Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [136] | next >> | Current column |

9571. Purdy and Fischer

The start of the Preface to How Fischer Won by C.J.S. Purdy (Sydney, 1972), page vii:

‘At least a thousand million people have heard of the new World Chess Champion, Bobby Fischer. Most of them, including almost all the non-players and moderate players, are inclined to dislike what they hear. The enthusiasts excuse what they don’t like because chess looms large in their lives, and Fischer plays chess that is out of this world.

In this book I have tried to show that there is really little to dislike, and therefore little to excuse.’

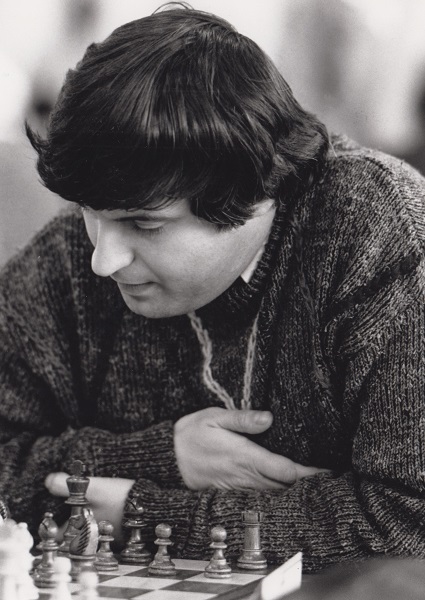

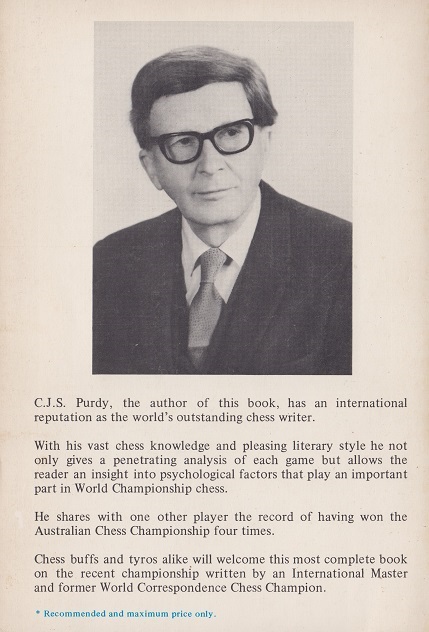

The back cover:

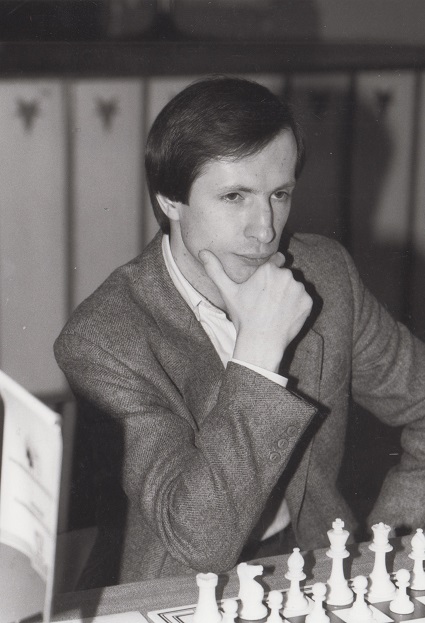

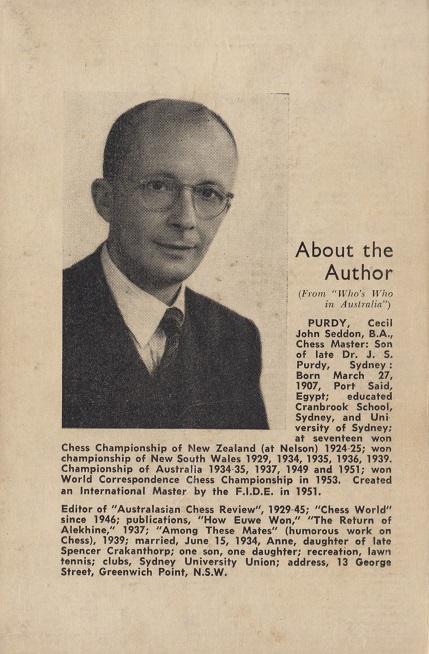

An earlier book, Guide to Good Chess (Sydney, 1954), had the following on its back cover:

Purdy’s year of birth was discussed in C.N. 4924.

9572.

Reshevsky in 1917

From page 6 of Das interessante Blatt, 13 September 1917:

This is a better version of the picture given in C.N. 6701.

9573. Who?

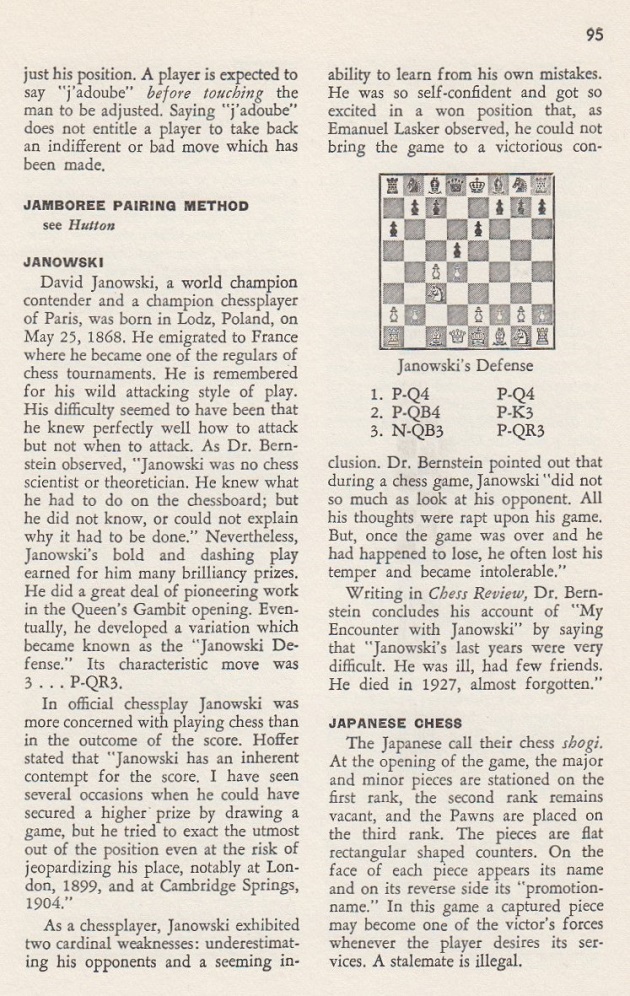

According to a reference book’s entry on him, this chessplayer attacked wildly, was unaware when to attack, was neither a scientist nor a theoretician, did not know, or was unable to explain, why what he did at the chessboard had to be done, cared relatively little about the outcome of a game, underestimated his opponents, appeared incapable of learning from his errors, was excessively self-confident, frequently lost his temper and was intolerable when defeated, did not have many friends and was virtually forgotten when he died.

9574. Verdoni (C.N.s 9565 & 9570)

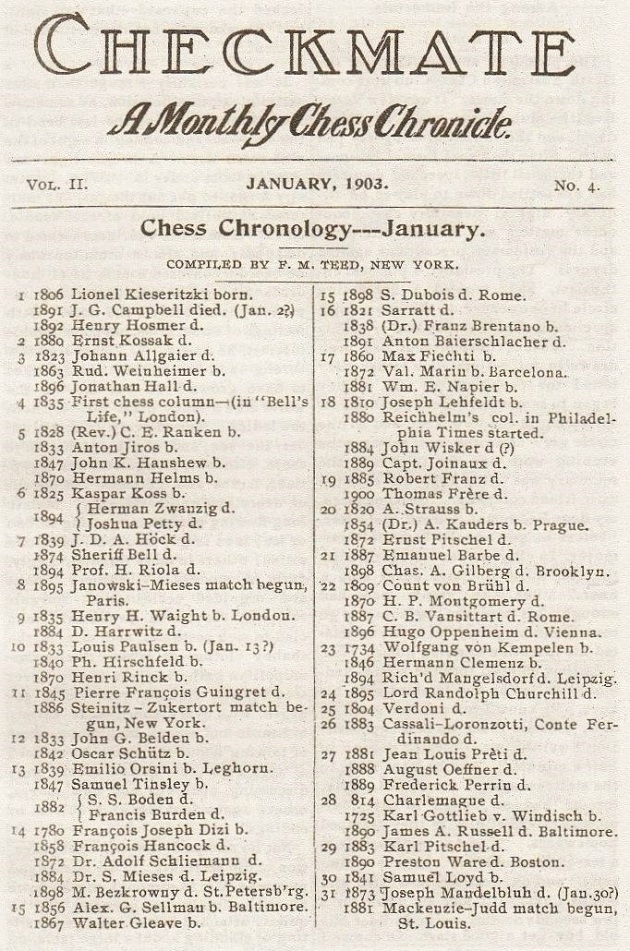

Verdoni’s death-date was also given as 25 January 1804 in the ‘Chess Chronology – January’ by F.M. Teed on page 73 of the January 1903 issue of Checkmate:

9575. The Grandmaster

Another specimen of poetry about Capablanca, by F.P. Hier, was published on page 163 of the September-October 1924 American Chess Bulletin:

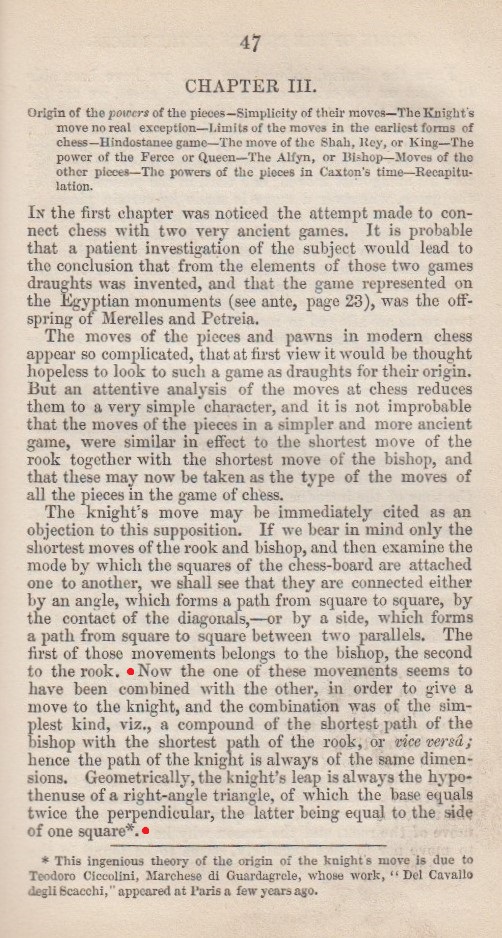

9576. The knight

The Knight Challenge quotes a line from page 154 of Amusements in Chess by Charles Tomlinson (London, 1845): ‘The move of the knight consists of the shortest rook’s move and the shortest bishop’s move, both at once.’

A similar remark was on page 47, alongside a more complex explanation:

‘Geometrically, the knight’s leap is always the hypothenuse of a right-angle triangle, of which the base equals twice the perpendicular, the latter being equal to the side of one square.’

Tomlinson’s text was originally published on page 191 of the Saturday Magazine, 13 November 1841.

From page 29 of Amusements in Chess:

9577. Europeana

Another photograph collection featuring many chessplayers is Europeana.

9578. Mate in six (C.N. 9560)

This problem was taken from page 11 of Spaß am Kombinieren by Albin Pötzsch (East Berlin, 1986), which gave the composer and source as V. Salonen, Uusi Suomi, 1935. The solution on page 171: 1 Rf2 f6 2 Rg2 g5 3 Rh2 Kb8 4 Rxh6 c5 5 Kb6 and 6 Rh8 mate.

9579. Feuerstein v Fischer

Dan Scoones (Port Coquitlam, BC, Canada) writes:

‘I have noted three versions (i.e. discrepancies in White’s 13th and 17th moves) of the game between Arthur Feuerstein and Bobby Fischer at the 1956 Eastern States Open in Washington, DC:

- Fischer’s Chess Games (Oxford, 1980) and The Games of Robert J Fischer by R.G. Wade and K.J. O’Connell (London, 1981):

1 Nf3 Nf6 2 c4 g6 3 g3 Bg7 4 Bg2 O-O 5 O-O d6 6 d4 Nbd7 7 Nc3 e5 8 e4 exd4 9 Nxd4 Nc5 10 f3 Nfd7 11 Be3 a5 12 Qc2 a4 13 Rfb1 c6 14 Bf1 Qe7 15 Qd2 Re8 16 Nc2 Ne5 17 Rd1 Bf8 18 Bh6 Bxh6 19 Qxh6 f5 20 exf5 Bxf5 21 Nd4 Bd3 22 Bxd3 Nexd3 Drawn.

- Bobby Fischer 1: 1955-1960 edited by S. Soloviov (Madrid, 1992):

1 Nf3 Nf6 2 c4 g6 3 g3 Bg7 4 Bg2 O-O 5 O-O d6 6 d4 Nbd7 7 Nc3 e5 8 e4 exd4 9 Nxd4 Nc5 10 f3 Nfd7 11 Be3 a5 12 Qc2 a4 13 Rfd1 c6 14 Bf1 Qe7 15 Qd2 Re8 16 Nc2 Ne5 17 Kg2 Bf8 18 Bh6 Bxh6 19 Qxh6 f5 20 exf5 Bxf5 21 Nd4 Bd3 22 Bxd3 Nexd3 Drawn.

- Bobby Fischer by K. Müller (Milford, 2009):

1 Nf3 Nf6 2 c4 g6 3 g3 Bg7 4 Bg2 O-O 5 O-O d6 6 d4 Nbd7 7 Nc3 e5 8 e4 exd4 9 Nxd4 Nc5 10 f3 Nfd7 11 Be3 a5 12 Qc2 a4 13 Rf2 c6 14 Bf1 Qe7 15 Qd2 Re8 16 Nc2 Ne5 17 Rd1 Bf8 18 Bh6 Bxh6 19 Qxh6 f5 20 exf5 Bxf5 21 Nd4 Bd3 22 Bxd3 Nexd3 Drawn.

The game did not appear in the earlier (1972) editions of the Wade/O’Connell book, in Die gesammelten Partien von Robert J. Fischer by C.M. Bijl (IJmuiden, 1976 and Nederhorst den Berg, 1986) or in the two-volume Russian collection of 744 games (Moscow, 1993).’

Did White play 13 Rfb1, Rfd1 or Rf2?

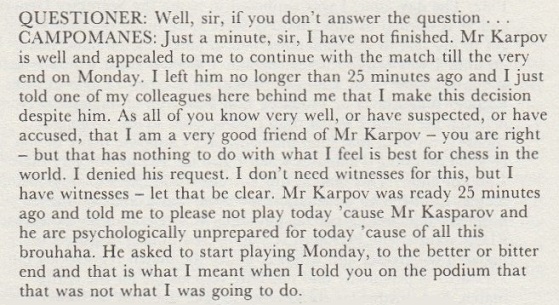

9580. Picked up on tape

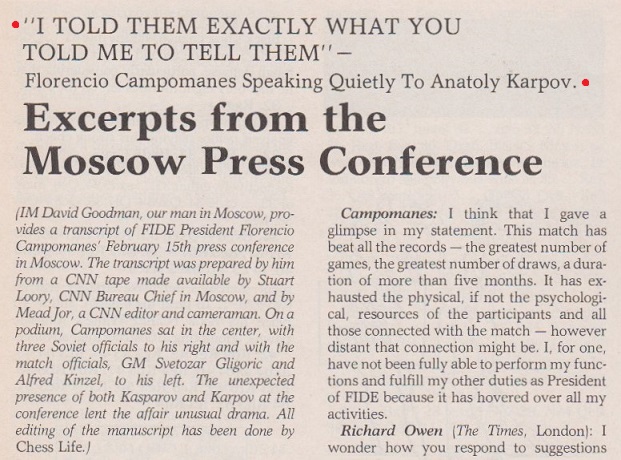

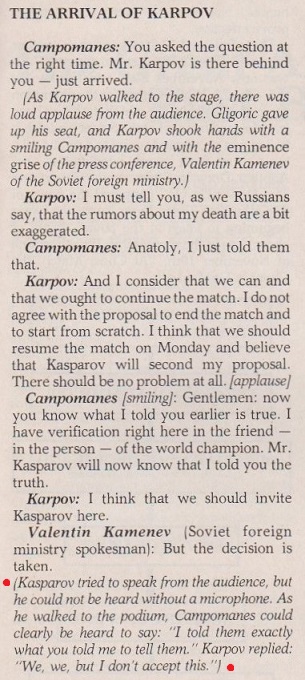

During the shambolic press conference in Moscow on 15 February 1985 at which Florencio Campomanes announced the termination of the first Karpov v Kasparov world championship match, some sotto voce words from the FIDE President to Karpov were reportedly ‘picked up on tape’. Below is the heading on page 28 of the May 1985 Chess Life:

And from the following page:

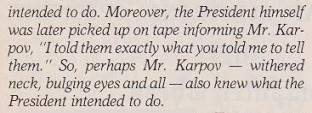

Another article by David Goodman began on page 22 of the same issue, and was introduced by an ‘Editor’s Note’ which included this:

At that time, Chess Life was in the worst imaginable editorial hands (Mr Larry Parr’s). The words ‘I told them exactly what you told me to tell them’ were taken up by another anti-Campomanes magazine, i.e. on page 29 of the May 1985 CHESS:

Next, an extract from page 6 of Manoeuvres in Moscow by R. Keene and D. Goodman (London, 1985):

No further information was offered regarding the claim in the footnote.

