Chess

Notes

Edward

Winter

When contacting

us

by e-mail, correspondents are asked to include

their name and full

postal address and, when providing

information, to quote exact book and magazine

sources. The word ‘chess’ needs to appear in the

subject-line or in the message itself.

6014. 1...f6 (C.N.s 451 & 1250)

An addition to the games mentioned in our earlier items

(see page 92 of Chess Explorations):

Johann Nepomuk Berger – Adolf Albin

Graz, January 1881

Irregular Opening

1 e4 f6 2 d4 e6 3 Bd3 g6 4 Nf3 Bg7 5 Be3 Ne7 6 Nc3 O-O

7 Qd2 d5 8 h4 dxe4 9 Bxe4 f5 10 Bd3 Nd7 11 O-O-O Nf6 12

Bc4 c6 13 Bg5 b5 14 Bb3 b4 15 Na4 a5 16 Bxf6 Rxf6 17 h5

Ra7 18 hxg6 Rxg6 19 g3 Qf8 20 Kb1 Bh6 21 Qe1 Bg7 22 Nc5

Nd5 23 Ne5 Bxe5 24 Qxe5 Qg7 25 Rde1 Qxe5 26 Rxe5 Kg7 27

Rhe1 Kf7 28 Kc1 Rc7 29 Kd2 Re7 30 c4 Nb6

31 d5 Rg4 32 Kd3 cxd5 33 cxd5 Kf6 34 d6 Ra7 35 Bxe6

Bxe6 36 Rxe6+ Kf7 37 d7 Nxd7 38 Re7+ Kg6 39 Nxd7 Kg5 40

f4+ Kh6 41 Rh1+ Kg6 42 Ne5+ Resigns.

Source: Probleme Studien und Partien by J.

Berger (Leipzig, 1914), page 175.

Further to a correspondent’s remarks in C.N. 5998

about the signature on an engraving of Staunton, we

note that the picture was published in the Chess

Monthly Portrait Gallery on page 193 of the

March 1890 issue and that the following month (page

225) an illustration of Lasker appeared, with the same

signature:

The only artist we recall seeing credited in the Chess

Monthly was ‘Mr E. Passingham, of Bradford’ on

page 234 of the April 1889 issue. However, his work

for the Portrait Gallery bore a different signature.

In C.N. 5905 a correspondent asked about Golombek’s

claim that Réti lost two consecutive tournament games

through being preoccupied by an idea for an endgame

study which occurred to him during play.

Now, Fabrizio Zavatarelli (Milan, Italy) draws

attention to a passage regarding the February 1928

tournament in Berlin in Jan Kalendovský’s monograph on

Réti (see page 211 of the Czech original and page 374

of the Italian edition). It is stated that, after

obtaining the better game against Brinckmann in round

ten, Réti played 44 Nh5 but was informed that he had

overstepped the time-limit. He then happily explained

that the position on another board had inspired him to

conceive a beautiful study. Still preoccupied with the

study, he also lost his games against Tartakower and

Steiner. His prize money was 500 Marks lower, but he

produced the study, for which he received five Marks.

Corroboration of this account is sought.

6017.

Faeroes

chess

We are grateful to Calle Erlandsson (Lund, Sweden) for

a copy of what seems to be our only chess book in

Faeroese, Føroysk telving í 20. øld by Suni

Merkistein (Tórshavn, 1997). A richly-illustrated

525-page hardback, it is available from H.N. Jacobsens Bókahandil.

A game from page 67:

Mikhail Tal – Olaf Durhuus

Simultaneous display, Reykjavik, 1 February 1964

Ruy López

1 e4 e5 2 Nf3 Nc6 3 Bb5 a6 4 Ba4 Nf6 5 O-O b5 6 Bb3 d6

7 c3 Be7 8 Re1 O-O 9 h3 Na5 10 Bc2 c5 11 d4 Qc7 12 Nbd2

Bd7 13 Nf1 cxd4 14 cxd4 Rac8 15 Ne3 Nc4 16 Nxc4 bxc4 17

Bd2 Rfe8 18 Bc3 Bf8 19 Qd2 Bc6 20 Rad1 exd4 21 Qxd4 Qb7

22 Nh4 Bd7 23 Re3 Rc5 24 Rg3 Rce5 25 f4 Nh5 26 Rf3

26...Rxe4 27 Bxe4 Rxe4 28 Qd2 Be7 29 Qd5 Qxd5 30 Rxd5

Nxf4 31 Rxf4 Rxf4 32 Nf3 Bc6 33 Ra5 Bb7 34 Nd4 d5 35 Nf3

f6 36 b3 cxb3 37 axb3 Kf7 38 Kf2 Bd8 39 Ra1 Bb6+ 40 Ke2

d4 41 Bd2 Rf5 42 b4 Bc6 43 Rc1 Bb5+ 44 Ke1 Ke7 45 Rc8

Rd5 46 Rg8 Kf7 47 Rb8 Bd8 48 Rb7+ Be7 49 Kd1 g5 50 Ne1

Ke6 51 Nf3 h5 52 Rb8 h4 53 Ke1 Bd6 54 Rb6 Kf5 55 Kf2 d3

56 Bc3 Be5 57 Nxe5 fxe5 58 Bd2 Rd4 59 Rb8 Rd6 60 Rf8+

Rf6 61 Rxf6+ Kxf6 62 g3 hxg3+ 63 Kxg3 Kf5 64 h4 gxh4+ 65

Kxh4 Ke4 66 Kg3 Kd4 67 Kf2 e4 Drawn.

