Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [139] | next >> | Current column |

9710. The First World War

Chess and the Code-Breakers, which focuses on the Second World War, prompts Vladislav Tkachiev (Moscow) to ask for information about chess figures who made a contribution, in whatever capacity, to the war effort of any country during the period 1914-18.

9711. Tidskrift för Schack

A run of this magazine is available online.

9712. Bauer v Porges (C.N. 9691)

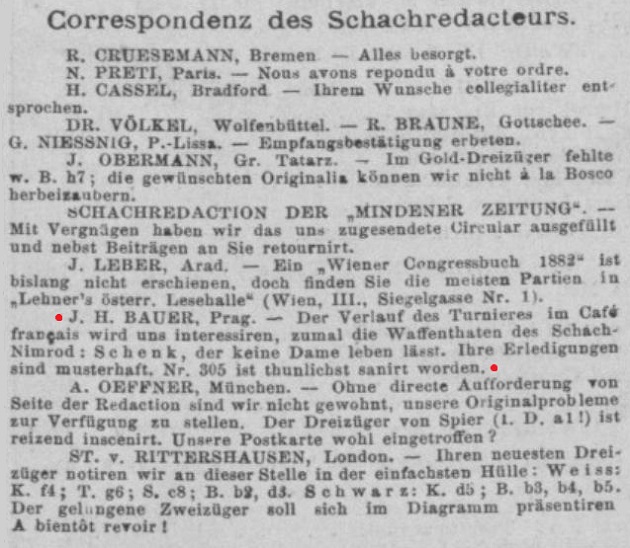

Jan Kalendovský (Brno, Czech Republic) reports a reference to J.H. Bauer and play at the Café français in Prague on page 474 of the Allgemeine Sport-Zeitung, 29 May 1884:

9713. Purdy on Logical Chess Move by Move

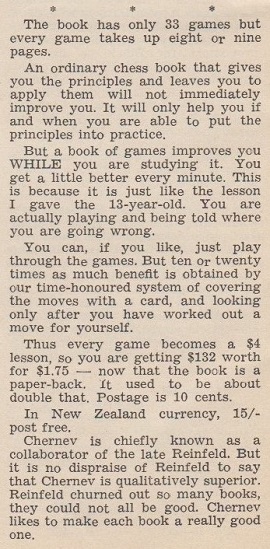

The above passage about Logical Chess Move by Move by Irving Chernev comes from page 80 of the March-April 1967 Chess World. It was omitted from page 65 of The Search for Chess Perfection II by C.J.S. Purdy (Davenport, 2006) and from page 147 of The Chess Gospel According to John edited by R.J. Tykodi and Bob Long (Davenport, 2010). In both books its place would have been just before the paragraph beginning ‘In this series ...’.

9714. Tabia/Tabiya (C.N.s 9689 & 9699)

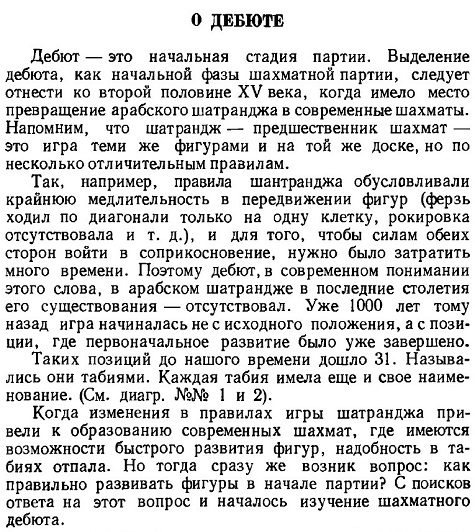

Dan Scoones (Port Coquitlam, BC, Canada) draws attention to the discussion on page 10 of Вопросы современной шахматной теории by Isaac Lipnitsky (Moscow, 1956):

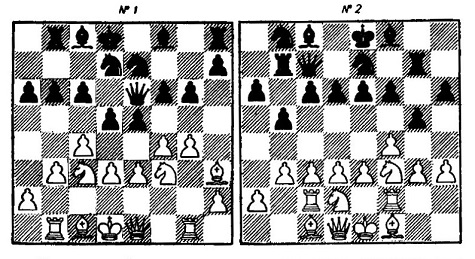

The diagrams mentioned by Lipnitsky in the penultimate paragraph were on page 11:

See too pages 12-13 of the English translation (by John Sugden), Questions of Modern Chess Theory (Glasgow, 2008).

9715. Spielmann’s tournament performances

From page 79 of Modern Master-Play by F.D. Yates and W. Winter (London, 1929), in the section on Rudolf Spielmann:

‘A curious feature of his record is the unevenness of his performances. He himself maintains that he plays as consistently well in tournaments where he has been less successful as in those which he has won, and he explains the difference in the results by what may almost be termed the luck of the game. If this really exists it is more applicable to the case of an attacking player, since he commits his whole game to an onslaught, the outcome of which it is in many cases impossible to foresee.’

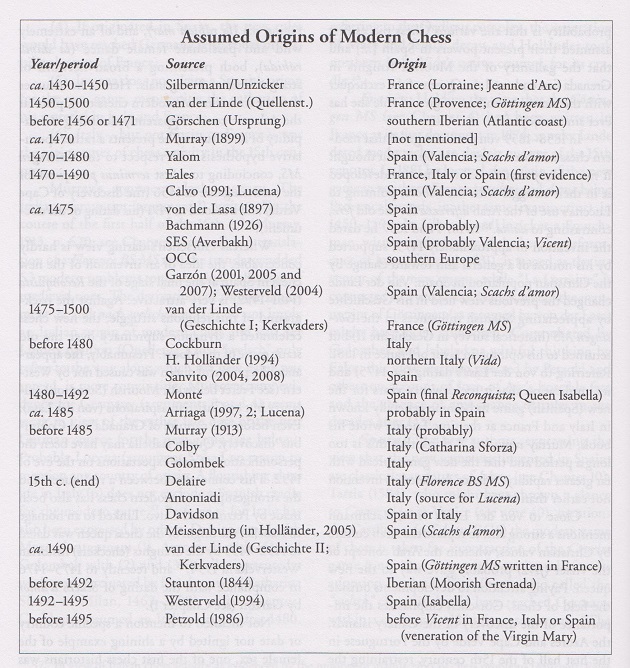

9716. The Classical Era of Modern Chess (C.N. 8856)

Wanted: references to authoritative reviews of the 594-page book The Classical Era of Modern Chess by Peter J. Monté (Jefferson, 2014).

As a small example of the book’s contents, below is a chart on page 22:

9717. Colonel Moreau (C.N.s 9441 & 9490)

Until now, no portrait of Colonel Moreau has been available, but Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) has found the photograph below, reproduced here courtesy of the London Borough of Hackney Archives (photograph reference number D/S/1/3 no.3):

9718. Chigorin

C.N. 1106 (see pages 192-193 of Chess Explorations) noted W.H. Watts’ remark that at Hastings, 1895 he ‘had expected Chigorin to be a great burly Russian, but found him in fact a small jerky man, no bigger than Steinitz’.

An addition from page 10 of the Columbia Chess Chronicle, 10 January 1889 (with an underestimation of his age):

‘On Wednesday, 9 January, Mr Tchigorin arrived in New York. Mr Tchigorin is in the diplomatic service of Russia. He is about 36 years old, short in stature and compactly built. He has black hair and flashing black eyes.’

9719. Corn

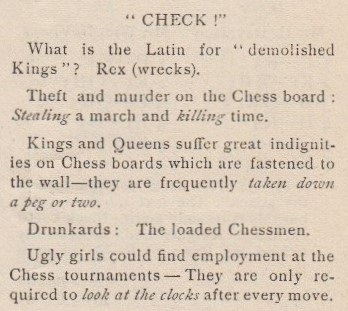

To Chess Corn Corner many additions from the Columbia Chess Chronicle could be made, but one extract will suffice, from page 145 of the 12 May 1888 issue:

9720. Sokolov book

Ivan’s Chess Journey by Ivan Sokolov (Ghent, 2016) shows no sign of involvement by anybody of English mother tongue.

9721. A German

publication

From page 24 of Bobby Fischer Goes to War by

David Edmonds and John Eidinow (London, 2004):

At the start of an article entitled ‘The Mystery of the Chess Spectator’ on pages 80-83 of the 1/2016 New in Chess Mr Edmonds has rightly dispensed with his claim about a ‘book ... containing three hundred blank pages’:

Another chess poser is why any writer would use the words ‘It is said that there was once ...’, and especially on a matter where the facts have been clearly established.

Our latest feature article, A Fictitious Chess Book, brings together the series of C.N. items about the German publication.

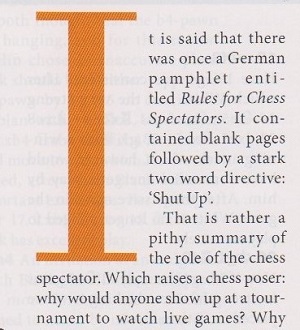

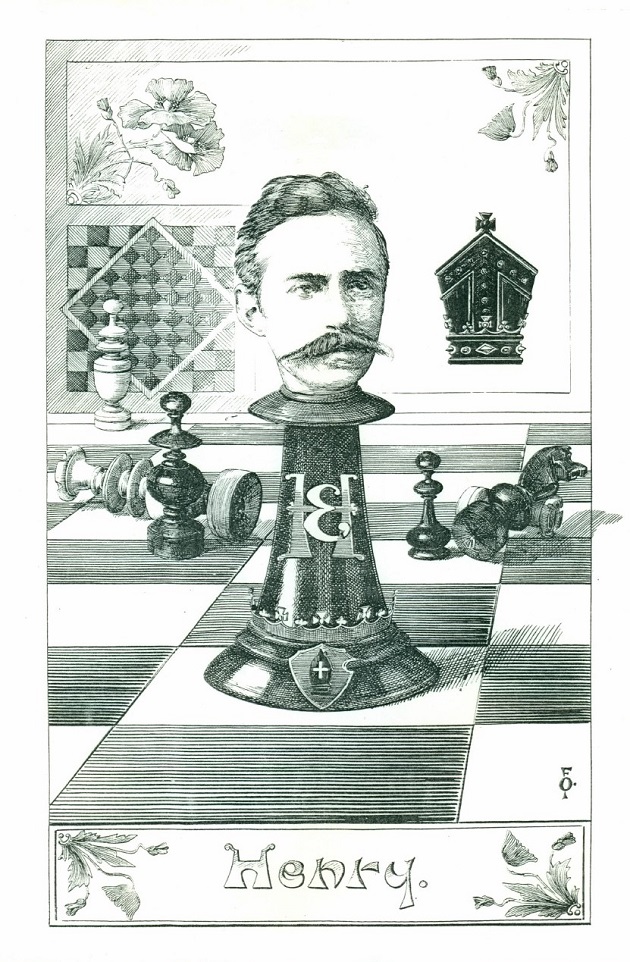

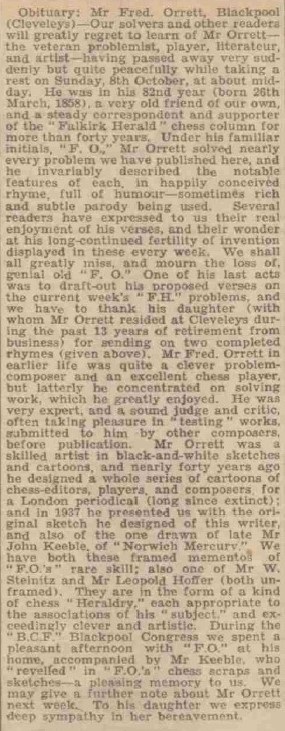

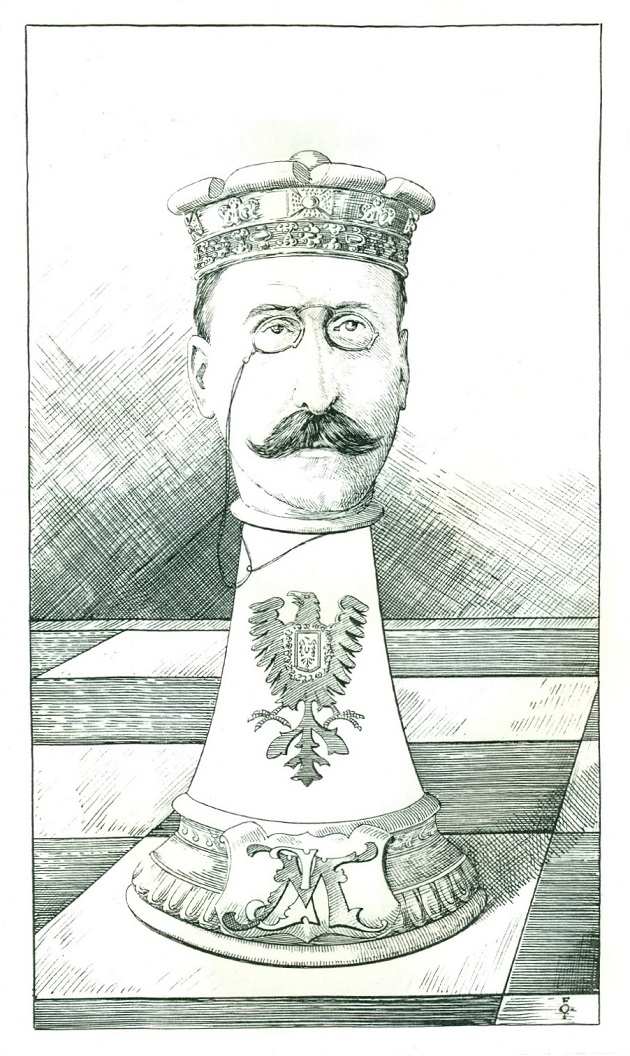

9722. Frederick Orrett

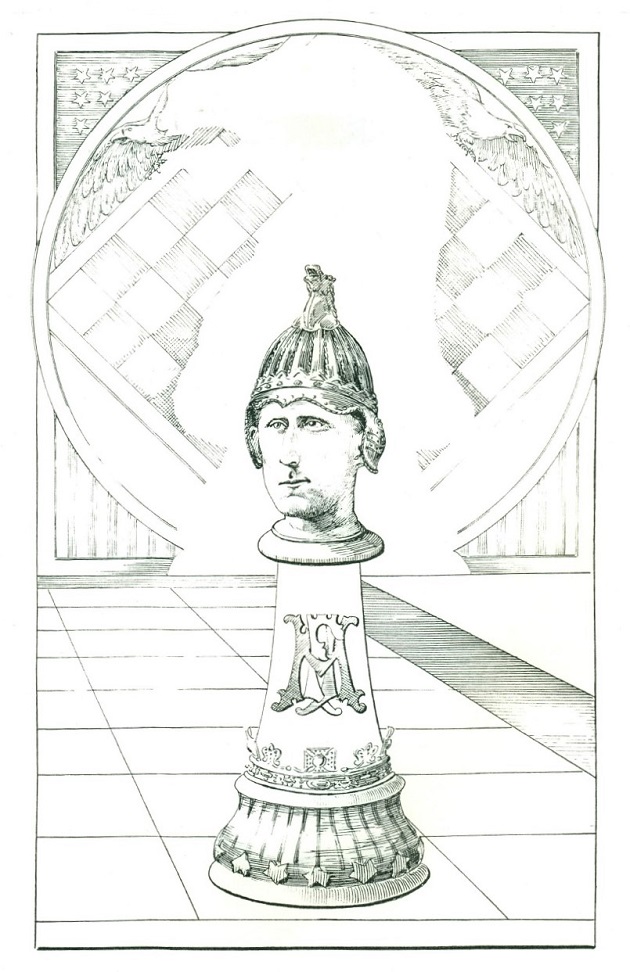

Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England) has sent us over 30 illustrations by Frederick Orrett (1858-1939), and we begin by showing his depiction of Eugene Henry (C.N. 9680):

J.H. Blackburne (with, in the background, que instead of qui) and F.J. Marshall:

Further material provided by Mr McDowell will be shown in future items.

