Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [115] | next >> | Current column |

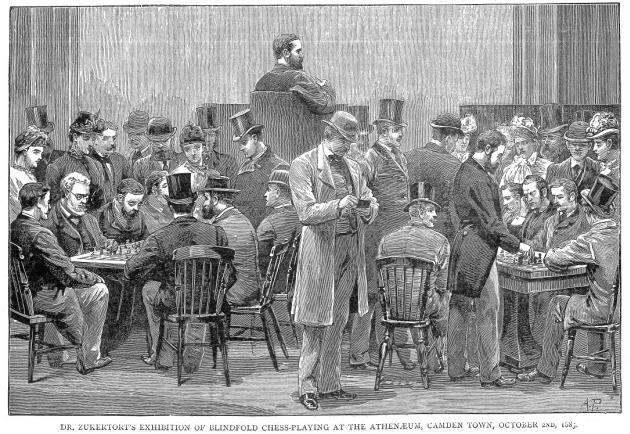

8514. Zukertort blindfold display

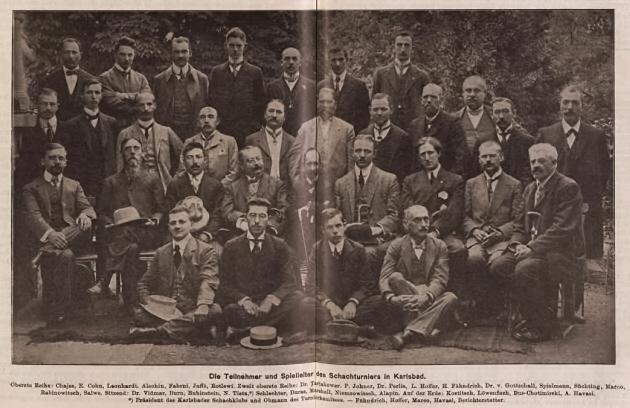

Hans Renette (Bierbeek, Belgium) has discovered this illustration on page 376 of Pictorial World, 22 October 1885:

As reported on pages 186-192 of the 28 October 1885 Chess Player’s Chronicle, page 66 of the November 1885 Chess Monthly and page 396 of the November 1885 BCM, Zukertort won four of the eight games, the others being left unfinished.

Although the above caption gave the date of the display as 2 October, all three periodicals specified that it took place the following day. The Chronicle gave all eight game-scores, and below are Zukertort’s victories:

Johannes Hermann Zukertort – G.L. Brooks

London, 3 October 1885

Vienna Gambit

1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Nc6 3 f4 exf4 4 Nf3 g5 5 h4 g4 6 Ng5 Ne5 7 d4 h6 8 Bxf4 Ng6 9 Nxf7 Kxf7 10 Bc4+ d5 11 Nxd5 Kg7 12 Bxc7 Qe8 13 O-O Be6 14 h5 N8e7 15 hxg6 Nxg6 16 Nf6 Qe7 17 Nh5+ Kh7 18 Bxe6 Qxe6

19 Qxg4 Qxg4 20 Nf6+ Kg7 21 Nxg4 Be7 22 Ne5 Bf6

23 Rxf6 Kxf6 24 Rf1+ Kg7 25 d5 Rac8 26 Nxg6 Kxg6 27 d6 Rh7. The Chronicle now gave ‘28 B to R4 Resigns’.

Johannes Hermann Zukertort – Schlesinger

London, 3 October 1885

King’s Gambit Declined

1 e4 e5 2 f4 Nc6 3 Nf3 Bc5 4 fxe5 d5 5 exd5 Qxd5 6 Nc3 Qd8 7 Bb5 Bd7 8 d4 Bb6 9 Be3 Nce7 10 Bc4 Be6 11 Qe2 Nd5 12 Bg5 Nge7 13 Nxd5 Bxd5 14 Bxd5 Qxd5 15 c4 Qe6 16 c5 Ba5+ 17 Kf2 c6 18 a3 Nd5 19 b4 Bd8 20 Rhf1 Bxg5 21 Nxg5 Qf5+ 22 Nf3 Nf4 23 Qd2 Rd8 24 Kg1 g5

25 Nxg5 Rxd4 26 Qxd4 Ne2+ 27 Kh1 Qxf1+ 28 Rxf1 Nxd4 29 Nxf7 Rf8 30 Nd6+ Ke7 31 Rxf8 Kxf8 32 Nxb7 Nc2 33 Na5 Nd4 34 a4 a6 35 Nc4 Ke7 36 Kg1 Ke6 37 Kf2 Kd5 38 Nb6+ Kxe5 39 Nd7+ Kd5 40 Nb8 a5 41 bxa5 Kxc5 42 Kg3 Kd6

43 Nxc6 Nxc6 and White won.

Johannes Hermann Zukertort – Smith

London, 3 October 1885

Queen’s Pawn Game

1 d4 d5 2 Nf3 f6 3 c4 e6 4 e3 Bb4+ 5 Nc3 Ne7 6 Bd3 O-O 7 O-O Bxc3 8 bxc3 f5 9 Ba3 Rf6 10 Qb3 c6 11 Rad1 Ng6 12 Rfe1 a5 13 cxd5 exd5 14 c4 a4 15 Qc2 Be6 16 Ng5 Bd7 17 cxd5 cxd5

18 e4 fxe4 19 Bxe4 Bc6 20 Bxg6 Rxg6 21 Be7 Qd7 22 Rd3 h5 23 Rf3 Qxe7 24 Rxe7 Rxg5 25 Rg3 Rxg3 26 hxg3 Resigns.

Johannes Hermann Zukertort – Kimmell

London, 3 October 1885

Evans Gambit Accepted

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 b4 Bxb4 5 c3 Bc5 6 O-O d6 7 d4 exd4 8 cxd4 Bb6 9 Nc3 Nce7 10 Qb3 Be6 11 Bxe6 fxe6 12 Ng5 Nc6 13 Nxe6 Qd7 14 d5 Na5 15 Qc2 a6 16 Bb2 Nc4 17 Na4 Nxb2 18 Nxb6 cxb6 19 Qxb2 Nf6 20 Qxb6 Kf7 21 Rac1 Rac8 22 f3 h6 23 Rb1 Rb8 24 Rfc1 Rhc8 25 Rxc8 Rxc8

26 Qxb7 Rc1+ 27 Rxc1 Qxb7 28 Nd8+ Ke7 29 Nxb7 Resigns.

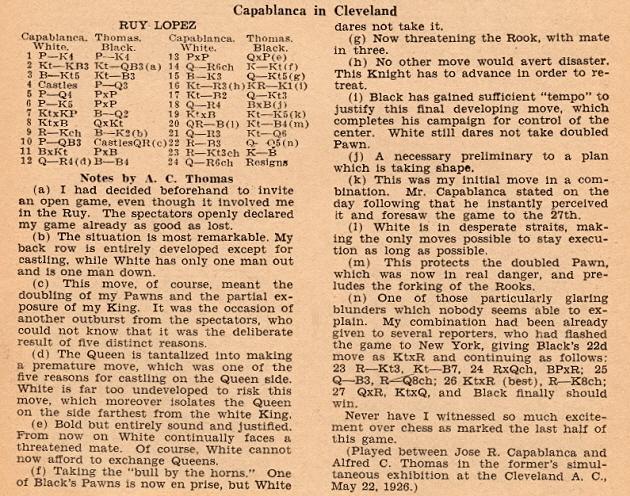

8515. Capablanca v Alfred C. Thomas

From page 147 of the November 1926 American Chess Bulletin:

The comments about Black’s 19th and 22nd moves are noteworthy.

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 Nf6 4 O-O d6 5 d4 exd4 6 e5 dxe5 7 Nxe5 Bd7 8 Nxd7 Qxd7 9 Re1+ Be7 10 c3 O-O-O 11 Bxc6 bxc6 12 Qa4 Bc5 13 cxd4 Qxd4 14 Qa6+ Kb8 15 Be3 Qb4 16 Na3 Rhe8 17 Nc2 Qb6 18 Qa4 Bxe3 19 Nxe3 Ne4 20 Rac1 Nc5 21 Qa3 Nd3 22 Rc3

22...Qd4 23 Rb3+ Kc8 24 Qa6+ Resigns.

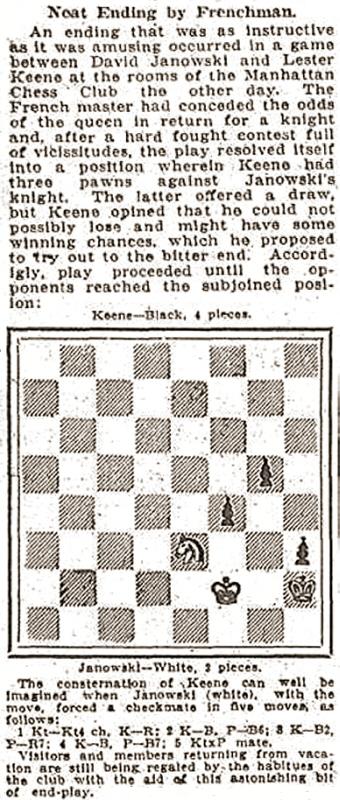

8516. An instructive and amusing ending

From Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) comes this item on page 12 of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 26 July 1917:

The position was given in C.N. 1108 and, when reproduced on pages 10-11 of Chess Explorations, caused Hans Ree to go off the rails on page 81 of the 8/1996 New in Chess.

The source specified in C.N. 1108 was page 313 of the October 1917 BCM, which took the position from the Brooklyn Daily Eagle. The newspaper’s text was also given on page 240 of the November 1917 American Chess Bulletin. See too page 7 of La Stratégie, January 1918. Furthermore, the position was discussed extensively on pages 38-39 of Jeugdschaak by L.G. Eggink and M. Euwe (Lochem, 1950), although White was named as Frank Marshall, and the position was said to have occurred at the Manhattan Chess Club in 1907.

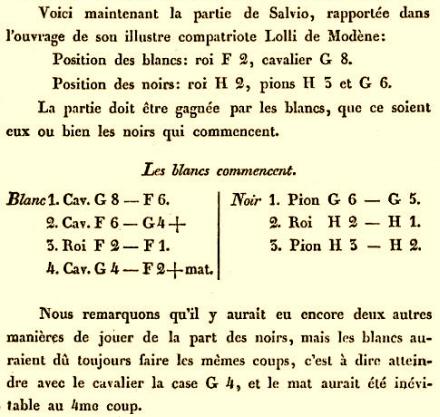

In the domain of chess compositions the manoeuvre leading to mate by a knight on f2 has been known centuries. Below, for instance, is an extract from page 8 of Découvertes sur le cavalier (aux échecs) by C.F. Jaenisch (St Petersburg, 1837):

About Lester Keene a comment by William Lombardy on page 268 of the May 1976 Chess Life & Review is added warily:

‘Long ago there was a player at the Manhattan Chess Club, Lester Keene by name, who customarily defended the mate threatened at KR7 simply by playing ...P-KR3!’

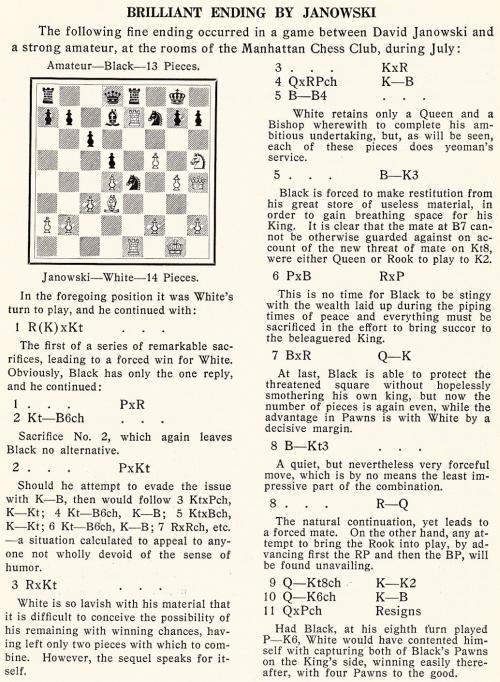

8517. Janowsky v N.N.

The other Janowsky position given in C.N. 1108, and on page 11 of Chess Explorations, was the conclusion of a game also played at the Manhattan Chess Club in July 1917. Below is its appearance on page 147 of the July-August 1917 American Chess Bulletin:

The full game has still not been found.

8518. Jasnogrodsky and Albin

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) forwards a photograph (New York, 1893) found at the Cleveland Public Library. It is reproduced here with permission.

Nicolai Jasnogrodsky and Adolf Albin

8519. Four-pawn boxes

Jason Childress (Belmont, CA, USA) asks whether a name exists for the box-like configuration (pawns on b7, c7, b6 and c6) which Nakamura had in his game against Anand in Zurich on 31 January 2014. No established term is known to us.

Occasionally the ‘pawn box’ is found on the centre squares. On page 420 of the November 1974 BCM D.J. Morgan wrote that ‘pawn squatters have truly taken over in this position, sent by I.D. Hunnable’ (Pachman v Fischer, Santiago, 1959). An earlier example is Alekhine v Bešťák, Plzeň, 1925, a game given on page 239 of the Skinner/Verhoeven volume on Alekhine.

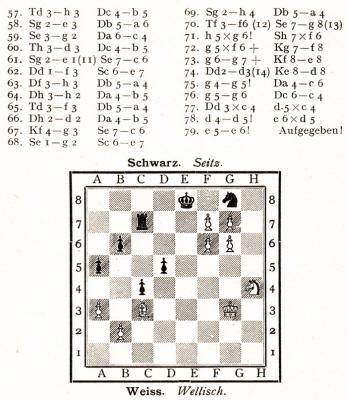

We recall no occurrence of such a configuration on the sixth and seventh ranks, although a diagram on page 40 of Schachjahrbuch 1921 by Ludwig Bachmann (Ansbach, 1923) showed a hypothetical conclusion to the game E. Wellisch v A. Seitz, Regensburg, 19 August 1921:

The full score as given on pages 39-42 of Bachmann’s book: 1 e4 c6 2 d4 d5 3 e5 Bf5 4 Bd3 Bxd3 5 Qxd3 e6 6 f4 Qb6 7 Nf3 Nd7 8 O-O c5 9 c3 g6 10 Nbd2 h5 11 Ng5 Nh6 12 Ndf3 Nf5 13 Re1 Be7 14 Be3 Kf8 15 Bf2 Kg7 16 Re2 Rac8 17 Rae1 Qa5 18 a3 Qb6 19 h3 cxd4 20 cxd4 h4 21 Kh2 Rc4 22 Rd2 Qa5 23 Red1 Qc7 24 Qe2 Rc1 25 Qe1 Rxd1 26 Rxd1 Rh5 27 Nxh4 Bxg5 28 fxg5 Qc2 29 Rd2 Qb3 30 Nf3 Nb6 31 Qe2 Rh8 32 Rd3 Qb4 33 g4 Ne7 34 Ng1 Qc4 35 Qf3 Nd7 36 Rc3 Qb5 37 Rb3 Qa6 38 Be1 Rc8 39 Qd1 b6 40 Rf3 Qc4 41 Bc3 a5 42 Rf1 Nc6 43 Ne2 Nf8 44 h4 Nh7 45 Rf3 Rh8 46 Kg3 Rc8 47 Nf4 Rc7 48 Nh3 Qa6 49 Nf4 Qc4 50 Ng2 Qa6 51 Kf4 Kf8 52 h5 Ne7 53 Nh4 Kg7 54 Rh3 Qc4 55 Ng2 Qa6 56 Rd3 Qc4 57 Rh3 Qb5 58 Ne3 Qa6 59 Ng2 Qc4 60 Rd3 Qb5 61 Ne1 Nc6 62 Qf3 Ne7 63 Qh3 Qa4 64 Qh2 Qb5 65 Rf3 Qa4 66 Qd2 Qb5 67 Kg3 Nc6 68 Ng2 Ne7 69 Nh4 Qa4 70 Rf6 Ng8 71 hxg6 Nhxf6 72 gxf6+ Kf8 73 g7+ Ke8 74 Qd3 Kd8 75 g5 Qc6 76 g6 Qc4 77 Qxc4 dxc4 78 d5 exd5 79 e6 Resigns. Wellisch: ‘Auf fe folgt natürlich f7 und auf einen anderen beliebigen Zug, z. B. Ke8 könnte nach ef+ eine Schlussstellung entstehen, die ein Unikum darstellt und festgehalten zu werden verdient.’

8520. Translations wanted

Timothy J. Bogan, (Chicago, IL, USA) comments on three books which he considers deserving of an English translation:

- Goldene Schachzeiten by M. Vidmar (Berlin, 1961): ‘Vidmar played all the greatest players of his time in many of the strongest tournaments of the first half of the twentieth century. A survey of the chess scene by a participant must be of great interest to any student of chess history.’

- 34 mal Schachlogik by A. O’Kelly de Galway (Berlin, 1964): ‘I remember struggling through parts of this collection of O’Kelly’s postal games with a German-English dictionary and being very impressed by the exciting play and by O’Kelly’s comments about the highest level of chess strategy.’

- Izbrannye partii i vospominanya by G. Levenfish (Moscow, 1967): ‘Levenfish was one of the strongest players of his time, scoring victories over Botvinnik, Lasker, Alekhine, Korchnoi and Smyslov though rarely traveling abroad. His memoirs offer much of interest about the Soviet chess scene, and I find his games fresh and sparkling with tactics. The text is extensive and the games are deeply annotated.’

