When contacting us by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include their name and full postal address and, when providing information, to quote exact book and magazine sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the subject-line or in the message itself.

| First column | << previous | Archives [28] | next >> | Current column |

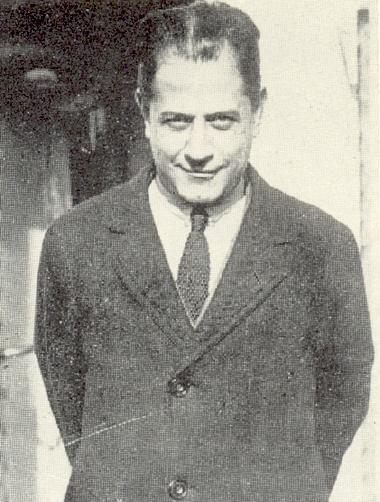

Luc Winants (Boirs, Belgium) has forwarded to us these two photographs of Richard Réti (Brussels, January 1924) from the collection of Daniël De Mol. Among the spectators is Edmond Lancel, who is standing second from the left in the first photograph and, in the other shot, sixth from the left, with Edgard Colle on his right. The photographs were taken during Réti’s tour of Belgium which was scheduled for late 1923 but was postponed owing to an accident sustained by Réti. Our correspondent draws attention to the following report to that effect in L’Indépendance Belge of 9 October 1923: ‘Par suite de l’accident dont Richard Réti a été victime il y a une quinzaine de jours, le grand maître tchécoslovaque nous prie d’annoncer que sa tournée en Belgique, prévue pour le début du mois d’octobre, ne pourra avoir lieu qu’au commencement du mois de novembre prochain.’ There were further delays, and the tour (Brussels, Ghent and Antwerp) eventually took place on 6-21 January 1924.

Mr Winants has a fine webpage regarding the tour but has so far been unable to establish the nature of Réti’s accident.

Joost van Winsen (Silvolde, the Netherlands) quotes a passage from pages 120-121 of The Principles of Chess in Theory and Practice by James Mason (London, 1894):

‘Formerly there was no time-limit. In those days, not so very long ago, a player finding himself in difficulties, real or imaginary, might rest and be thankful. Had he a bad or doubtful game? Well, if it could not be mended it need not be ended. A failing position afforded excellent food for thought. Not necessarily profound thought, but prolonged, and excellently calculated to discomfort, if not discomfit, the adversary. A comparatively short game (as to moves) in the American Chess Congress, New York, 1857, occupied 15 hours. This was between Morphy and Paulsen, the first and second prize-winners in that historic event. Paulsen was a slow player. Revelling in speculations – probable, possible, and perhaps impossible – he was wont to do his best, regardless of time, but not with the slightest or any idea of wearying his adversary by undue deliberation. Nevertheless, Morphy must have been sorely put to it when tears of impatience stood in his eyes – his opponent moved so very slowly.’

Above is the dedication page in Comment il faut commencer une partie d’échecs by E. Znosko-Borovsky. The book was first published in 1933, although the illustration comes from our copy of the fourth edition (1954). Further information about his illness and lengthy stay in the sanatorium would be appreciated.

The French version of the book was by Marcel Duchamp, and various editions have appeared in English, under the title How to Play the Chess Openings.

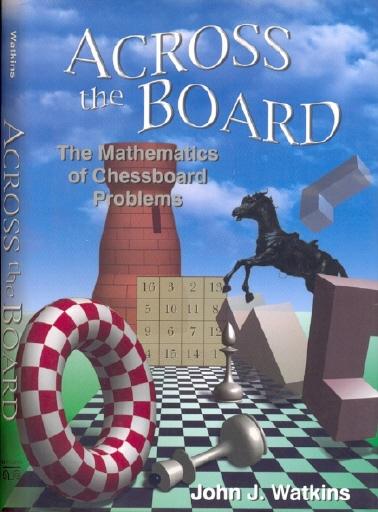

Pages 135-137 of A Chess Omnibus quoted over 30 descriptions/explanations, from the early nineteenth century onwards, of how the knight moves, but page 3 of Across the Board: The Mathematics of Chessboard Problems by John J. Watkins (Princeton and Oxford, 2004) offers a simple wording which may be better than any of them:

‘A knight can move on a chessboard by going two squares in any horizontal or vertical direction, and then turning either left or right one more square.’

This well written book, clear and entertaining, includes knights’ tours, magic squares and domination and has, for some reason, been virtually ignored by the chess world. On pages 2-3 Professor Watkins states that the earliest chessboard puzzle known to him dates from 1512: Guarini’s problem, in which the white knights and the black knights have to exchange places:

For a note on Paolo Guarini (or Guarino or Guerini or Guarinus), see pages 211-213 of Chess in Iceland and in Icelandic Literature by Willard Fiske (Florence, 1905).

An extract from Across the Board is available on-line at the website of the Princeton University Press.

A number of C.N. items have discussed this fake Alekhine-Capablanca photograph (see pages 309-311 of Chess Facts and Fables, as well as C.N.s 3680 and 3730), but one loose end concerns the Alekhine-Nimzowitsch picture (Semmering, 1926). C.N. 3730 reproduced it on a tobacco card ...

... but, strange to say, we have yet to find the photograph itself in a contemporary source. The Alekhine part has been seen in books, one example, quoted at random, being page 72 of Schach – ernst und heiter by Rolf Voland (Berlin, 1981), but what about the full Alekhine-Nimzowitsch photograph?

Improbably, this sketch was labelled ‘Dr Siegbert Tarrasch’ on page 8 of Aaron Nimzowitsch 1886-1935 Ein Leben für das Schach by Gero H. Marten (Hamburg, 1995).

On the subject of sketches and caricatures of chess masters, we suggest that some of the best are by Frank Stiefel in his book Was Sie schon immer über Schachweltmeister wissen wollten, ... aber nie zu fragen wagten (Schwieberdingen, 2000).

Simon Browne (Chelsea, Australia) refers to the participation of Capablanca and Alekhine in the Buenos Aires Olympiad, 1939 and to this comment on page 643 of Alexander Alekhine’s Chess Games, 1902-1946 by L.M. Skinner and R.G.P. Verhoeven (Jefferson, 1998):

‘Although both the French and Cuban teams got through to the final, the pair still did not play each other, since they both opted to take a rest day on the occasion of the France-Cuba match.’

As Mr Browne points out, Alekhine did play in that match, which took place on 14 September 1939. His win, over Alberto López Arce, was given on page 647 of the Alekhine book.

Our correspondent also refers to Capablanca’s explanation of his absence, in an article for the Argentine newspaper Crítica the following day. Below is the English translation from page 295 of our book on the Cuban:

‘Last night’s match between France and Cuba was drawn two-all. I should like to explain my absence, which was due to purely personal reasons.

Neither France nor Cuba was a leading contender in this competition, which meant that from that point of view there was no special significance in whether or not I played. There was only the question of the spectacle itself, which of course could not influence the course of the tournament.

Once more it is necessary to emphasize that the event being held at the Politeama is a tournament for teams, not individuals. A week ago I notified the Argentine Chess Federation that I did not intend to play against Alekhine, and I explained my reasons for this decision.

I made this announcement to the Federation so that my intentions were known in advance, and to prevent disappointment on the part of the public. My not playing yesterday was thus not an act of discourtesy to the Federation, nor a lack of consideration for the Buenos Aires public.

Therefore there was no question, as has incorrectly been stated, of my refusing a favour asked by the Federation. I have, and have always had, the best intentions towards the chess public and the organizing body.’

To some, unfortunately, this statement may be an irresistible springboard for speculation, and especially since it has not been established what reasons Capablanca gave to the Argentine Chess Federation or, indeed, whether he gave them in writing. Nor, incidentally, do we recall any public comment by Alekhine on Capablanca’s refusal to play him in the Olympiad.

The following week both masters wrote to the President of the Argentine Chess Federation, Augusto de Muro, regarding a possible world championship rematch. Page 240 of our book on Capablanca reproduced their respective letters, from page 34 of CHESS, 20 October 1939, and, rather than giving them again here, we quote Fred Reinfeld’s assessment on pages 194-195 of The Human Side of Chess (New York, 1952):

‘Capablanca was pathetically eager, even at this late date, to arrange a return match. He wrote a letter to the President of the Argentine Chess Federation, abounding in such phrases as, “I am disposed to play [...] whenever it can be arranged. ... I have not the slightest objection to make. ... I am disposed to accept this modification. ... Also I will accept whatever [reasonable] modification ... you will have no difficulty in coming to an agreement with me. ... I should be at your service.” Etc., etc.

It was a ticklish moment for Alekhine. Hurriedly snatching at the first available script, he wrapped himself in the Tricolor with great dignity, and sounded the note of “I would [could] not love thee, Dear, so much, loved I not honor more.” He gravely explained that “I am subject to mobilization as an official interpreter in the reserve”. Considering Alekhine’s age and world fame, there is little doubt that he could have obtained the necessary leave, in the period of “the phony war”. But he did not want to play Capablanca, as we know, and this time he adopted a subterfuge which would have served admirably in an Offenbach operetta ...’

It seems to us, though, that much more research is required, in the Argentine Federation’s archives (if any) and in local newspapers, before conclusions of any kind can be reached. The confusion prevailing at the time is reflected in articles in two consecutive issues (November and December 1939) of the chess magazine El Ajedrez Americano, which was published in Buenos Aires. Whereas the former (pages 321-322) spoke of a rematch as a virtually certainty, even stating that the Cuban was remaining in Buenos Aires until it came about, the latter (page 353) referred at length to the financial burden in the aftermath of the Olympiad. The November issue reported the masters’ purported standpoints, without giving sources.

We hope that readers will be able to assist us in piecing together additional facts about this final phase of the Alekhine-Capablanca rematch saga.

Joost van Winsen (Silvolde, the Netherlands) mentions that an article entitled ‘Van honderd naar zeshonderd’ by Jan Timman which was largely devoted to N.W. van Lennep was published on pages 8-11 of Schaakmagazine, May 1998. Our correspondent also refers to Hans Ree’s article ‘Norman Willem van Lennep de eerste hoofdredacteur’ on pages 23-26 of Schakend Nederland, June 1993. It was anthologized in Ree’s book Schitterend schaak (Amsterdam/Antwerp, 1997) and, as mentioned in C.N. 4664, has also appeared in an English version.

