Chess Notes

Edward Winter

When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [185] | next >> | Current column |

11576. J.H. Zukertort’s alleged accomplishments (C.N. 11575)

After reproducing the ‘Chess Crichton’ article on Zukertort which was discussed in our previous C.N. item, Jimmy Adams’ book Johannes Zukertort Artist of the Chessboard (Yorklyn, 1989 and Alkmaar, 2014 – respectively on pages 23-25 and 24-25) had a section entitled ‘The Zukertort Legend’. It began:

The reader may reasonably expect to be informed where exactly Ulrich Grammel published his ‘important piece of research’ on Zukertort, and it is scant help to be told, ‘in an article “Grandmasters are not gods” in the Rochade magazine’.

In connection with another book by Jimmy Adams, C.N. 10563 made an observation which could hardly seem more obvious or less controversial:

One of the many reasons why a book should give precise sources is that they enable readers to check information independently.

A note on page 225 of another monograph on Zukertort, Der Großmeister aus Lublin by Cezary W. Domański and Tomasz Lissowski (Berlin, 2005), shows the proper way of specifying where Ulrich Grammel’s research on Zukertort can be found:

For ease of reference, a feature article, J.H. Zukertort’s Alleged Accomplishments, has just been posted.

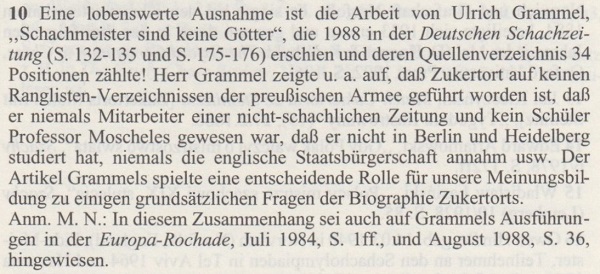

11577. Alekhine and Capablanca in St Petersburg

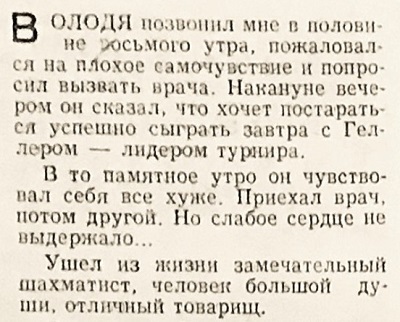

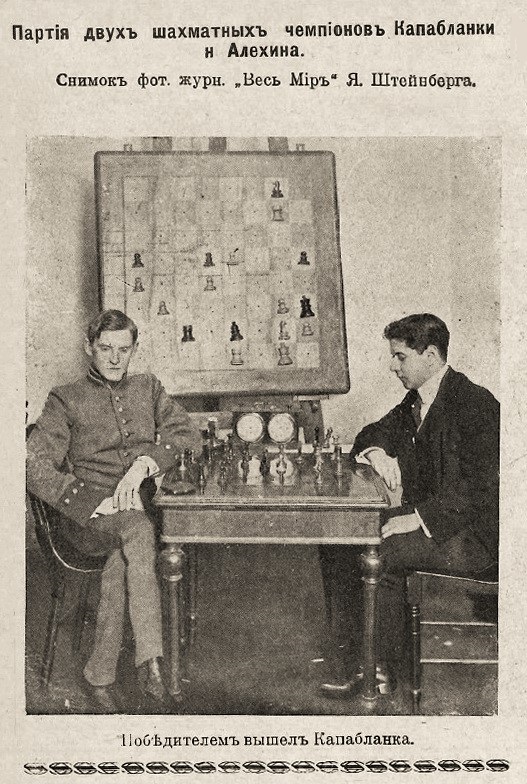

Marcel Klemmer (Bad Segeberg, Germany) raises the subject of a famous early photograph of Alekhine and Capablanca, of which a colourized version can be found on the Internet, and asks who the figure on the left is:

The above is the best-quality version of the photograph available to us, and readers’ assistance in identifying the figures on the far left and far right will be appreciated.

The demonstration board shows the final position in the first over-the-board encounter between the future world champions, an exhibition game played in St Petersburg on 14 December 1913; see pages 11-12 of Hooper and Brandreth’s The Unknown Capablanca. Our monograph on the Cuban had a small version of the photograph, cautiously captioned ‘St Petersburg, 1913/14’.

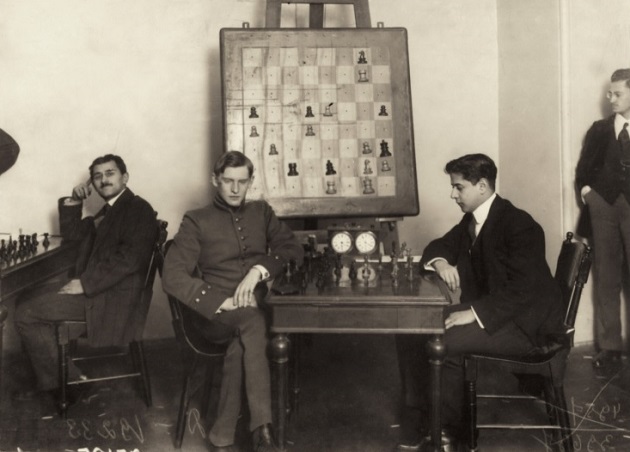

I. and V. Linder gave the picture in their Russian-language books on Capablanca (2005, page 183) and on Alekhine (2006, page 228), but whereas the former stated that the occasion was their first over-the-board meeting (i.e. in 1913), the latter asserted that it was their first tournament game, at St Petersburg, 1914 (an event which began in April):

When the Linders reproduced the photograph again, in 2011, on page 45 of another book on Capablanca, the date went back to 1913:

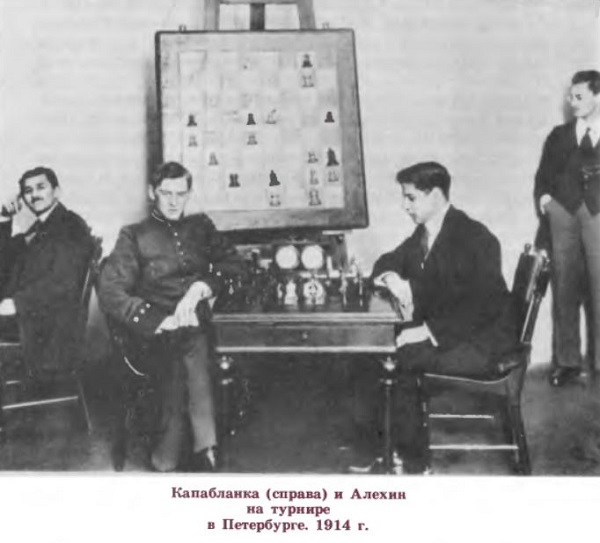

A figure standing on the right (also currently unidentified) is almost entirely visible in the version of the picture on page 38 of A.I. Sizonenko’s 1988 volume on the Cuban:

Similarly, on page 77 of a 1992 book on Alekhine by Y. Shaburov:

For bibliographical details concerning all these works, see Books about Capablanca and Alekhine.

Did the photograph appear in any Russian publications of the time, and, to reiterate our German correspondent’s enquiry, can the player on the left be positively identified?

11578. What should White play?

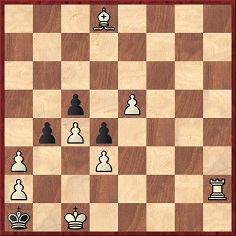

The conclusion of an endgame study:

11579. Octogenarians

John Donaldson (Berkeley, CA, USA) notes that two octogenarians who have produced fine games in 2019 are Viktors Pupols (v Tiglon Bryce at the Washington State Championship in February and v Dmitry Zilberstein at the Western States Open, Reno in October) and Anthony Saidy (v Vladimir Belous at the National Open, Las Vegas in June).

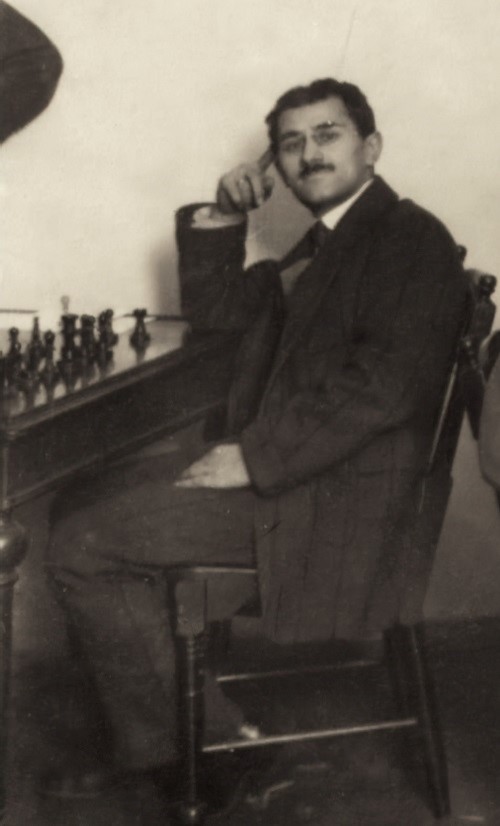

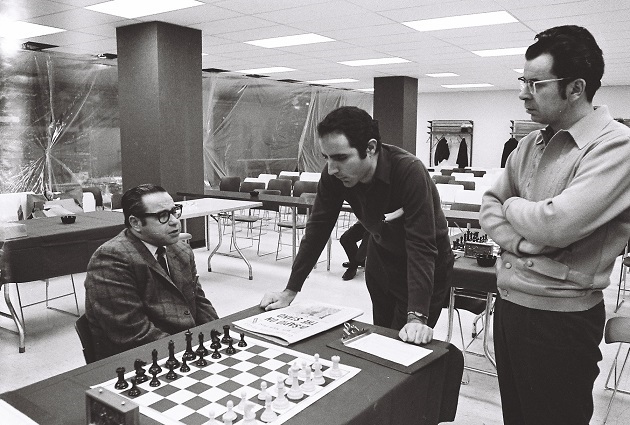

Our correspondent provides these archive photographs:

John Donaldson: ‘Viktors Pupols (left) and his fellow Latvian-American master Ivars Dahlbergs at a tournament in the Pacific Northwest, late 1960s. The photograph comes from the archive of the late Alex Liepnieks.’

John Donaldson: ‘Arthur Bisguier,

Anthony Saidy and Pal Benko

(photograph taken by the late Beth Cassidy).’

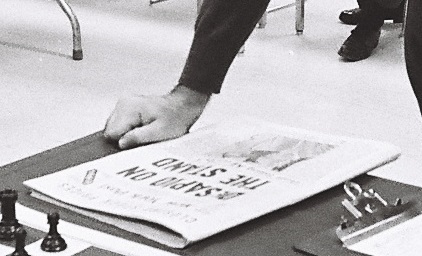

Although the above photograph is undated, the newspaper headline appears to be ‘De Sapio on the Stand’, i.e. a reference to the trial of Carmine De Sapio in December 1969. That month saw the conclusion of the US Championship in New York, in which Bisguier, Saidy and Benko all participated.

11580.

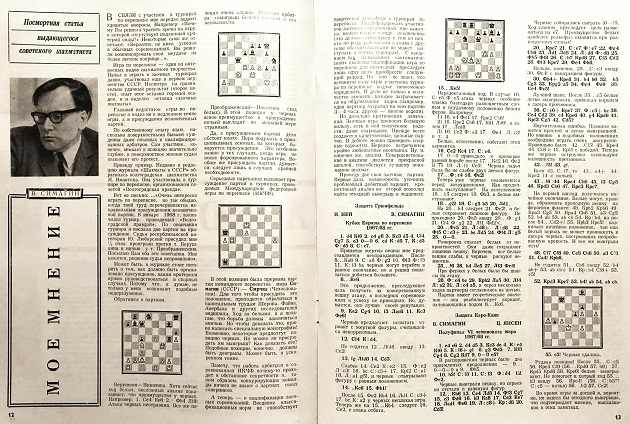

Vladimir Simagin (C.N. 11565)

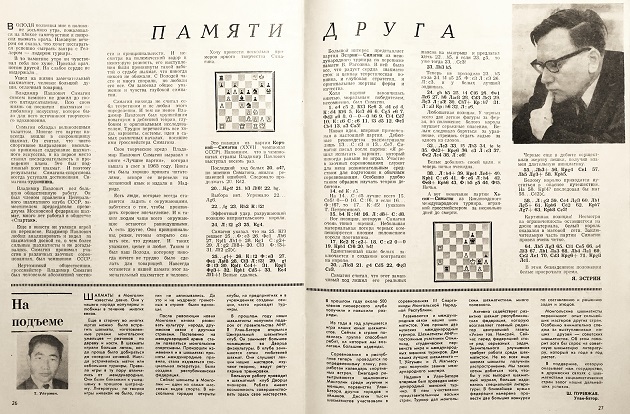

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) sends material regarding Simagin from Shakhmaty v SSSR, 1968 (issue 10, pages 12-13, and issue 12, pages 26-27):

On page 26 Yakov Estrin reported that Simagin fell ill and died before his scheduled game against Geller:

11581. Alekhine and Capablanca in St Petersburg (C.N. 11577)

A detail of the board position:

The position depicted occurred around move 18 in the Capablanca v Alekhine exhibition game (St Petersburg, 14 December 1913) mentioned in C.N. 11577.

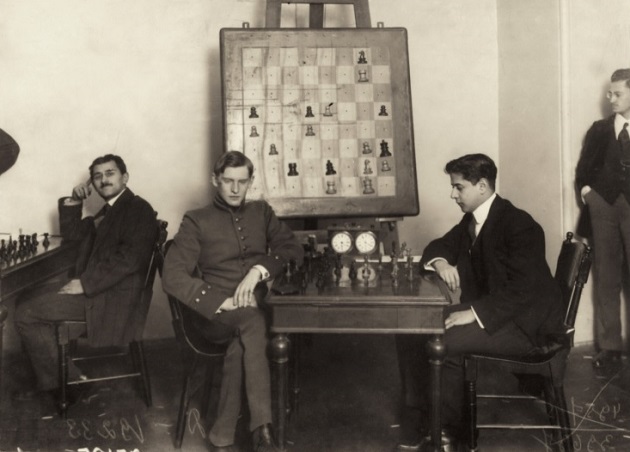

11582. What should White play? (C.N. 11578)

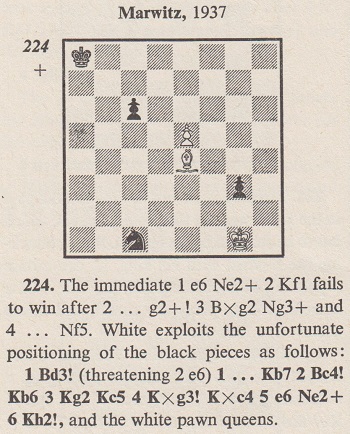

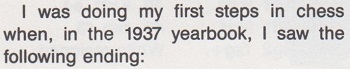

From page 98 of Practical Chess Endings by Irving Chernev (New York, 1961 and London, 1962):

This is only the conclusion of J.H. Marwitz’s study. The

full composition can be found on, for instance, page 85 of

volume two of

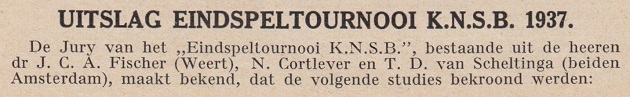

The date 1937 refers to the year of the endgame study contest organized by the Tijdschrift van den Koninklijken Nederlandschen Schaakbond. The winning entries were not announced and published until the March 1939 issue (pages 86-87):

11583. Writing

The recent death of two men of formidable intellect, Clive James and Jonathan Miller, prompts a few ruminations. Whether Miller had any particular interest in chess is unclear, but the prevalence of ineffectual criticism in the chess world and the dearth of rigorous interviewing (as mentioned in, for instance, Child of Change and Chess Thoughts) bring to mind a clever, documented remark of Miller’s which has been quoted in several of his obituaries:

‘Bernard Levin came down on me like an ounce of bricks.’

Concerning Clive James, all available chess references by him are in our feature article, but a general remark is worth pondering:

‘Writing is essentially a matter of saying things in the right order.’

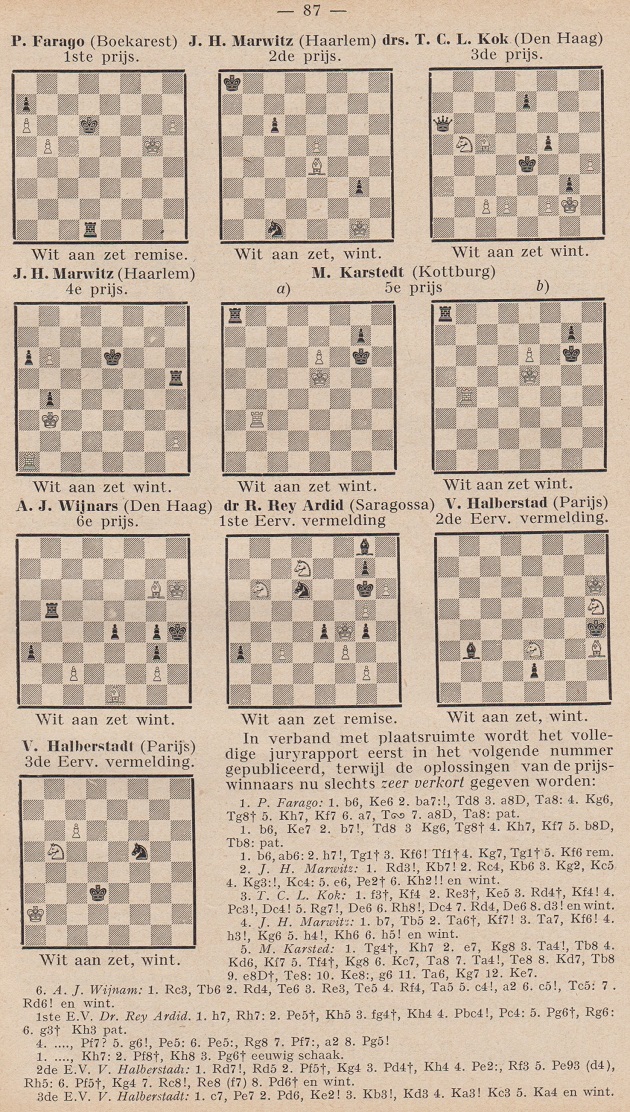

That comes from page 159 of Unreliable Memoirs (London, 1980), in a description of his employment at the Sydney Morning Herald in the early 1960s:

A regular theme in Clive James’ output is that many writers, including ‘professionals’, are unfit for the task. C.N. 1079 (see Chess and the English Language) cited this description of editing work from page 33 of his follow-up volume of autobiography, Falling Towards England (London, 1985):

‘... sorting out tenses, expunging solecisms and re-allocating misplaced clauses to the stump from which they had been torn loose by the sort of non-writing writer for whom grammar is not even a mystery, merely an irrelevance.’