Michael Clapham (Ipswich, England)

reports that on 19 February 2009 Swann

Galleries of New York sold this item by auction

for $2,880:

The catalogue described it as follows:

‘Portrait of early American chess master Paul Morphy

and a companion, with a chess game in progress between

them. Sixth-plate daguerreotype with delicate gilt

highlights; in a leather case. 1850s.’

6019. Who? (C.N. 6006)

This photograph of Max Romih (Massimiliano Romi)

accompanied an article by him, ‘A Strange Opponent’, on

pages 302-304 of CHESS, 17 June 1964.

Lawrence Totaro (Las Vegas, NV, USA) asks whether

evidence exists to back up this passage on page 46 of

Talent is Overrated by Geoff Colvin (New York,

2008):

‘The Czech master Richard Réti once played 29

blindfolded games simultaneously. (Afterward he left

his briefcase at the exhibition site and commented

on what a poor memory he had.)’

We recall that the following appeared, without any

source, on page 287 of Frank Marshall, United

States Chess Champion by A. Soltis (Jefferson,

1994):

‘In São Paulo the same year [1925] he broke the

blindfold record by playing 29 boards five days

after Alekhine had set his own record with 28 in

Paris. As the Czech master left the playing hall he

forgot his familiar green briefcase. When it was

returned to him Réti said, “Oh, thank you. I have

such a bad memory.”’

The earliest reference to Réti’s briefcase that we

can quote comes in a footnote on page 170 of Die

Hypermoderne Schachpartie by S. Tartakower

(Vienna, 1924):

On page 4 of Réti’s Best Games of Chess

(London, 1954) Harry Golombek made use of the passage:

‘To quote Tartakower again: “He forgot everything,

stick, hat, umbrella; above all, however, he would

always leave behind him his traditional yellow

leather briefcase, so that it was said of him:

wherever Réti’s briefcase is, there he himself is no

longer to be found. It is therefore evidence of

Réti’s pre-existence.”’

A different version was given by J. du Mont on page v

of Réti’s posthumous book Masters of the Chess

Board (London, 1933):

‘I can see him now, with his perennial smile on his

good-humoured features, bustling along with his

leather briefcase under his arm. It used to be a

saying amongst his friends that where Réti’s

briefcase was, there was Réti.’

Frederick S. Rhine (Park Ridge, IL, USA) cites Irving

Chernev on page 262 of 1000 Best Short Games of

Chess (New York, 1955):

‘Alvin Cass used to say, “My grandmother, when she

was a little girl, told me never to capture the

queen knight pawn with my queen”.’

6022. Fischer’s best game

Some observations by Wolfgang Heidenfeld on page 9 of

the January 1966 BCM (in D.J. Morgan’s Quotes

and Queries column):

‘In connection with the various “best game”

lists and their coupling with specific masters, it has

occurred to me that there is a slight ambiguity in the

meaning of the term “best game”. Take Fischer as an

example. The game which Fischer played best may be the

magnificent brilliancy against Donald Byrne, which he

won at the age of 13; or it may be his win against

Gligorić at the Candidates’ tournament, 1959; or again

it may be the much-advertised “game of the century” [sic]

against Robert Byrne. Yet I would call none of these

“Fischer’s best game”, because the opposition did not

play well enough. Fischer’s best game – that is the

best game in which Fischer was involved – was

undoubtedly his first-round draw against Gligorić at the

Bled tournament, 1961.’

The draw is game 30 in Fischer’s My 60 Memorable

Games. Heidenfeld annotated it on pages 145-146 of

his posthumous book Draw! (London, 1982).

How exactly did the famous 1918 encounter between

Capablanca and Marshall end? On page 90 of The

Immortal Games of Capablanca (New York, 1942)

Fred Reinfeld stated that after 35...Re3 ‘Capablanca

announced mate in five [sic]’, beginning with

36 Bxf7+.

On page 187 of My Chess Career

(London, 1920) Capablanca wrote after 35...Re3, ‘BxPch

and mate in five moves’. The Cuban also annotated the

game on page 12 of the New York, 1918 tournament book.