That C.N. item referred to a feature about van Lennep on pages 161-166 of the May 1897 BCM, and below we reproduce, from page 221 of the June 1897 issue, a brief letter of correction from van Lennep, written four months before he killed himself:

In our feature article an addition has now been made in the ‘Best introduction for children’ category.

C.N. 3809 gave an early problem by P.S. Milner-Barry. Below is another one, also composed when he was in his teens, which obtained the first honourable mention in a Morning Post three-mover tourney:

Source. BCM, November 1924, page 477.

We have received the following game from Luc Winants (Boirs, Belgium):

Alexander Alekhine (blindfold) – Léon Neirynck

Brussels, 18 March 1922

English Opening

1 c4 e5 2 g3 Nf6 3 Bg2 c6 4 Nc3 Bb4 5 Nf3 d6 6 d4 exd4 7 Nxd4 Be6 8 Nxe6 fxe6 9 Qb3 Na6 10 O-O Rb8 11 Bf4 e5 12 Be3 Bc5 13 Bxc5 Nxc5 14 Qc2 O-O 15 Rad1 Qe7 16 Rd2 Rbd8 17 h3 Ne6 18 e3 Nd7 19 Ne4 Ndc5 20 h4 Nxe4 21 Qxe4 Nc5 22 Qc2 Rf6 23 b4 Ne6 24 Qe4 Rf7 25 Bh3 Nc7 26 f4 exf4 27 Rxf4 Rdf8 28 Qxe7 Rxe7 29 Rxf8+ Kxf8 30 Rxd6 Rxe3 31 Rd7 Re7 32 Kf2 Rxd7 33 Bxd7 Drawn (at the proposal of Black).

Source: La Nation Belge, 29 March 1923 [sic].

The occasion was a 12-board blindfold display.

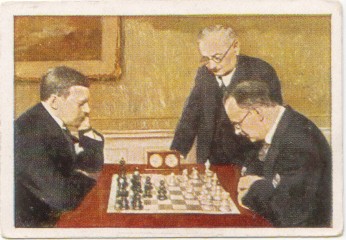

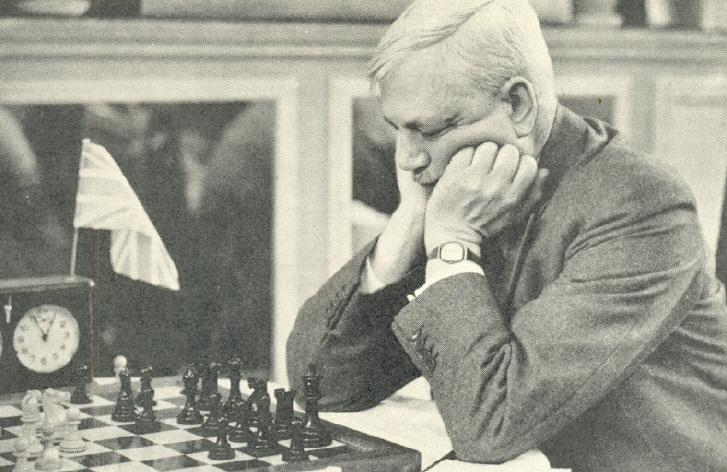

Luc Winants also provides this photograph:

Our correspondent comments:

‘This picture was taken during the third match-game between Victor Soultanbéieff and George Koltanowski in Brussels on 25 June 1935. I received it as a present from the daughter-in-law of Akiba Rubinstein (the widow of his eldest son), and I believe that it has never been published before. The persons standing are Demey and Van Meenen.’

As listed under ‘Broadcasting (radio and television)’ in the Factfinder, a number of C.N. items have discussed recordings of old masters in sound and/or vision, but very few specimens have yet been found, even though, in other fields, audio recordings from over a century ago are extant. For example, 19 sketches (patter and song) performed by Dan Leno (see C.N.s 4646 and 4647) between November 1901 and April 1903 are commercially available on a CD from Windyridge.

An immediate addition comes from page 315 of Emanuel Lasker The Life of a Chess Master by J. Hannak (London, 1959):

‘Next day Reuben Fine and his young wife came to see him [Lasker] for the last time. He could merely give them a feeble wave of his hand. When Fine had gone, Martha [Lasker’s wife] heard Emanuel whisper: “A King of Chess”.

These were the last words he was heard to speak. He died next day, on 13 January 1941.’

Lasker died on 11 January 1941.

Jerry Spinrad (Nashville, TN, USA) draws attention to the following passage in the obituary of Frederick Perrin in the Brooklyn Daily Eagle, 28 January 1889, page 1:

‘... yesterday afternoon at 3 o’clock he died as if in sleep. His last words to his physician were: “Doctor, I am puzzled over that last move of mine”.’

The following account by G.H. Diggle originally appeared in Newsflash, August 1980 and was republished on page 60 of Diggle’s book Chess Characters (Geneva, 1984):

‘Chess History contains many shadowy episodes on which only an uncertain light has been shed, chiefly because the sources of information lie in musty volumes now so rare that only eccentrics know where to find them. The six games played in London in May 1843 between Staunton and Saint Amant (six months before their Great Match in Paris) are a case in point. The scores were all preserved and the result (St A. 3, S. 2, Drawn 1) is not disputed – but did the games constitute a set match, or were they, as Murray claims, “six informal games which the Frenchman afterwards magnified into a chess match”?

Staunton (Chess Player’s Chronicle, 1843) published the games, but said nothing about a match, and informed his readers that “they were of inferior quality, affording nothing like a test of the relative skill of the two players”, that “he had entered the arena for the first time after severe indisposition”, that he ought to have won the second game “without difficulty” and the fifth “easily”, and that in the sixth game “the timidity, so foreign to Mr S.’s usual style of play, which he exhibits in this contest is undoubtedly attributable to the state of his health”.

But Saint Amant (Palamède, 1843), though he certainly “went to town” over his victory, is full of praise for the sportsmanship both of his opponent, who was “parfait de courtoisie” throughout, and of “la galerie” at the St George’s Chess Club – “comme beaux joueurs et vrais gentlemen les Anglais très certainement sont nos maîtres”. Moreover, his six-page account fairly established that, though hurriedly arranged and for a nominal stake of one guinea only, it was in fact a match, the winner of the first “trois parties” to be declared the victor, draws not counting. The arrangements at the St George’s, St A. informs us, showed commendable “savoir-vivre” – two “obligeants amateurs” sat recording the moves, and an “honorable assistance” instantly conveyed them to “une nombreuse réunion” who eagerly awaited them with chess sets at the ready in an adjoining apartment.

The first game (Sicilian Defence) was won by Staunton as Black after 69 moves and four hours; the second (Bishop’s Opening) was drawn after 90 moves and six hours, the third and fourth (two Giuoco Pianos of 36 and 30 moves played at one sitting resulted in one game all): the fifth (Sicilian) won by St A. after 60 moves and six hours; and the sixth and deciding game (QP Dutch Defence), won by Saint Amant after 58 moves (adjourned on 52nd move after 6½ hours – duration of final session not recorded, but Staunton occupied 57 minutes over his 56th move). The games themselves show that Staunton (though scarcely in the debilitated state he says he was) did not reveal the subtle positional strategy that he used with such effect in the later and greater match. The best game of the earlier series is probably the drawn one, a fine struggle which was included by R.N. Coles in Battles-Royal of the Chessboard (1948).’

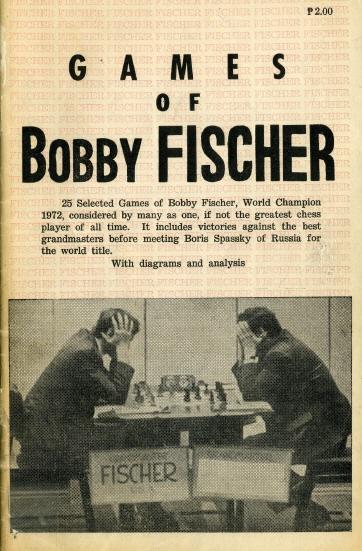

An addition to our Fischer book-list, Games of Bobby Fischer, has been provided by Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England), who writes:

‘There is no mention of any author, publisher, place or date of publication, but I think that it was published in the Philippines in about 1972. It contains a short biography of Fischer and 25 annotated games from 1965 to 1971.’

The front-cover text (‘... considered by many as one, if not the greatest chess player of all time’) is unfortunate.

This photograph of Fischer was published on page 107 of the May 1964 Chess Life, which stated that it came from the ‘Mazowsze Polish Song and Dance Co.’.

John Hilbert (Amherst, NY, USA) submits a passage from the New York Times of 12 January 1886, the day after the first game of the Steinitz v Zukertort match was played in New York:

‘Nobody has such a commercial interest in a “chess boom” as the makers of billiard tables have in a “billiard boom”. It is unlikely that the match between Steinitz and Zukertort will result in any popular revival of chess. There was such a revival following upon the victories of Morphy, and for a few years thereafter chess was much more actively and generally pursued than it has been since. The interest in Morphy’s success was patriotic, but that interest does not attach to a series of games between two Germans, one of whom happens to be a naturalized citizen of the United States. Of course, confirmed chessplayers will follow these matches with the interest that properly attaches to a contest between two players, either of whom is doubtless superior to any other than his present antagonist.’

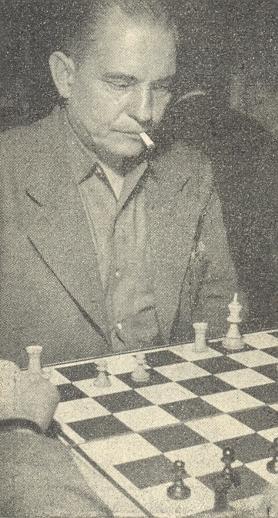

Who is this chess figure? The difficulty is such that a handsome clue is offered: D – T+C.

Of all the books dealing with chess lore and quotations, one in particular has been forgotten: “Chess-Humanics” by Wallace E. Nevill (San Francisco, 1905). Its mouthdrying subtitle was ‘A Philosophy of Chess. A Sociological Allegory. Parallelisms Between the Game of Chess and Our Larger Human Affairs.’ There was barely a word by Nevill himself, as the 238 pages consisted almost entirely of citations, often without precise sources and, even, without any direct link to chess. The third chapter, entitled ‘Black men and white men’, strayed far beyond the game to deal with race, citizenship and slavery, in a manner which would be impossible today. Throughout the book, quotes were bunched together, and the lay-out ensured maximum befuddlement for the reader.

