellowes, with whom Morphy had a law practice (from circa 1872 to 1874, according to pages 290-291 of David Lawson’s book on Morphy).

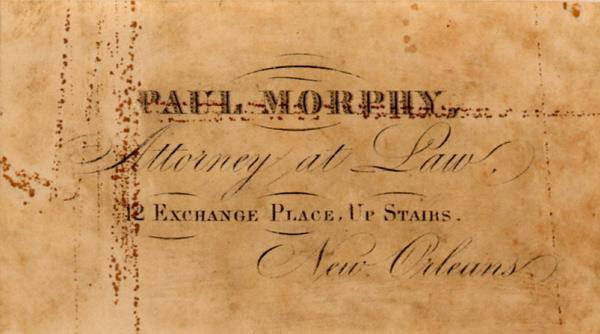

David DeLucia (Darien, CT, USA) has authorized us to show from his collection the two attorneys’ business card (as well as an earlier card of Morphy’s, dated November 1864):

8470. Last words (C.N.s 4704, 4705, 4713 & 5076)

C.N. 4704 quoted with all due disbelief the alleged last words of Tartakower, as related on page 60 of Mille et une anecdotes by Claude Scheidegger (Tirana, 1994).

The same book gave over an entire page (page 21) to an anecdote culminating in what Arnous de Rivière supposedly declared just before dying: the Chatard Gambit (1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 g3) is worthless (‘Le gambit Chatard ne vaut rien’). The long yarn, containing much direct speech, was reproduced almost word for word (without credit) from an article by Gustave Lazard in the Bulletin ouvrier des échecs, January 1947. That article had been reprinted (with credit) on pages 110-111 of Les échecs spectaculaires by Aldo Haïk and Carlos Fornasari (Paris, 1984).

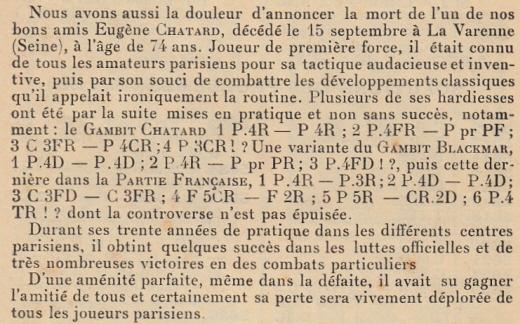

The little-known gambit was mentioned in Chatard’s obituary on page 229 of La Stratégie, September 1924:

8471. Die graphotranszendentale Schachpartie

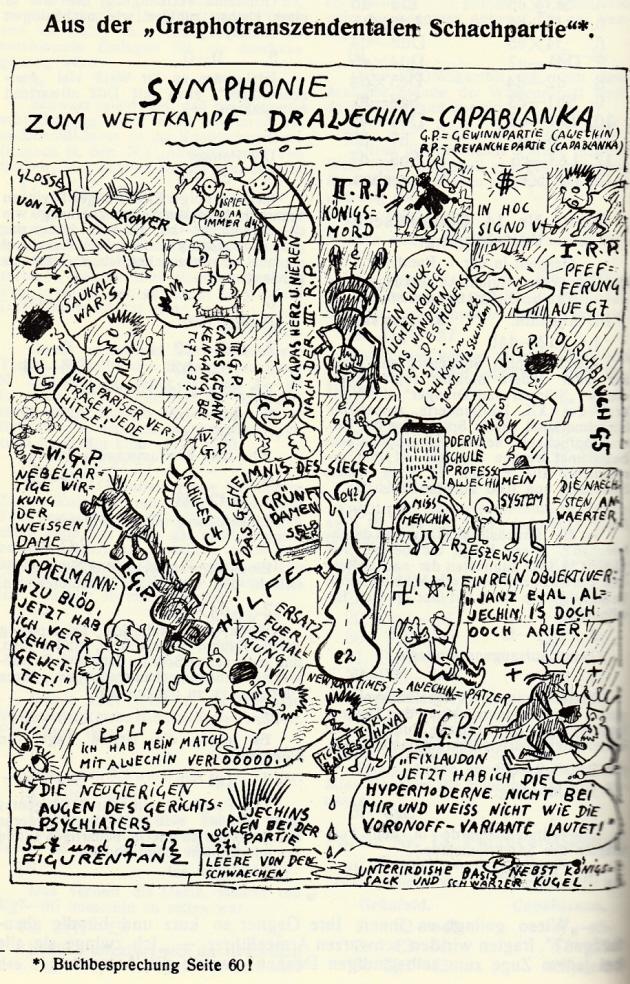

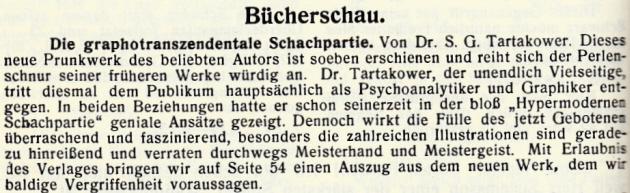

From page 54 of the February 1928 Wiener Schachzeitung:

And from page 60 of the same issue:

As reported by a correspondent in C.N. 7728, the Wiener Schachzeitung is available online at the ANNO website.

8472. Grandmasters (C.N. 8467)

Paul Dorion (Montreal, Canada) notes two players who achieved the grandmaster title in their mid-40s: Vasja Pirc (born 1907) in 1953, and Albéric O’Kelly de Galway (born 1911) in 1956.

8473. New York Clipper

Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England) has found that the New York Clipper can be viewed online, using the site’s ‘Browse Archive’ function. He comments that the chess column was usually published on page 6 of the Saturday edition and that there were also occasional chess features elsewhere.

Morphy’s only authenticated problem, composed some seven years previously, is on page 78 of the 28 June 1856 edition. (For further information, see pages 18-19 of David Lawson’s biography of Morphy.)

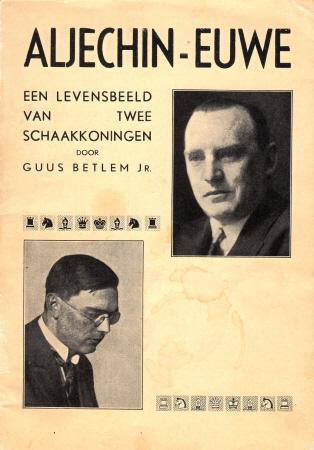

8474. Alekhine

and Euwe

‘He is a poet who creates a work of art out of something which would hardly inspire another man to send home a picture postcard.’

That well-known quote (Euwe on Alekhine) provides a small illustration of the current state of chess ‘scholarship’ on the Internet. It is commonly given sourcelessly, but what happens if, as is only reasonable, basic information is wanted about the occasion and context (e.g. whether Euwe was writing in general or was referring to a particular game or theme, and whether he expressed the sentiments before or after winning the world title from Alekhine)? We leave readers to try to find any websites which:

i) mention that the remark comes from Euwe’s book Meet the Masters (London, 1940). See pages 27-28.

ii) give the full paragraph with its context (Euwe’s introduction to Alekhine v Lasker, Zurich, 1934):

‘Curious is Alekhine’s knack of developing a seemingly harmless attack, within a few moves, into a hurricane which smashes down all resistance. His methods are simple; it is not so much any particular move which is important, as the whole series of moves – and the move after that! He is a poet who creates a work of art out of something which would hardly inspire another man to send home a picture postcard.’iii) provide, especially in the case of Dutch-language webpages, Euwe’s original text, from page 16 of Zóó schaken zij! (Amsterdam, 1938):

‘Eigenaardig is de kunst van Aljechin, een oogenschijnlijk onschuldigen aanval binnen enkele zetten te doen aangroeien tot een orkaan, welke alle tegenstand breekt. Hij gebruikt dan vaak heel eenvoudige middelen, waarbij niet elke zet afzonderlijk maar de heele reeks van zetten en vooral ook de volgende beslissende beteekenis heeft. Hij is dichter, die kunstwerken schept met dezelfde middelen, welke een ander nauwelijks voldoende zou vinden om een briefkaartje te schrijven.’

