Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [138] | next >> | Current column |

9662. Watson v Green brilliancy

Charles Gilbert Marriott Watson – Max Green

Championship of Victoria, Melbourne, 1936

Queen’s Pawn Opening

1 d4 Nf6 2 e3 b6 3 Bd3 Bb7 4 Nf3 e6 5 O-O c5 6 Nbd2 Nc6 7 c3 Qc7 8 e4 cxd4 9 cxd4 Nb4 10 Bb1 Ba6 11 Re1 Nd3 12 Bxd3 Bxd3 13 Re3 Bb5 14 Rc3 Qb7 15 Qc2 Bc6

16 d5 exd5 17 e5 Ne4 18 Nxe4 dxe4 19 Nd4 Bd5 20 Bf4 Be7 21 Nf5 g6 22 Rc7 Qa6 23 Nxe7 Kxe7 24 Rd1 Qxa2 25 Bg5+ Ke6 26 Bf6 Rhg8 27 g4 g5

28 Qc6+ Resigns. ‘The finish of this game is pretty enough for any book.’

Source: Australasian Chess Review, 10 September 1936, pages 256-257.

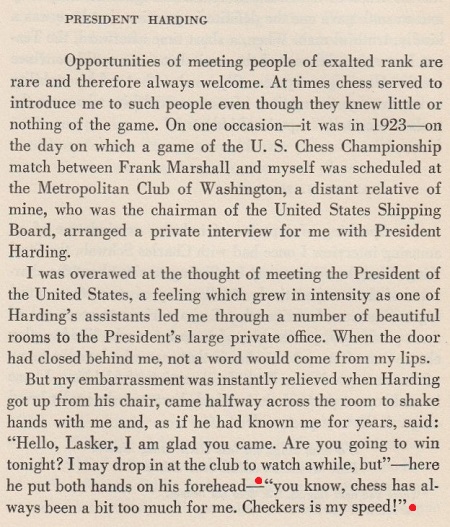

9663. President Warren G. Harding

‘... chess has always been a bit too much for me. Checkers is my speed!’

This remark by President Harding comes from page 181 of The Adventure of Chess by Edward Lasker (New York, 1950):

The only game of the Marshall v Lasker match that was played in Washington was the 15th, on 30 April and 1 May 1923 (American Chess Bulletin, May-June 1923, page 93). President Harding died three months later.

An inscription in one of our copies of Lasker’s book:

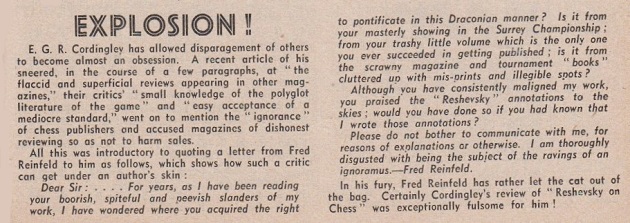

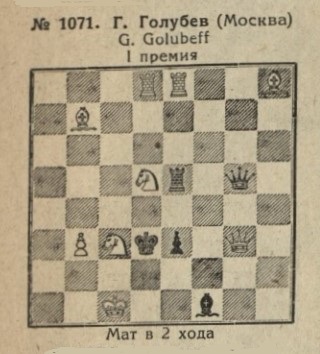

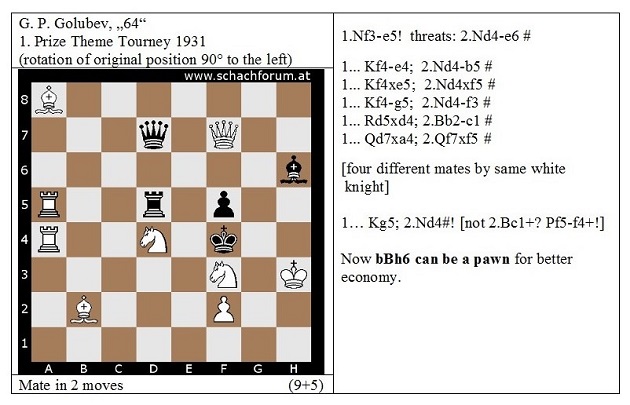

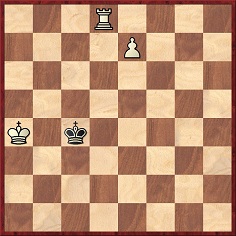

9664. Golubev composition

From Michael McDowell (Westcliff-on-sea, England):

‘This problem by G.P. Golubev won first prize in the 64 Theme Tourney, 1931:

Mate in two

1 Ne4 (threat: 2 Nf4). 1…Kd4 2 Ne7 (Nf6?). 1…Kxe4 2 Nxe3 (Ne7?). 1…Ke2 2 Ba6 or Ndc3. 1…Rxd5 2 Ba6. 1…Qxd8 2 Qxe3.

A very fine, well-keyed problem showing excellent line effects. Why the composer submitted a setting with a dual (2 Ba6/2 Ndc3) in one variation is a mystery (as is how the problem won a top award while containing such a flaw). The dual could be removed by adding a black knight at e1, eliminating 1…Ke2 2 Ba6. The problem has been reprinted many times, e.g. in the FIDE Album and the Overbrook volume A century of two-movers. Is it possible that the problem has been repeatedly misprinted? Can the original source be checked?’

It will be appreciated if a reader can verify what appeared in the original Soviet publication. We note that the diagram as given by Mr McDowell was published on page 550 of the December 1931 BCM. The solution on page 94 of the February 1932 issue was 1 Ne2, but that was corrected to 1 Ne4 on page 183 of the April 1932 BCM. The same position was on page 192 of the June 1932 Deutsche Schachzeitung. When the problem was published (in Forsyth notation only) on page 189 of the August 1943 BCM the solution printed was 1 Nd4 because the position was in reverse:

9665. The Polish Defence (C.N. 4014)

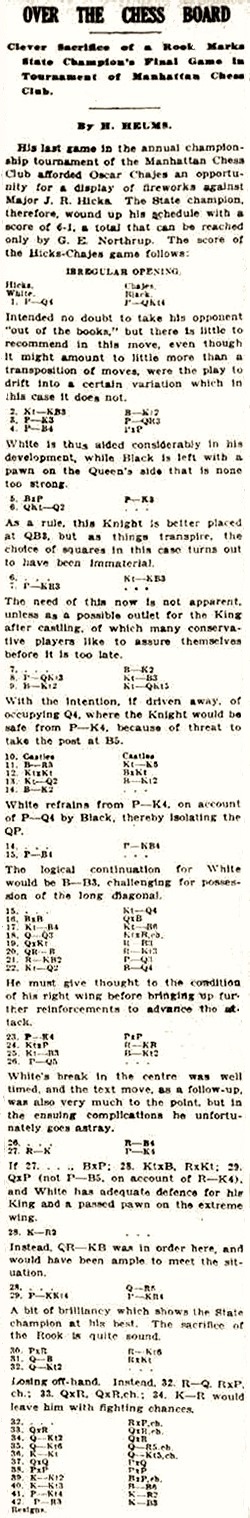

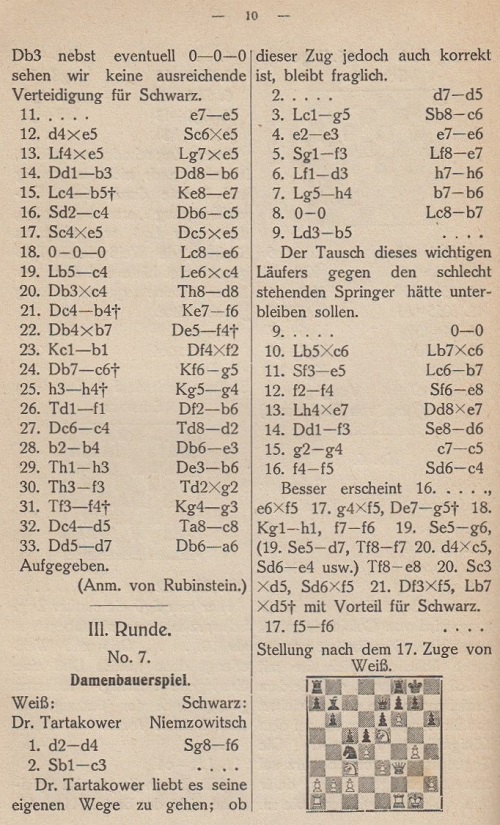

One of the games listed in C.N. 4014:

- Pages 224-225 of La Stratégie, October 1918 gave, courtesy of the Evening Post, a game between I.R. (J.R.?) Hicks and O. Chajes which began 1 d4 b5 2 Nf3 Bb7. It was ‘jouée au Manhattan Chess Club dans le Tournoi-championnat de l’Etat de New-York’, and we are seeking further particulars.

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) reports that the game was played in the Manhattan Chess Club championship and was published by Hermann Helms on page 16 of the New York Evening Post, 9 February 1918:

1 d4 b5 2 Nf3 Bb7 3 e3 a6 4 c4 bxc4 5 Bxc4 e6 6 Nbd2 Nf6 7 h3 Be7 8 b3 Nc6 9 Bb2 Nb4 10 O-O O-O 11 Ba3 Ne4 12 Nxe4 Bxe4 13 Nd2 Bb7 14 Be2 f5 15 f4 Nd5 16 Bxe7 Qxe7 17 Nc4 Nc3 18 Qd3 Nxe2+ 19 Qxe2 Rf6 20 Rac1 Rg6 21 Rf2 d6 22 Nd2 Bd5 23 e4 fxe4 24 Nxe4 Rf8 25 Nc3 Bb7 26 d5 Rf5 27 Re1 e5 28 Kh2 Qh4 29 g4

29...h5 30 gxf5 Rg3 31 Qf1 Rxc3 32 Qg2 Rxh3+ 33 Qxh3 Qxf2+ 34 Qg2 Qxe1 35 Qg6 Qh4+ 36 Kg1 Qg4+ 37 Qxg4 hxg4 38 fxe5 dxe5 39 Kg2 Bxd5+ 40 Kg3 Bf3 41 b4 Kf7 42 a3 Kf6 43 White resigns.

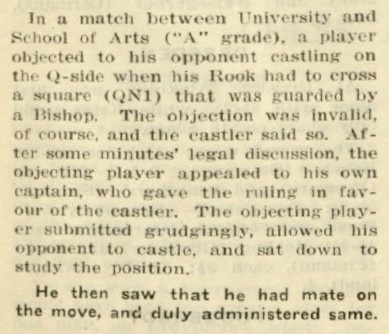

9666. Castling incident (C.N. 9644)

It is now possible, courtesy of the Cleveland Public Library, to show the earlier account of the castling story, published on page 238 of the 10 September 1936 issue of the Australasian Chess Review:

9667. Alexander McDonnell and hypermodernism

John Townsend (Wokingham, England) writes:

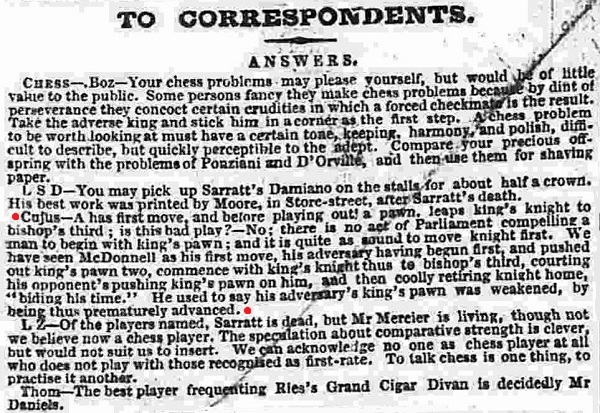

‘In Bell’s Life in London, 13 November 1842 George Walker recalls in a reply to a correspondent that Alexander McDonnell (1798-1835) had played an unusual variation of Alekhine’s Defence:

“We have seen McDonnell as his first move, his adversary having begun first, and pushed out king’s pawn two, commence with king’s knight thus to bishop’s third, courting his opponent’s pushing king’s pawn on him, and then coolly retiring knight home, “biding his time”. He used to say his adversary’s king’s pawn was weakened, by being thus prematurely advanced.”

This commentary on the variation 1 e4 Nf6 2 e5 Ng8 suggests that McDonnell possessed some understanding of what we would now regard as hypermodern principles of play.

I note your feature article on Alekhine’s Defence. Had Allgaier already explained any such principles in the course of his analysis?’

Below is the passage by Walker referred to, from page 2 of the 13 November 1842 edition of Bell’s Life in London:

Mr Townsend notes that the item can also be viewed at the Chess Archaeology website as part of the Jack O’Keefe Project. (The Project, we add, represents an astounding amount of work of great value.)