As mentioned in our feature article The Marshall Gambit,

the note appended to 36 Bxf7+ read, ‘White forces

checkmate in six moves’. No mate announcement was

suggested.

From the report on page 14 of the New York Times,

24 October 1918:

‘At the time of the evening adjournment Capablanca

had begun to get a real hold on the position. After

resumption of play in the evening session, Marshall

did not last much longer and was finally pushed to the

wall with a forced checkmate in five moves.’

At which move was the game adjourned? As regards the

playing arrangements, page 7 of the tournament book

stated:

‘There were two sessions daily, from 2.30 p.m. to

6.30 p.m. and from 8.00 p.m. to 11 p.m. The time-limit

was 30 moves in the first two hours and 15 moves an

hour thereafter.’

Above is an inscription by Capablanca in one of our

copies of My Chess Career. Ernest Graham-Little,

a Member of Parliament, appears in the photograph given

in C.N. 5602.

6024. Symmetry

As noted under ‘Symmetry’ in our Factfinder, some C.N.

items have dealt with symmetrical openings/games, and

Pascal Losekoot (Soest, the Netherlands) asks for more

information about a miniature in C.N. 1507: 1 e4 e5 2

Nf3 Nf6 3 Nc3 Nc6 4 Bb5 Bb4 5 O-O O-O 6 d3 d6 7 Bxc6

Bxc3 8 Bxb7 Bxb2 9 Bxa8 Bxa1 10 Bg5 Bg4 11 Qxa1 Qxa8 12

Bxf6 Bxf3 13 Bxe5 Bxe4 14 Bxg7 Bxg2

15 Bxf8 Bxf1 16 Qg7 mate.

The game was given on page 43 of Program Šachového

Turnaje Memoriál Ing. V. Olexy (Brno, 1987). Karel

Traxler defeated J. Šamánek on 20 August 1900 in a

tournament at Osyky, the source being specified as Zlatá

Praha of 14 September 1900. The booklet contained

about 80 of Traxler’s games, presented by Jan

Kalendovský.

Below is the crosstable, from page 141 of the 9/1900

issue of Šachové Listy:

Sometimes (see, for instance, page 139 of Gaige’s first

volume of crosstables) the venue is given as ‘Osyky u

Lomnice’, i.e. ‘Osyky near Lomnice’. Karel Mokrý

(Prostějov, Czech Republic) informs us:

‘Osyky, which means “the aspens”, is the

old name for the village. Later, with the new language

rules, it became Osiky. The tournament in question was

one of a number of events which Ladislav

Vetešnik organized or co-organized in the village,

where he lived.’

The accounts cited in C.N. 6020 disagreed as to

whether Réti’s briefcase was green or yellow, and now

Maurice Carter (Fairborn, OH, USA) quotes from page 57

of With the Chess Masters by George

Koltanowski (San Francisco, 1972):

‘He always carried an old black briefcase filled

with reams and reams of sheets on which he had

scrawled his comments, and dozens of addressed

envelopes.’

On the following page Koltanowski gave a game he

played against Réti, dating it 1929 instead of 1927.

6027. Lasker v Steinitz (C.N. 5020)

Can any photographs be found of Lasker and Steinitz in

Moscow during their 1896-97 world championship match?

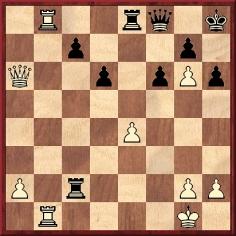

Concerning this position from Capablanca v Thomas,

Hastings, 1919 our earlier items mentioned how

Capablanca played 29 Qa8, missing the win of a rook

with 29 Rxe8 Qxe8 30 Qa4.

From Gerd Entrup (Herne, Germany):

‘A second winning move is 29 Qb5 (and if 29...c6

30 Rxe8 Qxe8 31 Qb8, with mate to follow). The

move was given on page 262 of Kasparov’s first

“Predecessors” volume, but I believe that the

first person to find it was Klaus-Jürgen Schulz.

In his column “Der Leser ist am Zug” on page 17 of

the 10/1986 Europa-Rochade he gave the

position before White’s 29th move, and on page 28

of the 12/1986 issue he indicated two winning

moves: 29 Rxe8 and 29 Qb5.

The diagrammed position was also included in a

column by N.H. Yazgac devoted to computer-testing

of positions on page 16 of the 11/1986 Europa-Rochade.

Only 29 Rxe8 Qxe8 30 Qa4 was given as the winning

line, but on page 22 of the 8/1987 issue the

second win, 29 Qb5, was pointed out by a reader,

Klaus Kiefert of Krefeld. It had been found by his

Psion Chess computer program, and a number of

variations were provided.’

