Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [159] | next >> | Current column |

10604. Alekhine photographs

Jan Kalendovský (Brno, Czech Republic) sends, from the archives of the Zlín Chess Club, two photographs of Alekhine giving a simultaneous display in Zlín on 17 February 1943:

10605. Combinations

Regarding What is a Chess Combination?, Jean-Pierre Rhéaume (Montreal, Canada) notes that Lasker’s Manual of Chess does not mention the word ‘sacrifice’ in the definition of a combination. From page 123 of the 1927 book and page 109 of the 1932 edition:

‘In the rare instances that the player can detect a variation or net of them which leads to a desirable issue by force, the totality of these variations and their logical connections, their structure, are named a “combination”. And he who follows in his play such a chain of moves is said to “make a combination”.’

We recall a position from Blackburne v Weiss, New York, 1 April 1889:

Black to move

52...Bh4+ 53 Kf1 Bxe1 54 Kxe1 Kd3 55 h4 Kxc3 56 h5 Kb3 57 h6 c3 58 h7 c2 59 Kd2 f2 60 h8(Q) c1(Q)+ 61 Kxc1 f1(Q)+ 62 Kd2 Qf2+ 63 Kd3 Qc2+ 64 Ke3 Qc3+ 65 Qxc3+ Kxc3 66 Ke4 Kb3 67 Kd4 Kxa3 68 Kc3 Ka2 69 Kc2 a3 70 Kc1 Kb3 71 White resigns.

On page 140 of The Most Instructive Games of Chess Ever Played (New York, 1965) Irving Chernev commented after 52...Bh4+:

‘This begins a 15-move combination. Despite its length, it is easy enough to visualize and understand it, if we break it down.’

Chernev then listed six stages in ‘the series of ideas’.

After 54...Kd3 Steinitz wrote on page 74 of the New York, 1889 tournament book:

‘The rest speaks for itself, for every move of the opponent is forced. Very likely, Herr Weiss had foreseen the present position and played for it some moves ago, before exchanging bishops, but, undoubtedly, he must have fore-calculated the very end of this game 16 moves later, when he did effect the exchange and relied on the move in the text.’

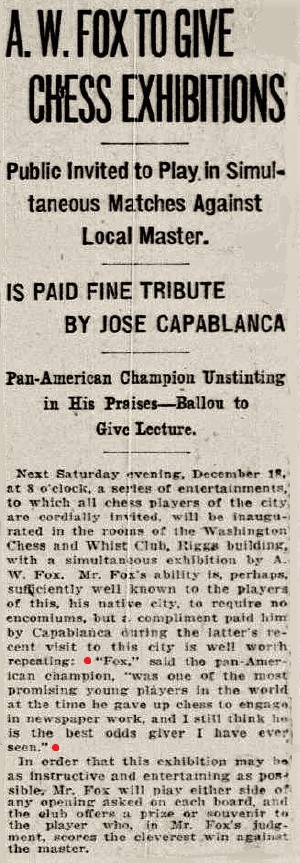

10606. Albert Whiting Fox (C.N. 2169)

John Hilbert (Amherst, NY, USA) reverts to C.N. 2169 (see page 330 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves), which sought corroboration of a claim by William M. Russell (American Chess Bulletin, April 1927, page 82) that Capablanca learned from A.W. Fox ‘his art of stalling and waiting for his opponent to blunder’.

Our correspondent notes that page 4 of the Washington Sunday Star, part five, 12 December 1915 quoted a compliment by Capablanca about Fox:

Capablanca’s quoted words: ‘Fox ... was one of the most promising young players in the world at the time he gave up chess to engage in newspaper work, and I still think he is the best odds giver I have ever seen.’

Dr Hilbert adds that in a 26-board simultaneous display in Washington on 20 November 1915 it was only Fox’s draw that denied Capablanca a clean score. Source: part five of the Sunday Star, 28 November 1915, page 4, which gave the (familiar) game-score.

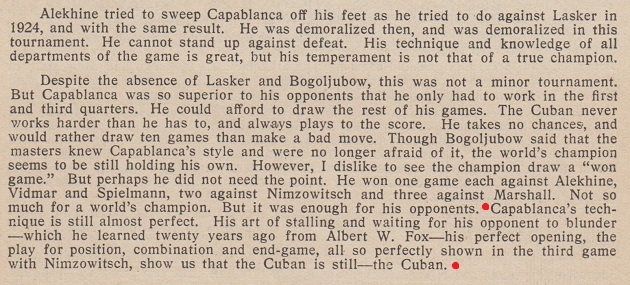

Below is the conclusion of William M. Russell’s above-mentioned article on New York, 1927:

See too The Fox Enigma.

10607. Louis Persinger (C.N. 10600)

Eric Fisher (Hull, England) reports that he has a copy of Marshall’s Chess “Swindles” (New York, 1914) inscribed by Marshall ‘to the great attacking master, Louis Persinger. With kind remembrances ...’ It was dated New York, 15 June 1940.

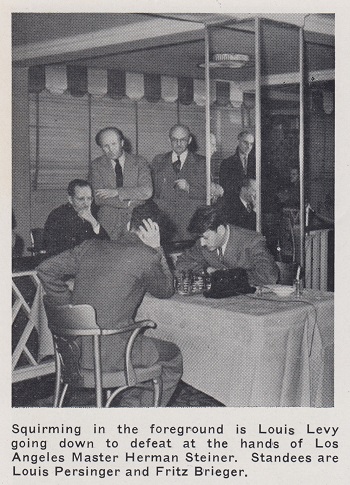

The photographs below show Persinger spectating at the 1942 US championship in New York and were published on, respectively, page 86 and page 92 of the April 1942 Chess Review:

Two games submitted by Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA):

Hermann Helms – Louis Persinger

Played at ten seconds per move (exact venue and

date?)

Petroff Defence

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 Nxe5 d6 4 Nf3 Nxe4 5 d4 d5 6 Bd3 f5 7 c4 c6 8 cxd5 cxd5 9 Nc3 Nc6 10 O-O Be7 11 Qe2 Nxc3 12 bxc3 O-O 13 Bf4 Re8 14 Rfe1 Bd7 15 Rab1 b6 16 Qc2 g6 17 Qb3 Bf6 18 Qxd5+ Kg7 19 Bc4 Rxe1+ 20 Rxe1 Rc8 21 Qf7+ Kh8

22 Re8+ Resigns.

Source: New York Post: 7 December 1942, page 50.

Herman Steiner – Louis Persinger

US championship, New York, 7 May 1944

Queen’s Gambit Declined

1 d4 d5 2 c4 e6 3 Nc3 Nf6 4 Bg5 Be7 5 e3 O-O 6 Nf3 c6 7 Qc2 Nbd7 8 a3 dxc4 9 Bxc4 Nd5 10 Bxe7 Qxe7 11 O-O b6 12 Ne4 Bb7 13 Neg5 g6 14 e4 N5f6 15 e5 Nd5 16 Ne4 Rad8 17 b4 Kg7 18 Rfe1 b5 19 Bb3 N7b6 20 Rac1 Ba8 21 Nc5 Nd7 22 Ne4 h6 23 h4 f5 24 exf6+ N7xf6 25 Nc5 Rd6

26 Ne5 Qe8 27 g3 g5 28 hxg5 hxg5 29 Kg2 Nh5 30 Bxd5 Rxd5 31 Rh1 Rf5 32 Rxh5 Rfxe5 33 Qh7+ Kf6 34 dxe5+ Resigns.

Source: Los Angeles Times, 28 May 1944, page 13.