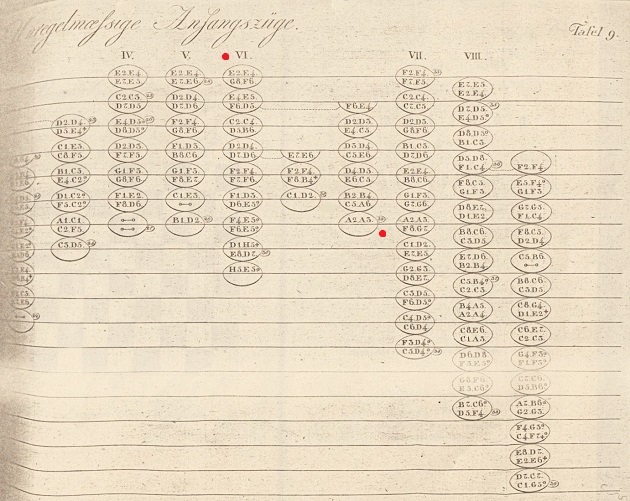

The answer to our correspondent’s question about Allgaier is that no explanation of principles was offered when the moves 1 e4 Nf6 were given in Tafel 9 of his book Neue theoretisch-praktische Anweisung zum Schachspiele (Vienna, 1819):

The relevant notes (30, 31 and 32) can be read in the Google Books scan of the work, on page 108.

The connection between Alexander McDonnell and hypermodernism is intriguing.

9668. Philidor’s legacy

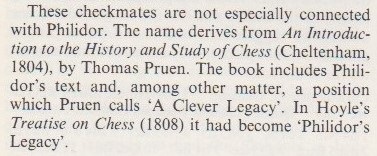

The final paragraph of the entry on Philidor’s legacy on page 306 of the second edition of The Oxford Companion to Chess by D. Hooper and K. Whyld (Oxford, 1992):

That information is inaccurate, and there was no reason to mention Hoyle. Strangely, the conclusion of the entry on page 252 of the first edition (Oxford, 1984) of the Companion was shorter and better:

Thomas Pruen’s book, which can be viewed on-line, used the term ‘Philidor’s legacy’ several times.

In his chess column on page 8 of the Cheltenham Chronicle and Gloucestershire Graphic, 5 February 1916, William Shelley Branch discussed, speculatively though also with a factual contribution from H.J.R. Murray, the origins of Philidor’s legacy, and suggested that it was given that name ‘perhaps for the first time in print’ in Pruen’s book.

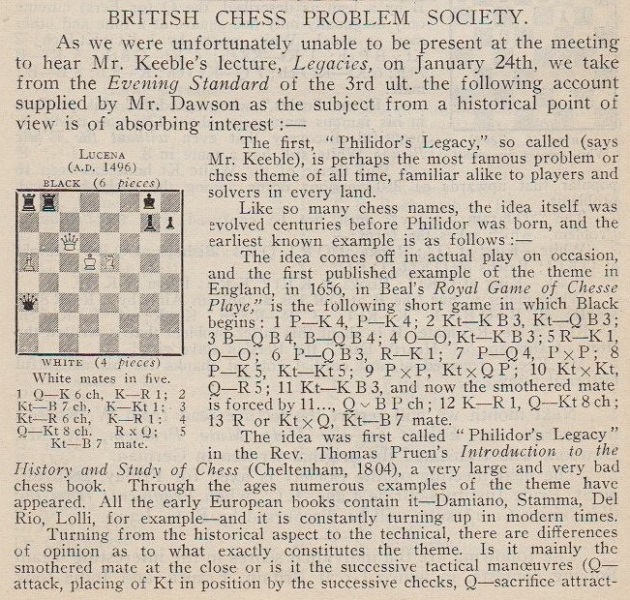

A detailed account of the topic was provided by John Keeble in a British Chess Problem Society lecture, entitled ‘Legacies’, on 24 January 1930. From pages 121-122 of the March 1930 BCM, in the ‘Problem World’ column by B.G. Laws and T.R. Dawson:

Can readers find the report in the Evening Standard of 3 February 1930, or offer a biographical note on Thomas Pruen? He had a dateless entry in the privately distributed 1994 edition of Chess Personalia by Jeremy Gaige.

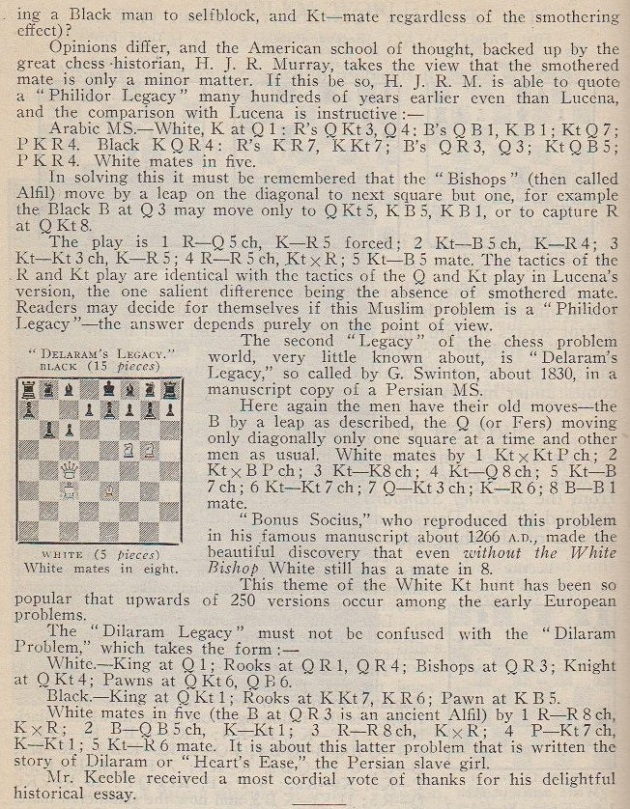

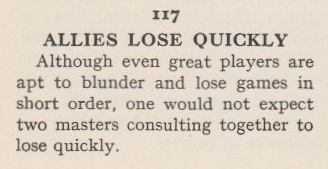

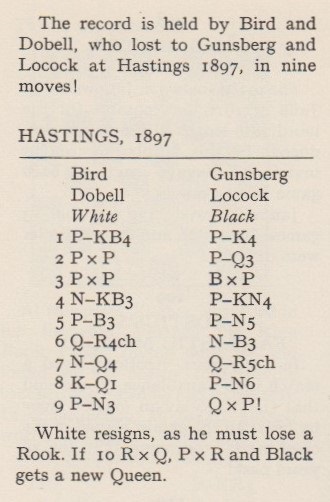

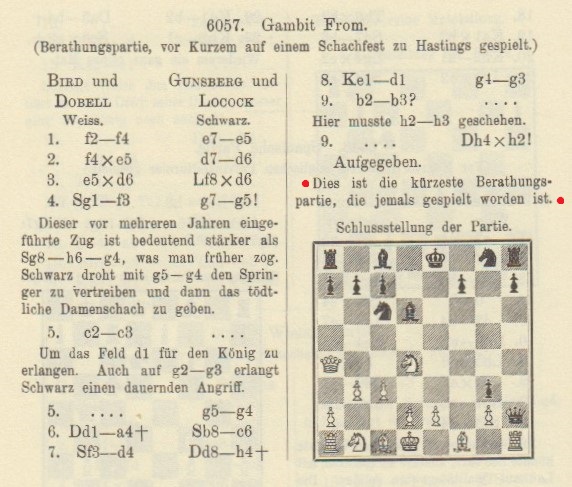

9669. Hastings, 1897

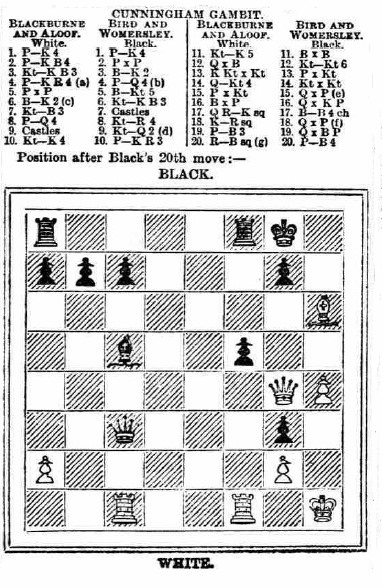

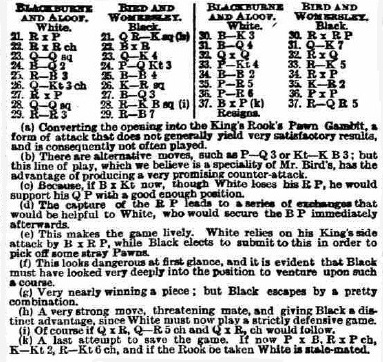

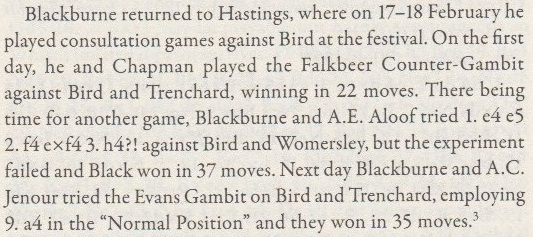

Another familiar consultation game played by F.W. Womersley, in partnership with Bird, was against Blackburne and Aloof (Hastings, 17 February 1897). Gerard Killoran (Ilkley, England) has sent us its appearance on page 6 of the Morning Post, 22 February 1897:

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 Be7 4 h4 d5 5 exd5 Bg4 6 Be2 Nf6 7 Nc3 O-O 8 d4 Nh5 9 O-O Nd7 10 Ne4 h6 11 Ne5 Bxe2 12 Qxe2 Ng3 13 Nxg3 fxg3 14 Qg4 Nxe5 15 dxe5 Qxd5 16 Bxh6 Qxe5 17 Rae1 Bc5+ 18 Kh1 Qxb2 19 c3 Qxc3 20 Rc1 f5 21 Rxf5 Rae8 22 Rxf8+ Bxf8 23 Qd1 Qe5 24 Bd2 b6 25 Rc3 Bc5 26 Qb3+ Kh8 27 Rxg3 Bd6 28 Qd1 Rf8 29 Rh3 Rf2 30 Be3 Rxa2 31 Bd4 Qe2 32 Qxe2 Rxe2 33 g4 Re4 34 Bf2 Rxg4 35 h5 Kh7 36 h6 gxh6

37 Bxb6 Ra4 38 White resigns.

Details of the Hastings Chess Festival programme were also related on pages 90-91 of the March 1897 BCM. Pages 91-92 had the Aloof and Blackburne v Bird and Womersley game, with notes by James Mason. (The conclusion was ‘34 B-B2 RxP. The game was continued some moves further and Black won.’)

In both the Morning Post and the BCM the opening moves were 1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 Be7 4 h4, but page 365 of Joseph Henry Blackburne A Chess Biography by Tim Harding (Jefferson, 2015) stated that h4 was played on move three:

The Morning Post and the BCM reported that the game involving Womersley occurred first, and that the Falkbeer Counter-Gambit game was played in the evening.

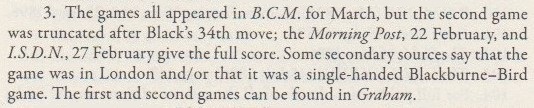

The endnote on page 554 of Harding’s book:

An example of ‘London’ as the venue, instead of Hastings, is on page 265 of Unorthodox Chess Openings by Eric Schiller (New York, 1998), in a section about 1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 h4. Finally, Harding was incorrect to write that the game involving Blackburne and Womersley can be found in Mr Blackburne’s Games at Chess by P. Anderson Graham (London, 1899).

9670. Myths exploded

Black to play

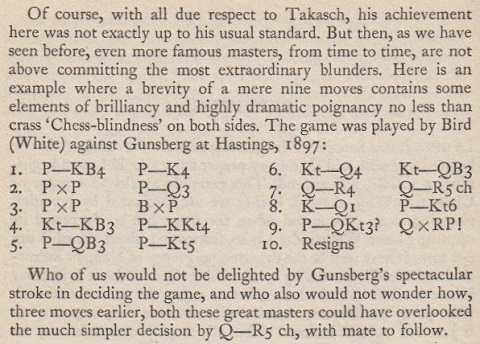

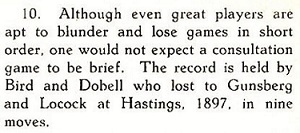

It seems extremely unlikely that Black, a former world championship challenger, missed an immediate, elementary win with 6...Qh4+, but that was the claim on page 104 of Adventure in Chess by Assiac (London, 1951):

As will be seen below, the move order given by Assiac was wrong; the white queen went to a4 on move six, not seven.