As regards content, it is, of course, vital to gauge accurately what readers do, and do not, need to be told, with matters seen from their standpoint. Poor writers often include information which is self-evident (or, at least, traceable via a quick Google search) while omitting information which is essential and requires elucidation by them. There should be no spoon-feeding of readers but also no off-loading of verification work onto them, or leaving them to guess what may or may not be true. With such basics accomplished, the writer’s skill comes into play at the next stage: attempting to produce prose whose flow is not impeded by the corroborative details.

Some writers have the peculiar habit of snippet-dangling, and the reference to Sydney in the above passage from Unreliable Memoirs indirectly reminds us of a small example: on page 1 of The United States Chess Championship, 1845-1996 by A. Soltis and G.H. McCormick (Jefferson, 1997) an aromatic morsel is waggled fleetingly under the reader’s nose. In a cursory list of some American chess masters’ professions, Sidney Bernstein is described as ‘a movie censor’. Nostrils atwitch, the reader hopes for some hard facts, but the book has already moved on to calling Jackson Showalter a cattle rancher. To rewind, though, what exactly is known about the assertion that Sidney Bernstein was a film censor? Where and when? Working for whom? In peacetime or in wartime, or both? Censoring what kind of films? What reliable source do the co-authors have for their tiny, if tantalizing, nibble?

When nothing is explained, everything and anything can be imagined; even, for instance, that – and stranger things have happened in chess literature – there has been a mix-up over, say, Sydney Sharp or Jacob Bernstein. Only with the rewarding discipline of real sourcing can the writer aspire to real clarity and real precision, and that is what readers deserve.

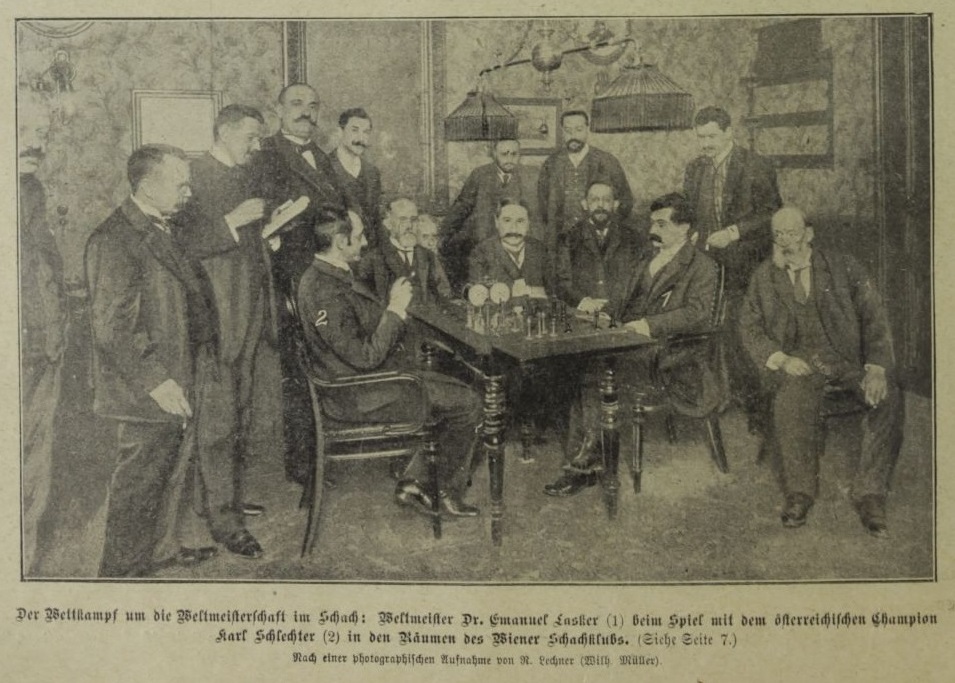

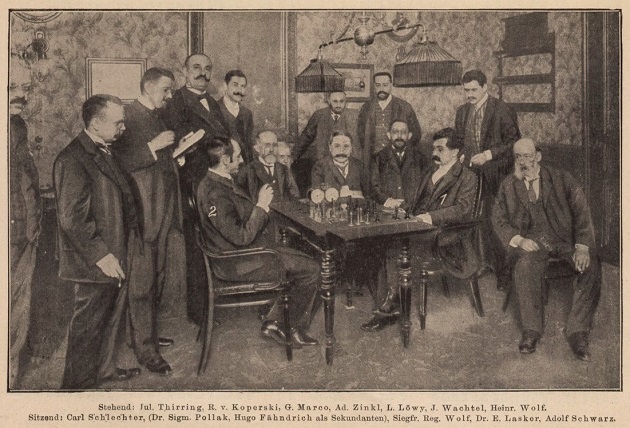

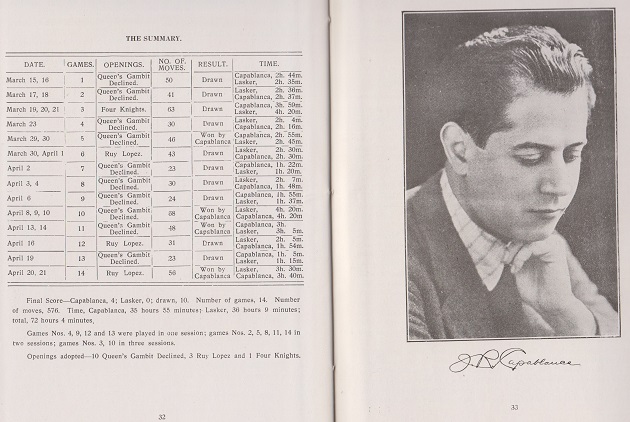

11584. The 1910 world championship match

The above photograph, from page 6 of Das interessante Blatt, 20 January 1910, is in The Lasker v Schlechter Controversy (1910), but, as Michael Lorenz (Vienna) notes, a version with a full caption was published on page 59 of the February-March 1910 Wiener Schachzeitung:

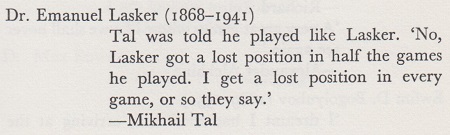

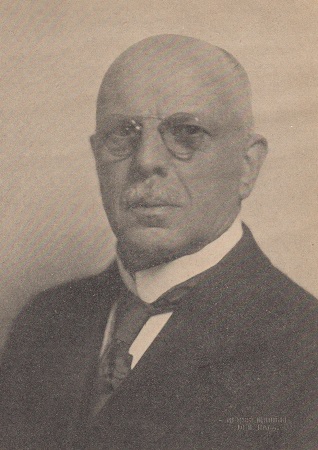

11585. Tal and Lasker

From page 129 of The Chess Scene by David Levy and Stewart Reuben (London, 1974):

The unspecified source proves a disappointment: the alleged Tal remark is on page 44 of the End-October 1965 issue of CHESS, in an article by Dimitrije Bjelica. It follows a brief reference to Tal’s win against Héctor Rossetto at the 1958 Interzonal tournament in Portorož and begins, ‘“You play like Lasker”, we said to Tal ...’

There was a different wording on page 237 of Bjelica’s Grandmasters in Profile (Sarajevo, 1973): ‘They say that Lasker is going to lose in every other game, about me they say that I am going to lose in every one.’

11586. Bleak House

As an addition to Charles Dickens and Chess, Ross Jackson (Raumati South, New Zealand) quotes two passages from Bleak House, in Chapters 5 and 20 respectively:

‘“Ah, cousin!” said Richard. “Strange, indeed! All this wasteful, wanton chess-playing is very strange. To see that composed court yesterday jogging on so serenely and to think of the wretchedness of the pieces on the board gave me the headache and the heartache both together. My head ached with wondering how it happened, if men were neither fools nor rascals; and my heart ached to think they could possibly be either ...”’‘Mr Guppy suspects everybody who enters on the occupation of a stool in Kenge and Carboy’s office of entertaining, as a matter of course, sinister designs upon him. He is clear that every such person wants to depose him. If he be ever asked how, why, when, or wherefore, he shuts up one eye and shakes his head. On the strength of these profound views, he in the most ingenious manner takes infinite pains to counterplot when there is no plot, and plays the deepest games of chess without any adversary.’

11587. A.E. van Foreest

The feature article Jacques Mieses refers to occasional confusion between Arnold and Dirk van Foreest (and notably regarding the famous ‘Youth has triumphed’ game against Mieses). A photograph of Dirk van Foreest has been given in the article, from Een Hulde aan Jhr. Dirk van Foreest by L. Prins (Lochem, 1945), and below is the portrait of Arnold van Foreest published on page 191 of the June 1938 Tijdschrift van den Koninklijken Nederlandschen Schaakbond:

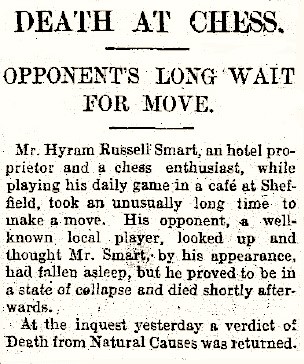

11588. Death at chess

From page 13 of the Daily Mail, 14 November 1923:

This ‘news item’ about Hyram Russell Smart was reproduced on page 66 of the Chess Amateur, December 1923.

11589. A surfeit of news

G.H. Diggle on page 4 of the BCM, January 1981:

‘Chess news is one long traffic jam, which editors find it almost impossible to contain or handle.’

11590. A scarcity of news

From page 239 of the American Chess Journal, January 1879:

‘We have but little news to chronicle this month, and like the rest of the chess world, are waiting for something to turn up.’

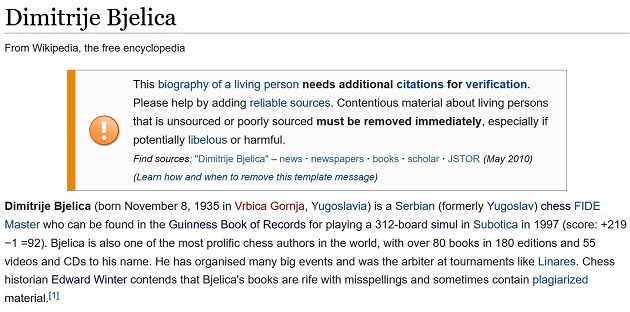

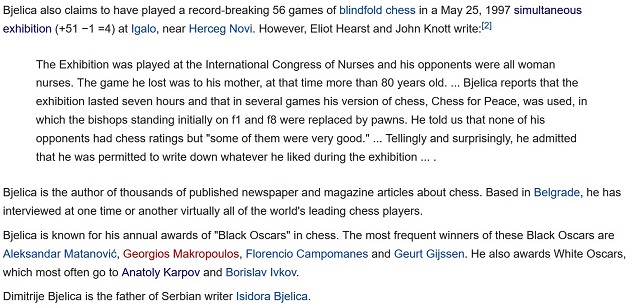

11591. Dimitrije Bjelica

Following the reference to D. Bjelica in C.N. 11585, a look at his current Wikipedia entry seems timely:

Given the alleged existence of ‘over 80 books in 180 editions’, it is an act of mercy that (contrary to the Wikipedia articles on, for instance, Bruce Pandolfini and Eric Schiller) the entry eschews a list and mentions only one alleged volume. However, that solitary reference, ‘Reyes del Ajedrez ISBN 84-88155-32-8’, is worthless because Bjelica had a series of books published under the generic title ‘Reyes del ajedrez’; the ISBN number given – randomly, it seems – is for the volume on Botvinnik (Madrid, 1994).

The first paragraph also affirms that Bjelica was ‘the arbiter at tournaments like Linares’. Which tournaments are ‘like Linares’ is an open question, and, in any case, no substantiation for the alleged role is provided. There is, at least, a little something on page 177 of the May 1988 BCM, in a report on the sixth ‘Ciudad de Linares’ tournament: ‘the chief arbiter was Viktor Baturinsky, helped by Dimitrije Bjelica and Diego Martinez Linares.’

Still in the first paragraph of the Wikipedia entry, we contend that ‘contends’ is far too weak a word in connection with the rifeness of misspellings and plagiarism in Bjelica’s books. It is not a contention, but the expression of an incontrovertible fact. The first of the two ‘References’ on the Wikipedia page will take the reader to Jan Timman’s description of Bjelica: ‘a gutter journalist who wrote books that were full of printing errors and plagiarisms.’

The references to ‘Black Oscars’ (with and without quotation marks) and ‘White Oscars’ (without quotation marks) appear outmoded, incomplete, unsubstantiated and irrelevant. Awards involving Bjelica need to be treated with the utmost caution. None of the ‘External links’ leads anywhere of value. The ChessBase one relates to a 2004 article with much dubious wording identical to what is still in the Wikipedia entry for Bjelica even today.

According to the first paragraph of the entry, Bjelica (a ‘FIDE Master’ with very few published games) ‘can be found in the Guinness Book of Records for playing a 312-board simul in Subotica in 1997 (score: +219 −1 =92)’, with the implication that the alleged record is still valid today. In which edition or editions of that book can such a display be found, and on whose authority was it included? We lack almost all pre-2005 editions of the Guinness work, but can confirm that Bjelica is not mentioned in any edition from 2005 to 2020.

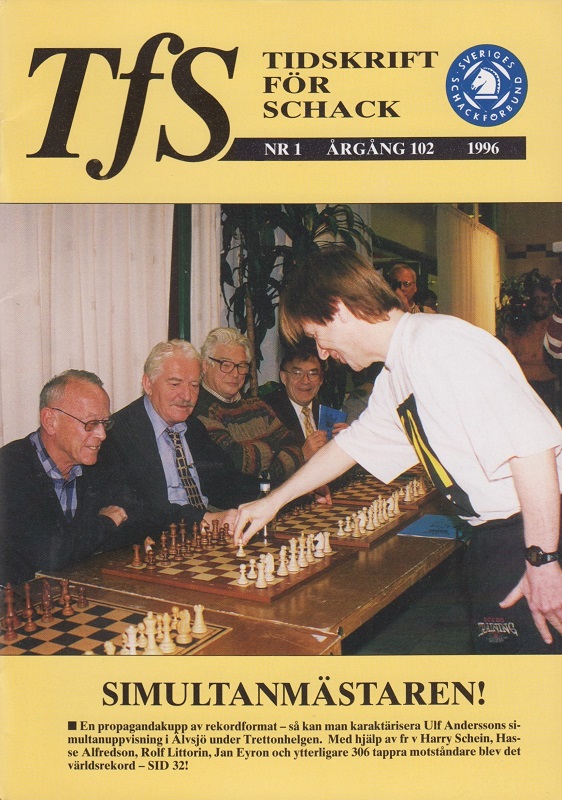

On that unspecified day in 1997 did the ‘FIDE Master’ really dethrone Ulf Andersson, who had (although his own Wikipedia entry does not mention it) played the previous year against 310 opponents simultaneously in Älvsjö, Sweden? On that performance an illustrated, documented report was published on pages 32-33 of the January 1996 issue of Tidskrift för Schack.

A basic search in Google Books shows that Bjelica was listed by Guinness in a number of editions in the 1980s, for an earlier alleged display:

‘Dimitrije Bjelica (Yugoslavia) played 301 opponents simultaneously (258 wins, 36 draws, 7 losses) in 9 hours on Sept. 18, 1982, at Sarajevo, Yugoslavia. Bjelica’s weight dropped by 4½ lb as he walked a total of 12.4 miles.’

Without demurral, that claim was presented as still being a record on page 132 of The Even More Complete Chess Addict by M. Fox and R. James (London, 1993), but on what grounds? Video coverage of record attempts today often shows a Guinness adjudicator, ascetically dressed, with a pair of severe glasses, an unforgiving stopwatch, and pen menacingly poised over clip-board, but was any such invigilator present in Sarajevo during Bjelica’s alleged display? And what proof or corroboration was published in reliable Yugoslav sources of the time?

Concerning any alleged exploit by Dimitrije Bjelica there is, at the very least, fog. Nowadays, Wikipedia has some excellent chess entries, but Bjelica’s is currently one of the worst.

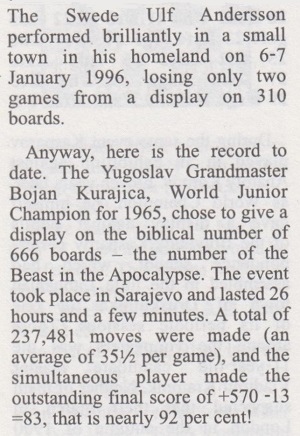

11592. Kurajica in Sarajevo

From page 238 of The Batsford Book of Chess Records by Y. Damsky (London, 2005), a messy work discussed in C.N. 3939:

No date (even the bare year – 1991) was given for Kurajica’s exhibition, and it is surprisingly difficult to find comprehensive information in either print or online sources.

11593. Rude reviews (C.N.s 7575, 9376 & 11208)

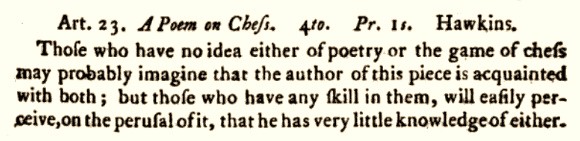

William Hartston (Cambridge, England) submits the oldest specimen that we have been able to give so far, from page 237 of the March 1764 edition of the Critical Review, concerning A Poem on Chess by Guy Hawkins:

‘Those who have no idea either of poetry or the game of chess may probably imagine that the author of this piece is acquainted with both; but those who have any skill in them, will easily perceive, on the perusal of it, that he has very little knowledge of either.’

11594. Örebro, 1938

Source: page 355 of Alt om Skak by Bjørn Nielsen (Odense, 1943).