We add that on page 49 of the February 1982 Chess

Life a Texas reader, John Wayland, suggested 29

Qa7. Pal Benko replied:

‘Don’t look for a more clear-cut win than the one

given: 29 Rxe8 Qxe8 30 Qa4! Your 29 Qa7 runs into

trouble after 29...Rc1+! 30 Rxc1 (or 30 Kf2 Rxb1)

30...Rxb8.’ [The notation and move numbering have

been adapted by us.]

From Mark Thornton (Cambridge, England):

‘In rook-odds games could the odds-giver castle

with the “phantom rook”? For example, if White

gave the odds of his queen’s rook, could he play

Ke1-c1? And, if so, were the castling rules the

same as if the rook were present?’

No consensus was ever reached, as is shown by the

selection of British quotes below. Firstly, Howard

Staunton on page 35 of Chess Praxis (London,

1860):

‘When a player gives the odds of his king’s or

queen’s rook, he must not castle (or, more properly

speaking, leap his king) on the side from whence he

takes off the rook, unless before commencing the

game or match he stipulates to have the privilege of

so doing.’

On page 35 of Chess (London, 1889) R.F. Green

wrote similarly:

‘A player giving the odds of a rook may not go

through the form of castling on the side from which

the rook has been removed.’

However, in a review of the book on pages 88-89 of

the March 1890 BCM Edward Freeborough

disagreed. After stating, with respect to level games,

that castling should be described as a move of the

king and that the king should therefore be moved

first, Freeborough observed:

‘It follows logically that the fact of giving the

odds of a rook ought not to deprive the king of his

privilege of taking two steps to the right or left

as his first move.’

Page 36 of The British Chess Code (London,

1903) stated:

‘In the absence of agreement to a different effect,

a player may castle (by moving his king as in

ordinary castling) on a side from which, before the

commencement of the game, the player’s rook has been

removed, provided that this rook’s square is

unoccupied and has been unoccupied throughout the

game, and that the same conditions as to squares and

as to the king are fulfilled which are required for

ordinary castling on this side.’

The above text was quoted on page 275 of the June

1916 Chess Amateur when a revised edition of

the Code was envisaged. Comments were invited, and on

page 305 of the July 1916 issue ‘Simplex’ wrote:

‘This I think sheer nonsense. If a player gave me a

rook and wanted to castle on this rook’s side, I

should say, “No, you don’t, you can’t castle without

a castle”. Let’s have no pretence. If a player gives

a rook, let him give it totally not half. Receivers

of odds are not strong players, and to see the

nominal giver of odds move his king a couple of

squares would be disconcerting. No; if a player

gives odds let him give them without pretence.’

A contrary view was expressed by W.S. Branch on pages

333-334 of the August 1916 Chess Amateur:

‘Re Chess Laws, page 305 (July), and as to

“castling without rook”, I would say, first, that

you can’t “castle the king” – the full and proper

term, of which “castles” is an abridgment – without

a castle. The phrase should be “moving the king as

in castling”.

I believe that the right of the odds-giver to move

his king, once in a game, as in castling, has always

been upheld since “castling” was invented (sixteenth

century). It existed, as part of the “king’s leap”,

long before “castling” was invented, and long before

the rook was ever called a “castle”. The giving of

the rook as odds should not deprive the king of any

of his rights.’

Branch then gave further historical details regarding

the king’s leap. By 1916, however, the practice of

giving odds was disappearing, without any formal

resolution of the ‘phantom rook’ question.

6030. Blackburne v Tuck

Page 202 of Mr Blackburne’s Games at Chess by

P. Anderson Graham (London, 1899) gave, with sketchy

information, an eight-move extract from a blindfold game

won by Blackburne in London against a player named Tuck.

Below is the full score, from page 326 of the Chess

Player’s Chronicle, 16 October 1895:

Joseph Henry Blackburne (blindfold) – F.W. Tuck

London, 5 October 1895

Vienna Gambit

1 e4 e5 2 Nc3 Nf6 3 f4 d6 4 Nf3 Nc6 5 Bb5 Be7 6 fxe5

dxe5 7 Nxe5 Bd7 8 Nxd7 Qxd7 9 d4 a6 10 Bxc6 bxc6 11 O-O

O-O 12 e5 Nd5 13 Ne4 Qe6 14 Qh5 f6 15 Bd2 f5 16 Ng3 g6

17 Qh3 c5 18 c4 Nb4

19 d5 Qxe5 20 Bc3 Qe3+ 21 Kh1 Qg5 22 Rae1 Nxa2 23 Be5

Bd6 24 Ne4 Qe7 25 Bxd6 cxd6 26 Nxc5 Qg5 27 Ne6 Qf6 28

Qa3 Rab8 29 Nxf8 Rxb2 30 Nd7 Resigns.

The game was played in an eight-game blindfold display

at the City of London Chess Club. The date is gleaned

from the report on page 307 of the 9 October 1895 issue

of the Chronicle. Blackburne scored +4 –0 =4,

‘completing the whole of the games in very quick time’.