The next problem with Assiac’s account is that he mentioned only Bird and Gunsberg, whereas it was a consultation game, and one of the most famous. From page 18 of Chess Review, October 1933, in an article entitled ‘Curious Chess Facts’ by Irving Chernev:

The same text was on page 47 of Chernev’s book Curious Chess Facts (New York, 1937), and he presented an expanded version on page 52 of Wonders and Curiosities of Chess (New York, 1974):

Chernev also gave it on page 15 of 1000 Best Short Games of Chess (New York, 1955). The score had been published too on page 276 of 200 Miniature Games of Chess by Julius du Mont (London, 1941) and was referred to as ‘the famous nine-mover’ on page 120 of the same author’s Chess More Miniature Games (London, 1953). See also page 12 of 666 Kurzpartien by Kurt Richter (Berlin-Frohnau, 1966). The game’s status as the shortest consultation game ever played had already been proclaimed in 1897, as shown by page 148 of the May Deutsche Schachzeitung:

The game was dated 1896 on page 883 of the Handbuch des Schachspiels (Berlin and Leipzig, 1922), whereas 1892 was given on page 649 of 500 Master Games of Chess by S. Tartakower and J. du Mont (London, 1952). In reality, it was played in the Hastings Chess Festival on 15 February 1897. The BCM did not publish the score but offered a description on page 90 of its March 1897 issue which shows that it was not a nine-mover at all:

‘The attraction of Monday afternoon was a consultation game, Messrs Bird and Dobell against Messrs Gunsberg and Locock. White adopted Bird’s favourite P-KB4, which Black turned into a From Gambit. The game caused much amusement to the company, as so early as the ninth move the White allies were in difficulties, owing to a peculiar oversight threatening the loss of a rook, and might have resigned after the 18th move, although the game was continued for several more moves before White resigned.’

Subsequent writers overlooked that report and the fact that the game was published by Gunsberg in his column in the Pall Mall Gazette, 22 February 1897, page 9:

1 f4 e5 2 fxe5 d6 3 exd6 Bxd6 4 Nf3 g5 5 c3 g4 6 Qa4+ Nc6 7 Nd4 Qh4+ 8 Kd1 g3 9 b3 Qxh2 10 Nxc6 Qxh1 11 Ke1 Qg1 12 Ne5+ c6 13 Nd3 Bf5 14 e4 O-O-O 15 exf5 Nf6 16 Kd1 Qxf1+ 17 Kc2 Qxf5 18 Qxa7

18...Qxd3+ and Black won.

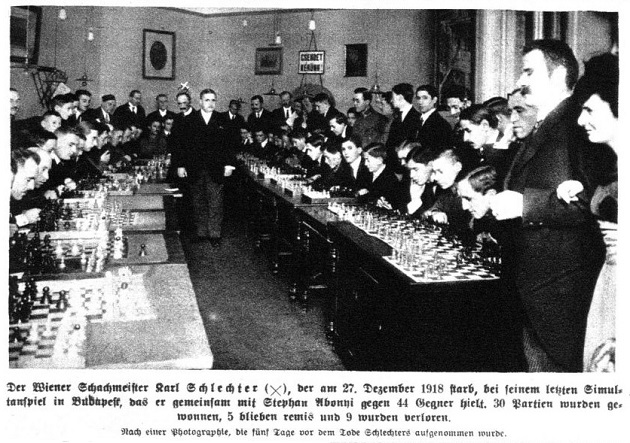

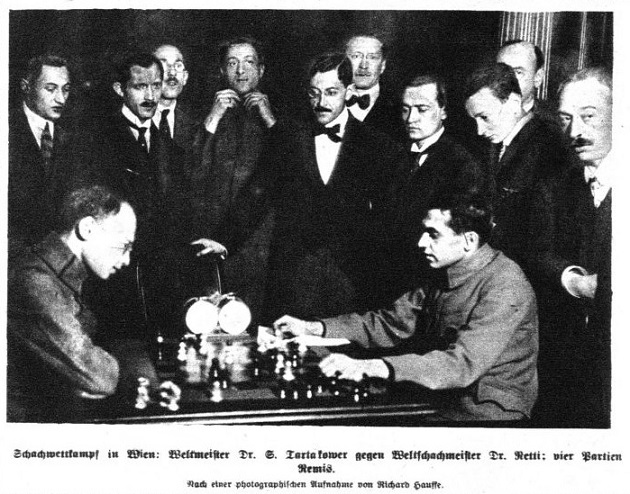

9671. Schlechter, Abonyi, Tartakower and Réti

Two photographs received from Jan Kalendovský (Brno, Czech Republic):

Wiener Bilder, 26 January 1919, page 11

Wiener Bilder, 9 February 1919, page 10.

9672. The first ten moves, Reshevsky and Horowitz

‘Your game is usually won or lost in the first ten moves.’

That assertion by Samuel Reshevsky was on the back cover of various paperback editions of How to Win in the Chess Openings by I.A. Horowitz:

Does the praise come from a book review by Reshevsky or was it given direct to Horowitz for publicity purposes?

How to Win in the Chess Openings, first published in 1951, was based on articles in Chess Review. For example, the section giving the game Euwe v Thomas, Hastings, 1934-35 began:

‘The Orthodox Defense to the Queen[’s] Gambit Declined is a low-geared starter. About midway during hostilities, it shifts to second gear and then quickly to high.’

That observation can be found on page 211 of Chess Review, July 1950. It is also on page 151 of the compendium (four of Horowitz’s books) How to Win at Chess (New York, 1968), subtitled ‘A Complete Course’ and described thus on the dust-jacket:

‘This may well be the nearest approach to the complete chess book yet devised.’

Below is the photograph of Al Horowitz on the back of the dust-jacket:

9673. Thomas

Pruen (C.N. 9668)

From William D. Rubinstein (Melbourne, Australia):

‘Page 873 of Murray’s A History of Chess referred to him as “Rev. Thomas Pruen”. He died on 22 March 1834 at Prince’s Street, Bristol, aged 62 (Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 3 April 1834, page 4). His estate was probated in the Prerogative Court of Canterbury in May 1834. A Thomas Pruen was baptized on 22 April 1772 at St Mary de Crypt Anglican Church, Gloucester, the son of Thomas and Catherine Pruen.’

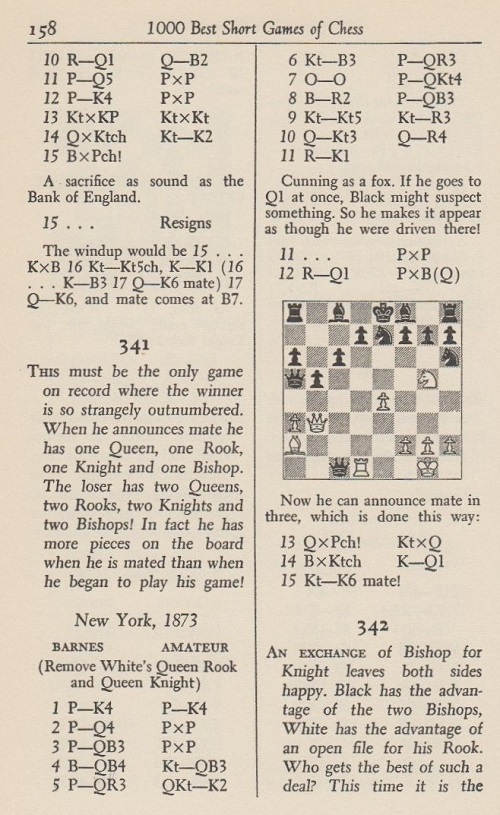

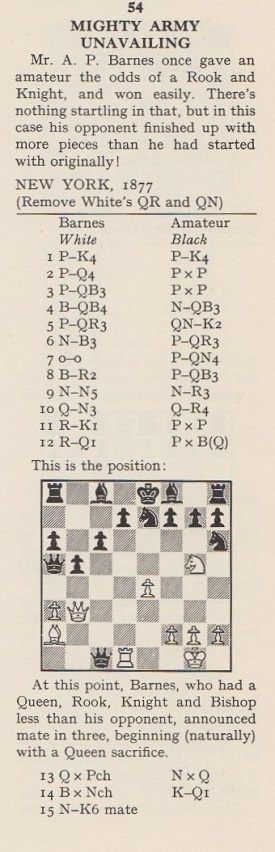

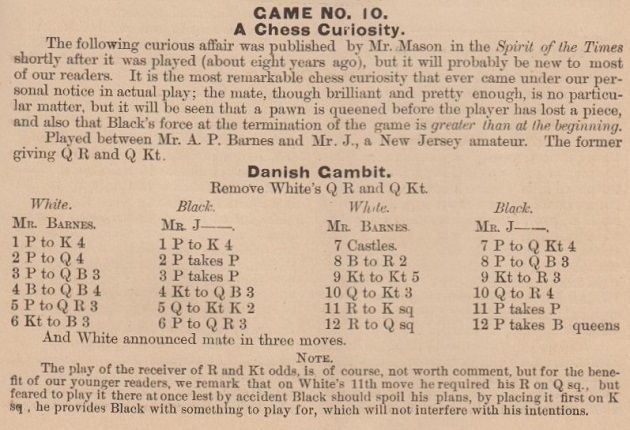

9674. Cunning as a fox

White to move

In this position, wrote Irving Chernev on page 158 of 1000

Best

Short

Games of Chess (New York, 1955), White was ‘cunning

as a fox’ by playing 11 Re1, and not Rd1.

Chernev also gave the game on page 29 of Wonders and Curiosities of Chess (New York, 1974), but this time dated 1877:

It is unclear why, in both books, Chernev stated that the venue was New York, given the references below to New Jersey.

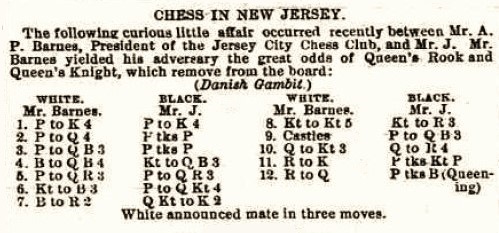

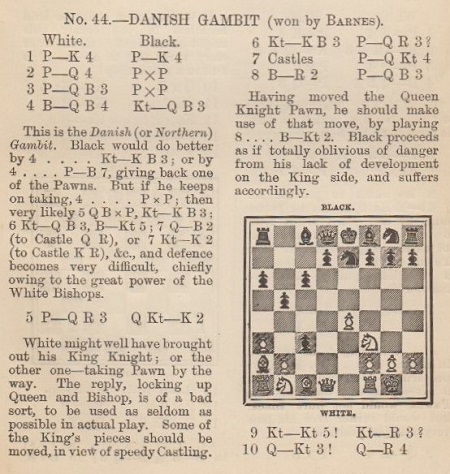

The cunning of Alfred P. Barnes in this game was remarked upon on page 29 of Brentano’s Chess Monthly, May 1881:

The game had been published by James Mason on page 483 of Wilkes’ Spirit of the Times, 26 December 1874:

However, when Mason included the score on pages 77-78 of Social Chess (London, 1900) it was not presented as an odds game:

9675. Noah’s Ark Trap

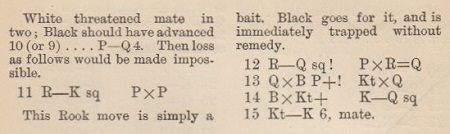

Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA) reverts to a topic discussed in C.N.s 2206, 3042 and 3045 (see page 340 of A Chess Omnibus and page 269 of Chess Facts and Fables) and notes an occurrence of ‘Noah’s Ark’ in a sketch, ‘Chess as She is Played’, on pages 139-140 of the January 1890 Chess Monthly:

