Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [184] | next >> | Current column |

11530. The Moves That Matter

Just received and to be savoured at a leisurely pace: The Moves That Matter by Jonathan Rowson (London and New York, 2019):

Jonathan Rowson is one of the best and cleverest chess writers.

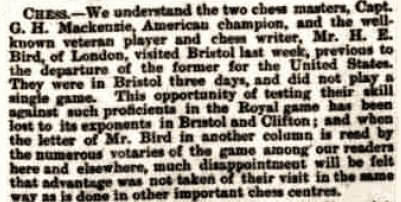

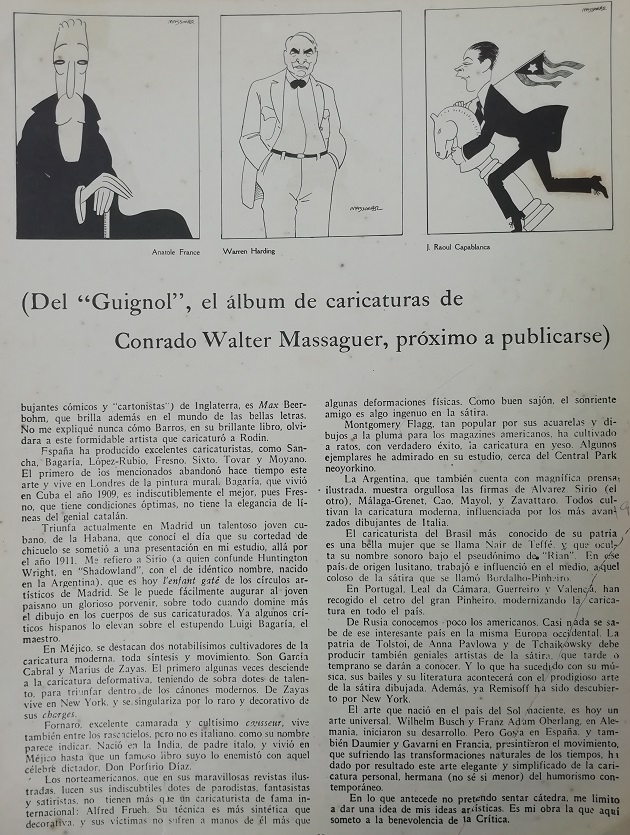

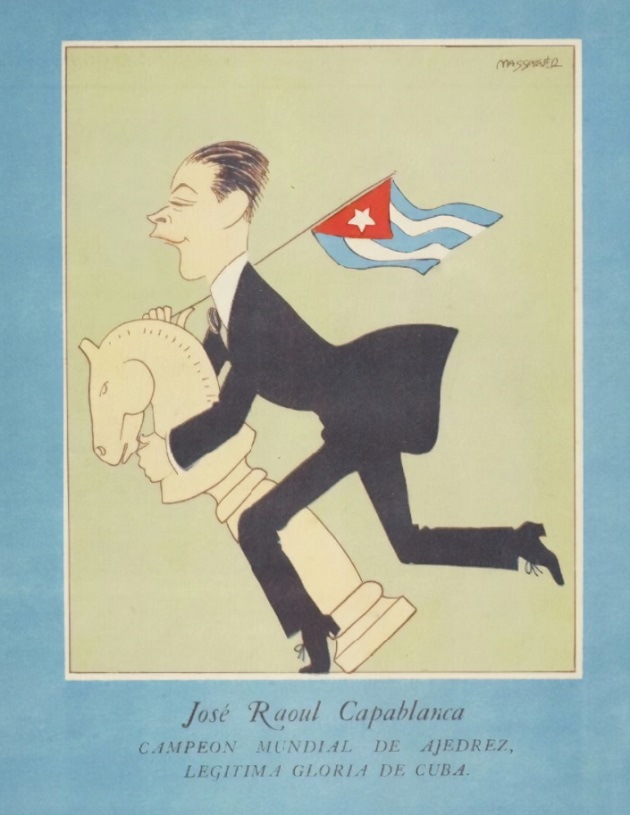

11531. Capablanca caricatures

This caricature is given at the start of Glorias del Tablero “Capablanca” by J.A. Gelabert (Havana, 1923) and at the end of the second edition (Havana, 1924):

Yandy Rojas Barrios (Cárdenas, Cuba) writes:

‘Concerning this widely-disseminated caricature by Conrado Massaguer, I can add that page 23 of the March 1923 edition of the magazine Social, which Massaguer edited, had another one of Capablanca:

A colour version was on the back cover of the January 1924 issue:

It is curious that the well-known 1922 caricature does not appear in any edition of Social that year.’

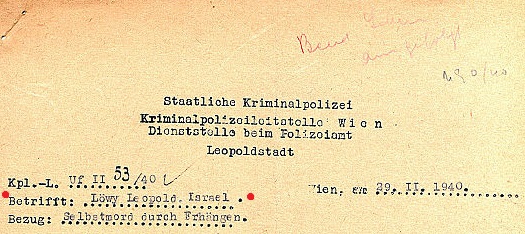

11532. Leopold Löwy (C.N.s 11511, 11520, 11521 & 11527)

The heading of the document shown in C.N. 11527:

From Alan McGowan (Waterloo, Canada):

‘As a result of some research for my Kurt Richter book, I noted that one of the “laws” introduced by the Nazis was that all female Jews had to adopt the name Sara and all males had to adopt the name Israel. Perhaps your correspondent in Vienna, Michael Lorenz, can clarify whether “Israel” was recorded as part of Leopold Löwy’s name at the time of his birth or whether it is on the document because Löwy was still considered Jewish by the Vienna authorities even though, as Mr Lorenz notes, Löwy had renounced Judaism in 1905.’

We have put the matter to Michael Lorenz, who replies:

‘Löwy was born with only one forename, Leopold. Because he was considered Jewish under the 1935 Nuremberg Laws, he was forced to adopt the second forename “Israel”. The Vienna authorities were implementing a law of the German Reich.’

In the light of the foregoing we shall refer to the master only as Leopold Löwy.

11533. Richard Réti (C.N.s 4834, 4856 & 5335)

The above-referenced C.N. items discussed whether Richard Réti was Jewish. Michael Lorenz now adds:

‘As far as is known, Réti was indeed Jewish. His father Samuel was Jewish and was buried in his parents’ grave in Vienna’s Jewish cemetery. He is not listed in Anna Staudacher’s book Jüdisch-protestantische Konvertiten in Wien 1782-1914 (Frankfurt am Main, 2004). Most Viennese chess masters were born Jewish, although many of them renounced Judaism. Prominent non-Jewish chess masters who come immediately to mind are Feyerfeil, Grünfeld, Hamppe, Kmoch, Krejcik, Liharzik, Marco, Mayerhofer, Müller, Schlechter and Seidl.’

11534. Sourceless quotes

How do such things happen?

11535. Fiction

Our latest feature article is Chess in Fiction.

11536. A constant struggle (C.N. 11506)

C.N. 11506 asked for more information about a remark ascribed to Jan Gustafsson:

‘Chess is a constant struggle between my desire not to lose and my desire not to think.’

In C.N. 7203 a correspondent drew attention to a comment by Dominic Lawson in an interview:

‘Someone once said, “Chess is a battle between your aversion to the pain of losing, and your aversion to the pain of thinking”.’

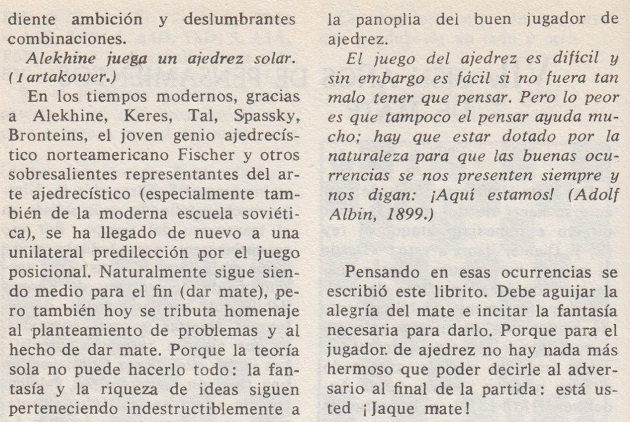

Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina) notes a passage attributed to Adolf Albin on page 106 of Jaque Mate by Kurt Richter (Barcelona, 1972):

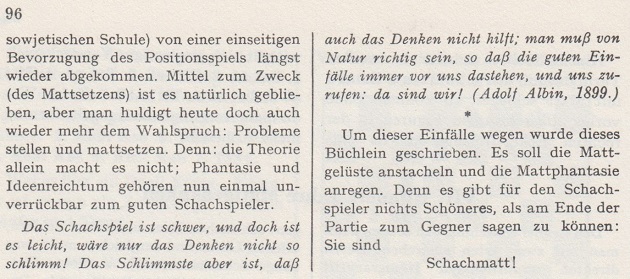

We add the corresponding passage on page 96 of the second edition of Richter’s Schachmatt (Berlin, 1958):

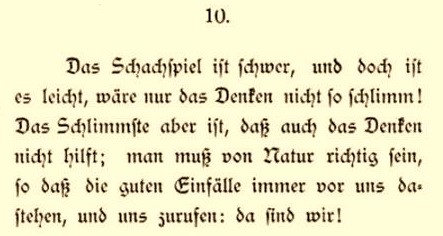

From page 10 of Schach-Aphorismen und Reminiscenzen by A. Albin (Hanover, 1899):

11537. Morphy v the Duke and Count

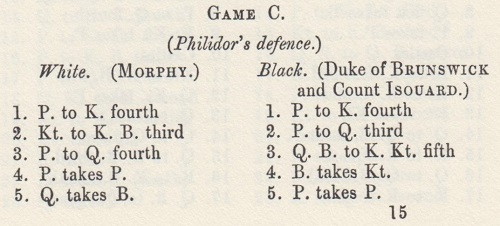

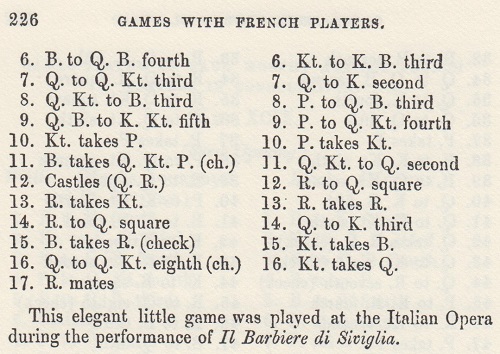

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) notes that pages 225-226 of Paul Morphy, Sketch from the Chess World by Max Lange (London, 1860) give the celebrated consultation game as played at the Italian Opera during a performance of The Barber of Seville, which, in accordance with the information provided by Fabrizio Zavatarelli in C.N. 6582, suggests 4 November 1858.

However, we add page 210 of a later German edition of Max Lange’s monograph, Paul Morphy Sein Leben und Schaffen (Leipzig, 1894), where the heading had a date (October 1858):

On the basis of the 1858 documentation about Paris opera performances which has been found so far, the statements ‘October 1858’ and ‘The Barber of Seville’ cannot both be correct.

