Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [110] | next >> | Current column |

8246. Women

A priceless addition to Chess

and Women comes from page 99 of the April 1924 American

Chess Bulletin. The passage is by Ernest Reel and

was quoted from the Milwaukee Sentinel:

‘A woman’s mind is a market place crowded with so many mental reflections that it is hardly fair to ask her to concentrate on what is purely a man’s game. Chess is the weak spot in her mental armor. When a woman plays at chess she is apt to rest her chin on her hand and incidentally display her rings. While in deep meditation as to how to capture the king she suddenly is attracted by the arrival of a friend clad in exquisite furs. The fair player’s thoughts are diverted to the smart apparel shop. As soon as her strict attention slips its anchor the winning move of the chess game, which would stick like a burr in a man’s mind, rises like a shadow across her memory. Her chess atmosphere then becomes foggy, and the social atmosphere decidedly clear.

Women trying to play chess are like people leading horses they dare not ride. It will never be a woman’s game. Sammy Rzeschewski need only fear the rivalry of Cecil [sic – Celia] Neimark until her avenue of understanding includes the boulevards of dress, society and love. Up to that period a woman may win at chess – after that she has other battles to conquer.’

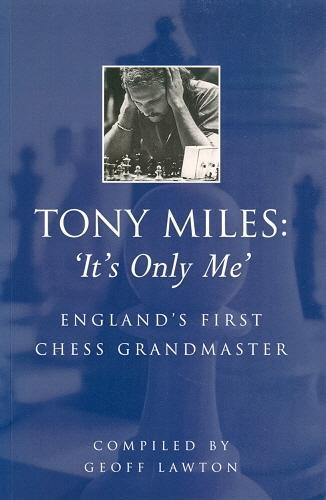

8247. Tony Miles’ three rooks

In an interview with Martijn Smit on pages 6-8 of the 4/1984 New in Chess Tony Miles said:

‘... I have a strong tendency to look at crazy things first. When promoting a pawn I prefer a bishop to a queen if that is possible ... I am very fond of, let us say, three rooks on the board. In a weekend tournament I had that once, and instead of resigning my opponent allowed himself to be mated beautifully, in the middle of the board. That appeals to me.’

The comments were reproduced on page 22 of Tony Miles: ‘It’s Only Me’ compiled by Geoff Lawton (London, 2003). Is the three-rook game extant?

8248. 2x2

The book mentioned in the previous item quotes two two-word remarks by Miles which have resonated. The first, on page 261, is a book review reproduced from the Autumn 1998 Kingpin, page 56. It can also be read at the lively new Kingpin website.

Chapter 3 of Tony Miles: ‘It’s Only Me’ is entitled ‘A cable’, referring to a well-known story about Dubna, 1976 (related on page 14). Prior to his departure for the tournament he was asked (by Eddie Penn, according to the book) to send a cable if he succeeded in qualifying for the grandmaster title. In due course, one was received from Dubna:

‘A cable – Tony Miles.’

Are further details available and, in particular, has the message been kept?

By becoming a grandmaster, Miles won the £5,000 prize offered by J.D. Slater. Reporting this, CHESS (March 1976, page 173) added, ‘not to mention Faber’s £1,000 in advance royalties for a book’. What subsequently happened is unclear; no such work was ever published by the company.

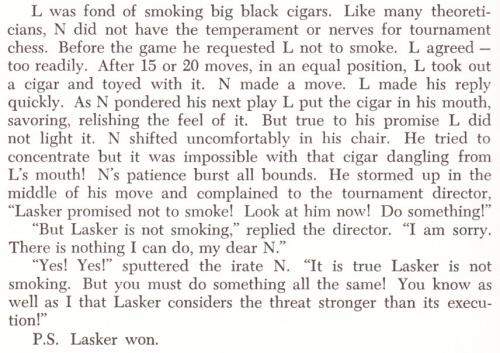

8249. Nimzowitsch and Lasker

The space-filling potential of the smoking-threat anecdote involving Nimzowitsch and a variable supporting cast (Lasker, Vidmar, Tartakower, Bogoljubow, Maróczy and Lederer) is a godsend for a certain type of ahistorical chess author. He may even decide to write a playlet:

Source: page 86 of Chess Beginner to Expert by Larry Evans (Wellesley Hills, 1967).

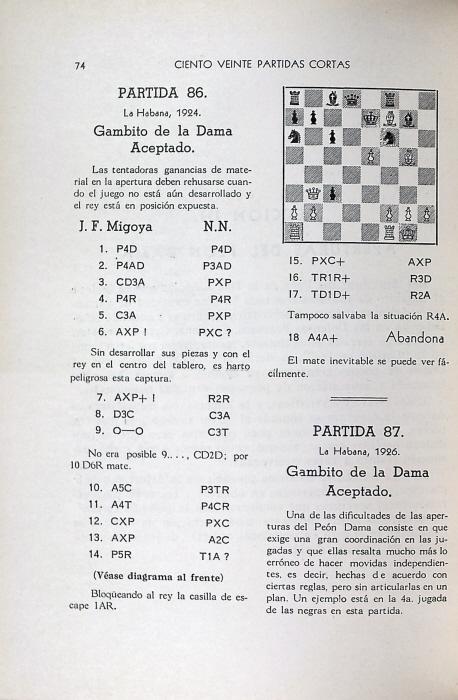

8250. Piece sacrifice anticipated (C.N.

4079)

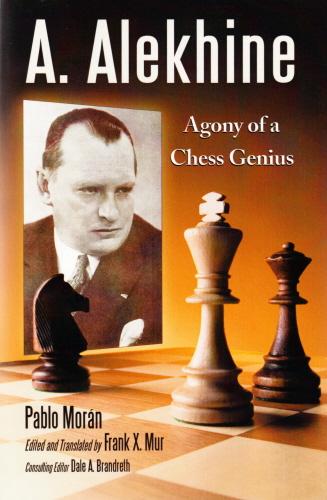

Concerning the sixth match-game against Euwe, 1937 the following remark by Alekhine appeared in his second Best Games collection after 1 d4 d5 2 c4 c6 3 Nc3 dxc4 4 e4:

‘It is almost incredible that this quite natural move has not been considered by the so-called theoreticians. White obtains now an appreciable advantage in development, no matter what Black replies.’

Following 4...e5 5 Bxc4 exd4 there came 6 Nf3, ‘yet another of Alekhine’s sacrificial hazards, which would hardly bear repetition’ in the words of R.N. Coles on page 77 of Dynamic Chess (London, 1956).

C.N. 1181 (see page 96 of Chess Explorations) gave a game dated 13 years earlier:

José Fernández Migoya – N.N.

Havana, 1924

Queen’s Gambit Declined

1 d4 d5 2 c4 c6 3 Nc3 dxc4 4 e4 e5 5 Nf3 exd4

6 Bxc4 dxc3 7 Bxf7+ Ke7 8 Qb3 Nf6 9 O-O Na6 10 Bg5 h6 11 Bh4 g5 12 Nxg5 hxg5 13 Bxg5 Bg7 14 e5 Rf8 15 exf6+ Bxf6 16 Rfe1+ Kd6 17 Rad1+ Kc7 18 Bf4+ Resigns.

At a library in Havana in 1986 we copied down this score from page 74 of 120 Partidas Cortas de Ajedrez by Gumersindo Martínez (Havana, 1947). Now we are able to show the page, courtesy of the Cleveland Public Library:

8251. Capablanca’s alleged income

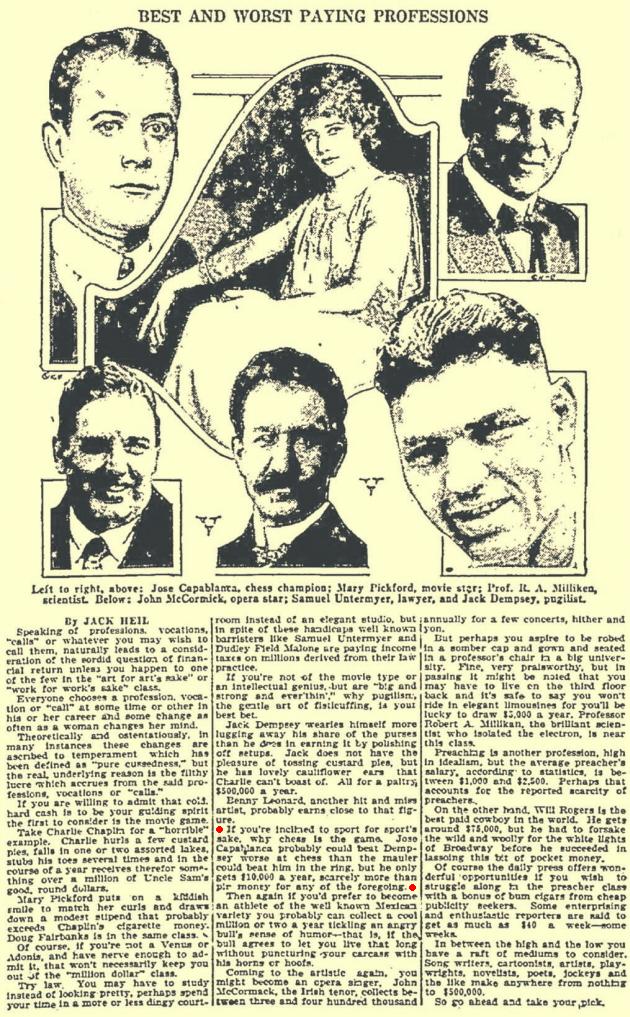

From page 3 of the Bellingham Herald (Bellingham, WA), 19 September 1922:

The same feature was published in other US newspapers in September/October 1922. The assertion that Capablanca’s annual income was $10,000 may result from a misunderstanding over the London Rules, which had just been agreed upon (‘The champion will not be compelled to defend his title for a purse below $10,000’).

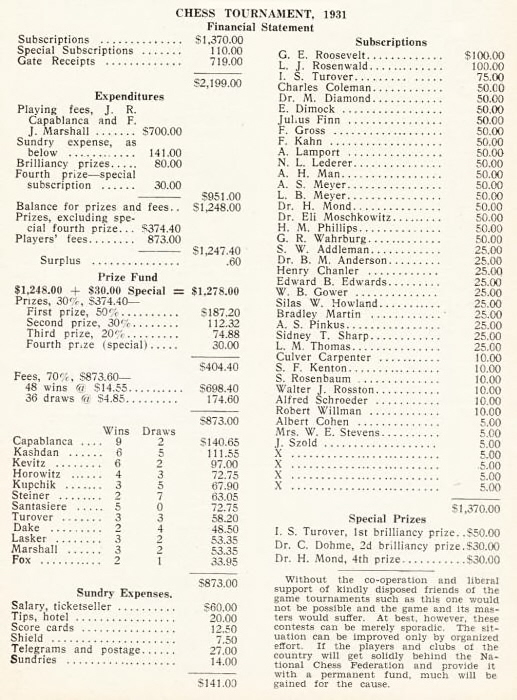

8252. New York, 1931

Page 97 of the May-June 1931 American Chess Bulletin set out in uncommon detail the budget for that year’s tournament in New York:

8253. ‘A cable’ (C.N. 8248)

Edward Penn (London) informs us that he asked Miles, prior to his departure for the Dubna, 1976 tournament, to send him a cable if he obtained the grandmaster title.

Miles’ message was indeed two words (‘A cable’). Mr Penn’s recollection is that Miles, a close friend, signed not with his full name but simply with ‘Tony’. However, he has not yet been able to find the cable to confirm this.

8254. Spot the chess master

8255. Sämisch in 1969 (C.N.s 8228, 8237, 8241 & 8242)

Roger Mylward (Lower Heswall, England) notes that Sämisch’s games from the two 1969 tournaments are available in the ChessBase Mega database 2013 and at the 365Chess.com website.

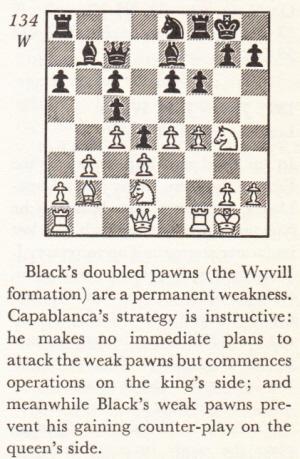

8256. The Wyvill formation

Seldom nowadays does a chess treatise use the term ‘Wyvill formation’ (or, indeed, the term ‘treatise’).

From page 153 of The Unknown Capablanca by D. Hooper and D. Brandreth (London, 1975), concerning the game Capablanca v Haussmann, Philadelphia, 1918:

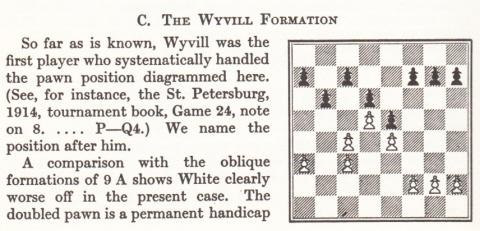

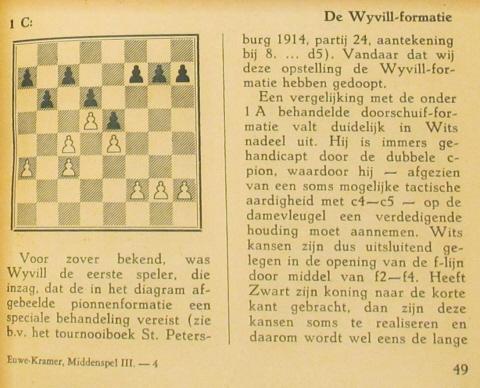

The ‘Wyvill formation’ was the description used in The Middle Game by M. Euwe and H. Kramer (London, 1964). Below, for example, is an extract from page 146 of book one:

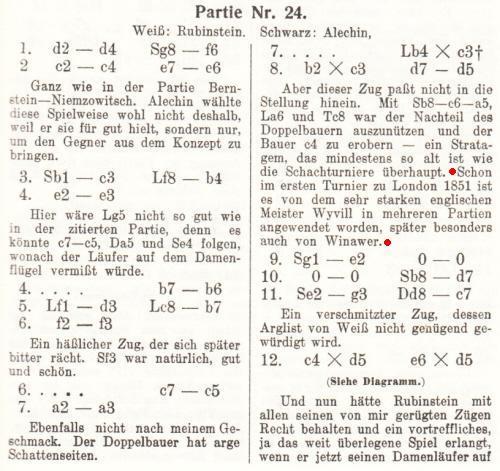

The Euwe/Kramer work was originally published in Dutch in the 1950s, in five parts, and we are grateful to Harrie Grondijs (Rijswijk, the Netherlands) for providing the text about ‘De Wyvill-formatie’ on page 49 of Het middenspel, part three (The Hague and Djakarta, 1953):

The Tarrasch passage referred to by Euwe and Kramer was on page 59 of Das Grossmeisterturnier zu St Petersburg im Jahre 1914 (Nuremberg, 1914):

Did Tarrasch refer to Wyvill elsewhere in his writings, perhaps even using the specific phrase ‘Wyvill formation’?

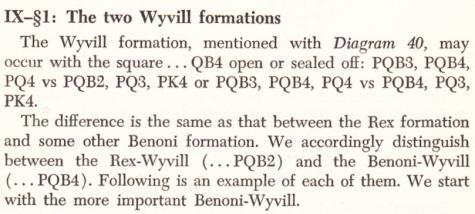

On page 27 of Die Kunst der Bauernführung (Berlin-Frohnau, 1956) Hans Kmoch discussed ‘Die Wyvill-Formation’ and on page 257 added the ‘Wyvill-Benoni’ and ‘Wyvill-Rudi’. On page 277 of the English edition, Pawn Power in Chess (New York, 1959), readers were treated to the ‘Rex-Wyvill’ and the ‘Benoni-Wyvill’:

8257. Duplication

Source: Chess Review, March 1953, page 77.

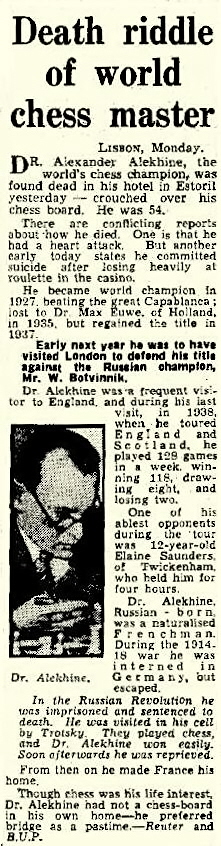

8258. Alekhine’s death

Alekhine’s death was reported on the front page of the Daily Mail, 25 March 1946, with a seamless blend of rumour and error:

8259. Royal Literary Fund (C.N.s 7277, 7287, 7288 & 8185)

In C.N. 8185 Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) gave the handwritten applications to the Royal Literary Fund of G.H.D. Gossip and B. Horwitz. Now he adds the submission by P.W. Sergeant.

C.N. 5943 listed the complete set of Sergeant’s non-chess books in our collection. They scarcely look like money-spinners.

