Chess Notes

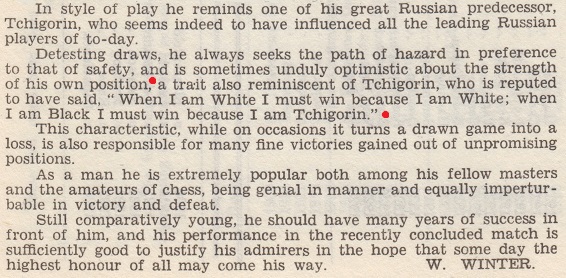

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [137] | next >> | Current column |

9611. An appreciation of James Mason

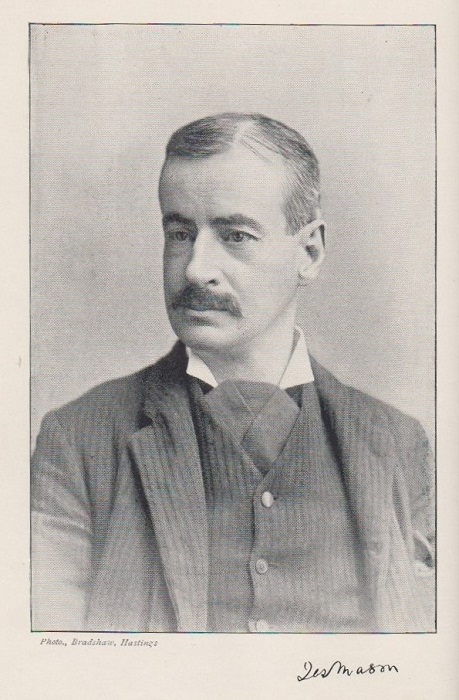

James Mason (Hastings, 1895 tournament book, opposite page 19)

‘For sheer chess genius James Mason was, in my opinion, probably the finest player who has ever lived. This may sound a somewhat tall statement, but it will be more readily accepted by those with a thorough knowledge of chess and chessplayers than by those whose knowledge is more superficial. If ever a player lived before his time, that man was Mason. He was a player most difficult to place definitely into one school. He did not live in a transition period which had it been true might have accounted for his mixed genius. He had not the opportunities of the modern player and yet he had ideas upon opening and development which are in strange accord with those of today. Again, as a contemporary of Steinitz, it is not strange that he should show allegiance to that master’s theories in much of his play, and in his writings. All the same, many of his games show him capable of the deepest combinative play – the grand style – the oft lamented old school of Morphy and Anderssen. A frequently quoted game of his was that against Winawer at Vienna in 1878 [sic – 1882]. It is really a fine game second to none in depth of combination although the material sacrificed may not be so much as in some better known games.’

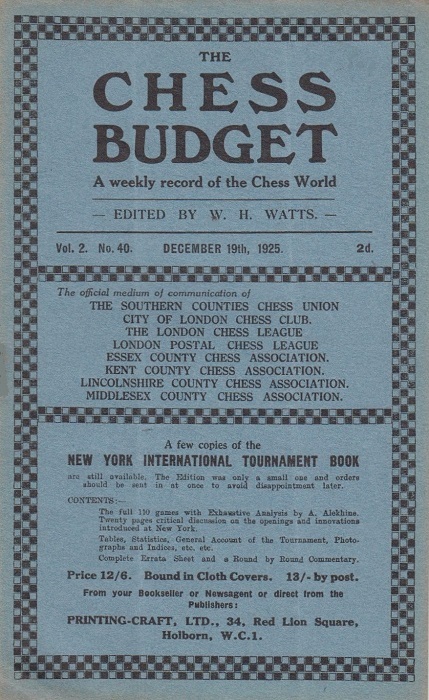

Source: An article entitled ‘James Mason’ by W.H. Watts on pages 82-83 of the Chess Budget, 19 December 1925.

W.H. Watts added:

‘Not one of the many hundreds of chess books that I have ever had has given me one tenth of the pleasure I got from The Art of Chess. It contains hundreds of positions all from actual play and shows how the winning combinations have been evolved – or having obtained winning positions how best to finish them off. In this way instruction is acquired incidentally and not laboriously. Many of them can be followed by a mere tyro without a board and men from the diagrams themselves. It was a book on an entirely new principle – and it had obviously meant a terrific amount of work – much more than merely reprinting the full score of a number of games and giving a few notes. The Principles of Chess was the finest book for the learner available, and although since his time there has been a great advance in chess text books, no better elementary text book has been produced. The selection of games and the annotations at the end of this book have never been surpassed.

Social Chess, as its name implies, is a less ambitious and less serious book. It contains a collection of short games with bright attacking finishes and examples of clever combinative play.

Mason had a marvellous command of the English language. His introductory chapters to these three books are models of really beautiful English. Clear, concise and to the point, what he writes can be read merely for its style, let alone the subject-matter. Again, his writings show him to have been a man of considerable education.’

The appreciation by Watts then discussed Mason on a more personal level:

‘As a man Mason always struck me as a sardonic misanthrope, a sort of disappointed man. In company with James Platt, of Carlisle, I played him a consultation game. It was a long game for a fee which Mason had already received. As soon as it was over he pushed up the pieces without a word and went off with just a typical glint of a smile – almost contemptuous. Other occasions when I saw him he seemed to have that same smile for opponents and friends alike. At the Hastings and London tournaments and at the City of London tournament – his last appearance and the one at which he did so very badly – I cannot ever remember hearing him speak a single word. All the same, socially, and away from chess, Mason was a bright and entertaining conversationalist, full of interesting anecdotes and reminiscences, and in convivial company he could be a great success – but suddenly he would become mute and nothing would move him.

Although in later years I knew him fairly well, he would never do more than nod – and always wore that queer smile which one can still see in the frontispiece to The Art of Chess.’

It was the same frontispiece as in The Principles of Chess in Theory and Practice, which was shown in C.N. 9610.

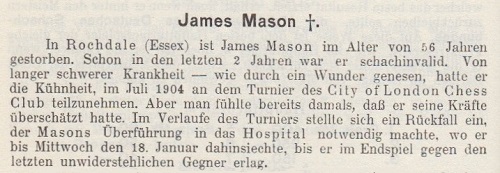

9612. James Mason’s death

Writing in the Chess Budget (C.N. 9611), W.H. Watts stated that James Mason died on 18 January 1905. No place was mentioned.

Many contradictory versions can be found, the most obviously wrong being what appeared in Harry Golombek’s Encyclopedia of Chess. In the entries on Mason in both the hardback and paperback editions (1977 and 1981 respectively), 15 January 1909 was given. From some other reference books:

- 17 January 1905 in London (Dictionary of Modern Chess by B.J. Horton);

- 15 January 1905 in Rochdale (Dizionario enciclopedico degli scacchi by A. Chicco and G. Porreca);

- 15 January 1905 in London (An illustrated Dictionary of Chess by E.R. Brace).

The British newspapers of 1905 that we have seen so far offer little information of substance. As regards chess magazines of the time, a selection is shown below, beginning with page 44 of the Wiener Schachzeitung, February 1905:

- ‘Der bekannte englische Schachmeister James Mason ist am 18. Januar im Krankenhause zu Rochdale (Essex) im Alter von 56 Jahren gestorben.’ (Deutsche Schachzeitung, February 1905, page 63);

- ‘M. Mason est décédé le 15 janvier à Rochdale; né en 1849, il avait 55 ans.’ (La Stratégie, 20 February 1905, page 52);

- ‘... Mr James Mason, whose mortal remains were interred on 17 January, in the church yard of Thundersley, Essex.’ (BCM, February 1905, page 51);

- ‘The news of Mr Mason’s death was conveyed to Mr J. Walter Russell, Secretary of the City of London Chess Club, in a letter from the Rev. Talfourd Major, of Thudersley [sic], Essex under date of 18 January as follows: “I write to inform you that James Mason was laid to rest in our little churchyard yesterday, having died in the Rochford Infirmary. This is also to thank you on behalf of Mrs Mason for your generous help to him in the past, and also that of the City Chess Club.”’ (Lasker’s Chess Magazine, February 1905, page 155);

- ‘[Mason] died during the second week of January 1905, at Rochford, England.’ (American Chess Bulletin, April 1905, page 191);

- ‘Mason ist nach längerer Krankheit am 15. Januar 1905 zu Rochdale (Essex) gestorben und wurde am 17. Januar 1905 auf dem Kirchhof zu Thundersley begraben.’ (Schachjahrbuch für 1905 II. Teil by L. Bachmann (Ansbach, 1906), page 232).

Page xi of the 1947 edition of The Art of Chess (revised and edited by F. Reinfeld and S. Bernstein) affirmed that Mason ‘died in Rochdale, England on 18 January 1905’. Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia (Jefferson, 1987 and the unpublished 1994 edition) had 15 January 1905 in Rochford, England. Page 141 of James Mason in America by J. van Winsen (Jefferson, 2011) gave 12 January 1905, with a footnote stating that ‘Mason’s death certificate has the date 12 January 1905’.

Further information is sought. The place name ‘Rochford’ (as opposed to Rochdale, Lancashire) is corroborated by a news paragraph on page 468 of the December 1904 BCM:

‘The Rev. Talfourd Major, Rector of Thundersley, Essex, informs us that Mr James Mason is lying dangerously ill in Rochford Infirmary, and it is feared will never be well enough to leave it alive.’

The earliest occurrence of ‘Rochdale’ that we have traced is in the obituary by Hoffer, which had several errors, in the Field, 21 January 1905:

‘With deep regret, which will be shared by chessplayers all over the world, we have to announce the death of James Mason, at Rochdale, Essex, at the age of 56 [sic – 55]. For nearly two years Mason had been an invalid. Recovering almost miraculously from a serious illness, he had the temerity to take part in the tournament at the City of London Chess Club in July, but it was felt that he overtaxed his energies and that this would be his last appearance in important events. He was, we might say, goaded into taking such a serious step by the irksome paragraphs about his illness which were supplied to the sensational press by unscrupulous news hunters. “I just wanted to show them that I am not dead yet”, he told us when asked why he decided to take part in the tournament. So reticent was he about private matters that upon inquiry about these reports he replied: “The pars in the press are right enough. But I cannot even surmise who authorized them. I had a strong epileptiform attack, but it passed, I believe – hope – without inflicting any permanent injury. But it is hard to tell. ‘Snaix is snaix!’ The fact is, I have been seriously ill for the last five years.” After the exertions in the tournament mentioned he had a serious relapse, necessitating his removal to the hospital, where he lingered on till Wednesday [which indicates Wednesday, 18 January], when he lost the endgame against the implacable adversary.’

9613. Jutta Hempel

From page 51 of Chess World, March-April 1967:

The caption reported that she was aged 5¾.

9614. Books with hardly any words

From a syndicated column (19 November 2000) by Larry Evans:

‘“His best books are those with hardly any words at all, but only diagrams, captions and solutions”, quipped a wag about Fred Reinfeld, the world’s most-prolific chess author.’

Evans did not bother to give a source or to name the ‘wag’.

The remark was by C.J.S. Purdy, on page 120 of the July-August 1967 Chess World. The passage can also be found on page 67 of The Search for Chess Perfection II by C.J.S. Purdy (Davenport, 2006) and on page 149 of The Chess Gospel According to John edited by R.J. Tykodi and Bob Long (Davenport, 2010).

In isolation and out of context, the words extracted by Evans give a false impression of Purdy’s view of Reinfeld as a chess writer. See, for instance, C.N. 9586.

9615. James Mason’s death (C.N. 9612)

From William D. Rubinstein (Melbourne, Australia):

‘James Mason’s entry in the printed indexes of the Principal Probate Registry of England and Wales, which are officially compiled and available on ancestry.co.uk, reads as follows:

“James Mason of Blodwin Cottage, New Thundersley, Essex, died 11 January 1905 at The Infirmary, Rochford, Essex. Effects £151. Administration to Annie Mason, widow.”’

C.N. 9612 quoted Hoffer’s statement in the Field of (Saturday) 21 January 1905 that Mason had died on Wednesday which, we noted, indicated 18 January. However, if Hoffer had in mind the previous Wednesday, his information would match that quoted by Professor Rubinstein.

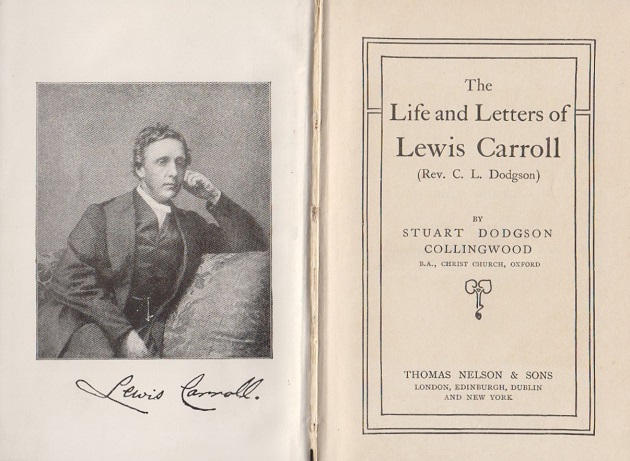

9616. Lewis Carroll

Harrie Grondijs (Maastricht, the Netherlands) forwards two references to chess on pages 92 and 211 of The Life and Letters of Lewis Carroll (Rev. C.L. Dodgson) by Stuart Dodgson Collingwood (New York, 1889).

Below is the text as it appeared in our slightly later edition (undated):

From pages 83-84 (1862):

From page 176 (1880):

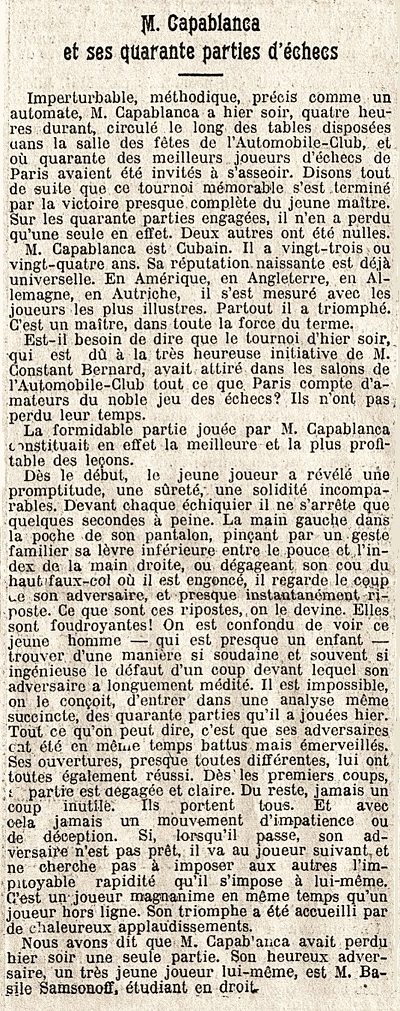

9617. Capablanca in Paris (C.N. 9558)

From Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) comes this report on page 4 of Le Temps, 13 November 1911:

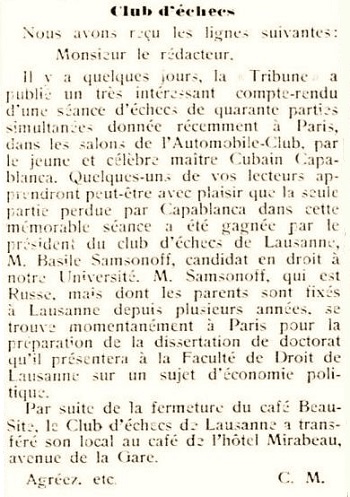

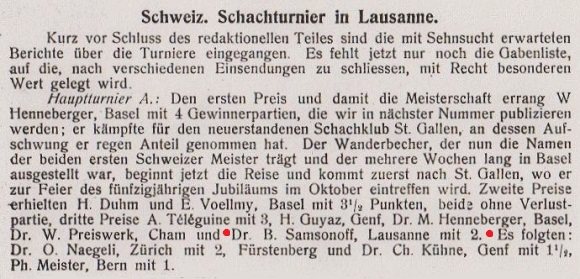

Regarding Basile Samsonoff, the only player to defeat Capablanca, Mr Thimognier also provides a cutting from page 2 of La Tribune de Lausanne et Estafette, 1 December 1911:

Our correspondent adds that the following year Samsonoff played in the Swiss championship in Lausanne, and we give below part of the report on page 159 of the September 1912 Schweizerische Schachzeitung:

9618. The Ultimate Chess Playing Guide

Avital Pilpel (Haifa, Israel) notes a pair of books published in 2015: The Ultimate Chess Playing Guide. The Best Openings, Closings, Strategies & Learn To Play Like A Pro by Terence North and Chess. Dominate Chess Openings, Closings, Chess Strategies and Tactics Like a Pro by Matt Sigs. From what is viewable at Amazon.com, including the sample content, strangely worded titles (both with ‘Closings’), unfamiliar authors’ names, and the large number of reviews, Mr Pilpel became both suspicious and curious, and he asked us for further information about the books.

We dutifully acquired them, and below, without comment but grouped together under our own headings, is an extensive sample of the chess instruction in the 46-page book by ‘Terence North’.

The book’s aim

‘All things considered, don’t stress. Comfortable page, I will layout 3 rules that will drastically assist you with enhancing at chess inside of 23 days!’ (Page 3)

The board and pieces

‘Winner is chosen by whoever solves the chess board puzzle. Chess is played on a squared board with 62 black and white alternating squares, each player set up there pieces so the light squares are on the right hand side, something to note is that the Queen piece is placed on the square of the same color.’ (Page 2)

‘The board’s squares [64] substitute in shading and are termed light, and dull squares.