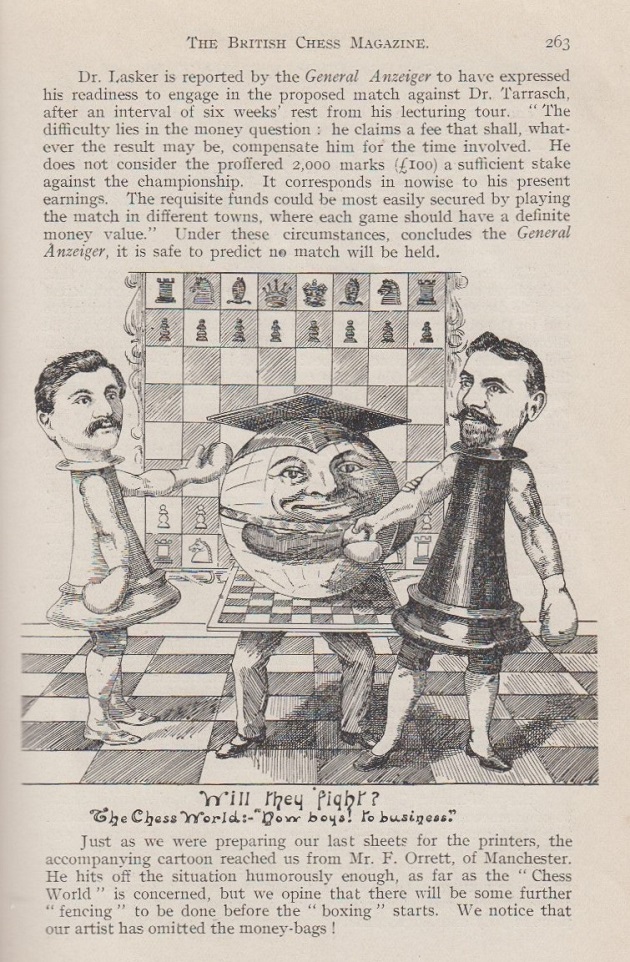

In the early twentieth century, Orrett’s artwork was often in the BCM. Examples: April 1905, page 142; September 1905, frontispiece (see C.N. 3694); October 1905, page 438; January 1906, frontispiece; November 1908, page 477; November 1910, page 484. Below is page 263 of the June 1908 BCM:

Page 8 of the Falkirk Herald, 19 August 1908 reported that ‘a short sketch and photo of Mr Orrett’ had been published in the Liverpool Weekly Courier, but we have yet to find that item. The discussion of Orrett’s work on page 84 of the February 1909 BCM was reproduced in C.N. 9680.

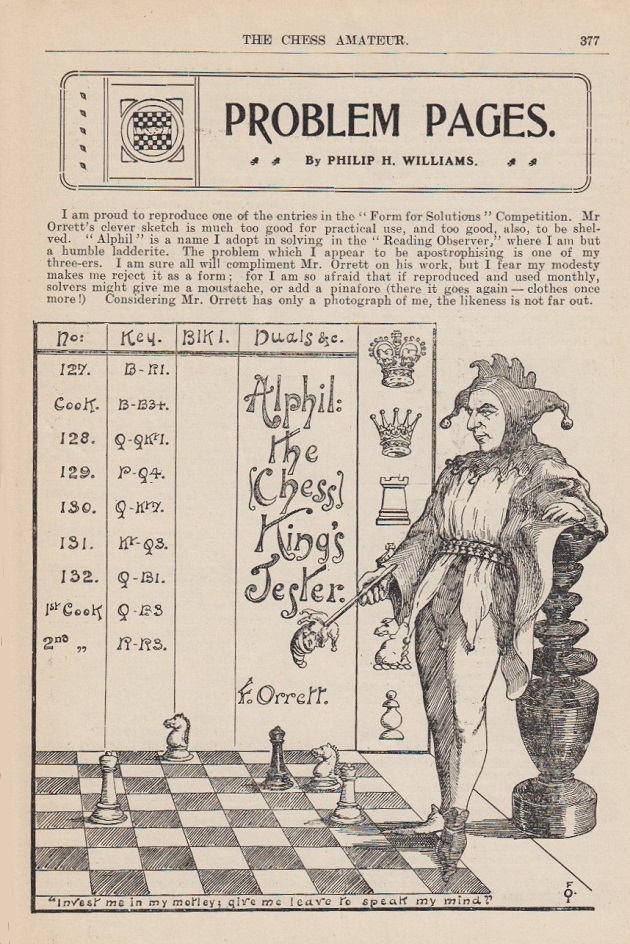

A number of sketches and cartoons by Orrett were published in Chess Chatter & Chaff by Philip H. Williams (Stroud, 1909), including the illustration shown at the beginning of The Chess Seesaw. Below is page 377 of the September 1908 Chess Amateur:

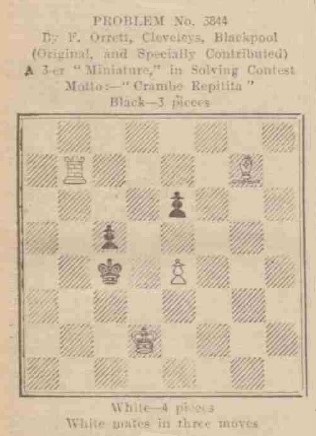

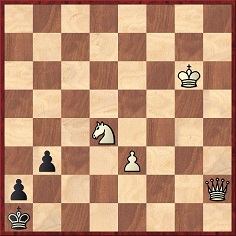

Orrett was also a problemist, and the composition below comes from page 10 of the Falkirk Herald, 20 November 1935:

Page 15 of the Falkirk Herald, 29 April 1938 reported on Orrett’s 80th birthday:

His death was announced on page 7 of the Manchester Evening News, 9 October 1939:

The most detailed obituary found was on page 10 of the Falkirk Herald, 18 October 1939:

On page 14 of its 20 December 1939 edition the Falkirk

Herald gave another problem by Orrett. [Addition

on 8 February 2016: see, however, C.N. 9725.]

Mate in three.

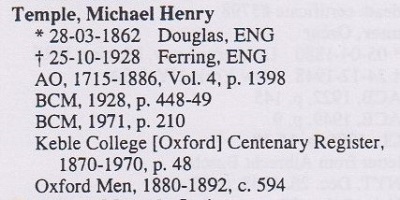

T.R. Dawson noted Orrett’s death on page 68 of the February 1940 BCM:

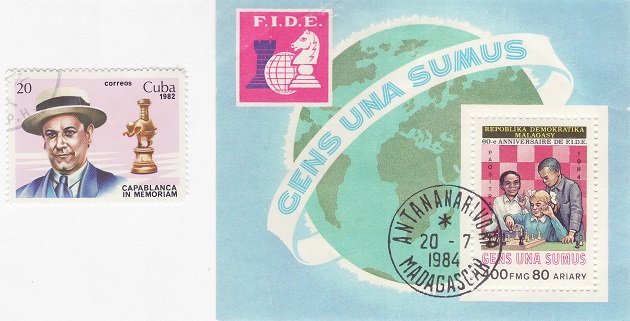

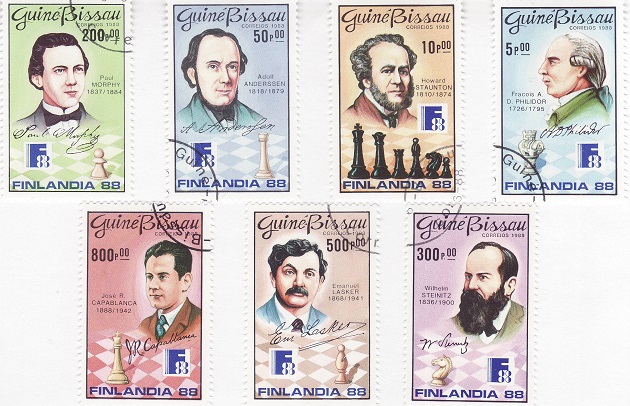

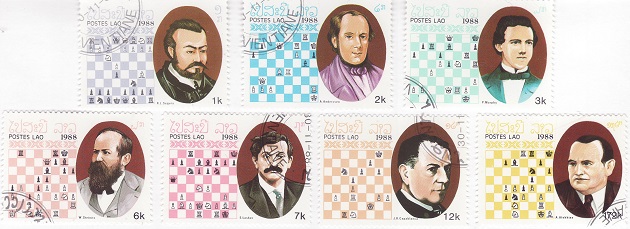

9723. Postage stamps

Vitaliy Yurchenko (Uhta, Komi, Russian Federation) informs us that his collection of postage stamps includes the following:

9724. Purdy

blindfold game

Blindfold games by C.J.S. Purdy are scarce, but one can be given here, from pages 257-258 of the 10 September 1936 issue of the Australasian Chess Review. It was played during his tour of New Zealand, in a six-board blindfold exhibition. As we do not have a complete run of the magazine in the mid-1930s, any further details which may have been published in another issue will be appreciated.

Cecil John Seddon Purdy (blindfold) – W.H. Joyce

Christchurch (date?)

‘Caro-Kann (in effect)’

1 d4 e6 2 c4 Nf6 3 Nc3 c6 4 e4 d5 5 e5 Nfd7 6 cxd5 cxd5 7 Nf3 a6 8 a4 Bb4 9 Bd3 Qc7 10 O-O Bxc3 11 bxc3 Qxc3 12 Ba3 Qa5 13 Qb3 Nc6 14 Rfc1 Qd8 15 Bd6 Qb6 16 Qa3 g6 17 Rab1 Qa7 18 a5 f5

19 Bc2 Nxd4 20 Nxd4 Qxd4 21 Ba4 h6 22 Rc7 Qh4 23 Rbxb7 Qd8 24 Bxd7+ Bxd7 25 Rxd7 Qxd7 26 Rxd7 Kxd7 27 Be7 Rhb8 28 h4 Rb7 29 Qd6+ Kc8 30 Qd8 mate.

9725. Frederick Orrett (C.N. 9722)

From Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England):

‘The first of the two problems in C.N. 9722 is certainly not original, being a version of a famous simplification of Loveday’s Indian problem from 1845 (Johann Berger, Akademisches Monatsheft für Schach, 1927):

Mate in three.Key: 1 Bc1, followed by 2 Rd2.

The second problem is by Walther Freiherr von Holzhausen, Deutsche Schachzeitung, September 1902, page 286. I think that it is clear from the Falkirk Herald of 20 December 1939 that it was not a problem by Orrett, but was one that he had solved.’

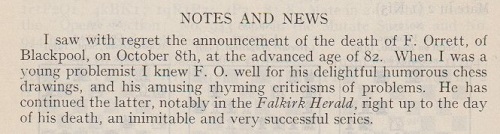

9726. Wartime censorship

From page 77 of the December 1915 Chess Amateur:

9727. The inventor of Kriegspiel (C.N.s 3487, 3496 & 6415)

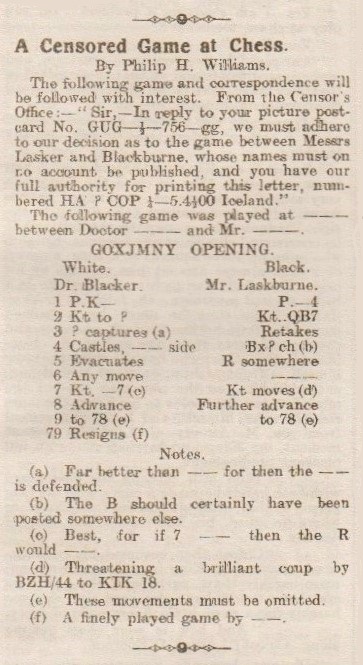

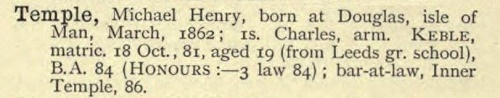

The entry on Michael Henry Temple in the unpublished 1994 edition of Chess Personalia by Jeremy Gaige:

Oxford Men can be viewed online, and below is Temple’s entry:

From page 10 of the Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer, 27 October 1928:

David Garnett, the sexton of St Andrew’s Church, Ferring, informs us that the Isle of Man Parish Registers record that he was the son of Charles and Hannah Maria Temple and was baptized in Onchan, Isle of Man on 20 April 1862. His death was briefly reported on page 17 of The Times, Saturday, 27 October 1928:

‘Mr Michael Henry Temple, author, journalist and naturalist, died on Thursday, at Ferring, Sussex, at the age of 66. The eldest son of Mr Charles Temple, of Douglas, Isle of Man, he went up to Keble College, Oxford, and took his degree in 1884. In 1886 he was called to the Bar by the Inner Temple. He was at one time on the staff of the Globe, and was known for his studies of Nature and rural life.’