From page 140 of Kasparov’s Child of Change (London, 1987), a book which included an acknowledgement to Messrs Keene and Goodman:

Two years later, however, there was a strange twist, on page 103 of a new autobiographical work by Kasparov, Безлимитный поединок (Moscow, 1989):

That book was a revised edition of Child of Change and was published in English as Unlimited Challenge (Glasgow, 1990). The relevant passage, from page 134:

(In the final indented line, ‘Kasparov’ should, of course, read ‘Karpov’.)

So now, suddenly, there was a statement by Kasparov that he himself heard Campomanes’ remark during the press conference. ‘Campomanes can clearly be heard on the Cable News Network tape’ in Child of Change became ‘I heard Campomanes saying to Karpov (and this is recorded on the tape)’ in Unlimited Challenge. The new version was reiterated on pages 257-258 of ‘Garry Kasparov on Modern Chess Part Two Kasparov vs Karpov 1975-1985 including the 1st and 2nd matches’ (London, 2008):

Other sources disagree about what Campomanes supposedly said and, for once, it is worth mentioning what Wikipedia states. Below is the text that currently appears in the English-language entry for Campomanes:

And in the Wikipedia entry on FIDE:

What role may have been played by Dlugy (who was aged 19 at the time of the Termination) is unclear, but in any case the words ascribed to Campomanes are completely different. Instead of ‘I told them exactly what you told me to tell them’, we now have ‘But Anatoly, I told them just what you said’ (Campomanes page) and ‘But Anatoly, I told them what you said’ (FIDE page). It remains to be discovered why such discrepancies exist.

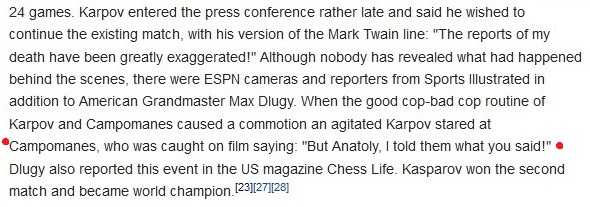

Our final extract from the press conference transcript is on page 136 of Child of Change, showing that Karpov had indeed been saying things to Campomanes:

As a test, let us now put the strongest possible pro-Kasparov construction on every aspect of the episode. Let us assume, firstly, that although the hall was full and noisy, Keene and Goodman were wrong to state that Campomanes made his remark to Karpov ‘as Kasparov walked down the stairs’, and that in reality Kasparov was near enough to the podium to hear Campomanes’ quiet words for himself. Next, let us assume that an audio and/or video recording still exists on which Campomanes can be heard saying to Karpov what Kasparov says that he heard (‘I told them exactly what you told me to tell them’), and/or one of the other versions (‘But Anatoly, I told them just what you said’ and ‘But Anatoly, I told them what you said’) and/or something at least vaguely similar. Let us go further still and imagine that Karpov himself now announces that he recalls the exact remark in question being made to him by the FIDE President. How, even after all that, would we be any further forward?

For reasons of their own, writers have presented the words allegedly picked up on tape as highly significant, and as so damningly revelatory that no further explanation is needed. The very phrase ‘picked up on tape’ invites the reader to imagine that masks have slipped and that a smoking gun has been discovered. But why? In the passages shown above (not one of which comes from a trustworthy source, it should be noted) all the versions of what Campomanes supposedly said to Karpov are open to so many interpretations (positive, neutral and negative) that no responsible writer would expect, or encourage, readers to draw one particular conclusion rather than another. Regardless of the rights and wrongs of the Termination Affair – and nobody can claim to know what happened in Moscow in February 1985 – the ‘picked up on tape’ matter is the dampest of squibs.

9581. Verdoni (C.N.s 9565, 9570 & 9574)

John Townsend (Wokingham, England) points out that both The Georgetown Chess Club Almanack for 1868 (C.N. 9570) and the list by F.M. Teed on page 73 of the January 1903 Checkmate (C.N. 9574) gave the death-date of J.H. Sarratt as 16 January 1821, whereas it is known from contemporary newspaper reports that he died in November 1819. Consequently, the unsourced statement by both publications that Verdoni died on 25 January 1804 cannot be taken on trust, and further investigation is required.

9582. Who? (C.N. 9573)

The effusion of criticism and ridicule referred to in C.N. 9573 was on page 95 of B.J. Horton’s Dictionary of Modern Chess (New York, 1959):

9583. Scholarship

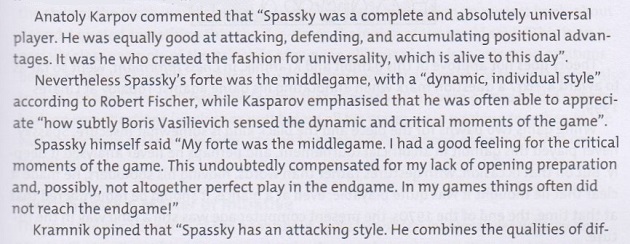

From page 13 of Spassky move by move by Zenón Franco (London, 2015):

And so on. This passage, typical of Franco’s approach to writing, does not state where or when Karpov, Fischer, Kasparov, Spassky and Kramnik made the remarks attributed to them. Why not?

Why can readers of McFarland books expect, or at least hope, to see exact sources for quotations, whereas so many other publishers show no sign of having even considered such a requirement? Why, if McFarland’s overall output is praised for its ‘scholarship’, do reviewers refrain from criticizing other publishers for a lack thereof? In any case, the issue at hand is ‘scholarship’ of a most basic kind. When an author says that someone said something, saying where and when it was said is not a donnish luxury or self-indulgence but an essential service to the reader which should be automatic.

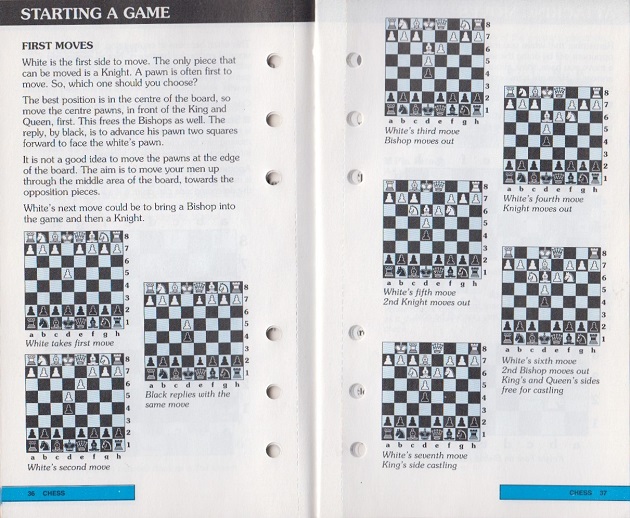

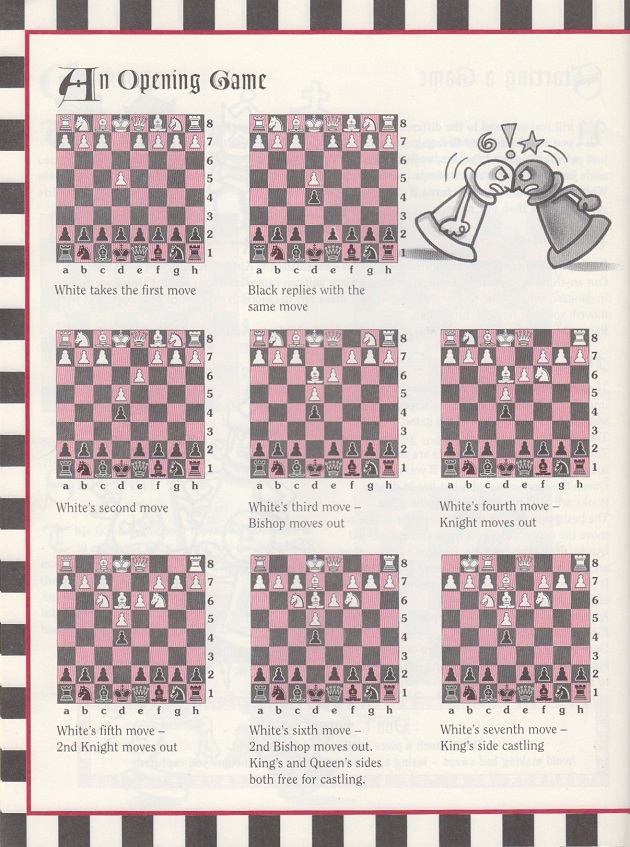

9584. Chess for children

How many chess writers or federations monitor children’s chess books, with a view to highlighting successes and failures?