“Chess-Humanics” was published by ‘The Whitaker & Ray Company’, and the imprint page stated ‘Author’s Edition of One Thousand Copies’. It was noticed favourably on pages 187-188 of the April 1905 American Chess Bulletin, which reported: ‘Although Mr Nevill is an Australian by birth, he is now a citizen of the United States (having come here some 11 years ago)’. The Bulletin also referred to his over-the-board successes in Mechanics’ Institute championships in San Francisco. What became of Nevill we do not know, but oblivion may seem a legitimate resting-place for “Chess-Humanics”.

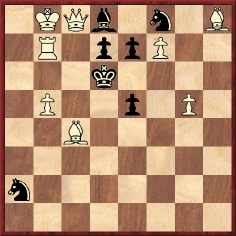

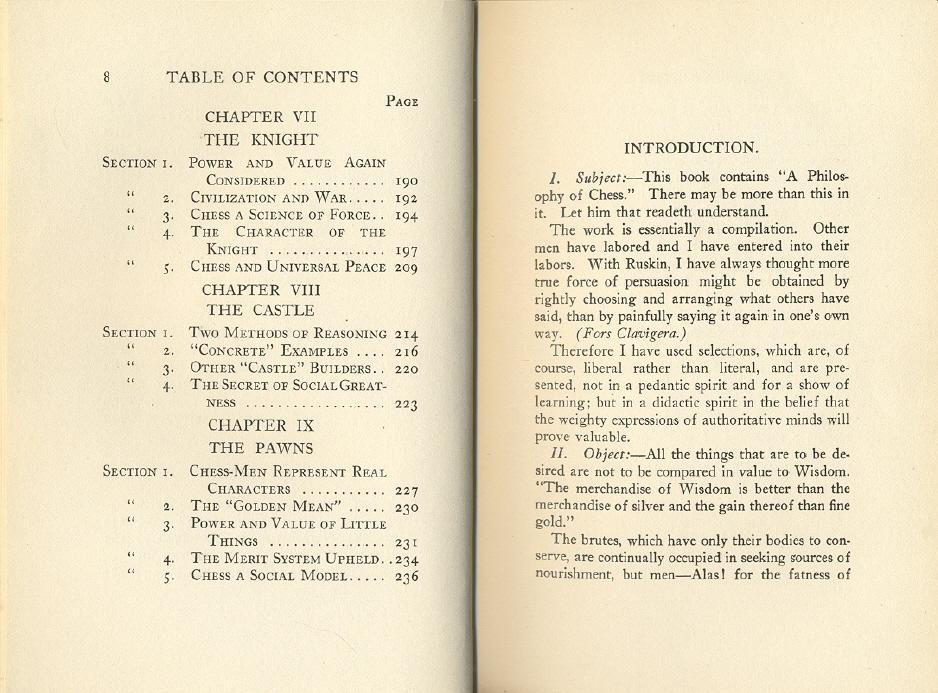

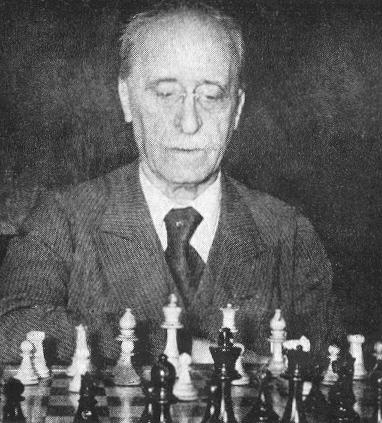

This famous position occurred in the game between Sämisch and Capablanca at the Carlsbad, 1929 tournament. All kinds of stories have been woven around the blunder 9...Ba6, such as this passage about Capablanca on page 31 of The Chess Scene by David Levy and Stewart Reuben (London, 1974):

‘In addition to being a chessplayer of genius he had a charming personality and was a great favourite with the ladies. This contributed to the break-down of his first marriage. While playing at the Carlsbad tournament in 1929, Capa had found himself a local mistress. This increased his enjoyment of an event in which he was playing well and he was looking forward to taking first prize even though the opposition was extremely strong. During his game with Sämisch (one of the tail-enders), Capablanca glanced up from the board and could hardly believe his eyes when he saw his wife, who had decided that it would be a nice surprise if she were to visit her spouse. Capablanca’s blunder in that game was possibly the worst of his career. He asked a friend, “Can I really continue a piece down?” His friend replied, “It is my responsibility that you play on”. He struggled for many hours but eventually lost and thus finished in a tie for second place, only half a point behind the winner.’

The anecdotists give no source for their account, and in particular it may be asked why this friend, conveniently unnamed, would have been consulted by Capablanca during the game and would have replied ‘It is my responsibility that you play on’. Moreover, is any historical narrative likely to be credible when it purports to quote direct speech?

José Raúl Capablanca

The story also cropped up on page 330 of ‘Garry Kasparov on My Great Predecessors Part I with the participation of Dmitry Plisetsky’ (London, 2003):

‘The secret of this “blunder of the year” was revealed by the victim himself. It turns out that before Capa’s ninth move a beautiful brunette appeared in the hall – his wife Gloria, who had turned up out of the blue from Havana. This “opening surprise” shocked the master: he was having an affair with a beautiful blonde ...’

Since it is affirmed by Kasparov-with-the-participation-of-Plisetsky that ‘the victim himself’ revealed what happened (with corroborative detail about hair hues), it is a pity that no further details were provided. In the Carlsbad, 1929 tournament book (page 309) A. Becker merely stated in his note to 9...Ba6 that after the game Capablanca explained that he had momentarily considered it possible to answer 10 Qa4 with 10...Na5 (‘Nach der Partie erklärte er, bei diesem Zuge momentan im Glauben gewesen zu sein, auf 10 Da4 mit Sa5 antworten zu können ...’). In other words, the Cuban thought that he had already castled.

When was feminine distraction first suggested? The earliest account we have found is by a participant in Carlsbad, 1929, Esteban Canal, in an article entitled ‘Il virtuoso Capablanca’ on page 127 of the June 1958 issue of L’Italia Scacchistica:

‘A questo proposito posso raccontarvi una sua tragicomica avventura della quale fui testimone e che pochi conoscono. Si svolgeva il torneo di Karlsbad 1929, uno dei più famosi del secolo, per lui importantissimo perché una sua vittoria gli avrebbe spianato la via della rivincita con Aljechin. Però invece di concentrare tutte le sue forze al raggiungimento dello scopo, alternava, lui quarantenne, le battaglie scacchistiche a schermaglie galanti, e ognuno sa quanto male vadano d’accordo la dama e il giuoco degli scacchi. Per colmo di mali le cose si complicarono di repente. Da alcuni giorni, verso la fine del torneo, egli aveva preso l’abitudine di appartarsi in dolce colloquio con una ragazzetta svenevole di buona famiglia, che era venuta coi genitori per la cura delle acque termali; il convegno avveniva in uno stanzino sperduto nel labirinto di sale, saloni e salotti del grande albergo, lontano da sguardi indiscreti. Una sera, mentre stavo per uscire a spasso, vedo una signora bruna nell’atrio fra un cumulo di valigie, con due marmocchi in calzoncini, che chiede di Capablanca al portiere. Intuisco la situazione, si tratta certamente della moglie che ha voluto preparare una lieta sorpresa arrivando così senza preavviso. Ho avuto sempre molta comprensione delle disgrazie del prossimo, eppoi gli ero molto amico, cosicché mi precipitai a dare l’allarme, spiegai le cose in fretta e furia, presi il suo posto accanto alla donzella, mentre egli si metteva a passeggiare di fronte a noi come se mi avesse scovato per caso in quel momento e volesse dirmi qualcosa di molto importante. La commedia era stata opportuna e tempestiva, perché subito dopo entrò in campo il nemico cioè la consorte e i ragazzi. Passato il primo momento delle effusioni, salutarono e uscirono con lui. Dallo sguardo che mi aveva gettato la buona donna io compresi che la finta non era riuscita, e infatti ho saputo più tardi che quella notte fu tempestosa per il cubano, un vero tornado delle Antille gli si era scatenato addosso. Il giorno dopo egli apparve nella sala di torneo compito e sorridente come al solito, però nella partita sua contro Sämisch si notarono le conseguenze del temporale: dopo solo nove mosse egli perse un pezzo, e così anche la partita e il primo premio. Questo e il piccolo tributo che l’uomo felice deve rendere ogni tanto agli invidiosi dei.’

In short, Capablanca was in the company of a young girl at the hotel in Carlsbad when his wife and two children unexpectedly arrived there. Canal tried to help Capablanca cover his tracks, but unsuccessfully. That night the Cuban faced his wife’s fury, and the following day he blundered against Sämisch. This article was reproduced on pages 102-104 of Esteban Canal by Alvise Zichichi (Brescia, 1991).

However, an altogether different version was attributed to Canal in an article by Román Torán on pages 8-9 of Ocho x Ocho Especial (April 1995). Torán stated that at a tournament in Venice in 1952 (we believe that he meant 1953) Canal gave him the following account of what happened at Carlsbad in 1929:

‘Paseaba por la sala esperando la jugada de mi adversario cuando, súbitamente, vi entrar a la acompañante de Capablanca de los últimos meses. Ajeno a su llegada, Capablanca conversaba con una joven en una salita del casino escenario del torneo. Quise evitar un incidente y me di buena prisa en advertir a Capablanca. Con su rapidez de reflejos me dijo: “Siéntate ahí”, de forma que la señorita quedase entre los dos y no se pudiera saber quién le acompañaba. Pero esta maniobra no convenció a la recién llegada, que armó un buen escándalo. Capablanca se reincorporó a la partida y cometió un grave error que le costó una pieza. Normalmente, hubiera abandonado, pero quería que se calmase el enfado de su acompañante, por lo que continuó jugando y, ante el asombro general, a punto estuvo de salvarse.’

This version refers only to a lady companion and a young girl, with no mention of Capablanca’s wife and children; nor was there any night of recriminations, since the incident is stated to have occurred during the Cuban’s game against Sämisch. The Ocho x Ocho article has been drawn to our attention by Christian Sánchez (Rosario, Argentina). Whether the account is faithful to what Canal had told Torán four decades previously is impossible to say.