In the 1944 US championship Persinger finished last, scoring +0 –17 =1. From page 27 of the April 1944 Chess Review:

‘Louis Persinger of the faculty of the Juilliard Music School had a complete explanation of his fractional score: “The boards were out of tune”.’

10608. Endgame studies

From page 22 of How To Get More Out Of Chess by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1957):

‘Chess studies are the riddles and whodunits of chess.’

10609. Bad Pistyan, 1912 group photographs (C.N.s 3447 & 6233)

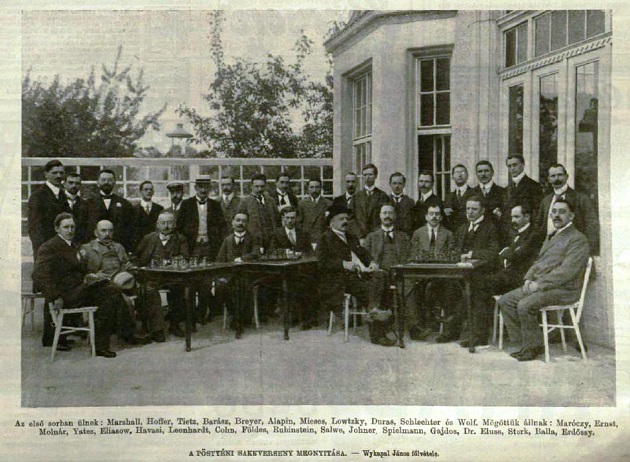

Three group photographs of the Bad Pistyan, 1912 tournament:

The first photograph is a better version of the one shown in C.N. 3447 and has been provided by Jan Kalendovský (Brno, Czech Republic) from page 105 of the 7/1912 Časopis českých šachistů. The second one comes from C.N. 6233, and the third is supplied by Mr Kalendovský from page 471 of Vasárnapi Ujság, 9 June 1912. Our correspondent draws attention to the discrepancies concerning the presence/absence of Pokorný and Hromádka with respect to the photographs and captions.

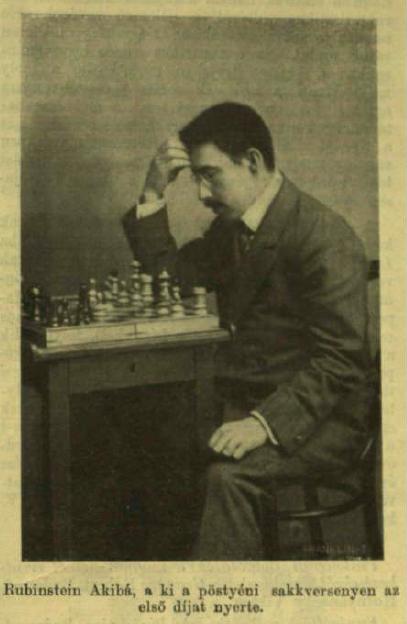

Also in connection with Pistyan, 1912 Mr Kalendovský gives this photograph from page 511 of Vasárnapi Ujság, 23 June 1912:

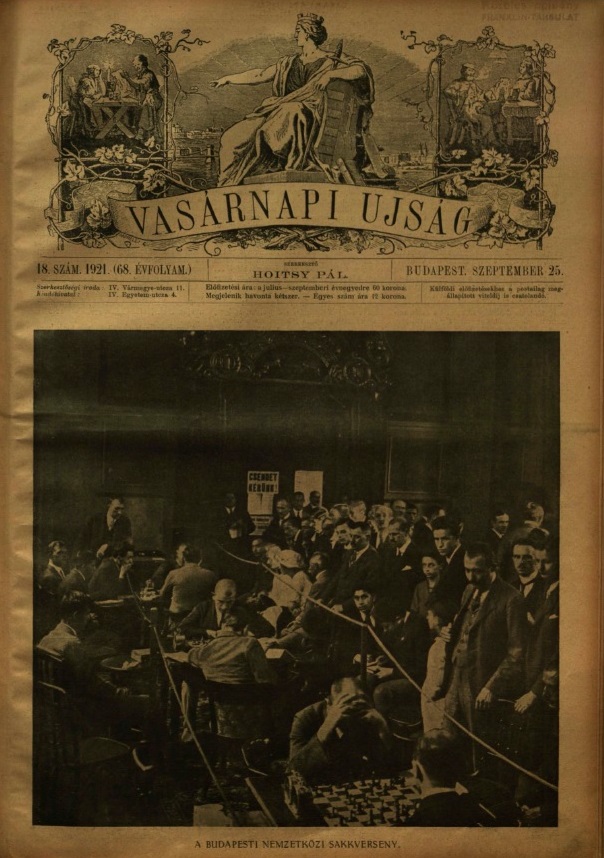

10610. Budapest, 1921

A further contribution from Jan Kalendovský concerns the 25 September 1921 issue of Vasárnapi Ujság, which had a number of chess illustrations, including one on the front page:

Mr Kalendovský notes that the game in the foreground appears to be between Tartakower (back to the camera) and Vajda, after 1 c4 c5 2 e3 e6 3 d4 d5 4 Nf3 Nc6 5 Nc3 Nf6 6 a3. Larger versions of the photograph and the board position are provided.

The same day (ninth round, 15 September 1921) Alekhine played 1...Nf6 against E. Steiner, in one of the future world champion’s earliest and most famous games with Alekhine’s Defence.

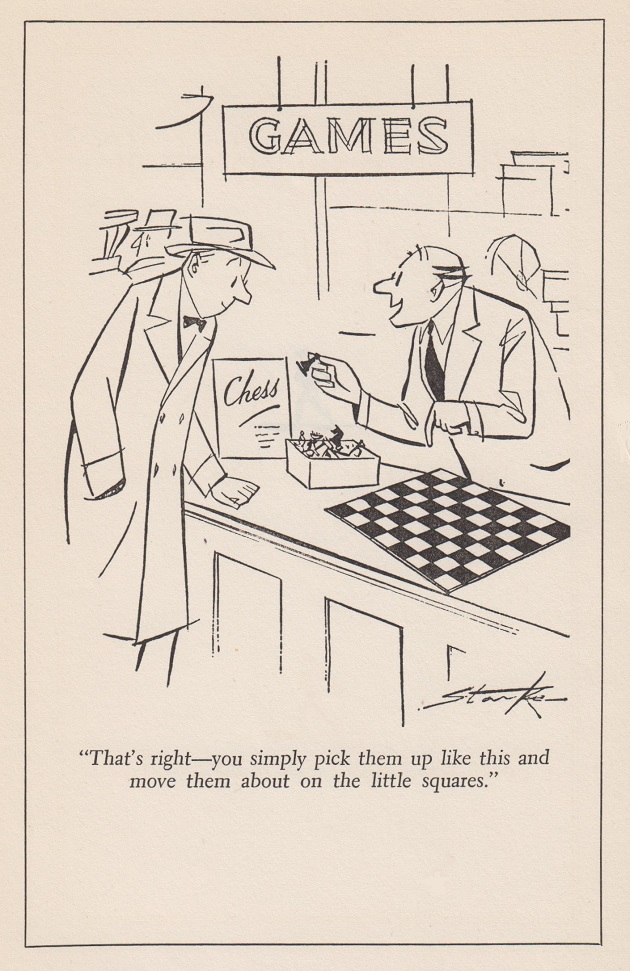

10611. Leslie Starke cartoon

This cartoon by Leslie Starke was the frontispiece of The Fireside Book of Chess by Irving Chernev and Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1949). The imprint page stated that it had appeared earlier the same year in the Saturday Evening Post.