There have also been, of course, many printed versions of the Euwe quote without a source. Curiously, a few English-language publications continue, after the word ‘postcard’, with:

‘The wilder and more involved a position, the more beautiful the conceptions he can evolve.’

See, for instance, page 50 of The New Yorker, 28 October 1972 (an article by George Steiner on the 1972 world championship match), pages 15-16 of Steiner’s book The Sporting Scene (London, 1973) and Kasparov’s Foreword to Alexander Alekhine’s Best Games (London, 1996). All three publications had ‘conception’ in the singular.

In fact, that sentence by Euwe came several pages later in Meet the Masters, on page 32. The Dutch text (on page 19 of Zóó schaken zij!) was:

‘Hoe wilder en verwarder een stelling is, des te fraaiere combinaties weet de wereldkampioen ons voor te tooveren.’

8475. Games and quotes

If modern games were to be presented as they often were a century or two ago, the reader would see headings such as ‘A brilliancy by Mr Carlsen a few years back’, ‘Played in Germany’, ‘Another recent skirmish produced by Mr Anand against Mr ****** on the Continent’ and ‘Mr K*****k won this finely contested game against a strong opponent some time since’. In short, the public record of chess games, devoid of exact places, dates and names, would be desolate.

Nowadays, of course, most games are published with basic factual information as a matter of routine, but is there any valid reason for quotes to be handled quite differently? If a book, magazine or website wishes to notify its readership that A stated B, why omit particulars about the context (e.g. the place and date) of the observation? Were the answer to be that the book, magazine or website does not have the information, why is it disseminating the quote at all?

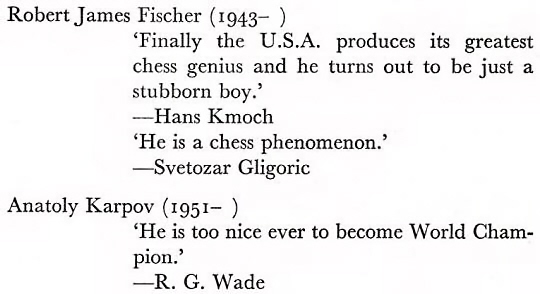

Chess literature and lore are a bog of ignorance, doubt and error regarding who said/wrote what and when. To give just one example of a book which makes no attempt to guide or inform the reader, below are the last two names in the chapter ‘On Players’ on pages 127-133 of The Chess Scene by David Levy and Stewart Reuben (London, 1974):

Not a source in sight.

We can offer at least some information about the most significant of these quotes, Kmoch on Fischer. Below is the first paragraph of an article, ‘The Selfmate of Bobby Fischer’, by Eliot Hearst on pages 166 and 183 of Chess Life, July 1964:

‘The “selfmate” theme of the chess problemist –a position in which one player compels his opponent to checkmate him – symbolizes suicide on the chess board. The chessplayer who prefers tournament competition to problem solving usually finds this kind of composition more amusing than artistic, and his amusement is probably due to the utter impracticality of the situation; tournament players are known to maintain a firm belief in the dictum that it is better to give checkmate than to receive it. Very few US chessplayers, however, are amused by Bobby Fischer’s equally impractical and unrealistic decision not to compete in the world championship qualification series and thus to surrender all of his rights to a world title match until at least 1969. The same mind that has produced some of the best chess combinations and positional gems of the past decade has also proved responsible for one of the most disappointing moments in American chess. As veteran chess analyst Hans Kmoch, who has observed and written about the games of world champions from Lasker to Petrosian, said in New York recently: “Finally the USA produces its greatest chess genius and he turns out to be just a stubborn boy.”’

See too Chess: the Need for Sources.

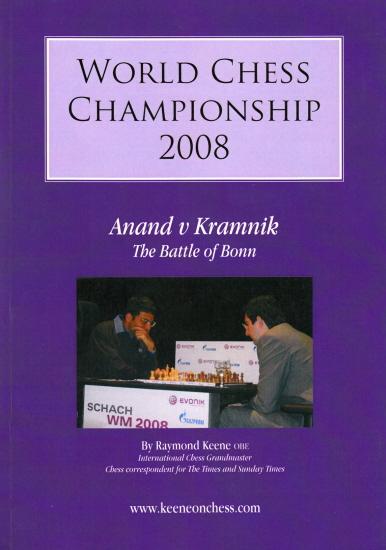

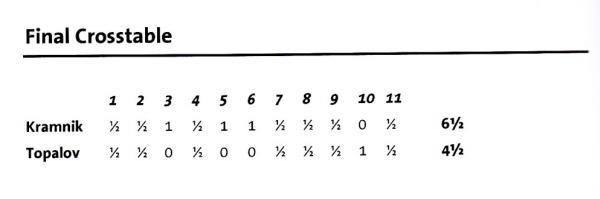

8476. World championship match book

From page 98:

For Kramnik read Anand. For Topalov read Kramnik.

8477. Grandmasters (C.N.s 8467 & 8472)

From Martin Weissenberg (Savyon, Israel):

‘Several players received the grandmaster title when in their 50s, including Julio Bolbochán (born 1920) in 1977 and Gösta Stoltz (born 1904) in 1954. Slightly younger title-holders: Isaac Kashdan (born 1905) became a grandmaster in 1954 and Raúl Sanguineti (born 1933) in 1982. Carlos Torre (born 1904 or 1905) was awarded the title in 1977, over half a century after almost completely retiring from competitive chess.

Not included on this list are honorary title-holders such as George Koltanowski, Esteban Canal, Erik Lundin and Vladas Mikėnas, who were granted the title when in their 80s or late 70s. Similarly, the group of veteran players Jacques Mieses, Géza Maróczy, Akiba Rubinstein, Ossip Bernstein, Oldřich Důras, Milan Vidmar, Boris Kostić, Savielly Tartakower, Grigory Levenfish, Ernst Grünfeld and Friedrich Sämisch, who were awarded the grandmaster title en bloc by FIDE in 1950 in recognition of their past achievements. Another old-timer, Efim Bogoljubow, who belonged to the same group of players, received the title the following year, the delay being for political reasons.’

After the general topic of the ‘oldest grandmaster’ was raised in C.N. 6146, Andrew Bull (Cheltenham, England) referred in C.N. 6155 to Tim Krabbé’s ‘Open Chess Diary’ (item 193), where it was noted that Jānis Klovāns (born 1935) became a grandmaster in 1997 by winning the world senior championship. Mr Bull added the case of Valery Grechihin (born 1937), who gained the title in 1998, and he now mentions Leif Øgaard (born 1952) in 2007 and Mark Tseitlin (born 1943) in 1997, as well as world senior champions (e.g. Yuri Shabanov, Larry Kaufman and Vladimir Okhotnik) who, by winning that championship, received the grandmaster title when over 60.

8478. Carlos Torre

Further to the reference in the previous item to ‘1904 or 1905’ as Carlos Torre’s year of birth, has it ever been satisfactorily explained why reference sources give different dates?