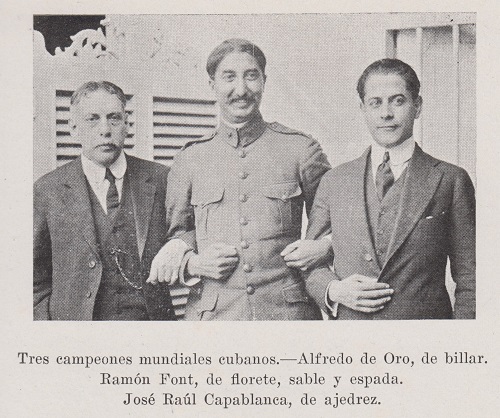

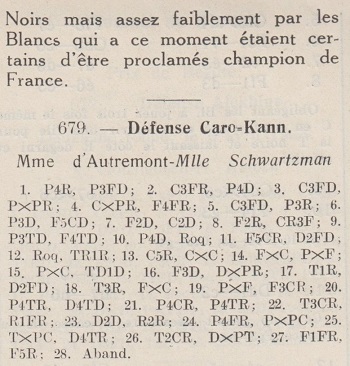

11595. Capablanca and Fonst

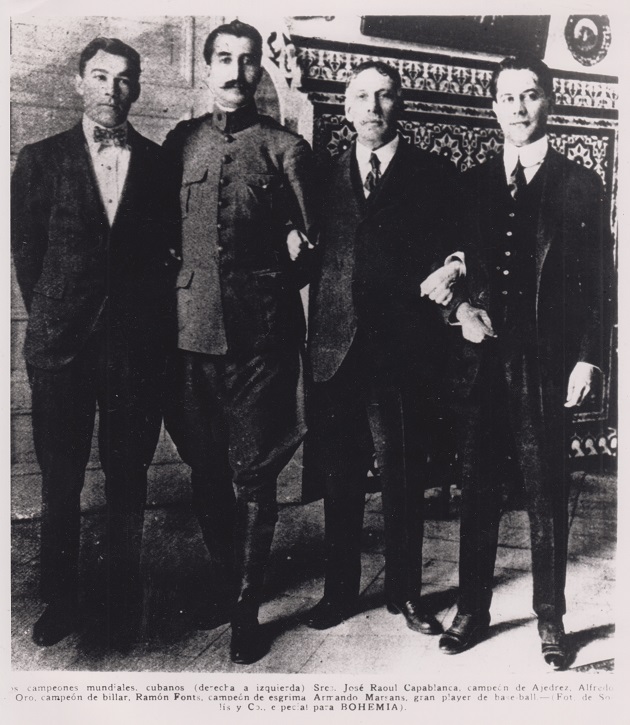

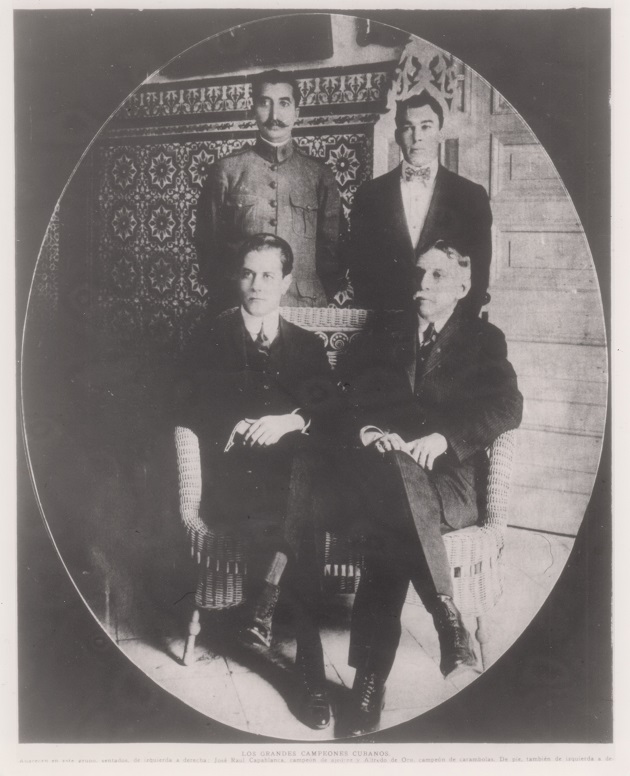

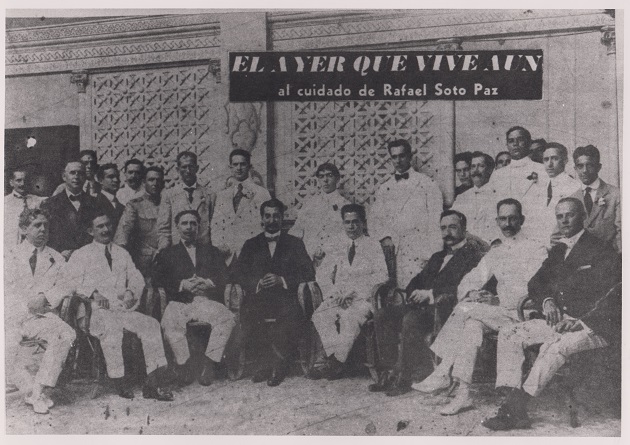

This photograph, owned by Ross Jackson (C.N.s 7727, 11563 and 11571), is one of several of Capablanca with the fencing champion Ramón Fonst (1883-1959).

In addition to ‘Fonts’ (see below), the spelling ‘Font’ is seen, as in Glorias del Tablero “Capablanca” by José A. Gelabert (Havana, 1923):

During a visit to the Biblioteca Nacional José Martí in Havana in 1986 we discovered a number of further photographs of Capablanca and Fonst:

Bohemia, 20 January 1918, page 13

The inversion of the names Alfredo de Oro (billiards) and Armando Marsans (baseball) in the original edition of our book on Capablanca was corrected in the second printing of the hardback and in the paperback.

Two further photographs from the same occasion were found in Bohemia (exact sources not currently to hand):

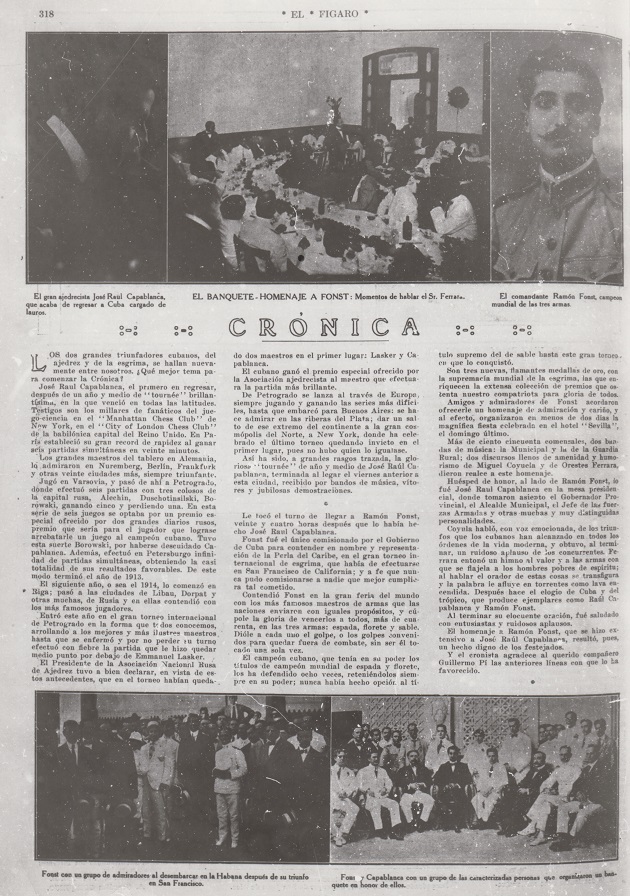

Page 318 of El Fígaro, 13 June 1915:

As ever, copies of better quality will be welcome. The final photograph above was reproduced in a feature in Bohemia, 31 August 1952, page 140:

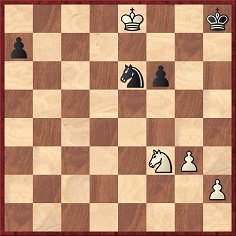

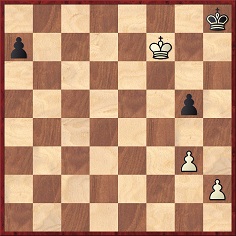

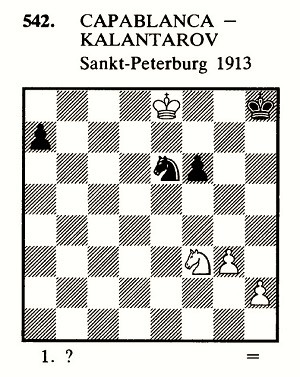

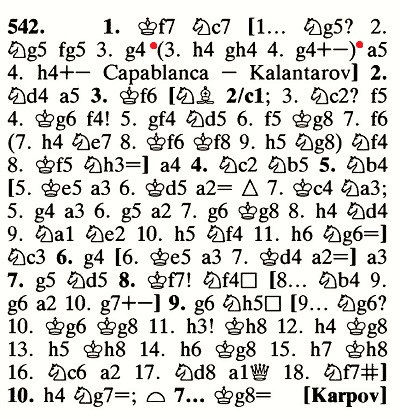

11596. Capablanca v Kalantarov

The first part of the endgame discussed in Capablanca v Kalantarov:

1 Kf7 Ng5+ 2 Nxg5 fxg5

This second diagram was given on page 196 of The ChessCafe Puzzle Book by Karsten Müller (Milford, 2004), and the detailed solution on page 285 began:

‘3 g4!! ... Black is now lost in all variations ... 3 h4? is the wrong way to implement the breakthrough because of 3...g4!’

Karsten Müller also pointed out those options in C.N. 2402.

José de Jesús García Ruvalcaba (San Diego, CA, USA) draws attention to pages 147 and 150 of volume five of the Encyclopedia of Chess Endings edited by A. Matanović (Belgrade, 1993):

The question is whether Karpov really made the highlighted assessment, with no mention of 3...g4.

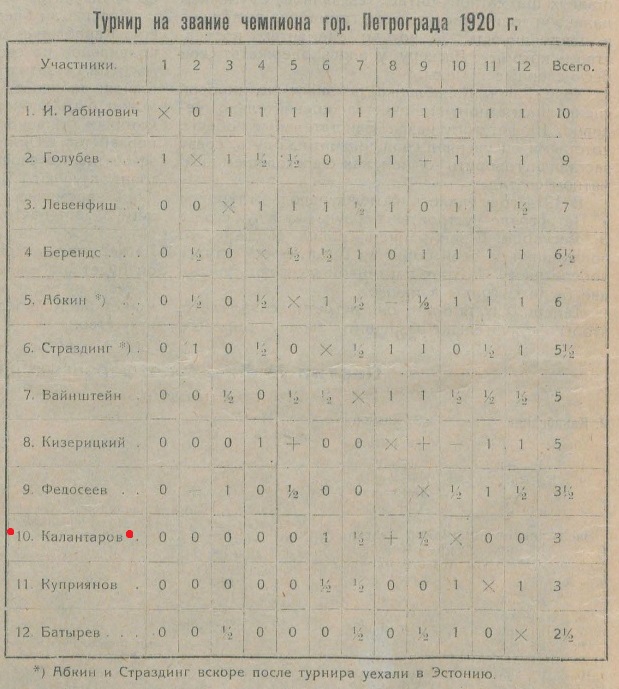

Mr García Ruvalcaba is attempting to trace biographical information about Kalantarov and reports that a player of that name was in a crosstable of the 1920 Petrograd championship on page 2 of the 1 May 1921 issue of Листок шахматного кружка Петрогубкоммуны (Listok shakhmatnogo kruzhka Petrogubkommuny):

11597. Alekhine and Capablanca in St Petersburg (C.N.s 11577 & 11581)

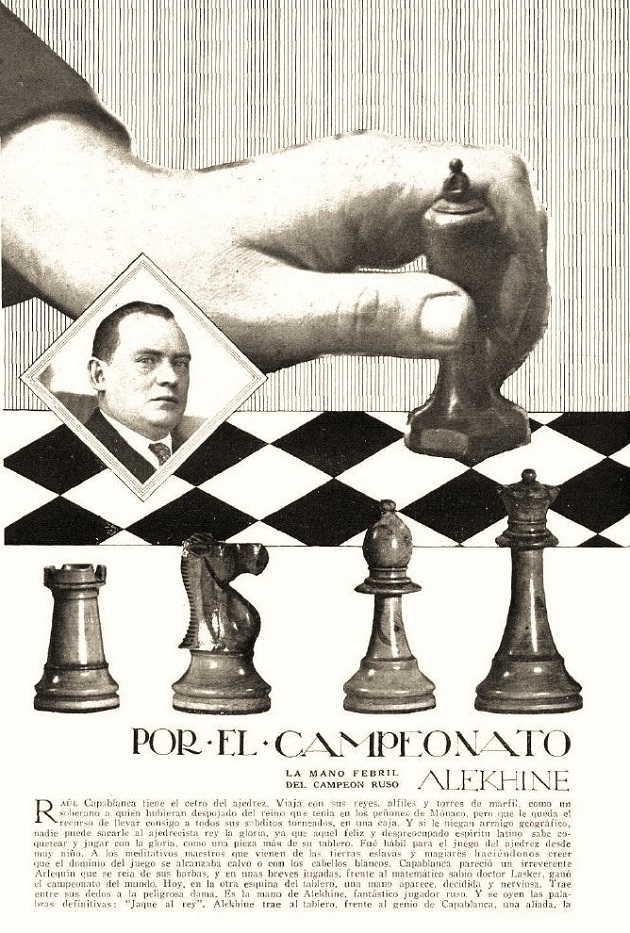

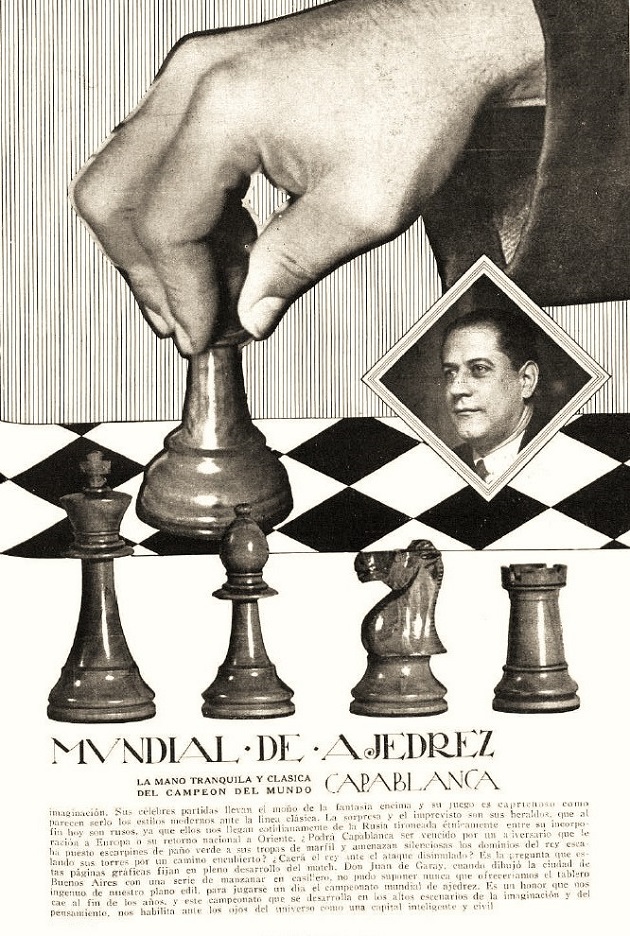

Yuri Kireev and Mikhail Sokolov (Moscow) send this early publication of the Alekhine v Capablanca photograph, on page 8 of the 50/1913 issue of the weekly magazine Весь мир:

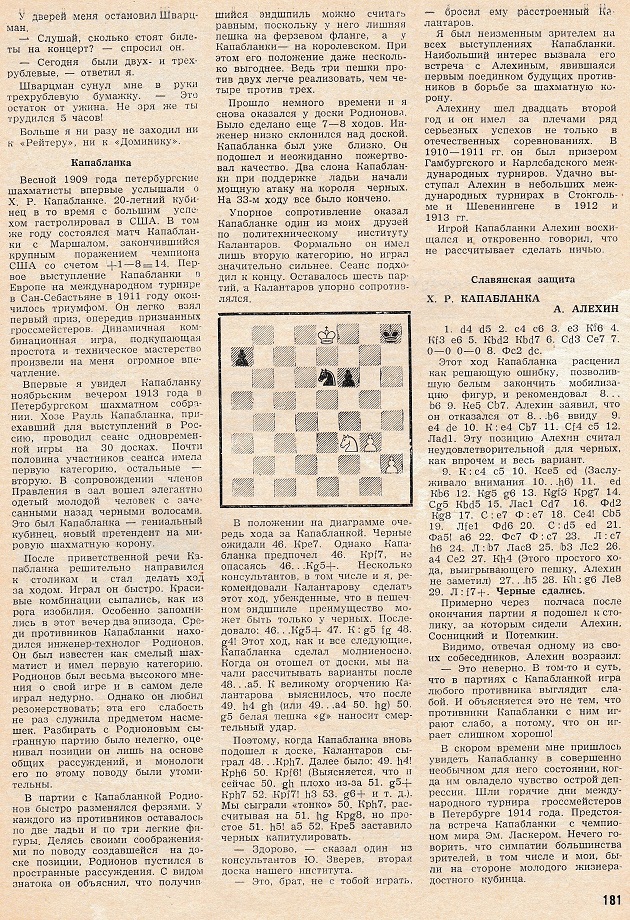

11598. Capablanca and Finis Barton

C.N. 3454 (see too Chess and Hollywood) showed a small, poor-quality photograph of Capablanca at the chessboard with Finis Barton (1911-78). Now, Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) has found another shot, on page 10 of Part II of the Los Angeles Times, 11 April 1933:

Can a high-quality copy of the photograph be found?

Regarding the game referred to, see Capablanca v Steiner (Living Chess).

11599. Hands (C.N.s 10616, 10812 & 11564)

See C.N. 11564 for the full page

The original publication of these illustrations, in Caras y Caretas, 24 September 1927, is provided by Olimpiu G. Urcan:

11600. Nonagenarians

John Donaldson (Berkeley, CA, USA) raises the topic of players still competing strongly in their 90s. In addition to Enrico Paoli (1908-2005), he mentions Erik Karklins (1915-2017), whose career has been chronicled by Bill Feldman and by Ken Marshall.

Franz/Francisco Benkö (1910-2010) was discussed in C.N. 3445.

11601. Vienna

Michael Lorenz (Vienna) writes:

‘This 1909 postcard, from the holdings of the Austrian National Library, shows the view from Vienna’s Marienbrücke towards the Rotenturmstraße. On the right-hand corner of Rotenturmstraße and Franz-Josefs-Kai is the Café Marienbrücke (also called the “Café Schwarz”), which was the venue, between 17 and 24 January 1910, for the fourth and fifth games of the Lasker v Schlechter match. The first-floor rooms where both games were played are above the white awning. The whole first row of buildings near the Donaukanal was destroyed during combat in April 1945. The area where the Café Marienbrücke was located is now a park and a parking lot.’

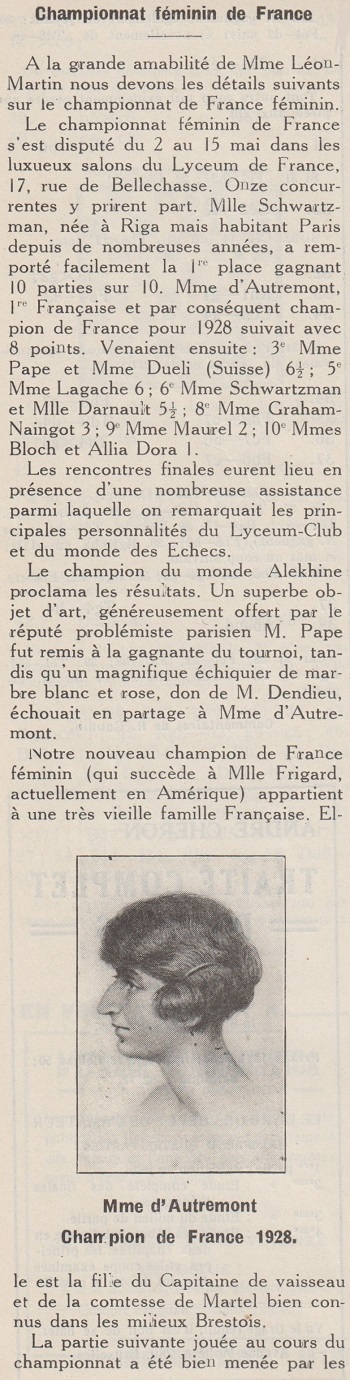

11602. Alekhine at the French ladies’ championship

A recent addition to the Gallica website is a photograph of Alekhine watching a game between Lucienne d’Autremont [regarding ‘Lucienne’, see C.N. 11613] and Paulette Schwartzman. Page 950 of L’Echiquier, June 1928 referred to the presence of the world champion at that year’s French ladies’ championship in Paris:

1 e4 c6 2 Nf3 d5 3 Nc3 dxe4 4 Nxe4 Bf5 5 Nc3 e6 6 d3 Bb4 7 Bd2 Nd7 8 Be2 Ngf6 9 a3 Ba5 10 d4 O-O 11 Bg5 Qc7 12 O-O Rfe8 13 Ne5 Nxe5 14 Bxf6 gxf6 15 dxe5 Rad8 16 Bd3 Qxe5 17 Re1 Qc7 18 Re3 Bxc3 19 bxc3 Bg6 20 h4 Qa5 21 g4 h5 22 Rg3 Kf8 23 Qd2 Ke7 24 f4 hxg4 25 Rxg4 Qh5 26 Rg2 Qxh4 27 Bf1 [sic] Be4 28 White resigns.