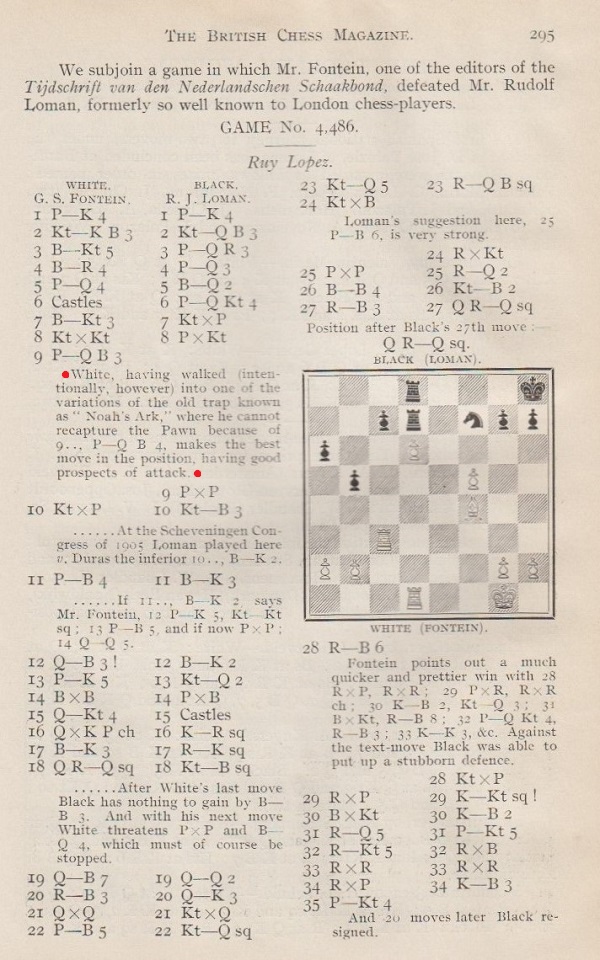

Concerning the question raised in C.N. 2206 (when the name was first applied to the trap in the Ruy López), we can currently offer nothing earlier than page 295 of the September 1917 BCM:

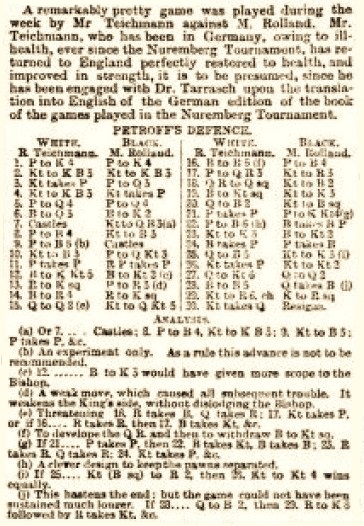

9676. Teichmann v Rolland

From page 8 of the Standard, 8 March 1897:

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 Nxe5 d6 4 Nf3 Nxe4 5 d4 d5 6 Bd3 Be7 7 O-O Nc6 8 c4 Nf6 9 c5 O-O 10 Nc3 b6 11 cxb6 axb6 12 Bg5 Bb7 13 Re1 h6 14 Bh4 Re8 15 Qd2 Nb4 16 Bf5 c5 17 a3 Na6 18 Rad1 Nc7 19 Bb1 Ne6 20 Qc2 Nf8 21 dxc5 g5

22 c6 Bxc6 23 Ne5 Bb7 24 Bxg5 hxg5 25 Qf5 Ne6 26 Nxf7 Ng7 27 Qg6 Qd7 28 Bf5 Qxf5 29 Nh6+ Kh8 30 Nxf5 Resigns.

9677. Flohr and Zlín

No substantiation has been found of claims by George Koltanowski, published in 1936 and 1937, that in Prague it was possible to find ‘Flohr collars’, ‘Flohr slippers’, ‘Flohr cigarettes’ and ‘Flohr eau-de-Cologne’. (See C.N.s 4177 and 4187.)

With regard to footwear, Thomas Niessen (Aachen, Germany) draws attention to a brief interview with Salo Flohr on page 13 of De Telegraaf, 22 March 1932. Flohr stated that he hoped to persuade the shoe manufacturer Tomáš Bat’a (Zlín, Czechoslovakia) to finance the greatest chess tournament of all time, with a fund of 300,000-400,000 Czech crowns. Less than four months after the interview was published, Bat’a died in a plane crash.

A brief news item on page 262 of the June 1932 BCM had stated:

‘... Zlín, where it is proposed to hold a grand masters tournament in October, is a thriving city and the home of the great Bata shoe-factory, which employs 25,000 hands.’

Mr Niessen points out that possible involvement in chess by the Bata company was also discussed in the late 1930s. Národní politika, 8 February 1938, page 10, reported that Flohr would be giving a simultaneous exhibition in the chess section of the Club SK Bata in Zlín in early March and would be discussing with the Bata management the possible organization of a world championship match in Zlín in 1940 (against Alekhine or Capablanca).

From page 302 of the 14 May 1938 CHESS:

‘“What has been decided?”, we asked Dr Alekhine, “with regard to an eventual match against Flohr?”

“I go to Prague at the end of May and will discuss there with Flohr and, probably, the representatives of the Czechoslovakian Chess Federation the arrangements of a possible match at the end of 1939.”

Rumour says that Bata, the Czechoslovakian boot and shoe magnate, is keenly interested in Flohr’s challenge and willing to finance a match.’

Page 215 of the May 1938 BCM reported:

‘... it is now fairly certain that Dr Alekhine will play S. Flohr next year at Zlín, in Czechoslovakia.’

In World Championship Disorder we commented that ‘there has probably never been another period in chess history with so many “projected matches” that failed to materialize’.

9678.

Tartakower and risk

From page 7 of Stein move by move by Thomas Engqvist (London, 2015):

From C.N. 8651:

Give the source of a quote if it is known. If it is not known, do not give the quote.

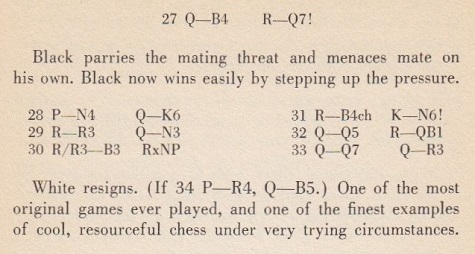

9679. One of the most original games

‘One of the most original games ever played, and one of the finest examples of cool, resourceful chess under very trying circumstances.’

That was the concluding remark by Fred Reinfeld about a game which he annotated on pages 69-73 of How to Play the Black Pieces (New York, 1955):

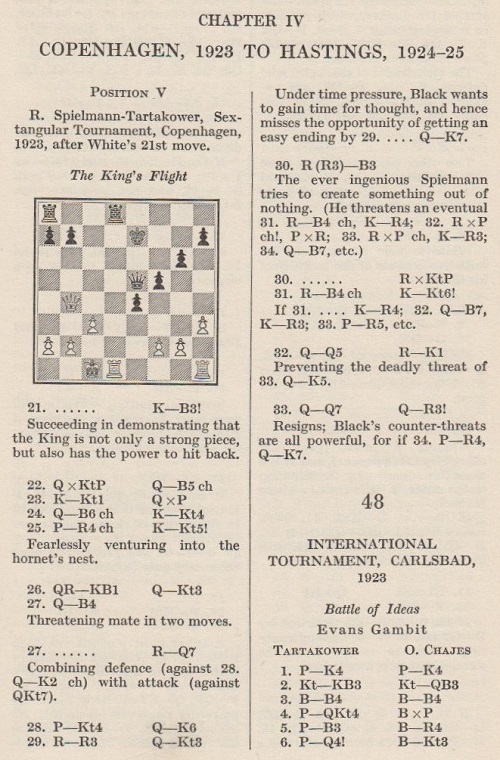

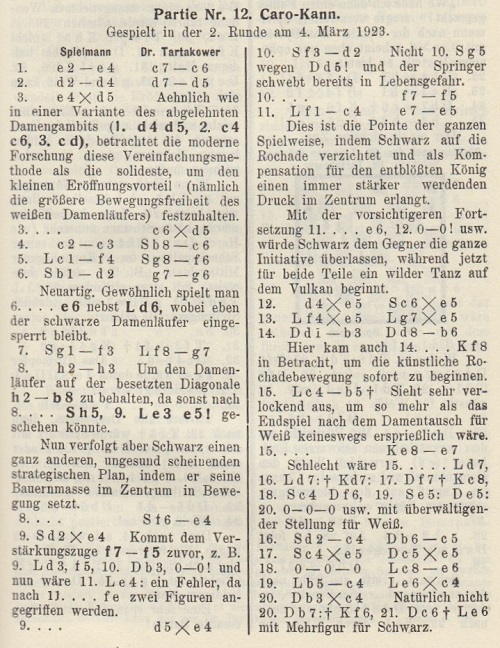

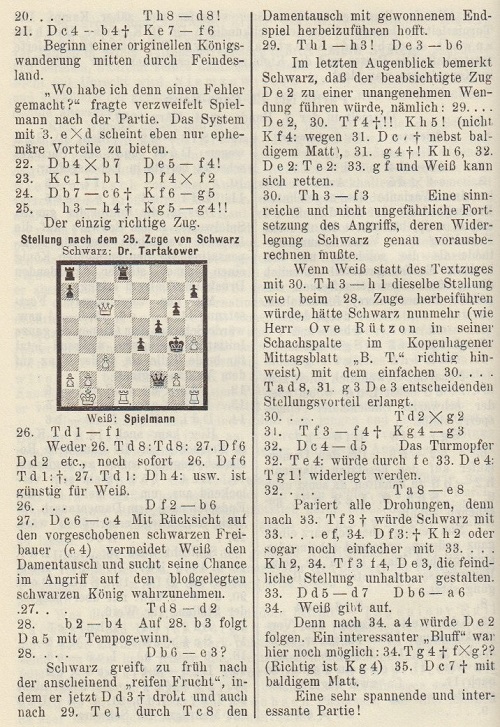

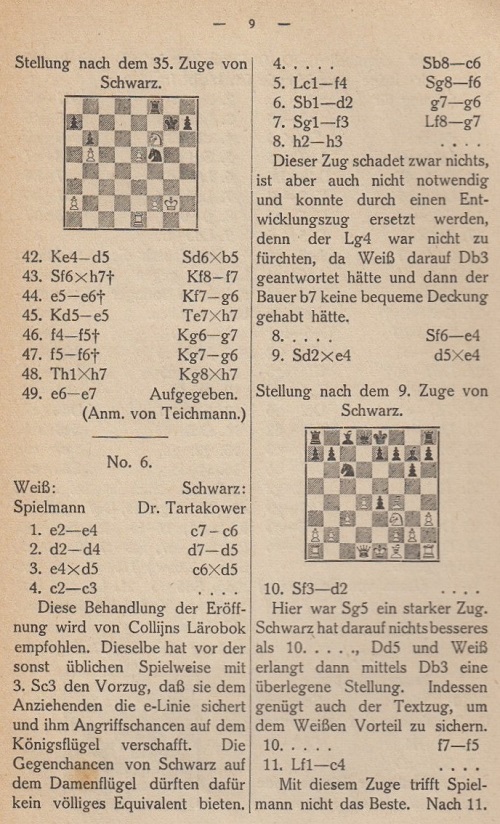

The players were not named, but the game was Spielmann v Tartakower, Copenhagen, 1923. Tartakower gave only the conclusion on page 115 of My Best Games of Chess 1905-1930 (London, 1953):

The full game was annotated by Tartakower on pages 35-36 of the April 1923 issue of the Wiener Schachzeitung:

The ‘bluff’ mentioned in the final note is of particular interest, and it will be seen that in both publications Tartakower gave his 32nd move as ...Ra8-e8. Reinfeld, however, put ‘...R-QB1’, and that was also the move in the tournament book, where notes by Rubinstein were given on pages 9-10:

The improbable 32...Rc8 could be answered by 33 Rxe4.

Position after 32 Qd5

The score as published by Tartakower in 1923: 1 e4 c6 2 d4 d5 3 exd5 cxd5 4 c3 Nc6 5 Bf4 Nf6 6 Nd2 g6 7 Ngf3 Bg7 8 h3 Ne4 9 Nxe4 dxe4 10 Nd2 f5 11 Bc4 e5 12 dxe5 Nxe5 13 Bxe5 Bxe5 14 Qb3 Qb6 15 Bb5+ Ke7 16 Nc4 Qc5 17 Nxe5 Qxe5 18 O-O-O Be6 19 Bc4 Bxc4 20 Qxc4 Rhd8 21 Qb4+ Kf6 22 Qxb7 Qf4+ 23 Kb1 Qxf2 24 Qc6+ Kg5 25 h4+ Kg4 26 Rdf1 Qb6 27 Qc4 Rd2 28 b4 Qe3 29 Rh3 Qb6 30 Rhf3 Rxg2 31 Rf4+ Kg3 32 Qd5 Re8 33 Qd7 Qa6 34 White resigns.

It was played in the same tournament as the Sämisch v Nimzowitsch ‘Immortal Zugzwang’ encounter, and neither game was widely published at first.