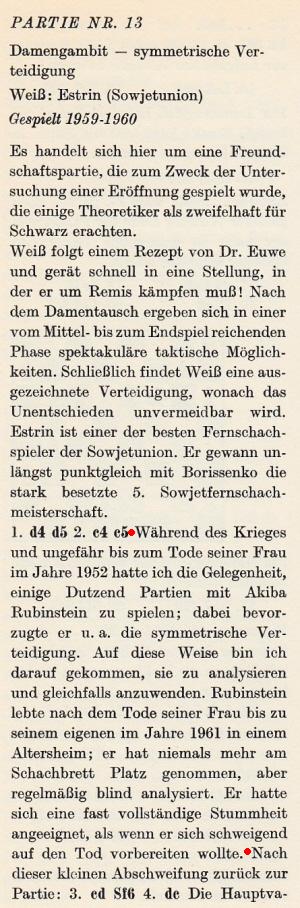

8521. O’Kelly and Rubinstein

Mr Bogan draws attention to a passage by O’Kelly on page 32 of 34 mal Schachlogik concerning Rubinstein’s later years:

To summarize: During the Second World War and until Rubinstein’s wife died, O’Kelly played several dozen games against Rubinstein, some of which featured the ‘Symmetrical Defence’ to the Queen’s Gambit, an opening which O’Kelly then analysed and played himself. As a widower, Rubinstein spent his final years in an old people’s home, no longer using a chess set but regularly analysing without a board. He remained almost silent, as if wishing to prepare himself for death.

8522. Three pawns against a knight (C.N. 8516)

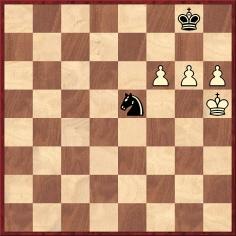

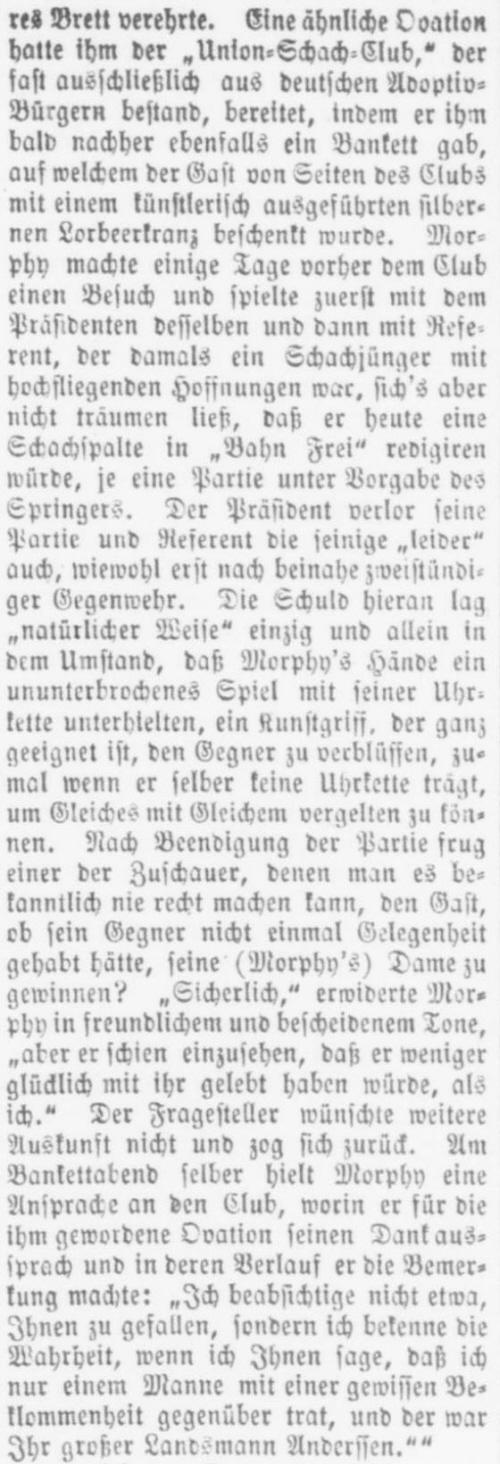

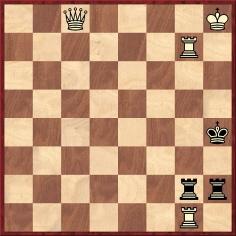

A position to ponder:

White to move

8523. Early rook moves

C.N. 1745 (see page 101 of Chess Explorations) mentioned a game which began 1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 Rg8. A worthy addition is ‘Duffre’s Defence’, which appeared in a satirical article by R.J. French, ‘Game Preserving’, on pages 27-28 of the October 1922 Chess Amateur: 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Rg1.

8524. Levenfish on Rotlewi

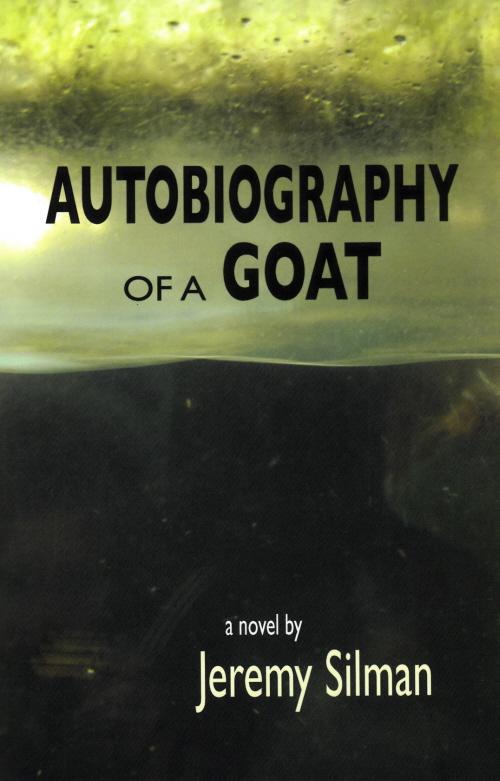

Avital Pilpel (Haifa, Israel) refers to an article by Mark Dvoretsky at the Chess Café (January 2004) which quoted from Levenfish’s memoirs with regard to Carlsbad, 1911:

‘A notable performance was given by young Rotlewi, who defeated powerful opposition, including Schlechter, Nimzowitsch, Marshall and Spielmann, in grand style. After the 17th round, Rotlewi shared the lead with Teichmann and Schlechter, a point and a half ahead of their nearest rival, Rubinstein. Whispers began to be heard among the representatives of the chess press, and an interview appeared with this new rising “star”.

Rotlewi’s family was very poor; his clothes were clear testimony to this unfortunate fact. City Councilman Tietz was upset. Imagine – a prizewinner of the Carlsbad tournament, appearing in pants which were quite evidently those of a younger brother! Tietz gave Rotlewi an advance against his prize, and suggested he buy some new clothes. The next day, Rotlewi arrived in a new suit and patent-leather shoes. With the jingle of kroner in his pocket, he was unrecognizable.

But Tietz had done Rotlewi no favor. Having become a dandy, the latter now partook of the pleasures of spa life, and grew unfit for serious chess. In the latter part of the tournament, Rotlewi suffered several losses, ending up in fourth place.

Soon after the tournament ended, Rotlewi fell prey to depression. Thus ended the chess career of a most talented master.’

Mr Pilpel asks whether this account can be substantiated from other sources.

Below is the original of Levenfish’s remarks, from page

30 of his book Izbrannye partii i vospominanya

(Moscow, 1967):

In the final paragraph the Russian text indicates that Rotlewi fell prey to ‘a mental disorder’ rather than ‘depression’.

Finally, a detail of Rotlewi from the Carlsbad, 1911 group photograph on pages 304-305 of the September-October 1911 Wiener Schachzeitung:

8525. Einstein

C.N.s 3533, 3667, 3691 and 4133 have touched on a game labelled Einstein v Oppenheimer. No evidence has been found that Albert Einstein had anything to do with it.

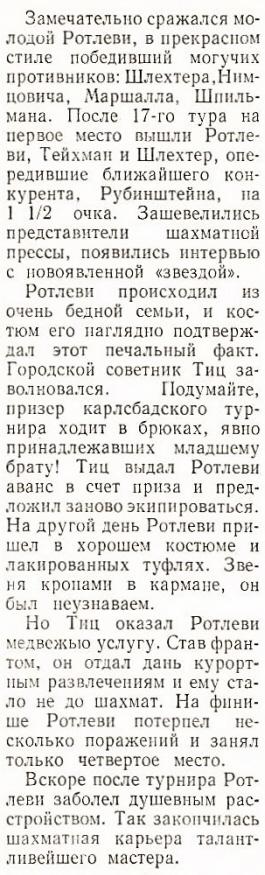

Over a century ago a player named B. Einstein was occasionally mentioned in chess literature. From page 273 of the September 1910 Deutsche Schachzeitung:

The reference in the caption ‘nicht V.M. in Barcelona’ indicated that Black was Dr V. Marín of Valencia, and not Valentín Marín y Llovet of Barcelona.

The game below was published on pages 13-14 of the January 1911 Deutsche Schachzeitung. Neither player had sight of the board.

B. Einstein – W. Ahrens

Valencia, October 1910

Giuoco Piano

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 O-O d6 5 h3 Nf6 6 c3 O-O 7 d4 exd4 8 cxd4 Bb6 9 Nc3 Kh8 10 a3 Nh5 11 Ng5 g6 12 Nxf7+ Rxf7 13 Bxf7 Qf6 14 Bb3 Bd7 15 e5 dxe5 16 dxe5 Nxe5 17 Nd5 Qc6 18 Re1 Rf8 19 Nxb6 Qxb6 20 Rxe5 Qxf2+ 21 Kh1 Ng3+ 22 Kh2 Nf1+

23 Qxf1 Qxf1 24 Bd2 Qxa1 25 Bc3 Rf6

26 Re1 Resigns.

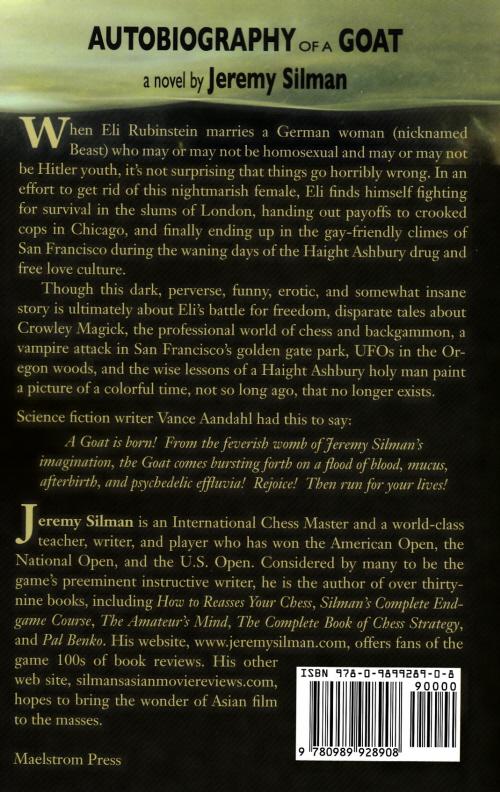

8526. Novel

Chess authors often write fiction, but Jeremy Silman has done so intentionally with a novel, Autobiography of a Goat (Los Angeles, 2013):

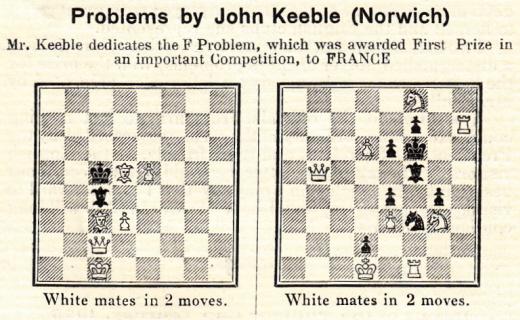

8527. Keeble problems

From page 16 of The Book of the Second Annual Chess Congress Hyères, 1926 (Hyères, 1926):

Information is sought about, in particular, the ‘F’ problem. Where had it appeared previously?

8528. Convict, vagabond and chessplayer

Our latest feature article discusses a strong chessplayer who was sentenced to death, had his sentence commuted to life imprisonment, eventually secured release and became a vagabond and author. The article includes his account of playing against Sir George Thomas when the latter visited Parkhurst Prison in 1935 to give a simultaneous display.

8529. Christian Hesse

C.N.s 7083, 8276 and 8319 drew attention to Christian Hesse’s inaccurate plundering of our work, and in C.N. 8276 we commented:

‘Naturally, other writers and researchers are also the victims of Hesse’s unconscionable approach.’

An entry dated 13 December 2013 in Tim Krabbé’s Open Chess Diary:

‘It’s about time Mr Christian Hesse (ChessBase, books) wrote something he couldn’t first have read in my work.’

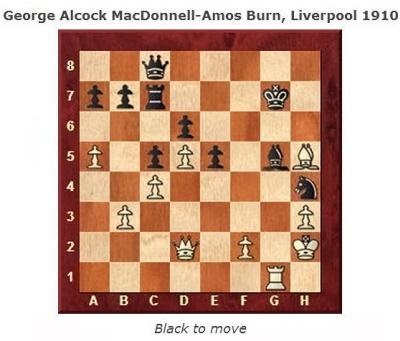

An article which Hesse somehow managed to have posted by ChessBase on 13 September 2013 still contains, even today, the blunders pointed out at the time in C.N. 8276, including the following:

George Alcock MacDonnell died in 1899.

8530. McFarland chess books (C.N. 8494)

On pages 52-53 of the 1/2014 New in Chess Nigel Short writes about rapid chess (defined in the article as games with ‘approximately half an hour per player’). The final paragraph:

‘In recent years, publishers have commissioned biographies of ever-more obscure, peripheral chess figures. I have read the weighty McFarland hardback of Albert Beauregard Hodges from beginning to end and I still can’t tell you anything about him. Quite possibly this is because I am a philistine, or an amnesiac, but the alternative explanation is that Hodges’ life is not an inherently interesting subject. Far better would be for some proper researcher to examine the enormous wealth of material on rapid chess and write its definitive history. With luck, this briefest of sketches may serve as a catalyst.’

A book on such a topic (ideally, on all forms of fast chess) could certainly be an excellent addition to the thematic chess books of McFarland & Company, Inc., which include Blindfold Chess by E. Hearst and J. Knott (2009) and, alas, Women in Chess by J. Graham (1987), although not much else. Chess prodigies is another subject which would lend itself to the McFarland treatment.

As regards biographical works, a number of world champions and other leading players have been covered by McFarland authors, and some books, such as Reuben Fine by A. Woodger (2004), have been strangely neglected. Comprehensive, academic volumes on figures like Euwe and Fischer would be highly desirable additions, as would English translations of the large volumes on, for instance, Tarrasch and Janowsky currently available only in German, as mentioned in C.N. 6803.

McFarland’s biographical tomes also feature many relatively unfamiliar masters (of whom Hodges is not the least familiar), and they are particularly welcome when, as is customarily the practice, they deal too with the overall chess context of the subject’s period and locality. For example, our Foreword to The Tragic Life and Short Chess Career of James A. Leonard, 1841-1862 by John S. Hilbert (2006) observed:

‘Yet while Leonard remains the focus of attention in these pages, the broader tableau of US chess in the early 1860s is also ably presented. So too is the agony of the Civil War, which cost Leonard his life.’

Writing such books demands much skill, to blend the proper level of documentary detail about the master (not an indiscriminate deluge) with a satisfying overview of the context (not simplistic waffle about geopolitics).

In certain areas McFarland needs to show considerably more rigour (in its choice of chess authors and in how it processes some books), but its catalogue continues to grow impressively. We hope to see many new books in all three categories mentioned above, i.e. on the world’s leading players, on unsung figures and on thematic topics.

8531. Karl Portius

Fabrizio Zavatarelli (Milan, Italy) has found a picture of the chess author Karl Julius Simon Portius (1797-1862) on page 354 of the Illustrirte Zeitung, 24 May 1862:

8532. The knight’s move

From Robert John McCrary (Columbia, SC, USA):

‘The “American Chess Code”, published in 1897 and the same as the “British Chess Code” published shortly beforehand, contains on page 24 the earliest official definition of a knight’s move in a Code that I have seen. It states that a square is commanded by a knight ...

“... when that square and the square on which the knight stands are as near to each other as, without being of the same rank or file or diagonal, it is possible for two squares to be ...”This appears to be an official definition that is essentially the same as saying that the knight moves to the nearest square that cannot be commanded by a queen.’

We add another explanation of the knight’s move, from page 19 of First Book of Chess by I.A. Horowitz and Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1952):

‘“The old one-two” is the phrase that aptly describes the knight’s move. Each knight move is a combination of one square and two squares:

(a) one square “North” or “South”; then two squares “East” or “West”.

(b) one square “East” or “West”; then two squares “North” or “South”.’