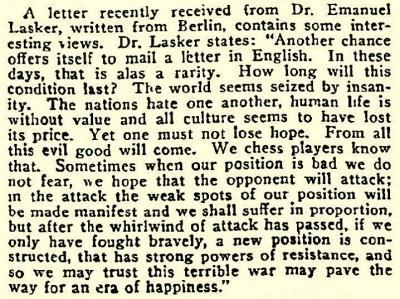

8260. Lasker on the Great War

Mr Urcan has also supplied a cutting from page 7 of the Philadelphia Inquirer Magazine, 18 October 1914, which quotes the views of Emanuel Lasker as expressed to Walter Penn Shipley:

8261. Stephen Fry

A number of C.N. items have referred to Stephen Fry, who gave us permission to reproduce a photograph of him playing chess with Hugh Laurie and to quote some extracts from his writings on the game.

These items, together with other information, have now been brought together in Stephen Fry and Chess.

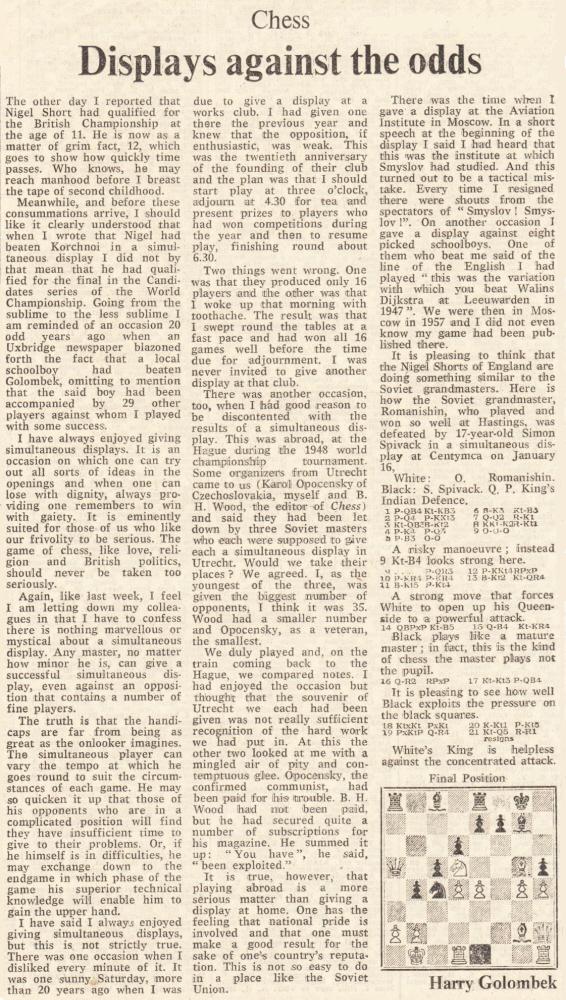

8262. Article on simultaneous chess in The

Times

1 c4 Nf6 2 d4 g6 3 Nc3 Bg7

4 e4 d6 5 f3 O-O 6 Be3 Nc6 7 Qd2 Re8 8 Nge2 Rb8 9 O-O-O

a6 10 h4 h5 11 Bg5 b5 12 g4 hxg4

13 Bg2 Na5 14 cxb5 Nc4 15 Qf4 Nh5 16 Qh2 axb5 17 Ng3 c5

18 Nxh5 gxh5 19 fxg4 Qa5 20 Kb1 b4 21 Nd5 Ra8 22 White

resigns.

Golombek’s column was published on page 11 of the 11 June 1977 Review section of The Times. Concerning the simultaneous display by Romanishin, further details and games were given in ‘Young London v the IGMs’ by Leonard Barden on pages 270-272 of the June 1977 BCM.

8263. Ambidexterity

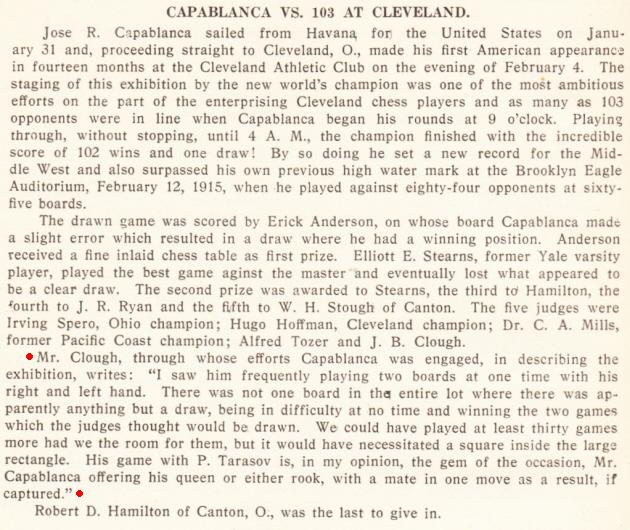

A report on page 22 of the February 1922 American Chess Bulletin:

The game against Tarasov was given on page 23 of that issue of the American Chess Bulletin, on page 8 of Wonders and Curiosities of Chess by Irving Chernev (New York, 1974) and on page 118 of our monograph on Capablanca.

A comment above by J.B. Clough about Capablanca is worth highlighting:

‘I saw him frequently playing two boards at one time with his right and left hand.’

This practice of the Cuban’s was also mentioned in a report about the Cleveland display on page 9 of The Times, 22 February 1922:

Capablanca’s score of +102 –0 =1 may furthermore be noted in the light of a remark cited on page 317 of our book:‘He was frequently seen to be playing two boards at once, one with his right hand and one with his left, a little habit of his we often noticed during his simultaneous tour in this country. The player at the board he had just left made a move; over his left arm would go Capablanca’s right hand, the left maintaining hold of the piece on the board he was at, and the right hand making the necessary reply on the other board with hardly a second’s delay.’

‘When I gave that exhibition against 103 players in Cleveland, USA early this year I had hardly touched a board for eight months and felt very hazy at the beginning, and yet towards the end I do not think my brain was ever working more clearly.’

Source: The Times, 12 July 1922, page 7 (not all editions). The text also appeared on page 464 of the Times Literary Supplement, 13 July 1922.

8264. Elmars Zemgalis

Two photographs taken during the US Open, Milwaukee, 1953 have been forwarded by John Donaldson (Berkeley, CA, USA), the author of Elmars Zemgalis Grandmaster without the Title (Berkeley, 2001), to mark the 90th birthday of Zemgalis (born in Riga on 9 September 1923):

Above, from left to

right: Eriks Gutmanis, Leonids Gaigals, Indrikis

(Heinrich) Kalnins,

Elmars Zemgalis, Leonids Dreibergs, Alexander(s)

Liepnieks and Nicholas (Nikolajs) Kampars

8265. Carl Walcker (C.N.s 7926 & 7930)

Further to C.N. 7930, Paweł Dudziński (Ostrów Wielkopolski, Poland) comments that his book Szachy wojenne 1939-1945. War chess (C.N. 8204) gave Walcker’s results in the Cracow championship as follows:

First championship:

December 1940-January 1941 (elimination tourney): 1. Schmek. Walcker and Nowarra were probably joint second.

February-March 1941 (final): 1. Walcker (7½/8).

Second championship:

November 1941: 1. Mross (7/7) ... 3-4. Walcker and Meynecke (4½/7).

Third championship:

February-March 1942: 1. Mross (6½/7) 2. Walcker (5/7).

Fourth championship:

December 1942 (?)-January 1943: 1. Meynecke (7/9) ... 6-7. Walcker and Antonetty (4½/9).

Fifth championship:

February-March 1944: results unknown, but the game won by Walcker as Black against Antonetty was given on page 200 of our correspondent’s book.

Mr Dudziński adds:

‘Games played by Walcker were published in the Goniec Krakowski on 31 October 1943, 16 January 1944 and 2 April 1944. The full run of the newspaper’s chess column can be viewed online.

Alekhine and Bogoljubow stayed at Walcker’s home during their visits to Cracow. A photograph of his daughter, Maria Pritulecka or Prytulecka, and a game played by her are on page 69 of my book.’

8266. Dawid Przepiórka

Another new book in Polish, Mistrz Przepiórka by Tomasz Lissowski, Jerzy Konikowski and Jerzy Moraś (Warsaw, 2013), is also notable. It is a 271-page softback containing a biography, games, problems and many photographs.

8267. ‘A cable’ (C.N.s 8248 & 8253)

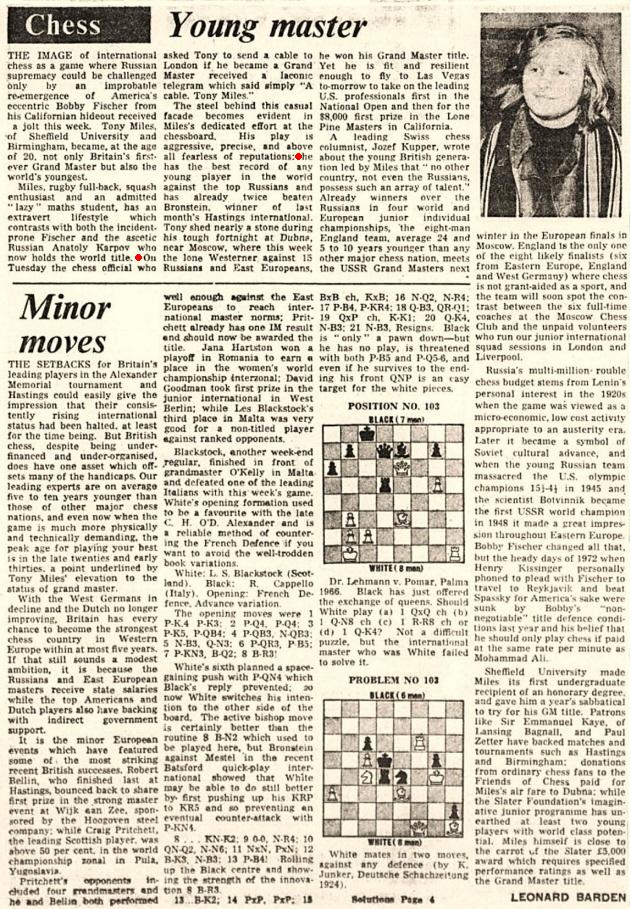

Financial Times, 28 February 1976, page 8

Quite by chance we have just discovered the following:

- From Leonard Barden’s chess column on page 8 of the Financial Times, 28 February 1976:

‘On Tuesday the chess official who asked Tony to send a cable to London if he became a Grand Master received a laconic telegram which said simply “A cable. Tony Miles.”

The steel behind this casual facade becomes evident in Miles’s dedicated effort at the chessboard. His play is aggressive, precise, and above all fearless of reputations ...’

- From pages 9-10 of The English Chess Explosion by Murray Chandler and Raymond Keene (London, 1981):

‘A British chess federation official who had asked Miles to send a cable to London if he ever became a Grandmaster received a laconic telegram which simply read “A cable. Tony Miles”. The steel behind this casual facade becomes evident in Miles’ dedicated effort at the board – aggressive, precise, and above all fearless of reputations.’

- From page 31 of Tony Miles England’s Chess Gladiator by Raymond Keene (Aylesbeare, 2006):

‘A British Chess Federation official who had asked Miles to send a cable to London if he ever became a Grandmaster received a laconic telegram which simply read “A cable. Tony Miles”.

The steel behind this casual facade becomes evident in Miles’ dedicated effort at the board – aggressive, precise, and above all fearless of reputations.’

Page 6 of The English Chess Explosion stated, ‘we would like to thank Leonard Barden for permission to quote from his articles in The Guardian and The Financial Times’. The above, of course, is not a case of ‘quotation’.

8268. The Wyvill formation (C.N. 8256)

From Joose Norri (Helsinki):

‘In an article in the 7-8/2003 issue of Suomen Shakki I pointed out, on pages 234 and 244, that there is some confusion about the Wyvill formation. Firstly, Tarrasch attributes to Wyvill the stratagem ...Na5, ...Ba6 and ...Rc8, whereas Euwe/Kramer and Kmoch use his name to describe the actual pawn structure. More importantly, I believe that Tarrasch was mistaken. No such game by Wyvill from London, 1851 exists. In one game, Wyvill v Anderssen, he had the doubled pawns, but he is supposed to have recognized the weakness of such pawns and not to have had them.

There are, however, two games played by Elijah Williams at London, 1851 (Staunton v Williams and particularly Löwenthal v Williams) which fit the description. Williams never had time to carry out the whole manoeuvre with the knight, bishop and rook, but he clearly intended it.

There remains the question of whether Wyvill used the idea somewhere else.’

8269. ‘Telemachus Brownsmith’ (C.N. 7422)

John Townsend (Wokingham, England) writes:

‘There is mention of “Telemachus Brownsmith” in H. Meyer’s chess column in The Gentleman’s Journal (8 September 1872, page 64). In the notices “To Correspondents” he refers to errors that have arisen in the printing of the names of composers of problems, and comments:

“We advise our correspondents to be more careful with the names, and to avoid anagrams or translations – for instance, not L. Travoli for V. Portilla, or Lonsdale for Löwenthal, or Frankenstein for Francopierre, or Miss Betty G. for Dr. A. Nowotny, or Drakon Rabey for Konrad Bayer, or Telemachus Brownsmith for ******, &c.”

One possibility is that “Telemachus Brownsmith” is an anagram. If it is, the letters “B.A.” should perhaps be included – in fact, they may have been deliberately added to make up the full set of letters needed.’

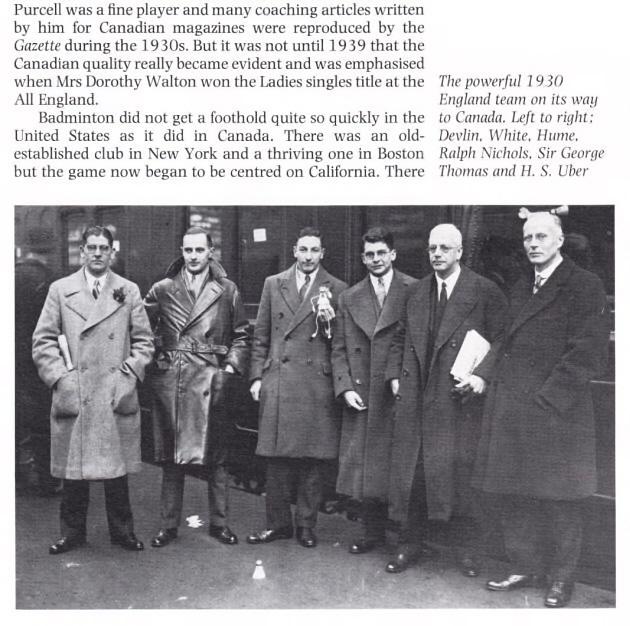

8270. Spot the chess master (C.N. 8254)

From page 75 of The Badminton Story by Bernard Adams (London, 1980):

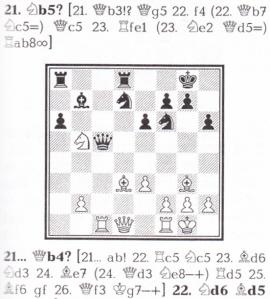

8271. Ståhlberg v Capablanca (C.N.s 8169, 8184 & 8189)

From Michael Spiekermann (Menden, Germany):

‘Concerning an earlier stage of the game Ståhlberg v Capablanca, Margate, 1936 ...

... White played 21 Nb5. It seems that 21...axb5 22 Rxc5 Nxc5 would have given Black a winning advantage. For example, 23 Be5 Nxd3 24 Bxf6 gxf6 25 Qh5 Kg7 26 Qxb5 Ba6. Consequently, an alternative such as 21 Ne4 would be better.

I note, though, that on page 128 of the second edition of Capablancas Verlustpartien by Fritz C. Görschen (Hamburg-Bergedorf, 1976) 21 Nb5 was given an exclamation mark.’

Below we add the relevant section on page 195 of the second ‘Chess Stars’ volume on Capablanca, published in 1997:

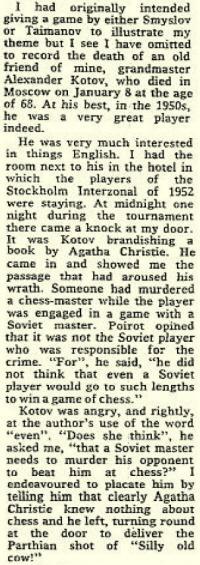

8272. Agatha Christie (C.N.s 4082, 4083 & 4105)

Alexander Kotov’s assessment of Agatha Christie was reported by Harry Golombek in The Times Saturday Review, 25 April 1981, page 9:

Below is the remark about ‘even a Russian’ (which was addressed to Hercule Poirot) in ‘A Chess Problem’, as published in the edition of Agatha Christie’s book The Big Four referred to in C.N. 4105:

8273. Fine’s challenge (C.N. 6165)

Regarding Reuben Fine’s post-Reykjavik challenge to Bobby Fischer for a world title match with a purse of one million dollars, a sourceless paragraph was published on page 125 of the February 1973 CHESS:

‘“I’d play Fischer for the world championship if the stakes were high enough”, said Reuben Fine to Robert Byrne recently. “How high?”, asked Byrne. “Say a million dollars”, replied Fine and was quite upset when Byrne thought he was joking.’