Below is a photograph of Canal from page 135 of La Scacchiera, June 1953:

Two other reports may be noted. The first was by Hans Kmoch, in an article entitled ‘My Personal Recollections of Capablanca’ on pages 362-363 of Chess Review, December 1967:

‘In 1929, Capablanca participated in the fourth Carlsbad tournament. But I had little contact with him there. When his wife (the first one) arrived, he lost to Sämisch, blundering away a piece in the opening, much to the satisfaction of Alekhine, who attended the contest as an observer.’

Alekhine was reporting on the tournament for the New York Times.

Further confusion was created when Salo Flohr wrote an account in the 9/1980 issue of 64. A translation of his article (‘El idioma materno de Capablanca’) was published on pages 28-30 of the 3/1981 issue of the Cuban magazine Boletín Ajedrez. Claiming that the ‘secret’ of what had happened in Sämisch v Capablanca had come from the latter’s own words (no source), Flohr asserted that while the Cuban was contemplating move nine his wife unexpectedly entered the tournament hall. According to Flohr, this displeased Capablanca because he was then frequenting another woman, Olga Chagodaef, whom he later married. As noted on pages 252 and 325 of our book on Capablanca, this is incorrect because he did not meet his second wife until 1934.

Taken jointly, the narratives by Canal, Kmoch and Flohr suggest that something involving one or more women occurred in the context of Capablanca’s loss to Sämisch. The unresolved questions are what, who, where and when.

From Chris Ravilious (Eastbourne, England):

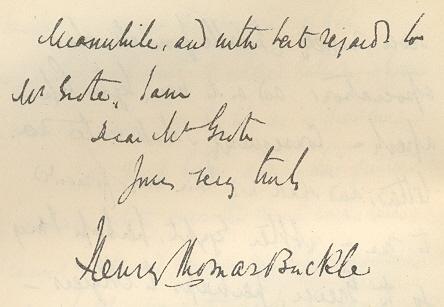

‘What were Buckle’s last words? The “purported” cry “Oh my book, my book. I shall never finish my book” was uttered on 17 May 1862, almost a fortnight before his death from typhoid. His last recorded words, as recalled by the British Acting Consul at Damascus, who was with him when he died, were “Poor little boys”, a reference to the two teenage sons of Mrs Huth, who accompanied him on his last journey. Full details are on pages 99-100 of Giles St Aubyn’s biography of Buckle, A Victorian Eminence, published in 1958.’

We note that a similar, though longer, account appeared on page 252 of volume two of The Life and Writings of Henry Thomas Buckle by Alfred Henry Huth (London, 1880). Moreover, page 52 of volume one of The Miscellaneous and Posthumous Works of Henry Thomas Buckle by Grant Allen (London, 1885) stated: ‘His last words were words of kindness to his two young companions.’

From the insert opposite page 111 of the above-mentioned Huth book we reproduce the conclusion of a letter written by Buckle on 18 October 1861:

The passage from the New York Times of 12 January 1886 in C.N. 4709 suggested that Steinitz was ‘a naturalized citizen of the United States’, but Robert John McCrary (Columbia, SC, USA) quotes from page 364 of the December 1888 International Chess Magazine to show that naturalization came later:

‘On the 23d ult. Mr Steinitz was sworn in as a citizen of the United States. The veteran Mr F. Perrin was his sponsor to testify to Mr Steinitz having resided for five years in the State of New York.’

Another point raised by our correspondent is whether Zukertort was a naturalized British citizen. We are not sure. His obituary on pages 307-309 of the July 1888 BCM stated, ‘... he settled in London, becoming naturalized in 1878’. However, page 24 of Johannes Zukertort Artist of the Chessboard by Jimmy Adams (Yorklyn, 1989) referred to that obituary and added, ‘... the Home Office, Nationality Department, has no record of this’.

In C.N. 4703 a correspondent asked about a chess author who was named as Trevangadacharya Shastree on the title page of Essays on Chess (Bombay, 1814). We noted regarding the original Sanskrit version that a nineteenth-century chess catalogue identified the author as ‘Trevangadâtschârya’ and the title of the work as Vilas muni munjuri.

From Professor Nagesh Havanur (Mumbai, India):

‘Without access to the original Sanskrit work I would suggest that both the name of the author and the Sanskrit title appear to be a distortion. The name of the author should be Thiruvenkatacharya Shastri. ‘Trevangadacharya’ is an improbable name, as it has no etymology to speak of. In India the custom is to name children after gods. Thiruvenkatesha, or Shri Venkatesha, is the incarnation of Lord Vishnu. It appears that the author was a Tamil Brahmin. Hence, the Tamil prefix Thiru, which forms part of his name. It is customary to address Brahmins, or members of the priestly class, with respect, so they are called acharyas in the South. A Shastri (not Shastree) is a scholar who has mastered holy books, i.e. shastras. The title of the Sanskrit book should be Vilasa Manimanjari. The word Vilasa indicates pleasure or enjoyment. Manimanjari means a collection of precious stones, such as pearls or gems. Roughly translated, the title is “collection of chess gems for pleasure”.’

Our recommendation in C.N. 3514 was ‘to dispense with any publication or website which offers “chess quotes” without indicating where and when the statements in question were purportedly made’. From our recent reading, nothing in this field compares with the quotes section (pages 155-169) of Check Mate and Word Games by Carlos Tortoza (Denver, 2006). A sample follows:

Sourceless quote-dumps are bad enough, but who would bring out a book with such an unmistakable (Germanic) reek of computer translation? A child, perhaps? The back cover provides some biographical information about Carlos Tortoza, who is Brazilian:

‘He is a psychologist and economist, with a postgraduate degree in economic projects, specializing in psychoanalysis. He is an academic professor of psychology, philosophy, sociology and economic business administration.’

Chess scandals are common enough, and tend to concern alleged cheating by players and/or maladministration by officials, and they may even briefly interest the mainstream press. In contrast, few eyelids are batted when a case is revealed of theft or other malpractice regarding the game’s literature. Coles reprinted the books of various writers (including Capablanca) under false names, but were many people bothered? A Spanish publisher deceived the public by bringing out a book whose author was named as ‘Garry Kaspartov’ (see C.N.s 4150, 4154, 4155 and 4225), but who minded? As shown in our feature article on Copying, all sorts of chess writers have freely passed off the output of others as their own, but how many cases resulted in an outcry?

Now we draw attention to another, extreme, instance. C.N. 4683 discussed A Guide To Chess by ‘Philip Robar’, published by Pankaj Books, New Delhi, and the company’s website shows a line-up of chess volumes whose authorship is ascribed to that same mysterious person. By way of example, we briefly look at one of them here, Techniques of End Game in Chess (New Delhi, 2002):

Different typefaces and notations are used in the book, and of necessity because 90 pages have been lifted, unascribed, from Chess endings for the practical player by L. Pachman (London, 1983) and about 100 pages have been stolen from Practical Chess Endgames by D. Hooper (London, 1968).

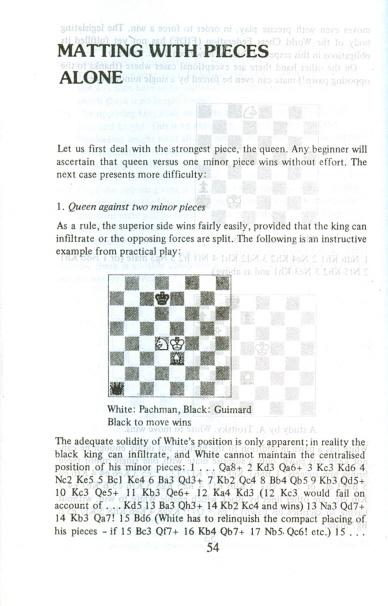

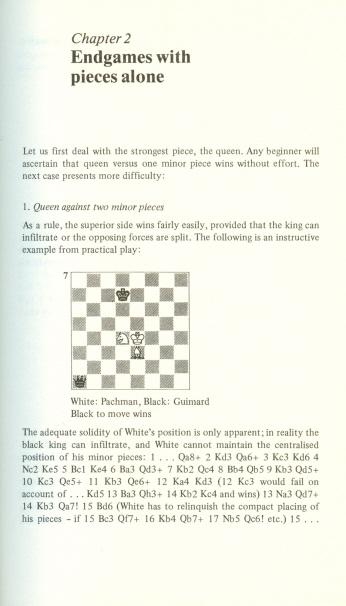

Sample pages are shown below:

Robar (left) and Pachman

Robar (left) and Hooper

It will be noted that the Robar book has amended the chapter endings, with a misspelling both times. Everything in Techniques of End Game in Chess from page 49 to the end (page 240, which chops off Pachman’s analysis in mid-flow) is by either Pachman or Hooper.

Not surprisingly, the other chess productions of Pankaj Books have also been put together, without attribution, from previous writers’ work, but does the chess world care?

Students and/or practitioners of cheating at chess en famille should consult the reminiscences by Simon Gray on pages 25-28 of The Year of the Jouncer (London, 2006).

Alexander Alekhine

Alekhine’s birth-date is often given as 1 November 1892, but we are aware of no authoritative book published in the past 20 years or so which deviates from the ‘established’ date of 31 October 1892 (Gregorian calendar); this is the equivalent of 19 October 1892 in the Julian calendar, the gap in the nineteenth century being 12 days, and not 13.

The Alekhine entry in Jeremy Gaige’s Chess Personalia states that page 20 of the 21/1972 issue of Shakhmaty gave a copy of Alekhine’s birth certificate; since we do not have that issue, perhaps a reader could kindly submit a copy. Alekhine’s birth-date used to appear mainly in the old-style version (19 October 1892), examples being on page 561 of the Teplitz-Schönau, 1922 tournament book and the ‘biographical note’ in his first volume of My Best Games (London, 1927). However, the equivalent note in his second Best Games collection (London, 1939) had the date as 1 November 1892. That could be dismissed as a conversion error by his British editors, but the real surprise comes in a feature article about Alekhine on pages 395-407 of issue 13 of Les Cahiers de l’Echiquier Français (1928). It began:

‘Les biographies du nouveau champion du monde sont presque toutes remplies d’inexactitudes. Celle qu’on va lire est rigoureusement exacte. C’est la traduction d’un article de l’annuaire biographique Who is who [sic] avec quelques rectifications par le maître lui-même.

Alexandre Alekhine naquit à Moscou le 1er novembre 1892 ...’