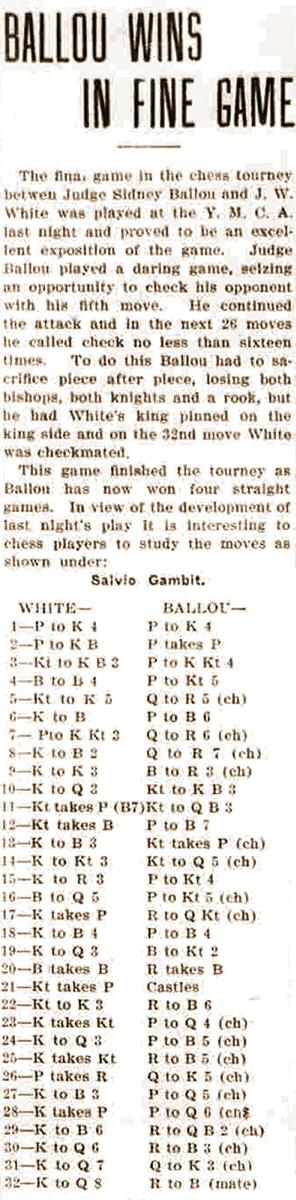

8533. White v Ballou

A royal walkabout submitted by Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA):

J.W. White – Sidney Miller Ballou

Fourth match-game, Honolulu, 24 October 1910

King’s Gambit Accepted

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 Bc4 g4 5 Ne5 Qh4+ 6 Kf1 f3 7 g3 Qh3+ 8 Kf2 Qg2+ 9 Ke3 Bh6+ 10 Kd3 Nf6 11 Nxf7 Nc6 12 Nxh6 f2 13 Kc3 Nxe4+ 14 Kb3 Nd4+ 15 Ka3

15...b5 16 Bd5 b4+ 17 Kxb4 Rb8+ 18 Kc4 c5 19 Kd3 Bb7 20 Bxb7 Rxb7 21 Nxg4 O-O 22 Ne3 Rf3 23 Kxe4 d5+ 24 Kd3 c4+ 25 Kxd4

25...Rf4+ 26 gxf4 Qe4+ 27 Kc3 d4+ 28 Kxc4 d3+ 29 Kc5 Rc7+ 30 Kd6 Rc6+ 31 Kd7 Qe6+ 32 Kd8 Rc8 mate.

Source: Hawaiian Star, 25 October 1910, page 6:

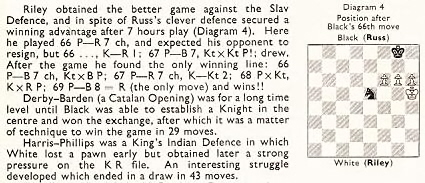

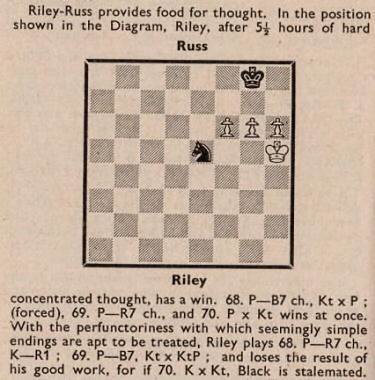

8534. Three pawns against a knight (C.N.s 8516 & 8522)

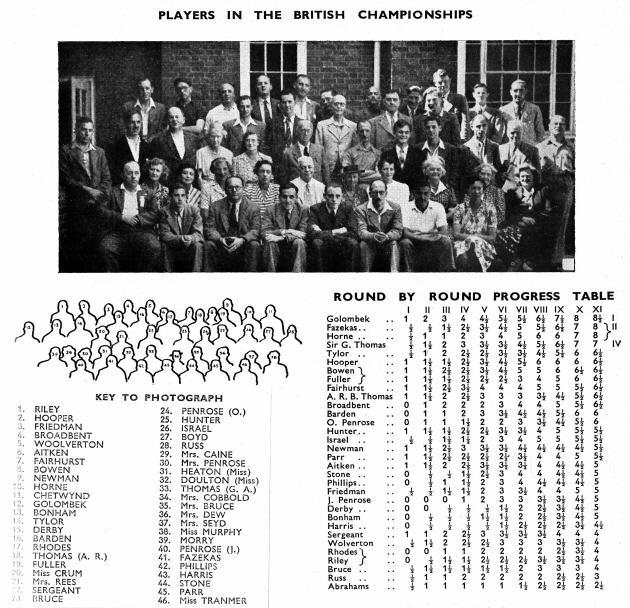

The position in C.N. 8522 arose in a game between Riley and Russ at the British championship in Felixstowe in August 1949 and was published on page 296 of the September 1949 BCM:

It also appeared on page 18 of the October 1949 CHESS:

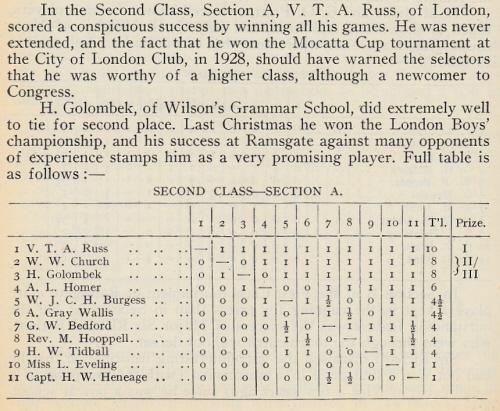

We should like to have the players’ full names. Page 311 of the September 1949 BCM had D.E.A. Riley and V.J.A. Russ, whereas page 17 of the October 1949 CHESS gave B.E.A. Riley and V.T.A. Russ. The BCM version is supported by page 8 of The Times, 8 August 1949, but we note references to ‘V.T.A. Russ’ on page 342 of the September 1929 BCM, in a report on that year’s British Chess Federation Congress in Ramsgate:

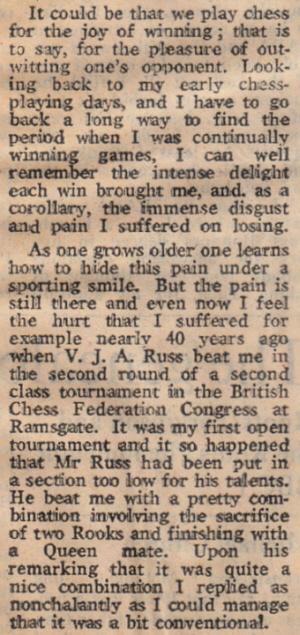

Page 270 of the June 1928 Chess Amateur reported that the Mocatta Cup had been won by ‘V.J.A. Russ’, which was also the name used by Golombek on page 10 of The Times, 9 April 1977 when discussing the pain of losing in Ramsgate:

Golombek (whose reference to ‘nearly 40 years ago’ is a typo or miscalculation) also mentioned ‘Russ’s quiet, almost timid, satisfaction with the beauty of his combination’. Can the game-score be found?

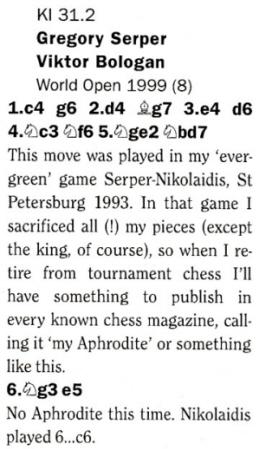

8535. Serper on his ‘evergreen’ game

From page 37 of the 5/1999 New in Chess:

The Serper v Nikolaidis game-score not having appeared in New in Chess, we gave it on page 97 of the following issue (C.N. 2312).

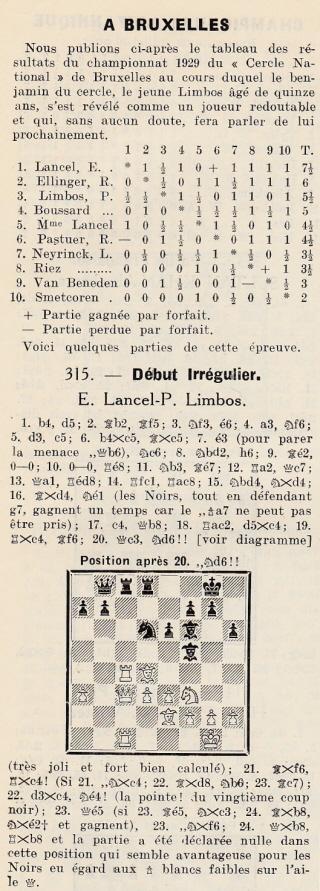

8536. Paul Limbos

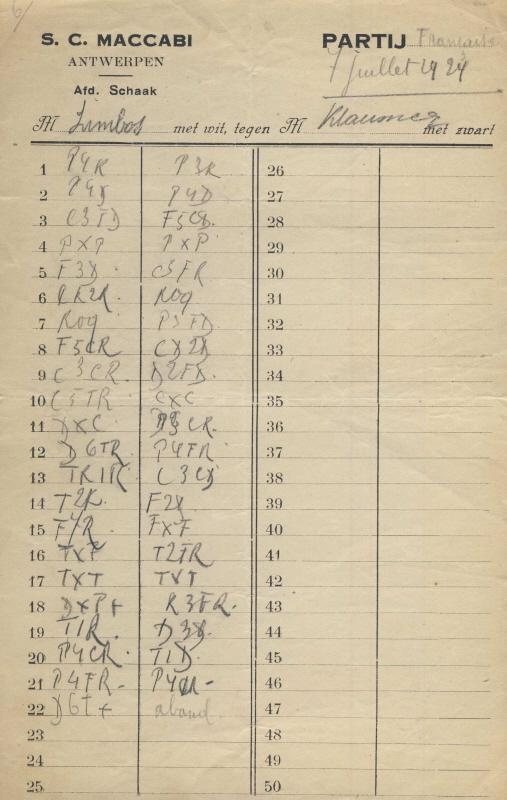

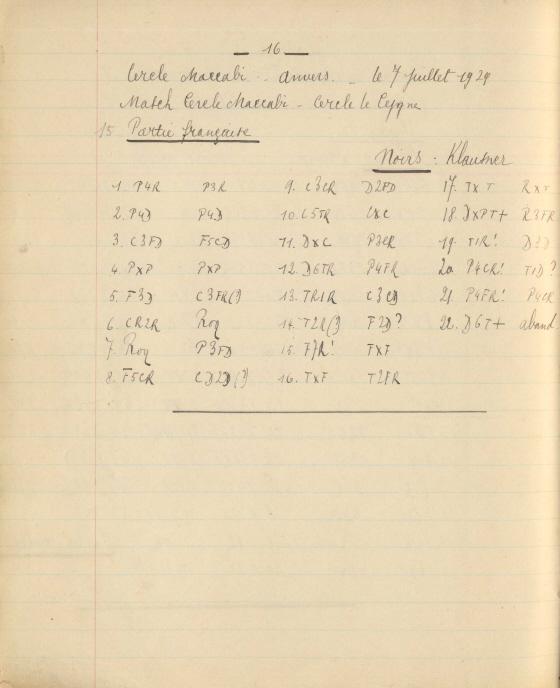

This photograph of Paul Limbos was published opposite page 376 of L’Echiquier, September 1929. As mentioned on page 402 of the same issue, he was aged 15 at the time:

1 b4 d5 2 Bb2 Bf5 3 Nf3 e6 4 a3 Nf6 5 d3 c5 6 bxc5 Bxc5 7 e3 Nc6 8 Nbd2 h6 9 Be2 O-O 10 O-O Re8 11 Nb3 Be7 12 Ra2 Qc7 13 Qa1 Red8 14 Rc1 Rac8 15 Nbd4 Nxd4 16 Bxd4 Ne8 17 c4 Qb8 18 Rac2 dxc4 19 Rxc4 Bf6 20 Qc3 Nd6 21 Bxf6 Rxc4 22 dxc4 Ne4 23 Qe5 Nxf6 24 Qxb8 Rxb8 Drawn.

There was a section about Limbos on pages 169-177 of Histoire des maîtres belges by Michel Wasnair and Michel Jadoul (1988). Pages 174-175 reproduced an article by him entitled ‘Ma rencontre avec Humphrey Bogart’ which related that one evening in 1951 in Stanleyville, during the shooting of The African Queen, he played a number of games with the actor, for small stakes. After midnight, Limbos reported, he had won 17 dollars, having lost no games but drawing two or three (‘pour “ménager le client”, comme aurait dit O’Kelly’). That evening, Bogart drank seven or eight glasses of whisky, merely part of his daily ration, and smoked continuously. His favourite openings were the Giuoco Piano and Scotch Game as White, and the French Defence as Black.

The book by Wasnair and Jadoul gave, on pages 174-175, a 22-move victory by Limbos against Bogart (a French Defence), with notes by Limbos.

The game has become well known, but Luc Winants (Boirs, Belgium) informs us that it has nothing to do with Humphrey Bogart:

‘I knew Paul Limbos quite well as we both played for the first team of the Cercle des échecs d’Anderlecht. Some time before his death, he made sure that Michel Jadoul would receive his early score-sheets and notebooks, dating from the late 1920s and early 1930s. A decade later, however, Jadoul considered that the documents would be safer in my hands, and I am therefore able to say that the game attributed to Humphrey Bogart was not played by him.

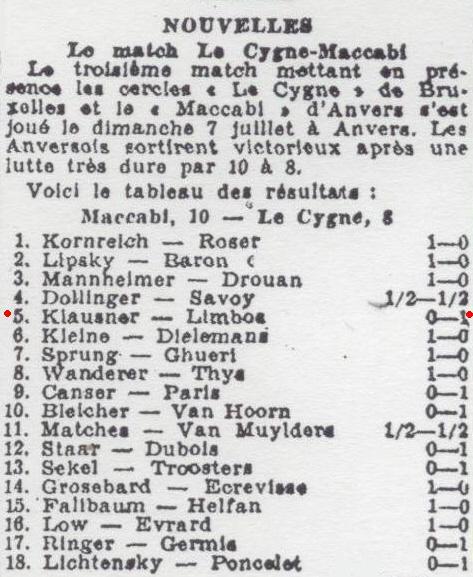

In fact, it is the game Limbos v Klausner, played on board five in a match between the chess clubs of Le Cygne (Brussels) and Maccabi (Antwerp) on 7 July 1929. This is proven by the original score-sheet, as well as by Limbos’ personal notebook, in which he rewrote his games. The final move was 22 Qh6+, and not 22 h4 as given in the book.

I also have the complete result of the match, as published by Edmond Lancel in La Nation Belge, 19 July 1929:

Why Limbos gave this game as played against Bogart is a mystery to me. Limbos certainly did not need the publicity, and I know that he disliked forgeries. He had a great passion for chess, and was a doctor and scientist of distinction, as well as being a very kindly man.’

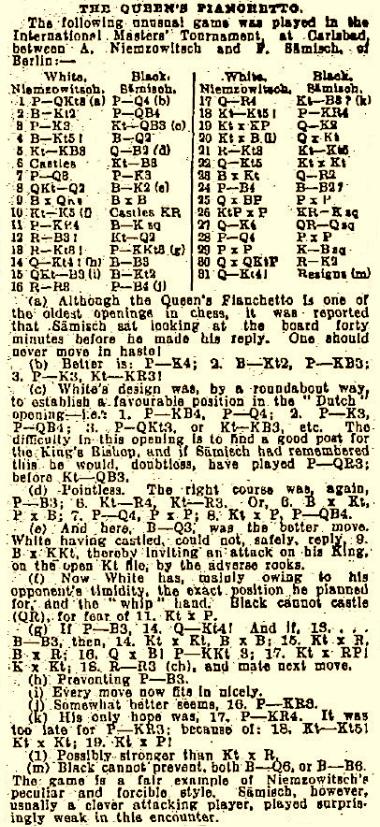

8537. Nimzowitsch v Sämisch, Carlsbad, 1929

Concerning lengthy reflection at the board, is it true that after Nimzowitsch played 1 b3 against Sämisch at Carlsbad, 1929, Black thought for 40 minutes? Such a suggestion was made on page 4 of the Sunday Times, 17 November 1929:

8538. Alekhine and alcohol

Jeremy Silman (Los Angeles, CA, USA) wishes to know the truth about suggestions that Alekhine was found drunk in a field during his 1935 world championship match against Euwe.

The Factfinder has an entry for ‘Alekhine, Alexander (alcohol)’, and further citations will be appreciated, after which all available documentation will be drawn together in a feature article. The word documentation is stressed; frequently elsewhere the subject is treated merely as good for a gossip and a giggle.

8539. Fischer and Boys’ Life

Dan Scoones (Port Coquitlam, BC, Canada) writes:

‘In your feature article on Fischer’s column in Boys’ Life, two obscure Soviet games are cited, Cherskikh-Cherepkov and Lipman-Zolotonos, and I have looked up the original sources, on page 342 of the 11/1965 issue of Shakhmatny Bulletin and on page 10 of the 4/1969 issue of Shakhmaty Riga.

Cherskikh-Cherepkov (Boys’ Life, June 1967) was played in the semi-final of the 1965 Trade Union Championship. I believe that the venue was Moscow but have not been able to confirm this.

K. Cherskikh (whose forename may have been Konstantin) finished near the bottom in the 35th USSR Championship at Kharkov in 1967, the large Swiss event won by Tal and Polugayevsky. In 1965 Alexander Cherepkov was already a well-known master, and the “sic” with reference to his surname is not required.

Lipman-Zolotonos (Boys’ Life, August 1969) was played in the 1968 DSO Team Championship in Riga. This event is incorrectly cited by a ChessBase database as the USSR Team Championship, but it is given correctly by RusBase. Vladimir Lipman was born in the Soviet Union in 1949 but seems to have emigrated to the United States sometime before 2002. His opponent, Leonid Zolotonos, is an obscure figure, and there are no games of his after 1973 in the standard databases. Despite the obscurity of the players, it is natural that Fischer would be interested in the game because it featured his own pet variation against the Sicilian Najdorf.’