8479. Bernhard Horwitz’s paintings

Wanted: information about paintings by Bernhard Horwitz. On page 210 of the May 1846 issue of Le Palamède Saint-Amant wrote:

‘M. Horwitz, peintre allemand distingué, a établi son chevalet au milieu du salon des Echecs, et manie alternativement ses pinceaux et les pièces de l’échiquier. Il lutte de combinaisons avec tous les membres et les immortalise ensuite sur sa toile.’

8480. Capablanca: rule-changes and variants (C.N.s 5618, 5619 & 6838)

In the chapter entitled ‘Changing the Rules’ page 176 of our book on Capablanca remarked that commentators have ‘repeatedly claimed – often with a sneer – that the suggested innovations came only after Capablanca’s match loss to Alekhine in 1927’.

The following page gave an English translation of Capablanca’s article ‘Chess Requires Modifications’ in the July 1928 issue of Revista Cubana de Ajedrez, pages 13-14. It included this passage:

‘Seven years ago, following my match with Lasker, I wrote that if the same form of methodical research and scientific progress continued, chess would be played out within a relatively short period, which I then set as a maximum of 50 years; two or three years later I again wrote on the same subject, indicating a period of only 25 years before such a state of affairs would be reached. If scientific research continues in the same way I believe today that with not more than ten years chess will be if not completely played out at least virtually so as regards contests between the world’s top half-dozen players; that is to say, I do not believe that ten years will pass without there being half a dozen players who can, when they so wish, draw virtually at will. If out of ten games they perhaps win one, it will be more by accident than anything else.’

Pages 181-182 of our book reproduced from the November 1929 Chess Amateur (pages 44-45) an article/interview with the Cuban (‘Brighter Chess’) which began:

‘It was immediately after my contest at Havana with Dr Lasker, in which I won the chess championship of the world, that I first put forward my suggestions for changes in the game of chess. The reasons for my proposals were obvious. For some time there had been a growing feeling among the general public that championship chess is a very dull pastime, giving too little scope to the imagination and to the creative power of the individual player.’

The Chess Amateur did not specify that the article had already appeared elsewhere, but it had been published on page 10 of the Straits Times, 11 October 1929 (‘Straits Times Copyright – Reproduction Rights Reserved’). Whether Capablanca’s text was indeed first printed in Singapore is unknown.

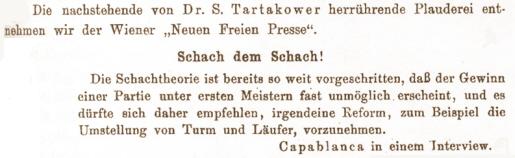

Nor is it yet possible to say what, and where, he wrote on the subject in 1921, although, as reported in C.N. 6838, on page 143 of the June 1921 Deutsche Schachzeitung Tartakower referred to an interview given by the new world champion:

Capablanca contributed a lengthy letter to the London Times, 24 November 1928, page 13. It was reproduced on pages 178-180 of our book, together with, on pages 180-181, a letter from Emanuel Lasker (on page 14 of the Manchester Guardian, 31 December 1928) strongly criticizing the proposals (‘cheap and inartistic’).

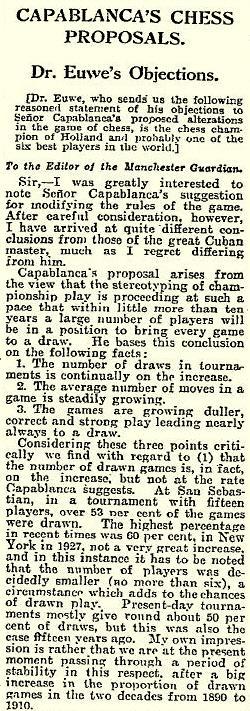

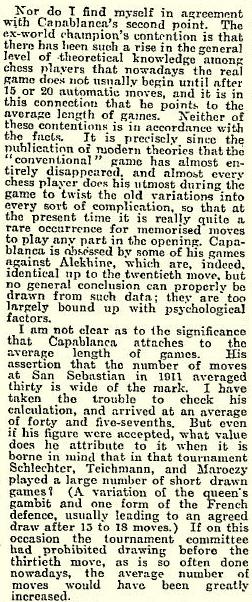

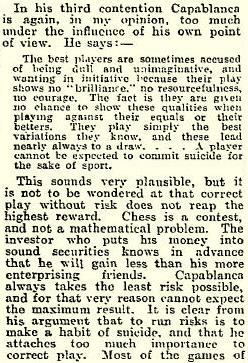

Earlier that month (on page 6 of the 15 December 1928 edition of the Manchester Guardian) Max Euwe had written as follows:

Finally, below is a letter which Tarrasch contributed on page 20 of the 18 January 1929 edition of the Manchester Guardian:

8481. Simultaneous displays in the Soviet Union

From Sarah Hurst (Reading, England):

‘I am interested in finding out about Soviet newspaper reports of simultaneous displays given in Moscow, Leningrad and other cities in the mid-1920s by leading Western masters such as Capablanca and Lasker. Which newspapers had such reports and are they accessible in either hard-copy form or online?

In particular, there was an exhibition which was reported as resulting in a clean score for the visiting master, an account later corrected to mention that a draw had been obtained by one Soviet opponent. I have a personal interest in obtaining information about that display.’

8482. Discovering Chess (C.N. 8460)

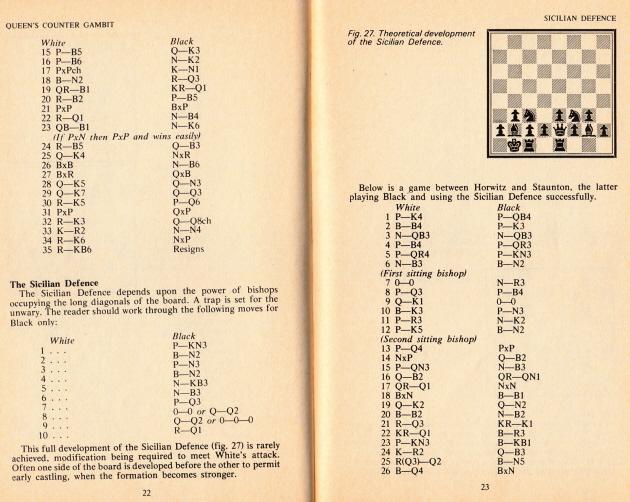

Charles Milton Ling (Vienna) draws attention to the coverage of the Sicilian Defence in Discovering Chess by R.C. Bell (Aylesbury, 1976):

8483. Original publisher expunged

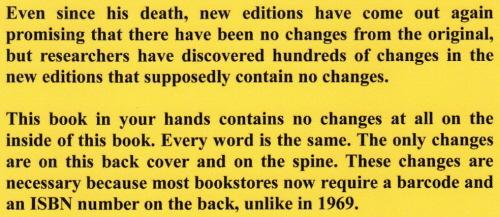

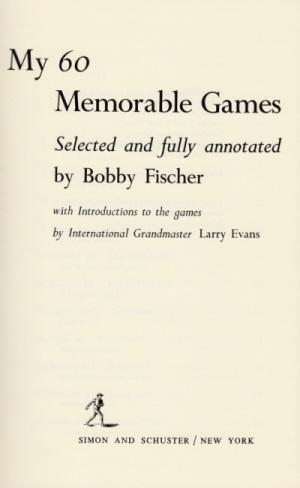

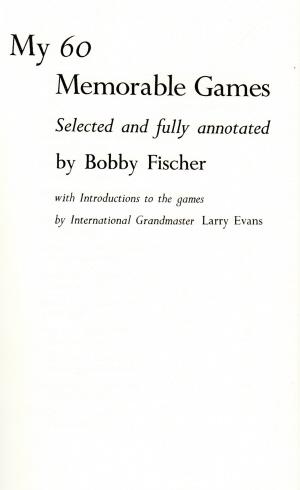

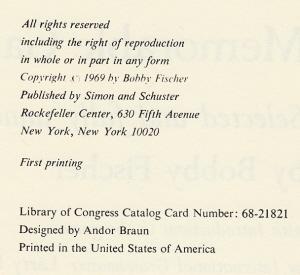

From the back cover of a reprint (issued by Ishi Press International in 2009) of the original descriptive-notation edition of My 60 Memorable Games by Bobby Fischer:

‘This book in your hands contains no changes at all on the inside of this book. Every word is the same.’