The Gallica database also has two general shots (first; second) of the tournament.

L’Echiquier, July 1928, page 970

11603. Nonagenarians (C.N. 11600)

Eduardo Bauzá Mercére (New York, NY, USA) forwards an Infobae report which mentions an exploit by Horacio Tomás Amil Meilán in his mid-90s: in 2018 he won a five-minute tournament at the Club Argentino de Ajedrez, Buenos Aires.

11604. Capablanca and Fonst (C.N. 11595)

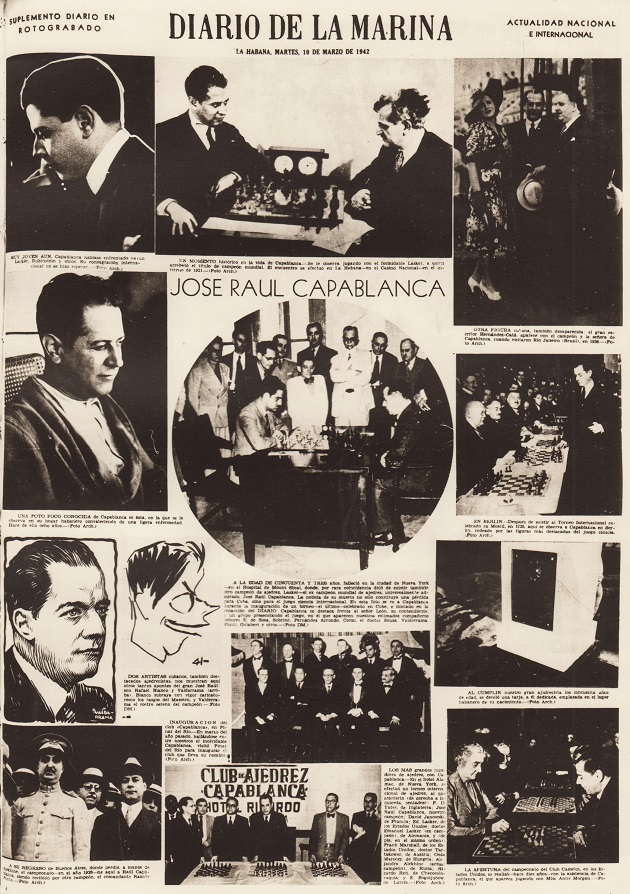

A further picture:

It comes from a Capablanca memorial page in the Diario de la Marina, 10 March 1942:

11605. Capablanca v Kalantarov (C.N. 11596)

Vitaliy Yurchenko (Uhta, Russian Federation) sends the full article by P. Romanovsky on pages 180-182 of the 6/1959 issue of Шахматы в СССР:

Larger versions of the three pages are given in the feature article on the Capablanca v Kalantarov game.

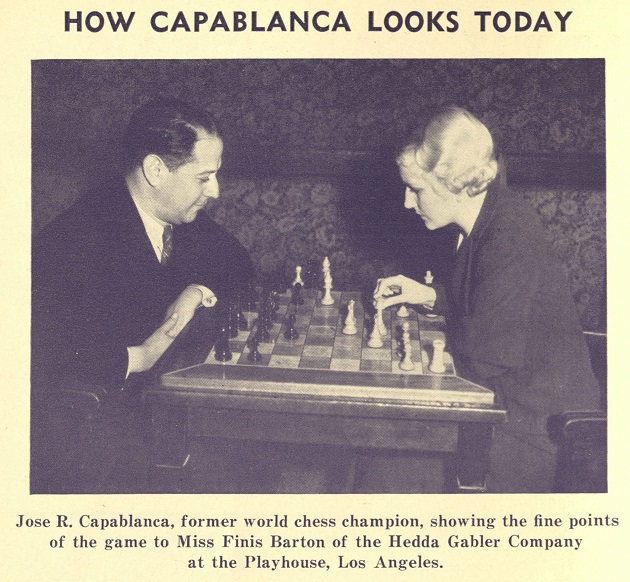

11606. Capablanca and Finis Barton (C.N.s 3454 & 11598)

The photograph shown in C.N. 3454 has been traced to page 2 of the North American Chess Reporter, April-May 1933. Below, courtesy of the Cleveland Public Library, is a fine copy:

11607. Alekhine in Paris

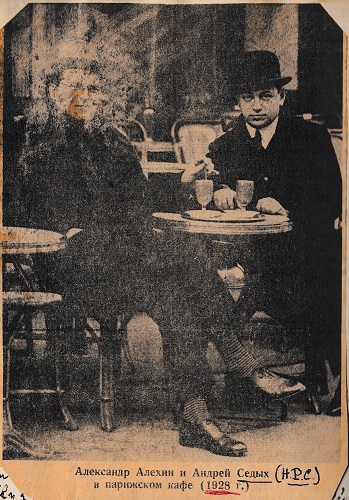

C.N. 5878 referred to a photograph of Alekhine in the November 2008 edition of the Moscow magazine Караван (page 346), and we now have permission to reproduce it (credit: Collections/Roger-Viollet Archives):

The Archives state that Alekhine and his unidentified companion were at the Café de la Paix in Paris in 1927.

11608. Capablanca in 1912

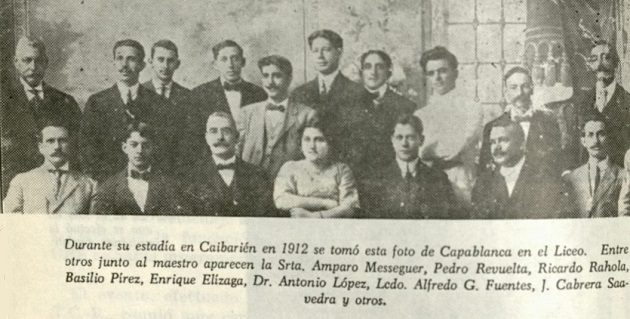

A sort-out of our Capablanca archives has resulted in many C.N. items on the Cuban this month, and below are photographs published on pages 166 and 167 of the February 1964 issue of Ajedrez (Havana), in an article by Alberto Entralgo entitled ‘Ajedrez en Las Villas’:

These two scans and the one in the next C.N. item have been provided by the Cleveland Public Library.

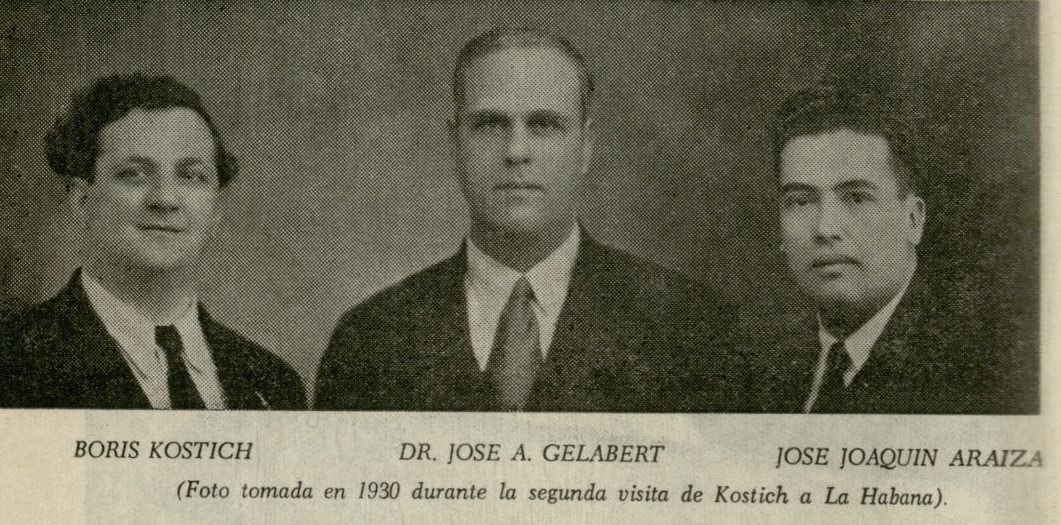

11609. Boris Kostić in Havana

This picture was published at the start of an article by José A. Gelabert, ‘Recuerdos del Match Capablanca vs. Kostich’, on pages 72-76 of Ajedrez, December 1963. See page 94 of our book on Capablanca.

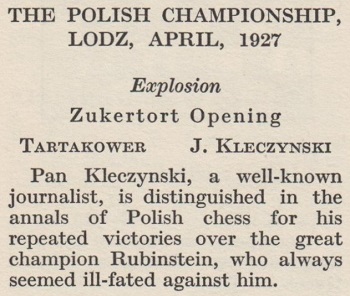

11610. Kleczyński and Rubinstein

From page 180 of My Best Games of Chess 1905-1930 by Savielly Tartakower (London, 1953):

Jan Kleczyński defeated Rubinstein in a well-known game in that Łódź tournament, but what grounds exist for Tartakower’s remark about ‘repeated victories’?

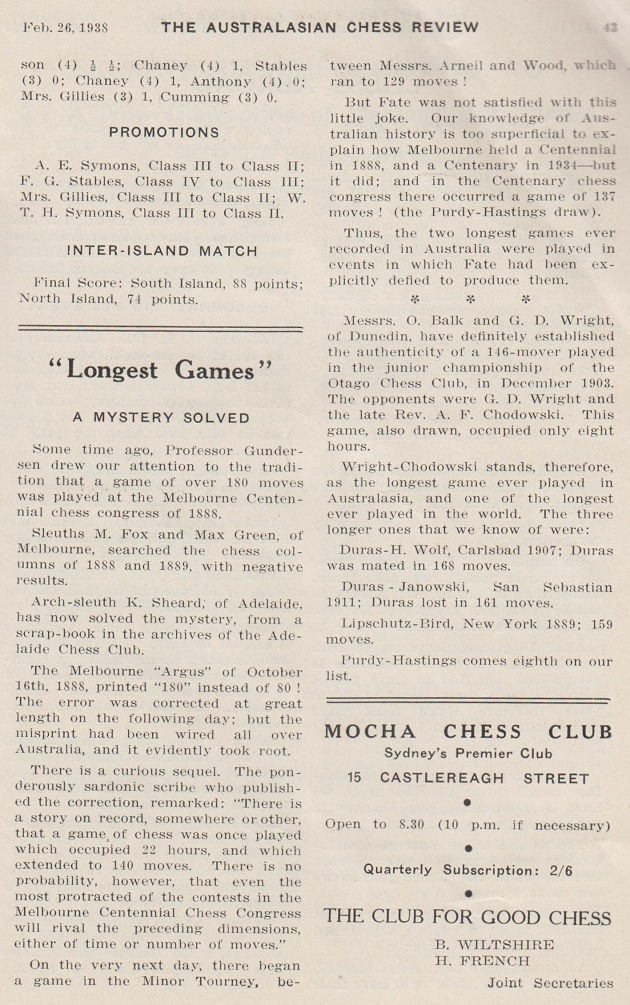

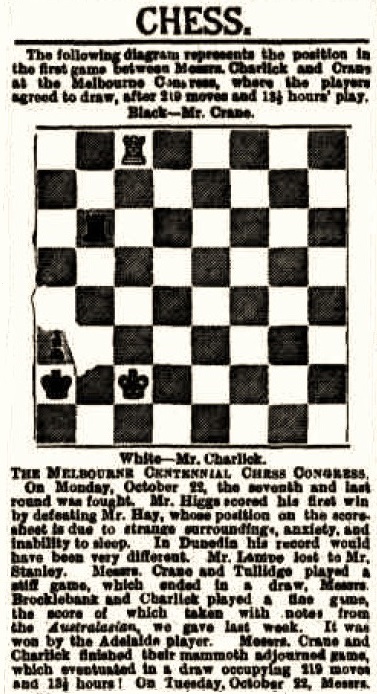

11611. A long Australian game

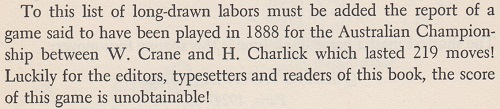

From page 70 of The Fireside Book of Chess by Irving Chernev and Fred Reinfeld (New York, 1949):

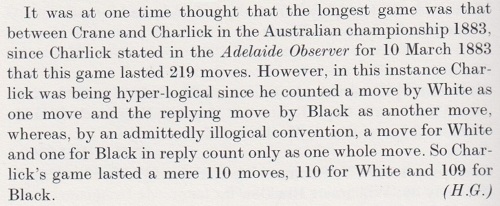

Such a ‘Crane v Charlick’ game is often mentioned in chess literature, and one or two books have added a twist. From the ‘Longest Game’ entry on page 186 of Harry Golombek’s The Encyclopedia of Chess (London, 1977):

The same account was on page 270 of the 1981 Penguin edition, but any confidence and excitement over seeing an exact source (‘the Adelaide Observer for 10 March 1883’) are misplaced.

Confidence and excitement over seeing an exact source are seldom a reaction to the output of Andrew Soltis, and on page 78 of The Book of Chess Lists (Jefferson, 1984) he was faithful to his customary ipse dixit approach:

A similar text is on page 76 of the second edition, Chess Lists (Jefferson, 2002), but what do all the above snippets offer the reader? Plenty of bare assertion, one ‘precise’ newspaper reference which will be shown to be wrong, and a discrepancy over the date of the game: ‘1888’ according to Chernev/Reinfeld; ‘1883’ according to Golombek and Soltis (two editions apiece).

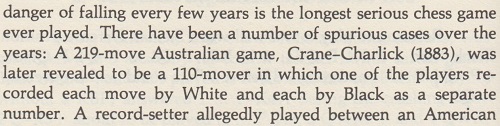

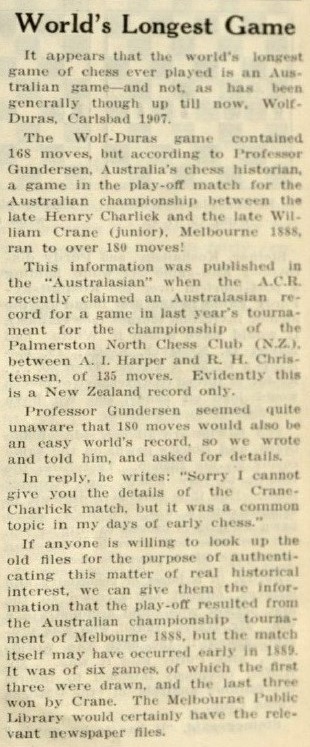

Unsurprisingly, the game, played in Melbourne, interested C.J.S. Purdy, and two of his features are reproduced here:

Page 67 of the Australasian Chess Review, 19 March 1937 (and not 1936 as in the page header)

In those columns too some details were faulty.

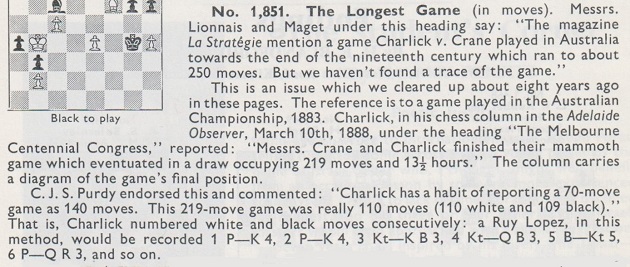

Much later on, D.J. Morgan’s Quotes and Queries column in the BCM grappled with the matter, but not without adding confusion. Four items (71, 168, 838 and 1851) were published:

BCM, September 1953, page 249

BCM, April 1954, page 112

BCM, February 1960, page 39

BCM, May 1968, page

137 (The diagram relates to a different item.)

Despite what was cited in the third of these Quotes and Queries items, the fourth one had a double mix-up over dates:

‘... the Australian Championship, 1883. Charlick, in his chess column in the Adelaide Observer, 10 March 1888, under the heading “The Melbourne Centennial Congress” reported ...’

In his Encyclopedia Golombek was perhaps trying to reconcile matters by changing ‘10 March 1888’ to ‘10 March 1883’, but all references to 1883 in connection with this game are wrong. Morgan’s ‘10 March 1888’, for which Golombek put ‘10 March 1883’, should read 10 November 1888 (the date quoted correctly by Morgan, courtesy of M.V. Anderson, in the February 1960 BCM).

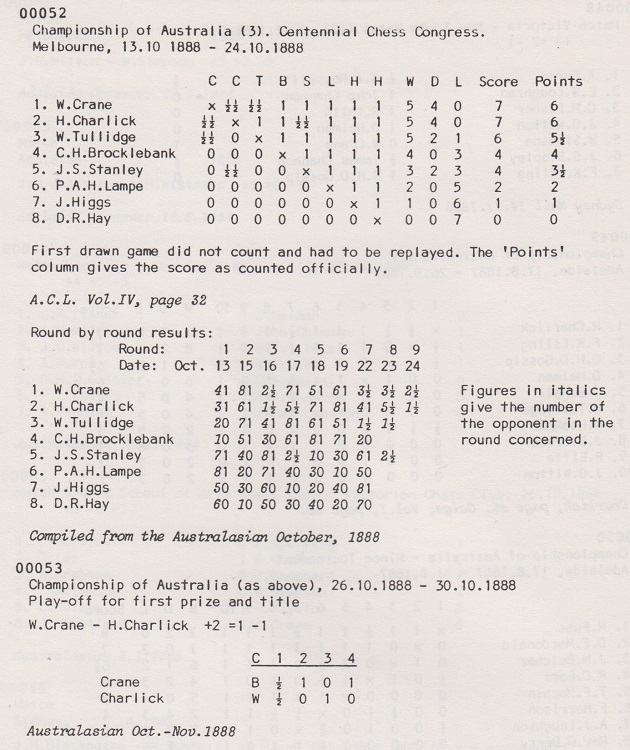

The Australian Championship was held in October 1888, and a valuable summary is on an unnumbered page of volume one of The Records of Australian Chess by John van Manen (Modbury Heights, 1986):

The key Australian press cuttings which follow demonstrate that the game occurred in the tournament itself (and not in the play-off match as stated by Gundersen/Purdy in 1937). Above all, and contrary to virtually all assertions, the game was Charlick v Crane and not Crane v Charlick.