Mr Garnett, who has taken three photographs of the cemetery in St Andrew’s Church, adds that the gravestone inscription reads:

‘In bright memory of Michael Henry Temple, barrister at law 1921-1923, resident in Ferring 1927-1928, born March 28th 1862, died October 25th, 1928.’

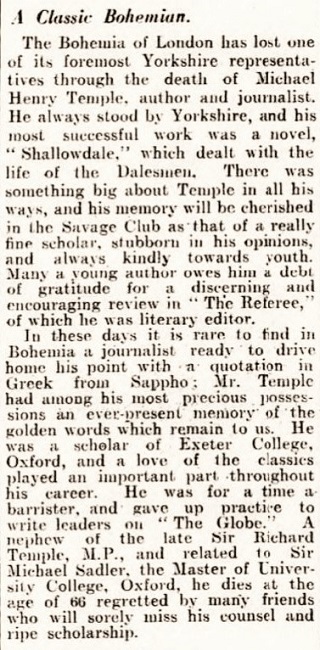

9728. Alekhine and Elaine Saunders

C.N. 3817 (see too Chess Prodigies) quoted from page 190 of CHESS, 14 February 1938 a remark by Alekhine about Elaine Saunders: ‘She is a genius.’

An addition from page 8 of the Daily Telegraph and Morning Post, 24 January 1938:

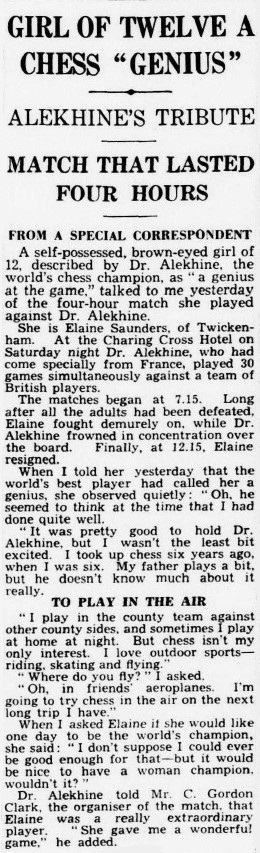

9729. The ‘Gentlemen’s World championship’

From page 151 of the June 1957 Chess World:

9730. Schachnovelle

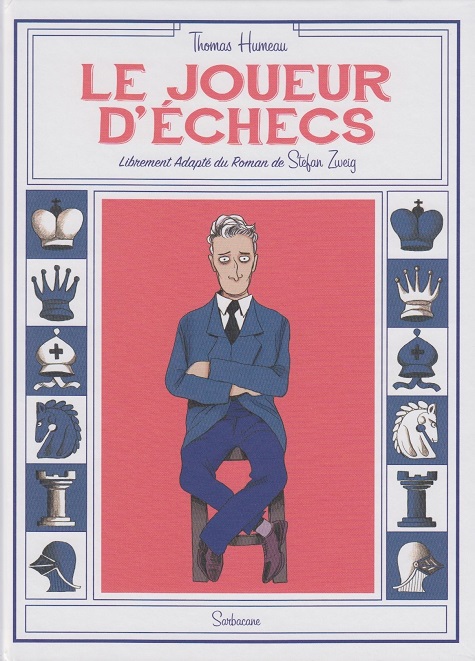

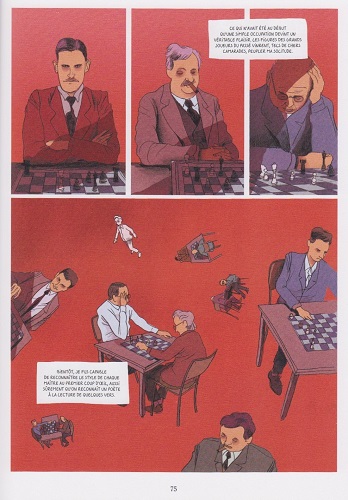

A very free French-language adaptation of Stefan Zweig’s story in comic-strip form has been produced by Thomas Humeau under the title Le joueur d’échecs (Paris, 2015):

9731. Madness

On the other side of the title page of Le joueur d’échecs (C.N. 9730) there is only this:

The customary English version of the remark attributed to Korchnoi is ‘No chess grandmaster is normal; they only differ in the extent of their madness’. That wording can be found, for instance, on page 13 of Essential Chess Quotations by John C. Knudsen (Osthofen, 1998), a booklet with no sources. How far back can the observation be traced, in any language?

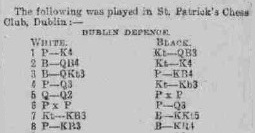

9732. The Dublin Defence

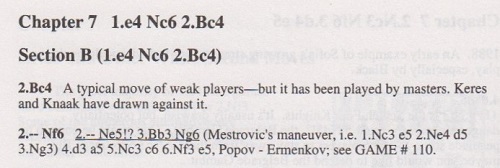

David McAlister (Hillsborough, Northern Ireland) sends a game published on page 3 of the Belfast News-Letter, 6 September 1888 with this heading:

1 e4 Nc6 2 Bc4 Ne5 3 Bb3

3...f5 4 d3 Nf6 5 Qe2 fxe4 6 dxe4 d6 7 Nf3 Bg4 8 h3 Bh5 9 Nbd2 Qd7 10 Qe3 c6 11 Nxe5 dxe5 12 O-O Qd4 13 c3 Qxe3 14 fxe3 O-O-O 15 Bc2 Bg6 16 Nc4 Bxe4 17 Bxe4 Nxe4 18 Nxe5 Rd5 19 Nf3 Ng3 20 Re1 e6 21 e4 Rd3 22 Bf4 Bc5+ 23 Kh2 Nh5 24 Be5 Rhd8 25 Bd4 Bxd4 26 cxd4 Nf4 27 Rad1 c5 28 Rxd3 Nxd3 29 Re3 Nxb2 30 dxc5 Rd3 31 Re2 Na4 32 Rc2 h6 33 e5 Kc7 34 Kg3 Kc6 35 Kg4 Nxc5 36 Kf4 Kd5 37 Re2 g5+ 38 Kg3 Ne4+ 39 Kh2 Nc3 40 Rb2 b6 41 a3 Re3 42 Rb3 Nd1 43 Rb5+ Kc4 44 a4 Rd3 45 Rb1 Nc3 46 Re1 Kb4 47 a5 Kxa5 48 Ra1+ Na4 49 Kg3 Kb4 50 Kg4 a5 51 Ra2 Kb3 52 Rf2 Nc5 53 Kh5 Ne4 54 White resigns.

The players were not identified, the score was without notes, and no other information was provided, either about the occasion or to explain the term ‘Dublin Defence’.

From page 96 of The Nimzovich Defense to 1. e4 by Hugh E. Myers (Yorklyn, 1995):

The Popov v Ermenkov game on pages 156-157 was played in the FIDE Zonal tournament, Warsaw, 1979.

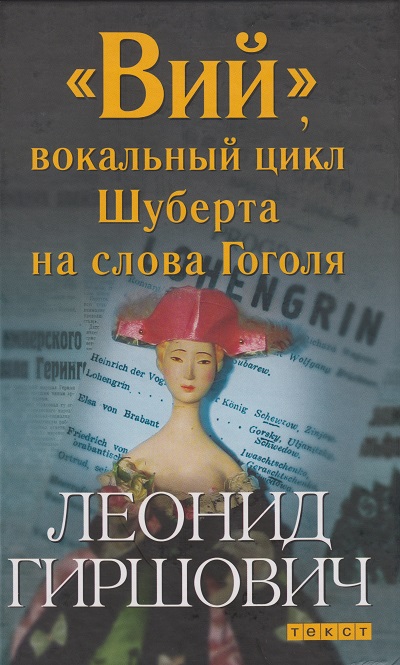

9733. A novel featuring Bohatirchuk (C.N. 9696)

We now also have the Russian original (Moscow, 2005):

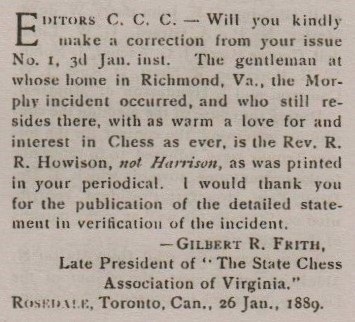

9734. A Morphy episode

Concerning a detailed Morphy page which includes the ‘Statement of Rev. R.R. Harrison’ from pages 4-5 of the Columbia Chess Chronicle, 3 January 1889, the following is to be noted from page 35 of the magazine’s 24 January 1889 issue:

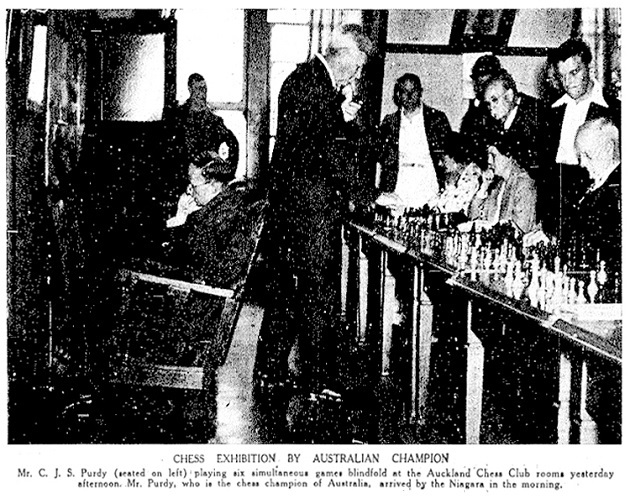

9735. Purdy in New Zealand (C.N. 9724)

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) reports that the blindfold game in Christchurch between Purdy and Joyce given in C.N. 9724 was played on 13 January 1936 and that a report was published on page 13 of the Christchurch Press the following day. Extensive information about Purdy’s 1935-36 tour of New Zealand is available via the website of the National Library of New Zealand, and our correspondent has sent this summary:

‘Auckland:

11 December (afternoon): blindfold simultaneous exhibition +2 –1 =3 (New Zealand Herald, 12 December 1935, page 14);

11 December (evening): simultaneous exhibition +17 –4 =10 (New Zealand Herald, 12 December 1935, page 14);

Hamilton:

12 December: simultaneous exhibition +22 –2 =4 (New Zealand Herald, 14 December 1935, page 17);

13 December: blindfold simultaneous exhibition +6 –0 =0 (New Zealand Herald, 16 December 1935, page 12);

13 December: consultation game against Hamilton team; Purdy won in 20 moves (New Zealand Herald, 16 December 1935, page 12);

Auckland:

18 December: simultaneous exhibition +16 –1 =1 (New Zealand Herald, 19 December 1935, page 12);

Tauranga:

23 December: blindfold simultaneous exhibition +4 –0 =3 (New Zealand Herald, 24 December 1935, page 12);

Wellington:

26 December to 6 January: New Zealand championship. Purdy was entitled to win any of the prizes, but not the New Zealand title, as he was born in Egypt and had not been a resident of the Dominion during the previous six months (Wellington Evening Post, 24 December 1935, page 16). Leading final scores: 1 Purdy, 12/13 (lost to Gyles); 2 A.W. Gyles 11 (won the championship), 3-4 Ian Burry and D.I. Jones, 8½; 5 J.A. Erskine 8.

7 January (afternoon): blindfold simultaneous exhibition +2 –0 =4 (draw with Joyce); (Wellington Evening Post, 8 January 1936, page 11);

7 January (evening): simultaneous exhibition +13 –2 =4;

8 January (afternoon): first match-game with Gyles (adjourned);

8 January (evening): simultaneous exhibition +20 –1 =5;

9 January (afternoon): won the adjourned game and the second game with Gyles; (evening) simultaneous exhibition +9 –1 =2;

Christchurch:

11 January (afternoon): Purdy-W.D. Khoury 1-0 (first match-game) (Christchurch Press, 13 January 1936, page 10);

11 January: simultaneous exhibition +17 –2 =5 (Christchurch Press, 13 January 1936, page 10);

13 January: blindfold simultaneous exhibition +4 –1 =1 (Christchurch Press, 14 January 1936, page 13);

14 January: W.D. Khoury-Purdy (second match-game?);

15 January (afternoon): Purdy-W.D. Khoury 1-0 (third match-game); (Christchurch Press, 15 January 1936, page 15);

15 January (evening): simultaneous exhibition +14 –3 =6 (Christchurch Press, 15 January 1936, page 15).’

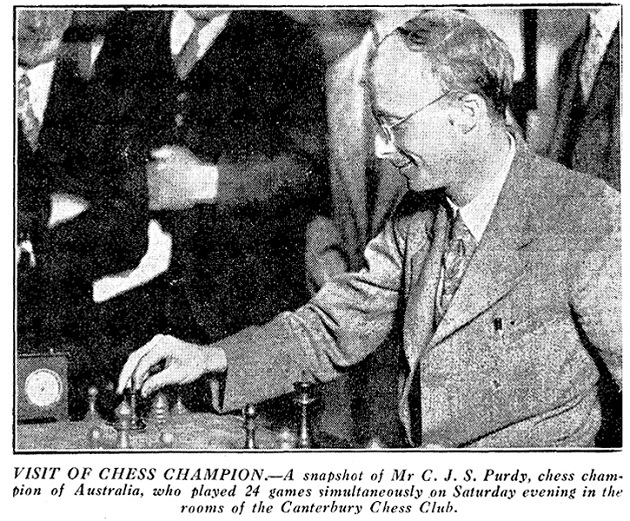

Mr Bauzá Mercére adds that although no game-scores have been found, two photographs from the tour can be shown:

New Zealand Herald, 12 December 1935, page 10

Christchurch Press, 13 January 1936, page 16.

9736. ‘Freak’ openings

From page 208 of Chess World, September 1957:

‘Many players imagine that “freak” openings are bad. But if you are White, they do no worse than put you in the position of Black, and are usually better than that, as moves like P-QB3, etc. are apt to become useful later on. Black should try to prevent that happening, but this is often difficult. Eccentric first moves for Black are less to be recommended.’