These squares are masterminded into lines and sections.

Lines are called positions and are numbered from 1-8.

Sections are called documents and are named from A-H.

Pieces are set up in lines which are parallel to the documents, and opposite to the board’s positions.’ (Page 14)

‘The white squares are placed on the right side of the chessboard.

The decision of which player goes first is determined by who has the white pieces, that player goes first.

Queen, Rook, Bishop or Knight can be exchanged by pawn if a piece is promoted with this the Queen, may or may not be able to check/checkmate the opponent’s King.’ (Page 7)

‘Every Chess player utilizes Chess sets that have 16 pieces: 1 ruler, 1 lord, 2 rooks, 2 knights, 2 religious administrators, and 8 pawns.’ (Page 41)

The king

‘Arguably the most imperative piece on the board, the game’s purpose is to attempt and catch your rival’s the best. The ruler can move in any heading one space.’ (Page 15)

‘Casteling is a move in which both the ruler and the rook move amid the same turn, to a predefined position, under extraordinary circumstances.’ (Page 17)

‘Safeguarding your ruler, perfect barrier, keeping up the trustworthiness of the castled lord.’ (Page 28)

The queen

‘This is the most powerful chess piece on the board and can move as far as it can without going through any similar pieces. The Queen can move in any direction and must avoid being captured. The Queen can even capture a King.’ (Page 9)

‘A capable piece the ruler can move in a straight line in any heading, similarly as the player needs, the length of another piece doesn’t act as a burden.’ (Page 15)

‘The Queen is one of the most powerful pieces on the board ...’ (Page 39)

The rook

‘The Rook can move in a straight line in any bearing, similarly as the player needs, the length of another piece doesn’t act as a burden.’ (Page 16)

The bishop

‘The religious administrator can move corner to corner in any bearing, similarly as the player needs, the length of another piece doesn’t act as a burden.’ (Page 15)

The knight

‘A Knight can propel two squares and one stage to the privilege or left. This move should be possible in any heading, the length of the same measure of separation is secured in the same way. The knight can likewise make his turn over different pieces.’ (Page 15)

‘Knights, on the other hand, should be in the middle to be successful. Besides, the way that they are moderate moving contrasted with different pieces, these pieces are disagreeing grown first before whatever remains of your armed force.’ (Page 38)

The pawn

‘As a rule they can just push ahead and can just move one space at once. Nonetheless, on their first propel they can go two spaces. Additionally, the main path for a pawn to catch a foe, is to move slantingly to take them.’ (Page 16)

‘En passant is a move done by two restricting pawns, in which one pawn can catch the other, under extraordinary conditions, without moving to his square.’ (Page 17)

‘On the off chance that amid play a pawn achieves the flip side of the board, they are advanced, and can be traded for an additional of any piece the player needs aside from the ruler. The game’s object is to catch your adversary’s top dog.’ (Page 17)

The value of the pieces

‘At the point when disposing of pieces, the “Chess Piece Point Values” gotten to be vital. An arrangement of focuses is doled out to every kind of piece. A Queen is generally justified regardless of 9 focuses, Rooks five, Bishops and Knights three focuses each, and Pawns one.’ (Page 30)

‘Taking a diocesan or knight with a pawn is a case for the move “giving up for a lower esteemed piece”.’ (Page 34)

The aim of the game

‘The last objective in the game comprises of checkmating the adversary’s above all else.’ (Page 41)

The opening

‘It is ordinarily said that a Chess game contains three different states which all offer route to the game in general. The Opening Stage is the place the board starts to be set by the players keeping in mind the end goal to dispatch their approaching assaults. This is the point at which the positions are invigorated and players prepared themselves for the approaching game.’ (Page 25)

‘Fool's Mate, this happens when the player leaves the King wide open for attack. The pawn’s on the King’s side move too early in the game and doesn’t alone the King to Castle.’ (Page 18)

‘Perceiving the open door for instituting a practiced or retained chess opening is critical to winning the opening game.’ (Page 35)

‘Then again, you truly can’t accuse these gentlemen for pouring a great deal of their endeavors in chess opening study. I know that it is so baffling to succumb to a gambit or trappy opening that you don’t think about and be forced to bear a smaller than expected.’ (Page 37)

‘In the opening, rather than snatching a stray flank pawn (which will in all likelihood slow down your advancement), make pawn moves like a3 or h3, and so forth., concentrate on adding to your armed force and getting them designed for the best in class middle-game fight.’ (Page 38)

‘Maybe a couple opening moves in the opening is sufficient more often than not. Presently, on the off chance that you are pondering what might be a decent advancement grouping, here it is (1) Knights ought to be produced first since they are the slowest moving pieces. (2) Bishops are next. Placed them in positions where they have greatest degree. (3) When there is no other creating move accessible, get your ruler to castling so as to well. (4) And last BUT not the slightest, interface your rooks and draw out the almighty ruler!’ (Page 44)

‘Know which openings you ought to take a gander at. Get down to earth and compelling opening exhortation and never stress over what to do in this phase of the game!’ (Page 45)

The middle-game

‘The Middle Game is hard and fast war. The objective for any one player is for the most part to catch a greater number of bits of the rival than the rival can catch of theirs, in spite of the fact that a definitive objective is to get into the best position for the Endgame. By and large, one needs to have the capacity to catch pieces, sacrificing so as to note free, however just lower pieces than the caught piece is worth.’ (Page 26)

‘Middle game strategies typically include checking the lord. This circumstance constrains the rival to move the ruler instead of take your piece.’ (Page 33)

‘The middle game starts toward the opening’s finishing game (obviously), which is typically around 10 turns in.’ (Page 35)

The endgame

‘Knowing a savvy endgame will just help in winning a game of Chess, yet it is likewise key to completely see each phase of the game. At exactly that point can one develop into a genuinely incredible Chess player.’ (Page 27)

Tactics and strategy

‘What really counts is the moves you make in chess. Each move has to be critical and it these moves are referred to as tactics. Tactics are a particular pattern that you can move certain pieces in order to checkmate a piece. Learn these tactics and you will be playing with the big boys in no time.’ (Page 24)

‘Chess mixes normally cover various sorts of strategic strategies that numerous middle game understudies characterize and give as exemplary cases of vital playing. These strategies pass by such colorful sounding names as pins, forks, sticks, found checks, zwischenzugs, redirections, fakes, penances, constraining moves, undermining, over-burdening and obstruction.’ (Page 31)

‘Pawn snatching ought to be maintained a strategic distance from.’ (Page 45)

‘The focal squares of the load up serve as a springboard for your pieces – giving a simpler time to move to different parts of the load up where they are required. With focal control, your pieces have more noteworthy portability and action.’ (Page 45)

Miscellaneous

‘Take a gander at how Mikhail Tal impacts the resistance into obscurity with his chess blends.’ (Page 5)

‘There are a great deal of spots on the Internet where you can figure out how to play Chess; you can without much of a stretch take in the essential rules of the game, for example, strategies, the middle’s hypothesis game, the end game and opening.’ (Page 42)

‘Finally, if you enjoyed this book, then I’d like to ask you for a favor, would you be kind enough to leave a review for this book on Amazon? It’d be greatly appreciated!’ (Page 46)

9619. Lewis Carroll (C.N. 9616)

Roger Scowen (Hampton, England) points out that the Lewis Carroll Society has a page about his interest in chess.

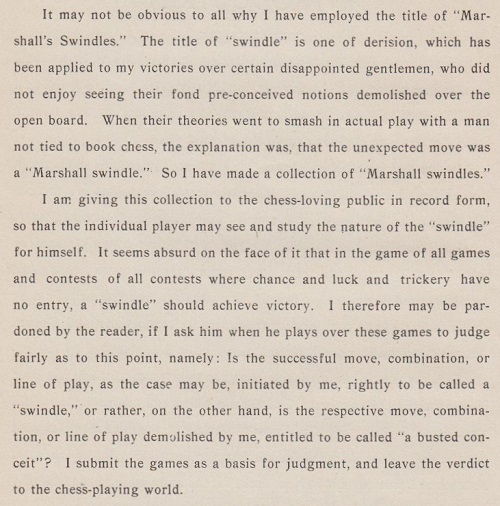

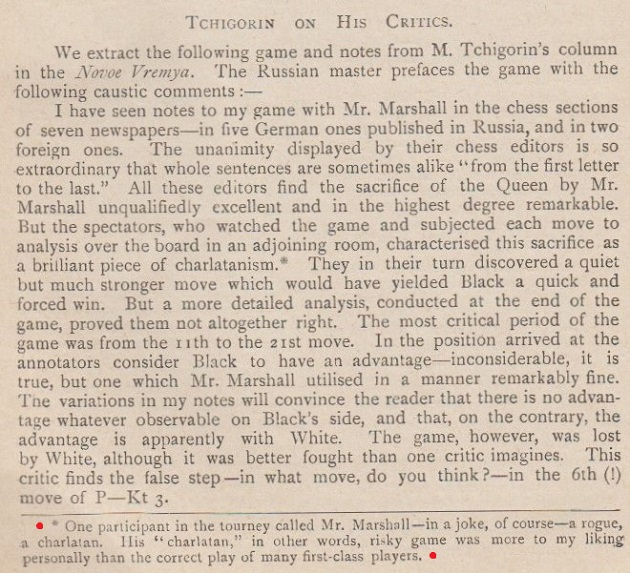

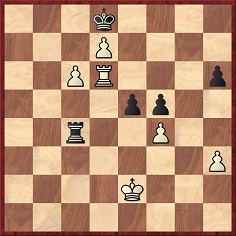

9620. Marshall’s swindles

From the third match-game between Janowsky and Marshall, Biarritz, 4 September 1912 (Black to move):

Marshall played 12...Qxf3, and commented on page 50 of Marshall’s Chess “Swindles” (New York, 1914):

‘Taking White completely by surprise, and I heard a murmur of a “swindle”.’

A similar remark was on page 141 of My Fifty Years of Chess by Frank J. Marshall (New York, 1942):

‘Before my opponent answered this surprise move, I heard him whisper, “Swindle!”’

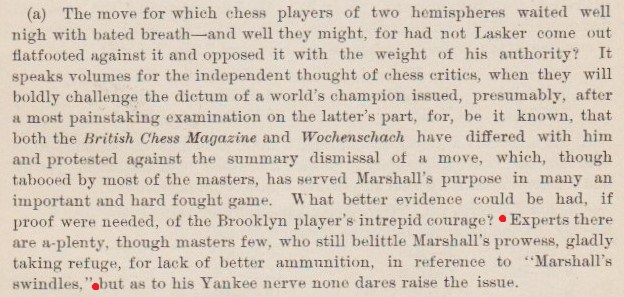

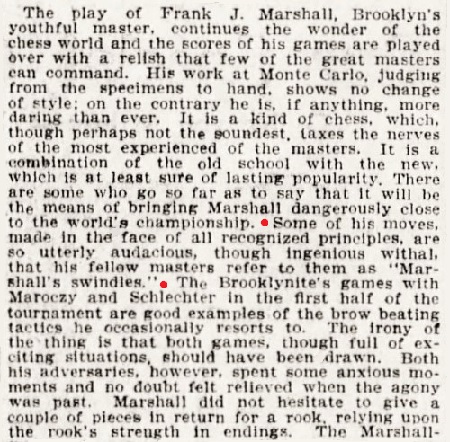

The Introduction to Marshall’s 1914 book had this note on the term:

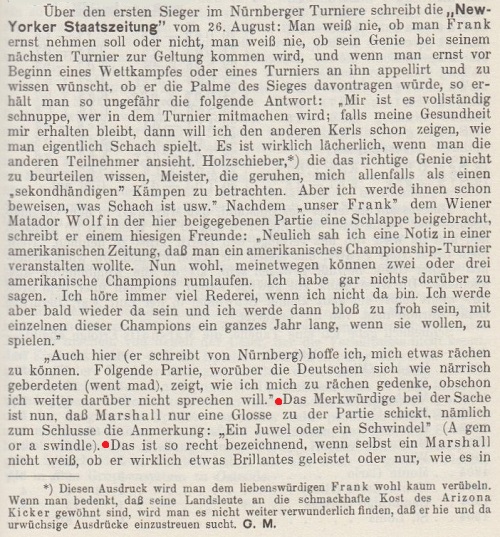

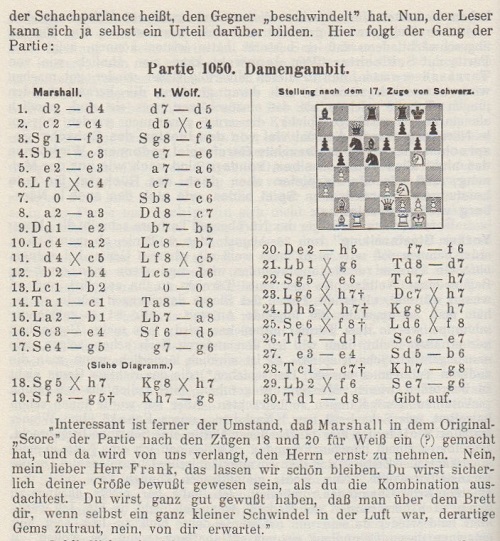

Proceeding in reverse chronological order, we give now an extract from pages 39-40 of the January-February 1907 Wiener Schachzeitung, in connection with Marshall’s game against Heinrich Wolf at Nuremberg, 8 August 1906:

From page 11 of Hermann Helms’ coverage of the Marshall v Tarrasch match on page 11 of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 15 October 1905:

‘One thing is sure, and that is, Dr Tarrasch has reduced the possibilities for the famous “Marshall’s swindles” to a minimum.’

Another remark by Helms is on page 85 of volume two of Halpern’s Chess Symposium (New York, 1905) – concerning the position after 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 f5 in the 14th match-game between Janowsky and Marshall in Paris, 25 February 1905:

The game with Helms’ notes is on pages 52-53 of Marshall’s Chess “Swindles”.

An earlier occurrence of the term, also in Helms’ journalism, was on page 24 of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 6 March 1904:

When was the word ‘swindle’ first used in connection with Marshall’s play?

The following paragraph is from page 51 of Frank Marshall, United States Chess Champion by A. Soltis (Jefferson, 1994):

Soltis did not specify his source or indicate whether the quoted words were his own translation. Can a reader provide the original Russian text? For now, we can give only the following on page 477 of the November 1903 BCM, with ‘rogue’ instead of ‘swindler’:

9621. Purdy on teaching

From page 132 of Chess World, September-October 1967:

‘The teaching gift is not the same thing as genius but fairly rare. The genius has a brain too far removed from most students. The great teacher understands better the real needs of students partly because his own mind is nearer to theirs. Many great players would be quite hopeless as teachers because they themselves play well but do not really know why they play well. The teacher is able to rationalize everything. Not that laying down rules is enough. He must discover or pick out the best rules to lay down.’

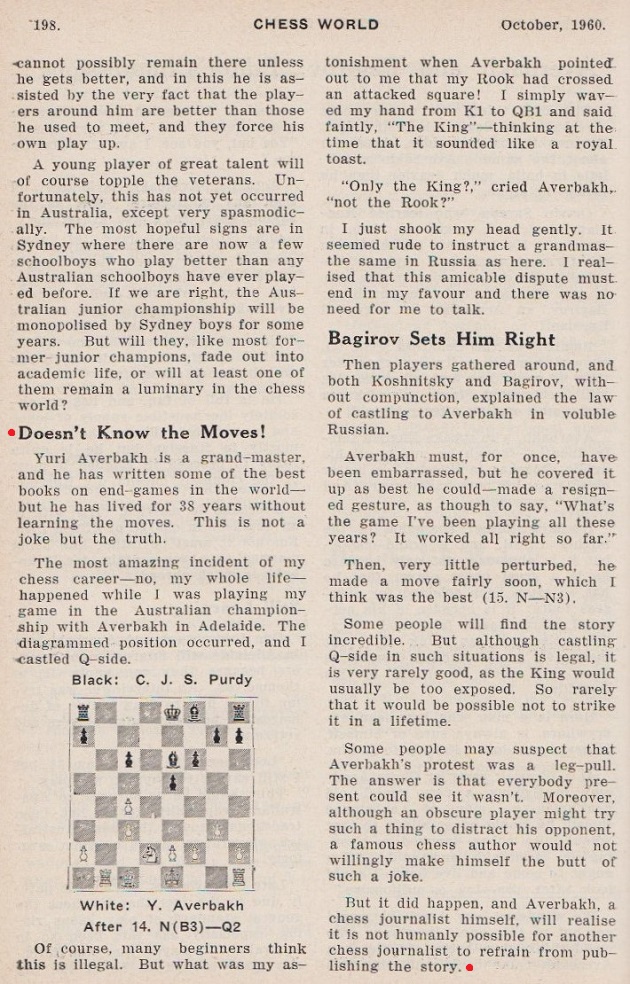

9622. Averbakh v Purdy

Position after 14 Nf3-d2 and before 14...O-O-O

C.N. 795 mentioned the castling incident which occurred in Averbakh v Purdy, Adelaide, 1960, as reported on page 110 of Wonders and Curiosities of Chess by Irving Chernev (New York, 1974). In The Facts about Larry Evans we commented:

In July 2000 [Chess Life] Evans presented a diagram from the famous game between Averbakh (Evans writes ‘Averbach’) and Purdy, played in 1960 in Australia (‘Austalia’), which had been published in his book Chess Catechism. In that volume (page 39) Evans had given an inaccurate diagram, omitting a white pawn on g3, so has his level of accuracy changed in the three decades since the book appeared? Yes, indeed. In his July 2000 column the white pawn on g3 is still missing, but now there is a second absconder, from the black side: a pawn at a7.