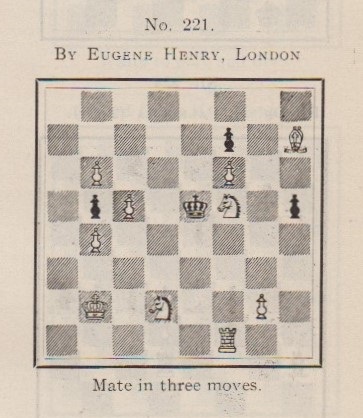

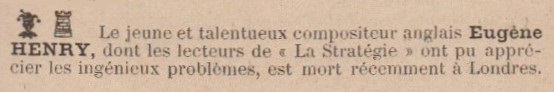

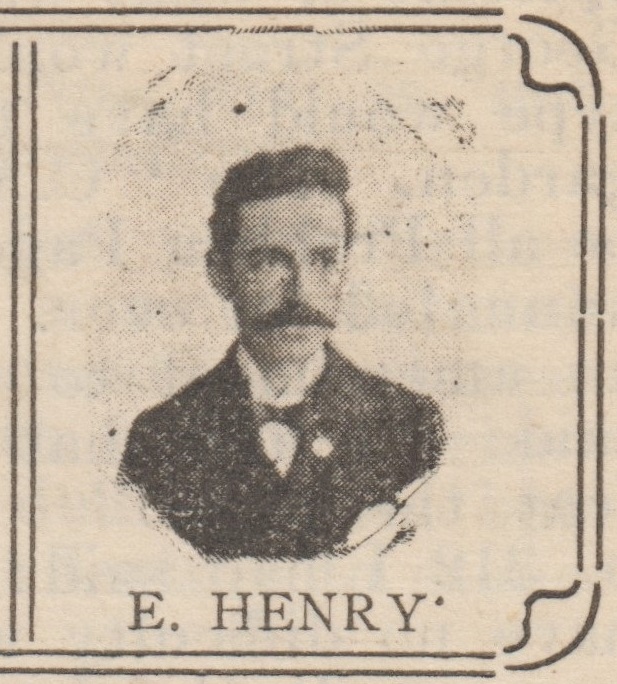

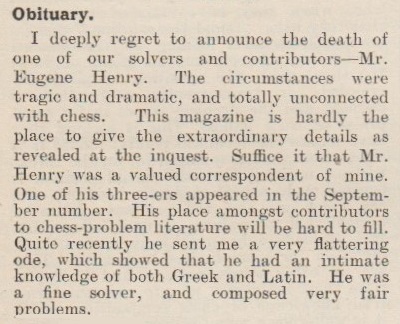

9680. Eugene Henry

From page 233 of Lasker’s Chess Magazine, September 1905:

Eugene Henry is a little-known problemist with a bare entry in Chess Personalia by Jeremy Gaige (Jefferson, 1987):

In the privately circulated 1994 edition, Gaige amended the Irish magazine’s publication details to ‘Winter, 1910-11, page 2’ and added a reference to what appeared in La Stratégie, January 1911, page 31:

The Four-Leaved Shamrock item:

The above cutting has been provided by the Cleveland Public Library, which informs us that it possesses about 50 sheets featuring problems by Henry.

A smaller version of the photograph had been in the heading to Philip H. Williams’ column on page 25 of the Chess Amateur, October 1910:

The picture had also been in the heading on page 55 of the November 1909 Chess Amateur.

From page 7 of the 19 January 1910 edition of the Falkirk Herald:

‘Saturday’s Ill. W.W. News has a good portrait of Mr Eugene Henry and a problem by this composer.’

The run of illustrations (which we have not seen) in the

Illustrated Western Weekly News was commented upon

in the February 1909 BCM, page 84:

The cause of Eugene Henry’s death was not mentioned by Philip H. Williams on page 89 of the December 1910 Chess Amateur:

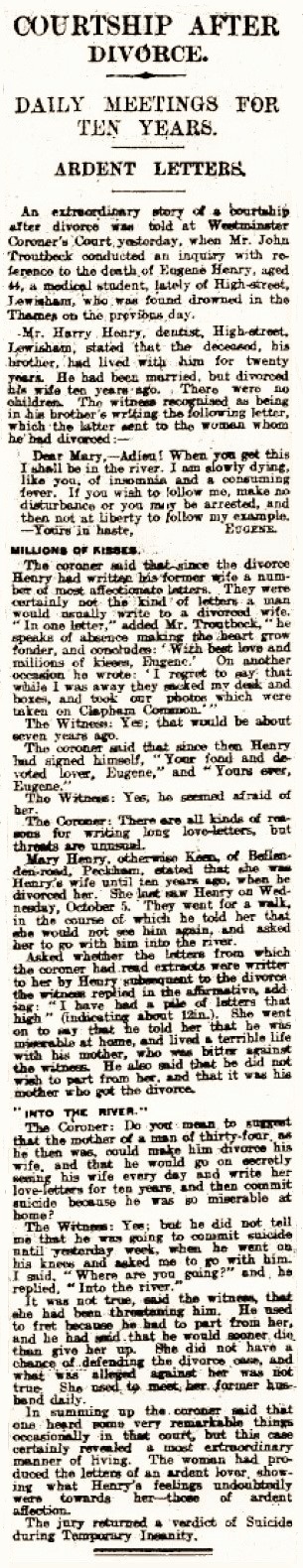

The newspapers of the time did not refer to Henry’s connection with chess but gave extensive information about his suicide. He drowned in the Thames at the age of 44. The most detailed account that we have seen was on page 5 of the Daily Mail, 14 October 1910:

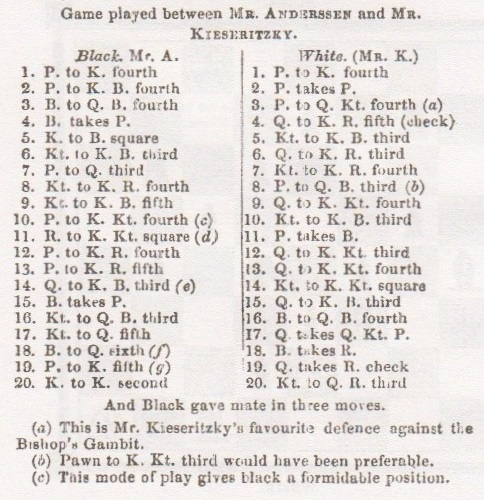

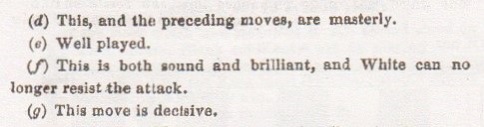

9681. The Immortal Game

As recorded in several C.N. items, there are chess books

which state that Kieseritzky won the Immortal Game against

Anderssen (London, 1851). Salvatore Tramacere (Aprilia,

Italy) suggests that the blunder arose from a

misunderstanding of the game-score when Anderssen was

named as Black, although the first player. Our

correspondent refers to pages 2-3 of the Chess Player,

19 July 1851:

The earlier C.N. material has been brought together in a feature article, The Immortal Game.

9682. Alekhine’s Defence

An addition to Alekhine’s Defence is an article by Réti (Tijdschrift van den Nederlandschen Schaakbond, February 1923, pages 50-54).

9683. To lose against a female

From page 209 of Winning with Chess Psychology by Pal Benko and Burt Hochberg (New York, 1991):

Wanted: the full text of, and exact source for, Andersson’s remarks in Svenska Dagbladet. His interview with the publication (early September 1989) was referred to in an editorial, ‘Kvinnligt och manligt’, on page 313 of the October 1989 Tidskrift för Schack.

There was a reprise of the phrase ‘unworthy and degrading’ on page 215 of Winning with Chess Psychology, when Benko was discussing Lone Pine, 1977, in which Nona Gaprindashvili was a participant:

That passage was used on page 163 of Players and Pawns by Gary Alan Fine (Chicago, 2015):

The endnote on page 254:

And so alleged words by Andersson about losing to women became a generality about losing to children.

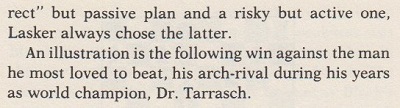

9684. Did Lasker deliberately play badly?

Réti’s claim that ‘Lasker often deliberately plays badly’ was discussed in C.N.s 5679, 6889 and 8660.

The idea was rejected on pages 18-19 of Benko and Hochberg’s Winning with Chess Psychology:

The book’s coverage of Lasker v Tarrasch, Mährisch-Ostrau, 1923 included the following on page 20:

Pages 286-287 of the Australasian Chess Review, 8 October 1936 published Lasker v Levenfish, Moscow, 1936, introduced thus:

‘Not often does one find an out-and-out Lasker game as described by Réti. Here is one that Réti would have seized on with shrieks of joy; the whole game pans out just as Réti would have it. First of all, the deliberately bad play, then the crisis when Lasker totters on the brink of the abyss, followed by the superb resourcefulness that upsets his opponent’s morale, culminating in the final collapse which makes Lasker the victor. It is all here, in this game.’

Levenfish’s annotations in the tournament book do not support the claim that Lasker deliberately played badly in that game (1 e4 c5 2 Nc3 Nc6 3 f4 e6 4 Be2 d5 5 d3 Nge7 6 Nf3 Nd4 7 O-O Nec6 8 Qd2 Be7 9 Bd1 O-O 10 Qf2 a6 11 Re1 Bf6 12 Ne2 dxe4 13 Nexd4 e3 14 Bxe3 cxd4 15 Bd2 Qd5 16 Qg3 Bd7 17 Ne5 Rfd8 18 c4 dxc3 19 bxc3 Be8 20 Bc2 g6 21 d4 Bg7 22 h4 Rac8 23 Be4 Qd6 24 Rad1 b5 25 h5 b4 26 hxg6 hxg6 27 Re3 bxc3 28 Bxc3 Nxe5 29 fxe5 Bxe5 30 Qh4 Rxc3 31 Rxc3 Bxd4+ 32 Kh1 Ba4 33 Rdd3 Bb5 34 Bxg6 fxg6 35 Rh3 Qd7 36 Rcg3 Bd3 37 Rxd3 Resigns).

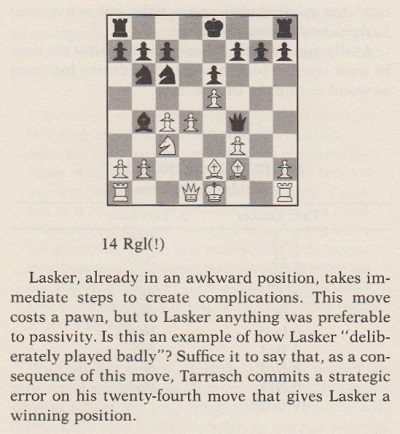

9685. London chess clubs

Vladislav Tkachiev (Moscow) asks where the main chess haunts were in London in 1918-19.

Strange to say, a detailed list that comes immediately to our mind is in a German source, page 146 of Ranneforths Schach-Kalender 1918 (Berlin-Halensee, 1918):

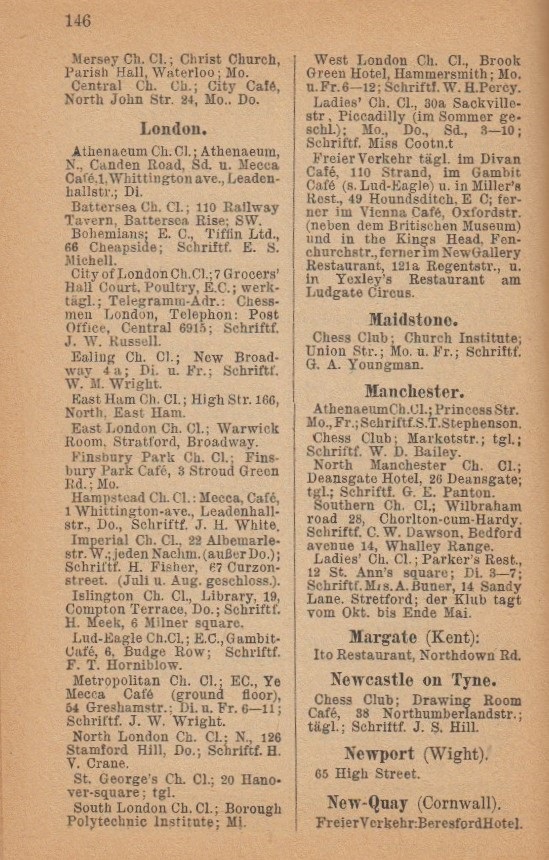

9686. Cordingley

From page 121 of CHESS, March 1952:

Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England) writes:

‘In your feature article Chess and Ghostwriting you mention, regarding the matter of Reinfeld and Reshevsky, that the full text of the letter from Reinfeld to Cordingley was in CHESS, March 1952. However, this was not the full text, and a longer version was published on page 450 of the Chess Students Quarterly, September 1951, the previous page being an article by Cordingley entitled “Book Reviewing”:

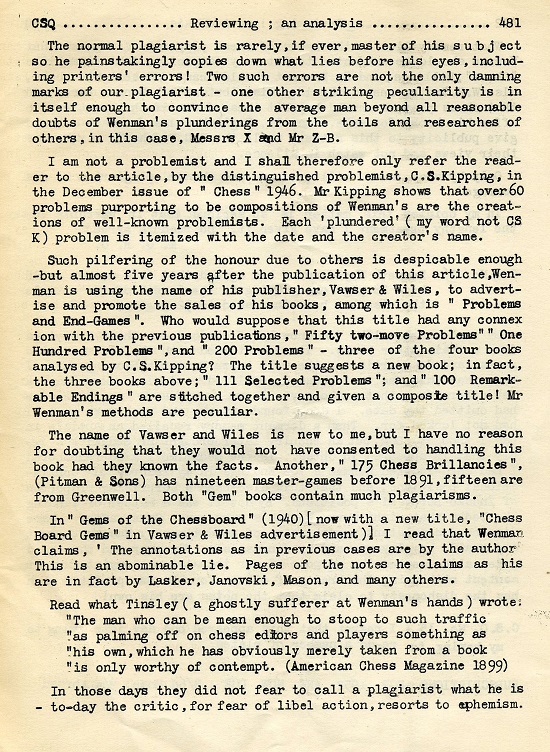

On pages 479-482 of the December 1951 issue of the Quarterly Cordingley wrote a further article, “Book Reviewing: An analysis: Quality – Originality – Plagiarism – Ostracism”:’

9687. Paintings by Carslake Winter Wood

Nick Blackett (Brisbane, Australia) informs us that he owns two paintings by Carslake Winter Wood (1849-1924), of Bergues Belfry and Katz am Rhein:

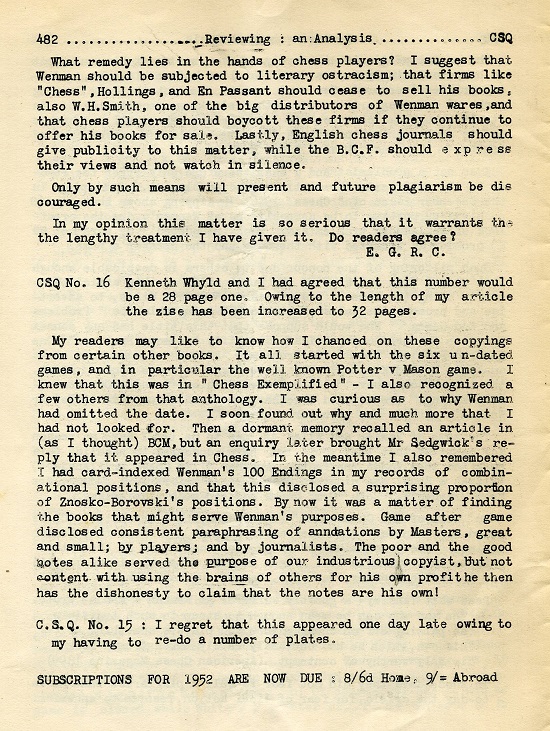

A photograph of Winter Wood was published on page 28 of The Chess Bouquet by F.R. Gittins (London, 1897):

A biographical article on pages 280-281 of the June 1891 BCM referred to his interest in art:

‘... he lived for several years with his maternal uncle, Major Sole, at Torquay; with whom and Mrs Sole he travelled through many of the European countries, spending several winters on the Riviera and the lakes of Italy, where he acquired and cultivated a taste for painting, and, for an amateur, displays skill of no mean order of merit; several specimens of his work he has given as chess prizes in various competitions.’

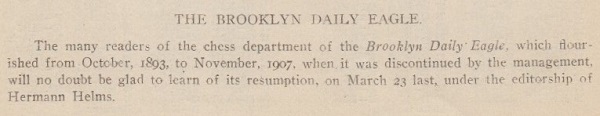

9688. Hermann Helms and the Brooklyn Daily Eagle

From page 124 of Wonders and Curiosities of Chess by Irving Chernev (New York, 1974):

In C.N. 4784 (see too Chess Records) a correspondent pointed out that Helms’ column in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle had a break of over three years, as reported on page 114 of the May 1911 American Chess Bulletin:

From Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore):

‘The earliest chess columns by Hermann Helms in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle appeared in the 13 October 1893 and 25 October 1893 editions (on page 8 in both cases). The last signed column by Helms in that run was on page 10 of section five of the 17 November 1907 edition.

The resumption of his column was announced on page 11 of the 21 March 1911 Eagle:

On page 4 of the Sporting Section of the 23 March 1911 edition a fully-fledged column signed by Helms was published. His last column was on 20 January 1955 (page 16).’

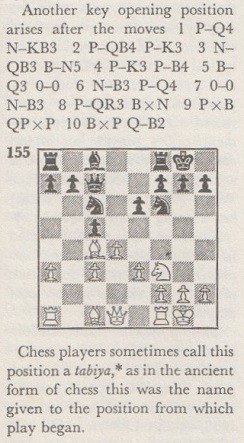

9689. Tabia/Tabiya

The article Earliest Occurrences of Chess Terms currently lacks citations for Tabia/Tabiya. Given that the word is from shatranj, a point of greater interest than its first appearance in connection with (modern) chess is why it has become such a popular term since around the 1980s. Who or what was chiefly responsible?

There was a section entitled ‘The Most Usual “Tabiya”’ on pages 52-53 of Chess: Serious; for Fun by I. Birbrager (Sutton Coldfield, 1975).

9690. Golubev position (C.N. 9664)

We are grateful to the Cleveland Public Library for providing the mate-in-two composition as published on page 252 of 64, 30 August 1931:

The position printed subsequently by magazines was indeed the same.

Hanspeter Suwe (Winsen in Holstein, Germany) puts forward a more economical amendment of the composition than the one suggested in C.N. 9664:

9691. Bauer v Porges

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 Nf6 4 O-O Nxe4 5 d4 Be7 6 Qe2 Nd6 7 Bxc6 bxc6 8 dxe5 Nb7 9 Nd4 O-O 10 Rd1 Qe8 11 Re1 Nc5 12 Nf5 Ne6 13 Qg4 f6 14 Bh6 Rf7

15 Bxg7 Nxg7 16 exf6 d5 17 Nh6+ Kf8 18 fxg7+ Rxg7 19 Qf4+ and wins.

There are databases which have this game as C. Bauer v M. Porges, 1937, but why?

Steinitz annotated it (‘A sprightly little game. Played in July last at the Café Français of Prague, Bohemia, between two of the strongest players of that city: White, J.H. Bauer. Black, M. Porges’) on pages 25-26 of the International Chess Magazine, January 1885. He also gave the game with six brief notes on pages 36-37 of The Modern Chess Instructor (New York, 1889).

9692. A cramped position

The conclusion of a comment by Botvinnik quoted on page 51 of Kasparov Teaches Chess by G. Kasparov (London, 1986):

‘... there is no better way to get into a cramped position than to strive merely for development.’

Kasparov stated that the remark was made by Botvinnik in his notes to a game against Alexander [sic] Sokolsky (Leningrad, 1938). The difficulty for anyone wishing to cite it with a complete source is that Botvinnik annotated the game a number of times. See, for instance, page 157 of Izbrannye partii 1926-1946 (Leningrad, 1949 and Moscow, 1951), page 500 of volume one of Shakhmatnoe tvorchestvo Botvinnika (Moscow, 1965) and page 217 of Analiticheskie i kriticheskie raboti (Moscow, 1984). Concerning English versions, see page 144 of One Hundred Selected Games (London, 1951) and page 248 of Botvinnik’s Best Games Volume I. 1925-1941 (Olomouc, 2000).

9693. Space

The opening paragraph of ‘How Does The World Champion Play Chess?’ by John Hammond on page 2 of Chess World, January 1967:

‘Petrosian sees chess as the organization of available chess space. This, basically, is what chess is. Mate in itself is the denial of space to the opposing king. The idea is as old as chess itself, but the difficulty is to make it work.’

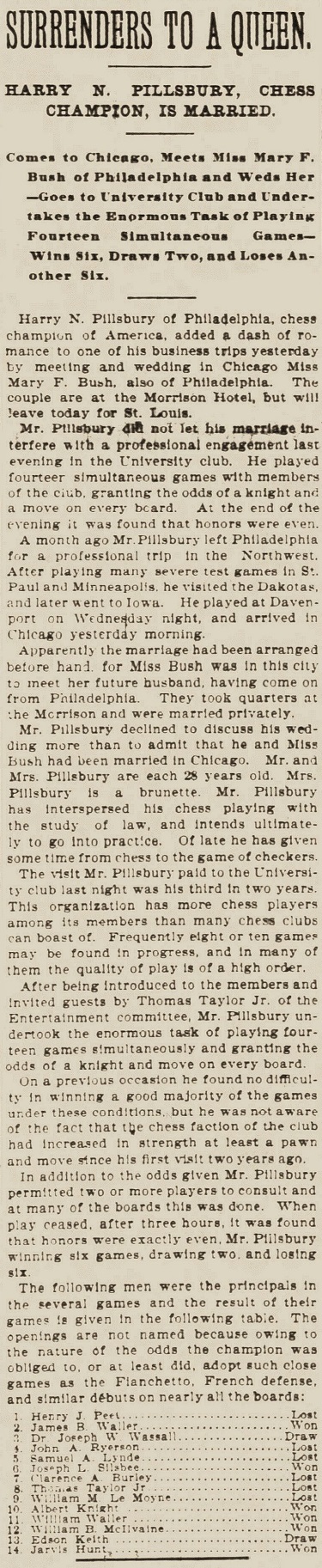

9694. Mr and Mrs Pillsbury (C.N. 9458)

Eduardo Ramirez (Chicago, IL, USA) sends this cutting from page 1 of the Chicago Daily Tribune, 18 January 1901:

9695. Benjamin Franklin and chess

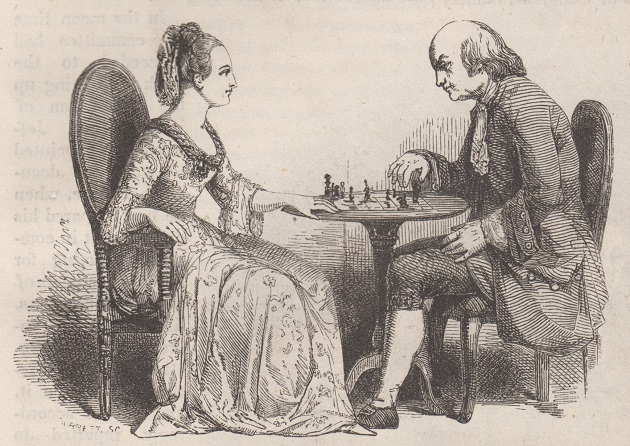

Pages 177-179 of a neglected book, Persönlichkeiten und das Schachspiel by B. Rüegsegger (Huttwil, 2000), have a section on Benjamin Franklin, and the illustrations include two postage stamps, from Equatorial Guinea and Paraguay, showing the famous painting by Edward Harrison May of Franklin playing chess with Caroline Howe. Another familiar picture of them, readily found through electronic searches and also reproduced on page 235 of the Chess Amateur, May 1915, was published on page 305 of Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, February 1852. Since we possess the bound volume, a good-quality version can be shown here:

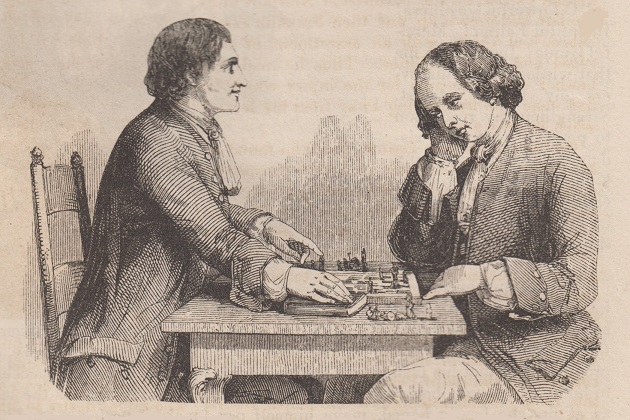

Another illustration of Franklin playing chess was published on page 164 of the January 1852 issue of Harper’s New Monthly Magazine:

There are no pictures of Franklin at the chessboard in Benjamin Franklin and Chess in Early America by Ralph K. Hagedorn (Philadelphia, 1958). The book was dedicated ‘To Ellie the most tolerant of chess widows’, and one of our copies has an inscription by the author with the same term:

The FamilySearch.org website records that Ralph K. Hagedorn was born in Wisconsin on 19 November 1912 and died in Los Angeles on 20 August 1962. A brief note of his death was published on page 29 of the California Chess Reporter, September 1962.