8540. Barcelona, 1929

Luc Winants (Boirs, Belgium) draws attention to an Ajedrez 365 webpage offering rich material on Barcelona, 1929.

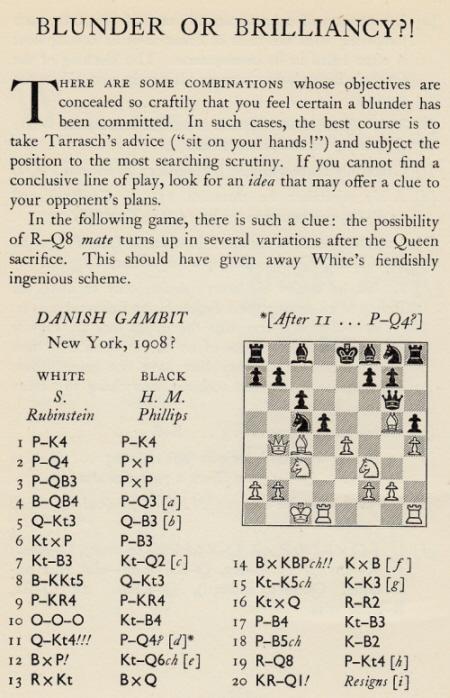

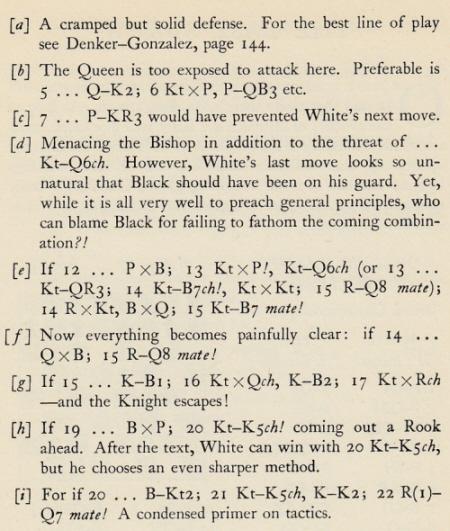

8541. S. Rubinstein v H.M. Phillips

Wanted: information about a game published by Fred Reinfeld on pages 42-43 of Relax with Chess (New York, 1948):

1 e4 e5 2 d4 exd4 3 c3 dxc3 4 Bc4 d6 5 Qb3 Qf6 6 Nxc3 c6 7 Nf3 Nd7 8 Bg5 Qg6 9 h4 h5 10 O-O-O Nc5 11 Qb4 d5 12 Bxd5 Nd3+ 13 Rxd3 Bxb4 14 Bxf7+ Kxf7 15 Ne5+ Ke6 16 Nxg6 Rh7 17 f4 Nf6 18 f5+ Kf7 19 Rd8 b5 20 Rhd1 Resigns.

We have seen the game in a database with a different move-order (1 e4 e5 2 d4 exd4 3 c3 dxc3 4 Nxc3 d6 5 Qb3 c6 6 Bc4 Qf6).

8542. Riley v Russ (C.N. 8534)

From John Saunders (Kingston-upon-Thames, England):

‘In C.N. 8534 you requested full names for Messrs Riley and Russ.

Douglas Eric Arnold Riley

Born 11 May 1912 (Croydon, Surrey)

Died circa June 1978 (Chiltern and Beaconsfield).Sources for the above: Ancestry.com (BMD) and 1930s electoral register records.

Riley was the 1954 Ulster Champion, and a photograph of him is available on-line. He seems to have been resident in the Brixton and Kennington area in the 1930s.

Victor John Anthony Russ

Born 2 January 1905 (Brentford, Middlesex)

Died 6 May 1985 (Yorkshire).Sources for the above: Ancestry.com (BMD/Census) and a Russ family website. Photographs of V.J.A. Russ are also available on-line.

Russ seems to have lived in Harrogate, Yorkshire from about 1964; telephone directories indicate that he was previously resident in Formby, Lancashire. The obituary in the BCM (August 1985, page 345) states:

“Another former Lancashire Champion V.J.A. Russ died recently at the age of 80. He was associated with the Leicester club in the post-War period when they were so formidable a side in the National Club Championship and had retired to Harrogate.”

Russ won the Leicestershire Championship in 1949 and 1950. In addition to the 1949 event, he played in the British Championship in 1952 and 1953, scoring 6/11 in 1952, and won the Lancashire Championship in 1960 (BCM, July 1960, page 198). In 1962 he represented Lancashire but by 1964 he was playing for Yorkshire in county chess.’

8543. Filipino chessplayers

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) submits a photograph of (from left to right) Renato Naranja, Rosendo Balinas and Florencio Campomanes:

Occasion/venue: Pesta Merdeka, Third Festival Championship of the Singapore Chess Federation, held at the Singapore Polytechnic on 10-20 August 1967. The photograph comes from the official tournament souvenir brochure.

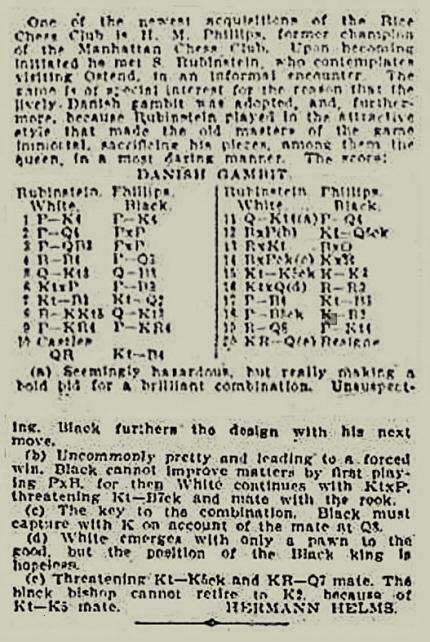

8544. S. Rubinstein v H.M. Phillips (C.N. 8541)

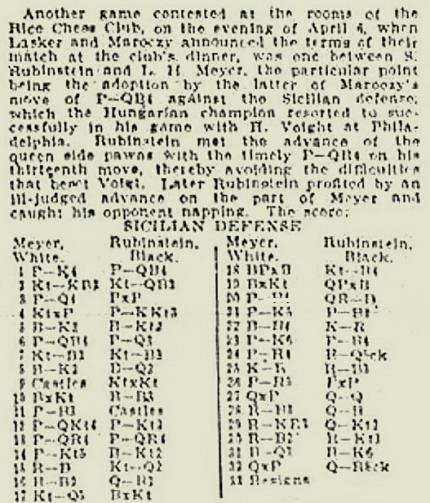

John Blackstone (Las Vegas, NV, USA) has found that the game discussed in C.N. 8541 is the second of two victories by Solomon Rubinstein published by Hermann Helms on page 9 of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 6 May 1906:

The Meyer v Rubinstein game (1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 g6 5 Be3 Bg7 6 c4 d6 7 Nc3 Nf6 8 Be2 Bd7 9 O-O Nxd4 10 Bxd4 Bc6 11 f3 O-O 12 b4 b6 13 a4 a5 14 b5 Bb7 15 Rc1 Nd7 16 Bf2 Qc7 17 Nd5 Bxd5 18 cxd5 Nc5 19 Bxc5 dxc5 20 f4 Rac8 21 e5 f6 22 Bc4 Kh8 23 e6 f5 24 h4 Bd4+ 25 Kh1 Rf6 26 h5 gxh5 27 Qxh5 Qd8 28 Rf3 Qf8 29 Rh3 Qg7 30 Rc2 Rg6 31 Bd3 Be3 32 Qxf5 Qa1+ 33 White resigns) is of relevance to the discussion on the origins of the Maróczy Bind on pages 147-148 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves.

8545. The Maróczy Bind

Further to C.N. 8544, Mr Blackstone sends the Maróczy v Voigt exhibition game mentioned by the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, from the supplement section of the Los Angeles Herald, 29 April 1906:

Géza Maróczy – Hermann G. Voigt

Philadelphia, 1906

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 c5 2 d4 cxd4 3 Nf3 g6 4 Nxd4 Bg7 5 c4 Nf6 6 Nc3 d6 7 Be2 O-O 8 Be3 Bd7 9 O-O Nc6 10 h3 Nxd4 11 Bxd4 Bc6 12 Bf3 Re8 13 b4 b6 14 a4 Rc8 15 a5 Qc7 16 axb6 axb6 17 Ra6 Nd7 18 Bxg7 Kxg7 19 Qa1 Ne5 20 Ra7 Qd8 21 Be2 Bd7 22 Nd5 Kg8 23 Rc1 e6 24 Ne3 h5 25 b5 Qh4 26 Rd1 Qf4 27 g3 Qh6 28 Rxd6 Resigns.

We add that brief notes by Maróczy were published on page 76 of the April 1906 American Chess Bulletin. After 5 c4 he wrote:

‘This continuation has been emphatically recommended by me. P-Q4 is no longer possible to Black and he obtains a cramped game.’

8546. One harmonious whole

From pages 138-139 of the February 1923 Chess Amateur, at the end of the well-known simultaneous game Capablanca v Santasiere, New York, 1922:

‘A game which the chessplayer will no doubt read, mark, learn and inwardly digest. White’s moves make one harmonious whole, and there is not a jarring note.’

This is reminiscent of a remark by David Hooper and Dale Brandreth about Capablanca v Germann, Miller and Skillicorn, London, 1920 on page 93 of The Unknown Capablanca (London, 1975):

‘This is one of those “inevitable” games so typical of Capablanca’s style: he seems to win without his opponent’s having made any perceptible error; he achieves an illusion of continuity, whereas it is self-evident that chess is a series of separate steps.’

8547. Felixstowe, 1949 (C.N.s 8534 & 8542)

From page 3 of the October 1949 CHESS:

The key is an errata slip inserted by the magazine over the list originally printed.

8548. My System

The conclusion of a review of Nimzowitsch’s My System contributed by T.R. Dawson on pages 29-30 of the November 1929 Chess Amateur:

‘The book is got up in Bell’s usual good style and is free from any great number of obvious errors. The translator shows an ignorance of many well-known technical terms, but that may even be an advantage for the average British player.’

8549. Harold Meyer Phillips (C.N.s 8541 & 8544)

From page 227 of the November 1906 American Chess Bulletin:

8550. Advice from Emanuel Lasker

Below is a brief extract from an article ‘Some Chess Celebrities Whom I Have Met’ by Rhoda A. Bowles on pages 23-27 of The Year-Book of Chess, 1907 by E.A. Michell (London, 1907):

‘Dr Lasker has also helped me considerably, and I well remember the first, and lasting, advice he gave me: “Attack always, and go on attacking. Never mind if you lose a game or two, you will benefit by these losses. Set yourself to learn a lesson from each, so that you may not lose in the same way again, and by degrees you will become stronger, and your attacking tactics will assist you greatly.”’

For Rhoda A. Bowles’s reminiscences of Steinitz, see Steinitz v von Bardeleben.

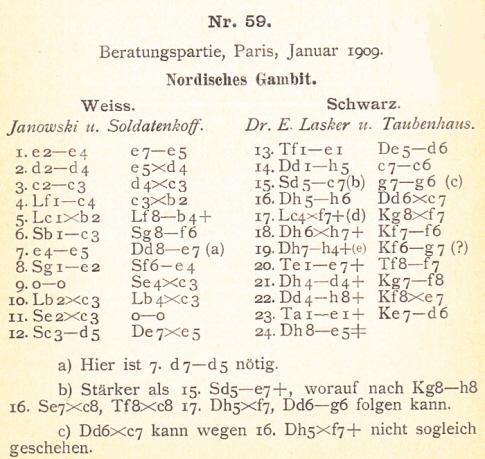

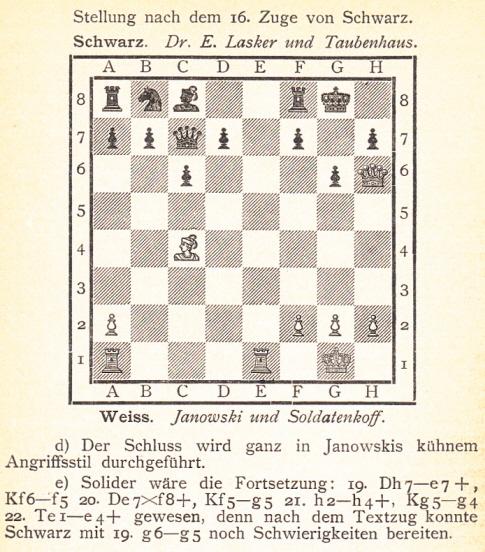

8551. An old

mystery

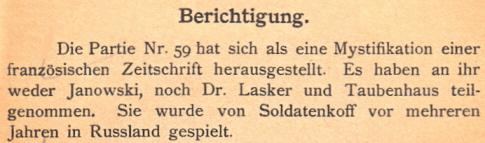

An addition concerning that notably complex mystery, The Consultation Game That Never Was:

Source: Schachjahrbuch für 1909 by Ludwig Bachmann (Ansbach, 1909), pages 79-80. A correction on page 215 stated that the game did not involve Janowsky, Lasker and Taubenhaus:

Most of the research into this game which has been presented so far was undertaken before newspapers and other publications became available on-line. Can readers find further particulars now?

8552. An alleged Morphy episode

Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA) forwards a report published on page 11 of Der deutsche Correspondent (Baltimore), 16 August 1884 which had previously appeared in Bahn Frei:

Mr Spinrad comments:

‘This report confirms that the Bennecke who played Morphy at the Union Club was H. Bennecke, who was later the chess editor of Bahn Frei, and not his brother L. Bennecke, who was also a club member and later a minor problem composer. It is also the only instance I know of where an opponent claimed that Morphy did anything distracting during play.’

Our correspondent seeks clarification of the meaning of Morphy’s alleged remark about taking the queen, as quoted in the report. It is indeed obscure, to say the least, and we should like to find the original report in Bahn Frei before embarking upon any detailed discussion of the episode.

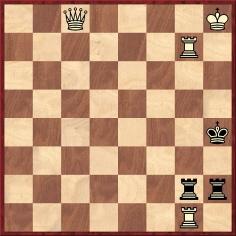

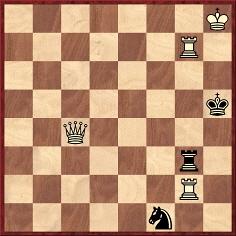

8553. Hassberg problem

Mate in two

Page 69 of The Personality of Chess by I.A. Horowitz and P.L. Rothenberg (New York, 1963) labelled this problem a ‘masterpiece’, and page 118 commented: ‘In all respects, this pawnless wonder is one of the great achievements in problem composition.’ The May-June 1945 American Chess Bulletin, page 74, described it as ‘the most economical rendering possible to make of the American Indian theme’.

The problem, by Eric M. Hassberg, first appeared in H.R. Bigelow’s chess column on page 15 of the New York Post, 21 April 1945, with this introduction:

‘Dedicated to the memory of our late President Franklin Delano Roosevelt. The composer, originally a native of Vienna, had just received the glad tidings of the liberation of his home town, but his joy was turned to sadness when the President’s sudden passing was announced a few moments later.’

It was also the first problem in Hassberg Ingenuity by Edgar Holladay (Rockford, 1978). From our copy:

8554. Eugène Chatard (C.N. 8470)

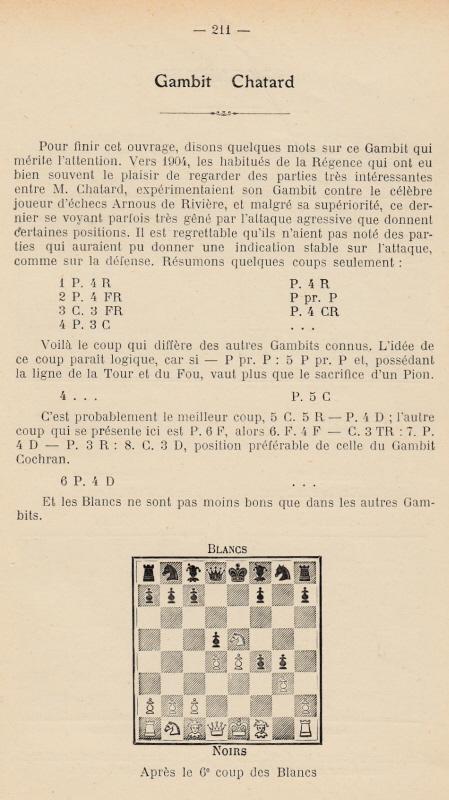

Page 211 of Traité du jeu des échecs by Jean Taubenhaus (Paris, 1910):

Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) sends five games which illustrate Eugène Chatard’s play and, in particular, his liking for unusual openings:

Samuel Rosenthal – Eugène Chatard

Simultaneous display (30 boards), Paris, 19 February

1887

Centre Counter Game

1 e4 d5 2 exd5 c6 (Rosenthal: ‘Le sacrifice du pion est dangereux, cependant M. Chatard inventeur de cette variante du contre Gambit du Centre l’a pratiquée avec succès contre de forts amateurs. En tout cas il a eu raison de la jouer contre nous, car il complique la position et nous ne pouvions rester plus d’une minute pour réfléchir.’) 3 dxc6 e5 4 Nc3 Bc5 5 Nf3 Nxc6 6 Bc4 Nf6 7 d3 O-O 8 O-O Bg4 9 Be3 Nd4 10 Bxd4 exd4 11 Ne4 Rc8 12 Ng3 Nd5 13 h3 Be6 14 Ne4 Bb6 15 Nfg5 h6 16 Nxe6 fxe6 17 Qg4 Qd7 18 Rae1 Kh8 19 Ng3 Rce8 20 Nh5 Re7 21 Bxd5 Qxd5 22 Nf4 Rxf4 23 Qxf4 Bc5 24 a3 e5 25 Qf5 Bd6 26 Re4 Rf7 27 Qg6 Rf6 28 Qe8+ Kh7 29 Rfe1 Re6 30 Qh5 g6 31 Qf3 Kg7 32 Qg4 h5

33 Rxd4 hxg4 34 Rxd5 gxh3 35 gxh3 Kf7 36 Kg2 Kf6 37 Re4 g5 38 d4 and Black resigned about ten moves later.

Sources, with comments by Rosenthal: Le Monde

Illustré, 5 March 1887 and La Stratégie, 15

April 1887, pages 118-119.