Subsequently (Chess Life, August 2002, page 47), Evans achieved a correct diagram.

The game was misdated 1961, instead of 1960, by T. Krabbé on page 281 of the May 1976 Chess Life & Review and on page 6 of Chess Curiosities (London, 1985), as well as by R. Timmer on page 49 of Startling Castling! (London, 1997) and by E. Schiller on page 396 of Encyclopedia of Chess Wisdom (New York, 1999). On pages 100-101 of The Book of Chess Lists (Jefferson, 1984) A. Soltis managed the right year but asserted that ‘R-QN7’ had been played by Averbakh.

Chernev’s above-mentioned account quoted Purdy’s words (albeit without specifying their provenance) and is the most detailed and accurate version found in a secondary source. Later writers took the matter backwards, not forwards.

Purdy had annotated his loss to Averbakh on pages 221-222 of Chess World, November 1960, and after 14...O-O-O he wrote: ‘Amusing incident here: see October, page 198’. In that earlier issue Purdy reported:

The episode was referred to again by Purdy on page 124 of the July-August 1967 Chess World (which included an impossible date, Sunday, 17 January, in connection with Averbakh’s further stay in Australia):

As regards Averbakh’s side of the story, however, the final paragraph of a review (by ‘B.C.’ – Bernard Cafferty) of his book V poiskakh istiny (Moscow, 1967) on page 2 of CHESS, October 1967 deserves attention:

Towards the end of the Adelaide tournament Averbakh spoke highly of Purdy in an interview with W.J. Geus (Chess World, October 1960, page 211):

‘One of the oldest competitors, but put all his strength into his games. His qualities as a fighter are wonderful. Had no luck in this tournament. His technical positional knowledge is first class, and one could say: “Understands chess.”’

9623. Kolisch

The latest McFarland book received is Ignaz Kolisch The Life and Chess Career by Fabrizio Zavatarelli (Jefferson, 2015). There have already been articles about it by speed-readers (or, better say, speed-reviewers), and whereas many people review books without reading them, we prefer to do the reverse. Based on an initial browse and spot-check, a single (tentative) comment is offered here: Fabrizio Zavatarelli’s monograph on Kolisch may prove to be one of the most accurate chess books that McFarland & Company, Inc. has ever published.

9624. Book reviews

Our latest feature article is Reviewing Chess Books.

9625. The knight

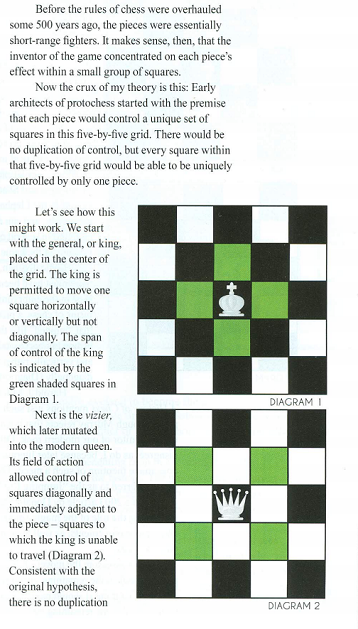

Bruce Monson (Colorado Springs, CO, USA) has pointed out an article, ‘The Mysterious Knight Move’, on pages 30-33 of the February 2015 Mensa Bulletin, and we are grateful to the writer, Frank Camaratta (Huntsville, AL, USA), for permission to reproduce extracts:

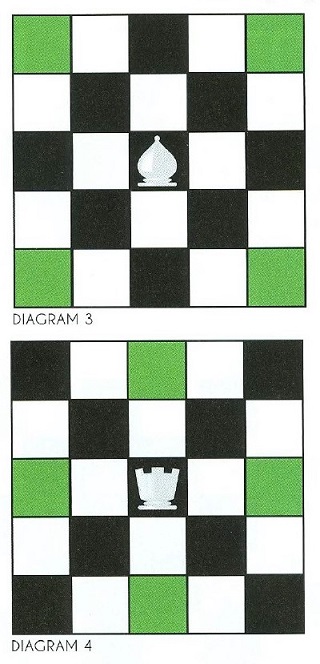

Diagram 3 showed how the ‘primordial bishop, or al-fil, ... has the ability to jump one square diagonally in any direction. It does not control the intervening square, nor can it be obstructed’, and Mr Camaratta then commented, in connection with Diagram 4 (showing a rook): ‘Logically then, there must have been, at least in the embryonic forms of chess, a piece that “jumped” like the bishop but horizontally and vertically rather than diagonally.’

9626. Photographic archives (15)

Victor Korchnoi

Lothar Schmid

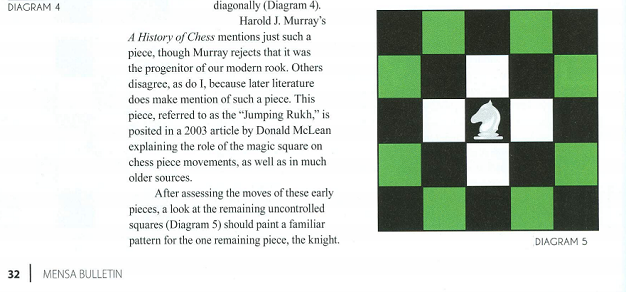

Matthias Wahls

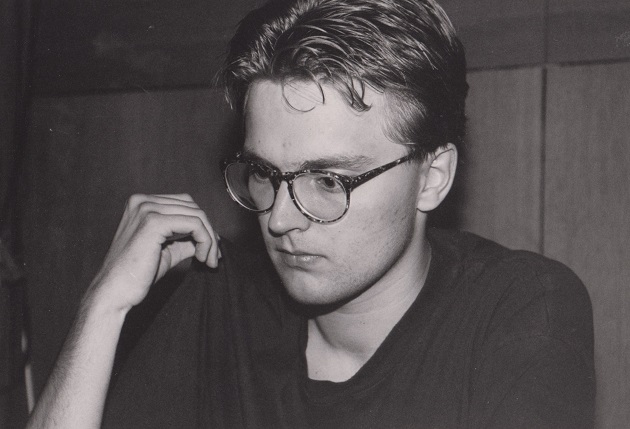

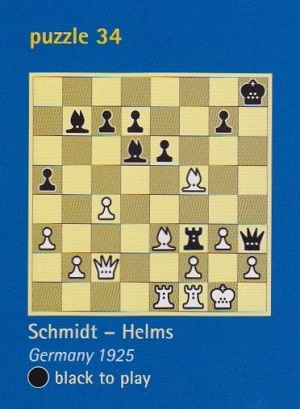

9627. A brilliancy by Helms

Black to move

Although well known, Hermann Helms’ brilliancy against Smyth, played in New York in 1915, sometimes appears as Schmidt v Helms, Germany, 1925. See, for instance, page 220 of A Complete Chess Course by Antonio Gude (London, 2015), as well as page 83 of Checkmate Tactics by Garry Kasparov (London, 2010):

9628. Mark Dvoretsky

We warmly recommend volumes one and two of For Friends & Colleagues by Mark Dvoretsky (Milford, 2014 and 2015).

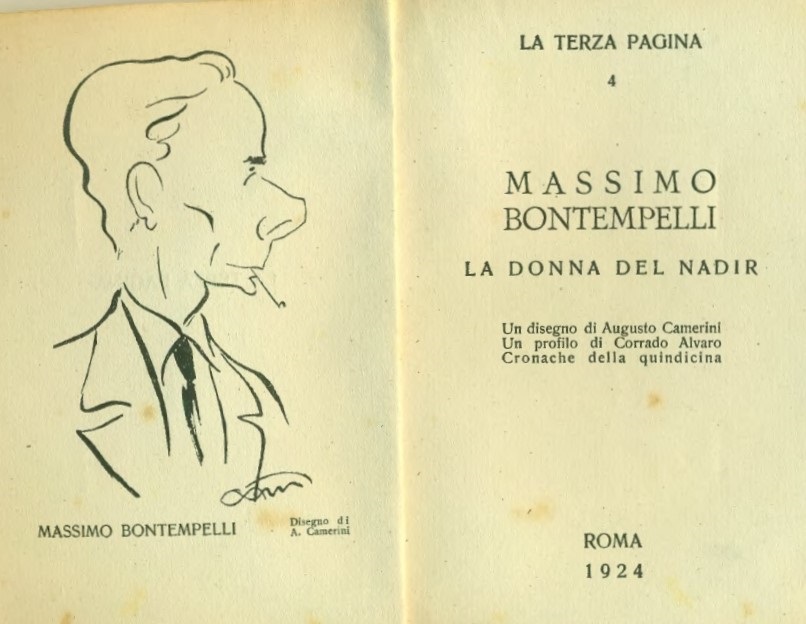

9629. Massimo Bontempelli

From Oliver Beck (Seattle, WA, USA):

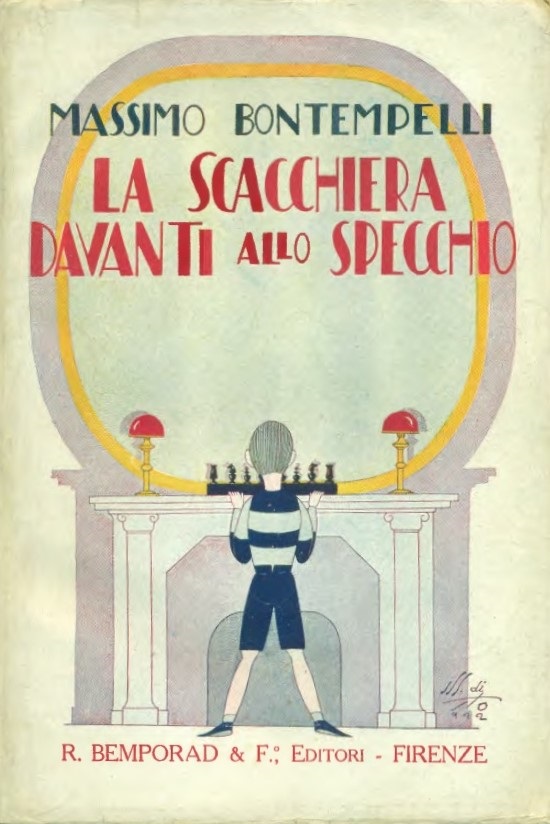

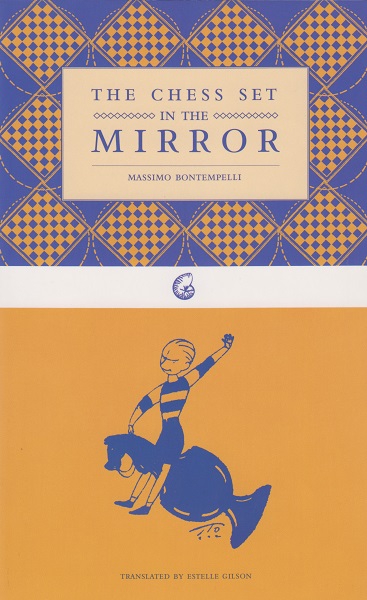

‘In Massimo Bontempelli’s La scacchiera davanti allo specchio (Florence, 1922), a children’s book with similarities to Through the Looking Glass, a child enters a mirrored world where he is told of the importance of chess pieces by a reflected white king:

“... e devi sapere che i pezzi degli scacchi sono molto molto più antichi degli uomini: molti secoli dopo che c’erano gli scacchi sono nati gli uomini, che sono all’ingrosso una specie di pedoni, con i loro alfieri, re e regine; e anche i cavalli, a imitazione dei nostri. Allora gli uomini hanno fabbricato delle torri per fare come noi. Hanno poi fatto anche molte altre cose, ma quelle sono tutte superflue. E tutto quello che accade tra gli uomini, specialmente le cose più importanti che si studiano poi nella storia, non sono altro che imitazioni confuse e variazioni impasticciate di grandi partite a scacchi, giocate da noi. Noi siamo gli esemplari e i governatori dell’umanità.” (Pages 98-101.)

In La donna del Nadir (Rome, 1924) Bontempelli returned to the history of chess in a short essay entitled “Clima sacro”. Commenting on a report of a ten-board blindfold exhibition by Alekhine in Milan, and after suggesting that this achievement was made possible only by Alekhine’s ability to operate outside of any human faculty, Bontempelli offered the following:

“Non senza ragione del gioco degli scacchi non si conosce l’origine: esso probabilmente preesisteva all’apparizione dell’uomo sulla terra, e forse anche alla creazione del mondo; e se il mondo ripiomberà nel caos, e il caos si ridissolverà nel nulla, il gioco degli scacchi rimarrà, fuori dello spazio e del tempo, partecipe dell’eternità delle Idee.” (Page 60.)

On page 186 of the Skinner/Verhoeven book on Alekhine there is an account of his ten-board blindfold exhibition in Milan on 25 March 1923, and the following page shows two games from the event: a spirited win by Luca Morelli, referred to in C.N. 6903, and a loss by Giuseppe Padulli. The Padulli game also appears on page 120 of L’antica Storia della Società Scacchistica Milanese dal 1881 agli anni ’60, volume 1 by Alessandro Sanvito (Bologna, 2014). However, there it is recorded as a draw after 50 Rc2 (instead of 50 Kc2 h5 and resigns, which indicates a double blunder).

The Sanvito book states too (page 62) that Alekhine visited the Società Scacchistica Milanese and faced 14 opponents in a simultaneous blindfold exhibition at the salons of the Società Artisiti e Patriottica, winning each game. No date is given.

Estelle Gilson has produced an English translation of La scacchiera davanti allo specchio, with original illustrations: The Chess Set in the Mirror (Philadelphia, 2007).’

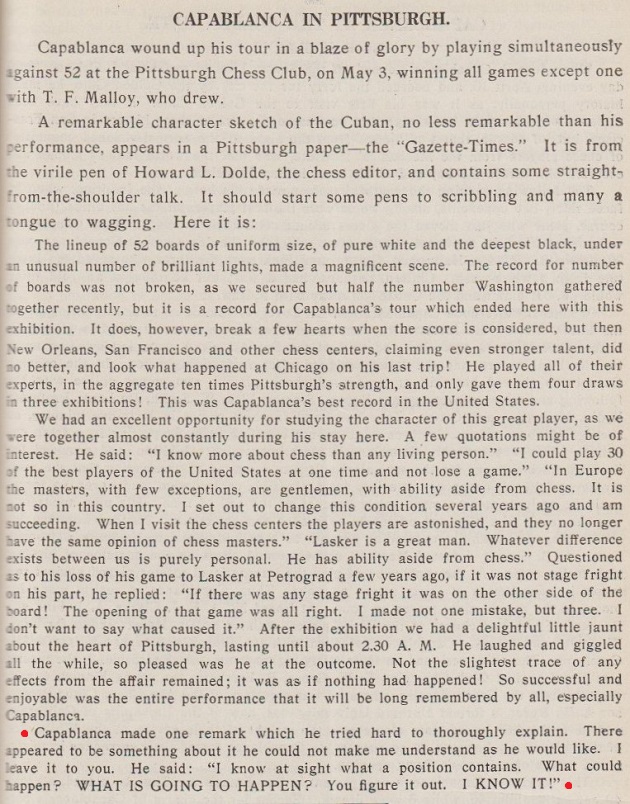

9630. A famous Capablanca quote (C.N. 6172)

Below is the text published on page 99 of the May-June 1916 American Chess Bulletin, which quoted from Howard L. Dolde’s column in the Pittsburgh Gazette Times of 7 May 1916, sixth section, page 8:

Chess chatterers have availed themselves of the remark, and the following ‘once’ version comes from page 112 of Impact of Genius by R.E. Fauber (Seattle, 1992):

‘In our age of chess databases and rapidly circulated tournament bulletins, Lasker’s accomplishments seem the more awesome. José Capablanca once winked at a friend during a master tournament and gestured to the hall of players worrying [sic] their games. “They think; I know”, he said. Lasker was the opposite. He was never sure, but he was always willing to think about how his opponent’s last move had altered the balance of position and to analyze in long steps.’

Also in the next paragraph (headed ‘The Curse of Capablanca’), almost every assertion by Fauber can be queried:

‘Since Capablanca’s first phenomenal success at San Sebastian, 1911 the Cuban had been trying to get a match with Lasker. The young man was supremely confident, and Lasker was consistently afraid. Put another way, Lasker did not need the money, having pocketed a bundle from 1909 to 1910. Why should he risk his principal asset?’

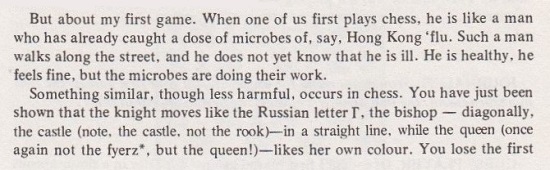

9631. The knight

Further to mention of the letter L in explanations of the knight’s move, it is worth adding that Russian-language sources often refer to the Г, as in the word Гамбит. A passage from page 7 of The Life and Games of Mikhail Tal (New York, 1976):

The text is on page 17 of the London, 1997 edition.