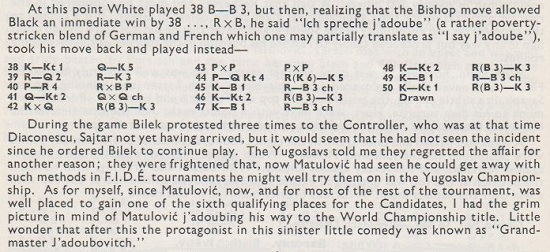

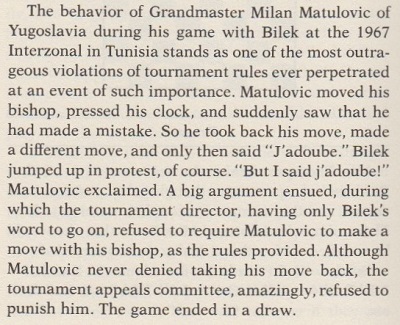

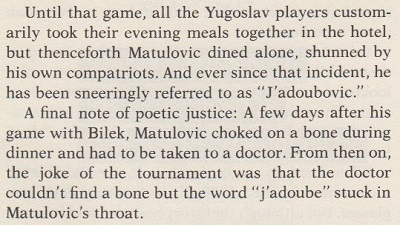

9737. Milan Matulović and j’adoube

From Harry Golombek’s column on page 26 of The Times, 2 December 1967, with regard to the touch-piece and j’adoube rule:

‘It seems hardly credible, but it was by an abuse of this custom that a player, an international grandmaster at that, was able to take a move back in the recent Interzonal Tournament at Sousse. In the ninth round, the Yugoslav player, Matulović, in sore straits against the Hungarian Bilek, played a move that would have lost out of hand. After he had played the move he said “Ich spreche j’adoube”, and while I doubt whether the French Academy would approve of this blend of German and French, the intention was quite clear. He wished as it were to make a retrospective adjustment. He took the losing move back, replaced it by another much better move, and eventually got away with a draw. His opponent, Bilek, protested three times to the arbiter, who, however, not having heard or seen the first part of this incident, ordered him to continue play. Poor Bilek, and fortunate Matulović, who very nearly qualified for the Candidates’ event as a result of this ill-earned half point. His fellow Yugoslavs, who witnessed the whole affair, are it seems much alarmed lest Matulović employs similar tactics in their next championship tournament.’

The above was quoted on pages 99-100 of the Christmas 1967 CHESS with this strangely-worded editorial remark:

‘Chess is perhaps the only game in which matches at such a high level as this do not have one referee detailed to watch every game, so that incidents like this can go unpenalized.’

In this position from Matulović v Bilek, Sousse, 26 October 1967 White played, in quick succession, 38 Bf3, 38 Be2 and 38 Kg1.

Below, from page 8 of the January 1968 BCM, is an extract from Harry Golombek’s report on the tournament:

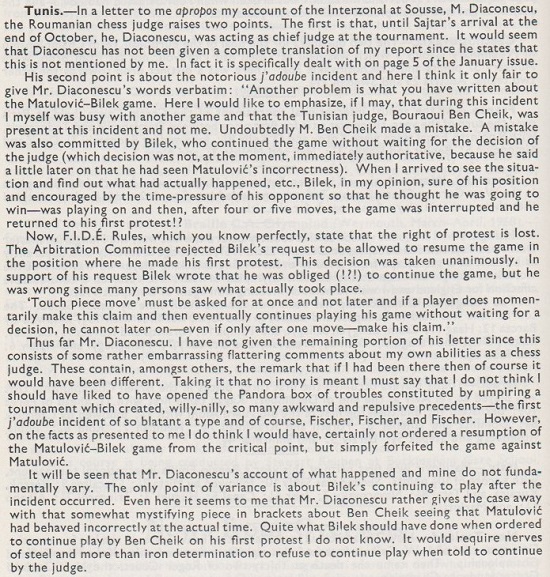

On page 64 of the March 1968 BCM a follow-up item appeared in News from Overseas section (edited by Golombek):

Golombek was not in Sousse at the time of the Matulović v Bilek game. He wrote on page 5 of the January 1968 BCM (concerning the tournament in general):

‘The chief arbiter was the Czechoslovak master Sajtar, and he was assisted by Diaconescu (Romania), Philippe (Austria) and two Tunisians. As a matter of fact, Sajtar, like myself, was engaged in the FIDE Congress at Venice during the earlier part of the tournament and he only arrived at the end of October, his place up to then as chief arbiter having been taken by Diaconescu. I arrived at the beginning of November and spent my first few days not only acquiring the official information as to what had taken place but finding out from the players all the action that had taken place behind the scenes as well (of which there was plenty).’

We have three books on the Sousse tournament, but only one of them provides information on the Matulović-Bilek incident. From pages 72-73 of Interzonal Chess Tournament Sousse 1967 by R.G. Wade (Nottingham, 1968):

‘Matulović-Bilek was a highly interesting game marred by an unpleasant dispute. On move 38 the Yugoslav champion Matulović is alleged to have taken back a move, then to have assured his opponent that he had said “j’adoube” and made another move. The only person present who accepted Matulović’s explanation was the Romanian judge, who semed [sic] more intent on the players passing the time control; Bilek stopped his clock three times to protest and each time the tournament judge immediately re-started it – equivalent to waving play on in football! It would be an undesirable extension of control of chess tournaments if – in time – an umpire is placed at every table, though in some events, e.g. the Capablanca Memorial Tournament, a scoring steward is placed by every table.’

In this incident even Matulović’s Yugoslav colleagues did not side with him. This is not the only example of a move being taken back during the tournament! Byrne states that a player (not a qualifier nor Matulović) took back a move in that player’s game with Byrne after completing the move, but Byrne did not protest. He would not identify the player to those curious like myself. Was the strongest move taken back?’

The full score of the Matulović v Bilek game: 1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Nc3 e5 6 Ndb5 h6 7 b3 Bc5 8 Nd6+ Ke7 9 Nf5+ Kf8 10 Bc4 Bb4 11 Bd2 Qa5 12 Qf3 d5 13 exd5 Nd4 14 Nxd4 exd4 15 Nb1 Bxd2+ 16 Nxd2 Bg4 17 Qf4 Re8+ 18 Kf1 Qc3 19 Rb1 Qxc2 20 f3 Bf5 21 Qxd4 Qxa2 22 Ra1 Bd3+ 23 Bxd3 Qxd2 24 Qc5+ Kg8 25 Bc4 g6 26 Qf2 Qc3 27 Rd1 b5 28 Be2 Re3 29 g3 Kg7 30 Kg2 a6 31 d6 Rhe8 32 Rhe1 Nd7 33 f4 Qb4 34 f5 g5 35 f6+ Kg8 36 h3 Qc3 37 Kf1 Qc6 38 Kg1 Qe4 39 Rd2 Re6 40 h4 Rxf6 41 Qg2 Qxg2+ 42 Kxg2 Rfe6 43 hxg5 hxg5 44 b4 R3e4 45 Kf1 Rf6+ 46 Kg2 Rfe6 47 Kf1 Rf6+ 48 Kg2 Rfe6 49 Kf1 Rf6+ 50 Kg1 Rfe6 Drawn. Pages 78-79 of Wade’s book had the game with this note after 38 Kg1:

‘Matulović is alleged to have played first 38 B-B3, withdrawn the move, said “Ich spreche j’aboube” [sic], and played as in the text.’

Page 186 was entitled ‘Matulović-Bilek’ and quoted from the above-mentioned Golombek material in the January and March 1968 BCM. (Wade explained that ‘the following important information on this incident has appeared since the earlier comments were written’.)

Page viii of Wade’s book had this list:

‘Referees: P. Diaconescu IJ – Principal Referee 15-31 October; J. Sajtar IJ – Principal Referee 1-20 November; R. Phillip IJ; B. Ben Cheikh IJ and S. Annabi.’

Concerning ‘Phillip’, Golombek put ‘Philippe’ in the BCM (see above). Chess Personalia by Jeremy Gaige has an entry for an International Arbiter named Robert A. Philipp (1895-1970).

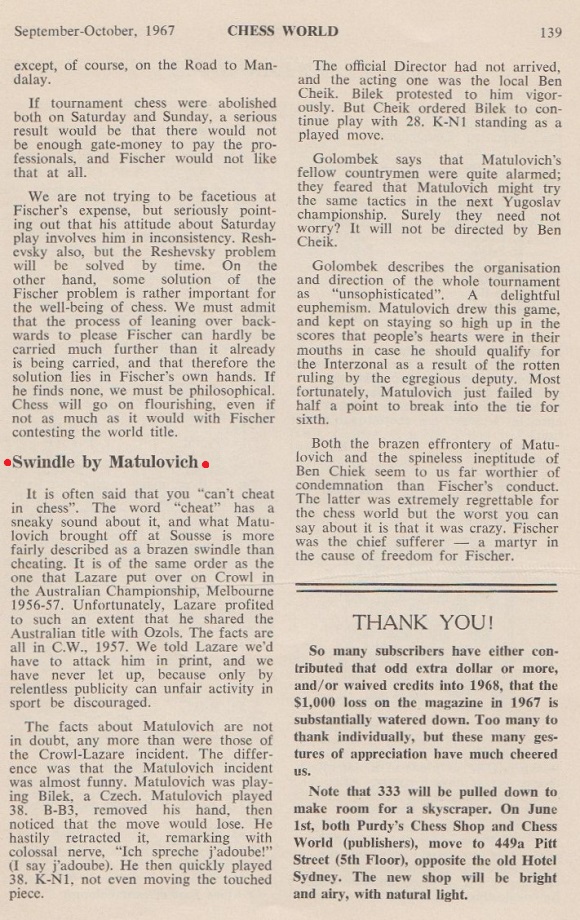

C.J.S. Purdy commented on the Matulović-Bilek affair on page 139 of Chess World, September-October 1967:

Coverage of the Sousse Interzonal in Chess Review was dominated by Fischer’s withdrawal, but in an article entitled ‘The Fischer Affair’ on pages 42-45 of the February 1968 issue, Petar Trifunovich wrote:

‘The arbiters did not shine in this tournament, as was proved by several examples. The most characteristic and worst example occurred in the game Matulović-Bilek, in which the rule of “touch-move” got a new explanation. A good part of the Fischer Affair must be charged against them because they did not act with authority and in time.’

On pages 328-329 of the November 1968 Chess Review Gligorić’s ‘Game of the Month’ column was devoted to Matulović v Fischer, Vinkovci, 1968, and after 29...Qd1 he wrote:

‘The moment is ripe for resignation. But Matulović is known for his “hobby” of adjourning, as long as is possible, to make his tournament standing look better “on paper”.’

The Review added an editorial footnote:

‘There are some other quaint tales about Milan Matulovich, such as his polygot “Ich sage j’adoube” at Sousse whereby he is now known as “J’adoubovich Matulovich”.’

The nickname was mentioned not only by Golombek on page 8 of the January 1968 BCM (see above) but also in an article entitled ‘I Was There’ by D. Bjelica on pages 49-50 of the February 1968 Chess Life. It claimed that Matulović’s response was, ‘All is fair in chess and war’.

We seek documented instances of Matulović, Bilek and the arbiters giving their respective versions of the case, e.g. in articles or interviews.

It is often affirmed that the Sousse game was not the only occasion when Matulović took back a move. From pages 123-124 of The Chess Scene by David Levy and Stewart Reuben (London, 1974):

‘Many spectators had witnessed Matulović’s move retraction but the controller was unwilling to make a decision against Matulović without having seen it himself. Bilek should have refused to play on, but the game was continued and eventually drawn. Matulović could not understand why, at its conclusion, Bilek refused to shake hands with him. Having got away with it once, Matulović pulled the same stunt against Bilek a few months later – and got away with it again!’

With respect to that last sentence, a similar claim in similar words, and similarly unsubstantiated, was written by Larry Evans in an article dated 25 August 2003 which was republished on page 288 of This Crazy World of Chess (New York, 2007):

‘A few months later, as fate would have it, Matulović got away with the same stunt against the same opponent! Thenceforth his colleagues dubbed him J’adoubovic.’

As shown above, the nickname had already been given to Matulović shortly after the episode in Sousse. Evans also mentioned the matter on page 19 of the November 1999 Chess Life, but merely quoted from a book whose title he gave as ‘The Oxford Encyclopedia Of Chess’.

David Levy referred to Matulović again in a report on the Lone Pine tournament on page 415 of the July 1975 Chess Life & Review:

‘The tournament list should also have included the well-known Yugoslav grandmaster Milan Matulović, known best for his tactics of taking back moves (e.g. against Bilek at the Sousse Interzonal in 1967), and for his selling of points.’

Levy then gave an alleged example of the latter charge.

As regards the allegation that Matulović retracted moves in other games, the following comes from a column by Golombek in The Times of 8 May 1976, page 14:

‘... Matulović, known as grandmaster Jadoubović for the skill with which he adjusted his pieces against Bilek on two notorious occasions.’

When was the second notorious occasion?

Further claims were made on pages 260-261 of Winning with Chess Psychology by Pal Benko and Burt Hochberg (New York, 1991):

Chess Review, January 1968, page 24

Chess writers being what they are, it is difficult to find an account of the 1967 Matulović v Bilek controversy in secondary sources which does not have elementary mistakes. For instance, page 24 of The World of Chess by A. Saidy and N. Lessing (New York, 1974) stated that the game was played in 1970 and added:

‘The astounded Bilek was too stunned to protest and Matulović went on to win the game.’

The two editions of the ‘Chess Addict’ book by M. Fox and R. James (London, 1987 and 1993) – see pages 160 and 225-226 respectively – also asserted that ‘Matulović went on to win’. Page 2 of The Batsford Encyclopedia of Chess by N. Divinsky (London, 1990) stated that the game was played ‘at the Suisse interzonal’.

9738. 1 O-O

Miron James Hazeltine – N.N.

Correspondence game (undated)

(Remove White’s king’s knight and king’s bishop.)

1 O-O e5 2 e4 Bc5 3 a3 d5 4 b4 Bb6 5 exd5 Nf6 6 c4 Bd4 7 Ra2 O-O 8 d3 Bg4 9 Qb3 h6 10 Nd2 c6 11 Ne4 Nxe4 12 dxe4 Qb6 13 Qg3 h5 14 h3. Black now discontinued the game.

Source: a letter from Hazeltine on pages 131-132 of the Brooklyn Chess Chronicle, 1 May 1883.