9696. A novel featuring Bohatirchuk

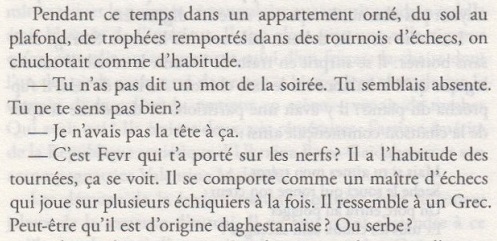

Alain Pallier (Lauris, France) notes that a character in Schubert à Kiev by Léonid Guirchovitch (Lagrasse, 2012) is ‘Fiodor Parfenievitch Bogatyrtchouk, gériatre et maître d’échecs’ (page 8). His wife Irina is also featured. See, in particular, pages 17, 73-74, 108-109 and 243-250.

From page 108:

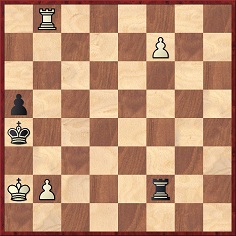

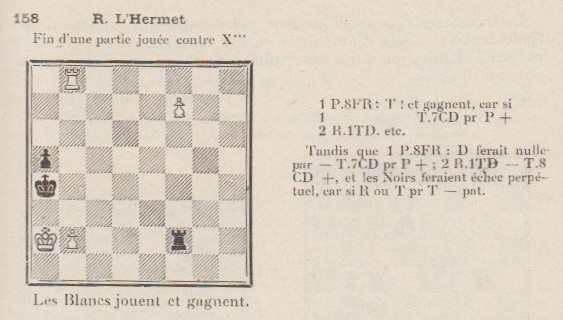

9697. White to move and win

White to move and win

From page 91 of Traité des fins de partie d’échecs by Un Amateur de l’Ex. U.A.A.R. (Paris, 1924):

See too page 130 of Test Tube Chess by A.J. Roycroft (London, 1972).

The position was published on page 277 of the September 1893 Deutsche Schachzeitung with this introduction:

‘Beim Analysiren einer kürzlich in Magdeburg zwischen R. L’hermet (Weiss) und H. (Schwarz) gespielten Partie stiess man auf die interessante Diagrammstellung ...’

Next, a problem by L’hermet (from the April 1888 Deutsche

Schachzeitung, page 124):

Mate in three

As regards the spellings L’hermet and L’Hermet, we note that German-language sources strongly favour the former.

He appeared in a group photograph (small format) in the Magdeburg, 1927 tournament book:

Aged 67, L’hermet finished last in the tournament and was defeated on 20 July 1927 in a famous game by Spielmann, who annotated it in the Münchner Zeitung of 30 July 1927 (see pages 75-76 of the tournament book) and on pages 38-40 of The Art of Sacrifice in Chess (London, 1935). It was awarded the first brilliancy prize.

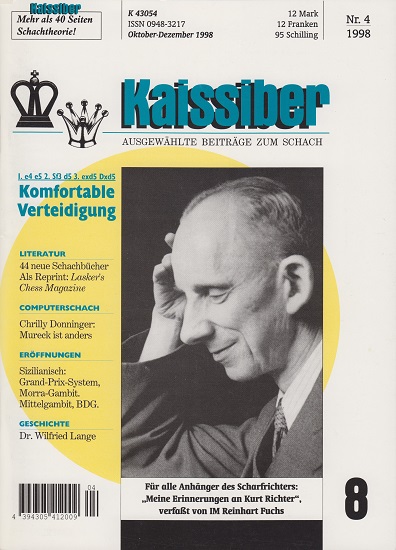

9698. A model chess magazine

If a chess magazine of the modern era had to be chosen as a model for quality content, including scholastic rigour and high production standards, the short list would be short indeed, and Kaissiber, edited by Stefan Bücker, would be hard to beat.

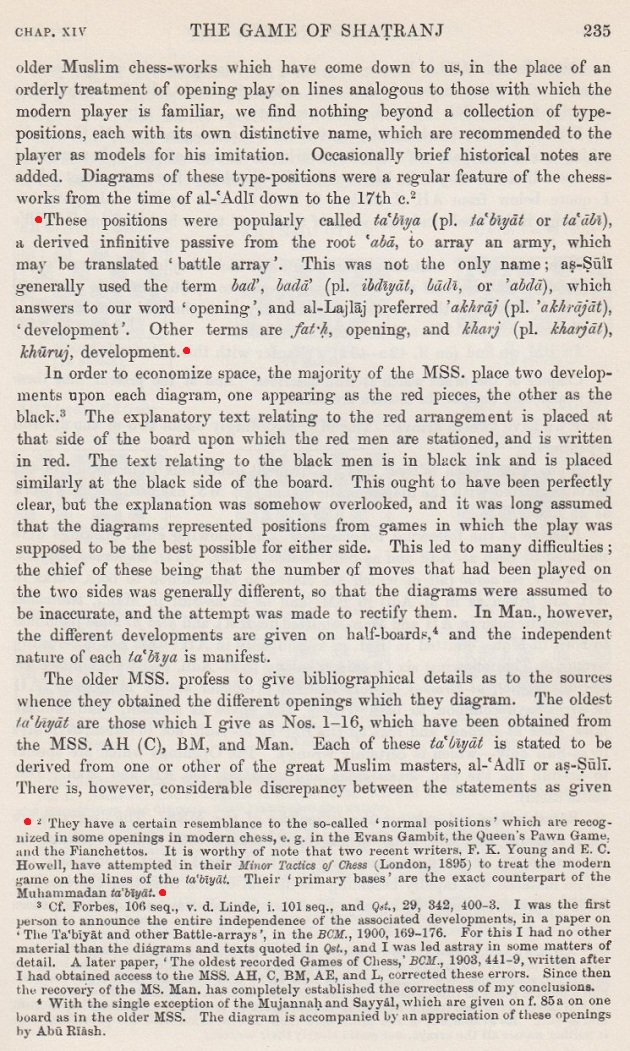

9699. Tabia/Tabiya (C.N. 9689)

In response to C.N. 9689, Timothy J. Bogan (Chicago, IL, USA) draws attention to ‘tabiya’ on page 183 of Think Like a Grandmaster by Alexander Kotov (London, 1971):

The footnote by the translator, Bernard Cafferty, mentioned page 235 of A History of Chess by H.J.R. Murray (Oxford, 1913):

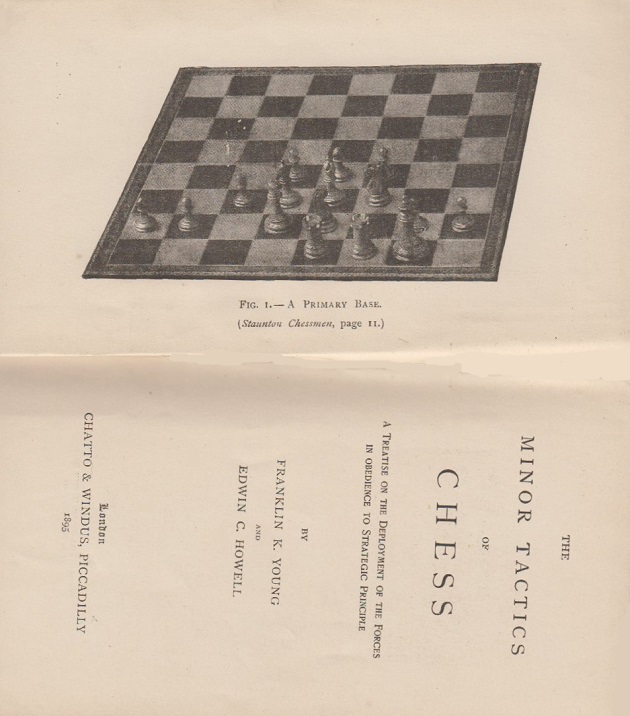

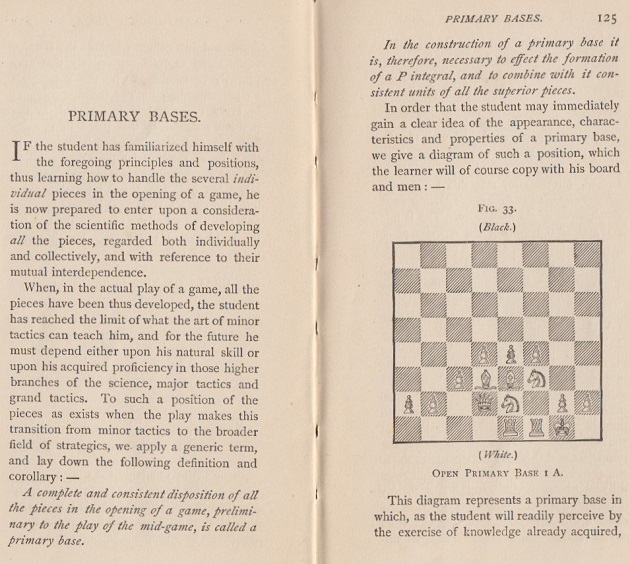

The term ‘primary base’ was in the frontispiece of the Young/Howell book referred to by Murray:

Below are the first two pages of the chapter on this topic:

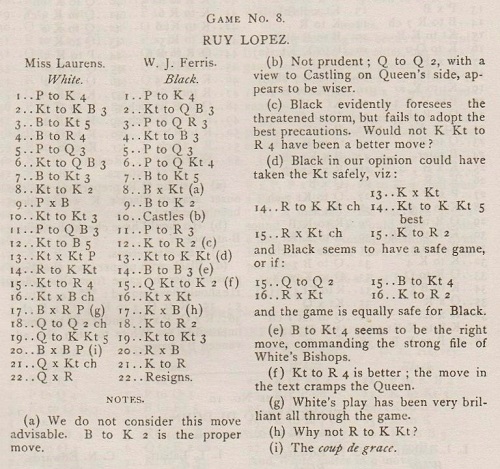

9700. Laurens v Ferris

From page 19 of the Brooklyn Chess Chronicle, 1 November 1882:

‘We recommend to our readers, as a gem, the game which we publish today, in the proper section, played by correspondence between Miss H. Edna Laurens, of South Carolina, and Mr W.J. Ferris of Delaware.’

The score was on page 21:

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 d3 d6 6 Nc3 b5 7 Bb3 Bg4 8 Ne2 Bxf3 9 gxf3 Be7 10 Ng3 O-O 11 c3 h6 12 Nf5 Kh7

13 Nxg7 Ng8 14 Rg1 Bf6 15 Nh5 Nce7 16 Nxf6+ Nxf6 17 Bxh6 Kxh6 18 Qd2+ Kh7 19 Qg5 Ng6 20 Bxf7 Rxf7 21 Qxg6+ Kh8 22 Qxf7 Resigns.

9701. The most poorest thing

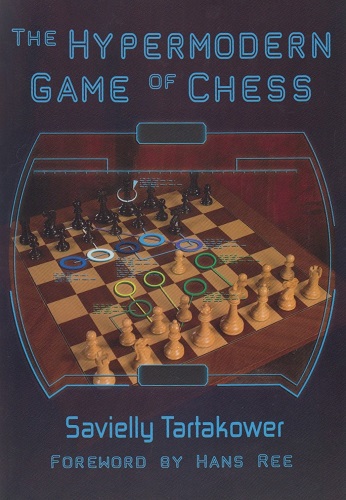

‘The sake of the mistake is that it be made.’

That string of words is on page 76 of The Hypermodern Game of Chess (Milford, 2015), a ‘translation’ of Tartakower’s book by Jared Becker. The imprint page also specifies, ‘Editorial Consultant: Hannes Langrock’.

‘The sake of the mistake is that it be made’ is Jared Becker’s rendering of a line included in The Most Famous Chess Quotations:

- ‘Die Fehler sind dazu da, um gemacht zu werden.’

Die Hypermoderne Schachpartie by S. Tartakower (Vienna, 1924), page 90.

- Customary English translation: ‘The mistakes are all there, waiting to be made.’

We commented in C.N. 4437 that Tartakower is one of the most difficult writers to translate into English (i.e. even by a competent linguist), and The Hypermodern Game of Chess is not remotely of publishable standard. Pages 52-53, for instance, have all kinds of mishaps, including ‘the most finest thing there is in chess’ and this challenging paragraph:

9702. Purdy on Fischer v Stein

‘Fischer, a New Tchigorin’ was the title of an article by C.J.S. Purdy on pages 134-136 of Chess World, September-October 1967. He annotated Fischer v Stein, Sousse, 1967 (the final game in Fischer’s My 60 Memorable Games) with this introduction:

‘Here is the game, which in the tournament doesn’t officially exist and yet was its masterpiece, symbolising the triumph of genius over schooled mastery.’