9632. A brilliancy by Helms (C.N. 9627)

When Irving Chernev gave the Smyth v Helms game on pages 488-489 of 1000 Best Short Games of Chess (New York, 1955), his final note quoted Helms:

‘Now comes an unusual finish, which was as pleasing to the loser as it was to the winner.’

Where did Helms make that remark?

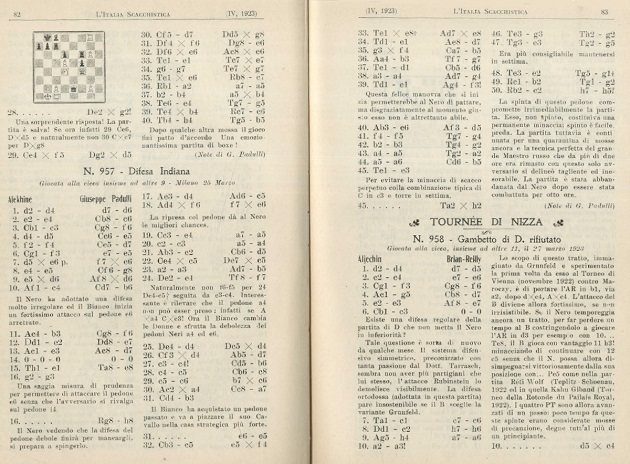

9633. Alekhine v Padulli (C.N. 9629)

Position after 49...Rg2

In C.N. 9629 a correspondent referred to a discrepancy in the conclusion of the blindfold game Alekhine v Padulli, Milan, 25 March 1923. Whereas page 187 of the Skinner/Verhoeven volume gave ‘50 Kc2 h5 1-0’, page 120 of L’antica Storia della Società Scacchistica Milanese dal 1881 agli anni ’60, volume 1 by Alessandro Sanvito (Bologna, 2014) stated that the game was drawn after 50 Rc2.

As always, the Skinner/Verhoeven book gave a source for the game, and it is shown below, courtesy of Henk Chervet of the Koninklijke Bibliotheek in The Hague. Pages 82-83 of the April 1923 L’Italia Scacchistica:

The final note by Padulli states that after his move 50...h5 (‘?’) play in this remaining game of the display continued for more than two hours (another 40 or so moves) before he resigned, and that the game lasted eight hours in all.

To summarize: L’Italia Scacchistica had ‘50 Rb2-c2’, a king move, given that the Italian word for king is Re, but it would give away the white rook on e2. The Skinner/Verhoeven volume nonetheless put 50 Kc2 and did not mention that the game continued for dozens more moves. The Sanvito book made a correction, to 50 Rc2, but, for reasons unknown, stated that the game was then drawn.

The score: 1 d4 d6 2 e4 Nc6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 d5 Ne5 5 f4 Ned7 6 Nf3 e5 7 dxe6 fxe6 8 e5 Ng8 9 exd6 Bxd6 10 Bc4 Nb6 11 Bb3 Nf6 12 Qe2 Qe7 13 Be3 Bd7 14 O-O-O O-O 15 Rhe1 Rae8 16 g3 Kh8 17 Bd4 Bc5 18 Bxf6 gxf6 19 Ne4 a5 20 c3 a4 21 Bc2 Nd5 22 Nxc5 Qxc5 23 a3 Bb5 24 Qe4 Rf7 25 Qd4 Qxd4 26 Nxd4 Bd7 27 c4 Nb6 28 c5 Nc8 29 c6 bxc6 30 Bxa4 Na7 31 Nb3 e5 32 Nc5 exf4 33 Rxe8+ Bxe8 34 Re1 Bd7 35 gxf4 Nb5 36 Bb3 Rg7 37 Rd1 Nd6 38 a4 Bg4 39 Re1 Bf3 40 Be6 Bd5 41 f5 Rg4 42 b3 Rg2 43 a5 Ra2 44 a6 Nb5 45 Re3 Rxh2 46 Rg3 Rg2 47 Re3 Rg5 48 Re2 Rg1+ 49 Kb2 Rg2 50 Rc2 h5, and White eventually won.

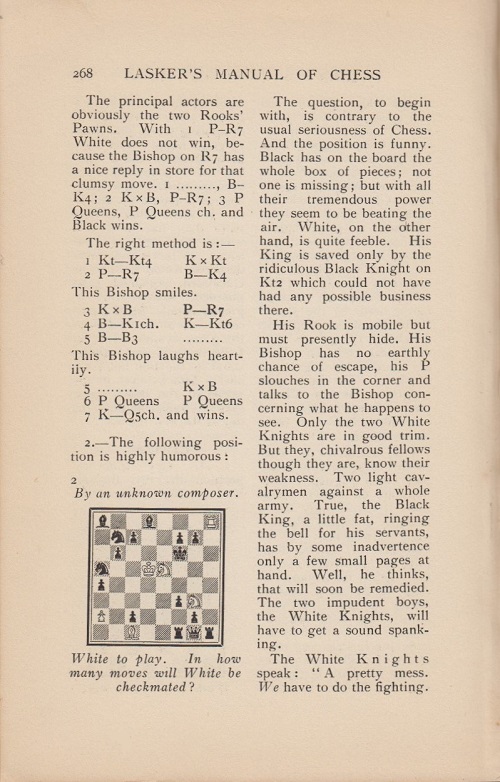

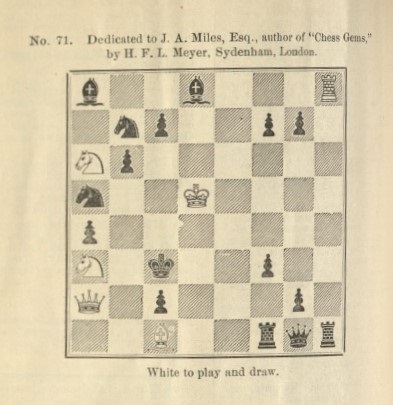

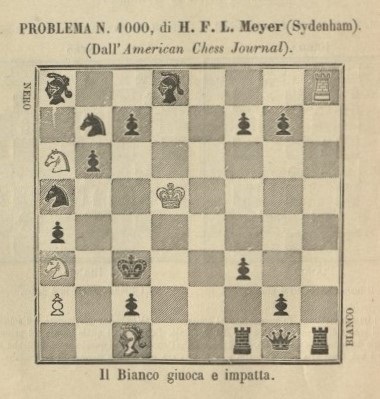

9634. A composition in Lasker’s Manual of Chess

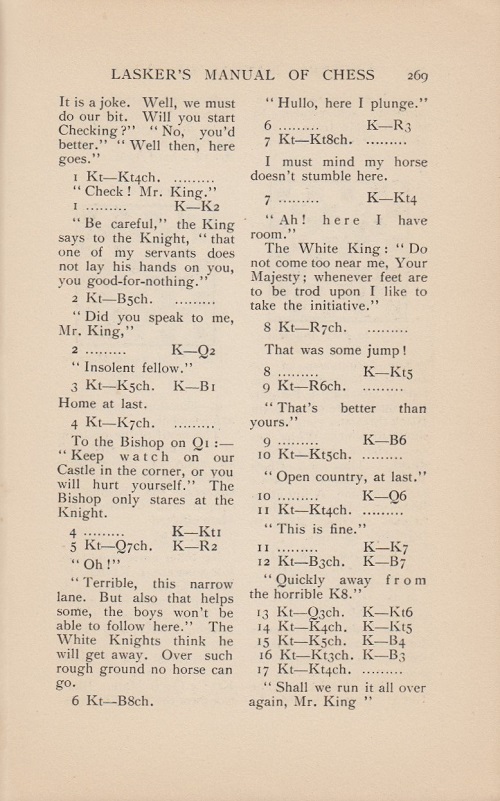

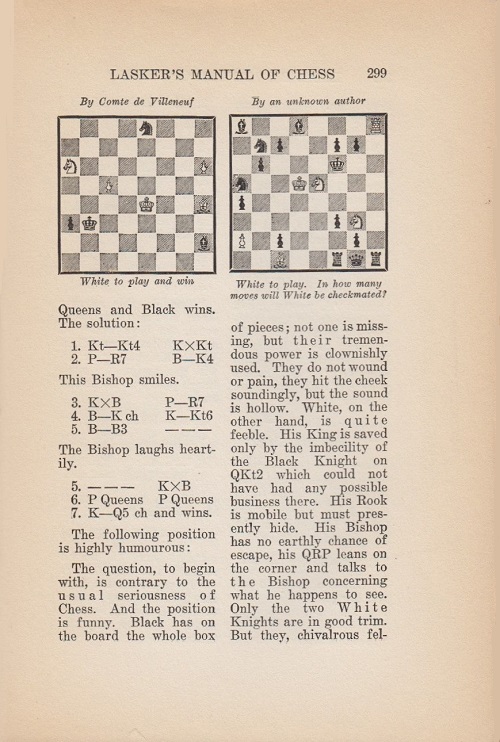

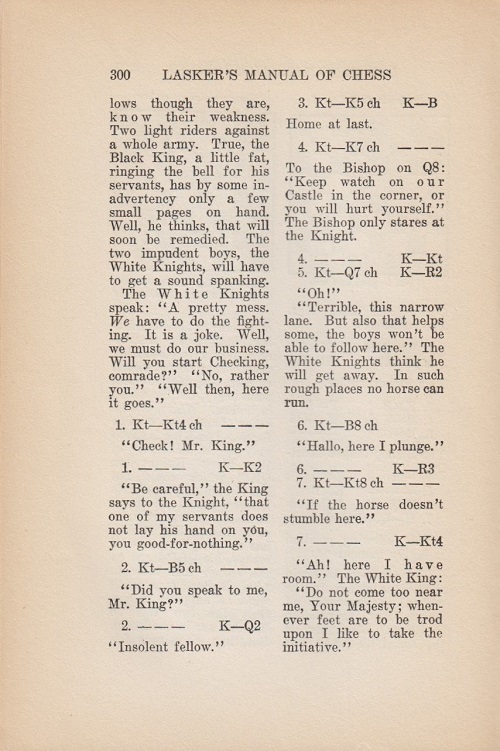

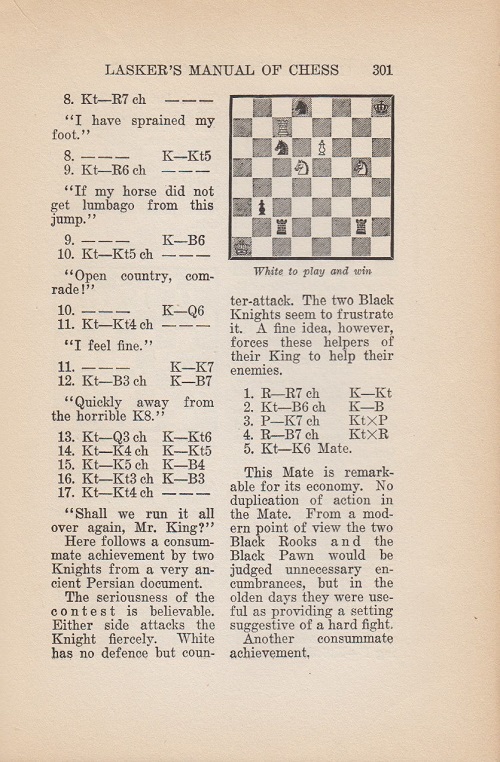

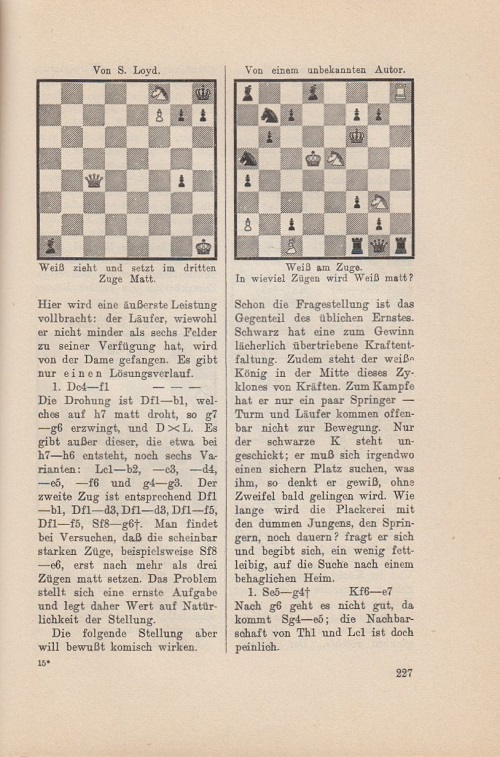

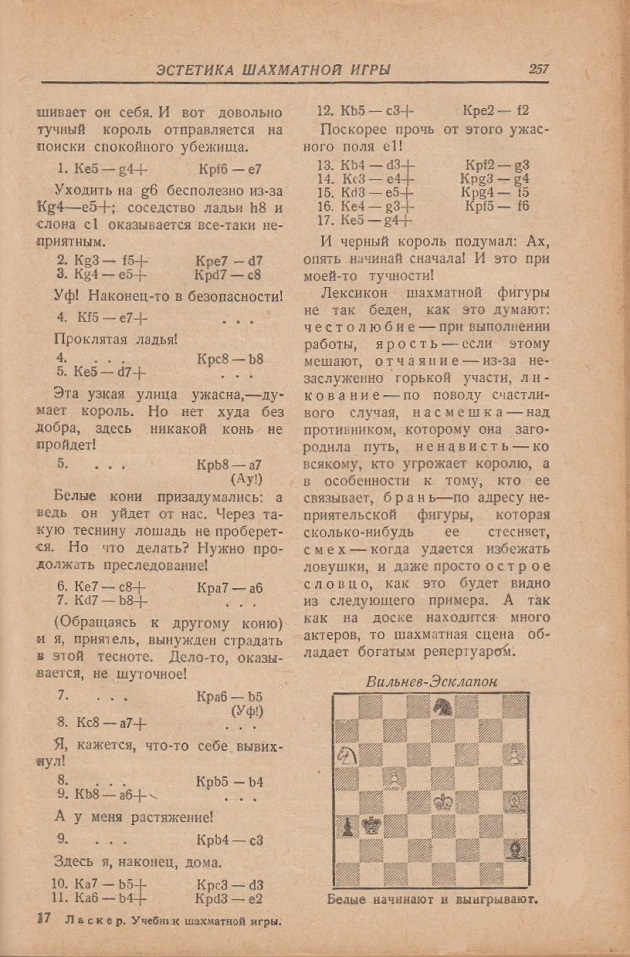

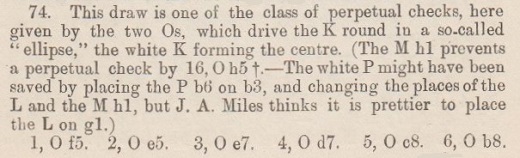

Jean-Pierre Rhéaume (Montreal, Canada) asks for information about a ‘highly humorous’ composition ‘by an unknown composer’ which was discussed by Emanuel Lasker on pages 268-269 of Lasker’s Manual of Chess (London, 1932):

That edition of the Manual is the best known, having been reissued by David McKay Company, Philadelphia in 1947 and by Dover Publications, Inc., New York in 1960.

The text on pages 299-301 of the first English-language edition (New York, 1927) differed in some respects:

The textual differences include one pointed out by our correspondent: the sentence ‘They do not wound or pain, they hit the cheek soundingly, but the sound is hollow’ was dropped by Lasker.