Not exactly, as a comparison with the original 1969 edition immediately shows:

8484. Babson and Pollock

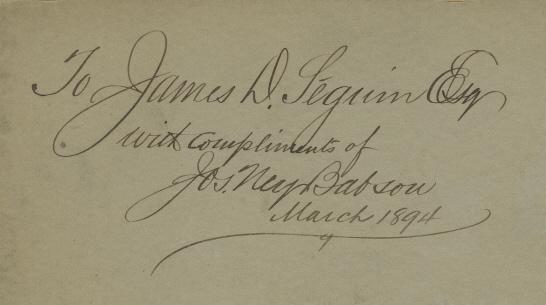

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) sends a photograph of J.N. Babson and W.H.K. Pollock:

The reverse is inscribed by Babson to James D. Séguin:

The photograph will be appearing in a McFarland book on Pollock which Mr Urcan is currently writing with John S. Hilbert.

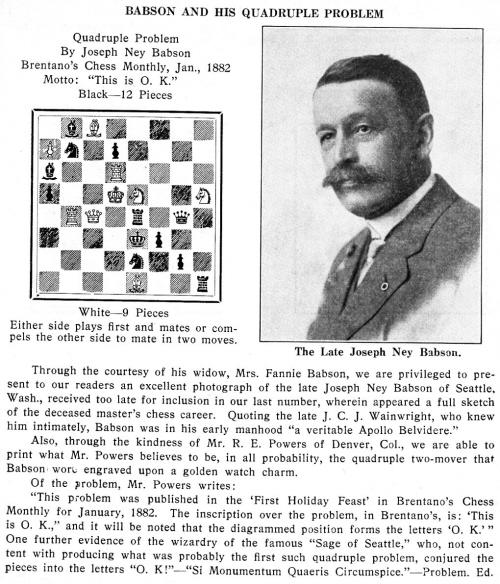

8485. Babson

From page 59 of the March 1930 American Chess Bulletin:

8486. The Budapest Defence

Our latest feature article is on the Budapest Defence.

8487. Bernhard Horwitz’s paintings (C.N. 8479)

John Townsend (Wokingham, England) has found this item in The Times, 8 June 1886, page 2:

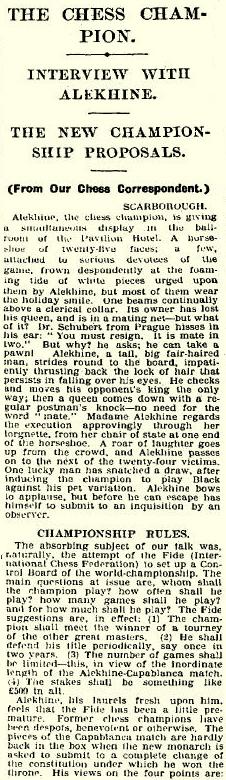

8488. An interview with Alekhine

From page 11 of the Observer, 3 June 1928:

The newspaper’s chess correspondent, Brian Harley, included the interview on pages 35-39 of his book Chess and its Stars (Leeds, 1936).

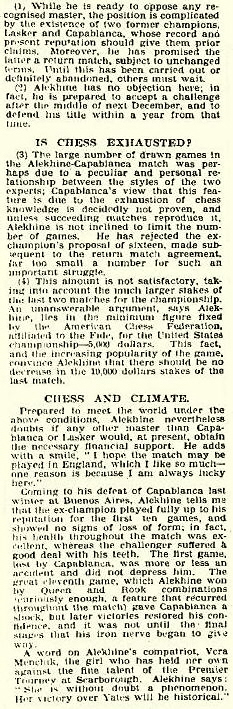

8489. World championship match stakes

Among the notable comments by Alekhine in his 1928 interview with Brian Harley (C.N. 8488) are those concerning the stakes for future world championship matches. Below is the text as it appeared on page 38 of Harley’s book Chess and its Stars:

Alekhine’s attitude to stakes of $10,000 was not always so positive in other public statements, but it is a subject on which many authors have written simplistically. From pages 266-267 of The Batsford Book of Chess Records by Yakov Damsky (London, 2005):

‘[Capablanca] offered to “defend” his chess crown for a prize fund of ten thousand dollars, almost a fairytale figure by the standards of the mid-1920s. Without that sum, no claimant to the throne could even think of an audience with His Chess Majesty. “Capa has cut himself off from everyone by a wall of gold”, the newspapers wrote at the time, and indeed the stake appeared incredibly high. As often in this life, however, it was a case of “Vengeance is mine; I will repay.” When Alexander Alekhine did succeed in finding sponsors and wresting the crown, he agreed to give Capablanca a return match – on those same conditions of Capablanca’s.’

Matters are far more complex than that, and any writer should avoid the technique of vaguely attributing a quote in the singular to ‘newspapers’ in the plural.

The London Rules stated: ‘The champion will not be compelled [our emphasis] to defend his title for a purse below $10,000.’ The implications of that wording are often overlooked, and in a statement published on page 90 of the July-August 1926 American Chess Bulletin Capablanca himself wrote regarding the Rules: ‘Among other conditions, they call for a minimum purse of $10,000.’ This was quoted on page 194 of our book on the Cuban, and we remarked on page 319 that it was a surprisingly loose interpretation of Clause 8.

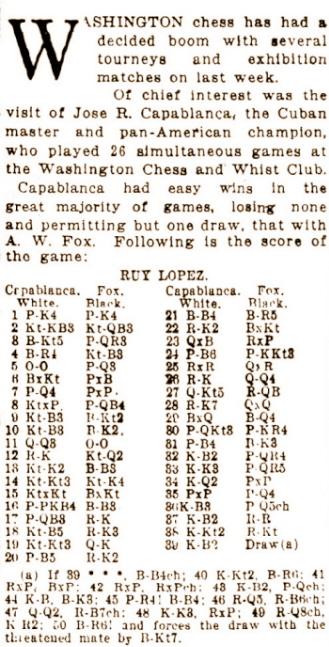

8490. Capablanca v Hamilton

Patsy A. D’Eramo (North East, MD, USA) forwards a game from page 5 of the Washington Post, 12 October 1919. It was played in a simultaneous exhibition (+45 –0 =3).