Why would that birth-date appear in an article said to have been verified by Alekhine himself?

From Harrie Grondijs (Rijswijk, the Netherlands):

‘For my book Steinitz with Zukertort (Rijswijk, 2006) I tried to retrace Zukertort’s travels and games in the United States in 1883-84. As shown on pages 97 and 239, next to nothing is known about his chess activities in Washington. I have, however, now found on page 188 of the Irish Sportsman, 22 March 1884 a game which he played in a three-board blindfold display at the Washington Chess Club.’

Johannes Hermann Zukertort (blindfold) – Jacob Frech

Washington, 21 December 1883

Evans’ Gambit Accepted

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bc4 Bc5 4 b4 Bxb4 5 c3 Be7 6 d4 d6 7 Qb3 Be6 8 Bxe6 fxe6 9 Qxe6 Qd7 10 Qb3 b6 11 O-O Na5 12 Qc2 Bf6 13 Rd1 Nc6 14 Na3 Nge7 15 Nc4 Ng6 16 dxe5 Ngxe5 17 Nfxe5 Nxe5 18 Nxe5 Bxe5 19 f4 Bf6 20 e5 Be7 21 Qb3 O-O-O

22 a4 Qc6 23 Ba3 Rhe8 24 a5 dxe5 25 Bxe7 Rxd1+ 26 Rxd1 Rxe7 27 fxe5 Qc5+ 28 Kh1 Qxe5 29 h3 Qxa5 30 Qg8+ Kb7 31 Qxh7 Qxc3 32 Qf5 Re1+ 33 Rxe1 Qxe1+ 34 Kh2 Qe7 35 Qc2 a5 36 Qc4 c6 37 h4 b5 38 Qd4 a4 39 Kh3 a3 40 g4 a2 41 h5 Qa3+ 42 White resigns.

A further addition to our list of volumes about Fischer comes from Calle Erlandsson (Lund, Sweden): Fischer. 100, published in 2003 by Alfil Chess Books in Bangalore. Our correspondent remarks:

‘It contains 100 games without annotations. There are some diagrams and just short remarks like “A wonderful game” and “Typical Fischer”. No dates or events are mentioned for any of the games. The booklet is described as volume one in a “Classics series – 1”, but I do not know whether further volumes in the series have been issued.’

This is Louis Malpas (1893-1973), in a photograph submitted by Luc Winants (Boirs, Belgium). Malpas co-authored with Henri Rinck a booklet Dame contre tour et cavalier (Brussels, 1947), which prompted the clue in C.N. 4710.

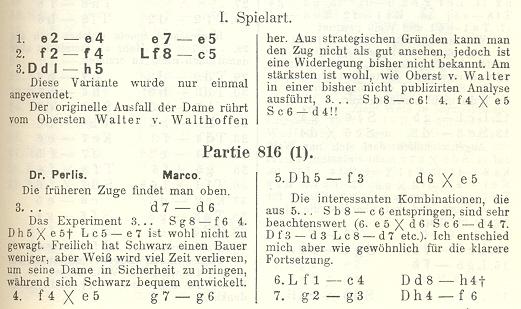

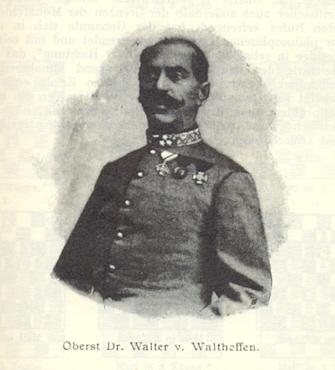

Rod Edwards (Victoria, BC, Canada) asks for information about Colonel (Oberst) Hippolyt Walter von Walthoffen (1830-1912), who had the ‘Walthoffen Attack’ named after him and won a well-known miniature against Gustav Zeissl in Vienna in 1899.

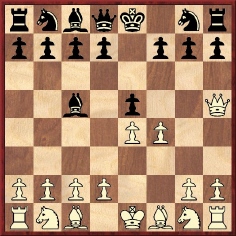

We begin by recalling that the Walthoffen Attack occurs in the King’s Gambit Declined: 1 e4 e5 f4 Bc5 3 Qh5.

White’s third move was mentioned on page 781 of Bilguer’s Handbuch des Schachspiels (Berlin and Leipzig, 1922), the only game reference being to Perlis v Marco, Vienna, 1904, as published on pages 99-100 of the April 1905 Wiener Schachzeitung:

At move three it was commented that 3 Qh5 came from von Walthoffen (‘Der originelle Ausfall der Dame rührt vom Obersten Walter v. Walthoffen her’). This is the earliest reference we can currently offer for the ‘Walthoffen Attack’.

Page 59 of the February 1895 Deutsche Schachzeitung described him as ‘the well-known analyst and problem composer’ (‘der bekannte Analytiker und Problemcomponist’), but whereas there is no shortage of compositions by him in chess magazines of the time, we have come across little analytical work by him. One article, about 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 f5, was published on pages 161-165 of the June 1890 Deutsche Schachzeitung, and Curt von Bardeleben presented a follow-up item on pages 257-260 of the September 1890 issue. The same magazine (November 1899, pages 335-336) published this game:

Hippolyt Walter von Walthoffen – Johann Hermann Bauer1 f4 d5 2 d4 e6 3 e3 c5 4 c4 Nf6 5 Nf3 Nc6 6 Nc3 a6 7 Ne5 cxd4 8 exd4 Bb4 9 a3 Bxc3+ 10 bxc3 Ne4 11 Qd3 Na5 12 c5 f6 13 Nf3 Nb3 14 Rb1 Nxc1 15 Rxc1 Qa5 16 Ra1 Qxc3+ 17 Qxc3 Nxc3 18 Bd3 Bd7 19 Kd2 Ne4+ 20 Ke3 Bc6 21 Bxe4 dxe4 22 Nd2 f5 23 Nc4 Bd5 24 Ne5 Rc8 25 Rac1 Rc7 26 g4 Rf8 27 g5 Ke7 28 a4 Rfc8 29 a5 Bc6 30 Rhg1 Rh8 31 Rg3 Kf8 32 Rh3 Kg8 33 Rc3 Be8 34 Rh4 h5

35 d5 exd5 36 Kd4 Bc6 37 Rb3 Rc8 38 Nxc6 bxc6 39 Rb6 g6 40 Rxa6 Rh7 41 Rb6 Ra7 42 a6 Kf7 43 Rh3 Ke7 44 Rhb3 Kd7 45 Rb7+ Rc7 46 R3b6 h4

47 h3 (‘Zugzwang’, comments the German magazine.) 47...Kc8 48 Rxa7 Rxa7 49 Rxc6+ Rc7 50 Rxg6 Resigns.

The familiar win by von Walthoffen against Zeissl went 1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 f5 4 d4 fxe4 5 Nxe5 Nxe5 6 dxe5 c6 7 Bc4 Qa5+ 8 Nc3 Qxe5 9 O-O d5 10 Bb3 Nf6 11 Be3 Bd6 12 g3 Bg4 13 Qd2 Bf3 14 Bf4, and Black announced mate in five with 14...Qf5 15 Nd1 Qh3 16 Ne3 Ng4 etc., although White has ‘spoilers’ at his disposal. Irving Chernev included the game in his book Logical Chess Move by Move, and it appears in a number of databases. The latter usually state ‘1898’, but on pages 79-80 of the May 1899 Wiener Schachzeitung the game was reported as having been played in the Vienna Chess Club on 25 March 1899.

That publication was in a section headed ‘casual games’ (‘Freie Partien’). On the other hand, page 39 of the March 1899 Wiener Schachzeitung had a crosstable for the 1898-99 Amateur Tournament of the Vienna Chess Club (won by L. Löwy) in which Zeissl lost a game to a player named as ‘Oberst v. Walter’. This was rendered as ‘von Walter’ on page 135 of the first volume of Chess Tournament Crosstables by Jeremy Gaige (Philadelphia, 1969).

The reference in Gaige’s book prompts another question from our correspondent, Rod Edwards: was that tournament participant Hippolyt Walter von Walthoffen? Leaving aside the plain surname ‘Walter’, we have found, in the innumerable occurrences of the names ‘von Walthoffen’ and ‘von Walter’ in the Deutsche Schachzeitung and the Wiener Schachzeitung, instances of each being described as a) a player, b) a problemist, c) an ‘Oberst’ and d) a ‘Doktor’. On the other hand, there are also cases of their being indexed as different persons. The question thus remains open. We add in passing that Gaige’s Chess Personalia (page 456) had ‘Walter von Walthofen [sic], Hippolyt’.

The illustration below appeared on page 77 of the February-March 1904 Wiener Schachzeitung, as an introduction to 60 of von Walthoffen’s problems (given on pages 78-83):

The article also announced the publication in early March 1904 of a philosophical work by him, Das Weltproblem und der Weltprozess. After his death a biographical note on page 147 of the May 1912 Deutsche Schachzeitung (taken from the Neue Wiener Tagblatt) listed three other philosophical works by him, as well as supplying an overview of his military career and his chess activity.

The ‘Walthoffen Attack’ was not mentioned in the above article, but it has not been forgotten. For an analytical discussion see, for instance, pages 15-18 of Das neue Königsgambit by Stefan Bücker (Stuttgart, 1986).

Lord Morgan (Oxford, England) submits a photograph of his father, D.J. Morgan (left), at the prize-giving ceremony of a bowls tournament in Aberystwyth, circa 1966:

It may be recalled that in C.N. 4203 Lord Morgan presented a personal memoir of the great BCM columnist.

When did ladder tournaments first appear?

Below is a description of the procedure, from page 205 of the March 1907 issue of Lasker’s Chess Magazine:

‘The Club [the Pittsburgh Chess Club] is conducting a so-called “ladder” continuous tournament. An arbitrary list of ten names was placed on a blackboard some two months ago, and in order to advance your position it is necessary to win a game with the player immediately above you. It is also necessary to play a game with the one immediately below, before a return match can be played with the one above.’

Who was the last surviving master who had come into personal contact (not necessarily over the board) with Zukertort?