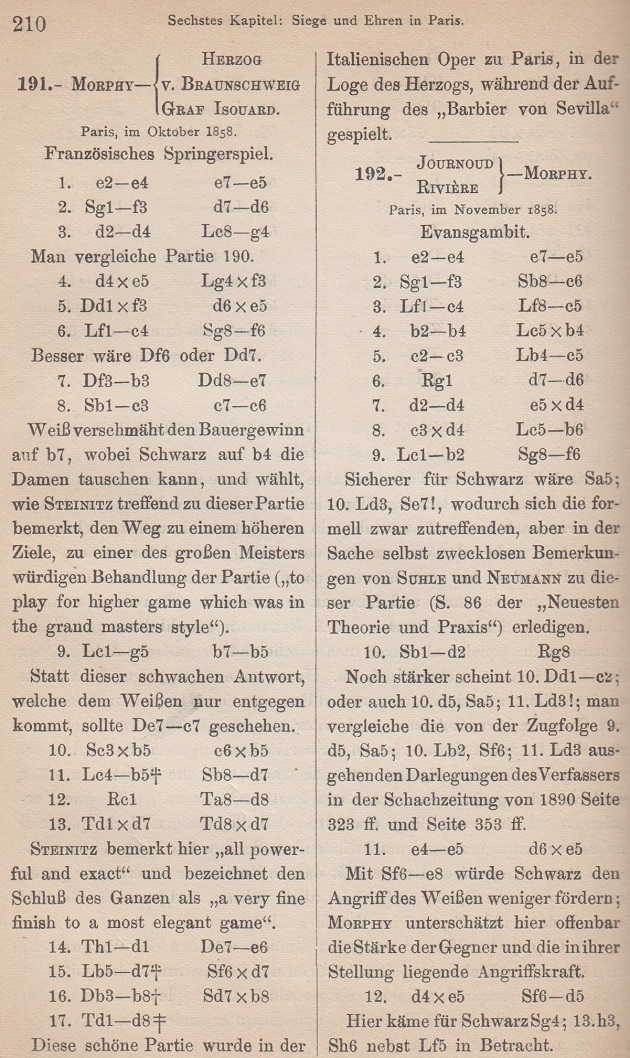

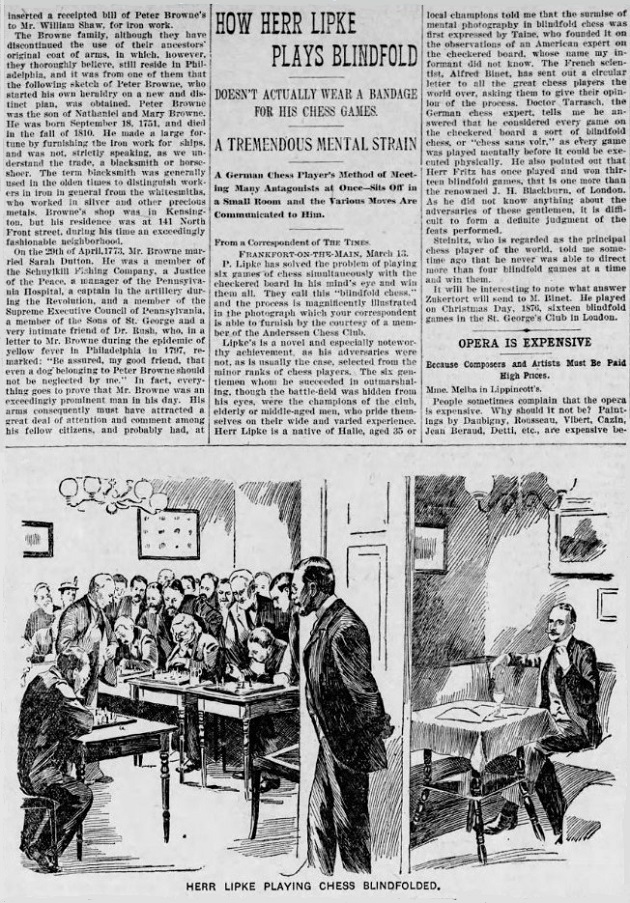

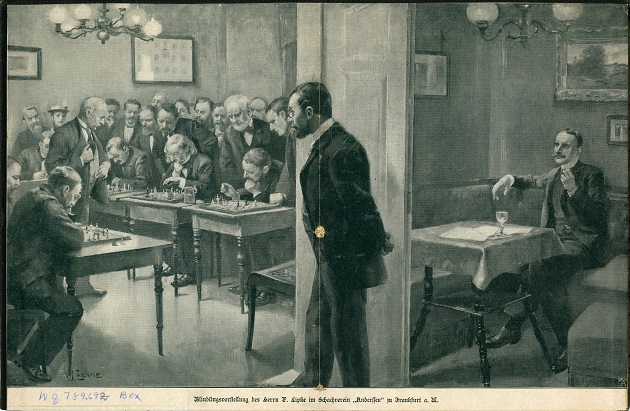

11538. Lipke playing blindfold (C.N. 9130)

Philadelphia Times, 24 March 1895, page 21

The above report was shown in C.N. 9130, and now we add, courtesy of the Cleveland Public Library, this image:

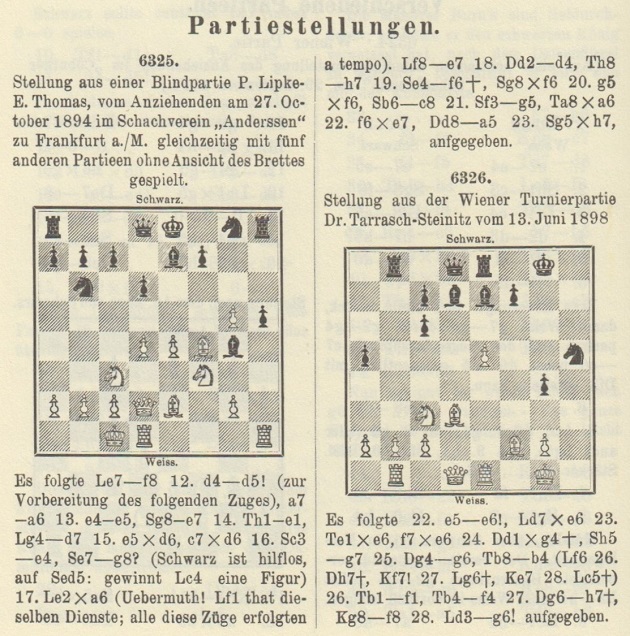

C.N. 9130 had a report on Lipke’s display in Frankfurt from page 347 of the November 1894 Deutsche Schachzeitung, and below is the conclusion of one of his games, against E. Thomas, on page 18 of the January 1899 issue:

Can more specimens of his blindfold play be found?

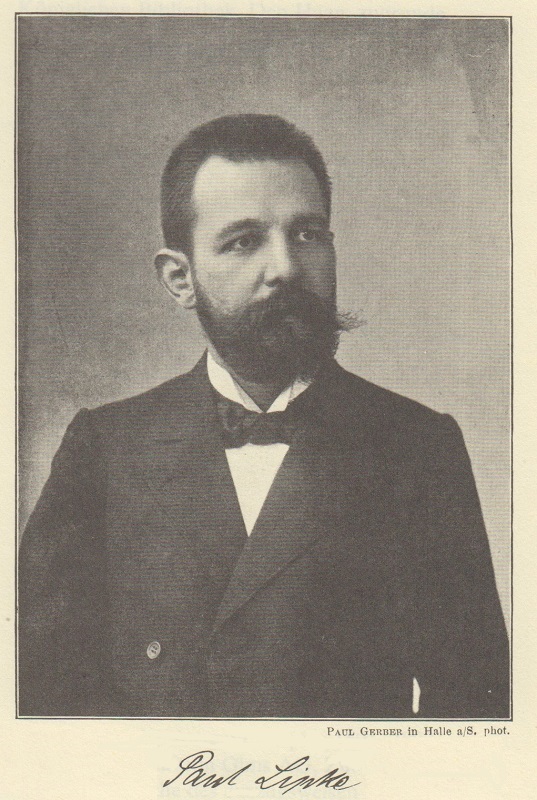

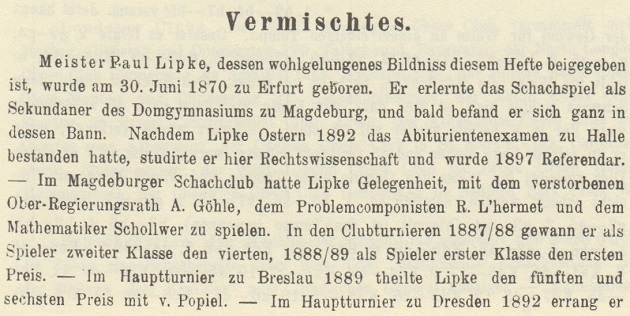

A photograph of Lipke was the frontispiece of the January 1900 Deutsche Schachzeitung, and a biographical note on pages 33-34 of the same issue mentioned his ability to play up to ten games simultaneously without sight of the board:

11539. Levenfish book (C.N. 8520)

On the topic of books deserving an English translation, in C.N. 8520 a correspondent nominated Izbrannye partii i vospominanya by G. Levenfish (Moscow, 1967).

Douglas Griffin (Insch, Scotland) informs us that Quality Chess has just published his translation of the book, with additional material, under the title Soviet Outcast (Glasgow, 2019).

11540. Guinness World Records

It may be mentioned à sa décharge that the Guinness company has, in addition to its books, a website with a database featuring many chess-related exploits.

11541. Morphy v the Duke and Count (C.N. 11537)

From Fabrizio Zavatarelli (Milan, Italy):

‘Morphy first dined with the Duke of Brunswick on 19 September 1858 (Lawson, page 158), which is a post quem date. C.N. 6582 reported my findings in the Parisian publication La presse, which announced daily the performances in Paris theatres. My search covered 19 September-31 December 1858.

As shown in C.N. 11537, Max Lange specified that the famous consultation game was played during a performance of Rossini’s The Barber of Seville at the Italiens. There are no possible dates in October, and the only ones in November are 4, 13 and 14; the last of those is unlikely, given the Deutsche Schachzeitung report mentioned below. There was a performance of The Barber of Seville on 23 December, but that has to be ruled out for the additional reason that Morphy was ill (during his match with Anderssen).

According to a report on pages 492-493 of the December 1858 Deutsche Schachzeitung, Morphy had played in consultation against the Duke and the Count more recently than against Chamouillet and Laroche. Although there are no extant consultation games involving Laroche, page 2 of the Supplement to Bell’s Life in London, 31 October 1858 published a “game just played by Paul Morphy (blindfold) against M. Chamouillet and the rest of the members of the Versailles Chess Club, all in consultation”.

On page 172 of his book on Morphy, F.M. Edge wrote regarding the Duke of Brunswick that “we were frequent visitors to his box at the Italian Opera”, and that on the first occasion the opera was Norma. The relevant possible dates are 21, 23, 26 and 30 October. Norma was also performed on 9 and 28 December, but those dates seem too late in view of the above-mentioned report in the Deutsche Schachzeitung.

To summarize, it appears that Morphy v the Duke and Count was played either during a performance of Norma on 21, 23, 26 or 30 October 1858 or, most probably, during The Barber of Seville on 4 November 1858.’

11542. F.M. Edge

The edition of Bell’s Life in London referred to in the previous item contained a brief correction:

‘We were mistaken in considering Mr Frederick Edge, Paul Morphy’s energetic friend, an American. Mr Edge is an Englishman, who had the honour to make Paul Morphy’s acquaintance at the New York great Chess Congress, where Mr E. officiated as one of the stewards.’

The previous week (page 3 of the 24 October 1858 edition) Bell’s Life in London had stated, ‘Mr Edge is an American merchant, travelling with Paul Morphy as his second and friend’. That came at the end of a letter from Edge on the Staunton-Morphy affair. For the full text, see pages 108-112 of his book on Morphy; page 143 of Lawson’s monograph gave only the final section. In the newspaper and in the Edge book the spelling of his name was ‘Frederick Milns Edge’, whereas Lawson put ‘Milne’. It may seem remarkable that Edge’s lengthy letter (approximately 1,500 words) was dated (Wednesday) 20 October and written in Paris yet could already be included in Bell’s Life in London on Sunday, 24 October. (Similarly, page 3 of the 10 October 1858 issue had a letter from Morphy in Paris dated Wednesday 6 October; it had reached the newspaper on 8 October.)

11543. Fischer in Münster

From John Donaldson (Berkeley, CA, USA):

‘The recent publication of all 20 games from Bobby Fischer’s simultaneous exhibition in Münster, Germany in 1970 resolved several mysteries and gave the chess world over a dozen new games played by the late world champion.

The display was previously known, although not the exact date. The fact that it took place on 27 September 1970 makes it probable, if not 100% certain, that the exhibition game Fischer v Andersson, sponsored by the Swedish newspaper Expressen, occurred the day before. The Siegen Olympiad ended on 27 September, but the last day of play was 25 September. It is conceivable, if unlikely, that the Fischer v Andersson game was on 25 September, as neither played in the final round of the Olympiad.

The complete set of games, both good and bad, in the Münster display makes it clear that Fischer did not follow the practice of some old-time masters of considering that his move was not completed until he had moved on the following board. In view of some of the blunders committed by him that evening, such as 35 Rb5 against Langhanke, giving a final score of 15½-4½, Fischer may have wished that he had.

The game against Eugen Kurz has a pretty finish with some affinity to Fischer v Benko, US Championship, 1963-64 (17 Rg6 in one game and 19 Rf6 in the other): 1 e4 e6 2 d4 d5 3 Nc3 dxe4 4 Nxe4 Nd7 5 Nf3 Ngf6 6 Bg5 Be7 7 Nxf6+ Nxf6 8 Bd3 O-O 9 Qe2 c6 10 O-O-O Qc7 11 h4 b6 12 Ne5 Bb7 13 Rh3 Rad8 14 Rg3 Kh8 15 Bxf6 Bxf6 16 Qh5 h6

17 Rg6 fxg6 18 Qxg6 Resigns.

Another question is whether the Münster display is the only one ever given by Fischer in which he took Black (in eight of the 20 games). Most exhibitors take White, and in this Fischer was no exception. In his 1964 exhibition tour of North America he gave over 40 displays, and in not one is there a record of him playing a single game as Black.’

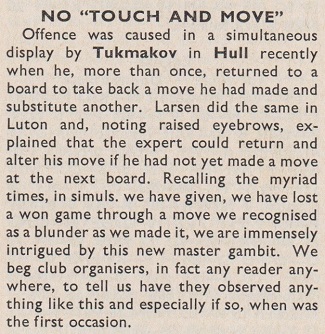

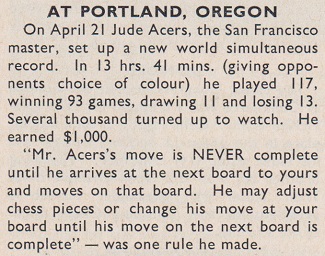

11544. Retracting moves in simultaneous displays

From page 157 of CHESS, March 1973:

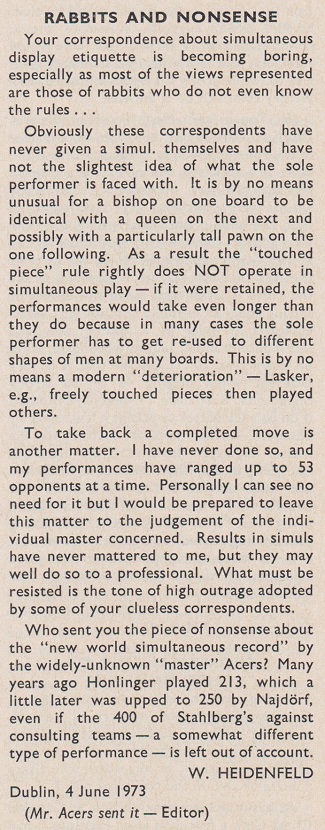

Readers related experiences and voiced opinions on pages 189, 196, 219 and 220 of the April 1973 CHESS and on pages 229 (see C.N. 11222) and 230 of the May 1973 issue. On page 257 of the June 1973 CHESS Wolfgang Heidenfeld contributed a letter referred to in C.N.s 9531 and 11222:

Heidenfeld’s final paragraph referred to a news item on page 221 of the May 1973 CHESS:

11545. F.D. Yates

C.N. 7910 drew attention to a surprising article by Stephen John Mann on the Yorkshire Chess History website which advocated, on the basis of extensive documentation, ‘Fred Dewhirst Yates’:

‘The popular rendering of his name as “Frederick Dewhurst Yates” is erroneous. There seems no evidence of any formal, official documents ever calling him “Frederick”; instead “Fred” seems to appear throughout. “Dewhurst” is a spelling mistake now widely copied in the literature.’