José Raúl Capablanca – Robert D. Hamilton

Cleveland, 13 January 1919

Bird’s Opening

1 f4 d5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 b3 Nf6 4 Bb2 Bf5 5 e3 e6 6 Be2 Bd6 7 O-O O-O 8 Ne5 Bxe5 9 fxe5 Nd7 10 d4 f6 11 exf6 Nxf6 12 Nd2 Nb4

13 Rxf5 exf5 14 Ba3 c5 15 c3 Nc6 16 Bxc5 Re8 17 Nf1 Ne4 18 c4 Nc3 19 Qc2 Nxe2+ 20 Qxe2 b6 21 cxd5 Qxd5 22 Ba3 f4 23 Rd1 Rad8 24 Bb2 Rd7 25 Qf2 fxe3 26 Nxe3 Qh5 27 g4 Qg5 28 Rd3 Ne5 29 Rd2 Nxg4 30 Nxg4 Qxg4+ 31 Qg2 Re1+ 32 Kf2 Qe6 33 Qa8+ Kf7 34 Qf3+ Kg8 35 Qa8+ Kf7 36 Qf3+ Kg8 Drawn.

8491. Hastings, 1919

Since Max Euwe’s name is not often associated with exceptionally fast play, the following passage is noteworthy:

‘He took part in a minor event, and few could suspect that the tall, slender, rosy-cheeked student of 18 would one day be at the top of the chess world. Max Euwe certainly made an impression at Hastings by the ingenuity and rapidity of his play. I remember particularly two games in which he overwhelmed his opponents, with his clock showing an expenditure of only five minutes. That was speed with a vengeance; but he has learned to restrain his youthful impetuosity in his later years of growing mastership.’

Source: Chess and its Stars by Brian Harley (Leeds, 1936), page 41. Harley wrote similarly on page 10 of the Observer, 17 August 1919:

‘The Dutch contingent, numbering seven all told, are very enthusiastic players. The youthful Euwe, who is playing in one of the first-class tournaments, spent just five minutes each on his last two match games, winning both.’

Euwe participated in the First Class, Section C

tournament in Hastings, finishing equal fourth. His

victory over J.J. O’Hanlon is well known, although it was

not included in From My Games 1920-1937 (London,

1938). According to pages 7-8 of Max Euwe by Hans

Kmoch (Berlin and Leipzig, 1938) it was played on 14

August 1919, but was it one of the two quickly-won games

referred to by Harley?

The earliest game of Euwe’s that we have seen is his victory over Jacques Davidson in a simultaneous exhibition given by the latter in Amsterdam in February 1912. The score was published in C.N. 1811 from the above-mentioned book by Kmoch; see page 80 of Chess Explorations.

8492. Dutch footage

Wijnand Engelkes (Zeist, the Netherlands) points out that at the Open Images website a number of Dutch-language film items concerning chess can be viewed by typing ‘schaken’ in the search-box.

Our correspondent mentions too that a search for ‘Euwe’ leads to an item on the 1956 Dutch elections which includes brief footage of the former world champion and provides an opportunity to hear the correct pronunciation of his name.

The link to Open Images will be added shortly to Chess Masters on Film.

8493. The Kalashnikov Variation (C.N.s 8450 & 8456)

Joose Norri (Helsinki) quotes a remark by Dirk Jan ten Geuzendam in a report on the Wijk aan Zee tournament on page 18 of the 2/1990 New in Chess:

‘In recent times Short has enriched the Kalashnikov – the semi-automatic, fast-firing version of the Sveshnikov – with many interesting ideas ...’

8494. McFarland chess books

McFarland & Company, Inc. is often said to produce the finest chess books, and the company’s catalogue certainly has many very good volumes, including a few of superb quality. Such is the company’s reputation that some reviewers tend to give an unthinkingly warm welcome to any new McFarland title, but blanket praise does a disservice to a truly exceptional book such as Aron Nimzowitsch On the Road to Chess Mastery, 1886-1924 by Per Skjoldager and Jørn Erik Nielsen and is far too generous to, for instance, Isaac Kashdan, American Chess Grandmaster by Peter P. Lahde.

In this sense, McFarland books may serve as a test of the book reviewer’s knowledge, judgement and reliability. If he writes that William Steinitz, Chess Champion by Kurt Landsberger is a dependable work of scholarship, alarm bells should ring.

As mentioned in C.N. 6266, the 1994 ‘Book of the Year’ prize from the British Chess Federation went to another handsome McFarland hardback, Frank Marshall, United States Chess Champion by Andrew Soltis, the judges being two non-historians, Raymond Edwards and John Littlewood. C.N. items have reported in detail on many of the book’s deficiencies; see, for instance, the remarks of two correspondents in C.N.s 4738 and 6266. To mention another example, in C.N. 2798 (an item also given on page 227 of Chess Facts and Fables) we quoted from an entry in the bibliography on page 371 of the Marshall book:

‘LeLionnais, Francois. Les Preix de Beatue aux Echecs. Payot. Paris 1970.’

Our comment was that ‘a proof-reader, had there been one, would have made four or five corrections to that single line’. The hypothetical correcteur would also have had his work cut out with the index, which has such entries as Clintrón, Lischütz, Jacque Mieses, Nimzovic, O’Briend, Rey Arduid, Carlose Torre, and Voight.

There has probably never been a chess book wholly free of error, but it is a question of degree and of whether the author, whatever his lapses, shows signs of caring. When McFarland brought out a paperback edition of the Marshall volume in 2013, no such signs were in evidence. All the faulty index entries mentioned above were left uncorrected, as were virtually all the historical mistakes pointed out in C.N. over the years.

8495. Book recommendations

Two volumes recommended by a correspondent have been added to The Very Best Chess Books in the category ‘Advanced instruction’.

8496. Alekhine and Landau in tandem

Luc Winants (Boirs, Belgium) submits the game below, which comes from an ‘alternating blindfold simultaneous display’ (six boards) given by Alekhine and Landau at the Hotel Atlanta, Rotterdam:

Alexander Alekhine and Salo Landau (blindfold, in

tandem) – C. Fontein, E.W. Beekman and P. van Reeuwijk

Rotterdam, 8 February 1934

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Nc3 d6 6 Bg5 e6 7 Be2 Be7 8 O-O O-O 9 Kh1 d5 10 exd5 Nxd5 11 Bxe7 Ncxe7 12 Nxd5 Nxd5 13 c4 Nf6 14 Nb5 Qe7 15 Qd6 Qxd6 16 Nxd6 b6 17 Rad1 Ba6 18 b3 Rfd8 19 Bf3

19...Nd5 20 cxd5 Rxd6 21 Rfe1 exd5 22 Rxd5 Rxd5 23 Bxd5 Rc8 24 h4 Kf8 Drawn.

Source: Rotterdamsche Nieuwsblad, 9 February 1934, page 23.

Mr Winants comments:

‘This game was played on board six. The book on Alekhine by Skinner and Verhoeven has four other games in the display (games 1767-1770 on pages 486-487). The game played on board four, against A.M. Broer, A. de Bruyn and P. van Os, is still missing.’

8497. Soviet archives

The lack of response so far to a correspondent’s enquiry in C.N. 8481 about the availability of old Soviet newspapers containing chess coverage highlights a difficulty often noted: few of our readers seem to have access to Soviet chess journalism published prior to the Second World War. Below, therefore, is an appeal by us to Russian-speaking chess enthusiasts for information about any such material that they possess or can access.

Редакция Chess Notes просит откликнуться русскоязычных любителей шахмат, в распоряжении которых имеются советские шахматные журналы, опубликованные перед Второй мировой войной, и которые смогут время от времени отвечать на исторические вопросы относительно их содержания. Кроме того, мы собираем информацию обо всех библиотеках и архивах, где в печатном или электронном формате хранятся старые русскоязычные газеты и периодические издания с тематической рубрикой или любыми другими материалами, посвященными шахматам. Мы будем очень рады любому отклику на данное сообщение.