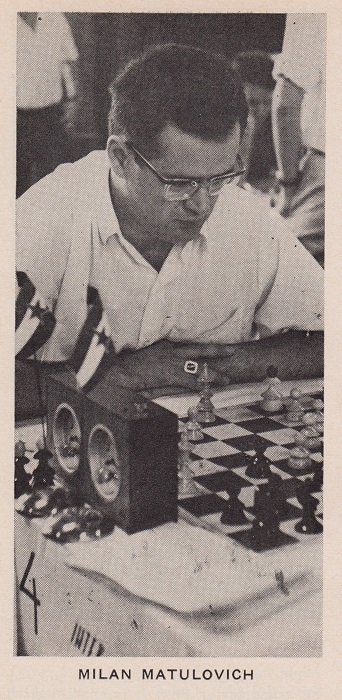

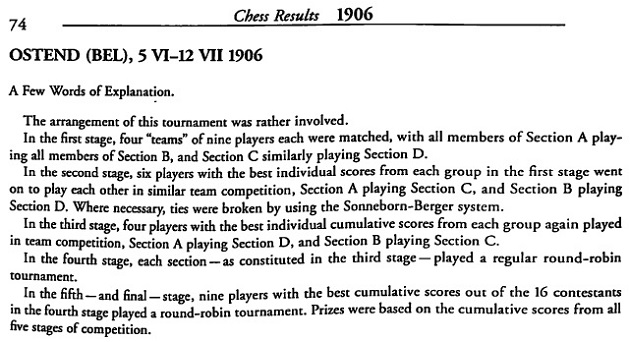

9739. Ostend, 1906

Hayoung Wong (Bayside, NY, USA) sends the following:

Page 253 of Chess Tournament Crosstables, volume two by Jeremy Gaige (Philadelphia, 1971)

Page 74 of Chess Results, 1901-1920 by G. Di Felice, (Jefferson, 2006)

C.N. 6671 mentioned an earlier, briefer instance of duplication. The excellence of Gaige’s research has been acknowledged in the Preface to each book in the Di Felice series. C.N. 3594 criticized the absence of sources in the first volume, Chess Results, 1747-1900 (Jefferson, 2004), a defect corrected as from Chess Results, 1941-1946 (Jefferson, 2008).

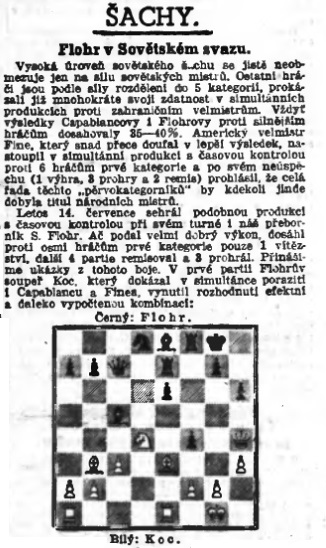

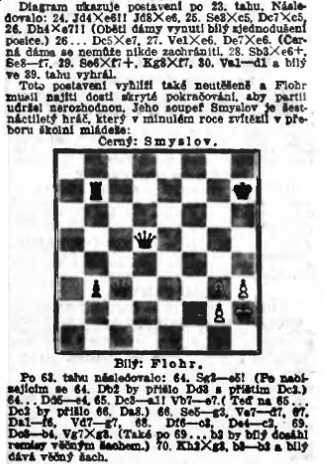

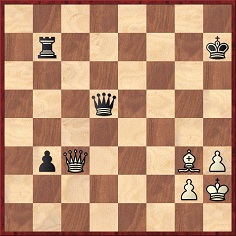

9740. Flohr v Smyslov, Moscow, 1938

Thomas Niessen (Aachen, Germany) provides an extract from page 7 of Národní politika, 29 July 1938:

The report states that on 14 July 1938 Salo Flohr scored +1 –3 =4 in a simultaneous exhibition with clocks against first-category players.

64 Be5 Qe4 65 Qa1 Re7 66 Bg3 Rd7 67 Qf6 Rg7 68 Qc3 Qc2 69 Qb4 Rxg3 70 Kxg3 b2 ‘and White gives perpetual check’.

Smyslov was aged 17.

9741. A trap in the Ruy López

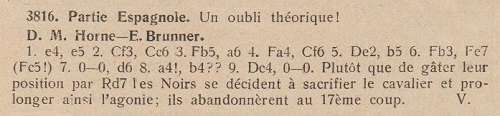

A familiar trap in an unfamiliar game:

Source: Schweizerische Schachzeitung, December 1947, page 200.

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 Qe2 b5 6 Bb3 Be7 7 O-O d6 8 a4 b4

9 Qc4 O-O, and Black resigned on move 17.

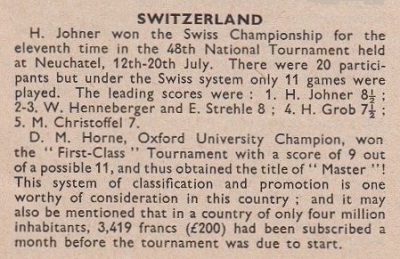

The game was played in the Tournoi principal I in Neuchâtel in July 1947. The crosstable was published on page 124 of the August-September 1947 Schweizerische Schachzeitung, and this brief report was on page 347 of CHESS, September 1947:

9742. Ernest Kim (C.N.s 8884 & 8886)

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) forwards an article from page 29 of Revista de Șah, February 1959:

Mr Urcan (who wonders whether a similar report can be found in Soviet chess literature of the time) has provided this translation from the Romanian:

‘“So It’s Not Propaganda ...”

In an earlier issue of our magazine we reported on the stupefying case of precocity involving little Ernest Kim of Tashkent, who, at only five, has the ability of a second-category player. Cheerful and intelligent, Kim adores chess, celebrates wildly when he wins and bursts into tears when he is compelled to resign.

Visitors to Tashkent do not pass up the opportunity to see Ernest Kim, who is now a veritable attraction point for the city. A group of American journalists who recently visited the Soviet Union manifested such a wish. Of course, they were introduced to little Kim. Unconvinced by the small, sun-tanned face before him, a “Michigan Telegraph” editor challenged him to a game. The chessmen were set up on the board, and after 15 moves the journalist was checkmated. Congratulating his opponent, the American editor exclaimed, “So it’s not propaganda ...”

And now here is a game by little Ernest Kim, played against Suvorov, a second-category player from Tashkent. Beforehand, the second-category player imprudently declared publicly that he “will quit chess if he loses this game”. Here is how Kim forced him to deal with a very unpleasant dilemma:

Ernest Kim – Suvorov 1 e4 e6 2 Nc3 d5 3 Nf3 Bb4 4 exd5 Bxc3 5 dxc3 exd5 6 Be2 Nf6 7 O-O Qe7 8 Re1 Be6 9 Bg5 Nbd7 10 Qd4 b6 11 Ne5 c5 12 Qa4 O-O 13 Nxd7 Bxd7 14 Bxf6 gxf6 15 Bb5 Qd6 16 Bxd7 a6. At this point Black could have resigned, but his hazardous statement before the game made him continue to seek salvation, in vain. 17 Qg4+ Kh8 18 Bf5 Rg8 19 Qh5 Rg7 20 Rad1 Rag8 21 g3 Qd8 22 c4 d4 23 c3 Qd6 24 Re4, and now Black resigned.’

9743. Michael Neckermann

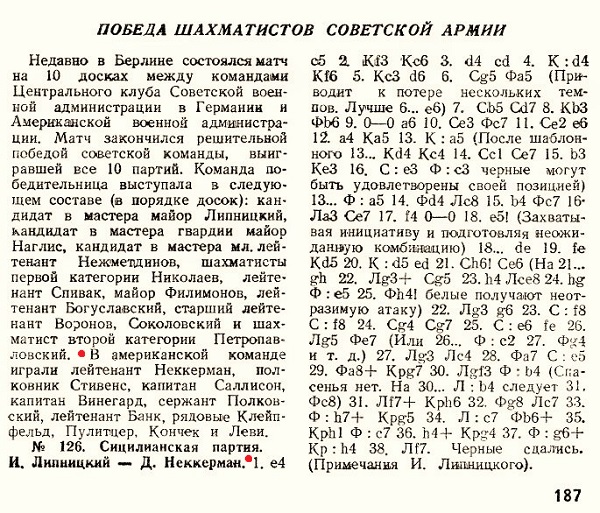

From Alan McGowan (Waterloo, Canada):

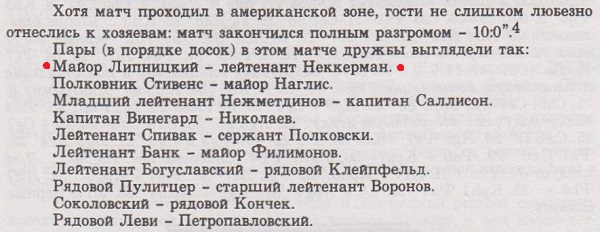

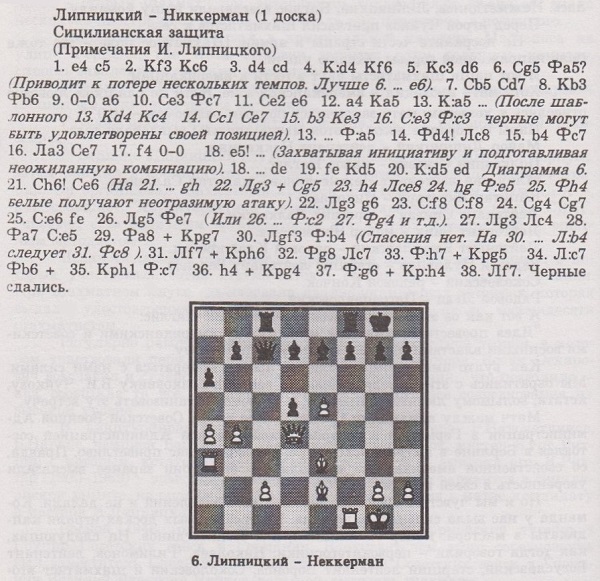

‘In 1946 a match took place in Berlin between members of the Soviet and American military administrations. The Soviet team won 10-0, and on top board Isaac Lipnitsky defeated Lieutenant Neckermann. Was this the Michael Neckermann who played in the 1939 New York congress and participated in Marshall Chess Club events in 1942 and 1943? Further information about him would be appreciated.’

Our correspondent notes the coverage of the 1946 team match on pages 13 and 14 of the monograph on Isaac Lipnitsky by Vadim Teplitsky (Bat Yam, 1993):

9744. Chess Budget biographical articles (C.N. 9611)

C.N. 9611 quoted from an article about James Mason by W.H. Watts in the Chess Budget. The magazine had many such biographical features, but how many? Below is a list of the articles in our incomplete run, and additions will be welcomed:

J.W. Showalter, 11 November 1925, pages 44-45;

D. Janowsky, 21 November 1925, pages 50-51;

S. Tarrasch, 28 November 1925, pages 60-61;

A. Burn (obituary), 5 December 1925, pages 66-68;

E. Schiffers, 12 December 1925, pages 74-75;

J. Mason, 19 December 1925, pages 82-84;

J.H. Blackburne, 2 January 1926, pages 90-92;

B. Englisch, 9 January 1926, pages 97-98.

9745. Bogoljubow’s ‘book’

From pages 162-163 of The World’s Great Chess Games by Reuben Fine (New York, 1951):

‘After that [i.e. after Bogoljubow’s greatest period, specified as 1925-31] he could not hold his own against the new masters. “The young people have read my book”, he would wail in his jovial manner. “Now I have no chance.”’

In a column reproduced on page 50 of The Chess Beat (Oxford, 1982) Larry Evans wrote:

‘He [Bogoljubow] blithely explained away his steady losses to the new generation: “The young demons have read my book. Now I have no chance.”’

A paragraph about Bogoljubow from page 216 of Impact of Genius by R.E. Fauber (Seattle, 1992):

‘He left as a literary legacy a single volume, Klassiche Schach [sic], which featured the games of the hypermoderns. When his results declined in the 1930s he lamented that he had trouble with the rising generation. “They have all read my book”, he complained.’

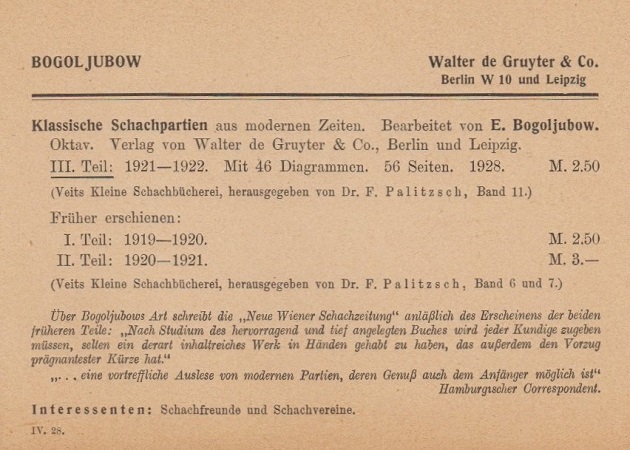

Bogoljubow wrote a number of books, including three volumes of Klassische Schachpartien (Berlin and Leipzig, 1926, 1926 and 1928). Our set includes this card:

Has any such Bogoljubow ‘my book’ story been related by a dependable writer?

9746. Lasker in Switzerland

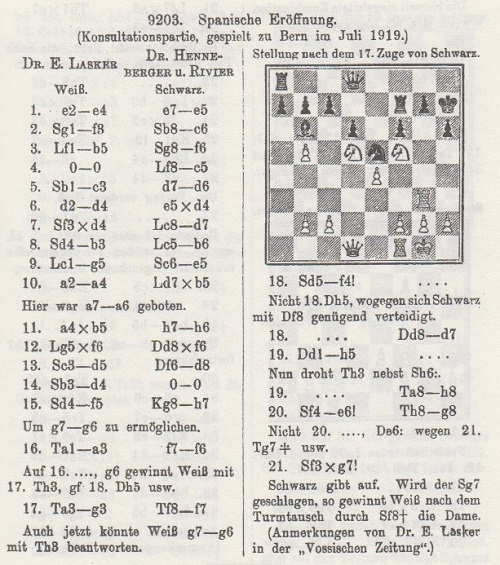

Several online databases indicate that Emanuel Lasker won a 21-move brilliancy (1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 Nf6 4 O-O Bc5 5 Nc3 d6 6 d4 exd4 7 Nxd4 Bd7 8 Nb3 Bb6 9 Bg5 Ne5 10 a4 Bxb5 11 axb5 h6 12 Bxf6 Qxf6 13 Nd5 Qd8 14 Nd4 O-O 15 Nf5 Kh7 16 Ra3 f6 17 Rg3 Rf7 18 Nf4 Qd7 19 Qh5 Rh8 20 Ne6 Rg8 21 Nfxg7 Resigns) against Henneberger and Rivier in a simultaneous exhibition in Zurich in 1919. In reality, the venue was Berne, and only one other game was played concurrently.