Below is the text as published in one of the many early editions of the Lehrbuch des Schachspiels (Berlin, 1926):

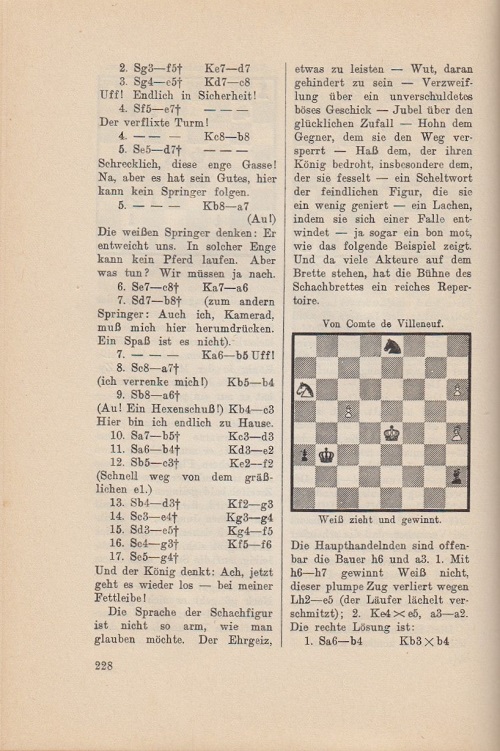

As regards the reference to ‘an unknown composer’, we noted in C.N. 7421 a letter from Richard Teasdel of Cardiff on page 342 of the August 1933 BCM:

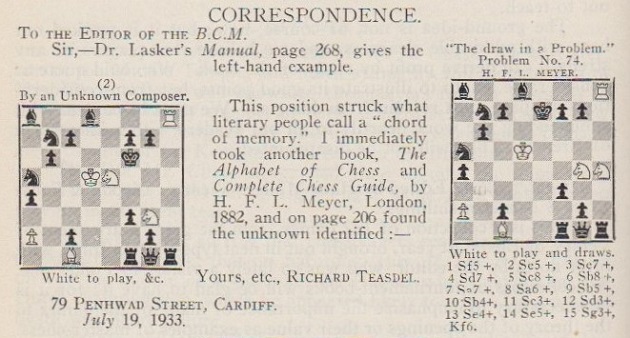

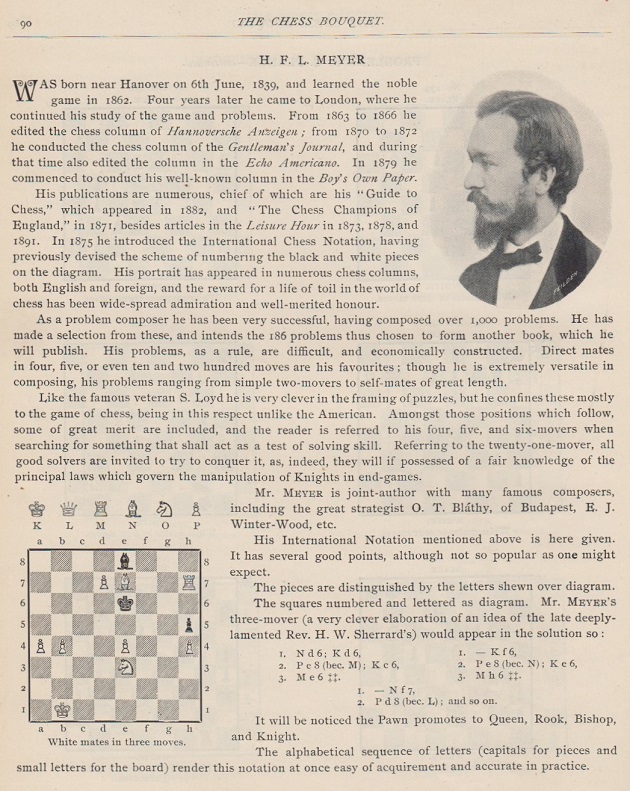

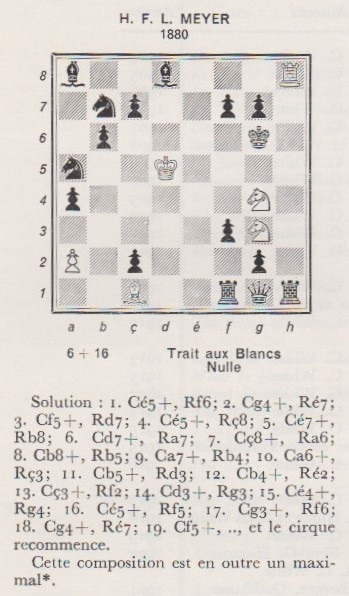

Subsequently, Russian editions of Lasker’s book (e.g. Moscow, 1937; Moscow, 2002; Moscow, 2011; Moscow, 2014) ascribed the position to Meyer, whereas the first edition (Moscow and Leningrad, 1926) had not done so. Below, for example, are two pages from the 1937 edition:

Meyer’s name has not been found in editions of Lasker’s Manual in other languages (English, Dutch, German, Greek and Spanish).

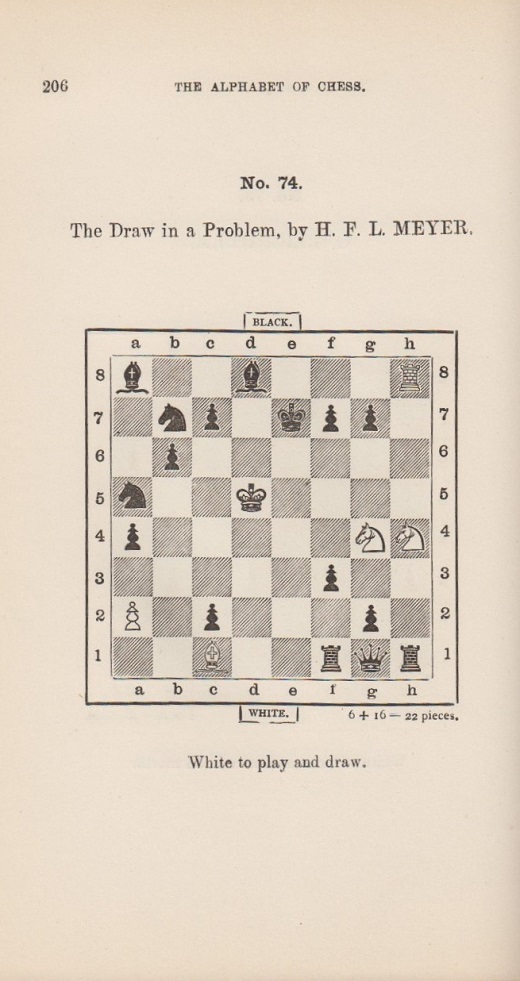

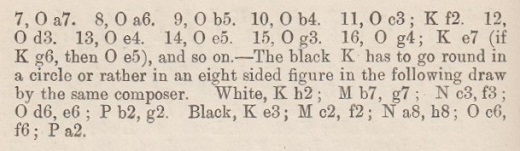

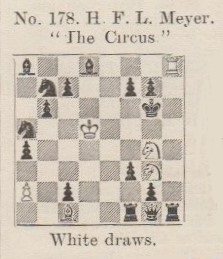

Below is page 206 of A Complete Guide to the Game of Chess by H.F.L. Meyer (London, 1882), as referred to by Richard Teasdel in his letter to the BCM:

The solution on pages 251-252:

In addition to the positions already shown (White knights on g3/e5 and g4/h4) a third version (a3/a6) can be given, from Harold van der Heijden’s Endgame study database III:

The solution given in the database: 1 Nb5+ Kd3 2 Nb4+ Ke2 3 Nc3+ Kf2 4 Nd3+ Kg3 5 Ne2+ Kg4 6 Ne5+ Kf5 7 Ng3+ Kf6 8 Ng4+ Ke7 9 Nf5+ Kd7 10 Ne5+ Kc8 11 Ne7+ Kb8 12 Nd7+ Ka7 13 Nc8+ Ka6 14 Nb8+ Kb5 15 Na7+ Kb4 16 Na6+ Kc3 17 Nb5+ Drawn.

Further information is sought concerning the source specified in the database, ‘American Chess Nuts, 1880’, bearing in mind that the book with that title by E.B. Cook, W.R. Henry and C.A. Gilberg was published in New York in 1868.

The composition, ascribed to Meyer but with white knights on g3 and e5, was included on page 171 of Secrets of Spectacular Chess by J. Levitt and D. Friedgood (London, 1995) the condition in the caption being specified as ‘Win’. That was corrected to ‘Draw’ on page 205 of the second edition (London, 2008).

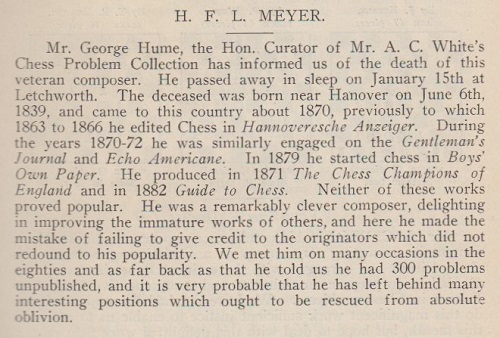

The exact origins of the three versions of the composition have yet to be sorted out, and another complication arises from a remark in the obituary of Meyer on page 101 of the February 1928 BCM:

‘He was a remarkably clever composer, delighting in improving the immature works of others, and here he made the mistake of failing to give credit to the originators which did not redound to his popularity.’

The BCM obituary failed to give credit to the source of some of its information, i.e. page 90 of The Chess Bouquet by F.R. Gittins (London, 1897):

A final puzzle for now: both the BCM and The Chess Bouquet referred to an 1871 publication by H.F.L. Meyer, The Chess Champions of England. What is known about it?

9635. Dirk Jan ten Geuzendam (C.N.s 9245, 9338 & 9401)

From Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore):

‘As New in Chess did not correct the record off its own bat, I sent the magazine this letter:

“Concerning page 16 of the 3/2015 New in Chess, Dirk Jan ten Geuzendam’s criticism of Edward Winter for disregarding the dark side of Fischer (as shown in published items from David DeLucia’s collection) is unfounded. Winter’s article Brad Darrach and the Dark Side of Bobby Fischer demonstrates that the truth is the exact opposite: in his Chess Notes column over the years, Winter has posted, courtesy of DeLucia, a large amount of such ‘dark’ Fischer material (more than all other chess writers combined, in fact). Moreover, DeLucia states that when he was sent a preview of the New in Chess article he specifically told Dirk Jan ten Geuzendam, prior to publication, that the planned criticism of Winter was wrong.”

My letter has not been published.’

9636. Book reviews

On the subject of book reviews, as shown on page 38 of volume two of Chess Characters (Geneva, 1987) G.H. Diggle wrote in the April 1986 Newsflash:

‘In the June 1887 BCM is a review of H.E. Bird’s Modern Chess, Part V, a shilling booklet of 36 pages devoted entirely to the Evans Gambit. Yet the reviewer, Edward Freeborough, devotes seven pages to dissecting Bird’s analysis, winding up however on a cheerful note: “... the student will certainly not be dissatisfied with his shilling’s worth. There is plenty of provender: he must supply his own digestive organs.”’

9637. Joseph Goebbels (C.N.s 3718, 3804 & 4381)

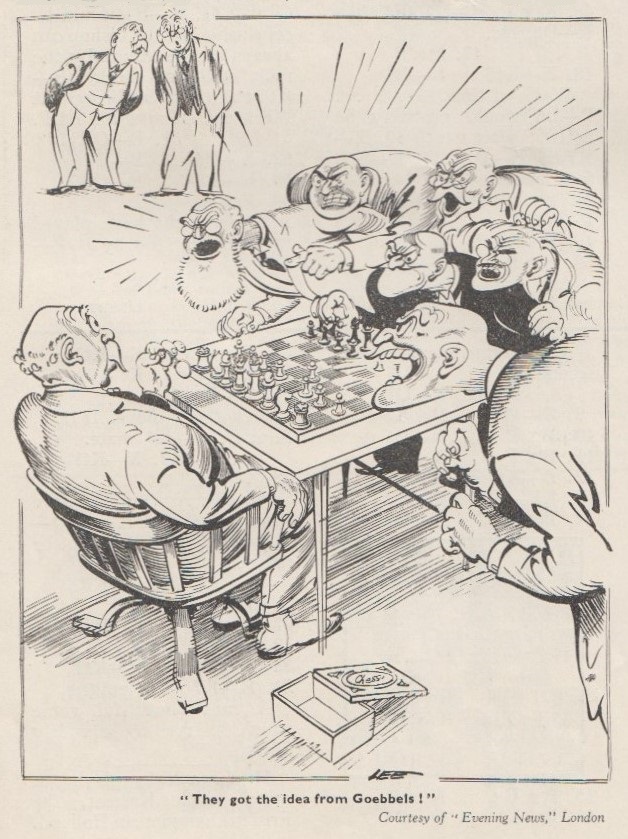

From page 93 of CHESS, January 1940:

9638. A composition in Lasker’s Manual of Chess (C.N. 9634)

As pointed out by Jean-Pierre Rhéaume (Montreal, Canada), the Meyer composition was also published on page 76 of the Dictionnaire des échecs by F. Le Lionnais and E. Maget (Paris, 1967 and 1974), with a fourth initial position for the white knights: g3 and g4. Only a date, 1880, was offered:

We note that the same information was given on page 1349 of Le guide des échecs by N. Giffard and A. Biénabe (Paris, 1993) and on page 1563 of the co-authors’ Le nouveau guide des échecs (Paris, 2009). On both occasions the term ‘problémiste américain’ was used to describe Meyer.

In the Dictionnaire des échecs Meyer’s composition was included in the entry on the problem theme Le Cirque. It appeared with that heading on page 87 of the December 1910 Chess Amateur, in the ‘Gems, Old & New’ column by Thomas S. Johnston:

Regarding the so-called publication The Chess Champions of England (C.N. 9634), Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England) recalls Meyer’s ‘Champions of British Chess’ photographic chess board, discussed in C.N. 3467.

9639. Busted

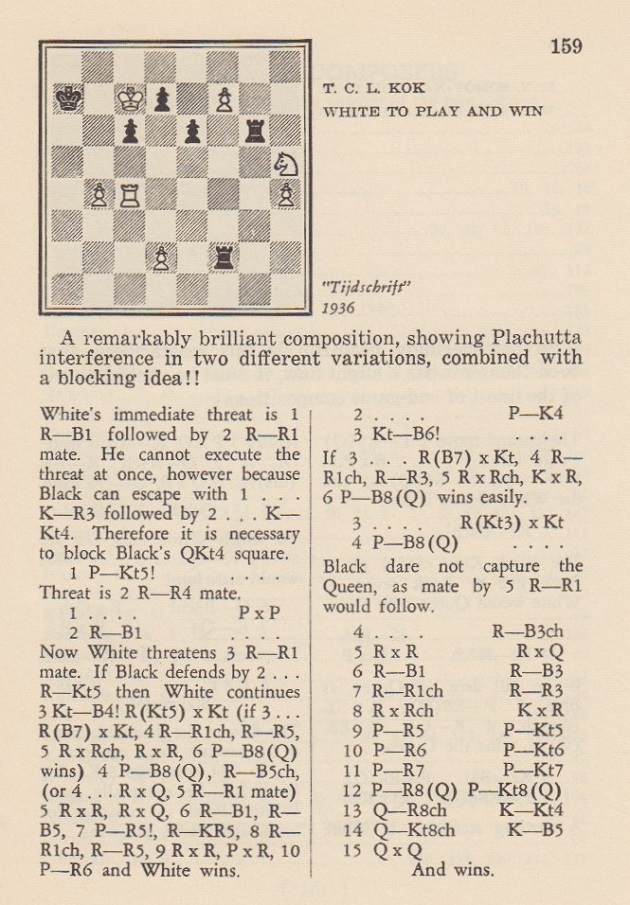

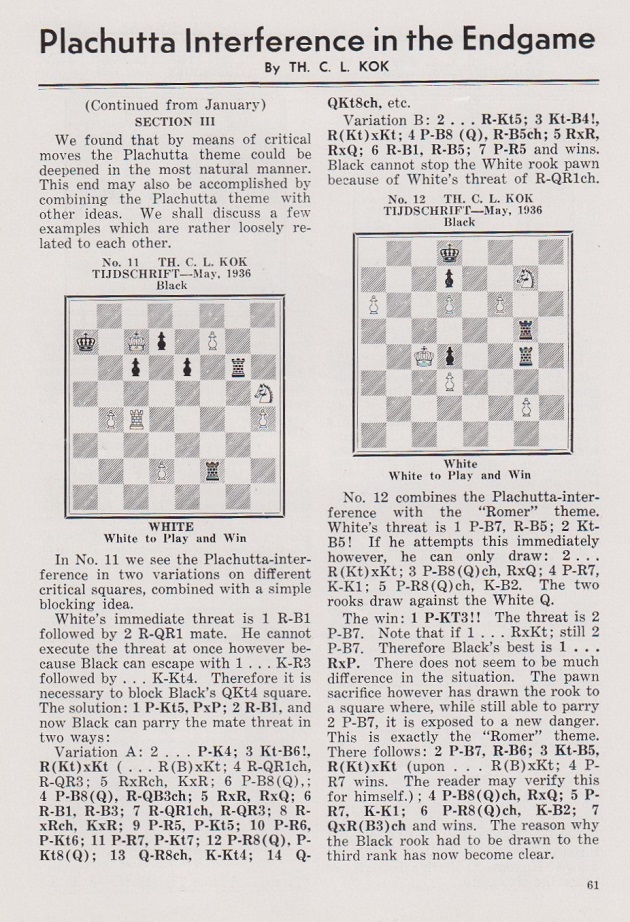

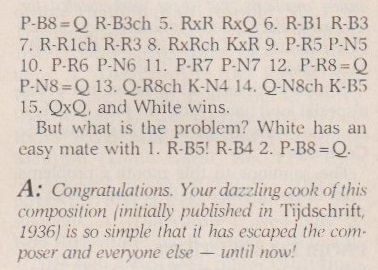

From page 159 of Chessboard Magic! by Irving Chernev (New York, 1943):

Part of the text is very similar to what appeared in an article by the composer, Theodorus Cornelis Louis Kok, on page 61 of the March 1937 Chess Review, translated from page 134 of the May 1936 Tijdschrift van den Koninklijken Nederlandschen Schaakbond:

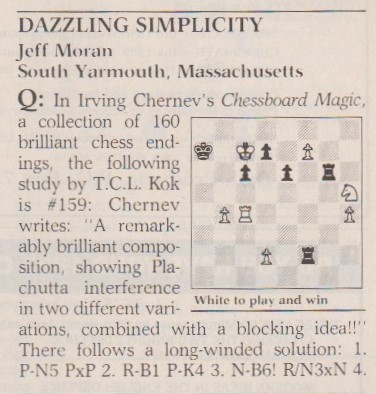

On page 50 of the March 1987 Chess Life a reader, Jeff Moran, made a contribution to the ‘Grandmaster Larry Evans on Chess’ column:

When subsequently writing to Larry Evans with other factual corrections to his column, we informed him:

‘To revert to an older matter: the 1936 endgame study by Kok on page 159 of Chernev’s Chessboard Magic!. In the March 1987 Chess Life you congratulated a reader thus: “your dazzling cook ... is so simple that it has escaped the composer and everyone else – until now!” Not so. The identical cook was given by W. Wren on page 188 of Chess World, 1 August 1950.’