Given that, in the seven years since C.N. 7910 carried that item on Yates, no historian has, to our knowledge, disputed Mr Mann’s conclusion, it would seem appropriate for efforts to be stepped up to eradicate occurrences of the previously-accepted version, ‘Frederick Dewhurst Yates’.

11546. H.G. Wells

C.N. 1554 mentioned that page 5 of a 1984 book by Nicolas Giffard, Les Echecs, attributed this quote to Oscar Wilde:

‘Si vous voulez détruire un homme, apprenez-lui à jouer aux échecs.’ [‘If you want to destroy a man, teach him to play chess.’]

A correspondent in Canada, C.D. Robinson, observed in C.N. 1566:

‘Surely this is not Wilde, but a neat compression of two sentences in H.G. Wells’ essay “Concerning Chess”: “You have, let us say, a promising politician, a rising artist, that you wish to destroy. Dagger or bomb are archaic, clumsy and unreliable – but teach him, inoculate him with chess!” The essay has been reprinted several times since its first publication in 1901, e.g. in Jerome Salzmann’s The Chess Reader (pages 194-198).’

See page 380 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves.

Wells’ essay had, in fact, first appeared on page 3 of the Pall Mall Gazette, 12 February 1895. Parts have often been quoted, and not least his observation, ‘though we revere Steinitz and Lasker, it is Bird we love’. Below is the full article in its original publication:

11547. Niels Lie and Arne Desler

From page 355 of Alt om Skak by Bjørn Nielsen (Odense, 1943):

A ‘famous’ correspondence game between two of the players, Niels Lie and Arne Desler, is discussed in Chess and The Prisoner.

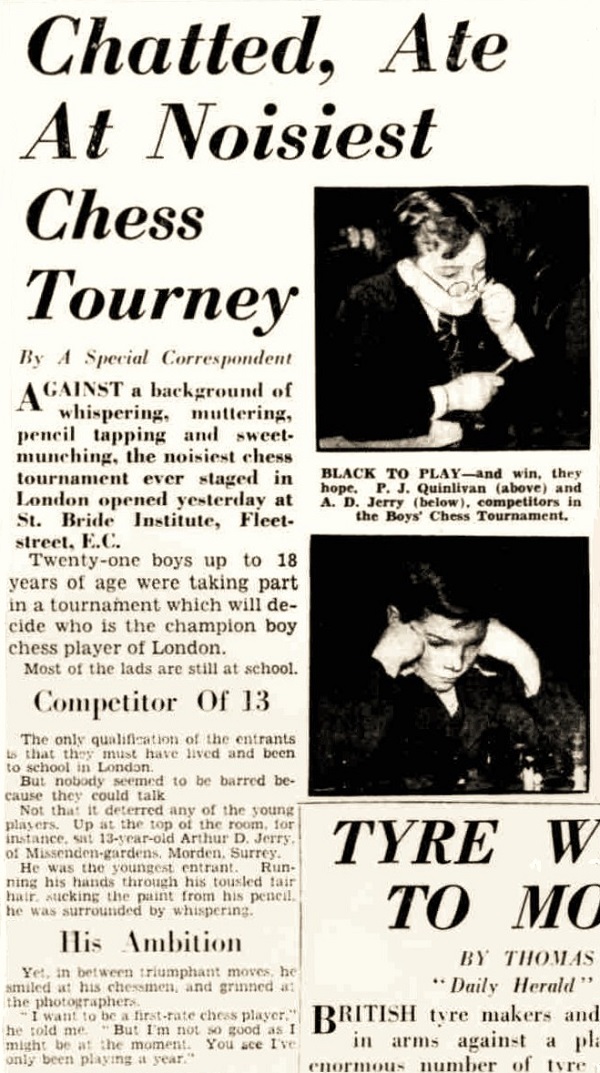

11548. Schoolboys

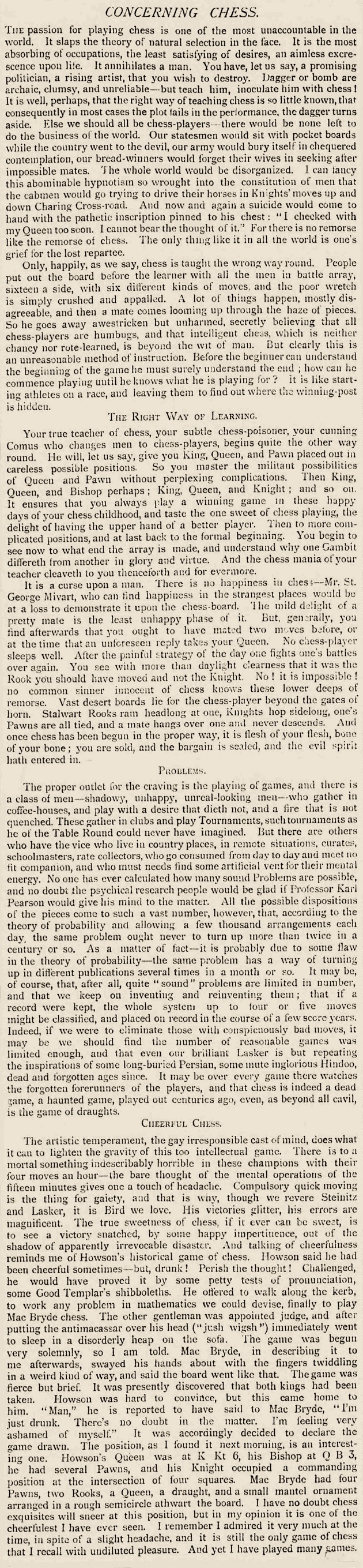

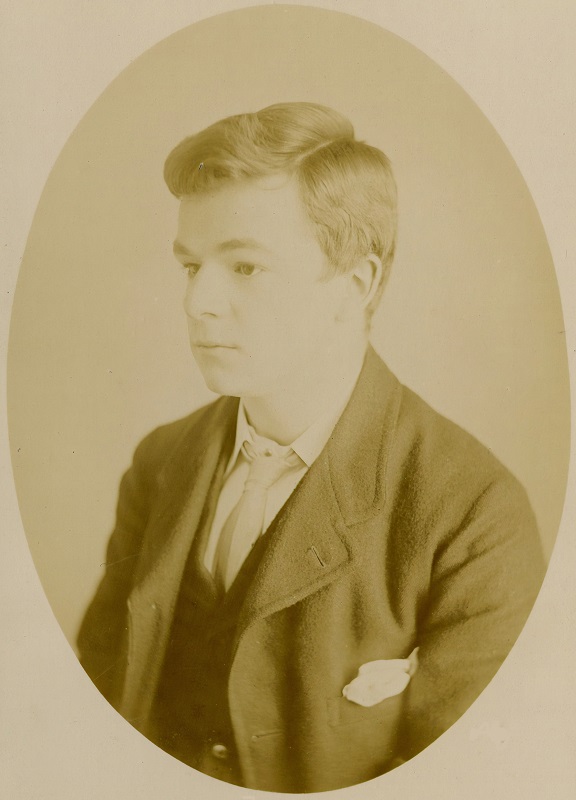

Half of page 23 of the Nielsen book referred to in the preceding item was taken up with this photograph:

There is no suggestion that the picture of ‘P. Quinliven’ was anything other than a random selection, from an unknown source. In its coverage of the London League New Year Congress, page 78 of the February 1937 BCM reported that in Section C of the Boys’ Championship the tail-ender, with no points, was ‘P.J. Quinlivan (who was the youngest competitor, aged 12)’.

In the same event two years later (as reported on page 73 of the February 1939 BCM) he finished equal last, with one point. Again his name was given as P.J. Quinlivan, as it was too on page 6 of the Daily Herald, 3 January 1939:

11549. Capablanca v Kalantarov

White to move

José de Jesús García Ruvalcaba (San Diego, CA, USA) asks whether there is any hope of finding the full score of Capablanca v Kalantarov, St Petersburg, 1913.

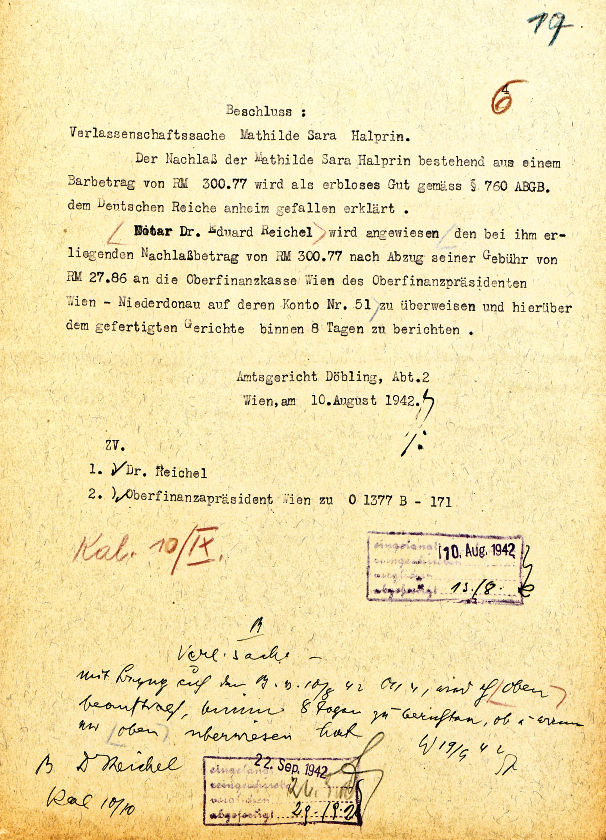

11550. Halprin

As an example of the Nazis’ imposition of Sara as a second forename (C.N. 11532), Michael Lorenz (Vienna) provides a page from the probate file of Alexander Halprin’s widow, Mathilde Halprin, who died in Vienna on 9 October 1941:

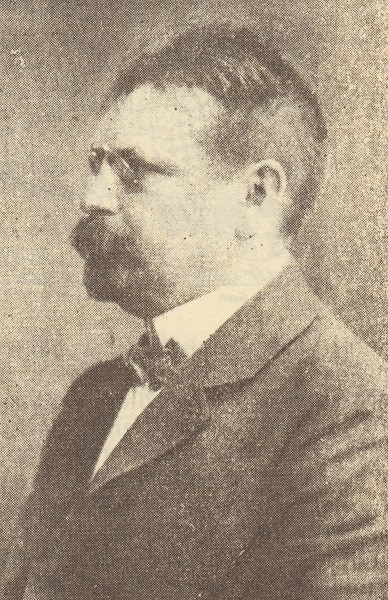

This photograph of Alexander Halprin (1868-1921) comes from page 101 of the 5 March 1938 issue of the Wiener Schachzeitung:

Pages 101-104 had a commemorative article on Halprin by Ernst Weizmann, including annotations by Heinrich Wolf to Halprin’s complex win against Carl Schlechter (Vienna, 1898).

11551. Alexander Halprin

As an addition to Graves of Chess Masters Michael Lorenz sends two photographs which he took on 24 May 2019:

Our correspondent writes:

‘As stated on pages 102-103 of the 5 March 1938 Wiener Schachzeitung, Alexander Halprin was buried at “Gruppe 10, Reihe 8, Grab 75” of the new Jewish cemetery at gate 4 of the Vienna Zentralfriedhof. His grave is the empty space to the left of the tree. The grave on the left (number 76 in row 8) is that of Sofie Morgenstern, who died on 20 May 1921 at the Rothschildspital in Währing.’

11552. Bishop takes pawn

C.N.s 9805, 9809, 9812, 9861, 9871 and 10264 have discussed captures similar to Fischer’s 29...Bxh2 against Spassky in the 1972 world championship match. Gerd Entrup (Herne, Germany) now points out this position in the game between Pillsbury and Steinitz in round 16, St Petersburg, 1895-96:

On page 50 of the tournament book W.H.K. Pollock wrote of 30 Bxh7:

‘A somewhat rash capture, owing to the white king being so much exposed to attack, leading to the successful corralling of the bishop. It was not easy to analyse, and doubtless Mr Pillsbury, as on other occasions about the 30th and 45th move, was short of time. As a quiet move, 30 R-Q sq might be suggested.’

The game continued 30...g6 31 Qd4 Ng7 and was won by Steinitz at move 100.