Hugh Myers’ book A Chess Explorer was

published in 2002, and the following year he sent us a

copy of a handwritten 12-page supplement which

included a letter to him dated 4 March 1954 from Max

Euwe. The former world champion commented, ‘your games

are excellent and I hope to publish at least one of

them in Ch. Arch.’. Myers wrote in 2003 that

he was not sure which of his games he had submitted to

Euwe. Did any of them appear in Chess Archives?

6032. Frank Skoff (1916-2009)

With much sadness we have learned of the death earlier

this month of Frank Skoff, who was one of Chess Notes’

most valued contributors in the 1980s. He developed a

particular interest in the ‘Staunton-Morphy

controversy’, and some extracts from his writings can be

read in the Edge, Morphy and

Staunton feature article. In all, he penned the

equivalent of a small monograph on the subject.

A fine chess historian, Frank Skoff abhorred

speculation. He combined knowledge (both deep and broad)

with outstanding research skills, an ear for the English

language and an eye for cant. His contributions to Chess

Notes began 27 years ago, and our personal debt to him

is enormous.

6033. 1930 cable match

The photograph below has been received from Lawrence

Totaro (Las Vegas, NV, USA):

From page 165 of the May 1930 BCM:

Our feature article Mysteries at Sabadell, 1945

has been unable to offer a logical explanation for the

Terrazas matter, which may be summarized as follows:

- The photographic and other local evidence indicates

that at Sabadell, 1945 the forename of the player

named Terrazas was Teodoro and that he was an adult.

Terrazas at Sabadell,

1945

- The player at Sabadell, 1945 was the 11-year-old

Filiberto Terrazas according to Pablo Morán’s book on

Alekhine, as well as testimony from Filiberto Terrazas

himself.

Above is a photograph of Filiberto Terrazas which we

have just added to the feature article, from page 143 of

With the Chess Masters by G. Koltanowski (San

Francisco, 1972). (Unsurprisingly, Koltanowski misspells

his friend’s name.) The apparent resemblance between

Filiberto and Teodoro Terrazas leaves us more puzzled

than ever.

6035. Castling with a phantom rook

(C.N. 6029)

Trevor Moore (Baughurst, England) quotes from page 47

of Chess Curiosities by Tim Krabbé (London,

1985):

‘When a player, who had conceded QR-odds, moved his

king from e1 to c1, his opponent protested, asking

what that move meant. The player said that in giving

rook’s odds, one did not lose the right to castle. By

playing Ke1-c1 he had castled with the phantom of his

rook.

In the next game, Black made mysterious bishop’s

moves: from g7 to a1, and back to g7. When White again

played Ke1-c1, Black argued that phantom castling was

out, since he had captured the rook’s phantom at a1.’

Hanspeter Suwe (Winsen in Holstein, Germany) notes that

the story appeared in an article ‘Some Chess Anecdotes’

by A.W. Mongredien on pages 352-353 of the August 1923 Chess

Amateur:

‘In a foreign café two excitable gentlemen were

playing chess, White giving the odds of queen’s rook.

After some opening moves White played his king from K1

to QB1.

“One square at a time”, exclaimed Black.

“Not at all!”, retorted White. “I castle queen’s

side.”

“Castle!”, cried Black. “Why, you haven’t a rook!”

“I give the odds of a rook”, loftily replied the

other, “but that doesn’t prevent my castling with the

ghost of my rook.”

Personally I thought the move, if not actually bad,

at least innocuous; but White knew its psychological

value. His adversary was so nettled at what he termed

a low-down trick that, making one mistake after

another, he speedily lost. A heated discussion ensued.

Just as a free fight seemed inevitable they started a

second game, at the same odds. Irregular scarcely

describes the opening. After some startling and costly

manoeuvres, Black succeeded in playing his bishop to

White’s vacant QR square. When, by sheer good luck, he

had got it safely away again, he leant back in his

chair and surveyed the onlookers with undisguised

satisfaction.

I ventured to remark that I did not entirely follow

his play.

“Ah!”, he replied in an audible whisper, “Let him try

to castle now. He hasn’t even the ghost of a

rook!”’

Source: BCM, February 1936, page 96 (in T.R.

Dawson’s ‘Problem World’ section).

Our feature article on Philip H. Williams has

an earlier specimen of the same technique, from opposite

page 17 of his book Chess Chatter & Chaff (Stroud,

1909):

6037. Women players

Michael Ehn (Vienna) sends us from his archives a

photograph dated 1872:

From Luc Winants (Boirs, Belgium) we have received a

set of photographs published on pages 116-117 of Le

miroir du monde, 24 January 1931 (with some

aberrations in the captions). Most of the photographs

were taken at the Hastings, 1930-31 tournament.

6039. Gunsberg odds game

Heppell – Isidor Gunsberg

London, 1883

(Remove Black’s f-pawn.)