Below is what had appeared in Purdy’s magazine:

Our above-mentioned letter (5 October 1990) was answered by Evans as follows (letter dated 23 October 1990):

‘Although the cook to Chernev’s Chessboard Magic may have been pointed out in a relatively obscure journal way back in 1950, it in no way invalidates the reader’s rediscovery. This correction never appeared before in Chess Life, which is the important point.’

We replied to Evans (2 November 1990) that a correction was clearly required in Chess Life, so that due credit was given to W. Wren and Chess World, but in a further letter (12 November 1990) Evans remained intransigent:

‘If I decide that a reader made a certain discovery on his own, then I don’t care where it first appeared. In chess, as in most other fields, not much is new under the sun anyway.’

He added some irrelevant denigration of C.J.S. Purdy:

‘... the relatively obscure Australian magazine Chess World (which probably never reached 1,000 subscribers) edited by a minor master to whom I could have given pawn and move ... If you care to place a wager – with the loser to pay for the cost of a poll – I maintain that not ten in a thousand subscribers to Chess Life have ever heard of or seen a copy of Purdy’s Chess World, which they would probably confuse with Frank Brady’s short-lived periodical.’

We responded to him on 30 November 1990:

‘Your attempts to introduce extraneous and erroneous arguments (such as the playing strength of Purdy and the alleged “obscurity” of Chess World, which, by the way, the latest New in Chess calls “a magazine highly esteemed both in Australia and abroad”) are futile.

... With regard to the Kok composition, I find your proposal of a wager childish, but, if you really want one, it must of course be on the central issue. Please therefore indicate whether you are prepared to accept Chess Life readers’ verdict on the following facts:

a) In the March 1987 Chess Life you said that a reader’s “dazzling cook ... is so simple that it has escaped the composer and everyone else – until now!”

b) I refuted these words by pointing out that the identical cook was published in Chess World, 1 August 1950.

c) You nonetheless claim that there is no reason to correct the record in Chess Life.

d) I say that a correction needs to be printed.’

And that was that. There was nothing more from Evans, and we do not know whether his insulting words about Purdy and Chess World reflected his real view or whether he was merely lashing out to divert attention from his failure to conduct the ‘Grandmaster Larry Evans on Chess’ column accurately and fairly.

The bust regarding the Kok study was also mentioned by Gerry Dyer on page 665 of the December 1994 BCM, in K. Whyld’s Quotes and Queries column. Again, it was not realized that 1 Rc5 had been discovered long ago.

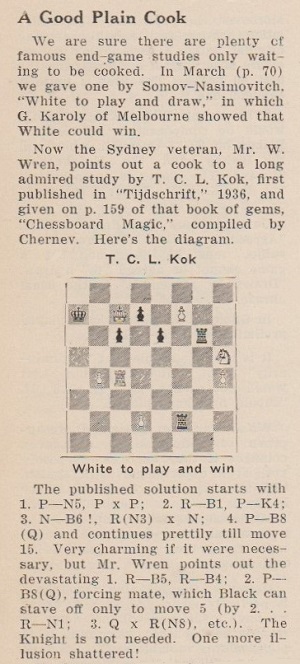

9640. San Remo, 1911

Source: Wiener Schachzeitung, April 1911, page 125.

9641. Reikiavik

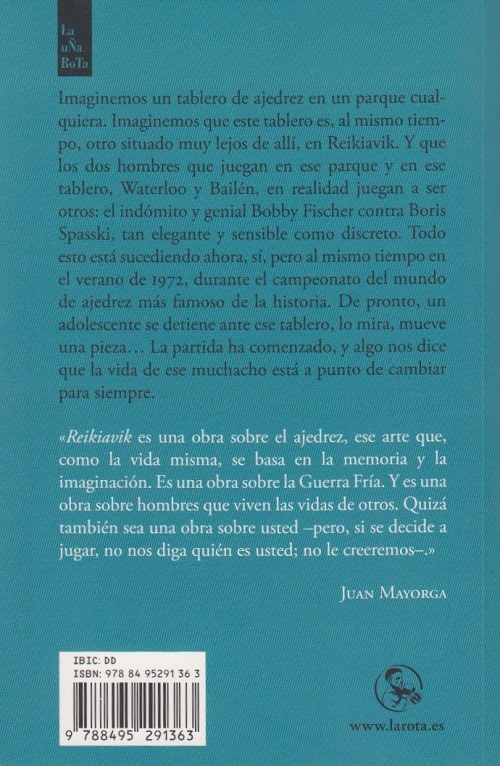

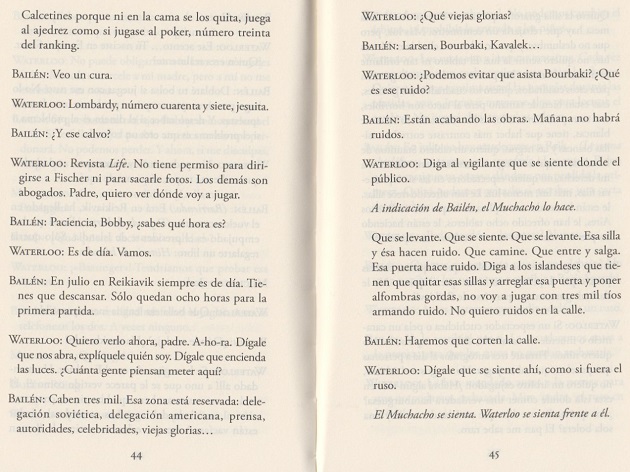

Claus Montonen (Helsinki) is seeking information about literary works which take real chess events as their subject, his request being prompted by the play Reikiavik by Juan Mayorga (Segovia, 2015). Below are the front and back covers, as well as two sample pages:

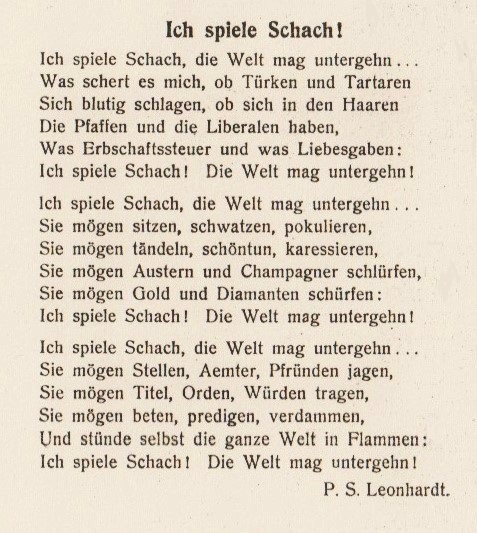

9642. A poem by Paul Saladin Leonhardt

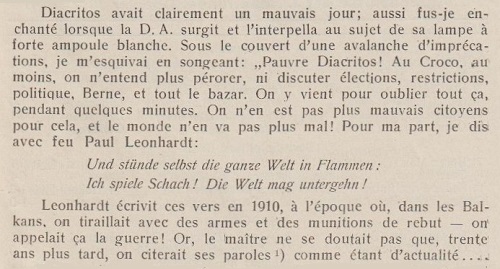

From an editorial entitled ‘1943 ...?’ by Jean-Charles de Watteville on pages 1-2 of the Schweizerische Schachzeitung, January 1943:

The footnote on page 1 read ‘Que l’on retrouvera en entier dans la R.S.E. de 1910, p. 144’, but that reference, to the magazine’s French name (Revue suisse d’échecs), had the wrong year. Leonhardt’s poem, ‘Ich spiele Schach!’, was published on page 144 of the August 1912 issue:

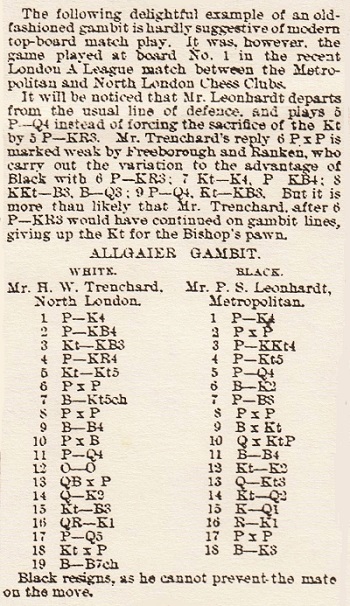

9643. Trenchard v Leonhardt

From the chess column by F.W. Markwick on page 9 of the Essex Times, 22 April 1905:

1 e4 e5 2 f4 exf4 3 Nf3 g5 4 h4 g4 5 Ng5 d5 6 exd5 Be7 7 Bb5+ c6 8 dxc6 bxc6 9 Bc4 Bxg5 10 hxg5 Qxg5 11 d4 Bf5 12 O-O Ne7 13 Bxf4 Qg6 14 Qe2 Nd7 15 Nc3 Kd8 16 Rae1 Re8 17 d5 cxd5 18 Nxd5 Be6 19 Bc7+ Resigns.

Herbert William Trenchard

9644. Averbakh v Purdy (C.N. 9622)

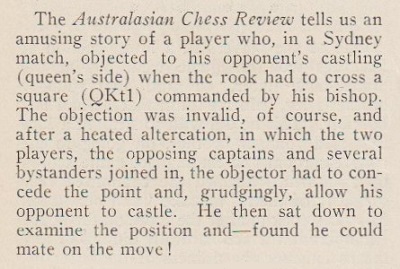

Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England) notes that a similar castling story was reported on page 156 of CHESS, 14 January 1937:

It will be appreciated if a reader can forward the original account in the Australasian Chess Review (edited by Purdy), since we lack the issue in question.

9645. Fischer and the world championship

Mr Clapham also quotes the final paragraph of an article, ‘Fischer Dialogue’, by Ed Edmondson in the June 1970 Chess Life & Review, pages 317-319:

‘What next for Fischer? At this writing he is reported still in Yugoslavia, considering whether or not to play in Skopje. Meantime, the entire chess world cannot help but be intrigued once again by the question C.J.S. Purdy posed in his Chess World shortly after Fischer’s withdrawal from the 1967 Interzonal: “Why all this ponderous succession of tournaments to select an official challenger? When the whole world can see that we have one sheer chess genius among us, why can’t we cut the red tape and let him play a match against the titleholder?”’

We consider this an excellent illustration of how all quoted material needs to be double-checked. Did Purdy really suggest in 1967 that the world championship qualification system should be set aside because of Fischer’s supposed supremacy over all possible challengers (with the consequence that Spassky would not have played his second title-match against Petrosian)?

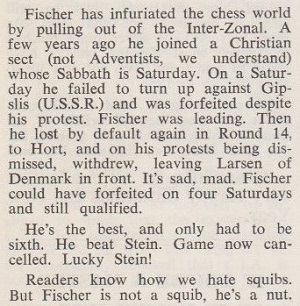

Firstly, a news item on page 108 of Chess World, July-August 1967 gave the background to Fischer’s withdrawal from that year’s Interzonal in Sousse:

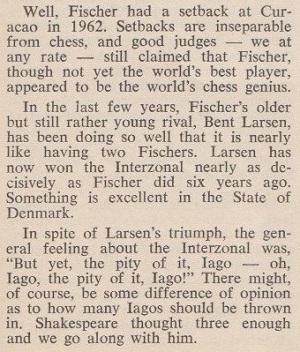

An article by Purdy entitled ‘The Fischer Problem’ on pages 137-139 of the September-October 1967 issue of Chess World contained the comments quoted in Chess Life & Review, but it will be observed that Edmondson did not respect their context:

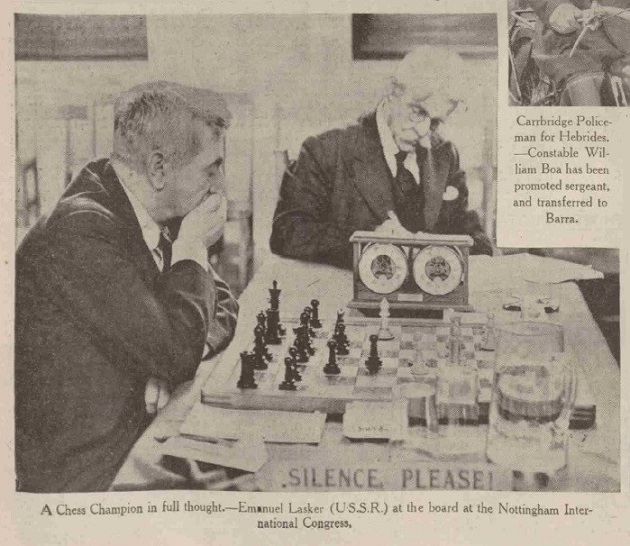

9646. The genesis of Nottingham, 1936

Leonard Barden (London) asks whether it is known why Nottingham, 1936 had an odd number of players (15), a bye therefore being required in each round. (In passing, Mr Barden mentions that he met over the board nine of the 15 participants, and had some slight contact with another three.)

So far, we have found no suggestion that an even number of players was ever intended in the Nottingham tournament, or that byes were considered undesirable. At present, we can do no better than offer an overview of how the tournament came about, based on accounts in English-language chess magazines of the time. The reports consulted indicate that 15 was the only figure that the organizers ever envisaged.

Page 363 of the August 1935 BCM announced an appeal for funds to hold an International Chess Congress in Nottingham the following year, including a ‘Masters’ Invitation Tournament’ in which the world champion (Alekhine) and his two predecessors (Capablanca and Lasker) ‘have definitely agreed to compete’. The Council of the Nottingham University had offered College buildings as the venue, and the support of the Lord Mayor and Corporation of Nottingham had been secured. The estimated net cost of the Congress was £2,200. The President of the Nottinghamshire Chess Association, J.N. Derbyshire, had offered to pay half of the net total, to commemorate a Nottingham tournament in which he had participated in 1886. The British Chess Federation was called upon to respond in equal measure, and an appeal for funds was launched.

Page 405 of the September 1935 BCM stated that Sir George Thomas would give a simultaneous display at each chess club which subscribed at least two guineas to the fund, and the following month (page 466) the BCM reported that the response to the appeal had been generous and that a meeting of the Executive Committee of the British Chess Federation on 19 October would decide whether the full programme could go ahead. As reported on page 495 of the November 1935 BCM, a positive decision was taken by the Executive Committee, given that by the time of its meeting about £800 of the required £1,100 had been guaranteed or subscribed by donations.

An editorial on pages 161-162 of CHESS, 14 January 1936 stated that the participation of the new world champion, Euwe, was uncertain because of his professional duties, and that Flohr might also be absent, owing to military service commitments.

The following month (14 February 1936 issue, page 201) CHESS wrote:

‘At the 25 January meeting of the British Chess Federation, definite plans were put in hand for Nottingham. Dr Max Euwe, world champion, will compete, and the participation of Alexander Alekhine, José Raoul Capablanca and Dr Lasker is practically certain. Each will receive travelling expenses and £200 “appearance money”; the other participants will receive travelling expenses and donations towards their hotel expenses. ... Among the 15 competitors, four will be British. A list – provisional, and liable to modification – of ten candidates for the remaining seven places open to players from abroad has been drawn up. Whilst details of this list can naturally not be lightly divulged, our American cousins can take it that it includes the names of Reuben Fine and Samuel Reshevsky.

Since several masters of high standing may have to be excluded, willy nilly, from the premier tournament, the prizes in the second tournament are to be substantial.’

Page 9 of the January 1936 American Chess Bulletin commented:

‘The United States will be represented by one or two experts, and, in this connection, Samuel Reshevsky and Reuben Fine, both of New York, winners of the tournaments at Margate and Hastings, respectively, are favorably mentioned. Isaac I. Kashdan, another New Yorker, is also regarded as having strong claims for consideration.’

The 14 February 1936 issue of CHESS, pages 201-202, accused Capablanca of stirring up unnecessary difficulties by insisting that Euwe, though an amateur, should demand an appearance fee, but the claim was denied by Euwe himself. From pages 272-273 of the 14 March 1936 CHESS:

In a letter published on page 315 of the 14 April 1936 issue of CHESS P.S. Milner-Barry confirmed Euwe’s recollection of their conversation in Hastings in 1935.

Page 17 of the January 1936 BCM stated: ‘Before long now the remaining invitations to participate will be issued, the exact date fixed and the supplementary programme completed.’ The following month (pages 73-74), the BCM wrote:

‘The fateful meeting of the Committee of the British Chess Federation was held on 25 January, when the final arrangements were made and the names of the masters selected for invitation.’

No names were printed, but page 120 of the March 1936 BCM stated:

‘The BCF Executive Committee announce that the Masters’ tournament at Nottingham will commence on 10 August and will continue until the 28th. It will consist of 15 competitors, of whom five will be British players, and it is hoped Sultan Khan will be one, and the prize list will be: 1st £200, 2nd £150, 3rd £100, 4th £75, while not less than £200 will be awarded to those competitors who do not win a prize, in the ratio of their final score.’

Details of the plans for other events in the Congress were given, and the report concluded (page 121): ‘The Congress will be held in Nottingham University College. There is to be no charge for admission to see the play.’

Page 223 of the May 1936 BCM reported:

‘Arrangements for the Nottingham Congress are proceeding satisfactorily, and on the 2nd instant the Executive Committee will review and settle the full compositions of the Masters’ Tournament, and the details in connection with the general Congress will then be available for publication.’

On page 275 of the June 1936 BCM, the participants in the Masters’ tournament were announced as follows:

Lasker’s name was omitted, but it was included in the list on page 325 of the 14 May 1936 CHESS, which added some opinions on the selections made:

The British championship (Bournemouth, June 1936) was won by William Winter.