11553. Death at the board

C.N. 1286 (see page 126 of Chess Explorations) referred to two players who died during chess games: Georg Olland (1933) and James Marshall (1926). Now, Avital Pilpel (Haifa, Israel) informs us that Moshe Roytman has drawn his attention to a case reported in Shaul Hon’s chess column on page 34 of the 8 December 1972 edition of Maariv. It concerned the inter-kibbutz team tournament, won by Hadera with 41 points:

Mr Pilpel’s translation of the highlighted passage:

‘The tournament was stopped prematurely owing to the sudden death of Mordechai Rudolfer of Givat Hayim (Meuchad), who suffered a heart attack in the middle of his last-round game. Games which had not yet been decided were declared drawn.’

11554. P.H. Williams

This portrait of Philip Hamilton Williams has been forwarded by Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore), courtesy of the London Borough of Hackney Archives (photograph reference number D/S/1/3 no.40):

11555. Rapid transit tournament

There are few photographs of fast chess events of times past, but a shot is given here from page 38 of The Book of the Pan-American Chess Tournament 1926 edited by Hermann Helms (New York, 1926):

The picture is also on page 91 of the American Chess Bulletin, July-August 1926.

11556. ‘Book of the year’

Awards for the so-called ‘best chess book of the year’ have seldom merited respect (especially in view of the judges’ lack of credentials), but we note that there is now a FIDE Book of the Year 2018 contest, with a short-list of three titles.

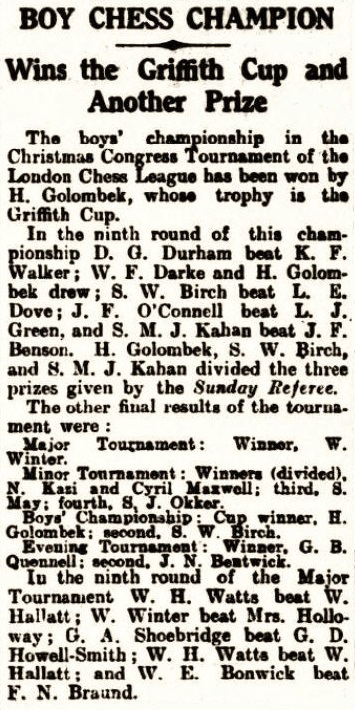

11557. Harry Golombek

The reference in C.N. 11548 to the London Boys’ Championship inevitably brings to mind Harry Golombek. From his obituary, by William Hartston, on page 12 of the Independent, 10 January 1995:

‘In 1928, Golombek played in his first London Boys’ Championship, finishing last in his section. The next year, however, he won it, an achievement of which he seemed never to tire of reminding his readers ...

Golombek went from Wilson’s Grammar to London University, though there is no record of his having completed his degree.’

Daily Herald, 7 January 1929, page 3

One of Golombek’s many mentions of the London Boys’ Champion title was quoted in C.N. 5215, from his column in The Times, 5 July 1975, page 7:

‘... it is true that, like everybody else, I started off as a player and that when I won the London Boys’ Championship some 48 [sic] years ago I had not the faintest inkling that I would end up as that thing of silk, a mere chess journalist.’

‘I was London Boy Champion and had a very quick sight of the board’, wrote Golombek when reviewing a book about Sultan Khan on page 175 of the June 1966 BCM. He also mentioned that ‘I was London Boy Champion’ in his semi-autobiographical obituary of Jacob Bronowski on pages 441-443 of the December 1974 BCM.

There are contradictory accounts of Golombek’s university studies. The entry for him in the Sunnucks Encyclopaedia referred to his ‘graduating in languages at London University’. The entry that he wrote about himself in his 1977 Encyclopedia of Chess stated (page 131):

‘Educated at Wilson’s Grammar School and the University of London, he became London Boy champion in 1929 and London University champion 1930-33.’

From the article about Golombek, by W.D. Rubinstein, in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography:

‘Golombek also began, but did not complete, a general degree at King’s College, London, leaving in 1932.’

For a photograph of the young Golombek, see C.N. 6555.

11558. Golombek’s grandmaster title

In his Independent obituary of Harry Golombek referred to in the previous item, William Hartston wrote:

‘He was awarded the title of International Grandmaster in 1985, which he liked to stress was not an honorary award, but a belated recognition of his playing achievements in the 1940s.’

Confusion sometimes arises over the status and terminology of such a title. In keeping with Jeremy Gaige’s usage in Chess Personalia, C.N. 1808 (see page 196 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves) stated that ‘in 1985 FIDE made Harry Golombek an emeritus GM’, but in addition to ‘emeritus’ and ‘honorary’ another possibility is ‘honoris causa’.

Page 121 of FIDE Golden book 1924-2016 by Willy Iclicki gave a single list, without different categories, of individuals awarded the grandmaster title in 1985. Golombek appeared, with the forename ‘Garry’.

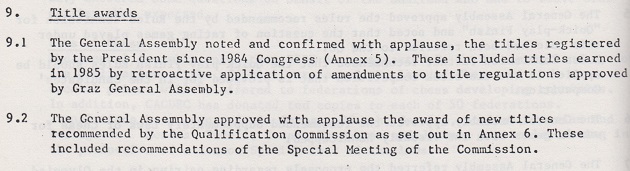

Some particulars are shown below from FIDE Congress, Graz 1985 Minutes & Annexes, beginning with an extract from page 4 of the minutes of the General Assembly (29-31 August):

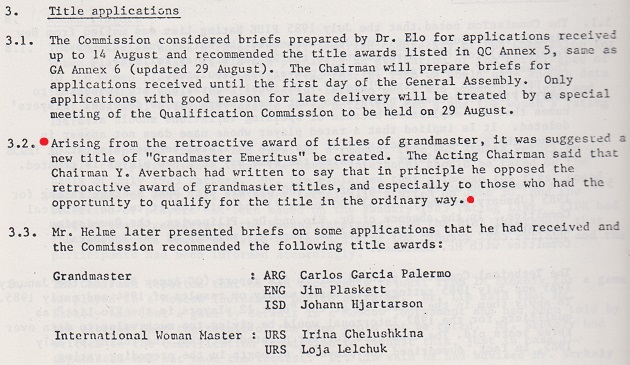

The FIDE document included a report on the meeting on 25-26 August of the Qualification Commission, whose Acting Chairman was Eero Helme (Finland):

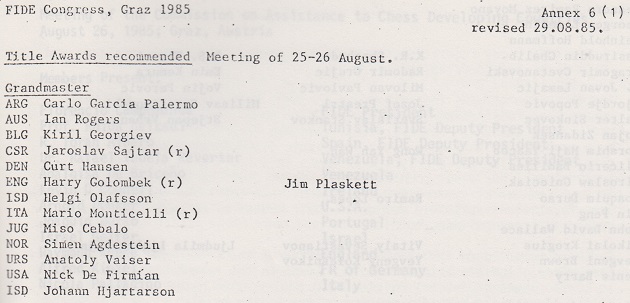

The relevant part of the above-mentioned list:

The documentation leaves a number of loose ends, and we shall welcome authoritative guidance on this topic, and not only concerning the particular case of Golombek.

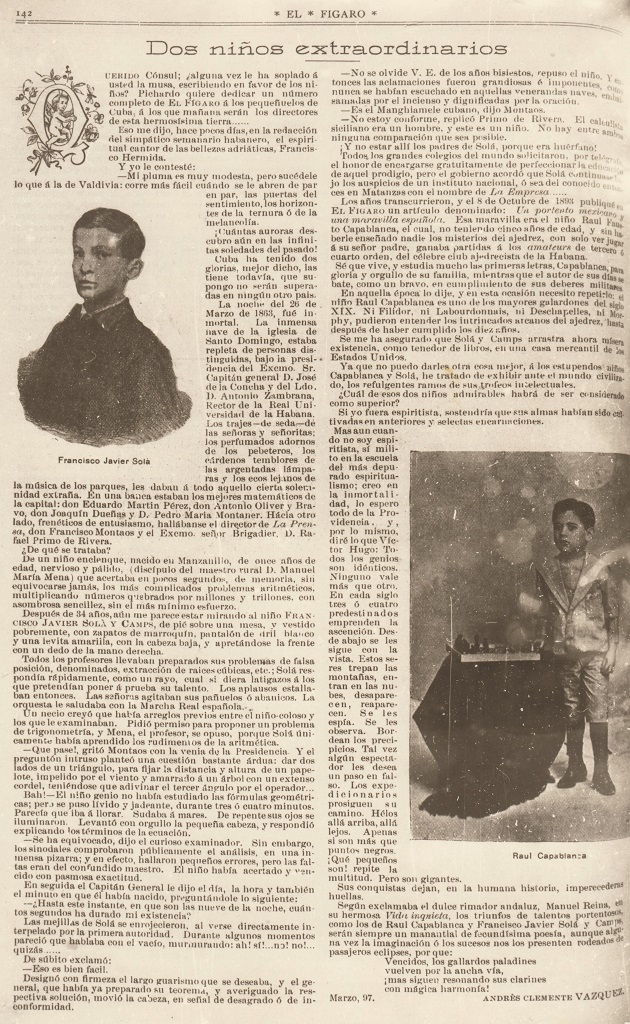

11559. Vázquez on Capablanca

Below is an article by Andrés Clemente Vázquez on page 142 of the Cuban publication El Fígaro, March 1897:

A translation of part of the article is on pages 3-4 of our monograph on Capablanca.