In the latter category are two books from the same publisher which offered this game: 1 d5 d4 2 e6 3 Bd6 4 Nf6 5 Nc6 6 Bd7 7 O-O (although 7 O-O-O was also deemed possible, notwithstanding the unmoved white queen on e8).

Below, firstly, is the game’s appearance on pages 36-37 of Beginner’s guide to Chess by Nic Brett (Woodbridge, 1994), a ‘Funfax’ publication:

The same company, Henderson Publishing Ltd (Suffolk, England), also brought out Chess compiled by Jackie Andrews (Woodbridge, 1997):

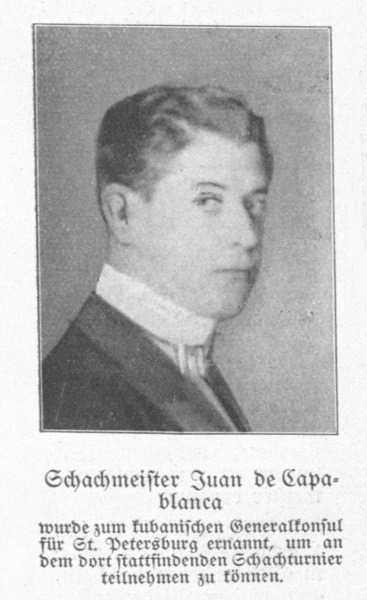

9585. Capablanca in 1913

A rare photograph of Capablanca (‘Juan de’) from page 67 of the Österreichische Illustrierte Zeitung, 12 October 1913:

9586. Reinfeld and Purdy (C.N. 9502)

Fred Reinfeld’s description of C.J.S. Purdy as ‘the world’s outstanding writer on chess’ (C.N. 9502) was mentioned by Purdy in his obituary of the American on pages 121-122 of the August 1964 Chess World. Entitled ‘A Whirling Pen is Stilled’, the tribute began with an interesting view of Reinfeld’s standing:

‘Too many books may spoil an author’s reputation. Critics are too inclined to average out rather than judge on the best. It doesn’t happen to the really great; for instance, Shakespeare is judged virtually on his best dozen or so plays, and even Wordsworth, though everyone knows he wrote much puerile drivel, is considered a great poet because of a few masterpieces. But if a writer is less than great, probably his best things do not become famous enough to induce people to ignore his mere pot-boilers. This is why Reinfeld is under-rated.

He never, like Wordsworth, wrote drivel, but he wrote many books that say much the same things in different ways. These books are for learners and average players. They are lucidly written and easy to follow, but not noticeably bespattered with brass tacks. Not meaty, but sugar-coated. Sugar-coating is quite a virtue in teaching, but there should be good medicine underneath.

However, leaving such books aside, Reinfeld made many notable contributions to chess literature.’

A number of Reinfeld books were then singled out for praise, including his two ‘1001’ volumes: ‘These are only books of diagrams (chess exercises) but two of the most useful books to any chessplayer.’

After personal reminiscences, Purdy concluded:

‘“A Whirling Pen is Stilled” is intended metaphorically. If Reinfeld had used a pen, his output would have been impossible. No, he used a typewriter. He used it too much! And yet of that too much, much deserves to live.’

9587. Reserving options

‘Reserving options is always good, provided you don’t lose more options than you reserve, or concede a valuable option to your opponent.’

Source: C.J.S. Purdy, Chess World, August 1964, page 123.

9588. Stamma (C.N. 9301)

Robert John McCrary (Columbia, SC, USA) writes:

‘C.N. 9301 referred to an Oxford Dictionary of National Biography article on Phillip Stamma which included this passage about the 1745 edition of his book:

“The Noble Game also ends with a rare example of the practice of an author confirming the authenticity of a printed work by use of his signature: the last words of the work read ‘The Author thinks proper to inform the Publick, that no Copies of this Book are genuine, but such as are sign’d by him’ (page 115). Several extant copies do contain signatures in both Arabic and Latin characters, presumably written by Stamma himself.”

The matter was mentioned in a footnote on pages 69-70 of The Life of Philidor by George Allen (Philadelphia, 1863):

“When Stamma publiſhed his Noble Game of Cheſs, in 1745, he informed the public, that ‘no Copies of the Book were genuine, but ſuch as were ſign’d by him’. The copies, which have this ſignature are very rare. It may, therefore, be inferred, that Stamma died pretty ſoon after the publication of this edition – or, at any rate, long before the whole of it had been diſpoſed of.”

Page 59 of A History of Card Games by David Parlett (Oxford, 1990) says that Edmund Hoyle and his publisher Thomas Osborne individually signed every copy of Hoyle’s 1742 book (at least editions after its first) by “way of certification” because of pirating problems.’

9589. Rosenthal v Zukertort match, 1880

From page 92 of The Book of Chess Lists by A. Soltis (Jefferson, 1984):

See too page 16 of the second edition (Jefferson, 2002). Both books had the odd sentence, ‘They had to eat lunch with one another and even take naps in tandem’. Another case of Soltis sans source.

Below is an item from page 57 of Curious Chess Facts by Irving Chernev (New York, 1937):

And from page 86 of Chernev’s Wonders and Curiosities of Chess (New York, 1974):

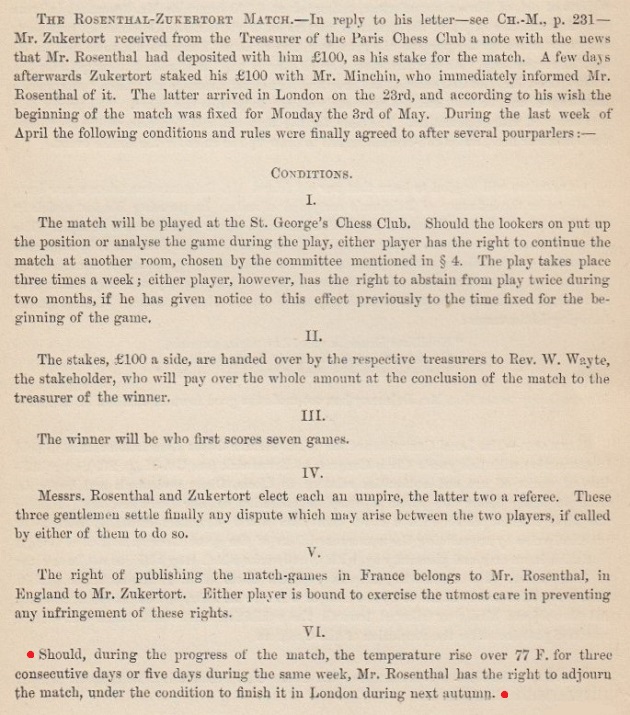

The terms of the Rosenthal v Zukertort match were set out on pages 133-134 of La Stratégie, 15 May 1880 and, as shown below, on pages 260-261 of the May 1880 Chess Monthly:

It is unclear why both Chernev and Soltis referred to a midday break, given that play began at 14.00. As regards the arrangements during the evening adjournment, in the Field, 8 May 1880 Steinitz, who was the referee, wrote in his report on the second match-game:

‘Rosenthal took nearly half an hour to consider his reply, and the time for adjournment (half-past six o’clock) having been reached, he marked his move on the score sheet, which was handed over in a sealed envelope to the editor of this department, who joined the two players at dinner at a West-end restaurant. It is one of the regulations of the match that the two opponents should not separate during the two hours of adjournment for refreshment. Such a provision is now always adopted in tournament [sic], and is obviously necessary where many different parties are interested in the contest. Both masters are expert blindfold players, and quite capable of analysing positions from memory, even when engaged in conversation. Yet their stopping together during the dinner hour must be satisfactory to both, and is calculated to keep up a friendly feeling between the opponents. At half-past eight o’clock the game was resumed ...’

Concerning the temperature provision, page 81 of La Stratégie, 14 March 1880 had reported that Rosenthal ...

‘... a émis le désir de ne commencer la lutte qu’en septembre prochain, ou si elle est commencée en avril et qu’elle se prolonge jusqu’aux chaleurs, il se réserve le droit de l’interrompre, sa santé ne lui permettant pas de jouer lorsque la température est élevée.’

As mentioned in C.N. 2451 (see page 172 of A Chess Omnibus), the maximum temperature in question was 25 degrees centigrade, which is 77, and not 67, degrees Fahrenheit. Page 119 of the 15 April 1880 issue of La Stratégie stated:

‘Le match sera commencé vers la fin de ce mois, et dans le cas où le thermomètre s’élèverait à 25 degrés centigrades, la lutte serait interrompue.’