Lasker’s annotations in Vossische Zeitung were reproduced on page 211 of the October 1919 Deutsche Schachzeitung:

The heading stated that the game (against Walter Henneberger and William Rivier) was played in July. The correct date, 7 June 1919, was given when extensive annotations from the Basler Nachrichten appeared on pages 6-8 of the January 1920 Schweizerische Schachzeitung. The heading specified that Lasker played one other game at the same time, also against two opponents.

Fred Reinfeld discussed the Lasker v Henneberger and Rivier game (accurately putting ‘Berne, 1919’) on pages 25-29 and 106-112 of Chess Mastery by Question and Answer (London, 1940). In his Evening Standard column of 30 December 2015 Leonard Barden reported that it was ‘the first book which really improved my own chess’ and that it ‘is still a worthwhile read’.

9747. Hedinger v Henneberger

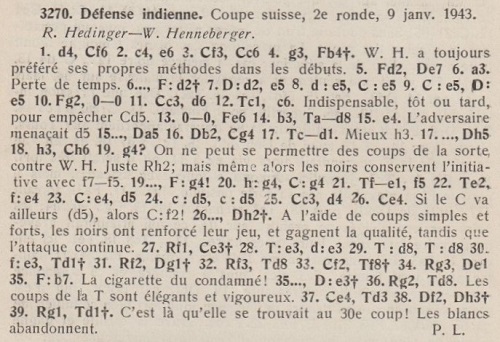

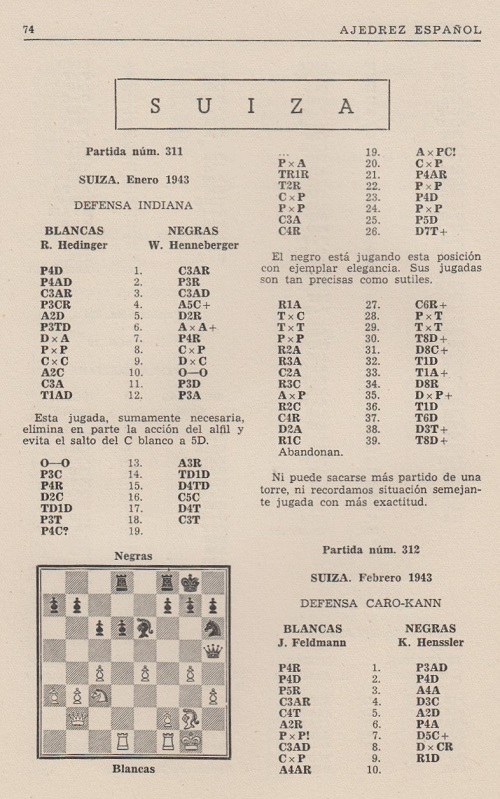

A specimen of Walter Henneberger’s attacking play (as Black against Rudolf Hedinger, Lucerne, 9 January 1943) comes from page 22 of the Schweizerische Schachzeitung, February 1943:

The game was also praised on page 74 of the March 1943 issue of Ajedrez Español:

1 d4 Nf6 2 c4 e6 3 Nf3 Nc6 4 g3 Bb4+ 5 Bd2 Qe7 6 a3 Bxd2+ 7 Qxd2 e5 8 dxe5 Nxe5 9 Nxe5 Qxe5 10 Bg2 O-O 11 Nc3 d6 12 Rc1 c6 13 O-O Be6 14 b3 Rad8 15 e4 Qa5 16 Qb2 Ng4 17 Rcd1 Qh5 18 h3 Nh6 19 g4 Bxg4 20 hxg4 Nxg4 21 Rfe1 f5 22 Re2 fxe4 23 Nxe4 d5 24 cxd5 cxd5 25 Nc3 d4 26 Ne4 Qh2+ 27 Kf1 Ne3+ 28 Rxe3 dxe3 29 Rxd8 Rxd8 30 fxe3 Rd1+ 31 Kf2 Qg1+ 32 Kf3

32...Rd8 33 Nf2 Rf8+ 34 Kg3 Qe1 35 Bxb7 Qxe3+ 36 Kg2 Rd8 37 Ne4 Rd3 38 Qf2 Qh3+ 39 Kg1 Rd1+ 40 White resigns.

9748. Chess Budget biographical articles (C.N.s 9611 & 9744)

Hans Renette (Bierbeek, Belgium) reports that during a visit to the Royal Library in The Hague he made copies of the following articles by W.H. Watts in the Chess Budget:

W. Steinitz, 29 September 1924, pages 4-5;

R. Charousek, 6 October 1924, pages 12-13;

H.E. Bird, 27 October 1924, pages 40-41.

Further additions to the list are sought.

9749. Swindle

‘The term “swindle” in chess is so widely used that we have to tolerate it. But it carries the implication we always fight against, i.e. that a player in a theoretically winning position has a sort of moral right to the game; if he fails to see through his opponent’s resourceful play, he says he was “swindled”.

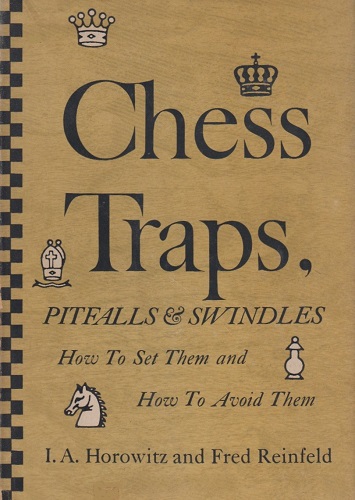

Showing that he hasn’t a moral right to the game is just what the authors are really doing – and doing very well.’

Source: Chess World, January 1957, page 22, in a brief notice regarding Chess Traps, Pitfalls, and Swindles by I.A. Horowitz and F. Reinfeld (New York, 1954). Purdy’s item began: ‘This is the best book on traps yet.’

9750.

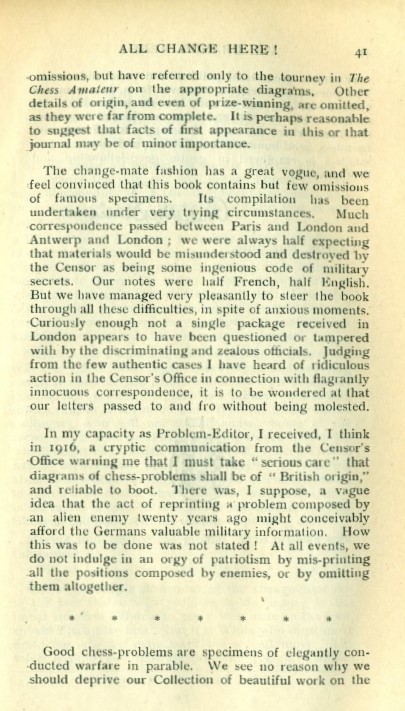

Wartime censorship (C.N. 9726)

Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England) draws attention to page 41 of All Change Here! by P.H. Williams and R. Gevers (Stroud, 1919):

9751. Frederick Orrett (C.N. 9722)

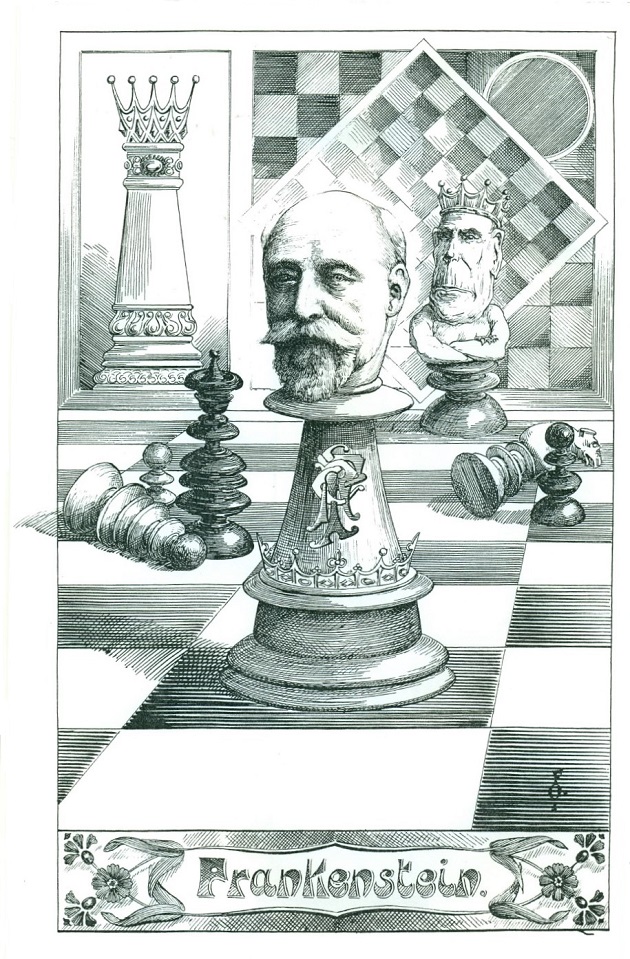

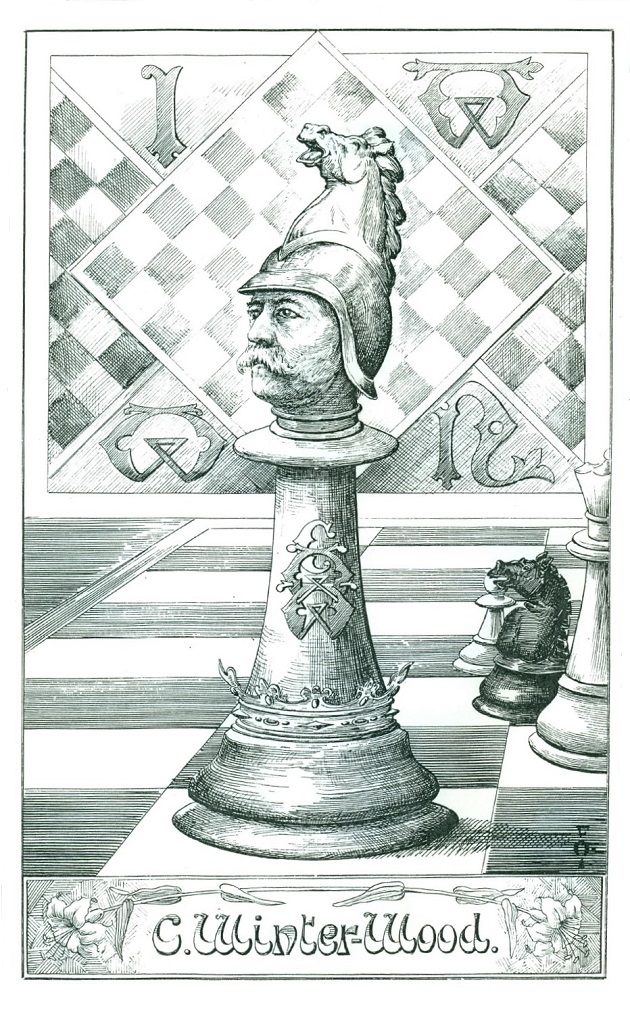

Also courtesy of Mr McDowell, we present a further selection of illustrations by Frederick Orrett (Edward Nathan Frankenstein, Jacques Mieses and Carslake Winter-Wood):

9752. Michael Neckermann (C.N. 9743)

Dan Scoones (Coquitlam, BC, Canada) notes that according to page 187 of Shakhmaty v SSSR, August-September 1946 Lipnitsky’s opponent was D. Nekkerman:

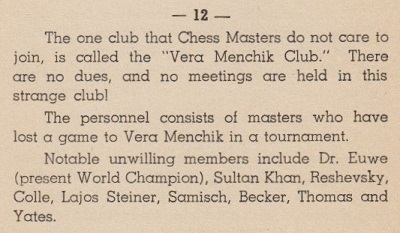

9753. The Vera Menchik Club (C.N. 3433)

From page 10 of Curious Chess Facts by Irving Chernev (New York, 1937):

See too pages 6-7 of Chernev’s Wonders and Curiosities of Chess (New York, 1974).

Max Euwe mentioned the Club on page 110 of the April 1953 Chess Review:

‘We know that Vera included in her list of victims the names of a number of reputable masters forced, in one contest or another, to bite the dust.

It has more than once been suggested that these losers band themselves together to form a “Menchik” Club, pressing me, as a two-time loser (Hastings, 1930-31 and Hastings, 1931-32), to become its president. These plans have remained plans.’

For reasons undisclosed, the account of the Club on page 237 of Impact of Genius by R.E. Fauber (Seattle) asserted that Vera Menchik ‘outraged the male players by accepting an invitation to the great Carlsbad, 1929 tourney’.

On pages 18-19 of Women in Chess (Jefferson, 1987) John Graham stated that at Carlsbad, 1929 Becker ‘jokingly suggested that if anyone lost to her they would be inducted into the Vera Menchik Club’. Graham concluded:

‘Menchik did not have a good result in the tournament, and finished in a tie for last place with Vasja Pirc, Gideon Stahlberg and others.’

In reality, Vera Menchik finished alone in bottom place at Carlsbad, 1929, three points adrift. Neither Pirc nor Ståhlberg played in the tournament.

Our latest feature article is The Vera Menchik Club.

9754. Alleged limitations

‘But being female does have its limitations. Since, in Australia anyway, women do not seem to have the same natural ability as men, they can never be serious threats in a mixed tournament, no matter how hard they may study and prepare.

However, as long as a woman does realize the limited heights that her chess can ever reach, then she can certainly find chess a most interesting pastime in an atmosphere where there is definitely no unfair bias against women.’