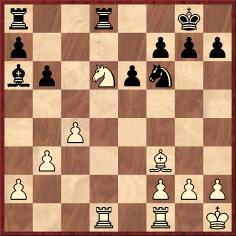

8498. Smith v Rosebault

A game from Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA):

Magnus Smith (blindfold) – Frederick D. Rosebault

Brooklyn, 1907

(Remove White’s king’s knight.)

1 e4 e5 2 Bc4 Nf6 3 Nc3 Bb4 4 O-O Bxc3 5 dxc3 d6 6 Bg5 h6 7 Bh4 Be6 8 Bd3 d5 9 exd5 Bxd5 10 Qe2 Nbd7 11 Rad1 Qe7 12 c4 Bc6 13 c3 O-O-O 14 b4 a6 15 a4 Bxa4 16 Ra1 Bc6 17 b5 Nc5 18 bxc6 Rxd3 19 cxb7+ Kxb7 20 Rfb1+ Ka7

21 f3 Rb8 22 Bf2 Rdd8, and White mates in three (23 Rxa6+ Kxa6 24 Qa2+ Na4 25 Qxa4).

Source: Winnipeg Free Press, 23 November 1907, page 27:

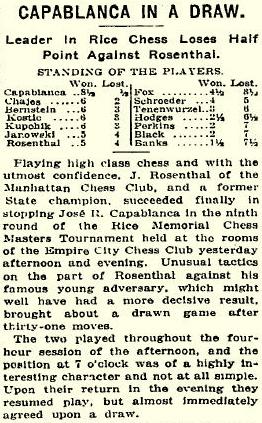

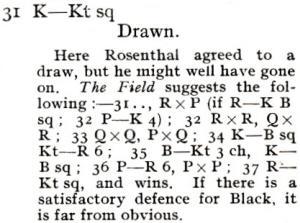

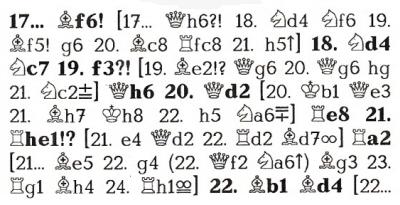

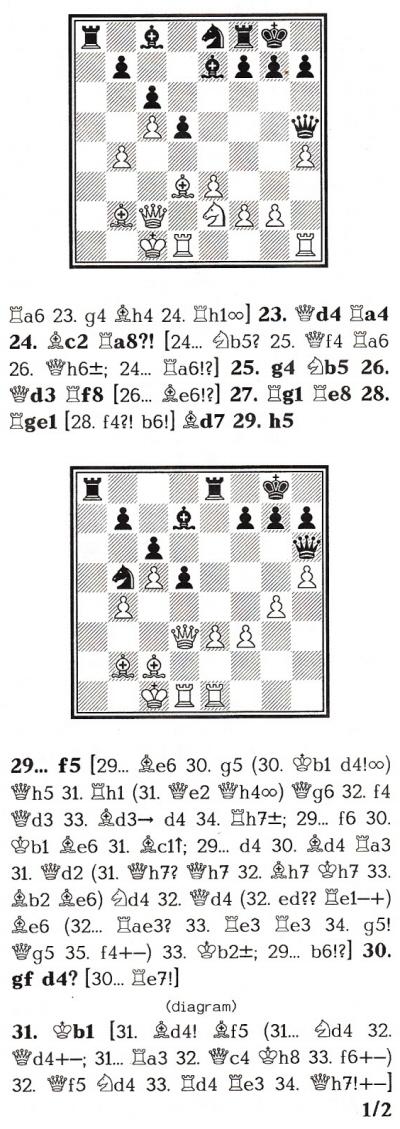

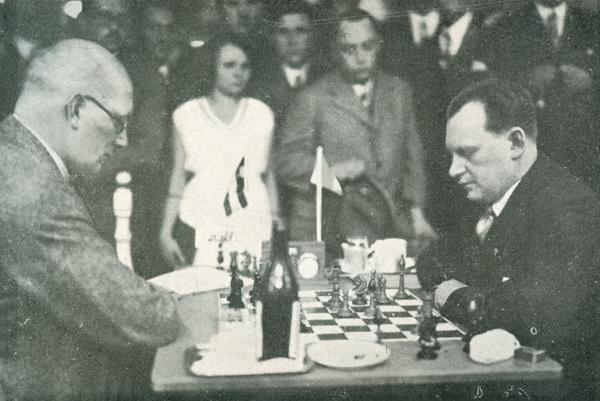

8499. Rosenthal v Capablanca

Capablanca began the Rice Memorial tournament (New York, 1916) with eight successive wins, but drew in the ninth round:

Jacob Carl Rosenthal – José Raúl Capablanca

New York, 28 January 1916

Queen’s Gambit Declined

1 d4 d5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 c4 e6 4 Nc3 Nbd7 5 e3 Bd6 6 c5 Be7 7 b4 c6 8 a3 Qc7 9 Bb2 O-O 10 Bd3 e5 11 dxe5 Nxe5 12 Nxe5 Qxe5 13 Qc2 Qh5 14 Ne2 Ne8 15 O-O-O a5 16 h4 axb4 17 axb4 Bf6 18 Nd4 Nc7 19 f3 Qh6 20 Qd2 Re8

21 Rde1 Ra2 22 Bb1 Bxd4 23 Qxd4 Ra4 24 Bc2 Ra8 25 g4 Nb5 26 Qd3 Rf8 27 Reg1 Re8 28 Re1 Bd7 29 h5 f5 30 gxf5 d4 31 Kb1 Drawn.

Sources: Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 29 January 1916, page 3; American Chess Bulletin, April 1916, page 86; The Rice Memorial Chess Tournament, New York, 1916 by P.W. Sergeant (Leeds, 1916), page 65.

The occasion was described, without the game-score, on page 10 of the New York Sun, 29 January 1916:

And on page 6 of the New York Times, 29 January 1916:

Regarding the final position ...

... P.W. Sergeant wrote in the tournament book:

The same text was reproduced on page 168 of the March 1927 Chess Amateur. Burn’s annotations in The Field had also been given on page 82 of La Stratégie, March 1916.

The game appears incorrectly in some databases (with 21 Rhe1 instead of 21 Rde1, or 21...Ra7 instead of 21...Ra2). The former mistake can be found too on page 182 of volume one of the ‘Chess Stars’ collection of Capablanca’s games (published in 1997), which thus had extensive analysis of positions which did not arise in the game:

8500. Prague, 1931

C.N. 5676 gave this photograph from the book on the 1931 Olympiad in Prague:

Ernst Grünfeld and Alexander Alekhine

Alexander Nikolaevich Zamega (Naberezhnye Chelny, Russia) comments on the apparent invisibility of the black queen, even allowing for the unusual chess set (e.g. the white king on g1).