Eugène Chatard and Edouard Pape – Lemarchand and L.

Maurat

Paris, 12 April 1902

French Defence

1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 Be7 5 e5 Nfd7 6 h4 c5 7 Nb5 f6

8 Bh6 Qa5+ 9 b4 cxb4 10 Bxg7 b3+ 11 Qd2 b2 12 Rb1 Qxd2+ 13 Kxd2 Rg8 14 Nc7+ Kf7 15 exf6 Bd6 16 Nxa8 Nc6 17 Nf3 Nxf6 18 Bxf6 Kxf6 19 Rxb2 e5 20 dxe5+ Nxe5 21 Nxe5 Bxe5 22 Rb3 Bf5 23 Rxb7 Bf4+ 24 Kd1 Rc8

25 Bd3 Bxd3 26 cxd3 Rc1+ 27 Ke2 Rxh1 28 Rxa7 Ra1 29 Nb6 Ke6 30 Ra6 d4 31 Nc4+ Kd5 32 Ra5+ Ke6 33 g3 Bb8 34 a3 Rb1 35 Ra6+ Kf5 36 Rb6 Rxb6 37 Nxb6 Kg4 38 a4 Kf5 39 Kf3 h5 40 a5 Bc7 41 Nc4 Bb8 42 a6 Resigns.

Source: with comments by Taubenhaus: La Stratégie, 20 June 1902, pages 182-183. A briefer set of notes by Taubenhaus was reproduced in Les Cahiers de L’Echiquier Français, issue 37 (September-October 1933), pages 152-153.

Mr Thimognier adds a remark by Arnous de Rivière about the 6 h4 gambit in L’Echo de Paris, 15 July 1901: ‘... il se présente un coup nouveau P4TR, imaginé récemment par M. Chatard; coup plus ingénieux que correct, amenant des positions intéressantes ...’

Eugène Chatard – William Ewart Napier

Paris, 4 July 1902

Bird’s Opening

1 f4 e5 2 d4 exd4 3 Qxd4 Nc6 4 Qd1 Nf6 5 Nc3 d5 6 e3 Bc5 7 Na4 Bb4+ 8 c3 Bd6 9 Bb5 O-O 10 b3 Ne7 11 Be2 Bd7 12 Nb2 Ne4 13 Qc2 Nf5 14 Nf3 Bc5 15 Nd1 Qe7 16 Bd3 Rad8 17 O-O Rfe8 18 Bxe4 dxe4 19 Nd4 Nh4 20 Qf2 Bd6 21 Bb2 c5 22 Ne2 c4 23 Nd4 Rc8 24 b4 Nf5 25 a3 b5 26 Qd2 Nh6 27 Nf2 f5 28 Rad1 Nf7 29 h3 g5 30 g3 gxf4 31 gxf4 Kh8 32 Kh1 Rg8 33 Rg1 Qf6 34 Ne2 Rcd8 35 Qd4 Qxd4 36 cxd4 h6 37 d5+ Kh7 38 Ng3 Be7 39 Nh5 Bc8 40 Bf6 Rxg1+ 41 Rxg1 Bxf6 42 Nxf6+ Kh8 43 Nd1 Bb7 44 Nc3 a6 45 h4 Rf8

46 Rg6 Rd8 47 Kg1 Ba8 48 Kf2 Bb7 49 Ke1 Ba8 50 Kd1 Bb7 51 Kc1 Ba8 52 Kb2 Bb7 53 a4 Ba8 54 axb5 axb5 55 Nxb5 Bxd5 56 Nd4 Bb7 57 Nxf5 Bc8 58 Nd4 Nd6 59 Nc6 Rf8 60 Nd7 Bxd7 61 Rxh6+ Kg7 62 Rxd6 Bc8 63 b5 Rh8 64 Rd8 Rxd8 65 Nxd8 Kh6 66 b6 Kh5 67 b7 Bxb7 68 Nxb7 Resigns.

Source: L’Echo de Paris, 8 September 1902.

Another game between the two players, won by Napier with the Queen’s Gambit Declined, is given on pages 156-157 of Napier The Forgotten Chessmaster by John S. Hilbert (Yorklyn, 1997).

Eugène Chatard and Henri Delaire – Arnous de

Rivière

Paris, 1903

King’s Gambit Accepted (Chatard Gambit)

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 g3 d5 5 Qe2 Be7 6 Ne5 Nc6 7 Qb5 Qd6 8 d4 a6 9 Qa4 Nf6 10 Nxc6 Bd7

11 Bb5 Bxc6 12 Bxc6+ bxc6 13 e5 Qe6 14 Nc3 O-O 15 Bd2 Nh5 16 Ne2 c5 17 O-O cxd4 18 Nxd4 Qb6 19 Ba5 Qg6 20 g4 Ng7 21 h3 Rfb8 22 Rae1 Bc5 23 Bc3 Ne6 24 Kg2 Bxd4 25 Bxd4 c5 26 Bg1 Rxb2 27 Re2 d4 28 Qc6 Rd8 29 Qf3 Rxa2 30 Rff2

30...c4 31 h4 d3 32 cxd3 Rxe2 33 Qxe2 Rxd3 34 Bh2 Nd4 35 h5 Qc6+ 36 White resigns.

Source: L’Echo de Paris, 28 September 1903.

Eugène Chatard – Wladimir Bienstock

Paris (Championnat de l’Union Amicale des Amateurs de la

Régence), 27 October 1917

Blackmar Gambit

1 d4 d5 2 e4 (Taubenhaus: ‘Imaginé en 1884 par l’américain A.E. Blackmar, de la Nouvelle-Orléans, ce coup a pour but, si P pr PR, de sacrifier un second pion par 3 P.3FR et d’en retirer un développement rapide.’) 2 ...dxe4 3 c4 (‘Cette continuation nouvelle appartient à M. Chatard qui la traite plaisamment de gambit du centre-gauche; elle semble correcte puisque les Blancs se développent plus aisément qu’avec la suite de Blackmar P.3FR.’) 3...e6 4 Nc3 f5 5 Nge2 Nf6 6 Be3 Bb4 7 Qa4+ Nc6

8 d5 exd5 9 O-O-O O-O 10 Nxd5 Bd6 11 c5 Nxd5 12 Rxd5 Be6 13 Rd1 Rc8 14 cxd6 cxd6 15 Kb1 a6 16 Nf4 Bf7 17 Bc4 b5 18 Bxf7+ Rxf7 19 Qb3 Na5 20 Qe6 Nc4 21 Bc1 Rb8 22 b3 Qa5 23 Nd5 Kf8 24 Bb2 Nd2+ 25 Rxd2 Resigns.

Source, with comments by Taubenhaus: La Stratégie, November 1917, pages 322-323. Only the first two notes are given above.

8555. 6 h4 in the French Defence

Further to the consultation game given in C.N. 8554 which involved Eugène Chatard and began 1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 Be7 5 e5 Nfd7 6 h4, we offer some historical notes on this opening, which was first mentioned in C.N. 345.

The most famous occurrence is in Alekhine v Fahrni, Mannheim, 1914, which is game 31 in Alekhine’s first volume of Best Games. He awarded 6 h4 an exclamation mark and commented:

‘This energetic move has been especially played in off-hand games by the ingenious Paris amateur, M. Eugène Chatard, and previously by the Viennese master, A. Albin.

It was during the present game that it was introduced for the first time in a Master Tournament.’

Alekhine’s note in Deux cents parties d’échecs (Rouen, 1936) was different:

‘Ce coup énergétique a été essayé depuis de longues années dans de nombreuses parties légères par l’amateur français Chatard. Le maître viennois A. Albin l’a aussi adopté dans deux parties vers 1900. Mais c’est dans la partie ci-jointe que le coup 6 h2-h4 a obtenu sa consécration internationale.’

It is unclear why Alekhine referred to two games played by Albin circa 1900, but Albin’s 89-move draw against Adolf Csánk at Vienna, 1890 is familiar nowadays and remains the earliest known example of 6 h4. After that move Warren H. Goldman wrote on page 89 of Vienna 1890 (Bamberg, 1983):

‘Familiar to present day players as the Alekhine-Chatard (Albin) Attack – but unknown as a separate and distinct variation in 1890!’

The game between Albin and Csánk, played in January 1890, was published on pages 95-97 of Deutsches Wochenschach, 16 March 1890 with notes by Caro and Csánk, but it was not the opening’s only appearance in the German magazine that year. Pages 395-396 of the 23 November 1890 issue had the following match-game, with notes by the winner:

Jakob Bendiner – Ignatz von Popiel

Vienna (Neue Wiener Schachklub), 4 February 1890

French Defence

1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 Be7 5 e5 Nfd7 6 h4 h6 7 Qh5 c5 8 Nb5 Qa5+ 9 Bd2 Qb6 10 Qg4 g6 11 h5 g5 12 a4 cxd4 13 Nf3 Nc6 14 a5 Qd8 15 Qg3 a6 16 Nbxd4 Ndxe5 17 Nxc6 Nxc6 18 Bc3

18...Bd6 19 Qg4 e5 20 Qa4 d4 21 Bd2 Bd7 22 Qb3 e4 23 Ng1 Qc7 24 Nh3 g4 25 Ng1 g3 26 f3 e3 27 Bxe3 dxe3 28 Qxe3+ Be6 29 Bc4 O-O-O 30 Bxe6+ fxe6 31 Ne2 Bb4+ 32 c3 Bxa5 33 Rh4 Bb6 34 Qxe6+ Kb8 35 Re4 Bf2+ 36 Kf1 Rd2 37 c4 Rhd8 38 Nc3 Nd4 39 b4 Nxe6 40 White resigns.

In the game heading, and elsewhere in the magazine although not in the index, White was identified as ‘S. Bendiner’.

Bendiner’s use of the move has seldom been noted, but even Albin’s involvement has often been overlooked, an example being on page 70 of Jacques Mieses’ Ergänzungsheft to the Handbuch des Schachspiels (Berlin and Leipzig, 1923), which had this note about 6 h4:

‘Von dem Franzosen Chatard stammend und von Aljechin in die Turnierpraxis eingeführt (Mannheim 1914).’

Later openings manuals often mentioned Albin, although not always accurately. Below is the first paragraph of the section on the ‘Albin-Chatard-Alekhine Attack’ on page 292 of Chess Openings Theory and Practice by I.A. Horowitz (New York, 1964):

‘This interesting continuation was first tested in the game Albin-Csank, Vienna 1897. Later, the move was investigated by the Parisian, Chatard, but it gained popularity only after Alekhine’s repeated adoption. Today this line is as important as the Classical Variation, but the struggle becomes more pitted.’

With regard to ‘repeated adoption’ by Alekhine, after 1914 he played 6 h4 in a number of simultaneous displays; in the Skinner/Verhoeven book see games 1361, 1367, 1848, 1859 and 1861. Moreover, Alekhine faced the move against Bogoljubow in a tournament game in Warsaw in 1942, and the following note appeared on page 264 of his posthumous book Gran Ajedrez (Madrid, 1947):

‘Este interesante ataque fué introducido por mí en Manerheim [sic] en 1914, habiendo sido desde entonces incorporada [sic] a la práctica de maestros.’

The Alekhine v Fahrni game was given on pages 395-396 of the November 1914 issue of La Stratégie with notes from the Tijdschrift van den Nederlandschen Schaakbond. The Dutch magazine’s remark that 6 h4 was an innovation of doubtful value prompted La Stratégie to add an editorial note:

‘Pardon, cher Monsieur Schelfhout, la valeur douteuse n’est nullement établie, le coup est une des nombreuses innovations de notre vieil ami M. E. Chatard, qui sera certainement très sensible à l’hommage que le maître Alekhine a fait à sa sagacité en choisissant cette variante qu’il a connue lors de son séjour à Paris, à l’Echiquier (Continental).’

The final words refer to a société parisienne established at the Hôtel Continental in 1913. It was the venue for the first match-game between Alekhine and Edward (then Eduard) Lasker on 6 September 1913; see La Stratégie, April 1913, page 149; September 1913, page 360; October 1913, pages 404-405.

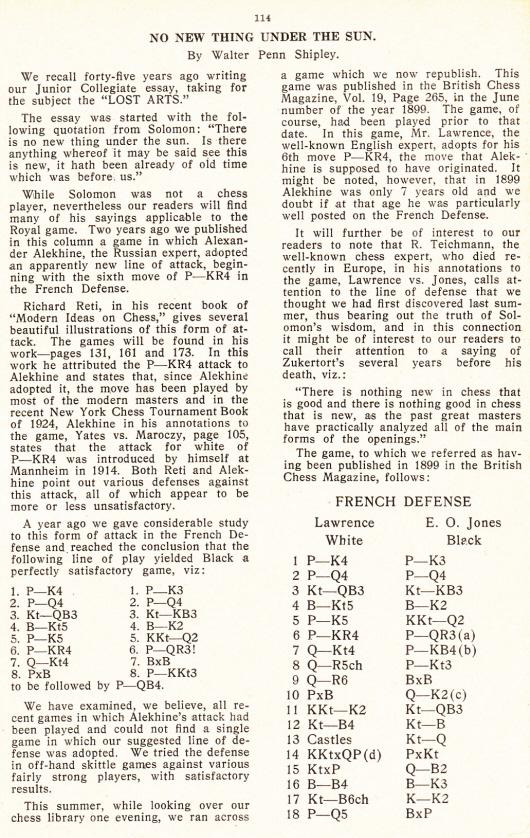

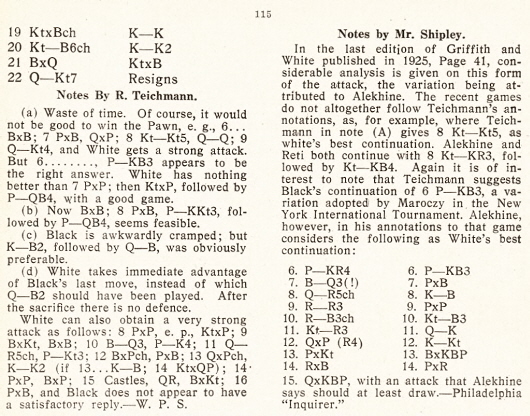

Between Albin’s use of 6 h4 in 1890 and the Alekhine v Fahrni game nearly a quarter of a century later, the move was seen occasionally. A game won by Mrs Fagan against Richmond, in the C division of the London Chess League Competition, was published on page 290 of the August 1897 BCM, White’s sixth move being described as ‘altogether unsound, but leads to a lively game’. The June 1899 BCM, page 265 had a game between T.F. Lawrence and E.O. Jones, annotated by Richard Teichmann, with no occasion specified. (See the feature below written by Walter Penn Shipley.) Pages 222-223 of the May 1909 BCM gave the bare score of Lawrence’s draw with J.F. Barry in the Anglo-American Cable Match. The following year Emanuel Lasker won a game in Buenos Aires against E. Zamudio; for the score, taken from page 78 of the Revista del Club Argentino de Ajedrez, 1910, see the 1976 and 1998 collections of Lasker’s games by K. Whyld.