The match was played at the St George’s Club in London from 3 May to 25 June 1880 and was won by Zukertort (+7 –1 =11). In the regulations reproduced above from the Chess Monthly, we also draw attention to condition V (publication rights to the games) and rule of play VI (repetition).

9590. Photographic archives (14)

Alexander Chernin

Victor Gavrikov

Werner Hug

9591. Icelandic database

The Icelandic database Tímarit.is has much interesting material, a good starting-point being searches with the words ‘skák’, ‘Spassky’ and ‘Fischer’.

9592. Book reviews

Do readers know of any magazines or websites which, systematically and comprehensively, produce authoritative reviews of new chess books?

‘Authoritative’ excludes all those easily pleased outlets making do with superficial impressions which could be written by virtually anybody. For example, a reviewer who praises The Joys of Chess by C. Hesse (Alkmaar, 2011), not realizing that it is unreliable and makes excessive, insufficiently credited use of earlier writers’ work, is unqualified to review books in, at the very least, that category. A reviewer of a new openings monograph needs proper knowledge of what has already been published on the same opening. A reviewer who imagines that all McFarland books (even the Steinitz biography by K. Landsberger) merit indiscriminate eulogies has no business publicly assessing works about chess history. Plaudits are deserved by many McFarland titles, but not all, and it is the critic’s task to make the requisite distinctions. A reviewer whose own volumes are notorious for blunders and other defects (plagiarism, for instance) should be neither reviewing nor authoring. Nor, of course, should any writer wish to quote favourable opinions received from such a reviewer. T. Harding rushing to cite R. Keene’s fulsome praise of his Blackburne book was a pathetic spectacle.

Some people are qualified to evaluate no chess books of any kind, but nobody is qualified to evaluate the full range of the game’s literature. C.N. 3766 referred to the skill of Brian Reilly, as editor of the BCM, in bringing together a team of excellent book reviewers which included J.M. Aitken, W.H. Cozens, G.H. Diggle, W. Heidenfeld and D.J. Morgan, each with his specialities.

It is relevant to recall the words of W.H. Watts on page 115 of the March 1933 BCM:

‘It has long been a grievance of mine that so far as chess books are concerned the art of reviewing has almost entirely disappeared. It seems that Editors imagine book publishers send copies of their new publications solely to get the little bit of publicity which a favourable puff will provide, and are averse to any form of criticism. Either this, or books are reviewed by writers not sufficiently qualified to criticize, or who do not know what a book review is. I remember in my early days book reviewing was taken quite seriously, and choosing reviewers for important books was a task requiring the most careful consideration. Editors took great care to see that books had adequate and suitable attention, and in no case would the trite clichés which now pass as reviews be accepted. “Well printed”, “On good paper”, “Many and very clear diagrams”, “Profound analysis”, “A splendid selection of brilliant games”, with a few other stock phrases similarly pleasant, culminating in “No chessplayer’s library is complete without it” exhaust almost every review of a chess book that has appeared for many years.

How different it was in the past. Comparatively speaking Chess Blossoms by Miss F.F. Beechey is a very unimportant book, and yet in the Chess Player’s Chronicle of 1883 no less than four pages were devoted to its review. This review is a critical examination of the contents, and is what I with my old-fashioned ideas always imagined a review had to be. The review of Horwitz and Kling’s End Games occupies two pages of the CPC for May 1884, and I could multiply these instances many times by reference to early issues of the BCM itself. It must happen occasionally that the most important chess event of the month is the publication of some new book on the game, and yet it gets but scant notice, on the lines indicated, and henceforward passes into oblivion.’

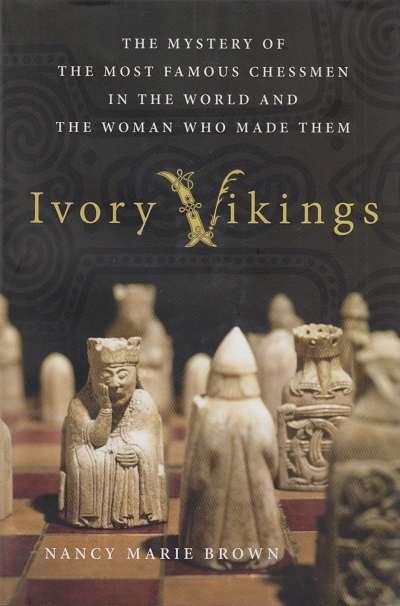

A chess publisher supplying review copies can be hopeful of an enthusiastic write-up, with or without cronyism and with or without thought. The very existence of chess titles produced by non-chess publishers may be overlooked. To take specific cases from recent years, below are three hardbacks, Birth of the Chess Queen by Marilyn Yalom (New York, 2004), Power Play by Jenny Adams (Philadelphia, 2006) and Ivory Vikings by Nancy Marie Brown (New York, 2015).

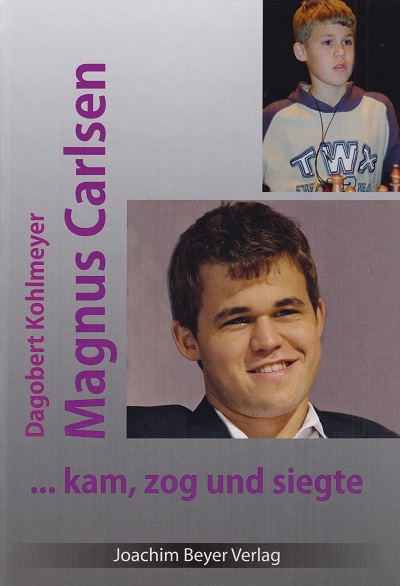

The third of those books has only just appeared, but which chess magazines and ‘review websites’ have offered their readers authoritative assessments of the earlier two works? And, lest all this be considered too arcane, to which magazines or websites can a reader turn when wishing to buy a book about Magnus Carlsen and seeking dependable, objective guidance on which ones are excellent, good, bad and awful from among the dozen or so titles available?

9593. Combination

‘We may define the magic word combination in two different ways: as a series of moves having a common object, or as the blending of objective with method.’

Source: Challenge To Chessplayers by Fred Reinfeld (Philadelphia, 1947), page 21.

As shown in What is a Chess Combination?, the ‘common object’ idea was mentioned by James Mason on page xi of The Art of Chess (London, 1898).

9594. Squares

From Stuart Rachels (Tuscaloosa, AL, USA):

‘Legend has it that Bobby Fischer said (or wrote) “To get squares, you gotta give squares”, or something similar. This “quotation” appears on various websites as well as on, for instance, page 11 of Soltis’ Bobby Fischer Rediscovered (London, 2003). However, I have never seen a source given for the comment. Is there any evidence that it emanates from Fischer? Does it occur in any of his writings or interviews, or are there witnesses who claim to have heard him say it?’

We see the remark in many books notable for their lack of sources. For instance:

- ‘There is also Fischer’s observation: “To get squares, you gotta give squares.”’

Karl Marx Plays Chess by A. Soltis (New York, 1991), page 18; reproduction of his column on pages 10-11 of the March 1981 Chess Life;

- ‘... or as Bobby Fischer would later say, “to get squares ya gotta give squares”’;

The 100 Best Chess Games of the 20th Century, Ranked by A. Soltis (Jefferson, 2000), page 144;

- ‘“To get squares, you gotta give squares”, as he [Fischer] put it’;

Bobby Fischer Rediscovered by A. Soltis (London, 2003), page 11;

- ‘“To get squares, ya gotta give squares.” Bobby Fischer’s insight, expressed in typical Bobby-talk ...’

The Wisest Things Ever Said About Chess by A. Soltis (London, 2008), page 249;

- ‘As Bobby Fischer put it, “to get squares you gotta give squares”.’

What It Takes to Become a Chess Master by A. Soltis (London, 2012), page 192.

9595. Verdoni (C.N.s 9565, 9570, 9574 & 9581)

From John Townsend (Wokingham, England):

‘C.N. 9565 mentioned Sarratt’s remark that Verdoni died in Panton Street, London. Below is a document (reference WR/A/035) in the London Metropolitan Archives from the Westminster Quarter Sessions records regarding enrolment, registration and deposit:

“In pursuance of the powers vested in me by his Majesty’s Proclamation for registering of Aliens, dated at Saint James, the Fifth day of July One Thousand Seven Hundred & Ninety Eight, I do hereby grant to Carmine Verdone an Alien, A Provisional Licence to reside in this Kingdom Viz. in the County of Middlesex for one Month from the date hereof.

Given under my hand & seal at Marlboro’ Street in the County of Middx. this 23d day of July 1798.

These are to certify the above Carmine Verdone is an Italian and has Lodged with me from the 15th of Decr. 1796 to the present time 30th July 1798.