8274. Chess and snooker (C.N. 7699)

C.N. 7699 quoted a remark by Clive James on page 285 of Snakecharmers in Texas (London, 1988 and 1989): ‘Whoever called snooker “chess with balls” was rude but right.’

We can now report that the observation was attributed to Mike Watterson in an article by Cynthia Bateman entitled ‘Chess with balls’ on page 16 of the Guardian, 3 April 1981:

This citation is included in a new feature article, Clive James and Chess, which also quotes a remark of his from page 48 of The Observer (Review section), 22 June 1980:

‘Golf is the only sport that has snooker beaten as a television event. Mediocre golf is like mediocre anything else, but top-level golf is like chess in Cinerama ...’

8275. Feature articles

Stephen Fry and Alan Davies, Radio Times, 24-30 August 2013, page 15

Our recent addition Stephen Fry and Chess has been expanded to include three articles from The Listener which Stephen Fry has kindly authorized us to reproduce.

Another new feature article is Jacob Bronowski and Chess. In a piece about Bronowski on page 13 of the 5 October 1974 issue of The Times Harry Golombek wrote, ‘I have no illustrative game of his available’, and we currently have the moves of only one game. Can any others be found?

8276. Copying (Christian Hesse)

Regarding The Joys of Chess by Christian Hesse (Alkmaar, 2011), C.N. 7083 observed that ‘many positions and other material are taken from Chess Notes, in exchange for a one-line mention of our website in a list on page 427)’. That C.N. item is included in the feature article Copying.

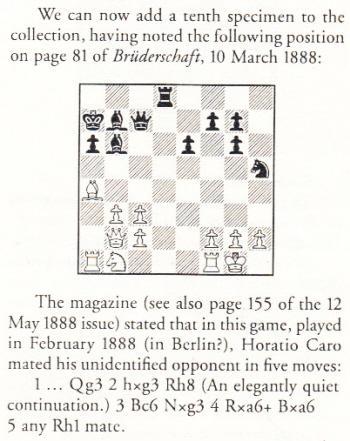

An article by Hesse posted at ChessBase on 13 September 2013 highlights his inability even to copy accurately. An example is his position ‘N.N.-Caro, Berlin 1898’. Below is part of C.N. 3096, posted on the Internet in 2003 and given on page 12 of Chess Facts and Fables. It concerns our research into queen sacrifices on g6 or g3 (as set out in The Fox Enigma):

Hesse availed himself of this position on page 175 of Expeditionen in die Schachwelt (Nettetal, 2006), on page 183 of the English edition, The Joys of Chess, and in his ChessBase article, without a word of attribution. All three times he stated categorically that the venue was Berlin (our cautious question mark was dispensed with) and he was ten years out with the date of the game, putting ‘1898’. His neglect to mention a source reduced his chances of realizing the 1888/1898 discrepancy during the seven years since he first published in his work an inaccurate, simplified version of ours.

Naturally, other writers and researchers are also the victims of Hesse’s unconscionable approach. His ChessBase article blunders spectacularly by attributing to G.A. MacDonnell a game played more than a decade after his death.

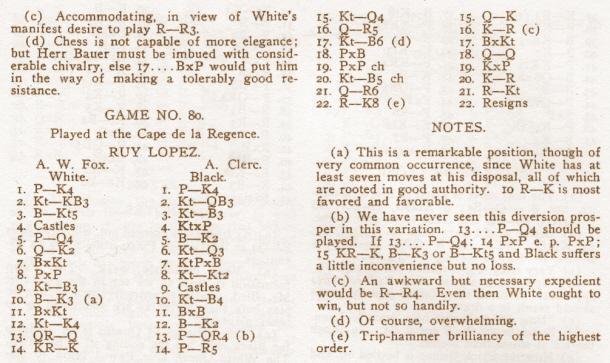

8277. Fox v Clerc

The Fox Enigma includes a game between A.W. Fox and A. Clerc played at the Café de la Régence, Paris and published on page 146 of the July 1901 issue of the American Chess World:

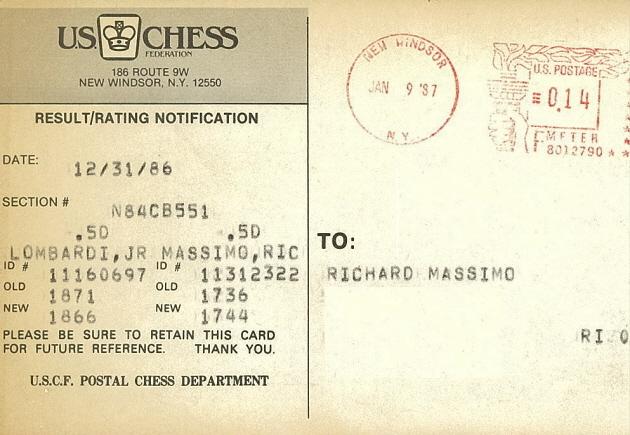

Rick Massimo (Providence, RI, USA) notes that the

conclusion was one of two positions on cards sent by the

United States Chess Federation to domestic postal players

to acknowledge receipt of a game result:

The second position on the card will be discussed in a later item.

8278. Unmoved pawns

Stuart Rachels (Tuscaloosa, AL, USA) forwards a game which he won at the age of 14 in the Alabama State Championship:

Stuart Rachels – Tom Denton

Mobile, 1 September 1984

Queen’s Indian Defence

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e6 3 Nf3 b6 4 a3 c5 5 d5 Ba6 6 Qc2 exd5 7 cxd5 g6 8 Nc3 d6 9 Bf4 Bg7 10 Qa4+ Qd7 11 Bxd6 b5 12 Qf4 b4 13 axb4 cxb4 14 Qe3+ Kd8 15 Bxb4 Re8 16 Ba5+ Kc8 17 Qc5+ Kb7 18 Ra3 Resigns.

Our correspondent asks whether there are longer games in which all four of the winner’s king’s-side pawns remained unmoved.

8279. Korchnoi’s name deleted from a match book?

In a review of Chess is my Life by Victor Korchnoi (London, 1977) on page 16 of The Times, 2 December 1977 Bernard Levin referred to Korchnoi’s departure from the Soviet Union in 1976 and added:

‘A new Soviet book on the 1974 Karpov-Korchnoi championship match had to have all references to Korchnoi deleted, so that he is simply referred to throughout as “the opponent”.’

To which book was Levin referring? Korchnoi’s

autobiography does not seem to make such a claim.

Nor do we have any books in Russian exclusively devoted to the 1974 Karpov-Korchnoi match, although all 24 match-games were annotated in Tri matcha Anatoliya Karpova by M. Botvinnik (Moscow, 1975), which also covered Karpov’s matches against Polugayevsky and Spassky. An English translation by Kenneth P. Neat was published under the title Anatoly Karpov His road to the World Championship (Oxford, 1978).

8280. Jacob Bronowski

Jacob Bronowski and Chess lists a number of compositions on which he collaborated with Norman Martin Gibbins, and Steven B. Dowd (Birmingham, AL, USA) points out a website offering information about Gibbins.

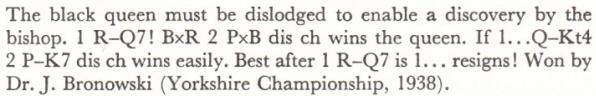

We add that a brief illustration of Bronowski’s play was published on page 15 of volume two of Learn Chess: A New Way for All by C.H.O’D. Alexander and T.J. Beach (Oxford, 1963):

The solution on page 185:

In the algebraic edition (Oxford, 1987) the page numbers are 13 and 156.

From W. Ritson Morry’s report about Hastings, 1961-62 on pages 33-34 of the February 1962 BCM:

‘The congress was opened, after the Mayor (Alderman G. [sic – C.] Barfoot, JP) had welcomed the competitors, by a chessplayer of no mean skill in the person of Dr J. Bronowski, who discarded most of the usual platitudes in favour of a really amusing account of his own chess career, which proceeded rather on the lines of the applicant for the Indian Civil Service who had “failed entrance examination Allahabad University 1922”. The good doctor had managed to lose to almost every grandmaster in the room and quite a few more, some of them when they were of very tender years, such as Sammy Reshevsky when a boy prodigy (for whom he was momentarily mistaken at a display and given a big round of applause), and Johnny Penrose way back in 1945. It was all excellent fun, and when someone accidentally “crowned” chairman Percy Morren [the President of the Hastings Chess Club] with a demonstration board the large crowd’s day was really complete.’

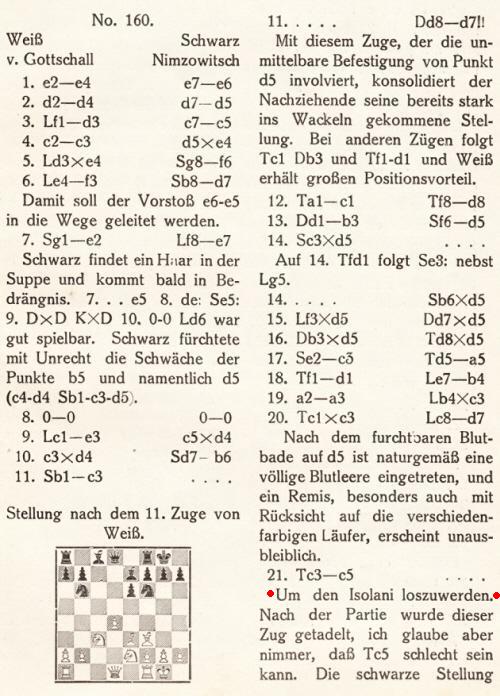

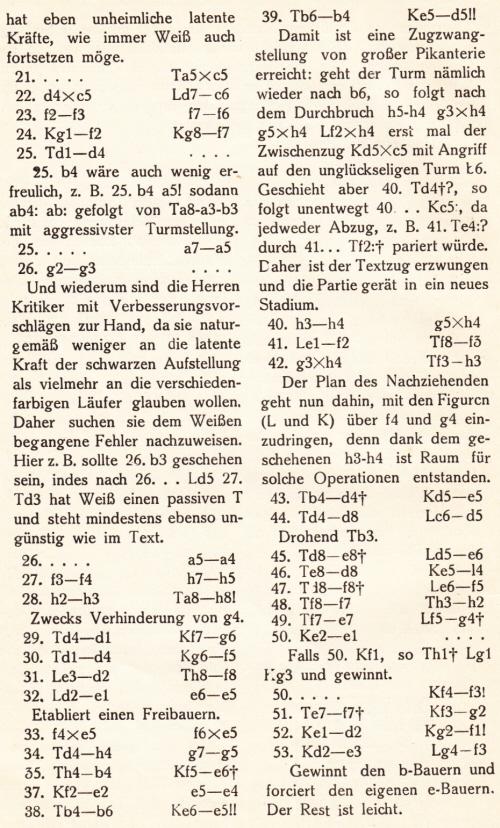

8281. Isolani (C.N.s 5047, 5083 & 5107)

Javier Asturiano Molina (Murcia, Spain) notes that Nimzowitsch used the word ‘isolani’ not only in Mein System but also, around the same time, on page 485 of the October-December 1926 issue of Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten. As his annotations to the game (H. von Gottschall v Nimzowitsch, Hanover, 1926) are different from those on pages 163-165 of his book Die Praxis meines Systems (Berlin, 1930), the full game is reproduced here from pages 485-487 of the magazine:

It is not only the annotations that are different. Quite

apart from the misnumbering of some moves above, there are

discrepancies in the score compared to the version in Die

Praxis meines Systems and on pages 66-67 of Kongreßbuch

Hannover 1926 (Berlin, 1926). Has either player’s

score-sheet survived?

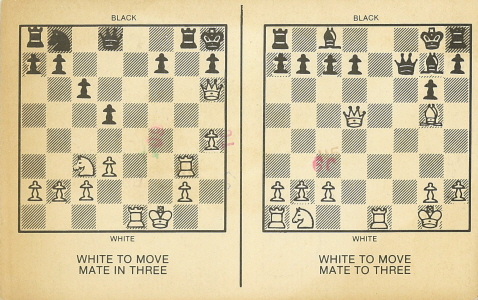

8282. Excelsior (C.N.s 8209 & 8210)

From Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England):

‘In a problem any pawn which begins on its starting square and promotes during the course of the solution (not necessarily in the minimum five moves) shows an excelsior. Nowadays the excelsior theme will usually be combined with other ideas.’

Mr McDowell has provided three illustrative compositions, by Robert B. Wormald, Poul Rasch Nielsen and Hans Peter Rehm.

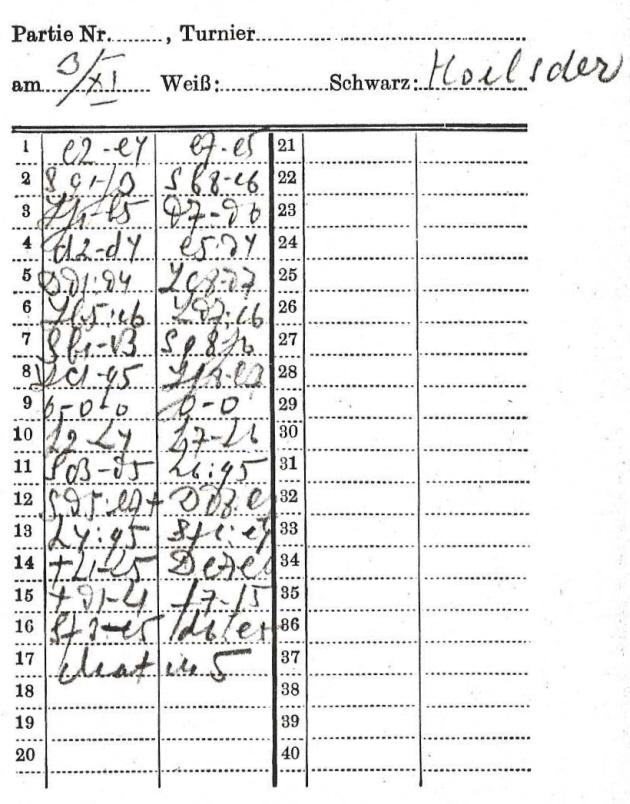

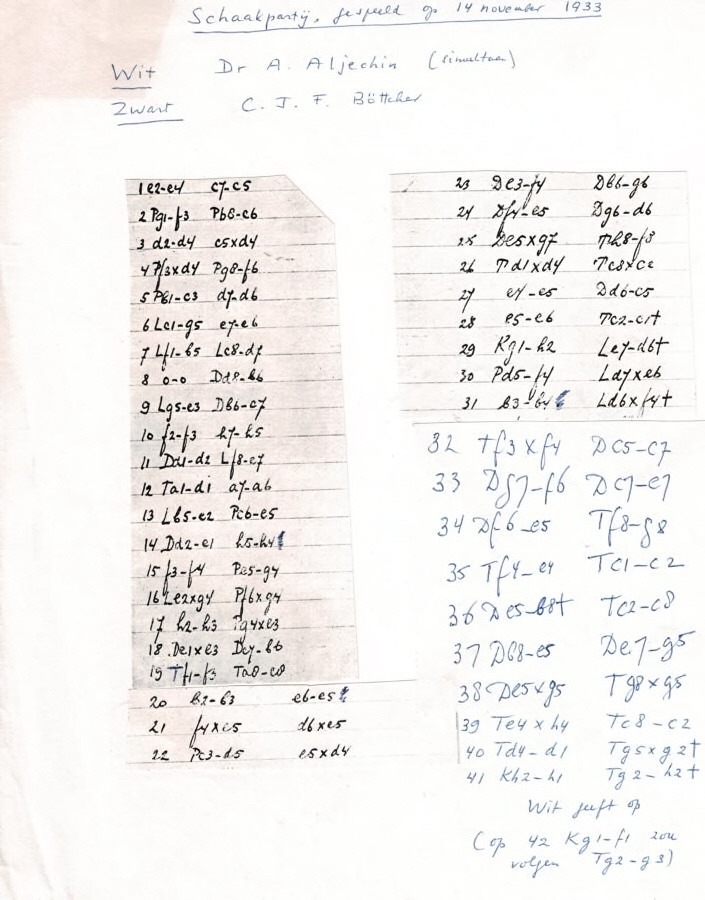

8283. Alekhine in the Netherlands (C.N. 8203)

Gene Gnandt (Houston, TX, USA) comments:

‘Concerning the page from Alekhine’s notebook shown in C.N. 8203, the letter d in the handwritten name does not match the letter d in the score-card, e.g. “4 d2-d4”, where the vertical line is much more upright and the lower curve more circular than the oval shape in the name. The oval shape is a closer match to a lower-case c in the score-card. For example, “5...Lc8-d7”.

I therefore suggest that it is a c followed by an h. In the score-card, Alekhine writes his letter h with an almost flat lower line. In fact, it looks like the letter l, e.g. “10 h2-h4 h7-h6”. This matches the letter in the name. I therefore suggest that the letter interpreted as d is really two letters, c and h, which would make the name Hoelscher.’

8284. Alekhine's French citizenship (C.N.s 8054 & 8058)

From Denis Teyssou (Paris):

‘I have consulted the 38 files of Alekhine’s naturalization record at the French national archives in Pierrefitte-sur-Seine and have posted a facts page.