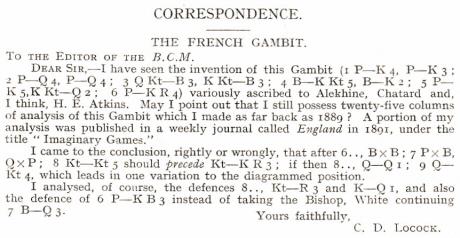

Magazines were often confused as to the origins of 6 h4. For example, in his notes to a team-match game between W.H. Watts and D. Miller on pages 325-326 of the September 1915 BCM, R.C. Griffith wrote that 6 h4 was ‘introduced by Mr T.F. Lawrence’. In its January 1924 issue, page 18, the BCM published a letter from C.D. Locock containing statements on which we should welcome further information:

The next item, the Walter Penn Shipley feature referred to earlier, comes from pages 114-115 of the July-August 1925 American Chess Bulletin:

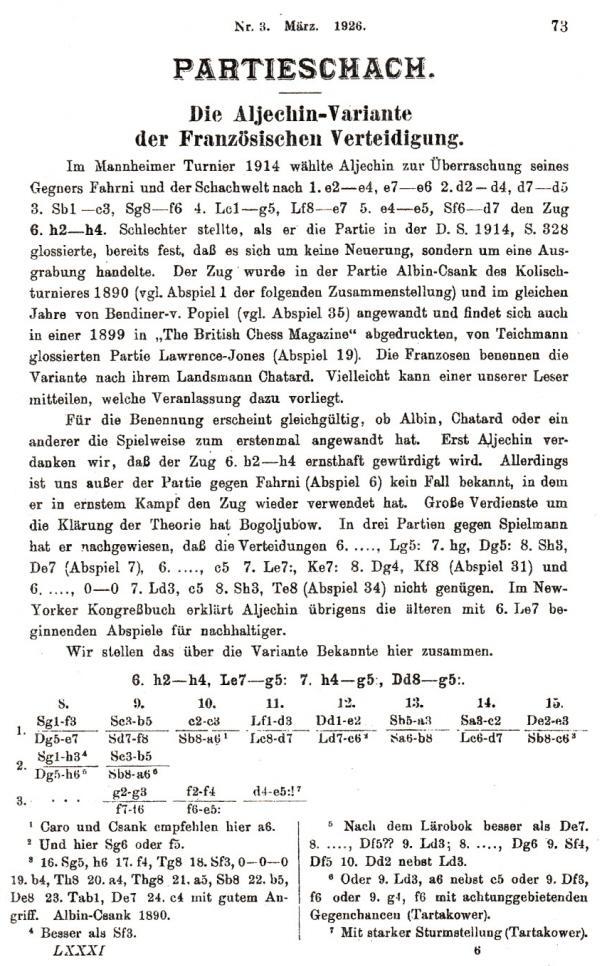

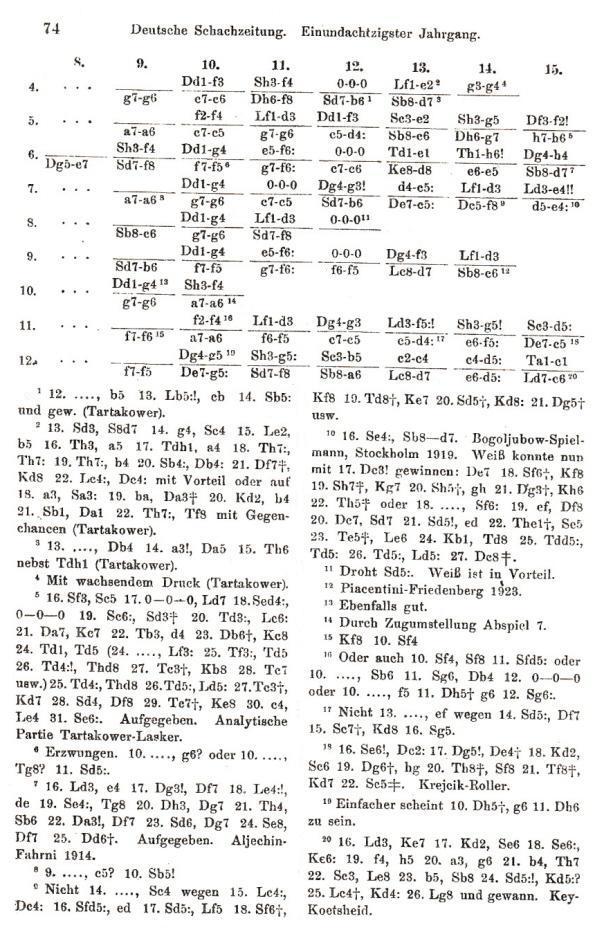

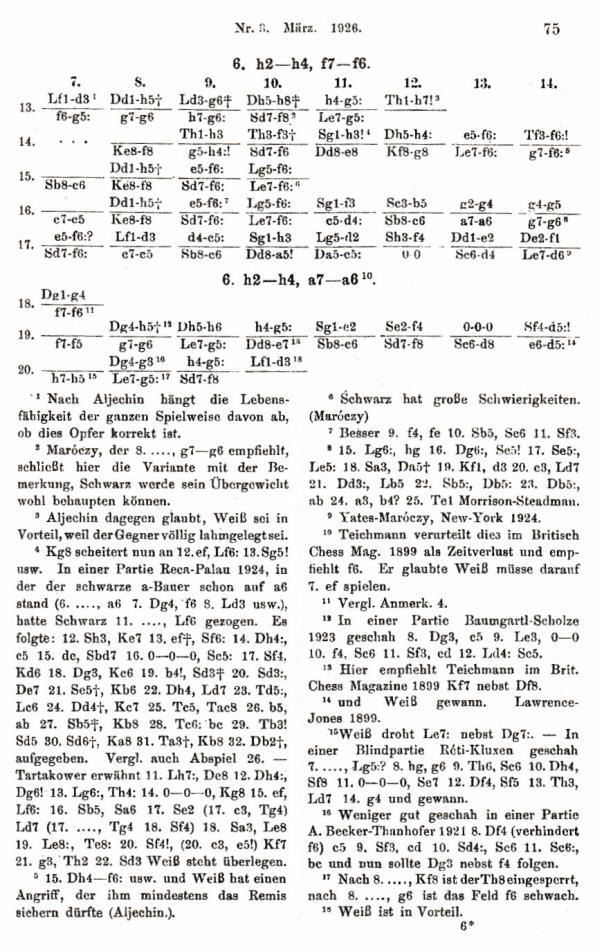

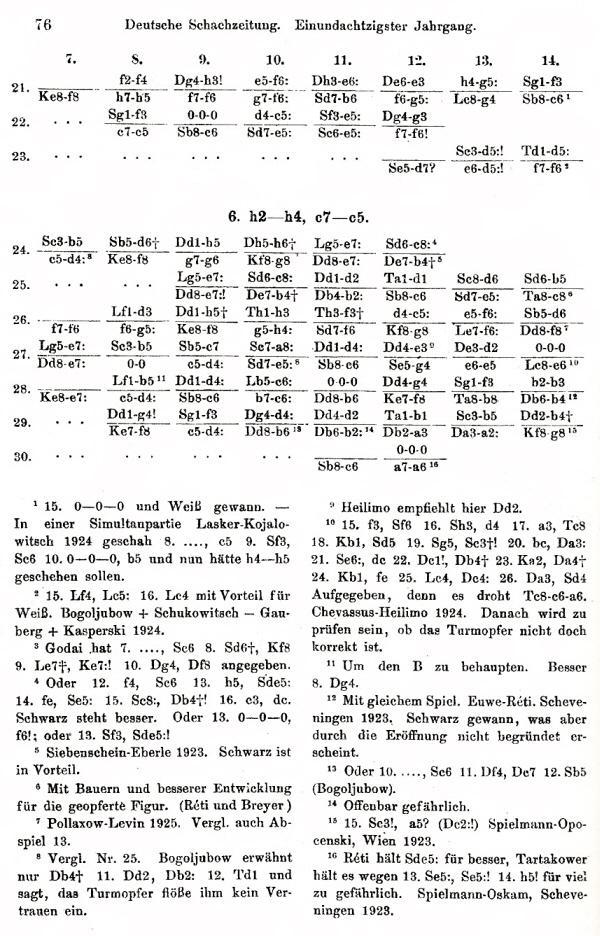

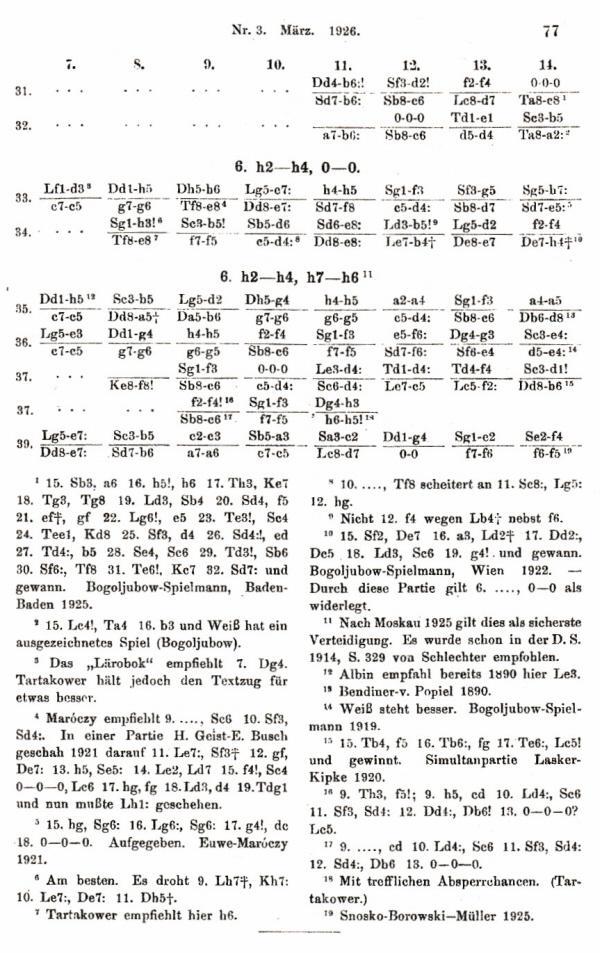

A detailed analytical article, ‘Die Aljechin-Variante der Französischen Verteidigung’, was published on pages 73-77 of the March 1926 Deutsche Schachzeitung:

The German magazine’s analysis was summarized on pages 265-266 of La Stratégie, December 1926, but with a change of title: ‘De la Variante Chatard dans la Partie Française’.

The opening also received attention in the Arbeiter-Schachzeitung, January 1928, pages 13-14 and 20-21. See too pages 330-332 of Tarrasch’s Schachzeitung, 1 August 1933 and pages 479-482 of the Social Chess Quarterly, January 1935. The latter item is an article on 6 h4 by Vera Menchik entitled ‘How to Meet an Attack’. Page 497 of the October 1937 BCM had a brief note on the ‘Albin-Chatard Attack’ by G. Levenfish, from Shakhmaty v SSSR.

There was a detailed series of articles entitled ‘The Alekhine-Chatard Attack in the French Defense’ by S. Belavenets and M. Yudovich, translated from 64, in Chess Review, January 1938 (pages 20-21), February 1938 (pages 46-47), March 1938 (page 78) and August 1938 (pages 194-195). Pages 84-86 of the April 1939 Chess Review had further material on the opening, translated from Shakhmaty v SSSR and focussing on the reply 6...f6.

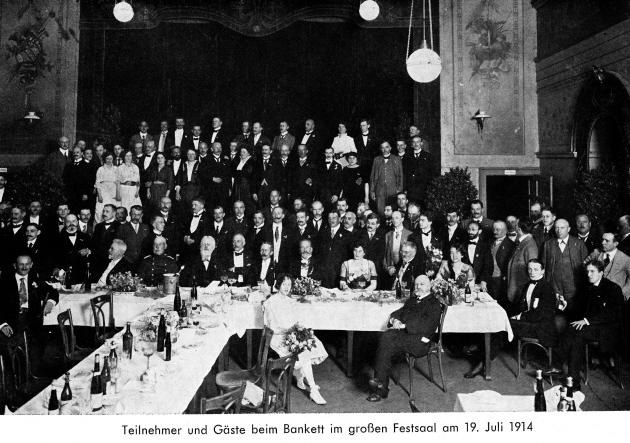

8556. Mannheim, 1914

A photograph from opposite page 16 of Mannheim 1914 by Werner Lauterbach (Kempten/Allgäu and Düsseldorf, 1964):

One of the few figures easily identified is the world champion.

8557. An old mystery (C.N. 8551)

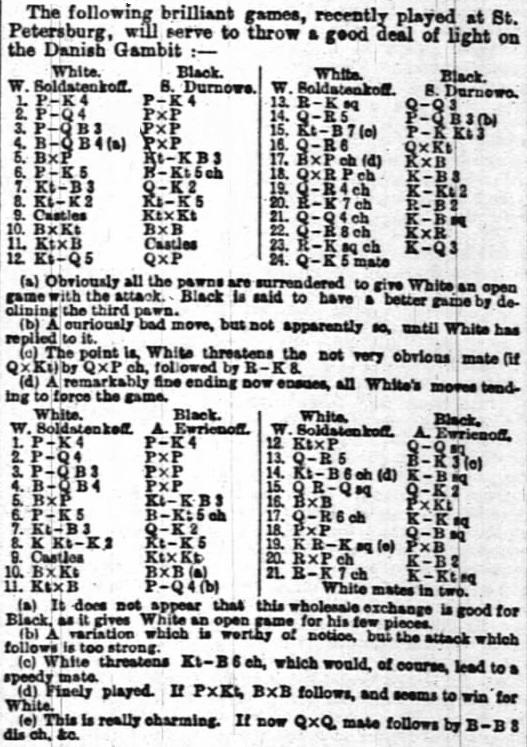

Patsy A. D’Eramo (North East, MD, USA) submits the chess column in The Times (London), 21 February 1898, page 14, which includes a pair of games:

The second game (Soldatenkov v ‘Ewrienoff’) is also intriguing:

1 e4 e5 2 d4 exd4 3 c3 dxc3 4 Bc4 cxb2 5 Bxb2 Nf6 6 e5 Bb4+ 7 Nc3 Qe7 8 Ne2 Ne4 9 O-O Nxc3 10 Bxc3 Bxc3 11 Nxc3 d5 12 Nxd5 Qd8 13 Qh5 Be6

14 Nf6+ Kf8 15 Rad1 Qe7 16 Bxe6 gxf6 17 Qh6+ Ke8 18 exf6 Qf8

19 Rfe1 fxe6 20 Rxe6+ Kf7 21 Re7+ Kg8 and White mates in two.

8558. More on Soldatenkov v Durnovo

Further material received from Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) and Vitaliy Yurchenko (Uhta, Komi, Russian Federation) has been added direct to The Consultation Game That Never Was.

8559. Stories

‘Curious, but true chess stories’ are promised on the front cover of Fried Liver & Burning Pants by “Coach Jay” Stallings, an execrable 89-page book published in 2012. To quote from pages 19-21:

‘Chess, too, has taken its toll on the sanity of men for many years. Alekhine was a great chessplayer, but his tendency to sometimes yell and knock over the chess pieces after a loss prompted players and fans to keep their distance when Alekhine’s opponent was on verge of victory ...

... At the Carlsbad tournament in Czechoslovakia (now known as the Czech Republic) in 1923, Alekhine had worked hard, as usual, and with only two rounds remaining was comfortable in his familiar position at the top of the standings. He fully expected to stay there; after all, he had spent a lot of time carefully preparing, as he always did. And then, something for which he had not prepared happened – he lost! He had abandoned a chance for a draw and was pushing for a win when his opponent (Frederick Yates) used his queen and bishop to take advantage of Alekhine’s exposed king. Alekhine’s frustration was enormous, but, as good sportsmanship requires, he politely shook his opponent’s hand and congratulated him on his victory. Then, Alexander Alekhine calmly walked back to his hotel room and destroyed every piece of furniture in the room!’

As noted in Chess with Violence, at Carlsbad, 1923 Alekhine was defeated by Yates in round seven (of 17). He lost two other games, to Treybal in round three and to Spielmann in round 16.

Lest there be doubt, we add that it is Spielmann who dominates the front cover, and the picture also fills page 22 (headed ‘Burning Pants & a Lap Full of Soup!’, to introduce further ‘true chess stories’). Stallings uses the word ‘true’ slackly, meaning any yarn written by anyone anywhere.

8560. Euwe March

Concerning Chess and Music, Wijnand Engelkes (Zeist, the Netherlands) points out the score and text of a march written in honour of Max Euwe.

8561. Pawnence

An addition to Unusual Chess Words is pawnence. From a ‘Chess Movies’ article on page 120 of the April 1950 Chess Review:

‘The board has been rent in two. The king-side belongs to White; the queen-side is Black’s. And Black is ready to collect pawnence! The isolated pawn is doomed.’

The same text is in I.A. Horowitz’s anthologies How to Win in the Chess Openings (New York, 1951), page 111, and How to Win at Chess (New York, 1968), page 117.

8562. Hassberg problem (C.N. 8553)

Mate in two

From Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England):

‘The comments on the Hassberg composition in the book by Horowitz and Rothenberg are bizarre. Although it is a pleasant miniature, it is hardly “a masterpiece”, and strictly speaking it is slightly uneconomical. The rook at h2 is a cook-stopper, preventing solutions by captures on g2 or Rh1+. With a little rearrangement the rook can be replaced by a knight, with the flight-giving key retained:

Mate in two

8563. Oldest chess author

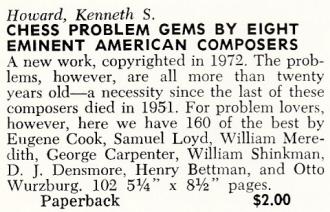

Mr McDowell also comments on an entry in Chess Records which notes that David Lawson (1886-1980) was aged 89 when his biography of Morphy was published in 1976:

‘The book Chess Problem Gems by Eight Eminent American Composers by Kenneth S. Howard (1882-1972) was published by Dover in 1972; or, to be more precise, the back cover says, “A Dover original, first published in 1973”, while an unnumbered inside page states, “Chess Problem Gems by Eight Eminent American Composers is a new work, first published by Dover Publications, Inc., in 1972”. The copyright reference on the same page gives 1972.’

We note that Howard’s book was first mentioned by Chess Life & Review on page 327 of the June 1973 issue:

8564. ‘The Immortal Blindfold Game’

On pages 273-275 of The Golden Dozen (Oxford,

1976) Irving Chernev gave the famous blindfold game

between Alekhine and N. Schwartz, London, 1926,

introduced as follows:

‘The highlight of this remarkable game, one of 15 played blindfold simultaneously, is a scintillating combination wherein Alekhine sacrifices a rook in order to queen two pawns – both of which are immediately captured.