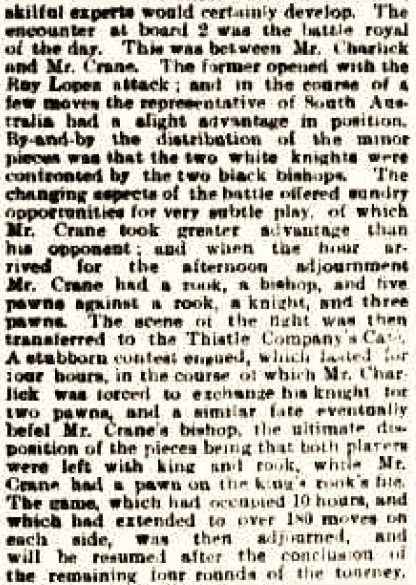

The Melbourne Argus, 17 October 1888, page 16 reported that the game had begun the previous day and had been adjourned in the afternoon. At the second adjournment, according to the column, play ‘had extended to over 180 moves on each side’:

On page 15 of the Melbourne Argus, 18 October 1888 a correction was published (80 moves, and not 180):

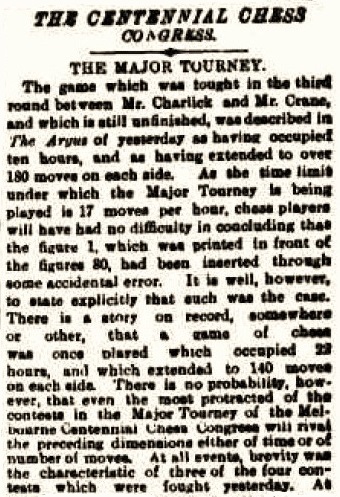

On 23 October 1888, page 10 of the Melbourne Argus

stated that the game had been resumed, and concluded, the

previous day, having lasted 110 moves. It was wrongly

indicated that Crane had the white pieces:

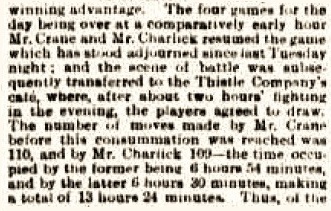

Charlick’s column in the Adelaide Observer of 10 November 1888, page 44, began with a diagram from the game, which, it said, had lasted 219 moves (i.e. on the basis of his idiosyncratic system of counting moves):

Finally, in the Adelaide Observer of 17 November 1888 (page 44) Charlick gave the first 79 moves, adding that the game ‘lasted 30 moves longer’, and also using the ‘219’ figure as the total:

The extant moves are in a number of databases but are included here for ease of reference:

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 Nf6 4 O-O Be7 5 d4 Nxe4 6 d5 Nd6 7 Bxc6 dxc6 8 dxc6 e4 9 Nd4 Bf6 10 Nc3 O-O 11 Re1 Re8 12 Bf4 bxc6 13 Bxd6 cxd6 14 Nxe4 Bb7 15 Nf5 d5 16 Nxf6+ Qxf6 17 Rxe8+ Rxe8 18 Ne3 Ba6 19 c3 Re4 20 Qb3 Qd6 21 Qa3 Qxa3 22 bxa3 Kf8 23 Rb1 Ra4 24 Rb3 Ke7 25 g3 Ke6 26 f3 c5 27 Kf2 c4 28 Rb2 Rxa3 29 Nd1 Kd6 30 Rd2 Kc5 31 Ne3 Bb7 32 Nd1 Bc8 33 Nb2 Bf5 34 Nd1 Bg6 35 Nb2 Rxa2 36 Ke3 Ra5 37 Kf4 Kc6 38 Nd1 Bd3 39 Ke5 Kc5 40 h4 Ra6 41 Rb2 Be2 42 Ne3 Bxf3 43 Rb7 Re6+ 44 Kf4 Rf6+ 45 Ke5 Re6+ 46 Kf4 Rf6+ 47 Ke5 a6 48 Nf5 Kc6 49 Rb4 Bh5 50 Nxg7 Rh6 51 Nf5 Re6+ 52 Kf4 Re4+ 53 Kg5 Bg6 54 Nd4+ Kc5 55 Rb8 Re3 56 Rc8+ Kb6 57 g4 Rxc3 58 Rc6+ Kb7 59 h5 Be4 60 Rf6 Rd3 61 Rxf7+ Kc8 62 Ne6 c3 63 Rc7+ Kb8 64 Kh6 Rg3 65 Rc5 Rd3 66 g5 d4 67 Nxd4 Rxd4 68 Rxc3 Rd6+ 69 Kg7 Kb7 70 Re3 Bc2 71 Re2 Rd7+ 72 Kh6 Rd6+ 73 Kg7 Rd7+ 74 Kh6 Bf5 75 Re5 Rf7 76 g6 hxg6 77 hxg6 Rf6 78 Kg5 Rxg6+ 79 Kxf5 Rd6 and the game was eventually drawn.

11612. Strategy and tactics

As an addition to Chess Strategy and Tactics, some observations by C.J.S. Purdy on page 74 of the Australasian Chess Review, 30 March 1938:

‘What is it that really distinguishes strategy from tactics?

... When the player begins calculating on the basis of possible replies, he enters the realm of tactics.

In other words, we must arrive at definitions which indicate that tactics is the part of chess thinking based on calculation move by move, and that strategy is the part of chess thinking that is concerned with aims and plans (which are one side’s moves only). In actual play, the two are sometimes inextricably interwoven, but however much you tangle two different pieces of string, they remain two different pieces.’

11613. Alekhine at the French ladies’ championship (C.N. 11602)

Dominique Thimognier (Fondettes, France) notes that the Gallica website erred by giving the forename ‘Lucienne’:

‘Jeanne d’Autremont, who was born in Brest on 24 May 1899 and died in Paris (7th arrondissement) on 4 November 1979, was customarily referred to by her husband’s forename, i.e. Mme Lucien d’Autremont. However, she was born Jeanne Marie Nancy de Martel. She married Lucien Bridet d’Autremont in 1926.’

Our correspondent has provided her birth certificate (reproduction here not permitted).

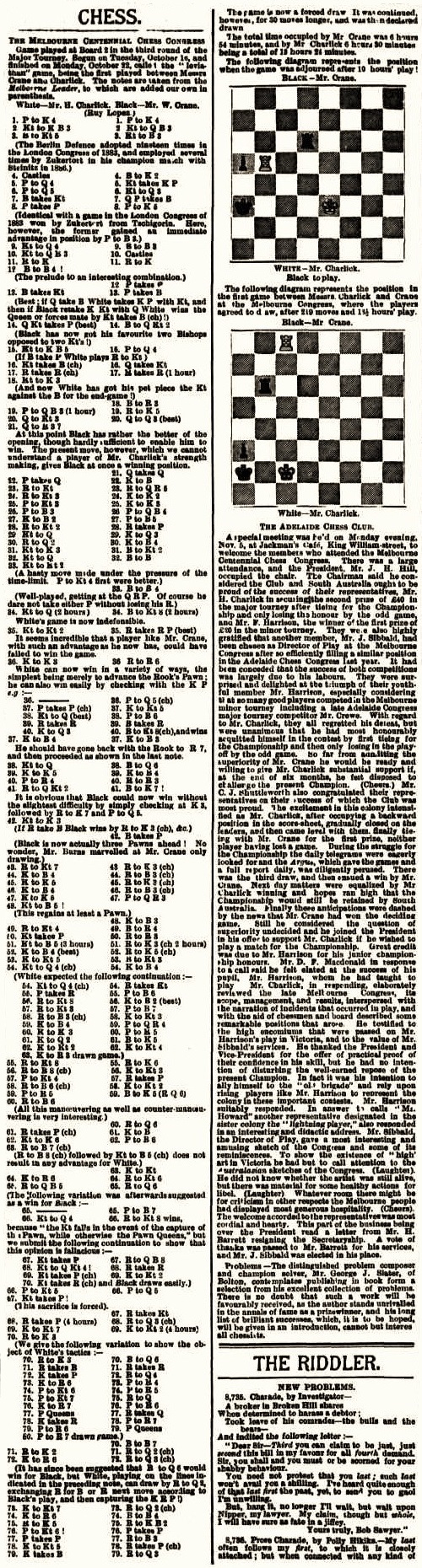

11614. Renaud and Crépeaux

Mr Thimognier also forwards two photographs published on the cover of L’Eclaireur de Nice (29 July 1923 and 14 September 1924 respectively):

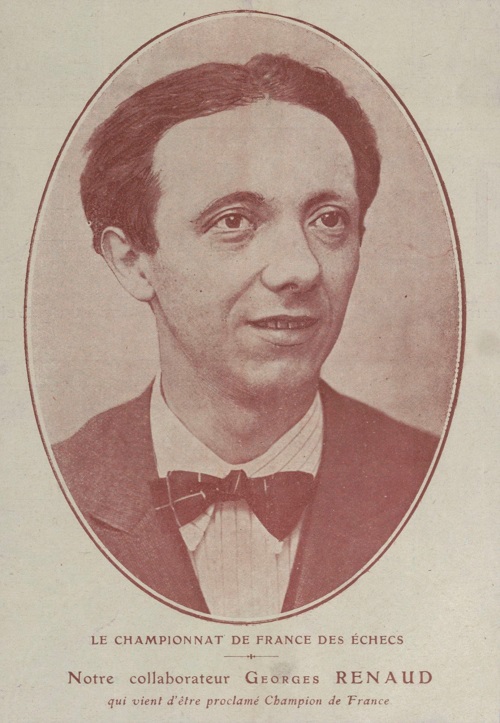

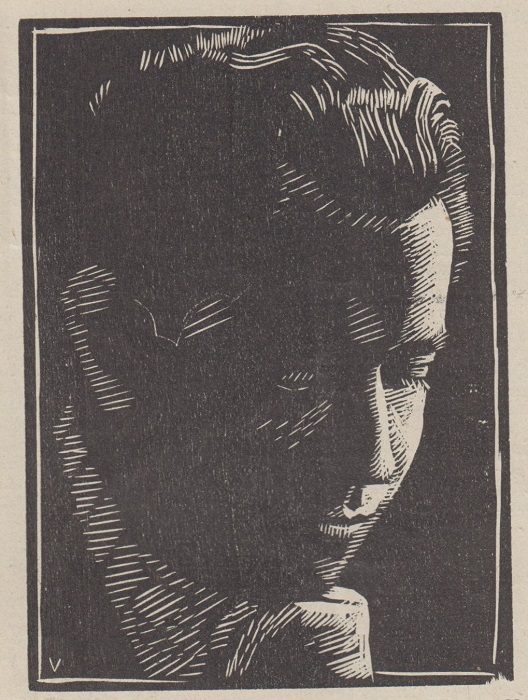

11615. Georges Renaud

This woodcut by Erwin Voellmy comes from page 19 of his book Schachkämpfer (Basle, 1927):

11616. Alekhine in Paris (C.N. 11607)

From Luc Winants (Boirs, Belgium):

‘In an old notebook of Victor Soultanbéieff’s I have found two cuttings with the same photograph, and they name Alekhine’s companion as Andrei Sedykh (Андрей Седых). He was a Russian emigrant and prominent writer, his real name being Yakov Moiseievich Tsvibak (1902-94).’

11617. Puzzles

A Brief History of Puzzles by William Hartston (London, 2019) has much chess content, including not only such classics as Sam Loyd’s ‘Excelsior’ problem but also some unfamiliar specimens, of which a sample follows here.

‘What do the following have in common: the musicians Britney Spears, Eric Clapton, Roger Daltrey and Fats Waller; chess grandmasters Nigel Short and Tony Miles; actors Meg Ryan and Tom Cruise; politician Clare Short; TV personality Steve Irwin?

Hint: Aristotle could join them, and Socrates could do so twice.’

‘What do the words sine, ride, chess and chat have in common that is shared by riots, pest and zone, but not in the same place?’

‘I began [at an annual dinner of chessplayers at a London club] by presenting them with the letters A, B, C, D, E, F and asking them which letter was the odd one out.’

‘... Then I posed them a question that is definitely one of my favourites. It demands no chess knowledge [unlike the previous puzzle] and would, by most logicians at any rate, be considered fair:

Which of the following is the odd one out?

KING, king, king, king, queen’

Full solutions are given in the book.

11618. Daniel Harrwitz

Ulrich Schimke (Cologne, Germany) writes:

‘I can confirm the conclusion of Luca D’Ambrosio in C.N. 6286 that Daniel Harrwitz was born on 22 February 1821, and not, as had previously been believed, on 29 April 1823.

Volumes on the birth of Breslau Jews can be consulted at the FamilySearch website. The film that I used is “Geburten 1804-1802, 1809-1822, 1825-1846 International Film 1184380 7989998”. (The parts from 1809-1822 were transcripts dating from 1933 for the Breslau Jewish Congregation; see the entry “PSR A022 Breslau, Schlesien Geburtsregister 1818-1822 Nach dem im Breslauer Polizeipräsidium befindlichen jüdischen Geburtsregistern, abgeschrieben für das Archiv der Synagogengemeinde Breslau im Jahre 1933” from the inventory of the Jewish Museum in Frankfurt.)

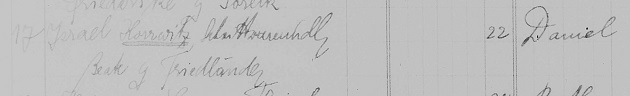

The entry 17/1821 of the original page 60 of the transcript [page 337/594 of the film] states that Daniel, the son of Israel Harrwitz and Beate Harrwitz (née Friedländer) was born on 22 February 1821:

He had several brothers and sisters, and the entries for two of them, Julius and Wilhelmine, provide an example of the information available concerning their parents.

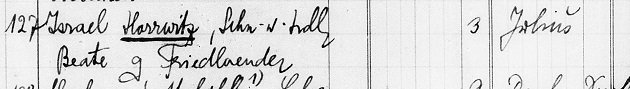

3 October 1819: entry for Julius 127/1819, on page 33 of the transcript (page 358/594 of the film):

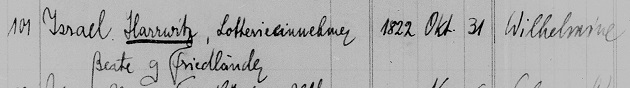

31 October 1822: entry for Wilhelmine 101/1822, on page 87 of the transcript (page 383/594 of the film):

The profession of Israel Harrwitz, Daniel’s father, is not always readable. One of the links below contains a merchant register from Breslau, where his business was recorded as “Tabak und Cigarrenhandlung und Lotterie-Collekte”, whereas in the Daniel Harrwitz entry it reads “[?]warenhdl”. The entry for Julius Harrwitz has the reference “Schn- w- hndl”.

Further information about Daniel’s brother Julius, who became a publisher in Berlin, is available on a Deutscher Schachbund page. See too the Stolpersteine in Berlin page for information about Maximilian Harrwitz, who was Julius’ son and thus Daniel’s nephew.’

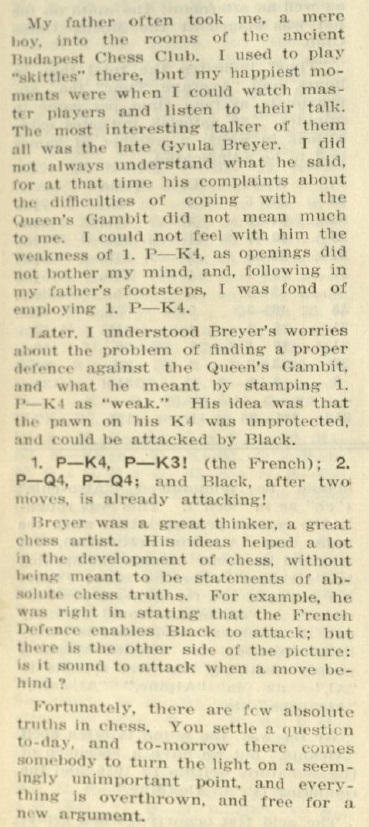

11619. Lajos Steiner on Gyula Breyer

From page 328 of the Australasian Chess Review, December 1936, at the start of an article by Lajos Steiner entitled ‘A Chat about the French Defence’:

This will be an addition to Breyer and the Last Throes.

11620. Milan Vidmar

‘Vidmar is just a divinely-gifted wood-shifter.’

That comment was by C.J.S. Purdy in the Australasian Chess Review, 12 November 1936, page 290, in an article on that year’s Nottingham tournament:

11621. A flash-light tournament

As an addition to Unusual Chess Words, Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA) forwards a snippet on page 7 of the Liverpool Mercury, 2 May 1896:

11622. Daniel Harrwitz (C.N. 11618)

Jean-Pierre Rhéaume (Montreal, Canada) notes the poor quality of the Harrwitz entry on pages 177-178 of the Dictionnaire des échecs by François Le Lionnais and Ernst Maget (Paris, 1967):

Half of the entry (‘On raconte ...’) is given over to an anecdote. (See Chess Cunning, Gamesmanship and Skulduggery.)