1 e4 Nc6 2 d4 d5 3 e5 Bf5 4 Nf3 e6 5 a3 Nge7 6 Nh4 Be4

7 Bg5 h6 8 Be3 g5 9 Nf3 Nf5 10 c3 g4 11 Nfd2 Nxe3 12

fxe3 Bf5 13 g3 Qg5 14 Qe2 h5 15 Bg2 O-O-O 16 Nf1 Qg6 17

e4 dxe4 18 Nbd2

18...e3 19 Nxe3 Bd3 20 Qf2 Bh6 21 Bxc6 bxc6 22 Ng2 Rhf8

23 Nf4 Rxf4 24 gxf4 Rf8 25 Rf1 Rxf4 26 Qxf4 Bxf4 27 Rxf4

Qh6 28 Rf1 Qe3+ 29 Kd1 Be2+ 30 Kc2 Qd3+ 31 White

resigns.

Source: Knowledge, 16 November 1883, pages

311-312.

Gunsberg wrote the chess column in Knowledge

under the pseudonym ‘Mephisto’. He reported that the

game had been played in a handicap tournament at

Purssell’s Chess Room and lasted two hours 40 minutes.

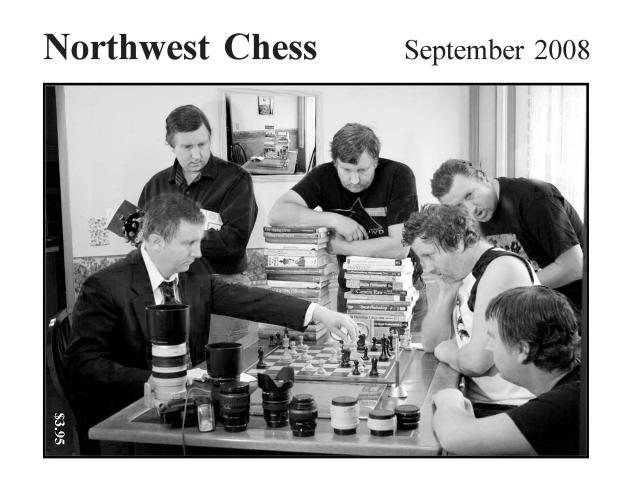

Russell Miller (Camas, WA, USA) draws

attention to the front cover of the September 2008

issue of Northwest

Chess:

On page 9 Philip Peterson explained how he put together

the multiple photographs of himself. We are grateful to

Mr Peterson and to the Editor of Northwest Chess,

Ralph Dubisch, for permission to reproduce the picture

here. A colour

version is available online.

6041. Nicolas Sphicas (C.N. 4185)

The above pictures have been sent to us by Nicolas Sphicas

(Thessaloníki, Greece), who informs us that they depict

two Capablanca games (respectively, against Rubinstein

at San Sebastián, 1911 and against Flohr at Moscow,

1935). C.N. 4185 mentioned that much of our

correspondent’s other chess artwork can be viewed online.

We are also grateful for the 56-page catalogue of an

exhibition of his work at the Municipal Art Gallery of

Thessaloníki in 2008:

Further acknowledgement in connection with the present

item: Michael Syngros (Amarousion, Greece).

There cannot be many chess books more liberal with

typos than Kasparov’s Best Games by K.R.

Seshadri (Madras, 1984). The first word of the Preface

gives Kasparov’s forename as Carri, and the first two

paragraphs have occurrences of Kasperov. Overleaf, the

forename becomes Gerry. The annotations, taken from

the writings of Kasparov and others, are continually

mutilated. Here, from page 46, is part of a note to

White’s 15th move in Korchnoi v Kasparov, Lucerne

(‘Lucerene’), 1982:

‘Hewever, the problamatic ideal manouvre 21 Nc4!

suggested by Yugoslav Grandmaster Kovachevic put an

end to the theoratical arguments n favour of White.’

6043. Chess and alcohol

An addition to C.N. 5940 and, in particular, to the

Blackburne-related material cited on pages 238-239 of Kings,

Commoners and Knaves:

Source: pages 86-87 of the Chess Player’s Chronicle,

3 May 1899.

Kings, Commoners and Knaves quoted a slightly

different version of Blackburne’s interview with Licensing

World (an anti-temperance journal) and gave the

score of an 1881 game he won against a player named

Brewer. It is not clear whether this is the H. Brewer

mentioned on page 104 of the Chess Monthly,

December 1880. In this connection we also recall the

game Blackburne v Lush (Melbourne, 8 January 1885) given

on page 238 of the April 1885 issue of the Chess

Monthly and on page 286 of P. Anderson Graham’s

monograph on Blackburne.