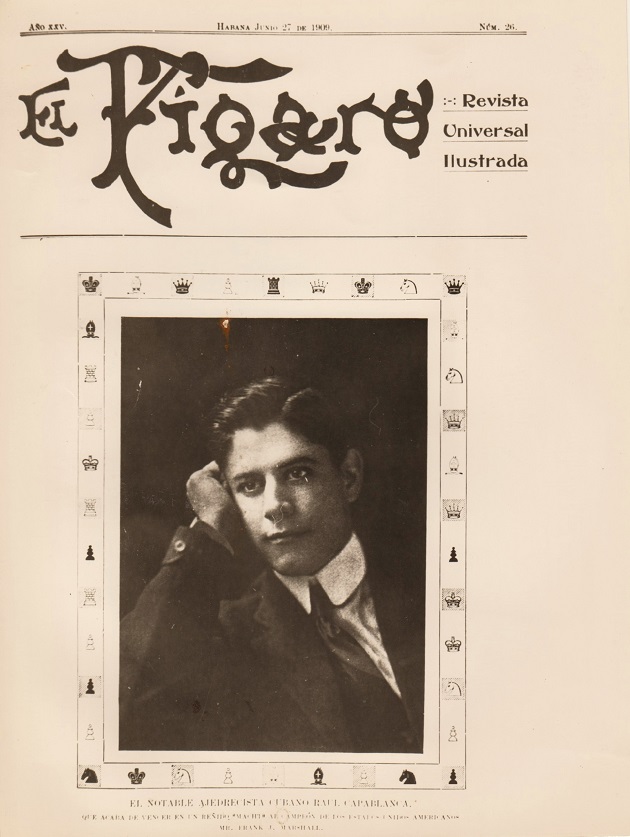

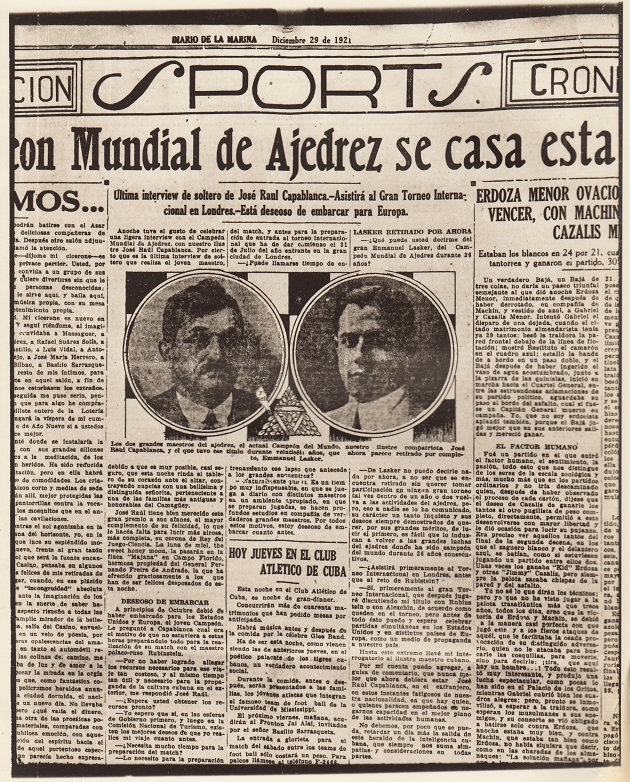

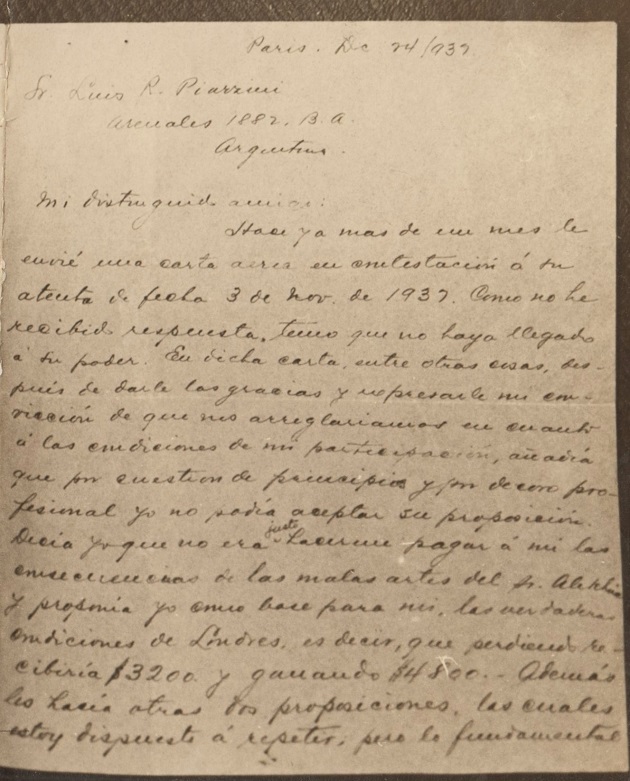

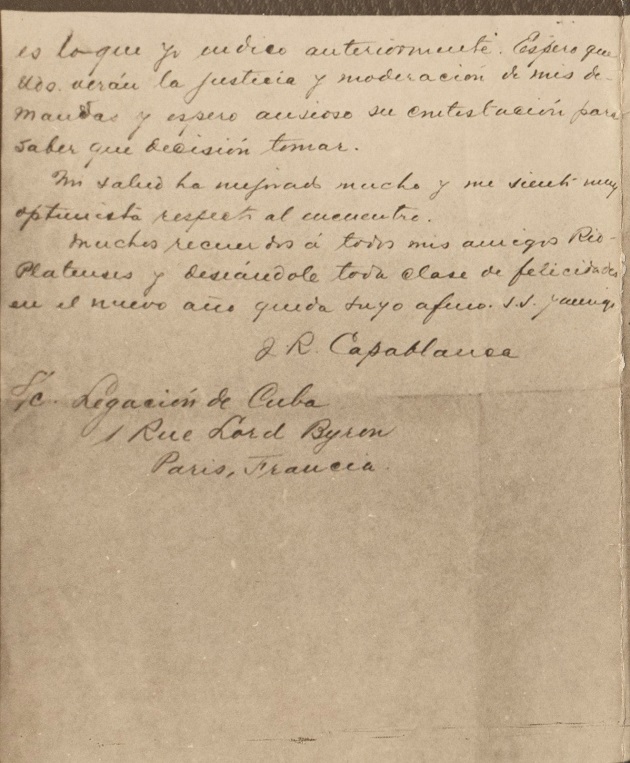

11560. Further Capablanca items

In raw scrapbook form, some Capablanca items are reproduced from our archives:

For a translation of the interview with Capablanca, see page 117 of our monograph on him.

A letter from Capablanca to the Argentinian master Luis R. Piazzini:

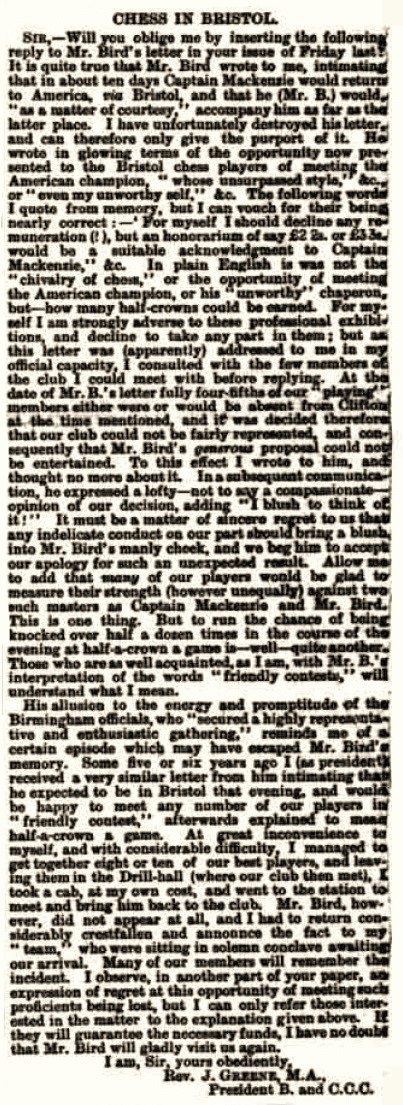

11561. Bird and Mackenzie in Bristol

Hans Renette (Bierbeek, Belgium) writes:

‘Some items in the Bristol Times and Mirror shed light on a small provincial tour by Bird and Mackenzie in 1885 (discussed on pages 353-354 of my book on Bird) and the Englishman’s controversial attitude to professionalism and amateurism in chess.

Bird and Mackenzie intended to visit Cardiff (as noted in my book), though not Swansea. Instead, they spent three days in Bristol, but without playing any chess games. In a letter published on page 3 of the 11 September 1885 edition of the Bristol Times and Mirror Bird complained about the lack of an initiative to arrange games with “any chess admirers in friendly contest”:

The same issue had a brief news report on page 5:

The President of the Bristol and Clifton Chess Club, the Rev. J. Greene, responded on page 7 of the newspaper’s 14 September 1885 edition, criticizing Bird’s attitude to payment for “friendly contests”:’

11562. Fischer and the Hedgehog

John Donaldson (Berkeley, CA, USA) writes:

‘Bobby Fischer’s contributions include countless opening innovations and original middlegame plans. His pioneering use of the King’s Indian Attack is an example of how he seamlessly combined the two, and his wins against Ivkov (Second Piatigorsky Cup, 1966), Myagmarsuren (Sousse Interzonal, 1967) and Panno (Buenos Aires, 1970) are still model games half a century later.

Fischer is also one of the founding fathers of the Hedgehog. Ulf Andersson and Ljubomir Ljubojević played it extensively in the 1970s and 1980s and are credited with being its creators, but, as will be shown below, this is not completely true.

García Soruco v Fischer, Havana Olympiad, 1966 is credited as the game where the plan …Kh8, ...Rg8, …g5, …Rg6 and …Rag8 was first seen, but this may not be so. On pages 18-20 of the 1974 book Morphy Chess Masterpieces by Fred Reinfeld and Andrew Soltis the latter points out that Fischer may have been influenced by Paulsen v Morphy, New York, 1857, where Black played ...Kh8, ...Rg8 and ...g5. The pawn structure is different, but there is some similarity. Here is how the Hedgehog may have developed.

Both players were without sight of the board in the game, which was played on 10 October 1857 and is on page 30 of Hans Renette’s monograph on Paulsen.

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Nc3 Bc5 4 Bb5 d6 5 d4 exd4 6 Nxd4 Bd7 7 Nxc6 bxc6 8 Ba4 Qf6 9 O-O Ne7 10 Be3 Bxe3 11 fxe3 Qh6 12 Qd3 Ng6 13 Rae1 Ne5 14 Qe2 O-O 15 h3

15...Kh8 16 Nd1 g5 17 Nf2 Rg8 18 Nd3 g4 19 Nxe5 dxe5 20 hxg4 Bxg4 21 Qf2 Rg6 22 Qxf7 Be6 23 Qxc7

Morphy now announced mate in five starting with 23…Rxg2+.

The next game, considered the first example of the plan being executed in its entirety, comes from the 1966 Olympiad in Havana (Julio García Soruco v Bobby Fischer):

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 d6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Nc3 a6 6 Bc4 e6 7 Bb3 b5 8 a3 Be7 9 Be3 O-O 10 O-O Bb7 11 f3 Nbd7 12 Qd2 Ne5 13 Qf2 Qc7 14 Rac1

14...Kh8

Passive moves (a3, f3 and Rac1) by the Bolivian Olympiad team member are just the encouragement that Fischer needs to implement what Kasparov calls the “compressed spring” strategy.

15 Nce2 Rg8 16 Kh1 g5 17 h3 Rg6

17...d5 is a good move, but it reduces the tension. The text gives White more problems to solve.

18 Ng3?

White cannot just sit tight. He had to try something active, such as 18 Rfd1 Rag8 19 c4, with the idea of 19...bxc4 20 Bxc4 Nxc4 21 b3.

18...Rag8

18...d5 was again quite good for Black, but Fischer adheres to his strategy and is soon rewarded.

19 Nxe6?

This simply loses, but it is hard to suggest a satisfactory defense.

19...fxe6 20 Bxe6 Nxe4 21 Nxe4 Rxe6 22 White resigns.

Fischer’s first try with the variation worked like a charm, his opponent allowing him to do everything he wanted. The second time around, matters were not so simple. The 19-year-old Ulf Andersson was not yet a world-class grandmaster, but he was a strong player (rated 2480 on the July 1970 FIDE rating list, which placed him in the top 100 players in the world at the time).

This game between Fischer and Andersson was played in a hotel room in Siegen on 26 September 1970, the day after the Olympiad ended. Fischer was paid a fee by a Swedish newspaper, which published the game-score a move a day over several months.

1 b3

This was not the first time that Fischer opened with 1 b3, as he had played it a few months before against Tukmakov in Buenos Aires. Fischer stated that 1 e4! is "best by test" (C.N. 4423), but he had a much better career record with 1 b3 – a perfect 4-0 score, in fact. All the games were played against quality opponents (Mecking and Filip were the two others) and were interesting fights in which Fischer introduced new ideas.

1...e5 2 Bb2 Nc6 3 c4 Nf6 4 e3 Be7 5 a3 O-O 6 Qc2

6 d3 d5 7 cxd5 Qxd5 8 Nc3 Qd6 9 Nf3 Bf5 10 Qc2 Rfd8 11 Rd1 h6 12 h3 Qe6 13 Nd2 Nd7 14 Be2 Kh8?! (14...Qg6 (Kasparov)) 15 O-O Bg6 16 b4 a6 17 Rc1 Rac8 18 Rfd1 f5 19 Na4 Na7 20 Nb3 b6 21 d4 f4 22 e4 and White soon won in Fischer v Tukmakov, Buenos Aires, 1970.

6...Re8

6...d5 7 cxd5 (7 d3) 7...Nxd5 8 Nf3 Bf6 9 d3 g6 10 Nbd2 Bg7 11 Rc1 was a dream Sicilian for White in Petrosian v Sosonko, Tilburg, 1981. Black is actually two tempi down on normal lines in the Scheveningen (colors reversed) as he has spent three moves with his king’s bishop instead of one.

7 d3 Bf8 8 Nf3 a5 9 Be2 d5 10 cxd5 Nxd5 11 Nbd2 f6

Andersson supports his e-pawn with the text, but step-by-step he is drifting into a passive position where he will soon have no constructive plan.

Soltis suggests 11...g6 followed by ...Bg7 as Sosonko played, but it would seem that ...g6, ...Bg7 and ...d5 in the opening save a couple moves over ...Be7-f8-g7.

12 O-O Be6 13 Kh1!!

“The exclamation points are not awarded to this move, but rather to Fischer’s entire plan. It is the originality of the plan that merits praise. Later, this plan became popular in Hedgehog positions, where (with colors reversed) White’s c-pawn is on his fourth rank.” (Alex Fishbein on page 48 of his 1996 book on Fischer.)

13...Qd7 14 Rg1 Rad8 15 Ne4!

15...Qf7

If 15...h5 then 16 h3 with g4 to follow. In fact, Black has no way to stop g4, as the noted Hedgehog expert Sergey Shipov points out:

15...Kh8 16 g4! Bxg4 17 Rxg4! Qxg4 18 Nxe5 Qe6 19 Bg4 Qg8 20 Nxc6 bxc6 21 Rg1! with powerful compensation for the exchange.

15...Nb6 16 g4! Bxg4 17 Nh4 f5 18 Nxf5 Qxf5 (or 18...Bxe2 19 Nf6+ Kh8 20 Nxd7 Bf3+ 21 Rg2 Rxd7 22 Nh4 Bxg2+ 23 Kxg2) 19 Bxg4 Qf7 20 d4 exd4 21 Ng5. In both cases White is winning.

16 g4! g6?!

This unforced weakening increases the strength of g4-g5.

16...Nb6 17 Nfd2 Be7 (Shipov) or 17...Bd5 (Kasparov) would have offered complicated play.

17 Rg3 Bg7 18 Rag1!

“A remarkable attacking construction! The original source, with reversed colours, was the game Soruco v Fischer (Havana Olympiad, 1966).” (Kasparov on page 353 of his 2004 book on Fischer in the Predecessors series.)

18...Nb6 19 Nc5! Bc8 20 Nh4 Nd7?

Black had to sacrifice the exchange for a pawn: 20...Rd5 21 Bf3 Rxc5 22 Qxc5 Qxb3 with chances for both sides (Shipov).

21 Ne4!

“An amazing paradox: with the board full of pieces, practically without coming into contact with the enemy army and not straying beyond his own half of the board, White has imperceptibly achieved a winning position.” (Kasparov on page 353 of his 2004 book on Fischer in the Predecessors series.)

21...Nf8 22 Nf5! Be6 23 Nc5 Ne7 24 Nxg7! Kxg7 25 g5! Nf5 26 Rf3 b6 27 gxf6+ Kh8 28 Nxe6 Rxe6

29 d4! exd4 30 Bc4 d3 31 Bxd3 Rxd3 32 Qxd3 Rd6 33 Qc4 Ne6 34 Be5 Rd8 35 h4 Nd6 36 Qg4 Nf8 37 h5 Ne8 38 e4 Rd2 39 Rh3 Kg8 40 hxg6 Nxg6 41 f4 Kf8 42 Qg5 Nd6 43 Bxd6+ Resigns.