The game as it appeared on pages 12-13 of the Czech tournament book (which gave Kostić’s notes, translated from pages 180-182 of the July-August 1931 issue of Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten): 1 d4 d5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 c4 e6 4 Nc3 c5 5 cxd5 Nxd5 6 e4 Nxc3 7 bxc3 cxd4 8 cxd4 Bb4+ 9 Bd2 Bxd2+ 10 Qxd2 O-O 11 Be2 Nd7 12 O-O b6 13 Rac1 Bb7 14 Qf4 Nf6 15 Bd3 Rc8 16 Rxc8 Bxc8 17 Rc1 Bb7 18 h3 Re8 19 e5 Nh5 20 Qg4 Bxf3 21 Qxf3 g6 22 g4 Ng7 23 Bb5 Rf8 24 Qe3 h5 25 Be2 Qd5 26 a3 Rd8 27 Bf3 Qd7 28 Qg5 hxg4 29 hxg4 Rc8 30 Rd1 Qd8 31 Qh6 Qf8 32 Kg2 Ne8 33 Qh4 Qxa3 34 Rh1 Kf8 35 Qg5 Resigns.

A further complication is that whereas both the book and the magazine gave White’s 30th move as Rd1 (as did page 236 of the August 1931 Wiener Schachzeitung), the Skinner/Verhoeven volume on Alekhine (page 398) and some databases have Re1.

8501. ‘Ideal development’ (C.N. 8453)

Another example, from page 7 of Improve Your Opening Play by Chris Ward (London, 2000):

8502. The knight’s move (C.N.s 8431 & 8465)

The statement in the previous item that ‘knights are the only pieces that can jump’ is at variance with C.H.O’D. Alexander’s remark quoted in C.N. 8465: ‘It is often inaccurately said that the knight “jumps” other pieces – actually, it simply moves between them.’

A similar point about the knight was made on page 4 of Learn Chess: A New Way for All by C.H.O’D. Alexander and T.J. Beach (Oxford, 1963):

‘It is not obstructed by pieces of either colour, since moving across the two by three box it passes between them.’

8503. Simultaneous games

Two further games have been submitted by Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA):

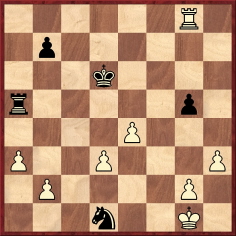

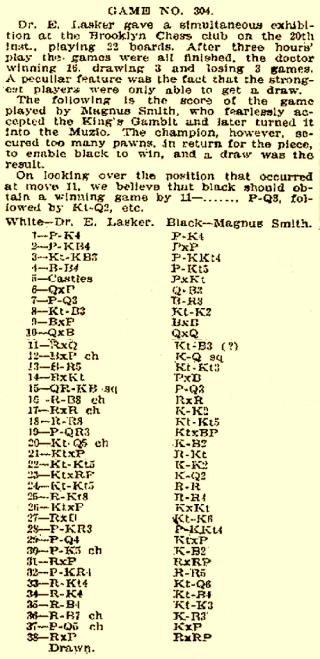

Emanuel Lasker – Magnus Smith

Brooklyn, 20 November 1907

Muzio Gambit

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 Bc4 g4 5 O-O gxf3 6 Qxf3 Qf6 7 d3 Bh6 8 Nc3 Ne7 9 Bxf4 Bxf4 10 Qxf4 Qxf4 11 Rxf4 Nbc6 12 Bxf7+ Kd8 13 Bh5 Ng6 14 Bxg6 hxg6 15 Raf1 d6 16 Rf8+ Rxf8 17 Rxf8+ Ke7 18 Rh8 Nb4 19 a3 Nxc2 20 Nd5+ Kf7 21 Nxc7 Rb8 22 Nb5 Ke7 23 Nxa7 Kd7 24 Nb5 Ra8 25 Rg8 Ra5 26 Nxd6 Kxd6 27 Rxc8 Ne3 28 h3 [The next two moves were omitted from the game-score.] 28...Nd1 29 Rg8 g5

30 d4 Nxb2 31 e5+ Kc7 32 Rxg5 Rxa3 33 h4 Ra4 34 Rg4 Nd3 35 Re4 Nc5 36 Rf4 Ne6 37 Rf7+ Kc6 38 d5+ Kxd5 39 Rxb7 Rxh4 Drawn.

Source: Winnipeg Free Press, 30 November 1907, page 6:

José Raúl Capablanca – Albert Whiting Fox

Washington, D.C., 20 November 1915

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 O-O d6 6 Bxc6+ bxc6 7 d4 exd4 8 Nxd4 c5 9 Nf3 Bb7 10 Nc3 Be7 11 Qd3 O-O 12 Re1 Nd7 13 Ne2 Bf6 14 Ng3 Ne5 15 Nxe5 Bxe5 16 f4 Bf6 17 c3 Re8 18 Nf5 Re6 19 Ng3 Qe8

20 f5 Re7 21 Bf4 Bh4 22 Re2 Bxg3 23 Qxg3 Rxe4 24 f6 g6 25 Rxe4 Qxe4 26 Re1 Qd5 27 Qg5 Rc8 28 Re7 Qxg5 29 Bxg5 Bd5 30 b3 h5 31 c4 Be6 32 Kf2 a5 33 Ke3 a4 34 Kd2 axb3 35 axb3 d5 36 Kc3 d4+ 37 Kc2 Ra8 38 Kb2 Rb8 39 Kc2 Drawn.

Source: Washington Post, 28 November 1915, page 2:

8504. 500 Master Games of Chess

Richard Hervert (Aberdeen, MD, USA) notes that 500 Master Games of Chess by S. Tartakower and J. du Mont (London, 1952) did not refer to ‘Boden’s Mate’ in connection with Schulder v Boden; the finish was described on page 200 as a ‘diagonal cross-mate’. Can instances of the term ‘Boden’s Mate’ be found prior to publication of L’art de faire mat by G. Renaud and V. Kahn (Monaco, 1947)?

As mentioned in C.N. 4436, the manuscript of 500 Master Games of Chess was delivered in 1939. C.N. 626 also discussed the book’s genesis and noted the final paragraph of the authors’ Preface, where thanks were expressed:

‘Also, and in particular, to Miss Joan Kealey, now Mrs Ronald Smith, who, out of over 8,000 games, copied and in part translated well over 2,000 for final selection, an undertaking which she carried out with exemplary thoroughness and accuracy.’

In C.N. 626 we wondered why such a lengthy process was necessary. Joan Kealey was acknowledged for playing a similar role in 200 Miniature Games of Chess by J. du Mont (London, 1941); see the book’s Preface. On 2 June 2011 Leonard Barden wrote about her at the English Chess Forum.

In 1954 Tartakower and du Mont brought out 100 Master Games of Modern Chess. Virtually all the games were played in the 1940s and 1950s.

8505. FIDE championship

With regard to the 1928 match between Bogoljubow and Euwe for the FIDE championship, C.N. 4056 quoted from an article by Kasparov on pages 104-105 of the 8/2005 New in Chess:

‘Prior to World War II FIDE failed to interest the champions, Alekhine publicly scoffing at Bogoljubow’s FIDE title.’

A passage can now be added from page 16 of the Observer, 27 May 1928, in a report on the Scarborough congress:

‘Dr and Madame Alekhine arrived at the end of play. Dr Alekhine states that a return match with Capablanca for the world championship is problematical. He has received no reply to the last letter, in which he protested against Capablanca’s proposal to change the match conditions.

Asked his opinion on the title of official champion of the International Chess Federation recently awarded to Bogoljubow, he laughingly said he thought it an excellent arrangement, but had no bearing on the world championship title.’

The text was quoted on pages 301-302 of the Chess Amateur, July 1928.

8506. Horowitz on Schlechter

‘He was widely known throughout his career as a drawing master, usually content to split the point even with much weaker players, but very difficult to beat.’

Source: The World Chess Championship A History

by Al Horowitz (New York, 1973), page 63. (Almost

identical sentiments appeared in Horowitz’s column in

the New York Times, 5 March 1972, page D 31.)