It’s all part of the plot, though, in this impressive ending, which Alekhine himself considered one of his best achievements in blindfold chess.

The pleasing, graceful blending of profound strategy and lively tactics moves me to nominate it to occupy the niche reserved for The Immortal Blindfold Game in Caissa’s Hall of Fame.’

Chernev was mistaken in his reference to ‘one of 15 played blindfold simultaneously’. From page 79 of Blindfold Chess by Eliot Hearst and John Knott (Jefferson, 2009):

‘While in London in 1926 Alekhine played what he considered one of his “best achievements in blindfold chess”, against N. Schwartz ... He even included the game in published collections of his most memorable games [his second volume of Best Games and Auf dem Wege zur Weltmeisterschaft]. However, this game was not part of a regular simultaneous display, but was one of two blindfold games he played while meeting 26 other opponents face to face – a point not made clear in his books. Obviously, it is easier to play only two blindfold games at the same time as playing 26 other games with sight of the board, compared with playing all 28 blindfolded.’

The headings in the two above-mentioned books by Alekhine were ‘Blindfold exhibition in London, January 1926’ and ‘Aus einem Blind-Simultanspiel in London am 15. Januar 1926’. The notes in both books were essentially the same as those contributed by Alekhine on pages 314-316 of Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten, April-June 1926, where the heading was ‘Gespielt in London am 15.1.26. Weiß: Dr Aljechin (ohne Ansicht des Brettes). Schwarz: N. Schwartz’. When a translation of the notes was published on pages 179-180 of La Stratégie, August 1926 the heading was longer: ‘Jouée le 15 janvier 1926 à Londres (Gambit Chess Rooms), sans voir avec une autre, ainsi que vingt-huit [sic] parties simultanées.’

Neither the BCM nor the Chess Amateur gave the game-score in 1926, although page 164 of the March 1926 Chess Amateur published another blindfold game between Alekhine and Schwartz played 11 days later (game 930 in the Skinner/Verhoeven book on Alekhine). Page 124 of the March 1926 BCM had a brief description of the display at which the ‘Immortal Blindfold Game’ was played:

‘On the following Friday he [Alekhine] was guest of Miss Price at the Gambit Chess Rooms, Budge Row, London; and here again 28 games (two sans voir) were played, the opposition being on the strong side. The blindfold games (N. Schwarz and J.H. Kahn) were beautifully won, but two players (C.A.S. Damante [sic – Damant] and E.T. Bazell) scored wins against the master, while others secured draws.’

The spelling ‘N. Schwarz’ apppears to be an error, since other issues of the BCM referred to ‘N. Schwartz’. Is it possible to find his full name?

8565. Fischer v Dely

With regard to Fischer v Dely, Skopje, 1967 (1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 d6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Nc3 Nc6 6 Bc4 e6 7 Bb3 a6 8 f4 Qa5 9 O-O Nxd4 10 Qxd4 d5 11 Be3 Nxe4 12 Nxe4 dxe4 13 f5 Qb4 14 fxe6 Bxe6 15 Bxe6 fxe6 16 Rxf8+ Qxf8 17 Qa4+ Resigns) Irving Chernev wrote on pages 128-129 of Wonders and Curiosities of Chess (New York, 1974):

‘... Bobby Fischer brought off a brilliancy in less than five minutes against grand master Dely, who nearly lost the game on time.’

A similar remark is to be found in Bojan Kurajica’s tournament report on page 115 of CHESS, 11 December 1967:

‘In this game Fischer caught his opponent unprepared and beat him in just 17 moves. He spent perhaps five minutes while grand master Dely nearly lost on time.’

Substantiation of the time taken by both players will be welcomed.

Concerning Péter Dely, it is unclear why both sources cited above said that he was a grandmaster. We believe that at the time of the tournament he was an international master, having been awarded that title by the FIDE Congress in Stockholm in 1962; see, for instance, page 182 of the September 1962 Schweizerische Schachzeitung. Strangely, though, many sources, including Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia, state that Dely did not become an international master until 1982. Another oddity is that when Harry Golombek gave the Fischer v Dely game on page 24 of The Times, 11 November 1967 (Review section) he wrote:

‘Here is how he [Fischer] recently disposed of another technically titled grandmaster at the international tournament of Skopje.’

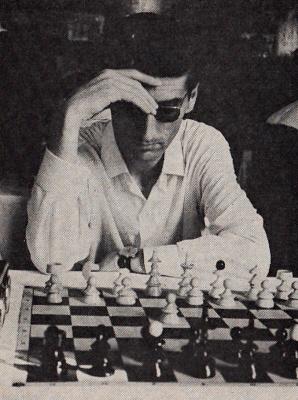

Péter Dely (Chess Review, January 1968, page 22)

8566. ‘Officially a grand master’

Chapter XI (pages 53-56) of Lessons from My Games by Reuben Fine (New York, 1958) was entitled ‘I Become a Grand Master’, and on page 53 he reiterated a claim already made on page xv: that as a result of winning Hastings, 1935-36 he ‘was officially a grand master’. What is the factual basis of that statement?

Fine also asserted on page 53 that after his first-round victory over Flohr ‘first prize was never in any doubt’. He annotated the game not only in Lessons from My Games but also on pages 3-4 of the January 1936 American Chess Bulletin and on pages 166-167 of CHESS, 14 January 1936.

8567. N. Schwartz (C.N. 8564)

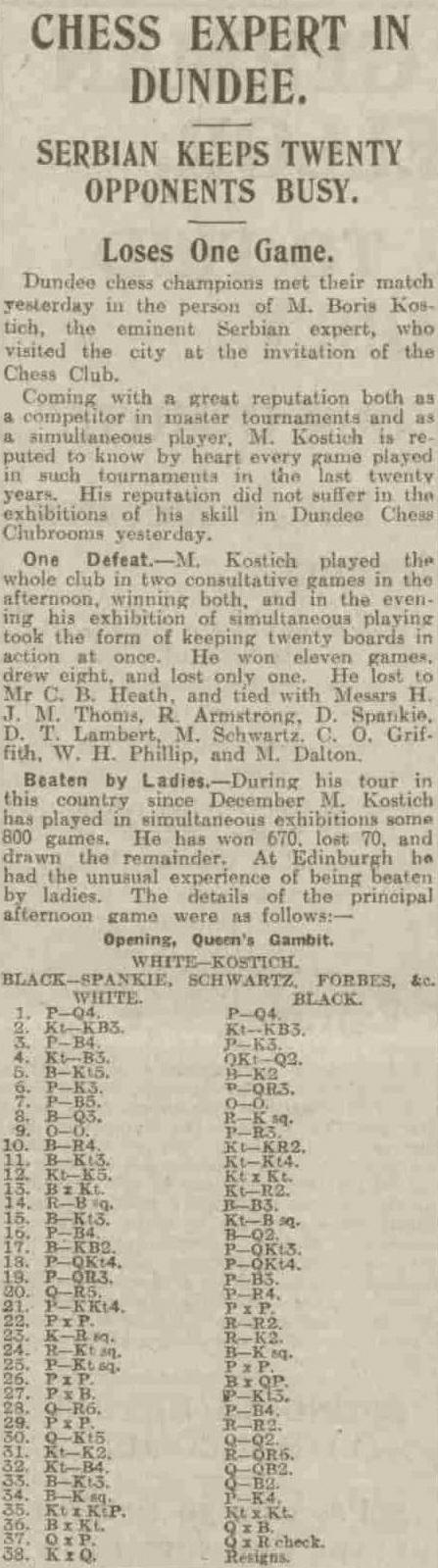

In the early 1920s the name N. Schwartz often appeared in connection with chess in Scotland. For instance, in 1922 he was one of seven participants in the Scottish championship in Perth (BCM, May 1922, pages 195-196), and other issues of the magazine (e.g. January 1922, page 22) referred to him as playing for Dundee. He was also mentioned on page 228 of the May 1922 Chess Amateur:

‘At Dundee Kostić played two consultation games, and won both, against Messrs. Heath, Thoms and Griffiths [sic – Griffith] at one board, and against Messrs. Spankie, Forbes, Schwartz, “etc.” at the other.’

The game involving Schwartz was published on page 6 of the Dundee Courier, 29 March 1922:

Boris Kostić – D. Spankie, N. Schwartz, C.S.

Forbes and others

Dundee, 28 March 1922

Queen’s Gambit Declined

1 d4 d5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 c4 e6 4 Nc3 Nbd7 5 Bg5 Be7 6 e3 a6 7 c5 O-O 8 Bd3 Re8 9 O-O h6 10 Bh4 Nh7 11 Bg3 Ng5 12 Ne5 Nxe5 13 Bxe5 Nh7 14 Rc1 Bf6 15 Bg3 Nf8 16 f4 Bd7 17 Bf2 b6 18 b4 b5 19 a3 c6 20 Qh5 a5 21 g4 axb4 22 axb4 Ra7 23 Kh1 Re7

24 Rg1 Be8 25 g5 hxg5 26 fxg5 Bxd4 27 exd4 g6 28 Qh6 f5 29 gxf6 Rh7 30 Qg5 Qd7 31 Ne2 Ra3 32 Nf4 Qc7 33 Bg3 Qf7 34 Be1 e5 35 Nxg6 Nxg6 36 Bxg6 Qxg6 37 Qxe5 Qxg1+ 38 Kxg1 Resigns.

The newspaper’s chess coverage at that time had many

references to ‘N. Schwartz’, and the initial ‘M.’ above

would appear to be an error. Although the crosstable for

the Scottish championship on page 196 of the May 1922 BCM

also had ‘M. Schwartz’, the Scottish newspaper reports

on the event that we have seen (e.g. the Dundee Courier,

19 April 1922, page 6) specify that the player was N.

Schwartz. In no newspaper has his forename been found.

8568. Kostić’s tour of the United Kingdom, 1921-22

From page 80 of the December 1921 Chess Amateur:

‘Mr Antony Guest says:

“Mr Boris Kostić, after taking a prominent part in the tournaments at Budapest and The Hague, is now visiting London, and will probably remain here most of the winter. He is desirous of giving exhibitions of blindfold and simultaneous play on terms arranged to meet the conditions of the smaller as well as the more important clubs. Communications should be sent to him at the Hampden Club, King’s Cross, NW1.”’

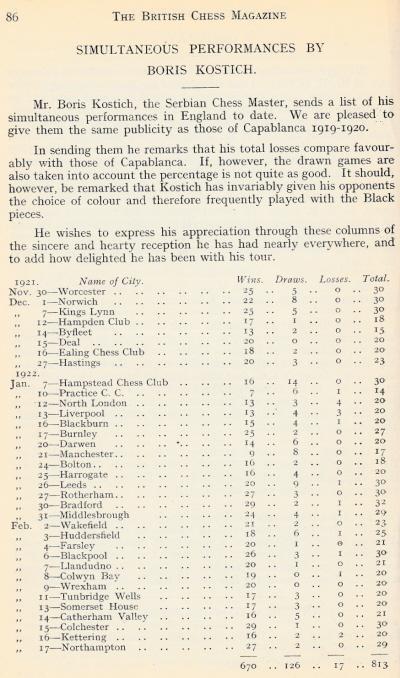

A detailed list of results in the first part of Kostić’s tour was published on page 86 of the March 1922 BCM:

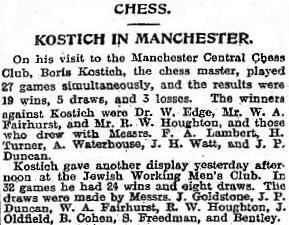

One of his simultaneous games, a draw in Manchester against the 18-year-old W.A. Fairhurst, was given on page 80 of A Chess Omnibus from pages 230-231 of the May 1922 Chess Amateur. The exact date was not available, but a brief report from page 3 of the Manchester Guardian, 20 March 1922 can be added here:

We thus tentatively propose 19 March 1922 as the date of Fairhurst’s draw.

With regard to another player mentioned in the above Manchester Guardian report, A. Waterhouse, a loss by him to Kostić in one of the displays in Manchester was published on page 314 of the July 1922 Chess Amateur:

1 d4 g6 2 e4 Bg7 3 Nf3 d5 4 e5 Bg4 5 h3 Bxf3 6 Qxf3 e6 7 Bd3 Nd7 8 O-O c5 9 c3 Rc8 10 Re1 Bh6 11 Nd2 Ne7 12 dxc5 Nxc5 13 Bb5+ Nc6

14 Nc4 dxc4 15 Bxh6 Qh4 16 Bxc6+ Rxc6 17 Bg7 Rg8 18 Bf6 Qh6 19 Rad1 Nd7 20 Qe4 Resigns.

The final move was given on page 344 of the August 1922 issue.

The Chess Amateur often had a carefree attitude to game details, and the score below was published on page 232 of the May 1922 issue with the vague heading ‘One of the six blindfold games simultaneously played by Kostić at Bradford. Kostić had White’:

1 e4 e5 2 f4 d5 3 exd5 e4 4 d3 Qxd5 5 Qe2 Nf6 6 Nc3 Bb4 7 Bd2 Bxc3 8 Bxc3 O-O 9 Bxf6 gxf6 10 dxe4 Qa5+ 11 c3 Nc6 12 Nf3 Bg4 13 Qf2 Rfe8 14 Bd3 Rad8 15 Bc2 Rd6 16 O-O Bxf3 17 gxf3 Qb6 18 Qxb6 axb6 19 Rad1 Red8 20 Rxd6 Rxd6 21 Rd1 Rxd1+ 22 Bxd1 Kg7 23 f5 Ne5 24 Be2 Nd7 25 Kf2 Nc5 26 b3 Nd7 27 Ke3 Nc5 28 Kd4 Nd7 29 b4 Kf8 30 c4 Ke7 31 f4 Kd6

32 c5+ bxc5+ 33 bxc5+ Nxc5 34 e5+ fxe5+ 35 fxe5+ Kc6 36 Bc4 Nd7 37 Bxf7 Nf8 38 Be8+ Kb6 39 e6 c5+ 40 Ke5 Kc7 41 e7 Nd7+ 42 Bxd7 Kxd7 43 Kf6 Ke8 and ‘White mates in three’.

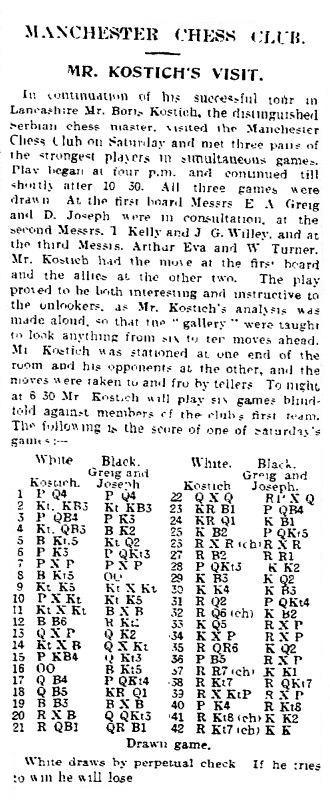

Whether a detailed check of local newspapers would provide many striking game-scores is an open question. The few games noted so far are rather ordinary draws, although page 9 of the Manchester Guardian, 23 January 1922 published a game against E.A. Greig and D. Joseph with an interesting rook ending:

1 d4 d5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 c4 e6 4 Nc3 Be7 5 Bg5 Nbd7 6 e3 b6 7 cxd5 exd5 8 Bb5 O-O 9 Ne5 Nxe5 10 dxe5 Ne4 11 Nxe4 Bxg5 12 Bc6 Rb8 13 Qxd5 Qe7 14 Nxg5 Qxg5 15 f4 Qg6 16 O-O Bg4 17 Qc4 b5 18 Qc5 Rfd8 19 Bf3 Bxf3 20 Rxf3 Qb6 21 Rc1 Rbc8 22 Qxb6 axb6 23 Rff1 c5 24 Rfd1 Kf8 25 Kf2 b4 26 Rxd8+ Rxd8

27 Rc2 Ra8 28 b3 Ke7 29 Kf3 Kd7 30 Ke4 Kc6 31 Rd2 b5 32 Rd6+ Kc7 33 Kd5 Rxa2 34 Kxc5 Rxg2 35 Ra6 Kd7 36 f5 Rxh2 37 Ra7+ Ke8 38 Rb7 Rb2 39 Rxb5 Rxb3 40 e4 Rb1 41 Rb8+ Ke7 42 Rb7+ Ke8 Drawn.

8569. Early Fairhurst games

A game between Capablanca and W.A. Fairhurst in a simultaneous exhibition at Castleton on 2 October 1922 was included on pages 120-121 of our book on the Cuban. Below are two more games played the same year by Fairhurst (who was born on 21 August 1903):

H.E. Thorne – William Albert Fairhurst

Semi-final of the Cheshire championship (exact venue

and date?)

Budapest Defence

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e5 3 Nc3 exd4 4 Qxd4 Nc6 5 Qd1 Bc5 6 e3 d6 7 Nf3 O-O 8 Bd3 Ne5 9 Nxe5 dxe5 10 Qc2 c6 11 O-O Bd6 12 b3 Re8 13 Bb2 e4 14 Nxe4 Nxe4 15 Bxe4 Qh4 16 f4 Bg4 17 Qc3 f6 18 Bf3 Bc5 19 Rae1 Bxf3 20 Rxf3 Rad8 21 Rh3

21...Rxe3 22 Rhxe3 Rd3 23 g3 Rxc3 24 gxh4 Rxe3 25 Kf1 Rf3+ 26 Kg2 Rf2+ and wins.