John Maynard

No. 9 Panton Street

Haymarket.”I have also found the following entry in the burials for March 1804 in the register of the parish of St Martin in the Fields (which includes Panton Street):

“7 Carmine Vendane Esq. M”.

“M” denotes an adult male, and Carmine is a male forename in Italy. It remains to be shown whether the “Carmine Verdone” referred to by John Maynard in 1798 and the “Carmine Vendane” in the 1804 register were indeed the chessplayer Verdoni.’

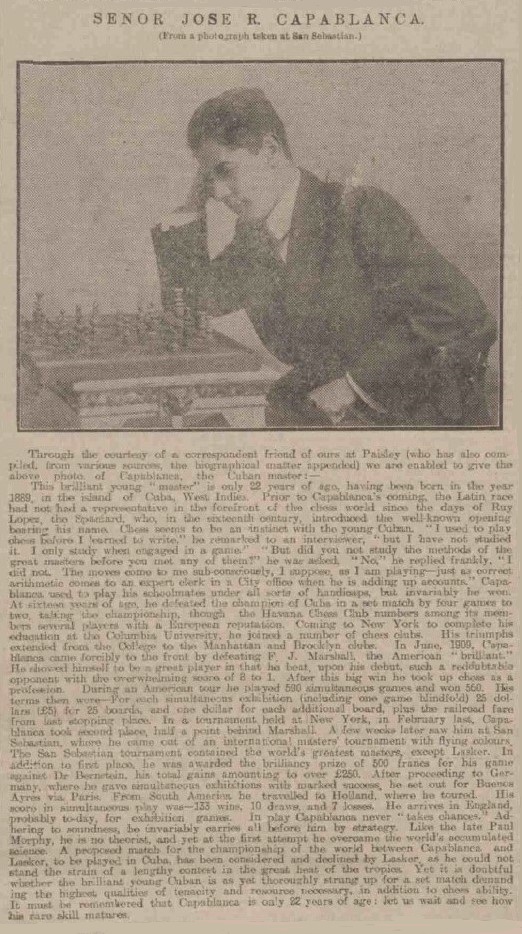

9596. Capablanca in 1911

Source: Falkirk Herald, 25 October 1911, page 7.

9597. A choice of en passant captures

Harlow Bussey Daly – J.L. McCudden

Rye Beach, 24 July 1918

Danvers Opening

1 e4 e5 2 Qh5 Nf6 3 Qxe5+ Be7 4 Nc3 Nc6 5 Qg3 Nb4 6 Kd1 d5 7 a3 d4 8 axb4 dxc3 9 bxc3 Nxe4 10 Qe3 Nf6 11 Bc4 a6 12 h3 O-O 13 Qd3 Bd7 14 Nf3 Bc6 15 Ne5 Bd5 16 Bxd5 Qxd5 17 Qxd5 Nxd5 18 Nd3 Rad8 19 Bb2 Rfe8 20 Re1 Kf8 21 Ba3 b5 22 Bb2 Rd6 23 Nc5 Bf6 24 Rxa6 Rxe1+ 25 Kxe1 Rxa6 26 Nxa6 c6 27 Ke2 Nb6 28 Nb8 Nc4 29 Nd7+ Ke7 30 Nxf6 Kxf6 31 Bc1 Ke5 32 d3 Nd6 33 Be3 Kd5 34 Kd2 Nf5 35 f4 Nh4 36 g4 Ng6 37 Ke2 f6 38 f5 Ne5 39 Bd4 Nd7 40 Kf3 h6 41 Kf4 Nf8 42 h4 Nh7 43 Bc5 h5 44 gxh5

44...g5+ 45 hxg6 Resigns.

The source for this game is the score-sheet shown in our new feature article, The Danvers Opening (1 e4 e5 2 Qh5).

We gave the game’s conclusion on page 220 of the May 1988 BCM, in a ‘Quotes & Queries’ discussion on positions with a choice of en passant captures. The topic had been raised on page 158 of the April 1981 BCM by J.M. Aitken, who gave his game against G. Bakker, Jersey, 28 October 1980. Aitken commented: ‘I think this possibility must be quite unusual; I have not met it previously in my own practice.’ On page 410 of the September 1981 issue, Ian Rogers submitted his win against Murray Smith in the 1980 Australian Championship.

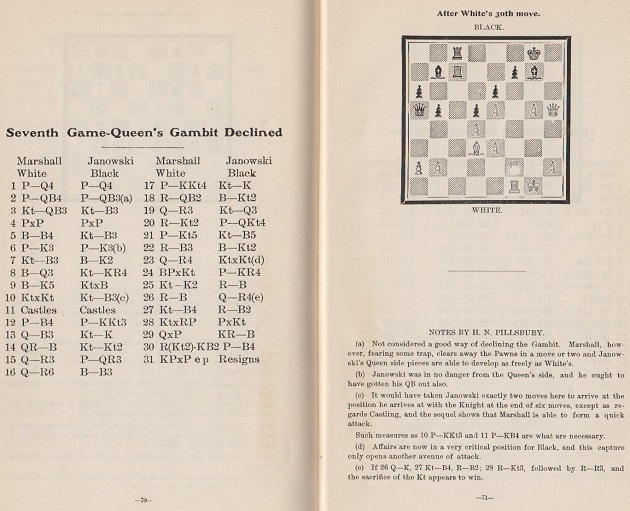

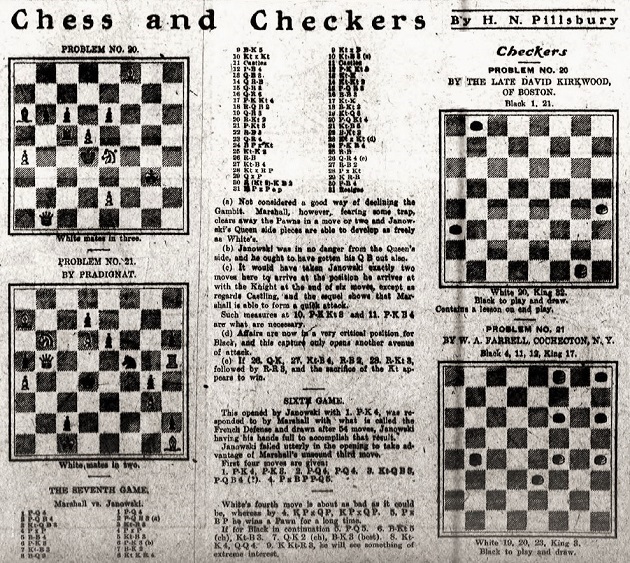

Computer searches today show that a choice of en passant captures is not rare. An old specimen between leading players is the seventh match-game Marshall v Janowsky, Paris, 9 February 1905, e.g. as published on pages 70-71 of volume two of Halpern’s Chess Symposium (New York, 1905):

Pillsbury’s notes were originally on page 2 of the Philadelphia Inquirer, 5 March 1905:

1 d4 d5 2 c4 c6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 cxd5 cxd5 5 Bf4 Nc6 6 e3 e6 7 Nf3 Be7 8 Bd3 Nh5 9 Be5 Nxe5 10 Nxe5 Nf6 11 O-O O-O 12 f4 g6 13 Qf3 Ne8 14 Rac1 Ng7 15 Qh3 a6 16 Qh6 Bf6 17 g4 Ne8 18 Rc2 Bg7 19 Qh3 Nd6 20 Rg2 b5 21 g5 Nc4 22 Rf3 Bb7 23 Qh4 Nxe5 24 fxe5 h5 25 Ne2 Rc8 26 Rf1 Qa5 27 Nf4 Rc7 28 Nxh5 gxh5 29 Qxh5 Rfc8 30 Rgf2

30...f5 31 exf6 Resigns.

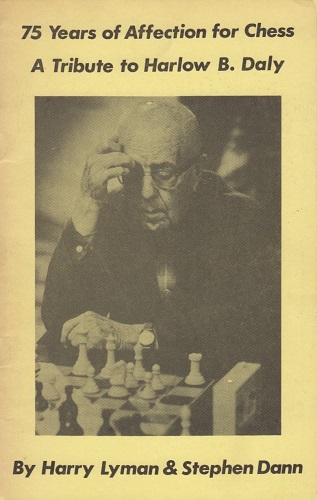

9598. H.B. Daly (C.N.s 5578 & 9597)

A 40-year-old 40-page booklet comprising 140 games (nearly all bare scores) by a little-known player may sound unenticing, but 75 Years of Affection for Chess A Tribute to Harlow B. Daly by Harry Lyman and Stephen Dann is well worth seeking out.