Sir George Thomas

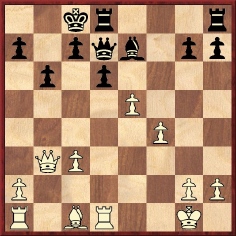

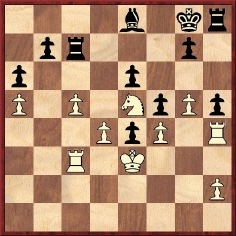

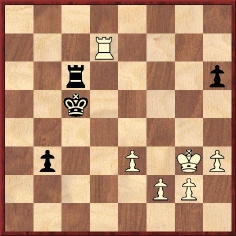

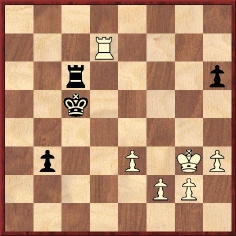

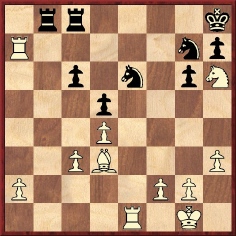

Sir George Thomas accused himself of ‘funk’ regarding the conclusion of his game against Capablanca at Carlsbad, 1929.

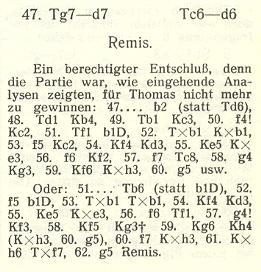

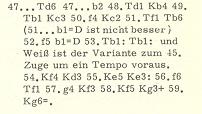

In this position Sir George (Black) played 47...Rd6, and a draw was agreed upon. However, page 43 of Assiac’s The Delights of Chess (London, 1960) quoted a brief comment he wrote at the end of his game-score:

‘Draw agreed. A case of funk. Black should win the ending.’

On the following page Assiac remarked that ‘readers can easily

see for themselves that the game was won for Black, and without

much risk either’. We wonder, though, how clear-cut matters are.

On page 53 of the Carlsbad, 1929 tournament book Alfred Brinckmann wrote that the draw after 47...Rd6 was justified, as thorough analysis showed that Black could not win:

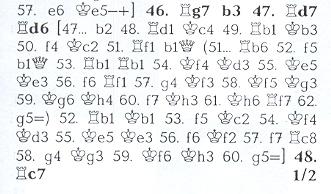

Similar analysis was given (without mention of Brinckmann) in the annotations booklet which accompanied the Weltgeschichte des Schachs volume on Capablanca by James Gilchrist and David Hooper (Hamburg, 1963):

See too page 89 of the second volume of the ‘Chess Stars’ book on Capablanca (Sofia, 1997), which also offered only a draw, although one further move (48 Rc7+) appeared in the game itself:

Has a winning method for Black at move 47 ever been demonstrated?

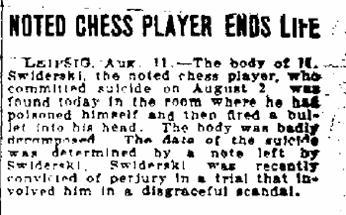

Rudolf Swiderski

The suicide of Rudolf Swiderski was discussed in C.N.s 2776 and 3654, and in the latter item a correspondent quoted a report in the Washington Post of 12 August 1909:

‘Famous Chess Player a Suicide.

Special to The Washington Post.

Berlin, Aug. 11. – Swiderski, the celebrated chess player, was found dead today. Apparently he had poisoned and shot himself.’

We asked how the dispatch from Berlin could be dated 11 August if, as stated in chess reference books, Swiderski died on 12 August (in Leipzig). Among other sources, we noted that the American Chess Bulletin (October 1909, page 227) gave his death-date as 2 August.

Now Olimpiu G. Urcan (Singapore) sends a report from the Trenton Evening Times of 11 August 1909:

‘Noted chess player ends life

Leipsig. Aug. 11. – The body of R. Swiderski, the noted chess player, who committed suicide on August 2, was found today in the room where he had poisoned himself and then fired a bullet into his head. The body was badly decomposed. The date of the suicide was determined by a note left by Swiderski. Swiderski was recently convicted of perjury in a trial that involved him in a disgraceful scandal.’

C.N. 3654 asked, unavailingly, if a reader in Germany could investigate what appeared in the local press, and there is now all the more reason to do so.

What are the origins of the famous ‘Mister Meises/Meister Mieses’ story? On page 182 of CHESS, 20 March 1960 B.H. Wood wrote, ‘This anecdote first appeared in print in CHESS many years ago’.

Yasser Seirawan (Amsterdam) writes regarding Capablanca v Thomas, Carlsbad, 1929:

‘A quick impression is that Black should win by direct means after 47 Rd7: 47...b2 48 Rd1 Kb4 49 Rb1 Kb3! 50 f4 Rc1! 51 Rxb2+ Kxb2 52 Kh4 (With the rook now on the first rank the advance 52 f5 is a mistake as 52...Rf1 53 e4 Kc3 makes the task easy.) 52...Rc6! (Covering the h6-pawn, cutting off the white king and preparing to bring the black king into play.) 53 g4 Kc3 54 Kh5 Kd3 55 g5 hxg5 56 fxg5 Ke4, and Black is in time to stop the pawns for a win.

This is by no means an exhaustive analysis, but just a check of the direct line. It is possible that 50 f4 is wrong, but I based my analysis on that move as it seemed to be the main line of others.’

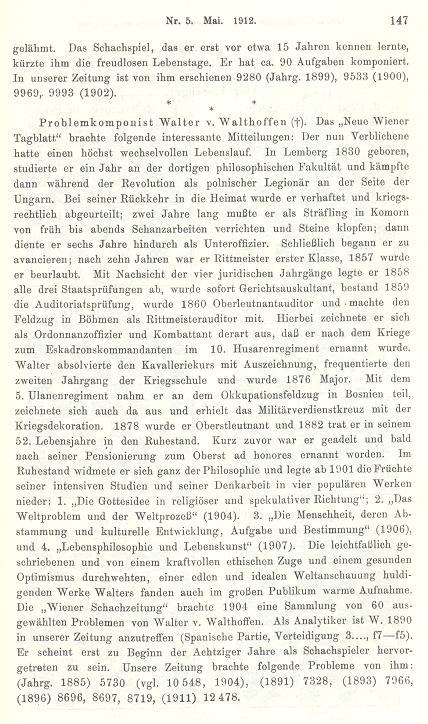

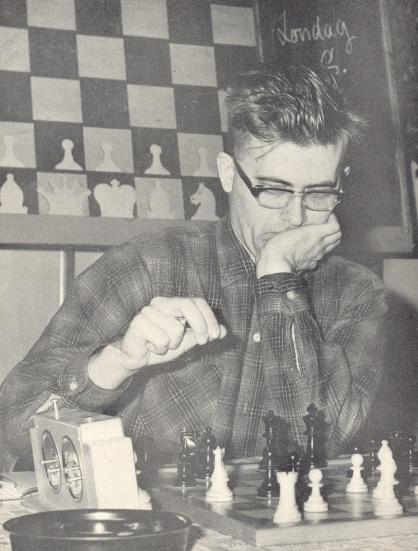

Bent Larsen

In C.N. 3933 a correspondent queried a remark by Ronald Gross in an interview quoted on page 414 of Pal Benko My Life, Games and Compositions by P. Benko and J. Silman (Los Angeles, 2003): ‘Larsen ... spoke 13 languages fluently.’

Bent Larsen (Martínez, Argentina) informs us:

‘Of course it is not exactly true. I simply spoke more languages than Ronnie Gross. Like Zukertort who spoke more languages than the Ipswich journalist, he was too tired to attend.

At the time I had not even studied Russian and, worse, I had not studied Spanish, and I still haven’t. So, Danish, English, German, French (very bad), and maybe Swedish and Dutch. I may have said six. Later I may have said eight. I do not include Portuguese, Italian or Serbo-Croatian. Norwegian? The Norwegian of Ibsen, yes, that is a variant of Danish. That of Garborg, no.

The only comment has to do with teachers. My middle-school teacher of German was horrible, a brutal man. So I did not study German at home. My Gymnasium teacher of French was not such a bad person, but he had very bad nerves. He went hysterical sometimes. My reaction was very simply not to be the best of the 24 in French.’

Below is the author’s inscription in one of our copies of Test Your Chess by Gerald Abrahams (London, 1963):

‘A book of chess problems by Britain’s leading expert’ was the dust-jacket’s daring encomium.

Jacques Mieses

Peter Anderberg (Harmstorf, Germany) points out that the story was published on pages 169-170 of Schachwart, September 1932, as follows:

‘Ein Wortspiel.

Als Mieses vor langen Jahren in England weilte, stellte ihn der damals recht bekannte englische Amateur Judd einem anderen englischen Spieler mit den Worten vor: “Mister Meises – ”. Hier unterbrach ihn Mieses lächelnd und wandte sich an den Engländer: “Entschuldigen Sie, aber ich bin nicht Mister Meises, sondern Meister Mieses.”’

Our correspondent comments that this report pre-dates B.H. Wood’s magazine CHESS, which was first published in 1935. The reference to a well-known English (sic) amateur named Judd is strange.

Assiac set the story not in England but in New York when relating it on page 186 of The Delights of Chess (London, 1960):

‘One day in New York he was asked by a German-American who mispronounced his name the English way: “Sind Sie Mister Meises?” “No, sir”, he answered like a shot, “Ich bin Meister Mieses.”

The old boy was full of such anecdotes and reminiscences when he was in a good mood.’

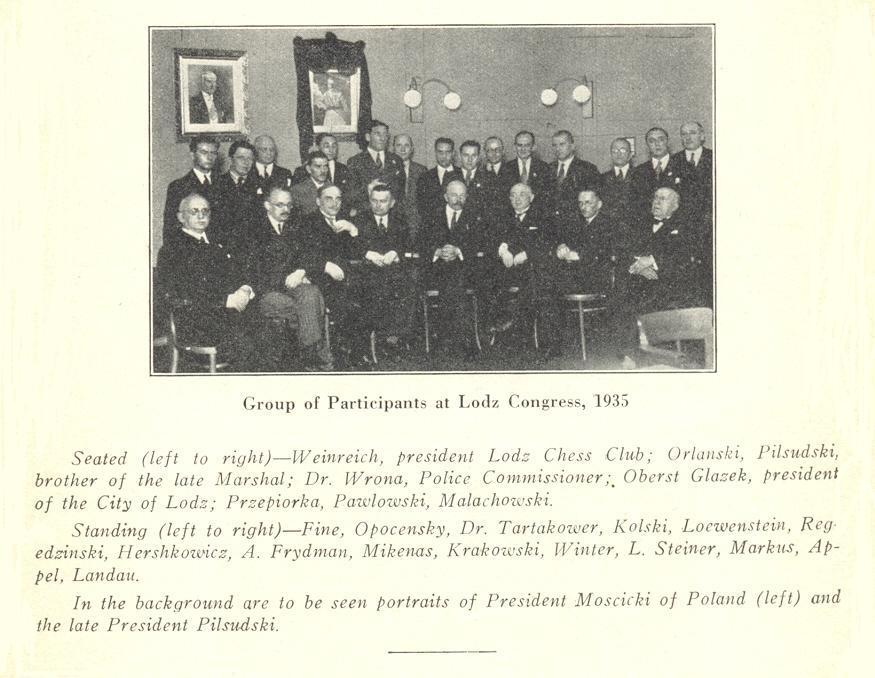

Further to the discussion about William Winter in C.N. 3959, below is a photograph taken at Łódź, 1935:

Source: American Chess Bulletin, September-October 1935, page 131.