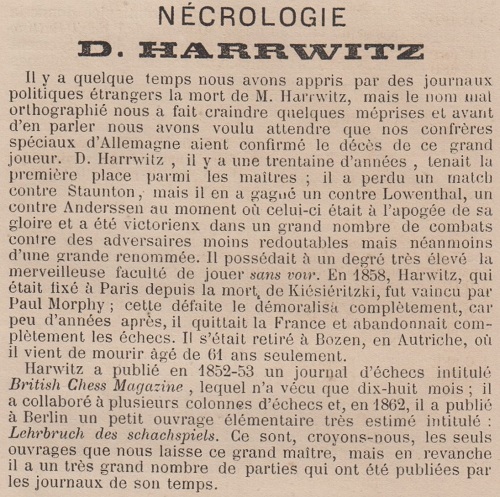

One of the few detailed obituaries of Harrwitz was by William Wayte on pages 136-139 of the April 1884 BCM:

11623. Anderssen v Harrwitz (C.N.s 6987 & 6993)

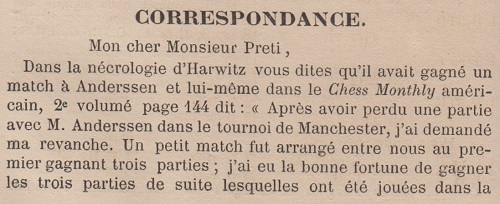

An obviously inaccurate obituary of Harrwitz on page 88 of La Stratégie, 15 March 1884:

A reader’s reply on pages 182-183 of the 15 June 1884 issue gave some information about Harrwitz’s encounters with Anderssen in Manchester, 1857:

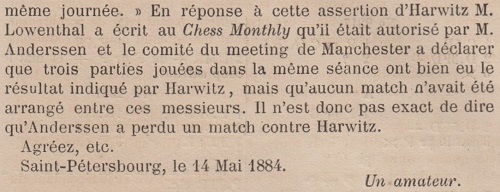

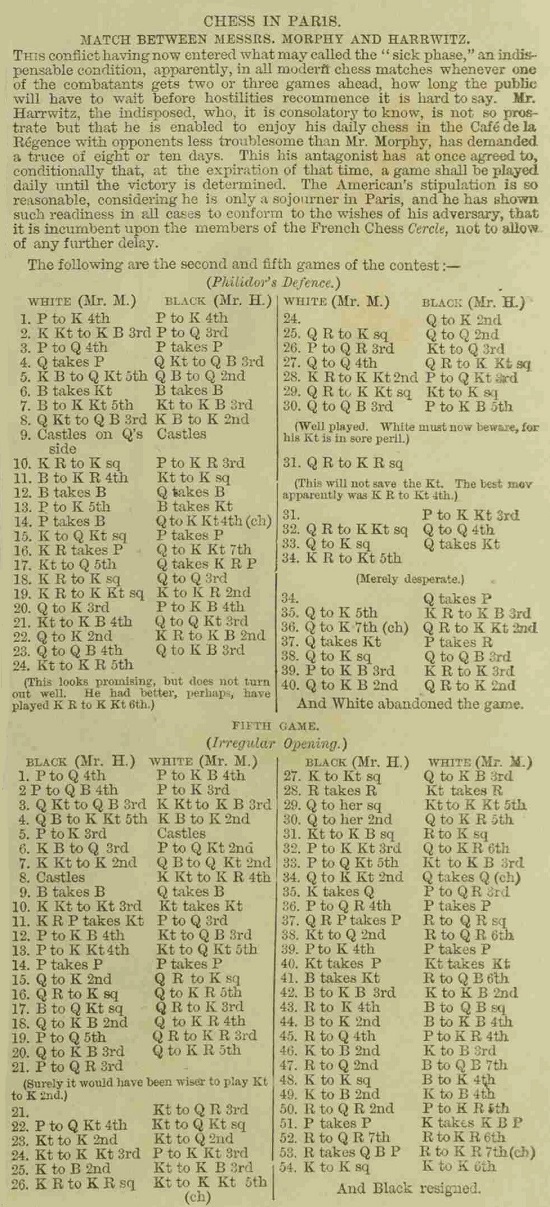

11624. Harrwitz’s defeat of Morphy

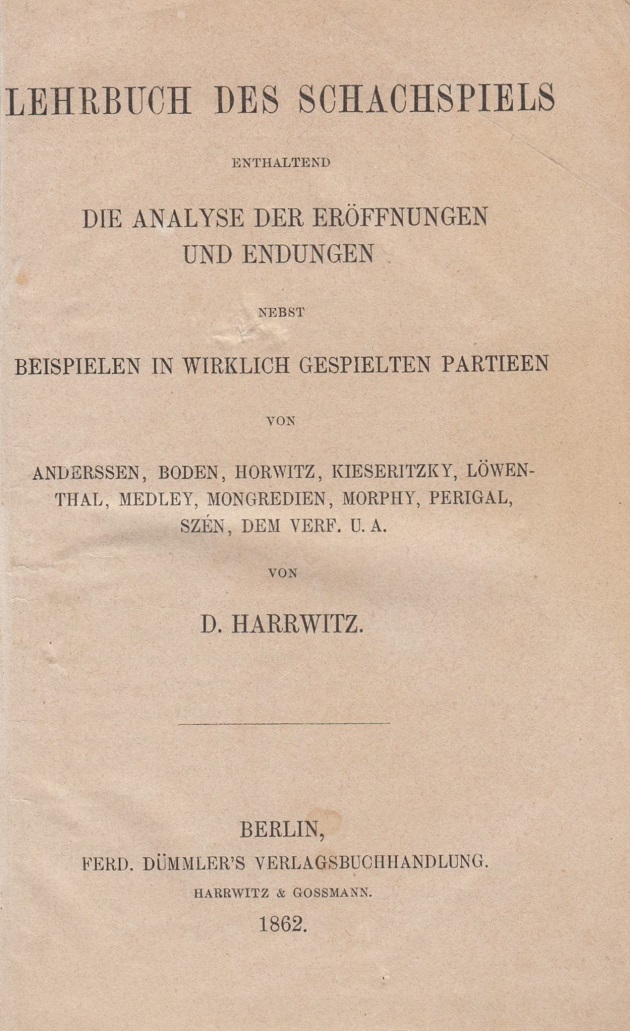

Another discrepancy involving Harrwitz was discussed in C.N. 3113, and that item (see too page 275 of Chess Facts and Fables) is reproduced here.

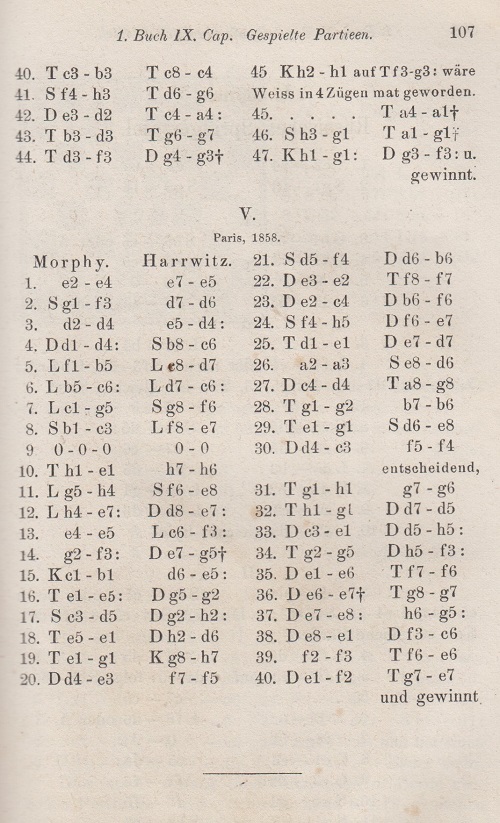

The various Morphy monographs consulted by us give the second match-game between Morphy and Harrwitz (Paris, 1858) as follows:

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 d6 3 d4 exd4 4 Qxd4 Nc6 5 Bb5 Bd7 6 Bxc6 Bxc6 7 Bg5 Nf6 8 Nc3 Be7 9 O-O-O O-O 10 Rhe1 h6 11 Bh4 Ne8 12 Bxe7 Qxe7 13 e5 Bxf3 14 gxf3 Qg5+ 15 Kb1 dxe5 16 Rxe5 Qg2 17 Nd5 Qxh2 18 Ree1 Qd6 19 Rg1 Kh7 20 Qe3 f5 21 Nf4 Qb6 22 Qe2 Rf7 23 Qc4 Qf6 24 Nh5 Qe7 25 Rde1 Qd7 26 a3 Nd6 27 Qd4 Rg8 28 Rg2

28…Ne8 29 Qc3 f4 30 Rh1 g6 31 Rhg1 Qd5 32 Qe1 Qxh5 33 Rg5 Qxf3 34 Qe6 Rf6 35 Qe7+ Rg7 36 Qxe8 hxg5 37 Qe1 Qc6 and wins.

However, we note that Harrwitz himself stated that from the above diagram the game went:

28…b6 29 Reg1 Ne8 30 Qc3 f4 31 Rh1 g6 32 Rhg1 Qd5 33 Qe1 Qxh5 34 Rg5 Qxf3 35 Qe6 Rf6 36 Qe7+ Rg7 37 Qxe8 hxg5 38 Qe1 Qc6 39 f3 Re6 40 Qf2 Rge7 and wins.

Source: Lehrbuch des Schachspiels by D. Harrwitz (Berlin, 1862), page 107.

Staunton also gave this latter version of the game-score in his Illustrated London News column of 2 October 1858.

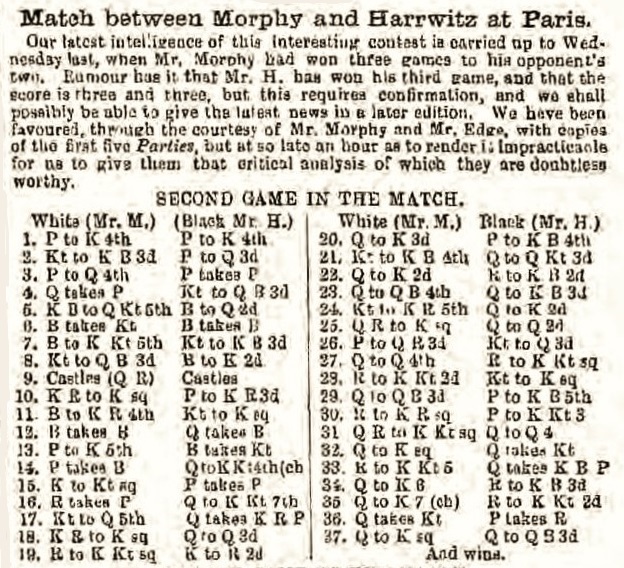

Some images are added now, beginning with Staunton’s column (page 317):

As noted above, that series of moves corresponded to what Harrwitz published four years later:

The game-score as published in various Morphy monographs (i.e. 28...Ne8, and not 28...b6) was on page 5 of the Era, 19 September 1858, ‘courtesy of Mr Morphy and Mr Edge’:

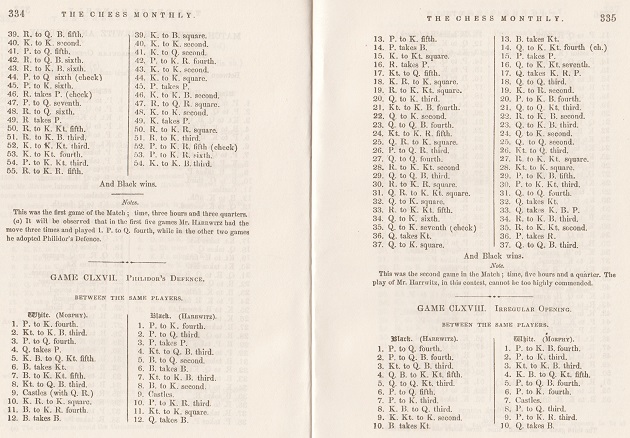

It was also on pages 334-335 of the November 1858 Chess Monthly:

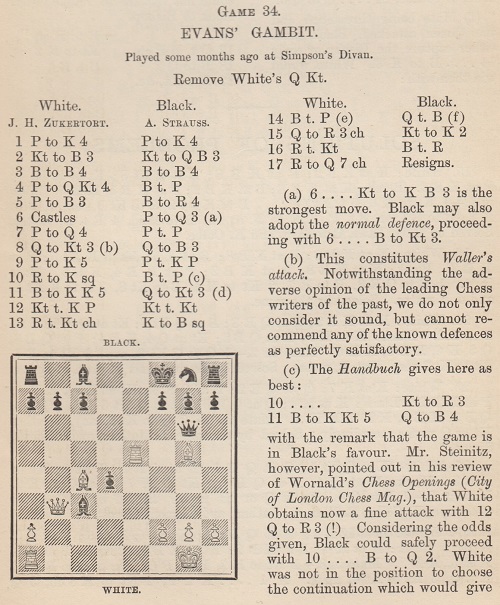

11625. Zukertort v Strauss

From pages 151-152 of the January 1880 Chess Monthly:

(Remove White’s queen’s knight.) 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 b4 Bxb4 5 c3 Ba5 6 O-O d6 7 d4 exd4 8 Qb3 Qf6 9 e5 dxe5 10 Re1 Bxc3 11 Bg5 Qg6 12 Nxe5 Nxe5 13 Rxe5+ Kf8 14 Bxf7 Qxf7 15 Qa3+ Ne7 16 Rxe7 Bxa1 17 Rd7+ Resigns.

Though lacking any particularly striking features, the game is relevant to the next C.N. item.

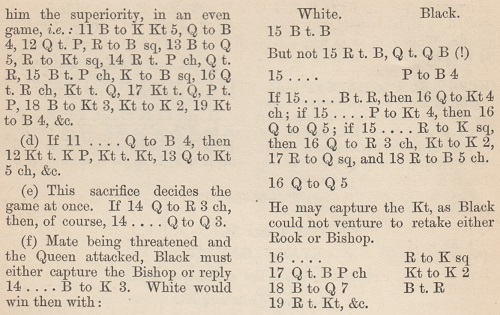

11626. Capablanca at the House of Commons

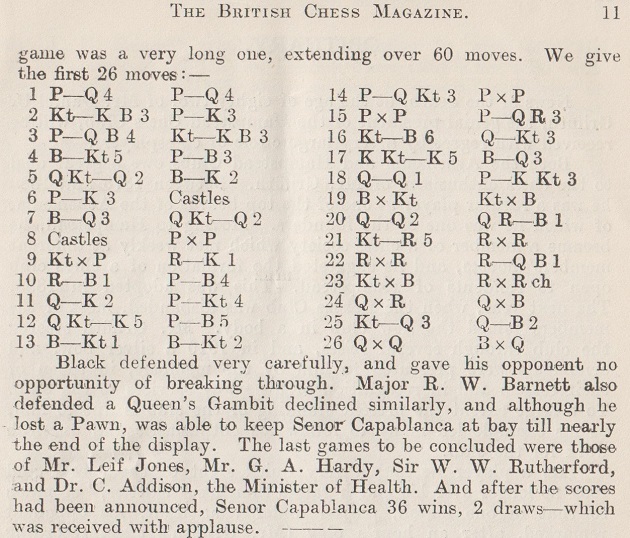

A report on pages 9-11 of the January 1920 BCM:

In showing the conclusion of Capablanca’s game against Albert Strauss on page 10, the BCM commented, ‘Mr Strauss in his youth had much practice with Zukertort’.

1...Rxe2+ 2 Kxe2 Bxc3 3 bxc3 Kg7 4 g4 Kf6 5 Ke3 Ke6 6 Ke4 d5+ 7 Kf3 h6 8 Kg3 Kf6 9 Kf2 Ke6 10 Kf3 Kf6 Drawn.

Databases and ‘complete games’ books often disregard such fragments.

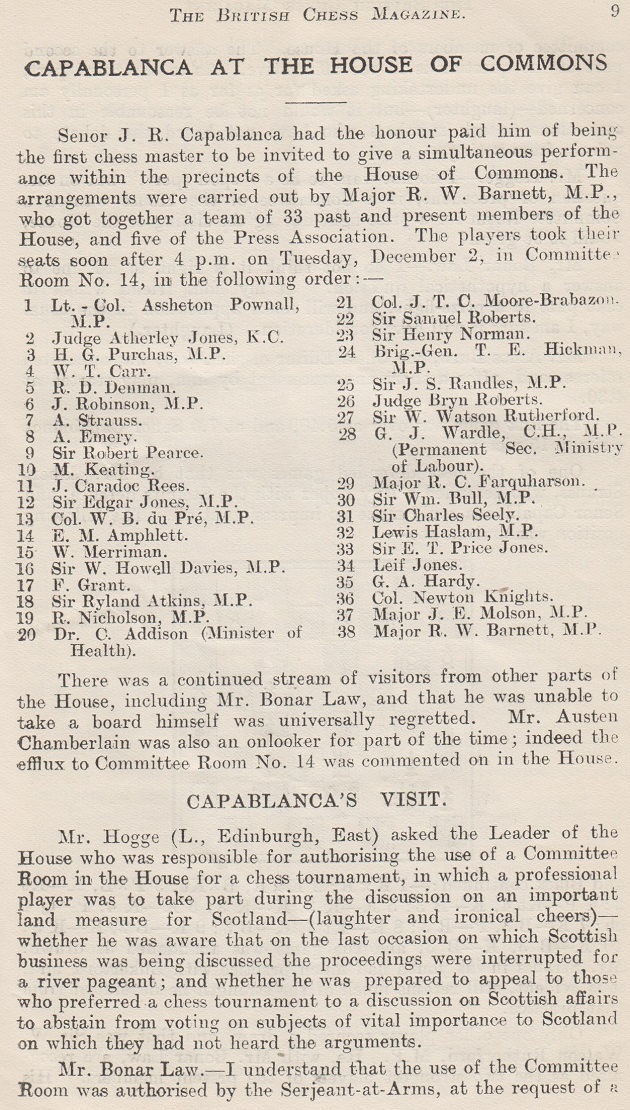

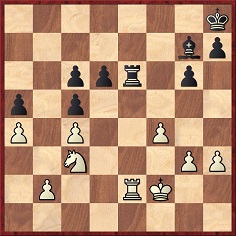

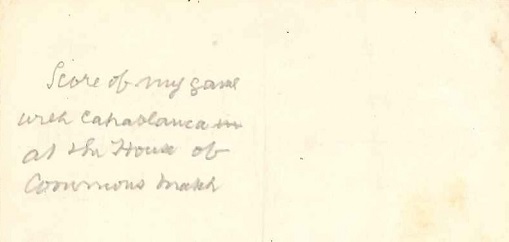

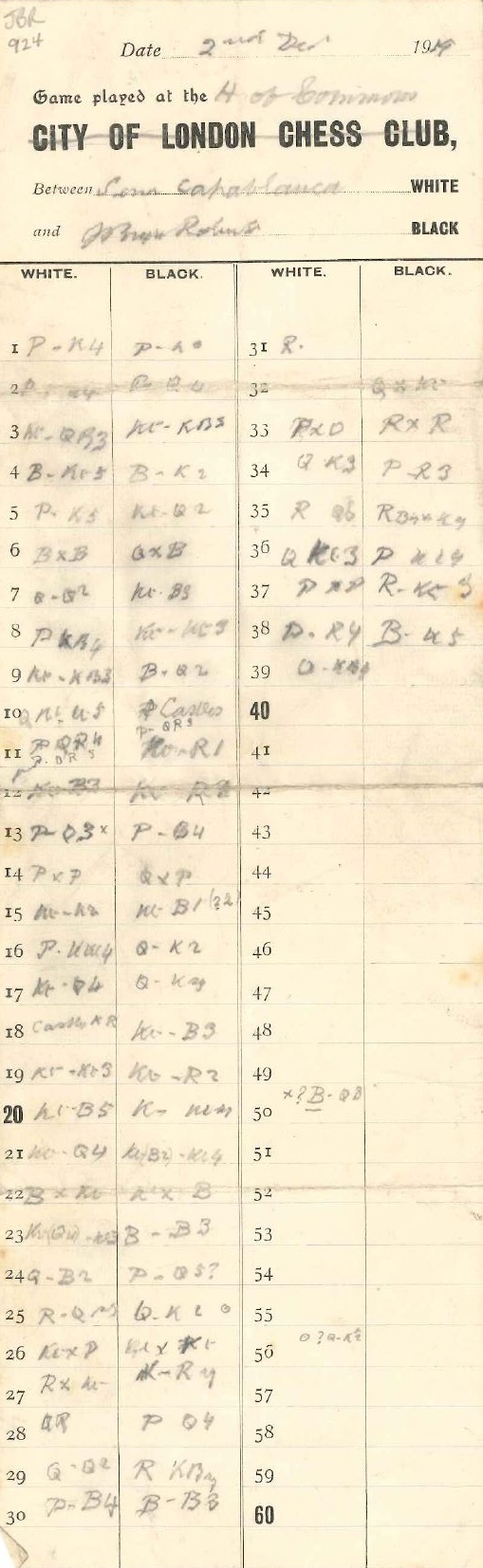

11627. Capablanca v Judge Bryn Roberts

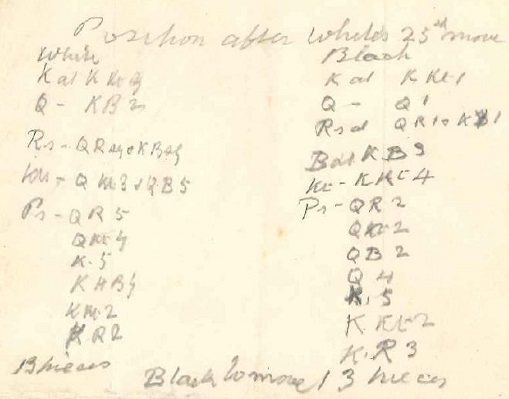

The score-sheet of Capablanca’s game against Judge Bryn

Roberts (1843-1931) in his House of Commons display on 2

December 1919 (C.N. 11626) has been found by Olimpiu G.