Those were the concluding paragraphs of an article ‘“Only Old Fogeys Play Chess”’ by Daphne Hewson on pages 103-104 of Chess World, May-June 1967. Purdy added an editorial note:

‘Miss Hewson’s second-last paragraph has no demonstrable scientific basis. The only boys who get good at chess are those who study it. Teach chess to more girls of around nine or ten, well before they get too interested in boys and inundated with homework at secondary school, and you’ll get results.’

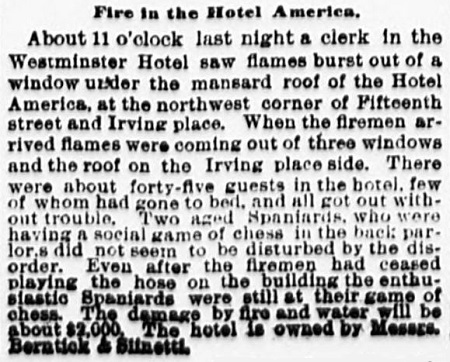

9755. Fire

From page 2 of the New York Sun, 10 January 1889:

The report was reproduced on page 11 of the Columbia Chess Chronicle, 10 January 1889.

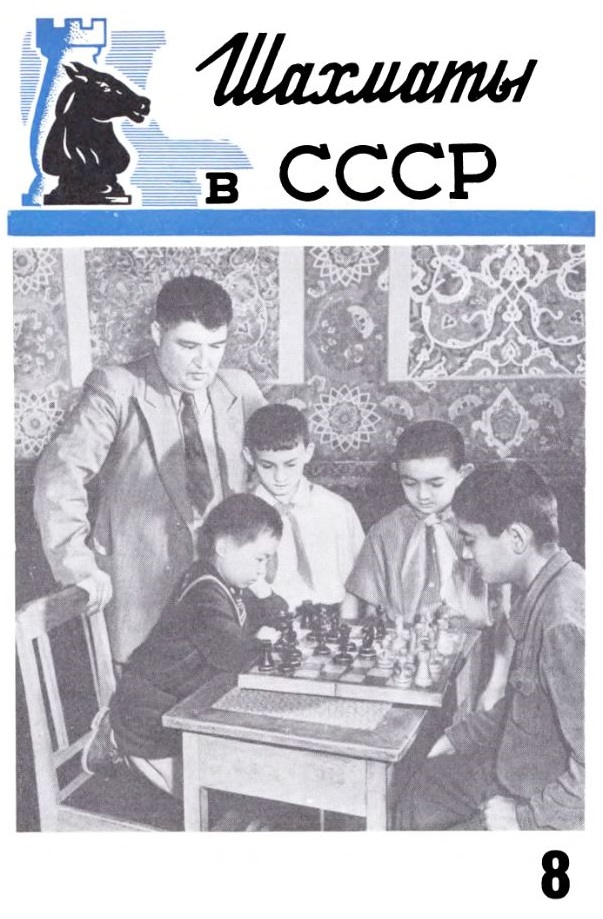

9756. Ernest Kim (C.N.s 8884, 8886 & 9742)

Dan Scoones (Port Coquitlam, BC, Canada) sends the front cover of the 8/1958 issue of Shakhmaty v SSSR:

Our correspondent adds a translation of the note on the inside cover:

‘In the Tashkent Pioneer Palace. Six-year-old third-category player Ernest Kim in play against the second-category player Khurshid Muratov. The chess group director G. Shakh-Zade is spectating.’

9757. Chess in Paris

Mr Scoones also draws attention to the chess content (reports and photographs) in La russie illustrée/Иллюстрированная Россия, and particularly in the issue dated 11 February 1928.

Readers should have little difficulty in identifying the board position in the front-cover photograph of Alekhine.

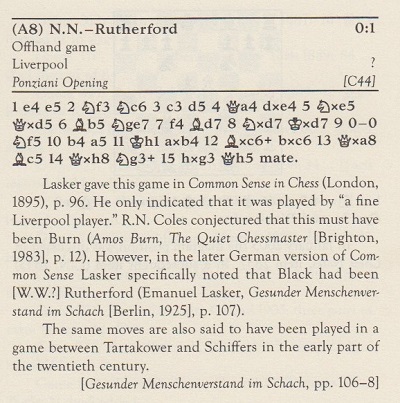

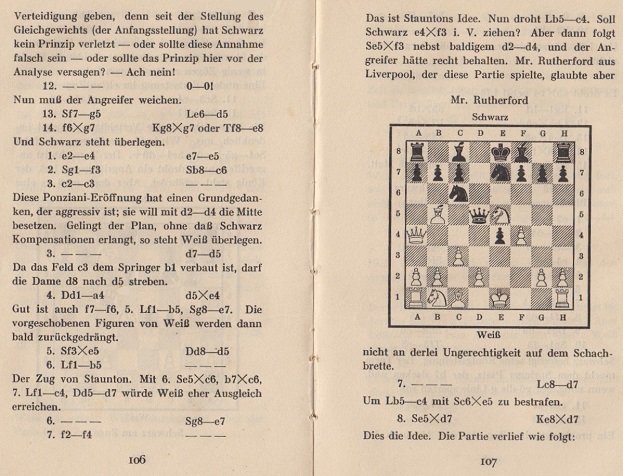

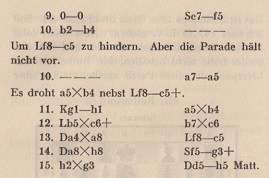

9758. A would-be Tartakower v Schiffers game

Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) asks about this game:

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 c3 d5 4 Bb5 dxe4 5 Nxe5 Qd5 6 Qa4 Ne7 7 f4 Bd7 8 Nxd7 Kxd7 9 O-O Nf5 10 b4 a5 11 Kh1

11...axb4 12 Bxc6+ bxc6 13 Qxa8 Bc5 14 Qxh8 Ng3+ 15 hxg3 Qh5 mate.

Our correspondent observes that page 10 of 200 megnyitási sakkcsapda by Emil Gelenczei (Budapest, 1958) stated that the players were Tartakower and Schiffers, no date being specified. On pages 36-37 of 300 miniaturas by A. Roizman (Barcelona, 1975) the heading, also without a date, was ‘NN-Schiffers’. There are databases which give the game as ‘Tartakower v Schiffers, Poland, 1910’, even though Emanuel Schiffers died in 1904. As noted on pages 141-142 of the September-October 1935 issue of Les Cahiers de l’Echiquier Français, the game had been published in Pitfalls of the Chessboard by E.A. Greig (where the opening moves were 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 c3 d5 4 Qa4 dxe4 5 Nxe5 Qd5 6 Bb5 Ne7) without any date or players’ names. The same move order was on pages 96-97 of Emanuel Lasker’s Common Sense in Chess (London, 1896), where the game appeared with the bare information that Black was ‘a fine Liverpool player’.

Mr Thimognier has raised an intriguing matter. First of all, we reproduce, concerning what Lasker wrote, an extract from page 903 of Amos Burn A Chess Biography by Richard Forster (Jefferson, 2004):

Below is the relevant part of the 1925 edition of Gesunder Menschenverstand im Schach:

Page 65 of the algebraic edition of Common Sense in Chess (Milford, 2007) amended the game heading to ‘N.N. vs. Rutherford. Liverpool, 1800s’.

Analysis on page 213 of Play the Ponziani by D. Taylor and K. Hayward (London, 2009) awarded an exclamation mark to 10 d4, adding: ‘Tartakower’s 10 b4? runs into Schiffers’ 10...a5!; e.g. 11 Kh1 axb4 12 Bxc6+ bxc6 13 Qxa8 Bc5 14 Qxh8 Ng3+ 15 hxg3 Qh5 mate’.

Regarding Tartakower, mention may be made of analysis on page 180 of Die Hypermoderne Schachpartie (Vienna, 1924):

See too page 196 of 500 Master Games of Chess by Tartakower and du Mont (London, 1952).

Page 133 of the eighth edition of Modern Chess Openings (London, 1952) gave the line 10 b4 a5 with the footnote ‘Black wins (Swinnerton-Dyer)’. The same page referred to a game between Swinnerton-Dyer and Barrett, Cambridge, 1949 in another variation of the Ponziani Opening. On page 75 of the ninth edition of Modern Chess Openings (London, 1957) the note after 10 b4 a5 became ‘Black wins (Schiffers). The threat is 11...PxP and 12...B-B4ch’.

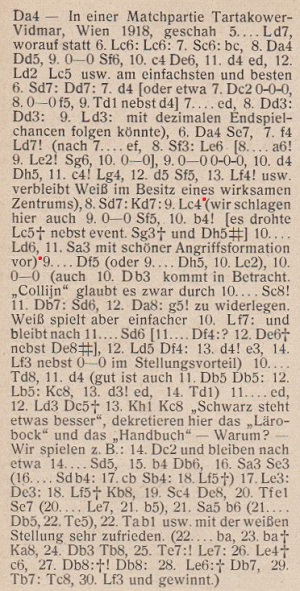

The 15-move game was the subject of a short story, ‘The Wiener Dog Gambit’ by Brent Haywood, on pages 34-35 of the February 1985 Chess Life. Prizes were offered to readers able to identify ‘which two famous masters really played this miniature’, and the result was published on page 57 of the May 1985 issue:

Tartakower, Schiffers, Vienna and 1908 were also referred to in a letter from Robert Probasco on page 7 of the May 1985 Chess Life, but why? As noted above, Schiffers died in 1904.

9759. Philidor in London

From John Townsend (Wokingham, England):

‘Contemporary newspaper reports of the death of Philidor acknowledged the assistance he received from an “old and worthy friend”. There were variations in the words used, but the following statement from the Kentish Weekly Post of 4 September 1795 was typical:

“For the last two months he was kept alive merely by art, and the kind attention of an old and worthy friend.”

George Allen discussed briefly the identity of the “old and worthy friend” on page 109 of The Life of Philidor, Musician and Chess-player (Philadelphia, 1863), but without arriving at a convincing answer:

“In a letter received after the preceding sheet had been printed, Mr Lewis (the eminent English Chess-author and player) kindly answered some inquiries of mine, by saying: ‘Who “the old and worthy friend” was, I know not. I always understood from Sarratt that a Mr Crawford, a very rich man, patronised Philidor, taking a lesson – or being supposed to take a lesson – daily, and giving him carte blanche to dinner, whenever it suited him.’”

A more telling remark, not mentioned by Allen, had previously been made by George Walker in the “To Correspondents” column on page 2 of Bell’s Life in London of 15 November 1840:

“Sir A. Carlisle, just dead, was a staunch friend of Philidor’s, when the latter was on his death bed.”

The expression “kept alive merely by art” suggests skilful medical attention. Anthony Carlisle (1768-1840) was a prominent surgeon. The Dictionary of National Biography notes that in 1793 he was appointed Surgeon at Westminster Hospital, where he continued to work for the rest of his life, being knighted in 1820. His death in Langham Place, London, was reported on page 3 of the Morning Post of 6 November 1840, and he was buried in Kensal Green Cemetery on 10 November.

Carlisle was a long-term resident of Soho Square, and George Walker and his father had lived at 17 Soho Square. A brief examination of rates assessments and land tax returns shows that they were both in Soho Square during the years 1819 to 1821, so it is possible that the Walkers knew Carlisle.

On page 127 of his Chess & Chess-Players (London, 1850) George Walker blamed “the mighty and the rich” for the poverty of Philidor’s last days:

“Alas ! for England ! the mighty and the rich suffered Philidor to die, if not in actual need of life’s necessities, at least without those comforts which gold can supply, to soothe down the harsh asperities of utter destitution! Philidor died almost literally in a garret. During his last hours, he was chiefly indebted for support to the assiduities of one kind friend …”

Walker says nothing here of Anthony Carlisle’s involvement. Although Walker’s main thrust above concerned Philidor’s poverty, it is perhaps worth reflecting that he could not have mentioned that Philidor was attended by a surgeon who later became eminent without detracting from his argument.

Walker’s final sentence tends to suggest that support came from one person alone. That is reinforced by a remark by George Allen on page 44 of The Life of Philidor: Musician and Chess-Player (Philadelphia, 1858):

“When among Englishmen were the sick-bed wants of a stranger, even less beloved than Philidor, known and ministered to by one friend and by one friend alone?”

On pages 42-43 of the same book George Allen countered Walker’s accusation by pointing out that ...

“... ‘the garret of Philidor’ (which was no garret) is not pretended to have been any other than such modest apartment as he had chosen to occupy through the whole of his last residence in London. There was not, therefore, the same reason for removing Philidor, during his sickness, as existed in the case of poor La Bourdonnais.”

Philidor’s “modest apartment” was in Little Ryder Street, which was a very short walk from the chess club at Parsloe’s on St James’s Street. Letters presented by Marcelle Benoît in Philidor, musicien et joueur d’échecs (Paris, 1995) suggest that his last known residence was at 10 Little Ryder Street. However, in the Chess Stalker Quarterly, June 2012, in an article entitled “Sleuthing for Philidor’s Grave”, Gordon Cadden reported on page 9 that he had found Philidor’s address entered as 8 Little Ryder Street in a burial ledger for St James’s Chapel of Ease, Hampstead Road.

In 1795, rate books for Little Ryder Street did not show house numbers, which makes it harder to identify the principal occupiers, who are assumed to include Philidor’s landlord. Both 8 and 10 were on the south side of Little Ryder Street, the occupiers of which were listed in an assessment for the Poor Rate (Collector’s Book), dated 18 April 1795 (Pall Mall Ward, parish of St James’s Westminster, Westminster Archives, D116, ff. 35-36). The entry below has been abbreviated:

Little Ryder Street South

Alexander Oswald 20

Thos Williams 24

Wm Fry 22

Wm King 14

Elizth Alexander 22

Chas Wadlow 15

Clement Baker 10

Raymond Baux 16.The figures represent the gross annual rentable values of the properties in pounds. Insurance records of Sun Fire Office, held at London Metropolitan Archives, indicate that on 30 December 1791 Elizabeth and Janet Alexander, of “10 Little Rider Street”, milliners, were insured. That seems to identify “Elizth Alexander” in the above list as the occupier of No. 10. A similar insurance record, dated 25 November 1796, names Thomas Williams, gentleman, of “8 Little Rider Street” as the insured, while in a Westminster coroner’s jury, on 13 August 1794, Thos. Williams, of Little Ryder Street, was described as a haberdasher. Another insurance record, dated 26 March 1799, associates William Fry, gentleman, with the address “9 Little Rider Street”, his wife a trimming maker; and another, dated 19 November 1791, gives Fry’s address as “Little Rider Street”, his wife a mantua and trimming maker. It is clear that in the above Poor Rate list the occupiers of the south side of Little Ryder Street appear in ascending order starting with 7. The only entry which remains in doubt is the one for “Wm King”, who could have occupied either part of No. 9 or part of No. 10.