An addition for the category ‘General overview of the endings’ has now been made in our feature article on The Very Best Chess Books.

A new feature article, Chess Mysteries, has just been posted. [New link.] It groups together a number of C.N. matters (only a small selection for now) which have yet to be resolved.

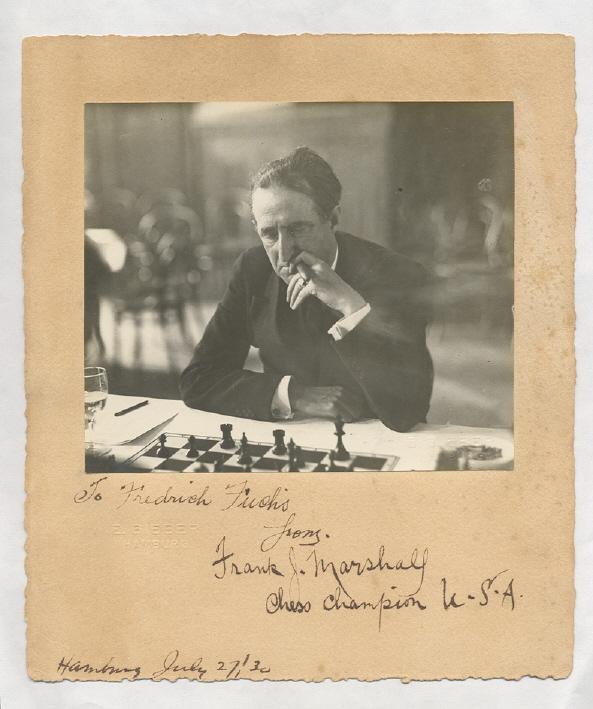

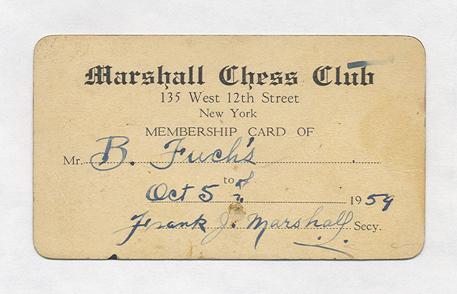

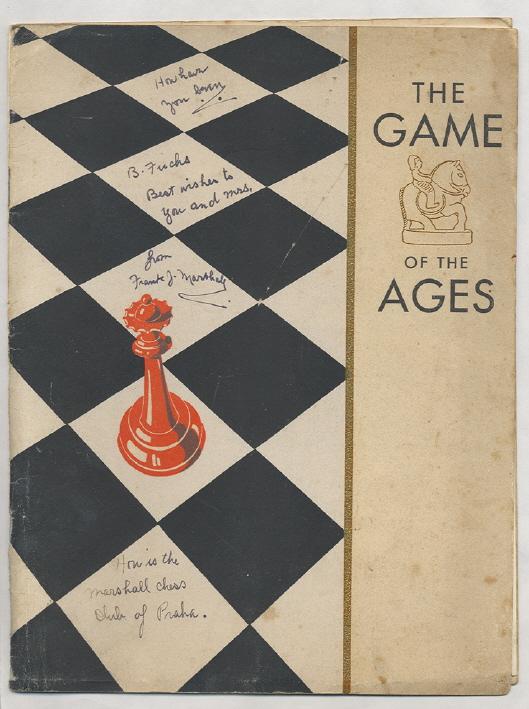

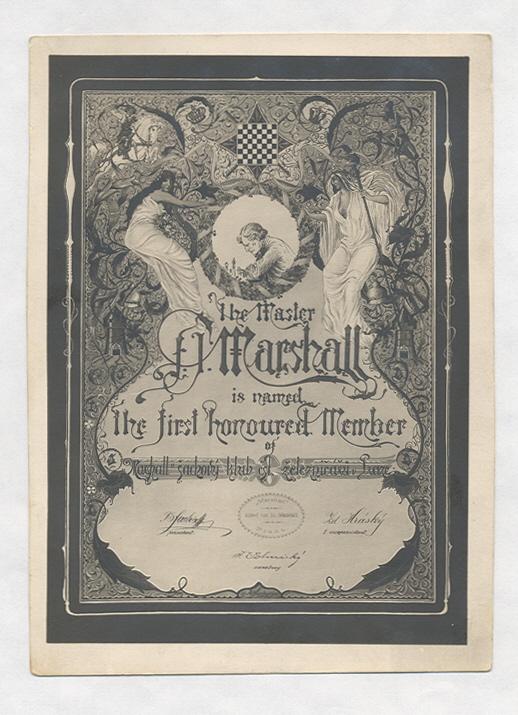

Karel Mokrý (Prostějov, Czech Republic) submits some pictures

relating to Frank J. Marshall and Bedřich Fuchs. The latter was

the President of the Marshall Chess Club in Prague, and

biographical information about him is being sought.

Frank J. Marshall, N.N., Bedřich Fuchs

Photograph of Marshall inscribed

to Fredrich [sic] Fuchs at the end

of the 1930 Hamburg Olympiad.

An inscription by Marshall on the 12-page publication of the Marshall Chess Club, The Game of the Ages

Copy of a certificate enrolling Marshall in the Marshall Chess Club in Prague.

Prague Olympiad, 1931. From left to right: F.J. Marshall, A.W. Dake, N.N., I.I. Kashdan, B. Fuchs, I.A. Horowitz, H. Steiner.

This group photograph was published in the Prague, 1931 book (without any names) and opposite page 416 of El Ajedrez Español, September 1935 (where Fuchs was merely identified as a suplente and the person between Dake and Kashdan was described as a delegado).

It may be recalled here that our correspondent Karel Mokrý runs an on-line chess shop which is notable for its attractive prices and impeccable service.

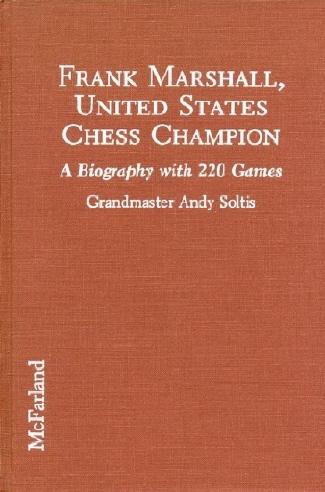

John Hilbert (Amherst, NY, USA) comments on the first chapter (pages 1-13) of Frank Marshall, United States Chess Champion by A. Soltis (Jefferson, 1994):

‘My knowledge of Frank Marshall’s chess career involves only his earliest playing days, between 1893 and 1900, and I therefore limit my remarks to the few pages by Soltis in which he covers that period. Corroboration of the various points can be found in my own book Young Marshall (Olomouc, 2002).

1. On page 3 Soltis quotes Marshall’s statement in “unpublished notes” that he “won Montreal Chess Club Championship at age 15”. Soltis accepts the truth of this, since on page 6 he writes, “Besides winning the Montreal club championship …” In fact, Marshall never won the Montreal Chess Club Championship. He played in the first Montreal Chess Club Championship (1893), finishing third behind J.P. Cooke and D.C. Robertson, and in a handicap tournament which was not for the club title. He finished sixth in the 1894-95 handicap event. There is no evidence that he played in any other Montreal Chess Club Championships.

2. “Pollock (1859-1896) spent the last four years of his life in Montreal …” (page 4).

Sources, including Pollock Memories, show that Pollock lived in Montreal for just under two and a half years.

3. “It was at the Manhattan C.C. that Marshall played his first serious match, with Vladimir Sournin …” (page 7).

Marshall’s first known serious match was for the New York State Junior Championship at Ontario Beach, New York in July 1896, which he just managed to win against Louis Karpinski. Marshall’s second and more significant match was against William Ewart Napier at the Brooklyn Chess Club from 8 October to 7 November 1896. Napier crushed Marshall +7 –1 =3. Soltis does not mention either of these matches. In the match table on page 367 the Sournin match is dated 1896 instead of 1897.

4. “Solomon Lipschütz” (page 8).

I am unaware of any conclusive evidence regarding Lipschütz’s first name. Gaige in Chess Personalia gives Sámuel, Simon and Solomon as versions found in multiple sources. The index of Soltis’ book (page 377) has the misspelling “Lischütz”.

5. “Marshall also encountered some illustrious foreigners, such as Emanuel Lasker, the German-born world champion who was then living in New York” (page 8).

Although dates are not given, the context for this comment concerns Marshall’s first years in New York, i.e. approximately 1895-1900. I know of no evidence that Lasker visited the United States between 1895 and 1900, let alone lived there during that period.

6. “Marshall’s principal young rivals were Hermann Helms, Napier and Albert W. Fox …” (page 8).

Helms was seven years older than Marshall. Albert Fox, about whom I have done considerable research, does not appear to have had a game published in the United States prior to 1900, and I am aware of no games between Marshall and Fox until 1904. In 1900 Fox was a teenager living in Europe, and his earliest published games played in the United States are from 1901.

7. “In 1899 he lost a Brooklyn Chess Club Championship match, 2-1, to Napier …” (page 8).

Marshall and Napier did contest a short play-off match following a Brooklyn Chess Club championship tournament. The final result was indeed 2-1. The year was 1898, not 1899. Marshall, not Napier, won.

8. “Marshall’s notes say he won the New York State Junior Championship in 1897 in a match” (page 8).