Purdy’s concluding observation:

‘By ordinary human standards, playing chess like White in this game would seem to require nerves of steel. Fischer’s powers of calculation and confidence in his judgment make it possible for him to conduct vital contests in a style which nobody else would venture over the board except in games played for fun. Tal certainly has played with at least equal daring, but it seems to me that he deliberately speculates. Fischer gives the impression of having everything sewn up.’

Irving Chernev tinkered with Purdy’s words on page 197 of The Golden Dozen (Oxford, 1976). The full annotations were reproduced on pages 90-92 of C.J.S. Purdy’s Fine Art of Chess Annotation and Other Thoughts by Ralph J. Tykodi (Davenport, 1992).

Purdy’s note after 25 Qg3 began:

‘The Purdy rule, “Always unpin”, is dead right here.’

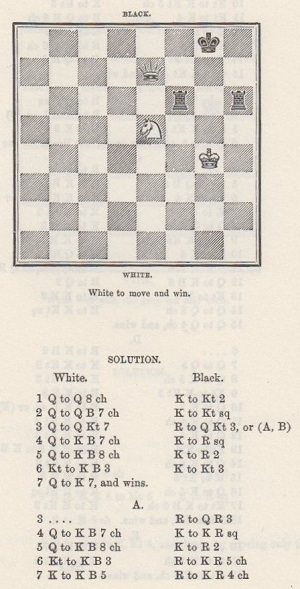

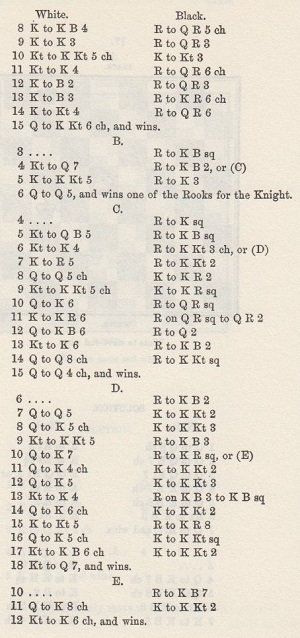

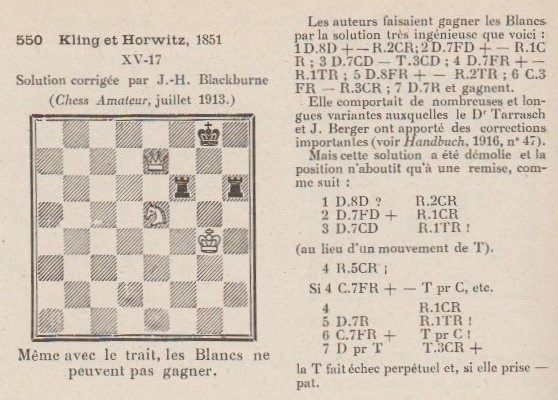

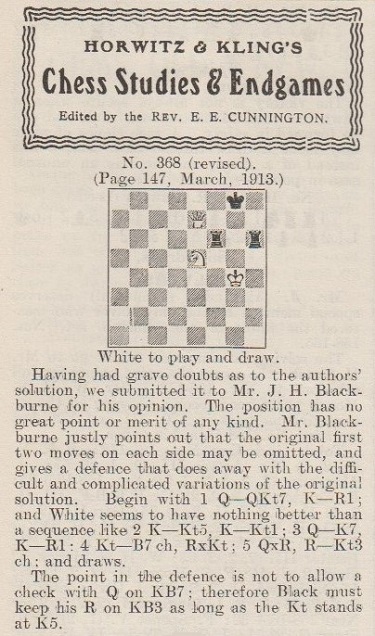

9703. Blackburne on a study by Horwitz and Kling

From pages 225-226 of Chess Studies and End-Games by B. Horwitz and J. Kling (London, 1889):

Without any particulars, page 193 of the May 1898 BCM queried whether the solution was conclusive. The position was discussed on page 304 of Traité des fins de partie d’échecs by Un Amateur de l’Ex. U.A.A.R. (Paris, 1924), which noted a correction by Blackburne:

Below is the item in question, from E.E. Cunnington’s column on page 305 of the July 1913 Chess Amateur:

9704. The two Jans (C.N. 9656)

A consultation game in which Dawid Janowsky (White) faced Frank J. Marshall shows the former’s liking for the bishop pair:

1 e4 e5 2 d4 exd4 3 c3 dxc3 4 Bc4 cxb2 5 Bxb2 Nf6 6 Nf3 d5 7 exd5 Bb4+ 8 Nc3 Qe7+ 9 Be2 Ne4 10 Rc1 O-O 11 O-O Nxc3

12 Rxc3 Bxc3 13 Bxc3 Nd7 14 Re1 Nf6 15 Bd3 Qd8 16 Re5 Re8 17 Rg5 h6 18 Rg3 Nh5 19 Bc2 Nxg3 20 hxg3 f5 21 g4 Re4

22 Ne5 Qg5 23 d6 cxd6 24 Qxd6 Qc1+ 25 Bd1 Rxe5 26 Bxe5 Kh7 27 Kh2 Be6 Drawn.

The game, played at the Automobile Club de France in Paris in October 1907, was published on pages 386-387 of La Stratégie, 20 November 1907 with Janowsky’s notes from Le Monde Illustré. Those annotations were the basis for what appeared on pages 289-290 of Voronkov and Plisetsky’s book on Janowsky (Moscow, 1987) and on pages 472-474 of Ackermann’s monograph (Ludwigshafen, 2005).

La Stratégie stated that Janowsky was partnered by Bonaparte Wyse, and Marshall by le baron de Laforie, although the annual index (page 454) gave le comte de Laforie. In the Soviet and German books the name was, respectively, Лафори and Lafore.

9705. Prague, 1942

Having just seen, for once in a long while, a copy of The Times (London), we note that Raymond Keene’s column is still shambling along with its trademark mix of inaccuracy, superficiality and cronyism.

Page 45 of the 26 January 2016 edition has this:

Oldřich Důras died in 1957. The 1942 tournament marked his 60th birthday.

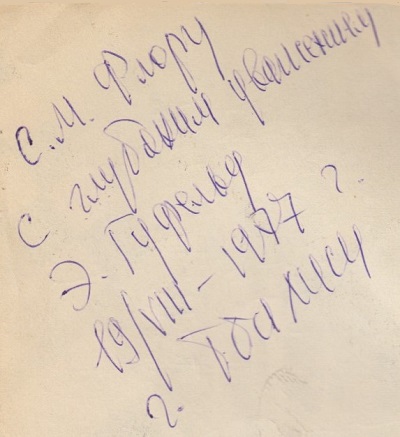

9706.

Inscription by Gufeld to Flohr

Book inscriptions by one master to another are relatively

scarce. An example from our collection is a dedication

(‘with deep respect’) by Gufeld to Flohr:

9707. Horatio Caro

From John Townsend (Wokingham, England):

‘Your feature article The Caro-Kann Defence includes a request for information about Horatio Caro’s final years, and I can provide some information on his last two and a half months. The admission and discharge register, 1919-1921, of the South Grove Institution, Mile End Road, London, a workhouse, includes the following entry for an admission:

“Date: Friday 1 October 1920

Name: Caro Horatio

Calling, if any: Laborer [sic] (Casl.)

Religious Persuasion: Hebrew

When Born: 1863

Infirm Adults: 1

Parish from which Admitted: Infirmary

By whose Order Admitted: Board’s

Date of the Order of Admission: 1.10.20.”In a separate discharge register for the South Grove Institution, an entry dated 15 December 1920 for “Caro Horatio”, an infirm adult, records simply that he is “Dead”.

Both the above records can be viewed on-line.

He was buried in the East Ham Jewish Cemetery in a grave on which a plaque gives his date of death as 15 December 1920. A good photograph of the grave, provided by Geoffrey Gillon, can be seen on the Find A Grave website.’

We note that the Find a Grave website has also lifted a photograph of Caro from C.N. 7249.

9708. A letter from Rudolf L’hermet

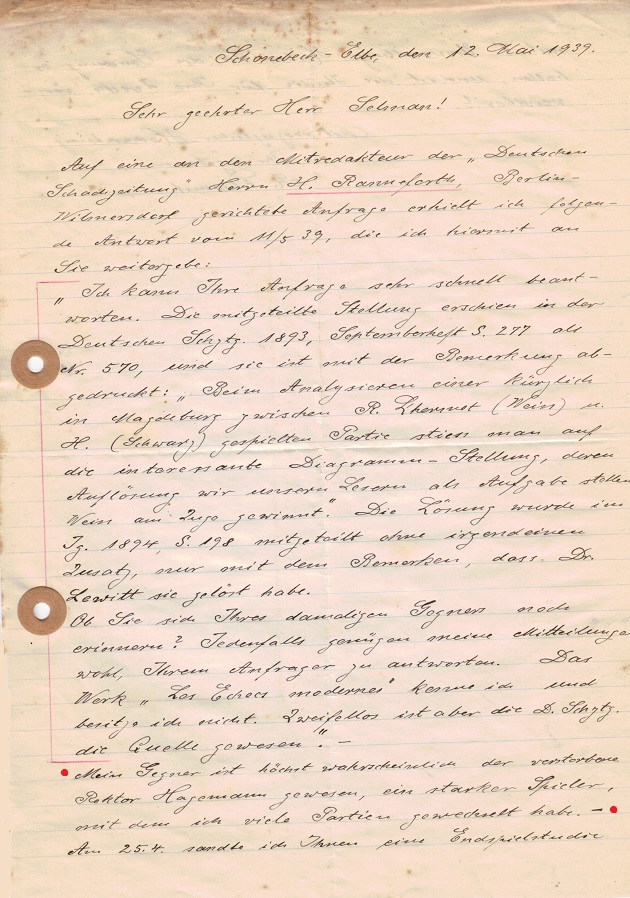

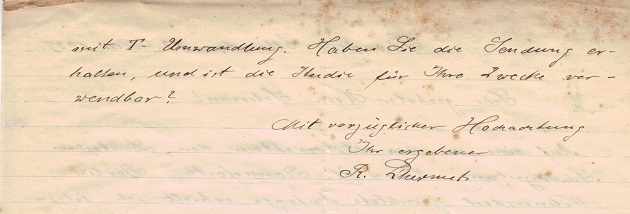

Harrie Grondijs (Maastricht, the Netherlands) has forwarded us a letter dated 12 May 1939 from Rudolf L’hermet to John Selman indicating that L’hermet’s opponent in the endgame discussed in C.N. 9697 was probably Rektor Hagemann:

9709. Eight question marks for a move

C.N. 582 (see Chess Punctuation) reported that on page 148 of the Australasian Chess Review, 17 June 1937 a move received eight question marks.

Another case was on pages 15-17 of Chess World, January 1967. The game was annotated by W.J. Geus, but only the punctuation is shown below:

Douglas Gibson Hamilton – Emanuel Basta

Championship of Victoria, Melbourne, 1966

Caro-Kann Defence

1 e4 c6 2 d3 d5 3 Nd2 e5! 4 g3 Nf6 5 Bg2 Be6 6 Ngf3 dxe4 7 dxe4 Nbd7 8 Qe2 Be7 9 h3 h6 10 O-O g5! 11 Nc4 Qc7 12 Nh2 O-O-O 13 a4 Bc5 14 c3 Nb6 15 Nxb6+ Bxb6 16 b4 a5! 17 Be3 axb4 18 a5!? Bxe3 19 fxe3!? Ne8 20 a6 b5 21 cxb4 Bc4 22 Qg4+ Kb8 23 Rfc1 Ka7 24 Bf1 Nd6 25 Qf3 h5 26 Be2 Rd7 27 Nf1 g4! 28 hxg4 hxg4 29 Qxg4

29...f5!! 30 exf5 Bd5! 31 Bd3 Rg7 32 Qe2 Rh1+ 33 Kf2 e4! 34 Bxb5 Nxb5 35 Kg2

35...Nd4?!? 36 Qb2! Nf3??

37 b5???????? Rxg3+! 38 Nxg3 Rh2+ 39 Kf1 Rxb2 40 White resigns.

After White’s 37th move Geus wrote:

‘This annotator believes that the difference between the winning move (37 KxR) and the text deserves as many ?s as the printer is likely to tolerate.’

| First column | << previous | Archives [138] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.