Alekhine tried several times to become a French citizen between 1924 and 1927 and finally obtained citizenship with the support of Fernand Gavarry, who was the President of the French Chess Federation and a Plenipotentiary Minister at the Foreign Affairs Ministry. On 20 April 1927 Gavarry sent a letter on the Federation’s stationery asking the French authorities to grant Alekhine French citizenship so that he could lead the national team at the first International Team Tournament, to be held in London in July 1927. However, Alekhine had to await the promulgation of a new Law on naturalization to obtain a French passport.

My page also comments on Alekhine’s date of birth (C.N.s 4719 and 4739). I report too that in April 1922, three months after his arrival in France, Alekhine was suspected of Bolshevism, which, besides his frequent trips abroad, contributed to delays in the processing of his naturalization application between 1924 and 1927.’

8285. F.M. Edge

John Townsend (Wokingham, England) writes:

‘An announcement of a performance of Hamlet in the New York Daily Times (26 November 1855, page 5) suggests that F.M. Edge was already a journalist in New York by that time:

“THE HAMLET NIGHT. – It is respectfully announced that the representation of HAMLET will take place at the Academy of Music TO-MORROW, (TUESDAY EVENING) Nov. 27.

In its cast of characters, the names will be found of many of our authors, artists, and others well known, apart from the dramatic art. The play will be produced in a novel manner, and with all the unrivaled elegance and splendor, both of mise en scène and wardrobe, for which the Academy is distinguished ...”

The cast list included:

“Osric .......... Fred. M. Edge ......... Editor.”

Hamlet was played by C.T.P. Ware, who was described as “Dramatist”.’

Can further information about stage performances by Edge be traced? This new line of enquiry opens up the possibility of finding a picture of him.

8286. Book trends

C.N. 8256 mentioned in passing that the word ‘treatise’ is no longer fashionable in chess book titles. The most marked change in vocabulary may be in works for children (or nowadays, more commonly, ‘kids’). Half a century or so ago, young newcomers to the game received solid tutelage from The Chess Apprentice by R. Bott and S. Morrison (London and Glasgow, 1960), but such a title would seem unthinkable today, as would, for instance, Instructions to Young Chess-Players by H. Golombek (London, 1958).

A number of titles ostensibly for older players reflect a trend towards fantasy violence, an example being The Chess Terrorist’s Handbook by L. Shamkovich (Macon, 1995). It was dedicated to Mikhail Tal (‘The Greatest Chess Terrorist!’).

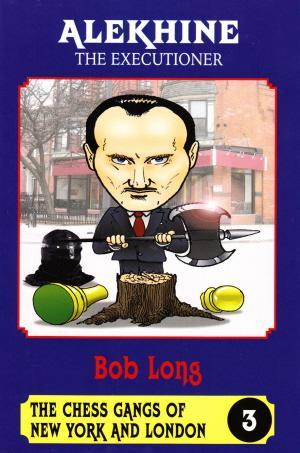

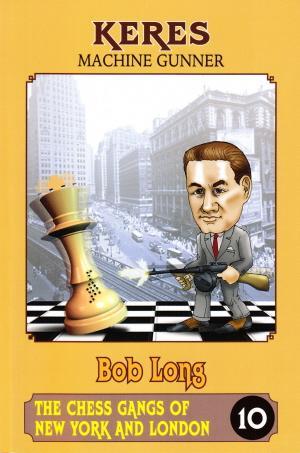

Then there are the productions of Thinkers’ Press, Davenport, such as The Chess Assassin’s Business Manual by Bob Long (2008) ...

... and a series of brief monographs including, to quote the covers, Alekhine The Executioner (2011) and Keres Machine Gunner (2012) or, to quote the title pages, Alexander Alekhine The Executioner and Paul Keres Machine Gun Keres.

A sociological study could be written on the evolution of chess book titles and covers. Doctorates have been awarded for less.

8287. A joke

This well-known jape is, rather inaptly, the opening passage in Chess for Young People by F. Reinfeld (New York, 1961), page 3.

Page 14 of another Reinfeld book published the same year, The Joys of Chess, also gave the story, the first player being described as an Englishman. That article of Reinfeld’s, ‘32 Ways to Go Crazy’, was reprinted from Esquire, March 1953.

8288. Mini-chess

Adam Ponting (Petersham, NSW, Australia) provides a link to a webpage concerning M. Mamikon’s ‘Mini-chess’, a puzzle which, it is stated, attracted the attention of Kasparov.

8289. Queen’s knight’s pawn (C.N.s 5827, 5865, 6021, 6669 & 6829)

Page 54 of the May-June 1937 American Chess Bulletin quoted an item from the South African Chess Magazine:

‘It is said a wealthy chess enthusiast left his son £1,000 a year on condition the lad never took the QKt pawn. The game (Botvinnik v Spielmann) once more serves to show how extremely wise the old gentleman was.’

On page 31 of the February 1970 BCM, in a report on Hastings 1969-70, Harry Golombek wrote with reference to Drimer v Portisch:

‘At move 17 he had to choose between taking Portisch’s queen’s pawn or queen’s knight’s pawn. The first capture would have left him a long, though uphill, fight, but the story of the Austrian nobleman who left his son a fortune provided that he never played QxQKtP has never penetrated the borders of Romania. Drimer took the queen’s knight’s pawn and found that two moves later he had either to lose his queen for a rook or be mated.’

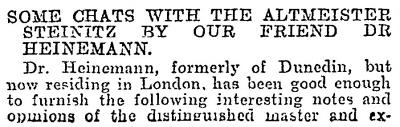

8290. Steinitz interview

Hans Renette (Bierbeek, Belgium) sends an interview with Steinitz by Wolf Heinemann which was published on page 48 of the Otago Witness, 5 October 1899:

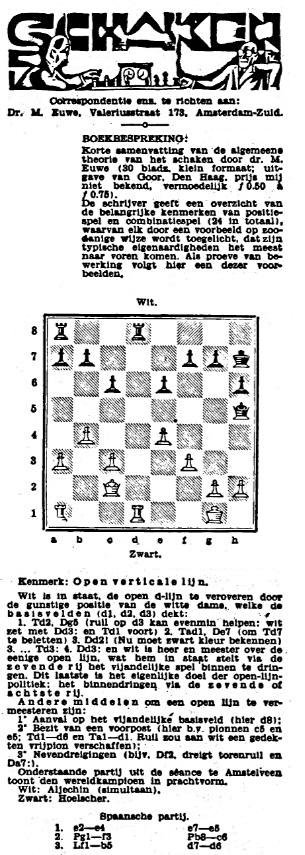

8291. Alekhine in the Netherlands (C.N.s 8203 & 8283)

Peter de Jong (De Meern, the Netherlands) and Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) have found that the game under discussion was given as Alekhine v Hoelscher (with the venue as Amstelveen) by Max Euwe in his column on page 8 of the 20 November 1933 edition of Het Volk:

Alekhine’s Amstelveen display took place on 3 November 1933 according to the report in the Tijdschrift van den Nederlandschen Schaakbond, November 1933 (C.N. 8203). In his notebook Alekhine dated the game 3 November.

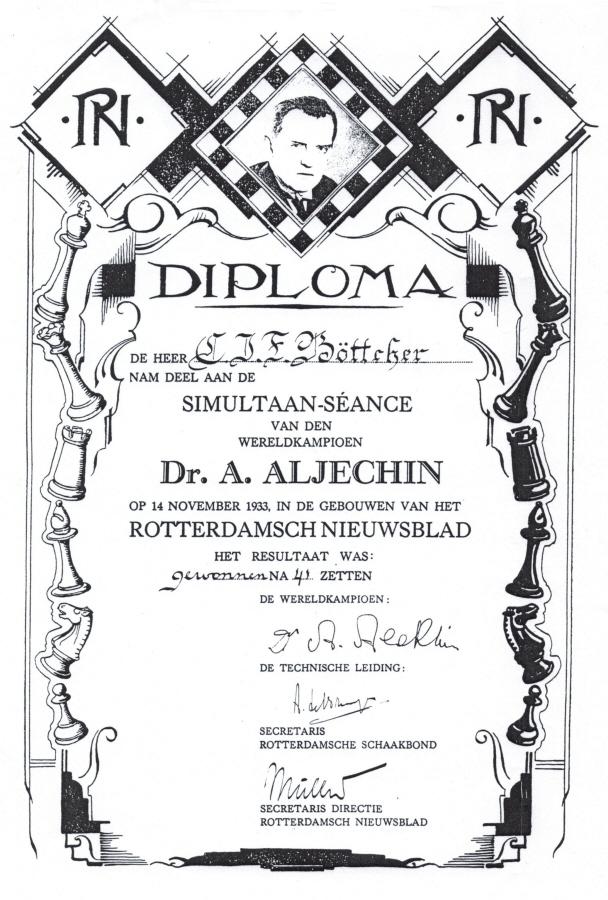

8292. Alekhine in Rotterdam, 1933

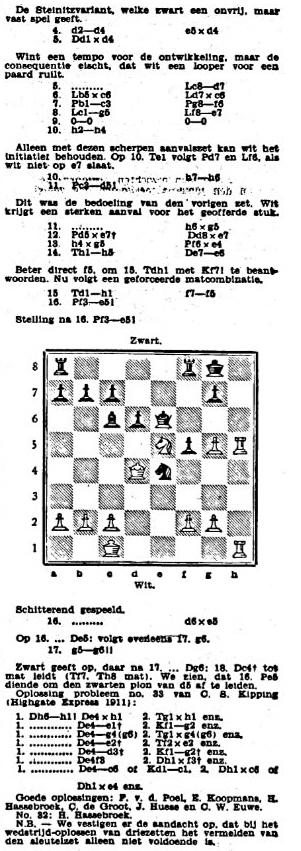

Harrie Grondijs (Rijswijk, the Netherlands) informs us that he recently acquired the score-sheet and certificate of C.J.F. Böttcher (1915-2008) for his victory over Alekhine in a 50-board simultaneous display:

Alexander Alekhine – Carl Johann Friedrich Böttcher

Rotterdam, 14 November 1933

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Nc3 d6 6 Bg5 e6 7 Bb5 Bd7 8 O-O Qb6 9 Be3 Qc7 10 f3 h5 11 Qd2 Be7 12 Rad1 a6 13 Be2 Ne5 14 Qc1 h4 15 f4 Neg4 16 Bxg4 Nxg4 17 h3 Nxe3 18 Qxe3 Qb6 19 Rf3 Rc8 20 b3

20...e5 21 fxe5 dxe5 22 Nd5 exd4 23 Qf4 Qg6 24 Qe5 Qd6 25 Qxg7 Rf8 26 Rxd4 Rxc2 27 e5 Qc5 28 e6

28...Rc1+ 29 Kh2 Bd6+ 30 Nf4 Bxe6 31 b4 Bxf4+ 32 Rfxf4 Qc7 33 Qf6 Qe7 34 Qe5 Rg8 35 Rfe4 Rc2 36 Qb8+ Rc8 37 Qe5 Qg5 38 Qxg5 Rxg5 39 Rxh4 Rc2 40 Rd1 Rgxg2+ 41 Kh1 Rh2+ 42 White resigns.

8293. Penalty moves (C.N.s 5381, 5384 & 5435)

Mike Forster (Horsham, England) reverts to the topic of

penalty moves, mentioning the well-known story about an

endgame in which Rubinstein allegedly sealed an

intentionally incorrect move, Kc2-c7.

The topic was discussed in C.N.s 903 and 956 (see pages 189-190 of Chess Explorations), and here we add pages 242-243 of Goldene Schachzeiten by Milan Vidmar (Berlin, 1961). It will be noted that, despite the length of the passage, Vidmar could not give particulars.

On page 502 of the September 1976 Chess Life & Review Tim Krabbé referred to Vidmar’s account, and his next paragraph turned to Breyer v Esser, Budapest, 1917, with a suggestion that White craftily touched his unmovable queen’s rook so as to be ‘forced’ to play a brilliant king move (14 Kf1). However, that was all related by Krabbé merely on a ‘the story has it that ...’ basis.

8294. Simultaneous display in Newcastle

From page 2 of the Newcastle Courant, 24 November 1894:

Joseph Henry Blackburne – H.W. Hawks

Newcastle, 13 or 14 November 1894

Vienna Gambit

1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Nf6 3 f4 d5 4 d3 Bb4 5 fxe5 Nxe4 6 dxe4 Qh4+ 7 Ke2 Bg4+ 8 Nf3 Bxc3 9 bxc3 dxe4 10 Qd4 Bh5 11 Ke3 Bxf3 12 Bb5+ c6 13 gxf3 cxb5 14 Qxe4 Qxe4+ 15 Kxe4 Nc6

16 Rg1 g6 17 Bg5 O-O 18 Bf6 Rac8 19 Rad1 Na5 20 Rd3 Rc4+ 21 Ke3 Rfc8 22 Rgd1 Rxc3 23 Rxc3 Rxc3+ 24 Kd2 Rc8 25 Kc1 h5 26 Rd7 Kf8 27 f4 Ke8 28 Re7+ Kf8 29 Rd7 Ke8 30 Rd5 a6 31 a4 Nc4 32 axb5 Ne3 33 Rd6 axb5 34 Rb6 Rxc2+ 35 Kb1 Rb2+ 36 Ka1 Nc4 37 Rxb7 Rxh2 38 Rxb5 Kd7 39 Rb7+ Ke6 40 Re7+ Kf5 41 Rxf7 Kxf4 42 e6 Rh1+ 43 Ka2 Rh2+ 44 Kb3 Na5+ 45 Ka4 (‘Mr Blackburne was pleased with this curious ending, and after playing it over to a number of amateurs he recommended it for publication.’) 45...Re2 46 e7 Nc6

47 Be5+ Kg5 48 e8(Q) Nxe5 49 Qd8+ Kh6 50 Re7 Re4+ 51 Kb3

51...Rb4+ 52 Ka3 Nc6 53 Qd2+ g5 54 Qd6 mate.

8295. Berger v Wimmer

Johann Berger – A. Wimmer

Austria, circa November 1894

King’s Gambit Accepted

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Bc4 d5 4 Bxd5 Qh4+ 5 Kf1 g5 6 Qf3 c6 7 Qc3 f6 8 d4 a5 9 a3

9...Bb4 10 axb4 axb4 11 Rxa8 bxc3 12 Nf3 cxb2 13 Bxb2 Qh5 14 Rxb8 cxd5 15 Rxc8+ Kd7 16 Rxg8 Rxg8 17 Nc3 dxe4 18 Nxe4 Qg6 19 Nc5+ Kc6 20 Nd3 Kd5 21 Kf2 Re8 22 Ra1 b5 23 Ra6 Qf5 24 Nb4+ Kc4

25 Nd2+ Kxb4 26 c3 mate.

Source: Newcastle Courant, 1 December 1894, page 2.

Can further information about this game be found?

8296. Charousek and the Handbuch

From page 260 of the October 1897 American Chess Magazine, in a report on that year’s international tournament in Berlin:

‘Charousek possesses indomitable courage, of which it is said he gave evidence while he was learning chess. Unable to procure the German Handbuch during his college days, he borrowed one and copied it – to those who are acquainted with the magnitude of that monument of German industry his task will be apparent.’

Page xix of Charousek’s Games of Chess by P.W. Sergeant (London, 1919) quoted from Armin Friedmann in Pester Lloyd, 20 June 1898:

‘At Kaschau he copied out Bilguer’s gigantic compendium, because of his pecuniary inability to secure the work.’

On page 11 of Chess Comet Charousek (Unterhaching, 1997) Victor A. Charuchin stated that after Charousek finished high school his mother gave him the sixth edition of the Handbuch.

There was a contribution on this subject by Ton Sibbing in K. Whyld’s ‘Quotes and Queries’ column on page 218 of the April 1997 BCM. It indicated that Charousek was given the Handbuch by his mother and that he copied some chapters, according to a letter written to a friend on 19 November 1891. The BCM item referred to ‘an unpublished biography (including 359 games), written in English by two Dutchmen, Marten [sic] de Zeeuw and the late Menno Ploeger’.