10612. Casablanca (C.N. 10495)

Ed Hamelrath (Dresden, Germany) draws attention to a webpage with many behind-the-scenes photographs taken during the production of Casablanca, including (fifth from the bottom) a shot of Humphrey Bogart playing chess against Paul Henreid.

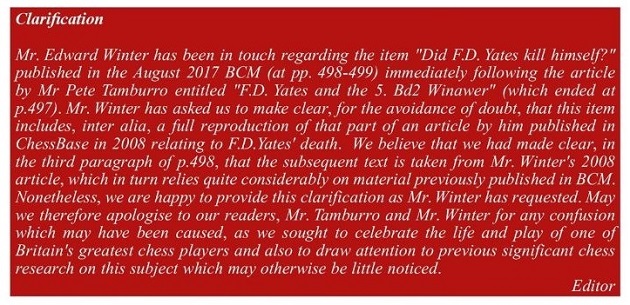

10613. F.D. Yates and the BCM

Further to C.N.s 10538 and 10579 (see The Death of F.D. Yates), page 614 of the October 2017 BCM has the following:

We were ‘in touch’ with the BCM in the sense that on 29 September 2017 we responded to a message (nearly 600 words) received the previous day from Mr Milan Dinic of the BCM. His main defence was that the Yates article in the August 2017 BCM had faulty typesetting (misuse of quotation marks), an argument not only absent from the October 2017 ‘Clarification’ but also in direct contradiction with the magazine’s assertion therein beginning ‘We believe that we had made clear ...’

Our e-mail reply of 29 September 2017:

Dear Mr Dinic,

Thank you for your e-mail message of 28 September 2017 regarding the unsigned article ‘Did F.D. Yates Kill Himself?’ on pages 498-499 of the August 2017 BCM. Please ensure that your apology in the magazine presents the following points:

1. Apart from an introductory overview of Yates’ career which the BCM lifted from Wikipedia, the entire BCM article was copied, word for word, from my feature on Yates at ChessBase in 2008. It should be stressed that that complete feature of mine was reproduced. (Please do not mislead your readers by claiming, as your e-mail message does, that you ‘took under a third of the full [ChessBase] article’; that is only because the rest of my ChessBase article consisted of other features which were nothing to do with Yates.)

2. Even without any BCM typesetting mistakes (concerning quotation marks) of the kind that you indicate, the BCM was obviously not entitled to reproduce an entire feature of mine (approximately 700 words). No fewer than 93 lines of the BCM article were written by me, i.e. about 80% of the text in the two-page BCM article.

3. In acknowledgement of its misappropriation of my work, I ask the BCM to make a substantial donation to charity, and I propose Dimbleby Cancer Care.

Thank you in advance.

Yours sincerely,

Edward Winter

No reply has been received.

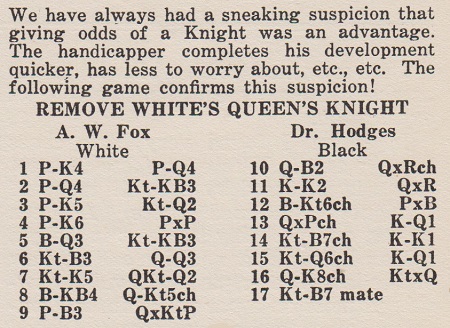

10614. Another Fox brilliancy

From John S. Hilbert (Amherst, NY, USA):

‘In working on a book about Albert W. Fox, I ran across a curious series of references to the following game, in which, playing White, he gave queen’s knight odds:

1 e4 d5 2 d4 Nf6 3 e5 Nfd7 4 e6 fxe6 5 Bd3 Nf6 6 Nf3 Qd6 7 Ne5 Nbd7 8 Bf4 Qb4+ 9 c3 Qxb2 10 Qc2 Qxa1+ 11 Ke2 Qxh1 12 Bg6+

The game is said to have concluded with 12...hxg6 13 Qxg6+ Kd8 14 Nf7+ Ke8 15 Nd6+ Kd8 16 Qe8+ Nxe8 17 Nf7 mate.

This version of the score appears in a series of publications, such as Irving Chernev’s 1955 book 1000 Best Short Games of Chess, pages 242-243, and Chess Review, March 1960, page 75 (in an article by Walter Korn, which quoted the game from Chernev’s book). Without any supporting details, both sources presented the game as Fox-Hodges, New York, 1937.

An earlier source is page 38 of Chess Review, February 1937:

That publication may explain why the game was said to have been contested in 1937. Chess Review does not state that it was played in New York, or in that year, but names Black as “Dr Hodges”. His poor play and the fact that he received knight odds indicate that he was not Albert B. Hodges, the well-known player of another generation.

How did the game-score get into Chess Review in February 1937? Albert Fox lived in Washington, DC. Israel Horowitz, the Editor of Chess Review, participated in a private consultation game at the residence of the chess player, patron and problemist, William K. Wimsatt, Sr, Albert Fox’s brother-in-law, on 1 December 1936, and Fox was present as the referee (Washington Post, 6 December 1936, page F4). It is possible that the game was shown to Horowitz at that time, although that still does not prove where, when and against whom the game was played.

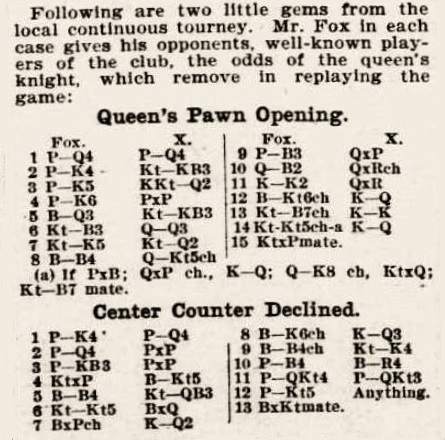

A far earlier source clears up some of these mysteries, while creating another significant one. Fox played against an unnamed opponent in the Washington, DC, Continuous Handicap Tourney, in early 1902 (the first of the two games below):

Washington Evening Star, 29 March 1902, page 22

In this version the conclusion is different: 12…Kd8 13 Nf7+ Ke8 14 Ng5+ Kd8 15 Nxe6 mate.

As regards Fox’s opponent, a “Dr Hodges” was an active Washington Chess Club member during at least the period 1897-1903. See, for instance, the Washington Evening Star of 13 April 1897, page 8; 20 January 1900, page 9, which includes a loss by Dr Hodges; 13 September 1902, page 9, where Dr J.W. Hodges was reported as leading the local continuous chess tournament; 11 January 1903, page 9, which stated that Dr J.W. Hodges had been elected a member of the Washington Chess Club’s executive committee.