‘The designation “drawing master” for Carl Schlechter can be taken with a grain of salt.’

Source: Solitaire Chess by Al Horowitz (New York, 1962), page 69. (The item originally appeared on page 209 of the July 1960 Chess Review.)

8507. The Baron (C.N.s 5115 & 5122)

Further to the search for information about Ladislaus Baron Döry, Mika Pirttimäki (Jyväskylä, Finland) points out webpages on Nikolaus Döry von Jobaháza (16 July 1860-12 September 1923) and his son László (17 November 1897-3 December 1979).

Our correspondent urges caution before it is concluded that László and Ladislaus were the same person. Can more details be found?

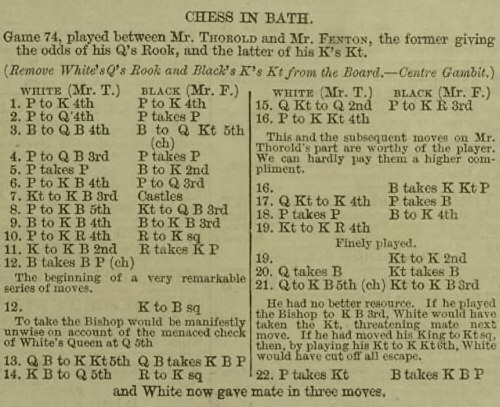

8508. Thorold v Fenton

Wanted: information about the game below, taken from pages 339-340 of the Chess World, December 1868:

Edmund Thorold – Richard Henry Falkland Fenton

Occasion?

(Remove White’s queen’s rook and Black’s king’s

knight.)

1 e4 e5 2 d4 exd4 3 Bc4 Bb4+ 4 c3 dxc3 5 bxc3 Be7 6 f4 d6 7 Nf3 O-O 8 f5 Nc6 9 Bf4 Bf6 10 h4 Re8 11 Kf2 Rxe4 12 Bxf7+ Kf8 13 Bg5 Bxf5 14 Bd5 Re8 15 Nbd2 h6

16 g4 Bxg4 17 Ne4 hxg5 18 hxg5 Be5

19 Nh4 Ne7 20 Qxg4 Nxd5 21 Qf5+ Nf6 22 gxf6 Bxf6 ‘and White now gave mate in three moves’.

When the game was published on page 48 of Chess Sparks by J.H. Ellis (London, 1895) the occasion was given as ‘Bath, about 1868’.

8509. Fifty-move limit

C.N.s 554, 677, 952 and 1551 (see pages 114-115 of Chess Explorations) discussed games drawn under the 50-move rule. Now Robert John McCrary (Columbia, SC, USA) writes:

‘The 50-move draw rule was hopelessly vague in the nineteenth century, and that vagueness had an effect on first prize in the Sixth American Chess Congress (New York, 1889). The rule in effect was that of the Chess Association of the United States of America, published on pages 167-168 of the Book of the Fifth American Chess Congress:

“Counting 50 moves. If, at any period during a game, either player persist in repeating a particular check, or series of checks, or persist in repeating any particular line of play which does not advance the game; or if ‘a game-ending’ be of doubtful character as to its being a win or a draw, or if a win be possible, but the skill to force the game questionable, then either player may demand judgment of the Umpire as to its being a proper game to be determined as drawn at the end of 50 additional moves, on each side ...”

In the first game at New York, 1889 between Max Judd and Mikhail Chigorin this position was reached with Black to play his 46th move:

Judd (White) demanded a 50-move count, and the Umpire allowed it. In the next 50 moves each side queened a pawn, and there were many pawn moves, but as these were not addressed by the rule Judd claimed a 50-move draw after Black’s 96th move, in this position:

Chigorin protested, and the Umpire demanded that the game continue. According to the game notes on page 33 of the tournament book, Judd said that his moves had been determined by the belief that the claim would be automatically allowed after the 50-move count. The Umpire forfeited the game to Chigorin, and Judd’s appeal was rejected, partly because he had not complied with the Umpire’s decision that the game should continue. Chigorin ultimately tied for first prize in the tournament.’

8510. The need for sources

It is still sometimes claimed that Rudolf Spielmann made the remark, ‘In the opening a master should play like a book, in the mid-game he should play like a magician, in the ending he should play like a machine’. Below, for example, is an abridged version which appeared on the home page of chessgames.com, 30 January 2014:

The matter has been discussed in C.N. a number of times. As shown in Chess: the Need for Sources, the quote pre-dates Spielmann, its attribution to him being based on a misreading of a book by Irving Chernev.

8511. Playing chess well

From page 2 of The Secret of Tactical Chess by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1958):

‘Some people avoid chess because they think it is a very difficult game, or because it is difficult to play well, or because it requires intelligence far beyond the ordinary. These are misconceptions.

There is no such thing as playing chess well by some absolute standard. Each chessplayer can consider himself a good or bad player merely in relation to the playing strength of his opponents. Chess of course requires intelligence; so do a great many other accomplishments which do not terrify us. For example, the person who can drive a car, play a musical instrument, or balance a check book need not be terrified by some purely imaginary standard of excellence he has set up for chessplaying.

My experience has been, by the way, that in chess great determination is more important than a high IQ. Highly intelligent but careless or feckless people will lose out in the long run to the player with greater fighting spirit and determination. I think one of the great practical lessons to be learned from chess is that our capacity for putting up with adversity is much greater than we think it is.

To such questions as, “Can everyone play chess? Safely?” I can only answer, “Yes, why not?” I have known a great many people who derive enormous pleasure and sometimes profit from chess. I have never known anyone who was harmed by it.’

8512. Thorold v Fenton (C.N. 8508)

Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA) reports that when the Thorold v Fenton game was published on page 435 of the Illustrated London News, 31 October 1868 the venue was given as Bath, although no additional details were supplied:

The notes are the same as those in the Chess World.

Our correspondent adds that the Illustrated London News can be viewed online.

8513. Tal v Spassky blitz game

Dan Scoones (Port Coquitlam, BC, Canada) forwards a neglected game for which each player had only five minutes:

Mikhail Tal – Boris Spassky

Rapid championship of Moscow, 1957

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 f5 4 Nc3 Nd4 5 exf5 Nf6 6 Nxe5

Bc5 7 O-O O-O 8 Nf3 c6 9 Nxd4 Bxd4 10 Ne2 Be5 11 Bc4+ d5

12 Bd3 c5 13 Ng3 c4 14 Be2 Bxg3 15 hxg3 Bxf5 16 d3 b5 17

a4 a6 18 axb5 axb5 19 Rxa8 Qxa8 20 dxc4 dxc4 21 Bf3

21...Qa2 22 Re1 Qb1 23 Qd6 Qxc2 24 Bd5+ Nxd5 25 Qxd5+ Kh8

26 Qf7 Rg8 27 Bh6 and White won.

Source: Chess Life, February 1963, page 38.

The game appeared in an article by Eliot Hearst which reported that the moves had been recorded by B. Weinstein. It was also noted that the same opening had occurred in the game between Tal and Spassky in the USSR championship earlier in 1957.

At move 15 Hearst commented: ‘For the last five moves the two players had consumed two minutes, a considerable time; for the next six moves they used some ten seconds only.’ Spassky spent some time on 21...Qa2, and ‘Tal also thought a while on his reply and prepared a pretty and decisive trap’.

The game will be added shortly to Fast Chess.

| First column | << previous | Archives [114] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.