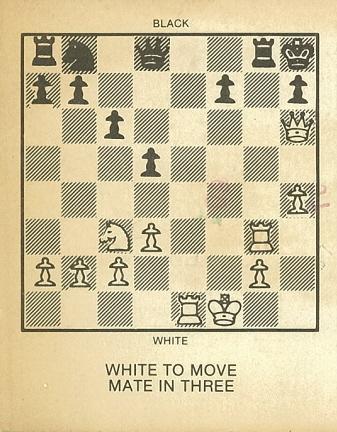

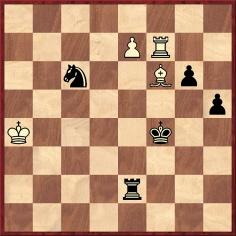

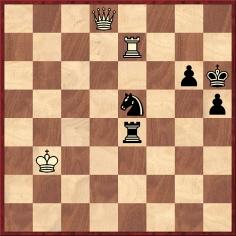

8297. USCF postcard (C.N. 8277)

Below are both positions on the United States Chess Federation postcard submitted by Rick Massimo (Providence, RI, USA):

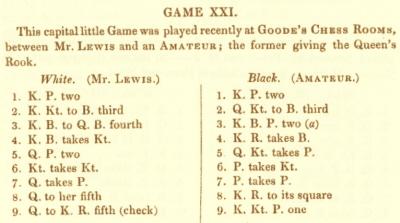

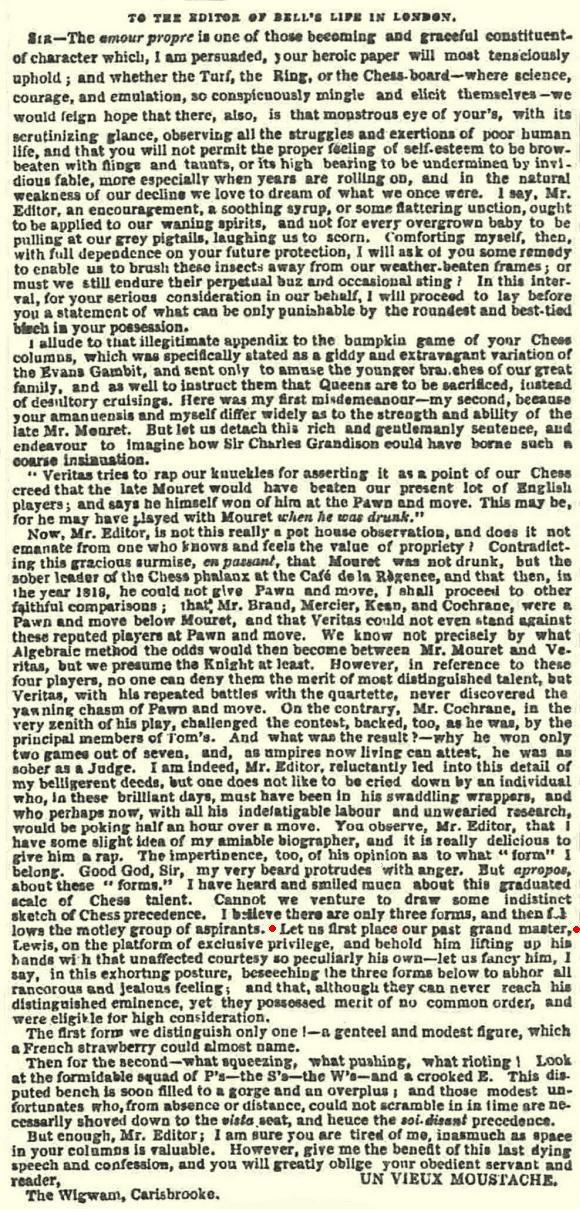

The second diagram shows the conclusion of a game won by William Lewis against an unnamed opponent. It is generally said to have been played in London in 1840; see, for instance, pages 145-146 of 200 Miniature Games of Chess by J. du Mont (London, 1941). When published on pages 68-69 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1841 the game was merely described as ‘played recently’:

The opening 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 f5 4 Bxg8 was discussed by Lewis on pages 124-125 of A Treatise on the Game of Chess (London, 1844).

8298. Past grand master

Following publication of the first edition of the Oxford Companion to Chess by David Hooper and Kenneth Whyld (Oxford, 1984), C.N. 848 quoted from the entry on ‘Grandmaster’ (page 132):

‘A correspondent writing to Bell’s Life 18 Feb. 1838 refers to Lewis as “our past grand master”, probably the first use of this term in connection with chess.’

On page 156 of the second edition of the Companion (Oxford, 1992) ‘grand master’ was changed, incorrectly, to ‘grandmaster’.

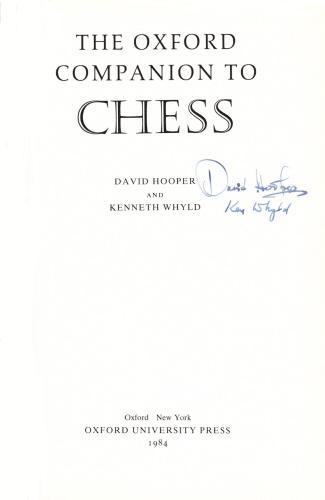

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) provides the full letter, from page 4 of the 18 February 1838 issue of Bell’s Life and Sporting Chronicle, contributed by ‘Un vieux moustache, The Wigwam, Carisbrooke’:

The relevant passage:

‘I have heard and smiled much about this graduated scale of Chess talent. Cannot we venture to draw some indistinct sketch of Chess precedence. I believe there are only three forms, and then follows the motley group of aspirants. Let us first place our past grand master, Lewis, on the platform of exclusive privilege, and behold him lifting up his hands with that unaffected courtesy so peculiarly his own – let us fancy him, I say, in this exhorting posture, beseeching the three forms below to abhor all rancorous and jealous feeling; and that, although they can never reach his distinguished eminence, yet they possessed merit of no common order, and were eligible for high consideration.’

See too our latest feature article, Chess Grandmasters.

William Lewis (detail from opposite page 197 of the New York, 1859 edition of F.M. Edge’s book on Morphy)

There have come to light no pre-1838 occurrences of the

term ‘grand master’ or ‘grandmaster’ in a chess context,

or any pre-1984 mentions of the Bell’s Life citation.

The

Companion should thus continue to receive full

credit for a significant discovery, and no honest writer

would hesitate to give such credit.

Under the title ‘Grandmasterly research’ Raymond Keene wrote on page 5 of The Times, 7 November 1994 about claims that the grandmaster title was created by Tsar Nicholas II at St Petersburg, 1914, and he then added:

‘Following up a clue from the Oxford Companion to Chess, Barry Martin, chess captain of the Chelsea Arts Club, has now demonstrated that the term is considerably older.

Martin’s research shows that in Bells Life [sic], a popular Sunday paper, of February 18, 1838, a leading British player, William Lewis, is referred to as “our past grandmaster” [sic]. Here is a sample of play by the man whom the latest research indicates to have been the first player described as a grandmaster in print.’

Barry Martin had not demonstrated or researched anything. In an article about Staunton in the October 1994 CHESS he had merely given the Bell’s Life quote about Lewis (see page 34), without bothering to acknowledge that it had been published by the Companion a decade previously. Nor was the Companion credited when Martin’s article was reproduced on pages 191-201 of Staunton’s City by Raymond Keene and Barry Martin (Aylesbeare, 2004).

It is also worth dwelling on Keene’s deceitful introductory words in The Times:

‘Following up a clue from the Oxford Companion to Chess, Barry Martin ... has now demonstrated ...’

The Companion did not supply ‘a clue’. It supplied the exact relevant text supported by a precisely dated reference.

Worse was to follow. On page 100 of The Spectator, 4 July 1998 Keene made no mention of the Companion and affirmed flatly:

‘Lewis, according to research by Barry Martin, the secretary of the Staunton Society, was the first player to be described as a grandmaster.’

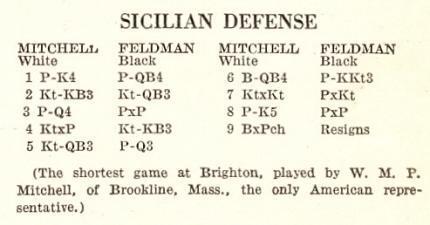

8299. Donner

It is possible to find Donner referred to as Hein, Jan

Hein, Jan-Hein, Jan H., J. Hein, H., J., J.H., Johannes

Hendrikus and perhaps other variants too.

Which version or versions should be preferred, and which are simply wrong?

8300. Lacking the Master Touch

It is hoped that a publisher will re-issue Lacking the Master Touch by Wolfgang Heidenfeld (Cape Town, 1970). It received an elegant, perceptive review from W.H. Cozens on pages 101-102 of the March 1972 BCM:

‘His personality comes out in his selection of games. He is a fighter. He gives us no brevities against pushover opposition, but hard-fought wins, some hard-fought draws and a few hard-fought losses. The spread of the games – 50 to cover a playing career of 40 years – is a guarantee of their quality; not that they are all deadly serious. One at least (Roele, 1954) is comical: the dénouement must be seen to be believed.

... The notes are ample, the 50 games occupying 100 double-column pages. Heidenfeld writes with a disarming openness, admitting his indecisions, his difficulties, his wrong judgements; never claiming to know all the answers. His notes show “how difficult chess is – not how easy it can be made to look”.’

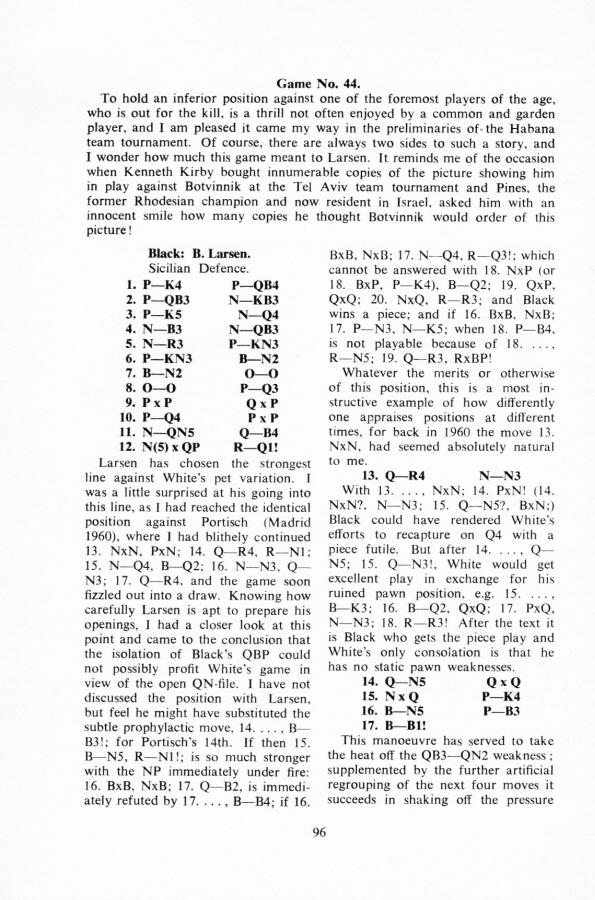

The book has Heidenfeld’s wins over Euwe and Najdorf, and the draws include Game 44, against Larsen (Havana, 1966). Below is the first page of his annotations:

Regarding the photograph reference in Heidenfeld’s introduction to the game, K.F. Kirby told the story against himself on page 72 of the May 1984 South African Chessplayer after annotating his game against Botvinnik:

‘Photographs of almost all the games were daily offered for sale by the Israeli photographers, and I lost no time in ordering half a dozen copies of Kirby v Botvinnik. It was Mike Pines who rather brought me down to earth when, with his mischievous smile, he said he wondered how many copies Botvinnik had ordered.’

8301. Alekhine and cats (C.N.s 4794 & 5575)

José Fernando Blanco (Madrid) enquires about reports that Alekhine had feline company at the board during his 1935 world championship match against Euwe.

The most direct evidence that we can quote is Euwe’s comment in an interview with Pal Benko on page 411 of the August 1978 Chess Life & Review:

‘Alekhine was very superstitious. He had a Siamese cat, and sometimes before a game he would put the cat on the chessboard to smell it. He could not play with the cat in his lap, so he wore a sweater with the cat’s picture on it. These things did not disturb me in the first match in 1935. Either Alekhine was not normal or the rest of us are not normal. Anyway, the fact that such a great player as Alekhine needed little tricks like that gave me encouragement.’

8302. Jacob Bronowski

Two more games have been found by Alan Smith (Stockport, England):

Jacob Bronowski – Arnold Yorwarth Green

Yorkshire Championship (final), 1935-36

Queen’s Gambit Declined

1 d4 d5 2 c4 c6 3 Nf3 Nf6 4 Nc3 Bf5 5 cxd5 cxd5 6 Qb3 Qb6 7 Nxd5 Qxb3 8 Nxf6+ exf6 9 axb3 Nc6 10 e3 Nb4 11 Bb5+ Kd8 12 O-O Nc2

13 Ra4 Bd6 14 Bd2 Ke7 15 Rc1 a6 16 Be2 b5 17 Ra5 Rhc8 18 Bd1 Bb4 19 Bxc2 Bxd2 20 Nxd2 Bxc2 21 f3 Bd3 22 Raa1 f5 23 b4 h5 24 Rc5 Kd6 25 Rac1 Rxc5 26 bxc5+ Kd5 27 Rc3 Bc4 28 b3 Be2 29 Kf2 b4 30 Rc1 Bd3 31 Nc4 Bxc4 32 Rxc4 a5 33 Rc2 a4 34 bxa4 b3 35 Rc3 Rb8 36 Rc1 f4 37 Rb1 b2 38 a5 Kc4 39 c6 fxe3+ 40 Kxe3 Kc3 41 d5 Resigns.

Source: Staffordshire Advertiser, 6 June 1936.

Jacob Bronowski – Reginald Joseph Broadbent

Hull v Bradford match, Hull, 21 January 1939

Dutch Defence

1 d4 e6 2 Nf3 f5 3 g3 Nf6 4 Bg2 Be7 5 O-O O-O 6 b3 d5 7 Ne5 b6 8 Bb2 Bb7 9 Nc3 Nbd7 10 e3 c5 11 Ne2 Bd6 12 Nf4 Qe7 13 c4 Rad8 14 cxd5 exd5 15 Nxd7 Qxd7 16 dxc5 Bxf4 17 c6 Bxc6 18 gxf4 Ne4 19 Rc1 Qe6 20 Qd4 Rf6 21 f3 Nc5

22 e4 Rg6 23 b4 Na4 24 exf5 Qxf5 25 Rxc6 Nxb2 26 Rxg6 hxg6 27 Qxb2 Resigns.

Source: Observer, 5 February 1939, page 21.

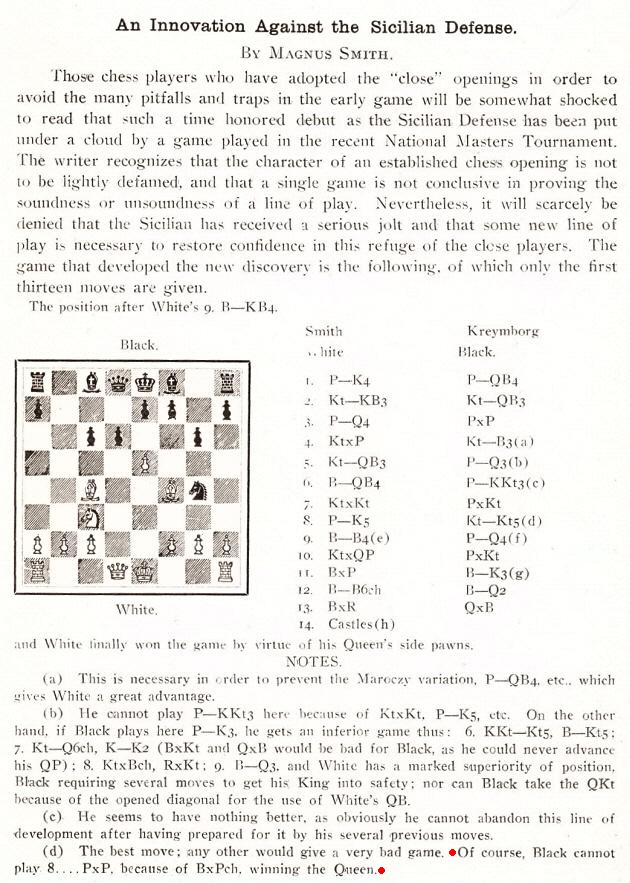

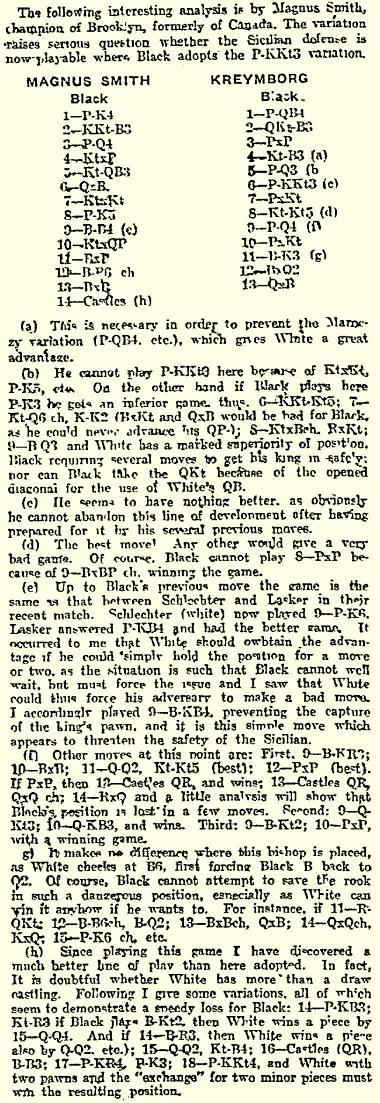

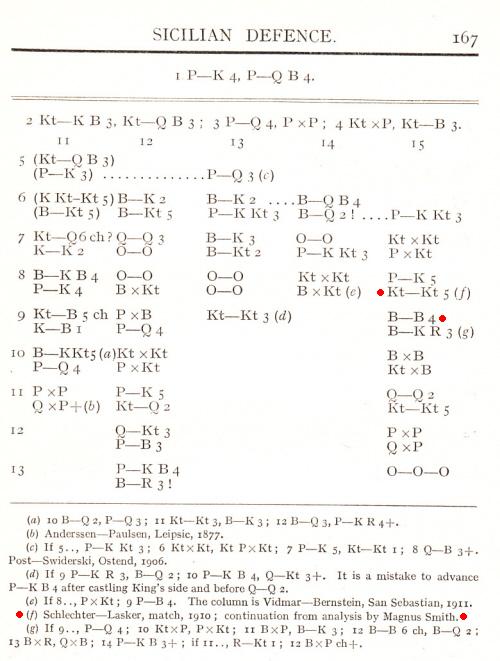

8303. Magnus Smith

Stephen Wright (Vancouver, Canada) asks why the moves 1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 d6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Nc3 Nc6 6 Bc4 g6 7 Nxc6 bxc6 8 e5 (8...dxe5 9 Bxf7+) are regularly referred to as the ‘Magnus Smith Trap’. He has been unable to find any game or analysis by Smith with that line.