From this it seems that Philidor resided “through the whole of his last residence in London” either at 10 Little Ryder Street with Elizabeth Alexander, a milliner (or possibly with William King), or at No. 8 with Thomas Williams. A milliner or a haberdasher might easily have taken on a lodger, as did John Maynard, a bookseller, who had Carmine Verdone lodging with him, as was reported in C.N. 9595.

Finally, in the same column on page 2 of Bell’s Life in London of 15 November 1840 the following interesting exchange with a different correspondent was inserted:

“EZ – Are there any chess players living who have played with Philidor? – Yes: Sir Griffin Wilson, and Sir W. Alexander, and doubtless many others. It is 45 years since Philidor’s death.”

Sir William Alexander (1755-1842), of Airdrie, was Chief Baron of the Exchequer at Westminster. A few weeks later, in the same newspaper, dated 13 December 1840, he was reported as having contributed five pounds to the De La Bourdonnais fund in a list of donors printed on page 1. His will was proved on 21 July 1842 in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury (PROB 11/1965/15).’

9760. No champion of the world

From a letter entitled ‘The Universality of Chess’ by Miron Hazeltine on pages 61-62 of the Brooklyn Chess Chronicle, 1 January 1883:

‘There is now, happily, no champion of the world – no King of Chess. In the best interests of chess may there never be another.’

9761. Spassky v Fischer, 1972

C.N. 9641 referred to a play in Spanish concerning the 1972 world chess championship match. Another work is Einvígid by Arnaldur Indriðason (Reykjavik, 2011). We also have the translations of the novel from Icelandic into German and French, Duell (Cologne, 2014) and Le duel (Paris, 2014).

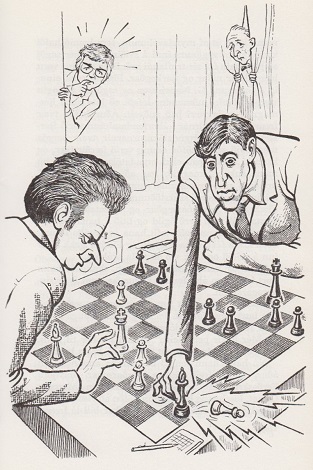

9762. Spassky v Fischer match cartoons

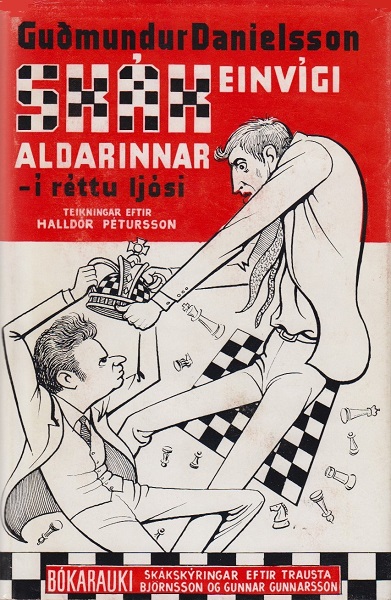

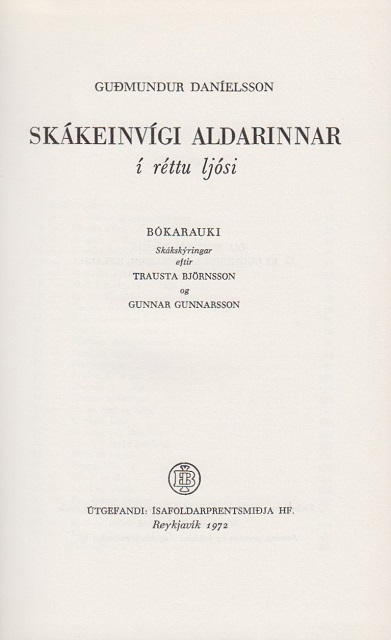

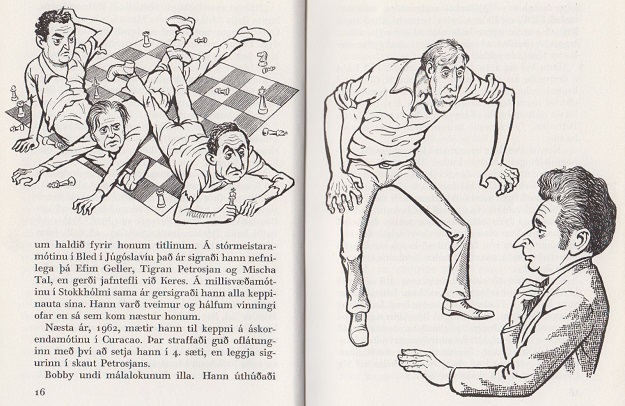

Of all the books on the 1972 Spassky v Fischer match, the one in our collection with the most cartoons is Skákeinvígi aldarinnar by Guðmundur Daníelsson (Reykjavik, 1972). A small sample (from pages 16-17, 103 and 163):

Although mainly a prose account of the Reykjavik match, the book concludes with annotations to the games (pages 291-345).

9763. Chess Budget biographical articles (C.N.s 9611, 9744 & 9748)

Henk Chervet of the Koninklijke Bibliotheek in The Hague has supplied these additions:

H.N. Pillsbury, 10 November 1924, pages 56-57;

C. Schlechter, 17 November 1924, pages 63-64;

M.I. Chigorin, 24 November 1924, pages 72-73;

R.P. Michell, 20 March 1926, pages 179-180;

J.J. Löwenthal, July-August 1926, pages 212-213.

9764. A sense of history

‘The historical treatment is the best; nobody can understand modern methods in chess without first understanding just what older ideas they replaced and why they replaced them.’

Source: an article (‘A Page of Hints’) by C.J.S. Purdy, Chess World, March 1957, page 80. He was discussing Chess from Morphy to Botwinnik by Imre König (London, 1951), ‘an important treatise on position play’.

9765. Tarrasch in Geneva

Siegbert Tarrasch’s prize-winning game against Edgard Colle, Meran, 14 February 1924:

1 d4 d5 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 c6 4 Nf3 Nf6 5 Bg5 Be7 6 e3 Nbd7 7 Bd3 dxc4 8 Bxc4 b5 9 Bd3 a6 10 O-O c5 11 Qe2 c4 12 Bc2 Bb7 13 e4 O-O 14 e5 Nd5 15 Qe4 g6 16 Qh4 f6 17 exf6 Bxf6 18 Ne4 Bxg5 19 Nexg5 Qe7 20 Rae1 Rf6 21 g3 Re8 22 Nd2 Nb4 23 Be4 Bxe4 24 Ndxe4 Rff8 25 Nd6 e5 26 Nxe8 Rxe8 27 dxe5 Nd3 28 Re2 h5 29 f4 Qc5+ 30 Kg2 Nf6 31 h3 b4 32 Nf3 Qc6 33 Kh2 Ne4

34 f5 Nxe5 35 Nd4 Qd5 36 Rxe4 Ng4+ 37 Rxg4 hxg4 38 Qxg4 Re4 39 Qxg6+ Resigns.

The position after Black’s 12th move had arisen in a forgotten game which Tarrasch played in Geneva on 5 April 1920 against an unnamed group of the strongest members of the city’s chess club:

1 d4 d5 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 Be7 5 e3 c6 6 Bd3 Nbd7 7 Nf3 dxc4 8 Bxc4 b5 9 Bd3 a6 10 O-O c5 11 Qe2 c4 12 Bc2 Bb7 13 Rad1 O-O 14 e4 Re8 15 e5 Nd5 16 Ne4 f6 17 exf6 gxf6 18 Bc1 Nf8 19 Ne1 f5 20 Ng3 Bg5 21 f4 Bh6 22 Qh5 Qf6 23 Qh3 Qg6 24 Nh5 Nf6 25 Nxf6+ Qxf6 26 Nf3 Bg7 27 Ne5 Rad8 28 Rfe1 Ng6 29 Be3 Qh4 30 Qg3 Bd5 31 Rd2 Qxg3 32 hxg3 Nf8

33 g4 Bxe5 34 fxe5 fxg4 35 Kf2 Rc8 36 Rdd1 Rc7 37 Rh1 g3+ 38 Kg1 Ng6 39 Rh3 Rf7 40 Rxg3 Kg7 41 Bg5 Rg8 42 Bf6+ Kf8 43 Rf1 Ke8 44 Rf2 Kd7 45 Ra3 Ra8 46 Rg3 Rg8 47 Kf1 Kc6 48 Ke1 a5 49 Rg5 a4 50 a3 Ra7 51 Rg3

51...b4 52 axb4 Kb5 53 Ra3 Kxb4 54 Bg5 Kb5 55 Bd2 Ne7 56 Bxh7 Rxg2 57 Rxg2 Bxg2 58 Rg3 Bd5 59 Rg7 Nc6 60 Rxa7 Nxa7 61 Ke2 Nc6 62 Bc3 Nb4 63 Ke3 a3 64 bxa3 Na2 65 Kd2 Ka4 66 Bb1 Kxa3 67 Bxa2 Drawn.

Source: Schweizerische Schachzeitung, June-July 1920, pages 86-89. The times were given as White 6½ hours and Black 5½ hours.

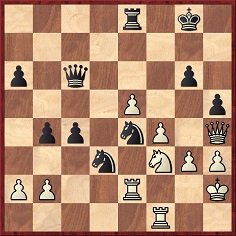

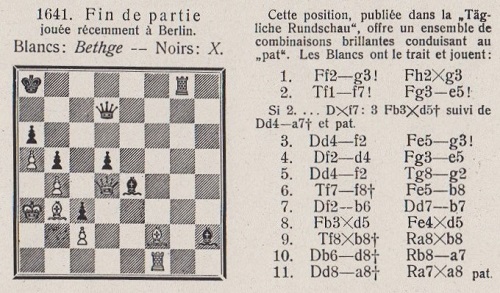

9766. Bethge v X

Information is wanted about this game from page 89 of the June-July 1920 Schweizerische Schachzeitung:

1 Bg3 Bxg3 2 Rf7 Be5 3 Qf2 Bg3 4 Qd4 Be5 5 Qf2 Rg2 6 Rf8+ Bb8 7 Qb6 Qb7 8 Bxd5 Bxd5 9 Rxb8+ Kxb8 10 Qd8+ Ka7

11 Qa8+ Kxa8 Stalemate.

9767. William W. Wheaton

From Robert John McCrary (Columbia, SC, USA):

‘In Chess and Baseball William R. Wheaton has already been mentioned as a pioneer in the birth of modern baseball, as well as organized chess. He may also be the first documented umpire. On pages 21-22 of A Game of Inches by Peter Morris (Chicago, 2010) the entry on the history of umpires has Wheaton as the first name listed. After briefly referring to the Olympic Ball Club of Philadelphia (which played town ball, a baseball variant, in 1838) the entry reads:

“The Knickerbockers’ rules outlined a similar role for the umpire. William R. Wheaton officiated during a game of 6 October 1845, that appears in the club’s scorebooks.”

It then adds that Wheaton was one of three umpires in a game between the New York Ball Club and the Brooklyn Club on 23 October 1845.’

9768. Fotoleren

Thomas Höpfl (Halle, Germany) points out that the Dutch website Fotoleren has many chess photographs.

9769. Icelandic photographs

Aðalsteinn Thorarensen (Reykjavik) has sent us a pair of Icelandic Chess Federation links (one and two) including a rich selection of photographs taken during the 1972 Spassky v Fischer match.

9770. Marshall’s gold coins game

Concerning the famous Marshall game, below is the first paragraph of an article (‘Shower of Gold’) by C.J.S. Purdy on pages 110-111 of Chess World, July-August 1967:

‘Most players know about the game Levitzky-Marshall, Breslau, 1912, when a move by Marshall inspired the German onlookers to shower the board with gold pieces. We disbelieved this story until we asked somebody to ask Marshall personally if it were true. Marshall said yes.’

9771. An unexpected move

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 b4 Bb6 5 b5 Na5 6 Be2 d6 7 O-O Ne7 8 d3 f5 9 Nc3 c6 10 a4 O-O 11 d4 fxe4 12 Nxe4 d5 13 Ng3 e4 14 Ne5 Be6 15 c3 Rc8 16 Bg4 Bxg4 17 Qxg4 Qd6 18 Nh5 Nf5 19 Bf4 Qe6 20 f3 cxb5 21 fxe4 dxe4 22 Bg3 Rc7

23 Nc4 Nxc4 24 Bxc7 Nce3 25 Qf4 Bxc7 26 Qxc7 Nxf1 27 Rxf1 g6 28 Rxf5 gxh5 29 Rg5+ and wins.

The game was played by J.A. Porterfield Rynd against J. Morphy and G.D. Soffe and was published, with annotations by the winner but no indication of the venue or date, on pages 125-127 of the Irish Chess Chronicle, 1 December 1887.

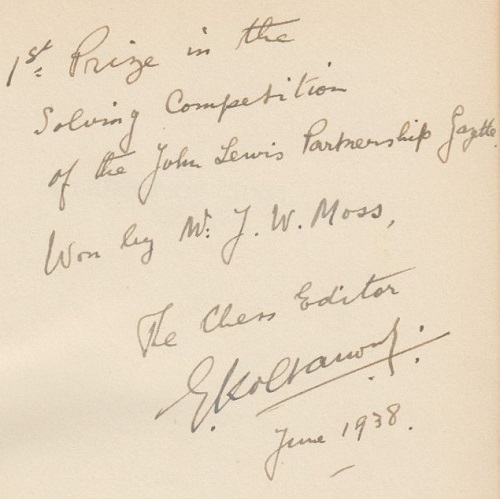

9772. Koltanowski inscription

From one of our copies of A Primer of Chess by J.R. Capablanca (London, 1935):

What is known about the John Lewis Partnership Gazette in connection with chess?

| First column | << previous | Archives [139] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.