From our archives:

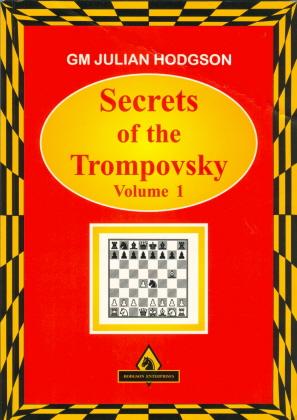

6045.

Trompowsky

In a recent article for ChessBase

we discussed faulty book covers and reproduced the above

specimen, our caption being ‘Trompovsky instead of

Trompowsky’.

Now Anthony Wood (London) mentions that the spelling

‘Trompovsky’ was deliberate on the part of Julian

Hodgson, who wrote on page 8:

‘... the opening was actually named after Octavio

Siqueiro Trompowsky, one time Brazilian Champion, who

popularised it in the 1930s and 1940s. For

simplicity’s sake I have renamed the opening itself

phonetically Trompovsky ...’

The article below by the ‘Badmaster’, G.H. Diggle, is

reproduced from page 25 of our publication Chess

Characters (Geneva, 1984). It originally

appeared in the August 1977 issue of Newsflash.

‘The bilious and impecunious Badmaster, glaring

over last month’s Newsflash with a

malevolent eye, was delighted to find that the price

of Modern Chess Literature, and Books on the

Openings in particular, seems to be coming under

fire. For if the BM ever agreed to be interviewed on

Television and was finally asked, “Looking back,

Badmaster, over half a century of lost games, is

there any particular factor which you feel has had

the greatest influence on your disastrous career?”,

he would reply in ringing tones: “Buying Books on

the Openings”.

A particularly shameful instance of the BM being

let down by these treacherous tomes occurred during

the London Championship Tournament 1945. An awful

morning had dawned when the official “Order of the

Day” ran (inter alia) – “Round 6. Sir George

Thomas (White) Badmaster (Black)”. Surmising

(correctly) that his august opponent would open P-K4

and go for a quick win, the BM sat up most of the

previous night with Modern Chess Openings

(Griffith and White), selected the Petroff Defence,

distended his brainbox with all 12 columns given,

and arrived at the arena next day with the full

cargo still on board. The result was that for the

first eight moves the BM played with a precision

which confounded the critics, but then Sir George

(who had previously played like the orthodox

gentleman that he was) suddenly revealed himself (in

Marxist language) a deviationist of the basest

stamp. In short, his ninth move was nowhere to be

found. Deserted by MCO, the BM found himself

in the same plight as David Balfour in Kidnapped

when he ascended the tower in total darkness, only

to find suddenly that “the stair had been carried no

further” and that he was left to proceed on his own

into the void. This he did, and perished about the

20th move. But the most infamous part of the story

has yet to come. Of the two unworthy authors

responsible for the BM’s downfall White (like Jacob

Marley) had long been dead; but R.C. Griffith (a

most sprightly “Scrooge”) was not only very much

alive but actually a spectator at this very

tournament. Just as the BM resigned, R.C.G., who was

standing by, bestowed upon him a whimsical yet

kindly smile, which plainly said: “Never mind, young

man, you’ll know that variation another time”. He

then went away beaming all over his face. But for

his benevolent appearance and charming manner, the

BM could have “felled him like a rotten tree”.’

6047. Bogoljubow on Capablanca

Regarding Bogoljubow v Capablanca, Bad Kissingen, 1928

Irving Chernev wrote on page 238 of Combinations The

Heart of Chess (New York, 1960):

‘For Capablanca this victory must have been

especially gratifying. It proved once again that

Bogoljubow had been deluding himself when he made the

statement, “There is nothing more to fear from the

Capablanca technique”.’

Where did Bogoljubow make such a statement?

Efim Bogoljubow

Stéphane Pilawski (Liège, Belgium) notes Capablanca’s

use of ‘Joseph’ as his first forename on the marriage

licence application (C.N. 6044) and asks whether other

such occurrences can be found. We recall none.

Page 250 of David DeLucia’s Chess Library A Few

Old Friends (Darien, 2007) reproduced

Capablanca’s identity card, issued by the Belgian

Foreign Affairs Ministry and dated 17 July 1935. His

name appeared as ‘José Raul Capablanca’.

The ‘standard’ spelling of his second

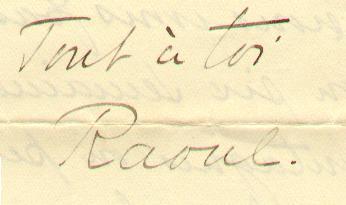

forename is ‘Raúl’, but it may be recalled from The Genius and the

Princess that in a love letter (dated 30 April

1935) in our collection Capablanca signed himself

‘Raoul’:

The caption to this photograph from C.N. 6038 prompts

us to reproduce two earlier items. C.N. 203 quoted the

following from page 176 of the Australasian Chess

Review, 20 July 1932:

‘In a recent number of the London Sphere

there is a fine photo of two of the players in the

London congress seated at the board with clocks and

score-sheets alongside them. Underneath is the

following priceless description:

“Concentration. W. Winter (England) and Dr S.