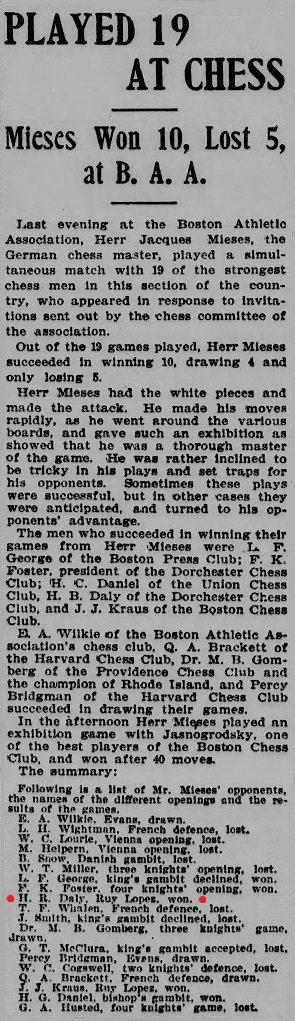

As shown by the booklet, in simultaneous exhibitions H.B. Daly (1883-1979) played, among others, Alekhine, Dake, Koltanowski, Lasker, Marshall, Mieses, Pillsbury and Torre. Below, from pages 7-8, is ‘one of Harlow’s best early games’:

Jacques Mieses – Harlow Bussey Daly

Simultaneous display, Boston, 5 December 1903

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 O-O Nxe4 6 Re1 Nc5 7 Nxe5 Nxe5 8 Rxe5+ Be7 9 Bb3 Nxb3 10 axb3 d5 11 Nc3 c6 12 Qe2 f6 13 Re3

13...d4 14 Rd3 Bf5 15 Ne4 Qd5 16 f3 O-O 17 c4 Qe6 18 Kh1 Rad8 19 Qf2 Bxe4 20 fxe4 Qxe4 21 Rf3 d3 22 Re3 Bc5 23 Rxe4 Bxf2 24 b4 Rfe8 25 Rxe8+ Rxe8 26 g3 Bd4 27 Kg2

27...Re1 28 b5 c5 29 bxa6 bxa6 30 Kf3 Kf7 31 Kf4 Kg6 32 g4 Be5+ 33 Kf3 Kg5 34 h3 g6 35 Kf2 Re2+ 36 Kf1 Kf4 37 Rxa6 Kf3 38 Ra3 Ke4 39 b3 Bd4 40 Ra2 (‘RR7’) Kf3 41 Bb2 Bf2 42 Ra1 Rxd2 43 Bxf6 Be3 44 Be5 Rg2 45 White resigns.

A report on the display was published on page 5 of the Boston Post, 6 December 1903:

Page 8 of the Daly booklet also gave a second win against Mieses, played two days later.

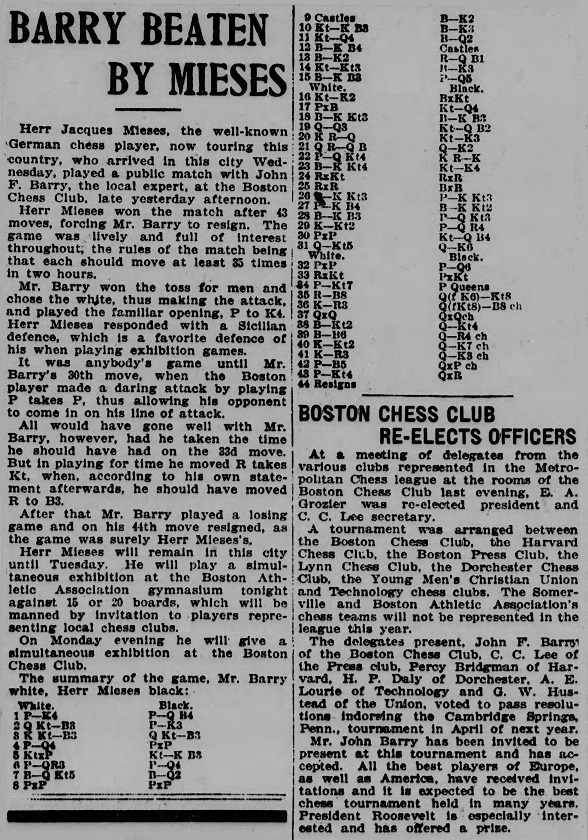

9599. Barry v Mieses

From page 3 of the Boston Post, 5 December 1903:

John Finan Barry – Jacques Mieses

Exhibition game, Boston, 4 December 1903

Sicilian Defence

1 e4 c5 2 Nc3 e6 3 Nf3 Nc6 4 d4 cxd4 5 Nxd4 Nf6 6 a3 d5 7

Bb5 Bd7 8 exd5 exd5 9 O-O Be7 10 Nf3 Be6 11 Nd4 Bd7 12 Bf4

O-O 13 Be2 Rc8 14 Nb3 Be6 15 Bf3 d4 16 Ne2 Bxb3 17 cxb3

Nd5 18 Bg3 Bf6 19 Qd3 Nc7 20 Rfd1 Ne6 21 Rac1 Qe7 22 b4

Rfe8 23 Bg4 Ne5 24 Bxe5 Rxc1 25 Rxc1 Bxe5 26 g3 g6 27 f4

Bg7 28 Bf3 b6 29 Kg2 a5 30 bxa5 Nc5 31 Qb5 Qe3 32 axb6

32...d3 33 Rxc5 dxe2 34 b7 e1(Q)

35 Rc8 Q3g1+ 36 Kh3 Qgf1+ 37 Qxf1 Qxf1+ 38 Bg2 Qb5 39 Bc6 Qh5+ 40 Kg2 Qe2+ 41 Kh3 Qe6+ 42 f5 Qxf5+ 43 g4 Qxc8 44 White resigns.

John Finan Barry

The draw between Barry and Mieses at Cambridge Springs, 1904 also began 1 e4 c5 2 Nc3 e6 (American Chess Bulletin, June 1904, page 10).

9600. My 61 Memorable Games

At our request, Aðalsteinn Thorarensen (Reykjavik) has kindly provided an English translation of a paragraph about My 61 Memorable Games on pages 168-169 of the new book mentioned in C.N. 9568, Yfir farinn veg með Bobby Fischer by Garðar Sverrisson (Reykjavik, 2015):

‘Some time after he came home [from hospital] we became aware of a new book in circulation, My 61 Memorable Games, which was claimed to be by Bobby. The book supposedly contained the 60 games that he had selected and annotated in his book My 60 Memorable Games with the addition of one game from his match against Spassky in 1992. Every time he had discussed the possibility of re-issuing this book [My 60 Memorable Games] he had been opposed to my idea of publishing it with revised annotations by himself and others, which I was convinced would make the book even more valuable. To Bobby, it was more important that the original sources should be preserved in their original form. To meddle with the text of an already published book was so ridiculous to him that I doubt whether he would have agreed to correct even obvious spelling mistakes, if found. My 60 Memorable Games was no less dear to him than many of his victories in chess. He was therefore very sad when I brought him the news of that counterfeit publication, which, we discovered later, had been illustrated with the Icelandic flag and photographs taken for private use by Icelanders with whom he was no longer associated.’

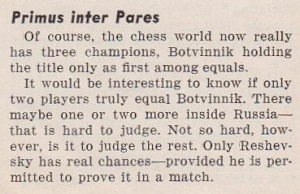

9601. Primus inter pares

Michael Henkhaus (Godfrey, IL, USA) asks for citations for the phrase primus inter pares (first among equals) with which Botvinnik is said to have described himself.

Below is an excerpt from William Hartston’s obituary of Botvinnik on page 12 of the Independent, 8 May 1995:

‘Twice coming back from defeat to regain the world title – the only man to do so – Botvinnik between 1948 and 1963 exerted an air of superiority over the chess world that has never since been matched. Even when, in the late 1950s, he commented that the days of a supreme world champion were long gone and described the reigning world champion as “primus inter pares”, everyone knew that Botvinnik himself was primus and the rest of them were the pares.’

From page 238 of the August 1954 Chess Review:

The final paragraph of Kmoch’s report (page 239):

9602. Sacrificing the opponent’s pieces

Tartakower is often attributed the remark that it is better to sacrifice the opponent’s pieces, but on what basis?

On page 1 of the New York Times, 16 February 1927 Capablanca wrote about Vidmar:

‘In London, in 1922 (where from the beginning he was a contender for chief honors), while talking about one of the weaker participants, he made the following typical remark:

“He has not learned yet to sacrifice his opponents’ pieces instead of his own.”

He meant, of course, that while a good many players will always look for a chance to sacrifice something in order to obtain a so-called brilliant victory, the real player knows that a sacrifice is only a means to an end, a weapon only to be used when no safer course is available.’