We believe that ‘Magnus Smith Trap’ is a misnomer,

although in the Sicilian Defence there is a ‘Magnus

Smith Variation’ (a very rare instance of a player’s

forename and surname being used jointly in openings

terminology).

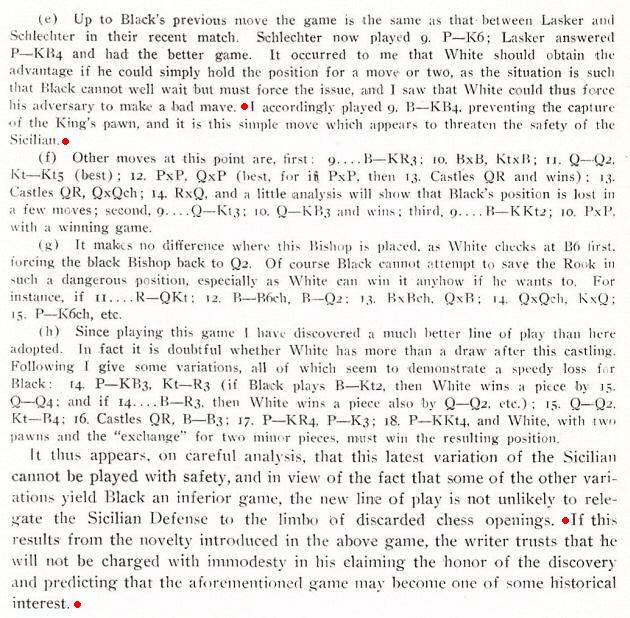

The bare score of his game against A. Kreymborg in round six of the New York, 1911 tournament, a win in 49 moves, was published on page 59 of the March 1911 American Chess Bulletin, and on pages 62-63 of the same issue he contributed an article entitled ‘An Innovation Against the Sicilian Defense’:

Although the line 8...dxe5 9 Bxf7+ was mentioned, in note (d), Magnus Smith’s innovation was 9 Bf4, proposed as an improvement over 9 e6, which Schlechter had played in his seventh match-game against Lasker the previous year.

The above analysis by Smith was also published on page 6 of the Philadelphia Inquirer (magazine section), 26 February 1911:

Annotating the game Lawrence v Fox in the United States v Great Britain cable match, Hermann Helms wrote on page 1 of the sports section of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 4 May 1911 and on page 129 of the June 1911 American Chess Bulletin:

‘Evidently leading up to the Magnus Smith variation, which continues as follows: 6 B-QB4 P-KKt3 7 KtxKt PxKt 8 P-K5 Kt-Kt5 9 B-B4 P-Q4 10 KtxQP PxKt 11 BxP, etc. The subsequent play, which yields a win for White, was analyzed exhaustively by Mr Smith in the March number of the American Chess Bulletin.’

Magnus Smith was mentioned for 9 Bf4 on page 167 of Modern Chess Openings by R.C. Griffith and J.H. White (London, 1913):

The term ‘Magnus-Smith variation’ for lines beginning with 9 Bf4 was used on, for instance, page 168 of the April 1927 BCM, as well as by W. Winter on page 76 of Kings of Chess (London, 1954) in his notes to the above-mentioned Schlechter v Lasker game.

A photograph of Magnus Smith, from page 251 of the December 1906 American Chess Bulletin is given in The Capablanca-Pokorny Fiasco. The portrait below comes from page 514 of the June 1899 American Chess Magazine:

Magnus Smith

The possibility of 8 e5 dxe5 9 Bxf7+ had been referred to in print when Magnus Smith was 12 years old, on page 175 of La Stratégie, 15 June 1882, in a note to Blackburne v Paulsen, Vienna, 1882 (where the moves 8 e5 Ng4 were played).

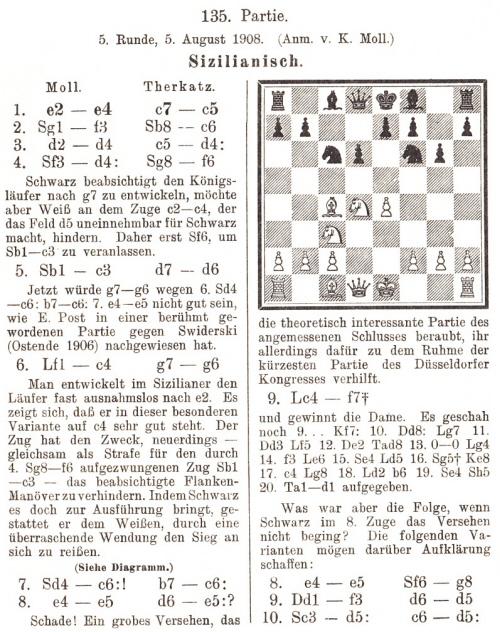

A game in which 8 e5 dxe5 occurred, and which predates Magnus Smith’s article, is K. Moll v W. Therkatz, Düsseldorf, 1908, as published on pages 150-151 of the tournament book:

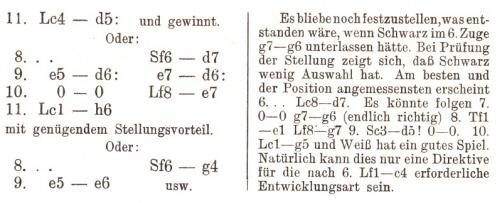

To quote one later case, Mitchell v Feldman, Brighton, 1938 was published on page 85 of the July-August 1938 American Chess Bulletin:

W.M.P. Mitchell and S. Feldman were participants in the

First Class B tournament of the British Chess Federation

Congress in Brighton (BCM, September 1938, page

418). As demonstrated in the present item, it would not be

justified to describe their game as featuring the ‘Magnus

Smith Trap’, but when was that term first used in print?

All bids will be welcome.

8304. Donner (C.N. 8299)

Thomas Niessen (Aachen, Germany) quotes from page 308 of The King by J.H. Donner (Alkmaar, 2006), at the end of a review originally published in Schaakbulletin, March 1979:

‘PS. In both books a “grandmaster Jan Hein Donner” appears on occasion, sometimes referred to as “our Jan Hein”. I’d like to point out that my name is: J.H. Donner, to my few friends: Hein. “Jan Hein”, however, I am not, have never been and wouldn’t want to be either.’

Even so:

Source: page xviii of Second Piatigorsky Cup (published by the Ward Ritchie Press, Los Angeles, 1968).

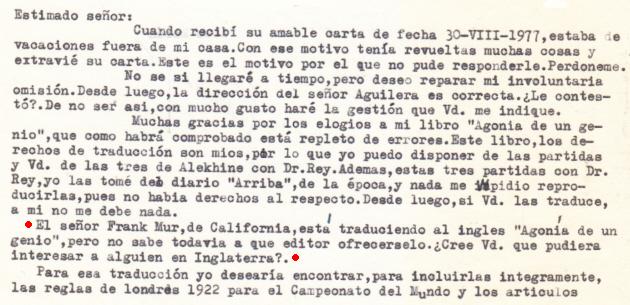

8305. Pablo Morán’s library (C.N. 4393)

Denis Teyssou (Paris) reports that a record of Pablo Morán’s chess library, held at the Biblioteca Provincial de Asturias ‘Ramón Pérez de Ayala’ in Oviedo, can be consulted online (1,246 books and magazines, but no private archives). It is necessary to a) click on ‘Aquí’, b) click on ‘Consultar el catálogo’, c) in the ‘Buscando en’ option, select ‘Bca. de Pablo Morán’, d) type ajedrez in the box labelled ‘Materia’ and e) click on ‘Buscar’.

Pablo Morán’s best-known book is his monograph on Alekhine, of which an English edition, edited and translated by Frank X. Mur, was published by McFarland & Company, Inc. in 1989. It was released in paperback in 2010:

The English translation was a long-term project, as is shown by a letter to us from Pablo Morán in September 1977:

8306. Fischer v Reshevsky

Concerning game 26 in Fischer’s My 60 Memorable Games (New York, 1969), Stuart Rachels (Tuscaloosa, AL, USA) notes that after 1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 g6 5 Nc3 Bg7 6 Be3 Nf6 7 Be2 Fischer wrote on pages 161-162:

‘In the 4th and 6th games of the match [against Reshevsky in 1961] I continued with 7 B-QB4 O-O 8 B-N3 N-KN5 [...] 9 QxN NxN and White got a clear advantage both with 10 Q-R4 and 10 Q-Q1, respectively.’

Position after 9...Nxd4

Mr Rachels points out that, given the play in the fourth and sixth match-games, this note should read ‘with 10 Q-Q1 and 10 Q-R4, respectively’. Moreover, he considers that after the latter move White has only a tiny advantage.

My 61 Memorable Games (pages 295-296) included additional material, of unestablished provenance, as shown in our feature article.

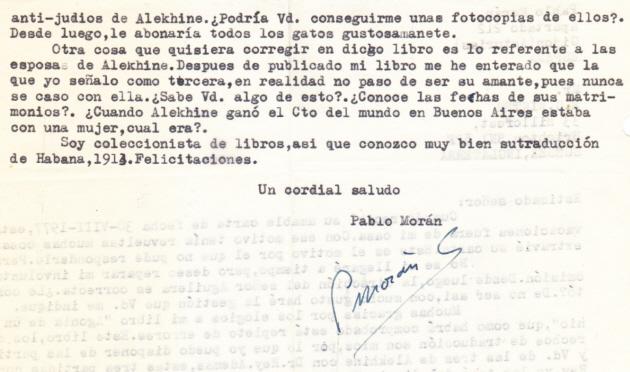

8307. Cartoon

Source: American Chess Bulletin, November 1918, page 234. The item came from the Evening World, 23 September 1918 and concerned a meeting of the Correspondence Chess League of America.

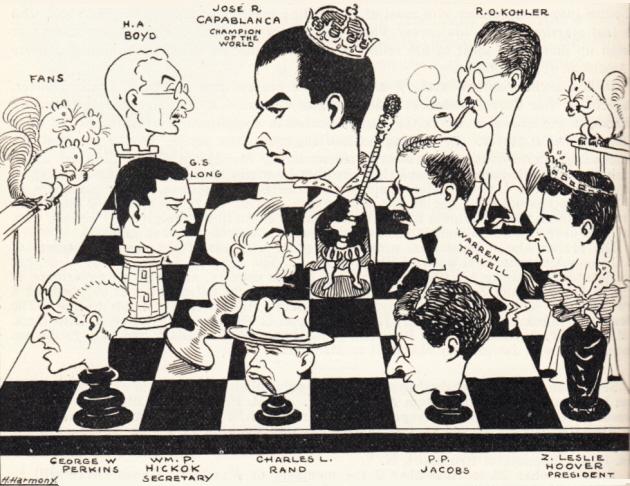

8308. ‘News’

From pages 84-85 of The Fireside Book of Chess by I. Chernev and F. Reinfeld (New York, 1949):

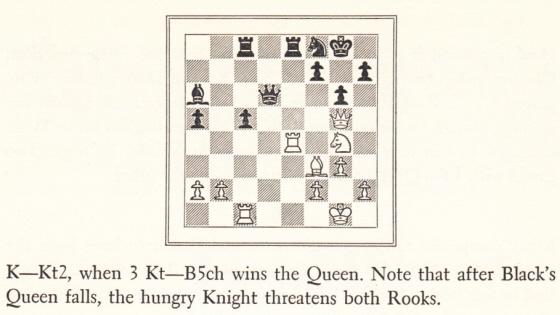

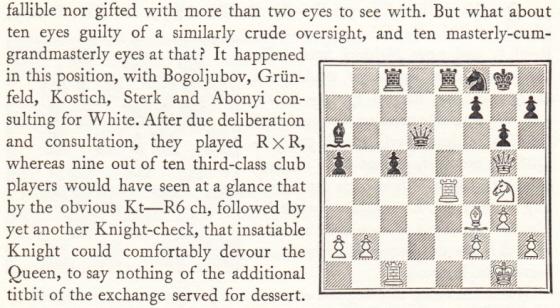

From page 30 of The Delights of Chess by Assiac (London, 1960):

Both books omitted to identify the venue, date and opposing side, yet they contradict each other as to whether Bogoljubow and his allies played White or Black, and whether the move was ...Rxe4 or Rxe8. Chernev and Reinfeld were correct on both points.

Bogoljubow and his allies had Black against Alekhine, Sämisch, Steiner, Tartakower and Vajda. The game took place in Budapest on 20 September 1921 and was published on pages 1-4 of the January 1922 issue of Kagans Neueste Schachnachrichten. The magazine reported that the rate of play was 20 moves per hour and that the Black allies were in time-trouble when they blundered with 32...Rxe4.

The full score is on pages 146-147 of Alexander Alekhine’s Chess Games, 1902-1946 by L. Skinner and R. Verhoeven (Jefferson, 1998).

8309. Columnists

C.N. 2331 (see page 157 of A Chess Omnibus) commented:

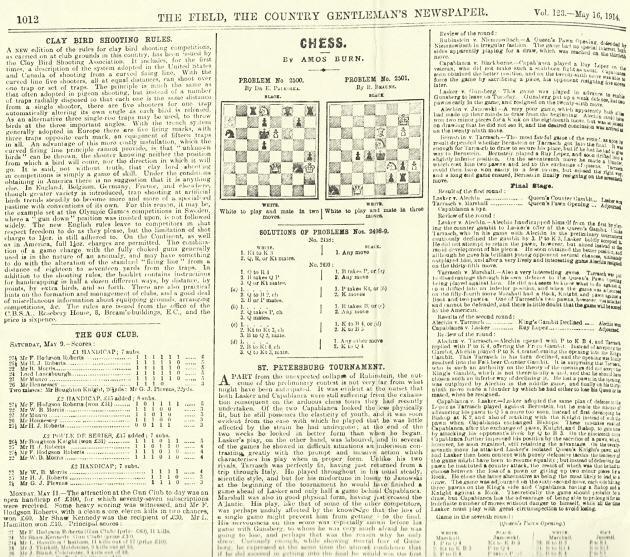

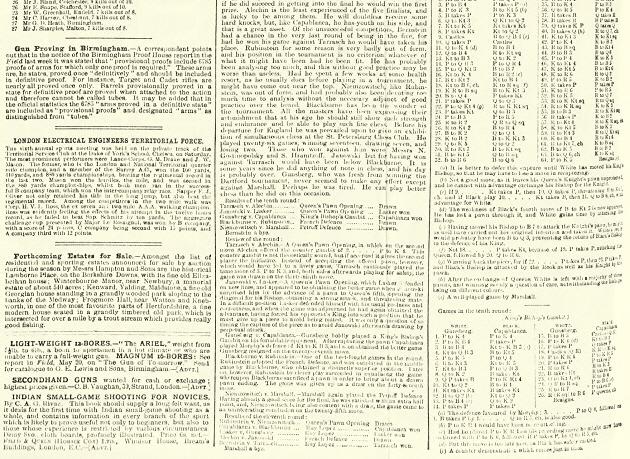

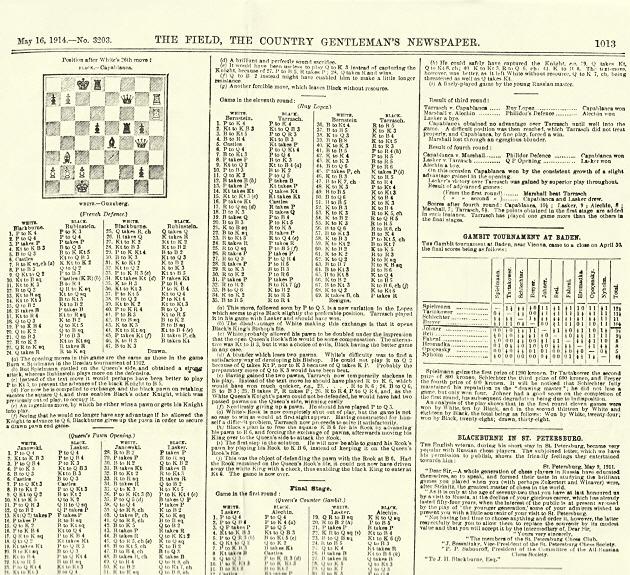

Some of today’s chess reporters may care to note how much work Amos Burn put into his weekly column in The Field. To take the 16 May 1914 issue (pages 1012-1013) as an example, the Englishman presented:

Two problems; the solutions to two previous compositions; a lengthy report (over 200 lines) on St Petersburg, 1914, including round-by-round results; eight annotated games from the tournament; an update on results (up to 14 May); a brief report on the Gambit Tournament in Baden, with the crosstable; a feature on Blackburne in Russia, with the text of a testimonial letter to him from the St Petersburg Chess Club; a replies-to-correspondents section (five items). Elsewhere in that issue of The Field was a portrait of the St Petersburg competitors and officials.