Tartakower (Poland) ponder their next move during

the international tournament. The clocks show how

much time each player has taken (for this is

limited by rule). The pencil and paper are used to

work out combinations before a move is made.”’

C.N. 1004 referred to a paragraph on page 247 of CHESS,

August 1940:

‘The London Evening Standard published a

picture of Norman Sortier, youngest competitor, in

play in the British Boys’ Championship. He was just

writing down a move on his pad. The bright caption

was, “He used a notebook to help him work out his

moves”.’

6050. Pachman v Hromádka

Efstratios Grivas (Athens) asks whether the full score

is available of a game between L. Pachman and K.

Hromádka which reached this position:

White to move

See, for example, pages 196-197 of Pachman’s Chess

endings for the practical player (London, 1983),

which stated that the position occurred ‘just before the

adjournment of a game that was important to me. It was

played in the Championships of Prague in 1944’. Instead

of the manoeuvre 1 Ne1, 2 Nf3 and 3 Nh4+, Pachman chose

1 Nxc5, to which he appended two question marks. The

game was then agreed drawn, at his proposal.

We have not found the complete game in any contemporary

source, including the 1944 volume of the Prague-based

magazine Šach.

From Roger Mylward (Lower Heswall, England):

‘Paul Adrien Maurice Dirac (1902-84) was a

theoretical physicist who made major contributions

to the development of quantum mechanics in the

first part of the twentieth century. His father

was French and his mother English; he was born and

brought up in Bristol but for most of his academic

life he was based in Cambridge. His last years

were spent in Florida. He was a member of staff at

Florida State University, where many of his papers

are held, in the Dirac Science Library.

A new biography of Dirac has been published, The

Strangest Man – The Hidden Life of Paul Dirac,

Quantum Genius by Graham Farmelo (London, 2009).

It refers on a number of occasions to Dirac’s

interest in chess.

In the 1920s “He worked all day long and

took time off only for his Sunday walk and to play

chess, a game he played well enough to beat most

students at the college chess club, sometimes

several at the same time” (pages 97-98). The

College was St. John’s, Cambridge.

In 1926, his father, Charles Dirac (with whom

Paul had a very difficult relationship), offered

to buy his son “a set of chessmen” as a

Christmas present (page 115).

Regarding the house of Peter Kapitza, a Russian

physicist, and his wife Anna (known as Rat), “Dirac

was at ease there, talking with Kapitza and Rat over

a Russian-style meal, playing chess and larking

about with their two rumbustious sons” (page

208).

On 5 January 1955 Dirac gave a public lecture, on

subatomic particles, to thousands of

spectators at the cricket ground in Baroda, near

Calcutta in India. Part of his lecture linked

these particles to chess:

“When you ask what are electrons and protons I

ought to answer that this question is not a

profitable one to ask and does not really have a

meaning. The important thing about electrons and

protons is not what they are but how they behave –

how they move. I can describe the situation by

comparing it to the game of chess. In chess, we

have various chessmen, kings, knights, pawns and

so on. If you ask what a chessman is, the answer

would be [that] it is a piece of wood, or a piece

of ivory, or perhaps just a sign written on paper,

[or anything whatever]. It does not matter. Each

chessman has a characteristic way of moving and

this is all that matters about it. The whole game

of chess follows from this way of moving the

various chessmen ...” (pages 353-354).

The text of this lecture is included in the

Dirac papers at Florida State University.

From his wife’s first marriage Dirac had a

stepson, Gabriel Dirac, who was a mathematician.

“Dirac was close to Gabriel and went out of his

way to promote his career, often exchanging

letters with him to chew over chess problems they

had read in newspapers (G.H. Hardy had described

such problems as the ‘hymn tunes of pure

mathematics’).” (page 366).

During the Second World War, Dirac was invited

to join the Government’s research station in

Bletchley Park (page 320). He declined and

therefore missed a chance to play chess against

some of the best British players of the time.’

Robert Sherwood (E. Dummerston, VT, USA) draws

attention to this passage by Bogoljubow on page ix of

his book on the Moscow, 1925 tournament:

Our correspondent’s translation:

‘The sporting result of the tournament is as

follows.

It has been shown that advanced age does not

preclude the highest achievements. Dr Lasker, who

for the third time finished ahead of Capablanca,

must without question be considered the most

successful master of all time. His play yet again is

enterprising and almost youthfully fresh.

Further, it is apparent that Capablanca finds it

very difficult to separate himself from his dry

style of play. His technique, on the other hand, has

been at least equalled by Bogoljubow and is not

especially feared by the other masters.’

Chess Notes Archives

Copyright: Edward Winter. All

rights reserved.

|