From page 365 of the August 1936 BCM:

‘We are advised by the Secretary of the British Chess Federation that all the masters have confirmed their acceptance to the BCF invitation ...’

Some observations on the choice of the British contingent appeared on pages 51-52 of Chess Pie No. 3, but details about the selection method for Nottingham, 1936 are sparse. Have any of the British Chess Federation’s archives, and particularly minutes of meetings in the mid-1930s, survived?

It is, for instance, unclear what role in the selection process was played by the fact that the Nottingham tournament clashed with the Munich International Team Tournament (in which both Eliskases and Keres participated). From page 362 of the 14 June 1936 CHESS:

‘Since, as the Deutsche Schachzeitung puts it, “the trouble of trying to get the English people to bring the date of the Nottingham congress forward has proved unavailing”, the unofficial international team tournament at Munich is to commence, with the active support of the German Government, on the date originally mentioned for it.’

This referred to a passage about the Munich event on page 129 of the May 1936 Deutsche Schachzeitung:

‘Die Bemühungen, die Engländer zu einer Vorverlegung des Nottinghamer Turniers zu bewegen, sind ohne Erfolg geblieben, und der Beginn der Münchner Veranstaltungen ist daher jetzt auf den 16. August, wie ursprünglich beabsichtigt, festgesetzt worden.’

Chess Pie remarked (page 38) in connection with the world championship:

‘Never before in chess history have four men who have held the title been alive at one time, and the present four [Euwe, Alekhine, Capablanca and Lasker] have never all met in the same tournament.’

Below is a picture which will be added shortly to Photographs of Nottingham, 1936, from page 12 of the Aberdeen Press and Journal, 27 August 1936:

A cropped version was published opposite page 80 of Kings of Chess by William Winter (London, 1954).

9647. A quote attributed to Bogoljubow and Chigorin

A letter published on page 129 of the May 1951 Chess Review:

C.N. 5063 asked for early sightings of the famous saying ‘When I am White I win because I am White. When I am Black I win because I am Bogoljubow’. The earliest that we can propose is on page 14 of the March 1947 Chess Review, in an article by Reuben Fine:

‘Because winning is so pleasant people are always ready to tell you how they lost but can rarely explain how they won. Many follow Bogoljubow’s well-known principle: “When I’m White I win because I’m White; when I’m Black I win because I’m Bogoljubow.”’

The article was reproduced on pages 76-80 of Fine’s book The World’s a Chessboard (Philadelphia, 1948).

From page 136 of The Adventure of Chess by Edward Lasker (New York, 1950):

‘More self-confident mortals are rarely encountered anywhere. A story, which has become a classic in chess circles, told of the Russian master, Efim Bogoljubow, bears amusing testimony to this fact. When an admirer asked him whether he preferred the white or the black pieces, he replied: “I have no preference. When I play White, I win because I have the first move. When I play Black, I win because I am Bogoljubow.”’

Some writers seem averse to mentioning Bogoljubow without relating the story, dressed up as the established truth. From page 252 of Capablanca move by move by Cyrus Lakdawala (London, 2012):

‘Bogo mistakenly plays for his now non-existent future attack. I read accounts of Bogoljubow’s legendary optimism. Like most super-GMs, Bogo was an unassuming and modest man, once making the claim: “When I am White, I win because I am White. When I am Black, I win because I am Bogoljubow!”’

As Jean-Pierre Rhéaume (Montreal, Canada) notes, the remark was attributed to Chigorin in the extract from pages 137-139 of the September-October 1967 Chess World shown in C.N. 9645:

‘There is something grandly memorable about Chigorin’s “When I am White I win because I am White, when I am Black I win because I am Chigorin”.’

We can add an earlier instance, from an article by Paul Hugo Little about Berlin, 1897 on pages 229-230 of the November 1939 Chess Review:

‘... Chigorin’s genius was so great that he could handicap himself in the opening and still win. He used to say, “When I am White, I must win because I am White; when I am Black, I must win because I am Chigorin.”’

On page 215 of William Steinitz, Chess Champion (Jefferson, 1993) Kurt Landsberger wrote, on the basis of nothing better than a second-hand 1961 source in German translated from Czech:

‘As he said, “When I am white, I win because I have white, but when I am black, I win because I am Chigorin”.’

Landsberger added this casual footnote:

‘The remark has also been attributed to other players.’

No names were supplied – not even Bogoljubow’s.

Impact of Genius by R.E. Fauber (Seattle, 1992) had only this about Chigorin (page 85):

‘When Chigorin had White, he played 1 e4 confident that he had a little bit the better game. When he had Black, he answered 1 e4 with e5 certain that he had at least equality.’

We can point out corroboration in Tarrasch’s essay on Chigorin towards the end of his book Die moderne Schachpartie (various editions, and page numbers vary). From page 415 of the Leipzig, 1924 edition:

The famous saying was included in the Bogoljubow section of Fauber’s Impact of Genius (page 212):

‘He had a simple view of chess theory: “When I am White, I win because I have the first move; and when I am Black I win because I am Bogoljubow.”’

It cannot be demonstrated whether Chigorin and/or Bogoljubow and/or any other master ‘once said’, or ‘often said’, or ‘used to say’, or ‘would say’, the phrase trustingly served up by so many chess writers. We can, though, offer a citation which not only stands as the earliest occurrence of the saying found so far but also involves both masters. It appeared on page 8 of Games Played in the World’s Championship Match by F.D. Yates and W. Winter (London, 1930), in a biographical note about Bogoljubow:

9648. F.J. Marshall as a problem-solver

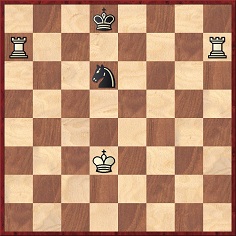

F.J. Marshall’s time for solving this problem: two minutes:

Mate in two

Our source is page 14 of the January 1944 Chess Review, which stated that ‘it took Grandmaster Frank J. Marshall just two minutes to find the key move ...’ We prefer the neutral wording at the start of the present item.

The problem dates from the thirteenth century (the Bonus Socius manuscript).

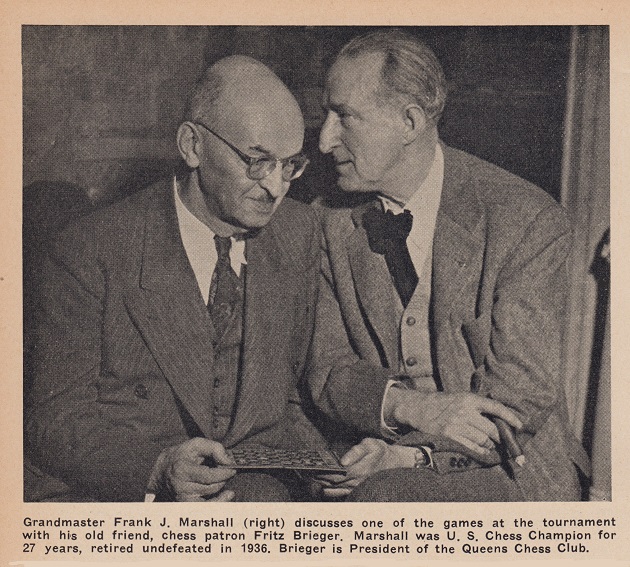

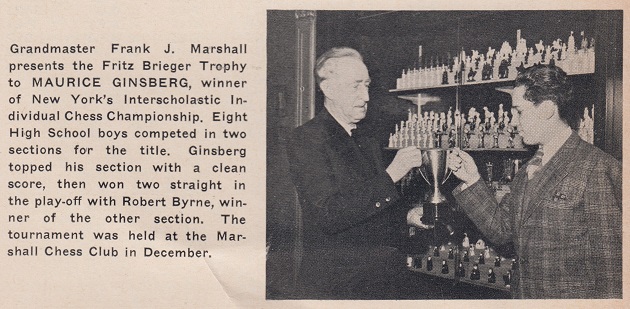

From page 30 of the April 1944 Chess Review, in the magazine’s coverage of the United States championship in New York:

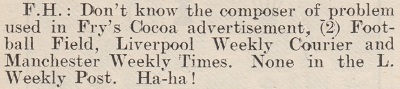

9649. Advertisements

On the subject of Chess in Advertisements, information is requested on a chess problem featured in advertising by Fry’s Cocoa over a century ago, as mentioned in the correspondence section of Thomas S. Johnston’s ‘Gems, Old & New’ column on page 151 of the February 1911 Chess Amateur:

9650. Notation

In old chess magazines (English-language ones, in particular), readers’ pertinacity often reached a peak in any ‘discussion’ of the relative merits of the descriptive and algebraic notations. The descriptive notation has now departed (see, for example, Capablanca Goes Algebraic), and an awkward tournure may sometimes result. The opening sentence of The Fox Enigma refers to ‘positions in which a player moved his queen to KKt6 (i.e. g6 or g3)’.

The text of C.N. 71 (‘The leisurely fianchetto’) provides another example:

What is the longest gap in master play between a g- or b- pawn being advanced and the subsequent placing of a bishop on one of the ‘knight two’ squares?

In C.N. 98 W.H. Cozens (Ilminster, England) remarked on the comparative merits of the two notations in such an instance:

1. (Descriptive): What is the longest gap in master play between P-Kt3 and the subsequent B-Kt2?

2. (Algebraic): What is the longest gap in master play between the playing of b3, b6, g3 or g6 and the subsequent Bb2, Bb7, Bg2 or Bg7, as the case may be?

Mr Cozens concluded:

‘Algebraic, for some purposes, can be downright silly.’

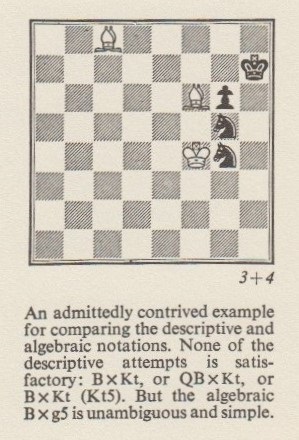

Regarding possible difficulties with the descriptive notation, below is a position on page 17 of Test Tube Chess by A.J. Roycroft (London, 1972):

9651. A Menchik v Yates billiards match

From page 86 of CHESS, January 1940:

9652. The value of the pieces

Robert John McCrary (Columbia, SC, USA) writes regarding The Value of the Chess Pieces:

‘Page 334 of The Boy’s Own Book, Improved Edition (Boston, 1851) has this in its chess section:

“The value of the men has been estimated as in the following proportion to each other: the queen, 95; a rook, 60; a bishop, 39; a knight, the same as the bishop; the king (estimated as a fighting piece) 26; a pawn, 8, or rather more, from its chance of promotion ...”

A chess set owned by Jon Crumiller, dated approximately mid-1800s, has a handwritten sheet inside its box, with the same values as those given above, but with the knight as 37 (the bishop is still 39) and the pawn “rather more than 9”. The rook is called “castle” on that sheet.

The first American edition of The Boy’s Own Book (Boston, 1829) states it was taken from a London book whose year is not given (although page 26 The Tecumsehs of the International Association by Brian Martin (Jefferson, 2015) says Boy’s Own Book was published in England in 1828) and that a “long treatise on chess” in the London work was omitted.

According to the Boston, 1829 edition, the reason for omitting “a long treatise on chess” from the English edition, as well as articles on several other pastimes, was that those articles would add to the cost but were “entirely useless on this side of the Atlantic” and would “have given no real additional value” to the book. The fact that chess was included in the 1851 “Improved” American edition indicates the game’s growth in popular esteem in the United States between 1829 and 1851.’

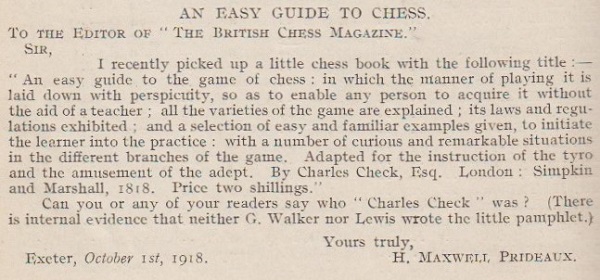

We note the following on page 25 of Easy Guide to the Game of Chess by Charles Check (London, 1818):

‘Value of the men. This has been estimated, reckoning their power of attack and defence only, as in the following proportion to each other. The queen 95: a rook 60: a bishop 39: a knight 37: the king 26: a pawn 8. The intrinsic value of the king, however, is, from the principle of the game, inestimable: and that of the pawn, from it’s [sic] chance of promotion, is calculated at 15.’

9653. Notation (C.N. 9650)

Easy Guide to the Game of Chess by Charles Check (London, 1818) used the algebraic notation, as explained on pages 7-8:

‘In order to be easily understood, and indicate clearly the places of the men and their moves, we shall distinguish the square on the same principle on which places are found in geography by their latitude and longitude. When the board is placed between the two players, there are eight rows of squares proceeding from one to the other. These, answering to the ranks of an army, we shall call A, B, C, D, E, F, G, H. These again form eight rows in the cross direction, or files, which we shall mark 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8. Thus any square on the board may readily be pointed out.’

A footnote on page 8 began:

‘The method above given is much more convenient for the learner than the usual mode of indicating the squares by the pieces that occupy them at the commencement for those on the line next each player; and for the rest their numeral position in front of these pieces as far as the middle of the board.’

The book was not well regarded by Howard Staunton, who wrote on page 323 of the Illustrated London News, 22 May 1847:

We lack information about Charles Check, notwithstanding an enquiry by H. Maxwell Prideaux on pages 324-325 of the November 1918 BCM:

9654. Marshall in 1944 (C.N. 9648)

Two further photographs published in the year Frank J. Marshall died:

Chess Review, January 1944, page 4

Chess Review, March 1944, page 5

9655. ‘Once, the story goes ...’

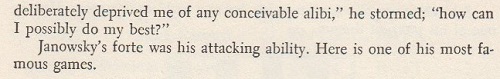

C.N. 9582 showed how Dawid Janowsky was derided on page 95 of B.J. Horton’s Dictionary of Modern Chess (New York, 1959). Another example, anchored in tittle-tattle, comes from pages 99-100 of The World’s Great Chess Games by Reuben Fine (New York, 1951):

The famous game published by Fine was against ‘Schallop’ (sic) at Nuremberg, 1896.

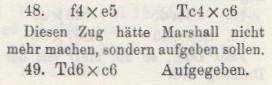

Dawid Janowsky (American Chess Bulletin, February 1927, page 28)

9656. The two Jans

However often Janowsky may or may not have been called ‘Jan’ orally, it is difficult to find the nickname in print during his lifetime. One instance occurs in G.C. Reichhelm’s annotations to the 16th match-game between Janowsky and Marshall, Paris, 4 March 1905, as published on pages 90-91 of volume two of Halpern’s Chess Symposium (New York, 1905). The note after 43...e5 was: ‘In the vain hope that “Jan” would take at once.’

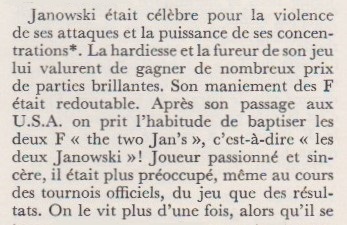

In passing, we mention a discrepancy over the game’s conclusion.

Reichhelm gave ‘48 PxP RxP (An “oversight”.) RxR wins’, whereas some sources state that Marshall resigned after White’s 48th move. Those sources include Marshall’s own brief coverage of the game on pages 36-37 of a booklet on the match (published in London in 1905 with his annotations from the Manchester Guardian). Two noteworthy publications which presented the conclusion as 48 fxe5 Rxc6 49 Rxc6 Resigns were pages 84-86 of La Stratégie, 17 March 1905 (notes by Alapin) and, as shown below, pages 106-107 of the April 1905 Deutsche Schachzeitung (notes by Tarrasch from the Berliner Lokal-Anzeiger):

Tarrasch gave similar annotations in Die Moderne Schachpartie (various editions, with different page numbers).

Moreover, according to the range of contemporary publications consulted, Black’s 47th move was ...Rc4, and not ...Rc5 as indicated by one or two unreliable databases.

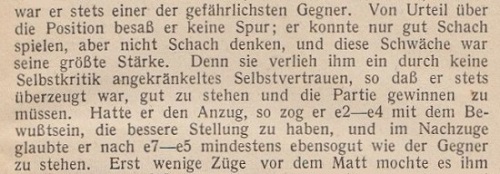

Concerning ‘the two Jans’, a number of reference works (see, for instance, the entries on Janowsky in the Dictionnaire des échecs, the hardback edition of Golombek’s Encyclopedia of Chess and the 1984 edition of The Oxford Companion to Chess) affirm that this was a common term in the United States to describe a bishop pair. An extract from page 206 of the Dictionnaire des échecs by F. Le Lionnais and E. Maget (Paris, 1967):

We have yet to trace the term in chess literature during Janowsky’s lifetime.

After presenting some victories by Janowsky, C.N. 351 commented:

... such games offer little support to the theory that Janowsky was obsessed with retention of the bishop pair. On the other hand, on page 330 of the October-November 1904 issue [of the Wiener Schachzeitung] Tarrasch, annotating the Cambridge Springs game Mieses v Janowsky remarks: ‘Janowski ist einer der wenigen Spieler, die das Geheimnis der Läufer begriffen haben und die latente Kraft dieser Figuren herauszuholen verstehen’.