Burn’s column (actually five long columns, taking up nearly two pages of the magazine) puts to shame the ‘work’ of most modern chess journalists.

At the time, our item did not show Burn’s column, but we do so now:

Far from envying Burn, a chess columnist today should be grateful for having infinitely less space to fill if he cannot, even in far smaller quantities, produce worthwhile, original material.

In such a case, the solution should be obvious ...

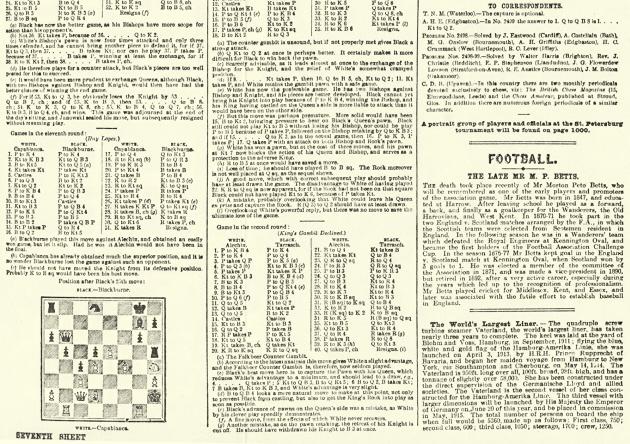

8310. A holiday from The Times

This feature was published in The Times on page 9 of the 6 June 1975 edition, and on many occasions subsequently. The competition diagram also appeared on posters at, for instance, London underground stations. The winner, P.F. Copping, was announced on page 4 of The Times, 7 February 1976, and the contest was discussed on pages 302-303 of the February 1976 issue of EG.

Harry Golombek wrote a lengthy article, ‘A Successful Experiment’, on pages 168-171 of the April 1976 BCM, and on page 170 he reported:

‘The set position was the finish of a game played at Smolensk in 1950 between Jesierski (White) and Lelczuk.’

In a database we note a game (1 e4 e5 2 f4 Nc6 3 Nf3 d6 4 fxe5 Nxe5 5 d4 Ng6 6 Bc4 Be7 7 O-O Nf6 8 Nc3 O-O 9 Qe1 Re8 10 Ng5 d5 11 Nxd5 Nxd5 12 Bxd5 Bxg5 13 Bxf7+ Kh8 14 Bxe8 Bxc1 15 Bxg6 Bxb2 16 Qh4 Qxh4 17 Rf8 mate) which is labelled Jezierski v Lelczuk, Smolensk, 1953. On pages 85-86 of Test Your Chess IQ: Book 2 by A. Livshitz (Oxford, 1981) the position appeared as Ezersky v Lelchuk, Smolensk, 1950.

Is it possible to find the game in a publication from the 1950s?

8311. Livshits

Wanted: a brief biographical note on A. Livshits, the author of the two volumes of Test Your Chess IQ (Oxford, 1981). His forename was given as August on the title pages of the second editions (Oxford, 1988 and 1989).

8312. Donner (C.N.s 8299 & 8304)

From Wijnand Engelkes (Zeist, the Netherlands):

‘The Dutch are extremely flexible with first names. Johannes is often abbreviated to Jan, Johan, Jo, John, Han, Hans or Hannes. Hendrikus can be abbreviated to Hendrik or Henk.

Donner was very consistent in being inconsistent. On page 25 of his book De Nederlander en andere korte verhalen (Amsterdam and Antwerp, 1974) he referred to himself as Jan Hein:

“Dat is een verdriet dat alleen wij kunnen begrijpen, wij Ton Sijbrands en Achilles, Patroclos en Harm Wiersma en ook Jan Hein Donner.”

[“That is a tragedy which only we can understand, we Ton Sijbrands and Achilles, Patroclos and Harm Wiersma and also Jan Hein Donner.”]

In Schaakbulletin, April 1972 Donner wrote an article entitled “Johannes Donner” which discussed a game with Quinteros, during which there was a power failure just after Quinteros had overlooked an easy win. The remainder of the game was postponed until ten o’clock in the evening:

“Het leek mij waarschijnlijk dat Quinteros voor tien uur ’s-avonds geheel andere plannen had dan het spelen van een partij schaak met Johannes Donner.”

[“It was highly likely, I thought, that Quinteros had completely different plans for ten o’clock that night than playing a game of chess against Johannes Donner.”]

This remark can be found on page 133 of the 2006 edition of his book The King.’

8313. Guinness World Records

The uncongenial annual task of reporting on Guinness World Records is upon us again. The 2014 edition (senselessly described on the front cover as ‘officially amazing’) has only three chess-related entries, the first of them on page 61:

‘Simultaneous blindfolded chess wins

In 1947, legendary chess player Miguel Najdorf (Argentina) took on 45 players, holding each game simultaneously in his head. Over 23 hr 25 min he won 39, drew four and lost two. Najdorf had been forced to leave his family in Poland at the start of World War II. All died in concentration camps, but Najdorf hoped that if he broke a record news might reach survivors. He was never contacted.’

Page 96 has a feature on ‘largest toys’ which shows a king 4 metres 46 high with a diameter of 1 metre 83 around the base (St Louis, MO, USA, 24 April 2012).

Finally, page 111 recounts a feat which seems readily beatable:

‘Mehak Gul (Pakistan) sorted a chess set into the opening set-up for a game in 45.48 seconds during the Punjab Youth Festival at Expo Centre Lahore in Pakistan, on 21 October 2012.’

Other achievements related on that same page include ‘Most toothpicks in a beard’, ‘Most mousetraps released on the tongue in one minute’, ‘Most underpants pulled on’, ‘Most rubber bands stretched over the face’ and ‘Longest time spinning a basketball on a toothbrush’.

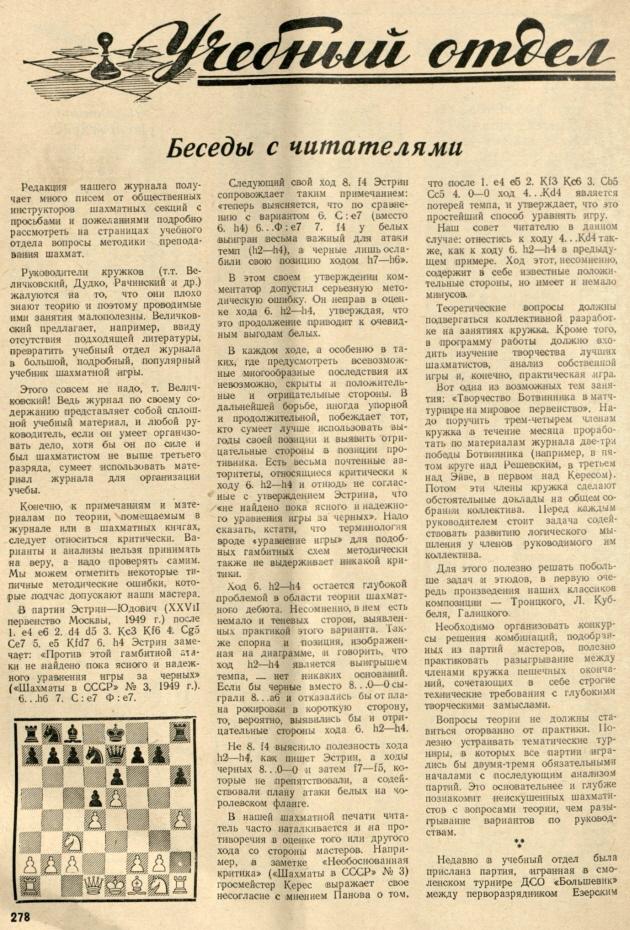

8314. A holiday from The Times (C.N. 8310)

Dan Scoones (Port Coquitlam, Canada) writes:

‘The game Ezersky v Lelchuk was published on page 279 of the 9/1950 issue of Shakhmaty v SSSR, in an article by Peter Romanovsky entitled “Dialogue with readers”. Ezersky, who had submitted the game for publication with his own comments, was identified as a first-category player, while Lelchuk was described as a second-category player. The Smolensk tournament was organized by the “Bolshevik” DSO (Voluntary Sports Society) and as such was intended for amateur players.

Romanovsky compared the finish of Ezersky v Lelchuk with the conclusion of the game Novotelnov v Rovner, 15th USSR Championship Semi-Final, Moscow, 1946, which also featured a deflection sacrifice.’

Romanovsky’s two-page article is given below, courtesy of the Cleveland Public Library:

8315. Donner and women

Alasdair Alexander (Dunfermline, Scotland) writes that he has been entertained by the views on women and chess in Donner’s The King (Alkmaar, 2006), e.g. the articles on pages 92-94, 151-152, 162-164, 256-257 and 278-280. Our correspondent quotes a line from page 280, at the end of an annotated game from the 1978 Dutch women’s championship:

‘A game as the one above can only be understood against the gigglingly nervous background – “we’re only girls, you know” – of women’s chess. It ought to be abolished.’

In the article on pages 162-164 Donner discussed the reaction to his view that ‘women cannot play chess’ (which he had expressed on the grounds, inter alia, ‘that women are much more stupid than men. And because they are much more stupid, they lack the ability to amuse themselves’):

‘I was even accused of racial discrimination. “Donner forgot to add blacks to his statement. It should read ‘women and blacks cannot play chess, because they are more stupid than we are’”, was foisted upon me by a lady of Amsterdam. This lady misunderstood. Black men can play chess all right, black women cannot. That is the whole point.’

That article was written in 1972. Mr Alexander observes that Donner adopted a different tone on pages 256-257 when writing about Nona Gaprindashvili after her performance at Lone Pine, 1977:

‘An unprecedented success for the women’s world champion and a severe blow for all those who, in the face of the rising mudslide of feminism, thought they had a final foothold in the conviction that women at least cannot play chess.

... There is no denying it any more: notions as to women’s physical or mental deficiency are as of now no longer based on fact. Even in the field of chess, there is at least one woman who rates as a world-class player. For inveterate masculinists and for those who must write jocular pieces to earn a living, this is a serious setback, which will naturally not prevent us in the least, for that matter, from continuing our courageous struggle unabatedly.’

8316. ‘I’d rather have a pawn than a finger’

A booklet not worth touching is Essential Chess Quotations by John C. Knudsen (Falls Church, 1998): about 40 pages of quotes; about five or six quotes per page; about sources – nothing.

The front cover highlights ‘“I’d rather have a pawn than a finger” – Reuben Fine’, an alleged remark which can be found, also devoid of specifics, on innumerable websites.

We note the following on pages 6-7 of the April 1944 Chess Review (in a report on that year’s US championship in New York):

8317. Parodying Harry Lauder

An odd suggestion about Dawid Janowsky by I.A. Horowitz on page 8 of Solitaire Chess (New York, 1962):

‘Parodying one of Harry Lauder’s songs, the Polish master averred: “I’d rather lose my queen than lose my bishop.”’

8318. Berger v Wimmer (C.N. 8295)

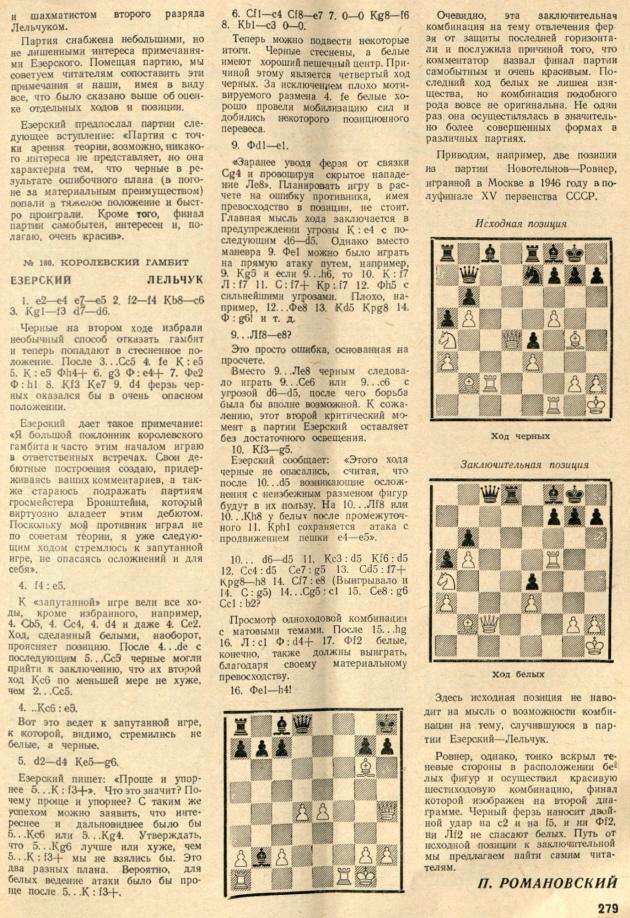

Alan Smith (Stockport, England) reports that the Berger v Wimmer game was played at the Graz Chess Club on 31 October 1894 and was annotated in Hoffer’s column in the Standard, 26 November 1894, page 7:

8319. Copying by Christian Hesse (C.N. 8276)

In 1899 George Alcock MacDonnell died, a fact which did not prevent Christian Hesse from stating in a ChessBase article that MacDonnell lost a game to Amos Burn in 1910 (see C.N. 8276). On page 183 of The Joys of Chess (Alkmaar, 2011) Hesse had been vaguer and therefore closer to the truth, White being identified only as ‘MacDonald’. He was Edmund E. Macdonald. (See, for instance, our feature article Macdonald v Burn, Liverpool, 1910.)

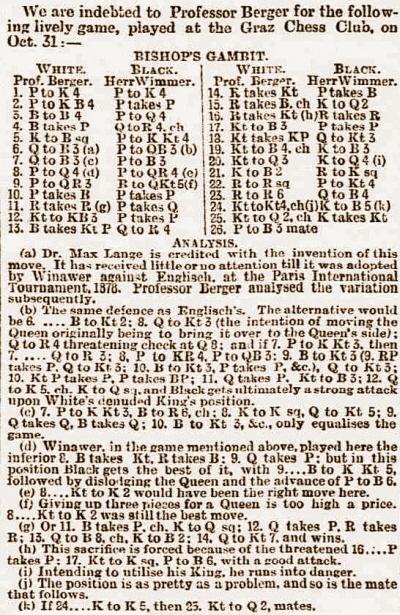

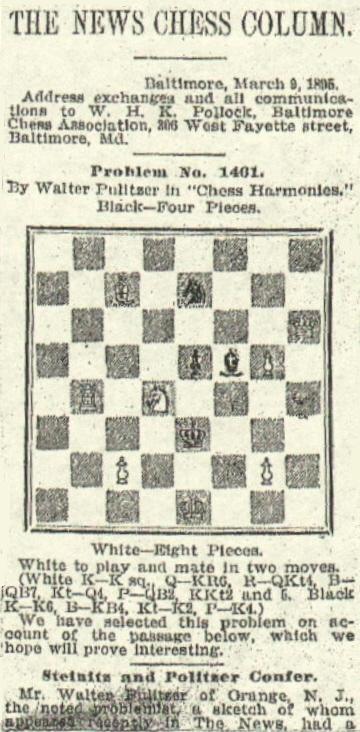

In 1900 Wilhelm/William Steinitz died, a fact which did not prevent Christian Hesse from quoting a remark by Steinitz about a mate-in-two problem by Pulitzer which, according to Hesse, was dated 1907. (See page 166 of The Joys of Chess.) Hesse miscopied from our presentation of the Pulitzer problem on page 11 of A Chess Omnibus (also included in Steinitz Stuck and Capa Caught). We gave Steinitz’s comments on the composition as quoted on page 60 of the Chess Player’s Scrap Book, April 1907, and that sufficed for Hesse to assume that the problem was composed in 1907.