“This game made such a great impression on Ulf Andersson that in the 1970s the talented Swedish grandmaster, who is well known for his skill in defence, became one of the main ideologists of the ‘hedgehog’ set-up and the ‘compressed spring’ method when playing Black. That is how the chess revolution of the 1970s began.” (Kasparov on page 354 of his 2004 book on Fischer in the Predecessors series.)

Here, just a day after the game with Andersson, Fischer has the opportunity to use his plan once again, as Black against Michels in the simultaneous display in Münster referred to in C.N. 11543. White’s fate is similar to what would have happened to García Soruco if he had not self-destructed with 19 Nxe6.

1 e4 c5 2 Nf3 d6 3 d4 cxd4 4 Nxd4 Nf6 5 Nc3 a6 6 Bd3 e6 7 Nb3 Be7 8 O-O Qc7 9 Qe2

9 Be3 Nbd7 10 f4 O-O 11 Qf3 is a popular main line.

9...Nbd7 10 Be3 O-O 11 f3?!

11 f4 is necessary as the text is too passive.

11...b6 12 Qf2 Bb7 13 Rfd1 Rac8 14 Rac1

White has no constructive plan.

14...b5 15 a3 Ne5 16 Kh1 Kh8

17 Bb6 Qb8 18 Rd2 Rg8 19 Rcd1 g5 20 Bd4 Rg6 21 Qf1 Rcg8 22 a4

White decides that he cannot wait forever.

22 Qe1 Bd8 23 Qf1 Bc7 followed by a break with ...d5 is another idea at Black’s disposal. If 22 Qg1 then 22...Nxd3 23 cxd3 e5 24 Be3 d5.

22...bxa4 23 Nxa4

23 Na5 had to be tried.

23...Rh6

23...g4! 24 f4 Nxd3 25 cxd3 g3! 26 h3 e5! 27 f5 Rg4! 28 hxg4 exd4 29 Nxd4 Qf8 wins even more quickly.

24 Bxe5 dxe5 25 Nac5 g4! 26 Nxb7 Qxb7

26...Nh5! would have ended matters faster.

27 Bxa6?

27 g3 had to be played.

27...Qa7 28 Qd3 gxf3 29 Na5

As 29 gxf3 is met by 29…Nh5.

29...Ng4 30 gxf3 Qf2 31 White resigns.

In view of these games, should Fischer be considered the father of the Hedgehog? He certainly discovered the key setup with …Kh8, …Rg8, …g5, …Rg6 and ...Rag8. We also know that he was very conscious of Black’s ability to break with …d5 (or when to avoid it). What we do not know for sure, since none of his opponents had their c-pawn on c4 or …c5, is whether he was aware of the …b5 break played independently or in conjunction with …d5. It does seem likely. Less clear is the maneuver …Bf8-e7-d8-c7, a now-standard Hedgehog line, which came into practice only after Fischer had stopped playing post-1972. All in all, it seems fairest to give credit to Fischer as the originator and to Andersson and Ljubojević for refining it.’

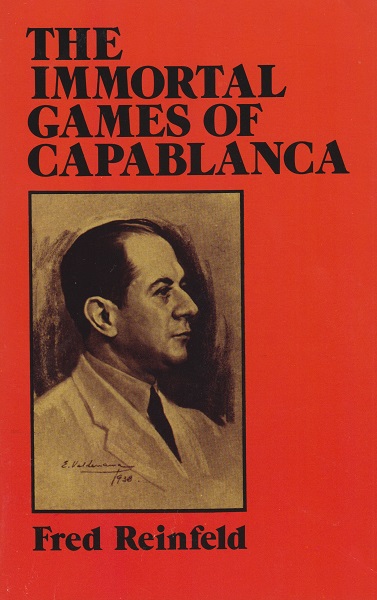

11563. Capablanca pictures

This photograph, with Capablanca seated in the centre, was given in C.N. 7727, courtesy of its owner, Ross Jackson.

Part of a painting of Capablanca is visible on the wall:

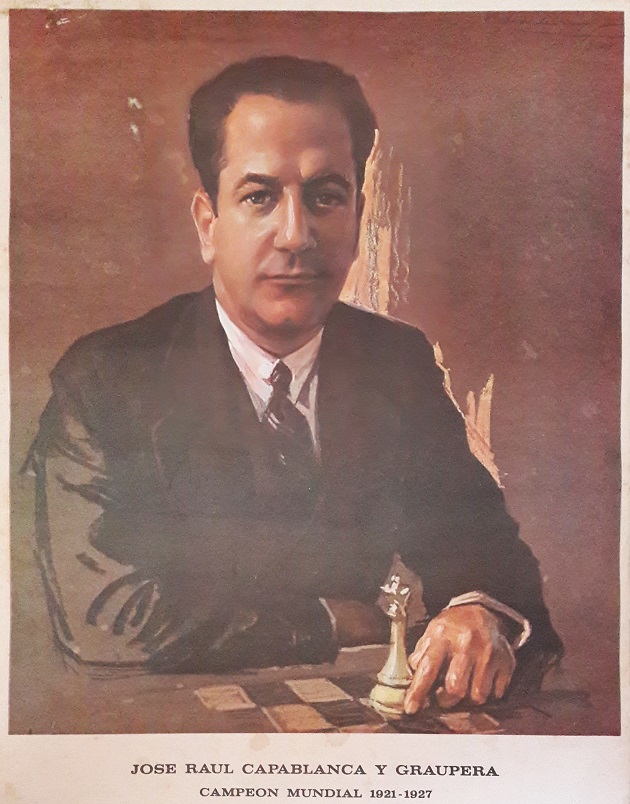

Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) notes that the portrait is by Esteban Valderrama, as shown in the 11 June 1933 edition of Diario de la Marina:

A painting of Capablanca by Valderrama dated 1938 is the frontispiece of The Immortal Games of Capablanca by Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1942) and is on the front cover of the 1990 Dover edition:

11564. Hands (C.N.s 10616 & 10812)

A further contribution from Mr Urcan concerns the photograph of Capablanca’s hand discussed in C.N.s 10616 and 10812. Our correspondent provides page 17 of Diario de la Marina, 5 November 1927:

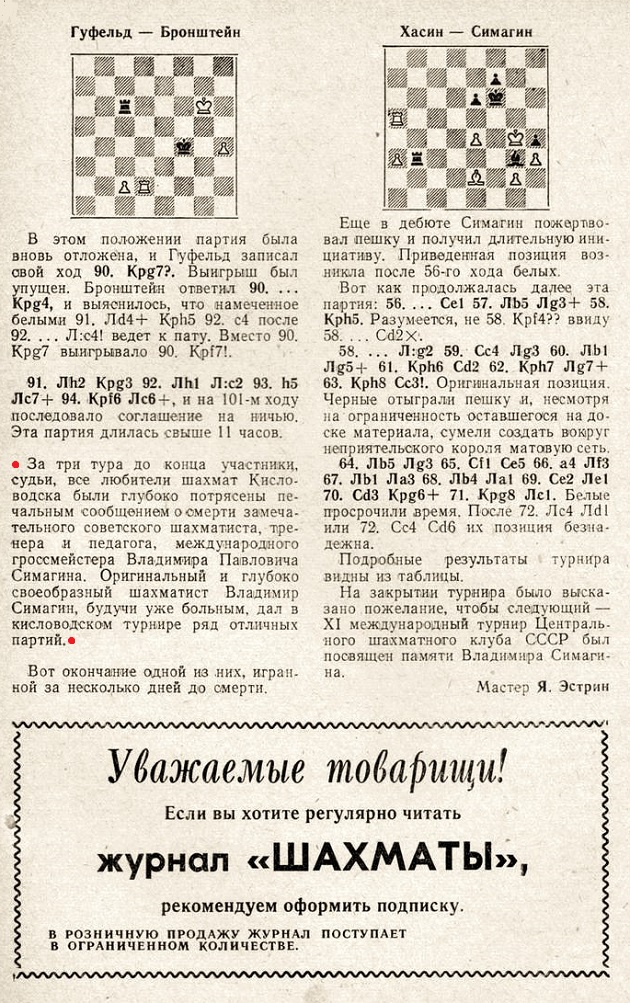

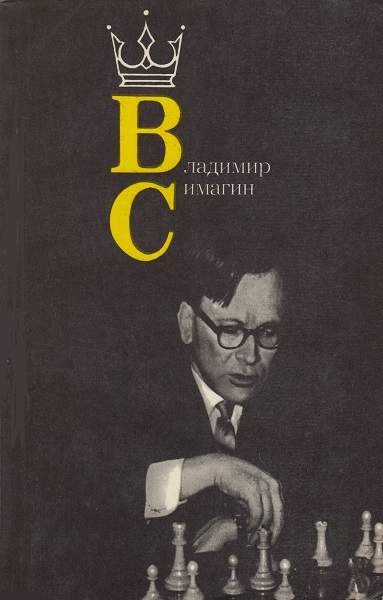

11565. Vladimir Simagin

Dan Scoones (Coquitlam, BC, Canada) asks which is the fullest contemporary account of Simagin’s death, at the age of 49, during the Kislovodsk tournament in September 1968. To open the topic, Mr Scoones forwards the brief notice, devoid of details, in the tournament report on page 7 of the 24/1968 issue of Shakhmaty Riga:

The front cover of the monograph on Simagin by S.B. Voronkov (Moscow, 1981):

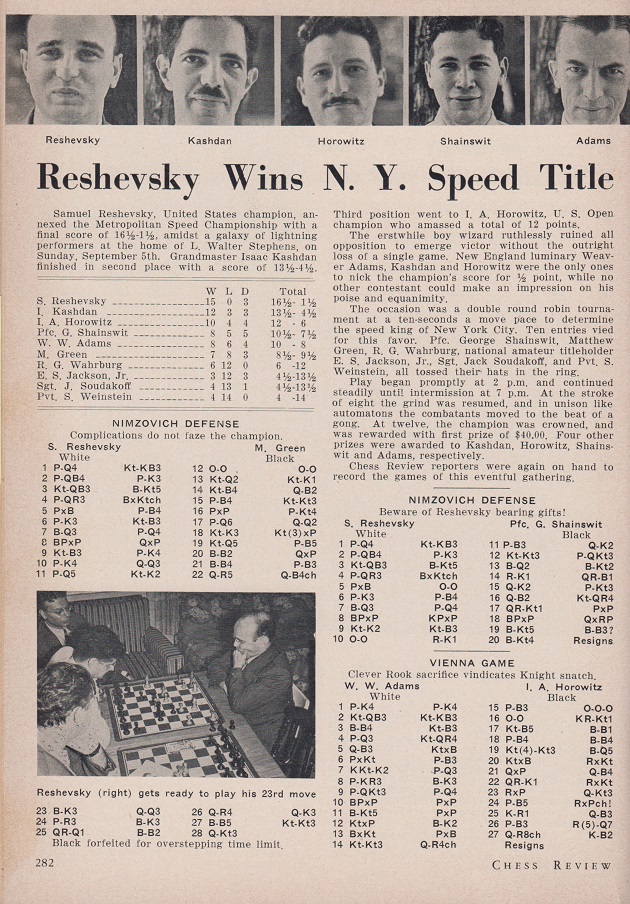

11566. Fast chess (C.N. 11555)

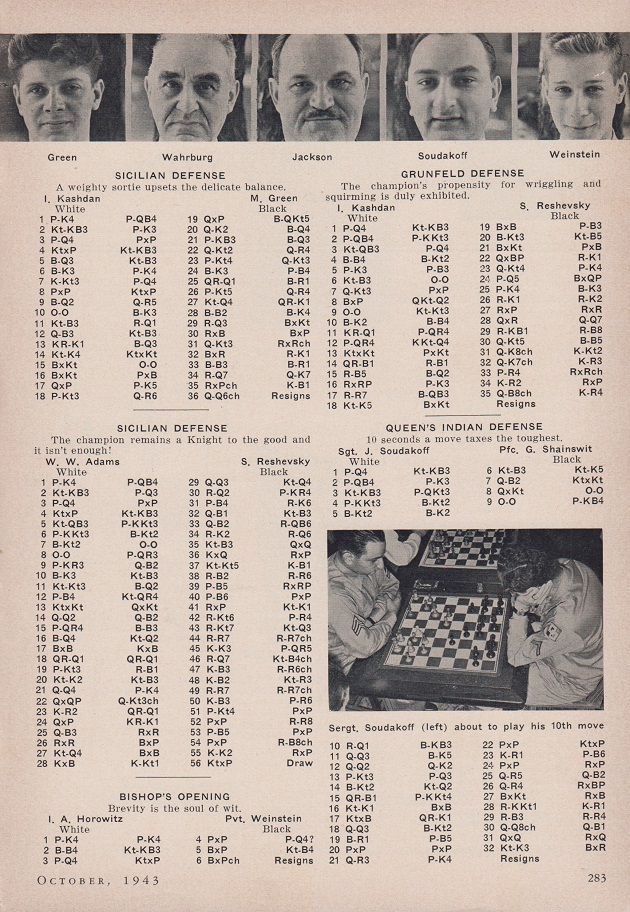

A report on the 1943 Metropolitan Speed Championship on pages 282-283 of the October 1943 Chess Review:

11567. Lasker playing Laska

From the Sammlung Archiv für Kunst und Geschichte, Berlin, Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) has obtained authorization for us to reproduce this photograph of Emanuel Lasker:

Pages 308-330 of Emanuel Lasker Denker Weltenbürger Schachweltmeister edited by Richard Forster, Stefan Hansen and Michael Negele (Berlin, 2009) consist of a chapter about Laska by Wolfgang Angerstein, with the following on page 308:

It will be noted that the identification of Lasker’s opponent as Leo Joseph is tentative. Page 1057 gives the source of the picture: Der Tag, 27 September 1911.