The match against Karpinski was, as I mentioned above, played in 1896, and not in 1897. Marshall was no better at remembering what events occurred in which years, in his own past, than he was at spelling.

9. “In his later writing Marshall also referred to a match with Fox but without giving a date. It is likely it was played about this time. Two games survive …” (page 8). Soltis gives Fox v Marshall, “circa 1897”, 0-1 in 16 moves (page 9).

It is unclear why Soltis should consider that the facts about the match between Marshall and Fox are uncertain. A photograph of the two players in their 1906 match at the Manhattan Chess Club appeared on page 24 of the February 1906 American Chess Bulletin. The 16-move game given by Soltis was on page 25 of the same issue, and was identified as the first match-game. Game two also appeared on that page, while the remaining four match-games (Marshall won +5 –0 =1) were published on page 95 of the May 1906 Bulletin. Thus, it is clear when the match was played and what the result was. All six games survive, having been published in the most common source for American chess during that period.

10. The Soltis book omits mention of a number of other significant events involving Marshall, including the Brooklyn Chess Club Championship of 1898 (although there is the faulty reference to Marshall losing 2-1 to Napier in 1899, when no club championship was held) and his drawn match against Jasnogrodsky in 1898. In 1900 Marshall won matches against Medinus, Delmar and Roething, but Soltis makes no mention of any of them.

I make no comment on the rest of Soltis’ book, i.e. after 1900. I would hope that it is more accurate and thorough, as Marshall had by then become a better known figure.’

Leonard M. Skinner (Cowbridge, Wales) sends the Alekhine item referred to in C.N. 4719 (pages 20-21 of the 21/1972 issue of Shakhmaty):

Our correspondent adds:

‘I also have an English translation of the vital parts. Briefly, “Alexander was born on 19 October 1892 and was baptised on 10 November of the same year. The parents were Alexander Ivanovich Alekhine and his lawful wife Anisiya Ivanova, both orthodox. The god-parents were Staff Captain Ivan Yefimovich Alekhine and the wife of high-born citizen Anna Sergeyevna Prokhorov”. The translation continues by giving details of the priest who performed the baptism and information certifying the authenticity of this extract from the Civil Register. Also in my possession are the marriage certificates of Alekhine with Nadezda Fabritsky and Grace Wishaar. I have too a copy of his naturalization certificate. All these documents give his birth-date as 19 October 1892.’

We shall be grateful if a reader can provide a detailed scan of the birth certificate from the Russian magazine.

Joost van Winsen (Silvolde, the Netherlands) submits the following game, which was annotated by Mason on pages 433-434 of the October 1890 BCM:

Siegbert Tarrasch – James Mason1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nf6 3 Nxe5 d6 4 Nf3 Nxe4 5 d4 d5 6 Bd3 Be7 7 O-O O-O 8 Re1 Nf6 9 Bf4 Bg4 10 Nbd2 Nh5 11 Be3 Nc6 12 h3 Bxf3 13 Qxf3 g6 14 c3 Qd7 15 Nf1 Nd8 16 Bh6 Ng7 17 Ne3 c6 18 Ng4 Nde6 19 Re2 Qd8 20 Rae1 Bg5 21 Bxg5 Nxg5 22 Qf6 Qxf6 23 Nxf6+ Kh8 24 Re7 N5e6 25 Rxb7 Rab8 26 Rxa7 Rxb2 27 Nd7 Rc8 28 Ne5 Rbb8 29 Nxf7+ Kg8 30 Nh6+ Kh8

31 Nf7+ Kg8 32 Nh6+ Kh8 33 Nf7+ Kg8 34 Ne5 Ra8 35 Rxa8 Rxa8 36 Nxc6 Rxa2 37 Ne7+ Kf8 38 Nxd5 Ra3 39 Bc4 h6 40 Nb6 Resigns. Mason: ‘The game was adjourned at this point, pro forma; but Black resigned without resuming, as his position was manifestly hopeless.’

Our correspondent comments:

‘When published in the International Chess Magazine (October 1890, pages 309-310) this game was stated to have lasted 37 moves, whereas its length was 38 moves in Tarrasch’s Dreihundert Schachpartien (Gouda, 1925), pages 284-288, and 39 moves in the Deutsche Schachzeitung, November 1890, pages 338-341. These last two publications had notes by Tarrasch.

The International Chess Magazine gave the following conclusion: 31 Nf7+ Kg8 32 Ne5 Ra8 33 Rxa8 Rxa8 34 Nxc6 Rxa2 35 Ne7+ Kf8 36 Nxd5 Ra3 37 Bc4 Resigns. Tarrasch’s book had 31 Nf7+ Kg8 32 Ne5 Ra8 33 Rxa8 Rxa8 34 Nxc6 Rxa2 35 Ne7+ Kf8 36 Nxd5 Ra3 37 Bc4 h6 38 Nb6 Resigns, whereas the Deutsche Schachzeitung put 31 Nf7+ Kg8 32 Ne5 Ra8 33 Rxa8 Rxa8 34 Nxc6 Rxa2 35 Ne7+ Kf8 36 Nxd5 Ra3 37 Bc4 h6 38 Nb6 Kf7 39 d5 Resigns.

The game, however, was adjourned (jokingly by Mason, according to page 271 of Tarrasch’s book). The time-limit in the Manchester tournament was 20 moves per hour.

To complicate matters further, however, the BCM stated that the game was “a friendly contest, played 28 August, at Manchester”. It should be noted that Tarrasch and Mason met in the tournament on 29 August.’

In San Sebastián 1911: El primer SuperTorneo de Ajedrez by Máximo López (Sta Eulalia de Morcin, 2006) our eye was caught on page 102 by a photograph of Capablanca (seated in centre) at the closing dinner in his honour. The book has been published by Editorial Chessy, and the photograph is reproduced below with permission.

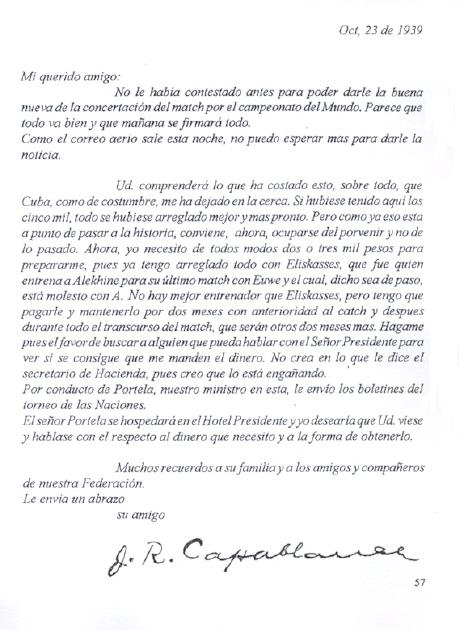

Willibald Müller (Munich, Germany) draws attention to the following letter on page 57 of Erich Eliskases, Caballero del Ajedrez by Guillermo G. Soppe and Raúl O. Grosso (Córdoba, 1997):

Page 20 describes the letter as ‘una inédita carta entregada por el presidente de la Federación cubana de Ajedrez’, and readers will certainly recognize its significance in several respects. Below is an English translation:

‘23 October 1939

My dear friend,

I did not reply to you earlier, so as to be able to give you the good news about the agreement on the match for the world championship. It appears that all is going well and that tomorrow everything will be signed.

As the airmail leaves tonight, I can wait no longer to give you the news.

You will understand what this has cost, and especially since Cuba, as usual, has left me in the lurch. If I had had the five thousand here, everything would have been settled better and faster. But that is about to pass into history, and now is the time to turn to the future and not to what has happened. Now, I need in any case two or three thousand pesos to prepare myself, as I have already arranged everything with Eliskases, who seconded Alekhine for his last match with Euwe and who, incidentally, is annoyed with A. There is no better second than Eliskases, but I have to pay him and retain him for two months before the match and then throughout the entire duration of the match, which will be another two months. Please therefore do me the kindness of seeking someone who can speak to the President to see whether it can be arranged for them to send me the money. Do not believe what you are told by the treasury secretary, as I believe that he is deceiving you.

Through Portela, our minister, I am sending you the bulletins of the Nations Tournament.

Señor Portela will be staying at the Hotel Presidente, and I should like you to see him and speak to him about the money I need and how to obtain it.

With best wishes to your family and to the friends and companions of our Federation.

Kind regards from your friend,

J.R. Capablanca.’

For ease of reference C.N. 4448 is reproduced below:

Psychologie de la bataille by A. Karpov and J.-F. Phelizon (Paris, 2004) is due to appear in an English edition in 2006, under the title Chess and the Art of Negotiation. It must be hoped that more care will be exercised than in the French original. Did Karpov really state (page 25) that Botvinnik’s fine health and form were shown by the fact that he was still world champion when 46 [sic] years old? It may be wondered too whether Karpov genuinely believes, as he asserts on page 141, that in 1927 Capablanca repeatedly declared that he would beat Alekhine and would remain world champion until he died (‘Capablanca répétait partout qu’il gagnerait et qu’il était né pour rester champion du monde jusqu’à sa mort’).

An editorial footnote on pages 65-66 even gives the false impression that Kasparov lost a world championship match to Karpov in 1993 (‘Kasparov ... ravit le titre de champion du monde à Karpov en 1985 mais le lui céda en 1993’). The same footnote also states, bizarrely, that Kasparov was still the reigning PCA champion in 2003 (‘En 2003, Kasparov était toujours champion en titre de la PCA’).

The book is a dialogue involving Karpov, Phelizon (a financial director) and Bachar Kouatly, the averred purpose being to deal with a piping-hot issue: what similarities exist between playing chess and negotiating?

At the time, we drew that C.N. item to the attention of the future publishers of the English-language edition, but all the above-mentioned defects (and many others) remain in Chess and the Art of Negotiation (Westport, 2006):

To give just one example, at least for now, of other defects, on page 57 of the English edition (from page 106 of the French original) Karpov states regarding Spassky:

‘Then he became world champion, wrote a book analyzing his various games, and started getting a little older.’

The book in question is named as ‘Boris Spassky, Fifty-One Annotated Games of the New World Champion, FDR Books, 1969’, but how could Karpov be unaware that Spassky wrote no such work and that it was merely a booklet by A. Soltis, published by the United States Chess Federation?

| First column | << previous | Archives [28] | next >> | Current column |

Copyright 2006 Edward Winter. All rights reserved.