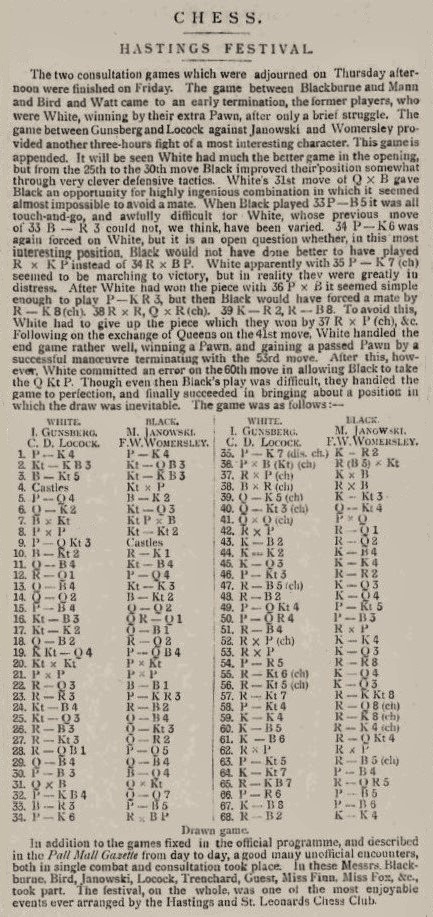

9657. Janowsky and Womersley

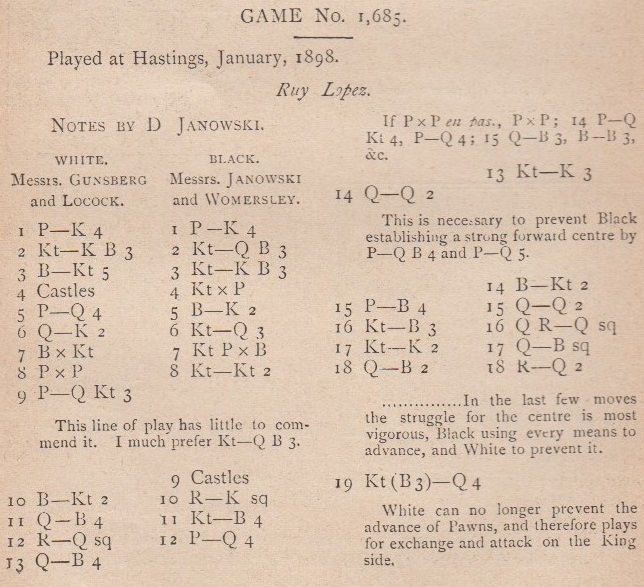

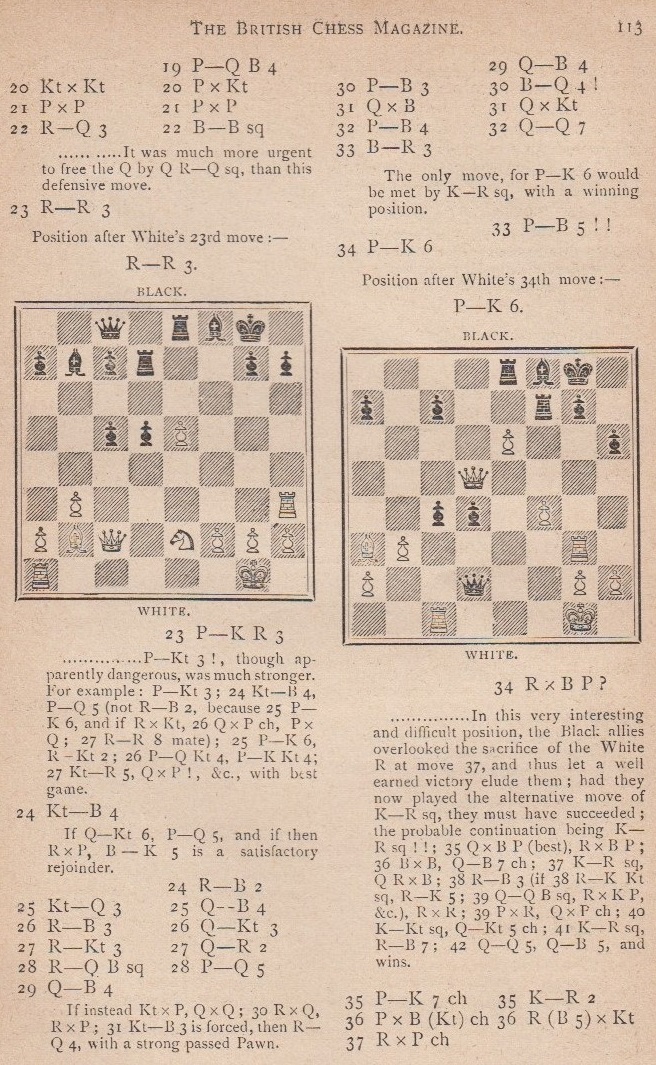

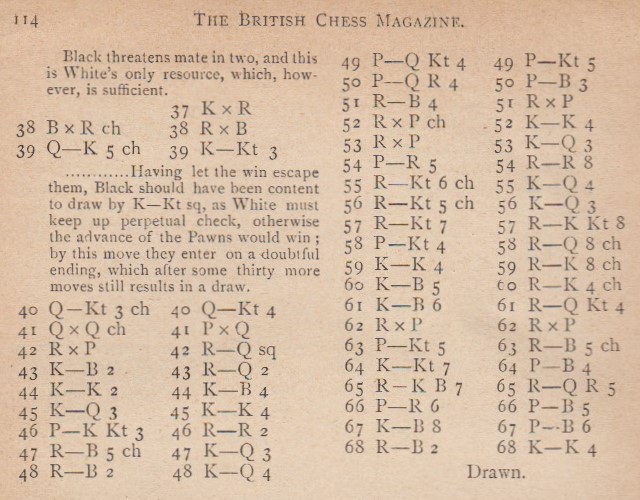

Further to the material in Chessplayer Shot Dead in Hastings, another consultation game involving F.W. Womersley and Janowsky, against Gunsberg and Locock, was published on page 9 of the Pall Mall Gazette of 29 January 1898 (chess column by Gunsberg) and on pages 112-114 of the March 1898 BCM (annotations by Janowsky):

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 Nf6 4 O-O Nxe4 5 d4 Be7 6 Qe2 Nd6 7 Bxc6 bxc6 8 dxe5 Nb7 9 b3 O-O 10 Bb2 Re8 11 Qc4 Nc5 12 Rd1 d5 13 Qf4 Ne6 14 Qd2 Bb7 15 c4 Qd7 16 Nc3 Rad8 17 Ne2 Qc8 18 Qc2 Rd7 19 Nfd4 c5 20 Nxe6 fxe6 21 cxd5 exd5 22 Rd3 Bf8 23 Rh3 h6 24 Nf4 Rf7 25 Nd3 Qf5 26 Rf3 Qg6 27 Rg3 Qh7 28 Rc1 d4 29 Qc4 Qf5 30 f3 Bd5 31 Qxd5 Qxd3 32 f4 Qd2 33 Ba3

33...c4 34 e6 Rxf4 35 e7+ Kh7 36 exf8(N)+ Rfxf8 37 Rxg7+ Kxg7 38 Bxf8+ Rxf8 39 Qe5+ Kg6 40 Qg3+ Qg5 41 Qxg5+ hxg5 42 Rxc4

42...Rd8 43 Kf2 Rd7 44 Ke2 Kf5 45 Kd3 Ke5 46 g3 Rh7 47 Rc5+ Kd6 48 Rc2 Kd5 49 b4 g4 50 a4 c6 51 Rc4 Rxh2 52 Rxd4+ Ke5 53 Rxg4 Kd6 54 a5 Rh1 55 Rg6+ Kd5 56 Rg5+ Kd6 57 Rg7 Rg1 58 g4 Rd1+ 59 Ke4 Re1+ 60 Kf5 Re5+ 61 Kf6 Rb5 62 Rxa7 Rxb4 63 g5 Rf4+ 64 Kg7 c5 65 Rf7 Ra4 66 a6 c4 67 Kf8 c3 68 Rf2 Ke5 Drawn.

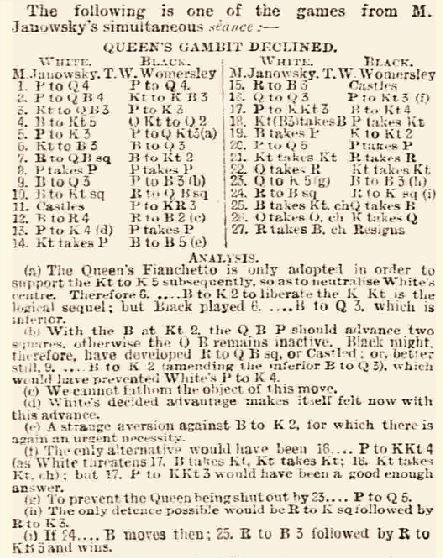

The game was played in Hastings on 27-28 January 1898. On 24 January Janowsky and Womersley had faced each other in the former’s 29-board simultaneous exhibition. Below is the game as published on page 7 of the Standard, 1 February 1898:

Black’s initials T.W. were amended to F.W. when the game was given on, for instance, page 2 of the 19 February 1898 edition of the Newcastle Courant.

1 d4 d5 2 c4 Nf6 3 Nc3 e6 4 Bg5 Nbd7 5 e3 b6 6 Nf3 Bd6 7 Rc1 Bb7 8 cxd5 exd5 9 Bd3 c6 10 Bb1 Rc8 11 O-O h6 12 Bh4 Rc7 13 e4 dxe4 14 Nxe4 Bf4 15 Rc3 O-O 16 Qd3 g6 17 g3 Bg5 18 Nfxg5 hxg5 19 Bxg5 Kg7

20 d5 cxd5 21 Nxf6 Rxc3 22 Qxc3 Nxf6 23 Qe5 Bc6 24 Rc1 Re8 25 Bxf6+ Qxf6 26 Qxf6+ Kxf6 27 Rxc6+ Resigns.

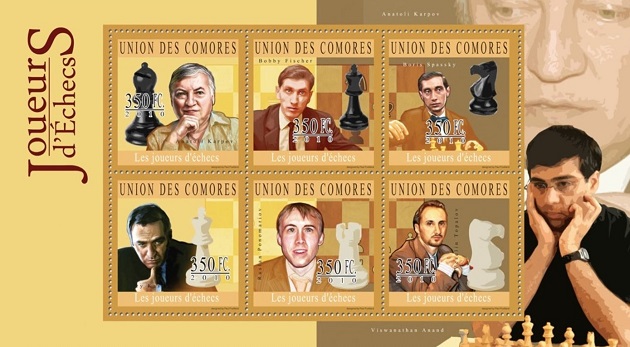

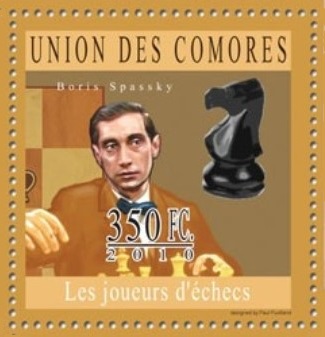

9658. Comoros stamps

Dan Scoones (Coquitlam, BC, Canada) draws attention to a set of postage stamps:

Our correspondent notes that ‘Boris Spassky’ is Vladek Sheybal, who played the role of Kronsteen in the 1963 film From Russia with Love.

9659. Notation (C.N.s 9650 & 9653)

From page 58 of NY Chess Since 1972 by Peter Julius Sloan (New York, 2012):

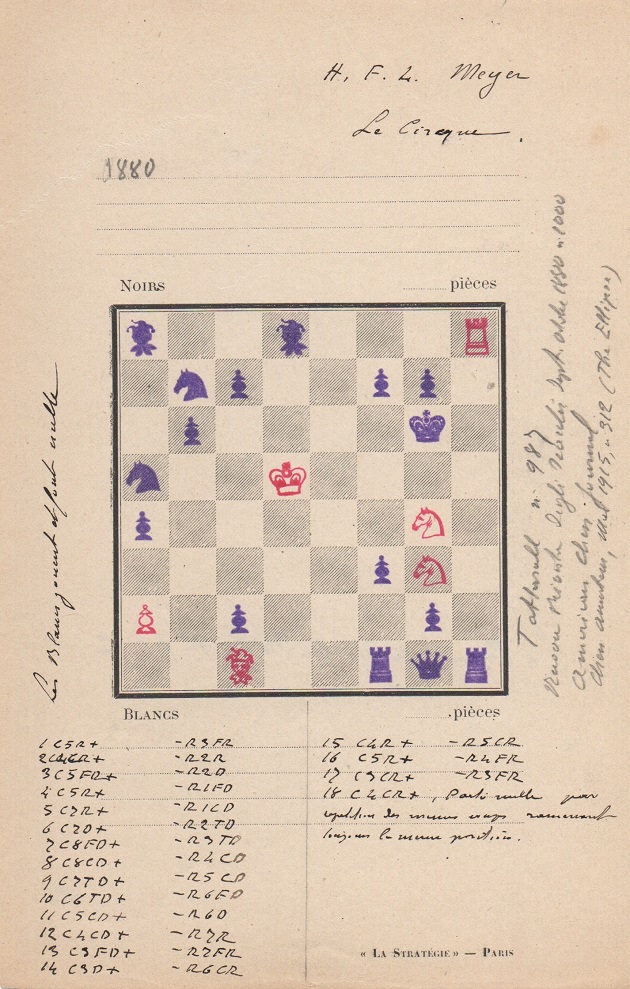

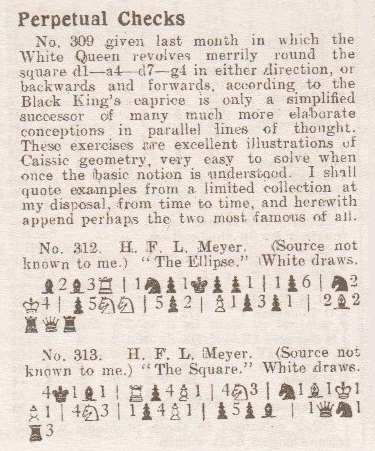

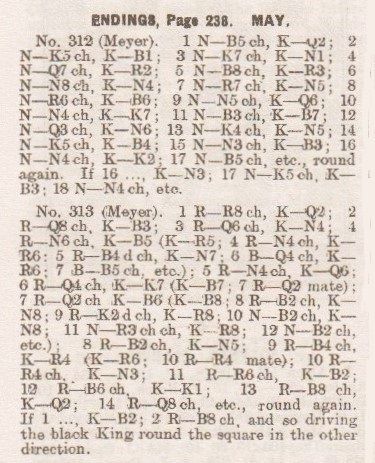

9660. A composition in Lasker’s Manual of Chess (C.N.s 9634 & 9638)

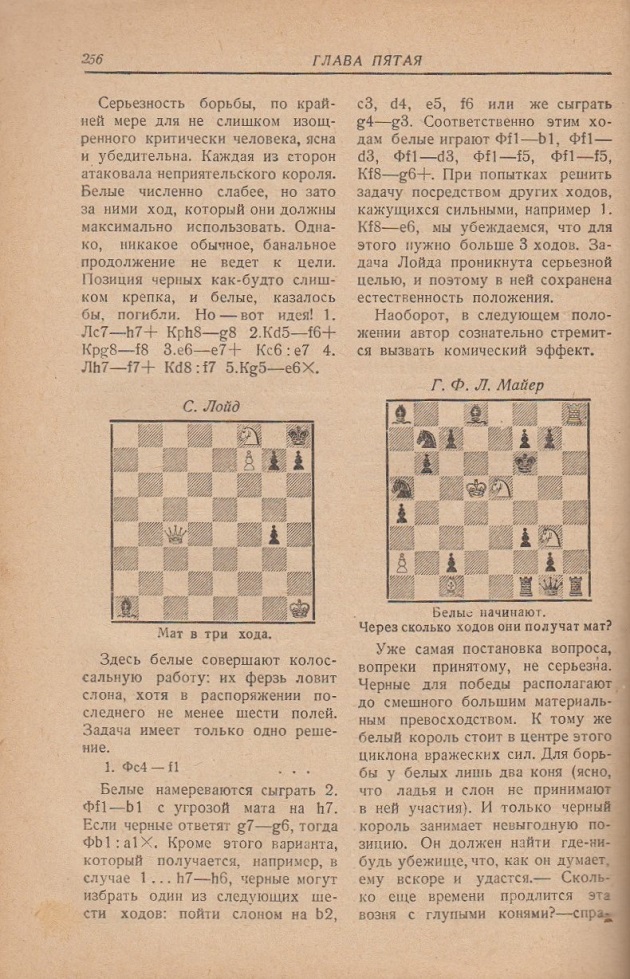

Alain Pallier (Lauris, France) refers us to the collection of Marcel Lamare (1856-1937), the subject of an article by our correspondent on pages 870-871 of issue 121 (July 1996) of EG. He has also forwarded a copy of the sheet on which Lamare recorded the composition by H.F.L. Meyer:

We are grateful to the Cleveland Public Library for the two 1880 items listed by Lamare:

American Chess Journal, July 1880, page 86

Nuova Rivista degli Scacchi, September-October 1880, page 256

Below is the last publication mentioned by Lamare, from page 238 of the May 1915 Chess Amateur (in T.R. Dawson’s ‘Endings’ column):

From page 280 of the June 1915 Chess Amateur:

9661. Shinkman

The frontispiece to the July 1880 issue of the American Chess Journal:

| First column | << previous | Archives [137] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.