Source: Chess Amateur, June 1922, page 264.

R. Rydz (Manchester Jewish Chess Club) – William

Albert Fairhurst (Manchester Chess Club)

Final for the Reyner Shield (venue and date?)

French Defence

1 e4 e6 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 e5 Nd5 4 d4 b6 5 Bc4 Bb7 6 c3 Ne7 7 Bg5 h6 8 Bh4 g5 9 Bg3 Ng6 10 0–0 h5 11 h3 g4 12 hxg4 hxg4 13 Nh2 Qg5 14 Nxg4 Nf4 15 Bxf4 Qxf4 16 f3 Nc6 17 Nf6+ Kd8 18 Kf2

18...Nxe5 19 dxe5 Bc5+ 20 Ke1 Qxe5+ 21 Be2 Qxf6 22 Qc2 Rh2 23 g4

23...Bxf3 24 Rxf3 Rh1+ 25 Kd2 Qg5+ 26 Kd3 Qd5 mate.

Source: Chess Amateur, August 1922, page 324.

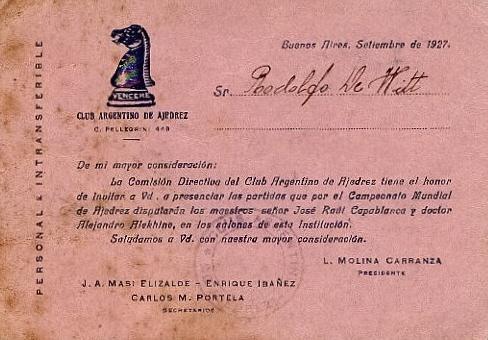

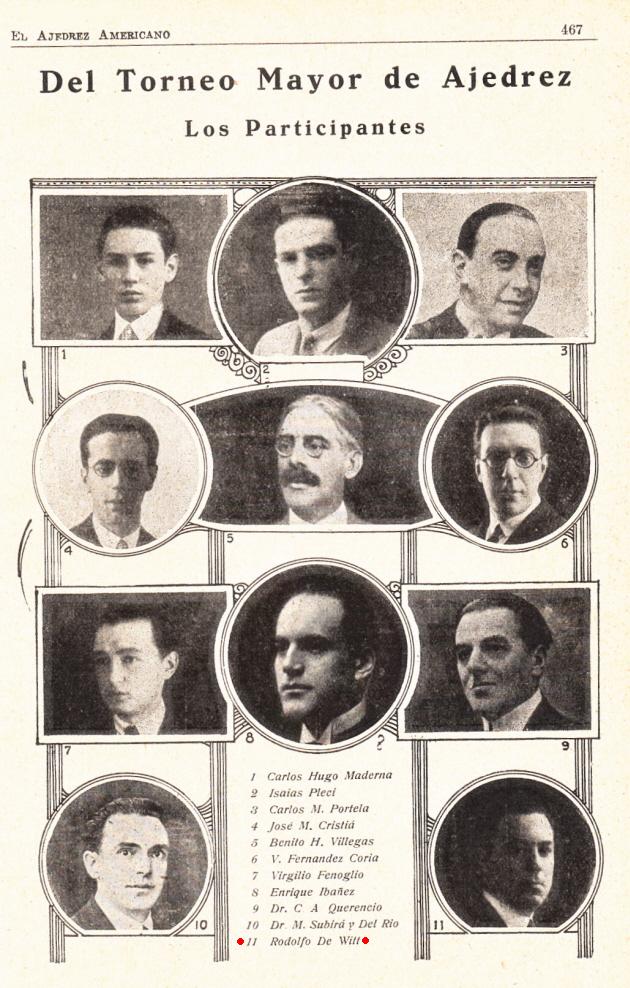

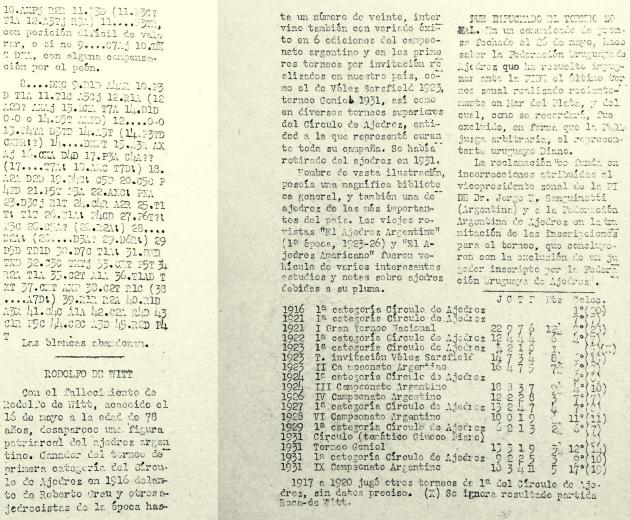

8570. Rodolfo De Witt

Having recently acquired this invitation card to the 1927 world championship match in Buenos Aires, Guy Gignac (Cap-Santé, Canada) seeks information about Rodolfo De Witt.

We have a few references on hand and shall welcome further information from readers. In the meantime, below is an illustration on page 467 of El Ajedrez Americano, December 1928:

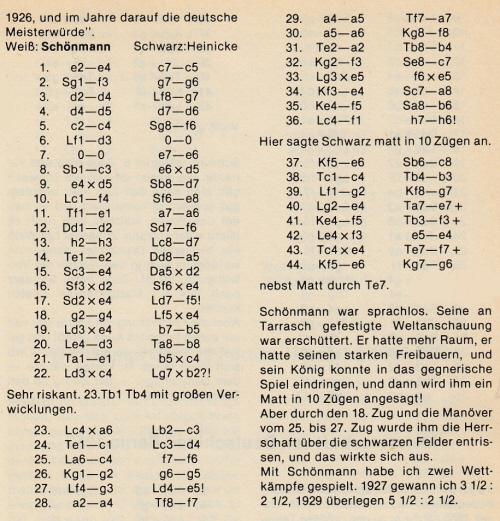

8571. Schönmann v Heinicke, Hamburg, 1952

Richard Hervert (Aberdeen, MD, USA) asks whether anything further can be found about the announcement of an alleged mate-in-ten first discussed in C.N. 1857. See page 83 of Chess Explorations, as well as pages 29-30 of A Chess Omnibus and a Chess Explorations article of ours at ChessBase.com dated 31 May 2008.

Below is the game as it appeared in our source, page 65 of Kunst des Positionsspiels by Herbert Heinicke (Hamburg, 1981):

Position before 36...h6

The latest computer check still suggests that there is no clear mate. Black wins in all lines, and 37 Kg6 offers more resistance than 37 Ke6.

8572. Goethe

Noting the discussion in C.N. 5901 about whether Goethe wrote ‘Chess is the touchstone of the intellect’, Michael Brooks (Lewes, England) asks for information about another remark frequently ascribed to Goethe:

‘Daring ideas are like chess men moved forward. They may be beaten, but they may start a winning game.’

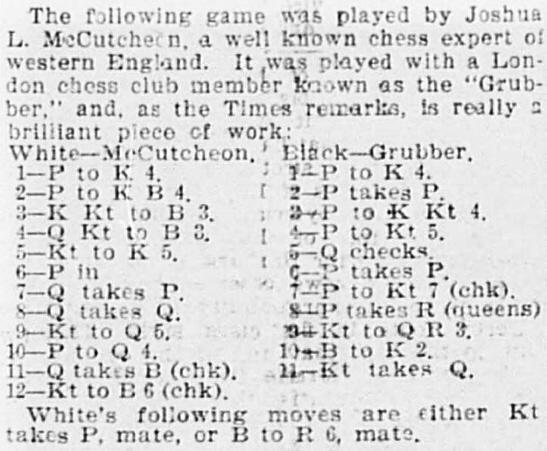

8573. A nineteenth-century skirmish

Thomas Niessen (Aachen, Germany) has found on-line four occurrences of a short nineteenth-century game:

Omaha Daily Bee, 5 December 1897, page 23 (Library of Congress)

New York Clipper, 1 January 1898, page 728 (University of Illinois)

Albany Evening Journal, 15 January 1898, page 7 (Fulton History)

Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 8 November 1900, page 14 (Brooklyn Public Library)

It has not yet been possible to trace the Times item mentioned in the first two cuttings.

In addition to noting the discrepancies over the identity of the players, the occasion, the conclusion of the game and the question of whether odds were given, our correspondent remarks that such a game (I.O. Howard Taylor v N.N., 15 August 1874) had been published on page 155 of the Dubuque Chess Journal, March 1875 and on pages 57-58 of Taylor’s Chess Skirmishes (Norwich, 1889). The book included information about a similar game played by Bird which appeared in Wit and Wisdom, 5 January 1889 (a copy of which is sought).

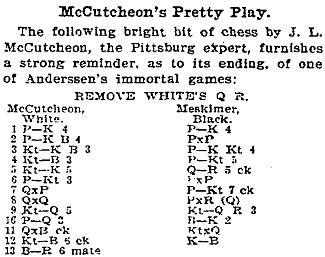

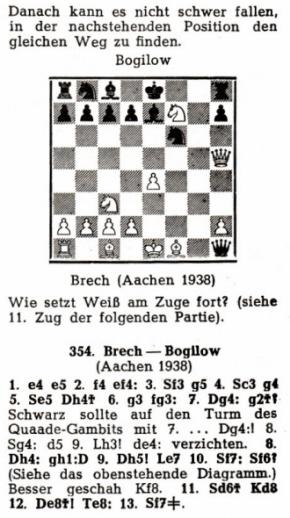

Mr Niessen mentions too that the Bird version of the game was given on page 122 of 666 Kurzpartien by Kurt Richter (Berlin-Frohnau, 1966) as having occurred between Brech and Bogilow in Aachen, 1938:

8574. Carlsbad, 1911 (C.N. 8524)

A detail of Rotlewi from the Carlsbad, 1911 group photograph (Wiener Schachzeitung, September-October 1911, pages 304-305) was shown in C.N. 8524. Some more are added now:

Erich Cohn

Alexander Alekhine

Charles Jaffe

Savielly Tartakower

Rudolf Spielmann

Akiba Rubinstein

Aron Nimzowitsch

Boris Kostić

8575. N.

Schwartz (C.N.s 8564 & 8567)

From Alan McGowan (Waterloo, Canada):

‘There are several references to “N. Schwartz” in The Story of Dundee Chess Club by Peter W. Walsh (Dundee, 1984). The spelling is invariably “Schwartz”.

The ScotlandsPeople website includes the Valuation Roll for 1920-21, page 98, County of Perth, Parish of Longforgan. For one of the houses on Errol Road, Invergowrie, Nicolai Schwartz (“Russian correspondent”) is mentioned as the occupier. There is also a record of his marriage on 19 February 1916, at St Stephen’s Church, Broughty Ferry, District of St Andrew in the Burgh of Dundee. He was listed as Nicolai Schwartz, Commercial Correspondent (Bachelor), aged 22, of Leabank, Broughty Ferry. The bride’s name is not completely clear, but it looks like J. Vernon Le Cocq (the maiden name of her mother is shown as Vernon), aged 24, of Craigiebarn Road, Dundee. A son, Nicholas Roy Schwartz, was born in 1920 in the Parish of Longforgan, in Perth County (377/00 0037).

A Dundee city website has a Roll of Honour for those who died in the Second World War and provides details of the son’s death in action on 17 December 1944, aged 23. His name was given as Nicolai Roy Schwartz, and his next of kin were Nicolai and Jeannie V. Schwartz of Clapham, London.’

8576. Rodolfo De Witt (C.N. 8570)

In the case of Rodolfo De Witt, Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia (page 92) has only one reference to support the information given about his death (said to have occurred in Buenos Aires on 16 May 1970 when he was aged 77): page 46 of Jaque Mate, 1970. Below is what appeared in that (Cuban) magazine:

Since the issue was dated January 1970, it is evident that De Witt died in 1969, and this is confirmed by material provided by two correspondents.

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) forwards De Witt’s obituary on pages 1215-1216 of the June 1969 issue of 1.P4R!!:

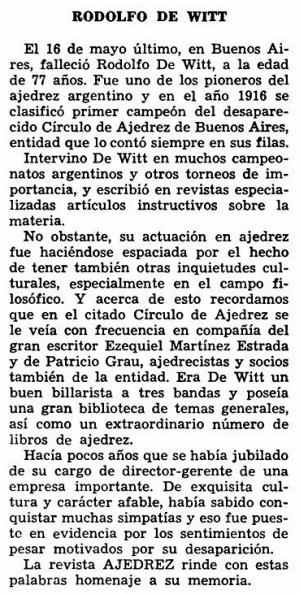

From Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) we have received page 283 of Ajedrez Revista Mensual, August 1969:

Mr Sánchez adds that there is a brief entry for Rodolfo De Witt (‘circa 1891-1969’) on page 24 of volume two of Historia del ajedrez argentino by José A. Copié (Buenos Aires, 2011).

Below is a loss sustained by De Witt, featuring unusual moves by the white queen along the third rank. It comes from volume two of Tratado general de ajedrez by Roberto Grau (page numbers vary according to the edition), the only information provided being that White was Guerra Boneo and that it was ‘una de las partidas más cortas disputadas nunca en los torneos mayores argentinos’:

1 Nf3 b6 2 d4 Bb7 3 Bf4 Nf6 4 c4 c5 5 Nc3 g6 6 dxc5 bxc5 7 Qb3 Qc8 8 Nb5 d6 (White’s next move received two exclamation marks from Grau.)

9 Qe3 Kd7 10 Ng5 Ng4 11 Qg3 Nh6 12 Qh3+ Kd8 13 Qc3 f6 14 Nxd6 Resigns.

Information about the occasion of this game is sought. As mentioned in C.N. 4777, Alejandro Guerra Boneo died in 1926.

8577. A nineteenth-century skirmish (C.N. 8573)

With regard to the version of the game given by Kurt Richter in 666 Kurzpartien (Brech v Bogilow, Aachen, 1938), Thomas Niessen (Aachen, Germany) adds that Otto Brech was the city’s leading player at the end of the 1920s and conducted the local chess column from 1934 until his death in 1937. It is unclear why Richter put 1938 for a game which had been published in the Aachener Anzeiger – Politisches Tageblatt on 5 August 1932. The newspaper called it a ‘freie Partie’ (offhand game) played in Aachen by Brech against Borobiloff.

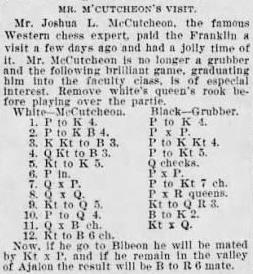

Two cuttings in C.N. 8573 referring to McCutcheon mentioned a newspaper identified only as ‘The Times’. Patsy A. D’Eramo (North East, MD, USA) has found that the publication in question was the Philadelphia Times, 28 November 1897, page 14:

The references to ‘Joshua’ and ‘Grubber’ have yet to be explained.

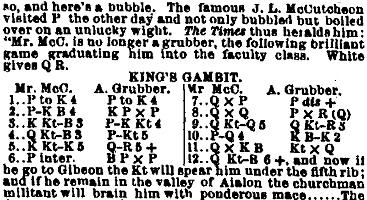

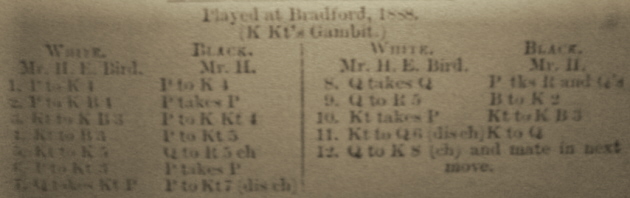

C.N. 8573 also discussed a version of the game involving Bird. Hans Renette (Bierbeek, Belgium) provides an extract from G.A. MacDonnell’s column in the Illustrated Sporting and Dramatic News, 6 April 1889, page 109:

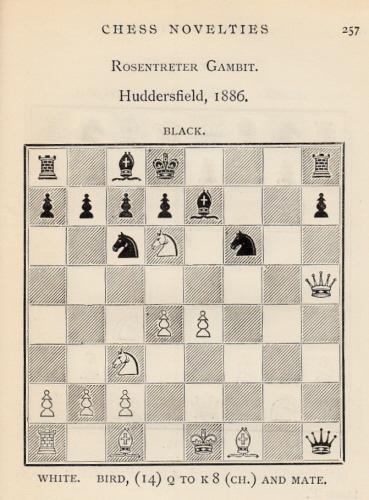

Although ‘Bradford, 1888’ was stated, Mr Renette adds that a similar finish was given by Bird on page 257 of his book Chess Novelties (London, 1895) with ‘Huddersfield, 1886’:

Our correspondent believes that 1885 would be correct given that, as reported on page 174 of the May 1885 BCM, Bird gave a simultaneous display in Huddersfield on 28 April 1885.

Readers are invited to send further citations for the games under discussion, after which we shall probably attempt in a feature article to set out the diverse strands of the farrago in a more structured way.

| First column | << previous | Archives [115] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.