It therefore appears reasonable to conclude tentatively that the 15-move game was contested between Albert W. Fox and Dr J.W. Hodges in the Washington Chess Club’s Continuous Handicap Tournament in 1902.

Why the scores diverge is unclear. Thirty-five years passed between the game’s appearance in the Washington Evening Star and its republication in Chess Review in 1937. If Fox intentionally replaced the 1902 game’s conclusion with a more spectacular variation, given to Horowitz in late 1936 and published by him in 1937, that could be seen as supporting the conclusion that other games by Fox (as discussed in The Fox Enigma) may also have been, in whole or in part, an invention or, even, a hoax.

Naturally, though, there are many other possibilities. It is unknown whether Fox gave the score to Horowitz for publication, let alone whether he intentionally altered it. Someone else (such as Wimsatt) may have shown Horowitz the game, confusing the actual score with the longer variation. Or Fox himself may have forgotten, in all honesty, which was which. The 35-year gap between play and republication offers a wide field for unintentional error. Then again, Horowitz himself may have confused game and variation when publishing the score in Chess Review a few months later, and especially if, in December 1936, he had merely been shown the game over the board. All that can be said for certain is that between 1902 and 1937 the game’s conclusion was made more spectacular.’

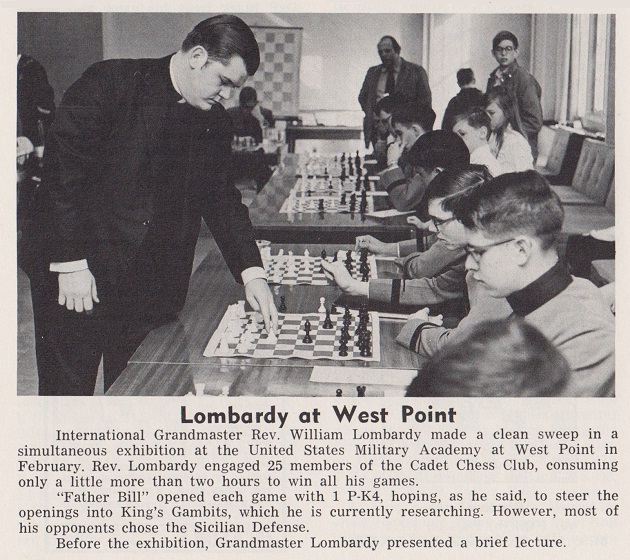

10615. William Lombardy (1937-2017)

Chess Life & Review, May 1971, page 274

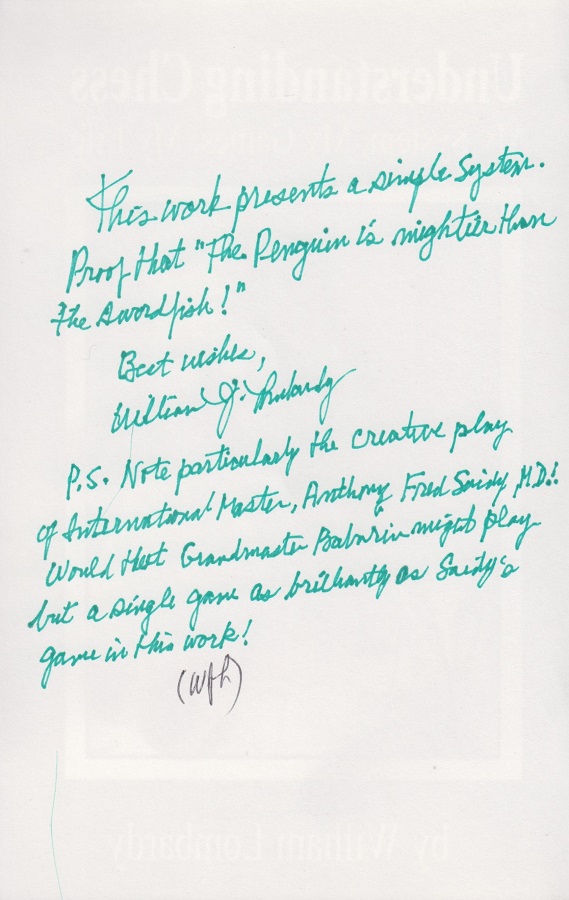

Lombardy’s inscription in our copy of his book Understanding Chess (Milford, 2011):

The reference is to Baburin v Saidy, Los Angeles, 1997 on

pages 306-307. Concerning Lombardy’s book, see too C.N.

7578.

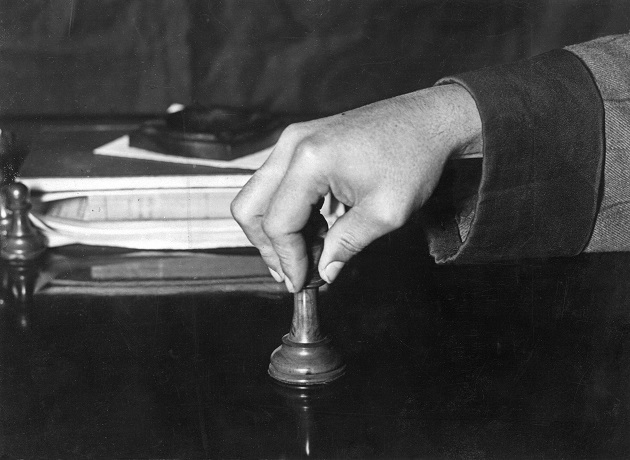

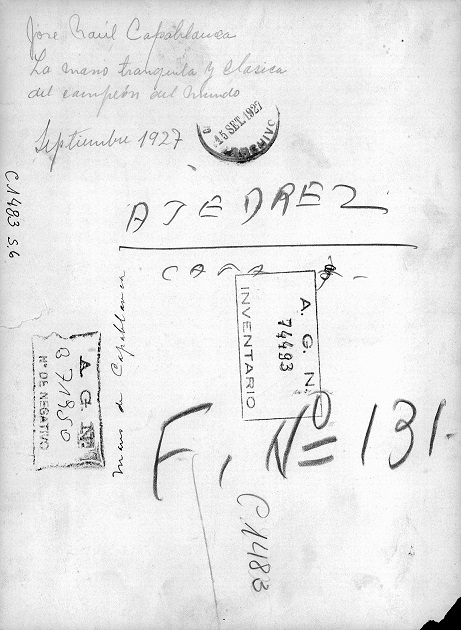

10616. Capablanca’s hand

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) forwards this photograph (reference AR_AGN_DDF/Consulta_INV: 74493) from Argentina’s Archivo General de la Nación, courtesy of the Ministerio del Interior, Obras Públicas y Vivienda:

‘José Raúl Capablanca

La mano tranquila y clásica

del campeón del mundo

Septiembre 1927’

10617. Rev. Roger John Wright

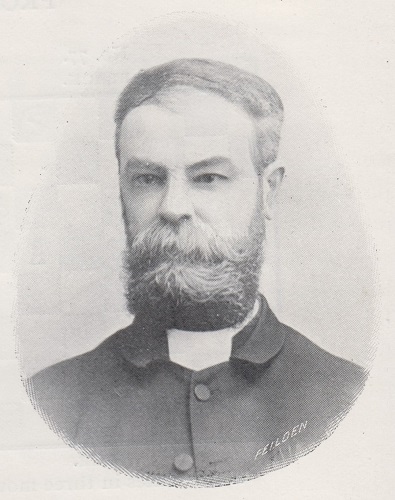

Roger J. Wright, mentioned in Chess and Poetry and in Chess Corn Corner, was a familiar name in the field of chess problems (see, for instance, C.N. 8121), and he received four pages in The Chess Bouquet by F.R. Gittins (London, 1897). The feature began, on page 34, with this portrait:

Reverend Roger John Wright (1849-1924)

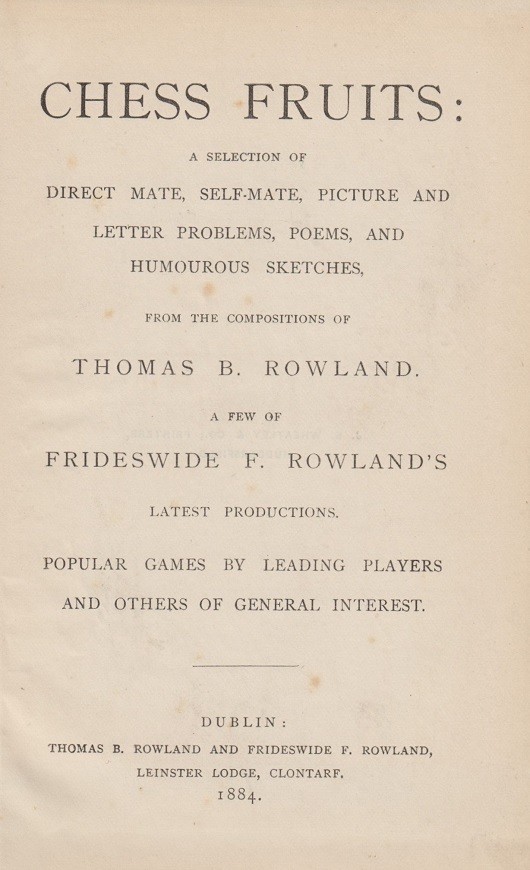

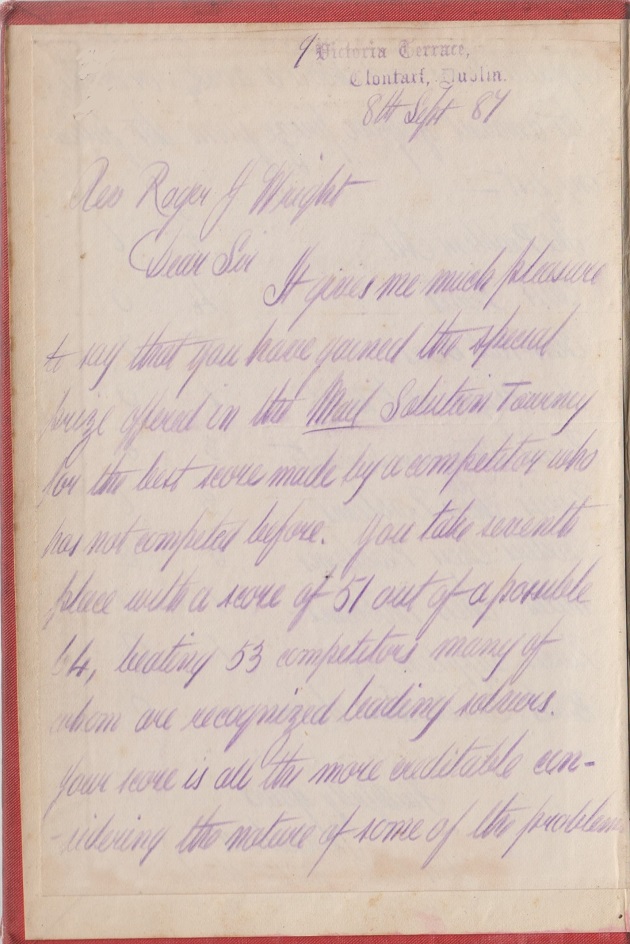

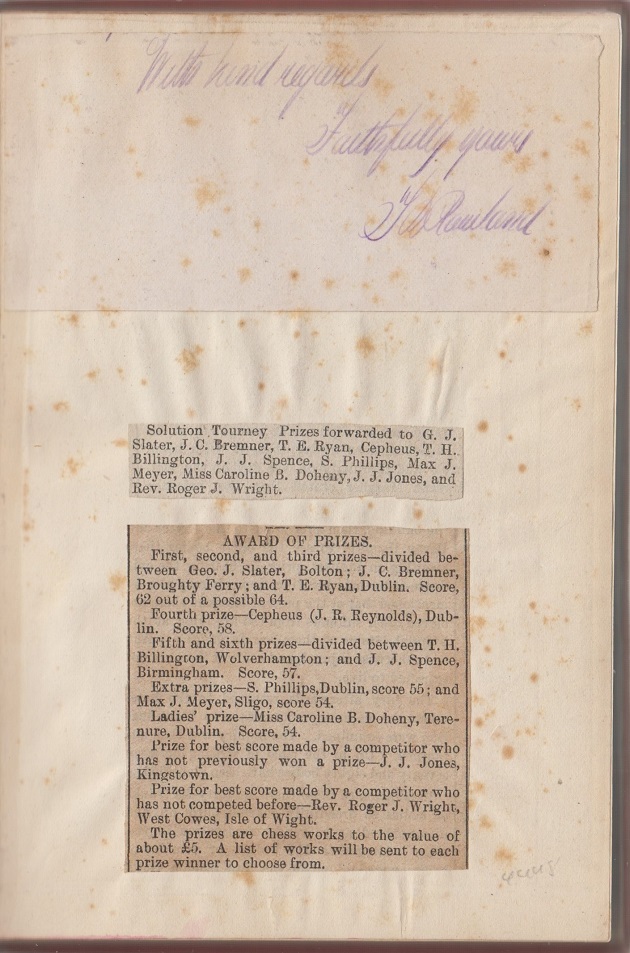

His copy of Chess Fruits by Thomas B. Rowland and Frideswide F. Rowland (Dublin, 1884), which we own, has a letter from the former pasted onto the front pages:

10618. White to move

The next C.N. item will discuss this position:

White to move

10619. White to move (C.N. 10618)

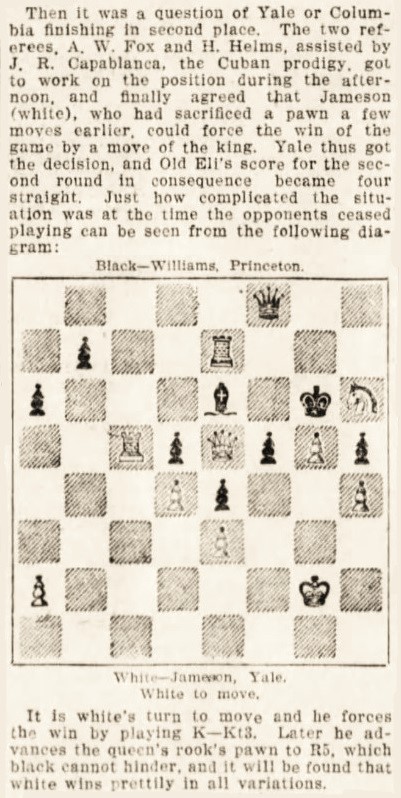

The diagram in C.N. 10618 was on page 5 of section 5 of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 24 December 1905, as provided by John Hilbert (Amherst, NY, USA):

So far, no additional information has been found about the adjudication analysis by Fox, Helms and Capablanca. Nor has the full game-score been traced.