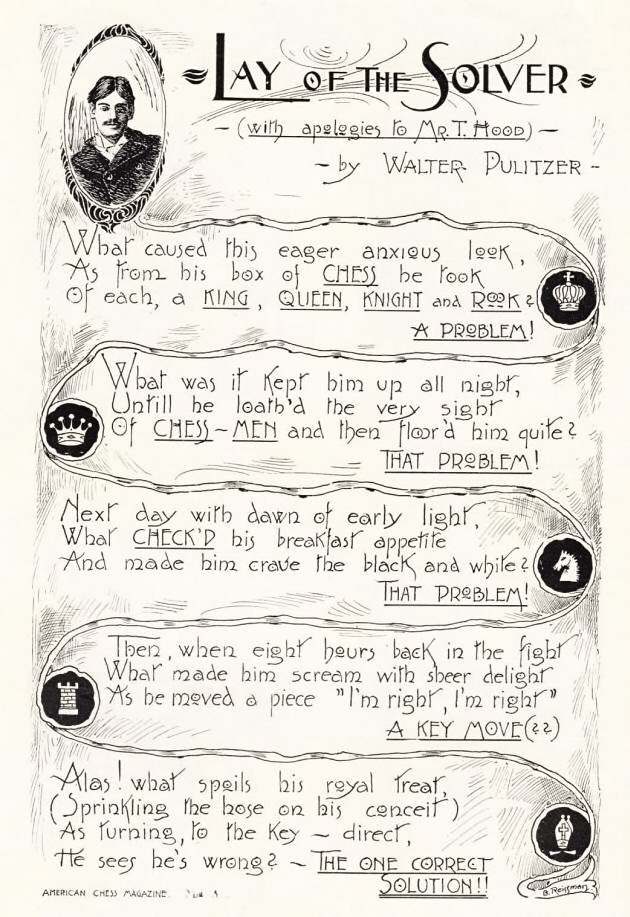

8320. Pulitzer’s problem

The problem discussed in the previous item is shown as it appeared on page 60 of the April 1907 issue of Emanuel Lasker’s magazine the Chess Player’s Scrap Book:

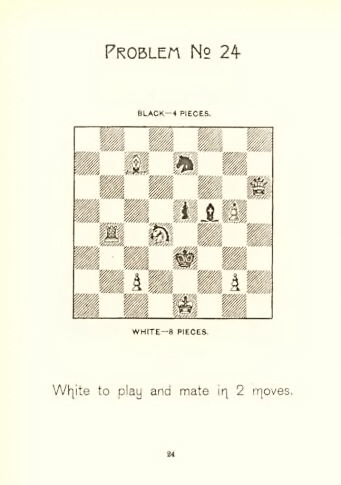

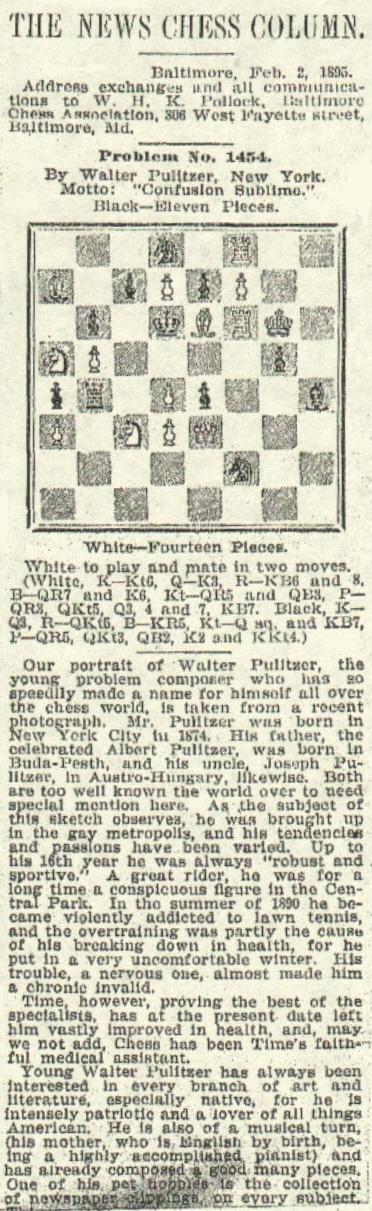

The composition had been published on page 24 of Chess Harmonies by Walter Pulitzer (New York, 1894):

The book said nothing else about the composition, apart from giving the key move (‘1 Q-KB6’) on page 107. It is uncertain whether the problem had been published before the appearance of Chess Harmonies, given that the Preface stated:

‘The collection embraces unpublished as well as published problems; but (as I have expressly followed no plan of classification throughout the whole work) I must leave it to the eagle eye of the practiced solver or composer to detect the former – for the most part, the more pretentious productions, composed most likely for tourney use, or some such design.’

We are grateful to Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) for investigating the background to Steinitz’s remarks about problem 24. He has found the following items in W.H.K. Pollock’s newspaper column:

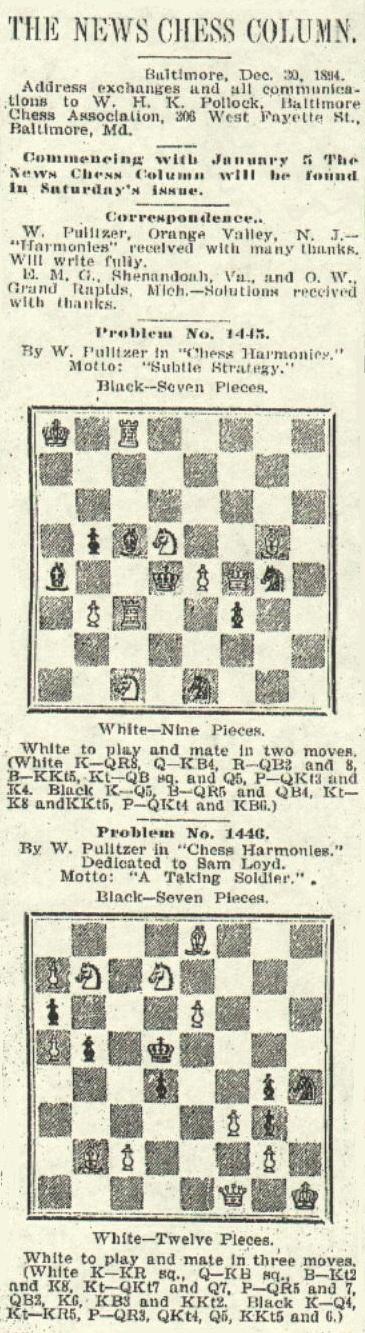

- Baltimore Sunday News, 30 December 1894 (review of Chess Harmonies with problems cited from the book):

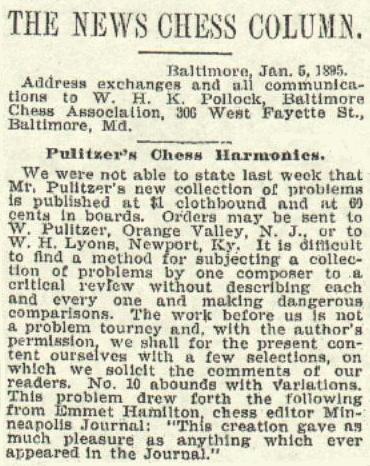

- Baltimore News, 5 January 1895 (further comments on Chess Harmonies):

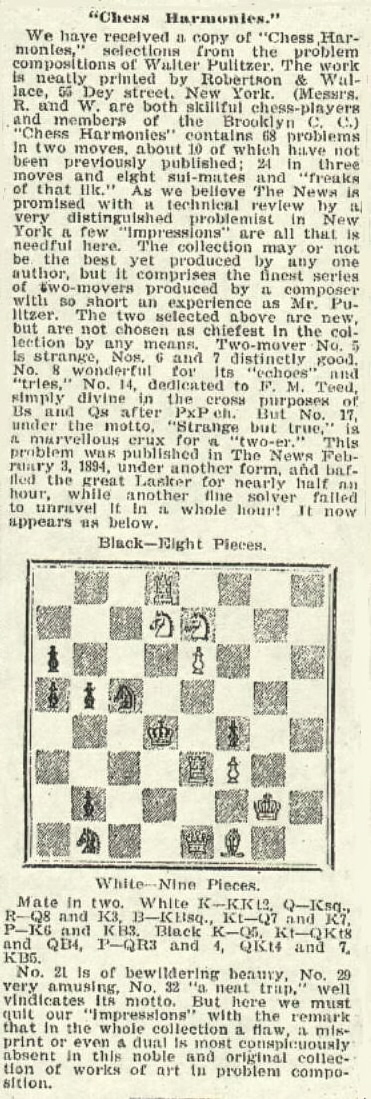

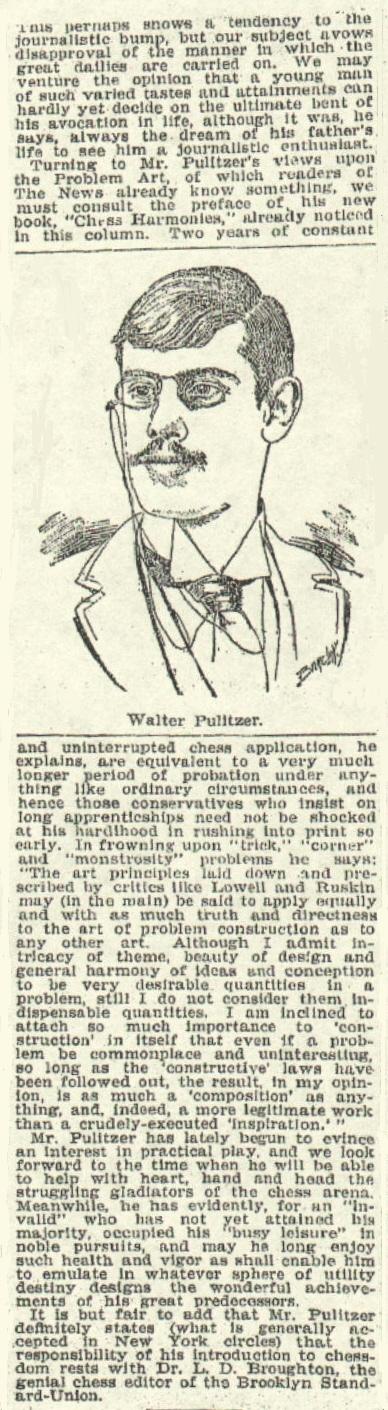

- Baltimore News, 2 February 1895 (a composition (problem 36) from Chess Harmonies and a biographical note on Pulitzer, including a sketch):

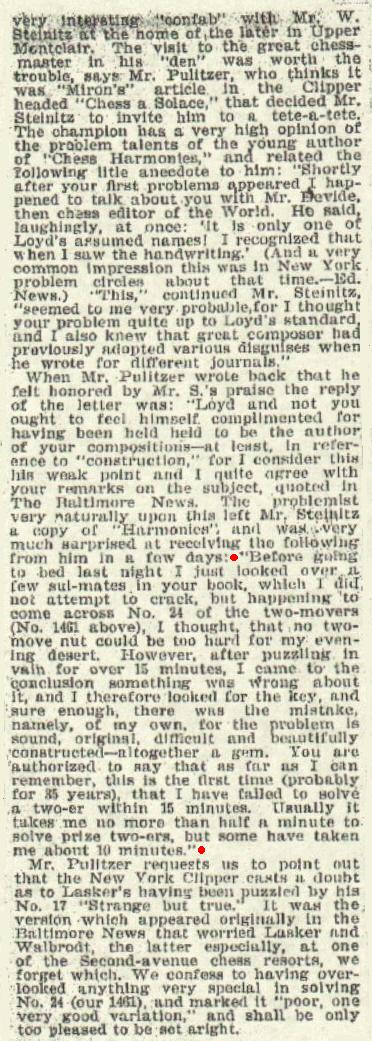

- Baltimore News, 9 March 1895 (a discussion of Steinitz’s view of the book, including a direct quote regarding problem 24 in Chess Harmonies):

Mr Urcan has also found a letter from Pulitzer about his visit to Steinitz, on page 7 of the Brooklyn Daily Standard Union, 9 February 1895:

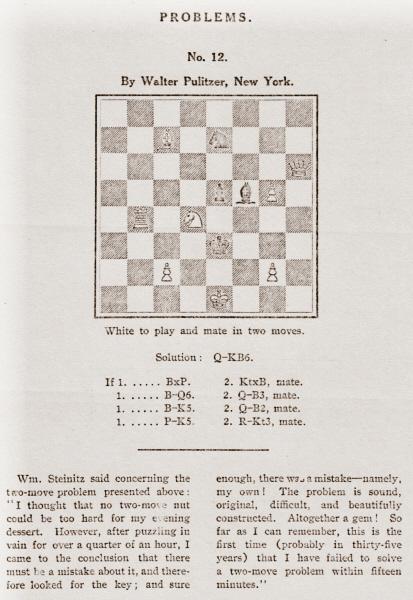

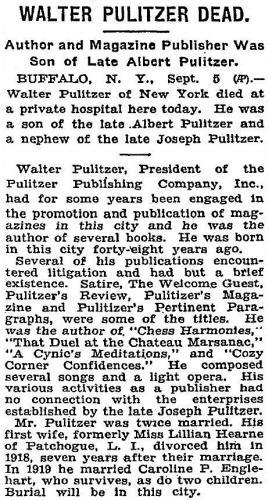

8321. Walter Pulitzer

A further picture of Walter Pulitzer was on page 32 of the June 1897 American Chess Magazine:

Below is his obituary in the New York Times, 6 September 1926, page 15:

The obituary states that Pulitzer was aged 48 at the time of his death, and it was one of the sources for his entry in Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia (Jefferson, 1987), which gave his birth-date as 4 April 1878. This would mean that Pulitzer was only 16 years old when Chess Harmonies was published.

However, W.H.K Pollock’s column in the Baltimore News, 2 February 1895 (see C.N. 8320) gave 1874 as Pulitzer’s year of birth. The records checked so far (e.g. at ancestry.com) offer evidence in favour of 1874, rather than 1878, but further investigation is required.

8322. Pointed out by Pillsbury

Black to move

What did Pillsbury point out when the game was over?

8323. Over the border

An article by G.H. Diggle published in the May 1984 Newsflash and reproduced on page 2 of the second volume of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1987):

‘The centenary of the Scottish Chess Association (founded 1884) has been commemorated in a fine book, the main authors being C.W. Pritchett and M.D. Thornton. The former has selected and annotated over 40 of the best games ever won by our friends “over the border”, beginning with Zukertort-Mackenzie, 1878 and ending with Motwani-Plaskett, 1983. The latter has dealt with chess in Scotland “before 1822 to the present age”. A full roll of honour of Scottish champions from 1884 to 1983 is given. Nor are the ladies, the juniors or the problemists forgotten, being “mentioned in despatches” in separate articles by David Levy and N.A. Macleod. In his historical review Mr Thornton gives us glimpses from the past of four great clubs – Edinburgh (founded 1822), Glasgow (soon after, but records destroyed in 1866), Dundee (1847) and Aberdeen (1853), the last-named being as formidable in propriety as in chess – “no spirituous liquors, no smoking, no betting or gambling, no dogs, and certainly no chess on the ‘Sawbath’” – and prospective new members receiving more than one “black ball” in six were “oot”. We are also introduced to such great nineteenth-century figures as James Donaldson, hero of the famous Edinburgh-London correspondence match, G.B. Fraser of Dundee, Cecil De Vere (Scottish by birth but English by residence) and Captain G.H. Mackenzie, “the strongest player ever to win the Scottish championship in the nineteenth century”, though he was mainly resident in America, and he took first prize at several US congresses and at Frankfurt in 1887, where he scored wins against Blackburne, Burn, Gunsberg, Paulsen and Tarrasch. Finally, we meet Sheriff Spens, the real driving force behind the foundation of the SCA and no mean writer and poet – it was he who called Morphy “The Pride and Sorrow of Chess” – and his skill over the board is shown in his clever “offhand” win (included by Mr Pritchett in the games section) against the then chess champion of the world, Emanuel Lasker.

Coming now to “living memory”, the book (both in its history and its games section) duly honours two most eminent players of whom we have been sadly deprived during the last two years – Dr W.A. Fairhurst, English by birth but Scottish champion 11 times, “the finest player Scotland has ever seen”, and Dr J.M. Aitken, ten times champion and his lifelong opponent in congresses, Scottish championships and club matches. It would be interesting to know the total score over the years between the two great combatants. In 1938 they played a set match of eight games, Aitken winning by five and a half points to two and a half, but this is described in the BCM as their second match, and the result of the first one the BM has not yet discovered. The BM never saw Fairhurst, but he has very pleasant memories of Dr Aitken, whom he once actually had to meet in the very first round of a tournament, and felt like a rabbit facing a python. After “it was all over” the Doctor, conducting the inquest, never once expatiated on “where Black had gone wrong” but shook his head over his own play, which at one point had been “terribly speculative”. Apart from his play, the Doctor (in the opinion of the BM) was one of the best chess book reviewers in the world.’

A photograph taken during the Aitken v Diggle game was given in C.N. 3766.

8324. An interview with Gunsberg

From page 2 of the 9 March 1895 edition of the Newcastle Courant:

A remark of Gunsberg’s which is worth highlighting:

‘... there are benefits to be obtained in this life beyond and above the mere accumulation of great riches, and I know no art which gives its votary a larger share of these than chess.’

| First column | << previous | Archives [110] | next >> | Current column |

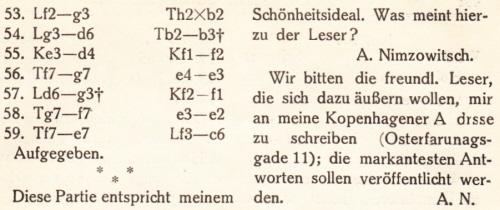

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.