Urcan (Singapore). The source is the John Bryn Roberts

Collection (GB 0210 JBROBERTS, item no. 924, ISYSARCHB34)

at the National Library of Wales.

Readers are offered a tough deciphering challenge:

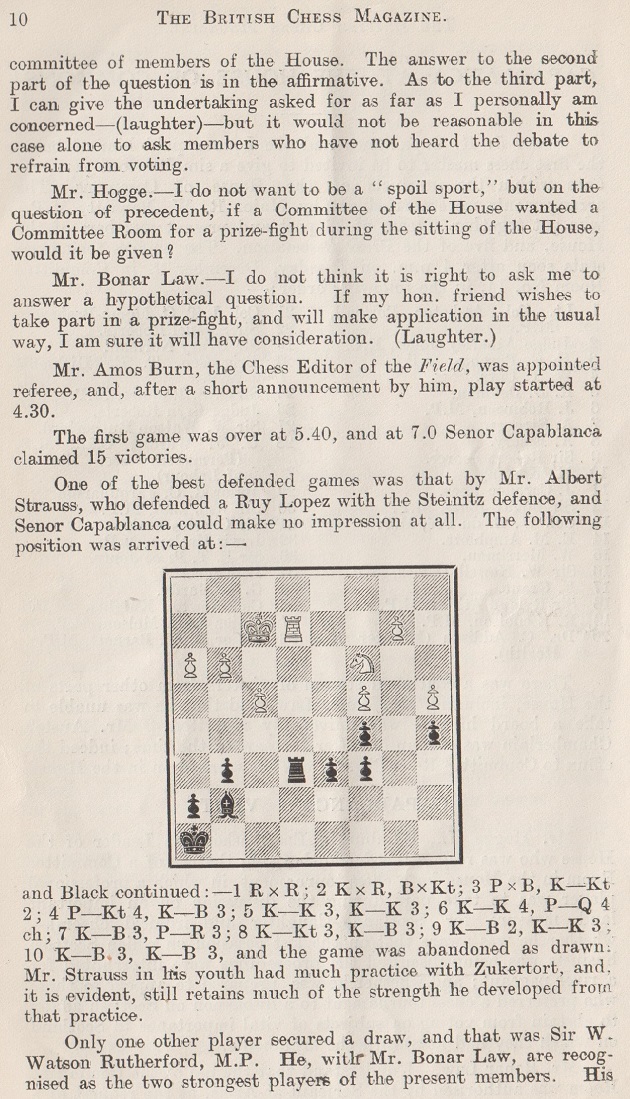

11628. Capablanca in Chess Pie

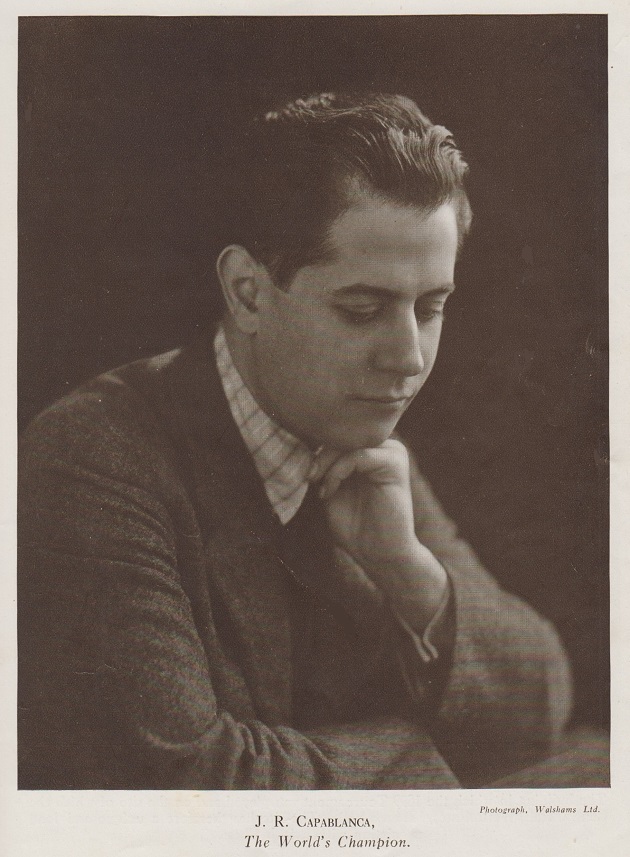

Chess Pie, 1922, page 17

This photograph, which has inspired many front covers of Capablanca books, is on page 85 of Fred Wilson’s A Picture History of Chess (New York, 1981) with the following caption:

‘Capablanca in 1922, when he was at the very height of his powers.’

However, the picture had been published the previous year, on page 33 of Capablanca’s book on his world title match against Lasker:

The picture credit in Chess Pie was to a London

firm, Walshams Ltd.

A woodcut by Erwin Voellmy on page 145 of the October 1927 Schweizerische Schachzeitung:

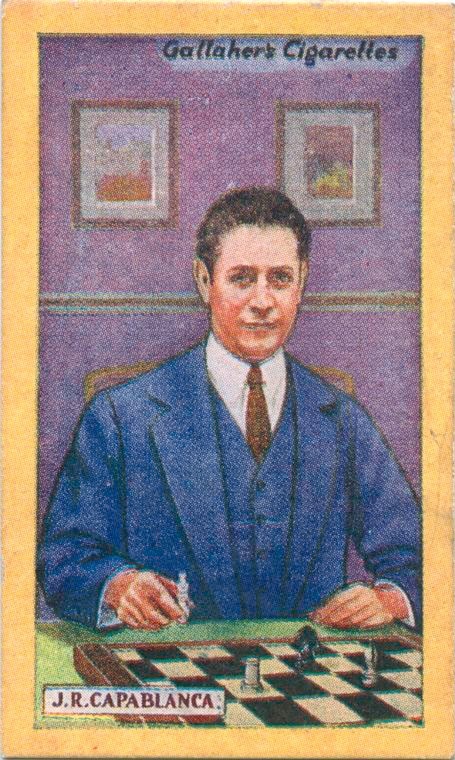

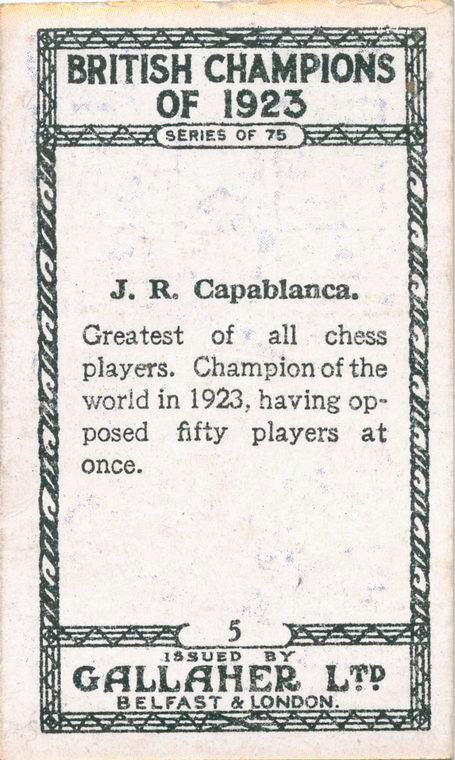

11629. Cigarette card

A comment about this cigarette card is on page 279 of Kings, Commoners and Knaves, but we recall no photograph on which the picture may have been based.

11630. Alekhine and Tartakower

Tim Bogan (Chicago, IL, USA) submits a pair of quotations:

- ‘But if, say, Alekhine and Tartakower are playing, then Alekhine’s standard of play is considerably better than that of his opponent. Alekhine’s plan proceeds unhindered. Tartakower does not understand it and so does not prevent it.’

Page 112 of Training for the Tournament Player by M. Dvoretsky and A. Yusupov (London, 1993), in the chapter ‘Studying the Classics’ by M. Shereshevsky;

- ‘Imagine, for example, that Alekhine is playing Tartakower. Alekhine comes up with a strategic plan and is able to carry it out to the letter, as Tartakower does not sense the danger and fails to prevent his opponent’s ideas.’

Page 90 of Chess Training for Candidate Masters by A. Kalinin (Alkmaar, 2017). The paragraph reported on a 1979 speech by Petrosian.

A general remark about the latter book is that although the imprint page promises, ‘we will collect all relevant corrections on the Errata page of our website’, a start has yet to be made.

11631. Analysis

It is healthy for games presented by historians to be taken up by analysts, and The Magic of Chess Tactics 2 by Claus Dieter Meyer and Karsten Müller (Milford, 2017) dissects a number of positions from C.N.:

- Pages 22-24: Talbot v Cattley, London, 1850 (C.N. 8096);

- Pages 60 and 164: Hammond v B., Boston, circa 1880 (C.N. 8077). In the book the contributor of the game to C.N., Eduardo Bauzá Mercére, has somehow been named as Black;

- Pages 61 and 164: Vargas v Kostić, Montevideo, 1913 (C.N. 8149);

- Pages 70-72: J. Polgar v Angelova, Thessaloniki, 1988 (C.N. 8111);

- Pages 84-86: Walker v Wilmarth, 1900 (C.N. 10169);

- Pages 159 and 181: Basta v Sarapu, Melbourne, 1956-57 (C.N. 10075).

11632 ‘The Mozart of Chess’

Courtesy of Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina), our feature article ‘The Mozart of Chess’ will now have a reference to Kasparov, although the citation is flimsy. From page 275 of Garry Kasparov on Garry Kasparov Part I: 1973-1985 (London, 2011):

From page 279 of volume one of Мой шахматный путь. 1973-1985 by Garry Kasparov (Moscow, 2011):

11633. ‘Edward Herley’

Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA) seeks information further to this paragraph on page 14 of the Era, 1 January 1865:

11634. ‘All rook endgames are drawn’ (C.N.s 5498, 5585, 5726, 5822 & 10012)

On page 46 of the January 1997 Chess Life an article entitled ‘Erroneous Transition to the Pawn Endgame’ by Lev Alburt and Leonid Verkhovsky with Leo Dykhno referred to a ‘diction’:

Citations for the dictum ‘the rook endgames are never won’ are sought. On page 86 of The Wisest Things Ever Said About Chess (London, 2008) Andrew Soltis referred to ...

‘... Tarrasch’s more sweeping claim that “rook and pawn endings are never won”. (A minority credits a version of this to Tartakower.)’

Page 240 of Turning Advantage Into Victory in Chess by Soltis (New York, 2004) had this:

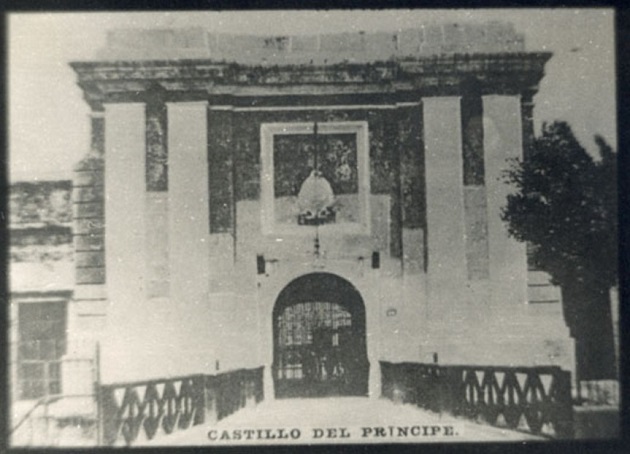

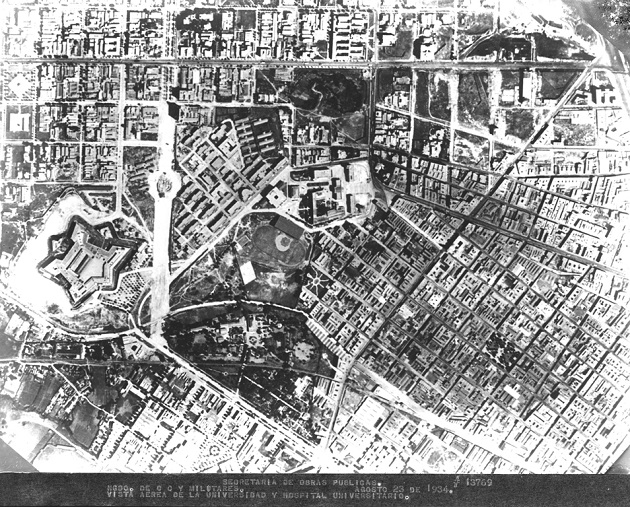

11635. The Castillo del Príncipe, Havana (C.N. 5789)

This photograph from opposite page 80 of Homenaje a José Raúl Capablanca (Havana, 1943) shows a tarja constructed in 1938 at Capablanca’s birth-place, the Castillo del Príncipe in Havana, to commemorate his 50th birthday:

Now, Yandy Rojas Barrios (Cárdenas, Cuba) sends a set of pictures of the Castillo, courtesy of the Photograph Library of the San Gerónimo de La Habana College and its Director, Eusebio Leal Spengler:

The first three photographs are undated. The others were taken in, respectively, 1928, 1929, 1934, 1935 and 1937.

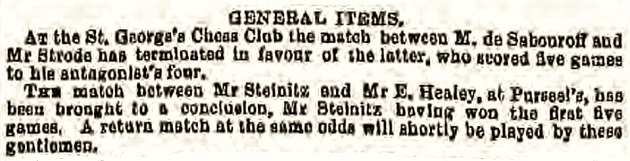

11636. ‘Edward Herley’ (C.N. 11633)

From Rod Edwards (Victoria, BC, Canada):

‘The opponent of Steinitz was Edward Healey (not Herley). The results of Steinitz’s two match victories against E. Healey at knight odds were given on page 8 of the Chess Player’s Magazine, January 1865: +5 –1 =0 and +5 –1 =1. The matches were also mentioned by P.W. Sergeant on page 136 of A Century of British Chess, where he gave the score of both as 5-1. The statement that Edward Healey was the brother of the better-known Frank Healey was made by Sergeant on page 134. At least one of the matches with Steinitz was completed before 10 April 1864, as announced in the Era that day (page 5)’:

Other references are given at Edo Ratings, Healey, E.’

11637. Coinages

Wanted: examples of non-chess words which have been coined by prominent chess figures.

From page 62 of William Hartston’s A Brief History of Puzzles (C.N. 11617):

‘For more than 50 years, crosswords were the only word puzzle that had a universally accepted name, but since the 1970s another has emerged and, in 1999, the new teaser was given a name. The word “ditloid” is not yet in the Oxford English Dictionary, but a Google search for “ditloid” produces tens of thousands of results. I am delighted by this, because it is a word I coined myself and is my only genuine contribution to the English language.’

11638. A fortress

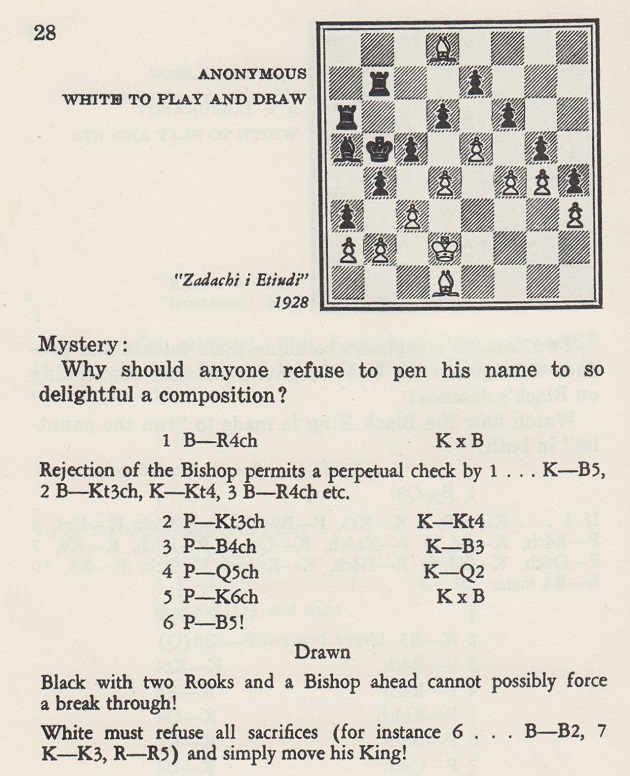

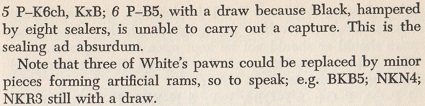

Only one composition in Irving Chernev’s Chessboard Magic! (New York, 1943) was marked ‘Anonymous’:

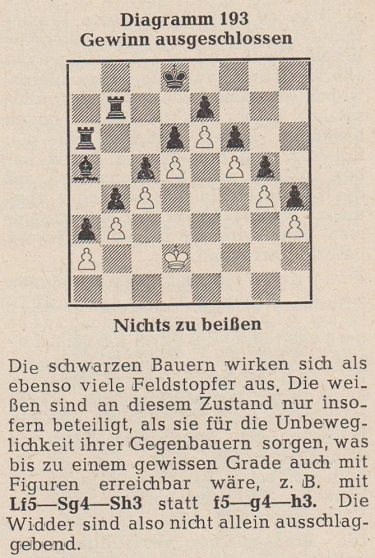

Later on, more information came to light. From page 118 of Die Kunst der Bauernführung by Hans Kmoch (Berlin-Frohnau, 1956):

Below is the English-language version, i.e. from pages 174-175 of Pawn Power in Chess (New York, 1959):