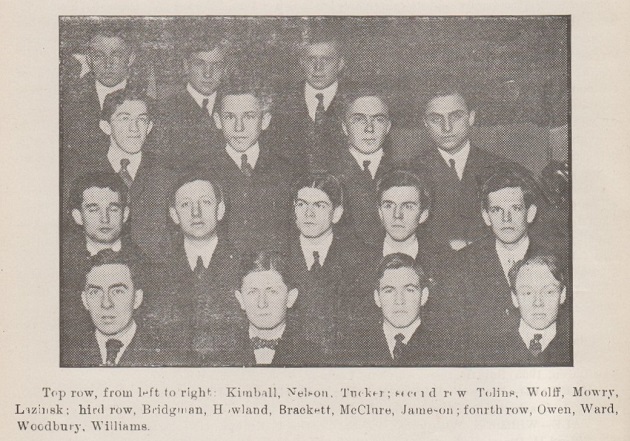

The outcome of the contest between Yale and Princeton, played on 22 December 1905 in the 14th ‘C.H.Y.P.’ (Columbia, Harvard, Yale, Princeton) match in New York, was in the report on pages 1-6 of the American Chess Bulletin, January 1906. Jameson and Williams had appeared in a group photograph for the previous year’s event:

Source: American Chess Bulletin, January 1905, page 4.

10620. ‘The Immortal Blindfold Game’ (C.N.s 8564, 8567 & 8575)

Nicholas Schwartz (São Paulo, Brazil) writes to us regarding the loser of ‘The Immortal Blindfold Game’ (Alekhine v Schwartz, London, 1926):

‘My paternal grandfather, Nicolai Eugen Schwartz, was born in Riga on 20 November 1893. He was from a merchant and banking family with business interests in the Baltic States, Russia, Germany and Great Britain, and was sent to Scotland in November 1913 to study the flax, jute and hemp industries and to seek out prospective business contacts. Dundee was chosen as his base because of the city’s association with those fibre industries and because Henry W. Rennie, a fairly prosperous Dundee merchant and shipowner, was my grandfather’s godfather. Above all, Nicolai Schwartz was sent to Dundee to invest a substantial sum in Rennie’s firm.

My grandmother’s maiden name was Jeanne Catherine Carolina Marie Vernon Le Cocq: her father, John Le Cocq, of Jersey and Alderney, had married Rose Vernon.

My grandfather never returned to Riga, but remained in Dundee. He had three children: Olga Stella, who was born in 1917, Alexander Nicolai (my father), born in 1918, and Nicolai Roy (born in 1920 and killed in 1944 whilst flying for the RAF). In the 1920s the family moved to London, first to Norwood, then Streatham and ultimately to Clapham.

In London, Nicolai Schwartz frequented the Gambit Chess Rooms and Simpson’s Divan. He had been brought up to live a very easy life and he never went to work. I well remember him sitting all day long solving chess and bridge problems in books and newspapers, while smoking and drinking tea endlessly. He was always discreetly and impeccably dressed, exceptionally well mannered, invariably kind and absolutely devoted to my grandmother until the day he died, in Putney, London, on 20 March 1965.

He talked about chess much of the time, and most of his gifts to me, when I was seven or eight, were books on chess problems. I still own his Staunton chess sets, his chess boards, one of which rolled up for travelling, and his wallet-type Jaques chess set.’

We are also grateful to our correspondent for this photograph (the reverse of which states ‘Taken in Dundee 1916’):

Nicolai Eugen Schwartz

10621. Alekhine photographs (C.N. 10604)

Ross Jackson (Raumati South, New Zealand) provides two photographs which he owns:

Kroměříž, 11 February 1943

Zlín, 17 February 1943

We have added the date of the Kroměříž exhibition from the table of the world champion’s simultaneous performances in Alechin v Československu by Jan Kalendovský (Brno, 1992).

10622. Small books on Fischer’s games

From Richard Reich (Fitchburg, WI, USA):

‘Michael Basman published four small books in a series called Turnover Chess. They ranged in length from 23 to 47 pages, and each consisted of one game, presented with notes and diagrams. No date of publication was indicated.’

The games were Fischer’s wins over Sherwin (New Jersey State Open Championship, 1957), Fine (New York, 1963 – and not 1960 as stated on the cover and on the first page), Weinstein (US Championship, 1960-61) and Gudmundsson (Reykjavik, 1960).

10623. Combination

Regarding the term ‘combination’, Leonard McLaren (Onehunga, New Zealand) quotes from page 89 of Learn Chess Tactics by John Nunn (London, 2003):

‘... now we focus exclusively on situations in which the winning idea depends on two or more tactical elements. In this book we use the word “combination” to describe such situations but, as with many chess terms, there is no generally accepted definition of “combination” and you should be aware that other authors may use this word in a different sense ...

There is no clear dividing line between a “tactic” and a “combination”, since there is a whole spectrum of difficulty from one-move tactics to massively complex multi-move combinations.’