The Berlin Archives have only the Lasker part of the photograph.

11568. Staunton ‘the Bird’

From John Townsend (Wokingham, England):

‘The Satirist, or Censor of the Times was a Sunday paper which specialized in scandal and innuendo. Chess was discussed occasionally, but the material needs to be viewed with great caution.

Page 4 of the 24 December 1843 issue carried the following reply to a correspondent, “Queer Gambit”, who, it is implied, had suspected some kind of skulduggery in the Staunton v Saint Amant match in Paris:

“Queer Gambit. – Ever since chess became a betting game, it is as little removed from ‘the cross system’, as the race, the ring, the river, or running matches. We believe the contest in the French capital to have been a fair one, notwithstanding what ‘Queer Gambit’ has heard.”

The “cross system” refers to a method of breeding racehorses in which strict pedigree requirements are watered down.

Howard Staunton may have been paying the price of newly-won fame, since, two weeks later, on 7 January 1844, he was featured again, on page 4:

“A correspondent asks us if it is true that the English champion at chess, Mr Staunton, used to be known in certain circles some years back by the jocular soubriquet of ‘the Bird’. Perhaps somebody will satisfy this curious gentleman.”

No follow-up insertions have been found. Enlightenment is sought as to the possible significance of the soubriquet “the Bird”, and what the “certain circles” may have been.

The Editor was Barnard Gregory (1796-1852), who was also the leader of a company of amateur actors called the Shaksperians. According to Frederic Boase’s Modern English Biography (volume 1, pages 1233-1234):

“... he libelled and blackmailed many persons, especially Charles, Duke of Brunswick and Lüneburg.”

The Duke played against Paul Morphy in the celebrated consultation game (Paris, 1858). The same source mentions that Gregory was twice imprisoned and that he played Hamlet at Covent Garden on 13 February 1843, “when there was a riot headed by the Duke of Brunswick”.

Gregory also edited The Penny Satirist, 1837-46.’

11569.

Botvinnik’s columbarium

Concerning this photograph, which he took at the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow in February 2019, Douglas Griffin (Insch, Scotland) comments:

‘It shows the columbarium for Mikhail Botvinnik, his wife Gayane Davidovna and his mother Serafima Samoilovna.’

With regard to the cremation of Max Euwe, discussed in C.N. 4116 (see Graves of Chess Masters), Mr Griffin notes that the Dutch National Archive site has four photographs.

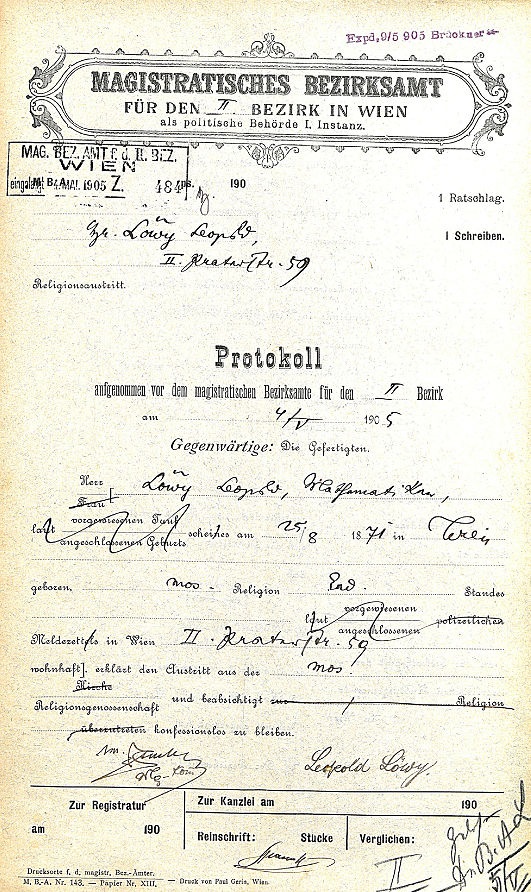

11570. Leopold Löwy (C.N.s 11511, 11520, 11521, 11527 & 11532)

From Michael Lorenz (Vienna):

‘This is the protocol of the Magistratisches Bezirksamt of the Leopoldstadt district, dated 4 May 1905, in which Leopold Löwy declared his intention to renounce Judaism and to adhere to no religion. It is the only known document where Löwy gave his profession as "Mathematiker”.’

11571. Group photograph (C.N.s 7727 & 11563)

Regarding this photograph, owned by Ross Jackson (Raumati South, New Zealand), we note that the painter Esteban Valderrama is standing on the left. On his left, next to Capablanca, is the fencer Ramón Fonst.

11572. Lasker in Weston-super-Mare

Richard Forster (Winterthur, Switzerland) sends this article by ‘W.H.C.’ from page 2 of the Weston Mercury and Somersetshire Herald, 7 March 1908 (Saturday):

‘World’s chess champion at Weston

A pen portrait of Dr Lasker

Marvellous exhibition of simultaneous playThe visit which Dr Emanuel Lasker, the world’s chess champion, paid to Weston-super-Mare on Tuesday will undoubtedly provide a potent stimulus not only to the local chess club, under whose auspices the visit took place, but to chess-lovers of the district generally. Dr Lasker’s visit embraced the giving of a lecture at Messrs Brown Bros. Popular Café and a subsequent exhibition of simultaneous play. Before entering upon details, however, it may not be uninteresting if we give a hastily penned sketch of the master and his methods as suggested by his recent visit. Dr Lasker is of Jewish extraction and, by way of preface, it may be mentioned that there is considerably more in that fact than would prima facie appear, for the championship in the king of games has been retained in Jewish hands for no less than 42 years, Steinitz holding it for 28 years until 1894, while the subject of the present notice has been champion ever since. Dr Lasker himself attributes predominance of the Jewish genius in chess to the fact that its rules are entirely based upon those of self-defence in the struggle for life, of which art Jews are adepts. The doctor is apparently some 40 years of age, of medium height, and possessing a physiognomy which, in addition to bewraying his nationality, strikingly suggests mental force. Yet, clothed in a homely tweed suit, unostentatious in deed and word, walking from table to table with a shuffling step begotten of tens of thousands of such rounds in thousands of saloons, one would not for the moment recognize in him the intellectual giant. That recognition comes later when the pieces are on the board and the champion sets about his work. It is then that one looks up across the board into the dark, short-sighted eyes peering through the steel-rimmed pince-nez and recognizes – Lasker! Playing as he did 20 games simultaneously on Tuesday evening the doctor afforded little or no sign of the strain necessarily involved by the ordeal. A momentary shifting of the unlighted cigar between his teeth or a hand rapidly rumpling the hair at the crown of the head were practically the only indications of the rapidly evolved mental processes within. Despite the necessary concentration, however, Dr Lasker on occasion manifested his sense of humour by such an enigmatic remark as “There’s trouble brewing here”. Whatever elation an opponent might experience over the momentary thought that he had placed the redoubtable doctor in a difficult position was speedily dispelled, however, by the subsequent discovery that the trouble had brewed and that the victim thereof was certainly not Lasker. The opposing players numbered 20, and an adequate idea of the champion’s genius may be gauged from the fact that for practically the first hour of play he visited and made his moves at each of the tables on an average of little more than two and a half minutes. The only player winning a game was the Rev. T.A. Robinson, of Hewish, who adopted the Giuoco Piano opening, and who throughout manifested initiative and resourceful method, while Mr Hans Price effected a meritorious draw. At 10.30 p.m. Messrs E.W. Greenway, J.G. Kemp and F.W. Crisp alone remained in play, but in each case the end came suddenly. The list of players with results is as follows: won – Rev T.A. Robinson. Drew – Mr Hans F. Price. Lost – Messrs P.H.P. Griess, F. Price, F.W. Crisp, J. Bennett, A.W. Bottomley, Capt. R.B. Beard, Messrs H.H. Hely, J. Grace, A.Y. Oag, M.E. Stahl, N. Minifie, H. Shorney, J.G Kemp, E.C. Robinson, E.W. Greenway, Rev. W. Blake-Atkinson and Master H.E. Huntley. As already mentioned, the evening was initiated with a lecture by the champion, in which connection be it said that, as a lecturer, Lasker stands in absolute contrast with the Lasker of the board. The doctor is a cosmopolitan, and therefore a linguist of considerable range, and while the matter of his English is perfect, his accent is so pronounced as to present some little difficulty to the auditor. The contrast, however, is particularly in regard to method, for whereas at the board he is a man of lightning intuition (we are not, of course, referring to games of weighty issue, wherein the proverbial thousand and one possibilities have to be weighed and considered) as a speaker his sentences are weighed with particular deliberation. His ideas are just as cultured and intellectual as one would expect in a man of his attainments, but so deliberately are they advanced that some of their undoubted forcefulness is sacrificed. Dr Lasker said, apart from the fact that chess taught us many virtues in life, they might well consider how closely chess and life were related. If they pondered the question they would find many more resemblances than would at first sight appear. The rule in chess that it was played between two opponents, and that one moved and then the other, constituted a profoundly philosophic observation on life, and it was the corresponding resistance we met in life that made us conquer. No man could play a fine game of chess unless he had a fine opponent; a fine game was a masterpiece produced by two minds contending with each other. And in life too the nation might be regarded as the one player, and the man, the individual, as the other. If the nation was a fine player so to speak – if it made fine laws and gave adequate rewards to its men of genius – then we found that nation producing great men. It might appear to the observer that the man who won at chess did so by reason of some unfathomable quality which was usually called genius. Intrinsically that argument meant nothing at all; it was shirking the question. And it was the same thing in life: when a man produced anything exceptional he was called a genius, and the thing was considered settled. Carlyle had defined genius as “an infinite capacity for taking pains”, but it was quite possible that a man might labour much without commanding success. And so it was in chess: many men studied the game, learned everything that was to be learned, and yet never attained the skill that others did. There was something needed beyond industry in order to command success, and in chess two things were required – first of all, economy of effort and, secondly, imagination. A fine chessplayer was so because he made his combinations with ease, and because he had imagination for possibilities which would otherwise be overlooked. And it was so in life: the great artist or businessman displayed economy in arriving at results for the attainment of which the ordinary worker needed a great deal of thought. After entering upon technicalities of chess, Dr Lasker said the essential genius of the game was capacity to see the possibilities of compensation for pieces given – in chess well-played one could never get the advantage without having to buy it. Those pieces of an opponent which had a great deal of mobility and activity generally meant a great deal of trouble, and it was nearly a law that the best aim for the attack one could select was those pieces of one’s opponent which distinguished themselves by doing much. Then an attack should also be directed on the pieces which lacked mobility, for in chess it was untrue that one must not knock a man when he was down; let them not only knock him but kill him as speedily as possible (laughter). And, to resume the parallel, he believed such things were not altogether unknown among businessmen (laughter). After giving other valuable advice, Dr Lasker deprecated loss of confidence on the part of players. He met many men who lost games simply because they were bluffed into the belief that they were beaten; they were impressed with a sense of danger that was entirely unreal, made defensive moves and withdrew an invaluable offensive piece. Moreover, a player should never defend except with the greatest reluctance, and unless sure that he was compelled to do so. Whenever one made an unnecessary defence one made trouble in forcing oneself to meet a strong attack, and being driven to further defence; courage, hope and faith were wanted, and the player should never defend until it was really necessary to do so. On the contrary, he should attack to the utmost extent he could, and ability to do this constituted one of the great secrets of success (applause). In concluding a highly interesting address, and after giving further comparisons, Dr Lasker said if we closely studied it, chess would be found an excellent exemplar in very many ways in connection with the occasions of everyday life.’