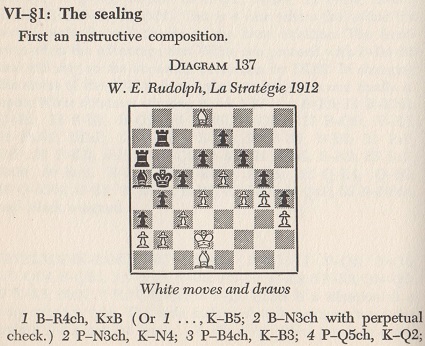

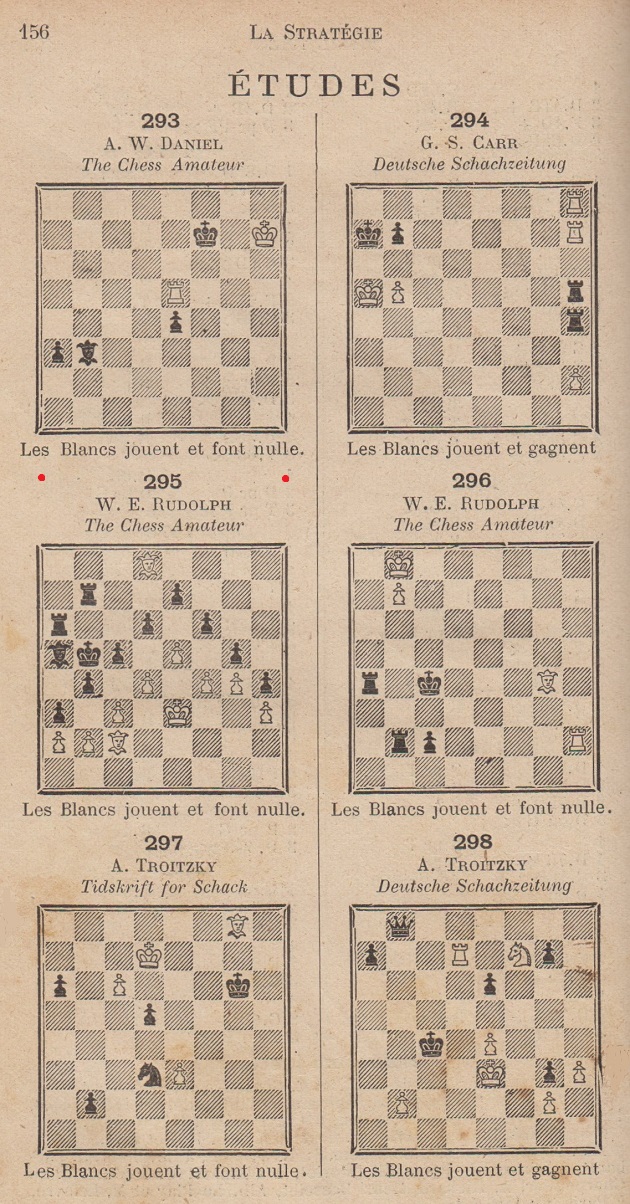

However, the reference to La Stratégie is sub-par, given that the French magazine (April 1912 issue, page 156) mentioned the study’s prior appearance elsewhere:

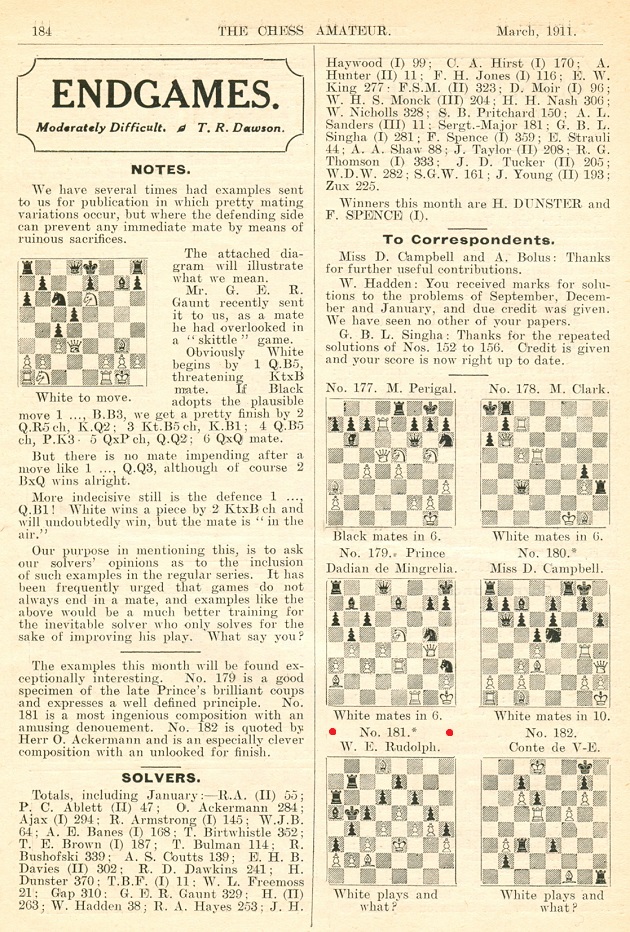

Below is that composition by Rudolph on page 184 of the March 1911 Chess Amateur:

The solution was published on page 224 of the April 1911 Chess Amateur. William E. Rudolph of Brooklyn, NY was a regular contributor to the magazine.

These historical details were confirmed exactly a decade ago; we assisted Frederic Friedel with his presentation of the study as a Christmas puzzle at ChessBase on 26 December 2009.

For many further examples of the theme, see the chapter ‘Building a Fortress’ on pages 183-198 of The Art of the Endgame by Jan Timman (Alkmaar, 2011).

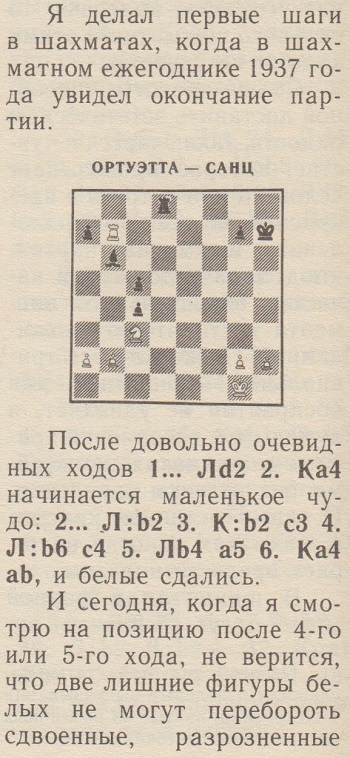

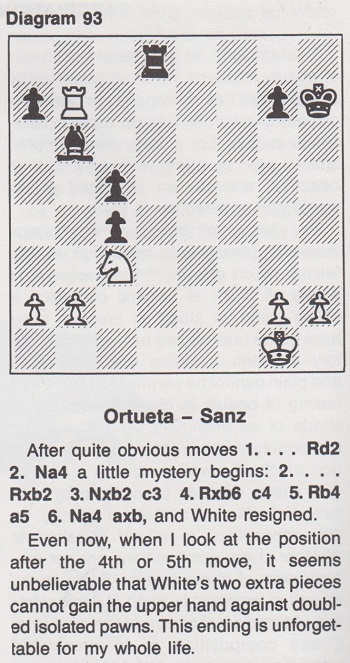

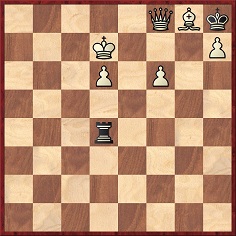

11639. Ortueta v Sanz

The Ortueta v Sanz ending was highly appreciated by Tigran Petrosian. From pages 136-137 of the posthumous anthology of his writings Шахматные лекции (Moscow, 1989):

Below is the translation on page 94 of the English edition, Petrosian’s Legacy (Los Angeles, 1990):

11640. Vladimir Korolkov

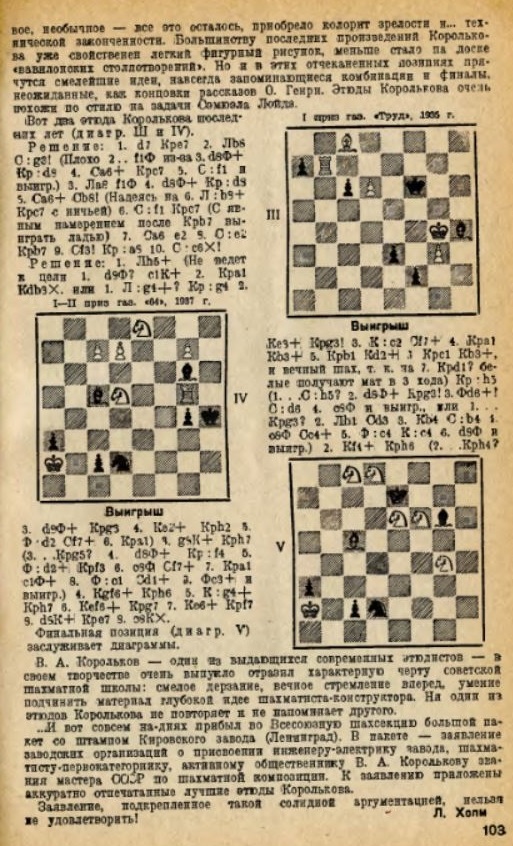

The Petrosian book mentioned in the previous item demonstrated his appreciation of endgame studies with a discussion of three compositions by V. Korolkov and three by H. Rinck. The Korolkov selection included the following:

White to move and win

1 Qg1 b1(Q) 2 Qxb1 g1(Q) 3 Qxg1

3...Rg3 4 Qg2 Rg4 5 Qg3 Rg5

6 Qg4 Rxg4 7 Ke7 Re4+ 8 Kxd7 Rd4 9 f8(Q)

9...Rxd6+ 10 Ke7 Rd7+ 11 Ke6

11...Re7+ 12 Kd6 Rd7+ 13 Ke5 Re7+ 14 Be6+.

This study won second prize in a competition held by Shakhmaty v SSSR in 1938 and was published on page 90 of the February 1938 issue.

Pages 101-103 of the March 1939 edition had a profile of Vladimir Alexandrovich Korolkov:

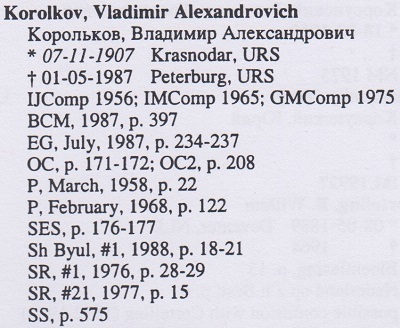

Chernev’s Chessboard Magic! (New York, 1943) gave nine studies by Korolkov (‘Korolikov’). The composer’s entry in the unpublished 1994 edition of Chess Personalia by Jeremy Gaige:

At present, Korolkov has no English-language Wikipedia entry.

11641. FIDE flag

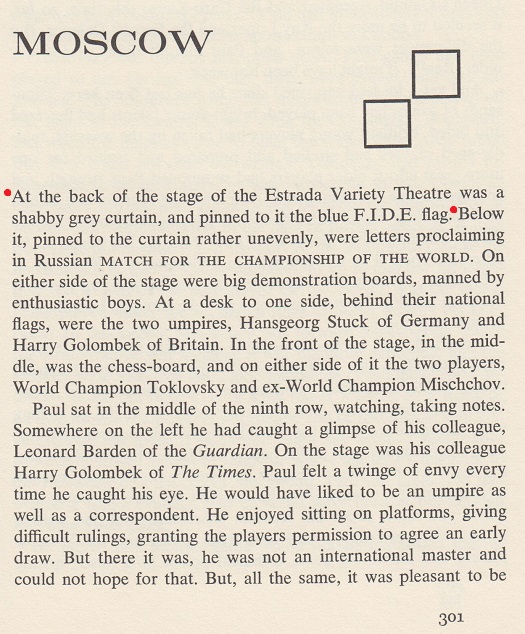

Page 301 of The Dragon Variation by Anthony Glyn (New York, 1969):

When did FIDE first have a flag? (And why exactly? Does a flag serve any greater purpose than an anthem, emblem, logo or motto?)

11642. Best-played game

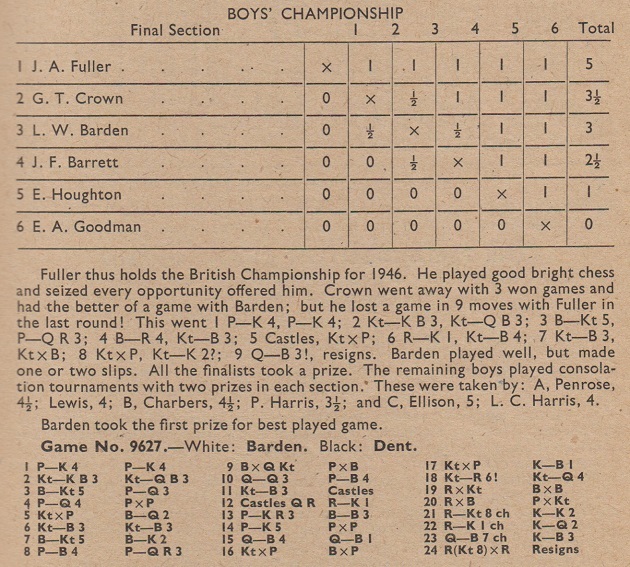

The earliest over-the-board game by Leonard Barden that we recall seeing was played in the British Boys’ Championship in Hastings in April 1946. From page 141 of the May 1946 BCM:

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 d6 4 d4 exd4 5 Nxd4 Bd7 6 Nc3 Nf6 7 Bg5 Be7 8 f4 a6 9 Bxc6 bxc6 10 Qd3 c5 11 Nf3 O-O 12 O-O-O Re8 13 h3 Bc6 14 e5 dxe5 15 Qc4 Qc8 16 Nxe5 Bxg2 17 Nxf7 Kf8

18 Nh6 Nd5 19 Rxd5 Bxg5 20 Rxg5 gxh6 21 Rg8+ Ke7 22 Re1+ Kd7 23 Qf7+ Kc6 24 Rgxe8 Resigns.

Page 168 of CHESS, May 1946 mentioned that the prize was given by Sir George Thomas. He was in the group photograph accompanying a report by A.J. Mackenzie on page 1 of the Hastings and St Leonards Observer, 20 April 1946. Can a better copy be found?

We sent a preview of the present item to Leonard Barden, who has commented:

‘I have no memory of that victory, though I recognize the opponent’s name. On the other hand, I have a strong negative memory of playing Fuller, where I chose the Wing Gambit and left my a5 rook en prise to a black knight quite early on, and a strong positive memory against Crown, where I stood slightly worse throughout as Black in a Queen’s Indian Defence but defended well to draw a difficult rook ending.

Sir George Thomas was an active spectator at major junior events in London and Hastings at that time and was very alert to pointing out tactical opportunities that the players had missed – including one of my own against Barrett at Hastings which could have enabled me to share second place.’

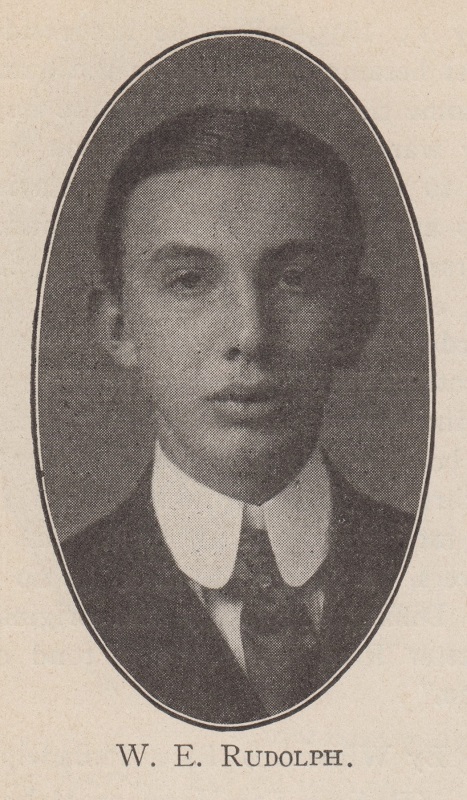

11643. W.E. Rudolph (C.N. 11638)

American Chess Bulletin, December 1912, page 274

From the following page of the Bulletin:

A brief mention of Rudolph’s victory over Frank Marshall was published in the New York Tribune of 17 December 1905, page 9:

The date of the display was thus 14 December 1905.

Richard Forster (Winterthur, Switzerland) sends the detailed information about Rudolph available at ancestry.com, and here we show just the heading:

In addition, Richard Forster has provided a number of newspaper cuttings, including the following from page 28 of the Arizona Daily Star, 2 August 1975:

Below is the first of two problems by Rudolph in the chess column of the St Louis Daily Globe-Democrat, 8 December 1912, page 4b:

Mate in four

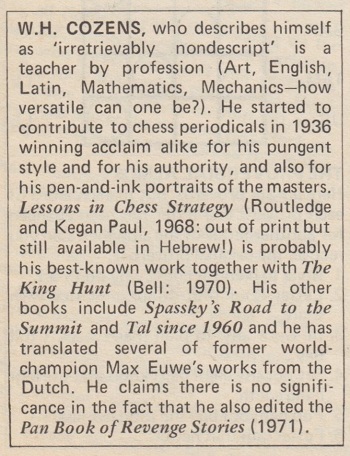

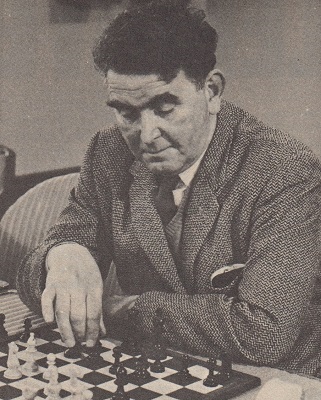

11644. Games & Puzzles

In the 1970s some fine chess writing appeared in the British magazine Games & Puzzles. A note about the chess editor, the ‘irretrievably nondescript’ W.H. Cozens, was on page 12 of the August 1975 edition:

The monthly chess column, several pages long and intended for inexperienced players, included notable guest contributors.

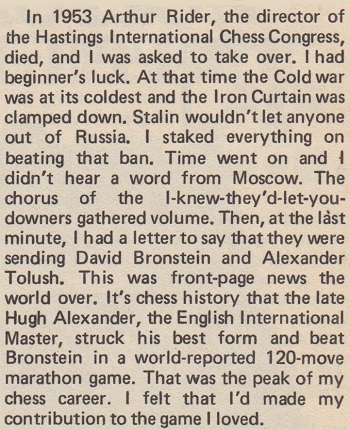

Page 21 of the September 1975 issue had an article by Frank Rhoden, ‘Pawns and People’, which serves as a reminder of the chess world’s debt to organizers:

In fact, Rider died on 24 January 1954 (C.N. 9107), but the Hastings, 1953-54 tournament was indeed run by Rhoden. See Chess and Politics (The Bordell Case).

Frank Rhoden (accompanying photograph in Games & Puzzles)

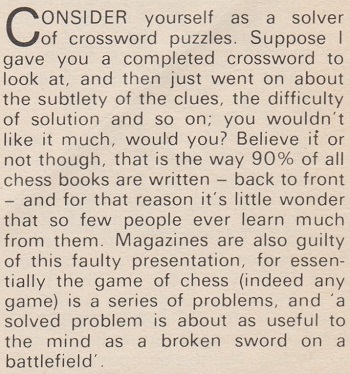

Some interesting points were made by Michael Basman at the start of an article, ‘Modern Methods’, on page 30 of the February 1977 issue:

From the following page:

On page 28 of the December 1976 issue of Games & Puzzles W.H. Cozens chose his favourite chess book, via a reference to a long-running BBC radio programme:

‘If ever Roy Plomley offers you the chance to take any one book along with your Desert Island Discs, take [Hermann von Gottschall’s] Adolf Anderssen. Sein Leben und Schaffen (long out of print, of course). It will thrill you for the rest of your life.’

| First column | << previous | Archives [185] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright: Edward Winter. All rights reserved.