The full article is on pages 154-156 of our monograph on Capablanca. As shown on page 249, the Cuban made similar points in a lecture in Cuba on 25 May 1932:

‘As regards play in general, you will often meet players, especially inexperienced ones, who readily give up pawns, and sometimes even pieces, for an attack. I do not criticize this, because I believe that players must hold the initiative and attack as much as possible. But they should do this as a means of developing their imagination, not in the belief that this is a better way of playing. In this connection I will relate an anecdote about Dr Vidmar, one of the best players in the world who is also a man of science and a man of great ingenuity. At the London Tournament in 1922, in which we both participated, there was a relatively young player who did not have much experience. On a certain occasion, in a game in which he was carrying out a violent attack he sacrificed a piece (or two or three pawns; I do not remember exactly), but it could be seen that this gentleman, despite the attack, would reach an endgame a piece (or pawns) down. With regard to this case, Vidmar remarked that “he had not yet learned that it was the opponent’s pieces that had to be sacrificed”. I mention this anecdote because in reality one should never sacrifice anything when one is playing to win. Although, I repeat, it is a good exercise for young players with little experience. But those who are already knowledgeable and aspire to the first rank should do what Vidmar said: try to sacrifice the opponent’s pieces, since otherwise the attack almost always makes no progress. I wish to insist on this point because sacrificing a piece for an uncertain attack can give a bad result; a piece is too valuable to give it up on the basis of pure speculation. To sacrifice a piece one should be absolutely sure that one will quickly gain compensation, and it is recommended to do so, as I said before and repeat now, in order to exercise the imagination when one is a beginner. The experience of a defeat can help him to prevent an attack against him from being successful and to prevent an opponent’s sacrifice when his combination would be correct. On the other hand, when the sacrifice is not good, you can see that the best players in the world have played for years and years without making such offers, although they are often faced with an attack; they have ended up by winning because they gave up nothing except when they saw that the sacrifice was completely sound.’

9603. Fischer move by move

The claim on the cover that Lakdawala ‘is a highly prolific and respected author’ is half right. On page 5 a minuscule ‘bibliography’ omits virtually all the important books on Fischer, but includes a potboiler by Eric Schiller, and lists My 60 Memorable Games with the information ‘Batsford, 1969’. In his annotations, as ever, Lakdawala writes 50 words where a respected author would write five or, more probably, none.

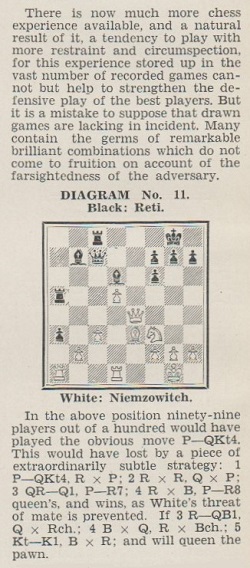

9604. Extraordinarily subtle strategy

Black has just played 21...a3.

‘In the above position ninety-nine players out of a hundred would have played the obvious move [xxx]. This would have lost by a piece of extraordinarily subtle strategy.’

The remark comes from page 14 of Modern Master-Play by F.D. Yates and W. Winter (London, 1929):

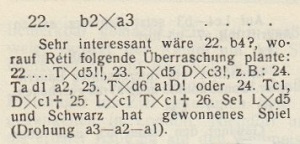

The game between Nimzowitsch and Réti occurred in the ninth round of a tournament in Berlin on 15 February 1928: 1 e4 c6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 dxe4 4 Nxe4 Nf6 5 Nxf6+ exf6 6 Bc4 Bd6 7 Qe2+ Be7 8 Nf3 O-O 9 O-O Bd6 10 Re1 b5 11 Bd3 Na6 12 a4 Nb4 13 axb5 Nxd3 14 Qxd3 cxb5 15 Qxb5 Qc7 16 Qd3 Bb7 17 d5 Rfc8 18 c3 a5 19 Be3 a4 20 Red1 Ra5 21 Qe4 a3 22 bxa3 Rxa3 23 Rxa3 Bxa3 24 c4 Qa5 25 Nd2 Bb4 26 h3 Qa2 27 Qb1 Qa4 28 Kh2 h6 29 Rc1 Ba6 30 c5 Bxc5 31 Rxc5 Rxc5 32 Bxc5 Qf4+ 33 Kg1 Qxd2 Drawn.

Modern Master-Play repeated analysis from Hans Kmoch’s annotations on pages 66-69 of the February 1928 Wiener Schachzeitung:

Whether or not, in the diagrammed position, nearly all players would select 22 b4 is an open question. In any case, computer analysis indicates, in Kmoch’s first variation, that after 25...a1(Q) ...

... White wins with 26 Qxb7.

9605. Photograph collection

The TopFoto website has a large collection of chess photographs. Interesting older pictures can be viewed by deselecting ‘RBG’ in ‘Image Attributes’.

9606. Photograph captions

There are worse ways of gauging magazines than by scrutinizing their photograph captions. Has care been taken? Are there babyish puns? Is worthwhile information conveyed, or are readers told what they can see for themselves?

As noted in How to Write about Chess, one caption trundled out occurs when people are shown laughing or smiling together: the reader is notified that they are ‘sharing a joke’ (or, for variety, ‘enjoying a joke’). Examples: ‘Producer Jimmy Komack (far left) and Erik Estrada share a joke’ (Chess Life, September 1988, page 32). ‘Short and Karpov enjoying a joke at Amsterdam 1991’ (CHESS, June 1992, page 11).

If caption-writers wish to entertain, and not just inform, a modicum of imagination is required.

9607. Reinfeld on Tartakower

‘Tartakower wrote many well-regarded books. Studded with brilliant insights and witty observations, they are nevertheless marred by a loquacity which often degenerates into mere chattiness and verbiage. In reading these books, it is therefore always necessary to seperate [sic] the gold from the dross, a task that calls for patience.’

Source: Great Moments in Chess by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1963), page 102.

9608. A capture with check

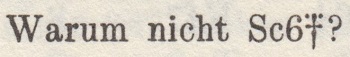

From page 38 of part one of Milan Vidmar’s Carlsbad, 1911 tournament book:

Quoting this (‘Warum nicht Sc6†?’) at the end of C.N. 9420, we intentionally simplified the check sign because although in HTML the character can be represented by the combination †̈ (i.e. two symbols), in most browsers the result is unsatisfactory.

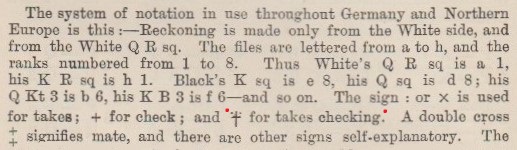

The dotted dagger was widely used in old chess literature, as shown by page 22 of The Principles of Chess in Theory and Practice by James Mason (London, 1894):

9609. Mason on changing the rules

The discussion in Mason’s The Principles of Chess in Theory and Practice regarding the stalemate and 50-move rules has been added to our respective feature articles.

9610. Mason and Reinfeld

From an article by Fred Reinfeld about Alexander Kevitz on pages 25-26 of the April 1946 Chess Review:

‘He credits much of his early interest and rapid progress to Mason’s Principles of Chess. (Years ago, by the way, the famous Mexican player Carlos Torre told me in almost the same words of his great debt to Mason’s books. Mason was not only a master of clear exposition; he also knew how to kindle the reader’s interest and how to stimulate his curiosity.)’

The same year, Reinfeld brought out a new edition of The Principles of Chess in Theory and Practice, published by David McKay Company, Philadelphia (and reprinted by Dover Publications, Inc., New York in 1960). The entire games section was replaced by 50 games annotated by Reinfeld.

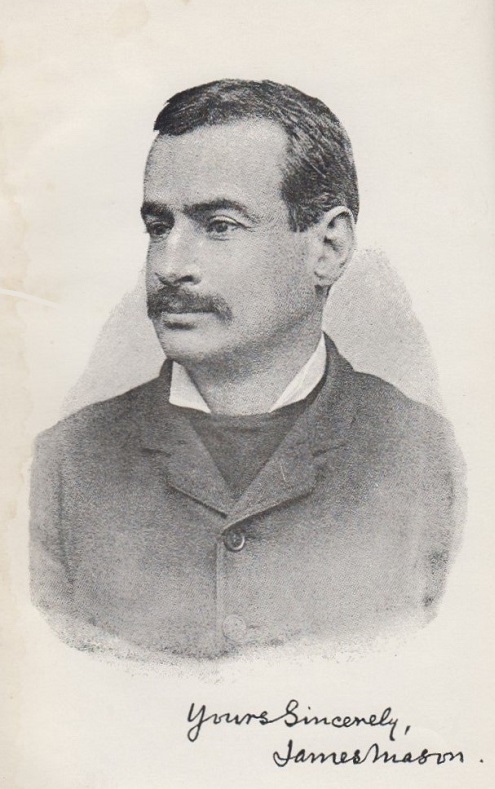

The frontispiece of the original (1894) edition of The Principles of Chess in Theory and Practice:

| First column | << previous | Archives [136] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.