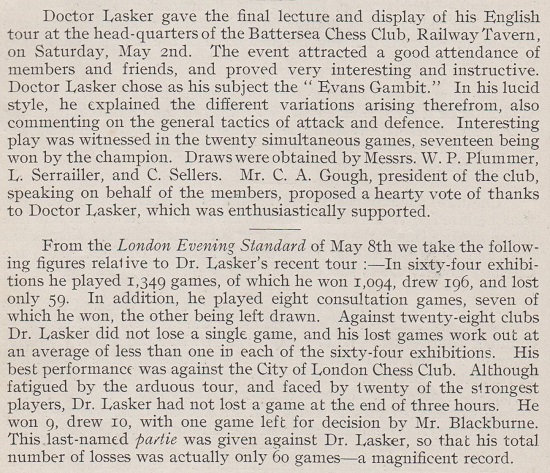

Lasker’s tour of England and Wales ran from late January 1908 to the beginning of May. From page 254 of the June 1908 BCM:

11573. Danish photographs

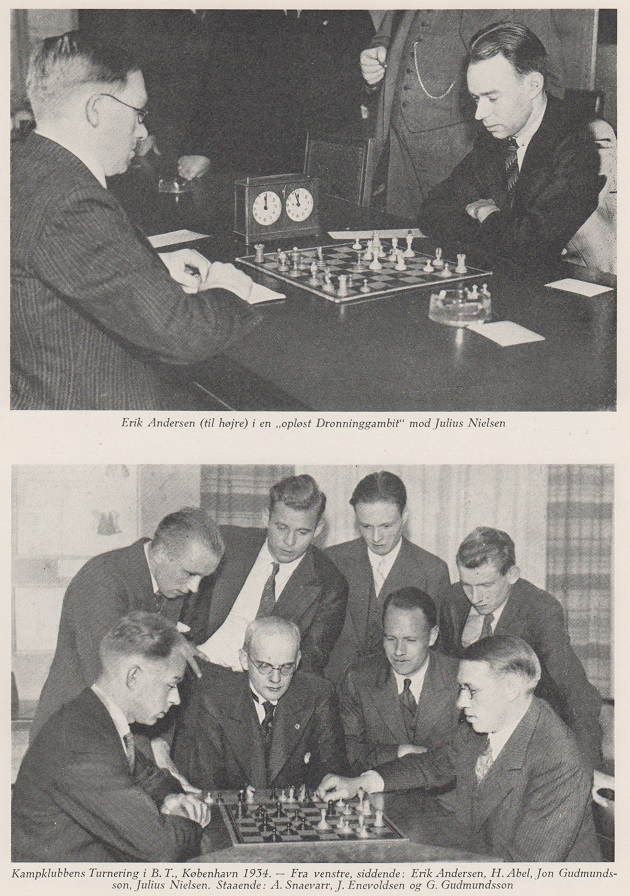

From page 195 of Alt om Skak by Bjørn Nielsen (Odense, 1943) two further Danish photographs:

11574. Capablanca and Valderrama (C.N.s 7727, 11563 & 11571)

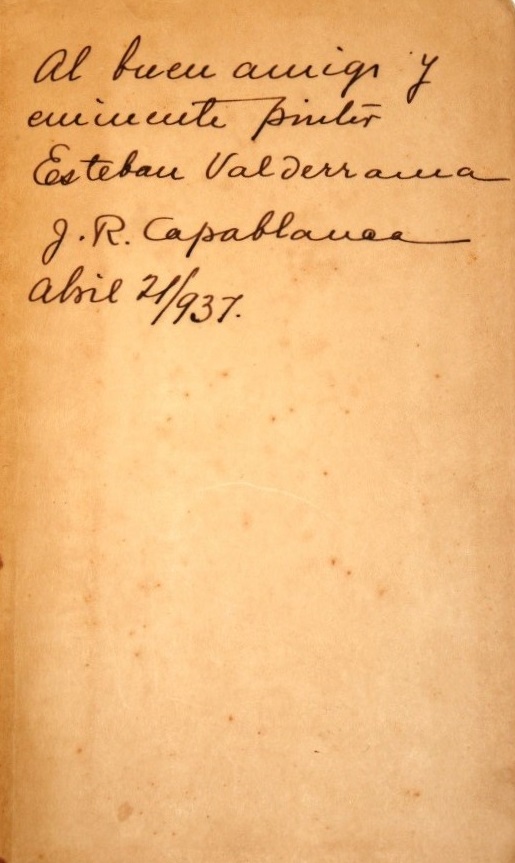

Ross Jackson (Raumati South, New Zealand) reports that he owns a copy of Capablanca’s A Primer of Chess (New York, 1935) inscribed to Esteban Valderrama:

Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England) possesses a large (68cm x 52cm) print of Valderrama’s portrait, with an indistinct inscription by the artist in the top right-hand corner:

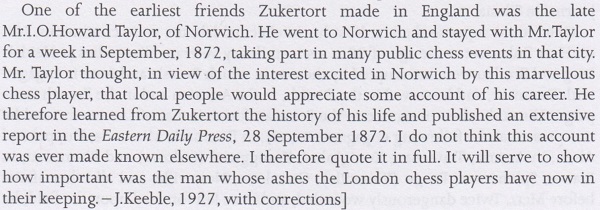

11575. J.H. Zukertort’s alleged accomplishments

‘He took up Sanskrit to trace the history of chess.’

That is one of innumerable claims about J.H. Zukertort presented sourcelessly by Andrew Soltis on pages 177-178 of Chess to Enjoy (New York, 1978). Chess literature offers many similar assertions; see, for instance, pages 144-145 of Wonders and Curiosities of Chess by Irving Chernev, where it was affirmed that Zukertort learned ‘Sanskrit in order to trace the origin of chess’. Chernev’s introduction to the item stated:

‘The most remarkable man that chess ever produced was Johannes Zukertort.’

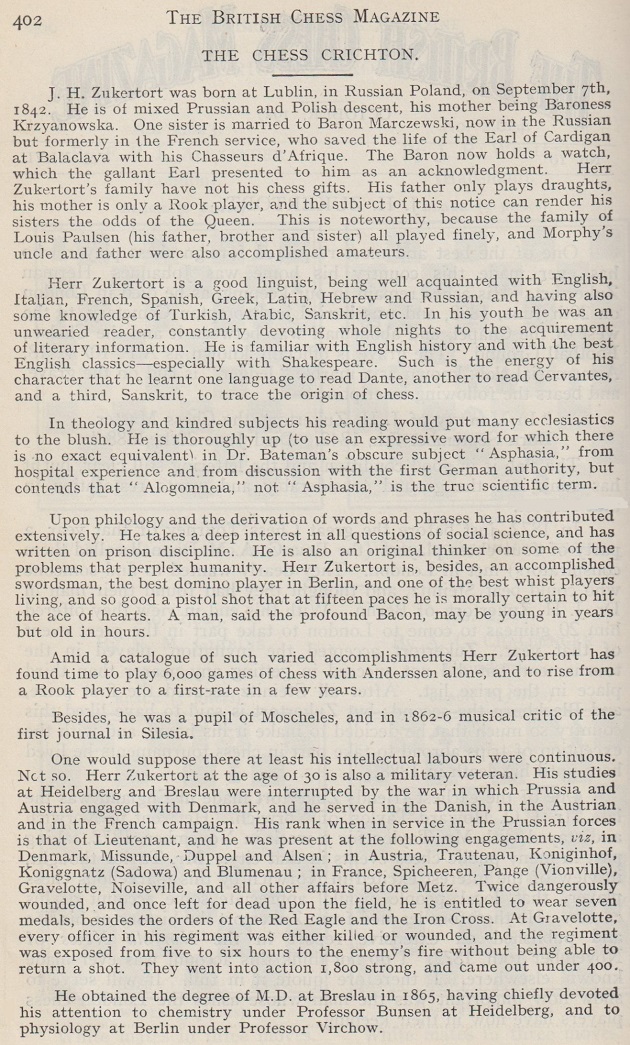

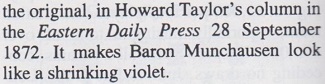

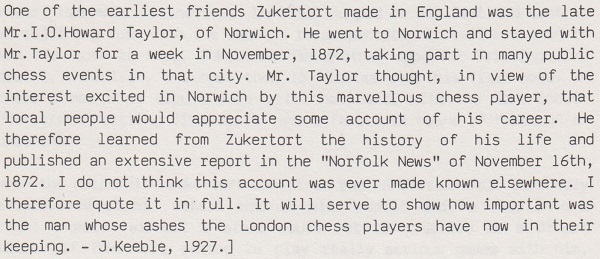

The litany of boasts on Zukertort’s behalf gained widespread attention after John Keeble published an article on pages 401-403 of the October 1927 BCM:

The source for the ‘Chess Crichton’ section was specified

by Keeble as being the Norfolk News of 16 November

1872, and this was taken on trust by subsequent writers;

see, for instance, the Zukertort entry in the first

edition (1984) of the Oxford Companion to Chess,

as well as Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia (1987).

Especially at a time when access to old newspapers was far

more difficult than it is today, it could seem reasonable

to assume that such a citation by John Keeble (of Norwich,

Norfolk) would be reliable.

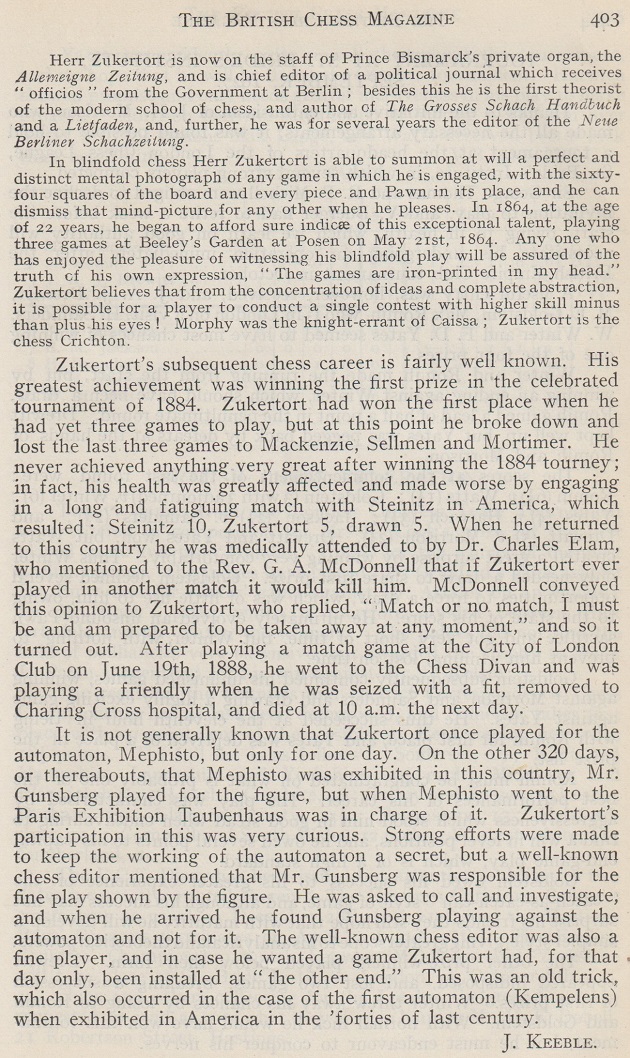

However, on page 108 of the February 1999 BCM (in K. Whyld’s Quotes and Queries column) Owen Hindle demonstrated that the reference to the Norfolk News was not right:

We have no information on any ‘suggestions that Keeble might have invented the whole legend’.

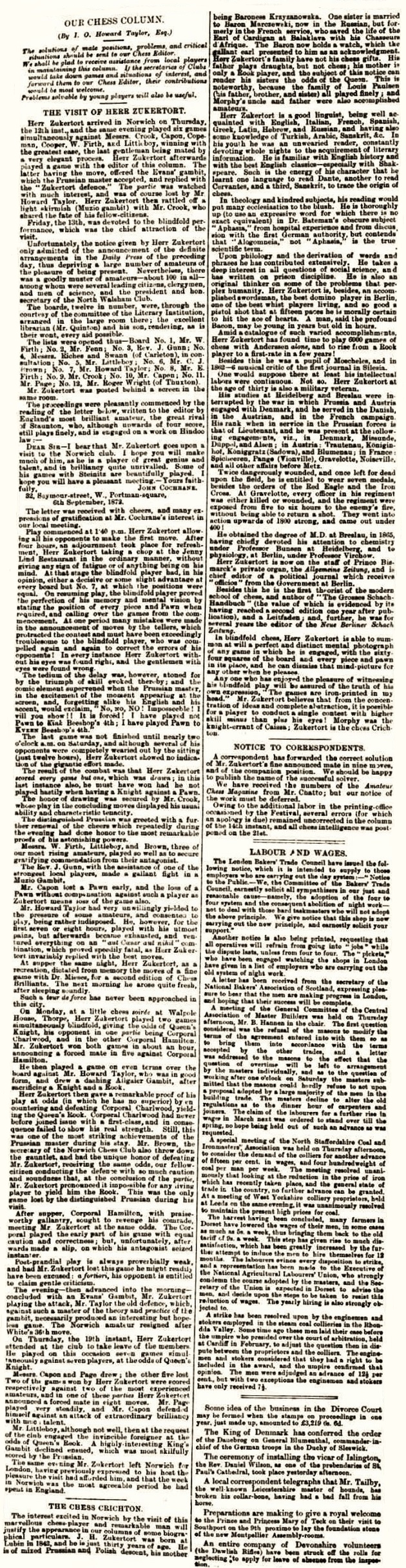

Below is the complete article, by I.O. Howard Taylor, published on page 4 of the Eastern Daily Press, 28 September 1872:

Whether anything similar about Zukertort ever appeared in the Norfolk News, a newspaper with which I.O. Howard Taylor was also connected, on another date (the 16 November 1872 edition published nothing) has not been ascertained.

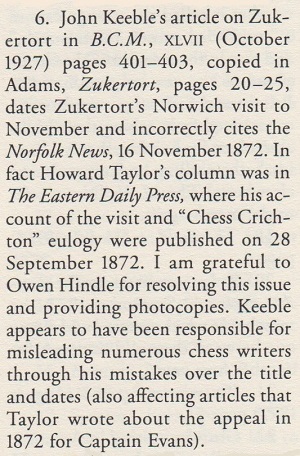

The Keeble article was discussed in an endnote on page 375 of Eminent Victorian Chess Players by Tim Harding (Jefferson, 2012), with a reference to Owen Hindle but without mention of the contribution that he had made to the BCM in 1999:

Finally for now, we show part of how Jimmy Adams’ monograph on Zukertort quoted Keeble in its two editions (1989 and 2014 – pages 20 and 21 respectively), i.e. before and after the Norfolk News reference was known to be wrong:

| First column | << previous | Archives [184] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.