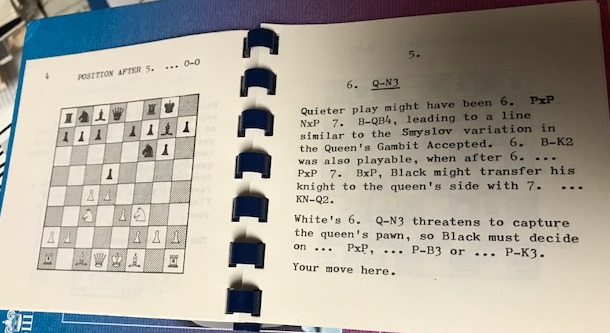

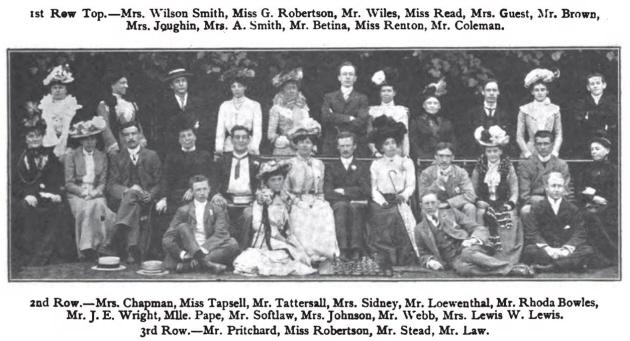

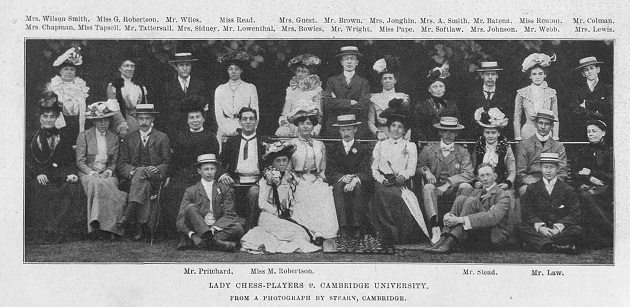

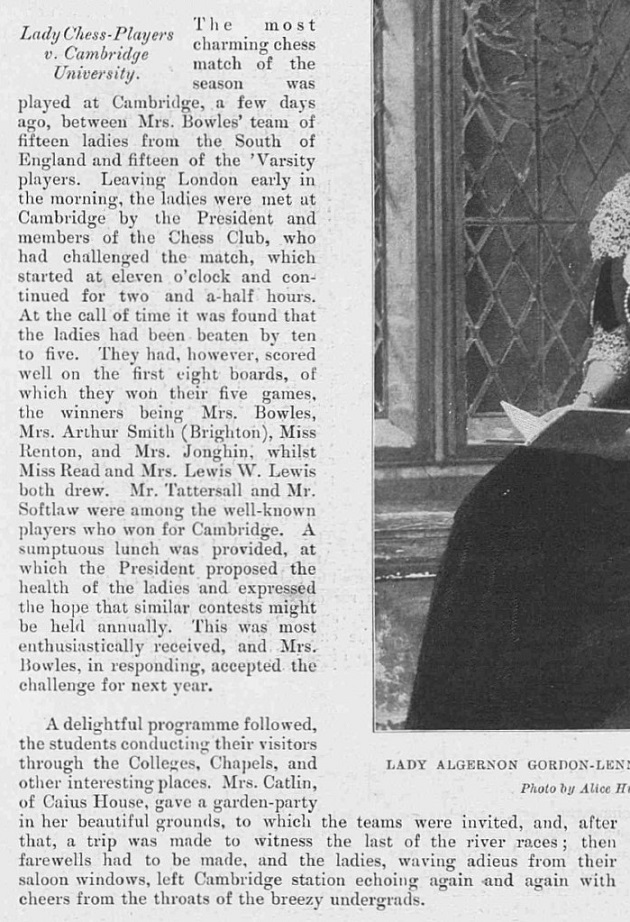

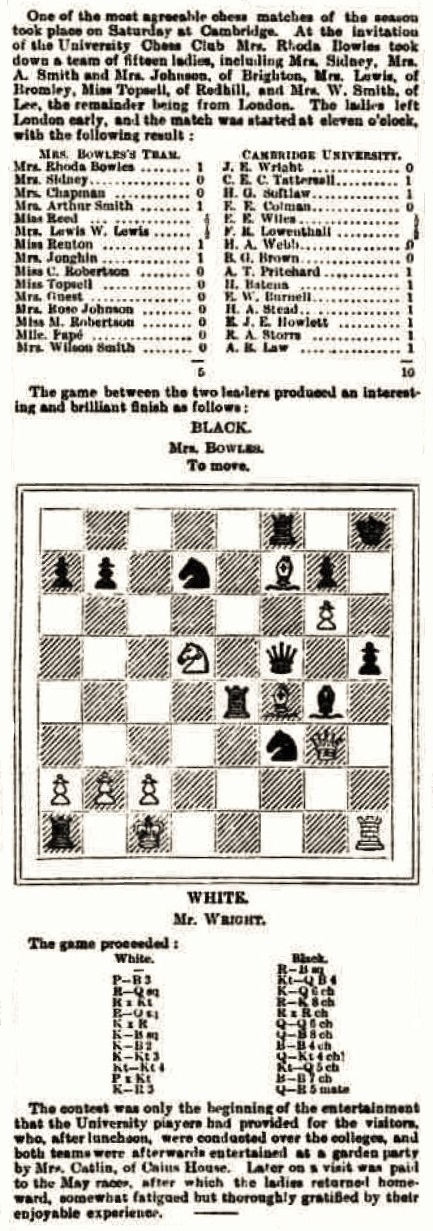

10624. Oxbridge photographs (C.N. 7470)

The above photograph was given in C.N. 7470, from page 129 of the July 1901 edition of Womanhood.

Gerard Killoran (Ilkley, England) now sends the following, published on page 335 of The Sketch, 19 June 1901:

The accompanying account:

Mr Killoran also provides a match report on page 3 of the Morning Post, 10 June 1901:

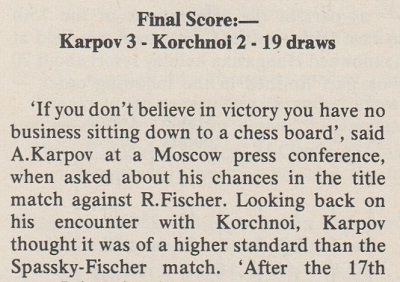

10625. Karpov quote

From page 16 of The Batsford Chess Yearbook by Kevin J. O’Connell (London, 1975):

‘Quote of the Year

“If you don’t believe in victory you have no business sitting down to a chess board.” Anatoly Karpov.’

No source was provided, but we give the following from page 3 of the January 1975 BCM:

Corroboration of the remarks in a Soviet source will be appreciated.

10626. White to move (C.N.s 10618 & 10619)

Frits Fritschy (Leiden, the Netherlands) wonders how much analysis Fox, Helms and Capablanca needed to undertake, given that after 1 Kg3 Black has very few options, e.g. 1...Qg7 2 Rxd5 and 1...Bg8 2 Qh8.

From Richard Forster (Zurich):

‘1 Kg3 clearly wins, as do some other moves. A cute, though unnecessary, combination is 1 Kg3 Kh7 2 Kf4 Kg6 3 Ng8 Bxg8

4 Rc8 and wins.’

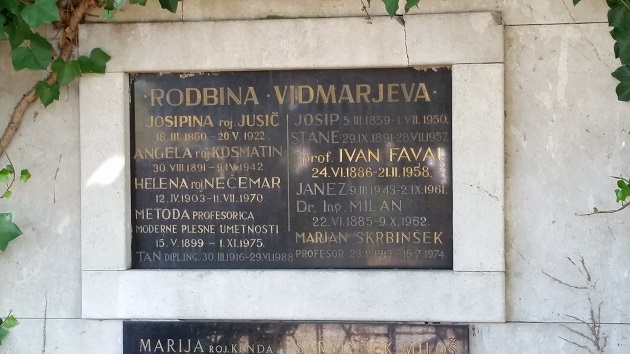

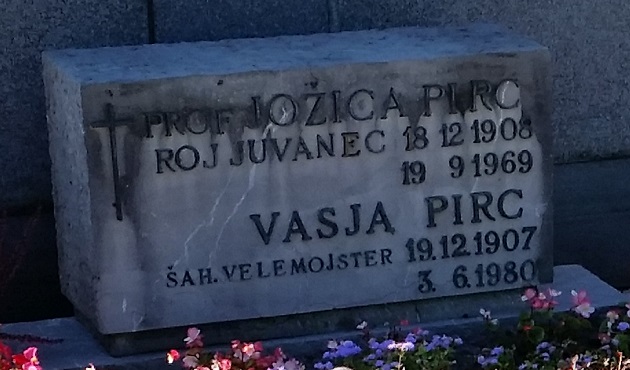

10627. Vidmar and Pirc

Further to Graves of Chess Masters, Jan Hessel (Rättvik, Sweden) reports that earlier this month he took these photographs in the Žale cemetery in Ljubljana:

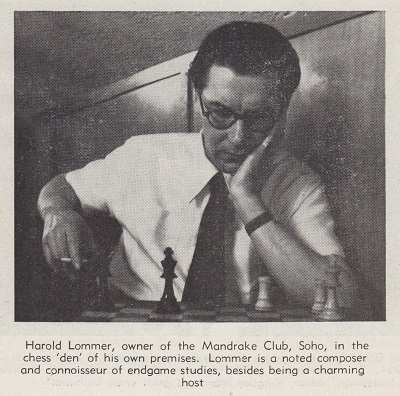

10628. Harold Lommer

A rare photograph of Harold Lommer (1904-80), from opposite page 40 of Chess Springbok by Wolfgang Heidenfeld (Cape Town, 1955):

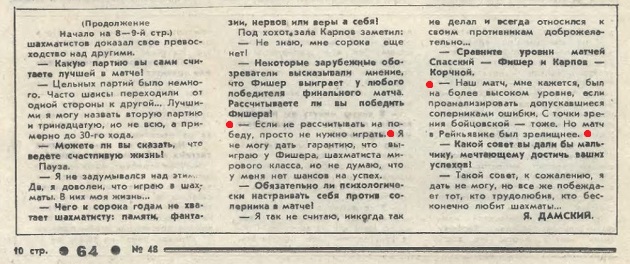

10629. Karpov quote (C.N. 10625)

Dan Scoones (Port Coquitlam, BC, Canada) provides part of an interview with Karpov on page 10 of the 48/1974 issue (29 November-5 December) of 64:

Asked whether he expected to defeat Fischer, the future world champion replied: ‘Если не рассчитывать на победу, просто не нужно играть’. One of several possible translations is, ‘If you do not expect to win, you simply do not need to play’.

Our correspondent also notes Karpov’s view that, in terms of competitiveness and the number of mistakes, his match with Korchnoi was on a higher level than the Spassky-Fischer contest in Reykjavik, although the latter was more entertaining.

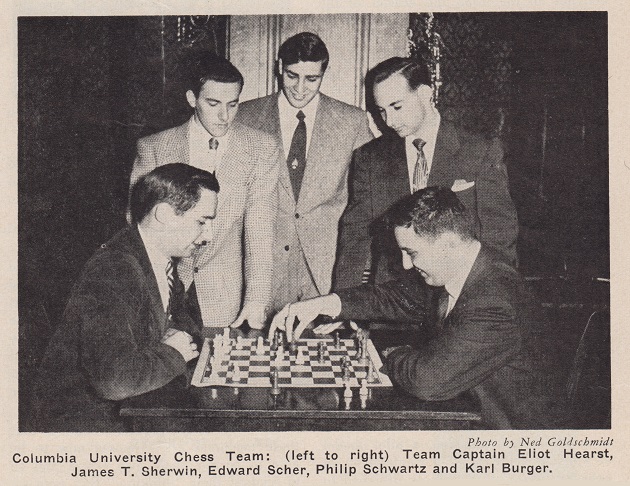

10630. Eliot Hearst and Karl Burger (C.N.s 10576 & 10584)

From page 35 of the February 1953 Chess Review:

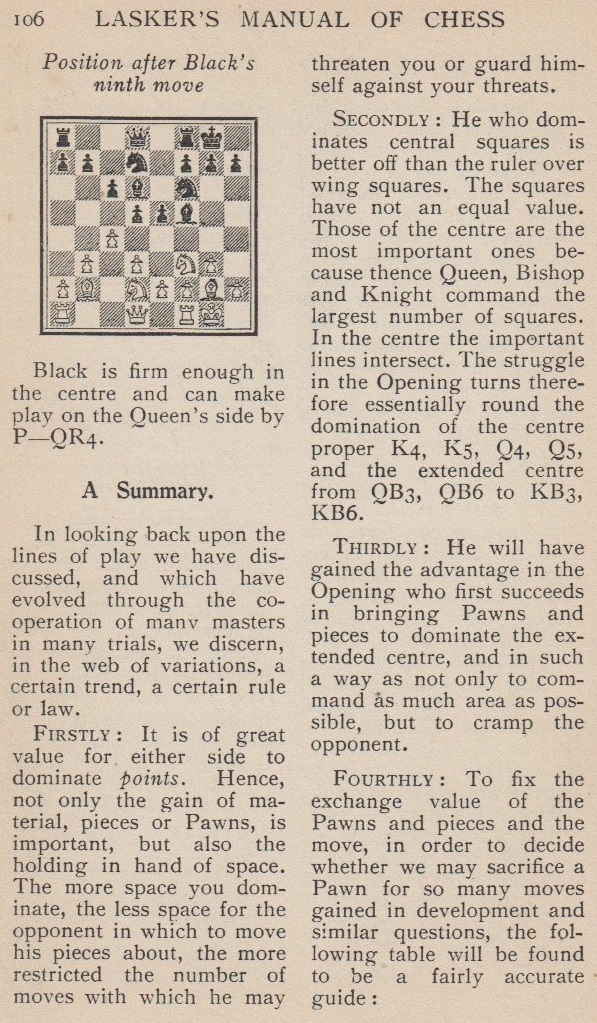

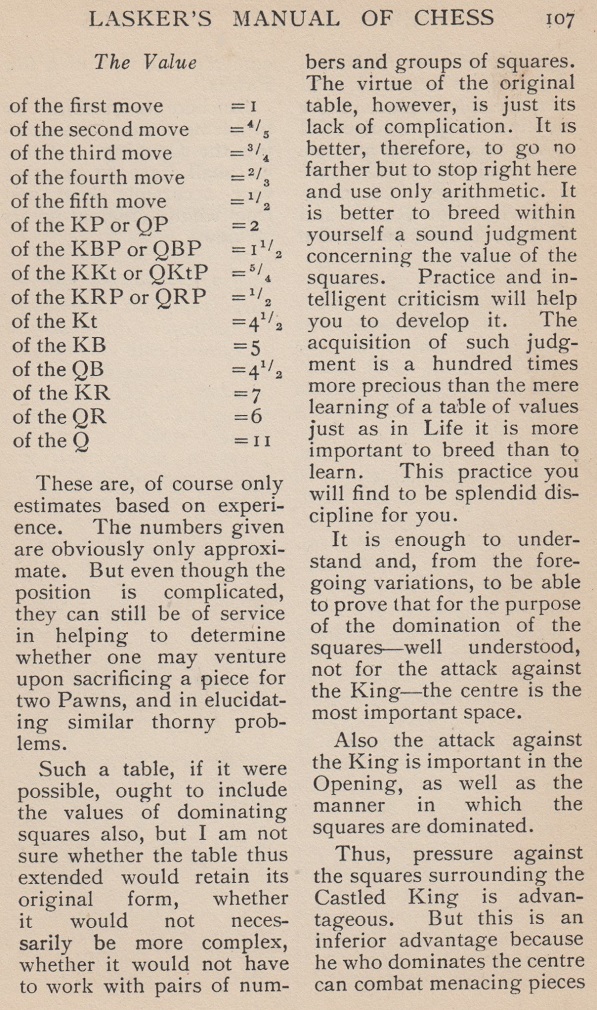

10631. Values

An addition to The Value of the Chess Pieces is provided by Peter Banks (Oldbury, England), from pages 106-107 of Lasker’s Manual of Chess (London, 1932):

In the original English-language edition (New York, 1927), the text was on pages 119-120.

| First column | << previous | Archives [159] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.